User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

The longevity gene: Healthy mutant reverses heart aging

Everybody wants a younger heart

As more people live well past 90, scientists have been taking a closer look at how they’ve been doing it. Mostly it boiled down to genetics. You either had it or you didn’t. Well, a recent study suggests that doesn’t have to be true anymore, at least for the heart.

Scientists from the United Kingdom and Italy found an antiaging gene in some centenarians that has shown possible antiaging effects in mice and in human heart cells. A single administration of the mutant antiaging gene, they found, stopped heart function decay in middle-aged mice and even reversed the biological clock by the human equivalent of 10 years in elderly mice.

When the researchers applied the antiaging gene to samples of human heart cells from elderly people with heart problems, the cells “resumed functioning properly, proving to be more efficient in building new blood vessels,” they said in a written statement. It all kind of sounds like something out of Dr. Frankenstein’s lab.

I want to believe … in better sleep

The “X-Files” theme song plays. Mulder and Scully are sitting in a diner, breakfast laid out around them. The diner is quiet, with only a few people inside.

Mulder: I’m telling you, Scully, there’s something spooky going on here.

Scully: You mean other than the fact that this town in Georgia looks suspiciously like Vancouver?

Mulder: Not one person we spoke to yesterday has gotten a full night’s sleep since the UFO sighting last month. I’m telling you, they’re here, they’re experimenting.

Scully: Do you really want me to do this to you again?

Mulder: Do what again?

Scully: There’s nothing going on here that can’t be explained by the current research. Why, in January 2023 a study was published revealing a link between poor sleep and belief in paranormal phenomena like UFOS, demons, or ghosts. Which probably explains why you’re on your third cup of coffee for the morning.

Mulder: Scully, you’ve literally been abducted by aliens. Do we have to play this game every time?

Scully: Look, it’s simple. In a sample of nearly 9,000 people, nearly two-thirds of those who reported experiencing sleep paralysis or exploding head syndrome reported believing in UFOs and aliens walking amongst humanity, despite making up just 3% of the overall sample.

Furthermore, about 60% of those reporting sleep paralysis also reported believing near-death experiences prove the soul lingers on after death, and those with stronger insomnia symptoms were more likely to believe in the devil.

Mulder: Aha!

Scully: Aha what?

Mulder: You’re a devout Christian. You believe in the devil and the soul.

Scully: Yes, but I don’t let it interfere with a good night’s sleep, Mulder. These people saw something strange, convinced themselves it was a UFO, and now they can’t sleep. It’s a vicious cycle. The study authors even said that people experiencing strange nighttime phenomena could interpret this as evidence of aliens or other paranormal beings, thus making them even more susceptible to further sleep disruption and deepening beliefs. Look who I’m talking to.

Mulder: Always with the facts, eh?

Scully: I am a doctor, after all. And if you want more research into how paranormal belief and poor sleep quality are linked, I’d be happy to dig out the literature, because the truth is out there, Mulder.

Mulder: I hate you sometimes.

It’s ChatGPT’s world. We’re just living in it

Have you heard about ChatGPT? The artificial intelligence chatbot was just launched in November and it’s already more important to the Internet than either Vladimir Putin or “Rick and Morty.”

What’s that? You’re wondering why you should care? Well, excuuuuuse us, but we thought you might want to know that ChatGPT is in the process of taking over the world. Let’s take a quick look at what it’s been up to.

“ChatGPT bot passes law school exam”

“ChatGPT passes MBA exam given by a Wharton professor”

“A freelance writer says ChatGPT wrote a $600 article in just 30 seconds”

And here’s one that might be of interest to those of the health care persuasion: “ChatGPT can pass part of the U.S. Medical Licensing Exam.” See? It’s coming for you, too.

The artificial intelligence known as ChatGPT “performed at >50% accuracy across [the three USMLE] examinations, exceeding 60% in most analyses,” a group of researchers wrote on the preprint server medRxiv, noting that 60% is usually the pass threshold for humans taking the exam in any given year.

ChatGPT was not given any special medical training before the exam, but the investigators pointed out that another AI, PubMedGPT, which is trained exclusively on biomedical domain literature, was only 50.8% accurate on the USMLE. Its reliance on “ongoing academic discourse that tends to be inconclusive, contradictory, or highly conservative or noncommittal in its language” was its undoing, the team suggested.

To top it off, ChatGPT is listed as one of the authors at the top of the medRxiv report, with an acknowledgment at the end saying that “ChatGPT contributed to the writing of several sections of this manuscript.”

We’ve said it before, and no doubt we’ll say it again: We’re doomed.

Everybody wants a younger heart

As more people live well past 90, scientists have been taking a closer look at how they’ve been doing it. Mostly it boiled down to genetics. You either had it or you didn’t. Well, a recent study suggests that doesn’t have to be true anymore, at least for the heart.

Scientists from the United Kingdom and Italy found an antiaging gene in some centenarians that has shown possible antiaging effects in mice and in human heart cells. A single administration of the mutant antiaging gene, they found, stopped heart function decay in middle-aged mice and even reversed the biological clock by the human equivalent of 10 years in elderly mice.

When the researchers applied the antiaging gene to samples of human heart cells from elderly people with heart problems, the cells “resumed functioning properly, proving to be more efficient in building new blood vessels,” they said in a written statement. It all kind of sounds like something out of Dr. Frankenstein’s lab.

I want to believe … in better sleep

The “X-Files” theme song plays. Mulder and Scully are sitting in a diner, breakfast laid out around them. The diner is quiet, with only a few people inside.

Mulder: I’m telling you, Scully, there’s something spooky going on here.

Scully: You mean other than the fact that this town in Georgia looks suspiciously like Vancouver?

Mulder: Not one person we spoke to yesterday has gotten a full night’s sleep since the UFO sighting last month. I’m telling you, they’re here, they’re experimenting.

Scully: Do you really want me to do this to you again?

Mulder: Do what again?

Scully: There’s nothing going on here that can’t be explained by the current research. Why, in January 2023 a study was published revealing a link between poor sleep and belief in paranormal phenomena like UFOS, demons, or ghosts. Which probably explains why you’re on your third cup of coffee for the morning.

Mulder: Scully, you’ve literally been abducted by aliens. Do we have to play this game every time?

Scully: Look, it’s simple. In a sample of nearly 9,000 people, nearly two-thirds of those who reported experiencing sleep paralysis or exploding head syndrome reported believing in UFOs and aliens walking amongst humanity, despite making up just 3% of the overall sample.

Furthermore, about 60% of those reporting sleep paralysis also reported believing near-death experiences prove the soul lingers on after death, and those with stronger insomnia symptoms were more likely to believe in the devil.

Mulder: Aha!

Scully: Aha what?

Mulder: You’re a devout Christian. You believe in the devil and the soul.

Scully: Yes, but I don’t let it interfere with a good night’s sleep, Mulder. These people saw something strange, convinced themselves it was a UFO, and now they can’t sleep. It’s a vicious cycle. The study authors even said that people experiencing strange nighttime phenomena could interpret this as evidence of aliens or other paranormal beings, thus making them even more susceptible to further sleep disruption and deepening beliefs. Look who I’m talking to.

Mulder: Always with the facts, eh?

Scully: I am a doctor, after all. And if you want more research into how paranormal belief and poor sleep quality are linked, I’d be happy to dig out the literature, because the truth is out there, Mulder.

Mulder: I hate you sometimes.

It’s ChatGPT’s world. We’re just living in it

Have you heard about ChatGPT? The artificial intelligence chatbot was just launched in November and it’s already more important to the Internet than either Vladimir Putin or “Rick and Morty.”

What’s that? You’re wondering why you should care? Well, excuuuuuse us, but we thought you might want to know that ChatGPT is in the process of taking over the world. Let’s take a quick look at what it’s been up to.

“ChatGPT bot passes law school exam”

“ChatGPT passes MBA exam given by a Wharton professor”

“A freelance writer says ChatGPT wrote a $600 article in just 30 seconds”

And here’s one that might be of interest to those of the health care persuasion: “ChatGPT can pass part of the U.S. Medical Licensing Exam.” See? It’s coming for you, too.

The artificial intelligence known as ChatGPT “performed at >50% accuracy across [the three USMLE] examinations, exceeding 60% in most analyses,” a group of researchers wrote on the preprint server medRxiv, noting that 60% is usually the pass threshold for humans taking the exam in any given year.

ChatGPT was not given any special medical training before the exam, but the investigators pointed out that another AI, PubMedGPT, which is trained exclusively on biomedical domain literature, was only 50.8% accurate on the USMLE. Its reliance on “ongoing academic discourse that tends to be inconclusive, contradictory, or highly conservative or noncommittal in its language” was its undoing, the team suggested.

To top it off, ChatGPT is listed as one of the authors at the top of the medRxiv report, with an acknowledgment at the end saying that “ChatGPT contributed to the writing of several sections of this manuscript.”

