User login

Heard of ApoB Testing? New Guidelines

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

I've been hearing a lot about apolipoprotein B (apoB) lately. It keeps popping up, but I've not been sure where it fits in or what I should do about it. The new Expert Clinical Consensus from the National Lipid Association now finally gives us clear guidance.

ApoB is the main protein that is found on all atherogenic lipoproteins. It is found on low-density lipoprotein (LDL) but also on other atherogenic lipoprotein particles. Because it is a part of all atherogenic particles, it predicts cardiovascular (CV) risk more accurately than does LDL cholesterol (LDL-C).

ApoB and LDL-C tend to run together, but not always. While they are correlated fairly well on a population level, for a given individual they can diverge; and when they do, apoB is the better predictor of future CV outcomes. This divergence occurs frequently, and it can occur even more frequently after treatment with statins. When LDL decreases to reach the LDL threshold for treatment, but apoB remains elevated, there is the potential for misclassification of CV risk and essentially the risk for undertreatment of someone whose CV risk is actually higher than it appears to be if we only look at their LDL-C. The consensus statement says, "Where there is discordance between apoB and LDL-C, risk follows apoB."

This understanding leads to the places where measurement of apoB may be helpful:

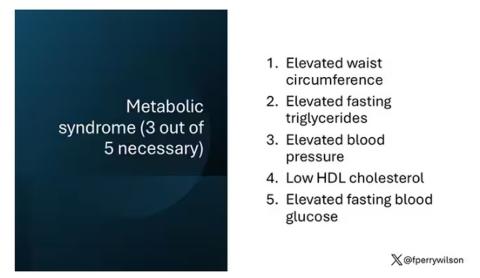

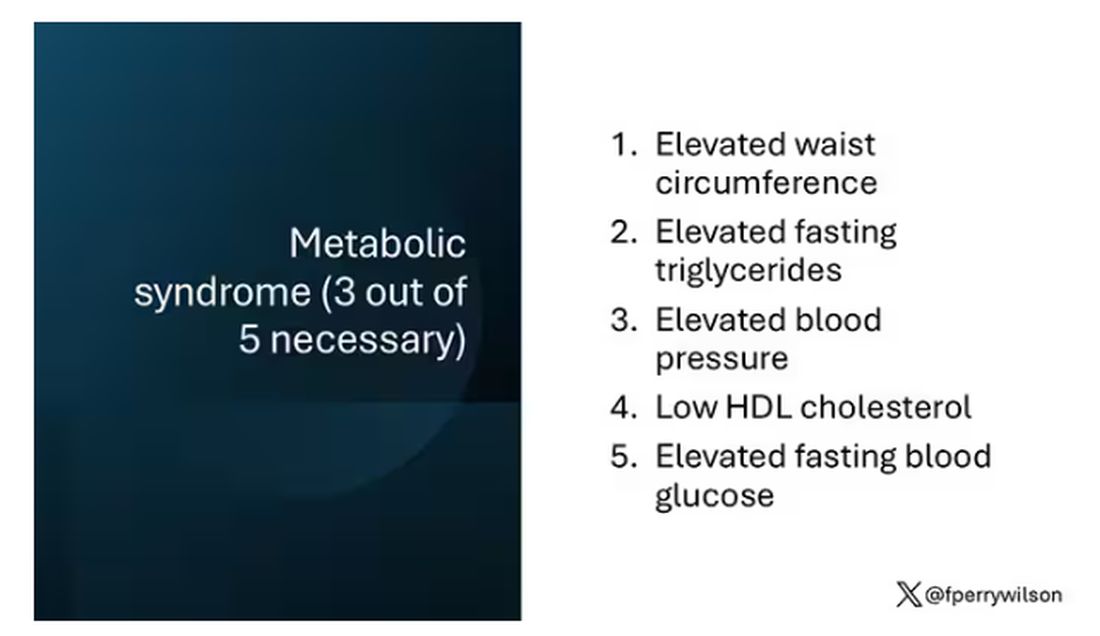

In patients with borderline atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk in whom a shared decision about statin therapy is being determined and the patient prefers not to start a statin, apoB can be useful for further risk stratification. If apoB suggests low risk, then statin therapy could be withheld, and if apoB is high, that would favor starting statin therapy. Certain common conditions, such as obesity and insulin resistance, can lead to smaller cholesterol-depleted LDL particles that result in lower LDL-C, but elevated apoB levels in this circumstance may drive the decision to treat with a statin.

In patients already treated with statins, but a decision must be made about whether treatment intensification is warranted. If the LDL-C is to goal and apoB is above threshold, treatment intensification may be considered. In patients who are not yet to goal, based on an elevated apoB, the first step is intensification of statin therapy. After that, intensification would be the same as has already been addressed in my review of the 2022 ACC Expert Consensus Decision Pathway on the Role of Nonstatin Therapies for LDL-Cholesterol Lowering.

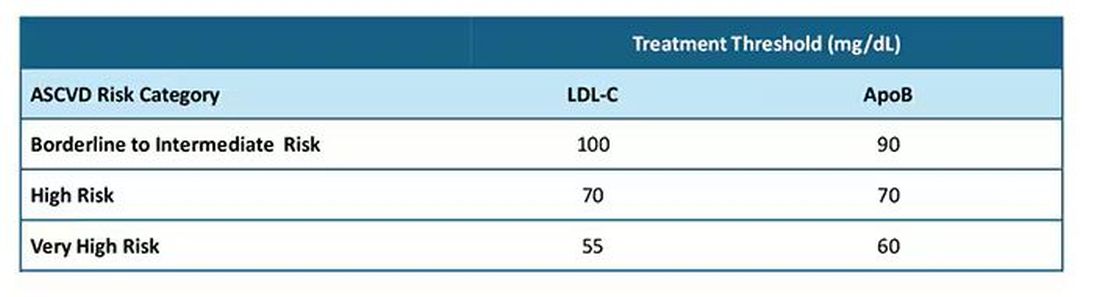

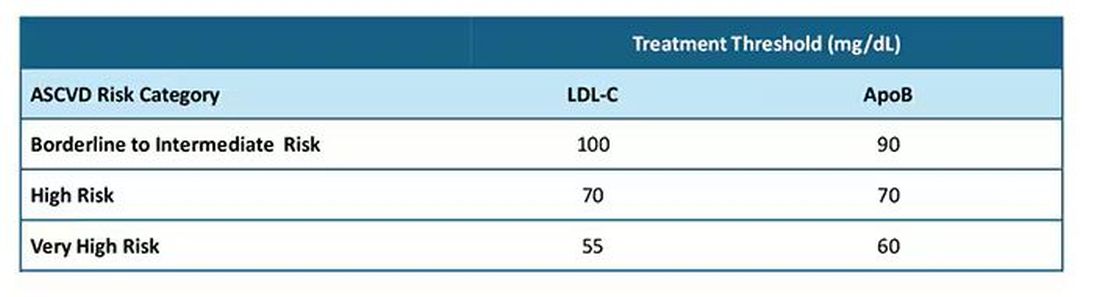

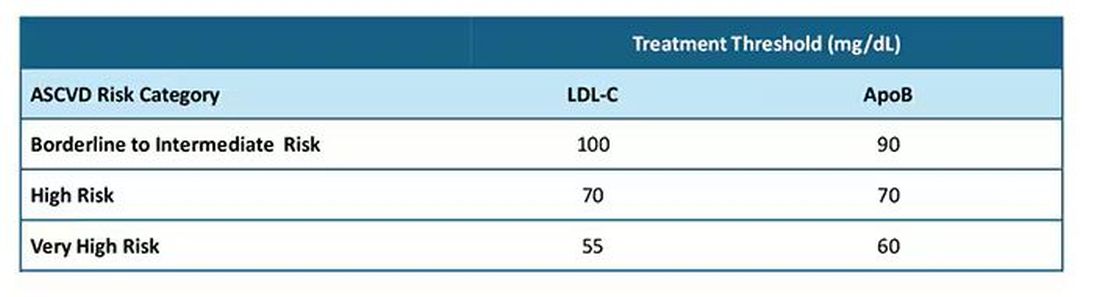

After clarifying the importance of apoB in providing additional discrimination of CV risk, the consensus statement clarifies the treatment thresholds, or goals for treatment, for apoB that correlate with established LDL-C thresholds, as shown in this table:

Let me be really clear: The consensus statement does not say that we need to measure apoB in all patients or that such measurement is the standard of care. It is not. It says, and I'll quote, "At present, the use of apoB to assess the effectiveness of lipid-lowering therapies remains a matter of clinical judgment." This guideline is helpful in pointing out the patients most likely to benefit from this additional measurement, including those with hypertriglyceridemia, diabetes, visceral adiposity, insulin resistance/metabolic syndrome, low HDL-C, or very low LDL-C levels.

