User login

Intrauterine vacuum device treatment of postpartum hemorrhage

Postpartum hemorrhage (PPH) is a common complication of birth. In 2019, 4.3% of births in the United States were complicated by at least one episode of PPH.1 Major causes of PPH include uterine atony, retained products of conception, reproductive tract trauma, and coagulopathy.2 Active management of the third stage of labor with the routine administration of postpartum uterotonics reduces the risk of PPH.3,4

PPH treatment requires a systematic approach using appropriate uterotonic medications, tranexamic acid, and procedures performed in a timely sequence to resolve the hemorrhage. Following vaginal birth, procedures that do not require a laparotomy to treat PPH include uterine massage, uterine evacuation to remove retained placental tissue, repair of lacerations, uterine balloon tamponade (UBT), uterine packing, a vacuum-induced hemorrhage control device (VHCD; JADA, Organon), and uterine artery embolization. Following cesarean birth, with an open laparotomy incision, interventions to treat PPH due to atony include vascular ligation, uterine compression sutures, UBT, VHCD, hysterectomy, and pelvic packing.2

Over the past 2 decades, UBT has been widely used for the treatment of PPH with a success rate in observational studies of approximately 86%.5 The uterine balloon creates pressure against the wall of the uterus permitting accumulation of platelets at bleeding sites, enhancing the activity of the clotting system. The uterine balloon provides direct pressure on the bleeding site(s). It is well known in trauma care that the first step to treat a bleeding wound is to apply direct pressure to the bleeding site. During the third stage of labor, a natural process is tetanic uterine contraction, which constricts myometrial vessels and the placenta bed. Placing a balloon in the uterus and inflating the balloon to 200 mL to 500 mL may delay the involution of the uterus that should occur following birth. An observation of great interest is the insight that inducing a vacuum in the uterine cavity may enhance tetanic uterine contraction and constriction of the myometrial vessels. Vacuum-induced hemorrhage control is discussed in detail in this editorial.

Vacuum-induced hemorrhage control device

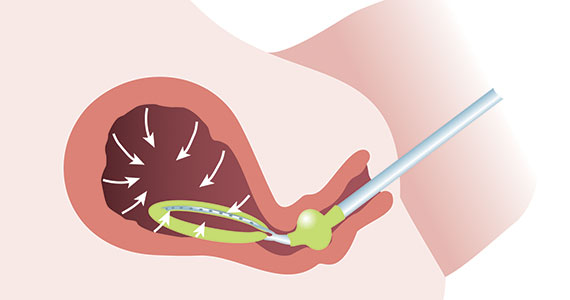

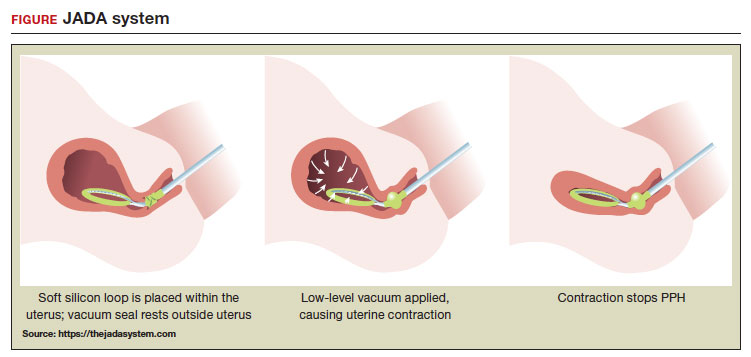

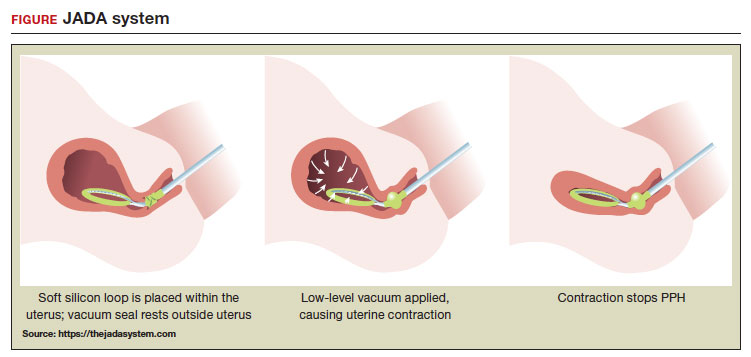

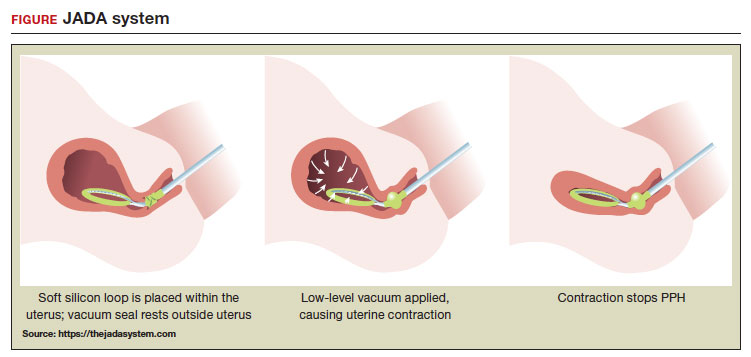

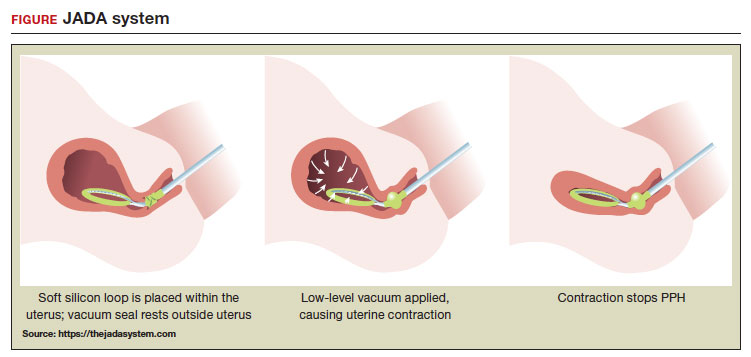

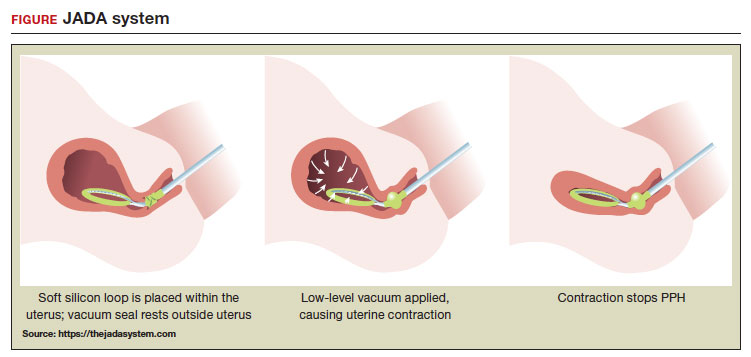

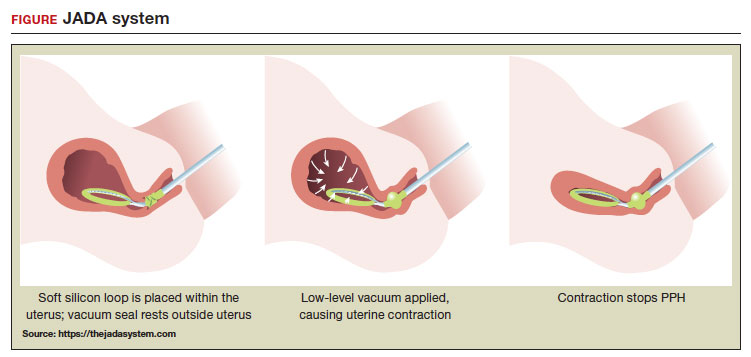

A new device for the treatment of PPH due to uterine atony is the JADA VHCD (FIGURE), which generates negative intrauterine pressure causing the uterus to contract, thereby constricting myometrial vessels and reducing uterine bleeding. The JADA VHCD system is indicated to provide control and treatment of abnormal postpartum uterine bleeding following vaginal or cesarean birth caused by uterine atony when conservative management is indicated.6

ILLUSTRATION: MARY ELLEN NIATAS FOR OBG MANAGEMENT

ILLUSTRATION: MARY ELLEN NIATAS FOR OBG MANAGEMENT

System components

The JADA VHCD consists of a leading portion intended to be inserted into the uterine cavity, which consists of a silicone elliptical loop with 20 vacuum pores. A soft shield covers the vacuum loop to reduce the risk of the vacuum pores being clogged with biological material, including blood and clots. The elliptical loop is attached to a catheter intended for connection to a vacuum source set to 80 mm Hg ±10 mm Hg (hospital wall suction or portable suction device) with an in-line cannister to collect blood. Approximately 16 cm from the tip of the elliptical loop is a balloon that should be positioned in the upper vagina, not inside the cervix, and inflated with fluid (60 mL to 120 mL) through a dedicated port to occlude the vagina, thereby preserving a stable intrauterine vacuum.

