User login

Time to retire race- and ethnicity-based carrier screening

The social reckoning of 2020 has led to many discussions and conversations around equity and disparities. With the COVID-19 pandemic, there has been a particular spotlight on health care disparities and race-based medicine. Racism in medicine is pervasive; little has been done over the years to dismantle and unlearn practices that continue to contribute to existing gaps and disparities. Race and ethnicity are both social constructs that have long been used within medical practice and in dictating the type of care an individual receives. Without a universal definition, race, ethnicity, and ancestry have long been used interchangeably within medicine and society. Appreciating that race and ethnicity-based constructs can have other social implications in health care, with their impact on structural racism beyond health care settings, these constructs may still be part of assessments and key modifiers to understanding health differences. It is imperative that medical providers examine the use of race and ethnicity within the care that they provide.

While racial determinants of health cannot be removed from historical access, utilization, and barriers related to reproductive care, guidelines structured around historical ethnicity and race further restrict universal access to carrier screening and informed reproductive testing decisions.

Carrier screening

The goal of preconception and prenatal carrier screening is to provide individuals and reproductive partners with information to optimize pregnancy outcomes based on personal values and preferences.1 The practice of carrier screening began almost half a century ago with screening for individual conditions seen more frequently in certain populations, such as Tay-Sachs disease in those of Ashkenazi Jewish descent and sickle cell disease in those of African descent. Cystic fibrosis carrier screening was first recommended for individuals of Northern European descent in 2001 before being recommended for pan ethnic screening a decade later. Other individual conditions are also recommended for screening based on race/ethnicity (eg, Canavan disease in the Ashkenazi Jewish population, Tay-Sachs disease in individuals of Cajun or French-Canadian descent).2-4 Practice guidelines from professional societies recommend offering carrier screening for individual conditions based on condition severity, race or ethnicity, prevalence, carrier frequency, detection rates, and residual risk.1 However, this process can be problematic, as the data frequently used in updating guidelines and recommendations come primarily from studies and databases where much of the cohort is White.5,6 Failing to identify genetic associations in diverse populations limits the ability to illuminate new discoveries that inform risk management and treatment, especially for populations that are disproportionately underserved in medicine.7

Need for expanded carrier screening

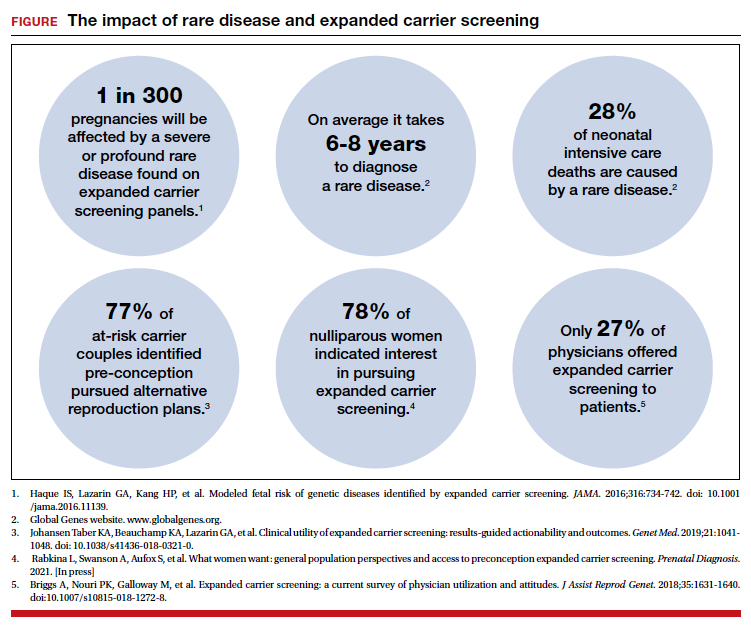

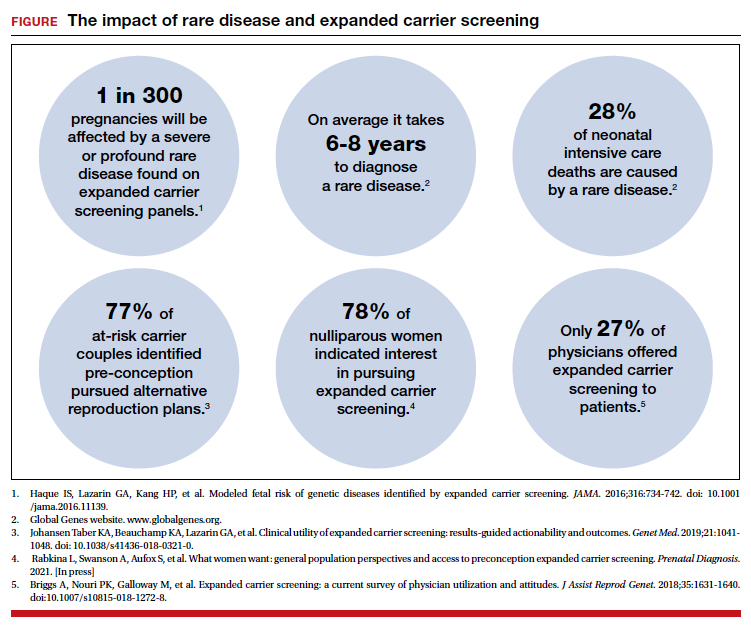

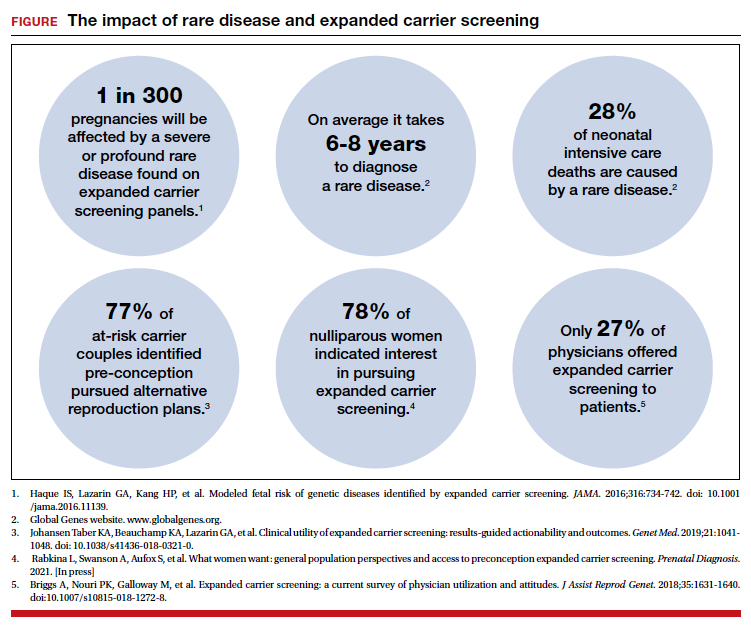

The evolution of genomics and technology within the realm of carrier screening has enabled the simultaneous screening for many serious Mendelian diseases, known as expanded carrier screening (ECS). A 2016 study illustrated that, in most racial/ethnic categories, the cumulative risk of severe and profound conditions found on ECS panels outside the guideline recommendations are greater than the risk identified by guideline-based panels.8 Additionally, a 2020 study showed that self-reported ethnicity was an imperfect indicator of genetic ancestry, with 9% of those in the cohort having a >50% genetic ancestry from a lineage inconsistent with their self-reported ethnicity.9 Data over the past decade have established the clinical utility,10 clinical validity,11 analytical validity,12 and cost-effectiveness13 of pan-ethnic ECS. In 2021, American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) recommended a panel of pan-ethnic conditions that should be offered to all patients due to smaller ethnicity-based panels failing to provide equitable evaluation of all racial and ethnic groups.14 The guidelines from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) fall short of recommending that ECS be offered to all individuals in lieu of screening based on self-reported ethnicity.3,4

Phasing out ethnicity-based carrier screening

This begs the question: Do race, ethnicity, or ancestry have a role in carrier screening? While each may have had a role at the inception of offering carrier screening due to high costs of technology, recent studies have shown the limitations of using self-reported ethnicity in screening. Guideline-based carrier screenings miss a significant percentage of pregnancies (13% to 94%) affected by serious conditions on expanded carrier screening panels.8 Additionally, 40% of Americans cannot identify the ethnicity of all 4 grandparents.15

Founder mutations due to ancestry patterns are still present; however, stratification of care should only be pursued when the presence or absence of these markers would alter clinical management. While the reproductive risk an individual may receive varies based on their self-reported ethnicity, the clinically indicated follow-up testing is the same: offering carrier screening for the reproductive partner or gamete donor. With increased detection rates via sequencing for most autosomal recessive conditions, if the reproductive partner or gamete donor is not identified as a carrier, no further testing is generally indicated regardless of ancestry. Genotyping platforms should not be used for partner carrier screening as they primarily target common pathogenic variants based on dominant ancestry groups and do not provide the same risk reduction.

