User login

Humira biosimilars: Five things to know

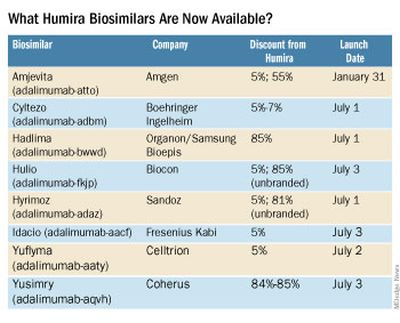

The best-selling drug Humira (adalimumab) now faces competition in the United States after a 20-year monopoly. The first adalimumab biosimilar, Amjevita, launched in the United States on January 31, and in July, seven additional biosimilars became available. These drugs have the potential to lower prescription drug prices, but when and by how much remains to be seen.

Here’s what you need to know about adalimumab biosimilars.

What Humira biosimilars are now available?

Eight different biosimilars have launched in 2023 with discounts as large at 85% from Humira’s list price of $6,922. A few companies also offer two price points.

Three of these biosimilars – Hadlima, Hyrimoz, and Yuflyma – are available in high concentration formulations. This high concentration formulation makes up 85% of Humira prescriptions, according to a report from Goodroot, a collection of companies focused on lowering health care costs.

Cyltezo is currently the only adalimumab biosimilar with an interchangeability designation, meaning that a pharmacist can substitute the biosimilar for an equivalent Humira prescription without the intervention of a clinician. A total of 47 states allow for these substitutions without prior approval from a clinician, according to Goodroot, and the clinician must be notified of the switch within a certain time frame. A total of 40 states require that patients be notified of the switch before substitution.

However, it’s not clear if this interchangeability designation will prove an advantage for Cyltezo, as it is interchangeable with the lower concentration version of Humira that makes up just 15% of prescriptions.

Most of the companies behind these biosimilars are pursuing interchangeability designations for their drugs, except for Fresenius Kabi (Idacio) and Coherus (Yusimry).

A ninth biosimilar, Pfizer’s adalimumab-afzb (Abrilada), is not yet on the market and is currently awaiting an approval decision from the Food and Drug Administration to add an interchangeability designation to its prior approval for a low-concentration formulation.

Why are they priced differently?

The two price points offer different deals to payers. Pharmacy benefit managers make confidential agreements with drug manufacturers to get a discount – called a rebate – to get the drug on the PBM’s formulary. The PBM keeps a portion of that rebate, and the rest is passed on to the insurance company and patients. Biosimilars at a higher price point will likely offer larger rebates. Biosimilars offered at lower price points incorporate this discount up front in their list pricing and likely will not offer large rebates.

Will biosimilars be covered by payers?

Currently, biosimilars are being offered on formularies at parity with Humira, meaning they are on the same tier. The PBM companies OptumRx and Cigna Group’s Express Scripts will offer Amjevita (at both price points), Cyltezo, and Hyrimoz (at both price points).

“This decision allows our clients flexibility to provide access to the lower list price, so members in high-deductible plans and benefit designs with coinsurance can experience lower out-of-pocket costs,” said OptumRx spokesperson Isaac Sorensen in an email.

Mark Cuban Cost Plus Drug Company, which uses a direct-to-consumer model, will offer Yusimry for $567.27 on its website. SmithRx, a PBM based in San Francisco, announced it would partner with Cost Plus Drugs to offer Yusimry, adding that SmithRx members can use their insurance benefits to further reduce out-of-pocket costs. RxPreferred, another PBM, will also offer Yusimry through its partnership with Cuban’s company.

The news website Formulary Watch previously reported that CVS Caremark, another of the biggest PBMs, will be offering Amjevita, but as a nonpreferred brand, while Humira remains the preferred brand. CVS Caremark did not respond to a request for comment.

Will patients pay less?

Biosimilars have been touted as a potential solution to lower spending on biologic drugs, but it’s unknown if patients will ultimately benefit with lower out-of-pocket costs. It’s “impossible to predict” if the discount that third-party payers pay will be passed on to consumers, said Mark Fendrick, MD, who directs the University of Michigan Center for Value-based Insurance Design in Ann Arbor.

Generally, a consumer’s copay is a percentage of a drug’s list price, so it stands to reason that a low drug price would result in lower out-of-pocket payments. While this is mostly true, Humira has a successful copay assistance program to lower prescription costs for consumers. According to a 2022 IQVIA report, 82% of commercial prescriptions cost patients less than $10 for Humira because of this program.

To appeal to patients, biosimilar companies will need to offer similar savings, Dr. Fendrick added. “There will be some discontent if patients are actually asked to pay more out-of-pocket for a less expensive drug,” he said.

All eight companies behind these biosimilars are offering or will be launching copay saving programs, many which advertise copays as low as $0 per month for eligible patients.

How will Humira respond?

Marta Wosińska, PhD, a health care economist at the Brookings Institute, Washington, predicts payers will use these lower biosimilar prices to negotiate better deals with AbbVie, Humira’s manufacturer. “We have a lot of players coming into [the market] right now, so the competition is really fierce,” she said. In response, AbbVie will need to increase rebates on Humira and/or lower its price to compete with these biosimilars.

“The ball is in AbbVie’s court,” she said. “If [the company] is not willing to drop price sufficiently, then payers will start switching to biosimilars.”

Dr. Fendrick reported past financial relationships and consulting arrangements with AbbVie, Amgen, Arnold Ventures, Bayer, CareFirst, BlueCross BlueShield, and many other companies. Dr. Wosińska has received funding from Arnold Ventures and serves as an expert witness on antitrust cases involving generic medication.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

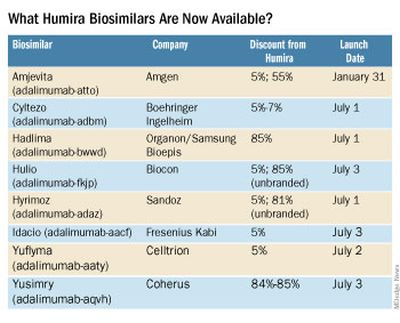

The best-selling drug Humira (adalimumab) now faces competition in the United States after a 20-year monopoly. The first adalimumab biosimilar, Amjevita, launched in the United States on January 31, and in July, seven additional biosimilars became available. These drugs have the potential to lower prescription drug prices, but when and by how much remains to be seen.

Here’s what you need to know about adalimumab biosimilars.

What Humira biosimilars are now available?

Eight different biosimilars have launched in 2023 with discounts as large at 85% from Humira’s list price of $6,922. A few companies also offer two price points.

Three of these biosimilars – Hadlima, Hyrimoz, and Yuflyma – are available in high concentration formulations. This high concentration formulation makes up 85% of Humira prescriptions, according to a report from Goodroot, a collection of companies focused on lowering health care costs.

Cyltezo is currently the only adalimumab biosimilar with an interchangeability designation, meaning that a pharmacist can substitute the biosimilar for an equivalent Humira prescription without the intervention of a clinician. A total of 47 states allow for these substitutions without prior approval from a clinician, according to Goodroot, and the clinician must be notified of the switch within a certain time frame. A total of 40 states require that patients be notified of the switch before substitution.

However, it’s not clear if this interchangeability designation will prove an advantage for Cyltezo, as it is interchangeable with the lower concentration version of Humira that makes up just 15% of prescriptions.

Most of the companies behind these biosimilars are pursuing interchangeability designations for their drugs, except for Fresenius Kabi (Idacio) and Coherus (Yusimry).

A ninth biosimilar, Pfizer’s adalimumab-afzb (Abrilada), is not yet on the market and is currently awaiting an approval decision from the Food and Drug Administration to add an interchangeability designation to its prior approval for a low-concentration formulation.

Why are they priced differently?

The two price points offer different deals to payers. Pharmacy benefit managers make confidential agreements with drug manufacturers to get a discount – called a rebate – to get the drug on the PBM’s formulary. The PBM keeps a portion of that rebate, and the rest is passed on to the insurance company and patients. Biosimilars at a higher price point will likely offer larger rebates. Biosimilars offered at lower price points incorporate this discount up front in their list pricing and likely will not offer large rebates.