In summary, measurement of apoB can be helpful for further risk stratification in patients with borderline or intermediate LDL-C levels, and for deciding whether further intensification of lipid-lowering therapy may be warranted when the LDL threshold has been reached.

Lipid management is something that we do every day in the office. This is new information, or at least clarifying information, for most of us. Hopefully it is helpful. I'm interested in your thoughts on this topic, including whether and how you plan to use apoB measurements.

Dr. Skolnik, Professor, Department of Family Medicine, Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia; Associate Director, Department of Family Medicine, Abington Jefferson Health, Abington, Pennsylvania, disclosed ties with AstraZeneca, Teva, Eli Lilly, Boehringer Ingelheim, Sanofi, Sanofi Pasteur, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, and Bayer.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

I've been hearing a lot about apolipoprotein B (apoB) lately. It keeps popping up, but I've not been sure where it fits in or what I should do about it. The new Expert Clinical Consensus from the National Lipid Association now finally gives us clear guidance.

ApoB is the main protein that is found on all atherogenic lipoproteins. It is found on low-density lipoprotein (LDL) but also on other atherogenic lipoprotein particles. Because it is a part of all atherogenic particles, it predicts cardiovascular (CV) risk more accurately than does LDL cholesterol (LDL-C).

ApoB and LDL-C tend to run together, but not always. While they are correlated fairly well on a population level, for a given individual they can diverge; and when they do, apoB is the better predictor of future CV outcomes. This divergence occurs frequently, and it can occur even more frequently after treatment with statins. When LDL decreases to reach the LDL threshold for treatment, but apoB remains elevated, there is the potential for misclassification of CV risk and essentially the risk for undertreatment of someone whose CV risk is actually higher than it appears to be if we only look at their LDL-C. The consensus statement says, "Where there is discordance between apoB and LDL-C, risk follows apoB."

This understanding leads to the places where measurement of apoB may be helpful:

In patients with borderline atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk in whom a shared decision about statin therapy is being determined and the patient prefers not to start a statin, apoB can be useful for further risk stratification. If apoB suggests low risk, then statin therapy could be withheld, and if apoB is high, that would favor starting statin therapy. Certain common conditions, such as obesity and insulin resistance, can lead to smaller cholesterol-depleted LDL particles that result in lower LDL-C, but elevated apoB levels in this circumstance may drive the decision to treat with a statin.

In patients already treated with statins, but a decision must be made about whether treatment intensification is warranted. If the LDL-C is to goal and apoB is above threshold, treatment intensification may be considered. In patients who are not yet to goal, based on an elevated apoB, the first step is intensification of statin therapy. After that, intensification would be the same as has already been addressed in my review of the 2022 ACC Expert Consensus Decision Pathway on the Role of Nonstatin Therapies for LDL-Cholesterol Lowering.

After clarifying the importance of apoB in providing additional discrimination of CV risk, the consensus statement clarifies the treatment thresholds, or goals for treatment, for apoB that correlate with established LDL-C thresholds, as shown in this table:

Let me be really clear: The consensus statement does not say that we need to measure apoB in all patients or that such measurement is the standard of care. It is not. It says, and I'll quote, "At present, the use of apoB to assess the effectiveness of lipid-lowering therapies remains a matter of clinical judgment." This guideline is helpful in pointing out the patients most likely to benefit from this additional measurement, including those with hypertriglyceridemia, diabetes, visceral adiposity, insulin resistance/metabolic syndrome, low HDL-C, or very low LDL-C levels.

In summary, measurement of apoB can be helpful for further risk stratification in patients with borderline or intermediate LDL-C levels, and for deciding whether further intensification of lipid-lowering therapy may be warranted when the LDL threshold has been reached.

Lipid management is something that we do every day in the office. This is new information, or at least clarifying information, for most of us. Hopefully it is helpful. I'm interested in your thoughts on this topic, including whether and how you plan to use apoB measurements.

Dr. Skolnik, Professor, Department of Family Medicine, Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia; Associate Director, Department of Family Medicine, Abington Jefferson Health, Abington, Pennsylvania, disclosed ties with AstraZeneca, Teva, Eli Lilly, Boehringer Ingelheim, Sanofi, Sanofi Pasteur, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, and Bayer.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

I've been hearing a lot about apolipoprotein B (apoB) lately. It keeps popping up, but I've not been sure where it fits in or what I should do about it. The new Expert Clinical Consensus from the National Lipid Association now finally gives us clear guidance.

ApoB is the main protein that is found on all atherogenic lipoproteins. It is found on low-density lipoprotein (LDL) but also on other atherogenic lipoprotein particles. Because it is a part of all atherogenic particles, it predicts cardiovascular (CV) risk more accurately than does LDL cholesterol (LDL-C).

ApoB and LDL-C tend to run together, but not always. While they are correlated fairly well on a population level, for a given individual they can diverge; and when they do, apoB is the better predictor of future CV outcomes. This divergence occurs frequently, and it can occur even more frequently after treatment with statins. When LDL decreases to reach the LDL threshold for treatment, but apoB remains elevated, there is the potential for misclassification of CV risk and essentially the risk for undertreatment of someone whose CV risk is actually higher than it appears to be if we only look at their LDL-C. The consensus statement says, "Where there is discordance between apoB and LDL-C, risk follows apoB."

This understanding leads to the places where measurement of apoB may be helpful:

In patients with borderline atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk in whom a shared decision about statin therapy is being determined and the patient prefers not to start a statin, apoB can be useful for further risk stratification. If apoB suggests low risk, then statin therapy could be withheld, and if apoB is high, that would favor starting statin therapy. Certain common conditions, such as obesity and insulin resistance, can lead to smaller cholesterol-depleted LDL particles that result in lower LDL-C, but elevated apoB levels in this circumstance may drive the decision to treat with a statin.

In patients already treated with statins, but a decision must be made about whether treatment intensification is warranted. If the LDL-C is to goal and apoB is above threshold, treatment intensification may be considered. In patients who are not yet to goal, based on an elevated apoB, the first step is intensification of statin therapy. After that, intensification would be the same as has already been addressed in my review of the 2022 ACC Expert Consensus Decision Pathway on the Role of Nonstatin Therapies for LDL-Cholesterol Lowering.

After clarifying the importance of apoB in providing additional discrimination of CV risk, the consensus statement clarifies the treatment thresholds, or goals for treatment, for apoB that correlate with established LDL-C thresholds, as shown in this table:

Let me be really clear: The consensus statement does not say that we need to measure apoB in all patients or that such measurement is the standard of care. It is not. It says, and I'll quote, "At present, the use of apoB to assess the effectiveness of lipid-lowering therapies remains a matter of clinical judgment." This guideline is helpful in pointing out the patients most likely to benefit from this additional measurement, including those with hypertriglyceridemia, diabetes, visceral adiposity, insulin resistance/metabolic syndrome, low HDL-C, or very low LDL-C levels.

In summary, measurement of apoB can be helpful for further risk stratification in patients with borderline or intermediate LDL-C levels, and for deciding whether further intensification of lipid-lowering therapy may be warranted when the LDL threshold has been reached.

Lipid management is something that we do every day in the office. This is new information, or at least clarifying information, for most of us. Hopefully it is helpful. I'm interested in your thoughts on this topic, including whether and how you plan to use apoB measurements.

Dr. Skolnik, Professor, Department of Family Medicine, Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia; Associate Director, Department of Family Medicine, Abington Jefferson Health, Abington, Pennsylvania, disclosed ties with AstraZeneca, Teva, Eli Lilly, Boehringer Ingelheim, Sanofi, Sanofi Pasteur, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, and Bayer.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Mechanism of Action

MOA — Mechanism of action — gets bandied about a lot.

Drug reps love it. Saying your product is a “first-in-class MOA” sounds great as they hand you a glossy brochure. It also features prominently in print ads, usually with pics of smiling people.

It’s a good thing to know, too, both medically and in a cool-science-geeky way. We want to understand what we’re prescribing will do to patients. We want to explain it to them, too.

It certainly helps to know that what we’re doing when treating a disorder using rational polypharmacy.

