User login

2019-2020 flu season starts off full throttle

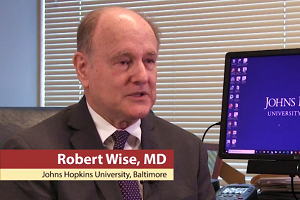

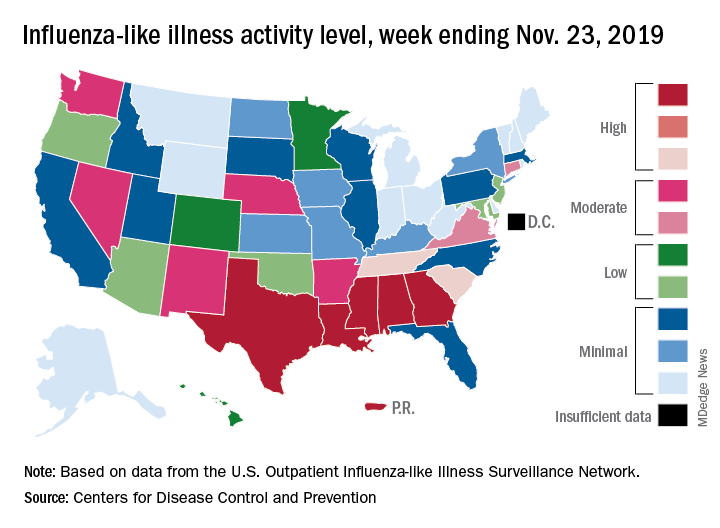

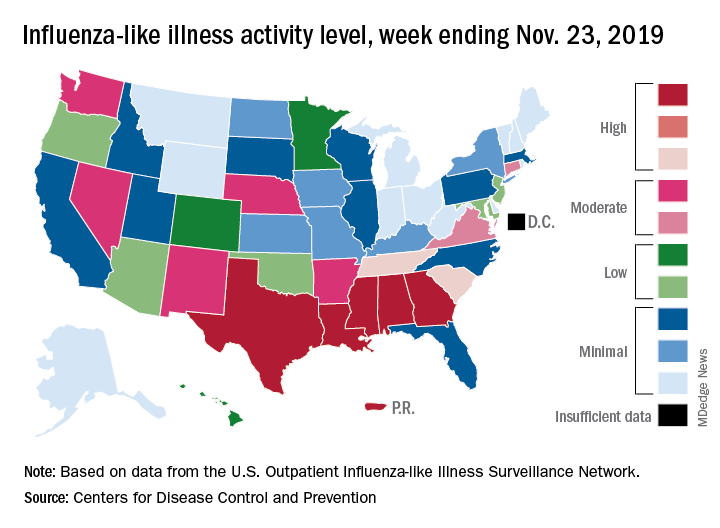

For the week ending Nov. 23, there were five states, along with Puerto Rico, at the highest level of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s 1-10 scale of flu activity. That’s more than any year since 2012, including the pandemic season of 2017-2018, according to CDC data, and may suggest either an early peak or the beginning of a particularly bad winter.

“Nationally, ILI [influenza-like illness] activity has been at or above baseline for 3 weeks; however, the amount of influenza activity across the country varies with the south and parts of the west seeing elevated activity while other parts of the country are still seeing low activity,” the CDC’s influenza division said in its weekly FluView report.

The five highest-activity states – Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Texas – are all at level 10, and they join two others – South Carolina and Tennessee, which are at level 8 – in the “high” range from 8-10 on the ILI activity scale; Puerto Rico also is at level 10. ILI is defined as “fever (temperature of 100° F [37.8° C] or greater) and a cough and/or a sore throat without a known cause other than influenza,” the CDC said.

The activity scale is based on the percentage of outpatient visits for ILI in each state, which is reported to the CDC’s Outpatient Influenza-like Illness Surveillance Network (ILINet) each week. The national rate for the week ending Nov. 23 was 2.9%, which is above the new-for-this-season baseline rate of 2.4%. For the three previous flu seasons, the national baseline was 2.2%, having been raised from its previous level of 2.1% in 2015-2016, CDC data show.

The peak month of flu activity occurs most often in February – 15 times from 1982-1983 to 2017-2018 – but there were seven peaks in December and six each in January and March over that time period, along with one peak each in October and November, the CDC said. The October peak occurred during the H1N1 pandemic year of 2009, when the national outpatient ILI rate climbed to just over 7.7%.

For the week ending Nov. 23, there were five states, along with Puerto Rico, at the highest level of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s 1-10 scale of flu activity. That’s more than any year since 2012, including the pandemic season of 2017-2018, according to CDC data, and may suggest either an early peak or the beginning of a particularly bad winter.

“Nationally, ILI [influenza-like illness] activity has been at or above baseline for 3 weeks; however, the amount of influenza activity across the country varies with the south and parts of the west seeing elevated activity while other parts of the country are still seeing low activity,” the CDC’s influenza division said in its weekly FluView report.

The five highest-activity states – Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Texas – are all at level 10, and they join two others – South Carolina and Tennessee, which are at level 8 – in the “high” range from 8-10 on the ILI activity scale; Puerto Rico also is at level 10. ILI is defined as “fever (temperature of 100° F [37.8° C] or greater) and a cough and/or a sore throat without a known cause other than influenza,” the CDC said.

The activity scale is based on the percentage of outpatient visits for ILI in each state, which is reported to the CDC’s Outpatient Influenza-like Illness Surveillance Network (ILINet) each week. The national rate for the week ending Nov. 23 was 2.9%, which is above the new-for-this-season baseline rate of 2.4%. For the three previous flu seasons, the national baseline was 2.2%, having been raised from its previous level of 2.1% in 2015-2016, CDC data show.

The peak month of flu activity occurs most often in February – 15 times from 1982-1983 to 2017-2018 – but there were seven peaks in December and six each in January and March over that time period, along with one peak each in October and November, the CDC said. The October peak occurred during the H1N1 pandemic year of 2009, when the national outpatient ILI rate climbed to just over 7.7%.

For the week ending Nov. 23, there were five states, along with Puerto Rico, at the highest level of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s 1-10 scale of flu activity. That’s more than any year since 2012, including the pandemic season of 2017-2018, according to CDC data, and may suggest either an early peak or the beginning of a particularly bad winter.

“Nationally, ILI [influenza-like illness] activity has been at or above baseline for 3 weeks; however, the amount of influenza activity across the country varies with the south and parts of the west seeing elevated activity while other parts of the country are still seeing low activity,” the CDC’s influenza division said in its weekly FluView report.

The five highest-activity states – Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Texas – are all at level 10, and they join two others – South Carolina and Tennessee, which are at level 8 – in the “high” range from 8-10 on the ILI activity scale; Puerto Rico also is at level 10. ILI is defined as “fever (temperature of 100° F [37.8° C] or greater) and a cough and/or a sore throat without a known cause other than influenza,” the CDC said.

The activity scale is based on the percentage of outpatient visits for ILI in each state, which is reported to the CDC’s Outpatient Influenza-like Illness Surveillance Network (ILINet) each week. The national rate for the week ending Nov. 23 was 2.9%, which is above the new-for-this-season baseline rate of 2.4%. For the three previous flu seasons, the national baseline was 2.2%, having been raised from its previous level of 2.1% in 2015-2016, CDC data show.

The peak month of flu activity occurs most often in February – 15 times from 1982-1983 to 2017-2018 – but there were seven peaks in December and six each in January and March over that time period, along with one peak each in October and November, the CDC said. The October peak occurred during the H1N1 pandemic year of 2009, when the national outpatient ILI rate climbed to just over 7.7%.

