User login

Strong link between muscle strength, mobility, and brain health

A new study shows a strong correlation between muscle strength, mobility, and brain volume, including in the hippocampus that underlies memory function, in adults with Alzheimer’s disease (AD).

Investigators found statistically significant relationships between better handgrip strength and mobility and hippocampal and lobar brain volumes in 38 cognitively impaired adults with biomarker evidence of AD.

study investigator Cyrus Raji, MD, PhD, Mallinckrodt Institute of Radiology, Washington University, St. Louis, told this news organization.

The study was published online in the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease.

Brain-body connection

The researchers measured handgrip strength in patients’ dominant and nondominant hands using a hand dynamometer and calculated handgrip asymmetry. Mobility was measured via the 2-minute walk test. Together, the test results were used to categorize patients as “frail” or “not frail.”

They measured regional brain volumes using Neuroreader (Brainreader), a U.S. Food and Drug Administration–approved software application that measures brain volumes on MRI scans.

The investigators found higher nondominant handgrip strength was significantly associated with larger volumes in the hippocampal volume (P = .02). In addition, higher dominant handgrip strength correlated with higher frontal lobe volume (P = .02).

Results also showed higher scores on the 2-minute walk test were associated with larger hippocampal (P = .04), frontal (P = .01), temporal (P = .03), parietal (P = .009), and occipital lobe (P = .005) volumes. Frailty was associated with reduced frontal, temporal, and parietal lobe volumes.

“In this study we combined objective evaluations of frailty with measurable determinants of brain structure on MRI to demonstrate a link between frailty and brain health in patients with both biomarker evidence of AD and cognitive impairment,” study investigator Somayeh Meysami, MD, with Pacific Brain Health Center, Pacific Neuroscience Institute Foundation (PNI), Santa Monica, Calif., told this news organization.

The researchers noted that it’s possible that interventions specifically focused on improving ambulatory mobility and handgrip strength could be beneficial in improving dementia trajectories.

‘Use it or lose it’

The chief limitation of the study is the cross-sectional design that precludes drawing firm conclusions about the causal relationships between handgrip strength and changes in brain structure.

In addition, the study used a relatively small convenience sample of outpatients from a specialty memory clinic.

The researchers say future longitudinal analyses with a larger sample size will be important to better understand the possible directions of causality between handgrip strength and progression of atrophy in AD.

However, despite these limitations, the findings emphasize the importance of “body-brain connections,” added David A. Merrill, MD, PhD, director of the Pacific Brain Health Center at PNI.

“Training our muscles helps sustain our brains and vice versa. It’s ‘use it or lose it’ for both body and mind. Exercise remains among the best strategies for maintaining a healthy body and mind with aging,” Dr. Merrill said in an interview.

“While it’s long been appreciated that aerobic training helps the brain, these findings add to the importance of strength training in supporting successful aging,” he added.

This work was supported by Providence St. Joseph Health, Seattle; Saint John’s Health Center Foundation; Pacific Neuroscience Institute Foundation; and the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Raji is a consultant for Brainreader, Apollo Health, Pacific Neuroscience Foundation, and Neurevolution. Dr. Merrill and Dr. Meysami reported no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A new study shows a strong correlation between muscle strength, mobility, and brain volume, including in the hippocampus that underlies memory function, in adults with Alzheimer’s disease (AD).

Investigators found statistically significant relationships between better handgrip strength and mobility and hippocampal and lobar brain volumes in 38 cognitively impaired adults with biomarker evidence of AD.

study investigator Cyrus Raji, MD, PhD, Mallinckrodt Institute of Radiology, Washington University, St. Louis, told this news organization.

The study was published online in the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease.

Brain-body connection

The researchers measured handgrip strength in patients’ dominant and nondominant hands using a hand dynamometer and calculated handgrip asymmetry. Mobility was measured via the 2-minute walk test. Together, the test results were used to categorize patients as “frail” or “not frail.”

They measured regional brain volumes using Neuroreader (Brainreader), a U.S. Food and Drug Administration–approved software application that measures brain volumes on MRI scans.

The investigators found higher nondominant handgrip strength was significantly associated with larger volumes in the hippocampal volume (P = .02). In addition, higher dominant handgrip strength correlated with higher frontal lobe volume (P = .02).

Results also showed higher scores on the 2-minute walk test were associated with larger hippocampal (P = .04), frontal (P = .01), temporal (P = .03), parietal (P = .009), and occipital lobe (P = .005) volumes. Frailty was associated with reduced frontal, temporal, and parietal lobe volumes.

“In this study we combined objective evaluations of frailty with measurable determinants of brain structure on MRI to demonstrate a link between frailty and brain health in patients with both biomarker evidence of AD and cognitive impairment,” study investigator Somayeh Meysami, MD, with Pacific Brain Health Center, Pacific Neuroscience Institute Foundation (PNI), Santa Monica, Calif., told this news organization.

The researchers noted that it’s possible that interventions specifically focused on improving ambulatory mobility and handgrip strength could be beneficial in improving dementia trajectories.

‘Use it or lose it’

The chief limitation of the study is the cross-sectional design that precludes drawing firm conclusions about the causal relationships between handgrip strength and changes in brain structure.

In addition, the study used a relatively small convenience sample of outpatients from a specialty memory clinic.

The researchers say future longitudinal analyses with a larger sample size will be important to better understand the possible directions of causality between handgrip strength and progression of atrophy in AD.

However, despite these limitations, the findings emphasize the importance of “body-brain connections,” added David A. Merrill, MD, PhD, director of the Pacific Brain Health Center at PNI.

“Training our muscles helps sustain our brains and vice versa. It’s ‘use it or lose it’ for both body and mind. Exercise remains among the best strategies for maintaining a healthy body and mind with aging,” Dr. Merrill said in an interview.

“While it’s long been appreciated that aerobic training helps the brain, these findings add to the importance of strength training in supporting successful aging,” he added.

This work was supported by Providence St. Joseph Health, Seattle; Saint John’s Health Center Foundation; Pacific Neuroscience Institute Foundation; and the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Raji is a consultant for Brainreader, Apollo Health, Pacific Neuroscience Foundation, and Neurevolution. Dr. Merrill and Dr. Meysami reported no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A new study shows a strong correlation between muscle strength, mobility, and brain volume, including in the hippocampus that underlies memory function, in adults with Alzheimer’s disease (AD).

Investigators found statistically significant relationships between better handgrip strength and mobility and hippocampal and lobar brain volumes in 38 cognitively impaired adults with biomarker evidence of AD.

study investigator Cyrus Raji, MD, PhD, Mallinckrodt Institute of Radiology, Washington University, St. Louis, told this news organization.

The study was published online in the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease.

Brain-body connection

The researchers measured handgrip strength in patients’ dominant and nondominant hands using a hand dynamometer and calculated handgrip asymmetry. Mobility was measured via the 2-minute walk test. Together, the test results were used to categorize patients as “frail” or “not frail.”

They measured regional brain volumes using Neuroreader (Brainreader), a U.S. Food and Drug Administration–approved software application that measures brain volumes on MRI scans.

The investigators found higher nondominant handgrip strength was significantly associated with larger volumes in the hippocampal volume (P = .02). In addition, higher dominant handgrip strength correlated with higher frontal lobe volume (P = .02).

Results also showed higher scores on the 2-minute walk test were associated with larger hippocampal (P = .04), frontal (P = .01), temporal (P = .03), parietal (P = .009), and occipital lobe (P = .005) volumes. Frailty was associated with reduced frontal, temporal, and parietal lobe volumes.

“In this study we combined objective evaluations of frailty with measurable determinants of brain structure on MRI to demonstrate a link between frailty and brain health in patients with both biomarker evidence of AD and cognitive impairment,” study investigator Somayeh Meysami, MD, with Pacific Brain Health Center, Pacific Neuroscience Institute Foundation (PNI), Santa Monica, Calif., told this news organization.

The researchers noted that it’s possible that interventions specifically focused on improving ambulatory mobility and handgrip strength could be beneficial in improving dementia trajectories.

