User login

Married docs remove girl’s lethal facial tumor in ‘excruciatingly difficult’ procedure

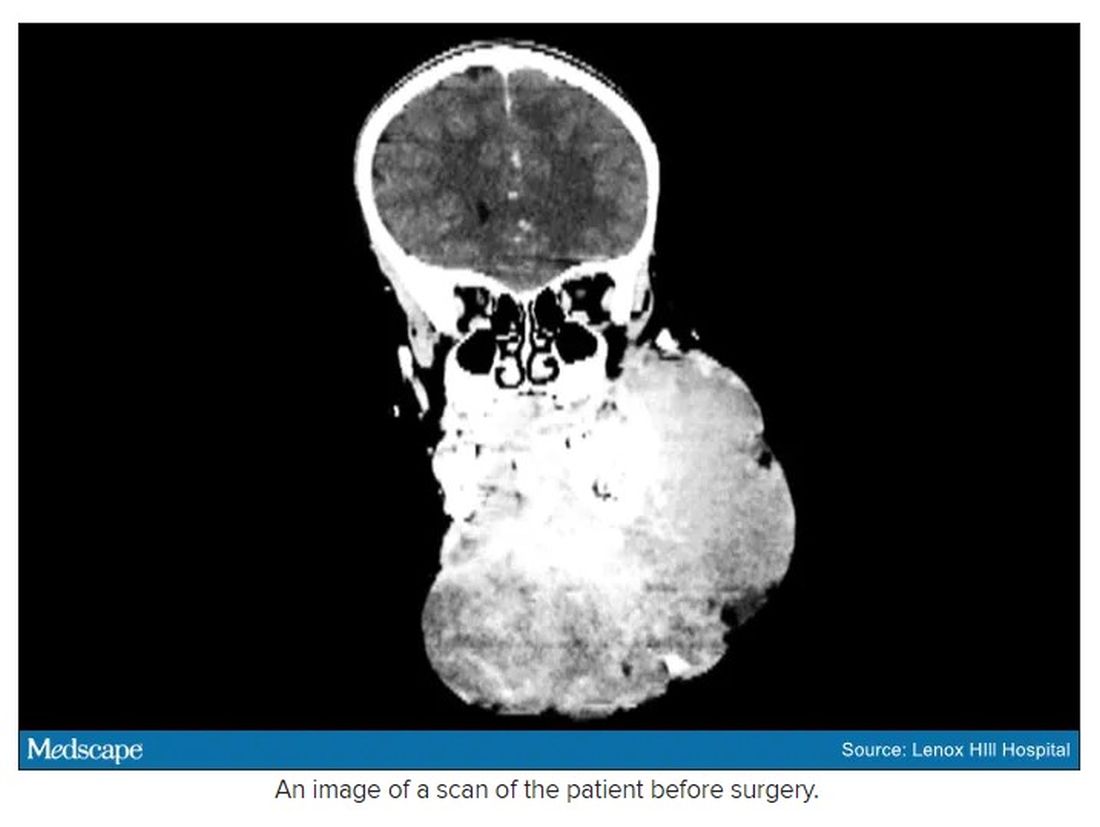

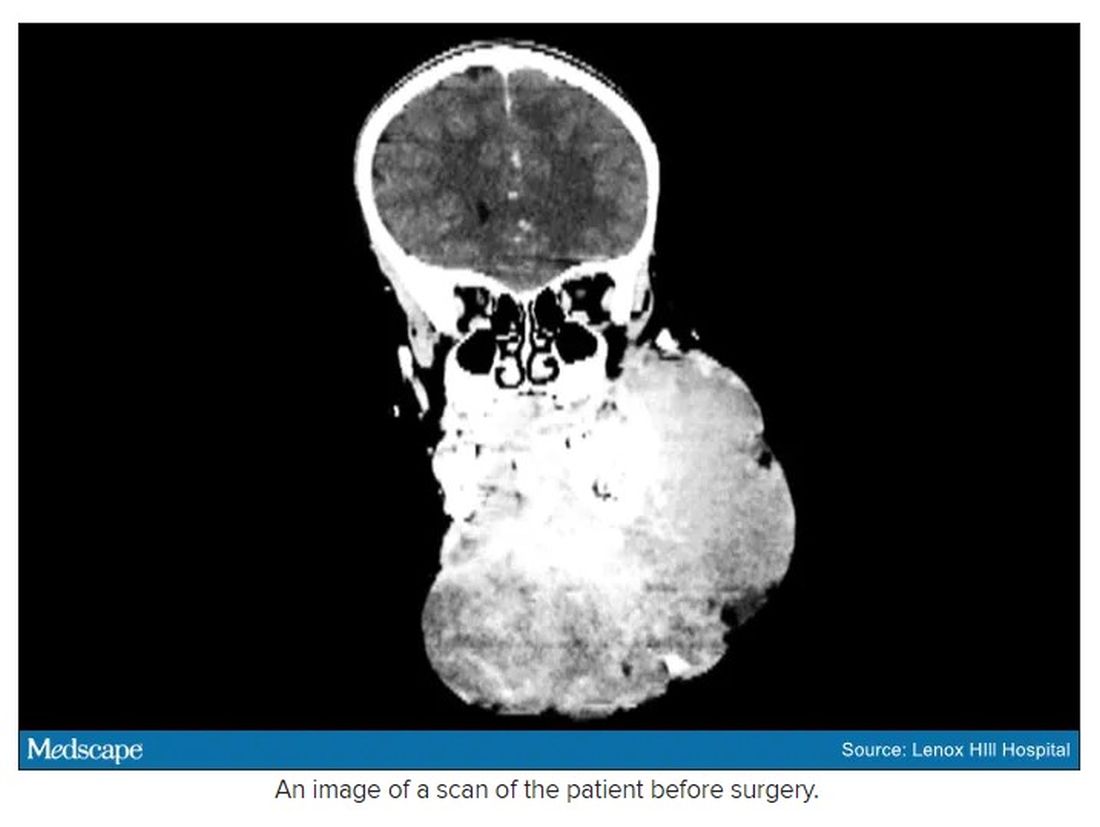

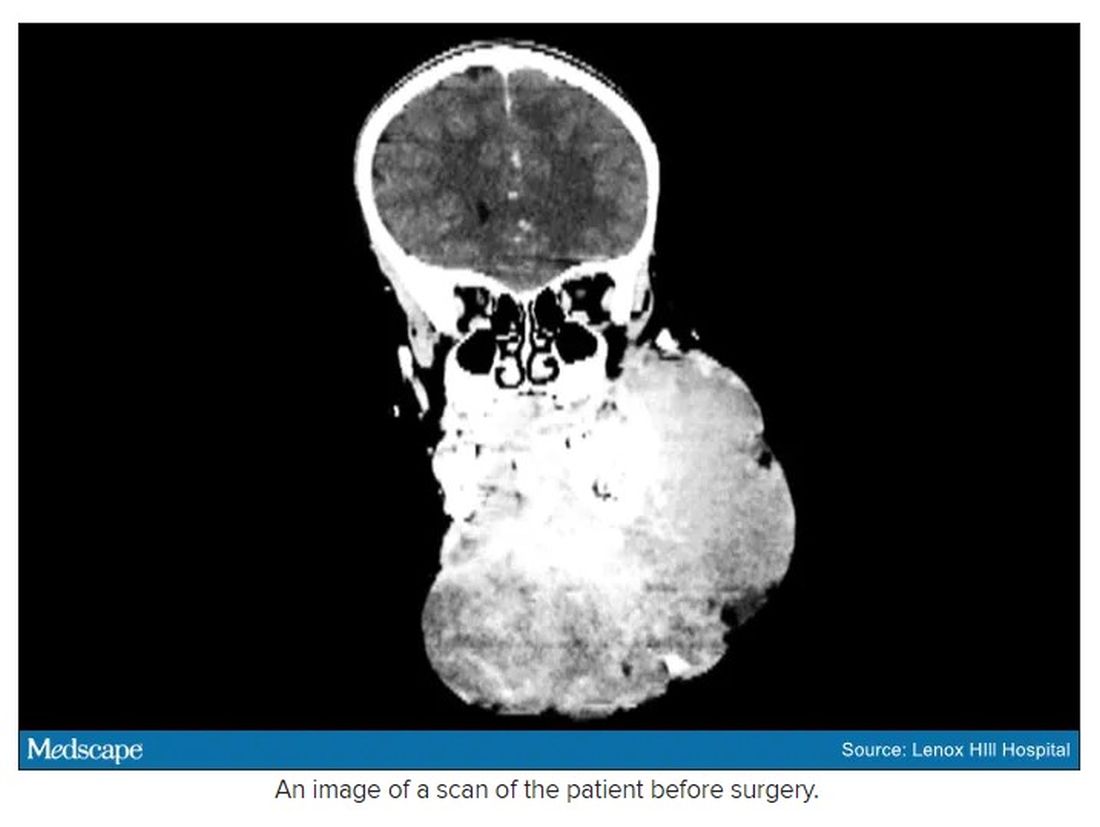

In 2019, doctors in London saw a 5-year old girl from rural Ethiopia with an enormous tumor extending from her cheek to her lower jaw. Her name was Negalem and the tumor was a vascular malformation, a life-threatening web of tangled blood vessels.

Surgery to remove it was impossible, the doctors told the foundation advocating for the girl. The child would never make it off the operating table. After a closer examination, the London group still declined to do the procedure, but told the child’s parents and advocates that if anyone was going to attempt this, they’d need to get the little girl to New York.

In New York City, on 64th St. in Manhattan, is the Vascular Birthmark Institute, founded by Milton Waner, MD, who has exclusively treated hemangiomas and vascular malformations for the last 30 years. “I’m the only person in the [United] States whose practice is exclusively [treating] vascular anomalies,” Dr. Waner said in an interview.

