User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

Atrophic Lesion on the Abdomen

The Diagnosis: Anetoderma of Prematurity

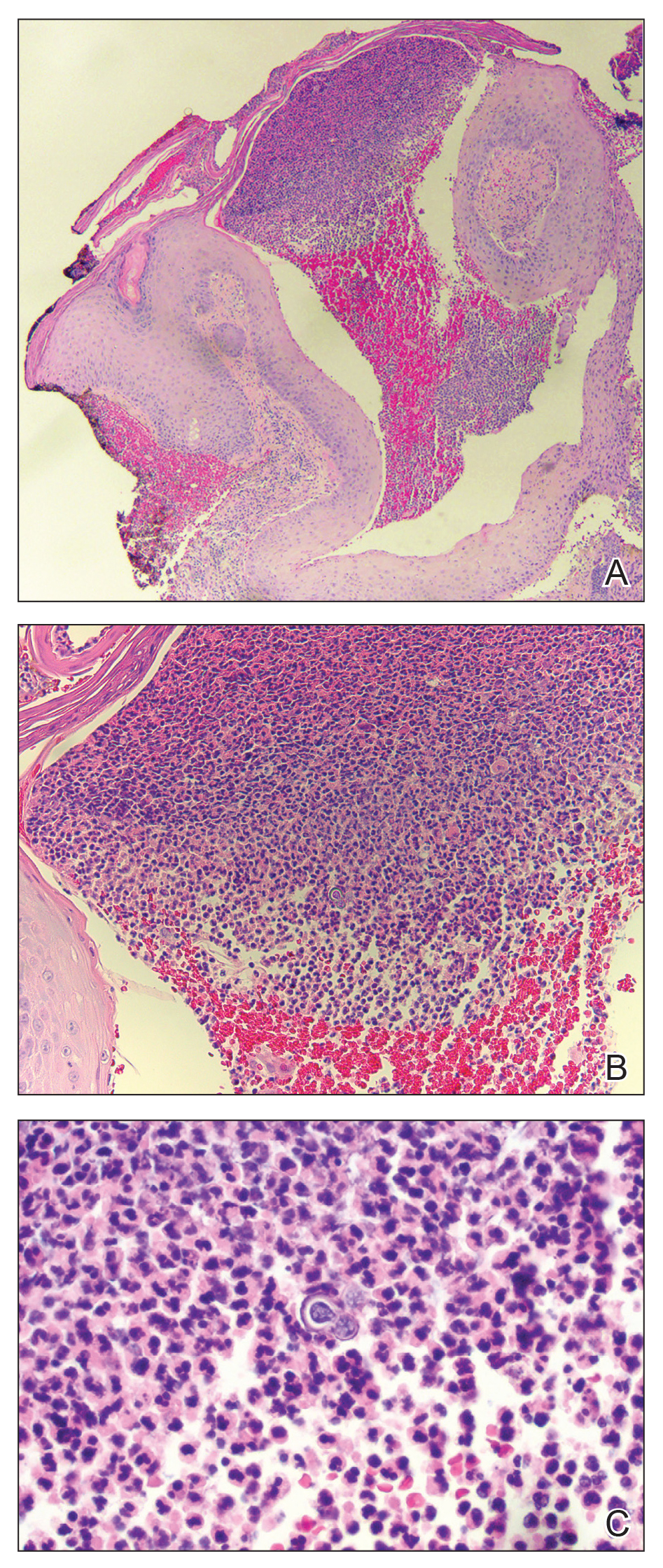

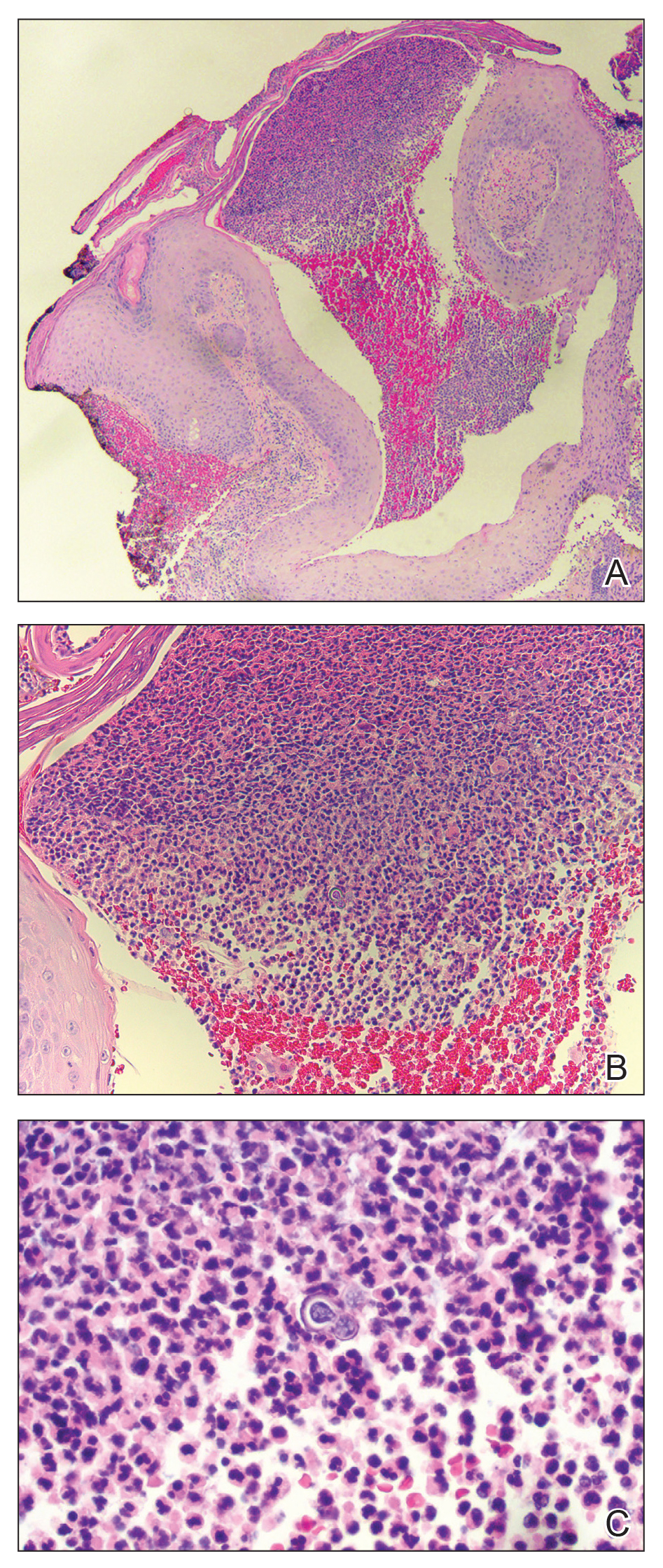

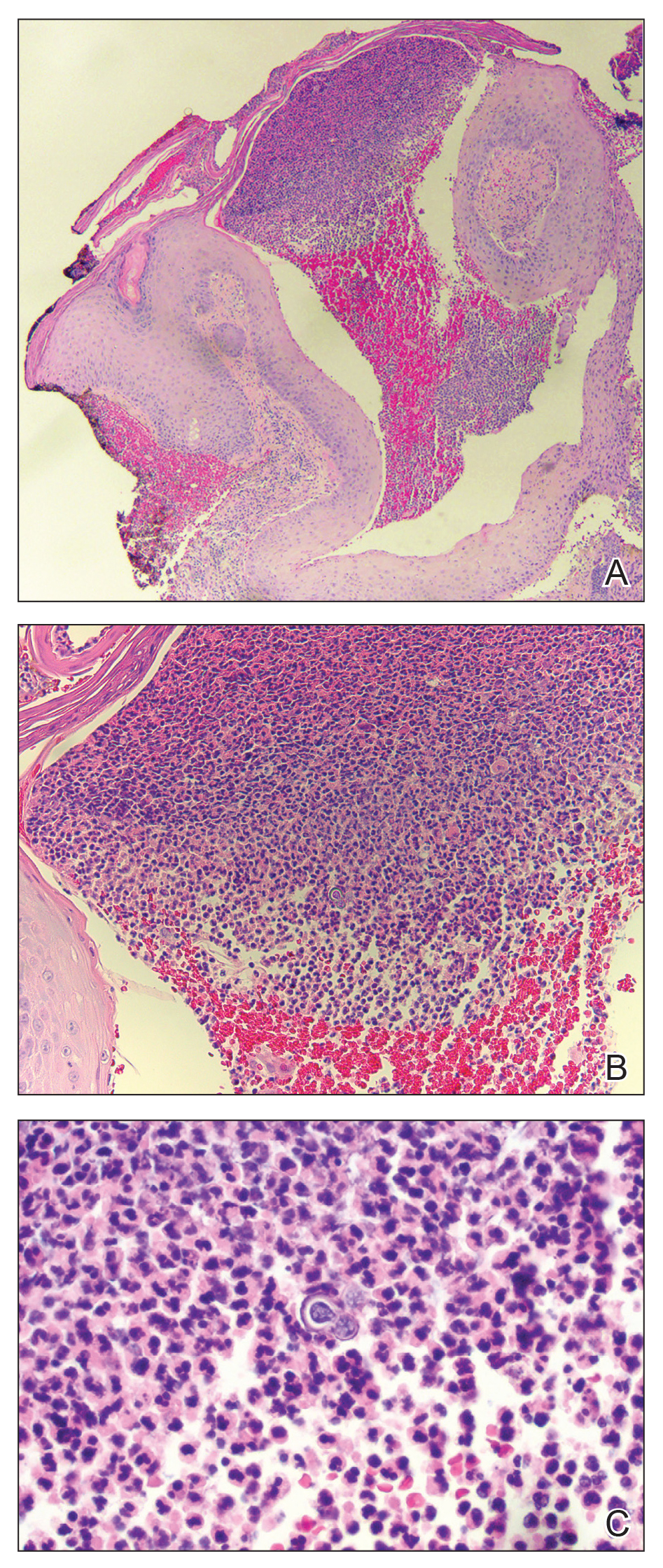

Anetoderma is a rare benign cutaneous disorder characterized by atrophic patches of skin due to dermal thinning. The term anetoderma is derived from the Greek words anetos (relaxed) and derma (skin).1 The physical appearance of the skin is associated with a reduction or loss of elastic tissue in the dermal layer, as seen on histolopathology.2

Two forms of anetoderma have been described. Primary anetoderma is an idiopathic form with no preceding inflammatory lesions. Secondary anetoderma is a reactive process linked to a known preceding inflammatory, infectious, autoimmune, or drug-induced condition.3 On histopathology, both primary and secondary anetoderma are characterized by a loss of elastic tissue or elastin fibers in the superficial to mid dermis.2

Anetoderma of prematurity was first described in 1996 by Prizant et al4 in 9 extremely premature (24-29 weeks' gestation) infants in neonatal intensive care units (NICUs). Although the exact mechanism behind anetoderma of prematurity is still unknown, Prizant et al4 and other investigators5 postulated that application of adhesive monitoring leads in the NICU played a role in the development of the lesions.

