User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

Firm Mobile Nodule on the Scalp

The Diagnosis: Metastatic Carcinoid Tumor

Carcinoid tumors are derived from neuroendocrine cell compartments and generally arise in the gastrointestinal tract, with a quarter of carcinoids arising in the small bowel.1 Carcinoid tumors have an incidence of approximately 2 to 5 per 100,000 patients.2 Metastasis of carcinoids is approximately 31.2% to 46.7%.1 Metastasis to the skin is uncommon; we present a rare case of a carcinoid tumor of the terminal ileum with metastasis to the scalp.

Unlike our patient, most patients with carcinoid tumors have an indolent clinical course. The most common cutaneous symptom is flushing, which occurs in 75% of patients.3 Secreted vasoactive peptides such as serotonin may cause other symptoms such as tachycardia, diarrhea, and bronchospasm; together, these symptoms comprise carcinoid syndrome. Carcinoid syndrome requires metastasis of the tumor to the liver or a site outside of the gastrointestinal tract because the liver will metabolize the secreted serotonin. However, even in patients with liver metastasis, carcinoid syndrome only occurs in approximately 10% of patients.4 Common skin findings of carcinoid syndrome include pellagralike dermatitis, flushing, and sclerodermalike changes.5 Our patient experienced several episodes of presyncope with symptoms of dyspnea, lightheadedness, and flushing but did not have bronchospasm or recurrent diarrhea. Intramuscular octreotide improved some symptoms.

The scalp accounts for approximately 15% of cutaneous metastases, the most common being from the lung, renal, and breast cancers.6 Cutaneous metastases of carcinoid tumors are rare. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms metastatic AND [carcinoid OR neuroendocrine] tumors AND [skin OR cutaneous] revealed 47 cases.7-11 Similar to other skin metastases, cutaneous metastases of carcinoid tumors commonly present as firm erythematous nodules of varying sizes that may be asymptomatic, tender, or pruritic (Figure 1). Cases of carcinoid tumors with cutaneous metastasis as the initial and only presenting sign are exceedingly rare.12

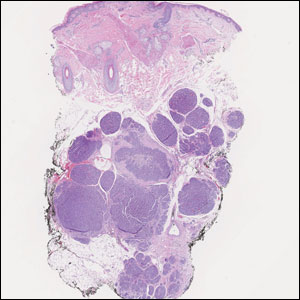

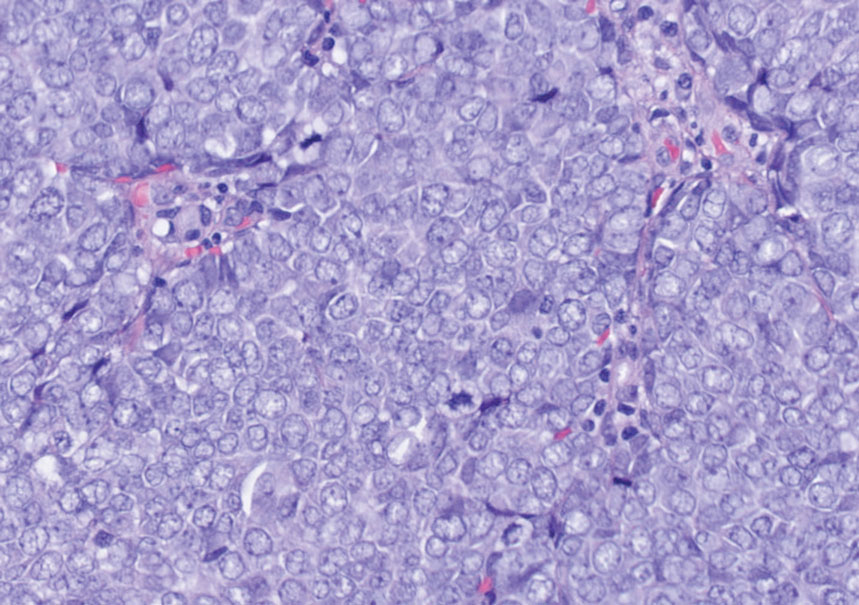

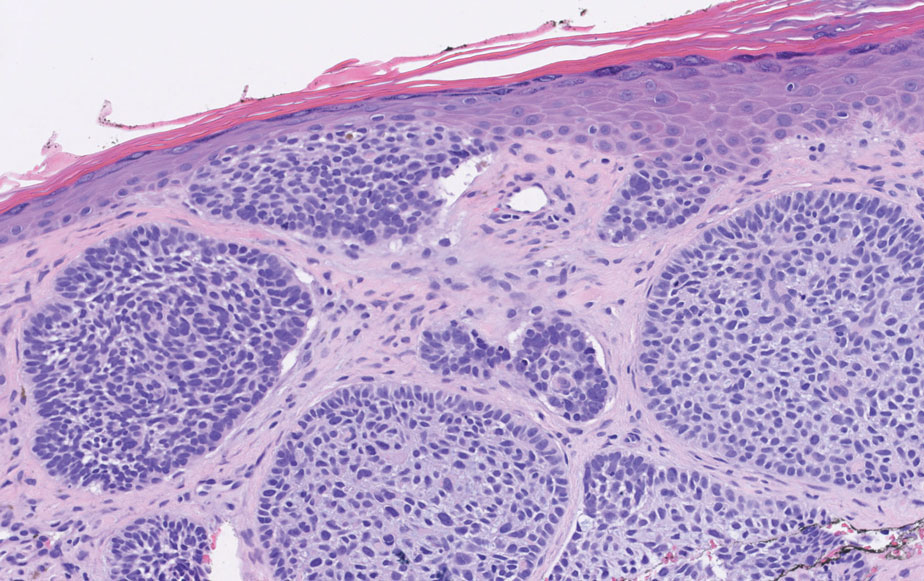

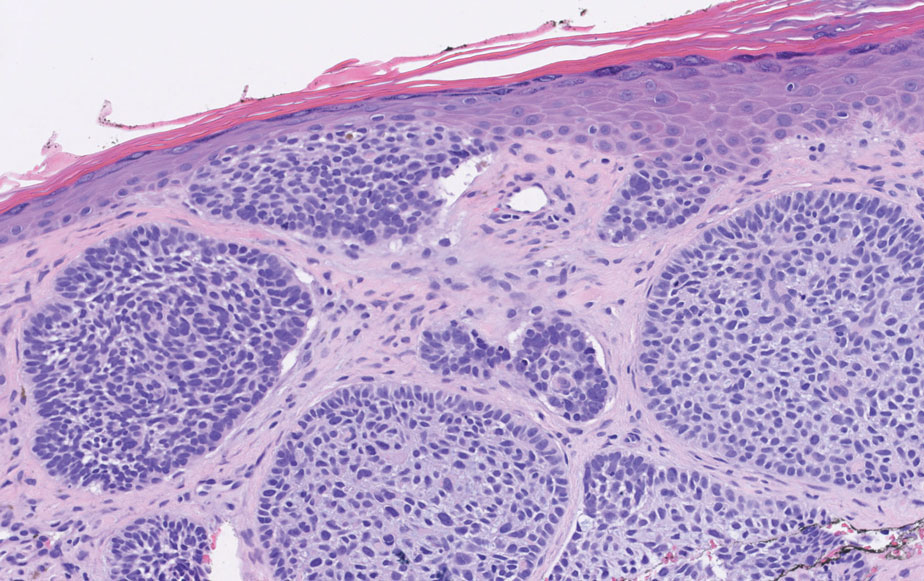

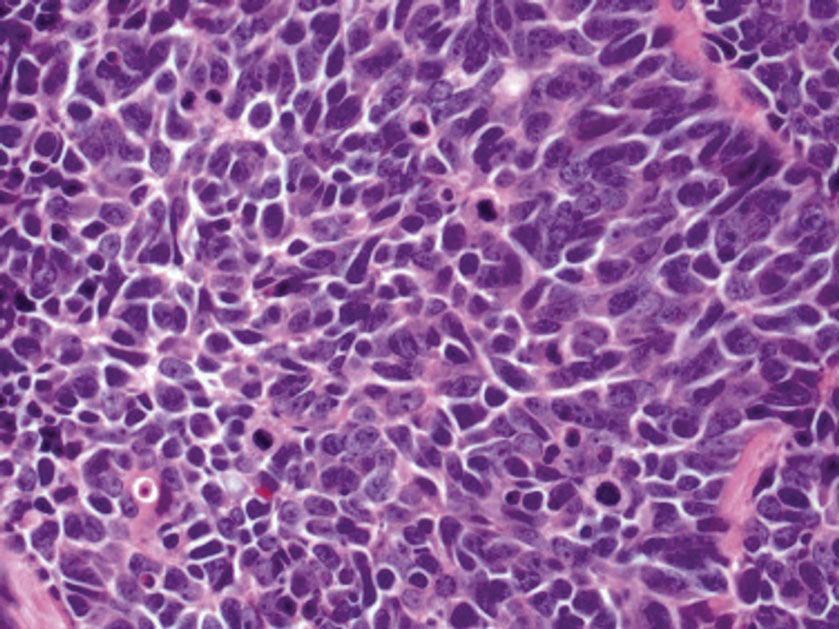

Histology of carcinoid tumors reveals a dermal neoplasm composed of loosely cohesive, mildly atypical, polygonal cells with salt-and-pepper chromatin and eosinophilic cytoplasm, which are similar findings to the primary tumor. The cells may grow in the typical trabecular or organoid neuroendocrine pattern or exhibit a pseudoglandular growth pattern with prominent vessels (quiz image, top).12 Positive chromogranin and synaptophysin immunostaining are the most common and reliable markers used for the diagnosis of carcinoid tumors.

