User login

Average-risk women with dense breasts—What breast screening is appropriate?

Text copyright DenseBreast-info.org.

Answer

A. For women with extremely dense breasts who are not otherwise at increased risk for breast cancer, screening magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is preferred, plus her mammogram or tomosynthesis. If MRI is not an option, consider ultrasonography or contrast-enhanced mammography.

The same screening considerations apply to women with heterogeneously dense breasts; however, there is limited capacity for MRI or even ultrasound screening at many facilities. Research supports MRI in dense breasts, and abbreviated, lower-cost protocols have been validated that address some of the barriers to MRI.1 Although not yet widely available, abbreviated MRI will likely have a greater role in screening women with dense breasts who are not high risk. It is important to note that preauthorization from insurance may be required for screening MRI, and in most US states, deductibles and copays apply.

The exam

Contrast-enhanced MRI requires IV injection of gadolinium-based contrast to look at the anatomy and blood flow patterns of the breast tissue. The patient lies face down with the breasts placed in two rectangular openings, or “coils.” The exam takes place inside the tunnel of the scanner, with the head facing out.After initial images are obtained, the contrast agent is injected into a vein in the arm, and additional images are taken, which will show areas of enhancement. The exam takes about 20 to 40 minutes. An “abbreviated” MRI can be performed for screening in some centers, which uses fewer sequences and takes about 10 minutes.

Benefits

At least 40% of cancers are missed on mammography in women with dense breasts.2 MRI is the most widely studied technique using a contrast agent, and it produces the highest additional cancer detection of all the supplemental technologies to date, yielding, in the first year, 10-16 additional cancers per 1,000 women screened after mammography/tomosynthesis (reviewed in Berg et al.3). The cancer-detection benefit is seen across all breast density categories, even among average-risk women.4 There is no ionizing radiation, and it has been shown to reduce the rate of interval cancers (those detected due to symptoms after a negative screening mammogram), as well as the rate of late-stage disease. Axillary lymph nodes can be examined at the same screening exam.

While tomosynthesis improves cancer detection in women with fatty breasts, scattered fibroglandular breast tissue, and heterogeneously dense breasts, it does not significantly improve cancer detection in women with extremely dense breasts.5,6 Current American Cancer Society and National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines recommend annual screening MRI for women at high risk for breast cancer (regardless of breast density); however, increasingly, research supports the effectiveness of MRI in women with dense breasts who are otherwise considered average risk. A large randomized controlled trial in the Netherlands compared outcomes in women with extremely dense breasts invited to have screening MRI after negative mammography to those assigned to continue receiving screening mammography only. The incremental cancer detection rate was 16.5 per 1,000 (79/4,783) women screened with MRI in the first round7 and 6 per 1,000 women screened in the second round 2 years later.8 The interval cancer rate was 0.8 per 1,000 (4/4,783) women screened with MRI, compared with 4.9 per 1,000 (16/3,278) women who declined MRI and received mammography only.7

Screening ultrasound will show up to 3 additional cancers per 1,000 women screened after mammography/tomosynthesis (reviewed in Vourtsis and Berg9 and Berg and Vourtsis10), far lower than the added cancer-detection rate of MRI. Consider screening ultrasound for women who cannot tolerate or access screening MRI.11 Contrast-enhanced mammography (CEM) uses iodinated contrast (as in computed tomography). CEM is not widely available but appears to show cancer-detection similar to MRI. For further discussion, see Berg et al’s 2021 review.3

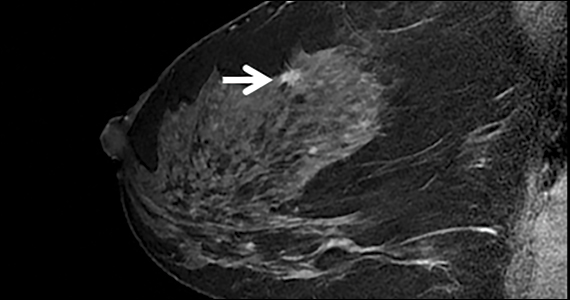

The FIGURE shows an example of an invasive cancer depicted on contrast-enhanced MRI in a 53-year-old woman with dense breasts and a family history of breast cancer that was not visible on tomosynthesis, even in retrospect, due to masking by dense tissue.

Considerations

Breast MRI increases callbacks even after mammography and ultrasound; however, such false alarms are reduced in subsequent screening rounds. MRI cannot be performed in women who have certain metal implants— some pacemakers or spinal fixation rods—and is not recommended for pregnant women. Claustrophobia may be an issue for some women. MRI is expensive and requires IV contrast. Gadolinium is known to accumulate in the brain, although the long-term effects of this are unknown and no harm has been shown.●

For more information, visit medically sourced DenseBreast-info.org. Comprehensive resources include a free CME opportunity, Dense Breasts and Supplemental Screening.

- Comstock CE, Gatsonis C, Newstead GM, et al. Comparison of abbreviated breast MRI vs digital breast tomosynthesis for breast cancer detection among women with dense breasts undergoing screening. JAMA. 2020;323:746-756. doi: 10.1001 /jama.2020.0572

- Kerlikowske K, Zhu W, Tosteson AN, et al. Identifying women with dense breasts at high risk for interval cancer: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162:673-681. doi: 10.7326/M14-1465.

- Berg WA, Rafferty EA, Friedewald SM, Hruska CB, Rahbar H. Screening Algorithms in Dense Breasts: AJR Expert Panel Narrative Review. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2021;216:275-294. doi: 10.2214/AJR.20.24436.

- Kuhl CK, Strobel K, Bieling H, et al. Supplemental breast MR imaging screening of women with average risk of breast cancer. Radiology. 2017;283:361-370. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2016161444.

- Rafferty EA, Durand MA, Conant EF, et al. Breast cancer screening using tomosynthesis and digital mammography in dense and nondense breasts. JAMA. 2016;315:1784-1786. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.1708.

- Osteras BH, Martinsen ACT, Gullien R, et al. Digital mammography versus breast tomosynthesis: impact of breast density on diagnostic performance in population-based screening. Radiology. 2019;293:60-68. doi: 10.1148 /radiol.2019190425.

- Bakker MF, de Lange SV, Pijnappel RM, et al. Supplemental MRI screening for women with extremely dense breast tissue. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:2091-2102. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1903986.

- Veenhuizen SGA, de Lange SV, Bakker MF, et al. Supplemental breast MRI for women with extremely dense breasts: results of the second screening round of the DENSE trial. Radiology. 2021;299:278-286. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2021203633.

- Vourtsis A, Berg WA. Breast density implications and supplemental screening. Eur Radiol. 2019;29:1762-1777. doi: 10.1007/s00330-018-5668-8.

- Berg WA, Vourtsis A. Screening ultrasound using handheld or automated technique in women with dense breasts. J Breast Imaging. 2019;1:283-296.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Breast Cancer Screening and Diagnosis (Version 1.2021). https://www.nccn. org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/breast-screening.pdf. Accessed November 18, 2021.

Text copyright DenseBreast-info.org.

Answer

A. For women with extremely dense breasts who are not otherwise at increased risk for breast cancer, screening magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is preferred, plus her mammogram or tomosynthesis. If MRI is not an option, consider ultrasonography or contrast-enhanced mammography.

The same screening considerations apply to women with heterogeneously dense breasts; however, there is limited capacity for MRI or even ultrasound screening at many facilities. Research supports MRI in dense breasts, and abbreviated, lower-cost protocols have been validated that address some of the barriers to MRI.1 Although not yet widely available, abbreviated MRI will likely have a greater role in screening women with dense breasts who are not high risk. It is important to note that preauthorization from insurance may be required for screening MRI, and in most US states, deductibles and copays apply.