Iatrogenic anetoderma of prematurity is clinically characterized by circumscribed areas of either wrinkled macular depression or pouchlike herniations, ranging from flesh-colored to violaceous hues. Lesion size varies from a few millimeters to several centimeters in diameter, and they often are oval or round in shape.2 Although not common, it is possible for the atrophic patches to be preceded by an area of ecchymosis without necrosis or atrophy and, if present, they usually evolve within a few days to the characteristic appearance of anetoderma.3 They are found at discrete sites where monitoring leads or other medical devices are commonly placed, such as the forehead, abdomen, chest, and proximal limbs.

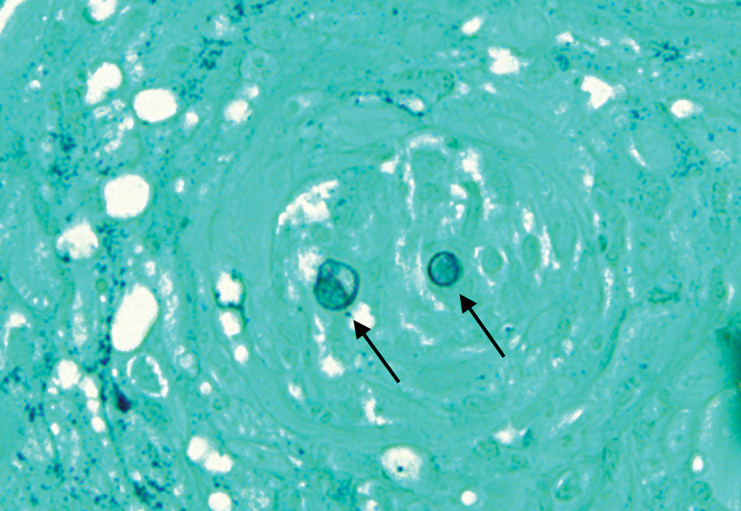

Lesions of anetoderma of prematurity are not present at birth, which distinguishes them from congenital anetoderma.6 It is unclear if the lesions are associated with the degree of prematurity, extremely low birth weight, or other associated factors of preterm birth. Although often clinically diagnosed, the diagnosis can be confirmed by a loss of elastic fibers on histopathology when stained with Verhoeff-van Gieson stain.1 Over time, the atrophic patches have the potential to evolve into herniated forms of anetoderma. Self-healing or improvement of the lesions often does not occur. Although the lesion is benign, it often requires surgical correction later in life for cosmesis.

Infants in the NICU are at risk for iatrogenic cutaneous injuries, which rarely may include anetoderma. Anetoderma of prematurity has been linked to the use of monitoring leads, adhesive tape, and other medical devices placed on the skin. Prizant et al4 postulated that the cause of anetoderma in these infants was irritants such as skin cleansers, urine, or sweat that may be trapped under the electrodes. Other hypotheses include local hypoxemia due to prolonged pressure from the electrodes on immature skin or excessive traction used when removing adhesive tape from the skin.7,8 Premature infants may be more susceptible to these lesions because of the reduced epidermal thickness of premature skin; immaturity of skin structure; or functional immaturity of elastin deposition regulators, such as elastase, lysyl oxidase, the complement system, and decay-accelerating factor.3 The diagnosis should be differentiated from congenital anetoderma, which also has been described in premature neonates but is characterized by lesions that are present at birth. Its origins are still unclear, despite having histopathologic features similar to iatrogenic anetoderma.9

Focal dermal hypoplasia (FDH) is the hallmark cutaneous finding in Goltz syndrome, a rare set of congenital abnormalities of the skin, oral structures, musculoskeletal system, and central nervous system. Similar to congenital anetoderma, FDH also is characterized by atrophic cutaneous lesions; however, the cutaneous lesions in FDH appear as linear, streaky atrophic lesions often with telangiectasias that follow Blaschko lines.10 The cutaneous lesions in FDH often are associated with other noncutaneous signs such as polydactyly or asymmetric limbs.10 Cutis laxa is caused by an abnormality in the elastic tissue resulting in a loose sagging appearance of the skin and frequently results in an aged facial appearance. There are both acquired and inherited forms that can be either solely cutaneous or present with extracutaneous features, such as cardiac abnormalities or emphysema.11

In contrast to the atrophic appearance of anetodermas, connective tissue nevi and nevus lipomatosus superficialis present as hamartomas that either can be present at birth or arise in infancy. Connective tissue nevi are hamartomas of dermal connective tissue that consist of excessive production of collagen, elastin, or glycosaminoglycans and appear as slightly elevated, flesh-colored to yellow nodules or plaques.12 Connective tissue nevi often are described in association with other diseases, most commonly tuberous sclerosis (shagreen patches) or familial cutaneous collagenoma. Nevus lipomatosus superficialis is an asymptomatic connective tissue hamartoma composed of mature adipocytes in the dermis. The lesions consist of clusters of flesh-colored to yellow, soft, rubbery papules or nodules with a smooth or verrucoid surface that do not cross the midline and may follow Blaschko lines.11

With advances in neonatal infant medical care, survival of extremely premature infants is increasing, and it is possible that this rare cutaneous disorder may become more prevalent. Care should be taken to avoid unnecessary pressure on surfaces where electrodes are placed and tightly applied adhesive tape. When electrodes are placed on the ventral side, the child should be placed supine; similarly, place electrodes on the dorsal side when the child is lying prone.5 A diagnosis of anetoderma of prematurity later in childhood may be difficult, so knowledge and awareness can help guide pediatricians and dermatologists to a correct diagnosis and prevent unnecessary evaluations and/or concerns.

- Misch KJ, Rhodes EL, Allen J, et al. Anetoderma of Jadassohn. J R Soc Med.1988;81:734-736.

- Venencie PY, Winkelmann RK. Histopathologic findings in anetoderma. Arch Dermatol. 1984;120:1040-1044.

- Maffeis L, Pugni L, Pietrasanta C, et al. Case report iatrogenic anetoderma of prematurity: a case report and review of the literature. 2014;2014:781493.

- Prizant TL, Lucky AW, Frieden IJ, et al. Spontaneous atrophic patches in extremely premature infants: anetoderma of prematurity. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:671-674.

- Goujon E, Beer F, Gay S, et al. Anetoderma of prematurity: an iatrogenic consequence of neonatal intensive care anetoderma of prematurity from NICU. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:565-567.

- Wain EM, Mellerio JE, Robson A, et al. Congenital anetoderma in a preterm infant. Pediatr Dermatol. 2008;25:626-629.

- Colditz PB, Dunster KR, Joy GJ, et al. Anetoderma of prematurity in association with electrocardiographic electrodes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:479-481.

- Goujan E, Beer F, Gay S, et al. Study supervision. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:565-567.

- Aberer E, Weissenbacher G. Congenital anetoderma induced by intrauterine infection? Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:526-527.

- Mallory SB, Krafchik BR, Moore DJ, et al. Goltz syndrome. Pediatr Dermatol. 1989;6:251-253.

- Bolognia J, Schaffer J, Cerroni L. Dermatology. Elsevier Saunders; 2017.

- Uitto J, Santa Cruz DJ, Eisen AZ. Connective tissue nevi of the skin. clinical, genetic, and histopathologic classification of hamartomas of the collagen, elastin, and proteoglycan type. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1980;3:441-461.

The Diagnosis: Anetoderma of Prematurity

Anetoderma is a rare benign cutaneous disorder characterized by atrophic patches of skin due to dermal thinning. The term anetoderma is derived from the Greek words anetos (relaxed) and derma (skin).1 The physical appearance of the skin is associated with a reduction or loss of elastic tissue in the dermal layer, as seen on histolopathology.2

Two forms of anetoderma have been described. Primary anetoderma is an idiopathic form with no preceding inflammatory lesions. Secondary anetoderma is a reactive process linked to a known preceding inflammatory, infectious, autoimmune, or drug-induced condition.3 On histopathology, both primary and secondary anetoderma are characterized by a loss of elastic tissue or elastin fibers in the superficial to mid dermis.2

Anetoderma of prematurity was first described in 1996 by Prizant et al4 in 9 extremely premature (24-29 weeks' gestation) infants in neonatal intensive care units (NICUs). Although the exact mechanism behind anetoderma of prematurity is still unknown, Prizant et al4 and other investigators5 postulated that application of adhesive monitoring leads in the NICU played a role in the development of the lesions.

Iatrogenic anetoderma of prematurity is clinically characterized by circumscribed areas of either wrinkled macular depression or pouchlike herniations, ranging from flesh-colored to violaceous hues. Lesion size varies from a few millimeters to several centimeters in diameter, and they often are oval or round in shape.2 Although not common, it is possible for the atrophic patches to be preceded by an area of ecchymosis without necrosis or atrophy and, if present, they usually evolve within a few days to the characteristic appearance of anetoderma.3 They are found at discrete sites where monitoring leads or other medical devices are commonly placed, such as the forehead, abdomen, chest, and proximal limbs.

