User login

CDC, SAMHSA commit $1.8 billion to combat opioid crisis

More financial reinforcements are arriving in the battle against the opioid crisis, with the Trump administration promising more than $1.8 billion in new funds to help states address the crisis.

Speaking at a Sept. 4 press conference announcing the funding, President Donald Trump said the money will be used “to increase access to medication and medication-assisted treatment and mental health resources, which are critical for ending homelessness and getting people the help they deserve.” The president added that the grants also will help state and local governments obtain high-quality, comprehensive data.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention will provide more than $900 million in new funding over the next 3 years to “advance the understanding of the opioid overdose epidemic and to scale-up prevention and response activities,” the Department of Health & Human Services said in a statement announcing the funding.

“This money will help states and local communities track overdose data and develop strategies that save lives,” HHS Secretary Alex Azar said during the press conference.

He noted that, when the Trump administration began, overdose data were published with a 12-month lag. That lag has since shortened to 6 months. One of the goals with the new funding is to bring data publishing as close to real time as possible.

Separately, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration awarded $932 million to all 50 states as part of its State Opioid Response grants, which “provide flexible funding to state governments to support prevention, treatment, and recovery services in the ways that meet the needs of their state,” according to the HHS statement.

That flexibility “can mean everything from expanding the use of medication-assisted treatment in criminal justice settings or in rural areas via telemedicine, to youth-focused community-based prevention efforts,” Secretary Azar explained. The funds can also support employment coaching and naloxone distribution, he added.

More financial reinforcements are arriving in the battle against the opioid crisis, with the Trump administration promising more than $1.8 billion in new funds to help states address the crisis.

Speaking at a Sept. 4 press conference announcing the funding, President Donald Trump said the money will be used “to increase access to medication and medication-assisted treatment and mental health resources, which are critical for ending homelessness and getting people the help they deserve.” The president added that the grants also will help state and local governments obtain high-quality, comprehensive data.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention will provide more than $900 million in new funding over the next 3 years to “advance the understanding of the opioid overdose epidemic and to scale-up prevention and response activities,” the Department of Health & Human Services said in a statement announcing the funding.

“This money will help states and local communities track overdose data and develop strategies that save lives,” HHS Secretary Alex Azar said during the press conference.

He noted that, when the Trump administration began, overdose data were published with a 12-month lag. That lag has since shortened to 6 months. One of the goals with the new funding is to bring data publishing as close to real time as possible.

Separately, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration awarded $932 million to all 50 states as part of its State Opioid Response grants, which “provide flexible funding to state governments to support prevention, treatment, and recovery services in the ways that meet the needs of their state,” according to the HHS statement.

That flexibility “can mean everything from expanding the use of medication-assisted treatment in criminal justice settings or in rural areas via telemedicine, to youth-focused community-based prevention efforts,” Secretary Azar explained. The funds can also support employment coaching and naloxone distribution, he added.

More financial reinforcements are arriving in the battle against the opioid crisis, with the Trump administration promising more than $1.8 billion in new funds to help states address the crisis.

Speaking at a Sept. 4 press conference announcing the funding, President Donald Trump said the money will be used “to increase access to medication and medication-assisted treatment and mental health resources, which are critical for ending homelessness and getting people the help they deserve.” The president added that the grants also will help state and local governments obtain high-quality, comprehensive data.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention will provide more than $900 million in new funding over the next 3 years to “advance the understanding of the opioid overdose epidemic and to scale-up prevention and response activities,” the Department of Health & Human Services said in a statement announcing the funding.

“This money will help states and local communities track overdose data and develop strategies that save lives,” HHS Secretary Alex Azar said during the press conference.

He noted that, when the Trump administration began, overdose data were published with a 12-month lag. That lag has since shortened to 6 months. One of the goals with the new funding is to bring data publishing as close to real time as possible.

Separately, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration awarded $932 million to all 50 states as part of its State Opioid Response grants, which “provide flexible funding to state governments to support prevention, treatment, and recovery services in the ways that meet the needs of their state,” according to the HHS statement.

That flexibility “can mean everything from expanding the use of medication-assisted treatment in criminal justice settings or in rural areas via telemedicine, to youth-focused community-based prevention efforts,” Secretary Azar explained. The funds can also support employment coaching and naloxone distribution, he added.

Cannabidiol may interact with rheumatologic drugs

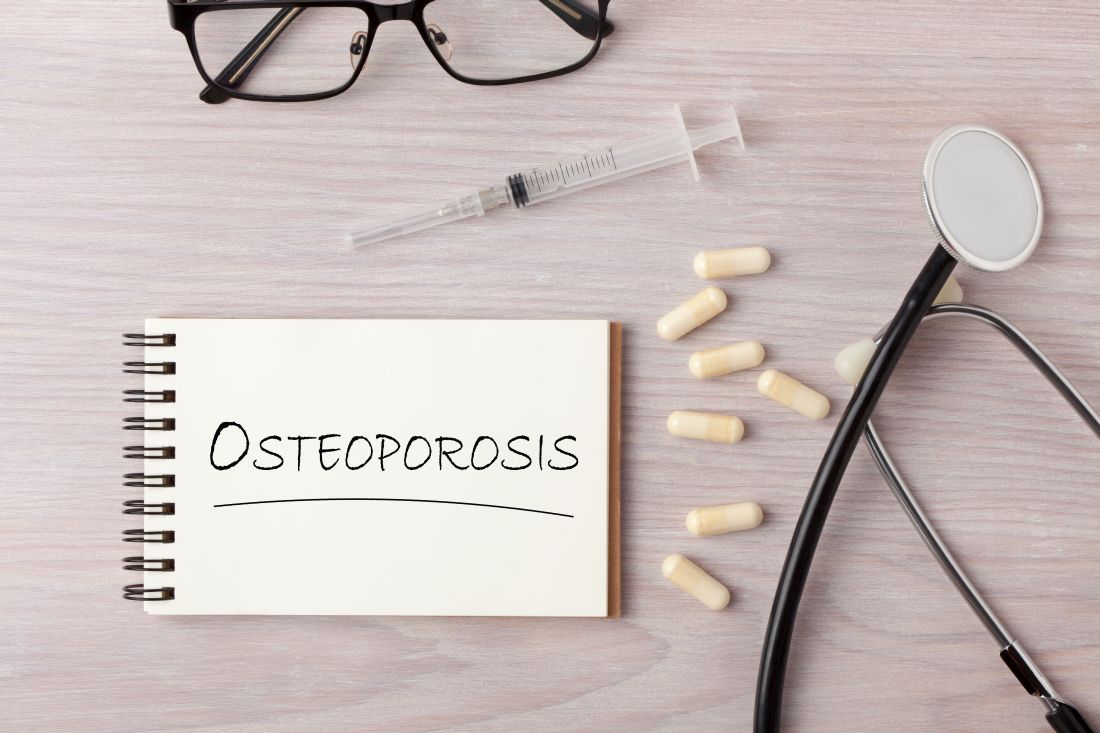

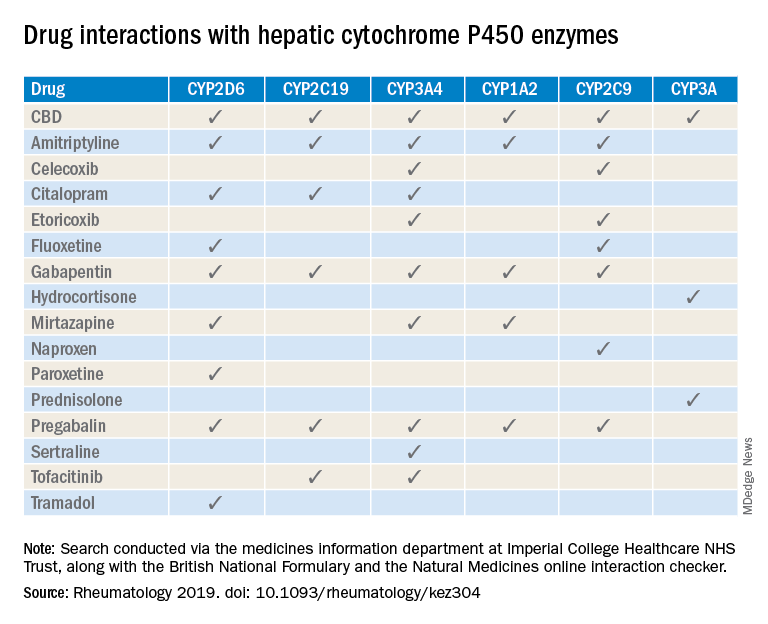

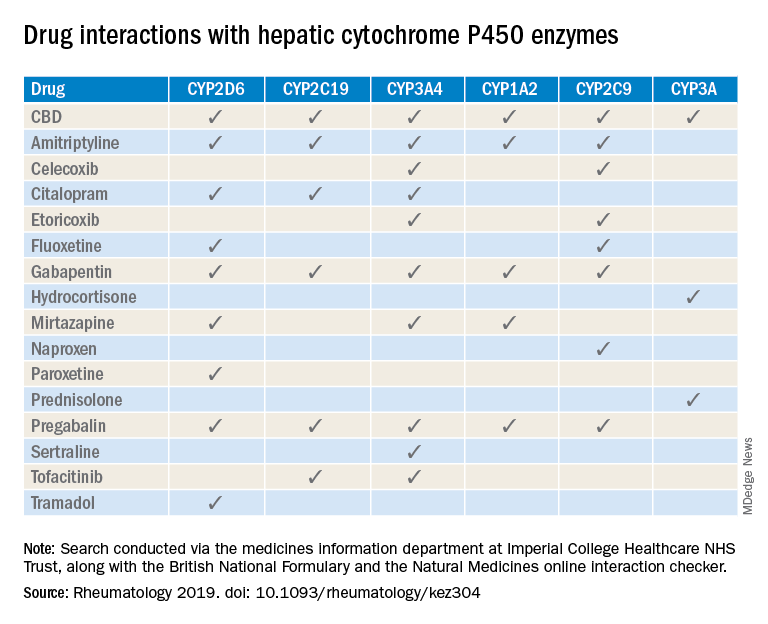

A number of medications commonly prescribed by rheumatologists may interact with cannabidiol oil, investigators at the Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust, London, reported.

