User login

COVID-19 complicates prescribing for children with inflammatory skin disease

designed to offer guidance to specialists and nonspecialists faced with tough choices about risks.

Some 87% reported that they were reducing the frequency of lab monitoring for some medications, while more than half said they had reached out to patients and their families to discuss the implications of continuing or stopping a drug.

Virtually all – 97% – said that the COVID-19 crisis had affected their decision to initiate immunosuppressive medications, with 84% saying the decision depended on a patient’s risk factors for contracting COVID-19 infection, and also the potential consequences of infection while treated, compared with the risks of not optimally treating the skin condition.

To develop a consensus-based guidance for clinicians, published online April 22 in Pediatric Dermatology, Kelly Cordoro, MD, professor of dermatology at the University of California, San Francisco, assembled a task force of pediatric dermatologists at academic institutions (the Pediatric Dermatology COVID-19 Response Task Force). Together with Sean Reynolds, MD, a pediatric dermatology fellow at UCSF and colleagues, they issued a survey to the 37 members of the task force with questions on how the pandemic has affected their prescribing decisions and certain therapies specifically. All the recipients responded.

The dermatologists were asked about conventional systemic and biologic medications. Most felt confident in continuing biologics, with 78% saying they would keep patients with no signs of COVID-19 exposure or infection on tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors. More than 90% of respondents said they would continue patients on dupilumab, as well as anti–interleukin (IL)–17, anti–IL-12/23, and anti–IL-23 therapies.

Responses varied more on approaches to the nonbiologic treatments. Fewer than half (46%) said they would continue patients without apparent COVID-19 exposure on systemic steroids, with another 46% saying it depended on the clinical context.

For other systemic therapies, respondents were more likely to want to continue their patients with no signs or symptoms of COVID-19 on methotrexate and apremilast (78% and 83%, respectively) than others (mycophenolate mofetil, azathioprine, cyclosporine, and JAK inhibitors), which saw between 50% and 60% support in the survey.

Patients on any immunosuppressive medications with likely exposure to COVID-19 or who test positive for the virus should be temporarily taken off their medications, the majority concurred. Exceptions were for systemic steroids, which must be tapered. And a significant minority of the dermatologists said that they would continue apremilast or dupilumab (24% and 16%, respectively) in the event of a confirmed COVID-19 infection.

In an interview, Dr. Cordoro commented that, even in normal times, most systemic or biological immunosuppressive treatments are used off-label by pediatric dermatologists. “There’s no way this could have been an evidence-based document, as we didn’t have the data to drive this. Many of the medications have been tested in children but not necessarily for dermatologic indications; some are chemotherapy agents or drugs used in rheumatologic diseases.”

The COVID-19 pandemic complicated an already difficult decision-making process, she said.

The researchers cautioned against attempting to make decisions about medications based on data on other infections from clinical trials. “Infection data from standard infections that were identified and watched for in clinical trials really still has no bearing on COVID-19 because it’s such a different virus,” Dr. Cordoro said.

And while some immunosuppressive medications could potentially attenuate a SARS-CoV-2–induced cytokine storm, “we certainly don’t assume this is necessarily going to help.”

The authors advised that physicians anxious about initiating an immunosuppressive treatment should take into consideration whether early intervention could “prevent permanent physical impairment or disfigurement” in diseases such as erythrodermic pustular psoriasis or rapidly progressive linear morphea.

Other diseases, such as atopic dermatitis, “may be acceptably, though not optimally, managed with topical and other home-based therapeutic options” during the pandemic, they wrote.

Dr. Cordoro commented that, given how fast new findings are emerging from the pandemic, the guidance on medications could change. “We will know so much more 3 months from now,” she said. And while there are no formal plans to reissue the survey, “we’re maintaining communication and will have some kind of follow up” with the academic dermatologists.

“If we recognize any signals that are counter to what we say in this work we will immediately let people know,” she said.

The researchers received no outside funding for their study. Of the study’s 24 coauthors, nine disclosed financial relationships with industry.

SOURCE: Add the first auSOURCE: Reynolds et al. Pediatr Dermatol. 2020. doi: 10.1111/pde.14202.

designed to offer guidance to specialists and nonspecialists faced with tough choices about risks.

Some 87% reported that they were reducing the frequency of lab monitoring for some medications, while more than half said they had reached out to patients and their families to discuss the implications of continuing or stopping a drug.

Virtually all – 97% – said that the COVID-19 crisis had affected their decision to initiate immunosuppressive medications, with 84% saying the decision depended on a patient’s risk factors for contracting COVID-19 infection, and also the potential consequences of infection while treated, compared with the risks of not optimally treating the skin condition.

To develop a consensus-based guidance for clinicians, published online April 22 in Pediatric Dermatology, Kelly Cordoro, MD, professor of dermatology at the University of California, San Francisco, assembled a task force of pediatric dermatologists at academic institutions (the Pediatric Dermatology COVID-19 Response Task Force). Together with Sean Reynolds, MD, a pediatric dermatology fellow at UCSF and colleagues, they issued a survey to the 37 members of the task force with questions on how the pandemic has affected their prescribing decisions and certain therapies specifically. All the recipients responded.

The dermatologists were asked about conventional systemic and biologic medications. Most felt confident in continuing biologics, with 78% saying they would keep patients with no signs of COVID-19 exposure or infection on tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors. More than 90% of respondents said they would continue patients on dupilumab, as well as anti–interleukin (IL)–17, anti–IL-12/23, and anti–IL-23 therapies.

Responses varied more on approaches to the nonbiologic treatments. Fewer than half (46%) said they would continue patients without apparent COVID-19 exposure on systemic steroids, with another 46% saying it depended on the clinical context.

For other systemic therapies, respondents were more likely to want to continue their patients with no signs or symptoms of COVID-19 on methotrexate and apremilast (78% and 83%, respectively) than others (mycophenolate mofetil, azathioprine, cyclosporine, and JAK inhibitors), which saw between 50% and 60% support in the survey.

Patients on any immunosuppressive medications with likely exposure to COVID-19 or who test positive for the virus should be temporarily taken off their medications, the majority concurred. Exceptions were for systemic steroids, which must be tapered. And a significant minority of the dermatologists said that they would continue apremilast or dupilumab (24% and 16%, respectively) in the event of a confirmed COVID-19 infection.

In an interview, Dr. Cordoro commented that, even in normal times, most systemic or biological immunosuppressive treatments are used off-label by pediatric dermatologists. “There’s no way this could have been an evidence-based document, as we didn’t have the data to drive this. Many of the medications have been tested in children but not necessarily for dermatologic indications; some are chemotherapy agents or drugs used in rheumatologic diseases.”

The COVID-19 pandemic complicated an already difficult decision-making process, she said.

The researchers cautioned against attempting to make decisions about medications based on data on other infections from clinical trials. “Infection data from standard infections that were identified and watched for in clinical trials really still has no bearing on COVID-19 because it’s such a different virus,” Dr. Cordoro said.

And while some immunosuppressive medications could potentially attenuate a SARS-CoV-2–induced cytokine storm, “we certainly don’t assume this is necessarily going to help.”

The authors advised that physicians anxious about initiating an immunosuppressive treatment should take into consideration whether early intervention could “prevent permanent physical impairment or disfigurement” in diseases such as erythrodermic pustular psoriasis or rapidly progressive linear morphea.

Other diseases, such as atopic dermatitis, “may be acceptably, though not optimally, managed with topical and other home-based therapeutic options” during the pandemic, they wrote.

Dr. Cordoro commented that, given how fast new findings are emerging from the pandemic, the guidance on medications could change. “We will know so much more 3 months from now,” she said. And while there are no formal plans to reissue the survey, “we’re maintaining communication and will have some kind of follow up” with the academic dermatologists.

“If we recognize any signals that are counter to what we say in this work we will immediately let people know,” she said.

The researchers received no outside funding for their study. Of the study’s 24 coauthors, nine disclosed financial relationships with industry.

SOURCE: Add the first auSOURCE: Reynolds et al. Pediatr Dermatol. 2020. doi: 10.1111/pde.14202.

designed to offer guidance to specialists and nonspecialists faced with tough choices about risks.

Some 87% reported that they were reducing the frequency of lab monitoring for some medications, while more than half said they had reached out to patients and their families to discuss the implications of continuing or stopping a drug.

