User login

Official news magazine of the Society of Hospital Medicine

Copyright by Society of Hospital Medicine or related companies. All rights reserved. ISSN 1553-085X

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-hospitalist')]

#WhiteCoats4BlackLives: A ‘platform for good’

like those on vivid display during the COVID-19 pandemic.

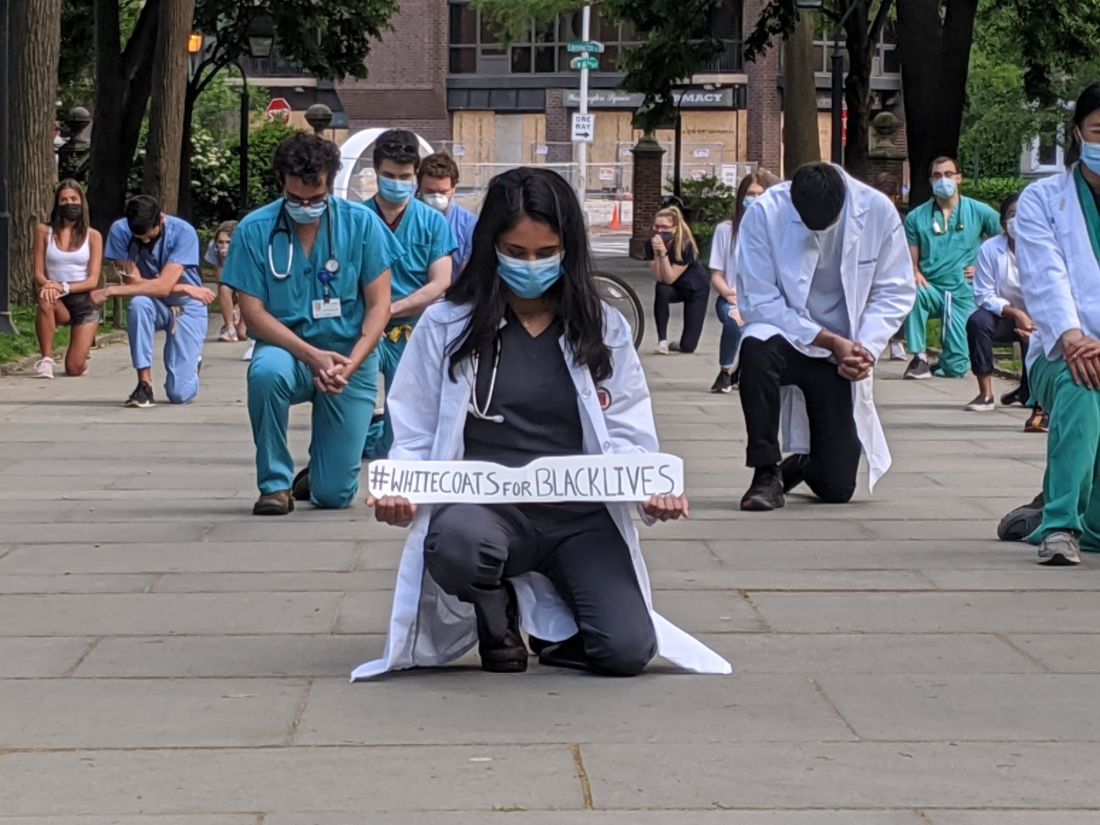

Sporadic protests – with participants in scrubs or white coats kneeling for 8 minutes and 46 seconds in memory of George Floyd – have quickly grown into organized, ongoing, large-scale events at hospitals, medical campuses, and city centers in New York, Indianapolis, Atlanta, Austin, Houston, Boston, Miami, Portland, Sacramento, Los Angeles, Philadelphia, and Albuquerque, among others.

The group WhiteCoats4BlackLives began with a “die-in” protest in 2014, and the medical student–run organization continues to organize, with a large number of protests scheduled to occur simultaneously on June 5 at 1:00 p.m. Eastern Time.

“It’s important to use our platform for good,” said Danielle Verghese, MD, a first-year internal medicine resident at Thomas Jefferson University Hospital in Philadelphia, who helped recruit a small group of students, residents, and pharmacy school students to take part in a kneel-in on May 31 in the city’s Washington Square Park.

“As a doctor, most people in society regard me with a certain amount of respect and may listen if I say something,” Dr. Verghese said.

Crystal Nnenne Azu, MD, a third-year internal medicine resident at Indiana University, who has long worked on increasing diversity in medicine, said she helped organize a march and kneel-in at the school’s Eskenazi Hospital campus on June 3 to educate and show support.

Some 500-1,000 health care providers in scrubs and white coats turned out, tweeted one observer.

“Racism is a public health crisis,” Dr. Azu said. “This COVID epidemic has definitely raised that awareness even more for many of our colleagues.”

Disproportionate death rates in blacks and Latinos are “not just related to individual choices but also systemic racism,” she said.

The march also called out police brutality and the “angst” that many people feel about it, said Dr. Azu. “People want an avenue to express their discomfort, to raise awareness, and also show their solidarity and support for peaceful protests,” she said.

A June 4 protest and “die-in” – held to honor black and indigenous lives at the University of New Mexico Health Sciences campus in Albuquerque – was personal for Jaron Kee, MD, a first-year family medicine resident. He was raised on the Navajo reservation in Crystal, New Mexico, and has watched COVID-19 devastate the tribe, adding insult to years of health disparities, police brutality, and neglect of thousands of missing and murdered indigenous women, he said.

Participating is a means of reassuring the community that “we’re allies and that their suffering and their livelihood is something that we don’t underrecognize,” Dr. Kee said. These values spurred him to enter medicine, he said.

Eileen Barrett, MD, MPH, a hospitalist and assistant professor of internal medicine at the University of New Mexico School of Medicine, who also attended the “die-in,” said she hopes that peers, in particular people of color, see that they have allies at work “who are committed to being anti-racist.”

It’s also “a statement to the community at large that physicians and other healthcare workers strive to be anti-racist and do our best to support our African American and indigenous peers, students, patients, and community members,” she said.

Now is different

Some residents said they felt particularly moved to act now – as the country entered a second week of protests in response to George Floyd’s death and as the COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the devastating toll of health disparities.

“This protest feels different to me,” said Ian Fields, MD, a urogynecology fellow at Oregon Health Sciences University (OHSU) School of Medicine. “The events over the last couple of weeks were just a big catalyst for this to explode,” he said.

“I was very intent, as a white male physician, just coming to acknowledge the privilege that I have, and to do something,” Dr. Fields said, adding that as an obstetrician-gynecologist, he sees the results of health disparities daily. He took part in a kneel-in and demonstration with OHSU colleagues on June 2 at Portland’s Pioneer Courthouse Square.

It’s okay to be sad and mourn, Dr. Fields said, but, he added, “nobody needs our tears necessarily right now. They need us to show up and to speak up about what we see going on.”

“It feels like it’s a national conversation,” said Dr. Verghese. The White Coats movement is “not an issue that’s confined to the black community – this is not an issue that’s a ‘black thing’ – this is a humanitarian thing,” she said.

Dr. Verghese, an Indian American who said that no one would mistake her for being white, said she still wants to acknowledge that she has privilege, as well as biases. All the patients in the COVID-19 unit where she works are African American, but she said she hadn’t initially noticed.

“What’s shocking is that I didn’t think about it,” she said. “I do have to recognize my own biases.”

Protesting During a Pandemic

Despite the demands of treating COVID-19 patients, healthcare professionals have made the White Coat protests a priority, they said. Most – but not all – of the White Coats protests have been on medical campuses, allowing health care professionals to quickly assemble and get back to work. Plus, all of the protests have called on attendees to march and gather safely – with masks and distancing.

“Seeing that we are working in the hospital, it’s important for us to be wearing our masks, to be social distancing,” Dr. Azu said. Organizers asked attendees to ensure that they protested in a way that kept them “from worsening the COVID epidemic,” said Dr. Azu.

Unlike many others, the first protest in Portland was in conjunction with a larger group that assembles every evening in the square, said Dr. Fields. The physician protesters were wearing masks and maintaining distance from each other, especially when they kneeled, he said.