Will biosimilars be covered by payers?

Currently, biosimilars are being offered on formularies at parity with Humira, meaning they are on the same tier. The PBM companies OptumRx and Cigna Group’s Express Scripts will offer Amjevita (at both price points), Cyltezo, and Hyrimoz (at both price points).

“This decision allows our clients flexibility to provide access to the lower list price, so members in high-deductible plans and benefit designs with coinsurance can experience lower out-of-pocket costs,” said OptumRx spokesperson Isaac Sorensen in an email.

Mark Cuban Cost Plus Drug Company, which uses a direct-to-consumer model, will offer Yusimry for $567.27 on its website. SmithRx, a PBM based in San Francisco, announced it would partner with Cost Plus Drugs to offer Yusimry, adding that SmithRx members can use their insurance benefits to further reduce out-of-pocket costs. RxPreferred, another PBM, will also offer Yusimry through its partnership with Cuban’s company.

The news website Formulary Watch previously reported that CVS Caremark, another of the biggest PBMs, will be offering Amjevita, but as a nonpreferred brand, while Humira remains the preferred brand. CVS Caremark did not respond to a request for comment.

Will patients pay less?

Biosimilars have been touted as a potential solution to lower spending on biologic drugs, but it’s unknown if patients will ultimately benefit with lower out-of-pocket costs. It’s “impossible to predict” if the discount that third-party payers pay will be passed on to consumers, said Mark Fendrick, MD, who directs the University of Michigan Center for Value-based Insurance Design in Ann Arbor.

Generally, a consumer’s copay is a percentage of a drug’s list price, so it stands to reason that a low drug price would result in lower out-of-pocket payments. While this is mostly true, Humira has a successful copay assistance program to lower prescription costs for consumers. According to a 2022 IQVIA report, 82% of commercial prescriptions cost patients less than $10 for Humira because of this program.

To appeal to patients, biosimilar companies will need to offer similar savings, Dr. Fendrick added. “There will be some discontent if patients are actually asked to pay more out-of-pocket for a less expensive drug,” he said.

All eight companies behind these biosimilars are offering or will be launching copay saving programs, many which advertise copays as low as $0 per month for eligible patients.

How will Humira respond?

Marta Wosińska, PhD, a health care economist at the Brookings Institute, Washington, predicts payers will use these lower biosimilar prices to negotiate better deals with AbbVie, Humira’s manufacturer. “We have a lot of players coming into [the market] right now, so the competition is really fierce,” she said. In response, AbbVie will need to increase rebates on Humira and/or lower its price to compete with these biosimilars.

“The ball is in AbbVie’s court,” she said. “If [the company] is not willing to drop price sufficiently, then payers will start switching to biosimilars.”

Dr. Fendrick reported past financial relationships and consulting arrangements with AbbVie, Amgen, Arnold Ventures, Bayer, CareFirst, BlueCross BlueShield, and many other companies. Dr. Wosińska has received funding from Arnold Ventures and serves as an expert witness on antitrust cases involving generic medication.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

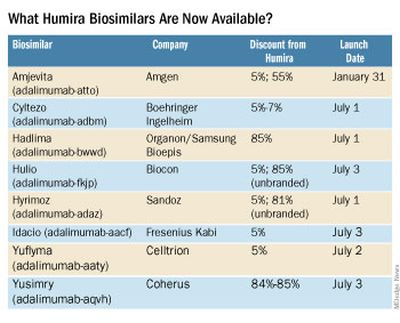

The best-selling drug Humira (adalimumab) now faces competition in the United States after a 20-year monopoly. The first adalimumab biosimilar, Amjevita, launched in the United States on January 31, and in July, seven additional biosimilars became available. These drugs have the potential to lower prescription drug prices, but when and by how much remains to be seen.

Here’s what you need to know about adalimumab biosimilars.

What Humira biosimilars are now available?

Eight different biosimilars have launched in 2023 with discounts as large at 85% from Humira’s list price of $6,922. A few companies also offer two price points.

Three of these biosimilars – Hadlima, Hyrimoz, and Yuflyma – are available in high concentration formulations. This high concentration formulation makes up 85% of Humira prescriptions, according to a report from Goodroot, a collection of companies focused on lowering health care costs.

Cyltezo is currently the only adalimumab biosimilar with an interchangeability designation, meaning that a pharmacist can substitute the biosimilar for an equivalent Humira prescription without the intervention of a clinician. A total of 47 states allow for these substitutions without prior approval from a clinician, according to Goodroot, and the clinician must be notified of the switch within a certain time frame. A total of 40 states require that patients be notified of the switch before substitution.

However, it’s not clear if this interchangeability designation will prove an advantage for Cyltezo, as it is interchangeable with the lower concentration version of Humira that makes up just 15% of prescriptions.

Most of the companies behind these biosimilars are pursuing interchangeability designations for their drugs, except for Fresenius Kabi (Idacio) and Coherus (Yusimry).

A ninth biosimilar, Pfizer’s adalimumab-afzb (Abrilada), is not yet on the market and is currently awaiting an approval decision from the Food and Drug Administration to add an interchangeability designation to its prior approval for a low-concentration formulation.

Why are they priced differently?

The two price points offer different deals to payers. Pharmacy benefit managers make confidential agreements with drug manufacturers to get a discount – called a rebate – to get the drug on the PBM’s formulary. The PBM keeps a portion of that rebate, and the rest is passed on to the insurance company and patients. Biosimilars at a higher price point will likely offer larger rebates. Biosimilars offered at lower price points incorporate this discount up front in their list pricing and likely will not offer large rebates.

Will biosimilars be covered by payers?

Currently, biosimilars are being offered on formularies at parity with Humira, meaning they are on the same tier. The PBM companies OptumRx and Cigna Group’s Express Scripts will offer Amjevita (at both price points), Cyltezo, and Hyrimoz (at both price points).

“This decision allows our clients flexibility to provide access to the lower list price, so members in high-deductible plans and benefit designs with coinsurance can experience lower out-of-pocket costs,” said OptumRx spokesperson Isaac Sorensen in an email.

Mark Cuban Cost Plus Drug Company, which uses a direct-to-consumer model, will offer Yusimry for $567.27 on its website. SmithRx, a PBM based in San Francisco, announced it would partner with Cost Plus Drugs to offer Yusimry, adding that SmithRx members can use their insurance benefits to further reduce out-of-pocket costs. RxPreferred, another PBM, will also offer Yusimry through its partnership with Cuban’s company.

The news website Formulary Watch previously reported that CVS Caremark, another of the biggest PBMs, will be offering Amjevita, but as a nonpreferred brand, while Humira remains the preferred brand. CVS Caremark did not respond to a request for comment.

Will patients pay less?

Biosimilars have been touted as a potential solution to lower spending on biologic drugs, but it’s unknown if patients will ultimately benefit with lower out-of-pocket costs. It’s “impossible to predict” if the discount that third-party payers pay will be passed on to consumers, said Mark Fendrick, MD, who directs the University of Michigan Center for Value-based Insurance Design in Ann Arbor.

Generally, a consumer’s copay is a percentage of a drug’s list price, so it stands to reason that a low drug price would result in lower out-of-pocket payments. While this is mostly true, Humira has a successful copay assistance program to lower prescription costs for consumers. According to a 2022 IQVIA report, 82% of commercial prescriptions cost patients less than $10 for Humira because of this program.

To appeal to patients, biosimilar companies will need to offer similar savings, Dr. Fendrick added. “There will be some discontent if patients are actually asked to pay more out-of-pocket for a less expensive drug,” he said.

All eight companies behind these biosimilars are offering or will be launching copay saving programs, many which advertise copays as low as $0 per month for eligible patients.

How will Humira respond?

