User login

Gestational diabetes may increase child’s risk of glucose intolerance

Obese children may have a higher risk of developing type 2 diabetes if their mothers had gestational diabetes during pregnancy, according to a recent study.

"The ever growing number of women with gestational diabetes (18%) suggests that the future will be filled with children with early diabetes at a rate that far exceeds the current prevalence," wrote Tara Holder of Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and her associates in Diabetologia.

"Offspring of GDM [gestational diabetes mellitus] mothers ought to be screened for impaired glucose tolerance and/or impaired fasting glucose, and preventive and therapeutic strategies should be considered before the development of full clinical manifestation of diabetes," the researchers reported online (Diabetologia 2014 Aug. 29 [doi: 10.1007/s00125-014-3345-2]).

The investigators conducted an oral glucose tolerance test to establish normal glucose tolerance among 210 obese teens who had not been exposed to GDM and 45 obese teens who had been exposed. Then they conducted another OGTT at an average follow-up of 2.8 years later.

A fasting glucose level of less than 5.55 mmol/L and a 2-hour glucose level of less than 7.77 mmol/L were defined as normal glucose tolerance. A fasting glucose of 5.55-6.88 mmol/L was considered impaired, and a fasting glucose greater than 6.88 mmol/ L or a 2-hour glucose greater than 11.05 mmol/L was designated type 2 diabetes.

At follow-up, 91.4% of the teens not exposed to GDM had normal glucose tolerance, compared with 68.9% of the teens exposed to GDM. Therefore, 8.6% of those not exposed to GDM and 31.1% of those exposed to GDM had developed either impaired glucose tolerance or type 2 diabetes.

The research and researchers were supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Science, the Yale Diabetes Endocrinology Research Center, the European Society of Pediatric Endocrinology, the American Heart Association, the Stephen Morse Diabetes Research Foundation, the National Institutes of Health, and the American Diabetes Association. The authors had no disclosures.

The study by Holder et al. confirms previous findings that a child’s exposure to maternal GDM can predispose him or her to developing impaired glucose tolerance or type 2 diabetes later in life. Seminal work by David Pettitt and Peter Bennett, who studied the Pima Indians in Arizona, showed that a child born to a mother without GDM and a child born to the same mother with GDM had different susceptibilities to developing metabolic disease. They found that the child exposed to GDM had a higher likelihood of developing diabetes.

The findings of Holder et al. reinforce the idea that maternal health can greatly influence the long-term health of her offspring. It is conceivable that diabetes may "imprint" information onto the islet cells of the developing fetus, thereby resulting in the reduced beta-cell function and reduced insulin sensitivity observed by the investigators. Although it remains to be elucidated, it is not unlikely that there are diabetes susceptibility genes, which women may pass on to their offspring. If so, this could explain why only some children of GDM mothers develop impaired glucose tolerance or type 2 diabetes mellitus while others do not.

|

|

Counseling children of diabetic mothers on the importance of a healthy lifestyle, maintaining an ideal weight, consuming a balanced diet, and getting enough physical exercise could reduce their risk of future metabolic disease. Because the exposure to maternal hyperglycemia cannot be reversed, it is vital that children of GDM mothers take steps needed to reduce their risks of developing diabetes.

Dr. E. Albert Reece, M.D., Ph.D., M.B.A., is the Vice President for Medical Affairs at the University of Maryland, Dean of the School of Medicine, and the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor in Obstetrics and Gynecology. He made these comments in an interview. Dr. Reece had no relevant financial disclosures.

The study by Holder et al. confirms previous findings that a child’s exposure to maternal GDM can predispose him or her to developing impaired glucose tolerance or type 2 diabetes later in life. Seminal work by David Pettitt and Peter Bennett, who studied the Pima Indians in Arizona, showed that a child born to a mother without GDM and a child born to the same mother with GDM had different susceptibilities to developing metabolic disease. They found that the child exposed to GDM had a higher likelihood of developing diabetes.

The findings of Holder et al. reinforce the idea that maternal health can greatly influence the long-term health of her offspring. It is conceivable that diabetes may "imprint" information onto the islet cells of the developing fetus, thereby resulting in the reduced beta-cell function and reduced insulin sensitivity observed by the investigators. Although it remains to be elucidated, it is not unlikely that there are diabetes susceptibility genes, which women may pass on to their offspring. If so, this could explain why only some children of GDM mothers develop impaired glucose tolerance or type 2 diabetes mellitus while others do not.

|

|

Counseling children of diabetic mothers on the importance of a healthy lifestyle, maintaining an ideal weight, consuming a balanced diet, and getting enough physical exercise could reduce their risk of future metabolic disease. Because the exposure to maternal hyperglycemia cannot be reversed, it is vital that children of GDM mothers take steps needed to reduce their risks of developing diabetes.

Dr. E. Albert Reece, M.D., Ph.D., M.B.A., is the Vice President for Medical Affairs at the University of Maryland, Dean of the School of Medicine, and the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor in Obstetrics and Gynecology. He made these comments in an interview. Dr. Reece had no relevant financial disclosures.

The study by Holder et al. confirms previous findings that a child’s exposure to maternal GDM can predispose him or her to developing impaired glucose tolerance or type 2 diabetes later in life. Seminal work by David Pettitt and Peter Bennett, who studied the Pima Indians in Arizona, showed that a child born to a mother without GDM and a child born to the same mother with GDM had different susceptibilities to developing metabolic disease. They found that the child exposed to GDM had a higher likelihood of developing diabetes.

The findings of Holder et al. reinforce the idea that maternal health can greatly influence the long-term health of her offspring. It is conceivable that diabetes may "imprint" information onto the islet cells of the developing fetus, thereby resulting in the reduced beta-cell function and reduced insulin sensitivity observed by the investigators. Although it remains to be elucidated, it is not unlikely that there are diabetes susceptibility genes, which women may pass on to their offspring. If so, this could explain why only some children of GDM mothers develop impaired glucose tolerance or type 2 diabetes mellitus while others do not.

|

|

Counseling children of diabetic mothers on the importance of a healthy lifestyle, maintaining an ideal weight, consuming a balanced diet, and getting enough physical exercise could reduce their risk of future metabolic disease. Because the exposure to maternal hyperglycemia cannot be reversed, it is vital that children of GDM mothers take steps needed to reduce their risks of developing diabetes.

Dr. E. Albert Reece, M.D., Ph.D., M.B.A., is the Vice President for Medical Affairs at the University of Maryland, Dean of the School of Medicine, and the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor in Obstetrics and Gynecology. He made these comments in an interview. Dr. Reece had no relevant financial disclosures.

Obese children may have a higher risk of developing type 2 diabetes if their mothers had gestational diabetes during pregnancy, according to a recent study.

"The ever growing number of women with gestational diabetes (18%) suggests that the future will be filled with children with early diabetes at a rate that far exceeds the current prevalence," wrote Tara Holder of Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and her associates in Diabetologia.

"Offspring of GDM [gestational diabetes mellitus] mothers ought to be screened for impaired glucose tolerance and/or impaired fasting glucose, and preventive and therapeutic strategies should be considered before the development of full clinical manifestation of diabetes," the researchers reported online (Diabetologia 2014 Aug. 29 [doi: 10.1007/s00125-014-3345-2]).

The investigators conducted an oral glucose tolerance test to establish normal glucose tolerance among 210 obese teens who had not been exposed to GDM and 45 obese teens who had been exposed. Then they conducted another OGTT at an average follow-up of 2.8 years later.

A fasting glucose level of less than 5.55 mmol/L and a 2-hour glucose level of less than 7.77 mmol/L were defined as normal glucose tolerance. A fasting glucose of 5.55-6.88 mmol/L was considered impaired, and a fasting glucose greater than 6.88 mmol/ L or a 2-hour glucose greater than 11.05 mmol/L was designated type 2 diabetes.

At follow-up, 91.4% of the teens not exposed to GDM had normal glucose tolerance, compared with 68.9% of the teens exposed to GDM. Therefore, 8.6% of those not exposed to GDM and 31.1% of those exposed to GDM had developed either impaired glucose tolerance or type 2 diabetes.

