User login

T2D Medications II

Buzz kill: Lung damage looks worse in pot smokers

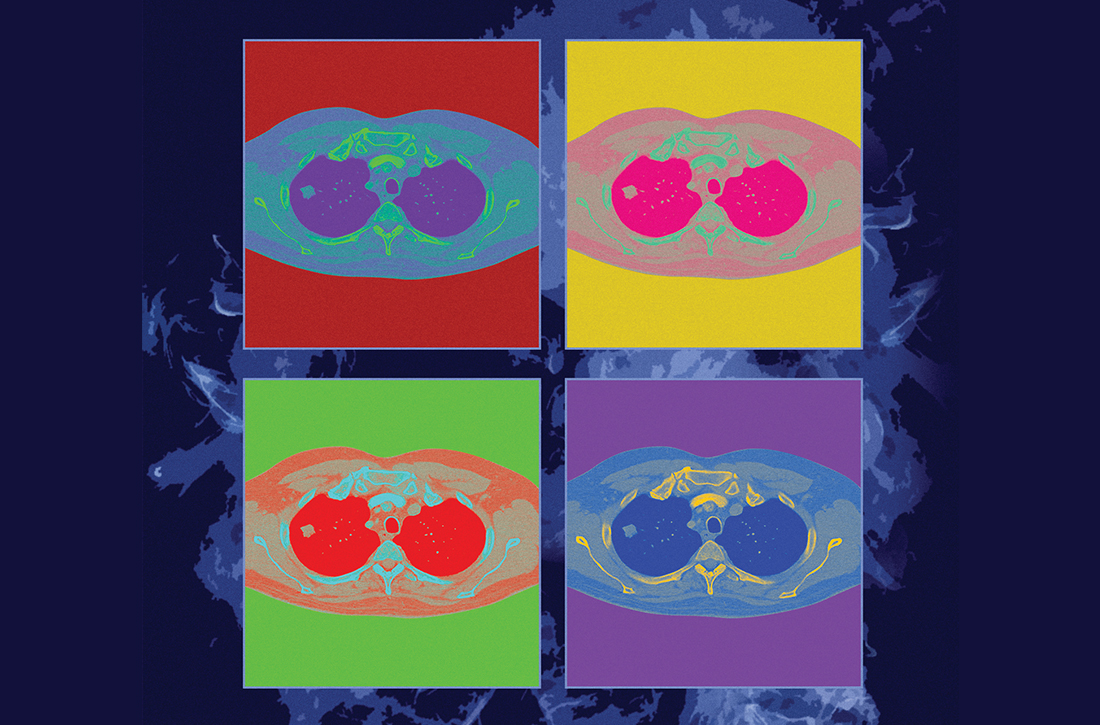

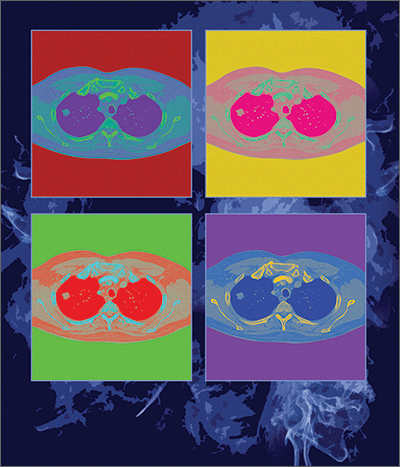

Scans of the lungs of pot users have turned up an alarming surprise:

“There’s a public perception that marijuana is safe,” said Giselle Revah, MD, a radiologist at the University of Ottawa. “This study is raising concern that this might not be true.”

Dr. Revah said she can often tell immediately if a CT scan is from a heavy or long-time cigarette smoker. But with the legalization and increased use of marijuana in Canada and many U.S. states, she began to wonder what cannabis use does to the lungs and whether she would be able to differentiate its effects from those of cigarette smoking.

She and her colleagues retrospectively examined chest CT scans from 56 marijuana smokers and compared them to scans of 57 nonsmokers and 33 users of tobacco alone.

Emphysema was significantly more common among marijuana smokers (75%) than among nonsmokers (5%). When matched for age and sex, 93% of marijuana smokers had emphysema, vs. 67% of those who smoked tobacco only (P = .009).

Without age matching, rates of emphysema remained slightly higher among the marijuana users (75% vs. 67%), although the difference was no longer statistically significant. Yet more than 40% of the marijuana group was younger than 50 years, and all of the tobacco-only users were 50 or older – meaning that marijuana smokers may develop lung damage earlier or with less exposure, Dr. Revah said.

Dr. Revah added that her colleagues in family medicine have said the findings match their clinical experience. “In their practices, they have younger patients with emphysema,” she said.

Marijuana smokers also showed higher rates of airway inflammation, including bronchial thickening, bronchiectasis, and mucoid impaction, with and without sex- and age-matching, the researchers found.

The findings are “not even a little bit surprising,” according to Alan Kaplan, MD, a family physician in Ontario who has expertise in respiratory health. He is the author of a 2021 review on cannabis and lung health.

In an editorial accompanying the journal article by Dr. Revah and colleagues , pulmonary experts noted that the new data give context to a recent uptick in referrals for nontraumatic pneumothorax. The authors said they had received 22 of these referrals during the past 2 years but that they had received only 6 between 2012 and 2020. “Many, but not all, of these patients have a documented history of marijuana use,” they wrote.