We’ve said it before, and no doubt we’ll say it again: We’re doomed.

Everybody wants a younger heart

As more people live well past 90, scientists have been taking a closer look at how they’ve been doing it. Mostly it boiled down to genetics. You either had it or you didn’t. Well, a recent study suggests that doesn’t have to be true anymore, at least for the heart.

Scientists from the United Kingdom and Italy found an antiaging gene in some centenarians that has shown possible antiaging effects in mice and in human heart cells. A single administration of the mutant antiaging gene, they found, stopped heart function decay in middle-aged mice and even reversed the biological clock by the human equivalent of 10 years in elderly mice.

When the researchers applied the antiaging gene to samples of human heart cells from elderly people with heart problems, the cells “resumed functioning properly, proving to be more efficient in building new blood vessels,” they said in a written statement. It all kind of sounds like something out of Dr. Frankenstein’s lab.

I want to believe … in better sleep

The “X-Files” theme song plays. Mulder and Scully are sitting in a diner, breakfast laid out around them. The diner is quiet, with only a few people inside.

Mulder: I’m telling you, Scully, there’s something spooky going on here.

Scully: You mean other than the fact that this town in Georgia looks suspiciously like Vancouver?

Mulder: Not one person we spoke to yesterday has gotten a full night’s sleep since the UFO sighting last month. I’m telling you, they’re here, they’re experimenting.

Scully: Do you really want me to do this to you again?

Mulder: Do what again?

Scully: There’s nothing going on here that can’t be explained by the current research. Why, in January 2023 a study was published revealing a link between poor sleep and belief in paranormal phenomena like UFOS, demons, or ghosts. Which probably explains why you’re on your third cup of coffee for the morning.

Mulder: Scully, you’ve literally been abducted by aliens. Do we have to play this game every time?

Scully: Look, it’s simple. In a sample of nearly 9,000 people, nearly two-thirds of those who reported experiencing sleep paralysis or exploding head syndrome reported believing in UFOs and aliens walking amongst humanity, despite making up just 3% of the overall sample.

Furthermore, about 60% of those reporting sleep paralysis also reported believing near-death experiences prove the soul lingers on after death, and those with stronger insomnia symptoms were more likely to believe in the devil.

Mulder: Aha!

Scully: Aha what?

Mulder: You’re a devout Christian. You believe in the devil and the soul.

Scully: Yes, but I don’t let it interfere with a good night’s sleep, Mulder. These people saw something strange, convinced themselves it was a UFO, and now they can’t sleep. It’s a vicious cycle. The study authors even said that people experiencing strange nighttime phenomena could interpret this as evidence of aliens or other paranormal beings, thus making them even more susceptible to further sleep disruption and deepening beliefs. Look who I’m talking to.

Mulder: Always with the facts, eh?

Scully: I am a doctor, after all. And if you want more research into how paranormal belief and poor sleep quality are linked, I’d be happy to dig out the literature, because the truth is out there, Mulder.

Mulder: I hate you sometimes.

It’s ChatGPT’s world. We’re just living in it

Have you heard about ChatGPT? The artificial intelligence chatbot was just launched in November and it’s already more important to the Internet than either Vladimir Putin or “Rick and Morty.”

What’s that? You’re wondering why you should care? Well, excuuuuuse us, but we thought you might want to know that ChatGPT is in the process of taking over the world. Let’s take a quick look at what it’s been up to.

“ChatGPT bot passes law school exam”

“ChatGPT passes MBA exam given by a Wharton professor”

“A freelance writer says ChatGPT wrote a $600 article in just 30 seconds”

And here’s one that might be of interest to those of the health care persuasion: “ChatGPT can pass part of the U.S. Medical Licensing Exam.” See? It’s coming for you, too.

The artificial intelligence known as ChatGPT “performed at >50% accuracy across [the three USMLE] examinations, exceeding 60% in most analyses,” a group of researchers wrote on the preprint server medRxiv, noting that 60% is usually the pass threshold for humans taking the exam in any given year.

ChatGPT was not given any special medical training before the exam, but the investigators pointed out that another AI, PubMedGPT, which is trained exclusively on biomedical domain literature, was only 50.8% accurate on the USMLE. Its reliance on “ongoing academic discourse that tends to be inconclusive, contradictory, or highly conservative or noncommittal in its language” was its undoing, the team suggested.

To top it off, ChatGPT is listed as one of the authors at the top of the medRxiv report, with an acknowledgment at the end saying that “ChatGPT contributed to the writing of several sections of this manuscript.”

We’ve said it before, and no doubt we’ll say it again: We’re doomed.

Over half of ED visits from cancer patients could be prevented

Overall, researchers found that 18.3 million (52%) ED visits among patients with cancer between 2012 and 2019 were potentially avoidable. Pain was the most common reason for such a visit. Notably, the number of potentially preventable ED visits documented each year increased over the study period.

“These findings highlight the need for cancer care programs to implement evidence-based interventions to better manage cancer treatment complications, such as uncontrolled pain, in outpatient and ambulatory settings,” said the authors, led by Amir Alishahi Tabriz, MD, PhD, MPH, department of health outcomes and behavior, Moffitt Cancer Center, Tampa.

Authors of an accompanying editorial agree, noting that “patients at risk for having uncontrolled pain could potentially be identified earlier, and steps could be taken that would address their pain and help prevent acute care visits.”

The study and the editorial were published online Jan. 19, 2022, in JAMA Network Open.

Patients with cancer experience a range of side effects from their cancer and treatment. Many such problems can be managed in the ambulatory setting but are often managed in the ED, which is far from optimal for patients with cancer from both a complications and cost perspective. Still, little is known about whether ED visits among patients with cancer are avoidable.

To better understand unnecessary emergency care use by these patients, Dr. Tabriz and colleagues evaluated trends and characteristics of potentially preventable ED visits among adults with cancer who had an ED visit between 2012 and 2019. The authors used the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services definition for a potentially preventable ED visit among patients receiving chemotherapy.

Among the 35.5 million ED visits made by patients with cancer during the study period, 18.3 million (52%) were identified as potentially preventable. Nearly 5.8 million of these visits (21%) were classified as being of “high acuity,” and almost 30% resulted in unplanned hospitalizations.

Pain was the most common reason for potentially preventable ED visits, accounting for 37% of these visits.

The absolute number of potentially preventable ED visits among cancer patients increased from about 1.8 million in 2012 to 3.2 million in 2019. The number of patients who visited the ED because of pain more than doubled, from roughly 1.2 million in 2012 to 2.4 million in 2019.

“The disproportionate increase in the number of ED visits by patients with cancer has put a substantial burden on EDs that are already operating at peak capacity” and “reinforces the need for cancer care programs to devise innovative ways to manage complications associated with cancer treatment in the outpatient and ambulatory settings,” Dr. Tabriz and coauthors wrote.

The increase could be an “unintended” consequence of efforts to decrease overall opioid administration in response to the opioid epidemic, Dr. Tabriz and colleagues noted. For example, the authors point to a recent study that found that about half of patients with cancer who had severe pain did not receive outpatient opioids in the week before visiting the ED.

“Even access to outpatient care does not mean patients can get the care they need outside an ED,” wrote editorialists Erek Majka, MD, with Summerlin Hospital, Las Vegas, and N. Seth Trueger, MD, MPH, with Northwestern University, Chicago. Thus, “it is no surprise that patients are sent to the ED if the alternatives do not have the staff or diagnostic and therapeutic capabilities the patients need.”

Overall, however, the “goal is not to eliminate ED visits for their own sake; rather, the goal is better care of patients with cancer, and secondarily, in a manner that is cost-effective,” Dr. Majka and Dr. Trueger explained.

No specific funding for the study was reported. The authors disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Trueger is digital media editor of JAMA Network Open, but he was not involved in decisions regarding review of the manuscript or its acceptance.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Overall, researchers found that 18.3 million (52%) ED visits among patients with cancer between 2012 and 2019 were potentially avoidable. Pain was the most common reason for such a visit. Notably, the number of potentially preventable ED visits documented each year increased over the study period.

“These findings highlight the need for cancer care programs to implement evidence-based interventions to better manage cancer treatment complications, such as uncontrolled pain, in outpatient and ambulatory settings,” said the authors, led by Amir Alishahi Tabriz, MD, PhD, MPH, department of health outcomes and behavior, Moffitt Cancer Center, Tampa.

Authors of an accompanying editorial agree, noting that “patients at risk for having uncontrolled pain could potentially be identified earlier, and steps could be taken that would address their pain and help prevent acute care visits.”

The study and the editorial were published online Jan. 19, 2022, in JAMA Network Open.

Patients with cancer experience a range of side effects from their cancer and treatment. Many such problems can be managed in the ambulatory setting but are often managed in the ED, which is far from optimal for patients with cancer from both a complications and cost perspective. Still, little is known about whether ED visits among patients with cancer are avoidable.

