User login

Müllerian anomalies – old problem, new approach and classification

The American Society for Reproductive Medicine’s classification system for müllerian anomalies was the standard until the revision in 2021 by ASRM, which updated and expanded the classification presenting nine classes and imaging criteria: müllerian agenesis, cervical agenesis, unicornuate, uterus didelphys, bicornuate, septate, longitudinal vaginal septum, transverse vaginal septum, and complex anomalies. This month’s article addresses müllerian anomalies from embryology to treatment options.

The early embryo has the capability of developing a wolffian (internal male) or müllerian (internal female) system. Unless anti-müllerian hormone (formerly müllerian-inhibiting substance) is produced, the embryo develops a female reproductive system beginning with two lateral uterine anlagen that fuse in the midline and canalize. Müllerian anomalies occur because of accidents during fusion and canalization (see Table).

The incidence of müllerian anomalies is difficult to discern, given the potential for a normal reproductive outcome precluding an evaluation and based on the population studied. Müllerian anomalies are found in approximately 4.3% of fertile women, 3.5%-8% of infertile patients, 12.3%-13% of those with recurrent pregnancy losses, and 24.5% of patients with miscarriage and infertility. Of the müllerian anomalies, the most common is septate (35%), followed by bicornuate (26%), arcuate (18%), unicornuate (10%), didelphys (8%), and agenesis (3%) (Hum Reprod Update. 2001;7[2]:161; Hum Reprod Update. 2011;17[6]:761-71).

In 20%-30% of patients with müllerian anomalies, particularly in women with a unicornuate uterus, renal anomalies exist that are typically ipsilateral to the absent or rudimentary contralateral uterine horn (J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2021;34[2]:154-60). As there is no definitive evidence to suggest an association between a septate uterus and renal anomalies, the renal system evaluation can be deferred in this population (Fertil Steril. 2021 Nov;116[5]:1238-52).

Diagnosis

2-D ultrasound can be a screen for müllerian anomalies and genitourinary anatomic variants. The diagnostic accuracy of 3-D ultrasound with müllerian anomalies is reported to be 97.6% with sensitivity and specificity of 98.3% and 99.4%, respectively (Hum. Reprod. 2016;31[1]:2-7). As a result, office 3-D has essentially replaced MRI in the diagnosis of müllerian anomalies (Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2015 Nov;46[5]:616-22), with one exception because of the avoidance of a transvaginal probe in the non–sexually active adult and younger adolescent/child. MRI is reserved for diagnosing complex müllerian anomalies or if there is a diagnostic challenge.

Criteria to diagnose müllerian anomalies by radiology begins with the “reference line,” i.e., a line joining both tubal ostia (interostial line). A septate uterus is diagnosed if the distance from the interostial line to the cephalad endometrium is more than 1 cm, otherwise it is considered normal or arcuate based on its appearance. An arcuate uterus has not been associated with impaired reproduction and can be viewed as a normal variant. Alternatively, a bicornuate uterus is diagnosed when the external fundal indentation is more than 1 cm (Fertil Steril. 2021 Nov;116[5]:1238-52).

Clinical course

Women with müllerian anomalies may experience pelvic pain and prolonged and/or abnormal bleeding at the time of menarche. While the ability to conceive may not be impaired from müllerian anomalies with the possible exception of the septate uterus, the pregnancy course can be affected, i.e., recurrent pregnancy loss, preterm birth, perinatal mortality, and malpresentation in labor (Reprod Biomed Online. 2014;29[6]:665). In women with septate, bicornuate, and uterine didelphys, fetal growth restriction appears to be increased. Spontaneous abortion rates of 32% and preterm birth rates of 28% have been reported in patients with uterus didelphys (Obstet Gynecol. 1990;75[6]:906).

Special consideration of the unicornuate is given because of the potential for a rudimentary horn that may communicate with the main uterine cavity and/or have functional endometrium which places the woman at risk of an ectopic pregnancy in the smaller horn. Patients with a unicornuate uterus are at higher risk for preterm labor and breech presentation. An obstructed (noncommunicating) functional rudimentary horn is a risk for endometriosis with cyclic pain because of outflow tract obstruction and an ectopic pregnancy prompting consideration for hemihysterectomy based on symptoms.

The septate uterus – old dogma revisited

The incidence of uterine septa is approximately 1-15 per 1,000. As the most common müllerian anomaly, the septate uterus has traditionally been associated with an increased risk for spontaneous abortion (21%-44%) and preterm birth (12%-33%). The live birth rate ranges from 50% to 72% (Hum Reprod Update. 2001;7[2]:161-74). A uterine septum is believed to develop as a result of failure of resorption of the tissue connecting the two paramesonephric (müllerian) ducts prior to the 20th embryonic week.

Incising the uterine septum (metroplasty) dates back to 1884 when Ruge described a blind transcervical metroplasty in a woman with two previous miscarriages who, postoperatively, delivered a healthy baby. In the early 1900s, Tompkins reported an abdominal metroplasty (Fertil Stertil. 2021;115:1140-2). The decision to proceed with metroplasty is based on only established observational studies (Fertil Steril. 2016;106:530-40). Until recently, the majority of studies suggested that metroplasty is associated with decreased spontaneous abortion rates and improved obstetrical outcomes. A retrospective case series of 361 patients with a septate uterus who had primary infertility of >2 years’ duration, a history of 1-2 spontaneous abortions, or recurrent pregnancy loss suggested a significant improvement in the live birth rate and reduction in miscarriage (Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2003;268:289-92). A meta-analysis found that the overall pregnancy rate after septum incision was 67.8% and the live-birth rate was 53.5% (J Minim Invas Gynecol. 2013;20:22-42).

Recently, two multinational studies question the prevailing dogma (Fertil Steril. 2021 Sep;116[3]:693-4). Both studies could not demonstrate any increase in live birth rate, reduction in preterm birth, or in pregnancy loss after metroplasty. A significant limitation was the lack of a uniform consensus on the definition of the septate uterus and allowing the discretion of the physician to diagnosis a septum (Hum Reprod. 2020;35:1578-88; Hum Reprod. 2021;36:1260-7).

Hysteroscopic metroplasty is not without complications. Uterine rupture during pregnancy or delivery, while rare, may be linked to significant entry into the myometrium and/or overzealous cauterization and perforation, which emphasizes the importance of appropriate techniques.

Conclusion

A diagnosis of müllerian anomalies justifies a comprehensive consultation with the patient given the risk of pregnancy complications. Management of the septate uterus has become controversial. In a patient with infertility, prior pregnancy loss, or poor obstetrical outcome, it is reasonable to consider metroplasty; otherwise, expectant management is an option.

Dr. Trolice is director of The IVF Center in Winter Park, Fla., and professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Central Florida, Orlando. Email him at [email protected].

The American Society for Reproductive Medicine’s classification system for müllerian anomalies was the standard until the revision in 2021 by ASRM, which updated and expanded the classification presenting nine classes and imaging criteria: müllerian agenesis, cervical agenesis, unicornuate, uterus didelphys, bicornuate, septate, longitudinal vaginal septum, transverse vaginal septum, and complex anomalies. This month’s article addresses müllerian anomalies from embryology to treatment options.

The early embryo has the capability of developing a wolffian (internal male) or müllerian (internal female) system. Unless anti-müllerian hormone (formerly müllerian-inhibiting substance) is produced, the embryo develops a female reproductive system beginning with two lateral uterine anlagen that fuse in the midline and canalize. Müllerian anomalies occur because of accidents during fusion and canalization (see Table).

The incidence of müllerian anomalies is difficult to discern, given the potential for a normal reproductive outcome precluding an evaluation and based on the population studied. Müllerian anomalies are found in approximately 4.3% of fertile women, 3.5%-8% of infertile patients, 12.3%-13% of those with recurrent pregnancy losses, and 24.5% of patients with miscarriage and infertility. Of the müllerian anomalies, the most common is septate (35%), followed by bicornuate (26%), arcuate (18%), unicornuate (10%), didelphys (8%), and agenesis (3%) (Hum Reprod Update. 2001;7[2]:161; Hum Reprod Update. 2011;17[6]:761-71).

In 20%-30% of patients with müllerian anomalies, particularly in women with a unicornuate uterus, renal anomalies exist that are typically ipsilateral to the absent or rudimentary contralateral uterine horn (J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2021;34[2]:154-60). As there is no definitive evidence to suggest an association between a septate uterus and renal anomalies, the renal system evaluation can be deferred in this population (Fertil Steril. 2021 Nov;116[5]:1238-52).

Diagnosis

2-D ultrasound can be a screen for müllerian anomalies and genitourinary anatomic variants. The diagnostic accuracy of 3-D ultrasound with müllerian anomalies is reported to be 97.6% with sensitivity and specificity of 98.3% and 99.4%, respectively (Hum. Reprod. 2016;31[1]:2-7). As a result, office 3-D has essentially replaced MRI in the diagnosis of müllerian anomalies (Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2015 Nov;46[5]:616-22), with one exception because of the avoidance of a transvaginal probe in the non–sexually active adult and younger adolescent/child. MRI is reserved for diagnosing complex müllerian anomalies or if there is a diagnostic challenge.

