User login

National Psoriasis Foundation recommends some stop methotrexate for 2 weeks after J&J vaccine

The , Joel M. Gelfand, MD, said at Innovations in Dermatology: Virtual Spring Conference 2021.

The new guidance states: “Patients 60 or older who have at least one comorbidity associated with an increased risk for poor COVID-19 outcomes, and who are taking methotrexate with well-controlled psoriatic disease, may, in consultation with their prescriber, consider holding it for 2 weeks after receiving the Ad26.COV2.S [Johnson & Johnson] vaccine in order to potentially improve vaccine response.”

The key word here is “potentially.” There is no hard evidence that a 2-week hold on methotrexate after receiving the killed adenovirus vaccine will actually provide a clinically meaningful benefit. But it’s a hypothetical possibility. The rationale stems from a small randomized trial conducted in South Korea several years ago in which patients with rheumatoid arthritis were assigned to hold or continue their methotrexate for the first 2 weeks after receiving an inactivated-virus influenza vaccine. The antibody response to the vaccine was better in those who temporarily halted their methotrexate, explained Dr. Gelfand, cochair of the NPF COVID-19 Task Force and professor of dermatology and of epidemiology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

“If you have a patient on methotrexate who’s 60 or older and whose psoriasis is completely controlled and quiescent and the patient is concerned about how well the vaccine is going to work, this is a reasonable thing to consider in someone who’s at higher risk for poor outcomes if they get infected,” he said.

If the informed patient wants to continue on methotrexate without interruption, that’s fine, too, in light of the lack of compelling evidence on this issue, the dermatologist added at the conference, sponsored by MedscapeLIVE! and the producers of the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar and Caribbean Dermatology Symposium.

The NPF task force does not extend the recommendation to consider holding methotrexate in recipients of the mRNA-based Moderna and Pfizer vaccines because of their very different mechanisms of action. Nor is it recommended to hold biologic agents after receiving any of the available COVID-19 vaccines. Studies have shown no altered immunologic response to influenza or pneumococcal vaccines in patients who continued on tumor necrosis factor inhibitors or interleukin-17 inhibitors. The interleukin-23 inhibitors haven’t been studied in this regard.

The task force recommends that most psoriasis patients should continue on treatment throughout the pandemic, and newly diagnosed patients should commence appropriate therapy as if there was no pandemic.

“We’ve learned that many patients who stopped their treatment for psoriatic disease early in the pandemic came to regret that decision because their psoriasis flared and got worse and required reinstitution of therapy,” Dr. Gelfand said. “The current data is largely reassuring that if there is an effect of our therapies on the risk of COVID, it must be rather small and therefore unlikely to be clinically meaningful for our patients.”

Dr. Gelfand reported serving as a consultant to and recipient of institutional research grants from Pfizer and numerous other pharmaceutical companies.

MedscapeLIVE and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

The , Joel M. Gelfand, MD, said at Innovations in Dermatology: Virtual Spring Conference 2021.

The new guidance states: “Patients 60 or older who have at least one comorbidity associated with an increased risk for poor COVID-19 outcomes, and who are taking methotrexate with well-controlled psoriatic disease, may, in consultation with their prescriber, consider holding it for 2 weeks after receiving the Ad26.COV2.S [Johnson & Johnson] vaccine in order to potentially improve vaccine response.”

The key word here is “potentially.” There is no hard evidence that a 2-week hold on methotrexate after receiving the killed adenovirus vaccine will actually provide a clinically meaningful benefit. But it’s a hypothetical possibility. The rationale stems from a small randomized trial conducted in South Korea several years ago in which patients with rheumatoid arthritis were assigned to hold or continue their methotrexate for the first 2 weeks after receiving an inactivated-virus influenza vaccine. The antibody response to the vaccine was better in those who temporarily halted their methotrexate, explained Dr. Gelfand, cochair of the NPF COVID-19 Task Force and professor of dermatology and of epidemiology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

“If you have a patient on methotrexate who’s 60 or older and whose psoriasis is completely controlled and quiescent and the patient is concerned about how well the vaccine is going to work, this is a reasonable thing to consider in someone who’s at higher risk for poor outcomes if they get infected,” he said.

If the informed patient wants to continue on methotrexate without interruption, that’s fine, too, in light of the lack of compelling evidence on this issue, the dermatologist added at the conference, sponsored by MedscapeLIVE! and the producers of the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar and Caribbean Dermatology Symposium.

The NPF task force does not extend the recommendation to consider holding methotrexate in recipients of the mRNA-based Moderna and Pfizer vaccines because of their very different mechanisms of action. Nor is it recommended to hold biologic agents after receiving any of the available COVID-19 vaccines. Studies have shown no altered immunologic response to influenza or pneumococcal vaccines in patients who continued on tumor necrosis factor inhibitors or interleukin-17 inhibitors. The interleukin-23 inhibitors haven’t been studied in this regard.

The task force recommends that most psoriasis patients should continue on treatment throughout the pandemic, and newly diagnosed patients should commence appropriate therapy as if there was no pandemic.

“We’ve learned that many patients who stopped their treatment for psoriatic disease early in the pandemic came to regret that decision because their psoriasis flared and got worse and required reinstitution of therapy,” Dr. Gelfand said. “The current data is largely reassuring that if there is an effect of our therapies on the risk of COVID, it must be rather small and therefore unlikely to be clinically meaningful for our patients.”

Dr. Gelfand reported serving as a consultant to and recipient of institutional research grants from Pfizer and numerous other pharmaceutical companies.

MedscapeLIVE and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

The , Joel M. Gelfand, MD, said at Innovations in Dermatology: Virtual Spring Conference 2021.

The new guidance states: “Patients 60 or older who have at least one comorbidity associated with an increased risk for poor COVID-19 outcomes, and who are taking methotrexate with well-controlled psoriatic disease, may, in consultation with their prescriber, consider holding it for 2 weeks after receiving the Ad26.COV2.S [Johnson & Johnson] vaccine in order to potentially improve vaccine response.”

The key word here is “potentially.” There is no hard evidence that a 2-week hold on methotrexate after receiving the killed adenovirus vaccine will actually provide a clinically meaningful benefit. But it’s a hypothetical possibility. The rationale stems from a small randomized trial conducted in South Korea several years ago in which patients with rheumatoid arthritis were assigned to hold or continue their methotrexate for the first 2 weeks after receiving an inactivated-virus influenza vaccine. The antibody response to the vaccine was better in those who temporarily halted their methotrexate, explained Dr. Gelfand, cochair of the NPF COVID-19 Task Force and professor of dermatology and of epidemiology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

“If you have a patient on methotrexate who’s 60 or older and whose psoriasis is completely controlled and quiescent and the patient is concerned about how well the vaccine is going to work, this is a reasonable thing to consider in someone who’s at higher risk for poor outcomes if they get infected,” he said.

If the informed patient wants to continue on methotrexate without interruption, that’s fine, too, in light of the lack of compelling evidence on this issue, the dermatologist added at the conference, sponsored by MedscapeLIVE! and the producers of the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar and Caribbean Dermatology Symposium.

The NPF task force does not extend the recommendation to consider holding methotrexate in recipients of the mRNA-based Moderna and Pfizer vaccines because of their very different mechanisms of action. Nor is it recommended to hold biologic agents after receiving any of the available COVID-19 vaccines. Studies have shown no altered immunologic response to influenza or pneumococcal vaccines in patients who continued on tumor necrosis factor inhibitors or interleukin-17 inhibitors. The interleukin-23 inhibitors haven’t been studied in this regard.

The task force recommends that most psoriasis patients should continue on treatment throughout the pandemic, and newly diagnosed patients should commence appropriate therapy as if there was no pandemic.

“We’ve learned that many patients who stopped their treatment for psoriatic disease early in the pandemic came to regret that decision because their psoriasis flared and got worse and required reinstitution of therapy,” Dr. Gelfand said. “The current data is largely reassuring that if there is an effect of our therapies on the risk of COVID, it must be rather small and therefore unlikely to be clinically meaningful for our patients.”

Dr. Gelfand reported serving as a consultant to and recipient of institutional research grants from Pfizer and numerous other pharmaceutical companies.

MedscapeLIVE and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

FROM INNOVATIONS IN DERMATOLOGY

Will psoriasis patients embrace proactive topical therapy?

Long-term proactive topical management of plaque psoriasis with twice-weekly calcipotriene/betamethasone dipropionate foam has been shown in a high-quality randomized trial to be more effective than conventional reactive management – but will patients go for it?

Bruce E. Strober, MD, PhD, has his doubts, and he shared them with Linda Stein Gold, MD, after she presented updated results from the 52-week PSO-LONG trial at Innovations in Dermatology: Virtual Spring Conference 2021.

. And while they did so in this study with an assist in the form of monthly office visits and nudging from investigators, in real-world clinical practice that’s unlikely to happen, according to Dr. Strober, of Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

“It makes sense to do what’s being done in this study, there’s no doubt, but I’m concerned about adherence and whether patients are really going to do it,” he said.

“Adherence is going to be everything here, and you know patients don’t like to apply topicals to their body. Once they’re clear they’re just going to walk away from the topical,” Dr. Strober predicted.

Dr. Stein Gold countered: “When a study goes on for a full year, it starts to reflect real life.”

Moreover, the PSO-LONG trial provides the first high-quality evidence physicians can share with patients demonstrating that proactive management pays off in terms of fewer relapses and more time in remission over the long haul, added Dr. Stein Gold, director of dermatology clinical research at the Henry Ford Health System in Detroit.

PSO-LONG was a double-blind, international, phase 3 study including 545 adults with plaque psoriasis who had clear or almost-clear skin after 4 weeks of once-daily calcipotriene 0.005%/betamethasone dipropionate 0.064% (Cal/BD) foam (Enstilar), and were then randomized to twice-weekly proactive management or to a reactive approach involving application of vehicle on the same twice-weekly schedule. Relapses resulted in rescue therapy with 4 weeks of once-daily Cal/BD foam.

