User login

Chilblain-like lesions reported in children thought to have COVID-19

Two and elsewhere.

These symptoms should be considered a sign of infection with the virus, but the symptoms themselves typically don’t require treatment, according to the authors of the two new reports, from hospitals in Milan and Madrid, published in Pediatric Dermatology.

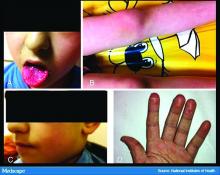

In the first study, Cristiana Colonna, MD, and colleagues at Hospital Maggiore Polyclinic in Milan described four cases of chilblain-like lesions in children ages 5-11 years with mild COVID-19 symptoms.

In the second, David Andina, MD, and colleagues in the ED and the departments of dermatology and pathology at the Child Jesus University Children’s Hospital in Madrid published a retrospective study of 22 cases in children and adolescents ages 6-17 years who reported to the hospital ED from April 6 to 17, the peak of the pandemic in Madrid.

In all four of the Milan cases, the skin lesions appeared several days after the onset of COVID-19 symptoms, although all four patients initially tested negative for COVID-19. However, Dr. Colonna and colleagues wrote that, “given the fact that the sensitivity and specificity of both nasopharyngeal swabs and antibody tests for COVID-19 (when available) are not 100% reliable, the question of the origin of these strange chilblain-like lesions is still elusive.” Until further studies are available, they emphasized that clinicians should be “alert to the presentation of chilblain-like findings” in children with mild symptoms “as a possible sign of COVID-19 infection.”

All the patients had lesions on their feet or toes, and a 5-year-old boy also had lesions on the right hand. One patient, an 11-year-old girl, had a biopsy that revealed dense lymphocytic perivascular cuffing and periadnexal infiltration.

“The finding of an elevated d-dimer in one of our patients, along with the clinical features suggestive of a vasoocclusive phenomenon, supports consideration of laboratory evaluation for coagulation defects in asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic children with acrovasculitis-like findings,” Dr. Colonna and colleagues wrote. None of the four cases in Milan required treatment, with three cases resolving within 5 days.

Like the Milan cases, all 22 patients in the Madrid series had foot or toe lesions and three had lesions on the fingers. This larger series also reported more detailed symptoms about the lesions: pruritus in nine patients (41%) and mild pain in seven (32%). A total of 10 patients had systemic symptoms of COVID-19, predominantly cough and rhinorrhea in 9 patients (41%), but 2 (9%) had abdominal pain and diarrhea. These symptoms, the authors said, appeared a median of 14 days (range, 1-28 days) before they developed chilblains.

A total of 19 patients were tested for COVID-19, but only 1 was positive.

This retrospective study also included contact information, with one patient having household contact with a single confirmed case of COVID-19; 12 patients recalled household contact who were considered probable cases of COVID-19, with respiratory symptoms.

Skin biopsies were obtained from the acral lesions in six patients, all showing similar results, although with varying degrees of intensity. All biopsies showed features of lymphocytic vasculopathy. Some cases showed mild dermal and perieccrine mucinosis, lymphocytic eccrine hidradenitis, vascular ectasia, red cell extravasation and focal thrombosis described as “mostly confined to scattered papillary dermal capillaries, but also in vessels of the reticular dermis.”

The only treatments Dr. Andina and colleagues reported were oral analgesics for pain and oral antihistamines for pruritus when needed. One patient was given topical corticosteroids and another a short course of oral steroids, both for erythema multiforme.

Dr. Andina and colleagues wrote that the skin lesions in these patients “were unequivocally categorized as chilblains, both clinically and histopathologically,” and, after 7-10 days, began to fade. None of the patients had complications, and had an “excellent outcome,” they noted.

Dr. Colonna and colleagues had no conflicts of interest to declare. Dr. Andina and colleagues provided no disclosure statement.

SOURCES: Colonna C et al. Ped Derm. 2020 May 6. doi: 10.1111/pde.14210; Andina D et al. Ped Derm. 2020 May 9. doi: 10.1111/pde.14215.

Two and elsewhere.

These symptoms should be considered a sign of infection with the virus, but the symptoms themselves typically don’t require treatment, according to the authors of the two new reports, from hospitals in Milan and Madrid, published in Pediatric Dermatology.

In the first study, Cristiana Colonna, MD, and colleagues at Hospital Maggiore Polyclinic in Milan described four cases of chilblain-like lesions in children ages 5-11 years with mild COVID-19 symptoms.

In the second, David Andina, MD, and colleagues in the ED and the departments of dermatology and pathology at the Child Jesus University Children’s Hospital in Madrid published a retrospective study of 22 cases in children and adolescents ages 6-17 years who reported to the hospital ED from April 6 to 17, the peak of the pandemic in Madrid.

In all four of the Milan cases, the skin lesions appeared several days after the onset of COVID-19 symptoms, although all four patients initially tested negative for COVID-19. However, Dr. Colonna and colleagues wrote that, “given the fact that the sensitivity and specificity of both nasopharyngeal swabs and antibody tests for COVID-19 (when available) are not 100% reliable, the question of the origin of these strange chilblain-like lesions is still elusive.” Until further studies are available, they emphasized that clinicians should be “alert to the presentation of chilblain-like findings” in children with mild symptoms “as a possible sign of COVID-19 infection.”

All the patients had lesions on their feet or toes, and a 5-year-old boy also had lesions on the right hand. One patient, an 11-year-old girl, had a biopsy that revealed dense lymphocytic perivascular cuffing and periadnexal infiltration.

“The finding of an elevated d-dimer in one of our patients, along with the clinical features suggestive of a vasoocclusive phenomenon, supports consideration of laboratory evaluation for coagulation defects in asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic children with acrovasculitis-like findings,” Dr. Colonna and colleagues wrote. None of the four cases in Milan required treatment, with three cases resolving within 5 days.

Like the Milan cases, all 22 patients in the Madrid series had foot or toe lesions and three had lesions on the fingers. This larger series also reported more detailed symptoms about the lesions: pruritus in nine patients (41%) and mild pain in seven (32%). A total of 10 patients had systemic symptoms of COVID-19, predominantly cough and rhinorrhea in 9 patients (41%), but 2 (9%) had abdominal pain and diarrhea. These symptoms, the authors said, appeared a median of 14 days (range, 1-28 days) before they developed chilblains.

A total of 19 patients were tested for COVID-19, but only 1 was positive.

This retrospective study also included contact information, with one patient having household contact with a single confirmed case of COVID-19; 12 patients recalled household contact who were considered probable cases of COVID-19, with respiratory symptoms.

Skin biopsies were obtained from the acral lesions in six patients, all showing similar results, although with varying degrees of intensity. All biopsies showed features of lymphocytic vasculopathy. Some cases showed mild dermal and perieccrine mucinosis, lymphocytic eccrine hidradenitis, vascular ectasia, red cell extravasation and focal thrombosis described as “mostly confined to scattered papillary dermal capillaries, but also in vessels of the reticular dermis.”

The only treatments Dr. Andina and colleagues reported were oral analgesics for pain and oral antihistamines for pruritus when needed. One patient was given topical corticosteroids and another a short course of oral steroids, both for erythema multiforme.

Dr. Andina and colleagues wrote that the skin lesions in these patients “were unequivocally categorized as chilblains, both clinically and histopathologically,” and, after 7-10 days, began to fade. None of the patients had complications, and had an “excellent outcome,” they noted.

Dr. Colonna and colleagues had no conflicts of interest to declare. Dr. Andina and colleagues provided no disclosure statement.

SOURCES: Colonna C et al. Ped Derm. 2020 May 6. doi: 10.1111/pde.14210; Andina D et al. Ped Derm. 2020 May 9. doi: 10.1111/pde.14215.

Two and elsewhere.

These symptoms should be considered a sign of infection with the virus, but the symptoms themselves typically don’t require treatment, according to the authors of the two new reports, from hospitals in Milan and Madrid, published in Pediatric Dermatology.

