User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

Children and COVID: Weekly cases may have doubled in early January

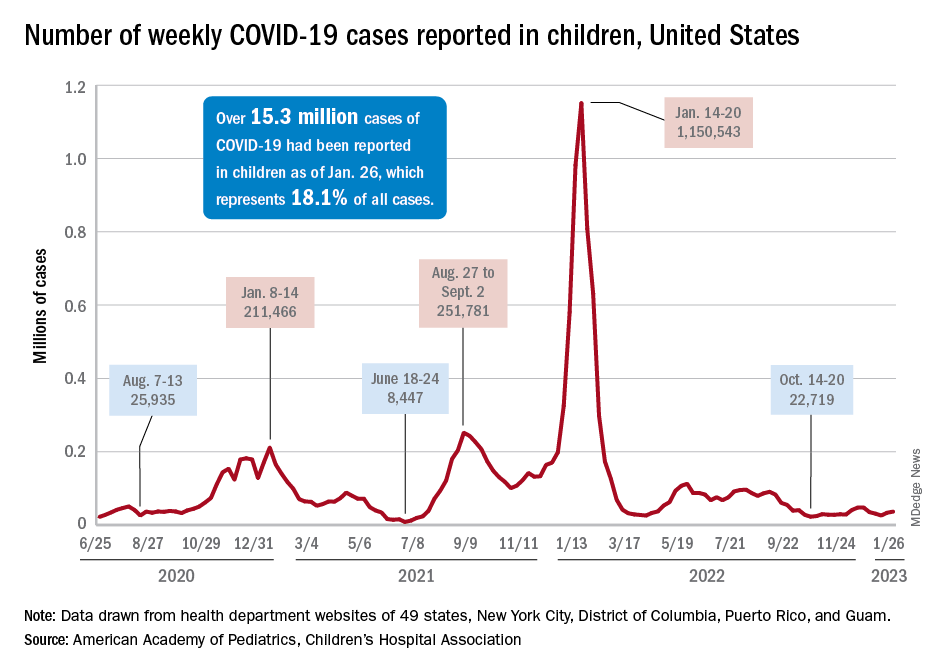

Although new COVID-19 cases in children, as measured by the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association, have remained fairly steady in recent months, data from the Centers for Diseases Control and Prevention suggest that weekly cases took a big jump in early January.

For the most recent week covered . New cases for the first 2 weeks of the year – 31,000 for the week of Dec. 30 to Jan. 5 and 26,000 during Jan. 6-12 – were consistent with the AAP/CHA assertion that “weekly reported child cases have plateaued at an average of about 32,000 cases ... over the past 4 months.”

The CDC data, however, show that new cases doubled during the week of Jan. 1-7 to over 65,000, compared with the end of December, and stayed at that level for Jan. 8-14, and since CDC figures are subject to a 6-week reporting delay, the final numbers are likely to be even higher. The composition by age changed somewhat between the 2 weeks, though, as those aged 0-4 years went from almost half of all cases in the first week down to 40% in the second, while cases rose for children aged 5-11 and 12-15, based on data from the COVID-19 response team.

Emergency department visits for January do not show a corresponding increase. ED visits among children aged 0-11 years with COVID-19, measured as a percentage of all ED visits, declined over the course of the month, as did visits for 16- and 17-year-olds, while those aged 12-15 started the month at 1.4% and were at 1.4% on Jan. 27, with a slight dip down to 1.2% in between, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker. Daily hospitalizations for children aged 0-17 also declined through mid-January and did not reflect the jump in new cases.

Meanwhile, vaccinated children are still in the minority: 57% of those under age 18 have received no COVID vaccine yet, the AAP said in a separate report. Just 7.4% of children under age 2 years had received at least one dose as of Jan. 25, as had 10.1% of those aged 2-4 years, 39.6% of 5- to 11-year-olds and 71.8% of those 12-17 years old, according to the CDC, with corresponding figures for completion of the primary series at 3.5%, 5.3%, 32.5%, and 61.5%.

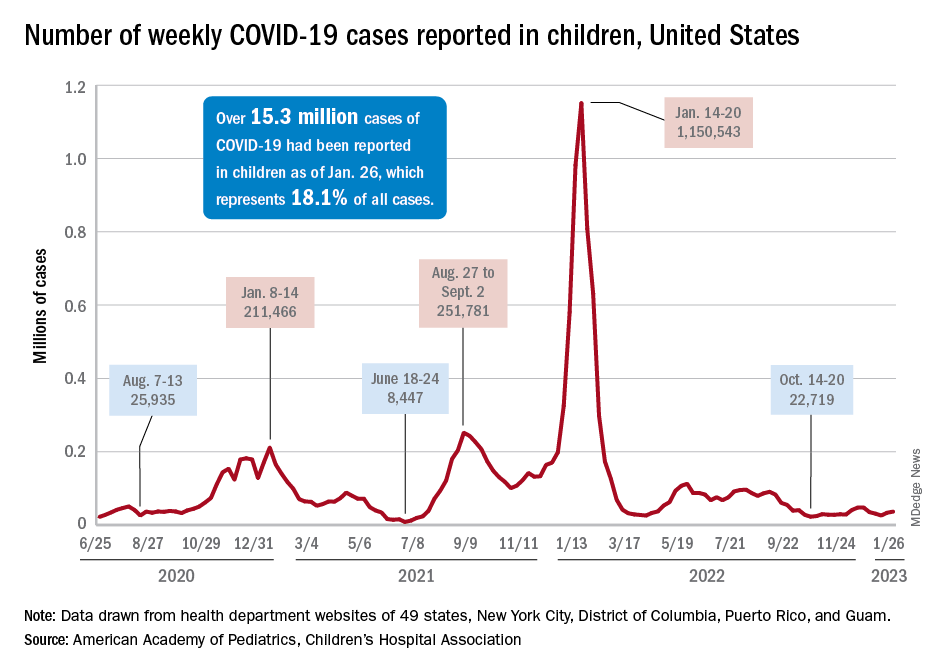

Although new COVID-19 cases in children, as measured by the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association, have remained fairly steady in recent months, data from the Centers for Diseases Control and Prevention suggest that weekly cases took a big jump in early January.

For the most recent week covered . New cases for the first 2 weeks of the year – 31,000 for the week of Dec. 30 to Jan. 5 and 26,000 during Jan. 6-12 – were consistent with the AAP/CHA assertion that “weekly reported child cases have plateaued at an average of about 32,000 cases ... over the past 4 months.”

The CDC data, however, show that new cases doubled during the week of Jan. 1-7 to over 65,000, compared with the end of December, and stayed at that level for Jan. 8-14, and since CDC figures are subject to a 6-week reporting delay, the final numbers are likely to be even higher. The composition by age changed somewhat between the 2 weeks, though, as those aged 0-4 years went from almost half of all cases in the first week down to 40% in the second, while cases rose for children aged 5-11 and 12-15, based on data from the COVID-19 response team.

Emergency department visits for January do not show a corresponding increase. ED visits among children aged 0-11 years with COVID-19, measured as a percentage of all ED visits, declined over the course of the month, as did visits for 16- and 17-year-olds, while those aged 12-15 started the month at 1.4% and were at 1.4% on Jan. 27, with a slight dip down to 1.2% in between, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker. Daily hospitalizations for children aged 0-17 also declined through mid-January and did not reflect the jump in new cases.

Meanwhile, vaccinated children are still in the minority: 57% of those under age 18 have received no COVID vaccine yet, the AAP said in a separate report. Just 7.4% of children under age 2 years had received at least one dose as of Jan. 25, as had 10.1% of those aged 2-4 years, 39.6% of 5- to 11-year-olds and 71.8% of those 12-17 years old, according to the CDC, with corresponding figures for completion of the primary series at 3.5%, 5.3%, 32.5%, and 61.5%.