To better understand unnecessary emergency care use by these patients, Dr. Tabriz and colleagues evaluated trends and characteristics of potentially preventable ED visits among adults with cancer who had an ED visit between 2012 and 2019. The authors used the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services definition for a potentially preventable ED visit among patients receiving chemotherapy.

Among the 35.5 million ED visits made by patients with cancer during the study period, 18.3 million (52%) were identified as potentially preventable. Nearly 5.8 million of these visits (21%) were classified as being of “high acuity,” and almost 30% resulted in unplanned hospitalizations.

Pain was the most common reason for potentially preventable ED visits, accounting for 37% of these visits.

The absolute number of potentially preventable ED visits among cancer patients increased from about 1.8 million in 2012 to 3.2 million in 2019. The number of patients who visited the ED because of pain more than doubled, from roughly 1.2 million in 2012 to 2.4 million in 2019.

“The disproportionate increase in the number of ED visits by patients with cancer has put a substantial burden on EDs that are already operating at peak capacity” and “reinforces the need for cancer care programs to devise innovative ways to manage complications associated with cancer treatment in the outpatient and ambulatory settings,” Dr. Tabriz and coauthors wrote.

The increase could be an “unintended” consequence of efforts to decrease overall opioid administration in response to the opioid epidemic, Dr. Tabriz and colleagues noted. For example, the authors point to a recent study that found that about half of patients with cancer who had severe pain did not receive outpatient opioids in the week before visiting the ED.

“Even access to outpatient care does not mean patients can get the care they need outside an ED,” wrote editorialists Erek Majka, MD, with Summerlin Hospital, Las Vegas, and N. Seth Trueger, MD, MPH, with Northwestern University, Chicago. Thus, “it is no surprise that patients are sent to the ED if the alternatives do not have the staff or diagnostic and therapeutic capabilities the patients need.”

Overall, however, the “goal is not to eliminate ED visits for their own sake; rather, the goal is better care of patients with cancer, and secondarily, in a manner that is cost-effective,” Dr. Majka and Dr. Trueger explained.

No specific funding for the study was reported. The authors disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Trueger is digital media editor of JAMA Network Open, but he was not involved in decisions regarding review of the manuscript or its acceptance.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Overall, researchers found that 18.3 million (52%) ED visits among patients with cancer between 2012 and 2019 were potentially avoidable. Pain was the most common reason for such a visit. Notably, the number of potentially preventable ED visits documented each year increased over the study period.

“These findings highlight the need for cancer care programs to implement evidence-based interventions to better manage cancer treatment complications, such as uncontrolled pain, in outpatient and ambulatory settings,” said the authors, led by Amir Alishahi Tabriz, MD, PhD, MPH, department of health outcomes and behavior, Moffitt Cancer Center, Tampa.

Authors of an accompanying editorial agree, noting that “patients at risk for having uncontrolled pain could potentially be identified earlier, and steps could be taken that would address their pain and help prevent acute care visits.”

The study and the editorial were published online Jan. 19, 2022, in JAMA Network Open.

Patients with cancer experience a range of side effects from their cancer and treatment. Many such problems can be managed in the ambulatory setting but are often managed in the ED, which is far from optimal for patients with cancer from both a complications and cost perspective. Still, little is known about whether ED visits among patients with cancer are avoidable.

To better understand unnecessary emergency care use by these patients, Dr. Tabriz and colleagues evaluated trends and characteristics of potentially preventable ED visits among adults with cancer who had an ED visit between 2012 and 2019. The authors used the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services definition for a potentially preventable ED visit among patients receiving chemotherapy.

Among the 35.5 million ED visits made by patients with cancer during the study period, 18.3 million (52%) were identified as potentially preventable. Nearly 5.8 million of these visits (21%) were classified as being of “high acuity,” and almost 30% resulted in unplanned hospitalizations.

Pain was the most common reason for potentially preventable ED visits, accounting for 37% of these visits.

The absolute number of potentially preventable ED visits among cancer patients increased from about 1.8 million in 2012 to 3.2 million in 2019. The number of patients who visited the ED because of pain more than doubled, from roughly 1.2 million in 2012 to 2.4 million in 2019.

“The disproportionate increase in the number of ED visits by patients with cancer has put a substantial burden on EDs that are already operating at peak capacity” and “reinforces the need for cancer care programs to devise innovative ways to manage complications associated with cancer treatment in the outpatient and ambulatory settings,” Dr. Tabriz and coauthors wrote.

The increase could be an “unintended” consequence of efforts to decrease overall opioid administration in response to the opioid epidemic, Dr. Tabriz and colleagues noted. For example, the authors point to a recent study that found that about half of patients with cancer who had severe pain did not receive outpatient opioids in the week before visiting the ED.

“Even access to outpatient care does not mean patients can get the care they need outside an ED,” wrote editorialists Erek Majka, MD, with Summerlin Hospital, Las Vegas, and N. Seth Trueger, MD, MPH, with Northwestern University, Chicago. Thus, “it is no surprise that patients are sent to the ED if the alternatives do not have the staff or diagnostic and therapeutic capabilities the patients need.”

Overall, however, the “goal is not to eliminate ED visits for their own sake; rather, the goal is better care of patients with cancer, and secondarily, in a manner that is cost-effective,” Dr. Majka and Dr. Trueger explained.

No specific funding for the study was reported. The authors disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Trueger is digital media editor of JAMA Network Open, but he was not involved in decisions regarding review of the manuscript or its acceptance.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

VEXAS syndrome: More common, variable, and severe than expected

A recently discovered inflammatory disease known as VEXAS syndrome is more common, variable, and dangerous than previously understood, according to results of a retrospective observational study of a large health care system database. The findings, published in JAMA, found that it struck 1 in 4,269 men over the age of 50 in a largely White population and caused a wide variety of symptoms.

“The disease is quite severe,” study lead author David Beck, MD, PhD, of the department of medicine at NYU Langone Health, said in an interview. Patients with the condition “have a variety of clinical symptoms affecting different parts of the body and are being managed by different medical specialties.”

Dr. Beck and colleagues first described VEXAS (vacuoles, E1-ubiquitin-activating enzyme, X-linked, autoinflammatory, somatic) syndrome in 2020. They linked it to mutations in the UBA1 (ubiquitin-like modifier activating enzyme 1) gene. The enzyme initiates a process that identifies misfolded proteins as targets for degradation.

“VEXAS syndrome is characterized by anemia and inflammation in the skin, lungs, cartilage, and joints,” Dr. Beck said. “These symptoms are frequently mistaken for other rheumatic or hematologic diseases. However, this syndrome has a different cause, is treated differently, requires additional monitoring, and can be far more severe.”

According to him, hundreds of people have been diagnosed with the disease in the short time since it was defined. The disease is believed to be fatal in some cases. A previous report found that the median survival was 9 years among patients with a certain variant; that was significantly less than patients with two other variants.

For the new study, researchers searched for UBA1 variants in genetic data from 163,096 subjects (mean age, 52.8 years; 94% White, 61% women) who took part in the Geisinger MyCode Community Health Initiative. The 1996-2022 data comes from patients at 10 Pennsylvania hospitals.

Eleven people (9 males, 2 females) had likely UBA1 variants, and all had anemia. The cases accounted for 1 in 13,591 unrelated people (95% confidence interval, 1:7,775-1:23,758), 1 in 4,269 men older than 50 years (95% CI, 1:2,319-1:7,859), and 1 in 26,238 women older than 50 years (95% CI, 1:7,196-1:147,669).

Other common findings included macrocytosis (91%), skin problems (73%), and pulmonary disease (91%). Ten patients (91%) required transfusions.

Five of the 11 subjects didn’t meet the previously defined criteria for VEXAS syndrome. None had been diagnosed with the condition, which is not surprising considering that it hadn’t been discovered and described until recently.

Just over half of the patients – 55% – had a clinical diagnosis that was previously linked to VEXAS syndrome. “This means that slightly less than half of the patients with VEXAS syndrome had no clear associated clinical diagnosis,” Dr. Beck said. “The lack of associated clinical diagnoses may be due to the variety of nonspecific clinical characteristics that span different subspecialities in VEXAS syndrome. VEXAS syndrome represents an example of a multisystem disease where patients and their symptoms may get lost in the shuffle.”

In the future, “professionals should look out for patients with unexplained inflammation – and some combination of hematologic, rheumatologic, pulmonary, and dermatologic clinical manifestations – that either don’t carry a clinical diagnosis or don’t respond to first-line therapies,” Dr. Beck said. “These patients will also frequently be anemic, have low platelet counts, elevated markers of inflammation in the blood, and be dependent on corticosteroids.”

Diagnosis can be made via genetic testing, but the study authors note that it “is not routinely offered on standard workup for myeloid neoplasms or immune dysregulation diagnostic panels.”

