User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

Margin Size for Unique Skin Tumors Treated With Mohs Micrographic Surgery: A Survey of Practice Patterns

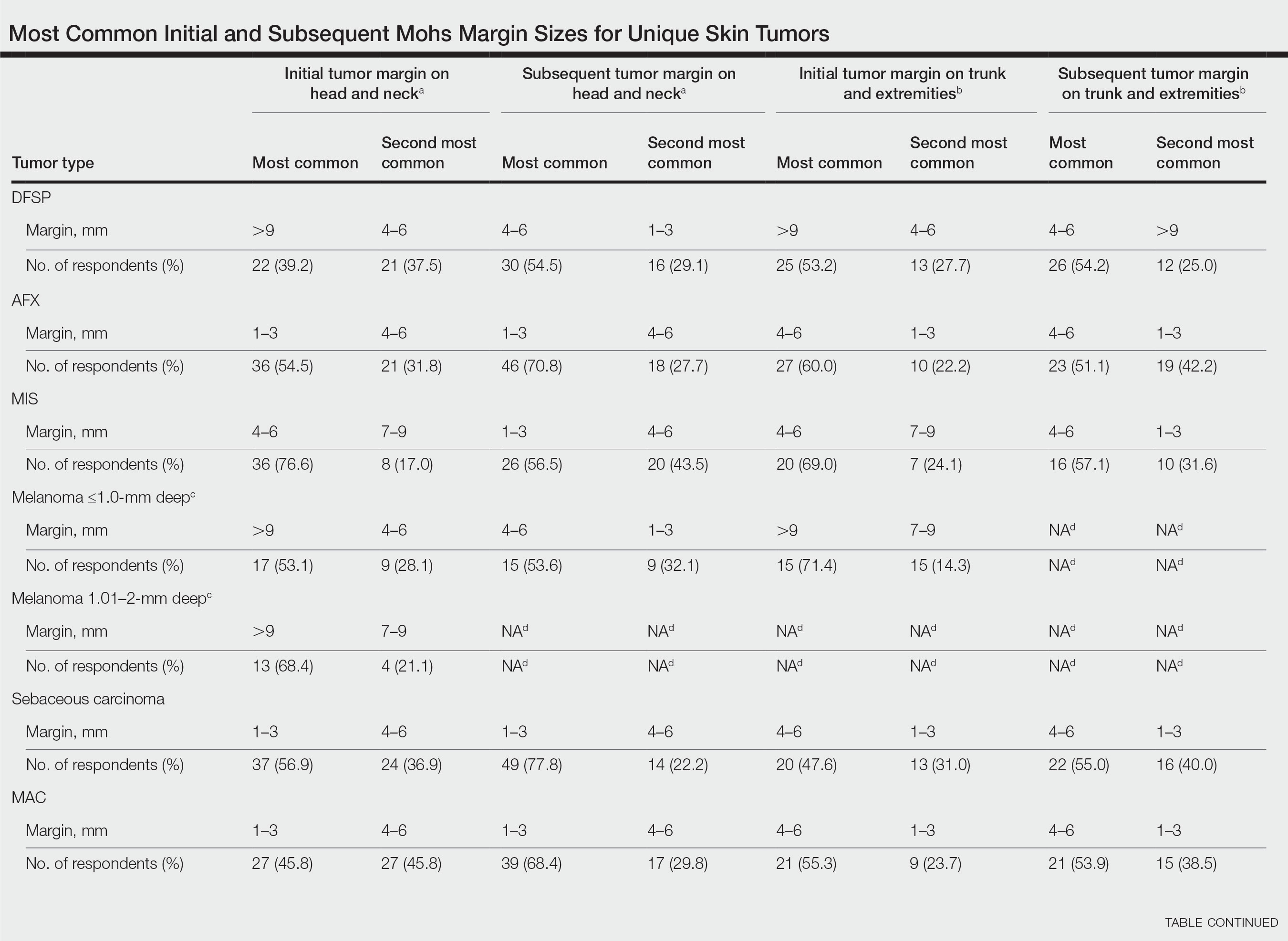

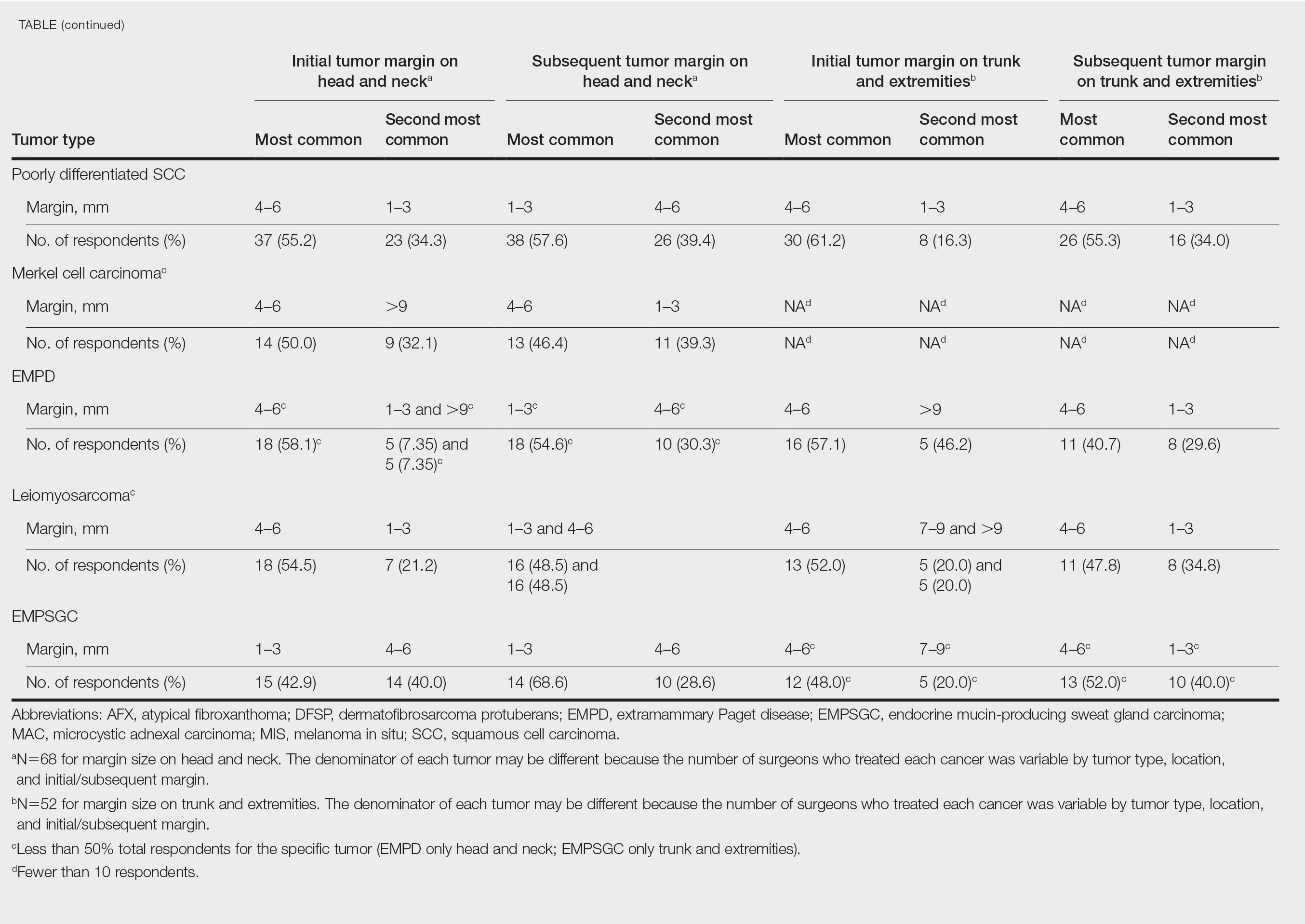

Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) is most commonly used for the surgical management of squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) and basal cell carcinomas (BCCs) in high-risk locations. The ability for 100% margin evaluation with MMS also has shown lower recurrence rates compared with wide local excision for less common and/or more aggressive tumors. However, there is a lack of standardization on initial and subsequent margin size when treating these less common skin tumors, such as dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP), atypical fibroxanthoma (AFX), and sebaceous carcinoma.

Because Mohs surgeons must balance normal tissue preservation with the importance of tumor clearance in the context of comprehensive margin control, we aimed to assess the practice patterns of Mohs surgeons regarding margin size for these unique tumors. The average margin size for each Mohs layer has been reported to be 1 to 3 mm for BCC compared with 3 to 6 mm or larger for other skin cancers, such as melanoma in situ (MIS).1-3 We hypothesized that the initial margin size would vary among surgeons and likely be greater for more aggressive and rarer malignancies as well as for lesions on the trunk and extremities.

Methods

A descriptive survey was created using SurveyMonkey and distributed to members of the American College of Mohs Surgery (ACMS). Survey participants and their responses were anonymous. Demographic information on survey participants was collected in addition to initial and subsequent MMS margin size for DFSP, AFX, MIS, invasive melanoma, sebaceous carcinoma, microcystic adnexal carcinoma (MAC), poorly differentiated SCC, Merkel cell carcinoma, extramammary Paget disease, leiomyosarcoma, and endocrine mucin-producing sweat gland carcinoma. Survey participants were asked to choose from a range of margin sizes: 1 to 3 mm, 4 to 6 mm, 7 to 9 mm, and greater than 9 mm. This study was approved by the University of Texas Southwest Medical Center (Dallas, Texas) institutional review board.