“Patients are increasingly requesting information concerning the safety of CBD oil,” Taryn Youngstein, MD, and associates said in letter to the editor in Rheumatology, but current guidelines on the use of medical cannabis do “not address the potential interactions between CBD oil and medicines frequently used in the rheumatology clinic.”

The most important potential CBD interaction, they suggested, may be with corticosteroids. Hydrocortisone and prednisolone both inhibit the cytochrome P450 enzyme CYP3A, but CBD is a potent inhibitor of CYP3A, so “concomitant use may decrease glucocorticoid clearance and increase risk of systemic [corticosteroid] side effects,” the investigators wrote.

CBD also is known to inhibit the cytochrome P450 isozymes CYP2C9, CYP2D6, CYP2C19, CYP3A4, and CYP1A2, which, alone or in combination, are involved in the metabolization of naproxen, tramadol, amitriptyline, and tofacitinib (Xeljanz), according to a literature search done via the college’s medicine information department that also used the British National Formulary and the Natural Medicines online interaction checker.

The Janus kinase inhibitor tofacitinib is included among the possible interactions, but the other Food and Drug Administration–approved JAK inhibitor, baricitinib (Olumiant), is primarily metabolized by the kidneys and should not have significant interaction with CBD, Dr. Youngstein and associates said. Most of the conventional synthetic and biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, including methotrexate, hydroxychloroquine, adalimumab (Humira), and abatacept (Orencia), also are expected to be relatively free from CBD interactions.

This first published report on interactions between CBD oil and common rheumatology medications “highlights the importance of taking comprehensive drug histories, by asking directly about drugs considered alternative medicines and food supplements,” they said.

The investigators declared no conflicts of interest, and there was no specific funding for the study.

SOURCE: Wilson-Morkeh H et al. Rheumatology. 2019 July 29. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kez304.

A number of medications commonly prescribed by rheumatologists may interact with cannabidiol oil, investigators at the Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust, London, reported.

“Patients are increasingly requesting information concerning the safety of CBD oil,” Taryn Youngstein, MD, and associates said in letter to the editor in Rheumatology, but current guidelines on the use of medical cannabis do “not address the potential interactions between CBD oil and medicines frequently used in the rheumatology clinic.”

The most important potential CBD interaction, they suggested, may be with corticosteroids. Hydrocortisone and prednisolone both inhibit the cytochrome P450 enzyme CYP3A, but CBD is a potent inhibitor of CYP3A, so “concomitant use may decrease glucocorticoid clearance and increase risk of systemic [corticosteroid] side effects,” the investigators wrote.

CBD also is known to inhibit the cytochrome P450 isozymes CYP2C9, CYP2D6, CYP2C19, CYP3A4, and CYP1A2, which, alone or in combination, are involved in the metabolization of naproxen, tramadol, amitriptyline, and tofacitinib (Xeljanz), according to a literature search done via the college’s medicine information department that also used the British National Formulary and the Natural Medicines online interaction checker.

The Janus kinase inhibitor tofacitinib is included among the possible interactions, but the other Food and Drug Administration–approved JAK inhibitor, baricitinib (Olumiant), is primarily metabolized by the kidneys and should not have significant interaction with CBD, Dr. Youngstein and associates said. Most of the conventional synthetic and biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, including methotrexate, hydroxychloroquine, adalimumab (Humira), and abatacept (Orencia), also are expected to be relatively free from CBD interactions.

This first published report on interactions between CBD oil and common rheumatology medications “highlights the importance of taking comprehensive drug histories, by asking directly about drugs considered alternative medicines and food supplements,” they said.

The investigators declared no conflicts of interest, and there was no specific funding for the study.

SOURCE: Wilson-Morkeh H et al. Rheumatology. 2019 July 29. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kez304.

A number of medications commonly prescribed by rheumatologists may interact with cannabidiol oil, investigators at the Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust, London, reported.

“Patients are increasingly requesting information concerning the safety of CBD oil,” Taryn Youngstein, MD, and associates said in letter to the editor in Rheumatology, but current guidelines on the use of medical cannabis do “not address the potential interactions between CBD oil and medicines frequently used in the rheumatology clinic.”

The most important potential CBD interaction, they suggested, may be with corticosteroids. Hydrocortisone and prednisolone both inhibit the cytochrome P450 enzyme CYP3A, but CBD is a potent inhibitor of CYP3A, so “concomitant use may decrease glucocorticoid clearance and increase risk of systemic [corticosteroid] side effects,” the investigators wrote.

CBD also is known to inhibit the cytochrome P450 isozymes CYP2C9, CYP2D6, CYP2C19, CYP3A4, and CYP1A2, which, alone or in combination, are involved in the metabolization of naproxen, tramadol, amitriptyline, and tofacitinib (Xeljanz), according to a literature search done via the college’s medicine information department that also used the British National Formulary and the Natural Medicines online interaction checker.

The Janus kinase inhibitor tofacitinib is included among the possible interactions, but the other Food and Drug Administration–approved JAK inhibitor, baricitinib (Olumiant), is primarily metabolized by the kidneys and should not have significant interaction with CBD, Dr. Youngstein and associates said. Most of the conventional synthetic and biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, including methotrexate, hydroxychloroquine, adalimumab (Humira), and abatacept (Orencia), also are expected to be relatively free from CBD interactions.

This first published report on interactions between CBD oil and common rheumatology medications “highlights the importance of taking comprehensive drug histories, by asking directly about drugs considered alternative medicines and food supplements,” they said.

The investigators declared no conflicts of interest, and there was no specific funding for the study.

SOURCE: Wilson-Morkeh H et al. Rheumatology. 2019 July 29. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kez304.

FROM RHEUMATOLOGY

Mediastinal granuloma due to histoplasmosis in a patient on infliximab

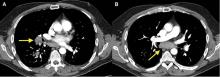

A 50-year-old man with Crohn disease and psoriatic arthritis treated with infliximab and methotrexate presented to a tertiary care hospital with fever, cough, and chest discomfort. The symptoms had first appeared 2 weeks earlier, and he had gone to an urgent care center, where he was prescribed a 5-day course of azithromycin and a corticosteroid, but this had not relieved his symptoms.

Bronchoscopy revealed edematous mucosa throughout, with minimal secretion. Specimens for bacterial, acid-fast bacillus, and fungal cultures were obtained from bronchoalveolar lavage. Endobronchial lymph node biopsy with ultrasonographic guidance revealed nonnecrotizing granuloma.

Bronchoalveolar lavage cultures showed no growth, but the patient’s serum histoplasma antigen was positive at 5.99 ng/dL (reference range: none detected), leading to the diagnosis of mediastinal granuloma due to histoplasmosis with possible dissemination. His immunosuppressant drugs were stopped, and oral itraconazole was started.

At a follow-up visit 2 months later, his serum antigen level had decreased to 0.68 ng/dL, and he had no symptoms whatsoever. At a visit 1 month after that, infliximab and methotrexate were restarted because of an exacerbation of Crohn disease. His oral itraconazole treatment was to be continued for at least 12 months, given the high suspicion for disseminated histoplasmosis while on immunosuppressant therapy.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF GRANULOMATOUS LUNG DISEASE AND LYMPHADENOPATHY

The differential diagnosis of granulomatous lung disease and lymphadenopathy is broad and includes noninfectious and infectious conditions.1

Noninfectious causes include lymphoma, sarcoidosis, inflammatory bowel disease, hypersensitivity pneumonia, side effects of drugs (eg, methotrexate, etanercept), rheumatoid nodules, vasculitis (eg, Churg-Strauss syndrome, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, primary amyloidosis, pneumoconiosis (eg, beryllium, cobalt), and Castleman disease.

There is concern that tumor necrosis factor antagonists may increase the risk of lymphoma, but a 2017 study found no evidence of this.2

Infectious conditions associated with granulomatous lung disease include tuberculosis, nontuberculous mycobacterial infection, fungal infection (eg, Cryptococcus, Coccidioides, Histoplasma, Blastomyces), brucellosis, tularemia (respiratory type B), parasitic infection (eg, Toxocara, Leishmania, Echinococcus, Schistosoma), and Whipple disease.