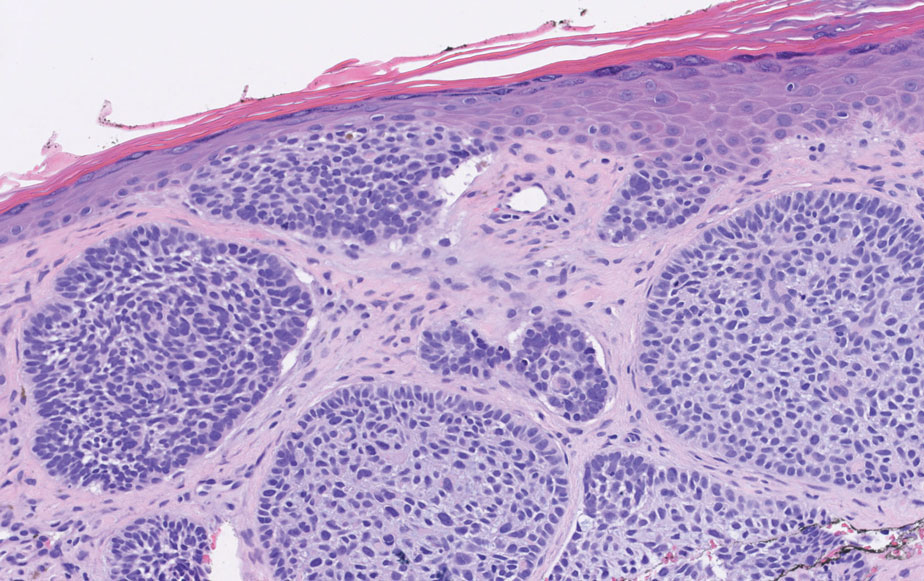

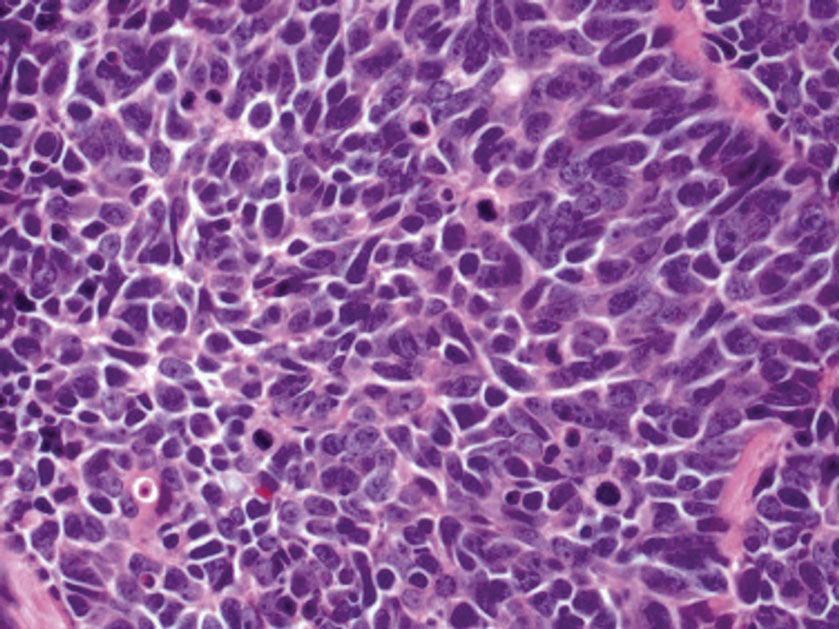

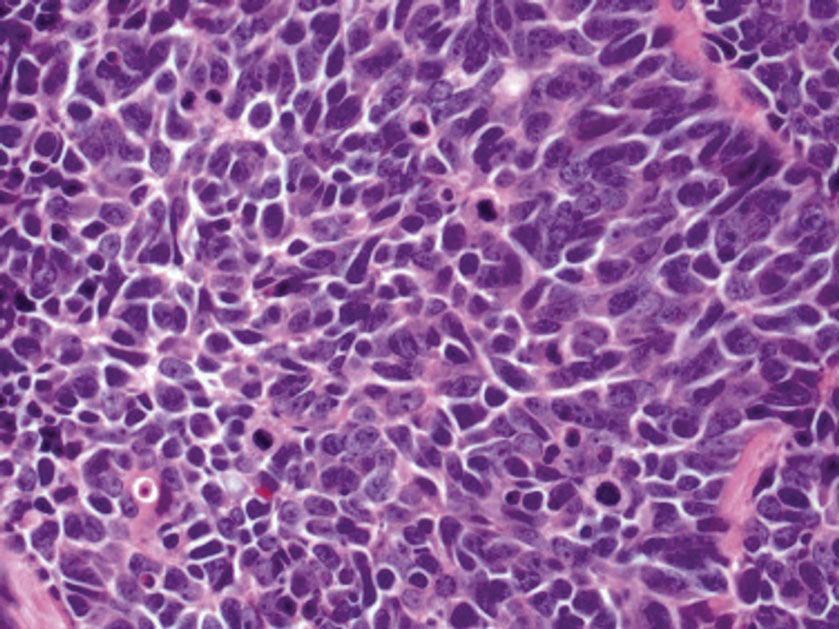

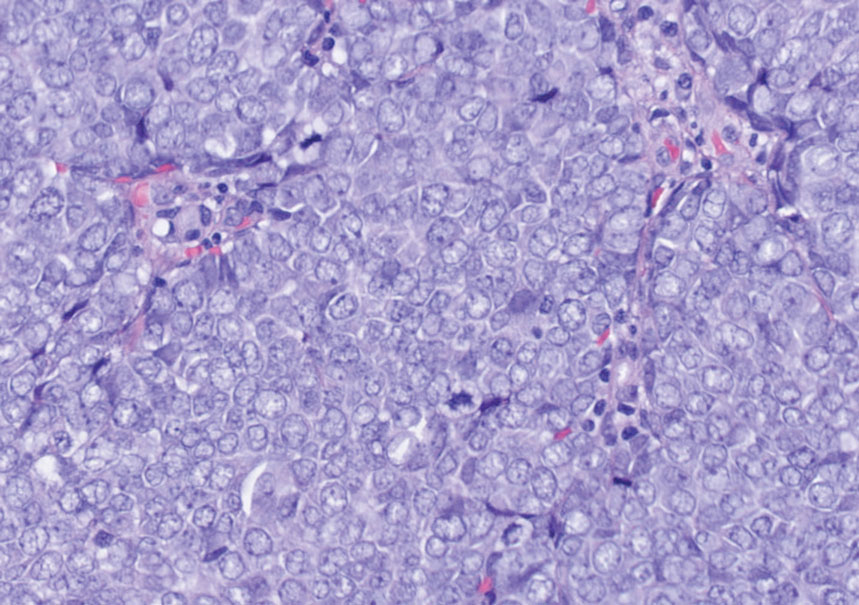

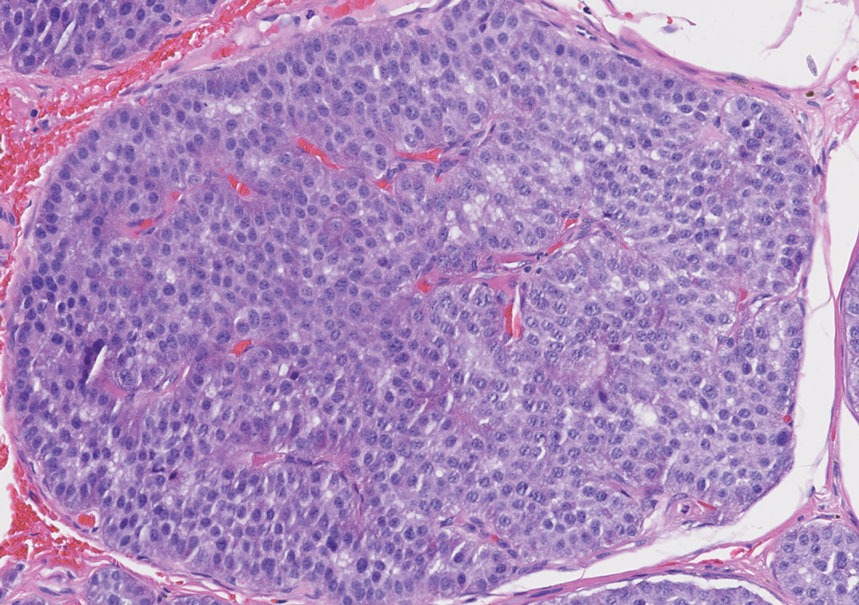

An important histopathologic differential diagnosis is the aggressive Merkel cell carcinoma, which also demonstrates homogenous salt-and-pepper chromatin but exhibits a higher mitotic rate and positive cytokeratin 20 staining (Figure 2).13 Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) also may display similar features, including a blue tumor at scanning magnification and nodular or infiltrative growth patterns. The cell morphology of BCC is characterized by islands of basaloid cells with minimal cytoplasm and frequent apoptosis, connecting to the epidermis with peripheral palisading, retraction artifact, and a myxoid stroma; BCC lacks the salt-and-pepper chromatin commonly seen in carcinoid tumors (Figure 3). Basal cell carcinoma is characterized by positive BerEP4 (epithelial cell adhesion molecule immunostain), cytokeratin 5/6, and cytokeratin 14 uptake. Cytokeratin 20, often used to diagnose Merkel cell carcinoma, is negative in BCC. Chromogranin and synaptophysin occasionally may be positive in BCC.14

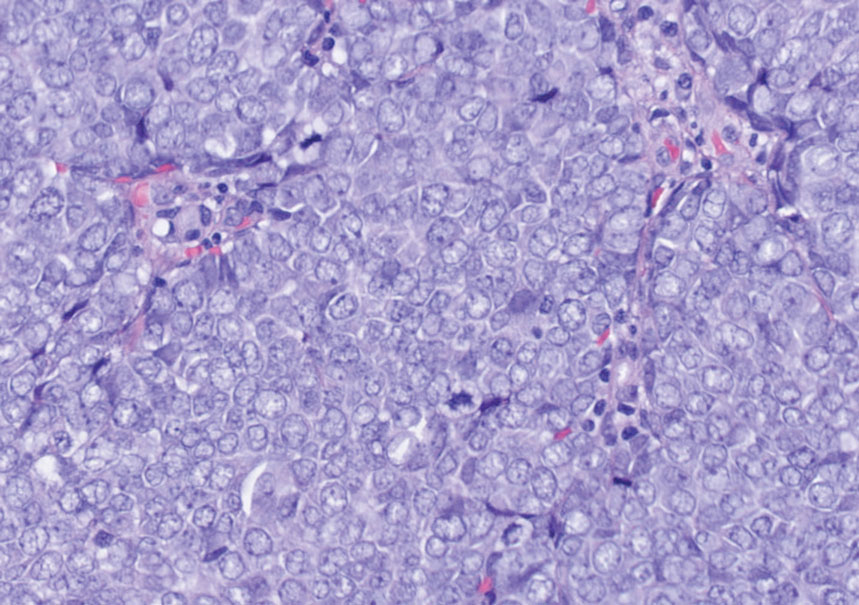

The superficial Ewing sarcoma family of tumors also may be included in the differential diagnosis of small round cell tumors of the skin, but they are very rare. These tumors possess strong positive membranous staining of cytokeratin 99 and also can stain positively for synaptophysin and chromogranin.15 Epithelial membrane antigen, which is negative in Ewing sarcomas, is positive in carcinoid tumors.16 Neuroendocrine tumors of all sites share similar basic morphologic patterns, and multiple primary tumors should be considered, including small cell lung carcinoma (Figure 4).17,18 Red granulations and true glandular lumina typically are not seen in the lungs but are common in gastrointestinal carcinoids.18 Regarding immunohistochemistry, TTF-1 is negative and CDX2 is positive in gastroenteropancreatic carcinoids, suggesting that these 2 markers can help distinguish carcinoids of unknown primary origin.19

Metastases in carcinoid tumors are common, with one study noting that the highest frequency of small intestinal metastases was from the ileal subset.20 At the time of diagnosis, 58% to 64% of patients with small intestine carcinoid tumors already had nonlocalized disease, with frequent sites being the lymph nodes (89.8%), liver (44.1%), lungs (13.6%), and peritoneum (13.6%). Regional and distant metastases are associated with substantially worse prognoses, with survival rates of 71.7% and 38.5%, respectively.1 Treatment of symptomatic unresectable disease focuses on symptomatic management with somatostatin analogs that also control tumor growth.21

We present a rare case of scalp metastasis of a carcinoid tumor of the terminal ileum. Distant metastasis is associated with poorer prognosis and should be considered in patients with a known history of a carcinoid tumor.