The primary endpoint was the median time to first relapse: 56 days with the proactive approach, a significant improvement over the 30 days with the reactive approach. Over the course of 52 weeks, the proactive group spent an additional 41 days in remission, compared with the reactive group. Patients randomized to twice-weekly Cal/BD foam averaged 3.1 relapses per year, compared with 4.8 with reactive management. The side-effect profiles in the two study arms were similar.

Mean Physician Global Assessment scores and Psoriasis Area and Activity Index scores for the proactive group clearly separated from the reactive group by week 4, with those differences maintained throughout the year. The area under the curve for distribution for the Physician Global Assessment score was 15% lower in the proactive group, and 20% lower for the modified PASI score.

“These results suggest that proactive management – a concept that’s been used for atopic dermatitis – could be applied to patients with psoriasis to prolong remission,” Dr. Stein Gold concluded at the conference, sponsored by MedscapeLIVE! and the producers of the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar and Caribbean Dermatology Symposium.

Asked how confident she is that patients in the real world truly will do this, Dr. Stein Gold replied: “You know, I don’t know. We hope so. Now we can tell them we actually have some data that supports treating the cleared areas. And it’s only twice a week, separated on Mondays and Thursdays.”

“I take a much more reactive approach,” Dr. Strober said. “I advise patients to get back in there with their topical steroid as soon as they see any signs of recurrence.

He added that he’s eager to see if a proactive management approach such as the one that was successful in PSO-LONG is also beneficial using some of the promising topical agents with nonsteroidal mechanisms of action, which are advancing through the developmental pipeline.

Late in 2020, the Food and Drug Administration approved an expanded indication for Cal/BD foam, which includes the PSO-LONG data on the efficacy and safety of long-term twice-weekly therapy in adults in product labeling. The combination spray/foam was previously approved by the FDA as once-daily therapy in psoriasis patients aged 12 years and older, but only for up to 4 weeks because of safety concerns regarding longer use of the potent topical steroid as daily therapy.

The PSO-LONG trial was funded by LEO Pharma. Dr. Stein Gold reported serving as a paid investigator and/or consultant to LEO and numerous other pharmaceutical companies. Dr. Strober, reported serving as a consultant to more than two dozen pharmaceutical companies. MedscapeLIVE! and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

Long-term proactive topical management of plaque psoriasis with twice-weekly calcipotriene/betamethasone dipropionate foam has been shown in a high-quality randomized trial to be more effective than conventional reactive management – but will patients go for it?

Bruce E. Strober, MD, PhD, has his doubts, and he shared them with Linda Stein Gold, MD, after she presented updated results from the 52-week PSO-LONG trial at Innovations in Dermatology: Virtual Spring Conference 2021.

. And while they did so in this study with an assist in the form of monthly office visits and nudging from investigators, in real-world clinical practice that’s unlikely to happen, according to Dr. Strober, of Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

“It makes sense to do what’s being done in this study, there’s no doubt, but I’m concerned about adherence and whether patients are really going to do it,” he said.

“Adherence is going to be everything here, and you know patients don’t like to apply topicals to their body. Once they’re clear they’re just going to walk away from the topical,” Dr. Strober predicted.

Dr. Stein Gold countered: “When a study goes on for a full year, it starts to reflect real life.”

Moreover, the PSO-LONG trial provides the first high-quality evidence physicians can share with patients demonstrating that proactive management pays off in terms of fewer relapses and more time in remission over the long haul, added Dr. Stein Gold, director of dermatology clinical research at the Henry Ford Health System in Detroit.

PSO-LONG was a double-blind, international, phase 3 study including 545 adults with plaque psoriasis who had clear or almost-clear skin after 4 weeks of once-daily calcipotriene 0.005%/betamethasone dipropionate 0.064% (Cal/BD) foam (Enstilar), and were then randomized to twice-weekly proactive management or to a reactive approach involving application of vehicle on the same twice-weekly schedule. Relapses resulted in rescue therapy with 4 weeks of once-daily Cal/BD foam.

The primary endpoint was the median time to first relapse: 56 days with the proactive approach, a significant improvement over the 30 days with the reactive approach. Over the course of 52 weeks, the proactive group spent an additional 41 days in remission, compared with the reactive group. Patients randomized to twice-weekly Cal/BD foam averaged 3.1 relapses per year, compared with 4.8 with reactive management. The side-effect profiles in the two study arms were similar.

Mean Physician Global Assessment scores and Psoriasis Area and Activity Index scores for the proactive group clearly separated from the reactive group by week 4, with those differences maintained throughout the year. The area under the curve for distribution for the Physician Global Assessment score was 15% lower in the proactive group, and 20% lower for the modified PASI score.

“These results suggest that proactive management – a concept that’s been used for atopic dermatitis – could be applied to patients with psoriasis to prolong remission,” Dr. Stein Gold concluded at the conference, sponsored by MedscapeLIVE! and the producers of the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar and Caribbean Dermatology Symposium.

Asked how confident she is that patients in the real world truly will do this, Dr. Stein Gold replied: “You know, I don’t know. We hope so. Now we can tell them we actually have some data that supports treating the cleared areas. And it’s only twice a week, separated on Mondays and Thursdays.”

“I take a much more reactive approach,” Dr. Strober said. “I advise patients to get back in there with their topical steroid as soon as they see any signs of recurrence.

He added that he’s eager to see if a proactive management approach such as the one that was successful in PSO-LONG is also beneficial using some of the promising topical agents with nonsteroidal mechanisms of action, which are advancing through the developmental pipeline.

Late in 2020, the Food and Drug Administration approved an expanded indication for Cal/BD foam, which includes the PSO-LONG data on the efficacy and safety of long-term twice-weekly therapy in adults in product labeling. The combination spray/foam was previously approved by the FDA as once-daily therapy in psoriasis patients aged 12 years and older, but only for up to 4 weeks because of safety concerns regarding longer use of the potent topical steroid as daily therapy.

The PSO-LONG trial was funded by LEO Pharma. Dr. Stein Gold reported serving as a paid investigator and/or consultant to LEO and numerous other pharmaceutical companies. Dr. Strober, reported serving as a consultant to more than two dozen pharmaceutical companies. MedscapeLIVE! and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

Long-term proactive topical management of plaque psoriasis with twice-weekly calcipotriene/betamethasone dipropionate foam has been shown in a high-quality randomized trial to be more effective than conventional reactive management – but will patients go for it?

Bruce E. Strober, MD, PhD, has his doubts, and he shared them with Linda Stein Gold, MD, after she presented updated results from the 52-week PSO-LONG trial at Innovations in Dermatology: Virtual Spring Conference 2021.

. And while they did so in this study with an assist in the form of monthly office visits and nudging from investigators, in real-world clinical practice that’s unlikely to happen, according to Dr. Strober, of Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

“It makes sense to do what’s being done in this study, there’s no doubt, but I’m concerned about adherence and whether patients are really going to do it,” he said.

“Adherence is going to be everything here, and you know patients don’t like to apply topicals to their body. Once they’re clear they’re just going to walk away from the topical,” Dr. Strober predicted.

Dr. Stein Gold countered: “When a study goes on for a full year, it starts to reflect real life.”

Moreover, the PSO-LONG trial provides the first high-quality evidence physicians can share with patients demonstrating that proactive management pays off in terms of fewer relapses and more time in remission over the long haul, added Dr. Stein Gold, director of dermatology clinical research at the Henry Ford Health System in Detroit.

PSO-LONG was a double-blind, international, phase 3 study including 545 adults with plaque psoriasis who had clear or almost-clear skin after 4 weeks of once-daily calcipotriene 0.005%/betamethasone dipropionate 0.064% (Cal/BD) foam (Enstilar), and were then randomized to twice-weekly proactive management or to a reactive approach involving application of vehicle on the same twice-weekly schedule. Relapses resulted in rescue therapy with 4 weeks of once-daily Cal/BD foam.

The primary endpoint was the median time to first relapse: 56 days with the proactive approach, a significant improvement over the 30 days with the reactive approach. Over the course of 52 weeks, the proactive group spent an additional 41 days in remission, compared with the reactive group. Patients randomized to twice-weekly Cal/BD foam averaged 3.1 relapses per year, compared with 4.8 with reactive management. The side-effect profiles in the two study arms were similar.

Mean Physician Global Assessment scores and Psoriasis Area and Activity Index scores for the proactive group clearly separated from the reactive group by week 4, with those differences maintained throughout the year. The area under the curve for distribution for the Physician Global Assessment score was 15% lower in the proactive group, and 20% lower for the modified PASI score.

“These results suggest that proactive management – a concept that’s been used for atopic dermatitis – could be applied to patients with psoriasis to prolong remission,” Dr. Stein Gold concluded at the conference, sponsored by MedscapeLIVE! and the producers of the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar and Caribbean Dermatology Symposium.

Asked how confident she is that patients in the real world truly will do this, Dr. Stein Gold replied: “You know, I don’t know. We hope so. Now we can tell them we actually have some data that supports treating the cleared areas. And it’s only twice a week, separated on Mondays and Thursdays.”

“I take a much more reactive approach,” Dr. Strober said. “I advise patients to get back in there with their topical steroid as soon as they see any signs of recurrence.

He added that he’s eager to see if a proactive management approach such as the one that was successful in PSO-LONG is also beneficial using some of the promising topical agents with nonsteroidal mechanisms of action, which are advancing through the developmental pipeline.

Late in 2020, the Food and Drug Administration approved an expanded indication for Cal/BD foam, which includes the PSO-LONG data on the efficacy and safety of long-term twice-weekly therapy in adults in product labeling. The combination spray/foam was previously approved by the FDA as once-daily therapy in psoriasis patients aged 12 years and older, but only for up to 4 weeks because of safety concerns regarding longer use of the potent topical steroid as daily therapy.