HISTOPLASMOSIS

Histoplasmosis, caused by infection with Histoplasma capsulatum, is the most prevalent endemic mycotic disease in the United States.3 The fungus is commonly found in the Ohio and Mississippi River valleys in the United States, and also in Central and South America and Asia.

Risk factors for histoplasmosis include living in or traveling to an endemic area, exposure to aerosolized soil that contains spores, and exposure to bats or birds and their droppings.4

Fewer than 5% of exposed individuals develop symptoms, which include fever, chills, headache, myalgia, anorexia, cough, and chest pain.5 Patients may experience symptoms shortly after exposure or may remain free of symptoms for years, with intermittent relapses of symptoms.6 Hilar or mediastinal lymphadenopathy is common in acute pulmonary histoplasmosis.7

The risk of disseminated histoplasmosis is greater in patients with reduced cell-mediated immunity, such as in human immunodeficiency virus infection, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, solid-organ or bone marrow transplant, hematologic malignancies, immunosuppression (corticosteroids, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, and tumor necrosis factor antagonists), and congenital T-cell deficiencies.8

In a retrospective study, infliximab was the tumor necrosis factor antagonist most commonly associated with histoplasmosis.9 In a study of patients with rheumatoid arthritis, the disease-modifying drug most commonly associated was methotrexate.10

GOLD STANDARD FOR DIAGNOSIS

Isolation of H capsulatum from clinical specimens remains the gold standard for confirmation of histoplasmosis. The sensitivity of culture to detect H capsulatum depends on the clinical manifestations: it is 74% in patients with disseminated histoplasmosis, but only 42% in patients with acute pulmonary histoplasmosis.11 The serum histoplasma antigen test has a sensitivity of 91.8% in disseminated histoplasmosis, 87.5% in chronic pulmonary histoplasmosis, and 83% in acute pulmonary histoplasmosis.12

Urine testing for histoplasma antigen has generally proven to be slightly more sensitive than serum testing in all manifestations of histoplasmosis.13 Combining urine and serum testing increases the likelihood of antigen detection.

TREATMENT

Asymptomatic patients with mediastinal histoplasmosis do not require treatment. (Note: in some cases, lymphadenopathy is found incidentally, and biopsy is done to rule out malignancy.)

Standard treatment of symptomatic mediastinal histoplasmosis is oral itraconazole 200 mg, 3 times daily for 3 days, followed by 200 mg orally once or twice daily for 6 to 12 weeks.14

Although stopping immunosuppressant drugs is considered the standard of care in treating histoplasmosis in immunocompromised patients, there are no guidelines on when to resume them. However, a retrospective study of 98 cases of histoplasmosis in patients on tumor necrosis factor antagonists found that resuming immunosuppressants might be safe with close monitoring during the course of antifungal therapy.9 The role of long-term suppressive therapy with antifungal agents in patients on chronic immunosuppressive therapy is still unknown and needs further study.

TAKE-HOME MESSAGES

- Histoplasmosis is the most prevalent endemic mycotic disease in the United States, and mediastinal lymphadenopathy is commonly seen in acute pulmonary histoplasmosis.

- Histoplasmosis should be included in the differential diagnosis of granulomatous lung disease in patients from an endemic area or with a history of travel to an endemic area.

- Immunosuppressive agents such as tumor necrosis factor antagonists and disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs can predispose to invasive fungal infection, including histoplasmosis.

- While isolation of H capsulatum from culture remains the gold standard for the diagnosis of histoplasmosis, the histoplasma antigen tests (serum and urine) is more sensitive than culture.

- Ohshimo S, Guzman J, Costabel U, Bonella F. Differential diagnosis of granulomatous lung disease: clues and pitfalls: number 4 in the Series “Pathology for the clinician.” Edited by Peter Dorfmüller and Alberto Cavazza. Eur Respir Rev 2017; 26(145). doi:10.1183/16000617.0012-2017

- Mercer LK, Galloway JB, Lunt M, et al. Risk of lymphoma in patients exposed to antitumour necrosis factor therapy: results from the British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register for Rheumatoid Arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2017; 76(3):497–503. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209389

- Chu JH, Feudtner C, Heydon K, Walsh TJ, Zaoutis TE. Hospitalizations for endemic mycoses: a population-based national study. Clin Infect Dis 2006; 42(6):822–825. doi:10.1086/500405

- Benedict K, Mody RK. Epidemiology of histoplasmosis outbreaks, United States, 1938–2013. Emerg Infect Dis 2016; 22(3):370–378. doi:10.3201/eid2203.151117

- Wheat LJ. Diagnosis and management of histoplasmosis. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 1989; 8(5):480–490. pmid:2502413

- Goodwin RA Jr, Shapiro JL, Thurman GH, Thurman SS, Des Prez RM. Disseminated histoplasmosis: clinical and pathologic correlations. Medicine (Baltimore) 1980; 59(1):1–33. pmid:7356773

- Wheat LJ, Conces D, Allen SD, Blue-Hnidy D, Loyd J. Pulmonary histoplasmosis syndromes: recognition, diagnosis, and management. Semin Respir Crit Care Med 2004; 25(2):129–144. doi:10.1055/s-2004-824898

- Assi MA, Sandid MS, Baddour LM, Roberts GD, Walker RC. Systemic histoplasmosis: a 15-year retrospective institutional review of 111 patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 2007; 86(3):162–169. doi:10.1097/md.0b013e3180679130

- Vergidis P, Avery RK, Wheat LJ, et al. Histoplasmosis complicating tumor necrosis factor-a blocker therapy: a retrospective analysis of 98 cases. Clin Infect Dis 2015; 61(3):409–417. doi:10.1093/cid/civ299

- Olson TC, Bongartz T, Crowson CS, Roberts GD, Orenstein R, Matteson EL. Histoplasmosis infection in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, 1998–2009. BMC Infect Dis 2011; 11:145. doi:10.1186/1471-2334-11-145

- Hage CA, Ribes JA, Wengenack NL, et al. A multicenter evaluation of tests for diagnosis of histoplasmosis. Clin Infect Dis 2011; 53(5):448–454. doi:10.1093/cid/cir435

- Azar MM, Hage CA. Laboratory diagnostics for histoplasmosis. J Clin Microbiol 2017; 55(6):1612–1620. doi:10.1128/JCM.02430-16

- Swartzentruber S, Rhodes L, Kurkjian K, et al. Diagnosis of acute pulmonary histoplasmosis by antigen detection. Clin Infect Dis 2009; 49(12):1878–1882. doi:10.1086/648421

- Wheat LJ, Freifeld AG, Kleiman MB, et al; Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of patients with histoplasmosis: 2007 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 2007; 45(7):807–825. doi:10.1086/521259

A 50-year-old man with Crohn disease and psoriatic arthritis treated with infliximab and methotrexate presented to a tertiary care hospital with fever, cough, and chest discomfort. The symptoms had first appeared 2 weeks earlier, and he had gone to an urgent care center, where he was prescribed a 5-day course of azithromycin and a corticosteroid, but this had not relieved his symptoms.

Bronchoscopy revealed edematous mucosa throughout, with minimal secretion. Specimens for bacterial, acid-fast bacillus, and fungal cultures were obtained from bronchoalveolar lavage. Endobronchial lymph node biopsy with ultrasonographic guidance revealed nonnecrotizing granuloma.

Bronchoalveolar lavage cultures showed no growth, but the patient’s serum histoplasma antigen was positive at 5.99 ng/dL (reference range: none detected), leading to the diagnosis of mediastinal granuloma due to histoplasmosis with possible dissemination. His immunosuppressant drugs were stopped, and oral itraconazole was started.

At a follow-up visit 2 months later, his serum antigen level had decreased to 0.68 ng/dL, and he had no symptoms whatsoever. At a visit 1 month after that, infliximab and methotrexate were restarted because of an exacerbation of Crohn disease. His oral itraconazole treatment was to be continued for at least 12 months, given the high suspicion for disseminated histoplasmosis while on immunosuppressant therapy.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF GRANULOMATOUS LUNG DISEASE AND LYMPHADENOPATHY

The differential diagnosis of granulomatous lung disease and lymphadenopathy is broad and includes noninfectious and infectious conditions.1

Noninfectious causes include lymphoma, sarcoidosis, inflammatory bowel disease, hypersensitivity pneumonia, side effects of drugs (eg, methotrexate, etanercept), rheumatoid nodules, vasculitis (eg, Churg-Strauss syndrome, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, primary amyloidosis, pneumoconiosis (eg, beryllium, cobalt), and Castleman disease.

There is concern that tumor necrosis factor antagonists may increase the risk of lymphoma, but a 2017 study found no evidence of this.2

Infectious conditions associated with granulomatous lung disease include tuberculosis, nontuberculous mycobacterial infection, fungal infection (eg, Cryptococcus, Coccidioides, Histoplasma, Blastomyces), brucellosis, tularemia (respiratory type B), parasitic infection (eg, Toxocara, Leishmania, Echinococcus, Schistosoma), and Whipple disease.