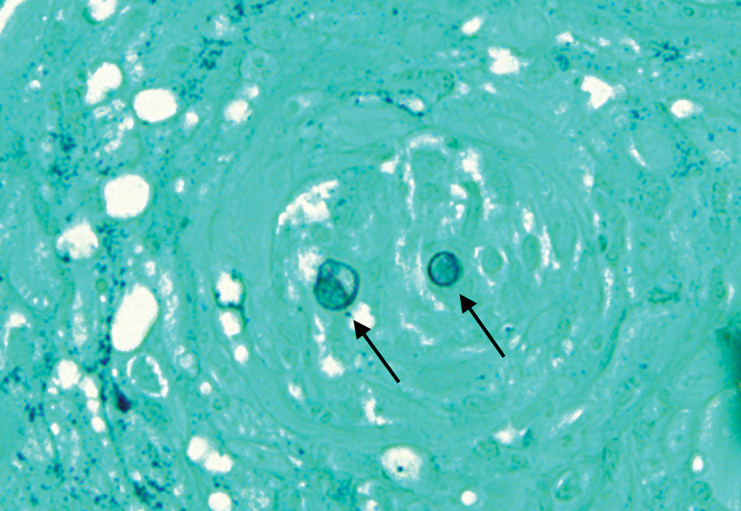

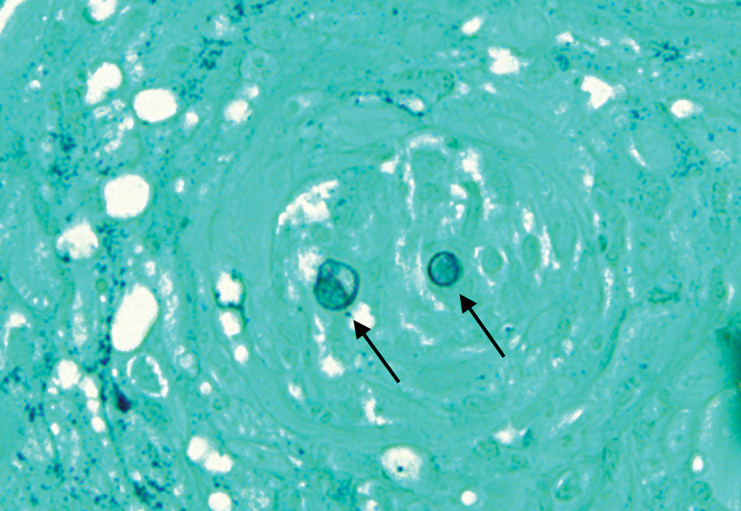

Lesions of anetoderma of prematurity are not present at birth, which distinguishes them from congenital anetoderma.6 It is unclear if the lesions are associated with the degree of prematurity, extremely low birth weight, or other associated factors of preterm birth. Although often clinically diagnosed, the diagnosis can be confirmed by a loss of elastic fibers on histopathology when stained with Verhoeff-van Gieson stain.1 Over time, the atrophic patches have the potential to evolve into herniated forms of anetoderma. Self-healing or improvement of the lesions often does not occur. Although the lesion is benign, it often requires surgical correction later in life for cosmesis.

Infants in the NICU are at risk for iatrogenic cutaneous injuries, which rarely may include anetoderma. Anetoderma of prematurity has been linked to the use of monitoring leads, adhesive tape, and other medical devices placed on the skin. Prizant et al4 postulated that the cause of anetoderma in these infants was irritants such as skin cleansers, urine, or sweat that may be trapped under the electrodes. Other hypotheses include local hypoxemia due to prolonged pressure from the electrodes on immature skin or excessive traction used when removing adhesive tape from the skin.7,8 Premature infants may be more susceptible to these lesions because of the reduced epidermal thickness of premature skin; immaturity of skin structure; or functional immaturity of elastin deposition regulators, such as elastase, lysyl oxidase, the complement system, and decay-accelerating factor.3 The diagnosis should be differentiated from congenital anetoderma, which also has been described in premature neonates but is characterized by lesions that are present at birth. Its origins are still unclear, despite having histopathologic features similar to iatrogenic anetoderma.9

Focal dermal hypoplasia (FDH) is the hallmark cutaneous finding in Goltz syndrome, a rare set of congenital abnormalities of the skin, oral structures, musculoskeletal system, and central nervous system. Similar to congenital anetoderma, FDH also is characterized by atrophic cutaneous lesions; however, the cutaneous lesions in FDH appear as linear, streaky atrophic lesions often with telangiectasias that follow Blaschko lines.10 The cutaneous lesions in FDH often are associated with other noncutaneous signs such as polydactyly or asymmetric limbs.10 Cutis laxa is caused by an abnormality in the elastic tissue resulting in a loose sagging appearance of the skin and frequently results in an aged facial appearance. There are both acquired and inherited forms that can be either solely cutaneous or present with extracutaneous features, such as cardiac abnormalities or emphysema.11

In contrast to the atrophic appearance of anetodermas, connective tissue nevi and nevus lipomatosus superficialis present as hamartomas that either can be present at birth or arise in infancy. Connective tissue nevi are hamartomas of dermal connective tissue that consist of excessive production of collagen, elastin, or glycosaminoglycans and appear as slightly elevated, flesh-colored to yellow nodules or plaques.12 Connective tissue nevi often are described in association with other diseases, most commonly tuberous sclerosis (shagreen patches) or familial cutaneous collagenoma. Nevus lipomatosus superficialis is an asymptomatic connective tissue hamartoma composed of mature adipocytes in the dermis. The lesions consist of clusters of flesh-colored to yellow, soft, rubbery papules or nodules with a smooth or verrucoid surface that do not cross the midline and may follow Blaschko lines.11

With advances in neonatal infant medical care, survival of extremely premature infants is increasing, and it is possible that this rare cutaneous disorder may become more prevalent. Care should be taken to avoid unnecessary pressure on surfaces where electrodes are placed and tightly applied adhesive tape. When electrodes are placed on the ventral side, the child should be placed supine; similarly, place electrodes on the dorsal side when the child is lying prone.5 A diagnosis of anetoderma of prematurity later in childhood may be difficult, so knowledge and awareness can help guide pediatricians and dermatologists to a correct diagnosis and prevent unnecessary evaluations and/or concerns.

The Diagnosis: Anetoderma of Prematurity

Anetoderma is a rare benign cutaneous disorder characterized by atrophic patches of skin due to dermal thinning. The term anetoderma is derived from the Greek words anetos (relaxed) and derma (skin).1 The physical appearance of the skin is associated with a reduction or loss of elastic tissue in the dermal layer, as seen on histolopathology.2

Two forms of anetoderma have been described. Primary anetoderma is an idiopathic form with no preceding inflammatory lesions. Secondary anetoderma is a reactive process linked to a known preceding inflammatory, infectious, autoimmune, or drug-induced condition.3 On histopathology, both primary and secondary anetoderma are characterized by a loss of elastic tissue or elastin fibers in the superficial to mid dermis.2

Anetoderma of prematurity was first described in 1996 by Prizant et al4 in 9 extremely premature (24-29 weeks' gestation) infants in neonatal intensive care units (NICUs). Although the exact mechanism behind anetoderma of prematurity is still unknown, Prizant et al4 and other investigators5 postulated that application of adhesive monitoring leads in the NICU played a role in the development of the lesions.

Iatrogenic anetoderma of prematurity is clinically characterized by circumscribed areas of either wrinkled macular depression or pouchlike herniations, ranging from flesh-colored to violaceous hues. Lesion size varies from a few millimeters to several centimeters in diameter, and they often are oval or round in shape.2 Although not common, it is possible for the atrophic patches to be preceded by an area of ecchymosis without necrosis or atrophy and, if present, they usually evolve within a few days to the characteristic appearance of anetoderma.3 They are found at discrete sites where monitoring leads or other medical devices are commonly placed, such as the forehead, abdomen, chest, and proximal limbs.

Lesions of anetoderma of prematurity are not present at birth, which distinguishes them from congenital anetoderma.6 It is unclear if the lesions are associated with the degree of prematurity, extremely low birth weight, or other associated factors of preterm birth. Although often clinically diagnosed, the diagnosis can be confirmed by a loss of elastic fibers on histopathology when stained with Verhoeff-van Gieson stain.1 Over time, the atrophic patches have the potential to evolve into herniated forms of anetoderma. Self-healing or improvement of the lesions often does not occur. Although the lesion is benign, it often requires surgical correction later in life for cosmesis.

Infants in the NICU are at risk for iatrogenic cutaneous injuries, which rarely may include anetoderma. Anetoderma of prematurity has been linked to the use of monitoring leads, adhesive tape, and other medical devices placed on the skin. Prizant et al4 postulated that the cause of anetoderma in these infants was irritants such as skin cleansers, urine, or sweat that may be trapped under the electrodes. Other hypotheses include local hypoxemia due to prolonged pressure from the electrodes on immature skin or excessive traction used when removing adhesive tape from the skin.7,8 Premature infants may be more susceptible to these lesions because of the reduced epidermal thickness of premature skin; immaturity of skin structure; or functional immaturity of elastin deposition regulators, such as elastase, lysyl oxidase, the complement system, and decay-accelerating factor.3 The diagnosis should be differentiated from congenital anetoderma, which also has been described in premature neonates but is characterized by lesions that are present at birth. Its origins are still unclear, despite having histopathologic features similar to iatrogenic anetoderma.9

Focal dermal hypoplasia (FDH) is the hallmark cutaneous finding in Goltz syndrome, a rare set of congenital abnormalities of the skin, oral structures, musculoskeletal system, and central nervous system. Similar to congenital anetoderma, FDH also is characterized by atrophic cutaneous lesions; however, the cutaneous lesions in FDH appear as linear, streaky atrophic lesions often with telangiectasias that follow Blaschko lines.10 The cutaneous lesions in FDH often are associated with other noncutaneous signs such as polydactyly or asymmetric limbs.10 Cutis laxa is caused by an abnormality in the elastic tissue resulting in a loose sagging appearance of the skin and frequently results in an aged facial appearance. There are both acquired and inherited forms that can be either solely cutaneous or present with extracutaneous features, such as cardiac abnormalities or emphysema.11