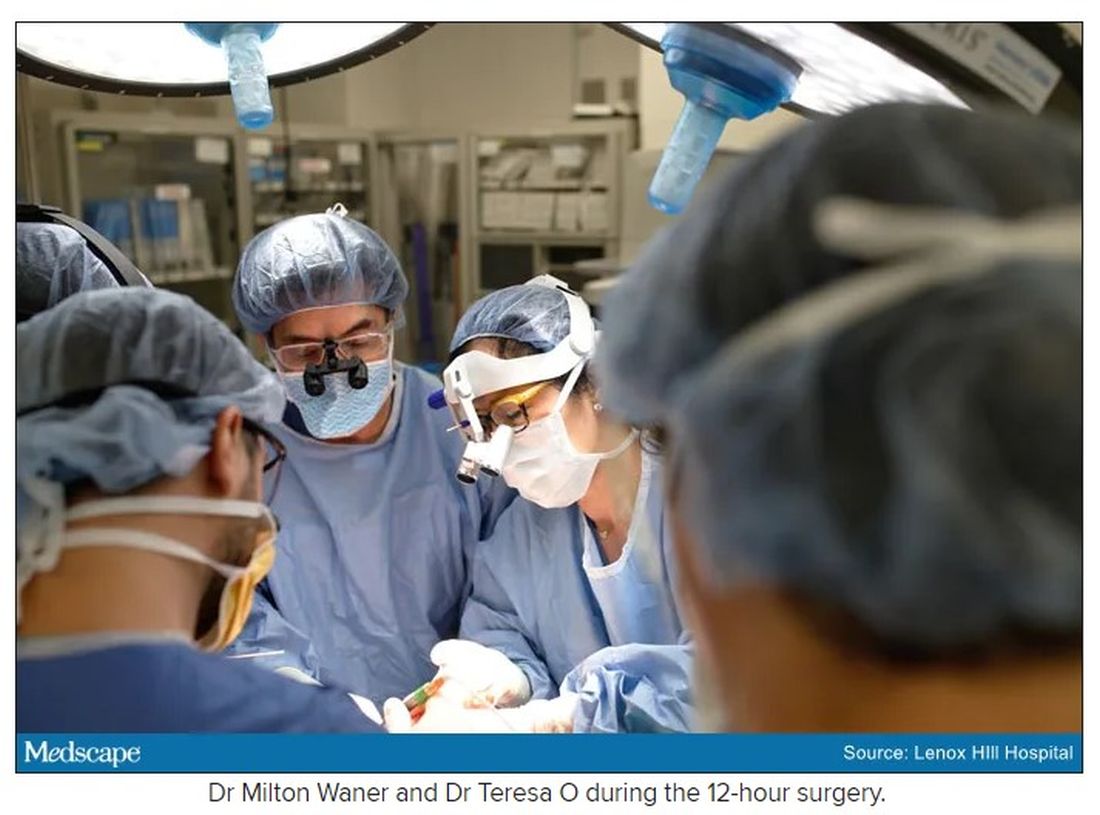

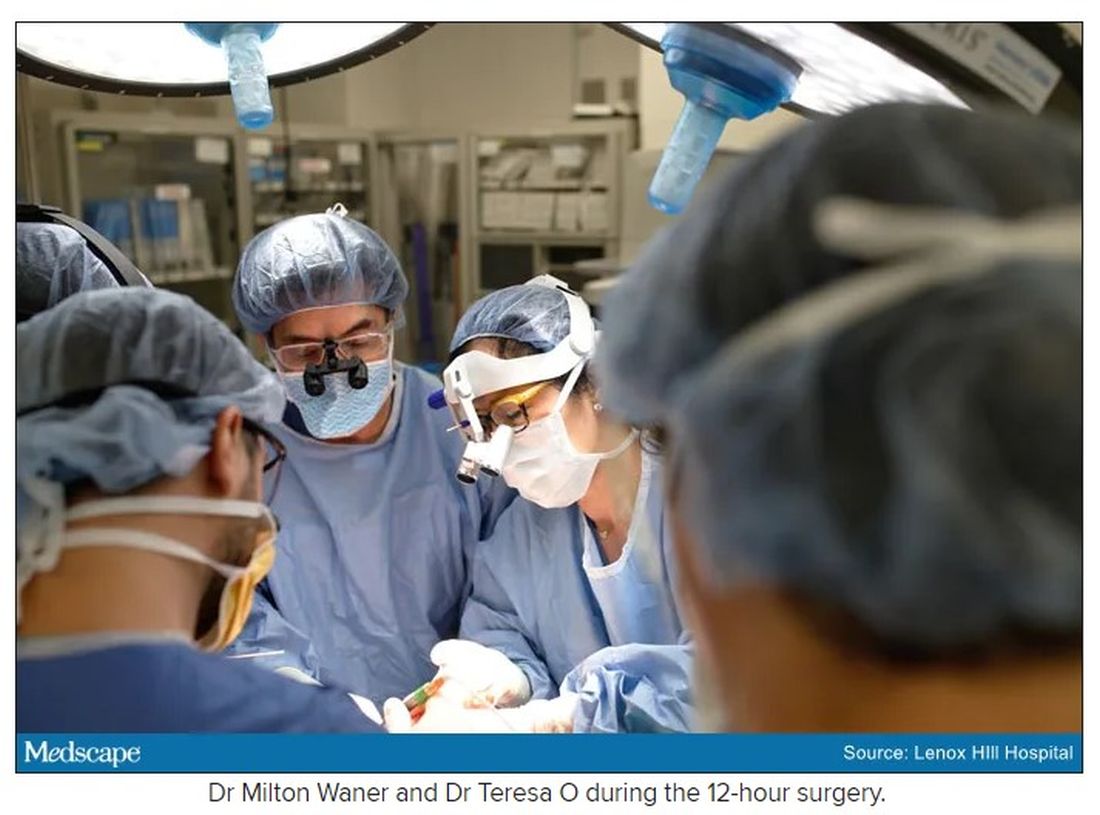

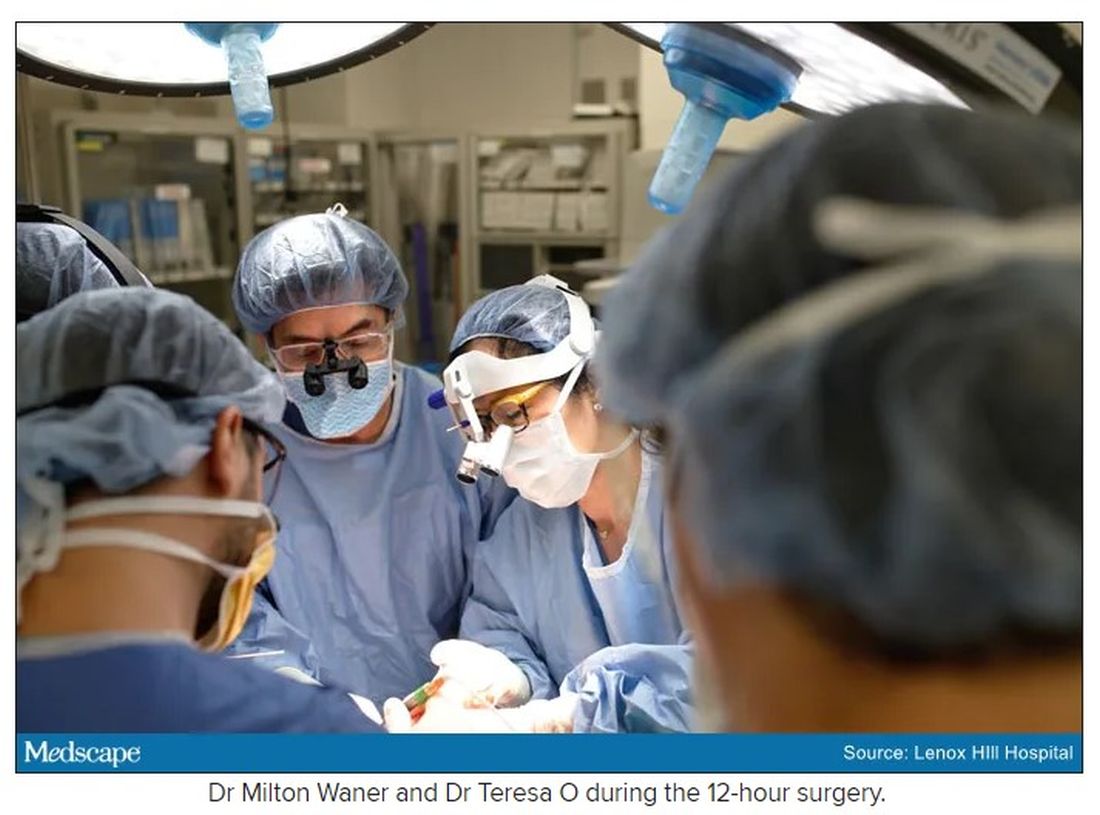

Dr. Waner has assembled a multidisciplinary team of experts at the institute’s offices in Lenox Hill – including his wife Teresa O, MD, a facial plastic and reconstructive surgeon and neurospecialist. “People often ask how the hell do you spend so much time with your spouse?” Dr. Waner says. “We work extremely well together. We complement each other.”

Dr. O and Dr. Waner each manage half of the cases at VBI. And in January they received an email about Negalem. After corresponding with the child’s advocate and reviewing images,

The challenge with vascular malformations in children, Dr. Waner said, is that they have a fraction of the blood an adult has. Where adults have an average of 5 L of blood, a child this age has only 1 L. To lose 200 or 300 mL of blood, “that’s 20% or 30% of their blood volume,” Dr. Waner said. So the removal of such a mass, which requires a meticulous dissection around many blood vessels, carries a high risk of the child bleeding out.

There were some logistical hurdles, but the patient arrived in Manhattan in mid-June, at no cost to her family. The medical visa was organized by a volunteer who also work for USAID. Healing the Children Northeast paid for her travel and the Waner Kids Foundation paid for her hotel stay. Lenox Hill Hospital and Northwell Health covered all hospital costs and postsurgery care. And Dr. O and Dr. Waner did the planning, consult visits, and procedure pro bono.

The surgery was possible because of the generosity of several organizations, but the two surgeons still had a limited time to remove the mass. Under different circumstances, and with the luxury of more time, the patient would have undergone several rounds of sclerotherapy. This procedure, done by interventional radiologists, involves injecting a toxin into the blood vessels, which causes them to clot. Done prior to surgery it can help limit bleeding risk.

On June 23, the morning of the surgery, the patient underwent one round of sclerotherapy. However, it didn’t have the intended effect, Dr. Waner said, “because the lesion was just so massive.”

The team had planned several of their moves ahead of time. But this isn’t the sort of surgery you’d find in a textbook. Because it’s such a unique field, Dr. Waner and Dr. O have developed many of their own techniques along the way. This patient was much like the cases they treat every day, only “several orders of magnitudes greater,” Dr. Waner said. “On a scale of 1 to 10 she was a 12.”

The morning of the surgery, “I was very apprehensive,” Dr. Waner recalled. He vividly remembers the girl’s father repeatedly kissing her to say goodbye as she lay on the operating table, fully aware that this procedure was a life-threatening one. And from the beginning there were challenges, like getting her under anesthesia when the anatomy of her mouth, deformed by the tumor, didn’t allow the anesthesiologists to use their typical tubing. Then, once the skin was removed, it became clear how dilated and tangled the involved blood vessels were. There were many vital structures tangled in the anomaly. “The jugular vein was right there. The carotid artery was right there,” Dr. Waner said. It was extremely difficult to delineate and preserve them, he said.

“That’s why we really took our time. We just went very slowly and deliberately,” Dr. O said. The blood vessels were so dilated that their only option was to move painstakingly slow – otherwise a small nick could be devastating.

