User login

AVXS-101 may result in long-term motor improvements in SMA

CHARLOTTE, N.C. – AVXS-101, the Food and Drug Administration–approved therapy for spinal muscular atrophy (SMA), yields rapid, sustained improvements in CHOP INTEND scores, better survival, and motor function improvements at long-term follow-up, according to an analysis presented at the annual meeting of the Child Neurology Society. The results provide a clinical demonstration of continuous expression of the SMN protein, according to the investigators. In addition, AVXS-101 is associated with reduced health care utilization in treated infants, which could decrease costs, lessen the burden on patients and caregivers, and improve quality of life.

SMA1 is a progressive neurologic disease that causes loss of the lower motor neurons in the spinal cord and brainstem. Patients have increasing muscle weakness that leads to death or the need for permanent ventilation by age 2 years. The disease results from mutations in the SMN1 gene. AVXS-101 replaces the missing or nonfunctional SMN1 with a healthy copy of a human SMN gene.

AveXis, the company that developed the therapy, enrolled 12 patients with SMA1 in a phase 1/2a study between December 2014 and December 2015. All participants received one intravenous infusion of AVXS-101. Omar Dabbous, MD, vice president of global health economics, outcomes research, and real world evidence at AveXis in Bannockburn, Ill., and colleagues evaluated participants’ rates of event-free survival (i.e., absence of death or need for permanent ventilation), pulmonary or nutritional interventions, swallowing, hospitalization, and CHOP INTEND scores, as well as therapeutic safety at 2 years.

At study completion, all patients who had received a therapeutic dose had event-free survival. Seven participants did not need daily noninvasive ventilation. Eleven participants had stable or improved swallowing. All of the latter patients fed orally, and six fed exclusively by mouth. Eleven patients spoke.

Participants had a mean of 1.4 respiratory hospitalizations per year. Mean proportion of time participants spent hospitalized was 4.4%. Mean hospitalization rate per year was 2.1, and mean length of hospital stay was 6.7 days. In addition, participants’ CHOP INTEND scores increased from baseline by 9.8 points at 1 month and by 15.4 points at 3 months. Patients who received a therapeutic dose of AVXS-101 have maintained their motor milestones at long-term follow-up, which suggests that treatment effects persist over the long term. Adverse events included elevated serum aminotransferase levels, which were reduced by prednisolone.

Dr. Dabbous is an employee of AveXis, which developed AVXS-101.

SOURCE: Dabbous O et al. CNS 2019. Abstract 199.

CHARLOTTE, N.C. – AVXS-101, the Food and Drug Administration–approved therapy for spinal muscular atrophy (SMA), yields rapid, sustained improvements in CHOP INTEND scores, better survival, and motor function improvements at long-term follow-up, according to an analysis presented at the annual meeting of the Child Neurology Society. The results provide a clinical demonstration of continuous expression of the SMN protein, according to the investigators. In addition, AVXS-101 is associated with reduced health care utilization in treated infants, which could decrease costs, lessen the burden on patients and caregivers, and improve quality of life.

SMA1 is a progressive neurologic disease that causes loss of the lower motor neurons in the spinal cord and brainstem. Patients have increasing muscle weakness that leads to death or the need for permanent ventilation by age 2 years. The disease results from mutations in the SMN1 gene. AVXS-101 replaces the missing or nonfunctional SMN1 with a healthy copy of a human SMN gene.

AveXis, the company that developed the therapy, enrolled 12 patients with SMA1 in a phase 1/2a study between December 2014 and December 2015. All participants received one intravenous infusion of AVXS-101. Omar Dabbous, MD, vice president of global health economics, outcomes research, and real world evidence at AveXis in Bannockburn, Ill., and colleagues evaluated participants’ rates of event-free survival (i.e., absence of death or need for permanent ventilation), pulmonary or nutritional interventions, swallowing, hospitalization, and CHOP INTEND scores, as well as therapeutic safety at 2 years.

At study completion, all patients who had received a therapeutic dose had event-free survival. Seven participants did not need daily noninvasive ventilation. Eleven participants had stable or improved swallowing. All of the latter patients fed orally, and six fed exclusively by mouth. Eleven patients spoke.

Participants had a mean of 1.4 respiratory hospitalizations per year. Mean proportion of time participants spent hospitalized was 4.4%. Mean hospitalization rate per year was 2.1, and mean length of hospital stay was 6.7 days. In addition, participants’ CHOP INTEND scores increased from baseline by 9.8 points at 1 month and by 15.4 points at 3 months. Patients who received a therapeutic dose of AVXS-101 have maintained their motor milestones at long-term follow-up, which suggests that treatment effects persist over the long term. Adverse events included elevated serum aminotransferase levels, which were reduced by prednisolone.

Dr. Dabbous is an employee of AveXis, which developed AVXS-101.

SOURCE: Dabbous O et al. CNS 2019. Abstract 199.

CHARLOTTE, N.C. – AVXS-101, the Food and Drug Administration–approved therapy for spinal muscular atrophy (SMA), yields rapid, sustained improvements in CHOP INTEND scores, better survival, and motor function improvements at long-term follow-up, according to an analysis presented at the annual meeting of the Child Neurology Society. The results provide a clinical demonstration of continuous expression of the SMN protein, according to the investigators. In addition, AVXS-101 is associated with reduced health care utilization in treated infants, which could decrease costs, lessen the burden on patients and caregivers, and improve quality of life.

SMA1 is a progressive neurologic disease that causes loss of the lower motor neurons in the spinal cord and brainstem. Patients have increasing muscle weakness that leads to death or the need for permanent ventilation by age 2 years. The disease results from mutations in the SMN1 gene. AVXS-101 replaces the missing or nonfunctional SMN1 with a healthy copy of a human SMN gene.

AveXis, the company that developed the therapy, enrolled 12 patients with SMA1 in a phase 1/2a study between December 2014 and December 2015. All participants received one intravenous infusion of AVXS-101. Omar Dabbous, MD, vice president of global health economics, outcomes research, and real world evidence at AveXis in Bannockburn, Ill., and colleagues evaluated participants’ rates of event-free survival (i.e., absence of death or need for permanent ventilation), pulmonary or nutritional interventions, swallowing, hospitalization, and CHOP INTEND scores, as well as therapeutic safety at 2 years.

At study completion, all patients who had received a therapeutic dose had event-free survival. Seven participants did not need daily noninvasive ventilation. Eleven participants had stable or improved swallowing. All of the latter patients fed orally, and six fed exclusively by mouth. Eleven patients spoke.

Participants had a mean of 1.4 respiratory hospitalizations per year. Mean proportion of time participants spent hospitalized was 4.4%. Mean hospitalization rate per year was 2.1, and mean length of hospital stay was 6.7 days. In addition, participants’ CHOP INTEND scores increased from baseline by 9.8 points at 1 month and by 15.4 points at 3 months. Patients who received a therapeutic dose of AVXS-101 have maintained their motor milestones at long-term follow-up, which suggests that treatment effects persist over the long term. Adverse events included elevated serum aminotransferase levels, which were reduced by prednisolone.

Dr. Dabbous is an employee of AveXis, which developed AVXS-101.

SOURCE: Dabbous O et al. CNS 2019. Abstract 199.

REPORTING FROM CNS 2019

Serum test sheds light on Merkel cell carcinoma

LAS VEGAS – Merkel cell carcinoma, an extremely rare form of skin cancer, is often caused by a subclinical virus that routinely inhabits the skin. Now, a serum test of virus antibody levels is offering insight into the state of the disease, according to one dermatologist.

“If you have these antibodies, you have a better prognosis. You can follow those antibodies to test for recurrence or progression,” Isaac Brownell, MD, PhD, of the Dermatology Branch of the National Institutes of Health said at Skin Disease Education Foundation’s annual Las Vegas Dermatology Seminar.

The cancer appears in the skin’s Merkel cells, which contribute to our sense of touch by helping us to discriminate textures. “When you put your hand in your pocket, and you can tell the difference between the front and back of a quarter,” he said, “you’re using the Merkel cells in your fingertips.”

Only about 2,500 cases of Merkel cell carcinoma appear in the United States each year, Dr. Brownell said. It appears more often in elderly white patients, is more common in men than women, and is more likely among immunosuppressed patients, whose risk is increased 15- to 20-fold. Cases are more common in sunnier regions – at least in men – and lesions frequently appear on the head, face, and neck.

Five-year survival is estimated at 51% if the cancer is localized, according to a 2016 study of 9,387 cases that Dr. Brownell highlighted. But survival declines dramatically if it has spread to lymph nodes or distant sites (Ann Surg Oncol. 2016 Oct;23[11]:3564-71).

In recent years, researchers have linked 80% of Merkel cell carcinoma cases to the Merkel cell polyomavirus, he said. The virus normally inhabits our skin with no ill effects, he said. “We all have this virus on our skin. It’s everywhere, and even children have antibodies,” he said. But mutations can lead to Merkel cell carcinoma.

