User login

Medtronic recalls HawkOne directional atherectomy system

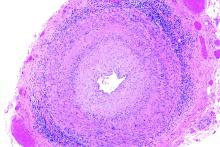

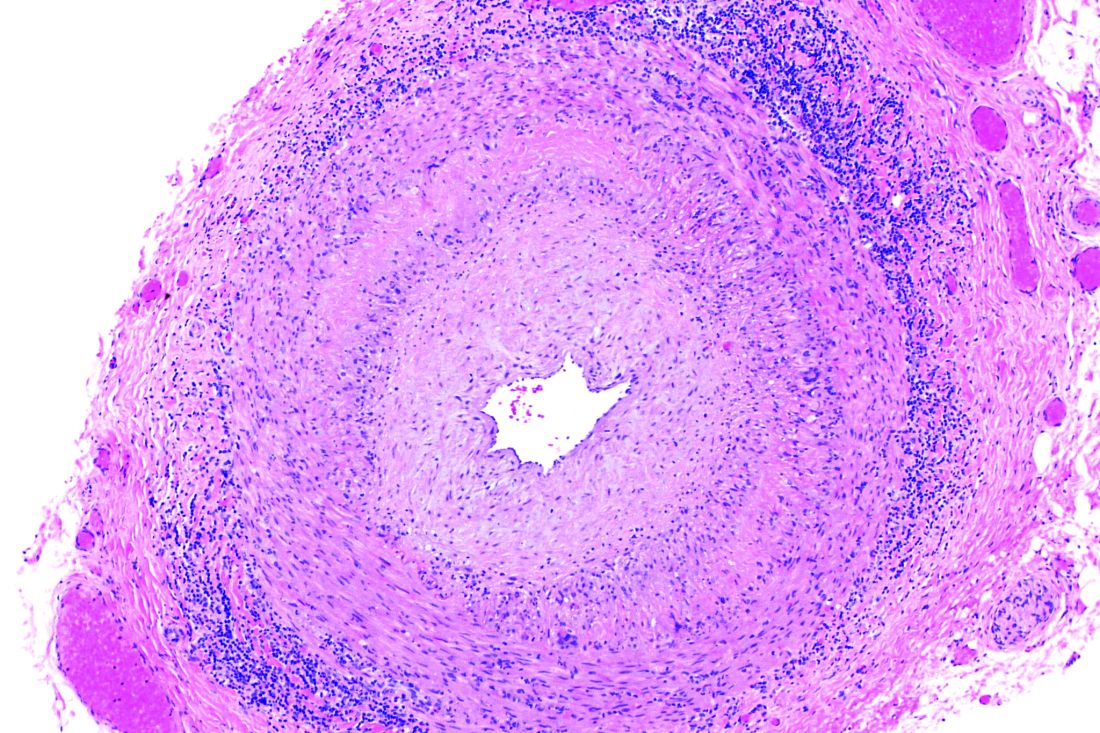

Medtronic has recalled 95,110 HawkOne Directional Atherectomy Systems because of the risk of the guidewire within the catheter moving downward or prolapsing during use, which may damage the tip of the catheter.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has identified this as a Class I recall, the most serious type, because of the potential for serious injury or death.

The HawkOne Directional Atherectomy system is used during procedures intended to remove blockage from peripheral arteries and improve blood flow.

If the guideline moves downward or prolapses during use, the “catheter tip may break off or separate, and this could lead to serious adverse events, including a tear along the inside wall of an artery (arterial dissection), a rupture or breakage of an artery (arterial rupture), decrease in blood flow to a part of the body because of a blocked artery (ischemia), and/or blood vessel complications that could require surgical repair and additional procedures to capture and remove the detached and/or migrated (embolized) tip,” the FDA says in a recall notice posted today on its website.

To date, there have been 55 injuries, no deaths, and 163 complaints reported for this device.

The recalled devices were distributed in the United States between Jan. 22, 2018 and Oct. 4, 2021. Product codes and lot numbers pertaining to the devices are listed on the FDA website.

Medtronic sent an urgent field safety notice to customers Dec. 6, 2021, requesting that they alert parties of the defect, review the instructions for use before using the device, and note the warnings and precautions listed in the letter.

Customers were also asked to complete the enclosed confirmation form and email to [email protected].

Health care providers can report adverse reactions or quality problems they experience using these devices to the FDA’s MedWatch program.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Medtronic has recalled 95,110 HawkOne Directional Atherectomy Systems because of the risk of the guidewire within the catheter moving downward or prolapsing during use, which may damage the tip of the catheter.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has identified this as a Class I recall, the most serious type, because of the potential for serious injury or death.

The HawkOne Directional Atherectomy system is used during procedures intended to remove blockage from peripheral arteries and improve blood flow.

If the guideline moves downward or prolapses during use, the “catheter tip may break off or separate, and this could lead to serious adverse events, including a tear along the inside wall of an artery (arterial dissection), a rupture or breakage of an artery (arterial rupture), decrease in blood flow to a part of the body because of a blocked artery (ischemia), and/or blood vessel complications that could require surgical repair and additional procedures to capture and remove the detached and/or migrated (embolized) tip,” the FDA says in a recall notice posted today on its website.

To date, there have been 55 injuries, no deaths, and 163 complaints reported for this device.

The recalled devices were distributed in the United States between Jan. 22, 2018 and Oct. 4, 2021. Product codes and lot numbers pertaining to the devices are listed on the FDA website.

Medtronic sent an urgent field safety notice to customers Dec. 6, 2021, requesting that they alert parties of the defect, review the instructions for use before using the device, and note the warnings and precautions listed in the letter.

Customers were also asked to complete the enclosed confirmation form and email to [email protected].

Health care providers can report adverse reactions or quality problems they experience using these devices to the FDA’s MedWatch program.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Medtronic has recalled 95,110 HawkOne Directional Atherectomy Systems because of the risk of the guidewire within the catheter moving downward or prolapsing during use, which may damage the tip of the catheter.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has identified this as a Class I recall, the most serious type, because of the potential for serious injury or death.

The HawkOne Directional Atherectomy system is used during procedures intended to remove blockage from peripheral arteries and improve blood flow.

If the guideline moves downward or prolapses during use, the “catheter tip may break off or separate, and this could lead to serious adverse events, including a tear along the inside wall of an artery (arterial dissection), a rupture or breakage of an artery (arterial rupture), decrease in blood flow to a part of the body because of a blocked artery (ischemia), and/or blood vessel complications that could require surgical repair and additional procedures to capture and remove the detached and/or migrated (embolized) tip,” the FDA says in a recall notice posted today on its website.

To date, there have been 55 injuries, no deaths, and 163 complaints reported for this device.

The recalled devices were distributed in the United States between Jan. 22, 2018 and Oct. 4, 2021. Product codes and lot numbers pertaining to the devices are listed on the FDA website.

Medtronic sent an urgent field safety notice to customers Dec. 6, 2021, requesting that they alert parties of the defect, review the instructions for use before using the device, and note the warnings and precautions listed in the letter.

Customers were also asked to complete the enclosed confirmation form and email to [email protected].

Health care providers can report adverse reactions or quality problems they experience using these devices to the FDA’s MedWatch program.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FFR-Guided or Angiography-Guided Nonculprit Lesion PCI in Patients With STEMI Without Cardiogenic Shock

Study Overview

Objective. To determine whether fractional flow reserve (FFR)-guided percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) of nonculprit lesion in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) is superior to angiography-guided PCI.

Design. Multicenter randomized control trial blinded to outcome, conducted in 41 sites in France.

Setting and participants. A total of 1163 patients with STEMI and multivessel coronary disease, who had undergone successful PCI to the culprit lesion were randomized to either FFR-guided PCI or angiography-guided PCI for nonculprit lesions. Randomization was stratified according to the trial site and timing of the procedure (immediate or staged).

Main outcome measures. The primary outcome was a composite of death from any cause, nonfatal myocardial infarction (MI) or unplanned hospitalization leading to urgent revascularization at 1 year.

Main results. At 1 year, the primary outcome occurred in 32 of 586 patients (5.5%) in the FFR-guided group and in 24 of 577 (4.2%) in the angiography-guided group (hazard ratio [HR], 1.32; 95% CI, 0.78-2.23; P = .31). The rate of death (1.5% vs 1.7%), nonfatal MI (3.1% vs 1.7%), and unplanned hospitalization leading to urgent revascularization (3.1% vs 1.7%) were also similar between FFR-guided and angiography-guided groups.

Conclusion. Among patients with STEMI and multivessel disease who had undergone successful PCI of the culprit vessel, an FFR-guided strategy for complete revascularization was not superior to angiography-guided strategy for reducing death, MI, or urgent revascularization at 1 year.

