User login

VIDEO: Recognizing the systemic impact of rosacea

LAS VEGAS – At its core, “we understand that rosacea is an inflammatory disease,” Linda Stein Gold, MD, said at the Skin Disease Education Foundation’s annual Las Vegas Dermatology Seminar.

As with psoriasis, she added, “we understand that rosacea might have some systemic implications.”

In fact, data suggest that cardiovascular disease is independently associated with rosacea after controlling for multiple variables, she noted. “So we now believe it’s important to get the inflammation under control, not just for the skin, but for the body as a whole,” Dr. Stein Gold, director of dermatology research, Henry Ford Health System, Detroit, said in a video interview.

She disclosed receiving research support, serving as a consultant, serving on the speakers bureau, and/or serving on the scientific advisory board for multiple pharmaceutical companies.

SDEF and this organization are owned by the same parent company.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

LAS VEGAS – At its core, “we understand that rosacea is an inflammatory disease,” Linda Stein Gold, MD, said at the Skin Disease Education Foundation’s annual Las Vegas Dermatology Seminar.

As with psoriasis, she added, “we understand that rosacea might have some systemic implications.”

In fact, data suggest that cardiovascular disease is independently associated with rosacea after controlling for multiple variables, she noted. “So we now believe it’s important to get the inflammation under control, not just for the skin, but for the body as a whole,” Dr. Stein Gold, director of dermatology research, Henry Ford Health System, Detroit, said in a video interview.

She disclosed receiving research support, serving as a consultant, serving on the speakers bureau, and/or serving on the scientific advisory board for multiple pharmaceutical companies.

SDEF and this organization are owned by the same parent company.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

LAS VEGAS – At its core, “we understand that rosacea is an inflammatory disease,” Linda Stein Gold, MD, said at the Skin Disease Education Foundation’s annual Las Vegas Dermatology Seminar.

As with psoriasis, she added, “we understand that rosacea might have some systemic implications.”

In fact, data suggest that cardiovascular disease is independently associated with rosacea after controlling for multiple variables, she noted. “So we now believe it’s important to get the inflammation under control, not just for the skin, but for the body as a whole,” Dr. Stein Gold, director of dermatology research, Henry Ford Health System, Detroit, said in a video interview.

She disclosed receiving research support, serving as a consultant, serving on the speakers bureau, and/or serving on the scientific advisory board for multiple pharmaceutical companies.

SDEF and this organization are owned by the same parent company.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

EXPERT ANALYSIS AT SDEF LAS VEGAS DERMATOLOGY SEMINAR

Cosmetic Corner: Dermatologists Weigh in on OTC Rosacea Treatments

To improve patient care and outcomes, leading dermatologists offered their recommendations on OTC rosacea treatments. Consideration must be given to:

- Eucerin Redness Relief

Beiersdorf Inc

Recommended by Gary Goldenberg, MD, New York, New York

- Rosaliac CC Cream

La Roche-Posay Laboratoire Dermatologique

“This product provides hydration and an even tint to correct and reduce the erythema of rosacea. It is made with both titanium dioxide and organic UV filters to give broad-spectrum coverage with SPF 30.”—Cherise Mizrahi-Levi, DO, New York, New York

- Vanicream

Pharmaceutical Specialties, Inc.

“I like Vanicream products since they are mild and hypoallergenic.”—Gary Goldenberg, MD, New York, New York

Cutis invites readers to send us their recommendations. Cleansing devices, skin-lightening agents, and self-tanners will be featured in upcoming editions of Cosmetic Corner. Please e-mail your recommendation(s) to the Editorial Office.

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect those of Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. and shall not be used for product endorsement purposes. Any reference made to a specific commercial product does not indicate or imply that Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. endorses, recommends, or favors the product mentioned. No guarantee is given to the effects of recommended products.

To improve patient care and outcomes, leading dermatologists offered their recommendations on OTC rosacea treatments. Consideration must be given to:

- Eucerin Redness Relief

Beiersdorf Inc

Recommended by Gary Goldenberg, MD, New York, New York

- Rosaliac CC Cream

La Roche-Posay Laboratoire Dermatologique

“This product provides hydration and an even tint to correct and reduce the erythema of rosacea. It is made with both titanium dioxide and organic UV filters to give broad-spectrum coverage with SPF 30.”—Cherise Mizrahi-Levi, DO, New York, New York

- Vanicream

Pharmaceutical Specialties, Inc.

“I like Vanicream products since they are mild and hypoallergenic.”—Gary Goldenberg, MD, New York, New York

Cutis invites readers to send us their recommendations. Cleansing devices, skin-lightening agents, and self-tanners will be featured in upcoming editions of Cosmetic Corner. Please e-mail your recommendation(s) to the Editorial Office.

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect those of Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. and shall not be used for product endorsement purposes. Any reference made to a specific commercial product does not indicate or imply that Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. endorses, recommends, or favors the product mentioned. No guarantee is given to the effects of recommended products.

To improve patient care and outcomes, leading dermatologists offered their recommendations on OTC rosacea treatments. Consideration must be given to:

- Eucerin Redness Relief

Beiersdorf Inc

Recommended by Gary Goldenberg, MD, New York, New York

- Rosaliac CC Cream

La Roche-Posay Laboratoire Dermatologique

“This product provides hydration and an even tint to correct and reduce the erythema of rosacea. It is made with both titanium dioxide and organic UV filters to give broad-spectrum coverage with SPF 30.”—Cherise Mizrahi-Levi, DO, New York, New York

- Vanicream

Pharmaceutical Specialties, Inc.

“I like Vanicream products since they are mild and hypoallergenic.”—Gary Goldenberg, MD, New York, New York

Cutis invites readers to send us their recommendations. Cleansing devices, skin-lightening agents, and self-tanners will be featured in upcoming editions of Cosmetic Corner. Please e-mail your recommendation(s) to the Editorial Office.

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect those of Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. and shall not be used for product endorsement purposes. Any reference made to a specific commercial product does not indicate or imply that Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. endorses, recommends, or favors the product mentioned. No guarantee is given to the effects of recommended products.

NRS awards grants for rosacea studies

The National Rosacea Society (NRS) is awarding funding to three new studies and continuing funding for two ongoing studies on topics that include the impact of epigenetics on rosacea, the society announced.

The first study, by Dr. Luis Garza at John Hopkins University, Baltimore, will examine epigenetic lesions in rosacea. Epigenetics, the study of how DNA can be modified to act in certain ways, “may be responsible for why rosacea persists even though keratinocytes … slough off and are replaced every 2 months,” the NRS said in a written statement.

The second study, by Dr. Wenqing Li of Brown University, Providence, R.I., will use data from the Nurses’ Health Study II to examine how hormone use and hormone levels during menopause and pregnancy affect the risk of developing rosacea.

The third study, by Dr. Anna Di Nardo of the University of California, San Diego, and her associates, is looking at “whether the release of cathelicidin antimicrobial peptides, key players in the body’s normal innate immune system response, is central to the connection between the nervous system and skin inflammation through the activation of mast cells in rosacea,” the NRS statement noted.

Ongoing studies that also are receiving funding include work by Dr. Gideon Smith of Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and his associates, who are examining the risk of vascular disorders in people with rosacea, and a study by Dr. Lori Lee Stohl of Cornell University, New York, who is researching how stress-related biochemicals can increase mast-cell count.

“Research supported by the NRS has led to important insights into the physiology of the disorder, providing an essential foundation for developing new and better treatments. In addition, our growing knowledge is now pointing toward potentially meaningful connections between rosacea and other systemic illnesses,” Dr. Martin Steinhoff, chairman of dermatology and director of the Charles Institute of Dermatology, University College, Dublin, and a member of the NRS Medical Advisory Board, said in the statement.

Find the full NRS statement on the society’s website.

The National Rosacea Society (NRS) is awarding funding to three new studies and continuing funding for two ongoing studies on topics that include the impact of epigenetics on rosacea, the society announced.

The first study, by Dr. Luis Garza at John Hopkins University, Baltimore, will examine epigenetic lesions in rosacea. Epigenetics, the study of how DNA can be modified to act in certain ways, “may be responsible for why rosacea persists even though keratinocytes … slough off and are replaced every 2 months,” the NRS said in a written statement.

The second study, by Dr. Wenqing Li of Brown University, Providence, R.I., will use data from the Nurses’ Health Study II to examine how hormone use and hormone levels during menopause and pregnancy affect the risk of developing rosacea.

The third study, by Dr. Anna Di Nardo of the University of California, San Diego, and her associates, is looking at “whether the release of cathelicidin antimicrobial peptides, key players in the body’s normal innate immune system response, is central to the connection between the nervous system and skin inflammation through the activation of mast cells in rosacea,” the NRS statement noted.

Ongoing studies that also are receiving funding include work by Dr. Gideon Smith of Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and his associates, who are examining the risk of vascular disorders in people with rosacea, and a study by Dr. Lori Lee Stohl of Cornell University, New York, who is researching how stress-related biochemicals can increase mast-cell count.

“Research supported by the NRS has led to important insights into the physiology of the disorder, providing an essential foundation for developing new and better treatments. In addition, our growing knowledge is now pointing toward potentially meaningful connections between rosacea and other systemic illnesses,” Dr. Martin Steinhoff, chairman of dermatology and director of the Charles Institute of Dermatology, University College, Dublin, and a member of the NRS Medical Advisory Board, said in the statement.

Find the full NRS statement on the society’s website.

The National Rosacea Society (NRS) is awarding funding to three new studies and continuing funding for two ongoing studies on topics that include the impact of epigenetics on rosacea, the society announced.

The first study, by Dr. Luis Garza at John Hopkins University, Baltimore, will examine epigenetic lesions in rosacea. Epigenetics, the study of how DNA can be modified to act in certain ways, “may be responsible for why rosacea persists even though keratinocytes … slough off and are replaced every 2 months,” the NRS said in a written statement.

The second study, by Dr. Wenqing Li of Brown University, Providence, R.I., will use data from the Nurses’ Health Study II to examine how hormone use and hormone levels during menopause and pregnancy affect the risk of developing rosacea.

The third study, by Dr. Anna Di Nardo of the University of California, San Diego, and her associates, is looking at “whether the release of cathelicidin antimicrobial peptides, key players in the body’s normal innate immune system response, is central to the connection between the nervous system and skin inflammation through the activation of mast cells in rosacea,” the NRS statement noted.

Ongoing studies that also are receiving funding include work by Dr. Gideon Smith of Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and his associates, who are examining the risk of vascular disorders in people with rosacea, and a study by Dr. Lori Lee Stohl of Cornell University, New York, who is researching how stress-related biochemicals can increase mast-cell count.

“Research supported by the NRS has led to important insights into the physiology of the disorder, providing an essential foundation for developing new and better treatments. In addition, our growing knowledge is now pointing toward potentially meaningful connections between rosacea and other systemic illnesses,” Dr. Martin Steinhoff, chairman of dermatology and director of the Charles Institute of Dermatology, University College, Dublin, and a member of the NRS Medical Advisory Board, said in the statement.

Find the full NRS statement on the society’s website.

Experts outline phenotype approach to rosacea

A phenotype approach should be used to diagnose and manage rosacea, according to an expert panel that included 17 dermatologists from North America, Europe, Asia, Africa, and South America.

“As individual treatments do not address multiple features simultaneously, consideration of specific phenotypical issues facilitates individualized optimization of rosacea,” the panel concluded. As individual presentations of rosacea can span more than one of the currently defined disease subtypes, and vary widely in severity, dermatologists have long expressed a need to move to a phenotype-based system for diagnosis and classification.

The goal of the panel was “to establish international consensus on diagnosis and severity determination to improve outcomes” for people with rosacea (Br J Dermatol. 2016 Oct 8. doi: 10.1111/bjd.15122).

Jerry L. Tan, MD, of the University of Western Ontario, Windsor, and coauthors, explained why they considered a transition to the phenotype-based approach important: “Subtype classification may not fully cover the range of clinical presentations and is likely to confound severity assessment, whereas a phenotype-based approach could improve patient outcomes by addressing an individual patient’s clinical presentation and concerns.”

The panel identified two phenotypes as independently diagnostic of rosacea: persistent, centrofacial erythema associated with periodic intensification, and phymatous changes. Flushing or transient erythema, telangiectasia, inflammatory lesions, and ocular manifestations – the other phenotypes identified in the study – were not considered individually diagnostic.

Severity measurements for each phenotype were defined with a high degree of consensus, and the panel agreed that the severity of each feature should be rated independently and not grouped into subtype. For flushing or transient erythema, for example, the panel recommended that clinicians consider the intensity and frequency of episodes along with the area of involvement. For phymatous changes, inflammation, skin thickening, and deformation were identified as the key severity measures.

Although the investigators acknowledged that their expert consensus was the product of clinical opinion in the absence of extensive evidence, they cited as one of the study’s strengths its broad expert representation across geographical regions, where rosacea presentations may differ. Erythema and telangiectasia, Dr. Tan and colleagues wrote, “may not be visible in skin phototypes V and VI, an issue that may be overcome with experience and appropriate history taking.” They added that “other techniques, including skin biopsy, can also be considered for diagnostic support.” They recommended the development of new validated scales to be used in darker-skinned patients.

The panel also identified the psychosocial impact of rosacea as one severely understudied area of rosacea, and advocated the development of a new research tool that would assess psychological comorbidities. The proposed tool, they wrote, “should go beyond those currently available and assess the psychosocial impact for all major phenotypes.” The only rosacea-specific quality of life scoring measure, RosaQoL, contains notable deficiencies, they noted, including a lack of a measure for phymatous changes.

“Since clinicians and patients often have disparate views of disease,” the researchers wrote, “objective and practical tools based on individual presenting features are likely to be of value in setting treatment targets and monitoring treatment progress for patients with rosacea.”

The panel included three ophthalmologists from Germany and the United States; their recommendations were considered exploratory.

The study, which consisted of both electronic surveys and in-person meetings, was funded by Galderma. Twelve of its coauthors, including Dr. Tan, disclosed financial relationships with manufacturers.

A phenotype approach should be used to diagnose and manage rosacea, according to an expert panel that included 17 dermatologists from North America, Europe, Asia, Africa, and South America.

“As individual treatments do not address multiple features simultaneously, consideration of specific phenotypical issues facilitates individualized optimization of rosacea,” the panel concluded. As individual presentations of rosacea can span more than one of the currently defined disease subtypes, and vary widely in severity, dermatologists have long expressed a need to move to a phenotype-based system for diagnosis and classification.

The goal of the panel was “to establish international consensus on diagnosis and severity determination to improve outcomes” for people with rosacea (Br J Dermatol. 2016 Oct 8. doi: 10.1111/bjd.15122).

Jerry L. Tan, MD, of the University of Western Ontario, Windsor, and coauthors, explained why they considered a transition to the phenotype-based approach important: “Subtype classification may not fully cover the range of clinical presentations and is likely to confound severity assessment, whereas a phenotype-based approach could improve patient outcomes by addressing an individual patient’s clinical presentation and concerns.”

The panel identified two phenotypes as independently diagnostic of rosacea: persistent, centrofacial erythema associated with periodic intensification, and phymatous changes. Flushing or transient erythema, telangiectasia, inflammatory lesions, and ocular manifestations – the other phenotypes identified in the study – were not considered individually diagnostic.

Severity measurements for each phenotype were defined with a high degree of consensus, and the panel agreed that the severity of each feature should be rated independently and not grouped into subtype. For flushing or transient erythema, for example, the panel recommended that clinicians consider the intensity and frequency of episodes along with the area of involvement. For phymatous changes, inflammation, skin thickening, and deformation were identified as the key severity measures.

Although the investigators acknowledged that their expert consensus was the product of clinical opinion in the absence of extensive evidence, they cited as one of the study’s strengths its broad expert representation across geographical regions, where rosacea presentations may differ. Erythema and telangiectasia, Dr. Tan and colleagues wrote, “may not be visible in skin phototypes V and VI, an issue that may be overcome with experience and appropriate history taking.” They added that “other techniques, including skin biopsy, can also be considered for diagnostic support.” They recommended the development of new validated scales to be used in darker-skinned patients.

The panel also identified the psychosocial impact of rosacea as one severely understudied area of rosacea, and advocated the development of a new research tool that would assess psychological comorbidities. The proposed tool, they wrote, “should go beyond those currently available and assess the psychosocial impact for all major phenotypes.” The only rosacea-specific quality of life scoring measure, RosaQoL, contains notable deficiencies, they noted, including a lack of a measure for phymatous changes.

“Since clinicians and patients often have disparate views of disease,” the researchers wrote, “objective and practical tools based on individual presenting features are likely to be of value in setting treatment targets and monitoring treatment progress for patients with rosacea.”

The panel included three ophthalmologists from Germany and the United States; their recommendations were considered exploratory.

The study, which consisted of both electronic surveys and in-person meetings, was funded by Galderma. Twelve of its coauthors, including Dr. Tan, disclosed financial relationships with manufacturers.

A phenotype approach should be used to diagnose and manage rosacea, according to an expert panel that included 17 dermatologists from North America, Europe, Asia, Africa, and South America.

“As individual treatments do not address multiple features simultaneously, consideration of specific phenotypical issues facilitates individualized optimization of rosacea,” the panel concluded. As individual presentations of rosacea can span more than one of the currently defined disease subtypes, and vary widely in severity, dermatologists have long expressed a need to move to a phenotype-based system for diagnosis and classification.

The goal of the panel was “to establish international consensus on diagnosis and severity determination to improve outcomes” for people with rosacea (Br J Dermatol. 2016 Oct 8. doi: 10.1111/bjd.15122).

Jerry L. Tan, MD, of the University of Western Ontario, Windsor, and coauthors, explained why they considered a transition to the phenotype-based approach important: “Subtype classification may not fully cover the range of clinical presentations and is likely to confound severity assessment, whereas a phenotype-based approach could improve patient outcomes by addressing an individual patient’s clinical presentation and concerns.”

The panel identified two phenotypes as independently diagnostic of rosacea: persistent, centrofacial erythema associated with periodic intensification, and phymatous changes. Flushing or transient erythema, telangiectasia, inflammatory lesions, and ocular manifestations – the other phenotypes identified in the study – were not considered individually diagnostic.

Severity measurements for each phenotype were defined with a high degree of consensus, and the panel agreed that the severity of each feature should be rated independently and not grouped into subtype. For flushing or transient erythema, for example, the panel recommended that clinicians consider the intensity and frequency of episodes along with the area of involvement. For phymatous changes, inflammation, skin thickening, and deformation were identified as the key severity measures.

Although the investigators acknowledged that their expert consensus was the product of clinical opinion in the absence of extensive evidence, they cited as one of the study’s strengths its broad expert representation across geographical regions, where rosacea presentations may differ. Erythema and telangiectasia, Dr. Tan and colleagues wrote, “may not be visible in skin phototypes V and VI, an issue that may be overcome with experience and appropriate history taking.” They added that “other techniques, including skin biopsy, can also be considered for diagnostic support.” They recommended the development of new validated scales to be used in darker-skinned patients.

The panel also identified the psychosocial impact of rosacea as one severely understudied area of rosacea, and advocated the development of a new research tool that would assess psychological comorbidities. The proposed tool, they wrote, “should go beyond those currently available and assess the psychosocial impact for all major phenotypes.” The only rosacea-specific quality of life scoring measure, RosaQoL, contains notable deficiencies, they noted, including a lack of a measure for phymatous changes.

“Since clinicians and patients often have disparate views of disease,” the researchers wrote, “objective and practical tools based on individual presenting features are likely to be of value in setting treatment targets and monitoring treatment progress for patients with rosacea.”

The panel included three ophthalmologists from Germany and the United States; their recommendations were considered exploratory.

The study, which consisted of both electronic surveys and in-person meetings, was funded by Galderma. Twelve of its coauthors, including Dr. Tan, disclosed financial relationships with manufacturers.

FROM THE BRITISH JOURNAL OF DERMATOLOGY

Key clinical point: Rosacea diagnosis, severity grading, and management should be based on disease phenotypes, which can span more than one of the currently recognized subtypes.

Major finding: Persistent centrofacial erythema with periodic intensification, and phymatous changes, are two phenotypes independently diagnostic of rosacea

Data source: An expert panel of 17 dermatologists from North America, Europe, Asia, Africa, and South America.

