User login

Official news magazine of the Society of Hospital Medicine

Copyright by Society of Hospital Medicine or related companies. All rights reserved. ISSN 1553-085X

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-hospitalist')]

Developing guidance for patient movement requests

Clear guidelines in policy needed

In hospital medicine, inpatients often request more freedom to move within the hospital complex for a wide range of both benign and potentially concerning reasons, says Sara Stream, MD.

“Hospitalists are often confronted with a dilemma when considering these patient requests: how to promote patient-centered care and autonomy while balancing patient safety, concerns for hospital liability, and the delivery of timely, efficient medical care,” said Dr. Stream, a hospitalist at the VA New York Harbor Healthcare System. Guidance from medical literature and institutional policies on inpatient movement are lacking, so Dr. Stream coauthored an article seeking to develop a framework with which hospitalists can approach patient requests for liberalized movement.

The authors concluded that for a small subset of patients, liberalized movement within the hospital may be clinically feasible: those who are medically, physically, and psychiatrically stable enough to move off their assigned floors without inordinate risk. “For the rest of inpatients, movement outside their monitored inpatient settings may interfere with appropriate medical care and undermine the indications for acute hospitalization,” Dr. Stream said.

Creating institutional policy that identifies relevant clinical, legal and ethical considerations, while incorporating the varied perspectives of physicians, patients, nurses, and hospital administration/risk management will allow requests for increased movement to be evaluated systematically and transparently.

“When patients request liberalized movement, hospitalists should consider the requests systematically: first to identify the intent behind requests, and then to follow a framework to determine whether increased movement would be safe and allow appropriate medical care without creating additional risks,” Dr. Stream said.

Hospitalists should assess and compile individual patient requests for liberalized movement and work with other physicians, nurses, hospital administration, and risk management to devise pertinent policy on this issue that is specific to their institutions. “By eventually creating clear guidelines in policy, health care providers will spend less time managing each individual request to leave the floor because they have a systematic strategy for making consistent decisions about patient movement,” the authors concluded.

Reference

1. Stream S, Alfandre D. “Just Getting a Cup of Coffee” – Considering Best Practices for Patients’ Movement off the Hospital Floor. J Hosp Med. 2019 Nov. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3227.

Clear guidelines in policy needed

Clear guidelines in policy needed

In hospital medicine, inpatients often request more freedom to move within the hospital complex for a wide range of both benign and potentially concerning reasons, says Sara Stream, MD.

“Hospitalists are often confronted with a dilemma when considering these patient requests: how to promote patient-centered care and autonomy while balancing patient safety, concerns for hospital liability, and the delivery of timely, efficient medical care,” said Dr. Stream, a hospitalist at the VA New York Harbor Healthcare System. Guidance from medical literature and institutional policies on inpatient movement are lacking, so Dr. Stream coauthored an article seeking to develop a framework with which hospitalists can approach patient requests for liberalized movement.

The authors concluded that for a small subset of patients, liberalized movement within the hospital may be clinically feasible: those who are medically, physically, and psychiatrically stable enough to move off their assigned floors without inordinate risk. “For the rest of inpatients, movement outside their monitored inpatient settings may interfere with appropriate medical care and undermine the indications for acute hospitalization,” Dr. Stream said.

Creating institutional policy that identifies relevant clinical, legal and ethical considerations, while incorporating the varied perspectives of physicians, patients, nurses, and hospital administration/risk management will allow requests for increased movement to be evaluated systematically and transparently.

“When patients request liberalized movement, hospitalists should consider the requests systematically: first to identify the intent behind requests, and then to follow a framework to determine whether increased movement would be safe and allow appropriate medical care without creating additional risks,” Dr. Stream said.

Hospitalists should assess and compile individual patient requests for liberalized movement and work with other physicians, nurses, hospital administration, and risk management to devise pertinent policy on this issue that is specific to their institutions. “By eventually creating clear guidelines in policy, health care providers will spend less time managing each individual request to leave the floor because they have a systematic strategy for making consistent decisions about patient movement,” the authors concluded.

Reference

1. Stream S, Alfandre D. “Just Getting a Cup of Coffee” – Considering Best Practices for Patients’ Movement off the Hospital Floor. J Hosp Med. 2019 Nov. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3227.

In hospital medicine, inpatients often request more freedom to move within the hospital complex for a wide range of both benign and potentially concerning reasons, says Sara Stream, MD.

“Hospitalists are often confronted with a dilemma when considering these patient requests: how to promote patient-centered care and autonomy while balancing patient safety, concerns for hospital liability, and the delivery of timely, efficient medical care,” said Dr. Stream, a hospitalist at the VA New York Harbor Healthcare System. Guidance from medical literature and institutional policies on inpatient movement are lacking, so Dr. Stream coauthored an article seeking to develop a framework with which hospitalists can approach patient requests for liberalized movement.

The authors concluded that for a small subset of patients, liberalized movement within the hospital may be clinically feasible: those who are medically, physically, and psychiatrically stable enough to move off their assigned floors without inordinate risk. “For the rest of inpatients, movement outside their monitored inpatient settings may interfere with appropriate medical care and undermine the indications for acute hospitalization,” Dr. Stream said.

Creating institutional policy that identifies relevant clinical, legal and ethical considerations, while incorporating the varied perspectives of physicians, patients, nurses, and hospital administration/risk management will allow requests for increased movement to be evaluated systematically and transparently.

“When patients request liberalized movement, hospitalists should consider the requests systematically: first to identify the intent behind requests, and then to follow a framework to determine whether increased movement would be safe and allow appropriate medical care without creating additional risks,” Dr. Stream said.

Hospitalists should assess and compile individual patient requests for liberalized movement and work with other physicians, nurses, hospital administration, and risk management to devise pertinent policy on this issue that is specific to their institutions. “By eventually creating clear guidelines in policy, health care providers will spend less time managing each individual request to leave the floor because they have a systematic strategy for making consistent decisions about patient movement,” the authors concluded.

Reference

1. Stream S, Alfandre D. “Just Getting a Cup of Coffee” – Considering Best Practices for Patients’ Movement off the Hospital Floor. J Hosp Med. 2019 Nov. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3227.

CDC: Opioid prescribing and use rates down since 2010

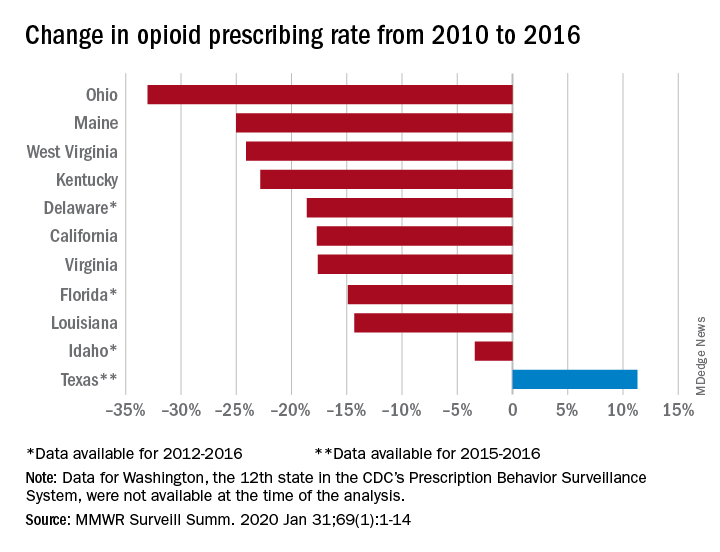

Trends in opioid prescribing and use from 2010 to 2016 offer some encouragement, but opioid-attributable deaths continued to increase over that period, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Prescribing rates dropped during that period, as did daily opioid dosage rates and the percentage of patients with high daily opioid dosages, Gail K. Strickler, PhD, of the Institute for Behavioral Health at Brandeis University in Waltham, Mass., and associates wrote in MMWR Surveillance Summaries.

Their analysis involved 11 of the 12 states (Washington was unable to provide data for the analysis) participating in the CDC’s Prescription Behavior Surveillance System, which uses data from the states’ prescription drug monitoring programs. The 11 states represented about 38% of the U.S. population in 2016.

The opioid prescribing rate fell in 10 of those 11 states, with declines varying from 3.4% in Idaho to 33.0% in Ohio. Prescribing went up in Texas by 11.3%, but the state only had data available for 2015 and 2016. Three other states – Delaware, Florida, and Idaho – were limited to data from 2012 to 2016, the investigators noted.

As for the other measures, all states showed declines for the mean daily opioid dosage. Texas had the smallest drop at 2.9% and Florida saw the largest, at 27.4%. All states also had reductions in the percentage of patients with high daily opioid dosage, with decreases varying from 5.7% in Idaho to 43.9% in Louisiana, Dr. Strickler and associates reported. A high daily dosage was defined as at least 90 morphine milligram equivalents for all class II-V opioid drugs.

“Despite these favorable trends ... opioid overdose deaths attributable to the most commonly prescribed opioids, the natural and semisynthetics (e.g., morphine and oxycodone), increased during 2010-2016,” they said.

It is possible that a change in mortality is lagging “behind changes in prescribing behaviors” or that “the trend in deaths related to these types of opioids has been driven by factors other than prescription opioid misuse rates, such as increasing mortality from heroin, which is frequently classified as morphine or found concomitantly with morphine postmortem, and a spike in deaths involving illicitly manufactured fentanyl combined with heroin and prescribed opioids since 2013,” the investigators suggested.