Results

Eighty-seven respondents from the ACMS listserve completed the survey (response rate <10%). Of these, 58 respondents (66.7%) reported practicing for more than 5 years, and 58 (66.7%) were male. Practice setting was primarily private/community (71.3% [62/87]), and survey respondents were located across the United States. More than 50% of survey respondents treated the following tumors on the head and neck in their respective practices: DFSP (80.9% [55/68]), AFX (95.6% [65/68]), MIS (67.7% [46/68]), sebaceous carcinoma (92.7% [63/68]), MAC (83.8% [57/68]), poorly differentiated SCC (97.1% [66/68]), and endocrine mucin-producing sweat gland carcinoma (51.5% [35/68]). More than 50% of survey respondents treated the following tumors on the trunk and extremities: DFSP (90.3% [47/52]), AFX (86.4% [45/52]), MIS (55.8% [29/52]), sebaceous carcinoma (80.8% [42/52]), MAC (73.1% [38/52]), poorly differentiated SCC (94.2% [49/52]), and extramammary Paget disease (53.9% [28/52]). Invasive melanoma, Merkel cell carcinoma, and leiomyosarcoma were overall less commonly treated.

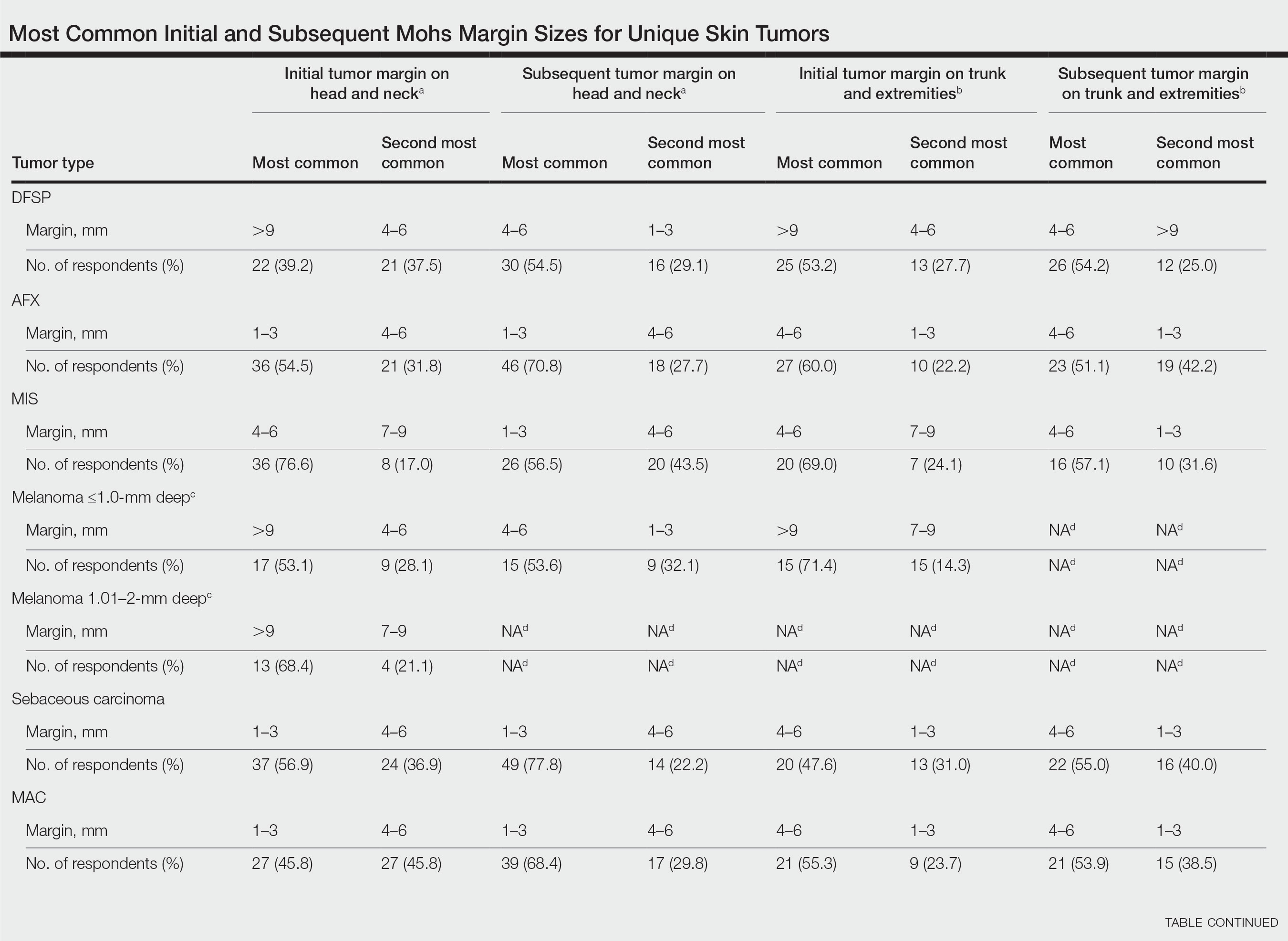

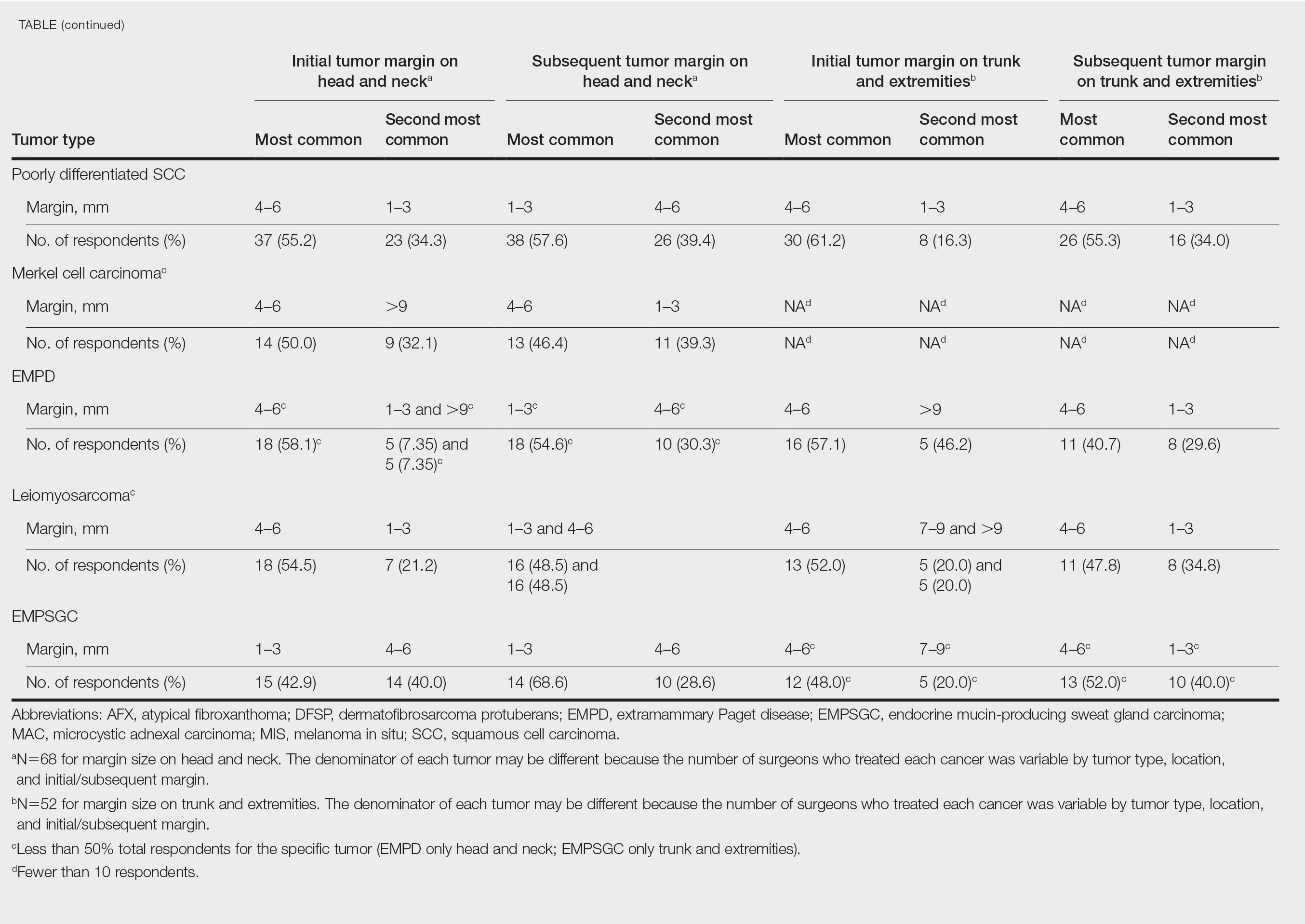

In general, respondent Mohs surgeons were more likely to take larger initial and subsequent margins for tumors treated on the trunk and extremities compared with the head and neck (Table). In addition, initial margin size often was larger than the 1- to 3-mm margin commonly used in Mohs surgery for BCCs and less aggressive SCCs (Table). A larger initial margin size (>9 mm) and subsequent margin size (4–6 mm) was more commonly reported for certain tumors known to be more aggressive and/or have extensive subclinical extension, such as DFSP and invasive melanoma. Of note, most respondents performed 4- to 6-mm margins (37/67 [55.2%]) for poorly differentiated SCC. Overall, there was a high range of margin size variability among Mohs surgeons for these unique and/or more aggressive skin tumors.

