User login

Feds charge 25 nursing school execs, staff in fake diploma scheme

The U.S. Department of Justice recently announced charges against 25 owners, operators, and employees of three Florida nursing schools in a fraud scheme in which they sold as many as 7,600 fake nursing degrees.

The purchasers in the diploma scheme paid $10,000 to $15,000 for degrees and transcripts and some 2,800 of the buyers passed the national nursing licensing exam to become registered nurses (RNs) and licensed practice nurses/vocational nurses (LPN/VNs) around the country, according to The New York Times.

Many of the degree recipients went on to work at hospitals, nursing homes, and Veterans Affairs medical centers, according to the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Southern District of Florida.

Several national nursing organizations cooperated with the investigation, and the Delaware Division of Professional Regulation already annulled 26 licenses, according to the Delaware Nurses Association. Fake licenses were issued in five states, according to federal reports.

“We are deeply unsettled by this egregious act,” DNA President Stephanie McClellan, MSN, RN, CMSRN, said in the group’s press statement. “We want all Delaware nurses to be aware of this active issue and to speak up if there is a concern regarding capacity to practice safely by a colleague/peer,” she said.

The Oregon State Board of Nursing is also investigating at least a dozen nurses who may have paid for their degrees, according to a Portland CBS affiliate.

The National Council of State Boards of Nursing said in a statement that it had helped authorities identify and monitor the individuals who allegedly provided the false degrees.

Nursing community reacts

News of the fraud scheme spread through the nursing community, including social media. “The recent report on falsified nursing school degrees is both heartbreaking and serves as an eye-opener,” tweeted Usha Menon, PhD, RN, FAAN, dean and health professor of the University of South Florida Health College of Nursing. “There was enough of a need that prompted these bad actors to develop a scheme that could’ve endangered dozens of lives.”

Jennifer Mensik Kennedy, PhD, MBA, RN, the new president of the American Nurses Association, also weighed in. “The accusation that personnel at once-accredited nursing schools allegedly participated in this scheme is simply deplorable. These unlawful and unethical acts disparage the reputation of actual nurses everywhere who have rightfully earned [their titles] through their education, hard work, dedication, and time.”

The false degrees and transcripts were issued by three once-accredited and now-shuttered nursing schools in South Florida: Palm Beach School of Nursing, Sacred Heart International Institute, and Sienna College.

The alleged co-conspirators reportedly made $114 million from the scheme, which dates back to 2016, according to several news reports. Each defendant faces up to 20 years in prison.

Most LPN programs charge $10,000 to $15,000 to complete a program, Robert Rosseter, a spokesperson for the American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN), told this news organization.

None were AACN members, and none were accredited by the Commission on Collegiate Nursing Education, which is AACN’s autonomous accrediting agency, Mr. Rosseter said. AACN membership is voluntary and is open to schools offering baccalaureate or higher degrees, he explained.

“What is disturbing about this investigation is that there are over 7,600 people around the country with fraudulent nursing credentials who are potentially in critical health care roles treating patients,” Chad Yarbrough, acting special agent in charge for the FBI in Miami, said in the federal justice department release.

‘Operation Nightingale’ based on tip

The federal action, dubbed “Operation Nightingale” after the nursing pioneer Florence Nightingale, began in 2019. It was based on a tip related to a case in Maryland, according to Nurse.org.

That case ensnared Palm Beach School of Nursing owner Johanah Napoleon, who reportedly was selling fake degrees for $6,000 to $18,000 each to two individuals in Maryland and Virginia. Ms. Napoleon was charged in 2021 and eventually pled guilty. The Florida Board of Nursing shut down the Palm Beach school in 2017 owing to its students’ low passing rate on the national licensing exam.

Two participants in the bigger scheme who had also worked with Ms. Napoleon – Geralda Adrien and Woosvelt Predestin – were indicted in 2021. Ms. Adrien owned private education companies for people who at aspired to be nurses, and Mr. Predestin was an employee. They were sentenced to 27 months in prison last year and helped the federal officials build the larger case.

The 25 individuals who were charged Jan. 25 operated in Delaware, New York, New Jersey, Texas, and Florida.

Schemes lured immigrants

In the scheme involving Siena College, some of the individuals acted as recruiters to direct nurses who were looking for employment to the school, where they allegedly would then pay for an RN or LPN/VN degree. The recipients of the false documents then used them to obtain jobs, including at a hospital in Georgia and a Veterans Affairs medical center in Maryland, according to one indictment. The president of Siena and her co-conspirators sold more than 2,000 fake diplomas, according to charging documents.

At the Palm Beach College of Nursing, individuals at various nursing prep and education programs allegedly helped others obtain fake degrees and transcripts, which were then used to pass RN and LPN/VN licensing exams in states that included Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, and Ohio, according to the indictment.

Some individuals then secured employment with a nursing home in Ohio, a home health agency for pediatric patients in Massachusetts, and skilled nursing facilities in New York and New Jersey.

Prosecutors allege that the president of Sacred Heart International Institute and two other co-conspirators sold 588 fake diplomas.

The FBI said that some of the aspiring nurses who were talked into buying the degrees were LPNs who wanted to become RNs and that most of those lured into the scheme were from South Florida’s Haitian American immigrant community, Nurse.org reported.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The U.S. Department of Justice recently announced charges against 25 owners, operators, and employees of three Florida nursing schools in a fraud scheme in which they sold as many as 7,600 fake nursing degrees.

The purchasers in the diploma scheme paid $10,000 to $15,000 for degrees and transcripts and some 2,800 of the buyers passed the national nursing licensing exam to become registered nurses (RNs) and licensed practice nurses/vocational nurses (LPN/VNs) around the country, according to The New York Times.

Many of the degree recipients went on to work at hospitals, nursing homes, and Veterans Affairs medical centers, according to the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Southern District of Florida.

Several national nursing organizations cooperated with the investigation, and the Delaware Division of Professional Regulation already annulled 26 licenses, according to the Delaware Nurses Association. Fake licenses were issued in five states, according to federal reports.

“We are deeply unsettled by this egregious act,” DNA President Stephanie McClellan, MSN, RN, CMSRN, said in the group’s press statement. “We want all Delaware nurses to be aware of this active issue and to speak up if there is a concern regarding capacity to practice safely by a colleague/peer,” she said.

The Oregon State Board of Nursing is also investigating at least a dozen nurses who may have paid for their degrees, according to a Portland CBS affiliate.

The National Council of State Boards of Nursing said in a statement that it had helped authorities identify and monitor the individuals who allegedly provided the false degrees.

Nursing community reacts

News of the fraud scheme spread through the nursing community, including social media. “The recent report on falsified nursing school degrees is both heartbreaking and serves as an eye-opener,” tweeted Usha Menon, PhD, RN, FAAN, dean and health professor of the University of South Florida Health College of Nursing. “There was enough of a need that prompted these bad actors to develop a scheme that could’ve endangered dozens of lives.”

Jennifer Mensik Kennedy, PhD, MBA, RN, the new president of the American Nurses Association, also weighed in. “The accusation that personnel at once-accredited nursing schools allegedly participated in this scheme is simply deplorable. These unlawful and unethical acts disparage the reputation of actual nurses everywhere who have rightfully earned [their titles] through their education, hard work, dedication, and time.”

The false degrees and transcripts were issued by three once-accredited and now-shuttered nursing schools in South Florida: Palm Beach School of Nursing, Sacred Heart International Institute, and Sienna College.

The alleged co-conspirators reportedly made $114 million from the scheme, which dates back to 2016, according to several news reports. Each defendant faces up to 20 years in prison.

Most LPN programs charge $10,000 to $15,000 to complete a program, Robert Rosseter, a spokesperson for the American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN), told this news organization.

None were AACN members, and none were accredited by the Commission on Collegiate Nursing Education, which is AACN’s autonomous accrediting agency, Mr. Rosseter said. AACN membership is voluntary and is open to schools offering baccalaureate or higher degrees, he explained.

“What is disturbing about this investigation is that there are over 7,600 people around the country with fraudulent nursing credentials who are potentially in critical health care roles treating patients,” Chad Yarbrough, acting special agent in charge for the FBI in Miami, said in the federal justice department release.

‘Operation Nightingale’ based on tip

The federal action, dubbed “Operation Nightingale” after the nursing pioneer Florence Nightingale, began in 2019. It was based on a tip related to a case in Maryland, according to Nurse.org.

That case ensnared Palm Beach School of Nursing owner Johanah Napoleon, who reportedly was selling fake degrees for $6,000 to $18,000 each to two individuals in Maryland and Virginia. Ms. Napoleon was charged in 2021 and eventually pled guilty. The Florida Board of Nursing shut down the Palm Beach school in 2017 owing to its students’ low passing rate on the national licensing exam.

Two participants in the bigger scheme who had also worked with Ms. Napoleon – Geralda Adrien and Woosvelt Predestin – were indicted in 2021. Ms. Adrien owned private education companies for people who at aspired to be nurses, and Mr. Predestin was an employee. They were sentenced to 27 months in prison last year and helped the federal officials build the larger case.

The 25 individuals who were charged Jan. 25 operated in Delaware, New York, New Jersey, Texas, and Florida.

Schemes lured immigrants

In the scheme involving Siena College, some of the individuals acted as recruiters to direct nurses who were looking for employment to the school, where they allegedly would then pay for an RN or LPN/VN degree. The recipients of the false documents then used them to obtain jobs, including at a hospital in Georgia and a Veterans Affairs medical center in Maryland, according to one indictment. The president of Siena and her co-conspirators sold more than 2,000 fake diplomas, according to charging documents.

At the Palm Beach College of Nursing, individuals at various nursing prep and education programs allegedly helped others obtain fake degrees and transcripts, which were then used to pass RN and LPN/VN licensing exams in states that included Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, and Ohio, according to the indictment.

Some individuals then secured employment with a nursing home in Ohio, a home health agency for pediatric patients in Massachusetts, and skilled nursing facilities in New York and New Jersey.

Prosecutors allege that the president of Sacred Heart International Institute and two other co-conspirators sold 588 fake diplomas.

The FBI said that some of the aspiring nurses who were talked into buying the degrees were LPNs who wanted to become RNs and that most of those lured into the scheme were from South Florida’s Haitian American immigrant community, Nurse.org reported.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The U.S. Department of Justice recently announced charges against 25 owners, operators, and employees of three Florida nursing schools in a fraud scheme in which they sold as many as 7,600 fake nursing degrees.

The purchasers in the diploma scheme paid $10,000 to $15,000 for degrees and transcripts and some 2,800 of the buyers passed the national nursing licensing exam to become registered nurses (RNs) and licensed practice nurses/vocational nurses (LPN/VNs) around the country, according to The New York Times.

Many of the degree recipients went on to work at hospitals, nursing homes, and Veterans Affairs medical centers, according to the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Southern District of Florida.

Several national nursing organizations cooperated with the investigation, and the Delaware Division of Professional Regulation already annulled 26 licenses, according to the Delaware Nurses Association. Fake licenses were issued in five states, according to federal reports.

“We are deeply unsettled by this egregious act,” DNA President Stephanie McClellan, MSN, RN, CMSRN, said in the group’s press statement. “We want all Delaware nurses to be aware of this active issue and to speak up if there is a concern regarding capacity to practice safely by a colleague/peer,” she said.