Virtually all – 97% – said that the COVID-19 crisis had affected their decision to initiate immunosuppressive medications, with 84% saying the decision depended on a patient’s risk factors for contracting COVID-19 infection, and also the potential consequences of infection while treated, compared with the risks of not optimally treating the skin condition.

To develop a consensus-based guidance for clinicians, published online April 22 in Pediatric Dermatology, Kelly Cordoro, MD, professor of dermatology at the University of California, San Francisco, assembled a task force of pediatric dermatologists at academic institutions (the Pediatric Dermatology COVID-19 Response Task Force). Together with Sean Reynolds, MD, a pediatric dermatology fellow at UCSF and colleagues, they issued a survey to the 37 members of the task force with questions on how the pandemic has affected their prescribing decisions and certain therapies specifically. All the recipients responded.

The dermatologists were asked about conventional systemic and biologic medications. Most felt confident in continuing biologics, with 78% saying they would keep patients with no signs of COVID-19 exposure or infection on tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors. More than 90% of respondents said they would continue patients on dupilumab, as well as anti–interleukin (IL)–17, anti–IL-12/23, and anti–IL-23 therapies.

Responses varied more on approaches to the nonbiologic treatments. Fewer than half (46%) said they would continue patients without apparent COVID-19 exposure on systemic steroids, with another 46% saying it depended on the clinical context.

For other systemic therapies, respondents were more likely to want to continue their patients with no signs or symptoms of COVID-19 on methotrexate and apremilast (78% and 83%, respectively) than others (mycophenolate mofetil, azathioprine, cyclosporine, and JAK inhibitors), which saw between 50% and 60% support in the survey.

Patients on any immunosuppressive medications with likely exposure to COVID-19 or who test positive for the virus should be temporarily taken off their medications, the majority concurred. Exceptions were for systemic steroids, which must be tapered. And a significant minority of the dermatologists said that they would continue apremilast or dupilumab (24% and 16%, respectively) in the event of a confirmed COVID-19 infection.

In an interview, Dr. Cordoro commented that, even in normal times, most systemic or biological immunosuppressive treatments are used off-label by pediatric dermatologists. “There’s no way this could have been an evidence-based document, as we didn’t have the data to drive this. Many of the medications have been tested in children but not necessarily for dermatologic indications; some are chemotherapy agents or drugs used in rheumatologic diseases.”

The COVID-19 pandemic complicated an already difficult decision-making process, she said.

The researchers cautioned against attempting to make decisions about medications based on data on other infections from clinical trials. “Infection data from standard infections that were identified and watched for in clinical trials really still has no bearing on COVID-19 because it’s such a different virus,” Dr. Cordoro said.

And while some immunosuppressive medications could potentially attenuate a SARS-CoV-2–induced cytokine storm, “we certainly don’t assume this is necessarily going to help.”

The authors advised that physicians anxious about initiating an immunosuppressive treatment should take into consideration whether early intervention could “prevent permanent physical impairment or disfigurement” in diseases such as erythrodermic pustular psoriasis or rapidly progressive linear morphea.

Other diseases, such as atopic dermatitis, “may be acceptably, though not optimally, managed with topical and other home-based therapeutic options” during the pandemic, they wrote.

Dr. Cordoro commented that, given how fast new findings are emerging from the pandemic, the guidance on medications could change. “We will know so much more 3 months from now,” she said. And while there are no formal plans to reissue the survey, “we’re maintaining communication and will have some kind of follow up” with the academic dermatologists.

“If we recognize any signals that are counter to what we say in this work we will immediately let people know,” she said.

The researchers received no outside funding for their study. Of the study’s 24 coauthors, nine disclosed financial relationships with industry.

SOURCE: Add the first auSOURCE: Reynolds et al. Pediatr Dermatol. 2020. doi: 10.1111/pde.14202.

FROM PEDIATRIC DERMATOLOGY

New crayons reflect the global palette of skin tones

After more than 8 months of development,

“With the world growing more diverse than ever before, Crayola hopes our new Colors of the World crayons will increase representation and foster a greater sense of belonging and acceptance,” CEO Rich Wuerthele said in a written statement.

The company partnered with a cosmetic industry foundation-color expert to create “colors that step down from light to deep shades across rose, almond, and golden undertones, resulting in a 24 global shade palette that authentically reflects the full spectrum of human complexions,” according to Crayola’s statement. The 24- and 32-count Colors of the World packs will start reaching stores in July. The pack of 32 crayons includes the 24 skin colors along with 4 hair and 4 eye colors.

After more than 8 months of development,

“With the world growing more diverse than ever before, Crayola hopes our new Colors of the World crayons will increase representation and foster a greater sense of belonging and acceptance,” CEO Rich Wuerthele said in a written statement.

The company partnered with a cosmetic industry foundation-color expert to create “colors that step down from light to deep shades across rose, almond, and golden undertones, resulting in a 24 global shade palette that authentically reflects the full spectrum of human complexions,” according to Crayola’s statement. The 24- and 32-count Colors of the World packs will start reaching stores in July. The pack of 32 crayons includes the 24 skin colors along with 4 hair and 4 eye colors.

After more than 8 months of development,

“With the world growing more diverse than ever before, Crayola hopes our new Colors of the World crayons will increase representation and foster a greater sense of belonging and acceptance,” CEO Rich Wuerthele said in a written statement.

The company partnered with a cosmetic industry foundation-color expert to create “colors that step down from light to deep shades across rose, almond, and golden undertones, resulting in a 24 global shade palette that authentically reflects the full spectrum of human complexions,” according to Crayola’s statement. The 24- and 32-count Colors of the World packs will start reaching stores in July. The pack of 32 crayons includes the 24 skin colors along with 4 hair and 4 eye colors.

Severe disease not uncommon in children hospitalized with COVID-19

Children with COVID-19 are more likely to develop severe illness and require intensive care than previously realized, data from a single-center study suggest.

Jerry Y. Chao, MD, of the department of anesthesiology, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York, and colleagues reported their findings in an article published online May 11 in the Journal of Pediatrics.

“Thankfully most children with COVID-19 fare well, and some do not have any symptoms at all, but this research is a sobering reminder that children are not immune to this virus and some do require a higher level of care,” senior author Shivanand S. Medar, MD, FAAP, attending physician, Cardiac Intensive Care, Children’s Hospital at Montefiore, and assistant professor of pediatrics, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, said in a Montefiore Medical Center news release.

The study included 67 patients aged 1 month to 21 years (median, 13.1 years) who were treated for COVID-19 at a tertiary care children’s hospital between March 15 and April 13. Of those, 21 (31.3%) were treated as outpatients.

“As the number of patients screened for COVID-19 was restricted during the first weeks of the outbreak because of limited testing availability, the number of mildly symptomatic patients is not known, and therefore these 21 patients are not included in the analysis,” the authors wrote.

Of the 46 hospitalized patients, 33 (72%) were admitted to a general pediatric medical ward, and 13 (28%) were admitted to the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU).

Almost one-third (14 children; 30.4%) of the admitted patients were obese, and almost one-quarter (11 children; 24.4%) had asthma, but neither factor was associated with an increased risk for PICU admission.

“We know that in adults, obesity is a risk factor for more severe disease, however, surprisingly, our study found that children admitted to the intensive care unit did not have a higher prevalence of obesity than those on the general unit,” Dr. Chao said in the news release.

Three of the PICU patients (25%) had preexisting seizure disorders, as did one (3%) patient on the general medical unit. “There was no significant difference in the usage of ibuprofen prior to hospitalization among patients admitted to medical unit compared with those admitted to the PICU,” the authors wrote.

Platelet counts were lower in patients admitted to the PICU compared with those on the general medical unit; however, C-reactive protein, procalcitonin, and pro–brain natriuretic peptide levels were all elevated in patients admitted to the PICU compared with those admitted to the general medical unit.

Patients admitted to the PICU were more likely to need high-flow nasal cannula. Ten (77%) patients in the PICU developed acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), and six (46.2%) of them needed “invasive mechanical ventilation for a median of 9 days.”

The only clinical symptom significantly linked to PICU admission was shortness of breath (92.3% vs 30.3%; P < .001).

Eight (61.5%) of the 13 patients treated in the PICU were discharged to home; four (30.7%) were still hospitalized and receiving ventilatory support on day 14. One patient had metastatic cancer and died as a result of the cancer after life-sustaining therapy was withdrawn.