The research and researchers were supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Science, the Yale Diabetes Endocrinology Research Center, the European Society of Pediatric Endocrinology, the American Heart Association, the Stephen Morse Diabetes Research Foundation, the National Institutes of Health, and the American Diabetes Association. The authors had no disclosures.

Obese children may have a higher risk of developing type 2 diabetes if their mothers had gestational diabetes during pregnancy, according to a recent study.

"The ever growing number of women with gestational diabetes (18%) suggests that the future will be filled with children with early diabetes at a rate that far exceeds the current prevalence," wrote Tara Holder of Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and her associates in Diabetologia.

"Offspring of GDM [gestational diabetes mellitus] mothers ought to be screened for impaired glucose tolerance and/or impaired fasting glucose, and preventive and therapeutic strategies should be considered before the development of full clinical manifestation of diabetes," the researchers reported online (Diabetologia 2014 Aug. 29 [doi: 10.1007/s00125-014-3345-2]).

The investigators conducted an oral glucose tolerance test to establish normal glucose tolerance among 210 obese teens who had not been exposed to GDM and 45 obese teens who had been exposed. Then they conducted another OGTT at an average follow-up of 2.8 years later.

A fasting glucose level of less than 5.55 mmol/L and a 2-hour glucose level of less than 7.77 mmol/L were defined as normal glucose tolerance. A fasting glucose of 5.55-6.88 mmol/L was considered impaired, and a fasting glucose greater than 6.88 mmol/ L or a 2-hour glucose greater than 11.05 mmol/L was designated type 2 diabetes.

At follow-up, 91.4% of the teens not exposed to GDM had normal glucose tolerance, compared with 68.9% of the teens exposed to GDM. Therefore, 8.6% of those not exposed to GDM and 31.1% of those exposed to GDM had developed either impaired glucose tolerance or type 2 diabetes.

The research and researchers were supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Science, the Yale Diabetes Endocrinology Research Center, the European Society of Pediatric Endocrinology, the American Heart Association, the Stephen Morse Diabetes Research Foundation, the National Institutes of Health, and the American Diabetes Association. The authors had no disclosures.

FROM DIABETOLOGIA

Key clinical point: Children whose mothers had gestational diabetes should be screened for impaired glucose tolerance and preventive strategies taught to forestall type 2 diabetes.

Major finding: A total of 31.1% of obese teens exposed to GDM had developed either impaired glucose tolerance or type 2 diabetes at follow-up, compared with 8.6% of those not exposed to GDM.

Data source: The findings are based on a cohort study of 255 obese adolescents followed for a mean 2.8 years.

Disclosures: The research and researchers were supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Science, the Yale Diabetes Endocrinology Research Center, the European Society of Pediatric Endocrinology, the American Heart Association, the Stephen Morse Diabetes Research Foundation, the National Institutes of Health, and the American Diabetes Association. The authors had no disclosures.

Was fetus’ wrist injured during cesarean delivery?

Was fetus’ wrist injured during cesarean delivery?

At 34 weeks’ gestation, a 39-year-old woman went to the hospital in preterm labor. Her history included a prior cesarean delivery. Ultrasonography (US) showed that the fetus was in a double-footling breech position. The ObGyn decided to perform a cesarean delivery when the fetal heart-rate monitor indicated distress.

After making a midline incision through the earlier scar, the ObGyn created a low transverse uterine incision with a scalpel. The mother’s uterus was thick because labor had not progressed. When the ObGyn was unable to deliver the baby through the low transverse incision, she performed a T-extension of the incision using bandage scissors while placing her free hand inside the uterus to shield the fetus from injury. After extensive manipulation, the baby was delivered and immediately handed to a neonatologist. After surgery, the neonatologist told the mother that the baby had sustained two lacerations to the ulnar side of the right wrist. The newborn was airlifted to another hospital for treatment of sepsis. There, an orthopedic hand surgeon examined the child and determined that the lacerations were superficial and only required sutures. The orthopedist saw the infant a month later and believed there was no significant wrist injury.

When the child began preschool, she started to experience cold intolerance and difficulty writing with her right hand. The child was referred to a pediatric neurologist, who found no nerve damage and ordered occupational therapy.

The original orthopedic surgeon examined the child when she was 7 years old and determined that the flexor carpi ulnaris tendon had been completely severed with a partial injury to the ulnar nerve. He recommended a return visit at age 14 for full assessment of the wrist injury.

PARENTS’ CLAIM The ObGyn did not properly shield the fetus when performing the T-extension incision during cesarean delivery. The child’s weakness will increase with age, ruling out some occupations.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE The ObGyn was not negligent; she had provided adequate protection of the fetus during both incisions.

VERDICT An Illinois defense verdict was returned.

Woman dies after tubal ligation

After a 42-year-old woman underwent tubal ligation, her surgeon was concerned about a possible bowel perforation and admitted her to the hospital. The next morning, a computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen did not reveal bowel injury.

That afternoon, when the patient reported shortness of breath, the surgeon called the hospitalist with concern for pulmonary embolism (PE). The hospitalist immediately ordered a CT scan of the chest, initiated PE protocol, and wrote “r/o PE” on the chart. A radiologist reminded the hospitalist of the earlier CT scan with concern for kidney damage from another dye study. The hospitalist cancelled the CT scan and PE protocol. After waiting 17 hours to run any further tests, a CT scan revealed massive bilateral PE. The patient was transferred to the ICU, but died the next day.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The 17-hour delay was negligent.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE There was no negligence. The patient died of septic shock, not PE.

VERDICT A $4 million Virginia verdict was returned.

Child born without hand and forearm

During prenatal care, a mother underwent US at 20 and 36 weeks; both studies were reported as normal. The child was born missing his left hand and part of his left forearm due to a congenital amputation. The child will require prosthetics for life.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The condition should have been seen during prenatal US; an abortion was still an option at 20 weeks.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE US was properly performed and evaluated. It can be difficult to differentiate the right from left extremities.

VERDICT A California defense verdict was returned.

After starting Yasmin, woman has stroke with permanent paralysis: $16.5M total award

When a 37-year-old woman reported irregular menstruation, her ObGyn prescribed drospirenone/ethinyl estradiol (Yasmin; Bayer). Thirteen days after starting the drug, the patient had a stroke. She is paralyzed on her left side, has limited ability to speak, cannot use her left arm and leg, and requires 24-hour care.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The ObGyn should have recognized that Yasmin was not appropriate for this patient because of the drug’s clotting risks. The patient’s risk factors included her age (over 35), borderline hypertension, overweight, history of smoking, and high cholesterol. The ObGyn should have offered safer alternatives, such as a progesterone-only pill. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued a safety warning that all drospirenone-containing drugs may be associated with a higher risk of venous thrombosis during the first 6 months of use.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE According to Bayer, Yasmin is safe, and remains on the market. It was an appropriate drug to treat her irregular bleeding.

VERDICT Claims against the medical center that referred the patient to the ObGyn were settled for $2.5 million before trial. A $14 million Illinois verdict was returned against the ObGyn, for a total award of $16.5 million.

Who is at fault when pelvic mesh erodes?

In January 2011, an ObGyn implanted the Gynecare TVT Obturator System (TVT‑O; Ethicon) during a midurethral sling procedure to treat stress urinary incontinence (SUI) in a woman in her 60s. Shortly thereafter, the ObGyn left practice because of early-onset Alzheimer’s disease, and the patient’s care was taken over by a gynecologist.

At the 2-month postoperative visit, the gynecologist found that the mesh had eroded into the patient’s vagina. The gynecologist simply cut the mesh with a scissor, charted that a small erosion was present, and prescribed estrogen cream.

The patient continued to report pain, discomfort, pressure, difficulty voiding urine, continued incontinence, vaginal discharge, scarring, infection, odor, and bleeding.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The polypropylene mesh used during the midurethral sling procedure has been shown to be incompatible with human tissue. It promotes an immune response, which stimulates degradation of the pelvic tissue and can contribute to the development of severe adverse reactions to the mesh. Ethicon negligently designed, manufactured, marketed, labeled, and packaged the pelvic mesh products.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE Proper warnings were provided about the health risks associated with polypropylene mesh products. The medical device was not properly sized.

