User login

Management of Trauma and Burn Scars: The Dermatologist’s Role in Expanding Patient Access to Care

Hypertrophic scarring secondary to trauma, burns, and surgical interventions is a major source of morbidity worldwide and often is mechanically, aesthetically, and symptomatically debilitating. Modern advances in acute trauma care protocols have resulted in survival rates greater than 90% in both civilian and military populations.1,2 Patients with wounds that have historically proven fatal are now surviving and are confronted with the long-term sequelae of their injuries. With more than 52,000 service members injured in military engagements from 2001 to 2015 and 8.5 million civilians presenting annually with injury patterns at risk for hypertrophic scarring, it is paramount that we ensure access to safe and effective long-term scar care.2,3

At its simplest level, hypertrophic scarring is believed to result from a disequilibrium between collagen production and degradation. This failure to properly transition through the stages of wound healing results in bothersome symptoms, a disfigured appearance, and mechanical dysfunction of the skin (Figure, A). Decreased elasticity and extensibility, increased dermal thickness, and scar contractures impair patient range of motion and functional mobility. Those affected commonly experience varying degrees of pruritus and dysesthesia along the scar. Combined with aesthetic variations in pigmentation, erythema, texture, and thickness, hypertrophic scarring often leads to long-term psychosocial impairment and decreased health-related quality of life.4

Treatment Approach

Treatment of hypertrophic scars requires a multimodal approach due to the spectrum of associated concerns and the natural recalcitrance of the scar to therapy. Protocols should be tailored to the individual but generally begin with tissue-conserving surgical interventions followed by selective photothermolysis of the scar vasculature. Subsequently, deep and superficial ablative fractional laser (AFL) treatment and local pharmacotherapy also are employed. Treatment can be accomplished in the outpatient setting under local anesthesia in a serial fashion. In the authors’ experience, these therapies behave in a synergistic fashion, achieving outcomes that far exceed the sum of their parts, often obviating the need for scar excision in the majority of cases (Figure, B).

Tissue-Conserving Surgical Intervention

Z-plasty is an indispensable surgical tool due to its ability to lengthen scars and reduce wound tension. Treatment is easily customizable to the patient and can be performed using the individual or multiple Z-plasty techniques. Undermining and step-off correction while suturing allow the physician to lower raised scars, elevate depressed scars, and obscure scar presence by minimizing the straight lines that draw the eye to the scar. Z-plasties rely on the creation and transposition of 2 triangular flaps and permit a 75% increase in length along the desired tension vector. As such, Z-plasties decrease wound tension and facilitate scar maturation.

Selective Photothermolysis of the Vasculature

Although there are several devices available to treat vascular and immature hypertrophic scars, the majority of studies have been conducted with the 595-nm pulsed dye laser. By preferentially heating oxyhemoglobin within the dermal microvasculature, the pulsed dye laser irreparably injures the vascular endothelium. The subsequent tissue hypoxia and collagen fiber heating results in collagen fiber realignment, normalization of collagen subtypes, and neocollagenesis.5 Pulsed dye laser therapy most effectively reduces erythema and pruritus; however, improvements in scar volume, pliability, and elasticity also have been reported.5 When targeting the fine vasculature of the scar, thermal confinement is critical to prevent injury to the surrounding dermis. As such, pulse widths of 0.45 to 1.5 milliseconds are routinely utilized with a fluence just sufficient to elicit transient purpura lasting 3 to 5 seconds. Employing a spot size of 7 to 10 mm, typical fluences range from 4.5 to 6.5 J/cm2. Engagement of the dynamic cooling device reduces the risk for complications, allowing the patient to proceed to the next step in their therapy regimen: the AFL.

Ablative Fractional Laser

The AFL creates a pixilated pattern of injury throughout the epidermis and dermis of the treatment area. Ablative fractional laser platforms include the 10,600-nm CO2 and 2940-nm erbium-doped YAG lasers, both targeting intracellular water. The AFL vaporizes columns of tissue, leaving minute vertical channels with narrow rims of protein coagulation referred to as microscopic treatment zones (MTZs).6 Scar collagen analysis after AFL treatment has shown a profile resembling unaffected skin.7 Consistently, patients report improvements in stiffness, range of motion, pain, pruritus, pigmentation, and erythema.Physician observers also have reported similar improvements in these end points.8,9 Recently, interim data from a prospective controlled trial were presented showing objective improvements in dermal thickness, elasticity, and extensibility after 3 treatments with the CO2 AFL.6 The UltraPulse CO2 laser (Lumenis) is the most well-studied and widely available AFL for scar therapy and as such we will outline common treatment parameters with this device. Of note, treatment end points may be generalized to any AFL.

The DeepFX UltraPulse configuration is utilized to achieve deep AFL therapy and has a fixed pulse width of 0.8 milliseconds, slightly less than the thermal relaxation time of the skin. The diameter of the MTZs is 120 µm, and MTZ density for scar treatment ranges from 1% to 10% with a goal depth of at least 80% of scar thickness. Maximal penetration of the AFL is 4 mm, which is directly proportional to fluence. The goal of deep AFL is the removal of scar tissue to facilitate remodeling and neocollagenesis. Superficial fractional ablation can then be achieved utilizing the ActiveFX UltraPulse configuration generating a 1.3-mm MTZ spot size. We commonly use a treatment level of 3 (82% density). Typical treatment energy ranges from 80 to 125 mJ, which correlates with depths of approximately 50 to 115 µm. With both configurations, the size and shape of the treatment area can be customized to the scar. In addition, frequency may be adjusted to control the speed of treatment while balancing the risk of bulk heating. The goal of superficial AFL is to minimize scar surface irregularities and ensure blending of deep AFL treatment. Once AFL treatment is complete, local pharmacotherapy can then be employed.

Pharmacotherapy

Intralesional corticosteroids have long represented the standard of care for hypertrophic scars, with concentrations between 2.5 and 40 mg/mL that are titrated to scar thickness and location to avoid unwanted atrophy. Visual blanching of the scar represents the clinical end point for treatment. Corticosteroids act by inhibiting fibroblast proliferation and enhancing collagen degradation.10 5-Fluorouracil (5-FU) also is used in scar management. In addition to inhibiting fibroblast proliferation and inducing fibroblast apoptosis, 5-FU inhibits myofibroblast proliferation, which is helpful in the prevention and treatment of scar contracture.11 As monotherapy, weekly injections with 1 to 3 mL of 50 mg/mL 5-FU has been safe and effective. Combination intralesional corticosteroid and 5-FU therapy has been reported and is associated with improved scar regression, reduced reoccurrence, and fewer side effects.11 In our experience, a 1:1 suspension is effective with appropriate titration of the corticosteroid component. Although less well defined, topical application of pharmacotherapy and massage to the newly created MTZs appears beneficial and offers another option for delivery of corticosteroids and 5-FU, in addition to a number of promising medications such as bimatoprost, poly-L-lactic acid, timolol, and rapamycin.12

Conclusion

Advances in laser surgery and our understanding of wound healing have created a paradigm shift in the treatment approach to trauma and burn scars. In lieu of extensive scar excisions, the summarized multimodal regimen emphasizing tissue conservation and autologous remodeling is gaining favor in the military, academic medical centers, and scar centers of excellence, but patients are finding local access to care difficult. Dermatologists are uniquely positioned to cost-effectively deliver this care in the outpatient setting utilizing devices and techniques they already possess. With the end goal of optimization of functional, symptomatic, and aesthetic state of the patient, it is critical that dermatologists seize this opportunity to truly make a difference for the military and civilian patients that need it most.

- American Burn Association, National Burn Repository. 2015 National burn repository report of data from 2005-2014. http://www.ameriburn.org/2015NBRAnnualReport.pdf. Accessed May 10, 2017.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2013 National hospital ambulatory medical care survey emergency department summary tables. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ahcd/nhamcs_emergency/2013_ed_web_tables.pdf. Accessed May 10, 2017.

- Fischer H. A guide to U.S. Military casualty statistics: Operation Freedom’s Sentinel, Operation Inherent Resolve, Operation New Dawn, Operation Iraqi Freedom, and Operation Enduring Freedom. Congressional Research Service website. https://fas.org/sgp/crs/natsec/RS22452.pdf. Published August 7, 2015. Accessed May 10, 2017.

- Van Loey NE, Van Son MJ. Psychopathology and psychological problems in patients with burn scars: epidemiology and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2003;4:245-272.

- Vrijman C, van Drooge AM, Limpens J, et al. Laser and intense pulsed light therapy for the treatment of hypertrophic scars: a systematic review. Br J Dermatol. 2011;165:934-942.

- Miletta N, Lee K, Siwy K, et al. Objective improvement in burn scars after treatment with fractionated CO2 laser. Paper presented at: American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery 36th Annual Conference; April 1-3, 2016; Boston, MA.

- Ozog DM, Liu A, Chaffins ML, et al. Evaluation of clinical results, histological architecture, and collagen expression following treatment of mature burn scars with a fraction carbon dioxide laser. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:50-57.

- Levi B, Ibrahim A, Mathews K, et al. The use of CO2 fractional photothermolysis for the treatment of burn scars. J Burn Care Res. 2016;37:106-114.

- van Drooge AM, Vrijman C, van der Veen W, et al. A randomized controlled pilot study on ablative fractional CO2 laser for consecutive patients presenting with various scar types. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41:371-377.

- Wang XQ, Lui YK, Wang ZY, et al. Antimitotic drug injections and radiotherapy: a review of the effectiveness of treatment for hypertrophic scars and keloids. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2008;7:151-159.

- Gupta S, Kalra A. Efficacy and safety of intralesional 5-fluorouracil in the treatment of keloids. Dermatology. 2002;204:130-132.

- Haedersdal M, Erlendsson AM, Paasch U, et al. Translational medicine in the field of AFL (AFXL)-assisted drug delivery: a critical review from basics to current clinical status. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:981-1004.