Those admitted to the PICU were more likely to receive treatment with remdesivir via compassionate use compared with those treated in the general medical unit. Seven (53.8%) patients in the PICU developed severe sepsis and septic shock syndromes.

The average hospital stay was 4 days longer for the children admitted to the PICU than for the children admitted to the general medical unit.

Cough (63%) and fever (60.9%) were the most frequently reported symptoms at admission. The median duration of symptoms before admission was 3 days. None of the children had traveled to an area affected by COVID-19 before becoming ill, and only 20 (43.5%) children were confirmed to have had contact with someone with COVID-19. “The lack of a known sick contact reported in our study may have implications for how healthcare providers identify and screen for potential cases,” the authors explained.

Although children are believed to experience milder SARS-CoV-2 illness, these results and those of an earlier study suggest that some pediatric patients develop illness severe enough to require PICU admission. “This subset had significantly higher markers of inflammation (CRP, pro-BNP, procalcitonin) compared with patients in the medical unit. Inflammation likely contributed to the high rate of ARDS we observed, although serum levels of IL-6 and other cytokines linked to ARDS were not determined,” the authors wrote.

A retrospective cohort study found that of 177 children and young adults treated in a single center, patients younger than 1 year and older than 15 years were more likely to become critically ill with COVID-19 (J Pediatr. 2020 May. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.05.007).

Each of the two age groups accounted for 32% of the hospitalized patients.

The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Children with COVID-19 are more likely to develop severe illness and require intensive care than previously realized, data from a single-center study suggest.

Jerry Y. Chao, MD, of the department of anesthesiology, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York, and colleagues reported their findings in an article published online May 11 in the Journal of Pediatrics.

“Thankfully most children with COVID-19 fare well, and some do not have any symptoms at all, but this research is a sobering reminder that children are not immune to this virus and some do require a higher level of care,” senior author Shivanand S. Medar, MD, FAAP, attending physician, Cardiac Intensive Care, Children’s Hospital at Montefiore, and assistant professor of pediatrics, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, said in a Montefiore Medical Center news release.

The study included 67 patients aged 1 month to 21 years (median, 13.1 years) who were treated for COVID-19 at a tertiary care children’s hospital between March 15 and April 13. Of those, 21 (31.3%) were treated as outpatients.

“As the number of patients screened for COVID-19 was restricted during the first weeks of the outbreak because of limited testing availability, the number of mildly symptomatic patients is not known, and therefore these 21 patients are not included in the analysis,” the authors wrote.

Of the 46 hospitalized patients, 33 (72%) were admitted to a general pediatric medical ward, and 13 (28%) were admitted to the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU).

Almost one-third (14 children; 30.4%) of the admitted patients were obese, and almost one-quarter (11 children; 24.4%) had asthma, but neither factor was associated with an increased risk for PICU admission.

“We know that in adults, obesity is a risk factor for more severe disease, however, surprisingly, our study found that children admitted to the intensive care unit did not have a higher prevalence of obesity than those on the general unit,” Dr. Chao said in the news release.

Three of the PICU patients (25%) had preexisting seizure disorders, as did one (3%) patient on the general medical unit. “There was no significant difference in the usage of ibuprofen prior to hospitalization among patients admitted to medical unit compared with those admitted to the PICU,” the authors wrote.

Platelet counts were lower in patients admitted to the PICU compared with those on the general medical unit; however, C-reactive protein, procalcitonin, and pro–brain natriuretic peptide levels were all elevated in patients admitted to the PICU compared with those admitted to the general medical unit.

Patients admitted to the PICU were more likely to need high-flow nasal cannula. Ten (77%) patients in the PICU developed acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), and six (46.2%) of them needed “invasive mechanical ventilation for a median of 9 days.”

The only clinical symptom significantly linked to PICU admission was shortness of breath (92.3% vs 30.3%; P < .001).

Eight (61.5%) of the 13 patients treated in the PICU were discharged to home; four (30.7%) were still hospitalized and receiving ventilatory support on day 14. One patient had metastatic cancer and died as a result of the cancer after life-sustaining therapy was withdrawn.

Those admitted to the PICU were more likely to receive treatment with remdesivir via compassionate use compared with those treated in the general medical unit. Seven (53.8%) patients in the PICU developed severe sepsis and septic shock syndromes.

The average hospital stay was 4 days longer for the children admitted to the PICU than for the children admitted to the general medical unit.

Cough (63%) and fever (60.9%) were the most frequently reported symptoms at admission. The median duration of symptoms before admission was 3 days. None of the children had traveled to an area affected by COVID-19 before becoming ill, and only 20 (43.5%) children were confirmed to have had contact with someone with COVID-19. “The lack of a known sick contact reported in our study may have implications for how healthcare providers identify and screen for potential cases,” the authors explained.

Although children are believed to experience milder SARS-CoV-2 illness, these results and those of an earlier study suggest that some pediatric patients develop illness severe enough to require PICU admission. “This subset had significantly higher markers of inflammation (CRP, pro-BNP, procalcitonin) compared with patients in the medical unit. Inflammation likely contributed to the high rate of ARDS we observed, although serum levels of IL-6 and other cytokines linked to ARDS were not determined,” the authors wrote.

A retrospective cohort study found that of 177 children and young adults treated in a single center, patients younger than 1 year and older than 15 years were more likely to become critically ill with COVID-19 (J Pediatr. 2020 May. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.05.007).

Each of the two age groups accounted for 32% of the hospitalized patients.

The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Children with COVID-19 are more likely to develop severe illness and require intensive care than previously realized, data from a single-center study suggest.

Jerry Y. Chao, MD, of the department of anesthesiology, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York, and colleagues reported their findings in an article published online May 11 in the Journal of Pediatrics.

“Thankfully most children with COVID-19 fare well, and some do not have any symptoms at all, but this research is a sobering reminder that children are not immune to this virus and some do require a higher level of care,” senior author Shivanand S. Medar, MD, FAAP, attending physician, Cardiac Intensive Care, Children’s Hospital at Montefiore, and assistant professor of pediatrics, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, said in a Montefiore Medical Center news release.

The study included 67 patients aged 1 month to 21 years (median, 13.1 years) who were treated for COVID-19 at a tertiary care children’s hospital between March 15 and April 13. Of those, 21 (31.3%) were treated as outpatients.

“As the number of patients screened for COVID-19 was restricted during the first weeks of the outbreak because of limited testing availability, the number of mildly symptomatic patients is not known, and therefore these 21 patients are not included in the analysis,” the authors wrote.

Of the 46 hospitalized patients, 33 (72%) were admitted to a general pediatric medical ward, and 13 (28%) were admitted to the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU).

Almost one-third (14 children; 30.4%) of the admitted patients were obese, and almost one-quarter (11 children; 24.4%) had asthma, but neither factor was associated with an increased risk for PICU admission.

“We know that in adults, obesity is a risk factor for more severe disease, however, surprisingly, our study found that children admitted to the intensive care unit did not have a higher prevalence of obesity than those on the general unit,” Dr. Chao said in the news release.

Three of the PICU patients (25%) had preexisting seizure disorders, as did one (3%) patient on the general medical unit. “There was no significant difference in the usage of ibuprofen prior to hospitalization among patients admitted to medical unit compared with those admitted to the PICU,” the authors wrote.

Platelet counts were lower in patients admitted to the PICU compared with those on the general medical unit; however, C-reactive protein, procalcitonin, and pro–brain natriuretic peptide levels were all elevated in patients admitted to the PICU compared with those admitted to the general medical unit.

Patients admitted to the PICU were more likely to need high-flow nasal cannula. Ten (77%) patients in the PICU developed acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), and six (46.2%) of them needed “invasive mechanical ventilation for a median of 9 days.”

The only clinical symptom significantly linked to PICU admission was shortness of breath (92.3% vs 30.3%; P < .001).

Eight (61.5%) of the 13 patients treated in the PICU were discharged to home; four (30.7%) were still hospitalized and receiving ventilatory support on day 14. One patient had metastatic cancer and died as a result of the cancer after life-sustaining therapy was withdrawn.

Those admitted to the PICU were more likely to receive treatment with remdesivir via compassionate use compared with those treated in the general medical unit. Seven (53.8%) patients in the PICU developed severe sepsis and septic shock syndromes.

The average hospital stay was 4 days longer for the children admitted to the PICU than for the children admitted to the general medical unit.