In the first study, Cristiana Colonna, MD, and colleagues at Hospital Maggiore Polyclinic in Milan described four cases of chilblain-like lesions in children ages 5-11 years with mild COVID-19 symptoms.

In the second, David Andina, MD, and colleagues in the ED and the departments of dermatology and pathology at the Child Jesus University Children’s Hospital in Madrid published a retrospective study of 22 cases in children and adolescents ages 6-17 years who reported to the hospital ED from April 6 to 17, the peak of the pandemic in Madrid.

In all four of the Milan cases, the skin lesions appeared several days after the onset of COVID-19 symptoms, although all four patients initially tested negative for COVID-19. However, Dr. Colonna and colleagues wrote that, “given the fact that the sensitivity and specificity of both nasopharyngeal swabs and antibody tests for COVID-19 (when available) are not 100% reliable, the question of the origin of these strange chilblain-like lesions is still elusive.” Until further studies are available, they emphasized that clinicians should be “alert to the presentation of chilblain-like findings” in children with mild symptoms “as a possible sign of COVID-19 infection.”

All the patients had lesions on their feet or toes, and a 5-year-old boy also had lesions on the right hand. One patient, an 11-year-old girl, had a biopsy that revealed dense lymphocytic perivascular cuffing and periadnexal infiltration.

“The finding of an elevated d-dimer in one of our patients, along with the clinical features suggestive of a vasoocclusive phenomenon, supports consideration of laboratory evaluation for coagulation defects in asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic children with acrovasculitis-like findings,” Dr. Colonna and colleagues wrote. None of the four cases in Milan required treatment, with three cases resolving within 5 days.

Like the Milan cases, all 22 patients in the Madrid series had foot or toe lesions and three had lesions on the fingers. This larger series also reported more detailed symptoms about the lesions: pruritus in nine patients (41%) and mild pain in seven (32%). A total of 10 patients had systemic symptoms of COVID-19, predominantly cough and rhinorrhea in 9 patients (41%), but 2 (9%) had abdominal pain and diarrhea. These symptoms, the authors said, appeared a median of 14 days (range, 1-28 days) before they developed chilblains.

A total of 19 patients were tested for COVID-19, but only 1 was positive.

This retrospective study also included contact information, with one patient having household contact with a single confirmed case of COVID-19; 12 patients recalled household contact who were considered probable cases of COVID-19, with respiratory symptoms.

Skin biopsies were obtained from the acral lesions in six patients, all showing similar results, although with varying degrees of intensity. All biopsies showed features of lymphocytic vasculopathy. Some cases showed mild dermal and perieccrine mucinosis, lymphocytic eccrine hidradenitis, vascular ectasia, red cell extravasation and focal thrombosis described as “mostly confined to scattered papillary dermal capillaries, but also in vessels of the reticular dermis.”

The only treatments Dr. Andina and colleagues reported were oral analgesics for pain and oral antihistamines for pruritus when needed. One patient was given topical corticosteroids and another a short course of oral steroids, both for erythema multiforme.

Dr. Andina and colleagues wrote that the skin lesions in these patients “were unequivocally categorized as chilblains, both clinically and histopathologically,” and, after 7-10 days, began to fade. None of the patients had complications, and had an “excellent outcome,” they noted.

Dr. Colonna and colleagues had no conflicts of interest to declare. Dr. Andina and colleagues provided no disclosure statement.

SOURCES: Colonna C et al. Ped Derm. 2020 May 6. doi: 10.1111/pde.14210; Andina D et al. Ped Derm. 2020 May 9. doi: 10.1111/pde.14215.

FROM PEDIATRIC DERMATOLOGY

School intervention on mental illness stigma boosts treatment-seeking

A school curriculum–based intervention aimed at reducing the stigma of mental illness was associated with a nearly fourfold increase in the likelihood of youth with significant symptoms seeking treatment.

Writing in Pediatrics, researchers reported the outcome of a 2-year, longitudinal, cluster-randomized trial involving 416 students in sixth-grade classes in 14 schools across Texas.

The intervention was a school-based curriculum program called Eliminating the Stigma of Differences (ESD); a 3-hour, three-module curriculum program delivered over 1 week, which contained a mix of teaching, group discussion, and homework exercises.

One module explored the idea of difference; the definition, causes and consequences of stigma; ways to end stigma; and the description, causes and treatments of mental illness as well as the barriers to seeking help. The other two modules explored specific mental illnesses in more detail but with content designed to stimulate empathy.

The study compared this with two other interventions – in-class presentations and discussions led by two young adults with a history of mental illness; or exposure to anti-stigma printed materials – and a no-intervention control.

The study found that involvement with the curriculum program was associated with a significant and sustained increase in knowledge of and attitudes to mental illness compared with the control and other interventions, and with significant decreases in social distance, which measures the extent to which children are unwilling to interact with someone who is identified as having a mental illness. This association was seen even after the researchers controlled for other factors such as a participants’ knowledge of or attitudes toward mental illness before the intervention, their age, sex, race or ethnicity, or their parents’ educational level.

“Our study, in combination with other studies, suggests strongly that youth can be positively influenced at a relatively young age, fostering changes in mental health attitudes and behaviors that last, as our study has shown, for at least 2 years,” wrote Bruce G. Link, PhD, of the School of Public Policy at the University of California, Riverside, and coauthors.

The study also found that among youth who were experiencing a high level of symptoms of mental illness, the curriculum-based intervention was associated with nearly fourfold higher odds of seeking treatment (odd ratio 3.9, P < .05), after adjustment for similar covariates.

The authors looked separately at whether this self-reported treatment-seeking was the first time that students had sought treatment, a continuation of treatment seeking, or a return to it. All three showed similar odds ratios but small sample sizes meant they did not reach statistical significance.

“We do know that negative attitudes toward mental illnesses and the exceptionally large percentage of people who experience but do not receive treatment for such illnesses are problems that have been with us for a long time,” Dr. Link and associates said. “Interventions such as ESD represent a partial but positive response to this public mental health challenge.”

The intervention didn’t lead to a significant increase in treatment-seeking behavior among students with low levels of mental illness symptoms.

There were no significant differences in the effectiveness of the intervention across race or ethnicity, sex, education level of caregivers, or the baseline attitudes toward mental illness. The only exception was seen with Latino youth, where the intervention was not associated with a decrease in social distancing.

Contact intervention, in which two young people with a history of mental illness came to talk to classes and participate in discussions, was not associated with any significant changes in attitudes.

“A potential explanation is that contact is not as effective in youth, a possibility that is supported by a meta-analysis showing diminished effects of contact compared with educational interventions in adolescents,” Dr. Link and associates said.

In an accompanying editorial, Nathaniel Beers, MD, of Children’s National Hospital in Washington, and Dr. Shashank V. Joshi, MD, of Stanford (Calif.) University, wrote that more than one-fifth of children and youth in the United States are diagnosed with behavioral health needs before they reach the age of 18, but the perception of stigma can make families reluctant to access treatment.

“Previous research has highlighted the importance of stigma reduction in school-based settings as a crucial component in changing the social norms about seeking help among diverse youth populations,” they said. Reducing stigma also can reduce detrimental outcomes from social isolation and bullying.

Dr. Beers and Dr. Joshi noted that school-based interventions can have a substantial and lasting effect, with the benefit of influencing parents and staff in addition to students.

“Combined with screening and improved access to school-based mental health services, this curriculum could add a critical component to addressing the mental health needs of children and youth in the United States,” they concluded.

The study was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health and National Institutes of Health. The authors said they had no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Beers and Dr. Joshi received no external funding, and they said they had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCES: Link B. et al. Pediatrics 2020, May 20. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-0780; Beers N and Joshi SV. Pediatrics. 2020, May 20. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-0127.