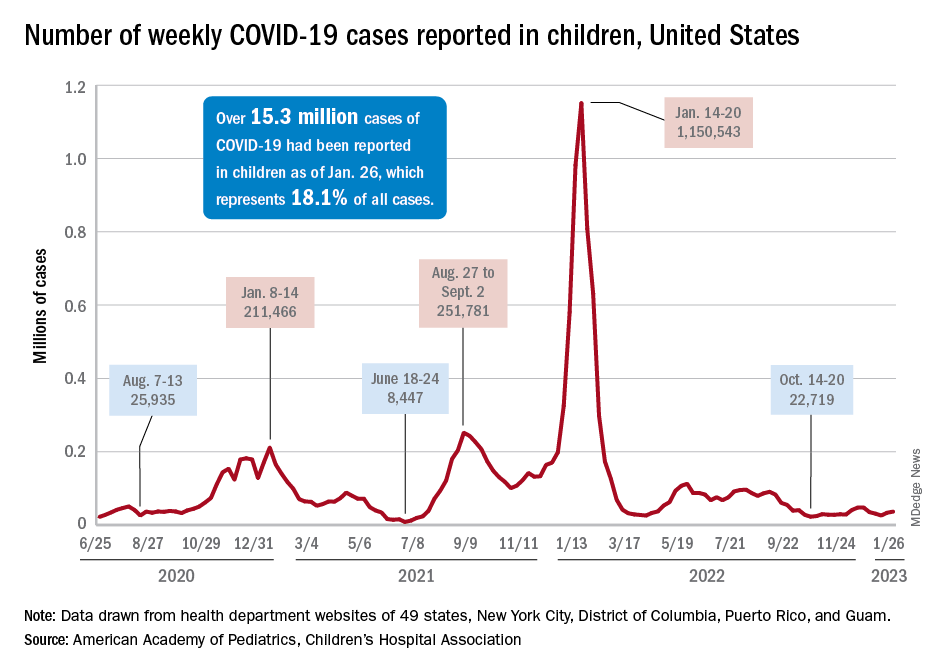

Although new COVID-19 cases in children, as measured by the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association, have remained fairly steady in recent months, data from the Centers for Diseases Control and Prevention suggest that weekly cases took a big jump in early January.

For the most recent week covered . New cases for the first 2 weeks of the year – 31,000 for the week of Dec. 30 to Jan. 5 and 26,000 during Jan. 6-12 – were consistent with the AAP/CHA assertion that “weekly reported child cases have plateaued at an average of about 32,000 cases ... over the past 4 months.”

The CDC data, however, show that new cases doubled during the week of Jan. 1-7 to over 65,000, compared with the end of December, and stayed at that level for Jan. 8-14, and since CDC figures are subject to a 6-week reporting delay, the final numbers are likely to be even higher. The composition by age changed somewhat between the 2 weeks, though, as those aged 0-4 years went from almost half of all cases in the first week down to 40% in the second, while cases rose for children aged 5-11 and 12-15, based on data from the COVID-19 response team.

Emergency department visits for January do not show a corresponding increase. ED visits among children aged 0-11 years with COVID-19, measured as a percentage of all ED visits, declined over the course of the month, as did visits for 16- and 17-year-olds, while those aged 12-15 started the month at 1.4% and were at 1.4% on Jan. 27, with a slight dip down to 1.2% in between, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker. Daily hospitalizations for children aged 0-17 also declined through mid-January and did not reflect the jump in new cases.

Meanwhile, vaccinated children are still in the minority: 57% of those under age 18 have received no COVID vaccine yet, the AAP said in a separate report. Just 7.4% of children under age 2 years had received at least one dose as of Jan. 25, as had 10.1% of those aged 2-4 years, 39.6% of 5- to 11-year-olds and 71.8% of those 12-17 years old, according to the CDC, with corresponding figures for completion of the primary series at 3.5%, 5.3%, 32.5%, and 61.5%.

Citing workplace violence, one-fourth of critical care workers are ready to quit

A surgeon in Tulsa shot by a disgruntled patient. A doctor in India beaten by a group of bereaved family members. A general practitioner in the United Kingdom threatened with stabbing. A new study identifies this trend and finds that 25% of health care workers polled were willing to quit because of such violence.

“That was pretty appalling,” Rahul Kashyap, MD, MBA, MBBS, recalls. Dr. Kashyap is one of the leaders of the Violence Study of Healthcare Workers and Systems (ViSHWaS), which polled an international sample of physicians, nurses, and hospital staff. This study has worrying implications, Dr. Kashyap says. In a time when hospital staff are reporting burnout in record numbers, further deterrents may be the last thing our health care system needs. But Dr. Kashyap hopes that bringing awareness to these trends may allow physicians, policymakers, and the public to mobilize and intervene before it’s too late.

Previous studies have revealed similar trends. The rate of workplace violence directed at U.S. health care workers is five times that of workers in any other industry, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. The same study found that attacks had increased 63% from 2011 to 2018. Other polls that focus on the pandemic show that nearly half of U.S. nurses believe that violence increased since the world shut down. Well before the pandemic, however, a study from the Indian Medical Association found that 75% of doctors experienced workplace violence.

With this history in mind, perhaps it’s not surprising that the idea for the study came from the authors’ personal experiences. They had seen coworkers go through attacks, or they had endured attacks themselves, Dr. Kashyap says. But they couldn’t find any global data to back up these experiences. So Dr. Kashyap and his colleagues formed a web of volunteers dedicated to creating a cross-sectional study.

They got in touch with researchers from countries across Asia, the Middle East, South America, North America, and Africa. The initial group agreed to reach out to their contacts, casting a wide net. Researchers used WhatsApp, LinkedIn, and text messages to distribute the survey. Health care workers in each country completed the brief questionnaire, recalling their prepandemic world and evaluating their current one.

Within 2 months, they had reached health care workers in more than 100 countries. They concluded the study when they received about 5,000 results, according to Dr. Kashyap, and then began the process of stratifying the data. For this report, they focused on critical care, emergency medicine, and anesthesiology, which resulted in 598 responses from 69 countries. Of these, India and the United States had the highest number of participants.

In all, 73% of participants reported facing physical or verbal violence while in the hospital; 48% said they felt less motivated to work because of that violence; 39% of respondents believed that the amount of violence they experienced was the same as before the COVID-19 pandemic; and 36% of respondents believed that violence had increased. Even though they were trained on guidelines from the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, 20% of participants felt unprepared to face violence.

Although the study didn’t analyze the reasons workers felt this way, Dr. Kashyap speculates that it could be related to the medical distrust that grew during the pandemic or the stress patients and health care professionals experienced during its peak.

Regardless, the researchers say their study is a starting point. Now that the trend has been highlighted, it may be acted on.

Moving forward, Dr. Kashyap believes that controlling for different variables could determine whether factors like gender or shift time put a worker at higher risk for violence. He hopes it’s possible to interrupt these patterns and reestablish trust in the hospital environment. “It’s aspirational, but you’re hoping that through studies like ViSHWaS, which means trust in Hindi ... [we could restore] the trust and confidence among health care providers for the patients and family members.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A surgeon in Tulsa shot by a disgruntled patient. A doctor in India beaten by a group of bereaved family members. A general practitioner in the United Kingdom threatened with stabbing. A new study identifies this trend and finds that 25% of health care workers polled were willing to quit because of such violence.

“That was pretty appalling,” Rahul Kashyap, MD, MBA, MBBS, recalls. Dr. Kashyap is one of the leaders of the Violence Study of Healthcare Workers and Systems (ViSHWaS), which polled an international sample of physicians, nurses, and hospital staff. This study has worrying implications, Dr. Kashyap says. In a time when hospital staff are reporting burnout in record numbers, further deterrents may be the last thing our health care system needs. But Dr. Kashyap hopes that bringing awareness to these trends may allow physicians, policymakers, and the public to mobilize and intervene before it’s too late.

Previous studies have revealed similar trends. The rate of workplace violence directed at U.S. health care workers is five times that of workers in any other industry, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. The same study found that attacks had increased 63% from 2011 to 2018. Other polls that focus on the pandemic show that nearly half of U.S. nurses believe that violence increased since the world shut down. Well before the pandemic, however, a study from the Indian Medical Association found that 75% of doctors experienced workplace violence.

With this history in mind, perhaps it’s not surprising that the idea for the study came from the authors’ personal experiences. They had seen coworkers go through attacks, or they had endured attacks themselves, Dr. Kashyap says. But they couldn’t find any global data to back up these experiences. So Dr. Kashyap and his colleagues formed a web of volunteers dedicated to creating a cross-sectional study.

They got in touch with researchers from countries across Asia, the Middle East, South America, North America, and Africa. The initial group agreed to reach out to their contacts, casting a wide net. Researchers used WhatsApp, LinkedIn, and text messages to distribute the survey. Health care workers in each country completed the brief questionnaire, recalling their prepandemic world and evaluating their current one.

Within 2 months, they had reached health care workers in more than 100 countries. They concluded the study when they received about 5,000 results, according to Dr. Kashyap, and then began the process of stratifying the data. For this report, they focused on critical care, emergency medicine, and anesthesiology, which resulted in 598 responses from 69 countries. Of these, India and the United States had the highest number of participants.