Hypertrophic scarring secondary to trauma, burns, and surgical interventions is a major source of morbidity worldwide and often is mechanically, aesthetically, and symptomatically debilitating. Modern advances in acute trauma care protocols have resulted in survival rates greater than 90% in both civilian and military populations.1,2 Patients with wounds that have historically proven fatal are now surviving and are confronted with the long-term sequelae of their injuries. With more than 52,000 service members injured in military engagements from 2001 to 2015 and 8.5 million civilians presenting annually with injury patterns at risk for hypertrophic scarring, it is paramount that we ensure access to safe and effective long-term scar care.2,3

At its simplest level, hypertrophic scarring is believed to result from a disequilibrium between collagen production and degradation. This failure to properly transition through the stages of wound healing results in bothersome symptoms, a disfigured appearance, and mechanical dysfunction of the skin (Figure, A). Decreased elasticity and extensibility, increased dermal thickness, and scar contractures impair patient range of motion and functional mobility. Those affected commonly experience varying degrees of pruritus and dysesthesia along the scar. Combined with aesthetic variations in pigmentation, erythema, texture, and thickness, hypertrophic scarring often leads to long-term psychosocial impairment and decreased health-related quality of life.4

Treatment Approach

Treatment of hypertrophic scars requires a multimodal approach due to the spectrum of associated concerns and the natural recalcitrance of the scar to therapy. Protocols should be tailored to the individual but generally begin with tissue-conserving surgical interventions followed by selective photothermolysis of the scar vasculature. Subsequently, deep and superficial ablative fractional laser (AFL) treatment and local pharmacotherapy also are employed. Treatment can be accomplished in the outpatient setting under local anesthesia in a serial fashion. In the authors’ experience, these therapies behave in a synergistic fashion, achieving outcomes that far exceed the sum of their parts, often obviating the need for scar excision in the majority of cases (Figure, B).

Tissue-Conserving Surgical Intervention

Z-plasty is an indispensable surgical tool due to its ability to lengthen scars and reduce wound tension. Treatment is easily customizable to the patient and can be performed using the individual or multiple Z-plasty techniques. Undermining and step-off correction while suturing allow the physician to lower raised scars, elevate depressed scars, and obscure scar presence by minimizing the straight lines that draw the eye to the scar. Z-plasties rely on the creation and transposition of 2 triangular flaps and permit a 75% increase in length along the desired tension vector. As such, Z-plasties decrease wound tension and facilitate scar maturation.

Selective Photothermolysis of the Vasculature

Although there are several devices available to treat vascular and immature hypertrophic scars, the majority of studies have been conducted with the 595-nm pulsed dye laser. By preferentially heating oxyhemoglobin within the dermal microvasculature, the pulsed dye laser irreparably injures the vascular endothelium. The subsequent tissue hypoxia and collagen fiber heating results in collagen fiber realignment, normalization of collagen subtypes, and neocollagenesis.5 Pulsed dye laser therapy most effectively reduces erythema and pruritus; however, improvements in scar volume, pliability, and elasticity also have been reported.5 When targeting the fine vasculature of the scar, thermal confinement is critical to prevent injury to the surrounding dermis. As such, pulse widths of 0.45 to 1.5 milliseconds are routinely utilized with a fluence just sufficient to elicit transient purpura lasting 3 to 5 seconds. Employing a spot size of 7 to 10 mm, typical fluences range from 4.5 to 6.5 J/cm2. Engagement of the dynamic cooling device reduces the risk for complications, allowing the patient to proceed to the next step in their therapy regimen: the AFL.

Ablative Fractional Laser

The AFL creates a pixilated pattern of injury throughout the epidermis and dermis of the treatment area. Ablative fractional laser platforms include the 10,600-nm CO2 and 2940-nm erbium-doped YAG lasers, both targeting intracellular water. The AFL vaporizes columns of tissue, leaving minute vertical channels with narrow rims of protein coagulation referred to as microscopic treatment zones (MTZs).6 Scar collagen analysis after AFL treatment has shown a profile resembling unaffected skin.7 Consistently, patients report improvements in stiffness, range of motion, pain, pruritus, pigmentation, and erythema.Physician observers also have reported similar improvements in these end points.8,9 Recently, interim data from a prospective controlled trial were presented showing objective improvements in dermal thickness, elasticity, and extensibility after 3 treatments with the CO2 AFL.6 The UltraPulse CO2 laser (Lumenis) is the most well-studied and widely available AFL for scar therapy and as such we will outline common treatment parameters with this device. Of note, treatment end points may be generalized to any AFL.

The DeepFX UltraPulse configuration is utilized to achieve deep AFL therapy and has a fixed pulse width of 0.8 milliseconds, slightly less than the thermal relaxation time of the skin. The diameter of the MTZs is 120 µm, and MTZ density for scar treatment ranges from 1% to 10% with a goal depth of at least 80% of scar thickness. Maximal penetration of the AFL is 4 mm, which is directly proportional to fluence. The goal of deep AFL is the removal of scar tissue to facilitate remodeling and neocollagenesis. Superficial fractional ablation can then be achieved utilizing the ActiveFX UltraPulse configuration generating a 1.3-mm MTZ spot size. We commonly use a treatment level of 3 (82% density). Typical treatment energy ranges from 80 to 125 mJ, which correlates with depths of approximately 50 to 115 µm. With both configurations, the size and shape of the treatment area can be customized to the scar. In addition, frequency may be adjusted to control the speed of treatment while balancing the risk of bulk heating. The goal of superficial AFL is to minimize scar surface irregularities and ensure blending of deep AFL treatment. Once AFL treatment is complete, local pharmacotherapy can then be employed.

Pharmacotherapy

Intralesional corticosteroids have long represented the standard of care for hypertrophic scars, with concentrations between 2.5 and 40 mg/mL that are titrated to scar thickness and location to avoid unwanted atrophy. Visual blanching of the scar represents the clinical end point for treatment. Corticosteroids act by inhibiting fibroblast proliferation and enhancing collagen degradation.10 5-Fluorouracil (5-FU) also is used in scar management. In addition to inhibiting fibroblast proliferation and inducing fibroblast apoptosis, 5-FU inhibits myofibroblast proliferation, which is helpful in the prevention and treatment of scar contracture.11 As monotherapy, weekly injections with 1 to 3 mL of 50 mg/mL 5-FU has been safe and effective. Combination intralesional corticosteroid and 5-FU therapy has been reported and is associated with improved scar regression, reduced reoccurrence, and fewer side effects.11 In our experience, a 1:1 suspension is effective with appropriate titration of the corticosteroid component. Although less well defined, topical application of pharmacotherapy and massage to the newly created MTZs appears beneficial and offers another option for delivery of corticosteroids and 5-FU, in addition to a number of promising medications such as bimatoprost, poly-L-lactic acid, timolol, and rapamycin.12

Conclusion

Advances in laser surgery and our understanding of wound healing have created a paradigm shift in the treatment approach to trauma and burn scars. In lieu of extensive scar excisions, the summarized multimodal regimen emphasizing tissue conservation and autologous remodeling is gaining favor in the military, academic medical centers, and scar centers of excellence, but patients are finding local access to care difficult. Dermatologists are uniquely positioned to cost-effectively deliver this care in the outpatient setting utilizing devices and techniques they already possess. With the end goal of optimization of functional, symptomatic, and aesthetic state of the patient, it is critical that dermatologists seize this opportunity to truly make a difference for the military and civilian patients that need it most.

Hypertrophic scarring secondary to trauma, burns, and surgical interventions is a major source of morbidity worldwide and often is mechanically, aesthetically, and symptomatically debilitating. Modern advances in acute trauma care protocols have resulted in survival rates greater than 90% in both civilian and military populations.1,2 Patients with wounds that have historically proven fatal are now surviving and are confronted with the long-term sequelae of their injuries. With more than 52,000 service members injured in military engagements from 2001 to 2015 and 8.5 million civilians presenting annually with injury patterns at risk for hypertrophic scarring, it is paramount that we ensure access to safe and effective long-term scar care.2,3

At its simplest level, hypertrophic scarring is believed to result from a disequilibrium between collagen production and degradation. This failure to properly transition through the stages of wound healing results in bothersome symptoms, a disfigured appearance, and mechanical dysfunction of the skin (Figure, A). Decreased elasticity and extensibility, increased dermal thickness, and scar contractures impair patient range of motion and functional mobility. Those affected commonly experience varying degrees of pruritus and dysesthesia along the scar. Combined with aesthetic variations in pigmentation, erythema, texture, and thickness, hypertrophic scarring often leads to long-term psychosocial impairment and decreased health-related quality of life.4

Treatment Approach

Treatment of hypertrophic scars requires a multimodal approach due to the spectrum of associated concerns and the natural recalcitrance of the scar to therapy. Protocols should be tailored to the individual but generally begin with tissue-conserving surgical interventions followed by selective photothermolysis of the scar vasculature. Subsequently, deep and superficial ablative fractional laser (AFL) treatment and local pharmacotherapy also are employed. Treatment can be accomplished in the outpatient setting under local anesthesia in a serial fashion. In the authors’ experience, these therapies behave in a synergistic fashion, achieving outcomes that far exceed the sum of their parts, often obviating the need for scar excision in the majority of cases (Figure, B).

Tissue-Conserving Surgical Intervention

Z-plasty is an indispensable surgical tool due to its ability to lengthen scars and reduce wound tension. Treatment is easily customizable to the patient and can be performed using the individual or multiple Z-plasty techniques. Undermining and step-off correction while suturing allow the physician to lower raised scars, elevate depressed scars, and obscure scar presence by minimizing the straight lines that draw the eye to the scar. Z-plasties rely on the creation and transposition of 2 triangular flaps and permit a 75% increase in length along the desired tension vector. As such, Z-plasties decrease wound tension and facilitate scar maturation.

