User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

Persistent abdominal pain: Not always IBS

Persistent abdominal pain may be caused by a whole range of different conditions, say French experts who call for more physician awareness to achieve early diagnosis and treatment so as to improve patient outcomes.

Benoit Coffin, MD, PhD, and Henri Duboc, MD, PhD, from Hôpital Louis Mourier, Colombes, France, conducted a literature review to identify rare and less well-known causes of persistent abdominal pain, identifying almost 50 across several categories.

“Some causes of persistent abdominal pain can be effectively treated using established approaches after a definitive diagnosis has been reached,” they wrote.

“Other causes are more complex and may benefit from a multidisciplinary approach involving gastroenterologists, pain specialists, allergists, immunologists, rheumatologists, psychologists, physiotherapists, dietitians, and primary care clinicians,” they wrote.

The research was published online in Alimentary Pharmacology and Therapeutics.

Frequent and frustrating symptoms

Although there is “no commonly accepted definition” for persistent abdominal pain, the authors said it may be defined as “continuous or intermittent abdominal discomfort that persists for at least 6 months and fails to respond to conventional therapeutic approaches.”

They highlight that it is “frequently encountered” by physicians and has a prevalence of 22.9 per 1,000 person-years, regardless of age group, ethnicity, or geographical region, with many patients experiencing pain for more than 5 years.

The cause of persistent abdominal pain can be organic with a clear cause or functional, making diagnosis and management “challenging and frustrating for patients and physicians.”

“Clinicians not only need to recognize somatic abnormalities, but they must also perceive the patient’s cognitions and emotions related to the pain,” they added, suggesting that clinicians take time to “listen to the patient and perceive psychological factors.”

Dr. Coffin and Dr. Duboc write that the most common conditions associated with persistent abdominal pain are irritable bowel syndrome and functional dyspepsia, as well as inflammatory bowel disease, chronic pancreatitis, and gallstones.

To examine the diagnosis and management of its less well-known causes, the authors conducted a literature review, beginning with the diagnosis of persistent abdominal pain.

Diagnostic workup

“Given its chronicity, many patients will have already undergone extensive and redundant medical testing,” they wrote, emphasizing that clinicians should be on the lookout for any change in the description of persistent abdominal pain or new symptoms.

“Other ‘red-flag’ symptoms include fever, vomiting, diarrhea, acute change in bowel habit, obstipation, syncope, tachycardia, hypotension, concomitant chest or back pain, unintentional weight loss, night sweats, and acute gastrointestinal bleeding,” the authors said.

They stressed the need to determine whether the origin of the pain is organic or functional, as well as the importance of identifying a “triggering event, such as an adverse life event, infection, initiating a new medication, or surgical procedure.” They also recommend discussing the patient’s diet.

There are currently no specific algorithms for diagnostic workup of persistent abdominal pain, the authors said. Patients will have undergone repeated laboratory tests, “upper and lower endoscopic examinations, abdominal ultrasounds, and computed tomography scans of the abdominal/pelvic area.”

Consequently, “in the absence of alarm features, any additional tests should be ordered in a conservative and cost-effective manner,” they advised.

They suggested that, at a tertiary center, patients should be assessed in three steps:

- In-depth questioning of the symptoms and medical history

- Summary of all previous investigations and treatments and their effectiveness

- Determination of the complementary explorations to be performed

The authors went on to list 49 rare or less well-known potential causes of persistent abdominal pain, some linked to digestive disorders, such as eosinophilic gastroenteritis, mesenteric panniculitis, and chronic mesenteric ischemia, as well as endometriosis, chronic abdominal wall pain, and referred osteoarticular pain.

Systemic causes of persistent abdominal pain may include adrenal insufficiency and mast cell activation syndrome, while acute hepatic porphyrias and Ehlers-Danlos syndrome may be genetic causes.

There are also centrally mediated disorders that lead to persistent abdominal pain, the authors noted, including postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome and narcotic bowel syndrome caused by opioid therapy, among others.

Writing support for the manuscript was funded by Alnylam Switzerland. Dr. Coffin has served as a speaker for Kyowa Kyrin and Mayoly Spindler and as an advisory board member for Sanofi and Alnylam. Dr. Duboc reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Persistent abdominal pain may be caused by a whole range of different conditions, say French experts who call for more physician awareness to achieve early diagnosis and treatment so as to improve patient outcomes.

Benoit Coffin, MD, PhD, and Henri Duboc, MD, PhD, from Hôpital Louis Mourier, Colombes, France, conducted a literature review to identify rare and less well-known causes of persistent abdominal pain, identifying almost 50 across several categories.

“Some causes of persistent abdominal pain can be effectively treated using established approaches after a definitive diagnosis has been reached,” they wrote.

“Other causes are more complex and may benefit from a multidisciplinary approach involving gastroenterologists, pain specialists, allergists, immunologists, rheumatologists, psychologists, physiotherapists, dietitians, and primary care clinicians,” they wrote.

The research was published online in Alimentary Pharmacology and Therapeutics.

Frequent and frustrating symptoms

Although there is “no commonly accepted definition” for persistent abdominal pain, the authors said it may be defined as “continuous or intermittent abdominal discomfort that persists for at least 6 months and fails to respond to conventional therapeutic approaches.”

They highlight that it is “frequently encountered” by physicians and has a prevalence of 22.9 per 1,000 person-years, regardless of age group, ethnicity, or geographical region, with many patients experiencing pain for more than 5 years.

The cause of persistent abdominal pain can be organic with a clear cause or functional, making diagnosis and management “challenging and frustrating for patients and physicians.”

“Clinicians not only need to recognize somatic abnormalities, but they must also perceive the patient’s cognitions and emotions related to the pain,” they added, suggesting that clinicians take time to “listen to the patient and perceive psychological factors.”

Dr. Coffin and Dr. Duboc write that the most common conditions associated with persistent abdominal pain are irritable bowel syndrome and functional dyspepsia, as well as inflammatory bowel disease, chronic pancreatitis, and gallstones.

To examine the diagnosis and management of its less well-known causes, the authors conducted a literature review, beginning with the diagnosis of persistent abdominal pain.

Diagnostic workup

“Given its chronicity, many patients will have already undergone extensive and redundant medical testing,” they wrote, emphasizing that clinicians should be on the lookout for any change in the description of persistent abdominal pain or new symptoms.

“Other ‘red-flag’ symptoms include fever, vomiting, diarrhea, acute change in bowel habit, obstipation, syncope, tachycardia, hypotension, concomitant chest or back pain, unintentional weight loss, night sweats, and acute gastrointestinal bleeding,” the authors said.

They stressed the need to determine whether the origin of the pain is organic or functional, as well as the importance of identifying a “triggering event, such as an adverse life event, infection, initiating a new medication, or surgical procedure.” They also recommend discussing the patient’s diet.

There are currently no specific algorithms for diagnostic workup of persistent abdominal pain, the authors said. Patients will have undergone repeated laboratory tests, “upper and lower endoscopic examinations, abdominal ultrasounds, and computed tomography scans of the abdominal/pelvic area.”

Consequently, “in the absence of alarm features, any additional tests should be ordered in a conservative and cost-effective manner,” they advised.

They suggested that, at a tertiary center, patients should be assessed in three steps:

- In-depth questioning of the symptoms and medical history

- Summary of all previous investigations and treatments and their effectiveness

- Determination of the complementary explorations to be performed

The authors went on to list 49 rare or less well-known potential causes of persistent abdominal pain, some linked to digestive disorders, such as eosinophilic gastroenteritis, mesenteric panniculitis, and chronic mesenteric ischemia, as well as endometriosis, chronic abdominal wall pain, and referred osteoarticular pain.

Systemic causes of persistent abdominal pain may include adrenal insufficiency and mast cell activation syndrome, while acute hepatic porphyrias and Ehlers-Danlos syndrome may be genetic causes.

There are also centrally mediated disorders that lead to persistent abdominal pain, the authors noted, including postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome and narcotic bowel syndrome caused by opioid therapy, among others.