Criteria to diagnose müllerian anomalies by radiology begins with the “reference line,” i.e., a line joining both tubal ostia (interostial line). A septate uterus is diagnosed if the distance from the interostial line to the cephalad endometrium is more than 1 cm, otherwise it is considered normal or arcuate based on its appearance. An arcuate uterus has not been associated with impaired reproduction and can be viewed as a normal variant. Alternatively, a bicornuate uterus is diagnosed when the external fundal indentation is more than 1 cm (Fertil Steril. 2021 Nov;116[5]:1238-52).

Clinical course

Women with müllerian anomalies may experience pelvic pain and prolonged and/or abnormal bleeding at the time of menarche. While the ability to conceive may not be impaired from müllerian anomalies with the possible exception of the septate uterus, the pregnancy course can be affected, i.e., recurrent pregnancy loss, preterm birth, perinatal mortality, and malpresentation in labor (Reprod Biomed Online. 2014;29[6]:665). In women with septate, bicornuate, and uterine didelphys, fetal growth restriction appears to be increased. Spontaneous abortion rates of 32% and preterm birth rates of 28% have been reported in patients with uterus didelphys (Obstet Gynecol. 1990;75[6]:906).

Special consideration of the unicornuate is given because of the potential for a rudimentary horn that may communicate with the main uterine cavity and/or have functional endometrium which places the woman at risk of an ectopic pregnancy in the smaller horn. Patients with a unicornuate uterus are at higher risk for preterm labor and breech presentation. An obstructed (noncommunicating) functional rudimentary horn is a risk for endometriosis with cyclic pain because of outflow tract obstruction and an ectopic pregnancy prompting consideration for hemihysterectomy based on symptoms.

The septate uterus – old dogma revisited

The incidence of uterine septa is approximately 1-15 per 1,000. As the most common müllerian anomaly, the septate uterus has traditionally been associated with an increased risk for spontaneous abortion (21%-44%) and preterm birth (12%-33%). The live birth rate ranges from 50% to 72% (Hum Reprod Update. 2001;7[2]:161-74). A uterine septum is believed to develop as a result of failure of resorption of the tissue connecting the two paramesonephric (müllerian) ducts prior to the 20th embryonic week.

Incising the uterine septum (metroplasty) dates back to 1884 when Ruge described a blind transcervical metroplasty in a woman with two previous miscarriages who, postoperatively, delivered a healthy baby. In the early 1900s, Tompkins reported an abdominal metroplasty (Fertil Stertil. 2021;115:1140-2). The decision to proceed with metroplasty is based on only established observational studies (Fertil Steril. 2016;106:530-40). Until recently, the majority of studies suggested that metroplasty is associated with decreased spontaneous abortion rates and improved obstetrical outcomes. A retrospective case series of 361 patients with a septate uterus who had primary infertility of >2 years’ duration, a history of 1-2 spontaneous abortions, or recurrent pregnancy loss suggested a significant improvement in the live birth rate and reduction in miscarriage (Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2003;268:289-92). A meta-analysis found that the overall pregnancy rate after septum incision was 67.8% and the live-birth rate was 53.5% (J Minim Invas Gynecol. 2013;20:22-42).

Recently, two multinational studies question the prevailing dogma (Fertil Steril. 2021 Sep;116[3]:693-4). Both studies could not demonstrate any increase in live birth rate, reduction in preterm birth, or in pregnancy loss after metroplasty. A significant limitation was the lack of a uniform consensus on the definition of the septate uterus and allowing the discretion of the physician to diagnosis a septum (Hum Reprod. 2020;35:1578-88; Hum Reprod. 2021;36:1260-7).

Hysteroscopic metroplasty is not without complications. Uterine rupture during pregnancy or delivery, while rare, may be linked to significant entry into the myometrium and/or overzealous cauterization and perforation, which emphasizes the importance of appropriate techniques.

Conclusion

A diagnosis of müllerian anomalies justifies a comprehensive consultation with the patient given the risk of pregnancy complications. Management of the septate uterus has become controversial. In a patient with infertility, prior pregnancy loss, or poor obstetrical outcome, it is reasonable to consider metroplasty; otherwise, expectant management is an option.

Dr. Trolice is director of The IVF Center in Winter Park, Fla., and professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Central Florida, Orlando. Email him at [email protected].

The American Society for Reproductive Medicine’s classification system for müllerian anomalies was the standard until the revision in 2021 by ASRM, which updated and expanded the classification presenting nine classes and imaging criteria: müllerian agenesis, cervical agenesis, unicornuate, uterus didelphys, bicornuate, septate, longitudinal vaginal septum, transverse vaginal septum, and complex anomalies. This month’s article addresses müllerian anomalies from embryology to treatment options.

The early embryo has the capability of developing a wolffian (internal male) or müllerian (internal female) system. Unless anti-müllerian hormone (formerly müllerian-inhibiting substance) is produced, the embryo develops a female reproductive system beginning with two lateral uterine anlagen that fuse in the midline and canalize. Müllerian anomalies occur because of accidents during fusion and canalization (see Table).

The incidence of müllerian anomalies is difficult to discern, given the potential for a normal reproductive outcome precluding an evaluation and based on the population studied. Müllerian anomalies are found in approximately 4.3% of fertile women, 3.5%-8% of infertile patients, 12.3%-13% of those with recurrent pregnancy losses, and 24.5% of patients with miscarriage and infertility. Of the müllerian anomalies, the most common is septate (35%), followed by bicornuate (26%), arcuate (18%), unicornuate (10%), didelphys (8%), and agenesis (3%) (Hum Reprod Update. 2001;7[2]:161; Hum Reprod Update. 2011;17[6]:761-71).

In 20%-30% of patients with müllerian anomalies, particularly in women with a unicornuate uterus, renal anomalies exist that are typically ipsilateral to the absent or rudimentary contralateral uterine horn (J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2021;34[2]:154-60). As there is no definitive evidence to suggest an association between a septate uterus and renal anomalies, the renal system evaluation can be deferred in this population (Fertil Steril. 2021 Nov;116[5]:1238-52).

Diagnosis

2-D ultrasound can be a screen for müllerian anomalies and genitourinary anatomic variants. The diagnostic accuracy of 3-D ultrasound with müllerian anomalies is reported to be 97.6% with sensitivity and specificity of 98.3% and 99.4%, respectively (Hum. Reprod. 2016;31[1]:2-7). As a result, office 3-D has essentially replaced MRI in the diagnosis of müllerian anomalies (Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2015 Nov;46[5]:616-22), with one exception because of the avoidance of a transvaginal probe in the non–sexually active adult and younger adolescent/child. MRI is reserved for diagnosing complex müllerian anomalies or if there is a diagnostic challenge.

Criteria to diagnose müllerian anomalies by radiology begins with the “reference line,” i.e., a line joining both tubal ostia (interostial line). A septate uterus is diagnosed if the distance from the interostial line to the cephalad endometrium is more than 1 cm, otherwise it is considered normal or arcuate based on its appearance. An arcuate uterus has not been associated with impaired reproduction and can be viewed as a normal variant. Alternatively, a bicornuate uterus is diagnosed when the external fundal indentation is more than 1 cm (Fertil Steril. 2021 Nov;116[5]:1238-52).

Clinical course

Women with müllerian anomalies may experience pelvic pain and prolonged and/or abnormal bleeding at the time of menarche. While the ability to conceive may not be impaired from müllerian anomalies with the possible exception of the septate uterus, the pregnancy course can be affected, i.e., recurrent pregnancy loss, preterm birth, perinatal mortality, and malpresentation in labor (Reprod Biomed Online. 2014;29[6]:665). In women with septate, bicornuate, and uterine didelphys, fetal growth restriction appears to be increased. Spontaneous abortion rates of 32% and preterm birth rates of 28% have been reported in patients with uterus didelphys (Obstet Gynecol. 1990;75[6]:906).

Special consideration of the unicornuate is given because of the potential for a rudimentary horn that may communicate with the main uterine cavity and/or have functional endometrium which places the woman at risk of an ectopic pregnancy in the smaller horn. Patients with a unicornuate uterus are at higher risk for preterm labor and breech presentation. An obstructed (noncommunicating) functional rudimentary horn is a risk for endometriosis with cyclic pain because of outflow tract obstruction and an ectopic pregnancy prompting consideration for hemihysterectomy based on symptoms.

The septate uterus – old dogma revisited

The incidence of uterine septa is approximately 1-15 per 1,000. As the most common müllerian anomaly, the septate uterus has traditionally been associated with an increased risk for spontaneous abortion (21%-44%) and preterm birth (12%-33%). The live birth rate ranges from 50% to 72% (Hum Reprod Update. 2001;7[2]:161-74). A uterine septum is believed to develop as a result of failure of resorption of the tissue connecting the two paramesonephric (müllerian) ducts prior to the 20th embryonic week.

Incising the uterine septum (metroplasty) dates back to 1884 when Ruge described a blind transcervical metroplasty in a woman with two previous miscarriages who, postoperatively, delivered a healthy baby. In the early 1900s, Tompkins reported an abdominal metroplasty (Fertil Stertil. 2021;115:1140-2). The decision to proceed with metroplasty is based on only established observational studies (Fertil Steril. 2016;106:530-40). Until recently, the majority of studies suggested that metroplasty is associated with decreased spontaneous abortion rates and improved obstetrical outcomes. A retrospective case series of 361 patients with a septate uterus who had primary infertility of >2 years’ duration, a history of 1-2 spontaneous abortions, or recurrent pregnancy loss suggested a significant improvement in the live birth rate and reduction in miscarriage (Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2003;268:289-92). A meta-analysis found that the overall pregnancy rate after septum incision was 67.8% and the live-birth rate was 53.5% (J Minim Invas Gynecol. 2013;20:22-42).

