User login

Medicaid implements waivers for some clinical trial coverage

Federal officials will allow some flexibility in meeting new requirements on covering the costs of clinical trials for people enrolled in Medicaid, seeking to accommodate states where legislatures will not meet in time to make needed changes in rules.

Congress in 2020 ordered U.S. states to have their Medicaid programs cover expenses related to participation in certain clinical trials, a move that was hailed by the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) and other groups as a boost to trials as well as to patients with serious illness who have lower incomes.

The mandate went into effect on Jan. 1, but the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services will allow accommodations in terms of implementation time for states that have not yet been able to make needed legislative changes, Daniel Tsai, deputy administrator and director of the Center for Medicaid and CHIP Services, wrote in a Dec. 7 letter. Mr. Tsai’s letter doesn’t mention specific states. The CMS did not immediately respond to a request seeking information on the states expected to apply for waivers.

Medicaid has in recent years been a rare large U.S. insurance program that does not cover the costs of clinical trials. The Affordable Care Act of 2010 mandated this coverage for people in private insurance plans. The federal government in 2000 decided that Medicare would do so.

‘A hidden opportunity’

A perspective article last May in the New England Journal of Medicine referred to the new Medicaid mandate on clinical trials as a “hidden opportunity,” referring to its genesis as an add-on in a massive federal spending package enacted in December 2020.

In the article, Samuel U. Takvorian, MD, MSHP, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and coauthors noted that rates of participation in clinical trials remain low for racial and ethnic minority groups, due in part to the lack of Medicaid coverage.

“For example, non-Hispanic White patients are nearly twice as likely as Black patients and three times as likely as Hispanic patients to enroll in cancer clinical trials – a gap that has widened over time,” Dr. Takvorian and coauthors wrote. “Inequities in enrollment have also manifested during the COVID-19 pandemic, which has disproportionately affected non-White patients, without their commensurate representation in trials of COVID-19 therapeutics.”

In October, researchers from the Arthur G. James Cancer Hospital and Ohio State University, Columbus, published results of a retrospective study of patients with stage I-IV pancreatic cancer that also found inequities in enrollment. Mariam F. Eskander, MD, MPH, and coauthors reported what they found by examining records for 1,127 patients (0.4%) enrolled in clinical trials and 301,340 (99.6%) who did not enroll. They found that enrollment in trials increased over the study period, but not for Black patients or patients on Medicaid.

In an interview, Dr. Eskander said the new Medicaid policy will remove a major obstacle to participation in clinical trials. An oncologist, Dr. Eskander said she is looking forward to being able to help more of her patients get access to experimental medicines and treatments.

But that may not be enough to draw more people with low incomes into these studies, said Dr. Eskander, who is now at Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey in New Brunswick. She urges greater use of patient navigators to help people on Medicaid understand the resources available to them, as well as broad use of Medicaid’s nonemergency medical transportation (NEMT) benefit.

“Some patients will be offered clinical trial enrollment and some will accept, but I really worry about the challenges low-income people face with things like transportation and getting time off work,” she said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Federal officials will allow some flexibility in meeting new requirements on covering the costs of clinical trials for people enrolled in Medicaid, seeking to accommodate states where legislatures will not meet in time to make needed changes in rules.

Congress in 2020 ordered U.S. states to have their Medicaid programs cover expenses related to participation in certain clinical trials, a move that was hailed by the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) and other groups as a boost to trials as well as to patients with serious illness who have lower incomes.

The mandate went into effect on Jan. 1, but the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services will allow accommodations in terms of implementation time for states that have not yet been able to make needed legislative changes, Daniel Tsai, deputy administrator and director of the Center for Medicaid and CHIP Services, wrote in a Dec. 7 letter. Mr. Tsai’s letter doesn’t mention specific states. The CMS did not immediately respond to a request seeking information on the states expected to apply for waivers.

Medicaid has in recent years been a rare large U.S. insurance program that does not cover the costs of clinical trials. The Affordable Care Act of 2010 mandated this coverage for people in private insurance plans. The federal government in 2000 decided that Medicare would do so.

‘A hidden opportunity’

A perspective article last May in the New England Journal of Medicine referred to the new Medicaid mandate on clinical trials as a “hidden opportunity,” referring to its genesis as an add-on in a massive federal spending package enacted in December 2020.

In the article, Samuel U. Takvorian, MD, MSHP, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and coauthors noted that rates of participation in clinical trials remain low for racial and ethnic minority groups, due in part to the lack of Medicaid coverage.

“For example, non-Hispanic White patients are nearly twice as likely as Black patients and three times as likely as Hispanic patients to enroll in cancer clinical trials – a gap that has widened over time,” Dr. Takvorian and coauthors wrote. “Inequities in enrollment have also manifested during the COVID-19 pandemic, which has disproportionately affected non-White patients, without their commensurate representation in trials of COVID-19 therapeutics.”

In October, researchers from the Arthur G. James Cancer Hospital and Ohio State University, Columbus, published results of a retrospective study of patients with stage I-IV pancreatic cancer that also found inequities in enrollment. Mariam F. Eskander, MD, MPH, and coauthors reported what they found by examining records for 1,127 patients (0.4%) enrolled in clinical trials and 301,340 (99.6%) who did not enroll. They found that enrollment in trials increased over the study period, but not for Black patients or patients on Medicaid.

In an interview, Dr. Eskander said the new Medicaid policy will remove a major obstacle to participation in clinical trials. An oncologist, Dr. Eskander said she is looking forward to being able to help more of her patients get access to experimental medicines and treatments.

But that may not be enough to draw more people with low incomes into these studies, said Dr. Eskander, who is now at Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey in New Brunswick. She urges greater use of patient navigators to help people on Medicaid understand the resources available to them, as well as broad use of Medicaid’s nonemergency medical transportation (NEMT) benefit.

“Some patients will be offered clinical trial enrollment and some will accept, but I really worry about the challenges low-income people face with things like transportation and getting time off work,” she said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Federal officials will allow some flexibility in meeting new requirements on covering the costs of clinical trials for people enrolled in Medicaid, seeking to accommodate states where legislatures will not meet in time to make needed changes in rules.

Congress in 2020 ordered U.S. states to have their Medicaid programs cover expenses related to participation in certain clinical trials, a move that was hailed by the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) and other groups as a boost to trials as well as to patients with serious illness who have lower incomes.

The mandate went into effect on Jan. 1, but the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services will allow accommodations in terms of implementation time for states that have not yet been able to make needed legislative changes, Daniel Tsai, deputy administrator and director of the Center for Medicaid and CHIP Services, wrote in a Dec. 7 letter. Mr. Tsai’s letter doesn’t mention specific states. The CMS did not immediately respond to a request seeking information on the states expected to apply for waivers.

Medicaid has in recent years been a rare large U.S. insurance program that does not cover the costs of clinical trials. The Affordable Care Act of 2010 mandated this coverage for people in private insurance plans. The federal government in 2000 decided that Medicare would do so.

‘A hidden opportunity’

A perspective article last May in the New England Journal of Medicine referred to the new Medicaid mandate on clinical trials as a “hidden opportunity,” referring to its genesis as an add-on in a massive federal spending package enacted in December 2020.

In the article, Samuel U. Takvorian, MD, MSHP, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and coauthors noted that rates of participation in clinical trials remain low for racial and ethnic minority groups, due in part to the lack of Medicaid coverage.

“For example, non-Hispanic White patients are nearly twice as likely as Black patients and three times as likely as Hispanic patients to enroll in cancer clinical trials – a gap that has widened over time,” Dr. Takvorian and coauthors wrote. “Inequities in enrollment have also manifested during the COVID-19 pandemic, which has disproportionately affected non-White patients, without their commensurate representation in trials of COVID-19 therapeutics.”

In October, researchers from the Arthur G. James Cancer Hospital and Ohio State University, Columbus, published results of a retrospective study of patients with stage I-IV pancreatic cancer that also found inequities in enrollment. Mariam F. Eskander, MD, MPH, and coauthors reported what they found by examining records for 1,127 patients (0.4%) enrolled in clinical trials and 301,340 (99.6%) who did not enroll. They found that enrollment in trials increased over the study period, but not for Black patients or patients on Medicaid.

