User login

Dialysis not always best option in advanced kidney disease

ORLANDO – , new research shows.

“Patients mostly start dialysis because of unpleasant symptoms that cause suffering, including high potassium levels and high levels of uremic toxins in the blood,” senior author Kamyar Kalantar-Zadeh, MD, PhD, MPH, told this news organization.

“Conservative management serves to address and manage these symptoms and levels of toxicities without dialysis, so conservative management is an alternative approach, and patients should always be given a choice between [the two],” stressed Dr. Kalantar-Zadeh, professor of medicine at the University of California, Irvine.

The results were presented during the annual meeting of the American Society of Nephrology.

“There has been growing recognition of the importance of conservative nondialytic management as an alternative patient-centered treatment strategy for advanced kidney disease. However, conservative management remains under-utilized in the United States, which may in part be due to uncertainties regarding which patients will most benefit from dialysis versus nondialytic treatment,” said first author Connie Rhee, MD, also of the University of California, Irvine.

“We hope that these findings and further research can help inform treatment options for patients, care partners, and providers in the shared decision-making process of conservative management versus dialysis,” added Dr. Rhee, in a press release from the American Society of Nephrology.

Asked for comment, Sarah Davison, MD, noted that part of the Society’s strategy is, in fact, to promote conservative kidney management (CKM) as a key component of integrated care for patients with kidney failure. Dr. Davison is professor of medicine and chair of the International Society Working Group for Kidney Supportive Care and Conservative Kidney Management.

“We’ve recognized for a long time that there are many patients for whom dialysis provides neither a survival advantage nor a quality of life advantage,” she told this news organization.

“These patients tend to be those who have multiple morbidities, who are more frail, and who tend to be older, and in fact, the patients can live as long, if not longer, with better symptom management and better quality of life by not being on dialysis,” she stressed.

Study details

In the study, using data from the Optum Labs Data Warehouse, patients with advanced CKD were categorized according to whether or not they received conservative management, defined as those who did not receive dialysis within 2 years of the index eGFR (first eGFR < 25 mL/min/1.73m2) versus receipt of dialysis parsed as late versus early dialysis transition (eGFR < 15 vs. ≥ 15 mL/min/1.73m2 at dialysis initiation).

Hospitalization rates were compared between those treated with conservative management, compared with late or early dialysis.

“Among 309,188 advanced CKD patients who met eligibility [criteria], 55% of patients had greater than or equal to 1 hospitalization(s) within 2 years of the index eGFR,” the authors report. The most common causes of hospitalization among all patients were congestive heart failure, respiratory symptoms, or hypertension.

In most racial groups (non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, and Hispanic patients), patients on dialysis had higher hospitalization rates than those who received conservative management, and patients who started dialysis early (transitioned to dialysis at higher levels of kidney function) demonstrated the highest rates across all age groups, compared with those who started dialysis late (transitioned to dialysis at lower levels of kidney function) or were treated with conservative management.

Among Asian patients, those on dialysis also had higher hospitalization rates than those receiving conservative management, but patients who started dialysis late had higher rates than those on early dialysis, especially in older age groups, possibly because they were sicker, Dr. Kalantar-Zadeh suggested.

Conservative care has pros and cons, but Canada has embraced it

As Dr. Kalantar-Zadeh explained, conservative management has its pros and cons, compared with dialysis. “Conservative management requires that patients work with the multidisciplinary team including nephrologists, nutritionists, and others to try to manage CKD without dialysis, so it requires patient participation.”

On the other hand, dialysis is both easier and more lucrative than conservative management, at least for nephrologists, as they are well-trained in dialysis care, and it can be systematically applied. As to which patients with CKD might be optimal candidates for conservative management, Dr. Kalantar-Zadeh agreed this requires further study.

But he acknowledged that most nephrologists are not hugely supportive of conservative management because they are less well-trained in it, and it is more time-consuming. The one promising change is a new model introduced in 2022, a value-based kidney care model, that, if implemented, will be more incentivizing for nephrologists to offer conservative care more widely.

Dr. Davison meanwhile believes the “vast majority” of nephrologists based in Canada – as she is – are “highly supportive” of CKM as an important modality.

“The challenge, however, is that many nephrologists remain unsure as to how to best deliver or optimize all aspects of CKM, whether that is symptom management, advanced care planning, or how they must manage symptoms to align with a patient’s goals,” Dr. Davison explained.

“But it’s not that they do not believe in the value of CKM.”

Indeed, in her province, Alberta, nephrologists have been offering CKM for decades, and while they are currently standardizing care to make it easier to deliver, there is no financial incentive to offer dialysis over CKM.

“We are now seeing those elements of kidney supportive care as part of core competencies to manage any person with chronic illness, including CKD,” Dr. Davison said.

“So it’s absolutely doable, and contrary to one of the myths about CKM, it is not more time-consuming than dialysis – not when you know how to do it. You are just shifting your focus,” she emphasized.

The study was funded by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Dr. Kalantar-Zadeh has reported receiving honoraria and medical directorship fees from Fresenius and DaVita. Dr. Davison has reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

ORLANDO – , new research shows.

“Patients mostly start dialysis because of unpleasant symptoms that cause suffering, including high potassium levels and high levels of uremic toxins in the blood,” senior author Kamyar Kalantar-Zadeh, MD, PhD, MPH, told this news organization.

“Conservative management serves to address and manage these symptoms and levels of toxicities without dialysis, so conservative management is an alternative approach, and patients should always be given a choice between [the two],” stressed Dr. Kalantar-Zadeh, professor of medicine at the University of California, Irvine.

The results were presented during the annual meeting of the American Society of Nephrology.

“There has been growing recognition of the importance of conservative nondialytic management as an alternative patient-centered treatment strategy for advanced kidney disease. However, conservative management remains under-utilized in the United States, which may in part be due to uncertainties regarding which patients will most benefit from dialysis versus nondialytic treatment,” said first author Connie Rhee, MD, also of the University of California, Irvine.

“We hope that these findings and further research can help inform treatment options for patients, care partners, and providers in the shared decision-making process of conservative management versus dialysis,” added Dr. Rhee, in a press release from the American Society of Nephrology.

Asked for comment, Sarah Davison, MD, noted that part of the Society’s strategy is, in fact, to promote conservative kidney management (CKM) as a key component of integrated care for patients with kidney failure. Dr. Davison is professor of medicine and chair of the International Society Working Group for Kidney Supportive Care and Conservative Kidney Management.

“We’ve recognized for a long time that there are many patients for whom dialysis provides neither a survival advantage nor a quality of life advantage,” she told this news organization.

“These patients tend to be those who have multiple morbidities, who are more frail, and who tend to be older, and in fact, the patients can live as long, if not longer, with better symptom management and better quality of life by not being on dialysis,” she stressed.

Study details

In the study, using data from the Optum Labs Data Warehouse, patients with advanced CKD were categorized according to whether or not they received conservative management, defined as those who did not receive dialysis within 2 years of the index eGFR (first eGFR < 25 mL/min/1.73m2) versus receipt of dialysis parsed as late versus early dialysis transition (eGFR < 15 vs. ≥ 15 mL/min/1.73m2 at dialysis initiation).

Hospitalization rates were compared between those treated with conservative management, compared with late or early dialysis.

“Among 309,188 advanced CKD patients who met eligibility [criteria], 55% of patients had greater than or equal to 1 hospitalization(s) within 2 years of the index eGFR,” the authors report. The most common causes of hospitalization among all patients were congestive heart failure, respiratory symptoms, or hypertension.

In most racial groups (non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, and Hispanic patients), patients on dialysis had higher hospitalization rates than those who received conservative management, and patients who started dialysis early (transitioned to dialysis at higher levels of kidney function) demonstrated the highest rates across all age groups, compared with those who started dialysis late (transitioned to dialysis at lower levels of kidney function) or were treated with conservative management.

