User login

FDA approves first IV migraine prevention drug

As previously reported by Medscape Medical News, the drug’s approval is based on results from two clinical studies – PROMISE-1 in episodic migraine and PROMISE-2 in chronic migraine.

The recommended dose is 100 mg every 3 months although some patients may benefit from a dose of 300 mg, the company notes. Lundbeck reports that the drug will likely be available in early April.

Roger Cady, MD, vice-president of neurology at Lundbeck, told Medscape Medical News the drug has almost immediate efficacy.

“Because it’s an IV [medication], it has very rapid benefit. In fact, we were able to demonstrate benefit on Day 1. Truly, it is going to impact on the unmet need for patients because of its profile, the way it’s delivered, and its uniqueness,” Cady said.

“Having preventive activity the day following an infusion is really important. We have in our data, if you take that time between the first day and the 28th day, whether they have episodic migraine or chronic migraine, that about 30% of the population had a 75% or more reduction in migraine days through that first month,” he added.

The clinical trial program demonstrated a treatment benefit over placebo that was observed for both doses of Vyepti as early as day 1 post-infusion, and the percentage of patients experiencing a migraine was lower for Vyepti than with placebo for most of the first 7 days, the company reports.

The safety of Vyepti was evaluated in 2076 patients with migraine who received at least one dose of the drug. The most common adverse reactions were nasopharyngitis and hypersensitivity. In PROMISE-1 and PROMISE-2, 1.9% of patients treated with Vyepti discontinued treatment as a result of adverse reactions.

“The PROMISE-2 data showed that many patients can achieve reduction in migraine days of at least 75% and experience a sustained migraine improvement through 6 months, which is clinically meaningful to both physicians and patients,” said Peter Goadsby, MD, professor of neurology at King’s College, London, UK, and the University of California, San Francisco, in a press release. “Vyepti is a valuable addition for the treatment of migraine, which can help reduce the burden of this serious disease.”

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

As previously reported by Medscape Medical News, the drug’s approval is based on results from two clinical studies – PROMISE-1 in episodic migraine and PROMISE-2 in chronic migraine.

The recommended dose is 100 mg every 3 months although some patients may benefit from a dose of 300 mg, the company notes. Lundbeck reports that the drug will likely be available in early April.

Roger Cady, MD, vice-president of neurology at Lundbeck, told Medscape Medical News the drug has almost immediate efficacy.

“Because it’s an IV [medication], it has very rapid benefit. In fact, we were able to demonstrate benefit on Day 1. Truly, it is going to impact on the unmet need for patients because of its profile, the way it’s delivered, and its uniqueness,” Cady said.

“Having preventive activity the day following an infusion is really important. We have in our data, if you take that time between the first day and the 28th day, whether they have episodic migraine or chronic migraine, that about 30% of the population had a 75% or more reduction in migraine days through that first month,” he added.

The clinical trial program demonstrated a treatment benefit over placebo that was observed for both doses of Vyepti as early as day 1 post-infusion, and the percentage of patients experiencing a migraine was lower for Vyepti than with placebo for most of the first 7 days, the company reports.

The safety of Vyepti was evaluated in 2076 patients with migraine who received at least one dose of the drug. The most common adverse reactions were nasopharyngitis and hypersensitivity. In PROMISE-1 and PROMISE-2, 1.9% of patients treated with Vyepti discontinued treatment as a result of adverse reactions.

“The PROMISE-2 data showed that many patients can achieve reduction in migraine days of at least 75% and experience a sustained migraine improvement through 6 months, which is clinically meaningful to both physicians and patients,” said Peter Goadsby, MD, professor of neurology at King’s College, London, UK, and the University of California, San Francisco, in a press release. “Vyepti is a valuable addition for the treatment of migraine, which can help reduce the burden of this serious disease.”

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

As previously reported by Medscape Medical News, the drug’s approval is based on results from two clinical studies – PROMISE-1 in episodic migraine and PROMISE-2 in chronic migraine.

The recommended dose is 100 mg every 3 months although some patients may benefit from a dose of 300 mg, the company notes. Lundbeck reports that the drug will likely be available in early April.

Roger Cady, MD, vice-president of neurology at Lundbeck, told Medscape Medical News the drug has almost immediate efficacy.

“Because it’s an IV [medication], it has very rapid benefit. In fact, we were able to demonstrate benefit on Day 1. Truly, it is going to impact on the unmet need for patients because of its profile, the way it’s delivered, and its uniqueness,” Cady said.

“Having preventive activity the day following an infusion is really important. We have in our data, if you take that time between the first day and the 28th day, whether they have episodic migraine or chronic migraine, that about 30% of the population had a 75% or more reduction in migraine days through that first month,” he added.

The clinical trial program demonstrated a treatment benefit over placebo that was observed for both doses of Vyepti as early as day 1 post-infusion, and the percentage of patients experiencing a migraine was lower for Vyepti than with placebo for most of the first 7 days, the company reports.

The safety of Vyepti was evaluated in 2076 patients with migraine who received at least one dose of the drug. The most common adverse reactions were nasopharyngitis and hypersensitivity. In PROMISE-1 and PROMISE-2, 1.9% of patients treated with Vyepti discontinued treatment as a result of adverse reactions.

“The PROMISE-2 data showed that many patients can achieve reduction in migraine days of at least 75% and experience a sustained migraine improvement through 6 months, which is clinically meaningful to both physicians and patients,” said Peter Goadsby, MD, professor of neurology at King’s College, London, UK, and the University of California, San Francisco, in a press release. “Vyepti is a valuable addition for the treatment of migraine, which can help reduce the burden of this serious disease.”

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM MEDSCAPE.COM

Prescription osteoarthritis relief gets OTC approval

The Food and Drug Administration has approved formerly prescription-only Voltaren Arthritis Pain (diclofenac sodium topical gel, 1%) for nonprescription use via a process known as a prescription to over-the-counter (Rx-to-OTC) switch, according to a news release from the agency.

“As a result of the Rx-to-OTC switch process, many products sold over the counter today use ingredients or dosage strengths that were available only by prescription 30 years ago,” Karen Mahoney, MD, acting deputy director of the Office of Nonprescription Drugs in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in the release.

This switch to nonprescription status is usually initiated by the manufacturer, who must provide data that demonstrates the drug in question is both safe and effective as self-medication in accordance with the proposed labeling and that consumers can use it safely and effectively without the supervision of a health care professional.

This particular therapy is a topical NSAID gel and was first approved by the FDA in 2007 with the indication for relief of osteoarthritis pain. It can take 7 days to have an effect, but if patients find it takes longer than that or they need to use it for more than 21 days, they should seek medical attention. The gel can cause severe allergic reactions, especially in people allergic to aspirin; patients who experience such reactions are advised to stop use and seek immediate medical care. Other concerns include potential for liver damage with extended use; the possibility of severe stomach bleeds; and risk of heart attack, heart failure, and stroke.

The gel will no longer be available in prescription form.

Full prescribing information can be found on the FDA website, as can the full news release regarding this approval.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved formerly prescription-only Voltaren Arthritis Pain (diclofenac sodium topical gel, 1%) for nonprescription use via a process known as a prescription to over-the-counter (Rx-to-OTC) switch, according to a news release from the agency.

“As a result of the Rx-to-OTC switch process, many products sold over the counter today use ingredients or dosage strengths that were available only by prescription 30 years ago,” Karen Mahoney, MD, acting deputy director of the Office of Nonprescription Drugs in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in the release.

This switch to nonprescription status is usually initiated by the manufacturer, who must provide data that demonstrates the drug in question is both safe and effective as self-medication in accordance with the proposed labeling and that consumers can use it safely and effectively without the supervision of a health care professional.

This particular therapy is a topical NSAID gel and was first approved by the FDA in 2007 with the indication for relief of osteoarthritis pain. It can take 7 days to have an effect, but if patients find it takes longer than that or they need to use it for more than 21 days, they should seek medical attention. The gel can cause severe allergic reactions, especially in people allergic to aspirin; patients who experience such reactions are advised to stop use and seek immediate medical care. Other concerns include potential for liver damage with extended use; the possibility of severe stomach bleeds; and risk of heart attack, heart failure, and stroke.

The gel will no longer be available in prescription form.

Full prescribing information can be found on the FDA website, as can the full news release regarding this approval.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved formerly prescription-only Voltaren Arthritis Pain (diclofenac sodium topical gel, 1%) for nonprescription use via a process known as a prescription to over-the-counter (Rx-to-OTC) switch, according to a news release from the agency.