Selective Photothermolysis of the Vasculature

Although there are several devices available to treat vascular and immature hypertrophic scars, the majority of studies have been conducted with the 595-nm pulsed dye laser. By preferentially heating oxyhemoglobin within the dermal microvasculature, the pulsed dye laser irreparably injures the vascular endothelium. The subsequent tissue hypoxia and collagen fiber heating results in collagen fiber realignment, normalization of collagen subtypes, and neocollagenesis.5 Pulsed dye laser therapy most effectively reduces erythema and pruritus; however, improvements in scar volume, pliability, and elasticity also have been reported.5 When targeting the fine vasculature of the scar, thermal confinement is critical to prevent injury to the surrounding dermis. As such, pulse widths of 0.45 to 1.5 milliseconds are routinely utilized with a fluence just sufficient to elicit transient purpura lasting 3 to 5 seconds. Employing a spot size of 7 to 10 mm, typical fluences range from 4.5 to 6.5 J/cm2. Engagement of the dynamic cooling device reduces the risk for complications, allowing the patient to proceed to the next step in their therapy regimen: the AFL.

Ablative Fractional Laser

The AFL creates a pixilated pattern of injury throughout the epidermis and dermis of the treatment area. Ablative fractional laser platforms include the 10,600-nm CO2 and 2940-nm erbium-doped YAG lasers, both targeting intracellular water. The AFL vaporizes columns of tissue, leaving minute vertical channels with narrow rims of protein coagulation referred to as microscopic treatment zones (MTZs).6 Scar collagen analysis after AFL treatment has shown a profile resembling unaffected skin.7 Consistently, patients report improvements in stiffness, range of motion, pain, pruritus, pigmentation, and erythema.Physician observers also have reported similar improvements in these end points.8,9 Recently, interim data from a prospective controlled trial were presented showing objective improvements in dermal thickness, elasticity, and extensibility after 3 treatments with the CO2 AFL.6 The UltraPulse CO2 laser (Lumenis) is the most well-studied and widely available AFL for scar therapy and as such we will outline common treatment parameters with this device. Of note, treatment end points may be generalized to any AFL.

The DeepFX UltraPulse configuration is utilized to achieve deep AFL therapy and has a fixed pulse width of 0.8 milliseconds, slightly less than the thermal relaxation time of the skin. The diameter of the MTZs is 120 µm, and MTZ density for scar treatment ranges from 1% to 10% with a goal depth of at least 80% of scar thickness. Maximal penetration of the AFL is 4 mm, which is directly proportional to fluence. The goal of deep AFL is the removal of scar tissue to facilitate remodeling and neocollagenesis. Superficial fractional ablation can then be achieved utilizing the ActiveFX UltraPulse configuration generating a 1.3-mm MTZ spot size. We commonly use a treatment level of 3 (82% density). Typical treatment energy ranges from 80 to 125 mJ, which correlates with depths of approximately 50 to 115 µm. With both configurations, the size and shape of the treatment area can be customized to the scar. In addition, frequency may be adjusted to control the speed of treatment while balancing the risk of bulk heating. The goal of superficial AFL is to minimize scar surface irregularities and ensure blending of deep AFL treatment. Once AFL treatment is complete, local pharmacotherapy can then be employed.

Pharmacotherapy

Intralesional corticosteroids have long represented the standard of care for hypertrophic scars, with concentrations between 2.5 and 40 mg/mL that are titrated to scar thickness and location to avoid unwanted atrophy. Visual blanching of the scar represents the clinical end point for treatment. Corticosteroids act by inhibiting fibroblast proliferation and enhancing collagen degradation.10 5-Fluorouracil (5-FU) also is used in scar management. In addition to inhibiting fibroblast proliferation and inducing fibroblast apoptosis, 5-FU inhibits myofibroblast proliferation, which is helpful in the prevention and treatment of scar contracture.11 As monotherapy, weekly injections with 1 to 3 mL of 50 mg/mL 5-FU has been safe and effective. Combination intralesional corticosteroid and 5-FU therapy has been reported and is associated with improved scar regression, reduced reoccurrence, and fewer side effects.11 In our experience, a 1:1 suspension is effective with appropriate titration of the corticosteroid component. Although less well defined, topical application of pharmacotherapy and massage to the newly created MTZs appears beneficial and offers another option for delivery of corticosteroids and 5-FU, in addition to a number of promising medications such as bimatoprost, poly-L-lactic acid, timolol, and rapamycin.12

Conclusion

Advances in laser surgery and our understanding of wound healing have created a paradigm shift in the treatment approach to trauma and burn scars. In lieu of extensive scar excisions, the summarized multimodal regimen emphasizing tissue conservation and autologous remodeling is gaining favor in the military, academic medical centers, and scar centers of excellence, but patients are finding local access to care difficult. Dermatologists are uniquely positioned to cost-effectively deliver this care in the outpatient setting utilizing devices and techniques they already possess. With the end goal of optimization of functional, symptomatic, and aesthetic state of the patient, it is critical that dermatologists seize this opportunity to truly make a difference for the military and civilian patients that need it most.

- American Burn Association, National Burn Repository. 2015 National burn repository report of data from 2005-2014. http://www.ameriburn.org/2015NBRAnnualReport.pdf. Accessed May 10, 2017.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2013 National hospital ambulatory medical care survey emergency department summary tables. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ahcd/nhamcs_emergency/2013_ed_web_tables.pdf. Accessed May 10, 2017.

- Fischer H. A guide to U.S. Military casualty statistics: Operation Freedom’s Sentinel, Operation Inherent Resolve, Operation New Dawn, Operation Iraqi Freedom, and Operation Enduring Freedom. Congressional Research Service website. https://fas.org/sgp/crs/natsec/RS22452.pdf. Published August 7, 2015. Accessed May 10, 2017.

- Van Loey NE, Van Son MJ. Psychopathology and psychological problems in patients with burn scars: epidemiology and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2003;4:245-272.

- Vrijman C, van Drooge AM, Limpens J, et al. Laser and intense pulsed light therapy for the treatment of hypertrophic scars: a systematic review. Br J Dermatol. 2011;165:934-942.

- Miletta N, Lee K, Siwy K, et al. Objective improvement in burn scars after treatment with fractionated CO2 laser. Paper presented at: American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery 36th Annual Conference; April 1-3, 2016; Boston, MA.

- Ozog DM, Liu A, Chaffins ML, et al. Evaluation of clinical results, histological architecture, and collagen expression following treatment of mature burn scars with a fraction carbon dioxide laser. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:50-57.

- Levi B, Ibrahim A, Mathews K, et al. The use of CO2 fractional photothermolysis for the treatment of burn scars. J Burn Care Res. 2016;37:106-114.

- van Drooge AM, Vrijman C, van der Veen W, et al. A randomized controlled pilot study on ablative fractional CO2 laser for consecutive patients presenting with various scar types. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41:371-377.

- Wang XQ, Lui YK, Wang ZY, et al. Antimitotic drug injections and radiotherapy: a review of the effectiveness of treatment for hypertrophic scars and keloids. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2008;7:151-159.

- Gupta S, Kalra A. Efficacy and safety of intralesional 5-fluorouracil in the treatment of keloids. Dermatology. 2002;204:130-132.

- Haedersdal M, Erlendsson AM, Paasch U, et al. Translational medicine in the field of AFL (AFXL)-assisted drug delivery: a critical review from basics to current clinical status. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:981-1004.

- American Burn Association, National Burn Repository. 2015 National burn repository report of data from 2005-2014. http://www.ameriburn.org/2015NBRAnnualReport.pdf. Accessed May 10, 2017.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2013 National hospital ambulatory medical care survey emergency department summary tables. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ahcd/nhamcs_emergency/2013_ed_web_tables.pdf. Accessed May 10, 2017.

- Fischer H. A guide to U.S. Military casualty statistics: Operation Freedom’s Sentinel, Operation Inherent Resolve, Operation New Dawn, Operation Iraqi Freedom, and Operation Enduring Freedom. Congressional Research Service website. https://fas.org/sgp/crs/natsec/RS22452.pdf. Published August 7, 2015. Accessed May 10, 2017.

- Van Loey NE, Van Son MJ. Psychopathology and psychological problems in patients with burn scars: epidemiology and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2003;4:245-272.

- Vrijman C, van Drooge AM, Limpens J, et al. Laser and intense pulsed light therapy for the treatment of hypertrophic scars: a systematic review. Br J Dermatol. 2011;165:934-942.

- Miletta N, Lee K, Siwy K, et al. Objective improvement in burn scars after treatment with fractionated CO2 laser. Paper presented at: American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery 36th Annual Conference; April 1-3, 2016; Boston, MA.

- Ozog DM, Liu A, Chaffins ML, et al. Evaluation of clinical results, histological architecture, and collagen expression following treatment of mature burn scars with a fraction carbon dioxide laser. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:50-57.

- Levi B, Ibrahim A, Mathews K, et al. The use of CO2 fractional photothermolysis for the treatment of burn scars. J Burn Care Res. 2016;37:106-114.

- van Drooge AM, Vrijman C, van der Veen W, et al. A randomized controlled pilot study on ablative fractional CO2 laser for consecutive patients presenting with various scar types. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41:371-377.

- Wang XQ, Lui YK, Wang ZY, et al. Antimitotic drug injections and radiotherapy: a review of the effectiveness of treatment for hypertrophic scars and keloids. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2008;7:151-159.

- Gupta S, Kalra A. Efficacy and safety of intralesional 5-fluorouracil in the treatment of keloids. Dermatology. 2002;204:130-132.

- Haedersdal M, Erlendsson AM, Paasch U, et al. Translational medicine in the field of AFL (AFXL)-assisted drug delivery: a critical review from basics to current clinical status. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:981-1004.

Practice Points

- Burn and trauma scarring represents a major source of morbidity in both the civilian and military populations worldwide and often is mechanically, aesthetically, and symptomatically debilitating.

- Advances in laser surgery and our understanding of wound healing have resulted in a scar therapy paradigm shift from large scar excisions and repair to a multimodal, tissue-conserving approach that relies on remodeling of the existing tissue.

- Dermatologists are uniquely positioned to increase patient access to cost-effective, outpatient-based burn and trauma scar care utilizing devices and techniques that they currently possess.

