User login

Official news magazine of the Society of Hospital Medicine

Copyright by Society of Hospital Medicine or related companies. All rights reserved. ISSN 1553-085X

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-hospitalist')]

Many Americans still concerned about access to health care

according to the results of a survey conducted Aug. 7-26.

Nationally, 23.8% of respondents said that they were very concerned about being able to receive care during the pandemic, and another 27.4% said that they were somewhat concerned. Just under a quarter, 24.3%, said they were not very concerned, while 20.4% were not at all concerned, the COVID-19 Consortium for Understanding the Public’s Policy Preferences Across States reported after surveying 21,196 adults.

At the state level, Mississippi had the most adults (35.5%) who were very concerned about their access to care, followed by Texas (32.7%) and Nevada (32.4%). The residents of Montana were least likely (10.5%) to be very concerned, with Vermont next at 11.6% and Wyoming slightly higher at 13.8%. Montana also had the highest proportion of adults, 30.2%, who were not at all concerned, the consortium’s data show.

When asked about getting the coronavirus themselves, 67.8% of U.S. adults came down on the concerned side (33.3% somewhat and 34.5% very concerned) versus 30.8% who were not concerned (18.6% were not very concerned; 12.2% were not concerned at all.). Respondents’ concern was higher for their family members’ risk of getting coronavirus: 30.2% were somewhat concerned and 47.6% were very concerned, the consortium said.

Among many other topics, respondents were asked how closely they had followed recommended health guidelines in the last week, with the two extremes shown here:

- Avoiding contact with other people: 49.3% very closely, 4.8% not at all closely.

- Frequently washing hands: 74.7% very, 1.6% not at all.

- Disinfecting often-touched surfaces: 54.4% very, 4.3% not at all.

- Wearing a face mask in public: 75.7% very, 3.5% not at all.

The consortium is a joint project of the Network Science Institute of Northeastern University; the Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics, and Public Policy of Harvard University; Harvard Medical School; the School of Communication and Information at Rutgers University; and the department of political science at Northwestern University. The project is supported by grants from the National Science Foundation.

according to the results of a survey conducted Aug. 7-26.

Nationally, 23.8% of respondents said that they were very concerned about being able to receive care during the pandemic, and another 27.4% said that they were somewhat concerned. Just under a quarter, 24.3%, said they were not very concerned, while 20.4% were not at all concerned, the COVID-19 Consortium for Understanding the Public’s Policy Preferences Across States reported after surveying 21,196 adults.

At the state level, Mississippi had the most adults (35.5%) who were very concerned about their access to care, followed by Texas (32.7%) and Nevada (32.4%). The residents of Montana were least likely (10.5%) to be very concerned, with Vermont next at 11.6% and Wyoming slightly higher at 13.8%. Montana also had the highest proportion of adults, 30.2%, who were not at all concerned, the consortium’s data show.

When asked about getting the coronavirus themselves, 67.8% of U.S. adults came down on the concerned side (33.3% somewhat and 34.5% very concerned) versus 30.8% who were not concerned (18.6% were not very concerned; 12.2% were not concerned at all.). Respondents’ concern was higher for their family members’ risk of getting coronavirus: 30.2% were somewhat concerned and 47.6% were very concerned, the consortium said.

Among many other topics, respondents were asked how closely they had followed recommended health guidelines in the last week, with the two extremes shown here:

- Avoiding contact with other people: 49.3% very closely, 4.8% not at all closely.

- Frequently washing hands: 74.7% very, 1.6% not at all.

- Disinfecting often-touched surfaces: 54.4% very, 4.3% not at all.

- Wearing a face mask in public: 75.7% very, 3.5% not at all.

The consortium is a joint project of the Network Science Institute of Northeastern University; the Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics, and Public Policy of Harvard University; Harvard Medical School; the School of Communication and Information at Rutgers University; and the department of political science at Northwestern University. The project is supported by grants from the National Science Foundation.

according to the results of a survey conducted Aug. 7-26.

Nationally, 23.8% of respondents said that they were very concerned about being able to receive care during the pandemic, and another 27.4% said that they were somewhat concerned. Just under a quarter, 24.3%, said they were not very concerned, while 20.4% were not at all concerned, the COVID-19 Consortium for Understanding the Public’s Policy Preferences Across States reported after surveying 21,196 adults.

At the state level, Mississippi had the most adults (35.5%) who were very concerned about their access to care, followed by Texas (32.7%) and Nevada (32.4%). The residents of Montana were least likely (10.5%) to be very concerned, with Vermont next at 11.6% and Wyoming slightly higher at 13.8%. Montana also had the highest proportion of adults, 30.2%, who were not at all concerned, the consortium’s data show.

When asked about getting the coronavirus themselves, 67.8% of U.S. adults came down on the concerned side (33.3% somewhat and 34.5% very concerned) versus 30.8% who were not concerned (18.6% were not very concerned; 12.2% were not concerned at all.). Respondents’ concern was higher for their family members’ risk of getting coronavirus: 30.2% were somewhat concerned and 47.6% were very concerned, the consortium said.

Among many other topics, respondents were asked how closely they had followed recommended health guidelines in the last week, with the two extremes shown here:

- Avoiding contact with other people: 49.3% very closely, 4.8% not at all closely.

- Frequently washing hands: 74.7% very, 1.6% not at all.

- Disinfecting often-touched surfaces: 54.4% very, 4.3% not at all.

- Wearing a face mask in public: 75.7% very, 3.5% not at all.

The consortium is a joint project of the Network Science Institute of Northeastern University; the Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics, and Public Policy of Harvard University; Harvard Medical School; the School of Communication and Information at Rutgers University; and the department of political science at Northwestern University. The project is supported by grants from the National Science Foundation.

2020-2021 respiratory viral season: Onset, presentations, and testing likely to differ in pandemic

Respiratory virus seasons usually follow a fairly well-known pattern. Enterovirus 68 (EV-D68) is a summer-to-early fall virus with biennial peak years. Rhinovirus (HRv) and adenovirus (Adv) occur nearly year-round but may have small upticks in the first month or so that children return to school. Early in the school year, upper respiratory infections from both HRv and Adv and viral sore throats from Adv are common, with conjunctivitis from Adv outbreaks in some years. October to November is human parainfluenza (HPiV) 1 and 2 season, often presenting as croup. Human metapneumovirus infections span October through April. In late November to December, influenza begins, usually with an A type, later transitioning to a B type in February through April. Also in December, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) starts, characteristically with bronchiolitis presentations, peaking in February to March and tapering off in May. In late March to April, HPiV 3 also appears for 4-6 weeks.

Will 2020-2021 be different?

Summer was remarkably free of expected enterovirus activity, suggesting that the seasonal parade may differ this year. Remember that the 2019-2020 respiratory season suddenly and nearly completely stopped in March because of social distancing and lockdowns needed to address the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic.

The mild influenza season in the southern hemisphere suggests that our influenza season also could be mild. But perhaps not – most southern hemisphere countries that are surveyed for influenza activities had the most intense SARS-CoV-2 mitigations, making the observed mildness potentially related more to social mitigation than less virulent influenza strains. If so, southern hemisphere influenza data may not apply to the United States, where social distancing and masks are ignored or used inconsistently by almost half the population.

Further, the stop-and-go pattern of in-person school/college attendance adds to uncertainties for the usual orderly virus-specific seasonality. The result may be multiple stop-and-go “pop-up” or “mini” outbreaks for any given virus potentially reflected as exaggerated local or regional differences in circulation of various viruses. The erratic seasonality also would increase coinfections, which could present with more severe or different symptoms.

SARS-CoV-2’s potential interaction

Will the relatively mild presentations for most children with SARS-CoV-2 hold up in the setting of coinfections or sequential respiratory viral infections? Could SARS-CoV-2 cause worse/more prolonged symptoms or more sequelae if paired simultaneously or in tandem with a traditional respiratory virus? To date, data on the frequency and severity of SARS-CoV-2 coinfections are conflicting and sparse, but it appears that non-SARS-CoV-2 viruses can be involved in 15%-50% pediatric acute respiratory infections.1,2

However, it may not be important to know about coinfecting viruses other than influenza (can be treated) or SARS-CoV-2 (needs quarantine and contact tracing), unless symptoms are atypical or more severe than usual. For example, a young child with bronchiolitis is most likely infected with RSV, but HPiV, influenza, metapneumovirus, HRv, and even SARS-CoV-2 can cause bronchiolitis. Even so, testing outpatients for RSV or non-influenza is not routine or even clinically helpful. Supportive treatment and restriction from daycare attendance are sufficient management for outpatient ARIs whether presenting as bronchiolitis or not.

