User login

Practical tips help quell pseudofolliculitis barbae

LAS VEGAS – Stubble is okay, and not just because it’s trendy to sport a beard. This was a key message during a presentation on pseudofolliculitis barbae at Skin Disease Education Foundation’s annual Las Vegas dermatology seminar.

Changing up personal grooming habits is an important tactic for men who are plagued with pseudofolliculitis barbae, according to Dr. Andrew F. Alexis, chair of the department of dermatology and director of The Skin of Color Center, Mount Sinai St. Luke’s and Mount Sinai Roosevelt, New York.

This very common skin condition, affecting 45%-83% of men of African ancestry, is best managed by avoiding close shaving and preventing a sharp hair shaft tip. For those who don’t want a full beard for personal or professional reasons, using single blade razors, electric clippers, and even depilatories can help, he said.

All of these techniques prevent curly beard hairs from repenetrating or recurving before emergence – the underpinning of the pathology of pseudofolliculitis barbae. The embedded hairs eventually form a papular or pustular lesion that mimics infectious folliculitis. The inflammatory process can also prompt keloid formation in susceptible individuals.

Providing treatment options is important because the condition can be disfiguring, with such long-term physical sequelae as scarring beard alopecia and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation – changes in appearance that can have a significant psychosocial impact on affected men, Dr. Alexis said.

Therapies are centered around avoiding close shaving and/or preventing a sharp hair shaft tip.

One primary treatment is to stop shaving. “Embedded hairs spontaneously release after about one centimeter of growth,” Dr. Alexis said. This process can take up to 2 months, he said, but military studies dating back to the 1970s showed that the vast majority of pseudofolliculitis barbae cases resolved when service members stopped close shaving practices.

However, many patients want a clean-shaven appearance. “We can work with them to modify their shaving practices. Historically, we have recommended single-blade razors over multiple blade razors” because they shave less closely, he said, pointing out that razor manufacturers have funded studies that challenge this finding.

“Electric clippers are a very good alternative” to razors, Dr. Alexis said. A blade setting that allows at least 0.5-1 mm stubble is desirable.

Chemical depilatories, which act by weakening keratin disulfide bonds, can be effective, since depilated hair does not have a sharp, beveled tip on regrowth and is therefore less likely to repuncture the skin. Patients should be aware, though, that these substances can cause irritant contact dermatitis, he pointed out. Newer formulations are less caustic, but also less efficacious, he said.

In terms of practical tips, shaving technique is important. “Don’t assume the patient knows. There are all sorts of varying techniques out there,” some of which can exacerbate pseudofolliculitis barbae, Dr. Alexis said.

Before shaving, men should wash with a mild cleanser, using a gentle circular technique to free any entrapped hairs, then a moisturizing shaving cream. Razors should be changed every five to seven shaves, and shaving should always be done in the direction of beard growth without pulling on the skin.

Post shave, topical benzoyl peroxide 5%/clindamycin 1% can significantly reduce papules and pustules. Topical retinoids are another effective option. A low-potency steroid can be helpful for inflammatory symptoms.

For cases that just don’t respond to conservative and medical management, laser hair removal is an option. A recent military-funded split-face study found further improvement when topical eflornithine was added to long-pulse Nd:Yag laser therapy, Dr. Alexis said.

Affected individuals may find it difficult to modify shaving practices when uniformed service regulations or office dress codes require men to be close shaven; a note from a physician can be helpful. Dr. Alexis provides patients with a form letter to show their employers, explaining that the patient has a skin disorder that is exacerbated by shaving, and that the patient should be permitted to maintain a well-groomed beard. “I end up writing a lot of these for New York police officers,” he said.

Dr. Alexis disclosed that he has received grants and research support from Allergan and Novartis, and speaker honoraria from Cipla. He has received consulting fees from Aclaris, Allergan, Amgen, Anacor, Bayer, Galderma, Johnson & Johnson, Leo, L’Oreal, Roche, Schick, Suneva, and Valeant.

SDEF and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

On Twitter @karioakes

LAS VEGAS – Stubble is okay, and not just because it’s trendy to sport a beard. This was a key message during a presentation on pseudofolliculitis barbae at Skin Disease Education Foundation’s annual Las Vegas dermatology seminar.

Changing up personal grooming habits is an important tactic for men who are plagued with pseudofolliculitis barbae, according to Dr. Andrew F. Alexis, chair of the department of dermatology and director of The Skin of Color Center, Mount Sinai St. Luke’s and Mount Sinai Roosevelt, New York.

This very common skin condition, affecting 45%-83% of men of African ancestry, is best managed by avoiding close shaving and preventing a sharp hair shaft tip. For those who don’t want a full beard for personal or professional reasons, using single blade razors, electric clippers, and even depilatories can help, he said.

All of these techniques prevent curly beard hairs from repenetrating or recurving before emergence – the underpinning of the pathology of pseudofolliculitis barbae. The embedded hairs eventually form a papular or pustular lesion that mimics infectious folliculitis. The inflammatory process can also prompt keloid formation in susceptible individuals.

Providing treatment options is important because the condition can be disfiguring, with such long-term physical sequelae as scarring beard alopecia and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation – changes in appearance that can have a significant psychosocial impact on affected men, Dr. Alexis said.

Therapies are centered around avoiding close shaving and/or preventing a sharp hair shaft tip.

One primary treatment is to stop shaving. “Embedded hairs spontaneously release after about one centimeter of growth,” Dr. Alexis said. This process can take up to 2 months, he said, but military studies dating back to the 1970s showed that the vast majority of pseudofolliculitis barbae cases resolved when service members stopped close shaving practices.

However, many patients want a clean-shaven appearance. “We can work with them to modify their shaving practices. Historically, we have recommended single-blade razors over multiple blade razors” because they shave less closely, he said, pointing out that razor manufacturers have funded studies that challenge this finding.

“Electric clippers are a very good alternative” to razors, Dr. Alexis said. A blade setting that allows at least 0.5-1 mm stubble is desirable.

Chemical depilatories, which act by weakening keratin disulfide bonds, can be effective, since depilated hair does not have a sharp, beveled tip on regrowth and is therefore less likely to repuncture the skin. Patients should be aware, though, that these substances can cause irritant contact dermatitis, he pointed out. Newer formulations are less caustic, but also less efficacious, he said.

In terms of practical tips, shaving technique is important. “Don’t assume the patient knows. There are all sorts of varying techniques out there,” some of which can exacerbate pseudofolliculitis barbae, Dr. Alexis said.

Before shaving, men should wash with a mild cleanser, using a gentle circular technique to free any entrapped hairs, then a moisturizing shaving cream. Razors should be changed every five to seven shaves, and shaving should always be done in the direction of beard growth without pulling on the skin.

Post shave, topical benzoyl peroxide 5%/clindamycin 1% can significantly reduce papules and pustules. Topical retinoids are another effective option. A low-potency steroid can be helpful for inflammatory symptoms.

For cases that just don’t respond to conservative and medical management, laser hair removal is an option. A recent military-funded split-face study found further improvement when topical eflornithine was added to long-pulse Nd:Yag laser therapy, Dr. Alexis said.

Affected individuals may find it difficult to modify shaving practices when uniformed service regulations or office dress codes require men to be close shaven; a note from a physician can be helpful. Dr. Alexis provides patients with a form letter to show their employers, explaining that the patient has a skin disorder that is exacerbated by shaving, and that the patient should be permitted to maintain a well-groomed beard. “I end up writing a lot of these for New York police officers,” he said.

Dr. Alexis disclosed that he has received grants and research support from Allergan and Novartis, and speaker honoraria from Cipla. He has received consulting fees from Aclaris, Allergan, Amgen, Anacor, Bayer, Galderma, Johnson & Johnson, Leo, L’Oreal, Roche, Schick, Suneva, and Valeant.

SDEF and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

On Twitter @karioakes

LAS VEGAS – Stubble is okay, and not just because it’s trendy to sport a beard. This was a key message during a presentation on pseudofolliculitis barbae at Skin Disease Education Foundation’s annual Las Vegas dermatology seminar.

Changing up personal grooming habits is an important tactic for men who are plagued with pseudofolliculitis barbae, according to Dr. Andrew F. Alexis, chair of the department of dermatology and director of The Skin of Color Center, Mount Sinai St. Luke’s and Mount Sinai Roosevelt, New York.

This very common skin condition, affecting 45%-83% of men of African ancestry, is best managed by avoiding close shaving and preventing a sharp hair shaft tip. For those who don’t want a full beard for personal or professional reasons, using single blade razors, electric clippers, and even depilatories can help, he said.

All of these techniques prevent curly beard hairs from repenetrating or recurving before emergence – the underpinning of the pathology of pseudofolliculitis barbae. The embedded hairs eventually form a papular or pustular lesion that mimics infectious folliculitis. The inflammatory process can also prompt keloid formation in susceptible individuals.

Providing treatment options is important because the condition can be disfiguring, with such long-term physical sequelae as scarring beard alopecia and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation – changes in appearance that can have a significant psychosocial impact on affected men, Dr. Alexis said.

Therapies are centered around avoiding close shaving and/or preventing a sharp hair shaft tip.

One primary treatment is to stop shaving. “Embedded hairs spontaneously release after about one centimeter of growth,” Dr. Alexis said. This process can take up to 2 months, he said, but military studies dating back to the 1970s showed that the vast majority of pseudofolliculitis barbae cases resolved when service members stopped close shaving practices.

However, many patients want a clean-shaven appearance. “We can work with them to modify their shaving practices. Historically, we have recommended single-blade razors over multiple blade razors” because they shave less closely, he said, pointing out that razor manufacturers have funded studies that challenge this finding.

“Electric clippers are a very good alternative” to razors, Dr. Alexis said. A blade setting that allows at least 0.5-1 mm stubble is desirable.

Chemical depilatories, which act by weakening keratin disulfide bonds, can be effective, since depilated hair does not have a sharp, beveled tip on regrowth and is therefore less likely to repuncture the skin. Patients should be aware, though, that these substances can cause irritant contact dermatitis, he pointed out. Newer formulations are less caustic, but also less efficacious, he said.

In terms of practical tips, shaving technique is important. “Don’t assume the patient knows. There are all sorts of varying techniques out there,” some of which can exacerbate pseudofolliculitis barbae, Dr. Alexis said.

