User login

Hyperpigmented Papules on the Tongue of a Child

The Diagnosis: Pigmented Fungiform Papillae of the Tongue

Our patient’s hyperpigmentation was confined to the fungiform papillae, leading to a diagnosis of pigmented fungiform papillae of the tongue (PFPT). A biopsy was not performed, and reassurance was provided regarding the benign nature of this finding, which did not require treatment.

Pigmented fungiform papillae of the tongue is a benign, nonprogressive, asymptomatic pigmentary condition that is most common among patients with skin of color and typically develops within the second or third decade of life.1,2 The pathogenesis is unclear, but activation of subepithelial melanophages without evidence of inflammation has been implicated.2 Although no standard treatment exists, cosmetic improvement with the use of the Q-switched ruby laser has been reported.3,4 Clinically, PFPT presents as asymptomatic hyperpigmentation confined to the fungiform papillae along the anterior and lateral portions of the tongue.1,2

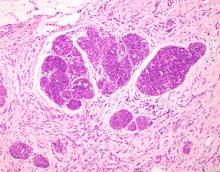

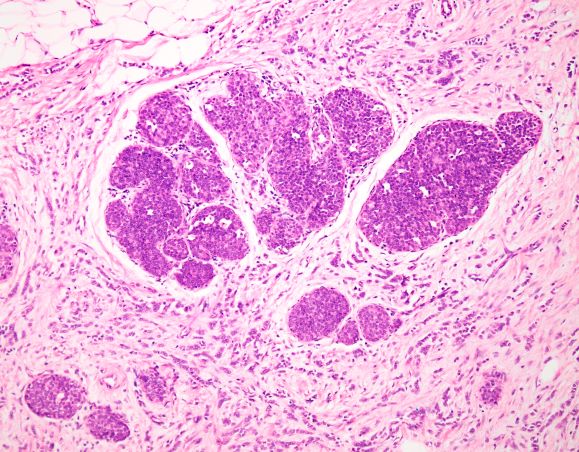

Pigmented fungiform papillae of the tongue typically is an isolated finding but rarely can be associated with hyperpigmentation of the nails (as in our patient) or gingiva.2 Three different clinical patterns of presentation have been described: (1) a single well-circumscribed collection of pigmented fungiform papillae, (2) few scattered pigmented fungiform papillae admixed with many nonpigmented fungiform papillae, or (3) pigmentation of all fungiform papillae on the dorsal aspect of the tongue.2,5,6 Pigmented fungiform papillae of the tongue is a clinical diagnosis based on visual recognition. Dermoscopic examination revealing a cobblestonelike or rose petal–like pattern may be helpful in diagnosing PFPT.2,5-7 Although not typically recommended in the evaluation of PFPT, a biopsy will reveal papillary structures with hyperpigmentation of basilar keratinocytes as well as melanophages in the lamina propria.8 The latter finding suggests a transient inflammatory process despite the hallmark absence of inflammation.5 Melanocytic neoplasia and exogenous granules of pigment typically are not seen.8

Other conditions that may present with dark-colored macules or papules on the tongue should be considered in the evaluation of a patient with these clinical findings. Black hairy tongue (BHT), or lingua villosa nigra, is a benign finding due to filiform papillae hypertrophy on the dorsum of the tongue.9 Food particle debris caught in BHT can lead to porphyrin production by chromogenic bacteria and fungi. These porphyrins result in discoloration ranging from brown-black to yellow and green occurring anteriorly to the circumvallate papillae while usually sparing the tip and lateral sides of the tongue. Dermoscopy can show thin discolored fibers with a hairy appearance. Although normal filiform papillae are less than 1-mm long, 3-mm long papillae are considered diagnostic of BHT.9 Treatment includes effective oral hygiene and desquamation measures, which can lead to complete resolution.10

Peutz-Jeghers syndrome is a rare genodermatosis that is characterized by focal hyperpigmentation and multiple gastrointestinal mucosal hamartomatous polyps. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome should be suspected in a patient with discrete, 1- to 5-mm, brown to black macules on the perioral or periocular skin, tongue, genitals, palms, soles, and buccal mucosa with a history of abdominal symptoms.11,12

Addison disease, or primary adrenal insufficiency, may present with brown hyperpigmentation on chronically sun-exposed areas; regions of friction or pressure; surrounding scar tissue; and mucosal surfaces such as the tongue, inner surface of the lip, and buccal and gingival mucosa.13 Addison disease is differentiated from PFPT by a more generalized hyperpigmentation due to increased melanin production as well as the presence of systemic symptoms related to hypocortisolism. The pigmentation seen on the buccal mucosa in Addison disease is patchy and diffuse, and histology reveals basal melanin hyperpigmentation with superficial dermal melanophages.13

Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia is an inherited disorder featuring telangiectasia and generally appears in the third decade of life.14 Telangiectases classically are 1 to 3 mm in diameter with or without slight elevation. Dermoscopic findings include small red clots, lacunae, and serpentine or linear vessels arranged in a radial conformation surrounding a homogenous pink center.15 These telangiectases typically occur on the skin or mucosa, particularly the face, lips, tongue, nail beds, and nasal mucosa; however, any organ can be affected with arteriovenous malformations. Recurrent epistaxis occurs in more than half of patients with hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia.14 Histopathology reveals dilated vessels and lacunae near the dermoepidermal junction displacing the epidermis and papillary dermis.15 It is distinguished from PFPT by the vascular nature of the lesions and by the presence of other characteristic symptoms such as recurrent epistaxis and visceral arteriovenous malformations.

- Romiti R, Molina De Medeiros L. Pigmented fungiform papillae of the tongue. Pediatr Dermatol. 2010;27:398-399. doi:10.1111/j .1525-1470.2010.01183.x

- Chessa MA, Patrizi A, Sechi A, et al. Pigmented fungiform lingual papillae: dermoscopic and clinical features. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:935-939. doi:10.1111/jdv.14809

- Rice SM, Lal K. Successful treatment of pigmented fungiform papillae of the tongue with Q-switched ruby laser. Dermatol Surg. 2022;48:368-369. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000003371

- Mizawa M, Makino T, Furukawa F, et al. Efficacy of Q-switched ruby laser treatment for pigmented fungiform papillae of the tongue. J Dermatol. 2022;49:E133-E134. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.16270

- Holzwanger JM, Rudolph RI, Heaton CL. Pigmented fungiform papillae of the tongue: a common variant of oral pigmentation. Int J Dermatol. 1974;13:403-408. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4362.1974. tb05073.x

- Mukamal LV, Ormiga P, Ramos-E-Silva M. Dermoscopy of the pigmented fungiform papillae of the tongue. J Dermatol. 2012;39:397-399. doi:10.1111/j.1346-8138.2011.01328.x

- Surboyo MDC, Santosh ABR, Hariyani N, et al. Clinical utility of dermoscopy on diagnosing pigmented papillary fungiform papillae of the tongue: a systematic review. J Oral Biol Craniofac Res. 2021;11:618-623. doi:10.1016/j.jobcr.2021.09.008

- Chamseddin B, Vandergriff T. Pigmented fungiform papillae of the tongue: a clinical and histologic description [published online September 15, 2019]. Dermatol Online J. 2019;25:13030/qt8674c519.

- Jayasree P, Kaliyadan F, Ashique KT. Black hairy tongue. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158:573. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.5314

- Schlager E, St Claire C, Ashack K, et al. Black hairy tongue: predisposing factors, diagnosis, and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18:563-569. doi:10.1007/s40257-017-0268-y

- Sandru F, Petca A, Dumitrascu MC, et al. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: skin manifestations and endocrine anomalies (review). Exp Ther Med. 2021;22:1387. doi:10.3892/etm.2021.10823

- Shah KR, Boland CR, Patel M, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of gastrointestinal disease: part I. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:189.e1-210. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2012.10.037

- Lee K, Lian C, Vaidya A, et al. Oral mucosal hyperpigmentation. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:993-995. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2020.08.013

- Haitjema T, Westermann CJ, Overtoom TT, et al. Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (Osler-Weber-Rendu disease): new insights in pathogenesis, complications, and treatment. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156:714-719.

- Tokoro S, Namiki T, Ugajin T, et al. Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (Rendu-Osler-Weber’s disease): detailed assessment of skin lesions by dermoscopy and ultrasound. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:E224-E226. doi:10.1111/ijd.14578

The Diagnosis: Pigmented Fungiform Papillae of the Tongue

Our patient’s hyperpigmentation was confined to the fungiform papillae, leading to a diagnosis of pigmented fungiform papillae of the tongue (PFPT). A biopsy was not performed, and reassurance was provided regarding the benign nature of this finding, which did not require treatment.