VERDICT A Texas jury rejected the patient’s claims that Ethicon did not provide proper warnings about the sling’s health risks and declined to award punitive damages.

However, the jury decided that the mesh implant was defectively designed, and returned a $1.2 million verdict against Ethicon.

Was suspected bowel injury treated properly?

A 40-year-old woman was referred to an ObGyn after reporting abnormal uterine bleeding to her primary care physician. The patient had very light menses every few weeks. The ObGyn performed an ablation procedure, without relief. A month later, the ObGyn performed robot-assisted laparoscopic hysterectomy. The next day, the patient reported abdominal pain. Suspecting a bowel injury, the ObGyn ordered a CT scan; the bowel appeared normal, so the ObGyn referred the patient to a surgeon. During exploratory laparotomy, the surgeon found and repaired a bowel injury. The patient developed significant complications from a necrotizing infection that included respiratory distress and ongoing wound care.

PATIENT’S CLAIM Conservative treatment should have been offered before surgery. The ObGyn should have waited longer after the ablation procedure before doing the hysterectomy. The ObGyn should have checked for a possible bowel injury before closing the hysterectomy.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE The bowel injury is a known complication of the procedure and was recognized and repaired in a timely manner.

VERDICT A Kentucky defense verdict was returned.

Pap smear improperly interpreted: Woman dies from cervical cancer

A 37-year-old woman underwent a pap smear in 2008 that was read by a cytotechnologist as normal. Two years later, the patient was found to have a golf-ball–sized cancerous tumor. She died from cervical cancer in 2011.

ESTATE’S CLAIM The cytotechnologist was negligent in misreading the 2008 Pap smear. If treatment had been started in 2008, the cancer could have been resolved with a simple conization biopsy.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE The Pap smear interpretation was reasonable. The cancer could not have been diagnosed in 2008. The patient was at fault for failing to follow-up Pap smears during the next 2 years.

VERDICT After assigning 75% fault to the cytotechnologist and 25% fault to the patient, a Florida jury returned a $20,870,200 verdict, which was reduced to $15,816,699.

Disastrous off-label use of anticoagulation

When a pelvic abscess was found, a 50-year-old woman was admitted to the hospital for treatment. She was taking warfarin due to a history of venous thromboembolism.

Before the procedure, her physicians attempted to temporarily reverse her anticoagulation by administering Factor IX Complex (Profilnine SD, Grifols Biologicals). The dose ordered for the patient was nearly double the maximum recommended weight-based dose. Almost immediately after receiving the infusion, the patient went into cardiopulmonary arrest and died. An autopsy found the cause of death to be pulmonary emboli (PE).

ESTATE’S CLAIM An excessive dose of Profilnine caused PE. At the time of the incident, Profilnine was not FDA approved for warfarin reversal, although some off-label uses were recognized in emergent situations, such as intracranial bleeds.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE The case was settled during the trial.

VERDICT A $1.25 million Virginia settlement was reached.

Vesicovaginal fistula from ureteral injury

At a women’s health clinic, a patient reported continuous, heavy vaginal bleeding; pain; and shortness of breath when walking. She had a history of endometritis and multiple abdominal surgeries. Examination disclosed a profuse vaginal discharge, a normal cervix, and an enlarged uterus. The patient consented to abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy performed by an ObGyn assisted by a resident.

During surgery, the ObGyn found that the patient’s uterus was at 16 to 20 weeks’ gestation size, with multiple serosal uterine fibroids and frank pus and necrosed fibroid tumors within the uterine cavity. The procedure took longer than planned because of extensive adhesions. After surgery, the patient was anemic and was given a beta-blocker for tachycardia. She was discharged 3 days later with 48 hours’ worth of intravenous antibiotics.

A month later, the patient reported urinary incontinence. She saw a urologist, who found a vesicovaginal fistula. The patient underwent nephrostomy-tube placement. Right ureterolysis and a right ureteral reimplant was performed 4 months later.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The ObGyn injured the right ureter during surgery.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE The ureter injury is a known risk of the procedure. The injury was due to an infection or delayed effects of ischemia. The patient had a good recovery with no residual injury.

VERDICT A Michigan defense verdict was returned.

Why did mother die after delivering twins?

After a 35-year-old woman gave birth to twins by cesarean delivery, she died. At autopsy, 4 liters of blood were found in her abdomen.

ESTATE’S CLAIM The ObGyn failed to recognize and treat an arterial or venous bleed during surgery.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE The patient died from amniotic fluid embolism. Autopsy results showed right ventricular heart failure, respiratory failure, and disseminated intravascular coagulation.

VERDICT A Florida defense verdict was returned.

These cases were selected by the editors of OBG Management from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements & Experts, with permission of the editor, Lewis Laska (www.verdictslaska.com). The information available to the editors about the cases presented here is sometimes incomplete. Moreover, the cases may or may not have merit. Nevertheless, these cases represent the types of clinical situations that typically result in litigation and are meant to illustrate nationwide variation in jury verdicts and awards.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Was fetus’ wrist injured during cesarean delivery?

At 34 weeks’ gestation, a 39-year-old woman went to the hospital in preterm labor. Her history included a prior cesarean delivery. Ultrasonography (US) showed that the fetus was in a double-footling breech position. The ObGyn decided to perform a cesarean delivery when the fetal heart-rate monitor indicated distress.

After making a midline incision through the earlier scar, the ObGyn created a low transverse uterine incision with a scalpel. The mother’s uterus was thick because labor had not progressed. When the ObGyn was unable to deliver the baby through the low transverse incision, she performed a T-extension of the incision using bandage scissors while placing her free hand inside the uterus to shield the fetus from injury. After extensive manipulation, the baby was delivered and immediately handed to a neonatologist. After surgery, the neonatologist told the mother that the baby had sustained two lacerations to the ulnar side of the right wrist. The newborn was airlifted to another hospital for treatment of sepsis. There, an orthopedic hand surgeon examined the child and determined that the lacerations were superficial and only required sutures. The orthopedist saw the infant a month later and believed there was no significant wrist injury.

When the child began preschool, she started to experience cold intolerance and difficulty writing with her right hand. The child was referred to a pediatric neurologist, who found no nerve damage and ordered occupational therapy.

The original orthopedic surgeon examined the child when she was 7 years old and determined that the flexor carpi ulnaris tendon had been completely severed with a partial injury to the ulnar nerve. He recommended a return visit at age 14 for full assessment of the wrist injury.

PARENTS’ CLAIM The ObGyn did not properly shield the fetus when performing the T-extension incision during cesarean delivery. The child’s weakness will increase with age, ruling out some occupations.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE The ObGyn was not negligent; she had provided adequate protection of the fetus during both incisions.

VERDICT An Illinois defense verdict was returned.

Woman dies after tubal ligation

After a 42-year-old woman underwent tubal ligation, her surgeon was concerned about a possible bowel perforation and admitted her to the hospital. The next morning, a computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen did not reveal bowel injury.

That afternoon, when the patient reported shortness of breath, the surgeon called the hospitalist with concern for pulmonary embolism (PE). The hospitalist immediately ordered a CT scan of the chest, initiated PE protocol, and wrote “r/o PE” on the chart. A radiologist reminded the hospitalist of the earlier CT scan with concern for kidney damage from another dye study. The hospitalist cancelled the CT scan and PE protocol. After waiting 17 hours to run any further tests, a CT scan revealed massive bilateral PE. The patient was transferred to the ICU, but died the next day.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The 17-hour delay was negligent.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE There was no negligence. The patient died of septic shock, not PE.

VERDICT A $4 million Virginia verdict was returned.

Child born without hand and forearm

During prenatal care, a mother underwent US at 20 and 36 weeks; both studies were reported as normal. The child was born missing his left hand and part of his left forearm due to a congenital amputation. The child will require prosthetics for life.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The condition should have been seen during prenatal US; an abortion was still an option at 20 weeks.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE US was properly performed and evaluated. It can be difficult to differentiate the right from left extremities.