Continue to: Correct usage...

Correct usage

A simple mnemonic to facilitate use of the JADA VHCD is “120/80”—fill the vaginal balloon with 120 mL of sterile fluid and attach the tubing to a source that is set to provide 80 mm Hg of vacuum with an in-line collection cannister. The VHCD may not work correctly if there is a substantial amount of blood in the uterus. Clinical experts advise that an important step prior to placing the elliptical loop in the uterus is to perform a sweep of the uterine cavity with a hand or instrument to remove clots and ensure there is no retained placental tissue. It is preferable to assemble the suction tubing, syringe, sterile fluid, and other instruments (eg, forceps, speculum) needed to insert the device prior to attempting to place the VHCD. When the elliptical loop is compressed for insertion, it is about 2 cm in diameter, necessitating that the cervix be dilated sufficiently to accommodate the device.

Immediately after placing the VHCD, contractions can be monitored by physical examination and the amount of ongoing bleeding can be estimated by observing the amount of blood accumulating in the cannister. Rapid onset of a palpable increase in uterine tone is a prominent feature of successful treatment of PPH with the VHCD. The VHCD should be kept in the uterus with active suction for at least 1 hour. Taping the tubing to the inner thigh may help stabilize the device. Once bleeding is controlled, prior to removing the device, the vacuum should be discontinued, and bleeding activityshould be assessed for at least 30 minutes. If the patient is stable, the vaginal balloon can be deflated, followed by removal of the device. The VHCD should be removed within 24 hours of placement.6

The JADA VHCD system should not be used with ongoing intrauterine pregnancy, untreated uterine rupture, unresolved uterine inversion, current cervical cancer, or serious infection of the uterus.6 The VHCD has not been evaluated for effectiveness in the treatment of placenta accreta or coagulopathy. The VHCD has not been specifically evaluated for safety and effectiveness in patients < 34 weeks’ duration, but clinicians report successful use of the device in cases of PPH that have occurred in the second and early-third trimesters. If the device can be appropriately placed with the elliptical loop in the uterus and the balloon in the vagina, it is theoretically possible to use the device for cases of PPH occurring before 34 weeks’ gestation.

When using the JADA VHCD system, it is important to simultaneously provide cardiovascular support, appropriate transfusion of blood products and timely surgical intervention, if indicated. All obstetricians know that in complicated cases of PPH, where conservative measures have not worked, uterine artery embolization or hysterectomy may be the only interventions that will prevent serious patient morbidity.

Effectiveness data

The VHCD has not been evaluated against an alternative approach, such as UBT, in published randomized clinical trials. However, prospective cohort studies have reported that the JADA is often successful in the treatment of PPH.7-10

In a multicenter cohort study of 107 patients with PPH, including 91 vaginal and 16 cesarean births, 100 patients (93%) were successfully treated with the JADA VHCD.7 Median blood loss before application of the system was 870 mL with vaginal birth and 1,300 mL with cesarean birth. Definitive control of the hemorrhage was observed at a median of 3 minutes after initiation of the intrauterine vacuum. In this study, 32% of patients had reproductive tract lacerations that needed to be repaired, and 2 patients required a hysterectomy. Forty patients required a blood transfusion.

Two patients were treated with a Bakri UBT when the VHCD did not resolve the PPH. In this cohort, the vacuum was applied for a median duration of 144 minutes, and a median total device dwell time was 191 minutes. Compared with UBT, the JADA VHCD intrauterine dwell time was shorter, facilitating patient progression and early transfer to the postpartum unit. The physicians who participated in the study reported that the device was easy to use. The complications reported in this cohort were minor and included endometritis (5 cases), vaginal infection (2 cases), and disruption of a vaginal laceration repair (1 case).7

Novel approaches to generating an intrauterine vacuum to treat PPH

The JADA VHCD is the only vacuum device approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for treatment of PPH. However, clinical innovators have reported alternative approaches to generating an intrauterine vacuum using equipment designed for other purposes. In one study, a Bakri balloon was used to generate intrauterine vacuum tamponade to treat PPH.11 In this study, a Bakri balloon was inserted into the uterus, and the balloon was inflated to 50 mL to 100 mL to seal the vacuum. The main Bakri port was attached to a suction aspiration device set to generate a vacuum of 450 mm Hg to 525 mm Hg, a much greater vacuum than used with the JADA VHCD. This study included 44 cases of PPH due to uterine atony and 22 cases due to placental pathology, with successful treatment of PPH in 86% and 73% of the cases, respectively.

Another approach to generate intrauterine vacuum tamponade involves using a Levin stomach tube (FG24 or FG36), which has an open end and 4 side ports near the open tip.12-14 The Levin stomach tube is low cost and has many favorable design features, including a rounded tip, wide-bore, and circumferentially placed side ports. The FG36 Levin stomach tube is 12 mm in diameter and has 10 mm side ports. A vacuum device set to deliver 100 mm Hg to 200 mm Hgwas used in some of the studies evaluating the Levin stomach tube for the treatment of PPH. In 3 cases of severe PPH unresponsive to standard interventions, creation of vacuum tamponade with flexible suction tubing with side ports was successful in controlling the hemorrhage.13

Dr. T.N. Vasudeva Panicker invented an intrauterine cannula 12 mm in diameter and 25 cm in length, with dozens of 4 mm side ports over the distal 12 cm of the cannula.15 The cannula, which is made of stainless steel or plastic, is inserted into the uterus and 700 mm Hgvacuum is applied, a level much greater than the 80 mm Hg vacuum recommended for use with the JADA VHCD. When successful, the high suction clears the uterus of blood and causes uterine contraction. In 4 cases of severe PPH, the device successfully controlled the hemorrhage. In 2 of the 4 cases the device that was initially placed became clogged with blood and needed to be replaced.

UBT vs VHCD

To date there are no published randomized controlled trials comparing Bakri UBT to the JADA VHCD. In one retrospective study, the frequency of massive transfusion of red blood cells (RBCs), defined as the transfusion of 4 units or greater of RBCs, was assessed among 78 patients treated with the Bakri UBT and 36 patients treated with the JADA VHCD.9 In this study, at baseline there was a non ̶ statistically significant trend for JADA VHCD to be used more frequently than the Bakri UBT in cases of PPH occurring during repeat cesarean delivery (33% vs 14%). The Bakri UBT was used more frequently than the JADA VHCD among patients having a PPH following a vaginal delivery (51% vs 31%). Both devices were used at similar rates for operative vaginal delivery (6%) and primary cesarean birth (31% VHCD and 28% UBT).

In this retrospective study, the percentage of patients treated with VHCD or UBT who received 4 or more units of RBCs was 3% and 21%, respectively (P < .01). Among patients treated with VHCD and UBT, the estimated median blood loss was 1,500 mL and 1,850 mL (P=.02), respectively. The median hemoglobin concentration at discharge was similar in the VHCD and UBT groups, 8.8 g/dL and 8.6 g/dL, respectively.9 A randomized controlled trial is necessary to refine our understanding of the comparative effectiveness of UBT and VHCD in controlling PPH following vaginal and cesarean birth.

A welcome addition to treatment options

Every obstetrician knows that, in the next 12 months of their practice, they will encounter multiple cases of PPH. One or two of these cases may require the physician to use every medication and procedure available for the treatment of PPH to save the life of the patient. To prepare to treat the next case of PPH rapidly and effectively, it is important for every obstetrician to develop a standardized cognitive plan for using all available treatmentmodalities in an appropriate and timely sequence, including both the Bakri balloon and the JADA VHCD. The insight that inducing an intrauterine vacuum causes uterine contraction, which may resolve PPH, is an important discovery. The JADA VHCD is a welcome addition to our armamentarium of treatments for PPH. ●

- Corbetta-Rastelli CM, Friedman AM, Sobhani NC, et al. Postpartum hemorrhage trends and outcomes in the United States, 2000-2019. Obstet Gynecol. 2023;141:152-161.

- Bienstock JL, Eke AC, Hueppchen NA. Postpartum hemorrhage. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:16351645.

- Salati JA, Leathersich SJ, Williams MJ, et al. Prophylactic oxytocin for the third stage of labour to prevent postpartum hemorrhage. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;CD001808.

- Begley CM, Gyte GMI, Devane D, et al. Active versus expectant management for women in the third stage of labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;CD007412.

- Suarez S, Conde-Agudelo A, Borovac-Pinheiro A, et al. Uterine balloon tamponade for the treatment of postpartum hemorrhage: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;222:293.e1-e52.

- US Food and Drug Administration. JADA system approval. Accessed July 25, 2023. https://www .accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/pdf21/K212757 .pdf

- D’Alton ME, Rood KM, Smid MC, et al. Intrauterine vacuum-induced hemorrhage control device for rapid treatment of postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;136:882-891.

- D’Alton M, Rood K, Simhan H, et al. Profile of the JADA System: the vacuum-induced hemorrhage control device for treating abnormal postpartum uterine bleeding and postpartum hemorrhage. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2021; 18:849-853.