The exam

Contrast-enhanced MRI requires IV injection of gadolinium-based contrast to look at the anatomy and blood flow patterns of the breast tissue. The patient lies face down with the breasts placed in two rectangular openings, or “coils.” The exam takes place inside the tunnel of the scanner, with the head facing out.After initial images are obtained, the contrast agent is injected into a vein in the arm, and additional images are taken, which will show areas of enhancement. The exam takes about 20 to 40 minutes. An “abbreviated” MRI can be performed for screening in some centers, which uses fewer sequences and takes about 10 minutes.

Benefits

At least 40% of cancers are missed on mammography in women with dense breasts.2 MRI is the most widely studied technique using a contrast agent, and it produces the highest additional cancer detection of all the supplemental technologies to date, yielding, in the first year, 10-16 additional cancers per 1,000 women screened after mammography/tomosynthesis (reviewed in Berg et al.3). The cancer-detection benefit is seen across all breast density categories, even among average-risk women.4 There is no ionizing radiation, and it has been shown to reduce the rate of interval cancers (those detected due to symptoms after a negative screening mammogram), as well as the rate of late-stage disease. Axillary lymph nodes can be examined at the same screening exam.

While tomosynthesis improves cancer detection in women with fatty breasts, scattered fibroglandular breast tissue, and heterogeneously dense breasts, it does not significantly improve cancer detection in women with extremely dense breasts.5,6 Current American Cancer Society and National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines recommend annual screening MRI for women at high risk for breast cancer (regardless of breast density); however, increasingly, research supports the effectiveness of MRI in women with dense breasts who are otherwise considered average risk. A large randomized controlled trial in the Netherlands compared outcomes in women with extremely dense breasts invited to have screening MRI after negative mammography to those assigned to continue receiving screening mammography only. The incremental cancer detection rate was 16.5 per 1,000 (79/4,783) women screened with MRI in the first round7 and 6 per 1,000 women screened in the second round 2 years later.8 The interval cancer rate was 0.8 per 1,000 (4/4,783) women screened with MRI, compared with 4.9 per 1,000 (16/3,278) women who declined MRI and received mammography only.7

Screening ultrasound will show up to 3 additional cancers per 1,000 women screened after mammography/tomosynthesis (reviewed in Vourtsis and Berg9 and Berg and Vourtsis10), far lower than the added cancer-detection rate of MRI. Consider screening ultrasound for women who cannot tolerate or access screening MRI.11 Contrast-enhanced mammography (CEM) uses iodinated contrast (as in computed tomography). CEM is not widely available but appears to show cancer-detection similar to MRI. For further discussion, see Berg et al’s 2021 review.3

The FIGURE shows an example of an invasive cancer depicted on contrast-enhanced MRI in a 53-year-old woman with dense breasts and a family history of breast cancer that was not visible on tomosynthesis, even in retrospect, due to masking by dense tissue.

Considerations

Breast MRI increases callbacks even after mammography and ultrasound; however, such false alarms are reduced in subsequent screening rounds. MRI cannot be performed in women who have certain metal implants— some pacemakers or spinal fixation rods—and is not recommended for pregnant women. Claustrophobia may be an issue for some women. MRI is expensive and requires IV contrast. Gadolinium is known to accumulate in the brain, although the long-term effects of this are unknown and no harm has been shown.●

For more information, visit medically sourced DenseBreast-info.org. Comprehensive resources include a free CME opportunity, Dense Breasts and Supplemental Screening.

Text copyright DenseBreast-info.org.

Answer

A. For women with extremely dense breasts who are not otherwise at increased risk for breast cancer, screening magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is preferred, plus her mammogram or tomosynthesis. If MRI is not an option, consider ultrasonography or contrast-enhanced mammography.

The same screening considerations apply to women with heterogeneously dense breasts; however, there is limited capacity for MRI or even ultrasound screening at many facilities. Research supports MRI in dense breasts, and abbreviated, lower-cost protocols have been validated that address some of the barriers to MRI.1 Although not yet widely available, abbreviated MRI will likely have a greater role in screening women with dense breasts who are not high risk. It is important to note that preauthorization from insurance may be required for screening MRI, and in most US states, deductibles and copays apply.

The exam

Contrast-enhanced MRI requires IV injection of gadolinium-based contrast to look at the anatomy and blood flow patterns of the breast tissue. The patient lies face down with the breasts placed in two rectangular openings, or “coils.” The exam takes place inside the tunnel of the scanner, with the head facing out.After initial images are obtained, the contrast agent is injected into a vein in the arm, and additional images are taken, which will show areas of enhancement. The exam takes about 20 to 40 minutes. An “abbreviated” MRI can be performed for screening in some centers, which uses fewer sequences and takes about 10 minutes.

Benefits

At least 40% of cancers are missed on mammography in women with dense breasts.2 MRI is the most widely studied technique using a contrast agent, and it produces the highest additional cancer detection of all the supplemental technologies to date, yielding, in the first year, 10-16 additional cancers per 1,000 women screened after mammography/tomosynthesis (reviewed in Berg et al.3). The cancer-detection benefit is seen across all breast density categories, even among average-risk women.4 There is no ionizing radiation, and it has been shown to reduce the rate of interval cancers (those detected due to symptoms after a negative screening mammogram), as well as the rate of late-stage disease. Axillary lymph nodes can be examined at the same screening exam.

While tomosynthesis improves cancer detection in women with fatty breasts, scattered fibroglandular breast tissue, and heterogeneously dense breasts, it does not significantly improve cancer detection in women with extremely dense breasts.5,6 Current American Cancer Society and National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines recommend annual screening MRI for women at high risk for breast cancer (regardless of breast density); however, increasingly, research supports the effectiveness of MRI in women with dense breasts who are otherwise considered average risk. A large randomized controlled trial in the Netherlands compared outcomes in women with extremely dense breasts invited to have screening MRI after negative mammography to those assigned to continue receiving screening mammography only. The incremental cancer detection rate was 16.5 per 1,000 (79/4,783) women screened with MRI in the first round7 and 6 per 1,000 women screened in the second round 2 years later.8 The interval cancer rate was 0.8 per 1,000 (4/4,783) women screened with MRI, compared with 4.9 per 1,000 (16/3,278) women who declined MRI and received mammography only.7

Screening ultrasound will show up to 3 additional cancers per 1,000 women screened after mammography/tomosynthesis (reviewed in Vourtsis and Berg9 and Berg and Vourtsis10), far lower than the added cancer-detection rate of MRI. Consider screening ultrasound for women who cannot tolerate or access screening MRI.11 Contrast-enhanced mammography (CEM) uses iodinated contrast (as in computed tomography). CEM is not widely available but appears to show cancer-detection similar to MRI. For further discussion, see Berg et al’s 2021 review.3

The FIGURE shows an example of an invasive cancer depicted on contrast-enhanced MRI in a 53-year-old woman with dense breasts and a family history of breast cancer that was not visible on tomosynthesis, even in retrospect, due to masking by dense tissue.

Considerations

Breast MRI increases callbacks even after mammography and ultrasound; however, such false alarms are reduced in subsequent screening rounds. MRI cannot be performed in women who have certain metal implants— some pacemakers or spinal fixation rods—and is not recommended for pregnant women. Claustrophobia may be an issue for some women. MRI is expensive and requires IV contrast. Gadolinium is known to accumulate in the brain, although the long-term effects of this are unknown and no harm has been shown.●

For more information, visit medically sourced DenseBreast-info.org. Comprehensive resources include a free CME opportunity, Dense Breasts and Supplemental Screening.

- Comstock CE, Gatsonis C, Newstead GM, et al. Comparison of abbreviated breast MRI vs digital breast tomosynthesis for breast cancer detection among women with dense breasts undergoing screening. JAMA. 2020;323:746-756. doi: 10.1001 /jama.2020.0572

- Kerlikowske K, Zhu W, Tosteson AN, et al. Identifying women with dense breasts at high risk for interval cancer: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162:673-681. doi: 10.7326/M14-1465.

