User login

CDC: Opioid prescribing and use rates down since 2010

Trends in opioid prescribing and use from 2010 to 2016 offer some encouragement, but opioid-attributable deaths continued to increase over that period, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Prescribing rates dropped during that period, as did daily opioid dosage rates and the percentage of patients with high daily opioid dosages, Gail K. Strickler, PhD, of the Institute for Behavioral Health at Brandeis University in Waltham, Mass., and associates wrote in MMWR Surveillance Summaries.

Their analysis involved 11 of the 12 states (Washington was unable to provide data for the analysis) participating in the CDC’s Prescription Behavior Surveillance System, which uses data from the states’ prescription drug monitoring programs. The 11 states represented about 38% of the U.S. population in 2016.

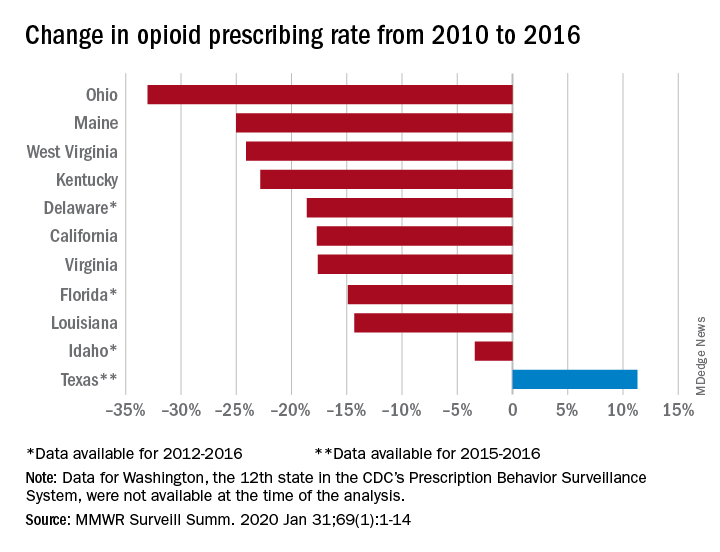

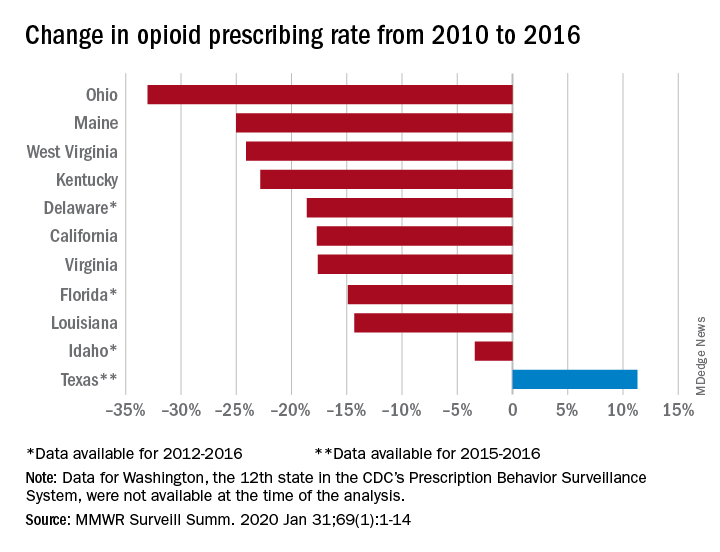

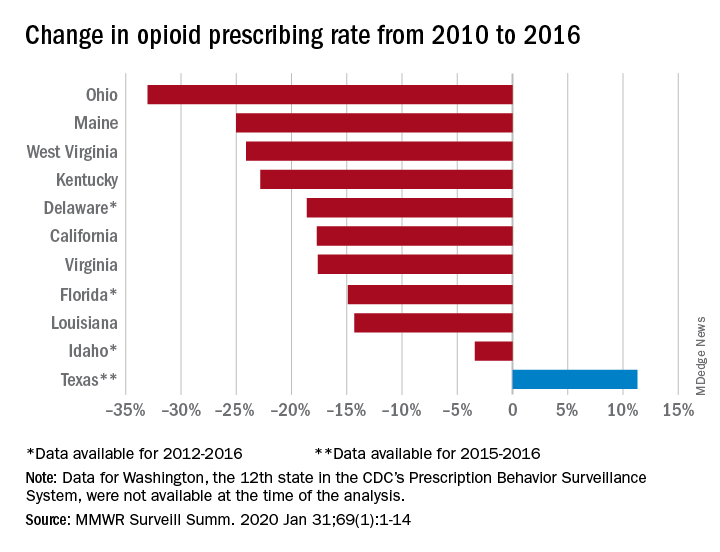

The opioid prescribing rate fell in 10 of those 11 states, with declines varying from 3.4% in Idaho to 33.0% in Ohio. Prescribing went up in Texas by 11.3%, but the state only had data available for 2015 and 2016. Three other states – Delaware, Florida, and Idaho – were limited to data from 2012 to 2016, the investigators noted.

As for the other measures, all states showed declines for the mean daily opioid dosage. Texas had the smallest drop at 2.9% and Florida saw the largest, at 27.4%. All states also had reductions in the percentage of patients with high daily opioid dosage, with decreases varying from 5.7% in Idaho to 43.9% in Louisiana, Dr. Strickler and associates reported. A high daily dosage was defined as at least 90 morphine milligram equivalents for all class II-V opioid drugs.

“Despite these favorable trends ... opioid overdose deaths attributable to the most commonly prescribed opioids, the natural and semisynthetics (e.g., morphine and oxycodone), increased during 2010-2016,” they said.

It is possible that a change in mortality is lagging “behind changes in prescribing behaviors” or that “the trend in deaths related to these types of opioids has been driven by factors other than prescription opioid misuse rates, such as increasing mortality from heroin, which is frequently classified as morphine or found concomitantly with morphine postmortem, and a spike in deaths involving illicitly manufactured fentanyl combined with heroin and prescribed opioids since 2013,” the investigators suggested.

SOURCE: Strickler GK et al. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2020 Jan 31;69(1):1-14.

Trends in opioid prescribing and use from 2010 to 2016 offer some encouragement, but opioid-attributable deaths continued to increase over that period, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Prescribing rates dropped during that period, as did daily opioid dosage rates and the percentage of patients with high daily opioid dosages, Gail K. Strickler, PhD, of the Institute for Behavioral Health at Brandeis University in Waltham, Mass., and associates wrote in MMWR Surveillance Summaries.

Their analysis involved 11 of the 12 states (Washington was unable to provide data for the analysis) participating in the CDC’s Prescription Behavior Surveillance System, which uses data from the states’ prescription drug monitoring programs. The 11 states represented about 38% of the U.S. population in 2016.

The opioid prescribing rate fell in 10 of those 11 states, with declines varying from 3.4% in Idaho to 33.0% in Ohio. Prescribing went up in Texas by 11.3%, but the state only had data available for 2015 and 2016. Three other states – Delaware, Florida, and Idaho – were limited to data from 2012 to 2016, the investigators noted.

As for the other measures, all states showed declines for the mean daily opioid dosage. Texas had the smallest drop at 2.9% and Florida saw the largest, at 27.4%. All states also had reductions in the percentage of patients with high daily opioid dosage, with decreases varying from 5.7% in Idaho to 43.9% in Louisiana, Dr. Strickler and associates reported. A high daily dosage was defined as at least 90 morphine milligram equivalents for all class II-V opioid drugs.

“Despite these favorable trends ... opioid overdose deaths attributable to the most commonly prescribed opioids, the natural and semisynthetics (e.g., morphine and oxycodone), increased during 2010-2016,” they said.

It is possible that a change in mortality is lagging “behind changes in prescribing behaviors” or that “the trend in deaths related to these types of opioids has been driven by factors other than prescription opioid misuse rates, such as increasing mortality from heroin, which is frequently classified as morphine or found concomitantly with morphine postmortem, and a spike in deaths involving illicitly manufactured fentanyl combined with heroin and prescribed opioids since 2013,” the investigators suggested.

SOURCE: Strickler GK et al. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2020 Jan 31;69(1):1-14.

Trends in opioid prescribing and use from 2010 to 2016 offer some encouragement, but opioid-attributable deaths continued to increase over that period, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Prescribing rates dropped during that period, as did daily opioid dosage rates and the percentage of patients with high daily opioid dosages, Gail K. Strickler, PhD, of the Institute for Behavioral Health at Brandeis University in Waltham, Mass., and associates wrote in MMWR Surveillance Summaries.

Their analysis involved 11 of the 12 states (Washington was unable to provide data for the analysis) participating in the CDC’s Prescription Behavior Surveillance System, which uses data from the states’ prescription drug monitoring programs. The 11 states represented about 38% of the U.S. population in 2016.

The opioid prescribing rate fell in 10 of those 11 states, with declines varying from 3.4% in Idaho to 33.0% in Ohio. Prescribing went up in Texas by 11.3%, but the state only had data available for 2015 and 2016. Three other states – Delaware, Florida, and Idaho – were limited to data from 2012 to 2016, the investigators noted.

As for the other measures, all states showed declines for the mean daily opioid dosage. Texas had the smallest drop at 2.9% and Florida saw the largest, at 27.4%. All states also had reductions in the percentage of patients with high daily opioid dosage, with decreases varying from 5.7% in Idaho to 43.9% in Louisiana, Dr. Strickler and associates reported. A high daily dosage was defined as at least 90 morphine milligram equivalents for all class II-V opioid drugs.

“Despite these favorable trends ... opioid overdose deaths attributable to the most commonly prescribed opioids, the natural and semisynthetics (e.g., morphine and oxycodone), increased during 2010-2016,” they said.

It is possible that a change in mortality is lagging “behind changes in prescribing behaviors” or that “the trend in deaths related to these types of opioids has been driven by factors other than prescription opioid misuse rates, such as increasing mortality from heroin, which is frequently classified as morphine or found concomitantly with morphine postmortem, and a spike in deaths involving illicitly manufactured fentanyl combined with heroin and prescribed opioids since 2013,” the investigators suggested.

SOURCE: Strickler GK et al. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2020 Jan 31;69(1):1-14.

FROM MMWR SURVEILLANCE SUMMARIES

What is the best treatment for wrist ganglion cysts?