The protests have provided an escape from the futility of not being able to do anything for COVID-19 patients except to provide support, said Dr. Verghese. “In so many ways, we find ourselves powerless,” she said.

Protesting, Dr. Verghese added, was “one tiny moment where I got to regain my sense of agency, that I could actually do something about this.”

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

like those on vivid display during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Sporadic protests – with participants in scrubs or white coats kneeling for 8 minutes and 46 seconds in memory of George Floyd – have quickly grown into organized, ongoing, large-scale events at hospitals, medical campuses, and city centers in New York, Indianapolis, Atlanta, Austin, Houston, Boston, Miami, Portland, Sacramento, Los Angeles, Philadelphia, and Albuquerque, among others.

The group WhiteCoats4BlackLives began with a “die-in” protest in 2014, and the medical student–run organization continues to organize, with a large number of protests scheduled to occur simultaneously on June 5 at 1:00 p.m. Eastern Time.

“It’s important to use our platform for good,” said Danielle Verghese, MD, a first-year internal medicine resident at Thomas Jefferson University Hospital in Philadelphia, who helped recruit a small group of students, residents, and pharmacy school students to take part in a kneel-in on May 31 in the city’s Washington Square Park.

“As a doctor, most people in society regard me with a certain amount of respect and may listen if I say something,” Dr. Verghese said.

Crystal Nnenne Azu, MD, a third-year internal medicine resident at Indiana University, who has long worked on increasing diversity in medicine, said she helped organize a march and kneel-in at the school’s Eskenazi Hospital campus on June 3 to educate and show support.

Some 500-1,000 health care providers in scrubs and white coats turned out, tweeted one observer.

“Racism is a public health crisis,” Dr. Azu said. “This COVID epidemic has definitely raised that awareness even more for many of our colleagues.”

Disproportionate death rates in blacks and Latinos are “not just related to individual choices but also systemic racism,” she said.

The march also called out police brutality and the “angst” that many people feel about it, said Dr. Azu. “People want an avenue to express their discomfort, to raise awareness, and also show their solidarity and support for peaceful protests,” she said.

A June 4 protest and “die-in” – held to honor black and indigenous lives at the University of New Mexico Health Sciences campus in Albuquerque – was personal for Jaron Kee, MD, a first-year family medicine resident. He was raised on the Navajo reservation in Crystal, New Mexico, and has watched COVID-19 devastate the tribe, adding insult to years of health disparities, police brutality, and neglect of thousands of missing and murdered indigenous women, he said.

Participating is a means of reassuring the community that “we’re allies and that their suffering and their livelihood is something that we don’t underrecognize,” Dr. Kee said. These values spurred him to enter medicine, he said.

Eileen Barrett, MD, MPH, a hospitalist and assistant professor of internal medicine at the University of New Mexico School of Medicine, who also attended the “die-in,” said she hopes that peers, in particular people of color, see that they have allies at work “who are committed to being anti-racist.”

It’s also “a statement to the community at large that physicians and other healthcare workers strive to be anti-racist and do our best to support our African American and indigenous peers, students, patients, and community members,” she said.

Now is different

Some residents said they felt particularly moved to act now – as the country entered a second week of protests in response to George Floyd’s death and as the COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the devastating toll of health disparities.

“This protest feels different to me,” said Ian Fields, MD, a urogynecology fellow at Oregon Health Sciences University (OHSU) School of Medicine. “The events over the last couple of weeks were just a big catalyst for this to explode,” he said.

“I was very intent, as a white male physician, just coming to acknowledge the privilege that I have, and to do something,” Dr. Fields said, adding that as an obstetrician-gynecologist, he sees the results of health disparities daily. He took part in a kneel-in and demonstration with OHSU colleagues on June 2 at Portland’s Pioneer Courthouse Square.

It’s okay to be sad and mourn, Dr. Fields said, but, he added, “nobody needs our tears necessarily right now. They need us to show up and to speak up about what we see going on.”

“It feels like it’s a national conversation,” said Dr. Verghese. The White Coats movement is “not an issue that’s confined to the black community – this is not an issue that’s a ‘black thing’ – this is a humanitarian thing,” she said.

Dr. Verghese, an Indian American who said that no one would mistake her for being white, said she still wants to acknowledge that she has privilege, as well as biases. All the patients in the COVID-19 unit where she works are African American, but she said she hadn’t initially noticed.

“What’s shocking is that I didn’t think about it,” she said. “I do have to recognize my own biases.”

Protesting During a Pandemic

Despite the demands of treating COVID-19 patients, healthcare professionals have made the White Coat protests a priority, they said. Most – but not all – of the White Coats protests have been on medical campuses, allowing health care professionals to quickly assemble and get back to work. Plus, all of the protests have called on attendees to march and gather safely – with masks and distancing.

“Seeing that we are working in the hospital, it’s important for us to be wearing our masks, to be social distancing,” Dr. Azu said. Organizers asked attendees to ensure that they protested in a way that kept them “from worsening the COVID epidemic,” said Dr. Azu.

Unlike many others, the first protest in Portland was in conjunction with a larger group that assembles every evening in the square, said Dr. Fields. The physician protesters were wearing masks and maintaining distance from each other, especially when they kneeled, he said.

The protests have provided an escape from the futility of not being able to do anything for COVID-19 patients except to provide support, said Dr. Verghese. “In so many ways, we find ourselves powerless,” she said.

Protesting, Dr. Verghese added, was “one tiny moment where I got to regain my sense of agency, that I could actually do something about this.”

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

like those on vivid display during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Sporadic protests – with participants in scrubs or white coats kneeling for 8 minutes and 46 seconds in memory of George Floyd – have quickly grown into organized, ongoing, large-scale events at hospitals, medical campuses, and city centers in New York, Indianapolis, Atlanta, Austin, Houston, Boston, Miami, Portland, Sacramento, Los Angeles, Philadelphia, and Albuquerque, among others.

The group WhiteCoats4BlackLives began with a “die-in” protest in 2014, and the medical student–run organization continues to organize, with a large number of protests scheduled to occur simultaneously on June 5 at 1:00 p.m. Eastern Time.

“It’s important to use our platform for good,” said Danielle Verghese, MD, a first-year internal medicine resident at Thomas Jefferson University Hospital in Philadelphia, who helped recruit a small group of students, residents, and pharmacy school students to take part in a kneel-in on May 31 in the city’s Washington Square Park.

“As a doctor, most people in society regard me with a certain amount of respect and may listen if I say something,” Dr. Verghese said.

Crystal Nnenne Azu, MD, a third-year internal medicine resident at Indiana University, who has long worked on increasing diversity in medicine, said she helped organize a march and kneel-in at the school’s Eskenazi Hospital campus on June 3 to educate and show support.

Some 500-1,000 health care providers in scrubs and white coats turned out, tweeted one observer.

“Racism is a public health crisis,” Dr. Azu said. “This COVID epidemic has definitely raised that awareness even more for many of our colleagues.”

Disproportionate death rates in blacks and Latinos are “not just related to individual choices but also systemic racism,” she said.

The march also called out police brutality and the “angst” that many people feel about it, said Dr. Azu. “People want an avenue to express their discomfort, to raise awareness, and also show their solidarity and support for peaceful protests,” she said.

A June 4 protest and “die-in” – held to honor black and indigenous lives at the University of New Mexico Health Sciences campus in Albuquerque – was personal for Jaron Kee, MD, a first-year family medicine resident. He was raised on the Navajo reservation in Crystal, New Mexico, and has watched COVID-19 devastate the tribe, adding insult to years of health disparities, police brutality, and neglect of thousands of missing and murdered indigenous women, he said.

Participating is a means of reassuring the community that “we’re allies and that their suffering and their livelihood is something that we don’t underrecognize,” Dr. Kee said. These values spurred him to enter medicine, he said.

Eileen Barrett, MD, MPH, a hospitalist and assistant professor of internal medicine at the University of New Mexico School of Medicine, who also attended the “die-in,” said she hopes that peers, in particular people of color, see that they have allies at work “who are committed to being anti-racist.”