Continue to: Variant reporting...

Variant reporting

We have long known that databases and registries in the United States have an increased representation of individuals from European ancestries.5,6 However, there have been limited conversations about how the lack of representation within our databases and registries leads to inequities in guidelines and the care that we provide to patients. As a result, studies have shown higher rates of variants of uncertain significance (VUS) identified during genetic testing in non-White individuals than in Whites.16 When it comes to reporting of variants, carrier screening laboratories follow guidelines set forth by the ACMG, and most laboratories only report likely pathogenic or pathogenic variants.17 It is unknown how the higher rate of VUSs in the non-White population, and lack of data and representation in databases and software used to calculate predicted phenotype, impacts identification of at-risk carrier couples in these underrepresented populations. It is imperative that we increase knowledge and representation of variants across ethnicities to improve sensitivity and specificity across the population and not just for those of European descent.

Moving forward

Being aware of social- and race-based biases in carrier screening is important, but modifying structural systems to increase representation, access, and utility of carrier screening is a critical next step. Organizations like ACOG and ACMG have committed not only to understanding but also to addressing factors that have led to disparities and inequities in health care delivery and access.18,19 Actionable steps include offering a universal carrier screening program to all preconception and prenatal patients that addresses conditions with increased carrier frequency, in any population, defined as severe and moderate phenotype with established natural history.3,4 Educational materials should be provided to detail risks, benefits, and limitations of carrier screening, as well as shared decision making between patient and provider to align the patient’s wishes for the information provided by carrier screening.

A broader number of conditions offered through carrier screening will increase the likelihood of positive carrier results. The increase in carriers identified should be viewed as more accurate reproductive risk assessment in the context of equitable care, rather than justification for panels to be limited to specific ancestries. Simultaneous or tandem reproductive partner or donor testing can be considered to reduce clinical workload and time for results return.

In addition, increased representation of individuals who are from diverse ancestries in promotional and educational resources can reinforce that risk for Mendelian conditions is not specific to single ancestries or for targeted conditions. Future research should be conducted to examine the role of racial disparities related to carrier screening and greater inclusion and recruitment of diverse populations in data sets and research studies.

Learned biases toward race, religion, gender identity, sexual orientation, and economic status in the context of carrier screening should be examined and challenged to increase access for all patients who may benefit from this testing. For example, the use of gendered language within carrier screening guidelines and policies and how such screening is offered to patients should be examined. Guidelines do not specify what to do when someone is adopted, for instance, or does not know their ethnicity. It is important that, as genomic testing becomes more available, individuals and groups are not left behind and existing gaps are not further widened. Assessing for genetic variation that modifies for disease or treatment will be more powerful than stratifying based on race. Carrier screening panels should be comprehensive regardless of ancestry to ensure coverage for global genetic variation and to increase access for all patients to risk assessments that promote informed reproductive decision making.

Health equity requires unlearning certain behaviors

As clinicians we all have a commitment to educate and empower one another to offer care that helps promote health equity. Equitable care requires us to look at the current gaps and figure out what programs and initiatives need to be designed to address those gaps. Carrier screening is one such area in which we can work together to improve the overall care that our patients receive, but it is imperative that we examine our practices and unlearn behaviors that contribute to existing disparities. ●

- Edwards JG, Feldman G, Goldberg J, et al. Expanded carrier screening in reproductive medicine—points to consider: a joint statement of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, National Society of Genetic Counselors, Perinatal Quality Foundation, and Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:653-662. doi: 10.1097 /AOG.0000000000000666.

- Grody WW, Thompson BH, Gregg AR, et al. ACMG position statement on prenatal/preconception expanded carrier screening. Genet Med. 2013;15:482-483. doi: 10.1038/gim.2013.47.

- Committee Opinion No. 690. Summary: carrier screening in the age of genomic medicine. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129: 595-596. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001947.

- Committee Opinion No. 691. Carrier screening for genetic conditions. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129:e41-e55. doi: 10.1097 /AOG.0000000000001952.

- Need AC, Goldstein DB. Next generation disparities in human genomics: concerns and remedies. Trends Genet. 2009;25:489-494. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2009.09.012.

- Popejoy A, Fullerton S. Genomics is failing on diversity. Nature. 2016;538;161-164. doi: 10.1038/538161a.

- Ewing A. Reimagining health equity in genetic testing. Medpage Today. June 17, 2021. https://www.medpagetoday.com /opinion/second-opinions/93173. Accessed October 27, 2021.

- Haque IS, Lazarin GA, Kang HP, et al. Modeled fetal risk of genetic diseases identified by expanded carrier screening. JAMA. 2016;316:734-742. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.11139.

- Kaseniit KE, Haque IS, Goldberg JD, et al. Genetic ancestry analysis on >93,000 individuals undergoing expanded carrier screening reveals limitations of ethnicity-based medical guidelines. Genet Med. 2020;22:1694-1702. doi: 10 .1038/s41436-020-0869-3.

- Johansen Taber KA, Beauchamp KA, Lazarin GA, et al. Clinical utility of expanded carrier screening: results-guided actionability and outcomes. Genet Med. 2019;21:1041-1048. doi: 10.1038/s41436-018-0321-0.

- Balzotti M, Meng L, Muzzey D, et al. Clinical validity of expanded carrier screening: Evaluating the gene-disease relationship in more than 200 conditions. Hum Mutat. 2020;41:1365-1371. doi: 10.1002/humu.24033.

- Hogan GJ, Vysotskaia VS, Beauchamp KA, et al. Validation of an expanded carrier screen that optimizes sensitivity via full-exon sequencing and panel-wide copy number variant identification. Clin Chem. 2018;64:1063-1073. doi: 10.1373 /clinchem.2018.286823.

- Beauchamp KA, Johansen Taber KA, Muzzey D. Clinical impact and cost-effectiveness of a 176-condition expanded carrier screen. Genet Med. 2019;21:1948-1957. doi: 10.1038/s41436-019-0455-8.

- Gregg AR, Aarabi M, Klugman S, et al. Screening for autosomal recessive and X-linked conditions during pregnancy and preconception: a practice resource of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG). Genet Med. 2021;23:1793-1806. doi: 10.1038/s41436-021-01203-z.

- Condit C, Templeton A, Bates BR, et al. Attitudinal barriers to delivery of race-targeted pharmacogenomics among informed lay persons. Genet Med. 2003;5:385-392. doi: 10 .1097/01.gim.0000087990.30961.72.

- Caswell-Jin J, Gupta T, Hall E, et al. Racial/ethnic differences in multiple-gene sequencing results for hereditary cancer risk. Genet Med. 2018;20:234-239.

- Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. 2015;17:405-424. doi:10.1038/gim.2015.30.

- Gregg AR. Message from ACMG President: overcoming disparities. Genet Med. 2020;22:1758.

The social reckoning of 2020 has led to many discussions and conversations around equity and disparities. With the COVID-19 pandemic, there has been a particular spotlight on health care disparities and race-based medicine. Racism in medicine is pervasive; little has been done over the years to dismantle and unlearn practices that continue to contribute to existing gaps and disparities. Race and ethnicity are both social constructs that have long been used within medical practice and in dictating the type of care an individual receives. Without a universal definition, race, ethnicity, and ancestry have long been used interchangeably within medicine and society. Appreciating that race and ethnicity-based constructs can have other social implications in health care, with their impact on structural racism beyond health care settings, these constructs may still be part of assessments and key modifiers to understanding health differences. It is imperative that medical providers examine the use of race and ethnicity within the care that they provide.

While racial determinants of health cannot be removed from historical access, utilization, and barriers related to reproductive care, guidelines structured around historical ethnicity and race further restrict universal access to carrier screening and informed reproductive testing decisions.