But even with the slow pace the surgery was “excruciatingly difficult,” Dr. Waner said. And early on in the dissection he wasn’t quite sure they’d make it out. The sclerotherapy hadn’t done much to prevent bleeding. “At one point every millimeter or 2 that we advanced we got into some bleeding,” Dr. Waner said. “Brisk bleeding.”

Once they got into the surgery they also realized that the growth had adhered to the jaw bone. “There were vessels traversing into the bone, which were hard to control,” Dr. O said.

But finally, both doctors realized they’d be able to remove it. With the lesion removed they began the work of reconstruction and reanimation.

The child’s jaw and cheek bone had grown beyond their normal size to support the growth. They had to shave them down to achieve facial symmetry. The tumor had also inhibited much of the child’s facial nerve control. With it gone, Dr. O began the work of finding all the facial nerve branches and assembling them to reanimate the child’s face.

Before medicine, Dr. O trained as an architect, which, according to Dr. Waner, has equipped her with very good spatial awareness – a valuable skill in the surgical reconstruction phase. After seeing a lecture by Dr. Waner, she immediately saw a fit for her unique interest and skill set. She did fellowship training with Dr. Waner in vascular anomalies, and then went on to specialize in facial nerve reanimation. The proof of Dr. O’s expertise is Negalem’s new, beautiful smile, Dr. Waner said.

The surgery drew out over 8 hours, as long as a day of surgeries for the two doctors. When Dr. O finally walked into the waiting room to inform the family of the success, the first words out of the father’s mouth were: “Is my daughter alive?”

A growth like Negalem had is not compatible with a normal life. Dr. Waner’s mantra is that every child has the right to look normal. But this case went beyond aesthetics. If the growth hadn’t been removed, the child was expected to live only 4-6 more years, Dr. Waner said. Without the surgery, she could have suffocated, starved without the ability to swallow, or suffered a fatal bleed.

Dr. O and Dr. Waner are uniquely equipped to do this kind of work, but both are adamant that treating vascular anomalies is a multidisciplinary, multimodal approach. Specialties in anesthesiology, radiology, lasers, facial nerves – they are all critical to these procedures. And often patients with these kinds of lesions require medical and radiologic interventions in addition to surgery. In this particular case, from logistics to post op, “it was a lot of teamwork,” Dr. O said, “a lot of international teams coming together.”

Though extremely difficult, “in the end the result was exactly what we wanted,” Dr. Waner said. Negalem can live a normal life. And as for the surgical duo, both feel very fortunate to do this work. Dr. O said, “I’m honored to have found this specialty and to be able to train with and work with Milton. I’m so happy to do what I do every day.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In 2019, doctors in London saw a 5-year old girl from rural Ethiopia with an enormous tumor extending from her cheek to her lower jaw. Her name was Negalem and the tumor was a vascular malformation, a life-threatening web of tangled blood vessels.

Surgery to remove it was impossible, the doctors told the foundation advocating for the girl. The child would never make it off the operating table. After a closer examination, the London group still declined to do the procedure, but told the child’s parents and advocates that if anyone was going to attempt this, they’d need to get the little girl to New York.

In New York City, on 64th St. in Manhattan, is the Vascular Birthmark Institute, founded by Milton Waner, MD, who has exclusively treated hemangiomas and vascular malformations for the last 30 years. “I’m the only person in the [United] States whose practice is exclusively [treating] vascular anomalies,” Dr. Waner said in an interview.

Dr. Waner has assembled a multidisciplinary team of experts at the institute’s offices in Lenox Hill – including his wife Teresa O, MD, a facial plastic and reconstructive surgeon and neurospecialist. “People often ask how the hell do you spend so much time with your spouse?” Dr. Waner says. “We work extremely well together. We complement each other.”

Dr. O and Dr. Waner each manage half of the cases at VBI. And in January they received an email about Negalem. After corresponding with the child’s advocate and reviewing images,

The challenge with vascular malformations in children, Dr. Waner said, is that they have a fraction of the blood an adult has. Where adults have an average of 5 L of blood, a child this age has only 1 L. To lose 200 or 300 mL of blood, “that’s 20% or 30% of their blood volume,” Dr. Waner said. So the removal of such a mass, which requires a meticulous dissection around many blood vessels, carries a high risk of the child bleeding out.

There were some logistical hurdles, but the patient arrived in Manhattan in mid-June, at no cost to her family. The medical visa was organized by a volunteer who also work for USAID. Healing the Children Northeast paid for her travel and the Waner Kids Foundation paid for her hotel stay. Lenox Hill Hospital and Northwell Health covered all hospital costs and postsurgery care. And Dr. O and Dr. Waner did the planning, consult visits, and procedure pro bono.

The surgery was possible because of the generosity of several organizations, but the two surgeons still had a limited time to remove the mass. Under different circumstances, and with the luxury of more time, the patient would have undergone several rounds of sclerotherapy. This procedure, done by interventional radiologists, involves injecting a toxin into the blood vessels, which causes them to clot. Done prior to surgery it can help limit bleeding risk.

On June 23, the morning of the surgery, the patient underwent one round of sclerotherapy. However, it didn’t have the intended effect, Dr. Waner said, “because the lesion was just so massive.”

The team had planned several of their moves ahead of time. But this isn’t the sort of surgery you’d find in a textbook. Because it’s such a unique field, Dr. Waner and Dr. O have developed many of their own techniques along the way. This patient was much like the cases they treat every day, only “several orders of magnitudes greater,” Dr. Waner said. “On a scale of 1 to 10 she was a 12.”

The morning of the surgery, “I was very apprehensive,” Dr. Waner recalled. He vividly remembers the girl’s father repeatedly kissing her to say goodbye as she lay on the operating table, fully aware that this procedure was a life-threatening one. And from the beginning there were challenges, like getting her under anesthesia when the anatomy of her mouth, deformed by the tumor, didn’t allow the anesthesiologists to use their typical tubing. Then, once the skin was removed, it became clear how dilated and tangled the involved blood vessels were. There were many vital structures tangled in the anomaly. “The jugular vein was right there. The carotid artery was right there,” Dr. Waner said. It was extremely difficult to delineate and preserve them, he said.

“That’s why we really took our time. We just went very slowly and deliberately,” Dr. O said. The blood vessels were so dilated that their only option was to move painstakingly slow – otherwise a small nick could be devastating.

But even with the slow pace the surgery was “excruciatingly difficult,” Dr. Waner said. And early on in the dissection he wasn’t quite sure they’d make it out. The sclerotherapy hadn’t done much to prevent bleeding. “At one point every millimeter or 2 that we advanced we got into some bleeding,” Dr. Waner said. “Brisk bleeding.”

Once they got into the surgery they also realized that the growth had adhered to the jaw bone. “There were vessels traversing into the bone, which were hard to control,” Dr. O said.

But finally, both doctors realized they’d be able to remove it. With the lesion removed they began the work of reconstruction and reanimation.

The child’s jaw and cheek bone had grown beyond their normal size to support the growth. They had to shave them down to achieve facial symmetry. The tumor had also inhibited much of the child’s facial nerve control. With it gone, Dr. O began the work of finding all the facial nerve branches and assembling them to reanimate the child’s face.

Before medicine, Dr. O trained as an architect, which, according to Dr. Waner, has equipped her with very good spatial awareness – a valuable skill in the surgical reconstruction phase. After seeing a lecture by Dr. Waner, she immediately saw a fit for her unique interest and skill set. She did fellowship training with Dr. Waner in vascular anomalies, and then went on to specialize in facial nerve reanimation. The proof of Dr. O’s expertise is Negalem’s new, beautiful smile, Dr. Waner said.

The surgery drew out over 8 hours, as long as a day of surgeries for the two doctors. When Dr. O finally walked into the waiting room to inform the family of the success, the first words out of the father’s mouth were: “Is my daughter alive?”

A growth like Negalem had is not compatible with a normal life. Dr. Waner’s mantra is that every child has the right to look normal. But this case went beyond aesthetics. If the growth hadn’t been removed, the child was expected to live only 4-6 more years, Dr. Waner said. Without the surgery, she could have suffocated, starved without the ability to swallow, or suffered a fatal bleed.

Dr. O and Dr. Waner are uniquely equipped to do this kind of work, but both are adamant that treating vascular anomalies is a multidisciplinary, multimodal approach. Specialties in anesthesiology, radiology, lasers, facial nerves – they are all critical to these procedures. And often patients with these kinds of lesions require medical and radiologic interventions in addition to surgery. In this particular case, from logistics to post op, “it was a lot of teamwork,” Dr. O said, “a lot of international teams coming together.”

Though extremely difficult, “in the end the result was exactly what we wanted,” Dr. Waner said. Negalem can live a normal life. And as for the surgical duo, both feel very fortunate to do this work. Dr. O said, “I’m honored to have found this specialty and to be able to train with and work with Milton. I’m so happy to do what I do every day.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In 2019, doctors in London saw a 5-year old girl from rural Ethiopia with an enormous tumor extending from her cheek to her lower jaw. Her name was Negalem and the tumor was a vascular malformation, a life-threatening web of tangled blood vessels.

Surgery to remove it was impossible, the doctors told the foundation advocating for the girl. The child would never make it off the operating table. After a closer examination, the London group still declined to do the procedure, but told the child’s parents and advocates that if anyone was going to attempt this, they’d need to get the little girl to New York.

In New York City, on 64th St. in Manhattan, is the Vascular Birthmark Institute, founded by Milton Waner, MD, who has exclusively treated hemangiomas and vascular malformations for the last 30 years. “I’m the only person in the [United] States whose practice is exclusively [treating] vascular anomalies,” Dr. Waner said in an interview.

Dr. Waner has assembled a multidisciplinary team of experts at the institute’s offices in Lenox Hill – including his wife Teresa O, MD, a facial plastic and reconstructive surgeon and neurospecialist. “People often ask how the hell do you spend so much time with your spouse?” Dr. Waner says. “We work extremely well together. We complement each other.”

Dr. O and Dr. Waner each manage half of the cases at VBI. And in January they received an email about Negalem. After corresponding with the child’s advocate and reviewing images,

The challenge with vascular malformations in children, Dr. Waner said, is that they have a fraction of the blood an adult has. Where adults have an average of 5 L of blood, a child this age has only 1 L. To lose 200 or 300 mL of blood, “that’s 20% or 30% of their blood volume,” Dr. Waner said. So the removal of such a mass, which requires a meticulous dissection around many blood vessels, carries a high risk of the child bleeding out.

There were some logistical hurdles, but the patient arrived in Manhattan in mid-June, at no cost to her family. The medical visa was organized by a volunteer who also work for USAID. Healing the Children Northeast paid for her travel and the Waner Kids Foundation paid for her hotel stay. Lenox Hill Hospital and Northwell Health covered all hospital costs and postsurgery care. And Dr. O and Dr. Waner did the planning, consult visits, and procedure pro bono.

