User login

EMERGENCY MEDICINE is a practical, peer-reviewed monthly publication and Web site that meets the educational needs of emergency clinicians and urgent care clinicians for their practice.

Use of mental health services soared during pandemic

By the end of August 2022, overall use of mental health services was almost 40% higher than before the COVID-19 pandemic, while spending increased by 54%, according to a new study by researchers at the RAND Corporation.

During the early phase of the pandemic, from mid-March to mid-December 2020, before the vaccine was available, in-person visits decreased by 40%, while telehealth visits increased by 1,000%, reported Jonathan H. Cantor, PhD, and colleagues at RAND, and at Castlight Health, a benefit coordination provider, in a paper published online in JAMA Health Forum.

Between December 2020 and August 2022, telehealth visits stayed stable, but in-person visits creeped back up, eventually reaching 80% of prepandemic levels. However, “total utilization was higher than before the pandemic,” Dr. Cantor, a policy researcher at RAND, told this news organization.

“It could be that it’s easier for individuals to receive care via telehealth, but it could also just be that there’s a greater demand or need since the pandemic,” said Dr. Cantor. “We’ll just need more research to actually unpack what’s going on,” he said.

Initial per capita spending increased by about a third and was up overall by more than half. But it’s not clear how much of that is due to utilization or to price of services, said Dr. Cantor. Spending for telehealth services remained stable in the post-vaccine period, while spending on in-person visits returned to prepandemic levels.

Dr. Cantor and his colleagues were not able to determine whether utilization was by new or existing patients, but he said that would be good data to have. “It would be really important to know whether or not folks are initiating care because telehealth is making it easier,” he said.

The authors analyzed about 1.5 million claims for anxiety disorders, major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and posttraumatic stress disorder, out of claims submitted by 7 million commercially insured adults whose self-insured employers used the Castlight benefit.

Dr. Cantor noted that this is just a small subset of the U.S. population. He said he’d like to have data from Medicare and Medicaid to fully assess the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health and of telehealth visits.

“This is a still-burgeoning field,” he said about telehealth. “We’re still trying to get a handle on how things are operating, given that there’s been so much change so rapidly.”

Meanwhile, 152 major employers responding to a large national survey this summer said that they’ve been grappling with how COVID-19 has affected workers. The employers include 72 Fortune 100 companies and provide health coverage for more than 60 million workers, retirees, and their families.

Seventy-seven percent said they are currently seeing an increase in depression, anxiety, and substance use disorders as a result of the pandemic, according to the Business Group on Health’s survey. That’s up from 44% in 2022.

Going forward, employers will focus on increasing access to mental health services, the survey reported.

“Our survey found that in 2024 and for the near future, employers will be acutely focused on addressing employees’ mental health needs while ensuring access and lowering cost barriers,” Ellen Kelsay, president and CEO of Business Group on Health, said in a statement.

The study was supported by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health and the National Institute on Aging. Coauthor Dena Bravata, MD, a Castlight employee, reported receiving personal fees from Castlight Health during the conduct of the study. Coauthor Christopher M. Whaley, a RAND employee, reported receiving personal fees from Castlight Health outside the submitted work.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

By the end of August 2022, overall use of mental health services was almost 40% higher than before the COVID-19 pandemic, while spending increased by 54%, according to a new study by researchers at the RAND Corporation.

During the early phase of the pandemic, from mid-March to mid-December 2020, before the vaccine was available, in-person visits decreased by 40%, while telehealth visits increased by 1,000%, reported Jonathan H. Cantor, PhD, and colleagues at RAND, and at Castlight Health, a benefit coordination provider, in a paper published online in JAMA Health Forum.

Between December 2020 and August 2022, telehealth visits stayed stable, but in-person visits creeped back up, eventually reaching 80% of prepandemic levels. However, “total utilization was higher than before the pandemic,” Dr. Cantor, a policy researcher at RAND, told this news organization.

“It could be that it’s easier for individuals to receive care via telehealth, but it could also just be that there’s a greater demand or need since the pandemic,” said Dr. Cantor. “We’ll just need more research to actually unpack what’s going on,” he said.

Initial per capita spending increased by about a third and was up overall by more than half. But it’s not clear how much of that is due to utilization or to price of services, said Dr. Cantor. Spending for telehealth services remained stable in the post-vaccine period, while spending on in-person visits returned to prepandemic levels.

Dr. Cantor and his colleagues were not able to determine whether utilization was by new or existing patients, but he said that would be good data to have. “It would be really important to know whether or not folks are initiating care because telehealth is making it easier,” he said.

The authors analyzed about 1.5 million claims for anxiety disorders, major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and posttraumatic stress disorder, out of claims submitted by 7 million commercially insured adults whose self-insured employers used the Castlight benefit.

Dr. Cantor noted that this is just a small subset of the U.S. population. He said he’d like to have data from Medicare and Medicaid to fully assess the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health and of telehealth visits.

“This is a still-burgeoning field,” he said about telehealth. “We’re still trying to get a handle on how things are operating, given that there’s been so much change so rapidly.”

Meanwhile, 152 major employers responding to a large national survey this summer said that they’ve been grappling with how COVID-19 has affected workers. The employers include 72 Fortune 100 companies and provide health coverage for more than 60 million workers, retirees, and their families.

Seventy-seven percent said they are currently seeing an increase in depression, anxiety, and substance use disorders as a result of the pandemic, according to the Business Group on Health’s survey. That’s up from 44% in 2022.

Going forward, employers will focus on increasing access to mental health services, the survey reported.

“Our survey found that in 2024 and for the near future, employers will be acutely focused on addressing employees’ mental health needs while ensuring access and lowering cost barriers,” Ellen Kelsay, president and CEO of Business Group on Health, said in a statement.

The study was supported by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health and the National Institute on Aging. Coauthor Dena Bravata, MD, a Castlight employee, reported receiving personal fees from Castlight Health during the conduct of the study. Coauthor Christopher M. Whaley, a RAND employee, reported receiving personal fees from Castlight Health outside the submitted work.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

By the end of August 2022, overall use of mental health services was almost 40% higher than before the COVID-19 pandemic, while spending increased by 54%, according to a new study by researchers at the RAND Corporation.

During the early phase of the pandemic, from mid-March to mid-December 2020, before the vaccine was available, in-person visits decreased by 40%, while telehealth visits increased by 1,000%, reported Jonathan H. Cantor, PhD, and colleagues at RAND, and at Castlight Health, a benefit coordination provider, in a paper published online in JAMA Health Forum.

Between December 2020 and August 2022, telehealth visits stayed stable, but in-person visits creeped back up, eventually reaching 80% of prepandemic levels. However, “total utilization was higher than before the pandemic,” Dr. Cantor, a policy researcher at RAND, told this news organization.

“It could be that it’s easier for individuals to receive care via telehealth, but it could also just be that there’s a greater demand or need since the pandemic,” said Dr. Cantor. “We’ll just need more research to actually unpack what’s going on,” he said.

Initial per capita spending increased by about a third and was up overall by more than half. But it’s not clear how much of that is due to utilization or to price of services, said Dr. Cantor. Spending for telehealth services remained stable in the post-vaccine period, while spending on in-person visits returned to prepandemic levels.

Dr. Cantor and his colleagues were not able to determine whether utilization was by new or existing patients, but he said that would be good data to have. “It would be really important to know whether or not folks are initiating care because telehealth is making it easier,” he said.

The authors analyzed about 1.5 million claims for anxiety disorders, major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and posttraumatic stress disorder, out of claims submitted by 7 million commercially insured adults whose self-insured employers used the Castlight benefit.

Dr. Cantor noted that this is just a small subset of the U.S. population. He said he’d like to have data from Medicare and Medicaid to fully assess the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health and of telehealth visits.

“This is a still-burgeoning field,” he said about telehealth. “We’re still trying to get a handle on how things are operating, given that there’s been so much change so rapidly.”

Meanwhile, 152 major employers responding to a large national survey this summer said that they’ve been grappling with how COVID-19 has affected workers. The employers include 72 Fortune 100 companies and provide health coverage for more than 60 million workers, retirees, and their families.

Seventy-seven percent said they are currently seeing an increase in depression, anxiety, and substance use disorders as a result of the pandemic, according to the Business Group on Health’s survey. That’s up from 44% in 2022.

Going forward, employers will focus on increasing access to mental health services, the survey reported.

“Our survey found that in 2024 and for the near future, employers will be acutely focused on addressing employees’ mental health needs while ensuring access and lowering cost barriers,” Ellen Kelsay, president and CEO of Business Group on Health, said in a statement.

The study was supported by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health and the National Institute on Aging. Coauthor Dena Bravata, MD, a Castlight employee, reported receiving personal fees from Castlight Health during the conduct of the study. Coauthor Christopher M. Whaley, a RAND employee, reported receiving personal fees from Castlight Health outside the submitted work.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Getting COVID shots in same arm may be more effective, study says

Scientists in Germany looked at health data for 303 people who got the mRNA vaccine and then a booster shot. Their antibody levels were measured two weeks after the second shot. None of the people had had COVID before the vaccinations.

Scientists found that the number of protective “killer T cells” was higher in the 147 study participants who got both shots in the same arm, said the study published in EBioMedicine.

The killer cells were found in 67% of cases in which both shots went into the same arm, compared with 43% of cases with different arms.

“That may suggest that that ipsilateral vaccination (in the same arm) is more likely to provide better protection should the vaccinated person become infected with the SARS-CoV-2 virus,” Laura Ziegler, a doctoral student at Saarland University, Germany, said in a news release.

William Schaffner, MD, a professor in the Division of Infectious Diseases at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn., told CBS News that same-arm vaccinations may work better because the cells that provide the immune response are in local lymph nodes.

There’s greater immunological response if the immune cells in the lymph nodes are restimulated in the same place, said Dr. Schaffner, who was not involved in the German study.

The scientists from Saarland University said more research is needed before they can be certain that having vaccinations in the same arm is actually more effective for COVID shots and sequential vaccinations against diseases such as the flu.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Scientists in Germany looked at health data for 303 people who got the mRNA vaccine and then a booster shot. Their antibody levels were measured two weeks after the second shot. None of the people had had COVID before the vaccinations.

Scientists found that the number of protective “killer T cells” was higher in the 147 study participants who got both shots in the same arm, said the study published in EBioMedicine.

The killer cells were found in 67% of cases in which both shots went into the same arm, compared with 43% of cases with different arms.

“That may suggest that that ipsilateral vaccination (in the same arm) is more likely to provide better protection should the vaccinated person become infected with the SARS-CoV-2 virus,” Laura Ziegler, a doctoral student at Saarland University, Germany, said in a news release.

William Schaffner, MD, a professor in the Division of Infectious Diseases at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn., told CBS News that same-arm vaccinations may work better because the cells that provide the immune response are in local lymph nodes.

There’s greater immunological response if the immune cells in the lymph nodes are restimulated in the same place, said Dr. Schaffner, who was not involved in the German study.

