User login

Official news magazine of the Society of Hospital Medicine

Copyright by Society of Hospital Medicine or related companies. All rights reserved. ISSN 1553-085X

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-hospitalist')]

Amplatzer devices outperform oral anticoagulation in atrial fib

PARIS – Percutaneous left atrial appendage closure with an Amplatzer device in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation was associated with significantly lower rates of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality, compared with oral anticoagulation, in a large propensity score–matched observational registry study.

Left atrial appendage closure (LAAC) also bested oral anticoagulation (OAC) with warfarin or a novel oral anticoagulant (NOAC) in terms of net clinical benefit on the basis of the device therapy’s greater protection against stroke and systemic embolism coupled with a trend, albeit not statistically significant, for fewer bleeding events, Steffen Gloekler, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions.

The Watchman LAAC device, commercially available both in Europe and the United States, has previously been shown to be superior to OAC in terms of efficacy and noninferior regarding safety. But there have been no randomized trials of an Amplatzer device versus OAC. This lack of data was the impetus for Dr. Gloekler and his coinvestigators to create a meticulously propensity-matched observational registry.

Five hundred consecutive patients with AF who received an Amplatzer Cardiac Plug or its second-generation version, the Amplatzer Amulet, during 2009-2014 were tightly matched to an equal number of AF patients on OAC based on age, sex, body mass index, left ventricular ejection fraction, renal function, coronary artery disease status, hemoglobin level, CHA2DS2-VASc score, and HAS-BLED score. During a mean 2.7 years, or 2,645 patient-years, of follow-up, the composite primary efficacy endpoint, composed of stroke, systemic embolism, and cardiovascular or unexplained death occurred in 5.6% of the LAAC group, compared with 7.8% of controls in the OAC arm, for a statistically significant 30% relative risk reduction. Disabling stroke occurred in 0.7% of Amplatzer patients versus 1.5% of controls. The ischemic stroke rate was 1.5% in the device therapy group and 2% in the OAC arm.

All-cause mortality occurred in 8.3% of Amplatzer patients and 11.6% of the OAC group, for a 28% relative risk reduction. The cardiovascular death rate was 4% in the Amplatzer group, compared with 6.5% of controls, for a 36% risk reduction.

The composite safety endpoint, comprising all major procedural adverse events and major or life-threatening bleeding during follow-up, occurred in 3.6% of the Amplatzer group and 4.6% of the OAC group, for a 20% relative risk reduction that is not significant at this point because of the low number of events. Major, life-threatening, or fatal bleeding occurred in 2% of Amplatzer recipients versus 5.5% of controls, added Dr. Gloekler of University Hospital in Bern, Switzerland.

The net clinical benefit, a composite of death, bleeding, or stroke, occurred in 8.1% of the Amplatzer group, compared with 10.9% of controls, for a significant 24% reduction in relative risk in favor of device therapy.

Of note, at 2.7 years of follow-up only 55% of the OAC group were still taking an anticoagulant: 38% of the original 500 patients were on warfarin, and 17% were taking a NOAC. At that point, 8% of the Amplatzer group were on any anticoagulation therapy.

Discussion of the study focused on that low rate of medication adherence in the OAC arm. Dr. Gloekler’s response was that, after looking at the literature, he was no longer surprised by the finding that only 55% of the control group were on OAC at follow-up.

“If you look in the literature, that’s exactly the real-world adherence for OACs. Even in all four certification trials for the NOACs, the rate of discontinuation was 30% after 2 years – and these were controlled studies. Ours was observational, and it depicts a good deal of the problem with any OAC in my eyes,” Dr. Gloekler said.

Patients on warfarin in the real-world Amplatzer registry study spent on average a mere 30% of time in the therapeutic international normalized ratio range of 2-3.

“That means 70% of the time patients are higher and have an increased bleeding risk or they are lower and don’t have adequate stroke protection,” he noted.

This prompted one observer to comment, “We either have to do a better job in our clinics with OAC or we have to occlude more appendages.”

A large pivotal U.S. trial aimed at winning FDA approval for the Amplatzer Amulet for LAAC is underway. Patients with AF are being randomized to the approved Watchman or investigational Amulet at roughly 100 U.S. and 50 foreign sites.

Dr. Gloekler reported receiving research funds for the registry from the Swiss Heart Foundation and Abbott.

PARIS – Percutaneous left atrial appendage closure with an Amplatzer device in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation was associated with significantly lower rates of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality, compared with oral anticoagulation, in a large propensity score–matched observational registry study.

Left atrial appendage closure (LAAC) also bested oral anticoagulation (OAC) with warfarin or a novel oral anticoagulant (NOAC) in terms of net clinical benefit on the basis of the device therapy’s greater protection against stroke and systemic embolism coupled with a trend, albeit not statistically significant, for fewer bleeding events, Steffen Gloekler, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions.

The Watchman LAAC device, commercially available both in Europe and the United States, has previously been shown to be superior to OAC in terms of efficacy and noninferior regarding safety. But there have been no randomized trials of an Amplatzer device versus OAC. This lack of data was the impetus for Dr. Gloekler and his coinvestigators to create a meticulously propensity-matched observational registry.

Five hundred consecutive patients with AF who received an Amplatzer Cardiac Plug or its second-generation version, the Amplatzer Amulet, during 2009-2014 were tightly matched to an equal number of AF patients on OAC based on age, sex, body mass index, left ventricular ejection fraction, renal function, coronary artery disease status, hemoglobin level, CHA2DS2-VASc score, and HAS-BLED score. During a mean 2.7 years, or 2,645 patient-years, of follow-up, the composite primary efficacy endpoint, composed of stroke, systemic embolism, and cardiovascular or unexplained death occurred in 5.6% of the LAAC group, compared with 7.8% of controls in the OAC arm, for a statistically significant 30% relative risk reduction. Disabling stroke occurred in 0.7% of Amplatzer patients versus 1.5% of controls. The ischemic stroke rate was 1.5% in the device therapy group and 2% in the OAC arm.

All-cause mortality occurred in 8.3% of Amplatzer patients and 11.6% of the OAC group, for a 28% relative risk reduction. The cardiovascular death rate was 4% in the Amplatzer group, compared with 6.5% of controls, for a 36% risk reduction.

The composite safety endpoint, comprising all major procedural adverse events and major or life-threatening bleeding during follow-up, occurred in 3.6% of the Amplatzer group and 4.6% of the OAC group, for a 20% relative risk reduction that is not significant at this point because of the low number of events. Major, life-threatening, or fatal bleeding occurred in 2% of Amplatzer recipients versus 5.5% of controls, added Dr. Gloekler of University Hospital in Bern, Switzerland.

The net clinical benefit, a composite of death, bleeding, or stroke, occurred in 8.1% of the Amplatzer group, compared with 10.9% of controls, for a significant 24% reduction in relative risk in favor of device therapy.

Of note, at 2.7 years of follow-up only 55% of the OAC group were still taking an anticoagulant: 38% of the original 500 patients were on warfarin, and 17% were taking a NOAC. At that point, 8% of the Amplatzer group were on any anticoagulation therapy.

Discussion of the study focused on that low rate of medication adherence in the OAC arm. Dr. Gloekler’s response was that, after looking at the literature, he was no longer surprised by the finding that only 55% of the control group were on OAC at follow-up.

“If you look in the literature, that’s exactly the real-world adherence for OACs. Even in all four certification trials for the NOACs, the rate of discontinuation was 30% after 2 years – and these were controlled studies. Ours was observational, and it depicts a good deal of the problem with any OAC in my eyes,” Dr. Gloekler said.

Patients on warfarin in the real-world Amplatzer registry study spent on average a mere 30% of time in the therapeutic international normalized ratio range of 2-3.

“That means 70% of the time patients are higher and have an increased bleeding risk or they are lower and don’t have adequate stroke protection,” he noted.

This prompted one observer to comment, “We either have to do a better job in our clinics with OAC or we have to occlude more appendages.”

A large pivotal U.S. trial aimed at winning FDA approval for the Amplatzer Amulet for LAAC is underway. Patients with AF are being randomized to the approved Watchman or investigational Amulet at roughly 100 U.S. and 50 foreign sites.

Dr. Gloekler reported receiving research funds for the registry from the Swiss Heart Foundation and Abbott.

PARIS – Percutaneous left atrial appendage closure with an Amplatzer device in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation was associated with significantly lower rates of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality, compared with oral anticoagulation, in a large propensity score–matched observational registry study.