Recently, two multinational studies question the prevailing dogma (Fertil Steril. 2021 Sep;116[3]:693-4). Both studies could not demonstrate any increase in live birth rate, reduction in preterm birth, or in pregnancy loss after metroplasty. A significant limitation was the lack of a uniform consensus on the definition of the septate uterus and allowing the discretion of the physician to diagnosis a septum (Hum Reprod. 2020;35:1578-88; Hum Reprod. 2021;36:1260-7).

Hysteroscopic metroplasty is not without complications. Uterine rupture during pregnancy or delivery, while rare, may be linked to significant entry into the myometrium and/or overzealous cauterization and perforation, which emphasizes the importance of appropriate techniques.

Conclusion

A diagnosis of müllerian anomalies justifies a comprehensive consultation with the patient given the risk of pregnancy complications. Management of the septate uterus has become controversial. In a patient with infertility, prior pregnancy loss, or poor obstetrical outcome, it is reasonable to consider metroplasty; otherwise, expectant management is an option.

Dr. Trolice is director of The IVF Center in Winter Park, Fla., and professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Central Florida, Orlando. Email him at [email protected].

Imiquimod cream offers alternative to surgery for vulvar lesions

Imiquimod cream is a safe, effective, first-line alternative to surgery for the treatment of vulvar high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (vHSILs), suggest the results from the first randomized trial to compare the two approaches directly.

The findings provide women with human papillomavirus (HPV)–related precancerous lesions with a new treatment option that can circumvent drawbacks of surgery, according to first author Gerda Trutnovsky, MD, deputy head of the Division of Gynecology at the Medical University of Graz, Austria.

“Surgical removal of [vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia] can cause wound healing disorders, scarring, and even sexual complaints later on,” she explained in a press statement. Further, recurrences are common, and repeat surgeries are often necessary, she said.

The results from the trial show that “imiquimod cream was effective and well tolerated, and the rate of success of this treatment equaled that of surgery,” Dr. Trutnovsky said.

The study was published online in The Lancet.

The findings are of note because HPV vaccination rates remain low, and the incidence of both cervical and vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia has increased in recent years, particularly among younger women, the authors comment.

First head-to-head trial

For the trial, Dr. Trutnovsky and her colleagues randomly assigned 110 women with vHSIL to receive either imiquimod treatment or surgery between June 2013 and January 2020. Of these patients, 78% had unifocal lesions, and 22% had multifocal lesions.

The participants (aged 18-90 years) were recruited from six hospitals in Austria. All had histologically confirmed vHSIL with visible unifocal or multifocal lesions. Those with suspected invasive disease, a history of vulvar cancer or severe inflammatory dermatosis of the vulva, or who had undergone active treatment for vHSIL in the prior 3 months were excluded.

Imiquimod treatment was self-administered. The dose was slowly escalated to no more than three times per week for 4-6 months. Surgery involved either excision or ablation.

The team reports that 98 patients (of the 110 who were randomly assigned) completed the study: 46 in the imiquinod arm and 52 in the surgery arm.

Complete clinical response rates at 6 months were 80% with imiquimod versus 79% with surgery. No significant difference was observed between the groups with respect to HPV clearance, adverse events, and treatment satisfaction, the authors report.

“Long-term follow-up ... is ongoing and will assess the effect of treatment modality on recurrence rates,” the team comments.

Dr. Trutnovsky and colleagues recommend that patients with vHSIL be counseled regarding the potential benefits and risks of treatment options. “On the basis of our results, the oncological safety of imiquimod treatment can be assumed as long as regular clinical check-ups are carried out,” they write.

They also note that good patient compliance is important for treatment with imiquimod to be successful and that surgery might remain the treatment of choice for patients who may not be adherent to treatment.

“In all other women with vHSIL, imiquimod can be considered a first-line treatment option,” the authors conclude.

The study was funded by the Austrian Science Fund and Austrian Gynaecological Oncology group. The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Imiquimod cream is a safe, effective, first-line alternative to surgery for the treatment of vulvar high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (vHSILs), suggest the results from the first randomized trial to compare the two approaches directly.

The findings provide women with human papillomavirus (HPV)–related precancerous lesions with a new treatment option that can circumvent drawbacks of surgery, according to first author Gerda Trutnovsky, MD, deputy head of the Division of Gynecology at the Medical University of Graz, Austria.

“Surgical removal of [vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia] can cause wound healing disorders, scarring, and even sexual complaints later on,” she explained in a press statement. Further, recurrences are common, and repeat surgeries are often necessary, she said.

The results from the trial show that “imiquimod cream was effective and well tolerated, and the rate of success of this treatment equaled that of surgery,” Dr. Trutnovsky said.

The study was published online in The Lancet.

The findings are of note because HPV vaccination rates remain low, and the incidence of both cervical and vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia has increased in recent years, particularly among younger women, the authors comment.

First head-to-head trial

For the trial, Dr. Trutnovsky and her colleagues randomly assigned 110 women with vHSIL to receive either imiquimod treatment or surgery between June 2013 and January 2020. Of these patients, 78% had unifocal lesions, and 22% had multifocal lesions.

The participants (aged 18-90 years) were recruited from six hospitals in Austria. All had histologically confirmed vHSIL with visible unifocal or multifocal lesions. Those with suspected invasive disease, a history of vulvar cancer or severe inflammatory dermatosis of the vulva, or who had undergone active treatment for vHSIL in the prior 3 months were excluded.

Imiquimod treatment was self-administered. The dose was slowly escalated to no more than three times per week for 4-6 months. Surgery involved either excision or ablation.

The team reports that 98 patients (of the 110 who were randomly assigned) completed the study: 46 in the imiquinod arm and 52 in the surgery arm.

Complete clinical response rates at 6 months were 80% with imiquimod versus 79% with surgery. No significant difference was observed between the groups with respect to HPV clearance, adverse events, and treatment satisfaction, the authors report.

“Long-term follow-up ... is ongoing and will assess the effect of treatment modality on recurrence rates,” the team comments.

Dr. Trutnovsky and colleagues recommend that patients with vHSIL be counseled regarding the potential benefits and risks of treatment options. “On the basis of our results, the oncological safety of imiquimod treatment can be assumed as long as regular clinical check-ups are carried out,” they write.

They also note that good patient compliance is important for treatment with imiquimod to be successful and that surgery might remain the treatment of choice for patients who may not be adherent to treatment.

“In all other women with vHSIL, imiquimod can be considered a first-line treatment option,” the authors conclude.

The study was funded by the Austrian Science Fund and Austrian Gynaecological Oncology group. The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Imiquimod cream is a safe, effective, first-line alternative to surgery for the treatment of vulvar high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (vHSILs), suggest the results from the first randomized trial to compare the two approaches directly.

The findings provide women with human papillomavirus (HPV)–related precancerous lesions with a new treatment option that can circumvent drawbacks of surgery, according to first author Gerda Trutnovsky, MD, deputy head of the Division of Gynecology at the Medical University of Graz, Austria.

“Surgical removal of [vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia] can cause wound healing disorders, scarring, and even sexual complaints later on,” she explained in a press statement. Further, recurrences are common, and repeat surgeries are often necessary, she said.

The results from the trial show that “imiquimod cream was effective and well tolerated, and the rate of success of this treatment equaled that of surgery,” Dr. Trutnovsky said.

The study was published online in The Lancet.

The findings are of note because HPV vaccination rates remain low, and the incidence of both cervical and vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia has increased in recent years, particularly among younger women, the authors comment.

First head-to-head trial

For the trial, Dr. Trutnovsky and her colleagues randomly assigned 110 women with vHSIL to receive either imiquimod treatment or surgery between June 2013 and January 2020. Of these patients, 78% had unifocal lesions, and 22% had multifocal lesions.

The participants (aged 18-90 years) were recruited from six hospitals in Austria. All had histologically confirmed vHSIL with visible unifocal or multifocal lesions. Those with suspected invasive disease, a history of vulvar cancer or severe inflammatory dermatosis of the vulva, or who had undergone active treatment for vHSIL in the prior 3 months were excluded.

Imiquimod treatment was self-administered. The dose was slowly escalated to no more than three times per week for 4-6 months. Surgery involved either excision or ablation.

The team reports that 98 patients (of the 110 who were randomly assigned) completed the study: 46 in the imiquinod arm and 52 in the surgery arm.

Complete clinical response rates at 6 months were 80% with imiquimod versus 79% with surgery. No significant difference was observed between the groups with respect to HPV clearance, adverse events, and treatment satisfaction, the authors report.

“Long-term follow-up ... is ongoing and will assess the effect of treatment modality on recurrence rates,” the team comments.

Dr. Trutnovsky and colleagues recommend that patients with vHSIL be counseled regarding the potential benefits and risks of treatment options. “On the basis of our results, the oncological safety of imiquimod treatment can be assumed as long as regular clinical check-ups are carried out,” they write.