The scientists from Saarland University said more research is needed before they can be certain that having vaccinations in the same arm is actually more effective for COVID shots and sequential vaccinations against diseases such as the flu.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Scientists in Germany looked at health data for 303 people who got the mRNA vaccine and then a booster shot. Their antibody levels were measured two weeks after the second shot. None of the people had had COVID before the vaccinations.

Scientists found that the number of protective “killer T cells” was higher in the 147 study participants who got both shots in the same arm, said the study published in EBioMedicine.

The killer cells were found in 67% of cases in which both shots went into the same arm, compared with 43% of cases with different arms.

“That may suggest that that ipsilateral vaccination (in the same arm) is more likely to provide better protection should the vaccinated person become infected with the SARS-CoV-2 virus,” Laura Ziegler, a doctoral student at Saarland University, Germany, said in a news release.

William Schaffner, MD, a professor in the Division of Infectious Diseases at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn., told CBS News that same-arm vaccinations may work better because the cells that provide the immune response are in local lymph nodes.

There’s greater immunological response if the immune cells in the lymph nodes are restimulated in the same place, said Dr. Schaffner, who was not involved in the German study.

The scientists from Saarland University said more research is needed before they can be certain that having vaccinations in the same arm is actually more effective for COVID shots and sequential vaccinations against diseases such as the flu.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM EBIOMEDICINE

A new (old) drug joins the COVID fray, and guess what? It works

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

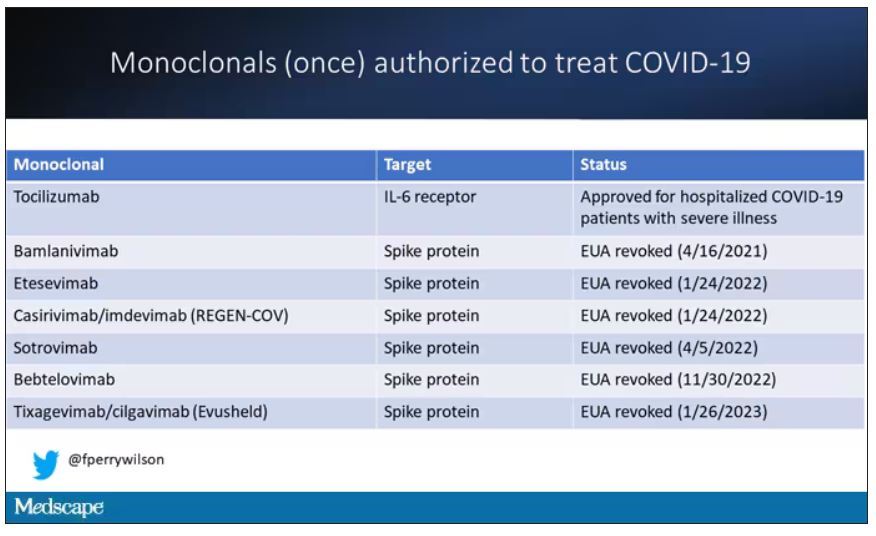

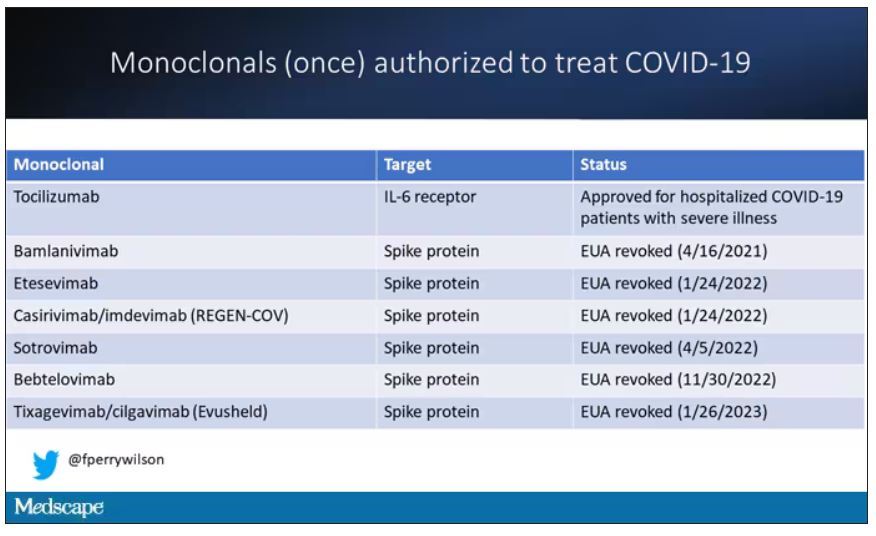

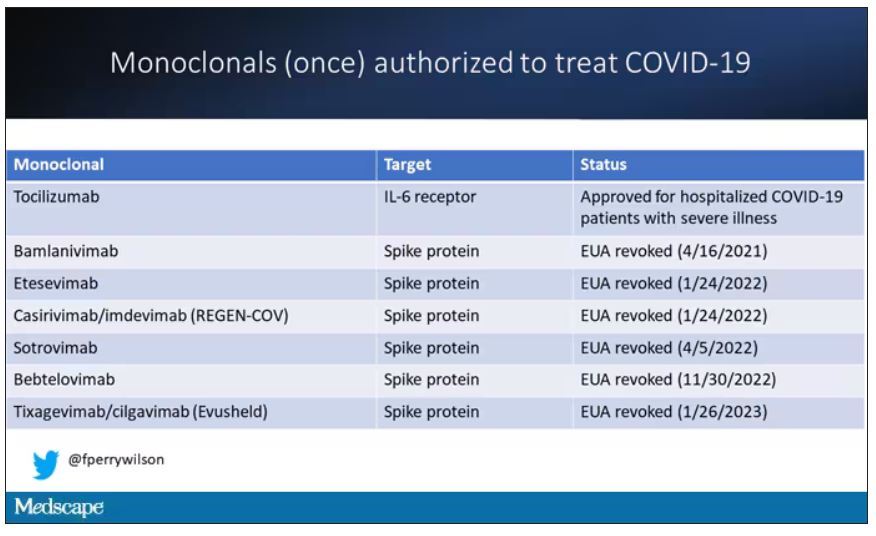

At this point, with the monoclonals found to be essentially useless, we are left with remdesivir with its modest efficacy and Paxlovid, which, for some reason, people don’t seem to be taking.

Part of the reason the monoclonals have failed lately is because of their specificity; they are homogeneous antibodies targeted toward a very specific epitope that may change from variant to variant. We need a broader therapeutic, one that has activity across all variants — maybe even one that has activity against all viruses? We’ve got one. Interferon.

The first mention of interferon as a potential COVID therapy was at the very start of the pandemic, so I’m sort of surprised that the first large, randomized trial is only being reported now in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Before we dig into the results, let’s talk mechanism. This is a trial of interferon-lambda, also known as interleukin-29.

The lambda interferons were only discovered in 2003. They differ from the more familiar interferons only in their cellular receptors; the downstream effects seem quite similar. As opposed to the cellular receptors for interferon alfa, which are widely expressed, the receptors for lambda are restricted to epithelial tissues. This makes it a good choice as a COVID treatment, since the virus also preferentially targets those epithelial cells.

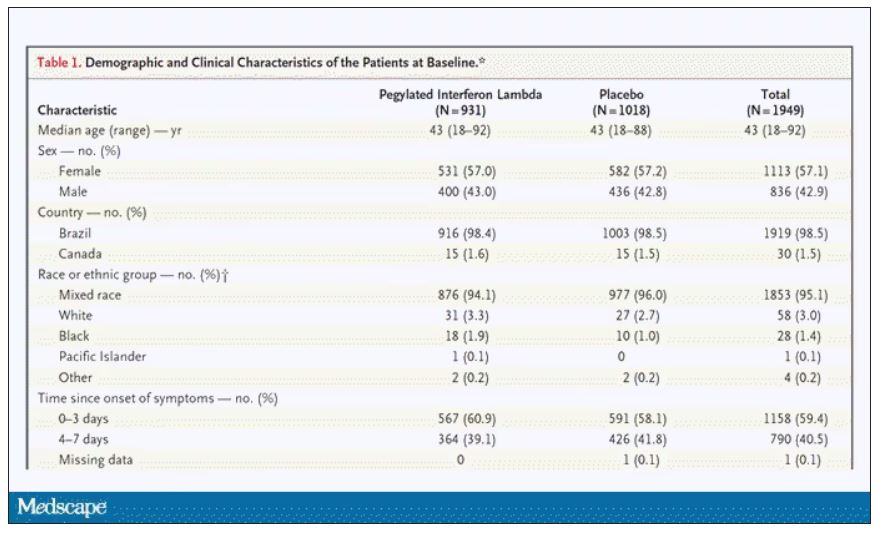

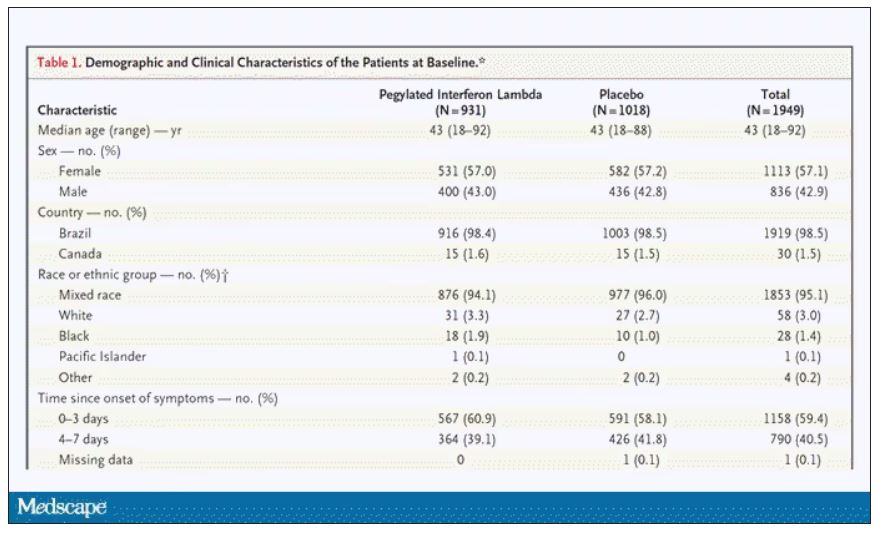

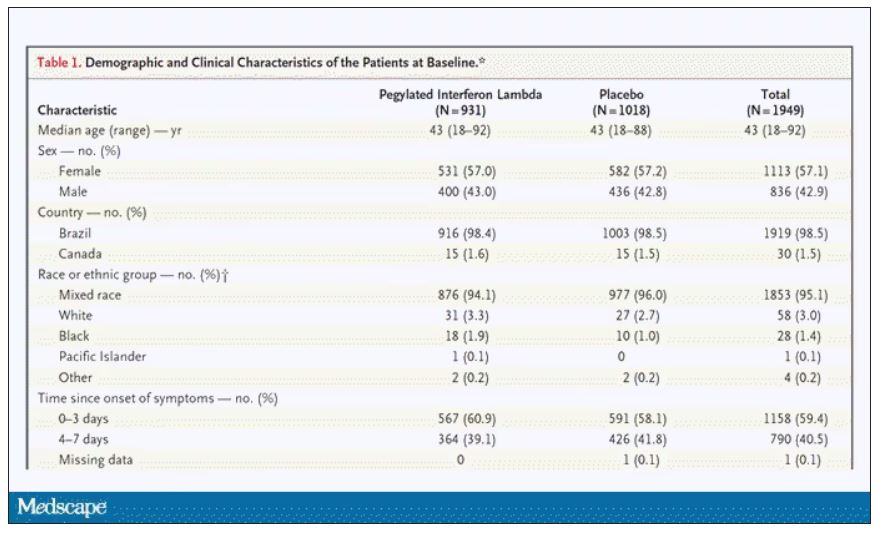

In this study, 1,951 participants from Brazil and Canada, but mostly Brazil, with new COVID infections who were not yet hospitalized were randomized to receive 180 mcg of interferon lambda or placebo.