Considerations for SARS-CoV-2 testing: Outpatient bronchiolitis

If a child presents with classic bronchiolitis but has above moderate to severe symptoms, is SARS-CoV-2 a consideration? Perhaps, if SARS-CoV-2 acts similarly to non-SARS-CoV-2s.

A recent report from the 30th Multicenter Airway Research Collaboration (MARC-30) surveillance study (2007-2014) of children hospitalized with clinical bronchiolitis evaluated respiratory viruses, including RSV and the four common non-SARS coronaviruses using molecular testing.3 Among 1,880 subjects, a CoV (alpha CoV: NL63 or 229E, or beta CoV: KKU1 or OC43) was detected in 12%. Yet most had only RSV (n = 1,661); 32 had only CoV (n = 32). But note that 219 had both.

Bronchiolitis subjects with CoV were older – median 3.7 (1.4-5.8) vs. 2.8 (1.9-7.2) years – and more likely male than were RSV subjects (68% vs. 58%). OC43 was most frequent followed by equal numbers of HKU1 and NL63, while 229E was the least frequent. Medical utilization and severity did not differ among the CoVs, or between RSV+CoV vs. RSV alone, unless one considered CoV viral load as a variable. ICU use increased when the polymerase chain reaction cycle threshold result indicated a high CoV viral load.

These data suggest CoVs are not infrequent coinfectors with RSV in bronchiolitis – and that SARS-CoV-2 is the same. Therefore, a bronchiolitis presentation doesn’t necessarily take us off the hook for the need to consider SARS-CoV-2 testing, particularly in the somewhat older bronchiolitis patient with more than mild symptoms.

Considerations for SARS-CoV-2 testing: Outpatient influenza-like illness

In 2020-2021, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends considering empiric antiviral treatment for ILIs (fever plus either cough or sore throat) based upon our clinical judgement, even in non-high-risk children.4

While pediatric COVID-19 illnesses are predominantly asymptomatic or mild, a febrile ARI is also a SARS-CoV-2 compatible presentation. So, if all we use is our clinical judgment, how do we know if the febrile ARI is due to influenza or SARS-CoV-2 or both? At least one study used a highly sensitive and specific molecular influenza test to show that the accuracy of clinically diagnosing influenza in children is not much better than flipping a coin and would lead to potential antiviral overuse.5

So, it seems ideal to test for influenza when possible. Point-of-care (POC) tests are frequently used for outpatients. Eight POC Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA)–waived kits, some also detecting RSV, are available but most have modest sensitivity (60%-80%) compared with lab-based molecular tests.6 That said, if supplies and kits for one of the POC tests are available to us during these SARS-CoV-2 stressed times (back orders seem more common this year), a positive influenza test in the first 48 hours of symptoms confirms the option to prescribe an antiviral. Yet how will we have confidence that the febrile ARI is not also partly due to SARS-CoV-2? Currently febrile ARIs usually are considered SARS-CoV-2 and the children are sent for SARS-CoV-2 testing. During influenza season, it seems we will need to continue to send febrile outpatients for SARS-CoV-2 testing, even if POC influenza positive, via whatever mechanisms are available as time goes on.

We expect more rapid pediatric testing modalities for SARS-CoV-2 (maybe even saliva tests) to become available over the next months. Indeed, rapid antigen tests and rapid molecular tests are being evaluated in adults and seem destined for CLIA waivers as POC tests, and even home testing kits. Pediatric approvals hopefully also will occur. So, the pathways for SARS-CoV-2 testing available now will likely change over this winter. But be aware that supplies/kits will be prioritized to locations within high need areas and bulk purchase contracts. So POC kits may remain scarce for practices, meaning a reference laboratory still could be the way to go for SARS-CoV-2 for at least the rest of 2020. Reference labs are becoming creative as well; one combined detection of influenza A, influenza B, RSV, and SARS-CoV-2 into one test, and hopes to get approval for swab collection that can be done by families at home and mailed in.

Summary

Expect variations on the traditional parade of seasonal respiratory viruses, with increased numbers of coinfections. Choosing the outpatient who needs influenza testing is the same as in past years, although we have CDC permissive recommendations to prescribe antivirals for any outpatient ILI within the first 48 hours of symptoms. Still, POC testing for influenza remains potentially valuable in the ILI patient. The choice of whether and how to test for SARS-CoV-2 given its potential to be a primary or coinfecting agent in presentations linked more closely to a traditional virus (e.g. RSV bronchiolitis) will be a test of our clinical judgement until more data and easier testing are available. Further complicating coinfection recognition is the fact that many sick visits occur by telehealth and much testing is done at drive-through SARS-CoV-2 testing facilities with no clinician exam. Unless we are liberal in SARS-CoV-2 testing, detecting SARS-CoV-2 coinfections is easier said than done given its usually mild presentation being overshadowed by any coinfecting virus.

But understanding who has SARS-CoV-2, even as a coinfection, still is essential in controlling the pandemic. We will need to be vigilant for evolving approaches to SARS-CoV-2 testing in the context of symptomatic ARI presentations, knowing this will likely remain a moving target for the foreseeable future.

Dr. Harrison is professor of pediatrics and pediatric infectious diseases at Children’s Mercy Hospital-Kansas City, Mo. Children’s Mercy Hospital receives grant funding to study two candidate RSV vaccines. The hospital also receives CDC funding under the New Vaccine Surveillance Network for multicenter surveillance of acute respiratory infections, including influenza, RSV, and parainfluenza virus. Email Dr. Harrison at [email protected].

References

1. Pediatrics. 2020;146(1):e20200961.

2. JAMA. 2020 May 26;323(20):2085-6.

3. Pediatrics. 2020. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-1267.

4. www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/antivirals/summary-clinicians.htm.

5. J. Pediatr. 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.08.007.

6. www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/diagnosis/table-nucleic-acid-detection.html.

Respiratory virus seasons usually follow a fairly well-known pattern. Enterovirus 68 (EV-D68) is a summer-to-early fall virus with biennial peak years. Rhinovirus (HRv) and adenovirus (Adv) occur nearly year-round but may have small upticks in the first month or so that children return to school. Early in the school year, upper respiratory infections from both HRv and Adv and viral sore throats from Adv are common, with conjunctivitis from Adv outbreaks in some years. October to November is human parainfluenza (HPiV) 1 and 2 season, often presenting as croup. Human metapneumovirus infections span October through April. In late November to December, influenza begins, usually with an A type, later transitioning to a B type in February through April. Also in December, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) starts, characteristically with bronchiolitis presentations, peaking in February to March and tapering off in May. In late March to April, HPiV 3 also appears for 4-6 weeks.

Will 2020-2021 be different?

Summer was remarkably free of expected enterovirus activity, suggesting that the seasonal parade may differ this year. Remember that the 2019-2020 respiratory season suddenly and nearly completely stopped in March because of social distancing and lockdowns needed to address the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic.

The mild influenza season in the southern hemisphere suggests that our influenza season also could be mild. But perhaps not – most southern hemisphere countries that are surveyed for influenza activities had the most intense SARS-CoV-2 mitigations, making the observed mildness potentially related more to social mitigation than less virulent influenza strains. If so, southern hemisphere influenza data may not apply to the United States, where social distancing and masks are ignored or used inconsistently by almost half the population.

Further, the stop-and-go pattern of in-person school/college attendance adds to uncertainties for the usual orderly virus-specific seasonality. The result may be multiple stop-and-go “pop-up” or “mini” outbreaks for any given virus potentially reflected as exaggerated local or regional differences in circulation of various viruses. The erratic seasonality also would increase coinfections, which could present with more severe or different symptoms.

SARS-CoV-2’s potential interaction

Will the relatively mild presentations for most children with SARS-CoV-2 hold up in the setting of coinfections or sequential respiratory viral infections? Could SARS-CoV-2 cause worse/more prolonged symptoms or more sequelae if paired simultaneously or in tandem with a traditional respiratory virus? To date, data on the frequency and severity of SARS-CoV-2 coinfections are conflicting and sparse, but it appears that non-SARS-CoV-2 viruses can be involved in 15%-50% pediatric acute respiratory infections.1,2

However, it may not be important to know about coinfecting viruses other than influenza (can be treated) or SARS-CoV-2 (needs quarantine and contact tracing), unless symptoms are atypical or more severe than usual. For example, a young child with bronchiolitis is most likely infected with RSV, but HPiV, influenza, metapneumovirus, HRv, and even SARS-CoV-2 can cause bronchiolitis. Even so, testing outpatients for RSV or non-influenza is not routine or even clinically helpful. Supportive treatment and restriction from daycare attendance are sufficient management for outpatient ARIs whether presenting as bronchiolitis or not.