A school curriculum–based intervention aimed at reducing the stigma of mental illness was associated with a nearly fourfold increase in the likelihood of youth with significant symptoms seeking treatment.

Writing in Pediatrics, researchers reported the outcome of a 2-year, longitudinal, cluster-randomized trial involving 416 students in sixth-grade classes in 14 schools across Texas.

The intervention was a school-based curriculum program called Eliminating the Stigma of Differences (ESD); a 3-hour, three-module curriculum program delivered over 1 week, which contained a mix of teaching, group discussion, and homework exercises.

One module explored the idea of difference; the definition, causes and consequences of stigma; ways to end stigma; and the description, causes and treatments of mental illness as well as the barriers to seeking help. The other two modules explored specific mental illnesses in more detail but with content designed to stimulate empathy.

The study compared this with two other interventions – in-class presentations and discussions led by two young adults with a history of mental illness; or exposure to anti-stigma printed materials – and a no-intervention control.

The study found that involvement with the curriculum program was associated with a significant and sustained increase in knowledge of and attitudes to mental illness compared with the control and other interventions, and with significant decreases in social distance, which measures the extent to which children are unwilling to interact with someone who is identified as having a mental illness. This association was seen even after the researchers controlled for other factors such as a participants’ knowledge of or attitudes toward mental illness before the intervention, their age, sex, race or ethnicity, or their parents’ educational level.

“Our study, in combination with other studies, suggests strongly that youth can be positively influenced at a relatively young age, fostering changes in mental health attitudes and behaviors that last, as our study has shown, for at least 2 years,” wrote Bruce G. Link, PhD, of the School of Public Policy at the University of California, Riverside, and coauthors.

The study also found that among youth who were experiencing a high level of symptoms of mental illness, the curriculum-based intervention was associated with nearly fourfold higher odds of seeking treatment (odd ratio 3.9, P < .05), after adjustment for similar covariates.

The authors looked separately at whether this self-reported treatment-seeking was the first time that students had sought treatment, a continuation of treatment seeking, or a return to it. All three showed similar odds ratios but small sample sizes meant they did not reach statistical significance.

“We do know that negative attitudes toward mental illnesses and the exceptionally large percentage of people who experience but do not receive treatment for such illnesses are problems that have been with us for a long time,” Dr. Link and associates said. “Interventions such as ESD represent a partial but positive response to this public mental health challenge.”

The intervention didn’t lead to a significant increase in treatment-seeking behavior among students with low levels of mental illness symptoms.

There were no significant differences in the effectiveness of the intervention across race or ethnicity, sex, education level of caregivers, or the baseline attitudes toward mental illness. The only exception was seen with Latino youth, where the intervention was not associated with a decrease in social distancing.

Contact intervention, in which two young people with a history of mental illness came to talk to classes and participate in discussions, was not associated with any significant changes in attitudes.

“A potential explanation is that contact is not as effective in youth, a possibility that is supported by a meta-analysis showing diminished effects of contact compared with educational interventions in adolescents,” Dr. Link and associates said.

In an accompanying editorial, Nathaniel Beers, MD, of Children’s National Hospital in Washington, and Dr. Shashank V. Joshi, MD, of Stanford (Calif.) University, wrote that more than one-fifth of children and youth in the United States are diagnosed with behavioral health needs before they reach the age of 18, but the perception of stigma can make families reluctant to access treatment.

“Previous research has highlighted the importance of stigma reduction in school-based settings as a crucial component in changing the social norms about seeking help among diverse youth populations,” they said. Reducing stigma also can reduce detrimental outcomes from social isolation and bullying.

Dr. Beers and Dr. Joshi noted that school-based interventions can have a substantial and lasting effect, with the benefit of influencing parents and staff in addition to students.

“Combined with screening and improved access to school-based mental health services, this curriculum could add a critical component to addressing the mental health needs of children and youth in the United States,” they concluded.

The study was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health and National Institutes of Health. The authors said they had no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Beers and Dr. Joshi received no external funding, and they said they had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCES: Link B. et al. Pediatrics 2020, May 20. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-0780; Beers N and Joshi SV. Pediatrics. 2020, May 20. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-0127.

A school curriculum–based intervention aimed at reducing the stigma of mental illness was associated with a nearly fourfold increase in the likelihood of youth with significant symptoms seeking treatment.

Writing in Pediatrics, researchers reported the outcome of a 2-year, longitudinal, cluster-randomized trial involving 416 students in sixth-grade classes in 14 schools across Texas.

The intervention was a school-based curriculum program called Eliminating the Stigma of Differences (ESD); a 3-hour, three-module curriculum program delivered over 1 week, which contained a mix of teaching, group discussion, and homework exercises.

One module explored the idea of difference; the definition, causes and consequences of stigma; ways to end stigma; and the description, causes and treatments of mental illness as well as the barriers to seeking help. The other two modules explored specific mental illnesses in more detail but with content designed to stimulate empathy.

The study compared this with two other interventions – in-class presentations and discussions led by two young adults with a history of mental illness; or exposure to anti-stigma printed materials – and a no-intervention control.

The study found that involvement with the curriculum program was associated with a significant and sustained increase in knowledge of and attitudes to mental illness compared with the control and other interventions, and with significant decreases in social distance, which measures the extent to which children are unwilling to interact with someone who is identified as having a mental illness. This association was seen even after the researchers controlled for other factors such as a participants’ knowledge of or attitudes toward mental illness before the intervention, their age, sex, race or ethnicity, or their parents’ educational level.

“Our study, in combination with other studies, suggests strongly that youth can be positively influenced at a relatively young age, fostering changes in mental health attitudes and behaviors that last, as our study has shown, for at least 2 years,” wrote Bruce G. Link, PhD, of the School of Public Policy at the University of California, Riverside, and coauthors.

The study also found that among youth who were experiencing a high level of symptoms of mental illness, the curriculum-based intervention was associated with nearly fourfold higher odds of seeking treatment (odd ratio 3.9, P < .05), after adjustment for similar covariates.

The authors looked separately at whether this self-reported treatment-seeking was the first time that students had sought treatment, a continuation of treatment seeking, or a return to it. All three showed similar odds ratios but small sample sizes meant they did not reach statistical significance.

“We do know that negative attitudes toward mental illnesses and the exceptionally large percentage of people who experience but do not receive treatment for such illnesses are problems that have been with us for a long time,” Dr. Link and associates said. “Interventions such as ESD represent a partial but positive response to this public mental health challenge.”

The intervention didn’t lead to a significant increase in treatment-seeking behavior among students with low levels of mental illness symptoms.

There were no significant differences in the effectiveness of the intervention across race or ethnicity, sex, education level of caregivers, or the baseline attitudes toward mental illness. The only exception was seen with Latino youth, where the intervention was not associated with a decrease in social distancing.

Contact intervention, in which two young people with a history of mental illness came to talk to classes and participate in discussions, was not associated with any significant changes in attitudes.

“A potential explanation is that contact is not as effective in youth, a possibility that is supported by a meta-analysis showing diminished effects of contact compared with educational interventions in adolescents,” Dr. Link and associates said.

In an accompanying editorial, Nathaniel Beers, MD, of Children’s National Hospital in Washington, and Dr. Shashank V. Joshi, MD, of Stanford (Calif.) University, wrote that more than one-fifth of children and youth in the United States are diagnosed with behavioral health needs before they reach the age of 18, but the perception of stigma can make families reluctant to access treatment.

“Previous research has highlighted the importance of stigma reduction in school-based settings as a crucial component in changing the social norms about seeking help among diverse youth populations,” they said. Reducing stigma also can reduce detrimental outcomes from social isolation and bullying.

Dr. Beers and Dr. Joshi noted that school-based interventions can have a substantial and lasting effect, with the benefit of influencing parents and staff in addition to students.

“Combined with screening and improved access to school-based mental health services, this curriculum could add a critical component to addressing the mental health needs of children and youth in the United States,” they concluded.