As for treatment, Dr. Beck said the disease “can be partially controlled by multiple different anticytokine therapies or biologics. However, in most cases, patients still need additional steroids and/or disease-modifying antirheumatic agents [DMARDs]. In addition, bone marrow transplantation has shown signs of being a highly effective therapy.”

The study authors say more research is needed to understand the disease’s prevalence in more diverse populations.

In an interview, Matthew J. Koster, MD, a rheumatologist at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., who’s studied the disease but didn’t take part in this research project, said the findings are valid and “highly important.

“The findings of this study highlight what many academic and quaternary referral centers were wondering: Is VEXAS really more common than we think, with patients hiding in plain sight? The answer is yes,” he said. “Currently, there are less than 400 cases reported in the literature of VEXAS, but large centers are diagnosing this condition with some frequency. For example, at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, we diagnose on average one new patient with VEXAS every 7-14 days and have diagnosed 60 in the past 18 months. A national collaborative group in France has diagnosed approximately 250 patients over that same time frame when pooling patients nationwide.”

The prevalence is high enough, he said, that “clinicians should consider that some of the patients with diseases that are not responding to treatment may in fact have VEXAS rather than ‘refractory’ relapsing polychondritis or ‘recalcitrant’ rheumatoid arthritis, etc.”

The National Institute of Health funded the study. Dr. Beck, the other authors, and Dr. Koster report no disclosures.

A recently discovered inflammatory disease known as VEXAS syndrome is more common, variable, and dangerous than previously understood, according to results of a retrospective observational study of a large health care system database. The findings, published in JAMA, found that it struck 1 in 4,269 men over the age of 50 in a largely White population and caused a wide variety of symptoms.

“The disease is quite severe,” study lead author David Beck, MD, PhD, of the department of medicine at NYU Langone Health, said in an interview. Patients with the condition “have a variety of clinical symptoms affecting different parts of the body and are being managed by different medical specialties.”

Dr. Beck and colleagues first described VEXAS (vacuoles, E1-ubiquitin-activating enzyme, X-linked, autoinflammatory, somatic) syndrome in 2020. They linked it to mutations in the UBA1 (ubiquitin-like modifier activating enzyme 1) gene. The enzyme initiates a process that identifies misfolded proteins as targets for degradation.

“VEXAS syndrome is characterized by anemia and inflammation in the skin, lungs, cartilage, and joints,” Dr. Beck said. “These symptoms are frequently mistaken for other rheumatic or hematologic diseases. However, this syndrome has a different cause, is treated differently, requires additional monitoring, and can be far more severe.”

According to him, hundreds of people have been diagnosed with the disease in the short time since it was defined. The disease is believed to be fatal in some cases. A previous report found that the median survival was 9 years among patients with a certain variant; that was significantly less than patients with two other variants.

For the new study, researchers searched for UBA1 variants in genetic data from 163,096 subjects (mean age, 52.8 years; 94% White, 61% women) who took part in the Geisinger MyCode Community Health Initiative. The 1996-2022 data comes from patients at 10 Pennsylvania hospitals.

Eleven people (9 males, 2 females) had likely UBA1 variants, and all had anemia. The cases accounted for 1 in 13,591 unrelated people (95% confidence interval, 1:7,775-1:23,758), 1 in 4,269 men older than 50 years (95% CI, 1:2,319-1:7,859), and 1 in 26,238 women older than 50 years (95% CI, 1:7,196-1:147,669).

Other common findings included macrocytosis (91%), skin problems (73%), and pulmonary disease (91%). Ten patients (91%) required transfusions.

Five of the 11 subjects didn’t meet the previously defined criteria for VEXAS syndrome. None had been diagnosed with the condition, which is not surprising considering that it hadn’t been discovered and described until recently.

Just over half of the patients – 55% – had a clinical diagnosis that was previously linked to VEXAS syndrome. “This means that slightly less than half of the patients with VEXAS syndrome had no clear associated clinical diagnosis,” Dr. Beck said. “The lack of associated clinical diagnoses may be due to the variety of nonspecific clinical characteristics that span different subspecialities in VEXAS syndrome. VEXAS syndrome represents an example of a multisystem disease where patients and their symptoms may get lost in the shuffle.”

In the future, “professionals should look out for patients with unexplained inflammation – and some combination of hematologic, rheumatologic, pulmonary, and dermatologic clinical manifestations – that either don’t carry a clinical diagnosis or don’t respond to first-line therapies,” Dr. Beck said. “These patients will also frequently be anemic, have low platelet counts, elevated markers of inflammation in the blood, and be dependent on corticosteroids.”

Diagnosis can be made via genetic testing, but the study authors note that it “is not routinely offered on standard workup for myeloid neoplasms or immune dysregulation diagnostic panels.”

As for treatment, Dr. Beck said the disease “can be partially controlled by multiple different anticytokine therapies or biologics. However, in most cases, patients still need additional steroids and/or disease-modifying antirheumatic agents [DMARDs]. In addition, bone marrow transplantation has shown signs of being a highly effective therapy.”

The study authors say more research is needed to understand the disease’s prevalence in more diverse populations.

In an interview, Matthew J. Koster, MD, a rheumatologist at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., who’s studied the disease but didn’t take part in this research project, said the findings are valid and “highly important.

“The findings of this study highlight what many academic and quaternary referral centers were wondering: Is VEXAS really more common than we think, with patients hiding in plain sight? The answer is yes,” he said. “Currently, there are less than 400 cases reported in the literature of VEXAS, but large centers are diagnosing this condition with some frequency. For example, at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, we diagnose on average one new patient with VEXAS every 7-14 days and have diagnosed 60 in the past 18 months. A national collaborative group in France has diagnosed approximately 250 patients over that same time frame when pooling patients nationwide.”

The prevalence is high enough, he said, that “clinicians should consider that some of the patients with diseases that are not responding to treatment may in fact have VEXAS rather than ‘refractory’ relapsing polychondritis or ‘recalcitrant’ rheumatoid arthritis, etc.”

The National Institute of Health funded the study. Dr. Beck, the other authors, and Dr. Koster report no disclosures.

A recently discovered inflammatory disease known as VEXAS syndrome is more common, variable, and dangerous than previously understood, according to results of a retrospective observational study of a large health care system database. The findings, published in JAMA, found that it struck 1 in 4,269 men over the age of 50 in a largely White population and caused a wide variety of symptoms.

“The disease is quite severe,” study lead author David Beck, MD, PhD, of the department of medicine at NYU Langone Health, said in an interview. Patients with the condition “have a variety of clinical symptoms affecting different parts of the body and are being managed by different medical specialties.”

Dr. Beck and colleagues first described VEXAS (vacuoles, E1-ubiquitin-activating enzyme, X-linked, autoinflammatory, somatic) syndrome in 2020. They linked it to mutations in the UBA1 (ubiquitin-like modifier activating enzyme 1) gene. The enzyme initiates a process that identifies misfolded proteins as targets for degradation.

“VEXAS syndrome is characterized by anemia and inflammation in the skin, lungs, cartilage, and joints,” Dr. Beck said. “These symptoms are frequently mistaken for other rheumatic or hematologic diseases. However, this syndrome has a different cause, is treated differently, requires additional monitoring, and can be far more severe.”

According to him, hundreds of people have been diagnosed with the disease in the short time since it was defined. The disease is believed to be fatal in some cases. A previous report found that the median survival was 9 years among patients with a certain variant; that was significantly less than patients with two other variants.

For the new study, researchers searched for UBA1 variants in genetic data from 163,096 subjects (mean age, 52.8 years; 94% White, 61% women) who took part in the Geisinger MyCode Community Health Initiative. The 1996-2022 data comes from patients at 10 Pennsylvania hospitals.

Eleven people (9 males, 2 females) had likely UBA1 variants, and all had anemia. The cases accounted for 1 in 13,591 unrelated people (95% confidence interval, 1:7,775-1:23,758), 1 in 4,269 men older than 50 years (95% CI, 1:2,319-1:7,859), and 1 in 26,238 women older than 50 years (95% CI, 1:7,196-1:147,669).

Other common findings included macrocytosis (91%), skin problems (73%), and pulmonary disease (91%). Ten patients (91%) required transfusions.

Five of the 11 subjects didn’t meet the previously defined criteria for VEXAS syndrome. None had been diagnosed with the condition, which is not surprising considering that it hadn’t been discovered and described until recently.

Just over half of the patients – 55% – had a clinical diagnosis that was previously linked to VEXAS syndrome. “This means that slightly less than half of the patients with VEXAS syndrome had no clear associated clinical diagnosis,” Dr. Beck said. “The lack of associated clinical diagnoses may be due to the variety of nonspecific clinical characteristics that span different subspecialities in VEXAS syndrome. VEXAS syndrome represents an example of a multisystem disease where patients and their symptoms may get lost in the shuffle.”