Pigmented fungiform papillae of the tongue is a benign, nonprogressive, asymptomatic pigmentary condition that is most common among patients with skin of color and typically develops within the second or third decade of life.1,2 The pathogenesis is unclear, but activation of subepithelial melanophages without evidence of inflammation has been implicated.2 Although no standard treatment exists, cosmetic improvement with the use of the Q-switched ruby laser has been reported.3,4 Clinically, PFPT presents as asymptomatic hyperpigmentation confined to the fungiform papillae along the anterior and lateral portions of the tongue.1,2

Pigmented fungiform papillae of the tongue typically is an isolated finding but rarely can be associated with hyperpigmentation of the nails (as in our patient) or gingiva.2 Three different clinical patterns of presentation have been described: (1) a single well-circumscribed collection of pigmented fungiform papillae, (2) few scattered pigmented fungiform papillae admixed with many nonpigmented fungiform papillae, or (3) pigmentation of all fungiform papillae on the dorsal aspect of the tongue.2,5,6 Pigmented fungiform papillae of the tongue is a clinical diagnosis based on visual recognition. Dermoscopic examination revealing a cobblestonelike or rose petal–like pattern may be helpful in diagnosing PFPT.2,5-7 Although not typically recommended in the evaluation of PFPT, a biopsy will reveal papillary structures with hyperpigmentation of basilar keratinocytes as well as melanophages in the lamina propria.8 The latter finding suggests a transient inflammatory process despite the hallmark absence of inflammation.5 Melanocytic neoplasia and exogenous granules of pigment typically are not seen.8

Other conditions that may present with dark-colored macules or papules on the tongue should be considered in the evaluation of a patient with these clinical findings. Black hairy tongue (BHT), or lingua villosa nigra, is a benign finding due to filiform papillae hypertrophy on the dorsum of the tongue.9 Food particle debris caught in BHT can lead to porphyrin production by chromogenic bacteria and fungi. These porphyrins result in discoloration ranging from brown-black to yellow and green occurring anteriorly to the circumvallate papillae while usually sparing the tip and lateral sides of the tongue. Dermoscopy can show thin discolored fibers with a hairy appearance. Although normal filiform papillae are less than 1-mm long, 3-mm long papillae are considered diagnostic of BHT.9 Treatment includes effective oral hygiene and desquamation measures, which can lead to complete resolution.10

Peutz-Jeghers syndrome is a rare genodermatosis that is characterized by focal hyperpigmentation and multiple gastrointestinal mucosal hamartomatous polyps. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome should be suspected in a patient with discrete, 1- to 5-mm, brown to black macules on the perioral or periocular skin, tongue, genitals, palms, soles, and buccal mucosa with a history of abdominal symptoms.11,12

Addison disease, or primary adrenal insufficiency, may present with brown hyperpigmentation on chronically sun-exposed areas; regions of friction or pressure; surrounding scar tissue; and mucosal surfaces such as the tongue, inner surface of the lip, and buccal and gingival mucosa.13 Addison disease is differentiated from PFPT by a more generalized hyperpigmentation due to increased melanin production as well as the presence of systemic symptoms related to hypocortisolism. The pigmentation seen on the buccal mucosa in Addison disease is patchy and diffuse, and histology reveals basal melanin hyperpigmentation with superficial dermal melanophages.13

Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia is an inherited disorder featuring telangiectasia and generally appears in the third decade of life.14 Telangiectases classically are 1 to 3 mm in diameter with or without slight elevation. Dermoscopic findings include small red clots, lacunae, and serpentine or linear vessels arranged in a radial conformation surrounding a homogenous pink center.15 These telangiectases typically occur on the skin or mucosa, particularly the face, lips, tongue, nail beds, and nasal mucosa; however, any organ can be affected with arteriovenous malformations. Recurrent epistaxis occurs in more than half of patients with hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia.14 Histopathology reveals dilated vessels and lacunae near the dermoepidermal junction displacing the epidermis and papillary dermis.15 It is distinguished from PFPT by the vascular nature of the lesions and by the presence of other characteristic symptoms such as recurrent epistaxis and visceral arteriovenous malformations.

The Diagnosis: Pigmented Fungiform Papillae of the Tongue

Our patient’s hyperpigmentation was confined to the fungiform papillae, leading to a diagnosis of pigmented fungiform papillae of the tongue (PFPT). A biopsy was not performed, and reassurance was provided regarding the benign nature of this finding, which did not require treatment.

Pigmented fungiform papillae of the tongue is a benign, nonprogressive, asymptomatic pigmentary condition that is most common among patients with skin of color and typically develops within the second or third decade of life.1,2 The pathogenesis is unclear, but activation of subepithelial melanophages without evidence of inflammation has been implicated.2 Although no standard treatment exists, cosmetic improvement with the use of the Q-switched ruby laser has been reported.3,4 Clinically, PFPT presents as asymptomatic hyperpigmentation confined to the fungiform papillae along the anterior and lateral portions of the tongue.1,2

Pigmented fungiform papillae of the tongue typically is an isolated finding but rarely can be associated with hyperpigmentation of the nails (as in our patient) or gingiva.2 Three different clinical patterns of presentation have been described: (1) a single well-circumscribed collection of pigmented fungiform papillae, (2) few scattered pigmented fungiform papillae admixed with many nonpigmented fungiform papillae, or (3) pigmentation of all fungiform papillae on the dorsal aspect of the tongue.2,5,6 Pigmented fungiform papillae of the tongue is a clinical diagnosis based on visual recognition. Dermoscopic examination revealing a cobblestonelike or rose petal–like pattern may be helpful in diagnosing PFPT.2,5-7 Although not typically recommended in the evaluation of PFPT, a biopsy will reveal papillary structures with hyperpigmentation of basilar keratinocytes as well as melanophages in the lamina propria.8 The latter finding suggests a transient inflammatory process despite the hallmark absence of inflammation.5 Melanocytic neoplasia and exogenous granules of pigment typically are not seen.8

Other conditions that may present with dark-colored macules or papules on the tongue should be considered in the evaluation of a patient with these clinical findings. Black hairy tongue (BHT), or lingua villosa nigra, is a benign finding due to filiform papillae hypertrophy on the dorsum of the tongue.9 Food particle debris caught in BHT can lead to porphyrin production by chromogenic bacteria and fungi. These porphyrins result in discoloration ranging from brown-black to yellow and green occurring anteriorly to the circumvallate papillae while usually sparing the tip and lateral sides of the tongue. Dermoscopy can show thin discolored fibers with a hairy appearance. Although normal filiform papillae are less than 1-mm long, 3-mm long papillae are considered diagnostic of BHT.9 Treatment includes effective oral hygiene and desquamation measures, which can lead to complete resolution.10

Peutz-Jeghers syndrome is a rare genodermatosis that is characterized by focal hyperpigmentation and multiple gastrointestinal mucosal hamartomatous polyps. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome should be suspected in a patient with discrete, 1- to 5-mm, brown to black macules on the perioral or periocular skin, tongue, genitals, palms, soles, and buccal mucosa with a history of abdominal symptoms.11,12

Addison disease, or primary adrenal insufficiency, may present with brown hyperpigmentation on chronically sun-exposed areas; regions of friction or pressure; surrounding scar tissue; and mucosal surfaces such as the tongue, inner surface of the lip, and buccal and gingival mucosa.13 Addison disease is differentiated from PFPT by a more generalized hyperpigmentation due to increased melanin production as well as the presence of systemic symptoms related to hypocortisolism. The pigmentation seen on the buccal mucosa in Addison disease is patchy and diffuse, and histology reveals basal melanin hyperpigmentation with superficial dermal melanophages.13

Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia is an inherited disorder featuring telangiectasia and generally appears in the third decade of life.14 Telangiectases classically are 1 to 3 mm in diameter with or without slight elevation. Dermoscopic findings include small red clots, lacunae, and serpentine or linear vessels arranged in a radial conformation surrounding a homogenous pink center.15 These telangiectases typically occur on the skin or mucosa, particularly the face, lips, tongue, nail beds, and nasal mucosa; however, any organ can be affected with arteriovenous malformations. Recurrent epistaxis occurs in more than half of patients with hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia.14 Histopathology reveals dilated vessels and lacunae near the dermoepidermal junction displacing the epidermis and papillary dermis.15 It is distinguished from PFPT by the vascular nature of the lesions and by the presence of other characteristic symptoms such as recurrent epistaxis and visceral arteriovenous malformations.