It’s also “a statement to the community at large that physicians and other healthcare workers strive to be anti-racist and do our best to support our African American and indigenous peers, students, patients, and community members,” she said.

Now is different

Some residents said they felt particularly moved to act now – as the country entered a second week of protests in response to George Floyd’s death and as the COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the devastating toll of health disparities.

“This protest feels different to me,” said Ian Fields, MD, a urogynecology fellow at Oregon Health Sciences University (OHSU) School of Medicine. “The events over the last couple of weeks were just a big catalyst for this to explode,” he said.

“I was very intent, as a white male physician, just coming to acknowledge the privilege that I have, and to do something,” Dr. Fields said, adding that as an obstetrician-gynecologist, he sees the results of health disparities daily. He took part in a kneel-in and demonstration with OHSU colleagues on June 2 at Portland’s Pioneer Courthouse Square.

It’s okay to be sad and mourn, Dr. Fields said, but, he added, “nobody needs our tears necessarily right now. They need us to show up and to speak up about what we see going on.”

“It feels like it’s a national conversation,” said Dr. Verghese. The White Coats movement is “not an issue that’s confined to the black community – this is not an issue that’s a ‘black thing’ – this is a humanitarian thing,” she said.

Dr. Verghese, an Indian American who said that no one would mistake her for being white, said she still wants to acknowledge that she has privilege, as well as biases. All the patients in the COVID-19 unit where she works are African American, but she said she hadn’t initially noticed.

“What’s shocking is that I didn’t think about it,” she said. “I do have to recognize my own biases.”

Protesting During a Pandemic

Despite the demands of treating COVID-19 patients, healthcare professionals have made the White Coat protests a priority, they said. Most – but not all – of the White Coats protests have been on medical campuses, allowing health care professionals to quickly assemble and get back to work. Plus, all of the protests have called on attendees to march and gather safely – with masks and distancing.

“Seeing that we are working in the hospital, it’s important for us to be wearing our masks, to be social distancing,” Dr. Azu said. Organizers asked attendees to ensure that they protested in a way that kept them “from worsening the COVID epidemic,” said Dr. Azu.

Unlike many others, the first protest in Portland was in conjunction with a larger group that assembles every evening in the square, said Dr. Fields. The physician protesters were wearing masks and maintaining distance from each other, especially when they kneeled, he said.

The protests have provided an escape from the futility of not being able to do anything for COVID-19 patients except to provide support, said Dr. Verghese. “In so many ways, we find ourselves powerless,” she said.

Protesting, Dr. Verghese added, was “one tiny moment where I got to regain my sense of agency, that I could actually do something about this.”

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

QI initiative can decrease unnecessary IV treatment of asymptomatic hypertension

Background: Limited research suggests IV treatment of asymptomatic hypertension may be widespread and unhelpful. There is potential for unnecessary treatment to have adverse outcomes, such as hypotension.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: A single academic hospital.

Synopsis: Of 2,306 inpatients with asymptomatic hypertension, 11% were treated with IV medications to lower their blood pressure. Patients with indications for stricter blood pressure control (such as stroke, intracranial hemorrhage, aortic dissection) were excluded from the study. Following the baseline period, an education intervention was employed that included presentations, handouts, and posters. A second phase of quality improvement intervention included adjustment of the electronic medical record blood pressure alert parameters from more than 160/90 to more than 180/90. After these interventions, a lower percentage of patients received IV blood pressure medications for asymptomatic hypertension without a significant change in the number of rapid response calls, ICU transfers, or code blues. Limitations include that this is a single-center study and it is unclear if the performance improvement seen will be maintained over time.

Bottom line: IV antihypertensive use for asymptomatic hypertension is common despite lack of data to support its use, and reduced use is possible using quality improvement interventions.

Citation: Jacobs Z et al. Reducing unnecessary treatment of asymptomatic elevated blood pressure with intravenous medications on the general internal medicine wards: a quality improvement initiative. J Hosp Med. 2019 Mar;14(3):144-50.

Dr. Sharma is associate medical director for clinical education in hospital medicine at Duke Regional Hospital and an assistant professor of medicine at Duke University.

Background: Limited research suggests IV treatment of asymptomatic hypertension may be widespread and unhelpful. There is potential for unnecessary treatment to have adverse outcomes, such as hypotension.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: A single academic hospital.

Synopsis: Of 2,306 inpatients with asymptomatic hypertension, 11% were treated with IV medications to lower their blood pressure. Patients with indications for stricter blood pressure control (such as stroke, intracranial hemorrhage, aortic dissection) were excluded from the study. Following the baseline period, an education intervention was employed that included presentations, handouts, and posters. A second phase of quality improvement intervention included adjustment of the electronic medical record blood pressure alert parameters from more than 160/90 to more than 180/90. After these interventions, a lower percentage of patients received IV blood pressure medications for asymptomatic hypertension without a significant change in the number of rapid response calls, ICU transfers, or code blues. Limitations include that this is a single-center study and it is unclear if the performance improvement seen will be maintained over time.

Bottom line: IV antihypertensive use for asymptomatic hypertension is common despite lack of data to support its use, and reduced use is possible using quality improvement interventions.

Citation: Jacobs Z et al. Reducing unnecessary treatment of asymptomatic elevated blood pressure with intravenous medications on the general internal medicine wards: a quality improvement initiative. J Hosp Med. 2019 Mar;14(3):144-50.

Dr. Sharma is associate medical director for clinical education in hospital medicine at Duke Regional Hospital and an assistant professor of medicine at Duke University.

Background: Limited research suggests IV treatment of asymptomatic hypertension may be widespread and unhelpful. There is potential for unnecessary treatment to have adverse outcomes, such as hypotension.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: A single academic hospital.

Synopsis: Of 2,306 inpatients with asymptomatic hypertension, 11% were treated with IV medications to lower their blood pressure. Patients with indications for stricter blood pressure control (such as stroke, intracranial hemorrhage, aortic dissection) were excluded from the study. Following the baseline period, an education intervention was employed that included presentations, handouts, and posters. A second phase of quality improvement intervention included adjustment of the electronic medical record blood pressure alert parameters from more than 160/90 to more than 180/90. After these interventions, a lower percentage of patients received IV blood pressure medications for asymptomatic hypertension without a significant change in the number of rapid response calls, ICU transfers, or code blues. Limitations include that this is a single-center study and it is unclear if the performance improvement seen will be maintained over time.

Bottom line: IV antihypertensive use for asymptomatic hypertension is common despite lack of data to support its use, and reduced use is possible using quality improvement interventions.

Citation: Jacobs Z et al. Reducing unnecessary treatment of asymptomatic elevated blood pressure with intravenous medications on the general internal medicine wards: a quality improvement initiative. J Hosp Med. 2019 Mar;14(3):144-50.

Dr. Sharma is associate medical director for clinical education in hospital medicine at Duke Regional Hospital and an assistant professor of medicine at Duke University.

COVID-19-related inflammatory condition more common in black children in small study

More evidence has linked the Kawasaki-like multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children to COVID-19 and suggests that black children have a greater risk of the condition, according to a study published in the BMJ.

A small observational study in Paris found more than half of the 21 children who were admitted for the condition at the city’s pediatric hospital for COVID-19 patients were of African ancestry.

“The observation of a higher proportion of patients of African ancestry is consistent with recent findings, suggesting an effect of either social and living conditions or genetic susceptibility,” wrote Julie Toubiana, MD, PhD, of the University of Paris and the Pasteur Institute, and colleagues.

The findings did not surprise Edward M. Behrens, MD, chief of the division of rheumatology at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, whose institution has seen similar disparities that he attributes to social disadvantages.

“Infection rate will be higher in vulnerable populations that are less able to socially distance, have disproportionate numbers of essential workers, and have less access to health care and other resources,” Dr. Behrens said in an interview. “While there may be a role for genetics, environment – including social disparities – is almost certainly playing a role.”

Although the study’s small size is a limitation, he said, “the features described seem to mirror the experience of our center and what has been discussed more broadly amongst U.S. physicians.”

