User login

About one in four youths prescribed stimulants also use the drugs nonmedically

SAN ANTONIO – Of 196 U.S. youth who reported use of at least one prescribed stimulant in their lifetimes, 25% also said they used the drugs nonmedically, based on a survey of children and adolescents aged 10-17 years.

Another 5% of the youth surveyed reported exclusively nonmedical use of stimulants. The survey participants lived in six U.S. cities and their outlying areas.

“Parents of both users and nonusers should warn their children of the dangers of using others’ stimulants and giving their own stimulants to others,” concluded Linda B. Cottler, PhD, MPH of the University of Florida, and colleagues.

“Physicians and pharmacists should make users and their families aware of the need to take medications as prescribed and not to share medications with others,” they wrote in their research poster at the annual meeting of the College on Problems of Drug Dependence. “Continuous monitoring of these medications in the community should be a priority.”

Though prevalence research has shown increasing stimulant misuse among youth, little data exist for younger children, the researchers noted. They therefore conducted a survey of 1,777 youth aged 10-17 years from September to October 2018 in six cities in California, Texas, and Florida, the most populous U.S. states.

The participants included youth from urban, rural, and suburban areas of Los Angeles, Dallas, Houston, Tampa, Orlando, and Miami. Trained graduate students and professional raters approached the respondents in entertainment venues and obtained assent but did not require parental consent. The respondents received $30 for completing the survey.

A total of 11.1% of respondents reporting having used prescription stimulants in their lifetime, and 7.6% had done so in the past 30 days. Just under a third of those who used stimulants (30.1%) did so for nonmedical purposes, defined as taking the stimulant nonorally (except for the patch Daytrana), getting the stimulant from someone else, or taking more of the drug than prescribed.

A quarter of the respondents who used stimulants reported both medical use and nonmedical use. And 5.1% of these youths reported only using stimulants nonmedically.

Among those with any lifetime stimulant use, 13.8% reported nonoral administration, including 9.7% who snorted or sniffed the drugs, 4.1% who smoked them, and 1.0% who injected them. Just over half (51.8%) of those reporting nonoral use had also used prescription stimulants orally.

The likelihood of using stimulants nonmedically increased with age (P less than .0001). The researchers found no significant associations between nonmedical use and geography or race/ethnicity. Among 10- to 12-year-olds, 3.1% reported only medical use of stimulants, and 0.7% (2 of 286 respondents in this age group) reported any nonmedical use of stimulants.

Of those aged 13-15 years, 2.1% reported any nonmedical stimulant use.

Nonmedical stimulant use was reported by twice as many boys (67.8%) as girls (32.2%), though this finding may not be surprising as the majority of nonmedical users were also medical users and stimulants are prescribed more frequently to boys than to girls (P less than .0006).

The research was funded by Arbor Pharmaceuticals. The authors noted no conflicts of interest.

SAN ANTONIO – Of 196 U.S. youth who reported use of at least one prescribed stimulant in their lifetimes, 25% also said they used the drugs nonmedically, based on a survey of children and adolescents aged 10-17 years.

Another 5% of the youth surveyed reported exclusively nonmedical use of stimulants. The survey participants lived in six U.S. cities and their outlying areas.

“Parents of both users and nonusers should warn their children of the dangers of using others’ stimulants and giving their own stimulants to others,” concluded Linda B. Cottler, PhD, MPH of the University of Florida, and colleagues.

“Physicians and pharmacists should make users and their families aware of the need to take medications as prescribed and not to share medications with others,” they wrote in their research poster at the annual meeting of the College on Problems of Drug Dependence. “Continuous monitoring of these medications in the community should be a priority.”

Though prevalence research has shown increasing stimulant misuse among youth, little data exist for younger children, the researchers noted. They therefore conducted a survey of 1,777 youth aged 10-17 years from September to October 2018 in six cities in California, Texas, and Florida, the most populous U.S. states.

The participants included youth from urban, rural, and suburban areas of Los Angeles, Dallas, Houston, Tampa, Orlando, and Miami. Trained graduate students and professional raters approached the respondents in entertainment venues and obtained assent but did not require parental consent. The respondents received $30 for completing the survey.

A total of 11.1% of respondents reporting having used prescription stimulants in their lifetime, and 7.6% had done so in the past 30 days. Just under a third of those who used stimulants (30.1%) did so for nonmedical purposes, defined as taking the stimulant nonorally (except for the patch Daytrana), getting the stimulant from someone else, or taking more of the drug than prescribed.

A quarter of the respondents who used stimulants reported both medical use and nonmedical use. And 5.1% of these youths reported only using stimulants nonmedically.

Among those with any lifetime stimulant use, 13.8% reported nonoral administration, including 9.7% who snorted or sniffed the drugs, 4.1% who smoked them, and 1.0% who injected them. Just over half (51.8%) of those reporting nonoral use had also used prescription stimulants orally.

The likelihood of using stimulants nonmedically increased with age (P less than .0001). The researchers found no significant associations between nonmedical use and geography or race/ethnicity. Among 10- to 12-year-olds, 3.1% reported only medical use of stimulants, and 0.7% (2 of 286 respondents in this age group) reported any nonmedical use of stimulants.

Of those aged 13-15 years, 2.1% reported any nonmedical stimulant use.

Nonmedical stimulant use was reported by twice as many boys (67.8%) as girls (32.2%), though this finding may not be surprising as the majority of nonmedical users were also medical users and stimulants are prescribed more frequently to boys than to girls (P less than .0006).

The research was funded by Arbor Pharmaceuticals. The authors noted no conflicts of interest.

SAN ANTONIO – Of 196 U.S. youth who reported use of at least one prescribed stimulant in their lifetimes, 25% also said they used the drugs nonmedically, based on a survey of children and adolescents aged 10-17 years.

Another 5% of the youth surveyed reported exclusively nonmedical use of stimulants. The survey participants lived in six U.S. cities and their outlying areas.

“Parents of both users and nonusers should warn their children of the dangers of using others’ stimulants and giving their own stimulants to others,” concluded Linda B. Cottler, PhD, MPH of the University of Florida, and colleagues.

“Physicians and pharmacists should make users and their families aware of the need to take medications as prescribed and not to share medications with others,” they wrote in their research poster at the annual meeting of the College on Problems of Drug Dependence. “Continuous monitoring of these medications in the community should be a priority.”

Though prevalence research has shown increasing stimulant misuse among youth, little data exist for younger children, the researchers noted. They therefore conducted a survey of 1,777 youth aged 10-17 years from September to October 2018 in six cities in California, Texas, and Florida, the most populous U.S. states.

The participants included youth from urban, rural, and suburban areas of Los Angeles, Dallas, Houston, Tampa, Orlando, and Miami. Trained graduate students and professional raters approached the respondents in entertainment venues and obtained assent but did not require parental consent. The respondents received $30 for completing the survey.

A total of 11.1% of respondents reporting having used prescription stimulants in their lifetime, and 7.6% had done so in the past 30 days. Just under a third of those who used stimulants (30.1%) did so for nonmedical purposes, defined as taking the stimulant nonorally (except for the patch Daytrana), getting the stimulant from someone else, or taking more of the drug than prescribed.

A quarter of the respondents who used stimulants reported both medical use and nonmedical use. And 5.1% of these youths reported only using stimulants nonmedically.

Among those with any lifetime stimulant use, 13.8% reported nonoral administration, including 9.7% who snorted or sniffed the drugs, 4.1% who smoked them, and 1.0% who injected them. Just over half (51.8%) of those reporting nonoral use had also used prescription stimulants orally.

The likelihood of using stimulants nonmedically increased with age (P less than .0001). The researchers found no significant associations between nonmedical use and geography or race/ethnicity. Among 10- to 12-year-olds, 3.1% reported only medical use of stimulants, and 0.7% (2 of 286 respondents in this age group) reported any nonmedical use of stimulants.

Of those aged 13-15 years, 2.1% reported any nonmedical stimulant use.

Nonmedical stimulant use was reported by twice as many boys (67.8%) as girls (32.2%), though this finding may not be surprising as the majority of nonmedical users were also medical users and stimulants are prescribed more frequently to boys than to girls (P less than .0006).

The research was funded by Arbor Pharmaceuticals. The authors noted no conflicts of interest.

REPORTING FROM CPDD 2019

Penicillin-susceptible Streptococcus pneumoniae most common cause of bacteremic CAP

A study found that only 2% of children hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) actually had any causative pathogen in their blood culture results, despite national guidelines that recommend blood cultures for all children hospitalized with moderate to severe CAP.