Writing support for the manuscript was funded by Alnylam Switzerland. Dr. Coffin has served as a speaker for Kyowa Kyrin and Mayoly Spindler and as an advisory board member for Sanofi and Alnylam. Dr. Duboc reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Persistent abdominal pain may be caused by a whole range of different conditions, say French experts who call for more physician awareness to achieve early diagnosis and treatment so as to improve patient outcomes.

Benoit Coffin, MD, PhD, and Henri Duboc, MD, PhD, from Hôpital Louis Mourier, Colombes, France, conducted a literature review to identify rare and less well-known causes of persistent abdominal pain, identifying almost 50 across several categories.

“Some causes of persistent abdominal pain can be effectively treated using established approaches after a definitive diagnosis has been reached,” they wrote.

“Other causes are more complex and may benefit from a multidisciplinary approach involving gastroenterologists, pain specialists, allergists, immunologists, rheumatologists, psychologists, physiotherapists, dietitians, and primary care clinicians,” they wrote.

The research was published online in Alimentary Pharmacology and Therapeutics.

Frequent and frustrating symptoms

Although there is “no commonly accepted definition” for persistent abdominal pain, the authors said it may be defined as “continuous or intermittent abdominal discomfort that persists for at least 6 months and fails to respond to conventional therapeutic approaches.”

They highlight that it is “frequently encountered” by physicians and has a prevalence of 22.9 per 1,000 person-years, regardless of age group, ethnicity, or geographical region, with many patients experiencing pain for more than 5 years.

The cause of persistent abdominal pain can be organic with a clear cause or functional, making diagnosis and management “challenging and frustrating for patients and physicians.”

“Clinicians not only need to recognize somatic abnormalities, but they must also perceive the patient’s cognitions and emotions related to the pain,” they added, suggesting that clinicians take time to “listen to the patient and perceive psychological factors.”

Dr. Coffin and Dr. Duboc write that the most common conditions associated with persistent abdominal pain are irritable bowel syndrome and functional dyspepsia, as well as inflammatory bowel disease, chronic pancreatitis, and gallstones.

To examine the diagnosis and management of its less well-known causes, the authors conducted a literature review, beginning with the diagnosis of persistent abdominal pain.

Diagnostic workup

“Given its chronicity, many patients will have already undergone extensive and redundant medical testing,” they wrote, emphasizing that clinicians should be on the lookout for any change in the description of persistent abdominal pain or new symptoms.

“Other ‘red-flag’ symptoms include fever, vomiting, diarrhea, acute change in bowel habit, obstipation, syncope, tachycardia, hypotension, concomitant chest or back pain, unintentional weight loss, night sweats, and acute gastrointestinal bleeding,” the authors said.

They stressed the need to determine whether the origin of the pain is organic or functional, as well as the importance of identifying a “triggering event, such as an adverse life event, infection, initiating a new medication, or surgical procedure.” They also recommend discussing the patient’s diet.

There are currently no specific algorithms for diagnostic workup of persistent abdominal pain, the authors said. Patients will have undergone repeated laboratory tests, “upper and lower endoscopic examinations, abdominal ultrasounds, and computed tomography scans of the abdominal/pelvic area.”

Consequently, “in the absence of alarm features, any additional tests should be ordered in a conservative and cost-effective manner,” they advised.

They suggested that, at a tertiary center, patients should be assessed in three steps:

- In-depth questioning of the symptoms and medical history

- Summary of all previous investigations and treatments and their effectiveness

- Determination of the complementary explorations to be performed

The authors went on to list 49 rare or less well-known potential causes of persistent abdominal pain, some linked to digestive disorders, such as eosinophilic gastroenteritis, mesenteric panniculitis, and chronic mesenteric ischemia, as well as endometriosis, chronic abdominal wall pain, and referred osteoarticular pain.

Systemic causes of persistent abdominal pain may include adrenal insufficiency and mast cell activation syndrome, while acute hepatic porphyrias and Ehlers-Danlos syndrome may be genetic causes.

There are also centrally mediated disorders that lead to persistent abdominal pain, the authors noted, including postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome and narcotic bowel syndrome caused by opioid therapy, among others.

Writing support for the manuscript was funded by Alnylam Switzerland. Dr. Coffin has served as a speaker for Kyowa Kyrin and Mayoly Spindler and as an advisory board member for Sanofi and Alnylam. Dr. Duboc reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ALIMENTARY PHARMACOLOGY AND THERAPEUTICS

More reflux after sleeve gastrectomy vs. gastric bypass at 10 years

Sleeve gastrectomy (SG) and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) each led to good and sustainable weight loss 10 years later, although reflux was more prevalent after SG, according to the Sleeve vs. Bypass (SLEEVEPASS) randomized clinical trial.

At 10 years, there were no statistically significant between-procedure differences in type 2 diabetes remission, dyslipidemia, or obstructive sleep apnea, but hypertension remission was greater with RYGB.

However, importantly, the cumulative incidence of Barrett’s esophagus was similar after both procedures (4%) and markedly lower than reported in previous trials (14%-17%).

To their knowledge, this is the largest randomized controlled trial with the longest follow-up comparing these two laparoscopic bariatric surgeries, Paulina Salminen, MD, PhD, and colleagues write in their study published online in JAMA Surgery.

They aimed to clarify the “controversial issues” of long-term gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) symptoms, endoscopic esophagitis, and Barrett’s esophagus after SG vs. RYGB.

The findings showed that “there was no difference in the prevalence of Barrett’s esophagus, contrary to previous reports of alarming rates of Barrett’s [esophagus] after sleeve gastrectomy,” Dr. Salminen from Turku (Finland) University Hospital, told this news organization in an email.

“However, our results also show that esophagitis and GERD symptoms are significantly more prevalent after sleeve [gastrectomy], and GERD is an important factor to be considered in the preoperative assessment of bariatric surgery and procedure choice,” she said.

The takeaway is that “we have two good procedures providing good and sustainable 10-year results for both weight loss and remission of comorbidities” for severe obesity, a major health risk, Dr. Salminen summarized.

10-year data analysis

Long-term outcomes from randomized clinical trials of laparoscopic SG vs. RYGB are limited, and recent studies have shown a high incidence of worsening of de novo GERD, esophagitis, and Barrett’s esophagus, after laparoscopic SG, Dr. Salminen and colleagues write.

To investigate, they analyzed 10-year data from SLEEVEPASS, which had randomized 240 adult patients with severe obesity to either SG or RYGB at three hospitals in Finland during 2008-2010.

At baseline, 121 patients were randomized to SG and 119 to RYGB. They had a mean age of 48 years, a mean body mass index of 45.9 kg/m2, and 70% were women.

Two patients never had the surgery, and at 10 years, 10 patients had died of causes unrelated to bariatric surgery.

At 10 years, 193 of the 288 remaining patients (85%) completed the follow-up for weight loss and other comorbidity outcomes, and 176 of 228 (77%) underwent gastroscopy.

The primary study endpoint of the trial was percent excess weight loss (%EWL). At 10 years, the median %EWL was 43.5% after SG vs. 50.7% after RYGB, with a wide range for both procedures (roughly 2%-110% excess weight loss). Mean estimate %EWL was not equivalent, with it being 8.4% in favor of RYGB.

After SG and RYGB, there were no statistically significant differences in type 2 diabetes remission (26% and 33%, respectively), dyslipidemia (19% and 35%, respectively), or obstructive sleep apnea (16% and 31%, respectively).

Hypertension remission was superior after RYGB (8% vs. 24%; P = .04).

Esophagitis was more prevalent after SG (31% vs. 7%; P < .001).

‘Very important study’

“This is a very important study, the first to report 10-year results of a randomized controlled trial comparing the two most frequently used bariatric operations, SG and RYGB,” Beat Peter Müller, MD, MBA, and Adrian Billeter, MD, PhD, who were not involved with this research, told this news organization in an email.

“The results will have a major impact on the future of bariatric surgery,” according to Dr. Müller and Dr. Billeter, from Heidelberg (Germany) University.