Cough (63%) and fever (60.9%) were the most frequently reported symptoms at admission. The median duration of symptoms before admission was 3 days. None of the children had traveled to an area affected by COVID-19 before becoming ill, and only 20 (43.5%) children were confirmed to have had contact with someone with COVID-19. “The lack of a known sick contact reported in our study may have implications for how healthcare providers identify and screen for potential cases,” the authors explained.

Although children are believed to experience milder SARS-CoV-2 illness, these results and those of an earlier study suggest that some pediatric patients develop illness severe enough to require PICU admission. “This subset had significantly higher markers of inflammation (CRP, pro-BNP, procalcitonin) compared with patients in the medical unit. Inflammation likely contributed to the high rate of ARDS we observed, although serum levels of IL-6 and other cytokines linked to ARDS were not determined,” the authors wrote.

A retrospective cohort study found that of 177 children and young adults treated in a single center, patients younger than 1 year and older than 15 years were more likely to become critically ill with COVID-19 (J Pediatr. 2020 May. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.05.007).

Each of the two age groups accounted for 32% of the hospitalized patients.

The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

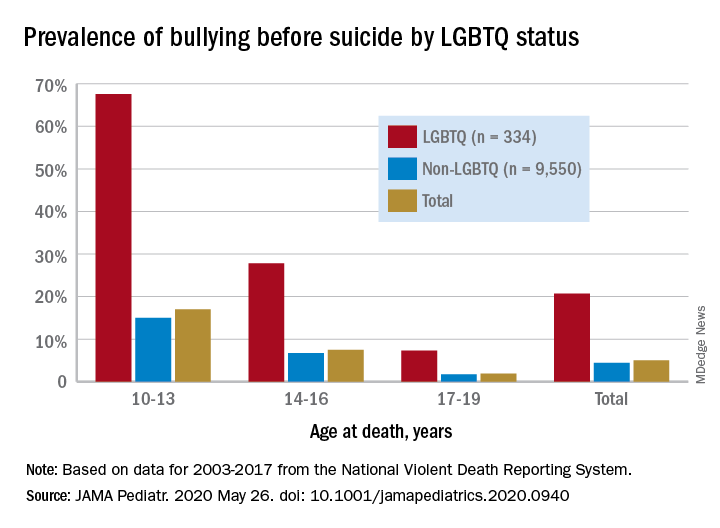

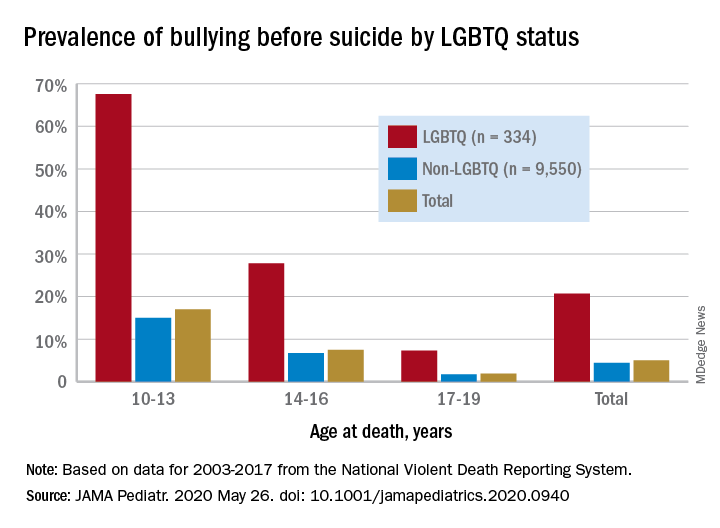

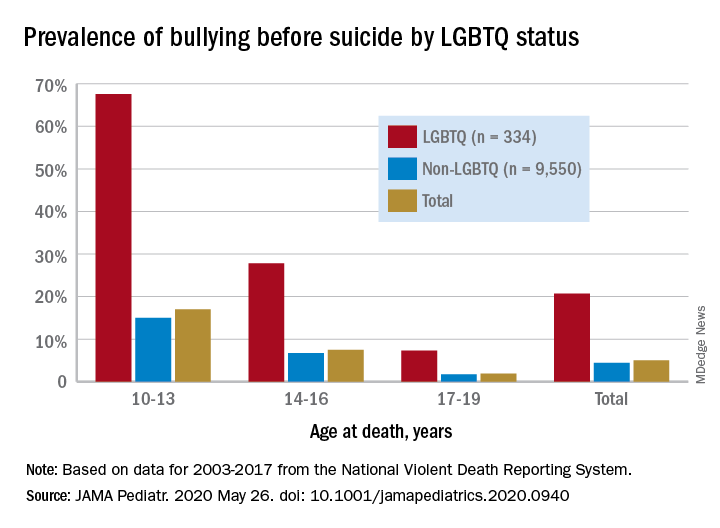

Suicide often associated with bullying in LGBTQ youth

based on analysis of a national database.

Among suicide decedents aged 10-19 years who were classified as LGBTQ, 21% had been bullied, compared with 4% of non-LGBTQ youths, and the discrepancy increased among younger individuals, Kirsty A. Clark, PhD, of Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and associates wrote in JAMA Pediatrics.

Here’s how the presence of bullying broke down by age group by LGBTQ/non-LGBTQ status: 68%/15% among 10- to 13-year-olds, 28%/7% for 14- to-16-year-olds, and 7%/2% among 17- to 19-year-olds, based on data for 2003-2017 from the National Violent Death Reporting System.

Postmortem records from that reporting system include “two narratives summarizing the coroner or medical examiner records and law enforcement reports describing suicide antecedents as reported by the decedent’s family or friends; the decedent’s diary, social media, and text or email messages; and any suicide note,” the investigators noted.

Although prevalence of bullying was higher among LGBTQ youth, non-LGBTQ individuals represented 97% of the 9,884 suicide decedents and 86% of the 490 bullying-associated deaths in the study, they wrote.

Other suicide antecedents also were more prevalent in the LGBTQ group: depressed mood (46% vs. 35%), suicide-thought history (37% vs. 21%), suicide-attempt history (28% vs. 21%), and school-related problem (27% vs. 18%), Dr. Clark and associates reported.

“Bullying can be a deadly antecedent to suicide, especially among LGBTQ youth,” the investigators wrote. “Pediatricians can help to reduce this risk through adopting clinical practice approaches sensitive to the vulnerabilities of LGBTQ youth.”

SOURCE: Clark KA et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2020 May 26. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.0940.

based on analysis of a national database.

Among suicide decedents aged 10-19 years who were classified as LGBTQ, 21% had been bullied, compared with 4% of non-LGBTQ youths, and the discrepancy increased among younger individuals, Kirsty A. Clark, PhD, of Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and associates wrote in JAMA Pediatrics.

Here’s how the presence of bullying broke down by age group by LGBTQ/non-LGBTQ status: 68%/15% among 10- to 13-year-olds, 28%/7% for 14- to-16-year-olds, and 7%/2% among 17- to 19-year-olds, based on data for 2003-2017 from the National Violent Death Reporting System.

Postmortem records from that reporting system include “two narratives summarizing the coroner or medical examiner records and law enforcement reports describing suicide antecedents as reported by the decedent’s family or friends; the decedent’s diary, social media, and text or email messages; and any suicide note,” the investigators noted.

Although prevalence of bullying was higher among LGBTQ youth, non-LGBTQ individuals represented 97% of the 9,884 suicide decedents and 86% of the 490 bullying-associated deaths in the study, they wrote.

Other suicide antecedents also were more prevalent in the LGBTQ group: depressed mood (46% vs. 35%), suicide-thought history (37% vs. 21%), suicide-attempt history (28% vs. 21%), and school-related problem (27% vs. 18%), Dr. Clark and associates reported.

“Bullying can be a deadly antecedent to suicide, especially among LGBTQ youth,” the investigators wrote. “Pediatricians can help to reduce this risk through adopting clinical practice approaches sensitive to the vulnerabilities of LGBTQ youth.”

SOURCE: Clark KA et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2020 May 26. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.0940.

based on analysis of a national database.

Among suicide decedents aged 10-19 years who were classified as LGBTQ, 21% had been bullied, compared with 4% of non-LGBTQ youths, and the discrepancy increased among younger individuals, Kirsty A. Clark, PhD, of Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and associates wrote in JAMA Pediatrics.