Commentary

Patients presenting with STEMI often have multivessel disease.1 Recently, multiple studies have reported the benefit of nonculprit vessel revascularization in patients presenting with hemodynamically stable STEMI compared to culprit-only strategy including the most recent COMPLETE trial which showed reduction in death and MI.2-6 However, the previous studies have variable design in evaluating the nonculprit vessel, some utilized FFR guidance, while others used angiography guidance. Whether FFR-guided PCI of nonculprit vessel can improve outcome in patients presenting STEMI remains unknown.

In the FLOWER-MI study, Puymirat et al investigated the use of FFR compared to angiography-guided nonculprit vessel PCI. A total of 1163 patients presenting with STEMI and multivessel disease who had undergone successful PCI to the culprit vessel, were randomized to either FFR guidance or angiography guidance among 41 centers in France. The authors found that after 1 year, there was no difference in composite endpoint of death, nonfatal MI or unplanned hospitalization leading to urgent revascularization in the FFR-guided group compared to angiography-guided group (5.5% vs 4.2%, HR, 1.32; 95% CI, 0.678-2.23; P = .31). There was also no difference in individual components of primary outcomes or secondary outcomes such as rate of stent thrombosis, any revascularization, or hospitalization.

There are a few interesting points to consider in this study. Ever since the Fractional Flow Reserve vs Angiography for Multivessel Evaluation (FAME) trial reported the lower incidence of major adverse events in routine FFR measurement during PCI compared to angiography-guided PCI, physiological assessment has become the gold standard for treatment of stable ischemic heart disease.7 However, the results of the current FLOWER-MI trial were not consistent with the FAME trial and there are few possible reasons to consider.

First, the use of FFR in the setting of STEMI is less validated compared to stable ischemic heart disease.8 Microvascular dysfunction during the acute phase can affect the FFR reading and the lesion severity can be underestimated.8 Second, the rate of composite endpoint was much lower in this study compared to FAME despite using the same composite endpoint of death, nonfatal MI, and unplanned hospitalization leading to urgent revascularization. At 1 year, the incidence of primary outcome was 13.5% in the FFR-guided group compared to 18.6% in the angiography-guided group in the FAME study compared to 5.5% and 4.2% in the FLOWER-MI study, despite having a sicker population presenting with STEMI. This is likely due to improvement in the PCI techniques such as radial approach, imaging guidance, and advancement in medical therapy such as use of more potent antiplatelet therapy. With lower incidence of primary outcome, larger number of patients are needed to detect the difference in the composite outcome. Finally, the operators’ visual assessment may have been calibrated to the physiologic assessment as the operators are routinely using FFR assessment which may have diminished the benefit of FFR guidance seen in the early FAME study.

Another interesting finding from this study was that although the study protocol encouraged the operators to perform the nonculprit PCI in the same setting, only 4% had nonculprit PCI in the same setting and 96% of the patients underwent a staged PCI. The advantage of performing the nonculprit PCI on the same setting is to have 1 fewer procedure for the patient. On the other hand, the disadvantage of this approach includes prolongation of the index procedure, theoretically higher risk of complication during the acute phase and vasospasm leading to overestimation of the lesion severity. A recent analysis from the COMPLETE study did not show any difference when comparing staged PCI during the index hospitalization vs after discharge.9 The optimal timing of the staged PCI needs to be investigated in future studies.

A limitation of this study is the lower than expected incidence of clinical events decreasing the statistical power of the study. However, there was no signal that FFR-guided PCI is better compared to the angiography-guided group. In fact, the curve started to diverge at 6 months favoring the angiography-guided group. In addition, there was no core-lab analysis for completeness of revascularization.

Applications for Clinical Practice

In patients presenting with hemodynamically stable STEMI for undergoing nonculprit vessel PCI, both FFR-guided or angiography-guided strategies can be considered.

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Park DW, Clare RM, Schulte PJ, et al. Extent, location, and clinical significance of non-infarct-related coronary artery disease among patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction. JAMA. 2014;312(19):2019-27. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.15095

2. Wald DS, Morris JK, Wald NJ, et al. Randomized trial of preventive angioplasty in myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(12):1115-23. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1305520

3. Gershlick AH, Khan JN, Kelly DJ, et al. Randomized trial of complete versus lesion-only revascularization in patients undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention for STEMI and multivessel disease: the CvLPRIT trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65(10):963-72. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2014.12.038

4. Engstrøm T, Kelbæk H, Helqvist S, et al. Complete revascularisation versus treatment of the culprit lesion only in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction and multivessel disease (DANAMI-3-PRIMULTI): an open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;386(9994):665-71. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(15)60648-1

5. Smits PC, Abdel-Wahab M, Neumann FJ, , et al. Fractional Flow Reserve-Guided Multivessel Angioplasty in Myocardial Infarction. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(13):1234-44. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1701067

6. Mehta SR, Wood DA, Storey RF, et al. Complete Revascularization with Multivessel PCI for Myocardial Infarction. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(15):1411-21. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1907775

7. Tonino PA, De Bruyne B, Pijls NH, et al. Fractional flow reserve versus angiography for guiding percutaneous coronary intervention. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(3):213-24. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0807611

8. Thim T, van der Hoeven NW, Musto C, et al. Evaluation and Management of Nonculprit Lesions in STEMI. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2020;13(10):1145-54. doi:10.1016/j.jcin.2020.02.030

9. Wood DA, Cairns JA, Wang J, et al. Timing of Staged Nonculprit Artery Revascularization in Patients With ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction: COMPLETE Trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;74(22):2713-23. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2019/09.051

Study Overview

Objective. To determine whether fractional flow reserve (FFR)-guided percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) of nonculprit lesion in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) is superior to angiography-guided PCI.

Design. Multicenter randomized control trial blinded to outcome, conducted in 41 sites in France.

Setting and participants. A total of 1163 patients with STEMI and multivessel coronary disease, who had undergone successful PCI to the culprit lesion were randomized to either FFR-guided PCI or angiography-guided PCI for nonculprit lesions. Randomization was stratified according to the trial site and timing of the procedure (immediate or staged).

Main outcome measures. The primary outcome was a composite of death from any cause, nonfatal myocardial infarction (MI) or unplanned hospitalization leading to urgent revascularization at 1 year.

Main results. At 1 year, the primary outcome occurred in 32 of 586 patients (5.5%) in the FFR-guided group and in 24 of 577 (4.2%) in the angiography-guided group (hazard ratio [HR], 1.32; 95% CI, 0.78-2.23; P = .31). The rate of death (1.5% vs 1.7%), nonfatal MI (3.1% vs 1.7%), and unplanned hospitalization leading to urgent revascularization (3.1% vs 1.7%) were also similar between FFR-guided and angiography-guided groups.

Conclusion. Among patients with STEMI and multivessel disease who had undergone successful PCI of the culprit vessel, an FFR-guided strategy for complete revascularization was not superior to angiography-guided strategy for reducing death, MI, or urgent revascularization at 1 year.

Commentary

Patients presenting with STEMI often have multivessel disease.1 Recently, multiple studies have reported the benefit of nonculprit vessel revascularization in patients presenting with hemodynamically stable STEMI compared to culprit-only strategy including the most recent COMPLETE trial which showed reduction in death and MI.2-6 However, the previous studies have variable design in evaluating the nonculprit vessel, some utilized FFR guidance, while others used angiography guidance. Whether FFR-guided PCI of nonculprit vessel can improve outcome in patients presenting STEMI remains unknown.

In the FLOWER-MI study, Puymirat et al investigated the use of FFR compared to angiography-guided nonculprit vessel PCI. A total of 1163 patients presenting with STEMI and multivessel disease who had undergone successful PCI to the culprit vessel, were randomized to either FFR guidance or angiography guidance among 41 centers in France. The authors found that after 1 year, there was no difference in composite endpoint of death, nonfatal MI or unplanned hospitalization leading to urgent revascularization in the FFR-guided group compared to angiography-guided group (5.5% vs 4.2%, HR, 1.32; 95% CI, 0.678-2.23; P = .31). There was also no difference in individual components of primary outcomes or secondary outcomes such as rate of stent thrombosis, any revascularization, or hospitalization.

There are a few interesting points to consider in this study. Ever since the Fractional Flow Reserve vs Angiography for Multivessel Evaluation (FAME) trial reported the lower incidence of major adverse events in routine FFR measurement during PCI compared to angiography-guided PCI, physiological assessment has become the gold standard for treatment of stable ischemic heart disease.7 However, the results of the current FLOWER-MI trial were not consistent with the FAME trial and there are few possible reasons to consider.