- Berg WA, Rafferty EA, Friedewald SM, Hruska CB, Rahbar H. Screening Algorithms in Dense Breasts: AJR Expert Panel Narrative Review. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2021;216:275-294. doi: 10.2214/AJR.20.24436.

- Kuhl CK, Strobel K, Bieling H, et al. Supplemental breast MR imaging screening of women with average risk of breast cancer. Radiology. 2017;283:361-370. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2016161444.

- Rafferty EA, Durand MA, Conant EF, et al. Breast cancer screening using tomosynthesis and digital mammography in dense and nondense breasts. JAMA. 2016;315:1784-1786. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.1708.

- Osteras BH, Martinsen ACT, Gullien R, et al. Digital mammography versus breast tomosynthesis: impact of breast density on diagnostic performance in population-based screening. Radiology. 2019;293:60-68. doi: 10.1148 /radiol.2019190425.

- Bakker MF, de Lange SV, Pijnappel RM, et al. Supplemental MRI screening for women with extremely dense breast tissue. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:2091-2102. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1903986.

- Veenhuizen SGA, de Lange SV, Bakker MF, et al. Supplemental breast MRI for women with extremely dense breasts: results of the second screening round of the DENSE trial. Radiology. 2021;299:278-286. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2021203633.

- Vourtsis A, Berg WA. Breast density implications and supplemental screening. Eur Radiol. 2019;29:1762-1777. doi: 10.1007/s00330-018-5668-8.

- Berg WA, Vourtsis A. Screening ultrasound using handheld or automated technique in women with dense breasts. J Breast Imaging. 2019;1:283-296.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Breast Cancer Screening and Diagnosis (Version 1.2021). https://www.nccn. org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/breast-screening.pdf. Accessed November 18, 2021.

- Comstock CE, Gatsonis C, Newstead GM, et al. Comparison of abbreviated breast MRI vs digital breast tomosynthesis for breast cancer detection among women with dense breasts undergoing screening. JAMA. 2020;323:746-756. doi: 10.1001 /jama.2020.0572

- Kerlikowske K, Zhu W, Tosteson AN, et al. Identifying women with dense breasts at high risk for interval cancer: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162:673-681. doi: 10.7326/M14-1465.

- Berg WA, Rafferty EA, Friedewald SM, Hruska CB, Rahbar H. Screening Algorithms in Dense Breasts: AJR Expert Panel Narrative Review. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2021;216:275-294. doi: 10.2214/AJR.20.24436.

- Kuhl CK, Strobel K, Bieling H, et al. Supplemental breast MR imaging screening of women with average risk of breast cancer. Radiology. 2017;283:361-370. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2016161444.

- Rafferty EA, Durand MA, Conant EF, et al. Breast cancer screening using tomosynthesis and digital mammography in dense and nondense breasts. JAMA. 2016;315:1784-1786. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.1708.

- Osteras BH, Martinsen ACT, Gullien R, et al. Digital mammography versus breast tomosynthesis: impact of breast density on diagnostic performance in population-based screening. Radiology. 2019;293:60-68. doi: 10.1148 /radiol.2019190425.

- Bakker MF, de Lange SV, Pijnappel RM, et al. Supplemental MRI screening for women with extremely dense breast tissue. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:2091-2102. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1903986.

- Veenhuizen SGA, de Lange SV, Bakker MF, et al. Supplemental breast MRI for women with extremely dense breasts: results of the second screening round of the DENSE trial. Radiology. 2021;299:278-286. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2021203633.

- Vourtsis A, Berg WA. Breast density implications and supplemental screening. Eur Radiol. 2019;29:1762-1777. doi: 10.1007/s00330-018-5668-8.

- Berg WA, Vourtsis A. Screening ultrasound using handheld or automated technique in women with dense breasts. J Breast Imaging. 2019;1:283-296.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Breast Cancer Screening and Diagnosis (Version 1.2021). https://www.nccn. org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/breast-screening.pdf. Accessed November 18, 2021.

Quiz developed in collaboration with

More Americans skipping medical care because of cost, survey says

That’s the highest reported number since the pandemic began and a tripling from March to October.

Even 20% of the country’s highest-income households – earning more than $120,000 per year – said they’ve also skipped care. That’s an increase of about seven times for higher-income families since March.

“Americans tend to think there is a group of lower-income people, and they have worse health care than the rest of us, and the rest of us, we’re okay,” Tim Lash, chief strategy officer for West Health, a nonprofit focused on lowering health care costs, told CBS News.

“What we are seeing now in this survey is this group of people who are identifying themselves as struggling with health care costs is growing,” he said.

As part of the 2021 Healthcare in America Report, researchers surveyed more than 6,000 people in September and October about their concerns and experiences with affording health care and treatment. About half of respondents said health care in America has gotten worse because of the pandemic, and more than half said they’re more worried about medical costs than before.

What’s more, many Americans put off routine doctor visits at the beginning of the pandemic, and now that they’re beginning to schedule appointments again, they’re facing major costs, the survey found. Some expenses have increased in the past year, including prescription medications.

The rising costs have led many people to skip care or treatment, which can have major consequences. About 1 in 20 adults said they know a friend or family member who died during the past year because they couldn’t afford medical care, the survey found. And about 20% of adults said they or someone in their household had a health issue that grew worse after postponing care because of price.

About 23% of survey respondents said that paying for health care represents a major financial burden, which increases to a third of respondents who earn less than $48,000 per year. Out-of-pocket costs such as deductibles and insurance premiums have increased, which have taken up larger portions of people’s budgets.

“We often overlook the side effect of costs, and it’s quite toxic – there is a financial toxicity that exists in health care,” Mr. Lash said. “We know when you skip treatment, that can have an impact on mortality.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

That’s the highest reported number since the pandemic began and a tripling from March to October.

Even 20% of the country’s highest-income households – earning more than $120,000 per year – said they’ve also skipped care. That’s an increase of about seven times for higher-income families since March.

“Americans tend to think there is a group of lower-income people, and they have worse health care than the rest of us, and the rest of us, we’re okay,” Tim Lash, chief strategy officer for West Health, a nonprofit focused on lowering health care costs, told CBS News.

“What we are seeing now in this survey is this group of people who are identifying themselves as struggling with health care costs is growing,” he said.

As part of the 2021 Healthcare in America Report, researchers surveyed more than 6,000 people in September and October about their concerns and experiences with affording health care and treatment. About half of respondents said health care in America has gotten worse because of the pandemic, and more than half said they’re more worried about medical costs than before.

What’s more, many Americans put off routine doctor visits at the beginning of the pandemic, and now that they’re beginning to schedule appointments again, they’re facing major costs, the survey found. Some expenses have increased in the past year, including prescription medications.

The rising costs have led many people to skip care or treatment, which can have major consequences. About 1 in 20 adults said they know a friend or family member who died during the past year because they couldn’t afford medical care, the survey found. And about 20% of adults said they or someone in their household had a health issue that grew worse after postponing care because of price.

About 23% of survey respondents said that paying for health care represents a major financial burden, which increases to a third of respondents who earn less than $48,000 per year. Out-of-pocket costs such as deductibles and insurance premiums have increased, which have taken up larger portions of people’s budgets.

“We often overlook the side effect of costs, and it’s quite toxic – there is a financial toxicity that exists in health care,” Mr. Lash said. “We know when you skip treatment, that can have an impact on mortality.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

That’s the highest reported number since the pandemic began and a tripling from March to October.

Even 20% of the country’s highest-income households – earning more than $120,000 per year – said they’ve also skipped care. That’s an increase of about seven times for higher-income families since March.

“Americans tend to think there is a group of lower-income people, and they have worse health care than the rest of us, and the rest of us, we’re okay,” Tim Lash, chief strategy officer for West Health, a nonprofit focused on lowering health care costs, told CBS News.

“What we are seeing now in this survey is this group of people who are identifying themselves as struggling with health care costs is growing,” he said.