VERDICT A California defense verdict was returned.

After starting Yasmin, woman has stroke with permanent paralysis: $16.5M total award

When a 37-year-old woman reported irregular menstruation, her ObGyn prescribed drospirenone/ethinyl estradiol (Yasmin; Bayer). Thirteen days after starting the drug, the patient had a stroke. She is paralyzed on her left side, has limited ability to speak, cannot use her left arm and leg, and requires 24-hour care.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The ObGyn should have recognized that Yasmin was not appropriate for this patient because of the drug’s clotting risks. The patient’s risk factors included her age (over 35), borderline hypertension, overweight, history of smoking, and high cholesterol. The ObGyn should have offered safer alternatives, such as a progesterone-only pill. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued a safety warning that all drospirenone-containing drugs may be associated with a higher risk of venous thrombosis during the first 6 months of use.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE According to Bayer, Yasmin is safe, and remains on the market. It was an appropriate drug to treat her irregular bleeding.

VERDICT Claims against the medical center that referred the patient to the ObGyn were settled for $2.5 million before trial. A $14 million Illinois verdict was returned against the ObGyn, for a total award of $16.5 million.

Who is at fault when pelvic mesh erodes?

In January 2011, an ObGyn implanted the Gynecare TVT Obturator System (TVT‑O; Ethicon) during a midurethral sling procedure to treat stress urinary incontinence (SUI) in a woman in her 60s. Shortly thereafter, the ObGyn left practice because of early-onset Alzheimer’s disease, and the patient’s care was taken over by a gynecologist.

At the 2-month postoperative visit, the gynecologist found that the mesh had eroded into the patient’s vagina. The gynecologist simply cut the mesh with a scissor, charted that a small erosion was present, and prescribed estrogen cream.

The patient continued to report pain, discomfort, pressure, difficulty voiding urine, continued incontinence, vaginal discharge, scarring, infection, odor, and bleeding.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The polypropylene mesh used during the midurethral sling procedure has been shown to be incompatible with human tissue. It promotes an immune response, which stimulates degradation of the pelvic tissue and can contribute to the development of severe adverse reactions to the mesh. Ethicon negligently designed, manufactured, marketed, labeled, and packaged the pelvic mesh products.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE Proper warnings were provided about the health risks associated with polypropylene mesh products. The medical device was not properly sized.

VERDICT A Texas jury rejected the patient’s claims that Ethicon did not provide proper warnings about the sling’s health risks and declined to award punitive damages.

However, the jury decided that the mesh implant was defectively designed, and returned a $1.2 million verdict against Ethicon.

Was suspected bowel injury treated properly?

A 40-year-old woman was referred to an ObGyn after reporting abnormal uterine bleeding to her primary care physician. The patient had very light menses every few weeks. The ObGyn performed an ablation procedure, without relief. A month later, the ObGyn performed robot-assisted laparoscopic hysterectomy. The next day, the patient reported abdominal pain. Suspecting a bowel injury, the ObGyn ordered a CT scan; the bowel appeared normal, so the ObGyn referred the patient to a surgeon. During exploratory laparotomy, the surgeon found and repaired a bowel injury. The patient developed significant complications from a necrotizing infection that included respiratory distress and ongoing wound care.

PATIENT’S CLAIM Conservative treatment should have been offered before surgery. The ObGyn should have waited longer after the ablation procedure before doing the hysterectomy. The ObGyn should have checked for a possible bowel injury before closing the hysterectomy.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE The bowel injury is a known complication of the procedure and was recognized and repaired in a timely manner.

VERDICT A Kentucky defense verdict was returned.

Pap smear improperly interpreted: Woman dies from cervical cancer

A 37-year-old woman underwent a pap smear in 2008 that was read by a cytotechnologist as normal. Two years later, the patient was found to have a golf-ball–sized cancerous tumor. She died from cervical cancer in 2011.

ESTATE’S CLAIM The cytotechnologist was negligent in misreading the 2008 Pap smear. If treatment had been started in 2008, the cancer could have been resolved with a simple conization biopsy.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE The Pap smear interpretation was reasonable. The cancer could not have been diagnosed in 2008. The patient was at fault for failing to follow-up Pap smears during the next 2 years.

VERDICT After assigning 75% fault to the cytotechnologist and 25% fault to the patient, a Florida jury returned a $20,870,200 verdict, which was reduced to $15,816,699.

Disastrous off-label use of anticoagulation

When a pelvic abscess was found, a 50-year-old woman was admitted to the hospital for treatment. She was taking warfarin due to a history of venous thromboembolism.

Before the procedure, her physicians attempted to temporarily reverse her anticoagulation by administering Factor IX Complex (Profilnine SD, Grifols Biologicals). The dose ordered for the patient was nearly double the maximum recommended weight-based dose. Almost immediately after receiving the infusion, the patient went into cardiopulmonary arrest and died. An autopsy found the cause of death to be pulmonary emboli (PE).

ESTATE’S CLAIM An excessive dose of Profilnine caused PE. At the time of the incident, Profilnine was not FDA approved for warfarin reversal, although some off-label uses were recognized in emergent situations, such as intracranial bleeds.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE The case was settled during the trial.

VERDICT A $1.25 million Virginia settlement was reached.

Vesicovaginal fistula from ureteral injury

At a women’s health clinic, a patient reported continuous, heavy vaginal bleeding; pain; and shortness of breath when walking. She had a history of endometritis and multiple abdominal surgeries. Examination disclosed a profuse vaginal discharge, a normal cervix, and an enlarged uterus. The patient consented to abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy performed by an ObGyn assisted by a resident.

During surgery, the ObGyn found that the patient’s uterus was at 16 to 20 weeks’ gestation size, with multiple serosal uterine fibroids and frank pus and necrosed fibroid tumors within the uterine cavity. The procedure took longer than planned because of extensive adhesions. After surgery, the patient was anemic and was given a beta-blocker for tachycardia. She was discharged 3 days later with 48 hours’ worth of intravenous antibiotics.

A month later, the patient reported urinary incontinence. She saw a urologist, who found a vesicovaginal fistula. The patient underwent nephrostomy-tube placement. Right ureterolysis and a right ureteral reimplant was performed 4 months later.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The ObGyn injured the right ureter during surgery.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE The ureter injury is a known risk of the procedure. The injury was due to an infection or delayed effects of ischemia. The patient had a good recovery with no residual injury.

VERDICT A Michigan defense verdict was returned.

Why did mother die after delivering twins?

After a 35-year-old woman gave birth to twins by cesarean delivery, she died. At autopsy, 4 liters of blood were found in her abdomen.

ESTATE’S CLAIM The ObGyn failed to recognize and treat an arterial or venous bleed during surgery.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE The patient died from amniotic fluid embolism. Autopsy results showed right ventricular heart failure, respiratory failure, and disseminated intravascular coagulation.

VERDICT A Florida defense verdict was returned.

These cases were selected by the editors of OBG Management from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements & Experts, with permission of the editor, Lewis Laska (www.verdictslaska.com). The information available to the editors about the cases presented here is sometimes incomplete. Moreover, the cases may or may not have merit. Nevertheless, these cases represent the types of clinical situations that typically result in litigation and are meant to illustrate nationwide variation in jury verdicts and awards.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Was fetus’ wrist injured during cesarean delivery?

At 34 weeks’ gestation, a 39-year-old woman went to the hospital in preterm labor. Her history included a prior cesarean delivery. Ultrasonography (US) showed that the fetus was in a double-footling breech position. The ObGyn decided to perform a cesarean delivery when the fetal heart-rate monitor indicated distress.

After making a midline incision through the earlier scar, the ObGyn created a low transverse uterine incision with a scalpel. The mother’s uterus was thick because labor had not progressed. When the ObGyn was unable to deliver the baby through the low transverse incision, she performed a T-extension of the incision using bandage scissors while placing her free hand inside the uterus to shield the fetus from injury. After extensive manipulation, the baby was delivered and immediately handed to a neonatologist. After surgery, the neonatologist told the mother that the baby had sustained two lacerations to the ulnar side of the right wrist. The newborn was airlifted to another hospital for treatment of sepsis. There, an orthopedic hand surgeon examined the child and determined that the lacerations were superficial and only required sutures. The orthopedist saw the infant a month later and believed there was no significant wrist injury.