SOURCE: Strickler GK et al. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2020 Jan 31;69(1):1-14.

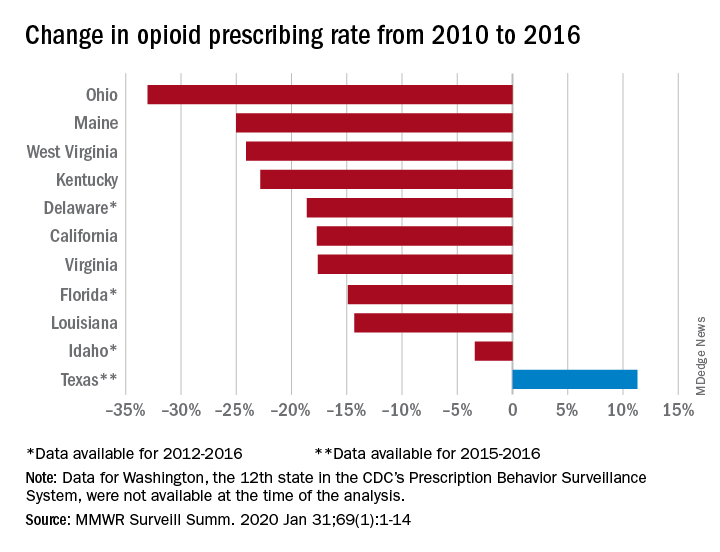

Trends in opioid prescribing and use from 2010 to 2016 offer some encouragement, but opioid-attributable deaths continued to increase over that period, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Prescribing rates dropped during that period, as did daily opioid dosage rates and the percentage of patients with high daily opioid dosages, Gail K. Strickler, PhD, of the Institute for Behavioral Health at Brandeis University in Waltham, Mass., and associates wrote in MMWR Surveillance Summaries.

Their analysis involved 11 of the 12 states (Washington was unable to provide data for the analysis) participating in the CDC’s Prescription Behavior Surveillance System, which uses data from the states’ prescription drug monitoring programs. The 11 states represented about 38% of the U.S. population in 2016.

The opioid prescribing rate fell in 10 of those 11 states, with declines varying from 3.4% in Idaho to 33.0% in Ohio. Prescribing went up in Texas by 11.3%, but the state only had data available for 2015 and 2016. Three other states – Delaware, Florida, and Idaho – were limited to data from 2012 to 2016, the investigators noted.

As for the other measures, all states showed declines for the mean daily opioid dosage. Texas had the smallest drop at 2.9% and Florida saw the largest, at 27.4%. All states also had reductions in the percentage of patients with high daily opioid dosage, with decreases varying from 5.7% in Idaho to 43.9% in Louisiana, Dr. Strickler and associates reported. A high daily dosage was defined as at least 90 morphine milligram equivalents for all class II-V opioid drugs.

“Despite these favorable trends ... opioid overdose deaths attributable to the most commonly prescribed opioids, the natural and semisynthetics (e.g., morphine and oxycodone), increased during 2010-2016,” they said.

It is possible that a change in mortality is lagging “behind changes in prescribing behaviors” or that “the trend in deaths related to these types of opioids has been driven by factors other than prescription opioid misuse rates, such as increasing mortality from heroin, which is frequently classified as morphine or found concomitantly with morphine postmortem, and a spike in deaths involving illicitly manufactured fentanyl combined with heroin and prescribed opioids since 2013,” the investigators suggested.

SOURCE: Strickler GK et al. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2020 Jan 31;69(1):1-14.

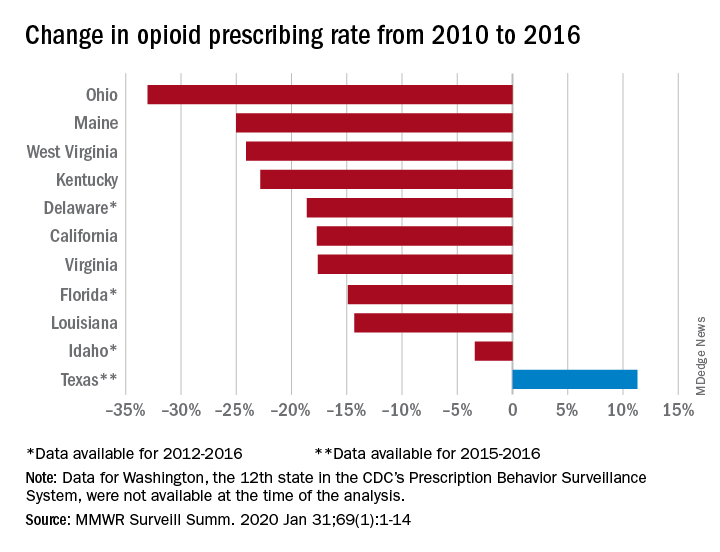

Trends in opioid prescribing and use from 2010 to 2016 offer some encouragement, but opioid-attributable deaths continued to increase over that period, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Prescribing rates dropped during that period, as did daily opioid dosage rates and the percentage of patients with high daily opioid dosages, Gail K. Strickler, PhD, of the Institute for Behavioral Health at Brandeis University in Waltham, Mass., and associates wrote in MMWR Surveillance Summaries.

Their analysis involved 11 of the 12 states (Washington was unable to provide data for the analysis) participating in the CDC’s Prescription Behavior Surveillance System, which uses data from the states’ prescription drug monitoring programs. The 11 states represented about 38% of the U.S. population in 2016.

The opioid prescribing rate fell in 10 of those 11 states, with declines varying from 3.4% in Idaho to 33.0% in Ohio. Prescribing went up in Texas by 11.3%, but the state only had data available for 2015 and 2016. Three other states – Delaware, Florida, and Idaho – were limited to data from 2012 to 2016, the investigators noted.

As for the other measures, all states showed declines for the mean daily opioid dosage. Texas had the smallest drop at 2.9% and Florida saw the largest, at 27.4%. All states also had reductions in the percentage of patients with high daily opioid dosage, with decreases varying from 5.7% in Idaho to 43.9% in Louisiana, Dr. Strickler and associates reported. A high daily dosage was defined as at least 90 morphine milligram equivalents for all class II-V opioid drugs.

“Despite these favorable trends ... opioid overdose deaths attributable to the most commonly prescribed opioids, the natural and semisynthetics (e.g., morphine and oxycodone), increased during 2010-2016,” they said.

It is possible that a change in mortality is lagging “behind changes in prescribing behaviors” or that “the trend in deaths related to these types of opioids has been driven by factors other than prescription opioid misuse rates, such as increasing mortality from heroin, which is frequently classified as morphine or found concomitantly with morphine postmortem, and a spike in deaths involving illicitly manufactured fentanyl combined with heroin and prescribed opioids since 2013,” the investigators suggested.

SOURCE: Strickler GK et al. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2020 Jan 31;69(1):1-14.

