User login

Commentary: Early Diagnosis of PsA, February 2023

Appropriate assessment of MSK symptoms and signs by dermatologists may lead to more appropriate referral to rheumatologists. MSUS is being increasingly explored for early identification of PsA. A handheld, chip-based ultrasound device (HHUD) is a novel promising instrument that can be easily implemented in clinical practice. In a prospective study including 140 patients with psoriasis who presented to dermatologists with arthralgia. Grobelski and colleagues screened for PsA using medical history, CE, and the German Psoriasis Arthritis Diagnostic PsA screening questionnaire (GEPARD) paired with MSUS examination of up to three painful joints by trained dermatologists. Nineteen patients (13.6%) were diagnosed with PsA by rheumatologists. Interestingly, in 45 of the 46 patients the preliminary diagnosis of PsA was revised to "no PsA" after MSUS. The addition of MSUS changed the sensitivity and specificity of early PsA screening strategy from 88.2% and 54.4% to 70.6% and 90.4%, respectively. The positive predictive value increased to 56.5% from 25.4% after MSUS. Thus, the use of a quick MSUS using HHUD may lead to more accurate referral to rheumatologists. The challenge is seamless integration of MSUS into busy dermatology practices.

The goal of PsA treatment is to achieve a state of remission or low disease activity. Criteria for minimal disease activity (MDA) have been established. Achieving MDA leads to better health-related quality of life (HRQOL), as well as less joint damage. In a prospective cohort study that included 240 patients with newly diagnosed disease-modifying antirheumatic drug-naive PsA, Snoeck Henkemans and colleagues demonstrate that failure to achieve MDA in the first year after the diagnosis of PsA was associated with worse HRQOL and health status, functional impairment, fatigue, pain, and higher anxiety and depression. Compared with patients who achieved sustained MDA in the first year after diagnosis, those who did not achieve MDA had higher scores for pain, fatigue, and functional ability and higher anxiety and depression during follow-up, which persisted despite treatment intensification. Thus, implementation of treat-to-target strategies with the aim of achieving sustained MDA within 1 year of diagnosis is likely to have better long-term benefits in this lifelong disease.

Another study emphasized the need for early treatment to improve long-term outcomes. In a post hoc analysis of two phase 3 trials including 1554 patients with PsA who received 300-mg or 150-mg secukinumab with or without a loading dose, Mease and colleagues showed that high baseline radiographic damage reduced the likelihood of achieving MDA.

Overall, these studies indicate that early diagnosis and treatment prior to developing joint damage with the aim to achieve sustained MDA within a year will lead to better long-term outcome for patients with PsA.

Appropriate assessment of MSK symptoms and signs by dermatologists may lead to more appropriate referral to rheumatologists. MSUS is being increasingly explored for early identification of PsA. A handheld, chip-based ultrasound device (HHUD) is a novel promising instrument that can be easily implemented in clinical practice. In a prospective study including 140 patients with psoriasis who presented to dermatologists with arthralgia. Grobelski and colleagues screened for PsA using medical history, CE, and the German Psoriasis Arthritis Diagnostic PsA screening questionnaire (GEPARD) paired with MSUS examination of up to three painful joints by trained dermatologists. Nineteen patients (13.6%) were diagnosed with PsA by rheumatologists. Interestingly, in 45 of the 46 patients the preliminary diagnosis of PsA was revised to "no PsA" after MSUS. The addition of MSUS changed the sensitivity and specificity of early PsA screening strategy from 88.2% and 54.4% to 70.6% and 90.4%, respectively. The positive predictive value increased to 56.5% from 25.4% after MSUS. Thus, the use of a quick MSUS using HHUD may lead to more accurate referral to rheumatologists. The challenge is seamless integration of MSUS into busy dermatology practices.

The goal of PsA treatment is to achieve a state of remission or low disease activity. Criteria for minimal disease activity (MDA) have been established. Achieving MDA leads to better health-related quality of life (HRQOL), as well as less joint damage. In a prospective cohort study that included 240 patients with newly diagnosed disease-modifying antirheumatic drug-naive PsA, Snoeck Henkemans and colleagues demonstrate that failure to achieve MDA in the first year after the diagnosis of PsA was associated with worse HRQOL and health status, functional impairment, fatigue, pain, and higher anxiety and depression. Compared with patients who achieved sustained MDA in the first year after diagnosis, those who did not achieve MDA had higher scores for pain, fatigue, and functional ability and higher anxiety and depression during follow-up, which persisted despite treatment intensification. Thus, implementation of treat-to-target strategies with the aim of achieving sustained MDA within 1 year of diagnosis is likely to have better long-term benefits in this lifelong disease.

Another study emphasized the need for early treatment to improve long-term outcomes. In a post hoc analysis of two phase 3 trials including 1554 patients with PsA who received 300-mg or 150-mg secukinumab with or without a loading dose, Mease and colleagues showed that high baseline radiographic damage reduced the likelihood of achieving MDA.

Overall, these studies indicate that early diagnosis and treatment prior to developing joint damage with the aim to achieve sustained MDA within a year will lead to better long-term outcome for patients with PsA.

Appropriate assessment of MSK symptoms and signs by dermatologists may lead to more appropriate referral to rheumatologists. MSUS is being increasingly explored for early identification of PsA. A handheld, chip-based ultrasound device (HHUD) is a novel promising instrument that can be easily implemented in clinical practice. In a prospective study including 140 patients with psoriasis who presented to dermatologists with arthralgia. Grobelski and colleagues screened for PsA using medical history, CE, and the German Psoriasis Arthritis Diagnostic PsA screening questionnaire (GEPARD) paired with MSUS examination of up to three painful joints by trained dermatologists. Nineteen patients (13.6%) were diagnosed with PsA by rheumatologists. Interestingly, in 45 of the 46 patients the preliminary diagnosis of PsA was revised to "no PsA" after MSUS. The addition of MSUS changed the sensitivity and specificity of early PsA screening strategy from 88.2% and 54.4% to 70.6% and 90.4%, respectively. The positive predictive value increased to 56.5% from 25.4% after MSUS. Thus, the use of a quick MSUS using HHUD may lead to more accurate referral to rheumatologists. The challenge is seamless integration of MSUS into busy dermatology practices.

The goal of PsA treatment is to achieve a state of remission or low disease activity. Criteria for minimal disease activity (MDA) have been established. Achieving MDA leads to better health-related quality of life (HRQOL), as well as less joint damage. In a prospective cohort study that included 240 patients with newly diagnosed disease-modifying antirheumatic drug-naive PsA, Snoeck Henkemans and colleagues demonstrate that failure to achieve MDA in the first year after the diagnosis of PsA was associated with worse HRQOL and health status, functional impairment, fatigue, pain, and higher anxiety and depression. Compared with patients who achieved sustained MDA in the first year after diagnosis, those who did not achieve MDA had higher scores for pain, fatigue, and functional ability and higher anxiety and depression during follow-up, which persisted despite treatment intensification. Thus, implementation of treat-to-target strategies with the aim of achieving sustained MDA within 1 year of diagnosis is likely to have better long-term benefits in this lifelong disease.

Another study emphasized the need for early treatment to improve long-term outcomes. In a post hoc analysis of two phase 3 trials including 1554 patients with PsA who received 300-mg or 150-mg secukinumab with or without a loading dose, Mease and colleagues showed that high baseline radiographic damage reduced the likelihood of achieving MDA.

Overall, these studies indicate that early diagnosis and treatment prior to developing joint damage with the aim to achieve sustained MDA within a year will lead to better long-term outcome for patients with PsA.

Dermatopathologist reflects on the early history of melanoma

SAN DIEGO – Evidence of melanoma in the ancient past is rare, but according to James W. Patterson, MD, .

“Radiocarbon dating indicated that these mummies were 2,400 years old,” Dr. Patterson, professor emeritus of pathology and dermatology at the University of Virginia, Charlottesville, said at the annual Cutaneous Malignancy Update.

John Hunter, a famous British surgeon who lived from 1728 to 1793, had the first known reported encounter with melanoma in 1787. “He thought it was a form of cancerous fungus,” said Dr. Patterson, a former president of the American Board of Dermatology. “That tumor was preserved in the Hunterian Museum of the Royal College of Surgeons in London, and in 1968 it was reexamined and turned out to be melanoma.”

René Laënnec, the French physician who invented the stethoscope in 1816, is believed to be the first person to lecture on melanoma while a medical student in 1804. The lecture was published about a year later. He originated the term “melanose” (becoming black), a French word derived from the Greek language, to describe metastatic melanoma and reported metastasis to the lungs. During the early part of his career, Dr. Laënnec had studied dissection in the laboratory of the French anatomist and military surgeon Guillaume Dupuytren, best known for his description of Dupuytren’s contracture. Dr. Dupuytren took exception to Dr. Laënnec’s publication about melanoma and called foul.

“As sometimes happens these days, there was some rivalry between these two outstanding physicians of their time,” Dr. Patterson said at the meeting, hosted by Scripps MD Anderson Cancer Center. “Dupuytren was unhappy that Laënnec took credit for this because he claimed credit for originally describing melanoma. He claimed that Laënnec stole the idea from his lectures. I’m not sure that issue was ever resolved.”

In 1820, William Norris, a general practitioner from Stourbridge, England, published the first English language report of melanoma in the Edinburgh Medical and Surgical Journal. “The report was titled ‘A case of fungoid disease,’ so it appears that melanoma was often regarded as a fungal infection back then,” Dr. Patterson said. In the report, Dr. Norris described the tumor in a 59-year-old man as “nearly half the size of a hen’s egg, of a deep brown color, of a firm and fleshy feel, [and] ulcerated on its surface.” Dr. Norris authored a later work titled “Eight cases of melanosis, with pathological and therapeutical remarks on that disease.”

In 1840, a full 2 decades following the first published report from Dr. Norris, the British surgeon Samuel Cooper published a book titled “First Lines of Theory and Practice of Surgery,” in which he described patients with advanced stage melanoma as untreatable and postulated that the only chance for survival was early removal of the tumor.