When the child began preschool, she started to experience cold intolerance and difficulty writing with her right hand. The child was referred to a pediatric neurologist, who found no nerve damage and ordered occupational therapy.

The original orthopedic surgeon examined the child when she was 7 years old and determined that the flexor carpi ulnaris tendon had been completely severed with a partial injury to the ulnar nerve. He recommended a return visit at age 14 for full assessment of the wrist injury.

PARENTS’ CLAIM The ObGyn did not properly shield the fetus when performing the T-extension incision during cesarean delivery. The child’s weakness will increase with age, ruling out some occupations.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE The ObGyn was not negligent; she had provided adequate protection of the fetus during both incisions.

VERDICT An Illinois defense verdict was returned.

Woman dies after tubal ligation

After a 42-year-old woman underwent tubal ligation, her surgeon was concerned about a possible bowel perforation and admitted her to the hospital. The next morning, a computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen did not reveal bowel injury.

That afternoon, when the patient reported shortness of breath, the surgeon called the hospitalist with concern for pulmonary embolism (PE). The hospitalist immediately ordered a CT scan of the chest, initiated PE protocol, and wrote “r/o PE” on the chart. A radiologist reminded the hospitalist of the earlier CT scan with concern for kidney damage from another dye study. The hospitalist cancelled the CT scan and PE protocol. After waiting 17 hours to run any further tests, a CT scan revealed massive bilateral PE. The patient was transferred to the ICU, but died the next day.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The 17-hour delay was negligent.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE There was no negligence. The patient died of septic shock, not PE.

VERDICT A $4 million Virginia verdict was returned.

Child born without hand and forearm

During prenatal care, a mother underwent US at 20 and 36 weeks; both studies were reported as normal. The child was born missing his left hand and part of his left forearm due to a congenital amputation. The child will require prosthetics for life.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The condition should have been seen during prenatal US; an abortion was still an option at 20 weeks.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE US was properly performed and evaluated. It can be difficult to differentiate the right from left extremities.

VERDICT A California defense verdict was returned.

After starting Yasmin, woman has stroke with permanent paralysis: $16.5M total award

When a 37-year-old woman reported irregular menstruation, her ObGyn prescribed drospirenone/ethinyl estradiol (Yasmin; Bayer). Thirteen days after starting the drug, the patient had a stroke. She is paralyzed on her left side, has limited ability to speak, cannot use her left arm and leg, and requires 24-hour care.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The ObGyn should have recognized that Yasmin was not appropriate for this patient because of the drug’s clotting risks. The patient’s risk factors included her age (over 35), borderline hypertension, overweight, history of smoking, and high cholesterol. The ObGyn should have offered safer alternatives, such as a progesterone-only pill. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued a safety warning that all drospirenone-containing drugs may be associated with a higher risk of venous thrombosis during the first 6 months of use.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE According to Bayer, Yasmin is safe, and remains on the market. It was an appropriate drug to treat her irregular bleeding.

VERDICT Claims against the medical center that referred the patient to the ObGyn were settled for $2.5 million before trial. A $14 million Illinois verdict was returned against the ObGyn, for a total award of $16.5 million.

Who is at fault when pelvic mesh erodes?

In January 2011, an ObGyn implanted the Gynecare TVT Obturator System (TVT‑O; Ethicon) during a midurethral sling procedure to treat stress urinary incontinence (SUI) in a woman in her 60s. Shortly thereafter, the ObGyn left practice because of early-onset Alzheimer’s disease, and the patient’s care was taken over by a gynecologist.

At the 2-month postoperative visit, the gynecologist found that the mesh had eroded into the patient’s vagina. The gynecologist simply cut the mesh with a scissor, charted that a small erosion was present, and prescribed estrogen cream.

The patient continued to report pain, discomfort, pressure, difficulty voiding urine, continued incontinence, vaginal discharge, scarring, infection, odor, and bleeding.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The polypropylene mesh used during the midurethral sling procedure has been shown to be incompatible with human tissue. It promotes an immune response, which stimulates degradation of the pelvic tissue and can contribute to the development of severe adverse reactions to the mesh. Ethicon negligently designed, manufactured, marketed, labeled, and packaged the pelvic mesh products.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE Proper warnings were provided about the health risks associated with polypropylene mesh products. The medical device was not properly sized.

VERDICT A Texas jury rejected the patient’s claims that Ethicon did not provide proper warnings about the sling’s health risks and declined to award punitive damages.

However, the jury decided that the mesh implant was defectively designed, and returned a $1.2 million verdict against Ethicon.

Was suspected bowel injury treated properly?

A 40-year-old woman was referred to an ObGyn after reporting abnormal uterine bleeding to her primary care physician. The patient had very light menses every few weeks. The ObGyn performed an ablation procedure, without relief. A month later, the ObGyn performed robot-assisted laparoscopic hysterectomy. The next day, the patient reported abdominal pain. Suspecting a bowel injury, the ObGyn ordered a CT scan; the bowel appeared normal, so the ObGyn referred the patient to a surgeon. During exploratory laparotomy, the surgeon found and repaired a bowel injury. The patient developed significant complications from a necrotizing infection that included respiratory distress and ongoing wound care.

PATIENT’S CLAIM Conservative treatment should have been offered before surgery. The ObGyn should have waited longer after the ablation procedure before doing the hysterectomy. The ObGyn should have checked for a possible bowel injury before closing the hysterectomy.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE The bowel injury is a known complication of the procedure and was recognized and repaired in a timely manner.

VERDICT A Kentucky defense verdict was returned.

Pap smear improperly interpreted: Woman dies from cervical cancer

A 37-year-old woman underwent a pap smear in 2008 that was read by a cytotechnologist as normal. Two years later, the patient was found to have a golf-ball–sized cancerous tumor. She died from cervical cancer in 2011.

ESTATE’S CLAIM The cytotechnologist was negligent in misreading the 2008 Pap smear. If treatment had been started in 2008, the cancer could have been resolved with a simple conization biopsy.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE The Pap smear interpretation was reasonable. The cancer could not have been diagnosed in 2008. The patient was at fault for failing to follow-up Pap smears during the next 2 years.

VERDICT After assigning 75% fault to the cytotechnologist and 25% fault to the patient, a Florida jury returned a $20,870,200 verdict, which was reduced to $15,816,699.

Disastrous off-label use of anticoagulation

When a pelvic abscess was found, a 50-year-old woman was admitted to the hospital for treatment. She was taking warfarin due to a history of venous thromboembolism.

Before the procedure, her physicians attempted to temporarily reverse her anticoagulation by administering Factor IX Complex (Profilnine SD, Grifols Biologicals). The dose ordered for the patient was nearly double the maximum recommended weight-based dose. Almost immediately after receiving the infusion, the patient went into cardiopulmonary arrest and died. An autopsy found the cause of death to be pulmonary emboli (PE).

ESTATE’S CLAIM An excessive dose of Profilnine caused PE. At the time of the incident, Profilnine was not FDA approved for warfarin reversal, although some off-label uses were recognized in emergent situations, such as intracranial bleeds.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE The case was settled during the trial.

VERDICT A $1.25 million Virginia settlement was reached.

Vesicovaginal fistula from ureteral injury

At a women’s health clinic, a patient reported continuous, heavy vaginal bleeding; pain; and shortness of breath when walking. She had a history of endometritis and multiple abdominal surgeries. Examination disclosed a profuse vaginal discharge, a normal cervix, and an enlarged uterus. The patient consented to abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy performed by an ObGyn assisted by a resident.

During surgery, the ObGyn found that the patient’s uterus was at 16 to 20 weeks’ gestation size, with multiple serosal uterine fibroids and frank pus and necrosed fibroid tumors within the uterine cavity. The procedure took longer than planned because of extensive adhesions. After surgery, the patient was anemic and was given a beta-blocker for tachycardia. She was discharged 3 days later with 48 hours’ worth of intravenous antibiotics.