Comment

Given that no guidelines exist on margins with MMS for less commonly treated skin tumors, this study helps give Mohs surgeons perspective on current practice patterns for both initial and subsequent Mohs margin sizes. High margin-size variability among Mohs surgeons is expected, as surgeons also need to account for high-risk features of the tumor or specific locations where tissue sparing is critical. Overall, Mohs surgeons are more likely to take larger initial margins for these less common skin tumors compared with BCCs or SCCs. Initial margin size was consistently larger on the trunk and extremities where tissue sparing often is less critical.

Our survey was limited by a small sample size and incomplete response of the ACMS membership. In addition, most respondents practiced in a private/community setting, which may have led to bias, as academic centers may manage rare malignancies more commonly and/or have increased access to immunostains and multispecialty care. Future registries for rare skin malignancies will hopefully be developed that will allow for further consensus on standardized margins. Additional studies on the average number of stages required to clear these less common tumors also are warranted.

- Muller FM, Dawe RS, Moseley H, et al. Randomized comparison of Mohs micrographic surgery and surgical excision for small nodular basal cell carcinoma: tissue‐sparing outcome. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:1349-1354.

- van Loo E, Mosterd K, Krekels GA, et al. Surgical excision versus Mohs’ micrographic surgery for basal cell carcinoma of the face: a randomised clinical trial with 10 year follow-up. Eur J Cancer. 2014;50:3011-3020.

- Ellison PM, Zitelli JA, Brodland DG. Mohs micrographic surgery for melanoma: a prospective multicenter study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:767-774.

Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) is most commonly used for the surgical management of squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) and basal cell carcinomas (BCCs) in high-risk locations. The ability for 100% margin evaluation with MMS also has shown lower recurrence rates compared with wide local excision for less common and/or more aggressive tumors. However, there is a lack of standardization on initial and subsequent margin size when treating these less common skin tumors, such as dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP), atypical fibroxanthoma (AFX), and sebaceous carcinoma.

Because Mohs surgeons must balance normal tissue preservation with the importance of tumor clearance in the context of comprehensive margin control, we aimed to assess the practice patterns of Mohs surgeons regarding margin size for these unique tumors. The average margin size for each Mohs layer has been reported to be 1 to 3 mm for BCC compared with 3 to 6 mm or larger for other skin cancers, such as melanoma in situ (MIS).1-3 We hypothesized that the initial margin size would vary among surgeons and likely be greater for more aggressive and rarer malignancies as well as for lesions on the trunk and extremities.

Methods

A descriptive survey was created using SurveyMonkey and distributed to members of the American College of Mohs Surgery (ACMS). Survey participants and their responses were anonymous. Demographic information on survey participants was collected in addition to initial and subsequent MMS margin size for DFSP, AFX, MIS, invasive melanoma, sebaceous carcinoma, microcystic adnexal carcinoma (MAC), poorly differentiated SCC, Merkel cell carcinoma, extramammary Paget disease, leiomyosarcoma, and endocrine mucin-producing sweat gland carcinoma. Survey participants were asked to choose from a range of margin sizes: 1 to 3 mm, 4 to 6 mm, 7 to 9 mm, and greater than 9 mm. This study was approved by the University of Texas Southwest Medical Center (Dallas, Texas) institutional review board.

Results

Eighty-seven respondents from the ACMS listserve completed the survey (response rate <10%). Of these, 58 respondents (66.7%) reported practicing for more than 5 years, and 58 (66.7%) were male. Practice setting was primarily private/community (71.3% [62/87]), and survey respondents were located across the United States. More than 50% of survey respondents treated the following tumors on the head and neck in their respective practices: DFSP (80.9% [55/68]), AFX (95.6% [65/68]), MIS (67.7% [46/68]), sebaceous carcinoma (92.7% [63/68]), MAC (83.8% [57/68]), poorly differentiated SCC (97.1% [66/68]), and endocrine mucin-producing sweat gland carcinoma (51.5% [35/68]). More than 50% of survey respondents treated the following tumors on the trunk and extremities: DFSP (90.3% [47/52]), AFX (86.4% [45/52]), MIS (55.8% [29/52]), sebaceous carcinoma (80.8% [42/52]), MAC (73.1% [38/52]), poorly differentiated SCC (94.2% [49/52]), and extramammary Paget disease (53.9% [28/52]). Invasive melanoma, Merkel cell carcinoma, and leiomyosarcoma were overall less commonly treated.

In general, respondent Mohs surgeons were more likely to take larger initial and subsequent margins for tumors treated on the trunk and extremities compared with the head and neck (Table). In addition, initial margin size often was larger than the 1- to 3-mm margin commonly used in Mohs surgery for BCCs and less aggressive SCCs (Table). A larger initial margin size (>9 mm) and subsequent margin size (4–6 mm) was more commonly reported for certain tumors known to be more aggressive and/or have extensive subclinical extension, such as DFSP and invasive melanoma. Of note, most respondents performed 4- to 6-mm margins (37/67 [55.2%]) for poorly differentiated SCC. Overall, there was a high range of margin size variability among Mohs surgeons for these unique and/or more aggressive skin tumors.

Comment

Given that no guidelines exist on margins with MMS for less commonly treated skin tumors, this study helps give Mohs surgeons perspective on current practice patterns for both initial and subsequent Mohs margin sizes. High margin-size variability among Mohs surgeons is expected, as surgeons also need to account for high-risk features of the tumor or specific locations where tissue sparing is critical. Overall, Mohs surgeons are more likely to take larger initial margins for these less common skin tumors compared with BCCs or SCCs. Initial margin size was consistently larger on the trunk and extremities where tissue sparing often is less critical.

Our survey was limited by a small sample size and incomplete response of the ACMS membership. In addition, most respondents practiced in a private/community setting, which may have led to bias, as academic centers may manage rare malignancies more commonly and/or have increased access to immunostains and multispecialty care. Future registries for rare skin malignancies will hopefully be developed that will allow for further consensus on standardized margins. Additional studies on the average number of stages required to clear these less common tumors also are warranted.

Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) is most commonly used for the surgical management of squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) and basal cell carcinomas (BCCs) in high-risk locations. The ability for 100% margin evaluation with MMS also has shown lower recurrence rates compared with wide local excision for less common and/or more aggressive tumors. However, there is a lack of standardization on initial and subsequent margin size when treating these less common skin tumors, such as dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP), atypical fibroxanthoma (AFX), and sebaceous carcinoma.

Because Mohs surgeons must balance normal tissue preservation with the importance of tumor clearance in the context of comprehensive margin control, we aimed to assess the practice patterns of Mohs surgeons regarding margin size for these unique tumors. The average margin size for each Mohs layer has been reported to be 1 to 3 mm for BCC compared with 3 to 6 mm or larger for other skin cancers, such as melanoma in situ (MIS).1-3 We hypothesized that the initial margin size would vary among surgeons and likely be greater for more aggressive and rarer malignancies as well as for lesions on the trunk and extremities.

Methods

A descriptive survey was created using SurveyMonkey and distributed to members of the American College of Mohs Surgery (ACMS). Survey participants and their responses were anonymous. Demographic information on survey participants was collected in addition to initial and subsequent MMS margin size for DFSP, AFX, MIS, invasive melanoma, sebaceous carcinoma, microcystic adnexal carcinoma (MAC), poorly differentiated SCC, Merkel cell carcinoma, extramammary Paget disease, leiomyosarcoma, and endocrine mucin-producing sweat gland carcinoma. Survey participants were asked to choose from a range of margin sizes: 1 to 3 mm, 4 to 6 mm, 7 to 9 mm, and greater than 9 mm. This study was approved by the University of Texas Southwest Medical Center (Dallas, Texas) institutional review board.

Results

Eighty-seven respondents from the ACMS listserve completed the survey (response rate <10%). Of these, 58 respondents (66.7%) reported practicing for more than 5 years, and 58 (66.7%) were male. Practice setting was primarily private/community (71.3% [62/87]), and survey respondents were located across the United States. More than 50% of survey respondents treated the following tumors on the head and neck in their respective practices: DFSP (80.9% [55/68]), AFX (95.6% [65/68]), MIS (67.7% [46/68]), sebaceous carcinoma (92.7% [63/68]), MAC (83.8% [57/68]), poorly differentiated SCC (97.1% [66/68]), and endocrine mucin-producing sweat gland carcinoma (51.5% [35/68]). More than 50% of survey respondents treated the following tumors on the trunk and extremities: DFSP (90.3% [47/52]), AFX (86.4% [45/52]), MIS (55.8% [29/52]), sebaceous carcinoma (80.8% [42/52]), MAC (73.1% [38/52]), poorly differentiated SCC (94.2% [49/52]), and extramammary Paget disease (53.9% [28/52]). Invasive melanoma, Merkel cell carcinoma, and leiomyosarcoma were overall less commonly treated.

In general, respondent Mohs surgeons were more likely to take larger initial and subsequent margins for tumors treated on the trunk and extremities compared with the head and neck (Table). In addition, initial margin size often was larger than the 1- to 3-mm margin commonly used in Mohs surgery for BCCs and less aggressive SCCs (Table). A larger initial margin size (>9 mm) and subsequent margin size (4–6 mm) was more commonly reported for certain tumors known to be more aggressive and/or have extensive subclinical extension, such as DFSP and invasive melanoma. Of note, most respondents performed 4- to 6-mm margins (37/67 [55.2%]) for poorly differentiated SCC. Overall, there was a high range of margin size variability among Mohs surgeons for these unique and/or more aggressive skin tumors.

Comment

Given that no guidelines exist on margins with MMS for less commonly treated skin tumors, this study helps give Mohs surgeons perspective on current practice patterns for both initial and subsequent Mohs margin sizes. High margin-size variability among Mohs surgeons is expected, as surgeons also need to account for high-risk features of the tumor or specific locations where tissue sparing is critical. Overall, Mohs surgeons are more likely to take larger initial margins for these less common skin tumors compared with BCCs or SCCs. Initial margin size was consistently larger on the trunk and extremities where tissue sparing often is less critical.