FROM MMWR SURVEILLANCE SUMMARIES

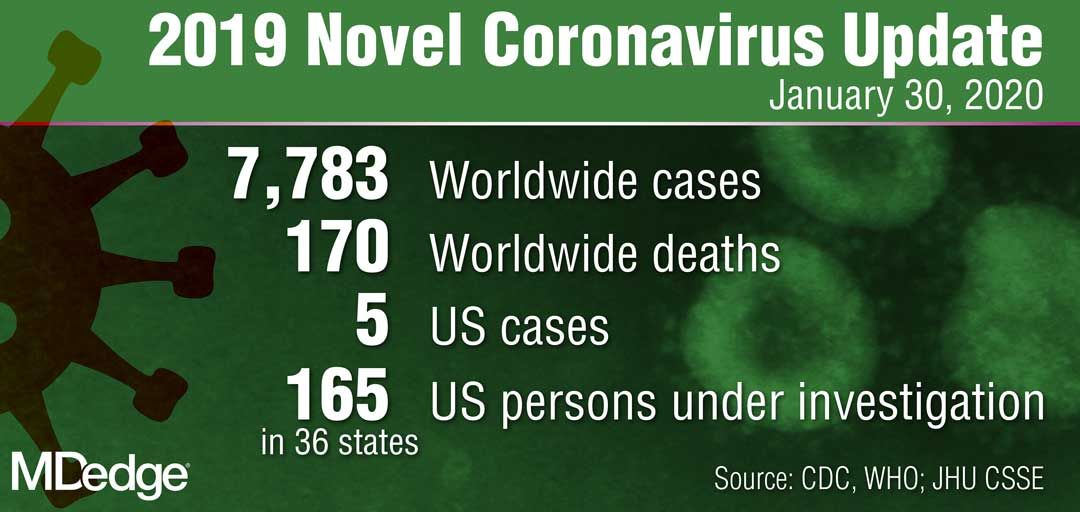

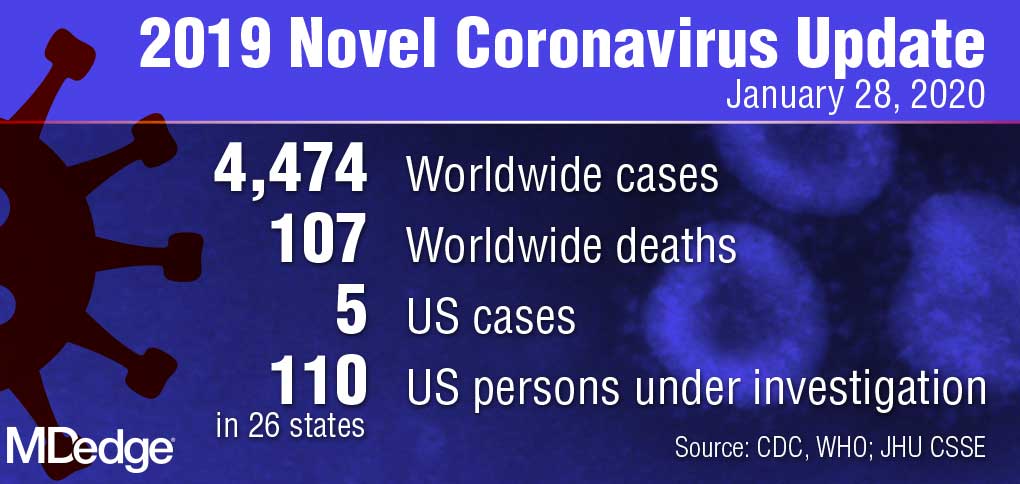

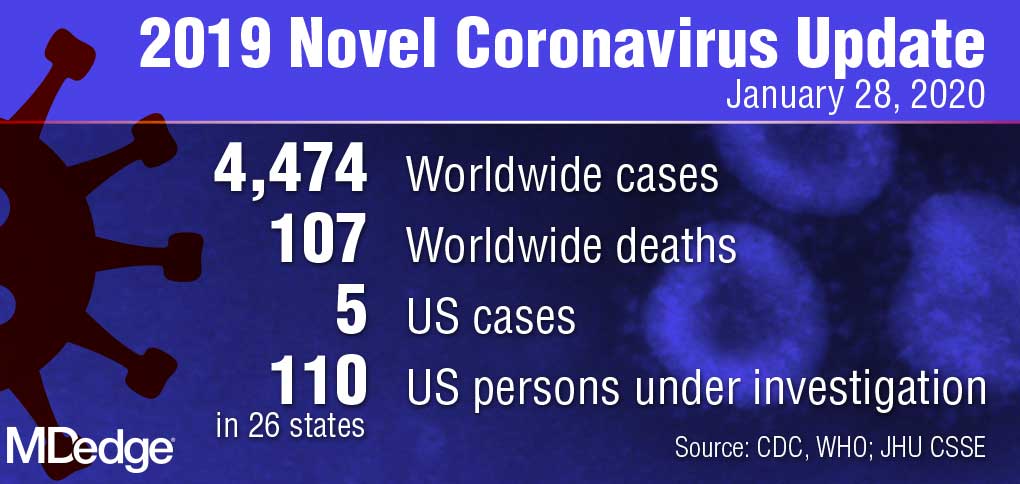

WHO declares public health emergency for novel coronavirus

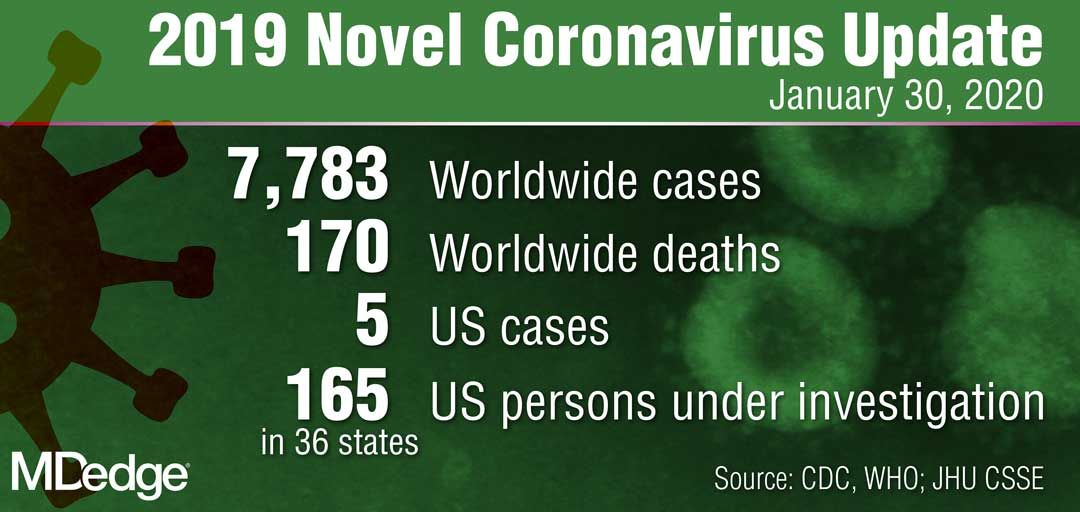

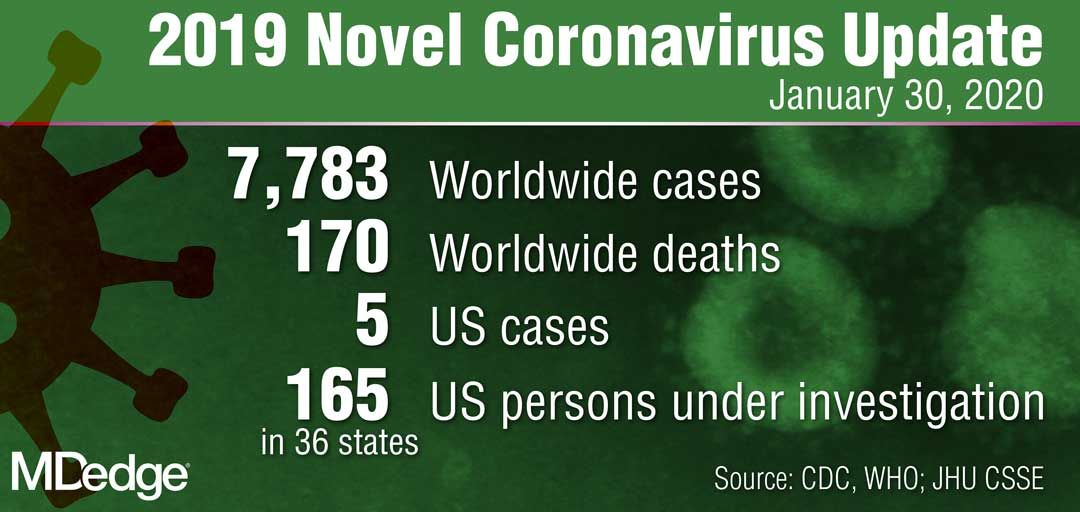

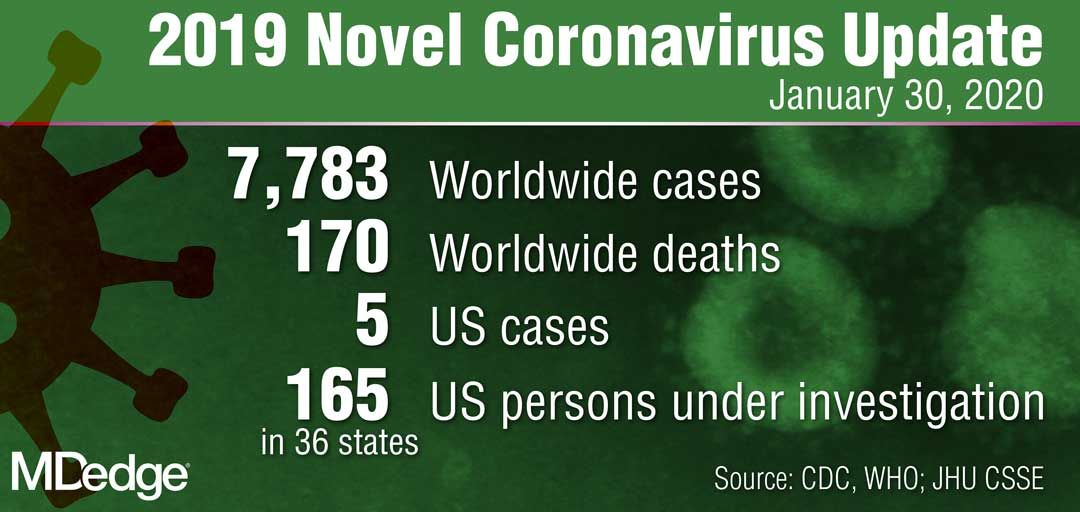

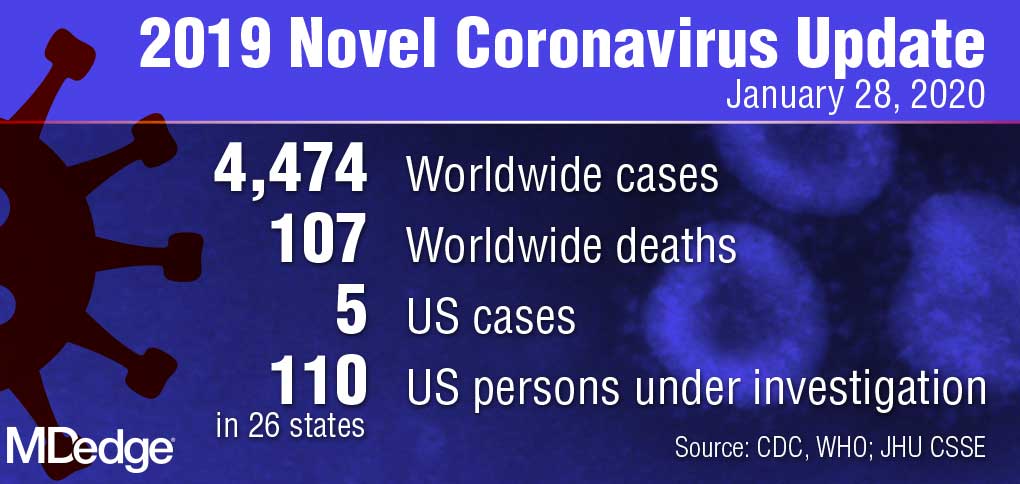

Amid the rising spread of the 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV),

The declaration was made during a press briefing on Jan. 30 after a week of growing concern and pressure on WHO to designate the virus at a higher emergency level. WHO’s Emergency Committee made the nearly unanimous decision after considering the increasing number of coronavirus cases in China, the rising infections outside of China, and the questionable measures some countries are taking regarding travel, said committee chair Didier Houssin, MD, said during the press conference.