First, the use of FFR in the setting of STEMI is less validated compared to stable ischemic heart disease.8 Microvascular dysfunction during the acute phase can affect the FFR reading and the lesion severity can be underestimated.8 Second, the rate of composite endpoint was much lower in this study compared to FAME despite using the same composite endpoint of death, nonfatal MI, and unplanned hospitalization leading to urgent revascularization. At 1 year, the incidence of primary outcome was 13.5% in the FFR-guided group compared to 18.6% in the angiography-guided group in the FAME study compared to 5.5% and 4.2% in the FLOWER-MI study, despite having a sicker population presenting with STEMI. This is likely due to improvement in the PCI techniques such as radial approach, imaging guidance, and advancement in medical therapy such as use of more potent antiplatelet therapy. With lower incidence of primary outcome, larger number of patients are needed to detect the difference in the composite outcome. Finally, the operators’ visual assessment may have been calibrated to the physiologic assessment as the operators are routinely using FFR assessment which may have diminished the benefit of FFR guidance seen in the early FAME study.

Another interesting finding from this study was that although the study protocol encouraged the operators to perform the nonculprit PCI in the same setting, only 4% had nonculprit PCI in the same setting and 96% of the patients underwent a staged PCI. The advantage of performing the nonculprit PCI on the same setting is to have 1 fewer procedure for the patient. On the other hand, the disadvantage of this approach includes prolongation of the index procedure, theoretically higher risk of complication during the acute phase and vasospasm leading to overestimation of the lesion severity. A recent analysis from the COMPLETE study did not show any difference when comparing staged PCI during the index hospitalization vs after discharge.9 The optimal timing of the staged PCI needs to be investigated in future studies.

A limitation of this study is the lower than expected incidence of clinical events decreasing the statistical power of the study. However, there was no signal that FFR-guided PCI is better compared to the angiography-guided group. In fact, the curve started to diverge at 6 months favoring the angiography-guided group. In addition, there was no core-lab analysis for completeness of revascularization.

Applications for Clinical Practice

In patients presenting with hemodynamically stable STEMI for undergoing nonculprit vessel PCI, both FFR-guided or angiography-guided strategies can be considered.

Financial disclosures: None.

Study Overview

Objective. To determine whether fractional flow reserve (FFR)-guided percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) of nonculprit lesion in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) is superior to angiography-guided PCI.

Design. Multicenter randomized control trial blinded to outcome, conducted in 41 sites in France.

Setting and participants. A total of 1163 patients with STEMI and multivessel coronary disease, who had undergone successful PCI to the culprit lesion were randomized to either FFR-guided PCI or angiography-guided PCI for nonculprit lesions. Randomization was stratified according to the trial site and timing of the procedure (immediate or staged).

Main outcome measures. The primary outcome was a composite of death from any cause, nonfatal myocardial infarction (MI) or unplanned hospitalization leading to urgent revascularization at 1 year.

Main results. At 1 year, the primary outcome occurred in 32 of 586 patients (5.5%) in the FFR-guided group and in 24 of 577 (4.2%) in the angiography-guided group (hazard ratio [HR], 1.32; 95% CI, 0.78-2.23; P = .31). The rate of death (1.5% vs 1.7%), nonfatal MI (3.1% vs 1.7%), and unplanned hospitalization leading to urgent revascularization (3.1% vs 1.7%) were also similar between FFR-guided and angiography-guided groups.

Conclusion. Among patients with STEMI and multivessel disease who had undergone successful PCI of the culprit vessel, an FFR-guided strategy for complete revascularization was not superior to angiography-guided strategy for reducing death, MI, or urgent revascularization at 1 year.

Commentary

Patients presenting with STEMI often have multivessel disease.1 Recently, multiple studies have reported the benefit of nonculprit vessel revascularization in patients presenting with hemodynamically stable STEMI compared to culprit-only strategy including the most recent COMPLETE trial which showed reduction in death and MI.2-6 However, the previous studies have variable design in evaluating the nonculprit vessel, some utilized FFR guidance, while others used angiography guidance. Whether FFR-guided PCI of nonculprit vessel can improve outcome in patients presenting STEMI remains unknown.

In the FLOWER-MI study, Puymirat et al investigated the use of FFR compared to angiography-guided nonculprit vessel PCI. A total of 1163 patients presenting with STEMI and multivessel disease who had undergone successful PCI to the culprit vessel, were randomized to either FFR guidance or angiography guidance among 41 centers in France. The authors found that after 1 year, there was no difference in composite endpoint of death, nonfatal MI or unplanned hospitalization leading to urgent revascularization in the FFR-guided group compared to angiography-guided group (5.5% vs 4.2%, HR, 1.32; 95% CI, 0.678-2.23; P = .31). There was also no difference in individual components of primary outcomes or secondary outcomes such as rate of stent thrombosis, any revascularization, or hospitalization.

There are a few interesting points to consider in this study. Ever since the Fractional Flow Reserve vs Angiography for Multivessel Evaluation (FAME) trial reported the lower incidence of major adverse events in routine FFR measurement during PCI compared to angiography-guided PCI, physiological assessment has become the gold standard for treatment of stable ischemic heart disease.7 However, the results of the current FLOWER-MI trial were not consistent with the FAME trial and there are few possible reasons to consider.

First, the use of FFR in the setting of STEMI is less validated compared to stable ischemic heart disease.8 Microvascular dysfunction during the acute phase can affect the FFR reading and the lesion severity can be underestimated.8 Second, the rate of composite endpoint was much lower in this study compared to FAME despite using the same composite endpoint of death, nonfatal MI, and unplanned hospitalization leading to urgent revascularization. At 1 year, the incidence of primary outcome was 13.5% in the FFR-guided group compared to 18.6% in the angiography-guided group in the FAME study compared to 5.5% and 4.2% in the FLOWER-MI study, despite having a sicker population presenting with STEMI. This is likely due to improvement in the PCI techniques such as radial approach, imaging guidance, and advancement in medical therapy such as use of more potent antiplatelet therapy. With lower incidence of primary outcome, larger number of patients are needed to detect the difference in the composite outcome. Finally, the operators’ visual assessment may have been calibrated to the physiologic assessment as the operators are routinely using FFR assessment which may have diminished the benefit of FFR guidance seen in the early FAME study.

Another interesting finding from this study was that although the study protocol encouraged the operators to perform the nonculprit PCI in the same setting, only 4% had nonculprit PCI in the same setting and 96% of the patients underwent a staged PCI. The advantage of performing the nonculprit PCI on the same setting is to have 1 fewer procedure for the patient. On the other hand, the disadvantage of this approach includes prolongation of the index procedure, theoretically higher risk of complication during the acute phase and vasospasm leading to overestimation of the lesion severity. A recent analysis from the COMPLETE study did not show any difference when comparing staged PCI during the index hospitalization vs after discharge.9 The optimal timing of the staged PCI needs to be investigated in future studies.

A limitation of this study is the lower than expected incidence of clinical events decreasing the statistical power of the study. However, there was no signal that FFR-guided PCI is better compared to the angiography-guided group. In fact, the curve started to diverge at 6 months favoring the angiography-guided group. In addition, there was no core-lab analysis for completeness of revascularization.

Applications for Clinical Practice

In patients presenting with hemodynamically stable STEMI for undergoing nonculprit vessel PCI, both FFR-guided or angiography-guided strategies can be considered.

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Park DW, Clare RM, Schulte PJ, et al. Extent, location, and clinical significance of non-infarct-related coronary artery disease among patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction. JAMA. 2014;312(19):2019-27. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.15095

2. Wald DS, Morris JK, Wald NJ, et al. Randomized trial of preventive angioplasty in myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(12):1115-23. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1305520

3. Gershlick AH, Khan JN, Kelly DJ, et al. Randomized trial of complete versus lesion-only revascularization in patients undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention for STEMI and multivessel disease: the CvLPRIT trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65(10):963-72. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2014.12.038

4. Engstrøm T, Kelbæk H, Helqvist S, et al. Complete revascularisation versus treatment of the culprit lesion only in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction and multivessel disease (DANAMI-3-PRIMULTI): an open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;386(9994):665-71. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(15)60648-1

5. Smits PC, Abdel-Wahab M, Neumann FJ, , et al. Fractional Flow Reserve-Guided Multivessel Angioplasty in Myocardial Infarction. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(13):1234-44. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1701067

6. Mehta SR, Wood DA, Storey RF, et al. Complete Revascularization with Multivessel PCI for Myocardial Infarction. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(15):1411-21. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1907775

7. Tonino PA, De Bruyne B, Pijls NH, et al. Fractional flow reserve versus angiography for guiding percutaneous coronary intervention. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(3):213-24. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0807611

