User login

The Role of Revascularization and Viability Testing in Patients With Multivessel Coronary Artery Disease and Severely Reduced Ejection Fraction

Study 1 Overview (STICHES Investigators)

Objective: To assess the survival benefit of coronary-artery bypass grafting (CABG) added to guideline-directed medical therapy, compared to optimal medical therapy (OMT) alone, in patients with coronary artery disease, heart failure, and severe left ventricular dysfunction. Design: Multicenter, randomized, prospective study with extended follow-up (median duration of 9.8 years).

Setting and participants: A total of 1212 patients with left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of 35% or less and coronary artery disease were randomized to medical therapy plus CABG or OMT alone at 127 clinical sites in 26 countries.

Main outcome measures: The primary endpoint was death from any cause. Main secondary endpoints were death from cardiovascular causes and a composite outcome of death from any cause or hospitalization for cardiovascular causes.

Main results: There were 359 primary outcome all-cause deaths (58.9%) in the CABG group and 398 (66.1%) in the medical therapy group (hazard ratio [HR], 0.84; 95% CI, 0.73-0.97; P = .02). Death from cardiovascular causes was reported in 247 patients (40.5%) in the CABG group and 297 patients (49.3%) in the medical therapy group (HR, 0.79; 95% CI, 0.66-0.93; P < .01). The composite outcome of death from any cause or hospitalization for cardiovascular causes occurred in 467 patients (76.6%) in the CABG group and 467 patients (87.0%) in the medical therapy group (HR, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.64-0.82; P < .01).

Conclusion: Over a median follow-up of 9.8 years in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy with severely reduced ejection fraction, the rates of death from any cause, death from cardiovascular causes, and the composite of death from any cause or hospitalization for cardiovascular causes were significantly lower in patients undergoing CABG than in patients receiving medical therapy alone.

Study 2 Overview (REVIVED BCIS Trial Group)

Objective: To assess whether percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) can improve survival and left ventricular function in patients with severe left ventricular systolic dysfunction as compared to OMT alone.

Design: Multicenter, randomized, prospective study.

Setting and participants: A total of 700 patients with LVEF <35% with severe coronary artery disease amendable to PCI and demonstrable myocardial viability were randomly assigned to either PCI plus optimal medical therapy (PCI group) or OMT alone (OMT group).

Main outcome measures: The primary outcome was death from any cause or hospitalization for heart failure. The main secondary outcomes were LVEF at 6 and 12 months and quality of life (QOL) scores.

Main results: Over a median follow-up of 41 months, the primary outcome was reported in 129 patients (37.2%) in the PCI group and in 134 patients (38.0%) in the OMT group (HR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.78-1.27; P = .96). The LVEF was similar in the 2 groups at 6 months (mean difference, –1.6 percentage points; 95% CI, –3.7 to 0.5) and at 12 months (mean difference, 0.9 percentage points; 95% CI, –1.7 to 3.4). QOL scores at 6 and 12 months favored the PCI group, but the difference had diminished at 24 months.

Conclusion: In patients with severe ischemic cardiomyopathy, revascularization by PCI in addition to OMT did not result in a lower incidence of death from any cause or hospitalization from heart failure.

Commentary

Coronary artery disease is the most common cause of heart failure with reduced ejection fraction and an important cause of mortality.1 Patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy with reduced ejection fraction are often considered for revascularization in addition to OMT and device therapies. Although there have been multiple retrospective studies and registries suggesting that cardiac outcomes and LVEF improve with revascularization, the number of large-scale prospective studies that assessed this clinical question and randomized patients to revascularization plus OMT compared to OMT alone has been limited.

In the Surgical Treatment for Ischemic Heart Failure (STICH) study,2,3 eligible patients had coronary artery disease amendable to CABG and a LVEF of 35% or less. Patients (N = 1212) were randomly assigned to CABG plus OMT or OMT alone between July 2002 and May 2007. The original study, with a median follow-up of 5 years, did not show survival benefit, but the investigators reported that the primary outcome of death from any cause was significantly lower in the CABG group compared to OMT alone when follow-up of the same study population was extended to 9.8 years (58.9% vs 66.1%, P = .02). The findings from this study led to a class I guideline recommendation of CABG over medical therapy in patients with multivessel disease and low ejection fraction.4

Since the STICH trial was designed, there have been significant improvements in devices and techniques used for PCI, and the procedure is now widely performed in patients with multivessel disease.5 The advantages of PCI over CABG include shorter recovery times and lower risk of immediate complications. In this context, the recently reported Revascularization for Ischemic Ventricular Dysfunction (REVIVED) study assessed clinical outcomes in patients with severe coronary artery disease and reduced ejection fraction by randomizing patients to either PCI with OMT or OMT alone.6 At a median follow-up of 3.5 years, the investigators found no difference in the primary outcome of death from any cause or hospitalization for heart failure (37.2% vs 38.0%; 95% CI, 0.78-1.28; P = .96). Moreover, the degree of LVEF improvement, assessed by follow-up echocardiogram read by the core lab, showed no difference in the degree of LVEF improvement between groups at 6 and 12 months. Finally, although results of the QOL assessment using the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ), a validated, patient-reported, heart-failure-specific QOL scale, favored the PCI group at 6 and 12 months of follow-up, the difference had diminished at 24 months.

The main strength of the REVIVED study was that it targeted a patient population with severe coronary artery disease, including left main disease and severely reduced ejection fraction, that historically have been excluded from large-scale randomized controlled studies evaluating PCI with OMT compared to OMT alone.7 However, there are several points to consider when interpreting the results of this study. First, further details of the PCI procedures are necessary. The REVIVED study recommended revascularization of all territories with viable myocardium; the anatomical revascularization index utilizing the British Cardiovascular Intervention Society (BCIS) Jeopardy Score was 71%. It is important to note that this jeopardy score was operator-reported and the core-lab adjudicated anatomical revascularization rate may be lower. Although viability testing primarily utilizing cardiac magnetic resonance imaging was performed in most patients, correlation between the revascularization territory and the viable segments has yet to be reported. Moreover, procedural details such as use of intravascular ultrasound and physiological testing, known to improve clinical outcome, need to be reported.8,9

Second, there is a high prevalence of ischemic cardiomyopathy, and it is important to note that the patients included in this study were highly selected from daily clinical practice, as evidenced by the prolonged enrollment period (8 years). Individuals were largely stable patients with less complex coronary anatomy as evidenced by the median interval from angiography to randomization of 80 days. Taking into consideration the degree of left ventricular dysfunction for patients included in the trial, only 14% of the patients had left main disease and half of the patients only had 2-vessel disease. The severity of the left main disease also needs to be clarified as it is likely that patients the operator determined to be critical were not enrolled in the study. Furthermore, the standard of care based on the STICH trial is to refer patients with severe multivessel coronary artery disease to CABG, making it more likely that patients with more severe and complex disease were not included in this trial. It is also important to note that this study enrolled patients with stable ischemic heart disease, and the data do not apply to patients presenting with acute coronary syndrome.

Third, although the primary outcome was similar between the groups, the secondary outcome of unplanned revascularization was lower in the PCI group. In addition, the rate of acute myocardial infarction (MI) was similar between the 2 groups, but the rate of spontaneous MI was lower in the PCI group compared to the OMT group (5.2% vs 9.3%) as 40% of MI cases in the PCI group were periprocedural MIs. The correlation between periprocedural MI and long-term outcomes has been modest compared to spontaneous MI. Moreover, with the longer follow-up, the number of spontaneous MI cases is expected to rise while the number of periprocedural MI cases is not. Extending the follow-up period is also important, as the STICH extension trial showed a statistically significant difference at 10-year follow up despite negative results at the time of the original publication.

Fourth, the REVIVED trial randomized a significantly lower number of patients compared to the STICH trial, and the authors reported fewer primary-outcome events than the estimated number needed to achieve the power to assess the primary hypothesis. In addition, significant improvements in medical treatment for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction since the STICH trial make comparison of PCI vs CABG in this patient population unfeasible.

Finally, although severe angina was not an exclusion criterion, two-thirds of the patients enrolled had no angina, and only 2% of the patients had baseline severe angina. This is important to consider when interpreting the results of the patient-reported health status as previous studies have shown that patients with worse angina at baseline derive the largest improvement in their QOL,10,11 and symptom improvement is the main indication for PCI in patients with stable ischemic heart disease.

Applications for Clinical Practice and System Implementation

In patients with severe left ventricular systolic dysfunction and multivessel stable ischemic heart disease who are well compensated and have little or no angina at baseline, OMT alone as an initial strategy may be considered against the addition of PCI after careful risk and benefit discussion. Further details about revascularization and extended follow-up data from the REVIVED trial are necessary.