Acknowledgment—We would like to acknowledge the Research Histology and Tissue Imaging Core at University of Illinois Chicago Research Resources Center for the immunohistochemistry studies.

- Modlin IM, Lye KD, Kidd M. A 5-decade analysis of 13,715 carcinoid tumors. Cancer. 2003;97:934-959.

- Lawrence B, Gustafsson BI, Chan A, et al. The epidemiology of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2011;40:1-18, vii.

- Sabir S, James WD, Schuchter LM. Cutaneous manifestations of cancer. Curr Opin Oncol. 1999;11:139-144.

- Tomassetti P. Clinical aspects of carcinoid tumours. Italian J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1999;31(suppl 2):S143-S146.

- Bell HK, Poston GJ, Vora J, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of the malignant carcinoid syndrome. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152:71-75.

- Lookingbill DP, Spangler N, Helm KF. Cutaneous metastases in patients with metastatic carcinoma: a retrospective study of 4020 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29(2 pt 1):228-236.

- Garcia A, Mays S, Silapunt S. Metastatic neuroendocrine carcinoma in the skin. Dermatol Online J. 2017;23:13030/qt9052w9x1.

- Ciliberti MP, Carbonara R, Grillo A, et al. Unexpected response to palliative radiotherapy for subcutaneous metastases of an advanced small cell pancreatic neuroendocrine carcinoma: a case report of two different radiation schedules. BMC Cancer. 2020;20:311.

- Devnani B, Kumar R, Pathy S, et al. Cutaneous metastases from neuroendocrine carcinoma of the cervix: an unusual metastatic lesion from an uncommon malignancy. Curr Probl Cancer. 2018; 42:527-533.

- Falto-Aizpurua L, Seyfer S, Krishnan B, et al. Cutaneous metastasis of a pulmonary carcinoid tumor. Cutis. 2017;99:E13-E15.

- Dhingra R, Tse JY, Saif MW. Cutaneous metastasis of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (GEP-Nets)[published online September 8, 2018]. JOP. 2018;19.

- Jedrych J, Busam K, Klimstra DS, et al. Cutaneous metastases as an initial manifestation of visceral well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumor: a report of four cases and a review of literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2014;41:113-122.

- Lloyd RV. Practical markers used in the diagnosis of neuroendocrine tumors. Endocr Pathol. 2003;14:293-301.

- Stanoszek LM, Wang GY, Harms PW. Histologic mimics of basal cell carcinoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2017;141:1490-1502.

- Machado I, Llombart B, Calabuig-Fariñas S, et al. Superficial Ewing’s sarcoma family of tumors: a clinicopathological study with differential diagnoses. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:636-643.

- D’Cruze L, Dutta R, Rao S, et al. The role of immunohistochemistry in the analysis of the spectrum of small round cell tumours at a tertiary care centre. J Clin Diagn Res. 2013;7:1377-1382.

- Chirila DN, Turdeanu NA, Constantea NA, et al. Multiple malignant tumors. Chirurgia (Bucur). 2013;108:498-502.

- Rekhtman N. Neuroendocrine tumors of the lung: an update. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2010;134:1628-1638.

- Lin X, Saad RS, Luckasevic TM, et al. Diagnostic value of CDX-2 and TTF-1 expressions in separating metastatic neuroendocrine neoplasms of unknown origin. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2007;15:407-414.

- Olney JR, Urdaneta LF, Al-Jurf AS, et al. Carcinoid tumors of the gastrointestinal tract. Am Surg. 1985;51:37-41.

- Strosberg JR, Halfdanarson TR, Bellizzi AM, et al. The North American Neuroendocrine Tumor Society consensus guidelines for surveillance and medical management of midgut neuroendocrine tumors. Pancreas. 2017;46:707-714.

The Diagnosis: Metastatic Carcinoid Tumor

Carcinoid tumors are derived from neuroendocrine cell compartments and generally arise in the gastrointestinal tract, with a quarter of carcinoids arising in the small bowel.1 Carcinoid tumors have an incidence of approximately 2 to 5 per 100,000 patients.2 Metastasis of carcinoids is approximately 31.2% to 46.7%.1 Metastasis to the skin is uncommon; we present a rare case of a carcinoid tumor of the terminal ileum with metastasis to the scalp.

Unlike our patient, most patients with carcinoid tumors have an indolent clinical course. The most common cutaneous symptom is flushing, which occurs in 75% of patients.3 Secreted vasoactive peptides such as serotonin may cause other symptoms such as tachycardia, diarrhea, and bronchospasm; together, these symptoms comprise carcinoid syndrome. Carcinoid syndrome requires metastasis of the tumor to the liver or a site outside of the gastrointestinal tract because the liver will metabolize the secreted serotonin. However, even in patients with liver metastasis, carcinoid syndrome only occurs in approximately 10% of patients.4 Common skin findings of carcinoid syndrome include pellagralike dermatitis, flushing, and sclerodermalike changes.5 Our patient experienced several episodes of presyncope with symptoms of dyspnea, lightheadedness, and flushing but did not have bronchospasm or recurrent diarrhea. Intramuscular octreotide improved some symptoms.

The scalp accounts for approximately 15% of cutaneous metastases, the most common being from the lung, renal, and breast cancers.6 Cutaneous metastases of carcinoid tumors are rare. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms metastatic AND [carcinoid OR neuroendocrine] tumors AND [skin OR cutaneous] revealed 47 cases.7-11 Similar to other skin metastases, cutaneous metastases of carcinoid tumors commonly present as firm erythematous nodules of varying sizes that may be asymptomatic, tender, or pruritic (Figure 1). Cases of carcinoid tumors with cutaneous metastasis as the initial and only presenting sign are exceedingly rare.12

Histology of carcinoid tumors reveals a dermal neoplasm composed of loosely cohesive, mildly atypical, polygonal cells with salt-and-pepper chromatin and eosinophilic cytoplasm, which are similar findings to the primary tumor. The cells may grow in the typical trabecular or organoid neuroendocrine pattern or exhibit a pseudoglandular growth pattern with prominent vessels (quiz image, top).12 Positive chromogranin and synaptophysin immunostaining are the most common and reliable markers used for the diagnosis of carcinoid tumors.

An important histopathologic differential diagnosis is the aggressive Merkel cell carcinoma, which also demonstrates homogenous salt-and-pepper chromatin but exhibits a higher mitotic rate and positive cytokeratin 20 staining (Figure 2).13 Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) also may display similar features, including a blue tumor at scanning magnification and nodular or infiltrative growth patterns. The cell morphology of BCC is characterized by islands of basaloid cells with minimal cytoplasm and frequent apoptosis, connecting to the epidermis with peripheral palisading, retraction artifact, and a myxoid stroma; BCC lacks the salt-and-pepper chromatin commonly seen in carcinoid tumors (Figure 3). Basal cell carcinoma is characterized by positive BerEP4 (epithelial cell adhesion molecule immunostain), cytokeratin 5/6, and cytokeratin 14 uptake. Cytokeratin 20, often used to diagnose Merkel cell carcinoma, is negative in BCC. Chromogranin and synaptophysin occasionally may be positive in BCC.14

The superficial Ewing sarcoma family of tumors also may be included in the differential diagnosis of small round cell tumors of the skin, but they are very rare. These tumors possess strong positive membranous staining of cytokeratin 99 and also can stain positively for synaptophysin and chromogranin.15 Epithelial membrane antigen, which is negative in Ewing sarcomas, is positive in carcinoid tumors.16 Neuroendocrine tumors of all sites share similar basic morphologic patterns, and multiple primary tumors should be considered, including small cell lung carcinoma (Figure 4).17,18 Red granulations and true glandular lumina typically are not seen in the lungs but are common in gastrointestinal carcinoids.18 Regarding immunohistochemistry, TTF-1 is negative and CDX2 is positive in gastroenteropancreatic carcinoids, suggesting that these 2 markers can help distinguish carcinoids of unknown primary origin.19

Metastases in carcinoid tumors are common, with one study noting that the highest frequency of small intestinal metastases was from the ileal subset.20 At the time of diagnosis, 58% to 64% of patients with small intestine carcinoid tumors already had nonlocalized disease, with frequent sites being the lymph nodes (89.8%), liver (44.1%), lungs (13.6%), and peritoneum (13.6%). Regional and distant metastases are associated with substantially worse prognoses, with survival rates of 71.7% and 38.5%, respectively.1 Treatment of symptomatic unresectable disease focuses on symptomatic management with somatostatin analogs that also control tumor growth.21

We present a rare case of scalp metastasis of a carcinoid tumor of the terminal ileum. Distant metastasis is associated with poorer prognosis and should be considered in patients with a known history of a carcinoid tumor.

Acknowledgment—We would like to acknowledge the Research Histology and Tissue Imaging Core at University of Illinois Chicago Research Resources Center for the immunohistochemistry studies.

The Diagnosis: Metastatic Carcinoid Tumor

Carcinoid tumors are derived from neuroendocrine cell compartments and generally arise in the gastrointestinal tract, with a quarter of carcinoids arising in the small bowel.1 Carcinoid tumors have an incidence of approximately 2 to 5 per 100,000 patients.2 Metastasis of carcinoids is approximately 31.2% to 46.7%.1 Metastasis to the skin is uncommon; we present a rare case of a carcinoid tumor of the terminal ileum with metastasis to the scalp.