A month later, the patient reported urinary incontinence. She saw a urologist, who found a vesicovaginal fistula. The patient underwent nephrostomy-tube placement. Right ureterolysis and a right ureteral reimplant was performed 4 months later.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The ObGyn injured the right ureter during surgery.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE The ureter injury is a known risk of the procedure. The injury was due to an infection or delayed effects of ischemia. The patient had a good recovery with no residual injury.

VERDICT A Michigan defense verdict was returned.

Why did mother die after delivering twins?

After a 35-year-old woman gave birth to twins by cesarean delivery, she died. At autopsy, 4 liters of blood were found in her abdomen.

ESTATE’S CLAIM The ObGyn failed to recognize and treat an arterial or venous bleed during surgery.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE The patient died from amniotic fluid embolism. Autopsy results showed right ventricular heart failure, respiratory failure, and disseminated intravascular coagulation.

VERDICT A Florida defense verdict was returned.

These cases were selected by the editors of OBG Management from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements & Experts, with permission of the editor, Lewis Laska (www.verdictslaska.com). The information available to the editors about the cases presented here is sometimes incomplete. Moreover, the cases may or may not have merit. Nevertheless, these cases represent the types of clinical situations that typically result in litigation and are meant to illustrate nationwide variation in jury verdicts and awards.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

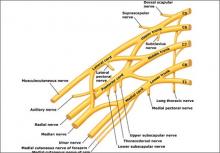

A summary of the new ACOG report on neonatal brachial plexus palsy. Part 1: Can it be predicted?

Neonatal brachial plexus palsy (NBPP) after a delivery involving shoulder dystocia is not only a clinical disaster—it constitutes the second largest category of litigation in obstetrics.1

Lawsuits that center on NBPP often feature plaintiff expert witnesses who claim that the only way a permanent brachial plexus injury can occur is by a clinician applying “excessive” traction on the fetal head during delivery. The same experts often claim that the mother had multiple risk factors for shoulder dystocia and should never have been allowed a trial of labor in the first place.

The jury is left suspecting that the NBPP was a disaster waiting to happen, with warning signs that were ignored by the clinician. Jurors also may be convinced that, when the dystocia occurred, the defendant handled it badly, causing a severe, lifelong injury to the beautiful child whose images they are shown in the courtroom.

But this scenario is far from accurate.

ACOG publishes new guidance on NBPPThe American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) periodically issues practice bulletins on the subject of shoulder dystocia, the most recent one written in 2002 and reaffirmed in 2013.2 These bulletins are, of necessity, relatively brief summaries of current thinking about the causes, pathophysiology, treatment, and preventability of shoulder dystocia and associated brachial plexus injuries.

In 2011, James Breeden, MD, then president-elect of ACOG, called for formation of a task force on NBPP. The task force’s report, Neonatal Brachial Plexus Palsy,3 was published earlier this year and represents ACOG’s official position on the important—but still controversial—subjects of shoulder dystocia and NBPP. This report should serve not only to help clinicians better understand and manage these entities but also as a foundational document in the prolific and complex medicolegal suits involving them.

Given the length of this report, however, a concise summary of the key takeaways is in order.

NBPP and shoulder dystocia are not always linked

Early in the report, ACOG presents three very important statements, all of which challenge claims that are frequently made by plaintiffs in brachial plexus injury cases:

- NBPP can occur without concomitant, clinically recognizable shoulder dystocia, although it often is associated with shoulder dystocia.

- In the presence of shoulder dystocia, all ancillary maneuvers necessarily increase strain on the brachial plexus, no matter how expertly the maneuvers are performed.

- Recent multidisciplinary research now indicates that the existence of NBPP after birth does not prove that exogenous forces are the sole cause of this injury.

These findings raise a number of questions, including:

- Can NBPP be predicted and prevented?

- What is the pathophysiologic mechanism for NBPP with and without shoulder dystocia?

- Are there specific interventions that may reduce the frequency of NBPP?

In Part 1 of this article, I summarize ACOG data on whether and how NBPP might be predicted. Part 2, to follow in October 2014, will discuss the pathophysiologic mechanism for NBPP and discuss potential interventions.

The data on NBPP without shoulder dystocia

The results of 12 reports published between 1990 and 2011 describe NBPP (temporary and persistent) that occurred without concomitant shoulder dystocia. These reports indicate that 46% of NBPP cases occurred without documented shoulder dystocia (0.9 cases/1,000 births).

Persistent NBPP. Two of these reports provide data on persistent NBPP without shoulder dystocia. Even when injury to the brachial plexus was documented as lasting more than 1 year, 26% of cases occurred in the absence of documented shoulder dystocia.

NBPP sometimes can occur during cesarean delivery. Four studies evaluated more than 240,000 births and found a rate of NBPP with cesarean delivery ranging from 0.3 to 1.5 cases per 1,000 live births.

All of these studies are described in the ACOG report.

When NBPP is related to shoulder dystocia

Shoulder dystocia may occur when there is a lack of fit of the transverse diameter of the fetal shoulders through the different pelvic diameters the shoulders encounter as they descend through the pelvis during the course of labor and delivery. This lack of fit can be related to excessive size of the fetal shoulders, inadequacy of pelvic dimensions to allow passage of a given fetus, or both. Abnormalities of fetal anatomy, fetal presentation, and soft tissue obstruction are rarely the cause of shoulder dystocia.

The difference between anterior shoulder obstruction behind the symphysis pubis and posterior shoulder obstruction from arrest at the level of the sacral promontory also is discussed in the ACOG report. In both cases, it is this obstruction of the affected shoulder while the long axis of the body continues to be pushed downward that widens the angle between the neck and impacted shoulder and stretches the brachial plexus.

The ACOG report acknowledges that may cases of NBPP do occur in conjunction with shoulder dystocia and that the same biomechanical factors that predispose a fetus to develop NBPP are associated with shoulder dystocia as well. However, the report takes pains to point out that the frequent conjunction of these two entities—NBPP and shoulder dystocia—may lead to an “erroneous retrospective inference of causation.”

Risk and predictive factors

The ACOG report states: “Various risk factors have been described in association with NBPP. Overall, however, these risk factors have not been shown to be statistically reliable or clinically useful predictors for...NBPP.”

For example, fetal macrosomia, defined as a birth weight of 4,000 g or more, has been reported as a risk factor for NBPP either alone or in conjunction with maternal diabetes. Although NBPP does occur more frequently as birth weight increases, seven studies over the past 20 years have shown that most cases of NBPP occur in infants of mothers without diabetes and in infants who weigh less than 4,000 g.

Other studies have shown that, if cesarean delivery were performed in cases of suspected macrosomia, it would have only a limited effect on reducing the incidence of NBPP. Specifically, in women with diabetes who have an estimated fetal weight of more than 4,500 g, the positive predictive value for NBPP is only 5%. Without maternal diabetes, that figure is less than 2%.

Estimating fetal weight by ultrasound does not significantly enhance our ability to predict NBPP. Ultrasound estimates of birth weight usually fall within 15% to 20% of actual birth weight, and the sensitivity of ultrasound in detecting birth weights more than 4,500 g is only 40%.

Therefore, ultrasound estimates of birth weight are of limited utility for contemporaneous clinical management. Furthermore, no data exist to support the claim that estimated fetal weight can be used prophylactically to reduce the incidence of NBPP.

Recurrent shoulder dystocia may be predictive of future NBPP

Whether studied alone or with NBPP, risk factors for shoulder dystocia are not reliable predictors of its occurrence. This is not the case, however, for recurrent shoulder dystocia, where the risk of neonatal brachial plexus palsy can be as high as 4.5%, compared with 1% to 2% for a first episode of shoulder dystocia.

NBPP is a rare phenomenon

The frequency of NBPP is “rare,” according to the ACOG report, which cites a rate of 1.5 cases for every 1,000 births. Favorable outcomes with complete recovery are estimated to range from 50% to 80%.3

Brachial plexus injuries are classically defined as Erb’s palsy—involving C5 and C6 nerve roots—or Klumpke’s palsy, in which there is damage to the C8 and T1 nerve roots.