The most relevant findings are the GERD outcomes, they said. Because of the high rate of upper endoscopies at 10 years (73%), the study allowed a good assessment of this.

“While this study confirms that SG is a GERD-prone procedure, it clearly demonstrates that GERD after SG does not induce severe esophagitis and Barrett’s esophagus,” they said.

Most importantly, the rate of Barrett’s esophagus, the precursor lesion of adenocarcinomas of the esophago-gastric junction is similar (4%) after both operations and there was no dysplasia in either group, they stressed.

“The main problem after SG remains new-onset GERD, for which still no predictive parameter exists,” according to Dr. Müller and Dr. Billeter.

“The take home message … is that GERD after SG is generally mild and the risk of Barrett’s esophagus is equally higher after SG and RYGB,” they said. “Therefore, all patients after any bariatric operations should undergo regular upper endoscopies.”

However, “RYGB still leads to an increase in proton-pump inhibitor use, despite RYGB being one of the most effective antireflux procedures,” they said. “This finding needs further investigation.”

Furthermore, “a 4% Barrett esophagus rate 10 years after RYGB is troublesome, and the reasons should be investigated,” they added.

“Another relevant finding is that after 10 years, RYGB has a statistically better weight loss, which reaches the primary endpoint of the SLEEVEPASS trial for the first time,” they noted, yet the clinical relevance of this is not clear, since there was no difference in resolution of comorbidities, except for hypertension.

Gyanprakash A. Ketwaroo, MD, of Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, who was not involved with this research, agreed that “the study shows durable and good weight loss for either type of laparoscopic surgery with important metabolic effects and confirms the long-term benefits of weight-loss surgery.”

“What is somewhat new is the lower levels of Barrett’s esophagus after sleeve gastrectomy compared with several earlier studies,” he told this news organization in an email.

“This is somewhat incongruent with the relatively high incidence of postsleeve esophagitis noted in the study, which is an accepted risk factor for Barrett’s esophagus,” he continued. “Thus, I believe concern will still remain about GERD-related complications, including Barrett’s [esophagus], after sleeve gastrectomy.”

“This paper highlights the need for larger prospective studies, especially those that include diverse, older populations with multiple risk factors for Barrett’s esophagus,” Dr. Ketwaroo said.

Looking ahead

Using a large data set, such as that from SLEEVEPASS and possibly with data from the SM-BOSS trial and the BariSurg trial, with machine learning and other sophisticated analyses might identify parameters that could be used to choose the best operation for an individual patient, Dr. Salminen speculated.

“I think what we have learned from these long-term follow-up results is that GERD assessment should be a part of the preoperative assessment, and for patients who have preoperative GERD symptoms and GERD-related endoscopic findings (e.g., hiatal hernia), gastric bypass would be a more optimal procedure choice, if there are no contraindications for it,” she said.

Patient discussions should also cover “long-term symptoms, for example, abdominal pain after RYGB,” she added.

“I am looking forward to our future 20-year follow-up results,” Dr. Salminen said, “which will shed more light on this topic of postoperative [endoscopic] surveillance.

In the meantime, “preoperative gastroscopy is necessary and beneficial, at least when considering sleeve gastrectomy,” she said.

The SLEEVEPASS trial was supported by the Mary and Georg C. Ehrnrooth Foundation, the Government Research Foundation (in a grant awarded to Turku University Hospital), the Orion Research Foundation, the Paulo Foundation, and the Gastroenterological Research Foundation. Dr. Salminen reported receiving grants from the Government Research Foundation awarded to Turku University Hospital and the Mary and Georg C. Ehrnrooth Foundation. Another coauthor received grants from the Orion Research Foundation, the Paulo Foundation, and the Gastroenterological Research Foundation during the study. No other disclosures were reported.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Sleeve gastrectomy (SG) and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) each led to good and sustainable weight loss 10 years later, although reflux was more prevalent after SG, according to the Sleeve vs. Bypass (SLEEVEPASS) randomized clinical trial.

At 10 years, there were no statistically significant between-procedure differences in type 2 diabetes remission, dyslipidemia, or obstructive sleep apnea, but hypertension remission was greater with RYGB.

However, importantly, the cumulative incidence of Barrett’s esophagus was similar after both procedures (4%) and markedly lower than reported in previous trials (14%-17%).

To their knowledge, this is the largest randomized controlled trial with the longest follow-up comparing these two laparoscopic bariatric surgeries, Paulina Salminen, MD, PhD, and colleagues write in their study published online in JAMA Surgery.

They aimed to clarify the “controversial issues” of long-term gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) symptoms, endoscopic esophagitis, and Barrett’s esophagus after SG vs. RYGB.

The findings showed that “there was no difference in the prevalence of Barrett’s esophagus, contrary to previous reports of alarming rates of Barrett’s [esophagus] after sleeve gastrectomy,” Dr. Salminen from Turku (Finland) University Hospital, told this news organization in an email.

“However, our results also show that esophagitis and GERD symptoms are significantly more prevalent after sleeve [gastrectomy], and GERD is an important factor to be considered in the preoperative assessment of bariatric surgery and procedure choice,” she said.

The takeaway is that “we have two good procedures providing good and sustainable 10-year results for both weight loss and remission of comorbidities” for severe obesity, a major health risk, Dr. Salminen summarized.

10-year data analysis

Long-term outcomes from randomized clinical trials of laparoscopic SG vs. RYGB are limited, and recent studies have shown a high incidence of worsening of de novo GERD, esophagitis, and Barrett’s esophagus, after laparoscopic SG, Dr. Salminen and colleagues write.

To investigate, they analyzed 10-year data from SLEEVEPASS, which had randomized 240 adult patients with severe obesity to either SG or RYGB at three hospitals in Finland during 2008-2010.

At baseline, 121 patients were randomized to SG and 119 to RYGB. They had a mean age of 48 years, a mean body mass index of 45.9 kg/m2, and 70% were women.

Two patients never had the surgery, and at 10 years, 10 patients had died of causes unrelated to bariatric surgery.

At 10 years, 193 of the 288 remaining patients (85%) completed the follow-up for weight loss and other comorbidity outcomes, and 176 of 228 (77%) underwent gastroscopy.

The primary study endpoint of the trial was percent excess weight loss (%EWL). At 10 years, the median %EWL was 43.5% after SG vs. 50.7% after RYGB, with a wide range for both procedures (roughly 2%-110% excess weight loss). Mean estimate %EWL was not equivalent, with it being 8.4% in favor of RYGB.

After SG and RYGB, there were no statistically significant differences in type 2 diabetes remission (26% and 33%, respectively), dyslipidemia (19% and 35%, respectively), or obstructive sleep apnea (16% and 31%, respectively).

Hypertension remission was superior after RYGB (8% vs. 24%; P = .04).

Esophagitis was more prevalent after SG (31% vs. 7%; P < .001).

‘Very important study’

“This is a very important study, the first to report 10-year results of a randomized controlled trial comparing the two most frequently used bariatric operations, SG and RYGB,” Beat Peter Müller, MD, MBA, and Adrian Billeter, MD, PhD, who were not involved with this research, told this news organization in an email.

“The results will have a major impact on the future of bariatric surgery,” according to Dr. Müller and Dr. Billeter, from Heidelberg (Germany) University.

The most relevant findings are the GERD outcomes, they said. Because of the high rate of upper endoscopies at 10 years (73%), the study allowed a good assessment of this.

“While this study confirms that SG is a GERD-prone procedure, it clearly demonstrates that GERD after SG does not induce severe esophagitis and Barrett’s esophagus,” they said.

Most importantly, the rate of Barrett’s esophagus, the precursor lesion of adenocarcinomas of the esophago-gastric junction is similar (4%) after both operations and there was no dysplasia in either group, they stressed.

“The main problem after SG remains new-onset GERD, for which still no predictive parameter exists,” according to Dr. Müller and Dr. Billeter.

“The take home message … is that GERD after SG is generally mild and the risk of Barrett’s esophagus is equally higher after SG and RYGB,” they said. “Therefore, all patients after any bariatric operations should undergo regular upper endoscopies.”