8. Thim T, van der Hoeven NW, Musto C, et al. Evaluation and Management of Nonculprit Lesions in STEMI. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2020;13(10):1145-54. doi:10.1016/j.jcin.2020.02.030

9. Wood DA, Cairns JA, Wang J, et al. Timing of Staged Nonculprit Artery Revascularization in Patients With ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction: COMPLETE Trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;74(22):2713-23. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2019/09.051

1. Park DW, Clare RM, Schulte PJ, et al. Extent, location, and clinical significance of non-infarct-related coronary artery disease among patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction. JAMA. 2014;312(19):2019-27. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.15095

2. Wald DS, Morris JK, Wald NJ, et al. Randomized trial of preventive angioplasty in myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(12):1115-23. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1305520

3. Gershlick AH, Khan JN, Kelly DJ, et al. Randomized trial of complete versus lesion-only revascularization in patients undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention for STEMI and multivessel disease: the CvLPRIT trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65(10):963-72. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2014.12.038

4. Engstrøm T, Kelbæk H, Helqvist S, et al. Complete revascularisation versus treatment of the culprit lesion only in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction and multivessel disease (DANAMI-3-PRIMULTI): an open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;386(9994):665-71. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(15)60648-1

5. Smits PC, Abdel-Wahab M, Neumann FJ, , et al. Fractional Flow Reserve-Guided Multivessel Angioplasty in Myocardial Infarction. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(13):1234-44. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1701067

6. Mehta SR, Wood DA, Storey RF, et al. Complete Revascularization with Multivessel PCI for Myocardial Infarction. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(15):1411-21. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1907775

7. Tonino PA, De Bruyne B, Pijls NH, et al. Fractional flow reserve versus angiography for guiding percutaneous coronary intervention. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(3):213-24. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0807611

8. Thim T, van der Hoeven NW, Musto C, et al. Evaluation and Management of Nonculprit Lesions in STEMI. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2020;13(10):1145-54. doi:10.1016/j.jcin.2020.02.030

9. Wood DA, Cairns JA, Wang J, et al. Timing of Staged Nonculprit Artery Revascularization in Patients With ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction: COMPLETE Trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;74(22):2713-23. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2019/09.051

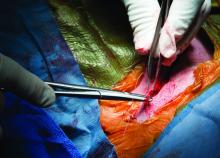

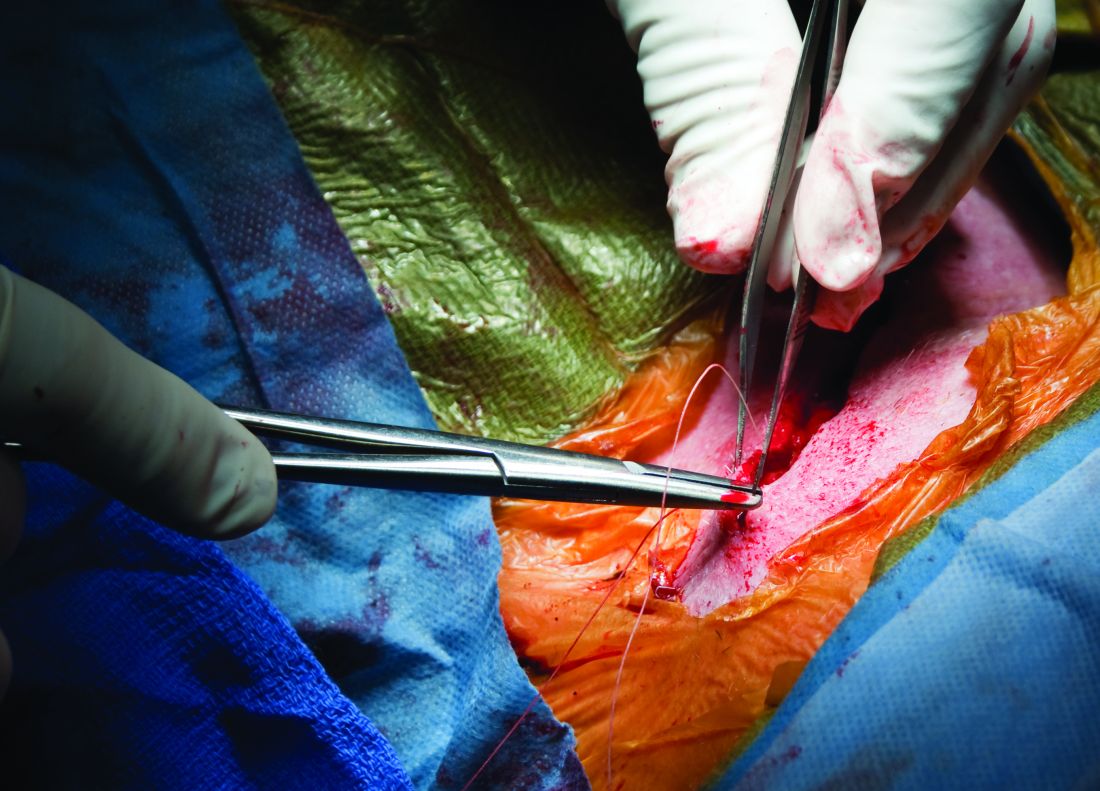

Cell therapy promising as long-term limb-saving treatment in diabetes

Bone marrow derived autologous cell therapy (ACT) has been shown to significantly reduce the rate of major amputation at 5 years in people with diabetes who developed critical limb-threatening ischemia (CLTI).

In a study of 130 patients, 64% of 42 patients who were treated conservatively needed a major amputation at 5 years versus just 30% of 45 patients who had been treated with ACT (P = .011).

This compared favorably to the results seen with repeated percutaneous angioplasty (re-PTA), where just 20.9% of 43 patients underwent limb salvage (P = .002 vs. conservative therapy).

Furthermore, amputation-free survival was significantly longer in both active groups, Michal Dubský, MD, PhD, FRSPH, reported at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes.

Dr. Dubský, of the Institute for Clinical and Experimental Medicine and Charles University in Prague, also reported that fewer patients who had undergone re-PTA or ACT than conservative treatment had died by 5 years (25.8% and 35.6%, respectively, vs. 61.9%), but that the difference was significant only for the revascularization procedure (P = .012).

Based on these findings, “we believe that autologous cell therapy seems to be an appropriate alternative to repeated PTA even for patients with no-option chronic limb-threatening ischemia,” he said.

“This is a very important area,” said Andrew J.M. Boulton, MBBS, MD, FRCP, who chaired the oral abstract presentation session during which the findings were presented.

“It is very difficult to get an evidence base from randomized studies in this area, because of the nature of the patients: They’re very sick and we all deal with them in our clinics very regularly,” added Dr. Boulton, professor of medicine within the division of diabetes, endocrinology and gastroenterology at the University of Manchester (England).

Dr. Boulton called the findings a “very important addition to what we know.”

New option for no-option CLTI

CLTI is associated with persistent pain at rest, ulcers, and gangrene, and can be the end result of longstanding peripheral arterial disease. Within the first year of presentation, there’s a 30% chance of having a major amputation and a 25% chance of dying.

Importantly, said Dr. Dubský, “there is a big difference in this diagnosis” between patients with diabetes and those without. For instance, CLTI is more diffuse in patients with diabetes than in those without, different arteries are affected and the sclerosis seen can be more rigid and “full of calcium.”

While surgery to improve blood flow is the standard of care, not everyone is suitable. Bypass surgery or endovascular procedures can be performed in only 40%-50% of patients, and even then a therapeutic effect may be seen in only a quarter of patients.

“We need some new therapeutic modalities for this diagnosis, and one of them could be autologous cell therapy,” said Dr. Dubský.

Study details

Dr. Dubský and coinvestigators consecutively recruited 130 patients with diabetic foot and CLTI who had been seen at their clinic over a 5-year period. Of these, 87 had not been eligible for standard revascularization and underwent ACT or were treated conservatively.

Of the patients who were not eligible for standard revascularization (‘no-option CLTI), 45 had undergone ACT and 42 had been treated conservatively. Dr. Dubský acknowledged that “his study was not prospective and randomized.”

All patients in the study had at least one unsuccessful revascularization procedure and diabetic foot ulcers, and low tissue oxygenation. The latter was defined as transcutaneous oxygen pressure (TcPO2) of below 30 mm Hg.

There were little differences in demographic characteristics between the treatment groups, the average age ranged from 62 to 67 years, there were more men (70%-80%) than women; most patients (90%) had type 2 diabetes for at least 20 years. There were similar rates of ischemic heart disease, hypertension, dialysis, and immunosuppressive therapy.