‘Use it or lose it’

The chief limitation of the study is the cross-sectional design that precludes drawing firm conclusions about the causal relationships between handgrip strength and changes in brain structure.

In addition, the study used a relatively small convenience sample of outpatients from a specialty memory clinic.

The researchers say future longitudinal analyses with a larger sample size will be important to better understand the possible directions of causality between handgrip strength and progression of atrophy in AD.

However, despite these limitations, the findings emphasize the importance of “body-brain connections,” added David A. Merrill, MD, PhD, director of the Pacific Brain Health Center at PNI.

“Training our muscles helps sustain our brains and vice versa. It’s ‘use it or lose it’ for both body and mind. Exercise remains among the best strategies for maintaining a healthy body and mind with aging,” Dr. Merrill said in an interview.

“While it’s long been appreciated that aerobic training helps the brain, these findings add to the importance of strength training in supporting successful aging,” he added.

This work was supported by Providence St. Joseph Health, Seattle; Saint John’s Health Center Foundation; Pacific Neuroscience Institute Foundation; and the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Raji is a consultant for Brainreader, Apollo Health, Pacific Neuroscience Foundation, and Neurevolution. Dr. Merrill and Dr. Meysami reported no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE

Quick Quiz Question 2

Q2. Correct answer: A. Enteric infection

Rationale

Despite the numerous side effects associated with long-term PPI use, the quality of evidence and risk of confounding from these studies limits the ability to ascribe sufficient cause and effect between PPI use and these outcomes. However, a recent large randomized controlled trial that evaluated the use of pantoprazole versus placebo demonstrated a statistically significant difference between the pantoprazole and placebo groups only in enteric infections (1.4% vs 1.0%; odds ratio, 1.33; 95% confidence interval, 1.01-1.75). Despite a nearly double increased risk of Clostridioides difficile infection in the PPI group, compared with the placebo group, the number of events was low, and the difference did not reach statistical significance. In the context of these data, and more recent studies suggesting an increased risk of COVID-19 in patients who take PPIs, compared with those who do not, the risk of enteric infections is likely small but significantly increased among long-term PPI users.

References

- Freedberg DE et al. Gastroenterology. 2017;152(4):706-15. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.01.031.

- Moayyedi P et al. Gastroenterology. 2019;157(3):682-91.e2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.05.056.

Q2. Correct answer: A. Enteric infection

Rationale

Despite the numerous side effects associated with long-term PPI use, the quality of evidence and risk of confounding from these studies limits the ability to ascribe sufficient cause and effect between PPI use and these outcomes. However, a recent large randomized controlled trial that evaluated the use of pantoprazole versus placebo demonstrated a statistically significant difference between the pantoprazole and placebo groups only in enteric infections (1.4% vs 1.0%; odds ratio, 1.33; 95% confidence interval, 1.01-1.75). Despite a nearly double increased risk of Clostridioides difficile infection in the PPI group, compared with the placebo group, the number of events was low, and the difference did not reach statistical significance. In the context of these data, and more recent studies suggesting an increased risk of COVID-19 in patients who take PPIs, compared with those who do not, the risk of enteric infections is likely small but significantly increased among long-term PPI users.

References

- Freedberg DE et al. Gastroenterology. 2017;152(4):706-15. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.01.031.

- Moayyedi P et al. Gastroenterology. 2019;157(3):682-91.e2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.05.056.

Q2. Correct answer: A. Enteric infection

Rationale

Despite the numerous side effects associated with long-term PPI use, the quality of evidence and risk of confounding from these studies limits the ability to ascribe sufficient cause and effect between PPI use and these outcomes. However, a recent large randomized controlled trial that evaluated the use of pantoprazole versus placebo demonstrated a statistically significant difference between the pantoprazole and placebo groups only in enteric infections (1.4% vs 1.0%; odds ratio, 1.33; 95% confidence interval, 1.01-1.75). Despite a nearly double increased risk of Clostridioides difficile infection in the PPI group, compared with the placebo group, the number of events was low, and the difference did not reach statistical significance. In the context of these data, and more recent studies suggesting an increased risk of COVID-19 in patients who take PPIs, compared with those who do not, the risk of enteric infections is likely small but significantly increased among long-term PPI users.

References

- Freedberg DE et al. Gastroenterology. 2017;152(4):706-15. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.01.031.

- Moayyedi P et al. Gastroenterology. 2019;157(3):682-91.e2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.05.056.

.

Quick Quiz Question 1

Q1. Correct answer: D. Rabeprazole

Rationale

Within-class switching of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) for patients with incomplete control of symptoms is frequently done in clinical practice. For the management of gastroesophageal reflux disease, this practice can be "considered" according to guidelines. More recent data suggest varying potencies of PPIs might be responsible for some patient's incomplete response. When measured as omeprazole equivalents, the relative potencies of standard-dose pantoprazole, lansoprazole, omeprazole, esomeprazole, and rabeprazole have been estimated at 0.23, 0.90, 1.00, 1.60, and 1.82 OEs, respectively.

References

- Graham DY and Tansel A. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16(6):800-8.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.09.033

- Katz PO et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2022;117(1):27-56. doi: 10.14309/ ajg.0000000000001538

- Kirchheiner J et al. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;65(1):19-31. doi: 10.1007/s00228-008-0576-5

Q1. Correct answer: D. Rabeprazole

Rationale

Within-class switching of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) for patients with incomplete control of symptoms is frequently done in clinical practice. For the management of gastroesophageal reflux disease, this practice can be "considered" according to guidelines. More recent data suggest varying potencies of PPIs might be responsible for some patient's incomplete response. When measured as omeprazole equivalents, the relative potencies of standard-dose pantoprazole, lansoprazole, omeprazole, esomeprazole, and rabeprazole have been estimated at 0.23, 0.90, 1.00, 1.60, and 1.82 OEs, respectively.

References

- Graham DY and Tansel A. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16(6):800-8.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.09.033

- Katz PO et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2022;117(1):27-56. doi: 10.14309/ ajg.0000000000001538

- Kirchheiner J et al. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;65(1):19-31. doi: 10.1007/s00228-008-0576-5

Q1. Correct answer: D. Rabeprazole

Rationale

Within-class switching of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) for patients with incomplete control of symptoms is frequently done in clinical practice. For the management of gastroesophageal reflux disease, this practice can be "considered" according to guidelines. More recent data suggest varying potencies of PPIs might be responsible for some patient's incomplete response. When measured as omeprazole equivalents, the relative potencies of standard-dose pantoprazole, lansoprazole, omeprazole, esomeprazole, and rabeprazole have been estimated at 0.23, 0.90, 1.00, 1.60, and 1.82 OEs, respectively.

References

- Graham DY and Tansel A. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16(6):800-8.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.09.033

- Katz PO et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2022;117(1):27-56. doi: 10.14309/ ajg.0000000000001538

- Kirchheiner J et al. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;65(1):19-31. doi: 10.1007/s00228-008-0576-5

.

Mild shortness of breath

This patient's clinical presentation of weight gain and associated symptoms are most closely related to a diagnosis of obesity. In addition, her laboratory findings are consistent with common obesity complications, including prediabetes and dyslipidemia, and her blood pressure is borderline high.

Obesity is a chronic, multifactorial disease with a complex pathogenesis comprising of genetic, biological, psychosocial, socioeconomic, and environmental factors. It is a heterogeneous disease characterized by a dysfunction of the normal pathways and mechanisms that are involved in body fat regulation (often referred to as weight regulation), which may lead to variable presentation and complications. According to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the highest age-adjusted prevalence of obesity is seen in non-Hispanic Black adults (49.9%), followed by Hispanic adults (45.6%), non-Hispanic White adults (41.4%), and non-Hispanic Asian adults (16.1%).

Epidemiologic studies have defined obesity as a BMI > 30, which is then subclassified into class 1 (BMI of 30-34.9), class 2 (BMI of 35-39.9), or class 3 (BMI ≥ 40) obesity. Though BMI is widely used to evaluate and classify obesity, it mainly represents general adiposity and can be confounded by excessive muscle mass or frailty. Guidelines from the American Diabetes Association state that in addition to weight and BMI, clinicians should consider weight distribution (including predisposition for central/visceral adipose deposition) and weight gain pattern and trajectory because these can help guide risk stratification and treatment options.