The surgery was possible because of the generosity of several organizations, but the two surgeons still had a limited time to remove the mass. Under different circumstances, and with the luxury of more time, the patient would have undergone several rounds of sclerotherapy. This procedure, done by interventional radiologists, involves injecting a toxin into the blood vessels, which causes them to clot. Done prior to surgery it can help limit bleeding risk.

On June 23, the morning of the surgery, the patient underwent one round of sclerotherapy. However, it didn’t have the intended effect, Dr. Waner said, “because the lesion was just so massive.”

The team had planned several of their moves ahead of time. But this isn’t the sort of surgery you’d find in a textbook. Because it’s such a unique field, Dr. Waner and Dr. O have developed many of their own techniques along the way. This patient was much like the cases they treat every day, only “several orders of magnitudes greater,” Dr. Waner said. “On a scale of 1 to 10 she was a 12.”

The morning of the surgery, “I was very apprehensive,” Dr. Waner recalled. He vividly remembers the girl’s father repeatedly kissing her to say goodbye as she lay on the operating table, fully aware that this procedure was a life-threatening one. And from the beginning there were challenges, like getting her under anesthesia when the anatomy of her mouth, deformed by the tumor, didn’t allow the anesthesiologists to use their typical tubing. Then, once the skin was removed, it became clear how dilated and tangled the involved blood vessels were. There were many vital structures tangled in the anomaly. “The jugular vein was right there. The carotid artery was right there,” Dr. Waner said. It was extremely difficult to delineate and preserve them, he said.

“That’s why we really took our time. We just went very slowly and deliberately,” Dr. O said. The blood vessels were so dilated that their only option was to move painstakingly slow – otherwise a small nick could be devastating.

But even with the slow pace the surgery was “excruciatingly difficult,” Dr. Waner said. And early on in the dissection he wasn’t quite sure they’d make it out. The sclerotherapy hadn’t done much to prevent bleeding. “At one point every millimeter or 2 that we advanced we got into some bleeding,” Dr. Waner said. “Brisk bleeding.”

Once they got into the surgery they also realized that the growth had adhered to the jaw bone. “There were vessels traversing into the bone, which were hard to control,” Dr. O said.

But finally, both doctors realized they’d be able to remove it. With the lesion removed they began the work of reconstruction and reanimation.

The child’s jaw and cheek bone had grown beyond their normal size to support the growth. They had to shave them down to achieve facial symmetry. The tumor had also inhibited much of the child’s facial nerve control. With it gone, Dr. O began the work of finding all the facial nerve branches and assembling them to reanimate the child’s face.

Before medicine, Dr. O trained as an architect, which, according to Dr. Waner, has equipped her with very good spatial awareness – a valuable skill in the surgical reconstruction phase. After seeing a lecture by Dr. Waner, she immediately saw a fit for her unique interest and skill set. She did fellowship training with Dr. Waner in vascular anomalies, and then went on to specialize in facial nerve reanimation. The proof of Dr. O’s expertise is Negalem’s new, beautiful smile, Dr. Waner said.

The surgery drew out over 8 hours, as long as a day of surgeries for the two doctors. When Dr. O finally walked into the waiting room to inform the family of the success, the first words out of the father’s mouth were: “Is my daughter alive?”

A growth like Negalem had is not compatible with a normal life. Dr. Waner’s mantra is that every child has the right to look normal. But this case went beyond aesthetics. If the growth hadn’t been removed, the child was expected to live only 4-6 more years, Dr. Waner said. Without the surgery, she could have suffocated, starved without the ability to swallow, or suffered a fatal bleed.

Dr. O and Dr. Waner are uniquely equipped to do this kind of work, but both are adamant that treating vascular anomalies is a multidisciplinary, multimodal approach. Specialties in anesthesiology, radiology, lasers, facial nerves – they are all critical to these procedures. And often patients with these kinds of lesions require medical and radiologic interventions in addition to surgery. In this particular case, from logistics to post op, “it was a lot of teamwork,” Dr. O said, “a lot of international teams coming together.”

Though extremely difficult, “in the end the result was exactly what we wanted,” Dr. Waner said. Negalem can live a normal life. And as for the surgical duo, both feel very fortunate to do this work. Dr. O said, “I’m honored to have found this specialty and to be able to train with and work with Milton. I’m so happy to do what I do every day.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Pandemic took a cut of cosmetic procedures in 2020

pandemic, according to the American Society of Plastic Surgeons.

There were an estimated 15.6 million cosmetic procedures performed in 2020, compared with 18.4 million in 2019, a drop of 15.2%. Meanwhile, society members reported that they stopped performing elective surgery for an average of 8.1 weeks, which works out to 15.6% of a 52-week year, the ASPS said in its annual statistics report.

“The pandemic isn’t over, but thanks to vaccines, a new normal is starting to define itself – and some surgeons’ offices that were closed or offered only limited services within the last year are seeing higher demand,” Lynn Jeffers, MD, MBA, immediate past president of the ASPS, said in a written statement.

Minimally invasive procedures, which made up the majority of cosmetic procedures in 2020, dropped by a slightly higher 16%, compared with 14% on the surgical side. “Injectables continued to be the most sought-after treatments in 2020,” the ASPS said, with survey respondents citing “a significant uptick in demand during the coronavirus pandemic.”

OnabotuliumtoxinA injection, the most popular form of minimally invasive procedure, was down by 13% from 2019, while use of soft-tissue fillers fell by 11%. Laser skin resurfacing was third in popularity and had the smallest drop, just 8%, among the top five from 2019 to 2020, the ASPS data show.

The drop in volume for chemical peels was large enough (33%), to move it from third place in 2019 to fourth in 2020, and a slightly less than average drop of 12% moved intense pulsed-light treatments from sixth place in 2019 to fifth in 2020, switching places with laser hair removal (down 28%), the ASPS reported.

Among the surgical procedures, rhinoplasty was the most popular in 2020, as it was in 2019, after dropping by just 3%. Blepharoplasty was down by 8% from 2019, but two other common procedures, liposuction and breast augmentation, fell by 20% and 33%, respectively, the ASPS said.

pandemic, according to the American Society of Plastic Surgeons.

There were an estimated 15.6 million cosmetic procedures performed in 2020, compared with 18.4 million in 2019, a drop of 15.2%. Meanwhile, society members reported that they stopped performing elective surgery for an average of 8.1 weeks, which works out to 15.6% of a 52-week year, the ASPS said in its annual statistics report.

“The pandemic isn’t over, but thanks to vaccines, a new normal is starting to define itself – and some surgeons’ offices that were closed or offered only limited services within the last year are seeing higher demand,” Lynn Jeffers, MD, MBA, immediate past president of the ASPS, said in a written statement.

Minimally invasive procedures, which made up the majority of cosmetic procedures in 2020, dropped by a slightly higher 16%, compared with 14% on the surgical side. “Injectables continued to be the most sought-after treatments in 2020,” the ASPS said, with survey respondents citing “a significant uptick in demand during the coronavirus pandemic.”

OnabotuliumtoxinA injection, the most popular form of minimally invasive procedure, was down by 13% from 2019, while use of soft-tissue fillers fell by 11%. Laser skin resurfacing was third in popularity and had the smallest drop, just 8%, among the top five from 2019 to 2020, the ASPS data show.

The drop in volume for chemical peels was large enough (33%), to move it from third place in 2019 to fourth in 2020, and a slightly less than average drop of 12% moved intense pulsed-light treatments from sixth place in 2019 to fifth in 2020, switching places with laser hair removal (down 28%), the ASPS reported.

Among the surgical procedures, rhinoplasty was the most popular in 2020, as it was in 2019, after dropping by just 3%. Blepharoplasty was down by 8% from 2019, but two other common procedures, liposuction and breast augmentation, fell by 20% and 33%, respectively, the ASPS said.

pandemic, according to the American Society of Plastic Surgeons.

There were an estimated 15.6 million cosmetic procedures performed in 2020, compared with 18.4 million in 2019, a drop of 15.2%. Meanwhile, society members reported that they stopped performing elective surgery for an average of 8.1 weeks, which works out to 15.6% of a 52-week year, the ASPS said in its annual statistics report.

“The pandemic isn’t over, but thanks to vaccines, a new normal is starting to define itself – and some surgeons’ offices that were closed or offered only limited services within the last year are seeing higher demand,” Lynn Jeffers, MD, MBA, immediate past president of the ASPS, said in a written statement.

Minimally invasive procedures, which made up the majority of cosmetic procedures in 2020, dropped by a slightly higher 16%, compared with 14% on the surgical side. “Injectables continued to be the most sought-after treatments in 2020,” the ASPS said, with survey respondents citing “a significant uptick in demand during the coronavirus pandemic.”

OnabotuliumtoxinA injection, the most popular form of minimally invasive procedure, was down by 13% from 2019, while use of soft-tissue fillers fell by 11%. Laser skin resurfacing was third in popularity and had the smallest drop, just 8%, among the top five from 2019 to 2020, the ASPS data show.

The drop in volume for chemical peels was large enough (33%), to move it from third place in 2019 to fourth in 2020, and a slightly less than average drop of 12% moved intense pulsed-light treatments from sixth place in 2019 to fifth in 2020, switching places with laser hair removal (down 28%), the ASPS reported.

Among the surgical procedures, rhinoplasty was the most popular in 2020, as it was in 2019, after dropping by just 3%. Blepharoplasty was down by 8% from 2019, but two other common procedures, liposuction and breast augmentation, fell by 20% and 33%, respectively, the ASPS said.

Counterfeits: An ugly truth in aesthetic medicine

according to the results of two recent surveys of such providers.

“Counterfeit medical devices and injectables may be more prevalent in aesthetic medicine than most practitioners might estimate,” Jordan V. Wang, MD, of Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Philadelphia, and associates wrote in Dermatologic Surgery, even though “the vast majority [believe] that they are inferior and even potentially harmful.”

In one of the online surveys, conducted among members of the American Society of Dermatologic Surgery, 41.1% of the 616 respondents said they had encountered counterfeit injectables, more than half (56.5%) of whom were solicited to buy such products. Just over 10% had purchased counterfeit injectables, although nearly 80% did so unknowingly, the investigators said.

In the second survey, 37.4% of the 765 respondents (members of the ASDS as well as the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery) said that they had encountered counterfeit medical devices, and nearly half had been approached to purchase such devices. Of those who were approached, 4.6% had actually purchased a counterfeit, but only 6.1% did so unknowingly, Dr. Wang and associates reported.

In the medical device survey, almost a quarter (24.2%) acknowledged that they know of other providers using them, while 29.3% of those surveyed about injectables know of others who use counterfeits, they said.

Over 90% of practitioners in each survey agreed that counterfeits are worse in terms of safety, reliability, and effectiveness, but the proportions were smaller when they were asked if counterfeits were either very or extremely endangering to patient safety: 70.5% for injectables and 59.2% for devices, the investigators said.

