User login

Expert calls for paradigm shift in lab monitoring of some dermatology drugs

From time to time, Joslyn Kirby, MD, asks other physicians about their experience with certain medications used in dermatology, especially when something new hits the market.

“Sometimes I get an answer like, ‘The last time I used that medicine, my patient needed a liver transplant,’ ” Dr. Kirby, associate professor of dermatology, Penn State University, Hershey, said during the Orlando Dermatology Aesthetic and Clinical Conference. “It’s typically a story of something rare, uncommon, and awful. The challenge with an anecdote is that for all its power, it has a lower level of evidence. But it sticks with us and influences us more than a better level of evidence because it’s a situation and a story that we might relate to.”

Dr. Kirby said that when she thinks about managing side effects from drugs used in dermatology, it usually relates to something common and low-risk such as sore, dry skin with isotretinoin use. In contrast, if there is an uncommon but serious side effect, then mitigation rather than management is key. “I want to mitigate the risk – meaning warn my patient about it or be careful about how I select my patients when it is a serious side effect that happens infrequently,” she said. “The worst combination is a frequent and severe side effect. That is something we should avoid, for sure.”

Isotretinoin

But another aspect of prescribing a new drug for patients can be less clear-cut, Dr. Kirby continued, such as the rationale for routine lab monitoring. She began by discussing one of her male patients with moderate to severe acne. After he failed oral antibiotics and topical retinoids, she recommended isotretinoin, which carries a risk of hypertriglyceridemia-associated pancreatitis. “Early in my career, I was getting a lot of monthly labs in patients on this drug that were totally normal and not influencing my practice,” Dr. Kirby recalled. “We’ve seen studies coming out on isotretinoin lab monitoring, showing us that we can keep our patients safe and that we really don’t need to be checking labs as often, because lab changes are infrequent.”

In one of those studies, researchers evaluated 1,863 patients treated with isotretinoin for acne between Jan. 1, 2008, and June 30, 2017 (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020 Jan;82[1]:72-9).Over time, fewer than 1% of patients screened developed grade 3 or greater triglyceride testing abnormalities, while fewer than 0.5% developed liver function testing (LFT) abnormalities. Authors of a separate systematic review concluded that for patients on isotretinoin therapy without elevated baseline triglycerides, or risk thereof, monitoring triglycerides is of little value (Br J Dermatol. 2017 Oct;177[4]:960-6). Of the 25 patients in the analysis who developed pancreatitis on isotretinoin, only 3 had elevated triglycerides at baseline.

“I was taught that I need to check triglycerides frequently due to the risk of pancreatitis developing with isotretinoin use,” Dr. Kirby said. “Lipid changes on therapy are expected, but they tend to peak early, meaning the first 3 months of treatment when we’re ramping up from a starting dose to a maintenance dose. It’s rare for somebody to be a late bloomer, meaning that they have totally normal labs in the first 3 months and then suddenly develop an abnormality. People are either going to demonstrate an abnormality early or not have one at all.”

When Dr. Kirby starts patients on isotretinoin, she orders baseline LFTs and a lipid panel and repeats them 60 days later. “If everything is fine or only mildly high, we don’t do more testing, only a review of systems,” she said. “This is valuable to our patients because fear of needles and fainting peak during adolescence.”

Spironolactone

The clinical use of regularly monitoring potassium levels in young women taking spironolactone for acne has also been questioned. The drug has been linked to an increased risk for hyperkalemia, but the prevalence is unclear. “I got a lot of normal potassium levels in these patients [when] I was in training and I really questioned, ‘Why am I doing this? What is the rationale?’ ” Dr. Kirby said.

In a study that informed her own practice, researchers reviewed the rate of hyperkalemia in 974 healthy young women taking spironolactone for acne or for an endocrine disorder with associated acne between Dec. 1, 2000, and March 31, 2014 (JAMA Dermatol. 2015 Sep;151[9]:941-4). Of the total of 1,802 serum potassium measurements taken during treatment, 13 (0.72%) were mildly elevated levels and none of the patients had a potassium level above 5.5 mEq/L. Retesting within 1 to 3 weeks in 6 of 13 patients with elevated levels found that potassium levels were normal. “The recommendation for spironolactone in healthy women is not to check the potassium level,” Dr. Kirby said, adding that she does counsel patients about the risk of breast tenderness (which can occur 5% to 40% of the time) and spotting (which can occur in 10% to 20% of patients). Gynecomastia can occur in 10% to 30% of men, which is one of the reasons she does not use spironolactone in male patients.

TB testing and biologics

Whether or not to test for TB in patients with psoriasis taking biologic therapies represents another conundrum, she continued. Patients taking biologics are at risk of reactivation of latent TB infection, but in her experience, package inserts contain language like “perform TB testing at baseline, then periodically,” or “use at baseline, then with active TB symptoms,” and “after treatment is discontinued.”

“What the inserts didn’t recommend was to perform TB testing every year, which is what my routine had been,” Dr. Kirby said. “In the United States, thankfully we don’t have a lot of TB.” In a study that informed her own practice, researchers at a single academic medical center retrospectively reviewed the TB seroconversion rate among 316 patients treated with second-generation biologics (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020 Oct 1;S0190-9622[20]32676-1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.09.075). It found that only six patients (2%) converted and had a positive TB test later during treatment with the biologic. “Of these six people, all had grown up outside the U.S., had traveled outside of the U.S., or were in a group living situation,” said Dr. Kirby, who was not affiliated with the study.

“This informs our rationale for how we can do this testing. If insurance requires it every year, fine. But if they don’t, I ask patients about travel, about their living situation, and how they’re feeling. If everything’s going great, I don’t order TB testing. I do favor the interferon-gamma release assays because they’re a lot more effective than PPDs [purified protein derivative skin tests]. Also, PPDs are difficult for patients who have a low rate of returning to have that test read.”

Terbinafine for onychomycosis

Dr. Kirby also discussed the rationale for ordering regular LFTs in patients taking terbinafine for onychomycosis. “There is a risk of drug-induced liver injury from taking terbinafine, but it’s rare,” she said. “Can we be thoughtful about which patients we expose?”

Evidence suggests that patients with hyperkeratosis greater than 2 mm, with nail matrix involvement, with 50% or more of the nail involved, or having concomitant peripheral vascular disease and diabetes are recalcitrant to treatment with terbinafine

(J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019 Apr;80[4]:853-67). “If we can frame this risk, then we can frame it for our patients,” she said. “We’re more likely to cause liver injury with an antibiotic. When it comes to an oral antifungal, itraconazole is more likely than terbinafine to cause liver injury. The rate of liver injury with terbinafine is only about 2 out of 100,000. It’s five times more likely with itraconazole and 21 times more likely with Augmentin.”

She recommends obtaining a baseline LFT in patients starting terbinafine therapy “to make sure their liver is normal from the start.” In addition, she advised, “let them know that there is a TB seroconversion risk of about 1 in 50,000 people, and that if it happens there would be symptomatic changes. They would maybe notice pruritus and have a darkening in their urine, and they’d have some flu-like symptoms, which would mean stop the drug and get some care.”

Dr. Kirby emphasized that a patient’s propensity for developing drug-induced liver injury from terbinafine use is not predictable from LFT monitoring. “What you’re more likely to find is an asymptomatic LFT rise in about 1% of people,” she said.

She disclosed that she has received honoraria from AbbVie, ChemoCentryx, Incyte, Janssen, Novartis, and UCB Pharma.

From time to time, Joslyn Kirby, MD, asks other physicians about their experience with certain medications used in dermatology, especially when something new hits the market.

“Sometimes I get an answer like, ‘The last time I used that medicine, my patient needed a liver transplant,’ ” Dr. Kirby, associate professor of dermatology, Penn State University, Hershey, said during the Orlando Dermatology Aesthetic and Clinical Conference. “It’s typically a story of something rare, uncommon, and awful. The challenge with an anecdote is that for all its power, it has a lower level of evidence. But it sticks with us and influences us more than a better level of evidence because it’s a situation and a story that we might relate to.”

Dr. Kirby said that when she thinks about managing side effects from drugs used in dermatology, it usually relates to something common and low-risk such as sore, dry skin with isotretinoin use. In contrast, if there is an uncommon but serious side effect, then mitigation rather than management is key. “I want to mitigate the risk – meaning warn my patient about it or be careful about how I select my patients when it is a serious side effect that happens infrequently,” she said. “The worst combination is a frequent and severe side effect. That is something we should avoid, for sure.”

Isotretinoin

But another aspect of prescribing a new drug for patients can be less clear-cut, Dr. Kirby continued, such as the rationale for routine lab monitoring. She began by discussing one of her male patients with moderate to severe acne. After he failed oral antibiotics and topical retinoids, she recommended isotretinoin, which carries a risk of hypertriglyceridemia-associated pancreatitis. “Early in my career, I was getting a lot of monthly labs in patients on this drug that were totally normal and not influencing my practice,” Dr. Kirby recalled. “We’ve seen studies coming out on isotretinoin lab monitoring, showing us that we can keep our patients safe and that we really don’t need to be checking labs as often, because lab changes are infrequent.”

