User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

Vision loss may be a risk with PRP facial injections

A systematic review was recently conducted by Wu and colleagues examining the risk of blindness associated with platelet-rich plasma (PRP) injection. In dermatology, PRP is used more commonly now than 5 years ago to promote hair growth with injections on the scalp, as an adjunct to microneedling procedures, and sometimes – in a similar way to facial fillers – to improve volume loss, and skin tone and texture (particularly to the tear trough region).

Total unilateral blindness occurred in all cases. In one of the seven reported cases, the patient experienced recovery of vision after 3 months, but with some residual deficits noted on the ophthalmologist examination. In this case, the patient was evaluated and treated by an ophthalmologist within 3 hours of symptom onset.

In addition, four cases were reported from Venezuela, one from the United States, one from the United Kingdom, and one from Malaysia. Similar to reports of blindness with facial fillers, the most common injection site reported with this adverse effect was the glabella (five cases);

Other reports involved injections of the forehead (two), followed by the nasolabial fold (one), lateral canthus (one), and temporomandibular joint (one). Two of the seven patients received injections at more than one site, resulting in the total number of injections reported (10) being higher than the number of patients.

The risk of blindness is inherent with deep injection into a vessel that anastomoses with the blood supply to the eye. No mention was made as to whether PRP or platelet-rich fibrin was used. Other details are lacking from the original articles as to injection technique and whether or not cannula injection was used. No treatment was attempted in four of seven cases.

As plasma is native to the arteries and dissolves in the blood stream naturally, the mechanism as to why retinal artery occlusion or blindness would occur is not completely clear. One theory is that it is volume related and results from the speed of injection, causing a large rapid bolus that temporarily occludes or compresses an involved vessel.

Another theory is that damage to the vessel results from the injection itself or injection technique, leading to a clotting cascade and clot of the involved vessel with subsequent retrograde flow or blockade of the retinal artery. But if this were the case, we would expect to hear about more cases of clots leading to vascular occlusion or skin necrosis, which does not typically occur or we do not hear about.

Details about proper collection materials and technique or mixing with some other materials are also unknown in these cases, thus leaving the possibility that a more occlusive material may have been injected, as opposed to the fluid-like composition of the typical PRP preparation.With regards to risk with scalp PRP injection, the frontal scalp does receive blood supply from the supratrochlear artery that anastomoses with the angular artery of the face – both of which anastomose with the retinal artery (where occlusion would occur via back flow). The scalp tributaries are small and far enough away from the retina at that point that risk of back flow the to retinal artery should be minimal. Additionally, no reports of vascular occlusion from PRP scalp injection leading to skin necrosis have ever been reported. Of note, this is also not a risk that has been reported with the use of PRP with microneedling procedures, where PRP is placed on top of the skin before, during and after microneedling.

Anything that occludes the blood supply to the eye, whether it be fat, filler, or PRP, has an inherent risk of blindness. As there is no reversal agent or designated treatment for PRP occlusion, care must be taken to minimize risk, including awareness of anatomy and avoidance of injection into high risk areas, and cannula use where appropriate. Gentle, slow, low-volume administration, and when possible, use of a retrograde injection technique, may also be helpful.

Dr. Wesley and Lily Talakoub, MD, are cocontributors to this column. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. This month’s column is by Dr. Wesley. Write to them at [email protected]. They had no relevant disclosures.

A systematic review was recently conducted by Wu and colleagues examining the risk of blindness associated with platelet-rich plasma (PRP) injection. In dermatology, PRP is used more commonly now than 5 years ago to promote hair growth with injections on the scalp, as an adjunct to microneedling procedures, and sometimes – in a similar way to facial fillers – to improve volume loss, and skin tone and texture (particularly to the tear trough region).

Total unilateral blindness occurred in all cases. In one of the seven reported cases, the patient experienced recovery of vision after 3 months, but with some residual deficits noted on the ophthalmologist examination. In this case, the patient was evaluated and treated by an ophthalmologist within 3 hours of symptom onset.

In addition, four cases were reported from Venezuela, one from the United States, one from the United Kingdom, and one from Malaysia. Similar to reports of blindness with facial fillers, the most common injection site reported with this adverse effect was the glabella (five cases);

Other reports involved injections of the forehead (two), followed by the nasolabial fold (one), lateral canthus (one), and temporomandibular joint (one). Two of the seven patients received injections at more than one site, resulting in the total number of injections reported (10) being higher than the number of patients.

The risk of blindness is inherent with deep injection into a vessel that anastomoses with the blood supply to the eye. No mention was made as to whether PRP or platelet-rich fibrin was used. Other details are lacking from the original articles as to injection technique and whether or not cannula injection was used. No treatment was attempted in four of seven cases.

As plasma is native to the arteries and dissolves in the blood stream naturally, the mechanism as to why retinal artery occlusion or blindness would occur is not completely clear. One theory is that it is volume related and results from the speed of injection, causing a large rapid bolus that temporarily occludes or compresses an involved vessel.

Another theory is that damage to the vessel results from the injection itself or injection technique, leading to a clotting cascade and clot of the involved vessel with subsequent retrograde flow or blockade of the retinal artery. But if this were the case, we would expect to hear about more cases of clots leading to vascular occlusion or skin necrosis, which does not typically occur or we do not hear about.

Details about proper collection materials and technique or mixing with some other materials are also unknown in these cases, thus leaving the possibility that a more occlusive material may have been injected, as opposed to the fluid-like composition of the typical PRP preparation.With regards to risk with scalp PRP injection, the frontal scalp does receive blood supply from the supratrochlear artery that anastomoses with the angular artery of the face – both of which anastomose with the retinal artery (where occlusion would occur via back flow). The scalp tributaries are small and far enough away from the retina at that point that risk of back flow the to retinal artery should be minimal. Additionally, no reports of vascular occlusion from PRP scalp injection leading to skin necrosis have ever been reported. Of note, this is also not a risk that has been reported with the use of PRP with microneedling procedures, where PRP is placed on top of the skin before, during and after microneedling.

Anything that occludes the blood supply to the eye, whether it be fat, filler, or PRP, has an inherent risk of blindness. As there is no reversal agent or designated treatment for PRP occlusion, care must be taken to minimize risk, including awareness of anatomy and avoidance of injection into high risk areas, and cannula use where appropriate. Gentle, slow, low-volume administration, and when possible, use of a retrograde injection technique, may also be helpful.

Dr. Wesley and Lily Talakoub, MD, are cocontributors to this column. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. This month’s column is by Dr. Wesley. Write to them at [email protected]. They had no relevant disclosures.

A systematic review was recently conducted by Wu and colleagues examining the risk of blindness associated with platelet-rich plasma (PRP) injection. In dermatology, PRP is used more commonly now than 5 years ago to promote hair growth with injections on the scalp, as an adjunct to microneedling procedures, and sometimes – in a similar way to facial fillers – to improve volume loss, and skin tone and texture (particularly to the tear trough region).

Total unilateral blindness occurred in all cases. In one of the seven reported cases, the patient experienced recovery of vision after 3 months, but with some residual deficits noted on the ophthalmologist examination. In this case, the patient was evaluated and treated by an ophthalmologist within 3 hours of symptom onset.

In addition, four cases were reported from Venezuela, one from the United States, one from the United Kingdom, and one from Malaysia. Similar to reports of blindness with facial fillers, the most common injection site reported with this adverse effect was the glabella (five cases);

Other reports involved injections of the forehead (two), followed by the nasolabial fold (one), lateral canthus (one), and temporomandibular joint (one). Two of the seven patients received injections at more than one site, resulting in the total number of injections reported (10) being higher than the number of patients.

The risk of blindness is inherent with deep injection into a vessel that anastomoses with the blood supply to the eye. No mention was made as to whether PRP or platelet-rich fibrin was used. Other details are lacking from the original articles as to injection technique and whether or not cannula injection was used. No treatment was attempted in four of seven cases.

As plasma is native to the arteries and dissolves in the blood stream naturally, the mechanism as to why retinal artery occlusion or blindness would occur is not completely clear. One theory is that it is volume related and results from the speed of injection, causing a large rapid bolus that temporarily occludes or compresses an involved vessel.

Another theory is that damage to the vessel results from the injection itself or injection technique, leading to a clotting cascade and clot of the involved vessel with subsequent retrograde flow or blockade of the retinal artery. But if this were the case, we would expect to hear about more cases of clots leading to vascular occlusion or skin necrosis, which does not typically occur or we do not hear about.

Details about proper collection materials and technique or mixing with some other materials are also unknown in these cases, thus leaving the possibility that a more occlusive material may have been injected, as opposed to the fluid-like composition of the typical PRP preparation.With regards to risk with scalp PRP injection, the frontal scalp does receive blood supply from the supratrochlear artery that anastomoses with the angular artery of the face – both of which anastomose with the retinal artery (where occlusion would occur via back flow). The scalp tributaries are small and far enough away from the retina at that point that risk of back flow the to retinal artery should be minimal. Additionally, no reports of vascular occlusion from PRP scalp injection leading to skin necrosis have ever been reported. Of note, this is also not a risk that has been reported with the use of PRP with microneedling procedures, where PRP is placed on top of the skin before, during and after microneedling.

Anything that occludes the blood supply to the eye, whether it be fat, filler, or PRP, has an inherent risk of blindness. As there is no reversal agent or designated treatment for PRP occlusion, care must be taken to minimize risk, including awareness of anatomy and avoidance of injection into high risk areas, and cannula use where appropriate. Gentle, slow, low-volume administration, and when possible, use of a retrograde injection technique, may also be helpful.

Dr. Wesley and Lily Talakoub, MD, are cocontributors to this column. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. This month’s column is by Dr. Wesley. Write to them at [email protected]. They had no relevant disclosures.

Atypical Localized Scleroderma Development During Nivolumab Therapy for Metastatic Lung Adenocarcinoma

To the Editor:

Immune checkpoint inhibitors such as anti–programmed cell death protein 1 (anti–PD-1) and anticytotoxic T lymphocyte–associated protein 4 therapies are a promising class of cancer therapeutics. However, they are associated with a variety of immune-related adverse events (irAEs), including cutaneous toxicity.1 The PD-1/programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) pathway is important for the maintenance of immune tolerance, and a blockade has been shown to lead to development of various autoimmune diseases.2 We present the case of a patient who developed new-onset localized scleroderma during treatment with the PD-1 inhibitor nivolumab.

A 65-year-old woman presented with a rash on the left thigh that was associated with pruritus, pain, and a pulling sensation. She had a history of stage IV lung adenocarcinoma, with a mass in the right upper lobe with metastatic foci to the left femur, right humerus, right hilar, and pretracheal lymph nodes. She received palliative radiation to the left femur and was started on carboplatin and pemetrexed. Metastasis to the liver was noted after completion of 6 cycles of therapy, and the patient’s treatment was changed to nivolumab. After 17 months on nivolumab therapy (2 years after initial diagnosis and 20 months after radiation therapy), she presented to our dermatology clinic with a cutaneous eruption on the buttocks that spread to the left thigh. The rash failed to improve after 1 month of treatment with emollients and triamcinolone cream 0.1%.