- Gulersen M, Gerber RP, Rochelson B, et al. Vacuum-induced hemorrhage control versus uterine balloon tamponade for postpartum hemorrhage. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2023;45:267-272.

- Purwosunnu Y, Sarkoen W, Arulkumaran S, et al. Control of postpartum hemorrhage using vacuum-induced uterine tamponade. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:33-36.

- Haslinger C, Weber K, Zimmerman R. Vacuuminduced tamponade for treatment of postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;138:361-365.

- Hofmeyr GJ, Middleton K, Singata-Madliki M. Randomized feasibility study of suction-tube uterine tamponade for postpartum hemorrhage. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2019;146:339-343.

- Hofmeyr GJ, Singata-Madliki M. Novel suction tube uterine tamponade for treating intractable postpartum hemorrhage: description of technique and report of three cases. BJOG. 2020;127:1280-1283.

- Cebekhulu SN, Abdul H, Batting J, et al. Suction tube uterine tamponade for treatment of refractory postpartum hemorrhage: internal feasibility and acceptability pilot of a randomized clinical trial. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2022;158: 79-85.

- Panicker TNV. Panicker’s vacuum suction haemostatic device for treating post-partum hemorrhage. J Obstet Gynaecol India. 2017;67:150-151.

Postpartum hemorrhage (PPH) is a common complication of birth. In 2019, 4.3% of births in the United States were complicated by at least one episode of PPH.1 Major causes of PPH include uterine atony, retained products of conception, reproductive tract trauma, and coagulopathy.2 Active management of the third stage of labor with the routine administration of postpartum uterotonics reduces the risk of PPH.3,4

PPH treatment requires a systematic approach using appropriate uterotonic medications, tranexamic acid, and procedures performed in a timely sequence to resolve the hemorrhage. Following vaginal birth, procedures that do not require a laparotomy to treat PPH include uterine massage, uterine evacuation to remove retained placental tissue, repair of lacerations, uterine balloon tamponade (UBT), uterine packing, a vacuum-induced hemorrhage control device (VHCD; JADA, Organon), and uterine artery embolization. Following cesarean birth, with an open laparotomy incision, interventions to treat PPH due to atony include vascular ligation, uterine compression sutures, UBT, VHCD, hysterectomy, and pelvic packing.2

Over the past 2 decades, UBT has been widely used for the treatment of PPH with a success rate in observational studies of approximately 86%.5 The uterine balloon creates pressure against the wall of the uterus permitting accumulation of platelets at bleeding sites, enhancing the activity of the clotting system. The uterine balloon provides direct pressure on the bleeding site(s). It is well known in trauma care that the first step to treat a bleeding wound is to apply direct pressure to the bleeding site. During the third stage of labor, a natural process is tetanic uterine contraction, which constricts myometrial vessels and the placenta bed. Placing a balloon in the uterus and inflating the balloon to 200 mL to 500 mL may delay the involution of the uterus that should occur following birth. An observation of great interest is the insight that inducing a vacuum in the uterine cavity may enhance tetanic uterine contraction and constriction of the myometrial vessels. Vacuum-induced hemorrhage control is discussed in detail in this editorial.

Vacuum-induced hemorrhage control device

A new device for the treatment of PPH due to uterine atony is the JADA VHCD (FIGURE), which generates negative intrauterine pressure causing the uterus to contract, thereby constricting myometrial vessels and reducing uterine bleeding. The JADA VHCD system is indicated to provide control and treatment of abnormal postpartum uterine bleeding following vaginal or cesarean birth caused by uterine atony when conservative management is indicated.6

ILLUSTRATION: MARY ELLEN NIATAS FOR OBG MANAGEMENT

ILLUSTRATION: MARY ELLEN NIATAS FOR OBG MANAGEMENT

System components

The JADA VHCD consists of a leading portion intended to be inserted into the uterine cavity, which consists of a silicone elliptical loop with 20 vacuum pores. A soft shield covers the vacuum loop to reduce the risk of the vacuum pores being clogged with biological material, including blood and clots. The elliptical loop is attached to a catheter intended for connection to a vacuum source set to 80 mm Hg ±10 mm Hg (hospital wall suction or portable suction device) with an in-line cannister to collect blood. Approximately 16 cm from the tip of the elliptical loop is a balloon that should be positioned in the upper vagina, not inside the cervix, and inflated with fluid (60 mL to 120 mL) through a dedicated port to occlude the vagina, thereby preserving a stable intrauterine vacuum.

Continue to: Correct usage...

Correct usage

A simple mnemonic to facilitate use of the JADA VHCD is “120/80”—fill the vaginal balloon with 120 mL of sterile fluid and attach the tubing to a source that is set to provide 80 mm Hg of vacuum with an in-line collection cannister. The VHCD may not work correctly if there is a substantial amount of blood in the uterus. Clinical experts advise that an important step prior to placing the elliptical loop in the uterus is to perform a sweep of the uterine cavity with a hand or instrument to remove clots and ensure there is no retained placental tissue. It is preferable to assemble the suction tubing, syringe, sterile fluid, and other instruments (eg, forceps, speculum) needed to insert the device prior to attempting to place the VHCD. When the elliptical loop is compressed for insertion, it is about 2 cm in diameter, necessitating that the cervix be dilated sufficiently to accommodate the device.

Immediately after placing the VHCD, contractions can be monitored by physical examination and the amount of ongoing bleeding can be estimated by observing the amount of blood accumulating in the cannister. Rapid onset of a palpable increase in uterine tone is a prominent feature of successful treatment of PPH with the VHCD. The VHCD should be kept in the uterus with active suction for at least 1 hour. Taping the tubing to the inner thigh may help stabilize the device. Once bleeding is controlled, prior to removing the device, the vacuum should be discontinued, and bleeding activityshould be assessed for at least 30 minutes. If the patient is stable, the vaginal balloon can be deflated, followed by removal of the device. The VHCD should be removed within 24 hours of placement.6

The JADA VHCD system should not be used with ongoing intrauterine pregnancy, untreated uterine rupture, unresolved uterine inversion, current cervical cancer, or serious infection of the uterus.6 The VHCD has not been evaluated for effectiveness in the treatment of placenta accreta or coagulopathy. The VHCD has not been specifically evaluated for safety and effectiveness in patients < 34 weeks’ duration, but clinicians report successful use of the device in cases of PPH that have occurred in the second and early-third trimesters. If the device can be appropriately placed with the elliptical loop in the uterus and the balloon in the vagina, it is theoretically possible to use the device for cases of PPH occurring before 34 weeks’ gestation.

When using the JADA VHCD system, it is important to simultaneously provide cardiovascular support, appropriate transfusion of blood products and timely surgical intervention, if indicated. All obstetricians know that in complicated cases of PPH, where conservative measures have not worked, uterine artery embolization or hysterectomy may be the only interventions that will prevent serious patient morbidity.

Effectiveness data

The VHCD has not been evaluated against an alternative approach, such as UBT, in published randomized clinical trials. However, prospective cohort studies have reported that the JADA is often successful in the treatment of PPH.7-10

In a multicenter cohort study of 107 patients with PPH, including 91 vaginal and 16 cesarean births, 100 patients (93%) were successfully treated with the JADA VHCD.7 Median blood loss before application of the system was 870 mL with vaginal birth and 1,300 mL with cesarean birth. Definitive control of the hemorrhage was observed at a median of 3 minutes after initiation of the intrauterine vacuum. In this study, 32% of patients had reproductive tract lacerations that needed to be repaired, and 2 patients required a hysterectomy. Forty patients required a blood transfusion.

Two patients were treated with a Bakri UBT when the VHCD did not resolve the PPH. In this cohort, the vacuum was applied for a median duration of 144 minutes, and a median total device dwell time was 191 minutes. Compared with UBT, the JADA VHCD intrauterine dwell time was shorter, facilitating patient progression and early transfer to the postpartum unit. The physicians who participated in the study reported that the device was easy to use. The complications reported in this cohort were minor and included endometritis (5 cases), vaginal infection (2 cases), and disruption of a vaginal laceration repair (1 case).7

Novel approaches to generating an intrauterine vacuum to treat PPH

The JADA VHCD is the only vacuum device approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for treatment of PPH. However, clinical innovators have reported alternative approaches to generating an intrauterine vacuum using equipment designed for other purposes. In one study, a Bakri balloon was used to generate intrauterine vacuum tamponade to treat PPH.11 In this study, a Bakri balloon was inserted into the uterus, and the balloon was inflated to 50 mL to 100 mL to seal the vacuum. The main Bakri port was attached to a suction aspiration device set to generate a vacuum of 450 mm Hg to 525 mm Hg, a much greater vacuum than used with the JADA VHCD. This study included 44 cases of PPH due to uterine atony and 22 cases due to placental pathology, with successful treatment of PPH in 86% and 73% of the cases, respectively.

