User login

Cellular Versus Acellular Grafts for Diabetic Foot Ulcers: Altering the Protocol to Improve Recruitment to a Comparative Efficacy Trial

Chronic diabetic foot ulcers (DFUs) remain a serious therapeutic challenge worldwide.1-2 Patients with DFUs are at higher risk for infections, which may lead to limb loss.1-5 In fact, 1 in 6 patients with DFUs will undergo an amputation.6 The long-term consequences of DFUs are numerous and can severely affect patients’ quality of life, including loss of productivity.7 The current standard of care for DFUs consists of debridement of the necrotic tissue, application of a moist dressing, and use of an off-loading device that protects the wound from pressure or trauma related to ambulation and other acts of daily living.4-6,8 Unfortunately, studies have shown that the best standard of care (SOC) only heals 30% of DFUs after 20 weeks of therapy.9 With the estimated cost per episode of care approaching $40,000, DFUs remain a costly and important problem.10

The altered extracellular matrix (ECM) in DFUs has been a target for the development of new therapeutic devices that provide a new matrix that is either devoid of cells or can be enriched with fibroblasts.8,11 These bioengineered skin substitutes stimulate the growth of new vessels and generate cytokines essential for tissue repair. In 2013, Lev-Tov et al12 published this study protocol (Dermagraft Oasis Longitudinal Comparative Efficacy [DOLCE] trial) to compare the effectiveness of 2 advanced wound care devices, specifically to evaluate the clinical efficacy of a cellular matrix versus an acellular matrix, which we have amended. The cellular matrix used in the study is a dermal substitute composed of viable newborn foreskin fibroblasts seeded onto a bioabsorbable polyglactin mesh on which fibroblasts generate an ECM.13,14 It is supplied frozen and requires specific thawing steps prior to application. The recommended regimen for treatment of DFUs for this cellular matrix is 8 weekly applications.13,14 In 2016, the cost of the product was reported as $1411 per 5.0×7.5-cm sheet.15 The acellular matrix product used in the study is a bioabsorbable ECM that is derived from porcine small intestinal submucosa.16,17 It is stored at room temperature and has a long shelf life, with a current price of $112.6 for a 3.0×3.5-cm single-layer fenestrated sheet ($1126.60 per box of 10 sheets). The industry-supported randomized controlled trials for each of these devices have reported a 20% added benefit in the rate of wound closure at week 12 compared to SOC.14,17

This article provides the interim report of the trial (registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov with the identifier NCT01450943) described in the published protocol and initiated in 2011,12 focusing on elements that required modification during the trial’s duration.

Methods

Study Protocol

The clinical trial was approved by the Veterans’ Affairs Institutional Research and Development Committee and their institutional review board. This study was funded by the Veteran’s Administration Merit Award (#10554640), which was awarded to 2 of the investigators (S.E.D. and R.R.I.). Eligible veterans were recruited from all 7 sites of the VA Northern California Healthcare System. This trial is a randomized, single-blinded, 3-armed, controlled clinical equivalence trial comparing the effectiveness of an SOC treatment, cellular ECM, and acellular ECM.

Study Products

The SOC dressing applied in the clinical trial included a sterile antimicrobial gel, a nonadherent dressing, and gauze.12 The SOC dressing also was used as a secondary dressing for the active treatment arms. Bacitracin antibiotic ointment was used as an alternative for patients with allergy to iodine.12

Randomization

The inclusion and exclusion criteria were previously outlined.12 After a 2-week screening phase to exclude rapid healers, patients were randomized into a treatment arm and entered the active phase for 12 weeks.

Primary and Secondary Outcomes

The primary outcome was complete wound closure by week 12.12 Complete healing was defined as full reepithelialization with no drainage or dressing requirement. The secondary outcomes included healing at 28 weeks, rate of healing, ulcer recurrence at week 20, association of wound healing with ulcer characteristics or patients’ characteristic, incidence of adverse events, and cost-effectiveness of each treatment compared to the SOC arm.12

Statistical Analysis

To detect a 25% difference in the incidence of ulcer closure between the 2 study groups and the SOC group, the estimation of the sample size was based on 80% power with a significance level of 0.05. Specifically, it was expected that 50% of the cellular and acellular matrix groups and 25% of the SOC group would reach complete wound closure. The protocol indicated that 57 participants would be enrolled in each arm (total of 171 participants). Lev-Tov et al12 discussed the statistical analysis in more detail.

Results

Study Protocol Amendments

Given the number of diabetic patients in the US veteran population, we anticipated that there would be enough participants meeting the inclusion and exclusion criteria; however, because of the difficulty with recruitment, the initial study criteria were modified. The study was initially designed to incorporate DFUs with a minimum size of 1.0 cm2.12

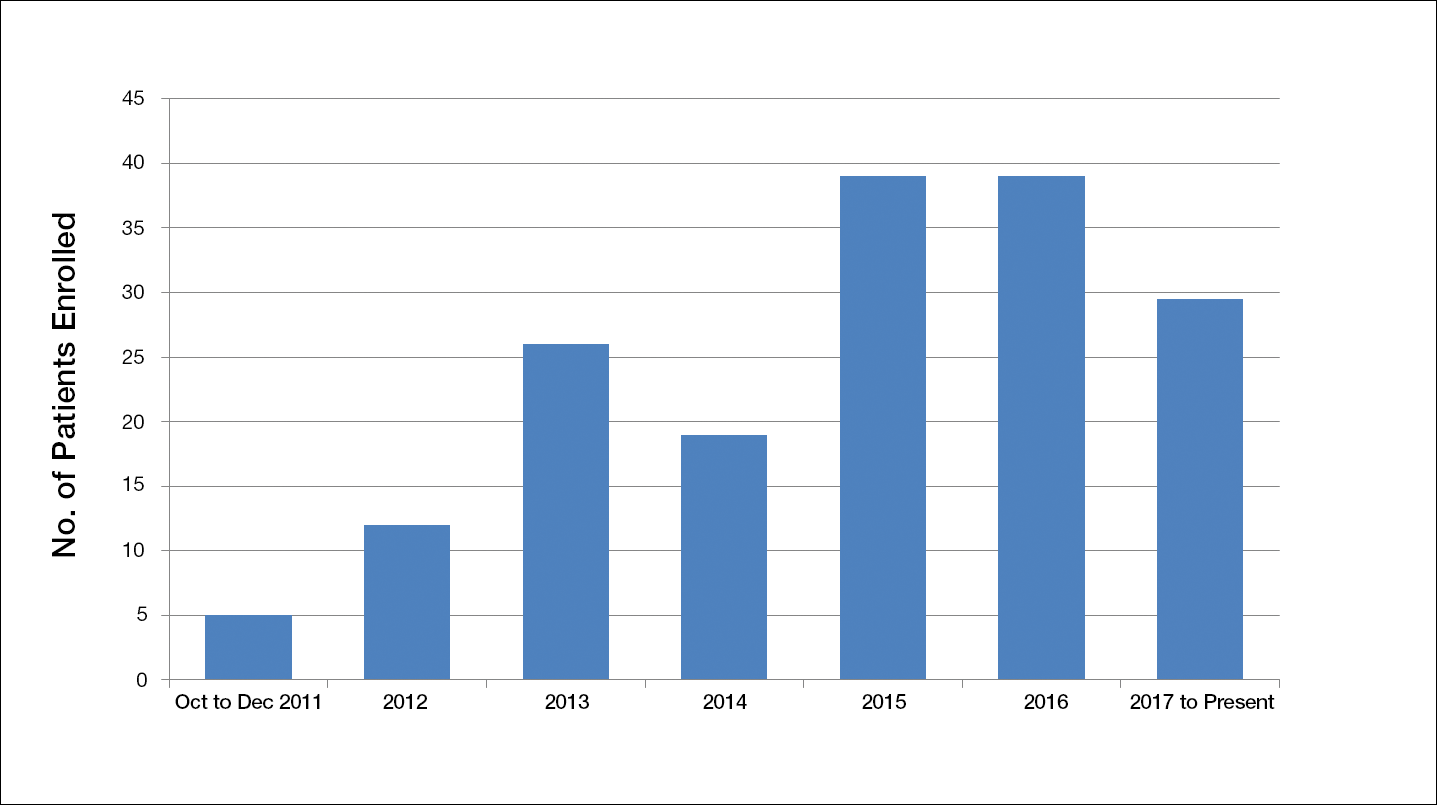

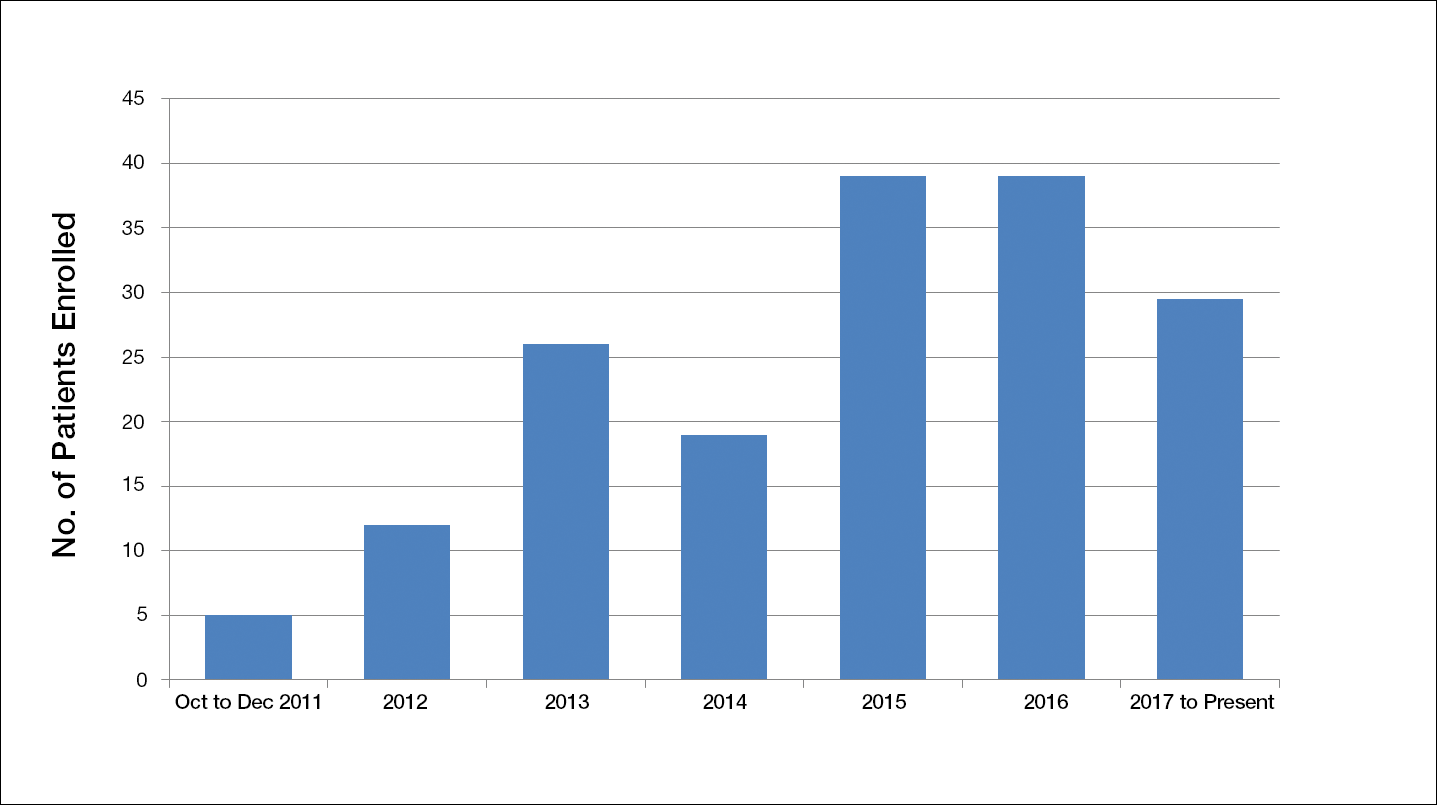

Another limiting criterion was the percentage of total hemoglobin level for hemoglobin A1C (HbA1C). The study was originally established to include participants with an HbA1C level of 10% of total hemoglobin or below.12 Unfortunately, the majority of the potential participants had values substantially higher, and thus could not be enrolled in the trial, requiring another amendment to the study protocol in 2014, which was approved to include patients with an HbA1C level less than 12% of total hemoglobin. This change contributed considerably to the noted increase in enrollment rates in 2015, which almost doubled relative to enrollment under the original exclusion criteria (Figure).