Carrier screening

The goal of preconception and prenatal carrier screening is to provide individuals and reproductive partners with information to optimize pregnancy outcomes based on personal values and preferences.1 The practice of carrier screening began almost half a century ago with screening for individual conditions seen more frequently in certain populations, such as Tay-Sachs disease in those of Ashkenazi Jewish descent and sickle cell disease in those of African descent. Cystic fibrosis carrier screening was first recommended for individuals of Northern European descent in 2001 before being recommended for pan ethnic screening a decade later. Other individual conditions are also recommended for screening based on race/ethnicity (eg, Canavan disease in the Ashkenazi Jewish population, Tay-Sachs disease in individuals of Cajun or French-Canadian descent).2-4 Practice guidelines from professional societies recommend offering carrier screening for individual conditions based on condition severity, race or ethnicity, prevalence, carrier frequency, detection rates, and residual risk.1 However, this process can be problematic, as the data frequently used in updating guidelines and recommendations come primarily from studies and databases where much of the cohort is White.5,6 Failing to identify genetic associations in diverse populations limits the ability to illuminate new discoveries that inform risk management and treatment, especially for populations that are disproportionately underserved in medicine.7

Need for expanded carrier screening

The evolution of genomics and technology within the realm of carrier screening has enabled the simultaneous screening for many serious Mendelian diseases, known as expanded carrier screening (ECS). A 2016 study illustrated that, in most racial/ethnic categories, the cumulative risk of severe and profound conditions found on ECS panels outside the guideline recommendations are greater than the risk identified by guideline-based panels.8 Additionally, a 2020 study showed that self-reported ethnicity was an imperfect indicator of genetic ancestry, with 9% of those in the cohort having a >50% genetic ancestry from a lineage inconsistent with their self-reported ethnicity.9 Data over the past decade have established the clinical utility,10 clinical validity,11 analytical validity,12 and cost-effectiveness13 of pan-ethnic ECS. In 2021, American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) recommended a panel of pan-ethnic conditions that should be offered to all patients due to smaller ethnicity-based panels failing to provide equitable evaluation of all racial and ethnic groups.14 The guidelines from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) fall short of recommending that ECS be offered to all individuals in lieu of screening based on self-reported ethnicity.3,4

Phasing out ethnicity-based carrier screening

This begs the question: Do race, ethnicity, or ancestry have a role in carrier screening? While each may have had a role at the inception of offering carrier screening due to high costs of technology, recent studies have shown the limitations of using self-reported ethnicity in screening. Guideline-based carrier screenings miss a significant percentage of pregnancies (13% to 94%) affected by serious conditions on expanded carrier screening panels.8 Additionally, 40% of Americans cannot identify the ethnicity of all 4 grandparents.15

Founder mutations due to ancestry patterns are still present; however, stratification of care should only be pursued when the presence or absence of these markers would alter clinical management. While the reproductive risk an individual may receive varies based on their self-reported ethnicity, the clinically indicated follow-up testing is the same: offering carrier screening for the reproductive partner or gamete donor. With increased detection rates via sequencing for most autosomal recessive conditions, if the reproductive partner or gamete donor is not identified as a carrier, no further testing is generally indicated regardless of ancestry. Genotyping platforms should not be used for partner carrier screening as they primarily target common pathogenic variants based on dominant ancestry groups and do not provide the same risk reduction.

Continue to: Variant reporting...

Variant reporting

We have long known that databases and registries in the United States have an increased representation of individuals from European ancestries.5,6 However, there have been limited conversations about how the lack of representation within our databases and registries leads to inequities in guidelines and the care that we provide to patients. As a result, studies have shown higher rates of variants of uncertain significance (VUS) identified during genetic testing in non-White individuals than in Whites.16 When it comes to reporting of variants, carrier screening laboratories follow guidelines set forth by the ACMG, and most laboratories only report likely pathogenic or pathogenic variants.17 It is unknown how the higher rate of VUSs in the non-White population, and lack of data and representation in databases and software used to calculate predicted phenotype, impacts identification of at-risk carrier couples in these underrepresented populations. It is imperative that we increase knowledge and representation of variants across ethnicities to improve sensitivity and specificity across the population and not just for those of European descent.

Moving forward

Being aware of social- and race-based biases in carrier screening is important, but modifying structural systems to increase representation, access, and utility of carrier screening is a critical next step. Organizations like ACOG and ACMG have committed not only to understanding but also to addressing factors that have led to disparities and inequities in health care delivery and access.18,19 Actionable steps include offering a universal carrier screening program to all preconception and prenatal patients that addresses conditions with increased carrier frequency, in any population, defined as severe and moderate phenotype with established natural history.3,4 Educational materials should be provided to detail risks, benefits, and limitations of carrier screening, as well as shared decision making between patient and provider to align the patient’s wishes for the information provided by carrier screening.

A broader number of conditions offered through carrier screening will increase the likelihood of positive carrier results. The increase in carriers identified should be viewed as more accurate reproductive risk assessment in the context of equitable care, rather than justification for panels to be limited to specific ancestries. Simultaneous or tandem reproductive partner or donor testing can be considered to reduce clinical workload and time for results return.

In addition, increased representation of individuals who are from diverse ancestries in promotional and educational resources can reinforce that risk for Mendelian conditions is not specific to single ancestries or for targeted conditions. Future research should be conducted to examine the role of racial disparities related to carrier screening and greater inclusion and recruitment of diverse populations in data sets and research studies.

Learned biases toward race, religion, gender identity, sexual orientation, and economic status in the context of carrier screening should be examined and challenged to increase access for all patients who may benefit from this testing. For example, the use of gendered language within carrier screening guidelines and policies and how such screening is offered to patients should be examined. Guidelines do not specify what to do when someone is adopted, for instance, or does not know their ethnicity. It is important that, as genomic testing becomes more available, individuals and groups are not left behind and existing gaps are not further widened. Assessing for genetic variation that modifies for disease or treatment will be more powerful than stratifying based on race. Carrier screening panels should be comprehensive regardless of ancestry to ensure coverage for global genetic variation and to increase access for all patients to risk assessments that promote informed reproductive decision making.

Health equity requires unlearning certain behaviors

As clinicians we all have a commitment to educate and empower one another to offer care that helps promote health equity. Equitable care requires us to look at the current gaps and figure out what programs and initiatives need to be designed to address those gaps. Carrier screening is one such area in which we can work together to improve the overall care that our patients receive, but it is imperative that we examine our practices and unlearn behaviors that contribute to existing disparities. ●

The social reckoning of 2020 has led to many discussions and conversations around equity and disparities. With the COVID-19 pandemic, there has been a particular spotlight on health care disparities and race-based medicine. Racism in medicine is pervasive; little has been done over the years to dismantle and unlearn practices that continue to contribute to existing gaps and disparities. Race and ethnicity are both social constructs that have long been used within medical practice and in dictating the type of care an individual receives. Without a universal definition, race, ethnicity, and ancestry have long been used interchangeably within medicine and society. Appreciating that race and ethnicity-based constructs can have other social implications in health care, with their impact on structural racism beyond health care settings, these constructs may still be part of assessments and key modifiers to understanding health differences. It is imperative that medical providers examine the use of race and ethnicity within the care that they provide.

While racial determinants of health cannot be removed from historical access, utilization, and barriers related to reproductive care, guidelines structured around historical ethnicity and race further restrict universal access to carrier screening and informed reproductive testing decisions.

Carrier screening

The goal of preconception and prenatal carrier screening is to provide individuals and reproductive partners with information to optimize pregnancy outcomes based on personal values and preferences.1 The practice of carrier screening began almost half a century ago with screening for individual conditions seen more frequently in certain populations, such as Tay-Sachs disease in those of Ashkenazi Jewish descent and sickle cell disease in those of African descent. Cystic fibrosis carrier screening was first recommended for individuals of Northern European descent in 2001 before being recommended for pan ethnic screening a decade later. Other individual conditions are also recommended for screening based on race/ethnicity (eg, Canavan disease in the Ashkenazi Jewish population, Tay-Sachs disease in individuals of Cajun or French-Canadian descent).2-4 Practice guidelines from professional societies recommend offering carrier screening for individual conditions based on condition severity, race or ethnicity, prevalence, carrier frequency, detection rates, and residual risk.1 However, this process can be problematic, as the data frequently used in updating guidelines and recommendations come primarily from studies and databases where much of the cohort is White.5,6 Failing to identify genetic associations in diverse populations limits the ability to illuminate new discoveries that inform risk management and treatment, especially for populations that are disproportionately underserved in medicine.7

Need for expanded carrier screening

The evolution of genomics and technology within the realm of carrier screening has enabled the simultaneous screening for many serious Mendelian diseases, known as expanded carrier screening (ECS). A 2016 study illustrated that, in most racial/ethnic categories, the cumulative risk of severe and profound conditions found on ECS panels outside the guideline recommendations are greater than the risk identified by guideline-based panels.8 Additionally, a 2020 study showed that self-reported ethnicity was an imperfect indicator of genetic ancestry, with 9% of those in the cohort having a >50% genetic ancestry from a lineage inconsistent with their self-reported ethnicity.9 Data over the past decade have established the clinical utility,10 clinical validity,11 analytical validity,12 and cost-effectiveness13 of pan-ethnic ECS. In 2021, American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) recommended a panel of pan-ethnic conditions that should be offered to all patients due to smaller ethnicity-based panels failing to provide equitable evaluation of all racial and ethnic groups.14 The guidelines from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) fall short of recommending that ECS be offered to all individuals in lieu of screening based on self-reported ethnicity.3,4