Practice Points

- Patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy with reduced ejection fraction have been an understudied population in previous studies.

- Further studies are necessary to understand the benefits of revascularization and the role of viability testing in this population.

– Taishi Hirai MD, and Ziad Sayed Ahmad, MD

University of Missouri, Columbia, MO

1. Nowbar AN, Gitto M, Howard JP, et al. Mortality from ischemic heart disease. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2019;12(6):e005375. doi:10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES

2. Velazquez EJ, Lee KL, Deja MA, et al; for the STICH Investigators. Coronary-artery bypass surgery in patients with left ventricular dysfunction. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(17):1607-1616. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1100356

3. Velazquez EJ, Lee KL, Jones RH, et al. Coronary-artery bypass surgery in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(16):1511-1520. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1602001

4. Lawton JS, Tamis-Holland JE, Bangalore S, et al. 2021 ACC/AHA/SCAI guideline for coronary artery revascularization: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;79(2):e21-e129. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2021.09.006

5. Kirtane AJ, Doshi D, Leon MB, et al. Treatment of higher-risk patients with an indication for revascularization: evolution within the field of contemporary percutaneous coronary intervention. Circulation. 2016;134(5):422-431. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA

6. Perera D, Clayton T, O’Kane PD, et al. Percutaneous revascularization for ischemic left ventricular dysfunction. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(15):1351-1360. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2206606

7. Maron DJ, Hochman JS, Reynolds HR, et al. Initial invasive or conservative strategy for stable coronary disease. Circulation. 2020;142(18):1725-1735. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA

8. De Bruyne B, Pijls NH, Kalesan B, et al. Fractional flow reserve-guided PCI versus medical therapy in stable coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(11):991-1001. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1205361

9. Zhang J, Gao X, Kan J, et al. Intravascular ultrasound versus angiography-guided drug-eluting stent implantation: The ULTIMATE trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72(24):3126-3137. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2018.09.013

10. Spertus JA, Jones PG, Maron DJ, et al. Health-status outcomes with invasive or conservative care in coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(15):1408-1419. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1916370

11. Hirai T, Grantham JA, Sapontis J, et al. Quality of life changes after chronic total occlusion angioplasty in patients with baseline refractory angina. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2019;12:e007558. doi:10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.118.007558

Study 1 Overview (STICHES Investigators)

Objective: To assess the survival benefit of coronary-artery bypass grafting (CABG) added to guideline-directed medical therapy, compared to optimal medical therapy (OMT) alone, in patients with coronary artery disease, heart failure, and severe left ventricular dysfunction. Design: Multicenter, randomized, prospective study with extended follow-up (median duration of 9.8 years).

Setting and participants: A total of 1212 patients with left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of 35% or less and coronary artery disease were randomized to medical therapy plus CABG or OMT alone at 127 clinical sites in 26 countries.

Main outcome measures: The primary endpoint was death from any cause. Main secondary endpoints were death from cardiovascular causes and a composite outcome of death from any cause or hospitalization for cardiovascular causes.

Main results: There were 359 primary outcome all-cause deaths (58.9%) in the CABG group and 398 (66.1%) in the medical therapy group (hazard ratio [HR], 0.84; 95% CI, 0.73-0.97; P = .02). Death from cardiovascular causes was reported in 247 patients (40.5%) in the CABG group and 297 patients (49.3%) in the medical therapy group (HR, 0.79; 95% CI, 0.66-0.93; P < .01). The composite outcome of death from any cause or hospitalization for cardiovascular causes occurred in 467 patients (76.6%) in the CABG group and 467 patients (87.0%) in the medical therapy group (HR, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.64-0.82; P < .01).

Conclusion: Over a median follow-up of 9.8 years in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy with severely reduced ejection fraction, the rates of death from any cause, death from cardiovascular causes, and the composite of death from any cause or hospitalization for cardiovascular causes were significantly lower in patients undergoing CABG than in patients receiving medical therapy alone.

Study 2 Overview (REVIVED BCIS Trial Group)

Objective: To assess whether percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) can improve survival and left ventricular function in patients with severe left ventricular systolic dysfunction as compared to OMT alone.

Design: Multicenter, randomized, prospective study.

Setting and participants: A total of 700 patients with LVEF <35% with severe coronary artery disease amendable to PCI and demonstrable myocardial viability were randomly assigned to either PCI plus optimal medical therapy (PCI group) or OMT alone (OMT group).

Main outcome measures: The primary outcome was death from any cause or hospitalization for heart failure. The main secondary outcomes were LVEF at 6 and 12 months and quality of life (QOL) scores.

Main results: Over a median follow-up of 41 months, the primary outcome was reported in 129 patients (37.2%) in the PCI group and in 134 patients (38.0%) in the OMT group (HR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.78-1.27; P = .96). The LVEF was similar in the 2 groups at 6 months (mean difference, –1.6 percentage points; 95% CI, –3.7 to 0.5) and at 12 months (mean difference, 0.9 percentage points; 95% CI, –1.7 to 3.4). QOL scores at 6 and 12 months favored the PCI group, but the difference had diminished at 24 months.

Conclusion: In patients with severe ischemic cardiomyopathy, revascularization by PCI in addition to OMT did not result in a lower incidence of death from any cause or hospitalization from heart failure.

Commentary

Coronary artery disease is the most common cause of heart failure with reduced ejection fraction and an important cause of mortality.1 Patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy with reduced ejection fraction are often considered for revascularization in addition to OMT and device therapies. Although there have been multiple retrospective studies and registries suggesting that cardiac outcomes and LVEF improve with revascularization, the number of large-scale prospective studies that assessed this clinical question and randomized patients to revascularization plus OMT compared to OMT alone has been limited.

In the Surgical Treatment for Ischemic Heart Failure (STICH) study,2,3 eligible patients had coronary artery disease amendable to CABG and a LVEF of 35% or less. Patients (N = 1212) were randomly assigned to CABG plus OMT or OMT alone between July 2002 and May 2007. The original study, with a median follow-up of 5 years, did not show survival benefit, but the investigators reported that the primary outcome of death from any cause was significantly lower in the CABG group compared to OMT alone when follow-up of the same study population was extended to 9.8 years (58.9% vs 66.1%, P = .02). The findings from this study led to a class I guideline recommendation of CABG over medical therapy in patients with multivessel disease and low ejection fraction.4

Since the STICH trial was designed, there have been significant improvements in devices and techniques used for PCI, and the procedure is now widely performed in patients with multivessel disease.5 The advantages of PCI over CABG include shorter recovery times and lower risk of immediate complications. In this context, the recently reported Revascularization for Ischemic Ventricular Dysfunction (REVIVED) study assessed clinical outcomes in patients with severe coronary artery disease and reduced ejection fraction by randomizing patients to either PCI with OMT or OMT alone.6 At a median follow-up of 3.5 years, the investigators found no difference in the primary outcome of death from any cause or hospitalization for heart failure (37.2% vs 38.0%; 95% CI, 0.78-1.28; P = .96). Moreover, the degree of LVEF improvement, assessed by follow-up echocardiogram read by the core lab, showed no difference in the degree of LVEF improvement between groups at 6 and 12 months. Finally, although results of the QOL assessment using the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ), a validated, patient-reported, heart-failure-specific QOL scale, favored the PCI group at 6 and 12 months of follow-up, the difference had diminished at 24 months.

The main strength of the REVIVED study was that it targeted a patient population with severe coronary artery disease, including left main disease and severely reduced ejection fraction, that historically have been excluded from large-scale randomized controlled studies evaluating PCI with OMT compared to OMT alone.7 However, there are several points to consider when interpreting the results of this study. First, further details of the PCI procedures are necessary. The REVIVED study recommended revascularization of all territories with viable myocardium; the anatomical revascularization index utilizing the British Cardiovascular Intervention Society (BCIS) Jeopardy Score was 71%. It is important to note that this jeopardy score was operator-reported and the core-lab adjudicated anatomical revascularization rate may be lower. Although viability testing primarily utilizing cardiac magnetic resonance imaging was performed in most patients, correlation between the revascularization territory and the viable segments has yet to be reported. Moreover, procedural details such as use of intravascular ultrasound and physiological testing, known to improve clinical outcome, need to be reported.8,9

Second, there is a high prevalence of ischemic cardiomyopathy, and it is important to note that the patients included in this study were highly selected from daily clinical practice, as evidenced by the prolonged enrollment period (8 years). Individuals were largely stable patients with less complex coronary anatomy as evidenced by the median interval from angiography to randomization of 80 days. Taking into consideration the degree of left ventricular dysfunction for patients included in the trial, only 14% of the patients had left main disease and half of the patients only had 2-vessel disease. The severity of the left main disease also needs to be clarified as it is likely that patients the operator determined to be critical were not enrolled in the study. Furthermore, the standard of care based on the STICH trial is to refer patients with severe multivessel coronary artery disease to CABG, making it more likely that patients with more severe and complex disease were not included in this trial. It is also important to note that this study enrolled patients with stable ischemic heart disease, and the data do not apply to patients presenting with acute coronary syndrome.