There were no differences in baseline values of TcPO2 between the groups, and similar improvements were seen in both the ACT and re-PTA groups versus conservative group.

ACT in practice

With such promising results, what about the practicalities of harvesting a patient’s bone marrow to make the ACT?

“Bone marrow harvesting usually takes about 20 minutes,” Dr. Dubský said. It then takes another 45 minutes to separate the cells and make the cell suspension, and then maybe another 10 minutes or so to administer this to the patient, which is done by injecting into the calf muscles and small muscles of the foot, aided by computed tomography. The whole process may take up to 2 hours, he said.

“Patients are under local or general anesthesia, so there is no pain during the procedure,” Dr. Dubský reassured. “Afterwards we sometimes see small hematoma[s], with low-intensity pain that responds well to usual analgesic therapy.”

Computed tomography was used to help guide the injections, which was advantageous, Dr. Boulton pointed out, because it was “less invasive than angioplasty in these very sick people with very distal lesions, many of whom already have renal problems.”

“It is surprising though, that everybody had re-PTA and not one had vascular surgery,” he suggested. Dr. Boulton added, however: “These are very important observations; they help us a lot in an area where there’s unlikely to be a full RCT.”

The next step in this research is to see if combining ACT and re-PTA could lead to even better results.

The study was funded by the Czech Republic Ministry of Health. Dr. Dubský had nothing to disclose. Dr. Boulton made no statement about his conflicts of interest.

Bone marrow derived autologous cell therapy (ACT) has been shown to significantly reduce the rate of major amputation at 5 years in people with diabetes who developed critical limb-threatening ischemia (CLTI).

In a study of 130 patients, 64% of 42 patients who were treated conservatively needed a major amputation at 5 years versus just 30% of 45 patients who had been treated with ACT (P = .011).

This compared favorably to the results seen with repeated percutaneous angioplasty (re-PTA), where just 20.9% of 43 patients underwent limb salvage (P = .002 vs. conservative therapy).

Furthermore, amputation-free survival was significantly longer in both active groups, Michal Dubský, MD, PhD, FRSPH, reported at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes.

Dr. Dubský, of the Institute for Clinical and Experimental Medicine and Charles University in Prague, also reported that fewer patients who had undergone re-PTA or ACT than conservative treatment had died by 5 years (25.8% and 35.6%, respectively, vs. 61.9%), but that the difference was significant only for the revascularization procedure (P = .012).

Based on these findings, “we believe that autologous cell therapy seems to be an appropriate alternative to repeated PTA even for patients with no-option chronic limb-threatening ischemia,” he said.

“This is a very important area,” said Andrew J.M. Boulton, MBBS, MD, FRCP, who chaired the oral abstract presentation session during which the findings were presented.

“It is very difficult to get an evidence base from randomized studies in this area, because of the nature of the patients: They’re very sick and we all deal with them in our clinics very regularly,” added Dr. Boulton, professor of medicine within the division of diabetes, endocrinology and gastroenterology at the University of Manchester (England).

Dr. Boulton called the findings a “very important addition to what we know.”

New option for no-option CLTI

CLTI is associated with persistent pain at rest, ulcers, and gangrene, and can be the end result of longstanding peripheral arterial disease. Within the first year of presentation, there’s a 30% chance of having a major amputation and a 25% chance of dying.

Importantly, said Dr. Dubský, “there is a big difference in this diagnosis” between patients with diabetes and those without. For instance, CLTI is more diffuse in patients with diabetes than in those without, different arteries are affected and the sclerosis seen can be more rigid and “full of calcium.”

While surgery to improve blood flow is the standard of care, not everyone is suitable. Bypass surgery or endovascular procedures can be performed in only 40%-50% of patients, and even then a therapeutic effect may be seen in only a quarter of patients.

“We need some new therapeutic modalities for this diagnosis, and one of them could be autologous cell therapy,” said Dr. Dubský.

Study details

Dr. Dubský and coinvestigators consecutively recruited 130 patients with diabetic foot and CLTI who had been seen at their clinic over a 5-year period. Of these, 87 had not been eligible for standard revascularization and underwent ACT or were treated conservatively.

Of the patients who were not eligible for standard revascularization (‘no-option CLTI), 45 had undergone ACT and 42 had been treated conservatively. Dr. Dubský acknowledged that “his study was not prospective and randomized.”

All patients in the study had at least one unsuccessful revascularization procedure and diabetic foot ulcers, and low tissue oxygenation. The latter was defined as transcutaneous oxygen pressure (TcPO2) of below 30 mm Hg.

There were little differences in demographic characteristics between the treatment groups, the average age ranged from 62 to 67 years, there were more men (70%-80%) than women; most patients (90%) had type 2 diabetes for at least 20 years. There were similar rates of ischemic heart disease, hypertension, dialysis, and immunosuppressive therapy.

There were no differences in baseline values of TcPO2 between the groups, and similar improvements were seen in both the ACT and re-PTA groups versus conservative group.

ACT in practice

With such promising results, what about the practicalities of harvesting a patient’s bone marrow to make the ACT?

“Bone marrow harvesting usually takes about 20 minutes,” Dr. Dubský said. It then takes another 45 minutes to separate the cells and make the cell suspension, and then maybe another 10 minutes or so to administer this to the patient, which is done by injecting into the calf muscles and small muscles of the foot, aided by computed tomography. The whole process may take up to 2 hours, he said.

“Patients are under local or general anesthesia, so there is no pain during the procedure,” Dr. Dubský reassured. “Afterwards we sometimes see small hematoma[s], with low-intensity pain that responds well to usual analgesic therapy.”

Computed tomography was used to help guide the injections, which was advantageous, Dr. Boulton pointed out, because it was “less invasive than angioplasty in these very sick people with very distal lesions, many of whom already have renal problems.”

“It is surprising though, that everybody had re-PTA and not one had vascular surgery,” he suggested. Dr. Boulton added, however: “These are very important observations; they help us a lot in an area where there’s unlikely to be a full RCT.”

The next step in this research is to see if combining ACT and re-PTA could lead to even better results.

The study was funded by the Czech Republic Ministry of Health. Dr. Dubský had nothing to disclose. Dr. Boulton made no statement about his conflicts of interest.

Bone marrow derived autologous cell therapy (ACT) has been shown to significantly reduce the rate of major amputation at 5 years in people with diabetes who developed critical limb-threatening ischemia (CLTI).

In a study of 130 patients, 64% of 42 patients who were treated conservatively needed a major amputation at 5 years versus just 30% of 45 patients who had been treated with ACT (P = .011).

This compared favorably to the results seen with repeated percutaneous angioplasty (re-PTA), where just 20.9% of 43 patients underwent limb salvage (P = .002 vs. conservative therapy).

Furthermore, amputation-free survival was significantly longer in both active groups, Michal Dubský, MD, PhD, FRSPH, reported at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes.

Dr. Dubský, of the Institute for Clinical and Experimental Medicine and Charles University in Prague, also reported that fewer patients who had undergone re-PTA or ACT than conservative treatment had died by 5 years (25.8% and 35.6%, respectively, vs. 61.9%), but that the difference was significant only for the revascularization procedure (P = .012).

Based on these findings, “we believe that autologous cell therapy seems to be an appropriate alternative to repeated PTA even for patients with no-option chronic limb-threatening ischemia,” he said.

“This is a very important area,” said Andrew J.M. Boulton, MBBS, MD, FRCP, who chaired the oral abstract presentation session during which the findings were presented.

“It is very difficult to get an evidence base from randomized studies in this area, because of the nature of the patients: They’re very sick and we all deal with them in our clinics very regularly,” added Dr. Boulton, professor of medicine within the division of diabetes, endocrinology and gastroenterology at the University of Manchester (England).

Dr. Boulton called the findings a “very important addition to what we know.”

New option for no-option CLTI

CLTI is associated with persistent pain at rest, ulcers, and gangrene, and can be the end result of longstanding peripheral arterial disease. Within the first year of presentation, there’s a 30% chance of having a major amputation and a 25% chance of dying.

Importantly, said Dr. Dubský, “there is a big difference in this diagnosis” between patients with diabetes and those without. For instance, CLTI is more diffuse in patients with diabetes than in those without, different arteries are affected and the sclerosis seen can be more rigid and “full of calcium.”

While surgery to improve blood flow is the standard of care, not everyone is suitable. Bypass surgery or endovascular procedures can be performed in only 40%-50% of patients, and even then a therapeutic effect may be seen in only a quarter of patients.

“We need some new therapeutic modalities for this diagnosis, and one of them could be autologous cell therapy,” said Dr. Dubský.

