User login

Prescribing Epilepsy Meds in Pregnancy: ‘We Can Do Better,’ Experts Say

HELSINKI, FINLAND — When it comes to caring for women with epilepsy who become pregnant, there is a great deal of room for improvement, experts say.

“Too many women with epilepsy receive information about epilepsy and pregnancy only after pregnancy. We can do better,” Torbjörn Tomson, MD, PhD, senior professor of neurology and epileptology, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden, told delegates attending the Congress of the European Academy of Neurology 2024.

The goal in epilepsy is to maintain seizure control while minimizing exposure to potentially teratogenic medications, Dr. Tomson said. He added that pregnancy planning in women with epilepsy is important but also conceded that most pregnancies in this patient population are unplanned.

Overall, it’s important to tell patients that “there is a high likelihood of an uneventful pregnancy and a healthy offspring,” he said.

In recent years, new data have emerged on the risks to the fetus with exposure to different antiseizure medications (ASMs), said Dr. Tomson. This has led regulators, such as the US Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency, to issue restrictions on the use of some ASMs, particularly valproate and topiramate, in females of childbearing age.

Session chair Marte Bjørk, MD, PhD, of the Department of Neurology of Haukeland University Hospital, Bergen, Norway, questioned whether the latest recommendations from regulatory authorities have “sacrificed seizure control at the expense of teratogenic safety.”

To an extent, this is true, said Dr. Tomson, “as the regulations prioritize fetal health over women’s health.” However, “we have not seen poorer seizure control with newer medications” in recent datasets.

It’s about good planning, said Dr. Bjork, who is responsible for the clinical guidelines for treatment of epilepsy in pregnancy in Norway.

Start With Folic Acid

One simple measure is to ensure that all women with epilepsy of childbearing age are prescribed low-dose folic acid, Dr. Tomson said — even those who report that they are not considering pregnancy.

When it comes to folic acid, recently published guidelines on ASM use during pregnancy are relatively straightforward, he said.

The data do not show that folic acid reduces the risk for major congenital malformations, but they do show that it improves neurocognitive outcomes in children of mothers who received folic acid supplements prior to and throughout pregnancy.

Dr. Tomson said the new American Academy of Neurology (AAN) guidelines recommend a dosage of 0.4 mg/d, which balances the demonstrated benefits of supplementation and potential negative consequences of high doses of folic acid.

“Consider 0.4 mg of folic acid for all women on ASMs that are of childbearing potential, whether they become pregnant or not,” he said. However, well-designed, preferably randomized, studies are needed to better define the optimal folic acid dosing for pregnancy in women with epilepsy.

Choosing the Right ASM

The choice of the most appropriate ASM in pregnancy is based on the potential for an individual drug to cause major congenital malformations and, in more recent years, the likelihood that a woman with epilepsy is using any other medications associated with neurodevelopmental disorders in offspring.

Balanced against this must be the effect of pregnancy on seizure control, and the maternal and fetal risks associated with seizures during pregnancy.

“There are ways to optimize seizure control and to reduce teratogenic risks,” said Dr. Tomson, adding that the new AAN guidelines provide updated evidence-based conclusions on this topic.

The good news is that “there has been almost a 40% decline in the rate of major congenital malformations associated with ASM use in pregnancy, in parallel with a shift from use of ASMs such as carbamazepine and valproate to lamotrigine and levetiracetam.” The latter two medications are associated with a much lower risk for such birth defects, he added.

This is based on the average rate of major congenital malformations in the EURAP registry that tracks the comparative risk for major fetal malformations after ASM use during pregnancy in over 40 countries. The latest reporting from the registry shows that this risk has decreased from 6.1% in 1998-2004 to 3.7% in 2015-2022.

Taking valproate during pregnancy is associated with a significantly increased risk for neurodevelopmental outcomes, including autism spectrum disorder. However, the jury is still out on whether topiramate escalates the risk for neurodevelopmental disorders, because findings across studies have been inconsistent.

Overall, the AAN guidance, and similar advice from European regulatory authorities, is that valproate is associated with high risk for major congenital malformations and neurodevelopmental disorders. Topiramate has also been shown to increase the risk for major congenital malformations. Consequently, these two anticonvulsants are generally contraindicated in pregnancy, Dr. Tomson noted.

On the other hand, levetiracetam, lamotrigine, and oxcarbazepine seem to be the safest ASMs with respect to congenital malformation risk, and lamotrigine has the best documented safety profile when it comes to the risk for neurodevelopmental disorders.

Although there are newer ASMs on the market, including brivaracetam, cannabidiol, cenobamate, eslicarbazepine acetate, fenfluramine, lacosamide, perampanel, and zonisamide, at this juncture data on the risk potential of these agents are insufficient.

“For some of these newer meds, we don’t even have a single exposure in our large databases, even if you combine them all. We need to collect more data, and that will take time,” Dr. Tomson said.

Dose Optimization

Dose optimization of ASMs is also important — and for this to be accurate, it’s important to document an individual’s optimal ASM serum levels before pregnancy that can be used as a baseline target during pregnancy. However, Dr. Tomson noted, this information is not always available.

He pointed out that, with many ASMs, there can be a significant decline in serum concentration levels during pregnancy, which can increase seizure risk.

To address the uncertainty surrounding this issue, Dr. Tomson recommended that physicians consider future pregnancy when prescribing ASMs to women of childbearing age. He also advised discussing contraception with these patients, even if they indicate they are not currently planning to conceive.

The data clearly show the importance of planning a pregnancy so that the most appropriate and safest medications are prescribed, he said.

Dr. Tomson reported receiving research support, on behalf of EURAP, from Accord, Angelini, Bial, EcuPharma, Eisai, GlaxoSmithKline, Glenmark, GW Pharma, Hazz, Sanofi, Teva, USB, Zentiva, and SF Group. He has received speakers’ honoraria from Angelini, Eisai, and UCB. Dr. Bjørk reports receiving speakers’ honoraria from Pfizer, Eisai, AbbVie, Best Practice, Lilly, Novartis, and Teva. She has received unrestricted educational grants from The Research Council of Norway, the Research Council of the Nordic Countries (NordForsk), and the Norwegian Epilepsy Association. She has received consulting honoraria from Novartis and is on the advisory board of Eisai, Lundbeck, Angelini Pharma, and Jazz Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Bjørk also received institutional grants from marked authorization holders of valproate.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

HELSINKI, FINLAND — When it comes to caring for women with epilepsy who become pregnant, there is a great deal of room for improvement, experts say.

“Too many women with epilepsy receive information about epilepsy and pregnancy only after pregnancy. We can do better,” Torbjörn Tomson, MD, PhD, senior professor of neurology and epileptology, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden, told delegates attending the Congress of the European Academy of Neurology 2024.

The goal in epilepsy is to maintain seizure control while minimizing exposure to potentially teratogenic medications, Dr. Tomson said. He added that pregnancy planning in women with epilepsy is important but also conceded that most pregnancies in this patient population are unplanned.

Overall, it’s important to tell patients that “there is a high likelihood of an uneventful pregnancy and a healthy offspring,” he said.

In recent years, new data have emerged on the risks to the fetus with exposure to different antiseizure medications (ASMs), said Dr. Tomson. This has led regulators, such as the US Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency, to issue restrictions on the use of some ASMs, particularly valproate and topiramate, in females of childbearing age.

Session chair Marte Bjørk, MD, PhD, of the Department of Neurology of Haukeland University Hospital, Bergen, Norway, questioned whether the latest recommendations from regulatory authorities have “sacrificed seizure control at the expense of teratogenic safety.”

To an extent, this is true, said Dr. Tomson, “as the regulations prioritize fetal health over women’s health.” However, “we have not seen poorer seizure control with newer medications” in recent datasets.

It’s about good planning, said Dr. Bjork, who is responsible for the clinical guidelines for treatment of epilepsy in pregnancy in Norway.

Start With Folic Acid

One simple measure is to ensure that all women with epilepsy of childbearing age are prescribed low-dose folic acid, Dr. Tomson said — even those who report that they are not considering pregnancy.

When it comes to folic acid, recently published guidelines on ASM use during pregnancy are relatively straightforward, he said.

The data do not show that folic acid reduces the risk for major congenital malformations, but they do show that it improves neurocognitive outcomes in children of mothers who received folic acid supplements prior to and throughout pregnancy.

Dr. Tomson said the new American Academy of Neurology (AAN) guidelines recommend a dosage of 0.4 mg/d, which balances the demonstrated benefits of supplementation and potential negative consequences of high doses of folic acid.

“Consider 0.4 mg of folic acid for all women on ASMs that are of childbearing potential, whether they become pregnant or not,” he said. However, well-designed, preferably randomized, studies are needed to better define the optimal folic acid dosing for pregnancy in women with epilepsy.

Choosing the Right ASM

The choice of the most appropriate ASM in pregnancy is based on the potential for an individual drug to cause major congenital malformations and, in more recent years, the likelihood that a woman with epilepsy is using any other medications associated with neurodevelopmental disorders in offspring.

Balanced against this must be the effect of pregnancy on seizure control, and the maternal and fetal risks associated with seizures during pregnancy.

“There are ways to optimize seizure control and to reduce teratogenic risks,” said Dr. Tomson, adding that the new AAN guidelines provide updated evidence-based conclusions on this topic.

The good news is that “there has been almost a 40% decline in the rate of major congenital malformations associated with ASM use in pregnancy, in parallel with a shift from use of ASMs such as carbamazepine and valproate to lamotrigine and levetiracetam.” The latter two medications are associated with a much lower risk for such birth defects, he added.

This is based on the average rate of major congenital malformations in the EURAP registry that tracks the comparative risk for major fetal malformations after ASM use during pregnancy in over 40 countries. The latest reporting from the registry shows that this risk has decreased from 6.1% in 1998-2004 to 3.7% in 2015-2022.

Taking valproate during pregnancy is associated with a significantly increased risk for neurodevelopmental outcomes, including autism spectrum disorder. However, the jury is still out on whether topiramate escalates the risk for neurodevelopmental disorders, because findings across studies have been inconsistent.

Overall, the AAN guidance, and similar advice from European regulatory authorities, is that valproate is associated with high risk for major congenital malformations and neurodevelopmental disorders. Topiramate has also been shown to increase the risk for major congenital malformations. Consequently, these two anticonvulsants are generally contraindicated in pregnancy, Dr. Tomson noted.

On the other hand, levetiracetam, lamotrigine, and oxcarbazepine seem to be the safest ASMs with respect to congenital malformation risk, and lamotrigine has the best documented safety profile when it comes to the risk for neurodevelopmental disorders.

Although there are newer ASMs on the market, including brivaracetam, cannabidiol, cenobamate, eslicarbazepine acetate, fenfluramine, lacosamide, perampanel, and zonisamide, at this juncture data on the risk potential of these agents are insufficient.