“As a result of the Rx-to-OTC switch process, many products sold over the counter today use ingredients or dosage strengths that were available only by prescription 30 years ago,” Karen Mahoney, MD, acting deputy director of the Office of Nonprescription Drugs in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in the release.

This switch to nonprescription status is usually initiated by the manufacturer, who must provide data that demonstrates the drug in question is both safe and effective as self-medication in accordance with the proposed labeling and that consumers can use it safely and effectively without the supervision of a health care professional.

This particular therapy is a topical NSAID gel and was first approved by the FDA in 2007 with the indication for relief of osteoarthritis pain. It can take 7 days to have an effect, but if patients find it takes longer than that or they need to use it for more than 21 days, they should seek medical attention. The gel can cause severe allergic reactions, especially in people allergic to aspirin; patients who experience such reactions are advised to stop use and seek immediate medical care. Other concerns include potential for liver damage with extended use; the possibility of severe stomach bleeds; and risk of heart attack, heart failure, and stroke.

The gel will no longer be available in prescription form.

Full prescribing information can be found on the FDA website, as can the full news release regarding this approval.

Tramadol use for noncancer pain linked with increased hip fracture risk

The risk of hip fracture was higher among patients treated with tramadol for chronic noncancer pain than among those treated with other commonly used NSAIDs in a large population-based cohort in the United Kingdom.

The incidence of hip fracture over a 12-month period among 293,912 propensity score-matched tramadol and codeine recipients in The Health Improvement Network (THIN) database during 2000-2017 was 3.7 vs. 2.9 per 1,000 person-years, respectively (hazard ratio for hip fracture, 1.28), Jie Wei, PhD, of Xiangya Hospital, Central South University, Changsha, China, and colleagues reported in the Journal of Bone and Mineral Research.

Hip fracture incidence per 1,000 person-years was also higher in propensity score–matched cohorts of patients receiving tramadol vs. naproxen (2.9 vs. 1.7; HR, 1.69), ibuprofen (3.4 vs. 2.0; HR, 1.65), celecoxib (3.4 vs. 1.8; HR, 1.85), or etoricoxib (2.9 vs. 1.5; HR, 1.96), the investigators found.

Tramadol is considered a weak opioid and is commonly used for the treatment of pain based on a lower perceived risk of serious cardiovascular and gastrointestinal effects versus NSAIDs, and of addiction and respiratory depression versus traditional opioids, they explained. Several professional organizations also have “strongly or conditionally recommended tramadol” as a first- or second-line treatment for conditions such as osteoarthritis, fibromyalgia, and chronic low back pain.

The potential mechanisms for the association between tramadol and hip fracture require further study, but “[c]onsidering the significant impact of hip fracture on morbidity, mortality, and health care costs, our results point to the need to consider tramadol’s associated risk of fracture in clinical practice and treatment guidelines,” they concluded.

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health, the National Natural Science Foundation of China, and the Postdoctoral Science Foundation of Central South University. The authors reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Wei J et al. J Bone Miner Res. 2019 Feb 5. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.3935.

The risk of hip fracture was higher among patients treated with tramadol for chronic noncancer pain than among those treated with other commonly used NSAIDs in a large population-based cohort in the United Kingdom.

The incidence of hip fracture over a 12-month period among 293,912 propensity score-matched tramadol and codeine recipients in The Health Improvement Network (THIN) database during 2000-2017 was 3.7 vs. 2.9 per 1,000 person-years, respectively (hazard ratio for hip fracture, 1.28), Jie Wei, PhD, of Xiangya Hospital, Central South University, Changsha, China, and colleagues reported in the Journal of Bone and Mineral Research.

Hip fracture incidence per 1,000 person-years was also higher in propensity score–matched cohorts of patients receiving tramadol vs. naproxen (2.9 vs. 1.7; HR, 1.69), ibuprofen (3.4 vs. 2.0; HR, 1.65), celecoxib (3.4 vs. 1.8; HR, 1.85), or etoricoxib (2.9 vs. 1.5; HR, 1.96), the investigators found.

Tramadol is considered a weak opioid and is commonly used for the treatment of pain based on a lower perceived risk of serious cardiovascular and gastrointestinal effects versus NSAIDs, and of addiction and respiratory depression versus traditional opioids, they explained. Several professional organizations also have “strongly or conditionally recommended tramadol” as a first- or second-line treatment for conditions such as osteoarthritis, fibromyalgia, and chronic low back pain.

The potential mechanisms for the association between tramadol and hip fracture require further study, but “[c]onsidering the significant impact of hip fracture on morbidity, mortality, and health care costs, our results point to the need to consider tramadol’s associated risk of fracture in clinical practice and treatment guidelines,” they concluded.

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health, the National Natural Science Foundation of China, and the Postdoctoral Science Foundation of Central South University. The authors reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Wei J et al. J Bone Miner Res. 2019 Feb 5. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.3935.

The risk of hip fracture was higher among patients treated with tramadol for chronic noncancer pain than among those treated with other commonly used NSAIDs in a large population-based cohort in the United Kingdom.

The incidence of hip fracture over a 12-month period among 293,912 propensity score-matched tramadol and codeine recipients in The Health Improvement Network (THIN) database during 2000-2017 was 3.7 vs. 2.9 per 1,000 person-years, respectively (hazard ratio for hip fracture, 1.28), Jie Wei, PhD, of Xiangya Hospital, Central South University, Changsha, China, and colleagues reported in the Journal of Bone and Mineral Research.

Hip fracture incidence per 1,000 person-years was also higher in propensity score–matched cohorts of patients receiving tramadol vs. naproxen (2.9 vs. 1.7; HR, 1.69), ibuprofen (3.4 vs. 2.0; HR, 1.65), celecoxib (3.4 vs. 1.8; HR, 1.85), or etoricoxib (2.9 vs. 1.5; HR, 1.96), the investigators found.

Tramadol is considered a weak opioid and is commonly used for the treatment of pain based on a lower perceived risk of serious cardiovascular and gastrointestinal effects versus NSAIDs, and of addiction and respiratory depression versus traditional opioids, they explained. Several professional organizations also have “strongly or conditionally recommended tramadol” as a first- or second-line treatment for conditions such as osteoarthritis, fibromyalgia, and chronic low back pain.

The potential mechanisms for the association between tramadol and hip fracture require further study, but “[c]onsidering the significant impact of hip fracture on morbidity, mortality, and health care costs, our results point to the need to consider tramadol’s associated risk of fracture in clinical practice and treatment guidelines,” they concluded.

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health, the National Natural Science Foundation of China, and the Postdoctoral Science Foundation of Central South University. The authors reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Wei J et al. J Bone Miner Res. 2019 Feb 5. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.3935.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF BONE AND MINERAL RESEARCH

Pharmacologic prophylaxis fails in pediatric migraine

Clinicians hoped that medications used in adults – such as antidepressants, antiepileptics, antihypertensive agents, calcium channel blockers, and food supplements – would find similar success in children. Unfortunately, researchers found only short-term signs of efficacy over placebo, with no benefit lasting more than 6 months.

The study, conducted by a team led by Cosima Locher, PhD, of Boston Children’s Hospital, included 23 double-blind, randomized, controlled trials with a total of 2,217 patients; the mean age was 11 years. They compared 12 pharmacologic agents with each other or with placebo in the study, published online in JAMA Pediatrics.

In a main efficacy analysis that included 19 studies, only two treatments outperformed placebo: propranolol (standardized mean difference, 0.60; 95% confidence interval, 0.03-1.17) and topiramate (SMD, 0.59; 95% CI, 0.03-1.15). There were no statistically significant between-treatment differences.

The results had an overall low to moderate certainty.

When propranolol was compared to placebo, the 95% prediction interval (–0.62 to 1.82) was wider than the significant confidence interval (0.03-1.17), and comprised both beneficial and detrimental effects. A similar result was found with topiramate, with a prediction interval of –0.62 to 1.80 extending into nonsignificant effects (95% CI, 0.03-1.15). In both cases, significant effects were found only when the prediction interval was 70%.

In a long-term analysis (greater than 6 months), no treatment outperformed placebo.

The treatments generally were acceptable. The researchers found no significant difference in tolerability between any of the treatments and each other or placebo. Safety data analyzed from 13 trials revealed no significant differences between treatments and placebo.