Study details

Dr. Dubský and coinvestigators consecutively recruited 130 patients with diabetic foot and CLTI who had been seen at their clinic over a 5-year period. Of these, 87 had not been eligible for standard revascularization and underwent ACT or were treated conservatively.

Of the patients who were not eligible for standard revascularization (‘no-option CLTI), 45 had undergone ACT and 42 had been treated conservatively. Dr. Dubský acknowledged that “his study was not prospective and randomized.”

All patients in the study had at least one unsuccessful revascularization procedure and diabetic foot ulcers, and low tissue oxygenation. The latter was defined as transcutaneous oxygen pressure (TcPO2) of below 30 mm Hg.

There were little differences in demographic characteristics between the treatment groups, the average age ranged from 62 to 67 years, there were more men (70%-80%) than women; most patients (90%) had type 2 diabetes for at least 20 years. There were similar rates of ischemic heart disease, hypertension, dialysis, and immunosuppressive therapy.

There were no differences in baseline values of TcPO2 between the groups, and similar improvements were seen in both the ACT and re-PTA groups versus conservative group.

ACT in practice

With such promising results, what about the practicalities of harvesting a patient’s bone marrow to make the ACT?

“Bone marrow harvesting usually takes about 20 minutes,” Dr. Dubský said. It then takes another 45 minutes to separate the cells and make the cell suspension, and then maybe another 10 minutes or so to administer this to the patient, which is done by injecting into the calf muscles and small muscles of the foot, aided by computed tomography. The whole process may take up to 2 hours, he said.

“Patients are under local or general anesthesia, so there is no pain during the procedure,” Dr. Dubský reassured. “Afterwards we sometimes see small hematoma[s], with low-intensity pain that responds well to usual analgesic therapy.”

Computed tomography was used to help guide the injections, which was advantageous, Dr. Boulton pointed out, because it was “less invasive than angioplasty in these very sick people with very distal lesions, many of whom already have renal problems.”

“It is surprising though, that everybody had re-PTA and not one had vascular surgery,” he suggested. Dr. Boulton added, however: “These are very important observations; they help us a lot in an area where there’s unlikely to be a full RCT.”

The next step in this research is to see if combining ACT and re-PTA could lead to even better results.

The study was funded by the Czech Republic Ministry of Health. Dr. Dubský had nothing to disclose. Dr. Boulton made no statement about his conflicts of interest.

FROM EASD 2021

Evaluation of a Digital Intervention for Hypertension Management in Primary Care Combining Self-monitoring of Blood Pressure With Guided Self-management

Study Overview

Objective. To evaluate whether a digital intervention comprising self-monitoring of blood pressure (BP) with reminders and predetermined drug changes combined with lifestyle change support resulted in lower systolic BP in people receiving treatment for hypertension that was poorly controlled, and whether this approach was cost effective.

Design. Unmasked randomized controlled trial.

Settings and participants. Eligible participants were identified from clinical codes recorded in the electronic health records of 76 collaborating general practices from the National Institute for Health Research Clinical Research Network, a United Kingdom government agency. The practices sent invitation letters to eligible participants to come to the clinic to establish eligibility, take consent, and collect baseline data via online questionnaires.

Eligible participants were aged 18 years or older with treated hypertension, a mean baseline BP reading of more than 140/90 mm Hg and were taking no more than 3 antihypertensive drugs. Participants also needed to be willing to self-monitor and have access to the internet (with support from a family member if needed). Exclusions included BP greater than 180/110 mm Hg, atrial fibrillation, hypertension not managed by their general practitioner, chronic kidney disease stage 4-5, postural hypotension (> 20 mm Hg systolic drop), an acute cardiovascular event in the previous 3 months, terminal disease, or another condition which in the opinion of their general practitioner made participation inappropriate.

Of the 11 399 invitation letters sent out, 1389 (12%) potential participants responded positively and were screened for eligibility. Those who declined to take part could optionally give their reasons, and responses were gained from 2426 of 10 010 (24%). The mean age of those who gave a reason for declining was 73 years. The most commonly selected reasons for declining were not having access to the internet (982, 41%), not wanting to participate in a research trial (617, 25%) or an internet study (543, 22%), and not wanting to change drugs (535, 22%). Of the 1389 screened, 734 were ineligible, and 33 did not complete baseline measures and randomization. The remaining 622 people who were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to receive the HOME BP intervention (n = 305) or usual care (n = 317).

Intervention vs usual care. The HOME BP intervention for the self-management of high BP consisted of an integrated patient and health care practitioner online digital intervention, BP self-monitoring (using an Omron M3 monitor), health care practitioner directed and supervised titration of antihypertensive drugs, and user-selected lifestyle modifications. Participants were advised via automated email reminders to take 2 morning BP readings for 7 days each month and to enter online each second reading. Mean home BP was calculated, accompanied by feedback of BP results to both patients and professionals with optional evidence-based lifestyle advice (for healthy eating, physical activity, losing weight if appropriate, and salt and alcohol reduction) and motivational support through practice nurses or health care assistances (using the CARE approach – congratulate, ask, reassure, encourage).

Participants allocated to usual care were not provided with self-monitoring equipment or the HOME BP intervention but had online access to the information provided in a patient leaflet for hypertension. This information comprised definitions of hypertension, causes, and brief guidance on treatment, including lifestyle changes and drugs. These participants received routine hypertension care that typically consisted of clinic BP monitoring to titrate drugs, with appointments and drug changes made at the discretion of the general practitioner. Participants were not prevented from self-monitoring, but data on self-monitoring practices were collected at the end of the trial from patients and practitioners.

Measures and analysis. The primary outcome measure was the difference in systolic BP at 12-month follow-up between the intervention and usual care groups (adjusting for baseline BP, practice, BP target levels, and sex). Secondary outcomes included systolic and diastolic BP at 6 and 12 months, weight, modified patient enablement instrument, drug adherence, health-related quality of life, and side effects from the symptoms section of an adjusted illness perceptions questionnaire. At trial, registration participants and general practitioners were asked about their use of self-monitoring in the usual care group.

The primary analysis used general linear modelling to compare systolic BP in the intervention and usual care groups at follow-up, adjusting for baseline BP, practice (as a random effect to take into account clustering), BP target levels, and sex. Analyses were on an intention-to-treat basis and used multiple imputation for missing data. Sensitivity analyses used complete cases and a repeated measures technique. Secondary analyses used similar techniques to assess differences between groups. A within-trial economic analysis estimated cost per unit reduction in systolic BP by using similar adjustments and multiple imputation for missing values. Repeated bootstrapping was used to estimate the probability of the intervention being cost-effective at different levels of willingness to pay per unit reduction in BP.

Main results. The intervention and usual care groups did not differ significantly – participants had a mean age of 66 years and mean baseline clinical BP of 151.6/85.3 mm Hg and 151.7/86.4 mm Hg (usual care and intervention, respectively). Most participants were White British (94%), just more than half were men, and the time since diagnosis averaged around 11 years. The most deprived group (based on the English Index of Multiple Deprivation) accounted for 63/622 (10%), with the least deprived group accounting for 326/622 (52%).

After 1 year, data were available from 552 participants (88.6%) with imputation for the remaining 70 participants (11.4%). Mean BP dropped from 151.7/86.4 to 138.4/80.2 mm Hg in the intervention group and from 151.6/85.3 to 141.8/79.8 mm Hg in the usual care group, giving a mean difference in systolic BP of −3.4 mm Hg (95% CI −6.1 to −0.8 mm Hg) and a mean difference in diastolic BP of −0.5 mm Hg (−1.9 to 0.9 mm Hg). Exploratory subgroup analyses suggested that participants aged 67 years or older had a smaller effect size than those younger than 67. Similarly, while the effect sizes in the standard and diabetes target groups were similar, those older than 80 years with a higher target of 145/85 mm Hg showed little evidence of benefit. Results for other subgroups, including sex, baseline BP, deprivation, and history of self-monitoring, were similar between groups.

Engagement with the digital intervention was high, with 281/305 (92%) participants completing the 2 core training sessions, 268/305 (88%) completing a week of practice BP readings, and 243/305 (80%) completing at least 3 weeks of BP entries. Furthermore, 214/305 (70%) were still monitoring in the last 3 months of participation. However, less than 1/3 of participants chose to register on 1 of the optional lifestyle change modules. In the usual care group, a post-hoc analysis after 12 months showed that 112/234 (47%) patients reported monitoring their own BP at home at least once per month during the trial.