Our survey was limited by a small sample size and incomplete response of the ACMS membership. In addition, most respondents practiced in a private/community setting, which may have led to bias, as academic centers may manage rare malignancies more commonly and/or have increased access to immunostains and multispecialty care. Future registries for rare skin malignancies will hopefully be developed that will allow for further consensus on standardized margins. Additional studies on the average number of stages required to clear these less common tumors also are warranted.

- Muller FM, Dawe RS, Moseley H, et al. Randomized comparison of Mohs micrographic surgery and surgical excision for small nodular basal cell carcinoma: tissue‐sparing outcome. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:1349-1354.

- van Loo E, Mosterd K, Krekels GA, et al. Surgical excision versus Mohs’ micrographic surgery for basal cell carcinoma of the face: a randomised clinical trial with 10 year follow-up. Eur J Cancer. 2014;50:3011-3020.

- Ellison PM, Zitelli JA, Brodland DG. Mohs micrographic surgery for melanoma: a prospective multicenter study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:767-774.

- Muller FM, Dawe RS, Moseley H, et al. Randomized comparison of Mohs micrographic surgery and surgical excision for small nodular basal cell carcinoma: tissue‐sparing outcome. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:1349-1354.

- van Loo E, Mosterd K, Krekels GA, et al. Surgical excision versus Mohs’ micrographic surgery for basal cell carcinoma of the face: a randomised clinical trial with 10 year follow-up. Eur J Cancer. 2014;50:3011-3020.

- Ellison PM, Zitelli JA, Brodland DG. Mohs micrographic surgery for melanoma: a prospective multicenter study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:767-774.

Practice Points

- It is common for initial margin size for uncommon skin tumors to be larger than the 1 to 3 mm commonly used in Mohs surgery for basal cell carcinomas and less aggressive squamous cell carcinomas.

- Mohs surgeons commonly take larger starting and subsequent margins for uncommon skin tumors treated on the trunk and extremities compared with the head and neck.

Too old to practice medicine?

Unlike for many other professions, there is no age limit for practicing medicine. According to international standards, airplane pilots, for example, who are responsible for the safety of many human lives, must retire by the age of 60 if they work alone, or 65 if they have a copilot. In Brazil, however, this age limit does not exist for pilots or physicians.

The only restriction on professional practice within the medical context is the mandatory retirement imposed on medical professors who teach at public (state and federal) universities, starting at the age of 75. Nevertheless, these professionals can continue practicing administrative and research-related activities. After “expulsion,” as this mandatory retirement is often called, professors who stood out or contributed to the institution and science may receive the title of professor emeritus.

In the private sector, age limits are not formally set, but the hiring of middle-aged professionals is limited.

At the Heart Institute of the University of São Paulo (Brazil) School of Medicine Clinical Hospital (InCor/HCFMUSP), one of the world’s largest teaching and research centers for cardiovascular and pulmonary diseases, several octogenarian specialists lead studies and teams. One of these is Noedir Stolf, MD, an 82-year-old cardiovascular surgeon who operates almost every day and coordinates studies on transplants, mechanical circulatory support, and aortic surgery. There is also Protásio Lemos da Luz, MD, an 82-year-old clinical cardiologist who guides research on subjects including atherosclerosis, the endothelium, microbiota, and diabetes. The protective effect of wine on atherosclerosis is one of his best-known studies.

No longer working is also not in the cards for Angelita Habr-Gama, MD, who, at 89 years old, is one of the oldest physicians in current practice. With a career spanning more than 7 decades, she is a world reference in coloproctology. She was the first woman to become a surgical resident at the HCFMUSP, where she later founded the coloproctology specialty and created the first residency program for the specialty. In April 2022, Dr. Habr-Gama joined the ranks of the 100 most influential scientists in the world, nominated by researchers at Stanford (Calif.) University, and published in PLOS Biology.

In 2020, she was sedated, intubated, and hospitalized in the intensive care unit of the Oswaldo Cruz German Hospital for 54 days because of a SARS-CoV-2 infection. After her discharge, she went back to work in less than 10 days – and added chess classes to her routine. “To get up and go to work makes me very happy. Work is my greatest hobby. No one has ever heard me complain about my life,” Dr. Habr-Gama told this news organization after having rescheduled the interview twice because of emergency surgeries.

“Doctors have a professional longevity that does not exist for other professions in which the person retires and stops practicing their profession or goes on to do something else for entertainment. Doctors can retire from one place of employment or public practice and continue practicing medicine in the office as an administrator or consultant,” Ângelo Vattimo, first secretary of the state of São Paulo Regional Board of Medicine (CREMESP), stated. The board regularly organizes a ceremony to honor professionals who have been practicing for 50 years, awarding them a certificate and engraved medal. “Many of them are around 80 years old, working and teaching. This always makes us very happy. What profession has such exceptional compliance for so long?” said Mr. Vattimo.

In the medical field, the older the age range, the smaller the number of women. According to the 2020 Medical Demographics in Brazil survey, only 2 out of 10 practicing professionals older than 70 are women.

Not everyone over 80 has Dr. Habr-Gama’s vitality, because the impact of aging is not equal. “If you look at a group of 80-year-olds, there will be much more variability than within a group of 40-year-olds,” stated Mark Katlic, MD, chief of surgery at LifeBridge Health System in the United States, who has dedicated his life to studying the subject. Dr. Katlic spoke on the subject in an interview that was published in the article “How Old Is Too Old to Work as a Doctor?” published by this news organization in April of 2022. The article discusses the evaluations of elderly physicians’ skills and competences that U.S. companies conduct. The subject has been leading to profound debate.

Dr. Katlic defends screening programs for elderly physicians, which already are in effect at the company for which he works, LifeBridge Health, and various others in the United States. “We do [screen elderly physicians at LifeBridge Health], and so do a few dozen other [U.S. institutions], but there are hundreds [of health care institutions] that do not conduct this screening,” he pointed out.

Age-related assessment faces great resistance in the United States. One physician who is against the initiative is Frank Stockdale, MD, PhD, an 86-year-old practicing oncologist affiliated with Stanford (Calif.) University Health. “It’s age discrimination ... Physicians [in the United States] receive assessments throughout their careers as part of the accreditation process – there’s no need to change that as physicians reach a certain age,” Dr. Stockdale told this news organization.

The U.S. initiative of instituting physician assessment programs for those of a certain age has even been tested in court. According to an article published in Medscape, “in New Haven, Connecticut, for instance, the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) filed a suit in 2020 on behalf of the Yale New Haven Hospital staff, alleging a discriminatory late career practitioner policy.”

Also, according to the article, a similar case in Minnesota reached a settlement in 2021, providing monetary relief to staff impacted by out-of-pocket costs for the assessment, in addition to requiring that the hospital in question report to the EEOC any complaints related to age discrimination.

In Brazil, the subject is of interest to more than 34,571 physicians between 65 and 69 years of age and 34,237 physicians older than 70. In all, this population represents approximately 14.3% of the country’s active workforce, according to the 2020 Medical Demographics in Brazil survey.

The significant participation of health care professionals over age 50 in a survey conducted by this news organization to learn what physicians think about the age limit for practicing their professions is evidence that the subject is a present concern. Of a total of 1,641 participants, 57% were age 60 or older, 17% were between 50 and 59 years, and 12% were between 40 and 49 years. Among all participants, 51% were against these limitations, 17% approved of the idea for all specialties, and 32% believed the restriction was appropriate only for some specialties. Regarding the possibility of older physicians undergoing regular assessments, the opinions were divided: Thirty-one percent thought they should be assessed in all specialties. Furthermore, 31% believed that cognitive abilities should be regularly tested in all specialties, 31% thought this should take place for some specialties, and 38% were against this approach.

Professionals want to know, for example, how (and whether) advanced age can interfere with performance, what are the competences required to practice their activities, and if the criteria vary by specialty. “A psychiatrist doesn’t have to have perfect visual acuity, as required from a dermatologist, but it is important that they have good hearing, for example,” argued Clóvis Constantino, MD, former president of the São Paulo Regional Medical Board (CRM-SP) and former vice president of the Brazilian Federal Medical Board (CFM). “However, a surgeon has to stand for several hours in positions that may be uncomfortable. It’s not easy,” he told this news organization.

In the opinion of 82-year-old Henrique Klajner, MD, the oldest pediatrician in practice at the Albert Einstein Israeli Hospital in São Paulo, the physician cannot be subjected to the types of evaluations that have been applied in the United States. “Physicians should conduct constant self-evaluations to see if they have the competences and skills needed to practice their profession ... Moreover, this is not a matter of age. It is a matter of ethics,” said Dr. Klajner.

The ability to adapt to change and implement innovation is critical to professional longevity, he said. “Nowadays, when I admit patients, I no longer do hospital rounds, which requires a mobility equal to physical abuse for me. Therefore, I work with physicians who take care of my hospitalized patients.”

Dr. Klajner also feels there is a distinction between innovations learned through studies and what can be offered safely to patients. “If I have to care for a hospitalized patient with severe pneumonia, for example, since I am not up to date in this specialty, I am going to call upon a pulmonologist I trust and forgo my honorarium for this admission. But I will remain on the team, monitoring the patient’s progression,” he said.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Dr. Klajner stopped seeing patients in person under the recommendation of his son, Sidney Klajner, MD, also a physician. The elder Dr. Klajner began exploring telemedicine, which opened a whole new world of possibilities. “I have conducted several online visits to provide educational instruction to mothers returning home post delivery, for example,” he told this news organization. The time to stop is not something that concerns Dr. Klajner. “I’m only going to stop when I have a really important reason to do so. For example, if I can no longer write or study, reading and rereading an article without being able to understand what is being said. At this time, none of that is happening.”