Considerations for SARS-CoV-2 testing: Outpatient bronchiolitis

If a child presents with classic bronchiolitis but has above moderate to severe symptoms, is SARS-CoV-2 a consideration? Perhaps, if SARS-CoV-2 acts similarly to non-SARS-CoV-2s.

A recent report from the 30th Multicenter Airway Research Collaboration (MARC-30) surveillance study (2007-2014) of children hospitalized with clinical bronchiolitis evaluated respiratory viruses, including RSV and the four common non-SARS coronaviruses using molecular testing.3 Among 1,880 subjects, a CoV (alpha CoV: NL63 or 229E, or beta CoV: KKU1 or OC43) was detected in 12%. Yet most had only RSV (n = 1,661); 32 had only CoV (n = 32). But note that 219 had both.

Bronchiolitis subjects with CoV were older – median 3.7 (1.4-5.8) vs. 2.8 (1.9-7.2) years – and more likely male than were RSV subjects (68% vs. 58%). OC43 was most frequent followed by equal numbers of HKU1 and NL63, while 229E was the least frequent. Medical utilization and severity did not differ among the CoVs, or between RSV+CoV vs. RSV alone, unless one considered CoV viral load as a variable. ICU use increased when the polymerase chain reaction cycle threshold result indicated a high CoV viral load.

These data suggest CoVs are not infrequent coinfectors with RSV in bronchiolitis – and that SARS-CoV-2 is the same. Therefore, a bronchiolitis presentation doesn’t necessarily take us off the hook for the need to consider SARS-CoV-2 testing, particularly in the somewhat older bronchiolitis patient with more than mild symptoms.

Considerations for SARS-CoV-2 testing: Outpatient influenza-like illness

In 2020-2021, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends considering empiric antiviral treatment for ILIs (fever plus either cough or sore throat) based upon our clinical judgement, even in non-high-risk children.4

While pediatric COVID-19 illnesses are predominantly asymptomatic or mild, a febrile ARI is also a SARS-CoV-2 compatible presentation. So, if all we use is our clinical judgment, how do we know if the febrile ARI is due to influenza or SARS-CoV-2 or both? At least one study used a highly sensitive and specific molecular influenza test to show that the accuracy of clinically diagnosing influenza in children is not much better than flipping a coin and would lead to potential antiviral overuse.5

So, it seems ideal to test for influenza when possible. Point-of-care (POC) tests are frequently used for outpatients. Eight POC Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA)–waived kits, some also detecting RSV, are available but most have modest sensitivity (60%-80%) compared with lab-based molecular tests.6 That said, if supplies and kits for one of the POC tests are available to us during these SARS-CoV-2 stressed times (back orders seem more common this year), a positive influenza test in the first 48 hours of symptoms confirms the option to prescribe an antiviral. Yet how will we have confidence that the febrile ARI is not also partly due to SARS-CoV-2? Currently febrile ARIs usually are considered SARS-CoV-2 and the children are sent for SARS-CoV-2 testing. During influenza season, it seems we will need to continue to send febrile outpatients for SARS-CoV-2 testing, even if POC influenza positive, via whatever mechanisms are available as time goes on.

We expect more rapid pediatric testing modalities for SARS-CoV-2 (maybe even saliva tests) to become available over the next months. Indeed, rapid antigen tests and rapid molecular tests are being evaluated in adults and seem destined for CLIA waivers as POC tests, and even home testing kits. Pediatric approvals hopefully also will occur. So, the pathways for SARS-CoV-2 testing available now will likely change over this winter. But be aware that supplies/kits will be prioritized to locations within high need areas and bulk purchase contracts. So POC kits may remain scarce for practices, meaning a reference laboratory still could be the way to go for SARS-CoV-2 for at least the rest of 2020. Reference labs are becoming creative as well; one combined detection of influenza A, influenza B, RSV, and SARS-CoV-2 into one test, and hopes to get approval for swab collection that can be done by families at home and mailed in.

Summary

Expect variations on the traditional parade of seasonal respiratory viruses, with increased numbers of coinfections. Choosing the outpatient who needs influenza testing is the same as in past years, although we have CDC permissive recommendations to prescribe antivirals for any outpatient ILI within the first 48 hours of symptoms. Still, POC testing for influenza remains potentially valuable in the ILI patient. The choice of whether and how to test for SARS-CoV-2 given its potential to be a primary or coinfecting agent in presentations linked more closely to a traditional virus (e.g. RSV bronchiolitis) will be a test of our clinical judgement until more data and easier testing are available. Further complicating coinfection recognition is the fact that many sick visits occur by telehealth and much testing is done at drive-through SARS-CoV-2 testing facilities with no clinician exam. Unless we are liberal in SARS-CoV-2 testing, detecting SARS-CoV-2 coinfections is easier said than done given its usually mild presentation being overshadowed by any coinfecting virus.

But understanding who has SARS-CoV-2, even as a coinfection, still is essential in controlling the pandemic. We will need to be vigilant for evolving approaches to SARS-CoV-2 testing in the context of symptomatic ARI presentations, knowing this will likely remain a moving target for the foreseeable future.

Dr. Harrison is professor of pediatrics and pediatric infectious diseases at Children’s Mercy Hospital-Kansas City, Mo. Children’s Mercy Hospital receives grant funding to study two candidate RSV vaccines. The hospital also receives CDC funding under the New Vaccine Surveillance Network for multicenter surveillance of acute respiratory infections, including influenza, RSV, and parainfluenza virus. Email Dr. Harrison at [email protected].

References

1. Pediatrics. 2020;146(1):e20200961.

2. JAMA. 2020 May 26;323(20):2085-6.

3. Pediatrics. 2020. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-1267.

4. www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/antivirals/summary-clinicians.htm.

5. J. Pediatr. 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.08.007.

6. www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/diagnosis/table-nucleic-acid-detection.html.

Respiratory virus seasons usually follow a fairly well-known pattern. Enterovirus 68 (EV-D68) is a summer-to-early fall virus with biennial peak years. Rhinovirus (HRv) and adenovirus (Adv) occur nearly year-round but may have small upticks in the first month or so that children return to school. Early in the school year, upper respiratory infections from both HRv and Adv and viral sore throats from Adv are common, with conjunctivitis from Adv outbreaks in some years. October to November is human parainfluenza (HPiV) 1 and 2 season, often presenting as croup. Human metapneumovirus infections span October through April. In late November to December, influenza begins, usually with an A type, later transitioning to a B type in February through April. Also in December, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) starts, characteristically with bronchiolitis presentations, peaking in February to March and tapering off in May. In late March to April, HPiV 3 also appears for 4-6 weeks.

Will 2020-2021 be different?

Summer was remarkably free of expected enterovirus activity, suggesting that the seasonal parade may differ this year. Remember that the 2019-2020 respiratory season suddenly and nearly completely stopped in March because of social distancing and lockdowns needed to address the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic.

The mild influenza season in the southern hemisphere suggests that our influenza season also could be mild. But perhaps not – most southern hemisphere countries that are surveyed for influenza activities had the most intense SARS-CoV-2 mitigations, making the observed mildness potentially related more to social mitigation than less virulent influenza strains. If so, southern hemisphere influenza data may not apply to the United States, where social distancing and masks are ignored or used inconsistently by almost half the population.

Further, the stop-and-go pattern of in-person school/college attendance adds to uncertainties for the usual orderly virus-specific seasonality. The result may be multiple stop-and-go “pop-up” or “mini” outbreaks for any given virus potentially reflected as exaggerated local or regional differences in circulation of various viruses. The erratic seasonality also would increase coinfections, which could present with more severe or different symptoms.

SARS-CoV-2’s potential interaction

Will the relatively mild presentations for most children with SARS-CoV-2 hold up in the setting of coinfections or sequential respiratory viral infections? Could SARS-CoV-2 cause worse/more prolonged symptoms or more sequelae if paired simultaneously or in tandem with a traditional respiratory virus? To date, data on the frequency and severity of SARS-CoV-2 coinfections are conflicting and sparse, but it appears that non-SARS-CoV-2 viruses can be involved in 15%-50% pediatric acute respiratory infections.1,2

However, it may not be important to know about coinfecting viruses other than influenza (can be treated) or SARS-CoV-2 (needs quarantine and contact tracing), unless symptoms are atypical or more severe than usual. For example, a young child with bronchiolitis is most likely infected with RSV, but HPiV, influenza, metapneumovirus, HRv, and even SARS-CoV-2 can cause bronchiolitis. Even so, testing outpatients for RSV or non-influenza is not routine or even clinically helpful. Supportive treatment and restriction from daycare attendance are sufficient management for outpatient ARIs whether presenting as bronchiolitis or not.