Byron Whyte, MD, a pediatrician in private practice in southeast Washington, found the differences in race interesting, but said the study was too small to draw any conclusions or generalize to the United States. But social disparities related to race are likely similar in France as they are in the United States, he said.

The prospective observational study assessed the clinical and demographic characteristics of all patients under age 18 who met the criteria for Kawasaki disease and were admitted between April 27 and May 20 to the Necker Hospital for Sick Children in Paris.

The 21 children had an average age of 8 years (ranging from 3 to 16), and 57% had at least one parent from sub-Saharan Africa or a Caribbean island; 14% had parents from Asia (two from China and one from Sri Lanka). The authors noted in their discussion that past U.S. and U.K. studies of Kawasaki disease have found a 2.5 times greater risk in Asian-American children and 1.5 times greater risk in African-American children compared with children with European ancestry.

Most of the patients (81%) needed intensive care, with 57% presenting with Kawasaki disease shock syndrome and 67% with myocarditis. Dr. Toubiana and associates also noted that “gastrointestinal symptoms were also unusually common, affecting all of our 21 patients.”

Only nine of the children reported having symptoms of a viral-like illness when they were admitted, primarily headache, cough, coryza, and fever, plus anosmia in one child. Among those children, the Kawasaki symptoms began a median 45 days after onset of the viral symptoms (range 18-79 days).

Only two children showed no positive test result for current COVID-19 infection or antibodies. Eight (38%) of the children had positive PCR tests for SARS-CoV2, and 19 (90%) had positive tests for IgG antibodies. The two patients with both negative tests did not require intensive care and did not have myocarditis.

About half the patients (52%) met all the criteria of Kawasaki disease, and the other 10 had “incomplete Kawasaki disease.” The most common Kawasaki symptoms were the polymorphous skin rash, occurring in 76% of the patients, changes to the lips and oral cavity (76%), and bilateral bulbar conjunctival injection (81%). Three patients (14%) had pleural effusion, and 10 of them (48%) had pericardial effusion, Dr. Toubiana and associates reported.

But Dr. Behrens said he disagrees with the assertion that the illness described in the paper and what he is seeing at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia is related to Kawasaki disease.

“Most experts here in the U.S. seem to agree this is not Kawasaki disease, but a distinct clinical syndrome called multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children, or MIS-C, that seems to have some overlap with the most nonspecific features of Kawasaki disease,” said Dr. Behrens, who is the Joseph Lee Hollander Chair in Pediatric Rheumatology at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. He has coauthored a study currently under review and available as a preprint soon that examines the biologic mechanisms underlying MIS-C.

Neither Dr. Behrens nor Dr. Whyte believed the findings had clinical implications that might change practice, but Dr. Whyte said he will be paying closer attention to the black children he treats – 99% of his practice – who are recovering from COVID-19.

“And, because we know that the concerns of African Americans are often overlooked in health care,” Dr. Whyte said, physicians should “pay a little more attention to symptom reporting on those kids, since there is a possibility that those kids would need hospitalization.”

All the patients in the study were treated with intravenous immunoglobulin, and corticosteroids were administered to 10 of them (48%). Their median hospital stay was 8 days (5 days in intensive care), and all were discharged without any deaths.

“Only one patient had symptoms suggestive of acute covid-19 and most had positive serum test results for IgG antibodies, suggesting that the development of Kawasaki disease in these patients is more likely to be the result of a postviral immunological reaction,” Dr. Toubiana and associates said.

The research received no external funding, and neither the authors nor other quoted physicians had any relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Toubiana J et al. BMJ. 2020 Jun 3, doi: 10.1136 bmj.m2094.

More evidence has linked the Kawasaki-like multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children to COVID-19 and suggests that black children have a greater risk of the condition, according to a study published in the BMJ.

A small observational study in Paris found more than half of the 21 children who were admitted for the condition at the city’s pediatric hospital for COVID-19 patients were of African ancestry.

“The observation of a higher proportion of patients of African ancestry is consistent with recent findings, suggesting an effect of either social and living conditions or genetic susceptibility,” wrote Julie Toubiana, MD, PhD, of the University of Paris and the Pasteur Institute, and colleagues.

The findings did not surprise Edward M. Behrens, MD, chief of the division of rheumatology at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, whose institution has seen similar disparities that he attributes to social disadvantages.

“Infection rate will be higher in vulnerable populations that are less able to socially distance, have disproportionate numbers of essential workers, and have less access to health care and other resources,” Dr. Behrens said in an interview. “While there may be a role for genetics, environment – including social disparities – is almost certainly playing a role.”

Although the study’s small size is a limitation, he said, “the features described seem to mirror the experience of our center and what has been discussed more broadly amongst U.S. physicians.”

Byron Whyte, MD, a pediatrician in private practice in southeast Washington, found the differences in race interesting, but said the study was too small to draw any conclusions or generalize to the United States. But social disparities related to race are likely similar in France as they are in the United States, he said.

The prospective observational study assessed the clinical and demographic characteristics of all patients under age 18 who met the criteria for Kawasaki disease and were admitted between April 27 and May 20 to the Necker Hospital for Sick Children in Paris.

The 21 children had an average age of 8 years (ranging from 3 to 16), and 57% had at least one parent from sub-Saharan Africa or a Caribbean island; 14% had parents from Asia (two from China and one from Sri Lanka). The authors noted in their discussion that past U.S. and U.K. studies of Kawasaki disease have found a 2.5 times greater risk in Asian-American children and 1.5 times greater risk in African-American children compared with children with European ancestry.

Most of the patients (81%) needed intensive care, with 57% presenting with Kawasaki disease shock syndrome and 67% with myocarditis. Dr. Toubiana and associates also noted that “gastrointestinal symptoms were also unusually common, affecting all of our 21 patients.”

Only nine of the children reported having symptoms of a viral-like illness when they were admitted, primarily headache, cough, coryza, and fever, plus anosmia in one child. Among those children, the Kawasaki symptoms began a median 45 days after onset of the viral symptoms (range 18-79 days).

Only two children showed no positive test result for current COVID-19 infection or antibodies. Eight (38%) of the children had positive PCR tests for SARS-CoV2, and 19 (90%) had positive tests for IgG antibodies. The two patients with both negative tests did not require intensive care and did not have myocarditis.

About half the patients (52%) met all the criteria of Kawasaki disease, and the other 10 had “incomplete Kawasaki disease.” The most common Kawasaki symptoms were the polymorphous skin rash, occurring in 76% of the patients, changes to the lips and oral cavity (76%), and bilateral bulbar conjunctival injection (81%). Three patients (14%) had pleural effusion, and 10 of them (48%) had pericardial effusion, Dr. Toubiana and associates reported.

But Dr. Behrens said he disagrees with the assertion that the illness described in the paper and what he is seeing at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia is related to Kawasaki disease.

“Most experts here in the U.S. seem to agree this is not Kawasaki disease, but a distinct clinical syndrome called multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children, or MIS-C, that seems to have some overlap with the most nonspecific features of Kawasaki disease,” said Dr. Behrens, who is the Joseph Lee Hollander Chair in Pediatric Rheumatology at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. He has coauthored a study currently under review and available as a preprint soon that examines the biologic mechanisms underlying MIS-C.

Neither Dr. Behrens nor Dr. Whyte believed the findings had clinical implications that might change practice, but Dr. Whyte said he will be paying closer attention to the black children he treats – 99% of his practice – who are recovering from COVID-19.

“And, because we know that the concerns of African Americans are often overlooked in health care,” Dr. Whyte said, physicians should “pay a little more attention to symptom reporting on those kids, since there is a possibility that those kids would need hospitalization.”

All the patients in the study were treated with intravenous immunoglobulin, and corticosteroids were administered to 10 of them (48%). Their median hospital stay was 8 days (5 days in intensive care), and all were discharged without any deaths.

“Only one patient had symptoms suggestive of acute covid-19 and most had positive serum test results for IgG antibodies, suggesting that the development of Kawasaki disease in these patients is more likely to be the result of a postviral immunological reaction,” Dr. Toubiana and associates said.