Disclosures: Galderma sponsored the study, for which all authors received honoraria; 12 disclosed additional funding from Galderma or other manufacturers.

Patient-Reported Outcomes of Azelaic Acid Foam 15% for Patients With Papulopustular Rosacea: Secondary Efficacy Results From a Randomized, Controlled, Double-blind, Phase 3 Trial

Rosacea is a chronic inflammatory disorder that may negatively impact patients’ quality of life (QOL).1,2 Papulopustular rosacea (PPR) is characterized by centrofacial inflammatory lesions and erythema as well as burning and stinging secondary to skin barrier dysfunction.3-5 Increasing rosacea severity is associated with greater rates of anxiety and depression and lower QOL6 as well as low self-esteem and feelings of embarrassment.7,8 Accordingly, assessing patient perceptions of rosacea treatments is necessary for understanding its impact on patient health.6,9

The Rosacea International Expert Group has emphasized the need to incorporate patient assessments of disease severity and QOL when developing therapeutic strategies for rosacea.7 Ease of use, sensory experience, and patient preference also are important dimensions in the evaluation of topical medications, as attributes of specific formulations may affect usability, adherence, and efficacy.10,11

An azelaic acid (AzA) 15% foam formulation, which was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2015, was developed to deliver AzA in a vehicle designed to improve treatment experience in patients with mild to moderate PPR.12 Results from a clinical trial demonstrated superiority of AzA foam to vehicle foam for primary end points that included therapeutic success rate and change in inflammatory lesion count.13,14 Secondary end points assessed in the current analysis included patient perception of product usability, efficacy, and effect on QOL. These patient-reported outcome (PRO) results are reported here.

Methods

Study Design

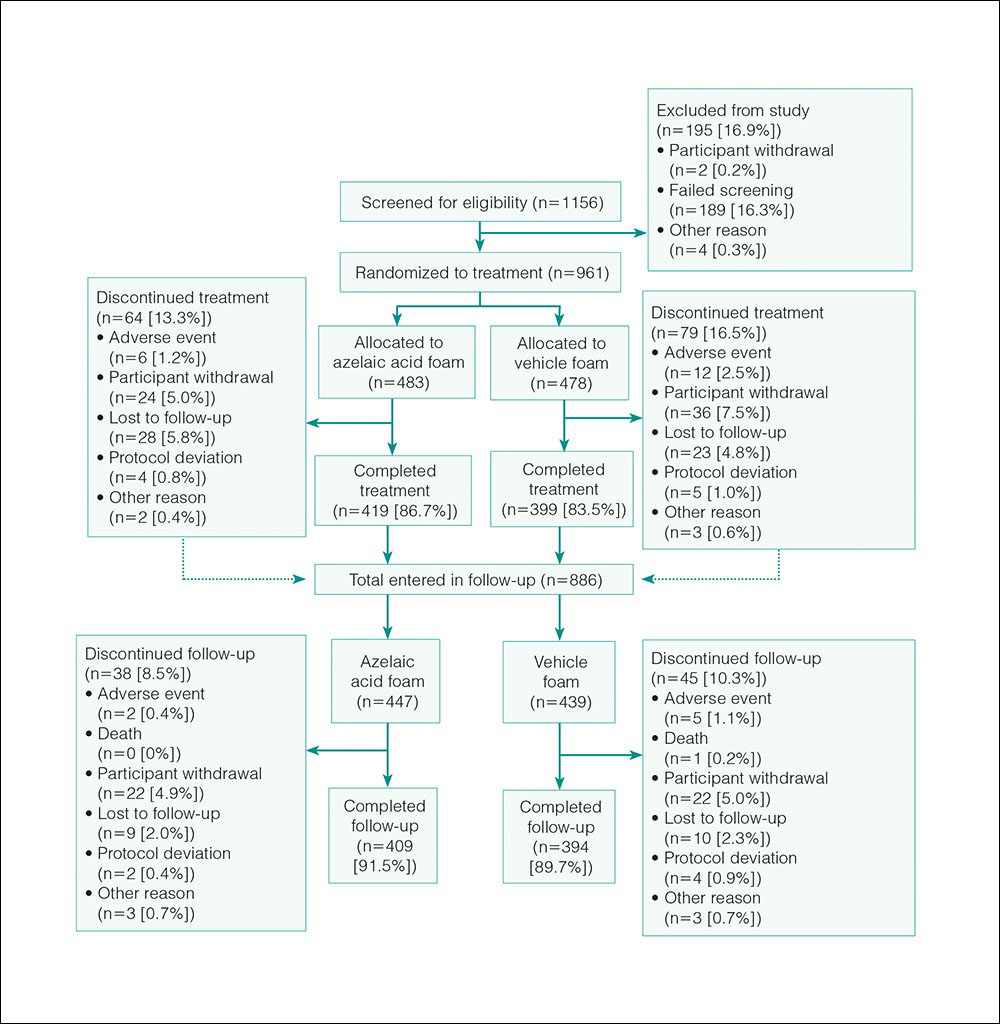

The design of this phase 3 multicenter, randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled, parallel-group clinical trial was described in more detail in an earlier report.13 This study was approved by all appropriate institutional review boards. Eligible participants were 18 years and older with moderate or severe PPR, 12 to 50 inflammatory lesions, and persistent erythema with or without telangiectasia. Exclusion criteria included known nonresponse to AzA, current or prior use (within 6 weeks of randomization) of noninvestigational products to treat rosacea, and presence of other dermatoses that could interfere with rosacea evaluation.

Participants were randomized into the AzA foam or vehicle group (1:1 ratio). The study medication (0.5 g) or vehicle foam was applied twice daily to the entire face until the end of treatment (EoT) at 12 weeks. Efficacy and safety parameters were evaluated at baseline and at 4, 8, and 12 weeks of treatment, and at a follow-up visit 4 weeks after EoT (week 16).

