User login

FDA okays ubrogepant for acute migraine treatment

The Food and Drug Administration has approved ubrogepant (Ubrelvy, Allergan) for the acute treatment of migraine with or without aura in adults.

Ubrogepant is the first drug in the class of oral calcitonin gene–related peptide receptor antagonists approved for the acute treatment of migraine. It is approved in two dose strengths (50 mg and 100 mg).

The drug is not indicated, however, for the preventive treatment of migraine.

“Migraine is an often disabling condition that affects an estimated 37 million people in the U.S.,” Billy Dunn, MD, acting director of the office of neuroscience in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in an FDA news release.

Ubrogepant represents “an important new option for the acute treatment of migraine in adults, as it is the first drug in its class approved for this indication. The FDA is pleased to approve a novel treatment for patients suffering from migraine and will continue to work with stakeholders to promote the development of new safe and effective migraine therapies,” added Dr. Dunn.

The safety and efficacy of ubrogepant for the acute treatment of migraine was demonstrated in two randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials (ACHIEVE I and ACHIEVE II). In total, 1,439 adults with a history of migraine, with and without aura, received ubrogepant to treat an ongoing migraine.

“Both 50-mg and 100-mg dose strengths demonstrated significantly greater rates of pain freedom and freedom from the most bothersome migraine-associated symptom at 2 hours, compared with placebo,” Allergan said in a news release announcing approval.

The most common side effects reported by patients in the clinical trials were nausea, tiredness, and dry mouth. Ubrogepant is contraindicated for coadministration with strong CYP3A4 inhibitors.

The company expects to have ubrogepant available in the first quarter of 2020.

A version of this story originally appeared on Medscape.com.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved ubrogepant (Ubrelvy, Allergan) for the acute treatment of migraine with or without aura in adults.

Ubrogepant is the first drug in the class of oral calcitonin gene–related peptide receptor antagonists approved for the acute treatment of migraine. It is approved in two dose strengths (50 mg and 100 mg).

The drug is not indicated, however, for the preventive treatment of migraine.

“Migraine is an often disabling condition that affects an estimated 37 million people in the U.S.,” Billy Dunn, MD, acting director of the office of neuroscience in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in an FDA news release.

Ubrogepant represents “an important new option for the acute treatment of migraine in adults, as it is the first drug in its class approved for this indication. The FDA is pleased to approve a novel treatment for patients suffering from migraine and will continue to work with stakeholders to promote the development of new safe and effective migraine therapies,” added Dr. Dunn.

The safety and efficacy of ubrogepant for the acute treatment of migraine was demonstrated in two randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials (ACHIEVE I and ACHIEVE II). In total, 1,439 adults with a history of migraine, with and without aura, received ubrogepant to treat an ongoing migraine.

“Both 50-mg and 100-mg dose strengths demonstrated significantly greater rates of pain freedom and freedom from the most bothersome migraine-associated symptom at 2 hours, compared with placebo,” Allergan said in a news release announcing approval.

The most common side effects reported by patients in the clinical trials were nausea, tiredness, and dry mouth. Ubrogepant is contraindicated for coadministration with strong CYP3A4 inhibitors.

The company expects to have ubrogepant available in the first quarter of 2020.

A version of this story originally appeared on Medscape.com.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved ubrogepant (Ubrelvy, Allergan) for the acute treatment of migraine with or without aura in adults.

Ubrogepant is the first drug in the class of oral calcitonin gene–related peptide receptor antagonists approved for the acute treatment of migraine. It is approved in two dose strengths (50 mg and 100 mg).

The drug is not indicated, however, for the preventive treatment of migraine.

“Migraine is an often disabling condition that affects an estimated 37 million people in the U.S.,” Billy Dunn, MD, acting director of the office of neuroscience in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in an FDA news release.

Ubrogepant represents “an important new option for the acute treatment of migraine in adults, as it is the first drug in its class approved for this indication. The FDA is pleased to approve a novel treatment for patients suffering from migraine and will continue to work with stakeholders to promote the development of new safe and effective migraine therapies,” added Dr. Dunn.

The safety and efficacy of ubrogepant for the acute treatment of migraine was demonstrated in two randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials (ACHIEVE I and ACHIEVE II). In total, 1,439 adults with a history of migraine, with and without aura, received ubrogepant to treat an ongoing migraine.

“Both 50-mg and 100-mg dose strengths demonstrated significantly greater rates of pain freedom and freedom from the most bothersome migraine-associated symptom at 2 hours, compared with placebo,” Allergan said in a news release announcing approval.

The most common side effects reported by patients in the clinical trials were nausea, tiredness, and dry mouth. Ubrogepant is contraindicated for coadministration with strong CYP3A4 inhibitors.

The company expects to have ubrogepant available in the first quarter of 2020.

A version of this story originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Well-tolerated topical capsaicin formulation reduces knee OA pain

ATLANTA – Use of high-concentration topical capsaicin was associated with reduced pain, a longer duration of clinical response, and was well tolerated in patients with knee osteoarthritis, compared with lower concentrations of capsaicin and placebo, according to recent research presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

While the ACR has recommended topical capsaicin for the relief of hand and knee OA pain, there are issues with using low-dose capsaicin, including the need for multiple applications and burning, stinging sensations at applications sites. As repeat exposure to capsaicin results in depletion of pain neurotransmitters and a reduction in nerve fibers in a dose-dependent fashion, higher doses of topical capsaicin are a potential topical treatment for OA pain relief, but their tolerability is low, Tim Warneke, vice president of clinical operations at Vizuri Health Sciences in Columbia, Md., said in his presentation.

“[P]oor tolerability has limited the ability to maximize the analgesic effect of capsaicin,” Mr. Warneke said. “While [over-the-counter] preparations of capsaicin provide some pain relief, poor tolerability with higher doses has really left us wondering if we haven’t maximized capsaicin’s ability to provide pain relief.”

Mr. Warneke and colleagues conducted a phase 2, multicenter, double-blind, parallel-group, vehicle-controlled trial where 120 patients with knee OA were randomized in a 1:1:1 ratio to receive 5% capsaicin topical liquid (CGS-200-5), 1% capsaicin topical liquid (CGS-200-1), or vehicle (CGS-200-0) and then followed up to 90 days. “The CGS-200 vehicle was developed to mitigate the burning, stinging pain of capsaicin,” Mr. Warneke said. “It allows the 5% concentration to be well tolerated, which opens the door for increased efficacy, including durability of response.”

Inclusion criteria were radiographically confirmed knee OA using 1986 ACR classification criteria, a Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) pain score of 250 mm or greater, and more than 3 months of chronic knee pain. While patients were excluded for use of topical, oral, or injectable corticosteroids in the month prior to enrollment, they were allowed to continue using analgesics such as NSAIDs if they maintained their daily dose throughout the trial. Mr. Warneke noted the study population was typical of an OA population with a mostly female, mostly Caucasian cohort who had a median age of 60 years and a body mass index of 30 kg/m2. Patients had moderate to severe OA and were refractory to previous pain treatments.

The interventions consisted of a single 60-minute application of capsaicin or vehicle to both knees once per day for 4 consecutive days, and patients performed the applications in the clinic. The investigators compared change in WOMAC pain scores between the groups at 31 days, 60 days, and 90 days post dose.

The results at 31 days showed a 46.2% reduction in WOMAC pain scores from baseline for patients using CGS-200-5, compared with a 28.3% reduction in the vehicle group (P = .02). At 60 days, there was a 49.1% reduction in WOMAC pain scores in the CGS-200-5 group, compared with 21.5% in patients using vehicle (P = .0001), and a 42.8% reduction for patients in the CGS-200-5 group at 90 days, compared with 22.8% in the vehicle group (P = .01). The CGS-200-1 group did not reach the primary efficacy WOMAC pain endpoint, compared with vehicle.

A post hoc analysis showed that there was a significantly greater mean reduction in WOMAC total score for patients using CGS-200-5, compared with vehicle at 31 days (P = .02), 60 days (P = .0005), and 90 days post dose (P = .005). “This durability of clinical response for single applications seems to be a promising feature of CGS-200-5,” Mr. Warneke said.