The PSO-LONG trial was funded by LEO Pharma. Dr. Stein Gold reported serving as a paid investigator and/or consultant to LEO and numerous other pharmaceutical companies. Dr. Strober, reported serving as a consultant to more than two dozen pharmaceutical companies. MedscapeLIVE! and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

FROM INNOVATIONS IN DERMATOLOGY

Treatment of Generalized Pustular Psoriasis of Pregnancy With Infliximab

Generalized pustular psoriasis of pregnancy (GPPP), formerly known as impetigo herpetiformis, is a rare dermatosis that causes maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality. It is characterized by widespread, circular, erythematous plaques with pustules at the periphery.1 Conventional first-line treatment includes systemic corticosteroids and cyclosporine. The National Psoriasis Foundation Medical Board also has included infliximab among the first-line treatment options for GPPP.2 Herein, we report a case of GPPP treated with infliximab at 30 weeks’ gestation and during the postpartum period.

Case Report

A 22-year-old woman was admitted to our inpatient clinic at 20 weeks’ gestation in her second pregnancy for evaluation of cutaneous eruptions covering the entire body. The lesions first appeared 3 to 4 days prior to her admission and dramatically progressed. She had a history of psoriasis vulgaris diagnosed during her first pregnancy 2 years prior that was treated with topical steroids throughout the pregnancy and methotrexate during lactation for a total of 11 months. She then was started on cyclosporine, which she used for 6 months due to ineffectiveness of the methotrexate, but she stopped treatment 4 months before the second pregnancy.