“Because specific effects of drugs are associated with the size of the placebo effect, the lack of drug efficacy in our NMA [network meta-analysis] could be owing to a comparatively high placebo effect in children. In fact, there is indirect evidence [from other studies] that the placebo effect is more pronounced in children and adolescents than in adults,” Dr. Locher and associates said. They suggested that studies were needed to quantify the placebo effect in pediatric migraine, and if it was large, to develop innovative therapies making use of this.

The findings should lead to some changes in practice, Boris Zernikow, MD, PhD, of Children’s and Adolescents’ Hospital Datteln (Germany) wrote in an accompanying editorial.

Pharmacological prophylactic treatment of childhood migraine should be an exception rather than the rule, and nonpharmacologic approaches should be emphasized, particularly because the placebo effect is magnified in children, he said.

Many who suffer migraines in childhood will continue to be affected in adulthood, so pediatric intervention is a good opportunity to instill effective strategies. These include: using abortive medication early in an attack and using antimigraine medications for only that specific type of headache; engaging in physical activity to reduce migraine attacks; getting sufficient sleep; and learning relaxation and other psychological approaches to counter migraines.

Dr. Zernikow had no relevant financial disclosures. One study author received grants from Amgen and other support from Grunenthal and Akelos. The study received funding from the Sara Page Mayo Endowment for Pediatric Pain Research, Education, and Treatment; the Swiss National Science Foundation; the Schweizer-Arau-Foundation; and the Theophrastus Foundation.

SOURCES: Locher C et al. JAMA Pediatrics. 2020 Feb 10. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.5856; Zernikow B. JAMA Pediatrics. 2020 Feb 10. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.5907.

Clinicians hoped that medications used in adults – such as antidepressants, antiepileptics, antihypertensive agents, calcium channel blockers, and food supplements – would find similar success in children. Unfortunately, researchers found only short-term signs of efficacy over placebo, with no benefit lasting more than 6 months.

The study, conducted by a team led by Cosima Locher, PhD, of Boston Children’s Hospital, included 23 double-blind, randomized, controlled trials with a total of 2,217 patients; the mean age was 11 years. They compared 12 pharmacologic agents with each other or with placebo in the study, published online in JAMA Pediatrics.

In a main efficacy analysis that included 19 studies, only two treatments outperformed placebo: propranolol (standardized mean difference, 0.60; 95% confidence interval, 0.03-1.17) and topiramate (SMD, 0.59; 95% CI, 0.03-1.15). There were no statistically significant between-treatment differences.

The results had an overall low to moderate certainty.

When propranolol was compared to placebo, the 95% prediction interval (–0.62 to 1.82) was wider than the significant confidence interval (0.03-1.17), and comprised both beneficial and detrimental effects. A similar result was found with topiramate, with a prediction interval of –0.62 to 1.80 extending into nonsignificant effects (95% CI, 0.03-1.15). In both cases, significant effects were found only when the prediction interval was 70%.

In a long-term analysis (greater than 6 months), no treatment outperformed placebo.

The treatments generally were acceptable. The researchers found no significant difference in tolerability between any of the treatments and each other or placebo. Safety data analyzed from 13 trials revealed no significant differences between treatments and placebo.

“Because specific effects of drugs are associated with the size of the placebo effect, the lack of drug efficacy in our NMA [network meta-analysis] could be owing to a comparatively high placebo effect in children. In fact, there is indirect evidence [from other studies] that the placebo effect is more pronounced in children and adolescents than in adults,” Dr. Locher and associates said. They suggested that studies were needed to quantify the placebo effect in pediatric migraine, and if it was large, to develop innovative therapies making use of this.

The findings should lead to some changes in practice, Boris Zernikow, MD, PhD, of Children’s and Adolescents’ Hospital Datteln (Germany) wrote in an accompanying editorial.

Pharmacological prophylactic treatment of childhood migraine should be an exception rather than the rule, and nonpharmacologic approaches should be emphasized, particularly because the placebo effect is magnified in children, he said.

Many who suffer migraines in childhood will continue to be affected in adulthood, so pediatric intervention is a good opportunity to instill effective strategies. These include: using abortive medication early in an attack and using antimigraine medications for only that specific type of headache; engaging in physical activity to reduce migraine attacks; getting sufficient sleep; and learning relaxation and other psychological approaches to counter migraines.

Dr. Zernikow had no relevant financial disclosures. One study author received grants from Amgen and other support from Grunenthal and Akelos. The study received funding from the Sara Page Mayo Endowment for Pediatric Pain Research, Education, and Treatment; the Swiss National Science Foundation; the Schweizer-Arau-Foundation; and the Theophrastus Foundation.

SOURCES: Locher C et al. JAMA Pediatrics. 2020 Feb 10. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.5856; Zernikow B. JAMA Pediatrics. 2020 Feb 10. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.5907.

Clinicians hoped that medications used in adults – such as antidepressants, antiepileptics, antihypertensive agents, calcium channel blockers, and food supplements – would find similar success in children. Unfortunately, researchers found only short-term signs of efficacy over placebo, with no benefit lasting more than 6 months.

The study, conducted by a team led by Cosima Locher, PhD, of Boston Children’s Hospital, included 23 double-blind, randomized, controlled trials with a total of 2,217 patients; the mean age was 11 years. They compared 12 pharmacologic agents with each other or with placebo in the study, published online in JAMA Pediatrics.

In a main efficacy analysis that included 19 studies, only two treatments outperformed placebo: propranolol (standardized mean difference, 0.60; 95% confidence interval, 0.03-1.17) and topiramate (SMD, 0.59; 95% CI, 0.03-1.15). There were no statistically significant between-treatment differences.

The results had an overall low to moderate certainty.

When propranolol was compared to placebo, the 95% prediction interval (–0.62 to 1.82) was wider than the significant confidence interval (0.03-1.17), and comprised both beneficial and detrimental effects. A similar result was found with topiramate, with a prediction interval of –0.62 to 1.80 extending into nonsignificant effects (95% CI, 0.03-1.15). In both cases, significant effects were found only when the prediction interval was 70%.

In a long-term analysis (greater than 6 months), no treatment outperformed placebo.

The treatments generally were acceptable. The researchers found no significant difference in tolerability between any of the treatments and each other or placebo. Safety data analyzed from 13 trials revealed no significant differences between treatments and placebo.

“Because specific effects of drugs are associated with the size of the placebo effect, the lack of drug efficacy in our NMA [network meta-analysis] could be owing to a comparatively high placebo effect in children. In fact, there is indirect evidence [from other studies] that the placebo effect is more pronounced in children and adolescents than in adults,” Dr. Locher and associates said. They suggested that studies were needed to quantify the placebo effect in pediatric migraine, and if it was large, to develop innovative therapies making use of this.

The findings should lead to some changes in practice, Boris Zernikow, MD, PhD, of Children’s and Adolescents’ Hospital Datteln (Germany) wrote in an accompanying editorial.

Pharmacological prophylactic treatment of childhood migraine should be an exception rather than the rule, and nonpharmacologic approaches should be emphasized, particularly because the placebo effect is magnified in children, he said.

Many who suffer migraines in childhood will continue to be affected in adulthood, so pediatric intervention is a good opportunity to instill effective strategies. These include: using abortive medication early in an attack and using antimigraine medications for only that specific type of headache; engaging in physical activity to reduce migraine attacks; getting sufficient sleep; and learning relaxation and other psychological approaches to counter migraines.

Dr. Zernikow had no relevant financial disclosures. One study author received grants from Amgen and other support from Grunenthal and Akelos. The study received funding from the Sara Page Mayo Endowment for Pediatric Pain Research, Education, and Treatment; the Swiss National Science Foundation; the Schweizer-Arau-Foundation; and the Theophrastus Foundation.

SOURCES: Locher C et al. JAMA Pediatrics. 2020 Feb 10. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.5856; Zernikow B. JAMA Pediatrics. 2020 Feb 10. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.5907.

FROM JAMA PEDIATRICS

Shift in approach is encouraged in assessing chronic pain

In many cases, dietary interventions can lead to less inflammation

SAN DIEGO – When clinicians ask patients to quantify their level of chronic pain on a scale of 1-10, and they rate it as a 7, what does that really mean?

Robert A. Bonakdar, MD, said posing such a question as the main determinator of the treatment approach during a pain assessment “depersonalizes medicine to the point where you’re making a patient a number.” Dr. Bonakdar spoke at Natural Supplements: An Evidence-Based Update, presented by Scripps Center for Integrative Medicine.

“It considers areas that are often overlooked, such as the role of the gut microbiome, mood, and epigenetics.”

