User login

Verrucous Kaposi Sarcoma in an HIV-Positive Man

To the Editor:

Verrucous Kaposi sarcoma (VKS) is an uncommon variant of Kaposi sarcoma (KS) that rarely is seen in clinical practice or reported in the literature. It is strongly associated with lymphedema in patients with AIDS.1 We present a case of VKS in a human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)–positive man with cutaneous lesions that demonstrated minimal response to treatment with efavirenz-emtricitabine-tenofovir, doxorubicin, paclitaxel, and alitretinoin.

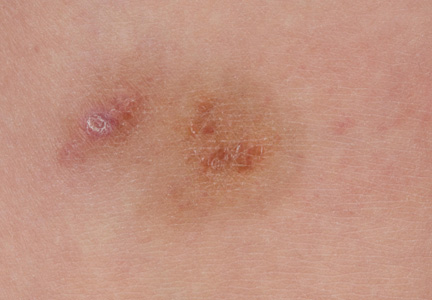

A 48-year-old man with a history of untreated HIV presented with a persistent eruption of heavily scaled, hyperpigmented, nonindurated, thin plaques in an ichthyosiform pattern on the bilateral lower legs and ankles of 4 years’ duration (Figure 1). He also had a number of soft, compressible, cystlike plaques without much overlying epidermal change on the lower extremities. He denied any prior episodes of skin breakdown, drainage, or secondary infection. Findings from the physical examination were otherwise unremarkable.

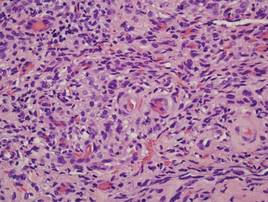

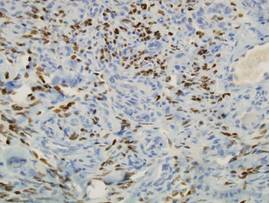

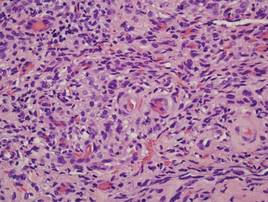

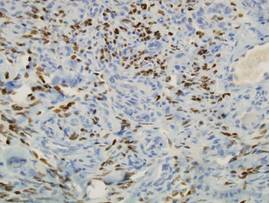

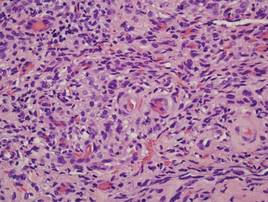

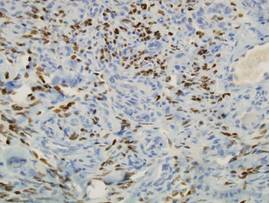

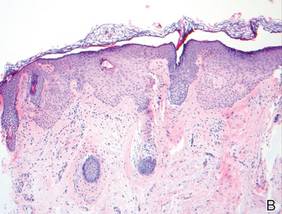

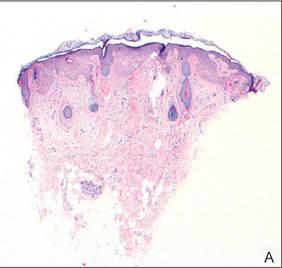

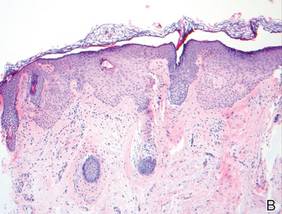

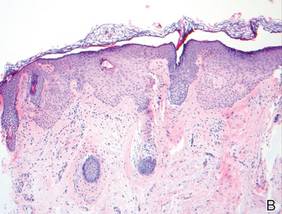

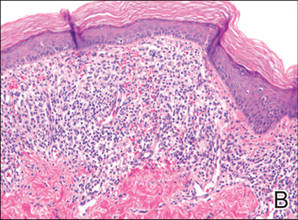

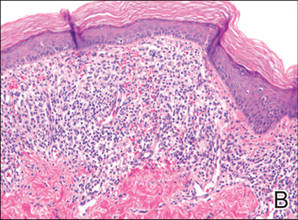

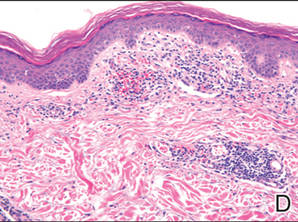

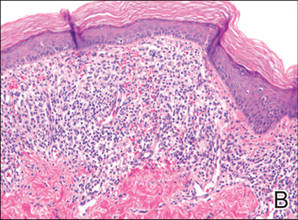

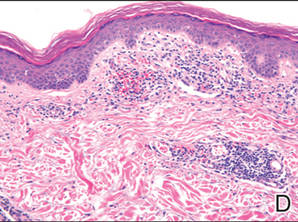

Two punch biopsies were performed on the lower legs, one from a scaly plaque and the other from a cystic area. The epidermis was hyperkeratotic and mildly hyperplastic with slitlike vascular spaces. A dense cellular proliferation of spindle-shaped cells was present in the dermis (Figure 2). Minimal cytologic atypia was noted. Immunohistochemical staining for human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8) was strongly positive (Figure 3). Histologically, the cutaneous lesions were consistent with VKS.

At the current presentation, the CD4 count was 355 cells/mm3 and the viral load was 919,223 copies/mL. The CD4 count and viral load initially had been responsive to efavirenz-emtricitabine-tenofovir therapy; 17 months prior to the current presentation, the CD4 count was 692 cells/mm3 and the viral load was less than 50 copies/mL. However, the cutaneous lesions persisted despite therapy with efavirenz-emtricitabine-tenofovir, alitretinoin gel, and intralesional chemotherapeutic agents such as doxorubicin and paclitaxel.

Kaposi sarcoma, first described by Moritz Kaposi in 1872, represents a group of vascular neoplasms. Multiple subtypes have been described including classic, African endemic, transplant/AIDS associated, anaplastic, lymphedematous, hyperkeratotic/verrucous, keloidal, micronodular, pyogenic granulomalike, ecchymotic, and intravascular.1-3 Human herpesvirus 8 is associated with all clinical subtypes of KS.3 Immunohistochemical staining for HHV-8 latent nuclear antigen-1 has been shown in the literature to be highly sensitive and specific for KS and can potentially facilitate the diagnosis of KS among patients with similarly appearing dermatologic conditions, such as angiosarcoma, kaposiform hemangioendothelioma, or verrucous hemangioma.1,4 Human herpesvirus 8 infects endothelial cells and induces the proliferation of vascular spindle cells via the secretion of basic fibroblast growth factor and vascular endothelial growth factor.5 Human herpesvirus 8 also can lead to lymph vessel obstruction and lymph node enlargement by infecting cells within the lymphatic system. In addition, chronic lymphedema can itself lead to verruciform epidermal hyperplasia and hyperkeratosis, which has a clinical presentation similar to VKS.1

AIDS-associated KS typically starts as 1 or more purple-red macules that rapidly progress into papules, nodules, and plaques.1 These lesions have a predilection for the head, neck, trunk, and mucous membranes. Albeit a rare presentation, VKS is strongly associated with lymphedema in patients with AIDS.1,3,5 Previously, KS was often the presenting clinical manifestation of HIV infection, but since the use of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) has become the standard of care, the incidence as well as the morbidity and mortality associated with KS has substantially decreased.1,5-7 Notably, in HIV patients who initially do not have signs or symptoms of KS, HHV-8 positivity is predictive of the development of KS within 2 to 4 years.6

In the literature, good prognostic indicators for KS include CD4 count greater than 150 cells/mm3, only cutaneous involvement, and negative B symptoms (eg, temperature >38°C, night sweats, unintentional weight loss >10% of normal body weight within 6 months).7 Kaposi sarcoma cannot be completely cured but can be appropriately managed with medical intervention. All KS subtypes are sensitive to radiation therapy; recalcitrant localized lesions can be treated with excision, cryotherapy, alitretinoin gel, laser ablation, or locally injected interferon or chemotherapeutic agents (eg, vincristine, vinblastine, actinomycin D).5,6 Liposomal anthracyclines (doxorubicin) and paclitaxel are first- and second-line agents for advanced KS, respectively.6

In HIV-associated KS, lesions frequently involute with the initiation of HAART; however, the cutaneous lesions in our patient persisted despite initiation of efavirenz-emtricitabine-tenofovir. He also was given intralesional doxorubicin andpaclitaxel as well as topical alitretinoin but did not experience complete resolution of the cutaneous lesions. It is possible that patients with VKS are recalcitrant to typical treatment modalities and therefore may require unconventional therapies to achieve maximal clearance of cutaneous lesions.

Verrucous Kaposi sarcoma is a rare presentation of KS that is infrequently seen in clinical practice or reported in the literature.3 A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search term verrucous Kaposi sarcoma yielded 13 articles, one of which included a case series of 5 patients with AIDS and hyperkeratotic KS in Germany in the 1990s.5 Four of the articles were written in French, German, or Portuguese.8-11 The remainder of the articles discussed variants of KS other than VKS.

Although most patients with HIV and KS effectively respond to HAART, it may be possible that VKS is more difficult to treat. In addition, immunohistochemical staining for HHV-8, in particular HHV-8 latent nuclear antigen-1, may be useful to diagnose KS in HIV patients with uncharacteristic or indeterminate cutaneous lesions. Further research is needed to identify and delineate various efficacious therapeutic options for recalcitrant KS, particularly VKS.

Acknowledgment

We are indebted to Antoinette F. Hood, MD, Norfolk, Virginia, who digitized our patient’s histopathology slides.