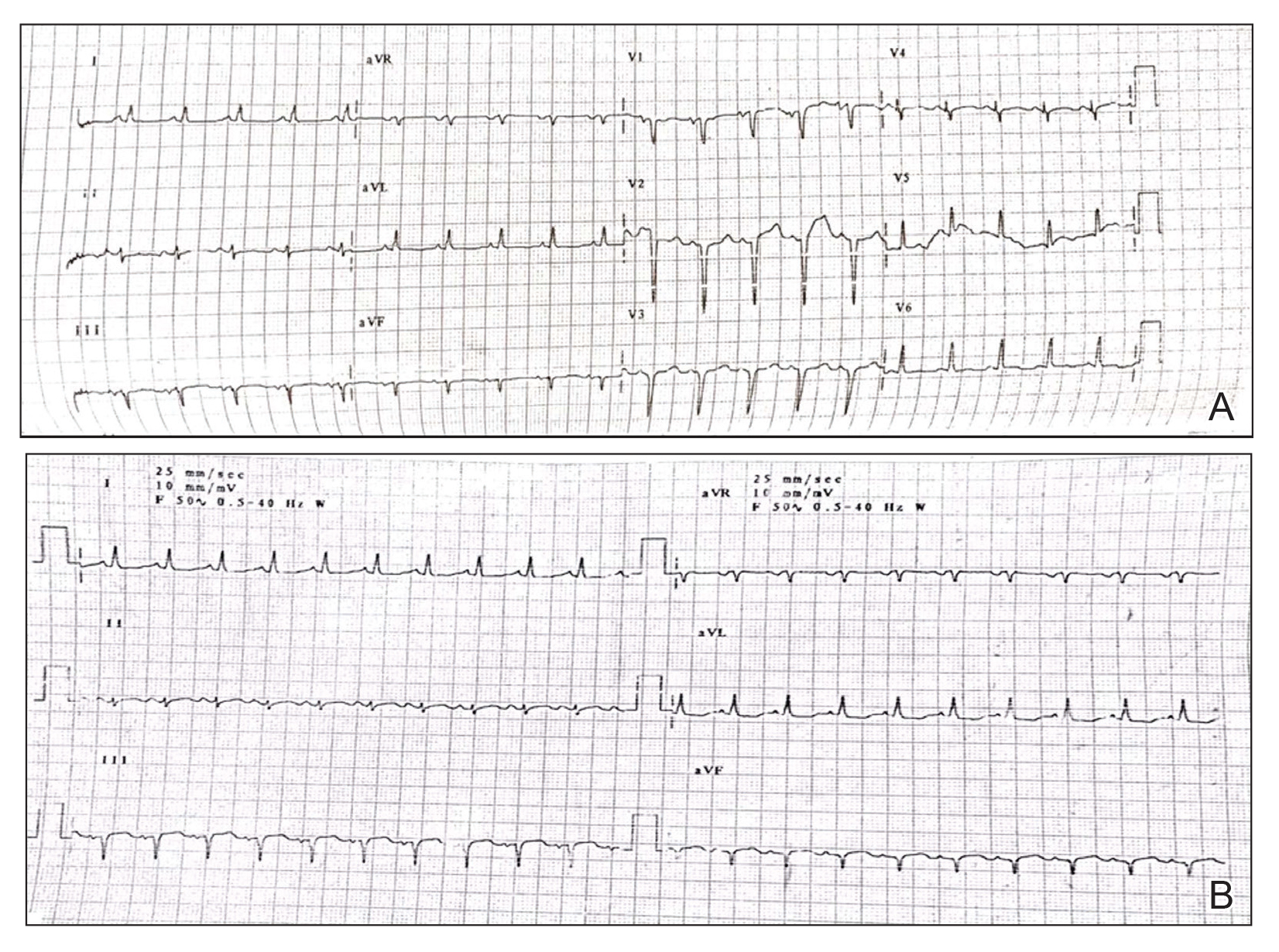

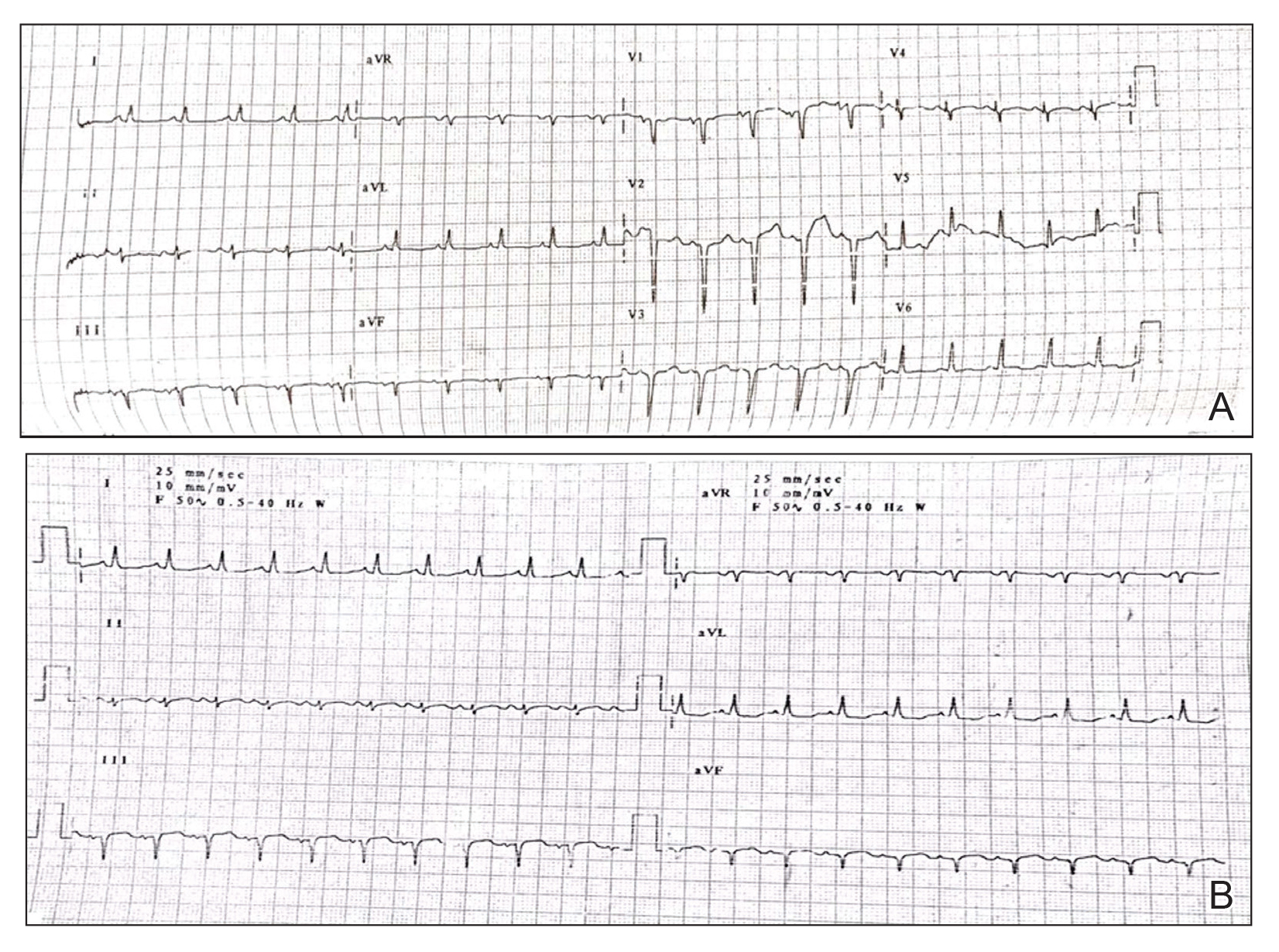

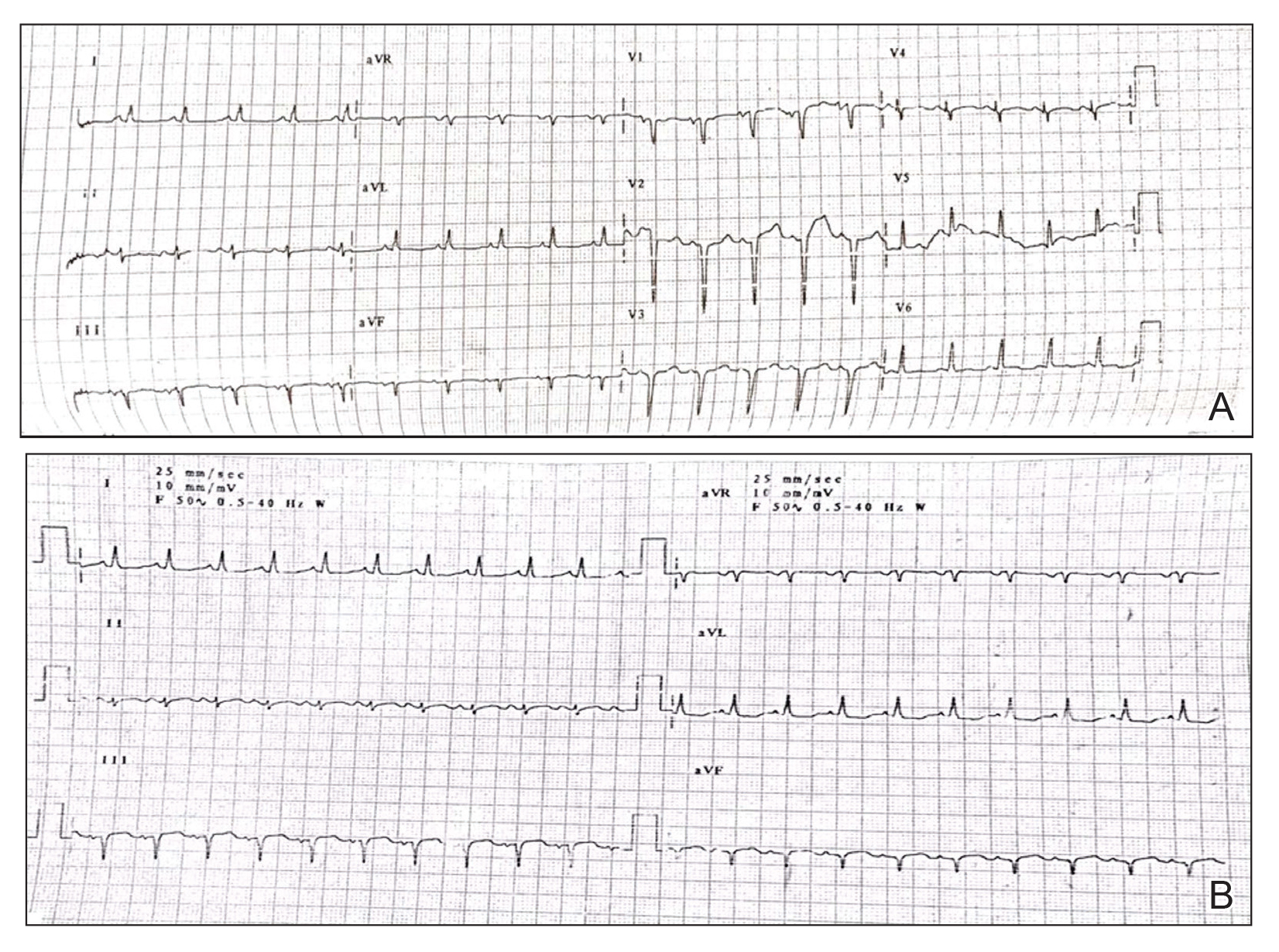

At the current presentation, physical examination revealed erythroderma and widespread pustules on the chest, abdomen, arms, and legs, including the intertriginous regions, that tended to coalesce and form lakes of pus over an erythematous base (Figure 1). The mucosae were normal. She exhibited a low blood pressure (85/50 mmHg) and high body temperature (102 °F [38.9 °C]). Routine laboratory examination revealed anemia and a normal leukocyte count. Her erythrocyte sedimentation rate (57 mm/h [reference range, <20 mm/h]) and C-reactive protein level (102 mg/L [reference range, <6 mg/L]) were elevated, whereas total calcium (8.11 mg/dL [reference range, 8.2–10.6 mg/dL]) and albumin (3.15 g/dL [reference range, >4.0 g/dL]) levels were low.

Empirical intravenous piperacillin/tazobactam was started due to hypotension, high fever, and elevated C-reactive protein levels; however, treatment was stopped after 4 days when microbiological cultures taken from blood and pustules revealed no bacterial growth, and therefore the fever was assumed to be caused by erythroderma. A skin biopsy before the start of topical and systemic treatment revealed changes consistent with GPPP.

Because her disease was extensive, systemic methylprednisolone 1.5 mg/kg once daily was started, and the dose was increased up to 2.5 mg/kg once daily on the tenth day of treatment to control new crops of eruptions. The dose was tapered to 2 mg/kg once daily when the lesions subsided 4 weeks into the treatment. The patient was discharged after 7 weeks at 27 weeks’ gestation.

Twelve days later, the patient was readmitted to the clinic in an erythrodermic state. The lesions were not controlled with increased doses of systemic corticosteroids. Treatment with cyclosporine was considered, but the patient refused; thus, infliximab treatment was planned. Isoniazid 300 mg once daily was started due to a risk of latent Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection revealed by a tuberculosis blood test. Other evaluations revealed no contraindications, and an infusion of infliximab 300 mg (5 mg/kg) was administered at 30 weeks’ gestation. There was visible improvement in the erythroderma and pustular lesions within the same day of treatment, and the lesions were completely cleared within 2 days of the infusion. The methylprednisolone dose was reduced to 1.5 mg/kg once daily.

Three days after treatment with infliximab, lesions with yellow encrustation appeared in the perioral region and on the oral mucosa and left ear. She was diagnosed with an oral herpes infection. Oral valacyclovir 1 g twice daily and topical mupirocin were started and the lesions subsided within 1 week. Twelve days after the infliximab infusion, new pustular lesions appeared, and a second infusion of infliximab was administered 13 days after the first, which cleared all lesions within 48 hours.

The patient’s methylprednisolone dose was tapered and stopped prior to delivery at 34 weeks’ gestation—2 weeks after the second dose of infliximab—as she did not have any new skin eruptions. A third infliximab infusion that normally would have occurred 4 weeks after the second treatment was postponed for a Cesarean section scheduled at 36 weeks’ gestation due to suspected intrauterine growth retardation. The patient stayed at the hospital until delivery without any new skin lesions. The gross and histopathologic examination of the placenta was normal. The neonate weighed 4.8 lb at birth and had neonatal jaundice that resolved spontaneously within 10 days but was otherwise healthy.

The patient returned to the clinic 3 weeks postpartum with a few pustules on erythematous plaques on the chest, abdomen, and back. At this time, she received a third infusion of infliximab 8 weeks after the second dose. For the past 5 years, the patient has been undergoing infliximab maintenance treatment, which she receives at the hospital every 8 weeks with excellent response. She has had no further pregnancies to date.

Comment

Generalized pustular psoriasis of pregnancy is a rare condition that typically occurs in the third trimester but also can start in the first and second trimesters. It may result in maternal and fetal morbidity by causing fluid and electrolyte imbalance and/or placental insufficiency, resulting in an increased risk for fetal abnormalities, stillbirth, and neonatal death.3 In subsequent pregnancies, GPPP has been observed to recur at an earlier gestational age with a more severe presentation.1,3

Generalized pustular psoriasis of pregnancy usually involves an eruption that begins symmetrically in the intertriginous areas and spreads to the rest of the body. The lesions present as erythematous annular plaques with pustules on the periphery and desquamation in the center due to older pustules.1,3 The mucous membranes also may be involved with erosive and exfoliative plaques, and there may be nail involvement. Patients often present with systemic symptoms such as fever, malaise, diarrhea, and vomiting.1 Laboratory investigations may reveal neutrophilic leukocytosis, high erythrocyte sedimentation rate, hypocalcemia, and hypoalbuminemia.4 Cultures from blood and pustules show no bacterial growth. A skin biopsy is helpful in diagnosis, with features similar to generalized pustular psoriasis, demonstrating spongiform pustules containing neutrophils, lymphocytic and neutrophilic infiltrates in the papillary dermis, and negative direct immunofluorescence.3

The differential diagnosis of GPPP includes subcorneal pustular dermatosis, dermatitis herpetiformis, herpes gestationis, impetigo, and acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis.1,3 Due to concerns of fetal implications, treatment options in GPPP are somewhat limited; however, the condition requires treatment because it may result in unfavorable pregnancy outcomes. Topical corticosteroids may be an option for limited disease.5,6 Systemic corticosteroids (eg, prednisone 60–80 mg/d) were previously considered as first-line agents, although they have shown limited efficacy in our case as well as in other case reports.7 Their ineffectiveness and risk for flare-up after dose tapering should be kept in mind when starting GPPP patients on systemic corticosteroids. Systemic cyclosporine (2–3 mg/kg/d) may be added to increase the efficacy of systemic steroids, which was done in several cases in literature.1,6,8 Although cyclosporine has been classified as a pregnancy category C drug, an analysis of pregnancy outcomes of 629 renal transplant patients revealed no association with adverse pregnancy outcomes compared to the general population and no increase in fetal malformations.9 Therefore, cyclosporine is a safe treatment option and was classified as a first-line drug for GPPP in a 2012 review by the National Psoriasis Foundation Medical Board.2 Narrowband UVB also has been reported to be used for the treatment of GPPP.10 Methotrexate and retinoids have been used in cases with lesions that persisted postpartum.1