Considerations for SARS-CoV-2 testing: Outpatient bronchiolitis

If a child presents with classic bronchiolitis but has above moderate to severe symptoms, is SARS-CoV-2 a consideration? Perhaps, if SARS-CoV-2 acts similarly to non-SARS-CoV-2s.

A recent report from the 30th Multicenter Airway Research Collaboration (MARC-30) surveillance study (2007-2014) of children hospitalized with clinical bronchiolitis evaluated respiratory viruses, including RSV and the four common non-SARS coronaviruses using molecular testing.3 Among 1,880 subjects, a CoV (alpha CoV: NL63 or 229E, or beta CoV: KKU1 or OC43) was detected in 12%. Yet most had only RSV (n = 1,661); 32 had only CoV (n = 32). But note that 219 had both.

Bronchiolitis subjects with CoV were older – median 3.7 (1.4-5.8) vs. 2.8 (1.9-7.2) years – and more likely male than were RSV subjects (68% vs. 58%). OC43 was most frequent followed by equal numbers of HKU1 and NL63, while 229E was the least frequent. Medical utilization and severity did not differ among the CoVs, or between RSV+CoV vs. RSV alone, unless one considered CoV viral load as a variable. ICU use increased when the polymerase chain reaction cycle threshold result indicated a high CoV viral load.

These data suggest CoVs are not infrequent coinfectors with RSV in bronchiolitis – and that SARS-CoV-2 is the same. Therefore, a bronchiolitis presentation doesn’t necessarily take us off the hook for the need to consider SARS-CoV-2 testing, particularly in the somewhat older bronchiolitis patient with more than mild symptoms.

Considerations for SARS-CoV-2 testing: Outpatient influenza-like illness

In 2020-2021, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends considering empiric antiviral treatment for ILIs (fever plus either cough or sore throat) based upon our clinical judgement, even in non-high-risk children.4

While pediatric COVID-19 illnesses are predominantly asymptomatic or mild, a febrile ARI is also a SARS-CoV-2 compatible presentation. So, if all we use is our clinical judgment, how do we know if the febrile ARI is due to influenza or SARS-CoV-2 or both? At least one study used a highly sensitive and specific molecular influenza test to show that the accuracy of clinically diagnosing influenza in children is not much better than flipping a coin and would lead to potential antiviral overuse.5

So, it seems ideal to test for influenza when possible. Point-of-care (POC) tests are frequently used for outpatients. Eight POC Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA)–waived kits, some also detecting RSV, are available but most have modest sensitivity (60%-80%) compared with lab-based molecular tests.6 That said, if supplies and kits for one of the POC tests are available to us during these SARS-CoV-2 stressed times (back orders seem more common this year), a positive influenza test in the first 48 hours of symptoms confirms the option to prescribe an antiviral. Yet how will we have confidence that the febrile ARI is not also partly due to SARS-CoV-2? Currently febrile ARIs usually are considered SARS-CoV-2 and the children are sent for SARS-CoV-2 testing. During influenza season, it seems we will need to continue to send febrile outpatients for SARS-CoV-2 testing, even if POC influenza positive, via whatever mechanisms are available as time goes on.

We expect more rapid pediatric testing modalities for SARS-CoV-2 (maybe even saliva tests) to become available over the next months. Indeed, rapid antigen tests and rapid molecular tests are being evaluated in adults and seem destined for CLIA waivers as POC tests, and even home testing kits. Pediatric approvals hopefully also will occur. So, the pathways for SARS-CoV-2 testing available now will likely change over this winter. But be aware that supplies/kits will be prioritized to locations within high need areas and bulk purchase contracts. So POC kits may remain scarce for practices, meaning a reference laboratory still could be the way to go for SARS-CoV-2 for at least the rest of 2020. Reference labs are becoming creative as well; one combined detection of influenza A, influenza B, RSV, and SARS-CoV-2 into one test, and hopes to get approval for swab collection that can be done by families at home and mailed in.

Summary

Expect variations on the traditional parade of seasonal respiratory viruses, with increased numbers of coinfections. Choosing the outpatient who needs influenza testing is the same as in past years, although we have CDC permissive recommendations to prescribe antivirals for any outpatient ILI within the first 48 hours of symptoms. Still, POC testing for influenza remains potentially valuable in the ILI patient. The choice of whether and how to test for SARS-CoV-2 given its potential to be a primary or coinfecting agent in presentations linked more closely to a traditional virus (e.g. RSV bronchiolitis) will be a test of our clinical judgement until more data and easier testing are available. Further complicating coinfection recognition is the fact that many sick visits occur by telehealth and much testing is done at drive-through SARS-CoV-2 testing facilities with no clinician exam. Unless we are liberal in SARS-CoV-2 testing, detecting SARS-CoV-2 coinfections is easier said than done given its usually mild presentation being overshadowed by any coinfecting virus.

But understanding who has SARS-CoV-2, even as a coinfection, still is essential in controlling the pandemic. We will need to be vigilant for evolving approaches to SARS-CoV-2 testing in the context of symptomatic ARI presentations, knowing this will likely remain a moving target for the foreseeable future.

Dr. Harrison is professor of pediatrics and pediatric infectious diseases at Children’s Mercy Hospital-Kansas City, Mo. Children’s Mercy Hospital receives grant funding to study two candidate RSV vaccines. The hospital also receives CDC funding under the New Vaccine Surveillance Network for multicenter surveillance of acute respiratory infections, including influenza, RSV, and parainfluenza virus. Email Dr. Harrison at [email protected].

References

1. Pediatrics. 2020;146(1):e20200961.

2. JAMA. 2020 May 26;323(20):2085-6.

3. Pediatrics. 2020. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-1267.

4. www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/antivirals/summary-clinicians.htm.

5. J. Pediatr. 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.08.007.

6. www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/diagnosis/table-nucleic-acid-detection.html.

Dr. Fauci: ‘About 40%-45% of infections are asymptomatic’

Anthony Fauci, MD, highlighting the latest COVID-19 developments on Friday, said, “It is now clear that about 40%-45% of infections are asymptomatic.”

Asymptomatic carriers can account for a large proportion — up to 50% — of virus transmissions, Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, told a virtual crowd of critical care clinicians gathered by the Society of Critical Care Medicine.

Such transmissions have made response strategies, such as contact tracing, extremely difficult, he said.

Lew Kaplan, MD, president of SCCM, told Medscape Medical News after the presentation: “That really supports the universal wearing of masks and the capstone message from that – you should protect one another.

“That kind of social responsibility that sits within the public health domain to me is as important as the vaccine candidates and the science behind the receptors. It underpins the necessary relationship and the interdependence of the medical community with the public,” Kaplan added.

Fauci’s plenary led the SCCM’s conference, “COVID-19: What’s Next/Preparing for the Second Wave,” running today and Saturday.

Why U.S. response lags behind Spain and Italy

“This virus has literally exploded upon the planet in a pandemic manner which is unparalleled to anything we’ve seen in the last 102 years since the pandemic of 1918,” Fauci said.

“Unfortunately, the United States has been hit harder than any other country in the world, with 6 million reported cases.”

He explained that in the European Union countries the disease spiked early on and returned to a low baseline. “Unfortunately for them,” Fauci said, “as they’re trying to open up their economy, it’s coming back up.”

The United States, he explained, plateaued at about 20,000 cases a day, then a surge of cases in Florida, California, Texas, and Arizona brought the cases to 70,000 a day. Now cases have returned to 35,000-40,000 a day.

The difference in the trajectory of the response, he said, is that, compared with Spain and Italy for example, the United States has not shut down mobility in parks, outdoor spaces, and grocery stores nearly as much as some European countries did.

He pointed to numerous clusters of cases, spread from social or work gatherings, including the well-known Skagit County Washington state choir practice in March, in which a symptomatic choir member infected 87% of the 61 people rehearsing.

Vaccine by end of the year

As for a vaccine timeline, Fauci told SCCM members, “We project that by the end of this year, namely November/December, we will know if we have a safe and effective vaccine and we are cautiously optimistic that we will be successful, based on promising data in the animal model as well as good immunological data that we see from the phase 1 and phase 2 trials.”