In the future, “professionals should look out for patients with unexplained inflammation – and some combination of hematologic, rheumatologic, pulmonary, and dermatologic clinical manifestations – that either don’t carry a clinical diagnosis or don’t respond to first-line therapies,” Dr. Beck said. “These patients will also frequently be anemic, have low platelet counts, elevated markers of inflammation in the blood, and be dependent on corticosteroids.”

Diagnosis can be made via genetic testing, but the study authors note that it “is not routinely offered on standard workup for myeloid neoplasms or immune dysregulation diagnostic panels.”

As for treatment, Dr. Beck said the disease “can be partially controlled by multiple different anticytokine therapies or biologics. However, in most cases, patients still need additional steroids and/or disease-modifying antirheumatic agents [DMARDs]. In addition, bone marrow transplantation has shown signs of being a highly effective therapy.”

The study authors say more research is needed to understand the disease’s prevalence in more diverse populations.

In an interview, Matthew J. Koster, MD, a rheumatologist at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., who’s studied the disease but didn’t take part in this research project, said the findings are valid and “highly important.

“The findings of this study highlight what many academic and quaternary referral centers were wondering: Is VEXAS really more common than we think, with patients hiding in plain sight? The answer is yes,” he said. “Currently, there are less than 400 cases reported in the literature of VEXAS, but large centers are diagnosing this condition with some frequency. For example, at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, we diagnose on average one new patient with VEXAS every 7-14 days and have diagnosed 60 in the past 18 months. A national collaborative group in France has diagnosed approximately 250 patients over that same time frame when pooling patients nationwide.”

The prevalence is high enough, he said, that “clinicians should consider that some of the patients with diseases that are not responding to treatment may in fact have VEXAS rather than ‘refractory’ relapsing polychondritis or ‘recalcitrant’ rheumatoid arthritis, etc.”

The National Institute of Health funded the study. Dr. Beck, the other authors, and Dr. Koster report no disclosures.

FROM JAMA

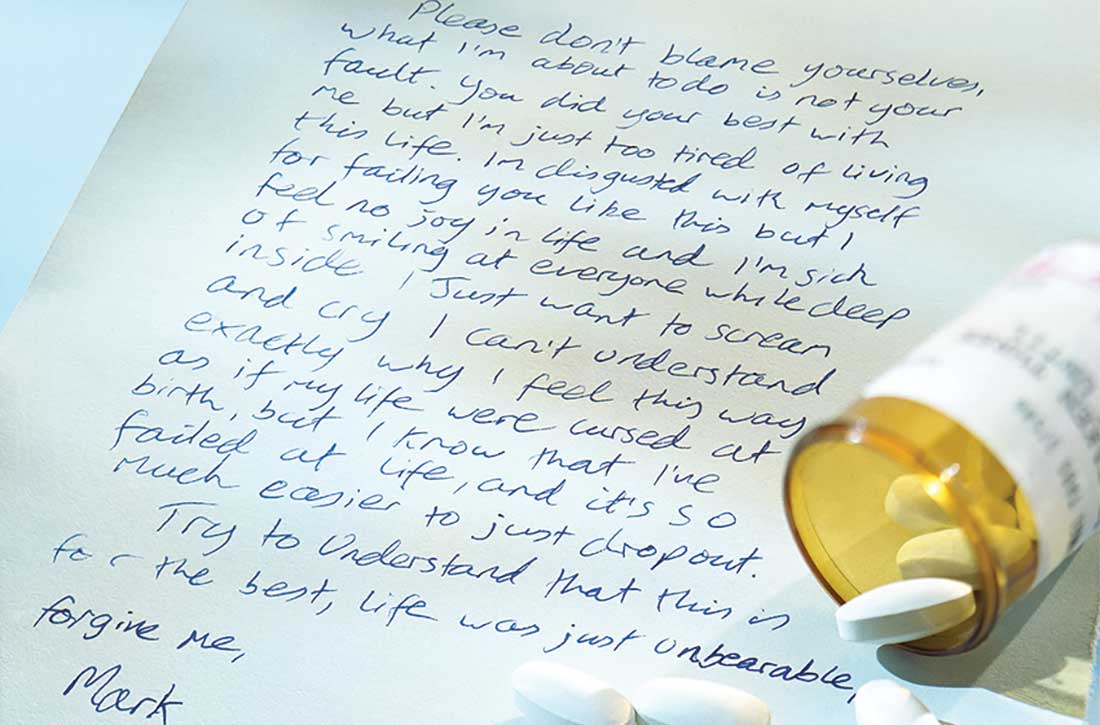

Evaluation after a suicide attempt: What to ask

In 2021, suicide was the 11th leading cause of death in the United States.1 Suicide resulted in 49,000 US deaths during 2021; it was the second most common cause of death in individuals age 10 to 34, and the fifth leading cause among children.1,2 Women are 3 to 4 times more likely than men to attempt suicide, but men are 4 times more likely to die by suicide.2

The evaluation of patients with suicidal ideation who have not made an attempt generally involves assessing 4 factors: the specific plan, access to lethal means, any recent social stressors, and the presence of a psychiatric disorder.3 The clinician should also assess which potential deterrents, such as religious beliefs or dependent children, might be present.

Mental health clinicians are often called upon to evaluate a patient after a suicide attempt to assess intent for continued self-harm and to determine appropriate disposition. Such an evaluation must consider multiple factors, including the method used, premeditation, consequences of the attempt, the presence of severe depression and/or psychosis, and the role of substance use. Assessment after a suicide attempt differs from the examination of individuals who harbor suicidal thoughts but have not made an attempt; the latter group may be more likely to respond to interventions such as intensive outpatient care, mobilization of family support, and religious proscriptions against suicide. However, for patients who make an attempt to end their life, whatever potential safeguards or deterrents to suicide that were in place obviously did not prevent the self-harm act. The consequences of the attempt, such as disabling injuries or medical complications, and possible involuntary commitment, need to be considered. Assessment of the patient’s feelings about having survived the attempt is important because the psychological impact of the attempt on family members may serve to intensify the patient’s depression and make a subsequent attempt more likely.

Many individuals who think of suicide have communicated self-harm thoughts or intentions, but such comments are often minimized or ignored. There is a common but erroneous belief that if patients are encouraged to discuss thoughts of self-harm, they will be more likely to act upon them. Because the opposite is true,4 clinicians should ask vulnerable patients about suicidal ideation or intent. Importantly, noncompliance with life-saving medical care, risk-taking behaviors, and substance use may also signal a desire for self-harm. Passive thoughts of death, typified by comments such as “I don’t care whether I wake up or not,” should also be elicited. Many patients who think of suicide speak of being in a “bad place” where reason and logic give way to an intense desire to end their misery.