Before shaving, men should wash with a mild cleanser, using a gentle circular technique to free any entrapped hairs, then a moisturizing shaving cream. Razors should be changed every five to seven shaves, and shaving should always be done in the direction of beard growth without pulling on the skin.

Post shave, topical benzoyl peroxide 5%/clindamycin 1% can significantly reduce papules and pustules. Topical retinoids are another effective option. A low-potency steroid can be helpful for inflammatory symptoms.

For cases that just don’t respond to conservative and medical management, laser hair removal is an option. A recent military-funded split-face study found further improvement when topical eflornithine was added to long-pulse Nd:Yag laser therapy, Dr. Alexis said.

Affected individuals may find it difficult to modify shaving practices when uniformed service regulations or office dress codes require men to be close shaven; a note from a physician can be helpful. Dr. Alexis provides patients with a form letter to show their employers, explaining that the patient has a skin disorder that is exacerbated by shaving, and that the patient should be permitted to maintain a well-groomed beard. “I end up writing a lot of these for New York police officers,” he said.

Dr. Alexis disclosed that he has received grants and research support from Allergan and Novartis, and speaker honoraria from Cipla. He has received consulting fees from Aclaris, Allergan, Amgen, Anacor, Bayer, Galderma, Johnson & Johnson, Leo, L’Oreal, Roche, Schick, Suneva, and Valeant.

SDEF and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

On Twitter @karioakes

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM SDEF LAS VEGAS DERMATOLOGY SEMINAR

A Novel Cream Formulation Containing Nicotinamide 4%, Arbutin 3%, Bisabolol 1%, and Retinaldehyde 0.05% for Treatment of Epidermal Melasma

Epidermal melasma is a common hyperpigmentation disorder that can be challenging to treat. The pathogenesis of melasma is not fully understood but has been associated with increased melanin and melanocyte activity.1,2 Melasma is characterized by jagged, light- to dark-brown patches on areas of the skin most often exposed to the sun—primarily the cheeks, forehead, upper lip, nose, and chin.3 Although it can affect both sexes and all races, melasma is more common in Fitzpatrick skin types II to IV and frequently is seen in Asian or Hispanic women residing in geographic locations with high levels of sun exposure (eg, tropical areas).2 Melasma presents more frequently in adult women of childbearing age, especially during pregnancy, but also can begin postmenopause. Onset may occur as early as menarche but typically is observed between the ages of 30 and 55 years.3,4 Only 10% of melasma cases are known to occur in males4 and are influenced by such factors as ethnicity, hormones, and level of sun exposure.2

Topical therapies for melasma attempt to inhibit melanocytic activation at each level of melanin formation until the deposited pigment is removed; however, results may vary greatly, as melasma often recurs due to the migration of new melanocytes from hair follicles to the skin’s surface, leading to new development of hyperpigmentation. The current standard of treatment for melasma involves the use of hydroquinone and other bleaching agents, but long-term use of these treatments has been associated with concerns regarding unstable preparations (which may lose their therapeutic properties) and adverse effects (eg, ochronosis, depigmentation).5 Cosmetic agents that recently have been evaluated for melasma treatment include nicotinamide (a form of vitamin B3), which inhibits the transfer of melanosomes from melanocytes to keratinocytes; arbutin, which inhibits melanin synthesis by inhibiting tyrosinase activity6; bisabolol, which prevents anti-inflammatory activity7; and retinaldehyde (RAL), a precursor of retinoic acid (RA) that has powerful bleaching action and low levels of cutaneous irritability.8

This prospective, single-arm, open-label study, evaluated the efficacy and safety of a novel cream formulation containing nicotinamide 4%, arbutin 3%, bisabolol 1%, and retinaldehyde 0.05% in the treatment of epidermal melasma.

Study Product Ingredients and Background

Nicotinamide

Nicotinamide is a water-soluble amide of nicotinic acid (niacin) and one of the 2 principal forms of vitamin B3. It is a component of the coenzymes nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide and nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate. Nicotinamide essentially acts as an antioxidant, with most of its effects exerted through poly(adenosine diphosphate–ribose) polymerase inhibition. Interest has increased in the role of nicotinamide in the prevention and treatment of several skin diseases, such as acne and UV radiation–induced deleterious molecular and immunological events. Nicotinamide also has gained consideration as a potential agent in sunscreen preparations due to its possible skin-lightening effects, stimulation of DNA repair, suppression of UV photocarcinogenesis, and other antiaging effects.9

Arbutin

Arbutin is a molecule that has proven effective in treating melasma.10 Its pigment-lightening ingredients include botanicals that are structurally similar to hydroquinone. Arbutin is obtained from the leaves of the bearberry plant but also is found in lesser quantities in cranberry and blueberry leaves. A naturally occurring gluconopyranoside, arbutin reduces tyrosinase activity without affecting messenger RNA expression.11 Arbutin also inhibits melanosome maturation, is nontoxic to melanocytes, and is used in Japan in a variety of pigment-lightening preparations at 3% concentrations.12

Bisabolol

Bisabolol is a natural monocyclic sesquiterpene alcohol found in the oils of chamomile and other plants. Bisabolol often is included in cosmetics due to its favorable anti-inflammatory and depigmentation properties. Its downregulation of inducible nitric oxide synthase and cyclooxygenase-2 suggests that it may have anti-inflammatory effects.7

Retinaldehyde

Retinaldehyde is an RA precursor that forms as an intermediate metabolite in the transformation of retinol to RA in human keratinocytes. Topical RAL is well tolerated by human skin, and several of its biologic effects are identical to those of RA. Using the tails of C57BL/6 mouse models, RAL 0.05% has been found to have significantly more potent depigmenting effects than RA 0.05% (P<.001 vs P<.01, respectively) when compared to vehicle.13

Although combination therapy with RAL and arbutin could potentially cause skin irritation, the addition of bisabolol to the combination cream used in this study is believed to have conferred anti-inflammatory properties because it inhibits the release of histamine and relieves irritation.

Methods

This single-center, single-arm, prospective, open-label study evaluated the efficacy and safety of a novel cream formulation containing nicotinamide 4%, arbutin 3%, bisabolol 1%, and RAL 0.05% in treating epidermal melasma. Clinical evaluation included assessment of Melasma Area and Severity Index (MASI) score, photographic analysis, and in vivo reflectance confocal microscopy (RCM) analysis.

The study population included women aged 18 to 50 years with Fitzpatrick skin types I through V who had clinically diagnosed epidermal melasma on the face. Eligibility requirements included confirmation of epidermal pigmentation on Wood lamp examination and RCM analysis and a MASI score of less than 10.5. A total of 35 participants were enrolled in the study (intention to treat [ITT] population). Thirty-three participants were included in the analysis of treatment effectiveness (ITTe population), as 2 were excluded due to lack of follow-up postbaseline. Four participants were prematurely withdrawn from the study—3 due to loss to follow-up and 1 due to treatment discontinuation following an adverse event (AE). The last observation carried forward method was used to input missing data from these 4 participants excluding repeated measure analysis that used the generalized estimated equation method.

At baseline, a 25-g tube of the study cream containing nicotinamide 4%, arbutin 3%, bisabolol 1%, and RAL 0.05% was distributed to all participants for once-daily application to the entire face for 30 days. Participants were instructed to apply the product in the evening after using a gentle cleanser, which also was to be used in the morning to remove the product residue. Additionally, participants were given a sunscreen with a sun protection factor of 30 to apply daily on the entire face in the morning, after lunch, and midafternoon. During the 30-day treatment period, treatment interruption of up to 5 consecutive days or 10 nonconsecutive days in total was permitted. At day 30, participants received another 30-day supply of the study product and sunscreen to be applied according to the same regimen for an additional 30-day treatment period.

Clinical Evaluation

At baseline, demographic data and medical history was recorded for all participants and dermatologic and physical examination was performed documenting weight, height, blood pressure, heart rate, and baseline MASI score. Following Wood lamp examination, participants’ faces were photographed and catalogued using medical imaging software that allowed for measurement of the total melasma surface area (Figure 1A). The photographs also were cross-polarized for further analysis of the pigmentation (Figure 1B).

|

| |

Figure 1. Clinical (A) and cross-polarized (B) photographs of a patient before treatment with the novel compound containing nicotinamide 4%, arbutin 3%, bisabolol 1%, and retinaldehyde 0.05%. | ||

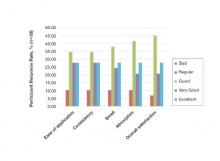

A questionnaire evaluating treatment satisfaction was administered to participants (ITTe population [n=33]) at baseline and days 30 and 60. Questionnaire items pertained to skin blemishes, signs of facial aging, overall appearance, texture, oiliness, brightness, and hydration. Participants were instructed to rate their satisfaction for each item on a scale of 1 to 10 (1=bad, 10=excellent). For investigator analysis, scores of 1 to 4 were classified as “dissatisfied,” scores of 5 to 6 were classified as “satisfied,” and scores of 7 to 10 were classified as “completely satisfied.” A questionnaire evaluating product appreciation was administered at day 60 to participants who completed the study (n=29). Questionnaire items asked participants to rate the study cream’s ease of application, consistency, smell, absorption, and overall satisfaction using ratings of “bad,” “regular,” “good,” “very good,” or “excellent.”

Treatment efficacy in all participants was assessed by the investigators at days 30 and 60. Investigators evaluated reductions in pigmentation and total melasma surface area using ratings of “none,” “regular,” “good,” “very good,” or “excellent.” Local tolerance also was evaluated at both time points, and AEs were recorded and analyzed with respect to their duration, intensity, frequency, and severity.

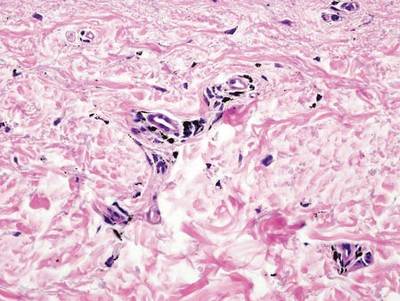

Targeted hyperpigmented skin was selected for in vivo RCM analysis. At each time point, a sequence of block images was acquired at 4 levels of skin: (1) superficial dermis, (2) suprabasal layer/ dermoepidermal junction, (3) spinous layer, and (4) superficial granular layer. Blind evaluation of these images to assess the reduction in melanin quantity was conducted by a dermatopathologist at baseline and days 30 and 60. Melanin quantity present in each layer was graded according to 4 categories (0%–25%, 25.1%–50%, 50.1%–75%, 75.1%–100%). The mean value was used for statistical evaluation.