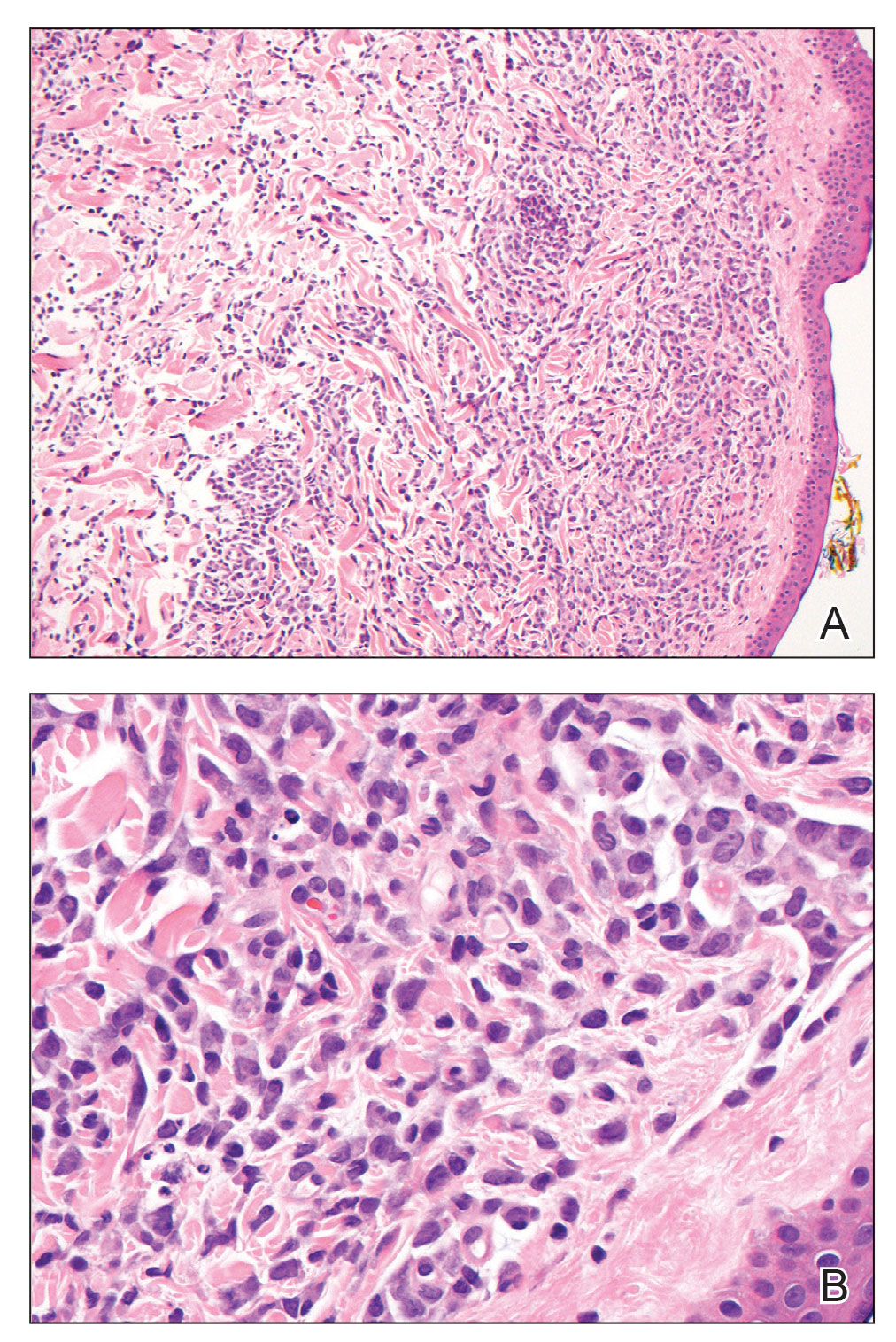

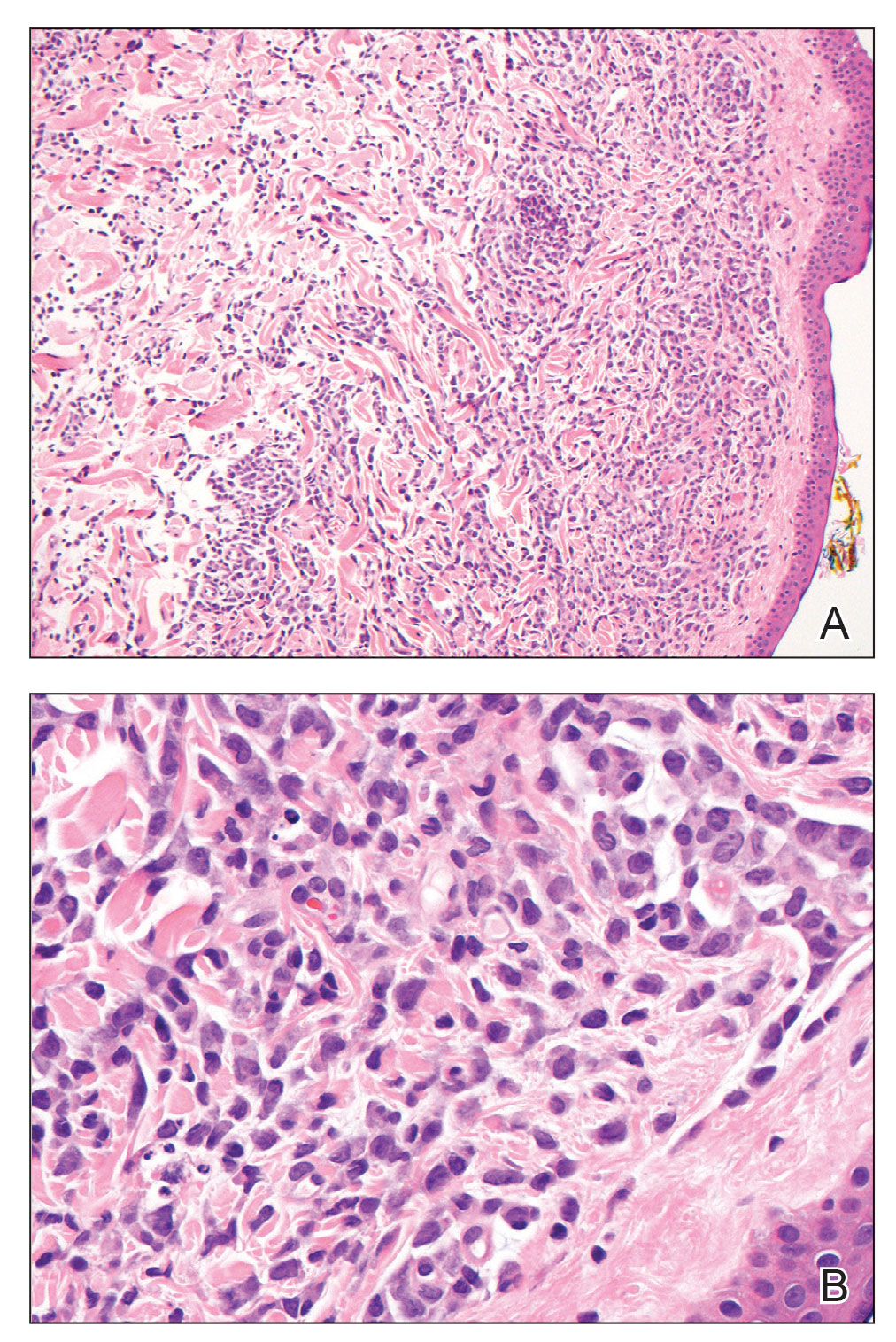

At the current presentation, which was 2 months after she initially presented to our clinic, dermatologic examination revealed erythematous and sclerotic plaques on the left lateral thigh (Figure 1A). Betamethasone cream 0.05% was prescribed, and nivolumab was discontinued due to progression of cutaneous symptoms. A punch biopsy from the left thigh demonstrated superficial dermal sclerosis that was suggestive of chronic radiation dermatitis; direct immunofluorescence testing was negative. The patient was started on prednisone 50 mg daily, which resulted in mild improvement in symptoms.