Erb’s palsy is recognizable by the characteristic “waiter’s tip” position of the hand, which is caused by muscle imbalance in the shoulder and upper arm. Most NBPP injuries are Erb’s palsy, which affect 1.2 infants in every 1,000 births.

Klumpke’s palsy results in weakness of the hand and medial forearm muscles. It affects 0.05 infants in every 1,000 births. The remaining cases involve a combination of the two types of palsy.

These injuries can be temporary, resolving by 12 months after birth, or permanent. The rate of persistence of NBPP at 12 months ranges from 3% to 33%.

Can clinician maneuvers increase the likelihood of NBPP?

The ACOG report addresses the direction and angle of clinician traction at delivery. The report confirms what clinicians generally have been taught: The application of fundal pressure during a delivery in which shoulder dystocia is recognized can exacerbate shoulder impaction and can lead to an increased risk of NBPP.

Traction applied by the clinician and lateral bending of the fetal neck often are implicated as causative factors of NBPP. However, ACOG presents evidence that NBPP can occur entirely unrelated to clinician traction. The report cites studies involving both transient and persistent NBPP in fetuses delivered vaginally without evident shoulder dystocia. The same types of injury are sometimes seen in fetuses delivered by cesarean, as has been mentioned.

The report goes on to state:

Recommendations for practice

At the close of its second chapter (“Risk and predictive factors”), the ACOG report offers the same official recommendations that appear in its current practice bulletin on shoulder dystocia. It notes that there are three clinical situations in which it may be prudent to alter usual obstetric management, with an aim of reducing the risk of shoulder dystocia and NBPP:

- when fetal macrosomia is suspected, with fetal weight estimated to exceed 5,000 g in a woman without diabetes or 4,500 g in a woman with diabetes

- when the mother has a history of recognized shoulder dystocia, especially when neonatal injury was severe

- when midpelvic operative vaginal delivery is contemplated with a fetus estimated to weigh more than 4,000 g.

It is interesting to note that these recommendations are made, according to the report, “notwithstanding the unreliability of specific risk factors to predict NBPP or clinically apparent shoulder dystocia in a specific case.” The report further adds:

More to come

For ACOG’s conclusions on the pathophysiology and causation of NBPP, with a view toward formulating specific protective interventions, see Part 2 of this article, which will appear in the October 2014 issue of OBG Management.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

1. Physician Insurers Association of America. http://www.piaa.us. Accessed August 21, 2014.

2. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice Bulletin #40: shoulder dystocia. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;100(5 pt 1):1045–1050.

3. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Executive summary: neonatal brachial plexus palsy. Report of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Task Force on neonatal brachial plexus palsy. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(4):902–904.

Neonatal brachial plexus palsy (NBPP) after a delivery involving shoulder dystocia is not only a clinical disaster—it constitutes the second largest category of litigation in obstetrics.1

Lawsuits that center on NBPP often feature plaintiff expert witnesses who claim that the only way a permanent brachial plexus injury can occur is by a clinician applying “excessive” traction on the fetal head during delivery. The same experts often claim that the mother had multiple risk factors for shoulder dystocia and should never have been allowed a trial of labor in the first place.

The jury is left suspecting that the NBPP was a disaster waiting to happen, with warning signs that were ignored by the clinician. Jurors also may be convinced that, when the dystocia occurred, the defendant handled it badly, causing a severe, lifelong injury to the beautiful child whose images they are shown in the courtroom.

But this scenario is far from accurate.

ACOG publishes new guidance on NBPPThe American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) periodically issues practice bulletins on the subject of shoulder dystocia, the most recent one written in 2002 and reaffirmed in 2013.2 These bulletins are, of necessity, relatively brief summaries of current thinking about the causes, pathophysiology, treatment, and preventability of shoulder dystocia and associated brachial plexus injuries.

In 2011, James Breeden, MD, then president-elect of ACOG, called for formation of a task force on NBPP. The task force’s report, Neonatal Brachial Plexus Palsy,3 was published earlier this year and represents ACOG’s official position on the important—but still controversial—subjects of shoulder dystocia and NBPP. This report should serve not only to help clinicians better understand and manage these entities but also as a foundational document in the prolific and complex medicolegal suits involving them.

Given the length of this report, however, a concise summary of the key takeaways is in order.

NBPP and shoulder dystocia are not always linked

Early in the report, ACOG presents three very important statements, all of which challenge claims that are frequently made by plaintiffs in brachial plexus injury cases:

- NBPP can occur without concomitant, clinically recognizable shoulder dystocia, although it often is associated with shoulder dystocia.

- In the presence of shoulder dystocia, all ancillary maneuvers necessarily increase strain on the brachial plexus, no matter how expertly the maneuvers are performed.

- Recent multidisciplinary research now indicates that the existence of NBPP after birth does not prove that exogenous forces are the sole cause of this injury.

These findings raise a number of questions, including:

- Can NBPP be predicted and prevented?

- What is the pathophysiologic mechanism for NBPP with and without shoulder dystocia?

- Are there specific interventions that may reduce the frequency of NBPP?

In Part 1 of this article, I summarize ACOG data on whether and how NBPP might be predicted. Part 2, to follow in October 2014, will discuss the pathophysiologic mechanism for NBPP and discuss potential interventions.

The data on NBPP without shoulder dystocia

The results of 12 reports published between 1990 and 2011 describe NBPP (temporary and persistent) that occurred without concomitant shoulder dystocia. These reports indicate that 46% of NBPP cases occurred without documented shoulder dystocia (0.9 cases/1,000 births).

Persistent NBPP. Two of these reports provide data on persistent NBPP without shoulder dystocia. Even when injury to the brachial plexus was documented as lasting more than 1 year, 26% of cases occurred in the absence of documented shoulder dystocia.

NBPP sometimes can occur during cesarean delivery. Four studies evaluated more than 240,000 births and found a rate of NBPP with cesarean delivery ranging from 0.3 to 1.5 cases per 1,000 live births.

All of these studies are described in the ACOG report.

When NBPP is related to shoulder dystocia

Shoulder dystocia may occur when there is a lack of fit of the transverse diameter of the fetal shoulders through the different pelvic diameters the shoulders encounter as they descend through the pelvis during the course of labor and delivery. This lack of fit can be related to excessive size of the fetal shoulders, inadequacy of pelvic dimensions to allow passage of a given fetus, or both. Abnormalities of fetal anatomy, fetal presentation, and soft tissue obstruction are rarely the cause of shoulder dystocia.

The difference between anterior shoulder obstruction behind the symphysis pubis and posterior shoulder obstruction from arrest at the level of the sacral promontory also is discussed in the ACOG report. In both cases, it is this obstruction of the affected shoulder while the long axis of the body continues to be pushed downward that widens the angle between the neck and impacted shoulder and stretches the brachial plexus.

The ACOG report acknowledges that may cases of NBPP do occur in conjunction with shoulder dystocia and that the same biomechanical factors that predispose a fetus to develop NBPP are associated with shoulder dystocia as well. However, the report takes pains to point out that the frequent conjunction of these two entities—NBPP and shoulder dystocia—may lead to an “erroneous retrospective inference of causation.”

Risk and predictive factors

The ACOG report states: “Various risk factors have been described in association with NBPP. Overall, however, these risk factors have not been shown to be statistically reliable or clinically useful predictors for...NBPP.”

For example, fetal macrosomia, defined as a birth weight of 4,000 g or more, has been reported as a risk factor for NBPP either alone or in conjunction with maternal diabetes. Although NBPP does occur more frequently as birth weight increases, seven studies over the past 20 years have shown that most cases of NBPP occur in infants of mothers without diabetes and in infants who weigh less than 4,000 g.

Other studies have shown that, if cesarean delivery were performed in cases of suspected macrosomia, it would have only a limited effect on reducing the incidence of NBPP. Specifically, in women with diabetes who have an estimated fetal weight of more than 4,500 g, the positive predictive value for NBPP is only 5%. Without maternal diabetes, that figure is less than 2%.