Results

Efficacy evaluation

The primary efficacy variable was the mean reduction in MASI score from baseline to the end of treatment (day 60), which was 2.25 ± 1.87 (P<.0001). The reduction in mean MASI score was significant from baseline to day 30 (P<.0001) and from day 30 to day 60 (P<.0001). The least root-mean-square error estimates of MASI score variation at days 30 and 60 were 1.40 and 2.25, respectively.

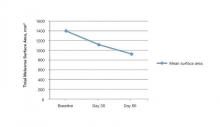

The mean total melasma surface area (as measured in analysis of clinical photographs using medical imaging software) was significantly reduced from 1398.5 mm2 at baseline to 1116.9 mm2 at day 30 (P<.0001) and 923.4 at day 60 (P<.0001). From baseline to end of treatment, the overall reduction in mean total melasma surface area was 475.1 mm2 (P<.0001)(Figure 2). Clinical and cross-polarized photographs taken at day 60 demonstrated a visible reduction in melasma surface area (Figure 3), which was confirmed using medical imaging software.

|

| |

Figure 3. Clinical (A) and cross-polarized (B) photographs of a patient after 60 days of treatment with the novel compound containing nicotinamide 4%, arbutin 3%, bisabolol 1%, and retinaldehyde 0.05%. | ||

In vivo RCM analyses at each time point showed reduction in pigmentation in the 4 levels of the skin that were evaluated, but the results were not statistically significant.

Participant satisfaction

There was strong statistical evidence of patient satisfaction with the treatment results at the end of the study period (P<.0001). At baseline, 75.8% (25/33) of participants were dissatisfied with the appearance of their skin as compared with 15.2% (5/33) at day 60. Additionally, 18.1% (6/33) and 6.1% (2/33) of the participants were satisfied and completely satisfied at baseline compared with 33.3% (11/33) and 51.5% (17/33) at day 60, respectively. Participant satisfaction with signs of facial aging also increased over the study period (P=.0104). At baseline, 60.6% (20/33) were dissatisfied, 12.1% (4/33) were satisfied, and 27.3% (9/33) were completely satisfied; at the end of treatment, 30.3% (10/33) were dissatisfied, 36.4% (12/33) were satisfied, and 33.3% (11/33) were completely satisfied with the improvement in signs of facial aging.

Increased patient satisfaction with facial skin texture at baseline compared to day 60 also was statistically significant (P=.0157). At baseline, 39.4% (13/33) of the participants were dissatisfied, 30.3% (10/33) were satisfied, and 30.3% (10/33) were completely satisfied with facial texture; at day 60, 15.1% (5/33) were dissatisfied, 30.3% (10/33) were satisfied, and 54.6% (18/33) were completely satisfied. Significant improvement from baseline to day 60 also was observed in participant assessment of skin oiliness (P=.0210), brightness (P=.0003), overall appearance (P<.0001), and hydration (P<.0001).

Product appreciation

At day 60, 89.7% (26/29) of the participants who completed the study rated the product’s ease of application as being at least “good,” with more than half of participants (55.2% [16/29]) rating it as “very good” or “excellent.” Overall satisfaction with the product was rated as “very good” or “excellent” by 48.3% (14/29) of the participants. Similar results were observed in participant assessments of consistency, smell, and absorption (Figure 4).

Safety evaluation

A total of 52 AEs were observed in 23 (69.7%) participants, which were recorded by participants in diary entries throughout treatment and evaluated by investigators at each time point. Among these AEs, 48 (92.3%) were considered possibly, probably, or conditionally related to treatment by the investigators based on clinical observation. The most common presumed treatment-related AE was a burning sensation on the skin, reported by 30.3% (10/33) of the participants at day 30 and 13.8% (4/29) at day 60. Of the reported AEs related to treatment, 91.7% (44/48) were of mild intensity and 93.8% (45/48) required no treatment or other action. There were no reported serious AEs related to the investigational product. Blood pressure, heart rate, and weight remained stable among all participants throughout the study.

The intensity of the AEs was described as “light” in 91.7% (44/48) of cases and “moderate” in 8.3% (4/48) of cases. The frequency of AEs was classified as “unique,” “intermittent,” or “continuous” in 45.8% (22/48), 39.6% (19/48), and14.6% (7/48) of cases, respectively. Of the 48 AEs, 3 (6.3%) occurred in 1 participant, necessitating interruption of treatment, application of the topical corticosteroid cream mometasone, and removal from the study.

Comment

Following treatment with the study cream containing nicotinamide 4%, arbutin 3%, bisabolol 1%, and RAL 0.05%, the mean reduction in MASI score (P<.0001) and the mean reduction in total melasma surface area from baseline to end of treatment were statistically significant (P<.0001). The study product was associated with strong statistical evidence of patient satisfaction (P<.0001) regarding improvement in facial skin texture, skin oiliness, brightness, overall appearance, and hydration. Participants also responded favorably to the product and considered it safe and effective. In vivo RCM analysis demonstrated a reduction in the amount of melanin in 4 levels of the skin (superficial dermis, suprabasal layer/dermoepidermal junction, spinous layer, superficial granular layer) following treatment with the study cream; however, over the course of the 60-day treatment period, it did not reveal statistically significant reductions. This finding likely is due to the large ranges used to classify the amount of melanin present in each layer of the skin. These limitations suggest that scales used in future in vivo RCM analyses of melasma should be narrower.

Epidermal melasma is one of the most difficult dermatologic diseases to treat and control. Maintenance of clear, undamaged skin remains a treatment target for all dermatologists. This novel cream formulation containing nicotinamide 4%, arbutin 3%, bisabolol 1%, and RAL 0.05% has proven to be an effective, safe, and tolerable treatment option for patients with epidermal melasma.

1. Grimes PE, Yamada N, Bhawan J. Light microscopic, immunohistochemical, and ultrastructural alterations in patients with melasma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:96-101.

2. Kang WH, Yoon KH, Lee ES, et al. Melasma: histopathological characteristics in 56 Korean patients. Br J Dermatol. 2002;146:228-237.

3. Cestari T, Arellano I, Hexsel D, et al. Melasma in Latin America: options the therapy and treatment algorithm. JEADV. 2009;23:760-772.

4. Miot LDB, Miot HA, Silva MG, et al. Fisiopatologia do Melasma. An Bras Dermatol. 2009;84:623-635.

5. Draelos Z. Skin lightening preparations and the hydroquinone controversy. Dermatol Ther. 2007;20:308-313.

6. Parvez S, Kang M, Chung HS, et al. Survey and mechanism of skin depigmenting and lightening agents. Phytoter Res. 2006;20:921-934.

7. Kim S, Jung E, Kim JH, et al. Inhibitory effects of (-)-α-bisabolol on LPS-induced inflammatory response in RAW264.7 macrophages. Food Chem Toxicol. 2011;49:2580-2585.

8. Ortonne JP. Retinoid therapy of pigmentary disorders. Dermatol Ther. 2006;19:280-288.

9. Namazi MR. Nicotinamide-containing sunscreens for use in Australasian countries and cancer-provoking conditions. Med Hypotheses. 2003;60:544-545.

10. Ertam I, Mutlu B, Unal I, et al. Efficiency of ellagic acid and arbutin in melasma: a randomized, prospective, open-label study. J Dermatol. 2008;35:570-574.

11. Hori I, Nihei K, Kubo I. Structural criteria for depigmenting mechanism of arbutin. Phytother Res. 2004;18:475-469.

12. Ethnic skin and pigmentation. In: Draelos ZD. Cosmetics and Dermatologic Problems and Solutions. 3rd ed. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2011:52-55.

13. Kasraee B, Tran C, Sorg O, et al. The depigmenting effect of RALGA in C57BL/6 mice. Dermatology. 2005;210(suppl 1):30-34.

Epidermal melasma is a common hyperpigmentation disorder that can be challenging to treat. The pathogenesis of melasma is not fully understood but has been associated with increased melanin and melanocyte activity.1,2 Melasma is characterized by jagged, light- to dark-brown patches on areas of the skin most often exposed to the sun—primarily the cheeks, forehead, upper lip, nose, and chin.3 Although it can affect both sexes and all races, melasma is more common in Fitzpatrick skin types II to IV and frequently is seen in Asian or Hispanic women residing in geographic locations with high levels of sun exposure (eg, tropical areas).2 Melasma presents more frequently in adult women of childbearing age, especially during pregnancy, but also can begin postmenopause. Onset may occur as early as menarche but typically is observed between the ages of 30 and 55 years.3,4 Only 10% of melasma cases are known to occur in males4 and are influenced by such factors as ethnicity, hormones, and level of sun exposure.2

Topical therapies for melasma attempt to inhibit melanocytic activation at each level of melanin formation until the deposited pigment is removed; however, results may vary greatly, as melasma often recurs due to the migration of new melanocytes from hair follicles to the skin’s surface, leading to new development of hyperpigmentation. The current standard of treatment for melasma involves the use of hydroquinone and other bleaching agents, but long-term use of these treatments has been associated with concerns regarding unstable preparations (which may lose their therapeutic properties) and adverse effects (eg, ochronosis, depigmentation).5 Cosmetic agents that recently have been evaluated for melasma treatment include nicotinamide (a form of vitamin B3), which inhibits the transfer of melanosomes from melanocytes to keratinocytes; arbutin, which inhibits melanin synthesis by inhibiting tyrosinase activity6; bisabolol, which prevents anti-inflammatory activity7; and retinaldehyde (RAL), a precursor of retinoic acid (RA) that has powerful bleaching action and low levels of cutaneous irritability.8

This prospective, single-arm, open-label study, evaluated the efficacy and safety of a novel cream formulation containing nicotinamide 4%, arbutin 3%, bisabolol 1%, and retinaldehyde 0.05% in the treatment of epidermal melasma.