In contrast to the atrophic appearance of anetodermas, connective tissue nevi and nevus lipomatosus superficialis present as hamartomas that either can be present at birth or arise in infancy. Connective tissue nevi are hamartomas of dermal connective tissue that consist of excessive production of collagen, elastin, or glycosaminoglycans and appear as slightly elevated, flesh-colored to yellow nodules or plaques.12 Connective tissue nevi often are described in association with other diseases, most commonly tuberous sclerosis (shagreen patches) or familial cutaneous collagenoma. Nevus lipomatosus superficialis is an asymptomatic connective tissue hamartoma composed of mature adipocytes in the dermis. The lesions consist of clusters of flesh-colored to yellow, soft, rubbery papules or nodules with a smooth or verrucoid surface that do not cross the midline and may follow Blaschko lines.11

With advances in neonatal infant medical care, survival of extremely premature infants is increasing, and it is possible that this rare cutaneous disorder may become more prevalent. Care should be taken to avoid unnecessary pressure on surfaces where electrodes are placed and tightly applied adhesive tape. When electrodes are placed on the ventral side, the child should be placed supine; similarly, place electrodes on the dorsal side when the child is lying prone.5 A diagnosis of anetoderma of prematurity later in childhood may be difficult, so knowledge and awareness can help guide pediatricians and dermatologists to a correct diagnosis and prevent unnecessary evaluations and/or concerns.

- Misch KJ, Rhodes EL, Allen J, et al. Anetoderma of Jadassohn. J R Soc Med.1988;81:734-736.

- Venencie PY, Winkelmann RK. Histopathologic findings in anetoderma. Arch Dermatol. 1984;120:1040-1044.

- Maffeis L, Pugni L, Pietrasanta C, et al. Case report iatrogenic anetoderma of prematurity: a case report and review of the literature. 2014;2014:781493.

- Prizant TL, Lucky AW, Frieden IJ, et al. Spontaneous atrophic patches in extremely premature infants: anetoderma of prematurity. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:671-674.

- Goujon E, Beer F, Gay S, et al. Anetoderma of prematurity: an iatrogenic consequence of neonatal intensive care anetoderma of prematurity from NICU. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:565-567.

- Wain EM, Mellerio JE, Robson A, et al. Congenital anetoderma in a preterm infant. Pediatr Dermatol. 2008;25:626-629.

- Colditz PB, Dunster KR, Joy GJ, et al. Anetoderma of prematurity in association with electrocardiographic electrodes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:479-481.

- Goujan E, Beer F, Gay S, et al. Study supervision. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:565-567.

- Aberer E, Weissenbacher G. Congenital anetoderma induced by intrauterine infection? Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:526-527.

- Mallory SB, Krafchik BR, Moore DJ, et al. Goltz syndrome. Pediatr Dermatol. 1989;6:251-253.

- Bolognia J, Schaffer J, Cerroni L. Dermatology. Elsevier Saunders; 2017.

- Uitto J, Santa Cruz DJ, Eisen AZ. Connective tissue nevi of the skin. clinical, genetic, and histopathologic classification of hamartomas of the collagen, elastin, and proteoglycan type. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1980;3:441-461.

- Misch KJ, Rhodes EL, Allen J, et al. Anetoderma of Jadassohn. J R Soc Med.1988;81:734-736.

- Venencie PY, Winkelmann RK. Histopathologic findings in anetoderma. Arch Dermatol. 1984;120:1040-1044.

- Maffeis L, Pugni L, Pietrasanta C, et al. Case report iatrogenic anetoderma of prematurity: a case report and review of the literature. 2014;2014:781493.

- Prizant TL, Lucky AW, Frieden IJ, et al. Spontaneous atrophic patches in extremely premature infants: anetoderma of prematurity. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:671-674.

- Goujon E, Beer F, Gay S, et al. Anetoderma of prematurity: an iatrogenic consequence of neonatal intensive care anetoderma of prematurity from NICU. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:565-567.

- Wain EM, Mellerio JE, Robson A, et al. Congenital anetoderma in a preterm infant. Pediatr Dermatol. 2008;25:626-629.

- Colditz PB, Dunster KR, Joy GJ, et al. Anetoderma of prematurity in association with electrocardiographic electrodes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:479-481.

- Goujan E, Beer F, Gay S, et al. Study supervision. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:565-567.

- Aberer E, Weissenbacher G. Congenital anetoderma induced by intrauterine infection? Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:526-527.

- Mallory SB, Krafchik BR, Moore DJ, et al. Goltz syndrome. Pediatr Dermatol. 1989;6:251-253.

- Bolognia J, Schaffer J, Cerroni L. Dermatology. Elsevier Saunders; 2017.

- Uitto J, Santa Cruz DJ, Eisen AZ. Connective tissue nevi of the skin. clinical, genetic, and histopathologic classification of hamartomas of the collagen, elastin, and proteoglycan type. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1980;3:441-461.

An 18-month-old child presented with a 4-cm, atrophic, flesh-colored plaque on the left lateral aspect of the abdomen with overlying wrinkling of the skin. There was no outpouching of the skin or pain associated with the lesion. No other skin abnormalities were noted. The child was born premature at 30 weeks’ gestation (birth weight, 1400 g). The postnatal course was complicated by respiratory distress syndrome requiring prolonged ventilator support. The infant was in the neonatal intensive care unit for 5 months. The atrophic lesion first developed at 5 months of life and remained stable. Although the lesion was not present at birth, the parents noted that it was preceded by an ecchymotic lesion without necrosis that was first noticed at 2 months of life while the patient was in the neonatal intensive care unit.

CRC risk in young adults: Not as high as previously reported

Implications for CRC screening.

New estimates for the risk of CRC in young adults, which differentiate colorectal adenocarcinoma from other types, are reported in a study published Dec. 15, 2020, in Annals of Internal Medicine.

They are important because this finding has implications for CRC screening, say a trio of experts in an accompanying editorial.

Reports of an increase in the incidence of CRC in younger adults have led to changes in screening for this cancer in the United States. The age for starting CRC screening has been lowered to 45 years (instead of 50 years) in recommendations issued in 2018 by the American Cancer Society, and also more recently in preliminary recommendations from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force.

However, that 2018 ACS recommendation to lower the starting age to 45 years was based to a large extent on a report of a higher incidence of CRC in younger adults from a 2017 study that used the SEER (Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results) database).

But that SEER-based study considered “colorectal cancer” as a homogeneous group defined by topology, the editorialists pointed out.

The new study, the editorialists said, uses that same SEER database but has “disentangled colorectal adenocarcinoma, the target for screening, from other histologic CRC types, including neuroendocrine (carcinoid) tumors, for which screening is not recommended.”

The study authors explained that adenocarcinoma is a target for prevention through screening because it arises from precancerous polyps. Those growths can be detected and removed before cancer develops. That doesn’t apply to carcinoid tumors, which are frequently incidental findings on flexible sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy.

These carcinoid tumors typically are indolent, with a better prognosis than most other cancer types, the editorialists added. “Most likely, the majority of carcinoid tumors identified by screening represent incidental findings with little health benefit from detection. In fact, many may be characterized as overdiagnosed tumors, which by definition increase the burden and harms of screening without the balance of additional benefit.”

This new analysis showed that 4%-20% of the lesions previously described as CRC were not adenocarcinoma but carcinoid tumors, the editorialists pointed out.

This figure rose even higher in the subgroup of findings pertaining to the rectum, the colonic segment with the largest reported increase in early-onset CRC. Here, up to 34% of lesions (depending on patient age) were carcinoid tumors rather than adenocarcinoma, they noted.

The three editorialists – Michael Bretthauer, MD, PhD, and Mette Kalager, MD, PhD, both of the University of Oslo, and David Weinberg, MD, MSc, of Fox Chase Cancer Center, Philadelphia – call for action based on the new findings.

“The ACS’s 2018 estimate of about 7,000 new CRC cases among persons aged 45-49 years in the United States (the justification for screening) needs to be adjusted downward on the basis of the new evidence,” the trio wrote.

They conclude that “caution is warranted when promoting the benefits of CRC screening for persons younger than 50 years.”

However, the senior author of the new study, Jordan Karlitz, MD, of Tulane University, New Orleans, strongly disagreed.

Contrary to the editorialists, Dr. Karlitz said in an interview that he and his colleagues firmly believe that colorectal cancer screening for average-risk patients should begin at age 45 and that their new research, despite its clarification about carcinoid tumors, provides evidence for that.

“There are a number of other studies that support screening at age 45 as well,” he said. “This [new] finding supports the presence of a large preclinical colorectal cancer case burden in patients in their 40s that is ultimately uncovered with screening initiation at age 50. Many of these cancers could be prevented or diagnosed at an earlier stage with screening at age 45.”

“This is the first study to analyze early-onset colorectal cancer by specific histologic subtype,” Dr. Karlitz also pointed out.

“Although colorectal carcinoids are increasing at a faster rate than adenocarcinomas, adenocarcinomas constitute the overwhelming majority of colorectal cancers in people in their 40s and are also steadily increasing, which has implications for beginning screening at age 45,” he said.

Adenocarcinomas also make up the “overwhelming majority” of colorectal cancers in patients under 50 overall and “are the main driving force behind the increased colorectal cancer burden we are seeing in young patients,” Dr. Karlitz added.

Furthermore, “modeling studies on which the USPSTF screening recommendations were based [which recommended starting at age 45] were confined to adenocarcinoma, thus excluding carcinoids from their analysis,” he said.

Steepest changes in adenocarcinomas in younger groups

In their study, Dr. Karlitz and colleagues assessed the incidence rates of early colorectal cancer, using SEER data from 2000 to 2016, and stratifying the data by histologic subtype (primarily adenocarcinoma and carcinoid tumors), age group (20-29, 30-39, 40-49, and 50-54 years), and subsite.