The study was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health and National Institutes of Health. The authors said they had no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Beers and Dr. Joshi received no external funding, and they said they had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCES: Link B. et al. Pediatrics 2020, May 20. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-0780; Beers N and Joshi SV. Pediatrics. 2020, May 20. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-0127.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Key clinical point: A curriculum-based intervention addressing stigma and mental illness had a significant impact on attitudes and treatment-seeking.

Major finding:

Study details: A longitudinal, cluster-randomized trial involving 416 students in sixth-grade classes across 14 schools.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health and National Institutes of Health. The authors said they had no relevant financial disclosures.

Source: Link B. et al. Pediatrics 2020 May 20. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-0780.

Radiation-associated childhood cancer quantified in congenital heart disease

Children with congenital heart disease exposed to low-dose ionizing radiation from cardiac procedures had a cancer risk more than triple that of pediatric congenital heart disease (CHD) patients without such exposures, according to a large Canadian nested case-control study presented at the joint scientific sessions of the American College of Cardiology and the World Heart Federation. The meeting was conducted online after its cancellation because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

This cancer risk was dose dependent. It rose stepwise with the number of cardiac procedures involving exposure to low-dose ionizing radiation (LDIR) and the total radiation dose. Moreover, roughly 80% of the cancers were of types known to be associated with radiation exposure in children, reported Elie Ganni, a medical student at McGill University, Montreal, working with MAUDE, the McGill Adult Unit for Congenital Heart Disease.

The MAUDE group previously published the first large, population-based study analyzing the association between LDIR from cardiac procedures and incident cancer in adults with CHD. The study, which included nearly 25,000 adult CHD patients aged 18-64 years with more than 250,000 person-years of follow-up, concluded that individuals with LDIR exposure from six or more cardiac procedures had a 140% greater cancer incidence than those with no or one exposure (Circulation. 2018 Mar 27;137[13]:1334-45).

Because children are considered to be more sensitive to the carcinogenic effects of LDIR than adults, the MAUDE group next did a similar study in a pediatric CHD population included in the Quebec Congenital Heart Disease Database. This nested case-control study included 232 children with CHD who were first diagnosed with cancer at a median age of 3.9 years and 8,160 pediatric CHD controls matched for gender and birth year. About 76% of cancers were diagnosed before age 7, 20% at ages 7-12 years, and the remaining 4% at ages 13-18. Hematologic malignancies accounted for 61% of the pediatric cancers, CNS cancers for another 12.5%, and thyroid cancers 6.6%; all three types of cancer are associated with radiation exposure.

After excluding all cardiac procedures involving LDIR performed within 6 months prior to cancer diagnosis, the risk of developing a pediatric cancer was 230% greater in children with LDIR exposure from cardiac procedures than in CHD patients without such exposure. For every 4 mSv in estimated LDIR exposure from cardiac procedures, the risk of cancer rose by 15.5%. In contrast, in the earlier study in adults with CHD, cancer risk climbed by 10% per 10 mSv. Patients with six or more LDIR cardiac procedures – not at all unusual in contemporary practice – were 2.4 times more likely to have cancer than those with no or one such radiation exposure.

Current ACC guidelines on radiation exposure from cardiac procedures recommend calculating an individual’s lifetime attributable cancer incidence and mortality risks, as well as adhering to the time-honored principle of ensuring that radiation exposure is as low as reasonably achievable without sacrificing quality of care.

“Our findings strongly support these ACC recommendations and moreover suggest that radiation surveillance for patients with congenital heart disease should be considered using radiation badges. Also, cancer surveillance guidelines should be considered for CHD patients exposed to LDIR,” Mr. Ganni said.

These suggestions for creation of patient radiation passports and cancer surveillance guidelines take on greater weight in light of two trends: the increasing life expectancy of children with CHD during the past 3 decades as a result of procedural advances that entail LDIR exposure, mostly for imaging, and the growing number of such procedures performed per patient earlier and earlier in life.

He and the MAUDE group plan to confirm their latest findings in other, larger data sets and hope to identify threshold effects for LDIR for specific cancers, with hematologic malignancies as the top priority.

Mr. Ganni reported having no financial conflicts regarding his study, funded by the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada, the Quebec Foundation for Health Research, and the Canadian Institutes for Health Research.

Children with congenital heart disease exposed to low-dose ionizing radiation from cardiac procedures had a cancer risk more than triple that of pediatric congenital heart disease (CHD) patients without such exposures, according to a large Canadian nested case-control study presented at the joint scientific sessions of the American College of Cardiology and the World Heart Federation. The meeting was conducted online after its cancellation because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

This cancer risk was dose dependent. It rose stepwise with the number of cardiac procedures involving exposure to low-dose ionizing radiation (LDIR) and the total radiation dose. Moreover, roughly 80% of the cancers were of types known to be associated with radiation exposure in children, reported Elie Ganni, a medical student at McGill University, Montreal, working with MAUDE, the McGill Adult Unit for Congenital Heart Disease.

The MAUDE group previously published the first large, population-based study analyzing the association between LDIR from cardiac procedures and incident cancer in adults with CHD. The study, which included nearly 25,000 adult CHD patients aged 18-64 years with more than 250,000 person-years of follow-up, concluded that individuals with LDIR exposure from six or more cardiac procedures had a 140% greater cancer incidence than those with no or one exposure (Circulation. 2018 Mar 27;137[13]:1334-45).

Because children are considered to be more sensitive to the carcinogenic effects of LDIR than adults, the MAUDE group next did a similar study in a pediatric CHD population included in the Quebec Congenital Heart Disease Database. This nested case-control study included 232 children with CHD who were first diagnosed with cancer at a median age of 3.9 years and 8,160 pediatric CHD controls matched for gender and birth year. About 76% of cancers were diagnosed before age 7, 20% at ages 7-12 years, and the remaining 4% at ages 13-18. Hematologic malignancies accounted for 61% of the pediatric cancers, CNS cancers for another 12.5%, and thyroid cancers 6.6%; all three types of cancer are associated with radiation exposure.

After excluding all cardiac procedures involving LDIR performed within 6 months prior to cancer diagnosis, the risk of developing a pediatric cancer was 230% greater in children with LDIR exposure from cardiac procedures than in CHD patients without such exposure. For every 4 mSv in estimated LDIR exposure from cardiac procedures, the risk of cancer rose by 15.5%. In contrast, in the earlier study in adults with CHD, cancer risk climbed by 10% per 10 mSv. Patients with six or more LDIR cardiac procedures – not at all unusual in contemporary practice – were 2.4 times more likely to have cancer than those with no or one such radiation exposure.

Current ACC guidelines on radiation exposure from cardiac procedures recommend calculating an individual’s lifetime attributable cancer incidence and mortality risks, as well as adhering to the time-honored principle of ensuring that radiation exposure is as low as reasonably achievable without sacrificing quality of care.

“Our findings strongly support these ACC recommendations and moreover suggest that radiation surveillance for patients with congenital heart disease should be considered using radiation badges. Also, cancer surveillance guidelines should be considered for CHD patients exposed to LDIR,” Mr. Ganni said.

These suggestions for creation of patient radiation passports and cancer surveillance guidelines take on greater weight in light of two trends: the increasing life expectancy of children with CHD during the past 3 decades as a result of procedural advances that entail LDIR exposure, mostly for imaging, and the growing number of such procedures performed per patient earlier and earlier in life.

He and the MAUDE group plan to confirm their latest findings in other, larger data sets and hope to identify threshold effects for LDIR for specific cancers, with hematologic malignancies as the top priority.

Mr. Ganni reported having no financial conflicts regarding his study, funded by the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada, the Quebec Foundation for Health Research, and the Canadian Institutes for Health Research.