The study has screened more than 600 patients. Among them, 137 were assessed for eligibility; 71 were excluded for various reasons, including screen failure (eg, decrease in wound size by >40% during the 2-week screening phase), loss to follow-up, and adverse events. Sixty-six participants reached the primary outcome at week 12, while 55 participants completed the study (19 in the SOC group; 18 in the cellular matrix group; 18 in the acellular matrix group).

We have stopped enrolling patients from all sites and the community, as we have reached our target enrollment.

Comment

One of the challenges of clinical trials is the recruitment of an adequate number of participants within an appropriate time frame, which is explained by Lasagna’s Law,18 a well-described phenomenon whereby the investigator overestimates the number of potential participants available to meet the inclusion criteria. This so-called funnel-effect was partly encountered in our selection process. A review of the veteran population with DFUs seemed to be more than adequate to fulfill the sample size; however, some important participant-related factors also played a substantial role.

In addition, the Veterans’ Affairs network centralizes health information, making it readily available to all providers participating in their care. As a result, patients with diabetes mellitus typically are seen by a primary care physician along with an endocrinologist, a diabetic nurse, and/or a dietician. Despite the collaboration with an interdisciplinary team, the glycemic control of the participants remains an issue along with other psychosocial factors that are deterrents in patient compliance. As a result, patients with poorly controlled diabetes and an HbA1C level above 10% (and less than 12%) of total hemoglobin who were initially excluded from the study were reincluded after modifying the inclusion criteria. Some patients were interested in joining the study, but physical limitations (eg, impaired mobility) prompted their decision not to join the trial, even though they met all the inclusion criteria.

As far as research-related factors that could affect participation, it is notable that most of the patients were retired; thus, the interventions did not cause additional burden of taking time off from work or loss of productivity. Although randomization could be a deterrent in many clinical trials, the majority of patients were willing to participate without demanding to be assigned to a particular treatment group.

There are many factors that are intertwined and can lead to enrollment and/or attrition rates. It was critical for our team to make some adjustment without compromising the controlled nature of a randomized trial.

Acknowledgment

The authors wish to acknowledge Huong Le, DPM, MPH, who was the coauthor of the study protocol.

- Sen CK, Gordillo GM, Roy S, et al. Human skin wounds: a major and snowballing threat to public health and the economy. Wound Repair Regen. 2009;17:763-771.

- Gurtner GC, Werner S, Barrandon Y, et al. Wound repair and regeneration. Nature. 2008;453:314-321.

- Falanga V. Wound healing and its impairment in the diabetic foot. Lancet. 2005;366:1736-1743.

- Boulton AJ. The diabetic foot: grand overview, epidemiology and pathogenesis. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2008;24(suppl 1):S3-S6.

- Singh N, Armstrong DG, Lipsky BA. Preventing foot ulcers in patients with diabetes. JAMA. 2005;293:217-228.

- Vuorisalo S, Venermo M, Lepäntalo M. Treatment of diabetic foot ulcers. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino). 2009;50:275-291.

- Meijer JW, Trip J, Jaegers SM, et al. Quality of life in patients with diabetic foot ulcers. Disabil Rehabil. 2001;23:336-340.

- Santema TB, Poyck PP, Ubbink DT. Skin grafting and tissue replacement for treating foot ulcers in people with diabetes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;2:CD011255.

- Margolis DJ, Kantor J, Berlin JA. Healing of diabetic neuropathic foot ulcers receiving standard treatment. a meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 1999;22:692-695.

- Cavanagh P, Attinger C, Abbas Z, et al. Cost of treating diabetic foot ulcers in five different countries. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2012;2(suppl 1):107-111.

- Panuncialman J, Falanga V. The science of wound bed preparation. Surg Clin North Am. 2009;89:611-626.

- Lev-Tov H, Li CS, Dahle S, et al. Cellular versus acellular matrix devices in treatment of diabetic foot ulcers: study protocol for a comparative efficacy randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2013;14:8.

- Gentzkow GD, Iwasaki SD, Hershon KS, et al. Use of dermagraft, a cultured human dermis, to treat diabetic foot ulcers. Diabetes Care. 1996;19:350-354.

- Marston WA, Hanft J, Norwood P, et al; Dermagraft Diabetic Foot Ulcer Study Group. The efficacy and safety of Dermagraft in improving the healing of chronic diabetic foot ulcers: results of a prospective randomized trial. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:1701-1705.

- 2016 Dermagraft® Medicare Product and Related Procedure Payment. http://www.dermagraft.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/1/Dermagraft_Hotsheet%202016%20Q1%20HOSPITAL_FINAL.pdf. Accessed November 23, 2017.

- Oasis® Wound Matrix. http://www.oasiswoundmatrix.com/aboutowm. Accessed November 23, 2017.

- Niezgoda JA, Van Gils CC, Frykberg RG, et al. Randomized clinical trial comparing OASIS Wound Matrix to Regranex Gel for diabetic ulcers. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2005;18(5, pt 1):258-266.

- Torgerson JS, Arlinger K, Käppi M, et al. Principles for enhanced recruitment of subjects in a large clinical trial. the XENDOS (XENical in the prevention of Diabetes in Obese Subjects) study experience. Controlled Clin Trials. 2001;22:515-525.

Chronic diabetic foot ulcers (DFUs) remain a serious therapeutic challenge worldwide.1-2 Patients with DFUs are at higher risk for infections, which may lead to limb loss.1-5 In fact, 1 in 6 patients with DFUs will undergo an amputation.6 The long-term consequences of DFUs are numerous and can severely affect patients’ quality of life, including loss of productivity.7 The current standard of care for DFUs consists of debridement of the necrotic tissue, application of a moist dressing, and use of an off-loading device that protects the wound from pressure or trauma related to ambulation and other acts of daily living.4-6,8 Unfortunately, studies have shown that the best standard of care (SOC) only heals 30% of DFUs after 20 weeks of therapy.9 With the estimated cost per episode of care approaching $40,000, DFUs remain a costly and important problem.10

The altered extracellular matrix (ECM) in DFUs has been a target for the development of new therapeutic devices that provide a new matrix that is either devoid of cells or can be enriched with fibroblasts.8,11 These bioengineered skin substitutes stimulate the growth of new vessels and generate cytokines essential for tissue repair. In 2013, Lev-Tov et al12 published this study protocol (Dermagraft Oasis Longitudinal Comparative Efficacy [DOLCE] trial) to compare the effectiveness of 2 advanced wound care devices, specifically to evaluate the clinical efficacy of a cellular matrix versus an acellular matrix, which we have amended. The cellular matrix used in the study is a dermal substitute composed of viable newborn foreskin fibroblasts seeded onto a bioabsorbable polyglactin mesh on which fibroblasts generate an ECM.13,14 It is supplied frozen and requires specific thawing steps prior to application. The recommended regimen for treatment of DFUs for this cellular matrix is 8 weekly applications.13,14 In 2016, the cost of the product was reported as $1411 per 5.0×7.5-cm sheet.15 The acellular matrix product used in the study is a bioabsorbable ECM that is derived from porcine small intestinal submucosa.16,17 It is stored at room temperature and has a long shelf life, with a current price of $112.6 for a 3.0×3.5-cm single-layer fenestrated sheet ($1126.60 per box of 10 sheets). The industry-supported randomized controlled trials for each of these devices have reported a 20% added benefit in the rate of wound closure at week 12 compared to SOC.14,17

This article provides the interim report of the trial (registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov with the identifier NCT01450943) described in the published protocol and initiated in 2011,12 focusing on elements that required modification during the trial’s duration.

Methods

Study Protocol

The clinical trial was approved by the Veterans’ Affairs Institutional Research and Development Committee and their institutional review board. This study was funded by the Veteran’s Administration Merit Award (#10554640), which was awarded to 2 of the investigators (S.E.D. and R.R.I.). Eligible veterans were recruited from all 7 sites of the VA Northern California Healthcare System. This trial is a randomized, single-blinded, 3-armed, controlled clinical equivalence trial comparing the effectiveness of an SOC treatment, cellular ECM, and acellular ECM.

Study Products

The SOC dressing applied in the clinical trial included a sterile antimicrobial gel, a nonadherent dressing, and gauze.12 The SOC dressing also was used as a secondary dressing for the active treatment arms. Bacitracin antibiotic ointment was used as an alternative for patients with allergy to iodine.12

Randomization

The inclusion and exclusion criteria were previously outlined.12 After a 2-week screening phase to exclude rapid healers, patients were randomized into a treatment arm and entered the active phase for 12 weeks.

Primary and Secondary Outcomes

The primary outcome was complete wound closure by week 12.12 Complete healing was defined as full reepithelialization with no drainage or dressing requirement. The secondary outcomes included healing at 28 weeks, rate of healing, ulcer recurrence at week 20, association of wound healing with ulcer characteristics or patients’ characteristic, incidence of adverse events, and cost-effectiveness of each treatment compared to the SOC arm.12

Statistical Analysis

To detect a 25% difference in the incidence of ulcer closure between the 2 study groups and the SOC group, the estimation of the sample size was based on 80% power with a significance level of 0.05. Specifically, it was expected that 50% of the cellular and acellular matrix groups and 25% of the SOC group would reach complete wound closure. The protocol indicated that 57 participants would be enrolled in each arm (total of 171 participants). Lev-Tov et al12 discussed the statistical analysis in more detail.

Results

Study Protocol Amendments

Given the number of diabetic patients in the US veteran population, we anticipated that there would be enough participants meeting the inclusion and exclusion criteria; however, because of the difficulty with recruitment, the initial study criteria were modified. The study was initially designed to incorporate DFUs with a minimum size of 1.0 cm2.12

Another limiting criterion was the percentage of total hemoglobin level for hemoglobin A1C (HbA1C). The study was originally established to include participants with an HbA1C level of 10% of total hemoglobin or below.12 Unfortunately, the majority of the potential participants had values substantially higher, and thus could not be enrolled in the trial, requiring another amendment to the study protocol in 2014, which was approved to include patients with an HbA1C level less than 12% of total hemoglobin. This change contributed considerably to the noted increase in enrollment rates in 2015, which almost doubled relative to enrollment under the original exclusion criteria (Figure).

The study has screened more than 600 patients. Among them, 137 were assessed for eligibility; 71 were excluded for various reasons, including screen failure (eg, decrease in wound size by >40% during the 2-week screening phase), loss to follow-up, and adverse events. Sixty-six participants reached the primary outcome at week 12, while 55 participants completed the study (19 in the SOC group; 18 in the cellular matrix group; 18 in the acellular matrix group).

We have stopped enrolling patients from all sites and the community, as we have reached our target enrollment.

Comment

One of the challenges of clinical trials is the recruitment of an adequate number of participants within an appropriate time frame, which is explained by Lasagna’s Law,18 a well-described phenomenon whereby the investigator overestimates the number of potential participants available to meet the inclusion criteria. This so-called funnel-effect was partly encountered in our selection process. A review of the veteran population with DFUs seemed to be more than adequate to fulfill the sample size; however, some important participant-related factors also played a substantial role.

In addition, the Veterans’ Affairs network centralizes health information, making it readily available to all providers participating in their care. As a result, patients with diabetes mellitus typically are seen by a primary care physician along with an endocrinologist, a diabetic nurse, and/or a dietician. Despite the collaboration with an interdisciplinary team, the glycemic control of the participants remains an issue along with other psychosocial factors that are deterrents in patient compliance. As a result, patients with poorly controlled diabetes and an HbA1C level above 10% (and less than 12%) of total hemoglobin who were initially excluded from the study were reincluded after modifying the inclusion criteria. Some patients were interested in joining the study, but physical limitations (eg, impaired mobility) prompted their decision not to join the trial, even though they met all the inclusion criteria.

As far as research-related factors that could affect participation, it is notable that most of the patients were retired; thus, the interventions did not cause additional burden of taking time off from work or loss of productivity. Although randomization could be a deterrent in many clinical trials, the majority of patients were willing to participate without demanding to be assigned to a particular treatment group.

There are many factors that are intertwined and can lead to enrollment and/or attrition rates. It was critical for our team to make some adjustment without compromising the controlled nature of a randomized trial.

Acknowledgment

The authors wish to acknowledge Huong Le, DPM, MPH, who was the coauthor of the study protocol.