In all, 73% of participants reported facing physical or verbal violence while in the hospital; 48% said they felt less motivated to work because of that violence; 39% of respondents believed that the amount of violence they experienced was the same as before the COVID-19 pandemic; and 36% of respondents believed that violence had increased. Even though they were trained on guidelines from the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, 20% of participants felt unprepared to face violence.

Although the study didn’t analyze the reasons workers felt this way, Dr. Kashyap speculates that it could be related to the medical distrust that grew during the pandemic or the stress patients and health care professionals experienced during its peak.

Regardless, the researchers say their study is a starting point. Now that the trend has been highlighted, it may be acted on.

Moving forward, Dr. Kashyap believes that controlling for different variables could determine whether factors like gender or shift time put a worker at higher risk for violence. He hopes it’s possible to interrupt these patterns and reestablish trust in the hospital environment. “It’s aspirational, but you’re hoping that through studies like ViSHWaS, which means trust in Hindi ... [we could restore] the trust and confidence among health care providers for the patients and family members.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A surgeon in Tulsa shot by a disgruntled patient. A doctor in India beaten by a group of bereaved family members. A general practitioner in the United Kingdom threatened with stabbing. A new study identifies this trend and finds that 25% of health care workers polled were willing to quit because of such violence.

“That was pretty appalling,” Rahul Kashyap, MD, MBA, MBBS, recalls. Dr. Kashyap is one of the leaders of the Violence Study of Healthcare Workers and Systems (ViSHWaS), which polled an international sample of physicians, nurses, and hospital staff. This study has worrying implications, Dr. Kashyap says. In a time when hospital staff are reporting burnout in record numbers, further deterrents may be the last thing our health care system needs. But Dr. Kashyap hopes that bringing awareness to these trends may allow physicians, policymakers, and the public to mobilize and intervene before it’s too late.

Previous studies have revealed similar trends. The rate of workplace violence directed at U.S. health care workers is five times that of workers in any other industry, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. The same study found that attacks had increased 63% from 2011 to 2018. Other polls that focus on the pandemic show that nearly half of U.S. nurses believe that violence increased since the world shut down. Well before the pandemic, however, a study from the Indian Medical Association found that 75% of doctors experienced workplace violence.

With this history in mind, perhaps it’s not surprising that the idea for the study came from the authors’ personal experiences. They had seen coworkers go through attacks, or they had endured attacks themselves, Dr. Kashyap says. But they couldn’t find any global data to back up these experiences. So Dr. Kashyap and his colleagues formed a web of volunteers dedicated to creating a cross-sectional study.

They got in touch with researchers from countries across Asia, the Middle East, South America, North America, and Africa. The initial group agreed to reach out to their contacts, casting a wide net. Researchers used WhatsApp, LinkedIn, and text messages to distribute the survey. Health care workers in each country completed the brief questionnaire, recalling their prepandemic world and evaluating their current one.

Within 2 months, they had reached health care workers in more than 100 countries. They concluded the study when they received about 5,000 results, according to Dr. Kashyap, and then began the process of stratifying the data. For this report, they focused on critical care, emergency medicine, and anesthesiology, which resulted in 598 responses from 69 countries. Of these, India and the United States had the highest number of participants.

In all, 73% of participants reported facing physical or verbal violence while in the hospital; 48% said they felt less motivated to work because of that violence; 39% of respondents believed that the amount of violence they experienced was the same as before the COVID-19 pandemic; and 36% of respondents believed that violence had increased. Even though they were trained on guidelines from the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, 20% of participants felt unprepared to face violence.

Although the study didn’t analyze the reasons workers felt this way, Dr. Kashyap speculates that it could be related to the medical distrust that grew during the pandemic or the stress patients and health care professionals experienced during its peak.

Regardless, the researchers say their study is a starting point. Now that the trend has been highlighted, it may be acted on.

Moving forward, Dr. Kashyap believes that controlling for different variables could determine whether factors like gender or shift time put a worker at higher risk for violence. He hopes it’s possible to interrupt these patterns and reestablish trust in the hospital environment. “It’s aspirational, but you’re hoping that through studies like ViSHWaS, which means trust in Hindi ... [we could restore] the trust and confidence among health care providers for the patients and family members.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Feds charge 25 nursing school execs, staff in fake diploma scheme

The U.S. Department of Justice recently announced charges against 25 owners, operators, and employees of three Florida nursing schools in a fraud scheme in which they sold as many as 7,600 fake nursing degrees.

The purchasers in the diploma scheme paid $10,000 to $15,000 for degrees and transcripts and some 2,800 of the buyers passed the national nursing licensing exam to become registered nurses (RNs) and licensed practice nurses/vocational nurses (LPN/VNs) around the country, according to The New York Times.

Many of the degree recipients went on to work at hospitals, nursing homes, and Veterans Affairs medical centers, according to the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Southern District of Florida.

Several national nursing organizations cooperated with the investigation, and the Delaware Division of Professional Regulation already annulled 26 licenses, according to the Delaware Nurses Association. Fake licenses were issued in five states, according to federal reports.

“We are deeply unsettled by this egregious act,” DNA President Stephanie McClellan, MSN, RN, CMSRN, said in the group’s press statement. “We want all Delaware nurses to be aware of this active issue and to speak up if there is a concern regarding capacity to practice safely by a colleague/peer,” she said.

The Oregon State Board of Nursing is also investigating at least a dozen nurses who may have paid for their degrees, according to a Portland CBS affiliate.

The National Council of State Boards of Nursing said in a statement that it had helped authorities identify and monitor the individuals who allegedly provided the false degrees.

Nursing community reacts

News of the fraud scheme spread through the nursing community, including social media. “The recent report on falsified nursing school degrees is both heartbreaking and serves as an eye-opener,” tweeted Usha Menon, PhD, RN, FAAN, dean and health professor of the University of South Florida Health College of Nursing. “There was enough of a need that prompted these bad actors to develop a scheme that could’ve endangered dozens of lives.”

Jennifer Mensik Kennedy, PhD, MBA, RN, the new president of the American Nurses Association, also weighed in. “The accusation that personnel at once-accredited nursing schools allegedly participated in this scheme is simply deplorable. These unlawful and unethical acts disparage the reputation of actual nurses everywhere who have rightfully earned [their titles] through their education, hard work, dedication, and time.”

The false degrees and transcripts were issued by three once-accredited and now-shuttered nursing schools in South Florida: Palm Beach School of Nursing, Sacred Heart International Institute, and Sienna College.

The alleged co-conspirators reportedly made $114 million from the scheme, which dates back to 2016, according to several news reports. Each defendant faces up to 20 years in prison.

Most LPN programs charge $10,000 to $15,000 to complete a program, Robert Rosseter, a spokesperson for the American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN), told this news organization.

None were AACN members, and none were accredited by the Commission on Collegiate Nursing Education, which is AACN’s autonomous accrediting agency, Mr. Rosseter said. AACN membership is voluntary and is open to schools offering baccalaureate or higher degrees, he explained.

“What is disturbing about this investigation is that there are over 7,600 people around the country with fraudulent nursing credentials who are potentially in critical health care roles treating patients,” Chad Yarbrough, acting special agent in charge for the FBI in Miami, said in the federal justice department release.

‘Operation Nightingale’ based on tip

The federal action, dubbed “Operation Nightingale” after the nursing pioneer Florence Nightingale, began in 2019. It was based on a tip related to a case in Maryland, according to Nurse.org.

That case ensnared Palm Beach School of Nursing owner Johanah Napoleon, who reportedly was selling fake degrees for $6,000 to $18,000 each to two individuals in Maryland and Virginia. Ms. Napoleon was charged in 2021 and eventually pled guilty. The Florida Board of Nursing shut down the Palm Beach school in 2017 owing to its students’ low passing rate on the national licensing exam.

Two participants in the bigger scheme who had also worked with Ms. Napoleon – Geralda Adrien and Woosvelt Predestin – were indicted in 2021. Ms. Adrien owned private education companies for people who at aspired to be nurses, and Mr. Predestin was an employee. They were sentenced to 27 months in prison last year and helped the federal officials build the larger case.

The 25 individuals who were charged Jan. 25 operated in Delaware, New York, New Jersey, Texas, and Florida.

Schemes lured immigrants

In the scheme involving Siena College, some of the individuals acted as recruiters to direct nurses who were looking for employment to the school, where they allegedly would then pay for an RN or LPN/VN degree. The recipients of the false documents then used them to obtain jobs, including at a hospital in Georgia and a Veterans Affairs medical center in Maryland, according to one indictment. The president of Siena and her co-conspirators sold more than 2,000 fake diplomas, according to charging documents.