Here’s how the presence of bullying broke down by age group by LGBTQ/non-LGBTQ status: 68%/15% among 10- to 13-year-olds, 28%/7% for 14- to-16-year-olds, and 7%/2% among 17- to 19-year-olds, based on data for 2003-2017 from the National Violent Death Reporting System.

Postmortem records from that reporting system include “two narratives summarizing the coroner or medical examiner records and law enforcement reports describing suicide antecedents as reported by the decedent’s family or friends; the decedent’s diary, social media, and text or email messages; and any suicide note,” the investigators noted.

Although prevalence of bullying was higher among LGBTQ youth, non-LGBTQ individuals represented 97% of the 9,884 suicide decedents and 86% of the 490 bullying-associated deaths in the study, they wrote.

Other suicide antecedents also were more prevalent in the LGBTQ group: depressed mood (46% vs. 35%), suicide-thought history (37% vs. 21%), suicide-attempt history (28% vs. 21%), and school-related problem (27% vs. 18%), Dr. Clark and associates reported.

“Bullying can be a deadly antecedent to suicide, especially among LGBTQ youth,” the investigators wrote. “Pediatricians can help to reduce this risk through adopting clinical practice approaches sensitive to the vulnerabilities of LGBTQ youth.”

SOURCE: Clark KA et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2020 May 26. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.0940.

FROM JAMA PEDIATRICS

Biologic approved for atopic dermatitis in children

The Food and Drug Administration has approved dupilumab for children aged 6-11 years with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis, the manufacturers announced.

The new indication is for children “whose disease is not adequately controlled with topical prescription therapies or when those therapies are not advisable,” Regeneron and Sanofi said in a press release, which points out that this is the first biologic approved for AD in this age group.

For children aged 6-11, the two available dupilumab (Dupixent) doses in prefilled syringes are given based on weight – 300 mg every 4 weeks for children between 15 to 29 kg and 200 mg every 2 weeks for children 30 to 59 kg – following an initial loading dose.

In phase 3 trials, children with severe AD who received dupilumab and topical corticosteroids improved significantly in overall disease severity, skin clearance, and itch, compared with those getting steroids alone. Eczema Area and Severity Index-75, for example, was reached by 75% of patients on either dupilumab dose, compared with 28% and 26% , respectively, for those receiving steroids alone every 4 and every 2 weeks, the statement said.

Over the 16-week treatment period, overall rates of adverse events were 65% for those getting dupilumab every 4 weeks and 61% for every 2 weeks – compared with steroids alone (72% and 75%, respectively), the statement said.

The fully human monoclonal antibody inhibits signaling of the interleukin-4 and interleukin-13 proteins and is already approved as an add-on maintenance treatment in children aged 12 years and older with moderate to severe asthma (eosinophilic phenotype or oral-corticosteroid dependent) and in adults with inadequately controlled chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyposis, according to the prescribing information.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved dupilumab for children aged 6-11 years with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis, the manufacturers announced.

The new indication is for children “whose disease is not adequately controlled with topical prescription therapies or when those therapies are not advisable,” Regeneron and Sanofi said in a press release, which points out that this is the first biologic approved for AD in this age group.

For children aged 6-11, the two available dupilumab (Dupixent) doses in prefilled syringes are given based on weight – 300 mg every 4 weeks for children between 15 to 29 kg and 200 mg every 2 weeks for children 30 to 59 kg – following an initial loading dose.

In phase 3 trials, children with severe AD who received dupilumab and topical corticosteroids improved significantly in overall disease severity, skin clearance, and itch, compared with those getting steroids alone. Eczema Area and Severity Index-75, for example, was reached by 75% of patients on either dupilumab dose, compared with 28% and 26% , respectively, for those receiving steroids alone every 4 and every 2 weeks, the statement said.

Over the 16-week treatment period, overall rates of adverse events were 65% for those getting dupilumab every 4 weeks and 61% for every 2 weeks – compared with steroids alone (72% and 75%, respectively), the statement said.

The fully human monoclonal antibody inhibits signaling of the interleukin-4 and interleukin-13 proteins and is already approved as an add-on maintenance treatment in children aged 12 years and older with moderate to severe asthma (eosinophilic phenotype or oral-corticosteroid dependent) and in adults with inadequately controlled chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyposis, according to the prescribing information.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved dupilumab for children aged 6-11 years with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis, the manufacturers announced.

The new indication is for children “whose disease is not adequately controlled with topical prescription therapies or when those therapies are not advisable,” Regeneron and Sanofi said in a press release, which points out that this is the first biologic approved for AD in this age group.

For children aged 6-11, the two available dupilumab (Dupixent) doses in prefilled syringes are given based on weight – 300 mg every 4 weeks for children between 15 to 29 kg and 200 mg every 2 weeks for children 30 to 59 kg – following an initial loading dose.

In phase 3 trials, children with severe AD who received dupilumab and topical corticosteroids improved significantly in overall disease severity, skin clearance, and itch, compared with those getting steroids alone. Eczema Area and Severity Index-75, for example, was reached by 75% of patients on either dupilumab dose, compared with 28% and 26% , respectively, for those receiving steroids alone every 4 and every 2 weeks, the statement said.

Over the 16-week treatment period, overall rates of adverse events were 65% for those getting dupilumab every 4 weeks and 61% for every 2 weeks – compared with steroids alone (72% and 75%, respectively), the statement said.

The fully human monoclonal antibody inhibits signaling of the interleukin-4 and interleukin-13 proteins and is already approved as an add-on maintenance treatment in children aged 12 years and older with moderate to severe asthma (eosinophilic phenotype or oral-corticosteroid dependent) and in adults with inadequately controlled chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyposis, according to the prescribing information.

Immunotherapy, steroids had positive outcomes in COVID-19–associated multisystem inflammatory syndrome

According to study of a cluster of patients in France and Switzerland, children may experience an acute cardiac decompensation from the severe inflammatory state following SARS-CoV-2 infection, termed multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C). Treatment with immunoglobulin appears to be associated with recovery of left ventricular systolic function.

“The pediatric and cardiology communities should be acutely aware of this new disease probably related to SARS-CoV-2 infection (MIS-C), that shares similarities with Kawasaki disease but has specificities in its presentation,” researchers led by Zahra Belhadjer, MD, of Necker-Enfants Malades Hospital in Paris, wrote in a cases series report published online in Circulation “Early diagnosis and management appear to lead to favorable outcome using classical therapies. Elucidating the immune mechanisms of this disease will afford further insights for treatment and potential global prevention of severe forms.”

Over a 2-month period that coincided with the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic in France and Switzerland, the researchers retrospectively collected clinical, biological, therapeutic, and early-outcomes data in 35 children who were admitted to pediatric ICUs in 14 centers for cardiogenic shock, left ventricular dysfunction, and severe inflammatory state. Their median age was 10 years, all presented with a fever, 80% had gastrointestinal symptoms of abdominal pain, vomiting, or diarrhea, and 28% had comorbidities that included body mass index of greater than 25 kg/m2 (17%), asthma (9%), and lupus (3%), and overweight. Only 17% presented with chest pain. The researchers observed that left ventricular ejection fraction was less than 30% in 28% of patients, and 80% required inotropic support with 28% treated with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO). All patients presented with a severe inflammatory state evidenced by elevated C-reactive protein and d-dimer. Interleukin 6 was elevated to a median of 135 pg/mL in 13 of the patients. Elevation of troponin I was constant but mild to moderate, and NT-proBNP or BNP elevation was present in all children.

Nearly all patients 35 (88%) patients tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 infection by polymerase chain reaction of nasopharyngeal swab or serology. Most patients (80%) received IV inotropic support, 71% received first-line IV immunoglobulin, 65% received anticoagulation with heparin, 34% received IV steroids having been considered high-risk patients with symptoms similar to an incomplete form of Kawasaki disease, and 8% received treatment with an interleukin-1 receptor antagonist because of a persistent severe inflammatory state. Left ventricular function was restored in 71% of those discharged from the intensive care unit. No patient died, and all patients treated with ECMO were successfully weaned after a median of 4.5 days.

“Some aspects of this emerging pediatric disease (MIS-C) are similar to those of Kawasaki disease: prolonged fever, multisystem inflammation with skin rash, lymphadenopathy, diarrhea, meningism, and high levels of inflammatory biomarkers,” the researchers wrote. “But differences are important and raise the question as to whether this syndrome is Kawasaki disease with SARS-CoV-2 as the triggering agent, or represents a different syndrome (MIS-C). Kawasaki disease predominantly affects young children younger than 5 years, whereas the median age in our series is 10 years. Incomplete forms of Kawasaki disease occur in infants who may have fever as the sole clinical finding, whereas older patients are more prone to exhibit the complete form.”