In the United States, as well as in Brazil, physicians rarely provide information to human resources departments on colleagues showing signs of cognitive or motor decline affecting their professional performance. “The expectation is that health care professionals will report colleagues with cognitive impairments, but that often does not happen,” Dr. Katlic said.

It is also not common for professionals to report their own deficits to their institutions. In large part, this is caused by a lack of well-defined policies for dealing with this issue. This news organization sought out several public and private hospitals in Brazil to see if there is any guidance on professional longevity: Most said that there is not. Only the A. C. Camargo Cancer Center reported, through its public relations team, that a committee is discussing the subject but that it is still in the early stages.

Brazilian specialist associations do not offer guidelines or instructions on the various aspects of professional longevity. Dr. Constantino tried to put the subject on the agenda during the years in which he was an administrator with the CFM. “We tried to open up discussions regarding truly elderly physicians, but the subject was not well received. I believe that it is precisely because there is a tradition of physicians working until they are no longer able that this is more difficult in Brazil ... No one exactly knows what to do in this respect.” Dr. Constantino is against the use of age as a criterion for quitting practice.

“Of course, this is a point that has to be considered, but I always defended the need for regular assessment of physicians, regardless of age range. And, although assessments are always welcome, in any profession, I also believe this would not be well received in Brazil.” He endorses an assessment of one’s knowledge and not of physical abilities, which are generally assessed through investigation when needed.

The absence of guidelines increases individual responsibility, as well as vulnerability. “Consciously, physicians will not put patients at risk if they do not have the competence to care for them or to perform a surgical procedure,” said Clystenes Odyr Soares Silva, MD, PhD, adjunct professor of pulmonology of the Federal University of São Paulo (Brazil) School of Medicine (UNIFESP). “Your peers will tell you if you are no longer able,” he added. The problem is that physicians rarely admit to or talk about their colleagues’ deficits, especially if they are in the spotlight because of advanced age. In this situation, the observation and opinion of family members regarding the health care professional’s competences and skills will hold more weight.

In case of health-related physical impairment, such as partial loss of hand movement, for example, “it is expected that this will set off an ethical warning in the person,” said Dr. Constantino. When this warning does not occur naturally, patients or colleagues can report the professional, and this may lead to the opening of an administrative investigation. If the report is found to be true, this investigation is used to suspend physicians who do not have the physical or mental ability to continue practicing medicine.

“If it’s something very serious, the physician’s license can be temporarily suspended while [the physician] is treated by a psychiatrist, with follow-up by the professional board. When discharged, the physician will get his or her [professional] license back and can go back to work,” Dr. Constantino explained. If an expert evaluation is needed, the physician will then be assessed by a forensic psychiatrist. One of the most in-demand forensic psychiatrists in Brazil is Guido Arturo Palomba, MD, 73 years old. “I have assessed some physicians for actions reported to see if they were normal people or not, but never for circumstances related to age,” Dr. Palomba said.

In practice, Brazilian medical entities do not have policies or programs to guide physicians who wish to grow old while they work or those who have started to notice they are not performing as they used to. “We have never lived as long; therefore, the quality of life in old age, as well as the concept of aging, are some of the most relevant questions of our time. These are subjects requiring additional discussion, broadening understanding and awareness in this regard,” observed Mr. Vattimo.

Dr. Constantino and Dr. Silva, who are completely against age-based assessments, believe that recertification of the specialist license every 5 years is the best path to confirming whether the physician is still able to practice. “A knowledge-based test every 5 years to recertify the specialist license has often been a topic of conversation. I think it’s an excellent idea. The person would provide a dossier of all they have done in terms of courses, conferences, and other activities, present it, and receive a score,” said Dr. Silva.

In practice, recertification of the specialist license is a topic of discussion that has been raised for years, and it is an idea that the Brazilian Medical Association (AMB) defends. In conjunction with the CFM, the association is studying a way to best implement this assessment. “It’s important to emphasize that this measure would not be retroactive at first. Instead, it would only be in effect for professionals licensed after the recertification requirement is established,” the AMB pointed out in a note sent to this news organization. Even so, the measure has faced significant resistance from a faction of the profession, and its enactment does not seem to be imminent.

The debate regarding professional longevity is taking place in various countries. In 2021, the American Medical Association Council on Medical Education released a report with a set of guidelines for the screening and assessment of physicians. The document is the product of a committee created in 2015 to study the subject. The AMA recommends that the assessment of elderly physicians be based on evidence and ethical, relevant, fair, equitable, transparent, verifiable, nonexhaustive principles, contemplating support and protecting against legal proceedings. In April of this year, a new AMA document highlighted the same principles.

Also in the United States, one of oldest initiatives created to support physicians in the process of recycling, the University of California San Diego Physician Assessment and Clinical Education Program (PACE), has a section focusing on the extended practice of medicine (Practicing Medicine Longer). For those wanting to learn more about discussions on this subject, there are online presentations on experiences in Quebec and Ontario with assessing aging physicians, neuropsychological perspectives on the aging medical population, and what to expect of healthy aging, among other subjects.

Created in 1996, PACE mostly provides services to physicians who need to address requirements of the state medical boards. Few physicians enroll on their own.

The first part of the program assesses knowledge and skills over approximately 2 days. In the second phase, the physician participates in a series of activities in a corresponding residency program. Depending on the results, the physician may have to go through a remedial program with varying activities to deal with performance deficiencies to clinical experiences at the residency level.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Unlike for many other professions, there is no age limit for practicing medicine. According to international standards, airplane pilots, for example, who are responsible for the safety of many human lives, must retire by the age of 60 if they work alone, or 65 if they have a copilot. In Brazil, however, this age limit does not exist for pilots or physicians.

The only restriction on professional practice within the medical context is the mandatory retirement imposed on medical professors who teach at public (state and federal) universities, starting at the age of 75. Nevertheless, these professionals can continue practicing administrative and research-related activities. After “expulsion,” as this mandatory retirement is often called, professors who stood out or contributed to the institution and science may receive the title of professor emeritus.

In the private sector, age limits are not formally set, but the hiring of middle-aged professionals is limited.

At the Heart Institute of the University of São Paulo (Brazil) School of Medicine Clinical Hospital (InCor/HCFMUSP), one of the world’s largest teaching and research centers for cardiovascular and pulmonary diseases, several octogenarian specialists lead studies and teams. One of these is Noedir Stolf, MD, an 82-year-old cardiovascular surgeon who operates almost every day and coordinates studies on transplants, mechanical circulatory support, and aortic surgery. There is also Protásio Lemos da Luz, MD, an 82-year-old clinical cardiologist who guides research on subjects including atherosclerosis, the endothelium, microbiota, and diabetes. The protective effect of wine on atherosclerosis is one of his best-known studies.

No longer working is also not in the cards for Angelita Habr-Gama, MD, who, at 89 years old, is one of the oldest physicians in current practice. With a career spanning more than 7 decades, she is a world reference in coloproctology. She was the first woman to become a surgical resident at the HCFMUSP, where she later founded the coloproctology specialty and created the first residency program for the specialty. In April 2022, Dr. Habr-Gama joined the ranks of the 100 most influential scientists in the world, nominated by researchers at Stanford (Calif.) University, and published in PLOS Biology.

In 2020, she was sedated, intubated, and hospitalized in the intensive care unit of the Oswaldo Cruz German Hospital for 54 days because of a SARS-CoV-2 infection. After her discharge, she went back to work in less than 10 days – and added chess classes to her routine. “To get up and go to work makes me very happy. Work is my greatest hobby. No one has ever heard me complain about my life,” Dr. Habr-Gama told this news organization after having rescheduled the interview twice because of emergency surgeries.

“Doctors have a professional longevity that does not exist for other professions in which the person retires and stops practicing their profession or goes on to do something else for entertainment. Doctors can retire from one place of employment or public practice and continue practicing medicine in the office as an administrator or consultant,” Ângelo Vattimo, first secretary of the state of São Paulo Regional Board of Medicine (CREMESP), stated. The board regularly organizes a ceremony to honor professionals who have been practicing for 50 years, awarding them a certificate and engraved medal. “Many of them are around 80 years old, working and teaching. This always makes us very happy. What profession has such exceptional compliance for so long?” said Mr. Vattimo.

In the medical field, the older the age range, the smaller the number of women. According to the 2020 Medical Demographics in Brazil survey, only 2 out of 10 practicing professionals older than 70 are women.

Not everyone over 80 has Dr. Habr-Gama’s vitality, because the impact of aging is not equal. “If you look at a group of 80-year-olds, there will be much more variability than within a group of 40-year-olds,” stated Mark Katlic, MD, chief of surgery at LifeBridge Health System in the United States, who has dedicated his life to studying the subject. Dr. Katlic spoke on the subject in an interview that was published in the article “How Old Is Too Old to Work as a Doctor?” published by this news organization in April of 2022. The article discusses the evaluations of elderly physicians’ skills and competences that U.S. companies conduct. The subject has been leading to profound debate.

Dr. Katlic defends screening programs for elderly physicians, which already are in effect at the company for which he works, LifeBridge Health, and various others in the United States. “We do [screen elderly physicians at LifeBridge Health], and so do a few dozen other [U.S. institutions], but there are hundreds [of health care institutions] that do not conduct this screening,” he pointed out.

Age-related assessment faces great resistance in the United States. One physician who is against the initiative is Frank Stockdale, MD, PhD, an 86-year-old practicing oncologist affiliated with Stanford (Calif.) University Health. “It’s age discrimination ... Physicians [in the United States] receive assessments throughout their careers as part of the accreditation process – there’s no need to change that as physicians reach a certain age,” Dr. Stockdale told this news organization.