As of Jan. 30, there were 8,236 confirmed cases of the coronavirus in China and 171 deaths, with another 112 cases identified outside of China in 21 other countries.

“Declaring a Public Health Emergency of International Concern is likely to facilitate [WHO’s] leadership role for public health measures, holding countries to account concerning additional measures they may take regarding travel, trade, quarantine or screening, research efforts, global coordination and anticipation of economic impact [and] support to vulnerable states,” Dr. Houssin said during the press conference. “Declaring a PHEIC should certainly not be seen as manifestation of distrust in the Chinese authorities and people which are doing tremendous efforts on the frontlines of this outbreak, with transparency, and let us hope, with success.”

What happens next?

Once a PHEIC is declared, WHO launches a series of steps, including the release of temporary recommendations for the affected country on health measures to implement and guidance for other countries on preventing and reducing the international spread of the disease, WHO spokesman Tarik Jasarevic said in an interview.

“The purpose of declaring a PHEIC is to advise the world on what measures need to be taken to enhance global health security by preventing international transmission of an infectious hazard,” he said.

Following the Jan. 30 press conference, WHO released temporary guidance for China and for other countries regarding identifying, managing, containing, and preventing the virus. China is advised to continue updating the population about the outbreak, continue enhancing its public health measures for containment and surveillance of cases, and to continue collaboration with WHO and other partners to investigate the epidemiology and evolution of the outbreak and share data on all human cases.

Other countries should be prepared for containment, including the active surveillance, early detection, isolation, case management, and prevention of virus transmission and to share full data with WHO, according to the recommendations.

Under the International Health Regulations (IHR), countries are required to share information and data with WHO. Additionally, WHO leaders advised the global community to support low- and middle-income countries with their response to the coronavirus and to facilitate diagnostics, potential vaccines, and therapeutics in these areas.

The IHR requires that countries implementing health measures that go beyond what WHO recommends must send to WHO the public health rationale and justification within 48 hours of their implementation for WHO review, Mr. Jasarevic noted.

“WHO is obliged to share the information about measures and the justification received with other countries involved,” he said.

PHEIC travel and resource impact

Declaration of a PHEIC means WHO will now oversee any travel restrictions made by other countries in response to 2019-nCoV. The agency recommends that countries conduct a risk and cost-benefit analysis before enacting travel restrictions and other countries are required to inform WHO about any travel measures taken.

“Countries will be asked to provide public health justification for any travel or trade measures that are not scientifically based, such as refusal of entry of suspect cases or unaffected persons to affected areas,” Mr. Jasarevic said in an interview.

As far as resources, the PHEIC mechanism is not a fundraising mechanism, but some donors might consider a PHEIC declaration as a trigger for releasing additional funding to respond to the health threat, he said.

Allison T. Chamberlain, PhD, acting director for the Emory Center for Public Health Preparedness and Research at the Emory Rollins School of Public Health in Atlanta, said national governments and nongovernmental aid organizations are among the most affected by a PHEIC because they are looked at to provide assistance to the most heavily affected areas and to bolster public health preparedness within their own borders.

“In terms of resources that are deployed, a Public Health Emergency of International Concern raises levels of international support and commitment to stopping the emergency,” Dr. Chamberlain said in an interview. “By doing so, it gives countries the needed flexibility to release financial resources of their own accord to support things like response teams that might go into heavily affected areas to assist, for instance.”

WHO Director-General Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus stressed that cooperation among countries is key during the PHEIC.

“We can only stop it together,” he said during the press conference. “This is the time for facts, not fear. This is the time for science, not rumors. This is the time for solidarity, not stigma.”

This is the sixth PHEIC declared by WHO in the last 10 years. Such declarations were made for the 2009 H1NI influenza pandemic, the 2014 polio resurgence, the 2014 Ebola outbreak in West Africa, the 2016 Zika virus, and the 2019 Kivu Ebola outbreak in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Amid the rising spread of the 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV),

The declaration was made during a press briefing on Jan. 30 after a week of growing concern and pressure on WHO to designate the virus at a higher emergency level. WHO’s Emergency Committee made the nearly unanimous decision after considering the increasing number of coronavirus cases in China, the rising infections outside of China, and the questionable measures some countries are taking regarding travel, said committee chair Didier Houssin, MD, said during the press conference.

As of Jan. 30, there were 8,236 confirmed cases of the coronavirus in China and 171 deaths, with another 112 cases identified outside of China in 21 other countries.

“Declaring a Public Health Emergency of International Concern is likely to facilitate [WHO’s] leadership role for public health measures, holding countries to account concerning additional measures they may take regarding travel, trade, quarantine or screening, research efforts, global coordination and anticipation of economic impact [and] support to vulnerable states,” Dr. Houssin said during the press conference. “Declaring a PHEIC should certainly not be seen as manifestation of distrust in the Chinese authorities and people which are doing tremendous efforts on the frontlines of this outbreak, with transparency, and let us hope, with success.”

What happens next?

Once a PHEIC is declared, WHO launches a series of steps, including the release of temporary recommendations for the affected country on health measures to implement and guidance for other countries on preventing and reducing the international spread of the disease, WHO spokesman Tarik Jasarevic said in an interview.

“The purpose of declaring a PHEIC is to advise the world on what measures need to be taken to enhance global health security by preventing international transmission of an infectious hazard,” he said.

Following the Jan. 30 press conference, WHO released temporary guidance for China and for other countries regarding identifying, managing, containing, and preventing the virus. China is advised to continue updating the population about the outbreak, continue enhancing its public health measures for containment and surveillance of cases, and to continue collaboration with WHO and other partners to investigate the epidemiology and evolution of the outbreak and share data on all human cases.

Other countries should be prepared for containment, including the active surveillance, early detection, isolation, case management, and prevention of virus transmission and to share full data with WHO, according to the recommendations.

Under the International Health Regulations (IHR), countries are required to share information and data with WHO. Additionally, WHO leaders advised the global community to support low- and middle-income countries with their response to the coronavirus and to facilitate diagnostics, potential vaccines, and therapeutics in these areas.

The IHR requires that countries implementing health measures that go beyond what WHO recommends must send to WHO the public health rationale and justification within 48 hours of their implementation for WHO review, Mr. Jasarevic noted.

“WHO is obliged to share the information about measures and the justification received with other countries involved,” he said.

PHEIC travel and resource impact

Declaration of a PHEIC means WHO will now oversee any travel restrictions made by other countries in response to 2019-nCoV. The agency recommends that countries conduct a risk and cost-benefit analysis before enacting travel restrictions and other countries are required to inform WHO about any travel measures taken.

“Countries will be asked to provide public health justification for any travel or trade measures that are not scientifically based, such as refusal of entry of suspect cases or unaffected persons to affected areas,” Mr. Jasarevic said in an interview.

As far as resources, the PHEIC mechanism is not a fundraising mechanism, but some donors might consider a PHEIC declaration as a trigger for releasing additional funding to respond to the health threat, he said.

Allison T. Chamberlain, PhD, acting director for the Emory Center for Public Health Preparedness and Research at the Emory Rollins School of Public Health in Atlanta, said national governments and nongovernmental aid organizations are among the most affected by a PHEIC because they are looked at to provide assistance to the most heavily affected areas and to bolster public health preparedness within their own borders.

“In terms of resources that are deployed, a Public Health Emergency of International Concern raises levels of international support and commitment to stopping the emergency,” Dr. Chamberlain said in an interview. “By doing so, it gives countries the needed flexibility to release financial resources of their own accord to support things like response teams that might go into heavily affected areas to assist, for instance.”

WHO Director-General Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus stressed that cooperation among countries is key during the PHEIC.

“We can only stop it together,” he said during the press conference. “This is the time for facts, not fear. This is the time for science, not rumors. This is the time for solidarity, not stigma.”

This is the sixth PHEIC declared by WHO in the last 10 years. Such declarations were made for the 2009 H1NI influenza pandemic, the 2014 polio resurgence, the 2014 Ebola outbreak in West Africa, the 2016 Zika virus, and the 2019 Kivu Ebola outbreak in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Amid the rising spread of the 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV),

The declaration was made during a press briefing on Jan. 30 after a week of growing concern and pressure on WHO to designate the virus at a higher emergency level. WHO’s Emergency Committee made the nearly unanimous decision after considering the increasing number of coronavirus cases in China, the rising infections outside of China, and the questionable measures some countries are taking regarding travel, said committee chair Didier Houssin, MD, said during the press conference.