Does it matter if cases are polyomavirus positive or polyomavirus negative? Not really, Dr. Brownell said, since the presence of the virus doesn’t appear to affect overall prognosis. However, he said, serum antibody testing can be helpful in polyomavirus-positive patients because it offers insight into prognosis and tumor burden. For example, “if the baseline titer falls and then starts to go up, they’re likely to have a recurrence, and you’ll want to look out for that,” he said.

Dr. Brownell offered another bit of advice: Be prepared to respond to patients who worry that they have a contagious virus and could be a danger to others. The proper answer, he said, is this: “You don’t have to worry about infecting people. Your tumor is not making the virus, you’re not infectious, and we have the virus on us already.”

For more information about the antibody test, visit merkelcell.org/sero.

Dr. Brownell reported having no relevant disclosures. SDEF and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

LAS VEGAS – Merkel cell carcinoma, an extremely rare form of skin cancer, is often caused by a subclinical virus that routinely inhabits the skin. Now, a serum test of virus antibody levels is offering insight into the state of the disease, according to one dermatologist.

“If you have these antibodies, you have a better prognosis. You can follow those antibodies to test for recurrence or progression,” Isaac Brownell, MD, PhD, of the Dermatology Branch of the National Institutes of Health said at Skin Disease Education Foundation’s annual Las Vegas Dermatology Seminar.

The cancer appears in the skin’s Merkel cells, which contribute to our sense of touch by helping us to discriminate textures. “When you put your hand in your pocket, and you can tell the difference between the front and back of a quarter,” he said, “you’re using the Merkel cells in your fingertips.”

Only about 2,500 cases of Merkel cell carcinoma appear in the United States each year, Dr. Brownell said. It appears more often in elderly white patients, is more common in men than women, and is more likely among immunosuppressed patients, whose risk is increased 15- to 20-fold. Cases are more common in sunnier regions – at least in men – and lesions frequently appear on the head, face, and neck.

Five-year survival is estimated at 51% if the cancer is localized, according to a 2016 study of 9,387 cases that Dr. Brownell highlighted. But survival declines dramatically if it has spread to lymph nodes or distant sites (Ann Surg Oncol. 2016 Oct;23[11]:3564-71).

In recent years, researchers have linked 80% of Merkel cell carcinoma cases to the Merkel cell polyomavirus, he said. The virus normally inhabits our skin with no ill effects, he said. “We all have this virus on our skin. It’s everywhere, and even children have antibodies,” he said. But mutations can lead to Merkel cell carcinoma.

Does it matter if cases are polyomavirus positive or polyomavirus negative? Not really, Dr. Brownell said, since the presence of the virus doesn’t appear to affect overall prognosis. However, he said, serum antibody testing can be helpful in polyomavirus-positive patients because it offers insight into prognosis and tumor burden. For example, “if the baseline titer falls and then starts to go up, they’re likely to have a recurrence, and you’ll want to look out for that,” he said.

Dr. Brownell offered another bit of advice: Be prepared to respond to patients who worry that they have a contagious virus and could be a danger to others. The proper answer, he said, is this: “You don’t have to worry about infecting people. Your tumor is not making the virus, you’re not infectious, and we have the virus on us already.”

For more information about the antibody test, visit merkelcell.org/sero.

Dr. Brownell reported having no relevant disclosures. SDEF and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

LAS VEGAS – Merkel cell carcinoma, an extremely rare form of skin cancer, is often caused by a subclinical virus that routinely inhabits the skin. Now, a serum test of virus antibody levels is offering insight into the state of the disease, according to one dermatologist.

“If you have these antibodies, you have a better prognosis. You can follow those antibodies to test for recurrence or progression,” Isaac Brownell, MD, PhD, of the Dermatology Branch of the National Institutes of Health said at Skin Disease Education Foundation’s annual Las Vegas Dermatology Seminar.

The cancer appears in the skin’s Merkel cells, which contribute to our sense of touch by helping us to discriminate textures. “When you put your hand in your pocket, and you can tell the difference between the front and back of a quarter,” he said, “you’re using the Merkel cells in your fingertips.”

Only about 2,500 cases of Merkel cell carcinoma appear in the United States each year, Dr. Brownell said. It appears more often in elderly white patients, is more common in men than women, and is more likely among immunosuppressed patients, whose risk is increased 15- to 20-fold. Cases are more common in sunnier regions – at least in men – and lesions frequently appear on the head, face, and neck.

Five-year survival is estimated at 51% if the cancer is localized, according to a 2016 study of 9,387 cases that Dr. Brownell highlighted. But survival declines dramatically if it has spread to lymph nodes or distant sites (Ann Surg Oncol. 2016 Oct;23[11]:3564-71).

In recent years, researchers have linked 80% of Merkel cell carcinoma cases to the Merkel cell polyomavirus, he said. The virus normally inhabits our skin with no ill effects, he said. “We all have this virus on our skin. It’s everywhere, and even children have antibodies,” he said. But mutations can lead to Merkel cell carcinoma.

Does it matter if cases are polyomavirus positive or polyomavirus negative? Not really, Dr. Brownell said, since the presence of the virus doesn’t appear to affect overall prognosis. However, he said, serum antibody testing can be helpful in polyomavirus-positive patients because it offers insight into prognosis and tumor burden. For example, “if the baseline titer falls and then starts to go up, they’re likely to have a recurrence, and you’ll want to look out for that,” he said.

Dr. Brownell offered another bit of advice: Be prepared to respond to patients who worry that they have a contagious virus and could be a danger to others. The proper answer, he said, is this: “You don’t have to worry about infecting people. Your tumor is not making the virus, you’re not infectious, and we have the virus on us already.”

For more information about the antibody test, visit merkelcell.org/sero.

Dr. Brownell reported having no relevant disclosures. SDEF and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

REPORTING FROM SDEF LAS VEGAS DERMATOLOGY SEMINAR

Cilofexor passes phase 2 for primary biliary cholangitis

BOSTON – Cilofexor, a nonsteroidal farnesoid X receptor (FXR) agonist, can improve disease biomarkers in patients with primary biliary cholangitis (PBC), based on results of a phase 2 trial.

Compared with placebo, patients treated with cilofexor had significant reductions in serum alkaline phosphatase (ALP), gamma-glutamyltransferase (GGT), C-reactive protein (CRP), and primary bile acids, reported lead author Kris V. Kowdley, MD, of Swedish Medical Center in Seattle, and colleagues.

Dr. Kowdley, who presented findings at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, began by offering some context for the trial.

“There’s a strong rationale for FXR agonist therapy in PBC,” he said. “FXR is the key regulator of bile acid homeostasis, and FXR agonists have shown favorable effects on fibrosis, inflammatory activity, bile acid export and synthesis, as well as possibly effects on the microbiome and downstream in the gut.” He went on to explain that cilofexor may benefit patients with PBC, primary sclerosing cholangitis, or nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), noting preclinical data that have demonstrated reductions in bile acids, inflammation, fibrosis, and portal pressure.

The present trial involved 71 patients with PBC who lacked cirrhosis and had a serum ALP level that was at least 1.67 times greater than the upper limit of normal, and an elevated serum total bilirubin that was less than 2 times the upper limit of normal. Patients were randomized to receive either cilofexor 30 mg, cilofexor 100 mg, or placebo, once daily for 12 weeks. Stratification was based on use of ursodeoxycholic acid, which was stable for at least the preceding year. Safety and efficacy were evaluated, with the latter based on liver biochemistry, serum C4, bile acids, and serum fibrosis markers.

Across the entire population, baseline median serum bilirubin was 0.6 mg/dL and median serum ALP was 286 U/L. After 12 weeks, compared with placebo, patients treated with cilofexor, particularly those who received the 100-mg dose, showed significant improvements across multiple measures of liver health. Specifically, patients in the 100-mg group achieved median reductions in ALP (–13.8%; P = .005), GGT (–47.7%; P less than .001), CRP (–33.6%; P = .03), and primary bile acids (–30.5%; P = .008). These patients also exhibited trends toward reduced aspartate aminotransferase and aminoterminal propeptide of type III procollagen; Dr. Kowdley attributed the lack of statistical significance to insufficient population size.

Highlighting magnitude of ALP improvement, Dr. Kowdley noted that reductions in ALP greater than 25% were observed in 17% and 18% of patients in the 100-mg and 30-mg cilofexor groups, respectively, versus 0% of patients in the placebo group.

Although the 100-mg dose of cilofexor appeared more effective, the higher dose did come with some trade-offs in tolerability; grade 2 or 3 pruritus was more common in patients treated with the higher dose than in those who received the 30-mg dose (39% vs. 10%). As such, 7% of patients in the 100-mg group discontinued therapy because of the pruritus, compared with no patients in the 30-mg or placebo group.