The research received no external funding, and neither the authors nor other quoted physicians had any relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Toubiana J et al. BMJ. 2020 Jun 3, doi: 10.1136 bmj.m2094.

More evidence has linked the Kawasaki-like multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children to COVID-19 and suggests that black children have a greater risk of the condition, according to a study published in the BMJ.

A small observational study in Paris found more than half of the 21 children who were admitted for the condition at the city’s pediatric hospital for COVID-19 patients were of African ancestry.

“The observation of a higher proportion of patients of African ancestry is consistent with recent findings, suggesting an effect of either social and living conditions or genetic susceptibility,” wrote Julie Toubiana, MD, PhD, of the University of Paris and the Pasteur Institute, and colleagues.

The findings did not surprise Edward M. Behrens, MD, chief of the division of rheumatology at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, whose institution has seen similar disparities that he attributes to social disadvantages.

“Infection rate will be higher in vulnerable populations that are less able to socially distance, have disproportionate numbers of essential workers, and have less access to health care and other resources,” Dr. Behrens said in an interview. “While there may be a role for genetics, environment – including social disparities – is almost certainly playing a role.”

Although the study’s small size is a limitation, he said, “the features described seem to mirror the experience of our center and what has been discussed more broadly amongst U.S. physicians.”

Byron Whyte, MD, a pediatrician in private practice in southeast Washington, found the differences in race interesting, but said the study was too small to draw any conclusions or generalize to the United States. But social disparities related to race are likely similar in France as they are in the United States, he said.

The prospective observational study assessed the clinical and demographic characteristics of all patients under age 18 who met the criteria for Kawasaki disease and were admitted between April 27 and May 20 to the Necker Hospital for Sick Children in Paris.

The 21 children had an average age of 8 years (ranging from 3 to 16), and 57% had at least one parent from sub-Saharan Africa or a Caribbean island; 14% had parents from Asia (two from China and one from Sri Lanka). The authors noted in their discussion that past U.S. and U.K. studies of Kawasaki disease have found a 2.5 times greater risk in Asian-American children and 1.5 times greater risk in African-American children compared with children with European ancestry.

Most of the patients (81%) needed intensive care, with 57% presenting with Kawasaki disease shock syndrome and 67% with myocarditis. Dr. Toubiana and associates also noted that “gastrointestinal symptoms were also unusually common, affecting all of our 21 patients.”

Only nine of the children reported having symptoms of a viral-like illness when they were admitted, primarily headache, cough, coryza, and fever, plus anosmia in one child. Among those children, the Kawasaki symptoms began a median 45 days after onset of the viral symptoms (range 18-79 days).

Only two children showed no positive test result for current COVID-19 infection or antibodies. Eight (38%) of the children had positive PCR tests for SARS-CoV2, and 19 (90%) had positive tests for IgG antibodies. The two patients with both negative tests did not require intensive care and did not have myocarditis.

About half the patients (52%) met all the criteria of Kawasaki disease, and the other 10 had “incomplete Kawasaki disease.” The most common Kawasaki symptoms were the polymorphous skin rash, occurring in 76% of the patients, changes to the lips and oral cavity (76%), and bilateral bulbar conjunctival injection (81%). Three patients (14%) had pleural effusion, and 10 of them (48%) had pericardial effusion, Dr. Toubiana and associates reported.

But Dr. Behrens said he disagrees with the assertion that the illness described in the paper and what he is seeing at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia is related to Kawasaki disease.

“Most experts here in the U.S. seem to agree this is not Kawasaki disease, but a distinct clinical syndrome called multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children, or MIS-C, that seems to have some overlap with the most nonspecific features of Kawasaki disease,” said Dr. Behrens, who is the Joseph Lee Hollander Chair in Pediatric Rheumatology at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. He has coauthored a study currently under review and available as a preprint soon that examines the biologic mechanisms underlying MIS-C.

Neither Dr. Behrens nor Dr. Whyte believed the findings had clinical implications that might change practice, but Dr. Whyte said he will be paying closer attention to the black children he treats – 99% of his practice – who are recovering from COVID-19.

“And, because we know that the concerns of African Americans are often overlooked in health care,” Dr. Whyte said, physicians should “pay a little more attention to symptom reporting on those kids, since there is a possibility that those kids would need hospitalization.”

All the patients in the study were treated with intravenous immunoglobulin, and corticosteroids were administered to 10 of them (48%). Their median hospital stay was 8 days (5 days in intensive care), and all were discharged without any deaths.

“Only one patient had symptoms suggestive of acute covid-19 and most had positive serum test results for IgG antibodies, suggesting that the development of Kawasaki disease in these patients is more likely to be the result of a postviral immunological reaction,” Dr. Toubiana and associates said.

The research received no external funding, and neither the authors nor other quoted physicians had any relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Toubiana J et al. BMJ. 2020 Jun 3, doi: 10.1136 bmj.m2094.

FROM BMJ

COVID-19 neurologic effects: Does the virus directly attack the brain?

A new review article summarizes what is known so far, and what clinicians need to look out for.

“We frequently see neurological conditions in people with COVID-19, but we understand very little about these effects. Is it the virus entering the brain/nerves or are they a result of a general inflammation or immune response – a bystander effect of people being severely ill. It is probably a combination of both,” said senior author Serena Spudich, MD, Gilbert H. Glaser Professor of Neurology; division chief of neurological infections & global neurology; and codirector of the Center for Neuroepidemiology and Clinical Neurological Research at Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

“Our message is that there are fairly frequent neurological sequelae of COVID-19 and we need to be alert to these, and to try to understand the potential long-term consequences,” she said.

The review was published online May 29 in JAMA Neurology.

Brain changes linked to loss of smell

In a separate article also published online in JAMA Neurology the same day, an Italian group describes a COVID-19 patient with anosmia (loss of sense of smell) who showed brain abnormalities on MRI in the areas associated with smell – the right gyrus rectus and the olfactory bulbs. These changes were resolved on later scan and the patient recovered her sense of smell.

“Based on the MRI findings, we can speculate that SARS-CoV-2 might invade the brain through the olfactory pathway,” conclude the researchers, led by first author Letterio S. Politi, MD, of the department of neuroradiology at IRCCS Istituto Clinico Humanitas and Humanitas University, Milan, Italy.

Can coronaviruses enter the CNS?

Dr. Spudich described this case report as “compelling evidence suggesting that loss of smell is a neurologic effect.”

“Loss of smell and/or taste is a common symptom in COVID-19, so this may suggest that an awful lot of people have some neurological involvement,” Dr. Spudich commented. “While a transient loss of smell or taste is not serious, if the virus has infected brain tissue the question is could this then spread to other parts of the brain and cause other more serious neurological effects,” she added.

In their review article, Dr. Spudich and colleagues present evidence showing that coronaviruses can enter the CNS.

“We know that SARS-1 and MERS have been shown to enter the nervous system and several coronaviruses have been shown to cause direct brain effects,” she said. “There is also some evidence that SARS-CoV-2 can do this too. As well as these latest MRI findings linked to loss of smell, there is a report of the virus being found in endothelial cells in the brain and a French autopsy study has also detected virus in the brain.”

Complications of other systemic effects?

Dr. Spudich is a neurologist specializing in neurologic consequences of infectious disease. “We don’t normally have such vast numbers of patients but in the last 3 months there has been an avalanche,” she says. From her personal experience, she believes the majority of neurologic symptoms in COVID-19 patients are most probably complications of other systemic effects, such as kidney, heart, or liver problems. But there is likely also a direct viral effect on the CNS in some patients.

“Reports from China suggested that serious neurologic effects were present in about one-third of hospitalized COVID-19 patients. I would say in our experience the figure would be less than that – maybe around 10%,” she noted.

Some COVID-19 patients are presenting with primary neurologic symptoms. For example, an elderly person may first develop confusion rather than a cough or shortness of breath; others have had severe headache as an initial COVID-19 symptom, Dr. Spudich reported. “Medical staff need to be aware of this – a severe headache in a patient who doesn’t normally get headaches could be a sign of the virus.”