Chronic diabetic foot ulcers (DFUs) remain a serious therapeutic challenge worldwide.1-2 Patients with DFUs are at higher risk for infections, which may lead to limb loss.1-5 In fact, 1 in 6 patients with DFUs will undergo an amputation.6 The long-term consequences of DFUs are numerous and can severely affect patients’ quality of life, including loss of productivity.7 The current standard of care for DFUs consists of debridement of the necrotic tissue, application of a moist dressing, and use of an off-loading device that protects the wound from pressure or trauma related to ambulation and other acts of daily living.4-6,8 Unfortunately, studies have shown that the best standard of care (SOC) only heals 30% of DFUs after 20 weeks of therapy.9 With the estimated cost per episode of care approaching $40,000, DFUs remain a costly and important problem.10

The altered extracellular matrix (ECM) in DFUs has been a target for the development of new therapeutic devices that provide a new matrix that is either devoid of cells or can be enriched with fibroblasts.8,11 These bioengineered skin substitutes stimulate the growth of new vessels and generate cytokines essential for tissue repair. In 2013, Lev-Tov et al12 published this study protocol (Dermagraft Oasis Longitudinal Comparative Efficacy [DOLCE] trial) to compare the effectiveness of 2 advanced wound care devices, specifically to evaluate the clinical efficacy of a cellular matrix versus an acellular matrix, which we have amended. The cellular matrix used in the study is a dermal substitute composed of viable newborn foreskin fibroblasts seeded onto a bioabsorbable polyglactin mesh on which fibroblasts generate an ECM.13,14 It is supplied frozen and requires specific thawing steps prior to application. The recommended regimen for treatment of DFUs for this cellular matrix is 8 weekly applications.13,14 In 2016, the cost of the product was reported as $1411 per 5.0×7.5-cm sheet.15 The acellular matrix product used in the study is a bioabsorbable ECM that is derived from porcine small intestinal submucosa.16,17 It is stored at room temperature and has a long shelf life, with a current price of $112.6 for a 3.0×3.5-cm single-layer fenestrated sheet ($1126.60 per box of 10 sheets). The industry-supported randomized controlled trials for each of these devices have reported a 20% added benefit in the rate of wound closure at week 12 compared to SOC.14,17

This article provides the interim report of the trial (registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov with the identifier NCT01450943) described in the published protocol and initiated in 2011,12 focusing on elements that required modification during the trial’s duration.

Methods

Study Protocol

The clinical trial was approved by the Veterans’ Affairs Institutional Research and Development Committee and their institutional review board. This study was funded by the Veteran’s Administration Merit Award (#10554640), which was awarded to 2 of the investigators (S.E.D. and R.R.I.). Eligible veterans were recruited from all 7 sites of the VA Northern California Healthcare System. This trial is a randomized, single-blinded, 3-armed, controlled clinical equivalence trial comparing the effectiveness of an SOC treatment, cellular ECM, and acellular ECM.

Study Products

The SOC dressing applied in the clinical trial included a sterile antimicrobial gel, a nonadherent dressing, and gauze.12 The SOC dressing also was used as a secondary dressing for the active treatment arms. Bacitracin antibiotic ointment was used as an alternative for patients with allergy to iodine.12

Randomization

The inclusion and exclusion criteria were previously outlined.12 After a 2-week screening phase to exclude rapid healers, patients were randomized into a treatment arm and entered the active phase for 12 weeks.

Primary and Secondary Outcomes

The primary outcome was complete wound closure by week 12.12 Complete healing was defined as full reepithelialization with no drainage or dressing requirement. The secondary outcomes included healing at 28 weeks, rate of healing, ulcer recurrence at week 20, association of wound healing with ulcer characteristics or patients’ characteristic, incidence of adverse events, and cost-effectiveness of each treatment compared to the SOC arm.12

Statistical Analysis

To detect a 25% difference in the incidence of ulcer closure between the 2 study groups and the SOC group, the estimation of the sample size was based on 80% power with a significance level of 0.05. Specifically, it was expected that 50% of the cellular and acellular matrix groups and 25% of the SOC group would reach complete wound closure. The protocol indicated that 57 participants would be enrolled in each arm (total of 171 participants). Lev-Tov et al12 discussed the statistical analysis in more detail.

Results

Study Protocol Amendments

Given the number of diabetic patients in the US veteran population, we anticipated that there would be enough participants meeting the inclusion and exclusion criteria; however, because of the difficulty with recruitment, the initial study criteria were modified. The study was initially designed to incorporate DFUs with a minimum size of 1.0 cm2.12

Another limiting criterion was the percentage of total hemoglobin level for hemoglobin A1C (HbA1C). The study was originally established to include participants with an HbA1C level of 10% of total hemoglobin or below.12 Unfortunately, the majority of the potential participants had values substantially higher, and thus could not be enrolled in the trial, requiring another amendment to the study protocol in 2014, which was approved to include patients with an HbA1C level less than 12% of total hemoglobin. This change contributed considerably to the noted increase in enrollment rates in 2015, which almost doubled relative to enrollment under the original exclusion criteria (Figure).

The study has screened more than 600 patients. Among them, 137 were assessed for eligibility; 71 were excluded for various reasons, including screen failure (eg, decrease in wound size by >40% during the 2-week screening phase), loss to follow-up, and adverse events. Sixty-six participants reached the primary outcome at week 12, while 55 participants completed the study (19 in the SOC group; 18 in the cellular matrix group; 18 in the acellular matrix group).

We have stopped enrolling patients from all sites and the community, as we have reached our target enrollment.

Comment

One of the challenges of clinical trials is the recruitment of an adequate number of participants within an appropriate time frame, which is explained by Lasagna’s Law,18 a well-described phenomenon whereby the investigator overestimates the number of potential participants available to meet the inclusion criteria. This so-called funnel-effect was partly encountered in our selection process. A review of the veteran population with DFUs seemed to be more than adequate to fulfill the sample size; however, some important participant-related factors also played a substantial role.

In addition, the Veterans’ Affairs network centralizes health information, making it readily available to all providers participating in their care. As a result, patients with diabetes mellitus typically are seen by a primary care physician along with an endocrinologist, a diabetic nurse, and/or a dietician. Despite the collaboration with an interdisciplinary team, the glycemic control of the participants remains an issue along with other psychosocial factors that are deterrents in patient compliance. As a result, patients with poorly controlled diabetes and an HbA1C level above 10% (and less than 12%) of total hemoglobin who were initially excluded from the study were reincluded after modifying the inclusion criteria. Some patients were interested in joining the study, but physical limitations (eg, impaired mobility) prompted their decision not to join the trial, even though they met all the inclusion criteria.

As far as research-related factors that could affect participation, it is notable that most of the patients were retired; thus, the interventions did not cause additional burden of taking time off from work or loss of productivity. Although randomization could be a deterrent in many clinical trials, the majority of patients were willing to participate without demanding to be assigned to a particular treatment group.

There are many factors that are intertwined and can lead to enrollment and/or attrition rates. It was critical for our team to make some adjustment without compromising the controlled nature of a randomized trial.

Acknowledgment

The authors wish to acknowledge Huong Le, DPM, MPH, who was the coauthor of the study protocol.

- Sen CK, Gordillo GM, Roy S, et al. Human skin wounds: a major and snowballing threat to public health and the economy. Wound Repair Regen. 2009;17:763-771.

- Gurtner GC, Werner S, Barrandon Y, et al. Wound repair and regeneration. Nature. 2008;453:314-321.

- Falanga V. Wound healing and its impairment in the diabetic foot. Lancet. 2005;366:1736-1743.

- Boulton AJ. The diabetic foot: grand overview, epidemiology and pathogenesis. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2008;24(suppl 1):S3-S6.

- Singh N, Armstrong DG, Lipsky BA. Preventing foot ulcers in patients with diabetes. JAMA. 2005;293:217-228.

- Vuorisalo S, Venermo M, Lepäntalo M. Treatment of diabetic foot ulcers. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino). 2009;50:275-291.

- Meijer JW, Trip J, Jaegers SM, et al. Quality of life in patients with diabetic foot ulcers. Disabil Rehabil. 2001;23:336-340.

- Santema TB, Poyck PP, Ubbink DT. Skin grafting and tissue replacement for treating foot ulcers in people with diabetes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;2:CD011255.

- Margolis DJ, Kantor J, Berlin JA. Healing of diabetic neuropathic foot ulcers receiving standard treatment. a meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 1999;22:692-695.

- Cavanagh P, Attinger C, Abbas Z, et al. Cost of treating diabetic foot ulcers in five different countries. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2012;2(suppl 1):107-111.

- Panuncialman J, Falanga V. The science of wound bed preparation. Surg Clin North Am. 2009;89:611-626.

- Lev-Tov H, Li CS, Dahle S, et al. Cellular versus acellular matrix devices in treatment of diabetic foot ulcers: study protocol for a comparative efficacy randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2013;14:8.

- Gentzkow GD, Iwasaki SD, Hershon KS, et al. Use of dermagraft, a cultured human dermis, to treat diabetic foot ulcers. Diabetes Care. 1996;19:350-354.

- Marston WA, Hanft J, Norwood P, et al; Dermagraft Diabetic Foot Ulcer Study Group. The efficacy and safety of Dermagraft in improving the healing of chronic diabetic foot ulcers: results of a prospective randomized trial. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:1701-1705.

- 2016 Dermagraft® Medicare Product and Related Procedure Payment. http://www.dermagraft.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/1/Dermagraft_Hotsheet%202016%20Q1%20HOSPITAL_FINAL.pdf. Accessed November 23, 2017.

- Oasis® Wound Matrix. http://www.oasiswoundmatrix.com/aboutowm. Accessed November 23, 2017.

- Niezgoda JA, Van Gils CC, Frykberg RG, et al. Randomized clinical trial comparing OASIS Wound Matrix to Regranex Gel for diabetic ulcers. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2005;18(5, pt 1):258-266.

- Torgerson JS, Arlinger K, Käppi M, et al. Principles for enhanced recruitment of subjects in a large clinical trial. the XENDOS (XENical in the prevention of Diabetes in Obese Subjects) study experience. Controlled Clin Trials. 2001;22:515-525.

- Sen CK, Gordillo GM, Roy S, et al. Human skin wounds: a major and snowballing threat to public health and the economy. Wound Repair Regen. 2009;17:763-771.

- Gurtner GC, Werner S, Barrandon Y, et al. Wound repair and regeneration. Nature. 2008;453:314-321.

- Falanga V. Wound healing and its impairment in the diabetic foot. Lancet. 2005;366:1736-1743.

- Boulton AJ. The diabetic foot: grand overview, epidemiology and pathogenesis. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2008;24(suppl 1):S3-S6.

- Singh N, Armstrong DG, Lipsky BA. Preventing foot ulcers in patients with diabetes. JAMA. 2005;293:217-228.

- Vuorisalo S, Venermo M, Lepäntalo M. Treatment of diabetic foot ulcers. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino). 2009;50:275-291.

- Meijer JW, Trip J, Jaegers SM, et al. Quality of life in patients with diabetic foot ulcers. Disabil Rehabil. 2001;23:336-340.

- Santema TB, Poyck PP, Ubbink DT. Skin grafting and tissue replacement for treating foot ulcers in people with diabetes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;2:CD011255.

- Margolis DJ, Kantor J, Berlin JA. Healing of diabetic neuropathic foot ulcers receiving standard treatment. a meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 1999;22:692-695.

- Cavanagh P, Attinger C, Abbas Z, et al. Cost of treating diabetic foot ulcers in five different countries. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2012;2(suppl 1):107-111.

- Panuncialman J, Falanga V. The science of wound bed preparation. Surg Clin North Am. 2009;89:611-626.

- Lev-Tov H, Li CS, Dahle S, et al. Cellular versus acellular matrix devices in treatment of diabetic foot ulcers: study protocol for a comparative efficacy randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2013;14:8.

- Gentzkow GD, Iwasaki SD, Hershon KS, et al. Use of dermagraft, a cultured human dermis, to treat diabetic foot ulcers. Diabetes Care. 1996;19:350-354.

- Marston WA, Hanft J, Norwood P, et al; Dermagraft Diabetic Foot Ulcer Study Group. The efficacy and safety of Dermagraft in improving the healing of chronic diabetic foot ulcers: results of a prospective randomized trial. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:1701-1705.

- 2016 Dermagraft® Medicare Product and Related Procedure Payment. http://www.dermagraft.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/1/Dermagraft_Hotsheet%202016%20Q1%20HOSPITAL_FINAL.pdf. Accessed November 23, 2017.

- Oasis® Wound Matrix. http://www.oasiswoundmatrix.com/aboutowm. Accessed November 23, 2017.

