User login

CagA-positive H. pylori patients at higher risk of osteoporosis, fracture

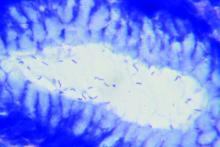

A new study has found that older patients who test positive for the cytotoxin associated gene-A (CagA) strain of Helicobacter pylori may be more at risk of both osteoporosis and fractures.

“Further studies will be required to replicate these findings in other cohorts and to better clarify the underlying pathogenetic mechanisms leading to increased bone fragility in subjects infected by CagA-positive H. pylori strains,” wrote Luigi Gennari, MD, PhD, of the University of Siena (Italy), and coauthors. The study was published in the Journal of Bone and Mineral Research.

To determine the effects of H. pylori on bone health and potential fracture risk, the researchers launched a population-based cohort study of 1,149 adults between the ages of 50 and 80 in Siena. The cohort comprised 174 males with an average (SD) age of 65.9 (plus or minus 6 years) and 975 females with an average age of 62.5 (plus or minus 6 years). All subjects were examined for H. pylori antibodies, and those who were infected were also examined for anti-CagA serum antibodies. As blood was sampled, bone mineral density (BMD) of the lumbar spine, femoral neck, total hip, and total body was measured via dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry.

In total, 53% of male participants and 49% of female participants tested positive for H. pylori, with CagA-positive strains found in 27% of males and 26% of females. No differences in infection rates were discovered in regard to socioeconomic status, age, weight, or height. Patients with normal BMD (45%), osteoporosis (51%), or osteopenia (49%) had similar prevalence of H. pylori infection, but CagA-positive strains were more frequently found in osteoporotic (30%) and osteopenic (26%) patients, compared to patients with normal BMD (21%, P < .01). CagA-positive female patients also had lower lumbar (0.950 g/cm2) and femoral (0.795 g/cm2) BMD, compared to CagA-negative (0.987 and 0.813 g/cm2) or H. pylori-negative women (0.997 and 0.821 g/cm2), respectively.

After an average follow-up period of 11.8 years, 199 nontraumatic fractures (72 vertebral and 127 nonvertebral) had occurred in 158 participants. Patients with CagA-positive strains of H. pylori had significantly increased risk of a clinical vertebral fracture (hazard ratio [HR], 5.27; 95% confidence interval, 2.23-12.63; P < .0001) or a nonvertebral incident fracture (HR, 2.09; 95% CI, 1.27-2.46; P < .01), compared to patients without H. pylori. After adjustment for age, sex, and body mass index, the risk among CagA-positive patients remained similarly significantly elevated for both vertebral (aHR, 4.78; 95% CI, 1.99-11.47; P < .0001) and nonvertebral fractures (aHR, 2.04; 95% CI, 1.22-3.41; P < .01).

The authors acknowledged their study’s limitations, including a cohort that was notably low in male participants, an inability to assess the effects of eradicating H. pylori on bone, and uncertainty as to which specific effects of H. pylori infection increase the risk of osteoporosis or fracture. Along those lines, they noted that an association between serum CagA antibody titer and gastric mucosal inflammation could lead to malabsorption of calcium, hypothesizing that antibody titer rather than antibody positivity “might be a more relevant marker for assessing the risk of bone fragility in patients affected by H. pylori infection.”

The study was supported in part by a grant from the Italian Association for Osteoporosis. The authors reported no potential conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Gennari L et al. J Bone Miner Res. 2020 Aug 13. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.4162.

A new study has found that older patients who test positive for the cytotoxin associated gene-A (CagA) strain of Helicobacter pylori may be more at risk of both osteoporosis and fractures.

“Further studies will be required to replicate these findings in other cohorts and to better clarify the underlying pathogenetic mechanisms leading to increased bone fragility in subjects infected by CagA-positive H. pylori strains,” wrote Luigi Gennari, MD, PhD, of the University of Siena (Italy), and coauthors. The study was published in the Journal of Bone and Mineral Research.

To determine the effects of H. pylori on bone health and potential fracture risk, the researchers launched a population-based cohort study of 1,149 adults between the ages of 50 and 80 in Siena. The cohort comprised 174 males with an average (SD) age of 65.9 (plus or minus 6 years) and 975 females with an average age of 62.5 (plus or minus 6 years). All subjects were examined for H. pylori antibodies, and those who were infected were also examined for anti-CagA serum antibodies. As blood was sampled, bone mineral density (BMD) of the lumbar spine, femoral neck, total hip, and total body was measured via dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry.

In total, 53% of male participants and 49% of female participants tested positive for H. pylori, with CagA-positive strains found in 27% of males and 26% of females. No differences in infection rates were discovered in regard to socioeconomic status, age, weight, or height. Patients with normal BMD (45%), osteoporosis (51%), or osteopenia (49%) had similar prevalence of H. pylori infection, but CagA-positive strains were more frequently found in osteoporotic (30%) and osteopenic (26%) patients, compared to patients with normal BMD (21%, P < .01). CagA-positive female patients also had lower lumbar (0.950 g/cm2) and femoral (0.795 g/cm2) BMD, compared to CagA-negative (0.987 and 0.813 g/cm2) or H. pylori-negative women (0.997 and 0.821 g/cm2), respectively.

After an average follow-up period of 11.8 years, 199 nontraumatic fractures (72 vertebral and 127 nonvertebral) had occurred in 158 participants. Patients with CagA-positive strains of H. pylori had significantly increased risk of a clinical vertebral fracture (hazard ratio [HR], 5.27; 95% confidence interval, 2.23-12.63; P < .0001) or a nonvertebral incident fracture (HR, 2.09; 95% CI, 1.27-2.46; P < .01), compared to patients without H. pylori. After adjustment for age, sex, and body mass index, the risk among CagA-positive patients remained similarly significantly elevated for both vertebral (aHR, 4.78; 95% CI, 1.99-11.47; P < .0001) and nonvertebral fractures (aHR, 2.04; 95% CI, 1.22-3.41; P < .01).

The authors acknowledged their study’s limitations, including a cohort that was notably low in male participants, an inability to assess the effects of eradicating H. pylori on bone, and uncertainty as to which specific effects of H. pylori infection increase the risk of osteoporosis or fracture. Along those lines, they noted that an association between serum CagA antibody titer and gastric mucosal inflammation could lead to malabsorption of calcium, hypothesizing that antibody titer rather than antibody positivity “might be a more relevant marker for assessing the risk of bone fragility in patients affected by H. pylori infection.”

The study was supported in part by a grant from the Italian Association for Osteoporosis. The authors reported no potential conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Gennari L et al. J Bone Miner Res. 2020 Aug 13. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.4162.

A new study has found that older patients who test positive for the cytotoxin associated gene-A (CagA) strain of Helicobacter pylori may be more at risk of both osteoporosis and fractures.

“Further studies will be required to replicate these findings in other cohorts and to better clarify the underlying pathogenetic mechanisms leading to increased bone fragility in subjects infected by CagA-positive H. pylori strains,” wrote Luigi Gennari, MD, PhD, of the University of Siena (Italy), and coauthors. The study was published in the Journal of Bone and Mineral Research.

To determine the effects of H. pylori on bone health and potential fracture risk, the researchers launched a population-based cohort study of 1,149 adults between the ages of 50 and 80 in Siena. The cohort comprised 174 males with an average (SD) age of 65.9 (plus or minus 6 years) and 975 females with an average age of 62.5 (plus or minus 6 years). All subjects were examined for H. pylori antibodies, and those who were infected were also examined for anti-CagA serum antibodies. As blood was sampled, bone mineral density (BMD) of the lumbar spine, femoral neck, total hip, and total body was measured via dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry.

In total, 53% of male participants and 49% of female participants tested positive for H. pylori, with CagA-positive strains found in 27% of males and 26% of females. No differences in infection rates were discovered in regard to socioeconomic status, age, weight, or height. Patients with normal BMD (45%), osteoporosis (51%), or osteopenia (49%) had similar prevalence of H. pylori infection, but CagA-positive strains were more frequently found in osteoporotic (30%) and osteopenic (26%) patients, compared to patients with normal BMD (21%, P < .01). CagA-positive female patients also had lower lumbar (0.950 g/cm2) and femoral (0.795 g/cm2) BMD, compared to CagA-negative (0.987 and 0.813 g/cm2) or H. pylori-negative women (0.997 and 0.821 g/cm2), respectively.