Responding to a question from a conference attendee, Dr. Kowdley said that ALP reductions to below the 1.67-fold threshold were achieved by 9% and 14% of patients who received the 30-mg dose and 100-mg dose of cilofexor, respectively.

“We believe these data support further evaluation of cilofexor for the treatment of cholestatic liver disorders,” Dr. Kowdley concluded.

The study was funded by Gilead. The investigators disclosed additional relationships with Allergan, Novartis, GlaxoSmithKline, and others.

SOURCE: Kowdley KV et al. The Liver Meeting 2019. Abstract 45.

BOSTON – Cilofexor, a nonsteroidal farnesoid X receptor (FXR) agonist, can improve disease biomarkers in patients with primary biliary cholangitis (PBC), based on results of a phase 2 trial.

Compared with placebo, patients treated with cilofexor had significant reductions in serum alkaline phosphatase (ALP), gamma-glutamyltransferase (GGT), C-reactive protein (CRP), and primary bile acids, reported lead author Kris V. Kowdley, MD, of Swedish Medical Center in Seattle, and colleagues.

Dr. Kowdley, who presented findings at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, began by offering some context for the trial.

“There’s a strong rationale for FXR agonist therapy in PBC,” he said. “FXR is the key regulator of bile acid homeostasis, and FXR agonists have shown favorable effects on fibrosis, inflammatory activity, bile acid export and synthesis, as well as possibly effects on the microbiome and downstream in the gut.” He went on to explain that cilofexor may benefit patients with PBC, primary sclerosing cholangitis, or nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), noting preclinical data that have demonstrated reductions in bile acids, inflammation, fibrosis, and portal pressure.

The present trial involved 71 patients with PBC who lacked cirrhosis and had a serum ALP level that was at least 1.67 times greater than the upper limit of normal, and an elevated serum total bilirubin that was less than 2 times the upper limit of normal. Patients were randomized to receive either cilofexor 30 mg, cilofexor 100 mg, or placebo, once daily for 12 weeks. Stratification was based on use of ursodeoxycholic acid, which was stable for at least the preceding year. Safety and efficacy were evaluated, with the latter based on liver biochemistry, serum C4, bile acids, and serum fibrosis markers.

Across the entire population, baseline median serum bilirubin was 0.6 mg/dL and median serum ALP was 286 U/L. After 12 weeks, compared with placebo, patients treated with cilofexor, particularly those who received the 100-mg dose, showed significant improvements across multiple measures of liver health. Specifically, patients in the 100-mg group achieved median reductions in ALP (–13.8%; P = .005), GGT (–47.7%; P less than .001), CRP (–33.6%; P = .03), and primary bile acids (–30.5%; P = .008). These patients also exhibited trends toward reduced aspartate aminotransferase and aminoterminal propeptide of type III procollagen; Dr. Kowdley attributed the lack of statistical significance to insufficient population size.

Highlighting magnitude of ALP improvement, Dr. Kowdley noted that reductions in ALP greater than 25% were observed in 17% and 18% of patients in the 100-mg and 30-mg cilofexor groups, respectively, versus 0% of patients in the placebo group.

Although the 100-mg dose of cilofexor appeared more effective, the higher dose did come with some trade-offs in tolerability; grade 2 or 3 pruritus was more common in patients treated with the higher dose than in those who received the 30-mg dose (39% vs. 10%). As such, 7% of patients in the 100-mg group discontinued therapy because of the pruritus, compared with no patients in the 30-mg or placebo group.

Responding to a question from a conference attendee, Dr. Kowdley said that ALP reductions to below the 1.67-fold threshold were achieved by 9% and 14% of patients who received the 30-mg dose and 100-mg dose of cilofexor, respectively.

“We believe these data support further evaluation of cilofexor for the treatment of cholestatic liver disorders,” Dr. Kowdley concluded.

The study was funded by Gilead. The investigators disclosed additional relationships with Allergan, Novartis, GlaxoSmithKline, and others.

SOURCE: Kowdley KV et al. The Liver Meeting 2019. Abstract 45.

BOSTON – Cilofexor, a nonsteroidal farnesoid X receptor (FXR) agonist, can improve disease biomarkers in patients with primary biliary cholangitis (PBC), based on results of a phase 2 trial.

Compared with placebo, patients treated with cilofexor had significant reductions in serum alkaline phosphatase (ALP), gamma-glutamyltransferase (GGT), C-reactive protein (CRP), and primary bile acids, reported lead author Kris V. Kowdley, MD, of Swedish Medical Center in Seattle, and colleagues.

Dr. Kowdley, who presented findings at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, began by offering some context for the trial.

“There’s a strong rationale for FXR agonist therapy in PBC,” he said. “FXR is the key regulator of bile acid homeostasis, and FXR agonists have shown favorable effects on fibrosis, inflammatory activity, bile acid export and synthesis, as well as possibly effects on the microbiome and downstream in the gut.” He went on to explain that cilofexor may benefit patients with PBC, primary sclerosing cholangitis, or nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), noting preclinical data that have demonstrated reductions in bile acids, inflammation, fibrosis, and portal pressure.

The present trial involved 71 patients with PBC who lacked cirrhosis and had a serum ALP level that was at least 1.67 times greater than the upper limit of normal, and an elevated serum total bilirubin that was less than 2 times the upper limit of normal. Patients were randomized to receive either cilofexor 30 mg, cilofexor 100 mg, or placebo, once daily for 12 weeks. Stratification was based on use of ursodeoxycholic acid, which was stable for at least the preceding year. Safety and efficacy were evaluated, with the latter based on liver biochemistry, serum C4, bile acids, and serum fibrosis markers.

Across the entire population, baseline median serum bilirubin was 0.6 mg/dL and median serum ALP was 286 U/L. After 12 weeks, compared with placebo, patients treated with cilofexor, particularly those who received the 100-mg dose, showed significant improvements across multiple measures of liver health. Specifically, patients in the 100-mg group achieved median reductions in ALP (–13.8%; P = .005), GGT (–47.7%; P less than .001), CRP (–33.6%; P = .03), and primary bile acids (–30.5%; P = .008). These patients also exhibited trends toward reduced aspartate aminotransferase and aminoterminal propeptide of type III procollagen; Dr. Kowdley attributed the lack of statistical significance to insufficient population size.

Highlighting magnitude of ALP improvement, Dr. Kowdley noted that reductions in ALP greater than 25% were observed in 17% and 18% of patients in the 100-mg and 30-mg cilofexor groups, respectively, versus 0% of patients in the placebo group.

Although the 100-mg dose of cilofexor appeared more effective, the higher dose did come with some trade-offs in tolerability; grade 2 or 3 pruritus was more common in patients treated with the higher dose than in those who received the 30-mg dose (39% vs. 10%). As such, 7% of patients in the 100-mg group discontinued therapy because of the pruritus, compared with no patients in the 30-mg or placebo group.

Responding to a question from a conference attendee, Dr. Kowdley said that ALP reductions to below the 1.67-fold threshold were achieved by 9% and 14% of patients who received the 30-mg dose and 100-mg dose of cilofexor, respectively.

“We believe these data support further evaluation of cilofexor for the treatment of cholestatic liver disorders,” Dr. Kowdley concluded.

The study was funded by Gilead. The investigators disclosed additional relationships with Allergan, Novartis, GlaxoSmithKline, and others.

SOURCE: Kowdley KV et al. The Liver Meeting 2019. Abstract 45.

REPORTING FROM THE LIVER MEETING 2019

Ataluren shows real-world benefit for nonsense mutation Duchenne muscular dystrophy

AUSTIN, TEX. – , according to new data.

“Participants in the STRIDE Registry [real-world patients] showed a reduction in functional decline over 48 weeks, compared with patients receiving placebo” in the trial, reported Abdallah Delage of PTC Therapeutics in Zug, Switzerland, and his associates.