- Niezgoda JA, Van Gils CC, Frykberg RG, et al. Randomized clinical trial comparing OASIS Wound Matrix to Regranex Gel for diabetic ulcers. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2005;18(5, pt 1):258-266.

- Torgerson JS, Arlinger K, Käppi M, et al. Principles for enhanced recruitment of subjects in a large clinical trial. the XENDOS (XENical in the prevention of Diabetes in Obese Subjects) study experience. Controlled Clin Trials. 2001;22:515-525.

Resident Pearl

- Deciding on the appropriate wound care regimen for diabetic foot ulcers is difficult given the vast amount of wound products on the market. This head-to-head clinical trial compared the use of an expensive cellular matrix and an inexpensive acellular matrix relative to the standard of care. We hope that this study will help to guide therapy based on cost-effectiveness of wound adjuncts without compromising patient care.

Exercise program speeds healing of venous leg ulcers

A supervised exercise program for patients with venous leg ulcers has shown improved healing times over compression therapy alone, according to a paper published online on Oct. 27 in the British Journal of Dermatology.

In a parallel group feasibility trial, researchers randomized 39 patients with venous ulcers either to a 12-week program of supervised exercise three times a week plus compression therapy (18 patients), or compression therapy alone (21 patients). The exercise program combined aerobic, resistance, and flexibility exercises.

This group showed a median ulcer healing time of 13 weeks (3.9-52 weeks), compared with 34.7 weeks (4.3-52 weeks) for the compression therapy–only group, although the median ulcer size was similar between the two groups at 12 months. At last follow-up of 12 months, 83% of the ulcers in the exercise group had healed, compared with 60% in the control group (Br J Dermatol. 2017 Oct 27. doi: 10.1111/bjd.16089).

The intervention group had a slightly higher quality of life at baseline, as measured by the EQ-5D utility score, and this difference was maintained throughout the study.

Nearly three-quarters (72%) of the exercise group participants went to all the scheduled exercise sessions, with an overall attendance rate of 79%, which the authors noted was high considering many were old, frail, and had no previous exercise experience.

“This was achieved without employing any specific adherence-enhancing components or provision of behavioral change support, which could have potentially improved attendance rates and the effect of the intervention even further,” wrote Markos Klonizakis, DPhil, from the Centre for Sport and Exercise Science at Sheffield (England) Hallam University, and his coinvestigators.

There were no serious adverse events, and only two exercise-related adverse events in the intervention group – both excessive discharge from the ulcer – which resulted in postponement of the exercise sessions for those two individuals.

The exercise regimen was associated with modest reductions in weight, while those in the control group showed an overall increase in weight.

Researchers also assessed the relative costs of the two interventions by getting participants to keep a diary of their use of National Health Service resources, health care visits, prescriptions, and other out-of-pocket expenses.

They calculated that the total mean National Health Service cost per participant for the exercise intervention was £813.27, and £2,298.57 for the control group who received compression therapy only.

The investigators noted that their initial plan had been met with some skepticism from clinicians and patients, some of whom felt that exercise would have a detrimental rather than positive effect on venous ulcer healing.

“Our results suggest that there may be significant potential benefit in healing rates and that, if this were confirmed in a full trial, the introduction of supervised exercise for venous leg ulcers may well also be cost-saving for the National Health Service.”

The study was funded by the National Institute for Health Research. No conflicts of interest were declared.

A supervised exercise program for patients with venous leg ulcers has shown improved healing times over compression therapy alone, according to a paper published online on Oct. 27 in the British Journal of Dermatology.

In a parallel group feasibility trial, researchers randomized 39 patients with venous ulcers either to a 12-week program of supervised exercise three times a week plus compression therapy (18 patients), or compression therapy alone (21 patients). The exercise program combined aerobic, resistance, and flexibility exercises.

This group showed a median ulcer healing time of 13 weeks (3.9-52 weeks), compared with 34.7 weeks (4.3-52 weeks) for the compression therapy–only group, although the median ulcer size was similar between the two groups at 12 months. At last follow-up of 12 months, 83% of the ulcers in the exercise group had healed, compared with 60% in the control group (Br J Dermatol. 2017 Oct 27. doi: 10.1111/bjd.16089).

The intervention group had a slightly higher quality of life at baseline, as measured by the EQ-5D utility score, and this difference was maintained throughout the study.

Nearly three-quarters (72%) of the exercise group participants went to all the scheduled exercise sessions, with an overall attendance rate of 79%, which the authors noted was high considering many were old, frail, and had no previous exercise experience.

“This was achieved without employing any specific adherence-enhancing components or provision of behavioral change support, which could have potentially improved attendance rates and the effect of the intervention even further,” wrote Markos Klonizakis, DPhil, from the Centre for Sport and Exercise Science at Sheffield (England) Hallam University, and his coinvestigators.

There were no serious adverse events, and only two exercise-related adverse events in the intervention group – both excessive discharge from the ulcer – which resulted in postponement of the exercise sessions for those two individuals.

The exercise regimen was associated with modest reductions in weight, while those in the control group showed an overall increase in weight.

Researchers also assessed the relative costs of the two interventions by getting participants to keep a diary of their use of National Health Service resources, health care visits, prescriptions, and other out-of-pocket expenses.

They calculated that the total mean National Health Service cost per participant for the exercise intervention was £813.27, and £2,298.57 for the control group who received compression therapy only.

The investigators noted that their initial plan had been met with some skepticism from clinicians and patients, some of whom felt that exercise would have a detrimental rather than positive effect on venous ulcer healing.

“Our results suggest that there may be significant potential benefit in healing rates and that, if this were confirmed in a full trial, the introduction of supervised exercise for venous leg ulcers may well also be cost-saving for the National Health Service.”

The study was funded by the National Institute for Health Research. No conflicts of interest were declared.

A supervised exercise program for patients with venous leg ulcers has shown improved healing times over compression therapy alone, according to a paper published online on Oct. 27 in the British Journal of Dermatology.

In a parallel group feasibility trial, researchers randomized 39 patients with venous ulcers either to a 12-week program of supervised exercise three times a week plus compression therapy (18 patients), or compression therapy alone (21 patients). The exercise program combined aerobic, resistance, and flexibility exercises.

This group showed a median ulcer healing time of 13 weeks (3.9-52 weeks), compared with 34.7 weeks (4.3-52 weeks) for the compression therapy–only group, although the median ulcer size was similar between the two groups at 12 months. At last follow-up of 12 months, 83% of the ulcers in the exercise group had healed, compared with 60% in the control group (Br J Dermatol. 2017 Oct 27. doi: 10.1111/bjd.16089).

The intervention group had a slightly higher quality of life at baseline, as measured by the EQ-5D utility score, and this difference was maintained throughout the study.

Nearly three-quarters (72%) of the exercise group participants went to all the scheduled exercise sessions, with an overall attendance rate of 79%, which the authors noted was high considering many were old, frail, and had no previous exercise experience.

“This was achieved without employing any specific adherence-enhancing components or provision of behavioral change support, which could have potentially improved attendance rates and the effect of the intervention even further,” wrote Markos Klonizakis, DPhil, from the Centre for Sport and Exercise Science at Sheffield (England) Hallam University, and his coinvestigators.

There were no serious adverse events, and only two exercise-related adverse events in the intervention group – both excessive discharge from the ulcer – which resulted in postponement of the exercise sessions for those two individuals.

The exercise regimen was associated with modest reductions in weight, while those in the control group showed an overall increase in weight.

Researchers also assessed the relative costs of the two interventions by getting participants to keep a diary of their use of National Health Service resources, health care visits, prescriptions, and other out-of-pocket expenses.

They calculated that the total mean National Health Service cost per participant for the exercise intervention was £813.27, and £2,298.57 for the control group who received compression therapy only.

The investigators noted that their initial plan had been met with some skepticism from clinicians and patients, some of whom felt that exercise would have a detrimental rather than positive effect on venous ulcer healing.

“Our results suggest that there may be significant potential benefit in healing rates and that, if this were confirmed in a full trial, the introduction of supervised exercise for venous leg ulcers may well also be cost-saving for the National Health Service.”

The study was funded by the National Institute for Health Research. No conflicts of interest were declared.

FROM THE BRITISH JOURNAL OF DERMATOLOGY

Key clinical point: A supervised exercise program for patients with venous leg ulcers has shown significantly improved healing times over compression therapy alone.

Major finding: Patients who underwent a program of supervised exercise in addition to compression therapy showed a median ulcer healing time of 13 weeks, compared with 35 weeks for patients who received compression therapy alone.

Data source: A randomized, parallel group feasibility trial in 39 patients with venous ulcers.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the National Institute for Health Research. No conflicts of interest were declared.