The difference in mean cost per patient was £38 (US $51.30, €41.9; 95% CI £27 to £47), which along with the decrease in systolic BP, gave an incremental cost per mm Hg BP reduction of £11 (£6 to £29). Bootstrapping analysis showed the intervention had high (90%) probability of being cost-effective at willingness to pay above £20 per unit reduction. The probabilities of being cost-effective for the intervention against usual care were 87%, 93%, and 97% at thresholds of £20, £30, and £50, respectively.

Conclusion. The HOME BP digital intervention for the management of hypertension by using self-monitored BP led to better control of systolic BP after 1 year than usual care, with low incremental costs. Implementation in primary care will require integration into clinical workflows and consideration of people who are digitally excluded.

Commentary

Elevated BP, also known as hypertension, is the most important, modifiable risk factor for cardiovascular disease and mortality.1 Clinically significant effects and improvements in mortality can be achieved with relatively small reductions in BP levels. Long-established lifestyle modifications that effectively lower BP include weight loss, reduced sodium intake, increased physical activity, and limited alcohol intake. However, motivating patients to achieve lifestyle modifications is among the most difficult aspects of managing hypertension. Importantly, for individuals taking antihypertensive medication, lifestyle modification is recommended as adjunctive therapy to reduce BP. Given that target blood pressure levels are reached for less than half of adults, novel interventions are needed to improve BP control – in particular, individualized cognitive behavioral interventions are more likely to be effective than standardized, single-component interventions.

Guided self-management for hypertension as part of systematic, planned care offers the potential for improvements in adherence and in turn improved long-term patient outcomes.2 Self-management can encompass a wide range of behaviors in addition to medication titration and monitoring of symptoms, such as individuals’ ability to manage physical, psychosocial and lifestyle behaviors related to their condition.3 Digital interventions leveraging apps, software, and/or technologies in particular have the potential to support people in self-management, allow for remote monitoring, and enable personalized and adaptive strategies for chronic disease management.4-5 An example of a digital intervention in the context of guided self-management for hypertension can be a web-based program delivered by computer or phone that combines health information with decision support to help inform behavior change in patients and remote monitoring of patient status by health professionals. Well-designed digital interventions can effectively change patient health-related behaviors, improve patient knowledge and confidence for self-management of health, and lead to better health outcomes.6-7

This study adds to the literature as a large, randomized controlled trial evaluating the effectiveness of a digital intervention in the field of hypertension and with follow-up for a year. The authors highlight that relatively few studies have been performed that combine self-monitoring with a digitally delivered cointervention, and none has shown a major effect in an adequately powered trial over a year. Results from this study showed that HOME BP, a digital intervention enabling self-management of hypertension, including self-monitoring, titration based on self-monitored BP, lifestyle advice, and behavioral support for patients and health care professionals, resulted in a worthwhile reduction of systolic BP. In addition, this reduction was achieved at modest cost based on the within trial cost effectiveness analysis.

There are many important strengths of this study, especially related to the design and analysis strategy, and some limitations. This study was designed as a randomized controlled trial with a 1 year follow-up period, although participants were unmasked to the group they were randomized to, which may have impacted their behaviors while in the study. As the authors state, the study was not only adequately powered to detect a difference in blood pressure, but also over-recruitment ensured such an effect was not missed. Recruiting from a large number of general practices ensured generalizability in terms of health care professionals. Importantly, while study participants mostly identified as predominantly White and tended to be of higher socioeconomic status, this is representative of the aged population in England and Wales. Nevertheless, generalizability of findings from this study is still limited to the demographic characteristics of the study population. Other strengths included inclusion of intention-to-treat analysis, multiple imputation for missing data, sensitivity analysis, as well as economic analysis and cost effectiveness analysis.

Of note, results from the study are only attributable to the digital interventions used in this study (digital web-based with limited mechanisms of behavior change and engagement built-in) and thus should not be generalized to all digital interventions for managing hypertension. Also, as the authors highlight, the relative importance of the different parts of the digital intervention were unable to be distinguished, although this type of analysis is important in multicomponent interventions to better understand the most effective mechanism impacting change in the primary outcome.

Applications for Clinical Practice

Results of this study demonstrated that among participants being treated with hypertension, those engaged with the HOME BP digital intervention (combining self-monitoring of blood pressure with guided self-management) had better control of systolic BP after 1 year compared to participants receiving usual care. While these findings have important implications in the management of hypertension in health care systems, its integration into clinical workflow, sustainability, long-term clinical effectiveness, and effectiveness among diverse populations is unclear. However, clinicians can still encourage and support the use of evidence-based digital tools for patient self-monitoring of BP and guided-management of lifestyle modifications to lower BP. Additionally, clinicians can proactively propose incorporating evidence-based digital interventions like HOME BP into routine clinical practice guidelines.

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Samadian F, Dalili N, Jamalian A. Lifestyle Modifications to Prevent and Control Hypertension. Iran J Kidney Dis. 2016;10(5):237-263.

2. McLean G, Band R, Saunderson K, et al. Digital interventions to promote self-management in adults with hypertension systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hypertens. 2016;34(4):600-612. doi:10.1097/HJH.0000000000000859

3. Bodenheimer T, Lorig K, Holman H, Grumbach K. Patient self-management of chronic disease in primary care. JAMA. 2002 Nov 20;288(19):2469-2475. doi:10.1001/jama.288.19.2469

4. Morton K, Dennison L, May C, et al. Using digital interventions for self-management of chronic physical health conditions: A meta-ethnography review of published studies. Patient Educ Couns. 2017;100(4):616-635. doi:10.1016/j.ped.2016.10.019

5. Kario K. Management of Hypertension in the Digital Era: Small Wearable Monitoring Devices for Remote Blood Pressure Monitoring. Hypertension. 2020;76(3):640-650. doi:10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.120.14742

6. Murray E, Burns J, See TS, et al. Interactive Health Communication Applications for people with chronic disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;(4):CD004274. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004274.pub4

7. Webb TL, Joseph J, Yardley L, Michie S. Using the internet to promote health behavior change: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of theoretical basis, use of behavior change techniques, and mode of delivery on efficacy. J Med Internet Res. 2010;12(1):e4. doi:10.2196/jmir.1376

Study Overview

Objective. To evaluate whether a digital intervention comprising self-monitoring of blood pressure (BP) with reminders and predetermined drug changes combined with lifestyle change support resulted in lower systolic BP in people receiving treatment for hypertension that was poorly controlled, and whether this approach was cost effective.

Design. Unmasked randomized controlled trial.

Settings and participants. Eligible participants were identified from clinical codes recorded in the electronic health records of 76 collaborating general practices from the National Institute for Health Research Clinical Research Network, a United Kingdom government agency. The practices sent invitation letters to eligible participants to come to the clinic to establish eligibility, take consent, and collect baseline data via online questionnaires.

Eligible participants were aged 18 years or older with treated hypertension, a mean baseline BP reading of more than 140/90 mm Hg and were taking no more than 3 antihypertensive drugs. Participants also needed to be willing to self-monitor and have access to the internet (with support from a family member if needed). Exclusions included BP greater than 180/110 mm Hg, atrial fibrillation, hypertension not managed by their general practitioner, chronic kidney disease stage 4-5, postural hypotension (> 20 mm Hg systolic drop), an acute cardiovascular event in the previous 3 months, terminal disease, or another condition which in the opinion of their general practitioner made participation inappropriate.

Of the 11 399 invitation letters sent out, 1389 (12%) potential participants responded positively and were screened for eligibility. Those who declined to take part could optionally give their reasons, and responses were gained from 2426 of 10 010 (24%). The mean age of those who gave a reason for declining was 73 years. The most commonly selected reasons for declining were not having access to the internet (982, 41%), not wanting to participate in a research trial (617, 25%) or an internet study (543, 22%), and not wanting to change drugs (535, 22%). Of the 1389 screened, 734 were ineligible, and 33 did not complete baseline measures and randomization. The remaining 622 people who were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to receive the HOME BP intervention (n = 305) or usual care (n = 317).

Intervention vs usual care. The HOME BP intervention for the self-management of high BP consisted of an integrated patient and health care practitioner online digital intervention, BP self-monitoring (using an Omron M3 monitor), health care practitioner directed and supervised titration of antihypertensive drugs, and user-selected lifestyle modifications. Participants were advised via automated email reminders to take 2 morning BP readings for 7 days each month and to enter online each second reading. Mean home BP was calculated, accompanied by feedback of BP results to both patients and professionals with optional evidence-based lifestyle advice (for healthy eating, physical activity, losing weight if appropriate, and salt and alcohol reduction) and motivational support through practice nurses or health care assistances (using the CARE approach – congratulate, ask, reassure, encourage).