Marta Wosińska, PhD, a health care economist at the Brookings Institute, Washington, predicts payers will use these lower biosimilar prices to negotiate better deals with AbbVie, Humira’s manufacturer. “We have a lot of players coming into [the market] right now, so the competition is really fierce,” she said. In response, AbbVie will need to increase rebates on Humira and/or lower its price to compete with these biosimilars.

“The ball is in AbbVie’s court,” she said. “If [the company] is not willing to drop price sufficiently, then payers will start switching to biosimilars.”

Dr. Fendrick reported past financial relationships and consulting arrangements with AbbVie, Amgen, Arnold Ventures, Bayer, CareFirst, BlueCross BlueShield, and many other companies. Dr. Wosińska has received funding from Arnold Ventures and serves as an expert witness on antitrust cases involving generic medication.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Phenotypes drive antibiotic response in youth with bronchiectasis

Indigenous children or children with new abnormal auscultatory findings were significantly more likely than children in other categories to respond to oral antibiotics for exacerbations related to bronchiectasis, based on data from more than 200 individuals in New Zealand.

Children and adolescents with bronchiectasis are often treated with antibiotics for respiratory exacerbations, but the effects of antibiotics can vary among individuals, and phenotypic features associated with greater symptom resolution have not been identified, wrote Vikas Goyal, PhD, of the Centre for Children’s Health Research, Brisbane, Australia, and colleagues.

Previous studies have suggested that nearly half of exacerbations in children and adolescents resolve spontaneously after 14 days, and more data are needed to identify which patients are mostly likely to benefit from antibiotics, they noted.

In a study published in the journal Chest, the researchers reviewed secondary data from 217 children and adolescents aged 1-18 years with bronchiectasis enrolled in a pair of randomized, controlled trials comparing oral antibiotics with placebo (known as BEST-1 and BEST-2). The median age of the participants was 6.6 years, 52% were boys, and 41% were Indigenous (defined as Australian First Nations, New Zealand Maori, or Pacific Islander). All participants in the analysis received at least 14 days of oral antibiotics for treatment of nonhospitalized respiratory exacerbations.

Overall, 130 children had resolution of symptoms by day 14, and 87 were nonresponders.

In a multivariate analysis, children who were Indigenous or who had new abnormal auscultatory findings were significantly more likely to respond than children in other categories (odds ratios, 3.59 and 3.85, respectively).

Patients with multiple bronchiectatic lobes at the time of diagnosis and those with higher cough scores at the start of treatment were significantly less likely to respond to antibiotics than patients without these features (OR, 0.66 and 0.55, respectively).

The researchers conducted a further analysis to examine the association between Indigenous ethnicity and treatment response. They found no differences in the other response variables of number of affected lobes at diagnosis and cough scores at the start of treatment between Indigenous and non-Indigenous children.

Given the strong response to antibiotics among Indigenous children, the researchers also conducted a mediation analysis. “Respiratory bacterial pathogens were mediated by Indigenous ethnicity and associated with being an antibiotic ‘responder,’ ” they wrote. For new abnormal chest auscultatory findings, both direct and indirect effects on day 14 response to oral antibiotics were mediated by Indigenous ethnicity. However, neither cough scores at the start of treatment nor the number of affected lobes at diagnosis showed a mediation effect from Indigenous ethnicity.

Among the nonresponders, 59 of 87 resolved symptoms with continuing oral antibiotics over the next 2-4 weeks, and 21 improved without antibiotics.

Additionally, the detection of a respiratory virus at the start of an exacerbation was not associated with antibiotic failure at 14 days, the researchers noted.

The findings were limited by several factors including the use of data from randomized trials that were not designed to address the question in the current study, the researchers noted. Other limitations included incomplete clinical data and lack of data on inflammatory indices, potential antibiotic-resistant pathogens in nonresponders, and the follow-up period of only 14 days, they said.

However, the results suggest a role for patient and exacerbation phenotypes in management of bronchiectasis in clinical practice and promoting antimicrobial stewardship, the researchers wrote. “Although there is benefit in treating exacerbations early to avoid treatment failure and subsequent intravenous antibiotics, future research also needs to identify exacerbations that can be managed without antibiotics,” they concluded.

The BEST-1 and BEST-2 studies were supported by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council and the NHMRC Centre for Research Excellence in Lung Health of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children. Dr. Goyal had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Indigenous children or children with new abnormal auscultatory findings were significantly more likely than children in other categories to respond to oral antibiotics for exacerbations related to bronchiectasis, based on data from more than 200 individuals in New Zealand.

Children and adolescents with bronchiectasis are often treated with antibiotics for respiratory exacerbations, but the effects of antibiotics can vary among individuals, and phenotypic features associated with greater symptom resolution have not been identified, wrote Vikas Goyal, PhD, of the Centre for Children’s Health Research, Brisbane, Australia, and colleagues.

Previous studies have suggested that nearly half of exacerbations in children and adolescents resolve spontaneously after 14 days, and more data are needed to identify which patients are mostly likely to benefit from antibiotics, they noted.

In a study published in the journal Chest, the researchers reviewed secondary data from 217 children and adolescents aged 1-18 years with bronchiectasis enrolled in a pair of randomized, controlled trials comparing oral antibiotics with placebo (known as BEST-1 and BEST-2). The median age of the participants was 6.6 years, 52% were boys, and 41% were Indigenous (defined as Australian First Nations, New Zealand Maori, or Pacific Islander). All participants in the analysis received at least 14 days of oral antibiotics for treatment of nonhospitalized respiratory exacerbations.

Overall, 130 children had resolution of symptoms by day 14, and 87 were nonresponders.

In a multivariate analysis, children who were Indigenous or who had new abnormal auscultatory findings were significantly more likely to respond than children in other categories (odds ratios, 3.59 and 3.85, respectively).

Patients with multiple bronchiectatic lobes at the time of diagnosis and those with higher cough scores at the start of treatment were significantly less likely to respond to antibiotics than patients without these features (OR, 0.66 and 0.55, respectively).

The researchers conducted a further analysis to examine the association between Indigenous ethnicity and treatment response. They found no differences in the other response variables of number of affected lobes at diagnosis and cough scores at the start of treatment between Indigenous and non-Indigenous children.

Given the strong response to antibiotics among Indigenous children, the researchers also conducted a mediation analysis. “Respiratory bacterial pathogens were mediated by Indigenous ethnicity and associated with being an antibiotic ‘responder,’ ” they wrote. For new abnormal chest auscultatory findings, both direct and indirect effects on day 14 response to oral antibiotics were mediated by Indigenous ethnicity. However, neither cough scores at the start of treatment nor the number of affected lobes at diagnosis showed a mediation effect from Indigenous ethnicity.

Among the nonresponders, 59 of 87 resolved symptoms with continuing oral antibiotics over the next 2-4 weeks, and 21 improved without antibiotics.

Additionally, the detection of a respiratory virus at the start of an exacerbation was not associated with antibiotic failure at 14 days, the researchers noted.

The findings were limited by several factors including the use of data from randomized trials that were not designed to address the question in the current study, the researchers noted. Other limitations included incomplete clinical data and lack of data on inflammatory indices, potential antibiotic-resistant pathogens in nonresponders, and the follow-up period of only 14 days, they said.

However, the results suggest a role for patient and exacerbation phenotypes in management of bronchiectasis in clinical practice and promoting antimicrobial stewardship, the researchers wrote. “Although there is benefit in treating exacerbations early to avoid treatment failure and subsequent intravenous antibiotics, future research also needs to identify exacerbations that can be managed without antibiotics,” they concluded.

The BEST-1 and BEST-2 studies were supported by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council and the NHMRC Centre for Research Excellence in Lung Health of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children. Dr. Goyal had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Indigenous children or children with new abnormal auscultatory findings were significantly more likely than children in other categories to respond to oral antibiotics for exacerbations related to bronchiectasis, based on data from more than 200 individuals in New Zealand.

Children and adolescents with bronchiectasis are often treated with antibiotics for respiratory exacerbations, but the effects of antibiotics can vary among individuals, and phenotypic features associated with greater symptom resolution have not been identified, wrote Vikas Goyal, PhD, of the Centre for Children’s Health Research, Brisbane, Australia, and colleagues.