However, also on Friday, Fauci told MSNBC’s Andrea Mitchell that a sense of normalcy is not likely before the middle of next year.

“By the time you mobilize the distribution of the vaccinations, and you get the majority, or more, of the population vaccinated and protected, that’s likely not going to happen [until] the mid- or end of 2021,” he said.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) case tracker, as of Thursday, COVID-19 had resulted in more than 190,000 deaths overall and more than 256,000 new cases in the United States in the past 7 days.

Fauci has warned that the next few months will be critical in the virus’ trajectory, with the double onslaught of COVID-19 and the flu season.

On Thursday, Fauci said, “We need to hunker down and get through this fall and winter because it’s not going to be easy.”

Fauci remains a top trusted source in COVID-19 information, poll numbers show.

A Kaiser Family Foundation poll released Thursday found that 68% of US adults had a fair amount or a great deal of trust that Fauci would provide reliable information on COVID-19, just slightly more that the 67% who said they trust the CDC information. About half (53%) say they trust Deborah Birx, MD, the coordinator for the White House Coronavirus Task Force, as a reliable source of information.

The poll also found that 54% of Americans said they would not get a COVID-19 vaccine if one was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration before the November election and was made available and free to all who wanted it.

Kaplan and Fauci report no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Anthony Fauci, MD, highlighting the latest COVID-19 developments on Friday, said, “It is now clear that about 40%-45% of infections are asymptomatic.”

Asymptomatic carriers can account for a large proportion — up to 50% — of virus transmissions, Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, told a virtual crowd of critical care clinicians gathered by the Society of Critical Care Medicine.

Such transmissions have made response strategies, such as contact tracing, extremely difficult, he said.

Lew Kaplan, MD, president of SCCM, told Medscape Medical News after the presentation: “That really supports the universal wearing of masks and the capstone message from that – you should protect one another.

“That kind of social responsibility that sits within the public health domain to me is as important as the vaccine candidates and the science behind the receptors. It underpins the necessary relationship and the interdependence of the medical community with the public,” Kaplan added.

Fauci’s plenary led the SCCM’s conference, “COVID-19: What’s Next/Preparing for the Second Wave,” running today and Saturday.

Why U.S. response lags behind Spain and Italy

“This virus has literally exploded upon the planet in a pandemic manner which is unparalleled to anything we’ve seen in the last 102 years since the pandemic of 1918,” Fauci said.

“Unfortunately, the United States has been hit harder than any other country in the world, with 6 million reported cases.”

He explained that in the European Union countries the disease spiked early on and returned to a low baseline. “Unfortunately for them,” Fauci said, “as they’re trying to open up their economy, it’s coming back up.”

The United States, he explained, plateaued at about 20,000 cases a day, then a surge of cases in Florida, California, Texas, and Arizona brought the cases to 70,000 a day. Now cases have returned to 35,000-40,000 a day.

The difference in the trajectory of the response, he said, is that, compared with Spain and Italy for example, the United States has not shut down mobility in parks, outdoor spaces, and grocery stores nearly as much as some European countries did.

He pointed to numerous clusters of cases, spread from social or work gatherings, including the well-known Skagit County Washington state choir practice in March, in which a symptomatic choir member infected 87% of the 61 people rehearsing.

Vaccine by end of the year

As for a vaccine timeline, Fauci told SCCM members, “We project that by the end of this year, namely November/December, we will know if we have a safe and effective vaccine and we are cautiously optimistic that we will be successful, based on promising data in the animal model as well as good immunological data that we see from the phase 1 and phase 2 trials.”

However, also on Friday, Fauci told MSNBC’s Andrea Mitchell that a sense of normalcy is not likely before the middle of next year.

“By the time you mobilize the distribution of the vaccinations, and you get the majority, or more, of the population vaccinated and protected, that’s likely not going to happen [until] the mid- or end of 2021,” he said.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) case tracker, as of Thursday, COVID-19 had resulted in more than 190,000 deaths overall and more than 256,000 new cases in the United States in the past 7 days.

Fauci has warned that the next few months will be critical in the virus’ trajectory, with the double onslaught of COVID-19 and the flu season.

On Thursday, Fauci said, “We need to hunker down and get through this fall and winter because it’s not going to be easy.”

Fauci remains a top trusted source in COVID-19 information, poll numbers show.

A Kaiser Family Foundation poll released Thursday found that 68% of US adults had a fair amount or a great deal of trust that Fauci would provide reliable information on COVID-19, just slightly more that the 67% who said they trust the CDC information. About half (53%) say they trust Deborah Birx, MD, the coordinator for the White House Coronavirus Task Force, as a reliable source of information.

The poll also found that 54% of Americans said they would not get a COVID-19 vaccine if one was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration before the November election and was made available and free to all who wanted it.

Kaplan and Fauci report no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Anthony Fauci, MD, highlighting the latest COVID-19 developments on Friday, said, “It is now clear that about 40%-45% of infections are asymptomatic.”

Asymptomatic carriers can account for a large proportion — up to 50% — of virus transmissions, Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, told a virtual crowd of critical care clinicians gathered by the Society of Critical Care Medicine.

Such transmissions have made response strategies, such as contact tracing, extremely difficult, he said.

Lew Kaplan, MD, president of SCCM, told Medscape Medical News after the presentation: “That really supports the universal wearing of masks and the capstone message from that – you should protect one another.

“That kind of social responsibility that sits within the public health domain to me is as important as the vaccine candidates and the science behind the receptors. It underpins the necessary relationship and the interdependence of the medical community with the public,” Kaplan added.

Fauci’s plenary led the SCCM’s conference, “COVID-19: What’s Next/Preparing for the Second Wave,” running today and Saturday.

Why U.S. response lags behind Spain and Italy

“This virus has literally exploded upon the planet in a pandemic manner which is unparalleled to anything we’ve seen in the last 102 years since the pandemic of 1918,” Fauci said.

“Unfortunately, the United States has been hit harder than any other country in the world, with 6 million reported cases.”

He explained that in the European Union countries the disease spiked early on and returned to a low baseline. “Unfortunately for them,” Fauci said, “as they’re trying to open up their economy, it’s coming back up.”

The United States, he explained, plateaued at about 20,000 cases a day, then a surge of cases in Florida, California, Texas, and Arizona brought the cases to 70,000 a day. Now cases have returned to 35,000-40,000 a day.

The difference in the trajectory of the response, he said, is that, compared with Spain and Italy for example, the United States has not shut down mobility in parks, outdoor spaces, and grocery stores nearly as much as some European countries did.

He pointed to numerous clusters of cases, spread from social or work gatherings, including the well-known Skagit County Washington state choir practice in March, in which a symptomatic choir member infected 87% of the 61 people rehearsing.

Vaccine by end of the year

As for a vaccine timeline, Fauci told SCCM members, “We project that by the end of this year, namely November/December, we will know if we have a safe and effective vaccine and we are cautiously optimistic that we will be successful, based on promising data in the animal model as well as good immunological data that we see from the phase 1 and phase 2 trials.”

However, also on Friday, Fauci told MSNBC’s Andrea Mitchell that a sense of normalcy is not likely before the middle of next year.

“By the time you mobilize the distribution of the vaccinations, and you get the majority, or more, of the population vaccinated and protected, that’s likely not going to happen [until] the mid- or end of 2021,” he said.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) case tracker, as of Thursday, COVID-19 had resulted in more than 190,000 deaths overall and more than 256,000 new cases in the United States in the past 7 days.

Fauci has warned that the next few months will be critical in the virus’ trajectory, with the double onslaught of COVID-19 and the flu season.

On Thursday, Fauci said, “We need to hunker down and get through this fall and winter because it’s not going to be easy.”

Fauci remains a top trusted source in COVID-19 information, poll numbers show.

A Kaiser Family Foundation poll released Thursday found that 68% of US adults had a fair amount or a great deal of trust that Fauci would provide reliable information on COVID-19, just slightly more that the 67% who said they trust the CDC information. About half (53%) say they trust Deborah Birx, MD, the coordinator for the White House Coronavirus Task Force, as a reliable source of information.

The poll also found that 54% of Americans said they would not get a COVID-19 vaccine if one was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration before the November election and was made available and free to all who wanted it.

Kaplan and Fauci report no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Many providers don’t follow hypertension guidelines

Many health care professionals are not following current, evidence-based guidelines to screen for and diagnose hypertension, and appear to have substantial gaps in knowledge, beliefs, and use of recommended practices, results from a large survey suggest.

“One surprising finding was that there was so much trust in the stethoscope, because the automated monitors are a better way to take blood pressure,” lead author Beverly Green, MD, of Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute, Seattle, said in an interview.