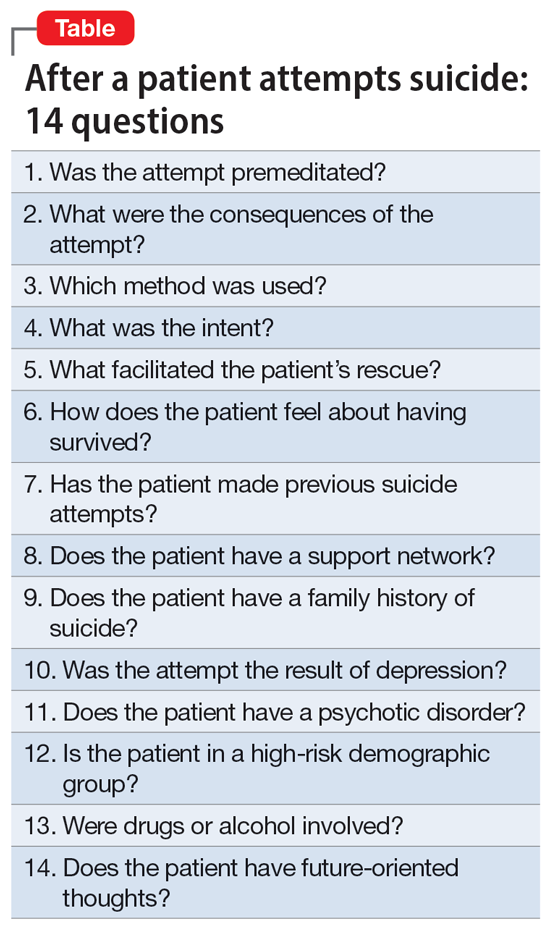

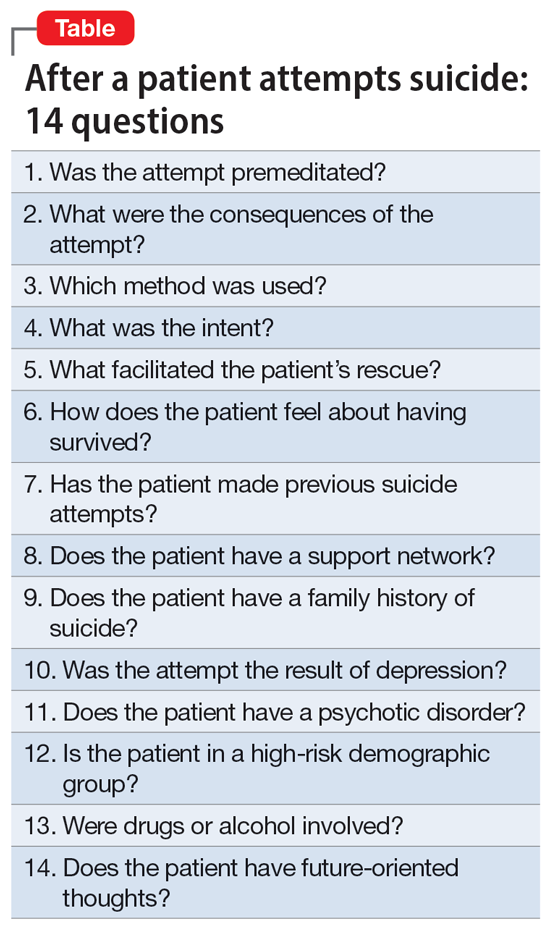

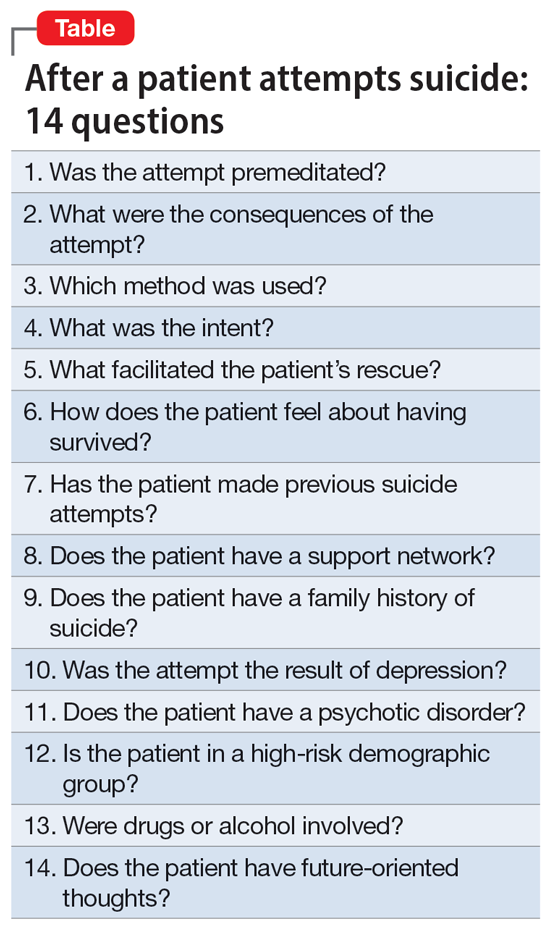

The evaluation of a patient who has attempted suicide is an important component of providing psychiatric care. This article reflects our 45 years of evaluating such patients. As such, it reflects our clinical experience and is not evidence-based. We offer a checklist of 14 questions that we have found helpful when determining if it would be best for a patient to receive inpatient psychiatric hospitalization or a discharge referral for outpatient care (Table). Questions 1 through 6 are specific for patients who have made a suicide attempt, while questions 7 through 14 are helpful for assessing global risk factors for suicide.

1. Was the attempt premeditated?

Determining premeditation vs impulsivity is an essential element of the assessment following a suicide attempt. Many such acts may occur without forethought in response to an unexpected stressor, such as an altercation between partners or family conflicts. Impulsive attempts can occur when an individual is involved in a distressing event and/or while intoxicated. Conversely, premeditation involves forethought and planning, which may increase the risk of suicide in the near future.

Examples of premeditated behavior include:

- Contemplating the attempt days or weeks beforehand

- Researching the effects of a medication or combination of medications in terms of potential lethality

- Engaging in behavior that would decrease the likelihood of their body being discovered after the attempt

- Obtaining weapons and/or stockpiling pills

- Canvassing potential sites such as bridges or tall buildings

- Engaging in a suicide attempt “practice run”

- Leaving a suicide note or message on social media

- Making funeral arrangements, such as choosing burial clothing

- Writing a will and arranging for the custody of dependent children

- Purchasing life insurance that does not deny payment of benefits in cases of death by suicide.

Continue to: Patients with a premeditated...

Patients with a premeditated suicide attempt generally do not expect to survive and are often surprised or upset that the act was not fatal. The presence of indicators that the attempt was premeditated should direct the disposition more toward hospitalization than discharge. In assessing the impact of premeditation, it is important to gauge not just the examples listed above, but also the patient’s perception of these issues (such as potential loss of child custody). Consider how much the patient is emotionally affected by such thinking.

2. What were the consequences of the attempt?

Assessing the reason for the attempt (if any) and determining whether the inciting circumstance has changed due to the suicide attempt are an important part of the evaluation. A suicide attempt may result in reconciliation with and/or renewed support from family members or partners, who might not have been aware of the patient’s emotional distress. Such unexpected support often results in the patient exhibiting improved mood and affect, and possibly temporary resolution of suicidal thoughts. This “flight into health” may be short-lived, but it also may be enough to engage the patient in a therapeutic alliance. That may permit a discharge with safe disposition to the outpatient clinic while in the custody of a family member, partner, or close friend.

Alternatively, some people experience a troubling worsening of precipitants following a suicide attempt. Preexisting medical conditions and financial, occupational, and/or social woes may be exacerbated. Child custody determinations may be affected, assuming the patient understands the possibility of this adverse consequence. Violent methods may result in disfigurement and body image issues. Individuals from small, close-knit communities may experience stigmatization and unwanted notoriety because of their suicide attempt. Such negative consequences may render some patients more likely to make another attempt to die by suicide. It is crucial to consider how a suicide attempt may have changed the original stress that led to the attempt.

3. Which method was used?

Most fatal suicides in the US are by firearms, and many individuals who survive such attempts do so because of unfamiliarity with the weapon, gun malfunction, faulty aim, or alcohol use.5-7 Some survivors report intending to shoot themselves in the heart, but instead suffered shoulder injuries. Unfortunately, for a patient who survives self-inflicted gunshot wounds, the sequelae of chronic pain, multiple surgical procedures, disability, and disfigurement may serve as constant negative reminders of the event. Some individuals with suicidal intent eschew the idea of using firearms because they hope to avoid having a family member be the first to discover them. Witnessing the aftermath of a fatal suicide by gunshot can induce symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder in family members and/or partners.8

For a patient with self-inflicted gunshot wounds, always determine whether the weapon has been secured or if the patient still has access to it. Asking about weapon availability is essential during the evaluation of any patient with depression, major life crises, or other factors that may yield a desire to die; this is especially true for individuals with substance use disorders (SUDs). Whenever readily available to such individuals, weapons need to be safely removed.

Continue to: Other self-harm methods...

Other self-harm methods with a high degree of lethality include jumping from bridges or buildings, poisonings, self-immolation, cutting, and hangings. Individuals who choose these approaches generally do not intend to survive. Many of these methods also entail premeditation, as in the case of individuals who canvass bridges and note time when traffic is light so they are less likely to be interrupted. Between 1937 and 2012, there were >1,600 deaths by suicide from San Francisco’s Golden Gate Bridge.9 Patients who choose highly lethal methods are often irritated during the postattempt evaluation because their plans were not fatal. Usually, patients who choose such potentially lethal methods are hospitalized initially on medical and surgical floors, and receive most of their psychiatric care from consultation psychiatrists. Following discharge, these patients may be at high risk for subsequent suicide attempts.

In the US, the most common method of attempting suicide is by overdose.4 Lethality is determined by the agent or combination of substances ingested, the amount taken, the person’s health status, and the length of time before they are discovered. Many patients mistakenly assume that readily available agents such as acetaminophen and aspirin are less likely to be fatal than prescription medications. Evaluators may want to assess for suicidality in individuals with erratic, risk-taking behaviors, who are at especially high risk for death. Learning about the method the patient used can help the clinician determine the imminent risk of another suicide attempt. The more potentially fatal the patient’s method, the more serious their suicide intent, and the higher the risk they will make another suicide attempt, possibly using an even more lethal method.

4. What was the intent?

“What did you want to happen when you made this attempt?” Many patients will respond that they wanted to die, sleep, not wake up, or did not care what happened. Others say it was a gesture to evoke a certain response from another person. If this is the case, it is important to know whether the desired outcome was achieved. These so-called gestures often involve making sure the intended person is aware of the attempt, often by writing a letter, sending a text, or posting on social media. Such behaviors may be exhibited by patients with personality disorders. While such attempts often are impulsive, if the attempt fails to generate the anticipated effect, the patient may try to gain more attention by escalating their suicide actions.