Left atrial appendage closure (LAAC) also bested oral anticoagulation (OAC) with warfarin or a novel oral anticoagulant (NOAC) in terms of net clinical benefit on the basis of the device therapy’s greater protection against stroke and systemic embolism coupled with a trend, albeit not statistically significant, for fewer bleeding events, Steffen Gloekler, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions.

The Watchman LAAC device, commercially available both in Europe and the United States, has previously been shown to be superior to OAC in terms of efficacy and noninferior regarding safety. But there have been no randomized trials of an Amplatzer device versus OAC. This lack of data was the impetus for Dr. Gloekler and his coinvestigators to create a meticulously propensity-matched observational registry.

Five hundred consecutive patients with AF who received an Amplatzer Cardiac Plug or its second-generation version, the Amplatzer Amulet, during 2009-2014 were tightly matched to an equal number of AF patients on OAC based on age, sex, body mass index, left ventricular ejection fraction, renal function, coronary artery disease status, hemoglobin level, CHA2DS2-VASc score, and HAS-BLED score. During a mean 2.7 years, or 2,645 patient-years, of follow-up, the composite primary efficacy endpoint, composed of stroke, systemic embolism, and cardiovascular or unexplained death occurred in 5.6% of the LAAC group, compared with 7.8% of controls in the OAC arm, for a statistically significant 30% relative risk reduction. Disabling stroke occurred in 0.7% of Amplatzer patients versus 1.5% of controls. The ischemic stroke rate was 1.5% in the device therapy group and 2% in the OAC arm.

All-cause mortality occurred in 8.3% of Amplatzer patients and 11.6% of the OAC group, for a 28% relative risk reduction. The cardiovascular death rate was 4% in the Amplatzer group, compared with 6.5% of controls, for a 36% risk reduction.

The composite safety endpoint, comprising all major procedural adverse events and major or life-threatening bleeding during follow-up, occurred in 3.6% of the Amplatzer group and 4.6% of the OAC group, for a 20% relative risk reduction that is not significant at this point because of the low number of events. Major, life-threatening, or fatal bleeding occurred in 2% of Amplatzer recipients versus 5.5% of controls, added Dr. Gloekler of University Hospital in Bern, Switzerland.

The net clinical benefit, a composite of death, bleeding, or stroke, occurred in 8.1% of the Amplatzer group, compared with 10.9% of controls, for a significant 24% reduction in relative risk in favor of device therapy.

Of note, at 2.7 years of follow-up only 55% of the OAC group were still taking an anticoagulant: 38% of the original 500 patients were on warfarin, and 17% were taking a NOAC. At that point, 8% of the Amplatzer group were on any anticoagulation therapy.

Discussion of the study focused on that low rate of medication adherence in the OAC arm. Dr. Gloekler’s response was that, after looking at the literature, he was no longer surprised by the finding that only 55% of the control group were on OAC at follow-up.

“If you look in the literature, that’s exactly the real-world adherence for OACs. Even in all four certification trials for the NOACs, the rate of discontinuation was 30% after 2 years – and these were controlled studies. Ours was observational, and it depicts a good deal of the problem with any OAC in my eyes,” Dr. Gloekler said.

Patients on warfarin in the real-world Amplatzer registry study spent on average a mere 30% of time in the therapeutic international normalized ratio range of 2-3.

“That means 70% of the time patients are higher and have an increased bleeding risk or they are lower and don’t have adequate stroke protection,” he noted.

This prompted one observer to comment, “We either have to do a better job in our clinics with OAC or we have to occlude more appendages.”

A large pivotal U.S. trial aimed at winning FDA approval for the Amplatzer Amulet for LAAC is underway. Patients with AF are being randomized to the approved Watchman or investigational Amulet at roughly 100 U.S. and 50 foreign sites.

Dr. Gloekler reported receiving research funds for the registry from the Swiss Heart Foundation and Abbott.

AT EUROPCR

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The primary composite efficacy endpoint of stroke, systemic embolism, or cardiovascular or unexplained death during a mean 2.7 years of follow-up occurred in 5.6% of Amplatzer device recipients, a 30% reduction, compared with the 7.8% rate in the oral anticoagulation group.

Data source: This observational registry included 500 patients with atrial fibrillation who received an Amplatzer left atrial appendage closure device and an equal number of carefully matched AF patients on oral anticoagulation.

Disclosures: The study presenter reported receiving research funds for the registry from the Swiss Heart Foundation and Abbott.

Opioid prescribing drops nationally, remains high in some counties

Opioid prescribing in the United States declined overall between 2010 and 2015, but remained stable or increased in some counties, according to a report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The findings were published online in the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

“The bottom line remains: We have too many people getting too many prescriptions at too high a dose,” Anne Schuchat, MD, acting director of the CDC, said in a July 6 teleconference.

CDC researchers calculated prescribing rates from 2006 to 2015 by dividing the number of opioid prescriptions by the population estimates from the U.S. census for each year and created quartiles using morphine milligram equivalent per capita to analyze opioid distribution. Annual opioid prescribing rates increased from 72 to 81 prescriptions per 100 persons from 2006 to 2010 and remained relatively constant from 2010 to 2012 before showing a 13% decrease to 71 prescriptions per 100 persons from 2012 to 2015 (MMWR. 2017 Jul 7;66[26]:697-704. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6626a4).

But despite these overall declines, “We are now experiencing the highest overdose death rates ever recorded in the United States,” Dr. Schuchat said. Quartiles were created using MME per capita to characterize the distribution of opioids prescribed.

In the report, areas associated with higher opioid prescribing rates on a county level included small cities or towns, areas that had a higher proportion of white residents, areas with more doctors and dentists, and areas with more cases of arthritis, diabetes, or other disabilities, she said.

The findings suggest a need for more consistency among health care providers about prescription opioids, Dr. Schuchat said. “Clinical practice is all over the place, which is a sign that you need better standards; we hope the 2016 guidelines are a turning point for better prescribing,” she said.

The CDC’s guidelines on opioid prescribing were released in 2016. The guidelines recommend alternatives when possible. Clinicians should instead consider nonopioid therapy, other types of pain medication, and nondrug pain relief options, such as physical therapy and cognitive-behavioral therapy. Other concerns include the length and strength of opioid prescriptions. Even taking opioids for a few months increases the risk for addiction, Dr. Schuchat said.

“Physicians must continue to lead efforts to reverse the epidemic by using prescription drug–monitoring programs, eliminating stigma, prescribing the overdose reversal drug naloxone, and enhancing their education about safe opioid prescribing and effective pain management,” Patrice A. Harris, MD, chair of the American Medical Association Opioid Task Force, said in a statement in response to the report. “Our country must do more to provide evidence-based, comprehensive treatment for pain and for substance use disorders,” she said.

“We really encourage clinicians to look to the guidelines and the tools that are available,” Dr. Schuchat said. “We do know that internists and other primary care physicians prescribe most of the opioids, so it is important for them to be aware.” The CDC has developed a checklist and a mobile app that have been downloaded by thousands of clinicians so far, she noted. Changes in annual prescribing hold promise that practices can improve, she said.

The researchers reported no conflicts of interest.

Opioid prescribing in the United States declined overall between 2010 and 2015, but remained stable or increased in some counties, according to a report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The findings were published online in the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

“The bottom line remains: We have too many people getting too many prescriptions at too high a dose,” Anne Schuchat, MD, acting director of the CDC, said in a July 6 teleconference.

CDC researchers calculated prescribing rates from 2006 to 2015 by dividing the number of opioid prescriptions by the population estimates from the U.S. census for each year and created quartiles using morphine milligram equivalent per capita to analyze opioid distribution. Annual opioid prescribing rates increased from 72 to 81 prescriptions per 100 persons from 2006 to 2010 and remained relatively constant from 2010 to 2012 before showing a 13% decrease to 71 prescriptions per 100 persons from 2012 to 2015 (MMWR. 2017 Jul 7;66[26]:697-704. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6626a4).

But despite these overall declines, “We are now experiencing the highest overdose death rates ever recorded in the United States,” Dr. Schuchat said. Quartiles were created using MME per capita to characterize the distribution of opioids prescribed.

In the report, areas associated with higher opioid prescribing rates on a county level included small cities or towns, areas that had a higher proportion of white residents, areas with more doctors and dentists, and areas with more cases of arthritis, diabetes, or other disabilities, she said.