The Oregon State Board of Nursing is also investigating at least a dozen nurses who may have paid for their degrees, according to a Portland CBS affiliate.

The National Council of State Boards of Nursing said in a statement that it had helped authorities identify and monitor the individuals who allegedly provided the false degrees.

Nursing community reacts

News of the fraud scheme spread through the nursing community, including social media. “The recent report on falsified nursing school degrees is both heartbreaking and serves as an eye-opener,” tweeted Usha Menon, PhD, RN, FAAN, dean and health professor of the University of South Florida Health College of Nursing. “There was enough of a need that prompted these bad actors to develop a scheme that could’ve endangered dozens of lives.”

Jennifer Mensik Kennedy, PhD, MBA, RN, the new president of the American Nurses Association, also weighed in. “The accusation that personnel at once-accredited nursing schools allegedly participated in this scheme is simply deplorable. These unlawful and unethical acts disparage the reputation of actual nurses everywhere who have rightfully earned [their titles] through their education, hard work, dedication, and time.”

The false degrees and transcripts were issued by three once-accredited and now-shuttered nursing schools in South Florida: Palm Beach School of Nursing, Sacred Heart International Institute, and Sienna College.

The alleged co-conspirators reportedly made $114 million from the scheme, which dates back to 2016, according to several news reports. Each defendant faces up to 20 years in prison.

Most LPN programs charge $10,000 to $15,000 to complete a program, Robert Rosseter, a spokesperson for the American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN), told this news organization.

None were AACN members, and none were accredited by the Commission on Collegiate Nursing Education, which is AACN’s autonomous accrediting agency, Mr. Rosseter said. AACN membership is voluntary and is open to schools offering baccalaureate or higher degrees, he explained.

“What is disturbing about this investigation is that there are over 7,600 people around the country with fraudulent nursing credentials who are potentially in critical health care roles treating patients,” Chad Yarbrough, acting special agent in charge for the FBI in Miami, said in the federal justice department release.

‘Operation Nightingale’ based on tip

The federal action, dubbed “Operation Nightingale” after the nursing pioneer Florence Nightingale, began in 2019. It was based on a tip related to a case in Maryland, according to Nurse.org.

That case ensnared Palm Beach School of Nursing owner Johanah Napoleon, who reportedly was selling fake degrees for $6,000 to $18,000 each to two individuals in Maryland and Virginia. Ms. Napoleon was charged in 2021 and eventually pled guilty. The Florida Board of Nursing shut down the Palm Beach school in 2017 owing to its students’ low passing rate on the national licensing exam.

Two participants in the bigger scheme who had also worked with Ms. Napoleon – Geralda Adrien and Woosvelt Predestin – were indicted in 2021. Ms. Adrien owned private education companies for people who at aspired to be nurses, and Mr. Predestin was an employee. They were sentenced to 27 months in prison last year and helped the federal officials build the larger case.

The 25 individuals who were charged Jan. 25 operated in Delaware, New York, New Jersey, Texas, and Florida.

Schemes lured immigrants

In the scheme involving Siena College, some of the individuals acted as recruiters to direct nurses who were looking for employment to the school, where they allegedly would then pay for an RN or LPN/VN degree. The recipients of the false documents then used them to obtain jobs, including at a hospital in Georgia and a Veterans Affairs medical center in Maryland, according to one indictment. The president of Siena and her co-conspirators sold more than 2,000 fake diplomas, according to charging documents.

At the Palm Beach College of Nursing, individuals at various nursing prep and education programs allegedly helped others obtain fake degrees and transcripts, which were then used to pass RN and LPN/VN licensing exams in states that included Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, and Ohio, according to the indictment.

Some individuals then secured employment with a nursing home in Ohio, a home health agency for pediatric patients in Massachusetts, and skilled nursing facilities in New York and New Jersey.

Prosecutors allege that the president of Sacred Heart International Institute and two other co-conspirators sold 588 fake diplomas.

The FBI said that some of the aspiring nurses who were talked into buying the degrees were LPNs who wanted to become RNs and that most of those lured into the scheme were from South Florida’s Haitian American immigrant community, Nurse.org reported.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Biden to end COVID emergencies in May

Doing so will have many effects, including the end of free vaccines and health services to fight the pandemic. The public health emergency has been renewed every 90 days since it was declared by the Trump administration in January 2020.

The declaration allowed major changes throughout the health care system to deal with the pandemic, including the free distribution of vaccines, testing, and treatments. In addition, telehealth services were expanded, and Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program were extended to millions more Americans.

Biden said the COVID-19 national emergency is set to expire March 1 while the declared public health emergency would currently expire on April 11. The president said both will be extended to end May 11.

There were nearly 300,000 newly reported COVID-19 cases in the United States for the week ending Jan. 25, according to CDC data, as well as more than 3,750 deaths.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Doing so will have many effects, including the end of free vaccines and health services to fight the pandemic. The public health emergency has been renewed every 90 days since it was declared by the Trump administration in January 2020.

The declaration allowed major changes throughout the health care system to deal with the pandemic, including the free distribution of vaccines, testing, and treatments. In addition, telehealth services were expanded, and Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program were extended to millions more Americans.

Biden said the COVID-19 national emergency is set to expire March 1 while the declared public health emergency would currently expire on April 11. The president said both will be extended to end May 11.

There were nearly 300,000 newly reported COVID-19 cases in the United States for the week ending Jan. 25, according to CDC data, as well as more than 3,750 deaths.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Doing so will have many effects, including the end of free vaccines and health services to fight the pandemic. The public health emergency has been renewed every 90 days since it was declared by the Trump administration in January 2020.

The declaration allowed major changes throughout the health care system to deal with the pandemic, including the free distribution of vaccines, testing, and treatments. In addition, telehealth services were expanded, and Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program were extended to millions more Americans.

Biden said the COVID-19 national emergency is set to expire March 1 while the declared public health emergency would currently expire on April 11. The president said both will be extended to end May 11.

There were nearly 300,000 newly reported COVID-19 cases in the United States for the week ending Jan. 25, according to CDC data, as well as more than 3,750 deaths.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Veteran study helps decode GWI phenotypes

To paraphrase Winston Churchill, Gulf War Illness (GWI) is a mystery wrapped in an enigma—a complex interplay of multiple symptoms, caused by a variety of environmental and chemical hazards. To make things more difficult, there are no diagnostic biomarkers or objective laboratory tests with which to confirm a GWI case. Instead, clinicians rely on patients’ reports of symptoms and the absence of other explanations for the symptoms.

Looking to provide more information on the epidemiology and biology of GWI, US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) researchers analyzed data from the VA Cooperative Studies Program 2006/Million Veteran Program 029 cohort, the largest sample of GW-era veterans available for research to date: 35,902 veterans, of whom 13,107 deployed to a post 9/11 Persian Gulf conflict.

The researchers used the Kansas (KS) and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) definitions of GWI, both of which are based on patient self-reports. The KS GWI criteria for phenotype KS Sym+ require ≥ 2 mild symptoms or ≥ 1 moderate or severe symptoms in at least 3 of 6 domains: fatigue/sleep problems, pain, neurologic/cognitive/mood, gastrointestinal, respiratory, and skin. The criteria for phenotype KS Sym+/Dx- also exclude some diagnosed health conditions, such as cancer, diabetes mellitus, and heart disease. The researchers examined both of these phenotypes.

They also used 2 phenotypes of the CDC definition: CDC GWI is met if the veteran reports ≥ 1 symptoms in 2 of 3 domains (fatigue, musculoskeletal, and mood/cognition). The second, CDC GWI severe, is met if the veteran rates ≥ 1 symptoms as severe in ≥ 2 domains.

Of the veterans studied, 67.1% met the KS Sym+ phenotype; 21.5% met the KS Sym+/Dx– definition. A majority (81.1%) met the CDC GWI phenotype; 18.6% met the severe phenotype. The most prevalent KS GWI domains were neurologic/cognitive/mood (81.9%), fatigue/sleep problems (73.9%), and pain (71.5%).

Although their findings mainly laid a foundation for further research, the researchers pointed to some potential new avenues for exploration. For instance, “Importantly,” the researchers say, “we consistently observed that deployed relative to nondeployed veterans had higher odds of meeting each GWI phenotype.” For both deployed and nondeployed veterans, those who served in the Army or Marine Corps had higher odds of meeting the KS Sym+, CDC GWI, and CDC GWI severe phenotypes. Among the deployed, Reservists had higher odds of CDC GWI and CDC GWI severe than did active-duty veterans.

Their findings also revealed that older age was associated with lower odds of meeting the GWI phenotypes. “[S]omewhat surprisingly,” they note, this finding held in both nondeployed and deployed samples, even after adjusting for military rank during the war. The researchers cite other research that has suggested younger service members are at greater risk for GWI (because they’re more likely, for example, to be exposed to deployment-related toxins). Most studies, the researchers note, have shown GWI and related symptoms to be more common among enlisted personnel than officers. Biomarkers of aging, such as epigenetic age acceleration, they suggest, “may be useful in untangling the relationship between age and GWI case status.”

Because they separately examined the association of demographic characteristics with the GWI phenotypes, the researchers also found that women, regardless of deployment status, had higher odds of meeting the GWI phenotypes compared with men.

Their findings will be used, the researchers say, “to understand how genetic variation is associated with the GWI phenotypes and to identify potential pathophysiologic underpinnings of GWI, pleiotropy with other traits, and gene by environment interactions.” With information from this large dataset of GW-era veterans, they will have a “powerful tool” for in-depth study of exposures and underlying genetic susceptibility to GWI—studies that could not be performed, they say, without the full description of the GWI phenotypes they have documented.

The study had several strengths, the researchers say. For example, unlike previous studies, this one had a sample size large enough to allow more representation of subpopulations, including age, sex, race, ethnicity, education, and military service. The researchers also collected data from surveys, especially data on veterans’ self-reported symptoms and other information “incompletely and infrequently documented in medical records.”

Finally, the data for the study were collected more than 27 years after the GW. It, therefore, gives an “updated, detailed description” of symptoms and conditions affecting GW-era veterans, decades after their return from service.

To paraphrase Winston Churchill, Gulf War Illness (GWI) is a mystery wrapped in an enigma—a complex interplay of multiple symptoms, caused by a variety of environmental and chemical hazards. To make things more difficult, there are no diagnostic biomarkers or objective laboratory tests with which to confirm a GWI case. Instead, clinicians rely on patients’ reports of symptoms and the absence of other explanations for the symptoms.

Looking to provide more information on the epidemiology and biology of GWI, US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) researchers analyzed data from the VA Cooperative Studies Program 2006/Million Veteran Program 029 cohort, the largest sample of GW-era veterans available for research to date: 35,902 veterans, of whom 13,107 deployed to a post 9/11 Persian Gulf conflict.

The researchers used the Kansas (KS) and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) definitions of GWI, both of which are based on patient self-reports. The KS GWI criteria for phenotype KS Sym+ require ≥ 2 mild symptoms or ≥ 1 moderate or severe symptoms in at least 3 of 6 domains: fatigue/sleep problems, pain, neurologic/cognitive/mood, gastrointestinal, respiratory, and skin. The criteria for phenotype KS Sym+/Dx- also exclude some diagnosed health conditions, such as cancer, diabetes mellitus, and heart disease. The researchers examined both of these phenotypes.