Study Product Ingredients and Background

Nicotinamide

Nicotinamide is a water-soluble amide of nicotinic acid (niacin) and one of the 2 principal forms of vitamin B3. It is a component of the coenzymes nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide and nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate. Nicotinamide essentially acts as an antioxidant, with most of its effects exerted through poly(adenosine diphosphate–ribose) polymerase inhibition. Interest has increased in the role of nicotinamide in the prevention and treatment of several skin diseases, such as acne and UV radiation–induced deleterious molecular and immunological events. Nicotinamide also has gained consideration as a potential agent in sunscreen preparations due to its possible skin-lightening effects, stimulation of DNA repair, suppression of UV photocarcinogenesis, and other antiaging effects.9

Arbutin

Arbutin is a molecule that has proven effective in treating melasma.10 Its pigment-lightening ingredients include botanicals that are structurally similar to hydroquinone. Arbutin is obtained from the leaves of the bearberry plant but also is found in lesser quantities in cranberry and blueberry leaves. A naturally occurring gluconopyranoside, arbutin reduces tyrosinase activity without affecting messenger RNA expression.11 Arbutin also inhibits melanosome maturation, is nontoxic to melanocytes, and is used in Japan in a variety of pigment-lightening preparations at 3% concentrations.12

Bisabolol

Bisabolol is a natural monocyclic sesquiterpene alcohol found in the oils of chamomile and other plants. Bisabolol often is included in cosmetics due to its favorable anti-inflammatory and depigmentation properties. Its downregulation of inducible nitric oxide synthase and cyclooxygenase-2 suggests that it may have anti-inflammatory effects.7

Retinaldehyde

Retinaldehyde is an RA precursor that forms as an intermediate metabolite in the transformation of retinol to RA in human keratinocytes. Topical RAL is well tolerated by human skin, and several of its biologic effects are identical to those of RA. Using the tails of C57BL/6 mouse models, RAL 0.05% has been found to have significantly more potent depigmenting effects than RA 0.05% (P<.001 vs P<.01, respectively) when compared to vehicle.13

Although combination therapy with RAL and arbutin could potentially cause skin irritation, the addition of bisabolol to the combination cream used in this study is believed to have conferred anti-inflammatory properties because it inhibits the release of histamine and relieves irritation.

Methods

This single-center, single-arm, prospective, open-label study evaluated the efficacy and safety of a novel cream formulation containing nicotinamide 4%, arbutin 3%, bisabolol 1%, and RAL 0.05% in treating epidermal melasma. Clinical evaluation included assessment of Melasma Area and Severity Index (MASI) score, photographic analysis, and in vivo reflectance confocal microscopy (RCM) analysis.

The study population included women aged 18 to 50 years with Fitzpatrick skin types I through V who had clinically diagnosed epidermal melasma on the face. Eligibility requirements included confirmation of epidermal pigmentation on Wood lamp examination and RCM analysis and a MASI score of less than 10.5. A total of 35 participants were enrolled in the study (intention to treat [ITT] population). Thirty-three participants were included in the analysis of treatment effectiveness (ITTe population), as 2 were excluded due to lack of follow-up postbaseline. Four participants were prematurely withdrawn from the study—3 due to loss to follow-up and 1 due to treatment discontinuation following an adverse event (AE). The last observation carried forward method was used to input missing data from these 4 participants excluding repeated measure analysis that used the generalized estimated equation method.

At baseline, a 25-g tube of the study cream containing nicotinamide 4%, arbutin 3%, bisabolol 1%, and RAL 0.05% was distributed to all participants for once-daily application to the entire face for 30 days. Participants were instructed to apply the product in the evening after using a gentle cleanser, which also was to be used in the morning to remove the product residue. Additionally, participants were given a sunscreen with a sun protection factor of 30 to apply daily on the entire face in the morning, after lunch, and midafternoon. During the 30-day treatment period, treatment interruption of up to 5 consecutive days or 10 nonconsecutive days in total was permitted. At day 30, participants received another 30-day supply of the study product and sunscreen to be applied according to the same regimen for an additional 30-day treatment period.

Clinical Evaluation

At baseline, demographic data and medical history was recorded for all participants and dermatologic and physical examination was performed documenting weight, height, blood pressure, heart rate, and baseline MASI score. Following Wood lamp examination, participants’ faces were photographed and catalogued using medical imaging software that allowed for measurement of the total melasma surface area (Figure 1A). The photographs also were cross-polarized for further analysis of the pigmentation (Figure 1B).

|

| |

Figure 1. Clinical (A) and cross-polarized (B) photographs of a patient before treatment with the novel compound containing nicotinamide 4%, arbutin 3%, bisabolol 1%, and retinaldehyde 0.05%. | ||

A questionnaire evaluating treatment satisfaction was administered to participants (ITTe population [n=33]) at baseline and days 30 and 60. Questionnaire items pertained to skin blemishes, signs of facial aging, overall appearance, texture, oiliness, brightness, and hydration. Participants were instructed to rate their satisfaction for each item on a scale of 1 to 10 (1=bad, 10=excellent). For investigator analysis, scores of 1 to 4 were classified as “dissatisfied,” scores of 5 to 6 were classified as “satisfied,” and scores of 7 to 10 were classified as “completely satisfied.” A questionnaire evaluating product appreciation was administered at day 60 to participants who completed the study (n=29). Questionnaire items asked participants to rate the study cream’s ease of application, consistency, smell, absorption, and overall satisfaction using ratings of “bad,” “regular,” “good,” “very good,” or “excellent.”

Treatment efficacy in all participants was assessed by the investigators at days 30 and 60. Investigators evaluated reductions in pigmentation and total melasma surface area using ratings of “none,” “regular,” “good,” “very good,” or “excellent.” Local tolerance also was evaluated at both time points, and AEs were recorded and analyzed with respect to their duration, intensity, frequency, and severity.

Targeted hyperpigmented skin was selected for in vivo RCM analysis. At each time point, a sequence of block images was acquired at 4 levels of skin: (1) superficial dermis, (2) suprabasal layer/ dermoepidermal junction, (3) spinous layer, and (4) superficial granular layer. Blind evaluation of these images to assess the reduction in melanin quantity was conducted by a dermatopathologist at baseline and days 30 and 60. Melanin quantity present in each layer was graded according to 4 categories (0%–25%, 25.1%–50%, 50.1%–75%, 75.1%–100%). The mean value was used for statistical evaluation.

Results

Efficacy evaluation

The primary efficacy variable was the mean reduction in MASI score from baseline to the end of treatment (day 60), which was 2.25 ± 1.87 (P<.0001). The reduction in mean MASI score was significant from baseline to day 30 (P<.0001) and from day 30 to day 60 (P<.0001). The least root-mean-square error estimates of MASI score variation at days 30 and 60 were 1.40 and 2.25, respectively.

The mean total melasma surface area (as measured in analysis of clinical photographs using medical imaging software) was significantly reduced from 1398.5 mm2 at baseline to 1116.9 mm2 at day 30 (P<.0001) and 923.4 at day 60 (P<.0001). From baseline to end of treatment, the overall reduction in mean total melasma surface area was 475.1 mm2 (P<.0001)(Figure 2). Clinical and cross-polarized photographs taken at day 60 demonstrated a visible reduction in melasma surface area (Figure 3), which was confirmed using medical imaging software.

|

| |

Figure 3. Clinical (A) and cross-polarized (B) photographs of a patient after 60 days of treatment with the novel compound containing nicotinamide 4%, arbutin 3%, bisabolol 1%, and retinaldehyde 0.05%. | ||

In vivo RCM analyses at each time point showed reduction in pigmentation in the 4 levels of the skin that were evaluated, but the results were not statistically significant.

Participant satisfaction

There was strong statistical evidence of patient satisfaction with the treatment results at the end of the study period (P<.0001). At baseline, 75.8% (25/33) of participants were dissatisfied with the appearance of their skin as compared with 15.2% (5/33) at day 60. Additionally, 18.1% (6/33) and 6.1% (2/33) of the participants were satisfied and completely satisfied at baseline compared with 33.3% (11/33) and 51.5% (17/33) at day 60, respectively. Participant satisfaction with signs of facial aging also increased over the study period (P=.0104). At baseline, 60.6% (20/33) were dissatisfied, 12.1% (4/33) were satisfied, and 27.3% (9/33) were completely satisfied; at the end of treatment, 30.3% (10/33) were dissatisfied, 36.4% (12/33) were satisfied, and 33.3% (11/33) were completely satisfied with the improvement in signs of facial aging.

Increased patient satisfaction with facial skin texture at baseline compared to day 60 also was statistically significant (P=.0157). At baseline, 39.4% (13/33) of the participants were dissatisfied, 30.3% (10/33) were satisfied, and 30.3% (10/33) were completely satisfied with facial texture; at day 60, 15.1% (5/33) were dissatisfied, 30.3% (10/33) were satisfied, and 54.6% (18/33) were completely satisfied. Significant improvement from baseline to day 60 also was observed in participant assessment of skin oiliness (P=.0210), brightness (P=.0003), overall appearance (P<.0001), and hydration (P<.0001).

Product appreciation

At day 60, 89.7% (26/29) of the participants who completed the study rated the product’s ease of application as being at least “good,” with more than half of participants (55.2% [16/29]) rating it as “very good” or “excellent.” Overall satisfaction with the product was rated as “very good” or “excellent” by 48.3% (14/29) of the participants. Similar results were observed in participant assessments of consistency, smell, and absorption (Figure 4).

Safety evaluation

A total of 52 AEs were observed in 23 (69.7%) participants, which were recorded by participants in diary entries throughout treatment and evaluated by investigators at each time point. Among these AEs, 48 (92.3%) were considered possibly, probably, or conditionally related to treatment by the investigators based on clinical observation. The most common presumed treatment-related AE was a burning sensation on the skin, reported by 30.3% (10/33) of the participants at day 30 and 13.8% (4/29) at day 60. Of the reported AEs related to treatment, 91.7% (44/48) were of mild intensity and 93.8% (45/48) required no treatment or other action. There were no reported serious AEs related to the investigational product. Blood pressure, heart rate, and weight remained stable among all participants throughout the study.

The intensity of the AEs was described as “light” in 91.7% (44/48) of cases and “moderate” in 8.3% (4/48) of cases. The frequency of AEs was classified as “unique,” “intermittent,” or “continuous” in 45.8% (22/48), 39.6% (19/48), and14.6% (7/48) of cases, respectively. Of the 48 AEs, 3 (6.3%) occurred in 1 participant, necessitating interruption of treatment, application of the topical corticosteroid cream mometasone, and removal from the study.