After an average follow-up period of 11.8 years, 199 nontraumatic fractures (72 vertebral and 127 nonvertebral) had occurred in 158 participants. Patients with CagA-positive strains of H. pylori had significantly increased risk of a clinical vertebral fracture (hazard ratio [HR], 5.27; 95% confidence interval, 2.23-12.63; P < .0001) or a nonvertebral incident fracture (HR, 2.09; 95% CI, 1.27-2.46; P < .01), compared to patients without H. pylori. After adjustment for age, sex, and body mass index, the risk among CagA-positive patients remained similarly significantly elevated for both vertebral (aHR, 4.78; 95% CI, 1.99-11.47; P < .0001) and nonvertebral fractures (aHR, 2.04; 95% CI, 1.22-3.41; P < .01).

The authors acknowledged their study’s limitations, including a cohort that was notably low in male participants, an inability to assess the effects of eradicating H. pylori on bone, and uncertainty as to which specific effects of H. pylori infection increase the risk of osteoporosis or fracture. Along those lines, they noted that an association between serum CagA antibody titer and gastric mucosal inflammation could lead to malabsorption of calcium, hypothesizing that antibody titer rather than antibody positivity “might be a more relevant marker for assessing the risk of bone fragility in patients affected by H. pylori infection.”

The study was supported in part by a grant from the Italian Association for Osteoporosis. The authors reported no potential conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Gennari L et al. J Bone Miner Res. 2020 Aug 13. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.4162.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF BONE AND MINERAL RESEARCH

Atypical fractures with bisphosphonates highest in Asians, study confirms

The latest findings regarding the risk for atypical femur fracture (AFF) with use of bisphosphonates for osteoporosis show a significant increase in risk when treatment extends beyond 5 years. The risk is notably higher risk among Asian women, compared with White women. However, the benefits in fracture reduction still appear to far outweigh the risk for AFF.

The research, published in the New England Journal of Medicine, importantly adds to findings from smaller studies by showing effects in a population of nearly 200,000 women in a diverse cohort, said Angela M. Cheung, MD, PhD.

“This study answers some important questions – Kaiser Permanente Southern California is a large health maintenance organization with a diverse racial population,” said Dr. Cheung, director of the Center of Excellence in Skeletal Health Assessment and osteoporosis program at the University of Toronto.

“This is the first study that included a diverse population to definitively show that Asians are at a much higher risk of atypical femur fractures than Caucasians,” she emphasized.

Although AFFs are rare, concerns about them remain pressing in the treatment of osteoporosis, Dr. Cheung noted. “This is a big concern for clinicians – they want to do no harm.”

Risk for AFF increases with longer duration of bisphosphonate use

For the study, Dennis M. Black, PhD, of the departments of epidemiology and biostatistics and orthopedic surgery at the University of California, San Francisco, and colleagues identified women aged 50 years or older enrolled in the Kaiser Permanente Southern California system who were treated with bisphosphonates and were followed from January 2007 to November 2017.

Among the 196,129 women identified in the study, 277 AFFs occurred.

After multivariate adjustment, compared with those treated for less than 3 months, for women who were treated for 3-5 years, the hazard ratio for experiencing an AFF was 8.86. For therapy of 5-8 years, the HR increased to 19.88, and for those treated with bisphosphonates for 8 years or longer, the HR was 43.51.

The risk for AFF declined quickly upon bisphosphonate discontinuation; compared with current users, the HR dropped to 0.52 within 3-15 months after the last bisphosphonate use. It declined to 0.26 at more than 4 years after discontinuation.

The risk for AFF with bisphosphonate use was higher for Asian women than for White women (HR, 4.84); this did not apply to any other ethnic groups (HR, 0.99).

Other risk factors for AFF included shorter height (HR, 1.28 per 5-cm decrement), greater weight (HR, 1.15 per 5-kg increment), and glucocorticoid use (HR, 2.28 for glucocorticoid use of 1 or more years).

Among White women, the number of fractures prevented with bisphosphonate use far outweighed the risk for bisphosphonate-associated AFFs.

For example, among White women, during a 3-year treatment period, there were two bisphosphonate-associated AFFs, whereas 149 hip fractures and 541 clinical fractures were prevented, the authors wrote.

After 5 years, there were eight AFFs, but 286 hip fractures and 859 clinical fractures were prevented.

Although the risk-benefit ratio among Asian women still favored prevention of fractures, the difference was less pronounced – eight bisphosphonate-associated AFFs had occurred at 3 years, whereas 91 hip fractures and 330 clinical fractures were prevented.

The authors noted that previous studies have also shown Asian women to be at a disproportionately higher risk for AFF.

An earlier Kaiser Permanente Southern California case series showed that 49% of 142 AFFs occurred in Asian patients, despite the fact that those patients made up only 10% of the study population.

Various factors could cause higher risk in Asian women

The reasons for the increased risk among Asian women are likely multifactorial and could include greater medication adherence among Asian women, genetic differences in drug metabolism and bone turnover, and, notably, increased lateral stress caused by bowed Asian femora, the authors speculated.

Further questions include whether the risk is limited to Asians living outside of Asia and whether cultural differences in diet or physical activity are risk factors, they added.

“At this early stage, further research into the cause of the increased risk among women of Asian ancestry is warranted,” they wrote.

Although the risk for AFF may be higher among Asian women, the incidence of hip and other osteoporotic fractures is lower among Asians as well as other non-White persons, compared with White persons, they added.

The findings have important implications in how clinicians should discuss treatment options with different patient groups, Dr. Cheung said.

“I think this is one of the key findings of the study,” she added. “In this day and age of personalized medicine, we need to keep the individual patient in mind, and that includes their racial/ethnic background, genetic characteristics, sex, medical conditions and medications, etc. So it is important for physicians to pay attention to this. The risk-benefit ratio of these drugs for Asians will be quite different, compared to Caucasians.”

No link between traditional fracture risk factors and AFF, study shows

Interestingly, although older age, previous fractures, and lower bone mineral density are key risk factors for hip and other osteoporotic fractures in the general population, they do not significantly increase the risk for AFF with bisphosphonate use, the study also showed.

“In fact, the oldest women in our cohort, who are at highest risk for hip and other fractures, were at lowest risk for AFF,” the authors wrote.

The collective findings “add to the risk-benefit balance of bisphosphonate treatment in these populations and could directly affect decisions regarding treatment initiation and duration.”

Notable limitations of the study include the fact that most women were treated with one particular bisphosphonate, alendronate, and that other bisphosphonates were underrepresented, Dr. Cheung said.

“This study examined bisphosphonate therapy, but the vast majority of the women were exposed to alendronate, so whether women on risedronate or other bisphosphonates have similar risks is unclear,” she observed.

“In addition, because they can only capture bisphosphonate use using their database, any bisphosphonate exposure prior to joining Kaiser Permanente will not be captured. So the study may underestimate the total cumulative duration of bisphosphonate use,” she added.

The study received support from Kaiser Permanente and discretionary funds from the University of California, San Francisco. The study began with a pilot grant from Merck Sharp & Dohme, which had no role in the conduct of the study. Dr. Cheung has served as a consultant for Amgen. She chaired and led the 2019 International Society for Clinical Densitometry Position Development Conference on Detection of Atypical Femur Fractures and currently is on the Osteoporosis Canada Guidelines Committee.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

The latest findings regarding the risk for atypical femur fracture (AFF) with use of bisphosphonates for osteoporosis show a significant increase in risk when treatment extends beyond 5 years. The risk is notably higher risk among Asian women, compared with White women. However, the benefits in fracture reduction still appear to far outweigh the risk for AFF.

The research, published in the New England Journal of Medicine, importantly adds to findings from smaller studies by showing effects in a population of nearly 200,000 women in a diverse cohort, said Angela M. Cheung, MD, PhD.

“This study answers some important questions – Kaiser Permanente Southern California is a large health maintenance organization with a diverse racial population,” said Dr. Cheung, director of the Center of Excellence in Skeletal Health Assessment and osteoporosis program at the University of Toronto.