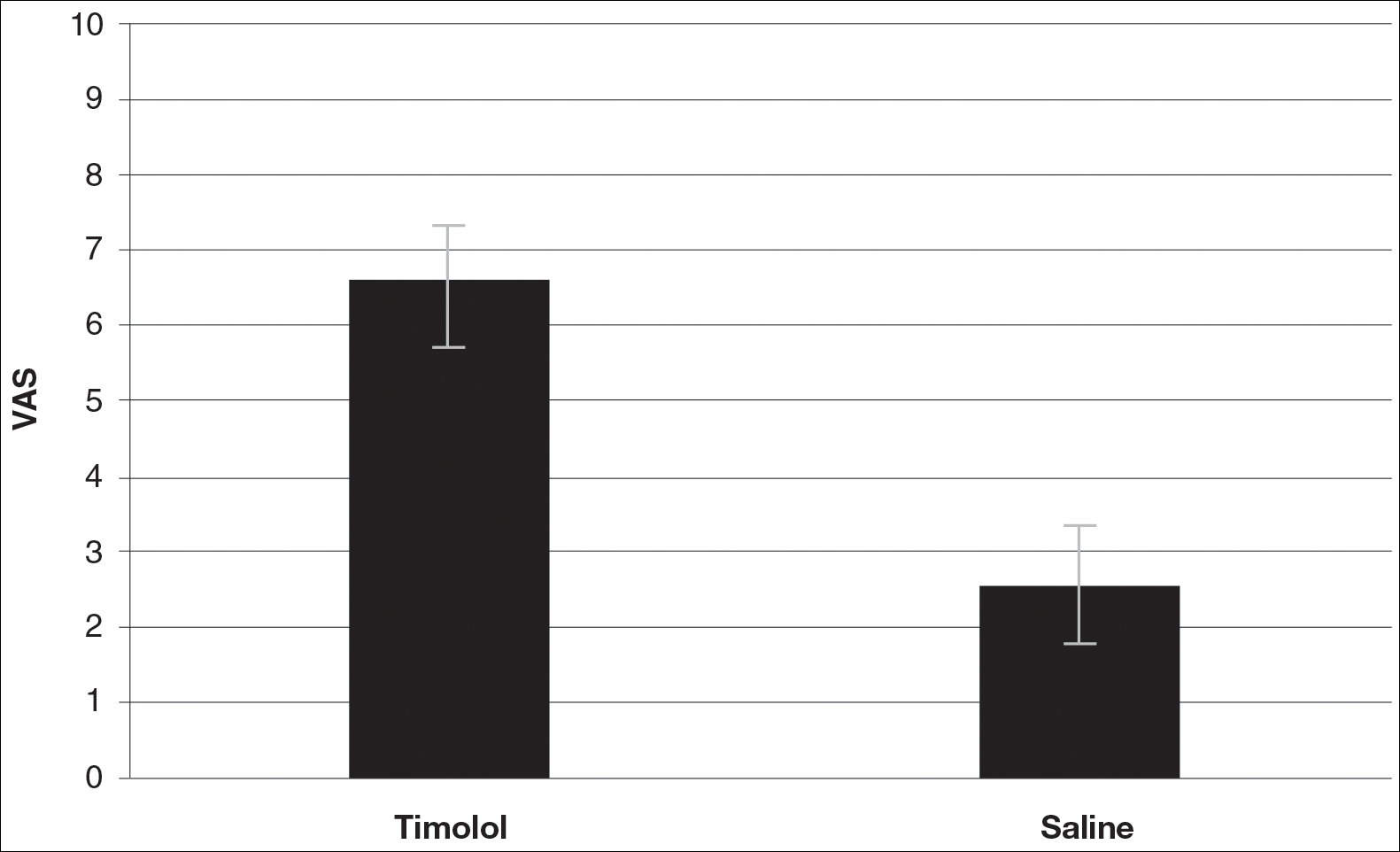

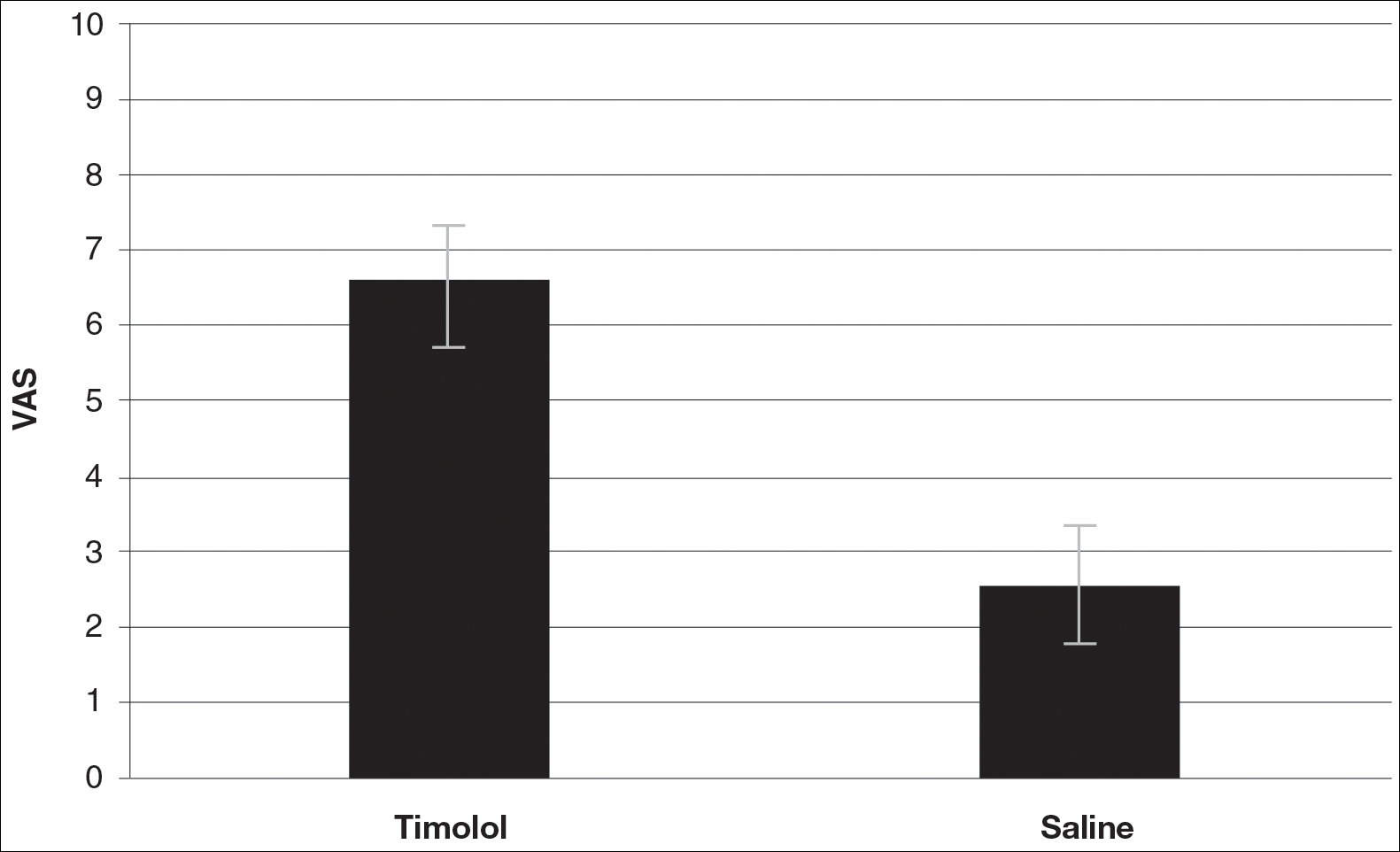

Topical timolol improved chronic leg ulcer healing

The use of topical timolol maleate as a treatment for chronic diabetic and chronic venous ulcers showed increased wound healing compared with controls, according to the results of a prospective observational study of 60 patients.

In the treatment group, 30 patients with chronic leg ulcer (15 diabetic ulcers; 15 venous) received topical application of 0.5% timolol maleate (a beta-blocker) plus conventional antibiotic and wound dressing therapy. In the control group, 30 patients (identical split between diabetic and venous ulcers) were treated with conventional therapy alone, according to a report published in the November issue of the Journal of Vascular Surgery: Venous and Lymphatic Disorders.

The researchers found no significant difference in healing rates due to sex, between smokers and nonsmokers, or alcohol consumers vs. nonconsumers and they saw no major adverse effects due to timolol application (J Vasc Surg: Venous and Lym Dis 2017;5:844-50).

They reported that the limitations of their study included the lack of randomization and a formal power assessment.

“Topical application of timolol maleate is an effective therapeutic option for the treatment of chronic diabetic ulcer and chronic venous ulcer patients to improve ulcer healing by promoting keratinocyte migration,” the researchers concluded.

They reported having no relevant conflicts.

The use of topical timolol maleate as a treatment for chronic diabetic and chronic venous ulcers showed increased wound healing compared with controls, according to the results of a prospective observational study of 60 patients.

In the treatment group, 30 patients with chronic leg ulcer (15 diabetic ulcers; 15 venous) received topical application of 0.5% timolol maleate (a beta-blocker) plus conventional antibiotic and wound dressing therapy. In the control group, 30 patients (identical split between diabetic and venous ulcers) were treated with conventional therapy alone, according to a report published in the November issue of the Journal of Vascular Surgery: Venous and Lymphatic Disorders.

The researchers found no significant difference in healing rates due to sex, between smokers and nonsmokers, or alcohol consumers vs. nonconsumers and they saw no major adverse effects due to timolol application (J Vasc Surg: Venous and Lym Dis 2017;5:844-50).

They reported that the limitations of their study included the lack of randomization and a formal power assessment.

“Topical application of timolol maleate is an effective therapeutic option for the treatment of chronic diabetic ulcer and chronic venous ulcer patients to improve ulcer healing by promoting keratinocyte migration,” the researchers concluded.

They reported having no relevant conflicts.

The use of topical timolol maleate as a treatment for chronic diabetic and chronic venous ulcers showed increased wound healing compared with controls, according to the results of a prospective observational study of 60 patients.

In the treatment group, 30 patients with chronic leg ulcer (15 diabetic ulcers; 15 venous) received topical application of 0.5% timolol maleate (a beta-blocker) plus conventional antibiotic and wound dressing therapy. In the control group, 30 patients (identical split between diabetic and venous ulcers) were treated with conventional therapy alone, according to a report published in the November issue of the Journal of Vascular Surgery: Venous and Lymphatic Disorders.

The researchers found no significant difference in healing rates due to sex, between smokers and nonsmokers, or alcohol consumers vs. nonconsumers and they saw no major adverse effects due to timolol application (J Vasc Surg: Venous and Lym Dis 2017;5:844-50).

They reported that the limitations of their study included the lack of randomization and a formal power assessment.

“Topical application of timolol maleate is an effective therapeutic option for the treatment of chronic diabetic ulcer and chronic venous ulcer patients to improve ulcer healing by promoting keratinocyte migration,” the researchers concluded.

They reported having no relevant conflicts.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF VASCULAR SURGERY: VENOUS AND LYMPHATIC DISORDERS

Clinical Pearl: A Simple and Effective Technique for Improving Surgical Closures for the Early-Learning Resident

Practice Gap

For first-year dermatology residents, dermatologic surgeries can present many challenges. Although approximation of wound edges following excision may be intuitive for the experienced surgeon, an early trainee may need some guidance. Infusion of anesthetics can distort the normal skin field or it may be difficult for the patient to remain in the same position for the required period of time; for example, an elderly patient who requires an excision on the posterior aspect of the neck may be unable to assume the same position for the full duration of the procedure. We offer a simple and effective technique for early-learning dermatology residents to improve surgical closures.