Unlike our patient, most patients with carcinoid tumors have an indolent clinical course. The most common cutaneous symptom is flushing, which occurs in 75% of patients.3 Secreted vasoactive peptides such as serotonin may cause other symptoms such as tachycardia, diarrhea, and bronchospasm; together, these symptoms comprise carcinoid syndrome. Carcinoid syndrome requires metastasis of the tumor to the liver or a site outside of the gastrointestinal tract because the liver will metabolize the secreted serotonin. However, even in patients with liver metastasis, carcinoid syndrome only occurs in approximately 10% of patients.4 Common skin findings of carcinoid syndrome include pellagralike dermatitis, flushing, and sclerodermalike changes.5 Our patient experienced several episodes of presyncope with symptoms of dyspnea, lightheadedness, and flushing but did not have bronchospasm or recurrent diarrhea. Intramuscular octreotide improved some symptoms.

The scalp accounts for approximately 15% of cutaneous metastases, the most common being from the lung, renal, and breast cancers.6 Cutaneous metastases of carcinoid tumors are rare. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms metastatic AND [carcinoid OR neuroendocrine] tumors AND [skin OR cutaneous] revealed 47 cases.7-11 Similar to other skin metastases, cutaneous metastases of carcinoid tumors commonly present as firm erythematous nodules of varying sizes that may be asymptomatic, tender, or pruritic (Figure 1). Cases of carcinoid tumors with cutaneous metastasis as the initial and only presenting sign are exceedingly rare.12

Histology of carcinoid tumors reveals a dermal neoplasm composed of loosely cohesive, mildly atypical, polygonal cells with salt-and-pepper chromatin and eosinophilic cytoplasm, which are similar findings to the primary tumor. The cells may grow in the typical trabecular or organoid neuroendocrine pattern or exhibit a pseudoglandular growth pattern with prominent vessels (quiz image, top).12 Positive chromogranin and synaptophysin immunostaining are the most common and reliable markers used for the diagnosis of carcinoid tumors.

An important histopathologic differential diagnosis is the aggressive Merkel cell carcinoma, which also demonstrates homogenous salt-and-pepper chromatin but exhibits a higher mitotic rate and positive cytokeratin 20 staining (Figure 2).13 Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) also may display similar features, including a blue tumor at scanning magnification and nodular or infiltrative growth patterns. The cell morphology of BCC is characterized by islands of basaloid cells with minimal cytoplasm and frequent apoptosis, connecting to the epidermis with peripheral palisading, retraction artifact, and a myxoid stroma; BCC lacks the salt-and-pepper chromatin commonly seen in carcinoid tumors (Figure 3). Basal cell carcinoma is characterized by positive BerEP4 (epithelial cell adhesion molecule immunostain), cytokeratin 5/6, and cytokeratin 14 uptake. Cytokeratin 20, often used to diagnose Merkel cell carcinoma, is negative in BCC. Chromogranin and synaptophysin occasionally may be positive in BCC.14

The superficial Ewing sarcoma family of tumors also may be included in the differential diagnosis of small round cell tumors of the skin, but they are very rare. These tumors possess strong positive membranous staining of cytokeratin 99 and also can stain positively for synaptophysin and chromogranin.15 Epithelial membrane antigen, which is negative in Ewing sarcomas, is positive in carcinoid tumors.16 Neuroendocrine tumors of all sites share similar basic morphologic patterns, and multiple primary tumors should be considered, including small cell lung carcinoma (Figure 4).17,18 Red granulations and true glandular lumina typically are not seen in the lungs but are common in gastrointestinal carcinoids.18 Regarding immunohistochemistry, TTF-1 is negative and CDX2 is positive in gastroenteropancreatic carcinoids, suggesting that these 2 markers can help distinguish carcinoids of unknown primary origin.19

Metastases in carcinoid tumors are common, with one study noting that the highest frequency of small intestinal metastases was from the ileal subset.20 At the time of diagnosis, 58% to 64% of patients with small intestine carcinoid tumors already had nonlocalized disease, with frequent sites being the lymph nodes (89.8%), liver (44.1%), lungs (13.6%), and peritoneum (13.6%). Regional and distant metastases are associated with substantially worse prognoses, with survival rates of 71.7% and 38.5%, respectively.1 Treatment of symptomatic unresectable disease focuses on symptomatic management with somatostatin analogs that also control tumor growth.21

We present a rare case of scalp metastasis of a carcinoid tumor of the terminal ileum. Distant metastasis is associated with poorer prognosis and should be considered in patients with a known history of a carcinoid tumor.

Acknowledgment—We would like to acknowledge the Research Histology and Tissue Imaging Core at University of Illinois Chicago Research Resources Center for the immunohistochemistry studies.

- Modlin IM, Lye KD, Kidd M. A 5-decade analysis of 13,715 carcinoid tumors. Cancer. 2003;97:934-959.

- Lawrence B, Gustafsson BI, Chan A, et al. The epidemiology of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2011;40:1-18, vii.

- Sabir S, James WD, Schuchter LM. Cutaneous manifestations of cancer. Curr Opin Oncol. 1999;11:139-144.

- Tomassetti P. Clinical aspects of carcinoid tumours. Italian J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1999;31(suppl 2):S143-S146.

- Bell HK, Poston GJ, Vora J, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of the malignant carcinoid syndrome. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152:71-75.

- Lookingbill DP, Spangler N, Helm KF. Cutaneous metastases in patients with metastatic carcinoma: a retrospective study of 4020 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29(2 pt 1):228-236.

- Garcia A, Mays S, Silapunt S. Metastatic neuroendocrine carcinoma in the skin. Dermatol Online J. 2017;23:13030/qt9052w9x1.

- Ciliberti MP, Carbonara R, Grillo A, et al. Unexpected response to palliative radiotherapy for subcutaneous metastases of an advanced small cell pancreatic neuroendocrine carcinoma: a case report of two different radiation schedules. BMC Cancer. 2020;20:311.

- Devnani B, Kumar R, Pathy S, et al. Cutaneous metastases from neuroendocrine carcinoma of the cervix: an unusual metastatic lesion from an uncommon malignancy. Curr Probl Cancer. 2018; 42:527-533.

- Falto-Aizpurua L, Seyfer S, Krishnan B, et al. Cutaneous metastasis of a pulmonary carcinoid tumor. Cutis. 2017;99:E13-E15.

- Dhingra R, Tse JY, Saif MW. Cutaneous metastasis of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (GEP-Nets)[published online September 8, 2018]. JOP. 2018;19.

- Jedrych J, Busam K, Klimstra DS, et al. Cutaneous metastases as an initial manifestation of visceral well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumor: a report of four cases and a review of literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2014;41:113-122.

- Lloyd RV. Practical markers used in the diagnosis of neuroendocrine tumors. Endocr Pathol. 2003;14:293-301.

- Stanoszek LM, Wang GY, Harms PW. Histologic mimics of basal cell carcinoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2017;141:1490-1502.

- Machado I, Llombart B, Calabuig-Fariñas S, et al. Superficial Ewing’s sarcoma family of tumors: a clinicopathological study with differential diagnoses. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:636-643.

- D’Cruze L, Dutta R, Rao S, et al. The role of immunohistochemistry in the analysis of the spectrum of small round cell tumours at a tertiary care centre. J Clin Diagn Res. 2013;7:1377-1382.

- Chirila DN, Turdeanu NA, Constantea NA, et al. Multiple malignant tumors. Chirurgia (Bucur). 2013;108:498-502.

- Rekhtman N. Neuroendocrine tumors of the lung: an update. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2010;134:1628-1638.

- Lin X, Saad RS, Luckasevic TM, et al. Diagnostic value of CDX-2 and TTF-1 expressions in separating metastatic neuroendocrine neoplasms of unknown origin. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2007;15:407-414.

- Olney JR, Urdaneta LF, Al-Jurf AS, et al. Carcinoid tumors of the gastrointestinal tract. Am Surg. 1985;51:37-41.

- Strosberg JR, Halfdanarson TR, Bellizzi AM, et al. The North American Neuroendocrine Tumor Society consensus guidelines for surveillance and medical management of midgut neuroendocrine tumors. Pancreas. 2017;46:707-714.

- Modlin IM, Lye KD, Kidd M. A 5-decade analysis of 13,715 carcinoid tumors. Cancer. 2003;97:934-959.

- Lawrence B, Gustafsson BI, Chan A, et al. The epidemiology of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2011;40:1-18, vii.

- Sabir S, James WD, Schuchter LM. Cutaneous manifestations of cancer. Curr Opin Oncol. 1999;11:139-144.

- Tomassetti P. Clinical aspects of carcinoid tumours. Italian J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1999;31(suppl 2):S143-S146.

- Bell HK, Poston GJ, Vora J, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of the malignant carcinoid syndrome. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152:71-75.

- Lookingbill DP, Spangler N, Helm KF. Cutaneous metastases in patients with metastatic carcinoma: a retrospective study of 4020 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29(2 pt 1):228-236.

- Garcia A, Mays S, Silapunt S. Metastatic neuroendocrine carcinoma in the skin. Dermatol Online J. 2017;23:13030/qt9052w9x1.

- Ciliberti MP, Carbonara R, Grillo A, et al. Unexpected response to palliative radiotherapy for subcutaneous metastases of an advanced small cell pancreatic neuroendocrine carcinoma: a case report of two different radiation schedules. BMC Cancer. 2020;20:311.

- Devnani B, Kumar R, Pathy S, et al. Cutaneous metastases from neuroendocrine carcinoma of the cervix: an unusual metastatic lesion from an uncommon malignancy. Curr Probl Cancer. 2018; 42:527-533.

- Falto-Aizpurua L, Seyfer S, Krishnan B, et al. Cutaneous metastasis of a pulmonary carcinoid tumor. Cutis. 2017;99:E13-E15.

- Dhingra R, Tse JY, Saif MW. Cutaneous metastasis of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (GEP-Nets)[published online September 8, 2018]. JOP. 2018;19.

- Jedrych J, Busam K, Klimstra DS, et al. Cutaneous metastases as an initial manifestation of visceral well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumor: a report of four cases and a review of literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2014;41:113-122.

- Lloyd RV. Practical markers used in the diagnosis of neuroendocrine tumors. Endocr Pathol. 2003;14:293-301.

- Stanoszek LM, Wang GY, Harms PW. Histologic mimics of basal cell carcinoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2017;141:1490-1502.