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A 2015 meta-analysis of 35 studies (7 RCTs, 6 cohort studies, 22 case series) of 2239 wrist ganglion cysts examined the recurrence rate of cysts after common treatments.1 Two RCTs and 4 cohort studies compared open surgical excision with aspiration with or without corticosteroid injection.

The RCTs found significantly lower recurrence rates following open surgical excision compared with aspiration (2 trials; 60 cysts; risk ratio [RR] = 0.24; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.08-0.71; number needed to treat [NNT] = 3). The cohort studies likewise found markedly less recurrence of cysts after open surgical excision than aspiration (4 studies; 461 cysts; RR = 0.42; 95% CI, 0.21-0.85; NNT = 4). Recurrence rates didn’t differ between aspiration and observation (2 cohort studies; 209 cysts; RR = 0.99; 95% CI, 0.77-1.28).

Overall, the RCT evidence was of moderate quality because of a lack of significant heterogeneity, and the cohort evidence was graded as very low quality because of heterogeneity.

More evidence of lower recurrence with surgical excision

A 2014 prospective RCT, not included in the foregoing meta-analysis because it was published after the search date, compared ganglion cyst recurrence at 6 months for 2 groups: one group received aspiration accompanied by corticosteroid injection and the other had surgical treatment.2 The trial included 173 patients ages 16 to 47 years with 187 ganglia of the wrist, ankle, or knee (143 wrist ganglia). Patients were excluded if they had a history of recurrent ganglia, prior treatment of ganglia, nearby joint injury, bleeding disorders, pregnancy, compound palmar ganglion, ganglion near arteries, infected ganglion, ganglion associated with arthritic disease, or ganglion measuring < 5 mm in size.

Patients were allowed to choose aspiration with corticosteroid injection or surgical excision. The aspiration group (143 ganglia: 106 wrist, 21 ankle, 16 knee) underwent aspiration using a 19-gauge needle and 10-mL syringe followed by injection of 0.25 to 1.0 mL of triamcinolone acetonide. Aspiration and injection were repeated if indicated at either 6 weeks or 3 months. The surgical excision group comprised 44 ganglia: 37 wrist and 7 ankle.

The success rate at 6 months following aspiration with corticosteroid injection was 81% compared with 93% after surgical excision (NNT = 8). Surgical treatment was associated with significantly less recurrence than aspiration and injection (7% vs 19%; P < .028).

Patients report symptomatic improvement after aspiration

A 2015 retrospective case series assessed the long-term outcomes of 21 patients following aspiration of wrist ganglia.3 The patients, who were 41 to 49 years of age, each had a single wrist ganglion that was treated with aspiration between 2001 and 2011 by a single surgeon. Mean time to follow-up was 6.3 years. Outcomes reviewed included recurrence, satisfaction, and improvement in symptoms—pain, function, range of motion, and appearance—using a 1 to 5 Likert scale (1 = significantly worse; 5 = significantly improved).

Continue to: Overall, 52.4% of patients...

Overall, 52.4% of patients experienced recurrence of their ganglia. However, 95% expressed satisfaction with treatment independent of recurrence. Mean symptom scores improved from baseline for pain (4.1 points), function (3.9 points), range of motion (3.8 points), and appearance (4.1 points). Improvements in all symptoms were independent of recurrence.

Aspiration plus steroids results in 43% recurrence rate

A 2015 prospective study examined the recurrence rate at 1 year after therapy in 30 patients, ages 15 to 55 years, with a wrist ganglion treated by aspiration and steroid injection.4 Patients chose aspiration and steroid injection with 40 mg/mL methyl-prednisolone acetate over reassurance or surgical intervention. The recurrence rate at 1-year follow-up was 43.3% (13 patients).

Editor’s takeaway

Surgical excision of ganglion cysts results in fewer recurrences than aspiration. However, moderately high-quality evidence shows that both methods help most patients.

1. Head L, Gencarelli JR, Allen M, et al. Wrist ganglion treatment: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hand Surg Am. 2015;40:546-553.e8.

2. Latif A, Ansar A, Butt MQ. Treatment of ganglions; a five year experience. J Pak Med Assoc. 2014;64:1278-1281.

3. Head L, Allen M, Boyd KU. Long-term outcomes and patient satisfaction following wrist ganglion aspiration. Plast Surg (Oakv). 2015;23:51-53.

4. Hussain S, Akhtar S, Aslam V, et al. Efficacy of aspiration and steroid injection in treatment of ganglion cyst. PJMHS. 2015;9:1403-1405.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A 2015 meta-analysis of 35 studies (7 RCTs, 6 cohort studies, 22 case series) of 2239 wrist ganglion cysts examined the recurrence rate of cysts after common treatments.1 Two RCTs and 4 cohort studies compared open surgical excision with aspiration with or without corticosteroid injection.

The RCTs found significantly lower recurrence rates following open surgical excision compared with aspiration (2 trials; 60 cysts; risk ratio [RR] = 0.24; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.08-0.71; number needed to treat [NNT] = 3). The cohort studies likewise found markedly less recurrence of cysts after open surgical excision than aspiration (4 studies; 461 cysts; RR = 0.42; 95% CI, 0.21-0.85; NNT = 4). Recurrence rates didn’t differ between aspiration and observation (2 cohort studies; 209 cysts; RR = 0.99; 95% CI, 0.77-1.28).

Overall, the RCT evidence was of moderate quality because of a lack of significant heterogeneity, and the cohort evidence was graded as very low quality because of heterogeneity.

More evidence of lower recurrence with surgical excision

A 2014 prospective RCT, not included in the foregoing meta-analysis because it was published after the search date, compared ganglion cyst recurrence at 6 months for 2 groups: one group received aspiration accompanied by corticosteroid injection and the other had surgical treatment.2 The trial included 173 patients ages 16 to 47 years with 187 ganglia of the wrist, ankle, or knee (143 wrist ganglia). Patients were excluded if they had a history of recurrent ganglia, prior treatment of ganglia, nearby joint injury, bleeding disorders, pregnancy, compound palmar ganglion, ganglion near arteries, infected ganglion, ganglion associated with arthritic disease, or ganglion measuring < 5 mm in size.

Patients were allowed to choose aspiration with corticosteroid injection or surgical excision. The aspiration group (143 ganglia: 106 wrist, 21 ankle, 16 knee) underwent aspiration using a 19-gauge needle and 10-mL syringe followed by injection of 0.25 to 1.0 mL of triamcinolone acetonide. Aspiration and injection were repeated if indicated at either 6 weeks or 3 months. The surgical excision group comprised 44 ganglia: 37 wrist and 7 ankle.

The success rate at 6 months following aspiration with corticosteroid injection was 81% compared with 93% after surgical excision (NNT = 8). Surgical treatment was associated with significantly less recurrence than aspiration and injection (7% vs 19%; P < .028).

Patients report symptomatic improvement after aspiration

A 2015 retrospective case series assessed the long-term outcomes of 21 patients following aspiration of wrist ganglia.3 The patients, who were 41 to 49 years of age, each had a single wrist ganglion that was treated with aspiration between 2001 and 2011 by a single surgeon. Mean time to follow-up was 6.3 years. Outcomes reviewed included recurrence, satisfaction, and improvement in symptoms—pain, function, range of motion, and appearance—using a 1 to 5 Likert scale (1 = significantly worse; 5 = significantly improved).

Continue to: Overall, 52.4% of patients...

Overall, 52.4% of patients experienced recurrence of their ganglia. However, 95% expressed satisfaction with treatment independent of recurrence. Mean symptom scores improved from baseline for pain (4.1 points), function (3.9 points), range of motion (3.8 points), and appearance (4.1 points). Improvements in all symptoms were independent of recurrence.

Aspiration plus steroids results in 43% recurrence rate

A 2015 prospective study examined the recurrence rate at 1 year after therapy in 30 patients, ages 15 to 55 years, with a wrist ganglion treated by aspiration and steroid injection.4 Patients chose aspiration and steroid injection with 40 mg/mL methyl-prednisolone acetate over reassurance or surgical intervention. The recurrence rate at 1-year follow-up was 43.3% (13 patients).

Editor’s takeaway

Surgical excision of ganglion cysts results in fewer recurrences than aspiration. However, moderately high-quality evidence shows that both methods help most patients.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A 2015 meta-analysis of 35 studies (7 RCTs, 6 cohort studies, 22 case series) of 2239 wrist ganglion cysts examined the recurrence rate of cysts after common treatments.1 Two RCTs and 4 cohort studies compared open surgical excision with aspiration with or without corticosteroid injection.

The RCTs found significantly lower recurrence rates following open surgical excision compared with aspiration (2 trials; 60 cysts; risk ratio [RR] = 0.24; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.08-0.71; number needed to treat [NNT] = 3). The cohort studies likewise found markedly less recurrence of cysts after open surgical excision than aspiration (4 studies; 461 cysts; RR = 0.42; 95% CI, 0.21-0.85; NNT = 4). Recurrence rates didn’t differ between aspiration and observation (2 cohort studies; 209 cysts; RR = 0.99; 95% CI, 0.77-1.28).

Overall, the RCT evidence was of moderate quality because of a lack of significant heterogeneity, and the cohort evidence was graded as very low quality because of heterogeneity.

More evidence of lower recurrence with surgical excision

A 2014 prospective RCT, not included in the foregoing meta-analysis because it was published after the search date, compared ganglion cyst recurrence at 6 months for 2 groups: one group received aspiration accompanied by corticosteroid injection and the other had surgical treatment.2 The trial included 173 patients ages 16 to 47 years with 187 ganglia of the wrist, ankle, or knee (143 wrist ganglia). Patients were excluded if they had a history of recurrent ganglia, prior treatment of ganglia, nearby joint injury, bleeding disorders, pregnancy, compound palmar ganglion, ganglion near arteries, infected ganglion, ganglion associated with arthritic disease, or ganglion measuring < 5 mm in size.

Patients were allowed to choose aspiration with corticosteroid injection or surgical excision. The aspiration group (143 ganglia: 106 wrist, 21 ankle, 16 knee) underwent aspiration using a 19-gauge needle and 10-mL syringe followed by injection of 0.25 to 1.0 mL of triamcinolone acetonide. Aspiration and injection were repeated if indicated at either 6 weeks or 3 months. The surgical excision group comprised 44 ganglia: 37 wrist and 7 ankle.