The findings suggest a need for more consistency among health care providers about prescription opioids, Dr. Schuchat said. “Clinical practice is all over the place, which is a sign that you need better standards; we hope the 2016 guidelines are a turning point for better prescribing,” she said.

The CDC’s guidelines on opioid prescribing were released in 2016. The guidelines recommend alternatives when possible. Clinicians should instead consider nonopioid therapy, other types of pain medication, and nondrug pain relief options, such as physical therapy and cognitive-behavioral therapy. Other concerns include the length and strength of opioid prescriptions. Even taking opioids for a few months increases the risk for addiction, Dr. Schuchat said.

“Physicians must continue to lead efforts to reverse the epidemic by using prescription drug–monitoring programs, eliminating stigma, prescribing the overdose reversal drug naloxone, and enhancing their education about safe opioid prescribing and effective pain management,” Patrice A. Harris, MD, chair of the American Medical Association Opioid Task Force, said in a statement in response to the report. “Our country must do more to provide evidence-based, comprehensive treatment for pain and for substance use disorders,” she said.

“We really encourage clinicians to look to the guidelines and the tools that are available,” Dr. Schuchat said. “We do know that internists and other primary care physicians prescribe most of the opioids, so it is important for them to be aware.” The CDC has developed a checklist and a mobile app that have been downloaded by thousands of clinicians so far, she noted. Changes in annual prescribing hold promise that practices can improve, she said.

The researchers reported no conflicts of interest.

Opioid prescribing in the United States declined overall between 2010 and 2015, but remained stable or increased in some counties, according to a report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The findings were published online in the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

“The bottom line remains: We have too many people getting too many prescriptions at too high a dose,” Anne Schuchat, MD, acting director of the CDC, said in a July 6 teleconference.

CDC researchers calculated prescribing rates from 2006 to 2015 by dividing the number of opioid prescriptions by the population estimates from the U.S. census for each year and created quartiles using morphine milligram equivalent per capita to analyze opioid distribution. Annual opioid prescribing rates increased from 72 to 81 prescriptions per 100 persons from 2006 to 2010 and remained relatively constant from 2010 to 2012 before showing a 13% decrease to 71 prescriptions per 100 persons from 2012 to 2015 (MMWR. 2017 Jul 7;66[26]:697-704. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6626a4).

But despite these overall declines, “We are now experiencing the highest overdose death rates ever recorded in the United States,” Dr. Schuchat said. Quartiles were created using MME per capita to characterize the distribution of opioids prescribed.

In the report, areas associated with higher opioid prescribing rates on a county level included small cities or towns, areas that had a higher proportion of white residents, areas with more doctors and dentists, and areas with more cases of arthritis, diabetes, or other disabilities, she said.

The findings suggest a need for more consistency among health care providers about prescription opioids, Dr. Schuchat said. “Clinical practice is all over the place, which is a sign that you need better standards; we hope the 2016 guidelines are a turning point for better prescribing,” she said.

The CDC’s guidelines on opioid prescribing were released in 2016. The guidelines recommend alternatives when possible. Clinicians should instead consider nonopioid therapy, other types of pain medication, and nondrug pain relief options, such as physical therapy and cognitive-behavioral therapy. Other concerns include the length and strength of opioid prescriptions. Even taking opioids for a few months increases the risk for addiction, Dr. Schuchat said.

“Physicians must continue to lead efforts to reverse the epidemic by using prescription drug–monitoring programs, eliminating stigma, prescribing the overdose reversal drug naloxone, and enhancing their education about safe opioid prescribing and effective pain management,” Patrice A. Harris, MD, chair of the American Medical Association Opioid Task Force, said in a statement in response to the report. “Our country must do more to provide evidence-based, comprehensive treatment for pain and for substance use disorders,” she said.

“We really encourage clinicians to look to the guidelines and the tools that are available,” Dr. Schuchat said. “We do know that internists and other primary care physicians prescribe most of the opioids, so it is important for them to be aware.” The CDC has developed a checklist and a mobile app that have been downloaded by thousands of clinicians so far, she noted. Changes in annual prescribing hold promise that practices can improve, she said.

The researchers reported no conflicts of interest.

FROM MMWR

Pediatrics Committee’s role amplified with subspecialty’s evolution

Editor’s note: Each month, SHM puts the spotlight on some of our most active members who are making substantial contributions to hospital medicine. For more information on how you can lend your expertise to help SHM improve the care of hospitalized patients, log on to www.hospitalmedicine.org/getinvolved.

This month, The Hospitalist spotlights Sandra Gage, MD, PhD, SFHM, associate professor of pediatrics in the section of hospital medicine at the Medical College of Wisconsin, newly appointed chair of SHM’s Pediatrics Committee, and SHM member of almost 20 years.

Why did you choose a career in pediatric hospital medicine, and how did you become an SHM member?

I would say that pediatric hospital medicine chose me. After obtaining a degree in physical therapy and spending five years treating children with a variety of neurological and neurodevelopmental disorders, I went back to school to get my MD and a PhD in neurobiology, thinking that I would specialize in either pediatric neurology or pediatric physical medicine and rehabilitation.

I always had an interest in treating children but never considered general pediatrics because spending my time in the outpatient clinic setting had little appeal for me. This was before the concept of being a “hospitalist” was widespread – and even before the phrase was coined – but there were a few providers in my academic pediatric group who focused on inpatient care. The pace, variety and challenge of treating hospitalized children was exactly what I was looking for, and, following completion of my pediatric residency, I slowly became a full-time hospitalist.

What is the Pediatrics Committee currently working on, and what do you hope to accomplish during your term as Committee Chair?

With subspecialty status coming soon, rapidly expanding interest in the profession and the introduction of hospitalists into more areas of care, the landscape of pediatric hospital medicine is ever-changing. This amplifies the importance of the Pediatrics Committee’s role. The overall goals of the committee are to promote the growth and development of pediatric hospital medicine as a field and to provide educational and practical resources for individual practitioners.

The 2017-2018 committee comprises enthusiastic members from a wide variety of practice settings. At our first meeting in May, we formulated many exciting and innovative ideas to achieve our goals. As we continue to narrow down our approach and finalize our tasks for the year, we are also beginning to determine the content for the pediatric track at HM18. An example of a project the committee has executed in the past is the development of hospitalist-specific American Board of Pediatrics Maintenance of Certification modules for the SHM Learning Portal. In addition, the 2017 Pediatric Hospital Medicine (PHM) meeting is hosted by SHM this July in Nashville, and many Pediatrics Committee members are hard at work on finalizing those plans.

How has the PHM meeting evolved since its inception, and what value do you find in attending?

I have been an attendee of PHM many times over the years. The meeting has grown from a small group of no more than 100 individuals in a few hotel meeting rooms to more than 1,000 attendees and a wide variety of tracks and offerings. The growth of this meeting is truly reflective of the growth of our subspecialty, and the meeting brings together practitioners, both old and new, in an atmosphere full of innovations and ideas. Like SHM’s annual meeting, the PHM meeting is a great place for learning, sharing, and networking.

What advice do you have for fellow pediatric hospitalists during this transformational time in health care?

The direction of health care has provided fodder for lively discussion since I started my career 20 years ago. The nature of the practice of medicine is evolving, and, as physicians, we must be adept at navigating the changing climate while maintaining our goal of providing excellent care for our patients. As hospitalists, we have the opportunity to be in the forefront of the changes that will impact hospital care and utilization.

Whether our work is done at a local or a national level, as a group or as individuals, I believe that hospitalists will have an active role in directing the course of the future of medicine. We spend much of our clinical time advocating for our patients, but your experience is important and your voice can make an important contribution to the direction of health care for one child or for all children. Whether it is in the hospital hallway or on the Hill, continue to strive to do what you already do best.

Felicia Steele is SHM’s communications coordinator.

Editor’s note: Each month, SHM puts the spotlight on some of our most active members who are making substantial contributions to hospital medicine. For more information on how you can lend your expertise to help SHM improve the care of hospitalized patients, log on to www.hospitalmedicine.org/getinvolved.

This month, The Hospitalist spotlights Sandra Gage, MD, PhD, SFHM, associate professor of pediatrics in the section of hospital medicine at the Medical College of Wisconsin, newly appointed chair of SHM’s Pediatrics Committee, and SHM member of almost 20 years.

Why did you choose a career in pediatric hospital medicine, and how did you become an SHM member?