However, “RYGB still leads to an increase in proton-pump inhibitor use, despite RYGB being one of the most effective antireflux procedures,” they said. “This finding needs further investigation.”

Furthermore, “a 4% Barrett esophagus rate 10 years after RYGB is troublesome, and the reasons should be investigated,” they added.

“Another relevant finding is that after 10 years, RYGB has a statistically better weight loss, which reaches the primary endpoint of the SLEEVEPASS trial for the first time,” they noted, yet the clinical relevance of this is not clear, since there was no difference in resolution of comorbidities, except for hypertension.

Gyanprakash A. Ketwaroo, MD, of Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, who was not involved with this research, agreed that “the study shows durable and good weight loss for either type of laparoscopic surgery with important metabolic effects and confirms the long-term benefits of weight-loss surgery.”

“What is somewhat new is the lower levels of Barrett’s esophagus after sleeve gastrectomy compared with several earlier studies,” he told this news organization in an email.

“This is somewhat incongruent with the relatively high incidence of postsleeve esophagitis noted in the study, which is an accepted risk factor for Barrett’s esophagus,” he continued. “Thus, I believe concern will still remain about GERD-related complications, including Barrett’s [esophagus], after sleeve gastrectomy.”

“This paper highlights the need for larger prospective studies, especially those that include diverse, older populations with multiple risk factors for Barrett’s esophagus,” Dr. Ketwaroo said.

Looking ahead

Using a large data set, such as that from SLEEVEPASS and possibly with data from the SM-BOSS trial and the BariSurg trial, with machine learning and other sophisticated analyses might identify parameters that could be used to choose the best operation for an individual patient, Dr. Salminen speculated.

“I think what we have learned from these long-term follow-up results is that GERD assessment should be a part of the preoperative assessment, and for patients who have preoperative GERD symptoms and GERD-related endoscopic findings (e.g., hiatal hernia), gastric bypass would be a more optimal procedure choice, if there are no contraindications for it,” she said.

Patient discussions should also cover “long-term symptoms, for example, abdominal pain after RYGB,” she added.

“I am looking forward to our future 20-year follow-up results,” Dr. Salminen said, “which will shed more light on this topic of postoperative [endoscopic] surveillance.

In the meantime, “preoperative gastroscopy is necessary and beneficial, at least when considering sleeve gastrectomy,” she said.

The SLEEVEPASS trial was supported by the Mary and Georg C. Ehrnrooth Foundation, the Government Research Foundation (in a grant awarded to Turku University Hospital), the Orion Research Foundation, the Paulo Foundation, and the Gastroenterological Research Foundation. Dr. Salminen reported receiving grants from the Government Research Foundation awarded to Turku University Hospital and the Mary and Georg C. Ehrnrooth Foundation. Another coauthor received grants from the Orion Research Foundation, the Paulo Foundation, and the Gastroenterological Research Foundation during the study. No other disclosures were reported.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Sleeve gastrectomy (SG) and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) each led to good and sustainable weight loss 10 years later, although reflux was more prevalent after SG, according to the Sleeve vs. Bypass (SLEEVEPASS) randomized clinical trial.

At 10 years, there were no statistically significant between-procedure differences in type 2 diabetes remission, dyslipidemia, or obstructive sleep apnea, but hypertension remission was greater with RYGB.

However, importantly, the cumulative incidence of Barrett’s esophagus was similar after both procedures (4%) and markedly lower than reported in previous trials (14%-17%).

To their knowledge, this is the largest randomized controlled trial with the longest follow-up comparing these two laparoscopic bariatric surgeries, Paulina Salminen, MD, PhD, and colleagues write in their study published online in JAMA Surgery.

They aimed to clarify the “controversial issues” of long-term gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) symptoms, endoscopic esophagitis, and Barrett’s esophagus after SG vs. RYGB.

The findings showed that “there was no difference in the prevalence of Barrett’s esophagus, contrary to previous reports of alarming rates of Barrett’s [esophagus] after sleeve gastrectomy,” Dr. Salminen from Turku (Finland) University Hospital, told this news organization in an email.

“However, our results also show that esophagitis and GERD symptoms are significantly more prevalent after sleeve [gastrectomy], and GERD is an important factor to be considered in the preoperative assessment of bariatric surgery and procedure choice,” she said.

The takeaway is that “we have two good procedures providing good and sustainable 10-year results for both weight loss and remission of comorbidities” for severe obesity, a major health risk, Dr. Salminen summarized.

10-year data analysis

Long-term outcomes from randomized clinical trials of laparoscopic SG vs. RYGB are limited, and recent studies have shown a high incidence of worsening of de novo GERD, esophagitis, and Barrett’s esophagus, after laparoscopic SG, Dr. Salminen and colleagues write.

To investigate, they analyzed 10-year data from SLEEVEPASS, which had randomized 240 adult patients with severe obesity to either SG or RYGB at three hospitals in Finland during 2008-2010.

At baseline, 121 patients were randomized to SG and 119 to RYGB. They had a mean age of 48 years, a mean body mass index of 45.9 kg/m2, and 70% were women.

Two patients never had the surgery, and at 10 years, 10 patients had died of causes unrelated to bariatric surgery.

At 10 years, 193 of the 288 remaining patients (85%) completed the follow-up for weight loss and other comorbidity outcomes, and 176 of 228 (77%) underwent gastroscopy.

The primary study endpoint of the trial was percent excess weight loss (%EWL). At 10 years, the median %EWL was 43.5% after SG vs. 50.7% after RYGB, with a wide range for both procedures (roughly 2%-110% excess weight loss). Mean estimate %EWL was not equivalent, with it being 8.4% in favor of RYGB.

After SG and RYGB, there were no statistically significant differences in type 2 diabetes remission (26% and 33%, respectively), dyslipidemia (19% and 35%, respectively), or obstructive sleep apnea (16% and 31%, respectively).

Hypertension remission was superior after RYGB (8% vs. 24%; P = .04).

Esophagitis was more prevalent after SG (31% vs. 7%; P < .001).

‘Very important study’

“This is a very important study, the first to report 10-year results of a randomized controlled trial comparing the two most frequently used bariatric operations, SG and RYGB,” Beat Peter Müller, MD, MBA, and Adrian Billeter, MD, PhD, who were not involved with this research, told this news organization in an email.

“The results will have a major impact on the future of bariatric surgery,” according to Dr. Müller and Dr. Billeter, from Heidelberg (Germany) University.

The most relevant findings are the GERD outcomes, they said. Because of the high rate of upper endoscopies at 10 years (73%), the study allowed a good assessment of this.

“While this study confirms that SG is a GERD-prone procedure, it clearly demonstrates that GERD after SG does not induce severe esophagitis and Barrett’s esophagus,” they said.

Most importantly, the rate of Barrett’s esophagus, the precursor lesion of adenocarcinomas of the esophago-gastric junction is similar (4%) after both operations and there was no dysplasia in either group, they stressed.

“The main problem after SG remains new-onset GERD, for which still no predictive parameter exists,” according to Dr. Müller and Dr. Billeter.

“The take home message … is that GERD after SG is generally mild and the risk of Barrett’s esophagus is equally higher after SG and RYGB,” they said. “Therefore, all patients after any bariatric operations should undergo regular upper endoscopies.”

However, “RYGB still leads to an increase in proton-pump inhibitor use, despite RYGB being one of the most effective antireflux procedures,” they said. “This finding needs further investigation.”

Furthermore, “a 4% Barrett esophagus rate 10 years after RYGB is troublesome, and the reasons should be investigated,” they added.

“Another relevant finding is that after 10 years, RYGB has a statistically better weight loss, which reaches the primary endpoint of the SLEEVEPASS trial for the first time,” they noted, yet the clinical relevance of this is not clear, since there was no difference in resolution of comorbidities, except for hypertension.

Gyanprakash A. Ketwaroo, MD, of Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, who was not involved with this research, agreed that “the study shows durable and good weight loss for either type of laparoscopic surgery with important metabolic effects and confirms the long-term benefits of weight-loss surgery.”