One reason for the additional damage may be the way marijuana is inhaled, Dr. Kaplan said. Marijuana smokers “take a big breath in, and they really push it into lungs and hold pressure on it, which may actually cause alveoli to distend over time.”

Because most marijuana smokers in the study also smoked cigarettes, whether the observed damage was caused by marijuana alone or occurred through a synergy with tobacco is impossible to discern, Dr. Revah said.

Still, the results are striking, she said, because the marijuana group was compared to tobacco users who had an extensive smoking history – 25 to 100 pack-years – and who were from a high-risk lung cancer screening program.

Dr. Revah and her colleagues are now conducting a larger, prospective study to see whether they can confirm their findings.

“The message to physicians is to ask about cannabis smoking,” Dr. Kaplan said. In the past, people have been reluctant to admit to using cannabis. Even with legalization, they may be slow to tell their physicians. But clinicians should still try to identify frequent users, especially those who are predisposed for lung conditions. If they intend to use the drug, the advice should be, “There are safer ways to use cannabis,” he said.

Dr. Revah and Dr. Kaplan have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Scans of the lungs of pot users have turned up an alarming surprise:

“There’s a public perception that marijuana is safe,” said Giselle Revah, MD, a radiologist at the University of Ottawa. “This study is raising concern that this might not be true.”

Dr. Revah said she can often tell immediately if a CT scan is from a heavy or long-time cigarette smoker. But with the legalization and increased use of marijuana in Canada and many U.S. states, she began to wonder what cannabis use does to the lungs and whether she would be able to differentiate its effects from those of cigarette smoking.

She and her colleagues retrospectively examined chest CT scans from 56 marijuana smokers and compared them to scans of 57 nonsmokers and 33 users of tobacco alone.

Emphysema was significantly more common among marijuana smokers (75%) than among nonsmokers (5%). When matched for age and sex, 93% of marijuana smokers had emphysema, vs. 67% of those who smoked tobacco only (P = .009).

Without age matching, rates of emphysema remained slightly higher among the marijuana users (75% vs. 67%), although the difference was no longer statistically significant. Yet more than 40% of the marijuana group was younger than 50 years, and all of the tobacco-only users were 50 or older – meaning that marijuana smokers may develop lung damage earlier or with less exposure, Dr. Revah said.

Dr. Revah added that her colleagues in family medicine have said the findings match their clinical experience. “In their practices, they have younger patients with emphysema,” she said.

Marijuana smokers also showed higher rates of airway inflammation, including bronchial thickening, bronchiectasis, and mucoid impaction, with and without sex- and age-matching, the researchers found.

The findings are “not even a little bit surprising,” according to Alan Kaplan, MD, a family physician in Ontario who has expertise in respiratory health. He is the author of a 2021 review on cannabis and lung health.

In an editorial accompanying the journal article by Dr. Revah and colleagues , pulmonary experts noted that the new data give context to a recent uptick in referrals for nontraumatic pneumothorax. The authors said they had received 22 of these referrals during the past 2 years but that they had received only 6 between 2012 and 2020. “Many, but not all, of these patients have a documented history of marijuana use,” they wrote.

One reason for the additional damage may be the way marijuana is inhaled, Dr. Kaplan said. Marijuana smokers “take a big breath in, and they really push it into lungs and hold pressure on it, which may actually cause alveoli to distend over time.”

Because most marijuana smokers in the study also smoked cigarettes, whether the observed damage was caused by marijuana alone or occurred through a synergy with tobacco is impossible to discern, Dr. Revah said.

Still, the results are striking, she said, because the marijuana group was compared to tobacco users who had an extensive smoking history – 25 to 100 pack-years – and who were from a high-risk lung cancer screening program.

Dr. Revah and her colleagues are now conducting a larger, prospective study to see whether they can confirm their findings.

“The message to physicians is to ask about cannabis smoking,” Dr. Kaplan said. In the past, people have been reluctant to admit to using cannabis. Even with legalization, they may be slow to tell their physicians. But clinicians should still try to identify frequent users, especially those who are predisposed for lung conditions. If they intend to use the drug, the advice should be, “There are safer ways to use cannabis,” he said.

Dr. Revah and Dr. Kaplan have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Scans of the lungs of pot users have turned up an alarming surprise:

“There’s a public perception that marijuana is safe,” said Giselle Revah, MD, a radiologist at the University of Ottawa. “This study is raising concern that this might not be true.”

Dr. Revah said she can often tell immediately if a CT scan is from a heavy or long-time cigarette smoker. But with the legalization and increased use of marijuana in Canada and many U.S. states, she began to wonder what cannabis use does to the lungs and whether she would be able to differentiate its effects from those of cigarette smoking.

She and her colleagues retrospectively examined chest CT scans from 56 marijuana smokers and compared them to scans of 57 nonsmokers and 33 users of tobacco alone.

Emphysema was significantly more common among marijuana smokers (75%) than among nonsmokers (5%). When matched for age and sex, 93% of marijuana smokers had emphysema, vs. 67% of those who smoked tobacco only (P = .009).

Without age matching, rates of emphysema remained slightly higher among the marijuana users (75% vs. 67%), although the difference was no longer statistically significant. Yet more than 40% of the marijuana group was younger than 50 years, and all of the tobacco-only users were 50 or older – meaning that marijuana smokers may develop lung damage earlier or with less exposure, Dr. Revah said.

Dr. Revah added that her colleagues in family medicine have said the findings match their clinical experience. “In their practices, they have younger patients with emphysema,” she said.