The success rate at 6 months following aspiration with corticosteroid injection was 81% compared with 93% after surgical excision (NNT = 8). Surgical treatment was associated with significantly less recurrence than aspiration and injection (7% vs 19%; P < .028).

Patients report symptomatic improvement after aspiration

A 2015 retrospective case series assessed the long-term outcomes of 21 patients following aspiration of wrist ganglia.3 The patients, who were 41 to 49 years of age, each had a single wrist ganglion that was treated with aspiration between 2001 and 2011 by a single surgeon. Mean time to follow-up was 6.3 years. Outcomes reviewed included recurrence, satisfaction, and improvement in symptoms—pain, function, range of motion, and appearance—using a 1 to 5 Likert scale (1 = significantly worse; 5 = significantly improved).

Continue to: Overall, 52.4% of patients...

Overall, 52.4% of patients experienced recurrence of their ganglia. However, 95% expressed satisfaction with treatment independent of recurrence. Mean symptom scores improved from baseline for pain (4.1 points), function (3.9 points), range of motion (3.8 points), and appearance (4.1 points). Improvements in all symptoms were independent of recurrence.

Aspiration plus steroids results in 43% recurrence rate

A 2015 prospective study examined the recurrence rate at 1 year after therapy in 30 patients, ages 15 to 55 years, with a wrist ganglion treated by aspiration and steroid injection.4 Patients chose aspiration and steroid injection with 40 mg/mL methyl-prednisolone acetate over reassurance or surgical intervention. The recurrence rate at 1-year follow-up was 43.3% (13 patients).

Editor’s takeaway

Surgical excision of ganglion cysts results in fewer recurrences than aspiration. However, moderately high-quality evidence shows that both methods help most patients.

1. Head L, Gencarelli JR, Allen M, et al. Wrist ganglion treatment: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hand Surg Am. 2015;40:546-553.e8.

2. Latif A, Ansar A, Butt MQ. Treatment of ganglions; a five year experience. J Pak Med Assoc. 2014;64:1278-1281.

3. Head L, Allen M, Boyd KU. Long-term outcomes and patient satisfaction following wrist ganglion aspiration. Plast Surg (Oakv). 2015;23:51-53.

4. Hussain S, Akhtar S, Aslam V, et al. Efficacy of aspiration and steroid injection in treatment of ganglion cyst. PJMHS. 2015;9:1403-1405.

1. Head L, Gencarelli JR, Allen M, et al. Wrist ganglion treatment: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hand Surg Am. 2015;40:546-553.e8.

2. Latif A, Ansar A, Butt MQ. Treatment of ganglions; a five year experience. J Pak Med Assoc. 2014;64:1278-1281.

3. Head L, Allen M, Boyd KU. Long-term outcomes and patient satisfaction following wrist ganglion aspiration. Plast Surg (Oakv). 2015;23:51-53.

4. Hussain S, Akhtar S, Aslam V, et al. Efficacy of aspiration and steroid injection in treatment of ganglion cyst. PJMHS. 2015;9:1403-1405.

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER:

Open surgical excision of wrist ganglion cysts is associated with a lower recurrence rate than aspiration with or without corticosteroid injection (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, systematic review of randomized clinical trials [RCTs] and observational trials and RCT).

Even though the recurrence rate with aspiration is about 50%, most patients are satisfied with aspiration and report a decrease in symptoms involving pain, function, and range of motion (SOR: B, individual cohort and case series).

56-year-old woman • worsening pain in left upper arm • influenza vaccination in the arm a few days prior to pain onset • Dx?

THE CASE

A 56-year-old woman presented with a 3-day complaint of worsening left upper arm pain. She denied having any specific initiating factors but reported receiving an influenza vaccination in the arm a few days prior to the onset of pain. The patient did not have any associated numbness or tingling in the arm. She reported that the pain was worse with movement—especially abduction. The patient reported taking an over-the-counter nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) without much relief.

On physical examination, the patient had difficulty with active range of motion and had erythema, swelling, and tenderness to palpation along the subacromial space and the proximal deltoid. Further examination of the shoulder revealed a positive Neer Impingement Test and a positive Hawkins–Kennedy Test. (For more on these tests, visit “MSK Clinic: Evaluating shoulder pain using IPASS.”). The patient demonstrated full passive range of motion, but her pain was exacerbated with abduction.