Increasingly, evidence supports visceral adiposity, or abdominal obesity, as a marker of cardiovascular risk. Abdominal obesity has been shown to be a strong independent predictor of mortality. On its own, BMI is an insufficient biomarker of abdominal obesity. Not all individuals with obesity have a central distribution of their weight; some individuals may have central obesity without meeting the criteria for the BMI definition of obesity. This can lead to misclassification and underdiagnosis of health risks in clinical practice. Consequently, numerous organizations and expert panels have recommended that waist circumference be measured along with BMI, specifically when the BMI < 35. Measurement of both BMI and waist circumference provides valuable opportunities to counsel patients regarding their risk for cardiovascular disease and other complications of obesity. Waist-to-hip ratio has also been shown to be a stronger predictor for mortality compared with BMI; however, it is rarely measured in clinical practice.

Although rarely performed outside of research settings, measurement of epicardial and pericardial fat via CT is also emerging as a potentially useful approach for informing predictive and precision medicine strategies. Recently, the Jackson Heart Study showed pericardial and visceral fat volumes were associated with incident heart failure, particularly heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, and all-cause mortality among Black participants even after adjusting for age, sex, education, and smoking status. Another recent study showed an increased risk of heart failure, particularly heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, among men and women with high pericardial fat volume. The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis showed that pericardial fat was associated with a higher risk of all-cause cardiovascular disease, hard atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, and heart failure. Epicardial fat is directly correlated with BMI, visceral adiposity, and waist circumference.

Best practices for the management of obesity begin with recognizing and treating it as a complex chronic disease rather than the result of an individual's lifestyle choices. According to a 2020 joint international consensus statement for ending the stigma of obesity, the assumption that choosing to eat less and/or exercise more can entirely prevent or reverse obesity is contradicted by a definitive body of biological and clinical evidence that shows obesity results primarily from a complex combination of genetic, epigenetic, and environmental factors. When diagnosing patients with obesity, it may be helpful for clinicians to acknowledge that the term obesity is often perceived as an undesirable term because it has been associated with stigma but that it is in fact a clinical diagnosis, not a judgement. Many patients prefer the neutral term unhealthy weight over obesity.

As with other chronic diseases, individualized treatment and long-term support along with shared decision-making are essential for optimizing outcomes. Key components of obesity management include diet, exercise, and behavioral modification. In addition, an increasing array of pharmacologic therapies are also showing unprecedented efficacy for weight management, including several drugs that are also approved for the management of type 2 diabetes. In particular, the glucagonlike peptide 1 (GLP-1) agonists, semaglutide and liraglutide, and the novel glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP)–GLP-1 receptor agonist, tirzepatide have been associated with significant weight loss. Semaglutide and liraglutide have been US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved for chronic weight management and tirzepatide was granted fast track designation for the treatment of obesity by the FDA in October 2022. These drugs may also help to prevent the progression of prediabetes to diabetes. For individuals with severe obesity, metabolic and bariatric surgery is an effective treatment option that is associated with clinically significant and relatively sustained weight reduction in addition to significant amelioration of related complications.

W. Scott Butsch, MD, MSc, Director of Obesity Medicine, Bariatric and Metabolic Institute, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, Ohio.

Dr. Butsch has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a director, officer, partner, employee, advisor, consultant, or trustee for: Novo Nordisk, Inc.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

This patient's clinical presentation of weight gain and associated symptoms are most closely related to a diagnosis of obesity. In addition, her laboratory findings are consistent with common obesity complications, including prediabetes and dyslipidemia, and her blood pressure is borderline high.

Obesity is a chronic, multifactorial disease with a complex pathogenesis comprising of genetic, biological, psychosocial, socioeconomic, and environmental factors. It is a heterogeneous disease characterized by a dysfunction of the normal pathways and mechanisms that are involved in body fat regulation (often referred to as weight regulation), which may lead to variable presentation and complications. According to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the highest age-adjusted prevalence of obesity is seen in non-Hispanic Black adults (49.9%), followed by Hispanic adults (45.6%), non-Hispanic White adults (41.4%), and non-Hispanic Asian adults (16.1%).

Epidemiologic studies have defined obesity as a BMI > 30, which is then subclassified into class 1 (BMI of 30-34.9), class 2 (BMI of 35-39.9), or class 3 (BMI ≥ 40) obesity. Though BMI is widely used to evaluate and classify obesity, it mainly represents general adiposity and can be confounded by excessive muscle mass or frailty. Guidelines from the American Diabetes Association state that in addition to weight and BMI, clinicians should consider weight distribution (including predisposition for central/visceral adipose deposition) and weight gain pattern and trajectory because these can help guide risk stratification and treatment options.

Increasingly, evidence supports visceral adiposity, or abdominal obesity, as a marker of cardiovascular risk. Abdominal obesity has been shown to be a strong independent predictor of mortality. On its own, BMI is an insufficient biomarker of abdominal obesity. Not all individuals with obesity have a central distribution of their weight; some individuals may have central obesity without meeting the criteria for the BMI definition of obesity. This can lead to misclassification and underdiagnosis of health risks in clinical practice. Consequently, numerous organizations and expert panels have recommended that waist circumference be measured along with BMI, specifically when the BMI < 35. Measurement of both BMI and waist circumference provides valuable opportunities to counsel patients regarding their risk for cardiovascular disease and other complications of obesity. Waist-to-hip ratio has also been shown to be a stronger predictor for mortality compared with BMI; however, it is rarely measured in clinical practice.

Although rarely performed outside of research settings, measurement of epicardial and pericardial fat via CT is also emerging as a potentially useful approach for informing predictive and precision medicine strategies. Recently, the Jackson Heart Study showed pericardial and visceral fat volumes were associated with incident heart failure, particularly heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, and all-cause mortality among Black participants even after adjusting for age, sex, education, and smoking status. Another recent study showed an increased risk of heart failure, particularly heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, among men and women with high pericardial fat volume. The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis showed that pericardial fat was associated with a higher risk of all-cause cardiovascular disease, hard atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, and heart failure. Epicardial fat is directly correlated with BMI, visceral adiposity, and waist circumference.

Best practices for the management of obesity begin with recognizing and treating it as a complex chronic disease rather than the result of an individual's lifestyle choices. According to a 2020 joint international consensus statement for ending the stigma of obesity, the assumption that choosing to eat less and/or exercise more can entirely prevent or reverse obesity is contradicted by a definitive body of biological and clinical evidence that shows obesity results primarily from a complex combination of genetic, epigenetic, and environmental factors. When diagnosing patients with obesity, it may be helpful for clinicians to acknowledge that the term obesity is often perceived as an undesirable term because it has been associated with stigma but that it is in fact a clinical diagnosis, not a judgement. Many patients prefer the neutral term unhealthy weight over obesity.

As with other chronic diseases, individualized treatment and long-term support along with shared decision-making are essential for optimizing outcomes. Key components of obesity management include diet, exercise, and behavioral modification. In addition, an increasing array of pharmacologic therapies are also showing unprecedented efficacy for weight management, including several drugs that are also approved for the management of type 2 diabetes. In particular, the glucagonlike peptide 1 (GLP-1) agonists, semaglutide and liraglutide, and the novel glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP)–GLP-1 receptor agonist, tirzepatide have been associated with significant weight loss. Semaglutide and liraglutide have been US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved for chronic weight management and tirzepatide was granted fast track designation for the treatment of obesity by the FDA in October 2022. These drugs may also help to prevent the progression of prediabetes to diabetes. For individuals with severe obesity, metabolic and bariatric surgery is an effective treatment option that is associated with clinically significant and relatively sustained weight reduction in addition to significant amelioration of related complications.

W. Scott Butsch, MD, MSc, Director of Obesity Medicine, Bariatric and Metabolic Institute, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, Ohio.