“What is somewhat new is the lower levels of Barrett’s esophagus after sleeve gastrectomy compared with several earlier studies,” he told this news organization in an email.

“This is somewhat incongruent with the relatively high incidence of postsleeve esophagitis noted in the study, which is an accepted risk factor for Barrett’s esophagus,” he continued. “Thus, I believe concern will still remain about GERD-related complications, including Barrett’s [esophagus], after sleeve gastrectomy.”

“This paper highlights the need for larger prospective studies, especially those that include diverse, older populations with multiple risk factors for Barrett’s esophagus,” Dr. Ketwaroo said.

Looking ahead

Using a large data set, such as that from SLEEVEPASS and possibly with data from the SM-BOSS trial and the BariSurg trial, with machine learning and other sophisticated analyses might identify parameters that could be used to choose the best operation for an individual patient, Dr. Salminen speculated.

“I think what we have learned from these long-term follow-up results is that GERD assessment should be a part of the preoperative assessment, and for patients who have preoperative GERD symptoms and GERD-related endoscopic findings (e.g., hiatal hernia), gastric bypass would be a more optimal procedure choice, if there are no contraindications for it,” she said.

Patient discussions should also cover “long-term symptoms, for example, abdominal pain after RYGB,” she added.

“I am looking forward to our future 20-year follow-up results,” Dr. Salminen said, “which will shed more light on this topic of postoperative [endoscopic] surveillance.

In the meantime, “preoperative gastroscopy is necessary and beneficial, at least when considering sleeve gastrectomy,” she said.

The SLEEVEPASS trial was supported by the Mary and Georg C. Ehrnrooth Foundation, the Government Research Foundation (in a grant awarded to Turku University Hospital), the Orion Research Foundation, the Paulo Foundation, and the Gastroenterological Research Foundation. Dr. Salminen reported receiving grants from the Government Research Foundation awarded to Turku University Hospital and the Mary and Georg C. Ehrnrooth Foundation. Another coauthor received grants from the Orion Research Foundation, the Paulo Foundation, and the Gastroenterological Research Foundation during the study. No other disclosures were reported.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA SURGERY

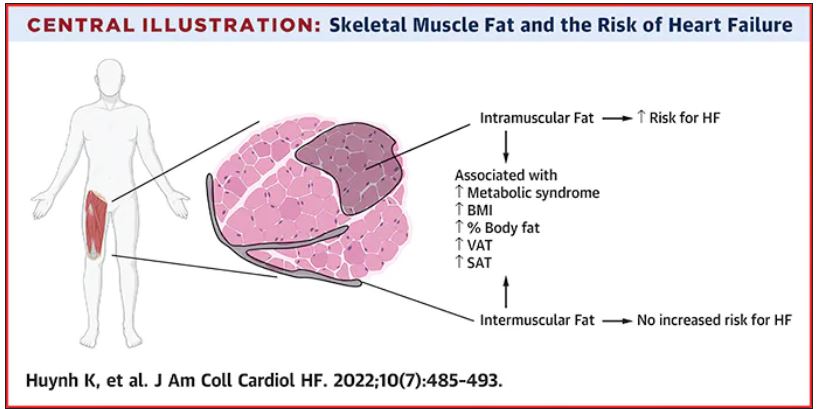

Thigh muscle fat predicts risk of developing heart failure

in a new study. The association was independent of other cardiometabolic risk factors and measures of adiposity such as body mass index.

The observation raises the possibility of new avenues of research aimed at modifying intramuscular fat levels as a strategy to reduce the risk of developing heart failure.

The study was published online in JACC: Heart Failure.

The authors, led by Kevin Huynh, MD, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, explained that obesity is a known risk for heart failure, and has been incorporated into risk calculators for heart failure.

However, obesity is a complex and heterogeneous disease with substantial regional variability of adipose deposition in body tissues, they noted. For example, variability in visceral adipose tissue and subcutaneous adipose tissue has been shown to have a differential impact on both cardiovascular risk factors and clinical cardiovascular disease outcomes.

The fat deposition around and within nonadipose tissues (termed “ectopic fat”), such as skeletal muscle, is also a known risk factor for cardiovascular disease, independent of adiposity. However, the impact of peripheral skeletal muscle fat deposition on heart failure risk is not as well studied.

The researchers noted that ectopic fat in skeletal muscle can be measured through imaging and categorized as either intermuscular or intramuscular fat according to the location of muscle fat around or within skeletal muscle, respectively.

The researchers conducted the current study to characterize the association of both intermuscular and intramuscular fat deposition with heart failure risk in a large cohort of older adults.

They used data from 2,399 individuals aged 70-79 years without heart failure at baseline who participated in the Health ABC (Health, Aging and Body Composition) study. Measures of intramuscular and intermuscular fat in the thigh were determined by CT, and the participants were followed for an average of 12 years.

During the follow-up period, there were 485 incident heart failure events. Higher sex-specific tertiles of intramuscular and intermuscular fat were each associated with heart failure risk.

After multivariable adjustment for age, sex, race, education, blood pressure, fasting blood sugar, current smoking, prevalent coronary disease, and creatinine, higher intramuscular fat, but not intermuscular fat, was significantly associated with higher risk for heart failure.

Individuals in the highest tertile of intramuscular fat had a 34% increased risk of developing heart failure, compared with those in the lowest tertile. This finding was independent of other cardiometabolic risk factors, measures of adiposity including body mass index and percent fat, muscle strength, and muscle mass.

The association was slightly attenuated when adjusted for inflammatory markers, suggesting that inflammation may be a contributor.

The association between higher intramuscular fat and heart failure appeared specific to higher risk of incident heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, but not with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction.

The researchers noted that skeletal muscle is a pivotal endocrine organ in addition to the role it plays in the production of mechanical power.

They pointed out that there are differences in the biology of intermuscular and intramuscular fat deposition, and that excess intramuscular fat deposition is a result of dysregulated lipid metabolism and is associated with insulin resistance (a known risk factor for the development of heart failure), inflammation, and muscle wasting conditions.

They concluded that, in patients with heart failure, alterations in skeletal muscle function are most likely affected by multiple contributors, including inflammation, oxidative stress, and neurohormonal factors. “As these factors are also implicated in the pathogenesis of heart failure, intramuscular fat deposition may indicate a biological milieu that increases the risk of heart failure.”

New approaches to reduce heart failure risk?

In an accompanying editorial, Salvatore Carbone, PhD, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, said the findings of the study are “exceptionally novel,” providing novel evidence that noncardiac body composition compartments, particularly intramuscular adipose tissue, can predict the risk for heart failure in a diverse population of older adults.

He called for further research to understand the mechanisms involved and to assess if this risk factor can be effectively modified to reduce the risk of developing heart failure.

Dr. Carbone reported that intramuscular adipose tissue can be influenced by dietary fat intake and can be worsened by accumulation of saturated fatty acids, which also contribute to insulin resistance.

He noted that saturated fatty acid–induced insulin resistance in the skeletal muscle appears to be mediated by proinflammatory pathways within the skeletal muscle itself, which can be reversed by monounsaturated fatty acids, like oleic acid, that can be found in the largest amount in food like olive oil, canola oil, and avocados, among others.

He added that sodium-glucose transporter 2 inhibitors, drugs used in the treatment of diabetes that have also been shown to prevent heart failure in individuals at risk, can also improve the composition of intramuscular adipose tissue by reducing its content of saturated fatty acids and increase the content of monosaturated fatty acids.

The study results suggest that the quality of intramuscular adipose tissue might also play an important role and could be targeted by therapeutic strategies, he commented.

Dr. Carbone concluded that “studies testing novel modalities of exercise training, intentional weight loss, diet quality improvements with and without weight loss (i.e., increase of dietary monounsaturated fatty acids, such as oleic acid), as well as pharmacological anti-inflammatory strategies should be encouraged in this population to test whether the reduction in intramuscular adipose tissue or improvements of its quality can ultimately reduce the risk for heart failure in this population.”