As of Jan. 30, there were 8,236 confirmed cases of the coronavirus in China and 171 deaths, with another 112 cases identified outside of China in 21 other countries.

“Declaring a Public Health Emergency of International Concern is likely to facilitate [WHO’s] leadership role for public health measures, holding countries to account concerning additional measures they may take regarding travel, trade, quarantine or screening, research efforts, global coordination and anticipation of economic impact [and] support to vulnerable states,” Dr. Houssin said during the press conference. “Declaring a PHEIC should certainly not be seen as manifestation of distrust in the Chinese authorities and people which are doing tremendous efforts on the frontlines of this outbreak, with transparency, and let us hope, with success.”

What happens next?

Once a PHEIC is declared, WHO launches a series of steps, including the release of temporary recommendations for the affected country on health measures to implement and guidance for other countries on preventing and reducing the international spread of the disease, WHO spokesman Tarik Jasarevic said in an interview.

“The purpose of declaring a PHEIC is to advise the world on what measures need to be taken to enhance global health security by preventing international transmission of an infectious hazard,” he said.

Following the Jan. 30 press conference, WHO released temporary guidance for China and for other countries regarding identifying, managing, containing, and preventing the virus. China is advised to continue updating the population about the outbreak, continue enhancing its public health measures for containment and surveillance of cases, and to continue collaboration with WHO and other partners to investigate the epidemiology and evolution of the outbreak and share data on all human cases.

Other countries should be prepared for containment, including the active surveillance, early detection, isolation, case management, and prevention of virus transmission and to share full data with WHO, according to the recommendations.

Under the International Health Regulations (IHR), countries are required to share information and data with WHO. Additionally, WHO leaders advised the global community to support low- and middle-income countries with their response to the coronavirus and to facilitate diagnostics, potential vaccines, and therapeutics in these areas.

The IHR requires that countries implementing health measures that go beyond what WHO recommends must send to WHO the public health rationale and justification within 48 hours of their implementation for WHO review, Mr. Jasarevic noted.

“WHO is obliged to share the information about measures and the justification received with other countries involved,” he said.

PHEIC travel and resource impact

Declaration of a PHEIC means WHO will now oversee any travel restrictions made by other countries in response to 2019-nCoV. The agency recommends that countries conduct a risk and cost-benefit analysis before enacting travel restrictions and other countries are required to inform WHO about any travel measures taken.

“Countries will be asked to provide public health justification for any travel or trade measures that are not scientifically based, such as refusal of entry of suspect cases or unaffected persons to affected areas,” Mr. Jasarevic said in an interview.

As far as resources, the PHEIC mechanism is not a fundraising mechanism, but some donors might consider a PHEIC declaration as a trigger for releasing additional funding to respond to the health threat, he said.

Allison T. Chamberlain, PhD, acting director for the Emory Center for Public Health Preparedness and Research at the Emory Rollins School of Public Health in Atlanta, said national governments and nongovernmental aid organizations are among the most affected by a PHEIC because they are looked at to provide assistance to the most heavily affected areas and to bolster public health preparedness within their own borders.

“In terms of resources that are deployed, a Public Health Emergency of International Concern raises levels of international support and commitment to stopping the emergency,” Dr. Chamberlain said in an interview. “By doing so, it gives countries the needed flexibility to release financial resources of their own accord to support things like response teams that might go into heavily affected areas to assist, for instance.”

WHO Director-General Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus stressed that cooperation among countries is key during the PHEIC.

“We can only stop it together,” he said during the press conference. “This is the time for facts, not fear. This is the time for science, not rumors. This is the time for solidarity, not stigma.”

This is the sixth PHEIC declared by WHO in the last 10 years. Such declarations were made for the 2009 H1NI influenza pandemic, the 2014 polio resurgence, the 2014 Ebola outbreak in West Africa, the 2016 Zika virus, and the 2019 Kivu Ebola outbreak in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

2019 Novel Coronavirus: Frequently asked questions for clinicians

The 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) outbreak has unfolded so rapidly that many clinicians are scrambling to stay on top of it. Here are the answers to some frequently asked questions about how to prepare your clinic to respond to this outbreak.

Keep in mind that the outbreak is moving rapidly. Though scientific and epidemiologic knowledge has increased at unprecedented speed, there is much we don’t know, and some of what we think we know will change. Follow the links for the most up-to-date information.

What should our clinic do first?

Plan ahead with the following:

- Develop a plan for office staff to take travel histories from anyone with a respiratory illness and provide training for those who need it. Travel history at present should include asking about travel to China in the past 14 days, specifically Wuhan city or Hubei province.

- Review up-to-date infection control practices with all office staff and provide training for those who need it.

- Take an inventory of supplies of personal protective equipment (PPE), such as gowns, gloves, masks, eye protection, and N95 respirators or powered air-purifying respirators (PAPRs), and order items that are missing or low in stock.

- Fit-test users of N95 masks for maximal effectiveness.

- Plan where a potential patient would be isolated while obtaining expert advice.

- Know whom to contact at the state or local health department if you have a patient with the appropriate travel history.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has prepared a toolkit to help frontline health care professionals prepare for this virus. Providers need to stay up to date on the latest recommendations, as the situation is changing rapidly.

When should I suspect 2019-nCoV illness, and what should I do?

Take the following steps to assess the concern and respond:

- If a patient with respiratory illness has traveled to China in the past 14 days, immediately put a mask on the patient and move the individual to a private room. Use a negative-pressure room if available.

- Put on appropriate PPE (including gloves, gown, eye protection, and mask) for contact, droplet, and airborne precautions. CDC recommends an N95 respirator mask if available, although we don’t know yet if there is true airborne spread.

- Obtain an accurate travel history, including dates and cities. (Tip: Get the correct spelling, as the English spelling of cities in China can cause confusion.)

- If the patient meets the current CDC definition of “person under investigation” or PUI, or if you need guidance on how to proceed, notify infection control (if you are in a facility that has it) and call your state or local health department immediately.

- Contact public health authorities who can help decide whether the patient should be admitted to airborne isolation or monitored at home with appropriate precautions.

What is the definition of a PUI?

The current definition of a PUI is a person who has fever and symptoms of a respiratory infection (cough, shortness of breath) AND who has EITHER been in Wuhan city or Hubei province in the past 14 days OR had close contact with a person either under investigation for 2019-nCoV infection or with confirmed infection. The definition of a PUI will change over time, so check this link.

How can I test for 2019-nCoV?

As of Jan. 30, 2020, testing is by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and is available in the United States only through the CDC in Atlanta. Testing should soon be available in state health department laboratories. If public health authorities decide that your patient should be tested, they will instruct you on which samples to obtain.

The full sequence of 2019-nCoV has been shared, so some reference laboratories may develop and validate tests, ideally with assistance from CDC. If testing becomes available, make certain that it is a reputable lab that has carefully validated the test.

Should I test for other viruses?

Because the symptoms of 2019-nCoV infection overlap with those of influenza and other respiratory viruses, PCR testing for other viruses should be considered if it will change management (i.e., change the decision to provide influenza antivirals). Use appropriate PPE while collecting specimens, including eye protection. If 2019-nCoV is a consideration, you may want to send the specimen to a hospital lab for testing, where the sample will be processed under a biosafety hood, rather than doing point-of-care testing in the office.

How dangerous is 2019-nCoV?

The current estimated mortality rate is 2%-3%. That is probably an overestimate, as those with severe disease and those who die are more likely to be tested and reported early in an epidemic.

Our current knowledge is based on preliminary reports from hospitalized patients and will probably change. From the speed of spread and a single family cluster, it seems likely that there are milder cases and perhaps asymptomatic infection.

What else do I need to know about coronaviruses?

Coronaviruses are a large and diverse group of viruses, many of which are animal viruses. Before the discovery of the 2019-nCoV, six coronaviruses were known to infect humans. Four of these (HKU1, NL63, OC43, and 229E) predominantly caused mild to moderate upper respiratory illness, and they are thought to be responsible for 10%-30% of colds. They occasionally cause viral pneumonia and can be detected by some commercial multiplex panels.

Two other coronaviruses have caused outbreaks of severe respiratory illness in people: SARS, which emerged in Southern China in 2002, and MERS in the Middle East, in 2012. Unlike SARS, sporadic cases of MERS continue to occur.

The current outbreak is caused by 2019-nCoV, a previously unknown beta coronavirus. It is most closely related (~96%) to a bat virus and shares about 80% sequence homology with SARS CoV.

Andrew T. Pavia, MD, is the George and Esther Gross Presidential Professor and chief of the division of pediatric infectious disease in the department of pediatrics at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City. He is also director of hospital epidemiology and associate director of antimicrobial stewardship at Primary Children’s Hospital, Salt Lake City. Dr. Pavia has disclosed that he has served as a consultant for Genentech, Merck, and Seqirus and that he has served as associate editor for The Sanford Guide.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) outbreak has unfolded so rapidly that many clinicians are scrambling to stay on top of it. Here are the answers to some frequently asked questions about how to prepare your clinic to respond to this outbreak.

Keep in mind that the outbreak is moving rapidly. Though scientific and epidemiologic knowledge has increased at unprecedented speed, there is much we don’t know, and some of what we think we know will change. Follow the links for the most up-to-date information.

What should our clinic do first?

Plan ahead with the following:

- Develop a plan for office staff to take travel histories from anyone with a respiratory illness and provide training for those who need it. Travel history at present should include asking about travel to China in the past 14 days, specifically Wuhan city or Hubei province.