Previous studies have suggested that nearly half of exacerbations in children and adolescents resolve spontaneously after 14 days, and more data are needed to identify which patients are mostly likely to benefit from antibiotics, they noted.

In a study published in the journal Chest, the researchers reviewed secondary data from 217 children and adolescents aged 1-18 years with bronchiectasis enrolled in a pair of randomized, controlled trials comparing oral antibiotics with placebo (known as BEST-1 and BEST-2). The median age of the participants was 6.6 years, 52% were boys, and 41% were Indigenous (defined as Australian First Nations, New Zealand Maori, or Pacific Islander). All participants in the analysis received at least 14 days of oral antibiotics for treatment of nonhospitalized respiratory exacerbations.

Overall, 130 children had resolution of symptoms by day 14, and 87 were nonresponders.

In a multivariate analysis, children who were Indigenous or who had new abnormal auscultatory findings were significantly more likely to respond than children in other categories (odds ratios, 3.59 and 3.85, respectively).

Patients with multiple bronchiectatic lobes at the time of diagnosis and those with higher cough scores at the start of treatment were significantly less likely to respond to antibiotics than patients without these features (OR, 0.66 and 0.55, respectively).

The researchers conducted a further analysis to examine the association between Indigenous ethnicity and treatment response. They found no differences in the other response variables of number of affected lobes at diagnosis and cough scores at the start of treatment between Indigenous and non-Indigenous children.

Given the strong response to antibiotics among Indigenous children, the researchers also conducted a mediation analysis. “Respiratory bacterial pathogens were mediated by Indigenous ethnicity and associated with being an antibiotic ‘responder,’ ” they wrote. For new abnormal chest auscultatory findings, both direct and indirect effects on day 14 response to oral antibiotics were mediated by Indigenous ethnicity. However, neither cough scores at the start of treatment nor the number of affected lobes at diagnosis showed a mediation effect from Indigenous ethnicity.

Among the nonresponders, 59 of 87 resolved symptoms with continuing oral antibiotics over the next 2-4 weeks, and 21 improved without antibiotics.

Additionally, the detection of a respiratory virus at the start of an exacerbation was not associated with antibiotic failure at 14 days, the researchers noted.

The findings were limited by several factors including the use of data from randomized trials that were not designed to address the question in the current study, the researchers noted. Other limitations included incomplete clinical data and lack of data on inflammatory indices, potential antibiotic-resistant pathogens in nonresponders, and the follow-up period of only 14 days, they said.

However, the results suggest a role for patient and exacerbation phenotypes in management of bronchiectasis in clinical practice and promoting antimicrobial stewardship, the researchers wrote. “Although there is benefit in treating exacerbations early to avoid treatment failure and subsequent intravenous antibiotics, future research also needs to identify exacerbations that can be managed without antibiotics,” they concluded.

The BEST-1 and BEST-2 studies were supported by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council and the NHMRC Centre for Research Excellence in Lung Health of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children. Dr. Goyal had no financial conflicts to disclose.

FROM THE JOURNAL CHEST

Goodbye, finger sticks; hello, CGMs

Nearly 90% of diabetes management in the United States is provided by primary care clinicians; diabetes is the fifth most common reason for a primary care visit. State-of-the-art technology such as continuous glucose monitors (CGMs) will inevitably transform the management of diabetes in primary care. Clinicians and staff must be ready to educate, counsel, and support primary care patients in the use of CGMs.

CGMs (also called glucose sensors) are small, minimally invasive devices that attach to the skin of the upper arm or trunk. A tiny electrode in the subcutaneous space prompts an enzyme reaction that measures the interstitial (rather than blood) glucose concentration, typically every 5 minutes. The results are displayed on an accompanying reader or transmitted to an app on the user’s mobile phone.

CGMs could eliminate the need for finger-stick blood glucose testing, which until now, has been the much-despised gold standard for self-monitoring of glucose levels in diabetes. Despite being relatively inexpensive and accurate, finger-stick glucose tests are inconvenient and often painful. But of greater significance is this downside: Finger-stick monitoring reveals the patient’s blood glucose concentration at a single point in time, which can be difficult to interpret. Is the blood glucose rising or falling? Multiple finger-stick tests are required to determine the trend of a patient’s glucose levels or the response to food or exercise.

In contrast, the graphic display from a CGM sensor is more like a movie, telling a story as it unfolds. Uninterrupted data provide valuable feedback to patients about the effects of diet, physical activity, stress, or pain on their glucose levels. And for the first time, it’s easy to determine the proportion of time the patient spends in or out of the target glucose range.

Incorporating new technology into your practice may seem like a burden, but the reward is better information that leads to better management of diabetes. If you’re new to glucose sensors, many excellent resources are available to learn how to use them.

I recommend starting with a website called diabeteswise.org, which has both a patient-facing and clinician-facing version. This unbranded site serves as a kind of Consumer Reports for diabetes technology, allowing both patients and professionals to compare and contrast currently available CGM devices.

DiabetesWisePro has information ranging from CGM device fundamentals and best practices to CGM prescribing and reimbursement.

Clinical Diabetes also provides multiple tools to help incorporate these devices into primary care clinical practice, including:

• Continuous Glucose Monitoring: Optimizing Diabetes Care (CME course).

• Diabetes Technology in Primary Care.

The next article in this series will cover two types of CGMs used in primary care: professional and personal devices.

Dr. Shubrook is a professor in the department of primary care, Touro University California College of Osteopathic Medicine, Vallejo, Calif., and director of diabetes services, Solano County Family Health Services, Fairfield, Calif. He disclosed ties with Abbott, Astra Zeneca, Bayer, Nevro, and Novo Nordisk.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Nearly 90% of diabetes management in the United States is provided by primary care clinicians; diabetes is the fifth most common reason for a primary care visit. State-of-the-art technology such as continuous glucose monitors (CGMs) will inevitably transform the management of diabetes in primary care. Clinicians and staff must be ready to educate, counsel, and support primary care patients in the use of CGMs.

CGMs (also called glucose sensors) are small, minimally invasive devices that attach to the skin of the upper arm or trunk. A tiny electrode in the subcutaneous space prompts an enzyme reaction that measures the interstitial (rather than blood) glucose concentration, typically every 5 minutes. The results are displayed on an accompanying reader or transmitted to an app on the user’s mobile phone.

CGMs could eliminate the need for finger-stick blood glucose testing, which until now, has been the much-despised gold standard for self-monitoring of glucose levels in diabetes. Despite being relatively inexpensive and accurate, finger-stick glucose tests are inconvenient and often painful. But of greater significance is this downside: Finger-stick monitoring reveals the patient’s blood glucose concentration at a single point in time, which can be difficult to interpret. Is the blood glucose rising or falling? Multiple finger-stick tests are required to determine the trend of a patient’s glucose levels or the response to food or exercise.

In contrast, the graphic display from a CGM sensor is more like a movie, telling a story as it unfolds. Uninterrupted data provide valuable feedback to patients about the effects of diet, physical activity, stress, or pain on their glucose levels. And for the first time, it’s easy to determine the proportion of time the patient spends in or out of the target glucose range.

Incorporating new technology into your practice may seem like a burden, but the reward is better information that leads to better management of diabetes. If you’re new to glucose sensors, many excellent resources are available to learn how to use them.

I recommend starting with a website called diabeteswise.org, which has both a patient-facing and clinician-facing version. This unbranded site serves as a kind of Consumer Reports for diabetes technology, allowing both patients and professionals to compare and contrast currently available CGM devices.

DiabetesWisePro has information ranging from CGM device fundamentals and best practices to CGM prescribing and reimbursement.

Clinical Diabetes also provides multiple tools to help incorporate these devices into primary care clinical practice, including:

• Continuous Glucose Monitoring: Optimizing Diabetes Care (CME course).

• Diabetes Technology in Primary Care.

The next article in this series will cover two types of CGMs used in primary care: professional and personal devices.