In an interview, Dr. Eskander said the new Medicaid policy will remove a major obstacle to participation in clinical trials. An oncologist, Dr. Eskander said she is looking forward to being able to help more of her patients get access to experimental medicines and treatments.

But that may not be enough to draw more people with low incomes into these studies, said Dr. Eskander, who is now at Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey in New Brunswick. She urges greater use of patient navigators to help people on Medicaid understand the resources available to them, as well as broad use of Medicaid’s nonemergency medical transportation (NEMT) benefit.

“Some patients will be offered clinical trial enrollment and some will accept, but I really worry about the challenges low-income people face with things like transportation and getting time off work,” she said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Are GI hospitalists the future of inpatient care?

Dear colleagues and friends,

After an excellent debate on the future of telemedicine in GI in our most recent Perspectives column, we continue to explore changes in the way we traditionally provide care. In this issue, we discuss the GI hospitalist service, a relatively new but growing model of providing inpatient care. Is this the new ideal, allowing for more efficient care? Or are traditional or alternative models more appropriate? As with most things, the answer often lies somewhere in the middle, driven by local needs and infrastructure. Dr. Tau and Dr. Mehendiratta explore the pros and cons of these different approaches to providing inpatient GI care. I look forward to hearing your thoughts and experiences on the AGA Community forum and by email ([email protected]).

Gyanprakash A. Ketwaroo, MD, MSc, is an assistant professor of medicine at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston. He is an associate editor for GI & Hepatology News.

The dedicated GI hospitalist: Taking ownership not ‘call’

By J. Andy Tau, MD

In my experience, a GI hospitalist provides mutual benefit to patients, employers, and consulting physicians. The patient benefits from more expedient consultations and expert endoscopic therapy, which translates to shorter hospitalizations and improved outcomes. The employer enjoys financial benefits as busy outpatient providers can stay busy without interruption. Consulting physicians enjoy having to only call a single phone number for trusted help from a familiar physician who does not rotate off service. Personally, the position provides the volume to develop valuable therapeutic endoscopy skills and techniques. With one stable physician at the helm, a sense of ownership can develop, rather than a sense of survival until “call” is over.

As a full-time GI hospitalist for a large single-specialty group, I provide inpatient GI and hepatology consultation from 7 a.m. to 5 p.m., Monday-Friday. I do not rotate off service. I cover three hospitals with a total of 1,000 beds with two advanced practice providers and one part-time physician. Except for endoscopic ultrasound, I perform all other endoscopic procedures. The census is usually 25-35 with an average of 10-15 new consults per day.

The most important benefit of a dedicated GI hospitalist is providing expedited consultation and expert endoscopy for patients. I can offer emergent (<6 hour) endoscopy for any patient. An esophageal food impaction is usually resolved within an hour of arrival to the ED during the day. I can help a surgeon intraoperatively on very short notice. As for acute GI bleeding cases, I oversee resuscitative efforts, while the endoscopy team prepares my preferred endoscopic equipment, eliminating surprises and delays before endoscopy. I have developed an expertise in hemostasis and managing esophageal perforations, along with a risk tolerance that cannot be matured in any setting other than daily emergency.

I have enacted evidence-based protocols for GI bleeding, iron-deficiency anemia, colonic pseudo-obstruction, pancreatitis, and liver decompensation, which internists have adopted over time, reducing phone calls and delays in prep or resuscitation.

While the day is unstructured and filled with interruptions, it is also very flexible. As opposed to the set time intervals of an outpatient clinic visit, I can spend an hour in a palliative care meeting or revisit high-risk patients multiple times a day to detect pending deterioration. Combined endoscopic and surgical cases are logistically easy to schedule given my flexibility. For example, patients with choledocholithiasis often can have a combined cholecystectomy and supine endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) in the OR, shaving a day off admission.

My employer benefits financially as the outpatient doctors can stay busy without interruption from the hospital. With secure group messaging, we are able to make joint decisions and arrange close follow up. The relative value units earned from the hospital are high. Combined with proceeds from the professional service agreement with the hospital, they are more than enough to cover my compensation.

Any physician in need of a GI consult needs only to call one number for help. I make it as easy as possible to obtain a consult and never push back, as banal as any consult may seem. I stake my reputation on providing a service that is able, affable, and available. By teaching a consistent message to consulting physicians, I have now effected best evidence-based practices for GI conditions even without engaging me. The most notable examples include antibiotics for variceal bleeding, fluid resuscitation and early feeding for acute pancreatitis, risk stratification for choledocholithiasis, and last but not least, abandoning the inpatient fecal occult blood test.

I am on a first-name basis with every nurse in the hospital now. In exchange for my availability and cell phone number, they place orders for me and protect me from avoidable nuisances.

Many physician groups cover the inpatient service by rotating a week at a time. There can be at times a reluctance to take ownership over a difficult patient and instead a sense of “survival of the call”. However, in my job, “the buck stops with me” even if it is in the form of readmission. For example, I have to take some ownership of indigent patients who cannot easily follow up. Who will remove the stent I placed? How will they pay for Helicobacter pylori eradication or biologic therapy? Another example is diverticular bleeding. While 80% stop on their own, I take extraordinary efforts to endoscopically find and halt the bleeding in order to reduce the recurrence rate. I must find durable solutions because these high-risk patients are my responsibility again when they bounce back to me via the ED.

By way of volume alone, this position has allowed me to develop many therapeutic skills outside of a standard 3-year GI fellowship. While I did only 200 ERCPs in fellowship, I have become proficient in ERCP with around 400 cases per year (mostly native papilla) and have grown comfortable with the needle knife. I have learned endoscopic suturing, luminal stenting, and endoscopic vacuum-assisted therapy for perforation closure independently. Out of necessity, I developed a novel technique in optimizing the use of hemostatic powder by using a bone-wax plug. As endoscopy chief, I can purchase a wide variety of endoscopy equipment, compare brands, and understand the nuances of each.

In conclusion, the dedicated GI hospitalist indirectly improves the efficiency of an outpatient practice, while directly improving inpatient outcomes, collegiality, and even one’s own skills as an endoscopist. While it can be challenging and hectic, with the right mentality towards ownership of the service, it is also an incredibly rewarding position.

Dr. Tau practices with Austin Gastroenterology in Austin, Tex. He disclosed relationships with Cook Medical and Conmed.

Inpatient-only GI hospitalist: Not so fast

By Vaibhav Mehendiratta, MD

Over the past 2 decades, the medical hospitalist system has assumed care of hospitalized patients with the promise of reduced length of stay (LOS) and improved outcomes. Although data on LOS is promising, there have been conflicting results in terms of total medical costs and resource utilization. Inpatient care for patients with complex medical histories often requires regular communication with other subspecialties and outpatient providers to achieve better patient-centered outcomes.

Providing inpatient gastrointestinal care is complicated. Traditional models rely on physicians trying to balance outpatient obligations with inpatient rounding and procedures, which can result in delayed endoscopy and an inability to participate fully in multidisciplinary rounds and family meetings. The complexity of hospitalized patients often requires a multidisciplinary approach with coordination of care that is hard to accomplish in between seeing outpatients. GI groups, both private practice and academics, need to adopt a strategy for inpatient care that is tailored to the hospital system in which they operate.

As one of the largest private practice groups in New England, our experience can provide a framework for others to follow. We provide inpatient GI care at eight hospitals across northern Connecticut. Our inpatient service at the largest tertiary care hospital is composed of one general gastroenterologist, one advanced endoscopist, one transplant hepatologist, two advanced practitioners, and two fellows in training. Each practitioner provides coverage on a rotating basis, typically 1 week at a time every 4-8 weeks. This model also offers flexibility, such that we can typically accommodate urgent outpatient endoscopy for patients who may otherwise require inpatient care. Coverage at the other seven hospitals is tailored to local needs and ranges from half-day to whole-day coverage by general gastroenterologists and advanced practitioners. We believe that our model is financially viable and, based on our experience, inpatient relative value units generated are quite similar to a typical day in outpatient GI practice.