Phasing out ethnicity-based carrier screening

This begs the question: Do race, ethnicity, or ancestry have a role in carrier screening? While each may have had a role at the inception of offering carrier screening due to high costs of technology, recent studies have shown the limitations of using self-reported ethnicity in screening. Guideline-based carrier screenings miss a significant percentage of pregnancies (13% to 94%) affected by serious conditions on expanded carrier screening panels.8 Additionally, 40% of Americans cannot identify the ethnicity of all 4 grandparents.15

Founder mutations due to ancestry patterns are still present; however, stratification of care should only be pursued when the presence or absence of these markers would alter clinical management. While the reproductive risk an individual may receive varies based on their self-reported ethnicity, the clinically indicated follow-up testing is the same: offering carrier screening for the reproductive partner or gamete donor. With increased detection rates via sequencing for most autosomal recessive conditions, if the reproductive partner or gamete donor is not identified as a carrier, no further testing is generally indicated regardless of ancestry. Genotyping platforms should not be used for partner carrier screening as they primarily target common pathogenic variants based on dominant ancestry groups and do not provide the same risk reduction.

Continue to: Variant reporting...

Variant reporting

We have long known that databases and registries in the United States have an increased representation of individuals from European ancestries.5,6 However, there have been limited conversations about how the lack of representation within our databases and registries leads to inequities in guidelines and the care that we provide to patients. As a result, studies have shown higher rates of variants of uncertain significance (VUS) identified during genetic testing in non-White individuals than in Whites.16 When it comes to reporting of variants, carrier screening laboratories follow guidelines set forth by the ACMG, and most laboratories only report likely pathogenic or pathogenic variants.17 It is unknown how the higher rate of VUSs in the non-White population, and lack of data and representation in databases and software used to calculate predicted phenotype, impacts identification of at-risk carrier couples in these underrepresented populations. It is imperative that we increase knowledge and representation of variants across ethnicities to improve sensitivity and specificity across the population and not just for those of European descent.

Moving forward

Being aware of social- and race-based biases in carrier screening is important, but modifying structural systems to increase representation, access, and utility of carrier screening is a critical next step. Organizations like ACOG and ACMG have committed not only to understanding but also to addressing factors that have led to disparities and inequities in health care delivery and access.18,19 Actionable steps include offering a universal carrier screening program to all preconception and prenatal patients that addresses conditions with increased carrier frequency, in any population, defined as severe and moderate phenotype with established natural history.3,4 Educational materials should be provided to detail risks, benefits, and limitations of carrier screening, as well as shared decision making between patient and provider to align the patient’s wishes for the information provided by carrier screening.

A broader number of conditions offered through carrier screening will increase the likelihood of positive carrier results. The increase in carriers identified should be viewed as more accurate reproductive risk assessment in the context of equitable care, rather than justification for panels to be limited to specific ancestries. Simultaneous or tandem reproductive partner or donor testing can be considered to reduce clinical workload and time for results return.

In addition, increased representation of individuals who are from diverse ancestries in promotional and educational resources can reinforce that risk for Mendelian conditions is not specific to single ancestries or for targeted conditions. Future research should be conducted to examine the role of racial disparities related to carrier screening and greater inclusion and recruitment of diverse populations in data sets and research studies.

Learned biases toward race, religion, gender identity, sexual orientation, and economic status in the context of carrier screening should be examined and challenged to increase access for all patients who may benefit from this testing. For example, the use of gendered language within carrier screening guidelines and policies and how such screening is offered to patients should be examined. Guidelines do not specify what to do when someone is adopted, for instance, or does not know their ethnicity. It is important that, as genomic testing becomes more available, individuals and groups are not left behind and existing gaps are not further widened. Assessing for genetic variation that modifies for disease or treatment will be more powerful than stratifying based on race. Carrier screening panels should be comprehensive regardless of ancestry to ensure coverage for global genetic variation and to increase access for all patients to risk assessments that promote informed reproductive decision making.

Health equity requires unlearning certain behaviors

As clinicians we all have a commitment to educate and empower one another to offer care that helps promote health equity. Equitable care requires us to look at the current gaps and figure out what programs and initiatives need to be designed to address those gaps. Carrier screening is one such area in which we can work together to improve the overall care that our patients receive, but it is imperative that we examine our practices and unlearn behaviors that contribute to existing disparities. ●

- Edwards JG, Feldman G, Goldberg J, et al. Expanded carrier screening in reproductive medicine—points to consider: a joint statement of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, National Society of Genetic Counselors, Perinatal Quality Foundation, and Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:653-662. doi: 10.1097 /AOG.0000000000000666.

- Grody WW, Thompson BH, Gregg AR, et al. ACMG position statement on prenatal/preconception expanded carrier screening. Genet Med. 2013;15:482-483. doi: 10.1038/gim.2013.47.

- Committee Opinion No. 690. Summary: carrier screening in the age of genomic medicine. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129: 595-596. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001947.

- Committee Opinion No. 691. Carrier screening for genetic conditions. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129:e41-e55. doi: 10.1097 /AOG.0000000000001952.

- Need AC, Goldstein DB. Next generation disparities in human genomics: concerns and remedies. Trends Genet. 2009;25:489-494. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2009.09.012.

- Popejoy A, Fullerton S. Genomics is failing on diversity. Nature. 2016;538;161-164. doi: 10.1038/538161a.

- Ewing A. Reimagining health equity in genetic testing. Medpage Today. June 17, 2021. https://www.medpagetoday.com /opinion/second-opinions/93173. Accessed October 27, 2021.

- Haque IS, Lazarin GA, Kang HP, et al. Modeled fetal risk of genetic diseases identified by expanded carrier screening. JAMA. 2016;316:734-742. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.11139.

- Kaseniit KE, Haque IS, Goldberg JD, et al. Genetic ancestry analysis on >93,000 individuals undergoing expanded carrier screening reveals limitations of ethnicity-based medical guidelines. Genet Med. 2020;22:1694-1702. doi: 10 .1038/s41436-020-0869-3.

- Johansen Taber KA, Beauchamp KA, Lazarin GA, et al. Clinical utility of expanded carrier screening: results-guided actionability and outcomes. Genet Med. 2019;21:1041-1048. doi: 10.1038/s41436-018-0321-0.

- Balzotti M, Meng L, Muzzey D, et al. Clinical validity of expanded carrier screening: Evaluating the gene-disease relationship in more than 200 conditions. Hum Mutat. 2020;41:1365-1371. doi: 10.1002/humu.24033.

- Hogan GJ, Vysotskaia VS, Beauchamp KA, et al. Validation of an expanded carrier screen that optimizes sensitivity via full-exon sequencing and panel-wide copy number variant identification. Clin Chem. 2018;64:1063-1073. doi: 10.1373 /clinchem.2018.286823.

- Beauchamp KA, Johansen Taber KA, Muzzey D. Clinical impact and cost-effectiveness of a 176-condition expanded carrier screen. Genet Med. 2019;21:1948-1957. doi: 10.1038/s41436-019-0455-8.

- Gregg AR, Aarabi M, Klugman S, et al. Screening for autosomal recessive and X-linked conditions during pregnancy and preconception: a practice resource of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG). Genet Med. 2021;23:1793-1806. doi: 10.1038/s41436-021-01203-z.

- Condit C, Templeton A, Bates BR, et al. Attitudinal barriers to delivery of race-targeted pharmacogenomics among informed lay persons. Genet Med. 2003;5:385-392. doi: 10 .1097/01.gim.0000087990.30961.72.

- Caswell-Jin J, Gupta T, Hall E, et al. Racial/ethnic differences in multiple-gene sequencing results for hereditary cancer risk. Genet Med. 2018;20:234-239.

- Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. 2015;17:405-424. doi:10.1038/gim.2015.30.

- Gregg AR. Message from ACMG President: overcoming disparities. Genet Med. 2020;22:1758.

- Edwards JG, Feldman G, Goldberg J, et al. Expanded carrier screening in reproductive medicine—points to consider: a joint statement of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, National Society of Genetic Counselors, Perinatal Quality Foundation, and Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:653-662. doi: 10.1097 /AOG.0000000000000666.