The guidelines are the 2011 guidelines for managing CAP published by the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society (PIDS) and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) (Clin Infect Dis. 2011 Oct;53[7]:617-30).

Cristin O. Fritz, MD, of the Children’s Hospital of Colorado, Aurora, and associates conducted a data analysis of the EPIC (Etiology of Pneumonia in the Community) study to estimate prevalence, risk factors, and clinical outcomes in children hospitalized with bacteremic CAP and to evaluate the relationship between positive blood culture results, empirical antibiotics, and changes in antibiotic treatment regimens.

Data were collected at two Tennessee hospitals and one Utah hospital during Jan. 1, 2010–June 30, 2012. Of the 2,358 children with CAP enrolled in the study, 2,143 (91%) with blood cultures were included in Dr. Fritz’s analysis. Of the 53 patients presenting with positive blood culture results, 46 (2%; 95% confidence interval: 1.6%-2.9%) were identified as having bacteremia. Half of all cases observed were caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae, with Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes noted less frequently, according to the study published in Pediatrics.

A previous meta-analysis of smaller studies also found that children with CAP rarely had positive blood culture results, a pooled prevalence of 5% (Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2013;32[7]:736-40). Although it is believed that positive blood culture results are key to narrowing the choice of antibiotic and predicting treatment outcomes, the literature – to date – reveals a paucity of data supporting this assumption.

Overall, children in the study presenting with bacteremia experienced more severe clinical outcomes, including longer length of stay, greater likelihood of ICU admission, and invasive mechanical ventilation and/or shock. The authors also observed that bacteremia was less likely to be detected in children given antibiotics after admission but before cultures were obtained (0.8% vs 3%; P = .021). Pleural effusion detected with chest radiograph also consistently indicated bacteremic pneumonia, an observation made within this and other similar studies.

Also of note in detection is the biomarker procalcitonin, which is typically present with bacterial disease. Dr. Fritz and colleagues stressed that because the procalcitonin rate was higher in patients presenting with bacteremia, “this information could influence decisions around culturing if results are rapidly available.” Risk-stratification tools also might serve a valuable purpose in ferreting out those patients presenting with moderate to severe pneumonia most at increased risk for bacterial CAP.

Compared with other studies reporting prevalence ranges of 1%-7%, the prevalence of bacteremia in this study is lower at 2%. The authors attributed the difference to a possible potential limitation with the other studies, for which culture data was only available for a median 47% of enrollees. Dr. Fritz and her colleagues caution that “because cultures were obtained at the discretion of the treating clinician in a majority of studies, blood cultures were likely obtained more often in those with more severe illness or who had not already received antibiotics.” In this scenario, the likelihood that prevalence of bacteremia was overestimated is noteworthy.

The authors observed that penicillin-susceptible S. pneumonia was the most common cause of bacteremic CAP. They further acknowledged that their study and findings by Neuman et al. in 2017 give credence to the joint 2011 PIDS/IDSA guideline recommending narrow-spectrum aminopenicillins specifically to treat children hospitalized due to suspected bacterial CAP.

Despite its small sample size, the results of this study clearly demonstrate that children with bacteremia because of S. pyogenes or S. aureus experience increased morbidity, compared with children with S. pneumoniae, they said

While this is acknowledged to be one of the largest studies of its kind to date, a key limitation was the small number of observable patients with bacteremia, which prevented the researchers from conducting a more in-depth analysis of risk factors and pathogen-specific differences. That one-fourth of patients received in-patient antibiotics before cultures could be collected also likely led to an underestimation of risk factors and misclassification bias. Lastly, the use of blood culture instead of whole-blood polymerase chain reaction, which is known to be more sensitive, also may have led to underestimation of overall bacteremia prevalence.

“In an era with widespread pneumococcal vaccination and low prevalence of bacteremia in the United States, noted Dr. Fritz and associates.

Dr. Fritz had no conflicts of interest to report. Some coauthors cited multiple sources of potential conflict of interest related to consulting fees, grant support, and research support from various pharmaceutical companies and agencies. The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health and in part by a grant from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

SOURCE: Fritz C et al. Pediatrics. 2019;144(1):e20183090.

A study found that only 2% of children hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) actually had any causative pathogen in their blood culture results, despite national guidelines that recommend blood cultures for all children hospitalized with moderate to severe CAP.

The guidelines are the 2011 guidelines for managing CAP published by the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society (PIDS) and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) (Clin Infect Dis. 2011 Oct;53[7]:617-30).

Cristin O. Fritz, MD, of the Children’s Hospital of Colorado, Aurora, and associates conducted a data analysis of the EPIC (Etiology of Pneumonia in the Community) study to estimate prevalence, risk factors, and clinical outcomes in children hospitalized with bacteremic CAP and to evaluate the relationship between positive blood culture results, empirical antibiotics, and changes in antibiotic treatment regimens.

Data were collected at two Tennessee hospitals and one Utah hospital during Jan. 1, 2010–June 30, 2012. Of the 2,358 children with CAP enrolled in the study, 2,143 (91%) with blood cultures were included in Dr. Fritz’s analysis. Of the 53 patients presenting with positive blood culture results, 46 (2%; 95% confidence interval: 1.6%-2.9%) were identified as having bacteremia. Half of all cases observed were caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae, with Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes noted less frequently, according to the study published in Pediatrics.

A previous meta-analysis of smaller studies also found that children with CAP rarely had positive blood culture results, a pooled prevalence of 5% (Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2013;32[7]:736-40). Although it is believed that positive blood culture results are key to narrowing the choice of antibiotic and predicting treatment outcomes, the literature – to date – reveals a paucity of data supporting this assumption.

Overall, children in the study presenting with bacteremia experienced more severe clinical outcomes, including longer length of stay, greater likelihood of ICU admission, and invasive mechanical ventilation and/or shock. The authors also observed that bacteremia was less likely to be detected in children given antibiotics after admission but before cultures were obtained (0.8% vs 3%; P = .021). Pleural effusion detected with chest radiograph also consistently indicated bacteremic pneumonia, an observation made within this and other similar studies.

Also of note in detection is the biomarker procalcitonin, which is typically present with bacterial disease. Dr. Fritz and colleagues stressed that because the procalcitonin rate was higher in patients presenting with bacteremia, “this information could influence decisions around culturing if results are rapidly available.” Risk-stratification tools also might serve a valuable purpose in ferreting out those patients presenting with moderate to severe pneumonia most at increased risk for bacterial CAP.

Compared with other studies reporting prevalence ranges of 1%-7%, the prevalence of bacteremia in this study is lower at 2%. The authors attributed the difference to a possible potential limitation with the other studies, for which culture data was only available for a median 47% of enrollees. Dr. Fritz and her colleagues caution that “because cultures were obtained at the discretion of the treating clinician in a majority of studies, blood cultures were likely obtained more often in those with more severe illness or who had not already received antibiotics.” In this scenario, the likelihood that prevalence of bacteremia was overestimated is noteworthy.

The authors observed that penicillin-susceptible S. pneumonia was the most common cause of bacteremic CAP. They further acknowledged that their study and findings by Neuman et al. in 2017 give credence to the joint 2011 PIDS/IDSA guideline recommending narrow-spectrum aminopenicillins specifically to treat children hospitalized due to suspected bacterial CAP.

Despite its small sample size, the results of this study clearly demonstrate that children with bacteremia because of S. pyogenes or S. aureus experience increased morbidity, compared with children with S. pneumoniae, they said

While this is acknowledged to be one of the largest studies of its kind to date, a key limitation was the small number of observable patients with bacteremia, which prevented the researchers from conducting a more in-depth analysis of risk factors and pathogen-specific differences. That one-fourth of patients received in-patient antibiotics before cultures could be collected also likely led to an underestimation of risk factors and misclassification bias. Lastly, the use of blood culture instead of whole-blood polymerase chain reaction, which is known to be more sensitive, also may have led to underestimation of overall bacteremia prevalence.

“In an era with widespread pneumococcal vaccination and low prevalence of bacteremia in the United States, noted Dr. Fritz and associates.

Dr. Fritz had no conflicts of interest to report. Some coauthors cited multiple sources of potential conflict of interest related to consulting fees, grant support, and research support from various pharmaceutical companies and agencies. The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health and in part by a grant from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

SOURCE: Fritz C et al. Pediatrics. 2019;144(1):e20183090.

A study found that only 2% of children hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) actually had any causative pathogen in their blood culture results, despite national guidelines that recommend blood cultures for all children hospitalized with moderate to severe CAP.