But at the same time we face the realization that it may not mean as much as we think it should. I don’t have to go back very far in my career to find Food and Drug Administration–approved medications that worked, but we didn’t have a clear reason why. I mean, we had a vague idea on a scientific basis, but we’re still guessing.

This didn’t stop us from using them, which is nothing new. The ancients had learned certain plants reduced pain and fever long before they understood what aspirin (and its MOA) was.

At the same time we’re now using drugs, such as the anti-amyloid treatments for Alzheimer’s disease, that should be more effective than one would think. Pulling the damaged molecules out of the brain should, on paper, make a dramatic difference ... but it doesn’t. I’m not saying they don’t have some benefit, but certainly not as much as you’d think. Of course, that’s based on our understanding of the disease mechanism being correct. We find there’s a lot more going on than we know.

Like so much in science (and this aspect of medicine is a science) the answers often lead to more questions.

Observation takes the lead over understanding in most things. Our ancestors knew what fire was, and how to use it, without any idea of what rapid exothermic oxidation was. (Admittedly, I have a degree in chemistry and can’t explain it myself anymore.)

The glossy ads and scientific data about MOA doesn’t mean much in my world if they don’t work. My patients would say the same.

Clinical medicine, after all, is both an art and a science.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Arizona.

MOA — Mechanism of action — gets bandied about a lot.

Drug reps love it. Saying your product is a “first-in-class MOA” sounds great as they hand you a glossy brochure. It also features prominently in print ads, usually with pics of smiling people.

It’s a good thing to know, too, both medically and in a cool-science-geeky way. We want to understand what we’re prescribing will do to patients. We want to explain it to them, too.

It certainly helps to know that what we’re doing when treating a disorder using rational polypharmacy.

But at the same time we face the realization that it may not mean as much as we think it should. I don’t have to go back very far in my career to find Food and Drug Administration–approved medications that worked, but we didn’t have a clear reason why. I mean, we had a vague idea on a scientific basis, but we’re still guessing.

This didn’t stop us from using them, which is nothing new. The ancients had learned certain plants reduced pain and fever long before they understood what aspirin (and its MOA) was.

At the same time we’re now using drugs, such as the anti-amyloid treatments for Alzheimer’s disease, that should be more effective than one would think. Pulling the damaged molecules out of the brain should, on paper, make a dramatic difference ... but it doesn’t. I’m not saying they don’t have some benefit, but certainly not as much as you’d think. Of course, that’s based on our understanding of the disease mechanism being correct. We find there’s a lot more going on than we know.

Like so much in science (and this aspect of medicine is a science) the answers often lead to more questions.

Observation takes the lead over understanding in most things. Our ancestors knew what fire was, and how to use it, without any idea of what rapid exothermic oxidation was. (Admittedly, I have a degree in chemistry and can’t explain it myself anymore.)

The glossy ads and scientific data about MOA doesn’t mean much in my world if they don’t work. My patients would say the same.

Clinical medicine, after all, is both an art and a science.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Arizona.

MOA — Mechanism of action — gets bandied about a lot.

Drug reps love it. Saying your product is a “first-in-class MOA” sounds great as they hand you a glossy brochure. It also features prominently in print ads, usually with pics of smiling people.

It’s a good thing to know, too, both medically and in a cool-science-geeky way. We want to understand what we’re prescribing will do to patients. We want to explain it to them, too.

It certainly helps to know that what we’re doing when treating a disorder using rational polypharmacy.

But at the same time we face the realization that it may not mean as much as we think it should. I don’t have to go back very far in my career to find Food and Drug Administration–approved medications that worked, but we didn’t have a clear reason why. I mean, we had a vague idea on a scientific basis, but we’re still guessing.

This didn’t stop us from using them, which is nothing new. The ancients had learned certain plants reduced pain and fever long before they understood what aspirin (and its MOA) was.

At the same time we’re now using drugs, such as the anti-amyloid treatments for Alzheimer’s disease, that should be more effective than one would think. Pulling the damaged molecules out of the brain should, on paper, make a dramatic difference ... but it doesn’t. I’m not saying they don’t have some benefit, but certainly not as much as you’d think. Of course, that’s based on our understanding of the disease mechanism being correct. We find there’s a lot more going on than we know.

Like so much in science (and this aspect of medicine is a science) the answers often lead to more questions.

Observation takes the lead over understanding in most things. Our ancestors knew what fire was, and how to use it, without any idea of what rapid exothermic oxidation was. (Admittedly, I have a degree in chemistry and can’t explain it myself anymore.)

The glossy ads and scientific data about MOA doesn’t mean much in my world if they don’t work. My patients would say the same.

Clinical medicine, after all, is both an art and a science.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Arizona.

What Should You Do When a Patient Asks for a PSA Test?

Many patients ask us to request a prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test. According to the Brazilian Ministry of Health, prostate cancer is the second most common type of cancer in the male population in all regions of our country. It is the second-leading cause of cancer death in the male population, reaffirming its epidemiologic importance in Brazil. On the other hand, a Ministry of Health technical paper recommends against population-based screening for prostate cancer. So, what should we do?

First, it is important to distinguish early diagnosis from screening. Early diagnosis is the identification of cancer in early stages in people with signs and symptoms. Screening is characterized by the systematic application of exams — digital rectal exam and PSA test — in asymptomatic people, with the aim of identifying cancer in an early stage.

A recent European epidemiologic study reinforced this thesis and helps guide us.

The study included men aged 35-84 years from 26 European countries. Data on cancer incidence and mortality were collected between 1980 and 2017. The data suggested overdiagnosis of prostate cancer, which varied over time and among populations. The findings supported previous recommendations that any implementation of prostate cancer screening should be carefully designed, with an emphasis on minimizing the harms of overdiagnosis.

The clinical evolution of prostate cancer is still not well understood. Increasing age is associated with increased mortality. Many men with less aggressive disease tend to die with cancer rather than die of cancer. However, it is not always possible at the time of diagnosis to determine which tumors will be aggressive and which will grow slowly.

On the other hand, with screening, many of these indolent cancers are unnecessarily detected, generating excessive exams and treatments with negative repercussions (eg, pain, bleeding, infections, stress, and urinary and sexual dysfunction).

So, how should we as clinicians proceed regarding screening?

We should request the PSA test and emphasize the importance of digital rectal exam by a urologist for those at high risk for prostatic neoplasia (ie, those with family history) or those with urinary symptoms that may be associated with prostate cancer.

In general, we should draw attention to the possible risks and benefits of testing and adopt a shared decision-making approach with asymptomatic men or those at low risk who wish to have the screening exam. But achieving a shared decision is not a simple task.

I always have a thorough conversation with patients, but I confess that I request the exam in most cases.

Dr. Wajngarten is a professor of cardiology, Faculty of Medicine, at the University of São Paulo in Brazil. Dr. Wajngarten reported no conflicts of interest.

This story was translated from the Medscape Portuguese edition using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Many patients ask us to request a prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test. According to the Brazilian Ministry of Health, prostate cancer is the second most common type of cancer in the male population in all regions of our country. It is the second-leading cause of cancer death in the male population, reaffirming its epidemiologic importance in Brazil. On the other hand, a Ministry of Health technical paper recommends against population-based screening for prostate cancer. So, what should we do?

First, it is important to distinguish early diagnosis from screening. Early diagnosis is the identification of cancer in early stages in people with signs and symptoms. Screening is characterized by the systematic application of exams — digital rectal exam and PSA test — in asymptomatic people, with the aim of identifying cancer in an early stage.

A recent European epidemiologic study reinforced this thesis and helps guide us.

The study included men aged 35-84 years from 26 European countries. Data on cancer incidence and mortality were collected between 1980 and 2017. The data suggested overdiagnosis of prostate cancer, which varied over time and among populations. The findings supported previous recommendations that any implementation of prostate cancer screening should be carefully designed, with an emphasis on minimizing the harms of overdiagnosis.

The clinical evolution of prostate cancer is still not well understood. Increasing age is associated with increased mortality. Many men with less aggressive disease tend to die with cancer rather than die of cancer. However, it is not always possible at the time of diagnosis to determine which tumors will be aggressive and which will grow slowly.

On the other hand, with screening, many of these indolent cancers are unnecessarily detected, generating excessive exams and treatments with negative repercussions (eg, pain, bleeding, infections, stress, and urinary and sexual dysfunction).

So, how should we as clinicians proceed regarding screening?

We should request the PSA test and emphasize the importance of digital rectal exam by a urologist for those at high risk for prostatic neoplasia (ie, those with family history) or those with urinary symptoms that may be associated with prostate cancer.