This was a relatively current COVID trial, as you can see from the participant characteristics. The majority had been vaccinated, and nearly half of the infections were during the Omicron phase of the pandemic.

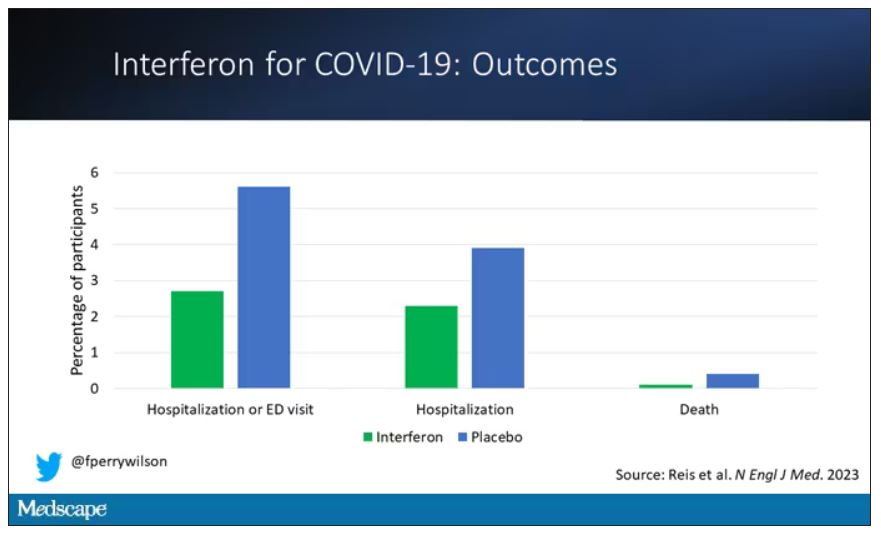

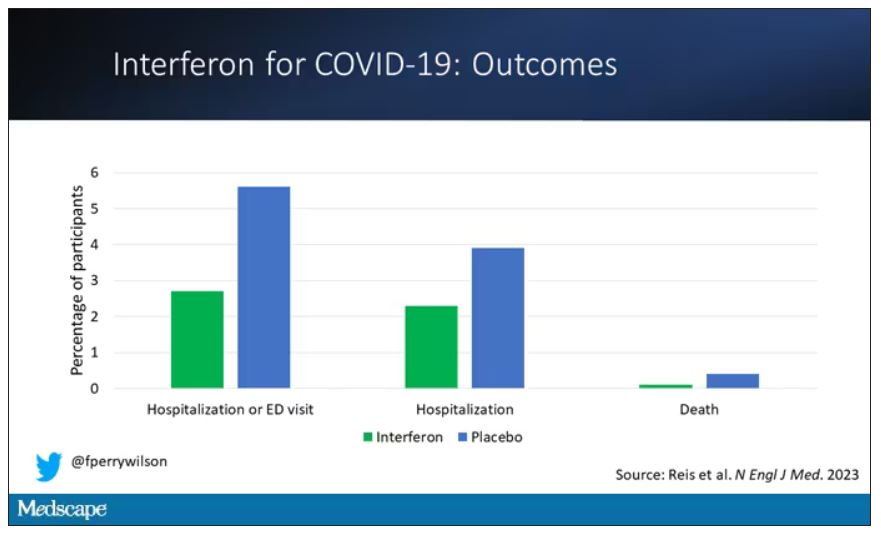

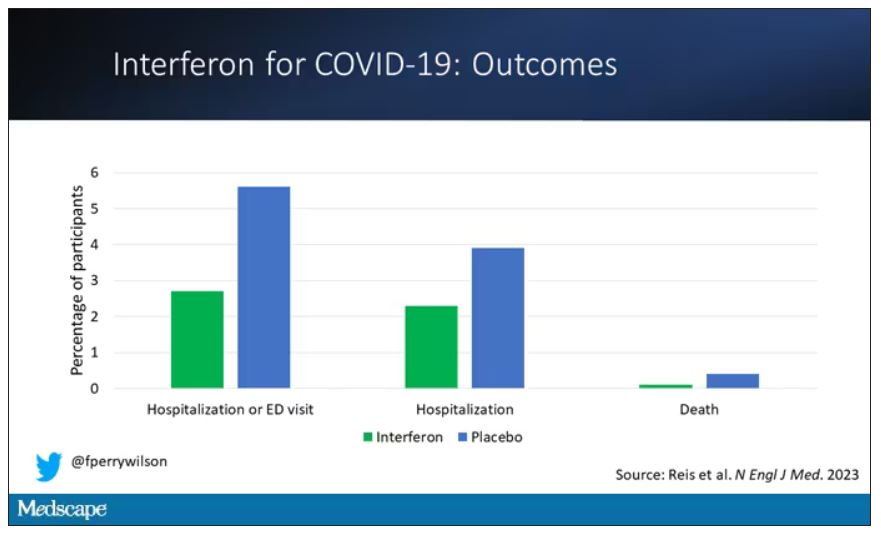

If you just want to cut to the chase, interferon worked.

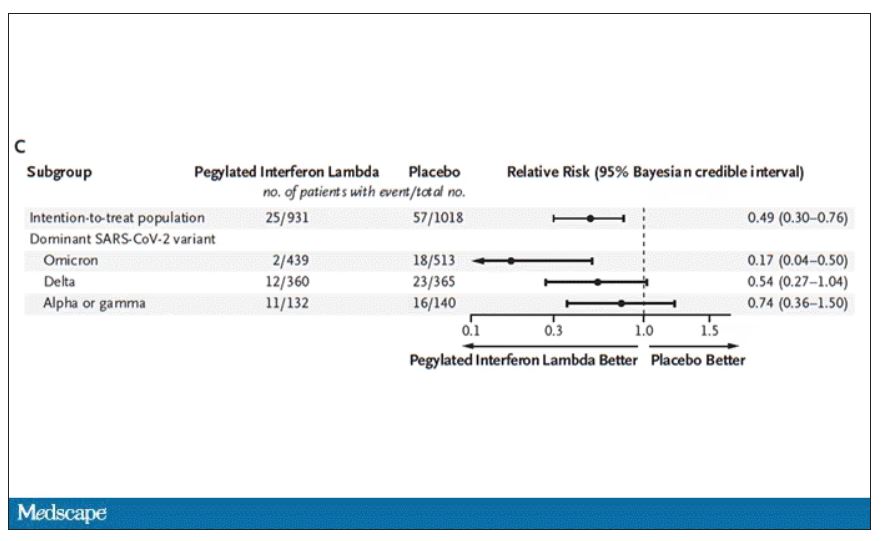

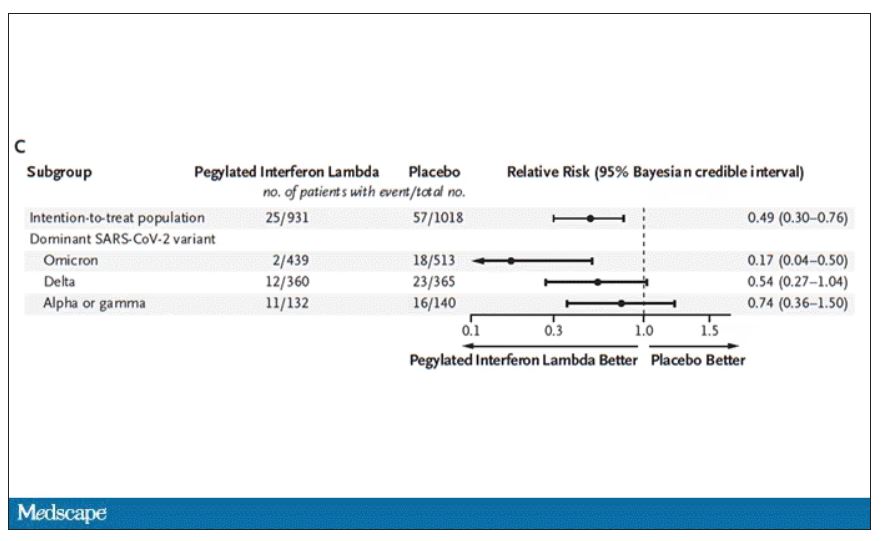

The primary outcome – hospitalization or a prolonged emergency room visit for COVID – was 50% lower in the interferon group.