Concerning safety and tolerability, there were no serious adverse events, and one patient discontinued treatment in the CGS-200-5 group. When assessing tolerability at predose, 15-minute, 30-minute, 60-minute, and 90-minute postdose time intervals, the investigators found patients experienced mild or moderate adverse events such as erythema, edema, scaling, and pruritus, with symptoms decreasing by the fourth consecutive day of application.

Mr. Warneke acknowledged the “robust placebo response” in the trial and noted it is not unusual to see in pain studies. “It’s something that is a challenge for all of us who are in this space to overcome, but we still have significant differences here and they are statistically significant as well,” he said. “You have to be pretty good these days to beat the wonder drug placebo, it appears.”

Four authors in addition to Mr. Warneke reported being employees of Vizuri Health Sciences, the company developing CGS-200-5. One author reported being a former consultant for Vizuri. Three authors reported they were current or former employees of CT Clinical Trial & Consulting, a contract research organization employed by Vizuri to execute and manage the study, perform data analysis, and create reports.

SOURCE: Warneke T et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71(suppl 10), Abstract 2760.

ATLANTA – Use of high-concentration topical capsaicin was associated with reduced pain, a longer duration of clinical response, and was well tolerated in patients with knee osteoarthritis, compared with lower concentrations of capsaicin and placebo, according to recent research presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

While the ACR has recommended topical capsaicin for the relief of hand and knee OA pain, there are issues with using low-dose capsaicin, including the need for multiple applications and burning, stinging sensations at applications sites. As repeat exposure to capsaicin results in depletion of pain neurotransmitters and a reduction in nerve fibers in a dose-dependent fashion, higher doses of topical capsaicin are a potential topical treatment for OA pain relief, but their tolerability is low, Tim Warneke, vice president of clinical operations at Vizuri Health Sciences in Columbia, Md., said in his presentation.

“[P]oor tolerability has limited the ability to maximize the analgesic effect of capsaicin,” Mr. Warneke said. “While [over-the-counter] preparations of capsaicin provide some pain relief, poor tolerability with higher doses has really left us wondering if we haven’t maximized capsaicin’s ability to provide pain relief.”

Mr. Warneke and colleagues conducted a phase 2, multicenter, double-blind, parallel-group, vehicle-controlled trial where 120 patients with knee OA were randomized in a 1:1:1 ratio to receive 5% capsaicin topical liquid (CGS-200-5), 1% capsaicin topical liquid (CGS-200-1), or vehicle (CGS-200-0) and then followed up to 90 days. “The CGS-200 vehicle was developed to mitigate the burning, stinging pain of capsaicin,” Mr. Warneke said. “It allows the 5% concentration to be well tolerated, which opens the door for increased efficacy, including durability of response.”

Inclusion criteria were radiographically confirmed knee OA using 1986 ACR classification criteria, a Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) pain score of 250 mm or greater, and more than 3 months of chronic knee pain. While patients were excluded for use of topical, oral, or injectable corticosteroids in the month prior to enrollment, they were allowed to continue using analgesics such as NSAIDs if they maintained their daily dose throughout the trial. Mr. Warneke noted the study population was typical of an OA population with a mostly female, mostly Caucasian cohort who had a median age of 60 years and a body mass index of 30 kg/m2. Patients had moderate to severe OA and were refractory to previous pain treatments.

The interventions consisted of a single 60-minute application of capsaicin or vehicle to both knees once per day for 4 consecutive days, and patients performed the applications in the clinic. The investigators compared change in WOMAC pain scores between the groups at 31 days, 60 days, and 90 days post dose.

The results at 31 days showed a 46.2% reduction in WOMAC pain scores from baseline for patients using CGS-200-5, compared with a 28.3% reduction in the vehicle group (P = .02). At 60 days, there was a 49.1% reduction in WOMAC pain scores in the CGS-200-5 group, compared with 21.5% in patients using vehicle (P = .0001), and a 42.8% reduction for patients in the CGS-200-5 group at 90 days, compared with 22.8% in the vehicle group (P = .01). The CGS-200-1 group did not reach the primary efficacy WOMAC pain endpoint, compared with vehicle.

A post hoc analysis showed that there was a significantly greater mean reduction in WOMAC total score for patients using CGS-200-5, compared with vehicle at 31 days (P = .02), 60 days (P = .0005), and 90 days post dose (P = .005). “This durability of clinical response for single applications seems to be a promising feature of CGS-200-5,” Mr. Warneke said.

Concerning safety and tolerability, there were no serious adverse events, and one patient discontinued treatment in the CGS-200-5 group. When assessing tolerability at predose, 15-minute, 30-minute, 60-minute, and 90-minute postdose time intervals, the investigators found patients experienced mild or moderate adverse events such as erythema, edema, scaling, and pruritus, with symptoms decreasing by the fourth consecutive day of application.

Mr. Warneke acknowledged the “robust placebo response” in the trial and noted it is not unusual to see in pain studies. “It’s something that is a challenge for all of us who are in this space to overcome, but we still have significant differences here and they are statistically significant as well,” he said. “You have to be pretty good these days to beat the wonder drug placebo, it appears.”

Four authors in addition to Mr. Warneke reported being employees of Vizuri Health Sciences, the company developing CGS-200-5. One author reported being a former consultant for Vizuri. Three authors reported they were current or former employees of CT Clinical Trial & Consulting, a contract research organization employed by Vizuri to execute and manage the study, perform data analysis, and create reports.

SOURCE: Warneke T et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71(suppl 10), Abstract 2760.

ATLANTA – Use of high-concentration topical capsaicin was associated with reduced pain, a longer duration of clinical response, and was well tolerated in patients with knee osteoarthritis, compared with lower concentrations of capsaicin and placebo, according to recent research presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

While the ACR has recommended topical capsaicin for the relief of hand and knee OA pain, there are issues with using low-dose capsaicin, including the need for multiple applications and burning, stinging sensations at applications sites. As repeat exposure to capsaicin results in depletion of pain neurotransmitters and a reduction in nerve fibers in a dose-dependent fashion, higher doses of topical capsaicin are a potential topical treatment for OA pain relief, but their tolerability is low, Tim Warneke, vice president of clinical operations at Vizuri Health Sciences in Columbia, Md., said in his presentation.

“[P]oor tolerability has limited the ability to maximize the analgesic effect of capsaicin,” Mr. Warneke said. “While [over-the-counter] preparations of capsaicin provide some pain relief, poor tolerability with higher doses has really left us wondering if we haven’t maximized capsaicin’s ability to provide pain relief.”

Mr. Warneke and colleagues conducted a phase 2, multicenter, double-blind, parallel-group, vehicle-controlled trial where 120 patients with knee OA were randomized in a 1:1:1 ratio to receive 5% capsaicin topical liquid (CGS-200-5), 1% capsaicin topical liquid (CGS-200-1), or vehicle (CGS-200-0) and then followed up to 90 days. “The CGS-200 vehicle was developed to mitigate the burning, stinging pain of capsaicin,” Mr. Warneke said. “It allows the 5% concentration to be well tolerated, which opens the door for increased efficacy, including durability of response.”

Inclusion criteria were radiographically confirmed knee OA using 1986 ACR classification criteria, a Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) pain score of 250 mm or greater, and more than 3 months of chronic knee pain. While patients were excluded for use of topical, oral, or injectable corticosteroids in the month prior to enrollment, they were allowed to continue using analgesics such as NSAIDs if they maintained their daily dose throughout the trial. Mr. Warneke noted the study population was typical of an OA population with a mostly female, mostly Caucasian cohort who had a median age of 60 years and a body mass index of 30 kg/m2. Patients had moderate to severe OA and were refractory to previous pain treatments.

The interventions consisted of a single 60-minute application of capsaicin or vehicle to both knees once per day for 4 consecutive days, and patients performed the applications in the clinic. The investigators compared change in WOMAC pain scores between the groups at 31 days, 60 days, and 90 days post dose.