They also note that good patient compliance is important for treatment with imiquimod to be successful and that surgery might remain the treatment of choice for patients who may not be adherent to treatment.

“In all other women with vHSIL, imiquimod can be considered a first-line treatment option,” the authors conclude.

The study was funded by the Austrian Science Fund and Austrian Gynaecological Oncology group. The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

CDC updates guidelines for hepatitis outbreak among children

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention updated its recommendations for doctors and public health officials regarding the unusual outbreak of acute hepatitis among children.

As of May 5, the CDC and state health departments are investigating 109 children with hepatitis of unknown origin across 25 states and territories.

More than half have tested positive for adenovirus, the CDC said. More than 90% have been hospitalized, and 14% have had liver transplants. Five deaths are under investigation.

This week’s CDC alert provides updated recommendations for testing, given the potential association between adenovirus infection and pediatric hepatitis, or liver inflammation.

“Clinicians are recommended to consider adenovirus testing for patients with hepatitis of unknown etiology and to report such cases to their state or jurisdictional public health authorities,” the CDC said.

Doctors should also consider collecting a blood sample, respiratory sample, and stool sample. They may also collect liver tissue if a biopsy occurred or an autopsy is available.

In November 2021, clinicians at a large children’s hospital in Alabama notified the CDC about five pediatric patients with significant liver injury, including three with acute liver failure, who also tested positive for adenovirus. All children were previously healthy, and none had COVID-19, according to a CDC alert in April.

Four additional pediatric patients with hepatitis and adenovirus infection were identified. After lab testing found adenovirus infection in all nine patients in the initial cluster, public health officials began investigating a possible association between pediatric hepatitis and adenovirus. Among the five specimens that could be sequenced, they were all adenovirus type 41.

Unexplained hepatitis cases have been reported in children worldwide, reaching 450 cases and 11 deaths, according to the latest update from the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control.

The cases have been reported in more than two dozen countries around the world, with 14 countries reporting more than five cases. The United Kingdom and the United States have reported the largest case counts so far.

In the United Kingdom, officials have identified 163 cases in children under age 16 years, including 11 that required liver transplants.

In the European Union, 14 countries have reported 106 cases collectively, with Italy reporting 35 cases and Spain reporting 22 cases. Outside of the European Union, Brazil has reported 16, Indonesia has reported 15, and Israel has reported 12.

Among the 11 deaths reported globally, the Uniyed States has reported five, Indonesia has reported five, and Palestine has reported one.

The cause of severe hepatitis remains a mystery, according to Ars Technica. Some cases have been identified retrospectively, dating back to the beginning of October 2021.

About 70% of the cases that have been tested for an adenovirus have tested positive, and subtype testing continues to show adenovirus type 41. The cases don’t appear to be linked to common causes, such as hepatitis viruses A, B, C, D, or E, which can cause liver inflammation and injury.

Adenoviruses aren’t known to cause hepatitis in healthy children, though the viruses have been linked to liver damage in children with compromised immune systems, according to Ars Technica. Adenoviruses typically cause respiratory infections in children, although type 41 tends to cause gastrointestinal illness.

“At present, the leading hypotheses remain those which involve adenovirus,” Philippa Easterbrook, a senior scientist at the WHO, said May 10 during a press briefing.

“I think [there’s] also still an important consideration about the role of COVID as well, either as a co-infection or as a past infection,” she said.

WHO officials expect data within a week from U.K. cases, Ms. Easterbrook said, which may indicate whether the adenovirus is an incidental infection or a more direct cause.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention updated its recommendations for doctors and public health officials regarding the unusual outbreak of acute hepatitis among children.

As of May 5, the CDC and state health departments are investigating 109 children with hepatitis of unknown origin across 25 states and territories.

More than half have tested positive for adenovirus, the CDC said. More than 90% have been hospitalized, and 14% have had liver transplants. Five deaths are under investigation.

This week’s CDC alert provides updated recommendations for testing, given the potential association between adenovirus infection and pediatric hepatitis, or liver inflammation.

“Clinicians are recommended to consider adenovirus testing for patients with hepatitis of unknown etiology and to report such cases to their state or jurisdictional public health authorities,” the CDC said.

Doctors should also consider collecting a blood sample, respiratory sample, and stool sample. They may also collect liver tissue if a biopsy occurred or an autopsy is available.

In November 2021, clinicians at a large children’s hospital in Alabama notified the CDC about five pediatric patients with significant liver injury, including three with acute liver failure, who also tested positive for adenovirus. All children were previously healthy, and none had COVID-19, according to a CDC alert in April.

Four additional pediatric patients with hepatitis and adenovirus infection were identified. After lab testing found adenovirus infection in all nine patients in the initial cluster, public health officials began investigating a possible association between pediatric hepatitis and adenovirus. Among the five specimens that could be sequenced, they were all adenovirus type 41.

Unexplained hepatitis cases have been reported in children worldwide, reaching 450 cases and 11 deaths, according to the latest update from the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control.

The cases have been reported in more than two dozen countries around the world, with 14 countries reporting more than five cases. The United Kingdom and the United States have reported the largest case counts so far.

In the United Kingdom, officials have identified 163 cases in children under age 16 years, including 11 that required liver transplants.

In the European Union, 14 countries have reported 106 cases collectively, with Italy reporting 35 cases and Spain reporting 22 cases. Outside of the European Union, Brazil has reported 16, Indonesia has reported 15, and Israel has reported 12.

Among the 11 deaths reported globally, the Uniyed States has reported five, Indonesia has reported five, and Palestine has reported one.

The cause of severe hepatitis remains a mystery, according to Ars Technica. Some cases have been identified retrospectively, dating back to the beginning of October 2021.

About 70% of the cases that have been tested for an adenovirus have tested positive, and subtype testing continues to show adenovirus type 41. The cases don’t appear to be linked to common causes, such as hepatitis viruses A, B, C, D, or E, which can cause liver inflammation and injury.

Adenoviruses aren’t known to cause hepatitis in healthy children, though the viruses have been linked to liver damage in children with compromised immune systems, according to Ars Technica. Adenoviruses typically cause respiratory infections in children, although type 41 tends to cause gastrointestinal illness.

“At present, the leading hypotheses remain those which involve adenovirus,” Philippa Easterbrook, a senior scientist at the WHO, said May 10 during a press briefing.

“I think [there’s] also still an important consideration about the role of COVID as well, either as a co-infection or as a past infection,” she said.

WHO officials expect data within a week from U.K. cases, Ms. Easterbrook said, which may indicate whether the adenovirus is an incidental infection or a more direct cause.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention updated its recommendations for doctors and public health officials regarding the unusual outbreak of acute hepatitis among children.

As of May 5, the CDC and state health departments are investigating 109 children with hepatitis of unknown origin across 25 states and territories.

More than half have tested positive for adenovirus, the CDC said. More than 90% have been hospitalized, and 14% have had liver transplants. Five deaths are under investigation.

This week’s CDC alert provides updated recommendations for testing, given the potential association between adenovirus infection and pediatric hepatitis, or liver inflammation.

“Clinicians are recommended to consider adenovirus testing for patients with hepatitis of unknown etiology and to report such cases to their state or jurisdictional public health authorities,” the CDC said.

Doctors should also consider collecting a blood sample, respiratory sample, and stool sample. They may also collect liver tissue if a biopsy occurred or an autopsy is available.

In November 2021, clinicians at a large children’s hospital in Alabama notified the CDC about five pediatric patients with significant liver injury, including three with acute liver failure, who also tested positive for adenovirus. All children were previously healthy, and none had COVID-19, according to a CDC alert in April.

Four additional pediatric patients with hepatitis and adenovirus infection were identified. After lab testing found adenovirus infection in all nine patients in the initial cluster, public health officials began investigating a possible association between pediatric hepatitis and adenovirus. Among the five specimens that could be sequenced, they were all adenovirus type 41.

Unexplained hepatitis cases have been reported in children worldwide, reaching 450 cases and 11 deaths, according to the latest update from the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control.

The cases have been reported in more than two dozen countries around the world, with 14 countries reporting more than five cases. The United Kingdom and the United States have reported the largest case counts so far.

In the United Kingdom, officials have identified 163 cases in children under age 16 years, including 11 that required liver transplants.

In the European Union, 14 countries have reported 106 cases collectively, with Italy reporting 35 cases and Spain reporting 22 cases. Outside of the European Union, Brazil has reported 16, Indonesia has reported 15, and Israel has reported 12.

Among the 11 deaths reported globally, the Uniyed States has reported five, Indonesia has reported five, and Palestine has reported one.

The cause of severe hepatitis remains a mystery, according to Ars Technica. Some cases have been identified retrospectively, dating back to the beginning of October 2021.

About 70% of the cases that have been tested for an adenovirus have tested positive, and subtype testing continues to show adenovirus type 41. The cases don’t appear to be linked to common causes, such as hepatitis viruses A, B, C, D, or E, which can cause liver inflammation and injury.

Adenoviruses aren’t known to cause hepatitis in healthy children, though the viruses have been linked to liver damage in children with compromised immune systems, according to Ars Technica. Adenoviruses typically cause respiratory infections in children, although type 41 tends to cause gastrointestinal illness.