Third, although the primary outcome was similar between the groups, the secondary outcome of unplanned revascularization was lower in the PCI group. In addition, the rate of acute myocardial infarction (MI) was similar between the 2 groups, but the rate of spontaneous MI was lower in the PCI group compared to the OMT group (5.2% vs 9.3%) as 40% of MI cases in the PCI group were periprocedural MIs. The correlation between periprocedural MI and long-term outcomes has been modest compared to spontaneous MI. Moreover, with the longer follow-up, the number of spontaneous MI cases is expected to rise while the number of periprocedural MI cases is not. Extending the follow-up period is also important, as the STICH extension trial showed a statistically significant difference at 10-year follow up despite negative results at the time of the original publication.

Fourth, the REVIVED trial randomized a significantly lower number of patients compared to the STICH trial, and the authors reported fewer primary-outcome events than the estimated number needed to achieve the power to assess the primary hypothesis. In addition, significant improvements in medical treatment for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction since the STICH trial make comparison of PCI vs CABG in this patient population unfeasible.

Finally, although severe angina was not an exclusion criterion, two-thirds of the patients enrolled had no angina, and only 2% of the patients had baseline severe angina. This is important to consider when interpreting the results of the patient-reported health status as previous studies have shown that patients with worse angina at baseline derive the largest improvement in their QOL,10,11 and symptom improvement is the main indication for PCI in patients with stable ischemic heart disease.

Applications for Clinical Practice and System Implementation

In patients with severe left ventricular systolic dysfunction and multivessel stable ischemic heart disease who are well compensated and have little or no angina at baseline, OMT alone as an initial strategy may be considered against the addition of PCI after careful risk and benefit discussion. Further details about revascularization and extended follow-up data from the REVIVED trial are necessary.

Practice Points

- Patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy with reduced ejection fraction have been an understudied population in previous studies.

- Further studies are necessary to understand the benefits of revascularization and the role of viability testing in this population.

– Taishi Hirai MD, and Ziad Sayed Ahmad, MD

University of Missouri, Columbia, MO

Study 1 Overview (STICHES Investigators)

Objective: To assess the survival benefit of coronary-artery bypass grafting (CABG) added to guideline-directed medical therapy, compared to optimal medical therapy (OMT) alone, in patients with coronary artery disease, heart failure, and severe left ventricular dysfunction. Design: Multicenter, randomized, prospective study with extended follow-up (median duration of 9.8 years).

Setting and participants: A total of 1212 patients with left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of 35% or less and coronary artery disease were randomized to medical therapy plus CABG or OMT alone at 127 clinical sites in 26 countries.

Main outcome measures: The primary endpoint was death from any cause. Main secondary endpoints were death from cardiovascular causes and a composite outcome of death from any cause or hospitalization for cardiovascular causes.

Main results: There were 359 primary outcome all-cause deaths (58.9%) in the CABG group and 398 (66.1%) in the medical therapy group (hazard ratio [HR], 0.84; 95% CI, 0.73-0.97; P = .02). Death from cardiovascular causes was reported in 247 patients (40.5%) in the CABG group and 297 patients (49.3%) in the medical therapy group (HR, 0.79; 95% CI, 0.66-0.93; P < .01). The composite outcome of death from any cause or hospitalization for cardiovascular causes occurred in 467 patients (76.6%) in the CABG group and 467 patients (87.0%) in the medical therapy group (HR, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.64-0.82; P < .01).

Conclusion: Over a median follow-up of 9.8 years in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy with severely reduced ejection fraction, the rates of death from any cause, death from cardiovascular causes, and the composite of death from any cause or hospitalization for cardiovascular causes were significantly lower in patients undergoing CABG than in patients receiving medical therapy alone.

Study 2 Overview (REVIVED BCIS Trial Group)

Objective: To assess whether percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) can improve survival and left ventricular function in patients with severe left ventricular systolic dysfunction as compared to OMT alone.

Design: Multicenter, randomized, prospective study.

Setting and participants: A total of 700 patients with LVEF <35% with severe coronary artery disease amendable to PCI and demonstrable myocardial viability were randomly assigned to either PCI plus optimal medical therapy (PCI group) or OMT alone (OMT group).

Main outcome measures: The primary outcome was death from any cause or hospitalization for heart failure. The main secondary outcomes were LVEF at 6 and 12 months and quality of life (QOL) scores.

Main results: Over a median follow-up of 41 months, the primary outcome was reported in 129 patients (37.2%) in the PCI group and in 134 patients (38.0%) in the OMT group (HR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.78-1.27; P = .96). The LVEF was similar in the 2 groups at 6 months (mean difference, –1.6 percentage points; 95% CI, –3.7 to 0.5) and at 12 months (mean difference, 0.9 percentage points; 95% CI, –1.7 to 3.4). QOL scores at 6 and 12 months favored the PCI group, but the difference had diminished at 24 months.

Conclusion: In patients with severe ischemic cardiomyopathy, revascularization by PCI in addition to OMT did not result in a lower incidence of death from any cause or hospitalization from heart failure.

Commentary

Coronary artery disease is the most common cause of heart failure with reduced ejection fraction and an important cause of mortality.1 Patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy with reduced ejection fraction are often considered for revascularization in addition to OMT and device therapies. Although there have been multiple retrospective studies and registries suggesting that cardiac outcomes and LVEF improve with revascularization, the number of large-scale prospective studies that assessed this clinical question and randomized patients to revascularization plus OMT compared to OMT alone has been limited.

In the Surgical Treatment for Ischemic Heart Failure (STICH) study,2,3 eligible patients had coronary artery disease amendable to CABG and a LVEF of 35% or less. Patients (N = 1212) were randomly assigned to CABG plus OMT or OMT alone between July 2002 and May 2007. The original study, with a median follow-up of 5 years, did not show survival benefit, but the investigators reported that the primary outcome of death from any cause was significantly lower in the CABG group compared to OMT alone when follow-up of the same study population was extended to 9.8 years (58.9% vs 66.1%, P = .02). The findings from this study led to a class I guideline recommendation of CABG over medical therapy in patients with multivessel disease and low ejection fraction.4

Since the STICH trial was designed, there have been significant improvements in devices and techniques used for PCI, and the procedure is now widely performed in patients with multivessel disease.5 The advantages of PCI over CABG include shorter recovery times and lower risk of immediate complications. In this context, the recently reported Revascularization for Ischemic Ventricular Dysfunction (REVIVED) study assessed clinical outcomes in patients with severe coronary artery disease and reduced ejection fraction by randomizing patients to either PCI with OMT or OMT alone.6 At a median follow-up of 3.5 years, the investigators found no difference in the primary outcome of death from any cause or hospitalization for heart failure (37.2% vs 38.0%; 95% CI, 0.78-1.28; P = .96). Moreover, the degree of LVEF improvement, assessed by follow-up echocardiogram read by the core lab, showed no difference in the degree of LVEF improvement between groups at 6 and 12 months. Finally, although results of the QOL assessment using the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ), a validated, patient-reported, heart-failure-specific QOL scale, favored the PCI group at 6 and 12 months of follow-up, the difference had diminished at 24 months.

The main strength of the REVIVED study was that it targeted a patient population with severe coronary artery disease, including left main disease and severely reduced ejection fraction, that historically have been excluded from large-scale randomized controlled studies evaluating PCI with OMT compared to OMT alone.7 However, there are several points to consider when interpreting the results of this study. First, further details of the PCI procedures are necessary. The REVIVED study recommended revascularization of all territories with viable myocardium; the anatomical revascularization index utilizing the British Cardiovascular Intervention Society (BCIS) Jeopardy Score was 71%. It is important to note that this jeopardy score was operator-reported and the core-lab adjudicated anatomical revascularization rate may be lower. Although viability testing primarily utilizing cardiac magnetic resonance imaging was performed in most patients, correlation between the revascularization territory and the viable segments has yet to be reported. Moreover, procedural details such as use of intravascular ultrasound and physiological testing, known to improve clinical outcome, need to be reported.8,9

Second, there is a high prevalence of ischemic cardiomyopathy, and it is important to note that the patients included in this study were highly selected from daily clinical practice, as evidenced by the prolonged enrollment period (8 years). Individuals were largely stable patients with less complex coronary anatomy as evidenced by the median interval from angiography to randomization of 80 days. Taking into consideration the degree of left ventricular dysfunction for patients included in the trial, only 14% of the patients had left main disease and half of the patients only had 2-vessel disease. The severity of the left main disease also needs to be clarified as it is likely that patients the operator determined to be critical were not enrolled in the study. Furthermore, the standard of care based on the STICH trial is to refer patients with severe multivessel coronary artery disease to CABG, making it more likely that patients with more severe and complex disease were not included in this trial. It is also important to note that this study enrolled patients with stable ischemic heart disease, and the data do not apply to patients presenting with acute coronary syndrome.