“This is the first study that included a diverse population to definitively show that Asians are at a much higher risk of atypical femur fractures than Caucasians,” she emphasized.

Although AFFs are rare, concerns about them remain pressing in the treatment of osteoporosis, Dr. Cheung noted. “This is a big concern for clinicians – they want to do no harm.”

Risk for AFF increases with longer duration of bisphosphonate use

For the study, Dennis M. Black, PhD, of the departments of epidemiology and biostatistics and orthopedic surgery at the University of California, San Francisco, and colleagues identified women aged 50 years or older enrolled in the Kaiser Permanente Southern California system who were treated with bisphosphonates and were followed from January 2007 to November 2017.

Among the 196,129 women identified in the study, 277 AFFs occurred.

After multivariate adjustment, compared with those treated for less than 3 months, for women who were treated for 3-5 years, the hazard ratio for experiencing an AFF was 8.86. For therapy of 5-8 years, the HR increased to 19.88, and for those treated with bisphosphonates for 8 years or longer, the HR was 43.51.

The risk for AFF declined quickly upon bisphosphonate discontinuation; compared with current users, the HR dropped to 0.52 within 3-15 months after the last bisphosphonate use. It declined to 0.26 at more than 4 years after discontinuation.

The risk for AFF with bisphosphonate use was higher for Asian women than for White women (HR, 4.84); this did not apply to any other ethnic groups (HR, 0.99).

Other risk factors for AFF included shorter height (HR, 1.28 per 5-cm decrement), greater weight (HR, 1.15 per 5-kg increment), and glucocorticoid use (HR, 2.28 for glucocorticoid use of 1 or more years).

Among White women, the number of fractures prevented with bisphosphonate use far outweighed the risk for bisphosphonate-associated AFFs.

For example, among White women, during a 3-year treatment period, there were two bisphosphonate-associated AFFs, whereas 149 hip fractures and 541 clinical fractures were prevented, the authors wrote.

After 5 years, there were eight AFFs, but 286 hip fractures and 859 clinical fractures were prevented.

Although the risk-benefit ratio among Asian women still favored prevention of fractures, the difference was less pronounced – eight bisphosphonate-associated AFFs had occurred at 3 years, whereas 91 hip fractures and 330 clinical fractures were prevented.

The authors noted that previous studies have also shown Asian women to be at a disproportionately higher risk for AFF.

An earlier Kaiser Permanente Southern California case series showed that 49% of 142 AFFs occurred in Asian patients, despite the fact that those patients made up only 10% of the study population.

Various factors could cause higher risk in Asian women

The reasons for the increased risk among Asian women are likely multifactorial and could include greater medication adherence among Asian women, genetic differences in drug metabolism and bone turnover, and, notably, increased lateral stress caused by bowed Asian femora, the authors speculated.

Further questions include whether the risk is limited to Asians living outside of Asia and whether cultural differences in diet or physical activity are risk factors, they added.

“At this early stage, further research into the cause of the increased risk among women of Asian ancestry is warranted,” they wrote.

Although the risk for AFF may be higher among Asian women, the incidence of hip and other osteoporotic fractures is lower among Asians as well as other non-White persons, compared with White persons, they added.

The findings have important implications in how clinicians should discuss treatment options with different patient groups, Dr. Cheung said.

“I think this is one of the key findings of the study,” she added. “In this day and age of personalized medicine, we need to keep the individual patient in mind, and that includes their racial/ethnic background, genetic characteristics, sex, medical conditions and medications, etc. So it is important for physicians to pay attention to this. The risk-benefit ratio of these drugs for Asians will be quite different, compared to Caucasians.”

No link between traditional fracture risk factors and AFF, study shows

Interestingly, although older age, previous fractures, and lower bone mineral density are key risk factors for hip and other osteoporotic fractures in the general population, they do not significantly increase the risk for AFF with bisphosphonate use, the study also showed.

“In fact, the oldest women in our cohort, who are at highest risk for hip and other fractures, were at lowest risk for AFF,” the authors wrote.

The collective findings “add to the risk-benefit balance of bisphosphonate treatment in these populations and could directly affect decisions regarding treatment initiation and duration.”

Notable limitations of the study include the fact that most women were treated with one particular bisphosphonate, alendronate, and that other bisphosphonates were underrepresented, Dr. Cheung said.

“This study examined bisphosphonate therapy, but the vast majority of the women were exposed to alendronate, so whether women on risedronate or other bisphosphonates have similar risks is unclear,” she observed.

“In addition, because they can only capture bisphosphonate use using their database, any bisphosphonate exposure prior to joining Kaiser Permanente will not be captured. So the study may underestimate the total cumulative duration of bisphosphonate use,” she added.

The study received support from Kaiser Permanente and discretionary funds from the University of California, San Francisco. The study began with a pilot grant from Merck Sharp & Dohme, which had no role in the conduct of the study. Dr. Cheung has served as a consultant for Amgen. She chaired and led the 2019 International Society for Clinical Densitometry Position Development Conference on Detection of Atypical Femur Fractures and currently is on the Osteoporosis Canada Guidelines Committee.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

The latest findings regarding the risk for atypical femur fracture (AFF) with use of bisphosphonates for osteoporosis show a significant increase in risk when treatment extends beyond 5 years. The risk is notably higher risk among Asian women, compared with White women. However, the benefits in fracture reduction still appear to far outweigh the risk for AFF.

The research, published in the New England Journal of Medicine, importantly adds to findings from smaller studies by showing effects in a population of nearly 200,000 women in a diverse cohort, said Angela M. Cheung, MD, PhD.

“This study answers some important questions – Kaiser Permanente Southern California is a large health maintenance organization with a diverse racial population,” said Dr. Cheung, director of the Center of Excellence in Skeletal Health Assessment and osteoporosis program at the University of Toronto.

“This is the first study that included a diverse population to definitively show that Asians are at a much higher risk of atypical femur fractures than Caucasians,” she emphasized.

Although AFFs are rare, concerns about them remain pressing in the treatment of osteoporosis, Dr. Cheung noted. “This is a big concern for clinicians – they want to do no harm.”

Risk for AFF increases with longer duration of bisphosphonate use

For the study, Dennis M. Black, PhD, of the departments of epidemiology and biostatistics and orthopedic surgery at the University of California, San Francisco, and colleagues identified women aged 50 years or older enrolled in the Kaiser Permanente Southern California system who were treated with bisphosphonates and were followed from January 2007 to November 2017.

Among the 196,129 women identified in the study, 277 AFFs occurred.

After multivariate adjustment, compared with those treated for less than 3 months, for women who were treated for 3-5 years, the hazard ratio for experiencing an AFF was 8.86. For therapy of 5-8 years, the HR increased to 19.88, and for those treated with bisphosphonates for 8 years or longer, the HR was 43.51.

The risk for AFF declined quickly upon bisphosphonate discontinuation; compared with current users, the HR dropped to 0.52 within 3-15 months after the last bisphosphonate use. It declined to 0.26 at more than 4 years after discontinuation.

The risk for AFF with bisphosphonate use was higher for Asian women than for White women (HR, 4.84); this did not apply to any other ethnic groups (HR, 0.99).

Other risk factors for AFF included shorter height (HR, 1.28 per 5-cm decrement), greater weight (HR, 1.15 per 5-kg increment), and glucocorticoid use (HR, 2.28 for glucocorticoid use of 1 or more years).

Among White women, the number of fractures prevented with bisphosphonate use far outweighed the risk for bisphosphonate-associated AFFs.

For example, among White women, during a 3-year treatment period, there were two bisphosphonate-associated AFFs, whereas 149 hip fractures and 541 clinical fractures were prevented, the authors wrote.

After 5 years, there were eight AFFs, but 286 hip fractures and 859 clinical fractures were prevented.

Although the risk-benefit ratio among Asian women still favored prevention of fractures, the difference was less pronounced – eight bisphosphonate-associated AFFs had occurred at 3 years, whereas 91 hip fractures and 330 clinical fractures were prevented.

The authors noted that previous studies have also shown Asian women to be at a disproportionately higher risk for AFF.

An earlier Kaiser Permanente Southern California case series showed that 49% of 142 AFFs occurred in Asian patients, despite the fact that those patients made up only 10% of the study population.