- Romiti R, Molina De Medeiros L. Pigmented fungiform papillae of the tongue. Pediatr Dermatol. 2010;27:398-399. doi:10.1111/j .1525-1470.2010.01183.x

- Chessa MA, Patrizi A, Sechi A, et al. Pigmented fungiform lingual papillae: dermoscopic and clinical features. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:935-939. doi:10.1111/jdv.14809

- Rice SM, Lal K. Successful treatment of pigmented fungiform papillae of the tongue with Q-switched ruby laser. Dermatol Surg. 2022;48:368-369. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000003371

- Mizawa M, Makino T, Furukawa F, et al. Efficacy of Q-switched ruby laser treatment for pigmented fungiform papillae of the tongue. J Dermatol. 2022;49:E133-E134. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.16270

- Holzwanger JM, Rudolph RI, Heaton CL. Pigmented fungiform papillae of the tongue: a common variant of oral pigmentation. Int J Dermatol. 1974;13:403-408. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4362.1974. tb05073.x

- Mukamal LV, Ormiga P, Ramos-E-Silva M. Dermoscopy of the pigmented fungiform papillae of the tongue. J Dermatol. 2012;39:397-399. doi:10.1111/j.1346-8138.2011.01328.x

- Surboyo MDC, Santosh ABR, Hariyani N, et al. Clinical utility of dermoscopy on diagnosing pigmented papillary fungiform papillae of the tongue: a systematic review. J Oral Biol Craniofac Res. 2021;11:618-623. doi:10.1016/j.jobcr.2021.09.008

- Chamseddin B, Vandergriff T. Pigmented fungiform papillae of the tongue: a clinical and histologic description [published online September 15, 2019]. Dermatol Online J. 2019;25:13030/qt8674c519.

- Jayasree P, Kaliyadan F, Ashique KT. Black hairy tongue. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158:573. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.5314

- Schlager E, St Claire C, Ashack K, et al. Black hairy tongue: predisposing factors, diagnosis, and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18:563-569. doi:10.1007/s40257-017-0268-y

- Sandru F, Petca A, Dumitrascu MC, et al. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: skin manifestations and endocrine anomalies (review). Exp Ther Med. 2021;22:1387. doi:10.3892/etm.2021.10823

- Shah KR, Boland CR, Patel M, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of gastrointestinal disease: part I. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:189.e1-210. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2012.10.037

- Lee K, Lian C, Vaidya A, et al. Oral mucosal hyperpigmentation. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:993-995. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2020.08.013

- Haitjema T, Westermann CJ, Overtoom TT, et al. Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (Osler-Weber-Rendu disease): new insights in pathogenesis, complications, and treatment. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156:714-719.

- Tokoro S, Namiki T, Ugajin T, et al. Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (Rendu-Osler-Weber’s disease): detailed assessment of skin lesions by dermoscopy and ultrasound. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:E224-E226. doi:10.1111/ijd.14578

- Romiti R, Molina De Medeiros L. Pigmented fungiform papillae of the tongue. Pediatr Dermatol. 2010;27:398-399. doi:10.1111/j .1525-1470.2010.01183.x

- Chessa MA, Patrizi A, Sechi A, et al. Pigmented fungiform lingual papillae: dermoscopic and clinical features. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:935-939. doi:10.1111/jdv.14809

- Rice SM, Lal K. Successful treatment of pigmented fungiform papillae of the tongue with Q-switched ruby laser. Dermatol Surg. 2022;48:368-369. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000003371

- Mizawa M, Makino T, Furukawa F, et al. Efficacy of Q-switched ruby laser treatment for pigmented fungiform papillae of the tongue. J Dermatol. 2022;49:E133-E134. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.16270

- Holzwanger JM, Rudolph RI, Heaton CL. Pigmented fungiform papillae of the tongue: a common variant of oral pigmentation. Int J Dermatol. 1974;13:403-408. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4362.1974. tb05073.x

- Mukamal LV, Ormiga P, Ramos-E-Silva M. Dermoscopy of the pigmented fungiform papillae of the tongue. J Dermatol. 2012;39:397-399. doi:10.1111/j.1346-8138.2011.01328.x

- Surboyo MDC, Santosh ABR, Hariyani N, et al. Clinical utility of dermoscopy on diagnosing pigmented papillary fungiform papillae of the tongue: a systematic review. J Oral Biol Craniofac Res. 2021;11:618-623. doi:10.1016/j.jobcr.2021.09.008

- Chamseddin B, Vandergriff T. Pigmented fungiform papillae of the tongue: a clinical and histologic description [published online September 15, 2019]. Dermatol Online J. 2019;25:13030/qt8674c519.

- Jayasree P, Kaliyadan F, Ashique KT. Black hairy tongue. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158:573. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.5314

- Schlager E, St Claire C, Ashack K, et al. Black hairy tongue: predisposing factors, diagnosis, and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18:563-569. doi:10.1007/s40257-017-0268-y

- Sandru F, Petca A, Dumitrascu MC, et al. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: skin manifestations and endocrine anomalies (review). Exp Ther Med. 2021;22:1387. doi:10.3892/etm.2021.10823

- Shah KR, Boland CR, Patel M, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of gastrointestinal disease: part I. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:189.e1-210. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2012.10.037

- Lee K, Lian C, Vaidya A, et al. Oral mucosal hyperpigmentation. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:993-995. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2020.08.013

- Haitjema T, Westermann CJ, Overtoom TT, et al. Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (Osler-Weber-Rendu disease): new insights in pathogenesis, complications, and treatment. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156:714-719.

- Tokoro S, Namiki T, Ugajin T, et al. Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (Rendu-Osler-Weber’s disease): detailed assessment of skin lesions by dermoscopy and ultrasound. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:E224-E226. doi:10.1111/ijd.14578

A 9-year-old Black boy presented to the dermatology clinic for evaluation of dark spots on the tongue. The family first noted these spots 5 months prior and reported that they remained stable during that time. The patient’s medical history was notable for autism spectrum disorder and multiple food allergies. His family history was negative for similar oral pigmentation or other pigmentary anomalies. A review of systems was positive only for selective eating and rare nosebleeds. Physical examination revealed numerous dark brown, pinpoint papules across the dorsal aspect of the tongue. No hyperpigmentation of the buccal mucosae, lips, palms, or soles was identified. Several light brown streaks were present on the fingernails and toenails, consistent with longitudinal melanonychia. A prior complete blood cell count was within reference range.

Time for a rest

“More than Jews have kept Shabbat, Shabbat has kept the Jews.” – Ahad Ha’am

You should all be well rested by now. After all, we’ve just come through the festive shutdown of the holiday season where all of your pumpkin/peppermint/marshmallow flavored coffees were sipped while walking around in your jimjams at 10 a.m. It was the time of year for you to take time off to get a proper rest and be energized to get back to work. Yet, I’m not feeling it from you.

So let’s talk about burnout – just kidding, that would only make it worse. “Burned-out’’ is a hackneyed and defective phrase to describe what many of us are feeling. We are not “destroyed, gutted by fire or by overheating.” No, we are, as one of our docs put it to me: “Just tired.” Ah, a much better Old English word! “Tired” captures it. It means to feel “in need of rest.” We are not ruined, we are just depleted. We don’t need discarding. We need some rest.

I asked some docs when they thought this feeling of exhaustion first began. We agreed that the pandemic, doubledemic, tripledemic, backlog have taken a toll. But The consumerization of medicine? All factors, but not the beginning. No, the beginning was before paper charts. Well, actually it was before paper. We have to go back to the 5th or 6th century BCE. That is when scholars believe the book of Genesis originated from the Yahwist source. In it, it is written that the 7th day be set aside as a day of rest from labor. It is not written that burnout would ensue if sabbath wasn’t observed; however, if you failed to keep it, then you might have been killed. They took rest seriously back then.

This innovation of setting aside a day each week to rest, reflect, and worship was such a good idea that it was codified as one of the 10 commandments. It spread widely. Early Christians kept the Jewish tradition of observing Shabbat from Friday sundown to Saturday until the ever practical Romans decided that Sunday would be a better day. Sunday was already the day to worship the sun god. The newly-converted Christian Emperor Constantine issued an edict on March 7th, 321 CE that all “city people and craftsmen shall rest from labor upon the venerable day of the sun.” And so Sunday it was.