- Machado I, Llombart B, Calabuig-Fariñas S, et al. Superficial Ewing’s sarcoma family of tumors: a clinicopathological study with differential diagnoses. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:636-643.

- D’Cruze L, Dutta R, Rao S, et al. The role of immunohistochemistry in the analysis of the spectrum of small round cell tumours at a tertiary care centre. J Clin Diagn Res. 2013;7:1377-1382.

- Chirila DN, Turdeanu NA, Constantea NA, et al. Multiple malignant tumors. Chirurgia (Bucur). 2013;108:498-502.

- Rekhtman N. Neuroendocrine tumors of the lung: an update. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2010;134:1628-1638.

- Lin X, Saad RS, Luckasevic TM, et al. Diagnostic value of CDX-2 and TTF-1 expressions in separating metastatic neuroendocrine neoplasms of unknown origin. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2007;15:407-414.

- Olney JR, Urdaneta LF, Al-Jurf AS, et al. Carcinoid tumors of the gastrointestinal tract. Am Surg. 1985;51:37-41.

- Strosberg JR, Halfdanarson TR, Bellizzi AM, et al. The North American Neuroendocrine Tumor Society consensus guidelines for surveillance and medical management of midgut neuroendocrine tumors. Pancreas. 2017;46:707-714.

A 47-year-old woman was admitted to the hospital with abdominal pain and flushing. She had a history of a midgut carcinoid that originated in the ileum with metastasis to the colon, liver, and pancreas. Dermatologic examination revealed a firm, nontender, mobile, 7-mm scalp nodule with a pink-purple overlying epidermis. The lesion was associated with a slight decrease in hair density. A 4-mm punch biopsy was performed.

Physicians speak out: Why they love or hate incentive bonuses

Incentive bonuses have long been part and parcel of many physicians’ compensation packages. They allow doctors in some specialties to boost their compensation by tens of thousands of dollars.

Often tied to metrics that doctors must hit,

A recent Medscape poll asked what physicians think about incentive bonuses and whether or not tying metrics to salary is an outdated practice that interferes with the integrity of a physician’s job or contributes to excellence in patient care and increased productivity.

Here is what 406 physicians who answered the poll, which ran from Aug. 17 to Sept. 1, had to say about incentive bonuses:

More than half the physicians polled (58%) received an incentive bonus in 2021. Of those who received a bonus, 44% received up to $25,000. Almost 30% received $25,001-$50,000 in incentive bonus money. Only 14% received more than $100,000.

When we asked physicians which metrics they prefer their bonus to be based on, a large majority (64%) agreed quality of care was most relevant. Other metrics that respondents think appropriate included professionalism (40%), patient outcomes (40%), patient satisfaction (34%), patient volume (26%), market expansion (7%), and other (3%).

The problem with bonuses

Once thought to improve quality and consistency of care, incentive bonuses may be falling out of favor. Developing, administrating, and tracking them may be cumbersome for the institutions that advocate for them. For instance, determining who gave quality care and how to measure that care can be difficult.

What’s more, some top health care employers, Mayo Clinic and Kaiser Permanente, have switched from the incentive bonus model to straight salaries. Data show that the number of tests patients have and the number of treatments they try decreases when doctors receive straight salaries.

In fact, 74% of the polled physicians think that bonuses can result in consequences like unnecessary tests and higher patient costs. Three-fourths of respondents don’t think incentives improve patient care either.

Physicians have long thought incentive bonuses can also have unintended consequences. For example, tying a physician’s monetary reward to metrics such as patient outcomes, like adherence to treatment protocols, may mean that noncompliant patients can jeopardize your metrics and prevent physicians from getting bonuses.

A Merritt Hawkins’ 2019 Review of Physician and Advanced Practitioner Recruiting Incentives found that 56% of bonuses are based in whole or in part on metrics like a patient’s adherence.

Additionally, tying monetary rewards to patient volume encourages some physicians to overbook patients, work more and longer hours, and risk burnout to meet their bonus criteria.

When we asked how hard it was to meet metrics in the Medscape poll, 45% of respondents who receive incentive bonuses said it was somewhat or very difficult. Only 9% consider it very easy. And 71% of physicians say their bonus is at risk because of not meeting their metrics.

Not surprisingly, large pay-for-performance bonuses are only offered to certain specialists and physician specialties in high demand. An orthopedist, for example, can earn up to an average of $126,000 in incentive bonuses, while a pediatrician brings in an average of $28,000, according to the Medscape Physician Compensation Report 2022.

Yet physicians are still torn

Despite these negatives, physicians are split about whether bonuses are good for doctors. The poll shows 51% said no, and 49% said yes. Further, physicians were split 50-50 on whether the bonus makes physicians more productive. Interestingly though, 76% think the bonus compensation method should be phased out in favor of straight salaries.

But many physicians may welcome the “lump sum” nature of receiving large bonuses at certain times of the year to help pay off student loan debt or other expenses, or are just comfortable having a bonus.

Financially speaking

If you have the choice, you may fare better by taking a higher salary and eliminating a bonus. Receiving your pay throughout the year may be preferable to receiving large lump sums only at certain times. Another thing to remember about your incentive bonus is that they are sometimes taxed more heavily based on “supplemental income.” The IRS considers bonuses supplemental to your income, so they may have a higher withholding rate, which can feel penalizing. You may have noticed the extra withholding in your last bonus check.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Incentive bonuses have long been part and parcel of many physicians’ compensation packages. They allow doctors in some specialties to boost their compensation by tens of thousands of dollars.

Often tied to metrics that doctors must hit,

A recent Medscape poll asked what physicians think about incentive bonuses and whether or not tying metrics to salary is an outdated practice that interferes with the integrity of a physician’s job or contributes to excellence in patient care and increased productivity.

Here is what 406 physicians who answered the poll, which ran from Aug. 17 to Sept. 1, had to say about incentive bonuses:

More than half the physicians polled (58%) received an incentive bonus in 2021. Of those who received a bonus, 44% received up to $25,000. Almost 30% received $25,001-$50,000 in incentive bonus money. Only 14% received more than $100,000.

When we asked physicians which metrics they prefer their bonus to be based on, a large majority (64%) agreed quality of care was most relevant. Other metrics that respondents think appropriate included professionalism (40%), patient outcomes (40%), patient satisfaction (34%), patient volume (26%), market expansion (7%), and other (3%).

The problem with bonuses

Once thought to improve quality and consistency of care, incentive bonuses may be falling out of favor. Developing, administrating, and tracking them may be cumbersome for the institutions that advocate for them. For instance, determining who gave quality care and how to measure that care can be difficult.

What’s more, some top health care employers, Mayo Clinic and Kaiser Permanente, have switched from the incentive bonus model to straight salaries. Data show that the number of tests patients have and the number of treatments they try decreases when doctors receive straight salaries.

In fact, 74% of the polled physicians think that bonuses can result in consequences like unnecessary tests and higher patient costs. Three-fourths of respondents don’t think incentives improve patient care either.

Physicians have long thought incentive bonuses can also have unintended consequences. For example, tying a physician’s monetary reward to metrics such as patient outcomes, like adherence to treatment protocols, may mean that noncompliant patients can jeopardize your metrics and prevent physicians from getting bonuses.

A Merritt Hawkins’ 2019 Review of Physician and Advanced Practitioner Recruiting Incentives found that 56% of bonuses are based in whole or in part on metrics like a patient’s adherence.

Additionally, tying monetary rewards to patient volume encourages some physicians to overbook patients, work more and longer hours, and risk burnout to meet their bonus criteria.

When we asked how hard it was to meet metrics in the Medscape poll, 45% of respondents who receive incentive bonuses said it was somewhat or very difficult. Only 9% consider it very easy. And 71% of physicians say their bonus is at risk because of not meeting their metrics.

Not surprisingly, large pay-for-performance bonuses are only offered to certain specialists and physician specialties in high demand. An orthopedist, for example, can earn up to an average of $126,000 in incentive bonuses, while a pediatrician brings in an average of $28,000, according to the Medscape Physician Compensation Report 2022.

Yet physicians are still torn

Despite these negatives, physicians are split about whether bonuses are good for doctors. The poll shows 51% said no, and 49% said yes. Further, physicians were split 50-50 on whether the bonus makes physicians more productive. Interestingly though, 76% think the bonus compensation method should be phased out in favor of straight salaries.

But many physicians may welcome the “lump sum” nature of receiving large bonuses at certain times of the year to help pay off student loan debt or other expenses, or are just comfortable having a bonus.

Financially speaking

If you have the choice, you may fare better by taking a higher salary and eliminating a bonus. Receiving your pay throughout the year may be preferable to receiving large lump sums only at certain times. Another thing to remember about your incentive bonus is that they are sometimes taxed more heavily based on “supplemental income.” The IRS considers bonuses supplemental to your income, so they may have a higher withholding rate, which can feel penalizing. You may have noticed the extra withholding in your last bonus check.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Incentive bonuses have long been part and parcel of many physicians’ compensation packages. They allow doctors in some specialties to boost their compensation by tens of thousands of dollars.

Often tied to metrics that doctors must hit,

A recent Medscape poll asked what physicians think about incentive bonuses and whether or not tying metrics to salary is an outdated practice that interferes with the integrity of a physician’s job or contributes to excellence in patient care and increased productivity.

Here is what 406 physicians who answered the poll, which ran from Aug. 17 to Sept. 1, had to say about incentive bonuses:

More than half the physicians polled (58%) received an incentive bonus in 2021. Of those who received a bonus, 44% received up to $25,000. Almost 30% received $25,001-$50,000 in incentive bonus money. Only 14% received more than $100,000.

When we asked physicians which metrics they prefer their bonus to be based on, a large majority (64%) agreed quality of care was most relevant. Other metrics that respondents think appropriate included professionalism (40%), patient outcomes (40%), patient satisfaction (34%), patient volume (26%), market expansion (7%), and other (3%).

The problem with bonuses

Once thought to improve quality and consistency of care, incentive bonuses may be falling out of favor. Developing, administrating, and tracking them may be cumbersome for the institutions that advocate for them. For instance, determining who gave quality care and how to measure that care can be difficult.

What’s more, some top health care employers, Mayo Clinic and Kaiser Permanente, have switched from the incentive bonus model to straight salaries. Data show that the number of tests patients have and the number of treatments they try decreases when doctors receive straight salaries.

In fact, 74% of the polled physicians think that bonuses can result in consequences like unnecessary tests and higher patient costs. Three-fourths of respondents don’t think incentives improve patient care either.