As part of the 2021 Healthcare in America Report, researchers surveyed more than 6,000 people in September and October about their concerns and experiences with affording health care and treatment. About half of respondents said health care in America has gotten worse because of the pandemic, and more than half said they’re more worried about medical costs than before.

What’s more, many Americans put off routine doctor visits at the beginning of the pandemic, and now that they’re beginning to schedule appointments again, they’re facing major costs, the survey found. Some expenses have increased in the past year, including prescription medications.

The rising costs have led many people to skip care or treatment, which can have major consequences. About 1 in 20 adults said they know a friend or family member who died during the past year because they couldn’t afford medical care, the survey found. And about 20% of adults said they or someone in their household had a health issue that grew worse after postponing care because of price.

About 23% of survey respondents said that paying for health care represents a major financial burden, which increases to a third of respondents who earn less than $48,000 per year. Out-of-pocket costs such as deductibles and insurance premiums have increased, which have taken up larger portions of people’s budgets.

“We often overlook the side effect of costs, and it’s quite toxic – there is a financial toxicity that exists in health care,” Mr. Lash said. “We know when you skip treatment, that can have an impact on mortality.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Physician gender pay gap isn’t news; health inequity is rampant

A recent study examined projected career earnings between the genders in a largely community-based physician population, finding a difference of about $2 million in career earnings. That a gender pay gap exists in medicine is not news – but the manner in which this study was done, the investigators’ ability to control for a number of confounding variables, and the size of the study group (over 80,000) are newsworthy.

Some of the key findings include that gender pay gaps start with your first job, and you never close the gap, even as you gain experience and efficiency. Also, the more highly remunerated your specialty, the larger the gap. The gender pay gap joins a growing list of inequities within health care. Although physician compensation is not the most important, given that nearly all physicians are well-paid, and we have much more significant inequities that lead to direct patient harm, the reasons for this discrepancy warrant further consideration.

When I was first being educated about social inequity as part of work in social determinants of health, I made the error of using “inequality” and “inequity” interchangeably. The subtle yet important difference between the two terms was quickly described to me. Inequality is a gastroenterologist getting paid more money to do a colonoscopy than a family physician. Inequity is a female gastroenterologist getting paid less than a male gastroenterologist. Global Health Europe boldly identifies that “inequity is the result of failure.” In looking at the inequity inherent in the gender pay gap, I consider what failed and why.

I’m currently making a major career change, leaving an executive leadership position to return to full-time clinical practice. There is a significant pay decrease that will accompany this change because I am in a primary care specialty. Beyond that, I am considering two employment contracts from different systems to do a similar clinical role.

One of the questions my husband asked was which will pay more over the long run. This is difficult to discern because the compensation formula each health system uses is different, even though they are based on standard national benchmarking data. It is possible that women, in general, are like I am and look for factors other than compensation to make a job decision – assuming, like I do, that it will be close enough to not matter or is generally fair. In fact, while compensation is most certainly a consideration for me, once I determined that it was likely to be in the same ballpark, I stopped comparing. Even as the sole breadwinner in our family, I take this (probably faulty) approach.

It’s time to reconsider how we pay physicians

Women may be more likely to gloss over compensation details that men evaluate and negotiate carefully. To change this, women must first take responsibility for being an active, informed, and engaged part of compensation negotiations. In addition, employers who value gender pay equity must negotiate in good faith, keeping in mind the well-described vulnerabilities in discussions about pay. Finally, male and female mentors and leaders should actively coach female physicians on how to approach these conversations with confidence and skill.

In primary care, female physicians spend, on average, about 15% more time with their patients during a visit. Despite spending as much time in clinic seeing patients per week, they see fewer patients, thereby generating less revenue. For compensation plans that are based on productivity, the extra time spent costs money. In this case, it costs the female physicians lost compensation.

The way in which women are more likely to practice medicine, which includes the amount of time they spend with patients, may affect clinical outcomes without directly increasing productivity. A 2017 study demonstrated that elderly patients had lower rates of mortality and readmission when cared for by a female rather than a male physician. These findings require health systems to critically evaluate what compensation plans value and to promote an appropriate balance between quality of care, quantity of care, and style of care.

Although I’ve seen gender pay inequity as blatant as two different salaries for physicians doing the same work – one male and one female – I think this is uncommon. Like many forms of inequity, the outputs are often related to a failed system rather than solely a series of individual failures. Making compensation formulas gender-blind is an important step – but it is only the first step, not the last. Recognizing that the structure of a compensation formula may be biased toward a style of medical practice more likely to be espoused by one gender is necessary as well.

The data, including the findings of this recent study, clearly identify the gender pay gap that exists in medicine, as it does in many other fields, and that it is not explainable solely by differences in specialties, work hours, family status, or title.

To address the inequity, it is imperative that women engage with employers and leaders to both understand and develop skills around effective and appropriate compensation negotiation. Recognizing that compensation plans, especially those built on productivity models, may fail to place adequate value on gender-specific practice styles.

Jennifer Frank is a family physician, physician leader, wife, and mother in Northeast Wisconsin.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A recent study examined projected career earnings between the genders in a largely community-based physician population, finding a difference of about $2 million in career earnings. That a gender pay gap exists in medicine is not news – but the manner in which this study was done, the investigators’ ability to control for a number of confounding variables, and the size of the study group (over 80,000) are newsworthy.

Some of the key findings include that gender pay gaps start with your first job, and you never close the gap, even as you gain experience and efficiency. Also, the more highly remunerated your specialty, the larger the gap. The gender pay gap joins a growing list of inequities within health care. Although physician compensation is not the most important, given that nearly all physicians are well-paid, and we have much more significant inequities that lead to direct patient harm, the reasons for this discrepancy warrant further consideration.

When I was first being educated about social inequity as part of work in social determinants of health, I made the error of using “inequality” and “inequity” interchangeably. The subtle yet important difference between the two terms was quickly described to me. Inequality is a gastroenterologist getting paid more money to do a colonoscopy than a family physician. Inequity is a female gastroenterologist getting paid less than a male gastroenterologist. Global Health Europe boldly identifies that “inequity is the result of failure.” In looking at the inequity inherent in the gender pay gap, I consider what failed and why.

I’m currently making a major career change, leaving an executive leadership position to return to full-time clinical practice. There is a significant pay decrease that will accompany this change because I am in a primary care specialty. Beyond that, I am considering two employment contracts from different systems to do a similar clinical role.

One of the questions my husband asked was which will pay more over the long run. This is difficult to discern because the compensation formula each health system uses is different, even though they are based on standard national benchmarking data. It is possible that women, in general, are like I am and look for factors other than compensation to make a job decision – assuming, like I do, that it will be close enough to not matter or is generally fair. In fact, while compensation is most certainly a consideration for me, once I determined that it was likely to be in the same ballpark, I stopped comparing. Even as the sole breadwinner in our family, I take this (probably faulty) approach.

It’s time to reconsider how we pay physicians

Women may be more likely to gloss over compensation details that men evaluate and negotiate carefully. To change this, women must first take responsibility for being an active, informed, and engaged part of compensation negotiations. In addition, employers who value gender pay equity must negotiate in good faith, keeping in mind the well-described vulnerabilities in discussions about pay. Finally, male and female mentors and leaders should actively coach female physicians on how to approach these conversations with confidence and skill.

In primary care, female physicians spend, on average, about 15% more time with their patients during a visit. Despite spending as much time in clinic seeing patients per week, they see fewer patients, thereby generating less revenue. For compensation plans that are based on productivity, the extra time spent costs money. In this case, it costs the female physicians lost compensation.

The way in which women are more likely to practice medicine, which includes the amount of time they spend with patients, may affect clinical outcomes without directly increasing productivity. A 2017 study demonstrated that elderly patients had lower rates of mortality and readmission when cared for by a female rather than a male physician. These findings require health systems to critically evaluate what compensation plans value and to promote an appropriate balance between quality of care, quantity of care, and style of care.