The results at 31 days showed a 46.2% reduction in WOMAC pain scores from baseline for patients using CGS-200-5, compared with a 28.3% reduction in the vehicle group (P = .02). At 60 days, there was a 49.1% reduction in WOMAC pain scores in the CGS-200-5 group, compared with 21.5% in patients using vehicle (P = .0001), and a 42.8% reduction for patients in the CGS-200-5 group at 90 days, compared with 22.8% in the vehicle group (P = .01). The CGS-200-1 group did not reach the primary efficacy WOMAC pain endpoint, compared with vehicle.

A post hoc analysis showed that there was a significantly greater mean reduction in WOMAC total score for patients using CGS-200-5, compared with vehicle at 31 days (P = .02), 60 days (P = .0005), and 90 days post dose (P = .005). “This durability of clinical response for single applications seems to be a promising feature of CGS-200-5,” Mr. Warneke said.

Concerning safety and tolerability, there were no serious adverse events, and one patient discontinued treatment in the CGS-200-5 group. When assessing tolerability at predose, 15-minute, 30-minute, 60-minute, and 90-minute postdose time intervals, the investigators found patients experienced mild or moderate adverse events such as erythema, edema, scaling, and pruritus, with symptoms decreasing by the fourth consecutive day of application.

Mr. Warneke acknowledged the “robust placebo response” in the trial and noted it is not unusual to see in pain studies. “It’s something that is a challenge for all of us who are in this space to overcome, but we still have significant differences here and they are statistically significant as well,” he said. “You have to be pretty good these days to beat the wonder drug placebo, it appears.”

Four authors in addition to Mr. Warneke reported being employees of Vizuri Health Sciences, the company developing CGS-200-5. One author reported being a former consultant for Vizuri. Three authors reported they were current or former employees of CT Clinical Trial & Consulting, a contract research organization employed by Vizuri to execute and manage the study, perform data analysis, and create reports.

SOURCE: Warneke T et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71(suppl 10), Abstract 2760.

REPORTING FROM ACR 2019

In addiction, abusive partners can wreak havoc

Gender-based violence could be driver of opioid epidemic, expert suggests

SAN DIEGO – Many factors drive addiction. But clinicians often fail to address the important role played by abusive intimate partners, a psychiatrist told colleagues at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Addiction Psychiatry.

Violence is not the only source of harm, said Carole Warshaw, MD, as abusers also turn to sabotage, gaslighting, and manipulation – especially when substance users seek help.

“Abusive partners deliberately engage in behaviors designed to undermine their partner’s sanity or sobriety,” said Dr. Warshaw, director of the National Center on Domestic Violence, Trauma & Mental Health in Chicago, in a presentation at the meeting. “We’ve talked a lot about drivers of the opioid epidemic, including pharmaceutical industry greed and disorders of despair. But nobody’s been really talking about gender-based violence as a potential driver of the opioid epidemic, including intimate-partner violence, trafficking, and commercial sex exploitation.”

Dr. Warshaw highlighted the findings of a 2014 study that examined the survey responses of 2,546 adult women (54% white, 19% black, 19% Hispanic) who called the National Domestic Violence Hotline. The study, led by Dr. Warshaw, only included women who had experienced domestic violence and were not in immediate crisis.

The women answered questions about abusive partners, and their responses were often emotional, Dr. Warshaw said. “People would say: ‘No one asked me this before,’ and they’d be in tears. It was just very moving for people to start thinking about this.”

Gaslighting, sabotage, and accusations of mental illness were common. More than 85% of respondents said their current or ex-partner had called them “crazy,” and 74% agreed that “your partner or ex-partner has ... deliberately done things to make you feel like you are going crazy or losing your mind.”

Strategies of abusive partners include sabotaging and discrediting their partners’ attempts at recovery, Dr. Warshaw said. Half of callers agreed that a partner or ex-partner “tried to prevent or discourage you from getting ... help or taking medication you were prescribed for your feelings.”

About 92% of callers who said they’d tried to get help in recent years “reported that their partner or ex-partner had threatened to report their alcohol or other drug use to authorities to keep them from getting something they wanted or needed,” the study found.

All of the abuse can create a kind of addiction feedback loop, she said. “Research has consistently documented that abuse by an intimate partner increases a person’s risk for developing a range of health and mental health conditions – including depression, PTSD, anxiety – that are risk factors for opioid and substance use.”

The toolkit, she said, provides insight into how to integrate questions about abusive partners into your practice and how to partner with domestic violence programs.

Dr. Warshaw reported no relevant disclosures.

Gender-based violence could be driver of opioid epidemic, expert suggests

Gender-based violence could be driver of opioid epidemic, expert suggests

SAN DIEGO – Many factors drive addiction. But clinicians often fail to address the important role played by abusive intimate partners, a psychiatrist told colleagues at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Addiction Psychiatry.

Violence is not the only source of harm, said Carole Warshaw, MD, as abusers also turn to sabotage, gaslighting, and manipulation – especially when substance users seek help.

“Abusive partners deliberately engage in behaviors designed to undermine their partner’s sanity or sobriety,” said Dr. Warshaw, director of the National Center on Domestic Violence, Trauma & Mental Health in Chicago, in a presentation at the meeting. “We’ve talked a lot about drivers of the opioid epidemic, including pharmaceutical industry greed and disorders of despair. But nobody’s been really talking about gender-based violence as a potential driver of the opioid epidemic, including intimate-partner violence, trafficking, and commercial sex exploitation.”

Dr. Warshaw highlighted the findings of a 2014 study that examined the survey responses of 2,546 adult women (54% white, 19% black, 19% Hispanic) who called the National Domestic Violence Hotline. The study, led by Dr. Warshaw, only included women who had experienced domestic violence and were not in immediate crisis.

The women answered questions about abusive partners, and their responses were often emotional, Dr. Warshaw said. “People would say: ‘No one asked me this before,’ and they’d be in tears. It was just very moving for people to start thinking about this.”

Gaslighting, sabotage, and accusations of mental illness were common. More than 85% of respondents said their current or ex-partner had called them “crazy,” and 74% agreed that “your partner or ex-partner has ... deliberately done things to make you feel like you are going crazy or losing your mind.”

Strategies of abusive partners include sabotaging and discrediting their partners’ attempts at recovery, Dr. Warshaw said. Half of callers agreed that a partner or ex-partner “tried to prevent or discourage you from getting ... help or taking medication you were prescribed for your feelings.”

About 92% of callers who said they’d tried to get help in recent years “reported that their partner or ex-partner had threatened to report their alcohol or other drug use to authorities to keep them from getting something they wanted or needed,” the study found.

All of the abuse can create a kind of addiction feedback loop, she said. “Research has consistently documented that abuse by an intimate partner increases a person’s risk for developing a range of health and mental health conditions – including depression, PTSD, anxiety – that are risk factors for opioid and substance use.”

The toolkit, she said, provides insight into how to integrate questions about abusive partners into your practice and how to partner with domestic violence programs.

Dr. Warshaw reported no relevant disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Many factors drive addiction. But clinicians often fail to address the important role played by abusive intimate partners, a psychiatrist told colleagues at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Addiction Psychiatry.

Violence is not the only source of harm, said Carole Warshaw, MD, as abusers also turn to sabotage, gaslighting, and manipulation – especially when substance users seek help.

“Abusive partners deliberately engage in behaviors designed to undermine their partner’s sanity or sobriety,” said Dr. Warshaw, director of the National Center on Domestic Violence, Trauma & Mental Health in Chicago, in a presentation at the meeting. “We’ve talked a lot about drivers of the opioid epidemic, including pharmaceutical industry greed and disorders of despair. But nobody’s been really talking about gender-based violence as a potential driver of the opioid epidemic, including intimate-partner violence, trafficking, and commercial sex exploitation.”

Dr. Warshaw highlighted the findings of a 2014 study that examined the survey responses of 2,546 adult women (54% white, 19% black, 19% Hispanic) who called the National Domestic Violence Hotline. The study, led by Dr. Warshaw, only included women who had experienced domestic violence and were not in immediate crisis.

The women answered questions about abusive partners, and their responses were often emotional, Dr. Warshaw said. “People would say: ‘No one asked me this before,’ and they’d be in tears. It was just very moving for people to start thinking about this.”

Gaslighting, sabotage, and accusations of mental illness were common. More than 85% of respondents said their current or ex-partner had called them “crazy,” and 74% agreed that “your partner or ex-partner has ... deliberately done things to make you feel like you are going crazy or losing your mind.”