In Vivo Reflectance Confocal Microscopy

Reflectance confocal microscopy (RCM) imaging received Category I Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services in January 2016 and can now be submitted to insurance companies with reimbursement comparable to a skin biopsy or a global skin pathology service.1 This fairly new technology is a US Food and Drug Administration–cleared noninvasive imaging modality that provides high-resolution in vivo cellular images of the skin. It has been shown to be efficacious in differentiating benign and malignant skin lesions, increasing diagnostic accuracy, and reducing the number of unnecessary skin biopsies that are performed. In addition to skin cancer diagnosis, RCM imaging also can help guide management of malignant lesions by detecting lateral margins prior to surgery as well as monitoring the lesion over time for treatment efficacy or recurrence. The potential impact of RCM imaging is tremendous, and reimbursement may lead to increased use in clinical practice to the benefit of our patients. Herein, we present a brief review of RCM imaging and reimbursement as well as the benefits and limitations of this new technology for dermatologists.

Reflectance Confocal Microscopy

In vivo RCM allows us to visualize the epidermis in real time on a cellular level down to the papillary dermis at a high resolution (×30) comparable to histologic examination. With optical sections 3- to 5-µm thick and a lateral resolution of 0.5 to 1.0 µm, RCM produces a stack of 500×500-µm2 images up to a depth of approximately 200 µm.2,3 At any chosen depth, these smaller images are stitched together with sophisticated software into a block, or mosaic, increasing the field of view to up to 8×8 mm2. Imaging is performed in en face planes oriented parallel to the skin surface, similar to dermoscopy.