I would say that pediatric hospital medicine chose me. After obtaining a degree in physical therapy and spending five years treating children with a variety of neurological and neurodevelopmental disorders, I went back to school to get my MD and a PhD in neurobiology, thinking that I would specialize in either pediatric neurology or pediatric physical medicine and rehabilitation.

I always had an interest in treating children but never considered general pediatrics because spending my time in the outpatient clinic setting had little appeal for me. This was before the concept of being a “hospitalist” was widespread – and even before the phrase was coined – but there were a few providers in my academic pediatric group who focused on inpatient care. The pace, variety and challenge of treating hospitalized children was exactly what I was looking for, and, following completion of my pediatric residency, I slowly became a full-time hospitalist.

What is the Pediatrics Committee currently working on, and what do you hope to accomplish during your term as Committee Chair?

With subspecialty status coming soon, rapidly expanding interest in the profession and the introduction of hospitalists into more areas of care, the landscape of pediatric hospital medicine is ever-changing. This amplifies the importance of the Pediatrics Committee’s role. The overall goals of the committee are to promote the growth and development of pediatric hospital medicine as a field and to provide educational and practical resources for individual practitioners.

The 2017-2018 committee comprises enthusiastic members from a wide variety of practice settings. At our first meeting in May, we formulated many exciting and innovative ideas to achieve our goals. As we continue to narrow down our approach and finalize our tasks for the year, we are also beginning to determine the content for the pediatric track at HM18. An example of a project the committee has executed in the past is the development of hospitalist-specific American Board of Pediatrics Maintenance of Certification modules for the SHM Learning Portal. In addition, the 2017 Pediatric Hospital Medicine (PHM) meeting is hosted by SHM this July in Nashville, and many Pediatrics Committee members are hard at work on finalizing those plans.

How has the PHM meeting evolved since its inception, and what value do you find in attending?

I have been an attendee of PHM many times over the years. The meeting has grown from a small group of no more than 100 individuals in a few hotel meeting rooms to more than 1,000 attendees and a wide variety of tracks and offerings. The growth of this meeting is truly reflective of the growth of our subspecialty, and the meeting brings together practitioners, both old and new, in an atmosphere full of innovations and ideas. Like SHM’s annual meeting, the PHM meeting is a great place for learning, sharing, and networking.

What advice do you have for fellow pediatric hospitalists during this transformational time in health care?

The direction of health care has provided fodder for lively discussion since I started my career 20 years ago. The nature of the practice of medicine is evolving, and, as physicians, we must be adept at navigating the changing climate while maintaining our goal of providing excellent care for our patients. As hospitalists, we have the opportunity to be in the forefront of the changes that will impact hospital care and utilization.

Whether our work is done at a local or a national level, as a group or as individuals, I believe that hospitalists will have an active role in directing the course of the future of medicine. We spend much of our clinical time advocating for our patients, but your experience is important and your voice can make an important contribution to the direction of health care for one child or for all children. Whether it is in the hospital hallway or on the Hill, continue to strive to do what you already do best.

Felicia Steele is SHM’s communications coordinator.

Editor’s note: Each month, SHM puts the spotlight on some of our most active members who are making substantial contributions to hospital medicine. For more information on how you can lend your expertise to help SHM improve the care of hospitalized patients, log on to www.hospitalmedicine.org/getinvolved.

This month, The Hospitalist spotlights Sandra Gage, MD, PhD, SFHM, associate professor of pediatrics in the section of hospital medicine at the Medical College of Wisconsin, newly appointed chair of SHM’s Pediatrics Committee, and SHM member of almost 20 years.

Why did you choose a career in pediatric hospital medicine, and how did you become an SHM member?

I would say that pediatric hospital medicine chose me. After obtaining a degree in physical therapy and spending five years treating children with a variety of neurological and neurodevelopmental disorders, I went back to school to get my MD and a PhD in neurobiology, thinking that I would specialize in either pediatric neurology or pediatric physical medicine and rehabilitation.

I always had an interest in treating children but never considered general pediatrics because spending my time in the outpatient clinic setting had little appeal for me. This was before the concept of being a “hospitalist” was widespread – and even before the phrase was coined – but there were a few providers in my academic pediatric group who focused on inpatient care. The pace, variety and challenge of treating hospitalized children was exactly what I was looking for, and, following completion of my pediatric residency, I slowly became a full-time hospitalist.

What is the Pediatrics Committee currently working on, and what do you hope to accomplish during your term as Committee Chair?

With subspecialty status coming soon, rapidly expanding interest in the profession and the introduction of hospitalists into more areas of care, the landscape of pediatric hospital medicine is ever-changing. This amplifies the importance of the Pediatrics Committee’s role. The overall goals of the committee are to promote the growth and development of pediatric hospital medicine as a field and to provide educational and practical resources for individual practitioners.

The 2017-2018 committee comprises enthusiastic members from a wide variety of practice settings. At our first meeting in May, we formulated many exciting and innovative ideas to achieve our goals. As we continue to narrow down our approach and finalize our tasks for the year, we are also beginning to determine the content for the pediatric track at HM18. An example of a project the committee has executed in the past is the development of hospitalist-specific American Board of Pediatrics Maintenance of Certification modules for the SHM Learning Portal. In addition, the 2017 Pediatric Hospital Medicine (PHM) meeting is hosted by SHM this July in Nashville, and many Pediatrics Committee members are hard at work on finalizing those plans.

How has the PHM meeting evolved since its inception, and what value do you find in attending?

I have been an attendee of PHM many times over the years. The meeting has grown from a small group of no more than 100 individuals in a few hotel meeting rooms to more than 1,000 attendees and a wide variety of tracks and offerings. The growth of this meeting is truly reflective of the growth of our subspecialty, and the meeting brings together practitioners, both old and new, in an atmosphere full of innovations and ideas. Like SHM’s annual meeting, the PHM meeting is a great place for learning, sharing, and networking.

What advice do you have for fellow pediatric hospitalists during this transformational time in health care?

The direction of health care has provided fodder for lively discussion since I started my career 20 years ago. The nature of the practice of medicine is evolving, and, as physicians, we must be adept at navigating the changing climate while maintaining our goal of providing excellent care for our patients. As hospitalists, we have the opportunity to be in the forefront of the changes that will impact hospital care and utilization.

Whether our work is done at a local or a national level, as a group or as individuals, I believe that hospitalists will have an active role in directing the course of the future of medicine. We spend much of our clinical time advocating for our patients, but your experience is important and your voice can make an important contribution to the direction of health care for one child or for all children. Whether it is in the hospital hallway or on the Hill, continue to strive to do what you already do best.

Felicia Steele is SHM’s communications coordinator.