Dr. Shubrook is a professor in the department of primary care, Touro University California College of Osteopathic Medicine, Vallejo, Calif., and director of diabetes services, Solano County Family Health Services, Fairfield, Calif. He disclosed ties with Abbott, Astra Zeneca, Bayer, Nevro, and Novo Nordisk.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Nearly 90% of diabetes management in the United States is provided by primary care clinicians; diabetes is the fifth most common reason for a primary care visit. State-of-the-art technology such as continuous glucose monitors (CGMs) will inevitably transform the management of diabetes in primary care. Clinicians and staff must be ready to educate, counsel, and support primary care patients in the use of CGMs.

CGMs (also called glucose sensors) are small, minimally invasive devices that attach to the skin of the upper arm or trunk. A tiny electrode in the subcutaneous space prompts an enzyme reaction that measures the interstitial (rather than blood) glucose concentration, typically every 5 minutes. The results are displayed on an accompanying reader or transmitted to an app on the user’s mobile phone.

CGMs could eliminate the need for finger-stick blood glucose testing, which until now, has been the much-despised gold standard for self-monitoring of glucose levels in diabetes. Despite being relatively inexpensive and accurate, finger-stick glucose tests are inconvenient and often painful. But of greater significance is this downside: Finger-stick monitoring reveals the patient’s blood glucose concentration at a single point in time, which can be difficult to interpret. Is the blood glucose rising or falling? Multiple finger-stick tests are required to determine the trend of a patient’s glucose levels or the response to food or exercise.

In contrast, the graphic display from a CGM sensor is more like a movie, telling a story as it unfolds. Uninterrupted data provide valuable feedback to patients about the effects of diet, physical activity, stress, or pain on their glucose levels. And for the first time, it’s easy to determine the proportion of time the patient spends in or out of the target glucose range.

Incorporating new technology into your practice may seem like a burden, but the reward is better information that leads to better management of diabetes. If you’re new to glucose sensors, many excellent resources are available to learn how to use them.

I recommend starting with a website called diabeteswise.org, which has both a patient-facing and clinician-facing version. This unbranded site serves as a kind of Consumer Reports for diabetes technology, allowing both patients and professionals to compare and contrast currently available CGM devices.

DiabetesWisePro has information ranging from CGM device fundamentals and best practices to CGM prescribing and reimbursement.

Clinical Diabetes also provides multiple tools to help incorporate these devices into primary care clinical practice, including:

• Continuous Glucose Monitoring: Optimizing Diabetes Care (CME course).

• Diabetes Technology in Primary Care.

The next article in this series will cover two types of CGMs used in primary care: professional and personal devices.

Dr. Shubrook is a professor in the department of primary care, Touro University California College of Osteopathic Medicine, Vallejo, Calif., and director of diabetes services, Solano County Family Health Services, Fairfield, Calif. He disclosed ties with Abbott, Astra Zeneca, Bayer, Nevro, and Novo Nordisk.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In new era of gene therapy, PCPs are ‘boots on the ground’

In Colorado and Wyoming, nearly every baby born since 2020 is tested for signs of a mutation in the SMN1 gene, an indicator of spinal muscular atrophy (SMA). And in 4 years, genetic counselor Melissa Gibbons has seen 24 positive results. She has prepped 24 different pediatricians and family doctors to deliver the news: A seemingly perfect newborn likely has a lethal genetic disease.

Most of these clinicians had never cared for a child with SMA before, nor did they know that lifesaving gene therapy for the condition now exists. Still, the physicians were foundational to getting babies emergency treatment and monitoring the child’s safety after the fact.

“They are boots on the ground for this kind of [work],” Ms. Gibbons, who is the newborn screen coordinator for SMA in both states, told this news organization. “I’m not even sure they realize it.” As of today, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has approved 16 gene therapies for the treatment of rare and debilitating diseases once considered lethal, such as SMA and cerebral adrenoleukodystrophy.

The newest addition to the list of approvals is Elevidys, Sarepta’s gene therapy for Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD). These conditions can now be mitigated, abated for years at a time, and even cured using treatments that tweak a patient’s DNA or RNA.

Hundreds of treatments are under development using the same mechanism. Viruses, liposomes, and other vectors of all kinds are being used to usher new genes into cells, correcting faulty copies or equipping a cell to fight disease. Cells gain the ability to make lifesaving proteins – proteins that heal wounds, restore muscle function, and fight cancer.

Within the decade, a significant fraction of the pediatric population will have gone through gene therapy, experts told this news organization. And primary care stands to be a linchpin in the scale-up of this kind of precision genetic medicine. Pediatricians and general practitioners will be central to finding and monitoring the patients that need these treatments. But the time and support doctors will need to fill that role remain scarce.

“This is a world we are creating right now, quite literally,” said Stanley Nelson, MD, director of the center for Duchenne muscular dystrophy at the University of California, Los Angeles. These cases – some before gene therapy and some after – will show up in primary care offices before the textbook is written.

Unknown side effects, new diseases

Even now, gene therapy is sequestered away in large academic medical research centers. The diagnosis, decision-making, and aftercare are handled by subspecialists working on clinical trials. While the research is ongoing, trial sponsors are keeping a close eye on enrolled patients. But that’s only until these drugs get market approval, Phil Beales, MD, chief medical officer at Congenica, a digital health company specializing in genome analysis support, said. Afterward, “the trialists will no longer have a role in looking after those patients.”

At that point, the role of primary care clinicians will be critically important. Although they probably will not manage gene-therapy patients on their own – comanaging them instead with subspecialists – they will be involved in the ordering and monitoring of safety labs and other tests.

General practitioners “need to know side effects because they are going to deal with side effects when someone calls them in the middle of the night,” said Dr. Beales, who also is chief executive officer of Axovia Therapeutics, a biotech company developing gene therapies.

Some of the side effects that come with gene therapy are established. Adeno-associated virus (AAV) or AAV-mediated gene therapies carry an increased risk for damage to the heart and liver, Dr. Nelson said. Other side effects are less well known and could be specific to the treatment and the tissue it targets. Primary care will be critical in detecting these unexpected side effects and expediting visits with subspecialists, he said.

In rural Wyoming, pediatricians and family doctors are especially important, Ms. Gibbons said. In the 30-90 days after gene therapy, patients need a lot of follow-up for safety reasons.

But aftercare for gene therapy will be more than just monitoring and managing side effects. The diseases themselves will change. Patients will be living with conditions that once were lethal.

In some cases, gene therapy may largely eliminate the disease. The data suggest that thalassemia, for example, can be largely cured for decades with one infusion of a patient’s genetically modified hematopoietic stem cells made using bluebird bio’s Zynteglo, according to Christy Duncan, MD, medical director of clinical research at the gene therapy program at Boston Children’s Hospital.

But other gene therapies, like the one for DMD, will offer a “spectrum of benefits,” Dr. Nelson said. They will be lifesaving, but the signs of the disease will linger. Clinicians will be learning alongside specialists what the new disease state for DMD and other rare diseases looks like after gene therapy.

“As we get hundreds of such therapies, [post–gene therapy] will amount to a substantial part of the pediatric population,” Dr. Nelson said.

Finding patients

Many of these rare diseases that plague young patients are unmistakable. Children with moderate or severe dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa, for instance, carry a mutation that prevents them from making type VII collagen. The babies suffer wounds and excessive bleeding and tend to receive a quick diagnosis within the first 6 months of life, according to Andy Orth, chief commercial officer at Krystal Bio, manufacturer of a new wound-healing gene therapy, Vyjuvek, for the disorder.

Other rare neurologic or muscular diseases can go undiagnosed for years. Until recently, drug companies and researchers have had little motivation to speed up the timeline because early diagnosis of a disease like DMD would not change the outcome, Dr. Nelson said.

But with gene therapy, prognoses are changing. And finding diseases early could soon mean preserving muscular function or preventing neurologic damage, Dr. Duncan said.

Newborn sequencing “is not standard of care yet, but it’s certainly coming,” Josh Peterson, MD, MPH, director of the center for precision medicine at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, in Nashville, Tenn., told this news organization.