Some of the neurologic symptoms could be caused by autoimmunity. Dr. Spudich explained that, in acute HIV infection a small proportion of patients can first present with autoimmune neurologic effects such as Guillain-Barré syndrome, an autoimmune condition of the nerves which causes a tingling sensation in the hands and feet. “This is well described in HIV, but we are also now seeing this in COVID-19 patients too,” she said. “A panoply of conditions can be caused by autoimmunity.”

On the increase in strokes that has been reported in COVID-19 patients, Dr. Spudich said, “this could be due to direct effects of the virus (e.g., causing an increase in coagulation or infecting the endothelial cells in the brain) or it could just be the final trigger for patients who were at risk of stroke anyway.”

There have been some very high-profile reports of younger patients with major strokes, she said, “but we haven’t seen that in our hospital. For the most part in my experience, strokes are happening in older COVID-19 patients with stroke risk factors such as AF [atrial fibrillation], hypertension, and diabetes. We haven’t seen a preponderance of strokes in young, otherwise healthy people.”

Even in patients who have neurologic effects as the first sign of COVID-19 infection, it is not known whether these symptoms are caused directly by the virus.

“We know that flu can cause people to have headaches, but that is because of an increase in inflammatory cytokines. On the other hand, patients with acute HIV infection often have headaches as a result of the virus getting into the brain. We don’t know where in this [cluster] COVID-19 virus falls,” Dr. Spudich said.

Much is still unknown

“The information we have is very sparse at this point. We need far more systematic information on this from CSF samples and imaging.” Dr. Spudich urged clinicians to try to collect such information in patients with neurologic symptoms.

Acknowledging that fewer such tests are being done at present because of concerns over infection risk, Dr. Spudich suggested that some changes in procedure may help. “In our hospital we have a portable MRI scanner which can be brought to the patient. This means the patient does not have to move across the hospital for a scan. This helps us to decide whether the patient has had a stroke, which can be missed when patients are on a ventilator.”

It is also unclear whether the neurologic effects seen during COVID-19 infection will last long term.

Dr. Spudich noted that there have been reports of COVID-19 patients discharged from intensive care having difficulty with higher cognitive function for some time thereafter. “This can happen after being in ICU but is it more pronounced in COVID-19 patients? An ongoing study is underway to look at this,” she said.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A new review article summarizes what is known so far, and what clinicians need to look out for.

“We frequently see neurological conditions in people with COVID-19, but we understand very little about these effects. Is it the virus entering the brain/nerves or are they a result of a general inflammation or immune response – a bystander effect of people being severely ill. It is probably a combination of both,” said senior author Serena Spudich, MD, Gilbert H. Glaser Professor of Neurology; division chief of neurological infections & global neurology; and codirector of the Center for Neuroepidemiology and Clinical Neurological Research at Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

“Our message is that there are fairly frequent neurological sequelae of COVID-19 and we need to be alert to these, and to try to understand the potential long-term consequences,” she said.

The review was published online May 29 in JAMA Neurology.

Brain changes linked to loss of smell

In a separate article also published online in JAMA Neurology the same day, an Italian group describes a COVID-19 patient with anosmia (loss of sense of smell) who showed brain abnormalities on MRI in the areas associated with smell – the right gyrus rectus and the olfactory bulbs. These changes were resolved on later scan and the patient recovered her sense of smell.

“Based on the MRI findings, we can speculate that SARS-CoV-2 might invade the brain through the olfactory pathway,” conclude the researchers, led by first author Letterio S. Politi, MD, of the department of neuroradiology at IRCCS Istituto Clinico Humanitas and Humanitas University, Milan, Italy.

Can coronaviruses enter the CNS?

Dr. Spudich described this case report as “compelling evidence suggesting that loss of smell is a neurologic effect.”

“Loss of smell and/or taste is a common symptom in COVID-19, so this may suggest that an awful lot of people have some neurological involvement,” Dr. Spudich commented. “While a transient loss of smell or taste is not serious, if the virus has infected brain tissue the question is could this then spread to other parts of the brain and cause other more serious neurological effects,” she added.

In their review article, Dr. Spudich and colleagues present evidence showing that coronaviruses can enter the CNS.

“We know that SARS-1 and MERS have been shown to enter the nervous system and several coronaviruses have been shown to cause direct brain effects,” she said. “There is also some evidence that SARS-CoV-2 can do this too. As well as these latest MRI findings linked to loss of smell, there is a report of the virus being found in endothelial cells in the brain and a French autopsy study has also detected virus in the brain.”

Complications of other systemic effects?

Dr. Spudich is a neurologist specializing in neurologic consequences of infectious disease. “We don’t normally have such vast numbers of patients but in the last 3 months there has been an avalanche,” she says. From her personal experience, she believes the majority of neurologic symptoms in COVID-19 patients are most probably complications of other systemic effects, such as kidney, heart, or liver problems. But there is likely also a direct viral effect on the CNS in some patients.

“Reports from China suggested that serious neurologic effects were present in about one-third of hospitalized COVID-19 patients. I would say in our experience the figure would be less than that – maybe around 10%,” she noted.

Some COVID-19 patients are presenting with primary neurologic symptoms. For example, an elderly person may first develop confusion rather than a cough or shortness of breath; others have had severe headache as an initial COVID-19 symptom, Dr. Spudich reported. “Medical staff need to be aware of this – a severe headache in a patient who doesn’t normally get headaches could be a sign of the virus.”

Some of the neurologic symptoms could be caused by autoimmunity. Dr. Spudich explained that, in acute HIV infection a small proportion of patients can first present with autoimmune neurologic effects such as Guillain-Barré syndrome, an autoimmune condition of the nerves which causes a tingling sensation in the hands and feet. “This is well described in HIV, but we are also now seeing this in COVID-19 patients too,” she said. “A panoply of conditions can be caused by autoimmunity.”

On the increase in strokes that has been reported in COVID-19 patients, Dr. Spudich said, “this could be due to direct effects of the virus (e.g., causing an increase in coagulation or infecting the endothelial cells in the brain) or it could just be the final trigger for patients who were at risk of stroke anyway.”

There have been some very high-profile reports of younger patients with major strokes, she said, “but we haven’t seen that in our hospital. For the most part in my experience, strokes are happening in older COVID-19 patients with stroke risk factors such as AF [atrial fibrillation], hypertension, and diabetes. We haven’t seen a preponderance of strokes in young, otherwise healthy people.”

Even in patients who have neurologic effects as the first sign of COVID-19 infection, it is not known whether these symptoms are caused directly by the virus.

“We know that flu can cause people to have headaches, but that is because of an increase in inflammatory cytokines. On the other hand, patients with acute HIV infection often have headaches as a result of the virus getting into the brain. We don’t know where in this [cluster] COVID-19 virus falls,” Dr. Spudich said.

Much is still unknown

“The information we have is very sparse at this point. We need far more systematic information on this from CSF samples and imaging.” Dr. Spudich urged clinicians to try to collect such information in patients with neurologic symptoms.

Acknowledging that fewer such tests are being done at present because of concerns over infection risk, Dr. Spudich suggested that some changes in procedure may help. “In our hospital we have a portable MRI scanner which can be brought to the patient. This means the patient does not have to move across the hospital for a scan. This helps us to decide whether the patient has had a stroke, which can be missed when patients are on a ventilator.”

It is also unclear whether the neurologic effects seen during COVID-19 infection will last long term.

Dr. Spudich noted that there have been reports of COVID-19 patients discharged from intensive care having difficulty with higher cognitive function for some time thereafter. “This can happen after being in ICU but is it more pronounced in COVID-19 patients? An ongoing study is underway to look at this,” she said.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A new review article summarizes what is known so far, and what clinicians need to look out for.

“We frequently see neurological conditions in people with COVID-19, but we understand very little about these effects. Is it the virus entering the brain/nerves or are they a result of a general inflammation or immune response – a bystander effect of people being severely ill. It is probably a combination of both,” said senior author Serena Spudich, MD, Gilbert H. Glaser Professor of Neurology; division chief of neurological infections & global neurology; and codirector of the Center for Neuroepidemiology and Clinical Neurological Research at Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

“Our message is that there are fairly frequent neurological sequelae of COVID-19 and we need to be alert to these, and to try to understand the potential long-term consequences,” she said.