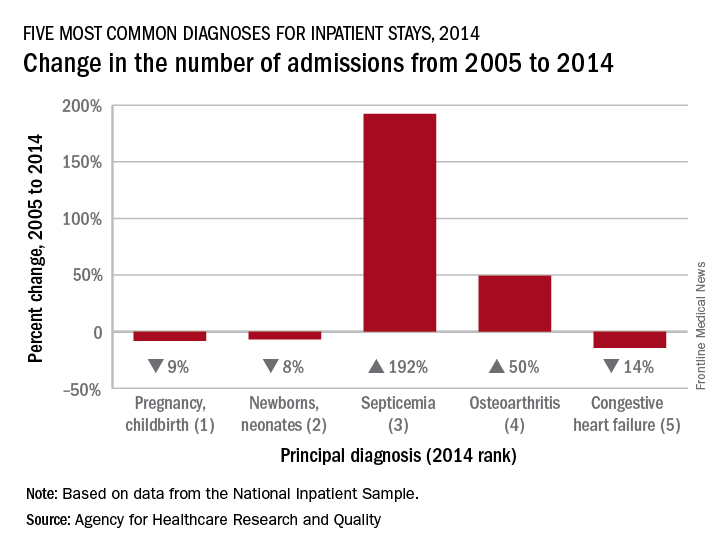

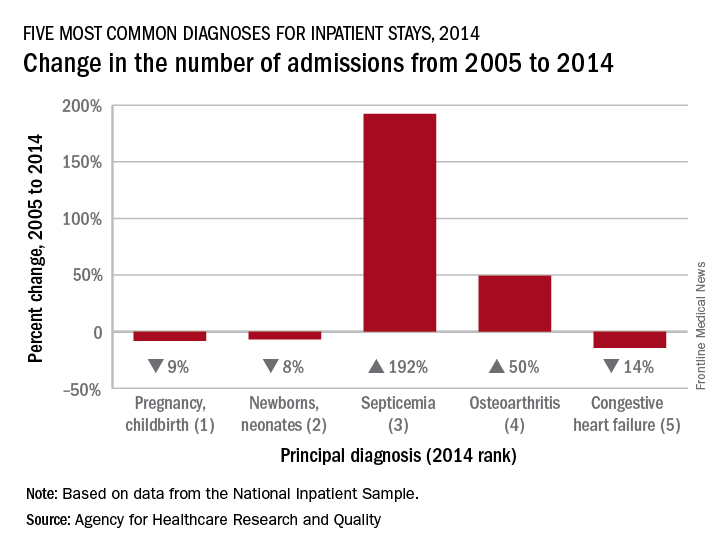

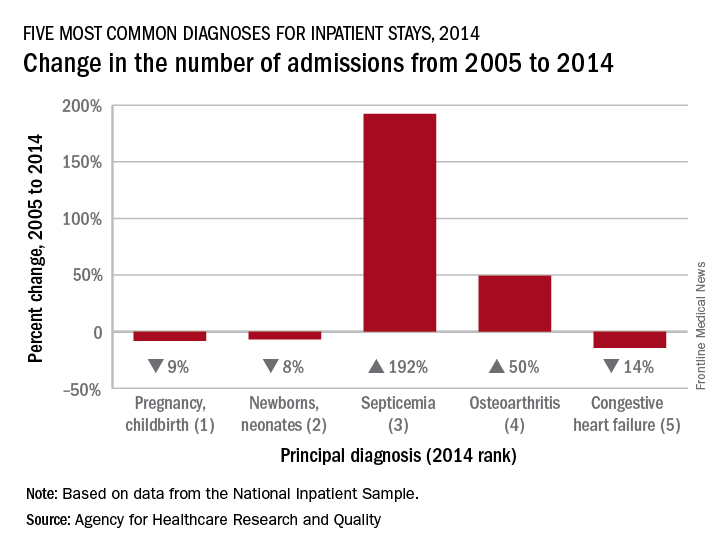

Septicemia admissions almost tripled from 2005 to 2014

Admissions for septicemia nearly tripled from 2005 to 2014, as it became the third most common diagnosis for hospital stays, according to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

There were over 1.5 million hospital stays with a principal diagnosis of septicemia in 2014, an increase of 192% over the 518,000 stays in 2005. The only diagnoses with more admissions in 2014 were pregnancy/childbirth with 4.1 million stays and newborns/neonates at almost 4 million, although both were down from 2005. That year, septicemia did not even rank among the top 10 diagnoses, the AHRQ reported.

Pneumonia, which was the third most common diagnosis in 2005, dropped by 32% and ended up in sixth place in 2014, while admissions for coronary atherosclerosis, which was fourth in 2005, decreased by 63%, dropping out of the top 10, by 2014, the AHRQ said.

Septicemia was the most common diagnosis for inpatient stays among those aged 75 years and older and the second most common for those aged 65-74 and 45-64. The leading nonmaternal, nonneonatal diagnosis in the two youngest age groups, 0-17 and 18-44 years, was mood disorders, and the most common cause of admissions for those aged 45-64 and 65-74 was osteoarthritis, the AHRQ reported.

Admissions for septicemia nearly tripled from 2005 to 2014, as it became the third most common diagnosis for hospital stays, according to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

There were over 1.5 million hospital stays with a principal diagnosis of septicemia in 2014, an increase of 192% over the 518,000 stays in 2005. The only diagnoses with more admissions in 2014 were pregnancy/childbirth with 4.1 million stays and newborns/neonates at almost 4 million, although both were down from 2005. That year, septicemia did not even rank among the top 10 diagnoses, the AHRQ reported.

Pneumonia, which was the third most common diagnosis in 2005, dropped by 32% and ended up in sixth place in 2014, while admissions for coronary atherosclerosis, which was fourth in 2005, decreased by 63%, dropping out of the top 10, by 2014, the AHRQ said.

Septicemia was the most common diagnosis for inpatient stays among those aged 75 years and older and the second most common for those aged 65-74 and 45-64. The leading nonmaternal, nonneonatal diagnosis in the two youngest age groups, 0-17 and 18-44 years, was mood disorders, and the most common cause of admissions for those aged 45-64 and 65-74 was osteoarthritis, the AHRQ reported.

Admissions for septicemia nearly tripled from 2005 to 2014, as it became the third most common diagnosis for hospital stays, according to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

There were over 1.5 million hospital stays with a principal diagnosis of septicemia in 2014, an increase of 192% over the 518,000 stays in 2005. The only diagnoses with more admissions in 2014 were pregnancy/childbirth with 4.1 million stays and newborns/neonates at almost 4 million, although both were down from 2005. That year, septicemia did not even rank among the top 10 diagnoses, the AHRQ reported.

Pneumonia, which was the third most common diagnosis in 2005, dropped by 32% and ended up in sixth place in 2014, while admissions for coronary atherosclerosis, which was fourth in 2005, decreased by 63%, dropping out of the top 10, by 2014, the AHRQ said.

Septicemia was the most common diagnosis for inpatient stays among those aged 75 years and older and the second most common for those aged 65-74 and 45-64. The leading nonmaternal, nonneonatal diagnosis in the two youngest age groups, 0-17 and 18-44 years, was mood disorders, and the most common cause of admissions for those aged 45-64 and 65-74 was osteoarthritis, the AHRQ reported.

Hospitalist burnout

Some things I’ve been thinking about:

- Physician well-being, morale, and burnout seem to be getting more attention in both the medical and the lay press.

- Leaders from 10 prestigious health systems and the CEO of the American Medical Association wrote a March 2017 post in the Health Affairs Blog titled “Physician Burnout is a Public Health Crisis: A Message To Our Fellow Health Care CEOs.”

- I’m now regularly hearing and reading mention of the “Quadruple Aim.” The “Triple Aim,” first described in 2008, is the pursuit of excellence in 1) patient experience – both quality of care and patient satisfaction; 2) population health; and 3) cost reduction. The November/December 2014 Annals of Family Medicine included an article recommending “that the Triple Aim be expanded to a Quadruple Aim by adding the goal of improving the work life of health care providers, including clinicians and staff.”1

- The CEO at a community hospital near me chose to make addressing physician burnout one of his top priorities and tied success in the effort to his own compensation bonus.

- In the course of my consulting work with hospitalist groups across the country, I’ve noticed a meaningful increase in the number of our colleagues who seem deeply unhappy with their work and/or burned out. The “Hospitalist Morale Index” may be a worthwhile way for a group to conduct an assessment.2

- I’m concerned that many other hospital care givers, including RNs, social workers, and others, are experiencing levels of distress and/or burnout that might be similar to that of physicians. From where I sit, they seem to be getting less attention, and I can’t tell if that is just because I’m not as immersed in their world or if it reflects reality. It’s pretty disappointing if it’s the latter.

For the most part, I think the causes of hospitalist distress and burnout are very similar to that of doctors in other specialties, and interventions to address the problem can be similar across specialties. Yet, each specialty probably differs in ways that are important to keep in mind.

Hospitalists also bear a huge burden related to observation status. Doctors in most other specialties rarely face complex decisions regarding whether observation is the right choice and are not so often the target of patient/family frustration and anger related to it.

Those seeking to address hospitalist burnout and well-being specifically should keep in mind these uniquely hospitalist issues. I think of them as a chronic disease to manage and mitigate, since “curing” them (making them go away entirely) is probably impossible for the foreseeable future.

What to do?

An Internet search on physician burnout, or other terms related to well-being, will yield more articles with advice to address the problem than you’ll ever have time to read. Trying to read all of them would likely lead to burnout! I think interventions can be divided into two broad categories: organizational efforts and personal efforts.

Like the 10 CEOs mentioned above, health care leaders should acknowledge physician distress and burnout as a meaningful issue that can impede organizational performance and that investments to address it can have a meaningful return on investment. The Health Affairs Blog post listed 11 things the CEOs committed to doing. It’s a list anyone working on this issue should review.

Doctors at The Mayo Clinic have published a great deal of research on physician burnout. In the March 7, 2017, JAMA, (summarized in a YouTube video) they describe several worthwhile organizational changes, as well as some personal strategies.3 They wrote about their experiences with interventions such as a deliberate curriculum to train doctors in self-care (self-reflection, mindfulness, etc.) in a series of one-hour lectures over several months.4 In November 2016, they published a meta-analysis of interventions to address burnout.5

In total, all of the worthwhile recommendations to address burnout leave me feeling like they’re a lot of work, and any individual intervention may not be as helpful as hoped, so that the best way to approach this is with a collection of interventions. In many ways, it is similar to the problem of readmissions: There is a lot of research out there, it’s hard to prove that any single intervention really works, and success lies in implementing a broad set of interventions. And success doesn’t equate to eliminating readmissions, only reducing them.