Various factors could cause higher risk in Asian women

The reasons for the increased risk among Asian women are likely multifactorial and could include greater medication adherence among Asian women, genetic differences in drug metabolism and bone turnover, and, notably, increased lateral stress caused by bowed Asian femora, the authors speculated.

Further questions include whether the risk is limited to Asians living outside of Asia and whether cultural differences in diet or physical activity are risk factors, they added.

“At this early stage, further research into the cause of the increased risk among women of Asian ancestry is warranted,” they wrote.

Although the risk for AFF may be higher among Asian women, the incidence of hip and other osteoporotic fractures is lower among Asians as well as other non-White persons, compared with White persons, they added.

The findings have important implications in how clinicians should discuss treatment options with different patient groups, Dr. Cheung said.

“I think this is one of the key findings of the study,” she added. “In this day and age of personalized medicine, we need to keep the individual patient in mind, and that includes their racial/ethnic background, genetic characteristics, sex, medical conditions and medications, etc. So it is important for physicians to pay attention to this. The risk-benefit ratio of these drugs for Asians will be quite different, compared to Caucasians.”

No link between traditional fracture risk factors and AFF, study shows

Interestingly, although older age, previous fractures, and lower bone mineral density are key risk factors for hip and other osteoporotic fractures in the general population, they do not significantly increase the risk for AFF with bisphosphonate use, the study also showed.

“In fact, the oldest women in our cohort, who are at highest risk for hip and other fractures, were at lowest risk for AFF,” the authors wrote.

The collective findings “add to the risk-benefit balance of bisphosphonate treatment in these populations and could directly affect decisions regarding treatment initiation and duration.”

Notable limitations of the study include the fact that most women were treated with one particular bisphosphonate, alendronate, and that other bisphosphonates were underrepresented, Dr. Cheung said.

“This study examined bisphosphonate therapy, but the vast majority of the women were exposed to alendronate, so whether women on risedronate or other bisphosphonates have similar risks is unclear,” she observed.

“In addition, because they can only capture bisphosphonate use using their database, any bisphosphonate exposure prior to joining Kaiser Permanente will not be captured. So the study may underestimate the total cumulative duration of bisphosphonate use,” she added.

The study received support from Kaiser Permanente and discretionary funds from the University of California, San Francisco. The study began with a pilot grant from Merck Sharp & Dohme, which had no role in the conduct of the study. Dr. Cheung has served as a consultant for Amgen. She chaired and led the 2019 International Society for Clinical Densitometry Position Development Conference on Detection of Atypical Femur Fractures and currently is on the Osteoporosis Canada Guidelines Committee.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

SGLT2 inhibitors with metformin look safe for bone

The combination of sodium-glucose transporter-2 (SGLT-2) inhibitors and metformin is not associated with an increase in fracture risk among patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D), according to a new meta-analysis of 25 randomized, controlled trials.

Researchers at The Second Clinical College of Dalian Medical University in Jiangsu, China, compared fracture risk associated with the metformin/SLGT2 combination to metformin alone as well as other T2D therapeutics, and found no differences in risk. The study was published online Aug. 11 in Osteoporosis International.

T2D is associated with an increased risk of fracture, though causative mechanisms remain uncertain. Some lines of evidence suggest multiple factors may contribute to fractures, including hyperglycemia, oxidative stress, toxic effects of advanced glycosylation end-products, altered insulin levels, and treatment-induced hypoglycemia, as well as an association between T2D and increased risk of falls.

Antidiabetes drugs can have positive or negative effects on bone. thiazolidinediones, insulin, and sulfonylureas may increase risk of fractures, while dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitors and glucagon-like peptide-2 (GLP-2) receptor agonists may be protective. Metformin may also reduce fracture risk.

SGLT-2 inhibitors interrupt glucose reabsorption in the kidney, leading to improved glycemic control. Other benefits include improved renal and cardiovascular outcomes, weight loss, and reduced blood pressure, liver fat, and serum uric acid levels.

These properties have made SGLT-2 inhibitors combined with metformin an important therapy for patients at high risk of atherosclerotic disease, or who have heart failure or chronic kidney disease.

But SGLT-2 inhibition increases osmotic diuresis, and this could alter the mineral balance within bone. Some studies also showed that SGLT-2 inhibitors led to changes in bone turnover markers, bone mineral density, and bone microarchitecture. Observational studies of the SGLT-2 inhibitor canagliflozin found associations with a higher rate of fracture risk in patients taking the drug.

Such studies carry the risk of confounding factors, so the researchers took advantage of the fact that many recent clinical trials have examined the impact of SGLT-2 inhibitors on T2D. They pooled data from 25 clinical trials with a total of 19,500 participants, 9,662 of whom received SGLT-2 inhibitors plus metformin; 9,838 received other active comparators.

The fracture rate was 0.91% in the SGLT-2 inhibitors/metformin group, and 0.80% among controls (odds ratio, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.71-1.32), with no heterogeneity. Metformin alone was not associated with a change in fracture rate (OR, 0.95; 95% CI, 0.44-2.08), nor were other forms of diabetes control (OR, 0.95; 95% CI, 0.69-1.31).

There were some differences in fracture risk among SGLT-2 inhibitors when studied individually, though none differed significantly from controls. The highest risk was associated with the canagliflozin/metformin (OR, 2.19; 95% CI, 0.66-7.27), followed by dapagliflozin/metformin (OR, 0.91; 95% CI, 0.50-1.64), empagliflozin/metformin (OR, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.59-1.50), and ertugliflozin/metformin (OR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.38-1.54).

There were no differences with respect to hip or lumbar spine fractures, or other fractures. The researchers found no differences in bone mineral density or bone turnover markers.

The meta-analysis is limited by the relatively short average follow-up in the included studies, which was 61 weeks. Bone damage may occur over longer time periods. Bone fractures were also not a prespecified adverse event in most included studies.

The studies also did not provide detailed information on the types of fractures experienced, such as whether they were result of a fall, or the location of the fracture, or bone health parameters. Although the results support a belief that SGLT-2 inhibitors do not adversely affect bone health, “given limited information on bone health outcomes, further work is needed to validate this conclusion,” the authors wrote.

The authors did not disclose any funding and had no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: B-B Qian et al. Osteoporosis Int. 2020 Aug 11. doi: 10.1007/s00198-020-05590-y.

The combination of sodium-glucose transporter-2 (SGLT-2) inhibitors and metformin is not associated with an increase in fracture risk among patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D), according to a new meta-analysis of 25 randomized, controlled trials.

Researchers at The Second Clinical College of Dalian Medical University in Jiangsu, China, compared fracture risk associated with the metformin/SLGT2 combination to metformin alone as well as other T2D therapeutics, and found no differences in risk. The study was published online Aug. 11 in Osteoporosis International.

T2D is associated with an increased risk of fracture, though causative mechanisms remain uncertain. Some lines of evidence suggest multiple factors may contribute to fractures, including hyperglycemia, oxidative stress, toxic effects of advanced glycosylation end-products, altered insulin levels, and treatment-induced hypoglycemia, as well as an association between T2D and increased risk of falls.

Antidiabetes drugs can have positive or negative effects on bone. thiazolidinediones, insulin, and sulfonylureas may increase risk of fractures, while dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitors and glucagon-like peptide-2 (GLP-2) receptor agonists may be protective. Metformin may also reduce fracture risk.

SGLT-2 inhibitors interrupt glucose reabsorption in the kidney, leading to improved glycemic control. Other benefits include improved renal and cardiovascular outcomes, weight loss, and reduced blood pressure, liver fat, and serum uric acid levels.

These properties have made SGLT-2 inhibitors combined with metformin an important therapy for patients at high risk of atherosclerotic disease, or who have heart failure or chronic kidney disease.

But SGLT-2 inhibition increases osmotic diuresis, and this could alter the mineral balance within bone. Some studies also showed that SGLT-2 inhibitors led to changes in bone turnover markers, bone mineral density, and bone microarchitecture. Observational studies of the SGLT-2 inhibitor canagliflozin found associations with a higher rate of fracture risk in patients taking the drug.