The guidelines are the 2011 guidelines for managing CAP published by the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society (PIDS) and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) (Clin Infect Dis. 2011 Oct;53[7]:617-30).

Cristin O. Fritz, MD, of the Children’s Hospital of Colorado, Aurora, and associates conducted a data analysis of the EPIC (Etiology of Pneumonia in the Community) study to estimate prevalence, risk factors, and clinical outcomes in children hospitalized with bacteremic CAP and to evaluate the relationship between positive blood culture results, empirical antibiotics, and changes in antibiotic treatment regimens.

Data were collected at two Tennessee hospitals and one Utah hospital during Jan. 1, 2010–June 30, 2012. Of the 2,358 children with CAP enrolled in the study, 2,143 (91%) with blood cultures were included in Dr. Fritz’s analysis. Of the 53 patients presenting with positive blood culture results, 46 (2%; 95% confidence interval: 1.6%-2.9%) were identified as having bacteremia. Half of all cases observed were caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae, with Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes noted less frequently, according to the study published in Pediatrics.

A previous meta-analysis of smaller studies also found that children with CAP rarely had positive blood culture results, a pooled prevalence of 5% (Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2013;32[7]:736-40). Although it is believed that positive blood culture results are key to narrowing the choice of antibiotic and predicting treatment outcomes, the literature – to date – reveals a paucity of data supporting this assumption.

Overall, children in the study presenting with bacteremia experienced more severe clinical outcomes, including longer length of stay, greater likelihood of ICU admission, and invasive mechanical ventilation and/or shock. The authors also observed that bacteremia was less likely to be detected in children given antibiotics after admission but before cultures were obtained (0.8% vs 3%; P = .021). Pleural effusion detected with chest radiograph also consistently indicated bacteremic pneumonia, an observation made within this and other similar studies.

Also of note in detection is the biomarker procalcitonin, which is typically present with bacterial disease. Dr. Fritz and colleagues stressed that because the procalcitonin rate was higher in patients presenting with bacteremia, “this information could influence decisions around culturing if results are rapidly available.” Risk-stratification tools also might serve a valuable purpose in ferreting out those patients presenting with moderate to severe pneumonia most at increased risk for bacterial CAP.

Compared with other studies reporting prevalence ranges of 1%-7%, the prevalence of bacteremia in this study is lower at 2%. The authors attributed the difference to a possible potential limitation with the other studies, for which culture data was only available for a median 47% of enrollees. Dr. Fritz and her colleagues caution that “because cultures were obtained at the discretion of the treating clinician in a majority of studies, blood cultures were likely obtained more often in those with more severe illness or who had not already received antibiotics.” In this scenario, the likelihood that prevalence of bacteremia was overestimated is noteworthy.

The authors observed that penicillin-susceptible S. pneumonia was the most common cause of bacteremic CAP. They further acknowledged that their study and findings by Neuman et al. in 2017 give credence to the joint 2011 PIDS/IDSA guideline recommending narrow-spectrum aminopenicillins specifically to treat children hospitalized due to suspected bacterial CAP.

Despite its small sample size, the results of this study clearly demonstrate that children with bacteremia because of S. pyogenes or S. aureus experience increased morbidity, compared with children with S. pneumoniae, they said

While this is acknowledged to be one of the largest studies of its kind to date, a key limitation was the small number of observable patients with bacteremia, which prevented the researchers from conducting a more in-depth analysis of risk factors and pathogen-specific differences. That one-fourth of patients received in-patient antibiotics before cultures could be collected also likely led to an underestimation of risk factors and misclassification bias. Lastly, the use of blood culture instead of whole-blood polymerase chain reaction, which is known to be more sensitive, also may have led to underestimation of overall bacteremia prevalence.

“In an era with widespread pneumococcal vaccination and low prevalence of bacteremia in the United States, noted Dr. Fritz and associates.

Dr. Fritz had no conflicts of interest to report. Some coauthors cited multiple sources of potential conflict of interest related to consulting fees, grant support, and research support from various pharmaceutical companies and agencies. The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health and in part by a grant from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

SOURCE: Fritz C et al. Pediatrics. 2019;144(1):e20183090.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Measles incidence has slowed as summer begins

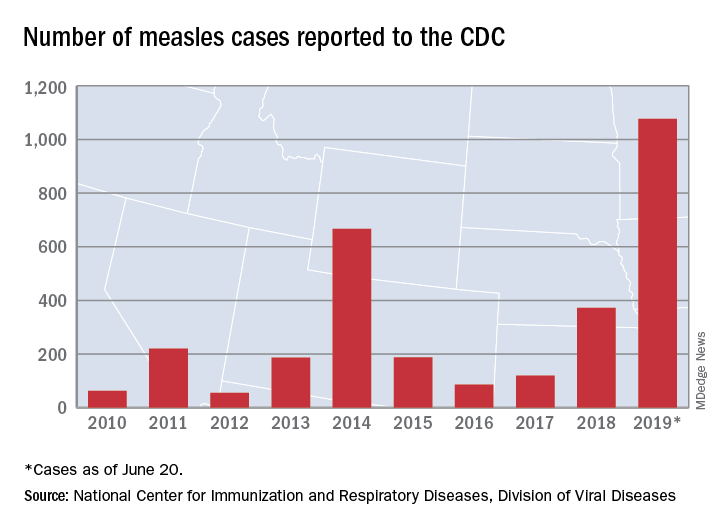

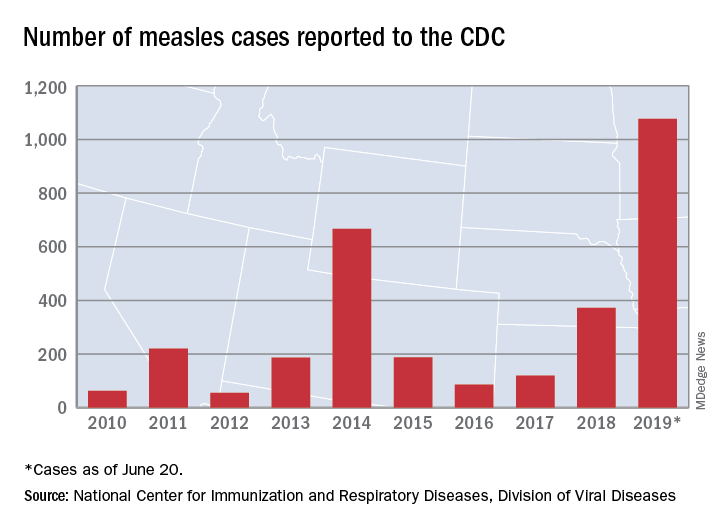

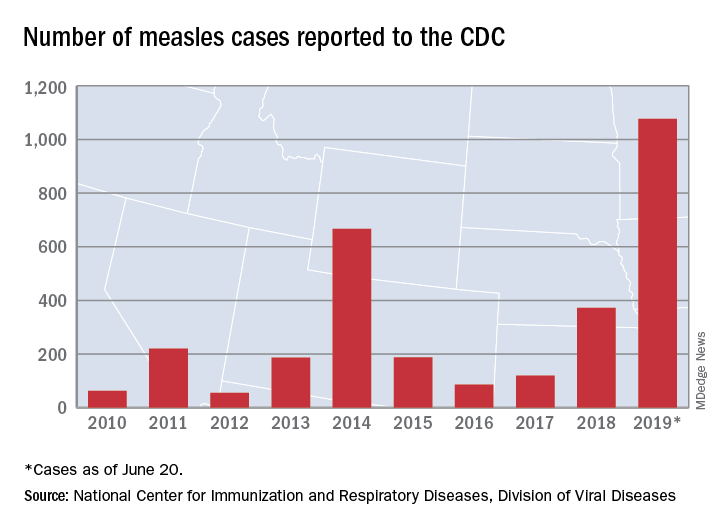

There were 33 new measles cases reported last week, bringing the U.S. total to 1,077 for the year through June 20, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The number of new cases is an increase from the 22 reported the week before, but weekly incidence has been trending downward since hitting a high of 90 in mid-April, CDC data show.

The two continuing outbreaks in New York State made up more than half of the new cases, as Rockland County reported nine cases and New York City reported eight (seven in Brooklyn and one in Queens). Only one new case was reported in California as of the CDC’s June 20 cutoff, but the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health said on June 22 that it was assessing two possible cases, with potential public exposures occurring in a theater and a restaurant.

In a survey conducted in April, a majority of physicians with experience treating measles said that summer travel would lead to increased measles outbreaks and deaths.