1. Grayson W, Pantanowitz L. Histological variants of cutaneous Kaposi sarcoma. Diagn Pathol. 2008;3:31.

2. Amodio E, Goedert JJ, Barozzi P, et al. Differences in Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-specific and herpesvirus-non-specific immune responses in classic Kaposi sarcoma cases and matched controls in Sicily. Cancer Sci. 2011;102:1769-1773.

3. Fagone S, Cavaleri A, Camuto M, et al. Hyperkeratotic Kaposi sarcoma with leg lymphedema after prolonged corticosteroid therapy for SLE. case report and review of the literature. Minerva Med. 2001;92:177-202.

4. Cheuk W, Wong KO, Wong CS, et al. Immunostaining for human herpesvirus 8 latent nuclear antigen-1 helps distinguish Kaposi sarcoma from its mimickers. Am J Clin Pathol. 2004;121:335-342.

5. Hengge UR, Stocks K, Goos M. Acquired immune deficiency syndrome-related hyperkeratotic Kaposi’s sarcoma with severe lymphedema: report of 5 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:501-505.

6. James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM, eds. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 2006.

7. Thomas S, Sindhu CB, Sreekumar S, et al. AIDS associated Kaposi’s Sarcoma. J Assoc Physicians India. 2011;59:387-389.

8. Mukai MM, Chaves T, Caldas L, et al. Primary Kaposi’s sarcoma of the penis [in Portuguese]. An Bras Dermatol. 2009;84:524-526.

9. Weidauer H, Tilgen W, Adler D. Kaposi’s sarcoma of the larynx [in German]. Laryngol Rhinol Otol (Stuttg). 1986;65:389-391.

10. Basset A. Clinical aspects of Kaposi’s disease [in French]. Bull Soc Pathol Exot Filiales. 1984;77(4, pt 2):529-532.

11. Wlotzke U, Hohenleutner U, Landthaler M. Dermatoses in leg amputees [in German]. Hautarzt. 1996;47:493-501.

To the Editor:

Verrucous Kaposi sarcoma (VKS) is an uncommon variant of Kaposi sarcoma (KS) that rarely is seen in clinical practice or reported in the literature. It is strongly associated with lymphedema in patients with AIDS.1 We present a case of VKS in a human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)–positive man with cutaneous lesions that demonstrated minimal response to treatment with efavirenz-emtricitabine-tenofovir, doxorubicin, paclitaxel, and alitretinoin.

A 48-year-old man with a history of untreated HIV presented with a persistent eruption of heavily scaled, hyperpigmented, nonindurated, thin plaques in an ichthyosiform pattern on the bilateral lower legs and ankles of 4 years’ duration (Figure 1). He also had a number of soft, compressible, cystlike plaques without much overlying epidermal change on the lower extremities. He denied any prior episodes of skin breakdown, drainage, or secondary infection. Findings from the physical examination were otherwise unremarkable.

Two punch biopsies were performed on the lower legs, one from a scaly plaque and the other from a cystic area. The epidermis was hyperkeratotic and mildly hyperplastic with slitlike vascular spaces. A dense cellular proliferation of spindle-shaped cells was present in the dermis (Figure 2). Minimal cytologic atypia was noted. Immunohistochemical staining for human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8) was strongly positive (Figure 3). Histologically, the cutaneous lesions were consistent with VKS.

At the current presentation, the CD4 count was 355 cells/mm3 and the viral load was 919,223 copies/mL. The CD4 count and viral load initially had been responsive to efavirenz-emtricitabine-tenofovir therapy; 17 months prior to the current presentation, the CD4 count was 692 cells/mm3 and the viral load was less than 50 copies/mL. However, the cutaneous lesions persisted despite therapy with efavirenz-emtricitabine-tenofovir, alitretinoin gel, and intralesional chemotherapeutic agents such as doxorubicin and paclitaxel.

Kaposi sarcoma, first described by Moritz Kaposi in 1872, represents a group of vascular neoplasms. Multiple subtypes have been described including classic, African endemic, transplant/AIDS associated, anaplastic, lymphedematous, hyperkeratotic/verrucous, keloidal, micronodular, pyogenic granulomalike, ecchymotic, and intravascular.1-3 Human herpesvirus 8 is associated with all clinical subtypes of KS.3 Immunohistochemical staining for HHV-8 latent nuclear antigen-1 has been shown in the literature to be highly sensitive and specific for KS and can potentially facilitate the diagnosis of KS among patients with similarly appearing dermatologic conditions, such as angiosarcoma, kaposiform hemangioendothelioma, or verrucous hemangioma.1,4 Human herpesvirus 8 infects endothelial cells and induces the proliferation of vascular spindle cells via the secretion of basic fibroblast growth factor and vascular endothelial growth factor.5 Human herpesvirus 8 also can lead to lymph vessel obstruction and lymph node enlargement by infecting cells within the lymphatic system. In addition, chronic lymphedema can itself lead to verruciform epidermal hyperplasia and hyperkeratosis, which has a clinical presentation similar to VKS.1

AIDS-associated KS typically starts as 1 or more purple-red macules that rapidly progress into papules, nodules, and plaques.1 These lesions have a predilection for the head, neck, trunk, and mucous membranes. Albeit a rare presentation, VKS is strongly associated with lymphedema in patients with AIDS.1,3,5 Previously, KS was often the presenting clinical manifestation of HIV infection, but since the use of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) has become the standard of care, the incidence as well as the morbidity and mortality associated with KS has substantially decreased.1,5-7 Notably, in HIV patients who initially do not have signs or symptoms of KS, HHV-8 positivity is predictive of the development of KS within 2 to 4 years.6

In the literature, good prognostic indicators for KS include CD4 count greater than 150 cells/mm3, only cutaneous involvement, and negative B symptoms (eg, temperature >38°C, night sweats, unintentional weight loss >10% of normal body weight within 6 months).7 Kaposi sarcoma cannot be completely cured but can be appropriately managed with medical intervention. All KS subtypes are sensitive to radiation therapy; recalcitrant localized lesions can be treated with excision, cryotherapy, alitretinoin gel, laser ablation, or locally injected interferon or chemotherapeutic agents (eg, vincristine, vinblastine, actinomycin D).5,6 Liposomal anthracyclines (doxorubicin) and paclitaxel are first- and second-line agents for advanced KS, respectively.6

In HIV-associated KS, lesions frequently involute with the initiation of HAART; however, the cutaneous lesions in our patient persisted despite initiation of efavirenz-emtricitabine-tenofovir. He also was given intralesional doxorubicin andpaclitaxel as well as topical alitretinoin but did not experience complete resolution of the cutaneous lesions. It is possible that patients with VKS are recalcitrant to typical treatment modalities and therefore may require unconventional therapies to achieve maximal clearance of cutaneous lesions.

Verrucous Kaposi sarcoma is a rare presentation of KS that is infrequently seen in clinical practice or reported in the literature.3 A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search term verrucous Kaposi sarcoma yielded 13 articles, one of which included a case series of 5 patients with AIDS and hyperkeratotic KS in Germany in the 1990s.5 Four of the articles were written in French, German, or Portuguese.8-11 The remainder of the articles discussed variants of KS other than VKS.

Although most patients with HIV and KS effectively respond to HAART, it may be possible that VKS is more difficult to treat. In addition, immunohistochemical staining for HHV-8, in particular HHV-8 latent nuclear antigen-1, may be useful to diagnose KS in HIV patients with uncharacteristic or indeterminate cutaneous lesions. Further research is needed to identify and delineate various efficacious therapeutic options for recalcitrant KS, particularly VKS.

Acknowledgment

We are indebted to Antoinette F. Hood, MD, Norfolk, Virginia, who digitized our patient’s histopathology slides.

To the Editor:

Verrucous Kaposi sarcoma (VKS) is an uncommon variant of Kaposi sarcoma (KS) that rarely is seen in clinical practice or reported in the literature. It is strongly associated with lymphedema in patients with AIDS.1 We present a case of VKS in a human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)–positive man with cutaneous lesions that demonstrated minimal response to treatment with efavirenz-emtricitabine-tenofovir, doxorubicin, paclitaxel, and alitretinoin.

A 48-year-old man with a history of untreated HIV presented with a persistent eruption of heavily scaled, hyperpigmented, nonindurated, thin plaques in an ichthyosiform pattern on the bilateral lower legs and ankles of 4 years’ duration (Figure 1). He also had a number of soft, compressible, cystlike plaques without much overlying epidermal change on the lower extremities. He denied any prior episodes of skin breakdown, drainage, or secondary infection. Findings from the physical examination were otherwise unremarkable.

Two punch biopsies were performed on the lower legs, one from a scaly plaque and the other from a cystic area. The epidermis was hyperkeratotic and mildly hyperplastic with slitlike vascular spaces. A dense cellular proliferation of spindle-shaped cells was present in the dermis (Figure 2). Minimal cytologic atypia was noted. Immunohistochemical staining for human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8) was strongly positive (Figure 3). Histologically, the cutaneous lesions were consistent with VKS.

At the current presentation, the CD4 count was 355 cells/mm3 and the viral load was 919,223 copies/mL. The CD4 count and viral load initially had been responsive to efavirenz-emtricitabine-tenofovir therapy; 17 months prior to the current presentation, the CD4 count was 692 cells/mm3 and the viral load was less than 50 copies/mL. However, the cutaneous lesions persisted despite therapy with efavirenz-emtricitabine-tenofovir, alitretinoin gel, and intralesional chemotherapeutic agents such as doxorubicin and paclitaxel.