Coda: Is a sabbatical uniquely valuable for hospitalists?

I think a sabbatical might be a good idea for hospitalists. It also seems practical for other doctors, such as radiologists, anesthesiologists, and ED doctors, who don’t have 1:1 continuity relationships with patients. However, it is problematic for primary care doctors and specialists who need to maintain continuity relationships with patients and referring doctors that could be disrupted by a lengthy absence.

I’m not sure a sabbatical would reduce burnout much on its own, but, if properly structured, it seems very likely to reduce staffing turnover, and the sabbatical could be spent in ways that help rejuvenate interest and satisfaction in our work rather than simply taking a long vacation to travel and play golf, etc. It should probably be at least 3 months and better if it lasts a year. A common arrangement is that a doctor becomes eligible for the sabbatical after 10 years and is paid half of her usual compensation while away. I’d like to see more hospitalist groups do this.

Dr. Nelson has had a career in clinical practice as a hospitalist starting in 1988. He is cofounder and past president of SHM and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is codirector for SHM’s practice management courses. Write to [email protected].

References

1. Bodenheimer, T and Sninsky, C. From Triple to Quadruple Aim: Care of the Patient Requires Care of the Provider. Ann Fam Med. Nov/Dec 2014.

2. Chandra, S et al. Introducing the Hospitalist Morale Index: A New Tool That May Be Relevant for Improving Provider Retention. JHM. June 2016.

3. Shanafelt, T, Dyrbye, L, West, C. Addressing Physician Burnout: The Way Forward. JAMA. March 7, 2017.

4. West, C et al. Intervention to Promote Physician Well-being, Job Satisfaction, and Professionalism: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(4):527-33.

5. West, C et al. Interventions to prevent and reduce physician burnout: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet. Nov 5, 2016.

Some things I’ve been thinking about:

- Physician well-being, morale, and burnout seem to be getting more attention in both the medical and the lay press.

- Leaders from 10 prestigious health systems and the CEO of the American Medical Association wrote a March 2017 post in the Health Affairs Blog titled “Physician Burnout is a Public Health Crisis: A Message To Our Fellow Health Care CEOs.”

- I’m now regularly hearing and reading mention of the “Quadruple Aim.” The “Triple Aim,” first described in 2008, is the pursuit of excellence in 1) patient experience – both quality of care and patient satisfaction; 2) population health; and 3) cost reduction. The November/December 2014 Annals of Family Medicine included an article recommending “that the Triple Aim be expanded to a Quadruple Aim by adding the goal of improving the work life of health care providers, including clinicians and staff.”1

- The CEO at a community hospital near me chose to make addressing physician burnout one of his top priorities and tied success in the effort to his own compensation bonus.

- In the course of my consulting work with hospitalist groups across the country, I’ve noticed a meaningful increase in the number of our colleagues who seem deeply unhappy with their work and/or burned out. The “Hospitalist Morale Index” may be a worthwhile way for a group to conduct an assessment.2

- I’m concerned that many other hospital care givers, including RNs, social workers, and others, are experiencing levels of distress and/or burnout that might be similar to that of physicians. From where I sit, they seem to be getting less attention, and I can’t tell if that is just because I’m not as immersed in their world or if it reflects reality. It’s pretty disappointing if it’s the latter.

For the most part, I think the causes of hospitalist distress and burnout are very similar to that of doctors in other specialties, and interventions to address the problem can be similar across specialties. Yet, each specialty probably differs in ways that are important to keep in mind.

Hospitalists also bear a huge burden related to observation status. Doctors in most other specialties rarely face complex decisions regarding whether observation is the right choice and are not so often the target of patient/family frustration and anger related to it.

Those seeking to address hospitalist burnout and well-being specifically should keep in mind these uniquely hospitalist issues. I think of them as a chronic disease to manage and mitigate, since “curing” them (making them go away entirely) is probably impossible for the foreseeable future.

What to do?

An Internet search on physician burnout, or other terms related to well-being, will yield more articles with advice to address the problem than you’ll ever have time to read. Trying to read all of them would likely lead to burnout! I think interventions can be divided into two broad categories: organizational efforts and personal efforts.

Like the 10 CEOs mentioned above, health care leaders should acknowledge physician distress and burnout as a meaningful issue that can impede organizational performance and that investments to address it can have a meaningful return on investment. The Health Affairs Blog post listed 11 things the CEOs committed to doing. It’s a list anyone working on this issue should review.

Doctors at The Mayo Clinic have published a great deal of research on physician burnout. In the March 7, 2017, JAMA, (summarized in a YouTube video) they describe several worthwhile organizational changes, as well as some personal strategies.3 They wrote about their experiences with interventions such as a deliberate curriculum to train doctors in self-care (self-reflection, mindfulness, etc.) in a series of one-hour lectures over several months.4 In November 2016, they published a meta-analysis of interventions to address burnout.5

In total, all of the worthwhile recommendations to address burnout leave me feeling like they’re a lot of work, and any individual intervention may not be as helpful as hoped, so that the best way to approach this is with a collection of interventions. In many ways, it is similar to the problem of readmissions: There is a lot of research out there, it’s hard to prove that any single intervention really works, and success lies in implementing a broad set of interventions. And success doesn’t equate to eliminating readmissions, only reducing them.

Coda: Is a sabbatical uniquely valuable for hospitalists?

I think a sabbatical might be a good idea for hospitalists. It also seems practical for other doctors, such as radiologists, anesthesiologists, and ED doctors, who don’t have 1:1 continuity relationships with patients. However, it is problematic for primary care doctors and specialists who need to maintain continuity relationships with patients and referring doctors that could be disrupted by a lengthy absence.

I’m not sure a sabbatical would reduce burnout much on its own, but, if properly structured, it seems very likely to reduce staffing turnover, and the sabbatical could be spent in ways that help rejuvenate interest and satisfaction in our work rather than simply taking a long vacation to travel and play golf, etc. It should probably be at least 3 months and better if it lasts a year. A common arrangement is that a doctor becomes eligible for the sabbatical after 10 years and is paid half of her usual compensation while away. I’d like to see more hospitalist groups do this.

Dr. Nelson has had a career in clinical practice as a hospitalist starting in 1988. He is cofounder and past president of SHM and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is codirector for SHM’s practice management courses. Write to [email protected].

References

1. Bodenheimer, T and Sninsky, C. From Triple to Quadruple Aim: Care of the Patient Requires Care of the Provider. Ann Fam Med. Nov/Dec 2014.

2. Chandra, S et al. Introducing the Hospitalist Morale Index: A New Tool That May Be Relevant for Improving Provider Retention. JHM. June 2016.

3. Shanafelt, T, Dyrbye, L, West, C. Addressing Physician Burnout: The Way Forward. JAMA. March 7, 2017.

4. West, C et al. Intervention to Promote Physician Well-being, Job Satisfaction, and Professionalism: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(4):527-33.

5. West, C et al. Interventions to prevent and reduce physician burnout: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet. Nov 5, 2016.

Some things I’ve been thinking about:

- Physician well-being, morale, and burnout seem to be getting more attention in both the medical and the lay press.

- Leaders from 10 prestigious health systems and the CEO of the American Medical Association wrote a March 2017 post in the Health Affairs Blog titled “Physician Burnout is a Public Health Crisis: A Message To Our Fellow Health Care CEOs.”

- I’m now regularly hearing and reading mention of the “Quadruple Aim.” The “Triple Aim,” first described in 2008, is the pursuit of excellence in 1) patient experience – both quality of care and patient satisfaction; 2) population health; and 3) cost reduction. The November/December 2014 Annals of Family Medicine included an article recommending “that the Triple Aim be expanded to a Quadruple Aim by adding the goal of improving the work life of health care providers, including clinicians and staff.”1

- The CEO at a community hospital near me chose to make addressing physician burnout one of his top priorities and tied success in the effort to his own compensation bonus.