The U.S. initiative of instituting physician assessment programs for those of a certain age has even been tested in court. According to an article published in Medscape, “in New Haven, Connecticut, for instance, the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) filed a suit in 2020 on behalf of the Yale New Haven Hospital staff, alleging a discriminatory late career practitioner policy.”

Also, according to the article, a similar case in Minnesota reached a settlement in 2021, providing monetary relief to staff impacted by out-of-pocket costs for the assessment, in addition to requiring that the hospital in question report to the EEOC any complaints related to age discrimination.

In Brazil, the subject is of interest to more than 34,571 physicians between 65 and 69 years of age and 34,237 physicians older than 70. In all, this population represents approximately 14.3% of the country’s active workforce, according to the 2020 Medical Demographics in Brazil survey.

The significant participation of health care professionals over age 50 in a survey conducted by this news organization to learn what physicians think about the age limit for practicing their professions is evidence that the subject is a present concern. Of a total of 1,641 participants, 57% were age 60 or older, 17% were between 50 and 59 years, and 12% were between 40 and 49 years. Among all participants, 51% were against these limitations, 17% approved of the idea for all specialties, and 32% believed the restriction was appropriate only for some specialties. Regarding the possibility of older physicians undergoing regular assessments, the opinions were divided: Thirty-one percent thought they should be assessed in all specialties. Furthermore, 31% believed that cognitive abilities should be regularly tested in all specialties, 31% thought this should take place for some specialties, and 38% were against this approach.

Professionals want to know, for example, how (and whether) advanced age can interfere with performance, what are the competences required to practice their activities, and if the criteria vary by specialty. “A psychiatrist doesn’t have to have perfect visual acuity, as required from a dermatologist, but it is important that they have good hearing, for example,” argued Clóvis Constantino, MD, former president of the São Paulo Regional Medical Board (CRM-SP) and former vice president of the Brazilian Federal Medical Board (CFM). “However, a surgeon has to stand for several hours in positions that may be uncomfortable. It’s not easy,” he told this news organization.

In the opinion of 82-year-old Henrique Klajner, MD, the oldest pediatrician in practice at the Albert Einstein Israeli Hospital in São Paulo, the physician cannot be subjected to the types of evaluations that have been applied in the United States. “Physicians should conduct constant self-evaluations to see if they have the competences and skills needed to practice their profession ... Moreover, this is not a matter of age. It is a matter of ethics,” said Dr. Klajner.

The ability to adapt to change and implement innovation is critical to professional longevity, he said. “Nowadays, when I admit patients, I no longer do hospital rounds, which requires a mobility equal to physical abuse for me. Therefore, I work with physicians who take care of my hospitalized patients.”

Dr. Klajner also feels there is a distinction between innovations learned through studies and what can be offered safely to patients. “If I have to care for a hospitalized patient with severe pneumonia, for example, since I am not up to date in this specialty, I am going to call upon a pulmonologist I trust and forgo my honorarium for this admission. But I will remain on the team, monitoring the patient’s progression,” he said.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Dr. Klajner stopped seeing patients in person under the recommendation of his son, Sidney Klajner, MD, also a physician. The elder Dr. Klajner began exploring telemedicine, which opened a whole new world of possibilities. “I have conducted several online visits to provide educational instruction to mothers returning home post delivery, for example,” he told this news organization. The time to stop is not something that concerns Dr. Klajner. “I’m only going to stop when I have a really important reason to do so. For example, if I can no longer write or study, reading and rereading an article without being able to understand what is being said. At this time, none of that is happening.”

In the United States, as well as in Brazil, physicians rarely provide information to human resources departments on colleagues showing signs of cognitive or motor decline affecting their professional performance. “The expectation is that health care professionals will report colleagues with cognitive impairments, but that often does not happen,” Dr. Katlic said.

It is also not common for professionals to report their own deficits to their institutions. In large part, this is caused by a lack of well-defined policies for dealing with this issue. This news organization sought out several public and private hospitals in Brazil to see if there is any guidance on professional longevity: Most said that there is not. Only the A. C. Camargo Cancer Center reported, through its public relations team, that a committee is discussing the subject but that it is still in the early stages.

Brazilian specialist associations do not offer guidelines or instructions on the various aspects of professional longevity. Dr. Constantino tried to put the subject on the agenda during the years in which he was an administrator with the CFM. “We tried to open up discussions regarding truly elderly physicians, but the subject was not well received. I believe that it is precisely because there is a tradition of physicians working until they are no longer able that this is more difficult in Brazil ... No one exactly knows what to do in this respect.” Dr. Constantino is against the use of age as a criterion for quitting practice.

“Of course, this is a point that has to be considered, but I always defended the need for regular assessment of physicians, regardless of age range. And, although assessments are always welcome, in any profession, I also believe this would not be well received in Brazil.” He endorses an assessment of one’s knowledge and not of physical abilities, which are generally assessed through investigation when needed.

The absence of guidelines increases individual responsibility, as well as vulnerability. “Consciously, physicians will not put patients at risk if they do not have the competence to care for them or to perform a surgical procedure,” said Clystenes Odyr Soares Silva, MD, PhD, adjunct professor of pulmonology of the Federal University of São Paulo (Brazil) School of Medicine (UNIFESP). “Your peers will tell you if you are no longer able,” he added. The problem is that physicians rarely admit to or talk about their colleagues’ deficits, especially if they are in the spotlight because of advanced age. In this situation, the observation and opinion of family members regarding the health care professional’s competences and skills will hold more weight.

In case of health-related physical impairment, such as partial loss of hand movement, for example, “it is expected that this will set off an ethical warning in the person,” said Dr. Constantino. When this warning does not occur naturally, patients or colleagues can report the professional, and this may lead to the opening of an administrative investigation. If the report is found to be true, this investigation is used to suspend physicians who do not have the physical or mental ability to continue practicing medicine.

“If it’s something very serious, the physician’s license can be temporarily suspended while [the physician] is treated by a psychiatrist, with follow-up by the professional board. When discharged, the physician will get his or her [professional] license back and can go back to work,” Dr. Constantino explained. If an expert evaluation is needed, the physician will then be assessed by a forensic psychiatrist. One of the most in-demand forensic psychiatrists in Brazil is Guido Arturo Palomba, MD, 73 years old. “I have assessed some physicians for actions reported to see if they were normal people or not, but never for circumstances related to age,” Dr. Palomba said.

In practice, Brazilian medical entities do not have policies or programs to guide physicians who wish to grow old while they work or those who have started to notice they are not performing as they used to. “We have never lived as long; therefore, the quality of life in old age, as well as the concept of aging, are some of the most relevant questions of our time. These are subjects requiring additional discussion, broadening understanding and awareness in this regard,” observed Mr. Vattimo.

Dr. Constantino and Dr. Silva, who are completely against age-based assessments, believe that recertification of the specialist license every 5 years is the best path to confirming whether the physician is still able to practice. “A knowledge-based test every 5 years to recertify the specialist license has often been a topic of conversation. I think it’s an excellent idea. The person would provide a dossier of all they have done in terms of courses, conferences, and other activities, present it, and receive a score,” said Dr. Silva.

In practice, recertification of the specialist license is a topic of discussion that has been raised for years, and it is an idea that the Brazilian Medical Association (AMB) defends. In conjunction with the CFM, the association is studying a way to best implement this assessment. “It’s important to emphasize that this measure would not be retroactive at first. Instead, it would only be in effect for professionals licensed after the recertification requirement is established,” the AMB pointed out in a note sent to this news organization. Even so, the measure has faced significant resistance from a faction of the profession, and its enactment does not seem to be imminent.

The debate regarding professional longevity is taking place in various countries. In 2021, the American Medical Association Council on Medical Education released a report with a set of guidelines for the screening and assessment of physicians. The document is the product of a committee created in 2015 to study the subject. The AMA recommends that the assessment of elderly physicians be based on evidence and ethical, relevant, fair, equitable, transparent, verifiable, nonexhaustive principles, contemplating support and protecting against legal proceedings. In April of this year, a new AMA document highlighted the same principles.

Also in the United States, one of oldest initiatives created to support physicians in the process of recycling, the University of California San Diego Physician Assessment and Clinical Education Program (PACE), has a section focusing on the extended practice of medicine (Practicing Medicine Longer). For those wanting to learn more about discussions on this subject, there are online presentations on experiences in Quebec and Ontario with assessing aging physicians, neuropsychological perspectives on the aging medical population, and what to expect of healthy aging, among other subjects.

Created in 1996, PACE mostly provides services to physicians who need to address requirements of the state medical boards. Few physicians enroll on their own.

The first part of the program assesses knowledge and skills over approximately 2 days. In the second phase, the physician participates in a series of activities in a corresponding residency program. Depending on the results, the physician may have to go through a remedial program with varying activities to deal with performance deficiencies to clinical experiences at the residency level.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Unlike for many other professions, there is no age limit for practicing medicine. According to international standards, airplane pilots, for example, who are responsible for the safety of many human lives, must retire by the age of 60 if they work alone, or 65 if they have a copilot. In Brazil, however, this age limit does not exist for pilots or physicians.

The only restriction on professional practice within the medical context is the mandatory retirement imposed on medical professors who teach at public (state and federal) universities, starting at the age of 75. Nevertheless, these professionals can continue practicing administrative and research-related activities. After “expulsion,” as this mandatory retirement is often called, professors who stood out or contributed to the institution and science may receive the title of professor emeritus.

In the private sector, age limits are not formally set, but the hiring of middle-aged professionals is limited.