Another approach to generate intrauterine vacuum tamponade involves using a Levin stomach tube (FG24 or FG36), which has an open end and 4 side ports near the open tip.12-14 The Levin stomach tube is low cost and has many favorable design features, including a rounded tip, wide-bore, and circumferentially placed side ports. The FG36 Levin stomach tube is 12 mm in diameter and has 10 mm side ports. A vacuum device set to deliver 100 mm Hg to 200 mm Hgwas used in some of the studies evaluating the Levin stomach tube for the treatment of PPH. In 3 cases of severe PPH unresponsive to standard interventions, creation of vacuum tamponade with flexible suction tubing with side ports was successful in controlling the hemorrhage.13

Dr. T.N. Vasudeva Panicker invented an intrauterine cannula 12 mm in diameter and 25 cm in length, with dozens of 4 mm side ports over the distal 12 cm of the cannula.15 The cannula, which is made of stainless steel or plastic, is inserted into the uterus and 700 mm Hgvacuum is applied, a level much greater than the 80 mm Hg vacuum recommended for use with the JADA VHCD. When successful, the high suction clears the uterus of blood and causes uterine contraction. In 4 cases of severe PPH, the device successfully controlled the hemorrhage. In 2 of the 4 cases the device that was initially placed became clogged with blood and needed to be replaced.

UBT vs VHCD

To date there are no published randomized controlled trials comparing Bakri UBT to the JADA VHCD. In one retrospective study, the frequency of massive transfusion of red blood cells (RBCs), defined as the transfusion of 4 units or greater of RBCs, was assessed among 78 patients treated with the Bakri UBT and 36 patients treated with the JADA VHCD.9 In this study, at baseline there was a non ̶ statistically significant trend for JADA VHCD to be used more frequently than the Bakri UBT in cases of PPH occurring during repeat cesarean delivery (33% vs 14%). The Bakri UBT was used more frequently than the JADA VHCD among patients having a PPH following a vaginal delivery (51% vs 31%). Both devices were used at similar rates for operative vaginal delivery (6%) and primary cesarean birth (31% VHCD and 28% UBT).

In this retrospective study, the percentage of patients treated with VHCD or UBT who received 4 or more units of RBCs was 3% and 21%, respectively (P < .01). Among patients treated with VHCD and UBT, the estimated median blood loss was 1,500 mL and 1,850 mL (P=.02), respectively. The median hemoglobin concentration at discharge was similar in the VHCD and UBT groups, 8.8 g/dL and 8.6 g/dL, respectively.9 A randomized controlled trial is necessary to refine our understanding of the comparative effectiveness of UBT and VHCD in controlling PPH following vaginal and cesarean birth.

A welcome addition to treatment options

Every obstetrician knows that, in the next 12 months of their practice, they will encounter multiple cases of PPH. One or two of these cases may require the physician to use every medication and procedure available for the treatment of PPH to save the life of the patient. To prepare to treat the next case of PPH rapidly and effectively, it is important for every obstetrician to develop a standardized cognitive plan for using all available treatmentmodalities in an appropriate and timely sequence, including both the Bakri balloon and the JADA VHCD. The insight that inducing an intrauterine vacuum causes uterine contraction, which may resolve PPH, is an important discovery. The JADA VHCD is a welcome addition to our armamentarium of treatments for PPH. ●

Postpartum hemorrhage (PPH) is a common complication of birth. In 2019, 4.3% of births in the United States were complicated by at least one episode of PPH.1 Major causes of PPH include uterine atony, retained products of conception, reproductive tract trauma, and coagulopathy.2 Active management of the third stage of labor with the routine administration of postpartum uterotonics reduces the risk of PPH.3,4

PPH treatment requires a systematic approach using appropriate uterotonic medications, tranexamic acid, and procedures performed in a timely sequence to resolve the hemorrhage. Following vaginal birth, procedures that do not require a laparotomy to treat PPH include uterine massage, uterine evacuation to remove retained placental tissue, repair of lacerations, uterine balloon tamponade (UBT), uterine packing, a vacuum-induced hemorrhage control device (VHCD; JADA, Organon), and uterine artery embolization. Following cesarean birth, with an open laparotomy incision, interventions to treat PPH due to atony include vascular ligation, uterine compression sutures, UBT, VHCD, hysterectomy, and pelvic packing.2

Over the past 2 decades, UBT has been widely used for the treatment of PPH with a success rate in observational studies of approximately 86%.5 The uterine balloon creates pressure against the wall of the uterus permitting accumulation of platelets at bleeding sites, enhancing the activity of the clotting system. The uterine balloon provides direct pressure on the bleeding site(s). It is well known in trauma care that the first step to treat a bleeding wound is to apply direct pressure to the bleeding site. During the third stage of labor, a natural process is tetanic uterine contraction, which constricts myometrial vessels and the placenta bed. Placing a balloon in the uterus and inflating the balloon to 200 mL to 500 mL may delay the involution of the uterus that should occur following birth. An observation of great interest is the insight that inducing a vacuum in the uterine cavity may enhance tetanic uterine contraction and constriction of the myometrial vessels. Vacuum-induced hemorrhage control is discussed in detail in this editorial.

Vacuum-induced hemorrhage control device

A new device for the treatment of PPH due to uterine atony is the JADA VHCD (FIGURE), which generates negative intrauterine pressure causing the uterus to contract, thereby constricting myometrial vessels and reducing uterine bleeding. The JADA VHCD system is indicated to provide control and treatment of abnormal postpartum uterine bleeding following vaginal or cesarean birth caused by uterine atony when conservative management is indicated.6

ILLUSTRATION: MARY ELLEN NIATAS FOR OBG MANAGEMENT

ILLUSTRATION: MARY ELLEN NIATAS FOR OBG MANAGEMENT

System components

The JADA VHCD consists of a leading portion intended to be inserted into the uterine cavity, which consists of a silicone elliptical loop with 20 vacuum pores. A soft shield covers the vacuum loop to reduce the risk of the vacuum pores being clogged with biological material, including blood and clots. The elliptical loop is attached to a catheter intended for connection to a vacuum source set to 80 mm Hg ±10 mm Hg (hospital wall suction or portable suction device) with an in-line cannister to collect blood. Approximately 16 cm from the tip of the elliptical loop is a balloon that should be positioned in the upper vagina, not inside the cervix, and inflated with fluid (60 mL to 120 mL) through a dedicated port to occlude the vagina, thereby preserving a stable intrauterine vacuum.

Continue to: Correct usage...

Correct usage

A simple mnemonic to facilitate use of the JADA VHCD is “120/80”—fill the vaginal balloon with 120 mL of sterile fluid and attach the tubing to a source that is set to provide 80 mm Hg of vacuum with an in-line collection cannister. The VHCD may not work correctly if there is a substantial amount of blood in the uterus. Clinical experts advise that an important step prior to placing the elliptical loop in the uterus is to perform a sweep of the uterine cavity with a hand or instrument to remove clots and ensure there is no retained placental tissue. It is preferable to assemble the suction tubing, syringe, sterile fluid, and other instruments (eg, forceps, speculum) needed to insert the device prior to attempting to place the VHCD. When the elliptical loop is compressed for insertion, it is about 2 cm in diameter, necessitating that the cervix be dilated sufficiently to accommodate the device.

Immediately after placing the VHCD, contractions can be monitored by physical examination and the amount of ongoing bleeding can be estimated by observing the amount of blood accumulating in the cannister. Rapid onset of a palpable increase in uterine tone is a prominent feature of successful treatment of PPH with the VHCD. The VHCD should be kept in the uterus with active suction for at least 1 hour. Taping the tubing to the inner thigh may help stabilize the device. Once bleeding is controlled, prior to removing the device, the vacuum should be discontinued, and bleeding activityshould be assessed for at least 30 minutes. If the patient is stable, the vaginal balloon can be deflated, followed by removal of the device. The VHCD should be removed within 24 hours of placement.6

The JADA VHCD system should not be used with ongoing intrauterine pregnancy, untreated uterine rupture, unresolved uterine inversion, current cervical cancer, or serious infection of the uterus.6 The VHCD has not been evaluated for effectiveness in the treatment of placenta accreta or coagulopathy. The VHCD has not been specifically evaluated for safety and effectiveness in patients < 34 weeks’ duration, but clinicians report successful use of the device in cases of PPH that have occurred in the second and early-third trimesters. If the device can be appropriately placed with the elliptical loop in the uterus and the balloon in the vagina, it is theoretically possible to use the device for cases of PPH occurring before 34 weeks’ gestation.

When using the JADA VHCD system, it is important to simultaneously provide cardiovascular support, appropriate transfusion of blood products and timely surgical intervention, if indicated. All obstetricians know that in complicated cases of PPH, where conservative measures have not worked, uterine artery embolization or hysterectomy may be the only interventions that will prevent serious patient morbidity.