- Grody WW, Thompson BH, Gregg AR, et al. ACMG position statement on prenatal/preconception expanded carrier screening. Genet Med. 2013;15:482-483. doi: 10.1038/gim.2013.47.

- Committee Opinion No. 690. Summary: carrier screening in the age of genomic medicine. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129: 595-596. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001947.

- Committee Opinion No. 691. Carrier screening for genetic conditions. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129:e41-e55. doi: 10.1097 /AOG.0000000000001952.

- Need AC, Goldstein DB. Next generation disparities in human genomics: concerns and remedies. Trends Genet. 2009;25:489-494. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2009.09.012.

- Popejoy A, Fullerton S. Genomics is failing on diversity. Nature. 2016;538;161-164. doi: 10.1038/538161a.

- Ewing A. Reimagining health equity in genetic testing. Medpage Today. June 17, 2021. https://www.medpagetoday.com /opinion/second-opinions/93173. Accessed October 27, 2021.

- Haque IS, Lazarin GA, Kang HP, et al. Modeled fetal risk of genetic diseases identified by expanded carrier screening. JAMA. 2016;316:734-742. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.11139.

- Kaseniit KE, Haque IS, Goldberg JD, et al. Genetic ancestry analysis on >93,000 individuals undergoing expanded carrier screening reveals limitations of ethnicity-based medical guidelines. Genet Med. 2020;22:1694-1702. doi: 10 .1038/s41436-020-0869-3.

- Johansen Taber KA, Beauchamp KA, Lazarin GA, et al. Clinical utility of expanded carrier screening: results-guided actionability and outcomes. Genet Med. 2019;21:1041-1048. doi: 10.1038/s41436-018-0321-0.

- Balzotti M, Meng L, Muzzey D, et al. Clinical validity of expanded carrier screening: Evaluating the gene-disease relationship in more than 200 conditions. Hum Mutat. 2020;41:1365-1371. doi: 10.1002/humu.24033.

- Hogan GJ, Vysotskaia VS, Beauchamp KA, et al. Validation of an expanded carrier screen that optimizes sensitivity via full-exon sequencing and panel-wide copy number variant identification. Clin Chem. 2018;64:1063-1073. doi: 10.1373 /clinchem.2018.286823.

- Beauchamp KA, Johansen Taber KA, Muzzey D. Clinical impact and cost-effectiveness of a 176-condition expanded carrier screen. Genet Med. 2019;21:1948-1957. doi: 10.1038/s41436-019-0455-8.

- Gregg AR, Aarabi M, Klugman S, et al. Screening for autosomal recessive and X-linked conditions during pregnancy and preconception: a practice resource of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG). Genet Med. 2021;23:1793-1806. doi: 10.1038/s41436-021-01203-z.

- Condit C, Templeton A, Bates BR, et al. Attitudinal barriers to delivery of race-targeted pharmacogenomics among informed lay persons. Genet Med. 2003;5:385-392. doi: 10 .1097/01.gim.0000087990.30961.72.

- Caswell-Jin J, Gupta T, Hall E, et al. Racial/ethnic differences in multiple-gene sequencing results for hereditary cancer risk. Genet Med. 2018;20:234-239.

- Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. 2015;17:405-424. doi:10.1038/gim.2015.30.

- Gregg AR. Message from ACMG President: overcoming disparities. Genet Med. 2020;22:1758.

Babies are dying of syphilis. It’s 100% preventable.

This story was originally published on ProPublica and was co-published with NPR.

When Mai Yang is looking for a patient, she travels light. She dresses deliberately — not too formal, so she won’t be mistaken for a police officer; not too casual, so people will look past her tiny 4-foot-10 stature and youthful face and trust her with sensitive health information. Always, she wears closed-toed shoes, “just in case I need to run.”

Yang carries a stack of cards issued by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that show what happens when the Treponema pallidum bacteria invades a patient’s body. There’s a photo of an angry red sore on a penis. There’s one of a tongue, marred by mucus-lined lesions. And there’s one of a newborn baby, its belly, torso and thighs dotted in a rash, its mouth open, as if caught midcry.

It was because of the prospect of one such baby that Yang found herself walking through a homeless encampment on a blazing July day in Huron, Calif., an hour’s drive southwest of her office at the Fresno County Department of Public Health. She was looking for a pregnant woman named Angelica, whose visit to a community clinic had triggered a report to the health department’s sexually transmitted disease program. Angelica had tested positive for syphilis. If she was not treated, her baby could end up like the one in the picture or worse — there was a 40% chance the baby would die.

Ms. Yang knew, though, that if she helped Angelica get treated with three weekly shots of penicillin at least 30 days before she gave birth, it was likely that the infection would be wiped out and her baby would be born without any symptoms at all. Every case of congenital syphilis, when a baby is born with the disease, is avoidable. Each is considered a “sentinel event,” a warning that the public health system is failing.

The alarms are now clamoring. In the United States, more than 129,800 syphilis cases were recorded in 2019, double the case count of five years prior. In the same time period, cases of congenital syphilis quadrupled: 1,870 babies were born with the disease; 128 died. Case counts from 2020 are still being finalized, but the CDC has said that reported cases of congenital syphilis have already exceeded the prior year. Black, Hispanic, and Native American babies are disproportionately at risk.

There was a time, not too long ago, when CDC officials thought they could eliminate the centuries-old scourge from the United States, for adults and babies. But the effort lost steam and cases soon crept up again. Syphilis is not an outlier. The United States goes through what former CDC director Dr. Tom Frieden calls “a deadly cycle of panic and neglect” in which emergencies propel officials to scramble and throw money at a problem — whether that’s Ebola, Zika, or COVID-19. Then, as fear ebbs, so does the attention and motivation to finish the task.

The last fraction of cases can be the hardest to solve, whether that’s eradicating a bug or getting vaccines into arms, yet too often, that’s exactly when political attention gets diverted to the next alarm. The result: The hardest to reach and most vulnerable populations are the ones left suffering, after everyone else looks away.

Ms. Yang first received Angelica’s lab report on June 17. The address listed was a P.O. box, and the phone number belonged to her sister, who said Angelica was living in Huron. That was a piece of luck: Huron is tiny; the city spans just 1.6 square miles. On her first visit, a worker at the Alamo Motel said she knew Angelica and directed Ms. Yang to a nearby homeless encampment. Angelica wasn’t there, so Ms. Yang returned a second time, bringing one of the health department nurses who could serve as an interpreter.

They made their way to the barren patch of land behind Huron Valley Foods, the local grocery store, where people took shelter in makeshift lean-tos composed of cardboard boxes, scrap wood ,and scavenged furniture, draped with sheets that served as ceilings and curtains. Yang stopped outside one of the structures, calling a greeting.

“Hi, I’m from the health department, I’m looking for Angelica.”

The nurse echoed her in Spanish.

Angelica emerged, squinting in the sunlight. Ms. Yang couldn’t tell if she was visibly pregnant yet, as her body was obscured by an oversized shirt. The two women were about the same age: Ms. Yang 26 and Angelica 27. Ms. Yang led her away from the tent, so they could speak privately. Angelica seemed reticent, surprised by the sudden appearance of the two health officers. “You’re not in trouble,” Ms. Yang said, before revealing the results of her blood test.

Angelica had never heard of syphilis.

“Have you been to prenatal care?”

Angelica shook her head. The local clinic had referred her to an obstetrician in Hanford, a 30-minute drive away. She had no car. She also mentioned that she didn’t intend to raise her baby; her two oldest children lived with her mother, and this one likely would, too.

Ms. Yang pulled out the CDC cards, showing them to Angelica and asking if she had experienced any of the symptoms illustrated. No, Angelica said, her lips pursed with disgust.

“Right now you still feel healthy, but this bacteria is still in your body,” Ms. Yang pressed. “You need to get the infection treated to prevent further health complications to yourself and your baby.”

The community clinic was just across the street. “Can we walk you over to the clinic and make sure you get seen so we can get this taken care of?”

Angelica demurred. She said she hadn’t showered for a week and wanted to wash up first. She said she’d go later.

Ms. Yang tried once more to extract a promise: “What time do you think you’ll go?”

“Today, for sure.”

Syphilis is called The Great Imitator: It can look like any number of diseases. In its first stage, the only evidence of infection is a painless sore at the bacteria’s point of entry. Weeks later, as the bacteria multiplies, skin rashes bloom on the palms of the hands and bottoms of the feet. Other traits of this stage include fever, headaches, muscle aches, sore throat, and fatigue. These symptoms eventually disappear and the patient progresses into the latent phase, which betrays no external signs. But if left untreated, after a decade or more, syphilis will reemerge in up to 30% of patients, capable of wreaking horror on a wide range of organ systems. Dr. Marion Sims, president of the American Medical Association in 1876, called it a “terrible scourge, which begins with lamb-like mildness and ends with lion-like rage that ruthlessly destroys everything in its way.”