Although I’ve seen gender pay inequity as blatant as two different salaries for physicians doing the same work – one male and one female – I think this is uncommon. Like many forms of inequity, the outputs are often related to a failed system rather than solely a series of individual failures. Making compensation formulas gender-blind is an important step – but it is only the first step, not the last. Recognizing that the structure of a compensation formula may be biased toward a style of medical practice more likely to be espoused by one gender is necessary as well.

The data, including the findings of this recent study, clearly identify the gender pay gap that exists in medicine, as it does in many other fields, and that it is not explainable solely by differences in specialties, work hours, family status, or title.

To address the inequity, it is imperative that women engage with employers and leaders to both understand and develop skills around effective and appropriate compensation negotiation. Recognizing that compensation plans, especially those built on productivity models, may fail to place adequate value on gender-specific practice styles.

Jennifer Frank is a family physician, physician leader, wife, and mother in Northeast Wisconsin.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A recent study examined projected career earnings between the genders in a largely community-based physician population, finding a difference of about $2 million in career earnings. That a gender pay gap exists in medicine is not news – but the manner in which this study was done, the investigators’ ability to control for a number of confounding variables, and the size of the study group (over 80,000) are newsworthy.

Some of the key findings include that gender pay gaps start with your first job, and you never close the gap, even as you gain experience and efficiency. Also, the more highly remunerated your specialty, the larger the gap. The gender pay gap joins a growing list of inequities within health care. Although physician compensation is not the most important, given that nearly all physicians are well-paid, and we have much more significant inequities that lead to direct patient harm, the reasons for this discrepancy warrant further consideration.

When I was first being educated about social inequity as part of work in social determinants of health, I made the error of using “inequality” and “inequity” interchangeably. The subtle yet important difference between the two terms was quickly described to me. Inequality is a gastroenterologist getting paid more money to do a colonoscopy than a family physician. Inequity is a female gastroenterologist getting paid less than a male gastroenterologist. Global Health Europe boldly identifies that “inequity is the result of failure.” In looking at the inequity inherent in the gender pay gap, I consider what failed and why.

I’m currently making a major career change, leaving an executive leadership position to return to full-time clinical practice. There is a significant pay decrease that will accompany this change because I am in a primary care specialty. Beyond that, I am considering two employment contracts from different systems to do a similar clinical role.

One of the questions my husband asked was which will pay more over the long run. This is difficult to discern because the compensation formula each health system uses is different, even though they are based on standard national benchmarking data. It is possible that women, in general, are like I am and look for factors other than compensation to make a job decision – assuming, like I do, that it will be close enough to not matter or is generally fair. In fact, while compensation is most certainly a consideration for me, once I determined that it was likely to be in the same ballpark, I stopped comparing. Even as the sole breadwinner in our family, I take this (probably faulty) approach.

It’s time to reconsider how we pay physicians

Women may be more likely to gloss over compensation details that men evaluate and negotiate carefully. To change this, women must first take responsibility for being an active, informed, and engaged part of compensation negotiations. In addition, employers who value gender pay equity must negotiate in good faith, keeping in mind the well-described vulnerabilities in discussions about pay. Finally, male and female mentors and leaders should actively coach female physicians on how to approach these conversations with confidence and skill.

In primary care, female physicians spend, on average, about 15% more time with their patients during a visit. Despite spending as much time in clinic seeing patients per week, they see fewer patients, thereby generating less revenue. For compensation plans that are based on productivity, the extra time spent costs money. In this case, it costs the female physicians lost compensation.

The way in which women are more likely to practice medicine, which includes the amount of time they spend with patients, may affect clinical outcomes without directly increasing productivity. A 2017 study demonstrated that elderly patients had lower rates of mortality and readmission when cared for by a female rather than a male physician. These findings require health systems to critically evaluate what compensation plans value and to promote an appropriate balance between quality of care, quantity of care, and style of care.

Although I’ve seen gender pay inequity as blatant as two different salaries for physicians doing the same work – one male and one female – I think this is uncommon. Like many forms of inequity, the outputs are often related to a failed system rather than solely a series of individual failures. Making compensation formulas gender-blind is an important step – but it is only the first step, not the last. Recognizing that the structure of a compensation formula may be biased toward a style of medical practice more likely to be espoused by one gender is necessary as well.

The data, including the findings of this recent study, clearly identify the gender pay gap that exists in medicine, as it does in many other fields, and that it is not explainable solely by differences in specialties, work hours, family status, or title.

To address the inequity, it is imperative that women engage with employers and leaders to both understand and develop skills around effective and appropriate compensation negotiation. Recognizing that compensation plans, especially those built on productivity models, may fail to place adequate value on gender-specific practice styles.

Jennifer Frank is a family physician, physician leader, wife, and mother in Northeast Wisconsin.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

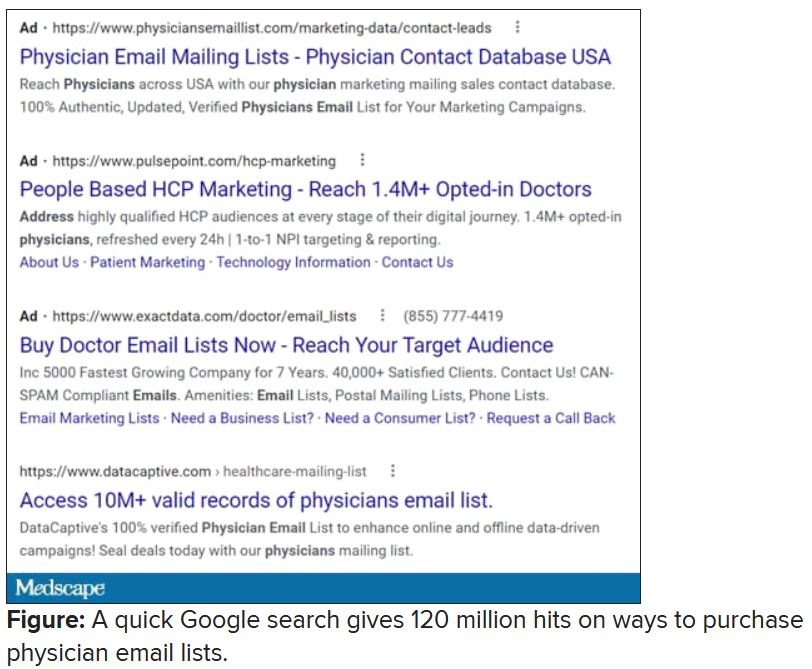

Spam filter failure: Selling physician emails equals big $$

Despite the best efforts of my institution’s spam filter, I’ve realized that I spend at least 4 minutes every day of the week removing junk email from my in basket: EMR vendors, predatory journals trying to lure me into paying their outrageous publication fees, people who want to help me with my billing software (evidently that .edu extension hasn’t clicked for them yet), headhunters trying to fill specialty positions in other states, market researchers offering a gift card for 40 minutes filling out a survey.

If you do the math, 4 minutes daily is 1,460 minutes per year. That’s an entire day of my life lost each year to this useless nonsense, which I never agreed to receive in the first place. Now multiply that by the 22 million health care workers in the United States, or even just by the 985,000 licensed physicians in this country. Then factor in the $638 per hour in gross revenue generated by the average primary care physician, as a conservative, well-documented value.

By my reckoning, these bozos owe the United States alone over $15 billion in lost GDP each year.

So why don’t we shut it down!? The CAN-SPAM Act of 2003 attempted to at least mitigate the problem. It applies only to commercial entities (I know, I’d love to report some political groups, too). To avoid violating the law and risking fines of up to $16,000 per individual email, senders must:

- Not use misleading header info (including domain name and email address)

- Not use deceptive subject lines

- Clearly label the email as an ad

- Give an actual physical address of the sender

- Tell recipients how to opt out of future emails

- Honor opt-out requests within 10 business days

- Monitor the activities of any subcontractor sending email on their behalf

I can say with certainty that much of the trash in my inbox violates at least one of these. But that doesn’t matter if there is not an efficient way to report the violators and ensure that they’ll be tracked down. Hard enough if they live here, impossible if the email is routed from overseas, as much of it clearly is.