Current CPT Guidelines and Reimbursement

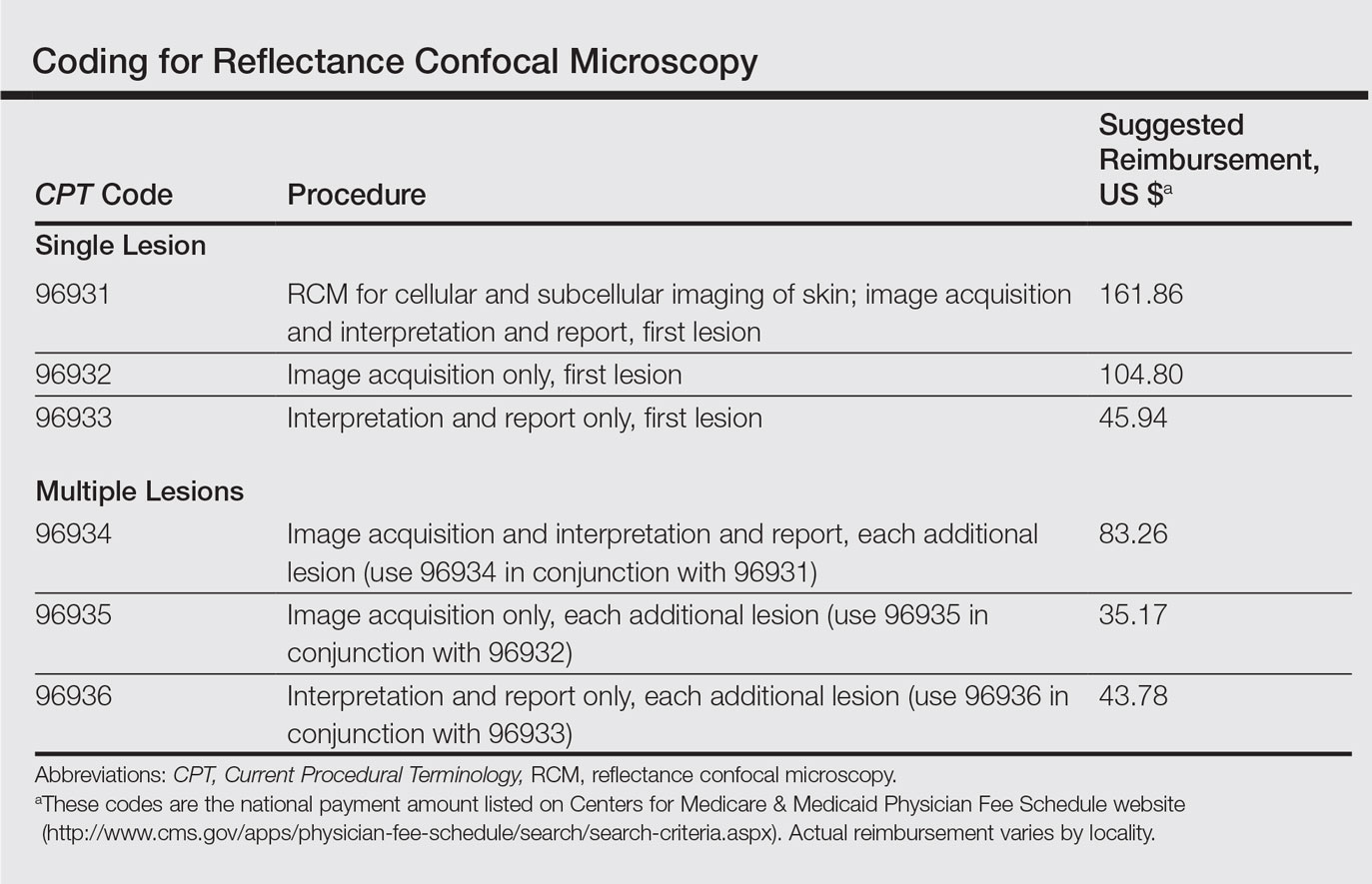

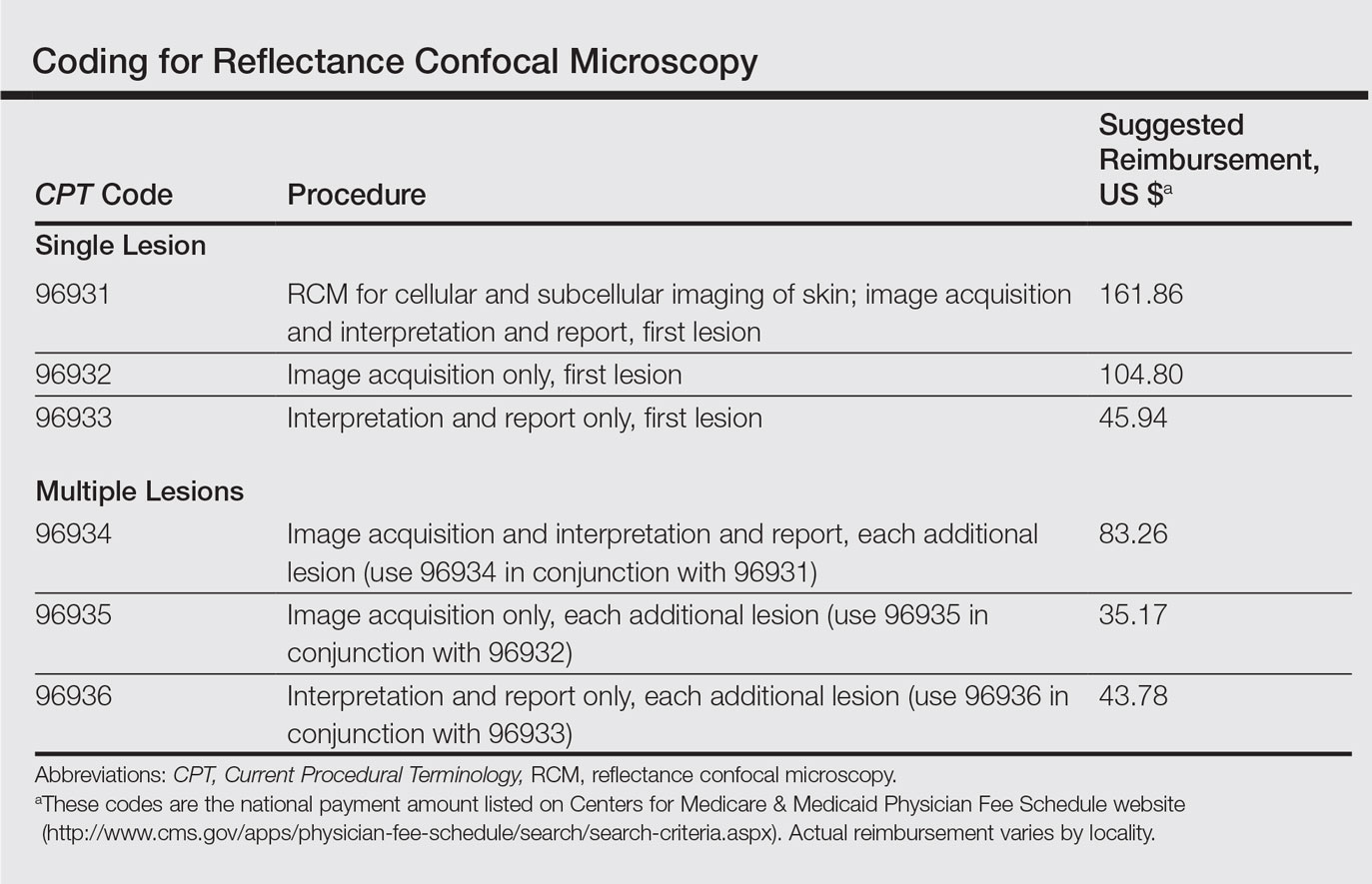

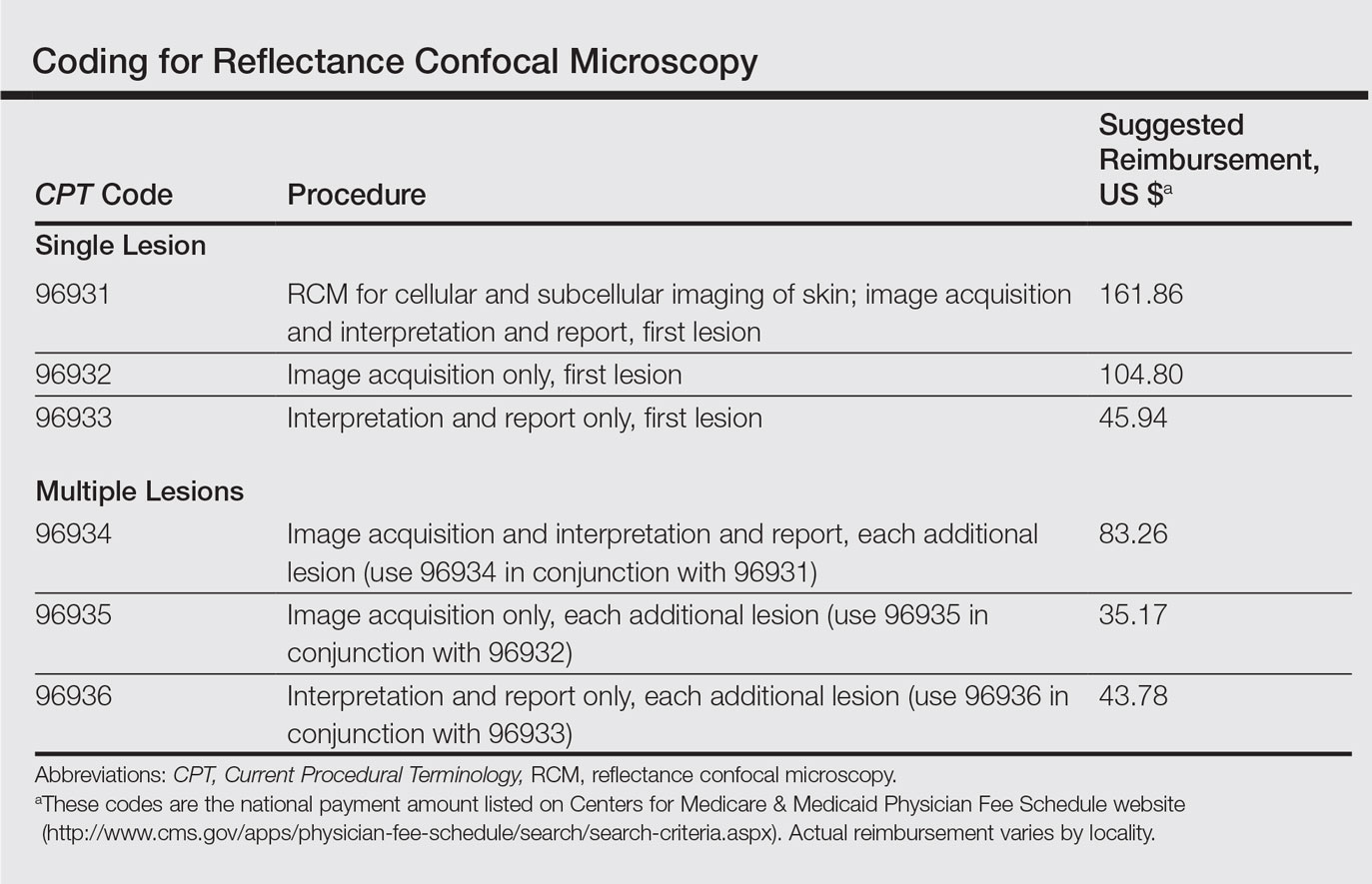

The CPT codes for RCM imaging provide reimbursement on a per-lesion basis and are similar to those used for skin biopsy and pathology (Table).1 Codes 96931 through 96933 are used for imaging of a single lesion on a patient. The first code—96931—is used when image acquisition, interpretation, and report creation are carried out by a single clinician. The next 2 codes are used when one clinician acquires the image—96932—comparable to the technical component of a pathology code, while another reads it and creates the report—96933—similar to a dermatopathologist billing for the professional component of a pathology report. For patients presenting with multiple lesions, the next 3 codes—96934, 96935, and 96936—are used in conjunction with the applicable first code for each additional lesion with similar global, technical, and professional components. Because these codes are not in the radiology or pathology sections of CPT, a single code cannot be used with modifier -TC (technical component) and modifier -26, as they are in those sections.

The wide-probe VivaScope 1500 (Caliber I.D., Inc) currently is the only confocal device that can be reported with a CPT code and routinely reimbursed. The handheld VivaScope 3000 (Caliber I.D., Inc) can only view a small stack and does not have the ability to acquire a full mosaic image; it is not covered by these codes.

Images can be viewed as a stack captured at the same horizontal position but at sequential depths or as a mosaic, which has a larger field of view but is limited to a single plane. To appropriately assess a lesion, clinicians must obtain a mosaic that needs to be assessed at multiple layers for a diagnosis to be made because it is a cross-section view.

Diagnosis

Studies have demonstrated the usefulness of RCM imaging in the diagnosis of a wide range of skin diseases, including melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancers, infectious diseases, and inflammatory and autoimmune conditions, as well as wound healing and skin aging. Reflectance confocal microscopy imaging is not limited to the skin; it can be used to evaluate the hair, nails, oral mucosa, and other organs.

According to several studies, RCM imaging notably increases the diagnostic accuracy and detection rate of skin cancers over clinical and dermoscopic examination alone and therefore can act as an aid in differentiating lesions that are benign versus those that are suspicious and should be biopsied.

Reflectance confocal microscopy has been shown to have a mean sensitivity of 94% (range, 92%–96%) and specificity of 83% (range, 81%–84%) for all types of skin cancer when used with dermoscopy.4 In particular, for melanocytic lesions that are ambiguous on dermoscopy, RCM used in addition to dermoscopy increases the mean sensitivity and specificity for melanoma diagnosis to 93% (range, 89%–96%) and 76% (range, 68%–83%), respectively.5 Although these reported sensitivities are comparable to dermoscopy, the specificity is superior, especially for detecting hypomelanotic and amelanotic melanomas, which often lack specific features on dermoscopy.6-8

The combination of RCM with dermoscopy has reduced the number of unnecessary excisions of benign nevi by more than 50% when compared to dermoscopy alone.9 One study showed that the number needed to treat (ie, excise) a melanoma decreased from 14.6 with dermoscopy alone to 6.8 when guided by dermoscopy and RCM imaging.9 In a similar study, the number needed to treat dropped from 19.41 with dermoscopy alone to 6.25 with dermoscopy and RCM.10

These studies were not looking to evaluate RCM as a replacement test but rather as an add-on test to dermoscopy. Reflectance confocal microscopy imaging takes longer than dermoscopy for each lesion; therefore, RCM should only be used as an adjunctive tool to dermoscopy and not as an initial screening test. Consequentially, a dermatologist skilled in dermoscopy is essential in deciding which lesions would be appropriate for subsequent RCM imaging.

In Vivo Margin Mapping as an Adjunct to Surgery

Oftentimes, tumor margins are poorly defined and can be difficult to map clinically and dermoscopically. Studies have demonstrated the use of RCM in delineation of surgical margins prior to surgery or excisional biopsies.11,12 Alternatively, when complete removal at biopsy would be impractical (eg, for extremely large lesions or lesions located in cosmetically sensitive areas such as the face), RCM can be used to pick the best site for an appropriate biopsy, which decreases the chance of sampling error due to skip lesions and increases histologic accuracy.

Nonsurgical Treatment Monitoring

One advantage of RCM over conventional histology is that RCM imaging leaves the tissue intact, allowing dynamic changes to be studied over time, which is useful for monitoring nonmelanoma skin cancers and lentigo maligna being treated with noninvasive therapeutic modalities.13 If not as a definitive treatment, RCM can act as an adjunct for surgery by monitoring reduction in lesion size prior to Mohs micrographic surgery, thereby decreasing the resulting surgical defect.14

Limitations

Imaging Depth

Although RCM is a revolutionary device in the field of dermatology, it has several limitations. With a maximal imaging depth of 350 µm, the imaging resolution decreases substantially with depth, limiting accurate interpretation to 200 µm. Reflectance confocal microscopy can only image the superficial portion of a lesion; therefore, deep tumor margins cannot be assessed. Hypertrophic or hyperkeratotic lesions, including lesions on the palms and soles, also are unable to be imaged with RCM. This limitation in depth penetration makes treatment monitoring impossible for invasive lesions that extend into the dermal layer.

Difficult-to-Reach Areas

Another limitation is the difficulty imaging areas such as the ocular canthi, nasal alae, or helices of the ear due to the wide probe size on the VivaScope 1500. The advent of the smaller handheld VivaScope 3000 device allows for improved imaging of concave services and difficult lesions at the risk of less accurate imaging, low field of view, and no reimbursement at present.

False-Positive Results

Although RCM has been shown to be helpful in reducing unnecessary biopsies, there still is the issue of false-positives on imaging. False-positives most commonly occur in nevi with severe atypia or when Langerhans cells are present that cannot always be differentiated from melanocytic cells.3,15,16 One prospective study found 7 false-positive results from 63 sites using RCM for the diagnosis of lentigo malignas.16 False-negatives can occur in the presence of inflammatory infiltrates and scar tissue that can hide cellular morphology or in sampling errors due to skip lesions.3,16

Time Efficiency

The time required for acquisition of RCM mosaics and stacks followed by reading and interpretation can be substantial depending on the size and complexity of the lesion, which is a major limitation for use of RCM in busy dermatology practices; therefore, RCM should be reserved for lesions selected to undergo biopsy that are clinically equivocal for malignancy prior to RCM examination.17 It would not be cost-effective or time effective to evaluate lesions that either clinically or dermoscopically have a high probability of malignancy; however, patients and physicians may opt for increased specificity at the expense of time, particularly when a lesion is located on a cosmetically sensitive area, as patients can avoid initial histologic biopsy and gain the cosmetic benefit of going straight to surgery versus obtaining an initial diagnostic biopsy.

Cost

Lastly, the high cost involved in purchasing an RCM device and the training involved to use and interpret RCM images currently limits RCM to large academic centers. Reimbursement may make more widespread use feasible. In any event, RCM imaging should be part of the curriculum for both dermatology and pathology trainees.