Dr. Patterson reported having no relevant disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Evidence of melanoma in the ancient past is rare, but according to James W. Patterson, MD, .

“Radiocarbon dating indicated that these mummies were 2,400 years old,” Dr. Patterson, professor emeritus of pathology and dermatology at the University of Virginia, Charlottesville, said at the annual Cutaneous Malignancy Update.

John Hunter, a famous British surgeon who lived from 1728 to 1793, had the first known reported encounter with melanoma in 1787. “He thought it was a form of cancerous fungus,” said Dr. Patterson, a former president of the American Board of Dermatology. “That tumor was preserved in the Hunterian Museum of the Royal College of Surgeons in London, and in 1968 it was reexamined and turned out to be melanoma.”

René Laënnec, the French physician who invented the stethoscope in 1816, is believed to be the first person to lecture on melanoma while a medical student in 1804. The lecture was published about a year later. He originated the term “melanose” (becoming black), a French word derived from the Greek language, to describe metastatic melanoma and reported metastasis to the lungs. During the early part of his career, Dr. Laënnec had studied dissection in the laboratory of the French anatomist and military surgeon Guillaume Dupuytren, best known for his description of Dupuytren’s contracture. Dr. Dupuytren took exception to Dr. Laënnec’s publication about melanoma and called foul.

“As sometimes happens these days, there was some rivalry between these two outstanding physicians of their time,” Dr. Patterson said at the meeting, hosted by Scripps MD Anderson Cancer Center. “Dupuytren was unhappy that Laënnec took credit for this because he claimed credit for originally describing melanoma. He claimed that Laënnec stole the idea from his lectures. I’m not sure that issue was ever resolved.”

In 1820, William Norris, a general practitioner from Stourbridge, England, published the first English language report of melanoma in the Edinburgh Medical and Surgical Journal. “The report was titled ‘A case of fungoid disease,’ so it appears that melanoma was often regarded as a fungal infection back then,” Dr. Patterson said. In the report, Dr. Norris described the tumor in a 59-year-old man as “nearly half the size of a hen’s egg, of a deep brown color, of a firm and fleshy feel, [and] ulcerated on its surface.” Dr. Norris authored a later work titled “Eight cases of melanosis, with pathological and therapeutical remarks on that disease.”

In 1840, a full 2 decades following the first published report from Dr. Norris, the British surgeon Samuel Cooper published a book titled “First Lines of Theory and Practice of Surgery,” in which he described patients with advanced stage melanoma as untreatable and postulated that the only chance for survival was early removal of the tumor.

Dr. Patterson reported having no relevant disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Evidence of melanoma in the ancient past is rare, but according to James W. Patterson, MD, .

“Radiocarbon dating indicated that these mummies were 2,400 years old,” Dr. Patterson, professor emeritus of pathology and dermatology at the University of Virginia, Charlottesville, said at the annual Cutaneous Malignancy Update.

John Hunter, a famous British surgeon who lived from 1728 to 1793, had the first known reported encounter with melanoma in 1787. “He thought it was a form of cancerous fungus,” said Dr. Patterson, a former president of the American Board of Dermatology. “That tumor was preserved in the Hunterian Museum of the Royal College of Surgeons in London, and in 1968 it was reexamined and turned out to be melanoma.”

René Laënnec, the French physician who invented the stethoscope in 1816, is believed to be the first person to lecture on melanoma while a medical student in 1804. The lecture was published about a year later. He originated the term “melanose” (becoming black), a French word derived from the Greek language, to describe metastatic melanoma and reported metastasis to the lungs. During the early part of his career, Dr. Laënnec had studied dissection in the laboratory of the French anatomist and military surgeon Guillaume Dupuytren, best known for his description of Dupuytren’s contracture. Dr. Dupuytren took exception to Dr. Laënnec’s publication about melanoma and called foul.

“As sometimes happens these days, there was some rivalry between these two outstanding physicians of their time,” Dr. Patterson said at the meeting, hosted by Scripps MD Anderson Cancer Center. “Dupuytren was unhappy that Laënnec took credit for this because he claimed credit for originally describing melanoma. He claimed that Laënnec stole the idea from his lectures. I’m not sure that issue was ever resolved.”

In 1820, William Norris, a general practitioner from Stourbridge, England, published the first English language report of melanoma in the Edinburgh Medical and Surgical Journal. “The report was titled ‘A case of fungoid disease,’ so it appears that melanoma was often regarded as a fungal infection back then,” Dr. Patterson said. In the report, Dr. Norris described the tumor in a 59-year-old man as “nearly half the size of a hen’s egg, of a deep brown color, of a firm and fleshy feel, [and] ulcerated on its surface.” Dr. Norris authored a later work titled “Eight cases of melanosis, with pathological and therapeutical remarks on that disease.”

In 1840, a full 2 decades following the first published report from Dr. Norris, the British surgeon Samuel Cooper published a book titled “First Lines of Theory and Practice of Surgery,” in which he described patients with advanced stage melanoma as untreatable and postulated that the only chance for survival was early removal of the tumor.

Dr. Patterson reported having no relevant disclosures.

AT MELANOMA 2023

14-year-old boy • aching midsternal pain following a basketball injury • worsening pain with direct pressure and when the patient sneezed • Dx?

THE CASE

A 14-year-old boy sought care at our clinic for persistent chest pain after being hit in the chest with a teammate’s shoulder during a basketball game 3 weeks earlier. He had aching midsternal chest pain that worsened with direct pressure and when he sneezed, twisted, or bent forward. There was no bruising or swelling.

On examination, the patient demonstrated normal perfusion and normal work of breathing. He had focal tenderness with palpation at the manubrium with no noticeable step-off, and mild tenderness at the adjacent costochondral junctions and over his pectoral muscles. His sternal pain along the proximal sternum was reproducible with a weighted wall push-up. Although the patient maintained full range of motion in his upper extremities, he did have sternal pain with flexion, abduction, and external rotation of the bilateral upper extremities against resistance. Anteroposterior (AP) and lateral chest radiographs were unremarkable.