Dr. Butsch has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a director, officer, partner, employee, advisor, consultant, or trustee for: Novo Nordisk, Inc.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

This patient's clinical presentation of weight gain and associated symptoms are most closely related to a diagnosis of obesity. In addition, her laboratory findings are consistent with common obesity complications, including prediabetes and dyslipidemia, and her blood pressure is borderline high.

Obesity is a chronic, multifactorial disease with a complex pathogenesis comprising of genetic, biological, psychosocial, socioeconomic, and environmental factors. It is a heterogeneous disease characterized by a dysfunction of the normal pathways and mechanisms that are involved in body fat regulation (often referred to as weight regulation), which may lead to variable presentation and complications. According to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the highest age-adjusted prevalence of obesity is seen in non-Hispanic Black adults (49.9%), followed by Hispanic adults (45.6%), non-Hispanic White adults (41.4%), and non-Hispanic Asian adults (16.1%).

Epidemiologic studies have defined obesity as a BMI > 30, which is then subclassified into class 1 (BMI of 30-34.9), class 2 (BMI of 35-39.9), or class 3 (BMI ≥ 40) obesity. Though BMI is widely used to evaluate and classify obesity, it mainly represents general adiposity and can be confounded by excessive muscle mass or frailty. Guidelines from the American Diabetes Association state that in addition to weight and BMI, clinicians should consider weight distribution (including predisposition for central/visceral adipose deposition) and weight gain pattern and trajectory because these can help guide risk stratification and treatment options.

Increasingly, evidence supports visceral adiposity, or abdominal obesity, as a marker of cardiovascular risk. Abdominal obesity has been shown to be a strong independent predictor of mortality. On its own, BMI is an insufficient biomarker of abdominal obesity. Not all individuals with obesity have a central distribution of their weight; some individuals may have central obesity without meeting the criteria for the BMI definition of obesity. This can lead to misclassification and underdiagnosis of health risks in clinical practice. Consequently, numerous organizations and expert panels have recommended that waist circumference be measured along with BMI, specifically when the BMI < 35. Measurement of both BMI and waist circumference provides valuable opportunities to counsel patients regarding their risk for cardiovascular disease and other complications of obesity. Waist-to-hip ratio has also been shown to be a stronger predictor for mortality compared with BMI; however, it is rarely measured in clinical practice.

Although rarely performed outside of research settings, measurement of epicardial and pericardial fat via CT is also emerging as a potentially useful approach for informing predictive and precision medicine strategies. Recently, the Jackson Heart Study showed pericardial and visceral fat volumes were associated with incident heart failure, particularly heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, and all-cause mortality among Black participants even after adjusting for age, sex, education, and smoking status. Another recent study showed an increased risk of heart failure, particularly heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, among men and women with high pericardial fat volume. The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis showed that pericardial fat was associated with a higher risk of all-cause cardiovascular disease, hard atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, and heart failure. Epicardial fat is directly correlated with BMI, visceral adiposity, and waist circumference.

Best practices for the management of obesity begin with recognizing and treating it as a complex chronic disease rather than the result of an individual's lifestyle choices. According to a 2020 joint international consensus statement for ending the stigma of obesity, the assumption that choosing to eat less and/or exercise more can entirely prevent or reverse obesity is contradicted by a definitive body of biological and clinical evidence that shows obesity results primarily from a complex combination of genetic, epigenetic, and environmental factors. When diagnosing patients with obesity, it may be helpful for clinicians to acknowledge that the term obesity is often perceived as an undesirable term because it has been associated with stigma but that it is in fact a clinical diagnosis, not a judgement. Many patients prefer the neutral term unhealthy weight over obesity.

As with other chronic diseases, individualized treatment and long-term support along with shared decision-making are essential for optimizing outcomes. Key components of obesity management include diet, exercise, and behavioral modification. In addition, an increasing array of pharmacologic therapies are also showing unprecedented efficacy for weight management, including several drugs that are also approved for the management of type 2 diabetes. In particular, the glucagonlike peptide 1 (GLP-1) agonists, semaglutide and liraglutide, and the novel glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP)–GLP-1 receptor agonist, tirzepatide have been associated with significant weight loss. Semaglutide and liraglutide have been US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved for chronic weight management and tirzepatide was granted fast track designation for the treatment of obesity by the FDA in October 2022. These drugs may also help to prevent the progression of prediabetes to diabetes. For individuals with severe obesity, metabolic and bariatric surgery is an effective treatment option that is associated with clinically significant and relatively sustained weight reduction in addition to significant amelioration of related complications.

W. Scott Butsch, MD, MSc, Director of Obesity Medicine, Bariatric and Metabolic Institute, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, Ohio.

Dr. Butsch has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a director, officer, partner, employee, advisor, consultant, or trustee for: Novo Nordisk, Inc.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

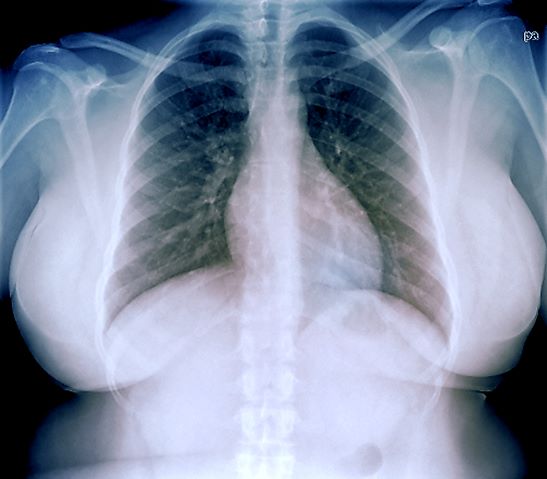

A 33-year-old African American woman presents for an initial consultation. The patient states that it has been several years since she received regular medical care because she did not have health insurance. She recently started a new job as an IT professional that has healthcare benefits. She does not currently take any medications. She reports mild shortness of breath upon exertion, which has worsened in the last year. She denies dizziness, chest pain, wheezing, cough, fever, or other associated symptoms. There is no history of any cardiac or pulmonary diseases as a child. The patient does not smoke or engage in recreational drug use. She is conscious of her diet and avoids red meat as well as sugary and processed foods. Although she was active in the past, she notes that she has been less intentional with her physical activity and has been living a more sedentary lifestyle recently. She has gained more than 40 lb over the past 3 years.

The patient is 5 ft 8 in, her weight is 266 lb (BMI 40.4), and her blood pressure is 140/90 mm Hg. Her pulse oximeter is 97%; however, this result should be interpreted with caution and in consideration of the patient's other signs and symptoms because numerous studies have shown inaccuracies in pulse oximeter readings among people with darker skin. Her physical exam is unremarkable except for a waist circumference of 49 in; breathing sounds are normal and no dermatologic abnormalities are noted.

An ECG is performed and is normal. A chest radiograph shows normal heart and blood vessel structures and airways of the lungs. Pertinent laboratory findings include A1c of 6.4%, HDL cholesterol of 37 mg/dL, LDL cholesterol of 185 mg/dL, serum creatinine of 1.1 mg/dL; AST of 27 U/L; ALT of 35 IU/L; and TSH of 4.2 mIU/L.

New treatments aim to tame vitiligo

LAS VEGAS – in a presentation at MedscapeLive’s annual Las Vegas Dermatology Seminar.

Vitiligo, an autoimmune condition that results in patches of skin depigmentation, occurs in 0.5% to 2% of the population. The average age of onset is 20 years, with 25% of cases occurring before age 10, and 70%-80% of cases by age 30 years, which means a long-term effect on quality of life, especially for younger patients, said Dr. Rosmarin, vice chair of education and research and director of the clinical trials unit at Tufts University, Boston.

Studies have shown that 95% of 15- to 17-year-olds with vitiligo are bothered by it, as are approximately 50% of children aged 6-14 years, he said. Although patients with more extensive lesions on the face, arms, legs, and hands report worse quality of life, they report that uncontrolled progression of vitiligo is more concerning than the presence of lesions in exposed areas, he noted.

The current strategy for getting vitiligo under control is a two-step process, said Dr. Rosmarin. First, improve the skin environment by suppressing the overactive immune system, then encourage repigmentation and “nudge the melanocytes to return,” he said.