There were 33 new measles cases reported last week, bringing the U.S. total to 1,077 for the year through June 20, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The number of new cases is an increase from the 22 reported the week before, but weekly incidence has been trending downward since hitting a high of 90 in mid-April, CDC data show.

The two continuing outbreaks in New York State made up more than half of the new cases, as Rockland County reported nine cases and New York City reported eight (seven in Brooklyn and one in Queens). Only one new case was reported in California as of the CDC’s June 20 cutoff, but the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health said on June 22 that it was assessing two possible cases, with potential public exposures occurring in a theater and a restaurant.

In a survey conducted in April, a majority of physicians with experience treating measles said that summer travel would lead to increased measles outbreaks and deaths.

There were 33 new measles cases reported last week, bringing the U.S. total to 1,077 for the year through June 20, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The number of new cases is an increase from the 22 reported the week before, but weekly incidence has been trending downward since hitting a high of 90 in mid-April, CDC data show.

The two continuing outbreaks in New York State made up more than half of the new cases, as Rockland County reported nine cases and New York City reported eight (seven in Brooklyn and one in Queens). Only one new case was reported in California as of the CDC’s June 20 cutoff, but the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health said on June 22 that it was assessing two possible cases, with potential public exposures occurring in a theater and a restaurant.

In a survey conducted in April, a majority of physicians with experience treating measles said that summer travel would lead to increased measles outbreaks and deaths.

CF drug picks up indication for children as young as 6

to include children as young as 6 years old who have cystic fibrosis.

The drug was approved in 2018 for patients aged 12 years and older who have the most common cause of the disease, two alleles for the F508del mutation in the gene that codes for the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) protein, or at least one other CFTR mutation responsive to the combination, as listed in labeling.

The original approval was based on three phase 3, double blind, placebo-controlled trials, which demonstrated improvements in lung function and other key measures of the disease. One trial that found a 6.8% mean improvement in lung function testing over placebo at 8 weeks, and another that found a 4% improvement at 24 weeks, with fewer respiratory exacerbations and improved respiratory-related quality of life. A third trial in patients without the indicated genetic mutations was ended early for futility.

The efficacy in children under 12 years was extrapolated from those trials, plus an open-label study that found similar effects.

Labeling warns of elevated liver enzymes and cataracts in children, and notes that the drug should be taken with food that contains fat. Labeling also recommends against use with strong cytochrome P450 3A4 (CYP3A) inducers – rifampin, phenobarbital, St. John’s wort, among others – because they might reduce efficacy, and against use with CYP3A inhibitors – ketoconazole, clarithromycin, Seville oranges, grapefruit juice, etc. – because of the risk of increased exposure.

The most common side effects are headache, nausea, sinus congestion, and dizziness. The FDA has cleared a CF gene test to check for the required mutations. Symdeko is marketed by Vertex Pharmaceuticals.

to include children as young as 6 years old who have cystic fibrosis.

The drug was approved in 2018 for patients aged 12 years and older who have the most common cause of the disease, two alleles for the F508del mutation in the gene that codes for the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) protein, or at least one other CFTR mutation responsive to the combination, as listed in labeling.

The original approval was based on three phase 3, double blind, placebo-controlled trials, which demonstrated improvements in lung function and other key measures of the disease. One trial that found a 6.8% mean improvement in lung function testing over placebo at 8 weeks, and another that found a 4% improvement at 24 weeks, with fewer respiratory exacerbations and improved respiratory-related quality of life. A third trial in patients without the indicated genetic mutations was ended early for futility.

The efficacy in children under 12 years was extrapolated from those trials, plus an open-label study that found similar effects.

Labeling warns of elevated liver enzymes and cataracts in children, and notes that the drug should be taken with food that contains fat. Labeling also recommends against use with strong cytochrome P450 3A4 (CYP3A) inducers – rifampin, phenobarbital, St. John’s wort, among others – because they might reduce efficacy, and against use with CYP3A inhibitors – ketoconazole, clarithromycin, Seville oranges, grapefruit juice, etc. – because of the risk of increased exposure.

The most common side effects are headache, nausea, sinus congestion, and dizziness. The FDA has cleared a CF gene test to check for the required mutations. Symdeko is marketed by Vertex Pharmaceuticals.

to include children as young as 6 years old who have cystic fibrosis.

The drug was approved in 2018 for patients aged 12 years and older who have the most common cause of the disease, two alleles for the F508del mutation in the gene that codes for the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) protein, or at least one other CFTR mutation responsive to the combination, as listed in labeling.

The original approval was based on three phase 3, double blind, placebo-controlled trials, which demonstrated improvements in lung function and other key measures of the disease. One trial that found a 6.8% mean improvement in lung function testing over placebo at 8 weeks, and another that found a 4% improvement at 24 weeks, with fewer respiratory exacerbations and improved respiratory-related quality of life. A third trial in patients without the indicated genetic mutations was ended early for futility.

The efficacy in children under 12 years was extrapolated from those trials, plus an open-label study that found similar effects.

Labeling warns of elevated liver enzymes and cataracts in children, and notes that the drug should be taken with food that contains fat. Labeling also recommends against use with strong cytochrome P450 3A4 (CYP3A) inducers – rifampin, phenobarbital, St. John’s wort, among others – because they might reduce efficacy, and against use with CYP3A inhibitors – ketoconazole, clarithromycin, Seville oranges, grapefruit juice, etc. – because of the risk of increased exposure.

The most common side effects are headache, nausea, sinus congestion, and dizziness. The FDA has cleared a CF gene test to check for the required mutations. Symdeko is marketed by Vertex Pharmaceuticals.

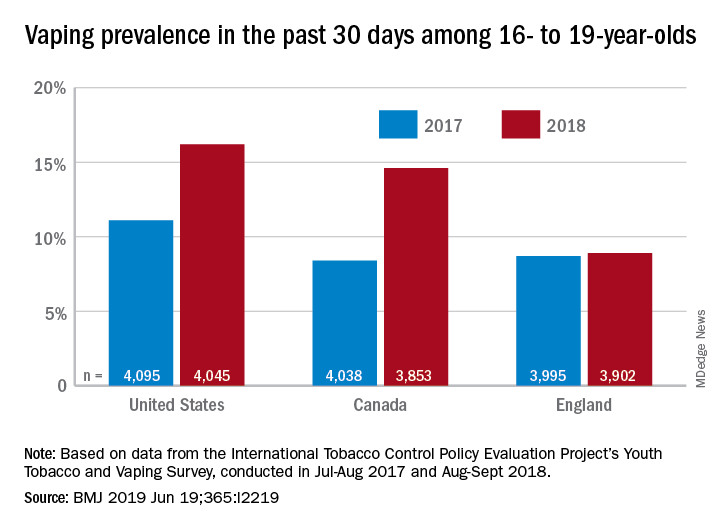

Cannabis vaping among teens tied to tobacco use

and that practice is associated with cigars, waterpipe and e-cigarette use, findings from a survey of nearly 3,000 adolescents have shown.

“Although the prevalence of e-cigarette use among youth has increased dramatically in the past decade, little epidemiologic data exist on the prevalence of using e-cigarette devices or other specialised devices to vaporise (‘vape’) cannabis in the form of hash oil, tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) wax or oil, or dried cannabis buds or leaves,” wrote Sarah D. Kowitt, PhD, of the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, and colleagues. “This is surprising given that (1) cannabis (also referred to as marijuana) and e-cigarettes are the most commonly used substances by adolescents in the USA, (2) evidence exists that adolescents dual use both tobacco e-cigarettes and cannabis, and (3) longitudinal research suggests that use of e-cigarettes is associated with progression to use of cannabis.”

In a study published in BMJ Open, the researchers used data from the 2017 North Carolina Youth Tobacco Survey, a school-based survey of students in grades 6-12. The study population included 2,835 adolescents in grades 9-12.

Overall, 9.6% of students reported ever vaping cannabis. In multivariate analysis, cannabis vaping was significantly more likely among adolescents who reported using e-cigarettes (adjusted odds ratio 3.18), cigars (aOR 3.76), or water pipes (aOR 2.32) in the past 30 days, compared with peers who didn’t use tobacco.

The researchers found no significant association between smokeless tobacco use or traditional cigarette use in the past 30 days and vaping cannabis.

In a bivariate analysis, vaping cannabis was significantly more common among males vs. females (11% vs. 8.2%) and among non-Hispanic white students (11.3%), Hispanic students (10.5%), and other non-Hispanic students (11.8%) compared with non-Hispanic black students (5.0%).

In addition, prevalence of cannabis vaping increased with grade level, from 4.7% of 9th graders to 15.5% of 12th graders.