Inpatient GI care accounts for a substantial portion of overall inpatient care in the United States. Endoscopy delays have been the focus of many research articles looking at inpatient GI care. The delays are caused by many factors, including endoscopy unit/staff availability, anesthesia availability, and patient factors. While having a dedicated inpatient GI Hospitalist offers the potential to streamline access for hospital consultations and endoscopy, an exclusive inpatient GI hospitalist may be less familiar with a patient’s chronic GI illness and have different (and perhaps, conflicting) priorities regarding a patient’s care. Having incomplete access to outpatient records or less familiarity with the intricacies of outpatient care could also lead to duplication of work and increase the number of inpatient procedures that may have otherwise been deferred to the outpatient setting.

Additionally, with physician burnout on the rise and particularly in the inpatient setting, one must question the sustainability of an exclusively inpatient GI practice. That is, the hours and demands of inpatient care typically do not allow the quality of life that outpatient care provides. Our model provides time for dedicated inpatient care, while allowing each practitioner ample opportunity to build a robust outpatient practice.

Some health care organizations are adopting an extensivist model to provide comprehensive care to patients with multiple medical problems. Extensivists are outpatient primary care providers who take the time to coordinate with inpatient hospitalists to provide comprehensive care to their patients. Constant contact with outpatient providers during admission is expected to improve patient satisfaction, reduce hospital readmissions, and decrease inpatient resource utilization.

In conclusion, our experience highlights sustained benefits, and distinct advantages, of providing inpatient GI care without a GI hospitalist model. The pendulum in inpatient care keeps swinging and with progress arise new challenges and questions. Close collaboration between gastroenterologists and health systems to develop a program that fits local needs and allows optimal resource allocation will ensure delivery of high-quality inpatient GI care.

Dr. Mehendiratta is a gastroenterologist with Connecticut GI PC, Hartford, and assistant clinical professor in the department of medicine at the University of Connecticut, Farmington. He has no relevant conflicts of interest to disclose.

Dear colleagues and friends,

After an excellent debate on the future of telemedicine in GI in our most recent Perspectives column, we continue to explore changes in the way we traditionally provide care. In this issue, we discuss the GI hospitalist service, a relatively new but growing model of providing inpatient care. Is this the new ideal, allowing for more efficient care? Or are traditional or alternative models more appropriate? As with most things, the answer often lies somewhere in the middle, driven by local needs and infrastructure. Dr. Tau and Dr. Mehendiratta explore the pros and cons of these different approaches to providing inpatient GI care. I look forward to hearing your thoughts and experiences on the AGA Community forum and by email ([email protected]).

Gyanprakash A. Ketwaroo, MD, MSc, is an assistant professor of medicine at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston. He is an associate editor for GI & Hepatology News.

The dedicated GI hospitalist: Taking ownership not ‘call’

By J. Andy Tau, MD

In my experience, a GI hospitalist provides mutual benefit to patients, employers, and consulting physicians. The patient benefits from more expedient consultations and expert endoscopic therapy, which translates to shorter hospitalizations and improved outcomes. The employer enjoys financial benefits as busy outpatient providers can stay busy without interruption. Consulting physicians enjoy having to only call a single phone number for trusted help from a familiar physician who does not rotate off service. Personally, the position provides the volume to develop valuable therapeutic endoscopy skills and techniques. With one stable physician at the helm, a sense of ownership can develop, rather than a sense of survival until “call” is over.

As a full-time GI hospitalist for a large single-specialty group, I provide inpatient GI and hepatology consultation from 7 a.m. to 5 p.m., Monday-Friday. I do not rotate off service. I cover three hospitals with a total of 1,000 beds with two advanced practice providers and one part-time physician. Except for endoscopic ultrasound, I perform all other endoscopic procedures. The census is usually 25-35 with an average of 10-15 new consults per day.

The most important benefit of a dedicated GI hospitalist is providing expedited consultation and expert endoscopy for patients. I can offer emergent (<6 hour) endoscopy for any patient. An esophageal food impaction is usually resolved within an hour of arrival to the ED during the day. I can help a surgeon intraoperatively on very short notice. As for acute GI bleeding cases, I oversee resuscitative efforts, while the endoscopy team prepares my preferred endoscopic equipment, eliminating surprises and delays before endoscopy. I have developed an expertise in hemostasis and managing esophageal perforations, along with a risk tolerance that cannot be matured in any setting other than daily emergency.

I have enacted evidence-based protocols for GI bleeding, iron-deficiency anemia, colonic pseudo-obstruction, pancreatitis, and liver decompensation, which internists have adopted over time, reducing phone calls and delays in prep or resuscitation.

While the day is unstructured and filled with interruptions, it is also very flexible. As opposed to the set time intervals of an outpatient clinic visit, I can spend an hour in a palliative care meeting or revisit high-risk patients multiple times a day to detect pending deterioration. Combined endoscopic and surgical cases are logistically easy to schedule given my flexibility. For example, patients with choledocholithiasis often can have a combined cholecystectomy and supine endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) in the OR, shaving a day off admission.

My employer benefits financially as the outpatient doctors can stay busy without interruption from the hospital. With secure group messaging, we are able to make joint decisions and arrange close follow up. The relative value units earned from the hospital are high. Combined with proceeds from the professional service agreement with the hospital, they are more than enough to cover my compensation.

Any physician in need of a GI consult needs only to call one number for help. I make it as easy as possible to obtain a consult and never push back, as banal as any consult may seem. I stake my reputation on providing a service that is able, affable, and available. By teaching a consistent message to consulting physicians, I have now effected best evidence-based practices for GI conditions even without engaging me. The most notable examples include antibiotics for variceal bleeding, fluid resuscitation and early feeding for acute pancreatitis, risk stratification for choledocholithiasis, and last but not least, abandoning the inpatient fecal occult blood test.

I am on a first-name basis with every nurse in the hospital now. In exchange for my availability and cell phone number, they place orders for me and protect me from avoidable nuisances.

Many physician groups cover the inpatient service by rotating a week at a time. There can be at times a reluctance to take ownership over a difficult patient and instead a sense of “survival of the call”. However, in my job, “the buck stops with me” even if it is in the form of readmission. For example, I have to take some ownership of indigent patients who cannot easily follow up. Who will remove the stent I placed? How will they pay for Helicobacter pylori eradication or biologic therapy? Another example is diverticular bleeding. While 80% stop on their own, I take extraordinary efforts to endoscopically find and halt the bleeding in order to reduce the recurrence rate. I must find durable solutions because these high-risk patients are my responsibility again when they bounce back to me via the ED.

By way of volume alone, this position has allowed me to develop many therapeutic skills outside of a standard 3-year GI fellowship. While I did only 200 ERCPs in fellowship, I have become proficient in ERCP with around 400 cases per year (mostly native papilla) and have grown comfortable with the needle knife. I have learned endoscopic suturing, luminal stenting, and endoscopic vacuum-assisted therapy for perforation closure independently. Out of necessity, I developed a novel technique in optimizing the use of hemostatic powder by using a bone-wax plug. As endoscopy chief, I can purchase a wide variety of endoscopy equipment, compare brands, and understand the nuances of each.

In conclusion, the dedicated GI hospitalist indirectly improves the efficiency of an outpatient practice, while directly improving inpatient outcomes, collegiality, and even one’s own skills as an endoscopist. While it can be challenging and hectic, with the right mentality towards ownership of the service, it is also an incredibly rewarding position.

Dr. Tau practices with Austin Gastroenterology in Austin, Tex. He disclosed relationships with Cook Medical and Conmed.

Inpatient-only GI hospitalist: Not so fast

By Vaibhav Mehendiratta, MD

Over the past 2 decades, the medical hospitalist system has assumed care of hospitalized patients with the promise of reduced length of stay (LOS) and improved outcomes. Although data on LOS is promising, there have been conflicting results in terms of total medical costs and resource utilization. Inpatient care for patients with complex medical histories often requires regular communication with other subspecialties and outpatient providers to achieve better patient-centered outcomes.