“For some of these newer meds, we don’t even have a single exposure in our large databases, even if you combine them all. We need to collect more data, and that will take time,” Dr. Tomson said.

Dose Optimization

Dose optimization of ASMs is also important — and for this to be accurate, it’s important to document an individual’s optimal ASM serum levels before pregnancy that can be used as a baseline target during pregnancy. However, Dr. Tomson noted, this information is not always available.

He pointed out that, with many ASMs, there can be a significant decline in serum concentration levels during pregnancy, which can increase seizure risk.

To address the uncertainty surrounding this issue, Dr. Tomson recommended that physicians consider future pregnancy when prescribing ASMs to women of childbearing age. He also advised discussing contraception with these patients, even if they indicate they are not currently planning to conceive.

The data clearly show the importance of planning a pregnancy so that the most appropriate and safest medications are prescribed, he said.

Dr. Tomson reported receiving research support, on behalf of EURAP, from Accord, Angelini, Bial, EcuPharma, Eisai, GlaxoSmithKline, Glenmark, GW Pharma, Hazz, Sanofi, Teva, USB, Zentiva, and SF Group. He has received speakers’ honoraria from Angelini, Eisai, and UCB. Dr. Bjørk reports receiving speakers’ honoraria from Pfizer, Eisai, AbbVie, Best Practice, Lilly, Novartis, and Teva. She has received unrestricted educational grants from The Research Council of Norway, the Research Council of the Nordic Countries (NordForsk), and the Norwegian Epilepsy Association. She has received consulting honoraria from Novartis and is on the advisory board of Eisai, Lundbeck, Angelini Pharma, and Jazz Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Bjørk also received institutional grants from marked authorization holders of valproate.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

HELSINKI, FINLAND — When it comes to caring for women with epilepsy who become pregnant, there is a great deal of room for improvement, experts say.

“Too many women with epilepsy receive information about epilepsy and pregnancy only after pregnancy. We can do better,” Torbjörn Tomson, MD, PhD, senior professor of neurology and epileptology, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden, told delegates attending the Congress of the European Academy of Neurology 2024.

The goal in epilepsy is to maintain seizure control while minimizing exposure to potentially teratogenic medications, Dr. Tomson said. He added that pregnancy planning in women with epilepsy is important but also conceded that most pregnancies in this patient population are unplanned.

Overall, it’s important to tell patients that “there is a high likelihood of an uneventful pregnancy and a healthy offspring,” he said.

In recent years, new data have emerged on the risks to the fetus with exposure to different antiseizure medications (ASMs), said Dr. Tomson. This has led regulators, such as the US Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency, to issue restrictions on the use of some ASMs, particularly valproate and topiramate, in females of childbearing age.

Session chair Marte Bjørk, MD, PhD, of the Department of Neurology of Haukeland University Hospital, Bergen, Norway, questioned whether the latest recommendations from regulatory authorities have “sacrificed seizure control at the expense of teratogenic safety.”

To an extent, this is true, said Dr. Tomson, “as the regulations prioritize fetal health over women’s health.” However, “we have not seen poorer seizure control with newer medications” in recent datasets.

It’s about good planning, said Dr. Bjork, who is responsible for the clinical guidelines for treatment of epilepsy in pregnancy in Norway.

Start With Folic Acid

One simple measure is to ensure that all women with epilepsy of childbearing age are prescribed low-dose folic acid, Dr. Tomson said — even those who report that they are not considering pregnancy.

When it comes to folic acid, recently published guidelines on ASM use during pregnancy are relatively straightforward, he said.

The data do not show that folic acid reduces the risk for major congenital malformations, but they do show that it improves neurocognitive outcomes in children of mothers who received folic acid supplements prior to and throughout pregnancy.

Dr. Tomson said the new American Academy of Neurology (AAN) guidelines recommend a dosage of 0.4 mg/d, which balances the demonstrated benefits of supplementation and potential negative consequences of high doses of folic acid.

“Consider 0.4 mg of folic acid for all women on ASMs that are of childbearing potential, whether they become pregnant or not,” he said. However, well-designed, preferably randomized, studies are needed to better define the optimal folic acid dosing for pregnancy in women with epilepsy.

Choosing the Right ASM

The choice of the most appropriate ASM in pregnancy is based on the potential for an individual drug to cause major congenital malformations and, in more recent years, the likelihood that a woman with epilepsy is using any other medications associated with neurodevelopmental disorders in offspring.

Balanced against this must be the effect of pregnancy on seizure control, and the maternal and fetal risks associated with seizures during pregnancy.

“There are ways to optimize seizure control and to reduce teratogenic risks,” said Dr. Tomson, adding that the new AAN guidelines provide updated evidence-based conclusions on this topic.

The good news is that “there has been almost a 40% decline in the rate of major congenital malformations associated with ASM use in pregnancy, in parallel with a shift from use of ASMs such as carbamazepine and valproate to lamotrigine and levetiracetam.” The latter two medications are associated with a much lower risk for such birth defects, he added.

This is based on the average rate of major congenital malformations in the EURAP registry that tracks the comparative risk for major fetal malformations after ASM use during pregnancy in over 40 countries. The latest reporting from the registry shows that this risk has decreased from 6.1% in 1998-2004 to 3.7% in 2015-2022.

Taking valproate during pregnancy is associated with a significantly increased risk for neurodevelopmental outcomes, including autism spectrum disorder. However, the jury is still out on whether topiramate escalates the risk for neurodevelopmental disorders, because findings across studies have been inconsistent.

Overall, the AAN guidance, and similar advice from European regulatory authorities, is that valproate is associated with high risk for major congenital malformations and neurodevelopmental disorders. Topiramate has also been shown to increase the risk for major congenital malformations. Consequently, these two anticonvulsants are generally contraindicated in pregnancy, Dr. Tomson noted.

On the other hand, levetiracetam, lamotrigine, and oxcarbazepine seem to be the safest ASMs with respect to congenital malformation risk, and lamotrigine has the best documented safety profile when it comes to the risk for neurodevelopmental disorders.

Although there are newer ASMs on the market, including brivaracetam, cannabidiol, cenobamate, eslicarbazepine acetate, fenfluramine, lacosamide, perampanel, and zonisamide, at this juncture data on the risk potential of these agents are insufficient.

“For some of these newer meds, we don’t even have a single exposure in our large databases, even if you combine them all. We need to collect more data, and that will take time,” Dr. Tomson said.

Dose Optimization

Dose optimization of ASMs is also important — and for this to be accurate, it’s important to document an individual’s optimal ASM serum levels before pregnancy that can be used as a baseline target during pregnancy. However, Dr. Tomson noted, this information is not always available.

He pointed out that, with many ASMs, there can be a significant decline in serum concentration levels during pregnancy, which can increase seizure risk.

To address the uncertainty surrounding this issue, Dr. Tomson recommended that physicians consider future pregnancy when prescribing ASMs to women of childbearing age. He also advised discussing contraception with these patients, even if they indicate they are not currently planning to conceive.

The data clearly show the importance of planning a pregnancy so that the most appropriate and safest medications are prescribed, he said.

Dr. Tomson reported receiving research support, on behalf of EURAP, from Accord, Angelini, Bial, EcuPharma, Eisai, GlaxoSmithKline, Glenmark, GW Pharma, Hazz, Sanofi, Teva, USB, Zentiva, and SF Group. He has received speakers’ honoraria from Angelini, Eisai, and UCB. Dr. Bjørk reports receiving speakers’ honoraria from Pfizer, Eisai, AbbVie, Best Practice, Lilly, Novartis, and Teva. She has received unrestricted educational grants from The Research Council of Norway, the Research Council of the Nordic Countries (NordForsk), and the Norwegian Epilepsy Association. She has received consulting honoraria from Novartis and is on the advisory board of Eisai, Lundbeck, Angelini Pharma, and Jazz Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Bjørk also received institutional grants from marked authorization holders of valproate.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM EAN 2024

Managing Cancer in Pregnancy: Improvements and Considerations

Introduction: Tremendous Progress on Cancer Extends to Cancer in Pregnancy

The biomedical research enterprise that took shape in the United States after World War II has had numerous positive effects, including significant progress made during the past 75-plus years in the diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of cancer.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s 1944 request of Dr. Vannevar Bush, director of the then Office of Scientific Research and Development, to organize a program that would advance and apply scientific knowledge for times of peace — just as it been advanced and applied in times of war — culminated in a historic report, Science – The Endless Frontier. Presented in 1945 to President Harry S. Truman, this report helped fuel decades of broad, bold, and coordinated government-sponsored biomedical research aimed at addressing disease and improving the health of the American people (National Science Foundation, 1945).

Discoveries made from research in basic and translational sciences deepened our knowledge of the cellular and molecular underpinnings of cancer, leading to advances in chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and other treatment approaches as well as continual refinements in their application. Similarly, our diagnostic armamentarium has significantly improved.

As a result, we have reduced both the incidence and mortality of cancer. Today, some cancers can be prevented. Others can be reversed or put in remission. Granted, progress has been variable, with some cancers such as ovarian cancer still having relatively low survival rates. Much more needs to be done. Overall, however, the positive effects of the U.S. biomedical research enterprise on cancer are evident. According to the National Cancer Institute’s most recent report on the status of cancer, death rates from cancer fell 1.9% per year on average in females from 2015 to 2019 (Cancer. 2022 Oct 22. doi: 10.1002/cncr.34479).

It is not only patients whose cancer occurs outside of pregnancy who have benefited. When treatment is appropriately selected and timing considerations are made, patients whose cancer is diagnosed during pregnancy — and their children — can have good outcomes.

To explain how the management of cancer in pregnancy has improved, we have invited Gautam G. Rao, MD, gynecologic oncologist and associate professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at the University of Maryland School of Medicine, to write this installment of the Master Class in Obstetrics. As Dr. Rao explains, radiation is not as dangerous to the fetus as once thought, and the safety of many chemotherapeutic regimens in pregnancy has been documented. Obstetricians can and should counsel patients, he explains, about the likelihood of good maternal and fetal outcomes.

E. Albert Reece, MD, PhD, MBA, a maternal-fetal medicine specialist, is dean emeritus of the University of Maryland School of Medicine, former university executive vice president; currently the endowed professor and director of the Center for Advanced Research Training and Innovation (CARTI), and senior scientist in the Center for Birth Defects Research. Dr. Reece reported no relevant disclosures. He is the medical editor of this column. Contact him at [email protected].

Managing Cancer in Pregnancy

Cancer can cause fear and distress for any patient, but when cancer is diagnosed during pregnancy, an expectant mother fears not only for her own health but for the health of her unborn child. Fortunately, ob.gyn.s and multidisciplinary teams have good reason to reassure patients about the likelihood of good outcomes.