The health impacts of vaping cannabis are not well researched, but the researchers note that among the potential safety issues are earlier initiation of tobacco or cannabis use, concomitant tobacco and cannabis use, increased frequency of use or misuse of tobacco or cannabis, or increased potency of cannabis.

The results of the study were limited by several factors including the use of data only from the state of North Carolina, the lack of data on frequency or current vaping cannabis behavior, lack of data on specific products, and lack of data on whether teens used specialized devices or e-cigarettes for cannabis vaping. However, the findings are consistent with studies on prevalence of cannabis vaping in other states such as Connecticut and California. “No studies to our knowledge have examined how adolescents who vape cannabis use other specific tobacco products (i.e., cigarettes, cigars, waterpipe, smokeless tobacco),” the researchers wrote.

The findings confirm that a large number of adolescents who use tobacco products have vaped cannabis as well, and this growing public health issue “is likely to affect and be affected by tobacco control and cannabis policies in states and at the federal level in the USA,” the researchers concluded.

“Increased research investigating how youth use e-cigarette devices for other purposes beyond vaping nicotine, like the current study, is needed,” they added.

The study was supported in part by the National Cancer Institute and the Food and Drug Administration’s Center for Tobacco Products. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Kowitt SD et al. BMJ Open. 2019 Jun 13. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-028535.

and that practice is associated with cigars, waterpipe and e-cigarette use, findings from a survey of nearly 3,000 adolescents have shown.

“Although the prevalence of e-cigarette use among youth has increased dramatically in the past decade, little epidemiologic data exist on the prevalence of using e-cigarette devices or other specialised devices to vaporise (‘vape’) cannabis in the form of hash oil, tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) wax or oil, or dried cannabis buds or leaves,” wrote Sarah D. Kowitt, PhD, of the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, and colleagues. “This is surprising given that (1) cannabis (also referred to as marijuana) and e-cigarettes are the most commonly used substances by adolescents in the USA, (2) evidence exists that adolescents dual use both tobacco e-cigarettes and cannabis, and (3) longitudinal research suggests that use of e-cigarettes is associated with progression to use of cannabis.”

In a study published in BMJ Open, the researchers used data from the 2017 North Carolina Youth Tobacco Survey, a school-based survey of students in grades 6-12. The study population included 2,835 adolescents in grades 9-12.

Overall, 9.6% of students reported ever vaping cannabis. In multivariate analysis, cannabis vaping was significantly more likely among adolescents who reported using e-cigarettes (adjusted odds ratio 3.18), cigars (aOR 3.76), or water pipes (aOR 2.32) in the past 30 days, compared with peers who didn’t use tobacco.

The researchers found no significant association between smokeless tobacco use or traditional cigarette use in the past 30 days and vaping cannabis.

In a bivariate analysis, vaping cannabis was significantly more common among males vs. females (11% vs. 8.2%) and among non-Hispanic white students (11.3%), Hispanic students (10.5%), and other non-Hispanic students (11.8%) compared with non-Hispanic black students (5.0%).

In addition, prevalence of cannabis vaping increased with grade level, from 4.7% of 9th graders to 15.5% of 12th graders.

The health impacts of vaping cannabis are not well researched, but the researchers note that among the potential safety issues are earlier initiation of tobacco or cannabis use, concomitant tobacco and cannabis use, increased frequency of use or misuse of tobacco or cannabis, or increased potency of cannabis.

The results of the study were limited by several factors including the use of data only from the state of North Carolina, the lack of data on frequency or current vaping cannabis behavior, lack of data on specific products, and lack of data on whether teens used specialized devices or e-cigarettes for cannabis vaping. However, the findings are consistent with studies on prevalence of cannabis vaping in other states such as Connecticut and California. “No studies to our knowledge have examined how adolescents who vape cannabis use other specific tobacco products (i.e., cigarettes, cigars, waterpipe, smokeless tobacco),” the researchers wrote.

The findings confirm that a large number of adolescents who use tobacco products have vaped cannabis as well, and this growing public health issue “is likely to affect and be affected by tobacco control and cannabis policies in states and at the federal level in the USA,” the researchers concluded.

“Increased research investigating how youth use e-cigarette devices for other purposes beyond vaping nicotine, like the current study, is needed,” they added.

The study was supported in part by the National Cancer Institute and the Food and Drug Administration’s Center for Tobacco Products. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Kowitt SD et al. BMJ Open. 2019 Jun 13. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-028535.

and that practice is associated with cigars, waterpipe and e-cigarette use, findings from a survey of nearly 3,000 adolescents have shown.

“Although the prevalence of e-cigarette use among youth has increased dramatically in the past decade, little epidemiologic data exist on the prevalence of using e-cigarette devices or other specialised devices to vaporise (‘vape’) cannabis in the form of hash oil, tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) wax or oil, or dried cannabis buds or leaves,” wrote Sarah D. Kowitt, PhD, of the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, and colleagues. “This is surprising given that (1) cannabis (also referred to as marijuana) and e-cigarettes are the most commonly used substances by adolescents in the USA, (2) evidence exists that adolescents dual use both tobacco e-cigarettes and cannabis, and (3) longitudinal research suggests that use of e-cigarettes is associated with progression to use of cannabis.”

In a study published in BMJ Open, the researchers used data from the 2017 North Carolina Youth Tobacco Survey, a school-based survey of students in grades 6-12. The study population included 2,835 adolescents in grades 9-12.

Overall, 9.6% of students reported ever vaping cannabis. In multivariate analysis, cannabis vaping was significantly more likely among adolescents who reported using e-cigarettes (adjusted odds ratio 3.18), cigars (aOR 3.76), or water pipes (aOR 2.32) in the past 30 days, compared with peers who didn’t use tobacco.

The researchers found no significant association between smokeless tobacco use or traditional cigarette use in the past 30 days and vaping cannabis.

In a bivariate analysis, vaping cannabis was significantly more common among males vs. females (11% vs. 8.2%) and among non-Hispanic white students (11.3%), Hispanic students (10.5%), and other non-Hispanic students (11.8%) compared with non-Hispanic black students (5.0%).

In addition, prevalence of cannabis vaping increased with grade level, from 4.7% of 9th graders to 15.5% of 12th graders.

The health impacts of vaping cannabis are not well researched, but the researchers note that among the potential safety issues are earlier initiation of tobacco or cannabis use, concomitant tobacco and cannabis use, increased frequency of use or misuse of tobacco or cannabis, or increased potency of cannabis.

The results of the study were limited by several factors including the use of data only from the state of North Carolina, the lack of data on frequency or current vaping cannabis behavior, lack of data on specific products, and lack of data on whether teens used specialized devices or e-cigarettes for cannabis vaping. However, the findings are consistent with studies on prevalence of cannabis vaping in other states such as Connecticut and California. “No studies to our knowledge have examined how adolescents who vape cannabis use other specific tobacco products (i.e., cigarettes, cigars, waterpipe, smokeless tobacco),” the researchers wrote.

The findings confirm that a large number of adolescents who use tobacco products have vaped cannabis as well, and this growing public health issue “is likely to affect and be affected by tobacco control and cannabis policies in states and at the federal level in the USA,” the researchers concluded.

“Increased research investigating how youth use e-cigarette devices for other purposes beyond vaping nicotine, like the current study, is needed,” they added.

The study was supported in part by the National Cancer Institute and the Food and Drug Administration’s Center for Tobacco Products. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Kowitt SD et al. BMJ Open. 2019 Jun 13. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-028535.

FROM BMJ OPEN

Key clinical point: Use of tobacco products was significantly associated with cannabis vaping in teens.

Major finding: Approximately 10% of adolescents reported vaping cannabis.

Study details: The data come from a survey of 2,835 adolescents in North Carolina.

Disclosures: The study was supported in part by the National Cancer Institute and the FDA Center for Tobacco Products. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Source: Kowitt SD et al. BMJ Open. 2019 Jun 13. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-028535.

Children with Down syndrome may need more screening for sleep-disordered breathing

because the condition frequently persists and recurs.

“Current screening recommendations to assess for SDB at a particular age may not be adequate in this population,” the authors of the study stated, adding that “persistence/recurrence of SDB is not easily predicted.”

The study, led by Joy Nehme, BSc, of Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario and the University of Ottawa, was published in Pediatric Pulmonology.

According to the study, research suggests that 43%-66% of children with Down syndrome have SDB, a category that encompasses sleep apnea (both obstructive and central) and hypoventilation. Those numbers are several times higher than the prevalence of SDB in children in the general population (1%-5%).