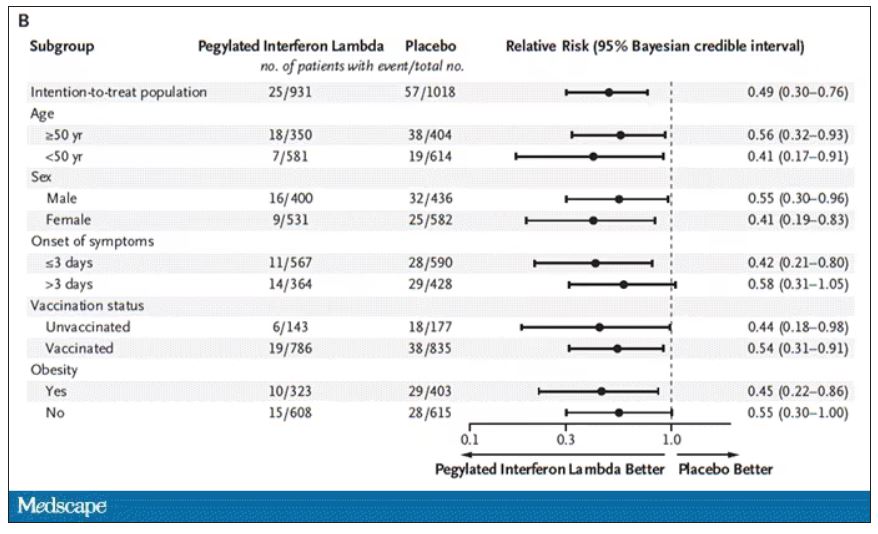

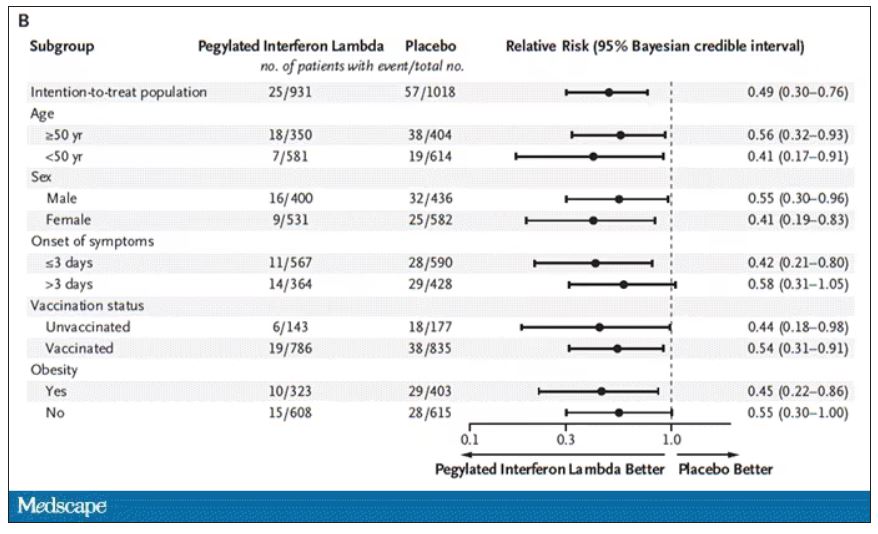

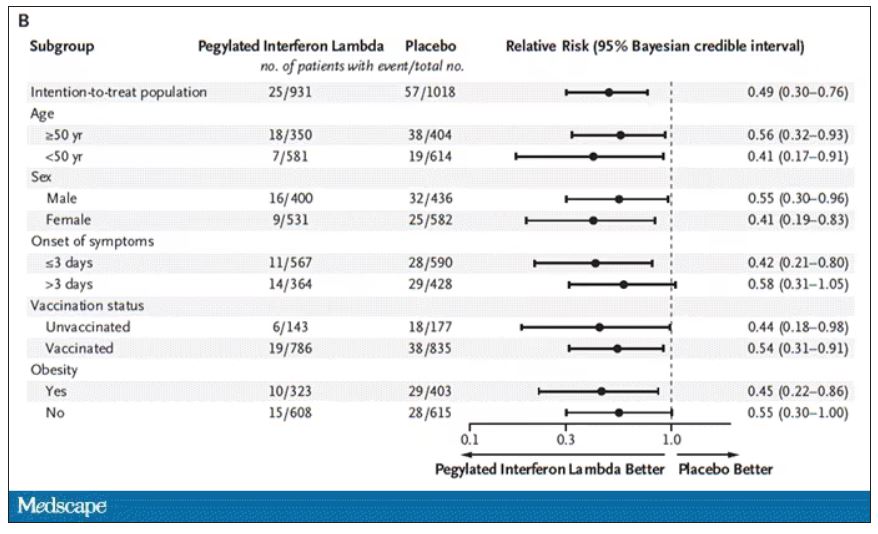

Key secondary outcomes, including death from COVID, were lower in the interferon group as well. These effects persisted across most of the subgroups I was looking out for.

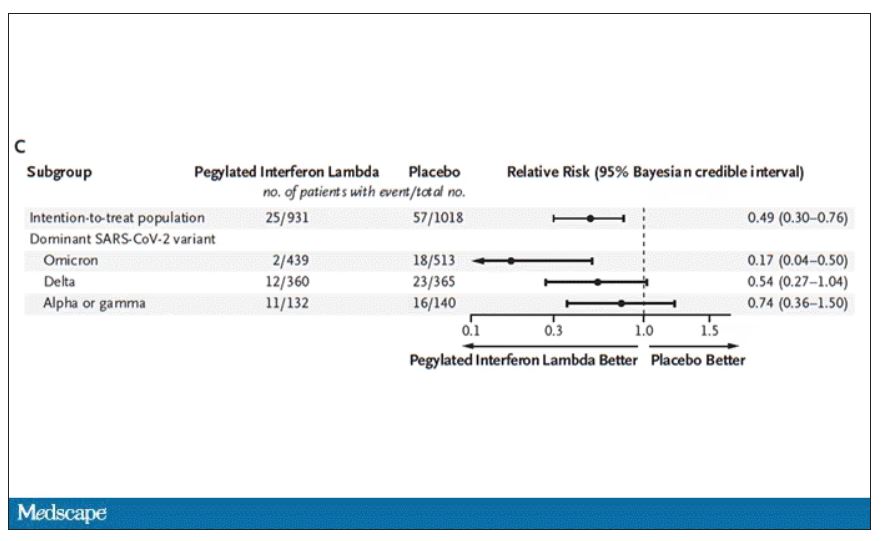

Interferon seemed to help those who were already vaccinated and those who were unvaccinated. There’s a hint that it works better within the first few days of symptoms, which isn’t surprising; we’ve seen this for many of the therapeutics, including Paxlovid. Time is of the essence. Encouragingly, the effect was a bit more pronounced among those infected with Omicron.

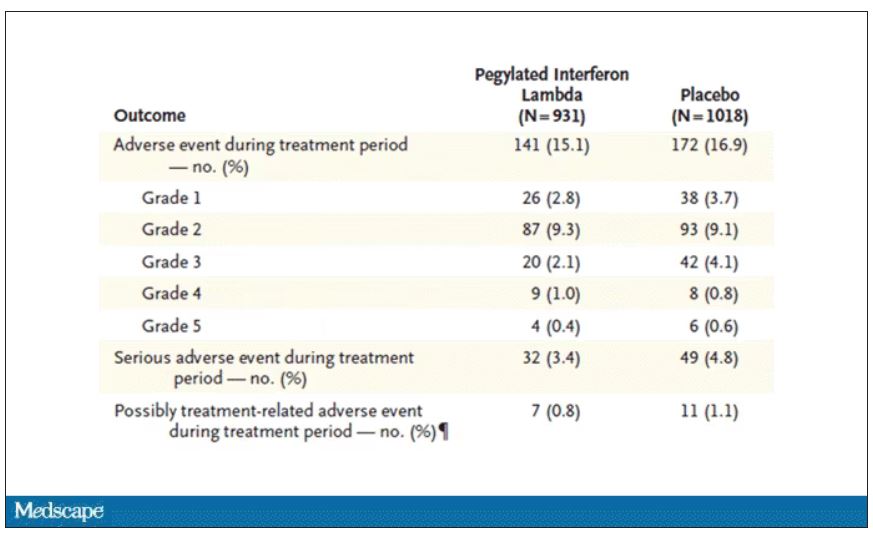

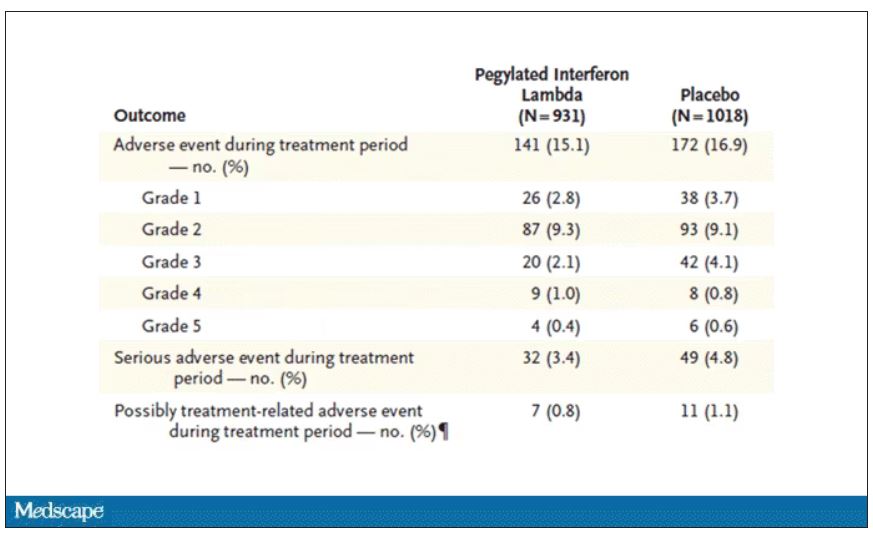

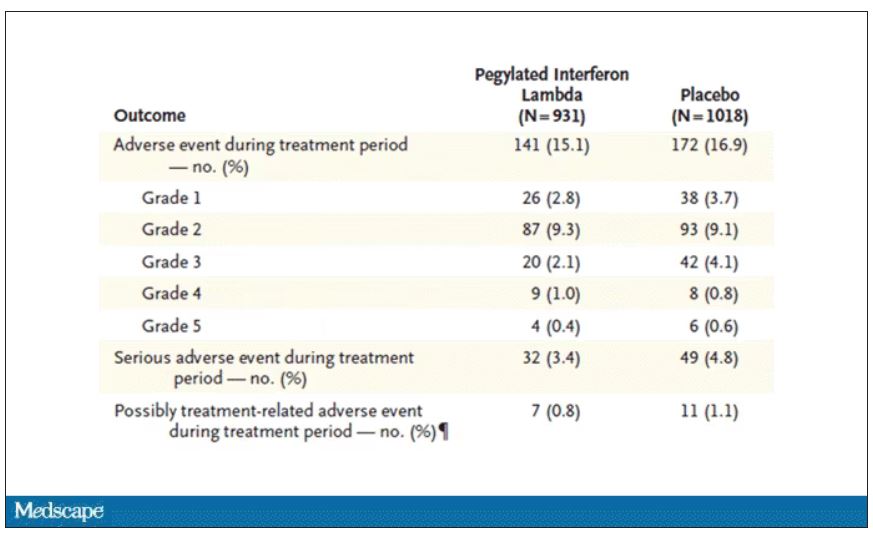

Of course, if you have any experience with interferon, you know that the side effects can be pretty rough. In the bad old days when we treated hepatitis C infection with interferon, patients would get their injections on Friday in anticipation of being essentially out of commission with flu-like symptoms through the weekend. But we don’t see much evidence of adverse events in this trial, maybe due to the greater specificity of interferon lambda.

Putting it all together, the state of play for interferons in COVID may be changing. To date, the FDA has not recommended the use of interferon alfa or -beta for COVID-19, citing some data that they are ineffective or even harmful in hospitalized patients with COVID. Interferon lambda is not FDA approved and thus not even available in the United States. But the reason it has not been approved is that there has not been a large, well-conducted interferon lambda trial. Now there is. Will this study be enough to prompt an emergency use authorization? The elephant in the room, of course, is Paxlovid, which at this point has a longer safety track record and, importantly, is oral. I’d love to see a head-to-head trial. Short of that, I tend to be in favor of having more options on the table.

Dr. Perry Wilson is associate professor, department of medicine, and director, Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator, at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

At this point, with the monoclonals found to be essentially useless, we are left with remdesivir with its modest efficacy and Paxlovid, which, for some reason, people don’t seem to be taking.

Part of the reason the monoclonals have failed lately is because of their specificity; they are homogeneous antibodies targeted toward a very specific epitope that may change from variant to variant. We need a broader therapeutic, one that has activity across all variants — maybe even one that has activity against all viruses? We’ve got one. Interferon.