Marijuana smokers also showed higher rates of airway inflammation, including bronchial thickening, bronchiectasis, and mucoid impaction, with and without sex- and age-matching, the researchers found.

The findings are “not even a little bit surprising,” according to Alan Kaplan, MD, a family physician in Ontario who has expertise in respiratory health. He is the author of a 2021 review on cannabis and lung health.

In an editorial accompanying the journal article by Dr. Revah and colleagues , pulmonary experts noted that the new data give context to a recent uptick in referrals for nontraumatic pneumothorax. The authors said they had received 22 of these referrals during the past 2 years but that they had received only 6 between 2012 and 2020. “Many, but not all, of these patients have a documented history of marijuana use,” they wrote.

One reason for the additional damage may be the way marijuana is inhaled, Dr. Kaplan said. Marijuana smokers “take a big breath in, and they really push it into lungs and hold pressure on it, which may actually cause alveoli to distend over time.”

Because most marijuana smokers in the study also smoked cigarettes, whether the observed damage was caused by marijuana alone or occurred through a synergy with tobacco is impossible to discern, Dr. Revah said.

Still, the results are striking, she said, because the marijuana group was compared to tobacco users who had an extensive smoking history – 25 to 100 pack-years – and who were from a high-risk lung cancer screening program.

Dr. Revah and her colleagues are now conducting a larger, prospective study to see whether they can confirm their findings.

“The message to physicians is to ask about cannabis smoking,” Dr. Kaplan said. In the past, people have been reluctant to admit to using cannabis. Even with legalization, they may be slow to tell their physicians. But clinicians should still try to identify frequent users, especially those who are predisposed for lung conditions. If they intend to use the drug, the advice should be, “There are safer ways to use cannabis,” he said.

Dr. Revah and Dr. Kaplan have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM RADIOLOGY

Is there a doctor on the plane? Tips for providing in-flight assistance

In most cases, passengers on an airline flight are representative of the general population, which means that anyone could have an emergency at any time.