At the Palm Beach College of Nursing, individuals at various nursing prep and education programs allegedly helped others obtain fake degrees and transcripts, which were then used to pass RN and LPN/VN licensing exams in states that included Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, and Ohio, according to the indictment.

Some individuals then secured employment with a nursing home in Ohio, a home health agency for pediatric patients in Massachusetts, and skilled nursing facilities in New York and New Jersey.

Prosecutors allege that the president of Sacred Heart International Institute and two other co-conspirators sold 588 fake diplomas.

The FBI said that some of the aspiring nurses who were talked into buying the degrees were LPNs who wanted to become RNs and that most of those lured into the scheme were from South Florida’s Haitian American immigrant community, Nurse.org reported.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The U.S. Department of Justice recently announced charges against 25 owners, operators, and employees of three Florida nursing schools in a fraud scheme in which they sold as many as 7,600 fake nursing degrees.

The purchasers in the diploma scheme paid $10,000 to $15,000 for degrees and transcripts and some 2,800 of the buyers passed the national nursing licensing exam to become registered nurses (RNs) and licensed practice nurses/vocational nurses (LPN/VNs) around the country, according to The New York Times.

Many of the degree recipients went on to work at hospitals, nursing homes, and Veterans Affairs medical centers, according to the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Southern District of Florida.

Several national nursing organizations cooperated with the investigation, and the Delaware Division of Professional Regulation already annulled 26 licenses, according to the Delaware Nurses Association. Fake licenses were issued in five states, according to federal reports.

“We are deeply unsettled by this egregious act,” DNA President Stephanie McClellan, MSN, RN, CMSRN, said in the group’s press statement. “We want all Delaware nurses to be aware of this active issue and to speak up if there is a concern regarding capacity to practice safely by a colleague/peer,” she said.

The Oregon State Board of Nursing is also investigating at least a dozen nurses who may have paid for their degrees, according to a Portland CBS affiliate.

The National Council of State Boards of Nursing said in a statement that it had helped authorities identify and monitor the individuals who allegedly provided the false degrees.

Nursing community reacts

News of the fraud scheme spread through the nursing community, including social media. “The recent report on falsified nursing school degrees is both heartbreaking and serves as an eye-opener,” tweeted Usha Menon, PhD, RN, FAAN, dean and health professor of the University of South Florida Health College of Nursing. “There was enough of a need that prompted these bad actors to develop a scheme that could’ve endangered dozens of lives.”

Jennifer Mensik Kennedy, PhD, MBA, RN, the new president of the American Nurses Association, also weighed in. “The accusation that personnel at once-accredited nursing schools allegedly participated in this scheme is simply deplorable. These unlawful and unethical acts disparage the reputation of actual nurses everywhere who have rightfully earned [their titles] through their education, hard work, dedication, and time.”

The false degrees and transcripts were issued by three once-accredited and now-shuttered nursing schools in South Florida: Palm Beach School of Nursing, Sacred Heart International Institute, and Sienna College.

The alleged co-conspirators reportedly made $114 million from the scheme, which dates back to 2016, according to several news reports. Each defendant faces up to 20 years in prison.

Most LPN programs charge $10,000 to $15,000 to complete a program, Robert Rosseter, a spokesperson for the American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN), told this news organization.

None were AACN members, and none were accredited by the Commission on Collegiate Nursing Education, which is AACN’s autonomous accrediting agency, Mr. Rosseter said. AACN membership is voluntary and is open to schools offering baccalaureate or higher degrees, he explained.

“What is disturbing about this investigation is that there are over 7,600 people around the country with fraudulent nursing credentials who are potentially in critical health care roles treating patients,” Chad Yarbrough, acting special agent in charge for the FBI in Miami, said in the federal justice department release.

‘Operation Nightingale’ based on tip

The federal action, dubbed “Operation Nightingale” after the nursing pioneer Florence Nightingale, began in 2019. It was based on a tip related to a case in Maryland, according to Nurse.org.

That case ensnared Palm Beach School of Nursing owner Johanah Napoleon, who reportedly was selling fake degrees for $6,000 to $18,000 each to two individuals in Maryland and Virginia. Ms. Napoleon was charged in 2021 and eventually pled guilty. The Florida Board of Nursing shut down the Palm Beach school in 2017 owing to its students’ low passing rate on the national licensing exam.

Two participants in the bigger scheme who had also worked with Ms. Napoleon – Geralda Adrien and Woosvelt Predestin – were indicted in 2021. Ms. Adrien owned private education companies for people who at aspired to be nurses, and Mr. Predestin was an employee. They were sentenced to 27 months in prison last year and helped the federal officials build the larger case.

The 25 individuals who were charged Jan. 25 operated in Delaware, New York, New Jersey, Texas, and Florida.

Schemes lured immigrants

In the scheme involving Siena College, some of the individuals acted as recruiters to direct nurses who were looking for employment to the school, where they allegedly would then pay for an RN or LPN/VN degree. The recipients of the false documents then used them to obtain jobs, including at a hospital in Georgia and a Veterans Affairs medical center in Maryland, according to one indictment. The president of Siena and her co-conspirators sold more than 2,000 fake diplomas, according to charging documents.

At the Palm Beach College of Nursing, individuals at various nursing prep and education programs allegedly helped others obtain fake degrees and transcripts, which were then used to pass RN and LPN/VN licensing exams in states that included Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, and Ohio, according to the indictment.

Some individuals then secured employment with a nursing home in Ohio, a home health agency for pediatric patients in Massachusetts, and skilled nursing facilities in New York and New Jersey.

Prosecutors allege that the president of Sacred Heart International Institute and two other co-conspirators sold 588 fake diplomas.

The FBI said that some of the aspiring nurses who were talked into buying the degrees were LPNs who wanted to become RNs and that most of those lured into the scheme were from South Florida’s Haitian American immigrant community, Nurse.org reported.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The U.S. Department of Justice recently announced charges against 25 owners, operators, and employees of three Florida nursing schools in a fraud scheme in which they sold as many as 7,600 fake nursing degrees.

The purchasers in the diploma scheme paid $10,000 to $15,000 for degrees and transcripts and some 2,800 of the buyers passed the national nursing licensing exam to become registered nurses (RNs) and licensed practice nurses/vocational nurses (LPN/VNs) around the country, according to The New York Times.

Many of the degree recipients went on to work at hospitals, nursing homes, and Veterans Affairs medical centers, according to the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Southern District of Florida.

Several national nursing organizations cooperated with the investigation, and the Delaware Division of Professional Regulation already annulled 26 licenses, according to the Delaware Nurses Association. Fake licenses were issued in five states, according to federal reports.

“We are deeply unsettled by this egregious act,” DNA President Stephanie McClellan, MSN, RN, CMSRN, said in the group’s press statement. “We want all Delaware nurses to be aware of this active issue and to speak up if there is a concern regarding capacity to practice safely by a colleague/peer,” she said.

The Oregon State Board of Nursing is also investigating at least a dozen nurses who may have paid for their degrees, according to a Portland CBS affiliate.

The National Council of State Boards of Nursing said in a statement that it had helped authorities identify and monitor the individuals who allegedly provided the false degrees.

Nursing community reacts

News of the fraud scheme spread through the nursing community, including social media. “The recent report on falsified nursing school degrees is both heartbreaking and serves as an eye-opener,” tweeted Usha Menon, PhD, RN, FAAN, dean and health professor of the University of South Florida Health College of Nursing. “There was enough of a need that prompted these bad actors to develop a scheme that could’ve endangered dozens of lives.”

Jennifer Mensik Kennedy, PhD, MBA, RN, the new president of the American Nurses Association, also weighed in. “The accusation that personnel at once-accredited nursing schools allegedly participated in this scheme is simply deplorable. These unlawful and unethical acts disparage the reputation of actual nurses everywhere who have rightfully earned [their titles] through their education, hard work, dedication, and time.”

The false degrees and transcripts were issued by three once-accredited and now-shuttered nursing schools in South Florida: Palm Beach School of Nursing, Sacred Heart International Institute, and Sienna College.

The alleged co-conspirators reportedly made $114 million from the scheme, which dates back to 2016, according to several news reports. Each defendant faces up to 20 years in prison.

Most LPN programs charge $10,000 to $15,000 to complete a program, Robert Rosseter, a spokesperson for the American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN), told this news organization.