They also used 2 phenotypes of the CDC definition: CDC GWI is met if the veteran reports ≥ 1 symptoms in 2 of 3 domains (fatigue, musculoskeletal, and mood/cognition). The second, CDC GWI severe, is met if the veteran rates ≥ 1 symptoms as severe in ≥ 2 domains.

Of the veterans studied, 67.1% met the KS Sym+ phenotype; 21.5% met the KS Sym+/Dx– definition. A majority (81.1%) met the CDC GWI phenotype; 18.6% met the severe phenotype. The most prevalent KS GWI domains were neurologic/cognitive/mood (81.9%), fatigue/sleep problems (73.9%), and pain (71.5%).

Although their findings mainly laid a foundation for further research, the researchers pointed to some potential new avenues for exploration. For instance, “Importantly,” the researchers say, “we consistently observed that deployed relative to nondeployed veterans had higher odds of meeting each GWI phenotype.” For both deployed and nondeployed veterans, those who served in the Army or Marine Corps had higher odds of meeting the KS Sym+, CDC GWI, and CDC GWI severe phenotypes. Among the deployed, Reservists had higher odds of CDC GWI and CDC GWI severe than did active-duty veterans.

Their findings also revealed that older age was associated with lower odds of meeting the GWI phenotypes. “[S]omewhat surprisingly,” they note, this finding held in both nondeployed and deployed samples, even after adjusting for military rank during the war. The researchers cite other research that has suggested younger service members are at greater risk for GWI (because they’re more likely, for example, to be exposed to deployment-related toxins). Most studies, the researchers note, have shown GWI and related symptoms to be more common among enlisted personnel than officers. Biomarkers of aging, such as epigenetic age acceleration, they suggest, “may be useful in untangling the relationship between age and GWI case status.”

Because they separately examined the association of demographic characteristics with the GWI phenotypes, the researchers also found that women, regardless of deployment status, had higher odds of meeting the GWI phenotypes compared with men.

Their findings will be used, the researchers say, “to understand how genetic variation is associated with the GWI phenotypes and to identify potential pathophysiologic underpinnings of GWI, pleiotropy with other traits, and gene by environment interactions.” With information from this large dataset of GW-era veterans, they will have a “powerful tool” for in-depth study of exposures and underlying genetic susceptibility to GWI—studies that could not be performed, they say, without the full description of the GWI phenotypes they have documented.

The study had several strengths, the researchers say. For example, unlike previous studies, this one had a sample size large enough to allow more representation of subpopulations, including age, sex, race, ethnicity, education, and military service. The researchers also collected data from surveys, especially data on veterans’ self-reported symptoms and other information “incompletely and infrequently documented in medical records.”

Finally, the data for the study were collected more than 27 years after the GW. It, therefore, gives an “updated, detailed description” of symptoms and conditions affecting GW-era veterans, decades after their return from service.

To paraphrase Winston Churchill, Gulf War Illness (GWI) is a mystery wrapped in an enigma—a complex interplay of multiple symptoms, caused by a variety of environmental and chemical hazards. To make things more difficult, there are no diagnostic biomarkers or objective laboratory tests with which to confirm a GWI case. Instead, clinicians rely on patients’ reports of symptoms and the absence of other explanations for the symptoms.

Looking to provide more information on the epidemiology and biology of GWI, US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) researchers analyzed data from the VA Cooperative Studies Program 2006/Million Veteran Program 029 cohort, the largest sample of GW-era veterans available for research to date: 35,902 veterans, of whom 13,107 deployed to a post 9/11 Persian Gulf conflict.

The researchers used the Kansas (KS) and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) definitions of GWI, both of which are based on patient self-reports. The KS GWI criteria for phenotype KS Sym+ require ≥ 2 mild symptoms or ≥ 1 moderate or severe symptoms in at least 3 of 6 domains: fatigue/sleep problems, pain, neurologic/cognitive/mood, gastrointestinal, respiratory, and skin. The criteria for phenotype KS Sym+/Dx- also exclude some diagnosed health conditions, such as cancer, diabetes mellitus, and heart disease. The researchers examined both of these phenotypes.

They also used 2 phenotypes of the CDC definition: CDC GWI is met if the veteran reports ≥ 1 symptoms in 2 of 3 domains (fatigue, musculoskeletal, and mood/cognition). The second, CDC GWI severe, is met if the veteran rates ≥ 1 symptoms as severe in ≥ 2 domains.

Of the veterans studied, 67.1% met the KS Sym+ phenotype; 21.5% met the KS Sym+/Dx– definition. A majority (81.1%) met the CDC GWI phenotype; 18.6% met the severe phenotype. The most prevalent KS GWI domains were neurologic/cognitive/mood (81.9%), fatigue/sleep problems (73.9%), and pain (71.5%).

Although their findings mainly laid a foundation for further research, the researchers pointed to some potential new avenues for exploration. For instance, “Importantly,” the researchers say, “we consistently observed that deployed relative to nondeployed veterans had higher odds of meeting each GWI phenotype.” For both deployed and nondeployed veterans, those who served in the Army or Marine Corps had higher odds of meeting the KS Sym+, CDC GWI, and CDC GWI severe phenotypes. Among the deployed, Reservists had higher odds of CDC GWI and CDC GWI severe than did active-duty veterans.

Their findings also revealed that older age was associated with lower odds of meeting the GWI phenotypes. “[S]omewhat surprisingly,” they note, this finding held in both nondeployed and deployed samples, even after adjusting for military rank during the war. The researchers cite other research that has suggested younger service members are at greater risk for GWI (because they’re more likely, for example, to be exposed to deployment-related toxins). Most studies, the researchers note, have shown GWI and related symptoms to be more common among enlisted personnel than officers. Biomarkers of aging, such as epigenetic age acceleration, they suggest, “may be useful in untangling the relationship between age and GWI case status.”

Because they separately examined the association of demographic characteristics with the GWI phenotypes, the researchers also found that women, regardless of deployment status, had higher odds of meeting the GWI phenotypes compared with men.

Their findings will be used, the researchers say, “to understand how genetic variation is associated with the GWI phenotypes and to identify potential pathophysiologic underpinnings of GWI, pleiotropy with other traits, and gene by environment interactions.” With information from this large dataset of GW-era veterans, they will have a “powerful tool” for in-depth study of exposures and underlying genetic susceptibility to GWI—studies that could not be performed, they say, without the full description of the GWI phenotypes they have documented.

The study had several strengths, the researchers say. For example, unlike previous studies, this one had a sample size large enough to allow more representation of subpopulations, including age, sex, race, ethnicity, education, and military service. The researchers also collected data from surveys, especially data on veterans’ self-reported symptoms and other information “incompletely and infrequently documented in medical records.”

Finally, the data for the study were collected more than 27 years after the GW. It, therefore, gives an “updated, detailed description” of symptoms and conditions affecting GW-era veterans, decades after their return from service.

Generalized Pustular Psoriasis Treated With Risankizumab

To the Editor:

Generalized pustular psoriasis (GPP) is a rare but severe subtype of psoriasis that can present with systemic symptoms and organ failure, sometimes leading to hospitalization and even death.1,2 Due to the rarity of this subtype and GPP being excluded from clinical trials for plaque psoriasis, there is limited information on the optimal treatment of this disease.

More than 20 systemic medications have been described in the literature for treating GPP, including systemic steroids, traditional immunosuppressants, retinoids, and biologics, which often are used in combination; none have been consistently effective.3 Among biologic therapies, the use of tumor necrosis factor α as well as IL-12/23 and IL-17 inhibitors has been reported, with the least amount of experience with IL-17 inhibitors.4

A 53-year-old Korean woman presented to the dermatology clinic for evaluation of a widespread painful rash involving the face, neck, torso, arms, and legs that had been treated intermittently with systemic steroids by her primary care physician for several months before presentation. She had no relevant medical or dermatologic history. She denied taking prescription or over-the-counter medications.

Physical examination revealed the patient was afebrile, but she reported general malaise and chills. She had widespread erythematous, annular, scaly plaques that coalesced into polycyclic plaques studded with nonfollicular-based pustules on the forehead, frontal hairline, neck, chest, abdomen, back, arms, and legs (Figure 1).

![Initial presentation (day 0 [prior to treatment with risankizumab]). A and B, Scaly plaques coalesced into polycyclic plaques studded with nonfollicular-based pustules on the leg and neck, respectively. Initial presentation (day 0 [prior to treatment with risankizumab]). A and B, Scaly plaques coalesced into polycyclic plaques studded with nonfollicular-based pustules on the leg and neck, respectively.](https://cdn.mdedge.com/files/s3fs-public/CT111002096_Fig1_AB.jpg)