Kaposi sarcoma, first described by Moritz Kaposi in 1872, represents a group of vascular neoplasms. Multiple subtypes have been described including classic, African endemic, transplant/AIDS associated, anaplastic, lymphedematous, hyperkeratotic/verrucous, keloidal, micronodular, pyogenic granulomalike, ecchymotic, and intravascular.1-3 Human herpesvirus 8 is associated with all clinical subtypes of KS.3 Immunohistochemical staining for HHV-8 latent nuclear antigen-1 has been shown in the literature to be highly sensitive and specific for KS and can potentially facilitate the diagnosis of KS among patients with similarly appearing dermatologic conditions, such as angiosarcoma, kaposiform hemangioendothelioma, or verrucous hemangioma.1,4 Human herpesvirus 8 infects endothelial cells and induces the proliferation of vascular spindle cells via the secretion of basic fibroblast growth factor and vascular endothelial growth factor.5 Human herpesvirus 8 also can lead to lymph vessel obstruction and lymph node enlargement by infecting cells within the lymphatic system. In addition, chronic lymphedema can itself lead to verruciform epidermal hyperplasia and hyperkeratosis, which has a clinical presentation similar to VKS.1

AIDS-associated KS typically starts as 1 or more purple-red macules that rapidly progress into papules, nodules, and plaques.1 These lesions have a predilection for the head, neck, trunk, and mucous membranes. Albeit a rare presentation, VKS is strongly associated with lymphedema in patients with AIDS.1,3,5 Previously, KS was often the presenting clinical manifestation of HIV infection, but since the use of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) has become the standard of care, the incidence as well as the morbidity and mortality associated with KS has substantially decreased.1,5-7 Notably, in HIV patients who initially do not have signs or symptoms of KS, HHV-8 positivity is predictive of the development of KS within 2 to 4 years.6

In the literature, good prognostic indicators for KS include CD4 count greater than 150 cells/mm3, only cutaneous involvement, and negative B symptoms (eg, temperature >38°C, night sweats, unintentional weight loss >10% of normal body weight within 6 months).7 Kaposi sarcoma cannot be completely cured but can be appropriately managed with medical intervention. All KS subtypes are sensitive to radiation therapy; recalcitrant localized lesions can be treated with excision, cryotherapy, alitretinoin gel, laser ablation, or locally injected interferon or chemotherapeutic agents (eg, vincristine, vinblastine, actinomycin D).5,6 Liposomal anthracyclines (doxorubicin) and paclitaxel are first- and second-line agents for advanced KS, respectively.6

In HIV-associated KS, lesions frequently involute with the initiation of HAART; however, the cutaneous lesions in our patient persisted despite initiation of efavirenz-emtricitabine-tenofovir. He also was given intralesional doxorubicin andpaclitaxel as well as topical alitretinoin but did not experience complete resolution of the cutaneous lesions. It is possible that patients with VKS are recalcitrant to typical treatment modalities and therefore may require unconventional therapies to achieve maximal clearance of cutaneous lesions.

Verrucous Kaposi sarcoma is a rare presentation of KS that is infrequently seen in clinical practice or reported in the literature.3 A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search term verrucous Kaposi sarcoma yielded 13 articles, one of which included a case series of 5 patients with AIDS and hyperkeratotic KS in Germany in the 1990s.5 Four of the articles were written in French, German, or Portuguese.8-11 The remainder of the articles discussed variants of KS other than VKS.

Although most patients with HIV and KS effectively respond to HAART, it may be possible that VKS is more difficult to treat. In addition, immunohistochemical staining for HHV-8, in particular HHV-8 latent nuclear antigen-1, may be useful to diagnose KS in HIV patients with uncharacteristic or indeterminate cutaneous lesions. Further research is needed to identify and delineate various efficacious therapeutic options for recalcitrant KS, particularly VKS.

Acknowledgment

We are indebted to Antoinette F. Hood, MD, Norfolk, Virginia, who digitized our patient’s histopathology slides.

1. Grayson W, Pantanowitz L. Histological variants of cutaneous Kaposi sarcoma. Diagn Pathol. 2008;3:31.

2. Amodio E, Goedert JJ, Barozzi P, et al. Differences in Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-specific and herpesvirus-non-specific immune responses in classic Kaposi sarcoma cases and matched controls in Sicily. Cancer Sci. 2011;102:1769-1773.

3. Fagone S, Cavaleri A, Camuto M, et al. Hyperkeratotic Kaposi sarcoma with leg lymphedema after prolonged corticosteroid therapy for SLE. case report and review of the literature. Minerva Med. 2001;92:177-202.

4. Cheuk W, Wong KO, Wong CS, et al. Immunostaining for human herpesvirus 8 latent nuclear antigen-1 helps distinguish Kaposi sarcoma from its mimickers. Am J Clin Pathol. 2004;121:335-342.

5. Hengge UR, Stocks K, Goos M. Acquired immune deficiency syndrome-related hyperkeratotic Kaposi’s sarcoma with severe lymphedema: report of 5 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:501-505.

6. James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM, eds. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 2006.

7. Thomas S, Sindhu CB, Sreekumar S, et al. AIDS associated Kaposi’s Sarcoma. J Assoc Physicians India. 2011;59:387-389.

8. Mukai MM, Chaves T, Caldas L, et al. Primary Kaposi’s sarcoma of the penis [in Portuguese]. An Bras Dermatol. 2009;84:524-526.

9. Weidauer H, Tilgen W, Adler D. Kaposi’s sarcoma of the larynx [in German]. Laryngol Rhinol Otol (Stuttg). 1986;65:389-391.

10. Basset A. Clinical aspects of Kaposi’s disease [in French]. Bull Soc Pathol Exot Filiales. 1984;77(4, pt 2):529-532.

11. Wlotzke U, Hohenleutner U, Landthaler M. Dermatoses in leg amputees [in German]. Hautarzt. 1996;47:493-501.

1. Grayson W, Pantanowitz L. Histological variants of cutaneous Kaposi sarcoma. Diagn Pathol. 2008;3:31.

2. Amodio E, Goedert JJ, Barozzi P, et al. Differences in Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-specific and herpesvirus-non-specific immune responses in classic Kaposi sarcoma cases and matched controls in Sicily. Cancer Sci. 2011;102:1769-1773.

3. Fagone S, Cavaleri A, Camuto M, et al. Hyperkeratotic Kaposi sarcoma with leg lymphedema after prolonged corticosteroid therapy for SLE. case report and review of the literature. Minerva Med. 2001;92:177-202.

4. Cheuk W, Wong KO, Wong CS, et al. Immunostaining for human herpesvirus 8 latent nuclear antigen-1 helps distinguish Kaposi sarcoma from its mimickers. Am J Clin Pathol. 2004;121:335-342.

5. Hengge UR, Stocks K, Goos M. Acquired immune deficiency syndrome-related hyperkeratotic Kaposi’s sarcoma with severe lymphedema: report of 5 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:501-505.

6. James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM, eds. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 2006.

7. Thomas S, Sindhu CB, Sreekumar S, et al. AIDS associated Kaposi’s Sarcoma. J Assoc Physicians India. 2011;59:387-389.

8. Mukai MM, Chaves T, Caldas L, et al. Primary Kaposi’s sarcoma of the penis [in Portuguese]. An Bras Dermatol. 2009;84:524-526.

9. Weidauer H, Tilgen W, Adler D. Kaposi’s sarcoma of the larynx [in German]. Laryngol Rhinol Otol (Stuttg). 1986;65:389-391.

10. Basset A. Clinical aspects of Kaposi’s disease [in French]. Bull Soc Pathol Exot Filiales. 1984;77(4, pt 2):529-532.

11. Wlotzke U, Hohenleutner U, Landthaler M. Dermatoses in leg amputees [in German]. Hautarzt. 1996;47:493-501.

The Spectrum of Pigmented Purpuric Dermatosis and Mycosis Fungoides: Atypical T-Cell Dyscrasia

Case Report

A healthy 17-year-old adolescent boy with an unremarkable medical history presented with an asymptomatic fixed rash on the abdomen, buttocks, and legs. The rash initially developed in a small area on the right leg 2 years prior and had slowly progressed. He was not currently taking any medications and did not participate in intense physical activity. Multiple biopsies had previously been performed by an outside physician, the most recent one demonstrating an interface and superficial perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate with extravasated red blood cells consistent with pigmented purpura. He did not respond to treatment with intralesional corticosteroids, high-potency topical steroids, or high-dose oral prednisone.

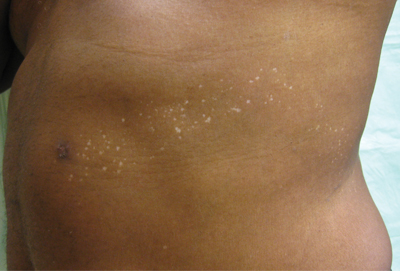

Clinical examination revealed multiple annular purpuric patches on the abdomen, buttocks, and legs that covered approximately 20% of the body surface area (Figure 1). Over several follow-up visits, a few of the lesions evolved from patches to thin plaques. There was no adenopathy or hepatosplenomegaly. Three additional biopsies taken over the next 4 months demonstrated a mixture of small mature lymphocytes with some atypical lymphocytes in the dermis and epidermis exhibiting diminished CD7 staining and lymphocytes lining up at the dermoepidermal junction. T-cell receptor g gene rearrangements demonstrated the same clonal population in all 3 specimens. The patient was diagnosed with stage IB mycosis fungoides (MF) of the pigmented purpura–like variant. Marked improvement of the lesions was noted after 6 weeks of psoralen plus UVA therapy 3 times weekly (Figure 2). Treatment was continued for 6 months but was discontinued due to the international shortage of methoxsalen. Two months after discontinuation, most of the lesions had completely resolved (Figure 3).

|

Comment

Mycoses fungoides is a rare cutaneous lymphoma that affects approximately 2000 patients in the United States.1 Only 5% of all cases are known to occur in the first 2 decades of life,2 and even fewer cases pre-sent with pigmented purpura, usually of the lichenoid variant.3 Although the patches and plaques of MF can masquerade as many other dermatoses (eg, dermatophytosis, psoriasis, dermatitis), there have been few reports of patients presenting with lesions with the clinical appearance of pigmented purpuric dermatosis (PPD).4 As with the many cases of early MF, which are histologically indistinguishable from dermatitis, the pigmented purpura–like variant of MF initially may have the histologic appearance of pigmented purpura and generally evolves to the histologic appearance of MF over time.