The first mention of interferon as a potential COVID therapy was at the very start of the pandemic, so I’m sort of surprised that the first large, randomized trial is only being reported now in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Before we dig into the results, let’s talk mechanism. This is a trial of interferon-lambda, also known as interleukin-29.

The lambda interferons were only discovered in 2003. They differ from the more familiar interferons only in their cellular receptors; the downstream effects seem quite similar. As opposed to the cellular receptors for interferon alfa, which are widely expressed, the receptors for lambda are restricted to epithelial tissues. This makes it a good choice as a COVID treatment, since the virus also preferentially targets those epithelial cells.

In this study, 1,951 participants from Brazil and Canada, but mostly Brazil, with new COVID infections who were not yet hospitalized were randomized to receive 180 mcg of interferon lambda or placebo.

This was a relatively current COVID trial, as you can see from the participant characteristics. The majority had been vaccinated, and nearly half of the infections were during the Omicron phase of the pandemic.

If you just want to cut to the chase, interferon worked.

The primary outcome – hospitalization or a prolonged emergency room visit for COVID – was 50% lower in the interferon group.

Key secondary outcomes, including death from COVID, were lower in the interferon group as well. These effects persisted across most of the subgroups I was looking out for.

Interferon seemed to help those who were already vaccinated and those who were unvaccinated. There’s a hint that it works better within the first few days of symptoms, which isn’t surprising; we’ve seen this for many of the therapeutics, including Paxlovid. Time is of the essence. Encouragingly, the effect was a bit more pronounced among those infected with Omicron.

Of course, if you have any experience with interferon, you know that the side effects can be pretty rough. In the bad old days when we treated hepatitis C infection with interferon, patients would get their injections on Friday in anticipation of being essentially out of commission with flu-like symptoms through the weekend. But we don’t see much evidence of adverse events in this trial, maybe due to the greater specificity of interferon lambda.

Putting it all together, the state of play for interferons in COVID may be changing. To date, the FDA has not recommended the use of interferon alfa or -beta for COVID-19, citing some data that they are ineffective or even harmful in hospitalized patients with COVID. Interferon lambda is not FDA approved and thus not even available in the United States. But the reason it has not been approved is that there has not been a large, well-conducted interferon lambda trial. Now there is. Will this study be enough to prompt an emergency use authorization? The elephant in the room, of course, is Paxlovid, which at this point has a longer safety track record and, importantly, is oral. I’d love to see a head-to-head trial. Short of that, I tend to be in favor of having more options on the table.

Dr. Perry Wilson is associate professor, department of medicine, and director, Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator, at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

At this point, with the monoclonals found to be essentially useless, we are left with remdesivir with its modest efficacy and Paxlovid, which, for some reason, people don’t seem to be taking.

Part of the reason the monoclonals have failed lately is because of their specificity; they are homogeneous antibodies targeted toward a very specific epitope that may change from variant to variant. We need a broader therapeutic, one that has activity across all variants — maybe even one that has activity against all viruses? We’ve got one. Interferon.

The first mention of interferon as a potential COVID therapy was at the very start of the pandemic, so I’m sort of surprised that the first large, randomized trial is only being reported now in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Before we dig into the results, let’s talk mechanism. This is a trial of interferon-lambda, also known as interleukin-29.

The lambda interferons were only discovered in 2003. They differ from the more familiar interferons only in their cellular receptors; the downstream effects seem quite similar. As opposed to the cellular receptors for interferon alfa, which are widely expressed, the receptors for lambda are restricted to epithelial tissues. This makes it a good choice as a COVID treatment, since the virus also preferentially targets those epithelial cells.

In this study, 1,951 participants from Brazil and Canada, but mostly Brazil, with new COVID infections who were not yet hospitalized were randomized to receive 180 mcg of interferon lambda or placebo.

This was a relatively current COVID trial, as you can see from the participant characteristics. The majority had been vaccinated, and nearly half of the infections were during the Omicron phase of the pandemic.

If you just want to cut to the chase, interferon worked.

The primary outcome – hospitalization or a prolonged emergency room visit for COVID – was 50% lower in the interferon group.

Key secondary outcomes, including death from COVID, were lower in the interferon group as well. These effects persisted across most of the subgroups I was looking out for.

Interferon seemed to help those who were already vaccinated and those who were unvaccinated. There’s a hint that it works better within the first few days of symptoms, which isn’t surprising; we’ve seen this for many of the therapeutics, including Paxlovid. Time is of the essence. Encouragingly, the effect was a bit more pronounced among those infected with Omicron.

Of course, if you have any experience with interferon, you know that the side effects can be pretty rough. In the bad old days when we treated hepatitis C infection with interferon, patients would get their injections on Friday in anticipation of being essentially out of commission with flu-like symptoms through the weekend. But we don’t see much evidence of adverse events in this trial, maybe due to the greater specificity of interferon lambda.

Putting it all together, the state of play for interferons in COVID may be changing. To date, the FDA has not recommended the use of interferon alfa or -beta for COVID-19, citing some data that they are ineffective or even harmful in hospitalized patients with COVID. Interferon lambda is not FDA approved and thus not even available in the United States. But the reason it has not been approved is that there has not been a large, well-conducted interferon lambda trial. Now there is. Will this study be enough to prompt an emergency use authorization? The elephant in the room, of course, is Paxlovid, which at this point has a longer safety track record and, importantly, is oral. I’d love to see a head-to-head trial. Short of that, I tend to be in favor of having more options on the table.

Dr. Perry Wilson is associate professor, department of medicine, and director, Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator, at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Novel resuscitation for patients with nonshockable rhythms in cardiac arrest

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Robert D. Glatter, MD: Welcome. I’m Dr Robert Glatter, medical adviser for Medscape Emergency Medicine. with a remarkable increase in neurologically intact survival. Welcome, gentlemen.

Dr. Pepe, I’d like to start off by thanking you for taking time to join us to discuss this novel concept of head-up or what you now refer to as a neuroprotective cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) bundle. Can you define what this entails and why it is referred to as a neuroprotective CPR bundle?

Paul E. Pepe, MD, MPH: CPR has been life saving for 60 years the way we’ve performed it, but probably only in a very small percentage of cases. That’s one of the problems. We have almost a thousand people a day who have sudden cardiac arrest out in the community alone and more in the hospital.

We know that early defibrillation and early CPR can contribute, but it’s still a small percentage of those. About 75%-85% of the cases that we go out to see will have nonshockable rhythms and flatlines. Some cases are what we call “pulseless electrical activity,” meaning that it looks like there is some kind of organized complex, but there is no pulse associated with it.

That’s why it’s a problem, because they don’t come back. Part of the reason why we see poor outcomes is not only that these cases tend to be people who, say, were in ventricular fibrillation and then just went on over time and were not witnessed or resuscitated or had a long response time. They basically either go into flatline or autoconvert into these bizarre rhythms.

The other issue is the way we perform CPR. CPR has been lifesaving, but it only generates about 20% and maybe 15% in some cases of normal blood flow, and particularly, cerebral perfusion pressure. We’ve looked at this nicely in the laboratory.

For example, during chest compressions, we’re hoping during the recoil phase to pull blood down and back into the right heart. The problem is that you’re not only setting a pressure rate up here to the arterial side but also, you’re setting back pressure wave on the venous side. Obviously, the arterial side always wins out, but it’s just not as efficient as it could be, at 20% or 30%.

What does this entail? It entails several independent mechanisms in terms of how they work, but they all do the same thing, which is they help to pull blood out of the brain and back into the right heart by basically manipulating intrathoracic pressure and creating more of a vacuum to get blood back there.

It’s so important that people do quality CPR. You have to have a good release and that helps us suck a little bit of blood and sucks the air in. As soon as the air rushes in, it neutralizes the pressure and there’s no more vacuum and nothing else is happening until the next squeeze.

What we have found is that we can cap the airway just for a second with a little pop-up valve. It acts like when you’re sucking a milkshake through a straw and it creates more of a vacuum in the chest. Just a little pop-up valve that pulls a little bit more blood out of the brain and the rest of the body and into the right heart.

We’ve shown in a human study that, for example, the systolic blood pressure almost doubles. It really goes from 40 mm Hg during standard CPR up to 80 mm Hg, and that would be sustained for 14-15 minutes. That was a nice little study that was done in Milwaukee a few years ago.

The other thing that happens is, if you add on something else, it’s like a toilet plunger. I think many people have seen it; it’s called “active compression-decompression.” It not only compresses, but it decompresses. Where it becomes even more effective is that if you had broken bones or stiff bones as you get older or whatever it may be, as you do the CPR, you’re still getting the push down and then you’re getting the pull out. It helps on several levels. More importantly, when you put the two together, they’re very synergistic.

We, have already done the clinical trial that is the proof of concept, and that was published in The Lancet about 10 years ago. In that study, we found that the combination of those two dramatically improved survival rates by 50%, with 1-year survival neurologically intact. That got us on the right track.

The interesting thing is that someone said, “Can we lift the head up a little bit?” We did a large amount of work in the laboratory over 10 years, fine tuning it. When do you first lift the head? How soon is too soon? It’s probably bad if you just go right to it.

We had to get the pump primed a little bit with these other things to get the flow going better, not only pulling blood out of the brain but now, you have a better flow this way. You have to prime at first for a couple of minutes, and we worked out the timing: Is it 3 or 4 minutes? It seems the timing is right at about 2 minutes, then you gradually elevate the head over about 2 minutes. We’re finding that seems to be the optimal way to do it. About 2 minutes of priming with those other two devices, the adjuncts, and then gradually elevate the head over 2 minutes.

When we do that in the laboratory, we’re getting normalized cerebral perfusion pressures. You’re normalizing the flow back again with that. We’re seeing profound differences in outcome as a result, even in these cases of the nonshockables.

Dr. Glatter: What you’re doing basically is resulting in an increase in cardiac output, essentially. That really is important, especially in these nonshockable rhythms, correct?

Dr. Pepe: Absolutely. As you’re doing this compression and you’re getting these intracranial pulse waves that are going up because they’re colliding up there. It could be even damaging in itself, but we’re seeing these intracranial raises. The intracranial pressure starts going up more and more over time. Also, peripherally in most people, you’re not getting good flow out there; then, your vasculature starts to relax. The arterials are starting to not get oxygen, so they don’t go out.

With this technique where we’re returning the pressure, we’re getting to 40% of normal now with the active compression-decompression CPR plus an impedance threshold device (ACD+ITD CPR) approach. Now, you add this, and you’re almost normalizing. In humans, even in these asystole patients, we’re seeing end-title CO2s which are generally in the 15-20 range with standard CPR are now up with ACD+ITD CPR in the 30%-40% range, where we’re getting through 30 or 40 end-tidal CO2s. Now, we’re seeing even the end-tidal CO2s moving up into the 40s and 50s. We know there’s a surrogate marker telling us that we are generating much better flows not only to the rest of the body, but most importantly, to the brain.

Dr. Glatter: Ryan, could you tell us about the approach in terms of on scene, what you’re doing and how you use the device itself? Maybe you could talk about the backpack that you developed with your fire department?