Cancer treatment in pregnancy has improved with advancements in imaging and chemotherapy, and while maternal and fetal outcomes of prenatal cancer treatment are not well reported, evidence acquired in recent years from case series and retrospective studies shows that most imaging studies and procedural diagnostic tests – and many treatments – can be performed safely in pregnancy.

Decades ago, we avoided CT scans during pregnancy because of concerns about radiation exposure to the fetus, leaving some patients without an accurate staging of their cancer. Today, we have evidence that a CT scan is generally safe in pregnancy. Similarly, the safety of many chemotherapeutic regimens in pregnancy has been documented in recent decades,and the use of chemotherapy during pregnancy has increased progressively. Radiation is also commonly utilized in the management of cancers that may occur during pregnancy, such as breast cancer.1

Considerations of timing are often central to decision-making; chemotherapy and radiotherapy are generally avoided in the first trimester to prevent structural fetal anomalies, for instance, and delaying cancer treatment is often warranted when the patient is a few weeks away from delivery. On occasion, iatrogenic preterm birth is considered when the risks to the mother of delaying a necessary cancer treatment outweigh the risks to the fetus of prematurity.1

Pregnancy termination is rarely indicated, however, and information gathered over the past 2 decades suggests that fetal and placental metastases are rare.1 There is broad agreement that prenatal treatment of cancer in pregnancy should adhere as much as possible to protocols and guidelines for nonpregnant patients and that treatment delays driven by fear of fetal anomalies and miscarriage are unnecessary.

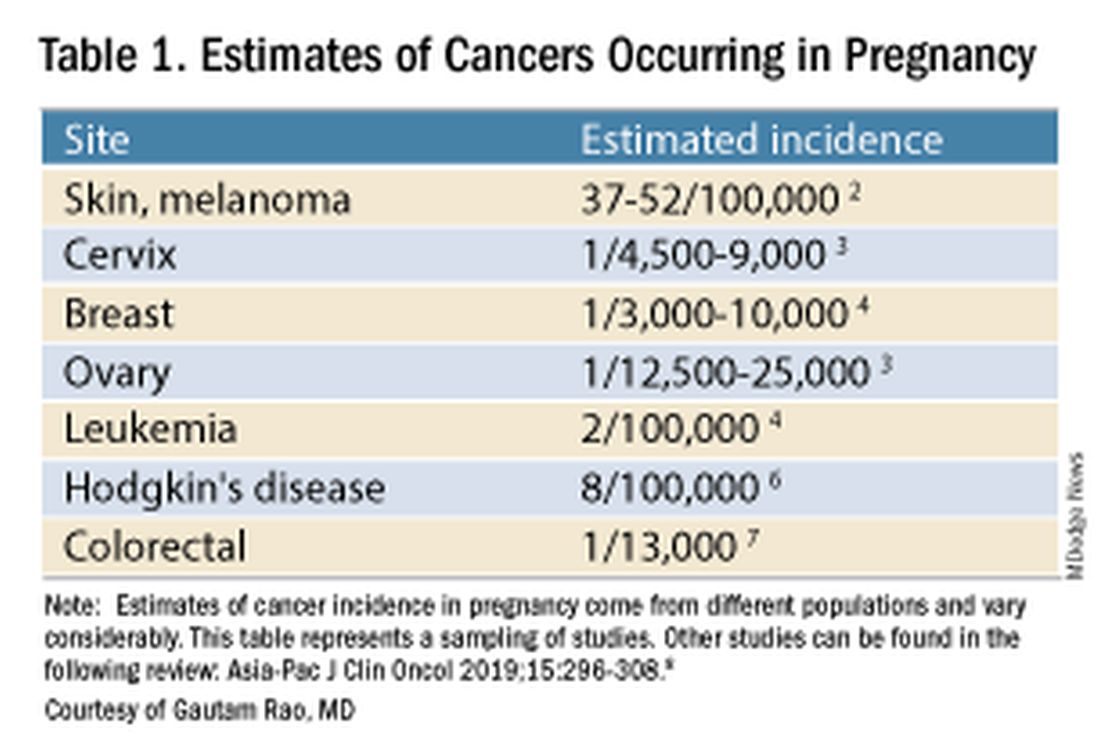

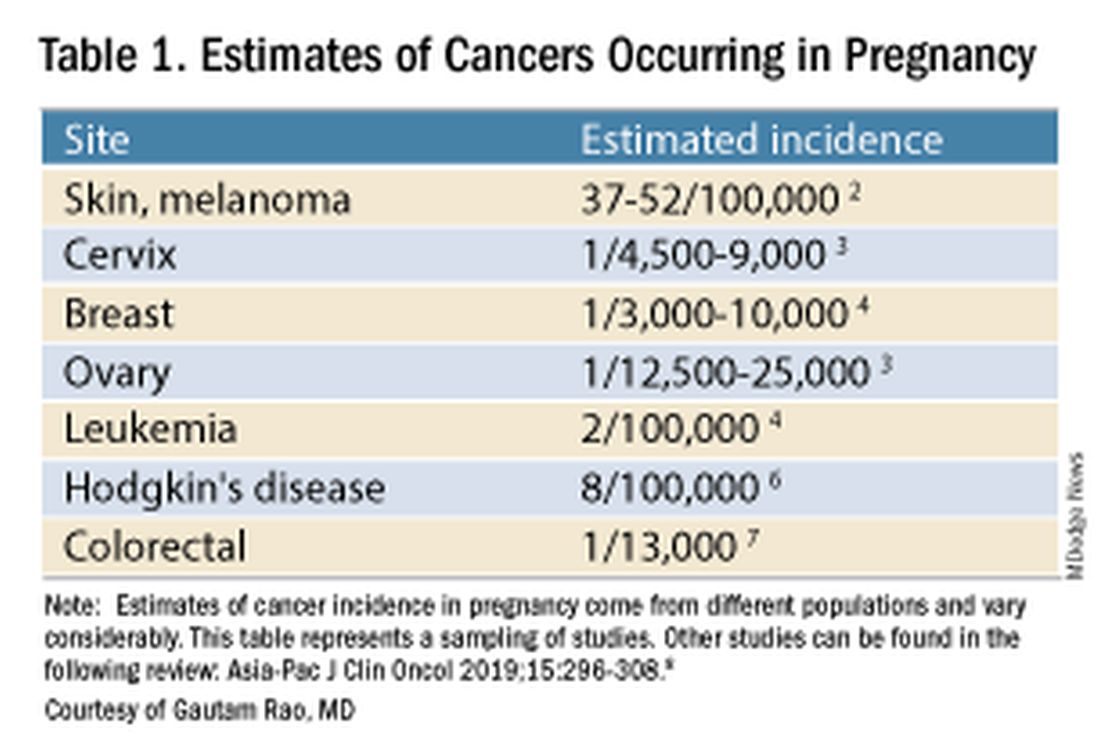

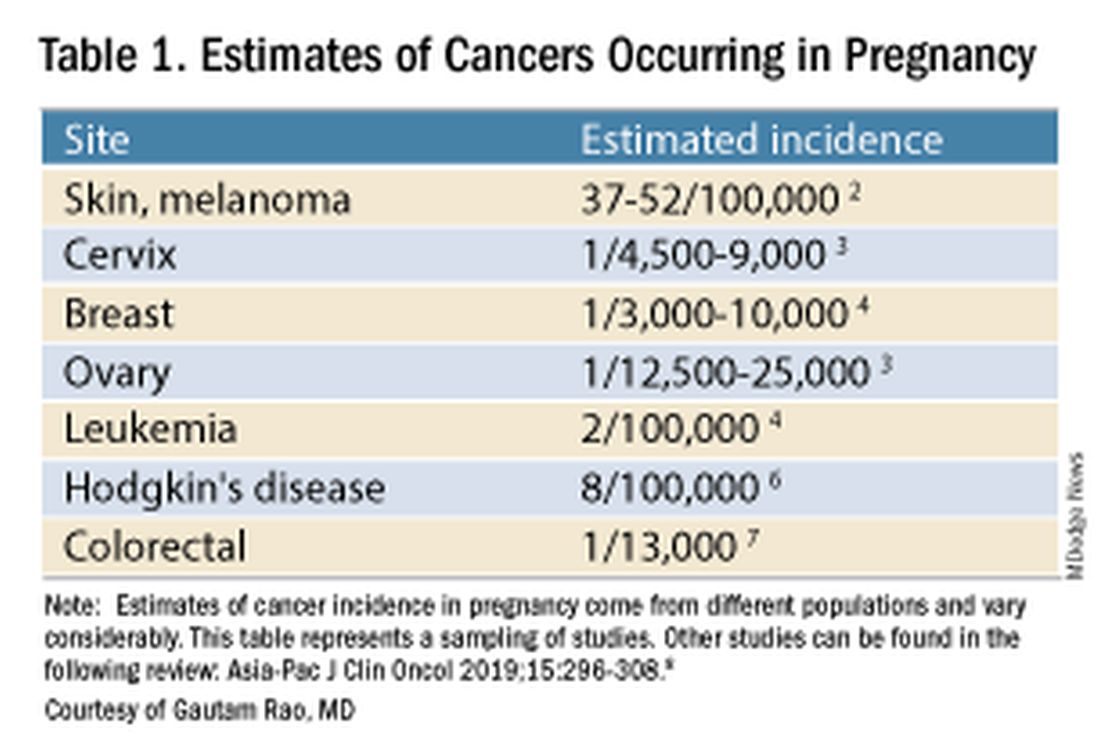

Cancer Incidence, Use of Diagnostic Imaging

Data on the incidence of cancer in pregnancy comes from population-based cancer registries, and unfortunately, these data are not standardized and are often incomplete. Many studies include cancer diagnosed up to 1 year after pregnancy, and some include preinvasive disease. Estimates therefore vary considerably (see Table 1 for a sampling of estimates incidences.)

It has been reported, and often cited in the literature, that invasive malignancy complicates one in 1,000 pregnancies and that the incidence of cancer in pregnancy (invasive and noninvasive malignancies) has been rising over time.8 Increasing maternal age is believed to be playing a role in this rise; as women delay childbearing, they enter the age range in which some cancers become more common. Additionally, improvements in screening and diagnostics have led to earlier cancer detection. The incidence of ovarian neoplasms found during pregnancy has increased, for instance, with the routine use of diagnostic ultrasound in pregnancy.1

Among the studies showing an increased incidence of pregnancy-associated cancer is a population-based study in Australia, which found that from 1994 to 2007 the crude incidence of pregnancy-associated cancer increased from 112.3 to 191.5 per 100,000 pregnancies (P < .001).9 A cohort study in the United States documented an increase in incidence from 75.0 per 100,000 pregnancies in 2002 to 138.5 per 100,000 pregnancies in 2012.10

Overall, the literature shows us that the skin, cervix, and breast are also common sites for malignancy during pregnancy.1 According to a 2022 review, breast cancer during pregnancy is less often hormone receptor–positive and more frequently triple negative compared with age-matched controls.11 The frequencies of other pregnancy-associated cancers appear overall to be similar to that of cancer occurring in all women across their reproductive years.1

Too often, diagnosis is delayed because cancer symptoms can be masked by or can mimic normal physiological changes in pregnancy. For instance, breast cancer can be difficult to diagnose during pregnancy and lactation due to anatomic changes in the breast parenchyma. Several studies published in the 1990s showed that breast cancer presents at a more advanced stage in pregnant patients than in nonpregnant patients because of this delay.1 Skin changes suggestive of melanoma can be attributed to hyperpigmentation of pregnancy, for instance. Several observational studies have suggested that thicker melanomas found in pregnancy may be because of delayed diagnosis.8

It is important that we thoroughly investigate signs and symptoms suggestive of a malignancy and not automatically attribute these symptoms to the pregnancy itself. Cervical biopsy of a mass or lesion suspicious for cervical cancer can be done safely during pregnancy and should not be delayed or deferred.