HISTOPLASMOSIS

Histoplasmosis, caused by infection with Histoplasma capsulatum, is the most prevalent endemic mycotic disease in the United States.3 The fungus is commonly found in the Ohio and Mississippi River valleys in the United States, and also in Central and South America and Asia.

Risk factors for histoplasmosis include living in or traveling to an endemic area, exposure to aerosolized soil that contains spores, and exposure to bats or birds and their droppings.4

Fewer than 5% of exposed individuals develop symptoms, which include fever, chills, headache, myalgia, anorexia, cough, and chest pain.5 Patients may experience symptoms shortly after exposure or may remain free of symptoms for years, with intermittent relapses of symptoms.6 Hilar or mediastinal lymphadenopathy is common in acute pulmonary histoplasmosis.7

The risk of disseminated histoplasmosis is greater in patients with reduced cell-mediated immunity, such as in human immunodeficiency virus infection, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, solid-organ or bone marrow transplant, hematologic malignancies, immunosuppression (corticosteroids, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, and tumor necrosis factor antagonists), and congenital T-cell deficiencies.8

In a retrospective study, infliximab was the tumor necrosis factor antagonist most commonly associated with histoplasmosis.9 In a study of patients with rheumatoid arthritis, the disease-modifying drug most commonly associated was methotrexate.10

GOLD STANDARD FOR DIAGNOSIS

Isolation of H capsulatum from clinical specimens remains the gold standard for confirmation of histoplasmosis. The sensitivity of culture to detect H capsulatum depends on the clinical manifestations: it is 74% in patients with disseminated histoplasmosis, but only 42% in patients with acute pulmonary histoplasmosis.11 The serum histoplasma antigen test has a sensitivity of 91.8% in disseminated histoplasmosis, 87.5% in chronic pulmonary histoplasmosis, and 83% in acute pulmonary histoplasmosis.12

Urine testing for histoplasma antigen has generally proven to be slightly more sensitive than serum testing in all manifestations of histoplasmosis.13 Combining urine and serum testing increases the likelihood of antigen detection.

TREATMENT

Asymptomatic patients with mediastinal histoplasmosis do not require treatment. (Note: in some cases, lymphadenopathy is found incidentally, and biopsy is done to rule out malignancy.)

Standard treatment of symptomatic mediastinal histoplasmosis is oral itraconazole 200 mg, 3 times daily for 3 days, followed by 200 mg orally once or twice daily for 6 to 12 weeks.14

Although stopping immunosuppressant drugs is considered the standard of care in treating histoplasmosis in immunocompromised patients, there are no guidelines on when to resume them. However, a retrospective study of 98 cases of histoplasmosis in patients on tumor necrosis factor antagonists found that resuming immunosuppressants might be safe with close monitoring during the course of antifungal therapy.9 The role of long-term suppressive therapy with antifungal agents in patients on chronic immunosuppressive therapy is still unknown and needs further study.

TAKE-HOME MESSAGES

- Histoplasmosis is the most prevalent endemic mycotic disease in the United States, and mediastinal lymphadenopathy is commonly seen in acute pulmonary histoplasmosis.

- Histoplasmosis should be included in the differential diagnosis of granulomatous lung disease in patients from an endemic area or with a history of travel to an endemic area.

- Immunosuppressive agents such as tumor necrosis factor antagonists and disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs can predispose to invasive fungal infection, including histoplasmosis.

- While isolation of H capsulatum from culture remains the gold standard for the diagnosis of histoplasmosis, the histoplasma antigen tests (serum and urine) is more sensitive than culture.

A 50-year-old man with Crohn disease and psoriatic arthritis treated with infliximab and methotrexate presented to a tertiary care hospital with fever, cough, and chest discomfort. The symptoms had first appeared 2 weeks earlier, and he had gone to an urgent care center, where he was prescribed a 5-day course of azithromycin and a corticosteroid, but this had not relieved his symptoms.

Bronchoscopy revealed edematous mucosa throughout, with minimal secretion. Specimens for bacterial, acid-fast bacillus, and fungal cultures were obtained from bronchoalveolar lavage. Endobronchial lymph node biopsy with ultrasonographic guidance revealed nonnecrotizing granuloma.

Bronchoalveolar lavage cultures showed no growth, but the patient’s serum histoplasma antigen was positive at 5.99 ng/dL (reference range: none detected), leading to the diagnosis of mediastinal granuloma due to histoplasmosis with possible dissemination. His immunosuppressant drugs were stopped, and oral itraconazole was started.

At a follow-up visit 2 months later, his serum antigen level had decreased to 0.68 ng/dL, and he had no symptoms whatsoever. At a visit 1 month after that, infliximab and methotrexate were restarted because of an exacerbation of Crohn disease. His oral itraconazole treatment was to be continued for at least 12 months, given the high suspicion for disseminated histoplasmosis while on immunosuppressant therapy.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF GRANULOMATOUS LUNG DISEASE AND LYMPHADENOPATHY

The differential diagnosis of granulomatous lung disease and lymphadenopathy is broad and includes noninfectious and infectious conditions.1

Noninfectious causes include lymphoma, sarcoidosis, inflammatory bowel disease, hypersensitivity pneumonia, side effects of drugs (eg, methotrexate, etanercept), rheumatoid nodules, vasculitis (eg, Churg-Strauss syndrome, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, primary amyloidosis, pneumoconiosis (eg, beryllium, cobalt), and Castleman disease.

There is concern that tumor necrosis factor antagonists may increase the risk of lymphoma, but a 2017 study found no evidence of this.2

Infectious conditions associated with granulomatous lung disease include tuberculosis, nontuberculous mycobacterial infection, fungal infection (eg, Cryptococcus, Coccidioides, Histoplasma, Blastomyces), brucellosis, tularemia (respiratory type B), parasitic infection (eg, Toxocara, Leishmania, Echinococcus, Schistosoma), and Whipple disease.

HISTOPLASMOSIS

Histoplasmosis, caused by infection with Histoplasma capsulatum, is the most prevalent endemic mycotic disease in the United States.3 The fungus is commonly found in the Ohio and Mississippi River valleys in the United States, and also in Central and South America and Asia.

Risk factors for histoplasmosis include living in or traveling to an endemic area, exposure to aerosolized soil that contains spores, and exposure to bats or birds and their droppings.4

Fewer than 5% of exposed individuals develop symptoms, which include fever, chills, headache, myalgia, anorexia, cough, and chest pain.5 Patients may experience symptoms shortly after exposure or may remain free of symptoms for years, with intermittent relapses of symptoms.6 Hilar or mediastinal lymphadenopathy is common in acute pulmonary histoplasmosis.7

The risk of disseminated histoplasmosis is greater in patients with reduced cell-mediated immunity, such as in human immunodeficiency virus infection, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, solid-organ or bone marrow transplant, hematologic malignancies, immunosuppression (corticosteroids, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, and tumor necrosis factor antagonists), and congenital T-cell deficiencies.8

In a retrospective study, infliximab was the tumor necrosis factor antagonist most commonly associated with histoplasmosis.9 In a study of patients with rheumatoid arthritis, the disease-modifying drug most commonly associated was methotrexate.10

GOLD STANDARD FOR DIAGNOSIS

Isolation of H capsulatum from clinical specimens remains the gold standard for confirmation of histoplasmosis. The sensitivity of culture to detect H capsulatum depends on the clinical manifestations: it is 74% in patients with disseminated histoplasmosis, but only 42% in patients with acute pulmonary histoplasmosis.11 The serum histoplasma antigen test has a sensitivity of 91.8% in disseminated histoplasmosis, 87.5% in chronic pulmonary histoplasmosis, and 83% in acute pulmonary histoplasmosis.12

Urine testing for histoplasma antigen has generally proven to be slightly more sensitive than serum testing in all manifestations of histoplasmosis.13 Combining urine and serum testing increases the likelihood of antigen detection.

TREATMENT

Asymptomatic patients with mediastinal histoplasmosis do not require treatment. (Note: in some cases, lymphadenopathy is found incidentally, and biopsy is done to rule out malignancy.)

Standard treatment of symptomatic mediastinal histoplasmosis is oral itraconazole 200 mg, 3 times daily for 3 days, followed by 200 mg orally once or twice daily for 6 to 12 weeks.14

Although stopping immunosuppressant drugs is considered the standard of care in treating histoplasmosis in immunocompromised patients, there are no guidelines on when to resume them. However, a retrospective study of 98 cases of histoplasmosis in patients on tumor necrosis factor antagonists found that resuming immunosuppressants might be safe with close monitoring during the course of antifungal therapy.9 The role of long-term suppressive therapy with antifungal agents in patients on chronic immunosuppressive therapy is still unknown and needs further study.

TAKE-HOME MESSAGES

- Histoplasmosis is the most prevalent endemic mycotic disease in the United States, and mediastinal lymphadenopathy is commonly seen in acute pulmonary histoplasmosis.