THE DIAGNOSIS

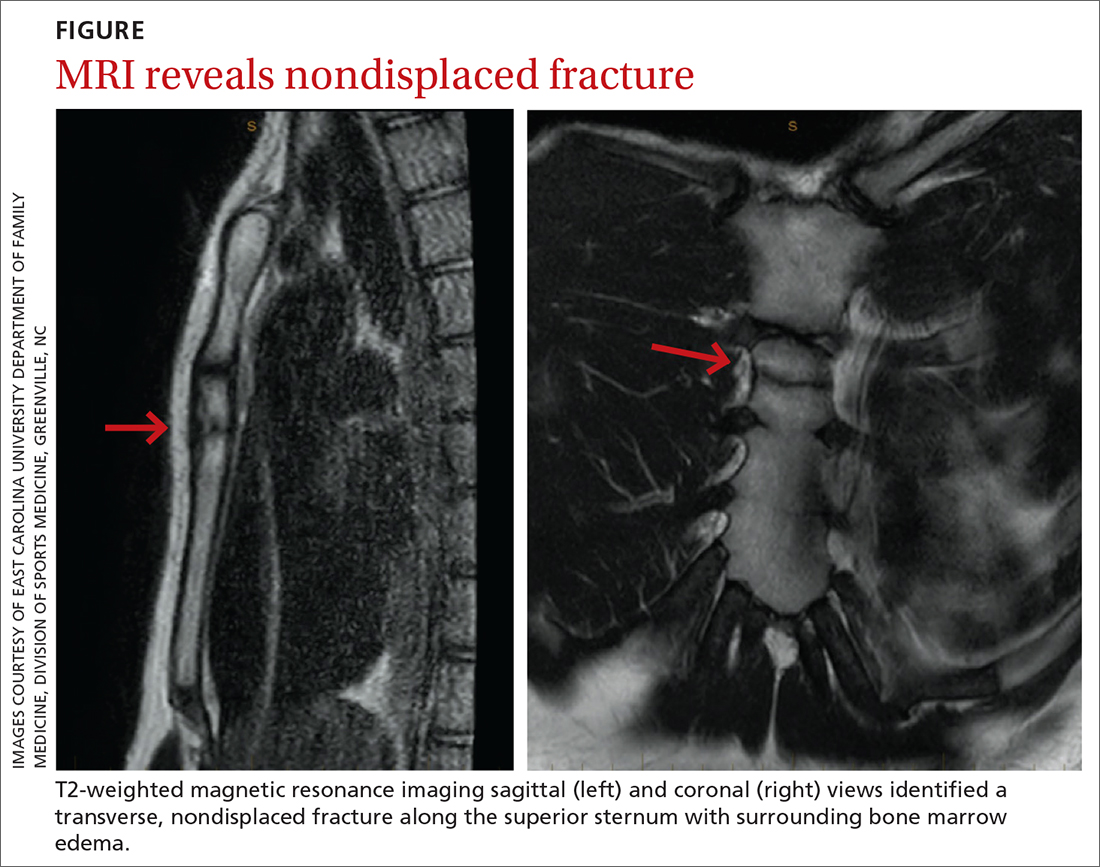

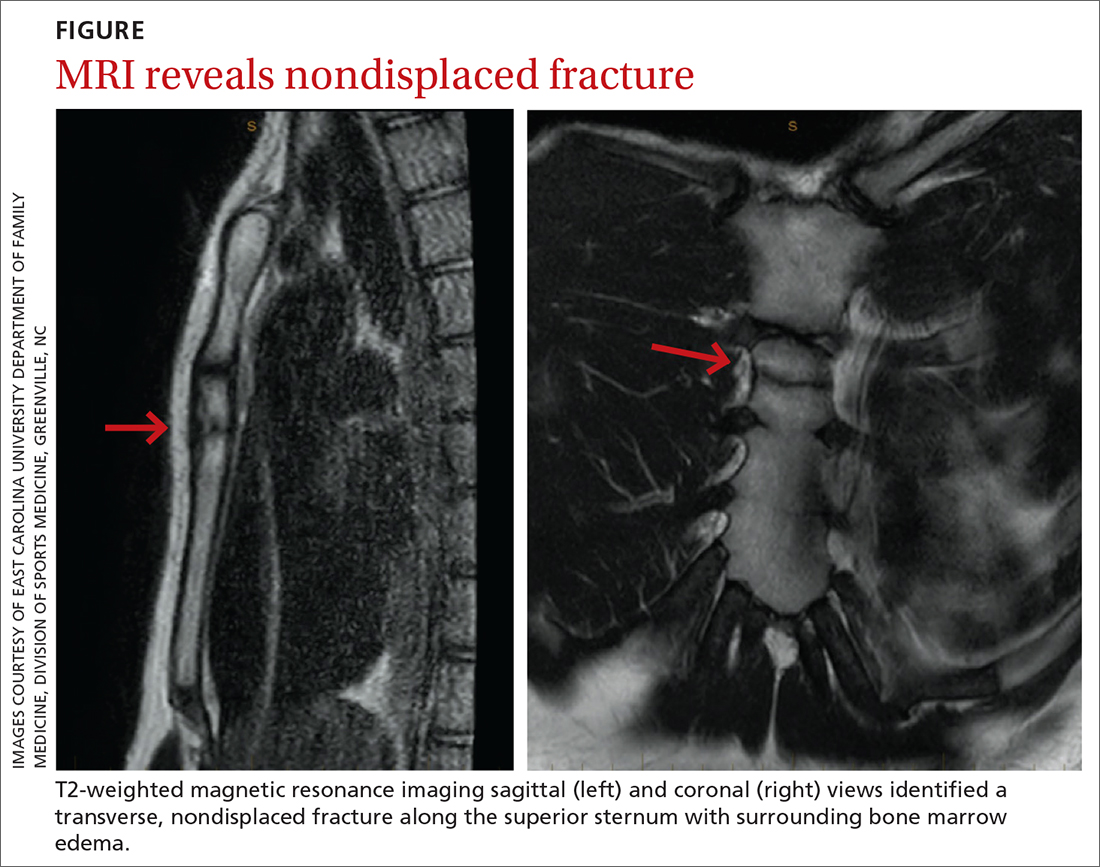

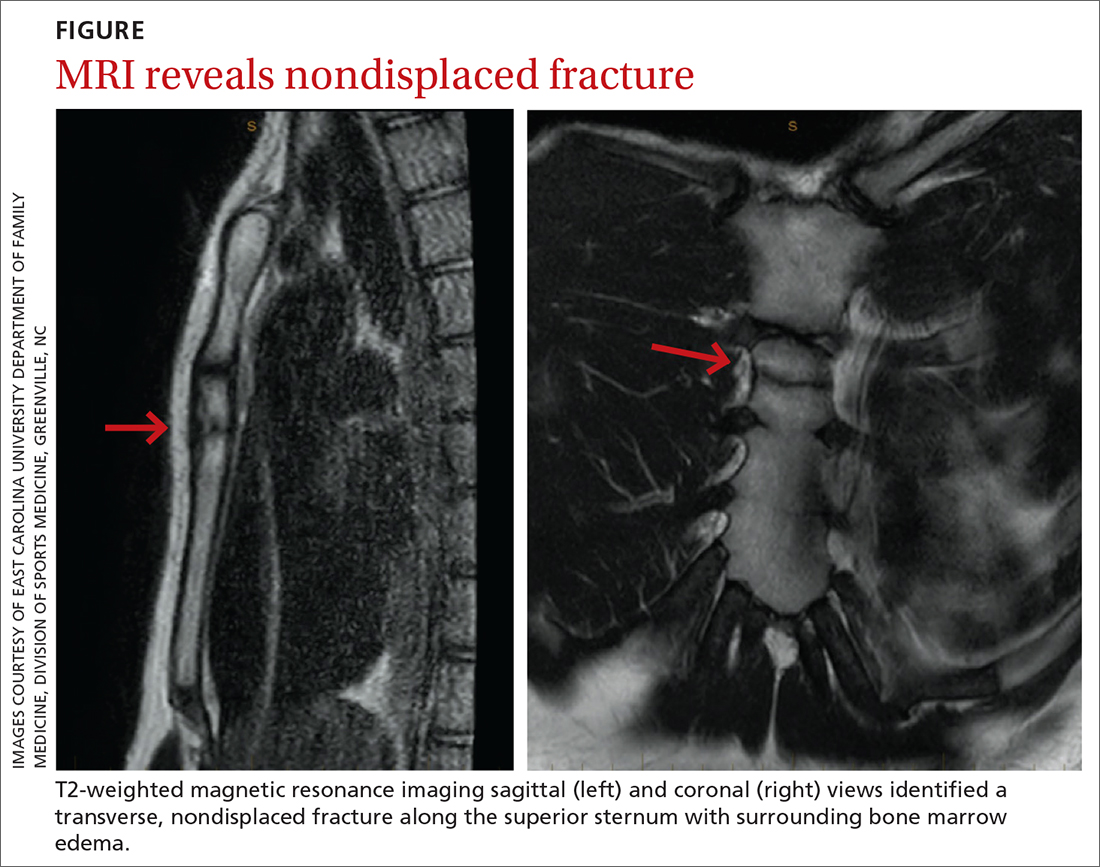

The unremarkable chest radiographs prompted further investigation with a diagnostic ultrasound, which revealed a small cortical defect with overlying anechoic fluid collection in the area of focal tenderness. T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the chest was performed; it revealed a transverse, nondisplaced fracture of the superior body of the sternum with surrounding bone marrow edema (FIGURE).

DISCUSSION

Fractures of the sternum comprise < 1% of traumatic fractures and have a low mortality rate (0.7%).1,2 The rarity of these fractures is attributed to the ribs’ elastic recoil, which protects the chest wall from anterior forces.1,3 These fractures are even more unusual in children due to the increased elasticity of their chest walls.4-6 Thus, it takes a significant amount of force for a child’s sternum to fracture.

While isolated sternum fractures can occur, two-thirds of sternum fractures are nonisolated and are associated with injuries to surrounding structures (including the heart, lungs, and vasculature) or fractures of the ribs and spine.2,3 Most often, these injuries are caused by significant blunt trauma to the anterior chest, rapid deceleration, or flexion-compression injury.2,3 They are typically transverse and localized, with 70% of fractures occurring in the mid-body and 17.6% at the manubriosternal joint.1,3,6

Athletes with a sternal fracture typically present as our patient did, with a history of blunt force trauma to the chest and with pain and tenderness over the anterior midline of the chest that increases with respiration or movement.1 A physical examination that includes chest palpation and auscultation of the heart and lungs must be performed to rule out damage to intrathoracic structures and assess the patient’s cardiac and pulmonary stability. An electrocardiogram should be performed to confirm that there are no cardiovascular complications.3,4

Initial imaging should include AP and lateral chest radiographs because any displacement will occur in the sagittal plane.1,2,4-6 If the radiograph shows no clear pathology, follow up with computed tomography, ultrasound, MRI, or technetium bone scans to gain additional information.1 Diagnosis of sternal fractures is especially difficult in children due to the presence of ossification centers for bone growth, which may be misinterpreted as a sternal fracture in the absence of a proper understanding of sternal development.5,6 On ultrasound, sternal fractures appear as a sharp step-off in the cortex, whereas in the absence of fracture, there is no cortical step-off and the cartilaginous plate between ossification centers appears in line with the cortex.7

Continue to: A self-limiting injury that requires proper pain control

A self-limiting injury that requires proper pain control

Isolated sternal fractures are typically self-limiting with a good prognosis.2 These injuries are managed supportively with rest, ice, and analgesics1; proper pain control is crucial to prevent respiratory compromise.8

Complete recovery for most patients occurs in 10 to 12 weeks.9 Recovery periods longer than 12 weeks are associated with nonisolated sternal fractures that are complicated by soft-tissue injury, injuries to the chest wall (such as sternoclavicular joint dislocation, usually from a fall on the shoulder), or fracture nonunion.1,2,5

Anterior sternoclavicular joint dislocations and stable posterior dislocations are managed with closed reduction and immobilization in a figure-of-eight brace.1 Operative management is reserved for patients with displaced fractures, sternal deformity, chest wall instability, respiratory insufficiency, uncontrolled pain, or fracture nonunion.1,3,8

A return-to-play protocol can begin once the patient is asymptomatic.1 The timeframe for a full return to play can vary from 6 weeks to 6 months, depending on the severity of the fracture.1 This process is guided by how quickly the symptoms resolve and by radiographic stability.9

Our patient was followed every 3 to 4 weeks and started physical therapy 6 weeks after his injury occurred. He was held from play for 10 weeks and gradually returned to play; he returned to full-contact activity after tolerating a practice without pain.

THE TAKEAWAY

Children typically have greater chest wall elasticity, and thus, it is unusual for them to sustain a sternal fracture. Diagnosis in children is complicated by the presence of ossification centers for bone growth on imaging. In this case, the fracture was first noticed on ultrasound and confirmed with MRI. Since these fractures can be associated with damage to surrounding structures, additional injuries should be considered when evaluating a patient with a sternum fracture.