In one of those studies, researchers evaluated 1,863 patients treated with isotretinoin for acne between Jan. 1, 2008, and June 30, 2017 (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020 Jan;82[1]:72-9).Over time, fewer than 1% of patients screened developed grade 3 or greater triglyceride testing abnormalities, while fewer than 0.5% developed liver function testing (LFT) abnormalities. Authors of a separate systematic review concluded that for patients on isotretinoin therapy without elevated baseline triglycerides, or risk thereof, monitoring triglycerides is of little value (Br J Dermatol. 2017 Oct;177[4]:960-6). Of the 25 patients in the analysis who developed pancreatitis on isotretinoin, only 3 had elevated triglycerides at baseline.

“I was taught that I need to check triglycerides frequently due to the risk of pancreatitis developing with isotretinoin use,” Dr. Kirby said. “Lipid changes on therapy are expected, but they tend to peak early, meaning the first 3 months of treatment when we’re ramping up from a starting dose to a maintenance dose. It’s rare for somebody to be a late bloomer, meaning that they have totally normal labs in the first 3 months and then suddenly develop an abnormality. People are either going to demonstrate an abnormality early or not have one at all.”

When Dr. Kirby starts patients on isotretinoin, she orders baseline LFTs and a lipid panel and repeats them 60 days later. “If everything is fine or only mildly high, we don’t do more testing, only a review of systems,” she said. “This is valuable to our patients because fear of needles and fainting peak during adolescence.”

Spironolactone

The clinical use of regularly monitoring potassium levels in young women taking spironolactone for acne has also been questioned. The drug has been linked to an increased risk for hyperkalemia, but the prevalence is unclear. “I got a lot of normal potassium levels in these patients [when] I was in training and I really questioned, ‘Why am I doing this? What is the rationale?’ ” Dr. Kirby said.

In a study that informed her own practice, researchers reviewed the rate of hyperkalemia in 974 healthy young women taking spironolactone for acne or for an endocrine disorder with associated acne between Dec. 1, 2000, and March 31, 2014 (JAMA Dermatol. 2015 Sep;151[9]:941-4). Of the total of 1,802 serum potassium measurements taken during treatment, 13 (0.72%) were mildly elevated levels and none of the patients had a potassium level above 5.5 mEq/L. Retesting within 1 to 3 weeks in 6 of 13 patients with elevated levels found that potassium levels were normal. “The recommendation for spironolactone in healthy women is not to check the potassium level,” Dr. Kirby said, adding that she does counsel patients about the risk of breast tenderness (which can occur 5% to 40% of the time) and spotting (which can occur in 10% to 20% of patients). Gynecomastia can occur in 10% to 30% of men, which is one of the reasons she does not use spironolactone in male patients.

TB testing and biologics

Whether or not to test for TB in patients with psoriasis taking biologic therapies represents another conundrum, she continued. Patients taking biologics are at risk of reactivation of latent TB infection, but in her experience, package inserts contain language like “perform TB testing at baseline, then periodically,” or “use at baseline, then with active TB symptoms,” and “after treatment is discontinued.”

“What the inserts didn’t recommend was to perform TB testing every year, which is what my routine had been,” Dr. Kirby said. “In the United States, thankfully we don’t have a lot of TB.” In a study that informed her own practice, researchers at a single academic medical center retrospectively reviewed the TB seroconversion rate among 316 patients treated with second-generation biologics (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020 Oct 1;S0190-9622[20]32676-1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.09.075). It found that only six patients (2%) converted and had a positive TB test later during treatment with the biologic. “Of these six people, all had grown up outside the U.S., had traveled outside of the U.S., or were in a group living situation,” said Dr. Kirby, who was not affiliated with the study.

“This informs our rationale for how we can do this testing. If insurance requires it every year, fine. But if they don’t, I ask patients about travel, about their living situation, and how they’re feeling. If everything’s going great, I don’t order TB testing. I do favor the interferon-gamma release assays because they’re a lot more effective than PPDs [purified protein derivative skin tests]. Also, PPDs are difficult for patients who have a low rate of returning to have that test read.”

Terbinafine for onychomycosis

Dr. Kirby also discussed the rationale for ordering regular LFTs in patients taking terbinafine for onychomycosis. “There is a risk of drug-induced liver injury from taking terbinafine, but it’s rare,” she said. “Can we be thoughtful about which patients we expose?”

Evidence suggests that patients with hyperkeratosis greater than 2 mm, with nail matrix involvement, with 50% or more of the nail involved, or having concomitant peripheral vascular disease and diabetes are recalcitrant to treatment with terbinafine

(J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019 Apr;80[4]:853-67). “If we can frame this risk, then we can frame it for our patients,” she said. “We’re more likely to cause liver injury with an antibiotic. When it comes to an oral antifungal, itraconazole is more likely than terbinafine to cause liver injury. The rate of liver injury with terbinafine is only about 2 out of 100,000. It’s five times more likely with itraconazole and 21 times more likely with Augmentin.”

She recommends obtaining a baseline LFT in patients starting terbinafine therapy “to make sure their liver is normal from the start.” In addition, she advised, “let them know that there is a TB seroconversion risk of about 1 in 50,000 people, and that if it happens there would be symptomatic changes. They would maybe notice pruritus and have a darkening in their urine, and they’d have some flu-like symptoms, which would mean stop the drug and get some care.”

Dr. Kirby emphasized that a patient’s propensity for developing drug-induced liver injury from terbinafine use is not predictable from LFT monitoring. “What you’re more likely to find is an asymptomatic LFT rise in about 1% of people,” she said.

She disclosed that she has received honoraria from AbbVie, ChemoCentryx, Incyte, Janssen, Novartis, and UCB Pharma.

From time to time, Joslyn Kirby, MD, asks other physicians about their experience with certain medications used in dermatology, especially when something new hits the market.

“Sometimes I get an answer like, ‘The last time I used that medicine, my patient needed a liver transplant,’ ” Dr. Kirby, associate professor of dermatology, Penn State University, Hershey, said during the Orlando Dermatology Aesthetic and Clinical Conference. “It’s typically a story of something rare, uncommon, and awful. The challenge with an anecdote is that for all its power, it has a lower level of evidence. But it sticks with us and influences us more than a better level of evidence because it’s a situation and a story that we might relate to.”

Dr. Kirby said that when she thinks about managing side effects from drugs used in dermatology, it usually relates to something common and low-risk such as sore, dry skin with isotretinoin use. In contrast, if there is an uncommon but serious side effect, then mitigation rather than management is key. “I want to mitigate the risk – meaning warn my patient about it or be careful about how I select my patients when it is a serious side effect that happens infrequently,” she said. “The worst combination is a frequent and severe side effect. That is something we should avoid, for sure.”

Isotretinoin

But another aspect of prescribing a new drug for patients can be less clear-cut, Dr. Kirby continued, such as the rationale for routine lab monitoring. She began by discussing one of her male patients with moderate to severe acne. After he failed oral antibiotics and topical retinoids, she recommended isotretinoin, which carries a risk of hypertriglyceridemia-associated pancreatitis. “Early in my career, I was getting a lot of monthly labs in patients on this drug that were totally normal and not influencing my practice,” Dr. Kirby recalled. “We’ve seen studies coming out on isotretinoin lab monitoring, showing us that we can keep our patients safe and that we really don’t need to be checking labs as often, because lab changes are infrequent.”

In one of those studies, researchers evaluated 1,863 patients treated with isotretinoin for acne between Jan. 1, 2008, and June 30, 2017 (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020 Jan;82[1]:72-9).Over time, fewer than 1% of patients screened developed grade 3 or greater triglyceride testing abnormalities, while fewer than 0.5% developed liver function testing (LFT) abnormalities. Authors of a separate systematic review concluded that for patients on isotretinoin therapy without elevated baseline triglycerides, or risk thereof, monitoring triglycerides is of little value (Br J Dermatol. 2017 Oct;177[4]:960-6). Of the 25 patients in the analysis who developed pancreatitis on isotretinoin, only 3 had elevated triglycerides at baseline.

“I was taught that I need to check triglycerides frequently due to the risk of pancreatitis developing with isotretinoin use,” Dr. Kirby said. “Lipid changes on therapy are expected, but they tend to peak early, meaning the first 3 months of treatment when we’re ramping up from a starting dose to a maintenance dose. It’s rare for somebody to be a late bloomer, meaning that they have totally normal labs in the first 3 months and then suddenly develop an abnormality. People are either going to demonstrate an abnormality early or not have one at all.”

When Dr. Kirby starts patients on isotretinoin, she orders baseline LFTs and a lipid panel and repeats them 60 days later. “If everything is fine or only mildly high, we don’t do more testing, only a review of systems,” she said. “This is valuable to our patients because fear of needles and fainting peak during adolescence.”

Spironolactone

The clinical use of regularly monitoring potassium levels in young women taking spironolactone for acne has also been questioned. The drug has been linked to an increased risk for hyperkalemia, but the prevalence is unclear. “I got a lot of normal potassium levels in these patients [when] I was in training and I really questioned, ‘Why am I doing this? What is the rationale?’ ” Dr. Kirby said.