- Histoplasmosis should be included in the differential diagnosis of granulomatous lung disease in patients from an endemic area or with a history of travel to an endemic area.

- Immunosuppressive agents such as tumor necrosis factor antagonists and disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs can predispose to invasive fungal infection, including histoplasmosis.

- While isolation of H capsulatum from culture remains the gold standard for the diagnosis of histoplasmosis, the histoplasma antigen tests (serum and urine) is more sensitive than culture.

- Ohshimo S, Guzman J, Costabel U, Bonella F. Differential diagnosis of granulomatous lung disease: clues and pitfalls: number 4 in the Series “Pathology for the clinician.” Edited by Peter Dorfmüller and Alberto Cavazza. Eur Respir Rev 2017; 26(145). doi:10.1183/16000617.0012-2017

- Mercer LK, Galloway JB, Lunt M, et al. Risk of lymphoma in patients exposed to antitumour necrosis factor therapy: results from the British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register for Rheumatoid Arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2017; 76(3):497–503. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209389

- Chu JH, Feudtner C, Heydon K, Walsh TJ, Zaoutis TE. Hospitalizations for endemic mycoses: a population-based national study. Clin Infect Dis 2006; 42(6):822–825. doi:10.1086/500405

- Benedict K, Mody RK. Epidemiology of histoplasmosis outbreaks, United States, 1938–2013. Emerg Infect Dis 2016; 22(3):370–378. doi:10.3201/eid2203.151117

- Wheat LJ. Diagnosis and management of histoplasmosis. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 1989; 8(5):480–490. pmid:2502413

- Goodwin RA Jr, Shapiro JL, Thurman GH, Thurman SS, Des Prez RM. Disseminated histoplasmosis: clinical and pathologic correlations. Medicine (Baltimore) 1980; 59(1):1–33. pmid:7356773

- Wheat LJ, Conces D, Allen SD, Blue-Hnidy D, Loyd J. Pulmonary histoplasmosis syndromes: recognition, diagnosis, and management. Semin Respir Crit Care Med 2004; 25(2):129–144. doi:10.1055/s-2004-824898

- Assi MA, Sandid MS, Baddour LM, Roberts GD, Walker RC. Systemic histoplasmosis: a 15-year retrospective institutional review of 111 patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 2007; 86(3):162–169. doi:10.1097/md.0b013e3180679130

- Vergidis P, Avery RK, Wheat LJ, et al. Histoplasmosis complicating tumor necrosis factor-a blocker therapy: a retrospective analysis of 98 cases. Clin Infect Dis 2015; 61(3):409–417. doi:10.1093/cid/civ299

- Olson TC, Bongartz T, Crowson CS, Roberts GD, Orenstein R, Matteson EL. Histoplasmosis infection in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, 1998–2009. BMC Infect Dis 2011; 11:145. doi:10.1186/1471-2334-11-145

- Hage CA, Ribes JA, Wengenack NL, et al. A multicenter evaluation of tests for diagnosis of histoplasmosis. Clin Infect Dis 2011; 53(5):448–454. doi:10.1093/cid/cir435

- Azar MM, Hage CA. Laboratory diagnostics for histoplasmosis. J Clin Microbiol 2017; 55(6):1612–1620. doi:10.1128/JCM.02430-16

- Swartzentruber S, Rhodes L, Kurkjian K, et al. Diagnosis of acute pulmonary histoplasmosis by antigen detection. Clin Infect Dis 2009; 49(12):1878–1882. doi:10.1086/648421

- Wheat LJ, Freifeld AG, Kleiman MB, et al; Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of patients with histoplasmosis: 2007 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 2007; 45(7):807–825. doi:10.1086/521259

- Ohshimo S, Guzman J, Costabel U, Bonella F. Differential diagnosis of granulomatous lung disease: clues and pitfalls: number 4 in the Series “Pathology for the clinician.” Edited by Peter Dorfmüller and Alberto Cavazza. Eur Respir Rev 2017; 26(145). doi:10.1183/16000617.0012-2017

- Mercer LK, Galloway JB, Lunt M, et al. Risk of lymphoma in patients exposed to antitumour necrosis factor therapy: results from the British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register for Rheumatoid Arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2017; 76(3):497–503. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209389

- Chu JH, Feudtner C, Heydon K, Walsh TJ, Zaoutis TE. Hospitalizations for endemic mycoses: a population-based national study. Clin Infect Dis 2006; 42(6):822–825. doi:10.1086/500405

- Benedict K, Mody RK. Epidemiology of histoplasmosis outbreaks, United States, 1938–2013. Emerg Infect Dis 2016; 22(3):370–378. doi:10.3201/eid2203.151117

- Wheat LJ. Diagnosis and management of histoplasmosis. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 1989; 8(5):480–490. pmid:2502413

- Goodwin RA Jr, Shapiro JL, Thurman GH, Thurman SS, Des Prez RM. Disseminated histoplasmosis: clinical and pathologic correlations. Medicine (Baltimore) 1980; 59(1):1–33. pmid:7356773

- Wheat LJ, Conces D, Allen SD, Blue-Hnidy D, Loyd J. Pulmonary histoplasmosis syndromes: recognition, diagnosis, and management. Semin Respir Crit Care Med 2004; 25(2):129–144. doi:10.1055/s-2004-824898

- Assi MA, Sandid MS, Baddour LM, Roberts GD, Walker RC. Systemic histoplasmosis: a 15-year retrospective institutional review of 111 patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 2007; 86(3):162–169. doi:10.1097/md.0b013e3180679130

- Vergidis P, Avery RK, Wheat LJ, et al. Histoplasmosis complicating tumor necrosis factor-a blocker therapy: a retrospective analysis of 98 cases. Clin Infect Dis 2015; 61(3):409–417. doi:10.1093/cid/civ299

- Olson TC, Bongartz T, Crowson CS, Roberts GD, Orenstein R, Matteson EL. Histoplasmosis infection in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, 1998–2009. BMC Infect Dis 2011; 11:145. doi:10.1186/1471-2334-11-145

- Hage CA, Ribes JA, Wengenack NL, et al. A multicenter evaluation of tests for diagnosis of histoplasmosis. Clin Infect Dis 2011; 53(5):448–454. doi:10.1093/cid/cir435

- Azar MM, Hage CA. Laboratory diagnostics for histoplasmosis. J Clin Microbiol 2017; 55(6):1612–1620. doi:10.1128/JCM.02430-16

- Swartzentruber S, Rhodes L, Kurkjian K, et al. Diagnosis of acute pulmonary histoplasmosis by antigen detection. Clin Infect Dis 2009; 49(12):1878–1882. doi:10.1086/648421

- Wheat LJ, Freifeld AG, Kleiman MB, et al; Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of patients with histoplasmosis: 2007 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 2007; 45(7):807–825. doi:10.1086/521259

Click for Credit: Fasting rules for surgery; Biomarkers for PSA vs OA; more

Here are 5 articles from the September issue of Clinician Reviews (individual articles are valid for one year from date of publication—expiration dates below):

1. No birth rate gains from levothyroxine in pregnancy

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2ZoXzK8

Expires March 23, 2020

2. Simple screening for risk of falling in elderly can guide prevention

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2NKXxu3

Expires March 24, 2020

3. Time to revisit fasting rules for surgery patients

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2HHwHiD

Expires March 26, 2020

4. Four biomarkers could distinguish psoriatic arthritis from osteoarthritis

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/344WPNS

Expires March 28, 2020

5. More chest compression–only CPR leads to increased survival rates

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/30CahGF

Expires April 1, 2020

Here are 5 articles from the September issue of Clinician Reviews (individual articles are valid for one year from date of publication—expiration dates below):

1. No birth rate gains from levothyroxine in pregnancy

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2ZoXzK8

Expires March 23, 2020

2. Simple screening for risk of falling in elderly can guide prevention

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2NKXxu3

Expires March 24, 2020

3. Time to revisit fasting rules for surgery patients

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2HHwHiD

Expires March 26, 2020

4. Four biomarkers could distinguish psoriatic arthritis from osteoarthritis

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/344WPNS

Expires March 28, 2020

5. More chest compression–only CPR leads to increased survival rates

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/30CahGF

Expires April 1, 2020

Here are 5 articles from the September issue of Clinician Reviews (individual articles are valid for one year from date of publication—expiration dates below):

1. No birth rate gains from levothyroxine in pregnancy

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2ZoXzK8

Expires March 23, 2020

2. Simple screening for risk of falling in elderly can guide prevention

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2NKXxu3

Expires March 24, 2020

3. Time to revisit fasting rules for surgery patients

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2HHwHiD

Expires March 26, 2020

4. Four biomarkers could distinguish psoriatic arthritis from osteoarthritis

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/344WPNS

Expires March 28, 2020

5. More chest compression–only CPR leads to increased survival rates

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/30CahGF

Expires April 1, 2020

Axial SpA guidelines updated with best practices for new drugs, imaging

The American College of Rheumatology, Spondylitis Association of America, and Spondyloarthritis Research and Treatment Network have updated their guidelines on management of ankylosing spondylitis and nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis.