Such studies carry the risk of confounding factors, so the researchers took advantage of the fact that many recent clinical trials have examined the impact of SGLT-2 inhibitors on T2D. They pooled data from 25 clinical trials with a total of 19,500 participants, 9,662 of whom received SGLT-2 inhibitors plus metformin; 9,838 received other active comparators.

The fracture rate was 0.91% in the SGLT-2 inhibitors/metformin group, and 0.80% among controls (odds ratio, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.71-1.32), with no heterogeneity. Metformin alone was not associated with a change in fracture rate (OR, 0.95; 95% CI, 0.44-2.08), nor were other forms of diabetes control (OR, 0.95; 95% CI, 0.69-1.31).

There were some differences in fracture risk among SGLT-2 inhibitors when studied individually, though none differed significantly from controls. The highest risk was associated with the canagliflozin/metformin (OR, 2.19; 95% CI, 0.66-7.27), followed by dapagliflozin/metformin (OR, 0.91; 95% CI, 0.50-1.64), empagliflozin/metformin (OR, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.59-1.50), and ertugliflozin/metformin (OR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.38-1.54).

There were no differences with respect to hip or lumbar spine fractures, or other fractures. The researchers found no differences in bone mineral density or bone turnover markers.

The meta-analysis is limited by the relatively short average follow-up in the included studies, which was 61 weeks. Bone damage may occur over longer time periods. Bone fractures were also not a prespecified adverse event in most included studies.

The studies also did not provide detailed information on the types of fractures experienced, such as whether they were result of a fall, or the location of the fracture, or bone health parameters. Although the results support a belief that SGLT-2 inhibitors do not adversely affect bone health, “given limited information on bone health outcomes, further work is needed to validate this conclusion,” the authors wrote.

The authors did not disclose any funding and had no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: B-B Qian et al. Osteoporosis Int. 2020 Aug 11. doi: 10.1007/s00198-020-05590-y.

The combination of sodium-glucose transporter-2 (SGLT-2) inhibitors and metformin is not associated with an increase in fracture risk among patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D), according to a new meta-analysis of 25 randomized, controlled trials.

Researchers at The Second Clinical College of Dalian Medical University in Jiangsu, China, compared fracture risk associated with the metformin/SLGT2 combination to metformin alone as well as other T2D therapeutics, and found no differences in risk. The study was published online Aug. 11 in Osteoporosis International.

T2D is associated with an increased risk of fracture, though causative mechanisms remain uncertain. Some lines of evidence suggest multiple factors may contribute to fractures, including hyperglycemia, oxidative stress, toxic effects of advanced glycosylation end-products, altered insulin levels, and treatment-induced hypoglycemia, as well as an association between T2D and increased risk of falls.

Antidiabetes drugs can have positive or negative effects on bone. thiazolidinediones, insulin, and sulfonylureas may increase risk of fractures, while dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitors and glucagon-like peptide-2 (GLP-2) receptor agonists may be protective. Metformin may also reduce fracture risk.

SGLT-2 inhibitors interrupt glucose reabsorption in the kidney, leading to improved glycemic control. Other benefits include improved renal and cardiovascular outcomes, weight loss, and reduced blood pressure, liver fat, and serum uric acid levels.

These properties have made SGLT-2 inhibitors combined with metformin an important therapy for patients at high risk of atherosclerotic disease, or who have heart failure or chronic kidney disease.

But SGLT-2 inhibition increases osmotic diuresis, and this could alter the mineral balance within bone. Some studies also showed that SGLT-2 inhibitors led to changes in bone turnover markers, bone mineral density, and bone microarchitecture. Observational studies of the SGLT-2 inhibitor canagliflozin found associations with a higher rate of fracture risk in patients taking the drug.

Such studies carry the risk of confounding factors, so the researchers took advantage of the fact that many recent clinical trials have examined the impact of SGLT-2 inhibitors on T2D. They pooled data from 25 clinical trials with a total of 19,500 participants, 9,662 of whom received SGLT-2 inhibitors plus metformin; 9,838 received other active comparators.

The fracture rate was 0.91% in the SGLT-2 inhibitors/metformin group, and 0.80% among controls (odds ratio, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.71-1.32), with no heterogeneity. Metformin alone was not associated with a change in fracture rate (OR, 0.95; 95% CI, 0.44-2.08), nor were other forms of diabetes control (OR, 0.95; 95% CI, 0.69-1.31).

There were some differences in fracture risk among SGLT-2 inhibitors when studied individually, though none differed significantly from controls. The highest risk was associated with the canagliflozin/metformin (OR, 2.19; 95% CI, 0.66-7.27), followed by dapagliflozin/metformin (OR, 0.91; 95% CI, 0.50-1.64), empagliflozin/metformin (OR, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.59-1.50), and ertugliflozin/metformin (OR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.38-1.54).

There were no differences with respect to hip or lumbar spine fractures, or other fractures. The researchers found no differences in bone mineral density or bone turnover markers.

The meta-analysis is limited by the relatively short average follow-up in the included studies, which was 61 weeks. Bone damage may occur over longer time periods. Bone fractures were also not a prespecified adverse event in most included studies.

The studies also did not provide detailed information on the types of fractures experienced, such as whether they were result of a fall, or the location of the fracture, or bone health parameters. Although the results support a belief that SGLT-2 inhibitors do not adversely affect bone health, “given limited information on bone health outcomes, further work is needed to validate this conclusion,” the authors wrote.

The authors did not disclose any funding and had no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: B-B Qian et al. Osteoporosis Int. 2020 Aug 11. doi: 10.1007/s00198-020-05590-y.

FROM OSTEOPOROSIS INTERNATIONAL

Fracture risk prediction: No benefit to repeat BMD testing in postmenopausal women

On the basis of the findings, published online in JAMA Internal Medicine, the authors recommend against routine repeat testing in postmenopausal women. Other experts, however, caution that the results may not be so broadly generalizable.

For the investigation, Carolyn J. Crandall, MD, of the division of general internal medicine and health services research at the University of California, Los Angeles, and colleagues analyzed data from 7,419 women enrolled in the prospective Women’s Health Initiative study and who underwent baseline and repeat dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) between 1993 and 2010. The researchers excluded patients who reported using bisphosphonates, calcitonin, or selective estrogen-receptor modulators, those with a history of major osteoporotic fracture, or those who lacked follow-up visits. The mean body mass index (BMI) of the study population was 28.7 kg/m2, and the mean age was 66.1 years.

The mean follow-up after the repeat BMD test was 9.0 years, during which period 732 (9.9%) of the women experienced a major osteoporotic fracture, and 139 (1.9%) experienced hip fractures.

To determine whether repeat testing improved fracture risk discrimination, the researchers calculated area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) for baseline BMD, absolute change in BMD, and the combination of baseline BMD and change in BMD.

With respect to any major osteoporotic fracture risk, the AUROC values for total hip BMD at baseline, change in total hip BMD at 3 years, and the combination of the two, respectively, were 0.61 (95% confidence interval, 0.59-0.63), 0.53 (95% CI, 0.51-0.55), and 0.61 (95% CI, 0.59-0.63). For hip fracture risk, the respective AUROC values were 0.71 (95% CI, 0.67-0.75), 0.61 (95% CI, 0.56-0.65), and 0.73 (95% CI, 0.69-0.77), the authors reported.

Similar results were observed for femoral neck and lumbar spine BMD measurements. The associations between BMD changes and fracture risk were consistent across age, race, ethnicity, BMI, and baseline BMD T-score subgroups.

Although baseline BMD and change in BMD were independently associated with incident fracture, the association was stronger for lower baseline BMD than the 3-year absolute change in BMD, the authors stated.

The findings, which are consistent with those of previous investigations that involved older adults, are notable because of the age range of the population, according to the authors. “To our knowledge, this is the first prospective study that addressed this issue in a study cohort that included younger postmenopausal U.S. women,” they wrote. “Forty-four percent of our study population was younger than 65 years.”

The authors wrote that, given the lack of benefit associated with repeat BMD testing, such tests should no longer be routinely performed. “Our findings further suggest that resources should be devoted to increasing the underuse of baseline BMD testing among women aged [between] 65 and 85 years, one-quarter of whom do not receive an initial BMD test.”