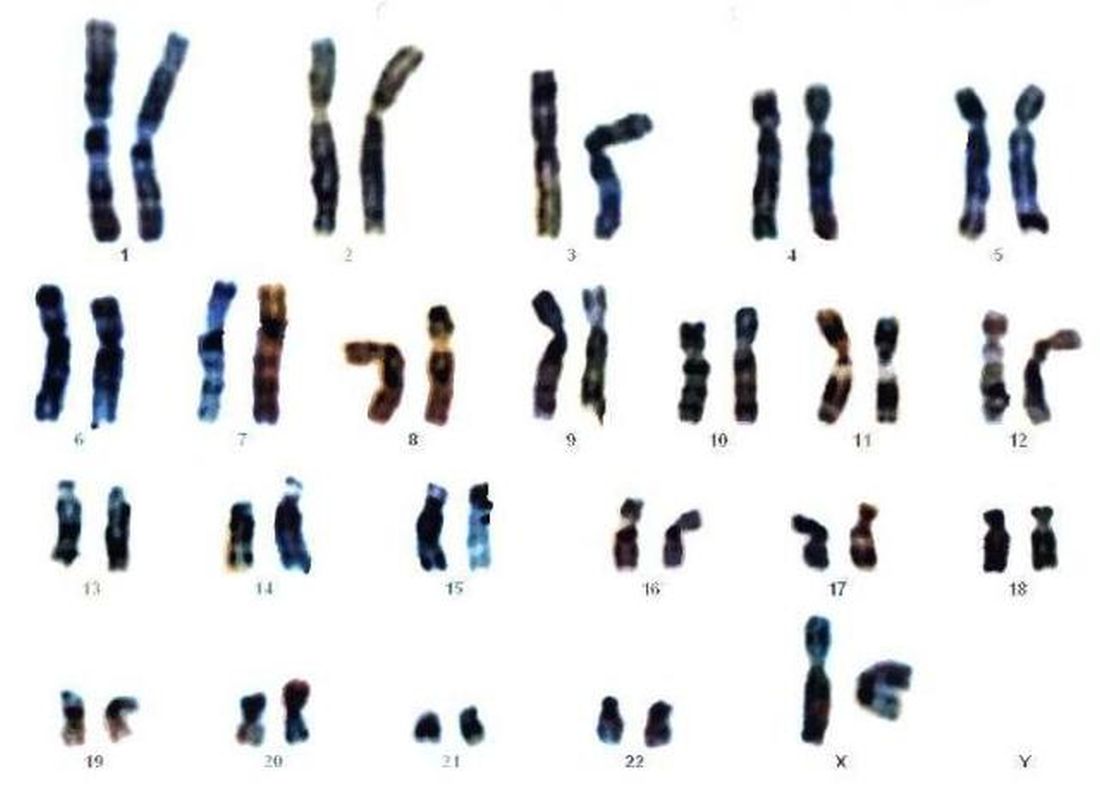

Duchenne muscular dystrophy affects an estimated 1 in 3,600-6,000 male births globally, about 10%-15% of whom have nonsense mutation DMD. This mutation causes a truncated, nonfunctional dystrophin protein due to a premature stop codon, the authors explained. Ataluren “promotes ribosomal read-through of the premature stop codon to produce a full-length dystrophin protein,” they explained.

Ataluren is currently approved for ambulatory patients age 2 and older with nonsense mutation DMD in the European Union and several other European countries. Israel, Korea, Chile, and Ukraine have approved it for patients aged 5 and older.

The Strategic Targeting of Registries and International Database of Excellence (STRIDE) Registry contains real-world data from patients using ataluren as part of an ongoing multicenter observational postapproval safety study. The investigators are tracking patients for at least 5 years after enrollment in 14 countries where ataluren is approved or commercially available through early-access programs. Patients take 40 mg/kg daily: 10 mg/kg in the morning, 10 mg/kg midday, and 20 mg/kg in the evening.

The researchers compared outcomes in 216 patients in the STRIDE Registry with participants in a randomized controlled phase 3 study of ataluren involving 228 boys, aged 7-16, who received ataluren (n = 114) or placebo (n = 114) for 48 weeks. Patients were an average 9 years old in STRIDE and in both arms of the randomized controlled trial.

The STRIDE Registry participants, comprising 184 ambulatory and 26 nonambulatory patients at enrollment, had at least 48 weeks between their first and last assessment. All of the patients in the phase 3 study and 88.6% of the STRIDE Registry patients were receiving corticosteroids along with ataluren. The researchers compared the 184 ambulatory STRIDE participants with the participants of the randomized controlled trial for one primary and four secondary endpoints from baseline to 48 weeks.

For the primary endpoint, 6-minute walk distance, average distance was 35 meters shorter than baseline in STRIDE Registry participants (n = 66), 42.2 meters shorter in the patients receiving ataluren in the phase 3 study (n = 109), and 57.6 meters shorter in RCT patients receiving placebo in the phase 3 trial (n = 109).

A secondary endpoint, the time it took patients to walk or run 10 meters, increased 1.6 seconds from baseline to 48 weeks in STRIDE Registry participants (n = 61), 2.3 seconds in participants receiving ataluren in the phase 3 trial (n = 109), and 3.5 seconds in study participants receiving placebo (n = 110).

Another secondary endpoint, the change in time it took for patients to stand from supine position from baseline to 48 weeks, was 2.9 additional seconds for STRIDE participants (n = 55), 3.8 additional seconds in study participants receiving ataluren (n = 101), and 3.9 additional seconds in study participants receiving placebo (n = 96).

Two final secondary endpoints were the changes in time to climb four stairs and to descend four stairs from baseline to 48 weeks. STRIDE participants (n = 47) climbed four stairs 1.2 seconds more slowly at 48 weeks, compared with 2.7 seconds more slowly in the participants who received ataluren in the phase 3 trial (n = 105) and 4.5 seconds more slowly in those who received placebo. Descending four stairs took 0.5 more seconds at 48 weeks in STRIDE participants (n = 40), 2.2 more seconds in participants who received ataluren in the phase 3 trial (n = 106), and 4.0 more seconds in those who received placebo (n = 100).

At least one adverse event occurred in 20.7% of registry participants; seven of these were considered treatment related. Treatment-related side effects included abdominal pain, vomiting, headache, stomach ache, diarrhea, and increased serum lipids.

The study and STRIDE Registry is funded by PTC Therapeutics with TREAT-NMD and the Cooperative International Neuromuscular Research Group. Mr. Delage and five other authors are employees of PTC Therapeutics, and six authors had received speaker or consultancy fees or served on the advisory board of a variety of companies.

SOURCE: Delage A et al. AANEM 2019, Abstract 115.

AUSTIN, TEX. – , according to new data.

“Participants in the STRIDE Registry [real-world patients] showed a reduction in functional decline over 48 weeks, compared with patients receiving placebo” in the trial, reported Abdallah Delage of PTC Therapeutics in Zug, Switzerland, and his associates.

Duchenne muscular dystrophy affects an estimated 1 in 3,600-6,000 male births globally, about 10%-15% of whom have nonsense mutation DMD. This mutation causes a truncated, nonfunctional dystrophin protein due to a premature stop codon, the authors explained. Ataluren “promotes ribosomal read-through of the premature stop codon to produce a full-length dystrophin protein,” they explained.

Ataluren is currently approved for ambulatory patients age 2 and older with nonsense mutation DMD in the European Union and several other European countries. Israel, Korea, Chile, and Ukraine have approved it for patients aged 5 and older.

The Strategic Targeting of Registries and International Database of Excellence (STRIDE) Registry contains real-world data from patients using ataluren as part of an ongoing multicenter observational postapproval safety study. The investigators are tracking patients for at least 5 years after enrollment in 14 countries where ataluren is approved or commercially available through early-access programs. Patients take 40 mg/kg daily: 10 mg/kg in the morning, 10 mg/kg midday, and 20 mg/kg in the evening.

The researchers compared outcomes in 216 patients in the STRIDE Registry with participants in a randomized controlled phase 3 study of ataluren involving 228 boys, aged 7-16, who received ataluren (n = 114) or placebo (n = 114) for 48 weeks. Patients were an average 9 years old in STRIDE and in both arms of the randomized controlled trial.

The STRIDE Registry participants, comprising 184 ambulatory and 26 nonambulatory patients at enrollment, had at least 48 weeks between their first and last assessment. All of the patients in the phase 3 study and 88.6% of the STRIDE Registry patients were receiving corticosteroids along with ataluren. The researchers compared the 184 ambulatory STRIDE participants with the participants of the randomized controlled trial for one primary and four secondary endpoints from baseline to 48 weeks.

For the primary endpoint, 6-minute walk distance, average distance was 35 meters shorter than baseline in STRIDE Registry participants (n = 66), 42.2 meters shorter in the patients receiving ataluren in the phase 3 study (n = 109), and 57.6 meters shorter in RCT patients receiving placebo in the phase 3 trial (n = 109).

A secondary endpoint, the time it took patients to walk or run 10 meters, increased 1.6 seconds from baseline to 48 weeks in STRIDE Registry participants (n = 61), 2.3 seconds in participants receiving ataluren in the phase 3 trial (n = 109), and 3.5 seconds in study participants receiving placebo (n = 110).

Another secondary endpoint, the change in time it took for patients to stand from supine position from baseline to 48 weeks, was 2.9 additional seconds for STRIDE participants (n = 55), 3.8 additional seconds in study participants receiving ataluren (n = 101), and 3.9 additional seconds in study participants receiving placebo (n = 96).

Two final secondary endpoints were the changes in time to climb four stairs and to descend four stairs from baseline to 48 weeks. STRIDE participants (n = 47) climbed four stairs 1.2 seconds more slowly at 48 weeks, compared with 2.7 seconds more slowly in the participants who received ataluren in the phase 3 trial (n = 105) and 4.5 seconds more slowly in those who received placebo. Descending four stairs took 0.5 more seconds at 48 weeks in STRIDE participants (n = 40), 2.2 more seconds in participants who received ataluren in the phase 3 trial (n = 106), and 4.0 more seconds in those who received placebo (n = 100).