- Review up-to-date infection control practices with all office staff and provide training for those who need it.

- Take an inventory of supplies of personal protective equipment (PPE), such as gowns, gloves, masks, eye protection, and N95 respirators or powered air-purifying respirators (PAPRs), and order items that are missing or low in stock.

- Fit-test users of N95 masks for maximal effectiveness.

- Plan where a potential patient would be isolated while obtaining expert advice.

- Know whom to contact at the state or local health department if you have a patient with the appropriate travel history.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has prepared a toolkit to help frontline health care professionals prepare for this virus. Providers need to stay up to date on the latest recommendations, as the situation is changing rapidly.

When should I suspect 2019-nCoV illness, and what should I do?

Take the following steps to assess the concern and respond:

- If a patient with respiratory illness has traveled to China in the past 14 days, immediately put a mask on the patient and move the individual to a private room. Use a negative-pressure room if available.

- Put on appropriate PPE (including gloves, gown, eye protection, and mask) for contact, droplet, and airborne precautions. CDC recommends an N95 respirator mask if available, although we don’t know yet if there is true airborne spread.

- Obtain an accurate travel history, including dates and cities. (Tip: Get the correct spelling, as the English spelling of cities in China can cause confusion.)

- If the patient meets the current CDC definition of “person under investigation” or PUI, or if you need guidance on how to proceed, notify infection control (if you are in a facility that has it) and call your state or local health department immediately.

- Contact public health authorities who can help decide whether the patient should be admitted to airborne isolation or monitored at home with appropriate precautions.

What is the definition of a PUI?

The current definition of a PUI is a person who has fever and symptoms of a respiratory infection (cough, shortness of breath) AND who has EITHER been in Wuhan city or Hubei province in the past 14 days OR had close contact with a person either under investigation for 2019-nCoV infection or with confirmed infection. The definition of a PUI will change over time, so check this link.

How can I test for 2019-nCoV?

As of Jan. 30, 2020, testing is by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and is available in the United States only through the CDC in Atlanta. Testing should soon be available in state health department laboratories. If public health authorities decide that your patient should be tested, they will instruct you on which samples to obtain.

The full sequence of 2019-nCoV has been shared, so some reference laboratories may develop and validate tests, ideally with assistance from CDC. If testing becomes available, make certain that it is a reputable lab that has carefully validated the test.

Should I test for other viruses?

Because the symptoms of 2019-nCoV infection overlap with those of influenza and other respiratory viruses, PCR testing for other viruses should be considered if it will change management (i.e., change the decision to provide influenza antivirals). Use appropriate PPE while collecting specimens, including eye protection. If 2019-nCoV is a consideration, you may want to send the specimen to a hospital lab for testing, where the sample will be processed under a biosafety hood, rather than doing point-of-care testing in the office.

How dangerous is 2019-nCoV?

The current estimated mortality rate is 2%-3%. That is probably an overestimate, as those with severe disease and those who die are more likely to be tested and reported early in an epidemic.

Our current knowledge is based on preliminary reports from hospitalized patients and will probably change. From the speed of spread and a single family cluster, it seems likely that there are milder cases and perhaps asymptomatic infection.

What else do I need to know about coronaviruses?

Coronaviruses are a large and diverse group of viruses, many of which are animal viruses. Before the discovery of the 2019-nCoV, six coronaviruses were known to infect humans. Four of these (HKU1, NL63, OC43, and 229E) predominantly caused mild to moderate upper respiratory illness, and they are thought to be responsible for 10%-30% of colds. They occasionally cause viral pneumonia and can be detected by some commercial multiplex panels.

Two other coronaviruses have caused outbreaks of severe respiratory illness in people: SARS, which emerged in Southern China in 2002, and MERS in the Middle East, in 2012. Unlike SARS, sporadic cases of MERS continue to occur.

The current outbreak is caused by 2019-nCoV, a previously unknown beta coronavirus. It is most closely related (~96%) to a bat virus and shares about 80% sequence homology with SARS CoV.

Andrew T. Pavia, MD, is the George and Esther Gross Presidential Professor and chief of the division of pediatric infectious disease in the department of pediatrics at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City. He is also director of hospital epidemiology and associate director of antimicrobial stewardship at Primary Children’s Hospital, Salt Lake City. Dr. Pavia has disclosed that he has served as a consultant for Genentech, Merck, and Seqirus and that he has served as associate editor for The Sanford Guide.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) outbreak has unfolded so rapidly that many clinicians are scrambling to stay on top of it. Here are the answers to some frequently asked questions about how to prepare your clinic to respond to this outbreak.

Keep in mind that the outbreak is moving rapidly. Though scientific and epidemiologic knowledge has increased at unprecedented speed, there is much we don’t know, and some of what we think we know will change. Follow the links for the most up-to-date information.

What should our clinic do first?

Plan ahead with the following:

- Develop a plan for office staff to take travel histories from anyone with a respiratory illness and provide training for those who need it. Travel history at present should include asking about travel to China in the past 14 days, specifically Wuhan city or Hubei province.

- Review up-to-date infection control practices with all office staff and provide training for those who need it.

- Take an inventory of supplies of personal protective equipment (PPE), such as gowns, gloves, masks, eye protection, and N95 respirators or powered air-purifying respirators (PAPRs), and order items that are missing or low in stock.

- Fit-test users of N95 masks for maximal effectiveness.

- Plan where a potential patient would be isolated while obtaining expert advice.

- Know whom to contact at the state or local health department if you have a patient with the appropriate travel history.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has prepared a toolkit to help frontline health care professionals prepare for this virus. Providers need to stay up to date on the latest recommendations, as the situation is changing rapidly.

When should I suspect 2019-nCoV illness, and what should I do?

Take the following steps to assess the concern and respond:

- If a patient with respiratory illness has traveled to China in the past 14 days, immediately put a mask on the patient and move the individual to a private room. Use a negative-pressure room if available.

- Put on appropriate PPE (including gloves, gown, eye protection, and mask) for contact, droplet, and airborne precautions. CDC recommends an N95 respirator mask if available, although we don’t know yet if there is true airborne spread.

- Obtain an accurate travel history, including dates and cities. (Tip: Get the correct spelling, as the English spelling of cities in China can cause confusion.)

- If the patient meets the current CDC definition of “person under investigation” or PUI, or if you need guidance on how to proceed, notify infection control (if you are in a facility that has it) and call your state or local health department immediately.

- Contact public health authorities who can help decide whether the patient should be admitted to airborne isolation or monitored at home with appropriate precautions.

What is the definition of a PUI?

The current definition of a PUI is a person who has fever and symptoms of a respiratory infection (cough, shortness of breath) AND who has EITHER been in Wuhan city or Hubei province in the past 14 days OR had close contact with a person either under investigation for 2019-nCoV infection or with confirmed infection. The definition of a PUI will change over time, so check this link.

How can I test for 2019-nCoV?

As of Jan. 30, 2020, testing is by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and is available in the United States only through the CDC in Atlanta. Testing should soon be available in state health department laboratories. If public health authorities decide that your patient should be tested, they will instruct you on which samples to obtain.

The full sequence of 2019-nCoV has been shared, so some reference laboratories may develop and validate tests, ideally with assistance from CDC. If testing becomes available, make certain that it is a reputable lab that has carefully validated the test.

Should I test for other viruses?

Because the symptoms of 2019-nCoV infection overlap with those of influenza and other respiratory viruses, PCR testing for other viruses should be considered if it will change management (i.e., change the decision to provide influenza antivirals). Use appropriate PPE while collecting specimens, including eye protection. If 2019-nCoV is a consideration, you may want to send the specimen to a hospital lab for testing, where the sample will be processed under a biosafety hood, rather than doing point-of-care testing in the office.

How dangerous is 2019-nCoV?

The current estimated mortality rate is 2%-3%. That is probably an overestimate, as those with severe disease and those who die are more likely to be tested and reported early in an epidemic.

Our current knowledge is based on preliminary reports from hospitalized patients and will probably change. From the speed of spread and a single family cluster, it seems likely that there are milder cases and perhaps asymptomatic infection.

What else do I need to know about coronaviruses?

Coronaviruses are a large and diverse group of viruses, many of which are animal viruses. Before the discovery of the 2019-nCoV, six coronaviruses were known to infect humans. Four of these (HKU1, NL63, OC43, and 229E) predominantly caused mild to moderate upper respiratory illness, and they are thought to be responsible for 10%-30% of colds. They occasionally cause viral pneumonia and can be detected by some commercial multiplex panels.

Two other coronaviruses have caused outbreaks of severe respiratory illness in people: SARS, which emerged in Southern China in 2002, and MERS in the Middle East, in 2012. Unlike SARS, sporadic cases of MERS continue to occur.

The current outbreak is caused by 2019-nCoV, a previously unknown beta coronavirus. It is most closely related (~96%) to a bat virus and shares about 80% sequence homology with SARS CoV.

Andrew T. Pavia, MD, is the George and Esther Gross Presidential Professor and chief of the division of pediatric infectious disease in the department of pediatrics at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City. He is also director of hospital epidemiology and associate director of antimicrobial stewardship at Primary Children’s Hospital, Salt Lake City. Dr. Pavia has disclosed that he has served as a consultant for Genentech, Merck, and Seqirus and that he has served as associate editor for The Sanford Guide.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

CDC: First person-to-person spread of novel coronavirus in U.S.