“At present, the leading hypotheses remain those which involve adenovirus,” Philippa Easterbrook, a senior scientist at the WHO, said May 10 during a press briefing.

“I think [there’s] also still an important consideration about the role of COVID as well, either as a co-infection or as a past infection,” she said.

WHO officials expect data within a week from U.K. cases, Ms. Easterbrook said, which may indicate whether the adenovirus is an incidental infection or a more direct cause.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Society of Gynecologic Surgeons meeting champions training of future gynecologic surgeons

It was such a pleasure at the 48th Annual Meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons (SGS) to witness record meeting attendance and strong enthusiasm after 2 depressing years with the COVID-19 pandemic. Evidently, everyone was tired of virtual gatherings and presentations. As a dedicated surgical educator and a passionate vaginal surgeon, SGS President Carl Zimmerman, MD, chose “Gynecologic surgery training: Lessons from the past, looking to the future” as the theme for this year’s meeting. Our keynote speakers, Patricia Turner, MD, MBA, Executive Director of the American College of Surgeons, and Marta Crispens, MD, MBA, Professor and Division Director of Gynecologic Oncology at Vanderbilt, were spot on. They reviewed the current status of surgical training eloquently with convincing statistics. They mapped out the path forward by stressing collaboration and proposing strategies that might produce competent surgeons in all fields.

The meeting featured 2 panel discussions. The first, titled “Innovations in training gynecologic surgeons,” reviewed tracking in residency, use of simulation for surgical proficiency, and European perspective on training. The panelists emphasized the dwindling numbers of surgical procedures, especially vaginal hysterectomies. Cecile Ferrando, MD, suggested that tracking might be part of the answer, based on their experience, which provided a structure for residents to obtain concentrated training in their areas of interest. Douglas Miyazaki, MD, presented the prospects for his innovative, federally funded vaginal surgery simulation model. Oliver Preyer, MD, presented Austrian trainees’ low case volumes, showing that the grass was not actually greener on the other side. Finally, this panel reinvigorated ongoing debate about separating Obstetrics and Gynecology.

The second panel, “Operating room safety and efficiency,” shed light on human and nontechnical factors that might be as critical as surgeons’ skills and experience, and it highlighted an innovative technology that monitored and analyzed all operating room parameters to improve operational processes and surgical technique. Points by Jason Wright, MD, on the relationship between surgical volume and outcomes complemented the meeting theme and the first panel discussion. He underlined how much surgical volume of individual surgeons and hospitals mattered, but he also indicated that restrictive credentialing strategies might lead to unintended consequences.

Importantly, the SGS Women’s Council held a panel on the “Impact of Texas legislation on the physician/patient relationship” to provide a platform for members who had mixed feelings about attending this meeting in Texas.

The SGS meeting also included several popular postgraduate courses on multidisciplinary management of Müllerian anomalies, pelvic fistula treatment, surgical simulation, management modalities for uterine fibroids, and medical innovation and entrepreneurship. In this special section and in the next issue of OBG M

It was such a pleasure at the 48th Annual Meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons (SGS) to witness record meeting attendance and strong enthusiasm after 2 depressing years with the COVID-19 pandemic. Evidently, everyone was tired of virtual gatherings and presentations. As a dedicated surgical educator and a passionate vaginal surgeon, SGS President Carl Zimmerman, MD, chose “Gynecologic surgery training: Lessons from the past, looking to the future” as the theme for this year’s meeting. Our keynote speakers, Patricia Turner, MD, MBA, Executive Director of the American College of Surgeons, and Marta Crispens, MD, MBA, Professor and Division Director of Gynecologic Oncology at Vanderbilt, were spot on. They reviewed the current status of surgical training eloquently with convincing statistics. They mapped out the path forward by stressing collaboration and proposing strategies that might produce competent surgeons in all fields.

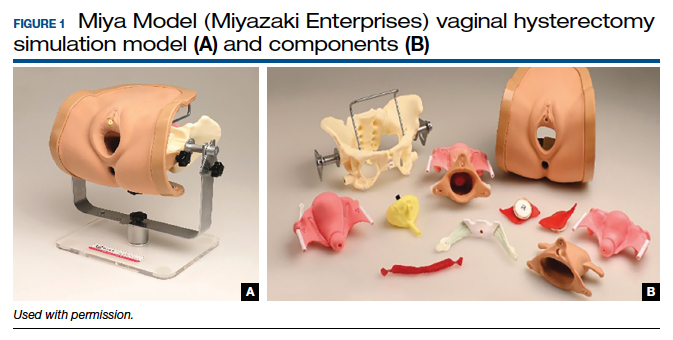

The meeting featured 2 panel discussions. The first, titled “Innovations in training gynecologic surgeons,” reviewed tracking in residency, use of simulation for surgical proficiency, and European perspective on training. The panelists emphasized the dwindling numbers of surgical procedures, especially vaginal hysterectomies. Cecile Ferrando, MD, suggested that tracking might be part of the answer, based on their experience, which provided a structure for residents to obtain concentrated training in their areas of interest. Douglas Miyazaki, MD, presented the prospects for his innovative, federally funded vaginal surgery simulation model. Oliver Preyer, MD, presented Austrian trainees’ low case volumes, showing that the grass was not actually greener on the other side. Finally, this panel reinvigorated ongoing debate about separating Obstetrics and Gynecology.

The second panel, “Operating room safety and efficiency,” shed light on human and nontechnical factors that might be as critical as surgeons’ skills and experience, and it highlighted an innovative technology that monitored and analyzed all operating room parameters to improve operational processes and surgical technique. Points by Jason Wright, MD, on the relationship between surgical volume and outcomes complemented the meeting theme and the first panel discussion. He underlined how much surgical volume of individual surgeons and hospitals mattered, but he also indicated that restrictive credentialing strategies might lead to unintended consequences.

Importantly, the SGS Women’s Council held a panel on the “Impact of Texas legislation on the physician/patient relationship” to provide a platform for members who had mixed feelings about attending this meeting in Texas.

The SGS meeting also included several popular postgraduate courses on multidisciplinary management of Müllerian anomalies, pelvic fistula treatment, surgical simulation, management modalities for uterine fibroids, and medical innovation and entrepreneurship. In this special section and in the next issue of OBG M

It was such a pleasure at the 48th Annual Meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons (SGS) to witness record meeting attendance and strong enthusiasm after 2 depressing years with the COVID-19 pandemic. Evidently, everyone was tired of virtual gatherings and presentations. As a dedicated surgical educator and a passionate vaginal surgeon, SGS President Carl Zimmerman, MD, chose “Gynecologic surgery training: Lessons from the past, looking to the future” as the theme for this year’s meeting. Our keynote speakers, Patricia Turner, MD, MBA, Executive Director of the American College of Surgeons, and Marta Crispens, MD, MBA, Professor and Division Director of Gynecologic Oncology at Vanderbilt, were spot on. They reviewed the current status of surgical training eloquently with convincing statistics. They mapped out the path forward by stressing collaboration and proposing strategies that might produce competent surgeons in all fields.

The meeting featured 2 panel discussions. The first, titled “Innovations in training gynecologic surgeons,” reviewed tracking in residency, use of simulation for surgical proficiency, and European perspective on training. The panelists emphasized the dwindling numbers of surgical procedures, especially vaginal hysterectomies. Cecile Ferrando, MD, suggested that tracking might be part of the answer, based on their experience, which provided a structure for residents to obtain concentrated training in their areas of interest. Douglas Miyazaki, MD, presented the prospects for his innovative, federally funded vaginal surgery simulation model. Oliver Preyer, MD, presented Austrian trainees’ low case volumes, showing that the grass was not actually greener on the other side. Finally, this panel reinvigorated ongoing debate about separating Obstetrics and Gynecology.

The second panel, “Operating room safety and efficiency,” shed light on human and nontechnical factors that might be as critical as surgeons’ skills and experience, and it highlighted an innovative technology that monitored and analyzed all operating room parameters to improve operational processes and surgical technique. Points by Jason Wright, MD, on the relationship between surgical volume and outcomes complemented the meeting theme and the first panel discussion. He underlined how much surgical volume of individual surgeons and hospitals mattered, but he also indicated that restrictive credentialing strategies might lead to unintended consequences.

Importantly, the SGS Women’s Council held a panel on the “Impact of Texas legislation on the physician/patient relationship” to provide a platform for members who had mixed feelings about attending this meeting in Texas.

The SGS meeting also included several popular postgraduate courses on multidisciplinary management of Müllerian anomalies, pelvic fistula treatment, surgical simulation, management modalities for uterine fibroids, and medical innovation and entrepreneurship. In this special section and in the next issue of OBG M

How to teach vaginal surgery through simulation

Vaginal surgery, including vaginal hysterectomy, is slowly becoming a dying art. According to the National Inpatient Sample and the Nationwide Ambulatory Surgery Sample from 2018, only 11.8% of all hysterectomies were performed vaginally.1 The combination of uterine-sparing surgeries, advances in conservative therapies for benign uterine conditions, and the diversification of minimally invasive routes (laparoscopic and robotic) has resulted in a continued downtrend in vaginal surgical volumes. This shift has led to fewer operative learning opportunities and declining graduating resident surgical volume.2 According to the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), the minimum number of vaginal hysterectomies is 15, which represents only the minimum accepted exposure and does not imply competency.