They went on to note that the overlapping features between MIS-C and Kawasaki disease “may be due to similar pathophysiology. The etiologic agent of Kawasaki disease is unknown but likely to be ubiquitous, causing asymptomatic childhood infection but triggering the immunologic cascade of Kawasaki disease in genetically susceptible individuals. Please note that infection with a novel RNA virus that enters through the upper respiratory tract has been proposed to be the cause of the disease (see PLoS One. 2008 Feb 13;3:e1582 and J Infect Dis. 2011 Apr 1;203:1021-30).”

Based on the work of authors, it appears that a high index of suspicion for MIS-C is important for children who develop Kawasaki-like symptoms, David J. Goldberg, MD, said in an interview. “Although children have largely been spared from the acute respiratory presentation of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, the recognition and understanding of what appears to be a postviral inflammatory response is a critical first step in developing treatment algorithms for this disease process,” said Dr. Goldberg, a board-certified attending cardiologist in the cardiac center and fetal heart program at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. “If inflammatory markers are elevated, particularly if there are accompanying gastrointestinal symptoms, the possibility of cardiac involvement suggests the utility of screening echocardiography. Given the potential need for inotropic or mechanical circulatory support, the presence of myocardial dysfunction dictates care in an intensive care unit capable of providing advanced therapies. While the evidence from Dr. Belhadjer’s cohort suggests that full recovery is probable, there is still much to be learned about this unique inflammatory syndrome and the alarm has rightly been sounded.”

The researchers and Dr. Goldberg reported having no disclosures.

SOURCE: Belhadjer Z et al. Circulation 2020 May 17; doi: 10.1161/circulationaha.120.048360.

According to study of a cluster of patients in France and Switzerland, children may experience an acute cardiac decompensation from the severe inflammatory state following SARS-CoV-2 infection, termed multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C). Treatment with immunoglobulin appears to be associated with recovery of left ventricular systolic function.

“The pediatric and cardiology communities should be acutely aware of this new disease probably related to SARS-CoV-2 infection (MIS-C), that shares similarities with Kawasaki disease but has specificities in its presentation,” researchers led by Zahra Belhadjer, MD, of Necker-Enfants Malades Hospital in Paris, wrote in a cases series report published online in Circulation “Early diagnosis and management appear to lead to favorable outcome using classical therapies. Elucidating the immune mechanisms of this disease will afford further insights for treatment and potential global prevention of severe forms.”

Over a 2-month period that coincided with the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic in France and Switzerland, the researchers retrospectively collected clinical, biological, therapeutic, and early-outcomes data in 35 children who were admitted to pediatric ICUs in 14 centers for cardiogenic shock, left ventricular dysfunction, and severe inflammatory state. Their median age was 10 years, all presented with a fever, 80% had gastrointestinal symptoms of abdominal pain, vomiting, or diarrhea, and 28% had comorbidities that included body mass index of greater than 25 kg/m2 (17%), asthma (9%), and lupus (3%), and overweight. Only 17% presented with chest pain. The researchers observed that left ventricular ejection fraction was less than 30% in 28% of patients, and 80% required inotropic support with 28% treated with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO). All patients presented with a severe inflammatory state evidenced by elevated C-reactive protein and d-dimer. Interleukin 6 was elevated to a median of 135 pg/mL in 13 of the patients. Elevation of troponin I was constant but mild to moderate, and NT-proBNP or BNP elevation was present in all children.

Nearly all patients 35 (88%) patients tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 infection by polymerase chain reaction of nasopharyngeal swab or serology. Most patients (80%) received IV inotropic support, 71% received first-line IV immunoglobulin, 65% received anticoagulation with heparin, 34% received IV steroids having been considered high-risk patients with symptoms similar to an incomplete form of Kawasaki disease, and 8% received treatment with an interleukin-1 receptor antagonist because of a persistent severe inflammatory state. Left ventricular function was restored in 71% of those discharged from the intensive care unit. No patient died, and all patients treated with ECMO were successfully weaned after a median of 4.5 days.

“Some aspects of this emerging pediatric disease (MIS-C) are similar to those of Kawasaki disease: prolonged fever, multisystem inflammation with skin rash, lymphadenopathy, diarrhea, meningism, and high levels of inflammatory biomarkers,” the researchers wrote. “But differences are important and raise the question as to whether this syndrome is Kawasaki disease with SARS-CoV-2 as the triggering agent, or represents a different syndrome (MIS-C). Kawasaki disease predominantly affects young children younger than 5 years, whereas the median age in our series is 10 years. Incomplete forms of Kawasaki disease occur in infants who may have fever as the sole clinical finding, whereas older patients are more prone to exhibit the complete form.”

They went on to note that the overlapping features between MIS-C and Kawasaki disease “may be due to similar pathophysiology. The etiologic agent of Kawasaki disease is unknown but likely to be ubiquitous, causing asymptomatic childhood infection but triggering the immunologic cascade of Kawasaki disease in genetically susceptible individuals. Please note that infection with a novel RNA virus that enters through the upper respiratory tract has been proposed to be the cause of the disease (see PLoS One. 2008 Feb 13;3:e1582 and J Infect Dis. 2011 Apr 1;203:1021-30).”

Based on the work of authors, it appears that a high index of suspicion for MIS-C is important for children who develop Kawasaki-like symptoms, David J. Goldberg, MD, said in an interview. “Although children have largely been spared from the acute respiratory presentation of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, the recognition and understanding of what appears to be a postviral inflammatory response is a critical first step in developing treatment algorithms for this disease process,” said Dr. Goldberg, a board-certified attending cardiologist in the cardiac center and fetal heart program at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. “If inflammatory markers are elevated, particularly if there are accompanying gastrointestinal symptoms, the possibility of cardiac involvement suggests the utility of screening echocardiography. Given the potential need for inotropic or mechanical circulatory support, the presence of myocardial dysfunction dictates care in an intensive care unit capable of providing advanced therapies. While the evidence from Dr. Belhadjer’s cohort suggests that full recovery is probable, there is still much to be learned about this unique inflammatory syndrome and the alarm has rightly been sounded.”

The researchers and Dr. Goldberg reported having no disclosures.

SOURCE: Belhadjer Z et al. Circulation 2020 May 17; doi: 10.1161/circulationaha.120.048360.

According to study of a cluster of patients in France and Switzerland, children may experience an acute cardiac decompensation from the severe inflammatory state following SARS-CoV-2 infection, termed multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C). Treatment with immunoglobulin appears to be associated with recovery of left ventricular systolic function.

“The pediatric and cardiology communities should be acutely aware of this new disease probably related to SARS-CoV-2 infection (MIS-C), that shares similarities with Kawasaki disease but has specificities in its presentation,” researchers led by Zahra Belhadjer, MD, of Necker-Enfants Malades Hospital in Paris, wrote in a cases series report published online in Circulation “Early diagnosis and management appear to lead to favorable outcome using classical therapies. Elucidating the immune mechanisms of this disease will afford further insights for treatment and potential global prevention of severe forms.”

Over a 2-month period that coincided with the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic in France and Switzerland, the researchers retrospectively collected clinical, biological, therapeutic, and early-outcomes data in 35 children who were admitted to pediatric ICUs in 14 centers for cardiogenic shock, left ventricular dysfunction, and severe inflammatory state. Their median age was 10 years, all presented with a fever, 80% had gastrointestinal symptoms of abdominal pain, vomiting, or diarrhea, and 28% had comorbidities that included body mass index of greater than 25 kg/m2 (17%), asthma (9%), and lupus (3%), and overweight. Only 17% presented with chest pain. The researchers observed that left ventricular ejection fraction was less than 30% in 28% of patients, and 80% required inotropic support with 28% treated with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO). All patients presented with a severe inflammatory state evidenced by elevated C-reactive protein and d-dimer. Interleukin 6 was elevated to a median of 135 pg/mL in 13 of the patients. Elevation of troponin I was constant but mild to moderate, and NT-proBNP or BNP elevation was present in all children.