Providing inpatient gastrointestinal care is complicated. Traditional models rely on physicians trying to balance outpatient obligations with inpatient rounding and procedures, which can result in delayed endoscopy and an inability to participate fully in multidisciplinary rounds and family meetings. The complexity of hospitalized patients often requires a multidisciplinary approach with coordination of care that is hard to accomplish in between seeing outpatients. GI groups, both private practice and academics, need to adopt a strategy for inpatient care that is tailored to the hospital system in which they operate.

As one of the largest private practice groups in New England, our experience can provide a framework for others to follow. We provide inpatient GI care at eight hospitals across northern Connecticut. Our inpatient service at the largest tertiary care hospital is composed of one general gastroenterologist, one advanced endoscopist, one transplant hepatologist, two advanced practitioners, and two fellows in training. Each practitioner provides coverage on a rotating basis, typically 1 week at a time every 4-8 weeks. This model also offers flexibility, such that we can typically accommodate urgent outpatient endoscopy for patients who may otherwise require inpatient care. Coverage at the other seven hospitals is tailored to local needs and ranges from half-day to whole-day coverage by general gastroenterologists and advanced practitioners. We believe that our model is financially viable and, based on our experience, inpatient relative value units generated are quite similar to a typical day in outpatient GI practice.

Inpatient GI care accounts for a substantial portion of overall inpatient care in the United States. Endoscopy delays have been the focus of many research articles looking at inpatient GI care. The delays are caused by many factors, including endoscopy unit/staff availability, anesthesia availability, and patient factors. While having a dedicated inpatient GI Hospitalist offers the potential to streamline access for hospital consultations and endoscopy, an exclusive inpatient GI hospitalist may be less familiar with a patient’s chronic GI illness and have different (and perhaps, conflicting) priorities regarding a patient’s care. Having incomplete access to outpatient records or less familiarity with the intricacies of outpatient care could also lead to duplication of work and increase the number of inpatient procedures that may have otherwise been deferred to the outpatient setting.

Additionally, with physician burnout on the rise and particularly in the inpatient setting, one must question the sustainability of an exclusively inpatient GI practice. That is, the hours and demands of inpatient care typically do not allow the quality of life that outpatient care provides. Our model provides time for dedicated inpatient care, while allowing each practitioner ample opportunity to build a robust outpatient practice.

Some health care organizations are adopting an extensivist model to provide comprehensive care to patients with multiple medical problems. Extensivists are outpatient primary care providers who take the time to coordinate with inpatient hospitalists to provide comprehensive care to their patients. Constant contact with outpatient providers during admission is expected to improve patient satisfaction, reduce hospital readmissions, and decrease inpatient resource utilization.

In conclusion, our experience highlights sustained benefits, and distinct advantages, of providing inpatient GI care without a GI hospitalist model. The pendulum in inpatient care keeps swinging and with progress arise new challenges and questions. Close collaboration between gastroenterologists and health systems to develop a program that fits local needs and allows optimal resource allocation will ensure delivery of high-quality inpatient GI care.

Dr. Mehendiratta is a gastroenterologist with Connecticut GI PC, Hartford, and assistant clinical professor in the department of medicine at the University of Connecticut, Farmington. He has no relevant conflicts of interest to disclose.

Dear colleagues and friends,

After an excellent debate on the future of telemedicine in GI in our most recent Perspectives column, we continue to explore changes in the way we traditionally provide care. In this issue, we discuss the GI hospitalist service, a relatively new but growing model of providing inpatient care. Is this the new ideal, allowing for more efficient care? Or are traditional or alternative models more appropriate? As with most things, the answer often lies somewhere in the middle, driven by local needs and infrastructure. Dr. Tau and Dr. Mehendiratta explore the pros and cons of these different approaches to providing inpatient GI care. I look forward to hearing your thoughts and experiences on the AGA Community forum and by email ([email protected]).

Gyanprakash A. Ketwaroo, MD, MSc, is an assistant professor of medicine at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston. He is an associate editor for GI & Hepatology News.

The dedicated GI hospitalist: Taking ownership not ‘call’

By J. Andy Tau, MD

In my experience, a GI hospitalist provides mutual benefit to patients, employers, and consulting physicians. The patient benefits from more expedient consultations and expert endoscopic therapy, which translates to shorter hospitalizations and improved outcomes. The employer enjoys financial benefits as busy outpatient providers can stay busy without interruption. Consulting physicians enjoy having to only call a single phone number for trusted help from a familiar physician who does not rotate off service. Personally, the position provides the volume to develop valuable therapeutic endoscopy skills and techniques. With one stable physician at the helm, a sense of ownership can develop, rather than a sense of survival until “call” is over.

As a full-time GI hospitalist for a large single-specialty group, I provide inpatient GI and hepatology consultation from 7 a.m. to 5 p.m., Monday-Friday. I do not rotate off service. I cover three hospitals with a total of 1,000 beds with two advanced practice providers and one part-time physician. Except for endoscopic ultrasound, I perform all other endoscopic procedures. The census is usually 25-35 with an average of 10-15 new consults per day.

The most important benefit of a dedicated GI hospitalist is providing expedited consultation and expert endoscopy for patients. I can offer emergent (<6 hour) endoscopy for any patient. An esophageal food impaction is usually resolved within an hour of arrival to the ED during the day. I can help a surgeon intraoperatively on very short notice. As for acute GI bleeding cases, I oversee resuscitative efforts, while the endoscopy team prepares my preferred endoscopic equipment, eliminating surprises and delays before endoscopy. I have developed an expertise in hemostasis and managing esophageal perforations, along with a risk tolerance that cannot be matured in any setting other than daily emergency.

I have enacted evidence-based protocols for GI bleeding, iron-deficiency anemia, colonic pseudo-obstruction, pancreatitis, and liver decompensation, which internists have adopted over time, reducing phone calls and delays in prep or resuscitation.

While the day is unstructured and filled with interruptions, it is also very flexible. As opposed to the set time intervals of an outpatient clinic visit, I can spend an hour in a palliative care meeting or revisit high-risk patients multiple times a day to detect pending deterioration. Combined endoscopic and surgical cases are logistically easy to schedule given my flexibility. For example, patients with choledocholithiasis often can have a combined cholecystectomy and supine endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) in the OR, shaving a day off admission.

My employer benefits financially as the outpatient doctors can stay busy without interruption from the hospital. With secure group messaging, we are able to make joint decisions and arrange close follow up. The relative value units earned from the hospital are high. Combined with proceeds from the professional service agreement with the hospital, they are more than enough to cover my compensation.

Any physician in need of a GI consult needs only to call one number for help. I make it as easy as possible to obtain a consult and never push back, as banal as any consult may seem. I stake my reputation on providing a service that is able, affable, and available. By teaching a consistent message to consulting physicians, I have now effected best evidence-based practices for GI conditions even without engaging me. The most notable examples include antibiotics for variceal bleeding, fluid resuscitation and early feeding for acute pancreatitis, risk stratification for choledocholithiasis, and last but not least, abandoning the inpatient fecal occult blood test.

I am on a first-name basis with every nurse in the hospital now. In exchange for my availability and cell phone number, they place orders for me and protect me from avoidable nuisances.

Many physician groups cover the inpatient service by rotating a week at a time. There can be at times a reluctance to take ownership over a difficult patient and instead a sense of “survival of the call”. However, in my job, “the buck stops with me” even if it is in the form of readmission. For example, I have to take some ownership of indigent patients who cannot easily follow up. Who will remove the stent I placed? How will they pay for Helicobacter pylori eradication or biologic therapy? Another example is diverticular bleeding. While 80% stop on their own, I take extraordinary efforts to endoscopically find and halt the bleeding in order to reduce the recurrence rate. I must find durable solutions because these high-risk patients are my responsibility again when they bounce back to me via the ED.