Third, although the primary outcome was similar between the groups, the secondary outcome of unplanned revascularization was lower in the PCI group. In addition, the rate of acute myocardial infarction (MI) was similar between the 2 groups, but the rate of spontaneous MI was lower in the PCI group compared to the OMT group (5.2% vs 9.3%) as 40% of MI cases in the PCI group were periprocedural MIs. The correlation between periprocedural MI and long-term outcomes has been modest compared to spontaneous MI. Moreover, with the longer follow-up, the number of spontaneous MI cases is expected to rise while the number of periprocedural MI cases is not. Extending the follow-up period is also important, as the STICH extension trial showed a statistically significant difference at 10-year follow up despite negative results at the time of the original publication.

Fourth, the REVIVED trial randomized a significantly lower number of patients compared to the STICH trial, and the authors reported fewer primary-outcome events than the estimated number needed to achieve the power to assess the primary hypothesis. In addition, significant improvements in medical treatment for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction since the STICH trial make comparison of PCI vs CABG in this patient population unfeasible.

Finally, although severe angina was not an exclusion criterion, two-thirds of the patients enrolled had no angina, and only 2% of the patients had baseline severe angina. This is important to consider when interpreting the results of the patient-reported health status as previous studies have shown that patients with worse angina at baseline derive the largest improvement in their QOL,10,11 and symptom improvement is the main indication for PCI in patients with stable ischemic heart disease.

Applications for Clinical Practice and System Implementation

In patients with severe left ventricular systolic dysfunction and multivessel stable ischemic heart disease who are well compensated and have little or no angina at baseline, OMT alone as an initial strategy may be considered against the addition of PCI after careful risk and benefit discussion. Further details about revascularization and extended follow-up data from the REVIVED trial are necessary.

Practice Points

- Patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy with reduced ejection fraction have been an understudied population in previous studies.

- Further studies are necessary to understand the benefits of revascularization and the role of viability testing in this population.

– Taishi Hirai MD, and Ziad Sayed Ahmad, MD

University of Missouri, Columbia, MO

1. Nowbar AN, Gitto M, Howard JP, et al. Mortality from ischemic heart disease. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2019;12(6):e005375. doi:10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES

2. Velazquez EJ, Lee KL, Deja MA, et al; for the STICH Investigators. Coronary-artery bypass surgery in patients with left ventricular dysfunction. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(17):1607-1616. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1100356

3. Velazquez EJ, Lee KL, Jones RH, et al. Coronary-artery bypass surgery in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(16):1511-1520. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1602001

4. Lawton JS, Tamis-Holland JE, Bangalore S, et al. 2021 ACC/AHA/SCAI guideline for coronary artery revascularization: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;79(2):e21-e129. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2021.09.006

5. Kirtane AJ, Doshi D, Leon MB, et al. Treatment of higher-risk patients with an indication for revascularization: evolution within the field of contemporary percutaneous coronary intervention. Circulation. 2016;134(5):422-431. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA

6. Perera D, Clayton T, O’Kane PD, et al. Percutaneous revascularization for ischemic left ventricular dysfunction. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(15):1351-1360. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2206606

7. Maron DJ, Hochman JS, Reynolds HR, et al. Initial invasive or conservative strategy for stable coronary disease. Circulation. 2020;142(18):1725-1735. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA

8. De Bruyne B, Pijls NH, Kalesan B, et al. Fractional flow reserve-guided PCI versus medical therapy in stable coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(11):991-1001. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1205361

9. Zhang J, Gao X, Kan J, et al. Intravascular ultrasound versus angiography-guided drug-eluting stent implantation: The ULTIMATE trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72(24):3126-3137. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2018.09.013

10. Spertus JA, Jones PG, Maron DJ, et al. Health-status outcomes with invasive or conservative care in coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(15):1408-1419. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1916370

11. Hirai T, Grantham JA, Sapontis J, et al. Quality of life changes after chronic total occlusion angioplasty in patients with baseline refractory angina. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2019;12:e007558. doi:10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.118.007558

1. Nowbar AN, Gitto M, Howard JP, et al. Mortality from ischemic heart disease. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2019;12(6):e005375. doi:10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES

2. Velazquez EJ, Lee KL, Deja MA, et al; for the STICH Investigators. Coronary-artery bypass surgery in patients with left ventricular dysfunction. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(17):1607-1616. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1100356

3. Velazquez EJ, Lee KL, Jones RH, et al. Coronary-artery bypass surgery in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(16):1511-1520. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1602001

4. Lawton JS, Tamis-Holland JE, Bangalore S, et al. 2021 ACC/AHA/SCAI guideline for coronary artery revascularization: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;79(2):e21-e129. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2021.09.006

5. Kirtane AJ, Doshi D, Leon MB, et al. Treatment of higher-risk patients with an indication for revascularization: evolution within the field of contemporary percutaneous coronary intervention. Circulation. 2016;134(5):422-431. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA

6. Perera D, Clayton T, O’Kane PD, et al. Percutaneous revascularization for ischemic left ventricular dysfunction. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(15):1351-1360. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2206606

7. Maron DJ, Hochman JS, Reynolds HR, et al. Initial invasive or conservative strategy for stable coronary disease. Circulation. 2020;142(18):1725-1735. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA

8. De Bruyne B, Pijls NH, Kalesan B, et al. Fractional flow reserve-guided PCI versus medical therapy in stable coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(11):991-1001. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1205361

9. Zhang J, Gao X, Kan J, et al. Intravascular ultrasound versus angiography-guided drug-eluting stent implantation: The ULTIMATE trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72(24):3126-3137. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2018.09.013

10. Spertus JA, Jones PG, Maron DJ, et al. Health-status outcomes with invasive or conservative care in coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(15):1408-1419. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1916370

11. Hirai T, Grantham JA, Sapontis J, et al. Quality of life changes after chronic total occlusion angioplasty in patients with baseline refractory angina. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2019;12:e007558. doi:10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.118.007558

ACC/AHA issues updated guidance on aortic disease

focusing on surgical intervention considerations, consistent imaging practices, genetic and familial screenings, and the importance of multidisciplinary care.

“There has been a host of new evidence-based research available for clinicians in the past decade when it comes to aortic disease. It was time to reevaluate and update the previous, existing guidelines,” Eric M. Isselbacher, MD, MSc, chair of the writing committee, said in a statement.

“We hope this new guideline can inform clinical practices with up-to-date and synthesized recommendations, targeted toward a full multidisciplinary aortic team working to provide the best possible care for this vulnerable patient population,” added Dr. Isselbacher, codirector of the Thoracic Aortic Center at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston.

The 2022 ACC/AHA Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Aortic Disease was simultaneously published online in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology and Circulation.

The new guideline replaces the 2010 ACCF/AHA Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Patients With Thoracic Aortic Disease and the 2015 Surgery for Aortic Dilation in Patients With Bicuspid Aortic Valves: A Statement of Clarification From the ACC/AHA Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines.

The new guideline is intended to be used with the 2020 ACC/AHA Guideline for the Management of Patients With Valvular Heart Disease.

It brings together guidelines for both the thoracic and abdominal aorta and is targeted to cardiovascular clinicians involved in the care of people with aortic disease, including general cardiovascular care clinicians and emergency medicine clinicians, the writing group says.

Among the key recommendations in the new guideline are the following:

- Screen first-degree relatives of individuals diagnosed with aneurysms of the aortic root or ascending thoracic aorta, or those with aortic dissection to identify individuals most at risk for aortic disease. Screening would include genetic testing and imaging.

- Be consistent in the way CT or MRI are obtained and reported; in the measurement of aortic size and features; and in how often images are used for monitoring before and after repair surgery or other intervention. Ideally, all surveillance imaging for an individual should be done using the same modality and in the same lab, the guideline notes.

- For individuals who require aortic intervention, know that outcomes are optimized when surgery is performed by an experienced surgeon working in a multidisciplinary aortic team. The new guideline recommends “a specialized hospital team with expertise in the evaluation and management of aortic disease, in which care is delivered in a comprehensive, multidisciplinary manner.”

- At centers with multidisciplinary aortic teams and experienced surgeons, the threshold for surgical intervention for sporadic aortic root and ascending aortic aneurysms has been lowered from 5.5 cm to 5.0 cm in select individuals, and even lower in specific scenarios among patients with heritable thoracic aortic aneurysms.