Nearly all patients 35 (88%) patients tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 infection by polymerase chain reaction of nasopharyngeal swab or serology. Most patients (80%) received IV inotropic support, 71% received first-line IV immunoglobulin, 65% received anticoagulation with heparin, 34% received IV steroids having been considered high-risk patients with symptoms similar to an incomplete form of Kawasaki disease, and 8% received treatment with an interleukin-1 receptor antagonist because of a persistent severe inflammatory state. Left ventricular function was restored in 71% of those discharged from the intensive care unit. No patient died, and all patients treated with ECMO were successfully weaned after a median of 4.5 days.

“Some aspects of this emerging pediatric disease (MIS-C) are similar to those of Kawasaki disease: prolonged fever, multisystem inflammation with skin rash, lymphadenopathy, diarrhea, meningism, and high levels of inflammatory biomarkers,” the researchers wrote. “But differences are important and raise the question as to whether this syndrome is Kawasaki disease with SARS-CoV-2 as the triggering agent, or represents a different syndrome (MIS-C). Kawasaki disease predominantly affects young children younger than 5 years, whereas the median age in our series is 10 years. Incomplete forms of Kawasaki disease occur in infants who may have fever as the sole clinical finding, whereas older patients are more prone to exhibit the complete form.”

They went on to note that the overlapping features between MIS-C and Kawasaki disease “may be due to similar pathophysiology. The etiologic agent of Kawasaki disease is unknown but likely to be ubiquitous, causing asymptomatic childhood infection but triggering the immunologic cascade of Kawasaki disease in genetically susceptible individuals. Please note that infection with a novel RNA virus that enters through the upper respiratory tract has been proposed to be the cause of the disease (see PLoS One. 2008 Feb 13;3:e1582 and J Infect Dis. 2011 Apr 1;203:1021-30).”

Based on the work of authors, it appears that a high index of suspicion for MIS-C is important for children who develop Kawasaki-like symptoms, David J. Goldberg, MD, said in an interview. “Although children have largely been spared from the acute respiratory presentation of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, the recognition and understanding of what appears to be a postviral inflammatory response is a critical first step in developing treatment algorithms for this disease process,” said Dr. Goldberg, a board-certified attending cardiologist in the cardiac center and fetal heart program at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. “If inflammatory markers are elevated, particularly if there are accompanying gastrointestinal symptoms, the possibility of cardiac involvement suggests the utility of screening echocardiography. Given the potential need for inotropic or mechanical circulatory support, the presence of myocardial dysfunction dictates care in an intensive care unit capable of providing advanced therapies. While the evidence from Dr. Belhadjer’s cohort suggests that full recovery is probable, there is still much to be learned about this unique inflammatory syndrome and the alarm has rightly been sounded.”

The researchers and Dr. Goldberg reported having no disclosures.

SOURCE: Belhadjer Z et al. Circulation 2020 May 17; doi: 10.1161/circulationaha.120.048360.

FROM CIRCULATION

Picky eating is stable in childhood, correlates with lower BMI

Picky eating at age 4 years is stable over an approximately 4-year period, research published in Pediatrics suggests.

In addition, picky eating is associated with lower body mass index (BMI). said Carmen Fernandez, MPH, a researcher and medical student at University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, and colleagues.

Whether picky eating is a stable trait and how it relates to weight status has been unclear. Furthermore, “previous longitudinal studies have not focused on low-income children, who are at elevated risk for being both overweight and picky,” said Ms. Fernandez and associates.

A stable trait

To examine trajectories of picky eating in a low-income population of children and how picky eating relates to BMI z score (BMIz) and maternal behavior, the researchers conducted a longitudinal cohort study. They recruited more than 300 mother-child dyads from Head Start programs in Southeastern Michigan between 2009 and 2011. Children were 3-4 years old at recruitment, and researchers collected data at five time points. Children had an average age of 4 years at the first time point and 9 years at the fifth time point. Investigators collected child BMIz scores at all time points, Children’s Eating Behavior Questionnaire (CEBQ) scores at four time points, and Child Feeding Questionnaire and Caregiver’s Feeding Styles Questionnaire scores at three time points. Mothers completed the Emotion Regulation Checklist at baseline.

Among 317 children, an analysis identified three trajectories of picky eating severity as measured by the CEBQ Food Fussiness subscale: persistently low (29% of the children), persistently medium (57%), and persistently high (14%). “Maternal feeding behaviors characterized by restriction and demandingness were associated with picky eating,” the authors said. In post hoc analyses, emotional regulation was higher and emotional lability was lower among children with low levels of picky eating, compared with children with medium and high levels of picky eating.

“High and medium picky eating was associated with lower average BMIz, in the healthy BMIz range, suggesting that picky eating could be protective against overweight and obesity, as others have proposed,” Ms. Fernandez and colleagues said. “We did not find evidence that picky eating was associated with being underweight, which is consistent with previous studies. ... Little is known, however, about the long-term weight gain trajectories of picky eaters into adulthood, and this is an important area for future research.”

The results from this cohort may not apply to other populations, the authors noted.

What to do about picky eating

“Health providers, researchers, and parents do not yet have a handle on the management and messaging of picky eating in children,” said Nancy L. Zucker, PhD, and Sheryl O. Hughes, PhD, in an accompanying editorial. “When a parent describes a child as often or always selective, it is beyond normative. … Roughly only 14% were described this way.”

The results suggest a need for early intervention, and age 24 months and younger may be when “children are more receptive to the exploration of new tastes,” said Dr. Zucker of the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences and the department of psychology and neuroscience at Duke University in Durham, NC., and Dr. Hughes of the Children’s Nutrition Research Center at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston.

Researchers should examine the impact of an authoritative feeding style, which combines elements of authoritarian and indulgent feeding styles, on a child’s willingness to explore foods, said Dr. Zucker and Dr. Hughes. This feeding style incorporates “structure and guidance while being sensitive to the child’s needs without being punitive,” they said. “According to theories of inhibitory learning ... we can think of children with elevated picky eating as having thousands of negative memories about food (e.g., conflict, unexpected tastes, discomfort). Thus, caregivers can work to create positive memories and experiences around food (e.g., cooking, gardening) to help picky eaters expand their preferences. However, in doing so, it is critical that caregivers let go of their need for a child to taste something and instead focus on accumulating pleasant experiences.”

Whether this approach reduces pickiness is unknown, but it may improve shared eating experiences, Dr. Zucker and Dr. Hughes said.

Ms. Fernandez and coauthors had no relevant financial disclosures. The study was supported by the American Heart Association, the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, and the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Zucker received funding from the National Science Foundation and National Institute of Mental Health; Dr. Hughes had no relevant financial disclosures. The editorial was funded by the National Institutes of Health.

SOURCES: Fernandez C et al. Pediatrics. 2020 May 26. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-2018; Zucker NL and Hughes SO. Pediatrics. 2020 May 26. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-0893.

Picky eating at age 4 years is stable over an approximately 4-year period, research published in Pediatrics suggests.

In addition, picky eating is associated with lower body mass index (BMI). said Carmen Fernandez, MPH, a researcher and medical student at University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, and colleagues.

Whether picky eating is a stable trait and how it relates to weight status has been unclear. Furthermore, “previous longitudinal studies have not focused on low-income children, who are at elevated risk for being both overweight and picky,” said Ms. Fernandez and associates.

A stable trait

To examine trajectories of picky eating in a low-income population of children and how picky eating relates to BMI z score (BMIz) and maternal behavior, the researchers conducted a longitudinal cohort study. They recruited more than 300 mother-child dyads from Head Start programs in Southeastern Michigan between 2009 and 2011. Children were 3-4 years old at recruitment, and researchers collected data at five time points. Children had an average age of 4 years at the first time point and 9 years at the fifth time point. Investigators collected child BMIz scores at all time points, Children’s Eating Behavior Questionnaire (CEBQ) scores at four time points, and Child Feeding Questionnaire and Caregiver’s Feeding Styles Questionnaire scores at three time points. Mothers completed the Emotion Regulation Checklist at baseline.

Among 317 children, an analysis identified three trajectories of picky eating severity as measured by the CEBQ Food Fussiness subscale: persistently low (29% of the children), persistently medium (57%), and persistently high (14%). “Maternal feeding behaviors characterized by restriction and demandingness were associated with picky eating,” the authors said. In post hoc analyses, emotional regulation was higher and emotional lability was lower among children with low levels of picky eating, compared with children with medium and high levels of picky eating.