“Because SDB is associated with cardiometabolic and neurocognitive morbidity, its prompt and accurate diagnosis is important,” the researchers wrote. However, diagnosis requires a sleep study, which is not always performed although the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends children with Down syndrome undergo one by age 4.

Treatments include adenotonsillectomy (considered first-line), positive airway pressure, and lingual tonsillectomy.

The study aims to fill in gaps in knowledge about the condition over the long term since “there is little available literature on the trajectory of SDB in children and youth with Down syndrome over time.”

The researchers launched a retrospective study of 560 children with Down syndrome who were treated from 2004 to 2015 at Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario. Of those, 120 showed signs of SDB and underwent sleep studies (48% male, median age 6.6 years [range 4.5-10.5], median total apnea‐hypopnea index events per hour = 3.4 [1.6-10.8]).

Of the 120 children, 67 (56%) had obstructive-mixed SDB, 9 (8%) had central sleep apnea, and 5 (4%) had hypoventilation. The others (39, 32%) had no SDB.

Fifty-four children underwent at least two sleep studies during the period of the study, with at least one undergoing seven.

Researchers found weak, nonsignificant evidence that SDB persistence/occurrence varied by age (odds ratio per year = 1.15; 95% confidence interval, 0.96-1.41; P = .13).

As for treatment, adenotonsillectomy was most common, although “previous studies have ... shown that moderate to severe OSA in children with Down syndrome is likely to persist after a tonsillectomy.”

In regard to obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) specifically, the authors wrote, “our study ... showed that OSA‐SDB persisted or recurred in the vast majority of children. Further, persistence/recurrence could not be predicted by clinical features or SDB severity in our study. This, therefore, highlights the need for serial longitudinal screening for SDB in this population and for follow‐up PSG to ensure the success of treatment interventions.”

No study funding was reported. The study authors reported no disclosures.

SOURCE: Nehme J et al. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2019 Jun 6. doi: 10.1002/ppul.24380.

because the condition frequently persists and recurs.

“Current screening recommendations to assess for SDB at a particular age may not be adequate in this population,” the authors of the study stated, adding that “persistence/recurrence of SDB is not easily predicted.”

The study, led by Joy Nehme, BSc, of Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario and the University of Ottawa, was published in Pediatric Pulmonology.

According to the study, research suggests that 43%-66% of children with Down syndrome have SDB, a category that encompasses sleep apnea (both obstructive and central) and hypoventilation. Those numbers are several times higher than the prevalence of SDB in children in the general population (1%-5%).

“Because SDB is associated with cardiometabolic and neurocognitive morbidity, its prompt and accurate diagnosis is important,” the researchers wrote. However, diagnosis requires a sleep study, which is not always performed although the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends children with Down syndrome undergo one by age 4.

Treatments include adenotonsillectomy (considered first-line), positive airway pressure, and lingual tonsillectomy.

The study aims to fill in gaps in knowledge about the condition over the long term since “there is little available literature on the trajectory of SDB in children and youth with Down syndrome over time.”

The researchers launched a retrospective study of 560 children with Down syndrome who were treated from 2004 to 2015 at Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario. Of those, 120 showed signs of SDB and underwent sleep studies (48% male, median age 6.6 years [range 4.5-10.5], median total apnea‐hypopnea index events per hour = 3.4 [1.6-10.8]).

Of the 120 children, 67 (56%) had obstructive-mixed SDB, 9 (8%) had central sleep apnea, and 5 (4%) had hypoventilation. The others (39, 32%) had no SDB.

Fifty-four children underwent at least two sleep studies during the period of the study, with at least one undergoing seven.

Researchers found weak, nonsignificant evidence that SDB persistence/occurrence varied by age (odds ratio per year = 1.15; 95% confidence interval, 0.96-1.41; P = .13).

As for treatment, adenotonsillectomy was most common, although “previous studies have ... shown that moderate to severe OSA in children with Down syndrome is likely to persist after a tonsillectomy.”

In regard to obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) specifically, the authors wrote, “our study ... showed that OSA‐SDB persisted or recurred in the vast majority of children. Further, persistence/recurrence could not be predicted by clinical features or SDB severity in our study. This, therefore, highlights the need for serial longitudinal screening for SDB in this population and for follow‐up PSG to ensure the success of treatment interventions.”

No study funding was reported. The study authors reported no disclosures.

SOURCE: Nehme J et al. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2019 Jun 6. doi: 10.1002/ppul.24380.

because the condition frequently persists and recurs.

“Current screening recommendations to assess for SDB at a particular age may not be adequate in this population,” the authors of the study stated, adding that “persistence/recurrence of SDB is not easily predicted.”

The study, led by Joy Nehme, BSc, of Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario and the University of Ottawa, was published in Pediatric Pulmonology.

According to the study, research suggests that 43%-66% of children with Down syndrome have SDB, a category that encompasses sleep apnea (both obstructive and central) and hypoventilation. Those numbers are several times higher than the prevalence of SDB in children in the general population (1%-5%).

“Because SDB is associated with cardiometabolic and neurocognitive morbidity, its prompt and accurate diagnosis is important,” the researchers wrote. However, diagnosis requires a sleep study, which is not always performed although the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends children with Down syndrome undergo one by age 4.

Treatments include adenotonsillectomy (considered first-line), positive airway pressure, and lingual tonsillectomy.

The study aims to fill in gaps in knowledge about the condition over the long term since “there is little available literature on the trajectory of SDB in children and youth with Down syndrome over time.”

The researchers launched a retrospective study of 560 children with Down syndrome who were treated from 2004 to 2015 at Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario. Of those, 120 showed signs of SDB and underwent sleep studies (48% male, median age 6.6 years [range 4.5-10.5], median total apnea‐hypopnea index events per hour = 3.4 [1.6-10.8]).

Of the 120 children, 67 (56%) had obstructive-mixed SDB, 9 (8%) had central sleep apnea, and 5 (4%) had hypoventilation. The others (39, 32%) had no SDB.

Fifty-four children underwent at least two sleep studies during the period of the study, with at least one undergoing seven.

Researchers found weak, nonsignificant evidence that SDB persistence/occurrence varied by age (odds ratio per year = 1.15; 95% confidence interval, 0.96-1.41; P = .13).

As for treatment, adenotonsillectomy was most common, although “previous studies have ... shown that moderate to severe OSA in children with Down syndrome is likely to persist after a tonsillectomy.”

In regard to obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) specifically, the authors wrote, “our study ... showed that OSA‐SDB persisted or recurred in the vast majority of children. Further, persistence/recurrence could not be predicted by clinical features or SDB severity in our study. This, therefore, highlights the need for serial longitudinal screening for SDB in this population and for follow‐up PSG to ensure the success of treatment interventions.”

No study funding was reported. The study authors reported no disclosures.

SOURCE: Nehme J et al. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2019 Jun 6. doi: 10.1002/ppul.24380.

FROM PEDIATRIC PULMONOLOGY

Key clinical point: Sleep-disordered breathing (SDB) can be persistent and recurrent in children with Down syndrome, and long-term monitoring is warranted.

Major finding: SDB persistence/recurrence did not vary by age (odds ratio per year = 1.15; 95% confidence interval, 0.96-1.41; P = .13).

Study details: Retrospective cohort analysis of 120 children with Down syndrome tested via sleep study at least once for SDB (48% male, median age 6.6 years).

Disclosures: No study funding or author disclosures were reported.

Source: Nehme J et al. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2019 Jun 6. doi: 10.1002/ppul.24380.

Efforts toward producing CNO/CRMO classification criteria show first results

MADRID – according to recent findings from international surveys of pediatric rheumatologists that were presented at the European Congress of Rheumatology.

Melissa Oliver, MD, a pediatric rheumatologist at Riley Hospital for Children, Indianapolis, and colleagues recently undertook the multiphase study as part of an international collaborative effort led by the Childhood Arthritis and Rheumatology Research Alliance to establish consensus-based diagnostic and classification criteria for CNO, an autoinflammatory bone disease of unknown cause that primarily affects children and adolescents. CNO is also known as chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis (CRMO). If this disease is not diagnosed and treated appropriately in a timely fashion, damage and long-term disability is possible. In the absence of widely accepted, consensus-driven criteria, treatment is based largely on expert opinion, Dr. Oliver explained in an interview.

“There is an urgent need for a new and more robust set of classification criteria for CRMO, based on large expert consensus and the analysis of a large sample of patients and controls,” she said.