This research was supported by the National Institute on Aging and the National Institute of Nursing Research. Dr. Huynh and Dr. Carbone disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

in a new study. The association was independent of other cardiometabolic risk factors and measures of adiposity such as body mass index.

The observation raises the possibility of new avenues of research aimed at modifying intramuscular fat levels as a strategy to reduce the risk of developing heart failure.

The study was published online in JACC: Heart Failure.

The authors, led by Kevin Huynh, MD, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, explained that obesity is a known risk for heart failure, and has been incorporated into risk calculators for heart failure.

However, obesity is a complex and heterogeneous disease with substantial regional variability of adipose deposition in body tissues, they noted. For example, variability in visceral adipose tissue and subcutaneous adipose tissue has been shown to have a differential impact on both cardiovascular risk factors and clinical cardiovascular disease outcomes.

The fat deposition around and within nonadipose tissues (termed “ectopic fat”), such as skeletal muscle, is also a known risk factor for cardiovascular disease, independent of adiposity. However, the impact of peripheral skeletal muscle fat deposition on heart failure risk is not as well studied.

The researchers noted that ectopic fat in skeletal muscle can be measured through imaging and categorized as either intermuscular or intramuscular fat according to the location of muscle fat around or within skeletal muscle, respectively.

The researchers conducted the current study to characterize the association of both intermuscular and intramuscular fat deposition with heart failure risk in a large cohort of older adults.

They used data from 2,399 individuals aged 70-79 years without heart failure at baseline who participated in the Health ABC (Health, Aging and Body Composition) study. Measures of intramuscular and intermuscular fat in the thigh were determined by CT, and the participants were followed for an average of 12 years.

During the follow-up period, there were 485 incident heart failure events. Higher sex-specific tertiles of intramuscular and intermuscular fat were each associated with heart failure risk.

After multivariable adjustment for age, sex, race, education, blood pressure, fasting blood sugar, current smoking, prevalent coronary disease, and creatinine, higher intramuscular fat, but not intermuscular fat, was significantly associated with higher risk for heart failure.

Individuals in the highest tertile of intramuscular fat had a 34% increased risk of developing heart failure, compared with those in the lowest tertile. This finding was independent of other cardiometabolic risk factors, measures of adiposity including body mass index and percent fat, muscle strength, and muscle mass.

The association was slightly attenuated when adjusted for inflammatory markers, suggesting that inflammation may be a contributor.

The association between higher intramuscular fat and heart failure appeared specific to higher risk of incident heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, but not with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction.

The researchers noted that skeletal muscle is a pivotal endocrine organ in addition to the role it plays in the production of mechanical power.

They pointed out that there are differences in the biology of intermuscular and intramuscular fat deposition, and that excess intramuscular fat deposition is a result of dysregulated lipid metabolism and is associated with insulin resistance (a known risk factor for the development of heart failure), inflammation, and muscle wasting conditions.

They concluded that, in patients with heart failure, alterations in skeletal muscle function are most likely affected by multiple contributors, including inflammation, oxidative stress, and neurohormonal factors. “As these factors are also implicated in the pathogenesis of heart failure, intramuscular fat deposition may indicate a biological milieu that increases the risk of heart failure.”

New approaches to reduce heart failure risk?

In an accompanying editorial, Salvatore Carbone, PhD, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, said the findings of the study are “exceptionally novel,” providing novel evidence that noncardiac body composition compartments, particularly intramuscular adipose tissue, can predict the risk for heart failure in a diverse population of older adults.

He called for further research to understand the mechanisms involved and to assess if this risk factor can be effectively modified to reduce the risk of developing heart failure.

Dr. Carbone reported that intramuscular adipose tissue can be influenced by dietary fat intake and can be worsened by accumulation of saturated fatty acids, which also contribute to insulin resistance.

He noted that saturated fatty acid–induced insulin resistance in the skeletal muscle appears to be mediated by proinflammatory pathways within the skeletal muscle itself, which can be reversed by monounsaturated fatty acids, like oleic acid, that can be found in the largest amount in food like olive oil, canola oil, and avocados, among others.

He added that sodium-glucose transporter 2 inhibitors, drugs used in the treatment of diabetes that have also been shown to prevent heart failure in individuals at risk, can also improve the composition of intramuscular adipose tissue by reducing its content of saturated fatty acids and increase the content of monosaturated fatty acids.

The study results suggest that the quality of intramuscular adipose tissue might also play an important role and could be targeted by therapeutic strategies, he commented.

Dr. Carbone concluded that “studies testing novel modalities of exercise training, intentional weight loss, diet quality improvements with and without weight loss (i.e., increase of dietary monounsaturated fatty acids, such as oleic acid), as well as pharmacological anti-inflammatory strategies should be encouraged in this population to test whether the reduction in intramuscular adipose tissue or improvements of its quality can ultimately reduce the risk for heart failure in this population.”

This research was supported by the National Institute on Aging and the National Institute of Nursing Research. Dr. Huynh and Dr. Carbone disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

in a new study. The association was independent of other cardiometabolic risk factors and measures of adiposity such as body mass index.

The observation raises the possibility of new avenues of research aimed at modifying intramuscular fat levels as a strategy to reduce the risk of developing heart failure.

The study was published online in JACC: Heart Failure.

The authors, led by Kevin Huynh, MD, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, explained that obesity is a known risk for heart failure, and has been incorporated into risk calculators for heart failure.

However, obesity is a complex and heterogeneous disease with substantial regional variability of adipose deposition in body tissues, they noted. For example, variability in visceral adipose tissue and subcutaneous adipose tissue has been shown to have a differential impact on both cardiovascular risk factors and clinical cardiovascular disease outcomes.

The fat deposition around and within nonadipose tissues (termed “ectopic fat”), such as skeletal muscle, is also a known risk factor for cardiovascular disease, independent of adiposity. However, the impact of peripheral skeletal muscle fat deposition on heart failure risk is not as well studied.

The researchers noted that ectopic fat in skeletal muscle can be measured through imaging and categorized as either intermuscular or intramuscular fat according to the location of muscle fat around or within skeletal muscle, respectively.

The researchers conducted the current study to characterize the association of both intermuscular and intramuscular fat deposition with heart failure risk in a large cohort of older adults.

They used data from 2,399 individuals aged 70-79 years without heart failure at baseline who participated in the Health ABC (Health, Aging and Body Composition) study. Measures of intramuscular and intermuscular fat in the thigh were determined by CT, and the participants were followed for an average of 12 years.

During the follow-up period, there were 485 incident heart failure events. Higher sex-specific tertiles of intramuscular and intermuscular fat were each associated with heart failure risk.

After multivariable adjustment for age, sex, race, education, blood pressure, fasting blood sugar, current smoking, prevalent coronary disease, and creatinine, higher intramuscular fat, but not intermuscular fat, was significantly associated with higher risk for heart failure.

Individuals in the highest tertile of intramuscular fat had a 34% increased risk of developing heart failure, compared with those in the lowest tertile. This finding was independent of other cardiometabolic risk factors, measures of adiposity including body mass index and percent fat, muscle strength, and muscle mass.

The association was slightly attenuated when adjusted for inflammatory markers, suggesting that inflammation may be a contributor.

The association between higher intramuscular fat and heart failure appeared specific to higher risk of incident heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, but not with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction.

The researchers noted that skeletal muscle is a pivotal endocrine organ in addition to the role it plays in the production of mechanical power.

They pointed out that there are differences in the biology of intermuscular and intramuscular fat deposition, and that excess intramuscular fat deposition is a result of dysregulated lipid metabolism and is associated with insulin resistance (a known risk factor for the development of heart failure), inflammation, and muscle wasting conditions.

They concluded that, in patients with heart failure, alterations in skeletal muscle function are most likely affected by multiple contributors, including inflammation, oxidative stress, and neurohormonal factors. “As these factors are also implicated in the pathogenesis of heart failure, intramuscular fat deposition may indicate a biological milieu that increases the risk of heart failure.”

New approaches to reduce heart failure risk?