In response, surgical simulation has been used for skill acquisition and maintenance outside of the operating room in a learning environment that is safe for the learners and does not expose patients to additional risk. Educators are uniquely poised to use simulation to teach residents and to evaluate their procedural competency. Although vaginal surgery, specifically vaginal hysterectomy, continues to decline, it can be resuscitated with the assistance of surgical simulation.

In this article, we provide a broad overview of vaginal surgical simulation. We discuss the basic tenets of simulation, review how to teach and evaluate vaginal surgical skills, and present some of the commonly available vaginal surgery simulation models and their associated resources, cost, setup time, fidelity, and limitations.

Simulation principles relevant for vaginal hysterectomy simulation

Here, we review simulation-based learning principles that will help place specific simulation models into perspective.

One size does not fit all

Simulation, like many educational interventions, does not work via a “one-size-fits-all” approach. While the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) Simulations Working Group (SWG) has created a toolkit (available online at https://www.acog.org/education-and-events/simulations/about/curriculum) with many ready-to-use how-to simulation descriptions and lesson plans that cover common topics, what works in one setting may not work in another. The SWG created those modules to help educators save time and resources and to avoid reinventing the wheel for each simulation session. However, these simulations need to be adapted to the local needs of trainees and resources, such as faculty time, space, models, and funding.

Cost vs fidelity

It is important to distinguish between cost and fidelity. “Low cost” is often incorrectly used interchangeably with “low fidelity” when referring to models and simulations. The most basic principle of fidelity is that it is associated with situational realism that in turn, drives learning.3,4 For example, the term high fidelity does apply to a virtual reality robotic surgery simulator, which also is high cost. However, a low-cost beef tongue model of fourth-degree laceration5 is high fidelity, while more expensive commercial models are less realistic, which makes them high cost and low fidelity.6 When selecting simulation models, educators need to consider cost based on their available resources and the level of fidelity needed for their learners.

Continue to: Task breakdown...

Task breakdown

As surgeon-educators, we love to teach! And while educators are passionate about imparting vaginal hysterectomy skills to the next generation of surgeons, it is important to assess where the learners are technically. Vaginal hysterectomy is a high-complexity procedure, with each step involving a unique skill set that is new to residents as learners; this is where the science of learning can help us teach more effectively.7 Focusing on doing the entire procedure all at once is more likely to result in cognitive overload, while a better approach is to break the procedure down into several components and practice those parts until goal proficiency is reached.

Deliberate practice

The idea of deliberate practice was popularized by Malcolm Gladwell in his book titled Outliers, in which he gives examples of how 10,000 hours of practice leads to mastery of complex skills. This concept was deepened by the work of cognitive psychologist Anders Ericsson, who emphasized that not only the duration but also the quality of practice—which involves concentration, analysis, and problem-solving—leads to the most effective training.8

In surgical education, this concept translates into many domains. For example, an individualized learning plan includes frequent low-stakes assessments, video recording for later viewing and analysis, surgical coaching, and detailed planning of future training sessions to incorporate past performance. “Just doing” surgery on a simulator (or in the operating room) results in missed learning opportunities.

Logistics and implementation: Who, where, when

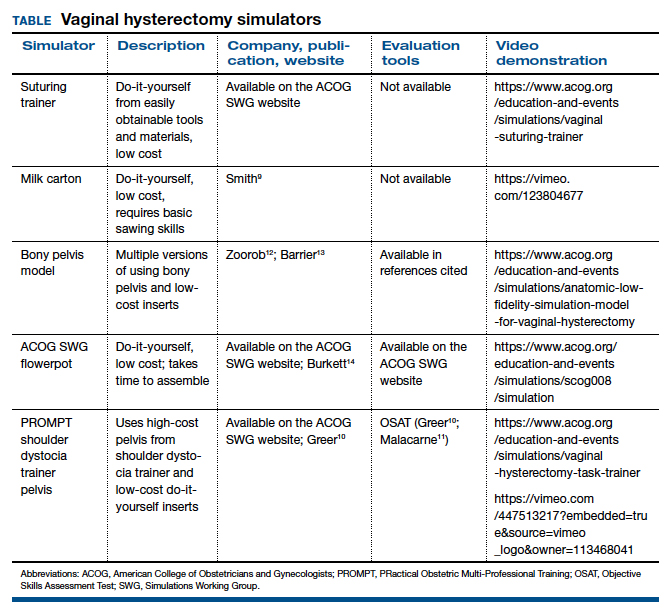

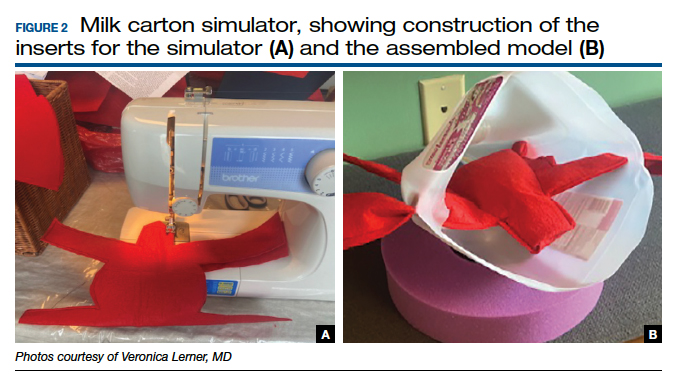

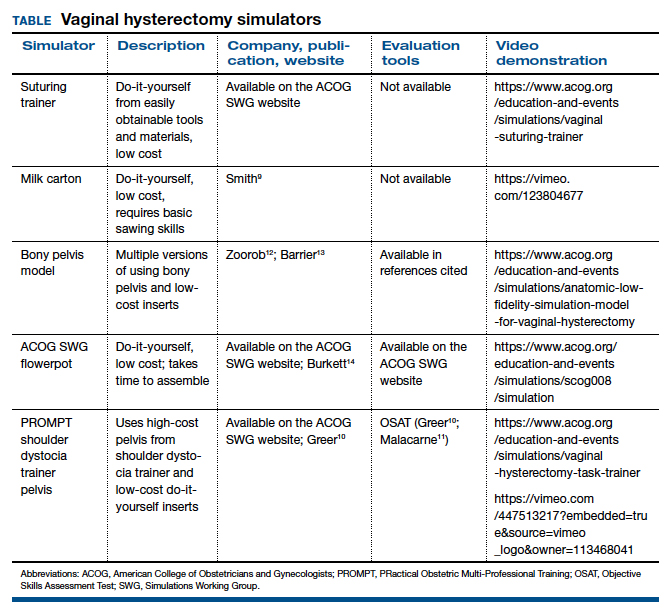

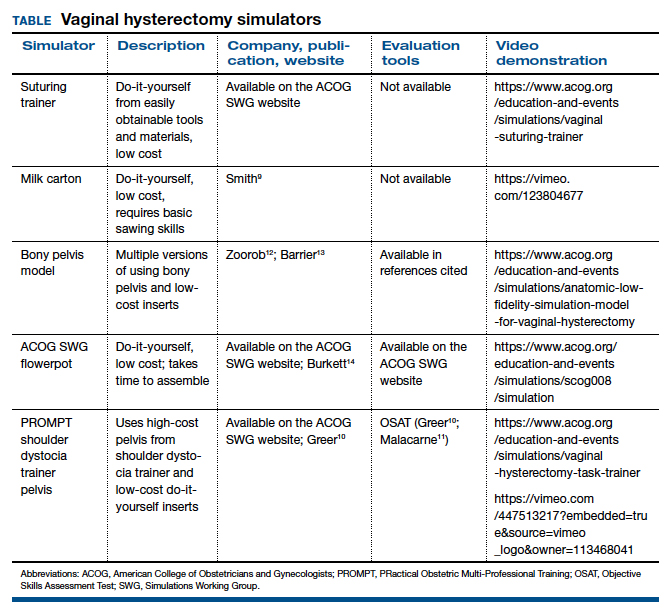

The simulation “formula” takes into account multiple factors but should start with learning objectives and then an assessment of what resources are available to address them. For example, if one surgeon-educator and one resident-learner are available for 30 minutes in between cases in the operating room, and the goal is to teach the resident clamp-and-tie technique on pedicles, the “milk carton” model9 and a few instruments from the vaginal hysterectomy tray are ideal for this training. On the other hand, if it is important to achieve competency for an entire procedure prior to operating room debut and a group of surgeon-educators is available to share the time commitment of 2-hour sessions per each resident, then the PROMPT (PRactical Obstetric Multi-Professional Training) shoulder dystocia model could be used (TABLE).10-14

Learning curves

Ideally, educators would like to know how many simulated training sessions are needed for a learner to reach a proficiency level and become operating room ready. Such information about learning curves, unfortunately, is not available yet for vaginal hysterectomies. The first step in the process is to establish a baseline for performance to know a starting point, with assessment tools specific to each simulator; the next step is to study how many “takes” are needed for learners to move through their learning curve.15 The use of assessment tools can help assess each learner’s progression.

Continue to: Evaluation, assessment, and feedback...