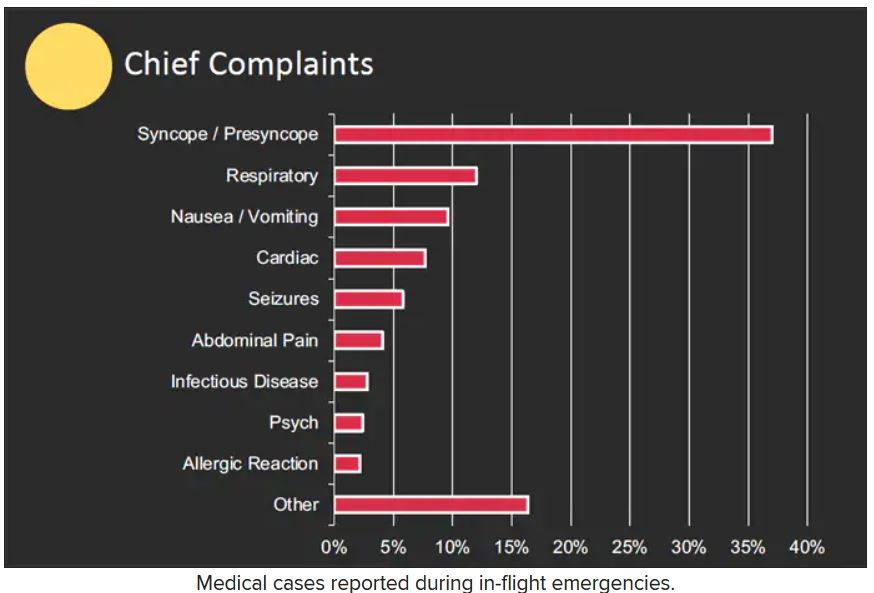

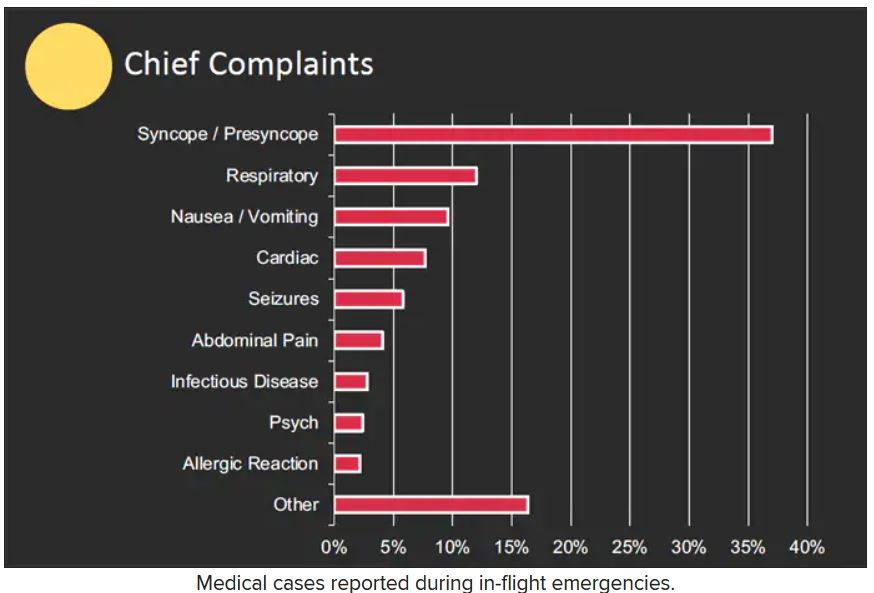

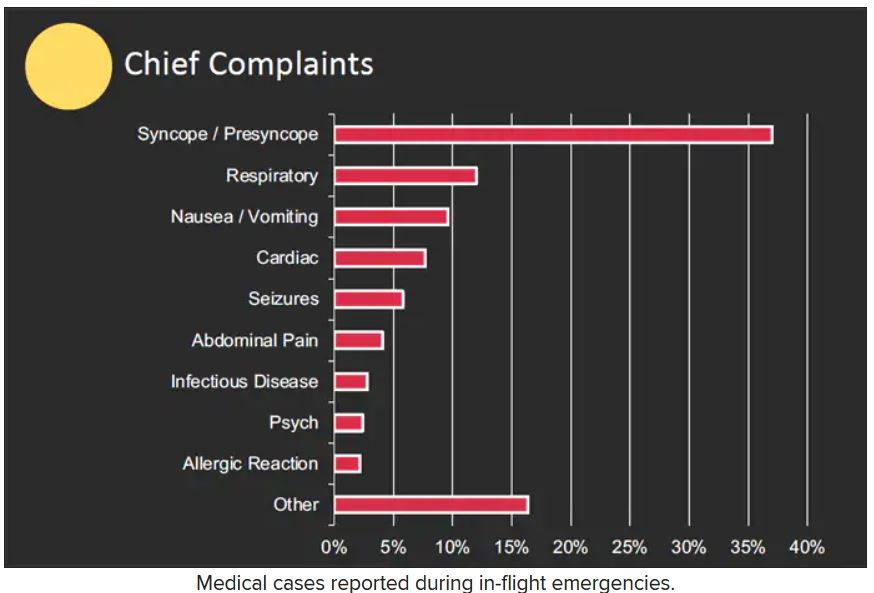

as determined on the basis of in-flight medical emergencies that resulted in calls to a physician-directed medical communications center, said Amy Faith Ho, MD, MPH of Integrative Emergency Services, Dallas–Fort Worth, in a presentation at the annual meeting of the American College of Emergency Physicians.

The study authors reviewed records of 11,920 in-flight medical emergencies between Jan. 1, 2008, and Oct. 31, 2010. The data showed that physician passengers provided medical assistance in nearly half of in-flight emergencies (48.1%) and that flights were diverted because of the emergency in 7.3% of cases.

The majority of the in-flight emergencies involved syncope or presyncope (37.4% of cases), followed by respiratory symptoms (12.1%) and nausea or vomiting (9.5%), according to the study.

When a physician is faced with an in-flight emergency, the medical team includes the physician himself, medical ground control, and the flight attendants, said Dr. Ho. Requirements may vary among airlines, but all flight attendants will be trained in cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) or basic life support, as well as use of automated external defibrillators (AEDs).

Physician call centers (medical ground control) can provide additional assistance remotely, she said.

The in-flight medical bag

Tools in a physician’s in-flight toolbox start with the first-aid kit. Airplanes also have an emergency medical kit (EMK), an oxygen tank, and an AED.

The minimum EMK contents are mandated by the Federal Aviation Administration, said Dr. Ho. The standard equipment includes a stethoscope, a sphygmomanometer, and three sizes of oropharyngeal airways. Other items include self-inflating manual resuscitation devices and CPR masks in thee sizes, alcohol sponges, gloves, adhesive tape, scissors, a tourniquet, as well as saline solution, needles, syringes, and an intravenous administration set consisting of tubing and two Y connectors.

An EMK also should contain the following medications: nonnarcotic analgesic tablets, antihistamine tablets, an injectable antihistamine, atropine, aspirin tablets, a bronchodilator, and epinephrine (both 1:1000; 1 injectable cc and 1:10,000; two injectable cc). Nitroglycerin tablets and 5 cc of 20 mg/mL injectable cardiac lidocaine are part of the mandated kit as well, according to Dr. Ho.

Some airlines carry additional supplies on all their flights, said Dr. Ho. Notably, American Airlines and British Airways carry EpiPens for adults and children, as well as opioid reversal medication (naloxone) and glucose for managing low blood sugar. American Airlines and Delta stock antiemetics, and Delta also carries naloxone. British Airways is unique in stocking additional cardiac medications, both oral and injectable.

How to handle an in-flight emergency

Physicians should always carry a copy of their medical license when traveling for documentation by the airline if they assist in a medical emergency during a flight, Dr. Ho emphasized. “Staff” personnel should be used. These include the flight attendants, medical ground control, and other passengers who might have useful skills, such as nursing, the ability to perform CPR, or therapy/counseling to calm a frightened patient. If needed, “crowdsource additional supplies from passengers,” such as a glucometer or pulse oximeter.

Legal lessons

Physicians are not obligated to assist during an in-flight medical emergency, said Dr. Ho. Legal jurisdiction can vary. In the United States, a bystander who assists in an emergency is generally protected by Good Samaritan laws; for international airlines, the laws may vary; those where the airline is based usually apply.

The Aviation Medical Assistance Act, passed in 1998, protects individuals from being sued for negligence while providing medical assistance, “unless the individual, while rendering such assistance, is guilty of gross negligence of willful misconduct,” Dr. Ho noted. The Aviation Medical Assistance Act also protects the airline itself “if the carrier in good faith believes that the passenger is a medically qualified individual.”