Similar to our case, there have been reports of clinical and histologic diagnosis of PPD preceding the histologic diagnosis of MF. In a small cohort study of 3 young men, Barnhill and Braverman5 first demonstrated the progression of PPD to MF over a 12-year period. The age of onset ranged from 14 to 30 years, with a mean age of 24.3 years. Biopsies in all 3 patients were consistent with PPD for many years prior to the diagnosis of MF, with an average length of time to diagnosis of 8.4 years. Atypical from most cases of PPD, the patients in this study demonstrated extensive involvement of the trunk, arms, and legs.5 It has been suggested that atypical PPD is a variant of PPD that evolves into MF over many years; however, we believe that PPD is a variant of MF, similar to the way an indolent dermatitis may evolve to classical MF over time. If characterized by a T-cell clone, this period preceding the diagnosis of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma could be characterized as a cutaneous T-cell lymphoid dyscrasia.

Guitart and Magro6 noted multiple chronic conditions that are associated with T-cell clones, including PPD. These conditions occurred without a known trigger, were unresponsive to topical therapies, and often did not meet diagnostic criteria for MF. The investigators felt the criteria that may indicate a cutaneous T-cell lymphoid dyscrasia include widespread distribution, lymphocytic infiltrate, diminished CD7 and CD62L expression, and clonality. Lymphocytes may be small without notable atypia.6

In a study of 43 patients with PPD, Magro et al3 found monoclonality and diminished CD7 expression in 18 participants, correlating with large surface area involvement. Approximately 40% of patients had histologic findings consistent with MF, suggesting that T-cell gene rearrangement studies should be obtained for prognostic evaluation in patients with widespread disease.3

|

|

To facilitate proper patient care, histopathology and molecular markers should be evaluated in conjunction with the clinical picture. A considerable increase in the size of the body surface area affected by purpuric patches combined with the presence of poikilodermatous changes and pruritus as well as disease lasting longer than 1 year should prompt an increased clinical suspicion of MF in patients with PPD.4,5 Histologically, the presence of Pautrier microabscesses, large cerebriform lymphocytes, and intraepidermal lymphocytic atypia extending beyond the dermis also would support a diagnosis of MF.3 Given the morphologic appearance and distribution of the lesions in our patient combined with epidermotropism, diminished CD7 expression, and monoclonality seen on pathology, we favored a diagnosis of MF. It would not be unreasonable to call this clonal variant of PPD a T-cell lymphoid dyscrasia. We appreciate that both PPD and MF will respond to phototherapy.7

Conclusion

We propose that there is a spectrum of disease presenting as PPD or MF sitting at either end of that spectrum and an intermediate stage, where not all criteria for cutaneous lymphoma are met, characterized as cutaneous T-cell lymphoid dyscrasia. Until the potential for evolution of PPD to malignant disease is better understood, patients with unusual presentations of pigmented purpura should be further evaluated for MF.

1. Criscione VD, Weinstock MA. Incidence of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma in the United States, 1973-2002. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:854-859.

2. Koch SE, Zackheim HS, Williams ML, et al. Mycosis fungoides beginning in childhood and adolescence. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;17:563-570.

3. Magro CM, Schaefer JT, Crowson AN, et al. Pigmented purpuric dermatosis: classification by phenotypic and molecular profiles. Am J Clin Pathol. 2007;128:218-229.

4. Hanna S, Walsh N, D’Intino Y, et al. Mycosis fungoides presenting as pigmented purpuric dermatitis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006;23:350-354.

5. Barnhill RL, Braverman IM. Progression of pigmented purpura-like eruptions to mycosis fungoides: report of three cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1988;19(1, pt 1):25-31.

6. Guitart J, Magro C. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoid dyscrasia: a unifying term for idiopathic chronic dermatoses with persistent T-cell clones. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:921-932.

7. Seckin D, Yazici Z, Senol A, et al. A case of Schamberg’s disease responding dramatically to PUVA treatment. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2008;24:95-96.

Case Report

A healthy 17-year-old adolescent boy with an unremarkable medical history presented with an asymptomatic fixed rash on the abdomen, buttocks, and legs. The rash initially developed in a small area on the right leg 2 years prior and had slowly progressed. He was not currently taking any medications and did not participate in intense physical activity. Multiple biopsies had previously been performed by an outside physician, the most recent one demonstrating an interface and superficial perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate with extravasated red blood cells consistent with pigmented purpura. He did not respond to treatment with intralesional corticosteroids, high-potency topical steroids, or high-dose oral prednisone.

Clinical examination revealed multiple annular purpuric patches on the abdomen, buttocks, and legs that covered approximately 20% of the body surface area (Figure 1). Over several follow-up visits, a few of the lesions evolved from patches to thin plaques. There was no adenopathy or hepatosplenomegaly. Three additional biopsies taken over the next 4 months demonstrated a mixture of small mature lymphocytes with some atypical lymphocytes in the dermis and epidermis exhibiting diminished CD7 staining and lymphocytes lining up at the dermoepidermal junction. T-cell receptor g gene rearrangements demonstrated the same clonal population in all 3 specimens. The patient was diagnosed with stage IB mycosis fungoides (MF) of the pigmented purpura–like variant. Marked improvement of the lesions was noted after 6 weeks of psoralen plus UVA therapy 3 times weekly (Figure 2). Treatment was continued for 6 months but was discontinued due to the international shortage of methoxsalen. Two months after discontinuation, most of the lesions had completely resolved (Figure 3).

|

Comment

Mycoses fungoides is a rare cutaneous lymphoma that affects approximately 2000 patients in the United States.1 Only 5% of all cases are known to occur in the first 2 decades of life,2 and even fewer cases pre-sent with pigmented purpura, usually of the lichenoid variant.3 Although the patches and plaques of MF can masquerade as many other dermatoses (eg, dermatophytosis, psoriasis, dermatitis), there have been few reports of patients presenting with lesions with the clinical appearance of pigmented purpuric dermatosis (PPD).4 As with the many cases of early MF, which are histologically indistinguishable from dermatitis, the pigmented purpura–like variant of MF initially may have the histologic appearance of pigmented purpura and generally evolves to the histologic appearance of MF over time.

Similar to our case, there have been reports of clinical and histologic diagnosis of PPD preceding the histologic diagnosis of MF. In a small cohort study of 3 young men, Barnhill and Braverman5 first demonstrated the progression of PPD to MF over a 12-year period. The age of onset ranged from 14 to 30 years, with a mean age of 24.3 years. Biopsies in all 3 patients were consistent with PPD for many years prior to the diagnosis of MF, with an average length of time to diagnosis of 8.4 years. Atypical from most cases of PPD, the patients in this study demonstrated extensive involvement of the trunk, arms, and legs.5 It has been suggested that atypical PPD is a variant of PPD that evolves into MF over many years; however, we believe that PPD is a variant of MF, similar to the way an indolent dermatitis may evolve to classical MF over time. If characterized by a T-cell clone, this period preceding the diagnosis of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma could be characterized as a cutaneous T-cell lymphoid dyscrasia.

Guitart and Magro6 noted multiple chronic conditions that are associated with T-cell clones, including PPD. These conditions occurred without a known trigger, were unresponsive to topical therapies, and often did not meet diagnostic criteria for MF. The investigators felt the criteria that may indicate a cutaneous T-cell lymphoid dyscrasia include widespread distribution, lymphocytic infiltrate, diminished CD7 and CD62L expression, and clonality. Lymphocytes may be small without notable atypia.6

In a study of 43 patients with PPD, Magro et al3 found monoclonality and diminished CD7 expression in 18 participants, correlating with large surface area involvement. Approximately 40% of patients had histologic findings consistent with MF, suggesting that T-cell gene rearrangement studies should be obtained for prognostic evaluation in patients with widespread disease.3

|

|

To facilitate proper patient care, histopathology and molecular markers should be evaluated in conjunction with the clinical picture. A considerable increase in the size of the body surface area affected by purpuric patches combined with the presence of poikilodermatous changes and pruritus as well as disease lasting longer than 1 year should prompt an increased clinical suspicion of MF in patients with PPD.4,5 Histologically, the presence of Pautrier microabscesses, large cerebriform lymphocytes, and intraepidermal lymphocytic atypia extending beyond the dermis also would support a diagnosis of MF.3 Given the morphologic appearance and distribution of the lesions in our patient combined with epidermotropism, diminished CD7 expression, and monoclonality seen on pathology, we favored a diagnosis of MF. It would not be unreasonable to call this clonal variant of PPD a T-cell lymphoid dyscrasia. We appreciate that both PPD and MF will respond to phototherapy.7

Conclusion

We propose that there is a spectrum of disease presenting as PPD or MF sitting at either end of that spectrum and an intermediate stage, where not all criteria for cutaneous lymphoma are met, characterized as cutaneous T-cell lymphoid dyscrasia. Until the potential for evolution of PPD to malignant disease is better understood, patients with unusual presentations of pigmented purpura should be further evaluated for MF.