There are two proposed diagnostic criteria, the 2007 classification of nonbacterial osteitis and the 2016 Bristol diagnostic criteria for CRMO, but both are derived from single-center cohort studies and have not been validated, Dr. Oliver explained.

The list of candidate items that have come out of the study is moving clinicians a step closer toward the design of a practical patient data collection form that appropriately weighs each item included in the classification criteria.

The study employed anonymous survey and nominal group techniques with the goal of developing a set of classification criteria sensitive and specific enough to identify CRMO/CNO patients. In phase 1, a Delphi survey was administered among international rheumatologists to generate candidate criteria items. Phase 2 sought to reduce candidate criteria items through consensus processes via input from physicians managing CNO and patients or caregivers of children with CNO.

Altogether, 259 of 865 pediatric rheumatologists (30%) completed an online questionnaire addressing features key to the classification of CNO, including 77 who practice in Europe (30%), 132 in North America (51%), and 50 on other continents (19%). Of these, 138 (53%) had greater than 10 years of clinical practice experience, and 108 (42%) had managed more than 10 CNO patients.

Initially, Dr. Oliver and colleagues identified 33 candidate criteria items that fell into six domains: clinical presentation, physical exam, laboratory findings, imaging findings, bone biopsy, and treatment response. The top eight weighted items that increased the likelihood of CNO/CRMO were exclusion of malignancy by bone biopsy; multifocal bone lesions; presence of bone pain, swelling, and/or warmth; signs of fibrosis and/or inflammation on bone biopsy; typical location of CNO/CRMO lesion, such as the clavicle, metaphysis of long bones, the mandible, and vertebrae; presence of CNO/CRMO–related comorbidities; normal C-reactive protein (CRP) or erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR); and typical MRI findings of CNO/CRMO.

By phase 2, candidate items, which were presented to 39 rheumatologists and 7 parents, were refined or eliminated using item-reduction techniques. A second survey was issued to 77 of 82 members of a work group so that the remaining items could be ranked by their power of distinguishing CNO from conditions that merely mimicked the disease. The greatest mean discriminatory scores were identified with multifocal lesions (ruling out malignancy and infection) and typical location on imaging. Normal C-reactive protein and/or an erythrocyte sedimentation rate more than three times the upper limit of normal had the greatest negative mean discriminatory scores.

The next steps will be to form an expert panel who will use 1000minds software to determine the final criteria and identify a threshold for disease. The investigators hope to build a large multinational case repository of at least 500 patients with CNO/CRMO and 500 patients with mimicking conditions from which to derive a development cohort and an external validation cohort. So far, 10 sites, including 4 in Europe, have obtained approval from an institutional review board. The group has also submitted a proposal for classification criteria to the American College of Rheumatology and the European League Against Rheumatism, Dr. Oliver said.

Dr. Oliver had no disclosures to report, but several coauthors reported financial ties to industry.

SOURCE: Oliver M et al. Ann Rheum Dis. Jun 2019;78(Suppl 2):254-5, Abstract OP0342. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-eular.1539.

MADRID – according to recent findings from international surveys of pediatric rheumatologists that were presented at the European Congress of Rheumatology.

Melissa Oliver, MD, a pediatric rheumatologist at Riley Hospital for Children, Indianapolis, and colleagues recently undertook the multiphase study as part of an international collaborative effort led by the Childhood Arthritis and Rheumatology Research Alliance to establish consensus-based diagnostic and classification criteria for CNO, an autoinflammatory bone disease of unknown cause that primarily affects children and adolescents. CNO is also known as chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis (CRMO). If this disease is not diagnosed and treated appropriately in a timely fashion, damage and long-term disability is possible. In the absence of widely accepted, consensus-driven criteria, treatment is based largely on expert opinion, Dr. Oliver explained in an interview.

“There is an urgent need for a new and more robust set of classification criteria for CRMO, based on large expert consensus and the analysis of a large sample of patients and controls,” she said.

There are two proposed diagnostic criteria, the 2007 classification of nonbacterial osteitis and the 2016 Bristol diagnostic criteria for CRMO, but both are derived from single-center cohort studies and have not been validated, Dr. Oliver explained.

The list of candidate items that have come out of the study is moving clinicians a step closer toward the design of a practical patient data collection form that appropriately weighs each item included in the classification criteria.

The study employed anonymous survey and nominal group techniques with the goal of developing a set of classification criteria sensitive and specific enough to identify CRMO/CNO patients. In phase 1, a Delphi survey was administered among international rheumatologists to generate candidate criteria items. Phase 2 sought to reduce candidate criteria items through consensus processes via input from physicians managing CNO and patients or caregivers of children with CNO.

Altogether, 259 of 865 pediatric rheumatologists (30%) completed an online questionnaire addressing features key to the classification of CNO, including 77 who practice in Europe (30%), 132 in North America (51%), and 50 on other continents (19%). Of these, 138 (53%) had greater than 10 years of clinical practice experience, and 108 (42%) had managed more than 10 CNO patients.

Initially, Dr. Oliver and colleagues identified 33 candidate criteria items that fell into six domains: clinical presentation, physical exam, laboratory findings, imaging findings, bone biopsy, and treatment response. The top eight weighted items that increased the likelihood of CNO/CRMO were exclusion of malignancy by bone biopsy; multifocal bone lesions; presence of bone pain, swelling, and/or warmth; signs of fibrosis and/or inflammation on bone biopsy; typical location of CNO/CRMO lesion, such as the clavicle, metaphysis of long bones, the mandible, and vertebrae; presence of CNO/CRMO–related comorbidities; normal C-reactive protein (CRP) or erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR); and typical MRI findings of CNO/CRMO.

By phase 2, candidate items, which were presented to 39 rheumatologists and 7 parents, were refined or eliminated using item-reduction techniques. A second survey was issued to 77 of 82 members of a work group so that the remaining items could be ranked by their power of distinguishing CNO from conditions that merely mimicked the disease. The greatest mean discriminatory scores were identified with multifocal lesions (ruling out malignancy and infection) and typical location on imaging. Normal C-reactive protein and/or an erythrocyte sedimentation rate more than three times the upper limit of normal had the greatest negative mean discriminatory scores.

The next steps will be to form an expert panel who will use 1000minds software to determine the final criteria and identify a threshold for disease. The investigators hope to build a large multinational case repository of at least 500 patients with CNO/CRMO and 500 patients with mimicking conditions from which to derive a development cohort and an external validation cohort. So far, 10 sites, including 4 in Europe, have obtained approval from an institutional review board. The group has also submitted a proposal for classification criteria to the American College of Rheumatology and the European League Against Rheumatism, Dr. Oliver said.

Dr. Oliver had no disclosures to report, but several coauthors reported financial ties to industry.

SOURCE: Oliver M et al. Ann Rheum Dis. Jun 2019;78(Suppl 2):254-5, Abstract OP0342. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-eular.1539.

MADRID – according to recent findings from international surveys of pediatric rheumatologists that were presented at the European Congress of Rheumatology.

Melissa Oliver, MD, a pediatric rheumatologist at Riley Hospital for Children, Indianapolis, and colleagues recently undertook the multiphase study as part of an international collaborative effort led by the Childhood Arthritis and Rheumatology Research Alliance to establish consensus-based diagnostic and classification criteria for CNO, an autoinflammatory bone disease of unknown cause that primarily affects children and adolescents. CNO is also known as chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis (CRMO). If this disease is not diagnosed and treated appropriately in a timely fashion, damage and long-term disability is possible. In the absence of widely accepted, consensus-driven criteria, treatment is based largely on expert opinion, Dr. Oliver explained in an interview.

“There is an urgent need for a new and more robust set of classification criteria for CRMO, based on large expert consensus and the analysis of a large sample of patients and controls,” she said.

There are two proposed diagnostic criteria, the 2007 classification of nonbacterial osteitis and the 2016 Bristol diagnostic criteria for CRMO, but both are derived from single-center cohort studies and have not been validated, Dr. Oliver explained.

The list of candidate items that have come out of the study is moving clinicians a step closer toward the design of a practical patient data collection form that appropriately weighs each item included in the classification criteria.

The study employed anonymous survey and nominal group techniques with the goal of developing a set of classification criteria sensitive and specific enough to identify CRMO/CNO patients. In phase 1, a Delphi survey was administered among international rheumatologists to generate candidate criteria items. Phase 2 sought to reduce candidate criteria items through consensus processes via input from physicians managing CNO and patients or caregivers of children with CNO.