Topical ruxolitinib, a Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor, is the latest tool for dermatologists to help give the melanocytes that nudge. In July 2022, the Food and Drug Administration approved ruxolitinib cream for treating nonsegmental vitiligo in patients 12 years of age and older – the first treatment approved to repigment patients with vitiligo.

Vitiligo is driven in part by interferon (IFN)-gamma signaling through JAK 1 and 2, and ruxolitinib acts as an inhibitor, Dr. Rosmarin said.

In the TRuE-V1 and TRuE-V2 studies presented at the 2022 European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology meeting in Milan, adolescents and adults with vitiligo who were randomized to 1.5% ruxolitinib cream twice daily showed significant improvement over those randomized to the vehicle by 24 weeks, at which time all patients could continue with ruxolitinib through 52 weeks, he said.

Dr. Rosmarin presented 52-week data from the TRuE-V1 and TRuE-V2 studies at the 2022 American Academy of Dermatology meeting in Boston. He was the lead author of the studies that were subsequently published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

In the two studies, 52.6% and 48% of the patients in the ruxolitinib groups achieved the primary outcome of at least 75% improvement on the Facial Vitiligo Area Scoring Index (F-VASI75) by 52 weeks, compared with 26.8% and 29.6% of patients on the vehicle, respectively.

In addition, at 52 weeks, 53.2% and 49.2% of patients treated with ruxolitinib in the two studies achieved 50% improvement on the Total Vitiligo Area Scoring Index (T-VASI50), a clinician assessment of affected body surface area and level of depigmentation, compared with 31.7% and 22.2% of those on vehicle, respectively.

Patient satisfaction was high with ruxolitinib, Dr. Rosmarin said. In the TRuE-V1 and TRuE-V2 studies, 39.9% and 32.8% of patients, respectively, achieved a successful treatment response based on the patient-reported Vitiligo Noticeability Scale (VNS) by week 52, versus 19.5% and 13.6% of those on vehicle.

Ruxolitinib cream was well tolerated, with “no clinically significant application site reactions or serious treatment-related adverse events,” he noted. The most common treatment-related adverse events across the TRuE-V1 and TRuE-V2 studies were acne at the application site (affecting about 6% of patients) and pruritus at the application site about (affecting 5%), said Dr. Rosmarin.

JAK inhibitors, including ruxolitinib, baricitinib, and tofacitinib, have shown effectiveness for vitiligo, which supports the potential role of the IFN-gamma-chemokine signaling axis in the pathogenesis of the disease, said Dr. Rosmarin. However, more studies are required to determine the ideal dosage of JAK inhibitors for the treatment of vitiligo, and to identify other inflammatory pathways that may be implicated in the pathogenesis of this condition.

Ruxolitinib’s success has been consistent across subgroups of age, gender, race, geographic region, and Fitzpatrick skin phototype. Notably, ruxolitinib was effective among the adolescent population, with approximately 60% achieving T-VASI50 and success based on VNS in TRuE-V1 and TRuE-V2.

An oral version of ruxolitinib is in clinical trials, which “makes a lot of sense,” Dr. Rosmarin said. “Patients don’t always have localized disease,” and such patients may benefit from an oral therapy. Topicals may have the advantage in terms of safety, but questions of maintenance remain, he said. Oral treatments may be useful for patients with large body surface areas affected, and those with unstable or progressive disease, he added.

Areas for additional research include combination therapy with ruxolitinib and phototherapy, and an anti-IL 15 therapy in the pipeline has the potential to drive vitiligo into remission, Dr. Rosmarin said. In a study known as REVEAL that is still recruiting patients, researchers will test the efficacy of an IL-15 inhibitor known as AMG 714 to induce facial repigmentation in adults with vitiligo.

Dr. Rosmarin disclosed ties with AbbVie, Abcuro, AltruBio, Amgen, Arena Pharmaceuticals, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb Company, Celgene, Concert Pharmaceuticals, CSL Behring, Dermavant, Dermira, Eli Lilly, Galderma, Incyte, Janssen, Kyowa Kirin, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron, Revolo, Sanofi, Sun, UCB, and Viela Bio.

MedscapeLive and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

LAS VEGAS – in a presentation at MedscapeLive’s annual Las Vegas Dermatology Seminar.

Vitiligo, an autoimmune condition that results in patches of skin depigmentation, occurs in 0.5% to 2% of the population. The average age of onset is 20 years, with 25% of cases occurring before age 10, and 70%-80% of cases by age 30 years, which means a long-term effect on quality of life, especially for younger patients, said Dr. Rosmarin, vice chair of education and research and director of the clinical trials unit at Tufts University, Boston.

Studies have shown that 95% of 15- to 17-year-olds with vitiligo are bothered by it, as are approximately 50% of children aged 6-14 years, he said. Although patients with more extensive lesions on the face, arms, legs, and hands report worse quality of life, they report that uncontrolled progression of vitiligo is more concerning than the presence of lesions in exposed areas, he noted.

The current strategy for getting vitiligo under control is a two-step process, said Dr. Rosmarin. First, improve the skin environment by suppressing the overactive immune system, then encourage repigmentation and “nudge the melanocytes to return,” he said.

Topical ruxolitinib, a Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor, is the latest tool for dermatologists to help give the melanocytes that nudge. In July 2022, the Food and Drug Administration approved ruxolitinib cream for treating nonsegmental vitiligo in patients 12 years of age and older – the first treatment approved to repigment patients with vitiligo.

Vitiligo is driven in part by interferon (IFN)-gamma signaling through JAK 1 and 2, and ruxolitinib acts as an inhibitor, Dr. Rosmarin said.

In the TRuE-V1 and TRuE-V2 studies presented at the 2022 European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology meeting in Milan, adolescents and adults with vitiligo who were randomized to 1.5% ruxolitinib cream twice daily showed significant improvement over those randomized to the vehicle by 24 weeks, at which time all patients could continue with ruxolitinib through 52 weeks, he said.

Dr. Rosmarin presented 52-week data from the TRuE-V1 and TRuE-V2 studies at the 2022 American Academy of Dermatology meeting in Boston. He was the lead author of the studies that were subsequently published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

In the two studies, 52.6% and 48% of the patients in the ruxolitinib groups achieved the primary outcome of at least 75% improvement on the Facial Vitiligo Area Scoring Index (F-VASI75) by 52 weeks, compared with 26.8% and 29.6% of patients on the vehicle, respectively.

In addition, at 52 weeks, 53.2% and 49.2% of patients treated with ruxolitinib in the two studies achieved 50% improvement on the Total Vitiligo Area Scoring Index (T-VASI50), a clinician assessment of affected body surface area and level of depigmentation, compared with 31.7% and 22.2% of those on vehicle, respectively.

Patient satisfaction was high with ruxolitinib, Dr. Rosmarin said. In the TRuE-V1 and TRuE-V2 studies, 39.9% and 32.8% of patients, respectively, achieved a successful treatment response based on the patient-reported Vitiligo Noticeability Scale (VNS) by week 52, versus 19.5% and 13.6% of those on vehicle.

Ruxolitinib cream was well tolerated, with “no clinically significant application site reactions or serious treatment-related adverse events,” he noted. The most common treatment-related adverse events across the TRuE-V1 and TRuE-V2 studies were acne at the application site (affecting about 6% of patients) and pruritus at the application site about (affecting 5%), said Dr. Rosmarin.

JAK inhibitors, including ruxolitinib, baricitinib, and tofacitinib, have shown effectiveness for vitiligo, which supports the potential role of the IFN-gamma-chemokine signaling axis in the pathogenesis of the disease, said Dr. Rosmarin. However, more studies are required to determine the ideal dosage of JAK inhibitors for the treatment of vitiligo, and to identify other inflammatory pathways that may be implicated in the pathogenesis of this condition.

Ruxolitinib’s success has been consistent across subgroups of age, gender, race, geographic region, and Fitzpatrick skin phototype. Notably, ruxolitinib was effective among the adolescent population, with approximately 60% achieving T-VASI50 and success based on VNS in TRuE-V1 and TRuE-V2.