In a study that informed her own practice, researchers reviewed the rate of hyperkalemia in 974 healthy young women taking spironolactone for acne or for an endocrine disorder with associated acne between Dec. 1, 2000, and March 31, 2014 (JAMA Dermatol. 2015 Sep;151[9]:941-4). Of the total of 1,802 serum potassium measurements taken during treatment, 13 (0.72%) were mildly elevated levels and none of the patients had a potassium level above 5.5 mEq/L. Retesting within 1 to 3 weeks in 6 of 13 patients with elevated levels found that potassium levels were normal. “The recommendation for spironolactone in healthy women is not to check the potassium level,” Dr. Kirby said, adding that she does counsel patients about the risk of breast tenderness (which can occur 5% to 40% of the time) and spotting (which can occur in 10% to 20% of patients). Gynecomastia can occur in 10% to 30% of men, which is one of the reasons she does not use spironolactone in male patients.

TB testing and biologics

Whether or not to test for TB in patients with psoriasis taking biologic therapies represents another conundrum, she continued. Patients taking biologics are at risk of reactivation of latent TB infection, but in her experience, package inserts contain language like “perform TB testing at baseline, then periodically,” or “use at baseline, then with active TB symptoms,” and “after treatment is discontinued.”

“What the inserts didn’t recommend was to perform TB testing every year, which is what my routine had been,” Dr. Kirby said. “In the United States, thankfully we don’t have a lot of TB.” In a study that informed her own practice, researchers at a single academic medical center retrospectively reviewed the TB seroconversion rate among 316 patients treated with second-generation biologics (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020 Oct 1;S0190-9622[20]32676-1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.09.075). It found that only six patients (2%) converted and had a positive TB test later during treatment with the biologic. “Of these six people, all had grown up outside the U.S., had traveled outside of the U.S., or were in a group living situation,” said Dr. Kirby, who was not affiliated with the study.

“This informs our rationale for how we can do this testing. If insurance requires it every year, fine. But if they don’t, I ask patients about travel, about their living situation, and how they’re feeling. If everything’s going great, I don’t order TB testing. I do favor the interferon-gamma release assays because they’re a lot more effective than PPDs [purified protein derivative skin tests]. Also, PPDs are difficult for patients who have a low rate of returning to have that test read.”

Terbinafine for onychomycosis

Dr. Kirby also discussed the rationale for ordering regular LFTs in patients taking terbinafine for onychomycosis. “There is a risk of drug-induced liver injury from taking terbinafine, but it’s rare,” she said. “Can we be thoughtful about which patients we expose?”

Evidence suggests that patients with hyperkeratosis greater than 2 mm, with nail matrix involvement, with 50% or more of the nail involved, or having concomitant peripheral vascular disease and diabetes are recalcitrant to treatment with terbinafine

(J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019 Apr;80[4]:853-67). “If we can frame this risk, then we can frame it for our patients,” she said. “We’re more likely to cause liver injury with an antibiotic. When it comes to an oral antifungal, itraconazole is more likely than terbinafine to cause liver injury. The rate of liver injury with terbinafine is only about 2 out of 100,000. It’s five times more likely with itraconazole and 21 times more likely with Augmentin.”

She recommends obtaining a baseline LFT in patients starting terbinafine therapy “to make sure their liver is normal from the start.” In addition, she advised, “let them know that there is a TB seroconversion risk of about 1 in 50,000 people, and that if it happens there would be symptomatic changes. They would maybe notice pruritus and have a darkening in their urine, and they’d have some flu-like symptoms, which would mean stop the drug and get some care.”

Dr. Kirby emphasized that a patient’s propensity for developing drug-induced liver injury from terbinafine use is not predictable from LFT monitoring. “What you’re more likely to find is an asymptomatic LFT rise in about 1% of people,” she said.

She disclosed that she has received honoraria from AbbVie, ChemoCentryx, Incyte, Janssen, Novartis, and UCB Pharma.

FROM ODAC 2021

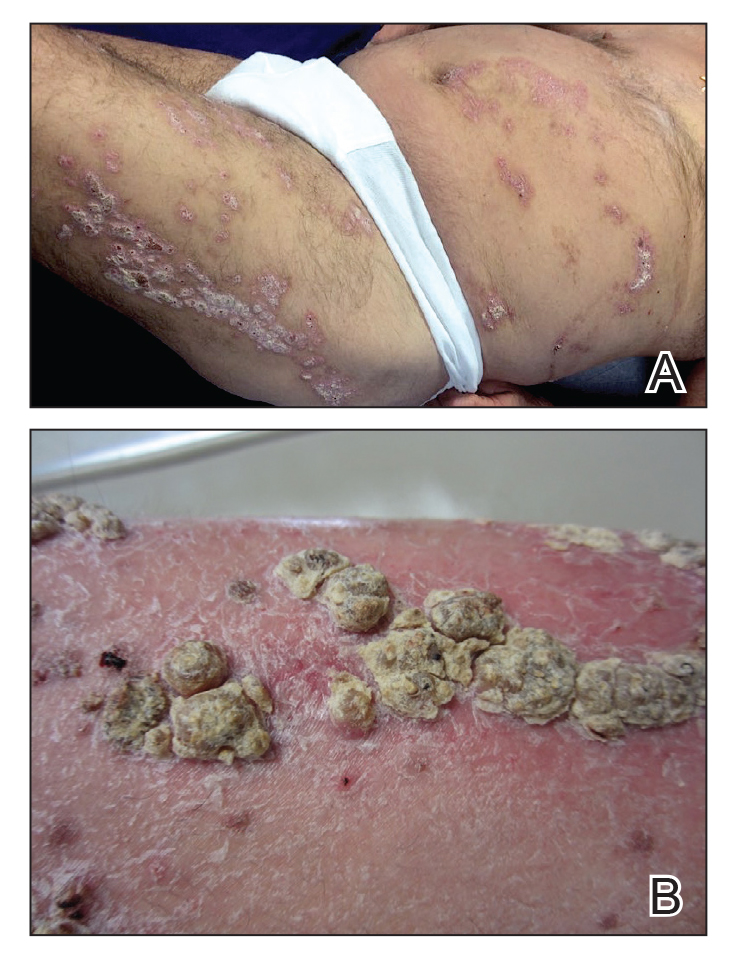

Anybody for a nanobody? Novel psoriasis therapy impresses in phase 2b

in a phase 2b randomized trial, Kim A. Papp, MD, PhD, reported at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

A nanobody is a tiny antibody fragment with a much smaller molecular weight than the monoclonal antibodies utilized today in treating psoriasis or atopic dermatitis. The sonelokinab nanobody, derived from animals in the camel family, is a recombinant sequence-optimized nanobody specific for human IL-17F, IL-17A, the heterodimer IL-17A/F, and serum albumin. The binding to serum albumin give sonelokinab a lengthy half-life of 10-12 hours, which may be therapeutically relevant, explained Dr. Papp, president and founder of Probity Medical Research in Waterloo, Ont.

He presented the 24-week results of a multicenter, double-blind, double-dummy randomized trial including 313 North American and European adults with an average 18-year history of psoriasis and a baseline Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) score of about 21. They were randomized to one of six treatment arms for the first 12 weeks: subcutaneous injection of sonelokinab at 30, 60, or 120 mg at weeks 0, 2, 4, and 8; enhanced–loading-dose sonelokinab at 120 mg every 2 weeks through week 10; the IL-17A inhibitor secukinumab (Cosentyx) at its standard dosing as an active comparator; or placebo. Data analysis was by rigorous nonresponder imputation, meaning anyone who didn’t complete the study was scored as a nonresponder.

“This yields a conservative data analysis somewhat biased against sonelokinab,” the dermatologist pointed out.

The primary outcome in the trial was the week-12 rate of an Investigator’s Global Assessment score of 0 or 1, indicative of clear or almost clear skin. This was achieved in 88.2% of patients in the highest-dose arm of sonelokinab. That group also had a week-12 PASI 90 response rate of 76.5% and a PASI 100 response rate of 33.3%. By comparison, patients on standard-dose secukinumab had a less robust week-12 IGA 0/1 rate of 77.4%, a PASI 90 of 64.2%, and a PASI 100 of 28.3%. Of note, however, this secukinumab performance was better than seen in the 30-mg sonelokinab group, and comparable to outcomes with 60 mg of sonelokinab.

Dose escalation was performed from weeks 12-24. Patients with a week-12 IGA score greater than 1 after being on sonelokinab at 30 or 60 mg were upgraded to 120 mg at week 12 and again every 4 weeks thereafter. Placebo-treated controls were switched to 120 mg at weeks 12, 14, 16, and every 4 weeks thereafter. The group on the enhanced–loading-dose sonelokinab moved to 120 mg every 4 weeks, while those who had gotten four doses of sonelokinab at 120 mg during the first 12 weeks were switched to 120 mg every 8 weeks. The secukinumab group remained on the approved dosing through week 24.