Click for Credit: PPI use & dementia; Weight loss after gastroplasty; more

Here are 5 articles from the December issue of Clinician Reviews (individual articles are valid for one year from date of publication—expiration dates below):

1. Sustainable weight loss seen 5 years after endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/37lteRX

Expires May 16, 2020

2. PT beats steroid injections for knee OA

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2KIWKY6

Expires May 17, 2020

3. Better screening needed to reduce pregnancy-related overdose, death

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2XEZyuG

Expires May 17, 2020

4. Meta-analysis finds no link between PPI use and risk of dementia

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2Xzs7JM

Expires June 3, 2020

5. Study: Cardiac biomarkers predicted CV events in CAP

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/33bAH2u

Expires August 13, 2020

Here are 5 articles from the December issue of Clinician Reviews (individual articles are valid for one year from date of publication—expiration dates below):

1. Sustainable weight loss seen 5 years after endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/37lteRX

Expires May 16, 2020

2. PT beats steroid injections for knee OA

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2KIWKY6

Expires May 17, 2020

3. Better screening needed to reduce pregnancy-related overdose, death

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2XEZyuG

Expires May 17, 2020

4. Meta-analysis finds no link between PPI use and risk of dementia

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2Xzs7JM

Expires June 3, 2020

5. Study: Cardiac biomarkers predicted CV events in CAP

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/33bAH2u

Expires August 13, 2020

Here are 5 articles from the December issue of Clinician Reviews (individual articles are valid for one year from date of publication—expiration dates below):

1. Sustainable weight loss seen 5 years after endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/37lteRX

Expires May 16, 2020

2. PT beats steroid injections for knee OA

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2KIWKY6

Expires May 17, 2020

3. Better screening needed to reduce pregnancy-related overdose, death

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2XEZyuG

Expires May 17, 2020

4. Meta-analysis finds no link between PPI use and risk of dementia

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2Xzs7JM

Expires June 3, 2020

5. Study: Cardiac biomarkers predicted CV events in CAP

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/33bAH2u

Expires August 13, 2020

Regular use of disinfectants at work associated with increased risk of COPD

“Clinicians should be aware of this new risk factor and systematically look for sources of exposure to cleaning products and disinfectants in addition to other occupational exposures in patients with COPD,” wrote Orianne Dumas, PhD, of the Université de Versailles St-Quentin-en-Yvelines (France) and coauthors. The study was published in JAMA Network Open.

To determine if regular use of disinfectants had a negative impact on respiratory health, the researchers analyzed data from 73,262 active female nurses who had no history of COPD and completed questionnaires every 2 years for the Nurses’ Health Study II. Their mean age at baseline was 54.7. Exposure to commonly used disinfectants was evaluated by a job-task-exposure matrix (JTEM) specific to nurses.

Between 2009 and 2015, 582 nurses reported incident physician-diagnosed COPD. Weekly use of disinfectants was associated with COPD incidence (adjusted hazard ratio 1.35; 95% confidence interval, 1.14-1.59). Additional associations were found in nurses who used disinfectants to clean surfaces (AHR, 1.38; 95% CI, 1.13-1.68) and to clean medical instruments (AHR, 1.31; 95% CI, 1.07-1.61). High-level exposure to certain disinfectants – including glutaraldehyde, bleach, hydrogen peroxide, alcohol, and quaternary ammonium compounds – were significantly associated with increased risk of COPD incidence.

The authors acknowledged their study’s limitations, including the JTEM only assessing exposure to seven of the major cleaning products commonly used in health care. In addition, detailed data on exposure to disinfectants was not available before 2009. However, they added that, because the study has been ongoing since 1989, it could be expected that women who had been nurses for decades had “already accumulated a long history of exposure.”

The study was supported in part by grants from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institutes of Health. Five of the authors reported receiving grants from the CDC’s National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH); one additional author reported being a consultant on a NIOSH grant and receiving personal fees from a health care system. No other conflicts of interest were reported.

SOURCE: Dumas O et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2019 Oct 18. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.13563.

“Clinicians should be aware of this new risk factor and systematically look for sources of exposure to cleaning products and disinfectants in addition to other occupational exposures in patients with COPD,” wrote Orianne Dumas, PhD, of the Université de Versailles St-Quentin-en-Yvelines (France) and coauthors. The study was published in JAMA Network Open.

To determine if regular use of disinfectants had a negative impact on respiratory health, the researchers analyzed data from 73,262 active female nurses who had no history of COPD and completed questionnaires every 2 years for the Nurses’ Health Study II. Their mean age at baseline was 54.7. Exposure to commonly used disinfectants was evaluated by a job-task-exposure matrix (JTEM) specific to nurses.

Between 2009 and 2015, 582 nurses reported incident physician-diagnosed COPD. Weekly use of disinfectants was associated with COPD incidence (adjusted hazard ratio 1.35; 95% confidence interval, 1.14-1.59). Additional associations were found in nurses who used disinfectants to clean surfaces (AHR, 1.38; 95% CI, 1.13-1.68) and to clean medical instruments (AHR, 1.31; 95% CI, 1.07-1.61). High-level exposure to certain disinfectants – including glutaraldehyde, bleach, hydrogen peroxide, alcohol, and quaternary ammonium compounds – were significantly associated with increased risk of COPD incidence.

The authors acknowledged their study’s limitations, including the JTEM only assessing exposure to seven of the major cleaning products commonly used in health care. In addition, detailed data on exposure to disinfectants was not available before 2009. However, they added that, because the study has been ongoing since 1989, it could be expected that women who had been nurses for decades had “already accumulated a long history of exposure.”

The study was supported in part by grants from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institutes of Health. Five of the authors reported receiving grants from the CDC’s National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH); one additional author reported being a consultant on a NIOSH grant and receiving personal fees from a health care system. No other conflicts of interest were reported.

SOURCE: Dumas O et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2019 Oct 18. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.13563.

“Clinicians should be aware of this new risk factor and systematically look for sources of exposure to cleaning products and disinfectants in addition to other occupational exposures in patients with COPD,” wrote Orianne Dumas, PhD, of the Université de Versailles St-Quentin-en-Yvelines (France) and coauthors. The study was published in JAMA Network Open.

To determine if regular use of disinfectants had a negative impact on respiratory health, the researchers analyzed data from 73,262 active female nurses who had no history of COPD and completed questionnaires every 2 years for the Nurses’ Health Study II. Their mean age at baseline was 54.7. Exposure to commonly used disinfectants was evaluated by a job-task-exposure matrix (JTEM) specific to nurses.

Between 2009 and 2015, 582 nurses reported incident physician-diagnosed COPD. Weekly use of disinfectants was associated with COPD incidence (adjusted hazard ratio 1.35; 95% confidence interval, 1.14-1.59). Additional associations were found in nurses who used disinfectants to clean surfaces (AHR, 1.38; 95% CI, 1.13-1.68) and to clean medical instruments (AHR, 1.31; 95% CI, 1.07-1.61). High-level exposure to certain disinfectants – including glutaraldehyde, bleach, hydrogen peroxide, alcohol, and quaternary ammonium compounds – were significantly associated with increased risk of COPD incidence.

The authors acknowledged their study’s limitations, including the JTEM only assessing exposure to seven of the major cleaning products commonly used in health care. In addition, detailed data on exposure to disinfectants was not available before 2009. However, they added that, because the study has been ongoing since 1989, it could be expected that women who had been nurses for decades had “already accumulated a long history of exposure.”

The study was supported in part by grants from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institutes of Health. Five of the authors reported receiving grants from the CDC’s National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH); one additional author reported being a consultant on a NIOSH grant and receiving personal fees from a health care system. No other conflicts of interest were reported.

SOURCE: Dumas O et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2019 Oct 18. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.13563.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

Guideline: Diagnosis and treatment of adults with community-acquired pneumonia

A new guideline has been published to update the 2007 guidelines for the management of adults with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP).

The practice guideline was jointly written by an ad hoc committee of the American Thoracic Society and Infectious Diseases Society of America. CAP refers to a pneumonia infection that was acquired by a patient in his or her community. Decisions about which antibiotics to use to treat this kind of infection are based on risk factors for resistant organisms and the severity of illness.

Pathogens

Traditionally, CAP is caused by common bacterial pathogens that include Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, Legionella species, Chlamydia pneumonia, and Moraxella catarrhalis. Risk factors for multidrug resistant pathogens such as methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) and Pseudomonas aeruginosa include previous infection with MRSA or P. aeruginosa, recent hospitalization, and requiring parenteral antibiotics in the last 90 days.

Defining severe community-acquired pneumonia

The health care–associated pneumonia, or HCAP, classification should no longer be used to determine empiric treatment. The recommendations for which antibiotics to use are linked to the severity of illness. Previously the site of treatment drove antibiotic selection, but since decision about the site of care can be affected by many considerations, the guidelines recommend using the CAP severity criteria. Severe CAP includes either one major or at least three minor criteria.