An oral version of ruxolitinib is in clinical trials, which “makes a lot of sense,” Dr. Rosmarin said. “Patients don’t always have localized disease,” and such patients may benefit from an oral therapy. Topicals may have the advantage in terms of safety, but questions of maintenance remain, he said. Oral treatments may be useful for patients with large body surface areas affected, and those with unstable or progressive disease, he added.

Areas for additional research include combination therapy with ruxolitinib and phototherapy, and an anti-IL 15 therapy in the pipeline has the potential to drive vitiligo into remission, Dr. Rosmarin said. In a study known as REVEAL that is still recruiting patients, researchers will test the efficacy of an IL-15 inhibitor known as AMG 714 to induce facial repigmentation in adults with vitiligo.

Dr. Rosmarin disclosed ties with AbbVie, Abcuro, AltruBio, Amgen, Arena Pharmaceuticals, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb Company, Celgene, Concert Pharmaceuticals, CSL Behring, Dermavant, Dermira, Eli Lilly, Galderma, Incyte, Janssen, Kyowa Kirin, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron, Revolo, Sanofi, Sun, UCB, and Viela Bio.

MedscapeLive and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

LAS VEGAS – in a presentation at MedscapeLive’s annual Las Vegas Dermatology Seminar.

Vitiligo, an autoimmune condition that results in patches of skin depigmentation, occurs in 0.5% to 2% of the population. The average age of onset is 20 years, with 25% of cases occurring before age 10, and 70%-80% of cases by age 30 years, which means a long-term effect on quality of life, especially for younger patients, said Dr. Rosmarin, vice chair of education and research and director of the clinical trials unit at Tufts University, Boston.

Studies have shown that 95% of 15- to 17-year-olds with vitiligo are bothered by it, as are approximately 50% of children aged 6-14 years, he said. Although patients with more extensive lesions on the face, arms, legs, and hands report worse quality of life, they report that uncontrolled progression of vitiligo is more concerning than the presence of lesions in exposed areas, he noted.

The current strategy for getting vitiligo under control is a two-step process, said Dr. Rosmarin. First, improve the skin environment by suppressing the overactive immune system, then encourage repigmentation and “nudge the melanocytes to return,” he said.

Topical ruxolitinib, a Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor, is the latest tool for dermatologists to help give the melanocytes that nudge. In July 2022, the Food and Drug Administration approved ruxolitinib cream for treating nonsegmental vitiligo in patients 12 years of age and older – the first treatment approved to repigment patients with vitiligo.

Vitiligo is driven in part by interferon (IFN)-gamma signaling through JAK 1 and 2, and ruxolitinib acts as an inhibitor, Dr. Rosmarin said.

In the TRuE-V1 and TRuE-V2 studies presented at the 2022 European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology meeting in Milan, adolescents and adults with vitiligo who were randomized to 1.5% ruxolitinib cream twice daily showed significant improvement over those randomized to the vehicle by 24 weeks, at which time all patients could continue with ruxolitinib through 52 weeks, he said.

Dr. Rosmarin presented 52-week data from the TRuE-V1 and TRuE-V2 studies at the 2022 American Academy of Dermatology meeting in Boston. He was the lead author of the studies that were subsequently published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

In the two studies, 52.6% and 48% of the patients in the ruxolitinib groups achieved the primary outcome of at least 75% improvement on the Facial Vitiligo Area Scoring Index (F-VASI75) by 52 weeks, compared with 26.8% and 29.6% of patients on the vehicle, respectively.

In addition, at 52 weeks, 53.2% and 49.2% of patients treated with ruxolitinib in the two studies achieved 50% improvement on the Total Vitiligo Area Scoring Index (T-VASI50), a clinician assessment of affected body surface area and level of depigmentation, compared with 31.7% and 22.2% of those on vehicle, respectively.

Patient satisfaction was high with ruxolitinib, Dr. Rosmarin said. In the TRuE-V1 and TRuE-V2 studies, 39.9% and 32.8% of patients, respectively, achieved a successful treatment response based on the patient-reported Vitiligo Noticeability Scale (VNS) by week 52, versus 19.5% and 13.6% of those on vehicle.

Ruxolitinib cream was well tolerated, with “no clinically significant application site reactions or serious treatment-related adverse events,” he noted. The most common treatment-related adverse events across the TRuE-V1 and TRuE-V2 studies were acne at the application site (affecting about 6% of patients) and pruritus at the application site about (affecting 5%), said Dr. Rosmarin.

JAK inhibitors, including ruxolitinib, baricitinib, and tofacitinib, have shown effectiveness for vitiligo, which supports the potential role of the IFN-gamma-chemokine signaling axis in the pathogenesis of the disease, said Dr. Rosmarin. However, more studies are required to determine the ideal dosage of JAK inhibitors for the treatment of vitiligo, and to identify other inflammatory pathways that may be implicated in the pathogenesis of this condition.

Ruxolitinib’s success has been consistent across subgroups of age, gender, race, geographic region, and Fitzpatrick skin phototype. Notably, ruxolitinib was effective among the adolescent population, with approximately 60% achieving T-VASI50 and success based on VNS in TRuE-V1 and TRuE-V2.

An oral version of ruxolitinib is in clinical trials, which “makes a lot of sense,” Dr. Rosmarin said. “Patients don’t always have localized disease,” and such patients may benefit from an oral therapy. Topicals may have the advantage in terms of safety, but questions of maintenance remain, he said. Oral treatments may be useful for patients with large body surface areas affected, and those with unstable or progressive disease, he added.

Areas for additional research include combination therapy with ruxolitinib and phototherapy, and an anti-IL 15 therapy in the pipeline has the potential to drive vitiligo into remission, Dr. Rosmarin said. In a study known as REVEAL that is still recruiting patients, researchers will test the efficacy of an IL-15 inhibitor known as AMG 714 to induce facial repigmentation in adults with vitiligo.

Dr. Rosmarin disclosed ties with AbbVie, Abcuro, AltruBio, Amgen, Arena Pharmaceuticals, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb Company, Celgene, Concert Pharmaceuticals, CSL Behring, Dermavant, Dermira, Eli Lilly, Galderma, Incyte, Janssen, Kyowa Kirin, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron, Revolo, Sanofi, Sun, UCB, and Viela Bio.

MedscapeLive and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

AT INNOVATIONS IN DERMATOLOGY

Oral minoxidil improves anticancer treatment–induced alopecia in women with breast cancer

Topical minoxidil is widely used to treat hair loss, but new findings suggest that

In a retrospective cohort study of women with breast cancer and anticancer therapy–induced alopecia, researchers found that combining low-dose oral minoxidil (LDOM) and topical minoxidil achieved better results than topical minoxidil alone and that the treatment was well tolerated. A total of 5 of the 37 patients (13.5%) in the combination therapy group achieved a complete response, defined as an improvement of alopecia severity from grade 2 to grade 1, compared with none of the 19 patients in the topical therapy–only group.

In contrast, none of the patients in the combination group experienced worsening of alopecia, compared with two (10.5%) in the topical monotherapy group.

The study was published online in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. Topical minoxidil is approved by the Food and Drug Administration to treat androgenetic alopecia. Oral minoxidil is not approved for treating hair loss but has been receiving increased attention as an adjunctive therapy for hair loss, particularly for women. Oral minoxidil is approved for treating hypertension but at much higher doses.

An increasing number of studies have been conducted on the use of oral minoxidil for the treatment of female pattern hair loss, dating back to a pilot study in 2017, with promising results. The findings suggest that LDOM might be more effective than topical therapy, well tolerated, and more convenient for individuals to take.

Hypothesis generating

In a comment, Kai Johnson, MD, a medical oncologist who specializes in treating patients with breast cancer at the Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center – Arthur G. James Cancer Hospital and Richard J. Solove Research Institute, Columbus, noted that the study, like most small-scale retrospective studies, is hypothesis generating. However, “I’d be hesitant to broadly recommend this practice of dual therapy – oral and topical minoxidil together – until we see a placebo-controlled prospective study performed demonstrating clinically meaningful benefits for patients.”