These guidelines serve as an update to the previous guidelines that were first published in 2015 (Arthritis Care Res. 2016;68:151–66). While the new guidelines did not review all recommendations from the 2015 guidelines, 20 questions on pharmacologic treatment were re-reviewed in addition to 26 new questions and recommendations.

Michael M. Ward, MD, chief of the Clinical Trials and Outcomes Branch at the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, said in an interview that the availability of new medications to treat axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA) prompted the updated guidelines.

“We took the opportunity to revisit some previous recommendations for which substantial new evidence was available, and also included new recommendations on some other topics, such as imaging,” said Dr. Ward, who is also first author of the new guidelines.

The panel that developed the questions focused on scenarios that a clinician would likely encounter in clinical practice, or situations in which how to manage a case is not clear. “Given this perspective, there were many questions that had limited evidence, but recommendations were made for all questions. For those questions that had less evidence in the literature, we relied more on the expertise of the panel,” Dr. Ward said.

The questions and recommendations for ankylosing spondylitis (AS) and nonradiographic axSpA centered around use of interleukin-17 (IL-17) inhibitors, tofacitinib (Xeljanz), and biosimilars of tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibitors (TNFi), as well as when to taper and discontinue these medications.

Strong recommendations for patients with AS included using NSAIDs (low level of evidence), using TNFi when active disease remains despite NSAID treatment (high level of evidence), and using secukinumab (Cosentyx) or ixekizumab (Taltz) when active disease remains despite NSAID treatment over no treatment (high level of evidence). The guidelines also strongly recommend the use of physical therapy for adults with stable AS over no physical therapy (low level of evidence), as well as total hip arthroplasty in cases of advanced hip arthritis. The writing panel also strongly advised that adults with AS-related comorbidities should receive treatment by an ophthalmologist in cases of acute iritis. Strong recommendations were made against switching to a biosimilar of a TNFi after receiving treatment with an originator TNFi (regardless of whether it is for active or stable AS), use of systemic glucocorticoids in adults with active AS, treatment with spinal manipulation in patients with spinal fusion or advanced spinal osteoporosis, and screening for cardiac conduction defects and valvular heart disease with electrocardiograms.

Strong recommendations for nonradiographic axSpA were similar to those made for patients with AS, and the panel made strong recommendations for use of NSAIDs in patients with active disease; for TNFi treatment when NSAIDs fail; against switching to a biosimilar of a TNFi after starting the originator TNFi; against using systemic glucocorticoids; and in favor of using physical therapy rather than not.

The panel also made a number of conditional recommendations for AS and nonradiographic axSpA patients with regard to biologic preference and imaging. TNFis were conditionally recommended over secukinumab or ixekizumab in patients with active disease despite NSAIDs treatment, and in cases where a patient is not responding to a first TNFi treatment, the panel conditionally recommended secukinumab or ixekizumab over a second TNFi (very low evidence for all). Secukinumab or ixekizumab were also conditionally recommended over tofacitinib (very low evidence). Sulfasalazine, methotrexate, and tofacitinib were conditionally recommended in cases where patients had prominent peripheral arthritis or when TNFis are not available (very low to moderate evidence). The panel recommended against adding sulfasalazine or methotrexate to existing TNFi treatment (very low evidence), and they also advised against tapering as a standard treatment approach or discontinuing the biologic (very low evidence). MRI of the spine or pelvis was conditionally recommended to examine disease activity in unclear cases, but the panel recommended against ordering MRI scans to monitor disease inactivity (very low evidence).

“Most of the recommendations are conditional, primarily because of the relatively low level of evidence in the literature that addressed many of the questions,” while stronger recommendations came from larger clinical trials, Dr. Ward said. “The need for this update demonstrates the rapid progress in treatment that is occurring in axial spondyloarthritis, but the low level of evidence for many questions indicates that much more research is needed.”

Nine authors reported personal and institutional relationships in the form of consultancies, educational advisory board memberships, and site investigator appointments for AbbVie, Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Galapagos, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer, and UCB. The other authors reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Ward MM et al. Arthritis Care Res. 2019 Aug 21. doi: 10.1002/acr.24025.

The American College of Rheumatology, Spondylitis Association of America, and Spondyloarthritis Research and Treatment Network have updated their guidelines on management of ankylosing spondylitis and nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis.

These guidelines serve as an update to the previous guidelines that were first published in 2015 (Arthritis Care Res. 2016;68:151–66). While the new guidelines did not review all recommendations from the 2015 guidelines, 20 questions on pharmacologic treatment were re-reviewed in addition to 26 new questions and recommendations.

Michael M. Ward, MD, chief of the Clinical Trials and Outcomes Branch at the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, said in an interview that the availability of new medications to treat axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA) prompted the updated guidelines.

“We took the opportunity to revisit some previous recommendations for which substantial new evidence was available, and also included new recommendations on some other topics, such as imaging,” said Dr. Ward, who is also first author of the new guidelines.

The panel that developed the questions focused on scenarios that a clinician would likely encounter in clinical practice, or situations in which how to manage a case is not clear. “Given this perspective, there were many questions that had limited evidence, but recommendations were made for all questions. For those questions that had less evidence in the literature, we relied more on the expertise of the panel,” Dr. Ward said.

The questions and recommendations for ankylosing spondylitis (AS) and nonradiographic axSpA centered around use of interleukin-17 (IL-17) inhibitors, tofacitinib (Xeljanz), and biosimilars of tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibitors (TNFi), as well as when to taper and discontinue these medications.

Strong recommendations for patients with AS included using NSAIDs (low level of evidence), using TNFi when active disease remains despite NSAID treatment (high level of evidence), and using secukinumab (Cosentyx) or ixekizumab (Taltz) when active disease remains despite NSAID treatment over no treatment (high level of evidence). The guidelines also strongly recommend the use of physical therapy for adults with stable AS over no physical therapy (low level of evidence), as well as total hip arthroplasty in cases of advanced hip arthritis. The writing panel also strongly advised that adults with AS-related comorbidities should receive treatment by an ophthalmologist in cases of acute iritis. Strong recommendations were made against switching to a biosimilar of a TNFi after receiving treatment with an originator TNFi (regardless of whether it is for active or stable AS), use of systemic glucocorticoids in adults with active AS, treatment with spinal manipulation in patients with spinal fusion or advanced spinal osteoporosis, and screening for cardiac conduction defects and valvular heart disease with electrocardiograms.

Strong recommendations for nonradiographic axSpA were similar to those made for patients with AS, and the panel made strong recommendations for use of NSAIDs in patients with active disease; for TNFi treatment when NSAIDs fail; against switching to a biosimilar of a TNFi after starting the originator TNFi; against using systemic glucocorticoids; and in favor of using physical therapy rather than not.

The panel also made a number of conditional recommendations for AS and nonradiographic axSpA patients with regard to biologic preference and imaging. TNFis were conditionally recommended over secukinumab or ixekizumab in patients with active disease despite NSAIDs treatment, and in cases where a patient is not responding to a first TNFi treatment, the panel conditionally recommended secukinumab or ixekizumab over a second TNFi (very low evidence for all). Secukinumab or ixekizumab were also conditionally recommended over tofacitinib (very low evidence). Sulfasalazine, methotrexate, and tofacitinib were conditionally recommended in cases where patients had prominent peripheral arthritis or when TNFis are not available (very low to moderate evidence). The panel recommended against adding sulfasalazine or methotrexate to existing TNFi treatment (very low evidence), and they also advised against tapering as a standard treatment approach or discontinuing the biologic (very low evidence). MRI of the spine or pelvis was conditionally recommended to examine disease activity in unclear cases, but the panel recommended against ordering MRI scans to monitor disease inactivity (very low evidence).

“Most of the recommendations are conditional, primarily because of the relatively low level of evidence in the literature that addressed many of the questions,” while stronger recommendations came from larger clinical trials, Dr. Ward said. “The need for this update demonstrates the rapid progress in treatment that is occurring in axial spondyloarthritis, but the low level of evidence for many questions indicates that much more research is needed.”

Nine authors reported personal and institutional relationships in the form of consultancies, educational advisory board memberships, and site investigator appointments for AbbVie, Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Galapagos, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer, and UCB. The other authors reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Ward MM et al. Arthritis Care Res. 2019 Aug 21. doi: 10.1002/acr.24025.

The American College of Rheumatology, Spondylitis Association of America, and Spondyloarthritis Research and Treatment Network have updated their guidelines on management of ankylosing spondylitis and nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis.

These guidelines serve as an update to the previous guidelines that were first published in 2015 (Arthritis Care Res. 2016;68:151–66). While the new guidelines did not review all recommendations from the 2015 guidelines, 20 questions on pharmacologic treatment were re-reviewed in addition to 26 new questions and recommendations.

Michael M. Ward, MD, chief of the Clinical Trials and Outcomes Branch at the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, said in an interview that the availability of new medications to treat axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA) prompted the updated guidelines.

“We took the opportunity to revisit some previous recommendations for which substantial new evidence was available, and also included new recommendations on some other topics, such as imaging,” said Dr. Ward, who is also first author of the new guidelines.