Future Directions

In vivo RCM is a noninvasive imaging modality that allows for real-time evaluation of the skin. Used in conjunction with dermoscopy, RCM can substantially improve diagnostic accuracy and reduce the number of unnecessary biopsies. Now that RCM has finally gained foundational CPT codes and insurance reimbursement, there may be a growing demand for clinicians to incorporate this technology into their clinical practice.

- Current Procedural Terminology 2017, Professional Edition. Chicago IL: American Medical Association; 2016.

- Que SK, Fraga-Braghiroli N, Grant-Kels JM, et al. Through the looking glass: basics and principles of reflectance confocal microscopy [published online June 4, 2015]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:276-284.

- Rajadhyaksha M, Marghoob A, Rossi A, et al. Reflectance confocal microscopy of skin in vivo: from bench to bedside [published online October 27, 2016]. Lasers Surg Med. 2017;49:7-19.

- Xiong YD, Ma S, Li X, et al. A meta-analysis of reflectance confocal microscopy for the diagnosis of malignant skin tumours. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:1295-1302.

- Stevenson AD, Mickan S, Mallett S, et al. Systematic review of diagnostic accuracy of reflectance confocal microscopy for melanoma diagnosis in patients with clinically equivocal skin lesions. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2013;3:19-27.

- Busam KJ, Hester K, Charles C, et al. Detection of clinically amelanotic malignant melanoma and assessment of its margins by in vivo confocal scanning laser microscopy. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:923-929.

- Losi A, Longo C, Cesinaro AM, et al. Hyporeflective pagetoid cells: a new clue for amelanotic melanoma diagnosis by reflectance confocal microscopy. Br J Dermatol. 2014;171:48-54.

- Guitera P, Menzies SQ, Argenziano G, et al. Dermoscopy and in vivo confocal microscopy are complementary techniques for the diagnosis of difficult amelanotic and light-coloured skin lesions [published online October 12, 2016]. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175:1311-1319.

- Pellacani G, Pepe P, Casari A, et al. Reflectance confocal microscopy as a second-level examination in skin oncology improves diagnostic accuracy and saves unnecessary excisions: a longitudinal prospective study. Br J Dermatol. 2014;171:1044-1051.

- Pellacani G, Witkowski A, Cesinaro AM, et al. Cost-benefit of reflectance confocal microscopy in the diagnostic performance of melanoma. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:413-419.

- Champin J, Perrot JL, Cinotti E, et al. In vivo reflectance confocal microscopy to optimize the spaghetti technique for defining surgical margins of lentigo maligna. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40:247-256.

- Hibler BP, Cordova M, Wong RJ, et al. Intraoperative real-time reflectance confocal microscopy for guiding surgical margins of lentigo maligna melanoma. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41:980-983.

- Ulrich M, Lange-Asschenfeldt S, Gonzalez S. The use of reflectance confocal microscopy for monitoring response to therapy of skin malignancies. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2012;2:202a10.

- Torres A, Niemeyer A, Berkes B, et al. 5% imiquimod cream and reflectance-mode confocal microscopy as adjunct modalities to Mohs micrographic surgery for treatment of basal cell carcinoma. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30(12, pt 1):1462-1469.

- Hashemi P, Pulitzer MP, Scope A, et al. Langerhans cells and melanocytes share similar morphologic features under in vivo reflectance confocal microscopy: a challenge for melanoma diagnosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:452-462.

- Menge TD, Hibler BP, Cordova MA, et al. Concordance of handheld reflectance confocal microscopy (RCM) with histopathology in the diagnosis of lentigo maligna (LM): a prospective study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:1114-1120.

- Borsari S, Pampena R, Lallas A, et al. Clinical indications for use of reflectance confocal microscopy for skin cancer diagnosis. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:1093-1098.

Reflectance confocal microscopy (RCM) imaging received Category I Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services in January 2016 and can now be submitted to insurance companies with reimbursement comparable to a skin biopsy or a global skin pathology service.1 This fairly new technology is a US Food and Drug Administration–cleared noninvasive imaging modality that provides high-resolution in vivo cellular images of the skin. It has been shown to be efficacious in differentiating benign and malignant skin lesions, increasing diagnostic accuracy, and reducing the number of unnecessary skin biopsies that are performed. In addition to skin cancer diagnosis, RCM imaging also can help guide management of malignant lesions by detecting lateral margins prior to surgery as well as monitoring the lesion over time for treatment efficacy or recurrence. The potential impact of RCM imaging is tremendous, and reimbursement may lead to increased use in clinical practice to the benefit of our patients. Herein, we present a brief review of RCM imaging and reimbursement as well as the benefits and limitations of this new technology for dermatologists.

Reflectance Confocal Microscopy

In vivo RCM allows us to visualize the epidermis in real time on a cellular level down to the papillary dermis at a high resolution (×30) comparable to histologic examination. With optical sections 3- to 5-µm thick and a lateral resolution of 0.5 to 1.0 µm, RCM produces a stack of 500×500-µm2 images up to a depth of approximately 200 µm.2,3 At any chosen depth, these smaller images are stitched together with sophisticated software into a block, or mosaic, increasing the field of view to up to 8×8 mm2. Imaging is performed in en face planes oriented parallel to the skin surface, similar to dermoscopy.

Current CPT Guidelines and Reimbursement

The CPT codes for RCM imaging provide reimbursement on a per-lesion basis and are similar to those used for skin biopsy and pathology (Table).1 Codes 96931 through 96933 are used for imaging of a single lesion on a patient. The first code—96931—is used when image acquisition, interpretation, and report creation are carried out by a single clinician. The next 2 codes are used when one clinician acquires the image—96932—comparable to the technical component of a pathology code, while another reads it and creates the report—96933—similar to a dermatopathologist billing for the professional component of a pathology report. For patients presenting with multiple lesions, the next 3 codes—96934, 96935, and 96936—are used in conjunction with the applicable first code for each additional lesion with similar global, technical, and professional components. Because these codes are not in the radiology or pathology sections of CPT, a single code cannot be used with modifier -TC (technical component) and modifier -26, as they are in those sections.

The wide-probe VivaScope 1500 (Caliber I.D., Inc) currently is the only confocal device that can be reported with a CPT code and routinely reimbursed. The handheld VivaScope 3000 (Caliber I.D., Inc) can only view a small stack and does not have the ability to acquire a full mosaic image; it is not covered by these codes.

Images can be viewed as a stack captured at the same horizontal position but at sequential depths or as a mosaic, which has a larger field of view but is limited to a single plane. To appropriately assess a lesion, clinicians must obtain a mosaic that needs to be assessed at multiple layers for a diagnosis to be made because it is a cross-section view.

Diagnosis

Studies have demonstrated the usefulness of RCM imaging in the diagnosis of a wide range of skin diseases, including melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancers, infectious diseases, and inflammatory and autoimmune conditions, as well as wound healing and skin aging. Reflectance confocal microscopy imaging is not limited to the skin; it can be used to evaluate the hair, nails, oral mucosa, and other organs.

According to several studies, RCM imaging notably increases the diagnostic accuracy and detection rate of skin cancers over clinical and dermoscopic examination alone and therefore can act as an aid in differentiating lesions that are benign versus those that are suspicious and should be biopsied.

Reflectance confocal microscopy has been shown to have a mean sensitivity of 94% (range, 92%–96%) and specificity of 83% (range, 81%–84%) for all types of skin cancer when used with dermoscopy.4 In particular, for melanocytic lesions that are ambiguous on dermoscopy, RCM used in addition to dermoscopy increases the mean sensitivity and specificity for melanoma diagnosis to 93% (range, 89%–96%) and 76% (range, 68%–83%), respectively.5 Although these reported sensitivities are comparable to dermoscopy, the specificity is superior, especially for detecting hypomelanotic and amelanotic melanomas, which often lack specific features on dermoscopy.6-8

The combination of RCM with dermoscopy has reduced the number of unnecessary excisions of benign nevi by more than 50% when compared to dermoscopy alone.9 One study showed that the number needed to treat (ie, excise) a melanoma decreased from 14.6 with dermoscopy alone to 6.8 when guided by dermoscopy and RCM imaging.9 In a similar study, the number needed to treat dropped from 19.41 with dermoscopy alone to 6.25 with dermoscopy and RCM.10

These studies were not looking to evaluate RCM as a replacement test but rather as an add-on test to dermoscopy. Reflectance confocal microscopy imaging takes longer than dermoscopy for each lesion; therefore, RCM should only be used as an adjunctive tool to dermoscopy and not as an initial screening test. Consequentially, a dermatologist skilled in dermoscopy is essential in deciding which lesions would be appropriate for subsequent RCM imaging.

In Vivo Margin Mapping as an Adjunct to Surgery

Oftentimes, tumor margins are poorly defined and can be difficult to map clinically and dermoscopically. Studies have demonstrated the use of RCM in delineation of surgical margins prior to surgery or excisional biopsies.11,12 Alternatively, when complete removal at biopsy would be impractical (eg, for extremely large lesions or lesions located in cosmetically sensitive areas such as the face), RCM can be used to pick the best site for an appropriate biopsy, which decreases the chance of sampling error due to skip lesions and increases histologic accuracy.

Nonsurgical Treatment Monitoring

One advantage of RCM over conventional histology is that RCM imaging leaves the tissue intact, allowing dynamic changes to be studied over time, which is useful for monitoring nonmelanoma skin cancers and lentigo maligna being treated with noninvasive therapeutic modalities.13 If not as a definitive treatment, RCM can act as an adjunct for surgery by monitoring reduction in lesion size prior to Mohs micrographic surgery, thereby decreasing the resulting surgical defect.14

Limitations

Imaging Depth

Although RCM is a revolutionary device in the field of dermatology, it has several limitations. With a maximal imaging depth of 350 µm, the imaging resolution decreases substantially with depth, limiting accurate interpretation to 200 µm. Reflectance confocal microscopy can only image the superficial portion of a lesion; therefore, deep tumor margins cannot be assessed. Hypertrophic or hyperkeratotic lesions, including lesions on the palms and soles, also are unable to be imaged with RCM. This limitation in depth penetration makes treatment monitoring impossible for invasive lesions that extend into the dermal layer.