However, some experts are not comfortable with the broad recommendation to skip repeat testing in the general population. “This is a great study, and it gives important information. However, we know, even in the real world, that patients can lose BMD in this time frame and not really fracture. This does not mean that they will not fracture further down the road,” said Pauline Camacho, MD, director of Loyola University Medical Center’s Osteoporosis and Metabolic Bone Disease Center in Chicago,. “The value of doing BMD goes beyond predicting fracture risk. It also helps assess patient compliance and detect the presence of uncorrected secondary causes of osteoporosis that are limiting the response to therapy, including failure to absorb oral bisphosphonates, vitamin D deficiency, or hyperparathyroidism.”

In addition, patients for whom treatment is initiated would want to know whether it’s working. “Seeing the BMD response to therapy is helpful to both clinicians and patients,” Dr. Camacho said in an interview.

Another concern is the study population. “The study was designed to assess the clinical utility of repeating a screening BMD test in a population of low-risk women -- older postmenopausal women with remarkably good BMD on initial testing,” according to E. Michael Lewiecki, MD, vice president of the National Osteoporosis Foundation and director of the New Mexico Clinical Research and Osteoporosis Center in Albuquerque. “Not surprisingly, with what we know about the expected age-related rate of bone loss, there was only a modest decrease in BMD and little clinical utility in repeating DXA in 3 years. However, repeat testing is an important component in the care of many patients seen in clinical practice.”

There are numerous situations in clinical practice in which repeat BMD testing can enhance patient care and potentially improve outcomes, Dr. Lewiecki said in an interview. “Repeating BMD 1-2 years after starting osteoporosis therapy is a useful way to assess response and determine whether the patient is on a pathway to achieving an acceptable level of fracture risk with a strategy called treat to target.”

Additionally, patients starting high-dose glucocorticoids who are at high risk for rapid bone loss may benefit from undergoing baseline BMD testing and having a follow-up test 1 year later or even sooner, he said. Further, for early postmenopausal women, the rate of bone loss may be accelerated and may be faster than age-related bone loss later in life. For this reason, “close monitoring of BMD may be used to determine when a treatment threshold has been crossed and pharmacological therapy is indicated.”

The most important message from this study for clinicians and healthcare policymakers is not the relative value of the repeat BMD testing, Dr. Lewiecki stated. Rather, it is the call to action regarding the underuse of BMD testing. “There is a global crisis in the care of osteoporosis that is characterized by underdiagnosis and undertreatment of patients at risk for fracture. Many patients who could benefit from treatment to reduce fracture risk are not receiving it, resulting in disability and deaths from fractures that might have been prevented. We need more bone density testing in appropriately selected patients to identify high-risk patients and intervene to reduce fracture risk,” he said. “DXA is an inexpensive and highly versatile clinical tool with many applications in clinical practice. When used wisely, it can be extraordinarily useful to identify and monitor high-risk patients, with the goal of reducing the burden of osteoporotic fractures.”

The barriers to performing baseline BMD measurement in this population are poorly understood and not well researched, Dr. Crandall said in an interview. “I expect that they relate to the multiple competing demands on primary care physicians, who are, for example, trying to juggle hypertension, a sprained ankle, diabetes, and complex social situations simultaneously with identifying appropriate candidates for osteoporosis screening and considering numerous other screening guidelines.”

The Women’s Health Initiative is funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National Institutes of Health; and the Department of Health & Human Services. The study authors reported relationships with multiple companies, including Amgen, Pfizer, Bayer, Mithra, Norton Rose Fulbright, TherapeuticsMD, AbbVie, Radius, and Allergan. Dr. Camacho reported relationships with Amgen and Shire. Dr. Lewiecki reported relationships with Amgen, Radius Health, Alexion, Samsung Bioepis, Sandoz, Mereo, and Bindex.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

On the basis of the findings, published online in JAMA Internal Medicine, the authors recommend against routine repeat testing in postmenopausal women. Other experts, however, caution that the results may not be so broadly generalizable.

For the investigation, Carolyn J. Crandall, MD, of the division of general internal medicine and health services research at the University of California, Los Angeles, and colleagues analyzed data from 7,419 women enrolled in the prospective Women’s Health Initiative study and who underwent baseline and repeat dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) between 1993 and 2010. The researchers excluded patients who reported using bisphosphonates, calcitonin, or selective estrogen-receptor modulators, those with a history of major osteoporotic fracture, or those who lacked follow-up visits. The mean body mass index (BMI) of the study population was 28.7 kg/m2, and the mean age was 66.1 years.

The mean follow-up after the repeat BMD test was 9.0 years, during which period 732 (9.9%) of the women experienced a major osteoporotic fracture, and 139 (1.9%) experienced hip fractures.

To determine whether repeat testing improved fracture risk discrimination, the researchers calculated area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) for baseline BMD, absolute change in BMD, and the combination of baseline BMD and change in BMD.

With respect to any major osteoporotic fracture risk, the AUROC values for total hip BMD at baseline, change in total hip BMD at 3 years, and the combination of the two, respectively, were 0.61 (95% confidence interval, 0.59-0.63), 0.53 (95% CI, 0.51-0.55), and 0.61 (95% CI, 0.59-0.63). For hip fracture risk, the respective AUROC values were 0.71 (95% CI, 0.67-0.75), 0.61 (95% CI, 0.56-0.65), and 0.73 (95% CI, 0.69-0.77), the authors reported.

Similar results were observed for femoral neck and lumbar spine BMD measurements. The associations between BMD changes and fracture risk were consistent across age, race, ethnicity, BMI, and baseline BMD T-score subgroups.

Although baseline BMD and change in BMD were independently associated with incident fracture, the association was stronger for lower baseline BMD than the 3-year absolute change in BMD, the authors stated.

The findings, which are consistent with those of previous investigations that involved older adults, are notable because of the age range of the population, according to the authors. “To our knowledge, this is the first prospective study that addressed this issue in a study cohort that included younger postmenopausal U.S. women,” they wrote. “Forty-four percent of our study population was younger than 65 years.”

The authors wrote that, given the lack of benefit associated with repeat BMD testing, such tests should no longer be routinely performed. “Our findings further suggest that resources should be devoted to increasing the underuse of baseline BMD testing among women aged [between] 65 and 85 years, one-quarter of whom do not receive an initial BMD test.”

However, some experts are not comfortable with the broad recommendation to skip repeat testing in the general population. “This is a great study, and it gives important information. However, we know, even in the real world, that patients can lose BMD in this time frame and not really fracture. This does not mean that they will not fracture further down the road,” said Pauline Camacho, MD, director of Loyola University Medical Center’s Osteoporosis and Metabolic Bone Disease Center in Chicago,. “The value of doing BMD goes beyond predicting fracture risk. It also helps assess patient compliance and detect the presence of uncorrected secondary causes of osteoporosis that are limiting the response to therapy, including failure to absorb oral bisphosphonates, vitamin D deficiency, or hyperparathyroidism.”

In addition, patients for whom treatment is initiated would want to know whether it’s working. “Seeing the BMD response to therapy is helpful to both clinicians and patients,” Dr. Camacho said in an interview.

Another concern is the study population. “The study was designed to assess the clinical utility of repeating a screening BMD test in a population of low-risk women -- older postmenopausal women with remarkably good BMD on initial testing,” according to E. Michael Lewiecki, MD, vice president of the National Osteoporosis Foundation and director of the New Mexico Clinical Research and Osteoporosis Center in Albuquerque. “Not surprisingly, with what we know about the expected age-related rate of bone loss, there was only a modest decrease in BMD and little clinical utility in repeating DXA in 3 years. However, repeat testing is an important component in the care of many patients seen in clinical practice.”

There are numerous situations in clinical practice in which repeat BMD testing can enhance patient care and potentially improve outcomes, Dr. Lewiecki said in an interview. “Repeating BMD 1-2 years after starting osteoporosis therapy is a useful way to assess response and determine whether the patient is on a pathway to achieving an acceptable level of fracture risk with a strategy called treat to target.”

Additionally, patients starting high-dose glucocorticoids who are at high risk for rapid bone loss may benefit from undergoing baseline BMD testing and having a follow-up test 1 year later or even sooner, he said. Further, for early postmenopausal women, the rate of bone loss may be accelerated and may be faster than age-related bone loss later in life. For this reason, “close monitoring of BMD may be used to determine when a treatment threshold has been crossed and pharmacological therapy is indicated.”