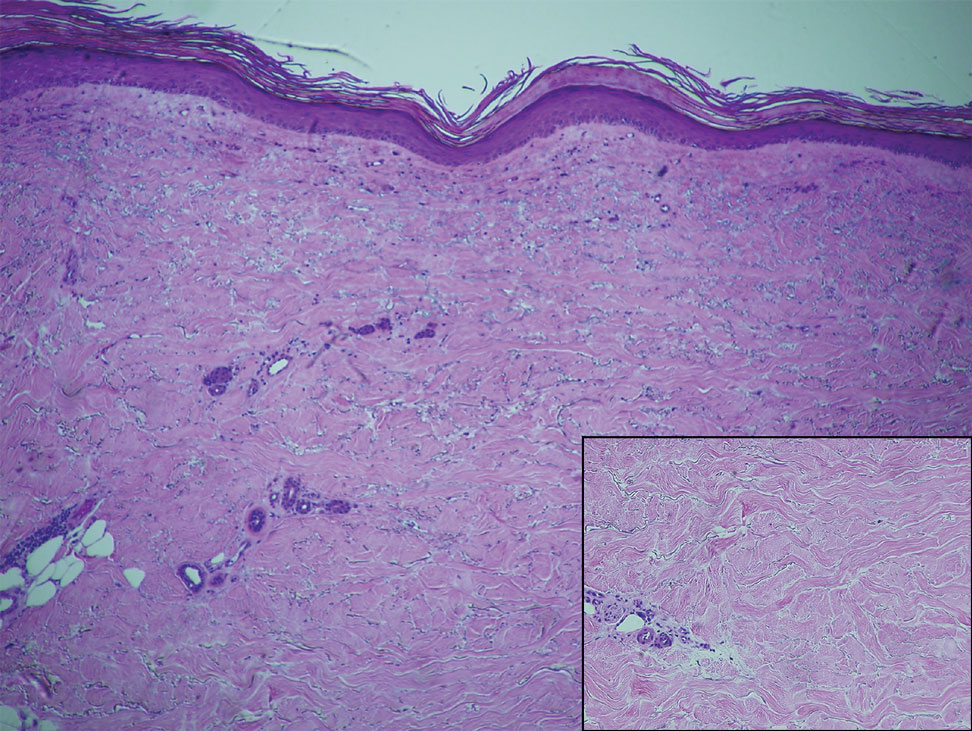

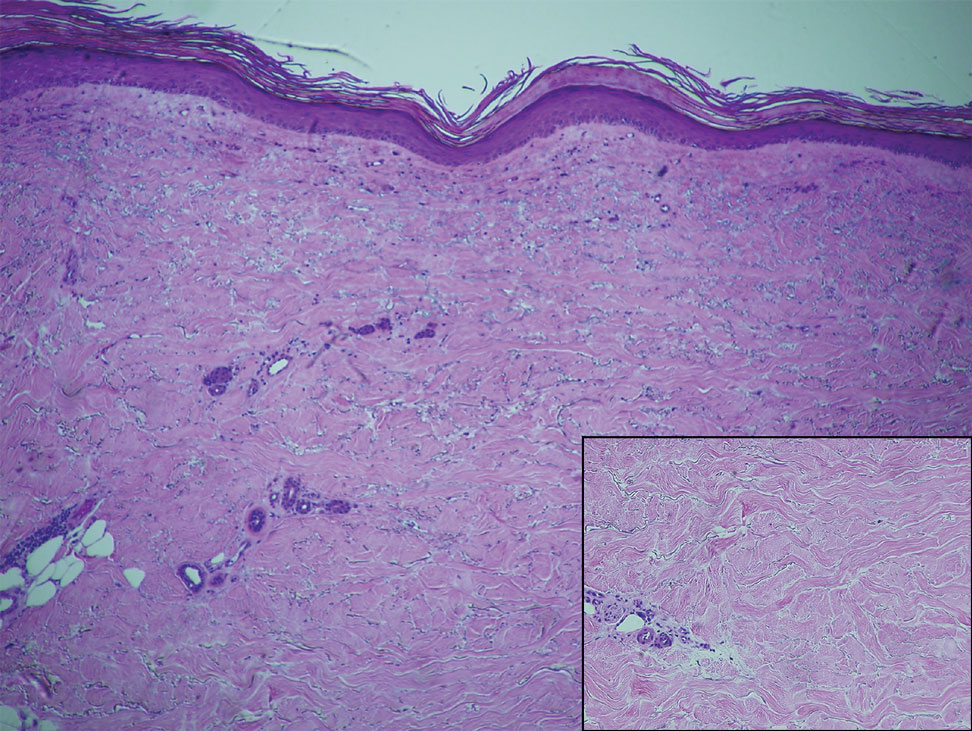

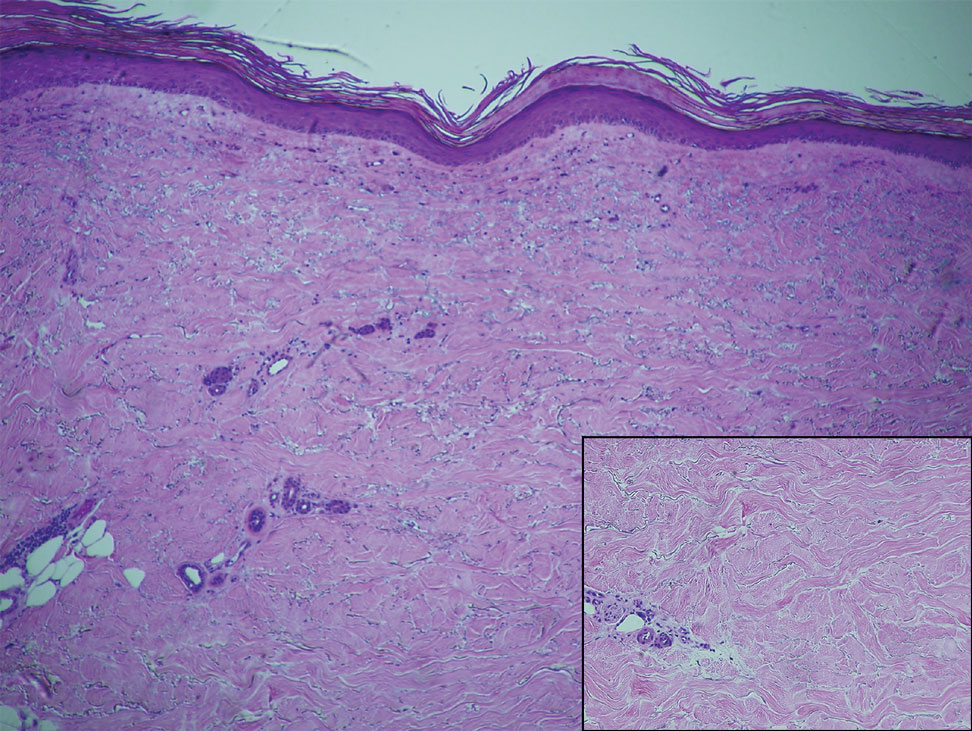

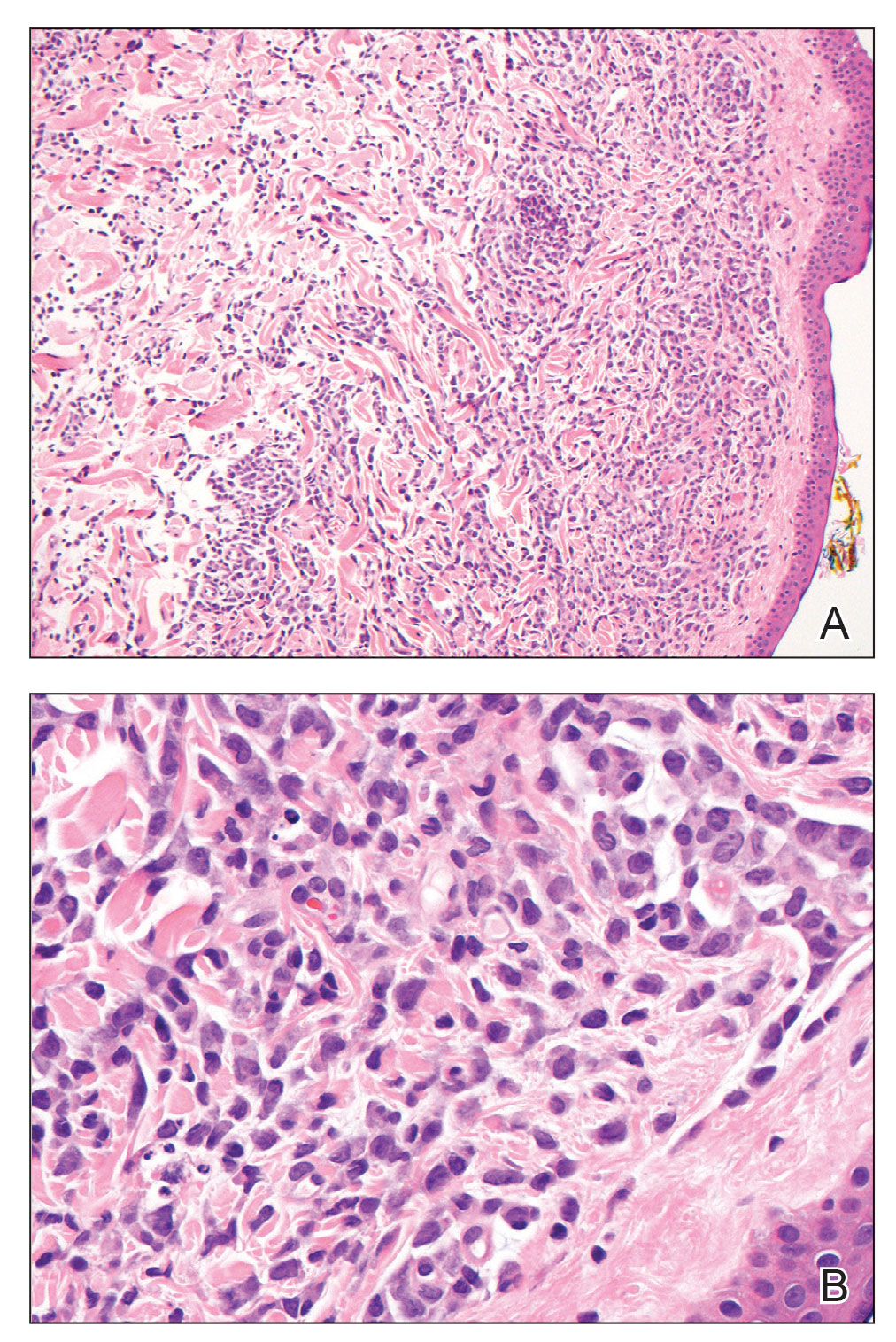

Within 6 months, new sclerotic plaques developed on the patient’s back and right thigh (Figure 1B). Because the lesions were located outside the radiation field of the left femur, a second biopsy was obtained from the right thigh. Histopathology revealed extensive dermal sclerosis and a perivascular lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate (Figure 2). An antinuclear antibody test was weakly positive (1:40, nucleolar pattern) with a negative extractable nuclear antigen panel result. Anti–double-stranded DNA, anti–topoisomerase 1, anti-Smith, antiribonucleoprotein, anti–Sjögren syndrome type A, anti–Sjögren syndrome type B, and anticentromere serology test results were negative. The patient denied decreased oral aperture, difficulty swallowing, or Raynaud phenomenon. Due to the atypical clinical presentation in the setting of PD-1 inhibitor therapy, the etiology of the eruption was potentially attributable to nivolumab. She was started on treatment with methotrexate 20 mg weekly and clobetasol cream 0.05% twice daily; she continued taking prednisone 5 mg daily. The cutaneous manifestations on the patient’s back completely resolved, and the legs continued to gradually improve on this regimen. Immunotherapy continued to be held due to skin toxicity.

Localized scleroderma is an autoimmune disorder characterized by inflammation and skin thickening. Overactive fibroblasts produce excess collagen, leading to the clinical symptoms of skin thickening, hardening, and discoloration.3 Lesions frequently develop on the arms, face, or legs and can present as patches or linear bands. Unlike systemic sclerosis, the internal organs typically are uninvolved; however, sclerotic lesions can be disfiguring and cause notable disability if they impede joint movement.

The PD-1/PD-L1 pathway is a negative regulator of the immune response that inactivates T cells and helps maintain self-tolerance. Modulation of the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway and overexpression of PD-L1 are seen in various cancers as a mechanism to help malignant cells avoid immune destruction.4 Conversely, inhibition of this pathway can be used to stimulate an antitumor immune response. This checkpoint inhibition strategy has been highly successful for the treatment of various cancers including melanoma and non–small cell lung carcinoma. There are several checkpoint inhibitors approved in the United States that are used for cancer therapy and target the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway, such as nivolumab, pembrolizumab, atezolizumab, durvalumab, and avelumab.4 A downside of checkpoint inhibitor treatment is that uncontrolled T-cell activation can lead to irAEs, including cutaneous eruptions, pruritus, diarrhea, colitis, hepatitis, endocrinopathies, pneumonitis, and renal insufficiency.5 These toxicities are reversible if treated appropriately but can cause notable morbidity and mortality if left unrecognized. Cutaneous eruption is one of the most common irAEs associated with anti–PD-1 and anti–PD-L1 therapies and can limit therapeutic efficacy, as the drug may need to be held or discontinued due to the severity of the eruption.6 Mid-potency to high-potency topical corticosteroids and systemic antihistamines are first-line treatments of grades 1 and 2 skin toxicities associated with PD-1 inhibitor therapy. For eruptions classified as grades 3 or 4 or refractory grade 2, discontinuation of the drug and systemic corticosteroids is recommended.7

The cutaneous eruption in immunotherapy-mediated dermatitis is thought to be largely mediated by activated T cells infiltrating the dermis.8 In localized scleroderma, increased tumor necrosis factor α, IFN-γ, IFN-γ–induced protein 10, and granulocyte macrophage colony stimulating factor activity have been shown to correlate with disease activity.9,10 Interestingly, increased tumor necrosis factor α and IFN-γ correlate with better response and increased overall survival in PD-1 inhibition therapy, suggesting a correlation between PD-1 inhibition and T helper activation as noted by the etiology of sclerosis in our patient.11 Additionally, history of radiation was a confounding factor in the diagnosis of our patient, as both sclerodermoid reactions and chronic radiation dermatitis can present with dermal sclerosis. However, the progression of disease outside of the radiation field excluded this etiology. Although new-onset sclerodermoid reactions have been reported with PD-1 inhibitors, they have been described secondary to sclerodermoid reactions from treatment with pembrolizumab.12,13 One case series reported a case of diffuse sclerodermoid reaction and a limited reaction in response to pembrolizumab treatment, while another case report described a relapse of generalized morphea in response to pembrolizumab treatment.12,13 One case of relapsing morphea in response to nivolumab treatment for stage IV lung adenocarcinoma also has been reported.14

Cutaneous toxicities are one of the most common irAEs associated with checkpoint inhibitors and are seen in more than one-third of treated patients. Most frequently, these irAEs manifest as spongiotic dermatitis on histopathology, but a broad spectrum of cutaneous reactions have been observed.15 Although sclerodermoid reactions have been reported with PD-1 inhibitors, most are described secondary to sclerodermoid reactions with pembrolizumab and involve relapse of previously diagnosed morphea rather than new-onset disease.12-14

Our case highlights new-onset localized scleroderma in the setting of nivolumab therapy that showed clinical improvement with methotrexate and topical and systemic steroids. This reaction pattern should be considered in all patients who develop cutaneous eruptions when treated with a PD-1 inhibitor. There should be a high index of suspicion for the potential occurrence of irAEs to ensure early recognition and treatment to minimize morbidity and maximize adherence to therapy for the underlying malignancy.

- Baxi S, Yang A, Gennarelli RL, et al. Immune-related adverse events for anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 drugs: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2018;360:k793.

- Dai S, Jia R, Zhang X, et al. The PD-1/PD-Ls pathway and autoimmune diseases. Cell Immunol. 2014;290:72-79.