Children with congenital heart disease exposed to low-dose ionizing radiation from cardiac procedures had a cancer risk more than triple that of pediatric congenital heart disease (CHD) patients without such exposures, according to a large Canadian nested case-control study presented at the joint scientific sessions of the American College of Cardiology and the World Heart Federation. The meeting was conducted online after its cancellation because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

This cancer risk was dose dependent. It rose stepwise with the number of cardiac procedures involving exposure to low-dose ionizing radiation (LDIR) and the total radiation dose. Moreover, roughly 80% of the cancers were of types known to be associated with radiation exposure in children, reported Elie Ganni, a medical student at McGill University, Montreal, working with MAUDE, the McGill Adult Unit for Congenital Heart Disease.

The MAUDE group previously published the first large, population-based study analyzing the association between LDIR from cardiac procedures and incident cancer in adults with CHD. The study, which included nearly 25,000 adult CHD patients aged 18-64 years with more than 250,000 person-years of follow-up, concluded that individuals with LDIR exposure from six or more cardiac procedures had a 140% greater cancer incidence than those with no or one exposure (Circulation. 2018 Mar 27;137[13]:1334-45).

Because children are considered to be more sensitive to the carcinogenic effects of LDIR than adults, the MAUDE group next did a similar study in a pediatric CHD population included in the Quebec Congenital Heart Disease Database. This nested case-control study included 232 children with CHD who were first diagnosed with cancer at a median age of 3.9 years and 8,160 pediatric CHD controls matched for gender and birth year. About 76% of cancers were diagnosed before age 7, 20% at ages 7-12 years, and the remaining 4% at ages 13-18. Hematologic malignancies accounted for 61% of the pediatric cancers, CNS cancers for another 12.5%, and thyroid cancers 6.6%; all three types of cancer are associated with radiation exposure.

After excluding all cardiac procedures involving LDIR performed within 6 months prior to cancer diagnosis, the risk of developing a pediatric cancer was 230% greater in children with LDIR exposure from cardiac procedures than in CHD patients without such exposure. For every 4 mSv in estimated LDIR exposure from cardiac procedures, the risk of cancer rose by 15.5%. In contrast, in the earlier study in adults with CHD, cancer risk climbed by 10% per 10 mSv. Patients with six or more LDIR cardiac procedures – not at all unusual in contemporary practice – were 2.4 times more likely to have cancer than those with no or one such radiation exposure.

Current ACC guidelines on radiation exposure from cardiac procedures recommend calculating an individual’s lifetime attributable cancer incidence and mortality risks, as well as adhering to the time-honored principle of ensuring that radiation exposure is as low as reasonably achievable without sacrificing quality of care.

“Our findings strongly support these ACC recommendations and moreover suggest that radiation surveillance for patients with congenital heart disease should be considered using radiation badges. Also, cancer surveillance guidelines should be considered for CHD patients exposed to LDIR,” Mr. Ganni said.

These suggestions for creation of patient radiation passports and cancer surveillance guidelines take on greater weight in light of two trends: the increasing life expectancy of children with CHD during the past 3 decades as a result of procedural advances that entail LDIR exposure, mostly for imaging, and the growing number of such procedures performed per patient earlier and earlier in life.

He and the MAUDE group plan to confirm their latest findings in other, larger data sets and hope to identify threshold effects for LDIR for specific cancers, with hematologic malignancies as the top priority.

Mr. Ganni reported having no financial conflicts regarding his study, funded by the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada, the Quebec Foundation for Health Research, and the Canadian Institutes for Health Research.

FROM ACC 2020

Vitamin D intake among U.S. infants has not improved, despite guidance

with breastfed infants less likely to have adequate levels than formula-fed infants, according to results of a study.

The American Association of Pediatrics has recommended since 2008 that breastfeeding babies under 1 year of age receive 400 IU of vitamin D supplementation daily, usually in the form of drops, to prevent rickets. For formula-fed infants, the AAP recommends that infants be fed one liter of formula daily, as formulas must contain 400 IU of vitamin D per liter.

A study looking at caregiver-reported dietary data through 2012 suggested that the guideline was having little impact, with only 27% of U.S. infants considered to be getting adequate vitamin D. The same researchers have now updated those findings with data through 2016 to report virtually no improvement over time. For their research, published in Pediatrics, Alan E. Simon, MD, of the National Institutes of Health in Rockville, Md., and Katherine A. Ahrens, PhD, of the University of Southern Maine in Portland, analyzed data for 1,435 infants aged 0-11 months. All data were recorded during 2009-2016 as part of the ongoing National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES).

Overall, 27% of infants in the study were considered likely to meet the guidelines. Among nonbreastfeeding infants, 31% were deemed to have adequate levels, compared with 21% of breastfeeding infants (P less than .01).

Parents’ income and education affected infants’ likelihood of meeting guidelines. Breastfeeding infants in families with incomes above 400% of the federal poverty level were twice as likely to meet guidelines (31% vs. 14%-16% for lower income brackets, P less than .05). Babies from families whose head of household had a college degree had a 26% likelihood of having enough vitamin D, compared with less than 11% of those in whose parents had less than a high school education (P less than .05). Babies from families with private insurance also had a better chance of meeting guidelines, compared with those with public insurance (24% vs. 13%; P less than .05).

Ethnicity was seen as affecting vitamin D intake only insofar as some groups had more formula use than breastfeeding. The only ethnic or racial subgroup in the study that saw more than 40% of infants likely to meet guidelines was nonbreastfeeding infants of Asian, American Indian, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, or multiracial parentage, with 46% considered to have adequate vitamin D levels. This group makes up 6% of the infant population in the United States.

“Reasons for low rates of meeting guidelines in the United States and little improvement over time are not fully known,” Dr. Simon and Dr. Ahrens wrote in their analysis. “One factor may be that the impact of low vitamin D in infancy is not highly visible to physicians because rickets is an uncommon diagnosis in the United States.” They noted that recent studies from Canada, where public health officials have done more to promote supplementation, have shown rates of adequate vitamin D in breastfeeding babies to be as high as 90%.

The researchers listed among limitations of their study the fact that the data source, NHANES, captured nutrition information only for the previous 24 hours; that it relied on parental report, and did not confirm serum levels of vitamin D; and that it was possible that cow’s milk – which is not recommended before age 1 but frequently given to older infants anyway – could be a hidden source of vitamin D that was not taken into consideration.

In an editorial comment, Jaspreet Loyal, MD, and Annette Cameron, MD, of Yale University in New Haven, Conn., faulted “a combination of inconsistent prescribing by clinicians and poor adherence to the use of a supplement by parents of infants … further complicated by a lack of awareness of the consequences of vitamin D deficiency in infants among the public” for the low adherence to guidelines in the United States, compared with other countries.

Also, the editorialists noted, the dropper used to administer liquid supplements has been associated with “inconsistent precision” and concerns about infants gagging on the liquid. More research is needed to better understand “prescribing patterns, barriers to adherence by parents of infants, and alternate strategies for vitamin D supplementation to inform novel public health programs in the United States,” they wrote.

The National Institutes of Health funded the study, and Dr. Ahrens is supported by a faculty development grant from the Maine Economic Improvement Fund. The researchers declared no conflicts of interest. Dr. Loyal and Dr. Cameron disclosed no funding and no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Simon AE and Ahrens KA. Pediatrics 2020 May. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-3574; Loyal J and Cameron A. Pediatrics. 2020 May. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-0504.

with breastfed infants less likely to have adequate levels than formula-fed infants, according to results of a study.

The American Association of Pediatrics has recommended since 2008 that breastfeeding babies under 1 year of age receive 400 IU of vitamin D supplementation daily, usually in the form of drops, to prevent rickets. For formula-fed infants, the AAP recommends that infants be fed one liter of formula daily, as formulas must contain 400 IU of vitamin D per liter.