Comment

Following treatment with the study cream containing nicotinamide 4%, arbutin 3%, bisabolol 1%, and RAL 0.05%, the mean reduction in MASI score (P<.0001) and the mean reduction in total melasma surface area from baseline to end of treatment were statistically significant (P<.0001). The study product was associated with strong statistical evidence of patient satisfaction (P<.0001) regarding improvement in facial skin texture, skin oiliness, brightness, overall appearance, and hydration. Participants also responded favorably to the product and considered it safe and effective. In vivo RCM analysis demonstrated a reduction in the amount of melanin in 4 levels of the skin (superficial dermis, suprabasal layer/dermoepidermal junction, spinous layer, superficial granular layer) following treatment with the study cream; however, over the course of the 60-day treatment period, it did not reveal statistically significant reductions. This finding likely is due to the large ranges used to classify the amount of melanin present in each layer of the skin. These limitations suggest that scales used in future in vivo RCM analyses of melasma should be narrower.

Epidermal melasma is one of the most difficult dermatologic diseases to treat and control. Maintenance of clear, undamaged skin remains a treatment target for all dermatologists. This novel cream formulation containing nicotinamide 4%, arbutin 3%, bisabolol 1%, and RAL 0.05% has proven to be an effective, safe, and tolerable treatment option for patients with epidermal melasma.

Epidermal melasma is a common hyperpigmentation disorder that can be challenging to treat. The pathogenesis of melasma is not fully understood but has been associated with increased melanin and melanocyte activity.1,2 Melasma is characterized by jagged, light- to dark-brown patches on areas of the skin most often exposed to the sun—primarily the cheeks, forehead, upper lip, nose, and chin.3 Although it can affect both sexes and all races, melasma is more common in Fitzpatrick skin types II to IV and frequently is seen in Asian or Hispanic women residing in geographic locations with high levels of sun exposure (eg, tropical areas).2 Melasma presents more frequently in adult women of childbearing age, especially during pregnancy, but also can begin postmenopause. Onset may occur as early as menarche but typically is observed between the ages of 30 and 55 years.3,4 Only 10% of melasma cases are known to occur in males4 and are influenced by such factors as ethnicity, hormones, and level of sun exposure.2

Topical therapies for melasma attempt to inhibit melanocytic activation at each level of melanin formation until the deposited pigment is removed; however, results may vary greatly, as melasma often recurs due to the migration of new melanocytes from hair follicles to the skin’s surface, leading to new development of hyperpigmentation. The current standard of treatment for melasma involves the use of hydroquinone and other bleaching agents, but long-term use of these treatments has been associated with concerns regarding unstable preparations (which may lose their therapeutic properties) and adverse effects (eg, ochronosis, depigmentation).5 Cosmetic agents that recently have been evaluated for melasma treatment include nicotinamide (a form of vitamin B3), which inhibits the transfer of melanosomes from melanocytes to keratinocytes; arbutin, which inhibits melanin synthesis by inhibiting tyrosinase activity6; bisabolol, which prevents anti-inflammatory activity7; and retinaldehyde (RAL), a precursor of retinoic acid (RA) that has powerful bleaching action and low levels of cutaneous irritability.8

This prospective, single-arm, open-label study, evaluated the efficacy and safety of a novel cream formulation containing nicotinamide 4%, arbutin 3%, bisabolol 1%, and retinaldehyde 0.05% in the treatment of epidermal melasma.

Study Product Ingredients and Background

Nicotinamide

Nicotinamide is a water-soluble amide of nicotinic acid (niacin) and one of the 2 principal forms of vitamin B3. It is a component of the coenzymes nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide and nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate. Nicotinamide essentially acts as an antioxidant, with most of its effects exerted through poly(adenosine diphosphate–ribose) polymerase inhibition. Interest has increased in the role of nicotinamide in the prevention and treatment of several skin diseases, such as acne and UV radiation–induced deleterious molecular and immunological events. Nicotinamide also has gained consideration as a potential agent in sunscreen preparations due to its possible skin-lightening effects, stimulation of DNA repair, suppression of UV photocarcinogenesis, and other antiaging effects.9

Arbutin

Arbutin is a molecule that has proven effective in treating melasma.10 Its pigment-lightening ingredients include botanicals that are structurally similar to hydroquinone. Arbutin is obtained from the leaves of the bearberry plant but also is found in lesser quantities in cranberry and blueberry leaves. A naturally occurring gluconopyranoside, arbutin reduces tyrosinase activity without affecting messenger RNA expression.11 Arbutin also inhibits melanosome maturation, is nontoxic to melanocytes, and is used in Japan in a variety of pigment-lightening preparations at 3% concentrations.12

Bisabolol

Bisabolol is a natural monocyclic sesquiterpene alcohol found in the oils of chamomile and other plants. Bisabolol often is included in cosmetics due to its favorable anti-inflammatory and depigmentation properties. Its downregulation of inducible nitric oxide synthase and cyclooxygenase-2 suggests that it may have anti-inflammatory effects.7

Retinaldehyde

Retinaldehyde is an RA precursor that forms as an intermediate metabolite in the transformation of retinol to RA in human keratinocytes. Topical RAL is well tolerated by human skin, and several of its biologic effects are identical to those of RA. Using the tails of C57BL/6 mouse models, RAL 0.05% has been found to have significantly more potent depigmenting effects than RA 0.05% (P<.001 vs P<.01, respectively) when compared to vehicle.13

Although combination therapy with RAL and arbutin could potentially cause skin irritation, the addition of bisabolol to the combination cream used in this study is believed to have conferred anti-inflammatory properties because it inhibits the release of histamine and relieves irritation.

Methods

This single-center, single-arm, prospective, open-label study evaluated the efficacy and safety of a novel cream formulation containing nicotinamide 4%, arbutin 3%, bisabolol 1%, and RAL 0.05% in treating epidermal melasma. Clinical evaluation included assessment of Melasma Area and Severity Index (MASI) score, photographic analysis, and in vivo reflectance confocal microscopy (RCM) analysis.

The study population included women aged 18 to 50 years with Fitzpatrick skin types I through V who had clinically diagnosed epidermal melasma on the face. Eligibility requirements included confirmation of epidermal pigmentation on Wood lamp examination and RCM analysis and a MASI score of less than 10.5. A total of 35 participants were enrolled in the study (intention to treat [ITT] population). Thirty-three participants were included in the analysis of treatment effectiveness (ITTe population), as 2 were excluded due to lack of follow-up postbaseline. Four participants were prematurely withdrawn from the study—3 due to loss to follow-up and 1 due to treatment discontinuation following an adverse event (AE). The last observation carried forward method was used to input missing data from these 4 participants excluding repeated measure analysis that used the generalized estimated equation method.

At baseline, a 25-g tube of the study cream containing nicotinamide 4%, arbutin 3%, bisabolol 1%, and RAL 0.05% was distributed to all participants for once-daily application to the entire face for 30 days. Participants were instructed to apply the product in the evening after using a gentle cleanser, which also was to be used in the morning to remove the product residue. Additionally, participants were given a sunscreen with a sun protection factor of 30 to apply daily on the entire face in the morning, after lunch, and midafternoon. During the 30-day treatment period, treatment interruption of up to 5 consecutive days or 10 nonconsecutive days in total was permitted. At day 30, participants received another 30-day supply of the study product and sunscreen to be applied according to the same regimen for an additional 30-day treatment period.

Clinical Evaluation

At baseline, demographic data and medical history was recorded for all participants and dermatologic and physical examination was performed documenting weight, height, blood pressure, heart rate, and baseline MASI score. Following Wood lamp examination, participants’ faces were photographed and catalogued using medical imaging software that allowed for measurement of the total melasma surface area (Figure 1A). The photographs also were cross-polarized for further analysis of the pigmentation (Figure 1B).

|

| |

Figure 1. Clinical (A) and cross-polarized (B) photographs of a patient before treatment with the novel compound containing nicotinamide 4%, arbutin 3%, bisabolol 1%, and retinaldehyde 0.05%. | ||

A questionnaire evaluating treatment satisfaction was administered to participants (ITTe population [n=33]) at baseline and days 30 and 60. Questionnaire items pertained to skin blemishes, signs of facial aging, overall appearance, texture, oiliness, brightness, and hydration. Participants were instructed to rate their satisfaction for each item on a scale of 1 to 10 (1=bad, 10=excellent). For investigator analysis, scores of 1 to 4 were classified as “dissatisfied,” scores of 5 to 6 were classified as “satisfied,” and scores of 7 to 10 were classified as “completely satisfied.” A questionnaire evaluating product appreciation was administered at day 60 to participants who completed the study (n=29). Questionnaire items asked participants to rate the study cream’s ease of application, consistency, smell, absorption, and overall satisfaction using ratings of “bad,” “regular,” “good,” “very good,” or “excellent.”

Treatment efficacy in all participants was assessed by the investigators at days 30 and 60. Investigators evaluated reductions in pigmentation and total melasma surface area using ratings of “none,” “regular,” “good,” “very good,” or “excellent.” Local tolerance also was evaluated at both time points, and AEs were recorded and analyzed with respect to their duration, intensity, frequency, and severity.

Targeted hyperpigmented skin was selected for in vivo RCM analysis. At each time point, a sequence of block images was acquired at 4 levels of skin: (1) superficial dermis, (2) suprabasal layer/ dermoepidermal junction, (3) spinous layer, and (4) superficial granular layer. Blind evaluation of these images to assess the reduction in melanin quantity was conducted by a dermatopathologist at baseline and days 30 and 60. Melanin quantity present in each layer was graded according to 4 categories (0%–25%, 25.1%–50%, 50.1%–75%, 75.1%–100%). The mean value was used for statistical evaluation.

Results

Efficacy evaluation

The primary efficacy variable was the mean reduction in MASI score from baseline to the end of treatment (day 60), which was 2.25 ± 1.87 (P<.0001). The reduction in mean MASI score was significant from baseline to day 30 (P<.0001) and from day 30 to day 60 (P<.0001). The least root-mean-square error estimates of MASI score variation at days 30 and 60 were 1.40 and 2.25, respectively.