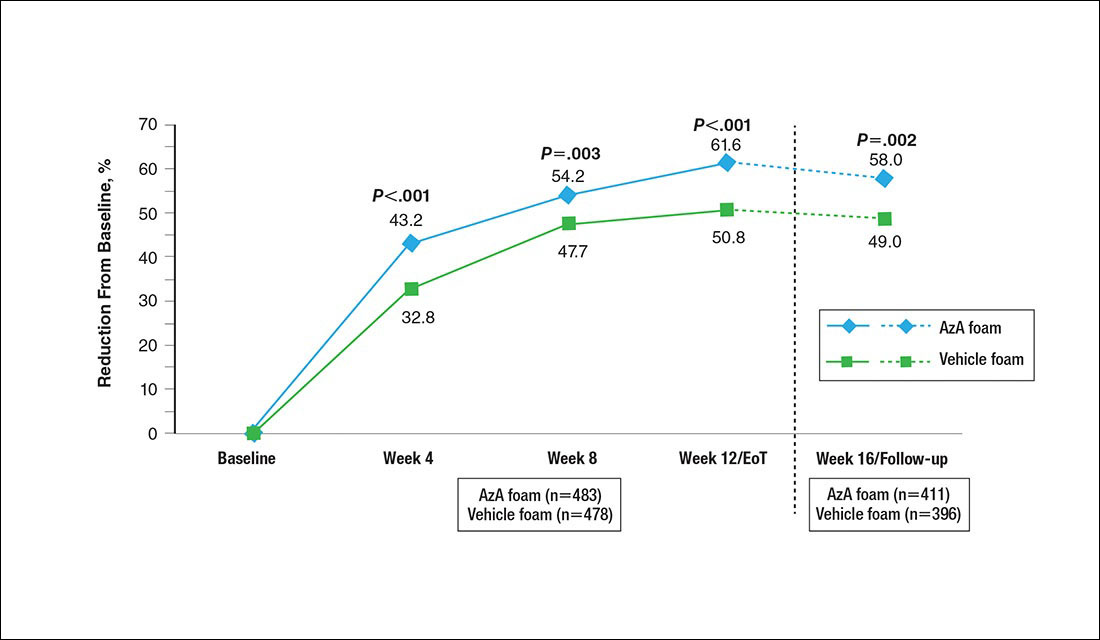

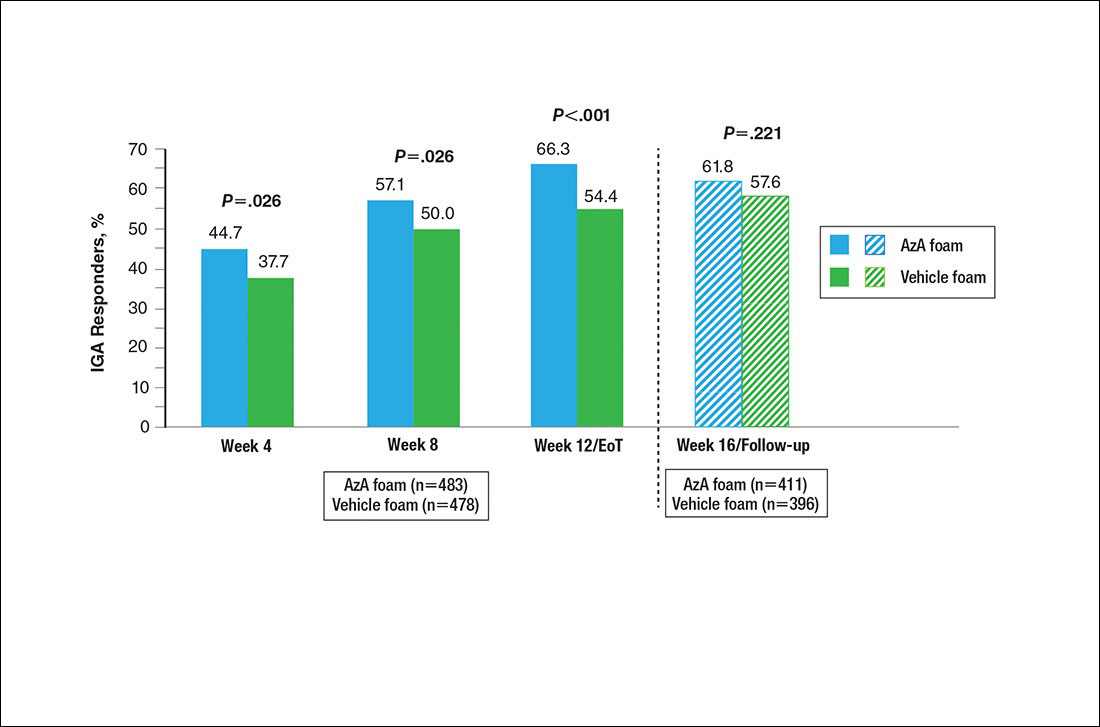

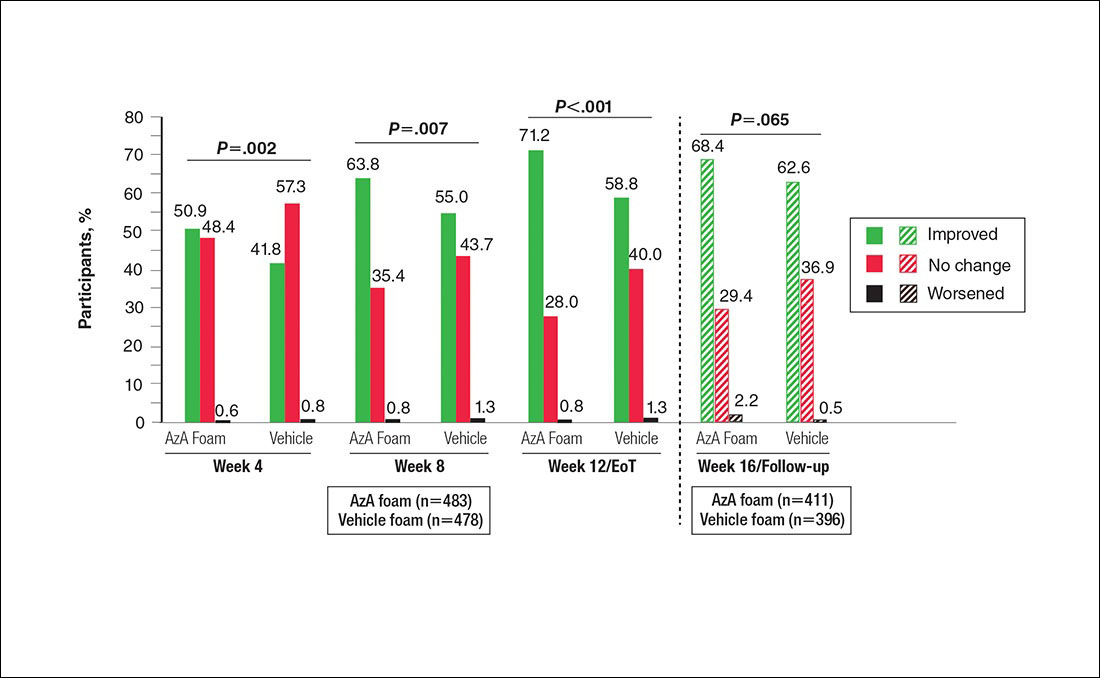

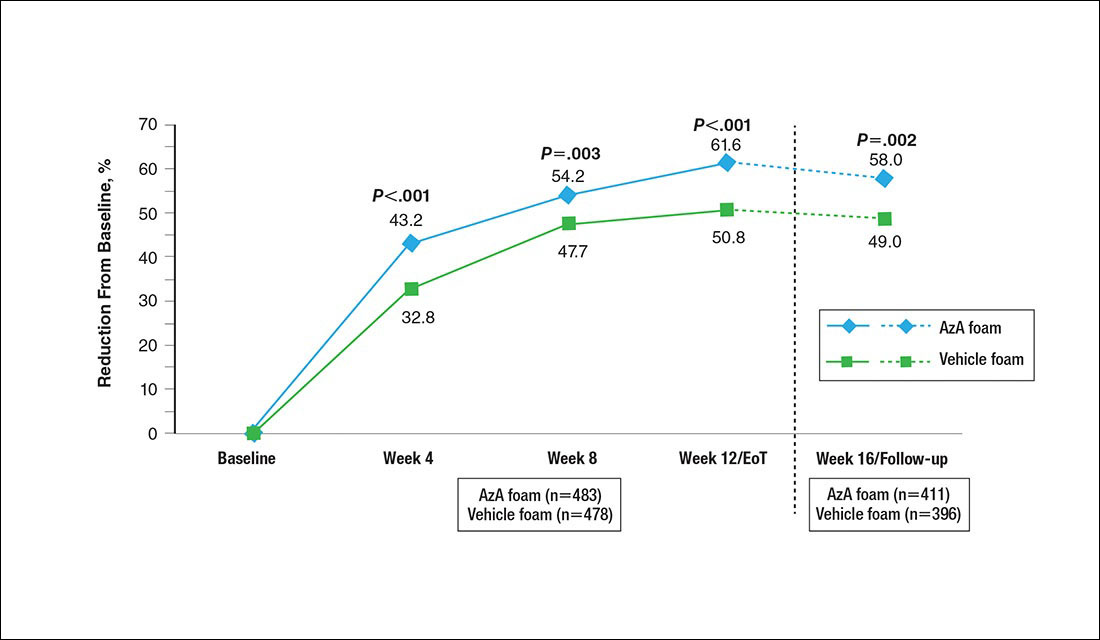

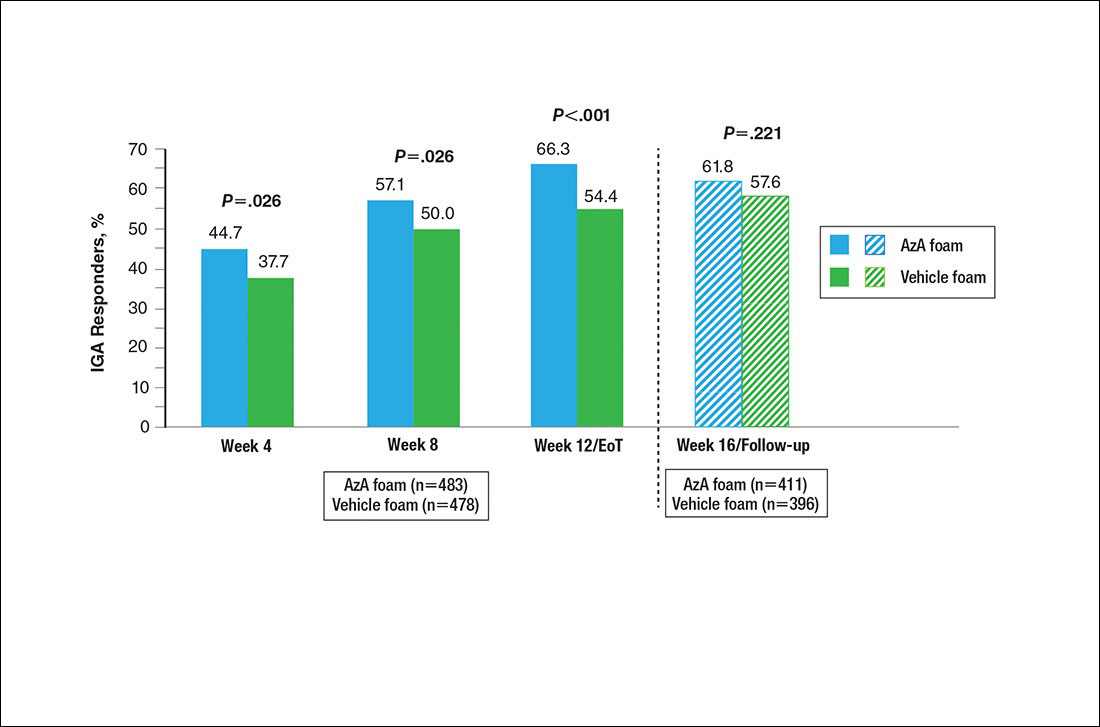

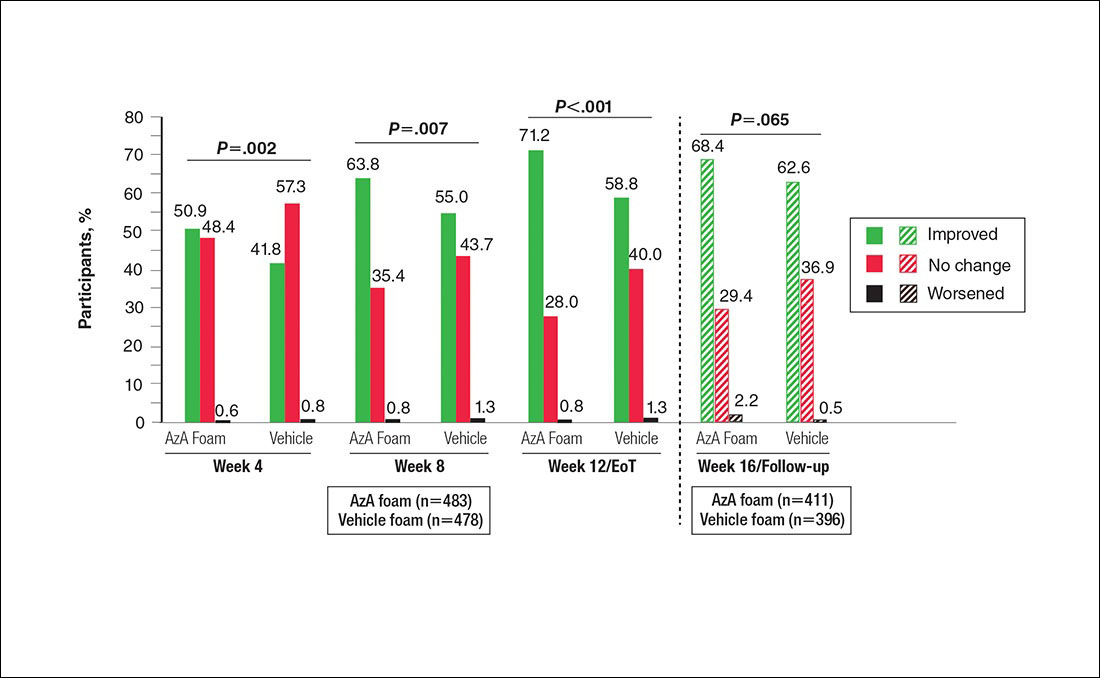

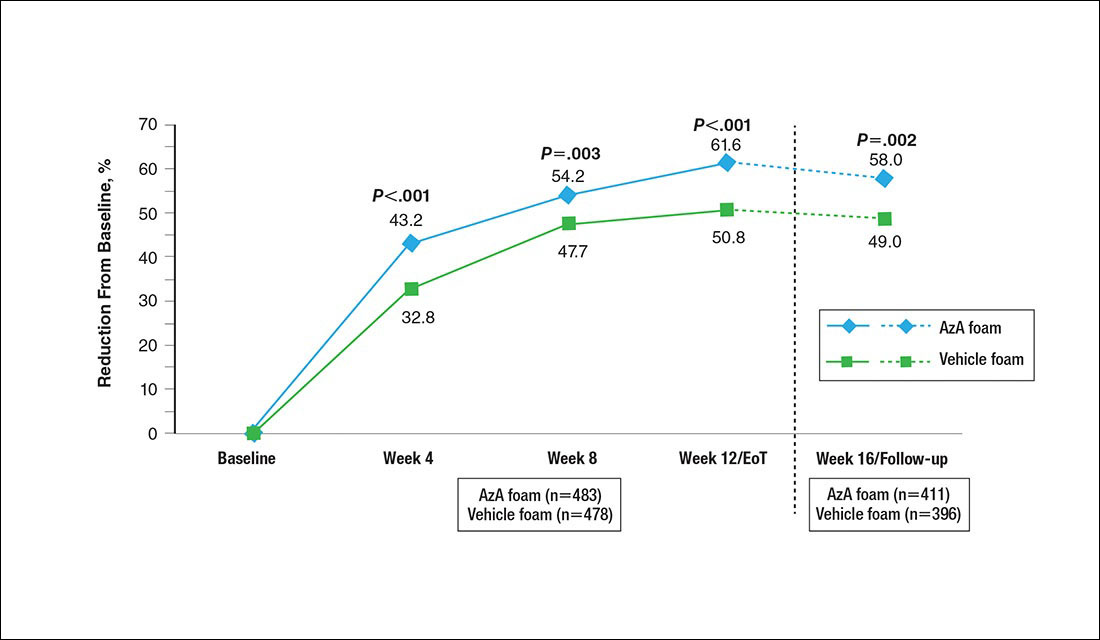

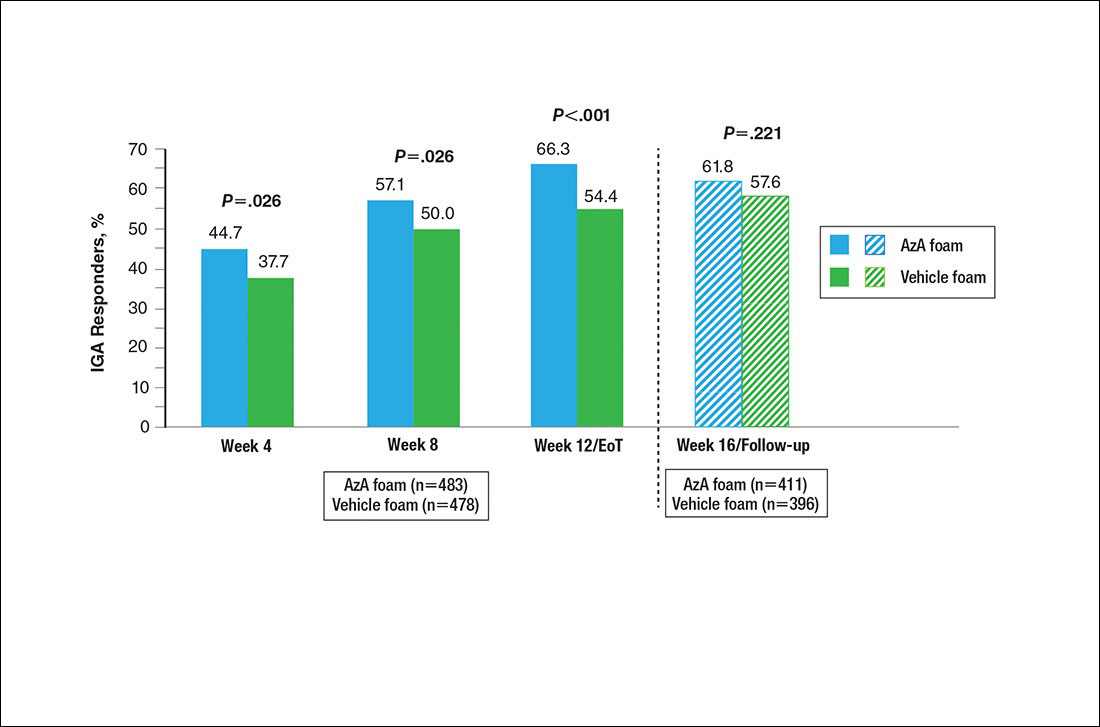

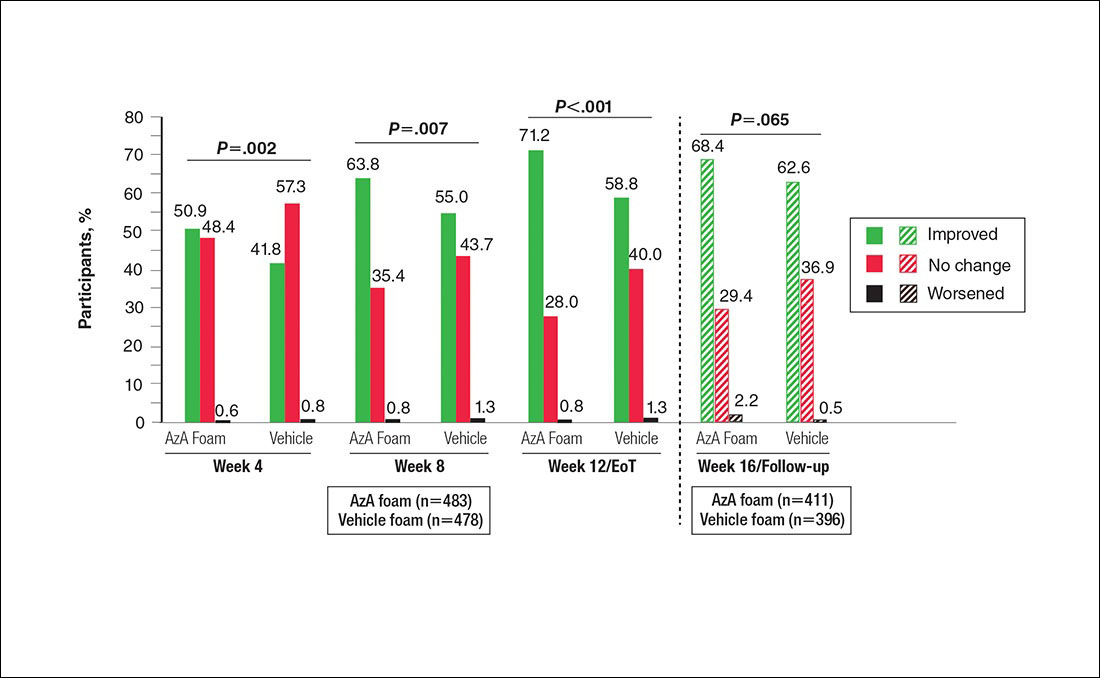

Results for the coprimary efficacy end points—therapeutic success rate according to investigator global assessment and nominal change in inflammatory lesion count—were previously reported,13 as well as secondary efficacy outcomes including change in inflammatory lesion count, therapeutic response rate, and change in erythema rating.14

Patient-Reported Secondary Efficacy Outcomes

The secondary PRO end points were patient-reported global assessment of treatment response (rated as excellent, good, fair, none, or worse), global assessment of tolerability (rated as excellent, good, acceptable despite minor irritation, less acceptable due to continuous irritation, not acceptable, or no opinion), and opinion on cosmetic acceptability and practicability of product use in areas adjacent to the hairline (rated as very good, good, satisfactory, poor, or no opinion).

Additionally, QOL was measured by 3 validated standardized PRO tools, including the Rosacea Quality of Life Index (RosaQOL),15 the EuroQOL 5-dimension 5-level questionnaire (EQ-5D-5L),16 and the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI). The RosaQOL is a rosacea-specific instrument assessing 3 constructs: (1) symptom, (2) emotion, and (3) function. The EQ-5D-5L questionnaire measures overall health status and comprises 5 constructs: (1) mobility, (2) self-care, (3) usual activities, (4) pain/discomfort, and (5) anxiety/depression. The DLQI is a general, dermatology-oriented instrument categorized into 6 constructs: (1) symptoms and feelings, (2) daily activities, (3) leisure, (4) work and school, (5) personal relationships, and (6) treatment.

Statistical Analyses

Patient-reported outcomes were analyzed in an exploratory manner and evaluated at EoT relative to baseline. Self-reported global assessment of treatment response and change in RosaQOL, EQ-5D-5L, and DLQI scores between AzA foam and vehicle foam groups were evaluated using the Wilcoxon rank sum test. Categorical change in the number of participants achieving an increase of 5 or more points in overall DLQI score was evaluated using a χ2 test.

Safety

Safety was analyzed for all randomized patients who were dispensed any study medication. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.2.