THE DIAGNOSIS

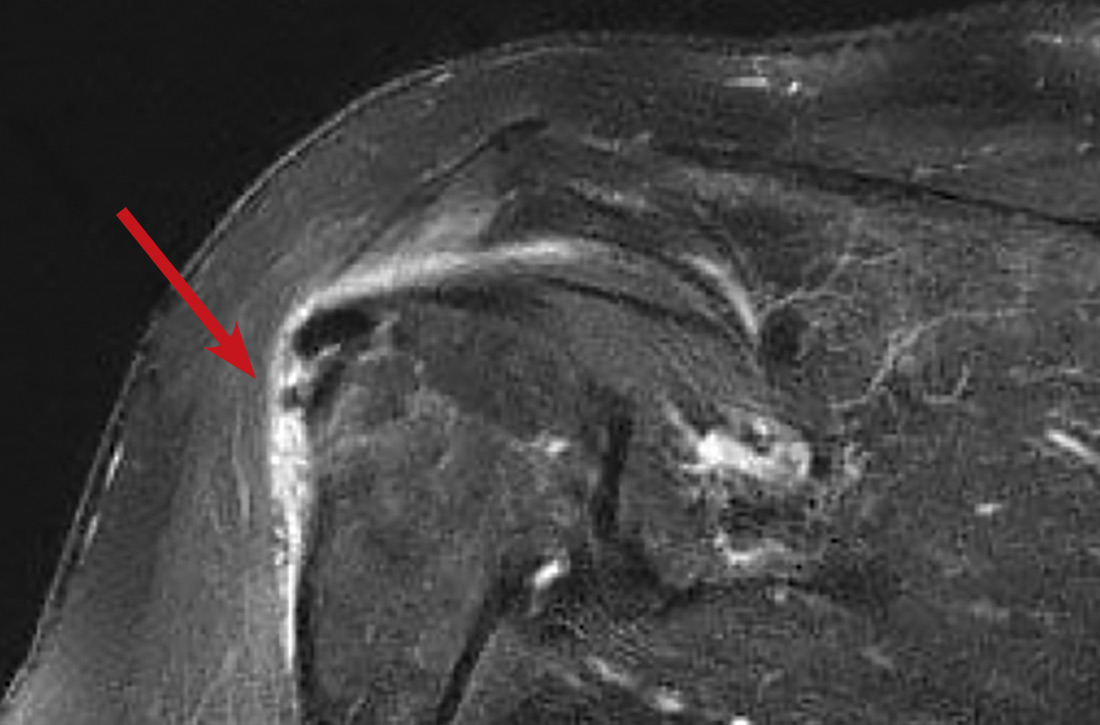

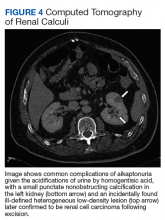

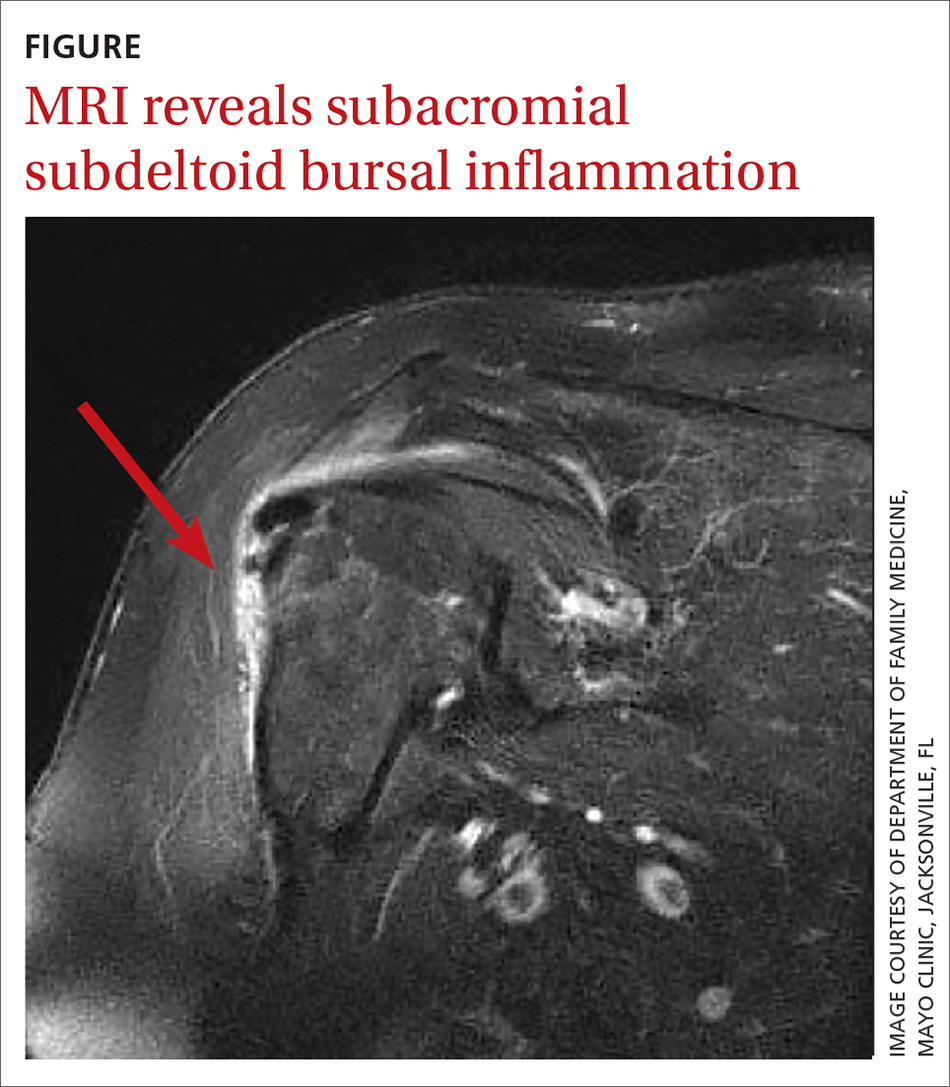

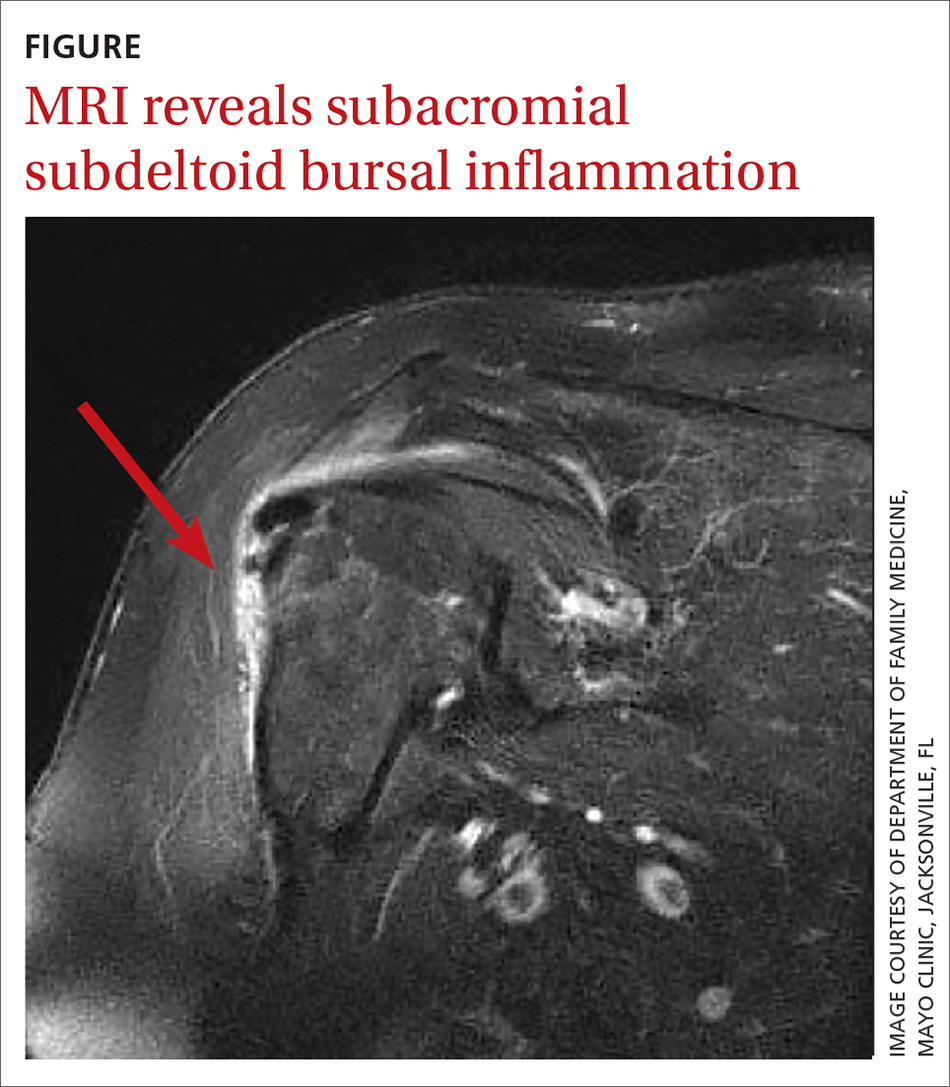

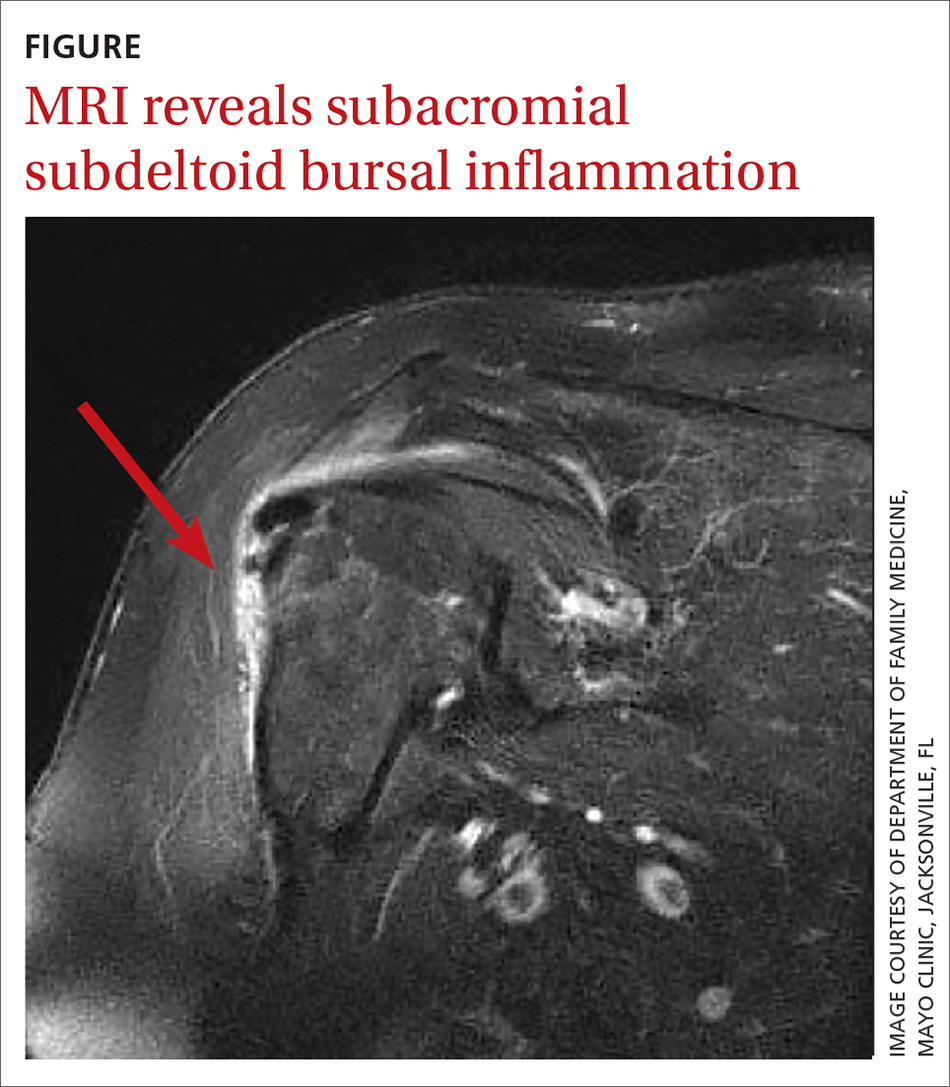

In light of the soft-tissue findings and the absence of trauma, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), rather than an x-ray, of the upper extremity was ordered. Imaging revealed subacromial subdeltoid bursal inflammation (FIGURE).

DISCUSSION

Shoulder injury related to vaccine administration (SIRVA) is the result of accidental injection of a vaccine into the tissue lying underneath the deltoid muscle or joint space, leading to a suspected immune-mediated inflammatory reaction.

A report from the National Vaccine Advisory Committee of the US Department of Health & Human Services showed an increase in the number of reported cases of SIRVA (59 reported cases in 2011-2014 and 202 cases reported in 2016).1 Additionally, in 2016 more than $29 million was awarded in compensation to patients with SIRVA.1,2 In a 2011 report, an Institute of Medicine committee found convincing evidence of a causal relationship between injection of vaccine, independent of the antigen involved, and deltoid bursitis, or frozen shoulder, characterized by shoulder pain and loss of motion.3

A review of 13 cases revealed that 50% of the patients reported pain immediately after the injection and 90% had developed pain within 24 hours.2 On physical exam, a limited range of motion and pain were the most common findings, while weakness and sensory changes were uncommon. In some cases, the pain lasted several years and 30% of the patients required surgery. Forty-six percent of the patients reported apprehension concerning the administration of the vaccine, specifically that the injection was administered “too high” into the deltoid.2

In the review of cases, routine x-rays of the shoulder did not provide beneficial diagnostic information; however, when an MRI was performed, it revealed fluid collections in the deep deltoid or overlying the rotator cuff tendons; bursitis; tendonitis; and rotator cuff tears.2

Continue to: Management of SIRVA

Management of SIRVA

Management of SIRVA is similar to that of other shoulder injuries. Treatment may include icing the shoulder, NSAIDs, intra-articular steroid injections, and physical therapy. If conservative management does not resolve the patient’s pain and improve function, then a consult with an orthopedic surgeon is recommended to determine if surgical intervention is required.

Another case report from Japan reported that a 45-year-old woman developed acute pain following a third injection of Cervarix, the prophylactic human papillomavirus-16/18 vaccine. An x-ray was ordered and was normal, but an MRI revealed acute subacromial bursitis. In an attempt to relieve the pain and improve her mobility, multiple cortisone injections were administered and physical therapy was performed. Despite the conservative treatment efforts, she continued to have pain and limited mobility in the shoulder 6 months following the onset of symptoms. As a result, the patient underwent arthroscopic synovectomy and subacromial decompression. One week following the surgery, the patient’s pain improved and at 1 year she had no pain and full range of motion.4

Prevention of SIRVA

By using appropriate techniques when administering intramuscular vaccinations, SIRVA can be prevented. The manufacturer recommended route of administration is based on studies showing maximum safety and immunogenicity, and should therefore be followed by the individual administering the vaccine.5 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends using a 22- to 25-gauge needle that is long enough to reach into the muscle and may range from ⅝" to 1½" depending on the patient’s weight.6 The vaccine should be injected at a 90° angle into the central and thickest portion of the deltoid muscle, about 2" below the acromion process and above the level of the axilla.5

Our patient’s outcome. The patient’s symptoms resolved within 10 days of receiving a steroid injection into the subacromial space. Although this case was the result of the influenza vaccine, any intramuscularly injected vaccine could lead to SIRVA.

THE TAKEAWAY

Inappropriate administration of routine intramuscularly injected vaccinations can lead to significant patient harm, including pain and disability. It is important for physicians to be aware of SIRVA and to be able to identify the signs and symptoms. Although an MRI of the shoulder is helpful in confirming the diagnosis, it is not necessary if the physician takes a thorough history and performs a comprehensive shoulder exam. Routine x-rays do not provide any beneficial clinical information.