The corkscrew-shaped bacteria can infiltrate the nervous system at any stage of the infection. Ms. Yang is haunted by her memory of interviewing a young man whose dementia was so severe that he didn’t know why he was in the hospital or how old he was. And regardless of symptoms or stage, the bacteria can penetrate the placenta to infect a fetus. Even in these cases the infection is unpredictable: Many babies are born with normal physical features, but others can have deformed bones or damaged brains, and they can struggle to hear, see, or breathe.

From its earliest days, syphilis has been shrouded in stigma. The first recorded outbreak was in the late 15th century, when Charles VIII led the French army to invade Naples. Italian physicians described French soldiers covered with pustules, dying from a sexually transmitted disease. As the affliction spread, Italians called it the French Disease. The French blamed the Neopolitans. It was also called the German, Polish, or Spanish disease, depending on which neighbor one wanted to blame. Even its name bears the taint of divine judgement: It comes from a 16th-century poem that tells of a shepherd, Syphilus, who offended the god Apollo and was punished with a hideous disease.

By 1937 in America, when former Surgeon General Thomas Parran wrote the book “Shadow on the Land,” he estimated some 680,000 people were under treatment for syphilis; about 60,000 babies were being born annually with congenital syphilis. There was no cure, and the stigma was so strong that public health officials feared even properly documenting cases.

Thanks to Dr. Parran’s ardent advocacy, Congress in 1938 passed the National Venereal Disease Control Act, which created grants for states to set up clinics and support testing and treatment. Other than a short-lived funding effort during World War I, this was the first coordinated federal push to respond to the disease.

Around the same time, the Public Health Service launched an effort to record the natural history of syphilis. Situated in Tuskegee, Ala., the infamous study recruited 600 black men. By the early 1940s, penicillin became widely available and was found to be a reliable cure, but the treatment was withheld from the study participants. Outrage over the ethical violations would cast a stain across syphilis research for decades to come and fuel generations of mistrust in the medical system among Black Americans that continues to this day.

With the introduction of penicillin, cases began to plummet. Twice, the CDC has announced efforts to wipe out the disease — once in the 1960s and again in 1999.

In the latest effort, the CDC announced that the United States had “a unique opportunity to eliminate syphilis within its borders,” thanks to historically low rates, with 80% of counties reporting zero cases. The concentration of cases in the South “identifies communities in which there is a fundamental failure of public health capacity,” the agency noted, adding that elimination — which it defined as fewer than 1,000 cases a year — would “decrease one of our most glaring racial disparities in health.”

Two years after the campaign began, cases started climbing, first among gay men and later, heterosexuals. Cases in women started accelerating in 2013, followed shortly by increasing numbers of babies born with syphilis.The reasons for failure are complex; people relaxed safer sex practices after the advent of potent HIV combination therapies, increased methamphetamine use drove riskier behavior and an explosion of online dating made it hard to track and test sexual partners, according to Dr. Ina Park, medical director of the California Prevention Training Center at the University of California San Francisco.

But federal and state public health efforts were hamstrung from the get-go. In 1999, the CDC said it would need about $35 million to $39 million in new federal funds annually for at least five years to eliminate syphilis. The agency got less than half of what it asked for, according to Jo Valentine, former program coordinator of the CDC’s Syphilis Elimination Effort. As cases rose, the CDC modified its goals in 2006 from 0.4 primary and secondary syphilis cases per 100,000 in population to 2.2 cases per 100,000. By 2013, as elimination seemed less and less viable, the CDC changed its focus to ending congenital syphilis only.

Since then, funding has remained anemic. From 2015 to 2020, the CDC’s budget for preventing sexually transmitted infections grew by 2.2%. Taking inflation into account, that’s a 7.4% reduction in purchasing power. In the same period, cases of syphilis, gonorrhea and chlamydia — the three STDs that have federally funded control programs — increased by nearly 30%.

“We have a long history of nearly eradicating something, then changing our attention, and seeing a resurgence in numbers,” said David Harvey, executive director of the National Coalition of STD Directors. “We have more congenital syphilis cases today in America than we ever had pediatric AIDS at the height of the AIDS epidemic. It’s heartbreaking.”

Adriane Casalotti, chief of government and public affairs at the National Association of County and City Health Officials, warns that the United States should not be surprised to see case counts continue to climb. “The bugs don’t go away,” she said. “They’re just waiting for the next opportunity, when you’re not paying attention.”

Ms. Yang waited until the end of the day, then called the clinic to see if Angelica had gone for her shot. She had not. Ms. Yang would have to block off another half day to visit Huron again, but she had three dozen other cases to deal with.

States in the South and West have seen the highest syphilis rates in recent years. In 2017, 64 babies in Fresno County were born with syphilis at a rate of 440 babies per 100,000 live births — about 19 times the national rate. While the county had managed to lower case counts in the two years that followed, the pandemic threatened to unravel that progress, forcing STD staffers to do COVID-19 contact tracing, pausing field visits to find infected people, and scaring patients from seeking care. Ms. Yang’s colleague handled three cases of stillbirth in 2020; in each, the woman was never diagnosed with syphilis because she feared catching the coronavirus and skipped prenatal care.

Ms. Yang, whose caseload peaked at 70 during a COVID-19 surge, knew she would not be able handle them all as thoroughly as she’d like to. “When I was being mentored by another investigator, he said: ‘You’re not a superhero. You can’t save everybody,’” she said. She prioritizes men who have sex with men, because there’s a higher prevalence of syphilis in that population, and pregnant people, because of the horrific consequences for babies.

The job of a disease intervention specialist isn’t for everyone: It means meeting patients whenever and wherever they are available — in the mop closet of a bus station, in a quiet parking lot — to inform them about the disease, to extract names of sex partners and to encourage treatment. Patients are often reluctant to talk. They can get belligerent, upset that “the government” has their personal information or shattered at the thought that a partner is likely cheating on them. Salaries typically start in the low $40,000s.

Jena Adams, Ms. Yang’s supervisor, has eight investigators working on HIV and syphilis. In the middle of 2020, she lost two and replaced them only recently. “It’s been exhausting,” Ms. Adams said. She has only one specialist who is trained to take blood samples in the field, crucial for guaranteeing that the partners of those who test positive for syphilis also get tested. Ms. Adams wants to get phlebotomy training for the rest of her staff, but it’s $2,000 per person. The department also doesn’t have anyone who can administer penicillin injections in the field; that would have been key when Ms. Yang met Angelica. For a while, a nurse who worked in the tuberculosis program would ride along to give penicillin shots on a volunteer basis. Then he, too, left the health department.

Much of the resources in public health trickle down from the CDC, which distributes money to states, which then parcel it out to counties. The CDC gets its budget from Congress, which tells the agency, by line item, exactly how much money it can spend to fight a disease or virus, in an uncommonly specific manner not seen in many other agencies. The decisions are often politically driven and can be detached from actual health needs.

When the House and Senate appropriations committees meet to decide how much the CDC will get for each line item, they are barraged by lobbyists for individual disease interests. Stephanie Arnold Pang, senior director of policy and government relations at the National Coalition of STD Directors, can pick out the groups by sight: breast cancer wears pink, Alzheimer’s goes in purple, multiple sclerosis comes in orange, HIV in red. STD prevention advocates, like herself, don a green ribbon, but they’re far outnumbered.

And unlike diseases that might already be familiar to lawmakers, or have patient and family spokespeople who can tell their own powerful stories, syphilis doesn’t have many willing poster children. “Congressmen don’t wake up one day and say, ‘Oh hey, there’s congenital syphilis in my jurisdiction.’ You have to raise awareness,” Arnold Pang said. It can be hard jockeying for a meeting. “Some offices might say, ‘I don’t have time for you because we’ve just seen HIV.’ ... Sometimes, it feels like you’re talking into a void.”

The consequences of the political nature of public health funding have become more obvious during the coronavirus pandemic. The 2014 Ebola epidemic was seen as a “global wakeup call” that the world wasn’t prepared for a major pandemic, yet in 2018, the CDC scaled back its epidemic prevention work as money ran out. “If you’ve got to choose between Alzheimer’s research and stopping an outbreak that may not happen? Stopping an outbreak that might not happen doesn’t do well,” said Dr. Frieden, the former CDC director. “The CDC needs to have more money and more flexible money. Otherwise, we’re going to be in this situation long term.”