Among Asian patients, those on dialysis also had higher hospitalization rates than those receiving conservative management, but patients who started dialysis late had higher rates than those on early dialysis, especially in older age groups, possibly because they were sicker, Dr. Kalantar-Zadeh suggested.

Conservative care has pros and cons, but Canada has embraced it

As Dr. Kalantar-Zadeh explained, conservative management has its pros and cons, compared with dialysis. “Conservative management requires that patients work with the multidisciplinary team including nephrologists, nutritionists, and others to try to manage CKD without dialysis, so it requires patient participation.”

On the other hand, dialysis is both easier and more lucrative than conservative management, at least for nephrologists, as they are well-trained in dialysis care, and it can be systematically applied. As to which patients with CKD might be optimal candidates for conservative management, Dr. Kalantar-Zadeh agreed this requires further study.

But he acknowledged that most nephrologists are not hugely supportive of conservative management because they are less well-trained in it, and it is more time-consuming. The one promising change is a new model introduced in 2022, a value-based kidney care model, that, if implemented, will be more incentivizing for nephrologists to offer conservative care more widely.

Dr. Davison meanwhile believes the “vast majority” of nephrologists based in Canada – as she is – are “highly supportive” of CKM as an important modality.

“The challenge, however, is that many nephrologists remain unsure as to how to best deliver or optimize all aspects of CKM, whether that is symptom management, advanced care planning, or how they must manage symptoms to align with a patient’s goals,” Dr. Davison explained.

“But it’s not that they do not believe in the value of CKM.”

Indeed, in her province, Alberta, nephrologists have been offering CKM for decades, and while they are currently standardizing care to make it easier to deliver, there is no financial incentive to offer dialysis over CKM.

“We are now seeing those elements of kidney supportive care as part of core competencies to manage any person with chronic illness, including CKD,” Dr. Davison said.

“So it’s absolutely doable, and contrary to one of the myths about CKM, it is not more time-consuming than dialysis – not when you know how to do it. You are just shifting your focus,” she emphasized.

The study was funded by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Dr. Kalantar-Zadeh has reported receiving honoraria and medical directorship fees from Fresenius and DaVita. Dr. Davison has reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

ORLANDO – , new research shows.

“Patients mostly start dialysis because of unpleasant symptoms that cause suffering, including high potassium levels and high levels of uremic toxins in the blood,” senior author Kamyar Kalantar-Zadeh, MD, PhD, MPH, told this news organization.

“Conservative management serves to address and manage these symptoms and levels of toxicities without dialysis, so conservative management is an alternative approach, and patients should always be given a choice between [the two],” stressed Dr. Kalantar-Zadeh, professor of medicine at the University of California, Irvine.

The results were presented during the annual meeting of the American Society of Nephrology.

“There has been growing recognition of the importance of conservative nondialytic management as an alternative patient-centered treatment strategy for advanced kidney disease. However, conservative management remains under-utilized in the United States, which may in part be due to uncertainties regarding which patients will most benefit from dialysis versus nondialytic treatment,” said first author Connie Rhee, MD, also of the University of California, Irvine.

“We hope that these findings and further research can help inform treatment options for patients, care partners, and providers in the shared decision-making process of conservative management versus dialysis,” added Dr. Rhee, in a press release from the American Society of Nephrology.

Asked for comment, Sarah Davison, MD, noted that part of the Society’s strategy is, in fact, to promote conservative kidney management (CKM) as a key component of integrated care for patients with kidney failure. Dr. Davison is professor of medicine and chair of the International Society Working Group for Kidney Supportive Care and Conservative Kidney Management.

“We’ve recognized for a long time that there are many patients for whom dialysis provides neither a survival advantage nor a quality of life advantage,” she told this news organization.

“These patients tend to be those who have multiple morbidities, who are more frail, and who tend to be older, and in fact, the patients can live as long, if not longer, with better symptom management and better quality of life by not being on dialysis,” she stressed.

Study details

In the study, using data from the Optum Labs Data Warehouse, patients with advanced CKD were categorized according to whether or not they received conservative management, defined as those who did not receive dialysis within 2 years of the index eGFR (first eGFR < 25 mL/min/1.73m2) versus receipt of dialysis parsed as late versus early dialysis transition (eGFR < 15 vs. ≥ 15 mL/min/1.73m2 at dialysis initiation).

Hospitalization rates were compared between those treated with conservative management, compared with late or early dialysis.

“Among 309,188 advanced CKD patients who met eligibility [criteria], 55% of patients had greater than or equal to 1 hospitalization(s) within 2 years of the index eGFR,” the authors report. The most common causes of hospitalization among all patients were congestive heart failure, respiratory symptoms, or hypertension.

In most racial groups (non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, and Hispanic patients), patients on dialysis had higher hospitalization rates than those who received conservative management, and patients who started dialysis early (transitioned to dialysis at higher levels of kidney function) demonstrated the highest rates across all age groups, compared with those who started dialysis late (transitioned to dialysis at lower levels of kidney function) or were treated with conservative management.

Among Asian patients, those on dialysis also had higher hospitalization rates than those receiving conservative management, but patients who started dialysis late had higher rates than those on early dialysis, especially in older age groups, possibly because they were sicker, Dr. Kalantar-Zadeh suggested.

Conservative care has pros and cons, but Canada has embraced it

As Dr. Kalantar-Zadeh explained, conservative management has its pros and cons, compared with dialysis. “Conservative management requires that patients work with the multidisciplinary team including nephrologists, nutritionists, and others to try to manage CKD without dialysis, so it requires patient participation.”

On the other hand, dialysis is both easier and more lucrative than conservative management, at least for nephrologists, as they are well-trained in dialysis care, and it can be systematically applied. As to which patients with CKD might be optimal candidates for conservative management, Dr. Kalantar-Zadeh agreed this requires further study.

But he acknowledged that most nephrologists are not hugely supportive of conservative management because they are less well-trained in it, and it is more time-consuming. The one promising change is a new model introduced in 2022, a value-based kidney care model, that, if implemented, will be more incentivizing for nephrologists to offer conservative care more widely.

Dr. Davison meanwhile believes the “vast majority” of nephrologists based in Canada – as she is – are “highly supportive” of CKM as an important modality.

“The challenge, however, is that many nephrologists remain unsure as to how to best deliver or optimize all aspects of CKM, whether that is symptom management, advanced care planning, or how they must manage symptoms to align with a patient’s goals,” Dr. Davison explained.

“But it’s not that they do not believe in the value of CKM.”

Indeed, in her province, Alberta, nephrologists have been offering CKM for decades, and while they are currently standardizing care to make it easier to deliver, there is no financial incentive to offer dialysis over CKM.

“We are now seeing those elements of kidney supportive care as part of core competencies to manage any person with chronic illness, including CKD,” Dr. Davison said.

“So it’s absolutely doable, and contrary to one of the myths about CKM, it is not more time-consuming than dialysis – not when you know how to do it. You are just shifting your focus,” she emphasized.

The study was funded by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Dr. Kalantar-Zadeh has reported receiving honoraria and medical directorship fees from Fresenius and DaVita. Dr. Davison has reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

AT KIDNEY WEEK 2022

Patients complain some obesity care startups offer pills, and not much else

Many Americans turn to the latest big idea to lose weight – fad diets, fitness crazes, dodgy herbs and pills, bariatric surgery, just to name a few. They’re rarely the magic solution people dream of.

Now a wave of startups offer access to a new category of drugs coupled with intensive behavioral coaching online. But already concerns are emerging.

These startups, spurred by hundreds of millions of dollars in funding from blue-chip venture capital firms, have signed up well over 100,000 patients and could reach millions more. These patients pay hundreds, if not thousands, of dollars to access new drugs, called glucagonlike peptide–1 (GLP-1) agonists, along with online coaching to encourage healthy habits.

The startups initially positioned themselves in lofty terms. “This is the last weight-loss program you’ll try,” said a 2020 marketing analysis by startup Calibrate Health, in messaging designed to reach one of its target demographics, the “working mom.” (Company spokesperson Michelle Wellington said the document does not reflect Calibrate’s current marketing strategy.)