Anti–tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α agents are another effective option for treatment of GPPP. Anti-TNF agents are classified as pregnancy category B due to results showing that anti-mouse TNF-α monoclonal antibodies did not cause embryotoxicity or teratogenicity in pregnant mice.11 Although Carter et al12 published a review of US Food and Drug Administration data on pregnant women receiving anti-TNF treatment and concluded that these agents were associated with the VACTERL group of malformations (vertebral defects, anal atresia, cardiac defect, tracheoesophageal fistula with esophageal atresia, cardiac defects, renal and limb anomalies), no such association was found in further studies. A 2014 study showed no difference in the rate of major malformations in infants born to women who were treated with anti-TNF drugs compared to the disease-matched group not treated with these agents and pregnant women counselled for nonteratogenic exposure.13 The same study detected an increase in preterm and low-birth-weight deliveries and suggested this might be caused by the increased severity of disease in patients requiring anti-TNF medication. The British Society of Rheumatology Biologics Register published data on pregnancy outcomes in 130 rheumatoid arthritis patients who had been exposed to anti-TNF agents.14 The results suggested an increased rate of spontaneous abortions in women exposed to anti-TNF treatment around the time of conception, especially in those taking these medications together with methotrexate or leflunomide; however, results also indicated that disease activity may have had an impact on the rate of spontaneous abortions in these patients. In a 2013 review of 462 women with inflammatory bowel disease who had been exposed to anti-TNF agents during pregnancy, the investigators concluded that pregnancy outcomes and the rate of congenital anomalies did not significantly differ from other inflammatory bowel disease patients not receiving anti-TNF drugs or the general population.15

In 2012, the National Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation put infliximab amongst the first-line treatment modalities for GPPP.2 In one case of GPPP in which the eruption persisted after delivery, the patient was treated with infliximab 7 weeks postpartum due to failure to control the disease with prednisolone 60 mg daily and cyclosporine 7.5 mg/kg daily. Unlike our patient, this patient was only started on an infliximab regimen after delivery.16 In another case reported in 2010, the patient was started on infliximab during the postpartum period of her first pregnancy following a pustular flare of previously diagnosed plaque psoriasis (not a generalized pustular psoriasis, as in our case).17 As a good response was obtained, infliximab treatment was continued in the patient throughout her second pregnancy.

Our case is unique in that infliximab was started during pregnancy because of intractable disease leading to systemic symptoms. Our patient showed an excellent response to infliximab after a 10-week disease course with repeated flare-ups and impairment to her overall condition. Delivery occurred at 36 weeks’ gestation due to suspected intrauterine growth retardation; however, the neonate was born with a 5-minute APGAR score of 10 and required no special medical care, which suggests that the low birth weight was constitutional due to the patient’s small frame (her height was 4 ft 11 in). The breast milk of patients with inflammatory bowel disease has been detected to contain very small amounts of infliximab (101 ng/mL, about 1/200 of the therapeutic blood level).18 Considering the large molecular weight of this agent and possible proteolysis in the stomach and intestines, infliximab is unlikely to affect the neonate.15 Thus, we encouraged our patient to breastfeed her baby. A case of fatal disseminated Bacille-Calmette-Guérin infection in an infant whose mother received infliximab treatment during pregnancy has been reported.19 It has been suggested that live vaccines should be avoided in neonates exposed to anti-TNF agents at least for the first 6 months of life or until the agent is no longer detectable in their blood.15 We therefore informed our patient’s family practitioner about this data.

Conclusion

We report a case of infliximab treatment for GPPP that was continued during the postpartum period. Infliximab was an effective treatment option in our patient with no detected serious adverse events and may be considered in other cases of GPPP that are not responsive to systemic steroids. However, further studies are warranted to evaluate the safety and efficacy of infliximab treatment for GPPP and psoriasis in pregnancy.

- Lerhoff S, Pomeranz MK. Specific dermatoses of pregnancy and their treatment. Dermatol Ther. 2013;26:274-284.

- Robinson A, Van Voorhees AS, Hsu S, et al. Treatment of pustular psoriasis: from the Medical Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:279-288.

- Oumeish OY, Parish JL. Impetigo herpetiformis. Clin Dermatol. 2006;24:101-104.

- Gao QQ, Xi MR, Yao Q. Impetigo herpetiformis during pregnancy: a case report and literature review. Dermatology. 2013;226:35-40.

- Bae YS, Van Voorhees AS, Hsu S, et al. Review of treatment options for psoriasis in pregnant or lactating women: from the Medical Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:459-477.

- Shaw CJ, Wu P, Sriemevan A. First trimester impetigo herpetiformis in multiparous female successfully treated with oral cyclosporine [published May 12, 2011]. BMJ Case Rep. doi:10.1136/bcr.02.2011.3915

- Hazarika D. Generalized pustular psoriasis of pregnancy successfully treated with cyclosporine. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:638.

- Luan L, Han S, Zhang Z, et al. Personal treatment experience for severe generalized pustular psoriasis of pregnancy: two case reports. Dermatol Ther. 2014;27:174-177.

- Lamarque V, Leleu MF, Monka C, et al. Analysis of 629 pregnancy outcomes in transplant recipients treated with Sandimmun. Transplant Proc. 1997;29:2480.

- Bozdag K, Ozturk S, Ermete M. A case of recurrent impetigo herpetiformis treated with systemic corticosteroids and narrowband UVB. Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2012;31:67-69.

- Treacy G. Using an analogous monoclonal antibody to evaluate the reproductive and chronic toxicity potential for a humanized anti-TNF alpha monoclonal antibody. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2000;19:226-228.

- Carter JD, Ladhani A, Ricca LR, et al. A safety assessment of tumor necrosis factor antagonists during pregnancy: a review of the Food and Drug Administration database. J Rheumatol. 2009;36:635-641.

- Diav-Citrin O, Otcheretianski-Volodarsky A, Shechtman S, et al. Pregnancy outcome following gestational exposure to TNF-alpha-inhibitors: a prospective, comparative, observational study. Reprod Toxicol. 2014;43:78-84.

- Verstappen SM, King Y, Watson KD, et al. Anti-TNF therapies and pregnancy: outcome of 130 pregnancies in the British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:823-826.

- Gisbert JP, Chaparro M. Safety of anti-TNF agents during pregnancy and breastfeeding in women with inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:1426-1438.

- Sheth N, Greenblatt DT, Acland K, et al. Generalized pustular psoriasis of pregnancy treated with infliximab. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:521-522.

- Puig L, Barco D, Alomar A. Treatment of psoriasis with anti-TNF drugs during pregnancy: case report and review of the literature. Dermatology. 2010;220:71-76.

- Ben-Horin S, Yavzori M, Kopylov U, et al. Detection of infliximab in breast milk of nursing mothers with inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2011;5:555-558.

- Cheent K, Nolan J, Shariq S, et al. Case report: fatal case of disseminated BCG infection in an infant born to a mother taking infliximab for Crohn’s disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2010;4:603-605.

Generalized pustular psoriasis of pregnancy (GPPP), formerly known as impetigo herpetiformis, is a rare dermatosis that causes maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality. It is characterized by widespread, circular, erythematous plaques with pustules at the periphery.1 Conventional first-line treatment includes systemic corticosteroids and cyclosporine. The National Psoriasis Foundation Medical Board also has included infliximab among the first-line treatment options for GPPP.2 Herein, we report a case of GPPP treated with infliximab at 30 weeks’ gestation and during the postpartum period.

Case Report

A 22-year-old woman was admitted to our inpatient clinic at 20 weeks’ gestation in her second pregnancy for evaluation of cutaneous eruptions covering the entire body. The lesions first appeared 3 to 4 days prior to her admission and dramatically progressed. She had a history of psoriasis vulgaris diagnosed during her first pregnancy 2 years prior that was treated with topical steroids throughout the pregnancy and methotrexate during lactation for a total of 11 months. She then was started on cyclosporine, which she used for 6 months due to ineffectiveness of the methotrexate, but she stopped treatment 4 months before the second pregnancy.

At the current presentation, physical examination revealed erythroderma and widespread pustules on the chest, abdomen, arms, and legs, including the intertriginous regions, that tended to coalesce and form lakes of pus over an erythematous base (Figure 1). The mucosae were normal. She exhibited a low blood pressure (85/50 mmHg) and high body temperature (102 °F [38.9 °C]). Routine laboratory examination revealed anemia and a normal leukocyte count. Her erythrocyte sedimentation rate (57 mm/h [reference range, <20 mm/h]) and C-reactive protein level (102 mg/L [reference range, <6 mg/L]) were elevated, whereas total calcium (8.11 mg/dL [reference range, 8.2–10.6 mg/dL]) and albumin (3.15 g/dL [reference range, >4.0 g/dL]) levels were low.

Empirical intravenous piperacillin/tazobactam was started due to hypotension, high fever, and elevated C-reactive protein levels; however, treatment was stopped after 4 days when microbiological cultures taken from blood and pustules revealed no bacterial growth, and therefore the fever was assumed to be caused by erythroderma. A skin biopsy before the start of topical and systemic treatment revealed changes consistent with GPPP.

Because her disease was extensive, systemic methylprednisolone 1.5 mg/kg once daily was started, and the dose was increased up to 2.5 mg/kg once daily on the tenth day of treatment to control new crops of eruptions. The dose was tapered to 2 mg/kg once daily when the lesions subsided 4 weeks into the treatment. The patient was discharged after 7 weeks at 27 weeks’ gestation.

Twelve days later, the patient was readmitted to the clinic in an erythrodermic state. The lesions were not controlled with increased doses of systemic corticosteroids. Treatment with cyclosporine was considered, but the patient refused; thus, infliximab treatment was planned. Isoniazid 300 mg once daily was started due to a risk of latent Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection revealed by a tuberculosis blood test. Other evaluations revealed no contraindications, and an infusion of infliximab 300 mg (5 mg/kg) was administered at 30 weeks’ gestation. There was visible improvement in the erythroderma and pustular lesions within the same day of treatment, and the lesions were completely cleared within 2 days of the infusion. The methylprednisolone dose was reduced to 1.5 mg/kg once daily.