In May 2021, President Joe Biden’s administration announced it would set aside $7.4 billion over the next five years to hire and train public health workers, including $1.1 billion for more disease intervention specialists like Ms. Yang. Public health officials are thrilled to have the chance to expand their workforce, but some worry the time horizon may be too short. “We’ve seen this movie before, right?” Dr. Frieden said. “Everyone gets concerned when there’s an outbreak, and when that outbreak stops, the headlines stop, and an economic downturn happens, the budget gets cut.”

Fresno’s STD clinic was shuttered in 2010 amid the Great Recession. Many others have vanished since the passage of the Affordable Care Act. Health leaders thought “by magically beefing up the primary care system, that we would do a better job of catching STIs and treating them,” said Mr. Harvey, the executive director of the National Coalition of STD Directors. That hasn’t worked out; people want access to anonymous services, and primary care doctors often don’t have STDs top of mind. The coalition is lobbying Congress for funding to support STD clinical services, proposing a three-year demonstration project funded at $600 million.

It’s one of Ms. Adams’ dreams to see Fresno’s STD clinic restored as it was. “You could come in for an HIV test and get other STDs checked,” she said. “And if a patient is positive, you can give a first injection on the spot.”

On Aug. 12, Ms. Yang set out for Huron again, speeding past groves of almond trees and fields of grapes in the department’s white Chevy Cruze. She brought along a colleague, Jorge Sevilla, who had recently transferred to the STD program from COVID-19 contact tracing. Ms. Yang was anxious to find Angelica again. “She’s probably in her second trimester now,” she said.

They found her outside of a pale yellow house a few blocks from the homeless encampment; the owner was letting her stay in a shed tucked in the corner of the dirt yard. This time, it was evident that she was pregnant. Ms. Yang noted that Angelica was wearing a wig; hair loss is a symptom of syphilis.

“Do you remember me?” Ms. Yang asked.

Angelica nodded. She didn’t seem surprised to see Ms. Yang again. (I came along, and Mr. Sevilla explained who I was and that I was writing about syphilis and the people affected by it. Angelica signed a release for me to report about her case, and she said she had no problem with me writing about her or even using her full name. ProPublica chose to only print her first name.)

“How are you doing? How’s the baby?”

“Bien.”

“So the last time we talked, we were going to have you go to United Healthcare Center to get treatment. Have you gone since?”

Angelica shook her head.

“We brought some gift cards...” Mr. Sevilla started in Spanish. The department uses them as incentives for completing injections. But Angelica was already shaking her head. The nearest Walmart was the next town over.

Ms. Yang turned to her partner. “Tell her: So the reason why we’re coming out here again is because we really need her to go in for treatment. ... We really are concerned for the baby’s health especially since she’s had the infection for quite a while.”

Angelica listened while Mr. Sevilla interpreted, her eyes on the ground. Then she looked up. “Orita?” she asked. Right now?

“I’ll walk with you,” Ms. Yang offered. Angelica shook her head. “She said she wants to shower first before she goes over there,” Mr. Sevilla said.

Ms. Yang made a face. “She said that to me last time.” Ms. Yang offered to wait, but Angelica didn’t want the health officers to linger by the house. She said she would meet them by the clinic in 15 minutes.

Ms. Yang was reluctant to let her go but again had no other option. She and Mr. Sevilla drove to the clinic, then stood on the corner of the parking lot, staring down the road.

Talk to the pediatricians, obstetricians, and families on the front lines of the congenital syphilis surge and it becomes clear why Ms. Yang and others are trying so desperately to prevent cases. Dr. J. B. Cantey, associate professor in pediatrics at UT Health San Antonio, remembers a baby girl born at 25 weeks gestation who weighed a pound and a half. Syphilis had spread through her bones and lungs. She spent five months in the neonatal intensive care unit, breathing through a ventilator, and was still eating through a tube when she was discharged.

Then, there are the miscarriages, the stillbirths and the inconsolable parents. Dr. Irene Stafford, an associate professor and maternal-fetal medicine specialist at UT Health in Houston, cannot forget a patient who came in at 36 weeks for a routine checkup, pregnant with her first child. Dr. Stafford realized that there was no heartbeat. “She could see on my face that something was really wrong,” Dr. Stafford recalled. She had to let the patient know that syphilis had killed her baby. “She was hysterical, just bawling,” Dr. Stafford said. “I’ve seen people’s families ripped apart and I’ve seen beautiful babies die.” Fewer than 10% of patients who experience a stillbirth are tested for syphilis, suggesting that cases are underdiagnosed.

A Texas grandmother named Solidad Odunuga offers a glimpse into what the future could hold for Angelica’s mother, who may wind up raising her baby.

In February of last year, Ms. Odunuga got a call from the Lyndon B. Johnson Hospital in Houston. A nurse told her that her daughter was about to give birth and that child protective services had been called. Ms. Odunuga had lost contact with her daughter, who struggled with homelessness and substance abuse. She arrived in time to see her grandson delivered, premature at 30 weeks old, weighing 2.7 pounds. He tested positive for syphilis.

When a child protective worker asked Ms. Odunuga to take custody of the infant, she felt a wave of dread. “I was in denial,” she recalled. “I did not plan to be a mom again.” The baby’s medical problems were daunting: “Global developmental delays ... concerns for visual impairments ... high risk of cerebral palsy,” read a note from the doctor at the time.

Still, Ms. Odunuga visited her grandson every day for three months, driving to the NICU from her job at the University of Houston. “I’d put him in my shirt to keep him warm and hold him there.” She fell in love. She named him Emmanuel.

Once Emmanuel was discharged, Ms. Odunuga realized she had no choice but to quit her job. While Medicaid covered the costs of Emmanuel’s treatment, it was on her to care for him. From infancy, Emmanuel’s life has been a whirlwind of constant therapy. Today, at 20 months old, Odunuga brings him to physical, occupational, speech, and developmental therapy, each a different appointment on a different day of the week.

Emmanuel has thrived beyond what his doctors predicted, toddling so fast that Ms. Odunuga can’t look away for a minute and beaming as he waves his favorite toy phone. Yet he still suffers from gagging issues, which means Ms. Odunuga can’t feed him any solid foods. Liquid gets into his lungs when he aspirates; it has led to pneumonia three times. Emmanuel has a special stroller that helps keep his head in a position that won’t aggravate his persistent reflux, but Odunuga said she still has to pull over on the side of the road sometimes when she hears him projectile vomiting from the backseat.

The days are endless. Once she puts Emmanuel to bed, Ms. Odunuga starts planning the next day’s appointments. “I’ve had to cry alone, scream out alone,” she said. “Sometimes I wake up and think, Is this real? And then I hear him in the next room.”

Putting aside the challenge of eliminating syphilis entirely, everyone agrees it’s both doable and necessary to prevent newborn cases. “There was a crisis in perinatal HIV almost 30 years ago and people stood up and said this is not OK — it’s not acceptable for babies to be born in that condition. ... [We] brought it down from 1,700 babies born each year with perinatal HIV to less than 40 per year today,” said Virginia Bowen, an epidemiologist at the CDC. “Now here we are with a slightly different condition. We can also stand up and say, ‘This is not acceptable.’” Belarus, Bermuda, Cuba, Malaysia, Thailand, and Sri Lanka are among countries recognized by the World Health Organization for eliminating congenital syphilis.

Success starts with filling gaps across the health care system.

For almost a century, public health experts have advocated for testing pregnant patients more than once for syphilis in order to catch the infection. But policies nationwide still don’t reflect this best practice. Six states have no prenatal screening requirement at all. Even in states that require three tests, public health officials say that many physicians aren’t aware of the requirements. Dr. Stafford, the maternal-fetal medicine specialist in Houston, says she’s tired of hearing her own peers in medicine tell her, “Oh, syphilis is a problem?”

It costs public health departments less than 25 cents a dose to buy penicillin, but for a private practice, it’s more than $1,000, according to Dr. Park of the University of California San Francisco. “There’s no incentive for a private physician to stock a dose that could expire before it’s used, so they often don’t have it. So a woman comes in, they say, ‘We’ll send you to the emergency department or health department to get it,’ then [the patients] don’t show up.”

A vaccine would be invaluable for preventing spread among people at high risk for reinfection. But there is none. Scientists only recently figured out how to grow the bacteria in the lab, prompting grants from the National Institutes of Health to fund research into a vaccine. Dr. Justin Radolf, a researcher at the University of Connecticut School of Medicine, said he hopes his team will have a vaccine candidate by the end of its five-year grant. But it’ll likely take years more to find a manufacturer and run human trials.