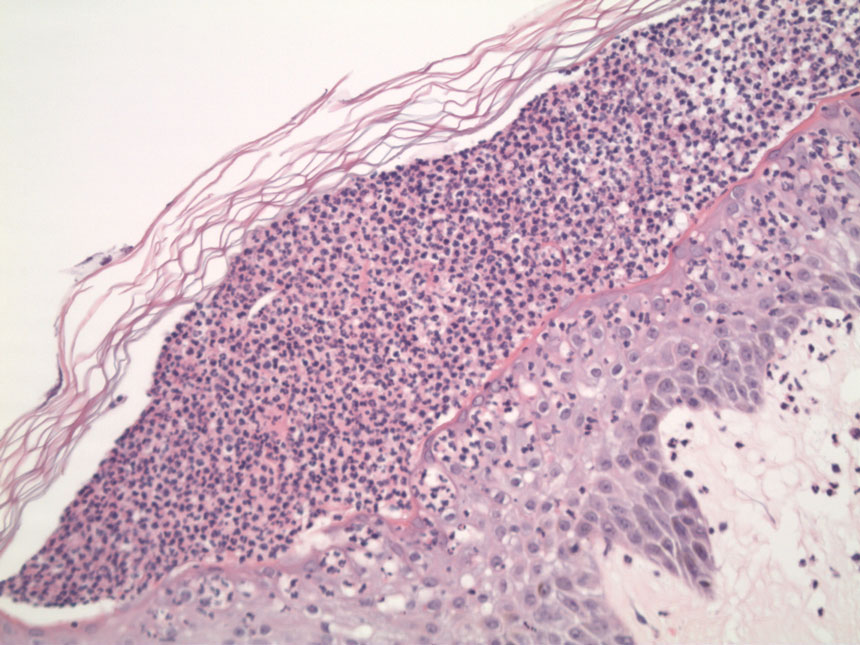

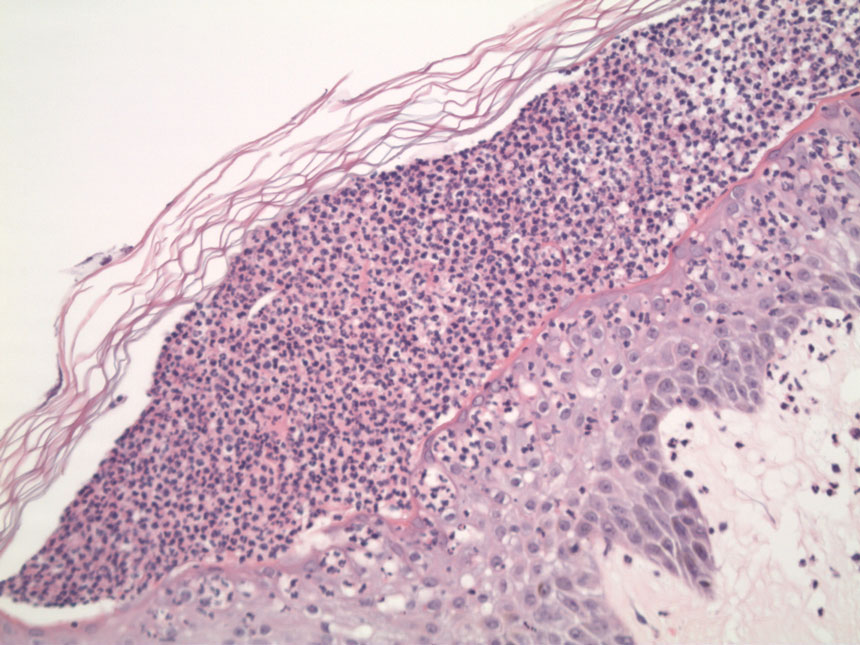

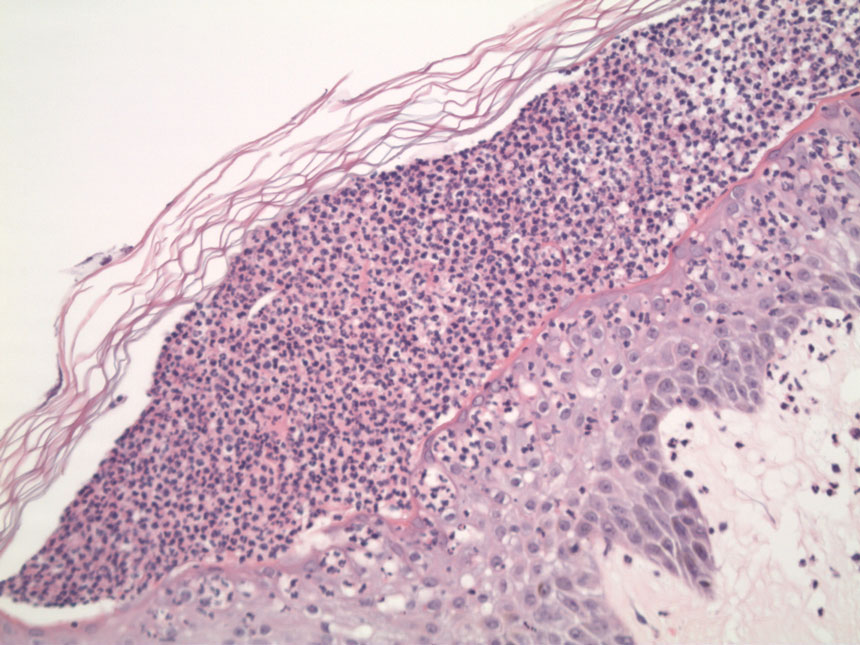

Two 4-mm punch biopsies were performed for hematoxylin and eosin staining and direct immunofluorescence. Histopathologic analysis showed prominent subcorneal neutrophilic pustules and spongiform collections of neutrophils in the spinous layer without notable eosinophils (Figure 2). Direct immunofluorescence was negative.

Based on the clinical history, physical examination, histopathology, and unremarkable drug history, a diagnosis of GPP was made. Initially, acitretin 25 mg/d was prescribed, but the patient was unable to start treatment because the cost of the drug was prohibitive. Her condition worsened, and she returned to the clinic 2 days later. Based on knowledge of an ongoing phase 3, open-label study for risankizumab in GPP, a sample of risankizumab 150 mg was administered subcutaneously in this patient. Three days later, most of the pustules on the upper half of the patient’s body had dried up and she began to desquamate from head to toe (Figure 3).The patient developed notable edema of the lower extremities, which required furosemide 20 mg/d andibuprofen 600 mg every 6 hours for symptom relief.

Ten days after the initial dose of risankizumab, the patient continued to steadily improve. All the pustules had dried up and she was already showing signs of re-epithelialization. Edema and pain also had notably improved. She received 2 additional samples of risankizumab 150 mg at weeks 4 and 16, at which point she was able to receive compassionate care through the drug manufacturer’s program. At follow-up 151 days after the initial dose of risankizumab, the patient’s skin was completely clear.

Generalized pustular psoriasis remains a difficult disease to study, given its rarity and unpredictable course. Spesolimab, a humanized anti–IL-36 receptor monoclonal antibody, was recently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of GPP.5 In the pivotal trial (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier NCT03782792),5 an astonishingly high 54% of patients (19/35) given a single dose of intravenous spesolimab reached the primary end point of no pustules at day 7. However, safety concerns, such as serious infections and severe cutaneous adverse reactions, as well as logistical challenges that come with intravenous administration for an acute disease, may prevent widespread adoption by community dermatologists.

Tumor necrosis factor α, IL-17, and IL-23 inhibitors currently are approved for the treatment of GPP in Japan, Thailand, and Taiwan based on small, nonrandomized, open-label studies.6-10 More recently, results from a phase 3, randomized, open-label study to assess the efficacy and safety of 2 different dosing regimens of risankizumab with 8 Japanese patients with GPP were published.11 However, there currently is only a single approved medication for GPP in Europe and the United States. Therefore, additional therapies, particularly those that have already been established in dermatology, would be welcome in treating this disease.

A number of questions still need to be answered regarding treating GPP with risankizumab:

• What is the optimal dose and schedule of this drug? Our patient received the standard 150-mg dose that is FDA approved for moderate to severe plaque psoriasis; would a higher dose, such as the FDA-approved 600-mg dosing used to treat Crohn disease, have led to a more rapid and durable response?12

• For how long should these patients be treated? Will their disease follow the same course as psoriasis vulgaris, requiring long-term, continuous treatment?

• An ongoing 5-year, open-label extension study of spesolimab might eventually answer that question and currently is recruiting participants (NCT03886246).

• Is there a way to predict a priori which patients will be responders? Biomarkers—especially through the use of tape stripping—are promising, but validation studies are still needed.13

• Because 69% (24/35) of enrolled patients in the treatment group of the spesolimab trial did not harbor a mutation of the IL36RN gene, how reliable is mutation status in predicting treatment response?5

Of note, some of these questions also apply to guttate psoriasis, a far more common subtype of psoriasis that also is worth exploring.

Nevertheless, these are exciting times for patients with GPP. What was once considered an obscure orphan disease is the focus of major recent publications3 and phase 3, randomized, placebo-controlled studies.5 We can be cautiously optimistic that in the next few years we will be in a better position to care for patients with GPP.

- Shah M, Aboud DM Al, Crane JS, et al. Pustular psoriasis. In. Zeichner J, ed. Acneiform Eruptions in Dermatology: A Differential Diagnosis. 2021:295-307. doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-8344-1_42

- Nestle FO, Kaplan DH, Barker J. Psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:496-509. doi:10.1056/NEJMra0804595

- Noe MH, Wan MT, Mostaghimi A, et al. Evaluation of a case series of patients with generalized pustular psoriasis in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158:73-78. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.4640

- Miyachi H, Konishi T, Kumazawa R, et al. Treatments and outcomes of generalized pustular psoriasis: a cohort of 1516 patients in a nationwide inpatient database in Japan. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:1266-1274. doi:10.1016/J.JAAD.2021.06.008

- Bachelez H, Choon S-E, Marrakchi S, et al; . Trial of spesolimab for generalized pustular psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:2431-2440. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2111563

- Robinson A, Van Voorhees AS, Hsu S, et al. Treatment of pustular psoriasis: from the Medical Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:279-288. doi:10.1016/J.JAAD.2011.01.032

- Torii H, Nakagawa H; . Long-term study of infliximab in Japanese patients with plaque psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, pustular psoriasis and psoriatic erythroderma. J Dermatol. 2011;38:321-334. doi:10.1111/J.1346-8138.2010.00971.X

- Saeki H, Nakagawa H, Ishii T, et al. Efficacy and safety of open-label ixekizumab treatment in Japanese patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis, erythrodermic psoriasis and generalized pustular psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:1148-1155. doi:10.1111/JDV.12773

- Imafuku S, Honma M, Okubo Y, et al. Efficacy and safety of secukinumab in patients with generalized pustular psoriasis: a 52-week analysis from phase III open-label multicenter Japanese study. J Dermatol. 2016;43:1011-1017. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.13306

- Torii H, Terui T, Matsukawa M, et al. Safety profiles and efficacy of infliximab therapy in Japanese patients with plaque psoriasis with or without psoriatic arthritis, pustular psoriasis or psoriatic erythroderma: results from the prospective post-marketing surveillance. J Dermatol. 2016;43:767-778. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.13214

- Yamanaka K, Okubo Y, Yasuda I, et al. Efficacy and safety of risankizumab in Japanese patients with generalized pustular psoriasis or erythrodermic psoriasis: primary analysis and 180-week follow-up results from the phase 3, multicenter IMMspire study [published online December 13, 2022]. J Dermatol. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.16667

- D’Haens G, Panaccione R, Baert F, et al. Risankizumab as induction therapy for Crohn’s disease: results from the phase 3 ADVANCE and MOTIVATE induction trials. Lancet. 2022;399:2015-2030. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00467-6

- Hughes AJ, Tawfik SS, Baruah KP, et al. Tape strips in dermatology research. Br J Dermatol. 2021;185:26-35. doi:10.1111/BJD.19760

To the Editor:

Generalized pustular psoriasis (GPP) is a rare but severe subtype of psoriasis that can present with systemic symptoms and organ failure, sometimes leading to hospitalization and even death.1,2 Due to the rarity of this subtype and GPP being excluded from clinical trials for plaque psoriasis, there is limited information on the optimal treatment of this disease.

More than 20 systemic medications have been described in the literature for treating GPP, including systemic steroids, traditional immunosuppressants, retinoids, and biologics, which often are used in combination; none have been consistently effective.3 Among biologic therapies, the use of tumor necrosis factor α as well as IL-12/23 and IL-17 inhibitors has been reported, with the least amount of experience with IL-17 inhibitors.4

A 53-year-old Korean woman presented to the dermatology clinic for evaluation of a widespread painful rash involving the face, neck, torso, arms, and legs that had been treated intermittently with systemic steroids by her primary care physician for several months before presentation. She had no relevant medical or dermatologic history. She denied taking prescription or over-the-counter medications.

Physical examination revealed the patient was afebrile, but she reported general malaise and chills. She had widespread erythematous, annular, scaly plaques that coalesced into polycyclic plaques studded with nonfollicular-based pustules on the forehead, frontal hairline, neck, chest, abdomen, back, arms, and legs (Figure 1).

![Initial presentation (day 0 [prior to treatment with risankizumab]). A and B, Scaly plaques coalesced into polycyclic plaques studded with nonfollicular-based pustules on the leg and neck, respectively. Initial presentation (day 0 [prior to treatment with risankizumab]). A and B, Scaly plaques coalesced into polycyclic plaques studded with nonfollicular-based pustules on the leg and neck, respectively.](https://cdn.mdedge.com/files/s3fs-public/CT111002096_Fig1_AB.jpg)

Two 4-mm punch biopsies were performed for hematoxylin and eosin staining and direct immunofluorescence. Histopathologic analysis showed prominent subcorneal neutrophilic pustules and spongiform collections of neutrophils in the spinous layer without notable eosinophils (Figure 2). Direct immunofluorescence was negative.