Dr. Ho disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In most cases, passengers on an airline flight are representative of the general population, which means that anyone could have an emergency at any time.

as determined on the basis of in-flight medical emergencies that resulted in calls to a physician-directed medical communications center, said Amy Faith Ho, MD, MPH of Integrative Emergency Services, Dallas–Fort Worth, in a presentation at the annual meeting of the American College of Emergency Physicians.

The study authors reviewed records of 11,920 in-flight medical emergencies between Jan. 1, 2008, and Oct. 31, 2010. The data showed that physician passengers provided medical assistance in nearly half of in-flight emergencies (48.1%) and that flights were diverted because of the emergency in 7.3% of cases.

The majority of the in-flight emergencies involved syncope or presyncope (37.4% of cases), followed by respiratory symptoms (12.1%) and nausea or vomiting (9.5%), according to the study.

When a physician is faced with an in-flight emergency, the medical team includes the physician himself, medical ground control, and the flight attendants, said Dr. Ho. Requirements may vary among airlines, but all flight attendants will be trained in cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) or basic life support, as well as use of automated external defibrillators (AEDs).

Physician call centers (medical ground control) can provide additional assistance remotely, she said.

The in-flight medical bag

Tools in a physician’s in-flight toolbox start with the first-aid kit. Airplanes also have an emergency medical kit (EMK), an oxygen tank, and an AED.

The minimum EMK contents are mandated by the Federal Aviation Administration, said Dr. Ho. The standard equipment includes a stethoscope, a sphygmomanometer, and three sizes of oropharyngeal airways. Other items include self-inflating manual resuscitation devices and CPR masks in thee sizes, alcohol sponges, gloves, adhesive tape, scissors, a tourniquet, as well as saline solution, needles, syringes, and an intravenous administration set consisting of tubing and two Y connectors.

An EMK also should contain the following medications: nonnarcotic analgesic tablets, antihistamine tablets, an injectable antihistamine, atropine, aspirin tablets, a bronchodilator, and epinephrine (both 1:1000; 1 injectable cc and 1:10,000; two injectable cc). Nitroglycerin tablets and 5 cc of 20 mg/mL injectable cardiac lidocaine are part of the mandated kit as well, according to Dr. Ho.

Some airlines carry additional supplies on all their flights, said Dr. Ho. Notably, American Airlines and British Airways carry EpiPens for adults and children, as well as opioid reversal medication (naloxone) and glucose for managing low blood sugar. American Airlines and Delta stock antiemetics, and Delta also carries naloxone. British Airways is unique in stocking additional cardiac medications, both oral and injectable.

How to handle an in-flight emergency

Physicians should always carry a copy of their medical license when traveling for documentation by the airline if they assist in a medical emergency during a flight, Dr. Ho emphasized. “Staff” personnel should be used. These include the flight attendants, medical ground control, and other passengers who might have useful skills, such as nursing, the ability to perform CPR, or therapy/counseling to calm a frightened patient. If needed, “crowdsource additional supplies from passengers,” such as a glucometer or pulse oximeter.

Legal lessons

Physicians are not obligated to assist during an in-flight medical emergency, said Dr. Ho. Legal jurisdiction can vary. In the United States, a bystander who assists in an emergency is generally protected by Good Samaritan laws; for international airlines, the laws may vary; those where the airline is based usually apply.

The Aviation Medical Assistance Act, passed in 1998, protects individuals from being sued for negligence while providing medical assistance, “unless the individual, while rendering such assistance, is guilty of gross negligence of willful misconduct,” Dr. Ho noted. The Aviation Medical Assistance Act also protects the airline itself “if the carrier in good faith believes that the passenger is a medically qualified individual.”

Dr. Ho disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In most cases, passengers on an airline flight are representative of the general population, which means that anyone could have an emergency at any time.

as determined on the basis of in-flight medical emergencies that resulted in calls to a physician-directed medical communications center, said Amy Faith Ho, MD, MPH of Integrative Emergency Services, Dallas–Fort Worth, in a presentation at the annual meeting of the American College of Emergency Physicians.

The study authors reviewed records of 11,920 in-flight medical emergencies between Jan. 1, 2008, and Oct. 31, 2010. The data showed that physician passengers provided medical assistance in nearly half of in-flight emergencies (48.1%) and that flights were diverted because of the emergency in 7.3% of cases.

The majority of the in-flight emergencies involved syncope or presyncope (37.4% of cases), followed by respiratory symptoms (12.1%) and nausea or vomiting (9.5%), according to the study.

When a physician is faced with an in-flight emergency, the medical team includes the physician himself, medical ground control, and the flight attendants, said Dr. Ho. Requirements may vary among airlines, but all flight attendants will be trained in cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) or basic life support, as well as use of automated external defibrillators (AEDs).

Physician call centers (medical ground control) can provide additional assistance remotely, she said.

The in-flight medical bag

Tools in a physician’s in-flight toolbox start with the first-aid kit. Airplanes also have an emergency medical kit (EMK), an oxygen tank, and an AED.

The minimum EMK contents are mandated by the Federal Aviation Administration, said Dr. Ho. The standard equipment includes a stethoscope, a sphygmomanometer, and three sizes of oropharyngeal airways. Other items include self-inflating manual resuscitation devices and CPR masks in thee sizes, alcohol sponges, gloves, adhesive tape, scissors, a tourniquet, as well as saline solution, needles, syringes, and an intravenous administration set consisting of tubing and two Y connectors.