Conversely, if a spouse or partner reconciles with the patient solely because of a suicide attempt, this may set a pattern for future self-harm events in which the patient hopes to achieve the same outcome. Nevertheless, it is better to err for safety because some of these patients will make another attempt, just to prove that they should have been taken more seriously. An exploration of such intent can help the evaluation because even supposed “gestures” can have dangerous consequences. Acts that do not result in the desired outcome should precipitate hospitalization rather than discharge.

5. What facilitated the patient’s rescue?

“Why is this patient still alive?” Determine if the patient did anything to save themself, such as calling an ambulance, inducing emesis, telling someone what they did, or coming to the hospital on their own. If yes, asking them what changed their mind may provide information about what exists in their lives to potentially prevent future attempts, or about wishes to stay alive. These issues can be used to guide outpatient therapy.

Continue to: How does the patient feel about having survived?

6. How does the patient feel about having survived?

When a patient is asked how they feel about having survived a suicide attempt, some will label their act “stupid” and profess embarrassment. Others exhibit future-oriented thought, which is a very good prognostic sign. More ominous is subsequent dysphoria or lamenting that “I could not even do this right.” Patients often express anger toward anyone who rescued them, especially those whose attempts were carefully planned or were discovered by accident. Some patients might also express ambivalence about having survived.

The patient’s response to this question may be shaped by their desire to avoid hospitalization, so beyond their verbal answers, be attentive to clinical cues that may suggest the patient is not being fully transparent. Anger or ambivalence about having survived, a lack of future-oriented thought, and a restricted affect despite verbalizing joy about still being alive are features that suggest psychiatric hospitalization may be warranted.

7. Has the patient made previous suicide attempts?

Compared to individuals with no previous suicide attempts, patients with a history of suicide attempts are 30 to 40 times more likely to die by suicide.2 Many patients who present after a suicide attempt have tried to kill themselves multiple times. Exploring the number of past attempts, how recent the attempts were, and what dispositions were made can be of benefit. Reviewing the potential lethality of past attempts (eg, was hospitalization required, was the patient placed in an intensive care unit, and/or was intubation needed) is recommended. If outpatient care was suggested or medication prescribed, was the patient adherent? Consider asking about passive suicidal behavior, such as not seeking care for medical issues, discontinuing life-saving medication, or engaging in reckless behavior. While such behaviors may not have been classified as a suicide attempt, it might indicate a feeling of indifference toward staying alive. A patient with a past attempt, especially if recent, merits consideration for inpatient care. Once again, referring previously nonadherent patients to outpatient treatment is less likely to be effective.

8. Does the patient have a support network?

Before discharging a patient who has made a suicide attempt, consider the quality of their support network. Gauging the response of the family and friends to the patient’s attempt can be beneficial. Indifference or resentment on the part of loved ones is a bad sign. Some patients have access to support networks they either did not know were available or chose not to utilize. In other instances, after realizing how depressed the patient has been, the family might provide a new safety net. Strong religious affiliations can also be valuable because devout spirituality can be a deterrent to suicide behaviors.10 For an individual whose attempt was motivated by loneliness or feeling unloved or underappreciated, a newly realized support network can be an additional protective deterrent.

9. Does the patient have a family history of suicide?

There may be a familial component to suicide. Knowing about any suicide history in the family contributes to future therapeutic planning. The clinician may want to explore the patient’s family suicide history in detail because such information can have substantial impact on the patient’s motivation for attempting suicide. The evaluator may want to determine if the anniversary of a family suicide is coming. Triggers for a suicide attempt could include the anniversary of a death, birthdays, family-oriented holidays, and similar events. It is productive to understand how the patient feels about family members who have died by suicide. Some will empathize with the deceased, commenting that they did the “right thing.” Others, upon realizing how their own attempt affected others, will be remorseful and determined not to inflict more pain on their family. Such patients may need to be reminded of the misery associated with their family being left without them. These understandings are helpful at setting a safe disposition. However, a history of death by suicide in the family should always be thoroughly evaluated, regardless of the patient’s attitude about that death.

Continue to: Was the attempt the result of depression?

10. Was the attempt the result of depression?

For a patient experiencing depressive symptoms, the prognosis is less positive; they are more likely to harbor serious intent, premeditation, hopelessness, and social isolation, and less likely to express future-oriented thought. They often exhibit a temporary “flight into health.” Such progress is often transitory and may not represent recovery. Because mood disorders may still be present despite a temporary improvement, inpatient and pharmacologic treatment may be needed. If a patient’s suicide attempt occurred as a result of severe depression, it is possible they will make another suicide attempt unless their depression is addressed in a safe and secure setting, such as inpatient hospitalization, or through close family observation while the patient is receiving intensive outpatient treatment.

11. Does the patient have a psychotic disorder?

Many patients with a psychotic illness die following their first attempt without ever having contact with a mental health professional.11 Features of psychosis might include malevolent auditory hallucinations that suggest self-destruction.11 Such “voices” can be intense and self-deprecating; many patients with this type of hallucination report having made a suicide attempt “just to make the voices stop.”

Symptoms of paranoia can make it less likely for individuals with psychosis to confide in family members, friends, or medical personnel. Religious elements are often of a delusional nature and can be dangerous. Psychosis is more difficult to hide than depression and the presence of psychoses concurrent with major depressive disorder (MDD) increases the probability of suicidality.11 Psychosis secondary to substance use may diminish inhibitions and heighten impulsivity, thereby exacerbating the likelihood of self-harm. Usually, the presence of psychotic features precipitating or following a suicide attempt leads to psychiatric hospitalization.

12. Is the patient in a high-risk demographic group?

When evaluating a patient who has attempted suicide, it helps to consider not just what they did, but who they are. Specifically, does the individual belong to a demographic group that traditionally has a high rate of suicide? For example, patients who are Native American or Alaska Natives warrant extra caution.2 Older White males, especially those who are divorced, widowed, retired, and/or have chronic health problems, are also at greater risk. Compared to the general population, individuals age >80 have a massively elevated chance for self-induced death.12 Some of the reasons include:

- medical comorbidities make surviving an attempt less likely

- access to large amounts of medications

- more irreversible issues, such as chronic pain, disability, or widowhood

- living alone, which may delay discovery.

Patients who are members of any of these demographic groups may deserve serious consideration for inpatient psychiatric admission, regardless of other factors.

Continue to: Were drugs or alcohol involved?

13. Were drugs or alcohol involved?

This factor is unique in that it is both a chronic risk factor (SUDs) and a warning sign for imminent suicide, as in the case of an individual who gets intoxicated to disinhibit their fear of death so they can attempt suicide. Alcohol use disorders are associated with depression and suicide. Overdoses by fentanyl and other opiates have become more frequent.13 In many cases, fatalities are unintentional because users overestimate their tolerance or ingest contaminated substances.14 Disinhibition by alcohol and/or other drugs is a risk factor for attempting suicide and can intensify the depth of MDD. Some patients will ingest substances before an attempt just to give them the courage to act; many think of suicide only when intoxicated. Toxicology screens are indicated as part of the evaluation after a suicide attempt.

Depressive and suicidal thoughts often occur in people “coming down” from cocaine or other stimulants. These circumstances require determining whether to refer the patient for treatment for an SUD or psychiatric hospitalization.

In summary, getting intoxicated solely to diminish anxiety about suicide is a dangerous feature, whereas attempting suicide due to intoxication is less concerning. The latter patient may not consider suicide unless they become intoxicated again. When available, dual diagnosis treatment facilities can be an appropriate referral for such patients. Emergency department holding beds can allow these individuals to detoxify prior to the evaluation.

14. Does the patient have future-oriented thoughts?

When evaluating a patient who has attempted suicide, the presence of future planning and anticipation can be reassuring, but these features should be carefully assessed.14-16

After-the-fact comments may be more reliable when a patient offers them spontaneously, as opposed to in response to direct questioning.

- the specificity of the future plans

- corroboration from the family and others about the patient’s previous investment in the upcoming event

- whether the patient mentions such plans spontaneously or only in response to direct questioning

- the patient’s emotional expression or affect when discussing their future

- whether such plans are reasonable, grandiose, and/or unrealistic.

Bottom Line

When assessing a patient after a suicide attempt, both the patient’s presentation and history and the clinician’s instincts are important. Careful consideration of the method, stated intent, premeditation vs impulsivity, feelings about having survived, presence of psychiatric illness, high-risk demographic, postattempt demeanor and affect, quality of support, presence of self-rescue behaviors, future-oriented thoughts, and other factors can help in making the appropriate disposition.