The Technique

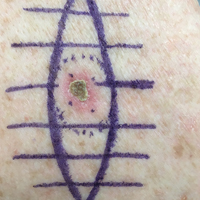

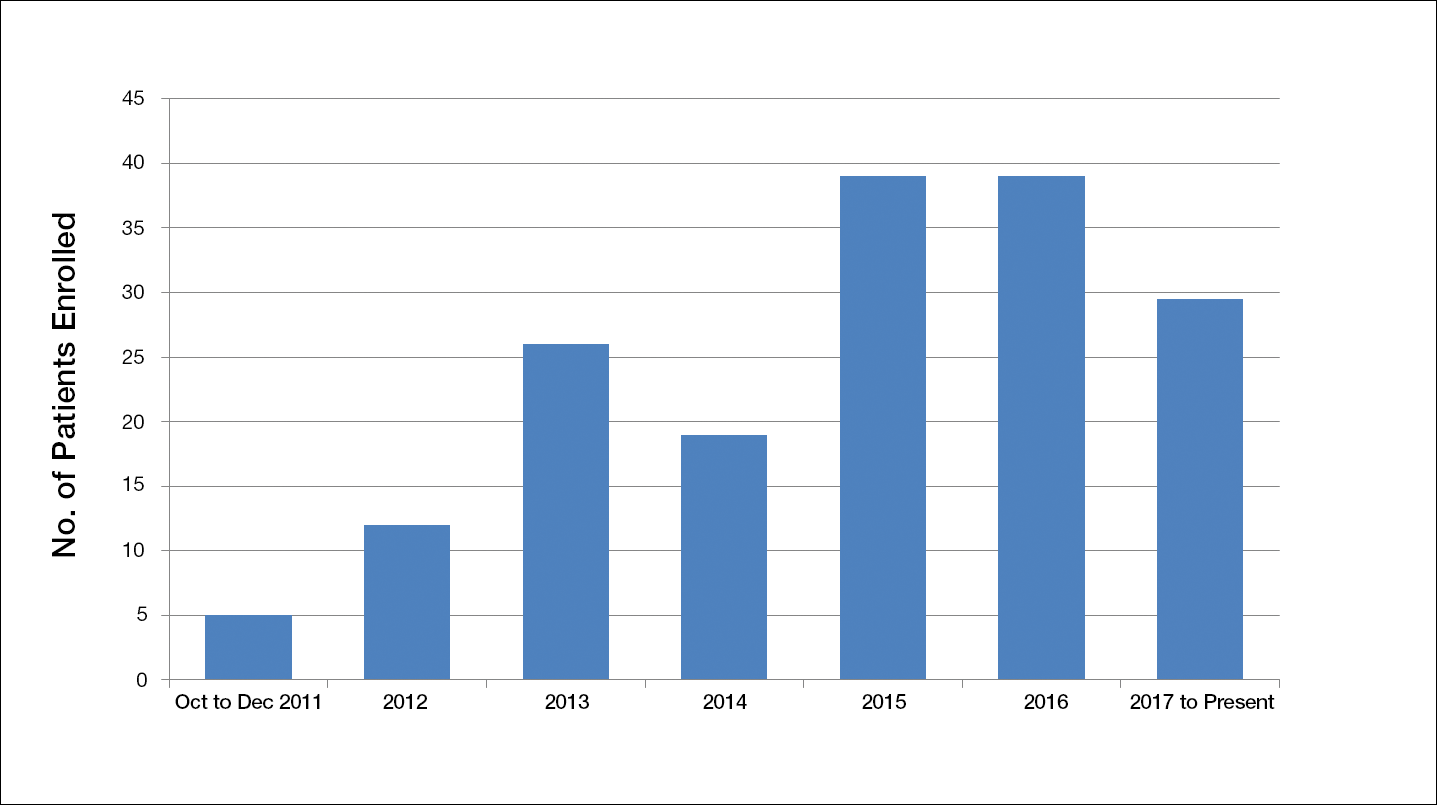

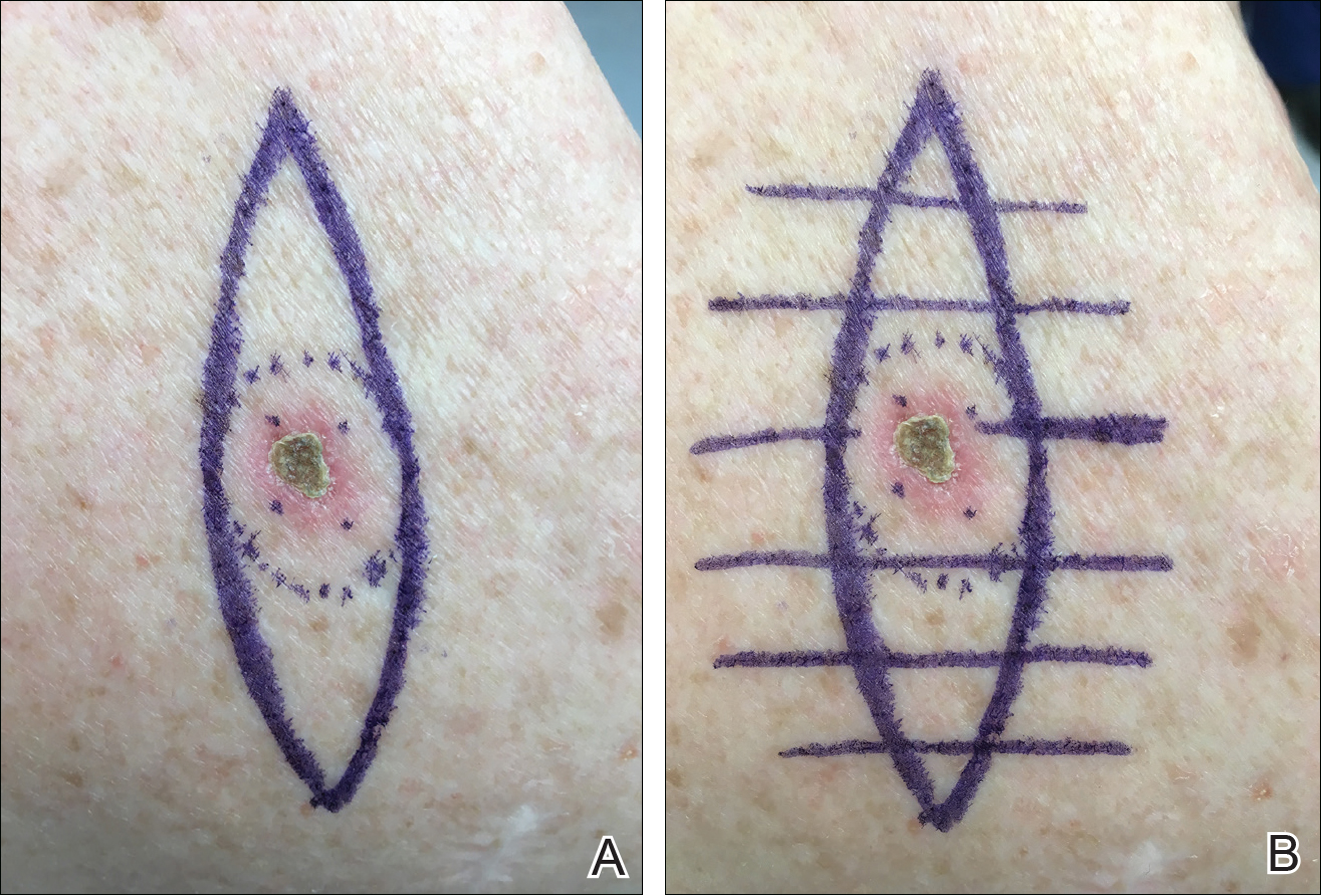

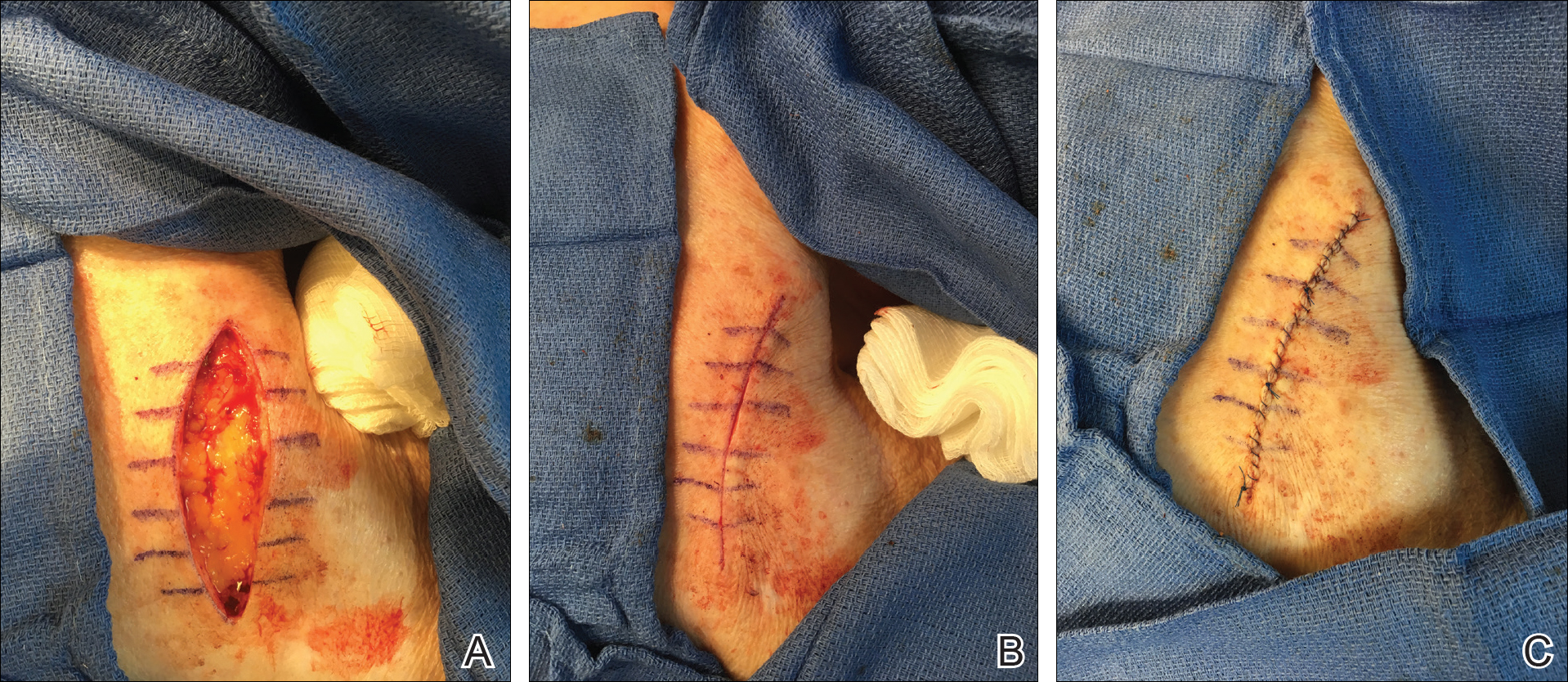

We propose drawing straight lines using a sterile marking pen perpendicular to the fusiform plane laid out for any simple, intermediate, or complex linear closure (Figure 1). These lines can then be used as scaffolding for the surgical closure (Figure 2). We recommend drawing the lines at the time of initial planning when the site of excision is in the normal anatomic position.

Practice Implications

By creating a sketch with perpendicular lines, approximation of skin edges and surgical closures may become easier for the learning resident. Patients also can rest more comfortably during the procedure, and the overall cosmesis, healing, and outcome of the procedure may improve. The addition of a sterile marking pen to the surgical tray may aide in highlighting faded pen markings for easier visualization after cleansing of the surgical site.

Practice Gap

For first-year dermatology residents, dermatologic surgeries can present many challenges. Although approximation of wound edges following excision may be intuitive for the experienced surgeon, an early trainee may need some guidance. Infusion of anesthetics can distort the normal skin field or it may be difficult for the patient to remain in the same position for the required period of time; for example, an elderly patient who requires an excision on the posterior aspect of the neck may be unable to assume the same position for the full duration of the procedure. We offer a simple and effective technique for early-learning dermatology residents to improve surgical closures.

The Technique

We propose drawing straight lines using a sterile marking pen perpendicular to the fusiform plane laid out for any simple, intermediate, or complex linear closure (Figure 1). These lines can then be used as scaffolding for the surgical closure (Figure 2). We recommend drawing the lines at the time of initial planning when the site of excision is in the normal anatomic position.

Practice Implications

By creating a sketch with perpendicular lines, approximation of skin edges and surgical closures may become easier for the learning resident. Patients also can rest more comfortably during the procedure, and the overall cosmesis, healing, and outcome of the procedure may improve. The addition of a sterile marking pen to the surgical tray may aide in highlighting faded pen markings for easier visualization after cleansing of the surgical site.

Practice Gap

For first-year dermatology residents, dermatologic surgeries can present many challenges. Although approximation of wound edges following excision may be intuitive for the experienced surgeon, an early trainee may need some guidance. Infusion of anesthetics can distort the normal skin field or it may be difficult for the patient to remain in the same position for the required period of time; for example, an elderly patient who requires an excision on the posterior aspect of the neck may be unable to assume the same position for the full duration of the procedure. We offer a simple and effective technique for early-learning dermatology residents to improve surgical closures.

The Technique

We propose drawing straight lines using a sterile marking pen perpendicular to the fusiform plane laid out for any simple, intermediate, or complex linear closure (Figure 1). These lines can then be used as scaffolding for the surgical closure (Figure 2). We recommend drawing the lines at the time of initial planning when the site of excision is in the normal anatomic position.

Practice Implications

By creating a sketch with perpendicular lines, approximation of skin edges and surgical closures may become easier for the learning resident. Patients also can rest more comfortably during the procedure, and the overall cosmesis, healing, and outcome of the procedure may improve. The addition of a sterile marking pen to the surgical tray may aide in highlighting faded pen markings for easier visualization after cleansing of the surgical site.