A Chicago woman in her 60s who tested positive for the 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) after returning from Wuhan, China, earlier this month has infected her husband, becoming the first known instance of person-to-person transmission of the 2019-nCoV in the United States.

“Limited person-to-person spread of this new virus outside of China has already been seen in nine close contacts, where travelers were infected and transmitted the virus to someone else,” Robert R. Redfield, MD, director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, said during a press briefing on Jan. 30, 2020. “However, the full picture of how easy and how sustainable this virus can spread is unclear. Today’s news underscores the important risk-dependent exposure. The vast majority of Americans have not had recent travel to China, where sustained human-to-human transmission is occurring. Individuals who are close personal contacts of cases, though, could have a risk.”

The affected man, also in his 60s, is the spouse of the first confirmed travel-associated case of 2019-nCoV to be reported in the state of Illinois, according to Ngozi O. Ezike, MD, director of the Illinois Department of Public Health. The man had no history of recent travel to China. “This person-to-person spread was between two very close contacts: a wife and husband,” said Dr. Ezike, who added that 21 individuals in the state are under investigation for 2019-nCoV. “The virus is not spreading widely across the community. At this time, we are not recommending that people in the general public take additional precautions such as canceling activities or avoiding going out. While there is concern with this second case, public health officials are actively monitoring close contacts, including health care workers, and we believe that people in Illinois are at low risk.”

Jennifer Layden, MD, state epidemiologist at the Illinois Department of Public Health, said that the infected Chicago woman returned from Wuhan, China on Jan. 13, 2020. She is hospitalized in stable condition “and continues to do well,” Dr. Layden said. “Public health officials have been actively and closely monitoring individuals who had contacts with her, including her husband, who had close contact for symptoms. He recently began reporting symptoms and was immediately admitted to the hospital and placed in an isolation room, where he is in stable condition. We are actively monitoring individuals such as health care workers, household contacts, and others who were in contact with either of the confirmed cases in the goal to contain and reduce the risk of additional transmission.”

Nancy Messonnier, MD, director, National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, expects that more cases of 2019-nCoV will transpire in the United States.

“More cases means the potential for more person-to-person spread,” Dr. Messonnier said. “We’re trying to strike a balance in our response right now. We want to be aggressive, but we want our actions to be evidence-based and appropriate for the current circumstance. For example, CDC does not currently recommend use of face masks for the general public. The virus is not spreading in the general community.”

A Chicago woman in her 60s who tested positive for the 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) after returning from Wuhan, China, earlier this month has infected her husband, becoming the first known instance of person-to-person transmission of the 2019-nCoV in the United States.

“Limited person-to-person spread of this new virus outside of China has already been seen in nine close contacts, where travelers were infected and transmitted the virus to someone else,” Robert R. Redfield, MD, director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, said during a press briefing on Jan. 30, 2020. “However, the full picture of how easy and how sustainable this virus can spread is unclear. Today’s news underscores the important risk-dependent exposure. The vast majority of Americans have not had recent travel to China, where sustained human-to-human transmission is occurring. Individuals who are close personal contacts of cases, though, could have a risk.”

The affected man, also in his 60s, is the spouse of the first confirmed travel-associated case of 2019-nCoV to be reported in the state of Illinois, according to Ngozi O. Ezike, MD, director of the Illinois Department of Public Health. The man had no history of recent travel to China. “This person-to-person spread was between two very close contacts: a wife and husband,” said Dr. Ezike, who added that 21 individuals in the state are under investigation for 2019-nCoV. “The virus is not spreading widely across the community. At this time, we are not recommending that people in the general public take additional precautions such as canceling activities or avoiding going out. While there is concern with this second case, public health officials are actively monitoring close contacts, including health care workers, and we believe that people in Illinois are at low risk.”

Jennifer Layden, MD, state epidemiologist at the Illinois Department of Public Health, said that the infected Chicago woman returned from Wuhan, China on Jan. 13, 2020. She is hospitalized in stable condition “and continues to do well,” Dr. Layden said. “Public health officials have been actively and closely monitoring individuals who had contacts with her, including her husband, who had close contact for symptoms. He recently began reporting symptoms and was immediately admitted to the hospital and placed in an isolation room, where he is in stable condition. We are actively monitoring individuals such as health care workers, household contacts, and others who were in contact with either of the confirmed cases in the goal to contain and reduce the risk of additional transmission.”

Nancy Messonnier, MD, director, National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, expects that more cases of 2019-nCoV will transpire in the United States.

“More cases means the potential for more person-to-person spread,” Dr. Messonnier said. “We’re trying to strike a balance in our response right now. We want to be aggressive, but we want our actions to be evidence-based and appropriate for the current circumstance. For example, CDC does not currently recommend use of face masks for the general public. The virus is not spreading in the general community.”

A Chicago woman in her 60s who tested positive for the 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) after returning from Wuhan, China, earlier this month has infected her husband, becoming the first known instance of person-to-person transmission of the 2019-nCoV in the United States.

“Limited person-to-person spread of this new virus outside of China has already been seen in nine close contacts, where travelers were infected and transmitted the virus to someone else,” Robert R. Redfield, MD, director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, said during a press briefing on Jan. 30, 2020. “However, the full picture of how easy and how sustainable this virus can spread is unclear. Today’s news underscores the important risk-dependent exposure. The vast majority of Americans have not had recent travel to China, where sustained human-to-human transmission is occurring. Individuals who are close personal contacts of cases, though, could have a risk.”

The affected man, also in his 60s, is the spouse of the first confirmed travel-associated case of 2019-nCoV to be reported in the state of Illinois, according to Ngozi O. Ezike, MD, director of the Illinois Department of Public Health. The man had no history of recent travel to China. “This person-to-person spread was between two very close contacts: a wife and husband,” said Dr. Ezike, who added that 21 individuals in the state are under investigation for 2019-nCoV. “The virus is not spreading widely across the community. At this time, we are not recommending that people in the general public take additional precautions such as canceling activities or avoiding going out. While there is concern with this second case, public health officials are actively monitoring close contacts, including health care workers, and we believe that people in Illinois are at low risk.”

Jennifer Layden, MD, state epidemiologist at the Illinois Department of Public Health, said that the infected Chicago woman returned from Wuhan, China on Jan. 13, 2020. She is hospitalized in stable condition “and continues to do well,” Dr. Layden said. “Public health officials have been actively and closely monitoring individuals who had contacts with her, including her husband, who had close contact for symptoms. He recently began reporting symptoms and was immediately admitted to the hospital and placed in an isolation room, where he is in stable condition. We are actively monitoring individuals such as health care workers, household contacts, and others who were in contact with either of the confirmed cases in the goal to contain and reduce the risk of additional transmission.”

Nancy Messonnier, MD, director, National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, expects that more cases of 2019-nCoV will transpire in the United States.

“More cases means the potential for more person-to-person spread,” Dr. Messonnier said. “We’re trying to strike a balance in our response right now. We want to be aggressive, but we want our actions to be evidence-based and appropriate for the current circumstance. For example, CDC does not currently recommend use of face masks for the general public. The virus is not spreading in the general community.”

Introduction to population management

Defining the key terms

Traditionally, U.S. health care has operated under a fee-for-service payment model, in which health care providers (such as physicians, hospitals, and health care systems) receive a fee for services such as office visits, hospital stays, procedures, and tests. However, reimbursement discussions are increasingly moving from fee-for-service to value-based, in which payments are tied to managing population health and total cost of care.

Because these changes will impact the entire system all the way down to individual providers, in the upcoming Population Management article series in The Hospitalist, we will discuss the nuances and implications that physicians, executives, and hospitals should be aware of. In this first article, we will examine the impetus for the shift toward population management and introduce common terminology to lay the foundation for the future content.

The traditional model: Fee for service

Under the traditional fee-for-service payment system, health care providers are paid per unit of service. For example, hospitals receive diagnosis-related group (DRG) payments for inpatient stays, and physicians are paid per patient visit. The more services that hospitals or physicians provide, the more money both get paid, without financial consequences for quality outcomes or total cost of care. Total cost of care includes clinic visits, outpatient procedures and tests, hospital and ED visits, home health, skilled nursing facilities, durable medical equipment, and sometimes drugs during an episode of care (for example, a hospital stay plus 90 days after discharge) or over a period of time (for example, a month or a year).

As a result of the fee-for-service payment system, the United States spends more money on health care than other wealthy countries, yet it lags behind other countries on many quality measures, such as disease burden, overall mortality, premature death, and preventable death.1,2

In 2007, the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) developed the Triple Aim framework that focused on the following:

- Improving the patient experience of care (including quality and satisfaction).

- Improving the health of populations.

- Reducing per capita cost of care.

Both public payers like Medicare and Medicaid, as well as private payers, embraced the Triple Aim to reform how health care is delivered and paid for. As such, health care delivery focus and financial incentives are shifting from managing discrete patient encounters for acute illness to managing population health and total cost of care.

A new approach: Population management

Before diving into population management, it is important to first understand the terms “population” and “population health.” A population can be defined geographically or may include employees of an organization, members of a health plan, or patients receiving care from a specific physician group or health care system. David A. Kindig, MD, PhD, professor emeritus of population health sciences at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, defined population health as “the health outcomes of a group of individuals, including the distribution of such outcomes within the group.”3 Dr. Kindig noted that population health outcomes have many determinants, such as the following:4

- Health care (access, cost, quantity, and quality of health care services).