Public health agencies also need to recognize that many of the hurdles to getting pregnant people treated involve access to care, economic stability, safe housing and transportation. In Fresno, Ms. Adams has been working on ways her department can collaborate with mental health services. Recently, one of her disease intervention specialists managed to get a pregnant woman treated with penicillin shots and, at the patient’s request, connected her with an addiction treatment center.

Gaining a patient’s cooperation means seeing them as complex humans instead of just a case to solve. “There may be past traumas with the health care system,” said Cynthia Deverson, project manager of the Houston Fetal Infant Morbidity Review. “There’s the fear of being discovered if she’s doing something illegal to survive. ... She may need to be in a certain place at a certain time so she can get something to eat, or maybe it’s the only time of the day that’s safe for her to sleep. They’re not going to tell you that. Yes, they understand there’s a problem, but it’s not an immediate threat, maybe they don’t feel bad yet, so obviously this is not urgent. ...

“What helps to gain trust is consistency,” she said. “Literally, it’s seeing that [disease specialist] constantly, daily. ... The woman can see that you’re not going to harm her, you’re saying, ‘I’m here at this time if you need me.’”

Ms. Yang stood outside the clinic, waiting for Angelica to show up, baking in the 90-degree heat. Her feelings ranged from irritation — Why didn’t she just go? I’d have more energy for other cases — to an appreciation for the parts of Angelica’s story that she didn’t know — She’s in survival mode. I need to be more patient.

Fifteen minutes ticked by, then 20.

“OK,” Ms. Yang announced. “We’re going back.”

She asked Sevilla if he would be OK if they drove Angelica to the clinic; they technically weren’t supposed to because of coronavirus precautions, but Ms. Yang wasn’t sure she could convince Angelica to walk. Mr. Sevilla gave her the thumbs up.

When they pulled up, they saw Angelica sitting in the backyard, chatting with a friend. She now wore a fresh T-shirt and had shoes on her feet. Angelica sat silently in the back seat as Ms. Yang drove to the clinic. A few minutes later, they pulled up to the parking lot.

Finally, Ms. Yang thought. We got her here.

The clinic was packed with people waiting for COVID-19 tests and vaccinations. A worker there had previously told Ms. Yang that a walk-in would be fine, but a receptionist now said they were too busy to treat Angelica. She would have to return.

Ms. Yang felt a surge of frustration, sensing that her hard-fought opportunity was slipping away. She tried to talk to the nurse supervisor, but he wasn’t available. She tried to leave the gift cards at the office to reward Angelica if she came, but the receptionist said she couldn’t hold them. While Ms. Yang negotiated, Mr. Sevilla sat with Angelica in the car, waiting.

Finally, Ms. Yang accepted this was yet another thing she couldn’t control.

She drove Angelica back to the yellow house. As they arrived, she tried once more to impress on her just how important it was to get treated, asking Mr. Sevilla to interpret. “We don’t want it to get any more serious, because she can go blind, she could go deaf, she could lose her baby.”

Angelica already had the door halfway open.

“So on a scale from one to 10, how important is this to get treated?” Ms. Yang asked.

“Ten,” Angelica said. Ms. Yang reminded her of the appointment that afternoon. Then Angelica stepped out and returned to the dusty yard.

Ms. Yang lingered for a moment, watching Angelica go. Then she turned the car back onto the highway and set off toward Fresno, knowing, already, that she’d be back.

Postscript: A reporter visited Huron twice more in the months that followed, including once independently to try to interview Angelica, but she wasn’t in town. Ms. Yang has visited Huron twice more as well — six times in total thus far. In October, a couple of men at the yellow house said Angelica was still in town, still pregnant. Ms. Yang and Mr. Sevilla spent an hour driving around, talking to residents, hoping to catch Angelica. But she was nowhere to be found.

ProPublica is a nonprofit newsroom that investigates abuses of power. Sign up to receive their biggest stories as soon as they’re published.

This story was originally published on ProPublica and was co-published with NPR.

When Mai Yang is looking for a patient, she travels light. She dresses deliberately — not too formal, so she won’t be mistaken for a police officer; not too casual, so people will look past her tiny 4-foot-10 stature and youthful face and trust her with sensitive health information. Always, she wears closed-toed shoes, “just in case I need to run.”

Yang carries a stack of cards issued by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that show what happens when the Treponema pallidum bacteria invades a patient’s body. There’s a photo of an angry red sore on a penis. There’s one of a tongue, marred by mucus-lined lesions. And there’s one of a newborn baby, its belly, torso and thighs dotted in a rash, its mouth open, as if caught midcry.

It was because of the prospect of one such baby that Yang found herself walking through a homeless encampment on a blazing July day in Huron, Calif., an hour’s drive southwest of her office at the Fresno County Department of Public Health. She was looking for a pregnant woman named Angelica, whose visit to a community clinic had triggered a report to the health department’s sexually transmitted disease program. Angelica had tested positive for syphilis. If she was not treated, her baby could end up like the one in the picture or worse — there was a 40% chance the baby would die.

Ms. Yang knew, though, that if she helped Angelica get treated with three weekly shots of penicillin at least 30 days before she gave birth, it was likely that the infection would be wiped out and her baby would be born without any symptoms at all. Every case of congenital syphilis, when a baby is born with the disease, is avoidable. Each is considered a “sentinel event,” a warning that the public health system is failing.

The alarms are now clamoring. In the United States, more than 129,800 syphilis cases were recorded in 2019, double the case count of five years prior. In the same time period, cases of congenital syphilis quadrupled: 1,870 babies were born with the disease; 128 died. Case counts from 2020 are still being finalized, but the CDC has said that reported cases of congenital syphilis have already exceeded the prior year. Black, Hispanic, and Native American babies are disproportionately at risk.

There was a time, not too long ago, when CDC officials thought they could eliminate the centuries-old scourge from the United States, for adults and babies. But the effort lost steam and cases soon crept up again. Syphilis is not an outlier. The United States goes through what former CDC director Dr. Tom Frieden calls “a deadly cycle of panic and neglect” in which emergencies propel officials to scramble and throw money at a problem — whether that’s Ebola, Zika, or COVID-19. Then, as fear ebbs, so does the attention and motivation to finish the task.

The last fraction of cases can be the hardest to solve, whether that’s eradicating a bug or getting vaccines into arms, yet too often, that’s exactly when political attention gets diverted to the next alarm. The result: The hardest to reach and most vulnerable populations are the ones left suffering, after everyone else looks away.

Ms. Yang first received Angelica’s lab report on June 17. The address listed was a P.O. box, and the phone number belonged to her sister, who said Angelica was living in Huron. That was a piece of luck: Huron is tiny; the city spans just 1.6 square miles. On her first visit, a worker at the Alamo Motel said she knew Angelica and directed Ms. Yang to a nearby homeless encampment. Angelica wasn’t there, so Ms. Yang returned a second time, bringing one of the health department nurses who could serve as an interpreter.

They made their way to the barren patch of land behind Huron Valley Foods, the local grocery store, where people took shelter in makeshift lean-tos composed of cardboard boxes, scrap wood ,and scavenged furniture, draped with sheets that served as ceilings and curtains. Yang stopped outside one of the structures, calling a greeting.

“Hi, I’m from the health department, I’m looking for Angelica.”

The nurse echoed her in Spanish.

Angelica emerged, squinting in the sunlight. Ms. Yang couldn’t tell if she was visibly pregnant yet, as her body was obscured by an oversized shirt. The two women were about the same age: Ms. Yang 26 and Angelica 27. Ms. Yang led her away from the tent, so they could speak privately. Angelica seemed reticent, surprised by the sudden appearance of the two health officers. “You’re not in trouble,” Ms. Yang said, before revealing the results of her blood test.

Angelica had never heard of syphilis.

“Have you been to prenatal care?”

Angelica shook her head. The local clinic had referred her to an obstetrician in Hanford, a 30-minute drive away. She had no car. She also mentioned that she didn’t intend to raise her baby; her two oldest children lived with her mother, and this one likely would, too.

Ms. Yang pulled out the CDC cards, showing them to Angelica and asking if she had experienced any of the symptoms illustrated. No, Angelica said, her lips pursed with disgust.

“Right now you still feel healthy, but this bacteria is still in your body,” Ms. Yang pressed. “You need to get the infection treated to prevent further health complications to yourself and your baby.”

The community clinic was just across the street. “Can we walk you over to the clinic and make sure you get seen so we can get this taken care of?”