At the Heart Institute of the University of São Paulo (Brazil) School of Medicine Clinical Hospital (InCor/HCFMUSP), one of the world’s largest teaching and research centers for cardiovascular and pulmonary diseases, several octogenarian specialists lead studies and teams. One of these is Noedir Stolf, MD, an 82-year-old cardiovascular surgeon who operates almost every day and coordinates studies on transplants, mechanical circulatory support, and aortic surgery. There is also Protásio Lemos da Luz, MD, an 82-year-old clinical cardiologist who guides research on subjects including atherosclerosis, the endothelium, microbiota, and diabetes. The protective effect of wine on atherosclerosis is one of his best-known studies.

No longer working is also not in the cards for Angelita Habr-Gama, MD, who, at 89 years old, is one of the oldest physicians in current practice. With a career spanning more than 7 decades, she is a world reference in coloproctology. She was the first woman to become a surgical resident at the HCFMUSP, where she later founded the coloproctology specialty and created the first residency program for the specialty. In April 2022, Dr. Habr-Gama joined the ranks of the 100 most influential scientists in the world, nominated by researchers at Stanford (Calif.) University, and published in PLOS Biology.

In 2020, she was sedated, intubated, and hospitalized in the intensive care unit of the Oswaldo Cruz German Hospital for 54 days because of a SARS-CoV-2 infection. After her discharge, she went back to work in less than 10 days – and added chess classes to her routine. “To get up and go to work makes me very happy. Work is my greatest hobby. No one has ever heard me complain about my life,” Dr. Habr-Gama told this news organization after having rescheduled the interview twice because of emergency surgeries.

“Doctors have a professional longevity that does not exist for other professions in which the person retires and stops practicing their profession or goes on to do something else for entertainment. Doctors can retire from one place of employment or public practice and continue practicing medicine in the office as an administrator or consultant,” Ângelo Vattimo, first secretary of the state of São Paulo Regional Board of Medicine (CREMESP), stated. The board regularly organizes a ceremony to honor professionals who have been practicing for 50 years, awarding them a certificate and engraved medal. “Many of them are around 80 years old, working and teaching. This always makes us very happy. What profession has such exceptional compliance for so long?” said Mr. Vattimo.

In the medical field, the older the age range, the smaller the number of women. According to the 2020 Medical Demographics in Brazil survey, only 2 out of 10 practicing professionals older than 70 are women.

Not everyone over 80 has Dr. Habr-Gama’s vitality, because the impact of aging is not equal. “If you look at a group of 80-year-olds, there will be much more variability than within a group of 40-year-olds,” stated Mark Katlic, MD, chief of surgery at LifeBridge Health System in the United States, who has dedicated his life to studying the subject. Dr. Katlic spoke on the subject in an interview that was published in the article “How Old Is Too Old to Work as a Doctor?” published by this news organization in April of 2022. The article discusses the evaluations of elderly physicians’ skills and competences that U.S. companies conduct. The subject has been leading to profound debate.

Dr. Katlic defends screening programs for elderly physicians, which already are in effect at the company for which he works, LifeBridge Health, and various others in the United States. “We do [screen elderly physicians at LifeBridge Health], and so do a few dozen other [U.S. institutions], but there are hundreds [of health care institutions] that do not conduct this screening,” he pointed out.

Age-related assessment faces great resistance in the United States. One physician who is against the initiative is Frank Stockdale, MD, PhD, an 86-year-old practicing oncologist affiliated with Stanford (Calif.) University Health. “It’s age discrimination ... Physicians [in the United States] receive assessments throughout their careers as part of the accreditation process – there’s no need to change that as physicians reach a certain age,” Dr. Stockdale told this news organization.

The U.S. initiative of instituting physician assessment programs for those of a certain age has even been tested in court. According to an article published in Medscape, “in New Haven, Connecticut, for instance, the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) filed a suit in 2020 on behalf of the Yale New Haven Hospital staff, alleging a discriminatory late career practitioner policy.”

Also, according to the article, a similar case in Minnesota reached a settlement in 2021, providing monetary relief to staff impacted by out-of-pocket costs for the assessment, in addition to requiring that the hospital in question report to the EEOC any complaints related to age discrimination.

In Brazil, the subject is of interest to more than 34,571 physicians between 65 and 69 years of age and 34,237 physicians older than 70. In all, this population represents approximately 14.3% of the country’s active workforce, according to the 2020 Medical Demographics in Brazil survey.

The significant participation of health care professionals over age 50 in a survey conducted by this news organization to learn what physicians think about the age limit for practicing their professions is evidence that the subject is a present concern. Of a total of 1,641 participants, 57% were age 60 or older, 17% were between 50 and 59 years, and 12% were between 40 and 49 years. Among all participants, 51% were against these limitations, 17% approved of the idea for all specialties, and 32% believed the restriction was appropriate only for some specialties. Regarding the possibility of older physicians undergoing regular assessments, the opinions were divided: Thirty-one percent thought they should be assessed in all specialties. Furthermore, 31% believed that cognitive abilities should be regularly tested in all specialties, 31% thought this should take place for some specialties, and 38% were against this approach.

Professionals want to know, for example, how (and whether) advanced age can interfere with performance, what are the competences required to practice their activities, and if the criteria vary by specialty. “A psychiatrist doesn’t have to have perfect visual acuity, as required from a dermatologist, but it is important that they have good hearing, for example,” argued Clóvis Constantino, MD, former president of the São Paulo Regional Medical Board (CRM-SP) and former vice president of the Brazilian Federal Medical Board (CFM). “However, a surgeon has to stand for several hours in positions that may be uncomfortable. It’s not easy,” he told this news organization.

In the opinion of 82-year-old Henrique Klajner, MD, the oldest pediatrician in practice at the Albert Einstein Israeli Hospital in São Paulo, the physician cannot be subjected to the types of evaluations that have been applied in the United States. “Physicians should conduct constant self-evaluations to see if they have the competences and skills needed to practice their profession ... Moreover, this is not a matter of age. It is a matter of ethics,” said Dr. Klajner.

The ability to adapt to change and implement innovation is critical to professional longevity, he said. “Nowadays, when I admit patients, I no longer do hospital rounds, which requires a mobility equal to physical abuse for me. Therefore, I work with physicians who take care of my hospitalized patients.”

Dr. Klajner also feels there is a distinction between innovations learned through studies and what can be offered safely to patients. “If I have to care for a hospitalized patient with severe pneumonia, for example, since I am not up to date in this specialty, I am going to call upon a pulmonologist I trust and forgo my honorarium for this admission. But I will remain on the team, monitoring the patient’s progression,” he said.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Dr. Klajner stopped seeing patients in person under the recommendation of his son, Sidney Klajner, MD, also a physician. The elder Dr. Klajner began exploring telemedicine, which opened a whole new world of possibilities. “I have conducted several online visits to provide educational instruction to mothers returning home post delivery, for example,” he told this news organization. The time to stop is not something that concerns Dr. Klajner. “I’m only going to stop when I have a really important reason to do so. For example, if I can no longer write or study, reading and rereading an article without being able to understand what is being said. At this time, none of that is happening.”

In the United States, as well as in Brazil, physicians rarely provide information to human resources departments on colleagues showing signs of cognitive or motor decline affecting their professional performance. “The expectation is that health care professionals will report colleagues with cognitive impairments, but that often does not happen,” Dr. Katlic said.

It is also not common for professionals to report their own deficits to their institutions. In large part, this is caused by a lack of well-defined policies for dealing with this issue. This news organization sought out several public and private hospitals in Brazil to see if there is any guidance on professional longevity: Most said that there is not. Only the A. C. Camargo Cancer Center reported, through its public relations team, that a committee is discussing the subject but that it is still in the early stages.

Brazilian specialist associations do not offer guidelines or instructions on the various aspects of professional longevity. Dr. Constantino tried to put the subject on the agenda during the years in which he was an administrator with the CFM. “We tried to open up discussions regarding truly elderly physicians, but the subject was not well received. I believe that it is precisely because there is a tradition of physicians working until they are no longer able that this is more difficult in Brazil ... No one exactly knows what to do in this respect.” Dr. Constantino is against the use of age as a criterion for quitting practice.

“Of course, this is a point that has to be considered, but I always defended the need for regular assessment of physicians, regardless of age range. And, although assessments are always welcome, in any profession, I also believe this would not be well received in Brazil.” He endorses an assessment of one’s knowledge and not of physical abilities, which are generally assessed through investigation when needed.

The absence of guidelines increases individual responsibility, as well as vulnerability. “Consciously, physicians will not put patients at risk if they do not have the competence to care for them or to perform a surgical procedure,” said Clystenes Odyr Soares Silva, MD, PhD, adjunct professor of pulmonology of the Federal University of São Paulo (Brazil) School of Medicine (UNIFESP). “Your peers will tell you if you are no longer able,” he added. The problem is that physicians rarely admit to or talk about their colleagues’ deficits, especially if they are in the spotlight because of advanced age. In this situation, the observation and opinion of family members regarding the health care professional’s competences and skills will hold more weight.

In case of health-related physical impairment, such as partial loss of hand movement, for example, “it is expected that this will set off an ethical warning in the person,” said Dr. Constantino. When this warning does not occur naturally, patients or colleagues can report the professional, and this may lead to the opening of an administrative investigation. If the report is found to be true, this investigation is used to suspend physicians who do not have the physical or mental ability to continue practicing medicine.

“If it’s something very serious, the physician’s license can be temporarily suspended while [the physician] is treated by a psychiatrist, with follow-up by the professional board. When discharged, the physician will get his or her [professional] license back and can go back to work,” Dr. Constantino explained. If an expert evaluation is needed, the physician will then be assessed by a forensic psychiatrist. One of the most in-demand forensic psychiatrists in Brazil is Guido Arturo Palomba, MD, 73 years old. “I have assessed some physicians for actions reported to see if they were normal people or not, but never for circumstances related to age,” Dr. Palomba said.