Major criteria are:

- Septic shock requiring vasopressors.

- Respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation.

Minor criteria are:

- Respiratory rate greater than or equal to 30 breaths/min.

- Ratio of arterial O2 partial pressure to fractional inspired O2 less than or equal to 250.

- Multilobar infiltrates.

- Confusion/disorientation.

- Uremia (blood urea nitrogen level greater than or equal to 20 mg/dL).

- Leukopenia (white blood cell count less than 4,000 cells/mcL).

- Thrombocytopenia (platelet count less than 100,000 mcL)

- Hypothermia (core temperature less than 36º C).

- Hypotension requiring aggressive fluid resuscitation.

Management and diagnostic testing

Clinicians should use the Pneumonia Severity Index (PSI) and clinical judgment to guide the site of treatment for patients. Gram stain, sputum, and blood culture should not be routinely obtained in an outpatient setting. Legionella antigen should not be routinely obtained unless indicated by epidemiological factors. During influenza season, a rapid influenza assay, preferably a nucleic acid amplification test, should be obtained to help guide treatment.

For patients with severe CAP or risk factors for MRSA or P. aeruginosa, gram stain and culture and Legionella antigen should be obtained to manage antibiotic choices. Also, blood cultures should be obtained for these patients.

Empiric antibiotic therapy should be initiated based on clinical judgment and radiographic confirmation of CAP. Serum procalcitonin should not be used to assess initiation of antibiotic therapy.

Empiric antibiotic therapy

Healthy adults without comorbidities should be treated with monotherapy of either:

- Amoxicillin 1 g three times daily.

- OR doxycycline 100 mg twice daily.

- OR a macrolide (azithromycin 500 mg on first day then 250 mg daily or clarithromycin 500 mg twice daily or clarithromycin extended release 1,000 mg daily) only in areas with pneumococcal resistance to macrolides less than 25%.

Adults with comorbidities such as chronic heart, lung, liver, or renal disease; diabetes mellitus; alcoholism; malignancy; or asplenia should be treated with:

- Amoxicillin/clavulanate 500 mg/125 mg three times daily, or amoxicillin/ clavulanate 875 mg/125 mg twice daily, or 2,000 mg/125 mg twice daily, or a cephalosporin (cefpodoxime 200 mg twice daily or cefuroxime 500 mg twice daily); and a macrolide (azithromycin 500 mg on first day then 250 mg daily, clarithromycin [500 mg twice daily or extended release 1,000 mg once daily]), or doxycycline 100 mg twice daily. (Some experts recommend that the first dose of doxycycline should be 200 mg.)

- OR monotherapy with respiratory fluoroquinolone (levofloxacin 750 mg daily, moxifloxacin 400 mg daily, or gemifloxacin 320 mg daily).

Inpatient pneumonia that is not severe, without risk factors for resistant organisms should be treated with:

- Beta-lactam (ampicillin 1 sulbactam 1.5-3 g every 6 h, cefotaxime 1-2 g every 8 h, ceftriaxone 1-2 g daily, or ceftaroline 600 mg every 12 h) and a macrolide (azithromycin 500 mg daily or clarithromycin 500 mg twice daily).

- OR monotherapy with a respiratory fluoroquinolone (levofloxacin 750 mg daily, moxifloxacin 400 mg daily).

If there is a contraindication for the use of both a macrolide and a fluoroquinolone, then doxycycline can be used instead.

Severe inpatient pneumonia without risk factors for resistant organisms should be treated with combination therapy of either (agents and doses the same as above):

- Beta-lactam and macrolide.

- OR fluoroquinolone and beta-lactam.

It is recommended to not routinely add anaerobic coverage for suspected aspiration pneumonia unless lung abscess or empyema is suspected. Clinicians should identify risk factors for MRSA or P. aeruginosa before adding additional agents.

Duration of antibiotic therapy is determined by the patient achieving clinical stability with no less than 5 days of antibiotics. In adults with symptom resolution within 5-7 days, no additional follow-up chest imaging is recommended. If patients test positive for influenza, then anti-influenza treatment such as oseltamivir should be used in addition to antibiotics regardless of length of influenza symptoms before presentation.

The bottom line

CAP treatment should be based on severity of illness and risk factors for resistant organisms. Blood and sputum cultures are recommended only for patients with severe pneumonia. There have been important changes in the recommendations for antibiotic treatment of CAP, with high-dose amoxicillin recommended for most patients with CAP who are treated as outpatients. Patients who exhibit clinical stability should be treated for at least 5 days and do not require follow up imaging studies.

For a podcast of this guideline, go to iTunes and download the Infectious Diseases Society of America guideline podcast.

Reference

Metlay JP, Waterer GW, Long AC, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of adults with community-acquired pneumonia. An official clinical practice guideline of the American Thoracic Society and Infectious Diseases Society of America. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019 Oct 1;200(7):e45-e67.

Tina Chuong, DO, is a second-year resident in the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health. Dr. Skolnik is professor of family and community medicine at Jefferson Medical College, Philadelphia, and an associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Jefferson Health.

A new guideline has been published to update the 2007 guidelines for the management of adults with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP).

The practice guideline was jointly written by an ad hoc committee of the American Thoracic Society and Infectious Diseases Society of America. CAP refers to a pneumonia infection that was acquired by a patient in his or her community. Decisions about which antibiotics to use to treat this kind of infection are based on risk factors for resistant organisms and the severity of illness.

Pathogens

Traditionally, CAP is caused by common bacterial pathogens that include Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, Legionella species, Chlamydia pneumonia, and Moraxella catarrhalis. Risk factors for multidrug resistant pathogens such as methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) and Pseudomonas aeruginosa include previous infection with MRSA or P. aeruginosa, recent hospitalization, and requiring parenteral antibiotics in the last 90 days.

Defining severe community-acquired pneumonia

The health care–associated pneumonia, or HCAP, classification should no longer be used to determine empiric treatment. The recommendations for which antibiotics to use are linked to the severity of illness. Previously the site of treatment drove antibiotic selection, but since decision about the site of care can be affected by many considerations, the guidelines recommend using the CAP severity criteria. Severe CAP includes either one major or at least three minor criteria.

Major criteria are:

- Septic shock requiring vasopressors.

- Respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation.

Minor criteria are:

- Respiratory rate greater than or equal to 30 breaths/min.

- Ratio of arterial O2 partial pressure to fractional inspired O2 less than or equal to 250.

- Multilobar infiltrates.

- Confusion/disorientation.

- Uremia (blood urea nitrogen level greater than or equal to 20 mg/dL).

- Leukopenia (white blood cell count less than 4,000 cells/mcL).

- Thrombocytopenia (platelet count less than 100,000 mcL)

- Hypothermia (core temperature less than 36º C).

- Hypotension requiring aggressive fluid resuscitation.

Management and diagnostic testing

Clinicians should use the Pneumonia Severity Index (PSI) and clinical judgment to guide the site of treatment for patients. Gram stain, sputum, and blood culture should not be routinely obtained in an outpatient setting. Legionella antigen should not be routinely obtained unless indicated by epidemiological factors. During influenza season, a rapid influenza assay, preferably a nucleic acid amplification test, should be obtained to help guide treatment.

For patients with severe CAP or risk factors for MRSA or P. aeruginosa, gram stain and culture and Legionella antigen should be obtained to manage antibiotic choices. Also, blood cultures should be obtained for these patients.

Empiric antibiotic therapy should be initiated based on clinical judgment and radiographic confirmation of CAP. Serum procalcitonin should not be used to assess initiation of antibiotic therapy.

Empiric antibiotic therapy

Healthy adults without comorbidities should be treated with monotherapy of either:

- Amoxicillin 1 g three times daily.

- OR doxycycline 100 mg twice daily.

- OR a macrolide (azithromycin 500 mg on first day then 250 mg daily or clarithromycin 500 mg twice daily or clarithromycin extended release 1,000 mg daily) only in areas with pneumococcal resistance to macrolides less than 25%.