At least one adverse event occurred in 20.7% of registry participants; seven of these were considered treatment related. Treatment-related side effects included abdominal pain, vomiting, headache, stomach ache, diarrhea, and increased serum lipids.

The study and STRIDE Registry is funded by PTC Therapeutics with TREAT-NMD and the Cooperative International Neuromuscular Research Group. Mr. Delage and five other authors are employees of PTC Therapeutics, and six authors had received speaker or consultancy fees or served on the advisory board of a variety of companies.

SOURCE: Delage A et al. AANEM 2019, Abstract 115.

AUSTIN, TEX. – , according to new data.

“Participants in the STRIDE Registry [real-world patients] showed a reduction in functional decline over 48 weeks, compared with patients receiving placebo” in the trial, reported Abdallah Delage of PTC Therapeutics in Zug, Switzerland, and his associates.

Duchenne muscular dystrophy affects an estimated 1 in 3,600-6,000 male births globally, about 10%-15% of whom have nonsense mutation DMD. This mutation causes a truncated, nonfunctional dystrophin protein due to a premature stop codon, the authors explained. Ataluren “promotes ribosomal read-through of the premature stop codon to produce a full-length dystrophin protein,” they explained.

Ataluren is currently approved for ambulatory patients age 2 and older with nonsense mutation DMD in the European Union and several other European countries. Israel, Korea, Chile, and Ukraine have approved it for patients aged 5 and older.

The Strategic Targeting of Registries and International Database of Excellence (STRIDE) Registry contains real-world data from patients using ataluren as part of an ongoing multicenter observational postapproval safety study. The investigators are tracking patients for at least 5 years after enrollment in 14 countries where ataluren is approved or commercially available through early-access programs. Patients take 40 mg/kg daily: 10 mg/kg in the morning, 10 mg/kg midday, and 20 mg/kg in the evening.

The researchers compared outcomes in 216 patients in the STRIDE Registry with participants in a randomized controlled phase 3 study of ataluren involving 228 boys, aged 7-16, who received ataluren (n = 114) or placebo (n = 114) for 48 weeks. Patients were an average 9 years old in STRIDE and in both arms of the randomized controlled trial.

The STRIDE Registry participants, comprising 184 ambulatory and 26 nonambulatory patients at enrollment, had at least 48 weeks between their first and last assessment. All of the patients in the phase 3 study and 88.6% of the STRIDE Registry patients were receiving corticosteroids along with ataluren. The researchers compared the 184 ambulatory STRIDE participants with the participants of the randomized controlled trial for one primary and four secondary endpoints from baseline to 48 weeks.

For the primary endpoint, 6-minute walk distance, average distance was 35 meters shorter than baseline in STRIDE Registry participants (n = 66), 42.2 meters shorter in the patients receiving ataluren in the phase 3 study (n = 109), and 57.6 meters shorter in RCT patients receiving placebo in the phase 3 trial (n = 109).

A secondary endpoint, the time it took patients to walk or run 10 meters, increased 1.6 seconds from baseline to 48 weeks in STRIDE Registry participants (n = 61), 2.3 seconds in participants receiving ataluren in the phase 3 trial (n = 109), and 3.5 seconds in study participants receiving placebo (n = 110).

Another secondary endpoint, the change in time it took for patients to stand from supine position from baseline to 48 weeks, was 2.9 additional seconds for STRIDE participants (n = 55), 3.8 additional seconds in study participants receiving ataluren (n = 101), and 3.9 additional seconds in study participants receiving placebo (n = 96).

Two final secondary endpoints were the changes in time to climb four stairs and to descend four stairs from baseline to 48 weeks. STRIDE participants (n = 47) climbed four stairs 1.2 seconds more slowly at 48 weeks, compared with 2.7 seconds more slowly in the participants who received ataluren in the phase 3 trial (n = 105) and 4.5 seconds more slowly in those who received placebo. Descending four stairs took 0.5 more seconds at 48 weeks in STRIDE participants (n = 40), 2.2 more seconds in participants who received ataluren in the phase 3 trial (n = 106), and 4.0 more seconds in those who received placebo (n = 100).

At least one adverse event occurred in 20.7% of registry participants; seven of these were considered treatment related. Treatment-related side effects included abdominal pain, vomiting, headache, stomach ache, diarrhea, and increased serum lipids.

The study and STRIDE Registry is funded by PTC Therapeutics with TREAT-NMD and the Cooperative International Neuromuscular Research Group. Mr. Delage and five other authors are employees of PTC Therapeutics, and six authors had received speaker or consultancy fees or served on the advisory board of a variety of companies.

SOURCE: Delage A et al. AANEM 2019, Abstract 115.

REPORTING FROM AANEM 2019

Better overall survival with nivolumab vs. chemo for advanced ESCC

BARCELONA – Nivolumab was associated with improved overall survival and a favorable safety profile, compared with chemotherapy, in patients with previously treated advanced esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) in the open-label phase 3 ATTRACTION-3 study.

The overall survival (OS) benefit was observed regardless of tumor programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression, Byoung Chul Cho, MD, reported at the European Society for Medical Oncology Congress.

The findings were reported online simultaneously in The Lancet Oncology.

Median OS at a minimum follow-up of 17.6 months was 10.9 vs. 8.4 months in 210 patients randomized to receive treatment with the PD-1 inhibitor nivolumab and 209 who received chemotherapy, respectively (hazard ratio, 0.77), said Dr. Cho of Yonsei Cancer Center, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, South Korea.

“Notably, there was a 13% and 10% improvement in overall survival rates at 12 months (47% vs. 34%) and 18 months (31% vs. 21%), respectively,” he said, also noting that the HRs for death favored nivolumab vs. chemotherapy across multiple prespecified subgroups, including those based on tumor PD-L1 expression (HRs, 0.69 and 0.84 for PD-L1 of 1% or greater and less than 1%, respectively).

No meaningful difference was seen in progression-free survival between the nivolumab and chemotherapy groups (12% vs. 7%; HR, 1.08), or in objective response rates (19% vs. 22%), he said.

“However, responses were substantially more durable with nivolumab, compared to chemotherapy; duration of response was 6.9 months with nivolumab vs. 3.9 months in the chemotherapy arm,” he said. “Notably, 21% of patients in the nivolumab arm were still in response, compared to only 6% in the chemotherapy arm.”

Patients enrolled in the open label study had unresectable advanced or recurrent ESCC refractory or intolerant to one prior fluoropyrimidine/platinum-based therapy. They were randomized 1:1 to receive 240 mg of nivolumab every 2 weeks or investigators’ choice of paclitaxel or docetaxel.

Fewer treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs) were reported with nivolumab, Dr. Cho said.

Any grade TRAEs occurred in 66% vs. 95% of patients in the groups, respectively, and grade 3-4 TRAEs occurred in 18% vs. 63%. The majority of select TRAEs – defined as those with potential immunologic etiology, including endocrine, gastrointestinal, hepatic, pulmonary, renal, and skin effects – were grade 1 or 2, and the only difference between the nivolumab and chemotherapy groups with respect to those was in endocrine effects, which affected 11% vs. less than 1% of patients, respectively.

Grade 3/4 select TRAEs occurred in less than 2% of patients, Dr. Cho noted.

An exploratory analysis further showed significant overall improvement in health-related quality of life with nivolumab through week 42 on treatment, he added.

The findings are of note, because metastatic esophageal cancer has a 5-year relative survival rate of less than 8%, and ESCC accounts for about 90% of cases worldwide, he said, adding that current second-line chemotherapy options for ESCC offer poor long-term survival and are associated with toxicity.

Nivolumab, which showed promising antitumor activity and manageable toxicity for advanced ESCC in patients who were refractory to or intolerant of standard chemotherapies in the phase 2 ATTRACTION-1 study, is the first immune checkpoint inhibitor to demonstrate a statistically significant, clinically meaningful improvement in OS vs. chemotherapy in this setting, he said.

The findings of this final analysis of ATTRACTION-3, which shows a 23% reduction in the risk of death, a 2.5-month improvement in median OS, benefit across PD-L1 subgroups, and a favorable safety profile, suggest that nivolumab represents a new standard second-line treatment option for patients with advanced ESCC, he concluded.

ATTRACTION-3 was funded by Ono Pharmaceutical Co., in collaboration with Bristol-Myers Squibb. Dr. Cho reported relationships with Bristol-Myers Squibb, Ono Pharmaceutical, and others. He also reported stock ownership and/or patents with TheraCanVac and Champions Oncology.

SOURCE: Cho B et al. ESMO 2019, Abstract LBA11.

BARCELONA – Nivolumab was associated with improved overall survival and a favorable safety profile, compared with chemotherapy, in patients with previously treated advanced esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) in the open-label phase 3 ATTRACTION-3 study.