A study looking at caregiver-reported dietary data through 2012 suggested that the guideline was having little impact, with only 27% of U.S. infants considered to be getting adequate vitamin D. The same researchers have now updated those findings with data through 2016 to report virtually no improvement over time. For their research, published in Pediatrics, Alan E. Simon, MD, of the National Institutes of Health in Rockville, Md., and Katherine A. Ahrens, PhD, of the University of Southern Maine in Portland, analyzed data for 1,435 infants aged 0-11 months. All data were recorded during 2009-2016 as part of the ongoing National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES).

Overall, 27% of infants in the study were considered likely to meet the guidelines. Among nonbreastfeeding infants, 31% were deemed to have adequate levels, compared with 21% of breastfeeding infants (P less than .01).

Parents’ income and education affected infants’ likelihood of meeting guidelines. Breastfeeding infants in families with incomes above 400% of the federal poverty level were twice as likely to meet guidelines (31% vs. 14%-16% for lower income brackets, P less than .05). Babies from families whose head of household had a college degree had a 26% likelihood of having enough vitamin D, compared with less than 11% of those in whose parents had less than a high school education (P less than .05). Babies from families with private insurance also had a better chance of meeting guidelines, compared with those with public insurance (24% vs. 13%; P less than .05).

Ethnicity was seen as affecting vitamin D intake only insofar as some groups had more formula use than breastfeeding. The only ethnic or racial subgroup in the study that saw more than 40% of infants likely to meet guidelines was nonbreastfeeding infants of Asian, American Indian, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, or multiracial parentage, with 46% considered to have adequate vitamin D levels. This group makes up 6% of the infant population in the United States.

“Reasons for low rates of meeting guidelines in the United States and little improvement over time are not fully known,” Dr. Simon and Dr. Ahrens wrote in their analysis. “One factor may be that the impact of low vitamin D in infancy is not highly visible to physicians because rickets is an uncommon diagnosis in the United States.” They noted that recent studies from Canada, where public health officials have done more to promote supplementation, have shown rates of adequate vitamin D in breastfeeding babies to be as high as 90%.

The researchers listed among limitations of their study the fact that the data source, NHANES, captured nutrition information only for the previous 24 hours; that it relied on parental report, and did not confirm serum levels of vitamin D; and that it was possible that cow’s milk – which is not recommended before age 1 but frequently given to older infants anyway – could be a hidden source of vitamin D that was not taken into consideration.

In an editorial comment, Jaspreet Loyal, MD, and Annette Cameron, MD, of Yale University in New Haven, Conn., faulted “a combination of inconsistent prescribing by clinicians and poor adherence to the use of a supplement by parents of infants … further complicated by a lack of awareness of the consequences of vitamin D deficiency in infants among the public” for the low adherence to guidelines in the United States, compared with other countries.

Also, the editorialists noted, the dropper used to administer liquid supplements has been associated with “inconsistent precision” and concerns about infants gagging on the liquid. More research is needed to better understand “prescribing patterns, barriers to adherence by parents of infants, and alternate strategies for vitamin D supplementation to inform novel public health programs in the United States,” they wrote.

The National Institutes of Health funded the study, and Dr. Ahrens is supported by a faculty development grant from the Maine Economic Improvement Fund. The researchers declared no conflicts of interest. Dr. Loyal and Dr. Cameron disclosed no funding and no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Simon AE and Ahrens KA. Pediatrics 2020 May. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-3574; Loyal J and Cameron A. Pediatrics. 2020 May. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-0504.

with breastfed infants less likely to have adequate levels than formula-fed infants, according to results of a study.

The American Association of Pediatrics has recommended since 2008 that breastfeeding babies under 1 year of age receive 400 IU of vitamin D supplementation daily, usually in the form of drops, to prevent rickets. For formula-fed infants, the AAP recommends that infants be fed one liter of formula daily, as formulas must contain 400 IU of vitamin D per liter.

A study looking at caregiver-reported dietary data through 2012 suggested that the guideline was having little impact, with only 27% of U.S. infants considered to be getting adequate vitamin D. The same researchers have now updated those findings with data through 2016 to report virtually no improvement over time. For their research, published in Pediatrics, Alan E. Simon, MD, of the National Institutes of Health in Rockville, Md., and Katherine A. Ahrens, PhD, of the University of Southern Maine in Portland, analyzed data for 1,435 infants aged 0-11 months. All data were recorded during 2009-2016 as part of the ongoing National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES).

Overall, 27% of infants in the study were considered likely to meet the guidelines. Among nonbreastfeeding infants, 31% were deemed to have adequate levels, compared with 21% of breastfeeding infants (P less than .01).

Parents’ income and education affected infants’ likelihood of meeting guidelines. Breastfeeding infants in families with incomes above 400% of the federal poverty level were twice as likely to meet guidelines (31% vs. 14%-16% for lower income brackets, P less than .05). Babies from families whose head of household had a college degree had a 26% likelihood of having enough vitamin D, compared with less than 11% of those in whose parents had less than a high school education (P less than .05). Babies from families with private insurance also had a better chance of meeting guidelines, compared with those with public insurance (24% vs. 13%; P less than .05).

Ethnicity was seen as affecting vitamin D intake only insofar as some groups had more formula use than breastfeeding. The only ethnic or racial subgroup in the study that saw more than 40% of infants likely to meet guidelines was nonbreastfeeding infants of Asian, American Indian, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, or multiracial parentage, with 46% considered to have adequate vitamin D levels. This group makes up 6% of the infant population in the United States.

“Reasons for low rates of meeting guidelines in the United States and little improvement over time are not fully known,” Dr. Simon and Dr. Ahrens wrote in their analysis. “One factor may be that the impact of low vitamin D in infancy is not highly visible to physicians because rickets is an uncommon diagnosis in the United States.” They noted that recent studies from Canada, where public health officials have done more to promote supplementation, have shown rates of adequate vitamin D in breastfeeding babies to be as high as 90%.

The researchers listed among limitations of their study the fact that the data source, NHANES, captured nutrition information only for the previous 24 hours; that it relied on parental report, and did not confirm serum levels of vitamin D; and that it was possible that cow’s milk – which is not recommended before age 1 but frequently given to older infants anyway – could be a hidden source of vitamin D that was not taken into consideration.

In an editorial comment, Jaspreet Loyal, MD, and Annette Cameron, MD, of Yale University in New Haven, Conn., faulted “a combination of inconsistent prescribing by clinicians and poor adherence to the use of a supplement by parents of infants … further complicated by a lack of awareness of the consequences of vitamin D deficiency in infants among the public” for the low adherence to guidelines in the United States, compared with other countries.

Also, the editorialists noted, the dropper used to administer liquid supplements has been associated with “inconsistent precision” and concerns about infants gagging on the liquid. More research is needed to better understand “prescribing patterns, barriers to adherence by parents of infants, and alternate strategies for vitamin D supplementation to inform novel public health programs in the United States,” they wrote.

The National Institutes of Health funded the study, and Dr. Ahrens is supported by a faculty development grant from the Maine Economic Improvement Fund. The researchers declared no conflicts of interest. Dr. Loyal and Dr. Cameron disclosed no funding and no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Simon AE and Ahrens KA. Pediatrics 2020 May. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-3574; Loyal J and Cameron A. Pediatrics. 2020 May. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-0504.

FROM PEDIATRICS

COVID-19 in kids: Severe illness most common in infants, teens

Children and young adults in all age groups can develop severe illness after SARS-CoV-2 infection, but the oldest and youngest appear most likely to be hospitalized and possibly critically ill, based on data from a retrospective cohort study of 177 pediatric patients seen at a single center.

“Although children and young adults clearly are susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 infection, attention has focused primarily on their potential role in influencing spread and community transmission rather than the potential severity of infection in children and young adults themselves,” wrote Roberta L. DeBiasi, MD, chief of the division of pediatric infectious diseases at Children’s National Hospital, Washington, and colleagues.