In an accompanying editorial, Salvatore Carbone, PhD, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, said the findings of the study are “exceptionally novel,” providing novel evidence that noncardiac body composition compartments, particularly intramuscular adipose tissue, can predict the risk for heart failure in a diverse population of older adults.

He called for further research to understand the mechanisms involved and to assess if this risk factor can be effectively modified to reduce the risk of developing heart failure.

Dr. Carbone reported that intramuscular adipose tissue can be influenced by dietary fat intake and can be worsened by accumulation of saturated fatty acids, which also contribute to insulin resistance.

He noted that saturated fatty acid–induced insulin resistance in the skeletal muscle appears to be mediated by proinflammatory pathways within the skeletal muscle itself, which can be reversed by monounsaturated fatty acids, like oleic acid, that can be found in the largest amount in food like olive oil, canola oil, and avocados, among others.

He added that sodium-glucose transporter 2 inhibitors, drugs used in the treatment of diabetes that have also been shown to prevent heart failure in individuals at risk, can also improve the composition of intramuscular adipose tissue by reducing its content of saturated fatty acids and increase the content of monosaturated fatty acids.

The study results suggest that the quality of intramuscular adipose tissue might also play an important role and could be targeted by therapeutic strategies, he commented.

Dr. Carbone concluded that “studies testing novel modalities of exercise training, intentional weight loss, diet quality improvements with and without weight loss (i.e., increase of dietary monounsaturated fatty acids, such as oleic acid), as well as pharmacological anti-inflammatory strategies should be encouraged in this population to test whether the reduction in intramuscular adipose tissue or improvements of its quality can ultimately reduce the risk for heart failure in this population.”

This research was supported by the National Institute on Aging and the National Institute of Nursing Research. Dr. Huynh and Dr. Carbone disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JACC: HEART FAILURE

Nurse who won’t give Viagra to White conservative men resigns

the day after her now-viral post.

The discriminatory tweet with political overtones comes just days after the U.S. Supreme Court handed down its decision to overturn Roe v. Wade, which permitted abortions.

Libs of TikTok, which featured the tweet, identified the nurse practitioner as Shawna Harris. More than a dozen visitors to WebMD’s healthcare directory, which indicates Ms. Harris specialized in family medicine, gave her a 1-star (out of 5 stars) review after the posting. Among the comments left on the site:

“By threatening patients that hold views she is against, she has broken the bond of trust between patient and doctor.” Still another visitor voiced: “If you are White and conservative I’d be careful going here because she tweeted she withholds medication based on race and political affiliation. That’s scary.”

Meanwhile, the health system where she worked, Sarah Bush Lincoln in Sullivan, Ill., in a since-deleted bio listed Ms. Harris’ rating as 4.8 out of 5 stars. The bio stated she was a certified family nurse practitioner and was board certified by the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners.

Sarah Bush Lincoln posted the APRN’s apology and resignation on Twitter. “I am deeply sorry for my posts on social media,” she wrote, according to the health system’s tweet. “I allowed my personal feelings to spill out. Those hateful words are not aligned with how I have provided care to my patients.”

Jerry Esker, the health system’s president and CEO, also stated in the post: “Our mission is to provide exceptional care to all. That means we provide care to everyone regardless of race, religion, gender, sexual orientation, disability, income, national origin, cultural personal values, beliefs, and preferences.”

Mr. Esker added that he wanted to talk with the APRN before taking any action and that “everyone is entitled to due process,” according to the health system post.

Sarah Bush Lincoln is a 145-bed, not-for-profit, regional hospital in east central Illinois, according to its website.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

the day after her now-viral post.

The discriminatory tweet with political overtones comes just days after the U.S. Supreme Court handed down its decision to overturn Roe v. Wade, which permitted abortions.

Libs of TikTok, which featured the tweet, identified the nurse practitioner as Shawna Harris. More than a dozen visitors to WebMD’s healthcare directory, which indicates Ms. Harris specialized in family medicine, gave her a 1-star (out of 5 stars) review after the posting. Among the comments left on the site:

“By threatening patients that hold views she is against, she has broken the bond of trust between patient and doctor.” Still another visitor voiced: “If you are White and conservative I’d be careful going here because she tweeted she withholds medication based on race and political affiliation. That’s scary.”

Meanwhile, the health system where she worked, Sarah Bush Lincoln in Sullivan, Ill., in a since-deleted bio listed Ms. Harris’ rating as 4.8 out of 5 stars. The bio stated she was a certified family nurse practitioner and was board certified by the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners.

Sarah Bush Lincoln posted the APRN’s apology and resignation on Twitter. “I am deeply sorry for my posts on social media,” she wrote, according to the health system’s tweet. “I allowed my personal feelings to spill out. Those hateful words are not aligned with how I have provided care to my patients.”

Jerry Esker, the health system’s president and CEO, also stated in the post: “Our mission is to provide exceptional care to all. That means we provide care to everyone regardless of race, religion, gender, sexual orientation, disability, income, national origin, cultural personal values, beliefs, and preferences.”

Mr. Esker added that he wanted to talk with the APRN before taking any action and that “everyone is entitled to due process,” according to the health system post.

Sarah Bush Lincoln is a 145-bed, not-for-profit, regional hospital in east central Illinois, according to its website.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

the day after her now-viral post.

The discriminatory tweet with political overtones comes just days after the U.S. Supreme Court handed down its decision to overturn Roe v. Wade, which permitted abortions.

Libs of TikTok, which featured the tweet, identified the nurse practitioner as Shawna Harris. More than a dozen visitors to WebMD’s healthcare directory, which indicates Ms. Harris specialized in family medicine, gave her a 1-star (out of 5 stars) review after the posting. Among the comments left on the site:

“By threatening patients that hold views she is against, she has broken the bond of trust between patient and doctor.” Still another visitor voiced: “If you are White and conservative I’d be careful going here because she tweeted she withholds medication based on race and political affiliation. That’s scary.”

Meanwhile, the health system where she worked, Sarah Bush Lincoln in Sullivan, Ill., in a since-deleted bio listed Ms. Harris’ rating as 4.8 out of 5 stars. The bio stated she was a certified family nurse practitioner and was board certified by the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners.

Sarah Bush Lincoln posted the APRN’s apology and resignation on Twitter. “I am deeply sorry for my posts on social media,” she wrote, according to the health system’s tweet. “I allowed my personal feelings to spill out. Those hateful words are not aligned with how I have provided care to my patients.”

Jerry Esker, the health system’s president and CEO, also stated in the post: “Our mission is to provide exceptional care to all. That means we provide care to everyone regardless of race, religion, gender, sexual orientation, disability, income, national origin, cultural personal values, beliefs, and preferences.”

Mr. Esker added that he wanted to talk with the APRN before taking any action and that “everyone is entitled to due process,” according to the health system post.

Sarah Bush Lincoln is a 145-bed, not-for-profit, regional hospital in east central Illinois, according to its website.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Mobile devices ‘addictive by design’: Obesity is one of many health effects

Wireless devices, like smart phones and tablets, appear to induce compulsive or even addictive use in many individuals, leading to adverse health consequences that are likely to be curtailed only through often difficult behavior modification, according to a pediatric endocrinologist’s take on the problem.

While the summary was based in part on the analysis of 234 published papers drawn from the medical literature, the lead author, Nidhi Gupta, MD, said the data reinforce her own clinical experience.

“As a pediatric endocrinologist, the trend in smartphone-associated health disorders, such as obesity, sleep, and behavior issues, worries me,” Dr. Gupta, director of KAP Pediatric Endocrinology, Nashville, Tenn., said at the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society.

Based on her search of the medical literature, the available data raise concern. In one study she cited, for example, each hour per day of screen time was found to translate into a body mass index increase of 0.5 to 0.7 kg/m2 (P < .001).

With this type of progressive rise in BMI comes prediabetes, dyslipidemia, and other metabolic disorders associated with major health risks, including cardiovascular disease. And there are others. Dr. Gupta cited data suggesting screen time before bed disturbs sleep, which has its own set of health risks.