Over the past two decades, the number of American adults suffering from pain has increased from 120 million to 178 million, or to 41% of the adult population, said Dr. Bonakdar, a family physician who is director of pain management at the Scripps Center for Integrative Medicine. Data from the National Institutes of Health estimate that Americans spend more than $600 billion each year on the treatment of pain, which surpasses monies spent on cancer, heart disease, and diabetes. According to a 2016 report from the United States Bone and Joint Initiative, arthritis and rheumatologic conditions resulted in an estimated 6.7 million annual hospitalizations, and the average annual cost per person for treatment of a musculoskeletal condition is $7,800.

“If we continue on our current trajectory, we are choosing to accept more prevalence and incidence of these disorders, spiraling costs, restricted access to needed services, and less success in alleviating pain and suffering – a high cost,” Edward H. Yelin, PhD, cochair of the report’s steering committee, and professor of medicine and health policy at the University of California, San Francisco, said in a prepared statement in 2016. That same year, Brian F. Mandell, MD, PhD, editor of the Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine, penned an editorial in which he stated that “The time has come to move past using a one-size-fits-all fifth vital sign . . . and reflexively prescribing an opioid when pain is characterized as severe” (Clev Clin J Med. 2016. Jun;83[6]:400-1). A decade earlier, authors of a cross-sectional review at a single Department of Veterans Affairs medical center set out to assess the impact of the VA’s “Pain as the 5th Vital Sign” initiative on the quality of pain management (J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21[6]:607–12). They found that patients with substantial pain documented by the fifth vital sign often had inadequate pain management. The preponderance of existing evidence suggests that a different approach is needed to prescribing opioids, Dr. Bonakdar said. “It’s coming from every voice in pain care: that what we are doing is not working,” he said. “It’s not only not working; it’s dangerous. That’s the consequence of depersonalized medicine. What’s the consequence of depersonalized nutrition? It’s the same industrialized approach.”

The typical American diet, he continued, is rife with processed foods and lacks an adequate proportion of plant-based products. “It’s basically a setup for inflammation,” Dr. Bonakdar said. “Most people who come into our clinic are eating 63% processed foods, 25% animal foods, and 12% plant foods. When we are eating, we’re oversizing it because that’s the American thing to do. At the end of the day, this process is not only killing us from heart disease and stroke as causes of death, but it’s also killing us as far as pain. The same diet that’s causing heart disease is the same diet that’s increasing pain.”

Dr. Bonakdar said that the ingestion of ultra-processed foods over time jumpstarts the process of dysbiosis, which increases gut permeability. “When gut permeability happens, and you have high levels of polysaccharides and inflammatory markers such as zonulin and lipopolysaccharide (LPS), it not only goes on to affect adipose tissue and insulin resistance, it can affect the muscle and joints,” he explained. “That is a setup for sarcopenia, or muscle loss, which then makes it harder for patients to be fully functional and active. It goes on to cause joint problems as well.”

He likened an increase in gut permeability to “a bomb going off in the gut.” Routine consumption of highly processed foods “creates this wave of inflammation that goes throughout your body affecting joints and muscles, and causes an increased amount of pain. Over time, patients make the connection but it’s much easier to say, ‘take this NSAID’ or ‘take this Cox-2 inhibitor’ to suppress the pain. But if all you’re doing is suppressing, you’re not going to the source of the pain.”

Dr. Bonakdar cited several recent articles that help to make the connection between dysbiosis and pain, including a review that concluded that dysbiosis of gut microbiota can influence the onset and progression of chronic degenerative diseases (Nutrients. 2019;11[8]:1707). Authors of a separate review concluded that human microbiome studies strongly suggest an incriminating role of microbes in the pathophysiology and progression of RA. Lastly, several studies have noted that pain conditions such as fibromyalgia may have microbiome “signatures” related to dysbiosis, which may pave the way for interventions, such as dietary shifting and probiotics that target individuals with microbiome abnormalities (Pain. 2019 Nov;160[11]:2589-602 and EBioMedicine. 2019 Aug 1;46:499-511).

Clinicians can begin to help patients who present with pain complaints “by listening to what their current pattern is: strategies that have worked, and those that haven’t,” he said. “If we’re not understanding the person and we’re just ordering genetic studies or microbiome studies and going off of the assessment, we sometime miss what interventions to start. In many cases, a simple intervention like a dietary shift is all that’s required.”

A survey of more than 1 million individuals found that BMI and daily pain are positively correlated in the United States (Obesity 2012;20[7]:1491-5). “This is increased more significantly for women and the elderly,” said Dr. Bonakdar, who was not affiliated with the study. “If we can change the diet that person is taking, that’s going to begin the process of reversing this to the point where they’re having less pain from inflammation that’s affecting the adipose tissue and adipokines traveling to their joints, which can cause less dysbiosis. It is very much a vicious cycle that patients follow, but if you begin to unwind it, it’s going to help multiple areas.”

In the Intensive Diet and Exercise for Arthritis (IDEA) trial, researchers randomized 450 patients with osteoarthritis to intensive dietary restriction only, exercise only, or a combination of both (BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2009;10:93). They found that a 5% weight loss over the course of 18 months led to a 30% reduction in pain and a 24% improvement in function.

Inspired by the IDEA trial design, Dr. Bonakdar and his colleagues completed an unpublished 12-week pilot program with 12 patients with a BMI of 27 kg/m2 or greater plus comorbidities. The program consisted of weekly group meetings, including a lecture by team clinicians, dietician, and fitness staff; group support sessions with a behavioral counselor; and a group exercise session. It also included weekly 1:1 personal training sessions and biweekly 1:1 dietitian meetings. The researchers also evaluated several deficiencies linked to pain, including magnesium, vitamin D, vitamins B1, B2, and B12, folate, calcium, amino acids, omega 3s, zinc, coenzyme Q10, carnitine, and vitamin C. The goal was a weight reduction of 5%.

The intervention consisted of a 28-day detox/protein shake consumed 1-3 times per day, which contained 17 g of protein per serving. Nutritional supplementation was added based on results of individual diagnostics.

According to preliminary results from the trial, the intended weight goal was achieved. “More importantly, there were significant improvements in markers of dysbiosis, including zonulin and lipopolysaccharide, as well as the adipokine leptin, which appeared to be associated with improvement in quality of life measures and pain,” Dr. Bonakdar said.

He concluded his presentation by highlighting a pilot study conducted in an Australian tertiary pain clinic. It found that a personalized dietitian-delivered dietary intervention can improve pain scores, quality of life, and dietary intake of people experiencing chronic pain (Nutrients. 2019 Jan 16;11[1] pii: E181). “This is another piece of the puzzle showing that these dietary interventions can be done in multiple settings, including tertiary centers with nutrition staff, and that this important step can improve pain and quality of life,” he said.

Dr. Bonakdar disclosed that he receives royalties from Oxford University Press, Lippincott, and Elsevier. He is also a consultant to Standard Process.

In many cases, dietary interventions can lead to less inflammation

In many cases, dietary interventions can lead to less inflammation

SAN DIEGO – When clinicians ask patients to quantify their level of chronic pain on a scale of 1-10, and they rate it as a 7, what does that really mean?

Robert A. Bonakdar, MD, said posing such a question as the main determinator of the treatment approach during a pain assessment “depersonalizes medicine to the point where you’re making a patient a number.” Dr. Bonakdar spoke at Natural Supplements: An Evidence-Based Update, presented by Scripps Center for Integrative Medicine.

“It considers areas that are often overlooked, such as the role of the gut microbiome, mood, and epigenetics.”

Over the past two decades, the number of American adults suffering from pain has increased from 120 million to 178 million, or to 41% of the adult population, said Dr. Bonakdar, a family physician who is director of pain management at the Scripps Center for Integrative Medicine. Data from the National Institutes of Health estimate that Americans spend more than $600 billion each year on the treatment of pain, which surpasses monies spent on cancer, heart disease, and diabetes. According to a 2016 report from the United States Bone and Joint Initiative, arthritis and rheumatologic conditions resulted in an estimated 6.7 million annual hospitalizations, and the average annual cost per person for treatment of a musculoskeletal condition is $7,800.