The mean total melasma surface area (as measured in analysis of clinical photographs using medical imaging software) was significantly reduced from 1398.5 mm2 at baseline to 1116.9 mm2 at day 30 (P<.0001) and 923.4 at day 60 (P<.0001). From baseline to end of treatment, the overall reduction in mean total melasma surface area was 475.1 mm2 (P<.0001)(Figure 2). Clinical and cross-polarized photographs taken at day 60 demonstrated a visible reduction in melasma surface area (Figure 3), which was confirmed using medical imaging software.

|

| |

Figure 3. Clinical (A) and cross-polarized (B) photographs of a patient after 60 days of treatment with the novel compound containing nicotinamide 4%, arbutin 3%, bisabolol 1%, and retinaldehyde 0.05%. | ||

In vivo RCM analyses at each time point showed reduction in pigmentation in the 4 levels of the skin that were evaluated, but the results were not statistically significant.

Participant satisfaction

There was strong statistical evidence of patient satisfaction with the treatment results at the end of the study period (P<.0001). At baseline, 75.8% (25/33) of participants were dissatisfied with the appearance of their skin as compared with 15.2% (5/33) at day 60. Additionally, 18.1% (6/33) and 6.1% (2/33) of the participants were satisfied and completely satisfied at baseline compared with 33.3% (11/33) and 51.5% (17/33) at day 60, respectively. Participant satisfaction with signs of facial aging also increased over the study period (P=.0104). At baseline, 60.6% (20/33) were dissatisfied, 12.1% (4/33) were satisfied, and 27.3% (9/33) were completely satisfied; at the end of treatment, 30.3% (10/33) were dissatisfied, 36.4% (12/33) were satisfied, and 33.3% (11/33) were completely satisfied with the improvement in signs of facial aging.

Increased patient satisfaction with facial skin texture at baseline compared to day 60 also was statistically significant (P=.0157). At baseline, 39.4% (13/33) of the participants were dissatisfied, 30.3% (10/33) were satisfied, and 30.3% (10/33) were completely satisfied with facial texture; at day 60, 15.1% (5/33) were dissatisfied, 30.3% (10/33) were satisfied, and 54.6% (18/33) were completely satisfied. Significant improvement from baseline to day 60 also was observed in participant assessment of skin oiliness (P=.0210), brightness (P=.0003), overall appearance (P<.0001), and hydration (P<.0001).

Product appreciation

At day 60, 89.7% (26/29) of the participants who completed the study rated the product’s ease of application as being at least “good,” with more than half of participants (55.2% [16/29]) rating it as “very good” or “excellent.” Overall satisfaction with the product was rated as “very good” or “excellent” by 48.3% (14/29) of the participants. Similar results were observed in participant assessments of consistency, smell, and absorption (Figure 4).

Safety evaluation

A total of 52 AEs were observed in 23 (69.7%) participants, which were recorded by participants in diary entries throughout treatment and evaluated by investigators at each time point. Among these AEs, 48 (92.3%) were considered possibly, probably, or conditionally related to treatment by the investigators based on clinical observation. The most common presumed treatment-related AE was a burning sensation on the skin, reported by 30.3% (10/33) of the participants at day 30 and 13.8% (4/29) at day 60. Of the reported AEs related to treatment, 91.7% (44/48) were of mild intensity and 93.8% (45/48) required no treatment or other action. There were no reported serious AEs related to the investigational product. Blood pressure, heart rate, and weight remained stable among all participants throughout the study.

The intensity of the AEs was described as “light” in 91.7% (44/48) of cases and “moderate” in 8.3% (4/48) of cases. The frequency of AEs was classified as “unique,” “intermittent,” or “continuous” in 45.8% (22/48), 39.6% (19/48), and14.6% (7/48) of cases, respectively. Of the 48 AEs, 3 (6.3%) occurred in 1 participant, necessitating interruption of treatment, application of the topical corticosteroid cream mometasone, and removal from the study.

Comment

Following treatment with the study cream containing nicotinamide 4%, arbutin 3%, bisabolol 1%, and RAL 0.05%, the mean reduction in MASI score (P<.0001) and the mean reduction in total melasma surface area from baseline to end of treatment were statistically significant (P<.0001). The study product was associated with strong statistical evidence of patient satisfaction (P<.0001) regarding improvement in facial skin texture, skin oiliness, brightness, overall appearance, and hydration. Participants also responded favorably to the product and considered it safe and effective. In vivo RCM analysis demonstrated a reduction in the amount of melanin in 4 levels of the skin (superficial dermis, suprabasal layer/dermoepidermal junction, spinous layer, superficial granular layer) following treatment with the study cream; however, over the course of the 60-day treatment period, it did not reveal statistically significant reductions. This finding likely is due to the large ranges used to classify the amount of melanin present in each layer of the skin. These limitations suggest that scales used in future in vivo RCM analyses of melasma should be narrower.

Epidermal melasma is one of the most difficult dermatologic diseases to treat and control. Maintenance of clear, undamaged skin remains a treatment target for all dermatologists. This novel cream formulation containing nicotinamide 4%, arbutin 3%, bisabolol 1%, and RAL 0.05% has proven to be an effective, safe, and tolerable treatment option for patients with epidermal melasma.

1. Grimes PE, Yamada N, Bhawan J. Light microscopic, immunohistochemical, and ultrastructural alterations in patients with melasma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:96-101.

2. Kang WH, Yoon KH, Lee ES, et al. Melasma: histopathological characteristics in 56 Korean patients. Br J Dermatol. 2002;146:228-237.

3. Cestari T, Arellano I, Hexsel D, et al. Melasma in Latin America: options the therapy and treatment algorithm. JEADV. 2009;23:760-772.

4. Miot LDB, Miot HA, Silva MG, et al. Fisiopatologia do Melasma. An Bras Dermatol. 2009;84:623-635.

5. Draelos Z. Skin lightening preparations and the hydroquinone controversy. Dermatol Ther. 2007;20:308-313.

6. Parvez S, Kang M, Chung HS, et al. Survey and mechanism of skin depigmenting and lightening agents. Phytoter Res. 2006;20:921-934.

7. Kim S, Jung E, Kim JH, et al. Inhibitory effects of (-)-α-bisabolol on LPS-induced inflammatory response in RAW264.7 macrophages. Food Chem Toxicol. 2011;49:2580-2585.

8. Ortonne JP. Retinoid therapy of pigmentary disorders. Dermatol Ther. 2006;19:280-288.

9. Namazi MR. Nicotinamide-containing sunscreens for use in Australasian countries and cancer-provoking conditions. Med Hypotheses. 2003;60:544-545.

10. Ertam I, Mutlu B, Unal I, et al. Efficiency of ellagic acid and arbutin in melasma: a randomized, prospective, open-label study. J Dermatol. 2008;35:570-574.

11. Hori I, Nihei K, Kubo I. Structural criteria for depigmenting mechanism of arbutin. Phytother Res. 2004;18:475-469.

12. Ethnic skin and pigmentation. In: Draelos ZD. Cosmetics and Dermatologic Problems and Solutions. 3rd ed. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2011:52-55.

13. Kasraee B, Tran C, Sorg O, et al. The depigmenting effect of RALGA in C57BL/6 mice. Dermatology. 2005;210(suppl 1):30-34.

1. Grimes PE, Yamada N, Bhawan J. Light microscopic, immunohistochemical, and ultrastructural alterations in patients with melasma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:96-101.

2. Kang WH, Yoon KH, Lee ES, et al. Melasma: histopathological characteristics in 56 Korean patients. Br J Dermatol. 2002;146:228-237.

3. Cestari T, Arellano I, Hexsel D, et al. Melasma in Latin America: options the therapy and treatment algorithm. JEADV. 2009;23:760-772.

4. Miot LDB, Miot HA, Silva MG, et al. Fisiopatologia do Melasma. An Bras Dermatol. 2009;84:623-635.

5. Draelos Z. Skin lightening preparations and the hydroquinone controversy. Dermatol Ther. 2007;20:308-313.

6. Parvez S, Kang M, Chung HS, et al. Survey and mechanism of skin depigmenting and lightening agents. Phytoter Res. 2006;20:921-934.

7. Kim S, Jung E, Kim JH, et al. Inhibitory effects of (-)-α-bisabolol on LPS-induced inflammatory response in RAW264.7 macrophages. Food Chem Toxicol. 2011;49:2580-2585.

8. Ortonne JP. Retinoid therapy of pigmentary disorders. Dermatol Ther. 2006;19:280-288.

9. Namazi MR. Nicotinamide-containing sunscreens for use in Australasian countries and cancer-provoking conditions. Med Hypotheses. 2003;60:544-545.

10. Ertam I, Mutlu B, Unal I, et al. Efficiency of ellagic acid and arbutin in melasma: a randomized, prospective, open-label study. J Dermatol. 2008;35:570-574.

11. Hori I, Nihei K, Kubo I. Structural criteria for depigmenting mechanism of arbutin. Phytother Res. 2004;18:475-469.

12. Ethnic skin and pigmentation. In: Draelos ZD. Cosmetics and Dermatologic Problems and Solutions. 3rd ed. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2011:52-55.

13. Kasraee B, Tran C, Sorg O, et al. The depigmenting effect of RALGA in C57BL/6 mice. Dermatology. 2005;210(suppl 1):30-34.

Practice Points

- Epidermal melasma is a common hyperpigmentation disorder characterized by the appearance of abnormal melanin deposits in different layers of the skin.

- Melasma can be difficult to treat and often recurs due to the migration of new melanocytes from hair follicles to the skin’s surface.

- A novel cream formulation containing nicotinamide 4%, arbutin 3%, bisabolol 1%, and retinaldehyde 0.05% offers a safe and effective option for treatment of epidermal melasma.