Case Report

A healthy 17-year-old adolescent boy with an unremarkable medical history presented with an asymptomatic fixed rash on the abdomen, buttocks, and legs. The rash initially developed in a small area on the right leg 2 years prior and had slowly progressed. He was not currently taking any medications and did not participate in intense physical activity. Multiple biopsies had previously been performed by an outside physician, the most recent one demonstrating an interface and superficial perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate with extravasated red blood cells consistent with pigmented purpura. He did not respond to treatment with intralesional corticosteroids, high-potency topical steroids, or high-dose oral prednisone.

Clinical examination revealed multiple annular purpuric patches on the abdomen, buttocks, and legs that covered approximately 20% of the body surface area (Figure 1). Over several follow-up visits, a few of the lesions evolved from patches to thin plaques. There was no adenopathy or hepatosplenomegaly. Three additional biopsies taken over the next 4 months demonstrated a mixture of small mature lymphocytes with some atypical lymphocytes in the dermis and epidermis exhibiting diminished CD7 staining and lymphocytes lining up at the dermoepidermal junction. T-cell receptor g gene rearrangements demonstrated the same clonal population in all 3 specimens. The patient was diagnosed with stage IB mycosis fungoides (MF) of the pigmented purpura–like variant. Marked improvement of the lesions was noted after 6 weeks of psoralen plus UVA therapy 3 times weekly (Figure 2). Treatment was continued for 6 months but was discontinued due to the international shortage of methoxsalen. Two months after discontinuation, most of the lesions had completely resolved (Figure 3).

|

Comment

Mycoses fungoides is a rare cutaneous lymphoma that affects approximately 2000 patients in the United States.1 Only 5% of all cases are known to occur in the first 2 decades of life,2 and even fewer cases pre-sent with pigmented purpura, usually of the lichenoid variant.3 Although the patches and plaques of MF can masquerade as many other dermatoses (eg, dermatophytosis, psoriasis, dermatitis), there have been few reports of patients presenting with lesions with the clinical appearance of pigmented purpuric dermatosis (PPD).4 As with the many cases of early MF, which are histologically indistinguishable from dermatitis, the pigmented purpura–like variant of MF initially may have the histologic appearance of pigmented purpura and generally evolves to the histologic appearance of MF over time.

Similar to our case, there have been reports of clinical and histologic diagnosis of PPD preceding the histologic diagnosis of MF. In a small cohort study of 3 young men, Barnhill and Braverman5 first demonstrated the progression of PPD to MF over a 12-year period. The age of onset ranged from 14 to 30 years, with a mean age of 24.3 years. Biopsies in all 3 patients were consistent with PPD for many years prior to the diagnosis of MF, with an average length of time to diagnosis of 8.4 years. Atypical from most cases of PPD, the patients in this study demonstrated extensive involvement of the trunk, arms, and legs.5 It has been suggested that atypical PPD is a variant of PPD that evolves into MF over many years; however, we believe that PPD is a variant of MF, similar to the way an indolent dermatitis may evolve to classical MF over time. If characterized by a T-cell clone, this period preceding the diagnosis of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma could be characterized as a cutaneous T-cell lymphoid dyscrasia.

Guitart and Magro6 noted multiple chronic conditions that are associated with T-cell clones, including PPD. These conditions occurred without a known trigger, were unresponsive to topical therapies, and often did not meet diagnostic criteria for MF. The investigators felt the criteria that may indicate a cutaneous T-cell lymphoid dyscrasia include widespread distribution, lymphocytic infiltrate, diminished CD7 and CD62L expression, and clonality. Lymphocytes may be small without notable atypia.6

In a study of 43 patients with PPD, Magro et al3 found monoclonality and diminished CD7 expression in 18 participants, correlating with large surface area involvement. Approximately 40% of patients had histologic findings consistent with MF, suggesting that T-cell gene rearrangement studies should be obtained for prognostic evaluation in patients with widespread disease.3

|

|

To facilitate proper patient care, histopathology and molecular markers should be evaluated in conjunction with the clinical picture. A considerable increase in the size of the body surface area affected by purpuric patches combined with the presence of poikilodermatous changes and pruritus as well as disease lasting longer than 1 year should prompt an increased clinical suspicion of MF in patients with PPD.4,5 Histologically, the presence of Pautrier microabscesses, large cerebriform lymphocytes, and intraepidermal lymphocytic atypia extending beyond the dermis also would support a diagnosis of MF.3 Given the morphologic appearance and distribution of the lesions in our patient combined with epidermotropism, diminished CD7 expression, and monoclonality seen on pathology, we favored a diagnosis of MF. It would not be unreasonable to call this clonal variant of PPD a T-cell lymphoid dyscrasia. We appreciate that both PPD and MF will respond to phototherapy.7

Conclusion

We propose that there is a spectrum of disease presenting as PPD or MF sitting at either end of that spectrum and an intermediate stage, where not all criteria for cutaneous lymphoma are met, characterized as cutaneous T-cell lymphoid dyscrasia. Until the potential for evolution of PPD to malignant disease is better understood, patients with unusual presentations of pigmented purpura should be further evaluated for MF.

1. Criscione VD, Weinstock MA. Incidence of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma in the United States, 1973-2002. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:854-859.

2. Koch SE, Zackheim HS, Williams ML, et al. Mycosis fungoides beginning in childhood and adolescence. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;17:563-570.

3. Magro CM, Schaefer JT, Crowson AN, et al. Pigmented purpuric dermatosis: classification by phenotypic and molecular profiles. Am J Clin Pathol. 2007;128:218-229.

4. Hanna S, Walsh N, D’Intino Y, et al. Mycosis fungoides presenting as pigmented purpuric dermatitis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006;23:350-354.

5. Barnhill RL, Braverman IM. Progression of pigmented purpura-like eruptions to mycosis fungoides: report of three cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1988;19(1, pt 1):25-31.

6. Guitart J, Magro C. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoid dyscrasia: a unifying term for idiopathic chronic dermatoses with persistent T-cell clones. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:921-932.

7. Seckin D, Yazici Z, Senol A, et al. A case of Schamberg’s disease responding dramatically to PUVA treatment. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2008;24:95-96.

1. Criscione VD, Weinstock MA. Incidence of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma in the United States, 1973-2002. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:854-859.

2. Koch SE, Zackheim HS, Williams ML, et al. Mycosis fungoides beginning in childhood and adolescence. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;17:563-570.

3. Magro CM, Schaefer JT, Crowson AN, et al. Pigmented purpuric dermatosis: classification by phenotypic and molecular profiles. Am J Clin Pathol. 2007;128:218-229.

4. Hanna S, Walsh N, D’Intino Y, et al. Mycosis fungoides presenting as pigmented purpuric dermatitis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006;23:350-354.

5. Barnhill RL, Braverman IM. Progression of pigmented purpura-like eruptions to mycosis fungoides: report of three cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1988;19(1, pt 1):25-31.

6. Guitart J, Magro C. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoid dyscrasia: a unifying term for idiopathic chronic dermatoses with persistent T-cell clones. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:921-932.

7. Seckin D, Yazici Z, Senol A, et al. A case of Schamberg’s disease responding dramatically to PUVA treatment. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2008;24:95-96.

Practice Points

- Pigmented purpuric dermatosis may lie on a spectrum with mycosis fungoides (MF).

- Pigmented purpuric dermatosis of MF should be closely followed and likely treated as MF.

- Pigmented purpuric dermatosis may have T-cell gene rearrangements that may or may not be associated with MF.

Hypopigmented Facial Papules on the Cheeks

The Diagnosis: Tumor of the Follicular Infundibulum

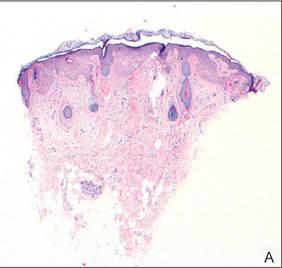

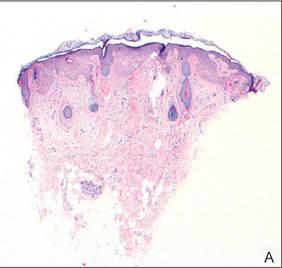

Histopathologic findings from a facial papule in our patient revealed multifocal hyperplasia of anastomosing follicular infundibular cells with multiple connections to the overlying epidermis (Figure). There was no atypia. Gomori methenamine-silver and periodic acid–Schiff stains for fungi were negative. The combined clinical presentation and histopathologic findings supported the diagnosis of multiple tumor of the follicular infundibulum (TFI).

Tumor of the follicular infundibulum was diagnosed based on a biopsy from the right cheek that revealed multifocal hyperplasia of anastomosing follicular infundibular cells with multiple connections to the overlying epidermis (A and B)(H&E, original magnifications ×40 and ×100). |

Tumor of the follicular infundibulum is an uncommon benign neoplasm that was first described in 1961 by Mehregan and Butler.1 The reported frequency is 10 per 100,000 biopsies.2 The majority of cases have been reported as solitary lesions, and multiple TFI are rare.3 Tumor of the follicular infundibulum affects middle-aged and elderly individuals with a female predominance.4 Multiple lesions generally range in number from 10 to 20, but there are few reports of more than 100 lesions.2,3,5,6 The solitary tumors often are initially misdiagnosed as basal cell carcinomas (BCCs) or seborrheic keratosis. Multiple TFI have been described variably as hypopigmented, flesh-colored and pink, flat and slightly depressed macules and thin papules. Sites of predilection include the scalp, face, neck, and upper trunk.2,3,5

There is no histopathologic difference between solitary and multiple TFI. Tumor of the follicular infundibulum displays a characteristic pale platelike proliferation of keratinocytes within the upper dermis attached to the overlying epidermis. The proliferating cells stain positive with periodic acid–Schiff, diastase-digestible glycogen is present in the cells at the base of the tumor, and a thickened network or brushlike pattern of elastic fibers surrounds the periphery of the tumor.1 Tumor of the follicular infundibulum is occasionally discovered incidentally on biopsy and has been observed in the margin of wide excisions of a variety of neoplasms including BCC.7 Based on the close association of TFI and BCC in the same specimens, Weyers et al7 concluded that TFI may be a nonaggressive type of BCC. Cribier and Grosshans2 reported 2 cases of TFI overlying a nevus sebaceous and a fibroma.