Another factor is the study endpoints. “While there was a statistically significant benefit documented with dual therapy in this study, it’s important to have study endpoints that are more patient oriented,” Dr. Johnson said. The most important endpoint for patients would be improvements “in the actual alopecia grade, which did occur in 5 of the 37 of dual-therapy patients, versus 0 topical minoxidil patients.”

George Cotsarelis, MD, chair of the department of dermatology and professor of dermatology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, also weighed in. He questioned whether adding the topical therapy to oral minoxidil actually improved the results. “What was missing was a study arm that used the oral alone,” he said in an interview. “So we don’t know how effective the oral therapy would be by itself and if combining it with the topical is really adding anything.”

Oral minoxidil as a treatment for hair loss is gaining traction, and it’s clear that it is effective. However, the risk of side effects is higher, he said. “The risk isn’t that high with the low dose, but it can grow hair on places other than the scalp, and that can be disconcerting.” In this study, two women who took the oral drug reported edema, and one reported headache and dizziness. Hypertrichosis was reported by five patients who received the combination.

Study details

In the study, Jeewoo Kang, MD, and colleagues from the Seoul National University evaluated the efficacy of LDOM in 100 patients with breast cancer who had been diagnosed with persistent chemotherapy-induced alopecia (pCIA) and endocrine therapy–induced alopecia (EIA) at a dermatology clinic.

They conducted an analysis of medical records, standardized clinical photographs, and trichoscopic images to evaluate the alopecia pattern, severity, treatment response, and posttreatment changes in vertex hair density and thickness.

Compared with those with EIA alone, patients with pCIA were significantly more likely to have diffuse alopecia (P < .001), and they were more likely to have more severe alopecia, although this difference was not significant (P = .058). Outcomes were evaluated for 56 patients who were treated with minoxidil (19 with topical minoxidil alone and 37 with both LDOM and topical minoxidil) and for whom clinical and trichoscopic photos were available at baseline and at the last follow-up (all patients were scheduled for follow-up at 3-month intervals).

The results showed that those treated with 1.25-5.0 mg/d of oral minoxidil and 5% topical minoxidil solution once a day had better responses (P = .002) and a higher percentage increase in hair density from baseline (P = .003), compared with those who received topical minoxidil monotherapy.

However, changes in hair thickness after treatment were not significantly different between the two groups (P = .540).

In addition to the five (13.5%) cases of hypertrichosis, two cases of edema (5.4%), and one case of headache/dizziness (2.7%) among those who received the combination, there was also one report of palpitations (2.7%). Palpitations were reported in one patient (5%) who received topical monotherapy, the only adverse event reported in this group.

Dr. Johnson noted that, at his institution, a dermatologist is conducting a clinical trial with oncology patients post chemotherapy and endocrine therapy. “She is looking at a similar question, although she is comparing oral minoxidil to topical minoxidil directly rather than in combination.” There is also an active clinical trial at Northwestern University, Chicago, of LDOM alone for patients with chemotherapy-induced alopecia.

“So there is a lot of momentum surrounding this concept, and I feel we will continue to see it come up as a possible treatment option, but more data are needed at this time before it can become standard of care,” Dr. Johnson added.

No funding for the study was reported. The authors disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Topical minoxidil is widely used to treat hair loss, but new findings suggest that

In a retrospective cohort study of women with breast cancer and anticancer therapy–induced alopecia, researchers found that combining low-dose oral minoxidil (LDOM) and topical minoxidil achieved better results than topical minoxidil alone and that the treatment was well tolerated. A total of 5 of the 37 patients (13.5%) in the combination therapy group achieved a complete response, defined as an improvement of alopecia severity from grade 2 to grade 1, compared with none of the 19 patients in the topical therapy–only group.

In contrast, none of the patients in the combination group experienced worsening of alopecia, compared with two (10.5%) in the topical monotherapy group.

The study was published online in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. Topical minoxidil is approved by the Food and Drug Administration to treat androgenetic alopecia. Oral minoxidil is not approved for treating hair loss but has been receiving increased attention as an adjunctive therapy for hair loss, particularly for women. Oral minoxidil is approved for treating hypertension but at much higher doses.

An increasing number of studies have been conducted on the use of oral minoxidil for the treatment of female pattern hair loss, dating back to a pilot study in 2017, with promising results. The findings suggest that LDOM might be more effective than topical therapy, well tolerated, and more convenient for individuals to take.

Hypothesis generating

In a comment, Kai Johnson, MD, a medical oncologist who specializes in treating patients with breast cancer at the Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center – Arthur G. James Cancer Hospital and Richard J. Solove Research Institute, Columbus, noted that the study, like most small-scale retrospective studies, is hypothesis generating. However, “I’d be hesitant to broadly recommend this practice of dual therapy – oral and topical minoxidil together – until we see a placebo-controlled prospective study performed demonstrating clinically meaningful benefits for patients.”

Another factor is the study endpoints. “While there was a statistically significant benefit documented with dual therapy in this study, it’s important to have study endpoints that are more patient oriented,” Dr. Johnson said. The most important endpoint for patients would be improvements “in the actual alopecia grade, which did occur in 5 of the 37 of dual-therapy patients, versus 0 topical minoxidil patients.”

George Cotsarelis, MD, chair of the department of dermatology and professor of dermatology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, also weighed in. He questioned whether adding the topical therapy to oral minoxidil actually improved the results. “What was missing was a study arm that used the oral alone,” he said in an interview. “So we don’t know how effective the oral therapy would be by itself and if combining it with the topical is really adding anything.”

Oral minoxidil as a treatment for hair loss is gaining traction, and it’s clear that it is effective. However, the risk of side effects is higher, he said. “The risk isn’t that high with the low dose, but it can grow hair on places other than the scalp, and that can be disconcerting.” In this study, two women who took the oral drug reported edema, and one reported headache and dizziness. Hypertrichosis was reported by five patients who received the combination.

Study details

In the study, Jeewoo Kang, MD, and colleagues from the Seoul National University evaluated the efficacy of LDOM in 100 patients with breast cancer who had been diagnosed with persistent chemotherapy-induced alopecia (pCIA) and endocrine therapy–induced alopecia (EIA) at a dermatology clinic.

They conducted an analysis of medical records, standardized clinical photographs, and trichoscopic images to evaluate the alopecia pattern, severity, treatment response, and posttreatment changes in vertex hair density and thickness.

Compared with those with EIA alone, patients with pCIA were significantly more likely to have diffuse alopecia (P < .001), and they were more likely to have more severe alopecia, although this difference was not significant (P = .058). Outcomes were evaluated for 56 patients who were treated with minoxidil (19 with topical minoxidil alone and 37 with both LDOM and topical minoxidil) and for whom clinical and trichoscopic photos were available at baseline and at the last follow-up (all patients were scheduled for follow-up at 3-month intervals).

The results showed that those treated with 1.25-5.0 mg/d of oral minoxidil and 5% topical minoxidil solution once a day had better responses (P = .002) and a higher percentage increase in hair density from baseline (P = .003), compared with those who received topical minoxidil monotherapy.

However, changes in hair thickness after treatment were not significantly different between the two groups (P = .540).

In addition to the five (13.5%) cases of hypertrichosis, two cases of edema (5.4%), and one case of headache/dizziness (2.7%) among those who received the combination, there was also one report of palpitations (2.7%). Palpitations were reported in one patient (5%) who received topical monotherapy, the only adverse event reported in this group.

Dr. Johnson noted that, at his institution, a dermatologist is conducting a clinical trial with oncology patients post chemotherapy and endocrine therapy. “She is looking at a similar question, although she is comparing oral minoxidil to topical minoxidil directly rather than in combination.” There is also an active clinical trial at Northwestern University, Chicago, of LDOM alone for patients with chemotherapy-induced alopecia.

“So there is a lot of momentum surrounding this concept, and I feel we will continue to see it come up as a possible treatment option, but more data are needed at this time before it can become standard of care,” Dr. Johnson added.