- Badea I, Taylor M, Rosenberg A, et al. Pathogenesis and therapeutic approaches for improved topical treatment in localized scleroderma and systemic sclerosis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2009;48:213-221.

- Constantinidou A, Alifieris C, Trafalis DT. Targeting programmed cell death-1 (PD-1) and ligand (PD-L1): a new era in cancer active immunotherapy. Pharmacol Ther. 2019;194:84-106.

- Villadolid J, Asim A. Immune checkpoint inhibitors in clinical practice: update on management of immune-related toxicities. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2015;4:560-575.

- Naidoo J, Page DB, Li BT, et al. Toxicities of the anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 immune checkpoint antibodies. Ann Oncol. 2016;27:1362.

- O’Kane GM, Labbé C, Doherty MK, et al. Monitoring and management of immune-related adverse events associated with programmed cell death protein-1 axis inhibitors in lung cancer. Oncologist. 2017;22:70-80.

- Shi VJ, Rodic N, Gettinger S, et al. Clinical and histologic features of lichenoid mucocutaneous eruptions due to anti-programmed celldeath 1 and anti-programmed cell death ligand 1 immunotherapy. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:1128-1136.

- Torok KS, Kurzinski K, Kelsey C, et al. Peripheral blood cytokine and chemokine profiles in juvenile localized scleroderma: T-helper cell-associated cytokine profiles. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2015;45:284-293.

- Guo X, Higgs BW, Bay-Jensen AC, et al. Suppression of T cell activation and collagen accumulation by an anti-IFNAR1 mAb, anifrolumab, in adult patients with systemic sclerosis. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135:2402-2409.

- Boutsikou E, Domvri K, Hardavella G, et al. Tumor necrosis factor, interferon-gamma and interleukins as predictive markers of antiprogrammed cell-death protein-1 treatment in advanced non-small cell lung cancer: a pragmatic approach in clinical practice. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2018;10:1758835918768238.

- Barbosa NS, Wetter DA, Wieland CN, et al. Scleroderma induced by pembrolizumab: a case series. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92:1158-1163.

- Cheng MW, Hisaw LD, Bernet L. Generalized morphea in the setting of pembrolizumab. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:736-738.

- Alegre-Sánchez A, Fonda-Pascual P, Saceda-Corralo D, et al. Relapse of morphea during nivolumab therapy for lung adenocarcinoma. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2017;108:69-70.

- Sibaud V. Dermatologic reactions to immune checkpoint inhibitors: skin toxicities and immunotherapy. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2018;19:345-361.

To the Editor:

Immune checkpoint inhibitors such as anti–programmed cell death protein 1 (anti–PD-1) and anticytotoxic T lymphocyte–associated protein 4 therapies are a promising class of cancer therapeutics. However, they are associated with a variety of immune-related adverse events (irAEs), including cutaneous toxicity.1 The PD-1/programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) pathway is important for the maintenance of immune tolerance, and a blockade has been shown to lead to development of various autoimmune diseases.2 We present the case of a patient who developed new-onset localized scleroderma during treatment with the PD-1 inhibitor nivolumab.

A 65-year-old woman presented with a rash on the left thigh that was associated with pruritus, pain, and a pulling sensation. She had a history of stage IV lung adenocarcinoma, with a mass in the right upper lobe with metastatic foci to the left femur, right humerus, right hilar, and pretracheal lymph nodes. She received palliative radiation to the left femur and was started on carboplatin and pemetrexed. Metastasis to the liver was noted after completion of 6 cycles of therapy, and the patient’s treatment was changed to nivolumab. After 17 months on nivolumab therapy (2 years after initial diagnosis and 20 months after radiation therapy), she presented to our dermatology clinic with a cutaneous eruption on the buttocks that spread to the left thigh. The rash failed to improve after 1 month of treatment with emollients and triamcinolone cream 0.1%.

At the current presentation, which was 2 months after she initially presented to our clinic, dermatologic examination revealed erythematous and sclerotic plaques on the left lateral thigh (Figure 1A). Betamethasone cream 0.05% was prescribed, and nivolumab was discontinued due to progression of cutaneous symptoms. A punch biopsy from the left thigh demonstrated superficial dermal sclerosis that was suggestive of chronic radiation dermatitis; direct immunofluorescence testing was negative. The patient was started on prednisone 50 mg daily, which resulted in mild improvement in symptoms.

Within 6 months, new sclerotic plaques developed on the patient’s back and right thigh (Figure 1B). Because the lesions were located outside the radiation field of the left femur, a second biopsy was obtained from the right thigh. Histopathology revealed extensive dermal sclerosis and a perivascular lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate (Figure 2). An antinuclear antibody test was weakly positive (1:40, nucleolar pattern) with a negative extractable nuclear antigen panel result. Anti–double-stranded DNA, anti–topoisomerase 1, anti-Smith, antiribonucleoprotein, anti–Sjögren syndrome type A, anti–Sjögren syndrome type B, and anticentromere serology test results were negative. The patient denied decreased oral aperture, difficulty swallowing, or Raynaud phenomenon. Due to the atypical clinical presentation in the setting of PD-1 inhibitor therapy, the etiology of the eruption was potentially attributable to nivolumab. She was started on treatment with methotrexate 20 mg weekly and clobetasol cream 0.05% twice daily; she continued taking prednisone 5 mg daily. The cutaneous manifestations on the patient’s back completely resolved, and the legs continued to gradually improve on this regimen. Immunotherapy continued to be held due to skin toxicity.

Localized scleroderma is an autoimmune disorder characterized by inflammation and skin thickening. Overactive fibroblasts produce excess collagen, leading to the clinical symptoms of skin thickening, hardening, and discoloration.3 Lesions frequently develop on the arms, face, or legs and can present as patches or linear bands. Unlike systemic sclerosis, the internal organs typically are uninvolved; however, sclerotic lesions can be disfiguring and cause notable disability if they impede joint movement.

The PD-1/PD-L1 pathway is a negative regulator of the immune response that inactivates T cells and helps maintain self-tolerance. Modulation of the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway and overexpression of PD-L1 are seen in various cancers as a mechanism to help malignant cells avoid immune destruction.4 Conversely, inhibition of this pathway can be used to stimulate an antitumor immune response. This checkpoint inhibition strategy has been highly successful for the treatment of various cancers including melanoma and non–small cell lung carcinoma. There are several checkpoint inhibitors approved in the United States that are used for cancer therapy and target the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway, such as nivolumab, pembrolizumab, atezolizumab, durvalumab, and avelumab.4 A downside of checkpoint inhibitor treatment is that uncontrolled T-cell activation can lead to irAEs, including cutaneous eruptions, pruritus, diarrhea, colitis, hepatitis, endocrinopathies, pneumonitis, and renal insufficiency.5 These toxicities are reversible if treated appropriately but can cause notable morbidity and mortality if left unrecognized. Cutaneous eruption is one of the most common irAEs associated with anti–PD-1 and anti–PD-L1 therapies and can limit therapeutic efficacy, as the drug may need to be held or discontinued due to the severity of the eruption.6 Mid-potency to high-potency topical corticosteroids and systemic antihistamines are first-line treatments of grades 1 and 2 skin toxicities associated with PD-1 inhibitor therapy. For eruptions classified as grades 3 or 4 or refractory grade 2, discontinuation of the drug and systemic corticosteroids is recommended.7

The cutaneous eruption in immunotherapy-mediated dermatitis is thought to be largely mediated by activated T cells infiltrating the dermis.8 In localized scleroderma, increased tumor necrosis factor α, IFN-γ, IFN-γ–induced protein 10, and granulocyte macrophage colony stimulating factor activity have been shown to correlate with disease activity.9,10 Interestingly, increased tumor necrosis factor α and IFN-γ correlate with better response and increased overall survival in PD-1 inhibition therapy, suggesting a correlation between PD-1 inhibition and T helper activation as noted by the etiology of sclerosis in our patient.11 Additionally, history of radiation was a confounding factor in the diagnosis of our patient, as both sclerodermoid reactions and chronic radiation dermatitis can present with dermal sclerosis. However, the progression of disease outside of the radiation field excluded this etiology. Although new-onset sclerodermoid reactions have been reported with PD-1 inhibitors, they have been described secondary to sclerodermoid reactions from treatment with pembrolizumab.12,13 One case series reported a case of diffuse sclerodermoid reaction and a limited reaction in response to pembrolizumab treatment, while another case report described a relapse of generalized morphea in response to pembrolizumab treatment.12,13 One case of relapsing morphea in response to nivolumab treatment for stage IV lung adenocarcinoma also has been reported.14

Cutaneous toxicities are one of the most common irAEs associated with checkpoint inhibitors and are seen in more than one-third of treated patients. Most frequently, these irAEs manifest as spongiotic dermatitis on histopathology, but a broad spectrum of cutaneous reactions have been observed.15 Although sclerodermoid reactions have been reported with PD-1 inhibitors, most are described secondary to sclerodermoid reactions with pembrolizumab and involve relapse of previously diagnosed morphea rather than new-onset disease.12-14

Our case highlights new-onset localized scleroderma in the setting of nivolumab therapy that showed clinical improvement with methotrexate and topical and systemic steroids. This reaction pattern should be considered in all patients who develop cutaneous eruptions when treated with a PD-1 inhibitor. There should be a high index of suspicion for the potential occurrence of irAEs to ensure early recognition and treatment to minimize morbidity and maximize adherence to therapy for the underlying malignancy.

To the Editor:

Immune checkpoint inhibitors such as anti–programmed cell death protein 1 (anti–PD-1) and anticytotoxic T lymphocyte–associated protein 4 therapies are a promising class of cancer therapeutics. However, they are associated with a variety of immune-related adverse events (irAEs), including cutaneous toxicity.1 The PD-1/programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) pathway is important for the maintenance of immune tolerance, and a blockade has been shown to lead to development of various autoimmune diseases.2 We present the case of a patient who developed new-onset localized scleroderma during treatment with the PD-1 inhibitor nivolumab.

A 65-year-old woman presented with a rash on the left thigh that was associated with pruritus, pain, and a pulling sensation. She had a history of stage IV lung adenocarcinoma, with a mass in the right upper lobe with metastatic foci to the left femur, right humerus, right hilar, and pretracheal lymph nodes. She received palliative radiation to the left femur and was started on carboplatin and pemetrexed. Metastasis to the liver was noted after completion of 6 cycles of therapy, and the patient’s treatment was changed to nivolumab. After 17 months on nivolumab therapy (2 years after initial diagnosis and 20 months after radiation therapy), she presented to our dermatology clinic with a cutaneous eruption on the buttocks that spread to the left thigh. The rash failed to improve after 1 month of treatment with emollients and triamcinolone cream 0.1%.

At the current presentation, which was 2 months after she initially presented to our clinic, dermatologic examination revealed erythematous and sclerotic plaques on the left lateral thigh (Figure 1A). Betamethasone cream 0.05% was prescribed, and nivolumab was discontinued due to progression of cutaneous symptoms. A punch biopsy from the left thigh demonstrated superficial dermal sclerosis that was suggestive of chronic radiation dermatitis; direct immunofluorescence testing was negative. The patient was started on prednisone 50 mg daily, which resulted in mild improvement in symptoms.

Within 6 months, new sclerotic plaques developed on the patient’s back and right thigh (Figure 1B). Because the lesions were located outside the radiation field of the left femur, a second biopsy was obtained from the right thigh. Histopathology revealed extensive dermal sclerosis and a perivascular lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate (Figure 2). An antinuclear antibody test was weakly positive (1:40, nucleolar pattern) with a negative extractable nuclear antigen panel result. Anti–double-stranded DNA, anti–topoisomerase 1, anti-Smith, antiribonucleoprotein, anti–Sjögren syndrome type A, anti–Sjögren syndrome type B, and anticentromere serology test results were negative. The patient denied decreased oral aperture, difficulty swallowing, or Raynaud phenomenon. Due to the atypical clinical presentation in the setting of PD-1 inhibitor therapy, the etiology of the eruption was potentially attributable to nivolumab. She was started on treatment with methotrexate 20 mg weekly and clobetasol cream 0.05% twice daily; she continued taking prednisone 5 mg daily. The cutaneous manifestations on the patient’s back completely resolved, and the legs continued to gradually improve on this regimen. Immunotherapy continued to be held due to skin toxicity.