But while doctors and patients are intrigued by the new model, some customers complain online that reality is short of the buildup: They say they got canned advice and unresponsive clinicians – and some report they couldn’t get the newest drugs.

Calibrate Health, a New York City–based startup, reported earlier in 2022 it had served 20,000 people. Another startup, Found, headquartered in San Francisco, has served 135,000 patients since July 2020, CEO Sarah Jones Simmer said in an interview. Calibrate costs patients nearly $1,600 a year, not counting the price of drugs, which can hit nearly $1,500 monthly without insurance, according to drug price savings site GoodRx. (Insurers reimburse for GLP-1agonists in limited circumstances, patients said.) Found offers a 6-month plan for nearly $600, a company spokesperson said. (That price includes generic drugs, but not the newer GLP-1 agonists, like Wegovy.)

The two companies are beneficiaries of over $200 million in combined venture funding, according to tracking by Crunchbase, a repository of venture capital investments. The firms say they’re on the vanguard of weight care, both citing the influence of biology and other scientific factors as key ingredients to their approaches.

There’s potentially a big market for these startups. Just over 4 in 10 Americans are obese, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, driving up their risk for cardiovascular conditions and type 2 diabetes. Effective medical treatments are elusive and hard to access.

Centers that provide this specialty care “are overwhelmed,” said Fatima Stanford, MD, an obesity medicine specialist at Massachusetts General in Boston, a teaching hospital affiliated with Harvard. Her own clinic has a wait list of 3,000.

Dr. Stanford, who said she has advised several of these telemedicine startups, is bullish on their potential.

Scott Butsch, MD, director of obesity medicine at the Cleveland Clinic, said the startups can offer care with less judgment and stigma than in-person peers. They’re also more convenient.

Dr. Butsch, who learned about the model through consultancies, patients, and colleagues, wonders whether the startups are operating “to strategically find which patients respond to which drug.” He said they should coordinate well with behavioral specialists, as antidepressants or other medications may be driving weight gain. “Obesity is a complex disease and requires treatments that match its complexity. I think programs that do not have a multidisciplinary team are less comprehensive and, in the long term, less effective.”

The startups market a two-pronged product: first, the new class of GLP-1 agonists. While these medications are effective at provoking weight loss, Wegovy, one of two in this class specifically approved for this purpose, is in short supply because of manufacturing difficulties, according to its maker, Novo Nordisk. Others in the category can be prescribed off label. But doctors generally aren’t familiar with the medications, Stanford said. In theory, the startups can bridge some of those gaps: They offer more specialized, knowledgeable clinicians.

Then there’s the other prong: behavioral changes. The companies use televisits and online messaging with nutritionists or coaches to help patients incorporate new diet and exercise habits. The weight loss figures achieved by participants in clinical trials for the new drugs – up to 15% of body mass – were tied to such changes, according to Novo Nordisk.

Social media sites are bursting with these startups’ ads, everywhere from podcasts to Instagram. A search of Meta’s ad library finds 40,000 ads on Facebook and Instagram between the two firms.

The ads complement people’s own postings on social media: Numerous Facebook groups are devoted to the new type of drugs – some even focused on helping patients manage side effects, like changes in their bowel movements. The buzz is quantifiable: On TikTok, mentions of the new GLP-1 agonists tripled from last June to this June, according to an analysis by investment bankers at Morgan Stanley.

There’s now a feverish, expectant appetite for these medications among the startups’ clientele. Patients often complained that their friends had obtained a drug they weren’t offered, recalled Alexandra Coults, a former pharmacist consultant for Found. Ms. Coults said patients may have perceived some sort of bait-and-switch when in reality clinical reasons – like drug contraindications – guide prescribing decisions.

Patient expectations influence care, Ms. Coults said. Customers came in with ideas shaped by the culture of fad diets and New Year’s resolutions. “Quite a few people would sign up for 1 month and not continue.”

In interviews with KHN and in online complaints, patients also questioned the quality of care they received. Some said intake – which began by filling out a form and proceeded to an online visit with a doctor – was perfunctory. Once medication began, they said, requests for counseling about side effects were slow to be answered.

Jess Garrant, a Found patient, recalled that after she was prescribed zonisamide, a generic anticonvulsant that has shown some ability to help with weight loss, she felt “absolutely weird.”

“I was up all night and my thoughts were racing,” she wrote in a blog post. She developed sores in her mouth.

She sought advice and help from Found physicians, but their replies “weren’t quick.” Nonemergency communications are routed through the company’s portal.

It took a week to complete a switch of medications and have a new prescription arrive at her home, she said. Meanwhile, she said, she went to an urgent care clinic for the mouth sores.

Found frequently prescribes generic medications – often off label – rather than just the new GLP-1 agonists, company executives said in an interview. Found said older generics like zonisamide are more accessible than the GLP-1 agonists advertised on social media and their own website. Both Dr. Butsch and Dr. Stanford said they’ve prescribed zonisamide successfully. Dr. Butsch said ramping up dosage rapidly can increase the risk of side effects.

But Kim Boyd, MD, chief medical officer of competitor Calibrate, said the older drugs “just haven’t worked.”

Patients of both companies have critiqued online and in interviews the startups’ behavioral care – which experts across the board maintain is integral to successful weight loss treatment. But some patients felt they simply had canned advice.

Other patients said they had ups and downs with their coaches. Dana Crom, an attorney, said she had gone through many coaches with Calibrate. Some were good, effective cheerleaders; others, not so good. But when kinks in the program arose, she said, the coach wasn’t able to help her navigate them. While the coach can report trouble with medications or the app, it appears those reports are no more effective than messages sent through the portal, Ms. Crom said.

And what about when her yearlong subscription ends? Ms. Crom said she’d consider continuing with Calibrate.

Relationships with coaches, given the need to change behavior, are a critical element of the business models. Patients’ results depend “on how adherent they are to lifestyle changes,” said Found’s chief medical officer, Rehka Kumar, MD.

While the startups offer care to a larger geographic footprint, it’s not clear whether the demographics of their patient populations are different from those of the traditional bricks-and-mortar model. Calibrate’s patients are overwhelmingly White; over 8 in 10 have at least an undergraduate degree; and over 8 in 10 are women, according to the company.

And its earlier marketing strategies reflected that. The September 2020 “segmentation” document laid out three types of customers the company could hope to attract: perimenopausal or menopausal women, with income ranging from $75,000 to $150,000 a year; working mothers, with a similar income; and “men.”

Isabelle Kenyon, Calibrate’s CEO, said the company now hopes to expand its reach to partner with large employers, and that will help diversify its patients.

Patients will need to be convinced that the model – more affordable, more accessible – works for them. For her part, Ms. Garrant, who no longer is using Found, reflected on her experience, writing in her blog post that she was hoping for more follow-up and a more personal approach. “I don’t think it’s a helpful way to lose weight,” she said.

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

Many Americans turn to the latest big idea to lose weight – fad diets, fitness crazes, dodgy herbs and pills, bariatric surgery, just to name a few. They’re rarely the magic solution people dream of.

Now a wave of startups offer access to a new category of drugs coupled with intensive behavioral coaching online. But already concerns are emerging.

These startups, spurred by hundreds of millions of dollars in funding from blue-chip venture capital firms, have signed up well over 100,000 patients and could reach millions more. These patients pay hundreds, if not thousands, of dollars to access new drugs, called glucagonlike peptide–1 (GLP-1) agonists, along with online coaching to encourage healthy habits.

The startups initially positioned themselves in lofty terms. “This is the last weight-loss program you’ll try,” said a 2020 marketing analysis by startup Calibrate Health, in messaging designed to reach one of its target demographics, the “working mom.” (Company spokesperson Michelle Wellington said the document does not reflect Calibrate’s current marketing strategy.)