Treatment of TFI includes topical keratolytics, topical retinoic acid,5 imiquimod,8 topical steroids, and oral etretinate,6 all of which result in minimal improvement or incomplete resolution. Destructive treatments include cryotherapy, curettage, electrosurgery, laser ablation, and surgical excision, but all may lead to an unacceptable cosmetic result.

1. Mehregan AH, Butler JD. A tumor of follicular infundibulum. Arch Dermatol. 1961;83:78-81.

2. Cribier B, Grosshans E. Tumor of the follicular infundibulum: a clinicopathologic study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:979-984.

3. Kolenik SA 3rd, Bolognia JL, Castiglione FM Jr, et al. Multiple tumors of the follicular infundibulum. Int J Dermatol. 1996;35:282-284.

4. Ackerman AB, Reddy VB, Soyer HP. Neoplasms With Follicular Differentiation. New York, NY: Ardor Scribendi; 2001.

5. Kossard S, Finley AG, Poyzer K, et al. Eruptive infundibulomas. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;21:361-366.

6. Schnitzler L, Civatte J, Robin F, et al. Multiple tumors of the follicular infundibulum with basocellular degeneration. apropos of a case [in French]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1987;114:551-556.

7. Weyers W, Horster S, Diaz-Cascajo C. Tumor of follicular infundibulum is basal cell carcinoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:634-641.

8. Martin JE, Hsu M, Wang LC. An unusual clinical presentation of multiple tumors of the follicular infundibulum. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:885-886.

The Diagnosis: Tumor of the Follicular Infundibulum

Histopathologic findings from a facial papule in our patient revealed multifocal hyperplasia of anastomosing follicular infundibular cells with multiple connections to the overlying epidermis (Figure). There was no atypia. Gomori methenamine-silver and periodic acid–Schiff stains for fungi were negative. The combined clinical presentation and histopathologic findings supported the diagnosis of multiple tumor of the follicular infundibulum (TFI).

Tumor of the follicular infundibulum was diagnosed based on a biopsy from the right cheek that revealed multifocal hyperplasia of anastomosing follicular infundibular cells with multiple connections to the overlying epidermis (A and B)(H&E, original magnifications ×40 and ×100). |

Tumor of the follicular infundibulum is an uncommon benign neoplasm that was first described in 1961 by Mehregan and Butler.1 The reported frequency is 10 per 100,000 biopsies.2 The majority of cases have been reported as solitary lesions, and multiple TFI are rare.3 Tumor of the follicular infundibulum affects middle-aged and elderly individuals with a female predominance.4 Multiple lesions generally range in number from 10 to 20, but there are few reports of more than 100 lesions.2,3,5,6 The solitary tumors often are initially misdiagnosed as basal cell carcinomas (BCCs) or seborrheic keratosis. Multiple TFI have been described variably as hypopigmented, flesh-colored and pink, flat and slightly depressed macules and thin papules. Sites of predilection include the scalp, face, neck, and upper trunk.2,3,5

There is no histopathologic difference between solitary and multiple TFI. Tumor of the follicular infundibulum displays a characteristic pale platelike proliferation of keratinocytes within the upper dermis attached to the overlying epidermis. The proliferating cells stain positive with periodic acid–Schiff, diastase-digestible glycogen is present in the cells at the base of the tumor, and a thickened network or brushlike pattern of elastic fibers surrounds the periphery of the tumor.1 Tumor of the follicular infundibulum is occasionally discovered incidentally on biopsy and has been observed in the margin of wide excisions of a variety of neoplasms including BCC.7 Based on the close association of TFI and BCC in the same specimens, Weyers et al7 concluded that TFI may be a nonaggressive type of BCC. Cribier and Grosshans2 reported 2 cases of TFI overlying a nevus sebaceous and a fibroma.

Treatment of TFI includes topical keratolytics, topical retinoic acid,5 imiquimod,8 topical steroids, and oral etretinate,6 all of which result in minimal improvement or incomplete resolution. Destructive treatments include cryotherapy, curettage, electrosurgery, laser ablation, and surgical excision, but all may lead to an unacceptable cosmetic result.

The Diagnosis: Tumor of the Follicular Infundibulum

Histopathologic findings from a facial papule in our patient revealed multifocal hyperplasia of anastomosing follicular infundibular cells with multiple connections to the overlying epidermis (Figure). There was no atypia. Gomori methenamine-silver and periodic acid–Schiff stains for fungi were negative. The combined clinical presentation and histopathologic findings supported the diagnosis of multiple tumor of the follicular infundibulum (TFI).

Tumor of the follicular infundibulum was diagnosed based on a biopsy from the right cheek that revealed multifocal hyperplasia of anastomosing follicular infundibular cells with multiple connections to the overlying epidermis (A and B)(H&E, original magnifications ×40 and ×100). |

Tumor of the follicular infundibulum is an uncommon benign neoplasm that was first described in 1961 by Mehregan and Butler.1 The reported frequency is 10 per 100,000 biopsies.2 The majority of cases have been reported as solitary lesions, and multiple TFI are rare.3 Tumor of the follicular infundibulum affects middle-aged and elderly individuals with a female predominance.4 Multiple lesions generally range in number from 10 to 20, but there are few reports of more than 100 lesions.2,3,5,6 The solitary tumors often are initially misdiagnosed as basal cell carcinomas (BCCs) or seborrheic keratosis. Multiple TFI have been described variably as hypopigmented, flesh-colored and pink, flat and slightly depressed macules and thin papules. Sites of predilection include the scalp, face, neck, and upper trunk.2,3,5

There is no histopathologic difference between solitary and multiple TFI. Tumor of the follicular infundibulum displays a characteristic pale platelike proliferation of keratinocytes within the upper dermis attached to the overlying epidermis. The proliferating cells stain positive with periodic acid–Schiff, diastase-digestible glycogen is present in the cells at the base of the tumor, and a thickened network or brushlike pattern of elastic fibers surrounds the periphery of the tumor.1 Tumor of the follicular infundibulum is occasionally discovered incidentally on biopsy and has been observed in the margin of wide excisions of a variety of neoplasms including BCC.7 Based on the close association of TFI and BCC in the same specimens, Weyers et al7 concluded that TFI may be a nonaggressive type of BCC. Cribier and Grosshans2 reported 2 cases of TFI overlying a nevus sebaceous and a fibroma.

Treatment of TFI includes topical keratolytics, topical retinoic acid,5 imiquimod,8 topical steroids, and oral etretinate,6 all of which result in minimal improvement or incomplete resolution. Destructive treatments include cryotherapy, curettage, electrosurgery, laser ablation, and surgical excision, but all may lead to an unacceptable cosmetic result.

1. Mehregan AH, Butler JD. A tumor of follicular infundibulum. Arch Dermatol. 1961;83:78-81.

2. Cribier B, Grosshans E. Tumor of the follicular infundibulum: a clinicopathologic study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:979-984.

3. Kolenik SA 3rd, Bolognia JL, Castiglione FM Jr, et al. Multiple tumors of the follicular infundibulum. Int J Dermatol. 1996;35:282-284.

4. Ackerman AB, Reddy VB, Soyer HP. Neoplasms With Follicular Differentiation. New York, NY: Ardor Scribendi; 2001.

5. Kossard S, Finley AG, Poyzer K, et al. Eruptive infundibulomas. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;21:361-366.

6. Schnitzler L, Civatte J, Robin F, et al. Multiple tumors of the follicular infundibulum with basocellular degeneration. apropos of a case [in French]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1987;114:551-556.

7. Weyers W, Horster S, Diaz-Cascajo C. Tumor of follicular infundibulum is basal cell carcinoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:634-641.

8. Martin JE, Hsu M, Wang LC. An unusual clinical presentation of multiple tumors of the follicular infundibulum. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:885-886.

1. Mehregan AH, Butler JD. A tumor of follicular infundibulum. Arch Dermatol. 1961;83:78-81.

2. Cribier B, Grosshans E. Tumor of the follicular infundibulum: a clinicopathologic study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:979-984.

3. Kolenik SA 3rd, Bolognia JL, Castiglione FM Jr, et al. Multiple tumors of the follicular infundibulum. Int J Dermatol. 1996;35:282-284.

4. Ackerman AB, Reddy VB, Soyer HP. Neoplasms With Follicular Differentiation. New York, NY: Ardor Scribendi; 2001.

5. Kossard S, Finley AG, Poyzer K, et al. Eruptive infundibulomas. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;21:361-366.

6. Schnitzler L, Civatte J, Robin F, et al. Multiple tumors of the follicular infundibulum with basocellular degeneration. apropos of a case [in French]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1987;114:551-556.

7. Weyers W, Horster S, Diaz-Cascajo C. Tumor of follicular infundibulum is basal cell carcinoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:634-641.