A recent survey of 238 specialists in rare diseases found that roughly 90% believe whole-genome sequencing should be available to all newborns. And 80% of those experts endorse 42 genes as disease predictors. Screening for rare diseases at birth could reveal a host of conditions in the first week of life and expedite treatment. But this strategy will often rely on primary care and pediatricians interpreting the results.

Most pediatricians think sequencing is a great idea, but they do not feel comfortable doing it themselves, Dr. Peterson said. The good news, he said, is that manufacturers have made screening tests straightforward. Some drug companies even offer free screenings for gene therapy candidates.

Dr. Peterson predicts pediatricians will need to be equipped to deliver negative results on their own, which will be the case for around 97%-99% of patients. They also will need to be clear on whether a negative result is definitive or if more testing is warranted.

Positive results are more nuanced. Genetic counseling is the ideal resource when delivering this kind of news to patients, but counselors are a scarce resource nationally – and particularly in rural areas, Dr. Nelson said. Physicians likely will have to rely on their own counseling training to some degree.

“I feel very strongly that genetic counselors are in short supply,” Ms. Gibbons in Colorado said. Patients need a friendly resource who can talk them through the disease and how it works. And that discussion is not a one-off, she said.

The number of board-certified genetic counselors in the United States has doubled to more than 6,000 in the past 10 years – a pace that is expected to continue, according to the National Society of Genetic Counselors. “However, the geographical distribution of genetic counselors is most concentrated in urban centers.”

Equally important to the counseling experience, according to Dr. Duncan at Boston Children’s, is a primary care physician’s network of connections. The best newborn screening rollouts across the country have succeeded because clinicians knew where to send people next and how to get families the help they needed, she said.

But she also cautioned that this learning curve will soon be overwhelming. As gene therapy expands, it may be difficult for primary care doctors to keep up with the science, treatment studies, and commercially available therapies. “It’s asking too much,” Dr. Duncan said.

The structure of primary care already stretches practitioners thin and will “affect how well precision medicine can be adopted and disseminated,” Dr. Peterson said. “I think that is a key issue.”

Artificial intelligence may offer a partial solution. Some genetic counseling models already exist, but their utility for clinicians so far is limited, Dr. Beales said. But he said he expects these tools to improve rapidly to help clinicians and patients. On the patient’s end, they may be able to answer questions and supplement basic genetic counseling. On the physician’s end, algorithms could help triage patients and help move them along to the next steps in the care pathway for these rare diseases.

The whole patient

Primary care physicians will not be expected to be experts in gene therapy or solely in charge of patient safety. They will have support from industry and subspecialists leading the development of these treatments, experts agreed.

But generalists should expect to be drawn into multidisciplinary care teams, be the sounding boards for patients making decisions about gene therapy, help arrange insurance coverage, and be the recipients of late-night phone calls about side effects.

All that, while never losing sight of the child’s holistic health. In children so sick, specialists, subspecialists, and even parents tend to focus only on the rare disease. The team can “get distracted from good normal routine care,” Dr. Nelson said. But these children aren’t exempt from check-ups, vaccine regimens, or the other diseases of childhood.

“In a world where we mitigate that core disease,” he said, “we need a partner in the general pediatrics community” investing in their long-term health.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In Colorado and Wyoming, nearly every baby born since 2020 is tested for signs of a mutation in the SMN1 gene, an indicator of spinal muscular atrophy (SMA). And in 4 years, genetic counselor Melissa Gibbons has seen 24 positive results. She has prepped 24 different pediatricians and family doctors to deliver the news: A seemingly perfect newborn likely has a lethal genetic disease.

Most of these clinicians had never cared for a child with SMA before, nor did they know that lifesaving gene therapy for the condition now exists. Still, the physicians were foundational to getting babies emergency treatment and monitoring the child’s safety after the fact.

“They are boots on the ground for this kind of [work],” Ms. Gibbons, who is the newborn screen coordinator for SMA in both states, told this news organization. “I’m not even sure they realize it.” As of today, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has approved 16 gene therapies for the treatment of rare and debilitating diseases once considered lethal, such as SMA and cerebral adrenoleukodystrophy.

The newest addition to the list of approvals is Elevidys, Sarepta’s gene therapy for Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD). These conditions can now be mitigated, abated for years at a time, and even cured using treatments that tweak a patient’s DNA or RNA.

Hundreds of treatments are under development using the same mechanism. Viruses, liposomes, and other vectors of all kinds are being used to usher new genes into cells, correcting faulty copies or equipping a cell to fight disease. Cells gain the ability to make lifesaving proteins – proteins that heal wounds, restore muscle function, and fight cancer.

Within the decade, a significant fraction of the pediatric population will have gone through gene therapy, experts told this news organization. And primary care stands to be a linchpin in the scale-up of this kind of precision genetic medicine. Pediatricians and general practitioners will be central to finding and monitoring the patients that need these treatments. But the time and support doctors will need to fill that role remain scarce.

“This is a world we are creating right now, quite literally,” said Stanley Nelson, MD, director of the center for Duchenne muscular dystrophy at the University of California, Los Angeles. These cases – some before gene therapy and some after – will show up in primary care offices before the textbook is written.

Unknown side effects, new diseases

Even now, gene therapy is sequestered away in large academic medical research centers. The diagnosis, decision-making, and aftercare are handled by subspecialists working on clinical trials. While the research is ongoing, trial sponsors are keeping a close eye on enrolled patients. But that’s only until these drugs get market approval, Phil Beales, MD, chief medical officer at Congenica, a digital health company specializing in genome analysis support, said. Afterward, “the trialists will no longer have a role in looking after those patients.”

At that point, the role of primary care clinicians will be critically important. Although they probably will not manage gene-therapy patients on their own – comanaging them instead with subspecialists – they will be involved in the ordering and monitoring of safety labs and other tests.

General practitioners “need to know side effects because they are going to deal with side effects when someone calls them in the middle of the night,” said Dr. Beales, who also is chief executive officer of Axovia Therapeutics, a biotech company developing gene therapies.

Some of the side effects that come with gene therapy are established. Adeno-associated virus (AAV) or AAV-mediated gene therapies carry an increased risk for damage to the heart and liver, Dr. Nelson said. Other side effects are less well known and could be specific to the treatment and the tissue it targets. Primary care will be critical in detecting these unexpected side effects and expediting visits with subspecialists, he said.

In rural Wyoming, pediatricians and family doctors are especially important, Ms. Gibbons said. In the 30-90 days after gene therapy, patients need a lot of follow-up for safety reasons.

But aftercare for gene therapy will be more than just monitoring and managing side effects. The diseases themselves will change. Patients will be living with conditions that once were lethal.

In some cases, gene therapy may largely eliminate the disease. The data suggest that thalassemia, for example, can be largely cured for decades with one infusion of a patient’s genetically modified hematopoietic stem cells made using bluebird bio’s Zynteglo, according to Christy Duncan, MD, medical director of clinical research at the gene therapy program at Boston Children’s Hospital.

But other gene therapies, like the one for DMD, will offer a “spectrum of benefits,” Dr. Nelson said. They will be lifesaving, but the signs of the disease will linger. Clinicians will be learning alongside specialists what the new disease state for DMD and other rare diseases looks like after gene therapy.

“As we get hundreds of such therapies, [post–gene therapy] will amount to a substantial part of the pediatric population,” Dr. Nelson said.

Finding patients

Many of these rare diseases that plague young patients are unmistakable. Children with moderate or severe dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa, for instance, carry a mutation that prevents them from making type VII collagen. The babies suffer wounds and excessive bleeding and tend to receive a quick diagnosis within the first 6 months of life, according to Andy Orth, chief commercial officer at Krystal Bio, manufacturer of a new wound-healing gene therapy, Vyjuvek, for the disorder.

Other rare neurologic or muscular diseases can go undiagnosed for years. Until recently, drug companies and researchers have had little motivation to speed up the timeline because early diagnosis of a disease like DMD would not change the outcome, Dr. Nelson said.