By way of volume alone, this position has allowed me to develop many therapeutic skills outside of a standard 3-year GI fellowship. While I did only 200 ERCPs in fellowship, I have become proficient in ERCP with around 400 cases per year (mostly native papilla) and have grown comfortable with the needle knife. I have learned endoscopic suturing, luminal stenting, and endoscopic vacuum-assisted therapy for perforation closure independently. Out of necessity, I developed a novel technique in optimizing the use of hemostatic powder by using a bone-wax plug. As endoscopy chief, I can purchase a wide variety of endoscopy equipment, compare brands, and understand the nuances of each.

In conclusion, the dedicated GI hospitalist indirectly improves the efficiency of an outpatient practice, while directly improving inpatient outcomes, collegiality, and even one’s own skills as an endoscopist. While it can be challenging and hectic, with the right mentality towards ownership of the service, it is also an incredibly rewarding position.

Dr. Tau practices with Austin Gastroenterology in Austin, Tex. He disclosed relationships with Cook Medical and Conmed.

Inpatient-only GI hospitalist: Not so fast

By Vaibhav Mehendiratta, MD

Over the past 2 decades, the medical hospitalist system has assumed care of hospitalized patients with the promise of reduced length of stay (LOS) and improved outcomes. Although data on LOS is promising, there have been conflicting results in terms of total medical costs and resource utilization. Inpatient care for patients with complex medical histories often requires regular communication with other subspecialties and outpatient providers to achieve better patient-centered outcomes.

Providing inpatient gastrointestinal care is complicated. Traditional models rely on physicians trying to balance outpatient obligations with inpatient rounding and procedures, which can result in delayed endoscopy and an inability to participate fully in multidisciplinary rounds and family meetings. The complexity of hospitalized patients often requires a multidisciplinary approach with coordination of care that is hard to accomplish in between seeing outpatients. GI groups, both private practice and academics, need to adopt a strategy for inpatient care that is tailored to the hospital system in which they operate.

As one of the largest private practice groups in New England, our experience can provide a framework for others to follow. We provide inpatient GI care at eight hospitals across northern Connecticut. Our inpatient service at the largest tertiary care hospital is composed of one general gastroenterologist, one advanced endoscopist, one transplant hepatologist, two advanced practitioners, and two fellows in training. Each practitioner provides coverage on a rotating basis, typically 1 week at a time every 4-8 weeks. This model also offers flexibility, such that we can typically accommodate urgent outpatient endoscopy for patients who may otherwise require inpatient care. Coverage at the other seven hospitals is tailored to local needs and ranges from half-day to whole-day coverage by general gastroenterologists and advanced practitioners. We believe that our model is financially viable and, based on our experience, inpatient relative value units generated are quite similar to a typical day in outpatient GI practice.

Inpatient GI care accounts for a substantial portion of overall inpatient care in the United States. Endoscopy delays have been the focus of many research articles looking at inpatient GI care. The delays are caused by many factors, including endoscopy unit/staff availability, anesthesia availability, and patient factors. While having a dedicated inpatient GI Hospitalist offers the potential to streamline access for hospital consultations and endoscopy, an exclusive inpatient GI hospitalist may be less familiar with a patient’s chronic GI illness and have different (and perhaps, conflicting) priorities regarding a patient’s care. Having incomplete access to outpatient records or less familiarity with the intricacies of outpatient care could also lead to duplication of work and increase the number of inpatient procedures that may have otherwise been deferred to the outpatient setting.

Additionally, with physician burnout on the rise and particularly in the inpatient setting, one must question the sustainability of an exclusively inpatient GI practice. That is, the hours and demands of inpatient care typically do not allow the quality of life that outpatient care provides. Our model provides time for dedicated inpatient care, while allowing each practitioner ample opportunity to build a robust outpatient practice.

Some health care organizations are adopting an extensivist model to provide comprehensive care to patients with multiple medical problems. Extensivists are outpatient primary care providers who take the time to coordinate with inpatient hospitalists to provide comprehensive care to their patients. Constant contact with outpatient providers during admission is expected to improve patient satisfaction, reduce hospital readmissions, and decrease inpatient resource utilization.

In conclusion, our experience highlights sustained benefits, and distinct advantages, of providing inpatient GI care without a GI hospitalist model. The pendulum in inpatient care keeps swinging and with progress arise new challenges and questions. Close collaboration between gastroenterologists and health systems to develop a program that fits local needs and allows optimal resource allocation will ensure delivery of high-quality inpatient GI care.

Dr. Mehendiratta is a gastroenterologist with Connecticut GI PC, Hartford, and assistant clinical professor in the department of medicine at the University of Connecticut, Farmington. He has no relevant conflicts of interest to disclose.

Chicago oncologist charged with insider trading

, according to a Dec. 20 press release issued by the U.S. Department of Justice.

Daniel V.T. Catenacci, MD, PhD, a gastrointestinal medical oncologist and associate professor of medicine at the University of Chicago, is alleged to have used confidential information to purchase shares of California-based biotechnology company Five Prime Therapeutics before it publicly announced positive results from a clinical trial of bemarituzumab, an experimental cancer drug.

Dr. Catenacci served as the lead investigator of the clinical trial that evaluated bemarituzumab. The drug, which earned breakthrough therapy designation from the Food and Drug Administration earlier this year, is designed to target fibroblast growth factor receptor 2b (FGFR2b), overexpressed in about 30% of patients with HER2-negative gastric cancer and other solid tumors.

Bemarituzumab is being positioned as a potential frontline therapy for advanced gastric or gastroesophageal junction cancer. A recent phase 2 trial found that adding bemarituzumab to chemotherapy in this patient population improved survival over chemotherapy alone.

According to the criminal information, filed on Dec. 17 in U.S. District Court in Chicago, the charges state that, in November 2020, Dr. Catenacci “used material, non-public information about the trial results to make more than $134,000 in illegal profits from the purchase and sale of securities in the company.”

More specifically, the SEC’s complaint alleges that Dr. Catenacci received confidential information about the company and its positive clinical trial results through his position as principal investigator. Dr. Catenacci then purchased almost 8,800 shares of Five Prime Therapeutics before the company announced the positive results. Dr. Catenacci subsequently sold those shares shortly after the trial results were announced. In the interim, the shares tripled or quadrupled in value.

He has been charged with one count of securities fraud, punishable by up to 20 years in federal prison. Arraignment in federal court in Chicago has yet to be scheduled.

In addition, the federal complaint alleges that Dr. Catenacci violated the antifraud provisions of the federal securities laws. According to a press release, “Catenacci has agreed to be permanently enjoined from violations of these provisions, and to pay a civil penalty in an amount to be determined by the court later.”

Erin E. Schneider, regional director of the SEC’s San Francisco Regional Office, stated in the press release that clinical drug trials typically involve sensitive and valuable information about the viability of an experimental drug.

“As alleged in our complaint, Catenacci was required to safeguard the material nonpublic information he learned about Five Prime’s clinical trial, and not trade on it,” said Mr. Schneider.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, according to a Dec. 20 press release issued by the U.S. Department of Justice.

Daniel V.T. Catenacci, MD, PhD, a gastrointestinal medical oncologist and associate professor of medicine at the University of Chicago, is alleged to have used confidential information to purchase shares of California-based biotechnology company Five Prime Therapeutics before it publicly announced positive results from a clinical trial of bemarituzumab, an experimental cancer drug.

Dr. Catenacci served as the lead investigator of the clinical trial that evaluated bemarituzumab. The drug, which earned breakthrough therapy designation from the Food and Drug Administration earlier this year, is designed to target fibroblast growth factor receptor 2b (FGFR2b), overexpressed in about 30% of patients with HER2-negative gastric cancer and other solid tumors.

Bemarituzumab is being positioned as a potential frontline therapy for advanced gastric or gastroesophageal junction cancer. A recent phase 2 trial found that adding bemarituzumab to chemotherapy in this patient population improved survival over chemotherapy alone.

According to the criminal information, filed on Dec. 17 in U.S. District Court in Chicago, the charges state that, in November 2020, Dr. Catenacci “used material, non-public information about the trial results to make more than $134,000 in illegal profits from the purchase and sale of securities in the company.”