Results

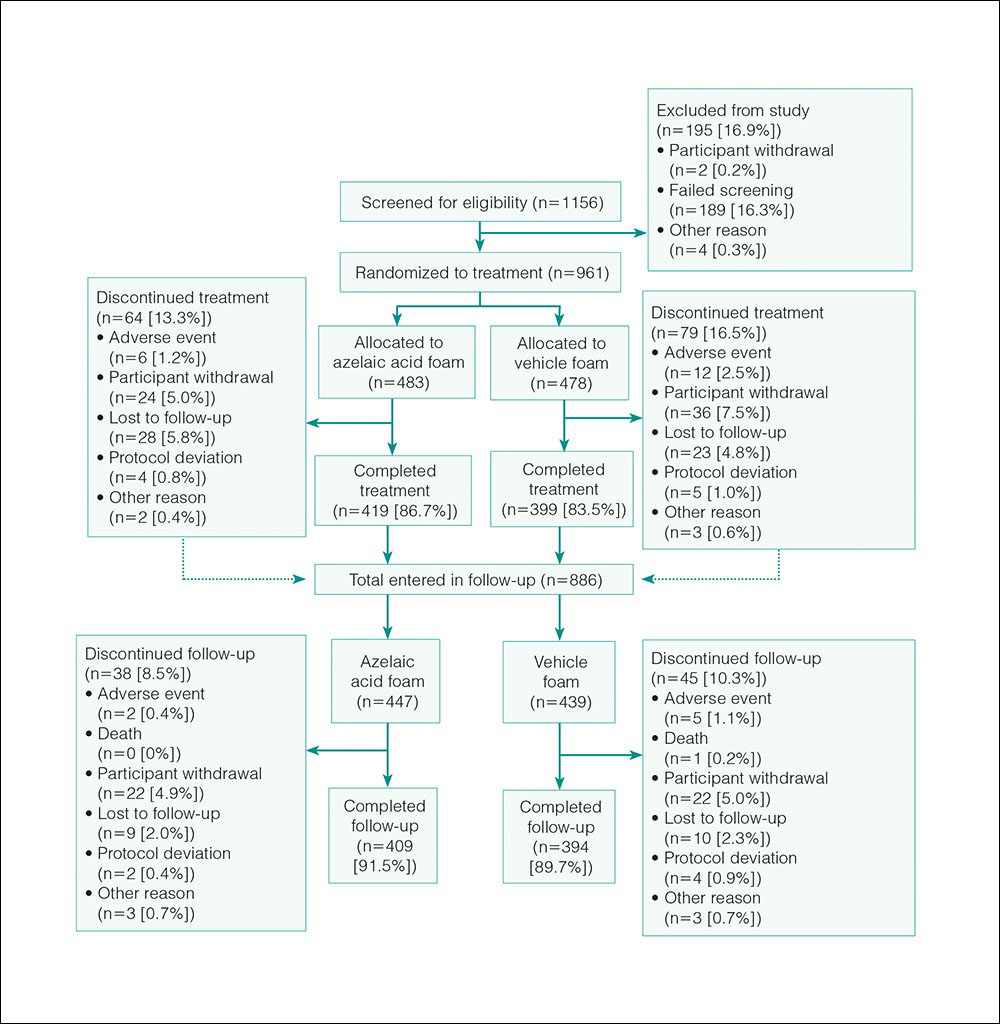

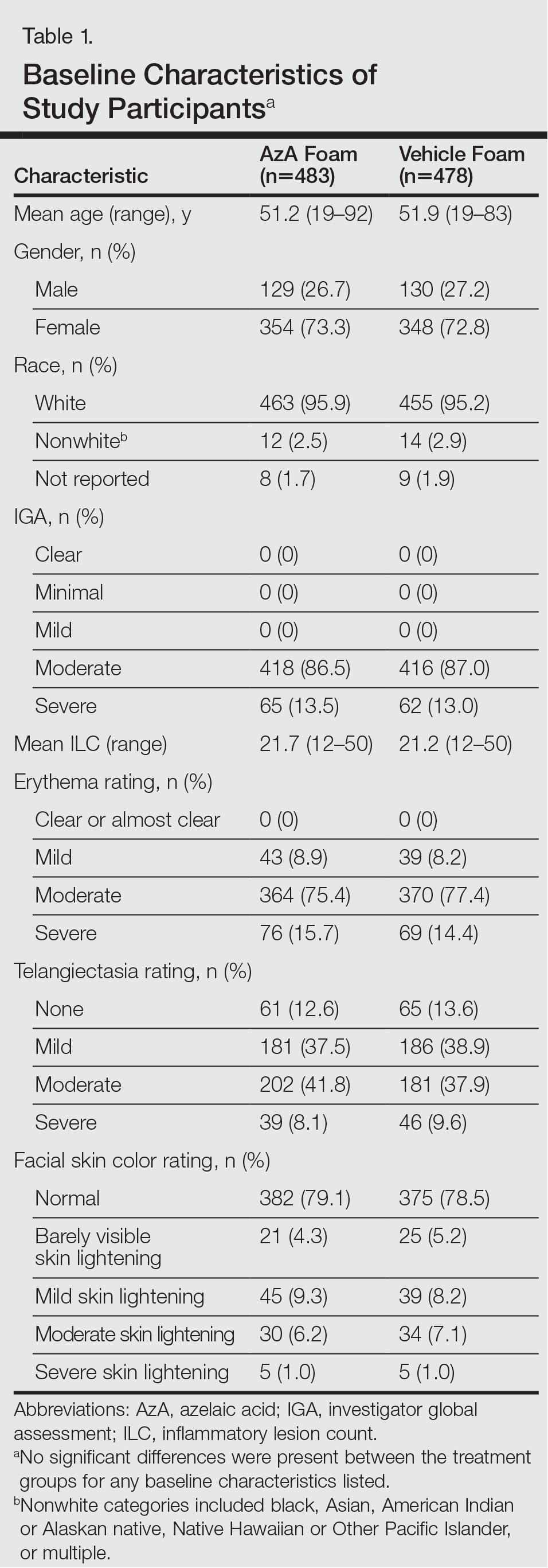

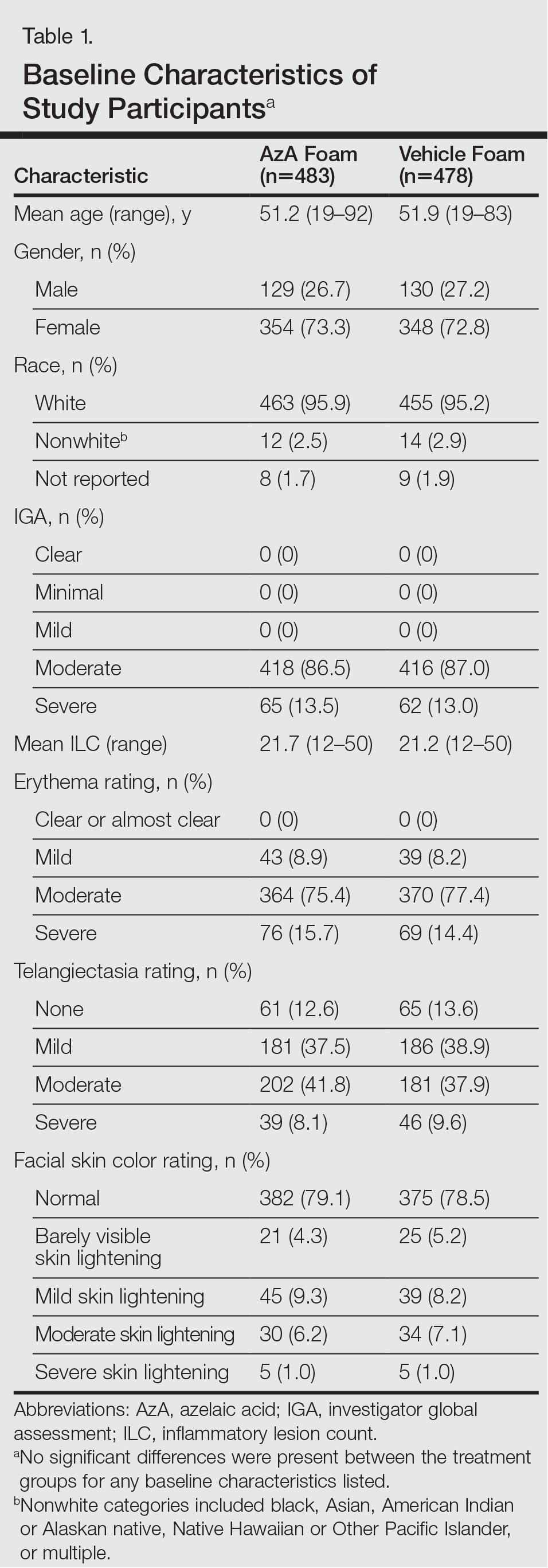

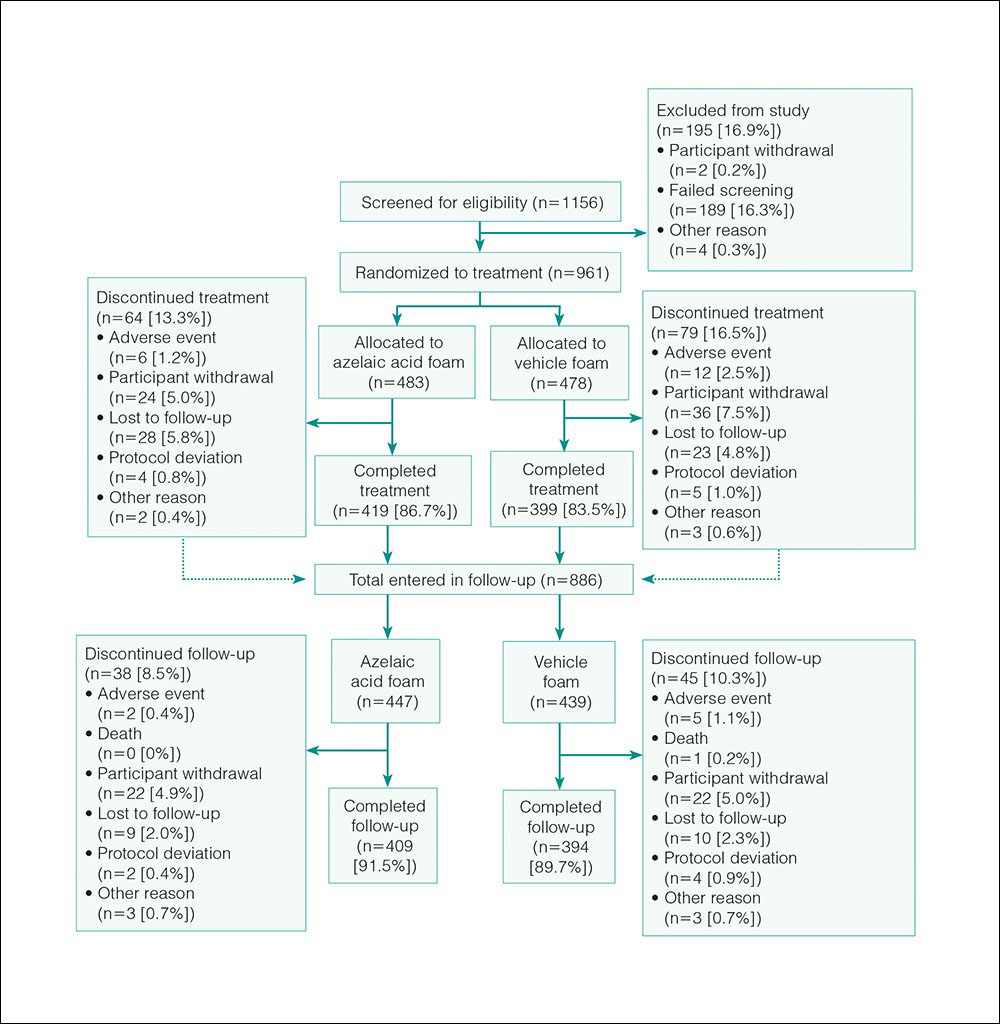

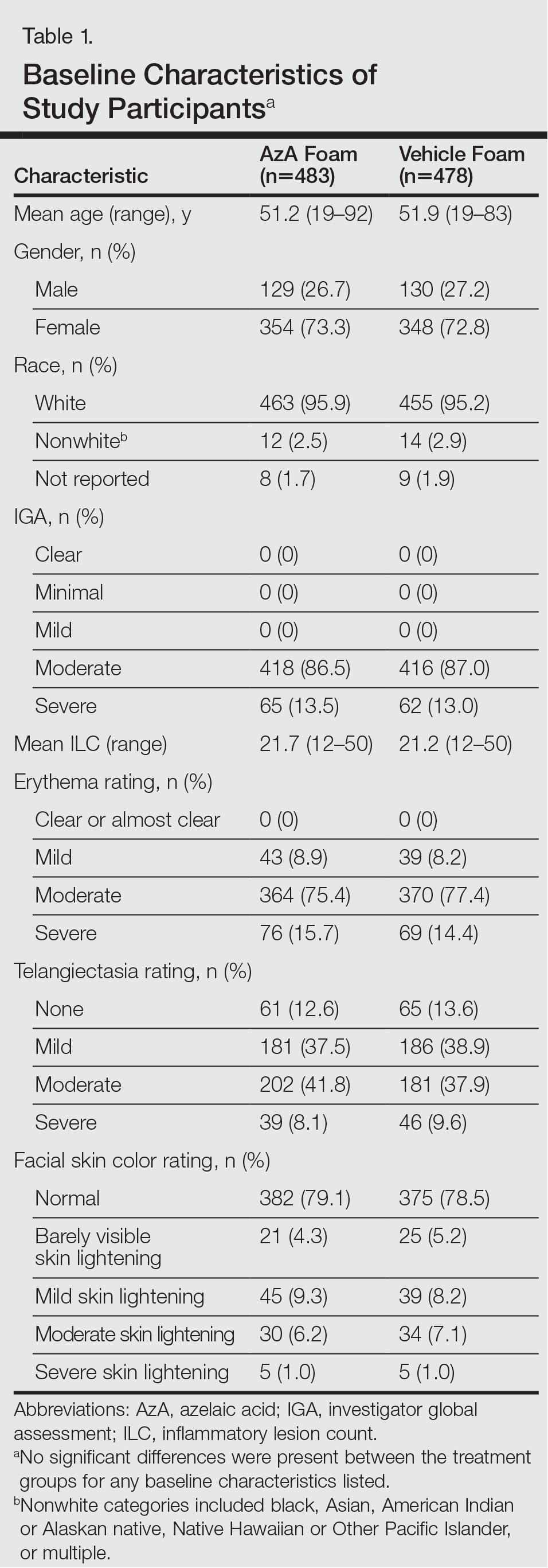

Of the 961 participants included in the study, 483 were randomized to receive AzA foam and 478 were randomized to receive vehicle foam. The mean age was 51.5 years, and the majority of participants were female (73.0%) and white (95.5%)(Table). At baseline, 834 (86.8%) participants had moderate PPR and 127 (13.2%) had severe PPR. The mean inflammatory lesion count (SD) was 21.4 (8.9). No significant differences in baseline characteristics were observed between treatment groups.

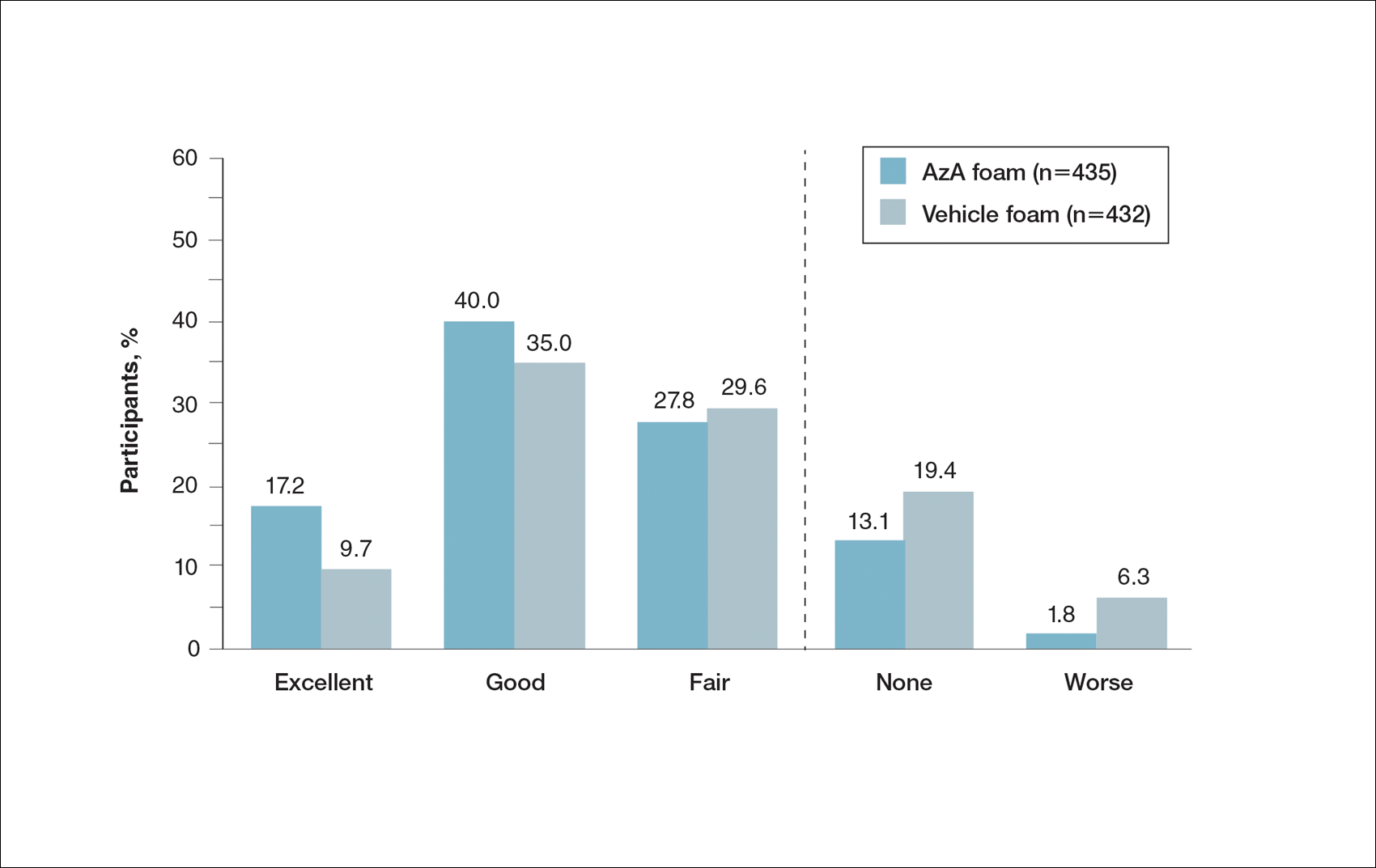

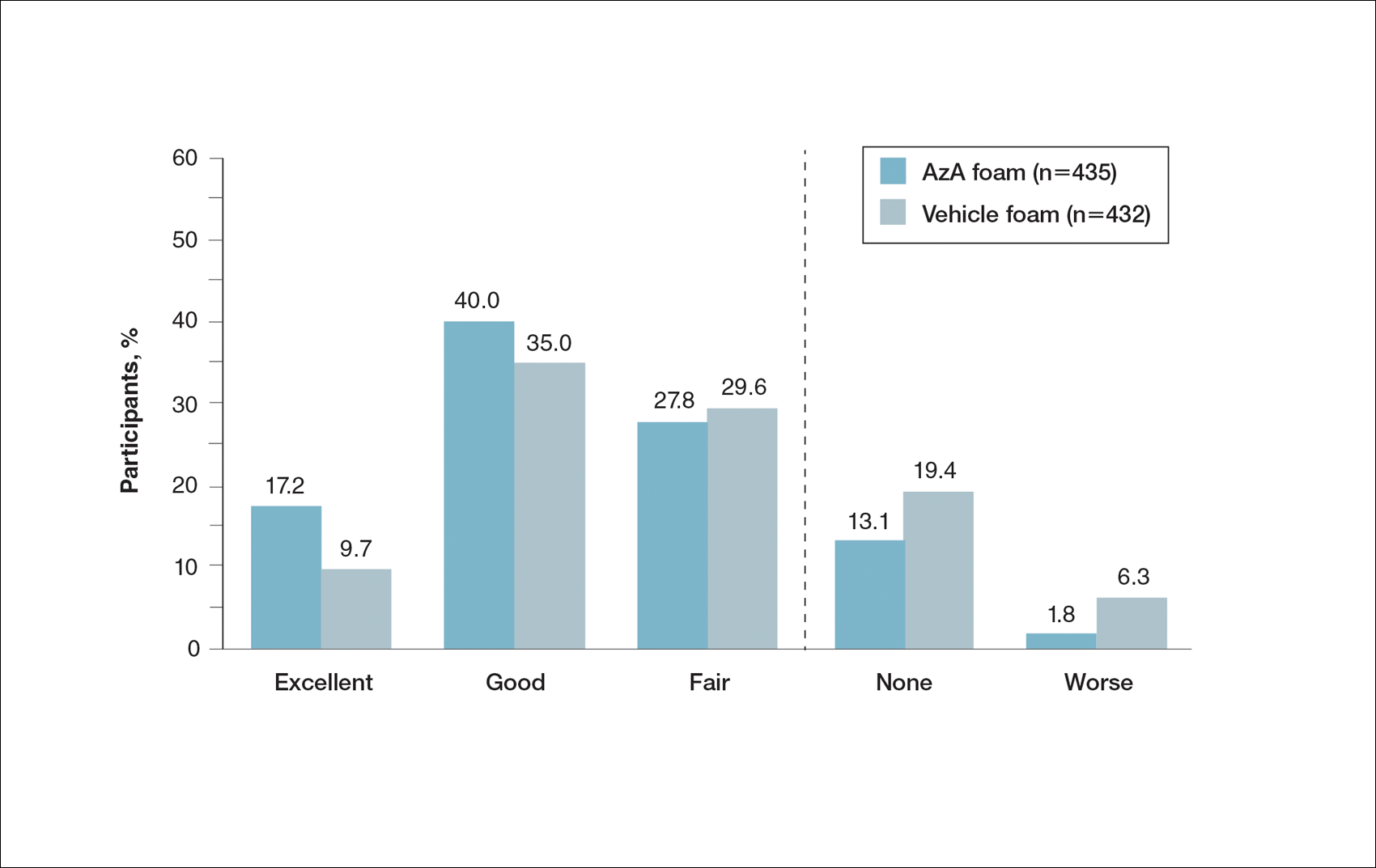

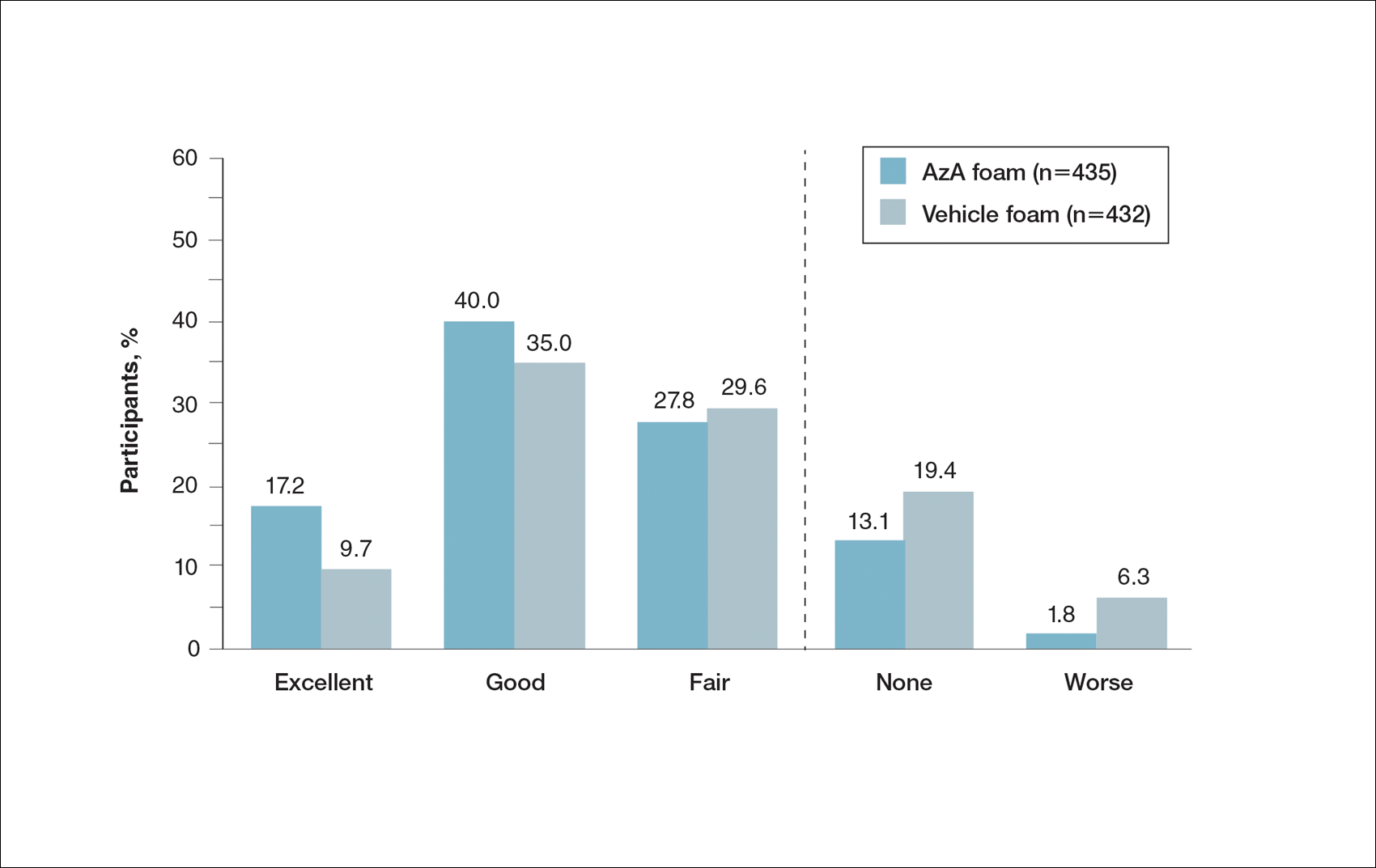

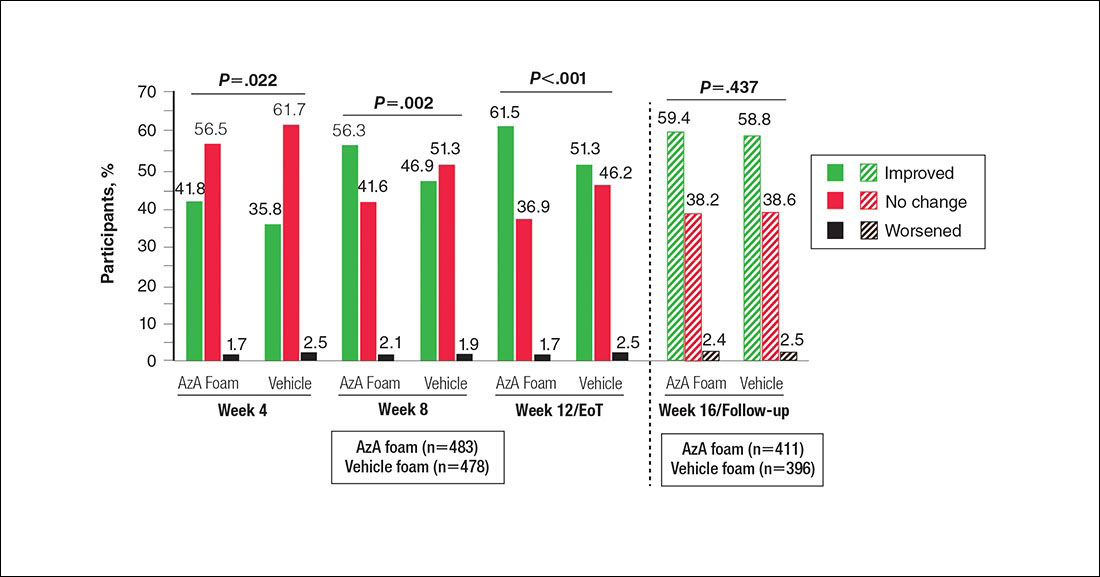

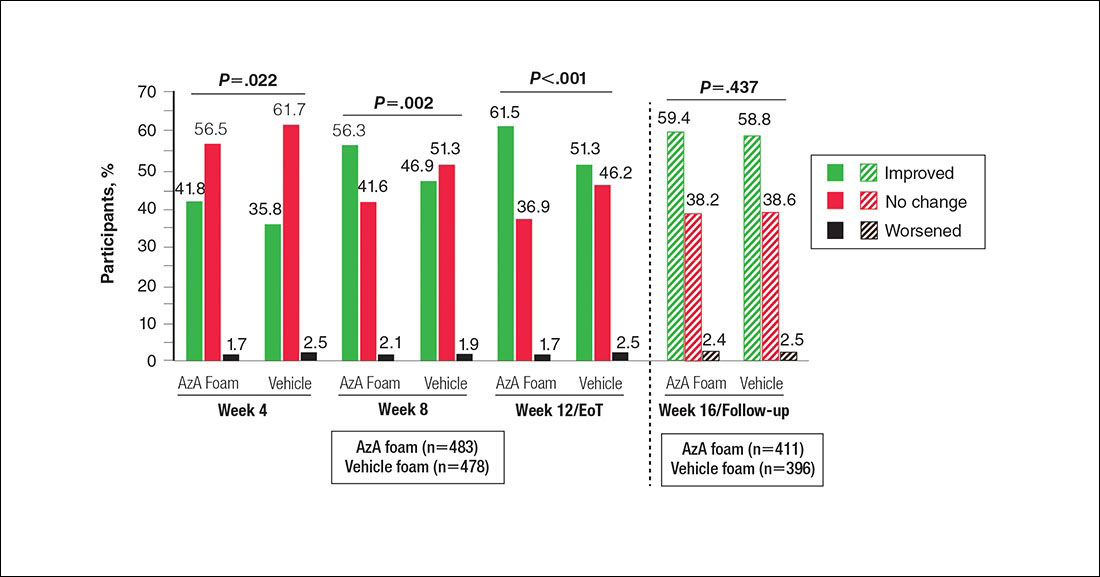

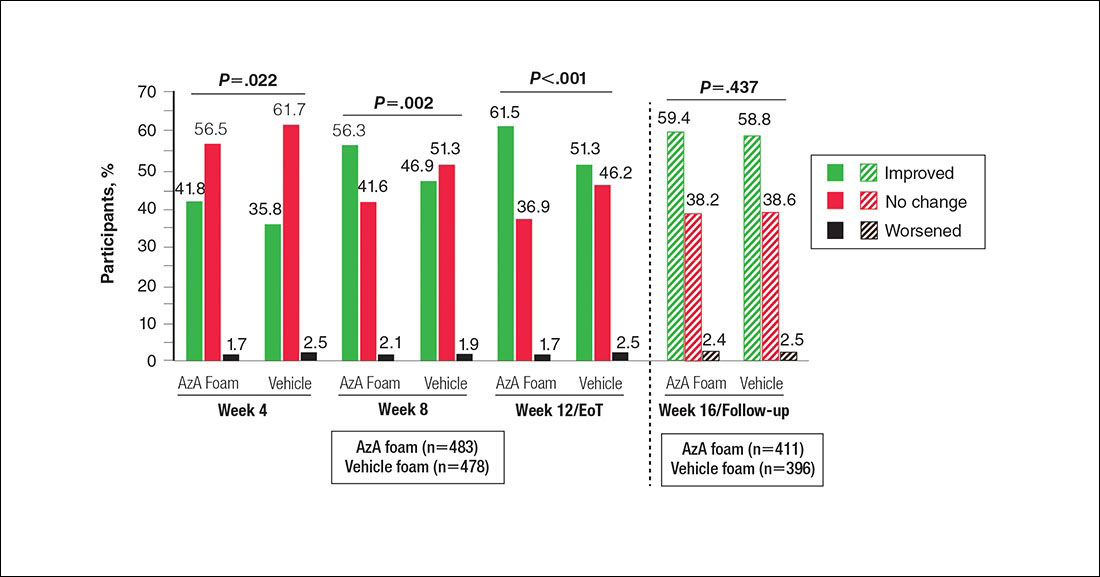

Patient-reported global assessment of treatment response differed between treatment groups at EoT (P<.001)(Figure 1). Higher ratings of treatment response were reported among the AzA foam group (excellent, 17.2%; good, 40.0%) versus vehicle foam (excellent, 9.7%; good, 35.0%). The number of participants reporting no treatment response was 13.1% in the AzA foam group, with 1.8% reporting worsening of their condition, while 19.4% of participants in the vehicle foam group reported no response, with 6.3% reporting worsening of their condition (Figure 1).