The panel that developed the questions focused on scenarios that a clinician would likely encounter in clinical practice, or situations in which how to manage a case is not clear. “Given this perspective, there were many questions that had limited evidence, but recommendations were made for all questions. For those questions that had less evidence in the literature, we relied more on the expertise of the panel,” Dr. Ward said.

The questions and recommendations for ankylosing spondylitis (AS) and nonradiographic axSpA centered around use of interleukin-17 (IL-17) inhibitors, tofacitinib (Xeljanz), and biosimilars of tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibitors (TNFi), as well as when to taper and discontinue these medications.

Strong recommendations for patients with AS included using NSAIDs (low level of evidence), using TNFi when active disease remains despite NSAID treatment (high level of evidence), and using secukinumab (Cosentyx) or ixekizumab (Taltz) when active disease remains despite NSAID treatment over no treatment (high level of evidence). The guidelines also strongly recommend the use of physical therapy for adults with stable AS over no physical therapy (low level of evidence), as well as total hip arthroplasty in cases of advanced hip arthritis. The writing panel also strongly advised that adults with AS-related comorbidities should receive treatment by an ophthalmologist in cases of acute iritis. Strong recommendations were made against switching to a biosimilar of a TNFi after receiving treatment with an originator TNFi (regardless of whether it is for active or stable AS), use of systemic glucocorticoids in adults with active AS, treatment with spinal manipulation in patients with spinal fusion or advanced spinal osteoporosis, and screening for cardiac conduction defects and valvular heart disease with electrocardiograms.

Strong recommendations for nonradiographic axSpA were similar to those made for patients with AS, and the panel made strong recommendations for use of NSAIDs in patients with active disease; for TNFi treatment when NSAIDs fail; against switching to a biosimilar of a TNFi after starting the originator TNFi; against using systemic glucocorticoids; and in favor of using physical therapy rather than not.

The panel also made a number of conditional recommendations for AS and nonradiographic axSpA patients with regard to biologic preference and imaging. TNFis were conditionally recommended over secukinumab or ixekizumab in patients with active disease despite NSAIDs treatment, and in cases where a patient is not responding to a first TNFi treatment, the panel conditionally recommended secukinumab or ixekizumab over a second TNFi (very low evidence for all). Secukinumab or ixekizumab were also conditionally recommended over tofacitinib (very low evidence). Sulfasalazine, methotrexate, and tofacitinib were conditionally recommended in cases where patients had prominent peripheral arthritis or when TNFis are not available (very low to moderate evidence). The panel recommended against adding sulfasalazine or methotrexate to existing TNFi treatment (very low evidence), and they also advised against tapering as a standard treatment approach or discontinuing the biologic (very low evidence). MRI of the spine or pelvis was conditionally recommended to examine disease activity in unclear cases, but the panel recommended against ordering MRI scans to monitor disease inactivity (very low evidence).

“Most of the recommendations are conditional, primarily because of the relatively low level of evidence in the literature that addressed many of the questions,” while stronger recommendations came from larger clinical trials, Dr. Ward said. “The need for this update demonstrates the rapid progress in treatment that is occurring in axial spondyloarthritis, but the low level of evidence for many questions indicates that much more research is needed.”

Nine authors reported personal and institutional relationships in the form of consultancies, educational advisory board memberships, and site investigator appointments for AbbVie, Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Galapagos, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer, and UCB. The other authors reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Ward MM et al. Arthritis Care Res. 2019 Aug 21. doi: 10.1002/acr.24025.

FROM ARTHRITIS CARE & RESEARCH

Prior DMARD use in RA may limit adalimumab treatment response

A history of using multiple conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) is a key predictor for poorer response to adalimumab therapy in rheumatoid arthritis patients, according to data from a pair of studies with a total of 274 patients.

Although patients with RA who have failed methotrexate or tumor necrosis factor inhibitor therapy respond less than methotrexate-naive patients, “it remains unknown if response to the first biologic DMARD, in particular a [tumor necrosis factor inhibitor], depends on disease duration or prior numbers of failed [conventional synthetic] DMARDs,” wrote Daniel Aletaha, MD, of the Medical University of Vienna and colleagues.

In a study published in Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, the researchers reviewed data from two randomized, controlled trials of patients with RA. In the larger trial of 207 adults (known as DE019), past use of two or more conventional synthetic DMARDs was associated with less improvement in 28-joint Disease Activity Score using C-reactive protein (DAS28-CRP) after 24 weeks of adalimumab (Humira), compared with use of one or no DMARDs (–1.8 vs. –2.2, respectively). Similarly, disease activity and disability scores improved significantly less in patients who had used two or more DMARDs, compared with those who used one or no DMARDs, according to the Simplified Disease Activity Index (SDAI; –22.1 vs. –26.9) and the Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index (HAQ-DI; –0.43 vs. –0.64).

The researchers also examined the role of disease duration on treatment response. Overall, patients with disease duration greater than 10 years showed more improvement at 24 weeks than did those with disease duration less than 1 year, based on HAQ-DI scores (1.1 vs. 0.7), but final scores on the SDAI and DAS28-CRP were not significantly different between those with disease duration greater than 10 years and those with duration of less than 1 year. These results suggest that the impact of DMARDs holds true regardless of disease duration, the researchers noted.

The findings were similar with regard to number of prior conventional synthetic DMARDs and the effects of disease duration in the second trial of 67 patients, known as the ARMADA study.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the post hoc analysis design, use of only adalimumab data, and the small number of patients in several subgroups, the researchers noted. However, the results support the need for more standardized treatment guidelines and suggest that RA patients who fail to respond to methotrexate soon after RA diagnosis may benefit most from adding adalimumab, they said.

“Furthermore, these findings should be considered in future trials when defining inclusion criteria not only by duration of disease but also by number of prior DMARDs,” they concluded.

The study was sponsored by AbbVie, which markets adalimumab. Dr. Aletaha disclosed grants and consulting fees from AbbVie, as well as other pharmaceutical companies. Four of the authors were current or former employees of AbbVie, and some other authors also reported financial relationships with the company.

SOURCE: Aletaha D et al. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019 Aug 21. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-214918.

A history of using multiple conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) is a key predictor for poorer response to adalimumab therapy in rheumatoid arthritis patients, according to data from a pair of studies with a total of 274 patients.

Although patients with RA who have failed methotrexate or tumor necrosis factor inhibitor therapy respond less than methotrexate-naive patients, “it remains unknown if response to the first biologic DMARD, in particular a [tumor necrosis factor inhibitor], depends on disease duration or prior numbers of failed [conventional synthetic] DMARDs,” wrote Daniel Aletaha, MD, of the Medical University of Vienna and colleagues.

In a study published in Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, the researchers reviewed data from two randomized, controlled trials of patients with RA. In the larger trial of 207 adults (known as DE019), past use of two or more conventional synthetic DMARDs was associated with less improvement in 28-joint Disease Activity Score using C-reactive protein (DAS28-CRP) after 24 weeks of adalimumab (Humira), compared with use of one or no DMARDs (–1.8 vs. –2.2, respectively). Similarly, disease activity and disability scores improved significantly less in patients who had used two or more DMARDs, compared with those who used one or no DMARDs, according to the Simplified Disease Activity Index (SDAI; –22.1 vs. –26.9) and the Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index (HAQ-DI; –0.43 vs. –0.64).

The researchers also examined the role of disease duration on treatment response. Overall, patients with disease duration greater than 10 years showed more improvement at 24 weeks than did those with disease duration less than 1 year, based on HAQ-DI scores (1.1 vs. 0.7), but final scores on the SDAI and DAS28-CRP were not significantly different between those with disease duration greater than 10 years and those with duration of less than 1 year. These results suggest that the impact of DMARDs holds true regardless of disease duration, the researchers noted.

The findings were similar with regard to number of prior conventional synthetic DMARDs and the effects of disease duration in the second trial of 67 patients, known as the ARMADA study.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the post hoc analysis design, use of only adalimumab data, and the small number of patients in several subgroups, the researchers noted. However, the results support the need for more standardized treatment guidelines and suggest that RA patients who fail to respond to methotrexate soon after RA diagnosis may benefit most from adding adalimumab, they said.

“Furthermore, these findings should be considered in future trials when defining inclusion criteria not only by duration of disease but also by number of prior DMARDs,” they concluded.

The study was sponsored by AbbVie, which markets adalimumab. Dr. Aletaha disclosed grants and consulting fees from AbbVie, as well as other pharmaceutical companies. Four of the authors were current or former employees of AbbVie, and some other authors also reported financial relationships with the company.

SOURCE: Aletaha D et al. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019 Aug 21. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-214918.

A history of using multiple conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) is a key predictor for poorer response to adalimumab therapy in rheumatoid arthritis patients, according to data from a pair of studies with a total of 274 patients.

Although patients with RA who have failed methotrexate or tumor necrosis factor inhibitor therapy respond less than methotrexate-naive patients, “it remains unknown if response to the first biologic DMARD, in particular a [tumor necrosis factor inhibitor], depends on disease duration or prior numbers of failed [conventional synthetic] DMARDs,” wrote Daniel Aletaha, MD, of the Medical University of Vienna and colleagues.