“If we continue on our current trajectory, we are choosing to accept more prevalence and incidence of these disorders, spiraling costs, restricted access to needed services, and less success in alleviating pain and suffering – a high cost,” Edward H. Yelin, PhD, cochair of the report’s steering committee, and professor of medicine and health policy at the University of California, San Francisco, said in a prepared statement in 2016. That same year, Brian F. Mandell, MD, PhD, editor of the Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine, penned an editorial in which he stated that “The time has come to move past using a one-size-fits-all fifth vital sign . . . and reflexively prescribing an opioid when pain is characterized as severe” (Clev Clin J Med. 2016. Jun;83[6]:400-1). A decade earlier, authors of a cross-sectional review at a single Department of Veterans Affairs medical center set out to assess the impact of the VA’s “Pain as the 5th Vital Sign” initiative on the quality of pain management (J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21[6]:607–12). They found that patients with substantial pain documented by the fifth vital sign often had inadequate pain management. The preponderance of existing evidence suggests that a different approach is needed to prescribing opioids, Dr. Bonakdar said. “It’s coming from every voice in pain care: that what we are doing is not working,” he said. “It’s not only not working; it’s dangerous. That’s the consequence of depersonalized medicine. What’s the consequence of depersonalized nutrition? It’s the same industrialized approach.”

The typical American diet, he continued, is rife with processed foods and lacks an adequate proportion of plant-based products. “It’s basically a setup for inflammation,” Dr. Bonakdar said. “Most people who come into our clinic are eating 63% processed foods, 25% animal foods, and 12% plant foods. When we are eating, we’re oversizing it because that’s the American thing to do. At the end of the day, this process is not only killing us from heart disease and stroke as causes of death, but it’s also killing us as far as pain. The same diet that’s causing heart disease is the same diet that’s increasing pain.”

Dr. Bonakdar said that the ingestion of ultra-processed foods over time jumpstarts the process of dysbiosis, which increases gut permeability. “When gut permeability happens, and you have high levels of polysaccharides and inflammatory markers such as zonulin and lipopolysaccharide (LPS), it not only goes on to affect adipose tissue and insulin resistance, it can affect the muscle and joints,” he explained. “That is a setup for sarcopenia, or muscle loss, which then makes it harder for patients to be fully functional and active. It goes on to cause joint problems as well.”

He likened an increase in gut permeability to “a bomb going off in the gut.” Routine consumption of highly processed foods “creates this wave of inflammation that goes throughout your body affecting joints and muscles, and causes an increased amount of pain. Over time, patients make the connection but it’s much easier to say, ‘take this NSAID’ or ‘take this Cox-2 inhibitor’ to suppress the pain. But if all you’re doing is suppressing, you’re not going to the source of the pain.”

Dr. Bonakdar cited several recent articles that help to make the connection between dysbiosis and pain, including a review that concluded that dysbiosis of gut microbiota can influence the onset and progression of chronic degenerative diseases (Nutrients. 2019;11[8]:1707). Authors of a separate review concluded that human microbiome studies strongly suggest an incriminating role of microbes in the pathophysiology and progression of RA. Lastly, several studies have noted that pain conditions such as fibromyalgia may have microbiome “signatures” related to dysbiosis, which may pave the way for interventions, such as dietary shifting and probiotics that target individuals with microbiome abnormalities (Pain. 2019 Nov;160[11]:2589-602 and EBioMedicine. 2019 Aug 1;46:499-511).

Clinicians can begin to help patients who present with pain complaints “by listening to what their current pattern is: strategies that have worked, and those that haven’t,” he said. “If we’re not understanding the person and we’re just ordering genetic studies or microbiome studies and going off of the assessment, we sometime miss what interventions to start. In many cases, a simple intervention like a dietary shift is all that’s required.”

A survey of more than 1 million individuals found that BMI and daily pain are positively correlated in the United States (Obesity 2012;20[7]:1491-5). “This is increased more significantly for women and the elderly,” said Dr. Bonakdar, who was not affiliated with the study. “If we can change the diet that person is taking, that’s going to begin the process of reversing this to the point where they’re having less pain from inflammation that’s affecting the adipose tissue and adipokines traveling to their joints, which can cause less dysbiosis. It is very much a vicious cycle that patients follow, but if you begin to unwind it, it’s going to help multiple areas.”

In the Intensive Diet and Exercise for Arthritis (IDEA) trial, researchers randomized 450 patients with osteoarthritis to intensive dietary restriction only, exercise only, or a combination of both (BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2009;10:93). They found that a 5% weight loss over the course of 18 months led to a 30% reduction in pain and a 24% improvement in function.

Inspired by the IDEA trial design, Dr. Bonakdar and his colleagues completed an unpublished 12-week pilot program with 12 patients with a BMI of 27 kg/m2 or greater plus comorbidities. The program consisted of weekly group meetings, including a lecture by team clinicians, dietician, and fitness staff; group support sessions with a behavioral counselor; and a group exercise session. It also included weekly 1:1 personal training sessions and biweekly 1:1 dietitian meetings. The researchers also evaluated several deficiencies linked to pain, including magnesium, vitamin D, vitamins B1, B2, and B12, folate, calcium, amino acids, omega 3s, zinc, coenzyme Q10, carnitine, and vitamin C. The goal was a weight reduction of 5%.

The intervention consisted of a 28-day detox/protein shake consumed 1-3 times per day, which contained 17 g of protein per serving. Nutritional supplementation was added based on results of individual diagnostics.

According to preliminary results from the trial, the intended weight goal was achieved. “More importantly, there were significant improvements in markers of dysbiosis, including zonulin and lipopolysaccharide, as well as the adipokine leptin, which appeared to be associated with improvement in quality of life measures and pain,” Dr. Bonakdar said.

He concluded his presentation by highlighting a pilot study conducted in an Australian tertiary pain clinic. It found that a personalized dietitian-delivered dietary intervention can improve pain scores, quality of life, and dietary intake of people experiencing chronic pain (Nutrients. 2019 Jan 16;11[1] pii: E181). “This is another piece of the puzzle showing that these dietary interventions can be done in multiple settings, including tertiary centers with nutrition staff, and that this important step can improve pain and quality of life,” he said.

Dr. Bonakdar disclosed that he receives royalties from Oxford University Press, Lippincott, and Elsevier. He is also a consultant to Standard Process.

SAN DIEGO – When clinicians ask patients to quantify their level of chronic pain on a scale of 1-10, and they rate it as a 7, what does that really mean?

Robert A. Bonakdar, MD, said posing such a question as the main determinator of the treatment approach during a pain assessment “depersonalizes medicine to the point where you’re making a patient a number.” Dr. Bonakdar spoke at Natural Supplements: An Evidence-Based Update, presented by Scripps Center for Integrative Medicine.

“It considers areas that are often overlooked, such as the role of the gut microbiome, mood, and epigenetics.”

Over the past two decades, the number of American adults suffering from pain has increased from 120 million to 178 million, or to 41% of the adult population, said Dr. Bonakdar, a family physician who is director of pain management at the Scripps Center for Integrative Medicine. Data from the National Institutes of Health estimate that Americans spend more than $600 billion each year on the treatment of pain, which surpasses monies spent on cancer, heart disease, and diabetes. According to a 2016 report from the United States Bone and Joint Initiative, arthritis and rheumatologic conditions resulted in an estimated 6.7 million annual hospitalizations, and the average annual cost per person for treatment of a musculoskeletal condition is $7,800.

“If we continue on our current trajectory, we are choosing to accept more prevalence and incidence of these disorders, spiraling costs, restricted access to needed services, and less success in alleviating pain and suffering – a high cost,” Edward H. Yelin, PhD, cochair of the report’s steering committee, and professor of medicine and health policy at the University of California, San Francisco, said in a prepared statement in 2016. That same year, Brian F. Mandell, MD, PhD, editor of the Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine, penned an editorial in which he stated that “The time has come to move past using a one-size-fits-all fifth vital sign . . . and reflexively prescribing an opioid when pain is characterized as severe” (Clev Clin J Med. 2016. Jun;83[6]:400-1). A decade earlier, authors of a cross-sectional review at a single Department of Veterans Affairs medical center set out to assess the impact of the VA’s “Pain as the 5th Vital Sign” initiative on the quality of pain management (J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21[6]:607–12). They found that patients with substantial pain documented by the fifth vital sign often had inadequate pain management. The preponderance of existing evidence suggests that a different approach is needed to prescribing opioids, Dr. Bonakdar said. “It’s coming from every voice in pain care: that what we are doing is not working,” he said. “It’s not only not working; it’s dangerous. That’s the consequence of depersonalized medicine. What’s the consequence of depersonalized nutrition? It’s the same industrialized approach.”