But with gene therapy, prognoses are changing. And finding diseases early could soon mean preserving muscular function or preventing neurologic damage, Dr. Duncan said.

Newborn sequencing “is not standard of care yet, but it’s certainly coming,” Josh Peterson, MD, MPH, director of the center for precision medicine at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, in Nashville, Tenn., told this news organization.

A recent survey of 238 specialists in rare diseases found that roughly 90% believe whole-genome sequencing should be available to all newborns. And 80% of those experts endorse 42 genes as disease predictors. Screening for rare diseases at birth could reveal a host of conditions in the first week of life and expedite treatment. But this strategy will often rely on primary care and pediatricians interpreting the results.

Most pediatricians think sequencing is a great idea, but they do not feel comfortable doing it themselves, Dr. Peterson said. The good news, he said, is that manufacturers have made screening tests straightforward. Some drug companies even offer free screenings for gene therapy candidates.

Dr. Peterson predicts pediatricians will need to be equipped to deliver negative results on their own, which will be the case for around 97%-99% of patients. They also will need to be clear on whether a negative result is definitive or if more testing is warranted.

Positive results are more nuanced. Genetic counseling is the ideal resource when delivering this kind of news to patients, but counselors are a scarce resource nationally – and particularly in rural areas, Dr. Nelson said. Physicians likely will have to rely on their own counseling training to some degree.

“I feel very strongly that genetic counselors are in short supply,” Ms. Gibbons in Colorado said. Patients need a friendly resource who can talk them through the disease and how it works. And that discussion is not a one-off, she said.

The number of board-certified genetic counselors in the United States has doubled to more than 6,000 in the past 10 years – a pace that is expected to continue, according to the National Society of Genetic Counselors. “However, the geographical distribution of genetic counselors is most concentrated in urban centers.”

Equally important to the counseling experience, according to Dr. Duncan at Boston Children’s, is a primary care physician’s network of connections. The best newborn screening rollouts across the country have succeeded because clinicians knew where to send people next and how to get families the help they needed, she said.

But she also cautioned that this learning curve will soon be overwhelming. As gene therapy expands, it may be difficult for primary care doctors to keep up with the science, treatment studies, and commercially available therapies. “It’s asking too much,” Dr. Duncan said.

The structure of primary care already stretches practitioners thin and will “affect how well precision medicine can be adopted and disseminated,” Dr. Peterson said. “I think that is a key issue.”

Artificial intelligence may offer a partial solution. Some genetic counseling models already exist, but their utility for clinicians so far is limited, Dr. Beales said. But he said he expects these tools to improve rapidly to help clinicians and patients. On the patient’s end, they may be able to answer questions and supplement basic genetic counseling. On the physician’s end, algorithms could help triage patients and help move them along to the next steps in the care pathway for these rare diseases.

The whole patient

Primary care physicians will not be expected to be experts in gene therapy or solely in charge of patient safety. They will have support from industry and subspecialists leading the development of these treatments, experts agreed.

But generalists should expect to be drawn into multidisciplinary care teams, be the sounding boards for patients making decisions about gene therapy, help arrange insurance coverage, and be the recipients of late-night phone calls about side effects.

All that, while never losing sight of the child’s holistic health. In children so sick, specialists, subspecialists, and even parents tend to focus only on the rare disease. The team can “get distracted from good normal routine care,” Dr. Nelson said. But these children aren’t exempt from check-ups, vaccine regimens, or the other diseases of childhood.

“In a world where we mitigate that core disease,” he said, “we need a partner in the general pediatrics community” investing in their long-term health.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In Colorado and Wyoming, nearly every baby born since 2020 is tested for signs of a mutation in the SMN1 gene, an indicator of spinal muscular atrophy (SMA). And in 4 years, genetic counselor Melissa Gibbons has seen 24 positive results. She has prepped 24 different pediatricians and family doctors to deliver the news: A seemingly perfect newborn likely has a lethal genetic disease.

Most of these clinicians had never cared for a child with SMA before, nor did they know that lifesaving gene therapy for the condition now exists. Still, the physicians were foundational to getting babies emergency treatment and monitoring the child’s safety after the fact.

“They are boots on the ground for this kind of [work],” Ms. Gibbons, who is the newborn screen coordinator for SMA in both states, told this news organization. “I’m not even sure they realize it.” As of today, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has approved 16 gene therapies for the treatment of rare and debilitating diseases once considered lethal, such as SMA and cerebral adrenoleukodystrophy.

The newest addition to the list of approvals is Elevidys, Sarepta’s gene therapy for Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD). These conditions can now be mitigated, abated for years at a time, and even cured using treatments that tweak a patient’s DNA or RNA.

Hundreds of treatments are under development using the same mechanism. Viruses, liposomes, and other vectors of all kinds are being used to usher new genes into cells, correcting faulty copies or equipping a cell to fight disease. Cells gain the ability to make lifesaving proteins – proteins that heal wounds, restore muscle function, and fight cancer.

Within the decade, a significant fraction of the pediatric population will have gone through gene therapy, experts told this news organization. And primary care stands to be a linchpin in the scale-up of this kind of precision genetic medicine. Pediatricians and general practitioners will be central to finding and monitoring the patients that need these treatments. But the time and support doctors will need to fill that role remain scarce.

“This is a world we are creating right now, quite literally,” said Stanley Nelson, MD, director of the center for Duchenne muscular dystrophy at the University of California, Los Angeles. These cases – some before gene therapy and some after – will show up in primary care offices before the textbook is written.

Unknown side effects, new diseases

Even now, gene therapy is sequestered away in large academic medical research centers. The diagnosis, decision-making, and aftercare are handled by subspecialists working on clinical trials. While the research is ongoing, trial sponsors are keeping a close eye on enrolled patients. But that’s only until these drugs get market approval, Phil Beales, MD, chief medical officer at Congenica, a digital health company specializing in genome analysis support, said. Afterward, “the trialists will no longer have a role in looking after those patients.”

At that point, the role of primary care clinicians will be critically important. Although they probably will not manage gene-therapy patients on their own – comanaging them instead with subspecialists – they will be involved in the ordering and monitoring of safety labs and other tests.

General practitioners “need to know side effects because they are going to deal with side effects when someone calls them in the middle of the night,” said Dr. Beales, who also is chief executive officer of Axovia Therapeutics, a biotech company developing gene therapies.

Some of the side effects that come with gene therapy are established. Adeno-associated virus (AAV) or AAV-mediated gene therapies carry an increased risk for damage to the heart and liver, Dr. Nelson said. Other side effects are less well known and could be specific to the treatment and the tissue it targets. Primary care will be critical in detecting these unexpected side effects and expediting visits with subspecialists, he said.

In rural Wyoming, pediatricians and family doctors are especially important, Ms. Gibbons said. In the 30-90 days after gene therapy, patients need a lot of follow-up for safety reasons.

But aftercare for gene therapy will be more than just monitoring and managing side effects. The diseases themselves will change. Patients will be living with conditions that once were lethal.

In some cases, gene therapy may largely eliminate the disease. The data suggest that thalassemia, for example, can be largely cured for decades with one infusion of a patient’s genetically modified hematopoietic stem cells made using bluebird bio’s Zynteglo, according to Christy Duncan, MD, medical director of clinical research at the gene therapy program at Boston Children’s Hospital.

But other gene therapies, like the one for DMD, will offer a “spectrum of benefits,” Dr. Nelson said. They will be lifesaving, but the signs of the disease will linger. Clinicians will be learning alongside specialists what the new disease state for DMD and other rare diseases looks like after gene therapy.

“As we get hundreds of such therapies, [post–gene therapy] will amount to a substantial part of the pediatric population,” Dr. Nelson said.

Finding patients

Many of these rare diseases that plague young patients are unmistakable. Children with moderate or severe dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa, for instance, carry a mutation that prevents them from making type VII collagen. The babies suffer wounds and excessive bleeding and tend to receive a quick diagnosis within the first 6 months of life, according to Andy Orth, chief commercial officer at Krystal Bio, manufacturer of a new wound-healing gene therapy, Vyjuvek, for the disorder.