In practice, Brazilian medical entities do not have policies or programs to guide physicians who wish to grow old while they work or those who have started to notice they are not performing as they used to. “We have never lived as long; therefore, the quality of life in old age, as well as the concept of aging, are some of the most relevant questions of our time. These are subjects requiring additional discussion, broadening understanding and awareness in this regard,” observed Mr. Vattimo.

Dr. Constantino and Dr. Silva, who are completely against age-based assessments, believe that recertification of the specialist license every 5 years is the best path to confirming whether the physician is still able to practice. “A knowledge-based test every 5 years to recertify the specialist license has often been a topic of conversation. I think it’s an excellent idea. The person would provide a dossier of all they have done in terms of courses, conferences, and other activities, present it, and receive a score,” said Dr. Silva.

In practice, recertification of the specialist license is a topic of discussion that has been raised for years, and it is an idea that the Brazilian Medical Association (AMB) defends. In conjunction with the CFM, the association is studying a way to best implement this assessment. “It’s important to emphasize that this measure would not be retroactive at first. Instead, it would only be in effect for professionals licensed after the recertification requirement is established,” the AMB pointed out in a note sent to this news organization. Even so, the measure has faced significant resistance from a faction of the profession, and its enactment does not seem to be imminent.

The debate regarding professional longevity is taking place in various countries. In 2021, the American Medical Association Council on Medical Education released a report with a set of guidelines for the screening and assessment of physicians. The document is the product of a committee created in 2015 to study the subject. The AMA recommends that the assessment of elderly physicians be based on evidence and ethical, relevant, fair, equitable, transparent, verifiable, nonexhaustive principles, contemplating support and protecting against legal proceedings. In April of this year, a new AMA document highlighted the same principles.

Also in the United States, one of oldest initiatives created to support physicians in the process of recycling, the University of California San Diego Physician Assessment and Clinical Education Program (PACE), has a section focusing on the extended practice of medicine (Practicing Medicine Longer). For those wanting to learn more about discussions on this subject, there are online presentations on experiences in Quebec and Ontario with assessing aging physicians, neuropsychological perspectives on the aging medical population, and what to expect of healthy aging, among other subjects.

Created in 1996, PACE mostly provides services to physicians who need to address requirements of the state medical boards. Few physicians enroll on their own.

The first part of the program assesses knowledge and skills over approximately 2 days. In the second phase, the physician participates in a series of activities in a corresponding residency program. Depending on the results, the physician may have to go through a remedial program with varying activities to deal with performance deficiencies to clinical experiences at the residency level.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Analysis of PsA guidelines reveals much room for improvement on conflicts of interest

, according to a retrospective analysis of all authors on the most recent guidelines issued by the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) and the Japanese Dermatological Association (JDA).

In addition to finding that the majority of the authors of psoriatic arthritis (PsA) clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) issued by the JDA and ACR received substantial personal payments from pharmaceutical companies before and during CPG development, researchers led by Hanano Mamada and Anju Murayama of the Medical Governance Research Institute, Tokyo, wrote in Arthritis Care & Research that “several CPG authors self-cited their articles without the disclosure of NFCOI [nonfinancial conflicts of interest], and most of the recommendations were based on low or very low quality of evidence. Although the COI policies used by JDA and ACR are clearly inadequate, no significant revisions have been made for the last 3 years.”

Based on their findings, which were made using payment data from major Japanese pharmaceutical companies and the U.S. Open Payments Database from 2016 to 2018, the researchers suggested that the medical societies should:

- Adopt global standard COI policies from organizations such as the National Academy of Medicine and Guidelines International Network, including a 3-year lookback period for COI declaration.

- Consider a comprehensive definition and rigorous management with full disclosure of NFCOI.

- Publish a list of authors making each recommendation to grasp the implications of COI in clinical practice guidelines.

- Mention the detailed date of the COI disclosure, which should be close to the publication date as much as possible.

Financial conflicts of interest

The researchers used payment data published between 2016 and 2018 for all 83 companies belonging to the Japan Pharmaceutical Manufacturers Association, focusing on personal payments (for lecturing, writing, and consultancy) and excluding research payments, “since in Japan, the name, institution, and position of the author or researcher who received the research payment is not disclosed, which makes assessing research payments difficult.” To evaluate authors’ FCOI in the ACR’s CPG, the researchers analyzed the U.S. Open Payments Database “for all categories of general payments such as speaking, consulting, meals, and travel expenses 3 years from before the guideline’s first online publication on November 30, 2018.”

The 2018 ACR/National Psoriasis Foundation Guideline for the Treatment of Psoriatic Arthritis had 36 authors and the JDA’s Clinical Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Psoriatic Arthritis 2019 had 23. Overall, 61% of JDA authors and half of ACR authors voluntarily declared FCOI with pharmaceutical companies; 25 of the ACR authors were U.S. physicians and could be included in the Open Payments Database search.

A total of 21 (91.3%) JDA authors and 21 (84.0%) ACR authors received at least one payment, with the combined total of $3,335,413 and $4,081,629 payments, respectively, over the 3 years. The average and median personal payments were $145,018 and $123,876 for JDA authors and $162,825 and $58,826 for ACR authors. When the payments to ACR authors were limited to lecturing, writing, and consulting fees that are required under the ACR’s COI policy, the mean was $130,102 and median was $39,375. The corresponding payments for JDA authors were $123,876 and $8,170, respectively,

The researchers found undisclosed payments for more than three-quarters of physician authors of the Japanese guideline, and nearly half of the doctors authoring the American guideline had undisclosed payments. These added up to $474,000 for the JDA, which amounted to 38% of the total for personal payments that must be reported to the JDA based on its COI policy for clinical practice guidelines, and $218,000 for the ACR, amounting to 18% of the total for personal payments that must be reported to the society based on its COI policy.

Of the 11 ACR authors who were not eligible for the U.S. Open Payments Database search, 5 declared FCOI with pharmaceutical companies in the guideline, meaning that 26 (72%) of the 36 authors had FCOI with pharmaceutical companies.

The ACR only required authors to declare FCOI covering 1 year before and during guideline development, and although the JDA required authors to declare their FCOI for the past 3 years of guideline development, the study authors noted that the JDA guideline disclosed them for only 2 years (between Jan. 1, 2017, and Dec. 31, 2018).

“It is true that influential doctors such as clinical practice guideline authors tend to receive various types of payments from pharmaceutical companies and that it is difficult to conduct research without funding from pharmaceutical companies. However, our current research mainly focuses on personal payments from pharmaceutical companies such as lecture fees and consulting fees. These payments are recognized as pocket money and are not used for research. Thus, it is questionable that the observed relationships are something evitable,” the researchers wrote.

Nonfinancial conflicts of interest

Many authors of the ACR’s CPG and the JDA’s CPG also had NFCOI, defined objectively in this study as self-citation rate. NFCOI have been more broadly defined by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) as “conflicts, such as personal relationships or rivalries, academic competition, and intellectual beliefs”; the ICMJE recommends reporting NFCOI on its COI form.

The JDA guideline included self-citations by 78% of its authors, compared with 32% of the ACR guideline authors, but this weighed differently among the two guidelines in that only 12 of the 354 (3.4%) citations in the JDA guideline were self-cited, compared with 46 of 137 (34%) citations in the ACR guideline.

The researchers noted that while the self-citation rates between JDA and ACR authors “differed remarkably,” the impact of ACR authors on CPG recommendations was much more direct. Three-quarters of JDA authors’ self-cited articles were about observational studies, whereas 52% of the ACR authors’ self-cited articles were clinical trials, most of which were randomized, controlled studies, and these NFCOI were not disclosed in the guideline.

Half of the strong recommendations in the JDA guideline were based on low or very low quality of evidence, whereas the ACR guideline had no strong recommendations based on low or very low quality of evidence.

This study was supported by the nonprofit Medical Governance Research Institute, which receives donations from Ain Pharmacies Inc., other organizations, and private individuals. The study also received support from the Tansa (formerly known as the Waseda Chronicle), an independent nonprofit news organization dedicated to investigative journalism. Three authors reported receiving personal fees from several pharmaceutical companies for work outside of the scope of this study.

, according to a retrospective analysis of all authors on the most recent guidelines issued by the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) and the Japanese Dermatological Association (JDA).

In addition to finding that the majority of the authors of psoriatic arthritis (PsA) clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) issued by the JDA and ACR received substantial personal payments from pharmaceutical companies before and during CPG development, researchers led by Hanano Mamada and Anju Murayama of the Medical Governance Research Institute, Tokyo, wrote in Arthritis Care & Research that “several CPG authors self-cited their articles without the disclosure of NFCOI [nonfinancial conflicts of interest], and most of the recommendations were based on low or very low quality of evidence. Although the COI policies used by JDA and ACR are clearly inadequate, no significant revisions have been made for the last 3 years.”

Based on their findings, which were made using payment data from major Japanese pharmaceutical companies and the U.S. Open Payments Database from 2016 to 2018, the researchers suggested that the medical societies should:

- Adopt global standard COI policies from organizations such as the National Academy of Medicine and Guidelines International Network, including a 3-year lookback period for COI declaration.

- Consider a comprehensive definition and rigorous management with full disclosure of NFCOI.

- Publish a list of authors making each recommendation to grasp the implications of COI in clinical practice guidelines.

- Mention the detailed date of the COI disclosure, which should be close to the publication date as much as possible.

Financial conflicts of interest