Localized scleroderma is an autoimmune disorder characterized by inflammation and skin thickening. Overactive fibroblasts produce excess collagen, leading to the clinical symptoms of skin thickening, hardening, and discoloration.3 Lesions frequently develop on the arms, face, or legs and can present as patches or linear bands. Unlike systemic sclerosis, the internal organs typically are uninvolved; however, sclerotic lesions can be disfiguring and cause notable disability if they impede joint movement.

The PD-1/PD-L1 pathway is a negative regulator of the immune response that inactivates T cells and helps maintain self-tolerance. Modulation of the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway and overexpression of PD-L1 are seen in various cancers as a mechanism to help malignant cells avoid immune destruction.4 Conversely, inhibition of this pathway can be used to stimulate an antitumor immune response. This checkpoint inhibition strategy has been highly successful for the treatment of various cancers including melanoma and non–small cell lung carcinoma. There are several checkpoint inhibitors approved in the United States that are used for cancer therapy and target the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway, such as nivolumab, pembrolizumab, atezolizumab, durvalumab, and avelumab.4 A downside of checkpoint inhibitor treatment is that uncontrolled T-cell activation can lead to irAEs, including cutaneous eruptions, pruritus, diarrhea, colitis, hepatitis, endocrinopathies, pneumonitis, and renal insufficiency.5 These toxicities are reversible if treated appropriately but can cause notable morbidity and mortality if left unrecognized. Cutaneous eruption is one of the most common irAEs associated with anti–PD-1 and anti–PD-L1 therapies and can limit therapeutic efficacy, as the drug may need to be held or discontinued due to the severity of the eruption.6 Mid-potency to high-potency topical corticosteroids and systemic antihistamines are first-line treatments of grades 1 and 2 skin toxicities associated with PD-1 inhibitor therapy. For eruptions classified as grades 3 or 4 or refractory grade 2, discontinuation of the drug and systemic corticosteroids is recommended.7

The cutaneous eruption in immunotherapy-mediated dermatitis is thought to be largely mediated by activated T cells infiltrating the dermis.8 In localized scleroderma, increased tumor necrosis factor α, IFN-γ, IFN-γ–induced protein 10, and granulocyte macrophage colony stimulating factor activity have been shown to correlate with disease activity.9,10 Interestingly, increased tumor necrosis factor α and IFN-γ correlate with better response and increased overall survival in PD-1 inhibition therapy, suggesting a correlation between PD-1 inhibition and T helper activation as noted by the etiology of sclerosis in our patient.11 Additionally, history of radiation was a confounding factor in the diagnosis of our patient, as both sclerodermoid reactions and chronic radiation dermatitis can present with dermal sclerosis. However, the progression of disease outside of the radiation field excluded this etiology. Although new-onset sclerodermoid reactions have been reported with PD-1 inhibitors, they have been described secondary to sclerodermoid reactions from treatment with pembrolizumab.12,13 One case series reported a case of diffuse sclerodermoid reaction and a limited reaction in response to pembrolizumab treatment, while another case report described a relapse of generalized morphea in response to pembrolizumab treatment.12,13 One case of relapsing morphea in response to nivolumab treatment for stage IV lung adenocarcinoma also has been reported.14

Cutaneous toxicities are one of the most common irAEs associated with checkpoint inhibitors and are seen in more than one-third of treated patients. Most frequently, these irAEs manifest as spongiotic dermatitis on histopathology, but a broad spectrum of cutaneous reactions have been observed.15 Although sclerodermoid reactions have been reported with PD-1 inhibitors, most are described secondary to sclerodermoid reactions with pembrolizumab and involve relapse of previously diagnosed morphea rather than new-onset disease.12-14

Our case highlights new-onset localized scleroderma in the setting of nivolumab therapy that showed clinical improvement with methotrexate and topical and systemic steroids. This reaction pattern should be considered in all patients who develop cutaneous eruptions when treated with a PD-1 inhibitor. There should be a high index of suspicion for the potential occurrence of irAEs to ensure early recognition and treatment to minimize morbidity and maximize adherence to therapy for the underlying malignancy.

- Baxi S, Yang A, Gennarelli RL, et al. Immune-related adverse events for anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 drugs: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2018;360:k793.

- Dai S, Jia R, Zhang X, et al. The PD-1/PD-Ls pathway and autoimmune diseases. Cell Immunol. 2014;290:72-79.

- Badea I, Taylor M, Rosenberg A, et al. Pathogenesis and therapeutic approaches for improved topical treatment in localized scleroderma and systemic sclerosis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2009;48:213-221.

- Constantinidou A, Alifieris C, Trafalis DT. Targeting programmed cell death-1 (PD-1) and ligand (PD-L1): a new era in cancer active immunotherapy. Pharmacol Ther. 2019;194:84-106.

- Villadolid J, Asim A. Immune checkpoint inhibitors in clinical practice: update on management of immune-related toxicities. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2015;4:560-575.

- Naidoo J, Page DB, Li BT, et al. Toxicities of the anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 immune checkpoint antibodies. Ann Oncol. 2016;27:1362.

- O’Kane GM, Labbé C, Doherty MK, et al. Monitoring and management of immune-related adverse events associated with programmed cell death protein-1 axis inhibitors in lung cancer. Oncologist. 2017;22:70-80.

- Shi VJ, Rodic N, Gettinger S, et al. Clinical and histologic features of lichenoid mucocutaneous eruptions due to anti-programmed celldeath 1 and anti-programmed cell death ligand 1 immunotherapy. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:1128-1136.

- Torok KS, Kurzinski K, Kelsey C, et al. Peripheral blood cytokine and chemokine profiles in juvenile localized scleroderma: T-helper cell-associated cytokine profiles. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2015;45:284-293.

- Guo X, Higgs BW, Bay-Jensen AC, et al. Suppression of T cell activation and collagen accumulation by an anti-IFNAR1 mAb, anifrolumab, in adult patients with systemic sclerosis. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135:2402-2409.

- Boutsikou E, Domvri K, Hardavella G, et al. Tumor necrosis factor, interferon-gamma and interleukins as predictive markers of antiprogrammed cell-death protein-1 treatment in advanced non-small cell lung cancer: a pragmatic approach in clinical practice. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2018;10:1758835918768238.

- Barbosa NS, Wetter DA, Wieland CN, et al. Scleroderma induced by pembrolizumab: a case series. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92:1158-1163.

- Cheng MW, Hisaw LD, Bernet L. Generalized morphea in the setting of pembrolizumab. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:736-738.

- Alegre-Sánchez A, Fonda-Pascual P, Saceda-Corralo D, et al. Relapse of morphea during nivolumab therapy for lung adenocarcinoma. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2017;108:69-70.

- Sibaud V. Dermatologic reactions to immune checkpoint inhibitors: skin toxicities and immunotherapy. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2018;19:345-361.

- Baxi S, Yang A, Gennarelli RL, et al. Immune-related adverse events for anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 drugs: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2018;360:k793.

- Dai S, Jia R, Zhang X, et al. The PD-1/PD-Ls pathway and autoimmune diseases. Cell Immunol. 2014;290:72-79.

- Badea I, Taylor M, Rosenberg A, et al. Pathogenesis and therapeutic approaches for improved topical treatment in localized scleroderma and systemic sclerosis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2009;48:213-221.

- Constantinidou A, Alifieris C, Trafalis DT. Targeting programmed cell death-1 (PD-1) and ligand (PD-L1): a new era in cancer active immunotherapy. Pharmacol Ther. 2019;194:84-106.

- Villadolid J, Asim A. Immune checkpoint inhibitors in clinical practice: update on management of immune-related toxicities. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2015;4:560-575.

- Naidoo J, Page DB, Li BT, et al. Toxicities of the anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 immune checkpoint antibodies. Ann Oncol. 2016;27:1362.

- O’Kane GM, Labbé C, Doherty MK, et al. Monitoring and management of immune-related adverse events associated with programmed cell death protein-1 axis inhibitors in lung cancer. Oncologist. 2017;22:70-80.

- Shi VJ, Rodic N, Gettinger S, et al. Clinical and histologic features of lichenoid mucocutaneous eruptions due to anti-programmed celldeath 1 and anti-programmed cell death ligand 1 immunotherapy. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:1128-1136.

- Torok KS, Kurzinski K, Kelsey C, et al. Peripheral blood cytokine and chemokine profiles in juvenile localized scleroderma: T-helper cell-associated cytokine profiles. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2015;45:284-293.

- Guo X, Higgs BW, Bay-Jensen AC, et al. Suppression of T cell activation and collagen accumulation by an anti-IFNAR1 mAb, anifrolumab, in adult patients with systemic sclerosis. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135:2402-2409.

- Boutsikou E, Domvri K, Hardavella G, et al. Tumor necrosis factor, interferon-gamma and interleukins as predictive markers of antiprogrammed cell-death protein-1 treatment in advanced non-small cell lung cancer: a pragmatic approach in clinical practice. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2018;10:1758835918768238.

- Barbosa NS, Wetter DA, Wieland CN, et al. Scleroderma induced by pembrolizumab: a case series. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92:1158-1163.

- Cheng MW, Hisaw LD, Bernet L. Generalized morphea in the setting of pembrolizumab. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:736-738.

- Alegre-Sánchez A, Fonda-Pascual P, Saceda-Corralo D, et al. Relapse of morphea during nivolumab therapy for lung adenocarcinoma. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2017;108:69-70.

- Sibaud V. Dermatologic reactions to immune checkpoint inhibitors: skin toxicities and immunotherapy. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2018;19:345-361.

Practice Points

- Immune checkpoint inhibitors such as nivolumab, a programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) inhibitor, are associated with immune-related adverse events (irAEs) such as skin toxicity.

- Scleroderma should be considered in the differential diagnosis of patients who develop cutaneous eruptions during treatment with PD-1 inhibitors.

- To ensure prompt recognition and treatment, health care providers should maintain a high index of suspicion for development of cutaneous irAEs in patients using checkpoint inhibitors.

Transitioning From an Intern to a Dermatology Resident

The transition from medical school to residency is a rewarding milestone but involves a steep learning curve wrought with new responsibilities, new colleagues, and a new schedule, often all within a new setting. This transition period has been a longstanding focus of graduate medical education research, and a recent study identified 6 key areas that residency programs need to address to better facilitate this transition: (1) a sense of community within the residency program, (2) relocation resources, (3) residency preparation courses in medical school, (4) readiness to address racism and bias, (5) connecting with peers, and (6) open communication with program leadership.1 There is considerable interest in ensuring that this transition is smooth for all graduates, as nearly all US medical schools feature some variety of a residency preparation course during the fourth year of medical school, which, alongside the subinternships, serves to better prepare their graduates for the healthcare workforce.2

What about the transition from intern to dermatology resident? Near the end of intern year, my categorical medicine colleagues experienced a crescendo of responsibilities, all in preparation for junior year. The senior medicine residents, themselves having previously experienced the graduated responsibilities, knew to ease their grip on the reins and provide the late spring interns an opportunity to lead rounds or run a code. This was not the case for the preliminary interns for whom there was no preview available for what was to come; little guidance exists on how to best transform from a preliminary or transitional postgraduate year (PGY) 1 to a dermatology PGY-2. A survey of 44 dermatology residents and 33 dermatology program directors found electives such as rheumatology, infectious diseases, and allergy and immunology to be helpful for this transition, and residents most often cited friendly and supportive senior and fellow residents as the factor that eased their transition to PGY-2.3 Notably, less than half of the residents (40%) surveyed stated that team-building exercises and dedicated time to meet colleagues were helpful for this transition. They identified studying principles of dermatologic disease, learning new clinical duties, and adjusting to new coworkers and supervisors as the greatest work-related stressors during entry to PGY-2.3

My transition from intern year to dermatology was shrouded in uncertainty, and I was fortunate to have supportive seniors and co-residents to ease the process. There is much about starting dermatology residency that cannot be prepared for by reading a book, and a natural metamorphosis into the new role is hard to articulate. Still, the following are pieces of information I wish I knew as a graduating intern, which I hope will prove useful for those graduating to their PGY-2 dermatology year.