Ryan P. Quinn, BS, EMS: Our approach has always been to get to the patient quickly, like everybody’s approach on a cardiac arrest when you’re responding. We are an advanced life-support paramedic ambulance service through the fire department – we’re all cross-trained firefighter paramedics. Our first vehicle from the fire department is typically the ambulance. It’s smaller and a little quicker than the fire engine. Two paramedics are going to jump out with two backpacks. One has the automated compressive device (we use the Lucas), and the other one is the sequential patient lifting device, the EleGARD.

Our two paramedics are quick to the patient’s side, and once they make contact with the patient to verify pulseless cardiac arrest, they will unpack. One person will go right to compressions if there’s nobody on compressions already. Sometimes we have a first responder police officer with an automated external defibrillator (AED). We go right to the patient’s side, concentrate on compressions, and within 90 seconds to 2 minutes, we have our bags unpacked, we’ve got the devices turned on, patient lifted up, slid under the device, and we have a supraglottic airway that is placed within 15 seconds already premade with the ITD on top. We have a sealed airway that we can continue to compress with Dr. Pepe’s original discussion of building on what’s previously been shown to work.

Dr. Pepe: Let me make a comment about this. This is so important, what Ryan is saying, because it’s something we found during the study. It’s really a true pit-crew approach. You’re not only getting these materials, which you think you need a medical Sherpa for, but you don’t. They set it up and then when they open it up, it’s all laid out just exactly as you need it. It’s not just how fast you get there; it’s how fast you get this done.

When we look at all cases combined against high-performance systems that had some of the highest survival rates around, when we compare it to those, we found that overall, even if you looked at the ones that had over 20-minute responses, the odds ratios were still three to four times higher. It was impressive.

If you looked at it under 15 minutes, which is really reasonable for most systems that get there by the way, the average time that people start CPR in any system in these studies has been about 8 minutes if you actually start this thing, which takes about 2 minutes more for this new bundle of care with this triad, it’s almost 12-14 times higher in terms of the odds ratio. I’ve never seen anything like that where the higher end is over 100 in terms of your confidence intervals.

Ryan’s system did really well and is one of those with even higher levels of outcomes, mostly because they got it on quickly. It’s like the AED for nonshockables but better because you have a wider range of efficacy where it will work.

Dr. Glatter: When the elapsed time was less than 11 minutes, that seemed to be an inflection point in the study, is that correct? You saw that 11-fold higher incidence in terms of neurologically intact survival, is that correct?

Dr. Pepe: We picked that number because that was the median time to get it on board. Half the people were getting it within that time period. The fact that you have a larger window, we’re talking about 13- almost 14-fold improvements in outcome if it was under 15 minutes. It doesn’t matter about the 11 or the 12. It’s the faster you get it on board, the better off you are.

Dr. Glatter: What’s the next step in the process of doing trials and having implementation on a larger scale based on your Annals of Emergency Medicine study? Where do you go from here?

Dr. Pepe: I’ve come to find out there are many confounding variables. What was the quality of CPR? How did people ventilate? Did they give the breath and hold it? Did they give a large enough breath so that blood can go across the transpulmonary system? There are many confounding variables. That’s why I think, in the future, it’s going to be more of looking at things like propensity score matching because we know all the variables that change outcomes. I think that’s going to be a way for me.

The other thing is that we were looking at only 380 cases here. When this doubles up in numbers, as we accrue more cases around the country of people who are implementing this, these numbers I just quoted are going to go up much higher. Unwitnessed asystole is considered futile, and you just don’t get them back. To be able to get these folks back now, even if it’s a small percentage, and the fact that we know that we’re producing this better flow, is pretty striking.

I’m really impressed, and the main thing is to make sure people are educated about it. Number two is that they understand that it has to be done right. It cannot be done wrong or you’re not going to see the differences. Getting it done right is not only following the procedures, the sequence, and how you do it, but it also has to do with getting there quickly, including assigning the right people to put it on and having well-trained people who know what they’re doing.

Dr. Glatter: In general, the lay public obviously should not attempt this in the field lifting someone’s head up in the sense of trying to do chest compressions. I think that message is important that you just said. It’s not ready for prime time yet in any way. It has to be done right.

Dr. Pepe: Bystanders have to learn CPR – they will buy us time and we’ll have better outcomes when they do that. That’s number one. Number two is that as more and more systems adopt this, you’re going to see more people coming back. If you think about what we’re doing now, if we only get back 5% of these nonshockable vs. less than 1%, it’s 5% of 800 people a day because a thousand people a day die. Several dozens of lives can be saved on a daily basis, coming back neurologically intact. That’s the key thing.

Dr. Glatter: Ryan, can you comment about your experience in the field? Is there anything in terms of your current approach that you think would be ideal to change at this point?

Mr. Quinn: We’ve established that this is the approach that we want to take and we’re just fine tuning it to be more efficient. Using the choreography of which person is going to do which role, we have clearly defined roles and clearly defined command of the scene so we’re not missing anything. Training is extremely important.

Dr. Glatter: Paul, I want to ask you about your anecdotal experience of people waking up quickly and talking after elevating their heads and going through this process. Having people talk about it and waking up is really fascinating. Maybe you can comment further on this.

Dr. Pepe: That’s a great point that you bring up because a 40- to 50-year-old guy who got saved with this approach, when he came around, he said he was hearing what people were saying. When he came out of it, he found out he had been getting CPR for about 25 minutes because he had persistent recurring ventricular fibrillation. He said, “How could I have survived that that long?”

When we told him about the new approach, he added, “Well, that’s like neuroprotective.” He’s right, because in the laboratory, we showed it was neuroprotective and we’re also getting better flows back there. It goes along with everything else, and so we’ve adopted the name because it is.

These are really high-powered systems we are comparing against, and we have the same level of return of spontaneous circulation. The major difference was when you started talking about the neurointact survival. We don’t have enough numbers yet, but next go around, we’re going to look at cerebral performance category (CPC) – CPC1 vs. the CPC2 – which were both considered intact, but CPC1 is actually better. We’re seeing many more of those, anecdotally.

I also wanted to mention that people do bring this up and say, “Well, let’s do a trial.” As far as we’re concerned, the trial’s been done in terms of The Lancet study 10 years ago that showed that the active compression-decompression had tremendously better outcomes. We show in the laboratories that you augment that a little bit. These are all [Food and Drug Administration] approved. You can go out and buy it tomorrow and get it done. I have no conflicts of interest, by the way, with any of this.

To have this device that’s going to have the potential of saving so many more lives is really an exciting breakthrough. More importantly, we’re understanding more now about the physiology of CPR and why it works. It could work much better with the approaches that we’ve been developing over the last 20 years or so.

Dr. Glatter: Absolutely. I want to thank both of you gentlemen. It’s been really an incredible experience to learn more about an advance in resuscitation that could truly be lifesaving. Thank you again for taking time to join us.

Dr. Glatter is an attending physician in the department of emergency medicine, Lenox Hill Hospital, New York. Dr. Pepe is professor, department of management, policy, and community health, University of Texas Health Sciences Center, Houston. Mr. Quinn is EMS Chief, Edina (Minn.) Fire Department. No conflicts of interest were reported.

A version of this article first appeared Jan. 26 on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Robert D. Glatter, MD: Welcome. I’m Dr Robert Glatter, medical adviser for Medscape Emergency Medicine. with a remarkable increase in neurologically intact survival. Welcome, gentlemen.

Dr. Pepe, I’d like to start off by thanking you for taking time to join us to discuss this novel concept of head-up or what you now refer to as a neuroprotective cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) bundle. Can you define what this entails and why it is referred to as a neuroprotective CPR bundle?

Paul E. Pepe, MD, MPH: CPR has been life saving for 60 years the way we’ve performed it, but probably only in a very small percentage of cases. That’s one of the problems. We have almost a thousand people a day who have sudden cardiac arrest out in the community alone and more in the hospital.

We know that early defibrillation and early CPR can contribute, but it’s still a small percentage of those. About 75%-85% of the cases that we go out to see will have nonshockable rhythms and flatlines. Some cases are what we call “pulseless electrical activity,” meaning that it looks like there is some kind of organized complex, but there is no pulse associated with it.

That’s why it’s a problem, because they don’t come back. Part of the reason why we see poor outcomes is not only that these cases tend to be people who, say, were in ventricular fibrillation and then just went on over time and were not witnessed or resuscitated or had a long response time. They basically either go into flatline or autoconvert into these bizarre rhythms.

The other issue is the way we perform CPR. CPR has been lifesaving, but it only generates about 20% and maybe 15% in some cases of normal blood flow, and particularly, cerebral perfusion pressure. We’ve looked at this nicely in the laboratory.

For example, during chest compressions, we’re hoping during the recoil phase to pull blood down and back into the right heart. The problem is that you’re not only setting a pressure rate up here to the arterial side but also, you’re setting back pressure wave on the venous side. Obviously, the arterial side always wins out, but it’s just not as efficient as it could be, at 20% or 30%.

What does this entail? It entails several independent mechanisms in terms of how they work, but they all do the same thing, which is they help to pull blood out of the brain and back into the right heart by basically manipulating intrathoracic pressure and creating more of a vacuum to get blood back there.

It’s so important that people do quality CPR. You have to have a good release and that helps us suck a little bit of blood and sucks the air in. As soon as the air rushes in, it neutralizes the pressure and there’s no more vacuum and nothing else is happening until the next squeeze.

What we have found is that we can cap the airway just for a second with a little pop-up valve. It acts like when you’re sucking a milkshake through a straw and it creates more of a vacuum in the chest. Just a little pop-up valve that pulls a little bit more blood out of the brain and the rest of the body and into the right heart.

We’ve shown in a human study that, for example, the systolic blood pressure almost doubles. It really goes from 40 mm Hg during standard CPR up to 80 mm Hg, and that would be sustained for 14-15 minutes. That was a nice little study that was done in Milwaukee a few years ago.

The other thing that happens is, if you add on something else, it’s like a toilet plunger. I think many people have seen it; it’s called “active compression-decompression.” It not only compresses, but it decompresses. Where it becomes even more effective is that if you had broken bones or stiff bones as you get older or whatever it may be, as you do the CPR, you’re still getting the push down and then you’re getting the pull out. It helps on several levels. More importantly, when you put the two together, they’re very synergistic.

We, have already done the clinical trial that is the proof of concept, and that was published in The Lancet about 10 years ago. In that study, we found that the combination of those two dramatically improved survival rates by 50%, with 1-year survival neurologically intact. That got us on the right track.

The interesting thing is that someone said, “Can we lift the head up a little bit?” We did a large amount of work in the laboratory over 10 years, fine tuning it. When do you first lift the head? How soon is too soon? It’s probably bad if you just go right to it.

We had to get the pump primed a little bit with these other things to get the flow going better, not only pulling blood out of the brain but now, you have a better flow this way. You have to prime at first for a couple of minutes, and we worked out the timing: Is it 3 or 4 minutes? It seems the timing is right at about 2 minutes, then you gradually elevate the head over about 2 minutes. We’re finding that seems to be the optimal way to do it. About 2 minutes of priming with those other two devices, the adjuncts, and then gradually elevate the head over 2 minutes.