The overall survival (OS) benefit was observed regardless of tumor programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression, Byoung Chul Cho, MD, reported at the European Society for Medical Oncology Congress.

The findings were reported online simultaneously in The Lancet Oncology.

Median OS at a minimum follow-up of 17.6 months was 10.9 vs. 8.4 months in 210 patients randomized to receive treatment with the PD-1 inhibitor nivolumab and 209 who received chemotherapy, respectively (hazard ratio, 0.77), said Dr. Cho of Yonsei Cancer Center, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, South Korea.

“Notably, there was a 13% and 10% improvement in overall survival rates at 12 months (47% vs. 34%) and 18 months (31% vs. 21%), respectively,” he said, also noting that the HRs for death favored nivolumab vs. chemotherapy across multiple prespecified subgroups, including those based on tumor PD-L1 expression (HRs, 0.69 and 0.84 for PD-L1 of 1% or greater and less than 1%, respectively).

No meaningful difference was seen in progression-free survival between the nivolumab and chemotherapy groups (12% vs. 7%; HR, 1.08), or in objective response rates (19% vs. 22%), he said.

“However, responses were substantially more durable with nivolumab, compared to chemotherapy; duration of response was 6.9 months with nivolumab vs. 3.9 months in the chemotherapy arm,” he said. “Notably, 21% of patients in the nivolumab arm were still in response, compared to only 6% in the chemotherapy arm.”

Patients enrolled in the open label study had unresectable advanced or recurrent ESCC refractory or intolerant to one prior fluoropyrimidine/platinum-based therapy. They were randomized 1:1 to receive 240 mg of nivolumab every 2 weeks or investigators’ choice of paclitaxel or docetaxel.

Fewer treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs) were reported with nivolumab, Dr. Cho said.

Any grade TRAEs occurred in 66% vs. 95% of patients in the groups, respectively, and grade 3-4 TRAEs occurred in 18% vs. 63%. The majority of select TRAEs – defined as those with potential immunologic etiology, including endocrine, gastrointestinal, hepatic, pulmonary, renal, and skin effects – were grade 1 or 2, and the only difference between the nivolumab and chemotherapy groups with respect to those was in endocrine effects, which affected 11% vs. less than 1% of patients, respectively.

Grade 3/4 select TRAEs occurred in less than 2% of patients, Dr. Cho noted.

An exploratory analysis further showed significant overall improvement in health-related quality of life with nivolumab through week 42 on treatment, he added.

The findings are of note, because metastatic esophageal cancer has a 5-year relative survival rate of less than 8%, and ESCC accounts for about 90% of cases worldwide, he said, adding that current second-line chemotherapy options for ESCC offer poor long-term survival and are associated with toxicity.

Nivolumab, which showed promising antitumor activity and manageable toxicity for advanced ESCC in patients who were refractory to or intolerant of standard chemotherapies in the phase 2 ATTRACTION-1 study, is the first immune checkpoint inhibitor to demonstrate a statistically significant, clinically meaningful improvement in OS vs. chemotherapy in this setting, he said.

The findings of this final analysis of ATTRACTION-3, which shows a 23% reduction in the risk of death, a 2.5-month improvement in median OS, benefit across PD-L1 subgroups, and a favorable safety profile, suggest that nivolumab represents a new standard second-line treatment option for patients with advanced ESCC, he concluded.

ATTRACTION-3 was funded by Ono Pharmaceutical Co., in collaboration with Bristol-Myers Squibb. Dr. Cho reported relationships with Bristol-Myers Squibb, Ono Pharmaceutical, and others. He also reported stock ownership and/or patents with TheraCanVac and Champions Oncology.

SOURCE: Cho B et al. ESMO 2019, Abstract LBA11.

BARCELONA – Nivolumab was associated with improved overall survival and a favorable safety profile, compared with chemotherapy, in patients with previously treated advanced esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) in the open-label phase 3 ATTRACTION-3 study.

The overall survival (OS) benefit was observed regardless of tumor programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression, Byoung Chul Cho, MD, reported at the European Society for Medical Oncology Congress.

The findings were reported online simultaneously in The Lancet Oncology.

Median OS at a minimum follow-up of 17.6 months was 10.9 vs. 8.4 months in 210 patients randomized to receive treatment with the PD-1 inhibitor nivolumab and 209 who received chemotherapy, respectively (hazard ratio, 0.77), said Dr. Cho of Yonsei Cancer Center, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, South Korea.

“Notably, there was a 13% and 10% improvement in overall survival rates at 12 months (47% vs. 34%) and 18 months (31% vs. 21%), respectively,” he said, also noting that the HRs for death favored nivolumab vs. chemotherapy across multiple prespecified subgroups, including those based on tumor PD-L1 expression (HRs, 0.69 and 0.84 for PD-L1 of 1% or greater and less than 1%, respectively).

No meaningful difference was seen in progression-free survival between the nivolumab and chemotherapy groups (12% vs. 7%; HR, 1.08), or in objective response rates (19% vs. 22%), he said.

“However, responses were substantially more durable with nivolumab, compared to chemotherapy; duration of response was 6.9 months with nivolumab vs. 3.9 months in the chemotherapy arm,” he said. “Notably, 21% of patients in the nivolumab arm were still in response, compared to only 6% in the chemotherapy arm.”

Patients enrolled in the open label study had unresectable advanced or recurrent ESCC refractory or intolerant to one prior fluoropyrimidine/platinum-based therapy. They were randomized 1:1 to receive 240 mg of nivolumab every 2 weeks or investigators’ choice of paclitaxel or docetaxel.

Fewer treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs) were reported with nivolumab, Dr. Cho said.

Any grade TRAEs occurred in 66% vs. 95% of patients in the groups, respectively, and grade 3-4 TRAEs occurred in 18% vs. 63%. The majority of select TRAEs – defined as those with potential immunologic etiology, including endocrine, gastrointestinal, hepatic, pulmonary, renal, and skin effects – were grade 1 or 2, and the only difference between the nivolumab and chemotherapy groups with respect to those was in endocrine effects, which affected 11% vs. less than 1% of patients, respectively.

Grade 3/4 select TRAEs occurred in less than 2% of patients, Dr. Cho noted.

An exploratory analysis further showed significant overall improvement in health-related quality of life with nivolumab through week 42 on treatment, he added.

The findings are of note, because metastatic esophageal cancer has a 5-year relative survival rate of less than 8%, and ESCC accounts for about 90% of cases worldwide, he said, adding that current second-line chemotherapy options for ESCC offer poor long-term survival and are associated with toxicity.

Nivolumab, which showed promising antitumor activity and manageable toxicity for advanced ESCC in patients who were refractory to or intolerant of standard chemotherapies in the phase 2 ATTRACTION-1 study, is the first immune checkpoint inhibitor to demonstrate a statistically significant, clinically meaningful improvement in OS vs. chemotherapy in this setting, he said.

The findings of this final analysis of ATTRACTION-3, which shows a 23% reduction in the risk of death, a 2.5-month improvement in median OS, benefit across PD-L1 subgroups, and a favorable safety profile, suggest that nivolumab represents a new standard second-line treatment option for patients with advanced ESCC, he concluded.

ATTRACTION-3 was funded by Ono Pharmaceutical Co., in collaboration with Bristol-Myers Squibb. Dr. Cho reported relationships with Bristol-Myers Squibb, Ono Pharmaceutical, and others. He also reported stock ownership and/or patents with TheraCanVac and Champions Oncology.

SOURCE: Cho B et al. ESMO 2019, Abstract LBA11.

REPORTING FROM ESMO 2019

Key clinical point: Nivolumab was associated with improved OS vs. chemotherapy, in previously treated advanced ESCC.

Major finding: Median OS was 10.9 vs. 8.4 months with nivolumab vs. chemotherapy, respectively (hazard ratio, 0.77).

Study details: A randomized, open-label, phase 3 study of 419 patients.

Disclosures: ATTRACTION-3 was funded by Ono Pharmaceutical Co., in collaboration with Bristol-Myers Squibb. Dr. Cho reported relationships with Bristol-Myers Squibb, Ono Pharmaceutical, and others. He reported stock ownership and/or patents with TheraCanVac and Champions Oncology.

Source: Cho B et al. ESMO 2019, Abstract LBA11.

Families face challenges of gene therapy

WASHINGTON– Gene therapy for the treatment of rare diseases continues to develop and new products are entering the pipeline; however, more work is needed to make the gene therapy experience easier on patients and their families, according to members of a panel at the NORD Rare Diseases & Orphan Product Breakthrough Summit, held by the National Organization for Rare Disorders.

Companies developing gene therapy cite their main challenges as identifying patients, developing clinical trials, coordinating treatment and supporting families, managing reimbursement, and manufacturing the treatment, said Mark Rothera, president and CEO of Orchard Therapeutics, developer of ex vivo autologous hematopoietic stem cell gene therapy.