8. Martin JE, Hsu M, Wang LC. An unusual clinical presentation of multiple tumors of the follicular infundibulum. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:885-886.

A 73-year-old woman presented with multiple mildly pruritic, hypopigmented, thin papules involving both cheeks of 5 months’ duration. The patient had no improvement with ketoconazole cream 2% and hydrocortisone cream 1% used daily for 1 month for presumed tinea versicolor. Physical examination revealed 10 ill-defined, 2- to 5-mm, round and oval, smooth hypopigmented, slightly raised papules located on the lower aspect of both cheeks.

Cosmetic Corner: Dermatologists Weigh in on OTC Pigment Control Products

To improve patient care and outcomes, leading dermatologists offered their recommendations on the top OTC pigment control products. Consideration must be given to:

- Even Better

Clinique Laboratories, LLC

“It also is useful as prevention and offers many different options.”—Antonella Tosti, MD, Miami, Florida

“These OTC products have good clinical data to support use for hyperpigmentation. Patients tell me that they feel good on their skin and aren’t irritating.”—Gary Goldenberg, MD, New York, New York

- Lumixyl Brightening System

Envy Medical, Inc

“A great option for patients who may be experiencing modest issues with pigmentation. Use of a retinoid with this product also may enhance its efficacy.”—Joel Schlessinger, MD, Omaha, Nebraska

- Lytera Skin Brightening Complex

SkinMedica

“With key ingredients such as hexylresorcinol, retinol, and niacinamide, it has been clinically shown to lighten dark patches in its trials as well as adding luminosity to the skin.”—Anthony Rossi, MD, New York, New York

Recommended by Elizabeth K. Hale, MD, New York, New York

- Pigmentclar Serum

La-Roche Posay Laboratoire Dermatologique

“It attacks pigment production at every stage.”—Whitney Bowe, MD, Brooklyn, New York

Cutis invites readers to send us their recommendations. Mineral makeup, eyelash enhancers, and facial scrubs will be featured in upcoming editions of Cosmetic Corner. Please e-mail your recommendation(s) to [email protected].

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect those of Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc and shall not be used for product endorsement purposes. Any reference made to a specific commercial product does not indicate or imply that Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc endorses, recommends, or favors the product mentioned. No guarantee is given to the effects of recommended products.

To improve patient care and outcomes, leading dermatologists offered their recommendations on the top OTC pigment control products. Consideration must be given to:

- Even Better

Clinique Laboratories, LLC

“It also is useful as prevention and offers many different options.”—Antonella Tosti, MD, Miami, Florida

“These OTC products have good clinical data to support use for hyperpigmentation. Patients tell me that they feel good on their skin and aren’t irritating.”—Gary Goldenberg, MD, New York, New York

- Lumixyl Brightening System

Envy Medical, Inc

“A great option for patients who may be experiencing modest issues with pigmentation. Use of a retinoid with this product also may enhance its efficacy.”—Joel Schlessinger, MD, Omaha, Nebraska

- Lytera Skin Brightening Complex

SkinMedica

“With key ingredients such as hexylresorcinol, retinol, and niacinamide, it has been clinically shown to lighten dark patches in its trials as well as adding luminosity to the skin.”—Anthony Rossi, MD, New York, New York

Recommended by Elizabeth K. Hale, MD, New York, New York

- Pigmentclar Serum

La-Roche Posay Laboratoire Dermatologique

“It attacks pigment production at every stage.”—Whitney Bowe, MD, Brooklyn, New York

Cutis invites readers to send us their recommendations. Mineral makeup, eyelash enhancers, and facial scrubs will be featured in upcoming editions of Cosmetic Corner. Please e-mail your recommendation(s) to [email protected].

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect those of Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc and shall not be used for product endorsement purposes. Any reference made to a specific commercial product does not indicate or imply that Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc endorses, recommends, or favors the product mentioned. No guarantee is given to the effects of recommended products.

To improve patient care and outcomes, leading dermatologists offered their recommendations on the top OTC pigment control products. Consideration must be given to:

- Even Better

Clinique Laboratories, LLC

“It also is useful as prevention and offers many different options.”—Antonella Tosti, MD, Miami, Florida

“These OTC products have good clinical data to support use for hyperpigmentation. Patients tell me that they feel good on their skin and aren’t irritating.”—Gary Goldenberg, MD, New York, New York

- Lumixyl Brightening System

Envy Medical, Inc

“A great option for patients who may be experiencing modest issues with pigmentation. Use of a retinoid with this product also may enhance its efficacy.”—Joel Schlessinger, MD, Omaha, Nebraska

- Lytera Skin Brightening Complex

SkinMedica

“With key ingredients such as hexylresorcinol, retinol, and niacinamide, it has been clinically shown to lighten dark patches in its trials as well as adding luminosity to the skin.”—Anthony Rossi, MD, New York, New York

Recommended by Elizabeth K. Hale, MD, New York, New York

- Pigmentclar Serum

La-Roche Posay Laboratoire Dermatologique

“It attacks pigment production at every stage.”—Whitney Bowe, MD, Brooklyn, New York

Cutis invites readers to send us their recommendations. Mineral makeup, eyelash enhancers, and facial scrubs will be featured in upcoming editions of Cosmetic Corner. Please e-mail your recommendation(s) to [email protected].

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect those of Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc and shall not be used for product endorsement purposes. Any reference made to a specific commercial product does not indicate or imply that Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc endorses, recommends, or favors the product mentioned. No guarantee is given to the effects of recommended products.

Granulomatous Changes Associated With Pigmented Purpuric Dermatosis

Pigmented purpuric dermatoses (PPDs) are a group of common chronic disorders characterized by speckled, cayenne pepper–like petechiae and orange-brown discoloration of the skin resulting from capillaritis.1 Pigmented purpuric dermatoses typically occur in the absence of underlying vascular insufficiency or other hematologic dysfunction. The 5 well-known clinicopathologic variants of PPD include Schamberg disease; purpura annularis telangiectodes of Majocchi; pigmented purpuric lichenoid dermatitis of Gougerot and Blum; eczematoidlike purpura of Doucas and Kapetanakis; and lichen aureus.2 All PPDs share common characteristic clinical and histologic features. Clinically, patients generally present with symmetric petechiae and/or pigmented macules. All 5 PPD variants share similar histologic findings, including a vasculocentric lymphocytic infiltrate in the papillary dermis, swelling of the endothelial cells, erythrocyte extravasation, and often hemosiderin-laden macrophages.1 Despite these clinical and histopathologic similarities, each variant contains additional distinctive features, such as telangiectasia (purpura annularis telangiectodes of Majocchi), a lichenoid infiltrate (pigmented purpuric lichenoid dermatitis of Gougerot and Blum), eczematous changes (eczematoidlike purpura of Doucas and Kapetanakis), and marked hemosiderin deposition (lichen aureus).

Granulomatous pigmented purpuric dermatosis (GPPD) is a rare variant of PPD.3-7 Clinically, these lesions appear similar to other PPDs; however, in addition to the characteristic changes associated with conventional PPD, histologic examination of GPPD reveals a granulomatous inflammatory reaction pattern. Although the pathogenesis of GPPD is not well understood, its association with hyperlipidemia may suggest a granulomatous response to capillaritis mediated by lipid deposition in the microvasculature.6,7

We present 3 cases of GPPD and provide a review of the literature. In all of our patients, biopsy specimens were fixed in 10% buffered formalin and embedded in paraffin by standard methodologies, and all stains were performed on sections by standard methodologies. Based on a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms granulomatous pigmented purpuric dermatosis, sarcoidosis, pigmented purpuric dermatosis, granulomas, and pigmented purpuric dermatosis, we review 5 additional reports describing 10 total patients.3-7

Case Reports

Patient 1

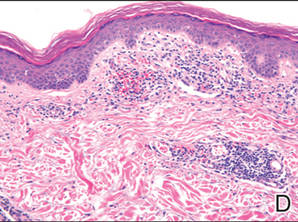

A 9-year-old white boy presented with a 3-cm asymptomatic light brown patch with a nonblanching violaceous center on the right posterior thigh that was studded with pinpoint yellow papules (Figure, A). The lesion appeared 3 to 4 years prior to presentation but had become progressively darker and centrally indurated over the last 2 years. The patient and his mother denied any history of trauma to the area. His medical history was unremarkable, and his current medications included fish oil and multivitamin tablets.

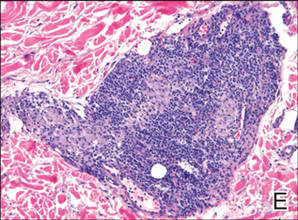

Histologic examination of a punch biopsy specimen taken from the center of the lesion revealed a lichenoid lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with marked red blood cell (RBC) extravasation and associated hemosiderin-laden macrophages. The lymphocytes comprising this infiltrate lacked cytologic atypia and exhibited minimal epidermotropism (Figure, B). Additionally, there was a superficial and deep perivascular mononuclear inflammatory infiltrate intermixed with numerous small granulomas comprised ofepithelioid histiocytes in the mid and deep dermis (Figure, C). Periodic acid–Schiff, acid-fast bacilli (AFB), and Fite stains were negative for organisms. Polarization was negative for refractile foreign material. Due to the patient’s age, no treatment was performed, and the lesion remains unchanged 1 year after biopsy.