An EMK also should contain the following medications: nonnarcotic analgesic tablets, antihistamine tablets, an injectable antihistamine, atropine, aspirin tablets, a bronchodilator, and epinephrine (both 1:1000; 1 injectable cc and 1:10,000; two injectable cc). Nitroglycerin tablets and 5 cc of 20 mg/mL injectable cardiac lidocaine are part of the mandated kit as well, according to Dr. Ho.

Some airlines carry additional supplies on all their flights, said Dr. Ho. Notably, American Airlines and British Airways carry EpiPens for adults and children, as well as opioid reversal medication (naloxone) and glucose for managing low blood sugar. American Airlines and Delta stock antiemetics, and Delta also carries naloxone. British Airways is unique in stocking additional cardiac medications, both oral and injectable.

How to handle an in-flight emergency

Physicians should always carry a copy of their medical license when traveling for documentation by the airline if they assist in a medical emergency during a flight, Dr. Ho emphasized. “Staff” personnel should be used. These include the flight attendants, medical ground control, and other passengers who might have useful skills, such as nursing, the ability to perform CPR, or therapy/counseling to calm a frightened patient. If needed, “crowdsource additional supplies from passengers,” such as a glucometer or pulse oximeter.

Legal lessons

Physicians are not obligated to assist during an in-flight medical emergency, said Dr. Ho. Legal jurisdiction can vary. In the United States, a bystander who assists in an emergency is generally protected by Good Samaritan laws; for international airlines, the laws may vary; those where the airline is based usually apply.

The Aviation Medical Assistance Act, passed in 1998, protects individuals from being sued for negligence while providing medical assistance, “unless the individual, while rendering such assistance, is guilty of gross negligence of willful misconduct,” Dr. Ho noted. The Aviation Medical Assistance Act also protects the airline itself “if the carrier in good faith believes that the passenger is a medically qualified individual.”

Dr. Ho disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ACEP 2022

34-year-old man • chronic lower back pain • peripheral neuropathy • leg spasms with increasing weakness • Dx?

THE CASE

A 34-year-old man was referred to the sports medicine clinic for evaluation of lumbar radiculopathy. He had a 2-year history of chronic lower back pain that started while he was working on power line towers in Puerto Rico. The back pain was achy, burning, shooting, and stabbing in nature. He had been treated with anti-inflammatories by a company health care provider while in Puerto Rico, but he did not have any imaging done.

At that time, he had tingling and burning that radiated down his left leg to his ankle. The patient also had leg spasms—in his left leg more than his right—and needed a cane when walking. His symptoms did not worsen at any particular time of day or with activity. He had no history of eating exotic foods or sustaining any venomous bites/stings. Ultimately, the back pain and leg spasms forced him to leave his job and return home to Louisiana.

Upon presentation to the sports medicine clinic, he explained that things had worsened since his return home. The pain and burning in his left leg had increased and were now present in his right leg, as well (bilateral paresthesias). In addition, he said he was feeling anxious (and described symptoms of forgetfulness, confusion, and agitation), was sleeping less, and was experiencing worsening fatigue.

Work-ups over the course of the previous 2 years had shed little light on the cause of his symptoms. X-rays of his lumbar spine revealed moderate degenerative changes at L5-S1. A lab work-up was negative and included a complete blood count, testing for HIV and herpes, a hepatitis panel, an antinuclear antibody screen, a C-reactive protein test, and a comprehensive metabolic panel. Thyroid-stimulating hormone, creatine kinase, rapid plasma reagin, and human leukocyte antigen B27 tests were also normal.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a cystic lesion in the right ilium near the sacroiliac joint. A more recent follow-up MRI and computed tomography scan of the pelvis found the cyst to be stable and well marginalized, with no cortical erosion. Attempts at physical therapy had been unsuccessful because of the pain and decreasing muscle strength in his lower extremities. The patient’s primary care provider was treating him with meloxicam 15 mg/d and duloxetine 60 mg/d, but that had not provided any relief.

Our physical examination revealed a patient who was in mild distress and had limited lumbar spine range of motion (secondary to pain in all planes) and significant paraspinal spasms on the right side in both the lumbar and thoracic regions. The patient had reduced vibratory sensation on his left side vs the right, with a 256-Hz tuning fork at the great toe, as well as reduced sensation to fine touch with a cotton swab and a positive Babinski sign bilaterally. Lower extremity reflexes were hyperreflexic on the left compared with the right. He had no pronator drift; Trendelenburg, straight leg raise, Hoover sign, and slump tests were all negative. His gait was antalgic with a cane, as he described bilateral paresthesias.

THE DIAGNOSIS

The differential diagnosis for low back pain is quite extensive and includes simple mechanical low back pain, lumbar radiculopathy, facet arthritis, spinal stenosis, spondylolysis/spondylolisthesis, and referred pain from the hip, knee, or upper back. It can also be caused by referred pain from visceral organs such as the liver, colon, or kidneys. Low back pain can also signal primary or metastatic disease. However, most of these potential diagnoses had been ruled out with imaging and lab tests.

Two things caught our attention. First: Mechanical low back pain and the associated discogenic radiculopathy would be unilateral, manifesting with asymmetric paresthesias and pain. Our patient had weakness in gait and pain and burning in both of his legs. Second: Our patient described decreased sleep and feeling anxious, with symptoms of forgetfulness, confusion, and agitation. These factors prompted us to look beyond the normal differential and consider a potential toxicity. A heavy metal screen was ordered, and the results were positive for arsenic toxicity.