More specifically, the SEC’s complaint alleges that Dr. Catenacci received confidential information about the company and its positive clinical trial results through his position as principal investigator. Dr. Catenacci then purchased almost 8,800 shares of Five Prime Therapeutics before the company announced the positive results. Dr. Catenacci subsequently sold those shares shortly after the trial results were announced. In the interim, the shares tripled or quadrupled in value.

He has been charged with one count of securities fraud, punishable by up to 20 years in federal prison. Arraignment in federal court in Chicago has yet to be scheduled.

In addition, the federal complaint alleges that Dr. Catenacci violated the antifraud provisions of the federal securities laws. According to a press release, “Catenacci has agreed to be permanently enjoined from violations of these provisions, and to pay a civil penalty in an amount to be determined by the court later.”

Erin E. Schneider, regional director of the SEC’s San Francisco Regional Office, stated in the press release that clinical drug trials typically involve sensitive and valuable information about the viability of an experimental drug.

“As alleged in our complaint, Catenacci was required to safeguard the material nonpublic information he learned about Five Prime’s clinical trial, and not trade on it,” said Mr. Schneider.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, according to a Dec. 20 press release issued by the U.S. Department of Justice.

Daniel V.T. Catenacci, MD, PhD, a gastrointestinal medical oncologist and associate professor of medicine at the University of Chicago, is alleged to have used confidential information to purchase shares of California-based biotechnology company Five Prime Therapeutics before it publicly announced positive results from a clinical trial of bemarituzumab, an experimental cancer drug.

Dr. Catenacci served as the lead investigator of the clinical trial that evaluated bemarituzumab. The drug, which earned breakthrough therapy designation from the Food and Drug Administration earlier this year, is designed to target fibroblast growth factor receptor 2b (FGFR2b), overexpressed in about 30% of patients with HER2-negative gastric cancer and other solid tumors.

Bemarituzumab is being positioned as a potential frontline therapy for advanced gastric or gastroesophageal junction cancer. A recent phase 2 trial found that adding bemarituzumab to chemotherapy in this patient population improved survival over chemotherapy alone.

According to the criminal information, filed on Dec. 17 in U.S. District Court in Chicago, the charges state that, in November 2020, Dr. Catenacci “used material, non-public information about the trial results to make more than $134,000 in illegal profits from the purchase and sale of securities in the company.”

More specifically, the SEC’s complaint alleges that Dr. Catenacci received confidential information about the company and its positive clinical trial results through his position as principal investigator. Dr. Catenacci then purchased almost 8,800 shares of Five Prime Therapeutics before the company announced the positive results. Dr. Catenacci subsequently sold those shares shortly after the trial results were announced. In the interim, the shares tripled or quadrupled in value.

He has been charged with one count of securities fraud, punishable by up to 20 years in federal prison. Arraignment in federal court in Chicago has yet to be scheduled.

In addition, the federal complaint alleges that Dr. Catenacci violated the antifraud provisions of the federal securities laws. According to a press release, “Catenacci has agreed to be permanently enjoined from violations of these provisions, and to pay a civil penalty in an amount to be determined by the court later.”

Erin E. Schneider, regional director of the SEC’s San Francisco Regional Office, stated in the press release that clinical drug trials typically involve sensitive and valuable information about the viability of an experimental drug.

“As alleged in our complaint, Catenacci was required to safeguard the material nonpublic information he learned about Five Prime’s clinical trial, and not trade on it,” said Mr. Schneider.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Average-risk women with dense breasts—What breast screening is appropriate?

Text copyright DenseBreast-info.org.

Answer

A. For women with extremely dense breasts who are not otherwise at increased risk for breast cancer, screening magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is preferred, plus her mammogram or tomosynthesis. If MRI is not an option, consider ultrasonography or contrast-enhanced mammography.

The same screening considerations apply to women with heterogeneously dense breasts; however, there is limited capacity for MRI or even ultrasound screening at many facilities. Research supports MRI in dense breasts, and abbreviated, lower-cost protocols have been validated that address some of the barriers to MRI.1 Although not yet widely available, abbreviated MRI will likely have a greater role in screening women with dense breasts who are not high risk. It is important to note that preauthorization from insurance may be required for screening MRI, and in most US states, deductibles and copays apply.

The exam

Contrast-enhanced MRI requires IV injection of gadolinium-based contrast to look at the anatomy and blood flow patterns of the breast tissue. The patient lies face down with the breasts placed in two rectangular openings, or “coils.” The exam takes place inside the tunnel of the scanner, with the head facing out.After initial images are obtained, the contrast agent is injected into a vein in the arm, and additional images are taken, which will show areas of enhancement. The exam takes about 20 to 40 minutes. An “abbreviated” MRI can be performed for screening in some centers, which uses fewer sequences and takes about 10 minutes.

Benefits

At least 40% of cancers are missed on mammography in women with dense breasts.2 MRI is the most widely studied technique using a contrast agent, and it produces the highest additional cancer detection of all the supplemental technologies to date, yielding, in the first year, 10-16 additional cancers per 1,000 women screened after mammography/tomosynthesis (reviewed in Berg et al.3). The cancer-detection benefit is seen across all breast density categories, even among average-risk women.4 There is no ionizing radiation, and it has been shown to reduce the rate of interval cancers (those detected due to symptoms after a negative screening mammogram), as well as the rate of late-stage disease. Axillary lymph nodes can be examined at the same screening exam.

While tomosynthesis improves cancer detection in women with fatty breasts, scattered fibroglandular breast tissue, and heterogeneously dense breasts, it does not significantly improve cancer detection in women with extremely dense breasts.5,6 Current American Cancer Society and National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines recommend annual screening MRI for women at high risk for breast cancer (regardless of breast density); however, increasingly, research supports the effectiveness of MRI in women with dense breasts who are otherwise considered average risk. A large randomized controlled trial in the Netherlands compared outcomes in women with extremely dense breasts invited to have screening MRI after negative mammography to those assigned to continue receiving screening mammography only. The incremental cancer detection rate was 16.5 per 1,000 (79/4,783) women screened with MRI in the first round7 and 6 per 1,000 women screened in the second round 2 years later.8 The interval cancer rate was 0.8 per 1,000 (4/4,783) women screened with MRI, compared with 4.9 per 1,000 (16/3,278) women who declined MRI and received mammography only.7

Screening ultrasound will show up to 3 additional cancers per 1,000 women screened after mammography/tomosynthesis (reviewed in Vourtsis and Berg9 and Berg and Vourtsis10), far lower than the added cancer-detection rate of MRI. Consider screening ultrasound for women who cannot tolerate or access screening MRI.11 Contrast-enhanced mammography (CEM) uses iodinated contrast (as in computed tomography). CEM is not widely available but appears to show cancer-detection similar to MRI. For further discussion, see Berg et al’s 2021 review.3

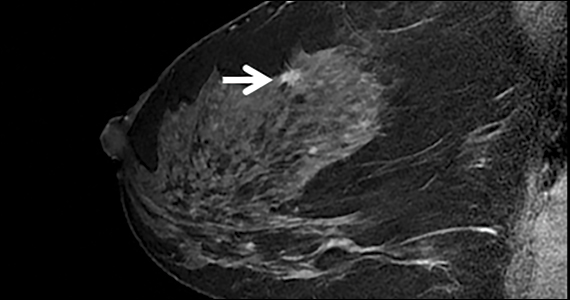

The FIGURE shows an example of an invasive cancer depicted on contrast-enhanced MRI in a 53-year-old woman with dense breasts and a family history of breast cancer that was not visible on tomosynthesis, even in retrospect, due to masking by dense tissue.

Considerations

Breast MRI increases callbacks even after mammography and ultrasound; however, such false alarms are reduced in subsequent screening rounds. MRI cannot be performed in women who have certain metal implants— some pacemakers or spinal fixation rods—and is not recommended for pregnant women. Claustrophobia may be an issue for some women. MRI is expensive and requires IV contrast. Gadolinium is known to accumulate in the brain, although the long-term effects of this are unknown and no harm has been shown.●

For more information, visit medically sourced DenseBreast-info.org. Comprehensive resources include a free CME opportunity, Dense Breasts and Supplemental Screening.