Adults with comorbidities such as chronic heart, lung, liver, or renal disease; diabetes mellitus; alcoholism; malignancy; or asplenia should be treated with:

- Amoxicillin/clavulanate 500 mg/125 mg three times daily, or amoxicillin/ clavulanate 875 mg/125 mg twice daily, or 2,000 mg/125 mg twice daily, or a cephalosporin (cefpodoxime 200 mg twice daily or cefuroxime 500 mg twice daily); and a macrolide (azithromycin 500 mg on first day then 250 mg daily, clarithromycin [500 mg twice daily or extended release 1,000 mg once daily]), or doxycycline 100 mg twice daily. (Some experts recommend that the first dose of doxycycline should be 200 mg.)

- OR monotherapy with respiratory fluoroquinolone (levofloxacin 750 mg daily, moxifloxacin 400 mg daily, or gemifloxacin 320 mg daily).

Inpatient pneumonia that is not severe, without risk factors for resistant organisms should be treated with:

- Beta-lactam (ampicillin 1 sulbactam 1.5-3 g every 6 h, cefotaxime 1-2 g every 8 h, ceftriaxone 1-2 g daily, or ceftaroline 600 mg every 12 h) and a macrolide (azithromycin 500 mg daily or clarithromycin 500 mg twice daily).

- OR monotherapy with a respiratory fluoroquinolone (levofloxacin 750 mg daily, moxifloxacin 400 mg daily).

If there is a contraindication for the use of both a macrolide and a fluoroquinolone, then doxycycline can be used instead.

Severe inpatient pneumonia without risk factors for resistant organisms should be treated with combination therapy of either (agents and doses the same as above):

- Beta-lactam and macrolide.

- OR fluoroquinolone and beta-lactam.

It is recommended to not routinely add anaerobic coverage for suspected aspiration pneumonia unless lung abscess or empyema is suspected. Clinicians should identify risk factors for MRSA or P. aeruginosa before adding additional agents.

Duration of antibiotic therapy is determined by the patient achieving clinical stability with no less than 5 days of antibiotics. In adults with symptom resolution within 5-7 days, no additional follow-up chest imaging is recommended. If patients test positive for influenza, then anti-influenza treatment such as oseltamivir should be used in addition to antibiotics regardless of length of influenza symptoms before presentation.

The bottom line

CAP treatment should be based on severity of illness and risk factors for resistant organisms. Blood and sputum cultures are recommended only for patients with severe pneumonia. There have been important changes in the recommendations for antibiotic treatment of CAP, with high-dose amoxicillin recommended for most patients with CAP who are treated as outpatients. Patients who exhibit clinical stability should be treated for at least 5 days and do not require follow up imaging studies.

For a podcast of this guideline, go to iTunes and download the Infectious Diseases Society of America guideline podcast.

Reference

Metlay JP, Waterer GW, Long AC, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of adults with community-acquired pneumonia. An official clinical practice guideline of the American Thoracic Society and Infectious Diseases Society of America. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019 Oct 1;200(7):e45-e67.

Tina Chuong, DO, is a second-year resident in the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health. Dr. Skolnik is professor of family and community medicine at Jefferson Medical College, Philadelphia, and an associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Jefferson Health.

A new guideline has been published to update the 2007 guidelines for the management of adults with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP).

The practice guideline was jointly written by an ad hoc committee of the American Thoracic Society and Infectious Diseases Society of America. CAP refers to a pneumonia infection that was acquired by a patient in his or her community. Decisions about which antibiotics to use to treat this kind of infection are based on risk factors for resistant organisms and the severity of illness.

Pathogens

Traditionally, CAP is caused by common bacterial pathogens that include Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, Legionella species, Chlamydia pneumonia, and Moraxella catarrhalis. Risk factors for multidrug resistant pathogens such as methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) and Pseudomonas aeruginosa include previous infection with MRSA or P. aeruginosa, recent hospitalization, and requiring parenteral antibiotics in the last 90 days.

Defining severe community-acquired pneumonia

The health care–associated pneumonia, or HCAP, classification should no longer be used to determine empiric treatment. The recommendations for which antibiotics to use are linked to the severity of illness. Previously the site of treatment drove antibiotic selection, but since decision about the site of care can be affected by many considerations, the guidelines recommend using the CAP severity criteria. Severe CAP includes either one major or at least three minor criteria.

Major criteria are:

- Septic shock requiring vasopressors.

- Respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation.

Minor criteria are:

- Respiratory rate greater than or equal to 30 breaths/min.

- Ratio of arterial O2 partial pressure to fractional inspired O2 less than or equal to 250.

- Multilobar infiltrates.

- Confusion/disorientation.

- Uremia (blood urea nitrogen level greater than or equal to 20 mg/dL).

- Leukopenia (white blood cell count less than 4,000 cells/mcL).

- Thrombocytopenia (platelet count less than 100,000 mcL)

- Hypothermia (core temperature less than 36º C).

- Hypotension requiring aggressive fluid resuscitation.

Management and diagnostic testing

Clinicians should use the Pneumonia Severity Index (PSI) and clinical judgment to guide the site of treatment for patients. Gram stain, sputum, and blood culture should not be routinely obtained in an outpatient setting. Legionella antigen should not be routinely obtained unless indicated by epidemiological factors. During influenza season, a rapid influenza assay, preferably a nucleic acid amplification test, should be obtained to help guide treatment.

For patients with severe CAP or risk factors for MRSA or P. aeruginosa, gram stain and culture and Legionella antigen should be obtained to manage antibiotic choices. Also, blood cultures should be obtained for these patients.

Empiric antibiotic therapy should be initiated based on clinical judgment and radiographic confirmation of CAP. Serum procalcitonin should not be used to assess initiation of antibiotic therapy.

Empiric antibiotic therapy

Healthy adults without comorbidities should be treated with monotherapy of either:

- Amoxicillin 1 g three times daily.

- OR doxycycline 100 mg twice daily.

- OR a macrolide (azithromycin 500 mg on first day then 250 mg daily or clarithromycin 500 mg twice daily or clarithromycin extended release 1,000 mg daily) only in areas with pneumococcal resistance to macrolides less than 25%.

Adults with comorbidities such as chronic heart, lung, liver, or renal disease; diabetes mellitus; alcoholism; malignancy; or asplenia should be treated with:

- Amoxicillin/clavulanate 500 mg/125 mg three times daily, or amoxicillin/ clavulanate 875 mg/125 mg twice daily, or 2,000 mg/125 mg twice daily, or a cephalosporin (cefpodoxime 200 mg twice daily or cefuroxime 500 mg twice daily); and a macrolide (azithromycin 500 mg on first day then 250 mg daily, clarithromycin [500 mg twice daily or extended release 1,000 mg once daily]), or doxycycline 100 mg twice daily. (Some experts recommend that the first dose of doxycycline should be 200 mg.)

- OR monotherapy with respiratory fluoroquinolone (levofloxacin 750 mg daily, moxifloxacin 400 mg daily, or gemifloxacin 320 mg daily).

Inpatient pneumonia that is not severe, without risk factors for resistant organisms should be treated with:

- Beta-lactam (ampicillin 1 sulbactam 1.5-3 g every 6 h, cefotaxime 1-2 g every 8 h, ceftriaxone 1-2 g daily, or ceftaroline 600 mg every 12 h) and a macrolide (azithromycin 500 mg daily or clarithromycin 500 mg twice daily).

- OR monotherapy with a respiratory fluoroquinolone (levofloxacin 750 mg daily, moxifloxacin 400 mg daily).

If there is a contraindication for the use of both a macrolide and a fluoroquinolone, then doxycycline can be used instead.

Severe inpatient pneumonia without risk factors for resistant organisms should be treated with combination therapy of either (agents and doses the same as above):

- Beta-lactam and macrolide.

- OR fluoroquinolone and beta-lactam.

It is recommended to not routinely add anaerobic coverage for suspected aspiration pneumonia unless lung abscess or empyema is suspected. Clinicians should identify risk factors for MRSA or P. aeruginosa before adding additional agents.

Duration of antibiotic therapy is determined by the patient achieving clinical stability with no less than 5 days of antibiotics. In adults with symptom resolution within 5-7 days, no additional follow-up chest imaging is recommended. If patients test positive for influenza, then anti-influenza treatment such as oseltamivir should be used in addition to antibiotics regardless of length of influenza symptoms before presentation.