“High and medium picky eating was associated with lower average BMIz, in the healthy BMIz range, suggesting that picky eating could be protective against overweight and obesity, as others have proposed,” Ms. Fernandez and colleagues said. “We did not find evidence that picky eating was associated with being underweight, which is consistent with previous studies. ... Little is known, however, about the long-term weight gain trajectories of picky eaters into adulthood, and this is an important area for future research.”

The results from this cohort may not apply to other populations, the authors noted.

What to do about picky eating

“Health providers, researchers, and parents do not yet have a handle on the management and messaging of picky eating in children,” said Nancy L. Zucker, PhD, and Sheryl O. Hughes, PhD, in an accompanying editorial. “When a parent describes a child as often or always selective, it is beyond normative. … Roughly only 14% were described this way.”

The results suggest a need for early intervention, and age 24 months and younger may be when “children are more receptive to the exploration of new tastes,” said Dr. Zucker of the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences and the department of psychology and neuroscience at Duke University in Durham, NC., and Dr. Hughes of the Children’s Nutrition Research Center at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston.

Researchers should examine the impact of an authoritative feeding style, which combines elements of authoritarian and indulgent feeding styles, on a child’s willingness to explore foods, said Dr. Zucker and Dr. Hughes. This feeding style incorporates “structure and guidance while being sensitive to the child’s needs without being punitive,” they said. “According to theories of inhibitory learning ... we can think of children with elevated picky eating as having thousands of negative memories about food (e.g., conflict, unexpected tastes, discomfort). Thus, caregivers can work to create positive memories and experiences around food (e.g., cooking, gardening) to help picky eaters expand their preferences. However, in doing so, it is critical that caregivers let go of their need for a child to taste something and instead focus on accumulating pleasant experiences.”

Whether this approach reduces pickiness is unknown, but it may improve shared eating experiences, Dr. Zucker and Dr. Hughes said.

Ms. Fernandez and coauthors had no relevant financial disclosures. The study was supported by the American Heart Association, the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, and the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Zucker received funding from the National Science Foundation and National Institute of Mental Health; Dr. Hughes had no relevant financial disclosures. The editorial was funded by the National Institutes of Health.

SOURCES: Fernandez C et al. Pediatrics. 2020 May 26. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-2018; Zucker NL and Hughes SO. Pediatrics. 2020 May 26. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-0893.

Picky eating at age 4 years is stable over an approximately 4-year period, research published in Pediatrics suggests.

In addition, picky eating is associated with lower body mass index (BMI). said Carmen Fernandez, MPH, a researcher and medical student at University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, and colleagues.

Whether picky eating is a stable trait and how it relates to weight status has been unclear. Furthermore, “previous longitudinal studies have not focused on low-income children, who are at elevated risk for being both overweight and picky,” said Ms. Fernandez and associates.

A stable trait

To examine trajectories of picky eating in a low-income population of children and how picky eating relates to BMI z score (BMIz) and maternal behavior, the researchers conducted a longitudinal cohort study. They recruited more than 300 mother-child dyads from Head Start programs in Southeastern Michigan between 2009 and 2011. Children were 3-4 years old at recruitment, and researchers collected data at five time points. Children had an average age of 4 years at the first time point and 9 years at the fifth time point. Investigators collected child BMIz scores at all time points, Children’s Eating Behavior Questionnaire (CEBQ) scores at four time points, and Child Feeding Questionnaire and Caregiver’s Feeding Styles Questionnaire scores at three time points. Mothers completed the Emotion Regulation Checklist at baseline.

Among 317 children, an analysis identified three trajectories of picky eating severity as measured by the CEBQ Food Fussiness subscale: persistently low (29% of the children), persistently medium (57%), and persistently high (14%). “Maternal feeding behaviors characterized by restriction and demandingness were associated with picky eating,” the authors said. In post hoc analyses, emotional regulation was higher and emotional lability was lower among children with low levels of picky eating, compared with children with medium and high levels of picky eating.

“High and medium picky eating was associated with lower average BMIz, in the healthy BMIz range, suggesting that picky eating could be protective against overweight and obesity, as others have proposed,” Ms. Fernandez and colleagues said. “We did not find evidence that picky eating was associated with being underweight, which is consistent with previous studies. ... Little is known, however, about the long-term weight gain trajectories of picky eaters into adulthood, and this is an important area for future research.”

The results from this cohort may not apply to other populations, the authors noted.

What to do about picky eating

“Health providers, researchers, and parents do not yet have a handle on the management and messaging of picky eating in children,” said Nancy L. Zucker, PhD, and Sheryl O. Hughes, PhD, in an accompanying editorial. “When a parent describes a child as often or always selective, it is beyond normative. … Roughly only 14% were described this way.”

The results suggest a need for early intervention, and age 24 months and younger may be when “children are more receptive to the exploration of new tastes,” said Dr. Zucker of the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences and the department of psychology and neuroscience at Duke University in Durham, NC., and Dr. Hughes of the Children’s Nutrition Research Center at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston.

Researchers should examine the impact of an authoritative feeding style, which combines elements of authoritarian and indulgent feeding styles, on a child’s willingness to explore foods, said Dr. Zucker and Dr. Hughes. This feeding style incorporates “structure and guidance while being sensitive to the child’s needs without being punitive,” they said. “According to theories of inhibitory learning ... we can think of children with elevated picky eating as having thousands of negative memories about food (e.g., conflict, unexpected tastes, discomfort). Thus, caregivers can work to create positive memories and experiences around food (e.g., cooking, gardening) to help picky eaters expand their preferences. However, in doing so, it is critical that caregivers let go of their need for a child to taste something and instead focus on accumulating pleasant experiences.”

Whether this approach reduces pickiness is unknown, but it may improve shared eating experiences, Dr. Zucker and Dr. Hughes said.

Ms. Fernandez and coauthors had no relevant financial disclosures. The study was supported by the American Heart Association, the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, and the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Zucker received funding from the National Science Foundation and National Institute of Mental Health; Dr. Hughes had no relevant financial disclosures. The editorial was funded by the National Institutes of Health.

SOURCES: Fernandez C et al. Pediatrics. 2020 May 26. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-2018; Zucker NL and Hughes SO. Pediatrics. 2020 May 26. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-0893.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Tool-less but not clueless

There is apparently some debate about which of our ancestors was the first to use tools. It probably was Homo habilis, the “handy man.” But it could have been a relative of Lucy, of the Australopithecus afarensis tribe. Regardless of which pile of chipped rocks looks more tool-like to you, it is generally agreed that our ability to make and use tools is one of the key ingredients to our evolutionary success.

I have always enjoyed the feel of good quality knife when I am woodcarving, and the tool collection hanging on the wall over my work bench is one of my most prized possessions. But when I was practicing general pediatrics, I could never really warm up to the screening tools that were being touted as must-haves for detecting developmental delays.

It turns out I was not alone. A recent study published in Pediatrics found that the number of pediatricians who reported using developmental screening tools increased from 21% to 63% between 2002 and 2016. (Pediatrics. 2020 Apr. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-0851). However, this means that, despite a significant increase in usage, more than a third of pediatricians still are not employing screening tools. Does this suggest that one out of every three pediatricians, including me and maybe you, is a knuckle-dragging pre–Homo sapiens practicing in blissful and clueless ignorance?

Mei Elansary MD, MPhil, and Michael Silverstein, MD, MPH, who wrote a companion commentary in the same journal, suggested that maybe those of us who have resisted the call to be tool users aren’t prehistoric ignoramuses (Pediatrics. 2020 Apr. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-0164). They observed that, regardless of whether the pediatricians were using screening tools, more than 40% of the those surveyed did not refer patients for early intervention.

The commentators pointed out that the decision of when, whom, and how to screen must be viewed as part of a “complicated web of changing epidemiology, time and reimbursement constraints, and service availability.” They observe that pediatricians facing this landscape in upheaval “default to what they know best: clinical judgment.” Citing one study of the management of febrile infants, the authors point out that relying on guidelines doesn’t always result in improved clinical care.

My decision of when to refer a patient for early intervention was based on what I had observed over a series of visits and whether I thought that the early intervention resources available in my community would have a significant benefit for any particular child. Because I crafted my practice around a model that put a strong emphasis on continuity, my patients almost never saw another provider for a health maintenance visit and usually saw me for their sick visits, including ear rechecks.