DISCUSSION

Arsenic toxicity is a global health problem that affects millions of people.1,2 Arsenic has been used for centuries in depilatories, cosmetics, poisons, and therapeutic agents. Today it is used as a treatment for leukemia and in several ayurvedic and homeopathic remedies.3-7 It is a common earth element found in ground water and a waste product from mining and the manufacturing of glass, computer chips, wood preservatives, and various pesticides.2,3,7,8

A great masquerader. Once in the body, arsenic can cause many serious ailments ranging from urinary tract, liver, and skin cancers to various peripheral and central nervous system disorders.2 Arsenic can cause symmetrical peripheral neuropathy characterized by sensory nerves being more sensitive than motor nerves.2,3,5,6 Clinically, it causes numbness and paresthesias of the distal extremities, with the lower extremities more severely affected.3,6 Symptoms can develop within 2 hours to 2 years of exposure, with vomiting, diarrhea, or both preceding the onset of the neuropathy.2,3,5,6 Arsenic is linked to forgetfulness, confusion, visual distortion, sleep disturbances, decreased concentration, disorientation, severe agitation, paranoid ideation, emotional lability, and decreases in locomotor activity.3,5,6

Testing and treatment. Arsenic levels in the body are measured by blood and urine testing. Blood arsenic levels are typically detectable immediately after exposure and with continued exposure, but quickly normalize as the metal integrates into the nonvascular tissues. Urine arsenic levels can be detected for weeks. Normal levels for arsenic in both urine and blood are ≤ 12 µg/L.3 Anything greater than 12 µg/L is considered high; critically high values are those above 50 µg/L.3,5 Our patient’s blood arsenic level was 13 µg/L.

Treatment involves removing the source of the arsenic. Chelation therapy should be pursued when urine arsenic levels are greater than 50 µg/L or when removing the source of the arsenic fails to reduce arsenic levels. Chelation therapy should be continued until urine arsenic levels are below 20 µg/L.5,6

Continue to: After discussing potential sources of exposure

After discussing potential sources of exposure, our patient decided to move out of the house he shared with his ex-wife. He started to recover soon after moving out. Two weeks after his clinic visit, he no longer needed a cane to walk, and his blood arsenic level had dropped to 6 µg/L. Two months after his clinic visit, the patient’s blood arsenic level was undetectable. The patient’s peripheral neuropathy symptoms continued to improve.

The source of this patient’s arsenic exposure was never confirmed. The exposure could have occurred in Puerto Rico or in Louisiana. Even though no one else in the Louisiana home became ill, the patient was instructed to contact the local health department and water department to have the water tested. However, when he returned to the clinic for follow-up, he had not followed through.

THE TAKEAWAY

When evaluating causes of peripheral neuropathy, consider the possibility of heavy metal toxicity, which can be easily overlooked by the busy clinician. In this case, the patient initially experienced asymmetric paresthesia that gradually increased to burning pain and weakness, with reduced motor control bilaterally. This was significant because mechanical low back pain and the associated discogenic radiculopathy would be unilateral, manifesting with asymmetric paresthesias and pain.

Our patient’s leg symptoms, the constellation of forgetfulness, confusion, and agitation, and his sleep issues prompted us to look outside our normal differential. Fortunately, once arsenic exposure ceases, patients will gradually improve because arsenic is rapidly cleared from the bloodstream.3,6

CORRESPONDENCE

Charles W. Webb, DO, CAQSM, FAMSSM, FAAFP, Department of Family Medicine, 1501 Kings Highway, PO Box 33932, Shreveport, LA 71130-3932; [email protected]

1. Ahmad SA, Khan MH, Haque M. Arsenic contamination in groundwater in Bangladesh: implications and challenges for healthcare policy. Risk Manag Health Policy. 2018;11:251-261. doi: 10.2147/RMHP.S153188

2. Roh T, Steinmaus C, Marshall G, et al. Age at exposure to arsenic in water and mortality 30-40 years after exposure cessation. Am J Epidemiol. 2018;187:2297-2305. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwy159

3. Baker BA, Cassano VA, Murray C, ACOEM Task Force on Arsenic Exposure. Arsenic exposure, assessment, toxicity, diagnosis, and management. J Occup Environ Med. 2018;60:634-639. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000001485

4. Lasky T, Sun W, Kadry A, Hoffman MK. Mean total arsenic concentrations in chicken 1989-2000 and estimated exposures for consumers of chicken. Environ Health Perspect. 2004;112:18-21. doi: 10.1289/ehp.6407

5. Lindenmeyer G, Hoggett K, Burrow J, et al. A sickening tale. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:75-80. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcps1716775

6. Rodríguez VM, Jímenez-Capdevill ME, Giordano M. The effects of arsenic exposure on the nervous system. Toxicol Lett. 2003;145: 1-18. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4274(03)00262-5

7. Saper RB, Phillips RS, Sehgal A, et al. Lead, mercury, and arsenic in US- and Indian- manufactured ayurvedic medicines sold via the internet. JAMA. 2008;300:915-923. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.8.915

8. Rose M, Lewis J, Langford N, et al. Arsenic in seaweed—forms, concentration and dietary exposure. Food Chem Toxicol. 2007;45:1263-1267. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2007.01.007

THE CASE

A 34-year-old man was referred to the sports medicine clinic for evaluation of lumbar radiculopathy. He had a 2-year history of chronic lower back pain that started while he was working on power line towers in Puerto Rico. The back pain was achy, burning, shooting, and stabbing in nature. He had been treated with anti-inflammatories by a company health care provider while in Puerto Rico, but he did not have any imaging done.