The typical American diet, he continued, is rife with processed foods and lacks an adequate proportion of plant-based products. “It’s basically a setup for inflammation,” Dr. Bonakdar said. “Most people who come into our clinic are eating 63% processed foods, 25% animal foods, and 12% plant foods. When we are eating, we’re oversizing it because that’s the American thing to do. At the end of the day, this process is not only killing us from heart disease and stroke as causes of death, but it’s also killing us as far as pain. The same diet that’s causing heart disease is the same diet that’s increasing pain.”

Dr. Bonakdar said that the ingestion of ultra-processed foods over time jumpstarts the process of dysbiosis, which increases gut permeability. “When gut permeability happens, and you have high levels of polysaccharides and inflammatory markers such as zonulin and lipopolysaccharide (LPS), it not only goes on to affect adipose tissue and insulin resistance, it can affect the muscle and joints,” he explained. “That is a setup for sarcopenia, or muscle loss, which then makes it harder for patients to be fully functional and active. It goes on to cause joint problems as well.”

He likened an increase in gut permeability to “a bomb going off in the gut.” Routine consumption of highly processed foods “creates this wave of inflammation that goes throughout your body affecting joints and muscles, and causes an increased amount of pain. Over time, patients make the connection but it’s much easier to say, ‘take this NSAID’ or ‘take this Cox-2 inhibitor’ to suppress the pain. But if all you’re doing is suppressing, you’re not going to the source of the pain.”

Dr. Bonakdar cited several recent articles that help to make the connection between dysbiosis and pain, including a review that concluded that dysbiosis of gut microbiota can influence the onset and progression of chronic degenerative diseases (Nutrients. 2019;11[8]:1707). Authors of a separate review concluded that human microbiome studies strongly suggest an incriminating role of microbes in the pathophysiology and progression of RA. Lastly, several studies have noted that pain conditions such as fibromyalgia may have microbiome “signatures” related to dysbiosis, which may pave the way for interventions, such as dietary shifting and probiotics that target individuals with microbiome abnormalities (Pain. 2019 Nov;160[11]:2589-602 and EBioMedicine. 2019 Aug 1;46:499-511).

Clinicians can begin to help patients who present with pain complaints “by listening to what their current pattern is: strategies that have worked, and those that haven’t,” he said. “If we’re not understanding the person and we’re just ordering genetic studies or microbiome studies and going off of the assessment, we sometime miss what interventions to start. In many cases, a simple intervention like a dietary shift is all that’s required.”

A survey of more than 1 million individuals found that BMI and daily pain are positively correlated in the United States (Obesity 2012;20[7]:1491-5). “This is increased more significantly for women and the elderly,” said Dr. Bonakdar, who was not affiliated with the study. “If we can change the diet that person is taking, that’s going to begin the process of reversing this to the point where they’re having less pain from inflammation that’s affecting the adipose tissue and adipokines traveling to their joints, which can cause less dysbiosis. It is very much a vicious cycle that patients follow, but if you begin to unwind it, it’s going to help multiple areas.”

In the Intensive Diet and Exercise for Arthritis (IDEA) trial, researchers randomized 450 patients with osteoarthritis to intensive dietary restriction only, exercise only, or a combination of both (BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2009;10:93). They found that a 5% weight loss over the course of 18 months led to a 30% reduction in pain and a 24% improvement in function.

Inspired by the IDEA trial design, Dr. Bonakdar and his colleagues completed an unpublished 12-week pilot program with 12 patients with a BMI of 27 kg/m2 or greater plus comorbidities. The program consisted of weekly group meetings, including a lecture by team clinicians, dietician, and fitness staff; group support sessions with a behavioral counselor; and a group exercise session. It also included weekly 1:1 personal training sessions and biweekly 1:1 dietitian meetings. The researchers also evaluated several deficiencies linked to pain, including magnesium, vitamin D, vitamins B1, B2, and B12, folate, calcium, amino acids, omega 3s, zinc, coenzyme Q10, carnitine, and vitamin C. The goal was a weight reduction of 5%.

The intervention consisted of a 28-day detox/protein shake consumed 1-3 times per day, which contained 17 g of protein per serving. Nutritional supplementation was added based on results of individual diagnostics.

According to preliminary results from the trial, the intended weight goal was achieved. “More importantly, there were significant improvements in markers of dysbiosis, including zonulin and lipopolysaccharide, as well as the adipokine leptin, which appeared to be associated with improvement in quality of life measures and pain,” Dr. Bonakdar said.

He concluded his presentation by highlighting a pilot study conducted in an Australian tertiary pain clinic. It found that a personalized dietitian-delivered dietary intervention can improve pain scores, quality of life, and dietary intake of people experiencing chronic pain (Nutrients. 2019 Jan 16;11[1] pii: E181). “This is another piece of the puzzle showing that these dietary interventions can be done in multiple settings, including tertiary centers with nutrition staff, and that this important step can improve pain and quality of life,” he said.

Dr. Bonakdar disclosed that he receives royalties from Oxford University Press, Lippincott, and Elsevier. He is also a consultant to Standard Process.

REPORTING FROM A NATURAL SUPPLEMENTS UPDATE

Lidocaine-prilocaine cream tops lidocaine injections for vulvar biopsy pain

The median highest pain score in a randomized trial of 38 women undergoing vulvar biopsies was 25.7 mm lower, on a 100 mm visual analogue scale, when they received 5% lidocaine-prilocaine cream instead of a 1% lidocaine injection, according to a report from Duke University, in Durham, N.C.

“In the current study, we found that application of lidocaine-prilocaine cream, alone, for a minimum of 10 minutes before vulvar biopsy on a non–hair-bearing surface results in a significantly lower maximum pain score and a significantly better patient rating of the biopsy experience,” said investigators led by Logan K. Williams, MD, of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at Duke University, Durham, N.C.

Given the “clear advantage” of the cream, it “should be considered as an anesthetic method for vulvar biopsy in a non-hair-bearing area,” Dr. Williams and colleagues concluded (Obstet Gynecol. 2020 Feb;135{2]:311-8).

Studies have pitted the cream against the injection before, but they did not compare patients’ maximal pain scores. The team wanted to do that because “comparing the highest score allows us to consider the possibility that the pain of anesthesia application” – injection versus cream – “may be greater than the pain of any other portion of the biopsy procedure.”

They randomized 19 women to the cream, approximately 5 g at the site of biopsy at least 10 minutes beforehand, and 18 others to the injection, 2 mL using a 27-gauge needle, at least 1 minute prior.

The median highest pain score in the lidocaine-prilocaine group was 20 mm, but 56.5 mm in the injection group. Patients randomized to lidocaine-prilocaine also had a significantly better (P = 0.02) experience than those receiving injected lidocaine, also assessed by visual analog scale (VAS). The median baseline pain level was 0 mm.

Anxiety was assessed after patients knew whether they were going to get the cream or the injection, but before the biopsy. The median score in the cream group was of 19 mm on another VAS, compared with 31.5 mm.

Participants were 60 years old on average, and almost all had prior vulvar biopsies. Two in the cream group and three in the injection group had punch biopsies; cervical biopsy forceps were used for the rest. More than half the women had benign findings, and most of the others had vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia, but there was one invasive cancer. At Duke, the cost of the injection was $0.99, compared with $7.36 for the cream.

Dr. Williams and colleagues cited a few limitations. One is that the patients and clinicians in the study were not blinded. Another is that most of the patients had undergone vulvar biopsy before, possibly predisposing them to bias.

“In the future, consideration could be taken to studying lidocaine-prilocaine cream applications to hair-bearing surfaces, which were excluded in this study.” Also, “there is a question of the histologic effect of lidocaine-prilocaine on tissues and whether this could affect pathologic diagnoses.

“We are conducting a separate ancillary study in conjunction with our dermatopathology colleagues to investigate this question,” the investigators said.

The work was funded by Duke and the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Williams had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Williams LK et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2020 Feb;135(2):311-8.

The median highest pain score in a randomized trial of 38 women undergoing vulvar biopsies was 25.7 mm lower, on a 100 mm visual analogue scale, when they received 5% lidocaine-prilocaine cream instead of a 1% lidocaine injection, according to a report from Duke University, in Durham, N.C.

“In the current study, we found that application of lidocaine-prilocaine cream, alone, for a minimum of 10 minutes before vulvar biopsy on a non–hair-bearing surface results in a significantly lower maximum pain score and a significantly better patient rating of the biopsy experience,” said investigators led by Logan K. Williams, MD, of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at Duke University, Durham, N.C.

Given the “clear advantage” of the cream, it “should be considered as an anesthetic method for vulvar biopsy in a non-hair-bearing area,” Dr. Williams and colleagues concluded (Obstet Gynecol. 2020 Feb;135{2]:311-8).