A total of 123,143 CRC cases were identified in 119,624 patients between the ages of 20-54 years during that time period.

The absolute incidence rates in the younger age groups (20-29 and 30-39 years) were very low, compared with those aged 40-49 and 50-54 years.

The greatest 3-year average annual incident rate changes in adenocarcinoma (2000-2002 vs. 2014-2016) for any age group or subsite were for rectal-only cases in the 20-29 years group (+39%), as well as rectal-only cases in those aged 30-39 years (+39%), and colon-only cases in the age 30-39 group (+20%).

There was also significant increase in rectal-only adenocarcinoma in individuals aged 50-54 years (+10%). A statistically significant increase in the annual percentage change for adenocarcinomas was observed for all age groups, except for colon-only cases in the 20-29 years group (0.7%) and for both colorectal (0.2%) and colon-only cases (–0.1%) in those aged 50-54 years.

Even though the absolute carcinoid tumor incidence rates were lower than for adenocarcinoma in all age groups and subsites, a statistically significant increase was observed in the 3-year average annual incidence rate of combined-site colorectal carcinoid tumors in all age groups from 2000–2002 and 2014–2016. This increase was largely the result of increases in rectal carcinoid tumors, the authors note.

The authors also highlighted the results in the 40- to 49-year age group “because of differing opinions on whether to begin average-risk screening at age 45 or 50 years.”

They reported that rates of rectal and colon adenocarcinoma are increasing “substantially,” whether measured by changes in 3-year average annual incidence rate or by annual percentage changes. The change in average annual incidence rate of colon-only adenocarcinoma for persons aged 40-49 years was 13% (12.21 to 13.85 per 100,000), and that of rectal adenocarcinoma was 16% (7.50 to 8.72 per 100,000). Corresponding annual percentage changes were 0.8% and 1.2%, respectively. “These significant increases in adenocarcinoma incident rates add to the debate over earlier screening at age 45 years,” they commented.

Calls for next steps

The editorialists emphasize restraint when promoting the benefits of colorectal screening for persons younger than 50 years.

They point out that the USPSTF released a provisional update of its CRC screening recommendations about lowering the age to initiate screening to 45 years, as reported by this news organization.

“No new empirical evidence has been found since the USPSTF update in 2016 to inform the effectiveness of screening in persons younger than 50 years,” they write, adding that similar to the American Cancer Society in 2018, the task force has relied exclusively on modeling studies.

This new data from Dr. Karlitz and colleagues “should prompt the modelers to recalculate their estimates of benefits and harms of screening,” they suggested. “Revisiting the model would also allow competing forms of CRC screening to be compared in light of new risk assumptions.

“Previous assumptions that screening tests are equally effective in younger and older patients and that screening adherence will approach 100% may also be reconsidered,” the editorialist commented.

The study authors concluded somewhat differently.

“In conclusion, adenocarcinoma rates increased in many early-onset subgroups but showed no significant increase in others, including colon-only cases in persons aged 20-29 and 50-54 years,” the investigators wrote.

They also observed that “rectal carcinoid tumors are increasing in young patients and may have a substantial impact on overall CRC incident rates.”

Those findings on rectal carcinoid tumors “underscore the importance of assessing histologic CRC subtypes independently,” the researchers said.

This new approach, of which the current study is a first effort, “may lead to a better understanding of the drivers of temporal changes in overall CRC incidence and a more accurate measurement of the outcomes of adenocarcinoma risk reduction efforts, and can guide future research.”

The study had no outside funding. Dr. Karlitz reported personal fees from Exact Sciences, personal fees from Myriad Genetics, and other fees from Gastro Girl and GI OnDEMAND, outside the submitted work. Dr. Bretthauer reports grants from Norwegian Research Council, grants from Norwegian Cancer Society for research in colorectal cancer screening. Dr. Weinberg and Dr. Kalager have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Implications for CRC screening.

Implications for CRC screening.

New estimates for the risk of CRC in young adults, which differentiate colorectal adenocarcinoma from other types, are reported in a study published Dec. 15, 2020, in Annals of Internal Medicine.

They are important because this finding has implications for CRC screening, say a trio of experts in an accompanying editorial.

Reports of an increase in the incidence of CRC in younger adults have led to changes in screening for this cancer in the United States. The age for starting CRC screening has been lowered to 45 years (instead of 50 years) in recommendations issued in 2018 by the American Cancer Society, and also more recently in preliminary recommendations from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force.

However, that 2018 ACS recommendation to lower the starting age to 45 years was based to a large extent on a report of a higher incidence of CRC in younger adults from a 2017 study that used the SEER (Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results) database).

But that SEER-based study considered “colorectal cancer” as a homogeneous group defined by topology, the editorialists pointed out.

The new study, the editorialists said, uses that same SEER database but has “disentangled colorectal adenocarcinoma, the target for screening, from other histologic CRC types, including neuroendocrine (carcinoid) tumors, for which screening is not recommended.”

The study authors explained that adenocarcinoma is a target for prevention through screening because it arises from precancerous polyps. Those growths can be detected and removed before cancer develops. That doesn’t apply to carcinoid tumors, which are frequently incidental findings on flexible sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy.

These carcinoid tumors typically are indolent, with a better prognosis than most other cancer types, the editorialists added. “Most likely, the majority of carcinoid tumors identified by screening represent incidental findings with little health benefit from detection. In fact, many may be characterized as overdiagnosed tumors, which by definition increase the burden and harms of screening without the balance of additional benefit.”

This new analysis showed that 4%-20% of the lesions previously described as CRC were not adenocarcinoma but carcinoid tumors, the editorialists pointed out.

This figure rose even higher in the subgroup of findings pertaining to the rectum, the colonic segment with the largest reported increase in early-onset CRC. Here, up to 34% of lesions (depending on patient age) were carcinoid tumors rather than adenocarcinoma, they noted.

The three editorialists – Michael Bretthauer, MD, PhD, and Mette Kalager, MD, PhD, both of the University of Oslo, and David Weinberg, MD, MSc, of Fox Chase Cancer Center, Philadelphia – call for action based on the new findings.

“The ACS’s 2018 estimate of about 7,000 new CRC cases among persons aged 45-49 years in the United States (the justification for screening) needs to be adjusted downward on the basis of the new evidence,” the trio wrote.

They conclude that “caution is warranted when promoting the benefits of CRC screening for persons younger than 50 years.”

However, the senior author of the new study, Jordan Karlitz, MD, of Tulane University, New Orleans, strongly disagreed.

Contrary to the editorialists, Dr. Karlitz said in an interview that he and his colleagues firmly believe that colorectal cancer screening for average-risk patients should begin at age 45 and that their new research, despite its clarification about carcinoid tumors, provides evidence for that.

“There are a number of other studies that support screening at age 45 as well,” he said. “This [new] finding supports the presence of a large preclinical colorectal cancer case burden in patients in their 40s that is ultimately uncovered with screening initiation at age 50. Many of these cancers could be prevented or diagnosed at an earlier stage with screening at age 45.”

“This is the first study to analyze early-onset colorectal cancer by specific histologic subtype,” Dr. Karlitz also pointed out.

“Although colorectal carcinoids are increasing at a faster rate than adenocarcinomas, adenocarcinomas constitute the overwhelming majority of colorectal cancers in people in their 40s and are also steadily increasing, which has implications for beginning screening at age 45,” he said.

Adenocarcinomas also make up the “overwhelming majority” of colorectal cancers in patients under 50 overall and “are the main driving force behind the increased colorectal cancer burden we are seeing in young patients,” Dr. Karlitz added.

Furthermore, “modeling studies on which the USPSTF screening recommendations were based [which recommended starting at age 45] were confined to adenocarcinoma, thus excluding carcinoids from their analysis,” he said.

Steepest changes in adenocarcinomas in younger groups

In their study, Dr. Karlitz and colleagues assessed the incidence rates of early colorectal cancer, using SEER data from 2000 to 2016, and stratifying the data by histologic subtype (primarily adenocarcinoma and carcinoid tumors), age group (20-29, 30-39, 40-49, and 50-54 years), and subsite.

A total of 123,143 CRC cases were identified in 119,624 patients between the ages of 20-54 years during that time period.

The absolute incidence rates in the younger age groups (20-29 and 30-39 years) were very low, compared with those aged 40-49 and 50-54 years.

The greatest 3-year average annual incident rate changes in adenocarcinoma (2000-2002 vs. 2014-2016) for any age group or subsite were for rectal-only cases in the 20-29 years group (+39%), as well as rectal-only cases in those aged 30-39 years (+39%), and colon-only cases in the age 30-39 group (+20%).

There was also significant increase in rectal-only adenocarcinoma in individuals aged 50-54 years (+10%). A statistically significant increase in the annual percentage change for adenocarcinomas was observed for all age groups, except for colon-only cases in the 20-29 years group (0.7%) and for both colorectal (0.2%) and colon-only cases (–0.1%) in those aged 50-54 years.

Even though the absolute carcinoid tumor incidence rates were lower than for adenocarcinoma in all age groups and subsites, a statistically significant increase was observed in the 3-year average annual incidence rate of combined-site colorectal carcinoid tumors in all age groups from 2000–2002 and 2014–2016. This increase was largely the result of increases in rectal carcinoid tumors, the authors note.

The authors also highlighted the results in the 40- to 49-year age group “because of differing opinions on whether to begin average-risk screening at age 45 or 50 years.”

They reported that rates of rectal and colon adenocarcinoma are increasing “substantially,” whether measured by changes in 3-year average annual incidence rate or by annual percentage changes. The change in average annual incidence rate of colon-only adenocarcinoma for persons aged 40-49 years was 13% (12.21 to 13.85 per 100,000), and that of rectal adenocarcinoma was 16% (7.50 to 8.72 per 100,000). Corresponding annual percentage changes were 0.8% and 1.2%, respectively. “These significant increases in adenocarcinoma incident rates add to the debate over earlier screening at age 45 years,” they commented.

Calls for next steps

The editorialists emphasize restraint when promoting the benefits of colorectal screening for persons younger than 50 years.