Effectiveness data

The VHCD has not been evaluated against an alternative approach, such as UBT, in published randomized clinical trials. However, prospective cohort studies have reported that the JADA is often successful in the treatment of PPH.7-10

In a multicenter cohort study of 107 patients with PPH, including 91 vaginal and 16 cesarean births, 100 patients (93%) were successfully treated with the JADA VHCD.7 Median blood loss before application of the system was 870 mL with vaginal birth and 1,300 mL with cesarean birth. Definitive control of the hemorrhage was observed at a median of 3 minutes after initiation of the intrauterine vacuum. In this study, 32% of patients had reproductive tract lacerations that needed to be repaired, and 2 patients required a hysterectomy. Forty patients required a blood transfusion.

Two patients were treated with a Bakri UBT when the VHCD did not resolve the PPH. In this cohort, the vacuum was applied for a median duration of 144 minutes, and a median total device dwell time was 191 minutes. Compared with UBT, the JADA VHCD intrauterine dwell time was shorter, facilitating patient progression and early transfer to the postpartum unit. The physicians who participated in the study reported that the device was easy to use. The complications reported in this cohort were minor and included endometritis (5 cases), vaginal infection (2 cases), and disruption of a vaginal laceration repair (1 case).7

Novel approaches to generating an intrauterine vacuum to treat PPH

The JADA VHCD is the only vacuum device approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for treatment of PPH. However, clinical innovators have reported alternative approaches to generating an intrauterine vacuum using equipment designed for other purposes. In one study, a Bakri balloon was used to generate intrauterine vacuum tamponade to treat PPH.11 In this study, a Bakri balloon was inserted into the uterus, and the balloon was inflated to 50 mL to 100 mL to seal the vacuum. The main Bakri port was attached to a suction aspiration device set to generate a vacuum of 450 mm Hg to 525 mm Hg, a much greater vacuum than used with the JADA VHCD. This study included 44 cases of PPH due to uterine atony and 22 cases due to placental pathology, with successful treatment of PPH in 86% and 73% of the cases, respectively.

Another approach to generate intrauterine vacuum tamponade involves using a Levin stomach tube (FG24 or FG36), which has an open end and 4 side ports near the open tip.12-14 The Levin stomach tube is low cost and has many favorable design features, including a rounded tip, wide-bore, and circumferentially placed side ports. The FG36 Levin stomach tube is 12 mm in diameter and has 10 mm side ports. A vacuum device set to deliver 100 mm Hg to 200 mm Hgwas used in some of the studies evaluating the Levin stomach tube for the treatment of PPH. In 3 cases of severe PPH unresponsive to standard interventions, creation of vacuum tamponade with flexible suction tubing with side ports was successful in controlling the hemorrhage.13

Dr. T.N. Vasudeva Panicker invented an intrauterine cannula 12 mm in diameter and 25 cm in length, with dozens of 4 mm side ports over the distal 12 cm of the cannula.15 The cannula, which is made of stainless steel or plastic, is inserted into the uterus and 700 mm Hgvacuum is applied, a level much greater than the 80 mm Hg vacuum recommended for use with the JADA VHCD. When successful, the high suction clears the uterus of blood and causes uterine contraction. In 4 cases of severe PPH, the device successfully controlled the hemorrhage. In 2 of the 4 cases the device that was initially placed became clogged with blood and needed to be replaced.

UBT vs VHCD

To date there are no published randomized controlled trials comparing Bakri UBT to the JADA VHCD. In one retrospective study, the frequency of massive transfusion of red blood cells (RBCs), defined as the transfusion of 4 units or greater of RBCs, was assessed among 78 patients treated with the Bakri UBT and 36 patients treated with the JADA VHCD.9 In this study, at baseline there was a non ̶ statistically significant trend for JADA VHCD to be used more frequently than the Bakri UBT in cases of PPH occurring during repeat cesarean delivery (33% vs 14%). The Bakri UBT was used more frequently than the JADA VHCD among patients having a PPH following a vaginal delivery (51% vs 31%). Both devices were used at similar rates for operative vaginal delivery (6%) and primary cesarean birth (31% VHCD and 28% UBT).

In this retrospective study, the percentage of patients treated with VHCD or UBT who received 4 or more units of RBCs was 3% and 21%, respectively (P < .01). Among patients treated with VHCD and UBT, the estimated median blood loss was 1,500 mL and 1,850 mL (P=.02), respectively. The median hemoglobin concentration at discharge was similar in the VHCD and UBT groups, 8.8 g/dL and 8.6 g/dL, respectively.9 A randomized controlled trial is necessary to refine our understanding of the comparative effectiveness of UBT and VHCD in controlling PPH following vaginal and cesarean birth.

A welcome addition to treatment options

Every obstetrician knows that, in the next 12 months of their practice, they will encounter multiple cases of PPH. One or two of these cases may require the physician to use every medication and procedure available for the treatment of PPH to save the life of the patient. To prepare to treat the next case of PPH rapidly and effectively, it is important for every obstetrician to develop a standardized cognitive plan for using all available treatmentmodalities in an appropriate and timely sequence, including both the Bakri balloon and the JADA VHCD. The insight that inducing an intrauterine vacuum causes uterine contraction, which may resolve PPH, is an important discovery. The JADA VHCD is a welcome addition to our armamentarium of treatments for PPH. ●

- Corbetta-Rastelli CM, Friedman AM, Sobhani NC, et al. Postpartum hemorrhage trends and outcomes in the United States, 2000-2019. Obstet Gynecol. 2023;141:152-161.

- Bienstock JL, Eke AC, Hueppchen NA. Postpartum hemorrhage. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:16351645.

- Salati JA, Leathersich SJ, Williams MJ, et al. Prophylactic oxytocin for the third stage of labour to prevent postpartum hemorrhage. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;CD001808.

- Begley CM, Gyte GMI, Devane D, et al. Active versus expectant management for women in the third stage of labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;CD007412.

- Suarez S, Conde-Agudelo A, Borovac-Pinheiro A, et al. Uterine balloon tamponade for the treatment of postpartum hemorrhage: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;222:293.e1-e52.

- US Food and Drug Administration. JADA system approval. Accessed July 25, 2023. https://www .accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/pdf21/K212757 .pdf

- D’Alton ME, Rood KM, Smid MC, et al. Intrauterine vacuum-induced hemorrhage control device for rapid treatment of postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;136:882-891.

- D’Alton M, Rood K, Simhan H, et al. Profile of the JADA System: the vacuum-induced hemorrhage control device for treating abnormal postpartum uterine bleeding and postpartum hemorrhage. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2021; 18:849-853.

- Gulersen M, Gerber RP, Rochelson B, et al. Vacuum-induced hemorrhage control versus uterine balloon tamponade for postpartum hemorrhage. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2023;45:267-272.

- Purwosunnu Y, Sarkoen W, Arulkumaran S, et al. Control of postpartum hemorrhage using vacuum-induced uterine tamponade. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:33-36.

- Haslinger C, Weber K, Zimmerman R. Vacuuminduced tamponade for treatment of postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;138:361-365.

- Hofmeyr GJ, Middleton K, Singata-Madliki M. Randomized feasibility study of suction-tube uterine tamponade for postpartum hemorrhage. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2019;146:339-343.

- Hofmeyr GJ, Singata-Madliki M. Novel suction tube uterine tamponade for treating intractable postpartum hemorrhage: description of technique and report of three cases. BJOG. 2020;127:1280-1283.

- Cebekhulu SN, Abdul H, Batting J, et al. Suction tube uterine tamponade for treatment of refractory postpartum hemorrhage: internal feasibility and acceptability pilot of a randomized clinical trial. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2022;158: 79-85.

- Panicker TNV. Panicker’s vacuum suction haemostatic device for treating post-partum hemorrhage. J Obstet Gynaecol India. 2017;67:150-151.

- Corbetta-Rastelli CM, Friedman AM, Sobhani NC, et al. Postpartum hemorrhage trends and outcomes in the United States, 2000-2019. Obstet Gynecol. 2023;141:152-161.

- Bienstock JL, Eke AC, Hueppchen NA. Postpartum hemorrhage. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:16351645.

- Salati JA, Leathersich SJ, Williams MJ, et al. Prophylactic oxytocin for the third stage of labour to prevent postpartum hemorrhage. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;CD001808.

- Begley CM, Gyte GMI, Devane D, et al. Active versus expectant management for women in the third stage of labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;CD007412.

- Suarez S, Conde-Agudelo A, Borovac-Pinheiro A, et al. Uterine balloon tamponade for the treatment of postpartum hemorrhage: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;222:293.e1-e52.

- US Food and Drug Administration. JADA system approval. Accessed July 25, 2023. https://www .accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/pdf21/K212757 .pdf

- D’Alton ME, Rood KM, Smid MC, et al. Intrauterine vacuum-induced hemorrhage control device for rapid treatment of postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;136:882-891.

- D’Alton M, Rood K, Simhan H, et al. Profile of the JADA System: the vacuum-induced hemorrhage control device for treating abnormal postpartum uterine bleeding and postpartum hemorrhage. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2021; 18:849-853.