Studies have pitted the cream against the injection before, but they did not compare patients’ maximal pain scores. The team wanted to do that because “comparing the highest score allows us to consider the possibility that the pain of anesthesia application” – injection versus cream – “may be greater than the pain of any other portion of the biopsy procedure.”

They randomized 19 women to the cream, approximately 5 g at the site of biopsy at least 10 minutes beforehand, and 18 others to the injection, 2 mL using a 27-gauge needle, at least 1 minute prior.

The median highest pain score in the lidocaine-prilocaine group was 20 mm, but 56.5 mm in the injection group. Patients randomized to lidocaine-prilocaine also had a significantly better (P = 0.02) experience than those receiving injected lidocaine, also assessed by visual analog scale (VAS). The median baseline pain level was 0 mm.

Anxiety was assessed after patients knew whether they were going to get the cream or the injection, but before the biopsy. The median score in the cream group was of 19 mm on another VAS, compared with 31.5 mm.

Participants were 60 years old on average, and almost all had prior vulvar biopsies. Two in the cream group and three in the injection group had punch biopsies; cervical biopsy forceps were used for the rest. More than half the women had benign findings, and most of the others had vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia, but there was one invasive cancer. At Duke, the cost of the injection was $0.99, compared with $7.36 for the cream.

Dr. Williams and colleagues cited a few limitations. One is that the patients and clinicians in the study were not blinded. Another is that most of the patients had undergone vulvar biopsy before, possibly predisposing them to bias.

“In the future, consideration could be taken to studying lidocaine-prilocaine cream applications to hair-bearing surfaces, which were excluded in this study.” Also, “there is a question of the histologic effect of lidocaine-prilocaine on tissues and whether this could affect pathologic diagnoses.

“We are conducting a separate ancillary study in conjunction with our dermatopathology colleagues to investigate this question,” the investigators said.

The work was funded by Duke and the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Williams had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Williams LK et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2020 Feb;135(2):311-8.

The median highest pain score in a randomized trial of 38 women undergoing vulvar biopsies was 25.7 mm lower, on a 100 mm visual analogue scale, when they received 5% lidocaine-prilocaine cream instead of a 1% lidocaine injection, according to a report from Duke University, in Durham, N.C.

“In the current study, we found that application of lidocaine-prilocaine cream, alone, for a minimum of 10 minutes before vulvar biopsy on a non–hair-bearing surface results in a significantly lower maximum pain score and a significantly better patient rating of the biopsy experience,” said investigators led by Logan K. Williams, MD, of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at Duke University, Durham, N.C.

Given the “clear advantage” of the cream, it “should be considered as an anesthetic method for vulvar biopsy in a non-hair-bearing area,” Dr. Williams and colleagues concluded (Obstet Gynecol. 2020 Feb;135{2]:311-8).

Studies have pitted the cream against the injection before, but they did not compare patients’ maximal pain scores. The team wanted to do that because “comparing the highest score allows us to consider the possibility that the pain of anesthesia application” – injection versus cream – “may be greater than the pain of any other portion of the biopsy procedure.”

They randomized 19 women to the cream, approximately 5 g at the site of biopsy at least 10 minutes beforehand, and 18 others to the injection, 2 mL using a 27-gauge needle, at least 1 minute prior.

The median highest pain score in the lidocaine-prilocaine group was 20 mm, but 56.5 mm in the injection group. Patients randomized to lidocaine-prilocaine also had a significantly better (P = 0.02) experience than those receiving injected lidocaine, also assessed by visual analog scale (VAS). The median baseline pain level was 0 mm.

Anxiety was assessed after patients knew whether they were going to get the cream or the injection, but before the biopsy. The median score in the cream group was of 19 mm on another VAS, compared with 31.5 mm.

Participants were 60 years old on average, and almost all had prior vulvar biopsies. Two in the cream group and three in the injection group had punch biopsies; cervical biopsy forceps were used for the rest. More than half the women had benign findings, and most of the others had vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia, but there was one invasive cancer. At Duke, the cost of the injection was $0.99, compared with $7.36 for the cream.

Dr. Williams and colleagues cited a few limitations. One is that the patients and clinicians in the study were not blinded. Another is that most of the patients had undergone vulvar biopsy before, possibly predisposing them to bias.

“In the future, consideration could be taken to studying lidocaine-prilocaine cream applications to hair-bearing surfaces, which were excluded in this study.” Also, “there is a question of the histologic effect of lidocaine-prilocaine on tissues and whether this could affect pathologic diagnoses.

“We are conducting a separate ancillary study in conjunction with our dermatopathology colleagues to investigate this question,” the investigators said.

The work was funded by Duke and the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Williams had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Williams LK et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2020 Feb;135(2):311-8.

FROM OBSTETRICS AND GYNECOLOGY

Patients remain satisfied despite reduced use of opioids post partum

GRAPEVINE, TEX. – The amount of opioids prescribed post partum may decline over time without affecting levels of pain control satisfaction, according to research presented at the meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

Data from a large center indicate that trends in opioid use significantly declined from 2017 to 2019, but not at the expense of adequate pain control, said Nevert Badreldin, MD, assistant professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Northwestern University in Chicago. Patients consistently reported that they were satisfied with inpatient pain control, while opioid use per inpatient day decreased from about 30 morphine milligram equivalents (MME) to less than 20 MME during that time.

To assess trends in postpartum opioid prescribing, opioid use, and pain control satisfaction, Dr. Badreldin and colleagues evaluated data from a prospective observational study. Their analysis included data from women who used an opioid during postpartum hospitalization between May 2017 and July 2019. The researchers excluded women with NSAID or morphine allergies or recent opioid use, as well as those who received general anesthesia without concurrent neuraxial anesthesia, those who underwent peripartum hysterectomy, and women admitted to the ICU.

The investigators used nonparametric tests of trend to assess the difference over time in the proportion of patients who received an opioid prescription at discharge and in the total MME prescribed post partum.

Of 900 women with inpatient opioid use, 471 agreed to be followed after discharge. In that group, the amount of opioid use per inpatient day significantly declined. In addition, the percentage who received an opioid prescription at discharge significantly declined, as did the total MME prescribed at discharge.

“Both inpatient and outpatient satisfaction with pain control were unchanged,” the researchers reported. “In this population, both the frequency and amount of opioid use in the postpartum period declined from 2017 to 2019, without any change in satisfaction with pain control.”

The study was supported by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine/AMAG 2017 Health Policy Award, and a coauthor received support from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

Source: Badreldin N et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020 Jan;222(1):S93, Abstract 120.

GRAPEVINE, TEX. – The amount of opioids prescribed post partum may decline over time without affecting levels of pain control satisfaction, according to research presented at the meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

Data from a large center indicate that trends in opioid use significantly declined from 2017 to 2019, but not at the expense of adequate pain control, said Nevert Badreldin, MD, assistant professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Northwestern University in Chicago. Patients consistently reported that they were satisfied with inpatient pain control, while opioid use per inpatient day decreased from about 30 morphine milligram equivalents (MME) to less than 20 MME during that time.

To assess trends in postpartum opioid prescribing, opioid use, and pain control satisfaction, Dr. Badreldin and colleagues evaluated data from a prospective observational study. Their analysis included data from women who used an opioid during postpartum hospitalization between May 2017 and July 2019. The researchers excluded women with NSAID or morphine allergies or recent opioid use, as well as those who received general anesthesia without concurrent neuraxial anesthesia, those who underwent peripartum hysterectomy, and women admitted to the ICU.

The investigators used nonparametric tests of trend to assess the difference over time in the proportion of patients who received an opioid prescription at discharge and in the total MME prescribed post partum.

Of 900 women with inpatient opioid use, 471 agreed to be followed after discharge. In that group, the amount of opioid use per inpatient day significantly declined. In addition, the percentage who received an opioid prescription at discharge significantly declined, as did the total MME prescribed at discharge.

“Both inpatient and outpatient satisfaction with pain control were unchanged,” the researchers reported. “In this population, both the frequency and amount of opioid use in the postpartum period declined from 2017 to 2019, without any change in satisfaction with pain control.”

The study was supported by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine/AMAG 2017 Health Policy Award, and a coauthor received support from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

Source: Badreldin N et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020 Jan;222(1):S93, Abstract 120.