None were AACN members, and none were accredited by the Commission on Collegiate Nursing Education, which is AACN’s autonomous accrediting agency, Mr. Rosseter said. AACN membership is voluntary and is open to schools offering baccalaureate or higher degrees, he explained.

“What is disturbing about this investigation is that there are over 7,600 people around the country with fraudulent nursing credentials who are potentially in critical health care roles treating patients,” Chad Yarbrough, acting special agent in charge for the FBI in Miami, said in the federal justice department release.

‘Operation Nightingale’ based on tip

The federal action, dubbed “Operation Nightingale” after the nursing pioneer Florence Nightingale, began in 2019. It was based on a tip related to a case in Maryland, according to Nurse.org.

That case ensnared Palm Beach School of Nursing owner Johanah Napoleon, who reportedly was selling fake degrees for $6,000 to $18,000 each to two individuals in Maryland and Virginia. Ms. Napoleon was charged in 2021 and eventually pled guilty. The Florida Board of Nursing shut down the Palm Beach school in 2017 owing to its students’ low passing rate on the national licensing exam.

Two participants in the bigger scheme who had also worked with Ms. Napoleon – Geralda Adrien and Woosvelt Predestin – were indicted in 2021. Ms. Adrien owned private education companies for people who at aspired to be nurses, and Mr. Predestin was an employee. They were sentenced to 27 months in prison last year and helped the federal officials build the larger case.

The 25 individuals who were charged Jan. 25 operated in Delaware, New York, New Jersey, Texas, and Florida.

Schemes lured immigrants

In the scheme involving Siena College, some of the individuals acted as recruiters to direct nurses who were looking for employment to the school, where they allegedly would then pay for an RN or LPN/VN degree. The recipients of the false documents then used them to obtain jobs, including at a hospital in Georgia and a Veterans Affairs medical center in Maryland, according to one indictment. The president of Siena and her co-conspirators sold more than 2,000 fake diplomas, according to charging documents.

At the Palm Beach College of Nursing, individuals at various nursing prep and education programs allegedly helped others obtain fake degrees and transcripts, which were then used to pass RN and LPN/VN licensing exams in states that included Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, and Ohio, according to the indictment.

Some individuals then secured employment with a nursing home in Ohio, a home health agency for pediatric patients in Massachusetts, and skilled nursing facilities in New York and New Jersey.

Prosecutors allege that the president of Sacred Heart International Institute and two other co-conspirators sold 588 fake diplomas.

The FBI said that some of the aspiring nurses who were talked into buying the degrees were LPNs who wanted to become RNs and that most of those lured into the scheme were from South Florida’s Haitian American immigrant community, Nurse.org reported.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Biden to end COVID emergencies in May

Doing so will have many effects, including the end of free vaccines and health services to fight the pandemic. The public health emergency has been renewed every 90 days since it was declared by the Trump administration in January 2020.

The declaration allowed major changes throughout the health care system to deal with the pandemic, including the free distribution of vaccines, testing, and treatments. In addition, telehealth services were expanded, and Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program were extended to millions more Americans.

Biden said the COVID-19 national emergency is set to expire March 1 while the declared public health emergency would currently expire on April 11. The president said both will be extended to end May 11.

There were nearly 300,000 newly reported COVID-19 cases in the United States for the week ending Jan. 25, according to CDC data, as well as more than 3,750 deaths.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Doing so will have many effects, including the end of free vaccines and health services to fight the pandemic. The public health emergency has been renewed every 90 days since it was declared by the Trump administration in January 2020.

The declaration allowed major changes throughout the health care system to deal with the pandemic, including the free distribution of vaccines, testing, and treatments. In addition, telehealth services were expanded, and Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program were extended to millions more Americans.

Biden said the COVID-19 national emergency is set to expire March 1 while the declared public health emergency would currently expire on April 11. The president said both will be extended to end May 11.

There were nearly 300,000 newly reported COVID-19 cases in the United States for the week ending Jan. 25, according to CDC data, as well as more than 3,750 deaths.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Doing so will have many effects, including the end of free vaccines and health services to fight the pandemic. The public health emergency has been renewed every 90 days since it was declared by the Trump administration in January 2020.

The declaration allowed major changes throughout the health care system to deal with the pandemic, including the free distribution of vaccines, testing, and treatments. In addition, telehealth services were expanded, and Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program were extended to millions more Americans.

Biden said the COVID-19 national emergency is set to expire March 1 while the declared public health emergency would currently expire on April 11. The president said both will be extended to end May 11.

There were nearly 300,000 newly reported COVID-19 cases in the United States for the week ending Jan. 25, according to CDC data, as well as more than 3,750 deaths.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Angioedema risk jumps when switching HF meds

New renin-angiotensin-system (RAS) inhibitor therapy using sacubitril-valsartan (Entresto) is no more likely to cause angioedema than starting out with an ACE inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB).

But the risk climbs when such patients start on an ACE inhibitor or ARB and then switch to sacubitril-valsartan, compared with those prescribed the newer drug, the only available angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitor (ARNI), in the first place.

Those findings and others from a large database analysis, by researchers at the Food and Drug Administration and Harvard Medical School, may clarify and help alleviate a residual safety concern about the ARNI – that it might promote angioedema – that persists after the drug’s major HF trials.

The angioedema risk increased the most right after the switch to the ARNI from one of the older RAS inhibitors. For example, the overall risk doubled for patients who started with an ARB then switched to sacubitril-valsartan, compared with those who started on the newer drug. But it went up about 2.5 times during the first 14 days after the switch.

A similar pattern emerged for ACE inhibitors, but the increased angioedema risk reached significance only within 2 weeks of the switch from an ACE inhibitor to sacubitril-valsartan compared to starting on the latter.

The analysis, based on data from the FDA’s Sentinel adverse event reporting system, was published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

A rare complication, but ...

Angioedema was rare overall in the study, with an unadjusted rate of about 6.75 per 1,000 person-years for users of ACE inhibitors, less than half that rate for ARB users, and only one-fifth that rate for sacubitril-valsartan recipients.

But even a rare complication can be a worry for drugs as widely used as RAS inhibitors. And it’s not unusual for patients cautiously started on an ACE inhibitor or ARB to be switched to sacubitril-valsartan, which is only recently a core guideline–recommended therapy for HF with reduced ejection fraction.

Such patients transitioning to the ARNI, the current study suggests, should probably be watched closely for signs of angioedema for 2 weeks but especially during the first few days. Indeed, the study’s event curves show most of the extra risk “popping up” right after the switch to sacubitril-valsartan, lead author Efe Eworuke, PhD, told this news organization.

The ARNI’s labeling, which states the drug should follow ACE inhibitors only after 36-hour washout period, “has done justice to this issue,” she said. But “whether clinicians are adhering to that, we can’t tell.”

Potentially, patients who miss the 36-hour washout between ACE inhibitors or ARBs and sacubitril-valsartan may account for the excess angioedema risk seen in the analysis, said Dr. Eworuke, with the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, Silver Spring, Md.

But the analysis doesn’t nail down the window of excess risk to only 36 hours. It suggests that patients switching to the ARNI – even those pausing for 36 hours in between drugs – should probably be monitored “2 weeks or longer,” she said. “They could still have angioedema after the washout period.”

Indeed, the “timing of the switch may be critical,” according to an editorial accompanying the report. “Perhaps a longer initial exposure period of ACE inhibitor or ARB,” beyond 2 weeks, “should be considered before switching to an ARNI,” contended Robert L. Page II, PharmD, MSPH, University of Colorado Skaggs School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, Aurora.

Moreover, he wrote, the study suggests that “initiation of an ARNI de novo may be safer compared with trialing an ACE inhibitor or ARB then switching to an ARNI,” and “should be a consideration when beginning guideline-directed medical therapy for patients with HF.”

New RAS inhibition with ARNI ‘protective’

Compared with ARNI “new users” who had not received any RAS inhibitor in the prior 6 months, patients in the study who switched from an ACE inhibitor to ARNI (41,548 matched pairs) showed a hazard ratio (HR) for angioedema of 1.62 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.91-2.89), that is, only a “trend,” the report states.

But that trend became significant when the analysis considered only angioedema cases in the first 14 days after the drug switch: HR, 1.98 (95% CI, 1.11-3.53).

Those switching from an ARB to ARNI, compared with ARNI new users (37,893 matched pairs), showed a significant HR for angioedema of 2.03 (95% CI, 1.16-3.54). The effect was more pronounced when considering only angioedema arising in the first 2 weeks: HR, 2.45 (95% CI, 1.36-4.43).