Physicians have long thought incentive bonuses can also have unintended consequences. For example, tying a physician’s monetary reward to metrics such as patient outcomes, like adherence to treatment protocols, may mean that noncompliant patients can jeopardize your metrics and prevent physicians from getting bonuses.

A Merritt Hawkins’ 2019 Review of Physician and Advanced Practitioner Recruiting Incentives found that 56% of bonuses are based in whole or in part on metrics like a patient’s adherence.

Additionally, tying monetary rewards to patient volume encourages some physicians to overbook patients, work more and longer hours, and risk burnout to meet their bonus criteria.

When we asked how hard it was to meet metrics in the Medscape poll, 45% of respondents who receive incentive bonuses said it was somewhat or very difficult. Only 9% consider it very easy. And 71% of physicians say their bonus is at risk because of not meeting their metrics.

Not surprisingly, large pay-for-performance bonuses are only offered to certain specialists and physician specialties in high demand. An orthopedist, for example, can earn up to an average of $126,000 in incentive bonuses, while a pediatrician brings in an average of $28,000, according to the Medscape Physician Compensation Report 2022.

Yet physicians are still torn

Despite these negatives, physicians are split about whether bonuses are good for doctors. The poll shows 51% said no, and 49% said yes. Further, physicians were split 50-50 on whether the bonus makes physicians more productive. Interestingly though, 76% think the bonus compensation method should be phased out in favor of straight salaries.

But many physicians may welcome the “lump sum” nature of receiving large bonuses at certain times of the year to help pay off student loan debt or other expenses, or are just comfortable having a bonus.

Financially speaking

If you have the choice, you may fare better by taking a higher salary and eliminating a bonus. Receiving your pay throughout the year may be preferable to receiving large lump sums only at certain times. Another thing to remember about your incentive bonus is that they are sometimes taxed more heavily based on “supplemental income.” The IRS considers bonuses supplemental to your income, so they may have a higher withholding rate, which can feel penalizing. You may have noticed the extra withholding in your last bonus check.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Three COVID scenarios that could spell trouble for the fall

As the United States enters a third fall with COVID-19, the virus for many is seemingly gone – or at least out of mind. But for those keeping watch, it is far from forgotten as deaths and infections continue to mount at a lower but steady pace.

What does that mean for the upcoming months? Experts predict different scenarios, some more dire than others – with one more encouraging.

In the United States, more than 300 people still die every day from COVID and more than 44,000 new daily cases are reported, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

But progress is undeniable. The stark daily death tolls of 2020 have plummeted. Vaccines and treatments have dramatically reduced severe illness, and mask requirements have mostly turned to personal preference.

among them more-resistant variants coupled with waning immunity, the potential for a “twindemic” with a flu/COVID onslaught, and underuse of lifesaving vaccines and treatments.

Variants loom/waning immunity

Omicron variant BA.5 still makes up about 80% of infections in the United States, followed by BA4.6, according to the CDC, but other subvariants are emerging and showing signs of resistance to current antiviral treatments.

Eric Topol, MD, founder and director of the Scripps Research Translational Institute in San Diego, said about COVID this fall: “There will be another wave, magnitude unknown.”

He said subvariants XBB and BQ.1.1 “have extreme levels of immune evasion and both could pose a challenge,” explaining that XBB is more likely to cause trouble than BQ.1.1 because it is even more resistant to natural or vaccine-induced immunity.

Dr. Topol pointed to new research on those variants in a preprint posted on bioRxiv. The authors’ conclusion: “These results suggest that current herd immunity and BA.5 vaccine boosters may not provide sufficiently broad protection against infection.”

Another variant to watch, some experts say, is Omicron subvariant BA.2.75.2, which has shown resistance to antiviral treatments. It is also growing at a rather alarming rate, says Michael Sweat, PhD, director of the Medical University of South Carolina Center for Global Health in Charleston. That subvariant currently makes up under 2% of U.S. cases but has spread to at least 55 countries and 43 U.S. states after first appearing at the end of last year globally and in mid-June in the United States.

A non–peer-reviewed preprint study from Sweden found that the variant in blood samples was neutralized on average “at titers approximately 6.5 times lower than BA.5, making BA.2.75.2 the most [neutralization-resistant] variant evaluated to date.”

Katelyn Jetelina, PhD, assistant professor in the department of epidemiology at University of Texas Health Science Center, Houston, said in an interview the U.S. waves often follow Europe’s, and Europe has seen a recent spike in cases and hospitalizations not related to Omicron subvariants, but to weather changes, waning immunity, and changes in behavior.

The World Health Organization reported on Oct. 5 that, while cases were down in every other region of the world, Europe’s numbers stand out, with an 8% increase in cases from the week before.

Dr. Jetelina cited events such as Oktoberfest in Germany, which ended in the first week of October after drawing nearly 6 million people over 2 weeks, as a potential contributor, and people heading indoors as weather patterns change in Europe.

Ali Mokdad, PhD, chief strategy officer for population health at the University of Washington, Seattle, said in an interview he is less worried about the documented variants we know about than he is about the potential for a new immune-escape variety yet to emerge.

“Right now we know the Chinese are gearing up to open up the country, and because they have low immunity and little infection, we expect in China there will be a lot of spread of Omicron,” he said. “It’s possible because of the number of infections we could see a new variant.”

Dr. Mokdad said waning immunity could also leave populations vulnerable to variants.

“Even if you get infected, after about 5 months, you’re susceptible again. Remember, most of the infections from Omicron happened in January or February 2022, and we had two waves after that,” he said.

The new bivalent vaccines tweaked to target some Omicron variants will help, Dr. Mokdad said, but he noted, “people are very reluctant to take it.”

Jennifer Nuzzo, DrPH, professor of epidemiology and director of the Pandemic Center at Brown University, Providence, R.I., worries that in the United States we have less ability this year to track variants as funding has receded for testing kits and testing sites. Most people are testing at home – which doesn’t show up in the numbers – and the United States is relying more on other countries’ data to spot trends.

“I think we’re just going to have less visibility into the circulation of this virus,” she said in an interview.

‘Twindemic’: COVID and flu

Dr. Jetelina noted Australia and New Zealand just wrapped up a flu season that saw flu numbers returning to normal after a sharp drop in the last 2 years, and North America typically follows suit.

“We do expect flu will be here in the United States and probably at levels that we saw prepandemic. We’re all holding our breath to see how our health systems hold up with COVID-19 and flu. We haven’t really experienced that yet,” she said.

There is some disagreement, however, about the possibility of a so-called “twindemic” of influenza and COVID.

Richard Webby, PhD, an infectious disease specialist at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis, said in an interview he thinks the possibility of both viruses spiking at the same time is unlikely.

“That’s not to say we won’t get flu and COVID activity in the same winter,” he explained, “but I think both roaring at the same time is unlikely.”

As an indicator, he said, at the beginning of the flu season last year in the Northern Hemisphere, flu activity started to pick up, but when the Omicron variant came along, “flu just wasn’t able to compete in that same environment and flu numbers dropped right off.” Previous literature suggests that when one virus is spiking it’s hard for another respiratory virus to take hold.

Vaccine, treatment underuse

Another threat is vaccines, boosters, and treatments sitting on shelves.

Dr. Sweat referred to frustration with vaccine uptake that seems to be “frozen in amber.”

As of Oct. 4, only 5.3% of people in the United States who were eligible had received the updated booster launched in early September.

Dr. Nuzzo said boosters for people at least 65 years old will be key to severity of COVID this season.

“I think that’s probably the biggest factor going into the fall and winter,” she said.

Only 38% of people at least 50 years old and 45% of those at least 65 years old had gotten a second booster as of early October.

“If we do nothing else, we have to increase booster uptake in that group,” Dr. Nuzzo said.

She said the treatment nirmatrelvir/ritonavir (Paxlovid, Pfizer) for treating mild to moderate COVID-19 in patients at high risk for severe disease is greatly underused, often because providers aren’t prescribing it because they don’t think it helps, are worried about drug interactions, or are worried about its “rebound” effect.

Dr. Nuzzo urged greater use of the drug and education on how to manage drug interactions.

“We have very strong data that it does help keep people out of hospital. Sure, there may be a rebound, but that pales in comparison to the risk of being hospitalized,” she said.

Calm COVID season?

Not all predictions are dire. There is another little-talked-about scenario, Dr. Sweat said – that we could be in for a calm COVID season, and those who seem to be only mildly concerned about COVID may find those thoughts justified in the numbers.

Omicron blew through with such strength, he noted, that it may have left wide immunity in its wake. Because variants seem to be staying in the Omicron family, that may signal optimism.

“If the next variant is a descendant of the Omicron lineage, I would suspect that all these people who just got infected will have some protection, not perfect, but quite a bit of protection,” Dr. Sweat said.

Dr. Topol, Dr. Nuzzo, Dr. Sweat, Dr. Webby, Dr. Mokdad, and Dr. Jetelina reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

As the United States enters a third fall with COVID-19, the virus for many is seemingly gone – or at least out of mind. But for those keeping watch, it is far from forgotten as deaths and infections continue to mount at a lower but steady pace.

What does that mean for the upcoming months? Experts predict different scenarios, some more dire than others – with one more encouraging.

In the United States, more than 300 people still die every day from COVID and more than 44,000 new daily cases are reported, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

But progress is undeniable. The stark daily death tolls of 2020 have plummeted. Vaccines and treatments have dramatically reduced severe illness, and mask requirements have mostly turned to personal preference.

among them more-resistant variants coupled with waning immunity, the potential for a “twindemic” with a flu/COVID onslaught, and underuse of lifesaving vaccines and treatments.

Variants loom/waning immunity

Omicron variant BA.5 still makes up about 80% of infections in the United States, followed by BA4.6, according to the CDC, but other subvariants are emerging and showing signs of resistance to current antiviral treatments.

Eric Topol, MD, founder and director of the Scripps Research Translational Institute in San Diego, said about COVID this fall: “There will be another wave, magnitude unknown.”

He said subvariants XBB and BQ.1.1 “have extreme levels of immune evasion and both could pose a challenge,” explaining that XBB is more likely to cause trouble than BQ.1.1 because it is even more resistant to natural or vaccine-induced immunity.

Dr. Topol pointed to new research on those variants in a preprint posted on bioRxiv. The authors’ conclusion: “These results suggest that current herd immunity and BA.5 vaccine boosters may not provide sufficiently broad protection against infection.”