In a study published in the Journal of Pediatrics, the researchers reviewed data from 44 hospitalized and 133 non-hospitalized children and young adults infected with SARS-CoV-2. Of the 44 hospitalized patients, 35 were noncritically ill and 9 were critically ill. The study population ranged from 0.1-34 years of age, with a median of 10 years, which was similar between hospitalized and nonhospitalized patients. However, the median age of critically ill patients was significantly higher, compared with noncritically ill patients (17 years vs. 4 years). All age groups were represented in all cohorts. “However, we noted a bimodal distribution of patients less than 1 year of age and patients greater than 15 years of age representing the largest proportion of patients within the SARS-CoV-2–infected hospitalized and critically ill cohorts,” the researchers noted. Children less than 1 year and adolescents/young adults over 15 years each represented 32% of the 44 hospitalized patients.

Overall, 39% of the 177 patients had underlying medical conditions, the most frequent of which was asthma (20%), which was not significantly more common between hospitalized/nonhospitalized patients or critically ill/noncritically ill patients. Patients also presented with neurologic conditions (6%), diabetes (3%), obesity (2%), cardiac conditions (3%), hematologic conditions (3%) and oncologic conditions (1%). Underlying conditions occurred more commonly in the hospitalized cohort (63%) than in the nonhospitalized cohort (32%).

Neurologic disorders, cardiac conditions, hematologic conditions, and oncologic conditions were significantly more common in hospitalized patients, but not significantly more common among those critically ill versus noncritically ill.

About 76% of the patients presented with respiratory symptoms including rhinorrhea, congestion, sore throat, cough, or shortness of breath – with or without fever; 66% had fevers; and 48% had both respiratory symptoms and fever. Shortness of breath was significantly more common among hospitalized patients versus nonhospitalized patients (26% vs. 12%), but less severe respiratory symptoms were significantly more common among nonhospitalized patients, the researchers noted.

Other symptoms – such as diarrhea, vomiting, chest pain, and loss of sense or smell occurred in a small percentage of patients – but were not more likely to occur in any of the cohorts.

Among the critically ill patients, eight of nine needed some level of respiratory support, and four were on ventilators.

“One patient had features consistent with the recently emerged Kawasaki disease–like presentation with hyperinflammatory state, hypotension, and profound myocardial depression,” Dr. DiBiasi and associates noted.

The researchers found coinfection with routine coronavirus, respiratory syncytial virus, or rhinovirus/enterovirus in 4 of 63 (6%) patients, but the clinical impact of these coinfections are unclear.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the retrospective design and the ongoing transmission of COVID-19 in the Washington area, the researchers noted. “One potential bias of this study is our regional role in providing critical care for young adults age 21-35 years with COVID-19.” In addition, “we plan to address the role of race and ethnicity after validation of current administrative data and have elected to defer this analysis until completed.”

“Our findings highlight the potential for severe disease in this age group and inform other regions to anticipate and prepare their COVID-19 response to include a significant burden of hospitalized and critically ill children and young adults. As SARS-CoV-2 spreads within the United States, regional differences may be apparent based on virus and host factors that are yet to be identified,” Dr. DeBiasi and colleagues concluded.

Robin Steinhorn, MD, serves as an associate editor for the Journal of Pediatrics. The other researchers declared no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: DeBiasi RL et al. J Pediatr. 2020 May 6. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.05.007.

This article was updated 5/19/20.

Children and young adults in all age groups can develop severe illness after SARS-CoV-2 infection, but the oldest and youngest appear most likely to be hospitalized and possibly critically ill, based on data from a retrospective cohort study of 177 pediatric patients seen at a single center.

“Although children and young adults clearly are susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 infection, attention has focused primarily on their potential role in influencing spread and community transmission rather than the potential severity of infection in children and young adults themselves,” wrote Roberta L. DeBiasi, MD, chief of the division of pediatric infectious diseases at Children’s National Hospital, Washington, and colleagues.

In a study published in the Journal of Pediatrics, the researchers reviewed data from 44 hospitalized and 133 non-hospitalized children and young adults infected with SARS-CoV-2. Of the 44 hospitalized patients, 35 were noncritically ill and 9 were critically ill. The study population ranged from 0.1-34 years of age, with a median of 10 years, which was similar between hospitalized and nonhospitalized patients. However, the median age of critically ill patients was significantly higher, compared with noncritically ill patients (17 years vs. 4 years). All age groups were represented in all cohorts. “However, we noted a bimodal distribution of patients less than 1 year of age and patients greater than 15 years of age representing the largest proportion of patients within the SARS-CoV-2–infected hospitalized and critically ill cohorts,” the researchers noted. Children less than 1 year and adolescents/young adults over 15 years each represented 32% of the 44 hospitalized patients.

Overall, 39% of the 177 patients had underlying medical conditions, the most frequent of which was asthma (20%), which was not significantly more common between hospitalized/nonhospitalized patients or critically ill/noncritically ill patients. Patients also presented with neurologic conditions (6%), diabetes (3%), obesity (2%), cardiac conditions (3%), hematologic conditions (3%) and oncologic conditions (1%). Underlying conditions occurred more commonly in the hospitalized cohort (63%) than in the nonhospitalized cohort (32%).

Neurologic disorders, cardiac conditions, hematologic conditions, and oncologic conditions were significantly more common in hospitalized patients, but not significantly more common among those critically ill versus noncritically ill.

About 76% of the patients presented with respiratory symptoms including rhinorrhea, congestion, sore throat, cough, or shortness of breath – with or without fever; 66% had fevers; and 48% had both respiratory symptoms and fever. Shortness of breath was significantly more common among hospitalized patients versus nonhospitalized patients (26% vs. 12%), but less severe respiratory symptoms were significantly more common among nonhospitalized patients, the researchers noted.

Other symptoms – such as diarrhea, vomiting, chest pain, and loss of sense or smell occurred in a small percentage of patients – but were not more likely to occur in any of the cohorts.

Among the critically ill patients, eight of nine needed some level of respiratory support, and four were on ventilators.

“One patient had features consistent with the recently emerged Kawasaki disease–like presentation with hyperinflammatory state, hypotension, and profound myocardial depression,” Dr. DiBiasi and associates noted.

The researchers found coinfection with routine coronavirus, respiratory syncytial virus, or rhinovirus/enterovirus in 4 of 63 (6%) patients, but the clinical impact of these coinfections are unclear.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the retrospective design and the ongoing transmission of COVID-19 in the Washington area, the researchers noted. “One potential bias of this study is our regional role in providing critical care for young adults age 21-35 years with COVID-19.” In addition, “we plan to address the role of race and ethnicity after validation of current administrative data and have elected to defer this analysis until completed.”

“Our findings highlight the potential for severe disease in this age group and inform other regions to anticipate and prepare their COVID-19 response to include a significant burden of hospitalized and critically ill children and young adults. As SARS-CoV-2 spreads within the United States, regional differences may be apparent based on virus and host factors that are yet to be identified,” Dr. DeBiasi and colleagues concluded.

Robin Steinhorn, MD, serves as an associate editor for the Journal of Pediatrics. The other researchers declared no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: DeBiasi RL et al. J Pediatr. 2020 May 6. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.05.007.

This article was updated 5/19/20.

Children and young adults in all age groups can develop severe illness after SARS-CoV-2 infection, but the oldest and youngest appear most likely to be hospitalized and possibly critically ill, based on data from a retrospective cohort study of 177 pediatric patients seen at a single center.

“Although children and young adults clearly are susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 infection, attention has focused primarily on their potential role in influencing spread and community transmission rather than the potential severity of infection in children and young adults themselves,” wrote Roberta L. DeBiasi, MD, chief of the division of pediatric infectious diseases at Children’s National Hospital, Washington, and colleagues.