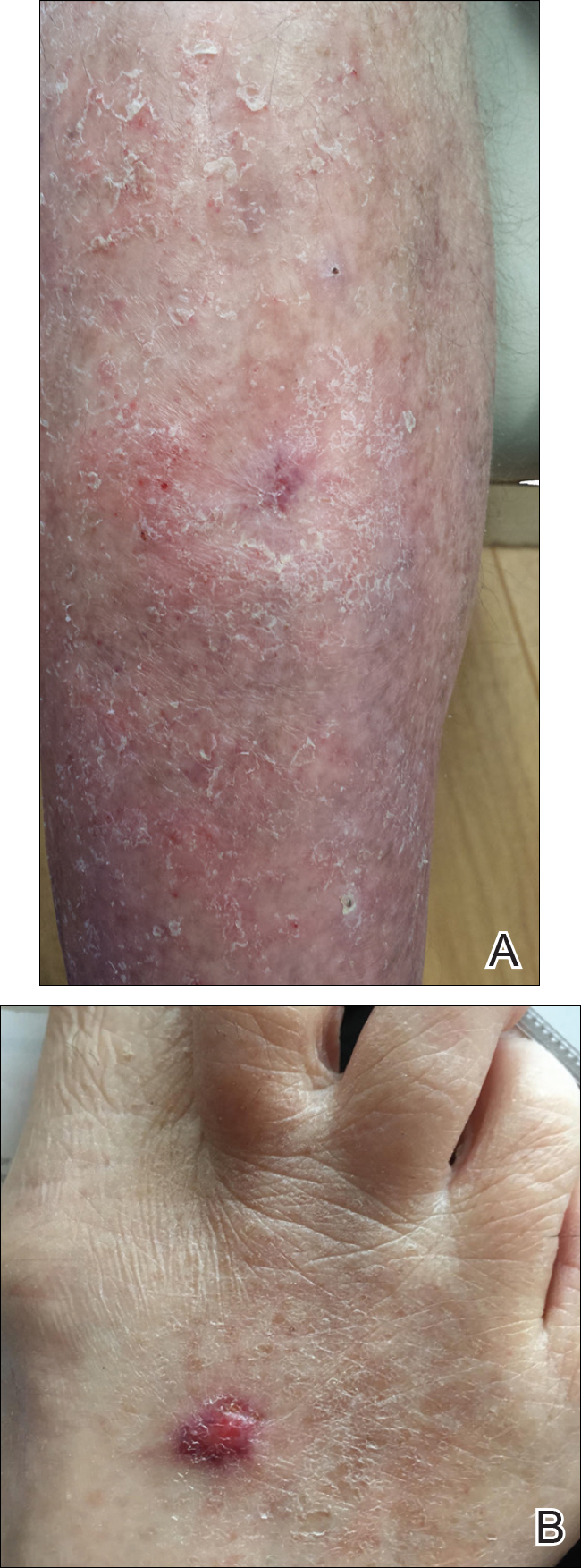

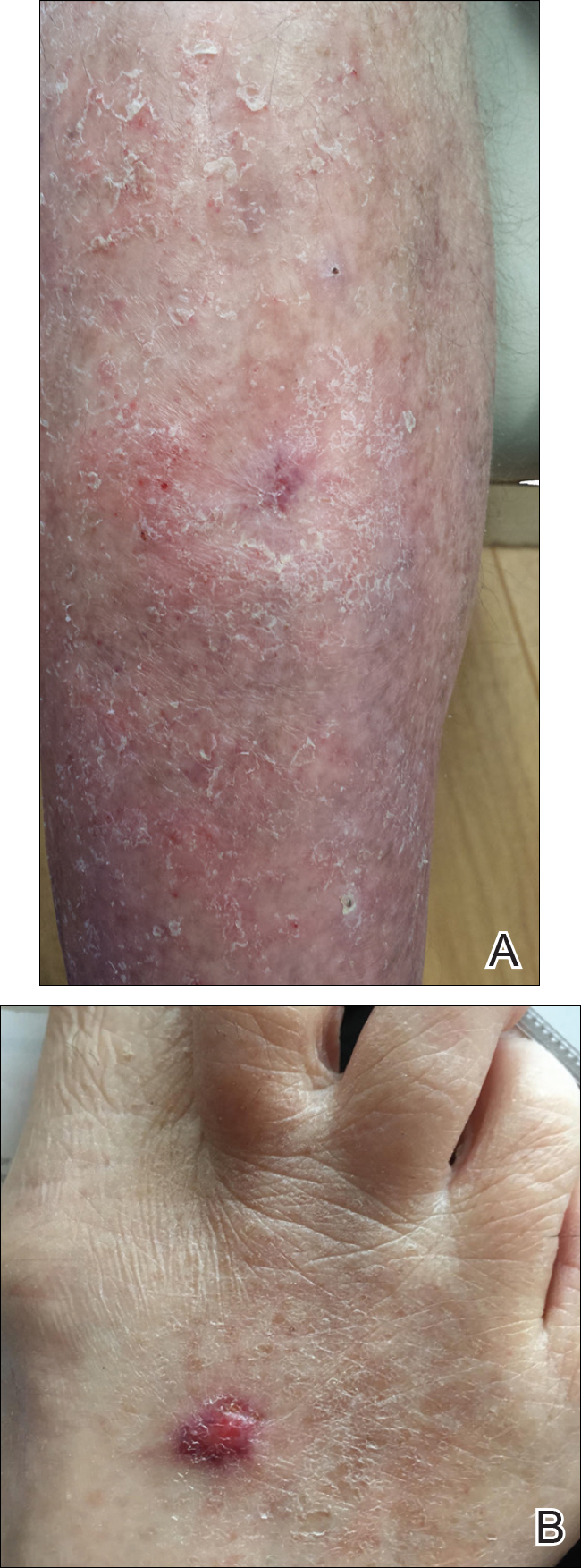

Recalcitrant Ulcer on the Lower Leg

The Diagnosis: Nonuremic Calciphylaxis

Histopathologic findings revealed ischemic necrosis and a subepidermal blister (Figure 1) with arteriosclerotic changes and fat necrosis. Foci of calcification were noted within the fat lobules. Arterioles within the deeper dermis and subcutis showed thickened hyalinized walls, narrowed lumina, and medial calcification (Figure 2). Multiple sections did not reveal any granulomatous inflammation. Periodic acid-Schiff and Gram stains were negative for fungal and bacterial elements, respectively. No dense neutrophilic infiltrate was seen. Multifocal calcific deposits within fat lobules and vessel walls (endothelium highlighted by the CD31 stain) suggested calciphylaxis.

Laboratory test results revealed a normal white blood cell count, international normalized ratio level of 4 (on warfarin), and an elevated sedimentation rate at 72 mm/h (reference range, 0-20 mm/h). Serum creatinine was 1.1 mg/dL (reference range, 0.6-1.2 mg/dL) and the calcium-phosphorous product was 40.8 mg2/dL (reference range, <55 mg2/dL). Hemoglobin A1C (glycated hemoglobin) was 8.2% (reference range, 4%-7%). Wound cultures grew Proteus mirabilis sensitive to cefazolin. Acid-fast bacilli and fungal cultures were negative. Computed tomography of the left lower leg without contrast showed no evidence of osteomyelitis. Of note, the popliteal arteries and distal vessels showed moderate vascular calcification.

Histopathology findings as well as a clinical picture of painful ulceration on the distal extremities and uncontrolled diabetes with normal renal function favored a diagnosis of nonuremic calciphylaxis (NUC). The patient was treated with intravenous infusions of sodium thiosulfate 25 mg 3 times weekly and oral cefazolin for superadded bacterial infection. Local wound care included collagenase dressings with light compression. Warfarin was discontinued, as it can worsen calciphylaxis. Complete reepithelialization of the ulcer along with substantial reduction in pain was noted within 4 weeks.

Ulceration of the lower legs is a relatively common condition in the Western world, the prevalence of which increases up to 5% in patients older than 65 years.1 Of the myriad of causes that lead to ulceration of the distal aspect of the leg, NUC is a rare but known phenomenon. The pathogenesis of NUC is complicated based on theories of derangement of receptor activator of nuclear factor κβ, receptor activator of nuclear factor κβ ligand, and osteoprotegerin, leading to calcium deposits in the media of the arteries.2 This deposition precipitates vascular occlusion coupled with ischemic necrosis of the subcutaneous tissue and skin.3 Some of the more common causes of NUC are primary hyperparathyroidism, malignancy, and rheumatoid arthritis. Type 2 diabetes mellitus is a less common cause but often is found in association with NUC, as noted by Nigwekar et al.2 According to their study, the laboratory parameters commonly found in NUC included a calcium-phosphorous product greater than 50 mg2/dL and serum creatinine of 1.2 mg/dL or less.2

Our patient displayed these laboratory findings. However, distinguishing NUC from other atypical lower extremity ulcers such as Martorell hypertensive ischemic ulcer, pyoderma gangrenosum, and warfarin necrosis can pose a challenge to the dermatologist. Martorell hypertensive ischemic ulcer is excruciatingly painful and occurs more frequently near the Achilles tendon, responding well to surgical debridement. Histopathologically, medial calcinosis and arteriosclerosis are seen.4

Pyoderma gangrenosum is a neutrophilic dermatosis wherein the classical ulcerative variant is painful. It occurs mostly on the pretibial area and worsens after debridement.5 Clinically and histopathologically, it is a diagnosis of exclusion in which a dense neutrophilic to mixed lymphocytic infiltrate is seen with necrosis of dermal vessels.6

Warfarin necrosis is extremely rare, affecting 0.01% to 0.1% of patients on warfarin-derived anticoagulant therapy.7 Necrosis occurs mostly on fat-bearing areas such as the breasts, abdomen, and thighs 3 to 5 days after initiating treatment. Histologically, fibrin deposits occlude dermal vessels without perivascular inflammation.8

Necrobiosis lipoidica is a rare cutaneous entity seen in 0.3% of diabetic patients.9 The exact pathogenesis is unknown; however, microangiopathy in collaboration with cross-linking of abnormal collagen fibers play a role. These lesions appear as erythematous plaques with a slightly depressed to atrophic center, ultimately taking on a waxy porcelain appearance. Although most of these lesions either resolve or become chronically persistent, approximately 15% undergo ulceration, which can be painful. Histologically, with hematoxylin and eosin staining, areas of necrobiosis are seen surrounded by an inflammatory infiltrate comprised mainly of histiocytes along with lymphocytes and plasma cells.9

Nonuremic calciphylaxis can mimic the aforementioned conditions to a greater extent in female patients with obesity, diabetes mellitus, and hypertension. However, microscopic calcium deposition in the media of dermal arterioles, extravascular calcification within fat lobules, and cutaneous necrosis, along with remarkable response to intravenous sodium thiosulfate, confirmed a diagnosis of NUC in our patient. Sodium thiosulfate scavenges reactive oxygen species and promotes nitric oxygen generation, thereby reducing endothelial damage.10 Although there are no randomized controlled trials to support its use, sodium thiosulfate has been successfully used to treat established cases of NUC.11

- Spentzouris G, Labropoulos N. The evaluation of lower-extremity ulcers. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2009;26:286-295.

- Nigwekar SU, Wolf M, Sterns RH, et al. Calciphylaxis from nonuremic causes: a systematic review. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3:1139-1143.

- Bardin T. Musculoskeletal manifestations of chronic renal failure. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2003;15:48-54.

- Hafner J, Nobbe S, Partsch H, et al. Martorell hypertensive ischemic leg ulcer: a model of ischemic subcutaneous arteriolosclerosis. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:961-968.

- Sedda S, Caruso R, Marafini I, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum in refractory celiac disease: a case report. BMC Gastroenterol. 2013;13:162.

- Su WP, Davis MD, Weenig RH, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum: clinicopathologic correlation and proposed diagnostic criteria. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:790-800.

- Breakey W, Hall C, Vann Jones S, et al. Warfarin-induced skin necrosis progressing to calciphylaxis. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2014;67:244-246.

- Kakagia DD, Papanas N, Karadimas E, et al. Warfarin-induced skin necrosis. Ann Dermatol. 2014;26:96-98.

- Kota SK, Jammula S, Kota SK, et al. Necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum: a case-based review of literature. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2012;16:614-620.

- Hayden MR, Goldsmith DJ. Sodium thiosulfate: new hope for the treatment of calciphylaxis. Semin Dial. 2010;23:258-262.

- Ning MS, Dahir KM, Castellanos EH, et al. Sodium thiosulfate in the treatment of non-uremic calciphylaxis. J Dermatol. 2013;40:649-652.

The Diagnosis: Nonuremic Calciphylaxis

Histopathologic findings revealed ischemic necrosis and a subepidermal blister (Figure 1) with arteriosclerotic changes and fat necrosis. Foci of calcification were noted within the fat lobules. Arterioles within the deeper dermis and subcutis showed thickened hyalinized walls, narrowed lumina, and medial calcification (Figure 2). Multiple sections did not reveal any granulomatous inflammation. Periodic acid-Schiff and Gram stains were negative for fungal and bacterial elements, respectively. No dense neutrophilic infiltrate was seen. Multifocal calcific deposits within fat lobules and vessel walls (endothelium highlighted by the CD31 stain) suggested calciphylaxis.

Laboratory test results revealed a normal white blood cell count, international normalized ratio level of 4 (on warfarin), and an elevated sedimentation rate at 72 mm/h (reference range, 0-20 mm/h). Serum creatinine was 1.1 mg/dL (reference range, 0.6-1.2 mg/dL) and the calcium-phosphorous product was 40.8 mg2/dL (reference range, <55 mg2/dL). Hemoglobin A1C (glycated hemoglobin) was 8.2% (reference range, 4%-7%). Wound cultures grew Proteus mirabilis sensitive to cefazolin. Acid-fast bacilli and fungal cultures were negative. Computed tomography of the left lower leg without contrast showed no evidence of osteomyelitis. Of note, the popliteal arteries and distal vessels showed moderate vascular calcification.

Histopathology findings as well as a clinical picture of painful ulceration on the distal extremities and uncontrolled diabetes with normal renal function favored a diagnosis of nonuremic calciphylaxis (NUC). The patient was treated with intravenous infusions of sodium thiosulfate 25 mg 3 times weekly and oral cefazolin for superadded bacterial infection. Local wound care included collagenase dressings with light compression. Warfarin was discontinued, as it can worsen calciphylaxis. Complete reepithelialization of the ulcer along with substantial reduction in pain was noted within 4 weeks.