Protestant Seventh-day denomination churches later shifted sabbath back to Saturday believing that Sunday must have been the Pope’s idea. The best deal seems to have been around 1273 when the Ethiopian Orthodox leader Ewostatewos decreed that both Saturday AND Sunday would be days of rest. (But when would one go to Costco?!) In Islam, there is Jumu’ah on Friday. Buddhists have Uposatha, a day of rest and observance every 7 or 8 days. Bah’ai keep Friday as a day of rest and worship. So vital are days of respite to the health of our communities that the state has made working on certain days a violation of the law, “blue laws” they are called. We’ve had blue laws on the books since the time of the Jamestown Colony in 1619 where the first Virginia Assembly required taking Sunday off for worship. Most of these laws have been repealed, although a few states, such as Rhode Island, still have blue laws prohibiting retail and grocery stores from opening on Thanksgiving or Christmas. So there – enjoy your two days off this year!

Ironically, this column, like most of mine, comes to you after my having written it on a Saturday and Sunday. I also just logged on to my EMR and checked results, renewed a few prescriptions, and answered a couple messages. If I didn’t, my Monday’s work would be crushingly heavy.

Maybe I need to be more efficient and finish my work during the week. Or maybe I need to realize that work has not let up since about 600 BCE and taking one day off each week to rest is an obligation to myself, my family and my community.

I wonder if I can choose Mondays.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at [email protected].

“More than Jews have kept Shabbat, Shabbat has kept the Jews.” – Ahad Ha’am

You should all be well rested by now. After all, we’ve just come through the festive shutdown of the holiday season where all of your pumpkin/peppermint/marshmallow flavored coffees were sipped while walking around in your jimjams at 10 a.m. It was the time of year for you to take time off to get a proper rest and be energized to get back to work. Yet, I’m not feeling it from you.

So let’s talk about burnout – just kidding, that would only make it worse. “Burned-out’’ is a hackneyed and defective phrase to describe what many of us are feeling. We are not “destroyed, gutted by fire or by overheating.” No, we are, as one of our docs put it to me: “Just tired.” Ah, a much better Old English word! “Tired” captures it. It means to feel “in need of rest.” We are not ruined, we are just depleted. We don’t need discarding. We need some rest.

I asked some docs when they thought this feeling of exhaustion first began. We agreed that the pandemic, doubledemic, tripledemic, backlog have taken a toll. But The consumerization of medicine? All factors, but not the beginning. No, the beginning was before paper charts. Well, actually it was before paper. We have to go back to the 5th or 6th century BCE. That is when scholars believe the book of Genesis originated from the Yahwist source. In it, it is written that the 7th day be set aside as a day of rest from labor. It is not written that burnout would ensue if sabbath wasn’t observed; however, if you failed to keep it, then you might have been killed. They took rest seriously back then.

This innovation of setting aside a day each week to rest, reflect, and worship was such a good idea that it was codified as one of the 10 commandments. It spread widely. Early Christians kept the Jewish tradition of observing Shabbat from Friday sundown to Saturday until the ever practical Romans decided that Sunday would be a better day. Sunday was already the day to worship the sun god. The newly-converted Christian Emperor Constantine issued an edict on March 7th, 321 CE that all “city people and craftsmen shall rest from labor upon the venerable day of the sun.” And so Sunday it was.

Protestant Seventh-day denomination churches later shifted sabbath back to Saturday believing that Sunday must have been the Pope’s idea. The best deal seems to have been around 1273 when the Ethiopian Orthodox leader Ewostatewos decreed that both Saturday AND Sunday would be days of rest. (But when would one go to Costco?!) In Islam, there is Jumu’ah on Friday. Buddhists have Uposatha, a day of rest and observance every 7 or 8 days. Bah’ai keep Friday as a day of rest and worship. So vital are days of respite to the health of our communities that the state has made working on certain days a violation of the law, “blue laws” they are called. We’ve had blue laws on the books since the time of the Jamestown Colony in 1619 where the first Virginia Assembly required taking Sunday off for worship. Most of these laws have been repealed, although a few states, such as Rhode Island, still have blue laws prohibiting retail and grocery stores from opening on Thanksgiving or Christmas. So there – enjoy your two days off this year!

Ironically, this column, like most of mine, comes to you after my having written it on a Saturday and Sunday. I also just logged on to my EMR and checked results, renewed a few prescriptions, and answered a couple messages. If I didn’t, my Monday’s work would be crushingly heavy.

Maybe I need to be more efficient and finish my work during the week. Or maybe I need to realize that work has not let up since about 600 BCE and taking one day off each week to rest is an obligation to myself, my family and my community.

I wonder if I can choose Mondays.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at [email protected].

“More than Jews have kept Shabbat, Shabbat has kept the Jews.” – Ahad Ha’am

You should all be well rested by now. After all, we’ve just come through the festive shutdown of the holiday season where all of your pumpkin/peppermint/marshmallow flavored coffees were sipped while walking around in your jimjams at 10 a.m. It was the time of year for you to take time off to get a proper rest and be energized to get back to work. Yet, I’m not feeling it from you.

So let’s talk about burnout – just kidding, that would only make it worse. “Burned-out’’ is a hackneyed and defective phrase to describe what many of us are feeling. We are not “destroyed, gutted by fire or by overheating.” No, we are, as one of our docs put it to me: “Just tired.” Ah, a much better Old English word! “Tired” captures it. It means to feel “in need of rest.” We are not ruined, we are just depleted. We don’t need discarding. We need some rest.

I asked some docs when they thought this feeling of exhaustion first began. We agreed that the pandemic, doubledemic, tripledemic, backlog have taken a toll. But The consumerization of medicine? All factors, but not the beginning. No, the beginning was before paper charts. Well, actually it was before paper. We have to go back to the 5th or 6th century BCE. That is when scholars believe the book of Genesis originated from the Yahwist source. In it, it is written that the 7th day be set aside as a day of rest from labor. It is not written that burnout would ensue if sabbath wasn’t observed; however, if you failed to keep it, then you might have been killed. They took rest seriously back then.

This innovation of setting aside a day each week to rest, reflect, and worship was such a good idea that it was codified as one of the 10 commandments. It spread widely. Early Christians kept the Jewish tradition of observing Shabbat from Friday sundown to Saturday until the ever practical Romans decided that Sunday would be a better day. Sunday was already the day to worship the sun god. The newly-converted Christian Emperor Constantine issued an edict on March 7th, 321 CE that all “city people and craftsmen shall rest from labor upon the venerable day of the sun.” And so Sunday it was.

Protestant Seventh-day denomination churches later shifted sabbath back to Saturday believing that Sunday must have been the Pope’s idea. The best deal seems to have been around 1273 when the Ethiopian Orthodox leader Ewostatewos decreed that both Saturday AND Sunday would be days of rest. (But when would one go to Costco?!) In Islam, there is Jumu’ah on Friday. Buddhists have Uposatha, a day of rest and observance every 7 or 8 days. Bah’ai keep Friday as a day of rest and worship. So vital are days of respite to the health of our communities that the state has made working on certain days a violation of the law, “blue laws” they are called. We’ve had blue laws on the books since the time of the Jamestown Colony in 1619 where the first Virginia Assembly required taking Sunday off for worship. Most of these laws have been repealed, although a few states, such as Rhode Island, still have blue laws prohibiting retail and grocery stores from opening on Thanksgiving or Christmas. So there – enjoy your two days off this year!

Ironically, this column, like most of mine, comes to you after my having written it on a Saturday and Sunday. I also just logged on to my EMR and checked results, renewed a few prescriptions, and answered a couple messages. If I didn’t, my Monday’s work would be crushingly heavy.

Maybe I need to be more efficient and finish my work during the week. Or maybe I need to realize that work has not let up since about 600 BCE and taking one day off each week to rest is an obligation to myself, my family and my community.

I wonder if I can choose Mondays.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at [email protected].

Commentary: Interstitial Lung Disease, Onset Time, and RA, January 2023

Though rheumatoid arthritis (RA)–associated interstitial lung disease (RA-ILD) is a feared complication that can significantly affect morbidity and mortality, the role of methotrexate in treatment and its possible contribution to ILD is yet unknown. Kim and colleagues performed a retrospective analysis of a series of 170 patients with RA-ILD to try to identify risk factors and protective factors for mortality and decline of lung function. Previously known risk factors included older age, smoking, and seropositivity for cyclic citrullinated peptide (CCP). In this series, patients who had exposure to methotrexate after a diagnosis of RA-ILD were found to have less progression of decline in lung function and decreased mortality compared with those who did not, which is a finding that warrants further examination. On the other hand, there was a suggestion that sulfasalazine use is associated with increased mortality, though this finding was not borne out in multivariate analysis.