The review was published online May 29 in JAMA Neurology.

Brain changes linked to loss of smell

In a separate article also published online in JAMA Neurology the same day, an Italian group describes a COVID-19 patient with anosmia (loss of sense of smell) who showed brain abnormalities on MRI in the areas associated with smell – the right gyrus rectus and the olfactory bulbs. These changes were resolved on later scan and the patient recovered her sense of smell.

“Based on the MRI findings, we can speculate that SARS-CoV-2 might invade the brain through the olfactory pathway,” conclude the researchers, led by first author Letterio S. Politi, MD, of the department of neuroradiology at IRCCS Istituto Clinico Humanitas and Humanitas University, Milan, Italy.

Can coronaviruses enter the CNS?

Dr. Spudich described this case report as “compelling evidence suggesting that loss of smell is a neurologic effect.”

“Loss of smell and/or taste is a common symptom in COVID-19, so this may suggest that an awful lot of people have some neurological involvement,” Dr. Spudich commented. “While a transient loss of smell or taste is not serious, if the virus has infected brain tissue the question is could this then spread to other parts of the brain and cause other more serious neurological effects,” she added.

In their review article, Dr. Spudich and colleagues present evidence showing that coronaviruses can enter the CNS.

“We know that SARS-1 and MERS have been shown to enter the nervous system and several coronaviruses have been shown to cause direct brain effects,” she said. “There is also some evidence that SARS-CoV-2 can do this too. As well as these latest MRI findings linked to loss of smell, there is a report of the virus being found in endothelial cells in the brain and a French autopsy study has also detected virus in the brain.”

Complications of other systemic effects?

Dr. Spudich is a neurologist specializing in neurologic consequences of infectious disease. “We don’t normally have such vast numbers of patients but in the last 3 months there has been an avalanche,” she says. From her personal experience, she believes the majority of neurologic symptoms in COVID-19 patients are most probably complications of other systemic effects, such as kidney, heart, or liver problems. But there is likely also a direct viral effect on the CNS in some patients.

“Reports from China suggested that serious neurologic effects were present in about one-third of hospitalized COVID-19 patients. I would say in our experience the figure would be less than that – maybe around 10%,” she noted.

Some COVID-19 patients are presenting with primary neurologic symptoms. For example, an elderly person may first develop confusion rather than a cough or shortness of breath; others have had severe headache as an initial COVID-19 symptom, Dr. Spudich reported. “Medical staff need to be aware of this – a severe headache in a patient who doesn’t normally get headaches could be a sign of the virus.”

Some of the neurologic symptoms could be caused by autoimmunity. Dr. Spudich explained that, in acute HIV infection a small proportion of patients can first present with autoimmune neurologic effects such as Guillain-Barré syndrome, an autoimmune condition of the nerves which causes a tingling sensation in the hands and feet. “This is well described in HIV, but we are also now seeing this in COVID-19 patients too,” she said. “A panoply of conditions can be caused by autoimmunity.”

On the increase in strokes that has been reported in COVID-19 patients, Dr. Spudich said, “this could be due to direct effects of the virus (e.g., causing an increase in coagulation or infecting the endothelial cells in the brain) or it could just be the final trigger for patients who were at risk of stroke anyway.”

There have been some very high-profile reports of younger patients with major strokes, she said, “but we haven’t seen that in our hospital. For the most part in my experience, strokes are happening in older COVID-19 patients with stroke risk factors such as AF [atrial fibrillation], hypertension, and diabetes. We haven’t seen a preponderance of strokes in young, otherwise healthy people.”

Even in patients who have neurologic effects as the first sign of COVID-19 infection, it is not known whether these symptoms are caused directly by the virus.

“We know that flu can cause people to have headaches, but that is because of an increase in inflammatory cytokines. On the other hand, patients with acute HIV infection often have headaches as a result of the virus getting into the brain. We don’t know where in this [cluster] COVID-19 virus falls,” Dr. Spudich said.

Much is still unknown

“The information we have is very sparse at this point. We need far more systematic information on this from CSF samples and imaging.” Dr. Spudich urged clinicians to try to collect such information in patients with neurologic symptoms.

Acknowledging that fewer such tests are being done at present because of concerns over infection risk, Dr. Spudich suggested that some changes in procedure may help. “In our hospital we have a portable MRI scanner which can be brought to the patient. This means the patient does not have to move across the hospital for a scan. This helps us to decide whether the patient has had a stroke, which can be missed when patients are on a ventilator.”

It is also unclear whether the neurologic effects seen during COVID-19 infection will last long term.

Dr. Spudich noted that there have been reports of COVID-19 patients discharged from intensive care having difficulty with higher cognitive function for some time thereafter. “This can happen after being in ICU but is it more pronounced in COVID-19 patients? An ongoing study is underway to look at this,” she said.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FDA approves new antibiotic for HABP/VABP treatment

in people aged 18 years and older.

Approval for Recarbrio was based on results of a randomized, controlled clinical trial of 535 hospitalized adults with hospital-acquired and ventilator-associated bacterial pneumonia who received either Recarbrio or piperacillin-tazobactam. After 28 days, 16% of patients who received Recarbrio and 21% of patients who received piperacillin-tazobactam had died.

The most common adverse events associated with Recarbrio are increased alanine aminotransferase/ aspartate aminotransferase, anemia, diarrhea, hypokalemia, and hyponatremia. Recarbrio was previously approved by the FDA to treat patients with complicated urinary tract infections and complicated intra-abdominal infections who have limited or no alternative treatment options, according to an FDA press release.

“As a public health agency, the FDA addresses the threat of antimicrobial-resistant infections by facilitating the development of safe and effective new treatments. These efforts provide more options to fight serious bacterial infections and get new, safe and effective therapies to patients as soon as possible,” said Sumathi Nambiar, MD, MPH, director of the division of anti-infectives within the office of infectious disease at the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research.

in people aged 18 years and older.

Approval for Recarbrio was based on results of a randomized, controlled clinical trial of 535 hospitalized adults with hospital-acquired and ventilator-associated bacterial pneumonia who received either Recarbrio or piperacillin-tazobactam. After 28 days, 16% of patients who received Recarbrio and 21% of patients who received piperacillin-tazobactam had died.

The most common adverse events associated with Recarbrio are increased alanine aminotransferase/ aspartate aminotransferase, anemia, diarrhea, hypokalemia, and hyponatremia. Recarbrio was previously approved by the FDA to treat patients with complicated urinary tract infections and complicated intra-abdominal infections who have limited or no alternative treatment options, according to an FDA press release.

“As a public health agency, the FDA addresses the threat of antimicrobial-resistant infections by facilitating the development of safe and effective new treatments. These efforts provide more options to fight serious bacterial infections and get new, safe and effective therapies to patients as soon as possible,” said Sumathi Nambiar, MD, MPH, director of the division of anti-infectives within the office of infectious disease at the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research.

in people aged 18 years and older.

Approval for Recarbrio was based on results of a randomized, controlled clinical trial of 535 hospitalized adults with hospital-acquired and ventilator-associated bacterial pneumonia who received either Recarbrio or piperacillin-tazobactam. After 28 days, 16% of patients who received Recarbrio and 21% of patients who received piperacillin-tazobactam had died.

The most common adverse events associated with Recarbrio are increased alanine aminotransferase/ aspartate aminotransferase, anemia, diarrhea, hypokalemia, and hyponatremia. Recarbrio was previously approved by the FDA to treat patients with complicated urinary tract infections and complicated intra-abdominal infections who have limited or no alternative treatment options, according to an FDA press release.

“As a public health agency, the FDA addresses the threat of antimicrobial-resistant infections by facilitating the development of safe and effective new treatments. These efforts provide more options to fight serious bacterial infections and get new, safe and effective therapies to patients as soon as possible,” said Sumathi Nambiar, MD, MPH, director of the division of anti-infectives within the office of infectious disease at the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research.