At week 24, superior outcomes were seen in the enhanced–loading-dose sonelokinab group, with an IGA 0/1 response rate of 94.2%, a PASI 90 of 90.4%, and a PASI 100 of 56.9%. The corresponding week-24 rates in patients on 120 mg of sonelokinab every 8 weeks from week 12 on were 80.4%, 79.2%, and 40.4%, outcomes similar to those seen with secukinumab.

The rapidity of response to sonelokinab at 120 mg was striking, with approximately one-third of treated patients achieving a PASI 90 response by week 4.

“This could reflect the smaller molecular profile. There is possibly rapid increased absorption or bioavailability, quicker time to achieving serum half-life, better penetration into target tissue, and perhaps more effective engagement at the target. All of those things are possibilities. These are things that are yet to be explored, but it’s very enticing to see that uncharacteristically rapid initial response. It’s all very gratifying – and tantalizing,” Dr. Papp said in response to an audience question.

The safety profile of sonelokinab was reassuring. The most common adverse events were nasopharyngitis in 13.5% of patients and pruritus in 6.7%, with most cases being mild or moderate. As with other IL-17 blockers, there was an increase in oral candidiasis. This side effect appeared to occur in dose-dependent fashion: The incidence was zero in the 30-mg group, 1.9% with 60 mg, 3.8% with sonelokinab at 120 mg without an enhanced loading dose, and 5.9% with the enhanced loading dose.

The study was conducted by Avillion in partnership with Merck. Dr. Papp reported receiving research funding from and serving as a consultant to those and numerous other pharmaceutical companies.

in a phase 2b randomized trial, Kim A. Papp, MD, PhD, reported at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

A nanobody is a tiny antibody fragment with a much smaller molecular weight than the monoclonal antibodies utilized today in treating psoriasis or atopic dermatitis. The sonelokinab nanobody, derived from animals in the camel family, is a recombinant sequence-optimized nanobody specific for human IL-17F, IL-17A, the heterodimer IL-17A/F, and serum albumin. The binding to serum albumin give sonelokinab a lengthy half-life of 10-12 hours, which may be therapeutically relevant, explained Dr. Papp, president and founder of Probity Medical Research in Waterloo, Ont.

He presented the 24-week results of a multicenter, double-blind, double-dummy randomized trial including 313 North American and European adults with an average 18-year history of psoriasis and a baseline Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) score of about 21. They were randomized to one of six treatment arms for the first 12 weeks: subcutaneous injection of sonelokinab at 30, 60, or 120 mg at weeks 0, 2, 4, and 8; enhanced–loading-dose sonelokinab at 120 mg every 2 weeks through week 10; the IL-17A inhibitor secukinumab (Cosentyx) at its standard dosing as an active comparator; or placebo. Data analysis was by rigorous nonresponder imputation, meaning anyone who didn’t complete the study was scored as a nonresponder.

“This yields a conservative data analysis somewhat biased against sonelokinab,” the dermatologist pointed out.

The primary outcome in the trial was the week-12 rate of an Investigator’s Global Assessment score of 0 or 1, indicative of clear or almost clear skin. This was achieved in 88.2% of patients in the highest-dose arm of sonelokinab. That group also had a week-12 PASI 90 response rate of 76.5% and a PASI 100 response rate of 33.3%. By comparison, patients on standard-dose secukinumab had a less robust week-12 IGA 0/1 rate of 77.4%, a PASI 90 of 64.2%, and a PASI 100 of 28.3%. Of note, however, this secukinumab performance was better than seen in the 30-mg sonelokinab group, and comparable to outcomes with 60 mg of sonelokinab.

Dose escalation was performed from weeks 12-24. Patients with a week-12 IGA score greater than 1 after being on sonelokinab at 30 or 60 mg were upgraded to 120 mg at week 12 and again every 4 weeks thereafter. Placebo-treated controls were switched to 120 mg at weeks 12, 14, 16, and every 4 weeks thereafter. The group on the enhanced–loading-dose sonelokinab moved to 120 mg every 4 weeks, while those who had gotten four doses of sonelokinab at 120 mg during the first 12 weeks were switched to 120 mg every 8 weeks. The secukinumab group remained on the approved dosing through week 24.

At week 24, superior outcomes were seen in the enhanced–loading-dose sonelokinab group, with an IGA 0/1 response rate of 94.2%, a PASI 90 of 90.4%, and a PASI 100 of 56.9%. The corresponding week-24 rates in patients on 120 mg of sonelokinab every 8 weeks from week 12 on were 80.4%, 79.2%, and 40.4%, outcomes similar to those seen with secukinumab.

The rapidity of response to sonelokinab at 120 mg was striking, with approximately one-third of treated patients achieving a PASI 90 response by week 4.

“This could reflect the smaller molecular profile. There is possibly rapid increased absorption or bioavailability, quicker time to achieving serum half-life, better penetration into target tissue, and perhaps more effective engagement at the target. All of those things are possibilities. These are things that are yet to be explored, but it’s very enticing to see that uncharacteristically rapid initial response. It’s all very gratifying – and tantalizing,” Dr. Papp said in response to an audience question.

The safety profile of sonelokinab was reassuring. The most common adverse events were nasopharyngitis in 13.5% of patients and pruritus in 6.7%, with most cases being mild or moderate. As with other IL-17 blockers, there was an increase in oral candidiasis. This side effect appeared to occur in dose-dependent fashion: The incidence was zero in the 30-mg group, 1.9% with 60 mg, 3.8% with sonelokinab at 120 mg without an enhanced loading dose, and 5.9% with the enhanced loading dose.

The study was conducted by Avillion in partnership with Merck. Dr. Papp reported receiving research funding from and serving as a consultant to those and numerous other pharmaceutical companies.

in a phase 2b randomized trial, Kim A. Papp, MD, PhD, reported at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

A nanobody is a tiny antibody fragment with a much smaller molecular weight than the monoclonal antibodies utilized today in treating psoriasis or atopic dermatitis. The sonelokinab nanobody, derived from animals in the camel family, is a recombinant sequence-optimized nanobody specific for human IL-17F, IL-17A, the heterodimer IL-17A/F, and serum albumin. The binding to serum albumin give sonelokinab a lengthy half-life of 10-12 hours, which may be therapeutically relevant, explained Dr. Papp, president and founder of Probity Medical Research in Waterloo, Ont.

He presented the 24-week results of a multicenter, double-blind, double-dummy randomized trial including 313 North American and European adults with an average 18-year history of psoriasis and a baseline Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) score of about 21. They were randomized to one of six treatment arms for the first 12 weeks: subcutaneous injection of sonelokinab at 30, 60, or 120 mg at weeks 0, 2, 4, and 8; enhanced–loading-dose sonelokinab at 120 mg every 2 weeks through week 10; the IL-17A inhibitor secukinumab (Cosentyx) at its standard dosing as an active comparator; or placebo. Data analysis was by rigorous nonresponder imputation, meaning anyone who didn’t complete the study was scored as a nonresponder.

“This yields a conservative data analysis somewhat biased against sonelokinab,” the dermatologist pointed out.

The primary outcome in the trial was the week-12 rate of an Investigator’s Global Assessment score of 0 or 1, indicative of clear or almost clear skin. This was achieved in 88.2% of patients in the highest-dose arm of sonelokinab. That group also had a week-12 PASI 90 response rate of 76.5% and a PASI 100 response rate of 33.3%. By comparison, patients on standard-dose secukinumab had a less robust week-12 IGA 0/1 rate of 77.4%, a PASI 90 of 64.2%, and a PASI 100 of 28.3%. Of note, however, this secukinumab performance was better than seen in the 30-mg sonelokinab group, and comparable to outcomes with 60 mg of sonelokinab.

Dose escalation was performed from weeks 12-24. Patients with a week-12 IGA score greater than 1 after being on sonelokinab at 30 or 60 mg were upgraded to 120 mg at week 12 and again every 4 weeks thereafter. Placebo-treated controls were switched to 120 mg at weeks 12, 14, 16, and every 4 weeks thereafter. The group on the enhanced–loading-dose sonelokinab moved to 120 mg every 4 weeks, while those who had gotten four doses of sonelokinab at 120 mg during the first 12 weeks were switched to 120 mg every 8 weeks. The secukinumab group remained on the approved dosing through week 24.

At week 24, superior outcomes were seen in the enhanced–loading-dose sonelokinab group, with an IGA 0/1 response rate of 94.2%, a PASI 90 of 90.4%, and a PASI 100 of 56.9%. The corresponding week-24 rates in patients on 120 mg of sonelokinab every 8 weeks from week 12 on were 80.4%, 79.2%, and 40.4%, outcomes similar to those seen with secukinumab.

The rapidity of response to sonelokinab at 120 mg was striking, with approximately one-third of treated patients achieving a PASI 90 response by week 4.

“This could reflect the smaller molecular profile. There is possibly rapid increased absorption or bioavailability, quicker time to achieving serum half-life, better penetration into target tissue, and perhaps more effective engagement at the target. All of those things are possibilities. These are things that are yet to be explored, but it’s very enticing to see that uncharacteristically rapid initial response. It’s all very gratifying – and tantalizing,” Dr. Papp said in response to an audience question.