CORRESPONDENCE

Bryan Farford, DO, Department of Family Medicine, Mayo Clinic, Davis Building, 4500 San Pablo Road South #358, Jacksonville, FL 32224; [email protected]

1. Nair N. Update on SIRVA National Vaccine Advisory Committee. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA). www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/Nair_Special%20Highlight_SIRVA%20remediated.pdf. Accessed January 14, 2020.

2. Atanasoff S, Ryan T, Lightfoot R, et al. Shoulder injury related to vaccine administration (SIRVA). Vaccine. 2010;28:8049-8052.

3. Institute of Medicine of the National Academies. Adverse Effects of Vaccines: Evidence and Causality. Washington DC: The National Academies Press; 2011.

4. Uchida S, Sakai A, Nakamura T. Subacromial bursitis following human papilloma virus vaccine misinjection. Vaccine. 2012;31:27-30.

5. Meissner HC. Shoulder injury related to vaccine administration reported more frequently. AAP News. September 1, 2017. www.aappublications.org/news/2017/09/01/IDSnapshot082917. Accessed January 14, 2020.

6. Immunization Action Coalition. How to administer intramuscular and subcutaneous vaccine injections to adults. https://www.immunize.org/catg.d/p2020a.pdf. Accessed January 14, 2020.

THE CASE

A 56-year-old woman presented with a 3-day complaint of worsening left upper arm pain. She denied having any specific initiating factors but reported receiving an influenza vaccination in the arm a few days prior to the onset of pain. The patient did not have any associated numbness or tingling in the arm. She reported that the pain was worse with movement—especially abduction. The patient reported taking an over-the-counter nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) without much relief.

On physical examination, the patient had difficulty with active range of motion and had erythema, swelling, and tenderness to palpation along the subacromial space and the proximal deltoid. Further examination of the shoulder revealed a positive Neer Impingement Test and a positive Hawkins–Kennedy Test. (For more on these tests, visit “MSK Clinic: Evaluating shoulder pain using IPASS.”). The patient demonstrated full passive range of motion, but her pain was exacerbated with abduction.

THE DIAGNOSIS

In light of the soft-tissue findings and the absence of trauma, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), rather than an x-ray, of the upper extremity was ordered. Imaging revealed subacromial subdeltoid bursal inflammation (FIGURE).

DISCUSSION

Shoulder injury related to vaccine administration (SIRVA) is the result of accidental injection of a vaccine into the tissue lying underneath the deltoid muscle or joint space, leading to a suspected immune-mediated inflammatory reaction.

A report from the National Vaccine Advisory Committee of the US Department of Health & Human Services showed an increase in the number of reported cases of SIRVA (59 reported cases in 2011-2014 and 202 cases reported in 2016).1 Additionally, in 2016 more than $29 million was awarded in compensation to patients with SIRVA.1,2 In a 2011 report, an Institute of Medicine committee found convincing evidence of a causal relationship between injection of vaccine, independent of the antigen involved, and deltoid bursitis, or frozen shoulder, characterized by shoulder pain and loss of motion.3

A review of 13 cases revealed that 50% of the patients reported pain immediately after the injection and 90% had developed pain within 24 hours.2 On physical exam, a limited range of motion and pain were the most common findings, while weakness and sensory changes were uncommon. In some cases, the pain lasted several years and 30% of the patients required surgery. Forty-six percent of the patients reported apprehension concerning the administration of the vaccine, specifically that the injection was administered “too high” into the deltoid.2

In the review of cases, routine x-rays of the shoulder did not provide beneficial diagnostic information; however, when an MRI was performed, it revealed fluid collections in the deep deltoid or overlying the rotator cuff tendons; bursitis; tendonitis; and rotator cuff tears.2

Continue to: Management of SIRVA

Management of SIRVA

Management of SIRVA is similar to that of other shoulder injuries. Treatment may include icing the shoulder, NSAIDs, intra-articular steroid injections, and physical therapy. If conservative management does not resolve the patient’s pain and improve function, then a consult with an orthopedic surgeon is recommended to determine if surgical intervention is required.

Another case report from Japan reported that a 45-year-old woman developed acute pain following a third injection of Cervarix, the prophylactic human papillomavirus-16/18 vaccine. An x-ray was ordered and was normal, but an MRI revealed acute subacromial bursitis. In an attempt to relieve the pain and improve her mobility, multiple cortisone injections were administered and physical therapy was performed. Despite the conservative treatment efforts, she continued to have pain and limited mobility in the shoulder 6 months following the onset of symptoms. As a result, the patient underwent arthroscopic synovectomy and subacromial decompression. One week following the surgery, the patient’s pain improved and at 1 year she had no pain and full range of motion.4

Prevention of SIRVA

By using appropriate techniques when administering intramuscular vaccinations, SIRVA can be prevented. The manufacturer recommended route of administration is based on studies showing maximum safety and immunogenicity, and should therefore be followed by the individual administering the vaccine.5 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends using a 22- to 25-gauge needle that is long enough to reach into the muscle and may range from ⅝" to 1½" depending on the patient’s weight.6 The vaccine should be injected at a 90° angle into the central and thickest portion of the deltoid muscle, about 2" below the acromion process and above the level of the axilla.5

Our patient’s outcome. The patient’s symptoms resolved within 10 days of receiving a steroid injection into the subacromial space. Although this case was the result of the influenza vaccine, any intramuscularly injected vaccine could lead to SIRVA.

THE TAKEAWAY

Inappropriate administration of routine intramuscularly injected vaccinations can lead to significant patient harm, including pain and disability. It is important for physicians to be aware of SIRVA and to be able to identify the signs and symptoms. Although an MRI of the shoulder is helpful in confirming the diagnosis, it is not necessary if the physician takes a thorough history and performs a comprehensive shoulder exam. Routine x-rays do not provide any beneficial clinical information.

CORRESPONDENCE

Bryan Farford, DO, Department of Family Medicine, Mayo Clinic, Davis Building, 4500 San Pablo Road South #358, Jacksonville, FL 32224; [email protected]

THE CASE

A 56-year-old woman presented with a 3-day complaint of worsening left upper arm pain. She denied having any specific initiating factors but reported receiving an influenza vaccination in the arm a few days prior to the onset of pain. The patient did not have any associated numbness or tingling in the arm. She reported that the pain was worse with movement—especially abduction. The patient reported taking an over-the-counter nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) without much relief.

On physical examination, the patient had difficulty with active range of motion and had erythema, swelling, and tenderness to palpation along the subacromial space and the proximal deltoid. Further examination of the shoulder revealed a positive Neer Impingement Test and a positive Hawkins–Kennedy Test. (For more on these tests, visit “MSK Clinic: Evaluating shoulder pain using IPASS.”). The patient demonstrated full passive range of motion, but her pain was exacerbated with abduction.

THE DIAGNOSIS

In light of the soft-tissue findings and the absence of trauma, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), rather than an x-ray, of the upper extremity was ordered. Imaging revealed subacromial subdeltoid bursal inflammation (FIGURE).

DISCUSSION

Shoulder injury related to vaccine administration (SIRVA) is the result of accidental injection of a vaccine into the tissue lying underneath the deltoid muscle or joint space, leading to a suspected immune-mediated inflammatory reaction.

A report from the National Vaccine Advisory Committee of the US Department of Health & Human Services showed an increase in the number of reported cases of SIRVA (59 reported cases in 2011-2014 and 202 cases reported in 2016).1 Additionally, in 2016 more than $29 million was awarded in compensation to patients with SIRVA.1,2 In a 2011 report, an Institute of Medicine committee found convincing evidence of a causal relationship between injection of vaccine, independent of the antigen involved, and deltoid bursitis, or frozen shoulder, characterized by shoulder pain and loss of motion.3

A review of 13 cases revealed that 50% of the patients reported pain immediately after the injection and 90% had developed pain within 24 hours.2 On physical exam, a limited range of motion and pain were the most common findings, while weakness and sensory changes were uncommon. In some cases, the pain lasted several years and 30% of the patients required surgery. Forty-six percent of the patients reported apprehension concerning the administration of the vaccine, specifically that the injection was administered “too high” into the deltoid.2

In the review of cases, routine x-rays of the shoulder did not provide beneficial diagnostic information; however, when an MRI was performed, it revealed fluid collections in the deep deltoid or overlying the rotator cuff tendons; bursitis; tendonitis; and rotator cuff tears.2

Continue to: Management of SIRVA

Management of SIRVA

Management of SIRVA is similar to that of other shoulder injuries. Treatment may include icing the shoulder, NSAIDs, intra-articular steroid injections, and physical therapy. If conservative management does not resolve the patient’s pain and improve function, then a consult with an orthopedic surgeon is recommended to determine if surgical intervention is required.

Another case report from Japan reported that a 45-year-old woman developed acute pain following a third injection of Cervarix, the prophylactic human papillomavirus-16/18 vaccine. An x-ray was ordered and was normal, but an MRI revealed acute subacromial bursitis. In an attempt to relieve the pain and improve her mobility, multiple cortisone injections were administered and physical therapy was performed. Despite the conservative treatment efforts, she continued to have pain and limited mobility in the shoulder 6 months following the onset of symptoms. As a result, the patient underwent arthroscopic synovectomy and subacromial decompression. One week following the surgery, the patient’s pain improved and at 1 year she had no pain and full range of motion.4

Prevention of SIRVA

By using appropriate techniques when administering intramuscular vaccinations, SIRVA can be prevented. The manufacturer recommended route of administration is based on studies showing maximum safety and immunogenicity, and should therefore be followed by the individual administering the vaccine.5 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends using a 22- to 25-gauge needle that is long enough to reach into the muscle and may range from ⅝" to 1½" depending on the patient’s weight.6 The vaccine should be injected at a 90° angle into the central and thickest portion of the deltoid muscle, about 2" below the acromion process and above the level of the axilla.5

Our patient’s outcome. The patient’s symptoms resolved within 10 days of receiving a steroid injection into the subacromial space. Although this case was the result of the influenza vaccine, any intramuscularly injected vaccine could lead to SIRVA.

THE TAKEAWAY

Inappropriate administration of routine intramuscularly injected vaccinations can lead to significant patient harm, including pain and disability. It is important for physicians to be aware of SIRVA and to be able to identify the signs and symptoms. Although an MRI of the shoulder is helpful in confirming the diagnosis, it is not necessary if the physician takes a thorough history and performs a comprehensive shoulder exam. Routine x-rays do not provide any beneficial clinical information.