The results of the survey were presented Sept. 10 at the virtual joint scientific sessions of the American Heart Association Council on Hypertension, AHA Council on Kidney in Cardiovascular Disease, and American Society of Hypertension.

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) and the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology recommend out-of-office blood pressure measurements – via ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM) or home BP monitoring – before making a new diagnosis of hypertension.

To gauge provider knowledge, beliefs, and practices related to BP diagnostic tests, the researchers surveyed 282 providers: 102 medical assistants (MA), 28 licensed practical nurses (LPNs), 33 registered nurses (RNs), 86 primary care physicians, and 33 advanced practitioners (APs).

More than three-quarters of providers (79%) felt that BP measured manually with a stethoscope and ABPM were “very or highly” accurate ways to measure BP when making a new diagnosis of hypertension.

Most did not think that automated clinic BPs, home BP, or kiosk BP measurements were very or highly accurate.

Nearly all providers surveyed (96%) reported that they “always or almost always” rely on clinic BP measurements when diagnosing hypertension, but the majority of physicians/APs would prefer using ABPM (61%) if available.

The problem with ABPM, said Dr. Green, is “it’s just not very available or convenient for patients, and a lot of providers think that patients won’t tolerate it.” Yet, without it, there is a risk for misclassification, she said.

Karen A. Griffin, MD, who chairs the AHA Council on Hypertension, said it became “customary to use clinic BP since ABPM was not previously reimbursed for the routine diagnosis of hypertension.

“Now that the payment for ABPM has been expanded, the number of machines at most institutions is not adequate for the need. Consequently, it will take some time to catch up with the current guidelines for diagnosing hypertension,” she said in an interview.

The provider survey by Dr. Green and colleagues also shows slow uptake of updated thresholds for high blood pressure.

Eighty-four percent of physicians/APs and 68% of MA/LPN/RNs said they used a clinic BP threshold of at least 140/90 mm Hg for making a new diagnosis of hypertension.

Only 3.5% and 9.0%, respectively, reported using the updated threshold of at least 130/80 mm Hg put forth in 2017.

Dr. Griffin said part of this stems from the fact that the survey began before the updated guidelines were released in 2017, “not to mention the fact that some societies have opposed the new threshold of 130/80 mm Hg.”

“I think, with time, the data on morbidity and mortality associated with the goal of 130/80 mm Hg will hopefully convince those who have not yet implemented these new guidelines that it is a safe and effective BP goal,” Dr. Griffin said.

This research had no specific funding. Dr. Green and Dr. Griffin have no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Many health care professionals are not following current, evidence-based guidelines to screen for and diagnose hypertension, and appear to have substantial gaps in knowledge, beliefs, and use of recommended practices, results from a large survey suggest.

“One surprising finding was that there was so much trust in the stethoscope, because the automated monitors are a better way to take blood pressure,” lead author Beverly Green, MD, of Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute, Seattle, said in an interview.

The results of the survey were presented Sept. 10 at the virtual joint scientific sessions of the American Heart Association Council on Hypertension, AHA Council on Kidney in Cardiovascular Disease, and American Society of Hypertension.

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) and the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology recommend out-of-office blood pressure measurements – via ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM) or home BP monitoring – before making a new diagnosis of hypertension.

To gauge provider knowledge, beliefs, and practices related to BP diagnostic tests, the researchers surveyed 282 providers: 102 medical assistants (MA), 28 licensed practical nurses (LPNs), 33 registered nurses (RNs), 86 primary care physicians, and 33 advanced practitioners (APs).

More than three-quarters of providers (79%) felt that BP measured manually with a stethoscope and ABPM were “very or highly” accurate ways to measure BP when making a new diagnosis of hypertension.

Most did not think that automated clinic BPs, home BP, or kiosk BP measurements were very or highly accurate.

Nearly all providers surveyed (96%) reported that they “always or almost always” rely on clinic BP measurements when diagnosing hypertension, but the majority of physicians/APs would prefer using ABPM (61%) if available.

The problem with ABPM, said Dr. Green, is “it’s just not very available or convenient for patients, and a lot of providers think that patients won’t tolerate it.” Yet, without it, there is a risk for misclassification, she said.

Karen A. Griffin, MD, who chairs the AHA Council on Hypertension, said it became “customary to use clinic BP since ABPM was not previously reimbursed for the routine diagnosis of hypertension.

“Now that the payment for ABPM has been expanded, the number of machines at most institutions is not adequate for the need. Consequently, it will take some time to catch up with the current guidelines for diagnosing hypertension,” she said in an interview.

The provider survey by Dr. Green and colleagues also shows slow uptake of updated thresholds for high blood pressure.

Eighty-four percent of physicians/APs and 68% of MA/LPN/RNs said they used a clinic BP threshold of at least 140/90 mm Hg for making a new diagnosis of hypertension.

Only 3.5% and 9.0%, respectively, reported using the updated threshold of at least 130/80 mm Hg put forth in 2017.

Dr. Griffin said part of this stems from the fact that the survey began before the updated guidelines were released in 2017, “not to mention the fact that some societies have opposed the new threshold of 130/80 mm Hg.”

“I think, with time, the data on morbidity and mortality associated with the goal of 130/80 mm Hg will hopefully convince those who have not yet implemented these new guidelines that it is a safe and effective BP goal,” Dr. Griffin said.

This research had no specific funding. Dr. Green and Dr. Griffin have no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Many health care professionals are not following current, evidence-based guidelines to screen for and diagnose hypertension, and appear to have substantial gaps in knowledge, beliefs, and use of recommended practices, results from a large survey suggest.

“One surprising finding was that there was so much trust in the stethoscope, because the automated monitors are a better way to take blood pressure,” lead author Beverly Green, MD, of Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute, Seattle, said in an interview.

The results of the survey were presented Sept. 10 at the virtual joint scientific sessions of the American Heart Association Council on Hypertension, AHA Council on Kidney in Cardiovascular Disease, and American Society of Hypertension.

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) and the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology recommend out-of-office blood pressure measurements – via ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM) or home BP monitoring – before making a new diagnosis of hypertension.

To gauge provider knowledge, beliefs, and practices related to BP diagnostic tests, the researchers surveyed 282 providers: 102 medical assistants (MA), 28 licensed practical nurses (LPNs), 33 registered nurses (RNs), 86 primary care physicians, and 33 advanced practitioners (APs).

More than three-quarters of providers (79%) felt that BP measured manually with a stethoscope and ABPM were “very or highly” accurate ways to measure BP when making a new diagnosis of hypertension.

Most did not think that automated clinic BPs, home BP, or kiosk BP measurements were very or highly accurate.

Nearly all providers surveyed (96%) reported that they “always or almost always” rely on clinic BP measurements when diagnosing hypertension, but the majority of physicians/APs would prefer using ABPM (61%) if available.

The problem with ABPM, said Dr. Green, is “it’s just not very available or convenient for patients, and a lot of providers think that patients won’t tolerate it.” Yet, without it, there is a risk for misclassification, she said.

Karen A. Griffin, MD, who chairs the AHA Council on Hypertension, said it became “customary to use clinic BP since ABPM was not previously reimbursed for the routine diagnosis of hypertension.

“Now that the payment for ABPM has been expanded, the number of machines at most institutions is not adequate for the need. Consequently, it will take some time to catch up with the current guidelines for diagnosing hypertension,” she said in an interview.

The provider survey by Dr. Green and colleagues also shows slow uptake of updated thresholds for high blood pressure.

Eighty-four percent of physicians/APs and 68% of MA/LPN/RNs said they used a clinic BP threshold of at least 140/90 mm Hg for making a new diagnosis of hypertension.

Only 3.5% and 9.0%, respectively, reported using the updated threshold of at least 130/80 mm Hg put forth in 2017.

Dr. Griffin said part of this stems from the fact that the survey began before the updated guidelines were released in 2017, “not to mention the fact that some societies have opposed the new threshold of 130/80 mm Hg.”

“I think, with time, the data on morbidity and mortality associated with the goal of 130/80 mm Hg will hopefully convince those who have not yet implemented these new guidelines that it is a safe and effective BP goal,” Dr. Griffin said.

This research had no specific funding. Dr. Green and Dr. Griffin have no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

COVID-19 and the psychological side effects of PPE

A few months ago, I published a short thought piece on the use of “sitters” with patients who were COVID-19 positive, or patients under investigation. In it, I recommended the use of telesitters for those who normally would warrant a human sitter, to decrease the discomfort of sitting in full personal protective equipment (PPE) (gown, mask, gloves, etc.) while monitoring a suicidal patient.