CORRESPONDENCE

Catherine Romaine, East Carolina University, Brody School of Medicine, 600 Moye Boulevard, Greenville, NC 27834; [email protected]

1. Alent J, Narducci DM, Moran B, et al. Sternal injuries in sport: a review of the literature. Sports Med. 2018;48:2715-2724. doi: 10.1007/s40279-018-0990-5

2. Khoriati A-A, Rajakulasingam R, Shah R. Sternal fractures and their management. J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2013;6:113-116. doi: 10.4103/0974-2700.110763

3. Athanassiadi K, Gerazounis M, Moustardas M, et al. Sternal fractures: retrospective analysis of 100 cases. World J Surg. 2002;26:1243-1246. doi: 10.1007/s00268-002-6511-5

4. Ferguson LP, Wilkinson AG, Beattie TF. Fracture of the sternum in children. Emerg Med J. 2003;20:518-520. doi: 10.1136/emj.20.6.518

5. Ramgopal S, Shaffiey SA, Conti KA. Pediatric sternal fractures from a Level 1 trauma center. J Pediatr Surg. 2019;54:1628-1631. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2018.08.040

6. Sesia SB, Prüfer F, Mayr J. Sternal fracture in children: diagnosis by ultrasonography. European J Pediatr Surg Rep. 2017;5:e39-e42. doi: 10.1055/s-0037-1606197

7. Nickson C, Rippey J. Ultrasonography of sternal fractures. Australas J Ultrasound Med. 2011;14:6-11. doi: 10.1002/j.2205-0140.2011.tb00131.x

8. Bauman ZM, Yanala U, Waibel BH, et al. Sternal fixation for isolated traumatic sternal fractures improves pain and upper extremity range of motion. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2022;48:225-230. doi: 10.1007/s00068-020-01568-x

9. Culp B, Hurbanek JG, Novak J, et al. Acute traumatic sternum fracture in a female college hockey player. Orthopedics. 2010;33:683. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20100722-17

THE CASE

A 14-year-old boy sought care at our clinic for persistent chest pain after being hit in the chest with a teammate’s shoulder during a basketball game 3 weeks earlier. He had aching midsternal chest pain that worsened with direct pressure and when he sneezed, twisted, or bent forward. There was no bruising or swelling.

On examination, the patient demonstrated normal perfusion and normal work of breathing. He had focal tenderness with palpation at the manubrium with no noticeable step-off, and mild tenderness at the adjacent costochondral junctions and over his pectoral muscles. His sternal pain along the proximal sternum was reproducible with a weighted wall push-up. Although the patient maintained full range of motion in his upper extremities, he did have sternal pain with flexion, abduction, and external rotation of the bilateral upper extremities against resistance. Anteroposterior (AP) and lateral chest radiographs were unremarkable.

THE DIAGNOSIS

The unremarkable chest radiographs prompted further investigation with a diagnostic ultrasound, which revealed a small cortical defect with overlying anechoic fluid collection in the area of focal tenderness. T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the chest was performed; it revealed a transverse, nondisplaced fracture of the superior body of the sternum with surrounding bone marrow edema (FIGURE).

DISCUSSION

Fractures of the sternum comprise < 1% of traumatic fractures and have a low mortality rate (0.7%).1,2 The rarity of these fractures is attributed to the ribs’ elastic recoil, which protects the chest wall from anterior forces.1,3 These fractures are even more unusual in children due to the increased elasticity of their chest walls.4-6 Thus, it takes a significant amount of force for a child’s sternum to fracture.

While isolated sternum fractures can occur, two-thirds of sternum fractures are nonisolated and are associated with injuries to surrounding structures (including the heart, lungs, and vasculature) or fractures of the ribs and spine.2,3 Most often, these injuries are caused by significant blunt trauma to the anterior chest, rapid deceleration, or flexion-compression injury.2,3 They are typically transverse and localized, with 70% of fractures occurring in the mid-body and 17.6% at the manubriosternal joint.1,3,6

Athletes with a sternal fracture typically present as our patient did, with a history of blunt force trauma to the chest and with pain and tenderness over the anterior midline of the chest that increases with respiration or movement.1 A physical examination that includes chest palpation and auscultation of the heart and lungs must be performed to rule out damage to intrathoracic structures and assess the patient’s cardiac and pulmonary stability. An electrocardiogram should be performed to confirm that there are no cardiovascular complications.3,4

Initial imaging should include AP and lateral chest radiographs because any displacement will occur in the sagittal plane.1,2,4-6 If the radiograph shows no clear pathology, follow up with computed tomography, ultrasound, MRI, or technetium bone scans to gain additional information.1 Diagnosis of sternal fractures is especially difficult in children due to the presence of ossification centers for bone growth, which may be misinterpreted as a sternal fracture in the absence of a proper understanding of sternal development.5,6 On ultrasound, sternal fractures appear as a sharp step-off in the cortex, whereas in the absence of fracture, there is no cortical step-off and the cartilaginous plate between ossification centers appears in line with the cortex.7

Continue to: A self-limiting injury that requires proper pain control

A self-limiting injury that requires proper pain control

Isolated sternal fractures are typically self-limiting with a good prognosis.2 These injuries are managed supportively with rest, ice, and analgesics1; proper pain control is crucial to prevent respiratory compromise.8

Complete recovery for most patients occurs in 10 to 12 weeks.9 Recovery periods longer than 12 weeks are associated with nonisolated sternal fractures that are complicated by soft-tissue injury, injuries to the chest wall (such as sternoclavicular joint dislocation, usually from a fall on the shoulder), or fracture nonunion.1,2,5

Anterior sternoclavicular joint dislocations and stable posterior dislocations are managed with closed reduction and immobilization in a figure-of-eight brace.1 Operative management is reserved for patients with displaced fractures, sternal deformity, chest wall instability, respiratory insufficiency, uncontrolled pain, or fracture nonunion.1,3,8

A return-to-play protocol can begin once the patient is asymptomatic.1 The timeframe for a full return to play can vary from 6 weeks to 6 months, depending on the severity of the fracture.1 This process is guided by how quickly the symptoms resolve and by radiographic stability.9

Our patient was followed every 3 to 4 weeks and started physical therapy 6 weeks after his injury occurred. He was held from play for 10 weeks and gradually returned to play; he returned to full-contact activity after tolerating a practice without pain.

THE TAKEAWAY

Children typically have greater chest wall elasticity, and thus, it is unusual for them to sustain a sternal fracture. Diagnosis in children is complicated by the presence of ossification centers for bone growth on imaging. In this case, the fracture was first noticed on ultrasound and confirmed with MRI. Since these fractures can be associated with damage to surrounding structures, additional injuries should be considered when evaluating a patient with a sternum fracture.

CORRESPONDENCE

Catherine Romaine, East Carolina University, Brody School of Medicine, 600 Moye Boulevard, Greenville, NC 27834; [email protected]

THE CASE

A 14-year-old boy sought care at our clinic for persistent chest pain after being hit in the chest with a teammate’s shoulder during a basketball game 3 weeks earlier. He had aching midsternal chest pain that worsened with direct pressure and when he sneezed, twisted, or bent forward. There was no bruising or swelling.

On examination, the patient demonstrated normal perfusion and normal work of breathing. He had focal tenderness with palpation at the manubrium with no noticeable step-off, and mild tenderness at the adjacent costochondral junctions and over his pectoral muscles. His sternal pain along the proximal sternum was reproducible with a weighted wall push-up. Although the patient maintained full range of motion in his upper extremities, he did have sternal pain with flexion, abduction, and external rotation of the bilateral upper extremities against resistance. Anteroposterior (AP) and lateral chest radiographs were unremarkable.

THE DIAGNOSIS

The unremarkable chest radiographs prompted further investigation with a diagnostic ultrasound, which revealed a small cortical defect with overlying anechoic fluid collection in the area of focal tenderness. T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the chest was performed; it revealed a transverse, nondisplaced fracture of the superior body of the sternum with surrounding bone marrow edema (FIGURE).

DISCUSSION

Fractures of the sternum comprise < 1% of traumatic fractures and have a low mortality rate (0.7%).1,2 The rarity of these fractures is attributed to the ribs’ elastic recoil, which protects the chest wall from anterior forces.1,3 These fractures are even more unusual in children due to the increased elasticity of their chest walls.4-6 Thus, it takes a significant amount of force for a child’s sternum to fracture.

While isolated sternum fractures can occur, two-thirds of sternum fractures are nonisolated and are associated with injuries to surrounding structures (including the heart, lungs, and vasculature) or fractures of the ribs and spine.2,3 Most often, these injuries are caused by significant blunt trauma to the anterior chest, rapid deceleration, or flexion-compression injury.2,3 They are typically transverse and localized, with 70% of fractures occurring in the mid-body and 17.6% at the manubriosternal joint.1,3,6

Athletes with a sternal fracture typically present as our patient did, with a history of blunt force trauma to the chest and with pain and tenderness over the anterior midline of the chest that increases with respiration or movement.1 A physical examination that includes chest palpation and auscultation of the heart and lungs must be performed to rule out damage to intrathoracic structures and assess the patient’s cardiac and pulmonary stability. An electrocardiogram should be performed to confirm that there are no cardiovascular complications.3,4

Initial imaging should include AP and lateral chest radiographs because any displacement will occur in the sagittal plane.1,2,4-6 If the radiograph shows no clear pathology, follow up with computed tomography, ultrasound, MRI, or technetium bone scans to gain additional information.1 Diagnosis of sternal fractures is especially difficult in children due to the presence of ossification centers for bone growth, which may be misinterpreted as a sternal fracture in the absence of a proper understanding of sternal development.5,6 On ultrasound, sternal fractures appear as a sharp step-off in the cortex, whereas in the absence of fracture, there is no cortical step-off and the cartilaginous plate between ossification centers appears in line with the cortex.7

Continue to: A self-limiting injury that requires proper pain control

A self-limiting injury that requires proper pain control

Isolated sternal fractures are typically self-limiting with a good prognosis.2 These injuries are managed supportively with rest, ice, and analgesics1; proper pain control is crucial to prevent respiratory compromise.8

Complete recovery for most patients occurs in 10 to 12 weeks.9 Recovery periods longer than 12 weeks are associated with nonisolated sternal fractures that are complicated by soft-tissue injury, injuries to the chest wall (such as sternoclavicular joint dislocation, usually from a fall on the shoulder), or fracture nonunion.1,2,5

Anterior sternoclavicular joint dislocations and stable posterior dislocations are managed with closed reduction and immobilization in a figure-of-eight brace.1 Operative management is reserved for patients with displaced fractures, sternal deformity, chest wall instability, respiratory insufficiency, uncontrolled pain, or fracture nonunion.1,3,8

A return-to-play protocol can begin once the patient is asymptomatic.1 The timeframe for a full return to play can vary from 6 weeks to 6 months, depending on the severity of the fracture.1 This process is guided by how quickly the symptoms resolve and by radiographic stability.9

Our patient was followed every 3 to 4 weeks and started physical therapy 6 weeks after his injury occurred. He was held from play for 10 weeks and gradually returned to play; he returned to full-contact activity after tolerating a practice without pain.