- Gulersen M, Gerber RP, Rochelson B, et al. Vacuum-induced hemorrhage control versus uterine balloon tamponade for postpartum hemorrhage. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2023;45:267-272.

- Purwosunnu Y, Sarkoen W, Arulkumaran S, et al. Control of postpartum hemorrhage using vacuum-induced uterine tamponade. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:33-36.

- Haslinger C, Weber K, Zimmerman R. Vacuuminduced tamponade for treatment of postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;138:361-365.

- Hofmeyr GJ, Middleton K, Singata-Madliki M. Randomized feasibility study of suction-tube uterine tamponade for postpartum hemorrhage. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2019;146:339-343.

- Hofmeyr GJ, Singata-Madliki M. Novel suction tube uterine tamponade for treating intractable postpartum hemorrhage: description of technique and report of three cases. BJOG. 2020;127:1280-1283.

- Cebekhulu SN, Abdul H, Batting J, et al. Suction tube uterine tamponade for treatment of refractory postpartum hemorrhage: internal feasibility and acceptability pilot of a randomized clinical trial. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2022;158: 79-85.

- Panicker TNV. Panicker’s vacuum suction haemostatic device for treating post-partum hemorrhage. J Obstet Gynaecol India. 2017;67:150-151.

Zuranolone: A novel postpartum depression treatment, with lingering questions

Postpartum depression (PPD) remains the most common complication in modern obstetrics, and a leading cause of postpartum mortality in the first year of life. The last 15 years have brought considerable progress with respect to adoption of systematic screening for PPD across America. Screening for PPD, most often using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS), has become part of routine obstetrical care, and is also widely used in pediatric settings.

That is the good news. But the flip side of the identification of those women whose scores on the EPDS suggest significant depressive symptoms is that the number of these patients who, following identification, receive referrals for adequate treatment that gets them well is unfortunately low. This “perinatal treatment cascade” refers to the majority of women who, on the other side of identification of PPD, fail to receive adequate treatment and continue to have persistent depression (Cox E. et al. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016 Sep;77[9]:1189-1200). This is perhaps the greatest challenge to the field and to clinicians – how do we, on the other side of screening, see that these women get access to care and get well with the available treatments at hand?

Recently, a widely read and circulated article was published in The Wall Street Journal about the challenges associated with navigating care resources for women suffering from PPD. In that article, it was made clear, based on clinical vignette after clinical vignette from postpartum women across America, that neither obstetricians, mental health professionals, nor pediatricians are the “clinical home” for women suffering from postpartum mood and anxiety disorders. The article painfully highlights the system-wide failure to coordinate mental health care for women suffering from postpartum psychiatric illness.

Within a day of the publication of The Wall Street Journal article, the Food and Drug Administration approved zuranolone (Zurzuvae; Sage Therapeutics; Cambridge, Mass.) for the treatment of PPD following the review of two studies demonstrating the superiority of the new medicine over placebo. Women who were enrolled met criteria for major depressive disorder based on Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders criteria beginning in no earlier than the third trimester of pregnancy or later than 4 weeks of delivery. The two studies included a combined sample size of approximately 350 patients suffering from severe PPD. In the studies, women received either 50 mg or 40 mg of zuranolone, or placebo for 14 days. Treatment was associated with a significant change in the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale at day 15, and treatment response was maintained at day 42, which was 4 weeks after the last dose of study medication.

Zuranolone is a neuroactive steroid, which is taken orally, unlike brexanolone (Zulresso; Sage Therapeutics; Cambridge, Mass.), which requires intravenous administration. Zuranolone will be commercially available based on estimates around the fourth quarter of 2023. The most common side effects are drowsiness, dizziness, and sedation, and the FDA label will have a boxed warning about zuranolone’s potential to impact a person’s driving ability, and performance of potentially hazardous activities.

It is noteworthy that while this new medication received FDA approval for the PPD indication, it did not receive FDA approval for the treatment of major depressive disorder (MDD), and the agency issued a Complete Response Letter to the manufacturers noting their application did not provide substantial evidence of effectiveness in MDD. The FDA said in the Complete Response Letter that an additional study or studies will be needed; the manufacturers are currently evaluating next steps.

Where zuranolone fits into the treatment algorithm for severe PPD

Many clinicians who support women with PPD will wonder, upon hearing this news, where zuranolone fits into the treatment algorithm for severe postpartum major depression. Some relevant issues that may determine the answer are the following:

Cost. The cost of brexanolone was substantial, at $34,000 per year, and was viewed by some as a limiting factor in terms of its very limited uptake. As of this column’s publication, zuranolone’s manufacturer has not stated how much the medication will cost.

Breastfeeding. Unlike selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, which have been demonstrated to be effective for the treatment of PPD and safe during pregnancy and lactation, we have sparse data on the safety of zuranolone for women who wish to breastfeed. It is also unclear whether women eligible for zuranolone would, based on the limited data on safety in lactation, choose deferral of breastfeeding for 14 days in exchange for treatment.

Duration of treatment. While zuranolone was studied in the context of 14 days of acute treatment, then out to day 42, we have no published data on what happens on the other side of this brief interval. As a simple example, in a patient with a history of recurrent major depression previously treated with antidepressants, but where antidepressants were perhaps deferred during pregnancy, is PPD to be treated with zuranolone for 14 days? Or, hypothetically, should it be followed by empiric antidepressant treatment at day 14? Alternatively, are patient and clinician supposed to wait until recurrence occurs before pursuing adjunctive antidepressant therapy whether it is pharmacologic, nonpharmacologic, or both?

Treatment in patients with bipolar disorder. It is also unclear whether treatment with zuranolone applies to other populations of postpartum women. Certainly, for women with bipolar depression, which is common in postpartum women given the vulnerability of bipolar women to new onset of depression or postpartum depressive relapse of underlying disorder, we simply have no data regarding where zuranolone might fit in with respect to this group of patients.

The answers to these questions may help to determine whether zuranolone, a new antidepressant with efficacy, quick time to onset, and a novel mechanism of action is a “game changer.” The article in The Wall Street Journal provided me with some optimism, as it gave PPD and the issues surrounding PPD the attention it deserves in a major periodical. As a new treatment, it may help alleviate suffering at a critical time for patients and their families. We are inching closer to mitigation of stigma associated with this common illness.

Thinking back across the last 3 decades of my treating women suffering from PPD, I have reflected on what has gotten these patients well. I concluded that , along with family and community-based support groups, as well as a culture that reduces stigma and by so doing lessens the toll of this important and too frequently incompletely-treated illness.

Dr. Cohen is the director of the Ammon-Pinizzotto Center for Women’s Mental Health at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) in Boston, which provides information resources and conducts clinical care and research in reproductive mental health. He has been a consultant to manufacturers of psychiatric medications. The Center for Women’s Mental Health at MGH was a non-enrolling site for the pivotal phase 3 SKYLARK trial evaluating zuranolone. Full disclosure information for Dr. Cohen is available at womensmentalhealth.org. Email Dr. Cohen at [email protected].

Postpartum depression (PPD) remains the most common complication in modern obstetrics, and a leading cause of postpartum mortality in the first year of life. The last 15 years have brought considerable progress with respect to adoption of systematic screening for PPD across America. Screening for PPD, most often using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS), has become part of routine obstetrical care, and is also widely used in pediatric settings.

That is the good news. But the flip side of the identification of those women whose scores on the EPDS suggest significant depressive symptoms is that the number of these patients who, following identification, receive referrals for adequate treatment that gets them well is unfortunately low. This “perinatal treatment cascade” refers to the majority of women who, on the other side of identification of PPD, fail to receive adequate treatment and continue to have persistent depression (Cox E. et al. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016 Sep;77[9]:1189-1200). This is perhaps the greatest challenge to the field and to clinicians – how do we, on the other side of screening, see that these women get access to care and get well with the available treatments at hand?

Recently, a widely read and circulated article was published in The Wall Street Journal about the challenges associated with navigating care resources for women suffering from PPD. In that article, it was made clear, based on clinical vignette after clinical vignette from postpartum women across America, that neither obstetricians, mental health professionals, nor pediatricians are the “clinical home” for women suffering from postpartum mood and anxiety disorders. The article painfully highlights the system-wide failure to coordinate mental health care for women suffering from postpartum psychiatric illness.

Within a day of the publication of The Wall Street Journal article, the Food and Drug Administration approved zuranolone (Zurzuvae; Sage Therapeutics; Cambridge, Mass.) for the treatment of PPD following the review of two studies demonstrating the superiority of the new medicine over placebo. Women who were enrolled met criteria for major depressive disorder based on Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders criteria beginning in no earlier than the third trimester of pregnancy or later than 4 weeks of delivery. The two studies included a combined sample size of approximately 350 patients suffering from severe PPD. In the studies, women received either 50 mg or 40 mg of zuranolone, or placebo for 14 days. Treatment was associated with a significant change in the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale at day 15, and treatment response was maintained at day 42, which was 4 weeks after the last dose of study medication.