The bottom line

CAP treatment should be based on severity of illness and risk factors for resistant organisms. Blood and sputum cultures are recommended only for patients with severe pneumonia. There have been important changes in the recommendations for antibiotic treatment of CAP, with high-dose amoxicillin recommended for most patients with CAP who are treated as outpatients. Patients who exhibit clinical stability should be treated for at least 5 days and do not require follow up imaging studies.

For a podcast of this guideline, go to iTunes and download the Infectious Diseases Society of America guideline podcast.

Reference

Metlay JP, Waterer GW, Long AC, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of adults with community-acquired pneumonia. An official clinical practice guideline of the American Thoracic Society and Infectious Diseases Society of America. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019 Oct 1;200(7):e45-e67.

Tina Chuong, DO, is a second-year resident in the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health. Dr. Skolnik is professor of family and community medicine at Jefferson Medical College, Philadelphia, and an associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Jefferson Health.

Newborns’ maternal protection against measles wanes within 6 months

according to new research.

In fact, most of the 196 infants’ maternal measles antibodies had dropped below the protective threshold by 3 months of age – well before the recommended age of 12-15 months for the first dose of MMR vaccine.

The odds of inadequate protection doubled for each additional month of age, Michelle Science, MD, of the University of Toronto and associates reported in Pediatrics.

“The widening gap between loss of maternal antibodies and measles vaccination described in our study leaves infants vulnerable to measles for much of their infancy and highlights the need for further research to support public health policy,” Dr. Science and colleagues wrote.

The findings are not surprising for a setting in which measles has been eliminated and align with results from past research, Huong Q. McLean, PhD, MPH, of the Marshfield (Wis.) Clinic Research Institute and Walter A. Orenstein, MD, of Emory University in Atlanta wrote in an accompanying editorial (Pediatrics. 2019 Nov 21. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-2541).

However, this susceptibility prior to receiving the MMR has taken on a new significance more recently, Dr. McLean and Dr. Orenstein suggested.

“In light of increasing measles outbreaks during the past year reaching levels not recorded in the United States since 1992 and increased measles elsewhere, coupled with the risk of severe illness in infants, there is increased concern regarding the protection of infants against measles,” the editorialists wrote.

Dr. Science and colleagues tested serum samples from 196 term infants, all under 12 months old, for antibodies against measles. The sera had been previously collected at a single tertiary care center in Ontario for clinical testing and then stored. Measles has been eliminated in Canada since 1998.

The researchers randomly selected 25 samples for each of eight different age groups: up to 30 days old; 1 month (31-60 days); 2 months (61-89 days); 3 months (90-119 days); 4 months; 5 months; 6-9 months; and 9-11 months.

Just over half the babies (56%) were male, and 35% had an underlying condition, but none had conditions that might affect antibody levels. The conditions were primarily a developmental delay or otherwise affecting the central nervous system, liver, or gastrointestinal function. Mean maternal age was 32 years.

To ensure high test sensitivity, the researchers used the plaque-reduction neutralization test (PRNT) to test for measles-neutralizing antibodies instead of using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) because “ELISA sensitivity decreases as antibody titers decrease,” Dr. Science and colleagues wrote. They used a neutralization titer of less than 192 mIU/mL as the threshold for protection against measles.

When the researchers calculated the predicted standardized mean antibody titer for infants with a mother aged 32 years, they determined their mean to be 541 mIU/mL at 1 month, 142 mIU/mL at 3 months (below the measles threshold of susceptibility of 192 mIU/mL) , and 64 mIU/mL at 6 months. None of the infants had measles antibodies above the protective threshold at 6 months old, the authors noted.

Children’s odds of susceptibility to measles doubled for each additional month of age, after adjustment for infant sex and maternal age (odds ratio, 2.13). Children’s likelihood of susceptibility to measles modestly increased as maternal age increased in 5-year increments from 25 to 40 years.

Children with an underlying conditions had greater susceptibility to measles (83%), compared with those without a comorbidity (68%, P = .03). No difference in susceptibility existed between males and females or based on gestational age at birth (ranging from 37 to 41 weeks).

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices permits measles vaccination “as early as 6 months for infants who plan to travel internationally, infants with ongoing risk for exposure during measles outbreaks and as postexposure prophylaxis,” Dr. McLean and Dr. Orenstein noted in their editorial.

They discussed the rationale for various changes in the recommended schedule for measles immunization, based on changes in epidemiology of the disease and improved understanding of the immune response to vaccination since the vaccine became available in 1963. Then they posed the question of whether the recommendation should be revised again.

“Ideally, the schedule should minimize the risk of measles and its complications and optimize vaccine-induced protection,” Dr. McLean and Dr. Orenstein wrote.

They argued that the evidence cannot currently support changing the first MMR dose to a younger age because measles incidence in the United States remains extremely low outside of the extraordinary outbreaks in 2014 and 2019. Further, infants under 12 months of age make up less than 15% of measles cases during outbreaks, and unvaccinated people make up more than 70% of cases.

Rather, they stated, this new study emphasizes the importance of following the current schedule, with consideration of an earlier schedule only warranted during outbreaks.

“Health care providers must work to maintain high levels of coverage with 2 doses of MMR among vaccine-eligible populations and minimize pockets of susceptibility to prevent transmission to infants and prevent reestablishment of endemic transmission,” they concluded.

The research was funded by the Public Health Ontario Project Initiation Fund. The authors had no relevant financial disclosures. The editorialists had no external funding and no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Science M et al. Pediatrics. 2019 Nov 21. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-0630.

according to new research.

In fact, most of the 196 infants’ maternal measles antibodies had dropped below the protective threshold by 3 months of age – well before the recommended age of 12-15 months for the first dose of MMR vaccine.

The odds of inadequate protection doubled for each additional month of age, Michelle Science, MD, of the University of Toronto and associates reported in Pediatrics.

“The widening gap between loss of maternal antibodies and measles vaccination described in our study leaves infants vulnerable to measles for much of their infancy and highlights the need for further research to support public health policy,” Dr. Science and colleagues wrote.

The findings are not surprising for a setting in which measles has been eliminated and align with results from past research, Huong Q. McLean, PhD, MPH, of the Marshfield (Wis.) Clinic Research Institute and Walter A. Orenstein, MD, of Emory University in Atlanta wrote in an accompanying editorial (Pediatrics. 2019 Nov 21. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-2541).

However, this susceptibility prior to receiving the MMR has taken on a new significance more recently, Dr. McLean and Dr. Orenstein suggested.

“In light of increasing measles outbreaks during the past year reaching levels not recorded in the United States since 1992 and increased measles elsewhere, coupled with the risk of severe illness in infants, there is increased concern regarding the protection of infants against measles,” the editorialists wrote.

Dr. Science and colleagues tested serum samples from 196 term infants, all under 12 months old, for antibodies against measles. The sera had been previously collected at a single tertiary care center in Ontario for clinical testing and then stored. Measles has been eliminated in Canada since 1998.

The researchers randomly selected 25 samples for each of eight different age groups: up to 30 days old; 1 month (31-60 days); 2 months (61-89 days); 3 months (90-119 days); 4 months; 5 months; 6-9 months; and 9-11 months.

Just over half the babies (56%) were male, and 35% had an underlying condition, but none had conditions that might affect antibody levels. The conditions were primarily a developmental delay or otherwise affecting the central nervous system, liver, or gastrointestinal function. Mean maternal age was 32 years.

To ensure high test sensitivity, the researchers used the plaque-reduction neutralization test (PRNT) to test for measles-neutralizing antibodies instead of using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) because “ELISA sensitivity decreases as antibody titers decrease,” Dr. Science and colleagues wrote. They used a neutralization titer of less than 192 mIU/mL as the threshold for protection against measles.

When the researchers calculated the predicted standardized mean antibody titer for infants with a mother aged 32 years, they determined their mean to be 541 mIU/mL at 1 month, 142 mIU/mL at 3 months (below the measles threshold of susceptibility of 192 mIU/mL) , and 64 mIU/mL at 6 months. None of the infants had measles antibodies above the protective threshold at 6 months old, the authors noted.

Children’s odds of susceptibility to measles doubled for each additional month of age, after adjustment for infant sex and maternal age (odds ratio, 2.13). Children’s likelihood of susceptibility to measles modestly increased as maternal age increased in 5-year increments from 25 to 40 years.