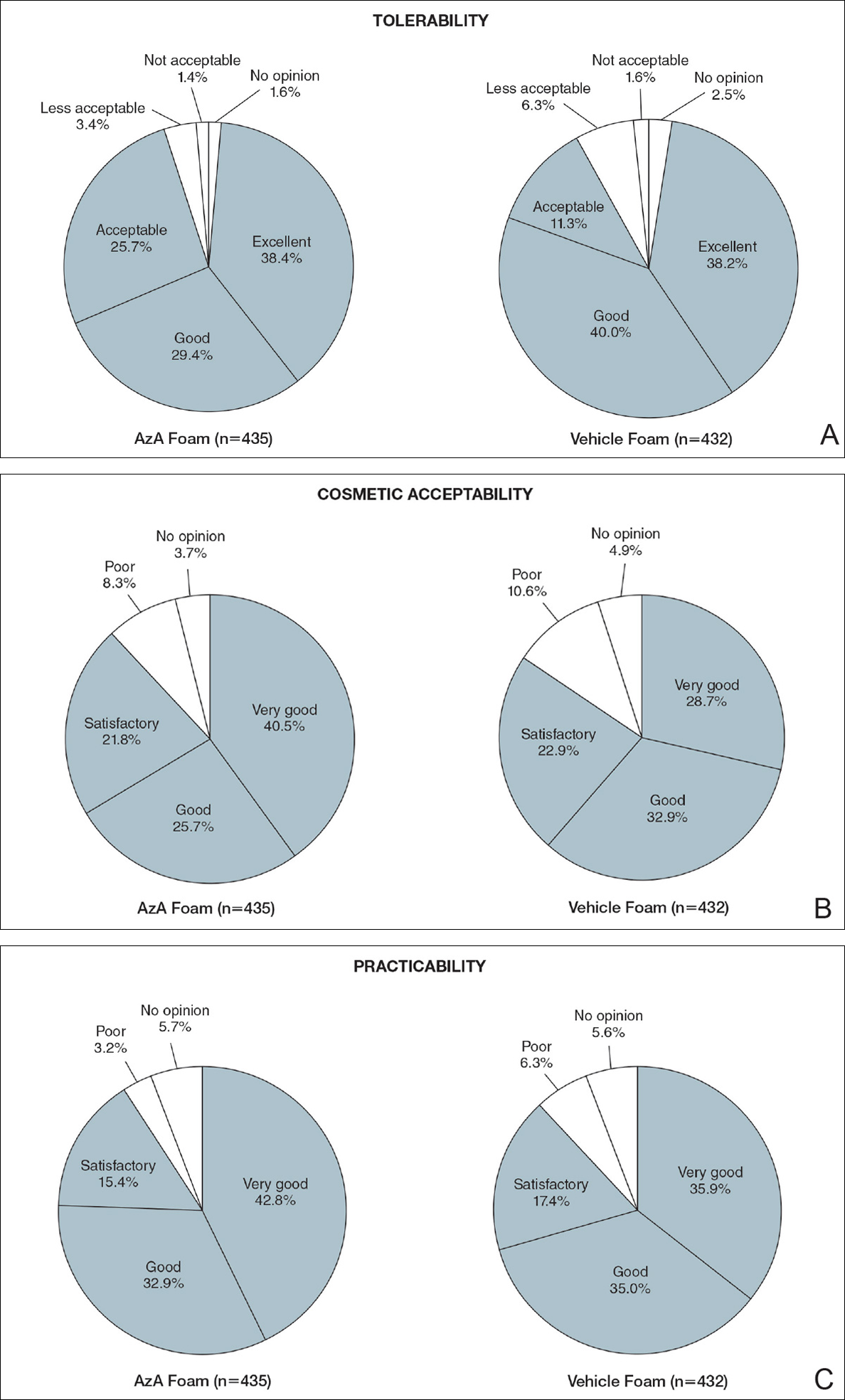

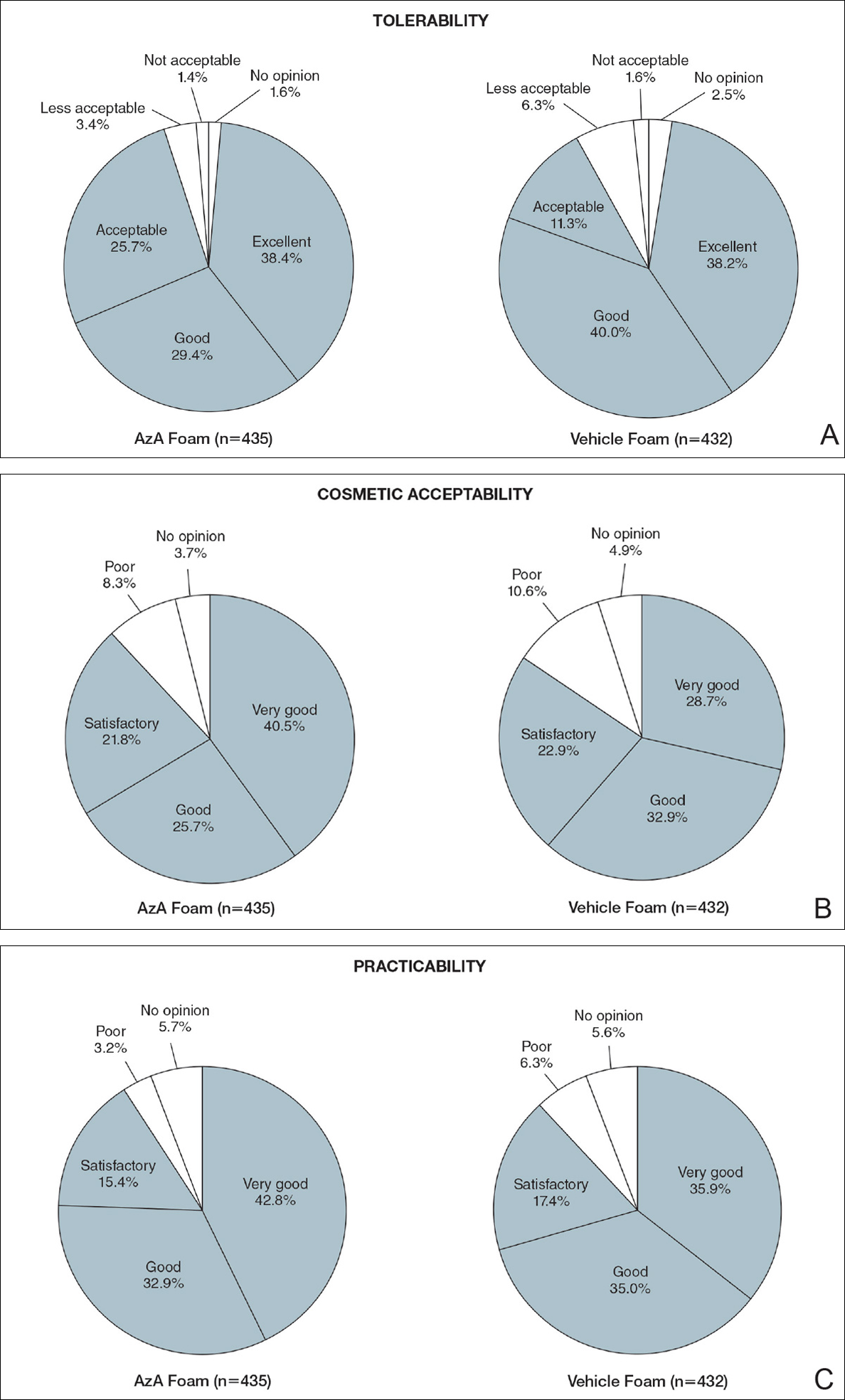

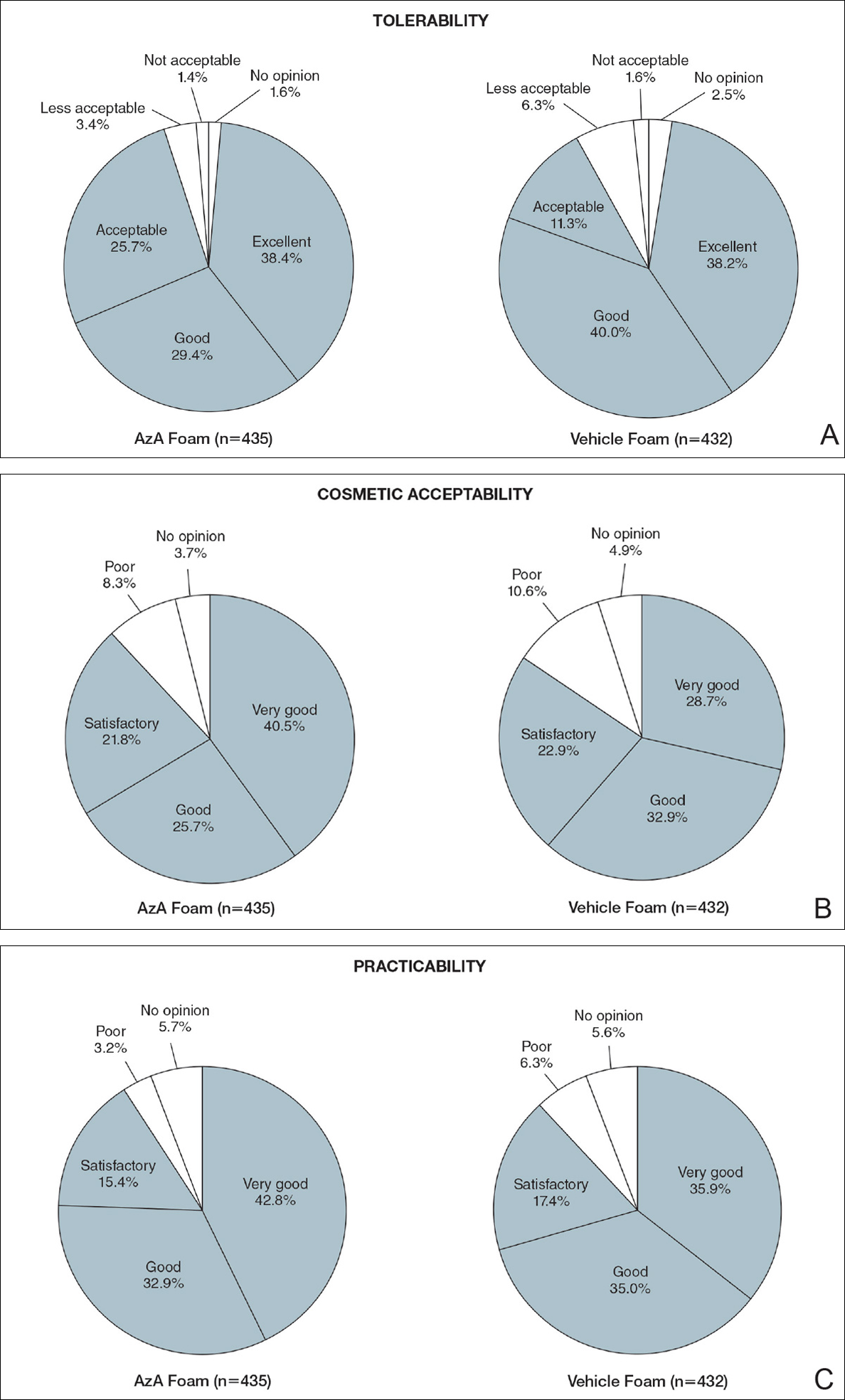

Tolerability was rated excellent or good in 67.8% of the AzA foam group versus 78.2% of the vehicle foam group (Figure 2A). Approximately 38.4% of the AzA foam group versus 38.2% of the vehicle foam group rated treatment tolerability as excellent, while 93.5% of the AzA foam group rated tolerability as acceptable, good, or excellent compared with 89.5% of the vehicle foam group. Only 1.4% of participants in the AzA foam group indicated that treatment was not acceptable due to irritation. In addition, a greater proportion of the AzA foam group reported cosmetic acceptability as very good versus the vehicle foam group (40.5% vs 28.7%)(Figure 2B), with two-thirds reporting cosmetic acceptability as very good or good. Practicability of product use in areas adjacent to the hairline was rated very good by substantial proportions of both the AzA foam and vehicle foam groups (42.8% vs 35.9%)(Figure 2C).