No funding for the study was reported. The authors disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Topical minoxidil is widely used to treat hair loss, but new findings suggest that

In a retrospective cohort study of women with breast cancer and anticancer therapy–induced alopecia, researchers found that combining low-dose oral minoxidil (LDOM) and topical minoxidil achieved better results than topical minoxidil alone and that the treatment was well tolerated. A total of 5 of the 37 patients (13.5%) in the combination therapy group achieved a complete response, defined as an improvement of alopecia severity from grade 2 to grade 1, compared with none of the 19 patients in the topical therapy–only group.

In contrast, none of the patients in the combination group experienced worsening of alopecia, compared with two (10.5%) in the topical monotherapy group.

The study was published online in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. Topical minoxidil is approved by the Food and Drug Administration to treat androgenetic alopecia. Oral minoxidil is not approved for treating hair loss but has been receiving increased attention as an adjunctive therapy for hair loss, particularly for women. Oral minoxidil is approved for treating hypertension but at much higher doses.

An increasing number of studies have been conducted on the use of oral minoxidil for the treatment of female pattern hair loss, dating back to a pilot study in 2017, with promising results. The findings suggest that LDOM might be more effective than topical therapy, well tolerated, and more convenient for individuals to take.

Hypothesis generating

In a comment, Kai Johnson, MD, a medical oncologist who specializes in treating patients with breast cancer at the Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center – Arthur G. James Cancer Hospital and Richard J. Solove Research Institute, Columbus, noted that the study, like most small-scale retrospective studies, is hypothesis generating. However, “I’d be hesitant to broadly recommend this practice of dual therapy – oral and topical minoxidil together – until we see a placebo-controlled prospective study performed demonstrating clinically meaningful benefits for patients.”

Another factor is the study endpoints. “While there was a statistically significant benefit documented with dual therapy in this study, it’s important to have study endpoints that are more patient oriented,” Dr. Johnson said. The most important endpoint for patients would be improvements “in the actual alopecia grade, which did occur in 5 of the 37 of dual-therapy patients, versus 0 topical minoxidil patients.”

George Cotsarelis, MD, chair of the department of dermatology and professor of dermatology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, also weighed in. He questioned whether adding the topical therapy to oral minoxidil actually improved the results. “What was missing was a study arm that used the oral alone,” he said in an interview. “So we don’t know how effective the oral therapy would be by itself and if combining it with the topical is really adding anything.”

Oral minoxidil as a treatment for hair loss is gaining traction, and it’s clear that it is effective. However, the risk of side effects is higher, he said. “The risk isn’t that high with the low dose, but it can grow hair on places other than the scalp, and that can be disconcerting.” In this study, two women who took the oral drug reported edema, and one reported headache and dizziness. Hypertrichosis was reported by five patients who received the combination.

Study details

In the study, Jeewoo Kang, MD, and colleagues from the Seoul National University evaluated the efficacy of LDOM in 100 patients with breast cancer who had been diagnosed with persistent chemotherapy-induced alopecia (pCIA) and endocrine therapy–induced alopecia (EIA) at a dermatology clinic.

They conducted an analysis of medical records, standardized clinical photographs, and trichoscopic images to evaluate the alopecia pattern, severity, treatment response, and posttreatment changes in vertex hair density and thickness.

Compared with those with EIA alone, patients with pCIA were significantly more likely to have diffuse alopecia (P < .001), and they were more likely to have more severe alopecia, although this difference was not significant (P = .058). Outcomes were evaluated for 56 patients who were treated with minoxidil (19 with topical minoxidil alone and 37 with both LDOM and topical minoxidil) and for whom clinical and trichoscopic photos were available at baseline and at the last follow-up (all patients were scheduled for follow-up at 3-month intervals).

The results showed that those treated with 1.25-5.0 mg/d of oral minoxidil and 5% topical minoxidil solution once a day had better responses (P = .002) and a higher percentage increase in hair density from baseline (P = .003), compared with those who received topical minoxidil monotherapy.

However, changes in hair thickness after treatment were not significantly different between the two groups (P = .540).

In addition to the five (13.5%) cases of hypertrichosis, two cases of edema (5.4%), and one case of headache/dizziness (2.7%) among those who received the combination, there was also one report of palpitations (2.7%). Palpitations were reported in one patient (5%) who received topical monotherapy, the only adverse event reported in this group.

Dr. Johnson noted that, at his institution, a dermatologist is conducting a clinical trial with oncology patients post chemotherapy and endocrine therapy. “She is looking at a similar question, although she is comparing oral minoxidil to topical minoxidil directly rather than in combination.” There is also an active clinical trial at Northwestern University, Chicago, of LDOM alone for patients with chemotherapy-induced alopecia.

“So there is a lot of momentum surrounding this concept, and I feel we will continue to see it come up as a possible treatment option, but more data are needed at this time before it can become standard of care,” Dr. Johnson added.

No funding for the study was reported. The authors disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF DERMATOLOGY

Adverse events linked to better survival with ICIs in melanoma

Among Survival is further improved if the immunotherapy is continued after the adverse event develops, a new study confirms.

“In the largest clinical cohort to date, our data support a positive association with overall survival for patients who develop clinically significant immune-related adverse events while receiving combination immune checkpoint blockade, in keeping with other reported series,” the authors wrote.

The study was published online in JAMA Network Open.

Immune-related adverse events are common with these drugs. Severe events of grade 3 or higher occur in 59% of trial patients who receive combination ICI therapy.

The adverse events have increasingly been positively associated with survival. However, the effects for patients with metastatic melanoma, in particular, are less clear. There is little research on the effects in relation to combination therapy with ipilimumab and nivolumab, which is the standard of care for many patients with metastatic melanoma.

To investigate, Alexander S. Watson, MD, and colleagues evaluated data on 492 patients with metastatic melanoma who had been treated with one or more doses of an anti–programmed death 1 agent as single or combination immune checkpoint blockade in the multicenter Alberta Immunotherapy Database from August 2013 to May 2020.

Of these 492 patients, 198 patients (40%) developed immune-related adverse events. The mean age of the patients who developed adverse events was 61.8 years; of those who did not develop adverse events, the mean age was 65.5 years. Men made up 69.2% and 62.2%, respectively.

A total of 288 patients received pembrolizumab as their first ICI therapy, 80 received nivolumab, and 124 received combination blockade with ipilimumab-nivolumab.

Overall, with a median follow-up of 36.6 months, among patients who experienced clinically significant immune-related adverse events, defined as requiring systemic corticosteroids and/or a treatment delay, median overall survival was significantly improved, at 56.3 months, compared with 18.5 months among those who did not experience immune-related adverse events (P < .001).

In addition, among those who received combination ICI treatment, the median overall survival was 56.2 months for those who experienced adverse events versus 19.0 months for those who did not (P < .001).

There were no significant differences in overall survival between those who were and those who were not hospitalized for their immune-related adverse events (P = .53).

For patients who resumed their ICI therapy following the adverse events, overall survival was longer, compared with those who did not resume the therapy (median, 56.3 months vs. 31.5 months; P = .009).

The improvements in overall survival seen with immune-related adverse events remained consistent after adjustment in a multivariable analysis (hazard ratio for death, 0.382; P < .001).

There were no significant differences in the median number of cycles of ICIs between those with and those without the adverse events.

The risk of recurrence of immune-related adverse events following the reintroduction of therapy after initial events was a concern, so the improved overall survival among those patients is encouraging, although further investigation is needed, commented lead author Dr. Watson, from the department of oncology, University of Calgary (Alta.).

“It may be, for certain patients with immune-related adverse events, that continued immune-priming is safe and optimizes anticancer response,” he told this news organization. “However, in a retrospective analysis such as ours, selection bias can have an impact.”

“Confirming this finding and better identifying patients who may benefit from resumption will be an area for future investigation,” he said.

Patients who developed immune-related adverse events were more likely to be younger than 50 years (21.8% vs. 13.9%), have normal albumin levels (86.4% vs. 74.8%), and have a more robust Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group status, which is consistent with other studies that have shown survival benefits among those who experience adverse events.

“We, and others, speculate this could be due to such groups having immune systems more ready to respond strongly to immunotherapy,” Dr. Watson explained.