- Comstock CE, Gatsonis C, Newstead GM, et al. Comparison of abbreviated breast MRI vs digital breast tomosynthesis for breast cancer detection among women with dense breasts undergoing screening. JAMA. 2020;323:746-756. doi: 10.1001 /jama.2020.0572

- Kerlikowske K, Zhu W, Tosteson AN, et al. Identifying women with dense breasts at high risk for interval cancer: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162:673-681. doi: 10.7326/M14-1465.

- Berg WA, Rafferty EA, Friedewald SM, Hruska CB, Rahbar H. Screening Algorithms in Dense Breasts: AJR Expert Panel Narrative Review. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2021;216:275-294. doi: 10.2214/AJR.20.24436.

- Kuhl CK, Strobel K, Bieling H, et al. Supplemental breast MR imaging screening of women with average risk of breast cancer. Radiology. 2017;283:361-370. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2016161444.

- Rafferty EA, Durand MA, Conant EF, et al. Breast cancer screening using tomosynthesis and digital mammography in dense and nondense breasts. JAMA. 2016;315:1784-1786. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.1708.

- Osteras BH, Martinsen ACT, Gullien R, et al. Digital mammography versus breast tomosynthesis: impact of breast density on diagnostic performance in population-based screening. Radiology. 2019;293:60-68. doi: 10.1148 /radiol.2019190425.

- Bakker MF, de Lange SV, Pijnappel RM, et al. Supplemental MRI screening for women with extremely dense breast tissue. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:2091-2102. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1903986.

- Veenhuizen SGA, de Lange SV, Bakker MF, et al. Supplemental breast MRI for women with extremely dense breasts: results of the second screening round of the DENSE trial. Radiology. 2021;299:278-286. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2021203633.

- Vourtsis A, Berg WA. Breast density implications and supplemental screening. Eur Radiol. 2019;29:1762-1777. doi: 10.1007/s00330-018-5668-8.

- Berg WA, Vourtsis A. Screening ultrasound using handheld or automated technique in women with dense breasts. J Breast Imaging. 2019;1:283-296.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Breast Cancer Screening and Diagnosis (Version 1.2021). https://www.nccn. org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/breast-screening.pdf. Accessed November 18, 2021.

Text copyright DenseBreast-info.org.

Answer

A. For women with extremely dense breasts who are not otherwise at increased risk for breast cancer, screening magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is preferred, plus her mammogram or tomosynthesis. If MRI is not an option, consider ultrasonography or contrast-enhanced mammography.

The same screening considerations apply to women with heterogeneously dense breasts; however, there is limited capacity for MRI or even ultrasound screening at many facilities. Research supports MRI in dense breasts, and abbreviated, lower-cost protocols have been validated that address some of the barriers to MRI.1 Although not yet widely available, abbreviated MRI will likely have a greater role in screening women with dense breasts who are not high risk. It is important to note that preauthorization from insurance may be required for screening MRI, and in most US states, deductibles and copays apply.

The exam

Contrast-enhanced MRI requires IV injection of gadolinium-based contrast to look at the anatomy and blood flow patterns of the breast tissue. The patient lies face down with the breasts placed in two rectangular openings, or “coils.” The exam takes place inside the tunnel of the scanner, with the head facing out.After initial images are obtained, the contrast agent is injected into a vein in the arm, and additional images are taken, which will show areas of enhancement. The exam takes about 20 to 40 minutes. An “abbreviated” MRI can be performed for screening in some centers, which uses fewer sequences and takes about 10 minutes.

Benefits

At least 40% of cancers are missed on mammography in women with dense breasts.2 MRI is the most widely studied technique using a contrast agent, and it produces the highest additional cancer detection of all the supplemental technologies to date, yielding, in the first year, 10-16 additional cancers per 1,000 women screened after mammography/tomosynthesis (reviewed in Berg et al.3). The cancer-detection benefit is seen across all breast density categories, even among average-risk women.4 There is no ionizing radiation, and it has been shown to reduce the rate of interval cancers (those detected due to symptoms after a negative screening mammogram), as well as the rate of late-stage disease. Axillary lymph nodes can be examined at the same screening exam.

While tomosynthesis improves cancer detection in women with fatty breasts, scattered fibroglandular breast tissue, and heterogeneously dense breasts, it does not significantly improve cancer detection in women with extremely dense breasts.5,6 Current American Cancer Society and National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines recommend annual screening MRI for women at high risk for breast cancer (regardless of breast density); however, increasingly, research supports the effectiveness of MRI in women with dense breasts who are otherwise considered average risk. A large randomized controlled trial in the Netherlands compared outcomes in women with extremely dense breasts invited to have screening MRI after negative mammography to those assigned to continue receiving screening mammography only. The incremental cancer detection rate was 16.5 per 1,000 (79/4,783) women screened with MRI in the first round7 and 6 per 1,000 women screened in the second round 2 years later.8 The interval cancer rate was 0.8 per 1,000 (4/4,783) women screened with MRI, compared with 4.9 per 1,000 (16/3,278) women who declined MRI and received mammography only.7

Screening ultrasound will show up to 3 additional cancers per 1,000 women screened after mammography/tomosynthesis (reviewed in Vourtsis and Berg9 and Berg and Vourtsis10), far lower than the added cancer-detection rate of MRI. Consider screening ultrasound for women who cannot tolerate or access screening MRI.11 Contrast-enhanced mammography (CEM) uses iodinated contrast (as in computed tomography). CEM is not widely available but appears to show cancer-detection similar to MRI. For further discussion, see Berg et al’s 2021 review.3

The FIGURE shows an example of an invasive cancer depicted on contrast-enhanced MRI in a 53-year-old woman with dense breasts and a family history of breast cancer that was not visible on tomosynthesis, even in retrospect, due to masking by dense tissue.

Considerations

Breast MRI increases callbacks even after mammography and ultrasound; however, such false alarms are reduced in subsequent screening rounds. MRI cannot be performed in women who have certain metal implants— some pacemakers or spinal fixation rods—and is not recommended for pregnant women. Claustrophobia may be an issue for some women. MRI is expensive and requires IV contrast. Gadolinium is known to accumulate in the brain, although the long-term effects of this are unknown and no harm has been shown.●

For more information, visit medically sourced DenseBreast-info.org. Comprehensive resources include a free CME opportunity, Dense Breasts and Supplemental Screening.

Text copyright DenseBreast-info.org.

Answer

A. For women with extremely dense breasts who are not otherwise at increased risk for breast cancer, screening magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is preferred, plus her mammogram or tomosynthesis. If MRI is not an option, consider ultrasonography or contrast-enhanced mammography.

The same screening considerations apply to women with heterogeneously dense breasts; however, there is limited capacity for MRI or even ultrasound screening at many facilities. Research supports MRI in dense breasts, and abbreviated, lower-cost protocols have been validated that address some of the barriers to MRI.1 Although not yet widely available, abbreviated MRI will likely have a greater role in screening women with dense breasts who are not high risk. It is important to note that preauthorization from insurance may be required for screening MRI, and in most US states, deductibles and copays apply.

The exam

Contrast-enhanced MRI requires IV injection of gadolinium-based contrast to look at the anatomy and blood flow patterns of the breast tissue. The patient lies face down with the breasts placed in two rectangular openings, or “coils.” The exam takes place inside the tunnel of the scanner, with the head facing out.After initial images are obtained, the contrast agent is injected into a vein in the arm, and additional images are taken, which will show areas of enhancement. The exam takes about 20 to 40 minutes. An “abbreviated” MRI can be performed for screening in some centers, which uses fewer sequences and takes about 10 minutes.