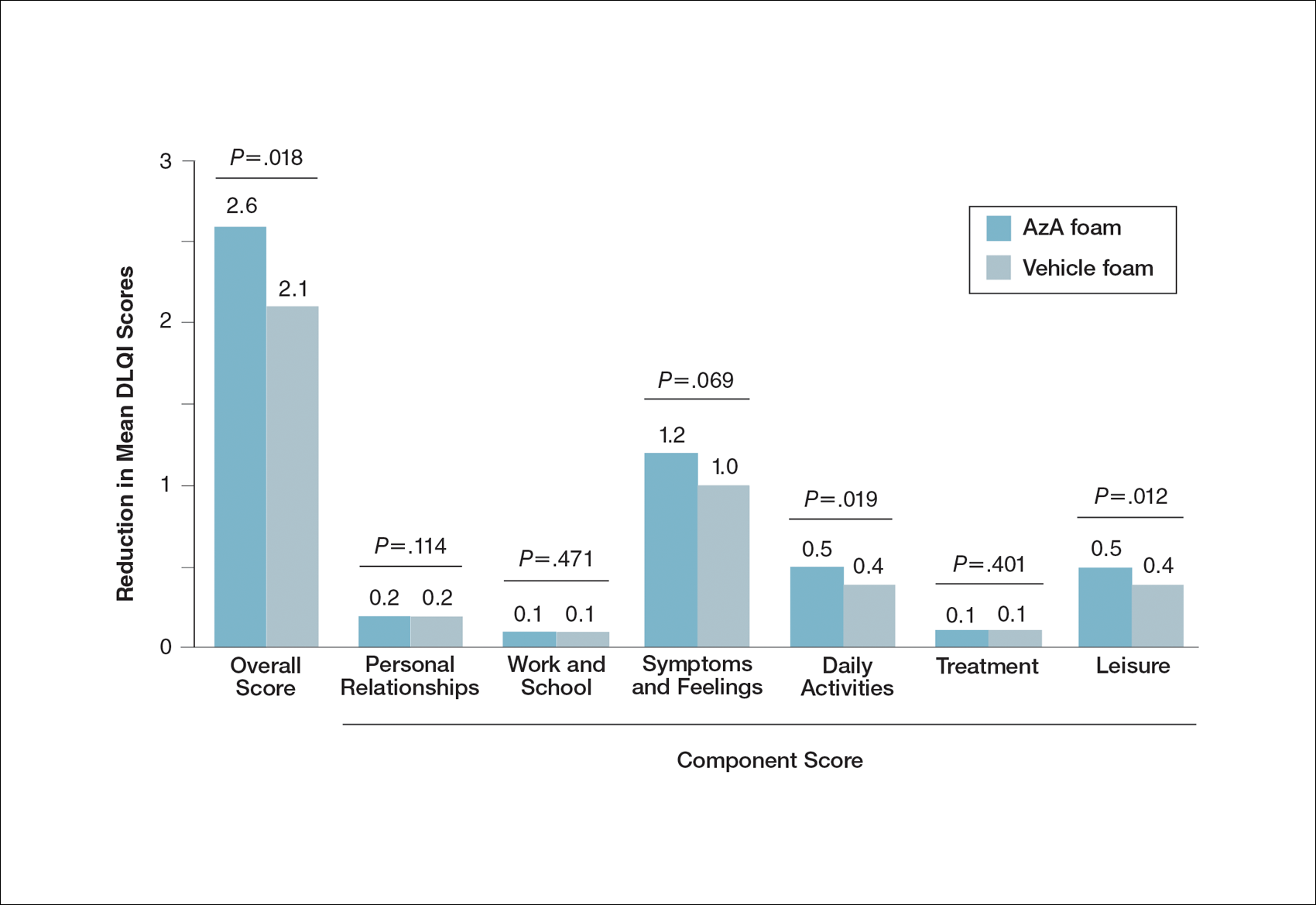

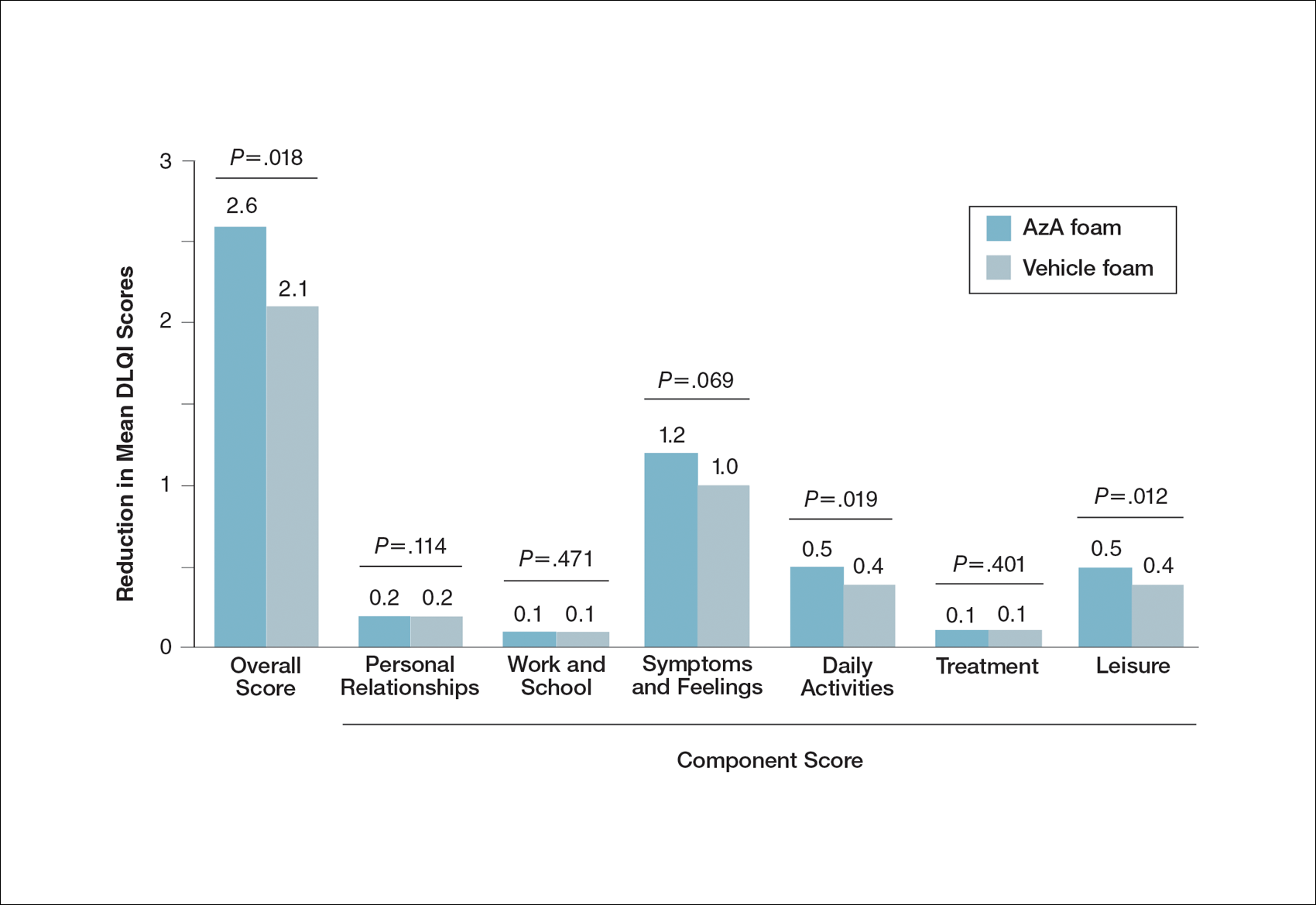

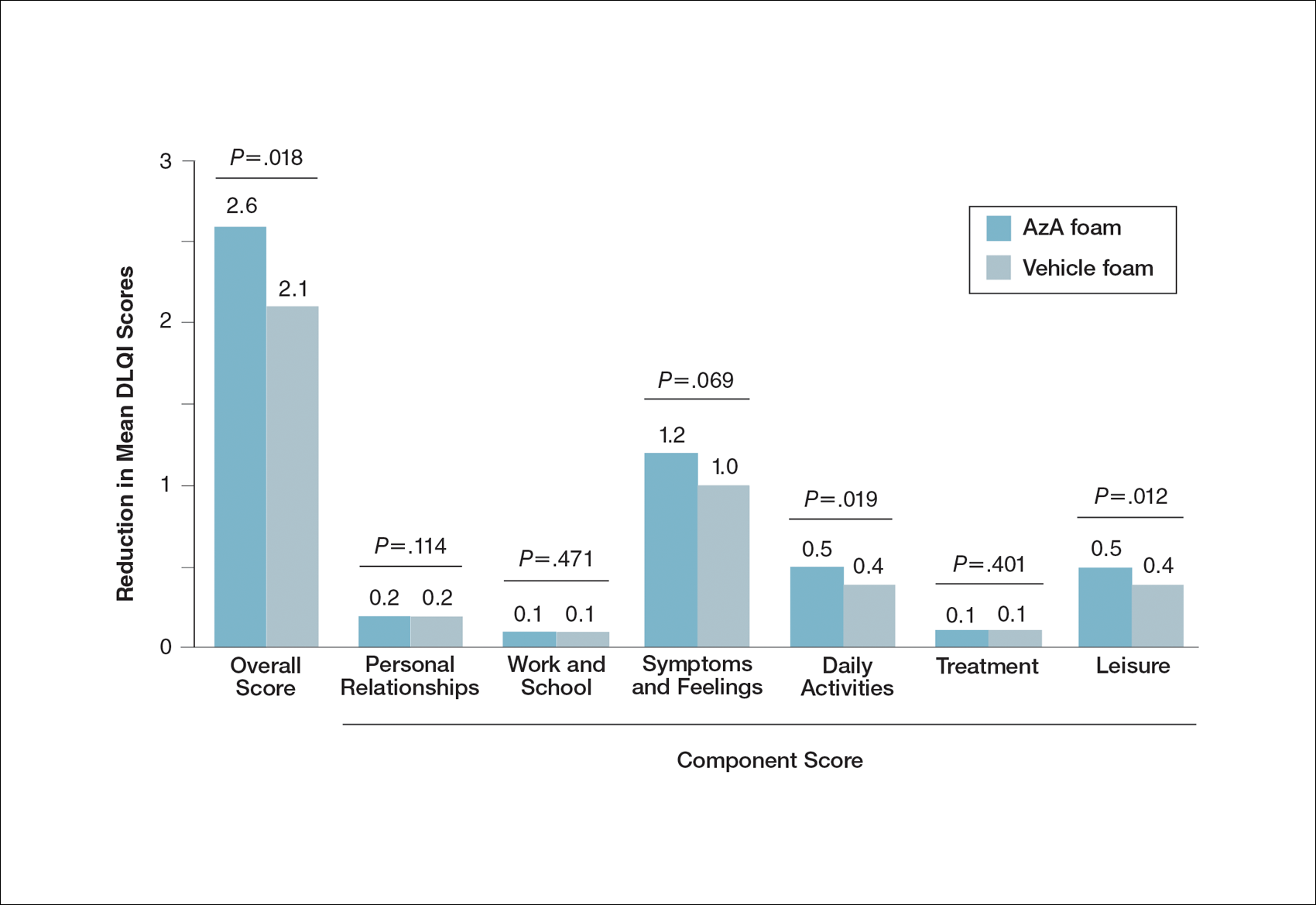

At baseline, average disease burden was moderate according to mean overall DLQI scores (SD) for the AzA foam (5.4 [4.8]) and vehicle foam (5.4 [4.9]) groups. Mean overall DLQI scores improved at EoT, with greater improvement occurring in the AzA foam group (2.6 vs 2.1; P=.018)(Figure 3). A larger proportion of participants in the AzA foam group versus the vehicle foam group also achieved a 5-point or more improvement in overall DLQI score (24.6% vs 19.0%; P=.047). Changes in specific DLQI subscore components were either balanced or in favor of the AzA foam group, including daily activities (0.5 vs 0.4; P=.019), symptoms and feelings (1.2 vs 1.0; P=.069), and leisure (0.5 vs 0.4; P=.012). Specific DLQI items with differences in scores between treatment groups from baseline included the following questions: Over the last week, how embarrassed or self-conscious have you been because of your skin? (P<.001); Over the last week, how much has your skin interfered with you going shopping or looking after your home or garden? (P=.005); Over the last week, how much has your skin affected any social or leisure activities? (P=.040); Over the last week, how much has your skin created problems with your partner or any of your close friends or relatives? (P=.001). Differences between treatment groups favored the AzA foam group for each of these items.

Participants in the AzA foam and vehicle foam groups also showed improvement in RosaQOL scores at EoT (6.8 vs 6.4; P=.67), while EQ-5D-5L scores changed minimally from baseline (0.006 vs 0.007; P=.50).

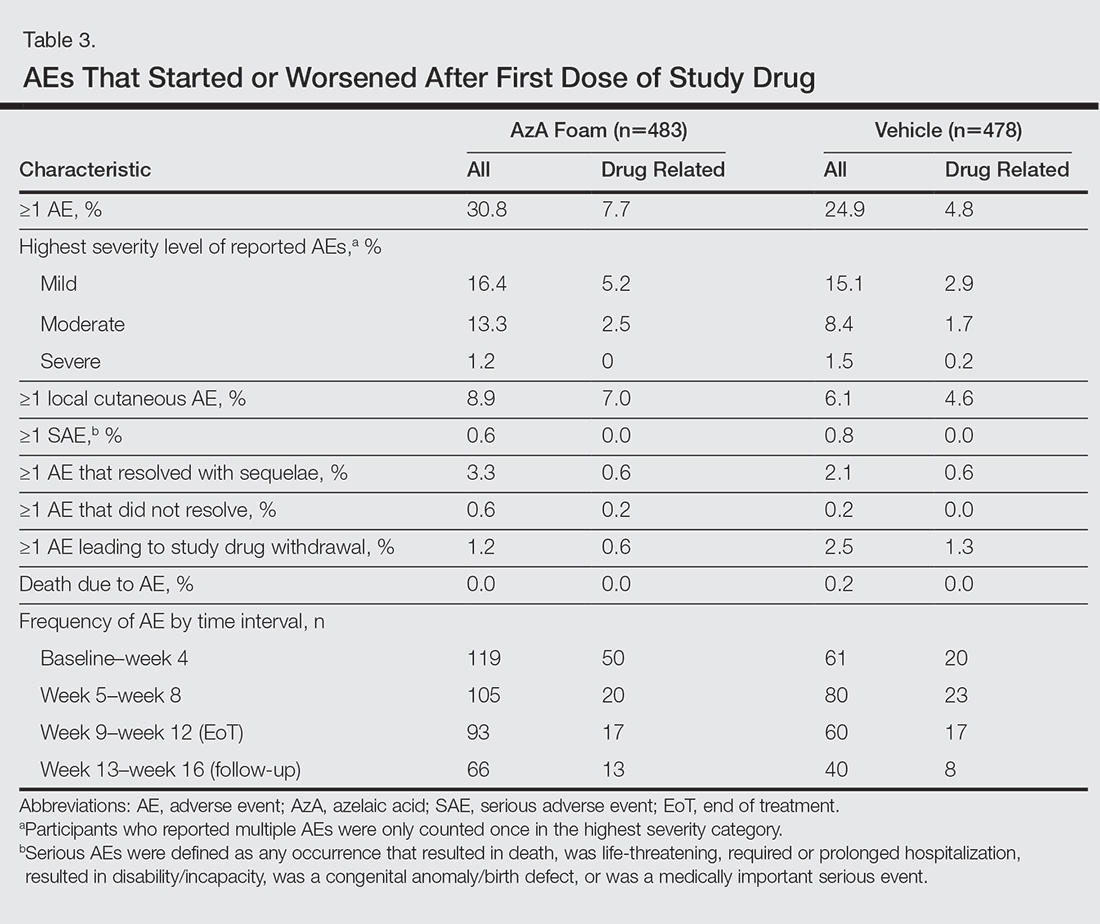

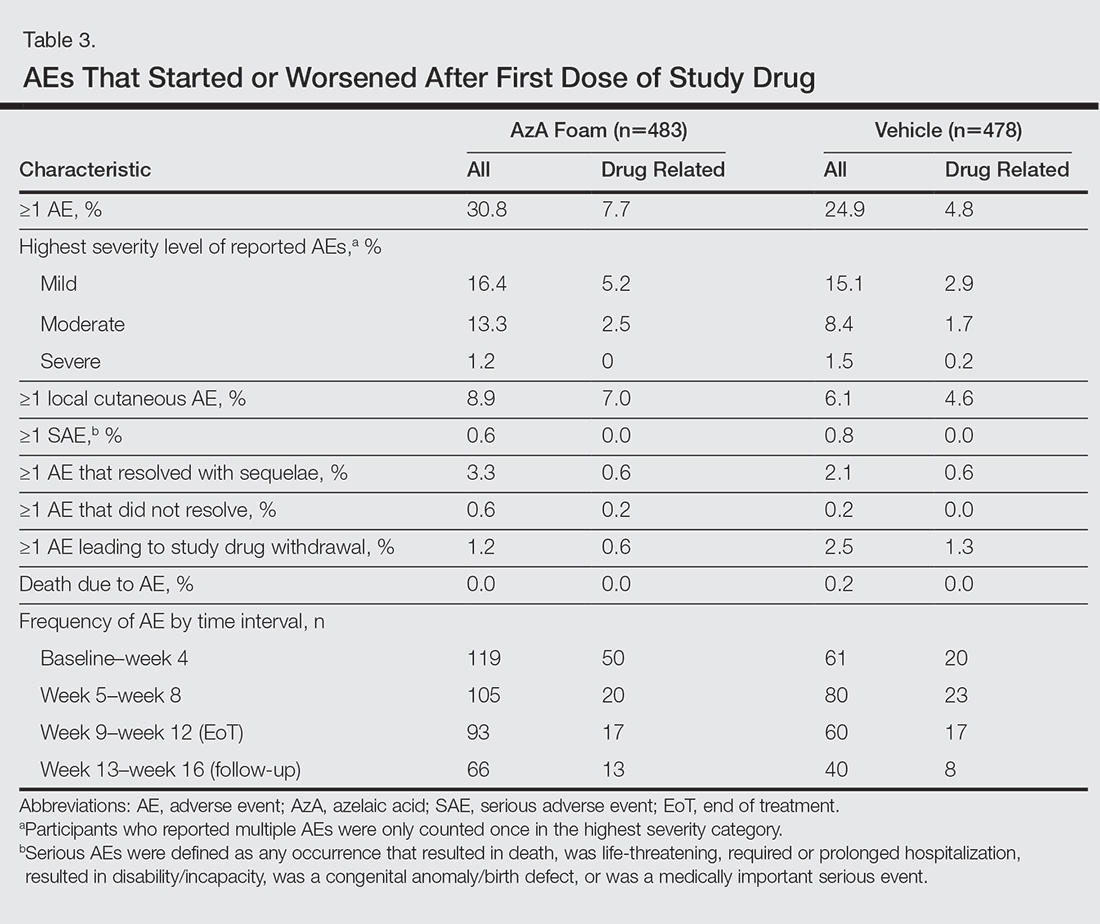

Safety

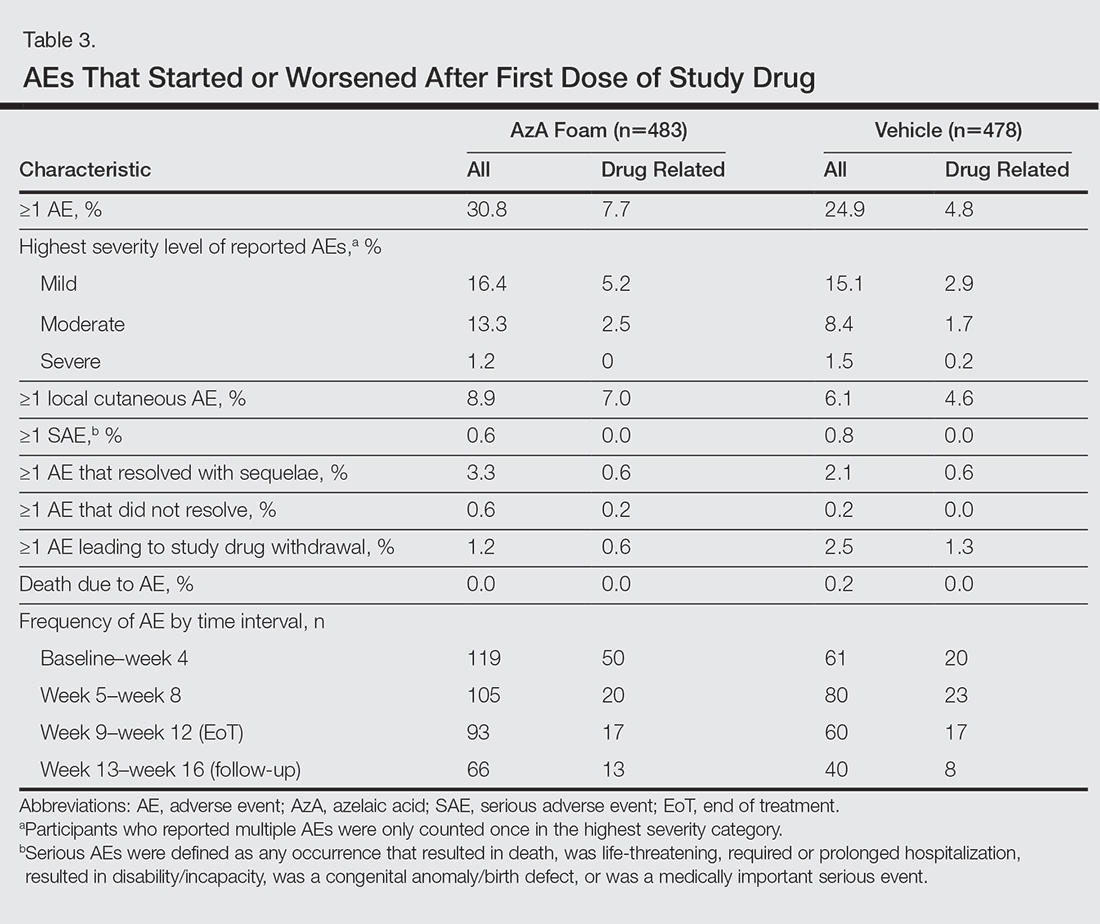

The incidence of drug-related adverse events (AEs) was greater in the AzA foam group versus the vehicle foam group (7.7% vs 4.8%). Drug-related AEs occurring in 1% of the AzA foam group were application-site pain including tenderness, stinging, and burning (3.5% for AzA foam vs 1.3% for vehicle foam); application-site pruritus (1.4% vs 0.4%); and application-site dryness (1.0% vs 0.6%). One drug-related AE of severe intensity—application-site dermatitis—occurred in the vehicle foam group; all other drug-related AEs were mild or moderate.14 More detailed safety results are described in a previous report.13

Comment

The PRO outcome data reported here are consistent with previously reported statistically significant improvements in investigator-assessed primary end points for the treatment of PPR with AzA foam.13,14 The data demonstrate that AzA foam benefits both clinical and patient-oriented dimensions of rosacea disease burden and suggest an association between positive treatment response and improved QOL.

Specifically, patient evaluation of treatment response to AzA foam was highly favorable, with 57.2% reporting excellent or good response and 85.1% reporting positive response overall. Recognizing the relapsing-remitting course of PPR, only 1.8% of the AzA foam group experienced worsening of disease at EoT.

The DLQI and RosaQOL instruments revealed notable improvements in QOL from baseline for both treatment groups. Although no significant differences in RosaQOL scores were observed between groups at EoT, significant differences in DLQI scores were detected. Almost one-quarter of participants in the AzA foam group achieved at least a 5-point improvement in DLQI score, exceeding the 4-point threshold for clinically meaningful change.17 Although little change in EQ-5D-5L scores was observed at EoT for both groups with no between-group differences, this finding is not unexpected, as this instrument assesses QOL dimensions such as loss of function, mobility, and ability to wash or dress, which are unlikely to be compromised in most rosacea patients.

Our results also underscore the importance of vehicle in the treatment of compromised skin. Studies of topical treatments for other dermatoses suggest that vehicle properties may reduce disease severity and improve QOL independent of active ingredients.10,18 For example, ease of application, minimal residue, and less time spent in application may explain the superiority of foam to other vehicles in the treatment of psoriasis.18 Our data demonstrating high cosmetic favorability of AzA foam are consistent with these prior observations. Increased tolerability of foam formulations also may affect response to treatment, in part by supporting adherence.18 Most participants receiving AzA foam described tolerability as excellent or good, and the discontinuation rate was low (1.2% of participants in the AzA foam group left the study due to AEs) in the setting of near-complete dosage administration (97% of expected doses applied).13

Conclusion

These results indicate that use of AzA foam as well as its novel vehicle results in high patient satisfaction and improved QOL. Although additional research is necessary to further delineate the relationship between PROs and other measures of clinical efficacy, our data demonstrate a positive treatment experience as perceived by patients that parallels the clinical efficacy of AzA foam for the treatment of PPR.13,14

Acknowledgment

Editorial support through inVentiv Medical Communications (New York, New York) was provided by Bayer Pharmaceuticals.

- Cardwell LA, Farhangian ME, Alinia H, et al. Psychological disorders associated with rosacea: analysis of unscripted comments. J Dermatol Surg. 2015;19:99-103.

- Moustafa F, Lewallen RS, Feldman SR. The psychological impact of rosacea and the influence of current management options. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:973-980.

- Wilkin J, Dahl M, Detmar M, et al. Standard classification of rosacea: report of the National Rosacea Society Expert Committee on the Classification and Staging of Rosacea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:584-587.

- Yamasaki K, Gallo RL. The molecular pathology of rosacea. J Dermatol Sci. 2009;55:77-81.