The safety profile of sonelokinab was reassuring. The most common adverse events were nasopharyngitis in 13.5% of patients and pruritus in 6.7%, with most cases being mild or moderate. As with other IL-17 blockers, there was an increase in oral candidiasis. This side effect appeared to occur in dose-dependent fashion: The incidence was zero in the 30-mg group, 1.9% with 60 mg, 3.8% with sonelokinab at 120 mg without an enhanced loading dose, and 5.9% with the enhanced loading dose.

The study was conducted by Avillion in partnership with Merck. Dr. Papp reported receiving research funding from and serving as a consultant to those and numerous other pharmaceutical companies.

FROM the eadv congress

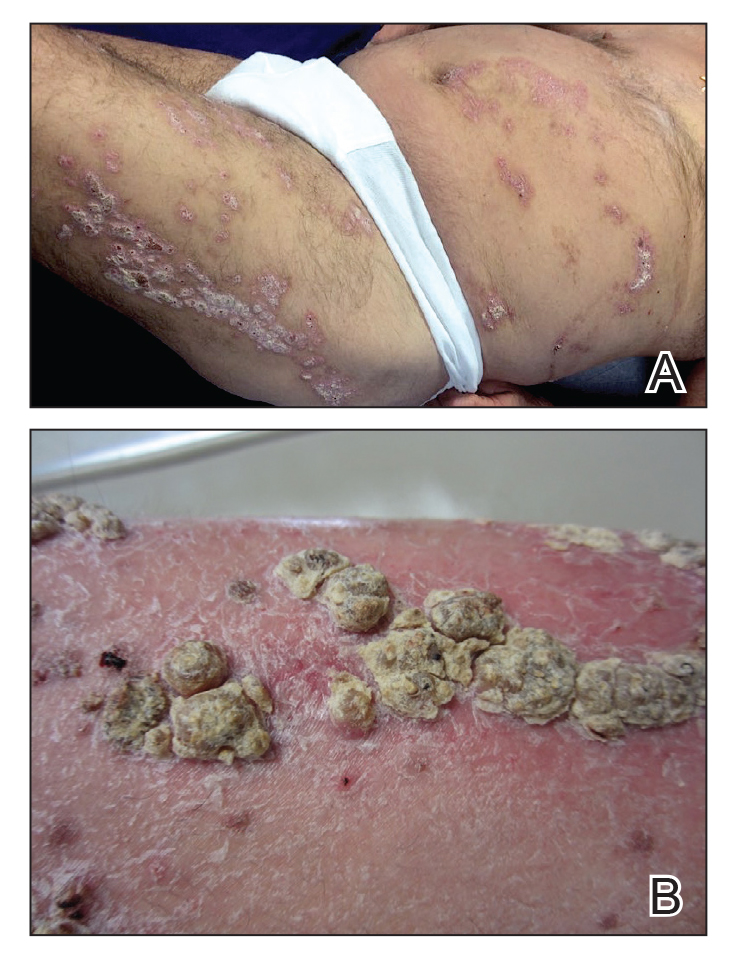

In head-to-head trial, two biologics differ markedly for control of psoriasis

with other biologics, according to data from two simultaneously published trials, one of which was a head-to-head comparison with ustekinumab.

In the head-to-head trial called BE VIVID, which included a placebo arm, there was a large advantage of bimekizumab over ustekinumab, a biologic that targets IL-12 and IL-23 and is approved for treating psoriasis, for both coprimary endpoints, according to a multinational group of investigators led by Kristian Reich, MD, PhD, professor of dermatology at the University Medical Center, Hamburg-Eppendorf, Germany.

The proportion of patients with skin clearance was not only greater but faster, “with responses observed after one dose,” Dr. Reich and coinvestigators reported.

The data from the BE VIVID trial was published simultaneously with the BE READY trial, which was placebo-controlled but did not include an active comparator.

Evaluated at week 16, the coprimary endpoints in both studies were skin clearance as measured by a Psoriasis Area Severity Index greater than 90% (PASI 90) and Investigators Global Assessment (IGA) score of 0 (clear) or 1 (almost clear).

In BE VIVID, 567 patients were randomized in 11 countries, including the United States. The dose of bimekizumab was 320 mg administered subcutaneously every 4 weeks. In a randomization scheme of 4:2:1, half as many patients (163) were randomized to ustekinumab (Stelara), which was administered in weight-based dosing of 45 mg or 90 mg at enrollment, at 4 weeks, and then every 12 weeks. The placebo arm had 83 patients. All were switched to bimekizumab at 16 weeks.

At week 16, PASI 90 was achieved in 85% of patients randomized to bimekizumab, compared with 50% of patients randomized to ustekinumab (P < .0001). The rate in the placebo group was 5%.

The bimekizumab advantage for an IGA response of 0 or 1 was of similar magnitude, relative to ustekinumab (84% vs. 53%; P < .0001) and placebo (5%). All secondary efficacy endpoints, such as PASI 90 at week 12 (85% vs. 44%) and PASI 100 at week 16 (59% vs. 21%), favored bimekizumab over ustekinumab.

In the BE READY trial, which evaluated the same dose and schedule of bimekizumab, the rates of PASI 90 at week 16 were 91% and 1% (P < .0001) for the experimental arm and placebo, respectively. The proportion of patients with an IGA score of 0 or 1 were 93% and 1% (P < .0001), respectively.

In BE READY, patients who achieved PASI 90 at week 16 were reallocated to receive bimekizumab every 4 weeks, bimekizumab every 8 weeks (also 320 mg), or placebo. Both schedules of bimekizumab maintained responses through week 56, according to the authors, led by Kenneth B. Gordon, MD, professor and chair of dermatology, Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee.

In both trials, safety was evaluated over the first 16 weeks as well as over a subsequent maintenance period, which extended to 52 weeks in BE VIVID and 56 weeks in BE READY. For bimekizumab, oral candidiasis was the most common treatment-related adverse event. In BE VIVID, this adverse event was reported in 9% of bimekizumab patients, compared with 0% of either the ustekinumab or placebo groups, up to week 16. Out to week 52, the rates were 15% in the bimekizumab group and 1% in the ustekinumab group.

In the BE READY trial, the rates of oral candidiasis were 6% and 0% for bimekizumab and placebo, respectively, through week 16. Over the maintenance periods, the rates were 9% and 11% for the every-8-week and every-4-week doses, respectively.

Discontinuation for adverse events was not higher on bimekizumab than placebo in either trial, nor was the proportion of serious treatment-emergent adverse events.

Nevertheless, the potential for adverse events was a key part of the discussion regarding the future role of bimekizumab, if approved, in an editorial that accompanied the publication of these studies.

“Bimekizumab might be our most effective biologic for psoriasis yet,” coauthors, William W. Huang, MD, PhD, associate professor of dermatology, and Steven R. Feldman, MD, PhD, professor of dermatology, both at Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, NC, wrote in the editorial. “If the goal of psoriasis treatment is complete clearance, bimekizumab seems like a good option from an efficacy perspective.”

However, they noted that other IL-17 blockers, like secukinumab (Cosentyx) and brodalumab (Siliq), have been associated with risks, including the development of inflammatory bowel disease. In addition to the oral candidiasis seen in the BE VIVID and BE READY trials, they cautioned that other issues might arise with longer follow-up and greater numbers of patients exposed to this therapy.

In an interview, Dr. Feldman said adequately informed patients might be willing to accept these risks for the potential of greater efficacy, but he emphasized the need for appropriate warnings and education.

“We have a lot of very good treatments that offer patients an excellent chance of an excellent outcome – treatments that have been around and in use in large numbers of people for years,” Dr. Feldman said. “Unless the doctor and patient felt strongly about the need to use this new, perhaps more potent option, I would be personally inclined to use treatment with well-established safety profiles first.”

The senior author of the BE VIVID trial, Mark Lebwohl, MD, dean for clinical therapeutics and professor of dermatology, at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, disagreed. He acknowledged that other agents targeting IL-17 have been associated with IBD, but risk of IBD is already elevated in patients with psoriasis and the risk appears to be lower with bimekizumab relative to prior agents in this class.

“Bimekizumab has now been studied in thousands of patients over several years. We can say with support from a sizable amount of data that IBD is very uncommon,” he said. While oral candidiasis is associated with bimekizumab, it is “easy to treat.”

Asked specifically if he will consider using bimekizumab as a first-line agent in psoriasis patients who are candidates for a biologic, Dr. Lebwohl said he would. Based on the evidence that this agent is more effective than other options and has manageable side effects, he believes it will be an important new treatment option.

Dr. Reich, Dr. Lebwohl, Dr. Gordon, and Dr. Feldman have financial relationships with multiple companies that produce therapies for psoriasis, including UCB Pharma, the sponsor of these studies.

with other biologics, according to data from two simultaneously published trials, one of which was a head-to-head comparison with ustekinumab.

In the head-to-head trial called BE VIVID, which included a placebo arm, there was a large advantage of bimekizumab over ustekinumab, a biologic that targets IL-12 and IL-23 and is approved for treating psoriasis, for both coprimary endpoints, according to a multinational group of investigators led by Kristian Reich, MD, PhD, professor of dermatology at the University Medical Center, Hamburg-Eppendorf, Germany.