If you receive email in violation of the act, experts recommend that you write down the email address and the business name of the sender, fill out a complaint form on the Federal Trade Commission website, or send an email to [email protected], then send an email to your Internet service provider’s abuse desk. If you’re not working within a big institution like mine that has hot and cold running IT personnel that operate their own abuse prevention office, the address you’ll need is likely abuse@domain_name or postmaster@domain_name. Just hitting the spam button at the top of your browser/email software may do the trick. There’s more good advice at the FTC’s consumer spam page.

The answer came, ironically, to my email inbox in the form of one of those emails that did indeed violate the law.

I rolled my eyes and started into my reporting subroutine but then stopped cold. Just 1 second. If this person is selling lists of email addresses of conference attendees, somebody within the conference structure must be providing them. How is that legal? I have never agreed, in registering for a medical conference, to allow them to share my email address with anyone. To think that they are making money from that is extremely galling.

Vermont, at least, has enacted a law requiring companies that traffic in such email lists to register with the state. Although it has been in effect for 2 years, the jury is out regarding its efficacy. Our European counterparts are protected by the General Data Protection Regulation, which specifies that commercial email can be sent only to individuals who have explicitly opted into such mailings, and that purchased email lists are not compliant with the requirement.

Anybody have the inside scoop on this? Can we demand that our professional societies safeguard their attendee databases so this won’t happen? If they won’t, why am I paying big money to attend their conferences, only for them to make even more money at my expense?

Dr. Hitchcock is assistant professor, department of radiation oncology, at the University of Florida, Gainesville. She reported receiving research grant money from Merck. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Despite the best efforts of my institution’s spam filter, I’ve realized that I spend at least 4 minutes every day of the week removing junk email from my in basket: EMR vendors, predatory journals trying to lure me into paying their outrageous publication fees, people who want to help me with my billing software (evidently that .edu extension hasn’t clicked for them yet), headhunters trying to fill specialty positions in other states, market researchers offering a gift card for 40 minutes filling out a survey.

If you do the math, 4 minutes daily is 1,460 minutes per year. That’s an entire day of my life lost each year to this useless nonsense, which I never agreed to receive in the first place. Now multiply that by the 22 million health care workers in the United States, or even just by the 985,000 licensed physicians in this country. Then factor in the $638 per hour in gross revenue generated by the average primary care physician, as a conservative, well-documented value.

By my reckoning, these bozos owe the United States alone over $15 billion in lost GDP each year.

So why don’t we shut it down!? The CAN-SPAM Act of 2003 attempted to at least mitigate the problem. It applies only to commercial entities (I know, I’d love to report some political groups, too). To avoid violating the law and risking fines of up to $16,000 per individual email, senders must:

- Not use misleading header info (including domain name and email address)

- Not use deceptive subject lines

- Clearly label the email as an ad

- Give an actual physical address of the sender

- Tell recipients how to opt out of future emails

- Honor opt-out requests within 10 business days

- Monitor the activities of any subcontractor sending email on their behalf

I can say with certainty that much of the trash in my inbox violates at least one of these. But that doesn’t matter if there is not an efficient way to report the violators and ensure that they’ll be tracked down. Hard enough if they live here, impossible if the email is routed from overseas, as much of it clearly is.

If you receive email in violation of the act, experts recommend that you write down the email address and the business name of the sender, fill out a complaint form on the Federal Trade Commission website, or send an email to [email protected], then send an email to your Internet service provider’s abuse desk. If you’re not working within a big institution like mine that has hot and cold running IT personnel that operate their own abuse prevention office, the address you’ll need is likely abuse@domain_name or postmaster@domain_name. Just hitting the spam button at the top of your browser/email software may do the trick. There’s more good advice at the FTC’s consumer spam page.

The answer came, ironically, to my email inbox in the form of one of those emails that did indeed violate the law.

I rolled my eyes and started into my reporting subroutine but then stopped cold. Just 1 second. If this person is selling lists of email addresses of conference attendees, somebody within the conference structure must be providing them. How is that legal? I have never agreed, in registering for a medical conference, to allow them to share my email address with anyone. To think that they are making money from that is extremely galling.

Vermont, at least, has enacted a law requiring companies that traffic in such email lists to register with the state. Although it has been in effect for 2 years, the jury is out regarding its efficacy. Our European counterparts are protected by the General Data Protection Regulation, which specifies that commercial email can be sent only to individuals who have explicitly opted into such mailings, and that purchased email lists are not compliant with the requirement.

Anybody have the inside scoop on this? Can we demand that our professional societies safeguard their attendee databases so this won’t happen? If they won’t, why am I paying big money to attend their conferences, only for them to make even more money at my expense?

Dr. Hitchcock is assistant professor, department of radiation oncology, at the University of Florida, Gainesville. She reported receiving research grant money from Merck. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Despite the best efforts of my institution’s spam filter, I’ve realized that I spend at least 4 minutes every day of the week removing junk email from my in basket: EMR vendors, predatory journals trying to lure me into paying their outrageous publication fees, people who want to help me with my billing software (evidently that .edu extension hasn’t clicked for them yet), headhunters trying to fill specialty positions in other states, market researchers offering a gift card for 40 minutes filling out a survey.

If you do the math, 4 minutes daily is 1,460 minutes per year. That’s an entire day of my life lost each year to this useless nonsense, which I never agreed to receive in the first place. Now multiply that by the 22 million health care workers in the United States, or even just by the 985,000 licensed physicians in this country. Then factor in the $638 per hour in gross revenue generated by the average primary care physician, as a conservative, well-documented value.

By my reckoning, these bozos owe the United States alone over $15 billion in lost GDP each year.

So why don’t we shut it down!? The CAN-SPAM Act of 2003 attempted to at least mitigate the problem. It applies only to commercial entities (I know, I’d love to report some political groups, too). To avoid violating the law and risking fines of up to $16,000 per individual email, senders must:

- Not use misleading header info (including domain name and email address)

- Not use deceptive subject lines

- Clearly label the email as an ad

- Give an actual physical address of the sender

- Tell recipients how to opt out of future emails

- Honor opt-out requests within 10 business days

- Monitor the activities of any subcontractor sending email on their behalf

I can say with certainty that much of the trash in my inbox violates at least one of these. But that doesn’t matter if there is not an efficient way to report the violators and ensure that they’ll be tracked down. Hard enough if they live here, impossible if the email is routed from overseas, as much of it clearly is.

If you receive email in violation of the act, experts recommend that you write down the email address and the business name of the sender, fill out a complaint form on the Federal Trade Commission website, or send an email to [email protected], then send an email to your Internet service provider’s abuse desk. If you’re not working within a big institution like mine that has hot and cold running IT personnel that operate their own abuse prevention office, the address you’ll need is likely abuse@domain_name or postmaster@domain_name. Just hitting the spam button at the top of your browser/email software may do the trick. There’s more good advice at the FTC’s consumer spam page.

The answer came, ironically, to my email inbox in the form of one of those emails that did indeed violate the law.

I rolled my eyes and started into my reporting subroutine but then stopped cold. Just 1 second. If this person is selling lists of email addresses of conference attendees, somebody within the conference structure must be providing them. How is that legal? I have never agreed, in registering for a medical conference, to allow them to share my email address with anyone. To think that they are making money from that is extremely galling.

Vermont, at least, has enacted a law requiring companies that traffic in such email lists to register with the state. Although it has been in effect for 2 years, the jury is out regarding its efficacy. Our European counterparts are protected by the General Data Protection Regulation, which specifies that commercial email can be sent only to individuals who have explicitly opted into such mailings, and that purchased email lists are not compliant with the requirement.