In general, we should draw attention to the possible risks and benefits of testing and adopt a shared decision-making approach with asymptomatic men or those at low risk who wish to have the screening exam. But achieving a shared decision is not a simple task.

I always have a thorough conversation with patients, but I confess that I request the exam in most cases.

Dr. Wajngarten is a professor of cardiology, Faculty of Medicine, at the University of São Paulo in Brazil. Dr. Wajngarten reported no conflicts of interest.

This story was translated from the Medscape Portuguese edition using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Many patients ask us to request a prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test. According to the Brazilian Ministry of Health, prostate cancer is the second most common type of cancer in the male population in all regions of our country. It is the second-leading cause of cancer death in the male population, reaffirming its epidemiologic importance in Brazil. On the other hand, a Ministry of Health technical paper recommends against population-based screening for prostate cancer. So, what should we do?

First, it is important to distinguish early diagnosis from screening. Early diagnosis is the identification of cancer in early stages in people with signs and symptoms. Screening is characterized by the systematic application of exams — digital rectal exam and PSA test — in asymptomatic people, with the aim of identifying cancer in an early stage.

A recent European epidemiologic study reinforced this thesis and helps guide us.

The study included men aged 35-84 years from 26 European countries. Data on cancer incidence and mortality were collected between 1980 and 2017. The data suggested overdiagnosis of prostate cancer, which varied over time and among populations. The findings supported previous recommendations that any implementation of prostate cancer screening should be carefully designed, with an emphasis on minimizing the harms of overdiagnosis.

The clinical evolution of prostate cancer is still not well understood. Increasing age is associated with increased mortality. Many men with less aggressive disease tend to die with cancer rather than die of cancer. However, it is not always possible at the time of diagnosis to determine which tumors will be aggressive and which will grow slowly.

On the other hand, with screening, many of these indolent cancers are unnecessarily detected, generating excessive exams and treatments with negative repercussions (eg, pain, bleeding, infections, stress, and urinary and sexual dysfunction).

So, how should we as clinicians proceed regarding screening?

We should request the PSA test and emphasize the importance of digital rectal exam by a urologist for those at high risk for prostatic neoplasia (ie, those with family history) or those with urinary symptoms that may be associated with prostate cancer.

In general, we should draw attention to the possible risks and benefits of testing and adopt a shared decision-making approach with asymptomatic men or those at low risk who wish to have the screening exam. But achieving a shared decision is not a simple task.

I always have a thorough conversation with patients, but I confess that I request the exam in most cases.

Dr. Wajngarten is a professor of cardiology, Faculty of Medicine, at the University of São Paulo in Brazil. Dr. Wajngarten reported no conflicts of interest.

This story was translated from the Medscape Portuguese edition using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Maternal Immunization to Prevent Serious Respiratory Illness

Editor’s Note: Sadly, this is the last column in the Master Class Obstetrics series. This award-winning column has been part of Ob.Gyn. News for 20 years. The deep discussion of cutting-edge topics in obstetrics by specialists and researchers will be missed as will the leadership and curation of topics by Dr. E. Albert Reece.

Introduction: The Need for Increased Vigilance About Maternal Immunization

Viruses are becoming increasingly prevalent in our world and the consequences of viral infections are implicated in a growing number of disease states. It is well established that certain cancers are caused by viruses and it is increasingly evident that viral infections can trigger the development of chronic illness. In pregnant women, viruses such as cytomegalovirus can cause infection in utero and lead to long-term impairments for the baby.

Likewise, it appears that the virulence of viruses is increasing, whether it be the respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) in children or the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) coronaviruses in adults. Clearly, our environment is changing, with increases in population growth and urbanization, for instance, and an intensification of climate change and its effects. Viruses are part of this changing background.

Vaccines are our most powerful tool to protect people of all ages against viral threats, and fortunately, we benefit from increasing expertise in vaccinology. Since 1974, the University of Maryland School of Medicine has a Center for Vaccine Development and Global Health that has conducted research on vaccines to defend against the Zika virus, H1N1, Ebola, and SARS-CoV-2.

We’re not alone. Other vaccinology centers across the country — as well as the National Institutes of Health at the national level, through its National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases — are doing research and developing vaccines to combat viral diseases.

In this column, we are focused on viral diseases in pregnancy and the role that vaccines can play in preventing serious respiratory illness in mothers and their newborns. I have invited Laura E. Riley, MD, the Given Foundation Professor and Chair of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Weill Cornell Medicine, to address the importance of maternal immunization and how we can best counsel our patients and improve immunization rates.

As Dr. Riley explains, we are in a new era, and it behooves us all to be more vigilant about recommending vaccines, combating misperceptions, addressing patients’ knowledge gaps, and administering vaccines whenever possible.

Dr. Reece is the former Dean of Medicine & University Executive VP, and The Distinguished University and Endowed Professor & Director of the Center for Advanced Research Training and Innovation (CARTI) at the University of Maryland School of Medicine, as well as senior scientist at the Center for Birth Defects Research.

The alarming decline in maternal immunization rates that occurred in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic means that, now more than ever, we must fully embrace our responsibility to recommend immunizations in pregnancy and to communicate what is known about their efficacy and safety. Data show that vaccination rates drop when we do not offer vaccines in our offices, so whenever possible, we should administer them as well.

The ob.gyn. is the patient’s most trusted person in pregnancy. When patients decline or express hesitancy about vaccines, it is incumbent upon us to ask why. Oftentimes, we can identify areas in which patients lack knowledge or have misperceptions and we can successfully educate the patient or change their perspective or misunderstanding concerning the importance of vaccination for themselves and their babies. (See Table 1.) We can also successfully address concerns about safety.

The safety of COVID-19 vaccinations in pregnancy is now backed by several years of data from multiple studies showing no increase in birth defects, preterm delivery, miscarriage, or stillbirth.

Data also show that pregnant patients are more likely than patients who are not pregnant to need hospitalization and intensive care when infected with SARS-CoV-2 and are at risk of having complications that can affect pregnancy and the newborn, including preterm birth and stillbirth. Vaccination has been shown to reduce the risk of severe illness and the risk of such adverse obstetrical outcomes, in addition to providing protection for the infant early on.

Similarly, influenza has long been more likely to be severe in pregnant patients, with an increased risk of poor obstetrical outcomes. Vaccines similarly provide “two for one protection,” protecting both mother and baby, and are, of course, backed by many years of safety and efficacy data.

With the new maternal respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) vaccine, now in its second year of availability, the goal is to protect the baby from RSV-caused serious lower respiratory tract illness. The illness has contributed to tens of thousands of annual hospitalizations and up to several hundred deaths every year in children younger than 5 years — particularly in those under age 6 months.

The RSV monoclonal antibody nirsevimab is available for the newborn as an alternative to maternal immunization but the maternal vaccine is optimal in that it will provide immediate rather than delayed protection for the newborn. The maternal vaccine is recommended during weeks 32-36 of pregnancy in mothers who were not vaccinated during last year’s RSV season. With real-world experience from year one, the available safety data are reassuring.

Counseling About Influenza and COVID-19 Vaccination

The COVID-19 pandemic took a toll on vaccination interest/receptivity broadly in pregnant and nonpregnant people. Among pregnant individuals, influenza vaccination coverage declined from 71% in the 2019-2020 influenza season to 56% in the 2021-2022 season, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Vaccine Safety Datalink.4 Coverage for the 2022-2023 and 2023-2024 influenza seasons was even worse: well under 50%.5

Fewer pregnant women have received updated COVID-19 vaccines. Only 13% of pregnant persons overall received the updated 2023-2024 COVID-19 booster vaccine (through March 30, 2024), according to the CDC.6

Maternal immunization for influenza has been recommended in the United States since 2004 (part of the recommendation that everyone over the age of 6 months receive an annual flu vaccine), and flu vaccines have been given to millions of pregnant women, but the H1N1 pandemic of 2009 reinforced its value as a priority for prenatal care. Most of the women who became severely ill from the H1N1 virus were young and healthy, without co-existing conditions known to increase risk.7

It became clearer during the H1N1 pandemic that pregnancy itself — which is associated with physiologic changes such as decreased lung capacity, increased nasal congestion and changes in the immune system – is its own significant risk factor for severe illness from the influenza virus. This increased risk applies to COVID-19 as well.