Another variant to watch, some experts say, is Omicron subvariant BA.2.75.2, which has shown resistance to antiviral treatments. It is also growing at a rather alarming rate, says Michael Sweat, PhD, director of the Medical University of South Carolina Center for Global Health in Charleston. That subvariant currently makes up under 2% of U.S. cases but has spread to at least 55 countries and 43 U.S. states after first appearing at the end of last year globally and in mid-June in the United States.

A non–peer-reviewed preprint study from Sweden found that the variant in blood samples was neutralized on average “at titers approximately 6.5 times lower than BA.5, making BA.2.75.2 the most [neutralization-resistant] variant evaluated to date.”

Katelyn Jetelina, PhD, assistant professor in the department of epidemiology at University of Texas Health Science Center, Houston, said in an interview the U.S. waves often follow Europe’s, and Europe has seen a recent spike in cases and hospitalizations not related to Omicron subvariants, but to weather changes, waning immunity, and changes in behavior.

The World Health Organization reported on Oct. 5 that, while cases were down in every other region of the world, Europe’s numbers stand out, with an 8% increase in cases from the week before.

Dr. Jetelina cited events such as Oktoberfest in Germany, which ended in the first week of October after drawing nearly 6 million people over 2 weeks, as a potential contributor, and people heading indoors as weather patterns change in Europe.

Ali Mokdad, PhD, chief strategy officer for population health at the University of Washington, Seattle, said in an interview he is less worried about the documented variants we know about than he is about the potential for a new immune-escape variety yet to emerge.

“Right now we know the Chinese are gearing up to open up the country, and because they have low immunity and little infection, we expect in China there will be a lot of spread of Omicron,” he said. “It’s possible because of the number of infections we could see a new variant.”

Dr. Mokdad said waning immunity could also leave populations vulnerable to variants.

“Even if you get infected, after about 5 months, you’re susceptible again. Remember, most of the infections from Omicron happened in January or February 2022, and we had two waves after that,” he said.

The new bivalent vaccines tweaked to target some Omicron variants will help, Dr. Mokdad said, but he noted, “people are very reluctant to take it.”

Jennifer Nuzzo, DrPH, professor of epidemiology and director of the Pandemic Center at Brown University, Providence, R.I., worries that in the United States we have less ability this year to track variants as funding has receded for testing kits and testing sites. Most people are testing at home – which doesn’t show up in the numbers – and the United States is relying more on other countries’ data to spot trends.

“I think we’re just going to have less visibility into the circulation of this virus,” she said in an interview.

‘Twindemic’: COVID and flu

Dr. Jetelina noted Australia and New Zealand just wrapped up a flu season that saw flu numbers returning to normal after a sharp drop in the last 2 years, and North America typically follows suit.

“We do expect flu will be here in the United States and probably at levels that we saw prepandemic. We’re all holding our breath to see how our health systems hold up with COVID-19 and flu. We haven’t really experienced that yet,” she said.

There is some disagreement, however, about the possibility of a so-called “twindemic” of influenza and COVID.

Richard Webby, PhD, an infectious disease specialist at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis, said in an interview he thinks the possibility of both viruses spiking at the same time is unlikely.

“That’s not to say we won’t get flu and COVID activity in the same winter,” he explained, “but I think both roaring at the same time is unlikely.”

As an indicator, he said, at the beginning of the flu season last year in the Northern Hemisphere, flu activity started to pick up, but when the Omicron variant came along, “flu just wasn’t able to compete in that same environment and flu numbers dropped right off.” Previous literature suggests that when one virus is spiking it’s hard for another respiratory virus to take hold.

Vaccine, treatment underuse

Another threat is vaccines, boosters, and treatments sitting on shelves.

Dr. Sweat referred to frustration with vaccine uptake that seems to be “frozen in amber.”

As of Oct. 4, only 5.3% of people in the United States who were eligible had received the updated booster launched in early September.

Dr. Nuzzo said boosters for people at least 65 years old will be key to severity of COVID this season.

“I think that’s probably the biggest factor going into the fall and winter,” she said.

Only 38% of people at least 50 years old and 45% of those at least 65 years old had gotten a second booster as of early October.

“If we do nothing else, we have to increase booster uptake in that group,” Dr. Nuzzo said.

She said the treatment nirmatrelvir/ritonavir (Paxlovid, Pfizer) for treating mild to moderate COVID-19 in patients at high risk for severe disease is greatly underused, often because providers aren’t prescribing it because they don’t think it helps, are worried about drug interactions, or are worried about its “rebound” effect.

Dr. Nuzzo urged greater use of the drug and education on how to manage drug interactions.

“We have very strong data that it does help keep people out of hospital. Sure, there may be a rebound, but that pales in comparison to the risk of being hospitalized,” she said.

Calm COVID season?

Not all predictions are dire. There is another little-talked-about scenario, Dr. Sweat said – that we could be in for a calm COVID season, and those who seem to be only mildly concerned about COVID may find those thoughts justified in the numbers.

Omicron blew through with such strength, he noted, that it may have left wide immunity in its wake. Because variants seem to be staying in the Omicron family, that may signal optimism.

“If the next variant is a descendant of the Omicron lineage, I would suspect that all these people who just got infected will have some protection, not perfect, but quite a bit of protection,” Dr. Sweat said.

Dr. Topol, Dr. Nuzzo, Dr. Sweat, Dr. Webby, Dr. Mokdad, and Dr. Jetelina reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

As the United States enters a third fall with COVID-19, the virus for many is seemingly gone – or at least out of mind. But for those keeping watch, it is far from forgotten as deaths and infections continue to mount at a lower but steady pace.

What does that mean for the upcoming months? Experts predict different scenarios, some more dire than others – with one more encouraging.

In the United States, more than 300 people still die every day from COVID and more than 44,000 new daily cases are reported, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

But progress is undeniable. The stark daily death tolls of 2020 have plummeted. Vaccines and treatments have dramatically reduced severe illness, and mask requirements have mostly turned to personal preference.

among them more-resistant variants coupled with waning immunity, the potential for a “twindemic” with a flu/COVID onslaught, and underuse of lifesaving vaccines and treatments.

Variants loom/waning immunity

Omicron variant BA.5 still makes up about 80% of infections in the United States, followed by BA4.6, according to the CDC, but other subvariants are emerging and showing signs of resistance to current antiviral treatments.

Eric Topol, MD, founder and director of the Scripps Research Translational Institute in San Diego, said about COVID this fall: “There will be another wave, magnitude unknown.”

He said subvariants XBB and BQ.1.1 “have extreme levels of immune evasion and both could pose a challenge,” explaining that XBB is more likely to cause trouble than BQ.1.1 because it is even more resistant to natural or vaccine-induced immunity.

Dr. Topol pointed to new research on those variants in a preprint posted on bioRxiv. The authors’ conclusion: “These results suggest that current herd immunity and BA.5 vaccine boosters may not provide sufficiently broad protection against infection.”

Another variant to watch, some experts say, is Omicron subvariant BA.2.75.2, which has shown resistance to antiviral treatments. It is also growing at a rather alarming rate, says Michael Sweat, PhD, director of the Medical University of South Carolina Center for Global Health in Charleston. That subvariant currently makes up under 2% of U.S. cases but has spread to at least 55 countries and 43 U.S. states after first appearing at the end of last year globally and in mid-June in the United States.

A non–peer-reviewed preprint study from Sweden found that the variant in blood samples was neutralized on average “at titers approximately 6.5 times lower than BA.5, making BA.2.75.2 the most [neutralization-resistant] variant evaluated to date.”

Katelyn Jetelina, PhD, assistant professor in the department of epidemiology at University of Texas Health Science Center, Houston, said in an interview the U.S. waves often follow Europe’s, and Europe has seen a recent spike in cases and hospitalizations not related to Omicron subvariants, but to weather changes, waning immunity, and changes in behavior.

The World Health Organization reported on Oct. 5 that, while cases were down in every other region of the world, Europe’s numbers stand out, with an 8% increase in cases from the week before.

Dr. Jetelina cited events such as Oktoberfest in Germany, which ended in the first week of October after drawing nearly 6 million people over 2 weeks, as a potential contributor, and people heading indoors as weather patterns change in Europe.

Ali Mokdad, PhD, chief strategy officer for population health at the University of Washington, Seattle, said in an interview he is less worried about the documented variants we know about than he is about the potential for a new immune-escape variety yet to emerge.

“Right now we know the Chinese are gearing up to open up the country, and because they have low immunity and little infection, we expect in China there will be a lot of spread of Omicron,” he said. “It’s possible because of the number of infections we could see a new variant.”

Dr. Mokdad said waning immunity could also leave populations vulnerable to variants.

“Even if you get infected, after about 5 months, you’re susceptible again. Remember, most of the infections from Omicron happened in January or February 2022, and we had two waves after that,” he said.

The new bivalent vaccines tweaked to target some Omicron variants will help, Dr. Mokdad said, but he noted, “people are very reluctant to take it.”

Jennifer Nuzzo, DrPH, professor of epidemiology and director of the Pandemic Center at Brown University, Providence, R.I., worries that in the United States we have less ability this year to track variants as funding has receded for testing kits and testing sites. Most people are testing at home – which doesn’t show up in the numbers – and the United States is relying more on other countries’ data to spot trends.

“I think we’re just going to have less visibility into the circulation of this virus,” she said in an interview.

‘Twindemic’: COVID and flu

Dr. Jetelina noted Australia and New Zealand just wrapped up a flu season that saw flu numbers returning to normal after a sharp drop in the last 2 years, and North America typically follows suit.

“We do expect flu will be here in the United States and probably at levels that we saw prepandemic. We’re all holding our breath to see how our health systems hold up with COVID-19 and flu. We haven’t really experienced that yet,” she said.

There is some disagreement, however, about the possibility of a so-called “twindemic” of influenza and COVID.

Richard Webby, PhD, an infectious disease specialist at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis, said in an interview he thinks the possibility of both viruses spiking at the same time is unlikely.

“That’s not to say we won’t get flu and COVID activity in the same winter,” he explained, “but I think both roaring at the same time is unlikely.”

As an indicator, he said, at the beginning of the flu season last year in the Northern Hemisphere, flu activity started to pick up, but when the Omicron variant came along, “flu just wasn’t able to compete in that same environment and flu numbers dropped right off.” Previous literature suggests that when one virus is spiking it’s hard for another respiratory virus to take hold.

Vaccine, treatment underuse

Another threat is vaccines, boosters, and treatments sitting on shelves.

Dr. Sweat referred to frustration with vaccine uptake that seems to be “frozen in amber.”

As of Oct. 4, only 5.3% of people in the United States who were eligible had received the updated booster launched in early September.