Zuranolone is a neuroactive steroid, which is taken orally, unlike brexanolone (Zulresso; Sage Therapeutics; Cambridge, Mass.), which requires intravenous administration. Zuranolone will be commercially available based on estimates around the fourth quarter of 2023. The most common side effects are drowsiness, dizziness, and sedation, and the FDA label will have a boxed warning about zuranolone’s potential to impact a person’s driving ability, and performance of potentially hazardous activities.

It is noteworthy that while this new medication received FDA approval for the PPD indication, it did not receive FDA approval for the treatment of major depressive disorder (MDD), and the agency issued a Complete Response Letter to the manufacturers noting their application did not provide substantial evidence of effectiveness in MDD. The FDA said in the Complete Response Letter that an additional study or studies will be needed; the manufacturers are currently evaluating next steps.

Where zuranolone fits into the treatment algorithm for severe PPD

Many clinicians who support women with PPD will wonder, upon hearing this news, where zuranolone fits into the treatment algorithm for severe postpartum major depression. Some relevant issues that may determine the answer are the following:

Cost. The cost of brexanolone was substantial, at $34,000 per year, and was viewed by some as a limiting factor in terms of its very limited uptake. As of this column’s publication, zuranolone’s manufacturer has not stated how much the medication will cost.

Breastfeeding. Unlike selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, which have been demonstrated to be effective for the treatment of PPD and safe during pregnancy and lactation, we have sparse data on the safety of zuranolone for women who wish to breastfeed. It is also unclear whether women eligible for zuranolone would, based on the limited data on safety in lactation, choose deferral of breastfeeding for 14 days in exchange for treatment.

Duration of treatment. While zuranolone was studied in the context of 14 days of acute treatment, then out to day 42, we have no published data on what happens on the other side of this brief interval. As a simple example, in a patient with a history of recurrent major depression previously treated with antidepressants, but where antidepressants were perhaps deferred during pregnancy, is PPD to be treated with zuranolone for 14 days? Or, hypothetically, should it be followed by empiric antidepressant treatment at day 14? Alternatively, are patient and clinician supposed to wait until recurrence occurs before pursuing adjunctive antidepressant therapy whether it is pharmacologic, nonpharmacologic, or both?

Treatment in patients with bipolar disorder. It is also unclear whether treatment with zuranolone applies to other populations of postpartum women. Certainly, for women with bipolar depression, which is common in postpartum women given the vulnerability of bipolar women to new onset of depression or postpartum depressive relapse of underlying disorder, we simply have no data regarding where zuranolone might fit in with respect to this group of patients.

The answers to these questions may help to determine whether zuranolone, a new antidepressant with efficacy, quick time to onset, and a novel mechanism of action is a “game changer.” The article in The Wall Street Journal provided me with some optimism, as it gave PPD and the issues surrounding PPD the attention it deserves in a major periodical. As a new treatment, it may help alleviate suffering at a critical time for patients and their families. We are inching closer to mitigation of stigma associated with this common illness.

Thinking back across the last 3 decades of my treating women suffering from PPD, I have reflected on what has gotten these patients well. I concluded that , along with family and community-based support groups, as well as a culture that reduces stigma and by so doing lessens the toll of this important and too frequently incompletely-treated illness.

Dr. Cohen is the director of the Ammon-Pinizzotto Center for Women’s Mental Health at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) in Boston, which provides information resources and conducts clinical care and research in reproductive mental health. He has been a consultant to manufacturers of psychiatric medications. The Center for Women’s Mental Health at MGH was a non-enrolling site for the pivotal phase 3 SKYLARK trial evaluating zuranolone. Full disclosure information for Dr. Cohen is available at womensmentalhealth.org. Email Dr. Cohen at [email protected].

Postpartum depression (PPD) remains the most common complication in modern obstetrics, and a leading cause of postpartum mortality in the first year of life. The last 15 years have brought considerable progress with respect to adoption of systematic screening for PPD across America. Screening for PPD, most often using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS), has become part of routine obstetrical care, and is also widely used in pediatric settings.

That is the good news. But the flip side of the identification of those women whose scores on the EPDS suggest significant depressive symptoms is that the number of these patients who, following identification, receive referrals for adequate treatment that gets them well is unfortunately low. This “perinatal treatment cascade” refers to the majority of women who, on the other side of identification of PPD, fail to receive adequate treatment and continue to have persistent depression (Cox E. et al. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016 Sep;77[9]:1189-1200). This is perhaps the greatest challenge to the field and to clinicians – how do we, on the other side of screening, see that these women get access to care and get well with the available treatments at hand?

Recently, a widely read and circulated article was published in The Wall Street Journal about the challenges associated with navigating care resources for women suffering from PPD. In that article, it was made clear, based on clinical vignette after clinical vignette from postpartum women across America, that neither obstetricians, mental health professionals, nor pediatricians are the “clinical home” for women suffering from postpartum mood and anxiety disorders. The article painfully highlights the system-wide failure to coordinate mental health care for women suffering from postpartum psychiatric illness.

Within a day of the publication of The Wall Street Journal article, the Food and Drug Administration approved zuranolone (Zurzuvae; Sage Therapeutics; Cambridge, Mass.) for the treatment of PPD following the review of two studies demonstrating the superiority of the new medicine over placebo. Women who were enrolled met criteria for major depressive disorder based on Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders criteria beginning in no earlier than the third trimester of pregnancy or later than 4 weeks of delivery. The two studies included a combined sample size of approximately 350 patients suffering from severe PPD. In the studies, women received either 50 mg or 40 mg of zuranolone, or placebo for 14 days. Treatment was associated with a significant change in the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale at day 15, and treatment response was maintained at day 42, which was 4 weeks after the last dose of study medication.

Zuranolone is a neuroactive steroid, which is taken orally, unlike brexanolone (Zulresso; Sage Therapeutics; Cambridge, Mass.), which requires intravenous administration. Zuranolone will be commercially available based on estimates around the fourth quarter of 2023. The most common side effects are drowsiness, dizziness, and sedation, and the FDA label will have a boxed warning about zuranolone’s potential to impact a person’s driving ability, and performance of potentially hazardous activities.

It is noteworthy that while this new medication received FDA approval for the PPD indication, it did not receive FDA approval for the treatment of major depressive disorder (MDD), and the agency issued a Complete Response Letter to the manufacturers noting their application did not provide substantial evidence of effectiveness in MDD. The FDA said in the Complete Response Letter that an additional study or studies will be needed; the manufacturers are currently evaluating next steps.

Where zuranolone fits into the treatment algorithm for severe PPD

Many clinicians who support women with PPD will wonder, upon hearing this news, where zuranolone fits into the treatment algorithm for severe postpartum major depression. Some relevant issues that may determine the answer are the following:

Cost. The cost of brexanolone was substantial, at $34,000 per year, and was viewed by some as a limiting factor in terms of its very limited uptake. As of this column’s publication, zuranolone’s manufacturer has not stated how much the medication will cost.

Breastfeeding. Unlike selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, which have been demonstrated to be effective for the treatment of PPD and safe during pregnancy and lactation, we have sparse data on the safety of zuranolone for women who wish to breastfeed. It is also unclear whether women eligible for zuranolone would, based on the limited data on safety in lactation, choose deferral of breastfeeding for 14 days in exchange for treatment.

Duration of treatment. While zuranolone was studied in the context of 14 days of acute treatment, then out to day 42, we have no published data on what happens on the other side of this brief interval. As a simple example, in a patient with a history of recurrent major depression previously treated with antidepressants, but where antidepressants were perhaps deferred during pregnancy, is PPD to be treated with zuranolone for 14 days? Or, hypothetically, should it be followed by empiric antidepressant treatment at day 14? Alternatively, are patient and clinician supposed to wait until recurrence occurs before pursuing adjunctive antidepressant therapy whether it is pharmacologic, nonpharmacologic, or both?

Treatment in patients with bipolar disorder. It is also unclear whether treatment with zuranolone applies to other populations of postpartum women. Certainly, for women with bipolar depression, which is common in postpartum women given the vulnerability of bipolar women to new onset of depression or postpartum depressive relapse of underlying disorder, we simply have no data regarding where zuranolone might fit in with respect to this group of patients.

The answers to these questions may help to determine whether zuranolone, a new antidepressant with efficacy, quick time to onset, and a novel mechanism of action is a “game changer.” The article in The Wall Street Journal provided me with some optimism, as it gave PPD and the issues surrounding PPD the attention it deserves in a major periodical. As a new treatment, it may help alleviate suffering at a critical time for patients and their families. We are inching closer to mitigation of stigma associated with this common illness.

Thinking back across the last 3 decades of my treating women suffering from PPD, I have reflected on what has gotten these patients well. I concluded that , along with family and community-based support groups, as well as a culture that reduces stigma and by so doing lessens the toll of this important and too frequently incompletely-treated illness.