GRAPEVINE, TEX. – The amount of opioids prescribed post partum may decline over time without affecting levels of pain control satisfaction, according to research presented at the meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

Data from a large center indicate that trends in opioid use significantly declined from 2017 to 2019, but not at the expense of adequate pain control, said Nevert Badreldin, MD, assistant professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Northwestern University in Chicago. Patients consistently reported that they were satisfied with inpatient pain control, while opioid use per inpatient day decreased from about 30 morphine milligram equivalents (MME) to less than 20 MME during that time.

To assess trends in postpartum opioid prescribing, opioid use, and pain control satisfaction, Dr. Badreldin and colleagues evaluated data from a prospective observational study. Their analysis included data from women who used an opioid during postpartum hospitalization between May 2017 and July 2019. The researchers excluded women with NSAID or morphine allergies or recent opioid use, as well as those who received general anesthesia without concurrent neuraxial anesthesia, those who underwent peripartum hysterectomy, and women admitted to the ICU.

The investigators used nonparametric tests of trend to assess the difference over time in the proportion of patients who received an opioid prescription at discharge and in the total MME prescribed post partum.

Of 900 women with inpatient opioid use, 471 agreed to be followed after discharge. In that group, the amount of opioid use per inpatient day significantly declined. In addition, the percentage who received an opioid prescription at discharge significantly declined, as did the total MME prescribed at discharge.

“Both inpatient and outpatient satisfaction with pain control were unchanged,” the researchers reported. “In this population, both the frequency and amount of opioid use in the postpartum period declined from 2017 to 2019, without any change in satisfaction with pain control.”

The study was supported by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine/AMAG 2017 Health Policy Award, and a coauthor received support from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

Source: Badreldin N et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020 Jan;222(1):S93, Abstract 120.

REPORTING FROM THE PREGNANCY MEETING

IBD quality initiative slashes ED utilization

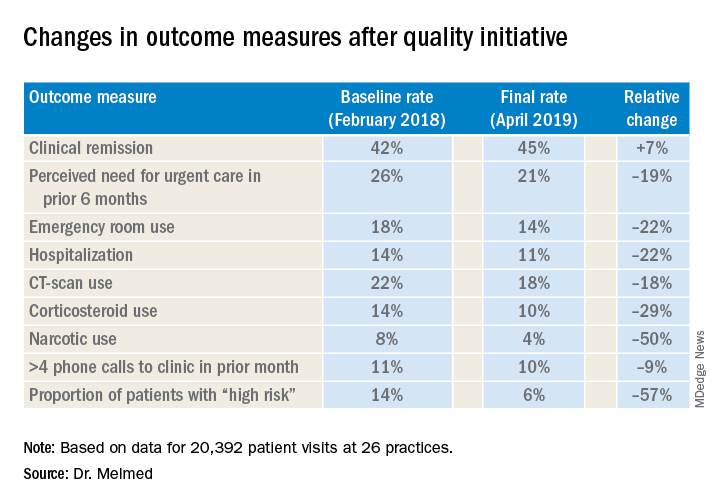

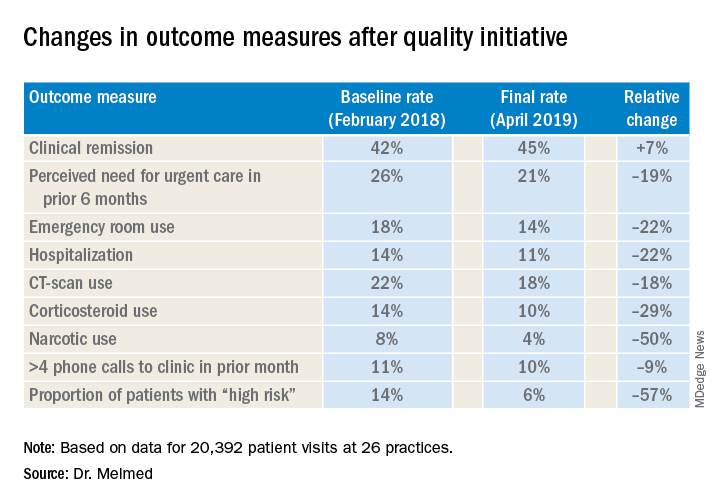

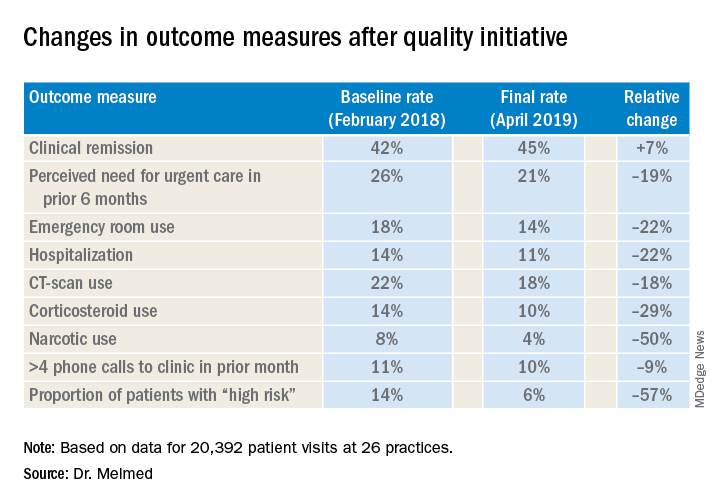

AUSTIN, TEX. – A quality improvement initiative aimed at patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) has reduced emergency department visits and hospitalizations by 20% or more and slashed opioid use by half, according to study results presented at the Crohn’s & Colitis Congress®, a partnership of the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation and the American Gastroenterological Association.

After 15 months, the quality improvement program saw emergency department visit rates decline from 18% to 14%, a 22% relative decrease, Gil Y. Melmed, MD, of Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, said. Additionally, the study documented a similar decrease in the rate of hospitalization, declining from 14% to 11%, while opioid utilization rates declined from 8% to 4%. “We also found decreases in special-cause variation in other measures of interest, including CT scan utilization as well as corticosteroid use, which was reduced 29% during the course of the program,” he said.

The quality initiative was conducted through the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation as an outgrowth of its IBD Qorus quality improvement program. The 15-month study involved 20,392 patient visits at 15 academic and 11 private/community practices from January 2018 to April 2019. “This specific project within Qorus is focused specifically around the concept of improving access during times of urgent care need,” Dr. Melmed told this news organization. The goal was to identify practice changes that can drive improvement.

The intervention consisted of 19 different strategies, called a “Change Package,” and participating sites could choose to test and implement one or more of them, Dr. Melmed said. Some examples included designating urgent care slots in the clinic schedule, installing a nurse hotline, a weekly “huddle” to review high-risk patients, and patient education on using urgent care.

One of the drivers of the program was to provide immediate care improvement to patients, Dr. Melmed said in the interview. “As opposed to investments into the cure of IBD that we need, but which can take years to develop, this research has immediate, practical applicability for patients today,” he said.

“The fact that we were able to demonstrate reduction in emergency room utilization and hospitalization, steroid use, and narcotic use has really energized the work that we were doing. We can now show that very-low-cost process changes at a site level lead to robust improvement in patient outcomes. These changes are potentially implementable in any practice setting,” Dr. Melmed said in the interview.

After Dr. Melmed’s presentation, Maria T. Abreu, MD, director of the Crohn’s and Colitis Center at the University of Miami, asked about the cost of the interventions. Dr. Melmed said the costs were nominal, such as paying for a new phone line for a patient hotline. “But overall the cost really involved in the program was the time that it took to review the high-risk list on a weekly basis with the team, and that is essentially a 15-minute huddle,” he said.

Later, Dr. Abreu said in an interview that the program was “a terrific example of how measuring outcomes and sharing ideas can make huge impacts in the lives of patients.” She added, “An enormous amount of money is spent on clinical trials of expensive biologics which have revolutionized treatment, yet the humanistic aspects of our care have just as great of an impact. In this study, each center focused on ways they could lower ER visits and hospitalizations. One size did not fit all, yet they could learn from each other. The very platform they used to conduct the study is a model for all of us.”

Corey A. Siegel, MD, of the Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, Lebanon, N.H., and Dr. Melmed's coprincipal investigator on Qorus, said the quality initiative now includes 49 GI practices across the country with plans to grow to 60 by the end of the year. "We have created this 'collaboratory' for providers from actross the country to work togetherr to learn how to best deliver high-qulaity care for patients with IBD," he said.

Another feature of the quality initiative allowed participating sites to see how they compared with others anonymously, Dr. Melmed said. “Using the data, we called out high-performing sites to teach the rest of us what they were doing that enabled them to improve, so that all of us could learn from their successes,” he said.