Compared with new use of ACE inhibitors, new ARNI use (41,998 matched pairs) was “protective,” the report states, with an HR for angioedema of 0.18 (95% CI, 0.11-0.29). So was a switch from ACE inhibitors to the ARNI (69,639 matched pairs), with an HR of 0.31 (95% CI, 0.23-0.43).

But compared with starting with an ARB, ARNI new use (43,755 matched pairs) had a null effect on angioedema risk, HR, 0.59 (95% CI, 0.35-1.01); as did switching from an ARB to ARNI (49,137 matched pairs), HR, 0.85 (95% CI, 0.58-1.26).

The analysis has limitations, Dr. Eworuke acknowledged. The comparator groups probably differed in unknown ways given the limits of propensity matching, for example, and because the FDA’s Sentinel system data can reflect only cases that are reported, the study probably underestimates the true prevalence of angioedema.

For example, a patient may see a clinician for a milder case that resolves without a significant intervention, she noted. But “those types of angioedema would not have been captured by our study.”

Dr. Eworuke disclosed that her comments reflect her views and are not those of the Food and Drug Administration; she and the other authors, as well as editorialist Dr. Page, report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

New renin-angiotensin-system (RAS) inhibitor therapy using sacubitril-valsartan (Entresto) is no more likely to cause angioedema than starting out with an ACE inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB).

But the risk climbs when such patients start on an ACE inhibitor or ARB and then switch to sacubitril-valsartan, compared with those prescribed the newer drug, the only available angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitor (ARNI), in the first place.

Those findings and others from a large database analysis, by researchers at the Food and Drug Administration and Harvard Medical School, may clarify and help alleviate a residual safety concern about the ARNI – that it might promote angioedema – that persists after the drug’s major HF trials.

The angioedema risk increased the most right after the switch to the ARNI from one of the older RAS inhibitors. For example, the overall risk doubled for patients who started with an ARB then switched to sacubitril-valsartan, compared with those who started on the newer drug. But it went up about 2.5 times during the first 14 days after the switch.

A similar pattern emerged for ACE inhibitors, but the increased angioedema risk reached significance only within 2 weeks of the switch from an ACE inhibitor to sacubitril-valsartan compared to starting on the latter.

The analysis, based on data from the FDA’s Sentinel adverse event reporting system, was published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

A rare complication, but ...

Angioedema was rare overall in the study, with an unadjusted rate of about 6.75 per 1,000 person-years for users of ACE inhibitors, less than half that rate for ARB users, and only one-fifth that rate for sacubitril-valsartan recipients.

But even a rare complication can be a worry for drugs as widely used as RAS inhibitors. And it’s not unusual for patients cautiously started on an ACE inhibitor or ARB to be switched to sacubitril-valsartan, which is only recently a core guideline–recommended therapy for HF with reduced ejection fraction.

Such patients transitioning to the ARNI, the current study suggests, should probably be watched closely for signs of angioedema for 2 weeks but especially during the first few days. Indeed, the study’s event curves show most of the extra risk “popping up” right after the switch to sacubitril-valsartan, lead author Efe Eworuke, PhD, told this news organization.

The ARNI’s labeling, which states the drug should follow ACE inhibitors only after 36-hour washout period, “has done justice to this issue,” she said. But “whether clinicians are adhering to that, we can’t tell.”

Potentially, patients who miss the 36-hour washout between ACE inhibitors or ARBs and sacubitril-valsartan may account for the excess angioedema risk seen in the analysis, said Dr. Eworuke, with the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, Silver Spring, Md.

But the analysis doesn’t nail down the window of excess risk to only 36 hours. It suggests that patients switching to the ARNI – even those pausing for 36 hours in between drugs – should probably be monitored “2 weeks or longer,” she said. “They could still have angioedema after the washout period.”

Indeed, the “timing of the switch may be critical,” according to an editorial accompanying the report. “Perhaps a longer initial exposure period of ACE inhibitor or ARB,” beyond 2 weeks, “should be considered before switching to an ARNI,” contended Robert L. Page II, PharmD, MSPH, University of Colorado Skaggs School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, Aurora.

Moreover, he wrote, the study suggests that “initiation of an ARNI de novo may be safer compared with trialing an ACE inhibitor or ARB then switching to an ARNI,” and “should be a consideration when beginning guideline-directed medical therapy for patients with HF.”

New RAS inhibition with ARNI ‘protective’

Compared with ARNI “new users” who had not received any RAS inhibitor in the prior 6 months, patients in the study who switched from an ACE inhibitor to ARNI (41,548 matched pairs) showed a hazard ratio (HR) for angioedema of 1.62 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.91-2.89), that is, only a “trend,” the report states.

But that trend became significant when the analysis considered only angioedema cases in the first 14 days after the drug switch: HR, 1.98 (95% CI, 1.11-3.53).

Those switching from an ARB to ARNI, compared with ARNI new users (37,893 matched pairs), showed a significant HR for angioedema of 2.03 (95% CI, 1.16-3.54). The effect was more pronounced when considering only angioedema arising in the first 2 weeks: HR, 2.45 (95% CI, 1.36-4.43).

Compared with new use of ACE inhibitors, new ARNI use (41,998 matched pairs) was “protective,” the report states, with an HR for angioedema of 0.18 (95% CI, 0.11-0.29). So was a switch from ACE inhibitors to the ARNI (69,639 matched pairs), with an HR of 0.31 (95% CI, 0.23-0.43).

But compared with starting with an ARB, ARNI new use (43,755 matched pairs) had a null effect on angioedema risk, HR, 0.59 (95% CI, 0.35-1.01); as did switching from an ARB to ARNI (49,137 matched pairs), HR, 0.85 (95% CI, 0.58-1.26).

The analysis has limitations, Dr. Eworuke acknowledged. The comparator groups probably differed in unknown ways given the limits of propensity matching, for example, and because the FDA’s Sentinel system data can reflect only cases that are reported, the study probably underestimates the true prevalence of angioedema.

For example, a patient may see a clinician for a milder case that resolves without a significant intervention, she noted. But “those types of angioedema would not have been captured by our study.”

Dr. Eworuke disclosed that her comments reflect her views and are not those of the Food and Drug Administration; she and the other authors, as well as editorialist Dr. Page, report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

New renin-angiotensin-system (RAS) inhibitor therapy using sacubitril-valsartan (Entresto) is no more likely to cause angioedema than starting out with an ACE inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB).

But the risk climbs when such patients start on an ACE inhibitor or ARB and then switch to sacubitril-valsartan, compared with those prescribed the newer drug, the only available angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitor (ARNI), in the first place.

Those findings and others from a large database analysis, by researchers at the Food and Drug Administration and Harvard Medical School, may clarify and help alleviate a residual safety concern about the ARNI – that it might promote angioedema – that persists after the drug’s major HF trials.

The angioedema risk increased the most right after the switch to the ARNI from one of the older RAS inhibitors. For example, the overall risk doubled for patients who started with an ARB then switched to sacubitril-valsartan, compared with those who started on the newer drug. But it went up about 2.5 times during the first 14 days after the switch.

A similar pattern emerged for ACE inhibitors, but the increased angioedema risk reached significance only within 2 weeks of the switch from an ACE inhibitor to sacubitril-valsartan compared to starting on the latter.

The analysis, based on data from the FDA’s Sentinel adverse event reporting system, was published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

A rare complication, but ...

Angioedema was rare overall in the study, with an unadjusted rate of about 6.75 per 1,000 person-years for users of ACE inhibitors, less than half that rate for ARB users, and only one-fifth that rate for sacubitril-valsartan recipients.

But even a rare complication can be a worry for drugs as widely used as RAS inhibitors. And it’s not unusual for patients cautiously started on an ACE inhibitor or ARB to be switched to sacubitril-valsartan, which is only recently a core guideline–recommended therapy for HF with reduced ejection fraction.

Such patients transitioning to the ARNI, the current study suggests, should probably be watched closely for signs of angioedema for 2 weeks but especially during the first few days. Indeed, the study’s event curves show most of the extra risk “popping up” right after the switch to sacubitril-valsartan, lead author Efe Eworuke, PhD, told this news organization.

The ARNI’s labeling, which states the drug should follow ACE inhibitors only after 36-hour washout period, “has done justice to this issue,” she said. But “whether clinicians are adhering to that, we can’t tell.”

Potentially, patients who miss the 36-hour washout between ACE inhibitors or ARBs and sacubitril-valsartan may account for the excess angioedema risk seen in the analysis, said Dr. Eworuke, with the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, Silver Spring, Md.