Strategies of abusive partners include sabotaging and discrediting their partners’ attempts at recovery, Dr. Warshaw said. Half of callers agreed that a partner or ex-partner “tried to prevent or discourage you from getting ... help or taking medication you were prescribed for your feelings.”

About 92% of callers who said they’d tried to get help in recent years “reported that their partner or ex-partner had threatened to report their alcohol or other drug use to authorities to keep them from getting something they wanted or needed,” the study found.

All of the abuse can create a kind of addiction feedback loop, she said. “Research has consistently documented that abuse by an intimate partner increases a person’s risk for developing a range of health and mental health conditions – including depression, PTSD, anxiety – that are risk factors for opioid and substance use.”

The toolkit, she said, provides insight into how to integrate questions about abusive partners into your practice and how to partner with domestic violence programs.

Dr. Warshaw reported no relevant disclosures.

REPORTING FROM AAAP 2019

Addiction specialists: Cannabis policies should go up in smoke

SAN DIEGO – Addiction specialists have a message for American policymakers who are rushing to create laws to allow the use of medical and recreational marijuana: You’re doing it wrong, but we know how you can do it right.

“We can have spirited debates on these policies, recreational, medical decriminalization, etc. But we can’t argue how we’ve done a poor job implementing these policies in the United States,” psychiatrist Kevin P. Hill, MD, of Harvard Medical School, Boston, said in a symposium about cannabis policy at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Addiction Psychiatry.

The AAAP is proposing a “model state law” regarding cannabis. Among other things, the proposal urges states to:

- Ban recreational use of cannabis until the age of 21, and perhaps even until 25.

- Not denote psychiatric indications such as posttraumatic stress disorder, anxiety, and depression as qualifying conditions for the use of medical marijuana.

- Educate the public about potential harms of cannabis.

- Provide state-level regulation that includes funding of high-grade analytic equipment to test cannabis.

- Maintain a public registry that reports annually on adverse outcomes.

Research suggests that marijuana use has spiked in recent years, Dr. Hill said. Meanwhile, states have dramatically broadened the legality of marijuana. According to the National Conference of State Legislatures, 33 states and the District of Columbia allow the medical use of marijuana. Of those, 11 states and the District of Columbia also allow the adult use of recreational marijuana. Several other states allow access to cannabidiol (CBD)/low-THC products in some cases (www.ncsl.org/research/health/state-medical-marijuana-laws.aspx).

The problem, Dr. Hill said, is that there’s “a big gap between what the science says and what the laws are saying, unfortunately. So we’re in this precarious spot.”

He pointed to his own 2015 review of cannabinoid studies that found high-quality evidence for an effect for just three conditions – chronic pain, neuropathic pain, and spasticity associated with multiple sclerosis. The study notes that Food and Drug Administration–approved cannabinoids are also available to treat nausea and vomiting linked to chemotherapy and to boost appetite in patients with wasting disease. (JAMA. 2015 Jun 23-30;313(24):2474-83).

However, states have listed dozens of conditions – 53 overall – as qualifying conditions for the use of medical marijuana, Dr. Hill said. And, he said, “the reality is that a lot of people who are using medical cannabis don’t have any of these conditions,” he said.

Researchers at the symposium focused on the use of cannabis as a treatment for addiction and other psychiatric illnesses.

Four states have legalized the use of cannabis in patients with opioid use disorder, said cannabis researcher Ziva D. Cooper, PhD, of the University of California, Los Angeles, who spoke at the symposium. But can cannabis actually reduce opioid use? Preliminary clinical data suggest THC could reduce opioid use, Dr. Cooper said, while population and state-level research is mixed.

What about other mental health disorders? Posttraumatic stress disorder is commonly listed as a qualifying condition for medical marijuana use in state laws. And some states, like California, give physicians wide leeway in recommending marijuana use for patients with conditions that aren’t listed in the law.

However, symposium speaker and psychiatrist Frances R. Levin, MD, of New York State Psychiatric Institute, pointed to a 2019 review that suggests “there is scarce evidence to suggest that cannabinoids improve depressive disorders and symptoms, anxiety disorders, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, Tourette syndrome, posttraumatic stress disorder, or psychosis” (Lancet Psychiatry. 2019 Dec;6[12]:995-1010).

What now? The AAAP hopes lawmakers will pay attention to its proposed model state law, which will be published soon in the association’s journal, the American Journal on Addictions.

SAN DIEGO – Addiction specialists have a message for American policymakers who are rushing to create laws to allow the use of medical and recreational marijuana: You’re doing it wrong, but we know how you can do it right.

“We can have spirited debates on these policies, recreational, medical decriminalization, etc. But we can’t argue how we’ve done a poor job implementing these policies in the United States,” psychiatrist Kevin P. Hill, MD, of Harvard Medical School, Boston, said in a symposium about cannabis policy at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Addiction Psychiatry.

The AAAP is proposing a “model state law” regarding cannabis. Among other things, the proposal urges states to:

- Ban recreational use of cannabis until the age of 21, and perhaps even until 25.

- Not denote psychiatric indications such as posttraumatic stress disorder, anxiety, and depression as qualifying conditions for the use of medical marijuana.

- Educate the public about potential harms of cannabis.

- Provide state-level regulation that includes funding of high-grade analytic equipment to test cannabis.

- Maintain a public registry that reports annually on adverse outcomes.

Research suggests that marijuana use has spiked in recent years, Dr. Hill said. Meanwhile, states have dramatically broadened the legality of marijuana. According to the National Conference of State Legislatures, 33 states and the District of Columbia allow the medical use of marijuana. Of those, 11 states and the District of Columbia also allow the adult use of recreational marijuana. Several other states allow access to cannabidiol (CBD)/low-THC products in some cases (www.ncsl.org/research/health/state-medical-marijuana-laws.aspx).

The problem, Dr. Hill said, is that there’s “a big gap between what the science says and what the laws are saying, unfortunately. So we’re in this precarious spot.”

He pointed to his own 2015 review of cannabinoid studies that found high-quality evidence for an effect for just three conditions – chronic pain, neuropathic pain, and spasticity associated with multiple sclerosis. The study notes that Food and Drug Administration–approved cannabinoids are also available to treat nausea and vomiting linked to chemotherapy and to boost appetite in patients with wasting disease. (JAMA. 2015 Jun 23-30;313(24):2474-83).

However, states have listed dozens of conditions – 53 overall – as qualifying conditions for the use of medical marijuana, Dr. Hill said. And, he said, “the reality is that a lot of people who are using medical cannabis don’t have any of these conditions,” he said.

Researchers at the symposium focused on the use of cannabis as a treatment for addiction and other psychiatric illnesses.

Four states have legalized the use of cannabis in patients with opioid use disorder, said cannabis researcher Ziva D. Cooper, PhD, of the University of California, Los Angeles, who spoke at the symposium. But can cannabis actually reduce opioid use? Preliminary clinical data suggest THC could reduce opioid use, Dr. Cooper said, while population and state-level research is mixed.

What about other mental health disorders? Posttraumatic stress disorder is commonly listed as a qualifying condition for medical marijuana use in state laws. And some states, like California, give physicians wide leeway in recommending marijuana use for patients with conditions that aren’t listed in the law.

However, symposium speaker and psychiatrist Frances R. Levin, MD, of New York State Psychiatric Institute, pointed to a 2019 review that suggests “there is scarce evidence to suggest that cannabinoids improve depressive disorders and symptoms, anxiety disorders, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, Tourette syndrome, posttraumatic stress disorder, or psychosis” (Lancet Psychiatry. 2019 Dec;6[12]:995-1010).

What now? The AAAP hopes lawmakers will pay attention to its proposed model state law, which will be published soon in the association’s journal, the American Journal on Addictions.

SAN DIEGO – Addiction specialists have a message for American policymakers who are rushing to create laws to allow the use of medical and recreational marijuana: You’re doing it wrong, but we know how you can do it right.

“We can have spirited debates on these policies, recreational, medical decriminalization, etc. But we can’t argue how we’ve done a poor job implementing these policies in the United States,” psychiatrist Kevin P. Hill, MD, of Harvard Medical School, Boston, said in a symposium about cannabis policy at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Addiction Psychiatry.