When we do that in the laboratory, we’re getting normalized cerebral perfusion pressures. You’re normalizing the flow back again with that. We’re seeing profound differences in outcome as a result, even in these cases of the nonshockables.

Dr. Glatter: What you’re doing basically is resulting in an increase in cardiac output, essentially. That really is important, especially in these nonshockable rhythms, correct?

Dr. Pepe: Absolutely. As you’re doing this compression and you’re getting these intracranial pulse waves that are going up because they’re colliding up there. It could be even damaging in itself, but we’re seeing these intracranial raises. The intracranial pressure starts going up more and more over time. Also, peripherally in most people, you’re not getting good flow out there; then, your vasculature starts to relax. The arterials are starting to not get oxygen, so they don’t go out.

With this technique where we’re returning the pressure, we’re getting to 40% of normal now with the active compression-decompression CPR plus an impedance threshold device (ACD+ITD CPR) approach. Now, you add this, and you’re almost normalizing. In humans, even in these asystole patients, we’re seeing end-title CO2s which are generally in the 15-20 range with standard CPR are now up with ACD+ITD CPR in the 30%-40% range, where we’re getting through 30 or 40 end-tidal CO2s. Now, we’re seeing even the end-tidal CO2s moving up into the 40s and 50s. We know there’s a surrogate marker telling us that we are generating much better flows not only to the rest of the body, but most importantly, to the brain.

Dr. Glatter: Ryan, could you tell us about the approach in terms of on scene, what you’re doing and how you use the device itself? Maybe you could talk about the backpack that you developed with your fire department?

Ryan P. Quinn, BS, EMS: Our approach has always been to get to the patient quickly, like everybody’s approach on a cardiac arrest when you’re responding. We are an advanced life-support paramedic ambulance service through the fire department – we’re all cross-trained firefighter paramedics. Our first vehicle from the fire department is typically the ambulance. It’s smaller and a little quicker than the fire engine. Two paramedics are going to jump out with two backpacks. One has the automated compressive device (we use the Lucas), and the other one is the sequential patient lifting device, the EleGARD.

Our two paramedics are quick to the patient’s side, and once they make contact with the patient to verify pulseless cardiac arrest, they will unpack. One person will go right to compressions if there’s nobody on compressions already. Sometimes we have a first responder police officer with an automated external defibrillator (AED). We go right to the patient’s side, concentrate on compressions, and within 90 seconds to 2 minutes, we have our bags unpacked, we’ve got the devices turned on, patient lifted up, slid under the device, and we have a supraglottic airway that is placed within 15 seconds already premade with the ITD on top. We have a sealed airway that we can continue to compress with Dr. Pepe’s original discussion of building on what’s previously been shown to work.

Dr. Pepe: Let me make a comment about this. This is so important, what Ryan is saying, because it’s something we found during the study. It’s really a true pit-crew approach. You’re not only getting these materials, which you think you need a medical Sherpa for, but you don’t. They set it up and then when they open it up, it’s all laid out just exactly as you need it. It’s not just how fast you get there; it’s how fast you get this done.

When we look at all cases combined against high-performance systems that had some of the highest survival rates around, when we compare it to those, we found that overall, even if you looked at the ones that had over 20-minute responses, the odds ratios were still three to four times higher. It was impressive.

If you looked at it under 15 minutes, which is really reasonable for most systems that get there by the way, the average time that people start CPR in any system in these studies has been about 8 minutes if you actually start this thing, which takes about 2 minutes more for this new bundle of care with this triad, it’s almost 12-14 times higher in terms of the odds ratio. I’ve never seen anything like that where the higher end is over 100 in terms of your confidence intervals.

Ryan’s system did really well and is one of those with even higher levels of outcomes, mostly because they got it on quickly. It’s like the AED for nonshockables but better because you have a wider range of efficacy where it will work.

Dr. Glatter: When the elapsed time was less than 11 minutes, that seemed to be an inflection point in the study, is that correct? You saw that 11-fold higher incidence in terms of neurologically intact survival, is that correct?

Dr. Pepe: We picked that number because that was the median time to get it on board. Half the people were getting it within that time period. The fact that you have a larger window, we’re talking about 13- almost 14-fold improvements in outcome if it was under 15 minutes. It doesn’t matter about the 11 or the 12. It’s the faster you get it on board, the better off you are.

Dr. Glatter: What’s the next step in the process of doing trials and having implementation on a larger scale based on your Annals of Emergency Medicine study? Where do you go from here?

Dr. Pepe: I’ve come to find out there are many confounding variables. What was the quality of CPR? How did people ventilate? Did they give the breath and hold it? Did they give a large enough breath so that blood can go across the transpulmonary system? There are many confounding variables. That’s why I think, in the future, it’s going to be more of looking at things like propensity score matching because we know all the variables that change outcomes. I think that’s going to be a way for me.

The other thing is that we were looking at only 380 cases here. When this doubles up in numbers, as we accrue more cases around the country of people who are implementing this, these numbers I just quoted are going to go up much higher. Unwitnessed asystole is considered futile, and you just don’t get them back. To be able to get these folks back now, even if it’s a small percentage, and the fact that we know that we’re producing this better flow, is pretty striking.

I’m really impressed, and the main thing is to make sure people are educated about it. Number two is that they understand that it has to be done right. It cannot be done wrong or you’re not going to see the differences. Getting it done right is not only following the procedures, the sequence, and how you do it, but it also has to do with getting there quickly, including assigning the right people to put it on and having well-trained people who know what they’re doing.

Dr. Glatter: In general, the lay public obviously should not attempt this in the field lifting someone’s head up in the sense of trying to do chest compressions. I think that message is important that you just said. It’s not ready for prime time yet in any way. It has to be done right.

Dr. Pepe: Bystanders have to learn CPR – they will buy us time and we’ll have better outcomes when they do that. That’s number one. Number two is that as more and more systems adopt this, you’re going to see more people coming back. If you think about what we’re doing now, if we only get back 5% of these nonshockable vs. less than 1%, it’s 5% of 800 people a day because a thousand people a day die. Several dozens of lives can be saved on a daily basis, coming back neurologically intact. That’s the key thing.

Dr. Glatter: Ryan, can you comment about your experience in the field? Is there anything in terms of your current approach that you think would be ideal to change at this point?

Mr. Quinn: We’ve established that this is the approach that we want to take and we’re just fine tuning it to be more efficient. Using the choreography of which person is going to do which role, we have clearly defined roles and clearly defined command of the scene so we’re not missing anything. Training is extremely important.

Dr. Glatter: Paul, I want to ask you about your anecdotal experience of people waking up quickly and talking after elevating their heads and going through this process. Having people talk about it and waking up is really fascinating. Maybe you can comment further on this.

Dr. Pepe: That’s a great point that you bring up because a 40- to 50-year-old guy who got saved with this approach, when he came around, he said he was hearing what people were saying. When he came out of it, he found out he had been getting CPR for about 25 minutes because he had persistent recurring ventricular fibrillation. He said, “How could I have survived that that long?”

When we told him about the new approach, he added, “Well, that’s like neuroprotective.” He’s right, because in the laboratory, we showed it was neuroprotective and we’re also getting better flows back there. It goes along with everything else, and so we’ve adopted the name because it is.

These are really high-powered systems we are comparing against, and we have the same level of return of spontaneous circulation. The major difference was when you started talking about the neurointact survival. We don’t have enough numbers yet, but next go around, we’re going to look at cerebral performance category (CPC) – CPC1 vs. the CPC2 – which were both considered intact, but CPC1 is actually better. We’re seeing many more of those, anecdotally.

I also wanted to mention that people do bring this up and say, “Well, let’s do a trial.” As far as we’re concerned, the trial’s been done in terms of The Lancet study 10 years ago that showed that the active compression-decompression had tremendously better outcomes. We show in the laboratories that you augment that a little bit. These are all [Food and Drug Administration] approved. You can go out and buy it tomorrow and get it done. I have no conflicts of interest, by the way, with any of this.

To have this device that’s going to have the potential of saving so many more lives is really an exciting breakthrough. More importantly, we’re understanding more now about the physiology of CPR and why it works. It could work much better with the approaches that we’ve been developing over the last 20 years or so.

Dr. Glatter: Absolutely. I want to thank both of you gentlemen. It’s been really an incredible experience to learn more about an advance in resuscitation that could truly be lifesaving. Thank you again for taking time to join us.

Dr. Glatter is an attending physician in the department of emergency medicine, Lenox Hill Hospital, New York. Dr. Pepe is professor, department of management, policy, and community health, University of Texas Health Sciences Center, Houston. Mr. Quinn is EMS Chief, Edina (Minn.) Fire Department. No conflicts of interest were reported.

A version of this article first appeared Jan. 26 on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Robert D. Glatter, MD: Welcome. I’m Dr Robert Glatter, medical adviser for Medscape Emergency Medicine. with a remarkable increase in neurologically intact survival. Welcome, gentlemen.

Dr. Pepe, I’d like to start off by thanking you for taking time to join us to discuss this novel concept of head-up or what you now refer to as a neuroprotective cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) bundle. Can you define what this entails and why it is referred to as a neuroprotective CPR bundle?

Paul E. Pepe, MD, MPH: CPR has been life saving for 60 years the way we’ve performed it, but probably only in a very small percentage of cases. That’s one of the problems. We have almost a thousand people a day who have sudden cardiac arrest out in the community alone and more in the hospital.

We know that early defibrillation and early CPR can contribute, but it’s still a small percentage of those. About 75%-85% of the cases that we go out to see will have nonshockable rhythms and flatlines. Some cases are what we call “pulseless electrical activity,” meaning that it looks like there is some kind of organized complex, but there is no pulse associated with it.

That’s why it’s a problem, because they don’t come back. Part of the reason why we see poor outcomes is not only that these cases tend to be people who, say, were in ventricular fibrillation and then just went on over time and were not witnessed or resuscitated or had a long response time. They basically either go into flatline or autoconvert into these bizarre rhythms.

The other issue is the way we perform CPR. CPR has been lifesaving, but it only generates about 20% and maybe 15% in some cases of normal blood flow, and particularly, cerebral perfusion pressure. We’ve looked at this nicely in the laboratory.

For example, during chest compressions, we’re hoping during the recoil phase to pull blood down and back into the right heart. The problem is that you’re not only setting a pressure rate up here to the arterial side but also, you’re setting back pressure wave on the venous side. Obviously, the arterial side always wins out, but it’s just not as efficient as it could be, at 20% or 30%.

What does this entail? It entails several independent mechanisms in terms of how they work, but they all do the same thing, which is they help to pull blood out of the brain and back into the right heart by basically manipulating intrathoracic pressure and creating more of a vacuum to get blood back there.

It’s so important that people do quality CPR. You have to have a good release and that helps us suck a little bit of blood and sucks the air in. As soon as the air rushes in, it neutralizes the pressure and there’s no more vacuum and nothing else is happening until the next squeeze.