The most important message from this study for clinicians and healthcare policymakers is not the relative value of the repeat BMD testing, Dr. Lewiecki stated. Rather, it is the call to action regarding the underuse of BMD testing. “There is a global crisis in the care of osteoporosis that is characterized by underdiagnosis and undertreatment of patients at risk for fracture. Many patients who could benefit from treatment to reduce fracture risk are not receiving it, resulting in disability and deaths from fractures that might have been prevented. We need more bone density testing in appropriately selected patients to identify high-risk patients and intervene to reduce fracture risk,” he said. “DXA is an inexpensive and highly versatile clinical tool with many applications in clinical practice. When used wisely, it can be extraordinarily useful to identify and monitor high-risk patients, with the goal of reducing the burden of osteoporotic fractures.”

The barriers to performing baseline BMD measurement in this population are poorly understood and not well researched, Dr. Crandall said in an interview. “I expect that they relate to the multiple competing demands on primary care physicians, who are, for example, trying to juggle hypertension, a sprained ankle, diabetes, and complex social situations simultaneously with identifying appropriate candidates for osteoporosis screening and considering numerous other screening guidelines.”

The Women’s Health Initiative is funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National Institutes of Health; and the Department of Health & Human Services. The study authors reported relationships with multiple companies, including Amgen, Pfizer, Bayer, Mithra, Norton Rose Fulbright, TherapeuticsMD, AbbVie, Radius, and Allergan. Dr. Camacho reported relationships with Amgen and Shire. Dr. Lewiecki reported relationships with Amgen, Radius Health, Alexion, Samsung Bioepis, Sandoz, Mereo, and Bindex.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

On the basis of the findings, published online in JAMA Internal Medicine, the authors recommend against routine repeat testing in postmenopausal women. Other experts, however, caution that the results may not be so broadly generalizable.

For the investigation, Carolyn J. Crandall, MD, of the division of general internal medicine and health services research at the University of California, Los Angeles, and colleagues analyzed data from 7,419 women enrolled in the prospective Women’s Health Initiative study and who underwent baseline and repeat dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) between 1993 and 2010. The researchers excluded patients who reported using bisphosphonates, calcitonin, or selective estrogen-receptor modulators, those with a history of major osteoporotic fracture, or those who lacked follow-up visits. The mean body mass index (BMI) of the study population was 28.7 kg/m2, and the mean age was 66.1 years.

The mean follow-up after the repeat BMD test was 9.0 years, during which period 732 (9.9%) of the women experienced a major osteoporotic fracture, and 139 (1.9%) experienced hip fractures.

To determine whether repeat testing improved fracture risk discrimination, the researchers calculated area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) for baseline BMD, absolute change in BMD, and the combination of baseline BMD and change in BMD.

With respect to any major osteoporotic fracture risk, the AUROC values for total hip BMD at baseline, change in total hip BMD at 3 years, and the combination of the two, respectively, were 0.61 (95% confidence interval, 0.59-0.63), 0.53 (95% CI, 0.51-0.55), and 0.61 (95% CI, 0.59-0.63). For hip fracture risk, the respective AUROC values were 0.71 (95% CI, 0.67-0.75), 0.61 (95% CI, 0.56-0.65), and 0.73 (95% CI, 0.69-0.77), the authors reported.

Similar results were observed for femoral neck and lumbar spine BMD measurements. The associations between BMD changes and fracture risk were consistent across age, race, ethnicity, BMI, and baseline BMD T-score subgroups.

Although baseline BMD and change in BMD were independently associated with incident fracture, the association was stronger for lower baseline BMD than the 3-year absolute change in BMD, the authors stated.

The findings, which are consistent with those of previous investigations that involved older adults, are notable because of the age range of the population, according to the authors. “To our knowledge, this is the first prospective study that addressed this issue in a study cohort that included younger postmenopausal U.S. women,” they wrote. “Forty-four percent of our study population was younger than 65 years.”

The authors wrote that, given the lack of benefit associated with repeat BMD testing, such tests should no longer be routinely performed. “Our findings further suggest that resources should be devoted to increasing the underuse of baseline BMD testing among women aged [between] 65 and 85 years, one-quarter of whom do not receive an initial BMD test.”

However, some experts are not comfortable with the broad recommendation to skip repeat testing in the general population. “This is a great study, and it gives important information. However, we know, even in the real world, that patients can lose BMD in this time frame and not really fracture. This does not mean that they will not fracture further down the road,” said Pauline Camacho, MD, director of Loyola University Medical Center’s Osteoporosis and Metabolic Bone Disease Center in Chicago,. “The value of doing BMD goes beyond predicting fracture risk. It also helps assess patient compliance and detect the presence of uncorrected secondary causes of osteoporosis that are limiting the response to therapy, including failure to absorb oral bisphosphonates, vitamin D deficiency, or hyperparathyroidism.”

In addition, patients for whom treatment is initiated would want to know whether it’s working. “Seeing the BMD response to therapy is helpful to both clinicians and patients,” Dr. Camacho said in an interview.

Another concern is the study population. “The study was designed to assess the clinical utility of repeating a screening BMD test in a population of low-risk women -- older postmenopausal women with remarkably good BMD on initial testing,” according to E. Michael Lewiecki, MD, vice president of the National Osteoporosis Foundation and director of the New Mexico Clinical Research and Osteoporosis Center in Albuquerque. “Not surprisingly, with what we know about the expected age-related rate of bone loss, there was only a modest decrease in BMD and little clinical utility in repeating DXA in 3 years. However, repeat testing is an important component in the care of many patients seen in clinical practice.”

There are numerous situations in clinical practice in which repeat BMD testing can enhance patient care and potentially improve outcomes, Dr. Lewiecki said in an interview. “Repeating BMD 1-2 years after starting osteoporosis therapy is a useful way to assess response and determine whether the patient is on a pathway to achieving an acceptable level of fracture risk with a strategy called treat to target.”

Additionally, patients starting high-dose glucocorticoids who are at high risk for rapid bone loss may benefit from undergoing baseline BMD testing and having a follow-up test 1 year later or even sooner, he said. Further, for early postmenopausal women, the rate of bone loss may be accelerated and may be faster than age-related bone loss later in life. For this reason, “close monitoring of BMD may be used to determine when a treatment threshold has been crossed and pharmacological therapy is indicated.”

The most important message from this study for clinicians and healthcare policymakers is not the relative value of the repeat BMD testing, Dr. Lewiecki stated. Rather, it is the call to action regarding the underuse of BMD testing. “There is a global crisis in the care of osteoporosis that is characterized by underdiagnosis and undertreatment of patients at risk for fracture. Many patients who could benefit from treatment to reduce fracture risk are not receiving it, resulting in disability and deaths from fractures that might have been prevented. We need more bone density testing in appropriately selected patients to identify high-risk patients and intervene to reduce fracture risk,” he said. “DXA is an inexpensive and highly versatile clinical tool with many applications in clinical practice. When used wisely, it can be extraordinarily useful to identify and monitor high-risk patients, with the goal of reducing the burden of osteoporotic fractures.”

The barriers to performing baseline BMD measurement in this population are poorly understood and not well researched, Dr. Crandall said in an interview. “I expect that they relate to the multiple competing demands on primary care physicians, who are, for example, trying to juggle hypertension, a sprained ankle, diabetes, and complex social situations simultaneously with identifying appropriate candidates for osteoporosis screening and considering numerous other screening guidelines.”

The Women’s Health Initiative is funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National Institutes of Health; and the Department of Health & Human Services. The study authors reported relationships with multiple companies, including Amgen, Pfizer, Bayer, Mithra, Norton Rose Fulbright, TherapeuticsMD, AbbVie, Radius, and Allergan. Dr. Camacho reported relationships with Amgen and Shire. Dr. Lewiecki reported relationships with Amgen, Radius Health, Alexion, Samsung Bioepis, Sandoz, Mereo, and Bindex.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Low vitamin D linked to increased COVID-19 risk

Low plasma vitamin D levels emerged as an independent risk factor for COVID-19 infection and hospitalization in a large, population-based study.