But while doctors and patients are intrigued by the new model, some customers complain online that reality is short of the buildup: They say they got canned advice and unresponsive clinicians – and some report they couldn’t get the newest drugs.

Calibrate Health, a New York City–based startup, reported earlier in 2022 it had served 20,000 people. Another startup, Found, headquartered in San Francisco, has served 135,000 patients since July 2020, CEO Sarah Jones Simmer said in an interview. Calibrate costs patients nearly $1,600 a year, not counting the price of drugs, which can hit nearly $1,500 monthly without insurance, according to drug price savings site GoodRx. (Insurers reimburse for GLP-1agonists in limited circumstances, patients said.) Found offers a 6-month plan for nearly $600, a company spokesperson said. (That price includes generic drugs, but not the newer GLP-1 agonists, like Wegovy.)

The two companies are beneficiaries of over $200 million in combined venture funding, according to tracking by Crunchbase, a repository of venture capital investments. The firms say they’re on the vanguard of weight care, both citing the influence of biology and other scientific factors as key ingredients to their approaches.

There’s potentially a big market for these startups. Just over 4 in 10 Americans are obese, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, driving up their risk for cardiovascular conditions and type 2 diabetes. Effective medical treatments are elusive and hard to access.

Centers that provide this specialty care “are overwhelmed,” said Fatima Stanford, MD, an obesity medicine specialist at Massachusetts General in Boston, a teaching hospital affiliated with Harvard. Her own clinic has a wait list of 3,000.

Dr. Stanford, who said she has advised several of these telemedicine startups, is bullish on their potential.

Scott Butsch, MD, director of obesity medicine at the Cleveland Clinic, said the startups can offer care with less judgment and stigma than in-person peers. They’re also more convenient.

Dr. Butsch, who learned about the model through consultancies, patients, and colleagues, wonders whether the startups are operating “to strategically find which patients respond to which drug.” He said they should coordinate well with behavioral specialists, as antidepressants or other medications may be driving weight gain. “Obesity is a complex disease and requires treatments that match its complexity. I think programs that do not have a multidisciplinary team are less comprehensive and, in the long term, less effective.”

The startups market a two-pronged product: first, the new class of GLP-1 agonists. While these medications are effective at provoking weight loss, Wegovy, one of two in this class specifically approved for this purpose, is in short supply because of manufacturing difficulties, according to its maker, Novo Nordisk. Others in the category can be prescribed off label. But doctors generally aren’t familiar with the medications, Stanford said. In theory, the startups can bridge some of those gaps: They offer more specialized, knowledgeable clinicians.

Then there’s the other prong: behavioral changes. The companies use televisits and online messaging with nutritionists or coaches to help patients incorporate new diet and exercise habits. The weight loss figures achieved by participants in clinical trials for the new drugs – up to 15% of body mass – were tied to such changes, according to Novo Nordisk.

Social media sites are bursting with these startups’ ads, everywhere from podcasts to Instagram. A search of Meta’s ad library finds 40,000 ads on Facebook and Instagram between the two firms.

The ads complement people’s own postings on social media: Numerous Facebook groups are devoted to the new type of drugs – some even focused on helping patients manage side effects, like changes in their bowel movements. The buzz is quantifiable: On TikTok, mentions of the new GLP-1 agonists tripled from last June to this June, according to an analysis by investment bankers at Morgan Stanley.

There’s now a feverish, expectant appetite for these medications among the startups’ clientele. Patients often complained that their friends had obtained a drug they weren’t offered, recalled Alexandra Coults, a former pharmacist consultant for Found. Ms. Coults said patients may have perceived some sort of bait-and-switch when in reality clinical reasons – like drug contraindications – guide prescribing decisions.

Patient expectations influence care, Ms. Coults said. Customers came in with ideas shaped by the culture of fad diets and New Year’s resolutions. “Quite a few people would sign up for 1 month and not continue.”

In interviews with KHN and in online complaints, patients also questioned the quality of care they received. Some said intake – which began by filling out a form and proceeded to an online visit with a doctor – was perfunctory. Once medication began, they said, requests for counseling about side effects were slow to be answered.

Jess Garrant, a Found patient, recalled that after she was prescribed zonisamide, a generic anticonvulsant that has shown some ability to help with weight loss, she felt “absolutely weird.”

“I was up all night and my thoughts were racing,” she wrote in a blog post. She developed sores in her mouth.

She sought advice and help from Found physicians, but their replies “weren’t quick.” Nonemergency communications are routed through the company’s portal.

It took a week to complete a switch of medications and have a new prescription arrive at her home, she said. Meanwhile, she said, she went to an urgent care clinic for the mouth sores.

Found frequently prescribes generic medications – often off label – rather than just the new GLP-1 agonists, company executives said in an interview. Found said older generics like zonisamide are more accessible than the GLP-1 agonists advertised on social media and their own website. Both Dr. Butsch and Dr. Stanford said they’ve prescribed zonisamide successfully. Dr. Butsch said ramping up dosage rapidly can increase the risk of side effects.

But Kim Boyd, MD, chief medical officer of competitor Calibrate, said the older drugs “just haven’t worked.”

Patients of both companies have critiqued online and in interviews the startups’ behavioral care – which experts across the board maintain is integral to successful weight loss treatment. But some patients felt they simply had canned advice.

Other patients said they had ups and downs with their coaches. Dana Crom, an attorney, said she had gone through many coaches with Calibrate. Some were good, effective cheerleaders; others, not so good. But when kinks in the program arose, she said, the coach wasn’t able to help her navigate them. While the coach can report trouble with medications or the app, it appears those reports are no more effective than messages sent through the portal, Ms. Crom said.

And what about when her yearlong subscription ends? Ms. Crom said she’d consider continuing with Calibrate.

Relationships with coaches, given the need to change behavior, are a critical element of the business models. Patients’ results depend “on how adherent they are to lifestyle changes,” said Found’s chief medical officer, Rehka Kumar, MD.

While the startups offer care to a larger geographic footprint, it’s not clear whether the demographics of their patient populations are different from those of the traditional bricks-and-mortar model. Calibrate’s patients are overwhelmingly White; over 8 in 10 have at least an undergraduate degree; and over 8 in 10 are women, according to the company.

And its earlier marketing strategies reflected that. The September 2020 “segmentation” document laid out three types of customers the company could hope to attract: perimenopausal or menopausal women, with income ranging from $75,000 to $150,000 a year; working mothers, with a similar income; and “men.”

Isabelle Kenyon, Calibrate’s CEO, said the company now hopes to expand its reach to partner with large employers, and that will help diversify its patients.

Patients will need to be convinced that the model – more affordable, more accessible – works for them. For her part, Ms. Garrant, who no longer is using Found, reflected on her experience, writing in her blog post that she was hoping for more follow-up and a more personal approach. “I don’t think it’s a helpful way to lose weight,” she said.

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

Many Americans turn to the latest big idea to lose weight – fad diets, fitness crazes, dodgy herbs and pills, bariatric surgery, just to name a few. They’re rarely the magic solution people dream of.

Now a wave of startups offer access to a new category of drugs coupled with intensive behavioral coaching online. But already concerns are emerging.

These startups, spurred by hundreds of millions of dollars in funding from blue-chip venture capital firms, have signed up well over 100,000 patients and could reach millions more. These patients pay hundreds, if not thousands, of dollars to access new drugs, called glucagonlike peptide–1 (GLP-1) agonists, along with online coaching to encourage healthy habits.

The startups initially positioned themselves in lofty terms. “This is the last weight-loss program you’ll try,” said a 2020 marketing analysis by startup Calibrate Health, in messaging designed to reach one of its target demographics, the “working mom.” (Company spokesperson Michelle Wellington said the document does not reflect Calibrate’s current marketing strategy.)

But while doctors and patients are intrigued by the new model, some customers complain online that reality is short of the buildup: They say they got canned advice and unresponsive clinicians – and some report they couldn’t get the newest drugs.