The proportion of patients with skin clearance was not only greater but faster, “with responses observed after one dose,” Dr. Reich and coinvestigators reported.

The data from the BE VIVID trial was published simultaneously with the BE READY trial, which was placebo-controlled but did not include an active comparator.

Evaluated at week 16, the coprimary endpoints in both studies were skin clearance as measured by a Psoriasis Area Severity Index greater than 90% (PASI 90) and Investigators Global Assessment (IGA) score of 0 (clear) or 1 (almost clear).

In BE VIVID, 567 patients were randomized in 11 countries, including the United States. The dose of bimekizumab was 320 mg administered subcutaneously every 4 weeks. In a randomization scheme of 4:2:1, half as many patients (163) were randomized to ustekinumab (Stelara), which was administered in weight-based dosing of 45 mg or 90 mg at enrollment, at 4 weeks, and then every 12 weeks. The placebo arm had 83 patients. All were switched to bimekizumab at 16 weeks.

At week 16, PASI 90 was achieved in 85% of patients randomized to bimekizumab, compared with 50% of patients randomized to ustekinumab (P < .0001). The rate in the placebo group was 5%.

The bimekizumab advantage for an IGA response of 0 or 1 was of similar magnitude, relative to ustekinumab (84% vs. 53%; P < .0001) and placebo (5%). All secondary efficacy endpoints, such as PASI 90 at week 12 (85% vs. 44%) and PASI 100 at week 16 (59% vs. 21%), favored bimekizumab over ustekinumab.

In the BE READY trial, which evaluated the same dose and schedule of bimekizumab, the rates of PASI 90 at week 16 were 91% and 1% (P < .0001) for the experimental arm and placebo, respectively. The proportion of patients with an IGA score of 0 or 1 were 93% and 1% (P < .0001), respectively.

In BE READY, patients who achieved PASI 90 at week 16 were reallocated to receive bimekizumab every 4 weeks, bimekizumab every 8 weeks (also 320 mg), or placebo. Both schedules of bimekizumab maintained responses through week 56, according to the authors, led by Kenneth B. Gordon, MD, professor and chair of dermatology, Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee.

In both trials, safety was evaluated over the first 16 weeks as well as over a subsequent maintenance period, which extended to 52 weeks in BE VIVID and 56 weeks in BE READY. For bimekizumab, oral candidiasis was the most common treatment-related adverse event. In BE VIVID, this adverse event was reported in 9% of bimekizumab patients, compared with 0% of either the ustekinumab or placebo groups, up to week 16. Out to week 52, the rates were 15% in the bimekizumab group and 1% in the ustekinumab group.

In the BE READY trial, the rates of oral candidiasis were 6% and 0% for bimekizumab and placebo, respectively, through week 16. Over the maintenance periods, the rates were 9% and 11% for the every-8-week and every-4-week doses, respectively.

Discontinuation for adverse events was not higher on bimekizumab than placebo in either trial, nor was the proportion of serious treatment-emergent adverse events.

Nevertheless, the potential for adverse events was a key part of the discussion regarding the future role of bimekizumab, if approved, in an editorial that accompanied the publication of these studies.

“Bimekizumab might be our most effective biologic for psoriasis yet,” coauthors, William W. Huang, MD, PhD, associate professor of dermatology, and Steven R. Feldman, MD, PhD, professor of dermatology, both at Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, NC, wrote in the editorial. “If the goal of psoriasis treatment is complete clearance, bimekizumab seems like a good option from an efficacy perspective.”

However, they noted that other IL-17 blockers, like secukinumab (Cosentyx) and brodalumab (Siliq), have been associated with risks, including the development of inflammatory bowel disease. In addition to the oral candidiasis seen in the BE VIVID and BE READY trials, they cautioned that other issues might arise with longer follow-up and greater numbers of patients exposed to this therapy.

In an interview, Dr. Feldman said adequately informed patients might be willing to accept these risks for the potential of greater efficacy, but he emphasized the need for appropriate warnings and education.

“We have a lot of very good treatments that offer patients an excellent chance of an excellent outcome – treatments that have been around and in use in large numbers of people for years,” Dr. Feldman said. “Unless the doctor and patient felt strongly about the need to use this new, perhaps more potent option, I would be personally inclined to use treatment with well-established safety profiles first.”

The senior author of the BE VIVID trial, Mark Lebwohl, MD, dean for clinical therapeutics and professor of dermatology, at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, disagreed. He acknowledged that other agents targeting IL-17 have been associated with IBD, but risk of IBD is already elevated in patients with psoriasis and the risk appears to be lower with bimekizumab relative to prior agents in this class.

“Bimekizumab has now been studied in thousands of patients over several years. We can say with support from a sizable amount of data that IBD is very uncommon,” he said. While oral candidiasis is associated with bimekizumab, it is “easy to treat.”

Asked specifically if he will consider using bimekizumab as a first-line agent in psoriasis patients who are candidates for a biologic, Dr. Lebwohl said he would. Based on the evidence that this agent is more effective than other options and has manageable side effects, he believes it will be an important new treatment option.

Dr. Reich, Dr. Lebwohl, Dr. Gordon, and Dr. Feldman have financial relationships with multiple companies that produce therapies for psoriasis, including UCB Pharma, the sponsor of these studies.

with other biologics, according to data from two simultaneously published trials, one of which was a head-to-head comparison with ustekinumab.

In the head-to-head trial called BE VIVID, which included a placebo arm, there was a large advantage of bimekizumab over ustekinumab, a biologic that targets IL-12 and IL-23 and is approved for treating psoriasis, for both coprimary endpoints, according to a multinational group of investigators led by Kristian Reich, MD, PhD, professor of dermatology at the University Medical Center, Hamburg-Eppendorf, Germany.

The proportion of patients with skin clearance was not only greater but faster, “with responses observed after one dose,” Dr. Reich and coinvestigators reported.

The data from the BE VIVID trial was published simultaneously with the BE READY trial, which was placebo-controlled but did not include an active comparator.

Evaluated at week 16, the coprimary endpoints in both studies were skin clearance as measured by a Psoriasis Area Severity Index greater than 90% (PASI 90) and Investigators Global Assessment (IGA) score of 0 (clear) or 1 (almost clear).

In BE VIVID, 567 patients were randomized in 11 countries, including the United States. The dose of bimekizumab was 320 mg administered subcutaneously every 4 weeks. In a randomization scheme of 4:2:1, half as many patients (163) were randomized to ustekinumab (Stelara), which was administered in weight-based dosing of 45 mg or 90 mg at enrollment, at 4 weeks, and then every 12 weeks. The placebo arm had 83 patients. All were switched to bimekizumab at 16 weeks.

At week 16, PASI 90 was achieved in 85% of patients randomized to bimekizumab, compared with 50% of patients randomized to ustekinumab (P < .0001). The rate in the placebo group was 5%.

The bimekizumab advantage for an IGA response of 0 or 1 was of similar magnitude, relative to ustekinumab (84% vs. 53%; P < .0001) and placebo (5%). All secondary efficacy endpoints, such as PASI 90 at week 12 (85% vs. 44%) and PASI 100 at week 16 (59% vs. 21%), favored bimekizumab over ustekinumab.

In the BE READY trial, which evaluated the same dose and schedule of bimekizumab, the rates of PASI 90 at week 16 were 91% and 1% (P < .0001) for the experimental arm and placebo, respectively. The proportion of patients with an IGA score of 0 or 1 were 93% and 1% (P < .0001), respectively.

In BE READY, patients who achieved PASI 90 at week 16 were reallocated to receive bimekizumab every 4 weeks, bimekizumab every 8 weeks (also 320 mg), or placebo. Both schedules of bimekizumab maintained responses through week 56, according to the authors, led by Kenneth B. Gordon, MD, professor and chair of dermatology, Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee.

In both trials, safety was evaluated over the first 16 weeks as well as over a subsequent maintenance period, which extended to 52 weeks in BE VIVID and 56 weeks in BE READY. For bimekizumab, oral candidiasis was the most common treatment-related adverse event. In BE VIVID, this adverse event was reported in 9% of bimekizumab patients, compared with 0% of either the ustekinumab or placebo groups, up to week 16. Out to week 52, the rates were 15% in the bimekizumab group and 1% in the ustekinumab group.

In the BE READY trial, the rates of oral candidiasis were 6% and 0% for bimekizumab and placebo, respectively, through week 16. Over the maintenance periods, the rates were 9% and 11% for the every-8-week and every-4-week doses, respectively.

Discontinuation for adverse events was not higher on bimekizumab than placebo in either trial, nor was the proportion of serious treatment-emergent adverse events.

Nevertheless, the potential for adverse events was a key part of the discussion regarding the future role of bimekizumab, if approved, in an editorial that accompanied the publication of these studies.

“Bimekizumab might be our most effective biologic for psoriasis yet,” coauthors, William W. Huang, MD, PhD, associate professor of dermatology, and Steven R. Feldman, MD, PhD, professor of dermatology, both at Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, NC, wrote in the editorial. “If the goal of psoriasis treatment is complete clearance, bimekizumab seems like a good option from an efficacy perspective.”