They point out that the USPSTF released a provisional update of its CRC screening recommendations about lowering the age to initiate screening to 45 years, as reported by this news organization.

“No new empirical evidence has been found since the USPSTF update in 2016 to inform the effectiveness of screening in persons younger than 50 years,” they write, adding that similar to the American Cancer Society in 2018, the task force has relied exclusively on modeling studies.

This new data from Dr. Karlitz and colleagues “should prompt the modelers to recalculate their estimates of benefits and harms of screening,” they suggested. “Revisiting the model would also allow competing forms of CRC screening to be compared in light of new risk assumptions.

“Previous assumptions that screening tests are equally effective in younger and older patients and that screening adherence will approach 100% may also be reconsidered,” the editorialist commented.

The study authors concluded somewhat differently.

“In conclusion, adenocarcinoma rates increased in many early-onset subgroups but showed no significant increase in others, including colon-only cases in persons aged 20-29 and 50-54 years,” the investigators wrote.

They also observed that “rectal carcinoid tumors are increasing in young patients and may have a substantial impact on overall CRC incident rates.”

Those findings on rectal carcinoid tumors “underscore the importance of assessing histologic CRC subtypes independently,” the researchers said.

This new approach, of which the current study is a first effort, “may lead to a better understanding of the drivers of temporal changes in overall CRC incidence and a more accurate measurement of the outcomes of adenocarcinoma risk reduction efforts, and can guide future research.”

The study had no outside funding. Dr. Karlitz reported personal fees from Exact Sciences, personal fees from Myriad Genetics, and other fees from Gastro Girl and GI OnDEMAND, outside the submitted work. Dr. Bretthauer reports grants from Norwegian Research Council, grants from Norwegian Cancer Society for research in colorectal cancer screening. Dr. Weinberg and Dr. Kalager have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

New estimates for the risk of CRC in young adults, which differentiate colorectal adenocarcinoma from other types, are reported in a study published Dec. 15, 2020, in Annals of Internal Medicine.

They are important because this finding has implications for CRC screening, say a trio of experts in an accompanying editorial.

Reports of an increase in the incidence of CRC in younger adults have led to changes in screening for this cancer in the United States. The age for starting CRC screening has been lowered to 45 years (instead of 50 years) in recommendations issued in 2018 by the American Cancer Society, and also more recently in preliminary recommendations from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force.

However, that 2018 ACS recommendation to lower the starting age to 45 years was based to a large extent on a report of a higher incidence of CRC in younger adults from a 2017 study that used the SEER (Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results) database).

But that SEER-based study considered “colorectal cancer” as a homogeneous group defined by topology, the editorialists pointed out.

The new study, the editorialists said, uses that same SEER database but has “disentangled colorectal adenocarcinoma, the target for screening, from other histologic CRC types, including neuroendocrine (carcinoid) tumors, for which screening is not recommended.”

The study authors explained that adenocarcinoma is a target for prevention through screening because it arises from precancerous polyps. Those growths can be detected and removed before cancer develops. That doesn’t apply to carcinoid tumors, which are frequently incidental findings on flexible sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy.

These carcinoid tumors typically are indolent, with a better prognosis than most other cancer types, the editorialists added. “Most likely, the majority of carcinoid tumors identified by screening represent incidental findings with little health benefit from detection. In fact, many may be characterized as overdiagnosed tumors, which by definition increase the burden and harms of screening without the balance of additional benefit.”

This new analysis showed that 4%-20% of the lesions previously described as CRC were not adenocarcinoma but carcinoid tumors, the editorialists pointed out.

This figure rose even higher in the subgroup of findings pertaining to the rectum, the colonic segment with the largest reported increase in early-onset CRC. Here, up to 34% of lesions (depending on patient age) were carcinoid tumors rather than adenocarcinoma, they noted.

The three editorialists – Michael Bretthauer, MD, PhD, and Mette Kalager, MD, PhD, both of the University of Oslo, and David Weinberg, MD, MSc, of Fox Chase Cancer Center, Philadelphia – call for action based on the new findings.

“The ACS’s 2018 estimate of about 7,000 new CRC cases among persons aged 45-49 years in the United States (the justification for screening) needs to be adjusted downward on the basis of the new evidence,” the trio wrote.

They conclude that “caution is warranted when promoting the benefits of CRC screening for persons younger than 50 years.”

However, the senior author of the new study, Jordan Karlitz, MD, of Tulane University, New Orleans, strongly disagreed.

Contrary to the editorialists, Dr. Karlitz said in an interview that he and his colleagues firmly believe that colorectal cancer screening for average-risk patients should begin at age 45 and that their new research, despite its clarification about carcinoid tumors, provides evidence for that.

“There are a number of other studies that support screening at age 45 as well,” he said. “This [new] finding supports the presence of a large preclinical colorectal cancer case burden in patients in their 40s that is ultimately uncovered with screening initiation at age 50. Many of these cancers could be prevented or diagnosed at an earlier stage with screening at age 45.”

“This is the first study to analyze early-onset colorectal cancer by specific histologic subtype,” Dr. Karlitz also pointed out.

“Although colorectal carcinoids are increasing at a faster rate than adenocarcinomas, adenocarcinomas constitute the overwhelming majority of colorectal cancers in people in their 40s and are also steadily increasing, which has implications for beginning screening at age 45,” he said.

Adenocarcinomas also make up the “overwhelming majority” of colorectal cancers in patients under 50 overall and “are the main driving force behind the increased colorectal cancer burden we are seeing in young patients,” Dr. Karlitz added.

Furthermore, “modeling studies on which the USPSTF screening recommendations were based [which recommended starting at age 45] were confined to adenocarcinoma, thus excluding carcinoids from their analysis,” he said.

Steepest changes in adenocarcinomas in younger groups

In their study, Dr. Karlitz and colleagues assessed the incidence rates of early colorectal cancer, using SEER data from 2000 to 2016, and stratifying the data by histologic subtype (primarily adenocarcinoma and carcinoid tumors), age group (20-29, 30-39, 40-49, and 50-54 years), and subsite.

A total of 123,143 CRC cases were identified in 119,624 patients between the ages of 20-54 years during that time period.

The absolute incidence rates in the younger age groups (20-29 and 30-39 years) were very low, compared with those aged 40-49 and 50-54 years.

The greatest 3-year average annual incident rate changes in adenocarcinoma (2000-2002 vs. 2014-2016) for any age group or subsite were for rectal-only cases in the 20-29 years group (+39%), as well as rectal-only cases in those aged 30-39 years (+39%), and colon-only cases in the age 30-39 group (+20%).

There was also significant increase in rectal-only adenocarcinoma in individuals aged 50-54 years (+10%). A statistically significant increase in the annual percentage change for adenocarcinomas was observed for all age groups, except for colon-only cases in the 20-29 years group (0.7%) and for both colorectal (0.2%) and colon-only cases (–0.1%) in those aged 50-54 years.

Even though the absolute carcinoid tumor incidence rates were lower than for adenocarcinoma in all age groups and subsites, a statistically significant increase was observed in the 3-year average annual incidence rate of combined-site colorectal carcinoid tumors in all age groups from 2000–2002 and 2014–2016. This increase was largely the result of increases in rectal carcinoid tumors, the authors note.

The authors also highlighted the results in the 40- to 49-year age group “because of differing opinions on whether to begin average-risk screening at age 45 or 50 years.”

They reported that rates of rectal and colon adenocarcinoma are increasing “substantially,” whether measured by changes in 3-year average annual incidence rate or by annual percentage changes. The change in average annual incidence rate of colon-only adenocarcinoma for persons aged 40-49 years was 13% (12.21 to 13.85 per 100,000), and that of rectal adenocarcinoma was 16% (7.50 to 8.72 per 100,000). Corresponding annual percentage changes were 0.8% and 1.2%, respectively. “These significant increases in adenocarcinoma incident rates add to the debate over earlier screening at age 45 years,” they commented.

Calls for next steps

The editorialists emphasize restraint when promoting the benefits of colorectal screening for persons younger than 50 years.

They point out that the USPSTF released a provisional update of its CRC screening recommendations about lowering the age to initiate screening to 45 years, as reported by this news organization.

“No new empirical evidence has been found since the USPSTF update in 2016 to inform the effectiveness of screening in persons younger than 50 years,” they write, adding that similar to the American Cancer Society in 2018, the task force has relied exclusively on modeling studies.

This new data from Dr. Karlitz and colleagues “should prompt the modelers to recalculate their estimates of benefits and harms of screening,” they suggested. “Revisiting the model would also allow competing forms of CRC screening to be compared in light of new risk assumptions.

“Previous assumptions that screening tests are equally effective in younger and older patients and that screening adherence will approach 100% may also be reconsidered,” the editorialist commented.

The study authors concluded somewhat differently.

“In conclusion, adenocarcinoma rates increased in many early-onset subgroups but showed no significant increase in others, including colon-only cases in persons aged 20-29 and 50-54 years,” the investigators wrote.

They also observed that “rectal carcinoid tumors are increasing in young patients and may have a substantial impact on overall CRC incident rates.”

Those findings on rectal carcinoid tumors “underscore the importance of assessing histologic CRC subtypes independently,” the researchers said.

This new approach, of which the current study is a first effort, “may lead to a better understanding of the drivers of temporal changes in overall CRC incidence and a more accurate measurement of the outcomes of adenocarcinoma risk reduction efforts, and can guide future research.”

The study had no outside funding. Dr. Karlitz reported personal fees from Exact Sciences, personal fees from Myriad Genetics, and other fees from Gastro Girl and GI OnDEMAND, outside the submitted work. Dr. Bretthauer reports grants from Norwegian Research Council, grants from Norwegian Cancer Society for research in colorectal cancer screening. Dr. Weinberg and Dr. Kalager have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Baseline body surface area may drive optimal baricitinib responses

results from an analysis of phase 3 data showed.