Based on the clinical history, physical examination, histopathology, and unremarkable drug history, a diagnosis of GPP was made. Initially, acitretin 25 mg/d was prescribed, but the patient was unable to start treatment because the cost of the drug was prohibitive. Her condition worsened, and she returned to the clinic 2 days later. Based on knowledge of an ongoing phase 3, open-label study for risankizumab in GPP, a sample of risankizumab 150 mg was administered subcutaneously in this patient. Three days later, most of the pustules on the upper half of the patient’s body had dried up and she began to desquamate from head to toe (Figure 3).The patient developed notable edema of the lower extremities, which required furosemide 20 mg/d andibuprofen 600 mg every 6 hours for symptom relief.

Ten days after the initial dose of risankizumab, the patient continued to steadily improve. All the pustules had dried up and she was already showing signs of re-epithelialization. Edema and pain also had notably improved. She received 2 additional samples of risankizumab 150 mg at weeks 4 and 16, at which point she was able to receive compassionate care through the drug manufacturer’s program. At follow-up 151 days after the initial dose of risankizumab, the patient’s skin was completely clear.

Generalized pustular psoriasis remains a difficult disease to study, given its rarity and unpredictable course. Spesolimab, a humanized anti–IL-36 receptor monoclonal antibody, was recently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of GPP.5 In the pivotal trial (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier NCT03782792),5 an astonishingly high 54% of patients (19/35) given a single dose of intravenous spesolimab reached the primary end point of no pustules at day 7. However, safety concerns, such as serious infections and severe cutaneous adverse reactions, as well as logistical challenges that come with intravenous administration for an acute disease, may prevent widespread adoption by community dermatologists.

Tumor necrosis factor α, IL-17, and IL-23 inhibitors currently are approved for the treatment of GPP in Japan, Thailand, and Taiwan based on small, nonrandomized, open-label studies.6-10 More recently, results from a phase 3, randomized, open-label study to assess the efficacy and safety of 2 different dosing regimens of risankizumab with 8 Japanese patients with GPP were published.11 However, there currently is only a single approved medication for GPP in Europe and the United States. Therefore, additional therapies, particularly those that have already been established in dermatology, would be welcome in treating this disease.

A number of questions still need to be answered regarding treating GPP with risankizumab:

• What is the optimal dose and schedule of this drug? Our patient received the standard 150-mg dose that is FDA approved for moderate to severe plaque psoriasis; would a higher dose, such as the FDA-approved 600-mg dosing used to treat Crohn disease, have led to a more rapid and durable response?12

• For how long should these patients be treated? Will their disease follow the same course as psoriasis vulgaris, requiring long-term, continuous treatment?

• An ongoing 5-year, open-label extension study of spesolimab might eventually answer that question and currently is recruiting participants (NCT03886246).

• Is there a way to predict a priori which patients will be responders? Biomarkers—especially through the use of tape stripping—are promising, but validation studies are still needed.13

• Because 69% (24/35) of enrolled patients in the treatment group of the spesolimab trial did not harbor a mutation of the IL36RN gene, how reliable is mutation status in predicting treatment response?5

Of note, some of these questions also apply to guttate psoriasis, a far more common subtype of psoriasis that also is worth exploring.

Nevertheless, these are exciting times for patients with GPP. What was once considered an obscure orphan disease is the focus of major recent publications3 and phase 3, randomized, placebo-controlled studies.5 We can be cautiously optimistic that in the next few years we will be in a better position to care for patients with GPP.

To the Editor:

Generalized pustular psoriasis (GPP) is a rare but severe subtype of psoriasis that can present with systemic symptoms and organ failure, sometimes leading to hospitalization and even death.1,2 Due to the rarity of this subtype and GPP being excluded from clinical trials for plaque psoriasis, there is limited information on the optimal treatment of this disease.

More than 20 systemic medications have been described in the literature for treating GPP, including systemic steroids, traditional immunosuppressants, retinoids, and biologics, which often are used in combination; none have been consistently effective.3 Among biologic therapies, the use of tumor necrosis factor α as well as IL-12/23 and IL-17 inhibitors has been reported, with the least amount of experience with IL-17 inhibitors.4

A 53-year-old Korean woman presented to the dermatology clinic for evaluation of a widespread painful rash involving the face, neck, torso, arms, and legs that had been treated intermittently with systemic steroids by her primary care physician for several months before presentation. She had no relevant medical or dermatologic history. She denied taking prescription or over-the-counter medications.

Physical examination revealed the patient was afebrile, but she reported general malaise and chills. She had widespread erythematous, annular, scaly plaques that coalesced into polycyclic plaques studded with nonfollicular-based pustules on the forehead, frontal hairline, neck, chest, abdomen, back, arms, and legs (Figure 1).

![Initial presentation (day 0 [prior to treatment with risankizumab]). A and B, Scaly plaques coalesced into polycyclic plaques studded with nonfollicular-based pustules on the leg and neck, respectively. Initial presentation (day 0 [prior to treatment with risankizumab]). A and B, Scaly plaques coalesced into polycyclic plaques studded with nonfollicular-based pustules on the leg and neck, respectively.](https://cdn.mdedge.com/files/s3fs-public/CT111002096_Fig1_AB.jpg)

Two 4-mm punch biopsies were performed for hematoxylin and eosin staining and direct immunofluorescence. Histopathologic analysis showed prominent subcorneal neutrophilic pustules and spongiform collections of neutrophils in the spinous layer without notable eosinophils (Figure 2). Direct immunofluorescence was negative.

Based on the clinical history, physical examination, histopathology, and unremarkable drug history, a diagnosis of GPP was made. Initially, acitretin 25 mg/d was prescribed, but the patient was unable to start treatment because the cost of the drug was prohibitive. Her condition worsened, and she returned to the clinic 2 days later. Based on knowledge of an ongoing phase 3, open-label study for risankizumab in GPP, a sample of risankizumab 150 mg was administered subcutaneously in this patient. Three days later, most of the pustules on the upper half of the patient’s body had dried up and she began to desquamate from head to toe (Figure 3).The patient developed notable edema of the lower extremities, which required furosemide 20 mg/d andibuprofen 600 mg every 6 hours for symptom relief.

Ten days after the initial dose of risankizumab, the patient continued to steadily improve. All the pustules had dried up and she was already showing signs of re-epithelialization. Edema and pain also had notably improved. She received 2 additional samples of risankizumab 150 mg at weeks 4 and 16, at which point she was able to receive compassionate care through the drug manufacturer’s program. At follow-up 151 days after the initial dose of risankizumab, the patient’s skin was completely clear.

Generalized pustular psoriasis remains a difficult disease to study, given its rarity and unpredictable course. Spesolimab, a humanized anti–IL-36 receptor monoclonal antibody, was recently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of GPP.5 In the pivotal trial (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier NCT03782792),5 an astonishingly high 54% of patients (19/35) given a single dose of intravenous spesolimab reached the primary end point of no pustules at day 7. However, safety concerns, such as serious infections and severe cutaneous adverse reactions, as well as logistical challenges that come with intravenous administration for an acute disease, may prevent widespread adoption by community dermatologists.

Tumor necrosis factor α, IL-17, and IL-23 inhibitors currently are approved for the treatment of GPP in Japan, Thailand, and Taiwan based on small, nonrandomized, open-label studies.6-10 More recently, results from a phase 3, randomized, open-label study to assess the efficacy and safety of 2 different dosing regimens of risankizumab with 8 Japanese patients with GPP were published.11 However, there currently is only a single approved medication for GPP in Europe and the United States. Therefore, additional therapies, particularly those that have already been established in dermatology, would be welcome in treating this disease.

A number of questions still need to be answered regarding treating GPP with risankizumab:

• What is the optimal dose and schedule of this drug? Our patient received the standard 150-mg dose that is FDA approved for moderate to severe plaque psoriasis; would a higher dose, such as the FDA-approved 600-mg dosing used to treat Crohn disease, have led to a more rapid and durable response?12

• For how long should these patients be treated? Will their disease follow the same course as psoriasis vulgaris, requiring long-term, continuous treatment?

• An ongoing 5-year, open-label extension study of spesolimab might eventually answer that question and currently is recruiting participants (NCT03886246).

• Is there a way to predict a priori which patients will be responders? Biomarkers—especially through the use of tape stripping—are promising, but validation studies are still needed.13

• Because 69% (24/35) of enrolled patients in the treatment group of the spesolimab trial did not harbor a mutation of the IL36RN gene, how reliable is mutation status in predicting treatment response?5

Of note, some of these questions also apply to guttate psoriasis, a far more common subtype of psoriasis that also is worth exploring.

Nevertheless, these are exciting times for patients with GPP. What was once considered an obscure orphan disease is the focus of major recent publications3 and phase 3, randomized, placebo-controlled studies.5 We can be cautiously optimistic that in the next few years we will be in a better position to care for patients with GPP.

- Shah M, Aboud DM Al, Crane JS, et al. Pustular psoriasis. In. Zeichner J, ed. Acneiform Eruptions in Dermatology: A Differential Diagnosis. 2021:295-307. doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-8344-1_42

- Nestle FO, Kaplan DH, Barker J. Psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:496-509. doi:10.1056/NEJMra0804595

- Noe MH, Wan MT, Mostaghimi A, et al. Evaluation of a case series of patients with generalized pustular psoriasis in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158:73-78. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.4640

- Miyachi H, Konishi T, Kumazawa R, et al. Treatments and outcomes of generalized pustular psoriasis: a cohort of 1516 patients in a nationwide inpatient database in Japan. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:1266-1274. doi:10.1016/J.JAAD.2021.06.008

- Bachelez H, Choon S-E, Marrakchi S, et al; . Trial of spesolimab for generalized pustular psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:2431-2440. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2111563

- Robinson A, Van Voorhees AS, Hsu S, et al. Treatment of pustular psoriasis: from the Medical Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:279-288. doi:10.1016/J.JAAD.2011.01.032

- Torii H, Nakagawa H; . Long-term study of infliximab in Japanese patients with plaque psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, pustular psoriasis and psoriatic erythroderma. J Dermatol. 2011;38:321-334. doi:10.1111/J.1346-8138.2010.00971.X

- Saeki H, Nakagawa H, Ishii T, et al. Efficacy and safety of open-label ixekizumab treatment in Japanese patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis, erythrodermic psoriasis and generalized pustular psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:1148-1155. doi:10.1111/JDV.12773

- Imafuku S, Honma M, Okubo Y, et al. Efficacy and safety of secukinumab in patients with generalized pustular psoriasis: a 52-week analysis from phase III open-label multicenter Japanese study. J Dermatol. 2016;43:1011-1017. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.13306

- Torii H, Terui T, Matsukawa M, et al. Safety profiles and efficacy of infliximab therapy in Japanese patients with plaque psoriasis with or without psoriatic arthritis, pustular psoriasis or psoriatic erythroderma: results from the prospective post-marketing surveillance. J Dermatol. 2016;43:767-778. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.13214

- Yamanaka K, Okubo Y, Yasuda I, et al. Efficacy and safety of risankizumab in Japanese patients with generalized pustular psoriasis or erythrodermic psoriasis: primary analysis and 180-week follow-up results from the phase 3, multicenter IMMspire study [published online December 13, 2022]. J Dermatol. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.16667