However, they noted that other IL-17 blockers, like secukinumab (Cosentyx) and brodalumab (Siliq), have been associated with risks, including the development of inflammatory bowel disease. In addition to the oral candidiasis seen in the BE VIVID and BE READY trials, they cautioned that other issues might arise with longer follow-up and greater numbers of patients exposed to this therapy.

In an interview, Dr. Feldman said adequately informed patients might be willing to accept these risks for the potential of greater efficacy, but he emphasized the need for appropriate warnings and education.

“We have a lot of very good treatments that offer patients an excellent chance of an excellent outcome – treatments that have been around and in use in large numbers of people for years,” Dr. Feldman said. “Unless the doctor and patient felt strongly about the need to use this new, perhaps more potent option, I would be personally inclined to use treatment with well-established safety profiles first.”

The senior author of the BE VIVID trial, Mark Lebwohl, MD, dean for clinical therapeutics and professor of dermatology, at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, disagreed. He acknowledged that other agents targeting IL-17 have been associated with IBD, but risk of IBD is already elevated in patients with psoriasis and the risk appears to be lower with bimekizumab relative to prior agents in this class.

“Bimekizumab has now been studied in thousands of patients over several years. We can say with support from a sizable amount of data that IBD is very uncommon,” he said. While oral candidiasis is associated with bimekizumab, it is “easy to treat.”

Asked specifically if he will consider using bimekizumab as a first-line agent in psoriasis patients who are candidates for a biologic, Dr. Lebwohl said he would. Based on the evidence that this agent is more effective than other options and has manageable side effects, he believes it will be an important new treatment option.

Dr. Reich, Dr. Lebwohl, Dr. Gordon, and Dr. Feldman have financial relationships with multiple companies that produce therapies for psoriasis, including UCB Pharma, the sponsor of these studies.

FROM THE LANCET

Home Phototherapy During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Office-based phototherapy practices have closed or are operating below capacity because of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic.1 Social distancing measures to reduce virus transmission are a significant driving factor.1-3 In the age of biologics, other options requiring fewer patient visits are available, such as UVB phototherapy. UV phototherapy is considered first line when more than 10% of the body surface area is affected.4 Although phototherapy often is performed in the office, it also may be delivered at home.2 Home-based phototherapy is safe, effective, and similar in cost to office-based phototherapy.4 Currently, there are limited COVID-19–specific guidelines for home-based phototherapy.

The risks and sequelae of COVID-19 are still being investigated, with cases varying by location. As such, local and national public health recommendations are evolving. Dermatologists must make individualized decisions about practice services, as local restrictions differ. As office-based phototherapy services may struggle to implement mitigation strategies, home-based phototherapy is an increasingly viable treatment option.1,4,5 Patient benefits of home therapy include improved treatment compliance; greater patient satisfaction; reduced travel/waiting time; and reduced long-term cost, including co-pays, depending on insurance coverage.2,4

We aim to provide recommendations on home-based phototherapy during the pandemic. Throughout the decision-making process, careful consideration of safety, risks, benefits, and treatment options for physicians, staff, and patients will be vital to the successful implementation of home-based phototherapy. Our recommendations are based on maximizing benefits and minimizing risks.

Considerations for Physicians

Physicians should take the following steps when assessing if home phototherapy is an option for each patient.1,2,4

• Determine patient eligibility for phototherapy treatment if currently not on phototherapy

• Carefully review patient and provider requirements for home phototherapy supplier

• Review patient history of treatment compliance

• Determine insurance coverage and consider exclusion criteria

• Review prior treatments

• Provide education on side effects

• Provide education on signs of adequate treatment response

• Indicate the type of UV light and unit on the prescription

• Consider whether the patient is in the maintenance or initiation phase when providing recommendations

• Work with the supplier if the light therapy unit is denied by submitting an appeal or prescribing a different unit

• Follow up with telemedicine to assess treatment effectiveness and monitor for adverse effects

Considerations for Patients

Counsel patients to weigh the risks and benefits of home phototherapy prescription and usage.1,2,4

• Evaluate cost

• Carefully review patient and provider requirements for home phototherapy supplier

• Ensure a complete understanding of treatment schedule

• Properly utilize protective equipment (eg, genital shields for men, eye shields for all)

• Avoid sharing phototherapy units with household members

• Disinfect and maintain units

• Maintain proper ventilation of spaces

• Maintain treatment log

• Attend follow-up

Treatment Alternatives

For patients with severe psoriasis, there are alternative treatments to office and home phototherapy. Biologics, immunosuppressive therapies, and other treatment options may be considered on a case-by-case basis.3,4,6 Currently, recommendations for the risk of COVID-19 with biologics or systemic immunosuppressive therapies remains inconsistent and should be carefully considered when providing alternative treatments.7-11

Final Thoughts

As restrictions are lifted according to local public health measures, prepandemic office phototherapy practices may resume operations. Home phototherapy is a practical and effective alternative for treatment of psoriasis when access to the office setting is limited.

- Lim HW, Feldman SR, Van Voorhees AS, et al. Recommendations for phototherapy during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:287-288.

Anderson KL, Feldman SR. A guide to prescribing home phototherapy for patients with psoriasis: the appropriate patient, the type of unit, the treatment regimen, and the potential obstacles. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:868.E1-878.E1. - Palmore TN, Smith BA. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): infection control in health care and home settings. UpToDate. Updated January 7, 2021. Accessed January 25, 2021.https://www.uptodate.com/contents/coronavirus-disease-2019-covid-19-infection-control-in-health-care-and-home-settings

- Koek MB, Buskens E, van Weelden H, et al. Home versus outpatient ultraviolet B phototherapy for mild to severe psoriasis: pragmatic multicentre randomised controlled non-inferiority trial (PLUTO study). BMJ. 2009;338:b1542.

- Sadeghinia A, Daneshpazhooh M. Immunosuppressive drugs for patients with psoriasis during the COVID-19 pandemic era. a review [published online November 3, 2020]. Dermatol Ther. 2020:E14498. doi:10.1111/dth.14498

- Damiani G, Pacifico A, Bragazzi NL, et al. Biologics increase the risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection and hospitalization, but not ICU admission and death: real-life data from a large cohort during red-zone declaration. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:E13475.

- Lebwohl M, Rivera-Oyola R, Murrell DF. Should biologics for psoriasis be interrupted in the era of COVID-19? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1217-1218.

- Mehta P, Ciurtin C, Scully M, et al. JAK inhibitors in COVID-19: the need for vigilance regarding increased inherent thrombotic risk. Eur Respir J. 2020;56:2001919.

- Walz L, Cohen AJ, Rebaza AP, et al. JAK-inhibitor and type I interferon ability to produce favorable clinical outcomes in COVID-19 patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect Dis. 2021;21:47.

- Carugno A, Gambini DM, Raponi F, et al. COVID-19 and biologics for psoriasis: a high-epidemic area experience-Bergamo, Lombardy, Italy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:292-294.

- Gisondi P, Piaserico S, Naldi L, et al. Incidence rates of hospitalization and death from COVID-19 in patients with psoriasis receiving biological treatment: a Northern Italy experience [published online November 5, 2020]. J Allergy Clin Immunol. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2020.10.032

Office-based phototherapy practices have closed or are operating below capacity because of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic.1 Social distancing measures to reduce virus transmission are a significant driving factor.1-3 In the age of biologics, other options requiring fewer patient visits are available, such as UVB phototherapy. UV phototherapy is considered first line when more than 10% of the body surface area is affected.4 Although phototherapy often is performed in the office, it also may be delivered at home.2 Home-based phototherapy is safe, effective, and similar in cost to office-based phototherapy.4 Currently, there are limited COVID-19–specific guidelines for home-based phototherapy.

The risks and sequelae of COVID-19 are still being investigated, with cases varying by location. As such, local and national public health recommendations are evolving. Dermatologists must make individualized decisions about practice services, as local restrictions differ. As office-based phototherapy services may struggle to implement mitigation strategies, home-based phototherapy is an increasingly viable treatment option.1,4,5 Patient benefits of home therapy include improved treatment compliance; greater patient satisfaction; reduced travel/waiting time; and reduced long-term cost, including co-pays, depending on insurance coverage.2,4

We aim to provide recommendations on home-based phototherapy during the pandemic. Throughout the decision-making process, careful consideration of safety, risks, benefits, and treatment options for physicians, staff, and patients will be vital to the successful implementation of home-based phototherapy. Our recommendations are based on maximizing benefits and minimizing risks.