- In patients who are significantly smaller or taller than average, surgical thresholds may incorporate indexing of the aortic root or ascending aortic diameter to either patient body surface area or height, or aortic cross-sectional area to patient height.

- Rapid aortic growth is a risk factor for rupture and the definition for rapid aneurysm growth rate has been updated. Surgery is now recommended for patients with aneurysms of aortic root and ascending thoracic aorta with a confirmed growth rate of ≥ 0.3 cm per year across 2 consecutive years or ≥ 0.5 cm in 1 year.

- In patients undergoing aortic root replacement surgery, valve-sparing aortic root replacement is reasonable if the valve is suitable for repair and when performed by experienced surgeons in a multidisciplinary aortic team.

- Patients with acute type A aortic dissection, if clinically stable, should be considered for transfer to a high-volume aortic center to improve survival. The operative repair of type A aortic dissection should entail at least an open distal anastomosis rather than just a simple supracoronary interposition graft.

- For management of uncomplicated type B aortic dissection, there is an increasing role for . Clinical trials of repair of thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysms with endografts are reporting results that suggest endovascular repair is an option for patients with suitable anatomy.

- Shared decision-making between the patient and multidisciplinary aortic team is highly encouraged, especially when the patient is on the borderline of thresholds for repair or eligible for different types of surgical repair.

- Shared decision-making should also be used with individuals who are pregnant or may become pregnant to consider the risks of pregnancy in individuals with aortic disease.

The guideline was developed in collaboration with and endorsed by the American Association for Thoracic Surgery, the American College of Radiology, the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists, the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, the Society of Thoracic Surgeons, and the Society for Vascular Medicine.

It has been endorsed by the Society of Interventional Radiology and the Society for Vascular Surgery.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

focusing on surgical intervention considerations, consistent imaging practices, genetic and familial screenings, and the importance of multidisciplinary care.

“There has been a host of new evidence-based research available for clinicians in the past decade when it comes to aortic disease. It was time to reevaluate and update the previous, existing guidelines,” Eric M. Isselbacher, MD, MSc, chair of the writing committee, said in a statement.

“We hope this new guideline can inform clinical practices with up-to-date and synthesized recommendations, targeted toward a full multidisciplinary aortic team working to provide the best possible care for this vulnerable patient population,” added Dr. Isselbacher, codirector of the Thoracic Aortic Center at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston.

The 2022 ACC/AHA Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Aortic Disease was simultaneously published online in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology and Circulation.

The new guideline replaces the 2010 ACCF/AHA Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Patients With Thoracic Aortic Disease and the 2015 Surgery for Aortic Dilation in Patients With Bicuspid Aortic Valves: A Statement of Clarification From the ACC/AHA Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines.

The new guideline is intended to be used with the 2020 ACC/AHA Guideline for the Management of Patients With Valvular Heart Disease.

It brings together guidelines for both the thoracic and abdominal aorta and is targeted to cardiovascular clinicians involved in the care of people with aortic disease, including general cardiovascular care clinicians and emergency medicine clinicians, the writing group says.

Among the key recommendations in the new guideline are the following:

- Screen first-degree relatives of individuals diagnosed with aneurysms of the aortic root or ascending thoracic aorta, or those with aortic dissection to identify individuals most at risk for aortic disease. Screening would include genetic testing and imaging.

- Be consistent in the way CT or MRI are obtained and reported; in the measurement of aortic size and features; and in how often images are used for monitoring before and after repair surgery or other intervention. Ideally, all surveillance imaging for an individual should be done using the same modality and in the same lab, the guideline notes.

- For individuals who require aortic intervention, know that outcomes are optimized when surgery is performed by an experienced surgeon working in a multidisciplinary aortic team. The new guideline recommends “a specialized hospital team with expertise in the evaluation and management of aortic disease, in which care is delivered in a comprehensive, multidisciplinary manner.”

- At centers with multidisciplinary aortic teams and experienced surgeons, the threshold for surgical intervention for sporadic aortic root and ascending aortic aneurysms has been lowered from 5.5 cm to 5.0 cm in select individuals, and even lower in specific scenarios among patients with heritable thoracic aortic aneurysms.

- In patients who are significantly smaller or taller than average, surgical thresholds may incorporate indexing of the aortic root or ascending aortic diameter to either patient body surface area or height, or aortic cross-sectional area to patient height.

- Rapid aortic growth is a risk factor for rupture and the definition for rapid aneurysm growth rate has been updated. Surgery is now recommended for patients with aneurysms of aortic root and ascending thoracic aorta with a confirmed growth rate of ≥ 0.3 cm per year across 2 consecutive years or ≥ 0.5 cm in 1 year.

- In patients undergoing aortic root replacement surgery, valve-sparing aortic root replacement is reasonable if the valve is suitable for repair and when performed by experienced surgeons in a multidisciplinary aortic team.

- Patients with acute type A aortic dissection, if clinically stable, should be considered for transfer to a high-volume aortic center to improve survival. The operative repair of type A aortic dissection should entail at least an open distal anastomosis rather than just a simple supracoronary interposition graft.

- For management of uncomplicated type B aortic dissection, there is an increasing role for . Clinical trials of repair of thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysms with endografts are reporting results that suggest endovascular repair is an option for patients with suitable anatomy.

- Shared decision-making between the patient and multidisciplinary aortic team is highly encouraged, especially when the patient is on the borderline of thresholds for repair or eligible for different types of surgical repair.

- Shared decision-making should also be used with individuals who are pregnant or may become pregnant to consider the risks of pregnancy in individuals with aortic disease.

The guideline was developed in collaboration with and endorsed by the American Association for Thoracic Surgery, the American College of Radiology, the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists, the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, the Society of Thoracic Surgeons, and the Society for Vascular Medicine.

It has been endorsed by the Society of Interventional Radiology and the Society for Vascular Surgery.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

focusing on surgical intervention considerations, consistent imaging practices, genetic and familial screenings, and the importance of multidisciplinary care.

“There has been a host of new evidence-based research available for clinicians in the past decade when it comes to aortic disease. It was time to reevaluate and update the previous, existing guidelines,” Eric M. Isselbacher, MD, MSc, chair of the writing committee, said in a statement.

“We hope this new guideline can inform clinical practices with up-to-date and synthesized recommendations, targeted toward a full multidisciplinary aortic team working to provide the best possible care for this vulnerable patient population,” added Dr. Isselbacher, codirector of the Thoracic Aortic Center at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston.

The 2022 ACC/AHA Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Aortic Disease was simultaneously published online in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology and Circulation.

The new guideline replaces the 2010 ACCF/AHA Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Patients With Thoracic Aortic Disease and the 2015 Surgery for Aortic Dilation in Patients With Bicuspid Aortic Valves: A Statement of Clarification From the ACC/AHA Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines.

The new guideline is intended to be used with the 2020 ACC/AHA Guideline for the Management of Patients With Valvular Heart Disease.

It brings together guidelines for both the thoracic and abdominal aorta and is targeted to cardiovascular clinicians involved in the care of people with aortic disease, including general cardiovascular care clinicians and emergency medicine clinicians, the writing group says.

Among the key recommendations in the new guideline are the following:

- Screen first-degree relatives of individuals diagnosed with aneurysms of the aortic root or ascending thoracic aorta, or those with aortic dissection to identify individuals most at risk for aortic disease. Screening would include genetic testing and imaging.

- Be consistent in the way CT or MRI are obtained and reported; in the measurement of aortic size and features; and in how often images are used for monitoring before and after repair surgery or other intervention. Ideally, all surveillance imaging for an individual should be done using the same modality and in the same lab, the guideline notes.

- For individuals who require aortic intervention, know that outcomes are optimized when surgery is performed by an experienced surgeon working in a multidisciplinary aortic team. The new guideline recommends “a specialized hospital team with expertise in the evaluation and management of aortic disease, in which care is delivered in a comprehensive, multidisciplinary manner.”

- At centers with multidisciplinary aortic teams and experienced surgeons, the threshold for surgical intervention for sporadic aortic root and ascending aortic aneurysms has been lowered from 5.5 cm to 5.0 cm in select individuals, and even lower in specific scenarios among patients with heritable thoracic aortic aneurysms.

- In patients who are significantly smaller or taller than average, surgical thresholds may incorporate indexing of the aortic root or ascending aortic diameter to either patient body surface area or height, or aortic cross-sectional area to patient height.

- Rapid aortic growth is a risk factor for rupture and the definition for rapid aneurysm growth rate has been updated. Surgery is now recommended for patients with aneurysms of aortic root and ascending thoracic aorta with a confirmed growth rate of ≥ 0.3 cm per year across 2 consecutive years or ≥ 0.5 cm in 1 year.