THE TAKEAWAY

Children typically have greater chest wall elasticity, and thus, it is unusual for them to sustain a sternal fracture. Diagnosis in children is complicated by the presence of ossification centers for bone growth on imaging. In this case, the fracture was first noticed on ultrasound and confirmed with MRI. Since these fractures can be associated with damage to surrounding structures, additional injuries should be considered when evaluating a patient with a sternum fracture.

CORRESPONDENCE

Catherine Romaine, East Carolina University, Brody School of Medicine, 600 Moye Boulevard, Greenville, NC 27834; [email protected]

1. Alent J, Narducci DM, Moran B, et al. Sternal injuries in sport: a review of the literature. Sports Med. 2018;48:2715-2724. doi: 10.1007/s40279-018-0990-5

2. Khoriati A-A, Rajakulasingam R, Shah R. Sternal fractures and their management. J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2013;6:113-116. doi: 10.4103/0974-2700.110763

3. Athanassiadi K, Gerazounis M, Moustardas M, et al. Sternal fractures: retrospective analysis of 100 cases. World J Surg. 2002;26:1243-1246. doi: 10.1007/s00268-002-6511-5

4. Ferguson LP, Wilkinson AG, Beattie TF. Fracture of the sternum in children. Emerg Med J. 2003;20:518-520. doi: 10.1136/emj.20.6.518

5. Ramgopal S, Shaffiey SA, Conti KA. Pediatric sternal fractures from a Level 1 trauma center. J Pediatr Surg. 2019;54:1628-1631. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2018.08.040

6. Sesia SB, Prüfer F, Mayr J. Sternal fracture in children: diagnosis by ultrasonography. European J Pediatr Surg Rep. 2017;5:e39-e42. doi: 10.1055/s-0037-1606197

7. Nickson C, Rippey J. Ultrasonography of sternal fractures. Australas J Ultrasound Med. 2011;14:6-11. doi: 10.1002/j.2205-0140.2011.tb00131.x

8. Bauman ZM, Yanala U, Waibel BH, et al. Sternal fixation for isolated traumatic sternal fractures improves pain and upper extremity range of motion. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2022;48:225-230. doi: 10.1007/s00068-020-01568-x

9. Culp B, Hurbanek JG, Novak J, et al. Acute traumatic sternum fracture in a female college hockey player. Orthopedics. 2010;33:683. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20100722-17

1. Alent J, Narducci DM, Moran B, et al. Sternal injuries in sport: a review of the literature. Sports Med. 2018;48:2715-2724. doi: 10.1007/s40279-018-0990-5

2. Khoriati A-A, Rajakulasingam R, Shah R. Sternal fractures and their management. J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2013;6:113-116. doi: 10.4103/0974-2700.110763

3. Athanassiadi K, Gerazounis M, Moustardas M, et al. Sternal fractures: retrospective analysis of 100 cases. World J Surg. 2002;26:1243-1246. doi: 10.1007/s00268-002-6511-5

4. Ferguson LP, Wilkinson AG, Beattie TF. Fracture of the sternum in children. Emerg Med J. 2003;20:518-520. doi: 10.1136/emj.20.6.518

5. Ramgopal S, Shaffiey SA, Conti KA. Pediatric sternal fractures from a Level 1 trauma center. J Pediatr Surg. 2019;54:1628-1631. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2018.08.040

6. Sesia SB, Prüfer F, Mayr J. Sternal fracture in children: diagnosis by ultrasonography. European J Pediatr Surg Rep. 2017;5:e39-e42. doi: 10.1055/s-0037-1606197

7. Nickson C, Rippey J. Ultrasonography of sternal fractures. Australas J Ultrasound Med. 2011;14:6-11. doi: 10.1002/j.2205-0140.2011.tb00131.x

8. Bauman ZM, Yanala U, Waibel BH, et al. Sternal fixation for isolated traumatic sternal fractures improves pain and upper extremity range of motion. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2022;48:225-230. doi: 10.1007/s00068-020-01568-x

9. Culp B, Hurbanek JG, Novak J, et al. Acute traumatic sternum fracture in a female college hockey player. Orthopedics. 2010;33:683. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20100722-17

Consider this tool to reduce antibiotic-associated adverse events in patients with sepsis

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 52-year-old woman presents to the emergency department complaining of dysuria and a fever. Her work-up yields a diagnosis of sepsis secondary to pyelonephritis and bacteremia. She is admitted and started on broad-spectrum antimicrobial therapy. The patient’s symptoms improve significantly over the next 48 hours of treatment. When should antibiotic therapy be discontinued to reduce the patient’s risk for antibiotic-associated AEs and to optimize antimicrobial stewardship?

Antimicrobial resistance is a growing public health risk associated with considerable morbidity and mortality, extended hospitalization, and increased medical expenditures.2-4 Antibiotic stewardship is vital in curbing antimicrobial resistance. The predictive biomarker PCT has emerged as both a diagnostic and prognostic agent for numerous infectious diseases. It has recently received much attention as an adjunct to clinical judgment for discontinuation of antibiotic therapy in hospitalized patients with lower respiratory tract infections and/or sepsis.5-11 Indeed, use of PCT guidance in these patients has resulted in decreased AEs, as well as an enhanced survival benefit.5-15

The utility of PCT-guided early discontinuation of antibiotics had yet to be studied in an expanded population of hospitalized patients with sepsis—especially with regard to AEs associated with multidrug-resistant organisms (MDROs) and Clostridioides difficile (formerly Clostridium difficile). The Surviving Sepsis Campaign’s 2021 international guidelines support the use of PCT in conjunction with clinical evaluation for shortening the duration of antibiotic therapy (“weak recommendation, low quality of evidence”).16 They also suggest daily reassessment for de-escalation of antibiotic use (“weak recommendation, very low quality of evidence”) as a possible way to decrease MDROs and AEs but state that more and better trials are needed.15

STUDY SUMMARY

PCT-guided intervention reduced infection-associated AEs

This pragmatic, real-world, multicenter, randomized clinical trial evaluated the use of PCT-guided early discontinuation of antibiotic therapy in patients with sepsis, in hopes of decreasing infection-associated AEs related to prolonged antibiotic exposure.1 The trial took place in 7 hospitals in Athens, Greece, with 266 patients randomized to the PCT-guided intervention or the standard of care (SOC)—the 2016 international guidelines for the management of sepsis and septic shock from the Surviving Sepsis campaign.17 Study participants had sepsis, as defined by a sequential organ failure assessment (SOFA) score ≥ 2, and infections that included pneumonia, pyelonephritis, or bacteremia.16 Pregnancy, lactation, HIV infection with a low CD4 count, neutropenia, cystic fibrosis, and viral, parasitic, or tuberculosis infections were exclusion criteria. Of note, all patients were managed on general medical wards and not in intensive care units.

Serum PCT samples were collected at baseline and then at Day 5 of therapy. Discontinuation of antibiotic therapy in the PCT trial arm occurred once PCT levels were ≤ 0.5 mcg/L or were reduced by at least 80%. If PCT levels did not meet one of these criteria, the lab test would be repeated daily and antibiotic therapy would continue until the rule was met. Neither patients nor investigators were blinded to the treatment assignments, but investigators in the SOC arm were kept unaware of Day 5 PCT results. In the PCT arm, 71% of participants met Day 5 criteria for stopping antibiotics, and a retrospective analysis indicated that a near-identical 70% in the SOC arm also would have met the same criteria.

The assessment of stool colonization with either C difficile or MDROs was done by stool cultures at baseline and on Days 7, 28, and 180.

The primary outcome of infection-associated AEs, which was evaluated at 180 days, was defined as new cases of C difficile or MDRO infection, or death associated with baseline infection with either C difficile or an MDRO. Of the 133 participants allocated to each trial arm, 8 patients in the intervention group and 2 in the SOC group withdrew consent prior to treatment in the intervention group, with the remaining 125 and 131 participants, respectively, completing the interventions and not lost to follow-up.

Continue to: In an intention-to-treat analysis...

In an intention-to-treat analysis, 9 participants (7.2%; 95% CI, 3.8%-13.1%) in the PCT group compared with 20 participants (15.3%; 95% CI, 10.1%-22.4%) in the SOC group experienced the primary outcome of an antibiotic-associated AE at 180 days, resulting in a hazard ratio (HR) of 0.45 (95% CI, 0.2-0.98).

Secondary outcomes also favored the PCT arm regarding 28-day mortality (19 vs 37 patients; HR = 0.51; 95% CI, 0.29-0.89), median length of antibiotic treatment (5 days in the PCT group and 10 days in the SOC group; P < .001), and median hospitalization cost (24% greater in the SOC group; P = .05). Results for 180-day mortality were 30.4% in the PCT arm and 38.2% in the SOC arm (HR = 0.71; 95% CI, 0.42-1.19), thereby not achieving statistical significance.

WHAT'S NEW

An effective tool in reducing AEs in patients with sepsis

In this multicenter trial, PCT proved successful as a clinical decision tool for discontinuing antibiotic therapy and decreasing infection-associated AEs in patients with sepsis.