Calibrate Health, a New York City–based startup, reported earlier in 2022 it had served 20,000 people. Another startup, Found, headquartered in San Francisco, has served 135,000 patients since July 2020, CEO Sarah Jones Simmer said in an interview. Calibrate costs patients nearly $1,600 a year, not counting the price of drugs, which can hit nearly $1,500 monthly without insurance, according to drug price savings site GoodRx. (Insurers reimburse for GLP-1agonists in limited circumstances, patients said.) Found offers a 6-month plan for nearly $600, a company spokesperson said. (That price includes generic drugs, but not the newer GLP-1 agonists, like Wegovy.)

The two companies are beneficiaries of over $200 million in combined venture funding, according to tracking by Crunchbase, a repository of venture capital investments. The firms say they’re on the vanguard of weight care, both citing the influence of biology and other scientific factors as key ingredients to their approaches.

There’s potentially a big market for these startups. Just over 4 in 10 Americans are obese, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, driving up their risk for cardiovascular conditions and type 2 diabetes. Effective medical treatments are elusive and hard to access.

Centers that provide this specialty care “are overwhelmed,” said Fatima Stanford, MD, an obesity medicine specialist at Massachusetts General in Boston, a teaching hospital affiliated with Harvard. Her own clinic has a wait list of 3,000.

Dr. Stanford, who said she has advised several of these telemedicine startups, is bullish on their potential.

Scott Butsch, MD, director of obesity medicine at the Cleveland Clinic, said the startups can offer care with less judgment and stigma than in-person peers. They’re also more convenient.

Dr. Butsch, who learned about the model through consultancies, patients, and colleagues, wonders whether the startups are operating “to strategically find which patients respond to which drug.” He said they should coordinate well with behavioral specialists, as antidepressants or other medications may be driving weight gain. “Obesity is a complex disease and requires treatments that match its complexity. I think programs that do not have a multidisciplinary team are less comprehensive and, in the long term, less effective.”

The startups market a two-pronged product: first, the new class of GLP-1 agonists. While these medications are effective at provoking weight loss, Wegovy, one of two in this class specifically approved for this purpose, is in short supply because of manufacturing difficulties, according to its maker, Novo Nordisk. Others in the category can be prescribed off label. But doctors generally aren’t familiar with the medications, Stanford said. In theory, the startups can bridge some of those gaps: They offer more specialized, knowledgeable clinicians.

Then there’s the other prong: behavioral changes. The companies use televisits and online messaging with nutritionists or coaches to help patients incorporate new diet and exercise habits. The weight loss figures achieved by participants in clinical trials for the new drugs – up to 15% of body mass – were tied to such changes, according to Novo Nordisk.

Social media sites are bursting with these startups’ ads, everywhere from podcasts to Instagram. A search of Meta’s ad library finds 40,000 ads on Facebook and Instagram between the two firms.

The ads complement people’s own postings on social media: Numerous Facebook groups are devoted to the new type of drugs – some even focused on helping patients manage side effects, like changes in their bowel movements. The buzz is quantifiable: On TikTok, mentions of the new GLP-1 agonists tripled from last June to this June, according to an analysis by investment bankers at Morgan Stanley.

There’s now a feverish, expectant appetite for these medications among the startups’ clientele. Patients often complained that their friends had obtained a drug they weren’t offered, recalled Alexandra Coults, a former pharmacist consultant for Found. Ms. Coults said patients may have perceived some sort of bait-and-switch when in reality clinical reasons – like drug contraindications – guide prescribing decisions.

Patient expectations influence care, Ms. Coults said. Customers came in with ideas shaped by the culture of fad diets and New Year’s resolutions. “Quite a few people would sign up for 1 month and not continue.”

In interviews with KHN and in online complaints, patients also questioned the quality of care they received. Some said intake – which began by filling out a form and proceeded to an online visit with a doctor – was perfunctory. Once medication began, they said, requests for counseling about side effects were slow to be answered.

Jess Garrant, a Found patient, recalled that after she was prescribed zonisamide, a generic anticonvulsant that has shown some ability to help with weight loss, she felt “absolutely weird.”

“I was up all night and my thoughts were racing,” she wrote in a blog post. She developed sores in her mouth.

She sought advice and help from Found physicians, but their replies “weren’t quick.” Nonemergency communications are routed through the company’s portal.

It took a week to complete a switch of medications and have a new prescription arrive at her home, she said. Meanwhile, she said, she went to an urgent care clinic for the mouth sores.

Found frequently prescribes generic medications – often off label – rather than just the new GLP-1 agonists, company executives said in an interview. Found said older generics like zonisamide are more accessible than the GLP-1 agonists advertised on social media and their own website. Both Dr. Butsch and Dr. Stanford said they’ve prescribed zonisamide successfully. Dr. Butsch said ramping up dosage rapidly can increase the risk of side effects.

But Kim Boyd, MD, chief medical officer of competitor Calibrate, said the older drugs “just haven’t worked.”

Patients of both companies have critiqued online and in interviews the startups’ behavioral care – which experts across the board maintain is integral to successful weight loss treatment. But some patients felt they simply had canned advice.

Other patients said they had ups and downs with their coaches. Dana Crom, an attorney, said she had gone through many coaches with Calibrate. Some were good, effective cheerleaders; others, not so good. But when kinks in the program arose, she said, the coach wasn’t able to help her navigate them. While the coach can report trouble with medications or the app, it appears those reports are no more effective than messages sent through the portal, Ms. Crom said.

And what about when her yearlong subscription ends? Ms. Crom said she’d consider continuing with Calibrate.

Relationships with coaches, given the need to change behavior, are a critical element of the business models. Patients’ results depend “on how adherent they are to lifestyle changes,” said Found’s chief medical officer, Rehka Kumar, MD.

While the startups offer care to a larger geographic footprint, it’s not clear whether the demographics of their patient populations are different from those of the traditional bricks-and-mortar model. Calibrate’s patients are overwhelmingly White; over 8 in 10 have at least an undergraduate degree; and over 8 in 10 are women, according to the company.

And its earlier marketing strategies reflected that. The September 2020 “segmentation” document laid out three types of customers the company could hope to attract: perimenopausal or menopausal women, with income ranging from $75,000 to $150,000 a year; working mothers, with a similar income; and “men.”

Isabelle Kenyon, Calibrate’s CEO, said the company now hopes to expand its reach to partner with large employers, and that will help diversify its patients.

Patients will need to be convinced that the model – more affordable, more accessible – works for them. For her part, Ms. Garrant, who no longer is using Found, reflected on her experience, writing in her blog post that she was hoping for more follow-up and a more personal approach. “I don’t think it’s a helpful way to lose weight,” she said.

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

Prednisone, colchicine equivalent in efficacy for CPP crystal arthritis

PHILADELPHIA – Prednisone appears to have the edge over colchicine for control of pain in patients with acute calcium pyrophosphate (CPP) crystal arthritis, an intensely painful rheumatic disease primarily affecting older patients.

Among 111 patients with acute CPP crystal arthritis randomized to receive either prednisone or colchicine for control of acute pain in a multicenter study, 2 days of therapy with the oral agents provided equivalent pain relief on the second day, and patients generally tolerated each agent well, reported Tristan Pascart, MD, from the Groupement Hospitalier de l’Institut Catholique de Lille (France).

“Almost three-fourths of patients are considered to be good responders to both drugs on day 3, and, maybe, safety is the key issue distinguishing the two treatments: Colchicine was generally well tolerated, but even with this very short time frame of treatment, one patient out of five had diarrhea, which is more of a concern in this elderly population at risk of dehydration,” he said in an oral abstract session at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

In contrast, only about 6% of patients assigned to prednisone had diarrhea, and other adverse events that occurred more frequently with the corticosteroid, including hypertension, hyperglycemia, and insomnia all resolved after the therapy was stopped.