Experience with adverse events from counterfeits in patients was reported by 39.7% of respondents to the injectables survey and by 20.1% of those in the device survey, they added.

Majorities in both surveys – 73.7% for injectables and 68.9% for devices – also said that they were either not familiar or only somewhat familiar with the Food and Drug Administration’s regulations on counterfeits. “This is especially problematic considering the potentially severe adverse events and steep punishments,” Dr. Wang and associates wrote.

The authors disclosed that they had no significant interest with commercial supporters. Dr. Wang is now a fellow at the Laser & Skin Surgery Center of New York.

SOURCE: Wang JV et al. Dermatol. Surg. 2020 Oct;46(10):1323-6.

according to the results of two recent surveys of such providers.

“Counterfeit medical devices and injectables may be more prevalent in aesthetic medicine than most practitioners might estimate,” Jordan V. Wang, MD, of Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Philadelphia, and associates wrote in Dermatologic Surgery, even though “the vast majority [believe] that they are inferior and even potentially harmful.”

In one of the online surveys, conducted among members of the American Society of Dermatologic Surgery, 41.1% of the 616 respondents said they had encountered counterfeit injectables, more than half (56.5%) of whom were solicited to buy such products. Just over 10% had purchased counterfeit injectables, although nearly 80% did so unknowingly, the investigators said.

In the second survey, 37.4% of the 765 respondents (members of the ASDS as well as the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery) said that they had encountered counterfeit medical devices, and nearly half had been approached to purchase such devices. Of those who were approached, 4.6% had actually purchased a counterfeit, but only 6.1% did so unknowingly, Dr. Wang and associates reported.

In the medical device survey, almost a quarter (24.2%) acknowledged that they know of other providers using them, while 29.3% of those surveyed about injectables know of others who use counterfeits, they said.

Over 90% of practitioners in each survey agreed that counterfeits are worse in terms of safety, reliability, and effectiveness, but the proportions were smaller when they were asked if counterfeits were either very or extremely endangering to patient safety: 70.5% for injectables and 59.2% for devices, the investigators said.

Experience with adverse events from counterfeits in patients was reported by 39.7% of respondents to the injectables survey and by 20.1% of those in the device survey, they added.

Majorities in both surveys – 73.7% for injectables and 68.9% for devices – also said that they were either not familiar or only somewhat familiar with the Food and Drug Administration’s regulations on counterfeits. “This is especially problematic considering the potentially severe adverse events and steep punishments,” Dr. Wang and associates wrote.

The authors disclosed that they had no significant interest with commercial supporters. Dr. Wang is now a fellow at the Laser & Skin Surgery Center of New York.

SOURCE: Wang JV et al. Dermatol. Surg. 2020 Oct;46(10):1323-6.

according to the results of two recent surveys of such providers.

“Counterfeit medical devices and injectables may be more prevalent in aesthetic medicine than most practitioners might estimate,” Jordan V. Wang, MD, of Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Philadelphia, and associates wrote in Dermatologic Surgery, even though “the vast majority [believe] that they are inferior and even potentially harmful.”

In one of the online surveys, conducted among members of the American Society of Dermatologic Surgery, 41.1% of the 616 respondents said they had encountered counterfeit injectables, more than half (56.5%) of whom were solicited to buy such products. Just over 10% had purchased counterfeit injectables, although nearly 80% did so unknowingly, the investigators said.

In the second survey, 37.4% of the 765 respondents (members of the ASDS as well as the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery) said that they had encountered counterfeit medical devices, and nearly half had been approached to purchase such devices. Of those who were approached, 4.6% had actually purchased a counterfeit, but only 6.1% did so unknowingly, Dr. Wang and associates reported.

In the medical device survey, almost a quarter (24.2%) acknowledged that they know of other providers using them, while 29.3% of those surveyed about injectables know of others who use counterfeits, they said.

Over 90% of practitioners in each survey agreed that counterfeits are worse in terms of safety, reliability, and effectiveness, but the proportions were smaller when they were asked if counterfeits were either very or extremely endangering to patient safety: 70.5% for injectables and 59.2% for devices, the investigators said.

Experience with adverse events from counterfeits in patients was reported by 39.7% of respondents to the injectables survey and by 20.1% of those in the device survey, they added.

Majorities in both surveys – 73.7% for injectables and 68.9% for devices – also said that they were either not familiar or only somewhat familiar with the Food and Drug Administration’s regulations on counterfeits. “This is especially problematic considering the potentially severe adverse events and steep punishments,” Dr. Wang and associates wrote.

The authors disclosed that they had no significant interest with commercial supporters. Dr. Wang is now a fellow at the Laser & Skin Surgery Center of New York.

SOURCE: Wang JV et al. Dermatol. Surg. 2020 Oct;46(10):1323-6.

FROM DERMATOLOGIC SURGERY

FDA proposes new breast implant labeling with a boxed warning

Breast implants sold in the United States may soon require a boxed warning in their label, along with other label changes proposed by the Food and Drug Administration aimed at better informing prospective patients and clinicians of the potential risks from breast implants.

Other elements of the proposed labeling changes include creation of a patient-decision checklist, new recommendations for follow-up imaging to monitor for implant rupture, inclusion of detailed and understandable information about materials in the device, and provision of a device card to each patient with details on the specific implant they received.

These labeling changes all stemmed from a breast implant hearing held by the agency’s General and Plastic Surgery Devices Panel in March 2019, according to the draft guidance document officially released by the FDA on Oct. 24.

The proposed labeling changes were generally welcomed by patient advocates and by clinicians as a reasonable response to the concerns discussed at the March hearing. In an earlier move to address issues brought up at the hearing, the FDA in July arranged for a recall for certain Allergan models of textured breast implants because of their link with the development of breast implant–associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma (BIA-ALCL).

The boxed warning proposed by the FDA would highlight four specific facts that patients, physicians, and surgeons should know about breast implants: They are not considered lifetime devices, the chance of developing complications from implants increases over time, some complications require additional surgery, and placement of breast implants has been associated with development of BIA-ALCL and may also be associated with certain systemic symptoms.

The FDA also proposed four other notable labeling changes:

- Creation of a patient-decision checklist to better systematize the informed consent process and make sure that certain aspects of breast implant placement are clearly brought to patients’ attention. The FDA proposed that patients sign their checklist attesting to having read and understood the information and that patients receive a take-home copy for their future reference. Proposed elements of the checklist include situations to not use breast implants; considerations for successful implant recipients; the risks of breast implant surgery; the importance of appropriate physician education, training, and experience; the risk for developing BIA-ALCL or systemic symptoms; and discussion of options other than breast implants.

- A new scheme for systematically and serially using imaging to screen for implant rupture that designates for the first time that ultrasound is an acceptable alternative to MRI and relies on a schedule by which either method initially screens the implant 5-6 years post operatively and then every 2 years thereafter.

- Detailed and understandable information about each material component of the implant with further information on possible adverse health effects of these compounds.

- A device card that patients should receive after their surgery with the implant’s name, serial number, and other identifiers; the boxed warning information; and a web link for accessing more up-to-date information.

The patient group Breast Implant Victim Advocacy praised the draft guidance. “The March Advisory Committee meeting seems to have prompted a shift by the FDA, surgeons, and industry,” said Jamee Cook, cofounder of the group. “We are definitely seeing a change in patient engagement. The FDA has been cooperating with patients and listening to our concerns. We still have a long way to go in raising public awareness of breast implant issues, but progress over the past 1-2 years has been amazing.”

Diana Zuckerman, PhD, president of the National Center for Health Research in Washington, gave the draft guidance a mixed review. “The FDA’s draft includes the types of information that we had proposed to the FDA in recent months in our work with patient advocates and plastic surgeons,” she said. “However, it is not as informative as it should be in describing well-designed studies indicating a risk of systemic illnesses. Patients deserve to make better-informed decisions in the future than most women considering breast implants have been able to make” in the past.

Patricia McGuire, MD, a St. Louis plastic surgeon who specializes in breast surgery and has studied breast implant illness, declared the guidance to be “reasonable.”

“I think the changes address the concerns expressed by patients during the [March] hearing; I agree with everything the FDA proposed in the guidance document,” Dr. McGuire said. “The boxed warning is reasonable and needs to be part of the informed consent process. I also agree with the changes in screening implants postoperatively. Most patients do not get MRI examinations. High-resolution ultrasound is more convenient and cost effective.”

The boxed warning was rated as “reasonably strong” and “the most serious step the FDA can take short of taking a device off the market,” but in the case of breast implants, a wider recall of textured implants than what the FDA arranged last July would be even more appropriate, commented Sidney M. Wolfe, MD, founder and senior adviser to Public Citizen. He also faulted the agency for not taking quicker action in mandating inclusion of the proposed boxed warning.

Issuing the labeling changes as draft guidance “is a ministep forward,” but also a process that “guarantees delay” and “creeps along at a dangerously slow pace,” Dr. Wolfe said. “The FDA is delaying what should be inevitable. The agency could put the boxed warning in place right now if they had the guts to do it.”

Dr. McGuire has been a consultant to Allergan, Establishment Labs, and Hans Biomed. Ms. Cook, Dr. Zuckerman, and Dr. Wolfe reported having no commercial disclosures.

Breast implants sold in the United States may soon require a boxed warning in their label, along with other label changes proposed by the Food and Drug Administration aimed at better informing prospective patients and clinicians of the potential risks from breast implants.

Other elements of the proposed labeling changes include creation of a patient-decision checklist, new recommendations for follow-up imaging to monitor for implant rupture, inclusion of detailed and understandable information about materials in the device, and provision of a device card to each patient with details on the specific implant they received.

These labeling changes all stemmed from a breast implant hearing held by the agency’s General and Plastic Surgery Devices Panel in March 2019, according to the draft guidance document officially released by the FDA on Oct. 24.

The proposed labeling changes were generally welcomed by patient advocates and by clinicians as a reasonable response to the concerns discussed at the March hearing. In an earlier move to address issues brought up at the hearing, the FDA in July arranged for a recall for certain Allergan models of textured breast implants because of their link with the development of breast implant–associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma (BIA-ALCL).

The boxed warning proposed by the FDA would highlight four specific facts that patients, physicians, and surgeons should know about breast implants: They are not considered lifetime devices, the chance of developing complications from implants increases over time, some complications require additional surgery, and placement of breast implants has been associated with development of BIA-ALCL and may also be associated with certain systemic symptoms.

The FDA also proposed four other notable labeling changes:

- Creation of a patient-decision checklist to better systematize the informed consent process and make sure that certain aspects of breast implant placement are clearly brought to patients’ attention. The FDA proposed that patients sign their checklist attesting to having read and understood the information and that patients receive a take-home copy for their future reference. Proposed elements of the checklist include situations to not use breast implants; considerations for successful implant recipients; the risks of breast implant surgery; the importance of appropriate physician education, training, and experience; the risk for developing BIA-ALCL or systemic symptoms; and discussion of options other than breast implants.