- D’Haens G, Panaccione R, Baert F, et al. Risankizumab as induction therapy for Crohn’s disease: results from the phase 3 ADVANCE and MOTIVATE induction trials. Lancet. 2022;399:2015-2030. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00467-6

- Hughes AJ, Tawfik SS, Baruah KP, et al. Tape strips in dermatology research. Br J Dermatol. 2021;185:26-35. doi:10.1111/BJD.19760

- Shah M, Aboud DM Al, Crane JS, et al. Pustular psoriasis. In. Zeichner J, ed. Acneiform Eruptions in Dermatology: A Differential Diagnosis. 2021:295-307. doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-8344-1_42

- Nestle FO, Kaplan DH, Barker J. Psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:496-509. doi:10.1056/NEJMra0804595

- Noe MH, Wan MT, Mostaghimi A, et al. Evaluation of a case series of patients with generalized pustular psoriasis in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158:73-78. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.4640

- Miyachi H, Konishi T, Kumazawa R, et al. Treatments and outcomes of generalized pustular psoriasis: a cohort of 1516 patients in a nationwide inpatient database in Japan. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:1266-1274. doi:10.1016/J.JAAD.2021.06.008

- Bachelez H, Choon S-E, Marrakchi S, et al; . Trial of spesolimab for generalized pustular psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:2431-2440. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2111563

- Robinson A, Van Voorhees AS, Hsu S, et al. Treatment of pustular psoriasis: from the Medical Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:279-288. doi:10.1016/J.JAAD.2011.01.032

- Torii H, Nakagawa H; . Long-term study of infliximab in Japanese patients with plaque psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, pustular psoriasis and psoriatic erythroderma. J Dermatol. 2011;38:321-334. doi:10.1111/J.1346-8138.2010.00971.X

- Saeki H, Nakagawa H, Ishii T, et al. Efficacy and safety of open-label ixekizumab treatment in Japanese patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis, erythrodermic psoriasis and generalized pustular psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:1148-1155. doi:10.1111/JDV.12773

- Imafuku S, Honma M, Okubo Y, et al. Efficacy and safety of secukinumab in patients with generalized pustular psoriasis: a 52-week analysis from phase III open-label multicenter Japanese study. J Dermatol. 2016;43:1011-1017. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.13306

- Torii H, Terui T, Matsukawa M, et al. Safety profiles and efficacy of infliximab therapy in Japanese patients with plaque psoriasis with or without psoriatic arthritis, pustular psoriasis or psoriatic erythroderma: results from the prospective post-marketing surveillance. J Dermatol. 2016;43:767-778. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.13214

- Yamanaka K, Okubo Y, Yasuda I, et al. Efficacy and safety of risankizumab in Japanese patients with generalized pustular psoriasis or erythrodermic psoriasis: primary analysis and 180-week follow-up results from the phase 3, multicenter IMMspire study [published online December 13, 2022]. J Dermatol. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.16667

- D’Haens G, Panaccione R, Baert F, et al. Risankizumab as induction therapy for Crohn’s disease: results from the phase 3 ADVANCE and MOTIVATE induction trials. Lancet. 2022;399:2015-2030. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00467-6

- Hughes AJ, Tawfik SS, Baruah KP, et al. Tape strips in dermatology research. Br J Dermatol. 2021;185:26-35. doi:10.1111/BJD.19760

PRACTICE POINTS

- Generalized pustular psoriasis (GPP) is a potentially life-threatening condition that can be precipitated by systemic steroids.

- Although more than 20 systemic medications have been tried with varying success, there has not been a single US Food and Drug Administration–approved medication for GPP until recently with the approval of spesolimab, an IL-36 receptor inhibitor.

- Risankizumab, a high-affinity humanized monoclonal antibody that targets the p19 subunit of the IL-23 cytokine, also has shown promise in a recent phase 3, open-label study for GPP.

Adverse Effects of the COVID-19 Vaccine in Patients With Psoriasis

To the Editor:

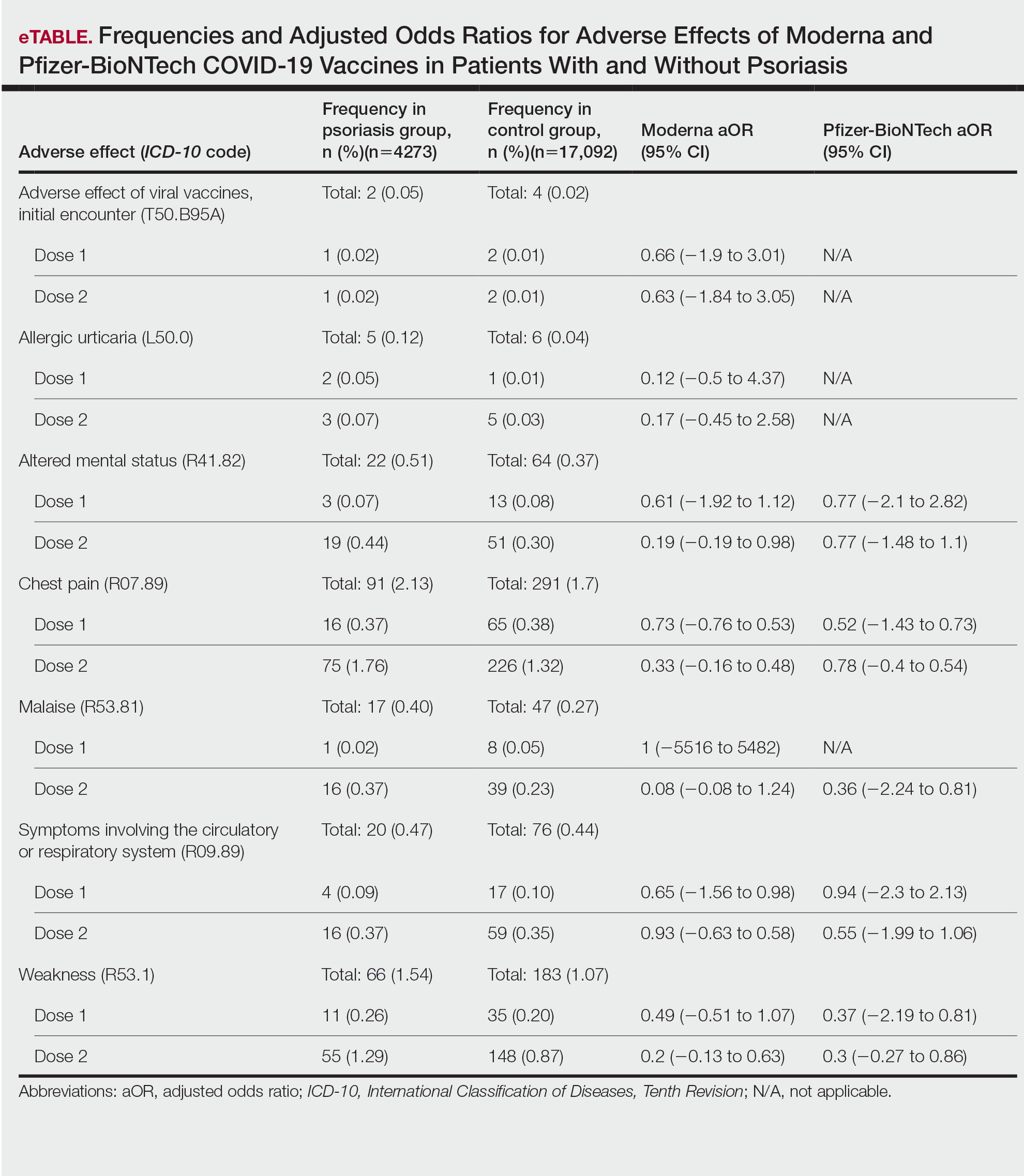

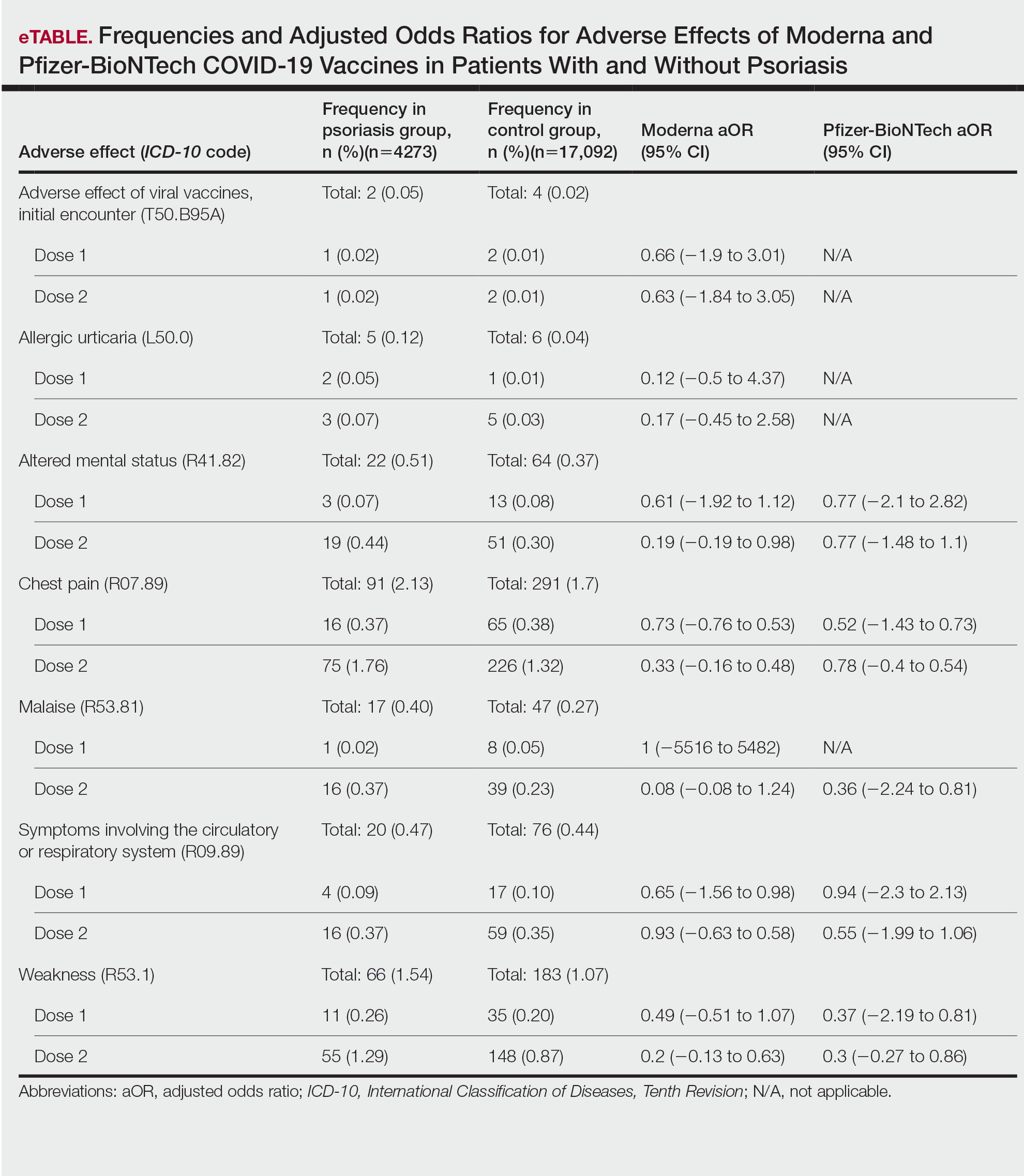

Because the SARS-CoV-2 virus is constantly changing, routine vaccination to prevent COVID-19 infection is recommended. The messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccines from Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna as well as the Ad26.COV2.S (Johnson & Johnson) and NVX-CoV2373 (Novavax) vaccines are the most commonly used COVID-19 vaccines in the United States. Adverse effects following vaccination against SARS-CoV-2 are well documented; recent studies report a small incidence of adverse effects in the general population, with most being minor (eg, headache, fever, muscle pain).1,2 Interestingly, reports of exacerbation of psoriasis and new-onset psoriasis following COVID-19 vaccination suggest a potential association.3,4 However, the literature investigating the vaccine adverse effect profile in this demographic is scarce. We examined the incidence of adverse effects from SARS-CoV-2 vaccines in patients with psoriasis.