As COVID-19 has become endemic, with hospitalizations and deaths not reaching the levels of previous surges — and with mask-wearing and other preventive measures having declined — patients understandably have become more complacent. Some patients are vaccine deniers, but in my practice, these patients are a much smaller group than those who believe COVID-19 “is no big deal,” especially if they have had infections recently.

This is why it’s important to actively listen to concerns and to ask patients who decline a vaccination why they are hesitant. Blanket messages about vaccine efficacy and safety are the first step, but individualized, more pointed conversations based on the patient’s personal experiences and beliefs have become increasingly important.

I routinely tell pregnant patients about the risks of COVID-19 and I explain that it has been difficult to predict who will develop severe illness. Sometimes more conversation is needed. For those who are still hesitant or who tell me they feel protected by a recent infection, for instance, I provide more detail on the unique risks of pregnancy — the fact that “pregnancy is different” — and that natural immunity wanes while the protection afforded by immunization is believed to last longer. Many women are also concerned about the safety of the COVID-19 vaccine, so having safety data at your fingertips is helpful. (See Table 2.)

The fact that influenza and COVID-19 vaccination protect the newborn as well as the mother is something that I find is underappreciated by many patients. Explaining that infants likely benefit from the passage of antibodies across the placenta should be part of patient counseling.

Counseling About RSV Vaccination

Importantly, for the 2024-2025 RSV season, the maternal RSV vaccine (Abrysvo, Pfizer) is recommended only for pregnant women who did not receive the vaccine during the 2023-2024 season. When more research is done and more data are obtained showing how long the immune response persists post vaccination, it may be that the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) will approve the maternal RSV vaccine for use in every pregnancy.

The later timing of the vaccination recommendation — 32-36 weeks’ gestation — reflects a conservative approach taken by the FDA in response to data from one of the pivotal trials showing a numerical trend toward more preterm deliveries among vaccinated compared with unvaccinated patients. This imbalance in the original trial, which administered the vaccine during 24-36 weeks of gestation, was seen only in low-income countries with no temporal association, however.

In our experience at two Weill Cornell Medical College–associated hospitals we did not see this trend. Our cohort study of almost 3000 pregnant patients who delivered at 32 weeks’ gestation or later found no increased risk of preterm birth among the 35% of patients who received the RSV vaccine during the 2023-2024 RSV season. We also did not see any difference in preeclampsia, in contrast with original trial data that showed a signal for increased risk.11

When fewer than 2 weeks have elapsed between maternal vaccination and delivery, the monoclonal antibody nirsevimab is recommended for the newborn — ideally before the newborn leaves the hospital. Nirsevimab is also recommended for newborns of mothers who decline vaccination or were not candidates (e.g. vaccinated in a previous pregnancy), or when there is concern about the adequacy of the maternal immune response to the vaccine (e.g. in cases of immunosuppression).

While there was a limited supply of the monoclonal antibody last year, limitations are not expected this year, especially after October.

The ultimate goal is that patients choose the vaccine or the immunoglobulin, given the severity of RSV disease. Patient preferences should be considered. However, given that it takes 2 weeks after vaccination for protection to build up, I stress to patients that if they’ve vaccinated themselves, their newborn will leave the hospital with protection. If nirsevimab is relied upon, I explain, their newborn may not be protected for some period of time.

Take-home Messages

- When patients decline or are hesitant about vaccines, ask why. Listen actively, and work to correct misperceptions and knowledge gaps.

- Whenever possible, offer vaccines in your practice. Vaccination rates drop when this does not occur.

- COVID-vaccine safety is backed by many studies showing no increase in birth defects, preterm delivery, miscarriage, or stillbirth.

- Pregnant women are more likely to have severe illness from the influenza and SARS-CoV-2 viruses. Vaccines can prevent severe illness and can protect the newborn as well as the mother.

- Recommend/administer the maternal RSV vaccine at 32-36 weeks’ gestation in women who did not receive the vaccine in the 2023-2024 season. If mothers aren’t eligible their babies should be offered nirsevimab.

Dr. Riley is the Given Foundation Professor and Chair of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Weill Cornell Medicine and the obstetrician and gynecologist-in-chief at New York Presbyterian Hospital. She disclosed that she has provided one-time consultations to Pfizer (Abrysvo RSV vaccine) and GSK (cytomegalovirus vaccine), and is providing consultant education on CMV for Moderna. She is chair of ACOG’s task force on immunization and emerging infectious diseases, serves on the medical advisory board for MAVEN, and serves as an editor or editorial board member for several medical publications.

References

1. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 741: Maternal Immunization. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131(6):e214-e217.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID-19 Vaccination for People Who are Pregnant or Breastfeeding. https://www.cdc.gov/covid/vaccines/pregnant-or-breastfeeding.html.

3. ACOG Practice Advisory on Maternal Respiratory Syncytial Virus Vaccination, September 2023. (Updated August 2024).4. Irving S et al. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2023;10(Suppl 2):ofad500.1002.

5. Flu Vaccination Dashboard, CDC, National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases.

6. Weekly COVID-19 Vaccination Dashboard, CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/covidvaxview/weekly-dashboard/index.html

7. Louie JK et al. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:27-35. 8. Ciapponi A et al. Vaccine. 2021;39(40):5891-908.

9. Prasad S et al. Nature Communications. 2022;13:2414. 10. Fleming-Dutra KE et al. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am 2023;50(2):279-97. 11. Mouen S et al. JAMA Network Open 2024;7(7):e2419268.

Editor’s Note: Sadly, this is the last column in the Master Class Obstetrics series. This award-winning column has been part of Ob.Gyn. News for 20 years. The deep discussion of cutting-edge topics in obstetrics by specialists and researchers will be missed as will the leadership and curation of topics by Dr. E. Albert Reece.

Introduction: The Need for Increased Vigilance About Maternal Immunization

Viruses are becoming increasingly prevalent in our world and the consequences of viral infections are implicated in a growing number of disease states. It is well established that certain cancers are caused by viruses and it is increasingly evident that viral infections can trigger the development of chronic illness. In pregnant women, viruses such as cytomegalovirus can cause infection in utero and lead to long-term impairments for the baby.

Likewise, it appears that the virulence of viruses is increasing, whether it be the respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) in children or the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) coronaviruses in adults. Clearly, our environment is changing, with increases in population growth and urbanization, for instance, and an intensification of climate change and its effects. Viruses are part of this changing background.

Vaccines are our most powerful tool to protect people of all ages against viral threats, and fortunately, we benefit from increasing expertise in vaccinology. Since 1974, the University of Maryland School of Medicine has a Center for Vaccine Development and Global Health that has conducted research on vaccines to defend against the Zika virus, H1N1, Ebola, and SARS-CoV-2.

We’re not alone. Other vaccinology centers across the country — as well as the National Institutes of Health at the national level, through its National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases — are doing research and developing vaccines to combat viral diseases.

In this column, we are focused on viral diseases in pregnancy and the role that vaccines can play in preventing serious respiratory illness in mothers and their newborns. I have invited Laura E. Riley, MD, the Given Foundation Professor and Chair of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Weill Cornell Medicine, to address the importance of maternal immunization and how we can best counsel our patients and improve immunization rates.

As Dr. Riley explains, we are in a new era, and it behooves us all to be more vigilant about recommending vaccines, combating misperceptions, addressing patients’ knowledge gaps, and administering vaccines whenever possible.

Dr. Reece is the former Dean of Medicine & University Executive VP, and The Distinguished University and Endowed Professor & Director of the Center for Advanced Research Training and Innovation (CARTI) at the University of Maryland School of Medicine, as well as senior scientist at the Center for Birth Defects Research.

The alarming decline in maternal immunization rates that occurred in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic means that, now more than ever, we must fully embrace our responsibility to recommend immunizations in pregnancy and to communicate what is known about their efficacy and safety. Data show that vaccination rates drop when we do not offer vaccines in our offices, so whenever possible, we should administer them as well.

The ob.gyn. is the patient’s most trusted person in pregnancy. When patients decline or express hesitancy about vaccines, it is incumbent upon us to ask why. Oftentimes, we can identify areas in which patients lack knowledge or have misperceptions and we can successfully educate the patient or change their perspective or misunderstanding concerning the importance of vaccination for themselves and their babies. (See Table 1.) We can also successfully address concerns about safety.

The safety of COVID-19 vaccinations in pregnancy is now backed by several years of data from multiple studies showing no increase in birth defects, preterm delivery, miscarriage, or stillbirth.