But the analysis doesn’t nail down the window of excess risk to only 36 hours. It suggests that patients switching to the ARNI – even those pausing for 36 hours in between drugs – should probably be monitored “2 weeks or longer,” she said. “They could still have angioedema after the washout period.”

Indeed, the “timing of the switch may be critical,” according to an editorial accompanying the report. “Perhaps a longer initial exposure period of ACE inhibitor or ARB,” beyond 2 weeks, “should be considered before switching to an ARNI,” contended Robert L. Page II, PharmD, MSPH, University of Colorado Skaggs School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, Aurora.

Moreover, he wrote, the study suggests that “initiation of an ARNI de novo may be safer compared with trialing an ACE inhibitor or ARB then switching to an ARNI,” and “should be a consideration when beginning guideline-directed medical therapy for patients with HF.”

New RAS inhibition with ARNI ‘protective’

Compared with ARNI “new users” who had not received any RAS inhibitor in the prior 6 months, patients in the study who switched from an ACE inhibitor to ARNI (41,548 matched pairs) showed a hazard ratio (HR) for angioedema of 1.62 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.91-2.89), that is, only a “trend,” the report states.

But that trend became significant when the analysis considered only angioedema cases in the first 14 days after the drug switch: HR, 1.98 (95% CI, 1.11-3.53).

Those switching from an ARB to ARNI, compared with ARNI new users (37,893 matched pairs), showed a significant HR for angioedema of 2.03 (95% CI, 1.16-3.54). The effect was more pronounced when considering only angioedema arising in the first 2 weeks: HR, 2.45 (95% CI, 1.36-4.43).

Compared with new use of ACE inhibitors, new ARNI use (41,998 matched pairs) was “protective,” the report states, with an HR for angioedema of 0.18 (95% CI, 0.11-0.29). So was a switch from ACE inhibitors to the ARNI (69,639 matched pairs), with an HR of 0.31 (95% CI, 0.23-0.43).

But compared with starting with an ARB, ARNI new use (43,755 matched pairs) had a null effect on angioedema risk, HR, 0.59 (95% CI, 0.35-1.01); as did switching from an ARB to ARNI (49,137 matched pairs), HR, 0.85 (95% CI, 0.58-1.26).

The analysis has limitations, Dr. Eworuke acknowledged. The comparator groups probably differed in unknown ways given the limits of propensity matching, for example, and because the FDA’s Sentinel system data can reflect only cases that are reported, the study probably underestimates the true prevalence of angioedema.

For example, a patient may see a clinician for a milder case that resolves without a significant intervention, she noted. But “those types of angioedema would not have been captured by our study.”

Dr. Eworuke disclosed that her comments reflect her views and are not those of the Food and Drug Administration; she and the other authors, as well as editorialist Dr. Page, report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OF CARDIOLOGY

Even one head injury boosts all-cause mortality risk

An analysis of more than 13,000 adult participants in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study showed a dose-response pattern in which one head injury was linked to a 66% increased risk for all-cause mortality, and two or more head injuries were associated with twice the risk in comparison with no head injuries.

These findings underscore the importance of preventing head injuries and of swift clinical intervention once a head injury occurs, lead author Holly Elser, MD, PhD, department of neurology, Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, told this news organization.

“Clinicians should counsel patients who are at risk for falls about head injuries and ensure patients are promptly evaluated in the hospital setting if they do have a fall – especially with loss of consciousness or other symptoms, such as headache or dizziness,” Dr. Elser added.

The findings were published online in JAMA Neurology.

Consistent evidence

There is “pretty consistent evidence” that mortality rates are increased in the short term after head injury, predominantly among hospitalized patients, Dr. Elser noted.

“But there’s less evidence about the long-term mortality implications of head injuries and less evidence from adults living in the community,” she added.

The analysis included 13,037 participants in the ARIC study, an ongoing study involving adults aged 45-65 years who were recruited from four geographically and racially diverse U.S. communities. The mean age at baseline (1987-1989) was 54 years; 57.7% were women; and 27.9% were Black.

Study participants are followed at routine in-person visits and semiannually via telephone.

Data on head injuries came from hospital diagnostic codes and self-reports. These reports included information on the number of injuries and whether the injury required medical care and involved loss of consciousness.

During the 27-year follow-up, 18.4% of the study sample had at least one head injury. Injuries occurred more frequently among women, which may reflect the predominance of women in the study population, said Dr. Elser.

Overall, about 56% of participants died during the study period. The estimated median amount of survival time after head injury was 4.7 years.

The most common causes of death were neoplasm, cardiovascular disease, and neurologic disorders. Regarding specific neurologic causes of death, the researchers found that 62.2% of deaths were due to neurodegenerative disease among individuals with head injury, vs. 51.4% among those without head injury.

This, said Dr. Elser, raises the possibility of reverse causality. “If you have a neurodegenerative disorder like Alzheimer’s disease dementia or Parkinson’s disease that leads to difficulty walking, you may be more likely to fall and have a head injury. The head injury in turn may lead to increased mortality,” she noted.

However, she stressed that the data on cause-specific mortality are exploratory. “Our research motivates future studies that really examine this time-dependent relationship between neurodegenerative disease and head injuries,” Dr. Elser said.

Dose-dependent response

In the unadjusted analysis, the hazard ratio of mortality among individuals with head injury was 2.21 (95% confidence interval, 2.09-2.34) compared with those who did not have head injury.

The association remained significant with adjustment for sociodemographic factors (HR, 1.99; 95% CI, 1.88-2.11) and with additional adjustment for vascular risk factors (HR, 1.92; 95% CI, 1.81-2.03).

The findings also showed a dose-response pattern in the association of head injuries with mortality. Compared with participants who did not have head injury, the HR was 1.66 (95% CI, 1.56-1.77) for those with one head injury and 2.11 (95% CI, 1.89-2.37) for those with two or more head injuries.

“It’s not as though once you’ve had one head injury, you’ve accrued all the damage you possibly can. We see pretty clearly here that recurrent head injury further increased the rate of deaths from all causes,” said Dr. Elser.

Injury severity was determined from hospital diagnostic codes using established algorithms. Results showed that mortality rates were increased with even mild head injury.

Interestingly, the association between head injury and all-cause mortality was weaker among those whose injuries were self-reported. One possibility is that these injuries were less severe, Dr. Elser noted.

“If you have head injury that’s mild enough that you don’t need to go to the hospital, it’s probably going to confer less long-term health risks than one that’s severe enough that you needed to be examined in an acute care setting,” she said.

Results were similar by race and for sex. “Even though there were more women with head injuries, the rate of mortality associated with head injury doesn’t differ from the rate among men,” Dr. Elser reported.

However, the association was stronger among those younger than 54 years at baseline (HR, 2.26) compared with older individuals (HR, 2.0) in the model that adjusted for demographics and lifestyle factors.

This may be explained by the reference group (those without a head injury) – the mortality rate was in general higher for the older participants, said Dr. Elser. It could also be that younger adults are more likely to have severe head injuries from, for example, motor vehicle accidents or violence, she added.

These new findings underscore the importance of public health measures, such as seatbelt laws, to reduce head injuries, the investigators note.

They add that clinicians with patients at risk for head injuries may recommend steps to lessen the risk of falls, such as having access to durable medical equipment, and ensuring driver safety.

Shorter life span

Commenting for this news organization, Frank Conidi, MD, director of the Florida Center for Headache and Sports Neurology in Port St. Lucie and past president of the Florida Society of Neurology, said the large number of participants “adds validity” to the finding that individuals with head injury are likely to have a shorter life span than those who do not suffer head trauma – and that this “was not purely by chance or from other causes.”

However, patients may not have accurately reported head injuries, in which case the rate of injury in the self-report subgroup would not reflect the actual incidence, noted Dr. Conidi, who was not involved with the research.

“In my practice, most patients have little knowledge as to the signs and symptoms of concussion and traumatic brain injury. Most think there needs to be some form of loss of consciousness to have a head injury, which is of course not true,” he said.

Dr. Conidi added that the finding of a higher incidence of death from neurodegenerative disorders supports the generally accepted consensus view that about 30% of patients with traumatic brain injury experience progression of symptoms and are at risk for early dementia.

The ARIC study is supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Dr. Elser and Dr. Conidi have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

An analysis of more than 13,000 adult participants in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study showed a dose-response pattern in which one head injury was linked to a 66% increased risk for all-cause mortality, and two or more head injuries were associated with twice the risk in comparison with no head injuries.