Three days after treatment with infliximab, lesions with yellow encrustation appeared in the perioral region and on the oral mucosa and left ear. She was diagnosed with an oral herpes infection. Oral valacyclovir 1 g twice daily and topical mupirocin were started and the lesions subsided within 1 week. Twelve days after the infliximab infusion, new pustular lesions appeared, and a second infusion of infliximab was administered 13 days after the first, which cleared all lesions within 48 hours.

The patient’s methylprednisolone dose was tapered and stopped prior to delivery at 34 weeks’ gestation—2 weeks after the second dose of infliximab—as she did not have any new skin eruptions. A third infliximab infusion that normally would have occurred 4 weeks after the second treatment was postponed for a Cesarean section scheduled at 36 weeks’ gestation due to suspected intrauterine growth retardation. The patient stayed at the hospital until delivery without any new skin lesions. The gross and histopathologic examination of the placenta was normal. The neonate weighed 4.8 lb at birth and had neonatal jaundice that resolved spontaneously within 10 days but was otherwise healthy.

The patient returned to the clinic 3 weeks postpartum with a few pustules on erythematous plaques on the chest, abdomen, and back. At this time, she received a third infusion of infliximab 8 weeks after the second dose. For the past 5 years, the patient has been undergoing infliximab maintenance treatment, which she receives at the hospital every 8 weeks with excellent response. She has had no further pregnancies to date.

Comment

Generalized pustular psoriasis of pregnancy is a rare condition that typically occurs in the third trimester but also can start in the first and second trimesters. It may result in maternal and fetal morbidity by causing fluid and electrolyte imbalance and/or placental insufficiency, resulting in an increased risk for fetal abnormalities, stillbirth, and neonatal death.3 In subsequent pregnancies, GPPP has been observed to recur at an earlier gestational age with a more severe presentation.1,3

Generalized pustular psoriasis of pregnancy usually involves an eruption that begins symmetrically in the intertriginous areas and spreads to the rest of the body. The lesions present as erythematous annular plaques with pustules on the periphery and desquamation in the center due to older pustules.1,3 The mucous membranes also may be involved with erosive and exfoliative plaques, and there may be nail involvement. Patients often present with systemic symptoms such as fever, malaise, diarrhea, and vomiting.1 Laboratory investigations may reveal neutrophilic leukocytosis, high erythrocyte sedimentation rate, hypocalcemia, and hypoalbuminemia.4 Cultures from blood and pustules show no bacterial growth. A skin biopsy is helpful in diagnosis, with features similar to generalized pustular psoriasis, demonstrating spongiform pustules containing neutrophils, lymphocytic and neutrophilic infiltrates in the papillary dermis, and negative direct immunofluorescence.3

The differential diagnosis of GPPP includes subcorneal pustular dermatosis, dermatitis herpetiformis, herpes gestationis, impetigo, and acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis.1,3 Due to concerns of fetal implications, treatment options in GPPP are somewhat limited; however, the condition requires treatment because it may result in unfavorable pregnancy outcomes. Topical corticosteroids may be an option for limited disease.5,6 Systemic corticosteroids (eg, prednisone 60–80 mg/d) were previously considered as first-line agents, although they have shown limited efficacy in our case as well as in other case reports.7 Their ineffectiveness and risk for flare-up after dose tapering should be kept in mind when starting GPPP patients on systemic corticosteroids. Systemic cyclosporine (2–3 mg/kg/d) may be added to increase the efficacy of systemic steroids, which was done in several cases in literature.1,6,8 Although cyclosporine has been classified as a pregnancy category C drug, an analysis of pregnancy outcomes of 629 renal transplant patients revealed no association with adverse pregnancy outcomes compared to the general population and no increase in fetal malformations.9 Therefore, cyclosporine is a safe treatment option and was classified as a first-line drug for GPPP in a 2012 review by the National Psoriasis Foundation Medical Board.2 Narrowband UVB also has been reported to be used for the treatment of GPPP.10 Methotrexate and retinoids have been used in cases with lesions that persisted postpartum.1

Anti–tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α agents are another effective option for treatment of GPPP. Anti-TNF agents are classified as pregnancy category B due to results showing that anti-mouse TNF-α monoclonal antibodies did not cause embryotoxicity or teratogenicity in pregnant mice.11 Although Carter et al12 published a review of US Food and Drug Administration data on pregnant women receiving anti-TNF treatment and concluded that these agents were associated with the VACTERL group of malformations (vertebral defects, anal atresia, cardiac defect, tracheoesophageal fistula with esophageal atresia, cardiac defects, renal and limb anomalies), no such association was found in further studies. A 2014 study showed no difference in the rate of major malformations in infants born to women who were treated with anti-TNF drugs compared to the disease-matched group not treated with these agents and pregnant women counselled for nonteratogenic exposure.13 The same study detected an increase in preterm and low-birth-weight deliveries and suggested this might be caused by the increased severity of disease in patients requiring anti-TNF medication. The British Society of Rheumatology Biologics Register published data on pregnancy outcomes in 130 rheumatoid arthritis patients who had been exposed to anti-TNF agents.14 The results suggested an increased rate of spontaneous abortions in women exposed to anti-TNF treatment around the time of conception, especially in those taking these medications together with methotrexate or leflunomide; however, results also indicated that disease activity may have had an impact on the rate of spontaneous abortions in these patients. In a 2013 review of 462 women with inflammatory bowel disease who had been exposed to anti-TNF agents during pregnancy, the investigators concluded that pregnancy outcomes and the rate of congenital anomalies did not significantly differ from other inflammatory bowel disease patients not receiving anti-TNF drugs or the general population.15

In 2012, the National Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation put infliximab amongst the first-line treatment modalities for GPPP.2 In one case of GPPP in which the eruption persisted after delivery, the patient was treated with infliximab 7 weeks postpartum due to failure to control the disease with prednisolone 60 mg daily and cyclosporine 7.5 mg/kg daily. Unlike our patient, this patient was only started on an infliximab regimen after delivery.16 In another case reported in 2010, the patient was started on infliximab during the postpartum period of her first pregnancy following a pustular flare of previously diagnosed plaque psoriasis (not a generalized pustular psoriasis, as in our case).17 As a good response was obtained, infliximab treatment was continued in the patient throughout her second pregnancy.

Our case is unique in that infliximab was started during pregnancy because of intractable disease leading to systemic symptoms. Our patient showed an excellent response to infliximab after a 10-week disease course with repeated flare-ups and impairment to her overall condition. Delivery occurred at 36 weeks’ gestation due to suspected intrauterine growth retardation; however, the neonate was born with a 5-minute APGAR score of 10 and required no special medical care, which suggests that the low birth weight was constitutional due to the patient’s small frame (her height was 4 ft 11 in). The breast milk of patients with inflammatory bowel disease has been detected to contain very small amounts of infliximab (101 ng/mL, about 1/200 of the therapeutic blood level).18 Considering the large molecular weight of this agent and possible proteolysis in the stomach and intestines, infliximab is unlikely to affect the neonate.15 Thus, we encouraged our patient to breastfeed her baby. A case of fatal disseminated Bacille-Calmette-Guérin infection in an infant whose mother received infliximab treatment during pregnancy has been reported.19 It has been suggested that live vaccines should be avoided in neonates exposed to anti-TNF agents at least for the first 6 months of life or until the agent is no longer detectable in their blood.15 We therefore informed our patient’s family practitioner about this data.

Conclusion

We report a case of infliximab treatment for GPPP that was continued during the postpartum period. Infliximab was an effective treatment option in our patient with no detected serious adverse events and may be considered in other cases of GPPP that are not responsive to systemic steroids. However, further studies are warranted to evaluate the safety and efficacy of infliximab treatment for GPPP and psoriasis in pregnancy.

Generalized pustular psoriasis of pregnancy (GPPP), formerly known as impetigo herpetiformis, is a rare dermatosis that causes maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality. It is characterized by widespread, circular, erythematous plaques with pustules at the periphery.1 Conventional first-line treatment includes systemic corticosteroids and cyclosporine. The National Psoriasis Foundation Medical Board also has included infliximab among the first-line treatment options for GPPP.2 Herein, we report a case of GPPP treated with infliximab at 30 weeks’ gestation and during the postpartum period.

Case Report

A 22-year-old woman was admitted to our inpatient clinic at 20 weeks’ gestation in her second pregnancy for evaluation of cutaneous eruptions covering the entire body. The lesions first appeared 3 to 4 days prior to her admission and dramatically progressed. She had a history of psoriasis vulgaris diagnosed during her first pregnancy 2 years prior that was treated with topical steroids throughout the pregnancy and methotrexate during lactation for a total of 11 months. She then was started on cyclosporine, which she used for 6 months due to ineffectiveness of the methotrexate, but she stopped treatment 4 months before the second pregnancy.

At the current presentation, physical examination revealed erythroderma and widespread pustules on the chest, abdomen, arms, and legs, including the intertriginous regions, that tended to coalesce and form lakes of pus over an erythematous base (Figure 1). The mucosae were normal. She exhibited a low blood pressure (85/50 mmHg) and high body temperature (102 °F [38.9 °C]). Routine laboratory examination revealed anemia and a normal leukocyte count. Her erythrocyte sedimentation rate (57 mm/h [reference range, <20 mm/h]) and C-reactive protein level (102 mg/L [reference range, <6 mg/L]) were elevated, whereas total calcium (8.11 mg/dL [reference range, 8.2–10.6 mg/dL]) and albumin (3.15 g/dL [reference range, >4.0 g/dL]) levels were low.

Empirical intravenous piperacillin/tazobactam was started due to hypotension, high fever, and elevated C-reactive protein levels; however, treatment was stopped after 4 days when microbiological cultures taken from blood and pustules revealed no bacterial growth, and therefore the fever was assumed to be caused by erythroderma. A skin biopsy before the start of topical and systemic treatment revealed changes consistent with GPPP.