Common and acutely painful

Acute CPP crystal arthritis is a common complication that often occurs during hospitalization for primarily nonrheumatologic causes, Dr. Pascart said, and “in the absence of clinical trials, the management relies on expert opinion, which stems from extrapolated data from gap studies” primarily with prednisone or colchicine, Dr. Pascart said.

To fill in the knowledge gap, Dr. Pascart and colleagues conducted the COLCHICORT study to evaluate whether the two drugs were comparable in efficacy and safety for control of acute pain in a vulnerable population.

The multicenter, open-label trial included patients older than age 65 years with an estimated glomerular filtration rate above 30 mL/min per 1.73 m2 who presented with acute CPP deposition arthritis with symptoms occurring within the previous 36 hours. CPP arthritis was defined by the identification of CPP crystals on synovial fluid analysis or typical clinical presentation with evidence of chondrocalcinosis on x-rays or ultrasound.

Patients with a history of gout, cognitive decline that could impair pain assessment, or contraindications to either of the study drugs were excluded.

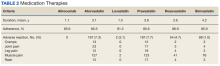

The participants were randomized to receive either colchicine 1.5 mg (1 mg to start, then 0.5 mg one hour later) at baseline and then 1 mg on day 1, or oral prednisone 30 mg at baseline and on day 1. The patients also received 1 g of systemic acetaminophen, and three 50-mg doses of tramadol during the first 24 hours.

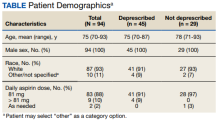

Of the 111 patients randomized, 54 were assigned to receive prednisone, and 57 were assigned to receive colchicine. Baseline characteristics were similar between the groups, with a mean age of about 86 years, body mass index of around 25 kg/m2, and blood pressure in the range of 130/69 mm Hg.

For nearly half of all patients in study each arm the most painful joint was the knee, followed by wrists and ankles.

There was no difference between the groups in the primary efficacy outcome of a change at 24 hours over baseline in visual analog scale (VAS) (0-100 mm) scores, either in a per-protocol analysis or modified intention-to-treat analysis. The mean change in VAS at 24 hours in the colchicine group was –36.6 mm, compared with –37.7 mm in the prednisone group. The investigators had previously determined that any difference between the two drugs of less than 13 mm on pain VAS at 24 hours would meet the definition for equivalent efficacy.

In both groups, a majority of patients had either an improvement greater than 50% in pain VAS scores and/or a pain VAS score less than 40 mm at both 24 and 48 hours.

At 7 days of follow-up, 21.8% of patients assigned to colchicine had diarrhea, compared with 5.6% of those assigned to prednisone. Adverse events occurring more frequently with prednisone included hyperglycemia, hypertension, and insomnia.

Patients who received colchicine and were also on statins had a trend toward a higher risk for diarrhea, but the study was not adequately powered to detect an association, and the trend was not statistically significant, Dr. Pascart said.

“Taken together, safety issues suggest that prednisone should be considered as the first-line therapy in acute CPP crystal arthritis. Future research is warranted to determine factors increasing the risk of colchicine-induced diarrhea,” he concluded.

Both drugs are used

Sara K. Tedeschi, MD, from Brigham & Women’s Hospital in Boston, who attended the session where the data were presented, has a special clinical interest in CPP deposition disease. She applauded Dr. Pascart and colleagues for conducting a rare clinical trial in CPP crystal arthritis.

In an interview, she said that the study suggests “we can keep in mind shorter courses of treatment for acute CPP crystal arthritis; I think that’s one big takeaway from this study.”

Asked whether she would change her practice based on the findings, Dr. Tedeschi replied: “I personally am not sure that I would be moved to use prednisone more than colchicine; I actually take away from this that colchicine is equivalent to prednisone for short-term use for CPP arthritis, but I think it’s also really important to note that this is in the context of quite a lot of acetaminophen and quite a lot of tramadol, and frankly I don’t usually use tramadol with my patients, but I might consider doing that, especially as there were no delirium events in this population.”

Dr. Tedeschi was not involved in the study.

Asked the same question, Michael Toprover, MD, from New York University Langone Medical Center, a moderator of the session who was not involved in the study, said: “I usually use a combination of medications. I generally, in someone who is hospitalized in particular and is in such severe pain, use a combination of colchicine and prednisone, unless I’m worried about infection, in which case I’ll start colchicine until we’ve proven that it’s CPPD, and then I’ll add prednisone.”

The study was funded by PHRC-1 GIRCI Nord Ouest, a clinical research program funded by the Ministry of Health in France. Dr. Pascart, Dr. Tedeschi, and Dr. Toprover all reported having no relevant conflicts of interest.

PHILADELPHIA – Prednisone appears to have the edge over colchicine for control of pain in patients with acute calcium pyrophosphate (CPP) crystal arthritis, an intensely painful rheumatic disease primarily affecting older patients.

Among 111 patients with acute CPP crystal arthritis randomized to receive either prednisone or colchicine for control of acute pain in a multicenter study, 2 days of therapy with the oral agents provided equivalent pain relief on the second day, and patients generally tolerated each agent well, reported Tristan Pascart, MD, from the Groupement Hospitalier de l’Institut Catholique de Lille (France).

“Almost three-fourths of patients are considered to be good responders to both drugs on day 3, and, maybe, safety is the key issue distinguishing the two treatments: Colchicine was generally well tolerated, but even with this very short time frame of treatment, one patient out of five had diarrhea, which is more of a concern in this elderly population at risk of dehydration,” he said in an oral abstract session at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

In contrast, only about 6% of patients assigned to prednisone had diarrhea, and other adverse events that occurred more frequently with the corticosteroid, including hypertension, hyperglycemia, and insomnia all resolved after the therapy was stopped.

Common and acutely painful

Acute CPP crystal arthritis is a common complication that often occurs during hospitalization for primarily nonrheumatologic causes, Dr. Pascart said, and “in the absence of clinical trials, the management relies on expert opinion, which stems from extrapolated data from gap studies” primarily with prednisone or colchicine, Dr. Pascart said.

To fill in the knowledge gap, Dr. Pascart and colleagues conducted the COLCHICORT study to evaluate whether the two drugs were comparable in efficacy and safety for control of acute pain in a vulnerable population.

The multicenter, open-label trial included patients older than age 65 years with an estimated glomerular filtration rate above 30 mL/min per 1.73 m2 who presented with acute CPP deposition arthritis with symptoms occurring within the previous 36 hours. CPP arthritis was defined by the identification of CPP crystals on synovial fluid analysis or typical clinical presentation with evidence of chondrocalcinosis on x-rays or ultrasound.

Patients with a history of gout, cognitive decline that could impair pain assessment, or contraindications to either of the study drugs were excluded.

The participants were randomized to receive either colchicine 1.5 mg (1 mg to start, then 0.5 mg one hour later) at baseline and then 1 mg on day 1, or oral prednisone 30 mg at baseline and on day 1. The patients also received 1 g of systemic acetaminophen, and three 50-mg doses of tramadol during the first 24 hours.

Of the 111 patients randomized, 54 were assigned to receive prednisone, and 57 were assigned to receive colchicine. Baseline characteristics were similar between the groups, with a mean age of about 86 years, body mass index of around 25 kg/m2, and blood pressure in the range of 130/69 mm Hg.

For nearly half of all patients in study each arm the most painful joint was the knee, followed by wrists and ankles.

There was no difference between the groups in the primary efficacy outcome of a change at 24 hours over baseline in visual analog scale (VAS) (0-100 mm) scores, either in a per-protocol analysis or modified intention-to-treat analysis. The mean change in VAS at 24 hours in the colchicine group was –36.6 mm, compared with –37.7 mm in the prednisone group. The investigators had previously determined that any difference between the two drugs of less than 13 mm on pain VAS at 24 hours would meet the definition for equivalent efficacy.

In both groups, a majority of patients had either an improvement greater than 50% in pain VAS scores and/or a pain VAS score less than 40 mm at both 24 and 48 hours.