What Is Your Diagnosis? Idiopathic Guttate Hypomelanosis

The Diagnosis: Idiopathic Guttate Hypomelanosis

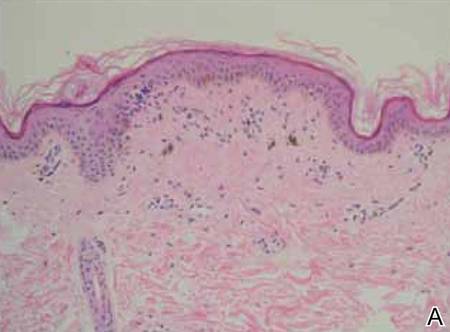

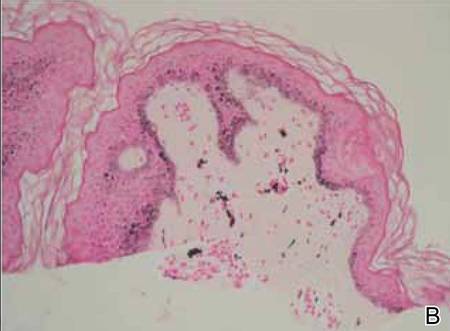

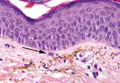

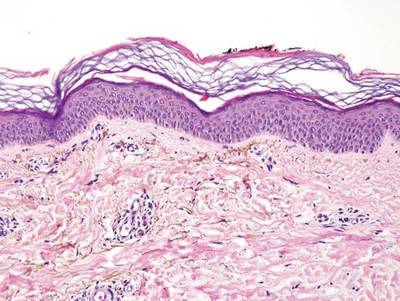

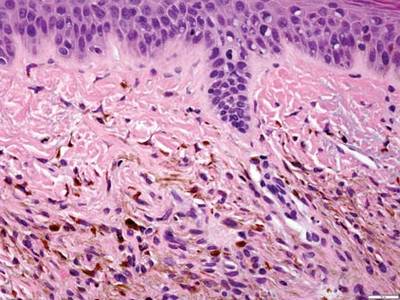

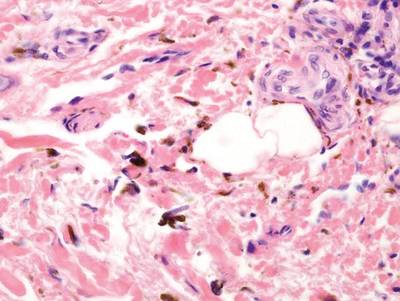

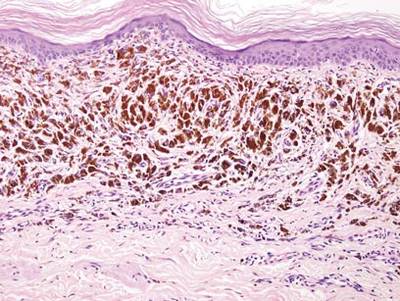

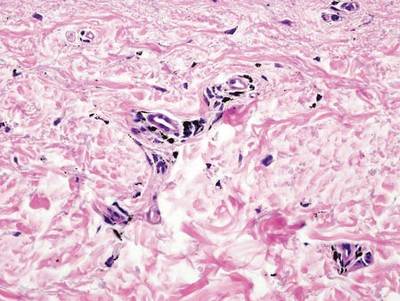

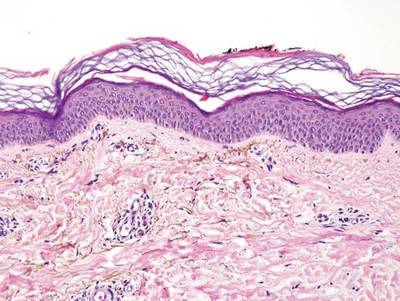

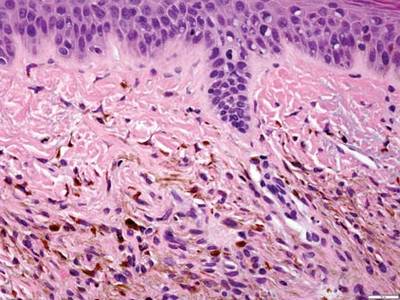

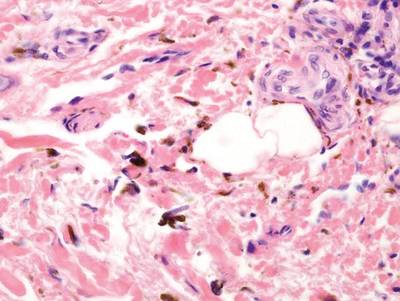

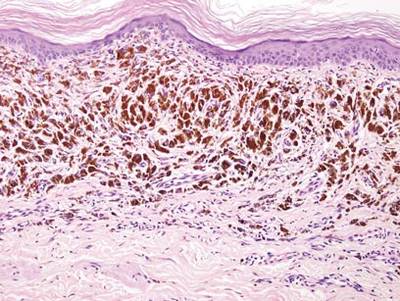

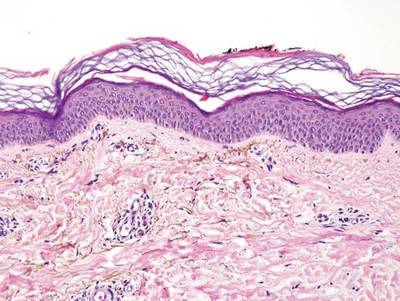

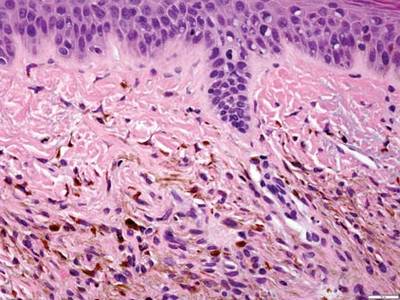

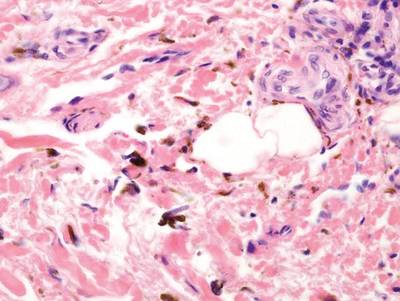

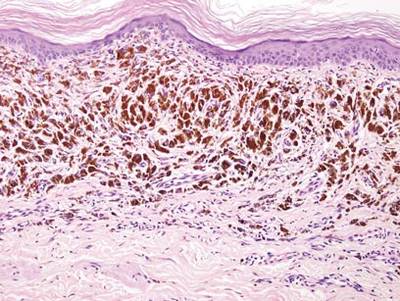

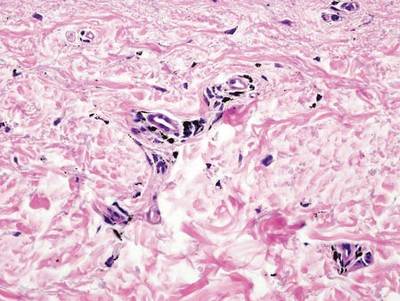

A biopsy of the largest lesion from the left leg superior to the lateral malleolus was performed. Histopathologic examination revealed solar elastosis, diminished number of focal melanocytes and pigment within keratinocytes compared to uninvolved skin, and presence of hyperkeratosis with flattening of rete ridges. The clinical presentation along with histopathologic analysis confirmed a diagnosis of idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis (IGH). The lesions were treated with short-exposure cryotherapy, which resulted in partial repigmentation after several treatments.

Idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis is a common but underreported condition in elderly patients that usually presents with small, discrete, asymptomatic, hypopigmented macules. The frequency of IGH increases with age.1 Frequency of the condition is much lower in patients aged 21 to 30 years and does not exceed 7%. Lesions of IGH have a predilection for sun-exposed areas such as the arms and legs but rarely can be seen on the face and trunk. Facial lesions of IGH are more frequently reported in women.1 The size of lesions can be up to 1.5 cm in diameter. The condition generally is self-limited, but some patients may express aesthetic concerns. Rare cases of IGH in children have been associated with prolonged sun exposure.2

The etiology of IGH is unknown but an association with sun exposure has been noted. Patients with IGH frequently show other signs of photoaging, such as numerous seborrheic keratoses, solar lentigines, xeroses, freckles, and actinic keratoses.1 Short-term exposure to UVB radiation and psoralen plus UVA therapy has been shown to cause IGH in patients with chronic diseases such as mycosis fungoides.3-5 One small study that examined renal transplant recipients determined an association between HLA-DQ3 antigens and IGH, whereas HLA-DR8 antigens were not identified in any patients with IGH, indicating it may have some advantage in preventing the development of IGH.6 Shin et al1 reported that IGH was prevalent among patients who regularly traumatized their skin by scrubbing.