- A new scheme for systematically and serially using imaging to screen for implant rupture that designates for the first time that ultrasound is an acceptable alternative to MRI and relies on a schedule by which either method initially screens the implant 5-6 years post operatively and then every 2 years thereafter.

- Detailed and understandable information about each material component of the implant with further information on possible adverse health effects of these compounds.

- A device card that patients should receive after their surgery with the implant’s name, serial number, and other identifiers; the boxed warning information; and a web link for accessing more up-to-date information.

The patient group Breast Implant Victim Advocacy praised the draft guidance. “The March Advisory Committee meeting seems to have prompted a shift by the FDA, surgeons, and industry,” said Jamee Cook, cofounder of the group. “We are definitely seeing a change in patient engagement. The FDA has been cooperating with patients and listening to our concerns. We still have a long way to go in raising public awareness of breast implant issues, but progress over the past 1-2 years has been amazing.”

Diana Zuckerman, PhD, president of the National Center for Health Research in Washington, gave the draft guidance a mixed review. “The FDA’s draft includes the types of information that we had proposed to the FDA in recent months in our work with patient advocates and plastic surgeons,” she said. “However, it is not as informative as it should be in describing well-designed studies indicating a risk of systemic illnesses. Patients deserve to make better-informed decisions in the future than most women considering breast implants have been able to make” in the past.

Patricia McGuire, MD, a St. Louis plastic surgeon who specializes in breast surgery and has studied breast implant illness, declared the guidance to be “reasonable.”

“I think the changes address the concerns expressed by patients during the [March] hearing; I agree with everything the FDA proposed in the guidance document,” Dr. McGuire said. “The boxed warning is reasonable and needs to be part of the informed consent process. I also agree with the changes in screening implants postoperatively. Most patients do not get MRI examinations. High-resolution ultrasound is more convenient and cost effective.”

The boxed warning was rated as “reasonably strong” and “the most serious step the FDA can take short of taking a device off the market,” but in the case of breast implants, a wider recall of textured implants than what the FDA arranged last July would be even more appropriate, commented Sidney M. Wolfe, MD, founder and senior adviser to Public Citizen. He also faulted the agency for not taking quicker action in mandating inclusion of the proposed boxed warning.

Issuing the labeling changes as draft guidance “is a ministep forward,” but also a process that “guarantees delay” and “creeps along at a dangerously slow pace,” Dr. Wolfe said. “The FDA is delaying what should be inevitable. The agency could put the boxed warning in place right now if they had the guts to do it.”

Dr. McGuire has been a consultant to Allergan, Establishment Labs, and Hans Biomed. Ms. Cook, Dr. Zuckerman, and Dr. Wolfe reported having no commercial disclosures.

Breast implants sold in the United States may soon require a boxed warning in their label, along with other label changes proposed by the Food and Drug Administration aimed at better informing prospective patients and clinicians of the potential risks from breast implants.

Other elements of the proposed labeling changes include creation of a patient-decision checklist, new recommendations for follow-up imaging to monitor for implant rupture, inclusion of detailed and understandable information about materials in the device, and provision of a device card to each patient with details on the specific implant they received.

These labeling changes all stemmed from a breast implant hearing held by the agency’s General and Plastic Surgery Devices Panel in March 2019, according to the draft guidance document officially released by the FDA on Oct. 24.

The proposed labeling changes were generally welcomed by patient advocates and by clinicians as a reasonable response to the concerns discussed at the March hearing. In an earlier move to address issues brought up at the hearing, the FDA in July arranged for a recall for certain Allergan models of textured breast implants because of their link with the development of breast implant–associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma (BIA-ALCL).

The boxed warning proposed by the FDA would highlight four specific facts that patients, physicians, and surgeons should know about breast implants: They are not considered lifetime devices, the chance of developing complications from implants increases over time, some complications require additional surgery, and placement of breast implants has been associated with development of BIA-ALCL and may also be associated with certain systemic symptoms.

The FDA also proposed four other notable labeling changes:

- Creation of a patient-decision checklist to better systematize the informed consent process and make sure that certain aspects of breast implant placement are clearly brought to patients’ attention. The FDA proposed that patients sign their checklist attesting to having read and understood the information and that patients receive a take-home copy for their future reference. Proposed elements of the checklist include situations to not use breast implants; considerations for successful implant recipients; the risks of breast implant surgery; the importance of appropriate physician education, training, and experience; the risk for developing BIA-ALCL or systemic symptoms; and discussion of options other than breast implants.

- A new scheme for systematically and serially using imaging to screen for implant rupture that designates for the first time that ultrasound is an acceptable alternative to MRI and relies on a schedule by which either method initially screens the implant 5-6 years post operatively and then every 2 years thereafter.

- Detailed and understandable information about each material component of the implant with further information on possible adverse health effects of these compounds.

- A device card that patients should receive after their surgery with the implant’s name, serial number, and other identifiers; the boxed warning information; and a web link for accessing more up-to-date information.

The patient group Breast Implant Victim Advocacy praised the draft guidance. “The March Advisory Committee meeting seems to have prompted a shift by the FDA, surgeons, and industry,” said Jamee Cook, cofounder of the group. “We are definitely seeing a change in patient engagement. The FDA has been cooperating with patients and listening to our concerns. We still have a long way to go in raising public awareness of breast implant issues, but progress over the past 1-2 years has been amazing.”

Diana Zuckerman, PhD, president of the National Center for Health Research in Washington, gave the draft guidance a mixed review. “The FDA’s draft includes the types of information that we had proposed to the FDA in recent months in our work with patient advocates and plastic surgeons,” she said. “However, it is not as informative as it should be in describing well-designed studies indicating a risk of systemic illnesses. Patients deserve to make better-informed decisions in the future than most women considering breast implants have been able to make” in the past.

Patricia McGuire, MD, a St. Louis plastic surgeon who specializes in breast surgery and has studied breast implant illness, declared the guidance to be “reasonable.”

“I think the changes address the concerns expressed by patients during the [March] hearing; I agree with everything the FDA proposed in the guidance document,” Dr. McGuire said. “The boxed warning is reasonable and needs to be part of the informed consent process. I also agree with the changes in screening implants postoperatively. Most patients do not get MRI examinations. High-resolution ultrasound is more convenient and cost effective.”

The boxed warning was rated as “reasonably strong” and “the most serious step the FDA can take short of taking a device off the market,” but in the case of breast implants, a wider recall of textured implants than what the FDA arranged last July would be even more appropriate, commented Sidney M. Wolfe, MD, founder and senior adviser to Public Citizen. He also faulted the agency for not taking quicker action in mandating inclusion of the proposed boxed warning.

Issuing the labeling changes as draft guidance “is a ministep forward,” but also a process that “guarantees delay” and “creeps along at a dangerously slow pace,” Dr. Wolfe said. “The FDA is delaying what should be inevitable. The agency could put the boxed warning in place right now if they had the guts to do it.”

Dr. McGuire has been a consultant to Allergan, Establishment Labs, and Hans Biomed. Ms. Cook, Dr. Zuckerman, and Dr. Wolfe reported having no commercial disclosures.

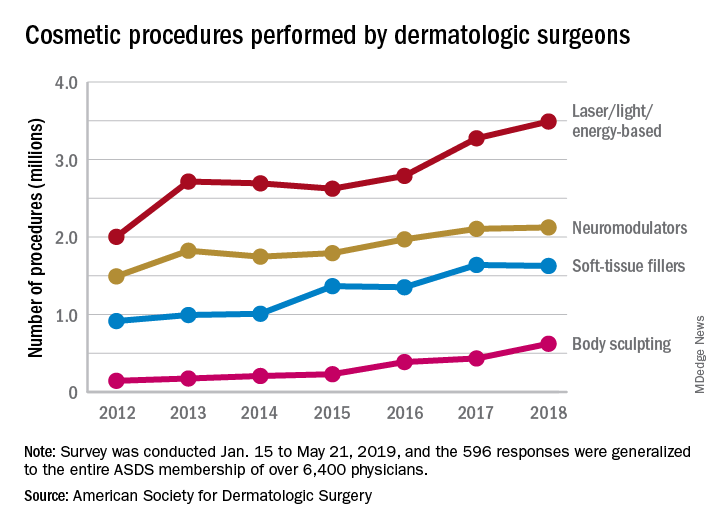

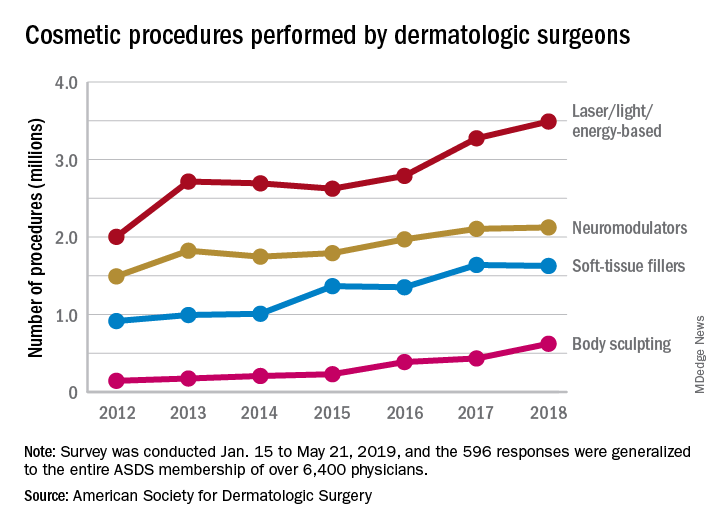

Body sculpting, microneedling show strong growth

, according to a survey by the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery.

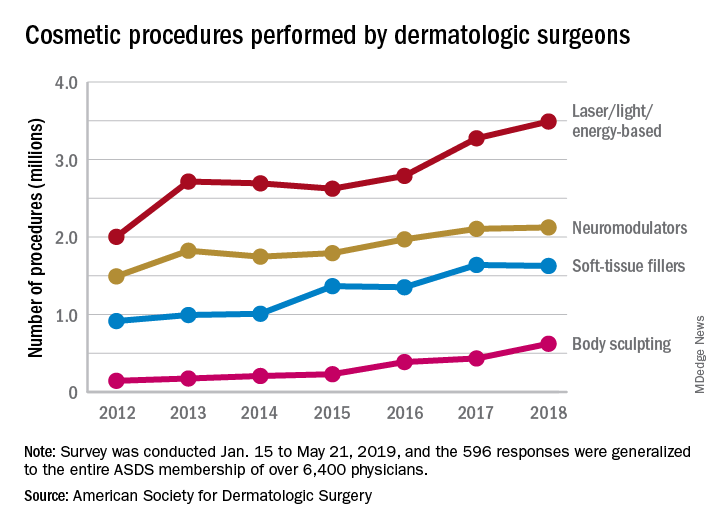

The society’s members performed an estimated 3.5 million laser/light/energy-based procedures and 2.1 million injectable neuromodulator procedures last year as the total volume of cosmetic treatments rose by more than 7% over 2017, the society reported. The total number of procedures in 2017 was 8.3 million, which represented an increase of 19% over 2016.