The Pace of Outpatient Dermatology

If the preliminary or transitional year did not have an ambulatory component, the switch from wards to clinic can be jarring. An outpatient encounter can be as short as 10 to 15 minutes, necessitating an efficient interview and examination to avoid a backup of patients. Unlike a hospital admission where the history of present illness can expound on multiple concerns and organ systems, the general dermatology visit must focus on the chief concern, with priority given to the clinical examination of the skin. For total-body skin examinations, a formulaic approach to assessing all areas of the body, with fluent transitions and minimal repositioning of the patient, is critical for patient comfort and to save time. Of course, accuracy and thoroughness are paramount, but the constant mindfulness of time and efficiency is uniquely emphasized in the outpatient setting.

Continuity of Care

On the wards, patients are admitted with an acute problem and discharged with the aim to prevent re-admission. However, in the dermatology clinic, the conditions encountered often are chronic, requiring repeated follow-ups that involve dosage tapers, laboratory monitoring, and trial and error. Unlike the rigid algorithm-based treatments utilized in the inpatient setting, the management of the same chronic disease can vary, as it is tailored to the patient based on their comorbidities and response. This longitudinal relationship with patients, whereby many disorders are managed rather than treated, stands in stark contrast to inpatient medicine, and learning to value symptom management rather than focusing on a cure is critical in a largely outpatient specialty such as dermatology.

Consulter to Consultant

Calling a consultation as an intern is challenging and requires succinct delivery of pertinent information while fearing pushback from the consultant. In a survey of 50 hospitalist attendings, only 11% responded that interns could be entrusted to call an effective consultation without supervision.4 When undertaking the role of a consultant, the goals should be to identify the team’s main question and to obtain key information necessary to formulate a differential diagnosis. The quality of the consultation will inevitably fluctuate; try to remember what it was like for you as a member of the primary team and remain patient and courteous during the exchange.5 In 1983, Goldman et al6 published a guideline on effective consultations that often is cited to this day, dubbed the “Ten Commandments for Effective Consultations,” which consists of the following: (1) determine the question that is being asked, (2) establish the urgency of the consultation, (3) gather primary data, (4) communicate as briefly as appropriate, (5) make specific recommendations, (6) provide contingency plans, (7) understand your own role in the process, (8) offer educational information, (9) communicate recommendations directly to the requesting physician, and (10) provide appropriate follow-up.

Consider Your Future

Frequently reflect on what you most enjoy about your job. Although it can be easy to passively engage with intern year as a mere stepping-stone to dermatology residency, the years in PGY-2 and onward require active introspection to find a future niche. What made you gravitate to the specialty of dermatology? Try to identify your predilections for dermatopathology, pediatric dermatology, dermatologic surgery, cosmetic dermatology, and academia. Be consistently cognizant of your life after residency, as some fellowships such as dermatopathology require applications to be submitted at the conclusion of the PGY-2 year. Seek out faculty mentors or alumni who are walking a path similar to the one you want to embark on, as the next stop after graduation may be your forever job.

Depth, Not Breadth

The practice of medicine changes when narrowing the focus to one organ system. In both medical school and intern year, my study habits and history-taking of patients cast a wide net across multiple organ systems, aiming to know just enough about any one specialty to address all chief concerns and to know when it was appropriate to consult a specialist. This paradigm inevitably shifts in dermatology residency, as residents are tasked with memorizing the endless number of diagnoses of the skin alone, comprehending the many shades of “erythematous,” including pink, salmon, red, and purple. Both on the wards and in clinics, I had to grow comfortable with telling patients that I did not have an answer for many of their nondermatologic concerns and directing them to the right specialist. As medicine continues trending to specialization, subspecialization, and sub-subspecialization, the scope of any given physician likely will continue to narrow,7 as evidenced by specialty clinics within dermatology such as those focusing on hair loss or immunobullous disease. In this health care system, it is imperative to remember that you are only one physician within a team of care providers—understand your own role in the process and become comfortable with not having the answer to all the questions.

Final Thoughts

In a study of 44 dermatology residents, 35 (83%) indicated zero to less than 1 hour per week of independent preparation for dermatology residency during PGY-1.3 Although the usefulness of preparing is debatable, this figure likely reflects the absence of any insight on how to best prepare for the transition. Recognizing the many contrasts between internal medicine and dermatology and embracing the changes will enable a seamless promotion from a medicine PGY-1 to a dermatology PGY-2.

- Staples H, Frank S, Mullen M, et al. Improving the medical school to residency transition: narrative experiences from first-year residents.J Surg Educ. 2022;S1931-7204(22)00146-5. doi:10.1016/j.jsurg.2022.06.001

- Heidemann LA, Walford E, Mack J, et al. Is there a role for internal medicine residency preparation courses in the fourth year curriculum? a single-center experience. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33:2048-2050.

- Hopkins C, Jalali O, Guffey D, et al. A survey of dermatology residents and program directors assessing the transition to dermatology residency. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2020;34:59-62.

- Marcus CH, Winn AS, Sectish TC, et al. How much supervision is required is the beginning of intern year? Acad Pediatr. 2016;16:E3-E4.

- Bly RA, Bly EG. Consult courtesy. J Grad Med Educ. 2013;5:533-534.

- Goldman L, Lee T, Rudd P. Ten commandments for effective consultations. Arch Intern Med. 1983;143:1753-1755.

- Oren O, Gersh BJ, Bhatt DL. On the pearls and perils of sub-subspecialization. Am J Med. 2020;133:158-159.

The transition from medical school to residency is a rewarding milestone but involves a steep learning curve wrought with new responsibilities, new colleagues, and a new schedule, often all within a new setting. This transition period has been a longstanding focus of graduate medical education research, and a recent study identified 6 key areas that residency programs need to address to better facilitate this transition: (1) a sense of community within the residency program, (2) relocation resources, (3) residency preparation courses in medical school, (4) readiness to address racism and bias, (5) connecting with peers, and (6) open communication with program leadership.1 There is considerable interest in ensuring that this transition is smooth for all graduates, as nearly all US medical schools feature some variety of a residency preparation course during the fourth year of medical school, which, alongside the subinternships, serves to better prepare their graduates for the healthcare workforce.2

What about the transition from intern to dermatology resident? Near the end of intern year, my categorical medicine colleagues experienced a crescendo of responsibilities, all in preparation for junior year. The senior medicine residents, themselves having previously experienced the graduated responsibilities, knew to ease their grip on the reins and provide the late spring interns an opportunity to lead rounds or run a code. This was not the case for the preliminary interns for whom there was no preview available for what was to come; little guidance exists on how to best transform from a preliminary or transitional postgraduate year (PGY) 1 to a dermatology PGY-2. A survey of 44 dermatology residents and 33 dermatology program directors found electives such as rheumatology, infectious diseases, and allergy and immunology to be helpful for this transition, and residents most often cited friendly and supportive senior and fellow residents as the factor that eased their transition to PGY-2.3 Notably, less than half of the residents (40%) surveyed stated that team-building exercises and dedicated time to meet colleagues were helpful for this transition. They identified studying principles of dermatologic disease, learning new clinical duties, and adjusting to new coworkers and supervisors as the greatest work-related stressors during entry to PGY-2.3

My transition from intern year to dermatology was shrouded in uncertainty, and I was fortunate to have supportive seniors and co-residents to ease the process. There is much about starting dermatology residency that cannot be prepared for by reading a book, and a natural metamorphosis into the new role is hard to articulate. Still, the following are pieces of information I wish I knew as a graduating intern, which I hope will prove useful for those graduating to their PGY-2 dermatology year.

The Pace of Outpatient Dermatology

If the preliminary or transitional year did not have an ambulatory component, the switch from wards to clinic can be jarring. An outpatient encounter can be as short as 10 to 15 minutes, necessitating an efficient interview and examination to avoid a backup of patients. Unlike a hospital admission where the history of present illness can expound on multiple concerns and organ systems, the general dermatology visit must focus on the chief concern, with priority given to the clinical examination of the skin. For total-body skin examinations, a formulaic approach to assessing all areas of the body, with fluent transitions and minimal repositioning of the patient, is critical for patient comfort and to save time. Of course, accuracy and thoroughness are paramount, but the constant mindfulness of time and efficiency is uniquely emphasized in the outpatient setting.

Continuity of Care

On the wards, patients are admitted with an acute problem and discharged with the aim to prevent re-admission. However, in the dermatology clinic, the conditions encountered often are chronic, requiring repeated follow-ups that involve dosage tapers, laboratory monitoring, and trial and error. Unlike the rigid algorithm-based treatments utilized in the inpatient setting, the management of the same chronic disease can vary, as it is tailored to the patient based on their comorbidities and response. This longitudinal relationship with patients, whereby many disorders are managed rather than treated, stands in stark contrast to inpatient medicine, and learning to value symptom management rather than focusing on a cure is critical in a largely outpatient specialty such as dermatology.

Consulter to Consultant

Calling a consultation as an intern is challenging and requires succinct delivery of pertinent information while fearing pushback from the consultant. In a survey of 50 hospitalist attendings, only 11% responded that interns could be entrusted to call an effective consultation without supervision.4 When undertaking the role of a consultant, the goals should be to identify the team’s main question and to obtain key information necessary to formulate a differential diagnosis. The quality of the consultation will inevitably fluctuate; try to remember what it was like for you as a member of the primary team and remain patient and courteous during the exchange.5 In 1983, Goldman et al6 published a guideline on effective consultations that often is cited to this day, dubbed the “Ten Commandments for Effective Consultations,” which consists of the following: (1) determine the question that is being asked, (2) establish the urgency of the consultation, (3) gather primary data, (4) communicate as briefly as appropriate, (5) make specific recommendations, (6) provide contingency plans, (7) understand your own role in the process, (8) offer educational information, (9) communicate recommendations directly to the requesting physician, and (10) provide appropriate follow-up.

Consider Your Future

Frequently reflect on what you most enjoy about your job. Although it can be easy to passively engage with intern year as a mere stepping-stone to dermatology residency, the years in PGY-2 and onward require active introspection to find a future niche. What made you gravitate to the specialty of dermatology? Try to identify your predilections for dermatopathology, pediatric dermatology, dermatologic surgery, cosmetic dermatology, and academia. Be consistently cognizant of your life after residency, as some fellowships such as dermatopathology require applications to be submitted at the conclusion of the PGY-2 year. Seek out faculty mentors or alumni who are walking a path similar to the one you want to embark on, as the next stop after graduation may be your forever job.

Depth, Not Breadth

The practice of medicine changes when narrowing the focus to one organ system. In both medical school and intern year, my study habits and history-taking of patients cast a wide net across multiple organ systems, aiming to know just enough about any one specialty to address all chief concerns and to know when it was appropriate to consult a specialist. This paradigm inevitably shifts in dermatology residency, as residents are tasked with memorizing the endless number of diagnoses of the skin alone, comprehending the many shades of “erythematous,” including pink, salmon, red, and purple. Both on the wards and in clinics, I had to grow comfortable with telling patients that I did not have an answer for many of their nondermatologic concerns and directing them to the right specialist. As medicine continues trending to specialization, subspecialization, and sub-subspecialization, the scope of any given physician likely will continue to narrow,7 as evidenced by specialty clinics within dermatology such as those focusing on hair loss or immunobullous disease. In this health care system, it is imperative to remember that you are only one physician within a team of care providers—understand your own role in the process and become comfortable with not having the answer to all the questions.