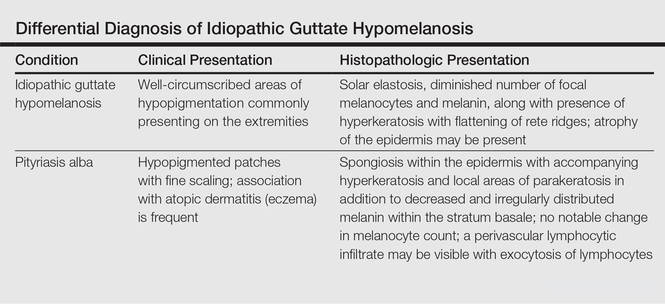

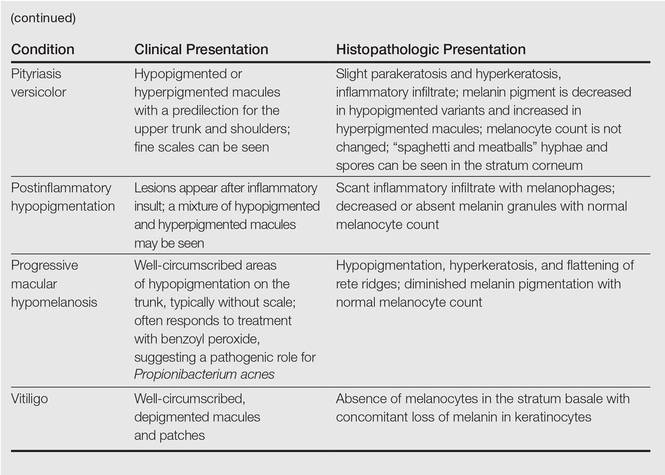

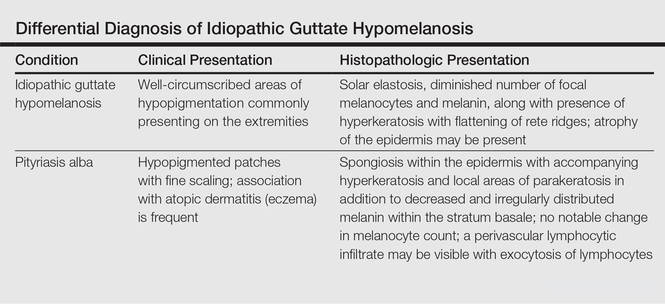

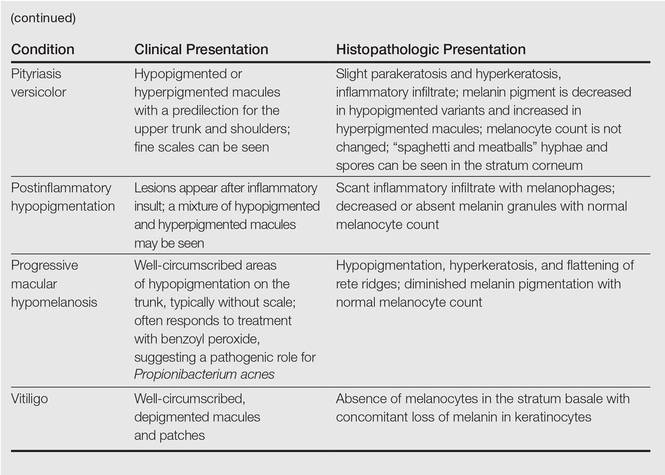

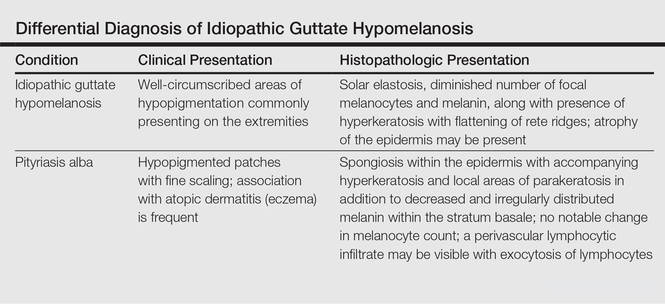

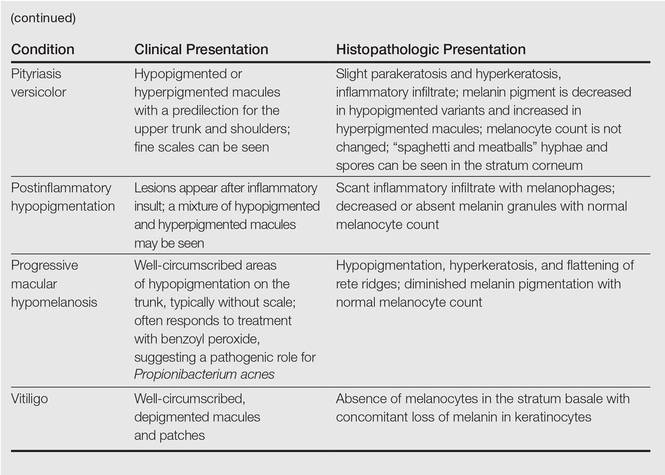

Clinically, IGH should be differentiated from other conditions characterized by hypopigmentation, such as pityriasis alba, pityriasis versicolor, postinflammatory hypopigmentation, progressive macular hypomelanosis, and vitiligo. Aside from clinical examination, histopathologic studies are helpful in making a definitive diagnosis. The differential diagnosis of IGH is presented in the Table.

Histopathology of IGH lesions usually reveals slight atrophy of the epidermis with flattening of rete ridges and concomitant hyperkeratosis. A thickened stratum granulosum also has been noted in lesions of IGH.2 The diminished number of melanocytes and melanin pigment granules along with hyperkeratosis both appear to contribute to the hypopigmentation noted in IGH.7 Ultrastructural studies of lesions of IGH can confirm melanocytic degeneration and a decreased number of melanosomes in melanocytes and keratinocytes.2,8

There is no uniformly effective treatment of IGH. Topical application of tacrolimus and tretinoin have shown efficacy in repigmenting IGH lesions.8,9 Short-exposure cryotherapy with a duration of 3 to 5 seconds, localized chemical peels, and/or local dermabrasion can be helpful.10-12 CO2 lasers also have demonstrated promising results.13

- Shin MK, Jeong KH, Oh IH, et al. Clinical features of idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis in 646 subjects and association with other aspects of photoaging. Int J Dermatol. 2011;50:798-805.

- Kim SK, Kim EH, Kang HY, et al. Comprehensive understanding of idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis: clinical and histopathological correlation. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49:162-166.

- Friedland R, David M, Feinmesser M, et al. Idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis-like lesions in patients with mycosis fungoides: a new adverse effect of phototherapy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:1026-1030.

- Kaya TI, Yazici AC, Tursen U, et al. Idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis: idiopathic or ultraviolet induced? Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2005;21:270-271.

- Loquai C, Metze D, Nashan D, et al. Confetti-like lesions with hyperkeratosis: a novel ultraviolet-induced hypomelanotic disorder? Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:190-193.

- Arrunategui A, Trujillo RA, Marulanda MP, et al. HLA-DQ3 is associated with idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis, whereas HLA-DR8 is not, in a group of renal transplant patients. Int J Dermatol. 2002;41:744-747.

- Wallace ML, Grichnik JM, Prieto VG, et al. Numbers and differentiation status of melanocytes in idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis. J Cutan Pathol. 1998;25:375-379.

- Ortonne JP, Perrot H. Idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis. ultrastructural study. Arch Dermatol. 1980;116:664-668.

- Rerknimitr P, Disphanurat W, Achariyakul M. Topical tacrolimus significantly promotes repigmentation in idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:460-464.

- Pagnoni A, Kligman AM, Sadiq I, et al. Hypopigmented macules of photodamaged skin and their treatment with topical tretinoin. Acta Derm Venereol. 1999;79:305-310.

- Kumarasinghe SP. 3-5 second cryotherapy is effective in idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis. J Dermatol. 2004;31:457-459.

- Hexsel DM. Treatment of idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis by localized superficial dermabrasion. Dermatol Surg. 1999;25:917-918.

- Shin J, Kim M, Park SH, et al. The effect of fractional carbon dioxide lasers on idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis: a preliminary study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:e243-e246.

The Diagnosis: Idiopathic Guttate Hypomelanosis

A biopsy of the largest lesion from the left leg superior to the lateral malleolus was performed. Histopathologic examination revealed solar elastosis, diminished number of focal melanocytes and pigment within keratinocytes compared to uninvolved skin, and presence of hyperkeratosis with flattening of rete ridges. The clinical presentation along with histopathologic analysis confirmed a diagnosis of idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis (IGH). The lesions were treated with short-exposure cryotherapy, which resulted in partial repigmentation after several treatments.

Idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis is a common but underreported condition in elderly patients that usually presents with small, discrete, asymptomatic, hypopigmented macules. The frequency of IGH increases with age.1 Frequency of the condition is much lower in patients aged 21 to 30 years and does not exceed 7%. Lesions of IGH have a predilection for sun-exposed areas such as the arms and legs but rarely can be seen on the face and trunk. Facial lesions of IGH are more frequently reported in women.1 The size of lesions can be up to 1.5 cm in diameter. The condition generally is self-limited, but some patients may express aesthetic concerns. Rare cases of IGH in children have been associated with prolonged sun exposure.2

The etiology of IGH is unknown but an association with sun exposure has been noted. Patients with IGH frequently show other signs of photoaging, such as numerous seborrheic keratoses, solar lentigines, xeroses, freckles, and actinic keratoses.1 Short-term exposure to UVB radiation and psoralen plus UVA therapy has been shown to cause IGH in patients with chronic diseases such as mycosis fungoides.3-5 One small study that examined renal transplant recipients determined an association between HLA-DQ3 antigens and IGH, whereas HLA-DR8 antigens were not identified in any patients with IGH, indicating it may have some advantage in preventing the development of IGH.6 Shin et al1 reported that IGH was prevalent among patients who regularly traumatized their skin by scrubbing.

Clinically, IGH should be differentiated from other conditions characterized by hypopigmentation, such as pityriasis alba, pityriasis versicolor, postinflammatory hypopigmentation, progressive macular hypomelanosis, and vitiligo. Aside from clinical examination, histopathologic studies are helpful in making a definitive diagnosis. The differential diagnosis of IGH is presented in the Table.

Histopathology of IGH lesions usually reveals slight atrophy of the epidermis with flattening of rete ridges and concomitant hyperkeratosis. A thickened stratum granulosum also has been noted in lesions of IGH.2 The diminished number of melanocytes and melanin pigment granules along with hyperkeratosis both appear to contribute to the hypopigmentation noted in IGH.7 Ultrastructural studies of lesions of IGH can confirm melanocytic degeneration and a decreased number of melanosomes in melanocytes and keratinocytes.2,8

There is no uniformly effective treatment of IGH. Topical application of tacrolimus and tretinoin have shown efficacy in repigmenting IGH lesions.8,9 Short-exposure cryotherapy with a duration of 3 to 5 seconds, localized chemical peels, and/or local dermabrasion can be helpful.10-12 CO2 lasers also have demonstrated promising results.13

The Diagnosis: Idiopathic Guttate Hypomelanosis

A biopsy of the largest lesion from the left leg superior to the lateral malleolus was performed. Histopathologic examination revealed solar elastosis, diminished number of focal melanocytes and pigment within keratinocytes compared to uninvolved skin, and presence of hyperkeratosis with flattening of rete ridges. The clinical presentation along with histopathologic analysis confirmed a diagnosis of idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis (IGH). The lesions were treated with short-exposure cryotherapy, which resulted in partial repigmentation after several treatments.

Idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis is a common but underreported condition in elderly patients that usually presents with small, discrete, asymptomatic, hypopigmented macules. The frequency of IGH increases with age.1 Frequency of the condition is much lower in patients aged 21 to 30 years and does not exceed 7%. Lesions of IGH have a predilection for sun-exposed areas such as the arms and legs but rarely can be seen on the face and trunk. Facial lesions of IGH are more frequently reported in women.1 The size of lesions can be up to 1.5 cm in diameter. The condition generally is self-limited, but some patients may express aesthetic concerns. Rare cases of IGH in children have been associated with prolonged sun exposure.2