Participants allocated to usual care were not provided with self-monitoring equipment or the HOME BP intervention but had online access to the information provided in a patient leaflet for hypertension. This information comprised definitions of hypertension, causes, and brief guidance on treatment, including lifestyle changes and drugs. These participants received routine hypertension care that typically consisted of clinic BP monitoring to titrate drugs, with appointments and drug changes made at the discretion of the general practitioner. Participants were not prevented from self-monitoring, but data on self-monitoring practices were collected at the end of the trial from patients and practitioners.

Measures and analysis. The primary outcome measure was the difference in systolic BP at 12-month follow-up between the intervention and usual care groups (adjusting for baseline BP, practice, BP target levels, and sex). Secondary outcomes included systolic and diastolic BP at 6 and 12 months, weight, modified patient enablement instrument, drug adherence, health-related quality of life, and side effects from the symptoms section of an adjusted illness perceptions questionnaire. At trial, registration participants and general practitioners were asked about their use of self-monitoring in the usual care group.

The primary analysis used general linear modelling to compare systolic BP in the intervention and usual care groups at follow-up, adjusting for baseline BP, practice (as a random effect to take into account clustering), BP target levels, and sex. Analyses were on an intention-to-treat basis and used multiple imputation for missing data. Sensitivity analyses used complete cases and a repeated measures technique. Secondary analyses used similar techniques to assess differences between groups. A within-trial economic analysis estimated cost per unit reduction in systolic BP by using similar adjustments and multiple imputation for missing values. Repeated bootstrapping was used to estimate the probability of the intervention being cost-effective at different levels of willingness to pay per unit reduction in BP.

Main results. The intervention and usual care groups did not differ significantly – participants had a mean age of 66 years and mean baseline clinical BP of 151.6/85.3 mm Hg and 151.7/86.4 mm Hg (usual care and intervention, respectively). Most participants were White British (94%), just more than half were men, and the time since diagnosis averaged around 11 years. The most deprived group (based on the English Index of Multiple Deprivation) accounted for 63/622 (10%), with the least deprived group accounting for 326/622 (52%).

After 1 year, data were available from 552 participants (88.6%) with imputation for the remaining 70 participants (11.4%). Mean BP dropped from 151.7/86.4 to 138.4/80.2 mm Hg in the intervention group and from 151.6/85.3 to 141.8/79.8 mm Hg in the usual care group, giving a mean difference in systolic BP of −3.4 mm Hg (95% CI −6.1 to −0.8 mm Hg) and a mean difference in diastolic BP of −0.5 mm Hg (−1.9 to 0.9 mm Hg). Exploratory subgroup analyses suggested that participants aged 67 years or older had a smaller effect size than those younger than 67. Similarly, while the effect sizes in the standard and diabetes target groups were similar, those older than 80 years with a higher target of 145/85 mm Hg showed little evidence of benefit. Results for other subgroups, including sex, baseline BP, deprivation, and history of self-monitoring, were similar between groups.

Engagement with the digital intervention was high, with 281/305 (92%) participants completing the 2 core training sessions, 268/305 (88%) completing a week of practice BP readings, and 243/305 (80%) completing at least 3 weeks of BP entries. Furthermore, 214/305 (70%) were still monitoring in the last 3 months of participation. However, less than 1/3 of participants chose to register on 1 of the optional lifestyle change modules. In the usual care group, a post-hoc analysis after 12 months showed that 112/234 (47%) patients reported monitoring their own BP at home at least once per month during the trial.

The difference in mean cost per patient was £38 (US $51.30, €41.9; 95% CI £27 to £47), which along with the decrease in systolic BP, gave an incremental cost per mm Hg BP reduction of £11 (£6 to £29). Bootstrapping analysis showed the intervention had high (90%) probability of being cost-effective at willingness to pay above £20 per unit reduction. The probabilities of being cost-effective for the intervention against usual care were 87%, 93%, and 97% at thresholds of £20, £30, and £50, respectively.

Conclusion. The HOME BP digital intervention for the management of hypertension by using self-monitored BP led to better control of systolic BP after 1 year than usual care, with low incremental costs. Implementation in primary care will require integration into clinical workflows and consideration of people who are digitally excluded.

Commentary

Elevated BP, also known as hypertension, is the most important, modifiable risk factor for cardiovascular disease and mortality.1 Clinically significant effects and improvements in mortality can be achieved with relatively small reductions in BP levels. Long-established lifestyle modifications that effectively lower BP include weight loss, reduced sodium intake, increased physical activity, and limited alcohol intake. However, motivating patients to achieve lifestyle modifications is among the most difficult aspects of managing hypertension. Importantly, for individuals taking antihypertensive medication, lifestyle modification is recommended as adjunctive therapy to reduce BP. Given that target blood pressure levels are reached for less than half of adults, novel interventions are needed to improve BP control – in particular, individualized cognitive behavioral interventions are more likely to be effective than standardized, single-component interventions.

Guided self-management for hypertension as part of systematic, planned care offers the potential for improvements in adherence and in turn improved long-term patient outcomes.2 Self-management can encompass a wide range of behaviors in addition to medication titration and monitoring of symptoms, such as individuals’ ability to manage physical, psychosocial and lifestyle behaviors related to their condition.3 Digital interventions leveraging apps, software, and/or technologies in particular have the potential to support people in self-management, allow for remote monitoring, and enable personalized and adaptive strategies for chronic disease management.4-5 An example of a digital intervention in the context of guided self-management for hypertension can be a web-based program delivered by computer or phone that combines health information with decision support to help inform behavior change in patients and remote monitoring of patient status by health professionals. Well-designed digital interventions can effectively change patient health-related behaviors, improve patient knowledge and confidence for self-management of health, and lead to better health outcomes.6-7

This study adds to the literature as a large, randomized controlled trial evaluating the effectiveness of a digital intervention in the field of hypertension and with follow-up for a year. The authors highlight that relatively few studies have been performed that combine self-monitoring with a digitally delivered cointervention, and none has shown a major effect in an adequately powered trial over a year. Results from this study showed that HOME BP, a digital intervention enabling self-management of hypertension, including self-monitoring, titration based on self-monitored BP, lifestyle advice, and behavioral support for patients and health care professionals, resulted in a worthwhile reduction of systolic BP. In addition, this reduction was achieved at modest cost based on the within trial cost effectiveness analysis.

There are many important strengths of this study, especially related to the design and analysis strategy, and some limitations. This study was designed as a randomized controlled trial with a 1 year follow-up period, although participants were unmasked to the group they were randomized to, which may have impacted their behaviors while in the study. As the authors state, the study was not only adequately powered to detect a difference in blood pressure, but also over-recruitment ensured such an effect was not missed. Recruiting from a large number of general practices ensured generalizability in terms of health care professionals. Importantly, while study participants mostly identified as predominantly White and tended to be of higher socioeconomic status, this is representative of the aged population in England and Wales. Nevertheless, generalizability of findings from this study is still limited to the demographic characteristics of the study population. Other strengths included inclusion of intention-to-treat analysis, multiple imputation for missing data, sensitivity analysis, as well as economic analysis and cost effectiveness analysis.

Of note, results from the study are only attributable to the digital interventions used in this study (digital web-based with limited mechanisms of behavior change and engagement built-in) and thus should not be generalized to all digital interventions for managing hypertension. Also, as the authors highlight, the relative importance of the different parts of the digital intervention were unable to be distinguished, although this type of analysis is important in multicomponent interventions to better understand the most effective mechanism impacting change in the primary outcome.

Applications for Clinical Practice

Results of this study demonstrated that among participants being treated with hypertension, those engaged with the HOME BP digital intervention (combining self-monitoring of blood pressure with guided self-management) had better control of systolic BP after 1 year compared to participants receiving usual care. While these findings have important implications in the management of hypertension in health care systems, its integration into clinical workflow, sustainability, long-term clinical effectiveness, and effectiveness among diverse populations is unclear. However, clinicians can still encourage and support the use of evidence-based digital tools for patient self-monitoring of BP and guided-management of lifestyle modifications to lower BP. Additionally, clinicians can proactively propose incorporating evidence-based digital interventions like HOME BP into routine clinical practice guidelines.

Financial disclosures: None.

Study Overview

Objective. To evaluate whether a digital intervention comprising self-monitoring of blood pressure (BP) with reminders and predetermined drug changes combined with lifestyle change support resulted in lower systolic BP in people receiving treatment for hypertension that was poorly controlled, and whether this approach was cost effective.

Design. Unmasked randomized controlled trial.

Settings and participants. Eligible participants were identified from clinical codes recorded in the electronic health records of 76 collaborating general practices from the National Institute for Health Research Clinical Research Network, a United Kingdom government agency. The practices sent invitation letters to eligible participants to come to the clinic to establish eligibility, take consent, and collect baseline data via online questionnaires.