- Del Rosso JQ. Advances in understanding and managing rosacea: part 1: connecting the dots between pathophysiological mechanisms and common clinical features of rosacea with emphasis on vascular changes and facial erythema. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2012;5:16-25.

- Bohm D, Schwanitz P, Stock Gissendanner S, et al. Symptom severity and psychological sequelae in rosacea: results of a survey. Psychol Health Med. 2014;19:586-591.

- Elewski BE, Draelos Z, Dreno B, et al. Rosacea—global diversity and optimized outcome: proposed international consensus from the Rosacea International Expert Group. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:188-200.

- Dirschka T, Micali G, Papadopoulos L, et al. Perceptions on the psychological impact of facial erythema associated with rosacea: results of international survey [published online May 29, 2015]. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2015;5:117-127.

- Abram K, Silm H, Maaroos HI, et al. Subjective disease perception and symptoms of depression in relation to healthcare-seeking behaviour in patients with rosacea. Acta Derm Venereol. 2009;89:488-491.

- Stein L. Clinical studies of a new vehicle formulation for topical corticosteroids in the treatment of psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53(1, suppl 1):S39-S49.

- Yentzer BA, Camacho FT, Young T, et al. Good adherence and early efficacy using desonide hydrogel for atopic dermatitis: results from a program addressing patient compliance. J Drugs Dermatol. 2010;9:324-329.

- Finacea (azelaic acid) foam 15% [package insert]. Whippany, NJ: Bayer Pharmaceuticals; 2015.

- Draelos ZD, Elewski BE, Harper JC, et al. A phase 3 randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled trial of azelaic acid foam 15% in the treatment of papulopustular rosacea. Cutis. 2015;96:54-61.

- Solomon JA, Tyring S, Staedtler G, et al. Investigator-reported efficacy of azelaic acid foam 15% in patients with papulopustular rosacea: secondary efficacy outcomes from a randomized, controlled, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Cutis. 2016;98:187-194.

- Nicholson K, Abramova L, Chren MM, et al. A pilot quality-of-life instrument for acne rosacea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:213-221.

- Herdman M, Gudex C, Lloyd A, et al. Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L). Qual Life Res. 2011;20:1727-1736.

- Basra MK, Salek MS, Camilleri L, et al. Determining the minimal clinically important difference and responsiveness of the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI): further data. Dermatology. 2015;230:27-33.

- Bergstrom KG, Arambula K, Kimball AB. Medication formulation affects quality of life: a randomized single-blind study of clobetasol propionate foam 0.05% compared with a combined program of clobetasol cream 0.05% and solution 0.05% for the treatment of psoriasis. Cutis. 2003;72:407-411.

Rosacea is a chronic inflammatory disorder that may negatively impact patients’ quality of life (QOL).1,2 Papulopustular rosacea (PPR) is characterized by centrofacial inflammatory lesions and erythema as well as burning and stinging secondary to skin barrier dysfunction.3-5 Increasing rosacea severity is associated with greater rates of anxiety and depression and lower QOL6 as well as low self-esteem and feelings of embarrassment.7,8 Accordingly, assessing patient perceptions of rosacea treatments is necessary for understanding its impact on patient health.6,9

The Rosacea International Expert Group has emphasized the need to incorporate patient assessments of disease severity and QOL when developing therapeutic strategies for rosacea.7 Ease of use, sensory experience, and patient preference also are important dimensions in the evaluation of topical medications, as attributes of specific formulations may affect usability, adherence, and efficacy.10,11

An azelaic acid (AzA) 15% foam formulation, which was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2015, was developed to deliver AzA in a vehicle designed to improve treatment experience in patients with mild to moderate PPR.12 Results from a clinical trial demonstrated superiority of AzA foam to vehicle foam for primary end points that included therapeutic success rate and change in inflammatory lesion count.13,14 Secondary end points assessed in the current analysis included patient perception of product usability, efficacy, and effect on QOL. These patient-reported outcome (PRO) results are reported here.

Methods

Study Design

The design of this phase 3 multicenter, randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled, parallel-group clinical trial was described in more detail in an earlier report.13 This study was approved by all appropriate institutional review boards. Eligible participants were 18 years and older with moderate or severe PPR, 12 to 50 inflammatory lesions, and persistent erythema with or without telangiectasia. Exclusion criteria included known nonresponse to AzA, current or prior use (within 6 weeks of randomization) of noninvestigational products to treat rosacea, and presence of other dermatoses that could interfere with rosacea evaluation.

Participants were randomized into the AzA foam or vehicle group (1:1 ratio). The study medication (0.5 g) or vehicle foam was applied twice daily to the entire face until the end of treatment (EoT) at 12 weeks. Efficacy and safety parameters were evaluated at baseline and at 4, 8, and 12 weeks of treatment, and at a follow-up visit 4 weeks after EoT (week 16).

Results for the coprimary efficacy end points—therapeutic success rate according to investigator global assessment and nominal change in inflammatory lesion count—were previously reported,13 as well as secondary efficacy outcomes including change in inflammatory lesion count, therapeutic response rate, and change in erythema rating.14

Patient-Reported Secondary Efficacy Outcomes

The secondary PRO end points were patient-reported global assessment of treatment response (rated as excellent, good, fair, none, or worse), global assessment of tolerability (rated as excellent, good, acceptable despite minor irritation, less acceptable due to continuous irritation, not acceptable, or no opinion), and opinion on cosmetic acceptability and practicability of product use in areas adjacent to the hairline (rated as very good, good, satisfactory, poor, or no opinion).

Additionally, QOL was measured by 3 validated standardized PRO tools, including the Rosacea Quality of Life Index (RosaQOL),15 the EuroQOL 5-dimension 5-level questionnaire (EQ-5D-5L),16 and the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI). The RosaQOL is a rosacea-specific instrument assessing 3 constructs: (1) symptom, (2) emotion, and (3) function. The EQ-5D-5L questionnaire measures overall health status and comprises 5 constructs: (1) mobility, (2) self-care, (3) usual activities, (4) pain/discomfort, and (5) anxiety/depression. The DLQI is a general, dermatology-oriented instrument categorized into 6 constructs: (1) symptoms and feelings, (2) daily activities, (3) leisure, (4) work and school, (5) personal relationships, and (6) treatment.

Statistical Analyses

Patient-reported outcomes were analyzed in an exploratory manner and evaluated at EoT relative to baseline. Self-reported global assessment of treatment response and change in RosaQOL, EQ-5D-5L, and DLQI scores between AzA foam and vehicle foam groups were evaluated using the Wilcoxon rank sum test. Categorical change in the number of participants achieving an increase of 5 or more points in overall DLQI score was evaluated using a χ2 test.

Safety

Safety was analyzed for all randomized patients who were dispensed any study medication. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.2.

Results

Of the 961 participants included in the study, 483 were randomized to receive AzA foam and 478 were randomized to receive vehicle foam. The mean age was 51.5 years, and the majority of participants were female (73.0%) and white (95.5%)(Table). At baseline, 834 (86.8%) participants had moderate PPR and 127 (13.2%) had severe PPR. The mean inflammatory lesion count (SD) was 21.4 (8.9). No significant differences in baseline characteristics were observed between treatment groups.

Patient-reported global assessment of treatment response differed between treatment groups at EoT (P<.001)(Figure 1). Higher ratings of treatment response were reported among the AzA foam group (excellent, 17.2%; good, 40.0%) versus vehicle foam (excellent, 9.7%; good, 35.0%). The number of participants reporting no treatment response was 13.1% in the AzA foam group, with 1.8% reporting worsening of their condition, while 19.4% of participants in the vehicle foam group reported no response, with 6.3% reporting worsening of their condition (Figure 1).

Tolerability was rated excellent or good in 67.8% of the AzA foam group versus 78.2% of the vehicle foam group (Figure 2A). Approximately 38.4% of the AzA foam group versus 38.2% of the vehicle foam group rated treatment tolerability as excellent, while 93.5% of the AzA foam group rated tolerability as acceptable, good, or excellent compared with 89.5% of the vehicle foam group. Only 1.4% of participants in the AzA foam group indicated that treatment was not acceptable due to irritation. In addition, a greater proportion of the AzA foam group reported cosmetic acceptability as very good versus the vehicle foam group (40.5% vs 28.7%)(Figure 2B), with two-thirds reporting cosmetic acceptability as very good or good. Practicability of product use in areas adjacent to the hairline was rated very good by substantial proportions of both the AzA foam and vehicle foam groups (42.8% vs 35.9%)(Figure 2C).

At baseline, average disease burden was moderate according to mean overall DLQI scores (SD) for the AzA foam (5.4 [4.8]) and vehicle foam (5.4 [4.9]) groups. Mean overall DLQI scores improved at EoT, with greater improvement occurring in the AzA foam group (2.6 vs 2.1; P=.018)(Figure 3). A larger proportion of participants in the AzA foam group versus the vehicle foam group also achieved a 5-point or more improvement in overall DLQI score (24.6% vs 19.0%; P=.047). Changes in specific DLQI subscore components were either balanced or in favor of the AzA foam group, including daily activities (0.5 vs 0.4; P=.019), symptoms and feelings (1.2 vs 1.0; P=.069), and leisure (0.5 vs 0.4; P=.012). Specific DLQI items with differences in scores between treatment groups from baseline included the following questions: Over the last week, how embarrassed or self-conscious have you been because of your skin? (P<.001); Over the last week, how much has your skin interfered with you going shopping or looking after your home or garden? (P=.005); Over the last week, how much has your skin affected any social or leisure activities? (P=.040); Over the last week, how much has your skin created problems with your partner or any of your close friends or relatives? (P=.001). Differences between treatment groups favored the AzA foam group for each of these items.

Participants in the AzA foam and vehicle foam groups also showed improvement in RosaQOL scores at EoT (6.8 vs 6.4; P=.67), while EQ-5D-5L scores changed minimally from baseline (0.006 vs 0.007; P=.50).

Safety

The incidence of drug-related adverse events (AEs) was greater in the AzA foam group versus the vehicle foam group (7.7% vs 4.8%). Drug-related AEs occurring in 1% of the AzA foam group were application-site pain including tenderness, stinging, and burning (3.5% for AzA foam vs 1.3% for vehicle foam); application-site pruritus (1.4% vs 0.4%); and application-site dryness (1.0% vs 0.6%). One drug-related AE of severe intensity—application-site dermatitis—occurred in the vehicle foam group; all other drug-related AEs were mild or moderate.14 More detailed safety results are described in a previous report.13

Comment

The PRO outcome data reported here are consistent with previously reported statistically significant improvements in investigator-assessed primary end points for the treatment of PPR with AzA foam.13,14 The data demonstrate that AzA foam benefits both clinical and patient-oriented dimensions of rosacea disease burden and suggest an association between positive treatment response and improved QOL.

Specifically, patient evaluation of treatment response to AzA foam was highly favorable, with 57.2% reporting excellent or good response and 85.1% reporting positive response overall. Recognizing the relapsing-remitting course of PPR, only 1.8% of the AzA foam group experienced worsening of disease at EoT.

The DLQI and RosaQOL instruments revealed notable improvements in QOL from baseline for both treatment groups. Although no significant differences in RosaQOL scores were observed between groups at EoT, significant differences in DLQI scores were detected. Almost one-quarter of participants in the AzA foam group achieved at least a 5-point improvement in DLQI score, exceeding the 4-point threshold for clinically meaningful change.17 Although little change in EQ-5D-5L scores was observed at EoT for both groups with no between-group differences, this finding is not unexpected, as this instrument assesses QOL dimensions such as loss of function, mobility, and ability to wash or dress, which are unlikely to be compromised in most rosacea patients.

Our results also underscore the importance of vehicle in the treatment of compromised skin. Studies of topical treatments for other dermatoses suggest that vehicle properties may reduce disease severity and improve QOL independent of active ingredients.10,18 For example, ease of application, minimal residue, and less time spent in application may explain the superiority of foam to other vehicles in the treatment of psoriasis.18 Our data demonstrating high cosmetic favorability of AzA foam are consistent with these prior observations. Increased tolerability of foam formulations also may affect response to treatment, in part by supporting adherence.18 Most participants receiving AzA foam described tolerability as excellent or good, and the discontinuation rate was low (1.2% of participants in the AzA foam group left the study due to AEs) in the setting of near-complete dosage administration (97% of expected doses applied).13

Conclusion

These results indicate that use of AzA foam as well as its novel vehicle results in high patient satisfaction and improved QOL. Although additional research is necessary to further delineate the relationship between PROs and other measures of clinical efficacy, our data demonstrate a positive treatment experience as perceived by patients that parallels the clinical efficacy of AzA foam for the treatment of PPR.13,14

Acknowledgment

Editorial support through inVentiv Medical Communications (New York, New York) was provided by Bayer Pharmaceuticals.

Rosacea is a chronic inflammatory disorder that may negatively impact patients’ quality of life (QOL).1,2 Papulopustular rosacea (PPR) is characterized by centrofacial inflammatory lesions and erythema as well as burning and stinging secondary to skin barrier dysfunction.3-5 Increasing rosacea severity is associated with greater rates of anxiety and depression and lower QOL6 as well as low self-esteem and feelings of embarrassment.7,8 Accordingly, assessing patient perceptions of rosacea treatments is necessary for understanding its impact on patient health.6,9

The Rosacea International Expert Group has emphasized the need to incorporate patient assessments of disease severity and QOL when developing therapeutic strategies for rosacea.7 Ease of use, sensory experience, and patient preference also are important dimensions in the evaluation of topical medications, as attributes of specific formulations may affect usability, adherence, and efficacy.10,11

An azelaic acid (AzA) 15% foam formulation, which was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2015, was developed to deliver AzA in a vehicle designed to improve treatment experience in patients with mild to moderate PPR.12 Results from a clinical trial demonstrated superiority of AzA foam to vehicle foam for primary end points that included therapeutic success rate and change in inflammatory lesion count.13,14 Secondary end points assessed in the current analysis included patient perception of product usability, efficacy, and effect on QOL. These patient-reported outcome (PRO) results are reported here.

Methods

Study Design

The design of this phase 3 multicenter, randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled, parallel-group clinical trial was described in more detail in an earlier report.13 This study was approved by all appropriate institutional review boards. Eligible participants were 18 years and older with moderate or severe PPR, 12 to 50 inflammatory lesions, and persistent erythema with or without telangiectasia. Exclusion criteria included known nonresponse to AzA, current or prior use (within 6 weeks of randomization) of noninvestigational products to treat rosacea, and presence of other dermatoses that could interfere with rosacea evaluation.

Participants were randomized into the AzA foam or vehicle group (1:1 ratio). The study medication (0.5 g) or vehicle foam was applied twice daily to the entire face until the end of treatment (EoT) at 12 weeks. Efficacy and safety parameters were evaluated at baseline and at 4, 8, and 12 weeks of treatment, and at a follow-up visit 4 weeks after EoT (week 16).

Results for the coprimary efficacy end points—therapeutic success rate according to investigator global assessment and nominal change in inflammatory lesion count—were previously reported,13 as well as secondary efficacy outcomes including change in inflammatory lesion count, therapeutic response rate, and change in erythema rating.14

Patient-Reported Secondary Efficacy Outcomes

The secondary PRO end points were patient-reported global assessment of treatment response (rated as excellent, good, fair, none, or worse), global assessment of tolerability (rated as excellent, good, acceptable despite minor irritation, less acceptable due to continuous irritation, not acceptable, or no opinion), and opinion on cosmetic acceptability and practicability of product use in areas adjacent to the hairline (rated as very good, good, satisfactory, poor, or no opinion).

Additionally, QOL was measured by 3 validated standardized PRO tools, including the Rosacea Quality of Life Index (RosaQOL),15 the EuroQOL 5-dimension 5-level questionnaire (EQ-5D-5L),16 and the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI). The RosaQOL is a rosacea-specific instrument assessing 3 constructs: (1) symptom, (2) emotion, and (3) function. The EQ-5D-5L questionnaire measures overall health status and comprises 5 constructs: (1) mobility, (2) self-care, (3) usual activities, (4) pain/discomfort, and (5) anxiety/depression. The DLQI is a general, dermatology-oriented instrument categorized into 6 constructs: (1) symptoms and feelings, (2) daily activities, (3) leisure, (4) work and school, (5) personal relationships, and (6) treatment.

Statistical Analyses

Patient-reported outcomes were analyzed in an exploratory manner and evaluated at EoT relative to baseline. Self-reported global assessment of treatment response and change in RosaQOL, EQ-5D-5L, and DLQI scores between AzA foam and vehicle foam groups were evaluated using the Wilcoxon rank sum test. Categorical change in the number of participants achieving an increase of 5 or more points in overall DLQI score was evaluated using a χ2 test.

Safety

Safety was analyzed for all randomized patients who were dispensed any study medication. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.2.

Results

Of the 961 participants included in the study, 483 were randomized to receive AzA foam and 478 were randomized to receive vehicle foam. The mean age was 51.5 years, and the majority of participants were female (73.0%) and white (95.5%)(Table). At baseline, 834 (86.8%) participants had moderate PPR and 127 (13.2%) had severe PPR. The mean inflammatory lesion count (SD) was 21.4 (8.9). No significant differences in baseline characteristics were observed between treatment groups.

Patient-reported global assessment of treatment response differed between treatment groups at EoT (P<.001)(Figure 1). Higher ratings of treatment response were reported among the AzA foam group (excellent, 17.2%; good, 40.0%) versus vehicle foam (excellent, 9.7%; good, 35.0%). The number of participants reporting no treatment response was 13.1% in the AzA foam group, with 1.8% reporting worsening of their condition, while 19.4% of participants in the vehicle foam group reported no response, with 6.3% reporting worsening of their condition (Figure 1).

Tolerability was rated excellent or good in 67.8% of the AzA foam group versus 78.2% of the vehicle foam group (Figure 2A). Approximately 38.4% of the AzA foam group versus 38.2% of the vehicle foam group rated treatment tolerability as excellent, while 93.5% of the AzA foam group rated tolerability as acceptable, good, or excellent compared with 89.5% of the vehicle foam group. Only 1.4% of participants in the AzA foam group indicated that treatment was not acceptable due to irritation. In addition, a greater proportion of the AzA foam group reported cosmetic acceptability as very good versus the vehicle foam group (40.5% vs 28.7%)(Figure 2B), with two-thirds reporting cosmetic acceptability as very good or good. Practicability of product use in areas adjacent to the hairline was rated very good by substantial proportions of both the AzA foam and vehicle foam groups (42.8% vs 35.9%)(Figure 2C).

At baseline, average disease burden was moderate according to mean overall DLQI scores (SD) for the AzA foam (5.4 [4.8]) and vehicle foam (5.4 [4.9]) groups. Mean overall DLQI scores improved at EoT, with greater improvement occurring in the AzA foam group (2.6 vs 2.1; P=.018)(Figure 3). A larger proportion of participants in the AzA foam group versus the vehicle foam group also achieved a 5-point or more improvement in overall DLQI score (24.6% vs 19.0%; P=.047). Changes in specific DLQI subscore components were either balanced or in favor of the AzA foam group, including daily activities (0.5 vs 0.4; P=.019), symptoms and feelings (1.2 vs 1.0; P=.069), and leisure (0.5 vs 0.4; P=.012). Specific DLQI items with differences in scores between treatment groups from baseline included the following questions: Over the last week, how embarrassed or self-conscious have you been because of your skin? (P<.001); Over the last week, how much has your skin interfered with you going shopping or looking after your home or garden? (P=.005); Over the last week, how much has your skin affected any social or leisure activities? (P=.040); Over the last week, how much has your skin created problems with your partner or any of your close friends or relatives? (P=.001). Differences between treatment groups favored the AzA foam group for each of these items.

Participants in the AzA foam and vehicle foam groups also showed improvement in RosaQOL scores at EoT (6.8 vs 6.4; P=.67), while EQ-5D-5L scores changed minimally from baseline (0.006 vs 0.007; P=.50).