Benefits

At least 40% of cancers are missed on mammography in women with dense breasts.2 MRI is the most widely studied technique using a contrast agent, and it produces the highest additional cancer detection of all the supplemental technologies to date, yielding, in the first year, 10-16 additional cancers per 1,000 women screened after mammography/tomosynthesis (reviewed in Berg et al.3). The cancer-detection benefit is seen across all breast density categories, even among average-risk women.4 There is no ionizing radiation, and it has been shown to reduce the rate of interval cancers (those detected due to symptoms after a negative screening mammogram), as well as the rate of late-stage disease. Axillary lymph nodes can be examined at the same screening exam.

While tomosynthesis improves cancer detection in women with fatty breasts, scattered fibroglandular breast tissue, and heterogeneously dense breasts, it does not significantly improve cancer detection in women with extremely dense breasts.5,6 Current American Cancer Society and National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines recommend annual screening MRI for women at high risk for breast cancer (regardless of breast density); however, increasingly, research supports the effectiveness of MRI in women with dense breasts who are otherwise considered average risk. A large randomized controlled trial in the Netherlands compared outcomes in women with extremely dense breasts invited to have screening MRI after negative mammography to those assigned to continue receiving screening mammography only. The incremental cancer detection rate was 16.5 per 1,000 (79/4,783) women screened with MRI in the first round7 and 6 per 1,000 women screened in the second round 2 years later.8 The interval cancer rate was 0.8 per 1,000 (4/4,783) women screened with MRI, compared with 4.9 per 1,000 (16/3,278) women who declined MRI and received mammography only.7

Screening ultrasound will show up to 3 additional cancers per 1,000 women screened after mammography/tomosynthesis (reviewed in Vourtsis and Berg9 and Berg and Vourtsis10), far lower than the added cancer-detection rate of MRI. Consider screening ultrasound for women who cannot tolerate or access screening MRI.11 Contrast-enhanced mammography (CEM) uses iodinated contrast (as in computed tomography). CEM is not widely available but appears to show cancer-detection similar to MRI. For further discussion, see Berg et al’s 2021 review.3

The FIGURE shows an example of an invasive cancer depicted on contrast-enhanced MRI in a 53-year-old woman with dense breasts and a family history of breast cancer that was not visible on tomosynthesis, even in retrospect, due to masking by dense tissue.

Considerations

Breast MRI increases callbacks even after mammography and ultrasound; however, such false alarms are reduced in subsequent screening rounds. MRI cannot be performed in women who have certain metal implants— some pacemakers or spinal fixation rods—and is not recommended for pregnant women. Claustrophobia may be an issue for some women. MRI is expensive and requires IV contrast. Gadolinium is known to accumulate in the brain, although the long-term effects of this are unknown and no harm has been shown.●

For more information, visit medically sourced DenseBreast-info.org. Comprehensive resources include a free CME opportunity, Dense Breasts and Supplemental Screening.

- Comstock CE, Gatsonis C, Newstead GM, et al. Comparison of abbreviated breast MRI vs digital breast tomosynthesis for breast cancer detection among women with dense breasts undergoing screening. JAMA. 2020;323:746-756. doi: 10.1001 /jama.2020.0572

- Kerlikowske K, Zhu W, Tosteson AN, et al. Identifying women with dense breasts at high risk for interval cancer: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162:673-681. doi: 10.7326/M14-1465.

- Berg WA, Rafferty EA, Friedewald SM, Hruska CB, Rahbar H. Screening Algorithms in Dense Breasts: AJR Expert Panel Narrative Review. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2021;216:275-294. doi: 10.2214/AJR.20.24436.

- Kuhl CK, Strobel K, Bieling H, et al. Supplemental breast MR imaging screening of women with average risk of breast cancer. Radiology. 2017;283:361-370. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2016161444.

- Rafferty EA, Durand MA, Conant EF, et al. Breast cancer screening using tomosynthesis and digital mammography in dense and nondense breasts. JAMA. 2016;315:1784-1786. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.1708.

- Osteras BH, Martinsen ACT, Gullien R, et al. Digital mammography versus breast tomosynthesis: impact of breast density on diagnostic performance in population-based screening. Radiology. 2019;293:60-68. doi: 10.1148 /radiol.2019190425.

- Bakker MF, de Lange SV, Pijnappel RM, et al. Supplemental MRI screening for women with extremely dense breast tissue. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:2091-2102. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1903986.

- Veenhuizen SGA, de Lange SV, Bakker MF, et al. Supplemental breast MRI for women with extremely dense breasts: results of the second screening round of the DENSE trial. Radiology. 2021;299:278-286. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2021203633.

- Vourtsis A, Berg WA. Breast density implications and supplemental screening. Eur Radiol. 2019;29:1762-1777. doi: 10.1007/s00330-018-5668-8.

- Berg WA, Vourtsis A. Screening ultrasound using handheld or automated technique in women with dense breasts. J Breast Imaging. 2019;1:283-296.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Breast Cancer Screening and Diagnosis (Version 1.2021). https://www.nccn. org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/breast-screening.pdf. Accessed November 18, 2021.

- Comstock CE, Gatsonis C, Newstead GM, et al. Comparison of abbreviated breast MRI vs digital breast tomosynthesis for breast cancer detection among women with dense breasts undergoing screening. JAMA. 2020;323:746-756. doi: 10.1001 /jama.2020.0572

- Kerlikowske K, Zhu W, Tosteson AN, et al. Identifying women with dense breasts at high risk for interval cancer: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162:673-681. doi: 10.7326/M14-1465.

- Berg WA, Rafferty EA, Friedewald SM, Hruska CB, Rahbar H. Screening Algorithms in Dense Breasts: AJR Expert Panel Narrative Review. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2021;216:275-294. doi: 10.2214/AJR.20.24436.

- Kuhl CK, Strobel K, Bieling H, et al. Supplemental breast MR imaging screening of women with average risk of breast cancer. Radiology. 2017;283:361-370. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2016161444.

- Rafferty EA, Durand MA, Conant EF, et al. Breast cancer screening using tomosynthesis and digital mammography in dense and nondense breasts. JAMA. 2016;315:1784-1786. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.1708.

- Osteras BH, Martinsen ACT, Gullien R, et al. Digital mammography versus breast tomosynthesis: impact of breast density on diagnostic performance in population-based screening. Radiology. 2019;293:60-68. doi: 10.1148 /radiol.2019190425.

- Bakker MF, de Lange SV, Pijnappel RM, et al. Supplemental MRI screening for women with extremely dense breast tissue. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:2091-2102. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1903986.

- Veenhuizen SGA, de Lange SV, Bakker MF, et al. Supplemental breast MRI for women with extremely dense breasts: results of the second screening round of the DENSE trial. Radiology. 2021;299:278-286. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2021203633.

- Vourtsis A, Berg WA. Breast density implications and supplemental screening. Eur Radiol. 2019;29:1762-1777. doi: 10.1007/s00330-018-5668-8.

- Berg WA, Vourtsis A. Screening ultrasound using handheld or automated technique in women with dense breasts. J Breast Imaging. 2019;1:283-296.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Breast Cancer Screening and Diagnosis (Version 1.2021). https://www.nccn. org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/breast-screening.pdf. Accessed November 18, 2021.

Quiz developed in collaboration with

More Americans skipping medical care because of cost, survey says

That’s the highest reported number since the pandemic began and a tripling from March to October.

Even 20% of the country’s highest-income households – earning more than $120,000 per year – said they’ve also skipped care. That’s an increase of about seven times for higher-income families since March.

“Americans tend to think there is a group of lower-income people, and they have worse health care than the rest of us, and the rest of us, we’re okay,” Tim Lash, chief strategy officer for West Health, a nonprofit focused on lowering health care costs, told CBS News.

“What we are seeing now in this survey is this group of people who are identifying themselves as struggling with health care costs is growing,” he said.

As part of the 2021 Healthcare in America Report, researchers surveyed more than 6,000 people in September and October about their concerns and experiences with affording health care and treatment. About half of respondents said health care in America has gotten worse because of the pandemic, and more than half said they’re more worried about medical costs than before.

What’s more, many Americans put off routine doctor visits at the beginning of the pandemic, and now that they’re beginning to schedule appointments again, they’re facing major costs, the survey found. Some expenses have increased in the past year, including prescription medications.