This retrospective cohort study used the COVID-19 Research Database (https://covid19researchdatabase.org/) to examine the adverse effects following the first and second doses of the mRNA vaccines in patients with and without psoriasis. The sample size for the Ad26.COV2.S vaccine was too small to analyze.

Claims were evaluated from August to October 2021 for 2 diagnoses of psoriasis prior to January 1, 2020, using the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) code L40.9 to increase the positive predictive value and ensure that the diagnosis preceded the COVID-19 pandemic. Patients younger than 18 years and those who did not receive 2 doses of a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine were excluded. Controls who did not have a diagnosis of psoriasis were matched for age, sex, and hypertension at a 4:1 ratio. Hypertension represented the most common comorbidity that could feasibly be controlled for in this study population. Other comorbidities recorded included obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, congestive heart failure, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic ischemic heart disease, rhinitis, and chronic kidney disease.

Common adverse effects as long as 30 days after vaccination were identified using ICD-10 codes. Adverse effects of interest were anaphylactic reaction, initial encounter of adverse effect of viral vaccines, fever, allergic urticaria, weakness, altered mental status, malaise, allergic reaction, chest pain, symptoms involving circulatory or respiratory systems, localized rash, axillary lymphadenopathy, infection, and myocarditis.5 Poisson regression was performed using Stata 17 analytical software.

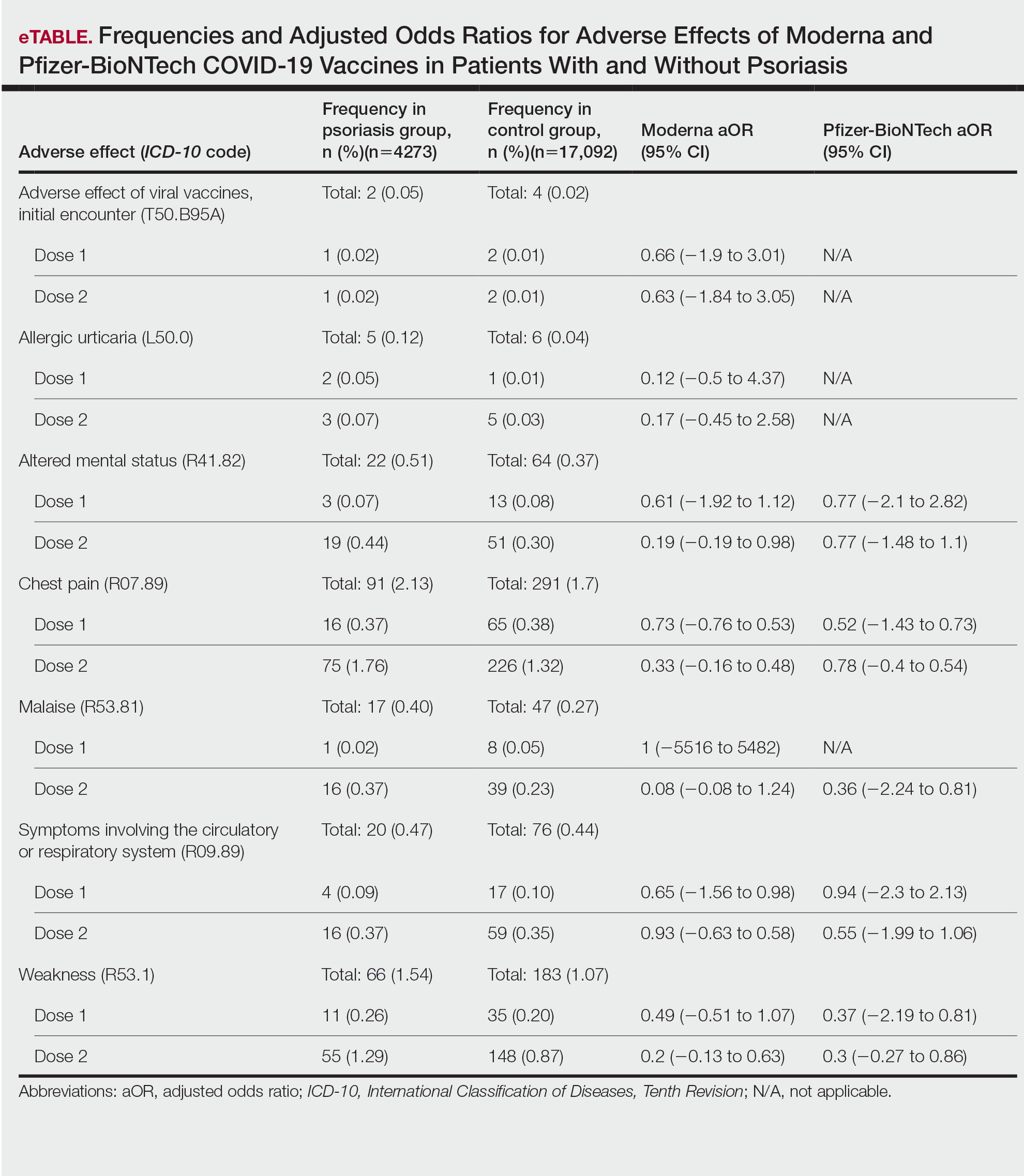

We identified 4273 patients with psoriasis and 17,092 controls who received mRNA COVID-19 vaccines (Table). Adjusted odds ratios (aORs) for doses 1 and 2 were calculated for each vaccine (eTable). Adverse effects with sufficient data to generate an aOR included weakness, altered mental status, malaise, chest pain, and symptoms involving the circulatory or respiratory system. The aORs for allergic urticaria and initial encounter of adverse effect of viral vaccines were only calculated for the Moderna mRNA vaccine due to low sample size.

This study demonstrated that patients with psoriasis do not appear to have a significantly increased risk of adverse effects from mRNA SARS-CoV-2 vaccines. Although the ORs in this study were not significant, most recorded adverse effects demonstrated an aOR less than 1, suggesting that there might be a lower risk of certain adverse effects in psoriasis patients. This could be explained by the immunomodulatory effects of certain systemic psoriasis treatments that might influence the adverse effect presentation.

The study is limited by the lack of treatment data, small sample size, and the fact that it did not assess flares or worsening of psoriasis with the vaccines. Underreporting of adverse effects by patients and underdiagnosis of adverse effects secondary to SARS-CoV-2 vaccines due to its novel nature, incompletely understood consequences, and limited ICD-10 codes associated with adverse effects all contributed to the small sample size.

Our findings suggest that the risk for immediate adverse effects from the mRNA SARS-CoV-2 vaccines is not increased among psoriasis patients. However, the impact of immunomodulatory agents on vaccine efficacy and expected adverse effects should be investigated. As more individuals receive the COVID-19 vaccine, the adverse effect profile in patients with psoriasis is an important area of investigation.

- Singh A, Khillan R, Mishra Y, et al. The safety profile of COVID-19 vaccinations in the United States. Am J Infect Control. 2022;50:15-19. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2021.10.015

- Beatty AL, Peyser ND, Butcher XE, et al. Analysis of COVID-19 vaccine type and adverse effects following vaccination. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4:e2140364. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.40364

- Bellinato F, Maurelli M, Gisondi P, et al. Cutaneous adverse reactions associated with SARS-CoV-2 vaccines. J Clin Med. 2021;10:5344. doi:10.3390/jcm10225344

- Elamin S, Hinds F, Tolland J. De novo generalized pustular psoriasis following Oxford-AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2022;47:153-155. doi:10.1111/ced.14895

- Remer EE. Coding COVID-19 vaccination. ICD10monitor. Published March 2, 2021. Updated October 18, 2022. Accessed January 17, 2023. https://icd10monitor.medlearn.com/coding-covid-19-vaccination/

To the Editor:

Because the SARS-CoV-2 virus is constantly changing, routine vaccination to prevent COVID-19 infection is recommended. The messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccines from Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna as well as the Ad26.COV2.S (Johnson & Johnson) and NVX-CoV2373 (Novavax) vaccines are the most commonly used COVID-19 vaccines in the United States. Adverse effects following vaccination against SARS-CoV-2 are well documented; recent studies report a small incidence of adverse effects in the general population, with most being minor (eg, headache, fever, muscle pain).1,2 Interestingly, reports of exacerbation of psoriasis and new-onset psoriasis following COVID-19 vaccination suggest a potential association.3,4 However, the literature investigating the vaccine adverse effect profile in this demographic is scarce. We examined the incidence of adverse effects from SARS-CoV-2 vaccines in patients with psoriasis.

This retrospective cohort study used the COVID-19 Research Database (https://covid19researchdatabase.org/) to examine the adverse effects following the first and second doses of the mRNA vaccines in patients with and without psoriasis. The sample size for the Ad26.COV2.S vaccine was too small to analyze.

Claims were evaluated from August to October 2021 for 2 diagnoses of psoriasis prior to January 1, 2020, using the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) code L40.9 to increase the positive predictive value and ensure that the diagnosis preceded the COVID-19 pandemic. Patients younger than 18 years and those who did not receive 2 doses of a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine were excluded. Controls who did not have a diagnosis of psoriasis were matched for age, sex, and hypertension at a 4:1 ratio. Hypertension represented the most common comorbidity that could feasibly be controlled for in this study population. Other comorbidities recorded included obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, congestive heart failure, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic ischemic heart disease, rhinitis, and chronic kidney disease.

Common adverse effects as long as 30 days after vaccination were identified using ICD-10 codes. Adverse effects of interest were anaphylactic reaction, initial encounter of adverse effect of viral vaccines, fever, allergic urticaria, weakness, altered mental status, malaise, allergic reaction, chest pain, symptoms involving circulatory or respiratory systems, localized rash, axillary lymphadenopathy, infection, and myocarditis.5 Poisson regression was performed using Stata 17 analytical software.

We identified 4273 patients with psoriasis and 17,092 controls who received mRNA COVID-19 vaccines (Table). Adjusted odds ratios (aORs) for doses 1 and 2 were calculated for each vaccine (eTable). Adverse effects with sufficient data to generate an aOR included weakness, altered mental status, malaise, chest pain, and symptoms involving the circulatory or respiratory system. The aORs for allergic urticaria and initial encounter of adverse effect of viral vaccines were only calculated for the Moderna mRNA vaccine due to low sample size.