The AAAP is proposing a “model state law” regarding cannabis. Among other things, the proposal urges states to:

- Ban recreational use of cannabis until the age of 21, and perhaps even until 25.

- Not denote psychiatric indications such as posttraumatic stress disorder, anxiety, and depression as qualifying conditions for the use of medical marijuana.

- Educate the public about potential harms of cannabis.

- Provide state-level regulation that includes funding of high-grade analytic equipment to test cannabis.

- Maintain a public registry that reports annually on adverse outcomes.

Research suggests that marijuana use has spiked in recent years, Dr. Hill said. Meanwhile, states have dramatically broadened the legality of marijuana. According to the National Conference of State Legislatures, 33 states and the District of Columbia allow the medical use of marijuana. Of those, 11 states and the District of Columbia also allow the adult use of recreational marijuana. Several other states allow access to cannabidiol (CBD)/low-THC products in some cases (www.ncsl.org/research/health/state-medical-marijuana-laws.aspx).

The problem, Dr. Hill said, is that there’s “a big gap between what the science says and what the laws are saying, unfortunately. So we’re in this precarious spot.”

He pointed to his own 2015 review of cannabinoid studies that found high-quality evidence for an effect for just three conditions – chronic pain, neuropathic pain, and spasticity associated with multiple sclerosis. The study notes that Food and Drug Administration–approved cannabinoids are also available to treat nausea and vomiting linked to chemotherapy and to boost appetite in patients with wasting disease. (JAMA. 2015 Jun 23-30;313(24):2474-83).

However, states have listed dozens of conditions – 53 overall – as qualifying conditions for the use of medical marijuana, Dr. Hill said. And, he said, “the reality is that a lot of people who are using medical cannabis don’t have any of these conditions,” he said.

Researchers at the symposium focused on the use of cannabis as a treatment for addiction and other psychiatric illnesses.

Four states have legalized the use of cannabis in patients with opioid use disorder, said cannabis researcher Ziva D. Cooper, PhD, of the University of California, Los Angeles, who spoke at the symposium. But can cannabis actually reduce opioid use? Preliminary clinical data suggest THC could reduce opioid use, Dr. Cooper said, while population and state-level research is mixed.

What about other mental health disorders? Posttraumatic stress disorder is commonly listed as a qualifying condition for medical marijuana use in state laws. And some states, like California, give physicians wide leeway in recommending marijuana use for patients with conditions that aren’t listed in the law.

However, symposium speaker and psychiatrist Frances R. Levin, MD, of New York State Psychiatric Institute, pointed to a 2019 review that suggests “there is scarce evidence to suggest that cannabinoids improve depressive disorders and symptoms, anxiety disorders, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, Tourette syndrome, posttraumatic stress disorder, or psychosis” (Lancet Psychiatry. 2019 Dec;6[12]:995-1010).

What now? The AAAP hopes lawmakers will pay attention to its proposed model state law, which will be published soon in the association’s journal, the American Journal on Addictions.

REPORTING FROM AAAP 2019

New opioid recommendations: Pain from most dermatologic procedures should be managed with acetaminophen, ibuprofen

has recommended.

Rotation flaps, interpolation flaps, wedge resections, cartilage alar-batten grafts, and Mustarde flaps were among the 20 procedures that can be managed with up to 10 oral oxycodone 5-mg equivalents, according to the panel. Only the Abbe procedure might warrant dispensing up to 15 oxycodone 5-mg pills, Justin McLawhorn, MD, and colleagues wrote in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. The recommended amount of opioids are in addition to nonopioid analgesics, the guidelines point out.

All the other procedures can – and should – be managed with a combination of acetaminophen and ibuprofen, either alone or in an alternating dose pattern, said Dr. McLawhorn, of the department of dermatology at the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Oklahoma City, and coauthors.

But limited opioid prescribing is an important part of healing for patients who undergo the most invasive procedures, they wrote. “The management of complications, including adequate pain control, should be tailored to each patient on a case-by-case basis. Moreover, any pain management plan should not strictly adhere to any single guideline, but rather should be formed with consideration of the expected pain from the procedure and/or closure and consider the patient’s expectations for pain control.”

The time is ripe for dermatologists to make a stand in combating the opioid crisis, according to a group email response to questions from Dr. McLawhorn, Thomas Stasko, MD, professor and chair of dermatology at the University of Oklahoma, Oklahoma City, and Lindsey Collins, MD, also of the University of Oklahoma.

“The opioid crisis has reached epidemic proportions. More than 70,000 Americans have died from an opioid overdose in 2017,” they wrote. “Moreover, recent data suggest that nearly 6% of postsurgical, opioid-naive patients become long-term users of opioids. The lack of specific evidence-based recommendations likely contributes to a wide variety in prescribing patterns and a steady supply of unused opioids. Countering the opioid crisis necessitates a restructuring of the opioid prescribing practices that addresses pain in a procedure-specific manner. These recommendations are one tool in the dermatologists’ arsenal that can be used as a reference to help guide opioid management and prevent excessive opioid prescriptions at discharge following dermatologic interventions.”

Unfortunately, they added, dermatologists have inadvertently fueled the opioid abuse fire.

“It is difficult to quantify which providers are responsible for the onslaught of opioids into our communities,” the authors wrote in the email interview. “However, we can deduce, based on recent opioid prescribing patterns, that dermatologists provide approximately 500,000 unused opioid pills to their communities on an annual basis. This is the result of a wide variation in practice patterns and narratives that have been previously circulated in an attempt to mitigate the providers’ perception of the addictive nature of opioid analgesics. Our hope is that by addressing pain in a procedure-specific manner, we can help to limit the excessive number of unused opioid pills that are provided by dermatologists and ultimately decrease the rate of opioid-related complications, including addiction and death.”

Still, patients need and deserve effective pain management after a procedure. In the guidelines, the investigators wrote that a “one-size-fits-all” approach “does not account for the mechanism of pain, the invasiveness of the procedure, or the anatomic structures that are manipulated. As a result, current guidelines cannot accurately predict the quantity of opioids that are necessary to manage postoperative pain.”

The panel brought together experts in general dermatology, dermatologic surgery, cosmetics, and phlebology to develop a consensus on opioid prescribing guidelines for 87 of the most common procedures. Everyone on the panel was a member of the American College of Mohs Surgery, American Academy of Dermatology, or the American Vein and Lymphatic Society. The panel conducted a literature review to determine which procedures might require opioids and which would not. At least 75% of the panel had to agree on a reasonable but effective opioid amount; they were then polled as to whether they might employ that recommendation in their own clinical practice.

The recommendations are aimed at patients who experienced no peri- or postoperative complications.

The panel agreed that acetaminophen and ibuprofen – alone, in combination, or with opioids – were reasonable choices for all the 87 procedures. In such instances, acetaminophen 1 g can be staggered with ibuprofen 400 mg every 4 or 8 hours.

“I think providers will encounter a mixed bag of preconceived notions regarding patients’ expectations for pain control,” Dr. McLawhorn and coauthors wrote in the interview. “The important point for providers to make is to emphasize the noninferiority of acetaminophen and/or ibuprofen in controlling acute pain for patients who are not dependent on opioids for the management of chronic pain. Our experience in caring for many surgical patients has shown that patients are usually receptive to the use of nonopioid analgesics as many are familiar with their addictive potential because of the uptick in the publicity of the opioid-related complications.”

In cases where opioids might be appropriate, the panel unanimously agreed that dose limits be imposed. For 15 of the 87 procedures, the panel recommend a maximum prescription of 10 oxycodone 5-mg equivalents. Only one other – the Abbe flap – might warrant more, with a maximum of 15 oxycodone 5-mg pills at discharge.

Sometimes called a “lip switch,” the Abbe flap is reconstruction for full-thickness lip defects. It is a composite flap that moves skin, muscle, mucosa, and blood supply from the lower lip to reconstruct a defect of the upper lip. This reconstruction attempts to respect the native anatomic landmarks of the lip and allow for a better functional outcome.