Children with an underlying conditions had greater susceptibility to measles (83%), compared with those without a comorbidity (68%, P = .03). No difference in susceptibility existed between males and females or based on gestational age at birth (ranging from 37 to 41 weeks).

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices permits measles vaccination “as early as 6 months for infants who plan to travel internationally, infants with ongoing risk for exposure during measles outbreaks and as postexposure prophylaxis,” Dr. McLean and Dr. Orenstein noted in their editorial.

They discussed the rationale for various changes in the recommended schedule for measles immunization, based on changes in epidemiology of the disease and improved understanding of the immune response to vaccination since the vaccine became available in 1963. Then they posed the question of whether the recommendation should be revised again.

“Ideally, the schedule should minimize the risk of measles and its complications and optimize vaccine-induced protection,” Dr. McLean and Dr. Orenstein wrote.

They argued that the evidence cannot currently support changing the first MMR dose to a younger age because measles incidence in the United States remains extremely low outside of the extraordinary outbreaks in 2014 and 2019. Further, infants under 12 months of age make up less than 15% of measles cases during outbreaks, and unvaccinated people make up more than 70% of cases.

Rather, they stated, this new study emphasizes the importance of following the current schedule, with consideration of an earlier schedule only warranted during outbreaks.

“Health care providers must work to maintain high levels of coverage with 2 doses of MMR among vaccine-eligible populations and minimize pockets of susceptibility to prevent transmission to infants and prevent reestablishment of endemic transmission,” they concluded.

The research was funded by the Public Health Ontario Project Initiation Fund. The authors had no relevant financial disclosures. The editorialists had no external funding and no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Science M et al. Pediatrics. 2019 Nov 21. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-0630.

according to new research.

In fact, most of the 196 infants’ maternal measles antibodies had dropped below the protective threshold by 3 months of age – well before the recommended age of 12-15 months for the first dose of MMR vaccine.

The odds of inadequate protection doubled for each additional month of age, Michelle Science, MD, of the University of Toronto and associates reported in Pediatrics.

“The widening gap between loss of maternal antibodies and measles vaccination described in our study leaves infants vulnerable to measles for much of their infancy and highlights the need for further research to support public health policy,” Dr. Science and colleagues wrote.

The findings are not surprising for a setting in which measles has been eliminated and align with results from past research, Huong Q. McLean, PhD, MPH, of the Marshfield (Wis.) Clinic Research Institute and Walter A. Orenstein, MD, of Emory University in Atlanta wrote in an accompanying editorial (Pediatrics. 2019 Nov 21. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-2541).

However, this susceptibility prior to receiving the MMR has taken on a new significance more recently, Dr. McLean and Dr. Orenstein suggested.

“In light of increasing measles outbreaks during the past year reaching levels not recorded in the United States since 1992 and increased measles elsewhere, coupled with the risk of severe illness in infants, there is increased concern regarding the protection of infants against measles,” the editorialists wrote.

Dr. Science and colleagues tested serum samples from 196 term infants, all under 12 months old, for antibodies against measles. The sera had been previously collected at a single tertiary care center in Ontario for clinical testing and then stored. Measles has been eliminated in Canada since 1998.

The researchers randomly selected 25 samples for each of eight different age groups: up to 30 days old; 1 month (31-60 days); 2 months (61-89 days); 3 months (90-119 days); 4 months; 5 months; 6-9 months; and 9-11 months.

Just over half the babies (56%) were male, and 35% had an underlying condition, but none had conditions that might affect antibody levels. The conditions were primarily a developmental delay or otherwise affecting the central nervous system, liver, or gastrointestinal function. Mean maternal age was 32 years.

To ensure high test sensitivity, the researchers used the plaque-reduction neutralization test (PRNT) to test for measles-neutralizing antibodies instead of using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) because “ELISA sensitivity decreases as antibody titers decrease,” Dr. Science and colleagues wrote. They used a neutralization titer of less than 192 mIU/mL as the threshold for protection against measles.

When the researchers calculated the predicted standardized mean antibody titer for infants with a mother aged 32 years, they determined their mean to be 541 mIU/mL at 1 month, 142 mIU/mL at 3 months (below the measles threshold of susceptibility of 192 mIU/mL) , and 64 mIU/mL at 6 months. None of the infants had measles antibodies above the protective threshold at 6 months old, the authors noted.

Children’s odds of susceptibility to measles doubled for each additional month of age, after adjustment for infant sex and maternal age (odds ratio, 2.13). Children’s likelihood of susceptibility to measles modestly increased as maternal age increased in 5-year increments from 25 to 40 years.

Children with an underlying conditions had greater susceptibility to measles (83%), compared with those without a comorbidity (68%, P = .03). No difference in susceptibility existed between males and females or based on gestational age at birth (ranging from 37 to 41 weeks).

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices permits measles vaccination “as early as 6 months for infants who plan to travel internationally, infants with ongoing risk for exposure during measles outbreaks and as postexposure prophylaxis,” Dr. McLean and Dr. Orenstein noted in their editorial.

They discussed the rationale for various changes in the recommended schedule for measles immunization, based on changes in epidemiology of the disease and improved understanding of the immune response to vaccination since the vaccine became available in 1963. Then they posed the question of whether the recommendation should be revised again.

“Ideally, the schedule should minimize the risk of measles and its complications and optimize vaccine-induced protection,” Dr. McLean and Dr. Orenstein wrote.

They argued that the evidence cannot currently support changing the first MMR dose to a younger age because measles incidence in the United States remains extremely low outside of the extraordinary outbreaks in 2014 and 2019. Further, infants under 12 months of age make up less than 15% of measles cases during outbreaks, and unvaccinated people make up more than 70% of cases.

Rather, they stated, this new study emphasizes the importance of following the current schedule, with consideration of an earlier schedule only warranted during outbreaks.

“Health care providers must work to maintain high levels of coverage with 2 doses of MMR among vaccine-eligible populations and minimize pockets of susceptibility to prevent transmission to infants and prevent reestablishment of endemic transmission,” they concluded.

The research was funded by the Public Health Ontario Project Initiation Fund. The authors had no relevant financial disclosures. The editorialists had no external funding and no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Science M et al. Pediatrics. 2019 Nov 21. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-0630.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Key clinical point: Infants’ maternal measles antibodies fell below protective levels by 6 months old.

Major finding: Infants were twice as likely not to have protective immunity against measles for each month of age after birth (odds ratio, 2.13).

Study details: The findings are based on measles antibody testing of 196 serum samples from infants born in a tertiary care center in Ontario.

Disclosures: The research was funded by the Public Health Ontario Project Initiation Fund. The authors had no relevant financial disclosures.

Source: Science M et al. Pediatrics. 2019 Nov 21. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-0630.

Vaping front and center at Hahn’s first FDA confirmation hearing

Stephen Hahn, MD, President Trump’s pick to head the Food and Drug Administration, faced questions from both sides of the aisle on youth vaping, but came up short when asked to commit to taking action, particularly on banning flavored vaping products.

Speaking at a Nov. 20 confirmation hearing before the Senate Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions Committee, Dr. Hahn said that youth vaping and e-cigarette use is “an important, urgent crisis in this country. I do not want to see another generation of Americans become addicted to tobacco and nicotine and I believe that we need to take aggressive to stop that.”

Sen. Patty Murray (D-Wash), the committee’s ranking member, asked Dr. Hahn whether he would work to finalize a ban flavored e-cigarette products, first proposed but then backed away from, by the president in September.

“I understand that the final compliance policy is under consideration by the administration, and I look forward to their decision,” Dr. Hahn said. “I am not privy to those decision-making processes, but I very much agree and support that aggressive action needs to be taken to protect our children.”

When pressed by Sen. Murray as to whether he told President Trump that he disagrees with the decision to back away the proposed ban, Dr. Hahn revealed that he has “not had a conversation with the president.”

Dr. Hahn, a radiation oncologist who currently serves as chief medical executive at MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, held firm to just coming up short of making that commitment when questioned by senators from both parties.

Sen. Mitt Romney (R-Utah) warned Dr. Hahn that the playing of politics would be unlike anything he has seen and is already being played out in the lobbying of the administration to change its stance on flavored e-cigarette products, which can run counter to the science about the harmful effects of these products.

“The question is how you will balance those things in which you put forward,” Sen. Romney asked. “How you will deal with this issue is a pretty good test case for how you would deal with this issue on an ongoing basis on matters not just related to vaping.”