In a study published in Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, the researchers reviewed data from two randomized, controlled trials of patients with RA. In the larger trial of 207 adults (known as DE019), past use of two or more conventional synthetic DMARDs was associated with less improvement in 28-joint Disease Activity Score using C-reactive protein (DAS28-CRP) after 24 weeks of adalimumab (Humira), compared with use of one or no DMARDs (–1.8 vs. –2.2, respectively). Similarly, disease activity and disability scores improved significantly less in patients who had used two or more DMARDs, compared with those who used one or no DMARDs, according to the Simplified Disease Activity Index (SDAI; –22.1 vs. –26.9) and the Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index (HAQ-DI; –0.43 vs. –0.64).

The researchers also examined the role of disease duration on treatment response. Overall, patients with disease duration greater than 10 years showed more improvement at 24 weeks than did those with disease duration less than 1 year, based on HAQ-DI scores (1.1 vs. 0.7), but final scores on the SDAI and DAS28-CRP were not significantly different between those with disease duration greater than 10 years and those with duration of less than 1 year. These results suggest that the impact of DMARDs holds true regardless of disease duration, the researchers noted.

The findings were similar with regard to number of prior conventional synthetic DMARDs and the effects of disease duration in the second trial of 67 patients, known as the ARMADA study.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the post hoc analysis design, use of only adalimumab data, and the small number of patients in several subgroups, the researchers noted. However, the results support the need for more standardized treatment guidelines and suggest that RA patients who fail to respond to methotrexate soon after RA diagnosis may benefit most from adding adalimumab, they said.

“Furthermore, these findings should be considered in future trials when defining inclusion criteria not only by duration of disease but also by number of prior DMARDs,” they concluded.

The study was sponsored by AbbVie, which markets adalimumab. Dr. Aletaha disclosed grants and consulting fees from AbbVie, as well as other pharmaceutical companies. Four of the authors were current or former employees of AbbVie, and some other authors also reported financial relationships with the company.

SOURCE: Aletaha D et al. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019 Aug 21. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-214918.

FROM ANNALS OF THE RHEUMATIC DISEASES

Zoledronic acid reduces symptomatic periodontal disease in patients with osteoporosis

according to Akira Taguchi, DDS, PhD, of the department of oral and maxillofacial radiology at Matsumoto Dental University, Nagano, Japan, and associates.

In a study published in Menopause, the investigators retrospectively analyzed 542 men and women with osteoporosis who participated in the randomized ZONE (Zoledronate Treatment in Efficacy to Osteoporosis) trial. Patients received either zoledronic acid (n = 258) or placebo (n = 284) once yearly for 2 years by IV infusion; mean age was 74 years in both groups. Patients were instructed to maintain good oral health at baseline and every 3 months afterward. Participants with signs or symptoms involving the oral cavity at the follow-up approximately every 3 months were referred to dentists for examination of oral disease.

Oral adverse events were significantly more common in the placebo group, compared with the zoledronic acid group (20% vs. 14%; P = .04); incidence of symptomatic periodontal disease also was significantly more common in those receiving placebo (12% vs. 5%; P = .002). While loss of teeth was more common in the control group than in those receiving zoledronic acid (11% vs. 7%), the difference was not significant.

“Because zoledronic acid can prevent symptomatic periodontal disease when combined with good oral hygiene management, it is possible that the procedures performed in this study could eventually suppress the development of [osteonecrosis of the jaw],” the investigators concluded.

The study was funded by Asahi-Kasei Pharma. The investigators reported employment or receiving consulting fees from numerous pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Taguchi A et al. Menopause. 2019 Aug 19. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000001393.

according to Akira Taguchi, DDS, PhD, of the department of oral and maxillofacial radiology at Matsumoto Dental University, Nagano, Japan, and associates.

In a study published in Menopause, the investigators retrospectively analyzed 542 men and women with osteoporosis who participated in the randomized ZONE (Zoledronate Treatment in Efficacy to Osteoporosis) trial. Patients received either zoledronic acid (n = 258) or placebo (n = 284) once yearly for 2 years by IV infusion; mean age was 74 years in both groups. Patients were instructed to maintain good oral health at baseline and every 3 months afterward. Participants with signs or symptoms involving the oral cavity at the follow-up approximately every 3 months were referred to dentists for examination of oral disease.

Oral adverse events were significantly more common in the placebo group, compared with the zoledronic acid group (20% vs. 14%; P = .04); incidence of symptomatic periodontal disease also was significantly more common in those receiving placebo (12% vs. 5%; P = .002). While loss of teeth was more common in the control group than in those receiving zoledronic acid (11% vs. 7%), the difference was not significant.

“Because zoledronic acid can prevent symptomatic periodontal disease when combined with good oral hygiene management, it is possible that the procedures performed in this study could eventually suppress the development of [osteonecrosis of the jaw],” the investigators concluded.

The study was funded by Asahi-Kasei Pharma. The investigators reported employment or receiving consulting fees from numerous pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Taguchi A et al. Menopause. 2019 Aug 19. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000001393.

according to Akira Taguchi, DDS, PhD, of the department of oral and maxillofacial radiology at Matsumoto Dental University, Nagano, Japan, and associates.

In a study published in Menopause, the investigators retrospectively analyzed 542 men and women with osteoporosis who participated in the randomized ZONE (Zoledronate Treatment in Efficacy to Osteoporosis) trial. Patients received either zoledronic acid (n = 258) or placebo (n = 284) once yearly for 2 years by IV infusion; mean age was 74 years in both groups. Patients were instructed to maintain good oral health at baseline and every 3 months afterward. Participants with signs or symptoms involving the oral cavity at the follow-up approximately every 3 months were referred to dentists for examination of oral disease.

Oral adverse events were significantly more common in the placebo group, compared with the zoledronic acid group (20% vs. 14%; P = .04); incidence of symptomatic periodontal disease also was significantly more common in those receiving placebo (12% vs. 5%; P = .002). While loss of teeth was more common in the control group than in those receiving zoledronic acid (11% vs. 7%), the difference was not significant.

“Because zoledronic acid can prevent symptomatic periodontal disease when combined with good oral hygiene management, it is possible that the procedures performed in this study could eventually suppress the development of [osteonecrosis of the jaw],” the investigators concluded.

The study was funded by Asahi-Kasei Pharma. The investigators reported employment or receiving consulting fees from numerous pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Taguchi A et al. Menopause. 2019 Aug 19. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000001393.

FROM MENOPAUSE

Zoledronate maintains bone loss after denosumab discontinuation

Women with postmenopausal osteoporosis who discontinued denosumab treatment after achieving osteopenia maintained bone mineral density at the spine and hip with a single infusion of zoledronate given 6 months after the last infusion of denosumab, according to results from a small, multicenter, randomized trial published in the Journal of Bone and Mineral Research.

The cessation of the monoclonal antibody denosumab is typically followed by a “rebound phenomenon” often attributed to an increase in bone turnover above pretreatment values caused by the up-regulation of osteoclastogenesis, according to Athanasios D. Anastasilakis, MD, of 424 General Military Hospital, Thessaloníki, Greece, and colleagues. Guidelines recommend that patients take a bisphosphonate to prevent this effect, but the optimal bisphosphonate regimen is unknown and evidence is inconsistent.

To address this question, the investigators randomized 57 postmenopausal women with osteoporosis who had received six monthly injections of denosumab (for an average of 2.2 years) and had achieved nonosteoporotic bone mineral density (BMD) T scores greater than –2.5 but no greater than –1 at the hip or the spine. A total of 27 received a single IV infusion of zoledronate 5 mg given 6 months after the last denosumab injection with a 3-week window, and 30 continued denosumab and received two additional monthly 60-mg injections. Following either the zoledronate infusion or the last denosumab injection, all women received no treatment and were followed until 2 years from randomization. All women were given vitamin D supplements and were seen in clinic appointments at baseline, 6, 12, 15, 18, and 24 months.

Areal BMD of the lumbar spine and femoral neck of the nondominant hip were measured at baseline, 12, and 24 months by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry, and least significant changes were 5% or less at the spine and 4% or less at the femoral neck, based on proposals from the International Foundation for Osteoporosis and the National Osteoporosis Foundation USA.

At 24 months, lumbar spine BMD (LS‐BMD) returned to baseline in the zoledronate group, but decreased in the denosumab group by 4.82% from the 12‐month value (P less than .001).

The difference in LS-BMD changes between the two groups from month 12 to 24, the primary endpoint of the study, was statistically significant (–0.018 with zoledronate vs. –0.045 with denosumab; P = .025). Differences in changes of femoral neck BMD were also statistically significant (–0.004 with zoledronate vs. –0.038 with denosumab; P = .005), the researchers reported.

The differences in BMD changes between the two groups 24 and 12 months after discontinuation of denosumab (6 months after the last injection) for the zoledronate and denosumab group respectively were also statistically significant both at the lumbar spine (–0.002 with zoledronate vs. –0.045 with denosumab; P = .03) and at the femoral neck (–0.004 with zoledronate vs. –0.038 with denosumab; P = .007).