At 7 days of follow-up, 21.8% of patients assigned to colchicine had diarrhea, compared with 5.6% of those assigned to prednisone. Adverse events occurring more frequently with prednisone included hyperglycemia, hypertension, and insomnia.

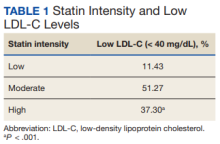

Patients who received colchicine and were also on statins had a trend toward a higher risk for diarrhea, but the study was not adequately powered to detect an association, and the trend was not statistically significant, Dr. Pascart said.

“Taken together, safety issues suggest that prednisone should be considered as the first-line therapy in acute CPP crystal arthritis. Future research is warranted to determine factors increasing the risk of colchicine-induced diarrhea,” he concluded.

Both drugs are used

Sara K. Tedeschi, MD, from Brigham & Women’s Hospital in Boston, who attended the session where the data were presented, has a special clinical interest in CPP deposition disease. She applauded Dr. Pascart and colleagues for conducting a rare clinical trial in CPP crystal arthritis.

In an interview, she said that the study suggests “we can keep in mind shorter courses of treatment for acute CPP crystal arthritis; I think that’s one big takeaway from this study.”

Asked whether she would change her practice based on the findings, Dr. Tedeschi replied: “I personally am not sure that I would be moved to use prednisone more than colchicine; I actually take away from this that colchicine is equivalent to prednisone for short-term use for CPP arthritis, but I think it’s also really important to note that this is in the context of quite a lot of acetaminophen and quite a lot of tramadol, and frankly I don’t usually use tramadol with my patients, but I might consider doing that, especially as there were no delirium events in this population.”

Dr. Tedeschi was not involved in the study.

Asked the same question, Michael Toprover, MD, from New York University Langone Medical Center, a moderator of the session who was not involved in the study, said: “I usually use a combination of medications. I generally, in someone who is hospitalized in particular and is in such severe pain, use a combination of colchicine and prednisone, unless I’m worried about infection, in which case I’ll start colchicine until we’ve proven that it’s CPPD, and then I’ll add prednisone.”

The study was funded by PHRC-1 GIRCI Nord Ouest, a clinical research program funded by the Ministry of Health in France. Dr. Pascart, Dr. Tedeschi, and Dr. Toprover all reported having no relevant conflicts of interest.

PHILADELPHIA – Prednisone appears to have the edge over colchicine for control of pain in patients with acute calcium pyrophosphate (CPP) crystal arthritis, an intensely painful rheumatic disease primarily affecting older patients.

Among 111 patients with acute CPP crystal arthritis randomized to receive either prednisone or colchicine for control of acute pain in a multicenter study, 2 days of therapy with the oral agents provided equivalent pain relief on the second day, and patients generally tolerated each agent well, reported Tristan Pascart, MD, from the Groupement Hospitalier de l’Institut Catholique de Lille (France).

“Almost three-fourths of patients are considered to be good responders to both drugs on day 3, and, maybe, safety is the key issue distinguishing the two treatments: Colchicine was generally well tolerated, but even with this very short time frame of treatment, one patient out of five had diarrhea, which is more of a concern in this elderly population at risk of dehydration,” he said in an oral abstract session at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

In contrast, only about 6% of patients assigned to prednisone had diarrhea, and other adverse events that occurred more frequently with the corticosteroid, including hypertension, hyperglycemia, and insomnia all resolved after the therapy was stopped.

Common and acutely painful

Acute CPP crystal arthritis is a common complication that often occurs during hospitalization for primarily nonrheumatologic causes, Dr. Pascart said, and “in the absence of clinical trials, the management relies on expert opinion, which stems from extrapolated data from gap studies” primarily with prednisone or colchicine, Dr. Pascart said.

To fill in the knowledge gap, Dr. Pascart and colleagues conducted the COLCHICORT study to evaluate whether the two drugs were comparable in efficacy and safety for control of acute pain in a vulnerable population.

The multicenter, open-label trial included patients older than age 65 years with an estimated glomerular filtration rate above 30 mL/min per 1.73 m2 who presented with acute CPP deposition arthritis with symptoms occurring within the previous 36 hours. CPP arthritis was defined by the identification of CPP crystals on synovial fluid analysis or typical clinical presentation with evidence of chondrocalcinosis on x-rays or ultrasound.

Patients with a history of gout, cognitive decline that could impair pain assessment, or contraindications to either of the study drugs were excluded.

The participants were randomized to receive either colchicine 1.5 mg (1 mg to start, then 0.5 mg one hour later) at baseline and then 1 mg on day 1, or oral prednisone 30 mg at baseline and on day 1. The patients also received 1 g of systemic acetaminophen, and three 50-mg doses of tramadol during the first 24 hours.

Of the 111 patients randomized, 54 were assigned to receive prednisone, and 57 were assigned to receive colchicine. Baseline characteristics were similar between the groups, with a mean age of about 86 years, body mass index of around 25 kg/m2, and blood pressure in the range of 130/69 mm Hg.

For nearly half of all patients in study each arm the most painful joint was the knee, followed by wrists and ankles.

There was no difference between the groups in the primary efficacy outcome of a change at 24 hours over baseline in visual analog scale (VAS) (0-100 mm) scores, either in a per-protocol analysis or modified intention-to-treat analysis. The mean change in VAS at 24 hours in the colchicine group was –36.6 mm, compared with –37.7 mm in the prednisone group. The investigators had previously determined that any difference between the two drugs of less than 13 mm on pain VAS at 24 hours would meet the definition for equivalent efficacy.

In both groups, a majority of patients had either an improvement greater than 50% in pain VAS scores and/or a pain VAS score less than 40 mm at both 24 and 48 hours.

At 7 days of follow-up, 21.8% of patients assigned to colchicine had diarrhea, compared with 5.6% of those assigned to prednisone. Adverse events occurring more frequently with prednisone included hyperglycemia, hypertension, and insomnia.

Patients who received colchicine and were also on statins had a trend toward a higher risk for diarrhea, but the study was not adequately powered to detect an association, and the trend was not statistically significant, Dr. Pascart said.

“Taken together, safety issues suggest that prednisone should be considered as the first-line therapy in acute CPP crystal arthritis. Future research is warranted to determine factors increasing the risk of colchicine-induced diarrhea,” he concluded.

Both drugs are used

Sara K. Tedeschi, MD, from Brigham & Women’s Hospital in Boston, who attended the session where the data were presented, has a special clinical interest in CPP deposition disease. She applauded Dr. Pascart and colleagues for conducting a rare clinical trial in CPP crystal arthritis.

In an interview, she said that the study suggests “we can keep in mind shorter courses of treatment for acute CPP crystal arthritis; I think that’s one big takeaway from this study.”

Asked whether she would change her practice based on the findings, Dr. Tedeschi replied: “I personally am not sure that I would be moved to use prednisone more than colchicine; I actually take away from this that colchicine is equivalent to prednisone for short-term use for CPP arthritis, but I think it’s also really important to note that this is in the context of quite a lot of acetaminophen and quite a lot of tramadol, and frankly I don’t usually use tramadol with my patients, but I might consider doing that, especially as there were no delirium events in this population.”

Dr. Tedeschi was not involved in the study.

Asked the same question, Michael Toprover, MD, from New York University Langone Medical Center, a moderator of the session who was not involved in the study, said: “I usually use a combination of medications. I generally, in someone who is hospitalized in particular and is in such severe pain, use a combination of colchicine and prednisone, unless I’m worried about infection, in which case I’ll start colchicine until we’ve proven that it’s CPPD, and then I’ll add prednisone.”

The study was funded by PHRC-1 GIRCI Nord Ouest, a clinical research program funded by the Ministry of Health in France. Dr. Pascart, Dr. Tedeschi, and Dr. Toprover all reported having no relevant conflicts of interest.