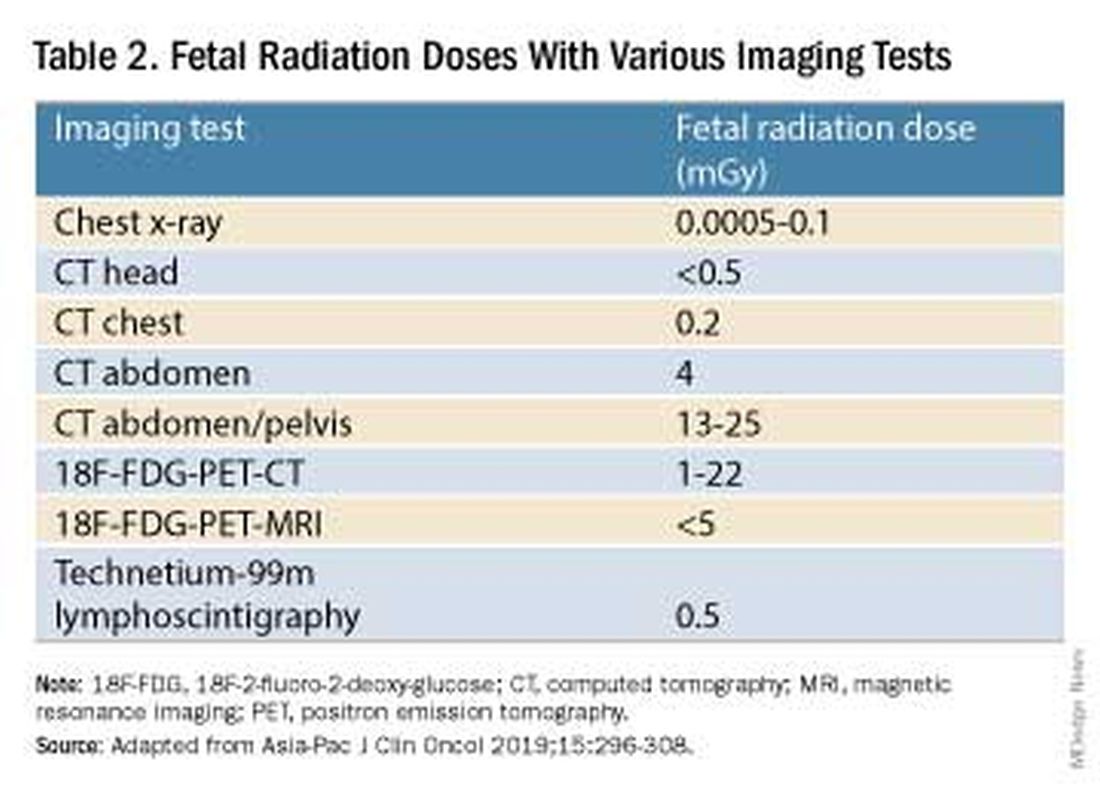

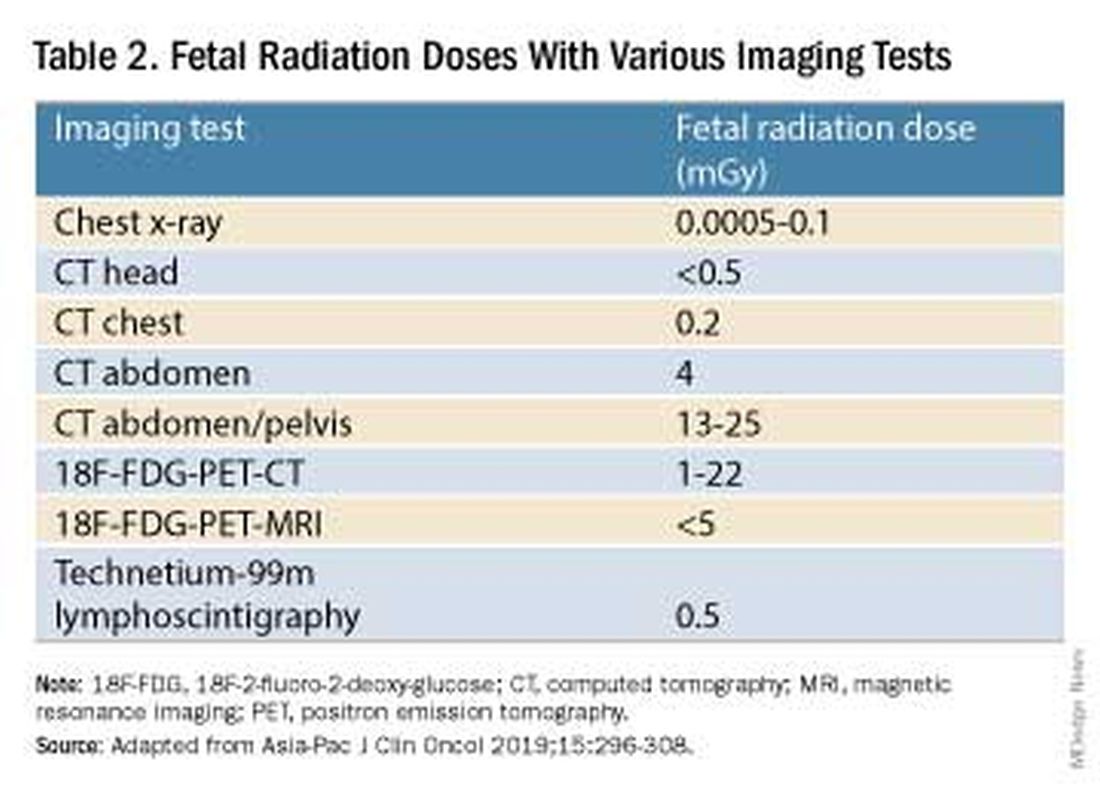

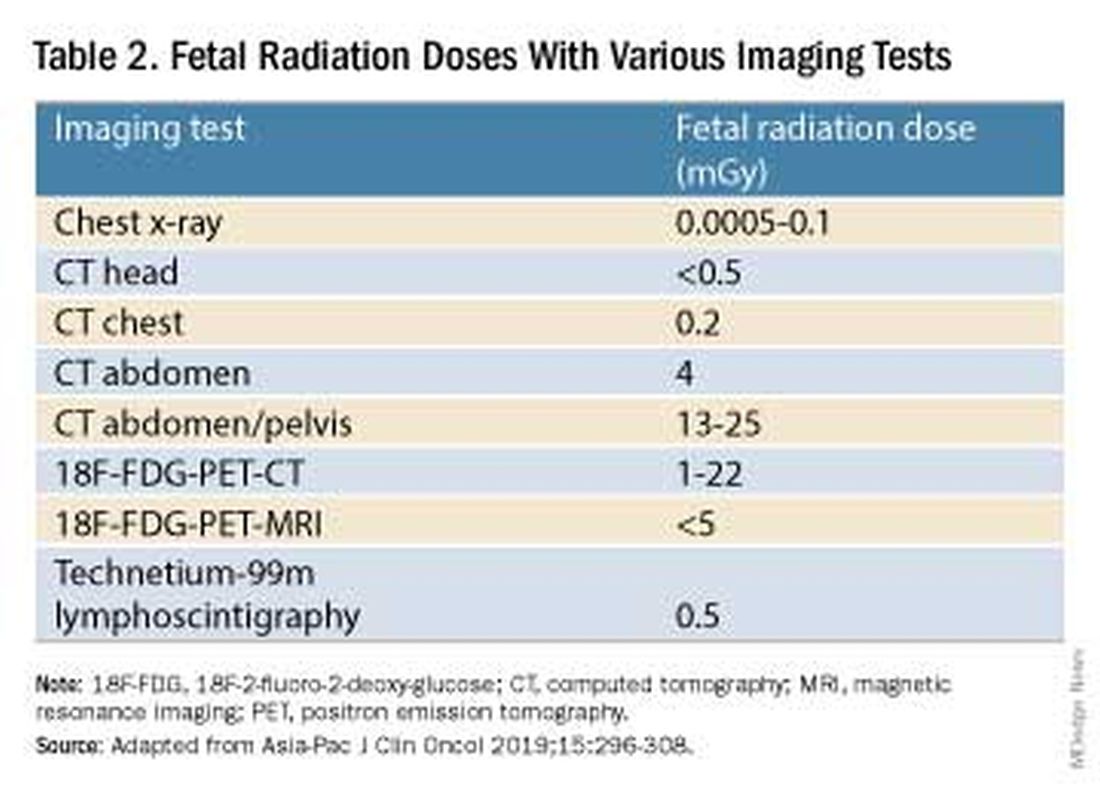

Fetal radiation exposure from radiologic examinations has long been a concern, but we know today that while the imaging modality should be chosen to minimize fetal radiation exposure, CT scans and even PET scans should be performed if these exams are deemed best for evaluation. Embryonic exposure to a dose of less than 50 mGy is rarely if at all associated with fetal malformations or miscarriage and a radiation dose of 100 mGy may be considered a floor for consideration of therapeutic termination of pregnancy.1,8

CT exams are associated with a fetal dose far less than 50 mGy (see Table 2 for radiation doses).