Data also show that pregnant patients are more likely than patients who are not pregnant to need hospitalization and intensive care when infected with SARS-CoV-2 and are at risk of having complications that can affect pregnancy and the newborn, including preterm birth and stillbirth. Vaccination has been shown to reduce the risk of severe illness and the risk of such adverse obstetrical outcomes, in addition to providing protection for the infant early on.

Similarly, influenza has long been more likely to be severe in pregnant patients, with an increased risk of poor obstetrical outcomes. Vaccines similarly provide “two for one protection,” protecting both mother and baby, and are, of course, backed by many years of safety and efficacy data.

With the new maternal respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) vaccine, now in its second year of availability, the goal is to protect the baby from RSV-caused serious lower respiratory tract illness. The illness has contributed to tens of thousands of annual hospitalizations and up to several hundred deaths every year in children younger than 5 years — particularly in those under age 6 months.

The RSV monoclonal antibody nirsevimab is available for the newborn as an alternative to maternal immunization but the maternal vaccine is optimal in that it will provide immediate rather than delayed protection for the newborn. The maternal vaccine is recommended during weeks 32-36 of pregnancy in mothers who were not vaccinated during last year’s RSV season. With real-world experience from year one, the available safety data are reassuring.

Counseling About Influenza and COVID-19 Vaccination

The COVID-19 pandemic took a toll on vaccination interest/receptivity broadly in pregnant and nonpregnant people. Among pregnant individuals, influenza vaccination coverage declined from 71% in the 2019-2020 influenza season to 56% in the 2021-2022 season, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Vaccine Safety Datalink.4 Coverage for the 2022-2023 and 2023-2024 influenza seasons was even worse: well under 50%.5

Fewer pregnant women have received updated COVID-19 vaccines. Only 13% of pregnant persons overall received the updated 2023-2024 COVID-19 booster vaccine (through March 30, 2024), according to the CDC.6

Maternal immunization for influenza has been recommended in the United States since 2004 (part of the recommendation that everyone over the age of 6 months receive an annual flu vaccine), and flu vaccines have been given to millions of pregnant women, but the H1N1 pandemic of 2009 reinforced its value as a priority for prenatal care. Most of the women who became severely ill from the H1N1 virus were young and healthy, without co-existing conditions known to increase risk.7

It became clearer during the H1N1 pandemic that pregnancy itself — which is associated with physiologic changes such as decreased lung capacity, increased nasal congestion and changes in the immune system – is its own significant risk factor for severe illness from the influenza virus. This increased risk applies to COVID-19 as well.

As COVID-19 has become endemic, with hospitalizations and deaths not reaching the levels of previous surges — and with mask-wearing and other preventive measures having declined — patients understandably have become more complacent. Some patients are vaccine deniers, but in my practice, these patients are a much smaller group than those who believe COVID-19 “is no big deal,” especially if they have had infections recently.

This is why it’s important to actively listen to concerns and to ask patients who decline a vaccination why they are hesitant. Blanket messages about vaccine efficacy and safety are the first step, but individualized, more pointed conversations based on the patient’s personal experiences and beliefs have become increasingly important.

I routinely tell pregnant patients about the risks of COVID-19 and I explain that it has been difficult to predict who will develop severe illness. Sometimes more conversation is needed. For those who are still hesitant or who tell me they feel protected by a recent infection, for instance, I provide more detail on the unique risks of pregnancy — the fact that “pregnancy is different” — and that natural immunity wanes while the protection afforded by immunization is believed to last longer. Many women are also concerned about the safety of the COVID-19 vaccine, so having safety data at your fingertips is helpful. (See Table 2.)

The fact that influenza and COVID-19 vaccination protect the newborn as well as the mother is something that I find is underappreciated by many patients. Explaining that infants likely benefit from the passage of antibodies across the placenta should be part of patient counseling.

Counseling About RSV Vaccination

Importantly, for the 2024-2025 RSV season, the maternal RSV vaccine (Abrysvo, Pfizer) is recommended only for pregnant women who did not receive the vaccine during the 2023-2024 season. When more research is done and more data are obtained showing how long the immune response persists post vaccination, it may be that the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) will approve the maternal RSV vaccine for use in every pregnancy.

The later timing of the vaccination recommendation — 32-36 weeks’ gestation — reflects a conservative approach taken by the FDA in response to data from one of the pivotal trials showing a numerical trend toward more preterm deliveries among vaccinated compared with unvaccinated patients. This imbalance in the original trial, which administered the vaccine during 24-36 weeks of gestation, was seen only in low-income countries with no temporal association, however.

In our experience at two Weill Cornell Medical College–associated hospitals we did not see this trend. Our cohort study of almost 3000 pregnant patients who delivered at 32 weeks’ gestation or later found no increased risk of preterm birth among the 35% of patients who received the RSV vaccine during the 2023-2024 RSV season. We also did not see any difference in preeclampsia, in contrast with original trial data that showed a signal for increased risk.11

When fewer than 2 weeks have elapsed between maternal vaccination and delivery, the monoclonal antibody nirsevimab is recommended for the newborn — ideally before the newborn leaves the hospital. Nirsevimab is also recommended for newborns of mothers who decline vaccination or were not candidates (e.g. vaccinated in a previous pregnancy), or when there is concern about the adequacy of the maternal immune response to the vaccine (e.g. in cases of immunosuppression).

While there was a limited supply of the monoclonal antibody last year, limitations are not expected this year, especially after October.

The ultimate goal is that patients choose the vaccine or the immunoglobulin, given the severity of RSV disease. Patient preferences should be considered. However, given that it takes 2 weeks after vaccination for protection to build up, I stress to patients that if they’ve vaccinated themselves, their newborn will leave the hospital with protection. If nirsevimab is relied upon, I explain, their newborn may not be protected for some period of time.

Take-home Messages

- When patients decline or are hesitant about vaccines, ask why. Listen actively, and work to correct misperceptions and knowledge gaps.

- Whenever possible, offer vaccines in your practice. Vaccination rates drop when this does not occur.

- COVID-vaccine safety is backed by many studies showing no increase in birth defects, preterm delivery, miscarriage, or stillbirth.

- Pregnant women are more likely to have severe illness from the influenza and SARS-CoV-2 viruses. Vaccines can prevent severe illness and can protect the newborn as well as the mother.

- Recommend/administer the maternal RSV vaccine at 32-36 weeks’ gestation in women who did not receive the vaccine in the 2023-2024 season. If mothers aren’t eligible their babies should be offered nirsevimab.

Dr. Riley is the Given Foundation Professor and Chair of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Weill Cornell Medicine and the obstetrician and gynecologist-in-chief at New York Presbyterian Hospital. She disclosed that she has provided one-time consultations to Pfizer (Abrysvo RSV vaccine) and GSK (cytomegalovirus vaccine), and is providing consultant education on CMV for Moderna. She is chair of ACOG’s task force on immunization and emerging infectious diseases, serves on the medical advisory board for MAVEN, and serves as an editor or editorial board member for several medical publications.

References

1. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 741: Maternal Immunization. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131(6):e214-e217.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID-19 Vaccination for People Who are Pregnant or Breastfeeding. https://www.cdc.gov/covid/vaccines/pregnant-or-breastfeeding.html.

3. ACOG Practice Advisory on Maternal Respiratory Syncytial Virus Vaccination, September 2023. (Updated August 2024).4. Irving S et al. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2023;10(Suppl 2):ofad500.1002.

5. Flu Vaccination Dashboard, CDC, National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases.

6. Weekly COVID-19 Vaccination Dashboard, CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/covidvaxview/weekly-dashboard/index.html

7. Louie JK et al. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:27-35. 8. Ciapponi A et al. Vaccine. 2021;39(40):5891-908.

9. Prasad S et al. Nature Communications. 2022;13:2414. 10. Fleming-Dutra KE et al. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am 2023;50(2):279-97. 11. Mouen S et al. JAMA Network Open 2024;7(7):e2419268.

Editor’s Note: Sadly, this is the last column in the Master Class Obstetrics series. This award-winning column has been part of Ob.Gyn. News for 20 years. The deep discussion of cutting-edge topics in obstetrics by specialists and researchers will be missed as will the leadership and curation of topics by Dr. E. Albert Reece.

Introduction: The Need for Increased Vigilance About Maternal Immunization

Viruses are becoming increasingly prevalent in our world and the consequences of viral infections are implicated in a growing number of disease states. It is well established that certain cancers are caused by viruses and it is increasingly evident that viral infections can trigger the development of chronic illness. In pregnant women, viruses such as cytomegalovirus can cause infection in utero and lead to long-term impairments for the baby.