CORRESPONDENCE

Bryan Farford, DO, Department of Family Medicine, Mayo Clinic, Davis Building, 4500 San Pablo Road South #358, Jacksonville, FL 32224; [email protected]

1. Nair N. Update on SIRVA National Vaccine Advisory Committee. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA). www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/Nair_Special%20Highlight_SIRVA%20remediated.pdf. Accessed January 14, 2020.

2. Atanasoff S, Ryan T, Lightfoot R, et al. Shoulder injury related to vaccine administration (SIRVA). Vaccine. 2010;28:8049-8052.

3. Institute of Medicine of the National Academies. Adverse Effects of Vaccines: Evidence and Causality. Washington DC: The National Academies Press; 2011.

4. Uchida S, Sakai A, Nakamura T. Subacromial bursitis following human papilloma virus vaccine misinjection. Vaccine. 2012;31:27-30.

5. Meissner HC. Shoulder injury related to vaccine administration reported more frequently. AAP News. September 1, 2017. www.aappublications.org/news/2017/09/01/IDSnapshot082917. Accessed January 14, 2020.

6. Immunization Action Coalition. How to administer intramuscular and subcutaneous vaccine injections to adults. https://www.immunize.org/catg.d/p2020a.pdf. Accessed January 14, 2020.

1. Nair N. Update on SIRVA National Vaccine Advisory Committee. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA). www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/Nair_Special%20Highlight_SIRVA%20remediated.pdf. Accessed January 14, 2020.

2. Atanasoff S, Ryan T, Lightfoot R, et al. Shoulder injury related to vaccine administration (SIRVA). Vaccine. 2010;28:8049-8052.

3. Institute of Medicine of the National Academies. Adverse Effects of Vaccines: Evidence and Causality. Washington DC: The National Academies Press; 2011.

4. Uchida S, Sakai A, Nakamura T. Subacromial bursitis following human papilloma virus vaccine misinjection. Vaccine. 2012;31:27-30.

5. Meissner HC. Shoulder injury related to vaccine administration reported more frequently. AAP News. September 1, 2017. www.aappublications.org/news/2017/09/01/IDSnapshot082917. Accessed January 14, 2020.

6. Immunization Action Coalition. How to administer intramuscular and subcutaneous vaccine injections to adults. https://www.immunize.org/catg.d/p2020a.pdf. Accessed January 14, 2020.

Cannabis for sleep: Short-term benefit, long-term disruption?

, new research shows.

Investigators found whole-plant medical cannabis use was associated with fewer problems with respect to waking up at night, but they also found that frequent medical cannabis use was associated with more problems initiating and maintaining sleep.

“Cannabis may improve overall sleep in the short term,” study investigator Sharon Sznitman, PhD, University of Haifa (Israel) Faculty of Social Welfare and Health Sciences, said in an interview. “But it’s also very interesting that when we looked at frequency of use in the group that used medical cannabis, individuals who had more frequent use also had poorer sleep in the long term.

“This suggests that while cannabis may improve overall sleep, it’s also possible that there is a tolerance that develops with either very frequent or long-term use,” she added.

The study was published online Jan. 20 in BMJ Supportive and Palliative Care.

A common problem

Estimates suggest chronic pain affects up to 37% of adults in the developed world. Individuals who suffer chronic pain often experience comorbid insomnia, which includes difficulty initiating sleep, sleep disruption, and early morning wakening.

For its part, medical cannabis to treat chronic pain symptoms and manage sleep problems has been widely reported as a prime motivation for medical cannabis use. Indeed, previous studies have concluded that the endocannabinoid system plays a role in sleep regulation, including sleep promotion and maintenance.

In recent years, investigators have reported the beneficial effects of medical cannabis for sleep. Nevertheless, some preclinical research has also concluded that chronic administration of tetrahydrocannabinol may result in tolerance to the sleep-enhancing effects of cannabis.

With that in mind, the researchers set out to examine the potential impact of whole-plant medicinal cannabis on sleep problems experienced by middle-aged patients suffering from chronic pain.

“People are self-reporting that they’re using cannabis for sleep and that it helps, but as we know, just because people are reporting that it works doesn’t mean that it will hold up in research,” Dr. Sznitman said.

The study included 128 individuals (mean age, 61±6 years; 51% females) with chronic neuropathic pain: 66 were medical cannabis users and 62 were not.

Three indicators of insomnia were measured using the 7-point Likert scale to assess issues with sleep initiation and maintenance.

In addition, investigators collected sociodemographic information, as well as data on daily consumption of tobacco, frequency of alcohol use, and pain severity. Finally, they collected patient data on the use of sleep-aid medications during the past month as well as tricyclic antidepressant use.

Frequent use, more sleep problems?

On average, medical cannabis users were 3 years younger than their nonusing counterparts (mean age, 60±6 vs. 63±6 years, respectively, P = .003) and more likely to be male (58% vs 40%, respectively, P = .038). Otherwise, the two groups were comparable.

Medical cannabis users reported taking the drug for an average of 4 years, at an average quantity of 31 g per month. The primary mode of administration was smoking (68.6%), followed by oil extracts (21.4%) and vaporization (20%).

Results showed that, of the total sample, 24.1% reported always waking up early and not falling back to sleep, 20.2% reported always having difficulty falling asleep, and 27.2% reported always waking up during the night.

After adjusting for patient age, sex, pain level, and use of sleep medications and antidepressants, medical cannabis use was associated with fewer problems with waking up at night, compared with nonmedical cannabis use. No differences were found between groups with respect to problems falling asleep or waking up early without being able to fall back to sleep, Dr. Sznitman and associates reported.

The final analysis of a subsample of patients that only included medical cannabis users showed frequency of medical cannabis use was associated with sleep problems, they said.

Specifically, more frequent cannabis use was associated with more problems related to waking up at night, as well as problems falling asleep.

Sleep problems associated with frequent medical cannabis use may signal the development of tolerance to the agent. However, frequent users of medical cannabis also maybsuffer pain or other comorbidities, which, in turn, may be linked to more sleep problems.

Either way, Dr. Sznitman said the study might open the door to another treatment option for patients suffering from chronic pain who struggle with sleep.

“If future research shows that the effect of medical cannabis on sleep is a consistent one, then we may be adding a new therapy for sleep problems, which are huge in society and especially in chronic pain patients,” she said.

Early days

Commenting on the findings in an interview, Ryan G. Vandrey, PhD, who was not involved in the study, said the findings are in line with previous research.

“I think the results make sense with respect to the data I’ve collected and from what I’ve seen,” said Dr. Vandrey, associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins Medicine in Baltimore.

“We typically only want to use sleep medications for short periods of time,” he continued. “When you think about recommended prescribing practices for any hypnotic medication, it’s usually short term, 2 weeks or less. Longer-term use often leads to tolerance, dependence, and withdrawal symptoms when the medication is stopped, which leads to an exacerbation of disordered sleep,” Dr. Vandrey said.

Nevertheless, he urged caution when interpreting the results.

“I think the study warrants caution about long-term daily use of cannabinoids with respect to sleep,” he said. “But we need more detailed evaluations, as the trial wasn’t testing a defined product, specific dose, or dose regimen.

“In addition, this was all done in the context of people with chronic pain and not treating disordered sleep or insomnia, but the study highlights the importance of recognizing that long-term chronic use of cannabis is not likely to fully resolve sleep problems.”

Dr. Sznitman agreed that the research is still in its very early stages.

“We’re still far from saying we have the evidence to support the use of medical cannabis for sleep,” she said. “For in the end it was just a cross-sectional, observational study, so we cannot say anything about cause and effect. But if these results pan out, they could be far-reaching and exciting.”

The study was funded by the University of Haifa and Rambam Hospital in Israel, and by the Evelyn Lipper Foundation. Dr. Sznitman and Dr. Vandrey have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, new research shows.

Investigators found whole-plant medical cannabis use was associated with fewer problems with respect to waking up at night, but they also found that frequent medical cannabis use was associated with more problems initiating and maintaining sleep.

“Cannabis may improve overall sleep in the short term,” study investigator Sharon Sznitman, PhD, University of Haifa (Israel) Faculty of Social Welfare and Health Sciences, said in an interview. “But it’s also very interesting that when we looked at frequency of use in the group that used medical cannabis, individuals who had more frequent use also had poorer sleep in the long term.

“This suggests that while cannabis may improve overall sleep, it’s also possible that there is a tolerance that develops with either very frequent or long-term use,” she added.

The study was published online Jan. 20 in BMJ Supportive and Palliative Care.

A common problem

Estimates suggest chronic pain affects up to 37% of adults in the developed world. Individuals who suffer chronic pain often experience comorbid insomnia, which includes difficulty initiating sleep, sleep disruption, and early morning wakening.

For its part, medical cannabis to treat chronic pain symptoms and manage sleep problems has been widely reported as a prime motivation for medical cannabis use. Indeed, previous studies have concluded that the endocannabinoid system plays a role in sleep regulation, including sleep promotion and maintenance.

In recent years, investigators have reported the beneficial effects of medical cannabis for sleep. Nevertheless, some preclinical research has also concluded that chronic administration of tetrahydrocannabinol may result in tolerance to the sleep-enhancing effects of cannabis.

With that in mind, the researchers set out to examine the potential impact of whole-plant medicinal cannabis on sleep problems experienced by middle-aged patients suffering from chronic pain.

“People are self-reporting that they’re using cannabis for sleep and that it helps, but as we know, just because people are reporting that it works doesn’t mean that it will hold up in research,” Dr. Sznitman said.

The study included 128 individuals (mean age, 61±6 years; 51% females) with chronic neuropathic pain: 66 were medical cannabis users and 62 were not.

Three indicators of insomnia were measured using the 7-point Likert scale to assess issues with sleep initiation and maintenance.

In addition, investigators collected sociodemographic information, as well as data on daily consumption of tobacco, frequency of alcohol use, and pain severity. Finally, they collected patient data on the use of sleep-aid medications during the past month as well as tricyclic antidepressant use.

Frequent use, more sleep problems?