Safety

The incidence of drug-related adverse events (AEs) was greater in the AzA foam group versus the vehicle foam group (7.7% vs 4.8%). Drug-related AEs occurring in 1% of the AzA foam group were application-site pain including tenderness, stinging, and burning (3.5% for AzA foam vs 1.3% for vehicle foam); application-site pruritus (1.4% vs 0.4%); and application-site dryness (1.0% vs 0.6%). One drug-related AE of severe intensity—application-site dermatitis—occurred in the vehicle foam group; all other drug-related AEs were mild or moderate.14 More detailed safety results are described in a previous report.13

Comment

The PRO outcome data reported here are consistent with previously reported statistically significant improvements in investigator-assessed primary end points for the treatment of PPR with AzA foam.13,14 The data demonstrate that AzA foam benefits both clinical and patient-oriented dimensions of rosacea disease burden and suggest an association between positive treatment response and improved QOL.

Specifically, patient evaluation of treatment response to AzA foam was highly favorable, with 57.2% reporting excellent or good response and 85.1% reporting positive response overall. Recognizing the relapsing-remitting course of PPR, only 1.8% of the AzA foam group experienced worsening of disease at EoT.

The DLQI and RosaQOL instruments revealed notable improvements in QOL from baseline for both treatment groups. Although no significant differences in RosaQOL scores were observed between groups at EoT, significant differences in DLQI scores were detected. Almost one-quarter of participants in the AzA foam group achieved at least a 5-point improvement in DLQI score, exceeding the 4-point threshold for clinically meaningful change.17 Although little change in EQ-5D-5L scores was observed at EoT for both groups with no between-group differences, this finding is not unexpected, as this instrument assesses QOL dimensions such as loss of function, mobility, and ability to wash or dress, which are unlikely to be compromised in most rosacea patients.

Our results also underscore the importance of vehicle in the treatment of compromised skin. Studies of topical treatments for other dermatoses suggest that vehicle properties may reduce disease severity and improve QOL independent of active ingredients.10,18 For example, ease of application, minimal residue, and less time spent in application may explain the superiority of foam to other vehicles in the treatment of psoriasis.18 Our data demonstrating high cosmetic favorability of AzA foam are consistent with these prior observations. Increased tolerability of foam formulations also may affect response to treatment, in part by supporting adherence.18 Most participants receiving AzA foam described tolerability as excellent or good, and the discontinuation rate was low (1.2% of participants in the AzA foam group left the study due to AEs) in the setting of near-complete dosage administration (97% of expected doses applied).13

Conclusion

These results indicate that use of AzA foam as well as its novel vehicle results in high patient satisfaction and improved QOL. Although additional research is necessary to further delineate the relationship between PROs and other measures of clinical efficacy, our data demonstrate a positive treatment experience as perceived by patients that parallels the clinical efficacy of AzA foam for the treatment of PPR.13,14

Acknowledgment

Editorial support through inVentiv Medical Communications (New York, New York) was provided by Bayer Pharmaceuticals.

- Cardwell LA, Farhangian ME, Alinia H, et al. Psychological disorders associated with rosacea: analysis of unscripted comments. J Dermatol Surg. 2015;19:99-103.

- Moustafa F, Lewallen RS, Feldman SR. The psychological impact of rosacea and the influence of current management options. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:973-980.

- Wilkin J, Dahl M, Detmar M, et al. Standard classification of rosacea: report of the National Rosacea Society Expert Committee on the Classification and Staging of Rosacea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:584-587.

- Yamasaki K, Gallo RL. The molecular pathology of rosacea. J Dermatol Sci. 2009;55:77-81.

- Del Rosso JQ. Advances in understanding and managing rosacea: part 1: connecting the dots between pathophysiological mechanisms and common clinical features of rosacea with emphasis on vascular changes and facial erythema. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2012;5:16-25.

- Bohm D, Schwanitz P, Stock Gissendanner S, et al. Symptom severity and psychological sequelae in rosacea: results of a survey. Psychol Health Med. 2014;19:586-591.

- Elewski BE, Draelos Z, Dreno B, et al. Rosacea—global diversity and optimized outcome: proposed international consensus from the Rosacea International Expert Group. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:188-200.

- Dirschka T, Micali G, Papadopoulos L, et al. Perceptions on the psychological impact of facial erythema associated with rosacea: results of international survey [published online May 29, 2015]. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2015;5:117-127.

- Abram K, Silm H, Maaroos HI, et al. Subjective disease perception and symptoms of depression in relation to healthcare-seeking behaviour in patients with rosacea. Acta Derm Venereol. 2009;89:488-491.

- Stein L. Clinical studies of a new vehicle formulation for topical corticosteroids in the treatment of psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53(1, suppl 1):S39-S49.

- Yentzer BA, Camacho FT, Young T, et al. Good adherence and early efficacy using desonide hydrogel for atopic dermatitis: results from a program addressing patient compliance. J Drugs Dermatol. 2010;9:324-329.

- Finacea (azelaic acid) foam 15% [package insert]. Whippany, NJ: Bayer Pharmaceuticals; 2015.

- Draelos ZD, Elewski BE, Harper JC, et al. A phase 3 randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled trial of azelaic acid foam 15% in the treatment of papulopustular rosacea. Cutis. 2015;96:54-61.

- Solomon JA, Tyring S, Staedtler G, et al. Investigator-reported efficacy of azelaic acid foam 15% in patients with papulopustular rosacea: secondary efficacy outcomes from a randomized, controlled, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Cutis. 2016;98:187-194.

- Nicholson K, Abramova L, Chren MM, et al. A pilot quality-of-life instrument for acne rosacea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:213-221.

- Herdman M, Gudex C, Lloyd A, et al. Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L). Qual Life Res. 2011;20:1727-1736.

- Basra MK, Salek MS, Camilleri L, et al. Determining the minimal clinically important difference and responsiveness of the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI): further data. Dermatology. 2015;230:27-33.

- Bergstrom KG, Arambula K, Kimball AB. Medication formulation affects quality of life: a randomized single-blind study of clobetasol propionate foam 0.05% compared with a combined program of clobetasol cream 0.05% and solution 0.05% for the treatment of psoriasis. Cutis. 2003;72:407-411.

- Cardwell LA, Farhangian ME, Alinia H, et al. Psychological disorders associated with rosacea: analysis of unscripted comments. J Dermatol Surg. 2015;19:99-103.

- Moustafa F, Lewallen RS, Feldman SR. The psychological impact of rosacea and the influence of current management options. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:973-980.

- Wilkin J, Dahl M, Detmar M, et al. Standard classification of rosacea: report of the National Rosacea Society Expert Committee on the Classification and Staging of Rosacea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:584-587.

- Yamasaki K, Gallo RL. The molecular pathology of rosacea. J Dermatol Sci. 2009;55:77-81.

- Del Rosso JQ. Advances in understanding and managing rosacea: part 1: connecting the dots between pathophysiological mechanisms and common clinical features of rosacea with emphasis on vascular changes and facial erythema. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2012;5:16-25.

- Bohm D, Schwanitz P, Stock Gissendanner S, et al. Symptom severity and psychological sequelae in rosacea: results of a survey. Psychol Health Med. 2014;19:586-591.

- Elewski BE, Draelos Z, Dreno B, et al. Rosacea—global diversity and optimized outcome: proposed international consensus from the Rosacea International Expert Group. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:188-200.

- Dirschka T, Micali G, Papadopoulos L, et al. Perceptions on the psychological impact of facial erythema associated with rosacea: results of international survey [published online May 29, 2015]. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2015;5:117-127.

- Abram K, Silm H, Maaroos HI, et al. Subjective disease perception and symptoms of depression in relation to healthcare-seeking behaviour in patients with rosacea. Acta Derm Venereol. 2009;89:488-491.

- Stein L. Clinical studies of a new vehicle formulation for topical corticosteroids in the treatment of psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53(1, suppl 1):S39-S49.

- Yentzer BA, Camacho FT, Young T, et al. Good adherence and early efficacy using desonide hydrogel for atopic dermatitis: results from a program addressing patient compliance. J Drugs Dermatol. 2010;9:324-329.

- Finacea (azelaic acid) foam 15% [package insert]. Whippany, NJ: Bayer Pharmaceuticals; 2015.

- Draelos ZD, Elewski BE, Harper JC, et al. A phase 3 randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled trial of azelaic acid foam 15% in the treatment of papulopustular rosacea. Cutis. 2015;96:54-61.

- Solomon JA, Tyring S, Staedtler G, et al. Investigator-reported efficacy of azelaic acid foam 15% in patients with papulopustular rosacea: secondary efficacy outcomes from a randomized, controlled, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Cutis. 2016;98:187-194.

- Nicholson K, Abramova L, Chren MM, et al. A pilot quality-of-life instrument for acne rosacea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:213-221.

- Herdman M, Gudex C, Lloyd A, et al. Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L). Qual Life Res. 2011;20:1727-1736.

- Basra MK, Salek MS, Camilleri L, et al. Determining the minimal clinically important difference and responsiveness of the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI): further data. Dermatology. 2015;230:27-33.

- Bergstrom KG, Arambula K, Kimball AB. Medication formulation affects quality of life: a randomized single-blind study of clobetasol propionate foam 0.05% compared with a combined program of clobetasol cream 0.05% and solution 0.05% for the treatment of psoriasis. Cutis. 2003;72:407-411.

Practice Points

- Patient perceptions of treatment are an important consideration in developing topical therapeutic strategies for papulopustular rosacea.

- A novel hydrophilic foam formulation of azelaic acid (AzA) provided substantial benefits in patient-reported measures of treatment response and quality of life.

- Patients reported high levels of satisfaction with the usability, tolerability, and practicability of AzA foam.

- The positive treatment experience described by patients parallels investigator-reported measures of clinical efficacy reported elsewhere.

Investigator-Reported Efficacy of Azelaic Acid Foam 15% in Patients With Papulopustular Rosacea: Secondary Efficacy Outcomes From a Randomized, Controlled, Double-blind, Phase 3 Trial

Papulopustular rosacea (PPR) is characterized by centrofacial papules, pustules, erythema, and occasionally telangiectasia.1,2 A myriad of factors, including genetic predisposition3 and environmental triggers,4 have been associated with dysregulated inflammatory responses,5 contributing to the disease pathogenesis and symptoms. Inflammation associated with PPR may decrease skin barrier function, increase transepidermal water loss, and reduce stratum corneum hydration,6,7 resulting in heightened skin sensitivity, pain, burning, and/or stinging.5,8

Azelaic acid (AzA), which historically has only been available in gel or cream formulations, is well established for the treatment of rosacea9; however, these formulations have been associated with application-site adverse events (AEs)(eg, burning, erythema, irritation), limited cosmetic acceptability, and reduced compliance or efficacy.10

For select skin conditions, active agents delivered in foam vehicles may offer superior tolerability with improved outcomes.11 An AzA foam 15% formulation was approved for the treatment of mild to moderate PPR. Primary outcomes from a phase 3 trial demonstrated the efficacy and safety of AzA foam in improving inflammatory lesion counts (ILCs) and disease severity in participants with PPR. The trial also evaluated additional secondary end points, including the effect of AzA foam on erythema, inflammatory lesions, treatment response, and other manifestations of PPR.12 The current study evaluated investigator-reported efficacy outcomes for these secondary end points for AzA foam 15% versus vehicle foam.

Methods

Study Design

This phase 3 multicenter, randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled, parallel-group clinical trial was conducted from September 2012 to January 2014 at 48 US study centers comparing the efficacy of AzA foam versus vehicle foam in patients with PPR. Eligible participants were 18 years and older with PPR rated as moderate or severe according to investigator global assessment (IGA), plus 12 to 50 inflammatory lesions and persistent erythema with or without telangiectasia. Exclusion criteria included known nonresponse to AzA, current or prior use (within 6 weeks of randomization) of noninvestigational products to treat rosacea, and presence of other dermatoses that could interfere with rosacea evaluation.

Participants were randomized into the AzA foam or vehicle group (1:1 ratio). The study medication was applied in 0.5-g doses twice daily until the end of treatment (EoT) at 12 weeks. Efficacy and safety parameters were evaluated at baseline and at 4, 8, and 12 weeks of treatment, and at a follow-up visit 4 weeks after EoT (week 16).

Results for the coprimary efficacy end points—therapeutic success rate according to IGA and nominal change in ILC—were previously reported.12

Investigator-Reported Secondary Efficacy Outcomes

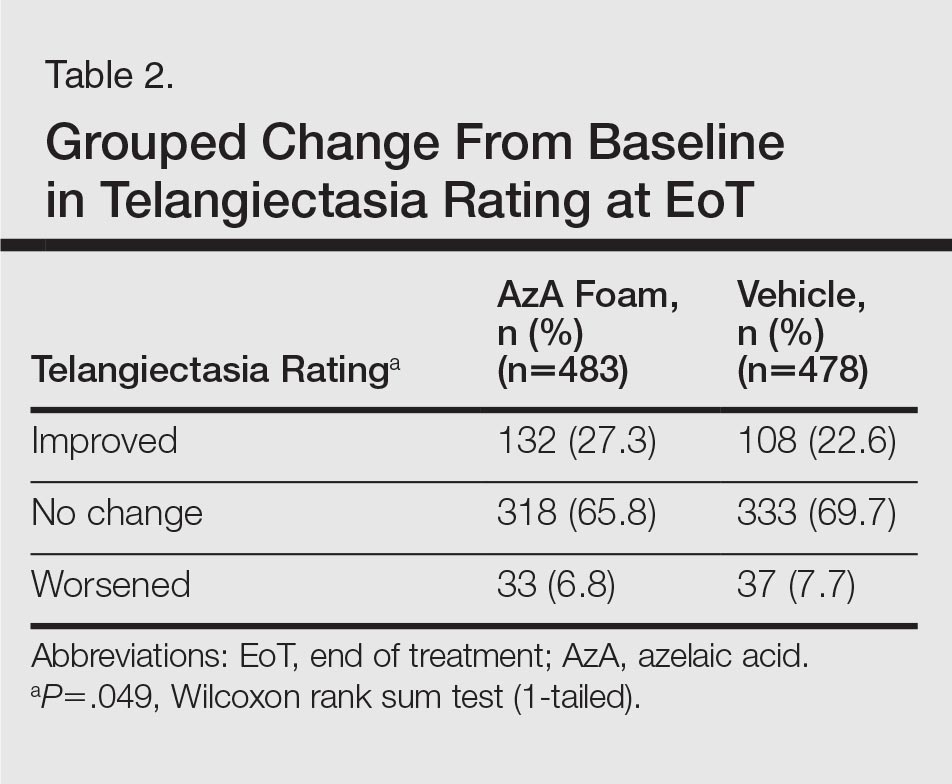

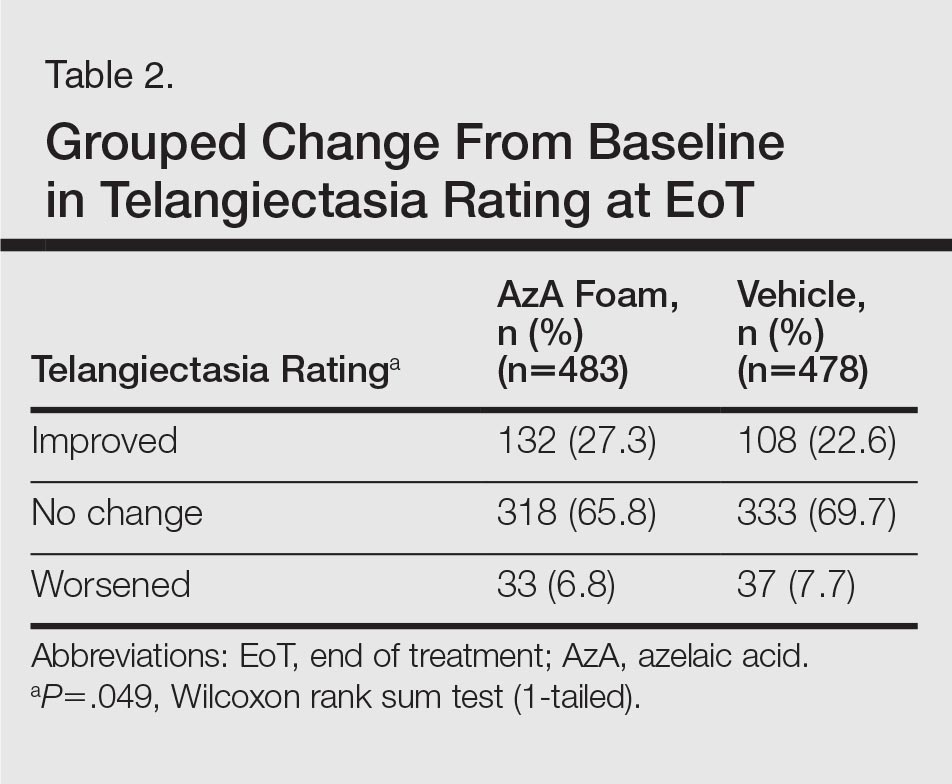

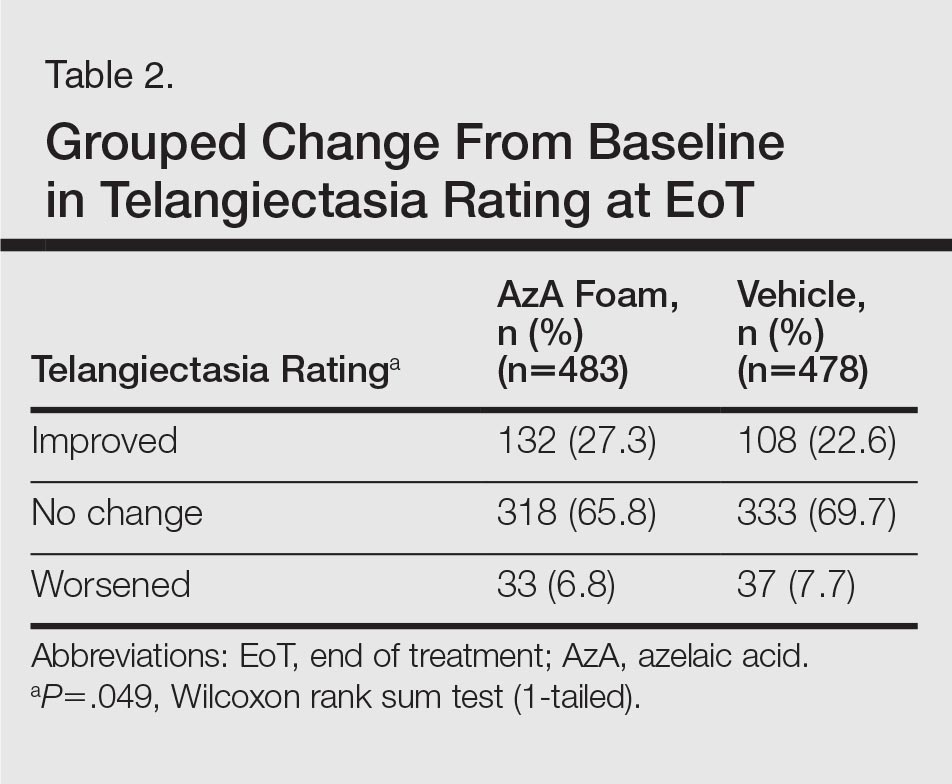

The secondary efficacy end points were grouped change in erythema rating, grouped change in telangiectasia rating, grouped change in IGA score, therapeutic response rate according to IGA, percentage change in ILC from baseline, and facial skin color rating at EoT.

Grouped change for all secondary end points was measured as improved, no change, or worsened relative to baseline. For grouped change in erythema and telangiectasia ratings, a participant was considered improved if the rating at the postbaseline visit was lower than the baseline rating, no change if the postbaseline and baseline ratings were identical, and worsened if the postbaseline rating was higher than at baseline. For grouped change in IGA score, a participant was considered improved if a responder showed at least a 1-step improvement postbaseline compared to baseline, no change if postbaseline and baseline ratings were identical, and worsened if the postbaseline rating was higher than at baseline.

For the therapeutic response rate, a participant was considered a treatment responder if the IGA score improved from baseline and resulted in clear, minimal, or mild disease severity at EoT.

Safety

Adverse events also were assessed.

Statistical Analyses

Secondary efficacy and safety end points were assessed for all randomized participants who were dispensed the study medication. Missing data were imputed using last observation carried forward.