He also brought up President Trump’s September announcement on a flavor ban and the administration’s signaling they are moving away from a flavor ban. “Is the FDA, under your leadership, able and willing to take action which will protect our kids, whether or not the White House wants you to take that action?”

Dr. Hahn cited his pledge as a doctor to always put the patient first and reiterated that “I take that pledge very seriously and I think if you ask anyone who has worked with me, they will tell you that I have upheld that pledge.”

But he fell short of saying that he would take actions that would oppose the White House, saying only that “patients need to come first and the decisions that we make need to be guided by science and data, congruent with the law.”

When asked by Sen. Romney if he saw any reason for holding off on a flavor ban, given the evidence that suggests flavored e-cigarette products are the gateway to youths nicotine addiction, Dr. Hahn said that he has seen the same evidence and that it requires “bold action,” but did not commit to a flavor ban. “I will use science and data to guide the decisions if I am fortunate enough to be confirmed, and I won’t back away from that.”

Sen. Doug Jones (D-Ala.) expressed concern about Dr. Hahn’s answers.

“I was less than happy with many of the answers you gave to members of this committee with regard to vaping and the potential ban on flavored e-cigarettes,” Sen. Jones said. “I think you can tell from the questions of so many senators that is one of the biggest issues that the United States Senate and Congress is facing right now. It is with this committee.”

Outside of vaping, much of the senators’ questioning was nonconfrontational, with questions spanning a gamut of issues facing the FDA.

Dr. Hahn offered his commitment to working with Congress to address drug shortages, noting nonspecifically that, “there are things that we can do to help.”

He also pledged to work with Congress on addressing patent reform to get more biosimilars to market in an effort to help drive down drug prices.

Regarding opioids, Dr. Hahn was asked about balancing the needs of those who legitimately need access to opioids against abuse and diversion.

“When I first went to medical school and started taking care of cancer patients, the teaching was that cancer patients should be treated liberally with opioids and that they don’t become addicted to pain medications,” he said. “We found out that wasn’t the case – and in some instances – with tragic consequences.”

He noted that pain therapy has evolved and that his institution now takes a multidisciplinary approach employing both opioid and nonopioid medications.

“I am very much a supporter of the multidisciplinary approach to treating pain,” he said. “I think it is something that we need to more of and if I am fortunate enough to be confirmed as commissioner of [FDA], I look forward to furthering the education efforts for providers and patients.”

Other areas he committed to included helping to improve clinical trial design for psychiatric medications and improving development of therapies for rare diseases.

Committee Chairman Lamar Alexander (R-Tenn.) said he plans to schedule a Dec. 3 vote to advance Dr. Hahn’s nomination to the full Senate for its consideration.

Stephen Hahn, MD, President Trump’s pick to head the Food and Drug Administration, faced questions from both sides of the aisle on youth vaping, but came up short when asked to commit to taking action, particularly on banning flavored vaping products.

Speaking at a Nov. 20 confirmation hearing before the Senate Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions Committee, Dr. Hahn said that youth vaping and e-cigarette use is “an important, urgent crisis in this country. I do not want to see another generation of Americans become addicted to tobacco and nicotine and I believe that we need to take aggressive to stop that.”

Sen. Patty Murray (D-Wash), the committee’s ranking member, asked Dr. Hahn whether he would work to finalize a ban flavored e-cigarette products, first proposed but then backed away from, by the president in September.

“I understand that the final compliance policy is under consideration by the administration, and I look forward to their decision,” Dr. Hahn said. “I am not privy to those decision-making processes, but I very much agree and support that aggressive action needs to be taken to protect our children.”

When pressed by Sen. Murray as to whether he told President Trump that he disagrees with the decision to back away the proposed ban, Dr. Hahn revealed that he has “not had a conversation with the president.”

Dr. Hahn, a radiation oncologist who currently serves as chief medical executive at MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, held firm to just coming up short of making that commitment when questioned by senators from both parties.

Sen. Mitt Romney (R-Utah) warned Dr. Hahn that the playing of politics would be unlike anything he has seen and is already being played out in the lobbying of the administration to change its stance on flavored e-cigarette products, which can run counter to the science about the harmful effects of these products.

“The question is how you will balance those things in which you put forward,” Sen. Romney asked. “How you will deal with this issue is a pretty good test case for how you would deal with this issue on an ongoing basis on matters not just related to vaping.”

He also brought up President Trump’s September announcement on a flavor ban and the administration’s signaling they are moving away from a flavor ban. “Is the FDA, under your leadership, able and willing to take action which will protect our kids, whether or not the White House wants you to take that action?”

Dr. Hahn cited his pledge as a doctor to always put the patient first and reiterated that “I take that pledge very seriously and I think if you ask anyone who has worked with me, they will tell you that I have upheld that pledge.”

But he fell short of saying that he would take actions that would oppose the White House, saying only that “patients need to come first and the decisions that we make need to be guided by science and data, congruent with the law.”

When asked by Sen. Romney if he saw any reason for holding off on a flavor ban, given the evidence that suggests flavored e-cigarette products are the gateway to youths nicotine addiction, Dr. Hahn said that he has seen the same evidence and that it requires “bold action,” but did not commit to a flavor ban. “I will use science and data to guide the decisions if I am fortunate enough to be confirmed, and I won’t back away from that.”

Sen. Doug Jones (D-Ala.) expressed concern about Dr. Hahn’s answers.

“I was less than happy with many of the answers you gave to members of this committee with regard to vaping and the potential ban on flavored e-cigarettes,” Sen. Jones said. “I think you can tell from the questions of so many senators that is one of the biggest issues that the United States Senate and Congress is facing right now. It is with this committee.”

Outside of vaping, much of the senators’ questioning was nonconfrontational, with questions spanning a gamut of issues facing the FDA.

Dr. Hahn offered his commitment to working with Congress to address drug shortages, noting nonspecifically that, “there are things that we can do to help.”

He also pledged to work with Congress on addressing patent reform to get more biosimilars to market in an effort to help drive down drug prices.

Regarding opioids, Dr. Hahn was asked about balancing the needs of those who legitimately need access to opioids against abuse and diversion.

“When I first went to medical school and started taking care of cancer patients, the teaching was that cancer patients should be treated liberally with opioids and that they don’t become addicted to pain medications,” he said. “We found out that wasn’t the case – and in some instances – with tragic consequences.”

He noted that pain therapy has evolved and that his institution now takes a multidisciplinary approach employing both opioid and nonopioid medications.

“I am very much a supporter of the multidisciplinary approach to treating pain,” he said. “I think it is something that we need to more of and if I am fortunate enough to be confirmed as commissioner of [FDA], I look forward to furthering the education efforts for providers and patients.”

Other areas he committed to included helping to improve clinical trial design for psychiatric medications and improving development of therapies for rare diseases.

Committee Chairman Lamar Alexander (R-Tenn.) said he plans to schedule a Dec. 3 vote to advance Dr. Hahn’s nomination to the full Senate for its consideration.

Stephen Hahn, MD, President Trump’s pick to head the Food and Drug Administration, faced questions from both sides of the aisle on youth vaping, but came up short when asked to commit to taking action, particularly on banning flavored vaping products.

Speaking at a Nov. 20 confirmation hearing before the Senate Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions Committee, Dr. Hahn said that youth vaping and e-cigarette use is “an important, urgent crisis in this country. I do not want to see another generation of Americans become addicted to tobacco and nicotine and I believe that we need to take aggressive to stop that.”

Sen. Patty Murray (D-Wash), the committee’s ranking member, asked Dr. Hahn whether he would work to finalize a ban flavored e-cigarette products, first proposed but then backed away from, by the president in September.

“I understand that the final compliance policy is under consideration by the administration, and I look forward to their decision,” Dr. Hahn said. “I am not privy to those decision-making processes, but I very much agree and support that aggressive action needs to be taken to protect our children.”

When pressed by Sen. Murray as to whether he told President Trump that he disagrees with the decision to back away the proposed ban, Dr. Hahn revealed that he has “not had a conversation with the president.”

Dr. Hahn, a radiation oncologist who currently serves as chief medical executive at MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, held firm to just coming up short of making that commitment when questioned by senators from both parties.