On average, medical cannabis users were 3 years younger than their nonusing counterparts (mean age, 60±6 vs. 63±6 years, respectively, P = .003) and more likely to be male (58% vs 40%, respectively, P = .038). Otherwise, the two groups were comparable.

Medical cannabis users reported taking the drug for an average of 4 years, at an average quantity of 31 g per month. The primary mode of administration was smoking (68.6%), followed by oil extracts (21.4%) and vaporization (20%).

Results showed that, of the total sample, 24.1% reported always waking up early and not falling back to sleep, 20.2% reported always having difficulty falling asleep, and 27.2% reported always waking up during the night.

After adjusting for patient age, sex, pain level, and use of sleep medications and antidepressants, medical cannabis use was associated with fewer problems with waking up at night, compared with nonmedical cannabis use. No differences were found between groups with respect to problems falling asleep or waking up early without being able to fall back to sleep, Dr. Sznitman and associates reported.

The final analysis of a subsample of patients that only included medical cannabis users showed frequency of medical cannabis use was associated with sleep problems, they said.

Specifically, more frequent cannabis use was associated with more problems related to waking up at night, as well as problems falling asleep.

Sleep problems associated with frequent medical cannabis use may signal the development of tolerance to the agent. However, frequent users of medical cannabis also maybsuffer pain or other comorbidities, which, in turn, may be linked to more sleep problems.

Either way, Dr. Sznitman said the study might open the door to another treatment option for patients suffering from chronic pain who struggle with sleep.

“If future research shows that the effect of medical cannabis on sleep is a consistent one, then we may be adding a new therapy for sleep problems, which are huge in society and especially in chronic pain patients,” she said.

Early days

Commenting on the findings in an interview, Ryan G. Vandrey, PhD, who was not involved in the study, said the findings are in line with previous research.

“I think the results make sense with respect to the data I’ve collected and from what I’ve seen,” said Dr. Vandrey, associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins Medicine in Baltimore.

“We typically only want to use sleep medications for short periods of time,” he continued. “When you think about recommended prescribing practices for any hypnotic medication, it’s usually short term, 2 weeks or less. Longer-term use often leads to tolerance, dependence, and withdrawal symptoms when the medication is stopped, which leads to an exacerbation of disordered sleep,” Dr. Vandrey said.

Nevertheless, he urged caution when interpreting the results.

“I think the study warrants caution about long-term daily use of cannabinoids with respect to sleep,” he said. “But we need more detailed evaluations, as the trial wasn’t testing a defined product, specific dose, or dose regimen.

“In addition, this was all done in the context of people with chronic pain and not treating disordered sleep or insomnia, but the study highlights the importance of recognizing that long-term chronic use of cannabis is not likely to fully resolve sleep problems.”

Dr. Sznitman agreed that the research is still in its very early stages.

“We’re still far from saying we have the evidence to support the use of medical cannabis for sleep,” she said. “For in the end it was just a cross-sectional, observational study, so we cannot say anything about cause and effect. But if these results pan out, they could be far-reaching and exciting.”

The study was funded by the University of Haifa and Rambam Hospital in Israel, and by the Evelyn Lipper Foundation. Dr. Sznitman and Dr. Vandrey have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, new research shows.

Investigators found whole-plant medical cannabis use was associated with fewer problems with respect to waking up at night, but they also found that frequent medical cannabis use was associated with more problems initiating and maintaining sleep.

“Cannabis may improve overall sleep in the short term,” study investigator Sharon Sznitman, PhD, University of Haifa (Israel) Faculty of Social Welfare and Health Sciences, said in an interview. “But it’s also very interesting that when we looked at frequency of use in the group that used medical cannabis, individuals who had more frequent use also had poorer sleep in the long term.

“This suggests that while cannabis may improve overall sleep, it’s also possible that there is a tolerance that develops with either very frequent or long-term use,” she added.

The study was published online Jan. 20 in BMJ Supportive and Palliative Care.

A common problem

Estimates suggest chronic pain affects up to 37% of adults in the developed world. Individuals who suffer chronic pain often experience comorbid insomnia, which includes difficulty initiating sleep, sleep disruption, and early morning wakening.

For its part, medical cannabis to treat chronic pain symptoms and manage sleep problems has been widely reported as a prime motivation for medical cannabis use. Indeed, previous studies have concluded that the endocannabinoid system plays a role in sleep regulation, including sleep promotion and maintenance.

In recent years, investigators have reported the beneficial effects of medical cannabis for sleep. Nevertheless, some preclinical research has also concluded that chronic administration of tetrahydrocannabinol may result in tolerance to the sleep-enhancing effects of cannabis.

With that in mind, the researchers set out to examine the potential impact of whole-plant medicinal cannabis on sleep problems experienced by middle-aged patients suffering from chronic pain.

“People are self-reporting that they’re using cannabis for sleep and that it helps, but as we know, just because people are reporting that it works doesn’t mean that it will hold up in research,” Dr. Sznitman said.

The study included 128 individuals (mean age, 61±6 years; 51% females) with chronic neuropathic pain: 66 were medical cannabis users and 62 were not.

Three indicators of insomnia were measured using the 7-point Likert scale to assess issues with sleep initiation and maintenance.

In addition, investigators collected sociodemographic information, as well as data on daily consumption of tobacco, frequency of alcohol use, and pain severity. Finally, they collected patient data on the use of sleep-aid medications during the past month as well as tricyclic antidepressant use.

Frequent use, more sleep problems?

On average, medical cannabis users were 3 years younger than their nonusing counterparts (mean age, 60±6 vs. 63±6 years, respectively, P = .003) and more likely to be male (58% vs 40%, respectively, P = .038). Otherwise, the two groups were comparable.

Medical cannabis users reported taking the drug for an average of 4 years, at an average quantity of 31 g per month. The primary mode of administration was smoking (68.6%), followed by oil extracts (21.4%) and vaporization (20%).

Results showed that, of the total sample, 24.1% reported always waking up early and not falling back to sleep, 20.2% reported always having difficulty falling asleep, and 27.2% reported always waking up during the night.

After adjusting for patient age, sex, pain level, and use of sleep medications and antidepressants, medical cannabis use was associated with fewer problems with waking up at night, compared with nonmedical cannabis use. No differences were found between groups with respect to problems falling asleep or waking up early without being able to fall back to sleep, Dr. Sznitman and associates reported.

The final analysis of a subsample of patients that only included medical cannabis users showed frequency of medical cannabis use was associated with sleep problems, they said.

Specifically, more frequent cannabis use was associated with more problems related to waking up at night, as well as problems falling asleep.

Sleep problems associated with frequent medical cannabis use may signal the development of tolerance to the agent. However, frequent users of medical cannabis also maybsuffer pain or other comorbidities, which, in turn, may be linked to more sleep problems.

Either way, Dr. Sznitman said the study might open the door to another treatment option for patients suffering from chronic pain who struggle with sleep.

“If future research shows that the effect of medical cannabis on sleep is a consistent one, then we may be adding a new therapy for sleep problems, which are huge in society and especially in chronic pain patients,” she said.

Early days

Commenting on the findings in an interview, Ryan G. Vandrey, PhD, who was not involved in the study, said the findings are in line with previous research.

“I think the results make sense with respect to the data I’ve collected and from what I’ve seen,” said Dr. Vandrey, associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins Medicine in Baltimore.

“We typically only want to use sleep medications for short periods of time,” he continued. “When you think about recommended prescribing practices for any hypnotic medication, it’s usually short term, 2 weeks or less. Longer-term use often leads to tolerance, dependence, and withdrawal symptoms when the medication is stopped, which leads to an exacerbation of disordered sleep,” Dr. Vandrey said.

Nevertheless, he urged caution when interpreting the results.

“I think the study warrants caution about long-term daily use of cannabinoids with respect to sleep,” he said. “But we need more detailed evaluations, as the trial wasn’t testing a defined product, specific dose, or dose regimen.

“In addition, this was all done in the context of people with chronic pain and not treating disordered sleep or insomnia, but the study highlights the importance of recognizing that long-term chronic use of cannabis is not likely to fully resolve sleep problems.”

Dr. Sznitman agreed that the research is still in its very early stages.

“We’re still far from saying we have the evidence to support the use of medical cannabis for sleep,” she said. “For in the end it was just a cross-sectional, observational study, so we cannot say anything about cause and effect. But if these results pan out, they could be far-reaching and exciting.”

The study was funded by the University of Haifa and Rambam Hospital in Israel, and by the Evelyn Lipper Foundation. Dr. Sznitman and Dr. Vandrey have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM BMJ SUPPORTIVE AND PALLIATIVE CARE

IBD: Inpatient opioids linked with outpatient use

, based on a retrospective analysis of more than 800 patients.

Awareness of this dose-dependent relationship and IBD-related risks of opioid use should encourage physicians to consider alternative analgesics, according to lead author Rahul S. Dalal, MD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and colleagues.

“Recent evidence has demonstrated that opioid use is associated with severe infections and increased mortality among IBD patients,” the investigators wrote in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. “Despite these concerns, opioids are commonly prescribed to IBD patients in the outpatient setting and to as many as 70% of IBD patients who are hospitalized.”

To look for a possible relationship between inpatient and outpatient opioid use, the investigators reviewed electronic medical records of 862 IBD patients who were treated at three urban hospitals in the University of Pennsylvania Health System. The primary outcome was opioid prescription within 12 months of discharge, including prescriptions at time of hospital dismissal.

During hospitalization, about two-thirds (67.6%) of patients received intravenous opioids. Of the total population, slightly more than half (54.6%) received intravenous hydromorphone and about one-quarter (25.9%) received intravenous morphine. Following discharge, almost half of the population (44.7%) was prescribed opioids, and about 3 out of 4 patients (77.9%) received an additional opioid prescription within the same year.

After accounting for confounders such as IBD severity, preadmission opioid use, pain scores, and psychiatric conditions, data analysis showed that inpatients who received intravenous opioids had a threefold (odds ratio [OR], 3.3) increased likelihood of receiving postdischarge opioid prescription, compared with patients who received no opioids while hospitalized. This association was stronger among those who had IBD flares (OR, 5.4). Furthermore, intravenous dose was positively correlated with postdischarge opioid prescription.