“This proposed clinical tailoring approach for baricitinib 2 mg allows for treatment of patients who are more likely to respond to therapy and rapid decision on discontinuation of treatment for those who are not likely to benefit from baricitinib 2 mg,” Eric L. Simpson, MD, said during a late-breaking abstract session at the Revolutionizing Atopic Dermatitis virtual symposium.

Baricitinib is an oral, reversible and selective Janus kinase 1/JAK2 inhibitor that is approved in Europe for the treatment of moderate to severe AD in adults who are candidates for systemic therapy. In the United States, it is approved for treating rheumatoid arthritis, and is currently under Food and Drug Administration review in the United States for AD.

For the current analysis, Dr. Simpson, professor of dermatology at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, and colleagues set out to identify responders to baricitinib 2 mg using a tailored approach based on baseline BSA affected and early clinical improvement in the phase 3 monotherapy trial BREEZE-AD5. The trial enrolled 440 patients: 147 to placebo, 147 to baricitinib 1 mg once daily, and 146 to baricitinib 2 mg once daily. The primary endpoint was Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI)–75 at week 16.

“Understanding which patients can benefit most from this treatment was our goal,” Dr. Simpson said. “By tailoring your therapy, you can significantly improve the patient experience, increase the cost-effectiveness of a therapy, and you can ensure that only patients who are likely to benefit are exposed to a drug.”

The researchers used a classification and regression tree algorithm that identified baseline BSA as the strongest predictor of EASI-75 response at week 16. A BSA cutoff of 50% was established as the optimal cutoff for sensitivity and negative predictive value. Results for EASI-75 and Validated Investigator Global Assessment for Atopic Dermatitis (vIGA-AD) scores of 0 or 1 were confirmed using a BSA of 10%-50% at baseline to predict response, compared with a BSA or greater than 50% at baseline.

Sensitivity analyses revealed that about 90% of patients with an EASI-75 response were in the BSA 10%-50% group. Conversely, among patients with a BSA greater than 50%, the negative predictive value was greater than 90%, “so there’s a 90% chance you’re not going to hit that EASI-75 at week 16 if your BSA is greater than 50%,” Dr. Simpson explained. “The same holds true for vIGA-AD, so that 50% cutoff is important for understanding whether someone is going to respond or not.”

On the EASI-75, 38% of patients in the BSA 10%-50% group responded to baricitinib at week 16, compared with 10% in the BSA greater than 50% group. A similar association was observed on the vIGA-AD, where 32% of patients in the BSA 10%-50% group responded to baricitinib at week 16, compared with 5% in the BSA greater than 50% group.

When stratified by early response assessed at week 4, based on a 4-point improvement or greater on the Itch Numeric Rating Scale, 55% of those patients became EASI-75 responders, compared with 17% who were not. A similar association was observed by early response assessed at week 8.

“Due to the rapid onset of response, clinical assessment of patients after 4-8 weeks of initiation of baricitinib 2 mg treatment provided a positive feedback to patients who are likely to benefit from long-term therapy,” Dr. Simpson said. “This analysis may allow for a precision-medicine approach to therapy in moderate to severe AD.”

The study was supported by Eli Lilly, and was under license from Incyte. Dr. Simpson reported serving as an investigator for and consultant to numerous pharmaceutical companies.

results from an analysis of phase 3 data showed.

“This proposed clinical tailoring approach for baricitinib 2 mg allows for treatment of patients who are more likely to respond to therapy and rapid decision on discontinuation of treatment for those who are not likely to benefit from baricitinib 2 mg,” Eric L. Simpson, MD, said during a late-breaking abstract session at the Revolutionizing Atopic Dermatitis virtual symposium.

Baricitinib is an oral, reversible and selective Janus kinase 1/JAK2 inhibitor that is approved in Europe for the treatment of moderate to severe AD in adults who are candidates for systemic therapy. In the United States, it is approved for treating rheumatoid arthritis, and is currently under Food and Drug Administration review in the United States for AD.

For the current analysis, Dr. Simpson, professor of dermatology at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, and colleagues set out to identify responders to baricitinib 2 mg using a tailored approach based on baseline BSA affected and early clinical improvement in the phase 3 monotherapy trial BREEZE-AD5. The trial enrolled 440 patients: 147 to placebo, 147 to baricitinib 1 mg once daily, and 146 to baricitinib 2 mg once daily. The primary endpoint was Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI)–75 at week 16.

“Understanding which patients can benefit most from this treatment was our goal,” Dr. Simpson said. “By tailoring your therapy, you can significantly improve the patient experience, increase the cost-effectiveness of a therapy, and you can ensure that only patients who are likely to benefit are exposed to a drug.”

The researchers used a classification and regression tree algorithm that identified baseline BSA as the strongest predictor of EASI-75 response at week 16. A BSA cutoff of 50% was established as the optimal cutoff for sensitivity and negative predictive value. Results for EASI-75 and Validated Investigator Global Assessment for Atopic Dermatitis (vIGA-AD) scores of 0 or 1 were confirmed using a BSA of 10%-50% at baseline to predict response, compared with a BSA or greater than 50% at baseline.

Sensitivity analyses revealed that about 90% of patients with an EASI-75 response were in the BSA 10%-50% group. Conversely, among patients with a BSA greater than 50%, the negative predictive value was greater than 90%, “so there’s a 90% chance you’re not going to hit that EASI-75 at week 16 if your BSA is greater than 50%,” Dr. Simpson explained. “The same holds true for vIGA-AD, so that 50% cutoff is important for understanding whether someone is going to respond or not.”

On the EASI-75, 38% of patients in the BSA 10%-50% group responded to baricitinib at week 16, compared with 10% in the BSA greater than 50% group. A similar association was observed on the vIGA-AD, where 32% of patients in the BSA 10%-50% group responded to baricitinib at week 16, compared with 5% in the BSA greater than 50% group.

When stratified by early response assessed at week 4, based on a 4-point improvement or greater on the Itch Numeric Rating Scale, 55% of those patients became EASI-75 responders, compared with 17% who were not. A similar association was observed by early response assessed at week 8.

“Due to the rapid onset of response, clinical assessment of patients after 4-8 weeks of initiation of baricitinib 2 mg treatment provided a positive feedback to patients who are likely to benefit from long-term therapy,” Dr. Simpson said. “This analysis may allow for a precision-medicine approach to therapy in moderate to severe AD.”

The study was supported by Eli Lilly, and was under license from Incyte. Dr. Simpson reported serving as an investigator for and consultant to numerous pharmaceutical companies.

results from an analysis of phase 3 data showed.

“This proposed clinical tailoring approach for baricitinib 2 mg allows for treatment of patients who are more likely to respond to therapy and rapid decision on discontinuation of treatment for those who are not likely to benefit from baricitinib 2 mg,” Eric L. Simpson, MD, said during a late-breaking abstract session at the Revolutionizing Atopic Dermatitis virtual symposium.

Baricitinib is an oral, reversible and selective Janus kinase 1/JAK2 inhibitor that is approved in Europe for the treatment of moderate to severe AD in adults who are candidates for systemic therapy. In the United States, it is approved for treating rheumatoid arthritis, and is currently under Food and Drug Administration review in the United States for AD.

For the current analysis, Dr. Simpson, professor of dermatology at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, and colleagues set out to identify responders to baricitinib 2 mg using a tailored approach based on baseline BSA affected and early clinical improvement in the phase 3 monotherapy trial BREEZE-AD5. The trial enrolled 440 patients: 147 to placebo, 147 to baricitinib 1 mg once daily, and 146 to baricitinib 2 mg once daily. The primary endpoint was Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI)–75 at week 16.

“Understanding which patients can benefit most from this treatment was our goal,” Dr. Simpson said. “By tailoring your therapy, you can significantly improve the patient experience, increase the cost-effectiveness of a therapy, and you can ensure that only patients who are likely to benefit are exposed to a drug.”

The researchers used a classification and regression tree algorithm that identified baseline BSA as the strongest predictor of EASI-75 response at week 16. A BSA cutoff of 50% was established as the optimal cutoff for sensitivity and negative predictive value. Results for EASI-75 and Validated Investigator Global Assessment for Atopic Dermatitis (vIGA-AD) scores of 0 or 1 were confirmed using a BSA of 10%-50% at baseline to predict response, compared with a BSA or greater than 50% at baseline.

Sensitivity analyses revealed that about 90% of patients with an EASI-75 response were in the BSA 10%-50% group. Conversely, among patients with a BSA greater than 50%, the negative predictive value was greater than 90%, “so there’s a 90% chance you’re not going to hit that EASI-75 at week 16 if your BSA is greater than 50%,” Dr. Simpson explained. “The same holds true for vIGA-AD, so that 50% cutoff is important for understanding whether someone is going to respond or not.”

On the EASI-75, 38% of patients in the BSA 10%-50% group responded to baricitinib at week 16, compared with 10% in the BSA greater than 50% group. A similar association was observed on the vIGA-AD, where 32% of patients in the BSA 10%-50% group responded to baricitinib at week 16, compared with 5% in the BSA greater than 50% group.

When stratified by early response assessed at week 4, based on a 4-point improvement or greater on the Itch Numeric Rating Scale, 55% of those patients became EASI-75 responders, compared with 17% who were not. A similar association was observed by early response assessed at week 8.

“Due to the rapid onset of response, clinical assessment of patients after 4-8 weeks of initiation of baricitinib 2 mg treatment provided a positive feedback to patients who are likely to benefit from long-term therapy,” Dr. Simpson said. “This analysis may allow for a precision-medicine approach to therapy in moderate to severe AD.”

The study was supported by Eli Lilly, and was under license from Incyte. Dr. Simpson reported serving as an investigator for and consultant to numerous pharmaceutical companies.

FROM REVOLUTIONIZING AD 2020

Avoiding atopic dermatitis triggers easier said than done

“Guidelines on trigger avoidance are written as if it’s easy to do,” Jonathan I. Silverberg, MD, PhD, MPH, said during the Revolutionizing Atopic Dermatitis virtual symposium. “It turns out that trigger avoidance is really complicated.”