- In the course of my consulting work with hospitalist groups across the country, I’ve noticed a meaningful increase in the number of our colleagues who seem deeply unhappy with their work and/or burned out. The “Hospitalist Morale Index” may be a worthwhile way for a group to conduct an assessment.2

- I’m concerned that many other hospital care givers, including RNs, social workers, and others, are experiencing levels of distress and/or burnout that might be similar to that of physicians. From where I sit, they seem to be getting less attention, and I can’t tell if that is just because I’m not as immersed in their world or if it reflects reality. It’s pretty disappointing if it’s the latter.

For the most part, I think the causes of hospitalist distress and burnout are very similar to that of doctors in other specialties, and interventions to address the problem can be similar across specialties. Yet, each specialty probably differs in ways that are important to keep in mind.

Hospitalists also bear a huge burden related to observation status. Doctors in most other specialties rarely face complex decisions regarding whether observation is the right choice and are not so often the target of patient/family frustration and anger related to it.

Those seeking to address hospitalist burnout and well-being specifically should keep in mind these uniquely hospitalist issues. I think of them as a chronic disease to manage and mitigate, since “curing” them (making them go away entirely) is probably impossible for the foreseeable future.

What to do?

An Internet search on physician burnout, or other terms related to well-being, will yield more articles with advice to address the problem than you’ll ever have time to read. Trying to read all of them would likely lead to burnout! I think interventions can be divided into two broad categories: organizational efforts and personal efforts.

Like the 10 CEOs mentioned above, health care leaders should acknowledge physician distress and burnout as a meaningful issue that can impede organizational performance and that investments to address it can have a meaningful return on investment. The Health Affairs Blog post listed 11 things the CEOs committed to doing. It’s a list anyone working on this issue should review.

Doctors at The Mayo Clinic have published a great deal of research on physician burnout. In the March 7, 2017, JAMA, (summarized in a YouTube video) they describe several worthwhile organizational changes, as well as some personal strategies.3 They wrote about their experiences with interventions such as a deliberate curriculum to train doctors in self-care (self-reflection, mindfulness, etc.) in a series of one-hour lectures over several months.4 In November 2016, they published a meta-analysis of interventions to address burnout.5

In total, all of the worthwhile recommendations to address burnout leave me feeling like they’re a lot of work, and any individual intervention may not be as helpful as hoped, so that the best way to approach this is with a collection of interventions. In many ways, it is similar to the problem of readmissions: There is a lot of research out there, it’s hard to prove that any single intervention really works, and success lies in implementing a broad set of interventions. And success doesn’t equate to eliminating readmissions, only reducing them.

Coda: Is a sabbatical uniquely valuable for hospitalists?

I think a sabbatical might be a good idea for hospitalists. It also seems practical for other doctors, such as radiologists, anesthesiologists, and ED doctors, who don’t have 1:1 continuity relationships with patients. However, it is problematic for primary care doctors and specialists who need to maintain continuity relationships with patients and referring doctors that could be disrupted by a lengthy absence.

I’m not sure a sabbatical would reduce burnout much on its own, but, if properly structured, it seems very likely to reduce staffing turnover, and the sabbatical could be spent in ways that help rejuvenate interest and satisfaction in our work rather than simply taking a long vacation to travel and play golf, etc. It should probably be at least 3 months and better if it lasts a year. A common arrangement is that a doctor becomes eligible for the sabbatical after 10 years and is paid half of her usual compensation while away. I’d like to see more hospitalist groups do this.

Dr. Nelson has had a career in clinical practice as a hospitalist starting in 1988. He is cofounder and past president of SHM and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is codirector for SHM’s practice management courses. Write to [email protected].

References

1. Bodenheimer, T and Sninsky, C. From Triple to Quadruple Aim: Care of the Patient Requires Care of the Provider. Ann Fam Med. Nov/Dec 2014.

2. Chandra, S et al. Introducing the Hospitalist Morale Index: A New Tool That May Be Relevant for Improving Provider Retention. JHM. June 2016.

3. Shanafelt, T, Dyrbye, L, West, C. Addressing Physician Burnout: The Way Forward. JAMA. March 7, 2017.

4. West, C et al. Intervention to Promote Physician Well-being, Job Satisfaction, and Professionalism: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(4):527-33.

5. West, C et al. Interventions to prevent and reduce physician burnout: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet. Nov 5, 2016.

VIDEO: Meta-analysis favors anticoagulation for patients with cirrhosis and portal vein thrombosis

Patients with cirrhosis and portal vein thrombosis (PVT) who received anticoagulation therapy had nearly fivefold greater odds of recanalization compared with untreated patients, and were no more likely to experience major or minor bleeding, in a pooled analysis of eight studies published in the August issue of Gastroenterology (doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.04.042).

Rates of any recanalization were 71% in treated patients and 42% in untreated patients (P less than .0001), wrote Lorenzo Loffredo, MD, of Sapienza University, Rome, and his coinvestigators. Rates of complete recanalization were 53% and 33%, respectively (P = .002), rates of spontaneous variceal bleeding were 2% and 12% (P = .04), and bleeding affected 11% of patients in each group. Together, the findings “show that anticoagulants are efficacious and safe for treatment of portal vein thrombosis in cirrhotic patients,” although larger, interventional clinical trials are needed to pinpoint the clinical role of anticoagulation in cirrhotic patients with PVT, the reviewers reported.

Source: American Gastroenterological Association

Bleeding from portal hypertension is a major complication in cirrhosis, but PVT affects about 20% of patients and predicts poor outcomes, they noted. Anticoagulation in this setting can be difficult because patients often have concurrent coagulopathies that are hard to assess with standard techniques, such as PT-INR (international normalized ratio). Although some studies support anticoagulating these patients, data are limited. Therefore, the reviewers searched PubMed, the ISI Web of Science, SCOPUS, and the Cochrane database through Feb. 14, 2017, for trials comparing anticoagulation with no treatment in patients with cirrhosis and PVT.

This search yielded eight trials of 353 patients who received low-molecular-weight heparin, warfarin, or no treatment for about 6 months, with a typical follow-up period of 2 years. The reviewers found no evidence of publication bias or significant heterogeneity among the trials. Six studies evaluated complete recanalization, another set of six studies tracked progression of PVT, a third set of six studies evaluated major or minor bleeding events, and four studies evaluated spontaneous variceal bleeding. Compared with no treatment, anticoagulation was tied to a significantly greater likelihood of complete recanalization (pooled odds ratio, 3.4; 95% confidence interval, 1.5-7.4; P = .002), a significantly lower chance of PVT progressing (9% vs. 33%; pooled odds ratio, 0.14; 95% CI, 0.06-0.31; P less than .0001), no difference in bleeding rates (11% in each pooled group), and a significantly lower risk of spontaneous variceal bleeding (OR, 0.23; 95% CI, 0.06-0.94; P = .04).

“Metaregression analysis showed that duration of anticoagulation did not influence outcomes,” the reviewers wrote. “Low-molecular-weight heparin, but not warfarin, was significantly associated with a complete PVT resolution as compared to untreated patients, while both low-molecular-weight heparin and warfarin were effective in reducing PVT progression.” That finding merits careful interpretation, however, because most studies on warfarin were retrospective and lacked data on the quality of anticoagulation, they added.

“It is a challenge to treat patients with cirrhosis using anticoagulants because of the perception that the coexistent coagulopathy could promote bleeding,” the researchers wrote. Nonetheless, their analysis suggests that anticoagulation has significant benefits and does not increase bleeding risk, regardless of the severity of liver failure, they concluded.

The reviewers reported having no funding sources or conflicts of interest.

Patients with cirrhosis and portal vein thrombosis (PVT) who received anticoagulation therapy had nearly fivefold greater odds of recanalization compared with untreated patients, and were no more likely to experience major or minor bleeding, in a pooled analysis of eight studies published in the August issue of Gastroenterology (doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.04.042).

Rates of any recanalization were 71% in treated patients and 42% in untreated patients (P less than .0001), wrote Lorenzo Loffredo, MD, of Sapienza University, Rome, and his coinvestigators. Rates of complete recanalization were 53% and 33%, respectively (P = .002), rates of spontaneous variceal bleeding were 2% and 12% (P = .04), and bleeding affected 11% of patients in each group. Together, the findings “show that anticoagulants are efficacious and safe for treatment of portal vein thrombosis in cirrhotic patients,” although larger, interventional clinical trials are needed to pinpoint the clinical role of anticoagulation in cirrhotic patients with PVT, the reviewers reported.