Difficult-to-Reach Areas

Another limitation is the difficulty imaging areas such as the ocular canthi, nasal alae, or helices of the ear due to the wide probe size on the VivaScope 1500. The advent of the smaller handheld VivaScope 3000 device allows for improved imaging of concave services and difficult lesions at the risk of less accurate imaging, low field of view, and no reimbursement at present.

False-Positive Results

Although RCM has been shown to be helpful in reducing unnecessary biopsies, there still is the issue of false-positives on imaging. False-positives most commonly occur in nevi with severe atypia or when Langerhans cells are present that cannot always be differentiated from melanocytic cells.3,15,16 One prospective study found 7 false-positive results from 63 sites using RCM for the diagnosis of lentigo malignas.16 False-negatives can occur in the presence of inflammatory infiltrates and scar tissue that can hide cellular morphology or in sampling errors due to skip lesions.3,16

Time Efficiency

The time required for acquisition of RCM mosaics and stacks followed by reading and interpretation can be substantial depending on the size and complexity of the lesion, which is a major limitation for use of RCM in busy dermatology practices; therefore, RCM should be reserved for lesions selected to undergo biopsy that are clinically equivocal for malignancy prior to RCM examination.17 It would not be cost-effective or time effective to evaluate lesions that either clinically or dermoscopically have a high probability of malignancy; however, patients and physicians may opt for increased specificity at the expense of time, particularly when a lesion is located on a cosmetically sensitive area, as patients can avoid initial histologic biopsy and gain the cosmetic benefit of going straight to surgery versus obtaining an initial diagnostic biopsy.

Cost

Lastly, the high cost involved in purchasing an RCM device and the training involved to use and interpret RCM images currently limits RCM to large academic centers. Reimbursement may make more widespread use feasible. In any event, RCM imaging should be part of the curriculum for both dermatology and pathology trainees.

Future Directions

In vivo RCM is a noninvasive imaging modality that allows for real-time evaluation of the skin. Used in conjunction with dermoscopy, RCM can substantially improve diagnostic accuracy and reduce the number of unnecessary biopsies. Now that RCM has finally gained foundational CPT codes and insurance reimbursement, there may be a growing demand for clinicians to incorporate this technology into their clinical practice.

Reflectance confocal microscopy (RCM) imaging received Category I Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services in January 2016 and can now be submitted to insurance companies with reimbursement comparable to a skin biopsy or a global skin pathology service.1 This fairly new technology is a US Food and Drug Administration–cleared noninvasive imaging modality that provides high-resolution in vivo cellular images of the skin. It has been shown to be efficacious in differentiating benign and malignant skin lesions, increasing diagnostic accuracy, and reducing the number of unnecessary skin biopsies that are performed. In addition to skin cancer diagnosis, RCM imaging also can help guide management of malignant lesions by detecting lateral margins prior to surgery as well as monitoring the lesion over time for treatment efficacy or recurrence. The potential impact of RCM imaging is tremendous, and reimbursement may lead to increased use in clinical practice to the benefit of our patients. Herein, we present a brief review of RCM imaging and reimbursement as well as the benefits and limitations of this new technology for dermatologists.

Reflectance Confocal Microscopy

In vivo RCM allows us to visualize the epidermis in real time on a cellular level down to the papillary dermis at a high resolution (×30) comparable to histologic examination. With optical sections 3- to 5-µm thick and a lateral resolution of 0.5 to 1.0 µm, RCM produces a stack of 500×500-µm2 images up to a depth of approximately 200 µm.2,3 At any chosen depth, these smaller images are stitched together with sophisticated software into a block, or mosaic, increasing the field of view to up to 8×8 mm2. Imaging is performed in en face planes oriented parallel to the skin surface, similar to dermoscopy.

Current CPT Guidelines and Reimbursement

The CPT codes for RCM imaging provide reimbursement on a per-lesion basis and are similar to those used for skin biopsy and pathology (Table).1 Codes 96931 through 96933 are used for imaging of a single lesion on a patient. The first code—96931—is used when image acquisition, interpretation, and report creation are carried out by a single clinician. The next 2 codes are used when one clinician acquires the image—96932—comparable to the technical component of a pathology code, while another reads it and creates the report—96933—similar to a dermatopathologist billing for the professional component of a pathology report. For patients presenting with multiple lesions, the next 3 codes—96934, 96935, and 96936—are used in conjunction with the applicable first code for each additional lesion with similar global, technical, and professional components. Because these codes are not in the radiology or pathology sections of CPT, a single code cannot be used with modifier -TC (technical component) and modifier -26, as they are in those sections.

The wide-probe VivaScope 1500 (Caliber I.D., Inc) currently is the only confocal device that can be reported with a CPT code and routinely reimbursed. The handheld VivaScope 3000 (Caliber I.D., Inc) can only view a small stack and does not have the ability to acquire a full mosaic image; it is not covered by these codes.

Images can be viewed as a stack captured at the same horizontal position but at sequential depths or as a mosaic, which has a larger field of view but is limited to a single plane. To appropriately assess a lesion, clinicians must obtain a mosaic that needs to be assessed at multiple layers for a diagnosis to be made because it is a cross-section view.

Diagnosis

Studies have demonstrated the usefulness of RCM imaging in the diagnosis of a wide range of skin diseases, including melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancers, infectious diseases, and inflammatory and autoimmune conditions, as well as wound healing and skin aging. Reflectance confocal microscopy imaging is not limited to the skin; it can be used to evaluate the hair, nails, oral mucosa, and other organs.

According to several studies, RCM imaging notably increases the diagnostic accuracy and detection rate of skin cancers over clinical and dermoscopic examination alone and therefore can act as an aid in differentiating lesions that are benign versus those that are suspicious and should be biopsied.

Reflectance confocal microscopy has been shown to have a mean sensitivity of 94% (range, 92%–96%) and specificity of 83% (range, 81%–84%) for all types of skin cancer when used with dermoscopy.4 In particular, for melanocytic lesions that are ambiguous on dermoscopy, RCM used in addition to dermoscopy increases the mean sensitivity and specificity for melanoma diagnosis to 93% (range, 89%–96%) and 76% (range, 68%–83%), respectively.5 Although these reported sensitivities are comparable to dermoscopy, the specificity is superior, especially for detecting hypomelanotic and amelanotic melanomas, which often lack specific features on dermoscopy.6-8

The combination of RCM with dermoscopy has reduced the number of unnecessary excisions of benign nevi by more than 50% when compared to dermoscopy alone.9 One study showed that the number needed to treat (ie, excise) a melanoma decreased from 14.6 with dermoscopy alone to 6.8 when guided by dermoscopy and RCM imaging.9 In a similar study, the number needed to treat dropped from 19.41 with dermoscopy alone to 6.25 with dermoscopy and RCM.10

These studies were not looking to evaluate RCM as a replacement test but rather as an add-on test to dermoscopy. Reflectance confocal microscopy imaging takes longer than dermoscopy for each lesion; therefore, RCM should only be used as an adjunctive tool to dermoscopy and not as an initial screening test. Consequentially, a dermatologist skilled in dermoscopy is essential in deciding which lesions would be appropriate for subsequent RCM imaging.

In Vivo Margin Mapping as an Adjunct to Surgery

Oftentimes, tumor margins are poorly defined and can be difficult to map clinically and dermoscopically. Studies have demonstrated the use of RCM in delineation of surgical margins prior to surgery or excisional biopsies.11,12 Alternatively, when complete removal at biopsy would be impractical (eg, for extremely large lesions or lesions located in cosmetically sensitive areas such as the face), RCM can be used to pick the best site for an appropriate biopsy, which decreases the chance of sampling error due to skip lesions and increases histologic accuracy.

Nonsurgical Treatment Monitoring

One advantage of RCM over conventional histology is that RCM imaging leaves the tissue intact, allowing dynamic changes to be studied over time, which is useful for monitoring nonmelanoma skin cancers and lentigo maligna being treated with noninvasive therapeutic modalities.13 If not as a definitive treatment, RCM can act as an adjunct for surgery by monitoring reduction in lesion size prior to Mohs micrographic surgery, thereby decreasing the resulting surgical defect.14

Limitations

Imaging Depth

Although RCM is a revolutionary device in the field of dermatology, it has several limitations. With a maximal imaging depth of 350 µm, the imaging resolution decreases substantially with depth, limiting accurate interpretation to 200 µm. Reflectance confocal microscopy can only image the superficial portion of a lesion; therefore, deep tumor margins cannot be assessed. Hypertrophic or hyperkeratotic lesions, including lesions on the palms and soles, also are unable to be imaged with RCM. This limitation in depth penetration makes treatment monitoring impossible for invasive lesions that extend into the dermal layer.

Difficult-to-Reach Areas

Another limitation is the difficulty imaging areas such as the ocular canthi, nasal alae, or helices of the ear due to the wide probe size on the VivaScope 1500. The advent of the smaller handheld VivaScope 3000 device allows for improved imaging of concave services and difficult lesions at the risk of less accurate imaging, low field of view, and no reimbursement at present.

False-Positive Results

Although RCM has been shown to be helpful in reducing unnecessary biopsies, there still is the issue of false-positives on imaging. False-positives most commonly occur in nevi with severe atypia or when Langerhans cells are present that cannot always be differentiated from melanocytic cells.3,15,16 One prospective study found 7 false-positive results from 63 sites using RCM for the diagnosis of lentigo malignas.16 False-negatives can occur in the presence of inflammatory infiltrates and scar tissue that can hide cellular morphology or in sampling errors due to skip lesions.3,16

Time Efficiency

The time required for acquisition of RCM mosaics and stacks followed by reading and interpretation can be substantial depending on the size and complexity of the lesion, which is a major limitation for use of RCM in busy dermatology practices; therefore, RCM should be reserved for lesions selected to undergo biopsy that are clinically equivocal for malignancy prior to RCM examination.17 It would not be cost-effective or time effective to evaluate lesions that either clinically or dermoscopically have a high probability of malignancy; however, patients and physicians may opt for increased specificity at the expense of time, particularly when a lesion is located on a cosmetically sensitive area, as patients can avoid initial histologic biopsy and gain the cosmetic benefit of going straight to surgery versus obtaining an initial diagnostic biopsy.