Dr. Nuzzo said boosters for people at least 65 years old will be key to severity of COVID this season.

“I think that’s probably the biggest factor going into the fall and winter,” she said.

Only 38% of people at least 50 years old and 45% of those at least 65 years old had gotten a second booster as of early October.

“If we do nothing else, we have to increase booster uptake in that group,” Dr. Nuzzo said.

She said the treatment nirmatrelvir/ritonavir (Paxlovid, Pfizer) for treating mild to moderate COVID-19 in patients at high risk for severe disease is greatly underused, often because providers aren’t prescribing it because they don’t think it helps, are worried about drug interactions, or are worried about its “rebound” effect.

Dr. Nuzzo urged greater use of the drug and education on how to manage drug interactions.

“We have very strong data that it does help keep people out of hospital. Sure, there may be a rebound, but that pales in comparison to the risk of being hospitalized,” she said.

Calm COVID season?

Not all predictions are dire. There is another little-talked-about scenario, Dr. Sweat said – that we could be in for a calm COVID season, and those who seem to be only mildly concerned about COVID may find those thoughts justified in the numbers.

Omicron blew through with such strength, he noted, that it may have left wide immunity in its wake. Because variants seem to be staying in the Omicron family, that may signal optimism.

“If the next variant is a descendant of the Omicron lineage, I would suspect that all these people who just got infected will have some protection, not perfect, but quite a bit of protection,” Dr. Sweat said.

Dr. Topol, Dr. Nuzzo, Dr. Sweat, Dr. Webby, Dr. Mokdad, and Dr. Jetelina reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Dupilumab study outlines benefits, safety profile in infants, preschoolers with atopic dermatitis

at 31 treatment centers in North America and Europe.

Children younger than 6 years with moderate to severe AD have few options if their symptoms are uncontrolled with topical therapies, and persistent itchiness has a negative impact on quality of life for patients and families, Amy S. Paller, MD, professor and chair of dermatology, and professor of pediatrics at Northwestern University, Chicago, and colleagues wrote in the study, published in the Lancet.

The study was the basis of the Food and Drug Administration expanded approval of dupilumab in June 2022, to include children aged 6 months to 5 years with moderate to severe AD, whose disease is not adequately controlled with topical prescription therapies or when those therapies are not advisable. Regulatory submission for this age group is under review by the European Medicines Agency, and by regulatory authorities in other countries, according to the manufacturers.

Dupilumab (Dupixent), which inhibits the signaling of the interleukin-4 and IL-13 pathways, was first approved in 2017 for treating adults with moderate to severe AD.

“There has not been a biologic approved before at such a young age, and for such a common disease,” Dr. Paller said in an interview. “This is the drug that has revolutionized care of the most common inflammatory skin disease in children, and this is the pivotal study that brought it to market for the youngest children who suffer from the severe forms.”

The study also sets a precedent for a lower threshold for starting systemic medication in young children for treating moderate to severe disease given the absence of severe side effects and no need for lab monitoring, Dr. Paller noted. However, dupilumab will also be closely watched “for both impact on the developing immune system and the possibility that it will alter the long-term course of the eczema and the development of allergic comorbidities, such as lowering the risk of developing asthma, GI, allergy, and possibly other conditions.”

In the study, the researchers randomized 83 children aged 6 months up to 6 years to treatment with dupilumab, administered subcutaneously, and 79 to placebo every 4 weeks for 16 weeks; both groups also received topical corticosteroids. Dosage of dupilumab was based on body weight; those with a body weight of 5-15 kg received 200 mg, while those with a body weight of 15-30 kg received 300 mg. The primary endpoint was the proportion of patients with clear or almost clear skin at 16 weeks, defined as scores of 0 or 1 on the Investigator’s Global Assessment.

After 16 weeks, 28% of dupilumab patients met the primary endpoint versus 4% of those on placebo (P < .0001). In addition, 53% of dupilumab patients met the key secondary endpoint of a 75% improvement from baseline in Eczema Area and Severity Index, compared with 11% of patients on placebo (P < .0001). Treatment with dupilumab also resulted in significantly greater improvements in pruritus and skin pain, and sleep quality, as well as improved quality of life for patients and their caregivers, the authors reported.

Overall, adverse event rates were slightly lower in the dupilumab-treated patients, compared with patients on placebo (64% vs. 74%); there were no adverse events related to dupilumab that were serious or resulted in treatment discontinuation. Treatment-emergent adverse effects that were reported in 3% or more of patients and affected more of those on dupilumab than those on placebo included molluscum contagiosum (5% vs. 3%), viral gastroenteritis (4% vs. 0), rhinorrhea (5% vs. 1%), dental caries (5% vs. 0), and conjunctivitis (4% vs 0).

The rate of skin infections among the children on dupilumab was 12% vs. 24% among those on placebo.

Severe and treatment-related adverse events also were similar in both subgroups of body weight.

The findings were limited by the small number of patients younger than 2 years and the lack of study sites outside of North America and Europe, the researchers noted. However, the results were strengthened by the randomized, double-blind design and use of background topical therapy to provide a real-world safety and efficacy assessment in a very young population.

Overcoming injection issues

The safety profile for dupilumab, which is of the highest importance, “did not surprise me at all,” Dr. Paller said in an interview. “My only surprise is that the placebo injections actually led to more injection site reactions than [with] dupilumab, but numbers were quite low in both groups.” (Rates were 2% among those on dupilumab and 3% among those on placebo.)

The major barrier to the use of dupilumab in clinical practice is the requirement for injection, which, she explained, can be “unbearable for some young children, and thus becomes impossible for parents because of lack of cooperation and their intensified concern about giving the injection,” because of their child’s response.

“We like to administer the first dose in the office, allowing us to teach parents a few tricks related to proper technique,” including audio and visual distraction, tactile stimulation before and during the injection, use of topical anesthetic if helpful, “and making sure that the medication is at room temperature before administration,” she said. Cost is another potential barrier; however, even public insurance has been covering the medication, often after optimized use of topical medications has been unsuccessful.

Future research questions

As for additional research, the current study had a relatively small number of patients younger than 2 years, and more data are needed for this age group, said Dr. Paller. “We also need better understanding of the safety of dupilumab administration when live vaccines are administered. Finally, we certainly want to know what additional effects dupilumab may have beyond just the efficacy for treating eczema.”

In particular, these questions include whether dupilumab modifies the long-term course of the disease, possibly reducing the risk of persistence of disease with advancing age, or even cures the disease if started at a young age, she said. In addition, research has yet to show whether dupilumab might reduce the risk of other atopic disorders, such as asthma, food allergy, and allergic rhinitis.

“Ongoing studies and real-life experiences in the next several years will help us to answer these questions,” Dr. Paller said.

Data support safety, efficacy, quality of life

AD is associated with immense quality of life impairment, Raj Chovatiya, MD, of Northwestern University, Chicago, said in an interview. Most AD is initially diagnosed in early childhood, but previous treatment options for those with moderate to severe disease have been limited by safety concerns, which adds to the burden on infants and young children, and their parents and caregivers, said Dr. Chovatiya, who was not involved in the study.

“This phase 3 study showed that dupilumab, a fully human monoclonal antibody that selectively inhibits IL-4 and IL-13 mediated type 2 inflammatory signaling, provided both meaningful and statistically significant improvement in AD severity, extent of disease, and itch in patients,” he said. Dupilumab also improved children’s sleep quality and the overall quality of life in both patients and caregivers.

“These findings were quite similar to those described in older children and adults, where dupilumab is already approved for the treatment of moderate-severe AD and has demonstrated real-world safety and efficacy,” said Dr. Chovatiya. However, “the current study was limited to only a short-term analysis of 16 weeks, an ongoing open-label study should further address long-term treatment responses.”

The study was supported by Sanofi and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals. In addition to being an investigator for Regeneron, and several other pharmaceutical companies, Dr. Paller has been a consultant with honorarium for Regeneron, Sanofi, and multiple other companies. Dr. Chovatiya disclosed serving as a consultant and speaker for Regeneron and Sanofi, but was not involved in the current study.

at 31 treatment centers in North America and Europe.

Children younger than 6 years with moderate to severe AD have few options if their symptoms are uncontrolled with topical therapies, and persistent itchiness has a negative impact on quality of life for patients and families, Amy S. Paller, MD, professor and chair of dermatology, and professor of pediatrics at Northwestern University, Chicago, and colleagues wrote in the study, published in the Lancet.

The study was the basis of the Food and Drug Administration expanded approval of dupilumab in June 2022, to include children aged 6 months to 5 years with moderate to severe AD, whose disease is not adequately controlled with topical prescription therapies or when those therapies are not advisable. Regulatory submission for this age group is under review by the European Medicines Agency, and by regulatory authorities in other countries, according to the manufacturers.

Dupilumab (Dupixent), which inhibits the signaling of the interleukin-4 and IL-13 pathways, was first approved in 2017 for treating adults with moderate to severe AD.

“There has not been a biologic approved before at such a young age, and for such a common disease,” Dr. Paller said in an interview. “This is the drug that has revolutionized care of the most common inflammatory skin disease in children, and this is the pivotal study that brought it to market for the youngest children who suffer from the severe forms.”

The study also sets a precedent for a lower threshold for starting systemic medication in young children for treating moderate to severe disease given the absence of severe side effects and no need for lab monitoring, Dr. Paller noted. However, dupilumab will also be closely watched “for both impact on the developing immune system and the possibility that it will alter the long-term course of the eczema and the development of allergic comorbidities, such as lowering the risk of developing asthma, GI, allergy, and possibly other conditions.”

In the study, the researchers randomized 83 children aged 6 months up to 6 years to treatment with dupilumab, administered subcutaneously, and 79 to placebo every 4 weeks for 16 weeks; both groups also received topical corticosteroids. Dosage of dupilumab was based on body weight; those with a body weight of 5-15 kg received 200 mg, while those with a body weight of 15-30 kg received 300 mg. The primary endpoint was the proportion of patients with clear or almost clear skin at 16 weeks, defined as scores of 0 or 1 on the Investigator’s Global Assessment.

After 16 weeks, 28% of dupilumab patients met the primary endpoint versus 4% of those on placebo (P < .0001). In addition, 53% of dupilumab patients met the key secondary endpoint of a 75% improvement from baseline in Eczema Area and Severity Index, compared with 11% of patients on placebo (P < .0001). Treatment with dupilumab also resulted in significantly greater improvements in pruritus and skin pain, and sleep quality, as well as improved quality of life for patients and their caregivers, the authors reported.