Caveats

A promising approach but its superiority is uncertain

The confidence interval for the AE hazard ratio was very wide, but significant, suggesting greater uncertainty and less precision in the chance of obtaining improved outcomes with PCT-guided intervention. However, these data also clarify that outcomes should (at least) not be worse with PCT-directed therapy.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Assay limitations and potential resistance to a new decision tool

The primary challenge to implementation is likely the availability of the PCT assay and the immediacy of turnaround time to enable physicians to make daily decisions regarding antibiotic therapy de-escalation. Additionally, as with any new knowledge, local culture and physician buy-in may limit implementation of this ever-more-valuable patient care tool.

1. Kyriazopoulou E, Liaskou-Antoniou L, Adamis G, et al. Procalcitonin to reduce long-term infection-associated adverse events in sepsis: a randomized trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021;203:202-210. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202004-1201OC

2. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. US CDC report on antibiotic resistance threats in the United States, 2013. ECDC comment. September 18, 2013. Accessed December 29, 2022. www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/news-events/us-cdc-report-antibiotic-resistance-threats-united-states-2013

3. Peters L, Olson L, Khu DTK, et al. Multiple antibiotic resistance as a risk factor for mortality and prolonged hospital stay: a cohort study among neonatal intensive care patients with hospital-acquired infections caused by gram-negative bacteria in Vietnam. PloS One. 2019;14:e0215666. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0215666

4. Cosgrove SE. The relationship between antimicrobial resistance and patient outcomes: mortality, length of hospital stay, and health care costs. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42(suppl 2):S82-S89. doi: 10.1086/499406

5. Schuetz P, Beishuizen A, Broyles M, et al. Procalcitonin (PCT)-guided antibiotic stewardship: an international experts consensus on optimized clinical use. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2019;57:1308-1318. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2018-1181

6. Schuetz P, Christ-Crain M, Thomann R, et al; ProHOSP Study Group. Effect of procalcitonin-based guidelines vs standard guidelines on antibiotic use in lower respiratory tract infections: the ProHOSP randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;302:1059-1066. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1297

7. Bouadma L, Luyt CE, Tubach F, et al; PRORATA trial group. Use of procalcitonin to reduce patients’ exposure to antibiotics in intensive care units (PRORATA trial): a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;375:463-474. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61879-1

8. Christ-Crain M, Jaccard-Stolz D, Bingisser R, et al. Effect of procalcitonin-guided treatment on antibiotic use and outcome in lower respiratory tract infections: cluster-randomised, single-blinded intervention trial. Lancet. 2004;363:600-607. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15591-8

9. Christ-Crain M, Stolz D, Bingisser R, et al. Procalcitonin guidance of antibiotic therapy in community-acquired pneumonia: a randomized trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174:84-93. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200512-1922OC

10. de Jong E, van Oers JA, Beishuizen A, et al. Efficacy and safety of procalcitonin guidance in reducing the duration of antibiotic treatment in critically ill patients: a randomised, controlled, open-label trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16:819-827. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)00053-0

11. Nobre V, Harbarth S, Graf JD, et al. Use of procalcitonin to shorten antibiotic treatment duration in septic patients: a randomized trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177:498-505. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200708-1238OC

12. Schuetz P, Wirz Y, Sager R, et al. Effect of procalcitonin-guided antibiotic treatment on mortality in acute respiratory infections: a patient level meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018;18:95-107. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30592-3

13. Schuetz P, Chiappa V, Briel M, et al. Procalcitonin algorithms for antibiotic therapy decisions: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials and recommendations for clinical algorithms. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:1322-1331. doi: 10.1001/archin ternmed.2011.318

14. Wirz Y, Meier MA, Bouadma L, et al. Effect of procalcitonin-guided antibiotic treatment on clinical outcomes in intensive care unit patients with infection and sepsis patients: a patient-level meta-analysis of randomized trials. Crit Care. 2018;22:191. doi: 10.1186/s13054-018-2125-7

15. Elnajdy D, El-Dahiyat F. Antibiotics duration guided by biomarkers in hospitalized adult patients; a systematic review and meta-analysis. Infect Dis (Lond). 2022;54:387-402. doi: 10.1080/23744235.2022.2037701

16. Evans L, Rhodes A, Alhazzani W, et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: international guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock 2021. Crit Care Med. 2021;49:e1063-e1143. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000005337

17. Rhodes A, Evans LE, Alhazzani W, et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: international guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock: 2016. Intensive Care Med. 2017;43:304-377. doi: 10.1007/s00134-017-4683-6

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 52-year-old woman presents to the emergency department complaining of dysuria and a fever. Her work-up yields a diagnosis of sepsis secondary to pyelonephritis and bacteremia. She is admitted and started on broad-spectrum antimicrobial therapy. The patient’s symptoms improve significantly over the next 48 hours of treatment. When should antibiotic therapy be discontinued to reduce the patient’s risk for antibiotic-associated AEs and to optimize antimicrobial stewardship?

Antimicrobial resistance is a growing public health risk associated with considerable morbidity and mortality, extended hospitalization, and increased medical expenditures.2-4 Antibiotic stewardship is vital in curbing antimicrobial resistance. The predictive biomarker PCT has emerged as both a diagnostic and prognostic agent for numerous infectious diseases. It has recently received much attention as an adjunct to clinical judgment for discontinuation of antibiotic therapy in hospitalized patients with lower respiratory tract infections and/or sepsis.5-11 Indeed, use of PCT guidance in these patients has resulted in decreased AEs, as well as an enhanced survival benefit.5-15

The utility of PCT-guided early discontinuation of antibiotics had yet to be studied in an expanded population of hospitalized patients with sepsis—especially with regard to AEs associated with multidrug-resistant organisms (MDROs) and Clostridioides difficile (formerly Clostridium difficile). The Surviving Sepsis Campaign’s 2021 international guidelines support the use of PCT in conjunction with clinical evaluation for shortening the duration of antibiotic therapy (“weak recommendation, low quality of evidence”).16 They also suggest daily reassessment for de-escalation of antibiotic use (“weak recommendation, very low quality of evidence”) as a possible way to decrease MDROs and AEs but state that more and better trials are needed.15

STUDY SUMMARY

PCT-guided intervention reduced infection-associated AEs

This pragmatic, real-world, multicenter, randomized clinical trial evaluated the use of PCT-guided early discontinuation of antibiotic therapy in patients with sepsis, in hopes of decreasing infection-associated AEs related to prolonged antibiotic exposure.1 The trial took place in 7 hospitals in Athens, Greece, with 266 patients randomized to the PCT-guided intervention or the standard of care (SOC)—the 2016 international guidelines for the management of sepsis and septic shock from the Surviving Sepsis campaign.17 Study participants had sepsis, as defined by a sequential organ failure assessment (SOFA) score ≥ 2, and infections that included pneumonia, pyelonephritis, or bacteremia.16 Pregnancy, lactation, HIV infection with a low CD4 count, neutropenia, cystic fibrosis, and viral, parasitic, or tuberculosis infections were exclusion criteria. Of note, all patients were managed on general medical wards and not in intensive care units.

Serum PCT samples were collected at baseline and then at Day 5 of therapy. Discontinuation of antibiotic therapy in the PCT trial arm occurred once PCT levels were ≤ 0.5 mcg/L or were reduced by at least 80%. If PCT levels did not meet one of these criteria, the lab test would be repeated daily and antibiotic therapy would continue until the rule was met. Neither patients nor investigators were blinded to the treatment assignments, but investigators in the SOC arm were kept unaware of Day 5 PCT results. In the PCT arm, 71% of participants met Day 5 criteria for stopping antibiotics, and a retrospective analysis indicated that a near-identical 70% in the SOC arm also would have met the same criteria.

The assessment of stool colonization with either C difficile or MDROs was done by stool cultures at baseline and on Days 7, 28, and 180.

The primary outcome of infection-associated AEs, which was evaluated at 180 days, was defined as new cases of C difficile or MDRO infection, or death associated with baseline infection with either C difficile or an MDRO. Of the 133 participants allocated to each trial arm, 8 patients in the intervention group and 2 in the SOC group withdrew consent prior to treatment in the intervention group, with the remaining 125 and 131 participants, respectively, completing the interventions and not lost to follow-up.

Continue to: In an intention-to-treat analysis...

In an intention-to-treat analysis, 9 participants (7.2%; 95% CI, 3.8%-13.1%) in the PCT group compared with 20 participants (15.3%; 95% CI, 10.1%-22.4%) in the SOC group experienced the primary outcome of an antibiotic-associated AE at 180 days, resulting in a hazard ratio (HR) of 0.45 (95% CI, 0.2-0.98).

Secondary outcomes also favored the PCT arm regarding 28-day mortality (19 vs 37 patients; HR = 0.51; 95% CI, 0.29-0.89), median length of antibiotic treatment (5 days in the PCT group and 10 days in the SOC group; P < .001), and median hospitalization cost (24% greater in the SOC group; P = .05). Results for 180-day mortality were 30.4% in the PCT arm and 38.2% in the SOC arm (HR = 0.71; 95% CI, 0.42-1.19), thereby not achieving statistical significance.

WHAT'S NEW

An effective tool in reducing AEs in patients with sepsis

In this multicenter trial, PCT proved successful as a clinical decision tool for discontinuing antibiotic therapy and decreasing infection-associated AEs in patients with sepsis.

Caveats

A promising approach but its superiority is uncertain

The confidence interval for the AE hazard ratio was very wide, but significant, suggesting greater uncertainty and less precision in the chance of obtaining improved outcomes with PCT-guided intervention. However, these data also clarify that outcomes should (at least) not be worse with PCT-directed therapy.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Assay limitations and potential resistance to a new decision tool

The primary challenge to implementation is likely the availability of the PCT assay and the immediacy of turnaround time to enable physicians to make daily decisions regarding antibiotic therapy de-escalation. Additionally, as with any new knowledge, local culture and physician buy-in may limit implementation of this ever-more-valuable patient care tool.