A different group of authors also examined the association with conventional disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARD) with ILD progression in a prospective analysis of 143 patients in the multicenter Korean RA-ILD cohort. Patients were classified regarding exposure to methotrexate, leflunomide, or tacrolimus as well as biologic DMARD and glucocorticoid exposure, with a primary outcome of ILD progression based on pulmonary function tests or mortality. The study did not detect any difference in time to ILD progression with methotrexate exposure, though it is not clear that the study would be able to detect a protective effect as was possible in the prior study. However, patients who were exposed to leflunomide had a shorter time to ILD progression than did those who were not, though this did not persist in multivariate analysis, and tacrolimus exposure had a statistically insignificant impact on ILD progression. Because the study is small, other associations which could affect use of leflunomide in these patients were not examined, though prior studies have suggested an association with leflunomide in ILD progression in patients with existing RA-ILD.

Li and colleagues addressed the characteristics and prognosis of late-onset RA (LORA) in people 60 years or older compared with younger-onset RA (YORA) in a prospective cohort study using a Canadian RA registry. Patients in the registry were enrolled early in the course of their illness and clinical characteristics as well as time to Disease Activity Score (DAS28) remission were analyzed. Of note, YORA and LORA patients had similar times to remission but were on less aggressive medication regimens, such as conventional DMARD without biologic DMARD or Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors. In this registry, a smaller percentage of LORA patients compared with YORA patients were seropositive, which, given the enrollment of patients early in their disease course, may affect the use of biologic DMARD and JAK inhibitors.

Finally, the issue of noninflammatory pain contributing to disease activity and quality of life in RA has received increased scrutiny recently. Choy and colleagues studied disproportionate articular pain (DP) and its response to sarilumab, adalimumab, or placebo in a post hoc analysis of data from prior randomized clinical trials. DP was defined as a tender joint count that exceeded swollen joint count by seven and was present in about 20% of patients in the three randomized clinical trials examined. In these studies, DP was reduced in patients treated with sarilumab compared with placebo or adalimumab. Although this finding is exciting in raising the possibility of an immunologic explanation for DP via interleukin 6 (IL-6), the results should be considered carefully in the context of this post hoc analysis, especially before considering sarilumab or other IL-6 inhibitors as viable treatment options for DP in RA.

Though rheumatoid arthritis (RA)–associated interstitial lung disease (RA-ILD) is a feared complication that can significantly affect morbidity and mortality, the role of methotrexate in treatment and its possible contribution to ILD is yet unknown. Kim and colleagues performed a retrospective analysis of a series of 170 patients with RA-ILD to try to identify risk factors and protective factors for mortality and decline of lung function. Previously known risk factors included older age, smoking, and seropositivity for cyclic citrullinated peptide (CCP). In this series, patients who had exposure to methotrexate after a diagnosis of RA-ILD were found to have less progression of decline in lung function and decreased mortality compared with those who did not, which is a finding that warrants further examination. On the other hand, there was a suggestion that sulfasalazine use is associated with increased mortality, though this finding was not borne out in multivariate analysis.

A different group of authors also examined the association with conventional disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARD) with ILD progression in a prospective analysis of 143 patients in the multicenter Korean RA-ILD cohort. Patients were classified regarding exposure to methotrexate, leflunomide, or tacrolimus as well as biologic DMARD and glucocorticoid exposure, with a primary outcome of ILD progression based on pulmonary function tests or mortality. The study did not detect any difference in time to ILD progression with methotrexate exposure, though it is not clear that the study would be able to detect a protective effect as was possible in the prior study. However, patients who were exposed to leflunomide had a shorter time to ILD progression than did those who were not, though this did not persist in multivariate analysis, and tacrolimus exposure had a statistically insignificant impact on ILD progression. Because the study is small, other associations which could affect use of leflunomide in these patients were not examined, though prior studies have suggested an association with leflunomide in ILD progression in patients with existing RA-ILD.

Li and colleagues addressed the characteristics and prognosis of late-onset RA (LORA) in people 60 years or older compared with younger-onset RA (YORA) in a prospective cohort study using a Canadian RA registry. Patients in the registry were enrolled early in the course of their illness and clinical characteristics as well as time to Disease Activity Score (DAS28) remission were analyzed. Of note, YORA and LORA patients had similar times to remission but were on less aggressive medication regimens, such as conventional DMARD without biologic DMARD or Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors. In this registry, a smaller percentage of LORA patients compared with YORA patients were seropositive, which, given the enrollment of patients early in their disease course, may affect the use of biologic DMARD and JAK inhibitors.

Finally, the issue of noninflammatory pain contributing to disease activity and quality of life in RA has received increased scrutiny recently. Choy and colleagues studied disproportionate articular pain (DP) and its response to sarilumab, adalimumab, or placebo in a post hoc analysis of data from prior randomized clinical trials. DP was defined as a tender joint count that exceeded swollen joint count by seven and was present in about 20% of patients in the three randomized clinical trials examined. In these studies, DP was reduced in patients treated with sarilumab compared with placebo or adalimumab. Although this finding is exciting in raising the possibility of an immunologic explanation for DP via interleukin 6 (IL-6), the results should be considered carefully in the context of this post hoc analysis, especially before considering sarilumab or other IL-6 inhibitors as viable treatment options for DP in RA.

Though rheumatoid arthritis (RA)–associated interstitial lung disease (RA-ILD) is a feared complication that can significantly affect morbidity and mortality, the role of methotrexate in treatment and its possible contribution to ILD is yet unknown. Kim and colleagues performed a retrospective analysis of a series of 170 patients with RA-ILD to try to identify risk factors and protective factors for mortality and decline of lung function. Previously known risk factors included older age, smoking, and seropositivity for cyclic citrullinated peptide (CCP). In this series, patients who had exposure to methotrexate after a diagnosis of RA-ILD were found to have less progression of decline in lung function and decreased mortality compared with those who did not, which is a finding that warrants further examination. On the other hand, there was a suggestion that sulfasalazine use is associated with increased mortality, though this finding was not borne out in multivariate analysis.

A different group of authors also examined the association with conventional disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARD) with ILD progression in a prospective analysis of 143 patients in the multicenter Korean RA-ILD cohort. Patients were classified regarding exposure to methotrexate, leflunomide, or tacrolimus as well as biologic DMARD and glucocorticoid exposure, with a primary outcome of ILD progression based on pulmonary function tests or mortality. The study did not detect any difference in time to ILD progression with methotrexate exposure, though it is not clear that the study would be able to detect a protective effect as was possible in the prior study. However, patients who were exposed to leflunomide had a shorter time to ILD progression than did those who were not, though this did not persist in multivariate analysis, and tacrolimus exposure had a statistically insignificant impact on ILD progression. Because the study is small, other associations which could affect use of leflunomide in these patients were not examined, though prior studies have suggested an association with leflunomide in ILD progression in patients with existing RA-ILD.

Li and colleagues addressed the characteristics and prognosis of late-onset RA (LORA) in people 60 years or older compared with younger-onset RA (YORA) in a prospective cohort study using a Canadian RA registry. Patients in the registry were enrolled early in the course of their illness and clinical characteristics as well as time to Disease Activity Score (DAS28) remission were analyzed. Of note, YORA and LORA patients had similar times to remission but were on less aggressive medication regimens, such as conventional DMARD without biologic DMARD or Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors. In this registry, a smaller percentage of LORA patients compared with YORA patients were seropositive, which, given the enrollment of patients early in their disease course, may affect the use of biologic DMARD and JAK inhibitors.

Finally, the issue of noninflammatory pain contributing to disease activity and quality of life in RA has received increased scrutiny recently. Choy and colleagues studied disproportionate articular pain (DP) and its response to sarilumab, adalimumab, or placebo in a post hoc analysis of data from prior randomized clinical trials. DP was defined as a tender joint count that exceeded swollen joint count by seven and was present in about 20% of patients in the three randomized clinical trials examined. In these studies, DP was reduced in patients treated with sarilumab compared with placebo or adalimumab. Although this finding is exciting in raising the possibility of an immunologic explanation for DP via interleukin 6 (IL-6), the results should be considered carefully in the context of this post hoc analysis, especially before considering sarilumab or other IL-6 inhibitors as viable treatment options for DP in RA.