“When I say health, it includes physical health, mental health, and emotional health,” said Dr. Gupta.

In the U.S. and other countries with a growing obesity epidemic, lack of physical activity and unhealthy eating are widely considered the major culprits. Excessive screen time contributes to both.

“When we are engaged with our devices, we are often snacking subconsciously and not very mindful that we are making unhealthy choices,” Dr. Gupta said.

The problem is that there is a vicious circle. Compulsive use of devices follows the same loop as other types of addictive behaviors, according to Dr. Gupta. She traced overuse of wireless devices to the dopaminergic system, which is a powerful neuroendocrine-mediated process of craving, response, and reward.

Like fat, sugar, and salt, which provoke a neuroendocrine reward signal, the chimes and buzzes of a cell phone provide their own cues for reward in the form of a dopamine surge. As a result, these become the “triggers of an irresistible and irrational urge to check our device that makes the dopamine go high in our brain,” Dr. Gupta explained.

Although the vicious cycle can be thwarted by turning off the device, Dr. Gupta characterized this as “impractical” when smartphones are so vital to daily communication. Rather, Dr. Gupta advocated a program of moderation, reserving the phone for useful tasks without succumbing to the siren song of apps that waste time.

The most conspicuous culprit is social media, which Dr. Gupta considers to be among the most Pavlovian triggers of cell phone addiction. However, she acknowledged that participation in social media has its justifications.

“I, myself, use social media for my own branding and marketing,” Dr. Gupta said.

The problem that users have is distinguishing between screen time that does and does not have value, according to Dr. Gupta. She indicated that many of those overusing their smart devices are being driven by the dopaminergic reward system, which is generally divorced from the real goals of life, such as personal satisfaction and activity that is rewarding monetarily or in other ways.

“I am not asking for these devices to be thrown out the window. I am advocating for moderation, balance, and real-life engagement,” Dr. Gupta said at the meeting, held in Atlanta and virtually.

She outlined a long list of practical suggestions, including turning off the alarms, chimes, and messages that engage the user into the vicious dopaminergic-reward system loop. She suggested mindfulness so that the user can distinguish between valuable device use and activity that is simply procrastination.

“The devices are designed to be addictive. They are designed to manipulate our brain,” she said. “Eliminate the reward. Let’s try to make our devices boring, unappealing, or enticing so that they only work as tools.”

The medical literature is filled with data that support the potential harms of excessive screen use, leading many others to make some of the same points. In 2017, Thomas N. Robinson, MD, professor of child health at Stanford (Calif.) University, reviewed data showing an association between screen media exposure and obesity in children and adolescents.

“This is an area crying out for more research,” Dr. Robinson said in an interview. The problem of screen time, sedentary behavior, and weight gain has been an issue since the television was invented, which was the point he made in his 2017 paper, but he agreed that the problem is only getting worse.

“Digital technology has become ubiquitous, touching nearly every aspect of people’s lives,” he said. Yet, as evidence grows that overuse of this technology can be harmful, it is creating a problem without a clear solution.

“There are few data about the efficacy of specific strategies to reduce harmful impacts of digital screen use,” he said.

While some of the solutions that Dr. Gupta described make sense, they are more easily described than executed. The dopaminergic reward system is strong and largely experienced subconsciously. Recruiting patients to recognize that dopaminergic rewards are not rewards in any true sense is already a challenge. Enlisting patients to take the difficult steps to avoid the behavioral cues might be even more difficult.

Dr. Gupta and Dr. Robinson report no potential conflicts of interest.

Wireless devices, like smart phones and tablets, appear to induce compulsive or even addictive use in many individuals, leading to adverse health consequences that are likely to be curtailed only through often difficult behavior modification, according to a pediatric endocrinologist’s take on the problem.

While the summary was based in part on the analysis of 234 published papers drawn from the medical literature, the lead author, Nidhi Gupta, MD, said the data reinforce her own clinical experience.

“As a pediatric endocrinologist, the trend in smartphone-associated health disorders, such as obesity, sleep, and behavior issues, worries me,” Dr. Gupta, director of KAP Pediatric Endocrinology, Nashville, Tenn., said at the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society.

Based on her search of the medical literature, the available data raise concern. In one study she cited, for example, each hour per day of screen time was found to translate into a body mass index increase of 0.5 to 0.7 kg/m2 (P < .001).

With this type of progressive rise in BMI comes prediabetes, dyslipidemia, and other metabolic disorders associated with major health risks, including cardiovascular disease. And there are others. Dr. Gupta cited data suggesting screen time before bed disturbs sleep, which has its own set of health risks.

“When I say health, it includes physical health, mental health, and emotional health,” said Dr. Gupta.

In the U.S. and other countries with a growing obesity epidemic, lack of physical activity and unhealthy eating are widely considered the major culprits. Excessive screen time contributes to both.

“When we are engaged with our devices, we are often snacking subconsciously and not very mindful that we are making unhealthy choices,” Dr. Gupta said.

The problem is that there is a vicious circle. Compulsive use of devices follows the same loop as other types of addictive behaviors, according to Dr. Gupta. She traced overuse of wireless devices to the dopaminergic system, which is a powerful neuroendocrine-mediated process of craving, response, and reward.

Like fat, sugar, and salt, which provoke a neuroendocrine reward signal, the chimes and buzzes of a cell phone provide their own cues for reward in the form of a dopamine surge. As a result, these become the “triggers of an irresistible and irrational urge to check our device that makes the dopamine go high in our brain,” Dr. Gupta explained.

Although the vicious cycle can be thwarted by turning off the device, Dr. Gupta characterized this as “impractical” when smartphones are so vital to daily communication. Rather, Dr. Gupta advocated a program of moderation, reserving the phone for useful tasks without succumbing to the siren song of apps that waste time.

The most conspicuous culprit is social media, which Dr. Gupta considers to be among the most Pavlovian triggers of cell phone addiction. However, she acknowledged that participation in social media has its justifications.

“I, myself, use social media for my own branding and marketing,” Dr. Gupta said.

The problem that users have is distinguishing between screen time that does and does not have value, according to Dr. Gupta. She indicated that many of those overusing their smart devices are being driven by the dopaminergic reward system, which is generally divorced from the real goals of life, such as personal satisfaction and activity that is rewarding monetarily or in other ways.

“I am not asking for these devices to be thrown out the window. I am advocating for moderation, balance, and real-life engagement,” Dr. Gupta said at the meeting, held in Atlanta and virtually.

She outlined a long list of practical suggestions, including turning off the alarms, chimes, and messages that engage the user into the vicious dopaminergic-reward system loop. She suggested mindfulness so that the user can distinguish between valuable device use and activity that is simply procrastination.

“The devices are designed to be addictive. They are designed to manipulate our brain,” she said. “Eliminate the reward. Let’s try to make our devices boring, unappealing, or enticing so that they only work as tools.”

The medical literature is filled with data that support the potential harms of excessive screen use, leading many others to make some of the same points. In 2017, Thomas N. Robinson, MD, professor of child health at Stanford (Calif.) University, reviewed data showing an association between screen media exposure and obesity in children and adolescents.

“This is an area crying out for more research,” Dr. Robinson said in an interview. The problem of screen time, sedentary behavior, and weight gain has been an issue since the television was invented, which was the point he made in his 2017 paper, but he agreed that the problem is only getting worse.

“Digital technology has become ubiquitous, touching nearly every aspect of people’s lives,” he said. Yet, as evidence grows that overuse of this technology can be harmful, it is creating a problem without a clear solution.

“There are few data about the efficacy of specific strategies to reduce harmful impacts of digital screen use,” he said.

While some of the solutions that Dr. Gupta described make sense, they are more easily described than executed. The dopaminergic reward system is strong and largely experienced subconsciously. Recruiting patients to recognize that dopaminergic rewards are not rewards in any true sense is already a challenge. Enlisting patients to take the difficult steps to avoid the behavioral cues might be even more difficult.

Dr. Gupta and Dr. Robinson report no potential conflicts of interest.