Considerations for Physicians

Physicians should take the following steps when assessing if home phototherapy is an option for each patient.1,2,4

• Determine patient eligibility for phototherapy treatment if currently not on phototherapy

• Carefully review patient and provider requirements for home phototherapy supplier

• Review patient history of treatment compliance

• Determine insurance coverage and consider exclusion criteria

• Review prior treatments

• Provide education on side effects

• Provide education on signs of adequate treatment response

• Indicate the type of UV light and unit on the prescription

• Consider whether the patient is in the maintenance or initiation phase when providing recommendations

• Work with the supplier if the light therapy unit is denied by submitting an appeal or prescribing a different unit

• Follow up with telemedicine to assess treatment effectiveness and monitor for adverse effects

Considerations for Patients

Counsel patients to weigh the risks and benefits of home phototherapy prescription and usage.1,2,4

• Evaluate cost

• Carefully review patient and provider requirements for home phototherapy supplier

• Ensure a complete understanding of treatment schedule

• Properly utilize protective equipment (eg, genital shields for men, eye shields for all)

• Avoid sharing phototherapy units with household members

• Disinfect and maintain units

• Maintain proper ventilation of spaces

• Maintain treatment log

• Attend follow-up

Treatment Alternatives

For patients with severe psoriasis, there are alternative treatments to office and home phototherapy. Biologics, immunosuppressive therapies, and other treatment options may be considered on a case-by-case basis.3,4,6 Currently, recommendations for the risk of COVID-19 with biologics or systemic immunosuppressive therapies remains inconsistent and should be carefully considered when providing alternative treatments.7-11

Final Thoughts

As restrictions are lifted according to local public health measures, prepandemic office phototherapy practices may resume operations. Home phototherapy is a practical and effective alternative for treatment of psoriasis when access to the office setting is limited.

Office-based phototherapy practices have closed or are operating below capacity because of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic.1 Social distancing measures to reduce virus transmission are a significant driving factor.1-3 In the age of biologics, other options requiring fewer patient visits are available, such as UVB phototherapy. UV phototherapy is considered first line when more than 10% of the body surface area is affected.4 Although phototherapy often is performed in the office, it also may be delivered at home.2 Home-based phototherapy is safe, effective, and similar in cost to office-based phototherapy.4 Currently, there are limited COVID-19–specific guidelines for home-based phototherapy.

The risks and sequelae of COVID-19 are still being investigated, with cases varying by location. As such, local and national public health recommendations are evolving. Dermatologists must make individualized decisions about practice services, as local restrictions differ. As office-based phototherapy services may struggle to implement mitigation strategies, home-based phototherapy is an increasingly viable treatment option.1,4,5 Patient benefits of home therapy include improved treatment compliance; greater patient satisfaction; reduced travel/waiting time; and reduced long-term cost, including co-pays, depending on insurance coverage.2,4

We aim to provide recommendations on home-based phototherapy during the pandemic. Throughout the decision-making process, careful consideration of safety, risks, benefits, and treatment options for physicians, staff, and patients will be vital to the successful implementation of home-based phototherapy. Our recommendations are based on maximizing benefits and minimizing risks.

Considerations for Physicians

Physicians should take the following steps when assessing if home phototherapy is an option for each patient.1,2,4

• Determine patient eligibility for phototherapy treatment if currently not on phototherapy

• Carefully review patient and provider requirements for home phototherapy supplier

• Review patient history of treatment compliance

• Determine insurance coverage and consider exclusion criteria

• Review prior treatments

• Provide education on side effects

• Provide education on signs of adequate treatment response

• Indicate the type of UV light and unit on the prescription

• Consider whether the patient is in the maintenance or initiation phase when providing recommendations

• Work with the supplier if the light therapy unit is denied by submitting an appeal or prescribing a different unit

• Follow up with telemedicine to assess treatment effectiveness and monitor for adverse effects

Considerations for Patients

Counsel patients to weigh the risks and benefits of home phototherapy prescription and usage.1,2,4

• Evaluate cost

• Carefully review patient and provider requirements for home phototherapy supplier

• Ensure a complete understanding of treatment schedule

• Properly utilize protective equipment (eg, genital shields for men, eye shields for all)

• Avoid sharing phototherapy units with household members

• Disinfect and maintain units

• Maintain proper ventilation of spaces

• Maintain treatment log

• Attend follow-up

Treatment Alternatives

For patients with severe psoriasis, there are alternative treatments to office and home phototherapy. Biologics, immunosuppressive therapies, and other treatment options may be considered on a case-by-case basis.3,4,6 Currently, recommendations for the risk of COVID-19 with biologics or systemic immunosuppressive therapies remains inconsistent and should be carefully considered when providing alternative treatments.7-11

Final Thoughts

As restrictions are lifted according to local public health measures, prepandemic office phototherapy practices may resume operations. Home phototherapy is a practical and effective alternative for treatment of psoriasis when access to the office setting is limited.

- Lim HW, Feldman SR, Van Voorhees AS, et al. Recommendations for phototherapy during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:287-288.

Anderson KL, Feldman SR. A guide to prescribing home phototherapy for patients with psoriasis: the appropriate patient, the type of unit, the treatment regimen, and the potential obstacles. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:868.E1-878.E1. - Palmore TN, Smith BA. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): infection control in health care and home settings. UpToDate. Updated January 7, 2021. Accessed January 25, 2021.https://www.uptodate.com/contents/coronavirus-disease-2019-covid-19-infection-control-in-health-care-and-home-settings

- Koek MB, Buskens E, van Weelden H, et al. Home versus outpatient ultraviolet B phototherapy for mild to severe psoriasis: pragmatic multicentre randomised controlled non-inferiority trial (PLUTO study). BMJ. 2009;338:b1542.

- Sadeghinia A, Daneshpazhooh M. Immunosuppressive drugs for patients with psoriasis during the COVID-19 pandemic era. a review [published online November 3, 2020]. Dermatol Ther. 2020:E14498. doi:10.1111/dth.14498

- Damiani G, Pacifico A, Bragazzi NL, et al. Biologics increase the risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection and hospitalization, but not ICU admission and death: real-life data from a large cohort during red-zone declaration. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:E13475.

- Lebwohl M, Rivera-Oyola R, Murrell DF. Should biologics for psoriasis be interrupted in the era of COVID-19? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1217-1218.

- Mehta P, Ciurtin C, Scully M, et al. JAK inhibitors in COVID-19: the need for vigilance regarding increased inherent thrombotic risk. Eur Respir J. 2020;56:2001919.

- Walz L, Cohen AJ, Rebaza AP, et al. JAK-inhibitor and type I interferon ability to produce favorable clinical outcomes in COVID-19 patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect Dis. 2021;21:47.

- Carugno A, Gambini DM, Raponi F, et al. COVID-19 and biologics for psoriasis: a high-epidemic area experience-Bergamo, Lombardy, Italy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:292-294.

- Gisondi P, Piaserico S, Naldi L, et al. Incidence rates of hospitalization and death from COVID-19 in patients with psoriasis receiving biological treatment: a Northern Italy experience [published online November 5, 2020]. J Allergy Clin Immunol. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2020.10.032

- Lim HW, Feldman SR, Van Voorhees AS, et al. Recommendations for phototherapy during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:287-288.

Anderson KL, Feldman SR. A guide to prescribing home phototherapy for patients with psoriasis: the appropriate patient, the type of unit, the treatment regimen, and the potential obstacles. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:868.E1-878.E1. - Palmore TN, Smith BA. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): infection control in health care and home settings. UpToDate. Updated January 7, 2021. Accessed January 25, 2021.https://www.uptodate.com/contents/coronavirus-disease-2019-covid-19-infection-control-in-health-care-and-home-settings

- Koek MB, Buskens E, van Weelden H, et al. Home versus outpatient ultraviolet B phototherapy for mild to severe psoriasis: pragmatic multicentre randomised controlled non-inferiority trial (PLUTO study). BMJ. 2009;338:b1542.

- Sadeghinia A, Daneshpazhooh M. Immunosuppressive drugs for patients with psoriasis during the COVID-19 pandemic era. a review [published online November 3, 2020]. Dermatol Ther. 2020:E14498. doi:10.1111/dth.14498

- Damiani G, Pacifico A, Bragazzi NL, et al. Biologics increase the risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection and hospitalization, but not ICU admission and death: real-life data from a large cohort during red-zone declaration. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:E13475.

- Lebwohl M, Rivera-Oyola R, Murrell DF. Should biologics for psoriasis be interrupted in the era of COVID-19? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1217-1218.

- Mehta P, Ciurtin C, Scully M, et al. JAK inhibitors in COVID-19: the need for vigilance regarding increased inherent thrombotic risk. Eur Respir J. 2020;56:2001919.

- Walz L, Cohen AJ, Rebaza AP, et al. JAK-inhibitor and type I interferon ability to produce favorable clinical outcomes in COVID-19 patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect Dis. 2021;21:47.

- Carugno A, Gambini DM, Raponi F, et al. COVID-19 and biologics for psoriasis: a high-epidemic area experience-Bergamo, Lombardy, Italy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:292-294.

- Gisondi P, Piaserico S, Naldi L, et al. Incidence rates of hospitalization and death from COVID-19 in patients with psoriasis receiving biological treatment: a Northern Italy experience [published online November 5, 2020]. J Allergy Clin Immunol. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2020.10.032

Practice Points

- Home phototherapy is a safe and effective option for patients with psoriasis during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic.

- Although a consensus has not been reached with systemic immunosuppressive therapies for patients with psoriasis and the risk of COVID-19, we continue to recommend caution and careful monitoring of clinical outcomes for patients.