Cost

Lastly, the high cost involved in purchasing an RCM device and the training involved to use and interpret RCM images currently limits RCM to large academic centers. Reimbursement may make more widespread use feasible. In any event, RCM imaging should be part of the curriculum for both dermatology and pathology trainees.

Future Directions

In vivo RCM is a noninvasive imaging modality that allows for real-time evaluation of the skin. Used in conjunction with dermoscopy, RCM can substantially improve diagnostic accuracy and reduce the number of unnecessary biopsies. Now that RCM has finally gained foundational CPT codes and insurance reimbursement, there may be a growing demand for clinicians to incorporate this technology into their clinical practice.

- Current Procedural Terminology 2017, Professional Edition. Chicago IL: American Medical Association; 2016.

- Que SK, Fraga-Braghiroli N, Grant-Kels JM, et al. Through the looking glass: basics and principles of reflectance confocal microscopy [published online June 4, 2015]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:276-284.

- Rajadhyaksha M, Marghoob A, Rossi A, et al. Reflectance confocal microscopy of skin in vivo: from bench to bedside [published online October 27, 2016]. Lasers Surg Med. 2017;49:7-19.

- Xiong YD, Ma S, Li X, et al. A meta-analysis of reflectance confocal microscopy for the diagnosis of malignant skin tumours. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:1295-1302.

- Stevenson AD, Mickan S, Mallett S, et al. Systematic review of diagnostic accuracy of reflectance confocal microscopy for melanoma diagnosis in patients with clinically equivocal skin lesions. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2013;3:19-27.

- Busam KJ, Hester K, Charles C, et al. Detection of clinically amelanotic malignant melanoma and assessment of its margins by in vivo confocal scanning laser microscopy. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:923-929.

- Losi A, Longo C, Cesinaro AM, et al. Hyporeflective pagetoid cells: a new clue for amelanotic melanoma diagnosis by reflectance confocal microscopy. Br J Dermatol. 2014;171:48-54.

- Guitera P, Menzies SQ, Argenziano G, et al. Dermoscopy and in vivo confocal microscopy are complementary techniques for the diagnosis of difficult amelanotic and light-coloured skin lesions [published online October 12, 2016]. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175:1311-1319.

- Pellacani G, Pepe P, Casari A, et al. Reflectance confocal microscopy as a second-level examination in skin oncology improves diagnostic accuracy and saves unnecessary excisions: a longitudinal prospective study. Br J Dermatol. 2014;171:1044-1051.

- Pellacani G, Witkowski A, Cesinaro AM, et al. Cost-benefit of reflectance confocal microscopy in the diagnostic performance of melanoma. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:413-419.

- Champin J, Perrot JL, Cinotti E, et al. In vivo reflectance confocal microscopy to optimize the spaghetti technique for defining surgical margins of lentigo maligna. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40:247-256.

- Hibler BP, Cordova M, Wong RJ, et al. Intraoperative real-time reflectance confocal microscopy for guiding surgical margins of lentigo maligna melanoma. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41:980-983.

- Ulrich M, Lange-Asschenfeldt S, Gonzalez S. The use of reflectance confocal microscopy for monitoring response to therapy of skin malignancies. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2012;2:202a10.

- Torres A, Niemeyer A, Berkes B, et al. 5% imiquimod cream and reflectance-mode confocal microscopy as adjunct modalities to Mohs micrographic surgery for treatment of basal cell carcinoma. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30(12, pt 1):1462-1469.

- Hashemi P, Pulitzer MP, Scope A, et al. Langerhans cells and melanocytes share similar morphologic features under in vivo reflectance confocal microscopy: a challenge for melanoma diagnosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:452-462.

- Menge TD, Hibler BP, Cordova MA, et al. Concordance of handheld reflectance confocal microscopy (RCM) with histopathology in the diagnosis of lentigo maligna (LM): a prospective study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:1114-1120.

- Borsari S, Pampena R, Lallas A, et al. Clinical indications for use of reflectance confocal microscopy for skin cancer diagnosis. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:1093-1098.

- Current Procedural Terminology 2017, Professional Edition. Chicago IL: American Medical Association; 2016.

- Que SK, Fraga-Braghiroli N, Grant-Kels JM, et al. Through the looking glass: basics and principles of reflectance confocal microscopy [published online June 4, 2015]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:276-284.

- Rajadhyaksha M, Marghoob A, Rossi A, et al. Reflectance confocal microscopy of skin in vivo: from bench to bedside [published online October 27, 2016]. Lasers Surg Med. 2017;49:7-19.

- Xiong YD, Ma S, Li X, et al. A meta-analysis of reflectance confocal microscopy for the diagnosis of malignant skin tumours. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:1295-1302.

- Stevenson AD, Mickan S, Mallett S, et al. Systematic review of diagnostic accuracy of reflectance confocal microscopy for melanoma diagnosis in patients with clinically equivocal skin lesions. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2013;3:19-27.

- Busam KJ, Hester K, Charles C, et al. Detection of clinically amelanotic malignant melanoma and assessment of its margins by in vivo confocal scanning laser microscopy. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:923-929.

- Losi A, Longo C, Cesinaro AM, et al. Hyporeflective pagetoid cells: a new clue for amelanotic melanoma diagnosis by reflectance confocal microscopy. Br J Dermatol. 2014;171:48-54.

- Guitera P, Menzies SQ, Argenziano G, et al. Dermoscopy and in vivo confocal microscopy are complementary techniques for the diagnosis of difficult amelanotic and light-coloured skin lesions [published online October 12, 2016]. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175:1311-1319.

- Pellacani G, Pepe P, Casari A, et al. Reflectance confocal microscopy as a second-level examination in skin oncology improves diagnostic accuracy and saves unnecessary excisions: a longitudinal prospective study. Br J Dermatol. 2014;171:1044-1051.

- Pellacani G, Witkowski A, Cesinaro AM, et al. Cost-benefit of reflectance confocal microscopy in the diagnostic performance of melanoma. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:413-419.

- Champin J, Perrot JL, Cinotti E, et al. In vivo reflectance confocal microscopy to optimize the spaghetti technique for defining surgical margins of lentigo maligna. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40:247-256.

- Hibler BP, Cordova M, Wong RJ, et al. Intraoperative real-time reflectance confocal microscopy for guiding surgical margins of lentigo maligna melanoma. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41:980-983.

- Ulrich M, Lange-Asschenfeldt S, Gonzalez S. The use of reflectance confocal microscopy for monitoring response to therapy of skin malignancies. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2012;2:202a10.

- Torres A, Niemeyer A, Berkes B, et al. 5% imiquimod cream and reflectance-mode confocal microscopy as adjunct modalities to Mohs micrographic surgery for treatment of basal cell carcinoma. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30(12, pt 1):1462-1469.

- Hashemi P, Pulitzer MP, Scope A, et al. Langerhans cells and melanocytes share similar morphologic features under in vivo reflectance confocal microscopy: a challenge for melanoma diagnosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:452-462.

- Menge TD, Hibler BP, Cordova MA, et al. Concordance of handheld reflectance confocal microscopy (RCM) with histopathology in the diagnosis of lentigo maligna (LM): a prospective study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:1114-1120.

- Borsari S, Pampena R, Lallas A, et al. Clinical indications for use of reflectance confocal microscopy for skin cancer diagnosis. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:1093-1098.

Practice Points

- Reflectance confocal microscopy (RCM) recently received Category I Current Procedural Terminology codes for reimbursement comparable to a skin biopsy.

- When used in combination with dermoscopy, RCM has been shown to increase diagnostic accuracy of skin cancer.

- Reflectance confocal microscopy also is useful in surgical treatment planning and monitoring nonsurgical treatments over time.

- Limitations of RCM imaging include low imaging depth, difficulty in imaging certain areas of the skin, learning curve for interpreting these images, and the cost of equipment.

Stem cell therapy significantly improves ulcer healing

PORTLAND, ORE. – Treating chronic venous leg ulcers with mesenchymal stem cells and fibrin spray significantly improved wound healing, compared with vehicle control or saline plus conventional therapy, according to the results of a small randomized, controlled, double-blind pilot trial.

“Topical application of autologous, bone-marrow–derived mesenchymal stem cells may be an effective way to promote healing in patients with difficult-to-heal wounds,” said Ayman Grada, MD, of the department of dermatology at Boston University. “However, larger studies are needed to confirm this finding.”

“Various treatment modalities have been used, but treatment outcomes are not always satisfactory,” said Dr. Grada. “In about 60% of cases, wounds fail to close, and there is also a high rate of recurrence.”

Preclinical work in several animal models indicated that applying mesenchymal stem cells to wounds accelerated healing through a variety of mechanisms, Dr. Grada noted. Based on that premise, he and his associates hypothesized that autologous cultured mesenchymal stem cells could accelerate wound healing in humans.

To test that idea, they randomly assigned the 11 trial participants to one of two control treatments or to the stem cell intervention. Four patients received normal saline with conventional standard care, three patients received fibrin spray plus conventional therapy, and four patients received conventional therapy plus autologous mesenchymal stem cells delivered in fibrin spray at a dose of 1 x 106 cells per square centimeter of wound surface. Patients were treated every 3 weeks, up to three times or until complete wound healing, and were followed for up to 24 weeks.

To acquire the stem cells, the researchers obtained 30- to 50-mL samples of bone marrow aspirate from the iliac crest, then separated and cultured the cells in-house. The controls underwent sham aspiration with needles that did not penetrate the bone, Dr. Grada said. At each 4-week follow-up visit, the investigators measured the perimeter and area of each wound and analyzed the results with public domain software called ImageJ. They calculated the linear advance of the wound margin by dividing change in area by average perimeter.