What we have found is that we can cap the airway just for a second with a little pop-up valve. It acts like when you’re sucking a milkshake through a straw and it creates more of a vacuum in the chest. Just a little pop-up valve that pulls a little bit more blood out of the brain and the rest of the body and into the right heart.

We’ve shown in a human study that, for example, the systolic blood pressure almost doubles. It really goes from 40 mm Hg during standard CPR up to 80 mm Hg, and that would be sustained for 14-15 minutes. That was a nice little study that was done in Milwaukee a few years ago.

The other thing that happens is, if you add on something else, it’s like a toilet plunger. I think many people have seen it; it’s called “active compression-decompression.” It not only compresses, but it decompresses. Where it becomes even more effective is that if you had broken bones or stiff bones as you get older or whatever it may be, as you do the CPR, you’re still getting the push down and then you’re getting the pull out. It helps on several levels. More importantly, when you put the two together, they’re very synergistic.

We, have already done the clinical trial that is the proof of concept, and that was published in The Lancet about 10 years ago. In that study, we found that the combination of those two dramatically improved survival rates by 50%, with 1-year survival neurologically intact. That got us on the right track.

The interesting thing is that someone said, “Can we lift the head up a little bit?” We did a large amount of work in the laboratory over 10 years, fine tuning it. When do you first lift the head? How soon is too soon? It’s probably bad if you just go right to it.

We had to get the pump primed a little bit with these other things to get the flow going better, not only pulling blood out of the brain but now, you have a better flow this way. You have to prime at first for a couple of minutes, and we worked out the timing: Is it 3 or 4 minutes? It seems the timing is right at about 2 minutes, then you gradually elevate the head over about 2 minutes. We’re finding that seems to be the optimal way to do it. About 2 minutes of priming with those other two devices, the adjuncts, and then gradually elevate the head over 2 minutes.

When we do that in the laboratory, we’re getting normalized cerebral perfusion pressures. You’re normalizing the flow back again with that. We’re seeing profound differences in outcome as a result, even in these cases of the nonshockables.

Dr. Glatter: What you’re doing basically is resulting in an increase in cardiac output, essentially. That really is important, especially in these nonshockable rhythms, correct?

Dr. Pepe: Absolutely. As you’re doing this compression and you’re getting these intracranial pulse waves that are going up because they’re colliding up there. It could be even damaging in itself, but we’re seeing these intracranial raises. The intracranial pressure starts going up more and more over time. Also, peripherally in most people, you’re not getting good flow out there; then, your vasculature starts to relax. The arterials are starting to not get oxygen, so they don’t go out.

With this technique where we’re returning the pressure, we’re getting to 40% of normal now with the active compression-decompression CPR plus an impedance threshold device (ACD+ITD CPR) approach. Now, you add this, and you’re almost normalizing. In humans, even in these asystole patients, we’re seeing end-title CO2s which are generally in the 15-20 range with standard CPR are now up with ACD+ITD CPR in the 30%-40% range, where we’re getting through 30 or 40 end-tidal CO2s. Now, we’re seeing even the end-tidal CO2s moving up into the 40s and 50s. We know there’s a surrogate marker telling us that we are generating much better flows not only to the rest of the body, but most importantly, to the brain.

Dr. Glatter: Ryan, could you tell us about the approach in terms of on scene, what you’re doing and how you use the device itself? Maybe you could talk about the backpack that you developed with your fire department?

Ryan P. Quinn, BS, EMS: Our approach has always been to get to the patient quickly, like everybody’s approach on a cardiac arrest when you’re responding. We are an advanced life-support paramedic ambulance service through the fire department – we’re all cross-trained firefighter paramedics. Our first vehicle from the fire department is typically the ambulance. It’s smaller and a little quicker than the fire engine. Two paramedics are going to jump out with two backpacks. One has the automated compressive device (we use the Lucas), and the other one is the sequential patient lifting device, the EleGARD.

Our two paramedics are quick to the patient’s side, and once they make contact with the patient to verify pulseless cardiac arrest, they will unpack. One person will go right to compressions if there’s nobody on compressions already. Sometimes we have a first responder police officer with an automated external defibrillator (AED). We go right to the patient’s side, concentrate on compressions, and within 90 seconds to 2 minutes, we have our bags unpacked, we’ve got the devices turned on, patient lifted up, slid under the device, and we have a supraglottic airway that is placed within 15 seconds already premade with the ITD on top. We have a sealed airway that we can continue to compress with Dr. Pepe’s original discussion of building on what’s previously been shown to work.

Dr. Pepe: Let me make a comment about this. This is so important, what Ryan is saying, because it’s something we found during the study. It’s really a true pit-crew approach. You’re not only getting these materials, which you think you need a medical Sherpa for, but you don’t. They set it up and then when they open it up, it’s all laid out just exactly as you need it. It’s not just how fast you get there; it’s how fast you get this done.

When we look at all cases combined against high-performance systems that had some of the highest survival rates around, when we compare it to those, we found that overall, even if you looked at the ones that had over 20-minute responses, the odds ratios were still three to four times higher. It was impressive.

If you looked at it under 15 minutes, which is really reasonable for most systems that get there by the way, the average time that people start CPR in any system in these studies has been about 8 minutes if you actually start this thing, which takes about 2 minutes more for this new bundle of care with this triad, it’s almost 12-14 times higher in terms of the odds ratio. I’ve never seen anything like that where the higher end is over 100 in terms of your confidence intervals.

Ryan’s system did really well and is one of those with even higher levels of outcomes, mostly because they got it on quickly. It’s like the AED for nonshockables but better because you have a wider range of efficacy where it will work.

Dr. Glatter: When the elapsed time was less than 11 minutes, that seemed to be an inflection point in the study, is that correct? You saw that 11-fold higher incidence in terms of neurologically intact survival, is that correct?

Dr. Pepe: We picked that number because that was the median time to get it on board. Half the people were getting it within that time period. The fact that you have a larger window, we’re talking about 13- almost 14-fold improvements in outcome if it was under 15 minutes. It doesn’t matter about the 11 or the 12. It’s the faster you get it on board, the better off you are.

Dr. Glatter: What’s the next step in the process of doing trials and having implementation on a larger scale based on your Annals of Emergency Medicine study? Where do you go from here?

Dr. Pepe: I’ve come to find out there are many confounding variables. What was the quality of CPR? How did people ventilate? Did they give the breath and hold it? Did they give a large enough breath so that blood can go across the transpulmonary system? There are many confounding variables. That’s why I think, in the future, it’s going to be more of looking at things like propensity score matching because we know all the variables that change outcomes. I think that’s going to be a way for me.

The other thing is that we were looking at only 380 cases here. When this doubles up in numbers, as we accrue more cases around the country of people who are implementing this, these numbers I just quoted are going to go up much higher. Unwitnessed asystole is considered futile, and you just don’t get them back. To be able to get these folks back now, even if it’s a small percentage, and the fact that we know that we’re producing this better flow, is pretty striking.

I’m really impressed, and the main thing is to make sure people are educated about it. Number two is that they understand that it has to be done right. It cannot be done wrong or you’re not going to see the differences. Getting it done right is not only following the procedures, the sequence, and how you do it, but it also has to do with getting there quickly, including assigning the right people to put it on and having well-trained people who know what they’re doing.

Dr. Glatter: In general, the lay public obviously should not attempt this in the field lifting someone’s head up in the sense of trying to do chest compressions. I think that message is important that you just said. It’s not ready for prime time yet in any way. It has to be done right.

Dr. Pepe: Bystanders have to learn CPR – they will buy us time and we’ll have better outcomes when they do that. That’s number one. Number two is that as more and more systems adopt this, you’re going to see more people coming back. If you think about what we’re doing now, if we only get back 5% of these nonshockable vs. less than 1%, it’s 5% of 800 people a day because a thousand people a day die. Several dozens of lives can be saved on a daily basis, coming back neurologically intact. That’s the key thing.

Dr. Glatter: Ryan, can you comment about your experience in the field? Is there anything in terms of your current approach that you think would be ideal to change at this point?

Mr. Quinn: We’ve established that this is the approach that we want to take and we’re just fine tuning it to be more efficient. Using the choreography of which person is going to do which role, we have clearly defined roles and clearly defined command of the scene so we’re not missing anything. Training is extremely important.

Dr. Glatter: Paul, I want to ask you about your anecdotal experience of people waking up quickly and talking after elevating their heads and going through this process. Having people talk about it and waking up is really fascinating. Maybe you can comment further on this.

Dr. Pepe: That’s a great point that you bring up because a 40- to 50-year-old guy who got saved with this approach, when he came around, he said he was hearing what people were saying. When he came out of it, he found out he had been getting CPR for about 25 minutes because he had persistent recurring ventricular fibrillation. He said, “How could I have survived that that long?”

When we told him about the new approach, he added, “Well, that’s like neuroprotective.” He’s right, because in the laboratory, we showed it was neuroprotective and we’re also getting better flows back there. It goes along with everything else, and so we’ve adopted the name because it is.

These are really high-powered systems we are comparing against, and we have the same level of return of spontaneous circulation. The major difference was when you started talking about the neurointact survival. We don’t have enough numbers yet, but next go around, we’re going to look at cerebral performance category (CPC) – CPC1 vs. the CPC2 – which were both considered intact, but CPC1 is actually better. We’re seeing many more of those, anecdotally.

I also wanted to mention that people do bring this up and say, “Well, let’s do a trial.” As far as we’re concerned, the trial’s been done in terms of The Lancet study 10 years ago that showed that the active compression-decompression had tremendously better outcomes. We show in the laboratories that you augment that a little bit. These are all [Food and Drug Administration] approved. You can go out and buy it tomorrow and get it done. I have no conflicts of interest, by the way, with any of this.

To have this device that’s going to have the potential of saving so many more lives is really an exciting breakthrough. More importantly, we’re understanding more now about the physiology of CPR and why it works. It could work much better with the approaches that we’ve been developing over the last 20 years or so.

Dr. Glatter: Absolutely. I want to thank both of you gentlemen. It’s been really an incredible experience to learn more about an advance in resuscitation that could truly be lifesaving. Thank you again for taking time to join us.

Dr. Glatter is an attending physician in the department of emergency medicine, Lenox Hill Hospital, New York. Dr. Pepe is professor, department of management, policy, and community health, University of Texas Health Sciences Center, Houston. Mr. Quinn is EMS Chief, Edina (Minn.) Fire Department. No conflicts of interest were reported.

A version of this article first appeared Jan. 26 on Medscape.com.

A patient named ‘Settle’ decides to sue instead

On Nov. 1, 2020, Dallas Settle went to Plateau Medical Center, Oak Hill, W.Va., complaining of pain that was later described in court documents as being “in his right mid-abdomen migrating to his right lower abdomen.” Following a CT scan, Mr. Settle was diagnosed with diverticulitis resulting in pneumoperitoneum, which is the presence of air or other gas in the abdominal cavity. The patient, it was decided, required surgery to correct the problem, but Plateau Medical Center didn’t have the staff to perform the procedure.