Because her disease was extensive, systemic methylprednisolone 1.5 mg/kg once daily was started, and the dose was increased up to 2.5 mg/kg once daily on the tenth day of treatment to control new crops of eruptions. The dose was tapered to 2 mg/kg once daily when the lesions subsided 4 weeks into the treatment. The patient was discharged after 7 weeks at 27 weeks’ gestation.

Twelve days later, the patient was readmitted to the clinic in an erythrodermic state. The lesions were not controlled with increased doses of systemic corticosteroids. Treatment with cyclosporine was considered, but the patient refused; thus, infliximab treatment was planned. Isoniazid 300 mg once daily was started due to a risk of latent Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection revealed by a tuberculosis blood test. Other evaluations revealed no contraindications, and an infusion of infliximab 300 mg (5 mg/kg) was administered at 30 weeks’ gestation. There was visible improvement in the erythroderma and pustular lesions within the same day of treatment, and the lesions were completely cleared within 2 days of the infusion. The methylprednisolone dose was reduced to 1.5 mg/kg once daily.

Three days after treatment with infliximab, lesions with yellow encrustation appeared in the perioral region and on the oral mucosa and left ear. She was diagnosed with an oral herpes infection. Oral valacyclovir 1 g twice daily and topical mupirocin were started and the lesions subsided within 1 week. Twelve days after the infliximab infusion, new pustular lesions appeared, and a second infusion of infliximab was administered 13 days after the first, which cleared all lesions within 48 hours.

The patient’s methylprednisolone dose was tapered and stopped prior to delivery at 34 weeks’ gestation—2 weeks after the second dose of infliximab—as she did not have any new skin eruptions. A third infliximab infusion that normally would have occurred 4 weeks after the second treatment was postponed for a Cesarean section scheduled at 36 weeks’ gestation due to suspected intrauterine growth retardation. The patient stayed at the hospital until delivery without any new skin lesions. The gross and histopathologic examination of the placenta was normal. The neonate weighed 4.8 lb at birth and had neonatal jaundice that resolved spontaneously within 10 days but was otherwise healthy.

The patient returned to the clinic 3 weeks postpartum with a few pustules on erythematous plaques on the chest, abdomen, and back. At this time, she received a third infusion of infliximab 8 weeks after the second dose. For the past 5 years, the patient has been undergoing infliximab maintenance treatment, which she receives at the hospital every 8 weeks with excellent response. She has had no further pregnancies to date.

Comment

Generalized pustular psoriasis of pregnancy is a rare condition that typically occurs in the third trimester but also can start in the first and second trimesters. It may result in maternal and fetal morbidity by causing fluid and electrolyte imbalance and/or placental insufficiency, resulting in an increased risk for fetal abnormalities, stillbirth, and neonatal death.3 In subsequent pregnancies, GPPP has been observed to recur at an earlier gestational age with a more severe presentation.1,3

Generalized pustular psoriasis of pregnancy usually involves an eruption that begins symmetrically in the intertriginous areas and spreads to the rest of the body. The lesions present as erythematous annular plaques with pustules on the periphery and desquamation in the center due to older pustules.1,3 The mucous membranes also may be involved with erosive and exfoliative plaques, and there may be nail involvement. Patients often present with systemic symptoms such as fever, malaise, diarrhea, and vomiting.1 Laboratory investigations may reveal neutrophilic leukocytosis, high erythrocyte sedimentation rate, hypocalcemia, and hypoalbuminemia.4 Cultures from blood and pustules show no bacterial growth. A skin biopsy is helpful in diagnosis, with features similar to generalized pustular psoriasis, demonstrating spongiform pustules containing neutrophils, lymphocytic and neutrophilic infiltrates in the papillary dermis, and negative direct immunofluorescence.3

The differential diagnosis of GPPP includes subcorneal pustular dermatosis, dermatitis herpetiformis, herpes gestationis, impetigo, and acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis.1,3 Due to concerns of fetal implications, treatment options in GPPP are somewhat limited; however, the condition requires treatment because it may result in unfavorable pregnancy outcomes. Topical corticosteroids may be an option for limited disease.5,6 Systemic corticosteroids (eg, prednisone 60–80 mg/d) were previously considered as first-line agents, although they have shown limited efficacy in our case as well as in other case reports.7 Their ineffectiveness and risk for flare-up after dose tapering should be kept in mind when starting GPPP patients on systemic corticosteroids. Systemic cyclosporine (2–3 mg/kg/d) may be added to increase the efficacy of systemic steroids, which was done in several cases in literature.1,6,8 Although cyclosporine has been classified as a pregnancy category C drug, an analysis of pregnancy outcomes of 629 renal transplant patients revealed no association with adverse pregnancy outcomes compared to the general population and no increase in fetal malformations.9 Therefore, cyclosporine is a safe treatment option and was classified as a first-line drug for GPPP in a 2012 review by the National Psoriasis Foundation Medical Board.2 Narrowband UVB also has been reported to be used for the treatment of GPPP.10 Methotrexate and retinoids have been used in cases with lesions that persisted postpartum.1

Anti–tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α agents are another effective option for treatment of GPPP. Anti-TNF agents are classified as pregnancy category B due to results showing that anti-mouse TNF-α monoclonal antibodies did not cause embryotoxicity or teratogenicity in pregnant mice.11 Although Carter et al12 published a review of US Food and Drug Administration data on pregnant women receiving anti-TNF treatment and concluded that these agents were associated with the VACTERL group of malformations (vertebral defects, anal atresia, cardiac defect, tracheoesophageal fistula with esophageal atresia, cardiac defects, renal and limb anomalies), no such association was found in further studies. A 2014 study showed no difference in the rate of major malformations in infants born to women who were treated with anti-TNF drugs compared to the disease-matched group not treated with these agents and pregnant women counselled for nonteratogenic exposure.13 The same study detected an increase in preterm and low-birth-weight deliveries and suggested this might be caused by the increased severity of disease in patients requiring anti-TNF medication. The British Society of Rheumatology Biologics Register published data on pregnancy outcomes in 130 rheumatoid arthritis patients who had been exposed to anti-TNF agents.14 The results suggested an increased rate of spontaneous abortions in women exposed to anti-TNF treatment around the time of conception, especially in those taking these medications together with methotrexate or leflunomide; however, results also indicated that disease activity may have had an impact on the rate of spontaneous abortions in these patients. In a 2013 review of 462 women with inflammatory bowel disease who had been exposed to anti-TNF agents during pregnancy, the investigators concluded that pregnancy outcomes and the rate of congenital anomalies did not significantly differ from other inflammatory bowel disease patients not receiving anti-TNF drugs or the general population.15

In 2012, the National Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation put infliximab amongst the first-line treatment modalities for GPPP.2 In one case of GPPP in which the eruption persisted after delivery, the patient was treated with infliximab 7 weeks postpartum due to failure to control the disease with prednisolone 60 mg daily and cyclosporine 7.5 mg/kg daily. Unlike our patient, this patient was only started on an infliximab regimen after delivery.16 In another case reported in 2010, the patient was started on infliximab during the postpartum period of her first pregnancy following a pustular flare of previously diagnosed plaque psoriasis (not a generalized pustular psoriasis, as in our case).17 As a good response was obtained, infliximab treatment was continued in the patient throughout her second pregnancy.

Our case is unique in that infliximab was started during pregnancy because of intractable disease leading to systemic symptoms. Our patient showed an excellent response to infliximab after a 10-week disease course with repeated flare-ups and impairment to her overall condition. Delivery occurred at 36 weeks’ gestation due to suspected intrauterine growth retardation; however, the neonate was born with a 5-minute APGAR score of 10 and required no special medical care, which suggests that the low birth weight was constitutional due to the patient’s small frame (her height was 4 ft 11 in). The breast milk of patients with inflammatory bowel disease has been detected to contain very small amounts of infliximab (101 ng/mL, about 1/200 of the therapeutic blood level).18 Considering the large molecular weight of this agent and possible proteolysis in the stomach and intestines, infliximab is unlikely to affect the neonate.15 Thus, we encouraged our patient to breastfeed her baby. A case of fatal disseminated Bacille-Calmette-Guérin infection in an infant whose mother received infliximab treatment during pregnancy has been reported.19 It has been suggested that live vaccines should be avoided in neonates exposed to anti-TNF agents at least for the first 6 months of life or until the agent is no longer detectable in their blood.15 We therefore informed our patient’s family practitioner about this data.

Conclusion

We report a case of infliximab treatment for GPPP that was continued during the postpartum period. Infliximab was an effective treatment option in our patient with no detected serious adverse events and may be considered in other cases of GPPP that are not responsive to systemic steroids. However, further studies are warranted to evaluate the safety and efficacy of infliximab treatment for GPPP and psoriasis in pregnancy.

- Lerhoff S, Pomeranz MK. Specific dermatoses of pregnancy and their treatment. Dermatol Ther. 2013;26:274-284.

- Robinson A, Van Voorhees AS, Hsu S, et al. Treatment of pustular psoriasis: from the Medical Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:279-288.

- Oumeish OY, Parish JL. Impetigo herpetiformis. Clin Dermatol. 2006;24:101-104.

- Gao QQ, Xi MR, Yao Q. Impetigo herpetiformis during pregnancy: a case report and literature review. Dermatology. 2013;226:35-40.

- Bae YS, Van Voorhees AS, Hsu S, et al. Review of treatment options for psoriasis in pregnant or lactating women: from the Medical Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:459-477.

- Shaw CJ, Wu P, Sriemevan A. First trimester impetigo herpetiformis in multiparous female successfully treated with oral cyclosporine [published May 12, 2011]. BMJ Case Rep. doi:10.1136/bcr.02.2011.3915

- Hazarika D. Generalized pustular psoriasis of pregnancy successfully treated with cyclosporine. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:638.