AT ACR 2022

Sham-controlled renal denervation trial for hypertension is a near miss

SPYRAL HTN–ON MED hits headwinds

CHICAGO – Renal denervation, relative to a sham procedure, was linked with statistically significant reductions in blood pressure in the newly completed SPYRAL HTN–ON MED trial, but several factors are likely to have worked in concert to prevent the study from meeting its primary endpoint.

Of these differences, probably none was more important than the substantially higher proportion of patients in the sham group that received additional BP-lowering medications over the course of the study, David E. Kandzari, MD, reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

The SPYRAL HTN–ON MED pivotal trial followed the previously completed SPYRAL HTN–ON MED pilot study, which did show a significant BP-lowering effect on antihypertensive medications followed radiofrequency denervation. In a recent update of the pilot study, the effect was persistent out to 3 years.

In the SPYRAL HTN–ON MED program, patients on their second screening visit were required to have a systolic pressure of between 140 and 170 mm Hg on 24-hour ambulatory BP monitoring (ABPM) while taking up to three antihypertensive medications. Patients who entered the study were randomized to renal denervation or sham control while maintaining their baseline antihypertensive therapies.

The previously reported pilot study comprised 80 patients. The expansion pivotal trial added 257 more patients for a total cohort of 337 patients. The primary efficacy endpoint was based on a Bayesian analysis of change in 24-hour systolic ABPM at 6 months for those in the experimental arm versus those on medications alone. Participants from both the pilot and pivotal trials were included.

The prespecified definition of success for renal denervation was a 97.5% threshold for probability of superiority on the basis of this Bayesian analysis. However, the Bayesian analysis was distorted by differences in the pilot and expansion cohorts, which complicated the superiority calculation. As a result, the analysis only yielded a 51% probability of superiority, a level substantially below the predefined threshold.

Despite differences seen in BP control in favor of renal denervation, several factors were identified that likely contributed to the missed primary endpoint. One stood out.

“Significant differences in medication prescriptions were disproportionate in favor of the sham group,” reported Dr. Kandzari, chief of Piedmont Heart Institute, Atlanta. He said these differences, which were a violation of the protocol mandate, led to a “bias toward the null” for the primary outcome.

The failure to meet the primary outcome was particularly disappointing in the wake of the favorable pilot study and the SPYRAL HTN–OFF MED pivotal trial, which were both positive.

In the pilot study, which did not have a medication imbalance, a 7.3–mm Hg reduction (P = .004) in 24-hour ABPM was seen at 6 months. Relative reductions in office-based systolic pressure reductions for renal denervation versus sham were 6.6 mm Hg (P = .03) and 4.0 mm Hg (P = .03) for the pilot and expansions groups, respectively.

On the basis of a Win ratio derived from a hierarchical analysis of ABMP and medication burden reduction, the 1.50 advantage (P = .005) for the renal denervation arm in the newly completed SPYRAL HTN–ON MED trial was also compelling.

At study entry, the median number of medications was 1.9 in both the renal denervation and sham arms. At the end of 6 months, the median number of medications was unchanged in the experimental arm but rose to 2.1 (P = .01) in the sham group. Similarly, there was little change in the medication burden from the start to the end of the trial in the denervation group (2.8 vs. 3.0), but a statistically significant change in the sham group (2.9 vs. 3.5; P = .04).

Furthermore, the net percentage change of patients receiving medications favoring BP reduction over the course of the study did not differ between the experimental and control arms of the pilot cohort, but was more than 10 times higher among controls in the expansion group (1.9% vs. 21.8%; P < .0001).

Medication changes over the course of the SPYRAL HTN–ON MED trial were even greater in some specific subgroups. Among Black participants, for example, 14.2% of those randomized to renal denervation and 54.6% of those randomized to the sham group increased their antihypertensive therapies over the course of the study.

The COVID-19 epidemic is suspected of playing another role in the negative results, according to Dr. Kandzari. After a brief pause in enrollment, the SPYRAL HTN–ON MED trial was resumed, but approximately 80% of the expansion cohort data were collected during this period. When compared, variances in office and 24-hour ABPM were observed for participants who were or were not evaluated during COVID.

“Significant differences in 24-hour ABPM patterns pre- and during COVID may reflect changes in patient behavior and lifestyle,” Dr. Kandzari speculated.

The data from this study differ from essentially all of the other studies in the SPYRAL HTN program as well as several other sham-controlled studies with renal denervation, according to Dr. Kandzari.

The AHA-invited discussant, Ajay J. Kirtane, MD, director of the Cardiac Catheterization Laboratories at Columbia University, New York, largely agreed that several variables appeared to conspire against a positive result in this trial, but he zeroed in on the imbalance of antihypertensive medications.

“Any trial that attempts to show a difference between renal denervation and a sham procedure must insure that antihypertensive medications are the same in the two arms. They cannot be different,” he said.

As an active investigator in the field of renal denervation, Dr. Kirtane thinks the evidence does support a benefit from renal denervation, but he believes data are still needed to determine which patients are candidates.

“Renal denervation is not going to be a replacement for previous established therapies, but it will be an adjunct,” he predicted. The preponderance of evidence supports clinically meaningful reductions in BP with this approach, “but we need to determine who to consider [for this therapy] and to have realistic expectations about the degree of benefit.”

Dr. Kandzari reported financial relationships with Abbott Vascular, Ablative Solutions, Biotronik, Boston Scientific, CSI, Medtronic Cardiovascular, OrbusNeich, and Teleflex. Dr. Kirtane reported financial relationships with Abbott Vascular, Abiomed, Boston Scientific, Cardiovascular Systems, Cathworks, Chiesi, Medtronic, Opens, Philipps, Regeneron, ReCor Medical, Siemens, Spectranetics, and Zoll.

SPYRAL HTN–ON MED hits headwinds

SPYRAL HTN–ON MED hits headwinds

CHICAGO – Renal denervation, relative to a sham procedure, was linked with statistically significant reductions in blood pressure in the newly completed SPYRAL HTN–ON MED trial, but several factors are likely to have worked in concert to prevent the study from meeting its primary endpoint.

Of these differences, probably none was more important than the substantially higher proportion of patients in the sham group that received additional BP-lowering medications over the course of the study, David E. Kandzari, MD, reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

The SPYRAL HTN–ON MED pivotal trial followed the previously completed SPYRAL HTN–ON MED pilot study, which did show a significant BP-lowering effect on antihypertensive medications followed radiofrequency denervation. In a recent update of the pilot study, the effect was persistent out to 3 years.

In the SPYRAL HTN–ON MED program, patients on their second screening visit were required to have a systolic pressure of between 140 and 170 mm Hg on 24-hour ambulatory BP monitoring (ABPM) while taking up to three antihypertensive medications. Patients who entered the study were randomized to renal denervation or sham control while maintaining their baseline antihypertensive therapies.

The previously reported pilot study comprised 80 patients. The expansion pivotal trial added 257 more patients for a total cohort of 337 patients. The primary efficacy endpoint was based on a Bayesian analysis of change in 24-hour systolic ABPM at 6 months for those in the experimental arm versus those on medications alone. Participants from both the pilot and pivotal trials were included.

The prespecified definition of success for renal denervation was a 97.5% threshold for probability of superiority on the basis of this Bayesian analysis. However, the Bayesian analysis was distorted by differences in the pilot and expansion cohorts, which complicated the superiority calculation. As a result, the analysis only yielded a 51% probability of superiority, a level substantially below the predefined threshold.

Despite differences seen in BP control in favor of renal denervation, several factors were identified that likely contributed to the missed primary endpoint. One stood out.

“Significant differences in medication prescriptions were disproportionate in favor of the sham group,” reported Dr. Kandzari, chief of Piedmont Heart Institute, Atlanta. He said these differences, which were a violation of the protocol mandate, led to a “bias toward the null” for the primary outcome.

The failure to meet the primary outcome was particularly disappointing in the wake of the favorable pilot study and the SPYRAL HTN–OFF MED pivotal trial, which were both positive.