For families of patients with rare diseases who are undergoing gene therapy, challenges include struggles such as language barriers, lack of wifi, and separation from other family members for extended periods, according to Amy Price, mother of a gene therapy recipient, as well as principal consultant to Rarallel and an advocate for metachromatic leukodystrophy.

Ms. Price cited a survey she conducted of families with children who underwent gene therapy. She collected data from 16 families about their initial visit as part of a gene therapy trial; the trials included 14 families in Milan; 1 in Bethesda, Md.; and 1 in Paris. The average age of the patients at the start of the trial was 3 years, with a range of 8 months to 11 years. The trials were conducted between 1990 and 2018.

Families participating in the trials spent an average of 5.5 months in the city where the trial was conducted, and an average of 48 days in an isolation ward with their child at the start of the study.

The five biggest challenges were financial well-being (cited by 60% of survey respondents), social isolation/being away from support system (60%), fear of the unknown/long-term treatment diagnosis (73%), family separation (67%), and caring for other children simultaneous during the trial period (60%).

In addition, patients averaged 12 follow-up visits, and the most common secondary challenges cited in the survey included time spent at the hospital, emotional and physical stress on the patient, fear of test results and outcomes, exhaustion, time away from work and school, and travel logistics.

Other stressors include language barriers and not being in children’s hospital, Ms. Price said.

Ms. Price proposed patient-focused solutions such as addressing cultural challenges, connecting families to local resources, and providing clinical follow-up locally to reduce the burden of travel to the trial site.

WASHINGTON– Gene therapy for the treatment of rare diseases continues to develop and new products are entering the pipeline; however, more work is needed to make the gene therapy experience easier on patients and their families, according to members of a panel at the NORD Rare Diseases & Orphan Product Breakthrough Summit, held by the National Organization for Rare Disorders.

Companies developing gene therapy cite their main challenges as identifying patients, developing clinical trials, coordinating treatment and supporting families, managing reimbursement, and manufacturing the treatment, said Mark Rothera, president and CEO of Orchard Therapeutics, developer of ex vivo autologous hematopoietic stem cell gene therapy.

For families of patients with rare diseases who are undergoing gene therapy, challenges include struggles such as language barriers, lack of wifi, and separation from other family members for extended periods, according to Amy Price, mother of a gene therapy recipient, as well as principal consultant to Rarallel and an advocate for metachromatic leukodystrophy.

Ms. Price cited a survey she conducted of families with children who underwent gene therapy. She collected data from 16 families about their initial visit as part of a gene therapy trial; the trials included 14 families in Milan; 1 in Bethesda, Md.; and 1 in Paris. The average age of the patients at the start of the trial was 3 years, with a range of 8 months to 11 years. The trials were conducted between 1990 and 2018.

Families participating in the trials spent an average of 5.5 months in the city where the trial was conducted, and an average of 48 days in an isolation ward with their child at the start of the study.

The five biggest challenges were financial well-being (cited by 60% of survey respondents), social isolation/being away from support system (60%), fear of the unknown/long-term treatment diagnosis (73%), family separation (67%), and caring for other children simultaneous during the trial period (60%).

In addition, patients averaged 12 follow-up visits, and the most common secondary challenges cited in the survey included time spent at the hospital, emotional and physical stress on the patient, fear of test results and outcomes, exhaustion, time away from work and school, and travel logistics.

Other stressors include language barriers and not being in children’s hospital, Ms. Price said.

Ms. Price proposed patient-focused solutions such as addressing cultural challenges, connecting families to local resources, and providing clinical follow-up locally to reduce the burden of travel to the trial site.

WASHINGTON– Gene therapy for the treatment of rare diseases continues to develop and new products are entering the pipeline; however, more work is needed to make the gene therapy experience easier on patients and their families, according to members of a panel at the NORD Rare Diseases & Orphan Product Breakthrough Summit, held by the National Organization for Rare Disorders.

Companies developing gene therapy cite their main challenges as identifying patients, developing clinical trials, coordinating treatment and supporting families, managing reimbursement, and manufacturing the treatment, said Mark Rothera, president and CEO of Orchard Therapeutics, developer of ex vivo autologous hematopoietic stem cell gene therapy.

For families of patients with rare diseases who are undergoing gene therapy, challenges include struggles such as language barriers, lack of wifi, and separation from other family members for extended periods, according to Amy Price, mother of a gene therapy recipient, as well as principal consultant to Rarallel and an advocate for metachromatic leukodystrophy.

Ms. Price cited a survey she conducted of families with children who underwent gene therapy. She collected data from 16 families about their initial visit as part of a gene therapy trial; the trials included 14 families in Milan; 1 in Bethesda, Md.; and 1 in Paris. The average age of the patients at the start of the trial was 3 years, with a range of 8 months to 11 years. The trials were conducted between 1990 and 2018.

Families participating in the trials spent an average of 5.5 months in the city where the trial was conducted, and an average of 48 days in an isolation ward with their child at the start of the study.

The five biggest challenges were financial well-being (cited by 60% of survey respondents), social isolation/being away from support system (60%), fear of the unknown/long-term treatment diagnosis (73%), family separation (67%), and caring for other children simultaneous during the trial period (60%).

In addition, patients averaged 12 follow-up visits, and the most common secondary challenges cited in the survey included time spent at the hospital, emotional and physical stress on the patient, fear of test results and outcomes, exhaustion, time away from work and school, and travel logistics.

Other stressors include language barriers and not being in children’s hospital, Ms. Price said.

Ms. Price proposed patient-focused solutions such as addressing cultural challenges, connecting families to local resources, and providing clinical follow-up locally to reduce the burden of travel to the trial site.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM NORD 2019

Adiposis Dolorosa Pain Management

Adiposis dolorosa (AD), or Dercum disease, is a rare disorder that was first described in 1888 and characterized by the National Organization of Rare Disorders (NORD) as a chronic pain condition of the adipose tissue generally found in patients who are overweight or obese.1,2 AD is more common in females aged 35 to 50 years and proposed to be a disease of postmenopausal women, though no prevalence studies exist.2 The etiology remains unclear.2 Several theories have been proposed, including endocrine and nervous system dysfunction, adipose tissue dysregulation, or pressure on peripheral nerves and chronic inflammation.2-4 Genetic, autoimmune, and trauma also have been proposed as a mechanism for developing the disease. Treatment modalities focusing on narcotic analgesics have been ineffective in long-term management.3

The objective of the case presentation is to report a variety of approaches for AD and their relative successes at pain control in order to assist other medical professionals who may come across patients with this rare condition.

Case Presentation

A 53-year-old male with a history of blast exposure-related traumatic brain injury, subsequent stroke with residual left hemiparesis, and seizure disorder presented with a 10-year history of nodule formation in his lower extremities causing restriction of motion and pain. The patient had previously undergone lower extremity fasciotomies for compartment syndrome with minimal pain relief. In addition, nodules over his abdomen and chest wall had been increasing over the past 5 years. He also experienced worsening fatigue, cramping, tightness, and paresthesias of the affected areas during this time. Erythema and temperature allodynia were noted in addition to an 80-pound weight gain. From the above symptoms and nodule excision showing histologic signs of lipomatous growth, a diagnosis of AD was made.

The following constitutes the approximate timetable of his treatments for 9 years. He was first diagnosed incidentally at the beginning of this period with AD during an electrodiagnostic examination. He had noticed the lipomas when he was in his 30s, but initially they were not painful. He was referred for treatment of pain to the physical medicine and rehabilitation department.

For the next 3 years, he was treated with prolotherapy. Five percent dextrose in water was injected around many of the painful lipomas in the upper extremities. He noted after the second round of neural prolotherapy that he had reduced swelling of his upper extremities and the lipomas decreased in size. He experienced mild improvement in pain and functional usage of his arms.

He continued to receive neural prolotherapy into the nodules in the arms, legs, abdomen, and chest wall. The number of painful nodules continued to increase, and the patient was started on hydrocodone 10 mg/acetaminophen 325 mg (1 tablet every 6 hours as needed) and methadone for pain relief. He was initially started on 5 mg per day of methadone and then was increased in a stepwise, gradual fashion to 10 mg in the morning and 15 mg in the evening. He transitioned to morphine sulfate, which was increased to a maximum dose of 45 mg twice daily. This medication was slowly tapered due to adverse effects (AEs), including sedation.

After weaning off morphine sulfate, the patient was started on lidocaine infusions every 3 months. Each infusion provided at least 50% pain reduction for 6 to 8 weeks. He was approved by the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) to have Vaser (Bausch Health, Laval, Canada) minimally invasive ultrasound liposuction treatment, performed at an outside facility. The patient was satisfied with the pain relief that he received and noted that the number of lipomas greatly diminished. However, due to funding issues, this treatment was discontinued after several months.