I received several queries, which I want to address here. In addition, I want to draw from my Army days in terms of the claustrophobia often experienced with PPE.

The first of the questions was about evidence-based practices. The second was about the discomfort of having sitters sit for many hours in the full gear.

I do not know of any evidence-based practices, but I hope we will develop them.

I agree that spending many hours in full PPE can be discomforting, which is why I wrote the essay.

As far as lessons learned from the Army time, I briefly learned how to wear a “gas mask” or Mission-Oriented Protective Posture (MOPP gear) while at Fort Bragg. We were run through the “gas chamber,” where sergeants released tear gas while we had the mask on. We were then asked to lift it up, and then tearing and sputtering, we could leave the small wooden building.

We wore the mask as part of our Army gear, usually on the right leg. After that, I mainly used the protective mask in its bag as a pillow when I was in the field.

Fast forward to August 1990. I arrived at Camp Casey, near the Korean demilitarized zone. Four days later, Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait. The gas mask moved from a pillow to something we had to wear while doing 12-mile road marches in “full ruck.” In full ruck, you have your uniform on, with TA-50, knapsack, and weapon. No, I do not remember any more what TA-50 stands for, but essentially it is the webbing that holds your bullets and bandages.

Many could not tolerate it. They developed claustrophobia – sweating, air hunger, and panic. If stationed in the Gulf for Operation Desert Storm, they were evacuated home.

I wrote a couple of short articles on treatment of gas mask phobia.1,2 I basically advised desensitization. Start by watching TV in it for 5 minutes. Graduate to ironing your uniform in the mask. Go then to shorter runs. Work up to the 12-mile road march.

In my second tour in Korea, we had exercises where we simulated being hit by nerve agents and had to operate the hospital for days at a time in partial or full PPE. It was tough but we did it, and felt more confident about surviving attacks from North Korea.

So back to the pandemic present. I have gotten more used to my constant wearing of a surgical mask. I get anxious when I see others with masks below their noses.

The pandemic is not going away anytime soon, in my opinion. Furthermore, there are other viruses that are worse, such as Ebola. It is only a matter of time.

So, let us train with our PPE. If health care workers cannot tolerate them, use desensitization- and anxiety-reducing techniques to help them.

There are no easy answers here, in the time of the COVID pandemic. However, we owe it to ourselves, our patients, and society to do the best we can.

References

1. Ritchie EC. Milit Med. 1992 Feb;157(2):104-6.

2. Ritchie EC. Milit Med. 2001 Dec;166. Suppl. 2(1)83-4.

Dr. Ritchie is chair of psychiatry at Medstar Washington Hospital Center and professor of psychiatry at Georgetown University, Washington. She has no disclosures and can be reached at [email protected].

A few months ago, I published a short thought piece on the use of “sitters” with patients who were COVID-19 positive, or patients under investigation. In it, I recommended the use of telesitters for those who normally would warrant a human sitter, to decrease the discomfort of sitting in full personal protective equipment (PPE) (gown, mask, gloves, etc.) while monitoring a suicidal patient.

I received several queries, which I want to address here. In addition, I want to draw from my Army days in terms of the claustrophobia often experienced with PPE.

The first of the questions was about evidence-based practices. The second was about the discomfort of having sitters sit for many hours in the full gear.

I do not know of any evidence-based practices, but I hope we will develop them.

I agree that spending many hours in full PPE can be discomforting, which is why I wrote the essay.

As far as lessons learned from the Army time, I briefly learned how to wear a “gas mask” or Mission-Oriented Protective Posture (MOPP gear) while at Fort Bragg. We were run through the “gas chamber,” where sergeants released tear gas while we had the mask on. We were then asked to lift it up, and then tearing and sputtering, we could leave the small wooden building.

We wore the mask as part of our Army gear, usually on the right leg. After that, I mainly used the protective mask in its bag as a pillow when I was in the field.

Fast forward to August 1990. I arrived at Camp Casey, near the Korean demilitarized zone. Four days later, Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait. The gas mask moved from a pillow to something we had to wear while doing 12-mile road marches in “full ruck.” In full ruck, you have your uniform on, with TA-50, knapsack, and weapon. No, I do not remember any more what TA-50 stands for, but essentially it is the webbing that holds your bullets and bandages.

Many could not tolerate it. They developed claustrophobia – sweating, air hunger, and panic. If stationed in the Gulf for Operation Desert Storm, they were evacuated home.

I wrote a couple of short articles on treatment of gas mask phobia.1,2 I basically advised desensitization. Start by watching TV in it for 5 minutes. Graduate to ironing your uniform in the mask. Go then to shorter runs. Work up to the 12-mile road march.

In my second tour in Korea, we had exercises where we simulated being hit by nerve agents and had to operate the hospital for days at a time in partial or full PPE. It was tough but we did it, and felt more confident about surviving attacks from North Korea.

So back to the pandemic present. I have gotten more used to my constant wearing of a surgical mask. I get anxious when I see others with masks below their noses.

The pandemic is not going away anytime soon, in my opinion. Furthermore, there are other viruses that are worse, such as Ebola. It is only a matter of time.

So, let us train with our PPE. If health care workers cannot tolerate them, use desensitization- and anxiety-reducing techniques to help them.

There are no easy answers here, in the time of the COVID pandemic. However, we owe it to ourselves, our patients, and society to do the best we can.

References

1. Ritchie EC. Milit Med. 1992 Feb;157(2):104-6.

2. Ritchie EC. Milit Med. 2001 Dec;166. Suppl. 2(1)83-4.

Dr. Ritchie is chair of psychiatry at Medstar Washington Hospital Center and professor of psychiatry at Georgetown University, Washington. She has no disclosures and can be reached at [email protected].

A few months ago, I published a short thought piece on the use of “sitters” with patients who were COVID-19 positive, or patients under investigation. In it, I recommended the use of telesitters for those who normally would warrant a human sitter, to decrease the discomfort of sitting in full personal protective equipment (PPE) (gown, mask, gloves, etc.) while monitoring a suicidal patient.

I received several queries, which I want to address here. In addition, I want to draw from my Army days in terms of the claustrophobia often experienced with PPE.

The first of the questions was about evidence-based practices. The second was about the discomfort of having sitters sit for many hours in the full gear.

I do not know of any evidence-based practices, but I hope we will develop them.

I agree that spending many hours in full PPE can be discomforting, which is why I wrote the essay.

As far as lessons learned from the Army time, I briefly learned how to wear a “gas mask” or Mission-Oriented Protective Posture (MOPP gear) while at Fort Bragg. We were run through the “gas chamber,” where sergeants released tear gas while we had the mask on. We were then asked to lift it up, and then tearing and sputtering, we could leave the small wooden building.

We wore the mask as part of our Army gear, usually on the right leg. After that, I mainly used the protective mask in its bag as a pillow when I was in the field.

Fast forward to August 1990. I arrived at Camp Casey, near the Korean demilitarized zone. Four days later, Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait. The gas mask moved from a pillow to something we had to wear while doing 12-mile road marches in “full ruck.” In full ruck, you have your uniform on, with TA-50, knapsack, and weapon. No, I do not remember any more what TA-50 stands for, but essentially it is the webbing that holds your bullets and bandages.

Many could not tolerate it. They developed claustrophobia – sweating, air hunger, and panic. If stationed in the Gulf for Operation Desert Storm, they were evacuated home.

I wrote a couple of short articles on treatment of gas mask phobia.1,2 I basically advised desensitization. Start by watching TV in it for 5 minutes. Graduate to ironing your uniform in the mask. Go then to shorter runs. Work up to the 12-mile road march.

In my second tour in Korea, we had exercises where we simulated being hit by nerve agents and had to operate the hospital for days at a time in partial or full PPE. It was tough but we did it, and felt more confident about surviving attacks from North Korea.

So back to the pandemic present. I have gotten more used to my constant wearing of a surgical mask. I get anxious when I see others with masks below their noses.

The pandemic is not going away anytime soon, in my opinion. Furthermore, there are other viruses that are worse, such as Ebola. It is only a matter of time.

So, let us train with our PPE. If health care workers cannot tolerate them, use desensitization- and anxiety-reducing techniques to help them.

There are no easy answers here, in the time of the COVID pandemic. However, we owe it to ourselves, our patients, and society to do the best we can.

References

1. Ritchie EC. Milit Med. 1992 Feb;157(2):104-6.

2. Ritchie EC. Milit Med. 2001 Dec;166. Suppl. 2(1)83-4.

Dr. Ritchie is chair of psychiatry at Medstar Washington Hospital Center and professor of psychiatry at Georgetown University, Washington. She has no disclosures and can be reached at [email protected].