Magnetic resonance imaging with a magnet strength of 3 Tesla or less in any trimester is not associated with an increased risk of harm to the fetus or in early childhood, but the contrast agent gadolinium should be avoided in pregnancy as it has been associated with an increased risk of stillbirth, neonatal death, and childhood inflammatory, rheumatologic, and infiltrative skin lesions.1,8,12

Chemotherapy, Surgery, and Radiation in Pregnancy

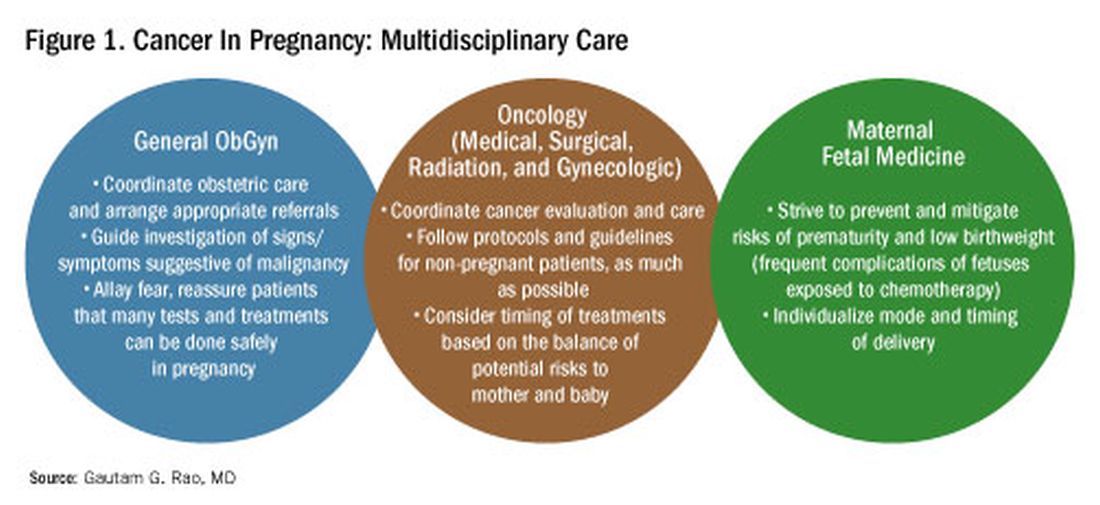

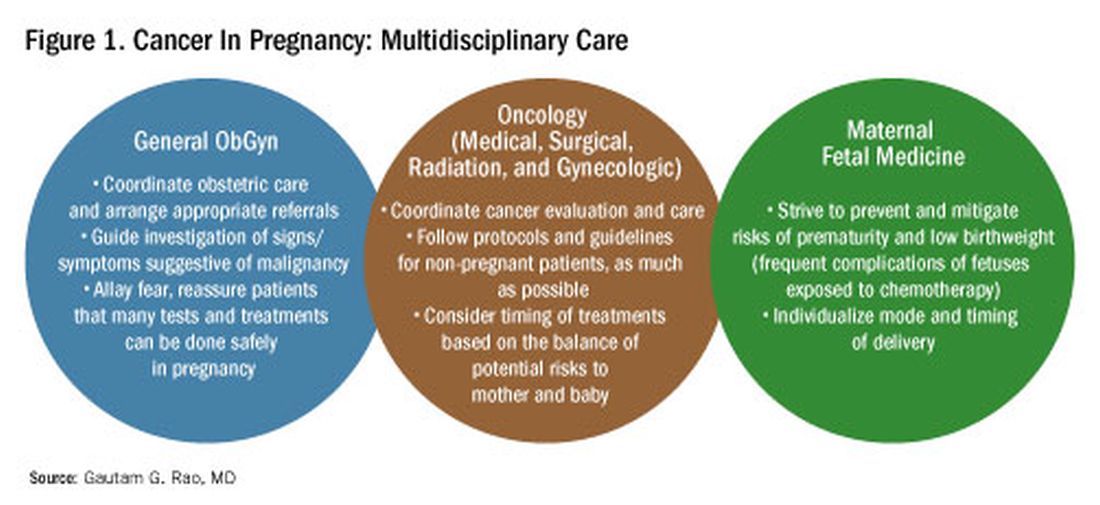

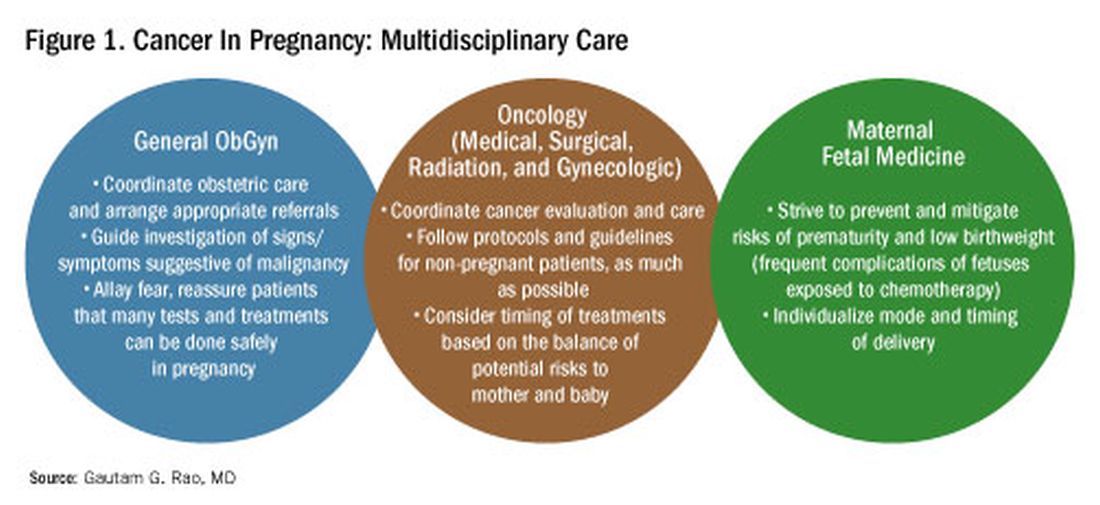

The management of cancer during pregnancy requires a multidisciplinary team including medical, gynecologic, or radiation oncologists, and maternal-fetal medicine specialists (Figure 1). Prematurity and low birth weight are frequent complications for fetuses exposed to chemotherapy, although there is some uncertainty as to whether the treatment is causative. However, congenital anomalies no longer are a major concern, provided that drugs are appropriately selected and that fetal exposure occurs during the second or third trimester.

For instance, alkylating agents including cisplatin (an important drug in the management of gynecologic malignancies) have been associated with congenital anomalies in the first trimester but not in the second and third trimesters, and a variety of antimetabolites — excluding methotrexate and aminopterin — similarly have been shown to be relatively safe when used after the first trimester.1

Small studies have shown no long-term effects of chemotherapy exposure on postnatal growth and long-term neurologic/neurocognitive function,1 but this is an area that needs more research.

Also in need of investigation is the safety of newer agents in pregnancy. Data are limited on the use of new targeted treatments, monoclonal antibodies, and immunotherapies in pregnancy and their effects on the fetus, with current knowledge coming mainly from single case reports.13

Until more is learned — a challenge given that pregnant women are generally excluded from clinical trials — management teams are generally postponing use of these therapies until after delivery. Considering the pace of new developments revolutionizing cancer treatment, this topic will likely get more complex and confusing before we begin acquiring sufficient knowledge.

The timing of surgery for malignancy in pregnancy is similarly based on the balance of maternal and fetal risks, including the risk of maternal disease progression, the risk of preterm delivery, and the prevention of fetal metastases. In general, the safest time is the second trimester.

Maternal surgery in the third trimester may be associated with a risk of premature labor and altered uteroplacental perfusion. A 2005 systematic review of 12,452 women who underwent nonobstetric surgery during pregnancy provides some reassurance, however; compared with the general obstetric population, there was no increase in the rate of miscarriage or major birth defects.14

Radiotherapy used to be contraindicated in pregnancy but many experts today believe it can be safely utilized provided the uterus is out of field and is protected from scattered radiation. The head, neck, and breast, for instance, can be treated with newer radiotherapies, including stereotactic ablative radiation therapy.8 Patients with advanced cervical cancer often receive chemotherapy during pregnancy to slow metastatic growth followed by definitive treatment with postpartum radiation or surgery.

More research is needed, but available data on maternal outcomes are encouraging. For instance, there appear to be no significant differences in short- and long-term complications or survival between women who are pregnant and nonpregnant when treated for invasive cervical cancer.8 Similarly, while earlier studies of breast cancer diagnosed during pregnancy suggested a poor prognosis, data now show similar prognoses for pregnant and nonpregnant patients when controlled for stage.1

Dr. Rao is a gynecologic oncologist and associate professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at the University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore. He reported no relevant disclosures.

References

1. Rao GG. Chapter 42. Clinical Obstetrics: The Fetus & Mother, 4th ed. Reece EA et al. (eds): 2021.

2. Bannister-Tyrrell M et al. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2014;55:116-122.

3. Oehler MK et al. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2003;43(6):414-420.

4. Ruiz R et al. Breast. 2017;35:136-141. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2017.07.008.

5. Nolan S et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;220(1):S480. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2018.11.752.

6. El-Messidi A et al. J Perinat Med. 2015;43(6):683-688. doi: 10.1515/jpm-2014-0133.

7. Pellino G et al. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;29(7):743-753. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000000863.

8. Eastwood-Wilshere N et al. Asia-Pac J Clin Oncol. 2019;15:296-308.

9. Lee YY et al. BJOG. 2012;119(13):1572-1582.

10. Cottreau CM et al. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2019 Feb;28(2):250-257.

11. Boere I et al. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2022;82:46-59.

12. Ray JG et al. JAMA 2016;316(9):952-961.

13. Schwab R et al. Cancers. (Basel) 2021;13(12):3048.

14. Cohen-Kerem et al. Am J Surg. 2005;190(3):467-473.

Introduction: Tremendous Progress on Cancer Extends to Cancer in Pregnancy

The biomedical research enterprise that took shape in the United States after World War II has had numerous positive effects, including significant progress made during the past 75-plus years in the diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of cancer.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s 1944 request of Dr. Vannevar Bush, director of the then Office of Scientific Research and Development, to organize a program that would advance and apply scientific knowledge for times of peace — just as it been advanced and applied in times of war — culminated in a historic report, Science – The Endless Frontier. Presented in 1945 to President Harry S. Truman, this report helped fuel decades of broad, bold, and coordinated government-sponsored biomedical research aimed at addressing disease and improving the health of the American people (National Science Foundation, 1945).

Discoveries made from research in basic and translational sciences deepened our knowledge of the cellular and molecular underpinnings of cancer, leading to advances in chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and other treatment approaches as well as continual refinements in their application. Similarly, our diagnostic armamentarium has significantly improved.

As a result, we have reduced both the incidence and mortality of cancer. Today, some cancers can be prevented. Others can be reversed or put in remission. Granted, progress has been variable, with some cancers such as ovarian cancer still having relatively low survival rates. Much more needs to be done. Overall, however, the positive effects of the U.S. biomedical research enterprise on cancer are evident. According to the National Cancer Institute’s most recent report on the status of cancer, death rates from cancer fell 1.9% per year on average in females from 2015 to 2019 (Cancer. 2022 Oct 22. doi: 10.1002/cncr.34479).