“Because of the extensive nature of the repair and the anatomic territories that are manipulated, including the suturing of the lower lip to the upper lip with delayed separation, adequate pain control may require opioid analgesics in the immediate postoperative period,” the team wrote in the interview.

The panel could not agree on pain management strategies for five other procedures: Karapandzic flaps, en bloc nail excisions, facial resurfacing with deep chemical peels, and small- or large-volume liposuction. This was partly because of a lack of personal experience. Only 8 of the 40 panelists performed Karapandzic flaps. The maximum number of 5-mg oxycodone tablets any panelist prescribed for Karapandzic flaps and en bloc nail excisions was 20.

Facial resurfacing was likewise an uncommon procedure for the panel, with just 11 members performing this using deep chemical peels. However, five of those panelists said that opioids were routinely needed for postoperative pain with a maximum of 15 oxycodone 5-mg equivalents. And just four panelists performed liposuction, for which they used a maximum of 15 oxycodone 5-mg equivalents.

“However,” they wrote in the guidelines, “these providers noted that the location where the procedure is performed strongly influences the need for opioid pain management, with small-volume removal in the neck, arms, or flanks being unlikely to require opioids for adequate pain control, whereas large-volume removal in the thighs, knees, and hips may routinely require opioids.”

Addressing patient expectations is a very important part of pain management, the panel noted. “Patients will invariably experience postoperative pain after cutaneous surgeries or other interventions, often peaking within 4 hours after surgery. Wound tension, size and type of repair, anatomical location/nerve innervation, and patient pain tolerance are all factors that contribute to postoperative discomfort and should be considered when developing a postoperative pain management plan.”

Ultimately, according to Dr. McLawhorn and coauthors, the decision to use opioids at discharge for postoperative pain control should be an individual one based on patients’ comorbidities and expectations.

“Admittedly, many of the procedures listed within the recommendations may result in a rather large or complex defect that requires an equally large or complex repair,” they wrote in the interview. “However, proper education of the patient and provider regarding the risks of addiction with the use of opioids even short term should be discussed as part of every preoperative consultation. Furthermore, the patient and the provider must discuss their expectations for postoperative pain interventions for adequate pain control.”

SOURCE: McLawhorn J et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019 Nov 12. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.09.080.

has recommended.

Rotation flaps, interpolation flaps, wedge resections, cartilage alar-batten grafts, and Mustarde flaps were among the 20 procedures that can be managed with up to 10 oral oxycodone 5-mg equivalents, according to the panel. Only the Abbe procedure might warrant dispensing up to 15 oxycodone 5-mg pills, Justin McLawhorn, MD, and colleagues wrote in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. The recommended amount of opioids are in addition to nonopioid analgesics, the guidelines point out.

All the other procedures can – and should – be managed with a combination of acetaminophen and ibuprofen, either alone or in an alternating dose pattern, said Dr. McLawhorn, of the department of dermatology at the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Oklahoma City, and coauthors.

But limited opioid prescribing is an important part of healing for patients who undergo the most invasive procedures, they wrote. “The management of complications, including adequate pain control, should be tailored to each patient on a case-by-case basis. Moreover, any pain management plan should not strictly adhere to any single guideline, but rather should be formed with consideration of the expected pain from the procedure and/or closure and consider the patient’s expectations for pain control.”

The time is ripe for dermatologists to make a stand in combating the opioid crisis, according to a group email response to questions from Dr. McLawhorn, Thomas Stasko, MD, professor and chair of dermatology at the University of Oklahoma, Oklahoma City, and Lindsey Collins, MD, also of the University of Oklahoma.

“The opioid crisis has reached epidemic proportions. More than 70,000 Americans have died from an opioid overdose in 2017,” they wrote. “Moreover, recent data suggest that nearly 6% of postsurgical, opioid-naive patients become long-term users of opioids. The lack of specific evidence-based recommendations likely contributes to a wide variety in prescribing patterns and a steady supply of unused opioids. Countering the opioid crisis necessitates a restructuring of the opioid prescribing practices that addresses pain in a procedure-specific manner. These recommendations are one tool in the dermatologists’ arsenal that can be used as a reference to help guide opioid management and prevent excessive opioid prescriptions at discharge following dermatologic interventions.”

Unfortunately, they added, dermatologists have inadvertently fueled the opioid abuse fire.

“It is difficult to quantify which providers are responsible for the onslaught of opioids into our communities,” the authors wrote in the email interview. “However, we can deduce, based on recent opioid prescribing patterns, that dermatologists provide approximately 500,000 unused opioid pills to their communities on an annual basis. This is the result of a wide variation in practice patterns and narratives that have been previously circulated in an attempt to mitigate the providers’ perception of the addictive nature of opioid analgesics. Our hope is that by addressing pain in a procedure-specific manner, we can help to limit the excessive number of unused opioid pills that are provided by dermatologists and ultimately decrease the rate of opioid-related complications, including addiction and death.”

Still, patients need and deserve effective pain management after a procedure. In the guidelines, the investigators wrote that a “one-size-fits-all” approach “does not account for the mechanism of pain, the invasiveness of the procedure, or the anatomic structures that are manipulated. As a result, current guidelines cannot accurately predict the quantity of opioids that are necessary to manage postoperative pain.”

The panel brought together experts in general dermatology, dermatologic surgery, cosmetics, and phlebology to develop a consensus on opioid prescribing guidelines for 87 of the most common procedures. Everyone on the panel was a member of the American College of Mohs Surgery, American Academy of Dermatology, or the American Vein and Lymphatic Society. The panel conducted a literature review to determine which procedures might require opioids and which would not. At least 75% of the panel had to agree on a reasonable but effective opioid amount; they were then polled as to whether they might employ that recommendation in their own clinical practice.

The recommendations are aimed at patients who experienced no peri- or postoperative complications.

The panel agreed that acetaminophen and ibuprofen – alone, in combination, or with opioids – were reasonable choices for all the 87 procedures. In such instances, acetaminophen 1 g can be staggered with ibuprofen 400 mg every 4 or 8 hours.

“I think providers will encounter a mixed bag of preconceived notions regarding patients’ expectations for pain control,” Dr. McLawhorn and coauthors wrote in the interview. “The important point for providers to make is to emphasize the noninferiority of acetaminophen and/or ibuprofen in controlling acute pain for patients who are not dependent on opioids for the management of chronic pain. Our experience in caring for many surgical patients has shown that patients are usually receptive to the use of nonopioid analgesics as many are familiar with their addictive potential because of the uptick in the publicity of the opioid-related complications.”

In cases where opioids might be appropriate, the panel unanimously agreed that dose limits be imposed. For 15 of the 87 procedures, the panel recommend a maximum prescription of 10 oxycodone 5-mg equivalents. Only one other – the Abbe flap – might warrant more, with a maximum of 15 oxycodone 5-mg pills at discharge.

Sometimes called a “lip switch,” the Abbe flap is reconstruction for full-thickness lip defects. It is a composite flap that moves skin, muscle, mucosa, and blood supply from the lower lip to reconstruct a defect of the upper lip. This reconstruction attempts to respect the native anatomic landmarks of the lip and allow for a better functional outcome.

“Because of the extensive nature of the repair and the anatomic territories that are manipulated, including the suturing of the lower lip to the upper lip with delayed separation, adequate pain control may require opioid analgesics in the immediate postoperative period,” the team wrote in the interview.

The panel could not agree on pain management strategies for five other procedures: Karapandzic flaps, en bloc nail excisions, facial resurfacing with deep chemical peels, and small- or large-volume liposuction. This was partly because of a lack of personal experience. Only 8 of the 40 panelists performed Karapandzic flaps. The maximum number of 5-mg oxycodone tablets any panelist prescribed for Karapandzic flaps and en bloc nail excisions was 20.

Facial resurfacing was likewise an uncommon procedure for the panel, with just 11 members performing this using deep chemical peels. However, five of those panelists said that opioids were routinely needed for postoperative pain with a maximum of 15 oxycodone 5-mg equivalents. And just four panelists performed liposuction, for which they used a maximum of 15 oxycodone 5-mg equivalents.