ObGyns united in a divided post-Dobbs America

While many anticipated the fall of Roe v Wade after the leaked Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) decision in the Dobbs v Jackson case, few may have fully comprehended the myriad of ways this ruling would create a national health care crisis overnight. Since the ruling, abortion has been banned, or a 6-week gestational age limit has been implemented, in a total of 13 states, all within the South

The 2022 American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) Annual Clinical and Scientific Meeting, held shortly after the leaked SCOTUS opinion, was unlike most others. ACOG staff appropriately recognized the vastly different ways this ruling would affect patients and providers alike, simply based on the states in which they reside. ACOG staff organized the large group of attendees according to self-identified status (ie, whether they worked in states with protected, restricted, or threatened access to abortion care). Since this is such a vast topic, attendees also were asked to identify an area upon which to focus, such as the provision of health care, advocacy, or education. As a clinician practicing in Massachusetts, Dr. Bradley found herself meeting with an ACOG leader from California as they brainstormed how to best help our own communities. In conversing with attendees from other parts of the country, it became apparent the challenges others would be facing elsewhere were far more substantive than those we would be facing in “blue states.” After the Dobbs ruling, those predictions became harsh realities.

As we begin to see and hear reports of the devastating consequences of this ruling in “red states,” those of us in protected states have been struggling to try and ascertain how to help. Many of us have worked with our own legislatures to further enshrine protections for our patients and clinicians. New York and Massachusetts exemplify these efforts.6,7 These legislative efforts have included liability protections for patients and their clinicians who care for those who travel from restricted to protected states. Others involve codifying the principles of Roe and clarifying existing law to improve access. An online fundraiser organized by physicians to assist Dr. Bernard with her legal costs as she faces politically motivated investigation by Indiana state authorities has raised more than $260,000.8 Many expressed the potential legal and medical peril for examiners and examinees if the American Board of Obstetrics and Gynecology held in-person oral examinations in Texas as previously scheduled.9 An online petition to change the format to virtual had 728 signatories, and the format was changed back to virtual.10

The implications on medical schools, residencies, and fellowships cannot be overstated. The Dobbs ruling almost immediately affected nearly half of the training programs, which is particularly problematic given the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education requirement that all ObGyn residents have access to abortion training.11 Other programs already are starting to try to meet this vast training need. The University of California San Francisco started offering training to physicians from Texas who were affected by the strict restrictions that predated Dobbs in the SB8 legislation, which turned ordinary citizens into vigilantes.12

ACOG has created an online resource (https://www.acog.org/advocacy/abortion-is-essential) with a number of different sections regarding clinical care, education and training, advocacy at the state level, and how to use effective language when talking about abortion in our communities. Planned Parenthood also suggests a myriad of ways those directly and indirectly affected could get involved:

- Donate to the National Network of Abortion Funds. This fund (https://secure.actblue.com/donate/fundabortionnow) facilitates care for those without the financial means to obtain it, supporting travel, lodging, and child care.

- Share #AbortionAccess posts on social media. These stories are a powerful reminder of the incredibly harmful impact this legislation can have on our patients.

- Donate to the If When How’s Legal Repro Defense Fund (https:/www.ifwhenhow.org/), which helps cover legal costs for those facing state persecution related to reproductive health care.

- Volunteer to help protect abortion health care at the state level.

- Engage with members of Congress in their home districts. (https://www.congress.gov/members/find-your-member)

- Contact the Planned Parenthood Local Engagement Team to facilitate your group, business, or organization’s involvement.

- Partner. Facilitate your organization and other companies to partner with Planned Parenthood and sign up for Bans off our Bodies (https://docs.google.com/forms/d/e/1FAIpQLSdrmxwMcwNXJ8I NE8S2gYjDDXuT76ws_Fr7CLm3 qbtR8dcZHw/viewform).

- Record your perspective about abortion (https://www.together.plannedparenthood.org/articles/6-share-abortion-story), whether it’s having had one, supported someone who had one, or advocated for others to have access to the procedure.13

ACOG also outlines several ways those of us in protected states could help shape the landscape in other communities in addition to advocating for state medical society resolutions, writing op-eds and letters to the editor, and utilizing ACOG’s social media graphics.14 In recognition of the often sensitive, polarizing nature of these discussions, ACOG is offering a workshop entitled “Building Evidence-Based Skills for Effective Conversations about Abortion.”15

Abortion traditionally was a policy issue other medical organizations shied away from developing official policy on and speaking out in support of, but recognizing the devastating scope of the public health crisis, 75 medical professional organizations recently released a strongly worded joint statement noting, “As leading medical and health care organizations dedicated to patient care and public health, we condemn this and all interference in the patient–clinician relationship.”16 Clinicians could work to expand this list to include all aspects of organized medicine. Initiatives to get out the vote may be helpful in vulnerable states, as well.

Clinicians in protected states are not necessarily directly affected in our daily interactions with patients, but we stand in solidarity with those who are. We must remain united as a profession as different state legislatures seek to divide us. We must support those who are struggling every day. Our colleagues and fellow citizens deserve nothing less. ●

- Tracking the states where abortion is now banned. New York Times. November 23, 2022. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2022/us/abortion-laws-roe-v-wade.html. Accessed November 28, 2022.

- Stanton A. ‘She’s 10’: child rape victims abortion denial spreads outrage on Twitter. Newsweek. July 2, 2022. https://www.newsweek.com/shes-10-child-rape-victims-abortion-denial-sparks-outrage-twitter-1721248. Accessed November 6, 2022.

- Judge-Golden C, Flink-Bochacki R. The burden of abortion restrictions and conservative diagnostic guidelines on patient-centered care for early pregnancy loss. Obstet Gynecol 2021;138:467071.

- Nambiar A, Patel S, Santiago-Munoz P, et al. Maternal morbidity and fetal outcomes among pregnant women at 22 weeks’ gestation or less with complications in 2 Texas hospitals after legislation on abortion. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2022;227:648-650.e1. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2022.06.060.

- Winter J. The Dobbs decision has unleashed legal chaos for doctors and patients. The New Yorker. July 2, 2022. https://www.newyorker.com/news/news-desk/the-dobbs-decision-has-unleashed-legal-chaos-for-doctors-and-patients. Accessed November 6, 2022.

- Lynch B, Mallow M, Bodde K, et al. Addressing a crisis in abortion access: a case study in advocacy. Obstet Gynecol. 2022;140:110-114.

- Evans M, Bradley T, Ireland L, et al. How the fall of Roe could change abortion care in Mass. Cognoscenti. July 26, 2022. https://www.wbur.org/cognoscenti/2022/07/26/dobbs-roe-abortion-massachusetts-megan-l-evans-erin-t-bradley-luu-ireland-chloe-zera. Accessed November 6, 2022.

- Spocchia G. Over $200k raised for doctor who performed abortion on 10-year-old rape victim. Independent. July 18, 2022. https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/americas/fundriaser-ohio-abortion-doctor-rape-b2125621.html. Accessed November 6, 2022.

- ABOG petition: convert to online examination to protect OBGYN providers. Change.org website. https://www.change.org/p/abog-petition?original_footer_petition_id=33459909&algorithm=promoted&source_location=petition_footer&grid_position=8&pt=AVBldGl0aW9uAHgWBQIAAAAAYs65vIyhbUxhZGM0MWVhZg%3D%3D. Accessed November 6, 2022.

- D’Ambrosio A. Ob/Gyn board certification exam stays virtual in light of Dobbs. MedPageToday. July 15, 2022. https://www.medpagetoday.com/special-reports/features/99758. Accessed November 6, 2022.

- Weiner S. How the repeal of Roe v. Wade will affect training in abortion and reproductive health. AAMC News. June 24, 2022. https://www.aamc.org/news-insights/how-repeal-roe-v-wade-will-affect-training-abortion-and-reproductive-health. Accessed November 6, 2022.

- Anderson N. The fall of Roe scrambles abortion training for university hospitals. The Washington Post. June 30, 2022. https://www.washingtonpost.com/education/2022/06/30/abortion-training-upheaval-dobbs/. Accessed November 6, 2022.

- Bans off our bodies. Planned Parenthood website. https://www.plannedparenthoodaction.org/rightfully-ours/bans-off-our-bodies. Accessed November 6, 2022.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Shape the public discourse. ACOG website. https://www.acog.org/advocacy/abortion-is-essential/connect-in-your-community. Accessed November 6, 2022.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Building evidence-based skills for effective conversations about abortion. ACOG website. https://www.acog.org/programs/impact/activities-initiatives/building-evidence-based-skills-for-effective-conversations-about-abortion. Accessed November 6, 2022.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. More than 75 health care organizations release joint statement in opposition to legislative interference. ACOG website. Published July 7, 2022. https://www.acog.org/news/news-releases/2022/07/more-than-75-health-care-organizations-release-joint-statement-in-opposition-to-legislative-interference. Accessed November 6, 2022.