Estimating fetal weight by ultrasound does not significantly enhance our ability to predict NBPP. Ultrasound estimates of birth weight usually fall within 15% to 20% of actual birth weight, and the sensitivity of ultrasound in detecting birth weights more than 4,500 g is only 40%.

Therefore, ultrasound estimates of birth weight are of limited utility for contemporaneous clinical management. Furthermore, no data exist to support the claim that estimated fetal weight can be used prophylactically to reduce the incidence of NBPP.

Recurrent shoulder dystocia may be predictive of future NBPP

Whether studied alone or with NBPP, risk factors for shoulder dystocia are not reliable predictors of its occurrence. This is not the case, however, for recurrent shoulder dystocia, where the risk of neonatal brachial plexus palsy can be as high as 4.5%, compared with 1% to 2% for a first episode of shoulder dystocia.

NBPP is a rare phenomenon

The frequency of NBPP is “rare,” according to the ACOG report, which cites a rate of 1.5 cases for every 1,000 births. Favorable outcomes with complete recovery are estimated to range from 50% to 80%.3

Brachial plexus injuries are classically defined as Erb’s palsy—involving C5 and C6 nerve roots—or Klumpke’s palsy, in which there is damage to the C8 and T1 nerve roots.

Erb’s palsy is recognizable by the characteristic “waiter’s tip” position of the hand, which is caused by muscle imbalance in the shoulder and upper arm. Most NBPP injuries are Erb’s palsy, which affect 1.2 infants in every 1,000 births.

Klumpke’s palsy results in weakness of the hand and medial forearm muscles. It affects 0.05 infants in every 1,000 births. The remaining cases involve a combination of the two types of palsy.

These injuries can be temporary, resolving by 12 months after birth, or permanent. The rate of persistence of NBPP at 12 months ranges from 3% to 33%.

Can clinician maneuvers increase the likelihood of NBPP?

The ACOG report addresses the direction and angle of clinician traction at delivery. The report confirms what clinicians generally have been taught: The application of fundal pressure during a delivery in which shoulder dystocia is recognized can exacerbate shoulder impaction and can lead to an increased risk of NBPP.

Traction applied by the clinician and lateral bending of the fetal neck often are implicated as causative factors of NBPP. However, ACOG presents evidence that NBPP can occur entirely unrelated to clinician traction. The report cites studies involving both transient and persistent NBPP in fetuses delivered vaginally without evident shoulder dystocia. The same types of injury are sometimes seen in fetuses delivered by cesarean, as has been mentioned.

The report goes on to state:

Recommendations for practice

At the close of its second chapter (“Risk and predictive factors”), the ACOG report offers the same official recommendations that appear in its current practice bulletin on shoulder dystocia. It notes that there are three clinical situations in which it may be prudent to alter usual obstetric management, with an aim of reducing the risk of shoulder dystocia and NBPP:

- when fetal macrosomia is suspected, with fetal weight estimated to exceed 5,000 g in a woman without diabetes or 4,500 g in a woman with diabetes

- when the mother has a history of recognized shoulder dystocia, especially when neonatal injury was severe

- when midpelvic operative vaginal delivery is contemplated with a fetus estimated to weigh more than 4,000 g.

It is interesting to note that these recommendations are made, according to the report, “notwithstanding the unreliability of specific risk factors to predict NBPP or clinically apparent shoulder dystocia in a specific case.” The report further adds:

More to come

For ACOG’s conclusions on the pathophysiology and causation of NBPP, with a view toward formulating specific protective interventions, see Part 2 of this article, which will appear in the October 2014 issue of OBG Management.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Neonatal brachial plexus palsy (NBPP) after a delivery involving shoulder dystocia is not only a clinical disaster—it constitutes the second largest category of litigation in obstetrics.1

Lawsuits that center on NBPP often feature plaintiff expert witnesses who claim that the only way a permanent brachial plexus injury can occur is by a clinician applying “excessive” traction on the fetal head during delivery. The same experts often claim that the mother had multiple risk factors for shoulder dystocia and should never have been allowed a trial of labor in the first place.

The jury is left suspecting that the NBPP was a disaster waiting to happen, with warning signs that were ignored by the clinician. Jurors also may be convinced that, when the dystocia occurred, the defendant handled it badly, causing a severe, lifelong injury to the beautiful child whose images they are shown in the courtroom.

But this scenario is far from accurate.

ACOG publishes new guidance on NBPPThe American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) periodically issues practice bulletins on the subject of shoulder dystocia, the most recent one written in 2002 and reaffirmed in 2013.2 These bulletins are, of necessity, relatively brief summaries of current thinking about the causes, pathophysiology, treatment, and preventability of shoulder dystocia and associated brachial plexus injuries.

In 2011, James Breeden, MD, then president-elect of ACOG, called for formation of a task force on NBPP. The task force’s report, Neonatal Brachial Plexus Palsy,3 was published earlier this year and represents ACOG’s official position on the important—but still controversial—subjects of shoulder dystocia and NBPP. This report should serve not only to help clinicians better understand and manage these entities but also as a foundational document in the prolific and complex medicolegal suits involving them.

Given the length of this report, however, a concise summary of the key takeaways is in order.

NBPP and shoulder dystocia are not always linked

Early in the report, ACOG presents three very important statements, all of which challenge claims that are frequently made by plaintiffs in brachial plexus injury cases:

- NBPP can occur without concomitant, clinically recognizable shoulder dystocia, although it often is associated with shoulder dystocia.

- In the presence of shoulder dystocia, all ancillary maneuvers necessarily increase strain on the brachial plexus, no matter how expertly the maneuvers are performed.

- Recent multidisciplinary research now indicates that the existence of NBPP after birth does not prove that exogenous forces are the sole cause of this injury.

These findings raise a number of questions, including:

- Can NBPP be predicted and prevented?

- What is the pathophysiologic mechanism for NBPP with and without shoulder dystocia?

- Are there specific interventions that may reduce the frequency of NBPP?

In Part 1 of this article, I summarize ACOG data on whether and how NBPP might be predicted. Part 2, to follow in October 2014, will discuss the pathophysiologic mechanism for NBPP and discuss potential interventions.

The data on NBPP without shoulder dystocia

The results of 12 reports published between 1990 and 2011 describe NBPP (temporary and persistent) that occurred without concomitant shoulder dystocia. These reports indicate that 46% of NBPP cases occurred without documented shoulder dystocia (0.9 cases/1,000 births).

Persistent NBPP. Two of these reports provide data on persistent NBPP without shoulder dystocia. Even when injury to the brachial plexus was documented as lasting more than 1 year, 26% of cases occurred in the absence of documented shoulder dystocia.

NBPP sometimes can occur during cesarean delivery. Four studies evaluated more than 240,000 births and found a rate of NBPP with cesarean delivery ranging from 0.3 to 1.5 cases per 1,000 live births.

All of these studies are described in the ACOG report.

When NBPP is related to shoulder dystocia

Shoulder dystocia may occur when there is a lack of fit of the transverse diameter of the fetal shoulders through the different pelvic diameters the shoulders encounter as they descend through the pelvis during the course of labor and delivery. This lack of fit can be related to excessive size of the fetal shoulders, inadequacy of pelvic dimensions to allow passage of a given fetus, or both. Abnormalities of fetal anatomy, fetal presentation, and soft tissue obstruction are rarely the cause of shoulder dystocia.

The difference between anterior shoulder obstruction behind the symphysis pubis and posterior shoulder obstruction from arrest at the level of the sacral promontory also is discussed in the ACOG report. In both cases, it is this obstruction of the affected shoulder while the long axis of the body continues to be pushed downward that widens the angle between the neck and impacted shoulder and stretches the brachial plexus.

The ACOG report acknowledges that may cases of NBPP do occur in conjunction with shoulder dystocia and that the same biomechanical factors that predispose a fetus to develop NBPP are associated with shoulder dystocia as well. However, the report takes pains to point out that the frequent conjunction of these two entities—NBPP and shoulder dystocia—may lead to an “erroneous retrospective inference of causation.”

Risk and predictive factors

The ACOG report states: “Various risk factors have been described in association with NBPP. Overall, however, these risk factors have not been shown to be statistically reliable or clinically useful predictors for...NBPP.”