In a study published in the Journal of Pediatrics, the researchers reviewed data from 44 hospitalized and 133 non-hospitalized children and young adults infected with SARS-CoV-2. Of the 44 hospitalized patients, 35 were noncritically ill and 9 were critically ill. The study population ranged from 0.1-34 years of age, with a median of 10 years, which was similar between hospitalized and nonhospitalized patients. However, the median age of critically ill patients was significantly higher, compared with noncritically ill patients (17 years vs. 4 years). All age groups were represented in all cohorts. “However, we noted a bimodal distribution of patients less than 1 year of age and patients greater than 15 years of age representing the largest proportion of patients within the SARS-CoV-2–infected hospitalized and critically ill cohorts,” the researchers noted. Children less than 1 year and adolescents/young adults over 15 years each represented 32% of the 44 hospitalized patients.

Overall, 39% of the 177 patients had underlying medical conditions, the most frequent of which was asthma (20%), which was not significantly more common between hospitalized/nonhospitalized patients or critically ill/noncritically ill patients. Patients also presented with neurologic conditions (6%), diabetes (3%), obesity (2%), cardiac conditions (3%), hematologic conditions (3%) and oncologic conditions (1%). Underlying conditions occurred more commonly in the hospitalized cohort (63%) than in the nonhospitalized cohort (32%).

Neurologic disorders, cardiac conditions, hematologic conditions, and oncologic conditions were significantly more common in hospitalized patients, but not significantly more common among those critically ill versus noncritically ill.

About 76% of the patients presented with respiratory symptoms including rhinorrhea, congestion, sore throat, cough, or shortness of breath – with or without fever; 66% had fevers; and 48% had both respiratory symptoms and fever. Shortness of breath was significantly more common among hospitalized patients versus nonhospitalized patients (26% vs. 12%), but less severe respiratory symptoms were significantly more common among nonhospitalized patients, the researchers noted.

Other symptoms – such as diarrhea, vomiting, chest pain, and loss of sense or smell occurred in a small percentage of patients – but were not more likely to occur in any of the cohorts.

Among the critically ill patients, eight of nine needed some level of respiratory support, and four were on ventilators.

“One patient had features consistent with the recently emerged Kawasaki disease–like presentation with hyperinflammatory state, hypotension, and profound myocardial depression,” Dr. DiBiasi and associates noted.

The researchers found coinfection with routine coronavirus, respiratory syncytial virus, or rhinovirus/enterovirus in 4 of 63 (6%) patients, but the clinical impact of these coinfections are unclear.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the retrospective design and the ongoing transmission of COVID-19 in the Washington area, the researchers noted. “One potential bias of this study is our regional role in providing critical care for young adults age 21-35 years with COVID-19.” In addition, “we plan to address the role of race and ethnicity after validation of current administrative data and have elected to defer this analysis until completed.”

“Our findings highlight the potential for severe disease in this age group and inform other regions to anticipate and prepare their COVID-19 response to include a significant burden of hospitalized and critically ill children and young adults. As SARS-CoV-2 spreads within the United States, regional differences may be apparent based on virus and host factors that are yet to be identified,” Dr. DeBiasi and colleagues concluded.

Robin Steinhorn, MD, serves as an associate editor for the Journal of Pediatrics. The other researchers declared no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: DeBiasi RL et al. J Pediatr. 2020 May 6. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.05.007.

This article was updated 5/19/20.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF PEDIATRICS

New research confirms the efficacy and safety of onasemnogene abeparvovec for SMA

The research was presented online as part of the 2020 AAN Science Highlights.

SMA results from a mutation in SMN1, which encodes the SMN protein necessary for motor function. Deficiency of this protein causes motor neurons to die, resulting in severe muscle weakness. At 2 years of age, untreated patients with SMA type 1 generally die or require permanent ventilation.

The Food and Drug Administration approved onasemnogene abeparvovec-xioi under the brand name Zolgensma in May 2019. The gene-replacement therapy, which is administered once intravenously, delivers a fully functional copy of human SMN1 into the target motor neuron cells. It is indicated as treatment for SMA in infants younger than 2 years of age.

Preliminary STR1VE data

Preliminary data from the phase 3 STR1VE study were scheduled to be presented at the meeting. The open-label, single-arm, single-dose study enrolled symptomatic patients with SMA type 1 (SMA1) at multiple US sites. Enrollment was completed in May 2019.

The study included 10 male patients and 12 female patients. Participants’ mean age at dosing was 3.7 months. Of 19 patients who could have reached age 13.6 months at data cutoff, 17 (89.5%) were surviving without permanent ventilation, compared with a 25% survival rate among untreated patients. One of the 19 patients died, and the event was judged to be unrelated to treatment. Another of the 19 reached a respiratory endpoint or withdrew consent.

The population’s mean baseline Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Infant Test of Neuromuscular Disorders (CHOP INTEND) score was 32. This score increased by 6.9, 11.7, and 14.3 points at months 1, 3, and 5, respectively. Half of the 22 infants sat independently for 30 or more seconds, and this milestone was achieved at a mean of 8.2 months after treatment. Five of six (83%) patients age 18 months or older sat independently for 30 or more seconds, which was one of the study’s primary endpoints. As of March 8, 2019, treatment-emergent adverse events of special interest were transient and not associated with any sequelae.

The STR1VE study was sponsored by AveXis, the maker of onasemnogene abeparvovec-xioi. Several of the investigators are employees of AveXis, and others received funding from the company.

Long-term follow-up in START

Long-term follow-up data for participants in the phase 1/2a START study also were scheduled to be presented. Patients who completed START were eligible to participate, and the trial’s primary aim was to evaluate the long-term safety of onasemnogene abeparvovec-xioi. Patients are intended to have five annual visits, followed by 10 annual phone calls, and the investigators request local physicians or neurologists to transfer patient records. Safety assessments include medical history and record review, physical examination, clinical laboratory evaluation, and pulmonary assessments. Efficacy assessments include evaluation of the maintenance of developmental milestones.

As of May 31, 2019, 13 patients in two cohorts had been enrolled and had had a baseline visit. For patients in Cohort 2, the mean age and time since dosing were 4.2 years and 3.9 years, respectively. All patients in Cohort 2 were alive and did not require permanent ventilation. Participants did not lose any developmental milestones that they had achieved at the end of START. Two patients were able to walk, and two could stand with assistance during long-term follow-up. This result suggests the durability of the treatment’s effect. No new treatment-related serious adverse events or adverse events of special interest had occurred as of March 8, 2019.

“We know from accumulating experience that treating infants by gene therapy is safe,” said Jerry R. Mendell, MD, the principal investigator and an attending neurologist at Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Columbus, Ohio. “Of the 15 patients we had in our first trial, only four adverse events related to the gene delivery were encountered, and only two of these were considered serious adverse events [i.e., liver enzymes that were 10 times greater than normal laboratory levels]. These laboratory tests occurred without accompanying clinical symptoms or signs. All were suppressed by corticosteroids and related to the liver inflammation. This pattern of safety has been seen in our very large gene therapy experience. No long-term surprises were encountered.”

The START study was sponsored by AveXis. Several of the investigators are employees of AveXis, and others received funding from the company.

Update on the SPR1NT study

Interim safety and efficacy data from the ongoing SPR1NT study, which includes presymptomatic patients, also were scheduled to be presented. The trial “was built on the basic premise that spinal motor neuron degeneration associated with SMN protein deficiency begins in utero, continues to progress rapidly during the first months of life, and is irreversible,” said Kevin Strauss, MD, medical director of the Clinic for Special Children in Strasburg, Pennsylvania. “SPR1NT leveraged the advantages conferred by carrier testing and newborn screening programs for SMA, which allowed the first 22 children enrolled to have a confirmed molecular diagnosis between 1 and 26 days of postnatal life, before the onset of dysphagia, respiratory compromise, or overt weakness.”

In this multicenter, open-label, phase 3 trial, presymptomatic patients age 6 weeks or younger who are expected to develop SMA receive onasemnogene abeparvovec-xioi once and are evaluated during 18 or 24 months. The primary outcomes are sitting for 30 or more seconds for infants with two copies of SMN2 and standing unassisted for infants with three copies of SMN2.