While many anticipated the fall of Roe v Wade after the leaked Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) decision in the Dobbs v Jackson case, few may have fully comprehended the myriad of ways this ruling would create a national health care crisis overnight. Since the ruling, abortion has been banned, or a 6-week gestational age limit has been implemented, in a total of 13 states, all within the South

The 2022 American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) Annual Clinical and Scientific Meeting, held shortly after the leaked SCOTUS opinion, was unlike most others. ACOG staff appropriately recognized the vastly different ways this ruling would affect patients and providers alike, simply based on the states in which they reside. ACOG staff organized the large group of attendees according to self-identified status (ie, whether they worked in states with protected, restricted, or threatened access to abortion care). Since this is such a vast topic, attendees also were asked to identify an area upon which to focus, such as the provision of health care, advocacy, or education. As a clinician practicing in Massachusetts, Dr. Bradley found herself meeting with an ACOG leader from California as they brainstormed how to best help our own communities. In conversing with attendees from other parts of the country, it became apparent the challenges others would be facing elsewhere were far more substantive than those we would be facing in “blue states.” After the Dobbs ruling, those predictions became harsh realities.

As we begin to see and hear reports of the devastating consequences of this ruling in “red states,” those of us in protected states have been struggling to try and ascertain how to help. Many of us have worked with our own legislatures to further enshrine protections for our patients and clinicians. New York and Massachusetts exemplify these efforts.6,7 These legislative efforts have included liability protections for patients and their clinicians who care for those who travel from restricted to protected states. Others involve codifying the principles of Roe and clarifying existing law to improve access. An online fundraiser organized by physicians to assist Dr. Bernard with her legal costs as she faces politically motivated investigation by Indiana state authorities has raised more than $260,000.8 Many expressed the potential legal and medical peril for examiners and examinees if the American Board of Obstetrics and Gynecology held in-person oral examinations in Texas as previously scheduled.9 An online petition to change the format to virtual had 728 signatories, and the format was changed back to virtual.10

The implications on medical schools, residencies, and fellowships cannot be overstated. The Dobbs ruling almost immediately affected nearly half of the training programs, which is particularly problematic given the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education requirement that all ObGyn residents have access to abortion training.11 Other programs already are starting to try to meet this vast training need. The University of California San Francisco started offering training to physicians from Texas who were affected by the strict restrictions that predated Dobbs in the SB8 legislation, which turned ordinary citizens into vigilantes.12

ACOG has created an online resource (https://www.acog.org/advocacy/abortion-is-essential) with a number of different sections regarding clinical care, education and training, advocacy at the state level, and how to use effective language when talking about abortion in our communities. Planned Parenthood also suggests a myriad of ways those directly and indirectly affected could get involved:

- Donate to the National Network of Abortion Funds. This fund (https://secure.actblue.com/donate/fundabortionnow) facilitates care for those without the financial means to obtain it, supporting travel, lodging, and child care.

- Share #AbortionAccess posts on social media. These stories are a powerful reminder of the incredibly harmful impact this legislation can have on our patients.

- Donate to the If When How’s Legal Repro Defense Fund (https:/www.ifwhenhow.org/), which helps cover legal costs for those facing state persecution related to reproductive health care.

- Volunteer to help protect abortion health care at the state level.

- Engage with members of Congress in their home districts. (https://www.congress.gov/members/find-your-member)

- Contact the Planned Parenthood Local Engagement Team to facilitate your group, business, or organization’s involvement.

- Partner. Facilitate your organization and other companies to partner with Planned Parenthood and sign up for Bans off our Bodies (https://docs.google.com/forms/d/e/1FAIpQLSdrmxwMcwNXJ8I NE8S2gYjDDXuT76ws_Fr7CLm3 qbtR8dcZHw/viewform).

- Record your perspective about abortion (https://www.together.plannedparenthood.org/articles/6-share-abortion-story), whether it’s having had one, supported someone who had one, or advocated for others to have access to the procedure.13

ACOG also outlines several ways those of us in protected states could help shape the landscape in other communities in addition to advocating for state medical society resolutions, writing op-eds and letters to the editor, and utilizing ACOG’s social media graphics.14 In recognition of the often sensitive, polarizing nature of these discussions, ACOG is offering a workshop entitled “Building Evidence-Based Skills for Effective Conversations about Abortion.”15

Abortion traditionally was a policy issue other medical organizations shied away from developing official policy on and speaking out in support of, but recognizing the devastating scope of the public health crisis, 75 medical professional organizations recently released a strongly worded joint statement noting, “As leading medical and health care organizations dedicated to patient care and public health, we condemn this and all interference in the patient–clinician relationship.”16 Clinicians could work to expand this list to include all aspects of organized medicine. Initiatives to get out the vote may be helpful in vulnerable states, as well.

Clinicians in protected states are not necessarily directly affected in our daily interactions with patients, but we stand in solidarity with those who are. We must remain united as a profession as different state legislatures seek to divide us. We must support those who are struggling every day. Our colleagues and fellow citizens deserve nothing less. ●

While many anticipated the fall of Roe v Wade after the leaked Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) decision in the Dobbs v Jackson case, few may have fully comprehended the myriad of ways this ruling would create a national health care crisis overnight. Since the ruling, abortion has been banned, or a 6-week gestational age limit has been implemented, in a total of 13 states, all within the South

The 2022 American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) Annual Clinical and Scientific Meeting, held shortly after the leaked SCOTUS opinion, was unlike most others. ACOG staff appropriately recognized the vastly different ways this ruling would affect patients and providers alike, simply based on the states in which they reside. ACOG staff organized the large group of attendees according to self-identified status (ie, whether they worked in states with protected, restricted, or threatened access to abortion care). Since this is such a vast topic, attendees also were asked to identify an area upon which to focus, such as the provision of health care, advocacy, or education. As a clinician practicing in Massachusetts, Dr. Bradley found herself meeting with an ACOG leader from California as they brainstormed how to best help our own communities. In conversing with attendees from other parts of the country, it became apparent the challenges others would be facing elsewhere were far more substantive than those we would be facing in “blue states.” After the Dobbs ruling, those predictions became harsh realities.

As we begin to see and hear reports of the devastating consequences of this ruling in “red states,” those of us in protected states have been struggling to try and ascertain how to help. Many of us have worked with our own legislatures to further enshrine protections for our patients and clinicians. New York and Massachusetts exemplify these efforts.6,7 These legislative efforts have included liability protections for patients and their clinicians who care for those who travel from restricted to protected states. Others involve codifying the principles of Roe and clarifying existing law to improve access. An online fundraiser organized by physicians to assist Dr. Bernard with her legal costs as she faces politically motivated investigation by Indiana state authorities has raised more than $260,000.8 Many expressed the potential legal and medical peril for examiners and examinees if the American Board of Obstetrics and Gynecology held in-person oral examinations in Texas as previously scheduled.9 An online petition to change the format to virtual had 728 signatories, and the format was changed back to virtual.10

The implications on medical schools, residencies, and fellowships cannot be overstated. The Dobbs ruling almost immediately affected nearly half of the training programs, which is particularly problematic given the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education requirement that all ObGyn residents have access to abortion training.11 Other programs already are starting to try to meet this vast training need. The University of California San Francisco started offering training to physicians from Texas who were affected by the strict restrictions that predated Dobbs in the SB8 legislation, which turned ordinary citizens into vigilantes.12

ACOG has created an online resource (https://www.acog.org/advocacy/abortion-is-essential) with a number of different sections regarding clinical care, education and training, advocacy at the state level, and how to use effective language when talking about abortion in our communities. Planned Parenthood also suggests a myriad of ways those directly and indirectly affected could get involved:

- Donate to the National Network of Abortion Funds. This fund (https://secure.actblue.com/donate/fundabortionnow) facilitates care for those without the financial means to obtain it, supporting travel, lodging, and child care.

- Share #AbortionAccess posts on social media. These stories are a powerful reminder of the incredibly harmful impact this legislation can have on our patients.

- Donate to the If When How’s Legal Repro Defense Fund (https:/www.ifwhenhow.org/), which helps cover legal costs for those facing state persecution related to reproductive health care.

- Volunteer to help protect abortion health care at the state level.

- Engage with members of Congress in their home districts. (https://www.congress.gov/members/find-your-member)

- Contact the Planned Parenthood Local Engagement Team to facilitate your group, business, or organization’s involvement.