It is not only patients whose cancer occurs outside of pregnancy who have benefited. When treatment is appropriately selected and timing considerations are made, patients whose cancer is diagnosed during pregnancy — and their children — can have good outcomes.

To explain how the management of cancer in pregnancy has improved, we have invited Gautam G. Rao, MD, gynecologic oncologist and associate professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at the University of Maryland School of Medicine, to write this installment of the Master Class in Obstetrics. As Dr. Rao explains, radiation is not as dangerous to the fetus as once thought, and the safety of many chemotherapeutic regimens in pregnancy has been documented. Obstetricians can and should counsel patients, he explains, about the likelihood of good maternal and fetal outcomes.

E. Albert Reece, MD, PhD, MBA, a maternal-fetal medicine specialist, is dean emeritus of the University of Maryland School of Medicine, former university executive vice president; currently the endowed professor and director of the Center for Advanced Research Training and Innovation (CARTI), and senior scientist in the Center for Birth Defects Research. Dr. Reece reported no relevant disclosures. He is the medical editor of this column. Contact him at [email protected].

Managing Cancer in Pregnancy

Cancer can cause fear and distress for any patient, but when cancer is diagnosed during pregnancy, an expectant mother fears not only for her own health but for the health of her unborn child. Fortunately, ob.gyn.s and multidisciplinary teams have good reason to reassure patients about the likelihood of good outcomes.

Cancer treatment in pregnancy has improved with advancements in imaging and chemotherapy, and while maternal and fetal outcomes of prenatal cancer treatment are not well reported, evidence acquired in recent years from case series and retrospective studies shows that most imaging studies and procedural diagnostic tests – and many treatments – can be performed safely in pregnancy.

Decades ago, we avoided CT scans during pregnancy because of concerns about radiation exposure to the fetus, leaving some patients without an accurate staging of their cancer. Today, we have evidence that a CT scan is generally safe in pregnancy. Similarly, the safety of many chemotherapeutic regimens in pregnancy has been documented in recent decades,and the use of chemotherapy during pregnancy has increased progressively. Radiation is also commonly utilized in the management of cancers that may occur during pregnancy, such as breast cancer.1

Considerations of timing are often central to decision-making; chemotherapy and radiotherapy are generally avoided in the first trimester to prevent structural fetal anomalies, for instance, and delaying cancer treatment is often warranted when the patient is a few weeks away from delivery. On occasion, iatrogenic preterm birth is considered when the risks to the mother of delaying a necessary cancer treatment outweigh the risks to the fetus of prematurity.1

Pregnancy termination is rarely indicated, however, and information gathered over the past 2 decades suggests that fetal and placental metastases are rare.1 There is broad agreement that prenatal treatment of cancer in pregnancy should adhere as much as possible to protocols and guidelines for nonpregnant patients and that treatment delays driven by fear of fetal anomalies and miscarriage are unnecessary.

Cancer Incidence, Use of Diagnostic Imaging

Data on the incidence of cancer in pregnancy comes from population-based cancer registries, and unfortunately, these data are not standardized and are often incomplete. Many studies include cancer diagnosed up to 1 year after pregnancy, and some include preinvasive disease. Estimates therefore vary considerably (see Table 1 for a sampling of estimates incidences.)

It has been reported, and often cited in the literature, that invasive malignancy complicates one in 1,000 pregnancies and that the incidence of cancer in pregnancy (invasive and noninvasive malignancies) has been rising over time.8 Increasing maternal age is believed to be playing a role in this rise; as women delay childbearing, they enter the age range in which some cancers become more common. Additionally, improvements in screening and diagnostics have led to earlier cancer detection. The incidence of ovarian neoplasms found during pregnancy has increased, for instance, with the routine use of diagnostic ultrasound in pregnancy.1

Among the studies showing an increased incidence of pregnancy-associated cancer is a population-based study in Australia, which found that from 1994 to 2007 the crude incidence of pregnancy-associated cancer increased from 112.3 to 191.5 per 100,000 pregnancies (P < .001).9 A cohort study in the United States documented an increase in incidence from 75.0 per 100,000 pregnancies in 2002 to 138.5 per 100,000 pregnancies in 2012.10

Overall, the literature shows us that the skin, cervix, and breast are also common sites for malignancy during pregnancy.1 According to a 2022 review, breast cancer during pregnancy is less often hormone receptor–positive and more frequently triple negative compared with age-matched controls.11 The frequencies of other pregnancy-associated cancers appear overall to be similar to that of cancer occurring in all women across their reproductive years.1

Too often, diagnosis is delayed because cancer symptoms can be masked by or can mimic normal physiological changes in pregnancy. For instance, breast cancer can be difficult to diagnose during pregnancy and lactation due to anatomic changes in the breast parenchyma. Several studies published in the 1990s showed that breast cancer presents at a more advanced stage in pregnant patients than in nonpregnant patients because of this delay.1 Skin changes suggestive of melanoma can be attributed to hyperpigmentation of pregnancy, for instance. Several observational studies have suggested that thicker melanomas found in pregnancy may be because of delayed diagnosis.8

It is important that we thoroughly investigate signs and symptoms suggestive of a malignancy and not automatically attribute these symptoms to the pregnancy itself. Cervical biopsy of a mass or lesion suspicious for cervical cancer can be done safely during pregnancy and should not be delayed or deferred.

Fetal radiation exposure from radiologic examinations has long been a concern, but we know today that while the imaging modality should be chosen to minimize fetal radiation exposure, CT scans and even PET scans should be performed if these exams are deemed best for evaluation. Embryonic exposure to a dose of less than 50 mGy is rarely if at all associated with fetal malformations or miscarriage and a radiation dose of 100 mGy may be considered a floor for consideration of therapeutic termination of pregnancy.1,8

CT exams are associated with a fetal dose far less than 50 mGy (see Table 2 for radiation doses).

Magnetic resonance imaging with a magnet strength of 3 Tesla or less in any trimester is not associated with an increased risk of harm to the fetus or in early childhood, but the contrast agent gadolinium should be avoided in pregnancy as it has been associated with an increased risk of stillbirth, neonatal death, and childhood inflammatory, rheumatologic, and infiltrative skin lesions.1,8,12

Chemotherapy, Surgery, and Radiation in Pregnancy

The management of cancer during pregnancy requires a multidisciplinary team including medical, gynecologic, or radiation oncologists, and maternal-fetal medicine specialists (Figure 1). Prematurity and low birth weight are frequent complications for fetuses exposed to chemotherapy, although there is some uncertainty as to whether the treatment is causative. However, congenital anomalies no longer are a major concern, provided that drugs are appropriately selected and that fetal exposure occurs during the second or third trimester.

For instance, alkylating agents including cisplatin (an important drug in the management of gynecologic malignancies) have been associated with congenital anomalies in the first trimester but not in the second and third trimesters, and a variety of antimetabolites — excluding methotrexate and aminopterin — similarly have been shown to be relatively safe when used after the first trimester.1

Small studies have shown no long-term effects of chemotherapy exposure on postnatal growth and long-term neurologic/neurocognitive function,1 but this is an area that needs more research.

Also in need of investigation is the safety of newer agents in pregnancy. Data are limited on the use of new targeted treatments, monoclonal antibodies, and immunotherapies in pregnancy and their effects on the fetus, with current knowledge coming mainly from single case reports.13

Until more is learned — a challenge given that pregnant women are generally excluded from clinical trials — management teams are generally postponing use of these therapies until after delivery. Considering the pace of new developments revolutionizing cancer treatment, this topic will likely get more complex and confusing before we begin acquiring sufficient knowledge.

The timing of surgery for malignancy in pregnancy is similarly based on the balance of maternal and fetal risks, including the risk of maternal disease progression, the risk of preterm delivery, and the prevention of fetal metastases. In general, the safest time is the second trimester.

Maternal surgery in the third trimester may be associated with a risk of premature labor and altered uteroplacental perfusion. A 2005 systematic review of 12,452 women who underwent nonobstetric surgery during pregnancy provides some reassurance, however; compared with the general obstetric population, there was no increase in the rate of miscarriage or major birth defects.14

Radiotherapy used to be contraindicated in pregnancy but many experts today believe it can be safely utilized provided the uterus is out of field and is protected from scattered radiation. The head, neck, and breast, for instance, can be treated with newer radiotherapies, including stereotactic ablative radiation therapy.8 Patients with advanced cervical cancer often receive chemotherapy during pregnancy to slow metastatic growth followed by definitive treatment with postpartum radiation or surgery.

More research is needed, but available data on maternal outcomes are encouraging. For instance, there appear to be no significant differences in short- and long-term complications or survival between women who are pregnant and nonpregnant when treated for invasive cervical cancer.8 Similarly, while earlier studies of breast cancer diagnosed during pregnancy suggested a poor prognosis, data now show similar prognoses for pregnant and nonpregnant patients when controlled for stage.1

Dr. Rao is a gynecologic oncologist and associate professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at the University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore. He reported no relevant disclosures.

References

1. Rao GG. Chapter 42. Clinical Obstetrics: The Fetus & Mother, 4th ed. Reece EA et al. (eds): 2021.

2. Bannister-Tyrrell M et al. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2014;55:116-122.

3. Oehler MK et al. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2003;43(6):414-420.

4. Ruiz R et al. Breast. 2017;35:136-141. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2017.07.008.

5. Nolan S et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;220(1):S480. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2018.11.752.

6. El-Messidi A et al. J Perinat Med. 2015;43(6):683-688. doi: 10.1515/jpm-2014-0133.

7. Pellino G et al. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;29(7):743-753. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000000863.

8. Eastwood-Wilshere N et al. Asia-Pac J Clin Oncol. 2019;15:296-308.

9. Lee YY et al. BJOG. 2012;119(13):1572-1582.

10. Cottreau CM et al. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2019 Feb;28(2):250-257.

11. Boere I et al. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2022;82:46-59.

12. Ray JG et al. JAMA 2016;316(9):952-961.

13. Schwab R et al. Cancers. (Basel) 2021;13(12):3048.

14. Cohen-Kerem et al. Am J Surg. 2005;190(3):467-473.

Introduction: Tremendous Progress on Cancer Extends to Cancer in Pregnancy

The biomedical research enterprise that took shape in the United States after World War II has had numerous positive effects, including significant progress made during the past 75-plus years in the diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of cancer.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s 1944 request of Dr. Vannevar Bush, director of the then Office of Scientific Research and Development, to organize a program that would advance and apply scientific knowledge for times of peace — just as it been advanced and applied in times of war — culminated in a historic report, Science – The Endless Frontier. Presented in 1945 to President Harry S. Truman, this report helped fuel decades of broad, bold, and coordinated government-sponsored biomedical research aimed at addressing disease and improving the health of the American people (National Science Foundation, 1945).