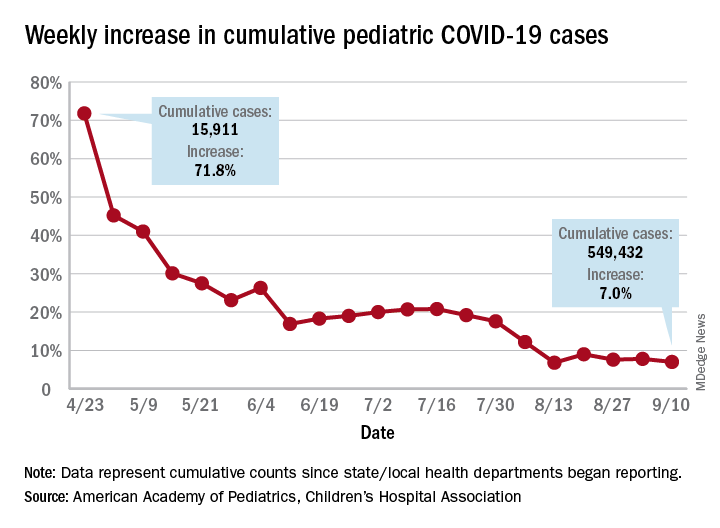

Children and COVID-19: New cases may be leveling off

Growth in new pediatric COVID-19 cases has evened out in recent weeks, but children now represent 10% of all COVID-19 cases in the United States, and that measurement has been rising throughout the pandemic, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

the AAP and the CHA said in the report, based on data from 49 states (New York City is included but not New York state), the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

The weekly percentage of increase in the number of new cases has not reached double digits since early August and has been no higher than 7.8% over the last 3 weeks. The number of child COVID-19 cases, however, has finally reached 10% of the total for Americans of all ages, which stands at 5.49 million in the jurisdictions included in the report, the AHA and CHA reported.

Measures, however, continue to show low levels of severe illness in children, they noted, including the following:

- Child cases as a proportion of all COVID-19 hospitalizations: 1.7%.

- Hospitalization rate for children: 1.8%.

- Child deaths as a proportion of all deaths: 0.07%.

- Percent of child cases resulting in death: 0.01%.

The number of cumulative cases per 100,000 children is now up to 728.5 nationally, with a range by state that goes from 154.0 in Vermont to 1,670.3 in Tennessee, which is one of only two states reporting cases in those aged 0-20 years as children (the other is South Carolina). The age range for children is 0-17 or 0-19 for most other states, although Florida uses a range of 0-14, the report notes.

Other than Tennessee, there are 10 states with overall rates higher than 1,000 COVID-19 cases per 100,000 children, and there are nine states with cumulative totals over 15,000 cases (California is the highest with just over 75,000), according to the report.

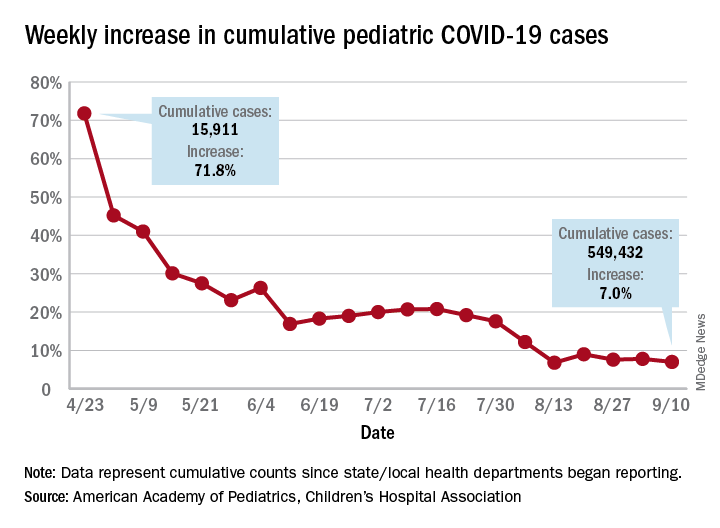

Growth in new pediatric COVID-19 cases has evened out in recent weeks, but children now represent 10% of all COVID-19 cases in the United States, and that measurement has been rising throughout the pandemic, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

the AAP and the CHA said in the report, based on data from 49 states (New York City is included but not New York state), the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

The weekly percentage of increase in the number of new cases has not reached double digits since early August and has been no higher than 7.8% over the last 3 weeks. The number of child COVID-19 cases, however, has finally reached 10% of the total for Americans of all ages, which stands at 5.49 million in the jurisdictions included in the report, the AHA and CHA reported.

Measures, however, continue to show low levels of severe illness in children, they noted, including the following:

- Child cases as a proportion of all COVID-19 hospitalizations: 1.7%.

- Hospitalization rate for children: 1.8%.

- Child deaths as a proportion of all deaths: 0.07%.

- Percent of child cases resulting in death: 0.01%.

The number of cumulative cases per 100,000 children is now up to 728.5 nationally, with a range by state that goes from 154.0 in Vermont to 1,670.3 in Tennessee, which is one of only two states reporting cases in those aged 0-20 years as children (the other is South Carolina). The age range for children is 0-17 or 0-19 for most other states, although Florida uses a range of 0-14, the report notes.

Other than Tennessee, there are 10 states with overall rates higher than 1,000 COVID-19 cases per 100,000 children, and there are nine states with cumulative totals over 15,000 cases (California is the highest with just over 75,000), according to the report.

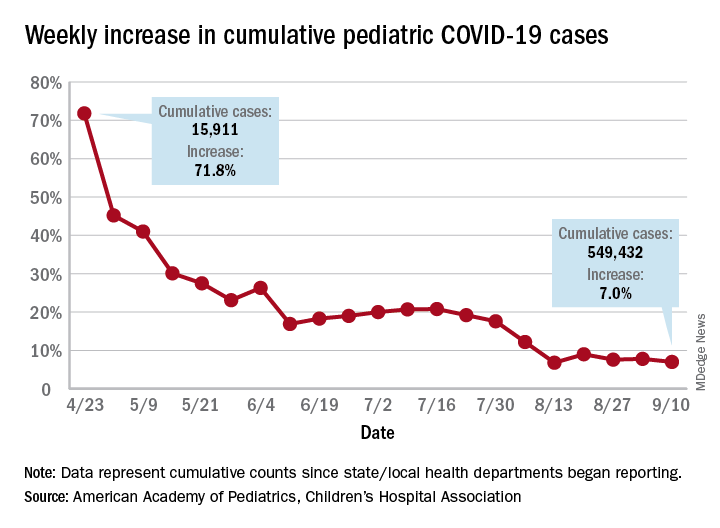

Growth in new pediatric COVID-19 cases has evened out in recent weeks, but children now represent 10% of all COVID-19 cases in the United States, and that measurement has been rising throughout the pandemic, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

the AAP and the CHA said in the report, based on data from 49 states (New York City is included but not New York state), the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

The weekly percentage of increase in the number of new cases has not reached double digits since early August and has been no higher than 7.8% over the last 3 weeks. The number of child COVID-19 cases, however, has finally reached 10% of the total for Americans of all ages, which stands at 5.49 million in the jurisdictions included in the report, the AHA and CHA reported.

Measures, however, continue to show low levels of severe illness in children, they noted, including the following:

- Child cases as a proportion of all COVID-19 hospitalizations: 1.7%.

- Hospitalization rate for children: 1.8%.

- Child deaths as a proportion of all deaths: 0.07%.

- Percent of child cases resulting in death: 0.01%.

The number of cumulative cases per 100,000 children is now up to 728.5 nationally, with a range by state that goes from 154.0 in Vermont to 1,670.3 in Tennessee, which is one of only two states reporting cases in those aged 0-20 years as children (the other is South Carolina). The age range for children is 0-17 or 0-19 for most other states, although Florida uses a range of 0-14, the report notes.

Other than Tennessee, there are 10 states with overall rates higher than 1,000 COVID-19 cases per 100,000 children, and there are nine states with cumulative totals over 15,000 cases (California is the highest with just over 75,000), according to the report.

Conspiracy theories

It ain’t what you don’t know that gets you into trouble. It’s what you know for sure that just ain’t so. – Josh Billings

and intends to use COVID vaccinations as a devious way to implant microchips in us. He will then, of course, use the new 5G towers to track us all (although what Gates will do with the information that I was shopping at a Trader Joe’s yesterday is yet unknown).