“However,” they wrote in the guidelines, “these providers noted that the location where the procedure is performed strongly influences the need for opioid pain management, with small-volume removal in the neck, arms, or flanks being unlikely to require opioids for adequate pain control, whereas large-volume removal in the thighs, knees, and hips may routinely require opioids.”

Addressing patient expectations is a very important part of pain management, the panel noted. “Patients will invariably experience postoperative pain after cutaneous surgeries or other interventions, often peaking within 4 hours after surgery. Wound tension, size and type of repair, anatomical location/nerve innervation, and patient pain tolerance are all factors that contribute to postoperative discomfort and should be considered when developing a postoperative pain management plan.”

Ultimately, according to Dr. McLawhorn and coauthors, the decision to use opioids at discharge for postoperative pain control should be an individual one based on patients’ comorbidities and expectations.

“Admittedly, many of the procedures listed within the recommendations may result in a rather large or complex defect that requires an equally large or complex repair,” they wrote in the interview. “However, proper education of the patient and provider regarding the risks of addiction with the use of opioids even short term should be discussed as part of every preoperative consultation. Furthermore, the patient and the provider must discuss their expectations for postoperative pain interventions for adequate pain control.”

SOURCE: McLawhorn J et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019 Nov 12. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.09.080.

has recommended.

Rotation flaps, interpolation flaps, wedge resections, cartilage alar-batten grafts, and Mustarde flaps were among the 20 procedures that can be managed with up to 10 oral oxycodone 5-mg equivalents, according to the panel. Only the Abbe procedure might warrant dispensing up to 15 oxycodone 5-mg pills, Justin McLawhorn, MD, and colleagues wrote in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. The recommended amount of opioids are in addition to nonopioid analgesics, the guidelines point out.

All the other procedures can – and should – be managed with a combination of acetaminophen and ibuprofen, either alone or in an alternating dose pattern, said Dr. McLawhorn, of the department of dermatology at the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Oklahoma City, and coauthors.

But limited opioid prescribing is an important part of healing for patients who undergo the most invasive procedures, they wrote. “The management of complications, including adequate pain control, should be tailored to each patient on a case-by-case basis. Moreover, any pain management plan should not strictly adhere to any single guideline, but rather should be formed with consideration of the expected pain from the procedure and/or closure and consider the patient’s expectations for pain control.”

The time is ripe for dermatologists to make a stand in combating the opioid crisis, according to a group email response to questions from Dr. McLawhorn, Thomas Stasko, MD, professor and chair of dermatology at the University of Oklahoma, Oklahoma City, and Lindsey Collins, MD, also of the University of Oklahoma.

“The opioid crisis has reached epidemic proportions. More than 70,000 Americans have died from an opioid overdose in 2017,” they wrote. “Moreover, recent data suggest that nearly 6% of postsurgical, opioid-naive patients become long-term users of opioids. The lack of specific evidence-based recommendations likely contributes to a wide variety in prescribing patterns and a steady supply of unused opioids. Countering the opioid crisis necessitates a restructuring of the opioid prescribing practices that addresses pain in a procedure-specific manner. These recommendations are one tool in the dermatologists’ arsenal that can be used as a reference to help guide opioid management and prevent excessive opioid prescriptions at discharge following dermatologic interventions.”

Unfortunately, they added, dermatologists have inadvertently fueled the opioid abuse fire.

“It is difficult to quantify which providers are responsible for the onslaught of opioids into our communities,” the authors wrote in the email interview. “However, we can deduce, based on recent opioid prescribing patterns, that dermatologists provide approximately 500,000 unused opioid pills to their communities on an annual basis. This is the result of a wide variation in practice patterns and narratives that have been previously circulated in an attempt to mitigate the providers’ perception of the addictive nature of opioid analgesics. Our hope is that by addressing pain in a procedure-specific manner, we can help to limit the excessive number of unused opioid pills that are provided by dermatologists and ultimately decrease the rate of opioid-related complications, including addiction and death.”

Still, patients need and deserve effective pain management after a procedure. In the guidelines, the investigators wrote that a “one-size-fits-all” approach “does not account for the mechanism of pain, the invasiveness of the procedure, or the anatomic structures that are manipulated. As a result, current guidelines cannot accurately predict the quantity of opioids that are necessary to manage postoperative pain.”

The panel brought together experts in general dermatology, dermatologic surgery, cosmetics, and phlebology to develop a consensus on opioid prescribing guidelines for 87 of the most common procedures. Everyone on the panel was a member of the American College of Mohs Surgery, American Academy of Dermatology, or the American Vein and Lymphatic Society. The panel conducted a literature review to determine which procedures might require opioids and which would not. At least 75% of the panel had to agree on a reasonable but effective opioid amount; they were then polled as to whether they might employ that recommendation in their own clinical practice.

The recommendations are aimed at patients who experienced no peri- or postoperative complications.

The panel agreed that acetaminophen and ibuprofen – alone, in combination, or with opioids – were reasonable choices for all the 87 procedures. In such instances, acetaminophen 1 g can be staggered with ibuprofen 400 mg every 4 or 8 hours.

“I think providers will encounter a mixed bag of preconceived notions regarding patients’ expectations for pain control,” Dr. McLawhorn and coauthors wrote in the interview. “The important point for providers to make is to emphasize the noninferiority of acetaminophen and/or ibuprofen in controlling acute pain for patients who are not dependent on opioids for the management of chronic pain. Our experience in caring for many surgical patients has shown that patients are usually receptive to the use of nonopioid analgesics as many are familiar with their addictive potential because of the uptick in the publicity of the opioid-related complications.”

In cases where opioids might be appropriate, the panel unanimously agreed that dose limits be imposed. For 15 of the 87 procedures, the panel recommend a maximum prescription of 10 oxycodone 5-mg equivalents. Only one other – the Abbe flap – might warrant more, with a maximum of 15 oxycodone 5-mg pills at discharge.

Sometimes called a “lip switch,” the Abbe flap is reconstruction for full-thickness lip defects. It is a composite flap that moves skin, muscle, mucosa, and blood supply from the lower lip to reconstruct a defect of the upper lip. This reconstruction attempts to respect the native anatomic landmarks of the lip and allow for a better functional outcome.

“Because of the extensive nature of the repair and the anatomic territories that are manipulated, including the suturing of the lower lip to the upper lip with delayed separation, adequate pain control may require opioid analgesics in the immediate postoperative period,” the team wrote in the interview.

The panel could not agree on pain management strategies for five other procedures: Karapandzic flaps, en bloc nail excisions, facial resurfacing with deep chemical peels, and small- or large-volume liposuction. This was partly because of a lack of personal experience. Only 8 of the 40 panelists performed Karapandzic flaps. The maximum number of 5-mg oxycodone tablets any panelist prescribed for Karapandzic flaps and en bloc nail excisions was 20.

Facial resurfacing was likewise an uncommon procedure for the panel, with just 11 members performing this using deep chemical peels. However, five of those panelists said that opioids were routinely needed for postoperative pain with a maximum of 15 oxycodone 5-mg equivalents. And just four panelists performed liposuction, for which they used a maximum of 15 oxycodone 5-mg equivalents.

“However,” they wrote in the guidelines, “these providers noted that the location where the procedure is performed strongly influences the need for opioid pain management, with small-volume removal in the neck, arms, or flanks being unlikely to require opioids for adequate pain control, whereas large-volume removal in the thighs, knees, and hips may routinely require opioids.”

Addressing patient expectations is a very important part of pain management, the panel noted. “Patients will invariably experience postoperative pain after cutaneous surgeries or other interventions, often peaking within 4 hours after surgery. Wound tension, size and type of repair, anatomical location/nerve innervation, and patient pain tolerance are all factors that contribute to postoperative discomfort and should be considered when developing a postoperative pain management plan.”

Ultimately, according to Dr. McLawhorn and coauthors, the decision to use opioids at discharge for postoperative pain control should be an individual one based on patients’ comorbidities and expectations.

“Admittedly, many of the procedures listed within the recommendations may result in a rather large or complex defect that requires an equally large or complex repair,” they wrote in the interview. “However, proper education of the patient and provider regarding the risks of addiction with the use of opioids even short term should be discussed as part of every preoperative consultation. Furthermore, the patient and the provider must discuss their expectations for postoperative pain interventions for adequate pain control.”