He and his colleagues conducted a study of most common triggers for itch based on a prospective dermatology practice–based study of 587 adults with AD . About two-thirds (65%) reported one or more itch trigger in the past week and 36% had three or more itch triggers in the past week. The two most common triggers were stress (35%) and sweat (31%).

“To me, this is provocative, because this is not how I was trained in residency,” said Dr. Silverberg, director of clinical research in the division of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington. “I was trained that it’s all about excess showering, dry air, or cold temperature. Those are important, but the most common triggers are stress and sweat.”

AD triggers are also commonly linked to seasonality. “If you ask patients when their AD is worse, sometimes it’s winter,” he said. “Sometimes it’s spring. Sometimes it’s summer. It turns out that there is a distinct set of triggers that are associated with AD seasonality.” Wintertime worsening of disease is associated with cold temperature and weather change, he continued, while springtime worsening of disease is often linked to weather change and dry air. Common summertime triggers for flares include hot temperature, heat, sweat, weather change, sunlight, humid air, and dry air. “In the fall, the weather change again comes up as a trigger. Humid air does as well.”

In their prospective study, Dr. Silverberg and colleagues found that 90% of those who had at least three itch triggers reported 3 months or less of AD remission in the past year, “meaning that 90% are reporting persistent disease when they have multiple itch triggers,” he said. In addition, 78% reported two or more flares per year and 61% reported that AD is worse during certain seasons.

Potential mitigation strategies for stress include stress management, biofeedback, meditation, relaxation training, and mindfulness. “These don’t necessarily require expensive psychotherapy,” he said. Freely available iPhone apps can be incorporated into daily practice, such as Calm, Relax with Andrew Johnson, Nature Sounds Relax and Sleep, Breathe2Relax, and Headspace.

Many AD patients are sedentary and avoid vigorous physical activity owing to heat and sweat as triggers. Simple solutions include exercising in a cooler temperature environment, “not just using fans,” he said. “Take a quick shower right after working out and consider pre- and/or post treatment with topical medication.”

High temperature and sweating can be problematic at bedtime, he continued. Even if the indoor temperature is 70° F, that might jump to 85° F or 90° F under a thick blanket. “That heat can trigger itch and may cause sweating, which can trigger itch,” said Dr. Silverberg, who has AD and is director of patch testing at George Washington University. Potential solutions include using a lighter blanket, lowering the indoor temperature, and wearing breathable pajamas.

Dryness, another common AD trigger, can be secondary to a combination of low outdoor and/or indoor humidity. “Lower outdoor humidity is a particular problem in the wintertime, because cold air doesn’t hold moisture as well,” he said. “That’s why the air feels much dryer in the wintertime. There’s also a problem of indoor heating and cooling. Sometimes central air systems can lower humidity to the point where it’s bone dry.”

In an effort to determine the impact of specific climatic factors on the U.S. prevalence of AD, Dr. Silverberg and colleagues conducted a study using a merged analysis of the 2007 National Survey of Children’s Health from a representative sample of 91,642 children aged 0-17 years and 2006-2007 measurements from the National Climate Data Center and Weather Service. They found that childhood AD prevalence was increased in geographical areas that use more indoor heat and cooling and had lower outdoor humidity. “So, we see that there’s a direct correlate of this dryness issue that is leading to more AD throughout the U.S.,” he said.

Practical solutions to mitigate the effect of dry air on AD include opening windows to allow entry of moist air, “which can be particularly helpful in residences that are overheated,” he said. “I deal with this a lot in patients who live in dormitories. Use humidifiers to add moisture back into the air. Aim for 40%-50% indoor humidity to avoid mold and dust mites. It’s better to use demineralized water to reduce bacterial growth. This can be helpful for aeroallergies. Of note, there are really no well-done studies that have examined the efficacy of humidifiers in AD, but based on our anecdotal experience, this is a good way to go.”

Cold temperatures and trigger intense itch, even in the setting of high humidity. “For me personally, this is one of my most brutal triggers,” Dr. Silverberg said. “When I’m in a place with extremes of cold, I get a rapid onset of itch, a mix of itch and pain, particularly on the dorsal hands. For solutions, you can encourage patients to avoid extremely low temperatures, to bundle up, and to potentially use hand warmers or other heating devices.”

Clothing can be a trigger as well, especially tight-fitting clothes, hot and nonbreathable clothes, and large-diameter wool, which has been shown to induce itching and irritation. Mitigation strategies include wearing loose-fitting, lightweight, nonirritating fabric. “Traditional cotton and silk fabrics have mixed evidence in improving AD but are generally safe,” he said. “Ultra- or superfine merino wool has been shown to be nonpruritic. There is sparse evidence to support chemically treated/coated clothing for AD, but this may be an emerging area.”

Dr. Silverberg pointed out variability of cultural perspectives and preferences for bathing practices, including temperature, duration, frequency, optimal bathing products, and the use of loofahs and other scrubbing products. “This stems from different perceptions of what it means to be clean, and how dry our skin should feel after a shower,” he said. “Many clinicians and patients were taught that regular bathing is harmful in AD. It turns out that’s not true.”

In a recently published systematic review and meta-analysis of 13 studies, he and his colleagues examined efficacy outcomes of different bathing/showering regimens in AD. All 13 studies showed numerically reduced AD severity with any bathing regimen in at least one time point. Numerical decreases over time were observed for body surface area (BSA), Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI), and/or SCORAD measures for daily and less than daily bathing, with or without application of emollients or topical corticosteroids. In random effects regression models, taking baths more than or less than seven times per week were not associated with significant differences of Cohen’s D scores for EASI, SCORAD, or BSA. “The take-home message here is, let your AD patients bathe,” Dr. Silverberg said. “Bathing is good. It can be channeled to help the eczema, but it has to be done the right way.”

Patients should be counseled to use nonirritating cleansers and shampoos, avoid excessively long baths/showers, avoid excessively hot baths/showers, avoid excessive rubbing or scrubbing of skin, and to apply emollients and/or topical corticosteroids immediately after the bath/shower.

PROMIS Itch-Triggers is a simple and feasible checklist to screen for the most common itch triggers in AD in clinical practice (patients are asked to check off which of the following have caused their itch in the previous 7 days: cold temperature, hot temperature, heat, sweat, tight clothing, fragrances, boredom, talking about itch, stress, weather change, sunlight, humid air, dry air). “It takes less than 1 minute to complete,” he said. “Additional testing with skin patch and/or prick testing may be warranted to identify allergenic triggers.”

Dr. Silverberg reported that he is a consultant to and/or an advisory board member for several pharmaceutical companies. He is also a speaker for Regeneron and Sanofi and has received a grant from Galderma.

“Guidelines on trigger avoidance are written as if it’s easy to do,” Jonathan I. Silverberg, MD, PhD, MPH, said during the Revolutionizing Atopic Dermatitis virtual symposium. “It turns out that trigger avoidance is really complicated.”

He and his colleagues conducted a study of most common triggers for itch based on a prospective dermatology practice–based study of 587 adults with AD . About two-thirds (65%) reported one or more itch trigger in the past week and 36% had three or more itch triggers in the past week. The two most common triggers were stress (35%) and sweat (31%).

“To me, this is provocative, because this is not how I was trained in residency,” said Dr. Silverberg, director of clinical research in the division of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington. “I was trained that it’s all about excess showering, dry air, or cold temperature. Those are important, but the most common triggers are stress and sweat.”

AD triggers are also commonly linked to seasonality. “If you ask patients when their AD is worse, sometimes it’s winter,” he said. “Sometimes it’s spring. Sometimes it’s summer. It turns out that there is a distinct set of triggers that are associated with AD seasonality.” Wintertime worsening of disease is associated with cold temperature and weather change, he continued, while springtime worsening of disease is often linked to weather change and dry air. Common summertime triggers for flares include hot temperature, heat, sweat, weather change, sunlight, humid air, and dry air. “In the fall, the weather change again comes up as a trigger. Humid air does as well.”

In their prospective study, Dr. Silverberg and colleagues found that 90% of those who had at least three itch triggers reported 3 months or less of AD remission in the past year, “meaning that 90% are reporting persistent disease when they have multiple itch triggers,” he said. In addition, 78% reported two or more flares per year and 61% reported that AD is worse during certain seasons.

Potential mitigation strategies for stress include stress management, biofeedback, meditation, relaxation training, and mindfulness. “These don’t necessarily require expensive psychotherapy,” he said. Freely available iPhone apps can be incorporated into daily practice, such as Calm, Relax with Andrew Johnson, Nature Sounds Relax and Sleep, Breathe2Relax, and Headspace.

Many AD patients are sedentary and avoid vigorous physical activity owing to heat and sweat as triggers. Simple solutions include exercising in a cooler temperature environment, “not just using fans,” he said. “Take a quick shower right after working out and consider pre- and/or post treatment with topical medication.”

High temperature and sweating can be problematic at bedtime, he continued. Even if the indoor temperature is 70° F, that might jump to 85° F or 90° F under a thick blanket. “That heat can trigger itch and may cause sweating, which can trigger itch,” said Dr. Silverberg, who has AD and is director of patch testing at George Washington University. Potential solutions include using a lighter blanket, lowering the indoor temperature, and wearing breathable pajamas.

Dryness, another common AD trigger, can be secondary to a combination of low outdoor and/or indoor humidity. “Lower outdoor humidity is a particular problem in the wintertime, because cold air doesn’t hold moisture as well,” he said. “That’s why the air feels much dryer in the wintertime. There’s also a problem of indoor heating and cooling. Sometimes central air systems can lower humidity to the point where it’s bone dry.”

In an effort to determine the impact of specific climatic factors on the U.S. prevalence of AD, Dr. Silverberg and colleagues conducted a study using a merged analysis of the 2007 National Survey of Children’s Health from a representative sample of 91,642 children aged 0-17 years and 2006-2007 measurements from the National Climate Data Center and Weather Service. They found that childhood AD prevalence was increased in geographical areas that use more indoor heat and cooling and had lower outdoor humidity. “So, we see that there’s a direct correlate of this dryness issue that is leading to more AD throughout the U.S.,” he said.