Other rare neurologic or muscular diseases can go undiagnosed for years. Until recently, drug companies and researchers have had little motivation to speed up the timeline because early diagnosis of a disease like DMD would not change the outcome, Dr. Nelson said.

But with gene therapy, prognoses are changing. And finding diseases early could soon mean preserving muscular function or preventing neurologic damage, Dr. Duncan said.

Newborn sequencing “is not standard of care yet, but it’s certainly coming,” Josh Peterson, MD, MPH, director of the center for precision medicine at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, in Nashville, Tenn., told this news organization.

A recent survey of 238 specialists in rare diseases found that roughly 90% believe whole-genome sequencing should be available to all newborns. And 80% of those experts endorse 42 genes as disease predictors. Screening for rare diseases at birth could reveal a host of conditions in the first week of life and expedite treatment. But this strategy will often rely on primary care and pediatricians interpreting the results.

Most pediatricians think sequencing is a great idea, but they do not feel comfortable doing it themselves, Dr. Peterson said. The good news, he said, is that manufacturers have made screening tests straightforward. Some drug companies even offer free screenings for gene therapy candidates.

Dr. Peterson predicts pediatricians will need to be equipped to deliver negative results on their own, which will be the case for around 97%-99% of patients. They also will need to be clear on whether a negative result is definitive or if more testing is warranted.

Positive results are more nuanced. Genetic counseling is the ideal resource when delivering this kind of news to patients, but counselors are a scarce resource nationally – and particularly in rural areas, Dr. Nelson said. Physicians likely will have to rely on their own counseling training to some degree.

“I feel very strongly that genetic counselors are in short supply,” Ms. Gibbons in Colorado said. Patients need a friendly resource who can talk them through the disease and how it works. And that discussion is not a one-off, she said.

The number of board-certified genetic counselors in the United States has doubled to more than 6,000 in the past 10 years – a pace that is expected to continue, according to the National Society of Genetic Counselors. “However, the geographical distribution of genetic counselors is most concentrated in urban centers.”

Equally important to the counseling experience, according to Dr. Duncan at Boston Children’s, is a primary care physician’s network of connections. The best newborn screening rollouts across the country have succeeded because clinicians knew where to send people next and how to get families the help they needed, she said.

But she also cautioned that this learning curve will soon be overwhelming. As gene therapy expands, it may be difficult for primary care doctors to keep up with the science, treatment studies, and commercially available therapies. “It’s asking too much,” Dr. Duncan said.

The structure of primary care already stretches practitioners thin and will “affect how well precision medicine can be adopted and disseminated,” Dr. Peterson said. “I think that is a key issue.”

Artificial intelligence may offer a partial solution. Some genetic counseling models already exist, but their utility for clinicians so far is limited, Dr. Beales said. But he said he expects these tools to improve rapidly to help clinicians and patients. On the patient’s end, they may be able to answer questions and supplement basic genetic counseling. On the physician’s end, algorithms could help triage patients and help move them along to the next steps in the care pathway for these rare diseases.

The whole patient

Primary care physicians will not be expected to be experts in gene therapy or solely in charge of patient safety. They will have support from industry and subspecialists leading the development of these treatments, experts agreed.

But generalists should expect to be drawn into multidisciplinary care teams, be the sounding boards for patients making decisions about gene therapy, help arrange insurance coverage, and be the recipients of late-night phone calls about side effects.

All that, while never losing sight of the child’s holistic health. In children so sick, specialists, subspecialists, and even parents tend to focus only on the rare disease. The team can “get distracted from good normal routine care,” Dr. Nelson said. But these children aren’t exempt from check-ups, vaccine regimens, or the other diseases of childhood.

“In a world where we mitigate that core disease,” he said, “we need a partner in the general pediatrics community” investing in their long-term health.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

‘Brain fitness program’ may aid memory loss, concussion, ADHD

new research shows.

The program, which consists of targeted cognitive training and EEG-based neurofeedback, coupled with meditation and diet/lifestyle coaching, led to improvements in memory, attention, mood, alertness, and sleep.

The program promotes “neuroplasticity and was equally effective for patients with all three conditions,” program creator Majid Fotuhi, MD, PhD, said in an interview.

Patients with mild to moderate cognitive symptoms often see “remarkable” results within 3 months of consistently following the program, said Dr. Fotuhi, adjunct professor of neuroscience at George Washington University, Washington, and medical director of NeuroGrow Brain Fitness Center, McLean, Va.

“It actually makes intuitive sense that a healthier and stronger brain would function better and that patients of all ages with various cognitive or emotional symptoms would all benefit from improving the biology of their brain,” Dr. Fotuhi added.

The study was published online in the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease Reports.

Personalized program

The findings are based on 223 children and adults who completed the 12-week NeuroGrow Brain Fitness Program (NeuroGrow BFP), including 71 with ADHD, 88 with PCS, and 64 with memory loss, defined as diagnosed mild cognitive impairment or subjective cognitive decline.

As part of the program, participants undergo a complete neurocognitive evaluation, including tests for verbal memory, complex attention, processing speed, executive functioning, and the Neurocognitive Index.

They also complete questionnaires regarding sleep, mood, diet, exercise, and anxiety/depression, and they undergo quantitative EEG at the beginning and end of the program.

A comparison of before and after neurocognitive test scores showed that all three patient subgroups experienced statistically significant improvements on most measures, the study team reports.

After completing the program, 60%-90% of patients scored higher on cognitive tests and reported having fewer cognitive, sleep, and emotional symptoms.

In all subgroups, the most significant improvement was observed in executive functioning.

“These preliminary findings appear to show that multimodal interventions which are known to increase neuroplasticity in the brain, when personalized, can have benefits for patients with cognitive symptoms from a variety of neurological conditions,” the investigators wrote.

The study’s strengths include a large, community-based sample of patients of different ages who had disruptive symptoms and abnormalities as determined using objective cognitive tests whose progress was monitored by objective and subjective measures.

The chief limitation is the lack of a control or placebo group.

“Though it is difficult to find a comparable group of patients with the exact same profile of cognitive deficits and brain-related symptoms, studying a larger group of patients – and comparing them with a wait-list group – may make it possible to do a more definitive assessment of the NeuroGrow BFP,” the researchers noted.

Dr. Fotuhi said the “secret to the success” of the program is that it involves a full assessment of all cognitive and neurobehavioral symptoms for each patient. This allows for individualized and targeted interventions for specific concerns and symptoms.

He said there is a need to recognize that patients who present to a neurology practice with a single complaint, such as a problem with memory or attention, often have other problems, such as anxiety/depression, stress, insomnia, sedentary lifestyle, obesity, diabetes, sleep apnea, or alcohol overuse.

“Each of these factors can affect their cognitive abilities and need a multimodal set of interventions in order to see full resolution of their cognitive symptoms,” Dr. Fotuhi said.

He has created a series of educational videos to demonstrate the program’s benefits.

The self-pay cost for the NeuroGrow BFP assessment and treatment sessions is approximately $7,000.

Dr. Fotuhi said all of the interventions included in the program are readily available at low cost.

He suggested that health care professionals who lack time or staff for conducting a comprehensive neurocognitive assessment for their patients can provide them with a copy of the Brain Health Index.

“Patients can then be instructed to work on the individual components of their brain health on their own – and measure their brain health index on a weekly basis,” Dr. Fotuhi said. “Private practices or academic centers can use the detailed information I have provided in my paper to develop their own brain fitness program.”

Not ready for prime time

Commenting on the study, Percy Griffin, PhD, director of scientific engagement for the Alzheimer’s Association, noted that “nonpharmacologic interventions can help alleviate some of the symptoms associated with dementia.

“The current study investigates nonpharmacologic interventions in a small number of patients with ADHD, postconcussion syndrome, or memory loss. The researchers found improvements on most measures following the brain rehabilitation program.