These findings underscore the importance of preventing head injuries and of swift clinical intervention once a head injury occurs, lead author Holly Elser, MD, PhD, department of neurology, Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, told this news organization.

“Clinicians should counsel patients who are at risk for falls about head injuries and ensure patients are promptly evaluated in the hospital setting if they do have a fall – especially with loss of consciousness or other symptoms, such as headache or dizziness,” Dr. Elser added.

The findings were published online in JAMA Neurology.

Consistent evidence

There is “pretty consistent evidence” that mortality rates are increased in the short term after head injury, predominantly among hospitalized patients, Dr. Elser noted.

“But there’s less evidence about the long-term mortality implications of head injuries and less evidence from adults living in the community,” she added.

The analysis included 13,037 participants in the ARIC study, an ongoing study involving adults aged 45-65 years who were recruited from four geographically and racially diverse U.S. communities. The mean age at baseline (1987-1989) was 54 years; 57.7% were women; and 27.9% were Black.

Study participants are followed at routine in-person visits and semiannually via telephone.

Data on head injuries came from hospital diagnostic codes and self-reports. These reports included information on the number of injuries and whether the injury required medical care and involved loss of consciousness.

During the 27-year follow-up, 18.4% of the study sample had at least one head injury. Injuries occurred more frequently among women, which may reflect the predominance of women in the study population, said Dr. Elser.

Overall, about 56% of participants died during the study period. The estimated median amount of survival time after head injury was 4.7 years.

The most common causes of death were neoplasm, cardiovascular disease, and neurologic disorders. Regarding specific neurologic causes of death, the researchers found that 62.2% of deaths were due to neurodegenerative disease among individuals with head injury, vs. 51.4% among those without head injury.

This, said Dr. Elser, raises the possibility of reverse causality. “If you have a neurodegenerative disorder like Alzheimer’s disease dementia or Parkinson’s disease that leads to difficulty walking, you may be more likely to fall and have a head injury. The head injury in turn may lead to increased mortality,” she noted.

However, she stressed that the data on cause-specific mortality are exploratory. “Our research motivates future studies that really examine this time-dependent relationship between neurodegenerative disease and head injuries,” Dr. Elser said.

Dose-dependent response

In the unadjusted analysis, the hazard ratio of mortality among individuals with head injury was 2.21 (95% confidence interval, 2.09-2.34) compared with those who did not have head injury.

The association remained significant with adjustment for sociodemographic factors (HR, 1.99; 95% CI, 1.88-2.11) and with additional adjustment for vascular risk factors (HR, 1.92; 95% CI, 1.81-2.03).

The findings also showed a dose-response pattern in the association of head injuries with mortality. Compared with participants who did not have head injury, the HR was 1.66 (95% CI, 1.56-1.77) for those with one head injury and 2.11 (95% CI, 1.89-2.37) for those with two or more head injuries.

“It’s not as though once you’ve had one head injury, you’ve accrued all the damage you possibly can. We see pretty clearly here that recurrent head injury further increased the rate of deaths from all causes,” said Dr. Elser.

Injury severity was determined from hospital diagnostic codes using established algorithms. Results showed that mortality rates were increased with even mild head injury.

Interestingly, the association between head injury and all-cause mortality was weaker among those whose injuries were self-reported. One possibility is that these injuries were less severe, Dr. Elser noted.

“If you have head injury that’s mild enough that you don’t need to go to the hospital, it’s probably going to confer less long-term health risks than one that’s severe enough that you needed to be examined in an acute care setting,” she said.

Results were similar by race and for sex. “Even though there were more women with head injuries, the rate of mortality associated with head injury doesn’t differ from the rate among men,” Dr. Elser reported.

However, the association was stronger among those younger than 54 years at baseline (HR, 2.26) compared with older individuals (HR, 2.0) in the model that adjusted for demographics and lifestyle factors.

This may be explained by the reference group (those without a head injury) – the mortality rate was in general higher for the older participants, said Dr. Elser. It could also be that younger adults are more likely to have severe head injuries from, for example, motor vehicle accidents or violence, she added.

These new findings underscore the importance of public health measures, such as seatbelt laws, to reduce head injuries, the investigators note.

They add that clinicians with patients at risk for head injuries may recommend steps to lessen the risk of falls, such as having access to durable medical equipment, and ensuring driver safety.

Shorter life span

Commenting for this news organization, Frank Conidi, MD, director of the Florida Center for Headache and Sports Neurology in Port St. Lucie and past president of the Florida Society of Neurology, said the large number of participants “adds validity” to the finding that individuals with head injury are likely to have a shorter life span than those who do not suffer head trauma – and that this “was not purely by chance or from other causes.”

However, patients may not have accurately reported head injuries, in which case the rate of injury in the self-report subgroup would not reflect the actual incidence, noted Dr. Conidi, who was not involved with the research.

“In my practice, most patients have little knowledge as to the signs and symptoms of concussion and traumatic brain injury. Most think there needs to be some form of loss of consciousness to have a head injury, which is of course not true,” he said.

Dr. Conidi added that the finding of a higher incidence of death from neurodegenerative disorders supports the generally accepted consensus view that about 30% of patients with traumatic brain injury experience progression of symptoms and are at risk for early dementia.

The ARIC study is supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Dr. Elser and Dr. Conidi have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

An analysis of more than 13,000 adult participants in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study showed a dose-response pattern in which one head injury was linked to a 66% increased risk for all-cause mortality, and two or more head injuries were associated with twice the risk in comparison with no head injuries.

These findings underscore the importance of preventing head injuries and of swift clinical intervention once a head injury occurs, lead author Holly Elser, MD, PhD, department of neurology, Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, told this news organization.

“Clinicians should counsel patients who are at risk for falls about head injuries and ensure patients are promptly evaluated in the hospital setting if they do have a fall – especially with loss of consciousness or other symptoms, such as headache or dizziness,” Dr. Elser added.

The findings were published online in JAMA Neurology.

Consistent evidence

There is “pretty consistent evidence” that mortality rates are increased in the short term after head injury, predominantly among hospitalized patients, Dr. Elser noted.

“But there’s less evidence about the long-term mortality implications of head injuries and less evidence from adults living in the community,” she added.

The analysis included 13,037 participants in the ARIC study, an ongoing study involving adults aged 45-65 years who were recruited from four geographically and racially diverse U.S. communities. The mean age at baseline (1987-1989) was 54 years; 57.7% were women; and 27.9% were Black.

Study participants are followed at routine in-person visits and semiannually via telephone.

Data on head injuries came from hospital diagnostic codes and self-reports. These reports included information on the number of injuries and whether the injury required medical care and involved loss of consciousness.

During the 27-year follow-up, 18.4% of the study sample had at least one head injury. Injuries occurred more frequently among women, which may reflect the predominance of women in the study population, said Dr. Elser.

Overall, about 56% of participants died during the study period. The estimated median amount of survival time after head injury was 4.7 years.

The most common causes of death were neoplasm, cardiovascular disease, and neurologic disorders. Regarding specific neurologic causes of death, the researchers found that 62.2% of deaths were due to neurodegenerative disease among individuals with head injury, vs. 51.4% among those without head injury.

This, said Dr. Elser, raises the possibility of reverse causality. “If you have a neurodegenerative disorder like Alzheimer’s disease dementia or Parkinson’s disease that leads to difficulty walking, you may be more likely to fall and have a head injury. The head injury in turn may lead to increased mortality,” she noted.

However, she stressed that the data on cause-specific mortality are exploratory. “Our research motivates future studies that really examine this time-dependent relationship between neurodegenerative disease and head injuries,” Dr. Elser said.

Dose-dependent response

In the unadjusted analysis, the hazard ratio of mortality among individuals with head injury was 2.21 (95% confidence interval, 2.09-2.34) compared with those who did not have head injury.

The association remained significant with adjustment for sociodemographic factors (HR, 1.99; 95% CI, 1.88-2.11) and with additional adjustment for vascular risk factors (HR, 1.92; 95% CI, 1.81-2.03).

The findings also showed a dose-response pattern in the association of head injuries with mortality. Compared with participants who did not have head injury, the HR was 1.66 (95% CI, 1.56-1.77) for those with one head injury and 2.11 (95% CI, 1.89-2.37) for those with two or more head injuries.

“It’s not as though once you’ve had one head injury, you’ve accrued all the damage you possibly can. We see pretty clearly here that recurrent head injury further increased the rate of deaths from all causes,” said Dr. Elser.

Injury severity was determined from hospital diagnostic codes using established algorithms. Results showed that mortality rates were increased with even mild head injury.