Likewise, it appears that the virulence of viruses is increasing, whether it be the respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) in children or the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) coronaviruses in adults. Clearly, our environment is changing, with increases in population growth and urbanization, for instance, and an intensification of climate change and its effects. Viruses are part of this changing background.

Vaccines are our most powerful tool to protect people of all ages against viral threats, and fortunately, we benefit from increasing expertise in vaccinology. Since 1974, the University of Maryland School of Medicine has a Center for Vaccine Development and Global Health that has conducted research on vaccines to defend against the Zika virus, H1N1, Ebola, and SARS-CoV-2.

We’re not alone. Other vaccinology centers across the country — as well as the National Institutes of Health at the national level, through its National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases — are doing research and developing vaccines to combat viral diseases.

In this column, we are focused on viral diseases in pregnancy and the role that vaccines can play in preventing serious respiratory illness in mothers and their newborns. I have invited Laura E. Riley, MD, the Given Foundation Professor and Chair of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Weill Cornell Medicine, to address the importance of maternal immunization and how we can best counsel our patients and improve immunization rates.

As Dr. Riley explains, we are in a new era, and it behooves us all to be more vigilant about recommending vaccines, combating misperceptions, addressing patients’ knowledge gaps, and administering vaccines whenever possible.

Dr. Reece is the former Dean of Medicine & University Executive VP, and The Distinguished University and Endowed Professor & Director of the Center for Advanced Research Training and Innovation (CARTI) at the University of Maryland School of Medicine, as well as senior scientist at the Center for Birth Defects Research.

The alarming decline in maternal immunization rates that occurred in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic means that, now more than ever, we must fully embrace our responsibility to recommend immunizations in pregnancy and to communicate what is known about their efficacy and safety. Data show that vaccination rates drop when we do not offer vaccines in our offices, so whenever possible, we should administer them as well.

The ob.gyn. is the patient’s most trusted person in pregnancy. When patients decline or express hesitancy about vaccines, it is incumbent upon us to ask why. Oftentimes, we can identify areas in which patients lack knowledge or have misperceptions and we can successfully educate the patient or change their perspective or misunderstanding concerning the importance of vaccination for themselves and their babies. (See Table 1.) We can also successfully address concerns about safety.

The safety of COVID-19 vaccinations in pregnancy is now backed by several years of data from multiple studies showing no increase in birth defects, preterm delivery, miscarriage, or stillbirth.

Data also show that pregnant patients are more likely than patients who are not pregnant to need hospitalization and intensive care when infected with SARS-CoV-2 and are at risk of having complications that can affect pregnancy and the newborn, including preterm birth and stillbirth. Vaccination has been shown to reduce the risk of severe illness and the risk of such adverse obstetrical outcomes, in addition to providing protection for the infant early on.

Similarly, influenza has long been more likely to be severe in pregnant patients, with an increased risk of poor obstetrical outcomes. Vaccines similarly provide “two for one protection,” protecting both mother and baby, and are, of course, backed by many years of safety and efficacy data.

With the new maternal respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) vaccine, now in its second year of availability, the goal is to protect the baby from RSV-caused serious lower respiratory tract illness. The illness has contributed to tens of thousands of annual hospitalizations and up to several hundred deaths every year in children younger than 5 years — particularly in those under age 6 months.

The RSV monoclonal antibody nirsevimab is available for the newborn as an alternative to maternal immunization but the maternal vaccine is optimal in that it will provide immediate rather than delayed protection for the newborn. The maternal vaccine is recommended during weeks 32-36 of pregnancy in mothers who were not vaccinated during last year’s RSV season. With real-world experience from year one, the available safety data are reassuring.

Counseling About Influenza and COVID-19 Vaccination

The COVID-19 pandemic took a toll on vaccination interest/receptivity broadly in pregnant and nonpregnant people. Among pregnant individuals, influenza vaccination coverage declined from 71% in the 2019-2020 influenza season to 56% in the 2021-2022 season, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Vaccine Safety Datalink.4 Coverage for the 2022-2023 and 2023-2024 influenza seasons was even worse: well under 50%.5

Fewer pregnant women have received updated COVID-19 vaccines. Only 13% of pregnant persons overall received the updated 2023-2024 COVID-19 booster vaccine (through March 30, 2024), according to the CDC.6

Maternal immunization for influenza has been recommended in the United States since 2004 (part of the recommendation that everyone over the age of 6 months receive an annual flu vaccine), and flu vaccines have been given to millions of pregnant women, but the H1N1 pandemic of 2009 reinforced its value as a priority for prenatal care. Most of the women who became severely ill from the H1N1 virus were young and healthy, without co-existing conditions known to increase risk.7

It became clearer during the H1N1 pandemic that pregnancy itself — which is associated with physiologic changes such as decreased lung capacity, increased nasal congestion and changes in the immune system – is its own significant risk factor for severe illness from the influenza virus. This increased risk applies to COVID-19 as well.

As COVID-19 has become endemic, with hospitalizations and deaths not reaching the levels of previous surges — and with mask-wearing and other preventive measures having declined — patients understandably have become more complacent. Some patients are vaccine deniers, but in my practice, these patients are a much smaller group than those who believe COVID-19 “is no big deal,” especially if they have had infections recently.

This is why it’s important to actively listen to concerns and to ask patients who decline a vaccination why they are hesitant. Blanket messages about vaccine efficacy and safety are the first step, but individualized, more pointed conversations based on the patient’s personal experiences and beliefs have become increasingly important.

I routinely tell pregnant patients about the risks of COVID-19 and I explain that it has been difficult to predict who will develop severe illness. Sometimes more conversation is needed. For those who are still hesitant or who tell me they feel protected by a recent infection, for instance, I provide more detail on the unique risks of pregnancy — the fact that “pregnancy is different” — and that natural immunity wanes while the protection afforded by immunization is believed to last longer. Many women are also concerned about the safety of the COVID-19 vaccine, so having safety data at your fingertips is helpful. (See Table 2.)

The fact that influenza and COVID-19 vaccination protect the newborn as well as the mother is something that I find is underappreciated by many patients. Explaining that infants likely benefit from the passage of antibodies across the placenta should be part of patient counseling.

Counseling About RSV Vaccination

Importantly, for the 2024-2025 RSV season, the maternal RSV vaccine (Abrysvo, Pfizer) is recommended only for pregnant women who did not receive the vaccine during the 2023-2024 season. When more research is done and more data are obtained showing how long the immune response persists post vaccination, it may be that the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) will approve the maternal RSV vaccine for use in every pregnancy.

The later timing of the vaccination recommendation — 32-36 weeks’ gestation — reflects a conservative approach taken by the FDA in response to data from one of the pivotal trials showing a numerical trend toward more preterm deliveries among vaccinated compared with unvaccinated patients. This imbalance in the original trial, which administered the vaccine during 24-36 weeks of gestation, was seen only in low-income countries with no temporal association, however.

In our experience at two Weill Cornell Medical College–associated hospitals we did not see this trend. Our cohort study of almost 3000 pregnant patients who delivered at 32 weeks’ gestation or later found no increased risk of preterm birth among the 35% of patients who received the RSV vaccine during the 2023-2024 RSV season. We also did not see any difference in preeclampsia, in contrast with original trial data that showed a signal for increased risk.11

When fewer than 2 weeks have elapsed between maternal vaccination and delivery, the monoclonal antibody nirsevimab is recommended for the newborn — ideally before the newborn leaves the hospital. Nirsevimab is also recommended for newborns of mothers who decline vaccination or were not candidates (e.g. vaccinated in a previous pregnancy), or when there is concern about the adequacy of the maternal immune response to the vaccine (e.g. in cases of immunosuppression).

While there was a limited supply of the monoclonal antibody last year, limitations are not expected this year, especially after October.

The ultimate goal is that patients choose the vaccine or the immunoglobulin, given the severity of RSV disease. Patient preferences should be considered. However, given that it takes 2 weeks after vaccination for protection to build up, I stress to patients that if they’ve vaccinated themselves, their newborn will leave the hospital with protection. If nirsevimab is relied upon, I explain, their newborn may not be protected for some period of time.

Take-home Messages

- When patients decline or are hesitant about vaccines, ask why. Listen actively, and work to correct misperceptions and knowledge gaps.

- Whenever possible, offer vaccines in your practice. Vaccination rates drop when this does not occur.