Related Resources

- Kim H, Kim Y, Shin MH, et al. Early psychiatric referral after attempted suicide helps prevent suicide reattempts: a longitudinal national cohort study in South Korea. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13:607892. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2022.607892

- Michaud L, Berva S, Ostertag L, et al. When to discharge and when to voluntary or compulsory hospitalize? Factors associated with treatment decision after self-harm. Psychiatry Res. 2022;317:114810. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2022.114810

1. Ten Leading Causes of Death, United States 2020. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention WISQARS. Accessed March 4, 2022. https://wisqars.cdc.gov/data/lcd/home

2. Norris D, Clark MS. Evaluation and treatment of suicidal patients. Am Fam Physician. 2012;15;85(6):602-605.

3. Gliatto MF, Rai AK. Evaluation and treatment patients with suicidal ideation. Am Fam Phys. 1999;59(6):1500-1506.

4. Dazzi T, Gribble R, Wessely S, et al. Does asking about suicide and related behaviors induce suicidal ideation? What is the evidence? Psychol Med. 2014;44(16):3361-3363.

5. Lewiecki EM, Miller SA. Suicide, guns and public policy. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(1):27-31.

6. Frierson RL. Women who shoot themselves. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1989;40(8):841-843.

7. Frierson RL, Lippmann SB. Psychiatric consultation for patients with self-inflicted gunshot wounds. Psychosomatics. 1990;31(1):67-74.

8. Mitchell AM, Terhorst L. PTSD symptoms in survivors bereaved by the suicide of a significant other. J Am Psychiatr Nurses Assoc. 2017;23(1):61-65.

9. Bateson J. The Golden Gate Bridge’s fatal flaw. Los Angeles Times. May 25, 2012. Accessed March 2, 2022. https://www.latimes.com/opinion/la-xpm-2012-may-25-la-oe-adv-bateson-golden-gate-20120525-story.html

10. Dervic K, Oquendoma MA, Grunebaum MF, et al. Religious affiliation and suicide attempt. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(12):2303-2308.

11. Nordentoft H, Madsen T, Fedyszyn IF. Suicidal behavior and mortality in first episode psychosis. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2015;203(5):387-392.

12. Frierson R, Lippmann S. Suicide attempts by the old and the very old. Arch Intern Med. 1991;151(1):141-144.

13. Braden JB, Edlund MJ, Sullivan MD. Suicide deaths with opiate poisonings in the United States: 1999-2014. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(3):421-426.

14. Morin KA, Acharya S, Eibl JK, et al: Evidence of increased fentanyl use during the COVID-19 pandemic among opioid agonist treated patients in Ontario, Canada. Int J Drug Policy. 2021;90:103088.

15. Shobassy A, Abu-Mohammad AS. Assessing imminent suicide risk: what about future planning? Current Psychiatry. 2022;21(2):12-17.

16. MacLeod AK, Pankhania B, Lee M, et al. Parasuicide, depression and the anticipation of positive and negative future experiences. Psychol Med. 1997;27(4):973-977.

17. Macleod AK, Tata P, Tyrer P, et al. Hopelessness and positive and negative future thinking in parasuicide. Br J Clin Psychol. 2010;44(Pt 4):495-504.

In 2021, suicide was the 11th leading cause of death in the United States.1 Suicide resulted in 49,000 US deaths during 2021; it was the second most common cause of death in individuals age 10 to 34, and the fifth leading cause among children.1,2 Women are 3 to 4 times more likely than men to attempt suicide, but men are 4 times more likely to die by suicide.2

The evaluation of patients with suicidal ideation who have not made an attempt generally involves assessing 4 factors: the specific plan, access to lethal means, any recent social stressors, and the presence of a psychiatric disorder.3 The clinician should also assess which potential deterrents, such as religious beliefs or dependent children, might be present.

Mental health clinicians are often called upon to evaluate a patient after a suicide attempt to assess intent for continued self-harm and to determine appropriate disposition. Such an evaluation must consider multiple factors, including the method used, premeditation, consequences of the attempt, the presence of severe depression and/or psychosis, and the role of substance use. Assessment after a suicide attempt differs from the examination of individuals who harbor suicidal thoughts but have not made an attempt; the latter group may be more likely to respond to interventions such as intensive outpatient care, mobilization of family support, and religious proscriptions against suicide. However, for patients who make an attempt to end their life, whatever potential safeguards or deterrents to suicide that were in place obviously did not prevent the self-harm act. The consequences of the attempt, such as disabling injuries or medical complications, and possible involuntary commitment, need to be considered. Assessment of the patient’s feelings about having survived the attempt is important because the psychological impact of the attempt on family members may serve to intensify the patient’s depression and make a subsequent attempt more likely.

Many individuals who think of suicide have communicated self-harm thoughts or intentions, but such comments are often minimized or ignored. There is a common but erroneous belief that if patients are encouraged to discuss thoughts of self-harm, they will be more likely to act upon them. Because the opposite is true,4 clinicians should ask vulnerable patients about suicidal ideation or intent. Importantly, noncompliance with life-saving medical care, risk-taking behaviors, and substance use may also signal a desire for self-harm. Passive thoughts of death, typified by comments such as “I don’t care whether I wake up or not,” should also be elicited. Many patients who think of suicide speak of being in a “bad place” where reason and logic give way to an intense desire to end their misery.

The evaluation of a patient who has attempted suicide is an important component of providing psychiatric care. This article reflects our 45 years of evaluating such patients. As such, it reflects our clinical experience and is not evidence-based. We offer a checklist of 14 questions that we have found helpful when determining if it would be best for a patient to receive inpatient psychiatric hospitalization or a discharge referral for outpatient care (Table). Questions 1 through 6 are specific for patients who have made a suicide attempt, while questions 7 through 14 are helpful for assessing global risk factors for suicide.

1. Was the attempt premeditated?

Determining premeditation vs impulsivity is an essential element of the assessment following a suicide attempt. Many such acts may occur without forethought in response to an unexpected stressor, such as an altercation between partners or family conflicts. Impulsive attempts can occur when an individual is involved in a distressing event and/or while intoxicated. Conversely, premeditation involves forethought and planning, which may increase the risk of suicide in the near future.

Examples of premeditated behavior include:

- Contemplating the attempt days or weeks beforehand

- Researching the effects of a medication or combination of medications in terms of potential lethality

- Engaging in behavior that would decrease the likelihood of their body being discovered after the attempt

- Obtaining weapons and/or stockpiling pills

- Canvassing potential sites such as bridges or tall buildings

- Engaging in a suicide attempt “practice run”

- Leaving a suicide note or message on social media

- Making funeral arrangements, such as choosing burial clothing

- Writing a will and arranging for the custody of dependent children

- Purchasing life insurance that does not deny payment of benefits in cases of death by suicide.

Continue to: Patients with a premeditated...

Patients with a premeditated suicide attempt generally do not expect to survive and are often surprised or upset that the act was not fatal. The presence of indicators that the attempt was premeditated should direct the disposition more toward hospitalization than discharge. In assessing the impact of premeditation, it is important to gauge not just the examples listed above, but also the patient’s perception of these issues (such as potential loss of child custody). Consider how much the patient is emotionally affected by such thinking.

2. What were the consequences of the attempt?

Assessing the reason for the attempt (if any) and determining whether the inciting circumstance has changed due to the suicide attempt are an important part of the evaluation. A suicide attempt may result in reconciliation with and/or renewed support from family members or partners, who might not have been aware of the patient’s emotional distress. Such unexpected support often results in the patient exhibiting improved mood and affect, and possibly temporary resolution of suicidal thoughts. This “flight into health” may be short-lived, but it also may be enough to engage the patient in a therapeutic alliance. That may permit a discharge with safe disposition to the outpatient clinic while in the custody of a family member, partner, or close friend.

Alternatively, some people experience a troubling worsening of precipitants following a suicide attempt. Preexisting medical conditions and financial, occupational, and/or social woes may be exacerbated. Child custody determinations may be affected, assuming the patient understands the possibility of this adverse consequence. Violent methods may result in disfigurement and body image issues. Individuals from small, close-knit communities may experience stigmatization and unwanted notoriety because of their suicide attempt. Such negative consequences may render some patients more likely to make another attempt to die by suicide. It is crucial to consider how a suicide attempt may have changed the original stress that led to the attempt.

3. Which method was used?

Most fatal suicides in the US are by firearms, and many individuals who survive such attempts do so because of unfamiliarity with the weapon, gun malfunction, faulty aim, or alcohol use.5-7 Some survivors report intending to shoot themselves in the heart, but instead suffered shoulder injuries. Unfortunately, for a patient who survives self-inflicted gunshot wounds, the sequelae of chronic pain, multiple surgical procedures, disability, and disfigurement may serve as constant negative reminders of the event. Some individuals with suicidal intent eschew the idea of using firearms because they hope to avoid having a family member be the first to discover them. Witnessing the aftermath of a fatal suicide by gunshot can induce symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder in family members and/or partners.8