- In patients undergoing aortic root replacement surgery, valve-sparing aortic root replacement is reasonable if the valve is suitable for repair and when performed by experienced surgeons in a multidisciplinary aortic team.

- Patients with acute type A aortic dissection, if clinically stable, should be considered for transfer to a high-volume aortic center to improve survival. The operative repair of type A aortic dissection should entail at least an open distal anastomosis rather than just a simple supracoronary interposition graft.

- For management of uncomplicated type B aortic dissection, there is an increasing role for . Clinical trials of repair of thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysms with endografts are reporting results that suggest endovascular repair is an option for patients with suitable anatomy.

- Shared decision-making between the patient and multidisciplinary aortic team is highly encouraged, especially when the patient is on the borderline of thresholds for repair or eligible for different types of surgical repair.

- Shared decision-making should also be used with individuals who are pregnant or may become pregnant to consider the risks of pregnancy in individuals with aortic disease.

The guideline was developed in collaboration with and endorsed by the American Association for Thoracic Surgery, the American College of Radiology, the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists, the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, the Society of Thoracic Surgeons, and the Society for Vascular Medicine.

It has been endorsed by the Society of Interventional Radiology and the Society for Vascular Surgery.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM CIRCULATION

Amulet, Watchman 2.5 LAAO outcomes neck and neck at 3 years

The Amplatzer Amulet (Abbott) and first-generation Watchman 2.5 (Boston Scientific) devices provide relatively comparable results out to 3 years after left atrial appendage occlusion (LAAO), longer follow-up from the Amplatzer Amulet Left Atrial Appendage Occluder Versus Watchman Device for Stroke Prophylaxis (Amulet IDE) trial shows.

“The dual-seal Amplatzer Amulet left atrial appendage occluder continued to demonstrate safety and effectiveness through 3 years,” principal investigator Dhanunjaya Lakkireddy, MD, said in a late-breaking session at the recent Transcatheter Cardiovascular Therapeutics annual meeting.

Preliminary results, reported last year, showed that procedural complications were higher with the Amplatzer but that it provided superior closure of the left atrial appendage (LAA) at 45 days and was noninferior with respect to safety at 12 months and efficacy at 18 months.

Amulet IDE is the largest head-to-head comparison of the two devices, enrolling 1,878 high-risk patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation undergoing LAA closure to reduce the risk of stroke.

Three-year follow-up was higher with the Amulet device than with the Watchman, at 721 vs. 659 patients, driven by increased deaths (85 vs. 63) and withdrawals (50 vs. 23) in the Watchman group within 18 months, noted Dr. Lakkireddy, Kansas City Heart Rhythm Institute and Research Foundation, Overland Park, Kan.

Use of oral anticoagulation was higher in the Watchman group at 6 months (2.8% vs. 4.7%; P = .04), 18 months (3.1% vs. 5.6%; P = .01), and 3 years (3.7% vs. 7.3%; P < .01).

This was primarily driven by more late device-related thrombus (DRT) after 6 months with the Watchman device than with the Amulet occluder (23 vs. 10). “Perhaps the dual-closure mechanism of the Amulet explains this fundamental difference, where you have a nice smooth disc that covers the ostium,” he posited.

At 3 years, rates of cardiovascular death trended lower with Amulet than with Watchman (6.6% vs. 8.5%; P = .14), as did all-cause deaths (14.6% vs. 17.9%; P = .07).

Most cardiovascular deaths in the Amulet group were not preceded by a device factor, whereas DRT (1 vs. 4) and peridevice leak 3 mm or more (5 vs. 15) frequently preceded these deaths in the Watchman group, Dr. Lakkireddy observed. No pericardial effusion-related deaths occurred in either group.

Major bleeding, however, trended higher for the Amulet, at 16.1%, compared with 14.7% for the Watchman (P = .46). Ischemic stroke and systemic embolic rates also trended higher for Amulet, at 5%, and 4.6% for Watchman.

The protocol recommended aspirin only for both groups after 6 months. None of the 29 Amulet and 3 of the 29 Watchman patients with an ischemic stroke were on oral anticoagulation at the time of the stroke.

Device factors, however, frequently preceded ischemic strokes in the Watchman group, Dr. Lakkireddy said. DRT occurred in 1 patient with Amulet and 2 patients with Watchman and peridevice leak in 3 with Amulet and 15 with Watchman. “Again, the peridevice leak issue really stands out as an important factor,” he said at the meeting, which was sponsored by the Cardiovascular Research Foundation.

Based on “data from the large trials, it’s clearly evident that the presence of peridevice leak significantly raises the risk of stroke in follow-up,” he said. “So, attention has to be paid to the choice of the device and how we can mitigate the risk of peridevice leaks in these patients.”

The composite of stroke, systemic embolism, and cardiovascular death occurred in 11.1% of patients with Amulet and 12.7% with Watchman (P = .31).

Asked following the formal presentation whether the results justify use of one device over the other for LAA occlusion, Dr. Lakkireddy said he likes the dual closure mechanism of the Amulet and is more likely to use it in patients with proximal lobes, very large appendages, or a relatively shallow appendage. “In the rest of the cases, I think it’s a toss-up.”

As for how generalizable the results are, he noted that the study tested the Amulet against the legacy Watchman 2.5 but that the second-generation Watchman FLX is available in a larger size and has shown improved performance.

The Amplatzer Amulet does not require oral anticoagulants at discharge. However, the indication for the Watchman FLX was recently expanded to include 45-day dual antiplatelet therapy as a postprocedure alternative to oral anticoagulation plus aspirin.

Going forward, the “next evolution” is to test the Watchman FLX and Amulet on either single antiplatelet or a dual antiplatelet regimen without oral anticoagulation, he suggested.

Results from SWISS APERO, the first randomized trial to compare the Amulet and Watchman FLX (and a handful of 2.5 devices) in 221 patients, showed that the devices are not interchangeable for rates of complications or leaks.

During a press conference prior to the presentation, discussant Federico Asch, MD, MedStar Health Research Institute, Washington, said, “the most exciting thing here is that we have good options. We now can start to tease out which patients will benefit best from one or the other because we actually have two options.”

The Amulet IDE trial was funded by Abbott. Dr. Lakkireddy reports that he or his spouse/partner have received grant/research support from Abbott, AtriCure, Alta Thera, Medtronic, Biosense Webster, Biotronik, and Boston Scientific; and speaker honoraria from Abbott, Medtronic, Biotronik, and Boston Scientific.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Amplatzer Amulet (Abbott) and first-generation Watchman 2.5 (Boston Scientific) devices provide relatively comparable results out to 3 years after left atrial appendage occlusion (LAAO), longer follow-up from the Amplatzer Amulet Left Atrial Appendage Occluder Versus Watchman Device for Stroke Prophylaxis (Amulet IDE) trial shows.

“The dual-seal Amplatzer Amulet left atrial appendage occluder continued to demonstrate safety and effectiveness through 3 years,” principal investigator Dhanunjaya Lakkireddy, MD, said in a late-breaking session at the recent Transcatheter Cardiovascular Therapeutics annual meeting.

Preliminary results, reported last year, showed that procedural complications were higher with the Amplatzer but that it provided superior closure of the left atrial appendage (LAA) at 45 days and was noninferior with respect to safety at 12 months and efficacy at 18 months.

Amulet IDE is the largest head-to-head comparison of the two devices, enrolling 1,878 high-risk patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation undergoing LAA closure to reduce the risk of stroke.

Three-year follow-up was higher with the Amulet device than with the Watchman, at 721 vs. 659 patients, driven by increased deaths (85 vs. 63) and withdrawals (50 vs. 23) in the Watchman group within 18 months, noted Dr. Lakkireddy, Kansas City Heart Rhythm Institute and Research Foundation, Overland Park, Kan.

Use of oral anticoagulation was higher in the Watchman group at 6 months (2.8% vs. 4.7%; P = .04), 18 months (3.1% vs. 5.6%; P = .01), and 3 years (3.7% vs. 7.3%; P < .01).

This was primarily driven by more late device-related thrombus (DRT) after 6 months with the Watchman device than with the Amulet occluder (23 vs. 10). “Perhaps the dual-closure mechanism of the Amulet explains this fundamental difference, where you have a nice smooth disc that covers the ostium,” he posited.

At 3 years, rates of cardiovascular death trended lower with Amulet than with Watchman (6.6% vs. 8.5%; P = .14), as did all-cause deaths (14.6% vs. 17.9%; P = .07).

Most cardiovascular deaths in the Amulet group were not preceded by a device factor, whereas DRT (1 vs. 4) and peridevice leak 3 mm or more (5 vs. 15) frequently preceded these deaths in the Watchman group, Dr. Lakkireddy observed. No pericardial effusion-related deaths occurred in either group.