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 52-year-old woman presents to the emergency department complaining of dysuria and a fever. Her work-up yields a diagnosis of sepsis secondary to pyelonephritis and bacteremia. She is admitted and started on broad-spectrum antimicrobial therapy. The patient’s symptoms improve significantly over the next 48 hours of treatment. When should antibiotic therapy be discontinued to reduce the patient’s risk for antibiotic-associated AEs and to optimize antimicrobial stewardship?

Antimicrobial resistance is a growing public health risk associated with considerable morbidity and mortality, extended hospitalization, and increased medical expenditures.2-4 Antibiotic stewardship is vital in curbing antimicrobial resistance. The predictive biomarker PCT has emerged as both a diagnostic and prognostic agent for numerous infectious diseases. It has recently received much attention as an adjunct to clinical judgment for discontinuation of antibiotic therapy in hospitalized patients with lower respiratory tract infections and/or sepsis.5-11 Indeed, use of PCT guidance in these patients has resulted in decreased AEs, as well as an enhanced survival benefit.5-15

The utility of PCT-guided early discontinuation of antibiotics had yet to be studied in an expanded population of hospitalized patients with sepsis—especially with regard to AEs associated with multidrug-resistant organisms (MDROs) and Clostridioides difficile (formerly Clostridium difficile). The Surviving Sepsis Campaign’s 2021 international guidelines support the use of PCT in conjunction with clinical evaluation for shortening the duration of antibiotic therapy (“weak recommendation, low quality of evidence”).16 They also suggest daily reassessment for de-escalation of antibiotic use (“weak recommendation, very low quality of evidence”) as a possible way to decrease MDROs and AEs but state that more and better trials are needed.15

STUDY SUMMARY

PCT-guided intervention reduced infection-associated AEs

This pragmatic, real-world, multicenter, randomized clinical trial evaluated the use of PCT-guided early discontinuation of antibiotic therapy in patients with sepsis, in hopes of decreasing infection-associated AEs related to prolonged antibiotic exposure.1 The trial took place in 7 hospitals in Athens, Greece, with 266 patients randomized to the PCT-guided intervention or the standard of care (SOC)—the 2016 international guidelines for the management of sepsis and septic shock from the Surviving Sepsis campaign.17 Study participants had sepsis, as defined by a sequential organ failure assessment (SOFA) score ≥ 2, and infections that included pneumonia, pyelonephritis, or bacteremia.16 Pregnancy, lactation, HIV infection with a low CD4 count, neutropenia, cystic fibrosis, and viral, parasitic, or tuberculosis infections were exclusion criteria. Of note, all patients were managed on general medical wards and not in intensive care units.

Serum PCT samples were collected at baseline and then at Day 5 of therapy. Discontinuation of antibiotic therapy in the PCT trial arm occurred once PCT levels were ≤ 0.5 mcg/L or were reduced by at least 80%. If PCT levels did not meet one of these criteria, the lab test would be repeated daily and antibiotic therapy would continue until the rule was met. Neither patients nor investigators were blinded to the treatment assignments, but investigators in the SOC arm were kept unaware of Day 5 PCT results. In the PCT arm, 71% of participants met Day 5 criteria for stopping antibiotics, and a retrospective analysis indicated that a near-identical 70% in the SOC arm also would have met the same criteria.

The assessment of stool colonization with either C difficile or MDROs was done by stool cultures at baseline and on Days 7, 28, and 180.

The primary outcome of infection-associated AEs, which was evaluated at 180 days, was defined as new cases of C difficile or MDRO infection, or death associated with baseline infection with either C difficile or an MDRO. Of the 133 participants allocated to each trial arm, 8 patients in the intervention group and 2 in the SOC group withdrew consent prior to treatment in the intervention group, with the remaining 125 and 131 participants, respectively, completing the interventions and not lost to follow-up.

Continue to: In an intention-to-treat analysis...

In an intention-to-treat analysis, 9 participants (7.2%; 95% CI, 3.8%-13.1%) in the PCT group compared with 20 participants (15.3%; 95% CI, 10.1%-22.4%) in the SOC group experienced the primary outcome of an antibiotic-associated AE at 180 days, resulting in a hazard ratio (HR) of 0.45 (95% CI, 0.2-0.98).

Secondary outcomes also favored the PCT arm regarding 28-day mortality (19 vs 37 patients; HR = 0.51; 95% CI, 0.29-0.89), median length of antibiotic treatment (5 days in the PCT group and 10 days in the SOC group; P < .001), and median hospitalization cost (24% greater in the SOC group; P = .05). Results for 180-day mortality were 30.4% in the PCT arm and 38.2% in the SOC arm (HR = 0.71; 95% CI, 0.42-1.19), thereby not achieving statistical significance.

WHAT'S NEW

An effective tool in reducing AEs in patients with sepsis

In this multicenter trial, PCT proved successful as a clinical decision tool for discontinuing antibiotic therapy and decreasing infection-associated AEs in patients with sepsis.

Caveats

A promising approach but its superiority is uncertain

The confidence interval for the AE hazard ratio was very wide, but significant, suggesting greater uncertainty and less precision in the chance of obtaining improved outcomes with PCT-guided intervention. However, these data also clarify that outcomes should (at least) not be worse with PCT-directed therapy.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Assay limitations and potential resistance to a new decision tool

The primary challenge to implementation is likely the availability of the PCT assay and the immediacy of turnaround time to enable physicians to make daily decisions regarding antibiotic therapy de-escalation. Additionally, as with any new knowledge, local culture and physician buy-in may limit implementation of this ever-more-valuable patient care tool.

1. Kyriazopoulou E, Liaskou-Antoniou L, Adamis G, et al. Procalcitonin to reduce long-term infection-associated adverse events in sepsis: a randomized trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021;203:202-210. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202004-1201OC

2. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. US CDC report on antibiotic resistance threats in the United States, 2013. ECDC comment. September 18, 2013. Accessed December 29, 2022. www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/news-events/us-cdc-report-antibiotic-resistance-threats-united-states-2013

3. Peters L, Olson L, Khu DTK, et al. Multiple antibiotic resistance as a risk factor for mortality and prolonged hospital stay: a cohort study among neonatal intensive care patients with hospital-acquired infections caused by gram-negative bacteria in Vietnam. PloS One. 2019;14:e0215666. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0215666

4. Cosgrove SE. The relationship between antimicrobial resistance and patient outcomes: mortality, length of hospital stay, and health care costs. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42(suppl 2):S82-S89. doi: 10.1086/499406

5. Schuetz P, Beishuizen A, Broyles M, et al. Procalcitonin (PCT)-guided antibiotic stewardship: an international experts consensus on optimized clinical use. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2019;57:1308-1318. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2018-1181

6. Schuetz P, Christ-Crain M, Thomann R, et al; ProHOSP Study Group. Effect of procalcitonin-based guidelines vs standard guidelines on antibiotic use in lower respiratory tract infections: the ProHOSP randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;302:1059-1066. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1297

7. Bouadma L, Luyt CE, Tubach F, et al; PRORATA trial group. Use of procalcitonin to reduce patients’ exposure to antibiotics in intensive care units (PRORATA trial): a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;375:463-474. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61879-1

8. Christ-Crain M, Jaccard-Stolz D, Bingisser R, et al. Effect of procalcitonin-guided treatment on antibiotic use and outcome in lower respiratory tract infections: cluster-randomised, single-blinded intervention trial. Lancet. 2004;363:600-607. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15591-8

9. Christ-Crain M, Stolz D, Bingisser R, et al. Procalcitonin guidance of antibiotic therapy in community-acquired pneumonia: a randomized trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174:84-93. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200512-1922OC

10. de Jong E, van Oers JA, Beishuizen A, et al. Efficacy and safety of procalcitonin guidance in reducing the duration of antibiotic treatment in critically ill patients: a randomised, controlled, open-label trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16:819-827. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)00053-0

11. Nobre V, Harbarth S, Graf JD, et al. Use of procalcitonin to shorten antibiotic treatment duration in septic patients: a randomized trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177:498-505. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200708-1238OC

12. Schuetz P, Wirz Y, Sager R, et al. Effect of procalcitonin-guided antibiotic treatment on mortality in acute respiratory infections: a patient level meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018;18:95-107. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30592-3

13. Schuetz P, Chiappa V, Briel M, et al. Procalcitonin algorithms for antibiotic therapy decisions: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials and recommendations for clinical algorithms. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:1322-1331. doi: 10.1001/archin ternmed.2011.318

14. Wirz Y, Meier MA, Bouadma L, et al. Effect of procalcitonin-guided antibiotic treatment on clinical outcomes in intensive care unit patients with infection and sepsis patients: a patient-level meta-analysis of randomized trials. Crit Care. 2018;22:191. doi: 10.1186/s13054-018-2125-7

15. Elnajdy D, El-Dahiyat F. Antibiotics duration guided by biomarkers in hospitalized adult patients; a systematic review and meta-analysis. Infect Dis (Lond). 2022;54:387-402. doi: 10.1080/23744235.2022.2037701

16. Evans L, Rhodes A, Alhazzani W, et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: international guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock 2021. Crit Care Med. 2021;49:e1063-e1143. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000005337

17. Rhodes A, Evans LE, Alhazzani W, et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: international guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock: 2016. Intensive Care Med. 2017;43:304-377. doi: 10.1007/s00134-017-4683-6

1. Kyriazopoulou E, Liaskou-Antoniou L, Adamis G, et al. Procalcitonin to reduce long-term infection-associated adverse events in sepsis: a randomized trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021;203:202-210. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202004-1201OC

2. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. US CDC report on antibiotic resistance threats in the United States, 2013. ECDC comment. September 18, 2013. Accessed December 29, 2022. www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/news-events/us-cdc-report-antibiotic-resistance-threats-united-states-2013

3. Peters L, Olson L, Khu DTK, et al. Multiple antibiotic resistance as a risk factor for mortality and prolonged hospital stay: a cohort study among neonatal intensive care patients with hospital-acquired infections caused by gram-negative bacteria in Vietnam. PloS One. 2019;14:e0215666. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0215666