The largest percent increase in 2018 by type of procedure came in the body-sculpting sector, which jumped 43% from 2017 to 2018. In terms of the total number, however, body sculpting was well behind the other major categories of cosmetic treatments at 624,000 procedures performed. The most popular form of body sculpting last year was cryolipolysis (287,000 procedures), followed by radiofrequency (163,000), and deoxycholic acid (66,000), the ASDS reported.

“The coupling of scientific research and technology [is] driving innovative options for consumers seeking noninvasive cosmetic treatments,” said ASDS President Murad Alam, MD.

Among those newer options is microneedling, which was up by 45% over its 2017 total with almost 263,000 procedures in 2018. Another innovative treatment, thread lifts, in which temporary sutures visibly lift the skin around the face, appears to be gaining awareness as nearly 33,000 procedures were performed last year, according to the ASDS.

Year-over-year increases were smaller among the more established procedures: laser/light/energy-based procedures were up by 6.6%, injectable neuromodulators rose just 0.9%, injectable soft-tissue fillers were down 0.8%, and chemical peels increased by 2.4%, the society’s data show.

The survey was conducted among ASDS members from Jan. 15 to May 21, 2019, and the 596 responses were generalized to the entire ASDS membership of over 6,400 physicians.

, according to a survey by the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery.

The society’s members performed an estimated 3.5 million laser/light/energy-based procedures and 2.1 million injectable neuromodulator procedures last year as the total volume of cosmetic treatments rose by more than 7% over 2017, the society reported. The total number of procedures in 2017 was 8.3 million, which represented an increase of 19% over 2016.

The largest percent increase in 2018 by type of procedure came in the body-sculpting sector, which jumped 43% from 2017 to 2018. In terms of the total number, however, body sculpting was well behind the other major categories of cosmetic treatments at 624,000 procedures performed. The most popular form of body sculpting last year was cryolipolysis (287,000 procedures), followed by radiofrequency (163,000), and deoxycholic acid (66,000), the ASDS reported.

“The coupling of scientific research and technology [is] driving innovative options for consumers seeking noninvasive cosmetic treatments,” said ASDS President Murad Alam, MD.

Among those newer options is microneedling, which was up by 45% over its 2017 total with almost 263,000 procedures in 2018. Another innovative treatment, thread lifts, in which temporary sutures visibly lift the skin around the face, appears to be gaining awareness as nearly 33,000 procedures were performed last year, according to the ASDS.

Year-over-year increases were smaller among the more established procedures: laser/light/energy-based procedures were up by 6.6%, injectable neuromodulators rose just 0.9%, injectable soft-tissue fillers were down 0.8%, and chemical peels increased by 2.4%, the society’s data show.

The survey was conducted among ASDS members from Jan. 15 to May 21, 2019, and the 596 responses were generalized to the entire ASDS membership of over 6,400 physicians.

, according to a survey by the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery.

The society’s members performed an estimated 3.5 million laser/light/energy-based procedures and 2.1 million injectable neuromodulator procedures last year as the total volume of cosmetic treatments rose by more than 7% over 2017, the society reported. The total number of procedures in 2017 was 8.3 million, which represented an increase of 19% over 2016.

The largest percent increase in 2018 by type of procedure came in the body-sculpting sector, which jumped 43% from 2017 to 2018. In terms of the total number, however, body sculpting was well behind the other major categories of cosmetic treatments at 624,000 procedures performed. The most popular form of body sculpting last year was cryolipolysis (287,000 procedures), followed by radiofrequency (163,000), and deoxycholic acid (66,000), the ASDS reported.

“The coupling of scientific research and technology [is] driving innovative options for consumers seeking noninvasive cosmetic treatments,” said ASDS President Murad Alam, MD.

Among those newer options is microneedling, which was up by 45% over its 2017 total with almost 263,000 procedures in 2018. Another innovative treatment, thread lifts, in which temporary sutures visibly lift the skin around the face, appears to be gaining awareness as nearly 33,000 procedures were performed last year, according to the ASDS.

Year-over-year increases were smaller among the more established procedures: laser/light/energy-based procedures were up by 6.6%, injectable neuromodulators rose just 0.9%, injectable soft-tissue fillers were down 0.8%, and chemical peels increased by 2.4%, the society’s data show.

The survey was conducted among ASDS members from Jan. 15 to May 21, 2019, and the 596 responses were generalized to the entire ASDS membership of over 6,400 physicians.

Minimally invasive cosmetic surgery: Steady growth in 2018

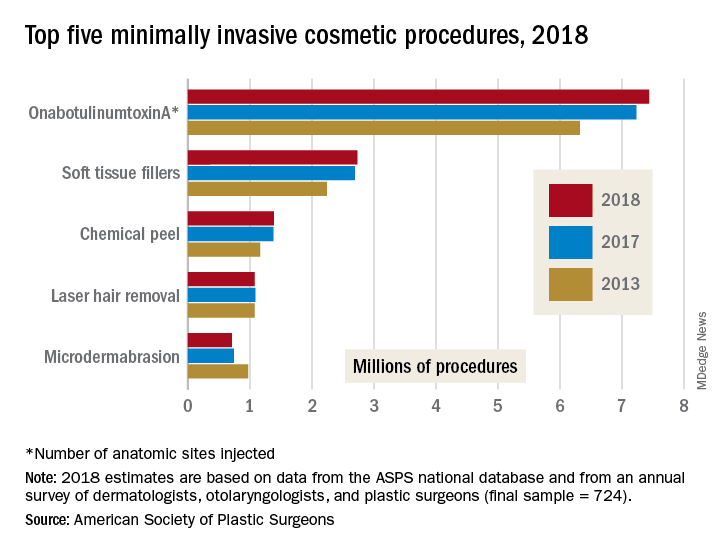

that brought the total to nearly 16 million procedures, according to the American Society of Plastic Surgeons.

The most popular form of minimally invasive cosmetic surgery among the estimated 15.9 million procedures performed in 2018 was, once again, onabotulinumtoxinA injection, which represented almost half of the total for the year with 7.4 million anatomic sites injected (up by 2.9%), the ASPS said in its 2018 Plastic Surgery Statistics Report.

Soft-tissue-filler injections, the next most popular type of surgery, were up 1.7% to almost 2.7 million procedures, while chemical peels rose 0.6% to nearly 1.4 million procedures. Numbers for 2018 were down, however, for the two other top-five surgeries: Laser hair removal slipped 0.9% from 2017 and microdermabrasion fell 4.2%, the ASPS reported.

Going back quite a bit further in time – the year 2000, to be exact – reveals 21st-century growth of 228% for the minimally invasive sector as a whole, but the long-term trend for cosmetic surgery was not quite as rosy – down by 4.7% since 2000. From 2017 to 2018, though, cosmetic surgery procedures were up by 1.2%, with breast augmentation the most popular, followed by liposuction, rhinoplasty, blepharoplasty, and abdominoplasty, according to the ASPS.

The 2018 statistics report was based on analysis of the society’s Tracking Operations and Outcomes for Plastic Surgeons database and an annual survey of board-certified dermatologists, otolaryngologists, and plastic surgeons (final sample = 724).

that brought the total to nearly 16 million procedures, according to the American Society of Plastic Surgeons.

The most popular form of minimally invasive cosmetic surgery among the estimated 15.9 million procedures performed in 2018 was, once again, onabotulinumtoxinA injection, which represented almost half of the total for the year with 7.4 million anatomic sites injected (up by 2.9%), the ASPS said in its 2018 Plastic Surgery Statistics Report.

Soft-tissue-filler injections, the next most popular type of surgery, were up 1.7% to almost 2.7 million procedures, while chemical peels rose 0.6% to nearly 1.4 million procedures. Numbers for 2018 were down, however, for the two other top-five surgeries: Laser hair removal slipped 0.9% from 2017 and microdermabrasion fell 4.2%, the ASPS reported.

Going back quite a bit further in time – the year 2000, to be exact – reveals 21st-century growth of 228% for the minimally invasive sector as a whole, but the long-term trend for cosmetic surgery was not quite as rosy – down by 4.7% since 2000. From 2017 to 2018, though, cosmetic surgery procedures were up by 1.2%, with breast augmentation the most popular, followed by liposuction, rhinoplasty, blepharoplasty, and abdominoplasty, according to the ASPS.

The 2018 statistics report was based on analysis of the society’s Tracking Operations and Outcomes for Plastic Surgeons database and an annual survey of board-certified dermatologists, otolaryngologists, and plastic surgeons (final sample = 724).

that brought the total to nearly 16 million procedures, according to the American Society of Plastic Surgeons.

The most popular form of minimally invasive cosmetic surgery among the estimated 15.9 million procedures performed in 2018 was, once again, onabotulinumtoxinA injection, which represented almost half of the total for the year with 7.4 million anatomic sites injected (up by 2.9%), the ASPS said in its 2018 Plastic Surgery Statistics Report.

Soft-tissue-filler injections, the next most popular type of surgery, were up 1.7% to almost 2.7 million procedures, while chemical peels rose 0.6% to nearly 1.4 million procedures. Numbers for 2018 were down, however, for the two other top-five surgeries: Laser hair removal slipped 0.9% from 2017 and microdermabrasion fell 4.2%, the ASPS reported.

Going back quite a bit further in time – the year 2000, to be exact – reveals 21st-century growth of 228% for the minimally invasive sector as a whole, but the long-term trend for cosmetic surgery was not quite as rosy – down by 4.7% since 2000. From 2017 to 2018, though, cosmetic surgery procedures were up by 1.2%, with breast augmentation the most popular, followed by liposuction, rhinoplasty, blepharoplasty, and abdominoplasty, according to the ASPS.

The 2018 statistics report was based on analysis of the society’s Tracking Operations and Outcomes for Plastic Surgeons database and an annual survey of board-certified dermatologists, otolaryngologists, and plastic surgeons (final sample = 724).

Social media use linked to acceptance of cosmetic surgery

Use of social media platforms such as Tinder, Snapchat, and Instagram, particularly in conjunction with photo-editing applications, may increase an individual’s acceptance of cosmetic surgery, a new study suggests.

In JAMA Facial Plastic Surgery, researchers report the outcomes of a web-based survey study involving 252 participants, 73.0% of whom were female. The survey asked participants about their use of social media, photo-editing tools such as Photoshop, VSCO, and Snapchat filters, and answered questionnaires to assess their self-esteem, self-worth, and attitudes toward cosmetic surgery.