Major bleeding, however, trended higher for the Amulet, at 16.1%, compared with 14.7% for the Watchman (P = .46). Ischemic stroke and systemic embolic rates also trended higher for Amulet, at 5%, and 4.6% for Watchman.

The protocol recommended aspirin only for both groups after 6 months. None of the 29 Amulet and 3 of the 29 Watchman patients with an ischemic stroke were on oral anticoagulation at the time of the stroke.

Device factors, however, frequently preceded ischemic strokes in the Watchman group, Dr. Lakkireddy said. DRT occurred in 1 patient with Amulet and 2 patients with Watchman and peridevice leak in 3 with Amulet and 15 with Watchman. “Again, the peridevice leak issue really stands out as an important factor,” he said at the meeting, which was sponsored by the Cardiovascular Research Foundation.

Based on “data from the large trials, it’s clearly evident that the presence of peridevice leak significantly raises the risk of stroke in follow-up,” he said. “So, attention has to be paid to the choice of the device and how we can mitigate the risk of peridevice leaks in these patients.”

The composite of stroke, systemic embolism, and cardiovascular death occurred in 11.1% of patients with Amulet and 12.7% with Watchman (P = .31).

Asked following the formal presentation whether the results justify use of one device over the other for LAA occlusion, Dr. Lakkireddy said he likes the dual closure mechanism of the Amulet and is more likely to use it in patients with proximal lobes, very large appendages, or a relatively shallow appendage. “In the rest of the cases, I think it’s a toss-up.”

As for how generalizable the results are, he noted that the study tested the Amulet against the legacy Watchman 2.5 but that the second-generation Watchman FLX is available in a larger size and has shown improved performance.

The Amplatzer Amulet does not require oral anticoagulants at discharge. However, the indication for the Watchman FLX was recently expanded to include 45-day dual antiplatelet therapy as a postprocedure alternative to oral anticoagulation plus aspirin.

Going forward, the “next evolution” is to test the Watchman FLX and Amulet on either single antiplatelet or a dual antiplatelet regimen without oral anticoagulation, he suggested.

Results from SWISS APERO, the first randomized trial to compare the Amulet and Watchman FLX (and a handful of 2.5 devices) in 221 patients, showed that the devices are not interchangeable for rates of complications or leaks.

During a press conference prior to the presentation, discussant Federico Asch, MD, MedStar Health Research Institute, Washington, said, “the most exciting thing here is that we have good options. We now can start to tease out which patients will benefit best from one or the other because we actually have two options.”

The Amulet IDE trial was funded by Abbott. Dr. Lakkireddy reports that he or his spouse/partner have received grant/research support from Abbott, AtriCure, Alta Thera, Medtronic, Biosense Webster, Biotronik, and Boston Scientific; and speaker honoraria from Abbott, Medtronic, Biotronik, and Boston Scientific.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Amplatzer Amulet (Abbott) and first-generation Watchman 2.5 (Boston Scientific) devices provide relatively comparable results out to 3 years after left atrial appendage occlusion (LAAO), longer follow-up from the Amplatzer Amulet Left Atrial Appendage Occluder Versus Watchman Device for Stroke Prophylaxis (Amulet IDE) trial shows.

“The dual-seal Amplatzer Amulet left atrial appendage occluder continued to demonstrate safety and effectiveness through 3 years,” principal investigator Dhanunjaya Lakkireddy, MD, said in a late-breaking session at the recent Transcatheter Cardiovascular Therapeutics annual meeting.

Preliminary results, reported last year, showed that procedural complications were higher with the Amplatzer but that it provided superior closure of the left atrial appendage (LAA) at 45 days and was noninferior with respect to safety at 12 months and efficacy at 18 months.

Amulet IDE is the largest head-to-head comparison of the two devices, enrolling 1,878 high-risk patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation undergoing LAA closure to reduce the risk of stroke.

Three-year follow-up was higher with the Amulet device than with the Watchman, at 721 vs. 659 patients, driven by increased deaths (85 vs. 63) and withdrawals (50 vs. 23) in the Watchman group within 18 months, noted Dr. Lakkireddy, Kansas City Heart Rhythm Institute and Research Foundation, Overland Park, Kan.

Use of oral anticoagulation was higher in the Watchman group at 6 months (2.8% vs. 4.7%; P = .04), 18 months (3.1% vs. 5.6%; P = .01), and 3 years (3.7% vs. 7.3%; P < .01).

This was primarily driven by more late device-related thrombus (DRT) after 6 months with the Watchman device than with the Amulet occluder (23 vs. 10). “Perhaps the dual-closure mechanism of the Amulet explains this fundamental difference, where you have a nice smooth disc that covers the ostium,” he posited.

At 3 years, rates of cardiovascular death trended lower with Amulet than with Watchman (6.6% vs. 8.5%; P = .14), as did all-cause deaths (14.6% vs. 17.9%; P = .07).

Most cardiovascular deaths in the Amulet group were not preceded by a device factor, whereas DRT (1 vs. 4) and peridevice leak 3 mm or more (5 vs. 15) frequently preceded these deaths in the Watchman group, Dr. Lakkireddy observed. No pericardial effusion-related deaths occurred in either group.

Major bleeding, however, trended higher for the Amulet, at 16.1%, compared with 14.7% for the Watchman (P = .46). Ischemic stroke and systemic embolic rates also trended higher for Amulet, at 5%, and 4.6% for Watchman.

The protocol recommended aspirin only for both groups after 6 months. None of the 29 Amulet and 3 of the 29 Watchman patients with an ischemic stroke were on oral anticoagulation at the time of the stroke.

Device factors, however, frequently preceded ischemic strokes in the Watchman group, Dr. Lakkireddy said. DRT occurred in 1 patient with Amulet and 2 patients with Watchman and peridevice leak in 3 with Amulet and 15 with Watchman. “Again, the peridevice leak issue really stands out as an important factor,” he said at the meeting, which was sponsored by the Cardiovascular Research Foundation.

Based on “data from the large trials, it’s clearly evident that the presence of peridevice leak significantly raises the risk of stroke in follow-up,” he said. “So, attention has to be paid to the choice of the device and how we can mitigate the risk of peridevice leaks in these patients.”

The composite of stroke, systemic embolism, and cardiovascular death occurred in 11.1% of patients with Amulet and 12.7% with Watchman (P = .31).

Asked following the formal presentation whether the results justify use of one device over the other for LAA occlusion, Dr. Lakkireddy said he likes the dual closure mechanism of the Amulet and is more likely to use it in patients with proximal lobes, very large appendages, or a relatively shallow appendage. “In the rest of the cases, I think it’s a toss-up.”

As for how generalizable the results are, he noted that the study tested the Amulet against the legacy Watchman 2.5 but that the second-generation Watchman FLX is available in a larger size and has shown improved performance.

The Amplatzer Amulet does not require oral anticoagulants at discharge. However, the indication for the Watchman FLX was recently expanded to include 45-day dual antiplatelet therapy as a postprocedure alternative to oral anticoagulation plus aspirin.

Going forward, the “next evolution” is to test the Watchman FLX and Amulet on either single antiplatelet or a dual antiplatelet regimen without oral anticoagulation, he suggested.

Results from SWISS APERO, the first randomized trial to compare the Amulet and Watchman FLX (and a handful of 2.5 devices) in 221 patients, showed that the devices are not interchangeable for rates of complications or leaks.

During a press conference prior to the presentation, discussant Federico Asch, MD, MedStar Health Research Institute, Washington, said, “the most exciting thing here is that we have good options. We now can start to tease out which patients will benefit best from one or the other because we actually have two options.”

The Amulet IDE trial was funded by Abbott. Dr. Lakkireddy reports that he or his spouse/partner have received grant/research support from Abbott, AtriCure, Alta Thera, Medtronic, Biosense Webster, Biotronik, and Boston Scientific; and speaker honoraria from Abbott, Medtronic, Biotronik, and Boston Scientific.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM TCT 2022

Diabetes Population Health Innovations in the Age of COVID-19: Insights From the T1D Exchange Quality Improvement Collaborative

From the T1D Exchange, Boston, MA (Ann Mungmode, Nicole Rioles, Jesse Cases, Dr. Ebekozien); The Leona M. and Harry B. Hemsley Charitable Trust, New York, NY (Laurel Koester); and the University of Mississippi School of Population Health, Jackson, MS (Dr. Ebekozien).