This study demonstrated that patients with psoriasis do not appear to have a significantly increased risk of adverse effects from mRNA SARS-CoV-2 vaccines. Although the ORs in this study were not significant, most recorded adverse effects demonstrated an aOR less than 1, suggesting that there might be a lower risk of certain adverse effects in psoriasis patients. This could be explained by the immunomodulatory effects of certain systemic psoriasis treatments that might influence the adverse effect presentation.

The study is limited by the lack of treatment data, small sample size, and the fact that it did not assess flares or worsening of psoriasis with the vaccines. Underreporting of adverse effects by patients and underdiagnosis of adverse effects secondary to SARS-CoV-2 vaccines due to its novel nature, incompletely understood consequences, and limited ICD-10 codes associated with adverse effects all contributed to the small sample size.

Our findings suggest that the risk for immediate adverse effects from the mRNA SARS-CoV-2 vaccines is not increased among psoriasis patients. However, the impact of immunomodulatory agents on vaccine efficacy and expected adverse effects should be investigated. As more individuals receive the COVID-19 vaccine, the adverse effect profile in patients with psoriasis is an important area of investigation.

To the Editor:

Because the SARS-CoV-2 virus is constantly changing, routine vaccination to prevent COVID-19 infection is recommended. The messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccines from Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna as well as the Ad26.COV2.S (Johnson & Johnson) and NVX-CoV2373 (Novavax) vaccines are the most commonly used COVID-19 vaccines in the United States. Adverse effects following vaccination against SARS-CoV-2 are well documented; recent studies report a small incidence of adverse effects in the general population, with most being minor (eg, headache, fever, muscle pain).1,2 Interestingly, reports of exacerbation of psoriasis and new-onset psoriasis following COVID-19 vaccination suggest a potential association.3,4 However, the literature investigating the vaccine adverse effect profile in this demographic is scarce. We examined the incidence of adverse effects from SARS-CoV-2 vaccines in patients with psoriasis.

This retrospective cohort study used the COVID-19 Research Database (https://covid19researchdatabase.org/) to examine the adverse effects following the first and second doses of the mRNA vaccines in patients with and without psoriasis. The sample size for the Ad26.COV2.S vaccine was too small to analyze.

Claims were evaluated from August to October 2021 for 2 diagnoses of psoriasis prior to January 1, 2020, using the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) code L40.9 to increase the positive predictive value and ensure that the diagnosis preceded the COVID-19 pandemic. Patients younger than 18 years and those who did not receive 2 doses of a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine were excluded. Controls who did not have a diagnosis of psoriasis were matched for age, sex, and hypertension at a 4:1 ratio. Hypertension represented the most common comorbidity that could feasibly be controlled for in this study population. Other comorbidities recorded included obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, congestive heart failure, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic ischemic heart disease, rhinitis, and chronic kidney disease.

Common adverse effects as long as 30 days after vaccination were identified using ICD-10 codes. Adverse effects of interest were anaphylactic reaction, initial encounter of adverse effect of viral vaccines, fever, allergic urticaria, weakness, altered mental status, malaise, allergic reaction, chest pain, symptoms involving circulatory or respiratory systems, localized rash, axillary lymphadenopathy, infection, and myocarditis.5 Poisson regression was performed using Stata 17 analytical software.

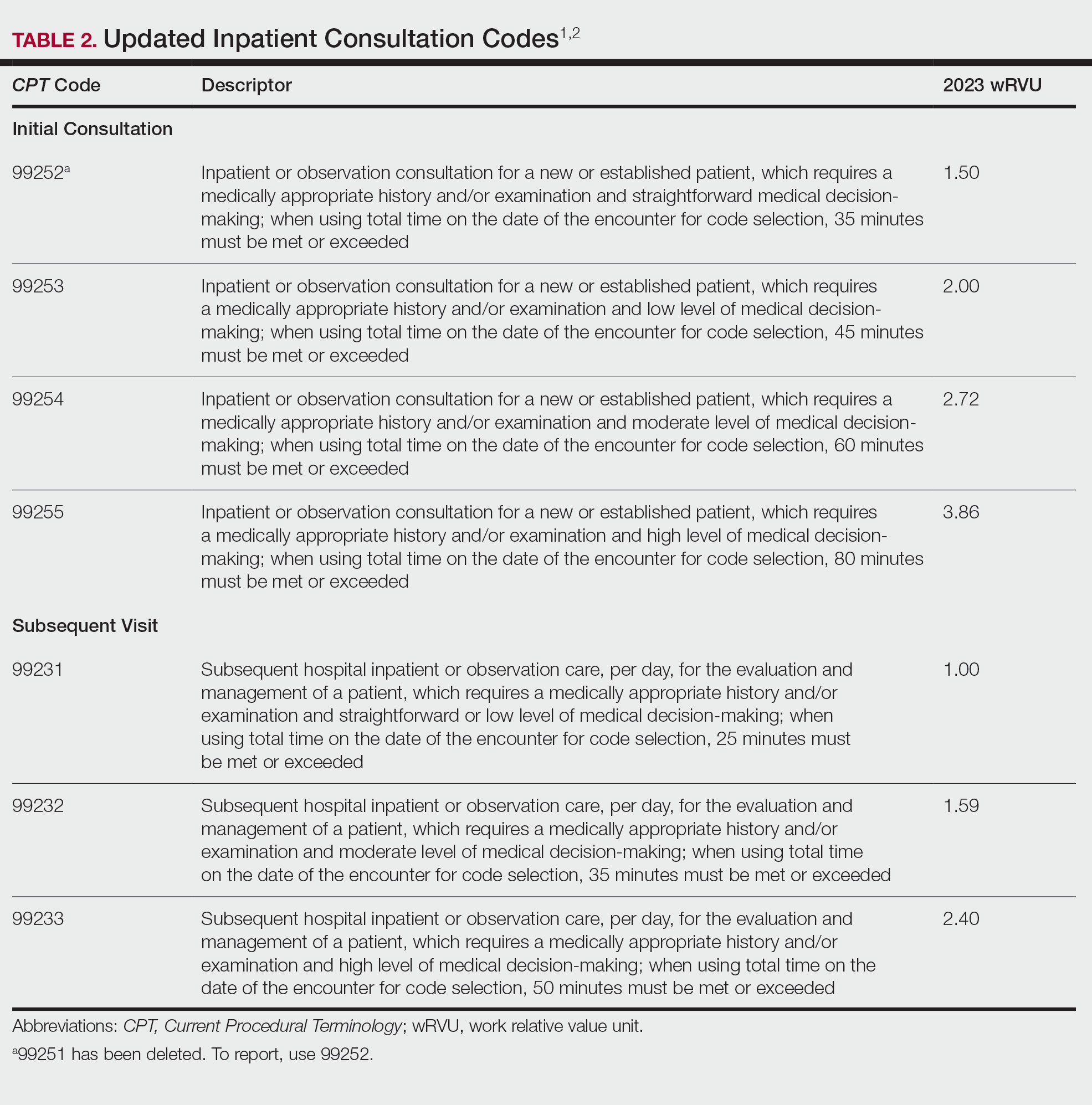

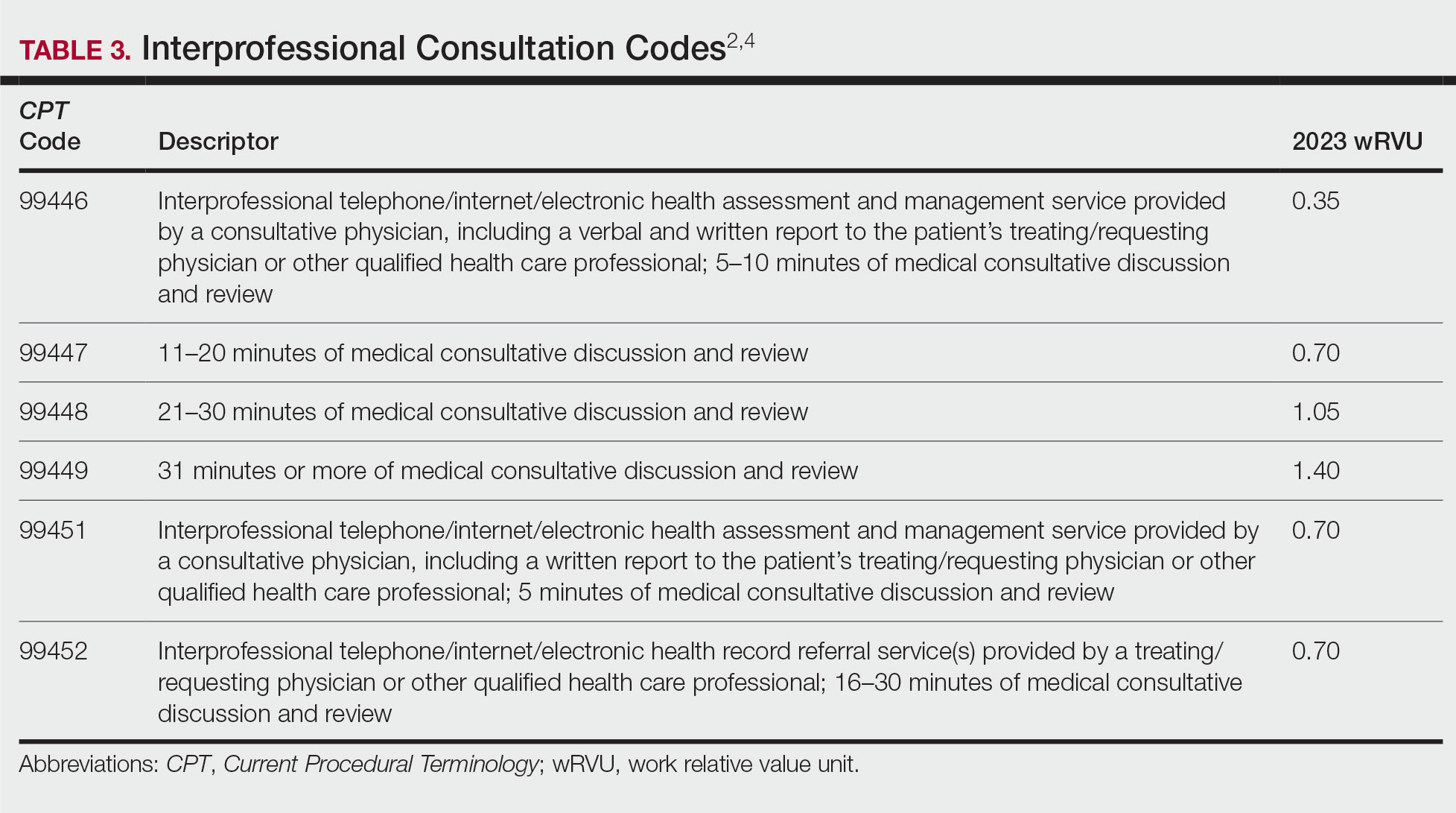

We identified 4273 patients with psoriasis and 17,092 controls who received mRNA COVID-19 vaccines (Table). Adjusted odds ratios (aORs) for doses 1 and 2 were calculated for each vaccine (eTable). Adverse effects with sufficient data to generate an aOR included weakness, altered mental status, malaise, chest pain, and symptoms involving the circulatory or respiratory system. The aORs for allergic urticaria and initial encounter of adverse effect of viral vaccines were only calculated for the Moderna mRNA vaccine due to low sample size.