Discoveries made from research in basic and translational sciences deepened our knowledge of the cellular and molecular underpinnings of cancer, leading to advances in chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and other treatment approaches as well as continual refinements in their application. Similarly, our diagnostic armamentarium has significantly improved.

As a result, we have reduced both the incidence and mortality of cancer. Today, some cancers can be prevented. Others can be reversed or put in remission. Granted, progress has been variable, with some cancers such as ovarian cancer still having relatively low survival rates. Much more needs to be done. Overall, however, the positive effects of the U.S. biomedical research enterprise on cancer are evident. According to the National Cancer Institute’s most recent report on the status of cancer, death rates from cancer fell 1.9% per year on average in females from 2015 to 2019 (Cancer. 2022 Oct 22. doi: 10.1002/cncr.34479).

It is not only patients whose cancer occurs outside of pregnancy who have benefited. When treatment is appropriately selected and timing considerations are made, patients whose cancer is diagnosed during pregnancy — and their children — can have good outcomes.

To explain how the management of cancer in pregnancy has improved, we have invited Gautam G. Rao, MD, gynecologic oncologist and associate professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at the University of Maryland School of Medicine, to write this installment of the Master Class in Obstetrics. As Dr. Rao explains, radiation is not as dangerous to the fetus as once thought, and the safety of many chemotherapeutic regimens in pregnancy has been documented. Obstetricians can and should counsel patients, he explains, about the likelihood of good maternal and fetal outcomes.

E. Albert Reece, MD, PhD, MBA, a maternal-fetal medicine specialist, is dean emeritus of the University of Maryland School of Medicine, former university executive vice president; currently the endowed professor and director of the Center for Advanced Research Training and Innovation (CARTI), and senior scientist in the Center for Birth Defects Research. Dr. Reece reported no relevant disclosures. He is the medical editor of this column. Contact him at [email protected].

Managing Cancer in Pregnancy

Cancer can cause fear and distress for any patient, but when cancer is diagnosed during pregnancy, an expectant mother fears not only for her own health but for the health of her unborn child. Fortunately, ob.gyn.s and multidisciplinary teams have good reason to reassure patients about the likelihood of good outcomes.

Cancer treatment in pregnancy has improved with advancements in imaging and chemotherapy, and while maternal and fetal outcomes of prenatal cancer treatment are not well reported, evidence acquired in recent years from case series and retrospective studies shows that most imaging studies and procedural diagnostic tests – and many treatments – can be performed safely in pregnancy.

Decades ago, we avoided CT scans during pregnancy because of concerns about radiation exposure to the fetus, leaving some patients without an accurate staging of their cancer. Today, we have evidence that a CT scan is generally safe in pregnancy. Similarly, the safety of many chemotherapeutic regimens in pregnancy has been documented in recent decades,and the use of chemotherapy during pregnancy has increased progressively. Radiation is also commonly utilized in the management of cancers that may occur during pregnancy, such as breast cancer.1

Considerations of timing are often central to decision-making; chemotherapy and radiotherapy are generally avoided in the first trimester to prevent structural fetal anomalies, for instance, and delaying cancer treatment is often warranted when the patient is a few weeks away from delivery. On occasion, iatrogenic preterm birth is considered when the risks to the mother of delaying a necessary cancer treatment outweigh the risks to the fetus of prematurity.1

Pregnancy termination is rarely indicated, however, and information gathered over the past 2 decades suggests that fetal and placental metastases are rare.1 There is broad agreement that prenatal treatment of cancer in pregnancy should adhere as much as possible to protocols and guidelines for nonpregnant patients and that treatment delays driven by fear of fetal anomalies and miscarriage are unnecessary.

Cancer Incidence, Use of Diagnostic Imaging

Data on the incidence of cancer in pregnancy comes from population-based cancer registries, and unfortunately, these data are not standardized and are often incomplete. Many studies include cancer diagnosed up to 1 year after pregnancy, and some include preinvasive disease. Estimates therefore vary considerably (see Table 1 for a sampling of estimates incidences.)

It has been reported, and often cited in the literature, that invasive malignancy complicates one in 1,000 pregnancies and that the incidence of cancer in pregnancy (invasive and noninvasive malignancies) has been rising over time.8 Increasing maternal age is believed to be playing a role in this rise; as women delay childbearing, they enter the age range in which some cancers become more common. Additionally, improvements in screening and diagnostics have led to earlier cancer detection. The incidence of ovarian neoplasms found during pregnancy has increased, for instance, with the routine use of diagnostic ultrasound in pregnancy.1

Among the studies showing an increased incidence of pregnancy-associated cancer is a population-based study in Australia, which found that from 1994 to 2007 the crude incidence of pregnancy-associated cancer increased from 112.3 to 191.5 per 100,000 pregnancies (P < .001).9 A cohort study in the United States documented an increase in incidence from 75.0 per 100,000 pregnancies in 2002 to 138.5 per 100,000 pregnancies in 2012.10

Overall, the literature shows us that the skin, cervix, and breast are also common sites for malignancy during pregnancy.1 According to a 2022 review, breast cancer during pregnancy is less often hormone receptor–positive and more frequently triple negative compared with age-matched controls.11 The frequencies of other pregnancy-associated cancers appear overall to be similar to that of cancer occurring in all women across their reproductive years.1

Too often, diagnosis is delayed because cancer symptoms can be masked by or can mimic normal physiological changes in pregnancy. For instance, breast cancer can be difficult to diagnose during pregnancy and lactation due to anatomic changes in the breast parenchyma. Several studies published in the 1990s showed that breast cancer presents at a more advanced stage in pregnant patients than in nonpregnant patients because of this delay.1 Skin changes suggestive of melanoma can be attributed to hyperpigmentation of pregnancy, for instance. Several observational studies have suggested that thicker melanomas found in pregnancy may be because of delayed diagnosis.8

It is important that we thoroughly investigate signs and symptoms suggestive of a malignancy and not automatically attribute these symptoms to the pregnancy itself. Cervical biopsy of a mass or lesion suspicious for cervical cancer can be done safely during pregnancy and should not be delayed or deferred.

Fetal radiation exposure from radiologic examinations has long been a concern, but we know today that while the imaging modality should be chosen to minimize fetal radiation exposure, CT scans and even PET scans should be performed if these exams are deemed best for evaluation. Embryonic exposure to a dose of less than 50 mGy is rarely if at all associated with fetal malformations or miscarriage and a radiation dose of 100 mGy may be considered a floor for consideration of therapeutic termination of pregnancy.1,8

CT exams are associated with a fetal dose far less than 50 mGy (see Table 2 for radiation doses).

Magnetic resonance imaging with a magnet strength of 3 Tesla or less in any trimester is not associated with an increased risk of harm to the fetus or in early childhood, but the contrast agent gadolinium should be avoided in pregnancy as it has been associated with an increased risk of stillbirth, neonatal death, and childhood inflammatory, rheumatologic, and infiltrative skin lesions.1,8,12

Chemotherapy, Surgery, and Radiation in Pregnancy

The management of cancer during pregnancy requires a multidisciplinary team including medical, gynecologic, or radiation oncologists, and maternal-fetal medicine specialists (Figure 1). Prematurity and low birth weight are frequent complications for fetuses exposed to chemotherapy, although there is some uncertainty as to whether the treatment is causative. However, congenital anomalies no longer are a major concern, provided that drugs are appropriately selected and that fetal exposure occurs during the second or third trimester.

For instance, alkylating agents including cisplatin (an important drug in the management of gynecologic malignancies) have been associated with congenital anomalies in the first trimester but not in the second and third trimesters, and a variety of antimetabolites — excluding methotrexate and aminopterin — similarly have been shown to be relatively safe when used after the first trimester.1

Small studies have shown no long-term effects of chemotherapy exposure on postnatal growth and long-term neurologic/neurocognitive function,1 but this is an area that needs more research.

Also in need of investigation is the safety of newer agents in pregnancy. Data are limited on the use of new targeted treatments, monoclonal antibodies, and immunotherapies in pregnancy and their effects on the fetus, with current knowledge coming mainly from single case reports.13

Until more is learned — a challenge given that pregnant women are generally excluded from clinical trials — management teams are generally postponing use of these therapies until after delivery. Considering the pace of new developments revolutionizing cancer treatment, this topic will likely get more complex and confusing before we begin acquiring sufficient knowledge.

The timing of surgery for malignancy in pregnancy is similarly based on the balance of maternal and fetal risks, including the risk of maternal disease progression, the risk of preterm delivery, and the prevention of fetal metastases. In general, the safest time is the second trimester.

Maternal surgery in the third trimester may be associated with a risk of premature labor and altered uteroplacental perfusion. A 2005 systematic review of 12,452 women who underwent nonobstetric surgery during pregnancy provides some reassurance, however; compared with the general obstetric population, there was no increase in the rate of miscarriage or major birth defects.14

Radiotherapy used to be contraindicated in pregnancy but many experts today believe it can be safely utilized provided the uterus is out of field and is protected from scattered radiation. The head, neck, and breast, for instance, can be treated with newer radiotherapies, including stereotactic ablative radiation therapy.8 Patients with advanced cervical cancer often receive chemotherapy during pregnancy to slow metastatic growth followed by definitive treatment with postpartum radiation or surgery.

More research is needed, but available data on maternal outcomes are encouraging. For instance, there appear to be no significant differences in short- and long-term complications or survival between women who are pregnant and nonpregnant when treated for invasive cervical cancer.8 Similarly, while earlier studies of breast cancer diagnosed during pregnancy suggested a poor prognosis, data now show similar prognoses for pregnant and nonpregnant patients when controlled for stage.1

Dr. Rao is a gynecologic oncologist and associate professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at the University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore. He reported no relevant disclosures.

References

1. Rao GG. Chapter 42. Clinical Obstetrics: The Fetus & Mother, 4th ed. Reece EA et al. (eds): 2021.

2. Bannister-Tyrrell M et al. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2014;55:116-122.

3. Oehler MK et al. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2003;43(6):414-420.

4. Ruiz R et al. Breast. 2017;35:136-141. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2017.07.008.

5. Nolan S et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;220(1):S480. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2018.11.752.

6. El-Messidi A et al. J Perinat Med. 2015;43(6):683-688. doi: 10.1515/jpm-2014-0133.

7. Pellino G et al. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;29(7):743-753. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000000863.

8. Eastwood-Wilshere N et al. Asia-Pac J Clin Oncol. 2019;15:296-308.

9. Lee YY et al. BJOG. 2012;119(13):1572-1582.

10. Cottreau CM et al. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2019 Feb;28(2):250-257.

11. Boere I et al. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2022;82:46-59.

12. Ray JG et al. JAMA 2016;316(9):952-961.

13. Schwab R et al. Cancers. (Basel) 2021;13(12):3048.

14. Cohen-Kerem et al. Am J Surg. 2005;190(3):467-473.

Benefit of Massage Therapy for Pain Unclear

The effectiveness of massage therapy for a range of painful adult health conditions remains uncertain. Despite hundreds of randomized clinical trials and dozens of systematic reviews, few studies have offered conclusions based on more than low-certainty evidence, a systematic review in JAMA Network Open has shown (doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.22259).