Abstract

There have been remarkable innovations in diabetes management since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, but these groundbreaking innovations are drawing limited focus as the field focuses on the adverse impact of the pandemic on patients with diabetes. This article reviews select population health innovations in diabetes management that have become available over the past 2 years of the COVID-19 pandemic from the perspective of the T1D Exchange Quality Improvement Collaborative, a learning health network that focuses on improving care and outcomes for individuals with type 1 diabetes (T1D). Such innovations include expanded telemedicine access, collection of real-world data, machine learning and artificial intelligence, and new diabetes medications and devices. In addition, multiple innovative studies have been undertaken to explore contributors to health inequities in diabetes, and advocacy efforts for specific populations have been successful. Looking to the future, work is required to explore additional health equity successes that do not further exacerbate inequities and to look for additional innovative ways to engage people with T1D in their health care through conversations on social determinants of health and societal structures.

Keywords: type 1 diabetes, learning health network, continuous glucose monitoring, health equity

One in 10 people in the United States has diabetes.1 Diabetes is the nation’s second leading cause of death, costing the US health system more than $300 billion annually.2 The COVID-19 pandemic presented additional health burdens for people living with diabetes. For example, preexisting diabetes was identified as a risk factor for COVID-19–associated morbidity and mortality.3,4 Over the past 2 years, there have been remarkable innovations in diabetes management, including stem cell therapy and new medication options. Additionally, improved technology solutions have aided in diabetes management through continuous glucose monitors (CGM), smart insulin pens, advanced hybrid closed-loop systems, and continuous subcutaneous insulin injections.5,6 Unfortunately, these groundbreaking innovations are drawing limited focus, as the field is rightfully focused on the adverse impact of the pandemic on patients with diabetes.

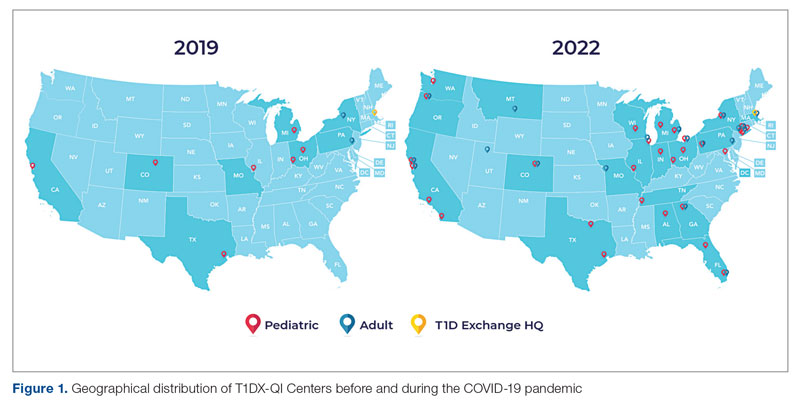

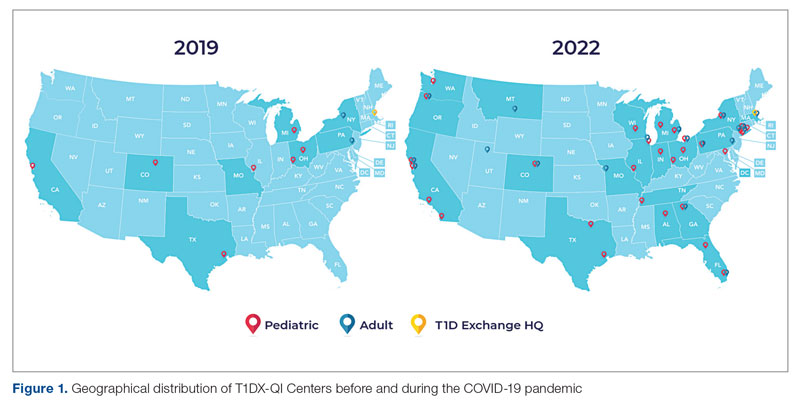

Learning health networks like the T1D Exchange Quality Improvement Collaborative (T1DX-QI) have implemented some of these innovative solutions to improve care for people with diabetes.7 T1DX-QI has more than 50 data-sharing endocrinology centers that care for over 75,000 people with diabetes across the United States (Figure 1). Centers participating in the T1DX-QI use quality improvement (QI) and implementation science methods to quickly translate research into evidence-based clinical practice. T1DX-QI leads diabetes population health and health system research and supports widespread transferability across health care organizations through regular collaborative calls, conferences, and case study documentation.8

In this review, we summarize impactful population health innovations in diabetes management that have become available over the past 2 years of the COVID-19 pandemic from the perspective of T1DX-QI (see Figure 2 for relevant definitions). This review is limited in scope and is not meant to be an exhaustive list of innovations. The review also reflects significant changes from the perspective of academic diabetes centers, which may not apply to rural or primary care diabetes practices.

Methods

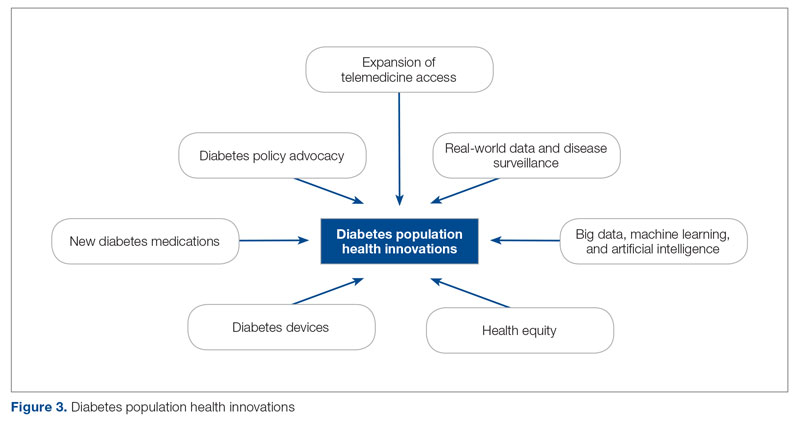

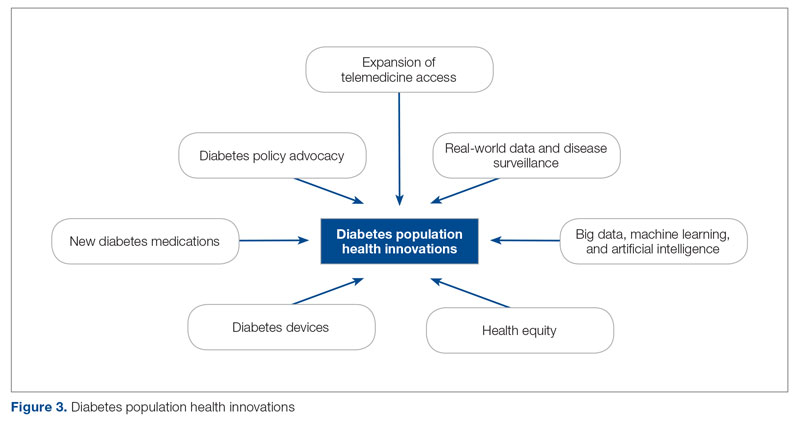

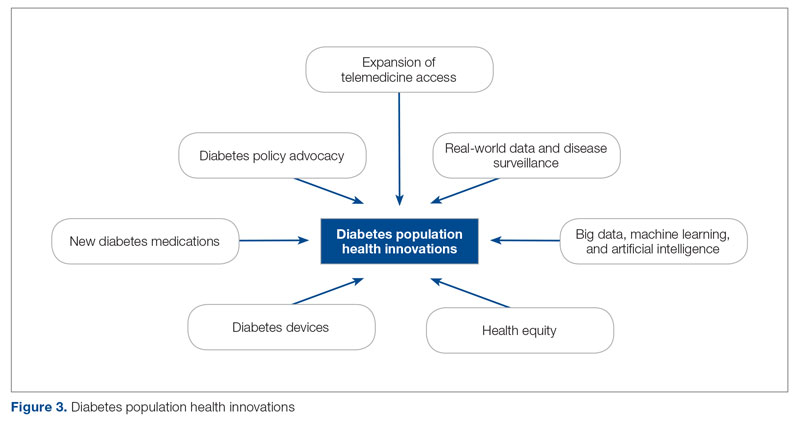

The first (A.M.), second (H.H.), and senior (O.E.) authors conducted a scoping review of published literature using terms related to diabetes, population health, and innovation on PubMed Central and Google Scholar for the period March 2020 to June 2022. To complement the review, A.M. and O.E. also reviewed abstracts from presentations at major international diabetes conferences, including the American Diabetes Association (ADA), the International Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Diabetes (ISPAD), the T1DX-QI Learning Session Conference, and the Advanced Technologies & Treatments for Diabetes (ATTD) 2020 to 2022 conferences.9-14 The authors also searched FDA.gov and ClinicalTrials.gov for relevant insights. A.M. and O.E. sorted the reviewed literature into major themes (Figure 3) from the population health improvement perspective of the T1DX-QI.

Population Health Innovations in Diabetes Management

Expansion of Telemedicine Access