SOURCE: McLawhorn J et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019 Nov 12. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.09.080.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF DERMATOLOGY

Functional heartburn: An underrecognized cause of PPI-refractory symptoms

A 44-year-old woman presents with an 8-year history of intermittent heartburn, and in the past year she has been experiencing her symptoms daily. She says the heartburn is constant and is worse immediately after eating spicy or acidic foods. She says she has had no dysphagia, weight loss, or vomiting. Her symptoms have persisted despite taking a histamine (H)2-receptor antagonist twice daily plus a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) before breakfast and dinner for more than 3 months.

She has undergone upper endoscopy 3 times in the past 8 years. Each time, the esophagus was normal with a regular Z-line and normal biopsy results from the proximal and distal esophagus.

The patient believes she has severe gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and asks if she is a candidate for fundoplication surgery.

HEARTBURN IS A SYMPTOM; GERD IS A CONDITION

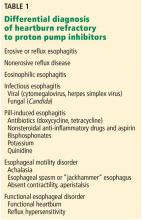

A distinction should be made between heartburn—the symptom of persistent retrosternal burning and discomfort—and gastroesophageal reflux disease—the condition in which reflux of stomach contents causes troublesome symptoms or complications.1 While many clinicians initially diagnose patients who have heartburn as having GERD, there are many other potential causes of their symptoms.

For patients with persistent heartburn, an empiric trial of a once-daily PPI is usually effective, but one-third of patients continue to have heartburn.2,3 The most common cause of this PPI-refractory heartburn is functional heartburn, a functional or hypersensitivity disorder of the esophagus.4

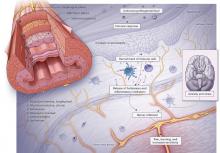

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY IS POORLY UNDERSTOOD

DIAGNOSTIC EVALUATION

Clinicians have several tests available for diagnosing these conditions.

Upper endoscopy

Upper endoscopy is recommended for patients with heartburn that does not respond to a 3-month trial of a PPI.9 Endoscopy is also indicated in any patient who has any of the following “alarm symptoms” that could be due to malignancy or peptic ulcer:

- Dysphagia

- Odynophagia

- Vomiting

- Unexplained weight loss or anemia

- Signs of gastrointestinal bleeding

- Anorexia

- New onset of dyspepsia in a patient over age 60.

During upper endoscopy, the esophagus is evaluated for reflux esophagitis, Barrett esophagus, and other inflammatory disorders such as infectious esophagitis. But even if the esophageal mucosa appears normal, the proximal and distal esophagus should be biopsied to rule out an inflammatory disorder such as eosinophilic or lymphocytic esophagitis.

Esophageal manometry

If endoscopic and esophageal biopsy results are inconclusive, a workup for an esophageal motility disorder is the next step. Dysphagia is the most common symptom of these disorders, although the initial presenting symptom may be heartburn or regurgitation that persists despite PPI therapy.

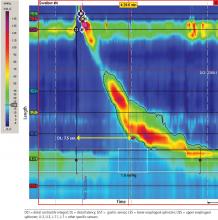

Manometry is used to test for motility disorders such as achalasia and esophageal spasm.10 After applying a local anesthetic inside the nares, the clinician inserts a flexible catheter (about 4 mm in diameter) with 36 pressure sensors spaced at 1-cm intervals into the nares and passes it through the esophagus and lower esophageal sphincter. The patient then swallows liquid, and the sensors relay the esophageal response, creating a topographic plot that shows esophageal peristalsis and lower esophageal sphincter relaxation.

Achalasia is identified by incomplete lower esophageal sphincter relaxation combined with 100% failed peristalsis in the body of the esophagus. Esophageal spasms are identified by a shortened distal latency, which corresponds to premature contraction of the esophagus during peristalsis.11

Esophageal pH testing

Measuring esophageal pH levels is an important step to quantify gastroesophageal reflux and determine if symptoms occur during reflux events. According to the updated Porto GERD consensus group recommendations,12 a pH test is positive if the acid exposure time is greater than 6% of the testing period. Testing the pH differentiates between GERD (abnormal acid exposure), reflux hypersensitivity (normal acid exposure, strong correlation between symptoms and reflux events), and functional heartburn (normal acid exposure, negative correlation between reflux events and symptoms).5 For this test, a pH probe is placed in the esophagus transnasally or endoscopically. The probe records esophageal pH levels for 24 to 96 hours in an outpatient setting. Antisecretory therapy needs to be withheld for 7 to 10 days before the test.

Transnasal pH probe. For this approach, a thin catheter is inserted through the nares and advanced until the tip is 5 cm proximal to the lower esophageal sphincter. (The placement is guided by the results of esophageal manometry, which is done immediately before pH catheter placement.) The tube is secured with clear tape on the side of the patient’s face, and the end is connected to a portable recorder that compiles the data. The patient pushes a button on the recorder when experiencing heartburn symptoms. (A nurse instructs the patient on proper procedure.) After 24 hours, the patient either removes the catheter or has the clinic remove it. The pH and symptom data are downloaded and analyzed.

Transnasal pH testing can be combined with impedance measurement, which can detect nonacid reflux or weakly acid reflux. However, the clinical significance of this measurement is unclear, as multiple studies have found total acid exposure time to be a better predictor of response to therapy than weakly acid or nonacid reflux.12

Wireless pH probe. This method uses a disposable, catheter-free, capsule device to measure esophageal pH. The capsule, about the size of a gel capsule or pencil eraser, is attached to the patient’s esophageal lining, usually during upper endoscopy. The capsule records pH levels in the lower esophagus for 48 to 96 hours and transmits the data wirelessly to a receiver the patient wears. The patient pushes buttons on the receiver to record symptom-specific data when experiencing heartburn, chest pain, regurgitation, or cough. The capsule detaches from the esophagus spontaneously, generally within 7 days, and is passed out of the body through a bowel movement.

Diagnosing functional heartburn

CASE CONTINUED: NORMAL RESULTS ON TESTING

Based on these results, her condition is diagnosed as functional heartburn, consistent with the Rome IV criteria.5

TREATMENT

Patient education is key

Patient education about the pathogenesis, natural history, and treatment options is the most important aspect of treating any functional gastrointestinal disorder. This includes the “brain-gut connection” and potential mechanisms of dysregulation. Patient education along with assessment of symptoms should be part of every visit, especially before discussing treatment options.

Patients whose condition is diagnosed as functional heartburn need reassurance that the condition is benign and, in particular, that the risk of progression to esophageal adenocarcinoma is minimal in the absence of Barrett esophagus.13 Also important to point out is that the disorder may spontaneously resolve: resolution rates of up to 40% have been reported for other functional gastrointestinal disorders.14

Antisecretory medications may work for some

A PPI or H2-receptor antagonist is the most common first-line treatment for heartburn symptoms. Although most patients with functional heartburn experience no improvement in symptoms with an antisecretory agent, a small number report some relief, which suggests that acid-suppression therapy may have an indirect impact on pain modulation in the esophagus.15 In patients who report symptom relief with an antisecretory agent, we suggest continuing the medication tapered to the lowest effective dose, with repeated reassurance that the medication can be discontinued safely at any time.

Antireflux surgery should be avoided

Antireflux surgery should be avoided in patients with normal pH testing and no objective finding of reflux, as this is associated with worse subjective outcomes than in patients with abnormal pH test results.16

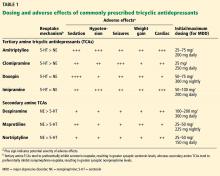

Neuromodulators

It is important to discuss with patients the concept of neuromodulation, including the fact that antidepressants are often used because of their effects on serotonin and norepinephrine, which decrease visceral hypersensitivity.

The selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor citalopram has been shown to reduce esophageal hypersensitivity,17 and a tricyclic antidepressant has been shown to improve quality of life.18 These results have led experts to recommend a trial of a low dose of either type of medication.19 The dose of tricyclic antidepressant often needs to be increased sequentially every 2 to 4 weeks.

Interestingly, melatonin 6 mg at bedtime has also shown efficacy for functional heartburn, potentially due to its antinociceptive properties.20