Ulceration of the lower legs is a relatively common condition in the Western world, the prevalence of which increases up to 5% in patients older than 65 years.1 Of the myriad of causes that lead to ulceration of the distal aspect of the leg, NUC is a rare but known phenomenon. The pathogenesis of NUC is complicated based on theories of derangement of receptor activator of nuclear factor κβ, receptor activator of nuclear factor κβ ligand, and osteoprotegerin, leading to calcium deposits in the media of the arteries.2 This deposition precipitates vascular occlusion coupled with ischemic necrosis of the subcutaneous tissue and skin.3 Some of the more common causes of NUC are primary hyperparathyroidism, malignancy, and rheumatoid arthritis. Type 2 diabetes mellitus is a less common cause but often is found in association with NUC, as noted by Nigwekar et al.2 According to their study, the laboratory parameters commonly found in NUC included a calcium-phosphorous product greater than 50 mg2/dL and serum creatinine of 1.2 mg/dL or less.2

Our patient displayed these laboratory findings. However, distinguishing NUC from other atypical lower extremity ulcers such as Martorell hypertensive ischemic ulcer, pyoderma gangrenosum, and warfarin necrosis can pose a challenge to the dermatologist. Martorell hypertensive ischemic ulcer is excruciatingly painful and occurs more frequently near the Achilles tendon, responding well to surgical debridement. Histopathologically, medial calcinosis and arteriosclerosis are seen.4

Pyoderma gangrenosum is a neutrophilic dermatosis wherein the classical ulcerative variant is painful. It occurs mostly on the pretibial area and worsens after debridement.5 Clinically and histopathologically, it is a diagnosis of exclusion in which a dense neutrophilic to mixed lymphocytic infiltrate is seen with necrosis of dermal vessels.6

Warfarin necrosis is extremely rare, affecting 0.01% to 0.1% of patients on warfarin-derived anticoagulant therapy.7 Necrosis occurs mostly on fat-bearing areas such as the breasts, abdomen, and thighs 3 to 5 days after initiating treatment. Histologically, fibrin deposits occlude dermal vessels without perivascular inflammation.8

Necrobiosis lipoidica is a rare cutaneous entity seen in 0.3% of diabetic patients.9 The exact pathogenesis is unknown; however, microangiopathy in collaboration with cross-linking of abnormal collagen fibers play a role. These lesions appear as erythematous plaques with a slightly depressed to atrophic center, ultimately taking on a waxy porcelain appearance. Although most of these lesions either resolve or become chronically persistent, approximately 15% undergo ulceration, which can be painful. Histologically, with hematoxylin and eosin staining, areas of necrobiosis are seen surrounded by an inflammatory infiltrate comprised mainly of histiocytes along with lymphocytes and plasma cells.9

Nonuremic calciphylaxis can mimic the aforementioned conditions to a greater extent in female patients with obesity, diabetes mellitus, and hypertension. However, microscopic calcium deposition in the media of dermal arterioles, extravascular calcification within fat lobules, and cutaneous necrosis, along with remarkable response to intravenous sodium thiosulfate, confirmed a diagnosis of NUC in our patient. Sodium thiosulfate scavenges reactive oxygen species and promotes nitric oxygen generation, thereby reducing endothelial damage.10 Although there are no randomized controlled trials to support its use, sodium thiosulfate has been successfully used to treat established cases of NUC.11

The Diagnosis: Nonuremic Calciphylaxis

Histopathologic findings revealed ischemic necrosis and a subepidermal blister (Figure 1) with arteriosclerotic changes and fat necrosis. Foci of calcification were noted within the fat lobules. Arterioles within the deeper dermis and subcutis showed thickened hyalinized walls, narrowed lumina, and medial calcification (Figure 2). Multiple sections did not reveal any granulomatous inflammation. Periodic acid-Schiff and Gram stains were negative for fungal and bacterial elements, respectively. No dense neutrophilic infiltrate was seen. Multifocal calcific deposits within fat lobules and vessel walls (endothelium highlighted by the CD31 stain) suggested calciphylaxis.

Laboratory test results revealed a normal white blood cell count, international normalized ratio level of 4 (on warfarin), and an elevated sedimentation rate at 72 mm/h (reference range, 0-20 mm/h). Serum creatinine was 1.1 mg/dL (reference range, 0.6-1.2 mg/dL) and the calcium-phosphorous product was 40.8 mg2/dL (reference range, <55 mg2/dL). Hemoglobin A1C (glycated hemoglobin) was 8.2% (reference range, 4%-7%). Wound cultures grew Proteus mirabilis sensitive to cefazolin. Acid-fast bacilli and fungal cultures were negative. Computed tomography of the left lower leg without contrast showed no evidence of osteomyelitis. Of note, the popliteal arteries and distal vessels showed moderate vascular calcification.

Histopathology findings as well as a clinical picture of painful ulceration on the distal extremities and uncontrolled diabetes with normal renal function favored a diagnosis of nonuremic calciphylaxis (NUC). The patient was treated with intravenous infusions of sodium thiosulfate 25 mg 3 times weekly and oral cefazolin for superadded bacterial infection. Local wound care included collagenase dressings with light compression. Warfarin was discontinued, as it can worsen calciphylaxis. Complete reepithelialization of the ulcer along with substantial reduction in pain was noted within 4 weeks.

Ulceration of the lower legs is a relatively common condition in the Western world, the prevalence of which increases up to 5% in patients older than 65 years.1 Of the myriad of causes that lead to ulceration of the distal aspect of the leg, NUC is a rare but known phenomenon. The pathogenesis of NUC is complicated based on theories of derangement of receptor activator of nuclear factor κβ, receptor activator of nuclear factor κβ ligand, and osteoprotegerin, leading to calcium deposits in the media of the arteries.2 This deposition precipitates vascular occlusion coupled with ischemic necrosis of the subcutaneous tissue and skin.3 Some of the more common causes of NUC are primary hyperparathyroidism, malignancy, and rheumatoid arthritis. Type 2 diabetes mellitus is a less common cause but often is found in association with NUC, as noted by Nigwekar et al.2 According to their study, the laboratory parameters commonly found in NUC included a calcium-phosphorous product greater than 50 mg2/dL and serum creatinine of 1.2 mg/dL or less.2

Our patient displayed these laboratory findings. However, distinguishing NUC from other atypical lower extremity ulcers such as Martorell hypertensive ischemic ulcer, pyoderma gangrenosum, and warfarin necrosis can pose a challenge to the dermatologist. Martorell hypertensive ischemic ulcer is excruciatingly painful and occurs more frequently near the Achilles tendon, responding well to surgical debridement. Histopathologically, medial calcinosis and arteriosclerosis are seen.4

Pyoderma gangrenosum is a neutrophilic dermatosis wherein the classical ulcerative variant is painful. It occurs mostly on the pretibial area and worsens after debridement.5 Clinically and histopathologically, it is a diagnosis of exclusion in which a dense neutrophilic to mixed lymphocytic infiltrate is seen with necrosis of dermal vessels.6

Warfarin necrosis is extremely rare, affecting 0.01% to 0.1% of patients on warfarin-derived anticoagulant therapy.7 Necrosis occurs mostly on fat-bearing areas such as the breasts, abdomen, and thighs 3 to 5 days after initiating treatment. Histologically, fibrin deposits occlude dermal vessels without perivascular inflammation.8

Necrobiosis lipoidica is a rare cutaneous entity seen in 0.3% of diabetic patients.9 The exact pathogenesis is unknown; however, microangiopathy in collaboration with cross-linking of abnormal collagen fibers play a role. These lesions appear as erythematous plaques with a slightly depressed to atrophic center, ultimately taking on a waxy porcelain appearance. Although most of these lesions either resolve or become chronically persistent, approximately 15% undergo ulceration, which can be painful. Histologically, with hematoxylin and eosin staining, areas of necrobiosis are seen surrounded by an inflammatory infiltrate comprised mainly of histiocytes along with lymphocytes and plasma cells.9

Nonuremic calciphylaxis can mimic the aforementioned conditions to a greater extent in female patients with obesity, diabetes mellitus, and hypertension. However, microscopic calcium deposition in the media of dermal arterioles, extravascular calcification within fat lobules, and cutaneous necrosis, along with remarkable response to intravenous sodium thiosulfate, confirmed a diagnosis of NUC in our patient. Sodium thiosulfate scavenges reactive oxygen species and promotes nitric oxygen generation, thereby reducing endothelial damage.10 Although there are no randomized controlled trials to support its use, sodium thiosulfate has been successfully used to treat established cases of NUC.11

- Spentzouris G, Labropoulos N. The evaluation of lower-extremity ulcers. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2009;26:286-295.

- Nigwekar SU, Wolf M, Sterns RH, et al. Calciphylaxis from nonuremic causes: a systematic review. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3:1139-1143.

- Bardin T. Musculoskeletal manifestations of chronic renal failure. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2003;15:48-54.

- Hafner J, Nobbe S, Partsch H, et al. Martorell hypertensive ischemic leg ulcer: a model of ischemic subcutaneous arteriolosclerosis. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:961-968.

- Sedda S, Caruso R, Marafini I, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum in refractory celiac disease: a case report. BMC Gastroenterol. 2013;13:162.

- Su WP, Davis MD, Weenig RH, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum: clinicopathologic correlation and proposed diagnostic criteria. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:790-800.

- Breakey W, Hall C, Vann Jones S, et al. Warfarin-induced skin necrosis progressing to calciphylaxis. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2014;67:244-246.

- Kakagia DD, Papanas N, Karadimas E, et al. Warfarin-induced skin necrosis. Ann Dermatol. 2014;26:96-98.

- Kota SK, Jammula S, Kota SK, et al. Necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum: a case-based review of literature. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2012;16:614-620.

- Hayden MR, Goldsmith DJ. Sodium thiosulfate: new hope for the treatment of calciphylaxis. Semin Dial. 2010;23:258-262.

- Ning MS, Dahir KM, Castellanos EH, et al. Sodium thiosulfate in the treatment of non-uremic calciphylaxis. J Dermatol. 2013;40:649-652.

- Spentzouris G, Labropoulos N. The evaluation of lower-extremity ulcers. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2009;26:286-295.

- Nigwekar SU, Wolf M, Sterns RH, et al. Calciphylaxis from nonuremic causes: a systematic review. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3:1139-1143.

- Bardin T. Musculoskeletal manifestations of chronic renal failure. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2003;15:48-54.

- Hafner J, Nobbe S, Partsch H, et al. Martorell hypertensive ischemic leg ulcer: a model of ischemic subcutaneous arteriolosclerosis. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:961-968.

- Sedda S, Caruso R, Marafini I, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum in refractory celiac disease: a case report. BMC Gastroenterol. 2013;13:162.

- Su WP, Davis MD, Weenig RH, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum: clinicopathologic correlation and proposed diagnostic criteria. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:790-800.

- Breakey W, Hall C, Vann Jones S, et al. Warfarin-induced skin necrosis progressing to calciphylaxis. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2014;67:244-246.

- Kakagia DD, Papanas N, Karadimas E, et al. Warfarin-induced skin necrosis. Ann Dermatol. 2014;26:96-98.

- Kota SK, Jammula S, Kota SK, et al. Necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum: a case-based review of literature. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2012;16:614-620.

- Hayden MR, Goldsmith DJ. Sodium thiosulfate: new hope for the treatment of calciphylaxis. Semin Dial. 2010;23:258-262.

- Ning MS, Dahir KM, Castellanos EH, et al. Sodium thiosulfate in the treatment of non-uremic calciphylaxis. J Dermatol. 2013;40:649-652.

An 80-year-old woman with a medical history notable for obesity (body mass index, 31.2), type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and chronic atrial fibrillation treated with warfarin presented with a chronic painful wound on the left lower calf of 1 month's duration. A 7×7-cm ulcer on the posterior aspect of the left calf with necrotic debris was seen surrounded by skin of mottled purple discoloration. The edge of the ulcer was not undermined. There were tense nonhemorrhagic bullae on the medial aspect of the left leg and on bilateral anterior tibial areas. Two punch biopsy specimens were obtained from the anterior tibial bulla and the edge of the ulcer.

Wound expert: Consider hyperbaric oxygen therapy for diabetic foot ulcers

SAN DIEGO – Hyperbaric oxygen therapy, a mainstay of wound care, has a long and controversial history as a treatment for diabetic foot ulcers. Conflicting studies have spawned plenty of debate, and the most recent Cochrane Library review of existing research didn’t shed much light on the value of the treatment because the evidence was weak (Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Jun 24;[6]:CD004123).

But William H. Tettelbach, MD, a wound care specialist, told an audience at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetic Association that hyperbaric treatments are worth a try in certain cases. And he brought evidence to prove it – a 2015 report he coauthored that reviewed studies and offered clinical practice guidelines for hyperbaric oxygen therapy for the treatment of diabetic foot ulcers (DFUs) (Undersea Hyperb Med. 2015 May-Jun;42[3]:205-47).

In an interview, Dr. Tettelbach discussed ideal candidates for the treatment and offered clinical advice to endocrinologists.

Question: What did your review of research tell you about the value of hyperbaric oxygen treatment for DFUs?

Answer: We came to the same conclusion that most of the papers have indicated over the years: Hyperbaric oxygen is effective and attains goals such as reducing rates of amputation in a select population of diabetic ulcer patients.

Patients who have Wagner grade 3 or greater ulcers or admitted for surgery due to a septic diabetic foot benefit from an evaluation by a hyperbaric medicine–trained physician and treatment when indicated. There is evidence and years of clinical experience indicating that these patients benefit and have improved outcomes when evaluated and treated appropriately with hyperbaric oxygen therapy.