All participants used at least one social media platform, with a mean of seven, and used a mean of two photo-editing applications; the analysis found that those who used more social media platforms were more likely to consider cosmetic surgery.

People who used Tinder and Snapchat – with or without photo filters – showed greater acceptance of cosmetic surgery, while those who used the photography mobile app VSCO and Instagram photo filters showed greater consideration but not acceptance of cosmetic surgery, compared with nonusers.

Participants whose self-worth was more closely tied to their appearance showed greater acceptance of cosmetic surgery. When it came to self-esteem, participants who used YouTube, WhatsApp, VSCO, and Photoshop had lower self-esteem scores, compared with nonusers.

Overall, nearly two-thirds of survey participants said they used photo-editing applications to change the lighting of images, but only 5.16% said they used these applications to make changes to face or body shape. This distinction was also seen in their acceptance of cosmetic surgery scores: Those who said they made changes to face and body shape showed higher acceptance scores than nonusers, but this was not seen in those who only used it for lighting adjustments.

“The rising trend of pursuing cosmetic surgery based on social media inspiration highlights the need to better understand patients’ motivations to seek cosmetic surgery,” wrote Jonlin Chen, a medical student at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and coauthors.

Commenting on the association between YouTube use, lower self-esteem, and higher acceptance of cosmetic surgery, the authors suggested that the platform may generate appearance comparisons between users by allowing them to access beauty-related videos and connect with other users interested in cosmetics.

Michael J. Reilly, MD, department of otolaryngology–head and neck surgery and Keon M. Parsa, MD, from the department of psychiatry at MedStar Georgetown University Hospital in Washington, commented in an accompanying editorial that the findings of this study illustrate an increased trend seen by facial plastic surgeons (JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2019 June 27. doi: 10.1001/jamafacial.2019.0419). The study “shows the importance of understanding the underlying motives and characteristics of individuals seeking cosmetic surgery.” They noted that facial plastic surgeons can play a role in helping patients to improve their self-esteem, but it is also important to be aware of the clinical signs of depression, anxiety, and social isolation and refer for appropriate nonsurgical support when there are mental health concerns that go beyond the knife and needle.

The authors of the study did note that their choice of a web-based survey meant the demographic was likely to be skewed toward a younger, more social media–savvy demographic, and may not necessarily represent the broader population of individuals seeking cosmetic surgery.

No funding or conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Chen J et al. JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2019 Jun 27. doi: 10.1001/jamafacial.2019.0328.

Use of social media platforms such as Tinder, Snapchat, and Instagram, particularly in conjunction with photo-editing applications, may increase an individual’s acceptance of cosmetic surgery, a new study suggests.

In JAMA Facial Plastic Surgery, researchers report the outcomes of a web-based survey study involving 252 participants, 73.0% of whom were female. The survey asked participants about their use of social media, photo-editing tools such as Photoshop, VSCO, and Snapchat filters, and answered questionnaires to assess their self-esteem, self-worth, and attitudes toward cosmetic surgery.

All participants used at least one social media platform, with a mean of seven, and used a mean of two photo-editing applications; the analysis found that those who used more social media platforms were more likely to consider cosmetic surgery.

People who used Tinder and Snapchat – with or without photo filters – showed greater acceptance of cosmetic surgery, while those who used the photography mobile app VSCO and Instagram photo filters showed greater consideration but not acceptance of cosmetic surgery, compared with nonusers.

Participants whose self-worth was more closely tied to their appearance showed greater acceptance of cosmetic surgery. When it came to self-esteem, participants who used YouTube, WhatsApp, VSCO, and Photoshop had lower self-esteem scores, compared with nonusers.

Overall, nearly two-thirds of survey participants said they used photo-editing applications to change the lighting of images, but only 5.16% said they used these applications to make changes to face or body shape. This distinction was also seen in their acceptance of cosmetic surgery scores: Those who said they made changes to face and body shape showed higher acceptance scores than nonusers, but this was not seen in those who only used it for lighting adjustments.

“The rising trend of pursuing cosmetic surgery based on social media inspiration highlights the need to better understand patients’ motivations to seek cosmetic surgery,” wrote Jonlin Chen, a medical student at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and coauthors.

Commenting on the association between YouTube use, lower self-esteem, and higher acceptance of cosmetic surgery, the authors suggested that the platform may generate appearance comparisons between users by allowing them to access beauty-related videos and connect with other users interested in cosmetics.

Michael J. Reilly, MD, department of otolaryngology–head and neck surgery and Keon M. Parsa, MD, from the department of psychiatry at MedStar Georgetown University Hospital in Washington, commented in an accompanying editorial that the findings of this study illustrate an increased trend seen by facial plastic surgeons (JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2019 June 27. doi: 10.1001/jamafacial.2019.0419). The study “shows the importance of understanding the underlying motives and characteristics of individuals seeking cosmetic surgery.” They noted that facial plastic surgeons can play a role in helping patients to improve their self-esteem, but it is also important to be aware of the clinical signs of depression, anxiety, and social isolation and refer for appropriate nonsurgical support when there are mental health concerns that go beyond the knife and needle.

The authors of the study did note that their choice of a web-based survey meant the demographic was likely to be skewed toward a younger, more social media–savvy demographic, and may not necessarily represent the broader population of individuals seeking cosmetic surgery.

No funding or conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Chen J et al. JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2019 Jun 27. doi: 10.1001/jamafacial.2019.0328.

Use of social media platforms such as Tinder, Snapchat, and Instagram, particularly in conjunction with photo-editing applications, may increase an individual’s acceptance of cosmetic surgery, a new study suggests.

In JAMA Facial Plastic Surgery, researchers report the outcomes of a web-based survey study involving 252 participants, 73.0% of whom were female. The survey asked participants about their use of social media, photo-editing tools such as Photoshop, VSCO, and Snapchat filters, and answered questionnaires to assess their self-esteem, self-worth, and attitudes toward cosmetic surgery.

All participants used at least one social media platform, with a mean of seven, and used a mean of two photo-editing applications; the analysis found that those who used more social media platforms were more likely to consider cosmetic surgery.

People who used Tinder and Snapchat – with or without photo filters – showed greater acceptance of cosmetic surgery, while those who used the photography mobile app VSCO and Instagram photo filters showed greater consideration but not acceptance of cosmetic surgery, compared with nonusers.

Participants whose self-worth was more closely tied to their appearance showed greater acceptance of cosmetic surgery. When it came to self-esteem, participants who used YouTube, WhatsApp, VSCO, and Photoshop had lower self-esteem scores, compared with nonusers.

Overall, nearly two-thirds of survey participants said they used photo-editing applications to change the lighting of images, but only 5.16% said they used these applications to make changes to face or body shape. This distinction was also seen in their acceptance of cosmetic surgery scores: Those who said they made changes to face and body shape showed higher acceptance scores than nonusers, but this was not seen in those who only used it for lighting adjustments.

“The rising trend of pursuing cosmetic surgery based on social media inspiration highlights the need to better understand patients’ motivations to seek cosmetic surgery,” wrote Jonlin Chen, a medical student at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and coauthors.

Commenting on the association between YouTube use, lower self-esteem, and higher acceptance of cosmetic surgery, the authors suggested that the platform may generate appearance comparisons between users by allowing them to access beauty-related videos and connect with other users interested in cosmetics.

Michael J. Reilly, MD, department of otolaryngology–head and neck surgery and Keon M. Parsa, MD, from the department of psychiatry at MedStar Georgetown University Hospital in Washington, commented in an accompanying editorial that the findings of this study illustrate an increased trend seen by facial plastic surgeons (JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2019 June 27. doi: 10.1001/jamafacial.2019.0419). The study “shows the importance of understanding the underlying motives and characteristics of individuals seeking cosmetic surgery.” They noted that facial plastic surgeons can play a role in helping patients to improve their self-esteem, but it is also important to be aware of the clinical signs of depression, anxiety, and social isolation and refer for appropriate nonsurgical support when there are mental health concerns that go beyond the knife and needle.

The authors of the study did note that their choice of a web-based survey meant the demographic was likely to be skewed toward a younger, more social media–savvy demographic, and may not necessarily represent the broader population of individuals seeking cosmetic surgery.

No funding or conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Chen J et al. JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2019 Jun 27. doi: 10.1001/jamafacial.2019.0328.

FROM JAMA FACIAL PLASTIC SURGERY

FDA opts not to ban textured breast implants

The Food and Drug Administration decided to continue to allow U.S. sales of textured breast implants, which have been identified as the cause of a rare but significant cancer, breast implant–associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma.

A statement the agency released on May 2 said “The FDA does not believe that, on the basis of available data and information, the device [textured implants] meets the banning standard set forth in the Federal Food and Drug Cosmetic Act.” roughly half of them in the United States.

In coming to this decision, following 2 days of public testimony and discussions by an advisory committee in late March, the FDA is bucking the path taken by regulatory bodies of the European Union as well as several other counties. The EU acted in December 2018 to produce the equivalent of a ban on sales of textured breast implants marketed by Allergan. Then in April 2019, the French drug and device regulatory agency expanded this ban to textured breast implants sold by five other companies.

During the FDA advisory committee meeting in March, one of the world’s experts on BIA-ALCL, Mark W. Clemens, MD, a plastic surgeon at MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, said that of about 500 case reports received by the FDA, not one had involved a confirmed and “pure” episode of BIA-ALCL linked with a smooth breast implant. A team of experts recently reached the same conclusion when reviewing the reported worldwide incidence of BIA-ALCL in a published review (Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019 March;143[3S]:30S-40S).

Despite these reports, the FDA said in its new statement that “While the majority of women who develop BIA-ALCL have had textured implants, there are known cases in women with smooth-surface breast implants, and many reports do not include the surface texture of the implant at the time of diagnosis.” The agency added that it is “focused on strengthening the evidence generated to help inform future regulatory action.” During the March advisory committee meeting, some members of the panel spoke against a marketing ban on textured implants for reasons such as the modest number of reported cases and because of the importance of having a textured implant option available.

The FDA took several other notable steps in its May 2 statement:

The agency formally acknowledged that many breast implant recipients have reported experiencing adverse effects that include chronic fatigue, cognitive issues, and joint and muscle pain. “While the FDA doesn’t have definitive evidence demonstrating breast implants cause these symptoms, the current evidence supports that some women experience systemic symptoms that may resolve when their breast implants are removed.” The agency also cited the term that patients have coined for these symptoms: Breast Implant Illness.

The FDA made a commitment to “take steps to improve the information available to women and health care professionals about the risks of breast implants,” including the risk for BIA-ALCL, the increased risk for this cancer with textured implants, and the risk for systemic symptoms. The agency said it would work with stakeholders on possible changes to breast implant labeling, including a possible boxed warning, and a patient-decision checklist.