Avoiding intravenous opioids had no impact on the relationship between inpatient and outpatient opioid use. Among inpatients who received only oral or transdermal opioids, a similarly increased likelihood of postdischarge opioid prescription was observed (OR, 4.2), although this was a small cohort (n = 67).

Compared with other physicians, gastroenterologists were the least likely to prescribe opioids. Considering that gastroenterologists were also most likely aware of IBD-related risks of opioid use, the investigators concluded that more interdisciplinary communication and education are needed.

“Alternative analgesics such as acetaminophen, dicyclomine, hyoscyamine, and celecoxib could be advised, as many of these therapies have been deemed relatively safe and effective in this population,” they wrote.The investigators disclosed relationships with Abbott, Gilead, Romark, and others.

SOURCE: Dalal RS et al. Clin Gastro Hepatol. 2019 Dec 27. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.12.024.

, based on a retrospective analysis of more than 800 patients.

Awareness of this dose-dependent relationship and IBD-related risks of opioid use should encourage physicians to consider alternative analgesics, according to lead author Rahul S. Dalal, MD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and colleagues.

“Recent evidence has demonstrated that opioid use is associated with severe infections and increased mortality among IBD patients,” the investigators wrote in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. “Despite these concerns, opioids are commonly prescribed to IBD patients in the outpatient setting and to as many as 70% of IBD patients who are hospitalized.”

To look for a possible relationship between inpatient and outpatient opioid use, the investigators reviewed electronic medical records of 862 IBD patients who were treated at three urban hospitals in the University of Pennsylvania Health System. The primary outcome was opioid prescription within 12 months of discharge, including prescriptions at time of hospital dismissal.

During hospitalization, about two-thirds (67.6%) of patients received intravenous opioids. Of the total population, slightly more than half (54.6%) received intravenous hydromorphone and about one-quarter (25.9%) received intravenous morphine. Following discharge, almost half of the population (44.7%) was prescribed opioids, and about 3 out of 4 patients (77.9%) received an additional opioid prescription within the same year.

After accounting for confounders such as IBD severity, preadmission opioid use, pain scores, and psychiatric conditions, data analysis showed that inpatients who received intravenous opioids had a threefold (odds ratio [OR], 3.3) increased likelihood of receiving postdischarge opioid prescription, compared with patients who received no opioids while hospitalized. This association was stronger among those who had IBD flares (OR, 5.4). Furthermore, intravenous dose was positively correlated with postdischarge opioid prescription.

Avoiding intravenous opioids had no impact on the relationship between inpatient and outpatient opioid use. Among inpatients who received only oral or transdermal opioids, a similarly increased likelihood of postdischarge opioid prescription was observed (OR, 4.2), although this was a small cohort (n = 67).

Compared with other physicians, gastroenterologists were the least likely to prescribe opioids. Considering that gastroenterologists were also most likely aware of IBD-related risks of opioid use, the investigators concluded that more interdisciplinary communication and education are needed.

“Alternative analgesics such as acetaminophen, dicyclomine, hyoscyamine, and celecoxib could be advised, as many of these therapies have been deemed relatively safe and effective in this population,” they wrote.The investigators disclosed relationships with Abbott, Gilead, Romark, and others.

SOURCE: Dalal RS et al. Clin Gastro Hepatol. 2019 Dec 27. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.12.024.

, based on a retrospective analysis of more than 800 patients.

Awareness of this dose-dependent relationship and IBD-related risks of opioid use should encourage physicians to consider alternative analgesics, according to lead author Rahul S. Dalal, MD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and colleagues.

“Recent evidence has demonstrated that opioid use is associated with severe infections and increased mortality among IBD patients,” the investigators wrote in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. “Despite these concerns, opioids are commonly prescribed to IBD patients in the outpatient setting and to as many as 70% of IBD patients who are hospitalized.”

To look for a possible relationship between inpatient and outpatient opioid use, the investigators reviewed electronic medical records of 862 IBD patients who were treated at three urban hospitals in the University of Pennsylvania Health System. The primary outcome was opioid prescription within 12 months of discharge, including prescriptions at time of hospital dismissal.

During hospitalization, about two-thirds (67.6%) of patients received intravenous opioids. Of the total population, slightly more than half (54.6%) received intravenous hydromorphone and about one-quarter (25.9%) received intravenous morphine. Following discharge, almost half of the population (44.7%) was prescribed opioids, and about 3 out of 4 patients (77.9%) received an additional opioid prescription within the same year.

After accounting for confounders such as IBD severity, preadmission opioid use, pain scores, and psychiatric conditions, data analysis showed that inpatients who received intravenous opioids had a threefold (odds ratio [OR], 3.3) increased likelihood of receiving postdischarge opioid prescription, compared with patients who received no opioids while hospitalized. This association was stronger among those who had IBD flares (OR, 5.4). Furthermore, intravenous dose was positively correlated with postdischarge opioid prescription.

Avoiding intravenous opioids had no impact on the relationship between inpatient and outpatient opioid use. Among inpatients who received only oral or transdermal opioids, a similarly increased likelihood of postdischarge opioid prescription was observed (OR, 4.2), although this was a small cohort (n = 67).

Compared with other physicians, gastroenterologists were the least likely to prescribe opioids. Considering that gastroenterologists were also most likely aware of IBD-related risks of opioid use, the investigators concluded that more interdisciplinary communication and education are needed.

“Alternative analgesics such as acetaminophen, dicyclomine, hyoscyamine, and celecoxib could be advised, as many of these therapies have been deemed relatively safe and effective in this population,” they wrote.The investigators disclosed relationships with Abbott, Gilead, Romark, and others.

SOURCE: Dalal RS et al. Clin Gastro Hepatol. 2019 Dec 27. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.12.024.

FROM CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

Key clinical point: Patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) who receive opioids while hospitalized are three times as likely to be prescribed opioids after discharge.

Major finding: Patients who were given intravenous opioids while hospitalized were three times as likely to receive a postdischarge opioid prescription, compared with patients who did not receive inpatient intravenous opioids (odds ratio, 3.3).

Study details: A retrospective cohort study involving 862 patients with inflammatory bowel disease.

Disclosures: The investigators disclosed relationships Abbott, Gilead, Romark, and others.

Source: Dalal RS et al. Clin Gastro Hepatol. 2019 Dec 27. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.12.024.

FDA advisers set high bar for new opioids

During an opioid-addiction epidemic, can any new opioid pain drug meet prevailing safety demands to gain regulatory approval?

On Jan. 14 and 15, a Food and Drug Administration advisory committee voted virtually unanimously against two new opioid formulations and evenly split for and against a third; the 2 days of data and discussion showed how high a bar new opioids face these days for getting onto the U.S. market.

The bar’s height is very understandable given how many Americans have become addicted to opioids over the past decade, more often than not by accident while using pain medications as they believed they had been directed, said experts during the sessions held on the FDA’s campus in White Oak, Md.

Among the many upshots of the opioid crisis, the meetings held to discuss these three contender opioids highlighted the bitter irony confronting attempts to bring new, safer opioids to the U.S. market: While less abusable pain-relief medications that still harness the potent analgesic power of mu opioid receptor agonists are desperately desired, new agents in this space now receive withering scrutiny over their safeguards against misuse and abuse, and over whether they add anything meaningfully new to what’s already available. While these demands seem reasonable, perhaps even essential, it’s unclear whether any new opioid-based pain drugs will ever fully meet the safety that researchers, clinicians, and the public now seek.

A special FDA advisory committee that combined the Anesthetic and Analgesic Drug Products Advisory Committee with members of the Drug Safety and Risk Management Advisory Committee considered the application for three different opioid drugs from three separate companies. None received a clear endorsement. Oxycodegol, a new type of orally delivered opioid molecule engineered to slow brain entry and thereby delay an abuser’s high, got voted down without any votes in favor and 27 votes against agency approval. Aximris XR, an extended-release oxycodone formulation that successfully deterred intravenous abuse but had no deterrence efficacy for intranasal or oral abuse failed by a 2-24 vote against. The third agent, CTC, a novel formulation of the schedule IV opioid tramadol with the NSAID celecoxib designed to be analgesic but with limited opioid-abuse appeal, came the closest to meaningful support with a tied 13-13 vote from advisory committee members for and against agency approval. FDA staff takes advisory committee opinions and votes into account when making their final decisions about drug marketing approvals.

In each case, the committee members, mostly the same roster assembled for each of the three agents, identified specific concerns with the data purported to show each drug’s safety and efficacy. But the gathered experts and consumer representatives also consistently cited holistic challenges to approving new opioids and the stiffer criteria these agents face amid a continuing wave of opioid misuse and abuse.

“In the context of the public health issues, we don’t want to be perceived in any way of taking shortcuts,” said Linda S. Tyler, PharmD,, an advisory committee member and professor of pharmacy and chief pharmacy officer at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City. “There is no question that for a new product to come to market in this space it needs to add to what’s on the market, meet a high bar, and provide advantages compared with what’s already on the market,” she said.

Tramadol plus celecoxib gains some support

The proposed combined formulation of tramadol and celecoxib came closest to meeting that bar, as far as the advisory committee was concerned, coming away with 13 votes favoring approval to match 13 votes against. The premise behind this agent, know as CTC (cocrystal of tramadol and celecoxib), was that it combined a modest dose (44 mg) of the schedule IV opioid tramadol with a 56-mg dose of celecoxib in a twice-daily pill. Eugene R. Viscusi, MD, professor of anesthesiology and director of acute pain management at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia and a speaker at the session on behalf of the applicant company, spelled out the rationale behind CTC: “We are caught in a dilemma. We need to reduce opioid use, but we also need to treat pain. We have an urgent need to have pain treatment options that are effective but have low potential for abuse and dependence. We are looking at multimodal analgesia, that uses combination of agents, recognizing that postoperative pain is a mixed pain syndrome. Multimodal pain treatments are now considered standard care. We want to minimize opioids to the lowest dose possible to produce safe analgesia. Tramadol is the least-preferred opioid for abuse,” and is rated as schedule IV, the U.S. designation for drugs considered to have a low level of potential for causing abuse or dependence. “Opioids used as stand-alone agents have contributed to the current opioid crisis,” Dr. Viscusi told the committee.

In contrast to tramadol’s schedule IV status, the mainstays of recent opioid pain therapy have been hydrocodone and oxycodone, schedule II opioids rated as having a “high potential for abuse.”