Dr. Cohen is the director of the Ammon-Pinizzotto Center for Women’s Mental Health at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) in Boston, which provides information resources and conducts clinical care and research in reproductive mental health. He has been a consultant to manufacturers of psychiatric medications. The Center for Women’s Mental Health at MGH was a non-enrolling site for the pivotal phase 3 SKYLARK trial evaluating zuranolone. Full disclosure information for Dr. Cohen is available at womensmentalhealth.org. Email Dr. Cohen at [email protected].

Postpartum depression risk increased among sexual minority women

However, with sexual orientation highly underdocumented among women giving birth, understanding of the prevalence is lacking.

“To our knowledge, this cohort study was the first to examine perinatal depression screening and symptom endorsement among sexual minority women in a major medical center in the U.S.,” reported the authors of the study published in JAMA Psychiatry.

The results “highlight the need for investigations that include strategies for measuring sexual orientation because reliance on medical record review has substantial limitations with regard to the research questions and the validity of the data,” they noted.

Clinical guidelines recommend universal perinatal depression screening at obstetric and pediatric well-infant visits; however, there are significant gaps in data on the issue when it comes to sexual minority women.

To assess the prevalence of sexual minority people giving birth and compare perinatal depression screening rates and scores with those of heterosexual cisgender women, the authors conducted a review of medical records of 18,243 female patients who gave birth at a large, diverse, university-based medical center in Chicago between January and December of 2019.

Of the patients, 57.3% of whom were non-Hispanic White, 1.5% (280) had documentation of their sexual orientation, or sexual minority status.

The results show that those identified as being in sexual minorities, including lesbian, bisexual, queer, pansexual or asexual, were more likely than were heterosexual women to be more engaged in their care – they were more likely to have attended at least one prenatal visit (20.0% vs. 13.7%; P = .002) and at least one postpartum care visit (18.6% vs. 12.8%; P = .004), and more likely to be screened for depression during postpartum care (odds ratio, 1.77; P = .002).

Sexual minority women were also significantly more likely to screen positive for depression during the postpartum period than were heterosexual women (odds ratio, 2.38; P = .03); however, all other comparisons were not significantly different.

The finding regarding postpartum depression was consistent with recent literature, including a systematic review indicating that the stress of being in a sexual minority may be heightened during the postpartum period, the authors noted.

Reasons for the heightened stress may include “being perceived as inadequate parents, heteronormativity in perinatal care, such as intake forms asking for information about the child’s father, and lack of familial social support due to nonacceptance of the parents’ sexual orientation,” the researchers explained.

The rate of only 1.5% of people giving birth who identified as a sexual minority was significantly lower than expected, and much lower that the 17% reported in a recent nationally representative sample of women, first author Leiszle Lapping-Carr, PhD, director of the sexual and relationship health program, department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences, Northwestern University, Chicago, said in an interview.

“I did not expect a rate as low at 1.5%,” she said. “I anticipated it would not be as high as the 17%, but this was quite low. I think one primary reason is that women are not interested in disclosing their sexual orientation to their ob.gyns. if they don’t have to.”

Furthermore, Dr. Lapping-Carr said, “most medical systems do not have an easy way to document sexual orientation or gender identity, and even if it exists many physicians are unaware of the process.”

On a broader level, the lower rates may be indicative of a lack of acknowledgment of sexual minorities in the ob.gyn. setting, Dr. Lapping-Carr added.

“There is a heteronormative bias implicit in most obstetrics clinics, in which pregnant people are automatically gendered as women and assumed to be heterosexual, especially if they present with a male partner,” she said.

Because of those factors, even if a pregnant person discloses sexual identity, that person may request that it not be documented in the chart, she noted.

The higher rates of postpartum depression are consistent with higher rates of mental illness that are reported in general among sexual minority women, pregnant or not, including depression, anxiety, higher rates of substance abuse, stressful life events, and intimate partner violence, compared with heterosexual women, the authors noted.

Develop more supportive systems

To address postpartum depression among sexual minority women, Dr. Lapping-Carr suggested that clinicians generally start by avoiding language and behaviors that could suggest the potential bias that sexual minority patients can face.

“The main change [in treatment] that would likely be helpful for postpartum depression treatment is removing heteronormative language, e.g., not referring to partners as ‘fathers,’ ” she said.

Also, patients may benefit from “discussion of issues of relevance to people with sexual minority identities, such as the process of adoption for female non-birthing partners,” Dr. Lapping-Carr added.

“Starting to create spaces that are inclusive and welcoming for people of all identities will go a long way in increasing your patient’s trust in you,” she said.

While there is a lack of published data regarding increases in rates of sexual minority patients who are giving birth, societal trends suggest the rates may likely be on the rise, Dr. Lapping-Carr said.

“We do know that among adolescents, endorsement of sexual and gender minority identities is much higher than in previous generations, so it would follow that the proportion of birthing people with sexual and gender minority identities would also increase,” she said.

Commenting on the study, K. Ashley Brandt, DO, obstetrics section chief and medical director of Gender Affirming Surgery at Reading Hospital, in West Reading, Pa., noted that limitations include a lack of information about the bigger picture of patients’ risk factors.

“There is no documentation of other risks factors, including rates of depression in the antenatal period, which is higher in LGBTQ individuals and also a risk factor for postpartum depression,” Dr. Brandt told this news organization.

She agreed, however, that patients may be reluctant to report their sexual minority status on the record – but such issues are often addressed.

“I believe that obstetricians do ask this question far more than other providers, but it may not be easily captured in medical records, and patients may also hesitate to disclose sexual practices and sexual orientation due to fear of medical discrimination, which is still extremely prevalent,” Dr. Brandt said.

The study underscores, however, that “same-sex parents are a reality that providers will face,” she said. “They have unique social determinants for health that often go undocumented and unaddressed, which could contribute to higher rates of depression in the postpartum period.”

Factors that may be ignored or undocumented, such as sexual minorities’ religious beliefs or social and familial support, can play significant roles in health care outcomes, Dr. Brandt added.

“Providers need to find ways to better educate themselves about LGBTQ individuals and develop more supportive systems to ensure patients feel safe in disclosing their identities.”

The authors and Dr. Brandt had no disclosures to report.

However, with sexual orientation highly underdocumented among women giving birth, understanding of the prevalence is lacking.

“To our knowledge, this cohort study was the first to examine perinatal depression screening and symptom endorsement among sexual minority women in a major medical center in the U.S.,” reported the authors of the study published in JAMA Psychiatry.

The results “highlight the need for investigations that include strategies for measuring sexual orientation because reliance on medical record review has substantial limitations with regard to the research questions and the validity of the data,” they noted.

Clinical guidelines recommend universal perinatal depression screening at obstetric and pediatric well-infant visits; however, there are significant gaps in data on the issue when it comes to sexual minority women.

To assess the prevalence of sexual minority people giving birth and compare perinatal depression screening rates and scores with those of heterosexual cisgender women, the authors conducted a review of medical records of 18,243 female patients who gave birth at a large, diverse, university-based medical center in Chicago between January and December of 2019.

Of the patients, 57.3% of whom were non-Hispanic White, 1.5% (280) had documentation of their sexual orientation, or sexual minority status.

The results show that those identified as being in sexual minorities, including lesbian, bisexual, queer, pansexual or asexual, were more likely than were heterosexual women to be more engaged in their care – they were more likely to have attended at least one prenatal visit (20.0% vs. 13.7%; P = .002) and at least one postpartum care visit (18.6% vs. 12.8%; P = .004), and more likely to be screened for depression during postpartum care (odds ratio, 1.77; P = .002).

Sexual minority women were also significantly more likely to screen positive for depression during the postpartum period than were heterosexual women (odds ratio, 2.38; P = .03); however, all other comparisons were not significantly different.

The finding regarding postpartum depression was consistent with recent literature, including a systematic review indicating that the stress of being in a sexual minority may be heightened during the postpartum period, the authors noted.

Reasons for the heightened stress may include “being perceived as inadequate parents, heteronormativity in perinatal care, such as intake forms asking for information about the child’s father, and lack of familial social support due to nonacceptance of the parents’ sexual orientation,” the researchers explained.

The rate of only 1.5% of people giving birth who identified as a sexual minority was significantly lower than expected, and much lower that the 17% reported in a recent nationally representative sample of women, first author Leiszle Lapping-Carr, PhD, director of the sexual and relationship health program, department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences, Northwestern University, Chicago, said in an interview.

“I did not expect a rate as low at 1.5%,” she said. “I anticipated it would not be as high as the 17%, but this was quite low. I think one primary reason is that women are not interested in disclosing their sexual orientation to their ob.gyns. if they don’t have to.”

Furthermore, Dr. Lapping-Carr said, “most medical systems do not have an easy way to document sexual orientation or gender identity, and even if it exists many physicians are unaware of the process.”

On a broader level, the lower rates may be indicative of a lack of acknowledgment of sexual minorities in the ob.gyn. setting, Dr. Lapping-Carr added.

“There is a heteronormative bias implicit in most obstetrics clinics, in which pregnant people are automatically gendered as women and assumed to be heterosexual, especially if they present with a male partner,” she said.