Evaluation, assessment, and feedback

With more emphasis being placed on patient safety and transparency in every aspect of health care, including surgical training, graduate medical education leaders increasingly highlight the importance of objective assessment tools and outcome-based standards for certification of competency in surgery.16,17 Commonly used assessment tools that have reliability and validity evidence include surgical checklists and global rating scales. Checklists for common gynecologic procedures, including vaginal hysterectomy, as well as a global rating scale specifically developed for vaginal surgery (Vaginal Surgical Skills Index, VSSI)18 are accessible on the ACOG Simulations Working Group Surgical Curriculum in Obstetrics and Gynecology website.19

While checklists contain the main steps of each procedure, these lists do not assess for how well each step of the procedure is performed. By contrast, global rating scales, such as the VSSI, can discriminate between surgeons with different skill levels both in the simulation and operating room settings; each metric within the global rating scale (for example, time and motion) does not pertain to the performance of a procedure’s specific step but rather to the overall performance of the entire procedure.18,20 Hence, to provide detailed feedback, especially for formative assessment, both checklists and global rating scales often are used together.

Although standardized, checklists and global rating scales ultimately are still subjective (not objective) assessment tools. Recently, more attention has been to use surgical data science, particularly artificial intelligence methods, to objectively assess surgical performance by analyzing data generated during the performance of surgery, such as instrumental motion and video.21 These methods have been applied to a wide range of surgical techniques, including open, laparoscopic, robotic, endoscopic, and microsurgical approaches. Most of these types of studies have used assessment of surgical skill as the main outcome, with fewer studies correlating skill with clinically relevant metrics, such as patient outcomes.22-25 Although this is an area of active research, these methods are still being developed, and their validity and utility are not well established. For now, educators should continue to use validated checklists and global rating skills to help assess any type of surgical performance, particularly vaginal surgery.

Vaginal surgical simulation models

Vaginal surgery requires a surgeon to operate in a narrow, deep space. This requires ambidexterity, accurate depth perception, understanding of how to handle tissues, and use of movements that are efficient, fluid, and rhythmic. Multiple proposed simulation models are relevant to vaginal surgery, and these vary based on level of fidelity, cost, feasibility, ability to maintain standardization, ease of construction (if required), and generalizability to all of pelvic surgery (that is, procedure specific vs basic skills focused).10,11,13,26-31

Below, we describe various simulation models that are available for teaching vaginal surgical skills.

Vaginal hysterectomy simulation model

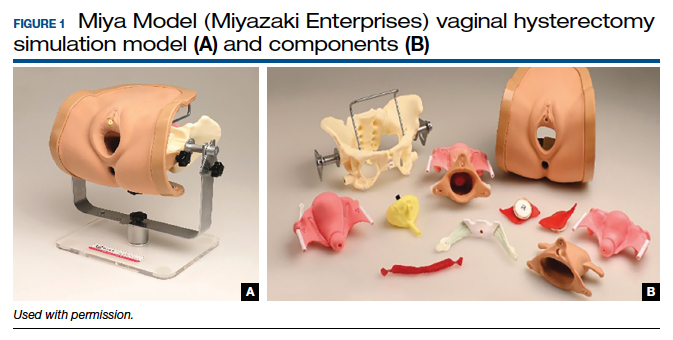

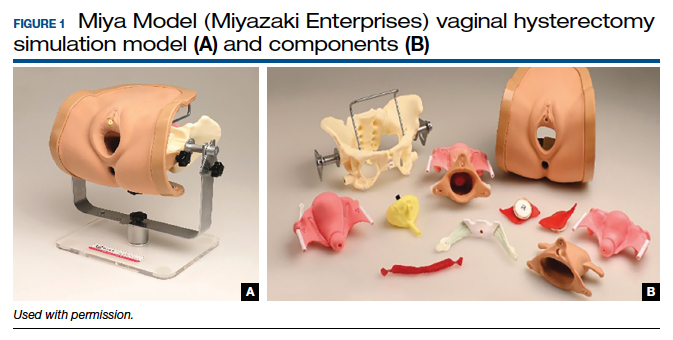

One commercially available simulation model for vaginal hysterectomy (as well as other vaginal surgical procedures, such as midurethral sling and anterior and posterior colporrhaphy) is the Miya Model (Miyazaki Enterprises) (FIGURE 1) and its accompanying MiyaMODEL App. In a multi-institutional study funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the Miya Model, when used with the VSSI, was shown to be a valid assessment tool in terms of ability to differentiate a competent from a noncompetent surgeon.20 Currently, an ongoing NIH-sponsored multi-institutional study is assessing the Miya Model as a teaching tool and whether skills acquired on the Miya Model are transferable to the operating room.

Continue to: Low-cost vaginal hysterectomy models...

Low-cost vaginal hysterectomy models

Multiple low-cost vaginal hysterectomy simulation models are described. Two models developed many years ago include the ACOG SWG flowerpot model14 and the PROMPT shoulder dystocia pelvic trainer model.10,11,14 The former model is low cost as it can be constructed from easily obtained household materials, but its downside is that it takes time and effort to obtain the materials and to assemble them. The latter model is faster to assemble but requires one to use a PROMPT pelvis for shoulder dystocia training, which has a considerable upfront cost. However, it is available in most hospitals with considerable obstetrical volume, and it allows for the most realistic perineum, which is helpful in recreating the feel of vaginal surgery, including retraction and exposure.

Many models created and described in the literature are variations of the models mentioned above, and many use commercially available low-cost bony pelvis models and polyvinyl chloride (PVC) pipes as a foundation for the soft tissue inserts to attach.12,13,31-33 Each model varies on what it “teaches best” regarding realism—for example, teaching anatomy, working in a tight space, dissection, or clamp placement and suture ligature.

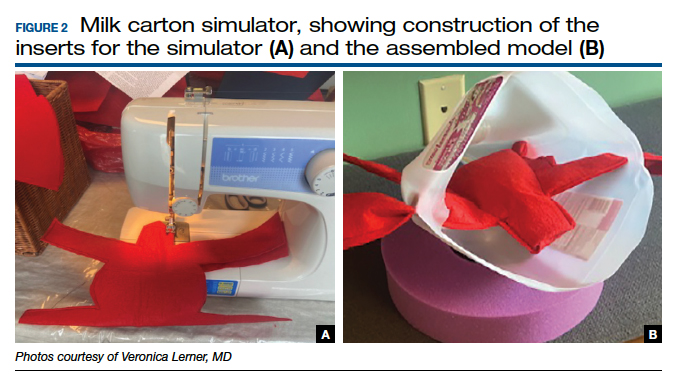

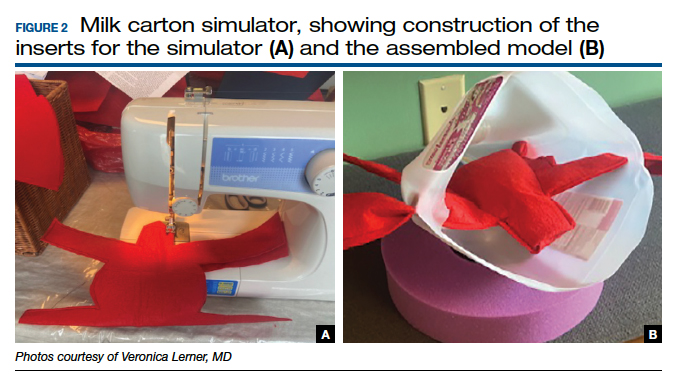

Furthermore, since vaginal hysterectomy is a high-complexity procedure in terms of skills (working in confined space, limited view, “upside-down” anatomy, and need to direct assistants for retraction and exposure), task breakdown is important for simulation learning, as it is not efficient to repeat the entire procedure until proficiency is reached. Two trainers have been described to address that need: the milk carton and the vaginal suturing trainer. The latter allows learners to practice clamp placement and pedicle ligation multiple times, including in confined space (FIGURE 2), and the former allows them to do the same in a procedural matter as the clamp placement moves caudad to cephalad during the procedure (FIGURE 3).

Native tissue pelvic floor surgery simulation

While there are few publications regarding surgical simulation models for native tissue pelvic floor surgeries, a low-cost anterior and posterior repair model was developed for the ACOG SWG Simulation Toolkit and published online in 2017, after their peer-review process. The fidelity is moderate for this low-cost model, which costs less than $5 per use. The simulation model requires a new vaginal insert for each learner, which is fast and easy to make and requires only a few components; however, the bony pelvis (for example, the flowerpot model) needs to be purchased or created. The stage of the anterior wall prolapse can be adjusted by the amount of fluid placed in the balloon, which is used to simulate the bladder. The more fluid that is placed in the “bladder,” the more severe the anterior wall prolapse appears. The vaginal caliber can be adjusted, if needed, by increasing or decreasing the size of the components to create the vagina, but the suggested sizes simulate a significantly widened vaginal caliber that would benefit from a posterior repair with perineorrhaphy. Although there is no validity evidence for this model, a skills assessment is available through the ACOG Simulation Surgical Curriculum. Of note, native tissue colpopexy repairs are also possible with this model (or another high-fidelity model, such as the Miya Model), if the sacrospinous ligaments and/or uterosacral ligaments are available on the pelvic model in use. This model’s limitations include the absence of a high-fidelity plane of dissection of the vaginal muscularis, and that no bleeding is encountered, which is the case for many low-cost models.19,34

Fundamentals of Vaginal Surgery (FVS) basic surgical skills simulation

The FVS simulation system, consisting of a task trainer paired with 6 selected surgical tasks, was developed to teach basic skills used in vaginal surgery.35 The FVS task trainer is 3D printed and has 3 main components: a base piece that allows for different surgical materials to be secured, a depth extender, and a width reducer. In addition, it has a mobile phone mount and a window into the system to enable video capture of skills exercises.