COVID-19: Use these strategies to help parents with and without special needs children

Most people can cope, to some degree, with the multiple weeks of social distancing and stressors related to the pandemic. But what if those stressors became a way of life for a year – or longer? What sorts of skills would be essential not only to survive but to have a renewed sense of resilience?

I know of one group that has had experiences that mirror the challenges faced by the parents of children: the parents of special needs children. As I argued previously, those parents have faced many of the challenges presented by COVID-19. Among those challenges are social distancing and difficulty accessing everyday common experiences. These parents know that they have to manage more areas of their children’s rearing than do their counterparts.

In addition to having to plan for how to deal with acute urgent or emergent medical situations involving their special needs children, these parents also must prepare for the long-term effects of managing children who require ongoing daily care, attention, and dedication.

These strategies can help the parents of special needs kids find a sense of mastery and comfort. The hope is that, after practicing them for long periods of time, the strategies become second nature.

Here are several strategies that might help patients with children during this pandemic:

- Take time to reset: Sometimes it is helpful for parents to take a minute away from a difficult impasse with their kids to reset and take their own “time out.” A few seconds of mental time away from the “scene” provides space and a mental reminder that the minute that just happened is finite, and that a whole new one is coming up next. The break provides a sense of hope. This cognitive reframing could be practiced often.

- Re-enter the challenging scene with a warm voice: Parents model for their children, but they also are telling their own brains that they, too, can calm down. This approach also de-escalates the situation and allows children to get used to hearing directions from someone who is in control – without hostility or irritability.

- Keep a sense of humor; it might come in handy: This is especially the case when tension is in the home, or when facing a set of challenging bad news. As an example, consider how some situations are so repetitive that they border on the ridiculous – such as a grown child having a tantrum at a store. Encourage the children to give themselves permission to cry first so they can laugh second, and then move on.

- Establish a routine for children that is self-reinforcing, and allows for together and separate times: They can, as an example: A) Get ready for the day all by themselves, or as much as they can do independently, before they come down and then B) have breakfast. Then, the child can C) do homework, and then D) go play outside. The routine would then continue on its own without outside reinforcers.

- Tell the children that they can get to the reinforcing activity only after completing the previous one. Over time, they learn to take pride in completing the first activity and doing so more independently. Not having to wait to be told what to do all the time fosters a sense of independence.

- Plan for meals and fun tasks together, and separate for individual work. This creates a sense of change and gives the day a certain flow. Establish routines that are predictable for the children that can be easily documented for the whole family on a calendar. Establish a beginning and an end time to the work day. Mark the end of the day with a chalk line establishing when the family can engage in a certain activity, for example, going for a family bike ride. Let the routine honor healthy circadian rhythms for sleep/wakeful times, and be consistent.

- Feed the brain and body the “good stuff”: Limit negative news, and surround the children with people who bring them joy or provide hope. Listen to inspirational messages and uplifting music. Give the children food that nourishes and energizes their bodies. Take in the view outside, the greenery, or the sky if there is no green around. Connect with family/friends who are far away.

- Make time to replenish with something that is meaningful/productive/helpful: Parents have very little time for themselves when they are “on,” so when they can actually take a little time to recharge, the activity should check many boxes. For example, encourage them to go for a walk (exercise) while listening to music (relax), make a phone call to someone who can relate to their situation (socialize), pray with someone (be spiritual), or sit in their rooms to get some alone quiet time (meditate). Reach out to those who are lonely. Network. Mentor. Volunteer.

- Develop an eye for noticing the positive: Instead of hoping for things to go back to the way they were, tell your patients to practice embracing without judgment the new norm. Get them to notice the time they spend with their families. Break all tasks into many smaller tasks, so there is more possibility of observing progress, and it is evident for everyone to see. Learn to notice the small changes that they want to see in their children. Celebrate all that can be celebrated by stating the obvious: “You wiped your face after eating. You are observant; you are noticing when you have something on your face.”

- State when a child is forgiving, helpful, or puts forward some effort. Label the growth witnessed. The child will learn that that is who they are over time (“observant”). Verbalizing these behaviors also will provide patients with a sense of mastery over parenting, because they are driving the emotional and behavioral development of their children in a way that also complements their family values.

- Make everyone in the family a contributor and foster a sense of gratitude: Give everyone a reason to claim that their collaboration and effort are a big part of the plan’s success. Take turns to lessen everyone’s burden and to thank them for their contributions. Older children can take on leadership roles, even in small ways. Younger children can practice being good listeners, following directions, and helping. Reverse the roles when possible.

Special needs families sometimes have to work harder than others to overcome obstacles, grow, and learn to support one another. Since the pandemic, many parents have been just as challenged. Mastering the above skills might provide a sense of fulfillment and agency, as well as an appreciation for the unexpected gifts that special children – and all children – have to offer.

Dr. Sotir is a psychiatrist with a private practice in Wheaton, Ill. As a parent of three children, one with special needs, she has extensive experience helping parents challenged by having special needs children find balance, support, direction, and joy in all dimensions of individual and family life. This area is the focus of her practice and public speaking. She has no disclosures.

Most people can cope, to some degree, with the multiple weeks of social distancing and stressors related to the pandemic. But what if those stressors became a way of life for a year – or longer? What sorts of skills would be essential not only to survive but to have a renewed sense of resilience?

I know of one group that has had experiences that mirror the challenges faced by the parents of children: the parents of special needs children. As I argued previously, those parents have faced many of the challenges presented by COVID-19. Among those challenges are social distancing and difficulty accessing everyday common experiences. These parents know that they have to manage more areas of their children’s rearing than do their counterparts.

In addition to having to plan for how to deal with acute urgent or emergent medical situations involving their special needs children, these parents also must prepare for the long-term effects of managing children who require ongoing daily care, attention, and dedication.

These strategies can help the parents of special needs kids find a sense of mastery and comfort. The hope is that, after practicing them for long periods of time, the strategies become second nature.

Here are several strategies that might help patients with children during this pandemic:

- Take time to reset: Sometimes it is helpful for parents to take a minute away from a difficult impasse with their kids to reset and take their own “time out.” A few seconds of mental time away from the “scene” provides space and a mental reminder that the minute that just happened is finite, and that a whole new one is coming up next. The break provides a sense of hope. This cognitive reframing could be practiced often.

- Re-enter the challenging scene with a warm voice: Parents model for their children, but they also are telling their own brains that they, too, can calm down. This approach also de-escalates the situation and allows children to get used to hearing directions from someone who is in control – without hostility or irritability.

- Keep a sense of humor; it might come in handy: This is especially the case when tension is in the home, or when facing a set of challenging bad news. As an example, consider how some situations are so repetitive that they border on the ridiculous – such as a grown child having a tantrum at a store. Encourage the children to give themselves permission to cry first so they can laugh second, and then move on.

- Establish a routine for children that is self-reinforcing, and allows for together and separate times: They can, as an example: A) Get ready for the day all by themselves, or as much as they can do independently, before they come down and then B) have breakfast. Then, the child can C) do homework, and then D) go play outside. The routine would then continue on its own without outside reinforcers.

- Tell the children that they can get to the reinforcing activity only after completing the previous one. Over time, they learn to take pride in completing the first activity and doing so more independently. Not having to wait to be told what to do all the time fosters a sense of independence.

- Plan for meals and fun tasks together, and separate for individual work. This creates a sense of change and gives the day a certain flow. Establish routines that are predictable for the children that can be easily documented for the whole family on a calendar. Establish a beginning and an end time to the work day. Mark the end of the day with a chalk line establishing when the family can engage in a certain activity, for example, going for a family bike ride. Let the routine honor healthy circadian rhythms for sleep/wakeful times, and be consistent.

- Feed the brain and body the “good stuff”: Limit negative news, and surround the children with people who bring them joy or provide hope. Listen to inspirational messages and uplifting music. Give the children food that nourishes and energizes their bodies. Take in the view outside, the greenery, or the sky if there is no green around. Connect with family/friends who are far away.