Patient 2

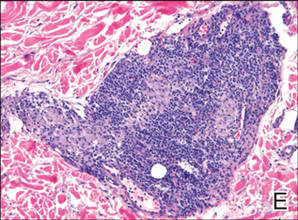

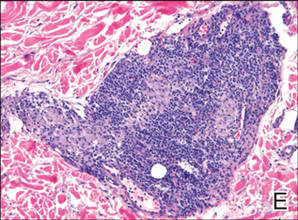

A 49-year-old white woman presented with a 2-cm yellow-brown patch with a faint, nonblanchable, violaceous center on the right lateral thigh of 4 months’ duration. The patch initially appeared as a small asymptomatic purple papule. The patient denied any history of trauma to the area. A purified protein derivative (tuberculin) skin test was negative at the time of examination. The patient’s medical history was remarkable for renal calculi. Her current medications included progesterone; estradiol; lansoprazole; prenatal vitamins; vitamins C and E; zinc; and calcium. The patient had no family history of sarcoidosis. Complete blood cell count, urinalysis, liver function tests, and angiotensin-converting enzyme levels were unremarkable. Pulmonary function tests were normal, and there was no evidence of sarcoidosis on chest radiography. Initial biopsy of the lesion revealed a perivascular and interstitial lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with abundant extravasated RBCs in the papillary dermis (Figure, D). Similar to patient 1, the infiltrate lacked cytologic atypia and did not involve the overlying epidermis. There was perivascular granulomatous inflammation in the mid dermis (Figure, E). Periodic acid–Schiff, Warthin-Starry, and AFB stains were negative for organisms. Polarization was negative for refractile foreign material.

The lesion was treated with clobetasol propionate ointment 0.05% twice daily for 6 weeks with transient improvement, but the lesion recurred upon treatment cessation. Subsequent treatment with intralesional triamcinolone resulted in slight improvement of the lesion. A therapeutic trial of targeted pulsed dye laser treatment was ineffective. The lesion gradually increased in size over the next year with no therapy, and a repeat biopsy revealed a lichenoid lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with abundant extravasated RBCs consistent with persistent PPD. A granulomatous infiltrate was not evident in the superficial shave biopsy specimen.

Patient 3

A 75-year-old white woman presented with scattered, speckled, cayenne pepper–like, red-brown macules on the legs. Two years prior to presentation, a few scattered symmetrical macules appeared on the dorsal aspects of the feet, which gradually increased in number to form larger confluent patches that spread to the lower legs. The patient denied itching or burning but reported that the patches became painful when scratched and were aggravated by sun exposure. Her medical history was remarkable for asthma, chronic renal insufficiency, coronary artery disease, Barrett esophagus, obstructive sleep apnea, hypothyroidism, renal calculi, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and hyperlipidemia. Her current medications included carvedilol, valsartan, levothyroxine, aspirin, clopidogrel, furosemide, nitrofurantoin, temazepam, insulin, ezetimibe-simvastatin, and lansoprazole. Computed tomography of the chest revealed no signs of sarcoidosis. Pulmonary function tests revealed moderate obstructive lung disease. An ophthalmology examination showed no evidence of sarcoidosis. Laboratory results revealed an elevated glucose, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, and triglyceride levels, as well as low hematocrit and vitamin D levels. Urinalysis, thyroid-stimulating hormone (thyrotropin) test, liver function tests, angiotensin-converting enzyme test, hepatitis B surface antigen, and IFN-g release assay were normal.

Histologic examination of a punch biopsy specimen revealed an inflammatory infiltrate confined to the papillary dermis. This infiltrate was comprised of an admixture of lymphocytes and histiocytes in a perivascular distribution with associated RBC extravasation and intimately associated granulomas (Figure, F). Additional inflammation in the deeper aspects of the dermis was not identified. Periodic acid–Schiff, AFB, and Fite stains were negative for organisms. Polarization was negative for refractile foreign material.

|

|

| ||

|

|

| ||

| A 3-cm asymptomatic light brown patch with a nonblanching violaceous center on the right posterior thigh that was studded with pinpoint yellow papules (A). Lichenoid lymphohistiocytic infiltrate in the papillary dermis with marked red blood cell extravasation (B)(H&E, original magnification ×20). Superficial and deep perivascular mononuclear inflammatory infiltrate intermixed with numerous small granulomas comprised of epithelioid histiocytes in the mid and deep dermis (C)(H&E, original magnification ×20). Perivascular and interstitial lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with abundant extravasated red blood cells in the papillary dermis (D)(H&E, original magnification ×10). Perivascular lymphohistiocytic inflammation with epithelioid granulomas in the mid dermis (E)(H&E, original magnification ×20). Lymphohistiocytic inflammation in the papillary dermis comprised of an admixture of lymphocytes and histiocytes in a perivascular distribution with associated red blood cell extravasation and intimately associated granulomas (F)(H&E, original magnification ×20). | ||||

The patient was treated with topical steroids and minocycline 50 mg twice daily without improvement. The lesions improved after the patient underwent treatment with oral corticosteroids for pulmonary disease.

Comment

Pigmented purpuric dermatoses comprise a spectrum of clinical and pathologic conditions.1,2 Granulomatous PPD is a much less common variant, characterized by a granulomatous infiltrate admixed with PPD. We report 3 additional cases and review the literature on this rare and interesting variant of PPD.

We noted several unifying clinicopathologic features among our patients and those previously reported in the literature (Table).3-7 Including our cases, our review yielded 13 GPPD patients ranging in age from 9 to 75 years, with a mean age of 49.1 years. Two of our patients—patients 1 and 3—were the youngest and oldest patients, respectively, among the cases we reviewed. The majority of the cases we reviewed included patients of East Asian descent (6 Taiwanese; 2 Japanese; 1 Korean) as well as 4 white patients. No distinctive gender predilection was apparent, as our review included 8 females and 5 males.

Our review revealed that GPPD lesions typically involve the lower extremities and usually are asymptomatic, with the exception of occasional pruritus. Additional lesions have been reported on the dorsal aspect of the hands, and 1 case noted exclusive involvement of the wrist.6 Lesions of GPPD can range in their clinical appearance. Three of 13 patients presented with purpuric papules and 2 had brown pigmentation with hemorrhagic papules3,4,6; the remaining 8 patients had erythematous or brown macules, papules, or plaques.5-7 The most commonly associated disease condition was hyperlipidemia, which was reported in 7 of 13 cases.5-7 Additional reported comorbidities included meningioma, renal calculi, obesity, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hepatitis C virus, ulcerative colitis, thrombocytopenia, and hyperuricemia. Reported serologic abnormalities included a rare positive antinuclear antibody, rheumatoid factor, and cryoglobulins.3,6 Therapeutic efficacy in the management of GPPD has not been well described; however, for the rare cases in which therapies were described, they were largely unsuccessful, with 1 patient exhibiting spontaneous improvement.3,4

Granulomatous PPD also appears to exhibit a range of histologic findings. All cases of GPPD shared fundamental components, such as a brisk perivascular infiltrate accompanied by RBC extravasation with variable hemosiderin-laden macrophages and a granulomatous infiltrate. All of the reports we reviewed described an intimate association between these components, with the granulomas being essentially superimposed on typical PPD. As for other types of PPD, obvious vasculitis characterized by a vasculocentric inflammatory infiltrate and evidence of vascular injury, such as fibrinoid necrosis of the vessel wall, has not been described in GPPD.3-7 Finally, histologic changes suggestive of a relationship with cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, cytologic atypia, and epidermotropism have been described for some forms of PPD but have not been described for GPPD.3-8

Our case reports expand the histologic spectrum of GPPD. Although patient 3 exhibited a relatively intimate association of granulomas and PPD, 2 of our cases (patients 1 and 2) demonstrated a granulomatous infiltrate in the mid to deep dermis, which is separate from the more superficially situated lichenoid lymphohistiocytic infiltrate, RBC extravasation, and hemosiderin-laden macrophages noted in the papillary dermis. Considered along with the absence of an obvious clinicopathologic explanation for the granulomatous infiltrates (eg, polarizable material, infectious organisms, systemic disease), these 2 cases (patients 1 and 2) suggest a composite form of PPD that combines the lichenoid pattern of PPD of Gougerot and Blum with a deep granulomatous component of GPPD. The importance of this distinction lies in the potential for physicians to overlook this potentially informative histologic pattern if only a superficial biopsy is performed. The clinical relevance is unclear; however, in our experience, it has been challenging to treat this relatively small subset of patients who have exhibited a limited response to treatment with topical steroids, intralesional steroids, pulsed dye laser, and vitamin supplementation.

The cause of the granulomatous infiltrate in GPPD is poorly understood. Seven of 13 cases included in our review occurred in patients with a history of hyperlipidemia.5-7 Some have postulated that the constellation of findings of GPPD in hyperlipidemic patients reflects an underlying vascular injury process induced by lipid deposition in the endothelial cells with subsequent RBC extravasation and a secondary granulomatous response to the lipid deposits.6,7 However, given the occurrence of GPPD in patients without hyperlipidemia, other mechanisms also must be considered in the pathogenesis of GPPD, including a reaction to medications, systemic diseases, and infectious etiologies (eg, hepatitis B virus).4,6 As additional cases are described in the literature, other unifying clinical etiologies for this histopathologic reaction pattern may emerge.

Conclusion

Granulomatous PPD may comprise an underrecognized variant of PPD in cases when only a superficial biopsy is evaluated. Clinicians and pathologists should be aware of this variant, and in refractory cases of PPD, deeper sampling may be warranted to identify granulomas.

1. Sardana K, Sarkar R, Sehgal VN. Pigmented purpuric dermatoses: an overview. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:482-488.

2. Piette WW. Purpura: mechanisms and differential diagnosis. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, eds. Dermatology. 2nd ed. London, England: Mosby; 2008:321-330.

3. Saito R, Matsuoka Y. Granulomatous pigmented purpuric dermatosis. J Dermatol. 1996;23:551-555.