Some moderate-certainty evidence, however, suggested massage therapy may alleviate pain related to such conditions as low-back problems, labor, and breast cancer surgery, concluded a group led by Selene Mak, PhD, MPH, program manager in the Evidence Synthesis Program at the Veterans Health Administration Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System in Los Angeles, California.

“More high-quality randomized clinical trials are needed to provide a stronger evidence base to assess the effect of massage therapy on pain,” Dr. Mak and colleagues wrote.

The review updates a previous Veterans Affairs evidence map covering reviews of massage therapy for pain published through 2018.

To categorize the evidence base for decision-making by policymakers and practitioners, the VA requested an updated evidence map of reviews to answer the question: “What is the certainty of evidence in systematic reviews of massage therapy for pain?”

The Analysis

The current review included studies published from 2018 to 2023 with formal ratings of evidence quality or certainty, excluding other nonpharmacologic techniques such as sports massage therapy, osteopathy, dry cupping, dry needling, and internal massage therapy, and self-administered techniques such as foam rolling.

Of 129 systematic reviews, only 41 formally rated evidence quality, and 17 were evidence-mapped for pain across 13 health states: cancer, back, neck and mechanical neck issues, fibromyalgia, labor, myofascial, palliative care need, plantar fasciitis, postoperative, post breast cancer surgery, and post cesarean/postpartum.

The investigators found no conclusions based on a high certainty of evidence, while seven based conclusions on moderate-certainty evidence. All remaining conclusions were rated as having low- or very-low-certainty evidence.

The priority, they added, should be studies comparing massage therapy with other recommended, accepted, and active therapies for pain and should have sufficiently long follow-up to allow any nonspecific outcomes to dissipate, At least 6 months’ follow-up has been suggested for studies of chronic pain.

While massage therapy is considered safe, in patients with central sensitizations more aggressive treatments may cause a flare of myofascial pain.

This study was funded by the Department of Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development. The authors had no conflicts of interest to disclose.

The effectiveness of massage therapy for a range of painful adult health conditions remains uncertain. Despite hundreds of randomized clinical trials and dozens of systematic reviews, few studies have offered conclusions based on more than low-certainty evidence, a systematic review in JAMA Network Open has shown (doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.22259).

Some moderate-certainty evidence, however, suggested massage therapy may alleviate pain related to such conditions as low-back problems, labor, and breast cancer surgery, concluded a group led by Selene Mak, PhD, MPH, program manager in the Evidence Synthesis Program at the Veterans Health Administration Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System in Los Angeles, California.

“More high-quality randomized clinical trials are needed to provide a stronger evidence base to assess the effect of massage therapy on pain,” Dr. Mak and colleagues wrote.

The review updates a previous Veterans Affairs evidence map covering reviews of massage therapy for pain published through 2018.

To categorize the evidence base for decision-making by policymakers and practitioners, the VA requested an updated evidence map of reviews to answer the question: “What is the certainty of evidence in systematic reviews of massage therapy for pain?”

The Analysis

The current review included studies published from 2018 to 2023 with formal ratings of evidence quality or certainty, excluding other nonpharmacologic techniques such as sports massage therapy, osteopathy, dry cupping, dry needling, and internal massage therapy, and self-administered techniques such as foam rolling.

Of 129 systematic reviews, only 41 formally rated evidence quality, and 17 were evidence-mapped for pain across 13 health states: cancer, back, neck and mechanical neck issues, fibromyalgia, labor, myofascial, palliative care need, plantar fasciitis, postoperative, post breast cancer surgery, and post cesarean/postpartum.

The investigators found no conclusions based on a high certainty of evidence, while seven based conclusions on moderate-certainty evidence. All remaining conclusions were rated as having low- or very-low-certainty evidence.

The priority, they added, should be studies comparing massage therapy with other recommended, accepted, and active therapies for pain and should have sufficiently long follow-up to allow any nonspecific outcomes to dissipate, At least 6 months’ follow-up has been suggested for studies of chronic pain.

While massage therapy is considered safe, in patients with central sensitizations more aggressive treatments may cause a flare of myofascial pain.

This study was funded by the Department of Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development. The authors had no conflicts of interest to disclose.

The effectiveness of massage therapy for a range of painful adult health conditions remains uncertain. Despite hundreds of randomized clinical trials and dozens of systematic reviews, few studies have offered conclusions based on more than low-certainty evidence, a systematic review in JAMA Network Open has shown (doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.22259).

Some moderate-certainty evidence, however, suggested massage therapy may alleviate pain related to such conditions as low-back problems, labor, and breast cancer surgery, concluded a group led by Selene Mak, PhD, MPH, program manager in the Evidence Synthesis Program at the Veterans Health Administration Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System in Los Angeles, California.

“More high-quality randomized clinical trials are needed to provide a stronger evidence base to assess the effect of massage therapy on pain,” Dr. Mak and colleagues wrote.

The review updates a previous Veterans Affairs evidence map covering reviews of massage therapy for pain published through 2018.

To categorize the evidence base for decision-making by policymakers and practitioners, the VA requested an updated evidence map of reviews to answer the question: “What is the certainty of evidence in systematic reviews of massage therapy for pain?”

The Analysis

The current review included studies published from 2018 to 2023 with formal ratings of evidence quality or certainty, excluding other nonpharmacologic techniques such as sports massage therapy, osteopathy, dry cupping, dry needling, and internal massage therapy, and self-administered techniques such as foam rolling.

Of 129 systematic reviews, only 41 formally rated evidence quality, and 17 were evidence-mapped for pain across 13 health states: cancer, back, neck and mechanical neck issues, fibromyalgia, labor, myofascial, palliative care need, plantar fasciitis, postoperative, post breast cancer surgery, and post cesarean/postpartum.

The investigators found no conclusions based on a high certainty of evidence, while seven based conclusions on moderate-certainty evidence. All remaining conclusions were rated as having low- or very-low-certainty evidence.

The priority, they added, should be studies comparing massage therapy with other recommended, accepted, and active therapies for pain and should have sufficiently long follow-up to allow any nonspecific outcomes to dissipate, At least 6 months’ follow-up has been suggested for studies of chronic pain.

While massage therapy is considered safe, in patients with central sensitizations more aggressive treatments may cause a flare of myofascial pain.

This study was funded by the Department of Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development. The authors had no conflicts of interest to disclose.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

Similar Outcomes With Labetalol, Nifedipine for Chronic Hypertension in Pregnancy

Treatment for chronic hypertension in pregnancy with labetalol showed no significant differences in maternal or neonatal outcomes, compared with treatment with nifedipine, new research indicates.

The open-label, multicenter, randomized CHAP (Chronic Hypertension in Pregnancy) trial showed that treating mild chronic hypertension was better than delaying treatment until severe hypertension developed, but still unclear was whether, or to what extent, the choice of first-line treatment affected outcomes.

Researchers, led by Ayodeji A. Sanusi, MD, MPH, with the Division of Maternal and Fetal Medicine at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, conducted a secondary analysis of CHAP to compare the primary treatments. Mild chronic hypertension in the study was defined as blood pressure of 140-159/90-104 mmHg before 20 weeks of gestation.

Three Comparisons

Three comparisons were performed in 2292 participants based on medications prescribed at enrollment: 720 (31.4%) received labetalol; 417 (18.2%) initially received nifedipine; and 1155 (50.4%) had standard care. Labetalol was compared with standard care; nifedipine was compared with standard care; and labetalol was compared with nifedipine.

The primary outcome was occurrence of superimposed preeclampsia with severe features; preterm birth before 35 weeks of gestation; placental abruption; or fetal or neonatal death. The key secondary outcome was a small-for-gestational age neonate. Researchers also compared adverse effects between groups.

Among the results were the following:

- The primary outcome occurred in 30.1% in the labetalol group; 31.2% in the nifedipine group; and 37% in the standard care group.

- Risk of the primary outcome was lower among those receiving treatment. For labetalol vs standard care, the adjusted relative risk (RR) was 0.82; 95% confidence interval (CI), 0.72-0.94. For nifedipine vs standard care, the adjusted RR was 0.84; 95% CI, 0.71-0.99. There was no significant difference in risk when labetalol was compared with nifedipine (adjusted RR, 0.98; 95% CI, 0.82-1.18).

- There were no significant differences in numbers of small-for-gestational age neonates or serious adverse events between those who received labetalol and those using nifedipine.

Any adverse events were significantly more common with nifedipine, compared with labetalol (35.7% vs 28.3%, P = .009), and with nifedipine, compared with standard care (35.7% vs 26.3%, P = .0003). Adverse event rates were not significantly higher with labetalol when compared with standard care (28.3% vs 26.3%, P = .34). The most frequently reported adverse events were headache, medication intolerance, dizziness, nausea, dyspepsia, neonatal jaundice, and vomiting.

“Thus, labetalol compared with nifedipine appeared to have fewer adverse events and to be better tolerated,” the authors write. They note that labetalol, a third-generation mixed alpha- and beta-adrenergic antagonist, is contraindicated for those who have obstructive pulmonary disease and nifedipine, a dihydropyridine calcium channel blocker, is contraindicated in people with tachycardia.

The authors write that their results align with other studies that have not found differences between labetalol and nifedipine. “[O]ur findings support the use of either labetalol or nifedipine as initial first-line agents for the management of mild chronic hypertension in pregnancy to reduce the risk of adverse maternal and other perinatal outcomes with no increased risk of fetal harm,” the authors write.

Dr. Sanusi reports no relevant financial relationships. Full coauthor disclosures are available with the full text of the paper.

Treatment for chronic hypertension in pregnancy with labetalol showed no significant differences in maternal or neonatal outcomes, compared with treatment with nifedipine, new research indicates.

The open-label, multicenter, randomized CHAP (Chronic Hypertension in Pregnancy) trial showed that treating mild chronic hypertension was better than delaying treatment until severe hypertension developed, but still unclear was whether, or to what extent, the choice of first-line treatment affected outcomes.

Researchers, led by Ayodeji A. Sanusi, MD, MPH, with the Division of Maternal and Fetal Medicine at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, conducted a secondary analysis of CHAP to compare the primary treatments. Mild chronic hypertension in the study was defined as blood pressure of 140-159/90-104 mmHg before 20 weeks of gestation.

Three Comparisons

Three comparisons were performed in 2292 participants based on medications prescribed at enrollment: 720 (31.4%) received labetalol; 417 (18.2%) initially received nifedipine; and 1155 (50.4%) had standard care. Labetalol was compared with standard care; nifedipine was compared with standard care; and labetalol was compared with nifedipine.