- Partner. Facilitate your organization and other companies to partner with Planned Parenthood and sign up for Bans off our Bodies (https://docs.google.com/forms/d/e/1FAIpQLSdrmxwMcwNXJ8I NE8S2gYjDDXuT76ws_Fr7CLm3 qbtR8dcZHw/viewform).

- Record your perspective about abortion (https://www.together.plannedparenthood.org/articles/6-share-abortion-story), whether it’s having had one, supported someone who had one, or advocated for others to have access to the procedure.13

ACOG also outlines several ways those of us in protected states could help shape the landscape in other communities in addition to advocating for state medical society resolutions, writing op-eds and letters to the editor, and utilizing ACOG’s social media graphics.14 In recognition of the often sensitive, polarizing nature of these discussions, ACOG is offering a workshop entitled “Building Evidence-Based Skills for Effective Conversations about Abortion.”15

Abortion traditionally was a policy issue other medical organizations shied away from developing official policy on and speaking out in support of, but recognizing the devastating scope of the public health crisis, 75 medical professional organizations recently released a strongly worded joint statement noting, “As leading medical and health care organizations dedicated to patient care and public health, we condemn this and all interference in the patient–clinician relationship.”16 Clinicians could work to expand this list to include all aspects of organized medicine. Initiatives to get out the vote may be helpful in vulnerable states, as well.

Clinicians in protected states are not necessarily directly affected in our daily interactions with patients, but we stand in solidarity with those who are. We must remain united as a profession as different state legislatures seek to divide us. We must support those who are struggling every day. Our colleagues and fellow citizens deserve nothing less. ●

- Tracking the states where abortion is now banned. New York Times. November 23, 2022. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2022/us/abortion-laws-roe-v-wade.html. Accessed November 28, 2022.

- Stanton A. ‘She’s 10’: child rape victims abortion denial spreads outrage on Twitter. Newsweek. July 2, 2022. https://www.newsweek.com/shes-10-child-rape-victims-abortion-denial-sparks-outrage-twitter-1721248. Accessed November 6, 2022.

- Judge-Golden C, Flink-Bochacki R. The burden of abortion restrictions and conservative diagnostic guidelines on patient-centered care for early pregnancy loss. Obstet Gynecol 2021;138:467071.

- Nambiar A, Patel S, Santiago-Munoz P, et al. Maternal morbidity and fetal outcomes among pregnant women at 22 weeks’ gestation or less with complications in 2 Texas hospitals after legislation on abortion. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2022;227:648-650.e1. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2022.06.060.

- Winter J. The Dobbs decision has unleashed legal chaos for doctors and patients. The New Yorker. July 2, 2022. https://www.newyorker.com/news/news-desk/the-dobbs-decision-has-unleashed-legal-chaos-for-doctors-and-patients. Accessed November 6, 2022.

- Lynch B, Mallow M, Bodde K, et al. Addressing a crisis in abortion access: a case study in advocacy. Obstet Gynecol. 2022;140:110-114.

- Evans M, Bradley T, Ireland L, et al. How the fall of Roe could change abortion care in Mass. Cognoscenti. July 26, 2022. https://www.wbur.org/cognoscenti/2022/07/26/dobbs-roe-abortion-massachusetts-megan-l-evans-erin-t-bradley-luu-ireland-chloe-zera. Accessed November 6, 2022.

- Spocchia G. Over $200k raised for doctor who performed abortion on 10-year-old rape victim. Independent. July 18, 2022. https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/americas/fundriaser-ohio-abortion-doctor-rape-b2125621.html. Accessed November 6, 2022.

- ABOG petition: convert to online examination to protect OBGYN providers. Change.org website. https://www.change.org/p/abog-petition?original_footer_petition_id=33459909&algorithm=promoted&source_location=petition_footer&grid_position=8&pt=AVBldGl0aW9uAHgWBQIAAAAAYs65vIyhbUxhZGM0MWVhZg%3D%3D. Accessed November 6, 2022.

- D’Ambrosio A. Ob/Gyn board certification exam stays virtual in light of Dobbs. MedPageToday. July 15, 2022. https://www.medpagetoday.com/special-reports/features/99758. Accessed November 6, 2022.

- Weiner S. How the repeal of Roe v. Wade will affect training in abortion and reproductive health. AAMC News. June 24, 2022. https://www.aamc.org/news-insights/how-repeal-roe-v-wade-will-affect-training-abortion-and-reproductive-health. Accessed November 6, 2022.

- Anderson N. The fall of Roe scrambles abortion training for university hospitals. The Washington Post. June 30, 2022. https://www.washingtonpost.com/education/2022/06/30/abortion-training-upheaval-dobbs/. Accessed November 6, 2022.

- Bans off our bodies. Planned Parenthood website. https://www.plannedparenthoodaction.org/rightfully-ours/bans-off-our-bodies. Accessed November 6, 2022.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Shape the public discourse. ACOG website. https://www.acog.org/advocacy/abortion-is-essential/connect-in-your-community. Accessed November 6, 2022.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Building evidence-based skills for effective conversations about abortion. ACOG website. https://www.acog.org/programs/impact/activities-initiatives/building-evidence-based-skills-for-effective-conversations-about-abortion. Accessed November 6, 2022.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. More than 75 health care organizations release joint statement in opposition to legislative interference. ACOG website. Published July 7, 2022. https://www.acog.org/news/news-releases/2022/07/more-than-75-health-care-organizations-release-joint-statement-in-opposition-to-legislative-interference. Accessed November 6, 2022.

- Tracking the states where abortion is now banned. New York Times. November 23, 2022. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2022/us/abortion-laws-roe-v-wade.html. Accessed November 28, 2022.

- Stanton A. ‘She’s 10’: child rape victims abortion denial spreads outrage on Twitter. Newsweek. July 2, 2022. https://www.newsweek.com/shes-10-child-rape-victims-abortion-denial-sparks-outrage-twitter-1721248. Accessed November 6, 2022.

- Judge-Golden C, Flink-Bochacki R. The burden of abortion restrictions and conservative diagnostic guidelines on patient-centered care for early pregnancy loss. Obstet Gynecol 2021;138:467071.

- Nambiar A, Patel S, Santiago-Munoz P, et al. Maternal morbidity and fetal outcomes among pregnant women at 22 weeks’ gestation or less with complications in 2 Texas hospitals after legislation on abortion. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2022;227:648-650.e1. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2022.06.060.

- Winter J. The Dobbs decision has unleashed legal chaos for doctors and patients. The New Yorker. July 2, 2022. https://www.newyorker.com/news/news-desk/the-dobbs-decision-has-unleashed-legal-chaos-for-doctors-and-patients. Accessed November 6, 2022.

- Lynch B, Mallow M, Bodde K, et al. Addressing a crisis in abortion access: a case study in advocacy. Obstet Gynecol. 2022;140:110-114.

- Evans M, Bradley T, Ireland L, et al. How the fall of Roe could change abortion care in Mass. Cognoscenti. July 26, 2022. https://www.wbur.org/cognoscenti/2022/07/26/dobbs-roe-abortion-massachusetts-megan-l-evans-erin-t-bradley-luu-ireland-chloe-zera. Accessed November 6, 2022.

- Spocchia G. Over $200k raised for doctor who performed abortion on 10-year-old rape victim. Independent. July 18, 2022. https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/americas/fundriaser-ohio-abortion-doctor-rape-b2125621.html. Accessed November 6, 2022.

- ABOG petition: convert to online examination to protect OBGYN providers. Change.org website. https://www.change.org/p/abog-petition?original_footer_petition_id=33459909&algorithm=promoted&source_location=petition_footer&grid_position=8&pt=AVBldGl0aW9uAHgWBQIAAAAAYs65vIyhbUxhZGM0MWVhZg%3D%3D. Accessed November 6, 2022.

- D’Ambrosio A. Ob/Gyn board certification exam stays virtual in light of Dobbs. MedPageToday. July 15, 2022. https://www.medpagetoday.com/special-reports/features/99758. Accessed November 6, 2022.

- Weiner S. How the repeal of Roe v. Wade will affect training in abortion and reproductive health. AAMC News. June 24, 2022. https://www.aamc.org/news-insights/how-repeal-roe-v-wade-will-affect-training-abortion-and-reproductive-health. Accessed November 6, 2022.

- Anderson N. The fall of Roe scrambles abortion training for university hospitals. The Washington Post. June 30, 2022. https://www.washingtonpost.com/education/2022/06/30/abortion-training-upheaval-dobbs/. Accessed November 6, 2022.

- Bans off our bodies. Planned Parenthood website. https://www.plannedparenthoodaction.org/rightfully-ours/bans-off-our-bodies. Accessed November 6, 2022.