Final Thoughts

In a study of 44 dermatology residents, 35 (83%) indicated zero to less than 1 hour per week of independent preparation for dermatology residency during PGY-1.3 Although the usefulness of preparing is debatable, this figure likely reflects the absence of any insight on how to best prepare for the transition. Recognizing the many contrasts between internal medicine and dermatology and embracing the changes will enable a seamless promotion from a medicine PGY-1 to a dermatology PGY-2.

The transition from medical school to residency is a rewarding milestone but involves a steep learning curve wrought with new responsibilities, new colleagues, and a new schedule, often all within a new setting. This transition period has been a longstanding focus of graduate medical education research, and a recent study identified 6 key areas that residency programs need to address to better facilitate this transition: (1) a sense of community within the residency program, (2) relocation resources, (3) residency preparation courses in medical school, (4) readiness to address racism and bias, (5) connecting with peers, and (6) open communication with program leadership.1 There is considerable interest in ensuring that this transition is smooth for all graduates, as nearly all US medical schools feature some variety of a residency preparation course during the fourth year of medical school, which, alongside the subinternships, serves to better prepare their graduates for the healthcare workforce.2

What about the transition from intern to dermatology resident? Near the end of intern year, my categorical medicine colleagues experienced a crescendo of responsibilities, all in preparation for junior year. The senior medicine residents, themselves having previously experienced the graduated responsibilities, knew to ease their grip on the reins and provide the late spring interns an opportunity to lead rounds or run a code. This was not the case for the preliminary interns for whom there was no preview available for what was to come; little guidance exists on how to best transform from a preliminary or transitional postgraduate year (PGY) 1 to a dermatology PGY-2. A survey of 44 dermatology residents and 33 dermatology program directors found electives such as rheumatology, infectious diseases, and allergy and immunology to be helpful for this transition, and residents most often cited friendly and supportive senior and fellow residents as the factor that eased their transition to PGY-2.3 Notably, less than half of the residents (40%) surveyed stated that team-building exercises and dedicated time to meet colleagues were helpful for this transition. They identified studying principles of dermatologic disease, learning new clinical duties, and adjusting to new coworkers and supervisors as the greatest work-related stressors during entry to PGY-2.3

My transition from intern year to dermatology was shrouded in uncertainty, and I was fortunate to have supportive seniors and co-residents to ease the process. There is much about starting dermatology residency that cannot be prepared for by reading a book, and a natural metamorphosis into the new role is hard to articulate. Still, the following are pieces of information I wish I knew as a graduating intern, which I hope will prove useful for those graduating to their PGY-2 dermatology year.

The Pace of Outpatient Dermatology

If the preliminary or transitional year did not have an ambulatory component, the switch from wards to clinic can be jarring. An outpatient encounter can be as short as 10 to 15 minutes, necessitating an efficient interview and examination to avoid a backup of patients. Unlike a hospital admission where the history of present illness can expound on multiple concerns and organ systems, the general dermatology visit must focus on the chief concern, with priority given to the clinical examination of the skin. For total-body skin examinations, a formulaic approach to assessing all areas of the body, with fluent transitions and minimal repositioning of the patient, is critical for patient comfort and to save time. Of course, accuracy and thoroughness are paramount, but the constant mindfulness of time and efficiency is uniquely emphasized in the outpatient setting.

Continuity of Care

On the wards, patients are admitted with an acute problem and discharged with the aim to prevent re-admission. However, in the dermatology clinic, the conditions encountered often are chronic, requiring repeated follow-ups that involve dosage tapers, laboratory monitoring, and trial and error. Unlike the rigid algorithm-based treatments utilized in the inpatient setting, the management of the same chronic disease can vary, as it is tailored to the patient based on their comorbidities and response. This longitudinal relationship with patients, whereby many disorders are managed rather than treated, stands in stark contrast to inpatient medicine, and learning to value symptom management rather than focusing on a cure is critical in a largely outpatient specialty such as dermatology.

Consulter to Consultant

Calling a consultation as an intern is challenging and requires succinct delivery of pertinent information while fearing pushback from the consultant. In a survey of 50 hospitalist attendings, only 11% responded that interns could be entrusted to call an effective consultation without supervision.4 When undertaking the role of a consultant, the goals should be to identify the team’s main question and to obtain key information necessary to formulate a differential diagnosis. The quality of the consultation will inevitably fluctuate; try to remember what it was like for you as a member of the primary team and remain patient and courteous during the exchange.5 In 1983, Goldman et al6 published a guideline on effective consultations that often is cited to this day, dubbed the “Ten Commandments for Effective Consultations,” which consists of the following: (1) determine the question that is being asked, (2) establish the urgency of the consultation, (3) gather primary data, (4) communicate as briefly as appropriate, (5) make specific recommendations, (6) provide contingency plans, (7) understand your own role in the process, (8) offer educational information, (9) communicate recommendations directly to the requesting physician, and (10) provide appropriate follow-up.

Consider Your Future

Frequently reflect on what you most enjoy about your job. Although it can be easy to passively engage with intern year as a mere stepping-stone to dermatology residency, the years in PGY-2 and onward require active introspection to find a future niche. What made you gravitate to the specialty of dermatology? Try to identify your predilections for dermatopathology, pediatric dermatology, dermatologic surgery, cosmetic dermatology, and academia. Be consistently cognizant of your life after residency, as some fellowships such as dermatopathology require applications to be submitted at the conclusion of the PGY-2 year. Seek out faculty mentors or alumni who are walking a path similar to the one you want to embark on, as the next stop after graduation may be your forever job.

Depth, Not Breadth

The practice of medicine changes when narrowing the focus to one organ system. In both medical school and intern year, my study habits and history-taking of patients cast a wide net across multiple organ systems, aiming to know just enough about any one specialty to address all chief concerns and to know when it was appropriate to consult a specialist. This paradigm inevitably shifts in dermatology residency, as residents are tasked with memorizing the endless number of diagnoses of the skin alone, comprehending the many shades of “erythematous,” including pink, salmon, red, and purple. Both on the wards and in clinics, I had to grow comfortable with telling patients that I did not have an answer for many of their nondermatologic concerns and directing them to the right specialist. As medicine continues trending to specialization, subspecialization, and sub-subspecialization, the scope of any given physician likely will continue to narrow,7 as evidenced by specialty clinics within dermatology such as those focusing on hair loss or immunobullous disease. In this health care system, it is imperative to remember that you are only one physician within a team of care providers—understand your own role in the process and become comfortable with not having the answer to all the questions.

Final Thoughts

In a study of 44 dermatology residents, 35 (83%) indicated zero to less than 1 hour per week of independent preparation for dermatology residency during PGY-1.3 Although the usefulness of preparing is debatable, this figure likely reflects the absence of any insight on how to best prepare for the transition. Recognizing the many contrasts between internal medicine and dermatology and embracing the changes will enable a seamless promotion from a medicine PGY-1 to a dermatology PGY-2.

- Staples H, Frank S, Mullen M, et al. Improving the medical school to residency transition: narrative experiences from first-year residents.J Surg Educ. 2022;S1931-7204(22)00146-5. doi:10.1016/j.jsurg.2022.06.001

- Heidemann LA, Walford E, Mack J, et al. Is there a role for internal medicine residency preparation courses in the fourth year curriculum? a single-center experience. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33:2048-2050.

- Hopkins C, Jalali O, Guffey D, et al. A survey of dermatology residents and program directors assessing the transition to dermatology residency. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2020;34:59-62.

- Marcus CH, Winn AS, Sectish TC, et al. How much supervision is required is the beginning of intern year? Acad Pediatr. 2016;16:E3-E4.

- Bly RA, Bly EG. Consult courtesy. J Grad Med Educ. 2013;5:533-534.

- Goldman L, Lee T, Rudd P. Ten commandments for effective consultations. Arch Intern Med. 1983;143:1753-1755.

- Oren O, Gersh BJ, Bhatt DL. On the pearls and perils of sub-subspecialization. Am J Med. 2020;133:158-159.

- Staples H, Frank S, Mullen M, et al. Improving the medical school to residency transition: narrative experiences from first-year residents.J Surg Educ. 2022;S1931-7204(22)00146-5. doi:10.1016/j.jsurg.2022.06.001

- Heidemann LA, Walford E, Mack J, et al. Is there a role for internal medicine residency preparation courses in the fourth year curriculum? a single-center experience. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33:2048-2050.

- Hopkins C, Jalali O, Guffey D, et al. A survey of dermatology residents and program directors assessing the transition to dermatology residency. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2020;34:59-62.

- Marcus CH, Winn AS, Sectish TC, et al. How much supervision is required is the beginning of intern year? Acad Pediatr. 2016;16:E3-E4.

- Bly RA, Bly EG. Consult courtesy. J Grad Med Educ. 2013;5:533-534.

- Goldman L, Lee T, Rudd P. Ten commandments for effective consultations. Arch Intern Med. 1983;143:1753-1755.

- Oren O, Gersh BJ, Bhatt DL. On the pearls and perils of sub-subspecialization. Am J Med. 2020;133:158-159.

Resident Pearl

- There is surprisingly little information on what to expect when transitioning from intern year to dermatology residency. Recognizing the unique aspects of a largely outpatient specialty and embracing the role of a specialist will help facilitate this transition.

Ossification and Migration of a Nodule Following Calcium Hydroxylapatite Injection

To the Editor:

Calcium hydroxylapatite is an injectable filler approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for moderate to severe rhytides of the face and the treatment of facial lipodystrophy in patients with HIV.1 This long-lasting filler generally is well tolerated with minimal side effects; however, there have been reports of nodules or granulomatous formation following injection.2 We present a case of a migrating nodule following injection of a calcium hydroxylapatite filler that appeared ossified on radiographic imaging. We highlight this rarely reported phenomenon to increase awareness of this complication.