- COVID-vaccine safety is backed by many studies showing no increase in birth defects, preterm delivery, miscarriage, or stillbirth.

- Pregnant women are more likely to have severe illness from the influenza and SARS-CoV-2 viruses. Vaccines can prevent severe illness and can protect the newborn as well as the mother.

- Recommend/administer the maternal RSV vaccine at 32-36 weeks’ gestation in women who did not receive the vaccine in the 2023-2024 season. If mothers aren’t eligible their babies should be offered nirsevimab.

Dr. Riley is the Given Foundation Professor and Chair of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Weill Cornell Medicine and the obstetrician and gynecologist-in-chief at New York Presbyterian Hospital. She disclosed that she has provided one-time consultations to Pfizer (Abrysvo RSV vaccine) and GSK (cytomegalovirus vaccine), and is providing consultant education on CMV for Moderna. She is chair of ACOG’s task force on immunization and emerging infectious diseases, serves on the medical advisory board for MAVEN, and serves as an editor or editorial board member for several medical publications.

References

1. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 741: Maternal Immunization. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131(6):e214-e217.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID-19 Vaccination for People Who are Pregnant or Breastfeeding. https://www.cdc.gov/covid/vaccines/pregnant-or-breastfeeding.html.

3. ACOG Practice Advisory on Maternal Respiratory Syncytial Virus Vaccination, September 2023. (Updated August 2024).4. Irving S et al. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2023;10(Suppl 2):ofad500.1002.

5. Flu Vaccination Dashboard, CDC, National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases.

6. Weekly COVID-19 Vaccination Dashboard, CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/covidvaxview/weekly-dashboard/index.html

7. Louie JK et al. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:27-35. 8. Ciapponi A et al. Vaccine. 2021;39(40):5891-908.

9. Prasad S et al. Nature Communications. 2022;13:2414. 10. Fleming-Dutra KE et al. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am 2023;50(2):279-97. 11. Mouen S et al. JAMA Network Open 2024;7(7):e2419268.

SAFE: Ensuring Access for Children With Neurodevelopmental Disabilities

We pediatricians consider ourselves as compassionate professionals, optimistic about the potential of all children. This is reflected in the American Academy of Pediatrics’ equity statement of “its mission to ensure the health and well-being of all children. This includes promoting nurturing, inclusive environments and actively opposing intolerance, bigotry, bias, and discrimination.”

A committee of the Developmental Behavioral Pediatric Network developed and published a consensus statement specifically about problems in the care of individuals with neurodevelopmental disabilities (NDD) called the Supporting Access for Everyone (SAFE) initiative. All of us care for children with NDD as one in six are affected with these conditions that impact cognition, communication, motor, social, and/or behavior skills such as autism, ADHD, intellectual disabilities (ID), learning disorders, hearing or vision impairment, and motor disabilities such as cerebral palsy. Children with NDD are overrepresented in our daily practice schedule due to their multiple medical, behavioral, and social needs. NDD are also more common among marginalized children with racial, ethnic, sexual, or gender identity minority status compounding their difficulties in accessing quality care.

NDD present similar challenges to care as other chronic conditions that also require longer visits, more documentation, long-term monitoring, team-based care, care coordination, and often referrals. But most chronic medical conditions we care for such as asthma, diabetes, cancer, hypertension, and renal disease have clear national guidelines and appropriate billing codes and are not stigmatizing. Most also do not intrinsically affect the nervous system or cause disability as for NDD that alter the behavioral presentation of the individual in a way that changes their care.

Discrimination against individuals with NDD and other disabilities, called “ableism,” can take many forms: assuming a child with communication difficulty or ID is unable to understand explanations about their care; the presence of one NDD condition ending the clinician’s search for other issues; complicated problems or difficult behaviors in the medical setting truncating care, etc.

Adjustments Needed for Special Needs

As pediatricians we already adjust our interactions, starting instinctively, to the development level of the child we perceive before us. We approach infants slowly and softly, we speak in shorter sentences to toddlers, we joke around with school-aged children, and we take extra care about privacy with teens. This serves the relationships well for neurotypical children. But our (and our staff’s) perceptions of children with autism, ID, genetic syndromes that include NDD, or motor disabilities based on their behavioral presentation may not accurately recognize or accommodate their abilities or needs. Communication and environmental adjustments may need to be much more individualized to provide respectful care, comfort and even safety.

As an example, at this time 1 in 36 children have autism with or without ID. Defining features of autism include differences in social communication, repetitive or restrictive interests or behaviors, and hypersensitivity to the environment plus any coexisting conditions such as anxiety and hyperactivity. But most children with autism have completely age appropriate and typical physical appearance and their underlying condition may not even be known. The office setting, without special attention to the needs of a child with autism, may be frightening, loud, too bright, too crowded, fast paced, and confusing. The result of their sensitivities and difficulty communicating may lead to increased agitation, repetitive behaviors (sometimes called “stimming”), shrieking, attempts to escape the room, refusal to allow for vital signs or undressing, even aggression. Strategies for calming a neurotypical child such as talking or touching may make matters worse instead of better. We need help from the child and family and a plan to optimize their medical encounters.

If not adequately accommodated, children with many varieties of NDD end up not getting all the routine healthcare they need (eg vaccinations, blood tests, vital signs, even complete physical exams including dental) as well as having more adverse events during health care, including traumatizing seclusion, not allowing a support person to be present, restraint, injuries, and accidents. When more complex procedures are needed, eg x-ray, MRI, EEG, lab studies, or surgery, successful outcomes may be lower. Children with NDD have higher rates of often avoidable morbidity and mortality than those without, in part due to these barriers to complete care. While environmental accommodations to wheelchair users for accessibility has greatly improved in recent years, access to other kinds of individualized accommodations have lagged behind.

Accommodation Planning

There are a variety of factors that need to be taken into consideration in accommodating an individual with NDD. The family becomes the expert, along with the child, in knowing the child’s triggers, preferences, abilities, and level of understanding to accept and consent for care. An accommodation plan should be created using shared and supported decision making with the family and child and allowing for child preferences, regardless of their ability level, whenever possible. Development of an accommodation plan may benefit from multidisciplinary input, eg psychology, physical therapy, speech pathology, depending on the child’s needs and the practice’s ability to adapt.

The SAFE initiative is in the process of creating a checklist aiming to facilitate a description being created for each individual to help plan for a successful medical encounter while optimizing the child’s comfort, participation, and safety. While the checklist is not yet ready, we can start now by asking families and children in preparation for or at the start of a visit about their needs and writing a shared document that can also be placed in the electronic health record for the entire care team for informing care going forward.

It is especially important for the family to keep a copy of the care plan and for it to be sent as part of referrals for procedures or specialty visits so that the professionals can prepare and adapt the encounter. An excellent example is a how some hospitals schedule a practice visit for the child to experience the sights and sounds and people the child will encounter, for example, before an EEG, when nothing is required of the child. Scheduling the actual procedure at times of day when clinics are less crowded and wait times are shorter can improve the chances of success.

Some categories and details that might be included in an accommodation plan are listed below:

You might start the plan with the child’s preferred name/nickname, family member or support person names, and diagnoses along with a brief overview of the child’s level of functioning. Then list categories of needs and preferences along with suggestions or requests.

- Motor: Does the child have or need assistance entering the building, visit room, bathroom, or transferring to the exam table? What kind of assistance, if any, and by whom?

- Sensory: Is the child disturbed by noise, lights, or being touched? Does the child want to use equipment to be comfortable such as headphones, earplugs, or sunglasses or need a quiet room, care without perfumes, or dimmed lighting? Does the child typically refuse aspects of the physical examination?

- Behavioral regulation: What helps the child to stay calm? Are there certain triggers to becoming upset? Are there early cues that an upset is coming? What and who can help in the case of an upset?

- Habits/preferences: Are there certain comfort objects or habits your child needs? Are there habits your child needs to do, such as a certain order of events, or use of social stories or pictures, to cooperate or feel comfortable?

- Communication: How does the child make his/her needs known? Does the child/family speak English or another language? Does he/she use sign language or an augmentative communication device? What level of understanding does your child have; for example, similar to what age for a typical child? Is there a care plan with accommodations already available that needs review or needs revision with the child’s development or is a new one needed? Was the care plan developed including the child’s participation and assent or is more collaboration needed?

- History: Has your child had any very upsetting experiences in healthcare settings? What happened? Has the trauma been addressed? Are there reminders of the trauma that should be avoided?