Source: American Gastroenterological Association

Bleeding from portal hypertension is a major complication in cirrhosis, but PVT affects about 20% of patients and predicts poor outcomes, they noted. Anticoagulation in this setting can be difficult because patients often have concurrent coagulopathies that are hard to assess with standard techniques, such as PT-INR (international normalized ratio). Although some studies support anticoagulating these patients, data are limited. Therefore, the reviewers searched PubMed, the ISI Web of Science, SCOPUS, and the Cochrane database through Feb. 14, 2017, for trials comparing anticoagulation with no treatment in patients with cirrhosis and PVT.

This search yielded eight trials of 353 patients who received low-molecular-weight heparin, warfarin, or no treatment for about 6 months, with a typical follow-up period of 2 years. The reviewers found no evidence of publication bias or significant heterogeneity among the trials. Six studies evaluated complete recanalization, another set of six studies tracked progression of PVT, a third set of six studies evaluated major or minor bleeding events, and four studies evaluated spontaneous variceal bleeding. Compared with no treatment, anticoagulation was tied to a significantly greater likelihood of complete recanalization (pooled odds ratio, 3.4; 95% confidence interval, 1.5-7.4; P = .002), a significantly lower chance of PVT progressing (9% vs. 33%; pooled odds ratio, 0.14; 95% CI, 0.06-0.31; P less than .0001), no difference in bleeding rates (11% in each pooled group), and a significantly lower risk of spontaneous variceal bleeding (OR, 0.23; 95% CI, 0.06-0.94; P = .04).

“Metaregression analysis showed that duration of anticoagulation did not influence outcomes,” the reviewers wrote. “Low-molecular-weight heparin, but not warfarin, was significantly associated with a complete PVT resolution as compared to untreated patients, while both low-molecular-weight heparin and warfarin were effective in reducing PVT progression.” That finding merits careful interpretation, however, because most studies on warfarin were retrospective and lacked data on the quality of anticoagulation, they added.

“It is a challenge to treat patients with cirrhosis using anticoagulants because of the perception that the coexistent coagulopathy could promote bleeding,” the researchers wrote. Nonetheless, their analysis suggests that anticoagulation has significant benefits and does not increase bleeding risk, regardless of the severity of liver failure, they concluded.

The reviewers reported having no funding sources or conflicts of interest.

Patients with cirrhosis and portal vein thrombosis (PVT) who received anticoagulation therapy had nearly fivefold greater odds of recanalization compared with untreated patients, and were no more likely to experience major or minor bleeding, in a pooled analysis of eight studies published in the August issue of Gastroenterology (doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.04.042).

Rates of any recanalization were 71% in treated patients and 42% in untreated patients (P less than .0001), wrote Lorenzo Loffredo, MD, of Sapienza University, Rome, and his coinvestigators. Rates of complete recanalization were 53% and 33%, respectively (P = .002), rates of spontaneous variceal bleeding were 2% and 12% (P = .04), and bleeding affected 11% of patients in each group. Together, the findings “show that anticoagulants are efficacious and safe for treatment of portal vein thrombosis in cirrhotic patients,” although larger, interventional clinical trials are needed to pinpoint the clinical role of anticoagulation in cirrhotic patients with PVT, the reviewers reported.

Source: American Gastroenterological Association

Bleeding from portal hypertension is a major complication in cirrhosis, but PVT affects about 20% of patients and predicts poor outcomes, they noted. Anticoagulation in this setting can be difficult because patients often have concurrent coagulopathies that are hard to assess with standard techniques, such as PT-INR (international normalized ratio). Although some studies support anticoagulating these patients, data are limited. Therefore, the reviewers searched PubMed, the ISI Web of Science, SCOPUS, and the Cochrane database through Feb. 14, 2017, for trials comparing anticoagulation with no treatment in patients with cirrhosis and PVT.

This search yielded eight trials of 353 patients who received low-molecular-weight heparin, warfarin, or no treatment for about 6 months, with a typical follow-up period of 2 years. The reviewers found no evidence of publication bias or significant heterogeneity among the trials. Six studies evaluated complete recanalization, another set of six studies tracked progression of PVT, a third set of six studies evaluated major or minor bleeding events, and four studies evaluated spontaneous variceal bleeding. Compared with no treatment, anticoagulation was tied to a significantly greater likelihood of complete recanalization (pooled odds ratio, 3.4; 95% confidence interval, 1.5-7.4; P = .002), a significantly lower chance of PVT progressing (9% vs. 33%; pooled odds ratio, 0.14; 95% CI, 0.06-0.31; P less than .0001), no difference in bleeding rates (11% in each pooled group), and a significantly lower risk of spontaneous variceal bleeding (OR, 0.23; 95% CI, 0.06-0.94; P = .04).

“Metaregression analysis showed that duration of anticoagulation did not influence outcomes,” the reviewers wrote. “Low-molecular-weight heparin, but not warfarin, was significantly associated with a complete PVT resolution as compared to untreated patients, while both low-molecular-weight heparin and warfarin were effective in reducing PVT progression.” That finding merits careful interpretation, however, because most studies on warfarin were retrospective and lacked data on the quality of anticoagulation, they added.

“It is a challenge to treat patients with cirrhosis using anticoagulants because of the perception that the coexistent coagulopathy could promote bleeding,” the researchers wrote. Nonetheless, their analysis suggests that anticoagulation has significant benefits and does not increase bleeding risk, regardless of the severity of liver failure, they concluded.

The reviewers reported having no funding sources or conflicts of interest.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

Key clinical point: Anticoagulation produced favorable outcomes with no increase in bleeding risk in patients with cirrhosis and portal vein thrombosis.

Major finding: Rates of any recanalization were 71% in treated patients and 42% in untreated patients (P less than .0001); rates of complete recanalization were 53% and 33%, respectively (P = .002), rates of spontaneous variceal bleeding were 2% and 12% (P = .04), and bleeding affected 11% of patients in each group.

Data source: A systematic review and meta-analysis of eight studies of 353 patients with cirrhosis and portal vein thrombosis.

Disclosures: The reviewers reported having no funding sources or conflicts of interest.

QI enthusiast to QI leader: John Bulger, DO

Editor’s Note: This SHM series highlights the professional pathways of quality improvement leaders. This month features the story of John Bulger, DO, chief medical officer for Geisinger Health Plan.

As chief medical officer for Geisinger Health Plan, John Bulger, DO, MBA, is intimately acquainted with the daily challenges that intersect with the delivery of safe, quality-driven care in the hospital system.

He’s also very familiar with the intricacies of carving out a professional road map. When Dr. Bulger began practicing as an internist at Geisinger Health System in the late 1990s, there wasn’t a formal hospitalist designation. He created one and became director of the hospital medicine program. Years later, when the opportunity arose to become chief quality officer, Dr. Bulger was a natural fit for the position, having led many improvement-centered committees and projects while running the hospital medicine group.

Early in his QI immersion, Dr. Bulger sought training where available from sources such as ACP and SHM, while familiarizing himself with methodologies such as PDSA and Lean. There are far more QI training opportunities available to hospitalists today than when Dr. Bulger began his journey, but the fundamentals of success come back to finding the right mentors, team building, and implementing projects built around SMART goals.

Getting started, Dr. Bulger suggests to “pick something within your scope, like medical reconciliation for every patient, or ensuring that every patient who leaves the hospital gets an appointment with their primary physician within 7 days. Early on, we were working on issues like pneumonia core measures and providing discharge instructions.”

He cautions those starting out in QI against viewing unintended outcomes or project setbacks as failure. “If your goal is to take a (scenario) from bad to perfect, you’ll end up getting discouraged. Any effort toward making things better is helpful. If it doesn’t work you try something else.”

While Dr. Bulger is fully supportive of the impact that quality improvement projects make at the institutional level, he encourages clinicians and researchers to always keep the Institute for Healthcare Improvement Triple Aim in sight.

“We need better measures and more discussion about what is best for patients,” Dr. Bulger said. “The things we talk about in (health care) – readmission rates, glycemic control – have a minimal impact on people’s health, but the social determinants of health – the patient’s housing and economic situation – play a bigger role than anything else. As we move from provider- to patient-centric communities by fixing the Triple Aim, the experience will be better for both providers and patients.”

Claudia Stahl is content manager for the Society of Hospital Medicine.

Editor’s Note: This SHM series highlights the professional pathways of quality improvement leaders. This month features the story of John Bulger, DO, chief medical officer for Geisinger Health Plan.

As chief medical officer for Geisinger Health Plan, John Bulger, DO, MBA, is intimately acquainted with the daily challenges that intersect with the delivery of safe, quality-driven care in the hospital system.