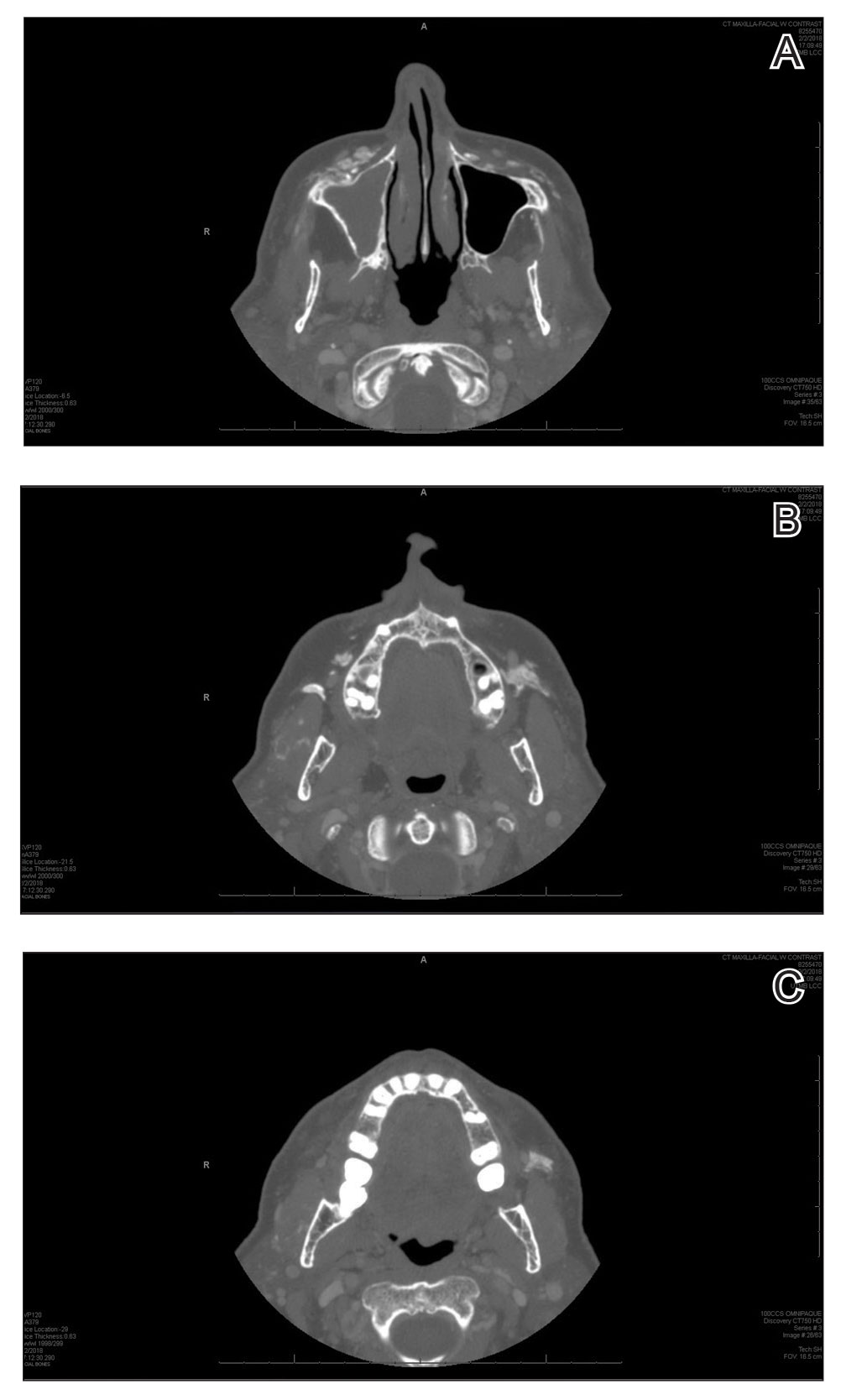

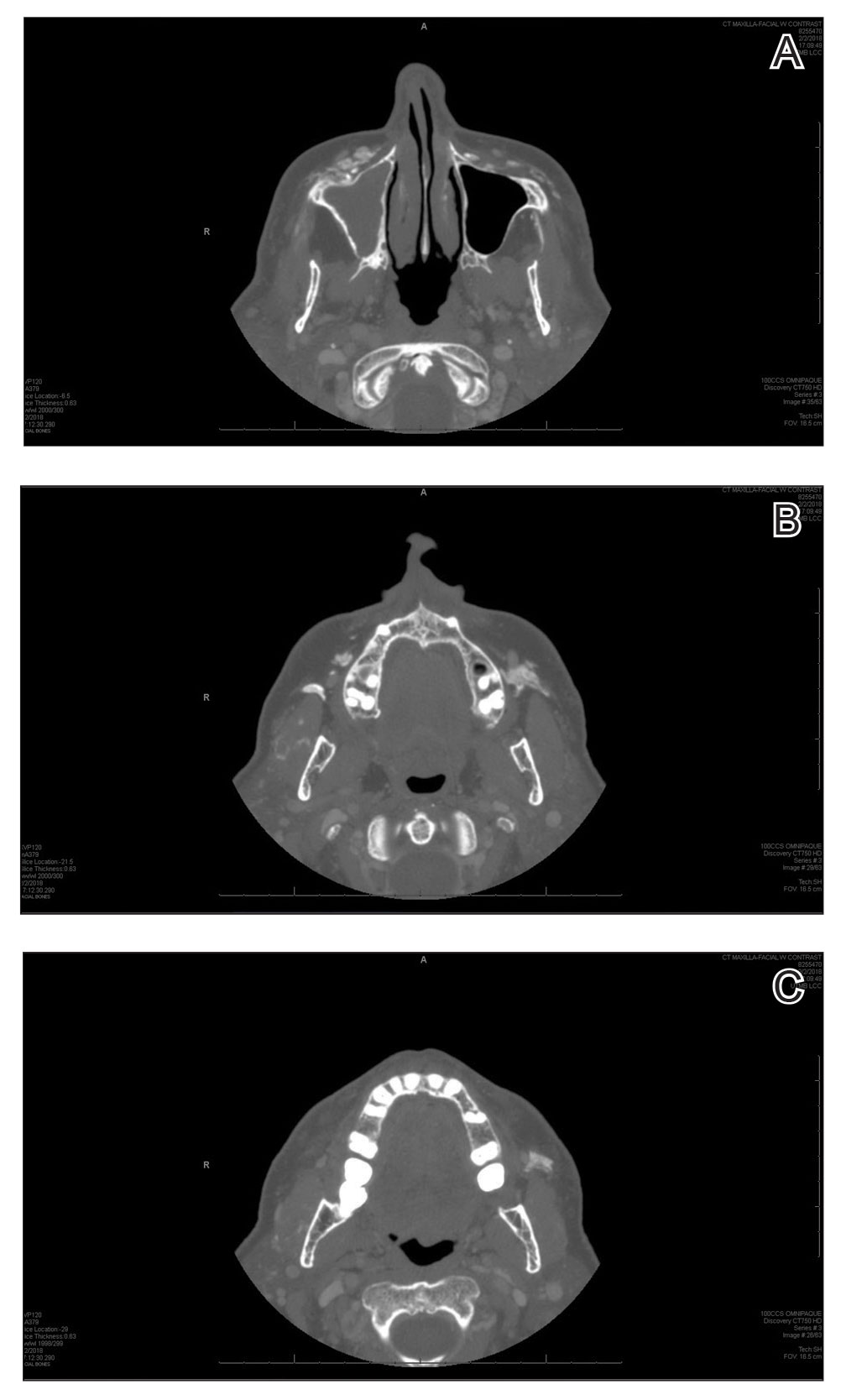

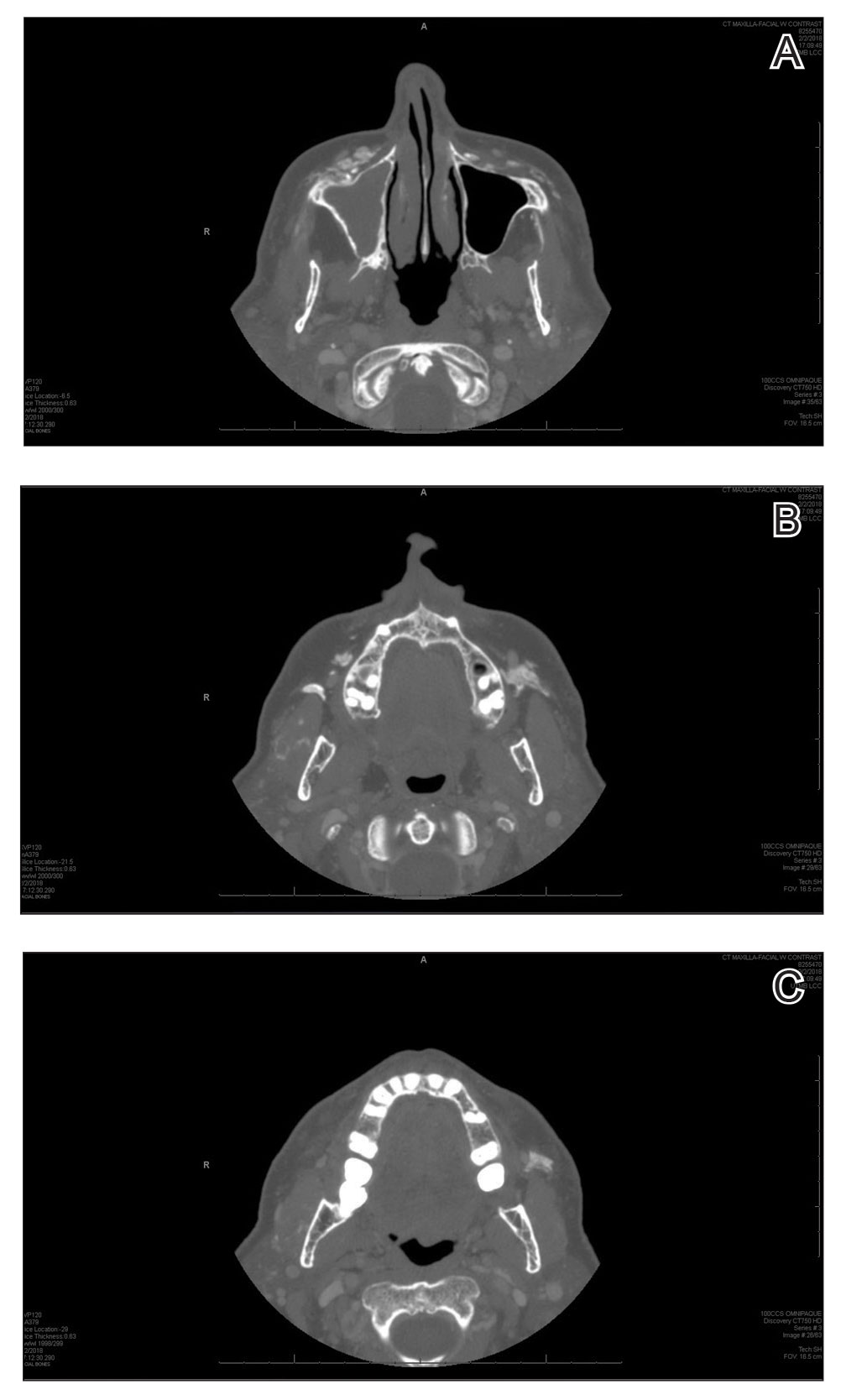

A 72-year-old woman presented to our clinic with a mass on the left cheek. The patient had a history of treatment with facial fillers but no notable medical conditions. She initially received hyaluronic acid injectable gel dermal filler twice—3 years apart—before switching to calcium hydroxylapatite injections twice—4 months apart—from an outside provider. One month after the second treatment, she noticed a mass on the left cheek and promptly returned to the provider who performed the calcium hydroxylapatite injections. The provider, who had originally injected in the infraorbital area, stated it was unlikely that the filler would have migrated to the mid cheek and referred the patient to a general dentist who suspected salivary gland pathology. The patient was referred to an oral and maxillofacial surgeon who suspected the mass was related to the parotid gland. Maxillofacial computed tomography (CT) revealed heterotopic ossification vs myositis ossificans, possibly related to the recent injection. The patient was eventually referred to the Division of Plastic Surgery, Department of Surgery, at the University of Texas Medical Branch (Galveston, Texas) for further evaluation. Physical examination revealed a 2×1-cm firm, mobile, nontender mass in the left cheek in the area of the buccinator muscles. The mass did not express any fluid and was most easily palpable from the oral cavity. Radiography findings showed that the calcium hydroxylapatite filler had migrated to this location and formed a nodule (Figure). Because calcium hydroxylapatite fillers generally last 12 to 18 months, we opted to observe the lesion for spontaneous resolution. Four months later, the patient presented to our clinic for follow-up and the mass had reduced in size and appeared to be spontaneously resolving.

We present a unique case of a migrating nodule that occurred after injection with calcium hydroxylapatite, which led to concern for neoplastic tumor formation. This complication is rare, and it is important for practitioners who inject calcium hydroxylapatite as well as those who these patients may be referred to for evaluation to be aware that migrating nodules can occur. This awareness can help reduce unnecessary referrals, medical procedures, and anxiety.

Calcium hydroxylapatite filler is composed of 30% calcium hydroxylapatite microspheres suspended in a 70% sodium carboxymethylcellulose gel. The water-soluble gel rapidly becomes absorbed upon injection; however, the microspheres form a scaffold for the production of newly synthesized collagen. The filling effect generally lasts 12 to 18 months.1