- Individual behavior (including diet, exercise, and substance abuse).

- Genetics.

- The social environment (education, income, occupation, class, and social support).

- Physical environment (air and water quality, lead exposure, and the design of neighborhoods).

IHI operationally defines population health by measures such as life expectancy, mortality rates, health and functional status, the incidence and/or prevalence of chronic disease, and behavioral and physiological factors such as smoking, physical activity, diet, blood pressure, body mass index, and cholesterol.5

On the other hand, population management is primarily concerned with health care determinants of health and, according to IHI, should be clearly distinguished from population health, which focuses on the broader determinants of health.5

According to Ron Greeno, MD, MHM, one of the founding members and a past-president of the Society of Hospital Medicine, population management is a “global approach of caring for an entire patient population to deliver safe and equitable care and to more intelligently allocate resources to keep people well.”

Population management requires understanding the patient population, which includes risk stratification and redesigning and delivering services that are guided by integrated clinical and administrative data and enabled by information technology.

Cost-sharing payment models

The cornerstone of population management is provider accountability for the cost of care, which can be accomplished through shared-risk models or population-based payments. Let’s take a closer look at each.

Under shared-risk models, providers receive payment based on their performance against cost targets. The goal is to generate cost savings by improving care coordination, engaging patients in shared decision making based on their health goals, and reducing utilization of care that provides little to no value for patients (for example, preventable hospital admissions or unnecessary imaging or procedures).

Cost targets and actual spending are reconciled retrospectively. If providers beat cost targets, they are eligible to keep a share of generated savings based on their performance on selected quality measures. However, if providers’ actual spending exceeds cost targets, they will compensate payers for a portion of the losses. Under one-sided risk models, providers are eligible for shared savings but not financially responsible for losses. Under two-sided risk models, providers are accountable for both savings and losses.

With prospective population-based payments, also known as capitation, providers receive in advance a fixed amount of money per patient per unit of time (for example, per month) that creates a budget to cover the cost of agreed-upon health care services. The prospective payments are risk adjusted and typically tied to performance on selected quality, effectiveness, and patient experience measures.

Professional services capitation arrangements between physician groups and payers cover the cost of physician services including primary care, specialty care, and related laboratory and radiology services. Under global capitation or global payment arrangements, health care systems receive payments that cover the total cost of care for the patient population for a defined period.

Population-based payments create incentives to provide high-quality and efficient care within a set budget.6 If actual cost of delivering services to the defined patient population comes under the budget, the providers will realize savings, but otherwise will encounter losses.

What is next?

Now that we have explained the impetus for population management and the terminology, in the next article in this series we will discuss the current state of population management. We will also delve into a hospitalist’s role and participation so you can be aware of impending changes and ensure you are set up for success, no matter how the payment models evolve.

Dr. Farah is a hospitalist, physician adviser, and Lean Six Sigma Black Belt. She is a performance improvement consultant based in Corvallis, Ore., and a member of The Hospitalist’s editorial advisory board.

References

1. Source: https://www.healthsystemtracker.org/chart-collection/health-spending-u-s-compare-countries/#item-start

2. Source: https://www.healthsystemtracker.org/brief/on-several-indicators-of-healthcare-quality the-u-s-falls-short/

3. Kindig D, Asada Y, Booske B. (2008). A Population Health Framework for Setting National and State Health Goals. JAMA, 299, 2081-2083.

4. Source: https://improvingpopulationhealth.typepad.com/blog/what-are-health-factorsdeterminants.html

5. Source: http://www.ihi.org/communities/blogs/population-health-population-management-terminology-in-us-health-care

6. Source: http://hcp-lan.org/workproducts/apm-refresh-whitepaper-final.pdf

Defining the key terms

Defining the key terms

Traditionally, U.S. health care has operated under a fee-for-service payment model, in which health care providers (such as physicians, hospitals, and health care systems) receive a fee for services such as office visits, hospital stays, procedures, and tests. However, reimbursement discussions are increasingly moving from fee-for-service to value-based, in which payments are tied to managing population health and total cost of care.

Because these changes will impact the entire system all the way down to individual providers, in the upcoming Population Management article series in The Hospitalist, we will discuss the nuances and implications that physicians, executives, and hospitals should be aware of. In this first article, we will examine the impetus for the shift toward population management and introduce common terminology to lay the foundation for the future content.

The traditional model: Fee for service

Under the traditional fee-for-service payment system, health care providers are paid per unit of service. For example, hospitals receive diagnosis-related group (DRG) payments for inpatient stays, and physicians are paid per patient visit. The more services that hospitals or physicians provide, the more money both get paid, without financial consequences for quality outcomes or total cost of care. Total cost of care includes clinic visits, outpatient procedures and tests, hospital and ED visits, home health, skilled nursing facilities, durable medical equipment, and sometimes drugs during an episode of care (for example, a hospital stay plus 90 days after discharge) or over a period of time (for example, a month or a year).

As a result of the fee-for-service payment system, the United States spends more money on health care than other wealthy countries, yet it lags behind other countries on many quality measures, such as disease burden, overall mortality, premature death, and preventable death.1,2

In 2007, the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) developed the Triple Aim framework that focused on the following:

- Improving the patient experience of care (including quality and satisfaction).

- Improving the health of populations.

- Reducing per capita cost of care.

Both public payers like Medicare and Medicaid, as well as private payers, embraced the Triple Aim to reform how health care is delivered and paid for. As such, health care delivery focus and financial incentives are shifting from managing discrete patient encounters for acute illness to managing population health and total cost of care.

A new approach: Population management

Before diving into population management, it is important to first understand the terms “population” and “population health.” A population can be defined geographically or may include employees of an organization, members of a health plan, or patients receiving care from a specific physician group or health care system. David A. Kindig, MD, PhD, professor emeritus of population health sciences at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, defined population health as “the health outcomes of a group of individuals, including the distribution of such outcomes within the group.”3 Dr. Kindig noted that population health outcomes have many determinants, such as the following:4

- Health care (access, cost, quantity, and quality of health care services).

- Individual behavior (including diet, exercise, and substance abuse).

- Genetics.

- The social environment (education, income, occupation, class, and social support).

- Physical environment (air and water quality, lead exposure, and the design of neighborhoods).

IHI operationally defines population health by measures such as life expectancy, mortality rates, health and functional status, the incidence and/or prevalence of chronic disease, and behavioral and physiological factors such as smoking, physical activity, diet, blood pressure, body mass index, and cholesterol.5

On the other hand, population management is primarily concerned with health care determinants of health and, according to IHI, should be clearly distinguished from population health, which focuses on the broader determinants of health.5

According to Ron Greeno, MD, MHM, one of the founding members and a past-president of the Society of Hospital Medicine, population management is a “global approach of caring for an entire patient population to deliver safe and equitable care and to more intelligently allocate resources to keep people well.”

Population management requires understanding the patient population, which includes risk stratification and redesigning and delivering services that are guided by integrated clinical and administrative data and enabled by information technology.

Cost-sharing payment models

The cornerstone of population management is provider accountability for the cost of care, which can be accomplished through shared-risk models or population-based payments. Let’s take a closer look at each.

Under shared-risk models, providers receive payment based on their performance against cost targets. The goal is to generate cost savings by improving care coordination, engaging patients in shared decision making based on their health goals, and reducing utilization of care that provides little to no value for patients (for example, preventable hospital admissions or unnecessary imaging or procedures).

Cost targets and actual spending are reconciled retrospectively. If providers beat cost targets, they are eligible to keep a share of generated savings based on their performance on selected quality measures. However, if providers’ actual spending exceeds cost targets, they will compensate payers for a portion of the losses. Under one-sided risk models, providers are eligible for shared savings but not financially responsible for losses. Under two-sided risk models, providers are accountable for both savings and losses.

With prospective population-based payments, also known as capitation, providers receive in advance a fixed amount of money per patient per unit of time (for example, per month) that creates a budget to cover the cost of agreed-upon health care services. The prospective payments are risk adjusted and typically tied to performance on selected quality, effectiveness, and patient experience measures.

Professional services capitation arrangements between physician groups and payers cover the cost of physician services including primary care, specialty care, and related laboratory and radiology services. Under global capitation or global payment arrangements, health care systems receive payments that cover the total cost of care for the patient population for a defined period.

Population-based payments create incentives to provide high-quality and efficient care within a set budget.6 If actual cost of delivering services to the defined patient population comes under the budget, the providers will realize savings, but otherwise will encounter losses.

What is next?

Now that we have explained the impetus for population management and the terminology, in the next article in this series we will discuss the current state of population management. We will also delve into a hospitalist’s role and participation so you can be aware of impending changes and ensure you are set up for success, no matter how the payment models evolve.

Dr. Farah is a hospitalist, physician adviser, and Lean Six Sigma Black Belt. She is a performance improvement consultant based in Corvallis, Ore., and a member of The Hospitalist’s editorial advisory board.

References

1. Source: https://www.healthsystemtracker.org/chart-collection/health-spending-u-s-compare-countries/#item-start

2. Source: https://www.healthsystemtracker.org/brief/on-several-indicators-of-healthcare-quality the-u-s-falls-short/

3. Kindig D, Asada Y, Booske B. (2008). A Population Health Framework for Setting National and State Health Goals. JAMA, 299, 2081-2083.