Anybody have the inside scoop on this? Can we demand that our professional societies safeguard their attendee databases so this won’t happen? If they won’t, why am I paying big money to attend their conferences, only for them to make even more money at my expense?

Dr. Hitchcock is assistant professor, department of radiation oncology, at the University of Florida, Gainesville. She reported receiving research grant money from Merck. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Are physician-owned large groups better than flying solo?

Large, physician-owned group practices are gaining ground as a popular form of practice, even as the number of physicians in solo and small practices declines, and employment maintains its appeal.

As physicians shift from owning private practices to employment in hospital systems, this countertrend is also taking place. Large group practices are growing in number, even as solo and small practices are in decline.

Do large, physician-owned groups bring benefits that beat employment? And how do large groups compare with smaller practices and new opportunities, such as private equity? You’ll find some answers here.

Working in large group practices

Large group practices with 50 or more physicians are enjoying a renaissance, even though physicians are still streaming into hospital systems. The share of physicians in large practices increased from 14.7% in 2018 to 17.2% in 2020, the largest 2-year change for this group, according to the American Medical Association.

“Physicians expect that large groups will treat them better than hospitals do,” says Robert Pearl, MD, former CEO of Permanente Medical Group, the nation’s largest physicians’ group.

Compared with hospitals, “doctors would prefer working in a group practice, if all other things are equal,” says Dr. Pearl, who is now a professor at Stanford (Calif.) University Medical School.

Large group practices can include both multispecialty groups and single-specialty groups. Groups in specialties like urology, orthopedics, and oncology have been growing in recent years, according to Gregory Mertz, managing director of Physician Strategies Group in Virginia Beach, Va.

A group practice could also be an independent physicians association – a federation of small practices that share functions like negotiations with insurers and management. Physicians can also form larger groups for single purposes like running an accountable care organization.

Some large group practices can have a mix of partners and employees. In these groups, “some doctors either don’t want a partnership or aren’t offered one,” says Nathan Miller, CEO of the Medicus Firm, a physician recruitment company in Dallas. The AMA reports that about 10% of physicians are employees of large practices.

“Large groups like the Permanente Medical Group are not partnerships,” Dr. Pearl says. “They tend to be a corporation with a board of directors, and all the physicians are employees, but it’s a physician-led organization.”

Doctors in these groups can enjoy a great deal of control. While Permanente Medical Group is exclusively affiliated with Kaiser, which runs hospitals and an HMO, the group is an independent corporation run by its doctors, who are both shareholders and employees, Dr. Pearl says.

The Cleveland Clinic and Mayo Clinic are not medical groups in the strict sense of the word. They describe themselves as academic medical centers, but Dr. Pearl says, “Doctors have a tremendous amount of control there, particularly those in the most remunerative specialties.”

Pros of large groups

Group practices are able to focus more on the physician participants’ needs and priorities, says Mr. Mertz. “In a hospital-based organization, physicians’ needs have to compete with the needs of the hospital. … In a large group, it can be easier to get policies changed and order equipment.”

However, for many physicians, their primary reason for joining a large group is having negotiating leverage with health insurance plans, and this leverage seems even more important today. It typically results in higher reimbursements, which could translate into higher pay. The higher practice income, however, could be negated by higher administrative overhead, which is endemic in large organizations.

Mr. Mertz says large groups also have the resources to recruit new doctors. Small practices, in contrast, often decide not to grow. The practice would at first need to guarantee the salary of a new partner, which could require existing partners to take a pay cut, which they often don’t want to do. “They’ll decide to ride the practice into the ground,” which means closing it down when they retire, he says.

Cons of large groups

One individual doctor may have relatively little input in decision-making in a large group, and strong leadership may be lacking. One study examining the pros and cons of large group practices found that lack of physician cooperation, investment, and leadership were the most frequently cited barriers in large groups.

Physicians in large groups can also divide into competing factions. Mr. Mertz says rifts are more likely to take place in multispecialty groups, where higher-reimbursed proceduralists resent having to financially support lower-reimbursed primary care physicians. But it’s rare that such rifts actually break up the practice, he says.

Private practice vs. employment

Even as more physicians enter large groups, physicians continue to flee private practice in general. In 2020, the AMA found that the number of physicians in private practices had dropped nearly 5 percentage points since 2018, the largest 2-year drop recorded by the AMA.

The hardest hit are small groups of 10 physicians or fewer, once the backbone of U.S. medicine. A 2020 survey found that 53.7% of physicians still work in small practices of 10 or fewer physicians, compared with 61.4% in 2012.

Private practices tend to be partnerships, but younger physicians, for their part, often don’t want to become a partner. In a 2016 survey, only 22% of medical residents surveyed said they anticipate owning a stake in a practice someday.

What’s good about private practice?

The obvious advantage of private practice is having control. Physician-owners can choose staff, oversee finances, and decide on the direction the practice should take. They don’t have to worry about being fired, because the partnership agreement virtually guarantees each doctor’s place in the group.

The atmosphere in a small practice is often more relaxed. “Private practices tend to offer a family-like environment,” Mr. Miller says. Owners of small practices tend to have lower burnout than large practices, a 2018 study found.

Unlike hospital-employed doctors, private practitioners get to keep their ancillary income. “Physicians own the equipment and receive income generated from ancillary services, not just professional fees,” says Mr. Miller.

What’s negative about private practice?

Since small groups have little negotiating power with private payers, they can’t get favorable reimbursement rates. And while partners are protected from being fired, the practice could still go bankrupt.

Running a private practice means putting on an entrepreneurial hat. To develop a strong practice, you need to learn about marketing, finance, IT, contract negotiations, and facility management. “Most young doctors have no interest in this work,” Mr. Mertz says.

Value-based contracting has added another disadvantage for small practices. “It can be harder for small, independent groups to compete,” says Mike Belkin, JD, a divisional vice president at Merritt Hawkins, a physician recruitment company based in Dallas. “They don’t have the data and integration of services that are necessary for this.”

Employment in hospital systems

More than one-third of all physicians worked for hospitals in 2018, and hospitals’ share has been growing since then. In 2020, for the first time, the AMA found that more than half of all physicians were employed, and employment is mainly a hospital phenomenon.

The trend shows no signs of stopping. In 2019 and 2020, hospitals and other corporate entities acquired 20,900 physician practices, representing 29,800 doctors. “This trend will continue,” Dr. Pearl says. “The bigger will get bigger. It’s all about market control. Everyone wants to be wider, more vertical, and more powerful.”

Pros of hospital employment

“The advantages of hospital employment are mostly financial,” Mr. Mertz says. Unlike a private practice, “there’s no financial risk to hospital employment because you don’t own it. You won’t be on the tab for any losses.”

“Hospitals usually offer a highly competitive salary with less emphasis on production than in a private practice,” he says. New physicians are typically paid a guaranteed salary in the first 1-3 years of employment.

“You don’t have any management responsibilities, as you would in a practice,” Mr. Mertz says. “The hospital has a professional management team to handle the business side. Most young doctors have no interest in this work.”

“Employed physicians have a built-in referral network at a hospital,” Mr. Miller says. This is especially an advantage for new physicians, who don’t yet have a referral network of their own.”

Cons of hospital employment

Physicians employed by a hospital lack control. “You don’t decide the hours you work, the schedules you follow, and the physical facility you work in, and, for the most part, you don’t pick your staff,” Mr. Mertz says.

Like any big organization, hospitals are bureaucratic. “If you want to purchase a new piece of equipment, your request goes up the chain of command,” Mr. Mertz says. “Your purchase has to fit into the budget.” (This can be the case with large groups, too.)

Many employed doctors chafe under this lack of control. In an earlier survey by Medscape, 45% of employed respondents didn’t like having limited influence in decision-making, and 32% said they had less control over their work or schedule.

It’s no wonder that a large percentage of physicians would rather work in practices than hospitals. According to a 2021 Medicus Firm survey, 23% of physicians are interested in working in hospitals, while 40% would rather work either in multispecialty or single-specialty groups, Mr. Miller reports.