The FVS simulator is designed to enable 6 surgical tasks, including one-handed knot tying, two-handed knot tying, running suturing, plication suturing, Heaney transfixion pedicle ligation, and free pedicle ligation (FIGURE 4). In a pilot study, the FVS simulation system was deemed representative of the intended surgical field, useful for inclusion in a training program, and favored as a tool for both training and testing. Additionally, an initial proficiency score of 400 was set, which discriminated between novice and expert surgeons.35

An advantage of this simulation system is that it allows learners to focus on basic skills, rather than on an entire specific procedure. Further, the system is standardized, as it is commercially manufactured; this also allows for easy assembly. The disadvantage of this model is that it cannot be modified to teach specific vaginal procedures, and it must be purchased, rather than constructed on site. Further studies are needed to create generalizable proficiency scores and to assess its use in training and testing. For more information on the FVS simulation model, visit the Arbor Simulation website (http://arborsim.com).

Surgical simulation’s important role

Surgical skills can be learned and improved in the simulation setting in a low-stakes, low-pressure environment. Simulation can enable basic skills development and then higher-level learning of complex procedures. Skill assessment is important to aid in learning (via formative assessments) and for examination or certification (summative assessments).

With decreasing vaginal surgical volumes occurring nationally, it is becoming even more important to use surgical simulation to teach and maintain vaginal surgical skills. In this article, we reviewed various different simulation models that can be used for developing vaginal surgical skills and presented the advantages, limitations, and resources relevant for each simulation model. ●

- Wright JD, Huang Y, Li AH, et al. Nationwide estimates of annual inpatient and outpatient hysterectomies performed in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2022;139:446-448.

- Gressel GM, Potts JR 3rd, Cha S, et al. Hysterectomy route and numbers reported by graduating residents in obstetrics and gynecology training programs. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135:268-273.

- Lioce L, ed. Healthcare Simulation Dictionary. 2nd ed. Rockville, MD; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: 2020. AHRQ Publication No. 20-0019.

- Norman G, Dore K, Grierson L. The minimal relationship between simulation fidelity and transfer of learning. Med Educ. 2012;46:636-647.

- Illston JD, Ballard AC, Ellington DR, et al. Modified beef tongue model for fourth-degree laceration repair simulation. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129:491-496.

- WorldPoint website. 3B Scientific Episiotomy and Suturing Trainer. https://www.worldpoint.com/3b-episiotomy-and-suturing-sim. Accessed April 20, 2022.

- Balafoutas D, Joukhadar R, Kiesel M, et al. The role of deconstructive teaching in the training of laparoscopy. JSLS. 2019;23:e2019.00020.

- Ericsson KA, Harwell KW. Deliberate practice and proposed limits on the effects of practice on the acquisition of expert performance: why the original definition matters and recommendations for future research. Front Psychol. 2019;10:2396.

- Smith TM, Fenner DE. Vaginal hysterectomy teaching model—an educational video. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2012;18:S43. Abstract.

- Greer JA, Segal S, Salva CR, et al. Development and validation of simulation training for vaginal hysterectomy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2014;21:74-82.

- Malacarne DR, Escobar CM, Lam CJ, et al. Teaching vaginal hysterectomy via simulation: creation and validation of the objective skills assessment tool for simulated vaginal hysterectomy on a task trainer and performance among different levels of trainees. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2019;25:298-304.

- Zoorob D, Frenn R, Moffitt M, et al. Multi-institutional validation of a vaginal hysterectomy simulation model for resident training. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2021;28:1490-1496.e1.

- Barrier BF, Thompson AB, McCullough MW, et al. A novel and inexpensive vaginal hysterectomy simulator. Simul Healthc. 2012;7:374-379.

- Burkett LS, Makin J, Ackenbom M, et al. Validation of transvaginal hysterectomy surgical model—modification of the flowerpot model to improve vesicovaginal plane simulation. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2021;28:1526-1530.

- Escobar C, Malacarne Pape D, Ferrante KL, et al. Who should be teaching vaginal hysterectomy on a task trainer? A multicenter randomized trial of peer versus expert coaching. J Surg Simul. 2020;7:63-72.

- The obstetrics and gynecology milestone project. J Grad Med Educ. 2014;6(1 suppl 1):129-143.

- Nasca TJ, Philibert I, Brigham T, et al. The next GME accreditation system—rationale and benefits. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1051-1056.

- Chen CCG, Korn A, Klingele C, et al. Objective assessment of vaginal surgical skills. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203:79.e1-8.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Surgical curriculum in obstetrics and gynecology. https://www.acog.org /education-and-events/simulations/surgical-curriculum-in-ob-gyn.

- Chen CCG, Lockrow EG, DeStephano CC, et al. Establishing validity for a vaginal hysterectomy simulation model for surgical skills assessment. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;136:942-949.

- Vedula SS, Hager GD. Surgical data science: the new knowledge domain. Innov Surg Sci. 2017;2:109-121.

- Witthaus MW, Farooq S, Melnyk R, et al. Incorporation and validation of clinically relevant performance metrics of simulation (CRPMS) into a novel full-immersion simulation platform for nerve-sparing robot-assisted radical prostatectomy (NS-RARP) utilizing three-dimensional printing and hydrogel casting technology. BJU Int. 2020;125:322-332.

- Vedula SS, Malpani A, Ahmidi N, et al. Task-level vs segment-level quantitative metrics for surgical skill assessment. J Surg Educ. 2016;73:482-489.

- Maier-Hein L, Eisenmann M, Sarikaya D, et al. Surgical data science—from concepts toward clinical translation. Med Image Anal. 2022;76:102306.

- Hung AJ, Chen J, Gill IS. Automated performance metrics and machine learning algorithms to measure surgeon performance and anticipate clinical outcomes in robotic surgery. JAMA Surg. 2018;153:770-771.

- Altman K, Chen G, Chou B, et al. Surgical curriculum in obstetrics and gynecology: vaginal hysterectomy simulation. https://cfweb.acog. org/scog/scog008/Simulation.cfm.

- DeLancey JOL. Basic Exercises: Surgical Technique. Davis + Geck; Brooklyn, NY: 1987.

- Geoffrion R, Suen MW, Koenig NA, et al. Teaching vaginal surgery to junior residents: initial validation of 3 novel procedure-specific low-fidelity models. J Surg Educ. 2016;73:157-161.

- Pandey VA, Wolfe JHN, Lindhal AK, et al. Validity of an exam assessment in surgical skill: EBSQ-VASC pilot study. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2004;27:341-348.

- Limbs&Things website. Knot Tying Trainer. https://limbsandthings. com/us/products/50050/50050-knot-tying-trainer. Accessed April 20, 2022.

- Vaughan MH, Kim-Fine S, Hullfish KL, et al. Validation of the simulated vaginal hysterectomy trainer. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2018;25:1101-1106.

- Braun K, Henley B, Ray C, et al. Teaching vaginal hysterectomy: low fidelity trainer provides effective simulation at low cost. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:44S.

- Anand M, Duffy CP, Vragovic O, et al. Surgical anatomy of vaginal hysterectomy—impact of a resident-constructed simulation model. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2018;24:176-182.

- Chen CC, Vaccaro CM. ACOG Simulation Consortium Surgical Curriculum: anterior and posterior repair. 2017. https://cfweb.acog. org/scog/.

- Schmidt PC, Fairchild PS, Fenner DE, et al. The Fundamentals of Vaginal Surgery pilot study: developing, validating, and setting proficiency scores for a vaginal surgical skills simulation system. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;225:558.e1-558.e11.

Vaginal surgery, including vaginal hysterectomy, is slowly becoming a dying art. According to the National Inpatient Sample and the Nationwide Ambulatory Surgery Sample from 2018, only 11.8% of all hysterectomies were performed vaginally.1 The combination of uterine-sparing surgeries, advances in conservative therapies for benign uterine conditions, and the diversification of minimally invasive routes (laparoscopic and robotic) has resulted in a continued downtrend in vaginal surgical volumes. This shift has led to fewer operative learning opportunities and declining graduating resident surgical volume.2 According to the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), the minimum number of vaginal hysterectomies is 15, which represents only the minimum accepted exposure and does not imply competency.

In response, surgical simulation has been used for skill acquisition and maintenance outside of the operating room in a learning environment that is safe for the learners and does not expose patients to additional risk. Educators are uniquely poised to use simulation to teach residents and to evaluate their procedural competency. Although vaginal surgery, specifically vaginal hysterectomy, continues to decline, it can be resuscitated with the assistance of surgical simulation.

In this article, we provide a broad overview of vaginal surgical simulation. We discuss the basic tenets of simulation, review how to teach and evaluate vaginal surgical skills, and present some of the commonly available vaginal surgery simulation models and their associated resources, cost, setup time, fidelity, and limitations.

Simulation principles relevant for vaginal hysterectomy simulation