Participants positive for COVID-19 were 50% more likely to have low vs normal 25(OH)D levels in a multivariate analysis that controlled for other confounders, for example.

The take home message for physicians is to “test patients’ vitamin D levels and keep them optimal for the overall health – as well as for a better immunoresponse to COVID-19,” senior author Milana Frenkel-Morgenstern, PhD, head of the Cancer Genomics and BioComputing of Complex Diseases Lab at Bar-Ilan University in Ramat Gan, Israel, said in an interview.

The study was published online July 23 in The FEBS Journal.

Previous and ongoing studies are evaluating a potential role for vitamin D to prevent or minimize the severity of SARS-CoV-2 infection, building on years of research addressing vitamin D for other viral respiratory infections. The evidence to date regarding COVID-19, primarily observational studies, has yielded mixed results.

Multiple experts weighed in on the controversy in a previous report. Many point out the limitations of observational data, particularly when it comes to ruling out other factors that could affect the severity of COVID-19 infection. In addition, in a video report, JoAnn E. Manson, MD, DrPH, of Harvard Medical School in Boston, cited an observational study from three South Asian hospitals that found more severe COVID-19 patients had lower vitamin D levels, as well as other “compelling evidence” suggesting an association.

Dr. Frenkel-Morgenstern and colleagues studied data for 7,807 people, of whom 10.1% were COVID-19 positive. They assessed electronic health records for demographics, potential confounders, and outcomes between February 1 and April 30.

Participants positive for COVID-19 tended to be younger and were more likely to be men and live in a lower socioeconomic area, compared with the participants who were negative for COVID-19, in a univariate analysis.

Key findings

A higher proportion of COVID-19–positive patients had low plasma 25(OH)D concentrations, about 90% versus 85% of participants who were negative for COVID-19. The difference was statistically significant (P < .001). Furthermore, the increased likelihood for low vitamin D levels among those positive for COVID-19 held in a multivariate analysis that controlled for demographics and psychiatric and somatic disorders (adjusted odds ratio, 1.50). The difference remained statistically significant (P < .001).

The study also was noteworthy for what it did not find among participants with COVID-19. For example, the prevalence of dementia, cardiovascular disease, chronic lung disorders, and hypertension were significantly higher among the COVID-19 negative participants.

“Severe social contacts restrictions that were imposed on all the population and were even more emphasized in this highly vulnerable population” could explain these findings, the researchers noted.

“We assume that following the Israeli Ministry of Health instructions, patients with chronic medical conditions significantly reduced their social contacts” and thereby reduced their infection risk.

In contrast to previous reports, obesity was not a significant factor associated with increased likelihood for COVID-19 infection or hospitalization in the current study.

The researchers also linked low plasma 25(OH)D level to an increased likelihood of hospitalization for COVID-19 infection (crude OR, 2.09; P < .05).

After controlling for demographics and chronic disorders, the aOR decreased to 1.95 (P = .061) in a multivariate analysis. The only factor that remained statistically significant for hospitalization was age over 50 years (aOR, 2.71; P < .001).

Implications and future plans

The large number of participants and the “real world,” population-based design are strengths of the study. Considering potential confounders is another strength, the researchers noted. The retrospective database design was a limitation.

Going forward, Dr. Frenkel-Morgenstern and colleagues will “try to decipher the potential role of vitamin D in prevention and/or treatment of COVID-19” through three additional studies, she said. Also, they would like to conduct a meta-analysis to combine data from different countries to further explore the potential role of vitamin D in COVID-19.

“A compelling case”

“This is a strong study – large, adjusted for confounders, consistent with the biology and other clinical studies of vitamin D, infections, and COVID-19,” Wayne Jonas, MD, a practicing family physician and executive director of Samueli Integrative Health Programs, said in an interview.

Because the research was retrospective and observational, a causative link between vitamin D levels and COVID-19 risk cannot be interpreted from the findings. “That would need a prospective, randomized study,” said Dr. Jonas, who was not involved with the current study.

However, “the study makes a compelling case for possibly screening vitamin D levels for judging risk of COVID infection and hospitalization,” Dr. Jonas said, “and the compelling need for a large, randomized vitamin D supplement study to see if it can help prevent infection.”

“Given that vitamin D is largely safe, such a study could be done quickly and on healthy people with minimal risk for harm,” he added.

More confounders likely?

“I think the study is of interest,” Naveed Sattar, PhD, professor of metabolic medicine at the University of Glasgow, who also was not affiliated with the research, said in an interview.

“Whilst the authors adjusted for some confounders, there is a strong potential for residual confounding,” said Dr. Sattar, a coauthor of a UK Biobank study that did not find an association between vitamin D stages and COVID-19 infection in multivariate models.

For example, Dr. Sattar said, “Robust adjustment for social class is important since both Vitamin D levels and COVID-19 severity are both strongly associated with social class.” Further, it remains unknown when and what time of year the vitamin D concentrations were measured in the current study.

“In the end, only a robust randomized trial can tell us whether vitamin D supplementation helps lessen COVID-19 severity,” Dr. Sattar added. “I am not hopeful we will find this is the case – but I am glad some such trials are [ongoing].”

Dr. Frenkel-Morgenstern received a COVID-19 Data Sciences Institute grant to support this work. Dr. Frenkel-Morgenstern, Dr. Jonas, and Dr. Sattar have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Low plasma vitamin D levels emerged as an independent risk factor for COVID-19 infection and hospitalization in a large, population-based study.

Participants positive for COVID-19 were 50% more likely to have low vs normal 25(OH)D levels in a multivariate analysis that controlled for other confounders, for example.

The take home message for physicians is to “test patients’ vitamin D levels and keep them optimal for the overall health – as well as for a better immunoresponse to COVID-19,” senior author Milana Frenkel-Morgenstern, PhD, head of the Cancer Genomics and BioComputing of Complex Diseases Lab at Bar-Ilan University in Ramat Gan, Israel, said in an interview.

The study was published online July 23 in The FEBS Journal.

Previous and ongoing studies are evaluating a potential role for vitamin D to prevent or minimize the severity of SARS-CoV-2 infection, building on years of research addressing vitamin D for other viral respiratory infections. The evidence to date regarding COVID-19, primarily observational studies, has yielded mixed results.

Multiple experts weighed in on the controversy in a previous report. Many point out the limitations of observational data, particularly when it comes to ruling out other factors that could affect the severity of COVID-19 infection. In addition, in a video report, JoAnn E. Manson, MD, DrPH, of Harvard Medical School in Boston, cited an observational study from three South Asian hospitals that found more severe COVID-19 patients had lower vitamin D levels, as well as other “compelling evidence” suggesting an association.

Dr. Frenkel-Morgenstern and colleagues studied data for 7,807 people, of whom 10.1% were COVID-19 positive. They assessed electronic health records for demographics, potential confounders, and outcomes between February 1 and April 30.

Participants positive for COVID-19 tended to be younger and were more likely to be men and live in a lower socioeconomic area, compared with the participants who were negative for COVID-19, in a univariate analysis.

Key findings

A higher proportion of COVID-19–positive patients had low plasma 25(OH)D concentrations, about 90% versus 85% of participants who were negative for COVID-19. The difference was statistically significant (P < .001). Furthermore, the increased likelihood for low vitamin D levels among those positive for COVID-19 held in a multivariate analysis that controlled for demographics and psychiatric and somatic disorders (adjusted odds ratio, 1.50). The difference remained statistically significant (P < .001).

The study also was noteworthy for what it did not find among participants with COVID-19. For example, the prevalence of dementia, cardiovascular disease, chronic lung disorders, and hypertension were significantly higher among the COVID-19 negative participants.

“Severe social contacts restrictions that were imposed on all the population and were even more emphasized in this highly vulnerable population” could explain these findings, the researchers noted.

“We assume that following the Israeli Ministry of Health instructions, patients with chronic medical conditions significantly reduced their social contacts” and thereby reduced their infection risk.

In contrast to previous reports, obesity was not a significant factor associated with increased likelihood for COVID-19 infection or hospitalization in the current study.

The researchers also linked low plasma 25(OH)D level to an increased likelihood of hospitalization for COVID-19 infection (crude OR, 2.09; P < .05).