Doctors have differing views of hospital employment

New physicians are apt to dismiss any negatives about hospitals. “Lack of autonomy often matters less to younger physicians, who were trained in team-based models,” Mr. Belkin says.

Many young doctors actually like working in a large organization. “Young doctors out of residency are used to having everything at their fingertips – labs and testing is in-house,” Mr. Mertz says.

On the other hand, doctors who were previously self-employed – a group that makes up almost one-third of all hospital-employed doctors – can often be dissatisfied with employment. In a 2014 Medscape survey, 26% of previously self-employed doctors said job satisfaction had not improved with employment.

Mr. Mertz says these doctors remember what it was like to be in charge of a practice. “If you once owned a practice, you can always compare what’s going on now with that experience, and that can make you frustrated.”

Hospitals have higher turnover

It’s much easier to leave an organization when you don’t have an ownership stake. The annual physician turnover rate at hospitals is 28%, compared with 7% at medical groups, according to a 2019 report.

Mr. Belkin says changing jobs has become a way of life for many doctors. “Staying at a job for only a few years is no longer a red flag,” he says. “Physicians are exploring different options. They might try group practice and switch to hospitals or vice versa.”

Physicians are now part of a high-turnover culture: Once in a new job, many are already thinking about the next one. A 2018 survey found that 46% of doctors planned to leave their position within 3 years.

Private equity ownership of practice

Selling majority control of your practice to a private equity firm is a relatively new phenomenon and accounts for a small share of physicians – just 4% in 2020. This trend was originally limited to certain specialties, such as anesthesiology, emergency medicine, and dermatology, but now many others are courted.

The deals work like this: Physicians sell majority control of their practice to investors in return for shares in the private equity practice, and they become employees of that practice. The private equity firm then adds more physicians to the practice and invests in infrastructure with the intention of selling the practice at a large profit, which is then shared with the original physicians.

Pros of private equity

The original owners of the practice stand to make a substantial profit if they are willing to wait several years for the practice to be built up and sold. “If they are patient, they could earn a bonanza,” Mr. Belkin says.

Private equity investment helps the practice expand. “It’s an alternative to going to the bank and borrowing money,” Mr. Mertz says.

Cons of private equity

Physicians lose control of their practice. A client of Mr. Mertz’s briefly considered a private equity offer and turned it down. “The private equity firm would have veto power over what the doctors wanted to do,” he says.

Mr. Belkin says the selling physicians typically lose income after the sale. “Money they earned from ancillary services now goes to the practice,” Mr. Belkin says. The selling doctors could potentially take up to a 30% cut in their compensation, according to Coker Capital Advisors.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Large, physician-owned group practices are gaining ground as a popular form of practice, even as the number of physicians in solo and small practices declines, and employment maintains its appeal.

As physicians shift from owning private practices to employment in hospital systems, this countertrend is also taking place. Large group practices are growing in number, even as solo and small practices are in decline.

Do large, physician-owned groups bring benefits that beat employment? And how do large groups compare with smaller practices and new opportunities, such as private equity? You’ll find some answers here.

Working in large group practices

Large group practices with 50 or more physicians are enjoying a renaissance, even though physicians are still streaming into hospital systems. The share of physicians in large practices increased from 14.7% in 2018 to 17.2% in 2020, the largest 2-year change for this group, according to the American Medical Association.

“Physicians expect that large groups will treat them better than hospitals do,” says Robert Pearl, MD, former CEO of Permanente Medical Group, the nation’s largest physicians’ group.

Compared with hospitals, “doctors would prefer working in a group practice, if all other things are equal,” says Dr. Pearl, who is now a professor at Stanford (Calif.) University Medical School.

Large group practices can include both multispecialty groups and single-specialty groups. Groups in specialties like urology, orthopedics, and oncology have been growing in recent years, according to Gregory Mertz, managing director of Physician Strategies Group in Virginia Beach, Va.

A group practice could also be an independent physicians association – a federation of small practices that share functions like negotiations with insurers and management. Physicians can also form larger groups for single purposes like running an accountable care organization.

Some large group practices can have a mix of partners and employees. In these groups, “some doctors either don’t want a partnership or aren’t offered one,” says Nathan Miller, CEO of the Medicus Firm, a physician recruitment company in Dallas. The AMA reports that about 10% of physicians are employees of large practices.

“Large groups like the Permanente Medical Group are not partnerships,” Dr. Pearl says. “They tend to be a corporation with a board of directors, and all the physicians are employees, but it’s a physician-led organization.”

Doctors in these groups can enjoy a great deal of control. While Permanente Medical Group is exclusively affiliated with Kaiser, which runs hospitals and an HMO, the group is an independent corporation run by its doctors, who are both shareholders and employees, Dr. Pearl says.

The Cleveland Clinic and Mayo Clinic are not medical groups in the strict sense of the word. They describe themselves as academic medical centers, but Dr. Pearl says, “Doctors have a tremendous amount of control there, particularly those in the most remunerative specialties.”

Pros of large groups

Group practices are able to focus more on the physician participants’ needs and priorities, says Mr. Mertz. “In a hospital-based organization, physicians’ needs have to compete with the needs of the hospital. … In a large group, it can be easier to get policies changed and order equipment.”

However, for many physicians, their primary reason for joining a large group is having negotiating leverage with health insurance plans, and this leverage seems even more important today. It typically results in higher reimbursements, which could translate into higher pay. The higher practice income, however, could be negated by higher administrative overhead, which is endemic in large organizations.

Mr. Mertz says large groups also have the resources to recruit new doctors. Small practices, in contrast, often decide not to grow. The practice would at first need to guarantee the salary of a new partner, which could require existing partners to take a pay cut, which they often don’t want to do. “They’ll decide to ride the practice into the ground,” which means closing it down when they retire, he says.

Cons of large groups

One individual doctor may have relatively little input in decision-making in a large group, and strong leadership may be lacking. One study examining the pros and cons of large group practices found that lack of physician cooperation, investment, and leadership were the most frequently cited barriers in large groups.

Physicians in large groups can also divide into competing factions. Mr. Mertz says rifts are more likely to take place in multispecialty groups, where higher-reimbursed proceduralists resent having to financially support lower-reimbursed primary care physicians. But it’s rare that such rifts actually break up the practice, he says.

Private practice vs. employment

Even as more physicians enter large groups, physicians continue to flee private practice in general. In 2020, the AMA found that the number of physicians in private practices had dropped nearly 5 percentage points since 2018, the largest 2-year drop recorded by the AMA.

The hardest hit are small groups of 10 physicians or fewer, once the backbone of U.S. medicine. A 2020 survey found that 53.7% of physicians still work in small practices of 10 or fewer physicians, compared with 61.4% in 2012.

Private practices tend to be partnerships, but younger physicians, for their part, often don’t want to become a partner. In a 2016 survey, only 22% of medical residents surveyed said they anticipate owning a stake in a practice someday.

What’s good about private practice?

The obvious advantage of private practice is having control. Physician-owners can choose staff, oversee finances, and decide on the direction the practice should take. They don’t have to worry about being fired, because the partnership agreement virtually guarantees each doctor’s place in the group.

The atmosphere in a small practice is often more relaxed. “Private practices tend to offer a family-like environment,” Mr. Miller says. Owners of small practices tend to have lower burnout than large practices, a 2018 study found.

Unlike hospital-employed doctors, private practitioners get to keep their ancillary income. “Physicians own the equipment and receive income generated from ancillary services, not just professional fees,” says Mr. Miller.

What’s negative about private practice?

Since small groups have little negotiating power with private payers, they can’t get favorable reimbursement rates. And while partners are protected from being fired, the practice could still go bankrupt.

Running a private practice means putting on an entrepreneurial hat. To develop a strong practice, you need to learn about marketing, finance, IT, contract negotiations, and facility management. “Most young doctors have no interest in this work,” Mr. Mertz says.