Sen. Mitt Romney (R-Utah) warned Dr. Hahn that the playing of politics would be unlike anything he has seen and is already being played out in the lobbying of the administration to change its stance on flavored e-cigarette products, which can run counter to the science about the harmful effects of these products.

“The question is how you will balance those things in which you put forward,” Sen. Romney asked. “How you will deal with this issue is a pretty good test case for how you would deal with this issue on an ongoing basis on matters not just related to vaping.”

He also brought up President Trump’s September announcement on a flavor ban and the administration’s signaling they are moving away from a flavor ban. “Is the FDA, under your leadership, able and willing to take action which will protect our kids, whether or not the White House wants you to take that action?”

Dr. Hahn cited his pledge as a doctor to always put the patient first and reiterated that “I take that pledge very seriously and I think if you ask anyone who has worked with me, they will tell you that I have upheld that pledge.”

But he fell short of saying that he would take actions that would oppose the White House, saying only that “patients need to come first and the decisions that we make need to be guided by science and data, congruent with the law.”

When asked by Sen. Romney if he saw any reason for holding off on a flavor ban, given the evidence that suggests flavored e-cigarette products are the gateway to youths nicotine addiction, Dr. Hahn said that he has seen the same evidence and that it requires “bold action,” but did not commit to a flavor ban. “I will use science and data to guide the decisions if I am fortunate enough to be confirmed, and I won’t back away from that.”

Sen. Doug Jones (D-Ala.) expressed concern about Dr. Hahn’s answers.

“I was less than happy with many of the answers you gave to members of this committee with regard to vaping and the potential ban on flavored e-cigarettes,” Sen. Jones said. “I think you can tell from the questions of so many senators that is one of the biggest issues that the United States Senate and Congress is facing right now. It is with this committee.”

Outside of vaping, much of the senators’ questioning was nonconfrontational, with questions spanning a gamut of issues facing the FDA.

Dr. Hahn offered his commitment to working with Congress to address drug shortages, noting nonspecifically that, “there are things that we can do to help.”

He also pledged to work with Congress on addressing patent reform to get more biosimilars to market in an effort to help drive down drug prices.

Regarding opioids, Dr. Hahn was asked about balancing the needs of those who legitimately need access to opioids against abuse and diversion.

“When I first went to medical school and started taking care of cancer patients, the teaching was that cancer patients should be treated liberally with opioids and that they don’t become addicted to pain medications,” he said. “We found out that wasn’t the case – and in some instances – with tragic consequences.”

He noted that pain therapy has evolved and that his institution now takes a multidisciplinary approach employing both opioid and nonopioid medications.

“I am very much a supporter of the multidisciplinary approach to treating pain,” he said. “I think it is something that we need to more of and if I am fortunate enough to be confirmed as commissioner of [FDA], I look forward to furthering the education efforts for providers and patients.”

Other areas he committed to included helping to improve clinical trial design for psychiatric medications and improving development of therapies for rare diseases.

Committee Chairman Lamar Alexander (R-Tenn.) said he plans to schedule a Dec. 3 vote to advance Dr. Hahn’s nomination to the full Senate for its consideration.

REPORTING FROM A SENATE SUBCOMMITTEE HEARING

Ask about vaping in patients with respiratory symptoms, CDC says

“Do you vape?” may be one of the most important questions health care can providers can ask patients who present with respiratory symptoms this winter.

according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Accordingly, providers need to ask patients with respiratory, gastrointestinal, or constitutional symptoms about their use of e-cigarette or vaping products, according to one several new CDC recommendations that appear in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Review.

“E-cigarette or vaping product use–associated lung injury (EVALI) remains a diagnosis of exclusion because, at present, no specific test or marker exists for its diagnosis, and evaluation should be guided by clinical judgment,” the CDC report reads.

As of Nov. 13, there have been 2,172 cases of EVALI reported to CDC, of which 42 (1.9%) have been fatal. Most of the patients with EVALI have been white (79%), male (68%), and under the age of 35 years (77%), according to CDC data.

Although vitamin E acetate was recently implicated as a potential cause of EVALI, the agency said evidence is “not sufficient” at this point in their investigation to rule out other chemicals of potential concern.

“Many different substances and product sources are still under investigation, and it might be that there is more than one cause of this outbreak,” CDC said.

Further recommendations

Beyond asking about vape use, providers should evaluate suspected EVALI with pulse oximetry and chest imaging, and should consider outpatient management for patients who are clinically stable, according to the recommendations.

The agency said influenza testing should be “strongly considered,” especially during influenza season, given that EVALI is a diagnosis of exclusion and that it may co-occur with other respiratory illnesses. Antimicrobials (including antivirals) should be given as warranted, they added.

Corticosteroids may be helpful in treating EVALI, but may worsen respiratory infections typically seen in outpatients, and so should be prescribed with caution in the outpatient setting, the CDC recommended.

Behavioral counseling, addiction treatment services, and Food and Drug Administration–approved cessation medications are recommended to help patients quit vaping or e-cigarette products, CDC said.

Health care providers should emphasize the importance of an annual flu shot for all patients 6 months of age or older, including those who use e-cigarette or vaping products, according to the agency.

“It is not known whether patients with EVALI are at higher risk for severe complications of influenza or other respiratory infections,” the report reads.

Blame it on vitamin E? THC? Other?

The report details how, as previously reported, vitamin E acetate was detected in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid samples from 29 patients with EVALI. Although other chemicals could contribute to EVALI, that finding provided “direct evidence” of vitamin E acetate at the primary site of injury, according to CDC.

Most patients with EVALI, 83%, have reported using a tetrahydrocannabinol (THC)-containing e-cigarette or vaping product, according to CDC, while 61% reported using a nicotine-containing product.

Based on that, CDC recommended that people avoid using THC-containing products. However, the agency cautioned that the specific cause or causes of EVALI remain to be elucidated.

“The only way for persons to assure that they are not at risk is to consider refraining from use of all e-cigarette, or vaping, products while this investigation continues,” CDC said in the report.

The need for this additional clinical guidance was assessed in anticipation of the seasonal uptick in influenza and other respiratory infections, according to the CDC, which said the recommendations were based in part on individual clinical perspectives from nine national experts who participated in a previously published clinical guidance on managing patients with EVALI.

SOURCES: Jatlaoui TC et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019 Nov 19. doi. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6846e2; Chatham-Stephens K et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019 Nov 19. doi. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6846e1.

“Do you vape?” may be one of the most important questions health care can providers can ask patients who present with respiratory symptoms this winter.

according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Accordingly, providers need to ask patients with respiratory, gastrointestinal, or constitutional symptoms about their use of e-cigarette or vaping products, according to one several new CDC recommendations that appear in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Review.

“E-cigarette or vaping product use–associated lung injury (EVALI) remains a diagnosis of exclusion because, at present, no specific test or marker exists for its diagnosis, and evaluation should be guided by clinical judgment,” the CDC report reads.

As of Nov. 13, there have been 2,172 cases of EVALI reported to CDC, of which 42 (1.9%) have been fatal. Most of the patients with EVALI have been white (79%), male (68%), and under the age of 35 years (77%), according to CDC data.

Although vitamin E acetate was recently implicated as a potential cause of EVALI, the agency said evidence is “not sufficient” at this point in their investigation to rule out other chemicals of potential concern.

“Many different substances and product sources are still under investigation, and it might be that there is more than one cause of this outbreak,” CDC said.

Further recommendations

Beyond asking about vape use, providers should evaluate suspected EVALI with pulse oximetry and chest imaging, and should consider outpatient management for patients who are clinically stable, according to the recommendations.

The agency said influenza testing should be “strongly considered,” especially during influenza season, given that EVALI is a diagnosis of exclusion and that it may co-occur with other respiratory illnesses. Antimicrobials (including antivirals) should be given as warranted, they added.

Corticosteroids may be helpful in treating EVALI, but may worsen respiratory infections typically seen in outpatients, and so should be prescribed with caution in the outpatient setting, the CDC recommended.

Behavioral counseling, addiction treatment services, and Food and Drug Administration–approved cessation medications are recommended to help patients quit vaping or e-cigarette products, CDC said.

Health care providers should emphasize the importance of an annual flu shot for all patients 6 months of age or older, including those who use e-cigarette or vaping products, according to the agency.