4. Cosgrove SE. The relationship between antimicrobial resistance and patient outcomes: mortality, length of hospital stay, and health care costs. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42(suppl 2):S82-S89. doi: 10.1086/499406

5. Schuetz P, Beishuizen A, Broyles M, et al. Procalcitonin (PCT)-guided antibiotic stewardship: an international experts consensus on optimized clinical use. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2019;57:1308-1318. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2018-1181

6. Schuetz P, Christ-Crain M, Thomann R, et al; ProHOSP Study Group. Effect of procalcitonin-based guidelines vs standard guidelines on antibiotic use in lower respiratory tract infections: the ProHOSP randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;302:1059-1066. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1297

7. Bouadma L, Luyt CE, Tubach F, et al; PRORATA trial group. Use of procalcitonin to reduce patients’ exposure to antibiotics in intensive care units (PRORATA trial): a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;375:463-474. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61879-1

8. Christ-Crain M, Jaccard-Stolz D, Bingisser R, et al. Effect of procalcitonin-guided treatment on antibiotic use and outcome in lower respiratory tract infections: cluster-randomised, single-blinded intervention trial. Lancet. 2004;363:600-607. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15591-8

9. Christ-Crain M, Stolz D, Bingisser R, et al. Procalcitonin guidance of antibiotic therapy in community-acquired pneumonia: a randomized trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174:84-93. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200512-1922OC

10. de Jong E, van Oers JA, Beishuizen A, et al. Efficacy and safety of procalcitonin guidance in reducing the duration of antibiotic treatment in critically ill patients: a randomised, controlled, open-label trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16:819-827. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)00053-0

11. Nobre V, Harbarth S, Graf JD, et al. Use of procalcitonin to shorten antibiotic treatment duration in septic patients: a randomized trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177:498-505. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200708-1238OC

12. Schuetz P, Wirz Y, Sager R, et al. Effect of procalcitonin-guided antibiotic treatment on mortality in acute respiratory infections: a patient level meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018;18:95-107. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30592-3

13. Schuetz P, Chiappa V, Briel M, et al. Procalcitonin algorithms for antibiotic therapy decisions: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials and recommendations for clinical algorithms. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:1322-1331. doi: 10.1001/archin ternmed.2011.318

14. Wirz Y, Meier MA, Bouadma L, et al. Effect of procalcitonin-guided antibiotic treatment on clinical outcomes in intensive care unit patients with infection and sepsis patients: a patient-level meta-analysis of randomized trials. Crit Care. 2018;22:191. doi: 10.1186/s13054-018-2125-7

15. Elnajdy D, El-Dahiyat F. Antibiotics duration guided by biomarkers in hospitalized adult patients; a systematic review and meta-analysis. Infect Dis (Lond). 2022;54:387-402. doi: 10.1080/23744235.2022.2037701

16. Evans L, Rhodes A, Alhazzani W, et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: international guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock 2021. Crit Care Med. 2021;49:e1063-e1143. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000005337

17. Rhodes A, Evans LE, Alhazzani W, et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: international guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock: 2016. Intensive Care Med. 2017;43:304-377. doi: 10.1007/s00134-017-4683-6

PRACTICE CHANGER

For patients hospitalized with sepsis, consider procalcitonin (PCT)-guided early discontinuation of antibiotic therapy for fewer infection-associated adverse events (AEs).

STRENGTH OF RECOMMENDATION

Kyriazopoulou E, Liaskou-Antoniou L, Adamis G, et al. Procalcitonin to reduce long-term infection-associated adverse events in sepsis. A randomized trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021;203:202-210. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202004-1201OC

Does regular walking improve lipid levels in adults?

Evidence summary

Walking’s impact on cholesterol levels is modest, inconsistent

A 2022 systematic review and meta-analysis of 21 studies (n = 1129) evaluated the effects of walking on lipids and lipoproteins in women older than 18 years who were overweight or obese and were not taking any lipid-lowering medications. Median TC was 206 mg/dL and median LDL was 126 mg/dL.1

The primary outcome found that walking decreased TC and LDL levels independent of diet and weight loss. Twenty studies reported on TC and showed that walking significantly decreased TC levels compared to the control groups (raw mean difference [RMD] = 6.7 mg/dL; 95% CI, 0.4-12.9; P = .04). Fifteen studies examined LDL and showed a significant decrease in LDL levels with walking compared to control groups (RMD = 7.4 mg/dL; 95% CI, 0.3-14.5; P = .04). However, the small magnitude of the changes may have little clinical impact.1

There were no significant changes in the walking groups compared to the control groups for triglycerides (17 studies; RMD = 2.2 mg/dL; 95% CI, –8.4 to 12.8; P = .68) or high-density lipoprotein (HDL) (18 studies; RMD = 1.5 mg/dL; 95% CI, –0.4 to 3.3; P = .12). Included studies were required to be controlled but were otherwise not described. The overall risk for bias was determined to be low.1

A 2020 RCT (n = 22) assessed the effects of a walking intervention on cholesterol and cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk in individuals ages 40 to 65 years with moderate CVD risk but without diabetes or CVD.2 Moderate CVD risk was defined as a 2% to 5% 10-year risk for a CVD event using the European HeartScore, which incorporates age, sex, blood pressure, lipid levels, and smoking status3; however, study participants were not required to have hyperlipidemia. Participants were enrolled in a 12-week, nurse-led intervention of moderate-paced walking for 30 to 45 minutes 5 times weekly.

Individuals in the intervention group had significant decreases in average TC levels from baseline to follow-up (244.6 mg/dL vs 213.7 mg/dL; P = .001). As a result, participants’ average 10-year CVD risk was significantly reduced from moderate risk to low risk (2.6% vs 1.8%; P = 038) and was significantly lower in the intervention group than in the control group at follow-up (1.8% vs 3.1%; P = .019). No blinding was used, and the use of lipid-lowering medications was not reported, which could have impacted the results.2

A 2008 RCT (n = 67) examined the effect of a home-based walking program (12 weeks of brisk walking, at least 30 min/d and at least 5 d/wk, with at least 300 kcal burned per walk) vs a sedentary control group in men ages 45 to 65 years with hyperlipidemia (TC > 240 mg/dL and/or TC/HDL-C ratio ≥ 6) who were not receiving lipid-lowering medication. There were no significant changes from baseline to follow-up in the walking group compared to the control group in TC (adjusted mean difference [AMD] = –9.3 mg/dL; 95% CI, –22.8 to 4.64; P = .19), HDL-C (AMD = 2.7 mg/dL; 95% CI, –0.4 to 5.4; P = .07) or triglycerides (AMD = –26.6 mg/dL; 95% CI, –56.7 to 2.7; P = .07).4

A 2002 RCT (n = 111) of sedentary men and women (BMI, 25-35; ages, 40-65 years) with dyslipidemia (LDL of 130-190 mg/dL, or HDL < 40 mg/dL for men or < 45 mg/dL for women) examined the impact of various physical activity levels for 8 months when compared to a control group observed for 6 months. The group assigned to low-amount, moderate-intensity physical activity walked an equivalent of 12 miles per week.5

Continue to: In this group...

In this group, there was a significant decrease in average triglyceride concentrations from baseline to follow-up (mean ± standard error = 196.8 ± 30.5 mg/dL vs 145.2 ± 16.0 mg/dL; P < .001). Significance of the change compared with changes in the control group was not reported, although triglycerides in the control group increased from baseline to follow-up (132.1 ± 11.0 vs 155.8 ± 14.9 mg/dL). There were no significant changes from baseline to follow-up in TC (194 ± 4.8 vs 197.9 ± 5.4 mg/dL), LDL (122.7 ± 4.0 vs 127.8 ± 4.1 mg/dL), or HDL (42.0 ± 1.9 vs 43.1 ± 2.5 mg/dL); P values of pre-post changes and comparison to control group were not reported.5

Recommendations from others

The Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans, published by the Department of Health and Human Services and updated in 2018, cite adherence to the published guidelines as a protective factor against high LDL and total lipids in both adults and children.6 The guidelines for adults recommend 150 to 300 minutes of moderate-intensity or 75 to 150 minutes of vigorous-intensity aerobic exercise per week, as well as muscle-strengthening activities of moderate or greater intensity 2 or more days per week. Brisk walking is included as an example of a moderate-intensity activity. These same guidelines are cited and endorsed by the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Heart Association.7,8

Editor’s takeaway

The lipid reductions achieved from walking—if any—are minimal. By themselves, these small reductions will not accomplish our lipid-lowering goals. However, cholesterol goals are primarily disease oriented. This evidence does not directly inform us of important patient-oriented outcomes, such as morbidity, mortality, and vitality.

1. Ballard AM, Davis A, Wong B, et al. The effects of exclusive walking on lipids and lipoproteins in women with overweight and obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Health Promot. 2022;36:328-339. doi: 10.1177/08901171211048135

2. Akgöz AD, Gözüm S. Effectiveness of a nurse-led physical activity intervention to decrease cardiovascular disease risk in middle-aged adults: a pilot randomized controlled study. J Vasc Nurs. 2020;38:140-148. doi: 10.1016/j.jvn.2020.05.002

3. European Association of Preventive Cardiology. HeartScore. Accessed December 23, 2022. www.heartscore.org/en_GB

4. Coghill N, Cooper AR. The effect of a home-based walking program on risk factors for coronary heart disease in hypercholesterolaemic men: a randomized controlled trial. Prev Med. 2008; 46:545-551. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.01.002

5. Kraus WE, Houmard JA, Duscha BD, et al. Effects of the amount and intensity of exercise on plasma lipoproteins. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1483-1492. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020194

6. US Department of Health and Human Services. Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans, 2nd edition. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2018. Accessed December 23, 2022. https://health.gov/sites/default/files/2019-09/Physical_Activity_Guidelines_2nd_edition.pdf