The patient had moderately good pain relief with methadone 5 mg in the morning, and 15 mg in the evening. However, the patient reported significant somnolence during the daytime with the regimen. Attempts to wean the patient off methadone was met with uncontrollable daytime pain. With suboptimal oral pain regimen, difficulty obtaining Vaser treatments, and limitation in frequency of neural prolotherapy, the decision was made to initiate 12 treatments of Calmare (Fairfield, CT) cutaneous electrostimulation.

During his first treatment, he had the electrodes placed on his lower extremities. The pre- and posttreatment 10-point visual analog scale (VAS) scores were 9 and 0, respectively, after the first visit. The position of the electrodes varied, depending on the location of his pain, including upper extremities and abdominal wall. During the treatment course, the patient experienced an improvement in subjective functional status. He was able to sleep in the same bed as his wife, shake hands without severe pain, and walk .25 mile, all of which he was unable to do before the electrostimulative treatment. He also reported overall improvement in emotional well-being, resumption of his hobbies (eg, playing the guitar), and social engagement. Methadone was successfully weaned off during this trial without breakthrough pain. This improvement in pain and functional status continued for several weeks; however, he had an exacerbation of his pain following a long plane flight. Due to uncertain reliability of pain relief with the procedure, the pain management service initiated a regimen of methadone 10 mg twice daily to be initiated when a procedure does not provide the desired duration of pain relief and gradually discontinued following the next interventional procedure.

The patient continued a regimen that included lidocaine infusions, neural prolotherapy, Calmare electrostimulative therapy, as well as lymphedema massage. Additionally, he began receiving weekly acupuncture treatments. He started with traditional full body acupuncture and then transitioned to battlefield acupuncture (BFA). Each acupuncture treatment provided about 50% improvement in pain on the VAS, and improved sleep for 3 days posttreatment.

However, after 18 months of the above treatment protocol, the patient experienced a general tonic-clonic seizure at home. Due to concern for the lowered seizure threshold, lidocaine infusions and methadone were discontinued. Long-acting oral morphine was initiated. The patient continued Calmare treatments and neural prolotherapy after a seizure-free interval. This regimen provided the patient with temporary pain relief but for a shorter duration than prior interventions.

Ketamine infusions were eventually initiated about 5 years after the diagnosis of AD was made, with postprocedure pain as 0/10 on the VAS. Pain relief was sustained for 3 months, with the notable AEs of hallucinations in the immediate postinfusion period. Administration consisted of the following: 500 mg of ketamine in a 500 mL bag of 0.9% NaCl. A 60-mg slow IV push was given followed by 60 mg/h increased every 15 min by 10 mg/h for a maximum dose of 150 mg/h. In a single visit the maximum total dose of ketamine administered was 500 mg. The protocol, which usually delivered 200 mg in a visit but was increased to 500 mg because the 200-mg dose was ineffective, was based on protocols at other institutions to accommodate the level of monitoring available in the Interventional Pain Clinic. The clinic also developed an infusion protocol with at least 1 month between treatments. The patient continues to undergo scheduled ketamine infusions every 14 weeks in addition to monthly BFA. The patient reported near total pain relief for about a month following ketamine infusion, with about 3 months of sustained pain relief. Each BFA session continues to provide 3 days of relief from insomnia. Calmare treatments and the neural prolotherapy regimen continue to provide effective but temporary relief from pain.

Discussion

Currently there is no curative treatment for AD. The majority of the literature is composed of case reports without summaries of potential interventions and their efficacies. AD therapies focus on symptom relief and mainly include pharmacologic and surgical intervention. In this case report several novel treatment modalities have been shown to be partially effective.

Surgical Intervention

Liposuction and lipoma resection have been described as effective only in the short term for AD.2,4-6 Hansson and colleagues suggested liposuction avulsion for sensory nerves and a portion of the proposed abnormal nerve connections between the peripheral nervous system and sensory nerves as a potential therapy for pain improvement.5 But the clinical significance of pain relief from liposuction is unclear and is contraindicated in recurrent lipomas.5

Pharmaceutical Approach

Although relief with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and narcotic analgesics have been unpredictable, Herbst and Asare-Bediako described significant pain relief in a subset of patients with AD with a variety of oral analgesics.7,8 However, the duration of this relief was not clearly stated, and the types or medications or combinations were not discussed. Other pharmacologic agents trialed in the treatment of AD include methotrexate, infliximab, Interferon α-2b, and calcium channel modulators (pregabalin and oxcarbazepine).2,9-11 However, the mechanism and significance of pain relief from these medications remain unclear.

Subanesthesia Therapy

Lidocaine has been used as both a topical agent and an IV infusion in the treatment of chronic pain due to AD for decades. Desai and colleagues described 60% sustained pain reduction in a patient using lidocaine 5% transdermal patches.4 IV infusion of lidocaine has been described in various dosages, though the mechanism of pain relief is ambiguous, and the duration of effect is longer than the biologic half-life.2-4,9 Kosseifi and colleagues describe a patient treated with local injections of lidocaine 1% and obtained symptomatic relief for 3 weeks.9 Animal studies suggest the action of lidocaine involves the sodium channels in peripheral nerves, while another study suggested there may be an increase in sympathetic nervous system activity after the infusion of lidocaine.2,9

Ketamine infusions not previously described in the treatment of AD have long been used to treat other chronic pain syndromes (chronic cancer pain, complex regional pain syndrome [CRPS], fibromyalgia, migraine, ischemic pain, and neuropathic pain).9,12,13 Ketamine has been shown to decrease pain intensity and reduce the amount of opioid analgesic necessary to achieve pain relief, likely through the antagonism of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors.12 A retrospective review by Patil and Anitescu described subanesthetic ketamine infusions used as a last-line therapy in refractory pain syndromes. They found ketamine reduced VAS scores from mean 8.5 prior to infusion to 0.8 after infusion in patients with CRPS and from 7.0 prior to infusion to 1.0 in patient with non-CRPS refractory pain syndromes.13 Hypertension and sedation were the most frequent AEs of ketamine infusion, though a higher incidence of hallucination and confusion were noted in non-CRPS patients. Hocking and Cousins suggest that psychotomimetic AEs of ketamine infusion may be more likely in patients with anxiety.14 However, it is important to note that ketamine infusion studies have been heterogeneous in their protocol, and only recently have standardization guidelines been proposed.

Physical Modalities

Manual lymphatic massage has been described in multiple reports for symptom relief in patients with cancer with malignant growth causing outflow lymphatic obstruction. This technique also has been used to treat the obstructive symptoms seen with the lipomatous growths of AD. Lange and colleagues described a case as providing reduction in pain and the diameter of extremities with twice weekly massage.14 Herbst and colleagues noted that patients had an equivocal response to massage, with some patients finding that it worsened the progression of lipomatous growths.7

Electrocutaneous Stimulation

In a case study by Martinenghi and colleagues, a patient with AD improved following transcutaneous frequency rhythmic electrical modulation system (FREMS) treatment.16 The treatment involved 4 cycles of 30 minutes each for 6 months. The patient had an improvement of pain on the VAS from 6.4 to 1.7 and an increase from 12 to 18 on the 100-point Barthel index scale for performance in activities of daily living, suggesting an improvement of functional independence as well.16

The MC5-A Calmare is another cutaneous electrostimulation modality that previously has been used for chronic cancer pain management. This FDA-cleared device is indicated for the treatment of various chronic pain syndromes. The device is proposed to stimulate 5 separate pain areas via cutaneous electrodes applied beyond and above the painful areas in order to “scramble” pain information and reduce perception of chronic pain intensity. Ricci and colleagues included cancer and noncancer subjects in their study and observed reduction in pain intensity by 74% (on numeric rating scale) in the entire subject group after 10 days of treatments. Further, no AEs were reported in either group, and most of the subjects were willing to continue treatment.17 However, this modality was limited by concerns with insurance coverage, access to a Calmare machine, operator training, and reproducibility of electrode placement to achieve “zero pain” as is the determinant of device treatment cycle output by the manufacturer.

Perineural Injection/Prolotherapy

Perineural injection therapy (PIT) involves the injection of dextrose solution into tissues surrounding an inflamed nerve to reduce neuropathic inflammation. The proposed source of this inflammation is the stimulation of the superficial branches of peptidergic peripheral nerves. Injections are SC and target the affected superficial nerve pathway. Pain relief is usually immediate but requires several treatments to ensure a lasting benefit. There have been no research studies or case reports on the use of PIT or prolotherapy and AD. Although there is a paucity of published literature on the efficacy of PIT, it remains an alternative modality for treatment of chronic pain syndromes. In a systematic review of prolotherapy for chronic musculoskeletal pain, Hauser and colleagues supported the use of dextrose prolotherapy to treat chronic tendinopathies, osteoarthritis of finger and knee joints, spinal and pelvic pain if conservative measures had failed. However, the efficacy on acute musculoskeletal pain was uncertain.18 In addition to the paucity of published literature, prolotherapy is not available to many patients due to lack of insurance coverage or lack of providers able to perform the procedure.

Hypobaric Pressure Therapy