- Luan L, Han S, Zhang Z, et al. Personal treatment experience for severe generalized pustular psoriasis of pregnancy: two case reports. Dermatol Ther. 2014;27:174-177.

- Lamarque V, Leleu MF, Monka C, et al. Analysis of 629 pregnancy outcomes in transplant recipients treated with Sandimmun. Transplant Proc. 1997;29:2480.

- Bozdag K, Ozturk S, Ermete M. A case of recurrent impetigo herpetiformis treated with systemic corticosteroids and narrowband UVB. Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2012;31:67-69.

- Treacy G. Using an analogous monoclonal antibody to evaluate the reproductive and chronic toxicity potential for a humanized anti-TNF alpha monoclonal antibody. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2000;19:226-228.

- Carter JD, Ladhani A, Ricca LR, et al. A safety assessment of tumor necrosis factor antagonists during pregnancy: a review of the Food and Drug Administration database. J Rheumatol. 2009;36:635-641.

- Diav-Citrin O, Otcheretianski-Volodarsky A, Shechtman S, et al. Pregnancy outcome following gestational exposure to TNF-alpha-inhibitors: a prospective, comparative, observational study. Reprod Toxicol. 2014;43:78-84.

- Verstappen SM, King Y, Watson KD, et al. Anti-TNF therapies and pregnancy: outcome of 130 pregnancies in the British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:823-826.

- Gisbert JP, Chaparro M. Safety of anti-TNF agents during pregnancy and breastfeeding in women with inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:1426-1438.

- Sheth N, Greenblatt DT, Acland K, et al. Generalized pustular psoriasis of pregnancy treated with infliximab. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:521-522.

- Puig L, Barco D, Alomar A. Treatment of psoriasis with anti-TNF drugs during pregnancy: case report and review of the literature. Dermatology. 2010;220:71-76.

- Ben-Horin S, Yavzori M, Kopylov U, et al. Detection of infliximab in breast milk of nursing mothers with inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2011;5:555-558.

- Cheent K, Nolan J, Shariq S, et al. Case report: fatal case of disseminated BCG infection in an infant born to a mother taking infliximab for Crohn’s disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2010;4:603-605.

- Lerhoff S, Pomeranz MK. Specific dermatoses of pregnancy and their treatment. Dermatol Ther. 2013;26:274-284.

- Robinson A, Van Voorhees AS, Hsu S, et al. Treatment of pustular psoriasis: from the Medical Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:279-288.

- Oumeish OY, Parish JL. Impetigo herpetiformis. Clin Dermatol. 2006;24:101-104.

- Gao QQ, Xi MR, Yao Q. Impetigo herpetiformis during pregnancy: a case report and literature review. Dermatology. 2013;226:35-40.

- Bae YS, Van Voorhees AS, Hsu S, et al. Review of treatment options for psoriasis in pregnant or lactating women: from the Medical Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:459-477.

- Shaw CJ, Wu P, Sriemevan A. First trimester impetigo herpetiformis in multiparous female successfully treated with oral cyclosporine [published May 12, 2011]. BMJ Case Rep. doi:10.1136/bcr.02.2011.3915

- Hazarika D. Generalized pustular psoriasis of pregnancy successfully treated with cyclosporine. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:638.

- Luan L, Han S, Zhang Z, et al. Personal treatment experience for severe generalized pustular psoriasis of pregnancy: two case reports. Dermatol Ther. 2014;27:174-177.

- Lamarque V, Leleu MF, Monka C, et al. Analysis of 629 pregnancy outcomes in transplant recipients treated with Sandimmun. Transplant Proc. 1997;29:2480.

- Bozdag K, Ozturk S, Ermete M. A case of recurrent impetigo herpetiformis treated with systemic corticosteroids and narrowband UVB. Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2012;31:67-69.

- Treacy G. Using an analogous monoclonal antibody to evaluate the reproductive and chronic toxicity potential for a humanized anti-TNF alpha monoclonal antibody. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2000;19:226-228.

- Carter JD, Ladhani A, Ricca LR, et al. A safety assessment of tumor necrosis factor antagonists during pregnancy: a review of the Food and Drug Administration database. J Rheumatol. 2009;36:635-641.

- Diav-Citrin O, Otcheretianski-Volodarsky A, Shechtman S, et al. Pregnancy outcome following gestational exposure to TNF-alpha-inhibitors: a prospective, comparative, observational study. Reprod Toxicol. 2014;43:78-84.

- Verstappen SM, King Y, Watson KD, et al. Anti-TNF therapies and pregnancy: outcome of 130 pregnancies in the British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:823-826.

- Gisbert JP, Chaparro M. Safety of anti-TNF agents during pregnancy and breastfeeding in women with inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:1426-1438.

- Sheth N, Greenblatt DT, Acland K, et al. Generalized pustular psoriasis of pregnancy treated with infliximab. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:521-522.

- Puig L, Barco D, Alomar A. Treatment of psoriasis with anti-TNF drugs during pregnancy: case report and review of the literature. Dermatology. 2010;220:71-76.

- Ben-Horin S, Yavzori M, Kopylov U, et al. Detection of infliximab in breast milk of nursing mothers with inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2011;5:555-558.

- Cheent K, Nolan J, Shariq S, et al. Case report: fatal case of disseminated BCG infection in an infant born to a mother taking infliximab for Crohn’s disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2010;4:603-605.

Practice Points

- Generalized pustular psoriasis of pregnancy (GPPP) is a rare and severe condition that may lead to complications in both the mother and the fetus. Effective treatment with low impact on the fetus is essential.

- Infliximab, among other biologic agents, may be considered for the rapid clearing of skin lesions in GPPP.

To improve psoriatic arthritis outcomes, address common comorbidities

Only about 30% or fewer of patients with psoriatic arthritis (PsA) on therapy achieve disease remission by any definition. One reason for this may be inadequate attention to common comorbid conditions, Alexis Ogdie, MD, MSCE, declared at the 2021 Rheumatology Winter Clinical Symposium.

“I believe that addressing off-target aspects of disease is really important to improving the patient experience of their disease. We might need to target these directly in order to improve outcomes,” said Dr. Ogdie, a rheumatologist and epidemiologist at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, who coauthored the current American College of Rheumatology/National Psoriasis Foundation PsA guidelines.

Since rheumatologists are by now well informed about the increased cardiovascular risk associated with PsA, she focused on two common comorbidities that get less attention, both of which are associated with worse clinical outcomes in PsA: obesity and mental health issues.

Anxiety and depression

Dr. Ogdie was first author of a large, population-based, longitudinal cohort study of cause-specific mortality in 8,706 U.K. patients with PsA, 41,752 with RA, and more than 81,000 controls. Particularly striking was the finding of elevated mortality because of suicide in the rheumatic disease patients: a 203% increased risk in the PsA population, compared with the general population, and a 147% greater risk in patients with RA.

Overall, 30%-40% of PsA patients have comorbid depression and/or anxiety.

“That’s pretty striking. It’s also true for rheumatoid arthritis and axial spondyloarthritis. And if you’re depressed, you’re much less likely to respond to therapy in the way that we are measuring response to therapy,” Dr. Ogdie said.

Her approach to screening for depression and anxiety in her PsA patients, and indeed in all her other patients, is to begin by normalizing the topic, explaining to them that these affective disorders are common among patients with these disorders. She lets her patients know they can talk to her about it. And she informs them that, while effective treatment of their rheumatic disease may improve their depression or anxiety, managing those is also important for improving their disease. Additionally, understanding whether depression is present is important prior to prescribing certain medications. Apremilast (Otezla), for example, can worsen preexisting depression.

“Ask about signs and symptoms of depression,” Dr. Ogdie urged her colleagues. “I do this at every single visit in my review of symptoms. This is one I don’t skip. I ask: ‘Do you have any symptoms of depression or anxiety?’ ”

Structured evidence-based screening tools, many of which are well suited for completion during a patient’s preappointment check-in survey, include the Patient Health Questionnaire–2, the PHQ-9, the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measure Information System–10, PROMIS–Depression, and Routine Assessment of Patient Index Data 3.

“I also really like the PROMIS-29. It covers many domains of interest: depression and anxiety, sleep, fatigue, pain, physical function. It gives a lot of information about what’s going on in a patient’s life right now,” according to the rheumatologist.

The main thing is to regularly screen for anxiety and depression and then refer symptomatic patients for further assessment and treatment. This is not something that all rheumatologists have been trained to do.

Obesity

Dr. Ogdie was lead author of a national CORRONA Registry study which concluded that obese patients with PsA were only half as likely to achieve remission on a tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitor, compared with nonobese patients. She believes the same holds true for all other types of therapy: Across the board, obesity is associated with a poor response. And obesity is much more common in PsA patients than the general population in every age group. Moreover, obesity is associated with risk factors for cardiovascular disease and is associated with fatty liver disease, two other major comorbid conditions in the PsA population.

The CORRONA Registry findings are supportive of an earlier Italian prospective, observational study of 135 obese and an equal number of normal-weight PsA patients, all of whom started on a TNF inhibitor and were followed for 24 months. In a multivariate-adjusted analysis, obesity was independently associated with a 390% higher risk of not achieving minimal disease activity.

The same Italian group subsequently conducted a prospective dietary intervention study in 138 overweight or obese patients with PsA starting anti-TNF therapy. A total of 59% of participants randomized to either of the two dietary interventions experienced at least a 5% weight loss at 6 months. The key study finding: Compared with the subjects with less than 5% weight loss, those with 5%-10% weight loss were 275% more likely to achieve minimal disease activity at 6 months, and in those with greater than 10% weight loss the likelihood of attaining minimal disease activity increased by 567%.

“We’re talking about a disease where treatments tested in clinical trials have odds ratios in the 1.2 range, compared with other therapies, so this is a really striking difference,” she observed.