Altogether, 259 of 865 pediatric rheumatologists (30%) completed an online questionnaire addressing features key to the classification of CNO, including 77 who practice in Europe (30%), 132 in North America (51%), and 50 on other continents (19%). Of these, 138 (53%) had greater than 10 years of clinical practice experience, and 108 (42%) had managed more than 10 CNO patients.

Initially, Dr. Oliver and colleagues identified 33 candidate criteria items that fell into six domains: clinical presentation, physical exam, laboratory findings, imaging findings, bone biopsy, and treatment response. The top eight weighted items that increased the likelihood of CNO/CRMO were exclusion of malignancy by bone biopsy; multifocal bone lesions; presence of bone pain, swelling, and/or warmth; signs of fibrosis and/or inflammation on bone biopsy; typical location of CNO/CRMO lesion, such as the clavicle, metaphysis of long bones, the mandible, and vertebrae; presence of CNO/CRMO–related comorbidities; normal C-reactive protein (CRP) or erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR); and typical MRI findings of CNO/CRMO.

By phase 2, candidate items, which were presented to 39 rheumatologists and 7 parents, were refined or eliminated using item-reduction techniques. A second survey was issued to 77 of 82 members of a work group so that the remaining items could be ranked by their power of distinguishing CNO from conditions that merely mimicked the disease. The greatest mean discriminatory scores were identified with multifocal lesions (ruling out malignancy and infection) and typical location on imaging. Normal C-reactive protein and/or an erythrocyte sedimentation rate more than three times the upper limit of normal had the greatest negative mean discriminatory scores.

The next steps will be to form an expert panel who will use 1000minds software to determine the final criteria and identify a threshold for disease. The investigators hope to build a large multinational case repository of at least 500 patients with CNO/CRMO and 500 patients with mimicking conditions from which to derive a development cohort and an external validation cohort. So far, 10 sites, including 4 in Europe, have obtained approval from an institutional review board. The group has also submitted a proposal for classification criteria to the American College of Rheumatology and the European League Against Rheumatism, Dr. Oliver said.

Dr. Oliver had no disclosures to report, but several coauthors reported financial ties to industry.

SOURCE: Oliver M et al. Ann Rheum Dis. Jun 2019;78(Suppl 2):254-5, Abstract OP0342. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-eular.1539.

REPORTING FROM EULAR 2019 CONGRESS

Scoring below the cut but still depressed: What to do?

Depression is one of the most common mental health conditions in childhood, especially during socially turbulent adolescence when the brain is rapidly changing and parent-child relationships are strained by the teen’s striving for independence and identity. Often parents of teens call me worrying about possible depression, but in the next breath say “but maybe it is just puberty.” Because suicide is one of the most common causes of death among teens and is often associated with depression, we pediatricians have the scary job of sorting out symptoms and making a plan.

The Guidelines for Adolescent Depression in Primary Care (GLAD-PC)1,2 were revised in 2018 to help. This expert consensus document contains specific and practical guidance for all levels of depression. But for mild depression, GLAD-PC now advises pediatricians in Recommendation II to go beyond “watchful waiting.” It states, “After initial diagnosis,

Although a little vague, mild depression is diagnosed when there are “closer to 5” significant symptoms of depression, with “distressing but manageable” severity and only “mildly impaired” functioning. The most commonly used self-report adolescent depression screen, the Patient Health Questionnaire–Modified–9 (PHQ-9), has a recommended cut score of greater than 10, but 5-9 is considered mild depression symptoms. A clinical interview also is always required.

So what is this “active support” being recommended? After making an assessment of symptoms, severity, and impact – and ruling out significant suicide risk – the task is rather familiar to us from other medical conditions. We need to talk clearly and empathetically with the teen (and parents with consent) about depression and its neurological etiology, ask about contributing stress and genetic factors, and describe the typical course with optimism. This discussion is critical to pushing guilt or blame aside to rally family support. Substance use – (including alcohol) both a cause and attempted coping strategy for depression – must be addressed because it adds to risk for suicide or crashes and because it interacts with medicines.

Perhaps the biggest difference between active support for depression versus that for other conditions is that teens are likely reluctant, hopeless, and/or lacking energy to participate in the plan. The plan, therefore, needs to be approached in smaller steps and build on prior teen strengths, goals, or talents to motivate them and create reward to counteract general lethargy. You may know this teen used to play basketball, or sing at church, or love playing with a baby sister – all activities to try to reawaken. Parents can help recall these and are key to setting up opportunities.

GLAD-PC provides a “Self-Care Success!” worksheet of categories for goal setting for active support. These goals include:

- Stay physically active. Specified days/month, minutes/session, and dates and times.

- Engage spirituality and fun activities. Specify times/week, when, and with whom).

- Eat balanced meals. Specify number/day and names of foods.

- Spend time with people who can support you. Specify number/month, minutes/time, with whom, and doing what.

- Spend time relaxing. Specify days/week, minutes/time, and doing what.

- Determine small goals and simple steps. Establish these for a specified problem.

There is now evidence for these you can share with your teen patients and families.

Exercise

Exercise has a moderate effect size of 0.56 on depression, comparable to medications for mild to moderate depression and a useful adjunct to medications. The national Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion recommends that 6- to 17-year-olds get 60 minutes/day of moderate exercise or undertake vigorous “out of breath” exercise three times a week to maintain health. A meta-analysis of studies of yoga for people with depressive symptoms (not necessarily diagnosed depression) found reduced symptoms in 14 of 23 studies.

Pleasure

Advising fun has to include acknowledgment that a depressed teen is not motivated to do formerly fun things and may not get as much/any pleasure from it. You need to explain that “doing precedes feeling.” While what is fun is personal, new findings indicate that 2 hours/week “in nature” lowers stress, boosts mental health, and increases sense of well-being.

Nutrition

The MIND diet (Mediterranean-type diet high in leafy vegetables and berries but low in red meat) has evidence for lower odds of depression and psychological distress. Fatty acid supplements, specifically eicosapentaenoic acid at greater than 800 mg/day (930 mg), is better than placebo (P less than .001) for reducing mild depression within as little as 4 weeks. Natural S-Adenosyl-L-methionine (SAMe) has many studies showing benefit, according to National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine, a government-run website. NCCAM notes that St. John’s Wort has evidence for effectiveness equal to prescribed antidepressants for mild depression but with dangerous potential side effects, such as worsening of psychotic symptoms in bipolar disorder or schizophrenia, plus potentially life threatening drug interactions. While safe, valerian and probiotics have no evidence for reducing depression.

Social support

Family is usually the most important support for depressed teens even though they may be pushing family away, may refuse to come on outings, or may even refuse to come out of the bedroom. We should encourage parents and siblings to “hang out,” sitting quietly, available to listen rather than probing, cajoling, or nagging as they may have been doing. Parents also provide support by assuring adherence to visits, goals, and medications. Peer support helps a teen feel less alone and may increase social skills, but it can be difficult to sustain because friends may find depression threatening or give up when the teen avoids them and refuses activities. The National Association for Mental Illness has an online support group (www.strengthofus.org), as well as many excellent family resources. Sometimes medical efforts to be nonsectarian result in failure to recognize and remind teens and families of the value of religion, which is free and universally available, as a source of social support.

Relaxation

An evaluation of 15 studies concluded that relaxation techniques reduced depressive symptoms better than no treatment but not as much cognitive-behavior therapy (CBT). Yoga is another source of relaxation training. Mindfulness includes relaxation and specifies working to stay nonjudgmental about thoughts passing through one’s mind, recognizing and “arguing” with negative thinking, which is also part of CBT. Guided relaxation with a person, audiotape, or app (Calm or Headspace, among others) may be better for depressed teens because it inserts a voice to guide thoughts, which could potentially fend off ruminating on sad things.

Setting goals to address problems

In mild depression, compared with more endogenous moderate to severe major depressive disorder, a specific life stressor or relationship issue may be the precipitant. Identifying such factors (never forgetting possible trauma or abuse, which are harder to reveal), empathizing with the pain, and addressing them such as using Problem Solving Treatment for Primary Care (PST-PC) are within primary care skills. PST-PC involves four to six 30-minute sessions over 6-10 weeks during which you can provide perspective, help your patient set realistic goals and solutions to try out for situations that can be changed or coping strategies for emotion-focused unchangeable issues, iteratively check on progress via calls or televisits (the monitoring component), and renew problem-solving efforts as needed.

If mild depression fails to improve over several months or worsens, GLAD-PC describes evidence-based treatments. Even if it remits, your active support and monitoring should continue because depression tends to recur. You may not realize how valuable these seemingly simple active supports are to keeping mild depression in your teen patients at bay.