At that time, he had tingling and burning that radiated down his left leg to his ankle. The patient also had leg spasms—in his left leg more than his right—and needed a cane when walking. His symptoms did not worsen at any particular time of day or with activity. He had no history of eating exotic foods or sustaining any venomous bites/stings. Ultimately, the back pain and leg spasms forced him to leave his job and return home to Louisiana.

Upon presentation to the sports medicine clinic, he explained that things had worsened since his return home. The pain and burning in his left leg had increased and were now present in his right leg, as well (bilateral paresthesias). In addition, he said he was feeling anxious (and described symptoms of forgetfulness, confusion, and agitation), was sleeping less, and was experiencing worsening fatigue.

Work-ups over the course of the previous 2 years had shed little light on the cause of his symptoms. X-rays of his lumbar spine revealed moderate degenerative changes at L5-S1. A lab work-up was negative and included a complete blood count, testing for HIV and herpes, a hepatitis panel, an antinuclear antibody screen, a C-reactive protein test, and a comprehensive metabolic panel. Thyroid-stimulating hormone, creatine kinase, rapid plasma reagin, and human leukocyte antigen B27 tests were also normal.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a cystic lesion in the right ilium near the sacroiliac joint. A more recent follow-up MRI and computed tomography scan of the pelvis found the cyst to be stable and well marginalized, with no cortical erosion. Attempts at physical therapy had been unsuccessful because of the pain and decreasing muscle strength in his lower extremities. The patient’s primary care provider was treating him with meloxicam 15 mg/d and duloxetine 60 mg/d, but that had not provided any relief.

Our physical examination revealed a patient who was in mild distress and had limited lumbar spine range of motion (secondary to pain in all planes) and significant paraspinal spasms on the right side in both the lumbar and thoracic regions. The patient had reduced vibratory sensation on his left side vs the right, with a 256-Hz tuning fork at the great toe, as well as reduced sensation to fine touch with a cotton swab and a positive Babinski sign bilaterally. Lower extremity reflexes were hyperreflexic on the left compared with the right. He had no pronator drift; Trendelenburg, straight leg raise, Hoover sign, and slump tests were all negative. His gait was antalgic with a cane, as he described bilateral paresthesias.

THE DIAGNOSIS

The differential diagnosis for low back pain is quite extensive and includes simple mechanical low back pain, lumbar radiculopathy, facet arthritis, spinal stenosis, spondylolysis/spondylolisthesis, and referred pain from the hip, knee, or upper back. It can also be caused by referred pain from visceral organs such as the liver, colon, or kidneys. Low back pain can also signal primary or metastatic disease. However, most of these potential diagnoses had been ruled out with imaging and lab tests.

Two things caught our attention. First: Mechanical low back pain and the associated discogenic radiculopathy would be unilateral, manifesting with asymmetric paresthesias and pain. Our patient had weakness in gait and pain and burning in both of his legs. Second: Our patient described decreased sleep and feeling anxious, with symptoms of forgetfulness, confusion, and agitation. These factors prompted us to look beyond the normal differential and consider a potential toxicity. A heavy metal screen was ordered, and the results were positive for arsenic toxicity.

DISCUSSION

Arsenic toxicity is a global health problem that affects millions of people.1,2 Arsenic has been used for centuries in depilatories, cosmetics, poisons, and therapeutic agents. Today it is used as a treatment for leukemia and in several ayurvedic and homeopathic remedies.3-7 It is a common earth element found in ground water and a waste product from mining and the manufacturing of glass, computer chips, wood preservatives, and various pesticides.2,3,7,8

A great masquerader. Once in the body, arsenic can cause many serious ailments ranging from urinary tract, liver, and skin cancers to various peripheral and central nervous system disorders.2 Arsenic can cause symmetrical peripheral neuropathy characterized by sensory nerves being more sensitive than motor nerves.2,3,5,6 Clinically, it causes numbness and paresthesias of the distal extremities, with the lower extremities more severely affected.3,6 Symptoms can develop within 2 hours to 2 years of exposure, with vomiting, diarrhea, or both preceding the onset of the neuropathy.2,3,5,6 Arsenic is linked to forgetfulness, confusion, visual distortion, sleep disturbances, decreased concentration, disorientation, severe agitation, paranoid ideation, emotional lability, and decreases in locomotor activity.3,5,6

Testing and treatment. Arsenic levels in the body are measured by blood and urine testing. Blood arsenic levels are typically detectable immediately after exposure and with continued exposure, but quickly normalize as the metal integrates into the nonvascular tissues. Urine arsenic levels can be detected for weeks. Normal levels for arsenic in both urine and blood are ≤ 12 µg/L.3 Anything greater than 12 µg/L is considered high; critically high values are those above 50 µg/L.3,5 Our patient’s blood arsenic level was 13 µg/L.

Treatment involves removing the source of the arsenic. Chelation therapy should be pursued when urine arsenic levels are greater than 50 µg/L or when removing the source of the arsenic fails to reduce arsenic levels. Chelation therapy should be continued until urine arsenic levels are below 20 µg/L.5,6

Continue to: After discussing potential sources of exposure

After discussing potential sources of exposure, our patient decided to move out of the house he shared with his ex-wife. He started to recover soon after moving out. Two weeks after his clinic visit, he no longer needed a cane to walk, and his blood arsenic level had dropped to 6 µg/L. Two months after his clinic visit, the patient’s blood arsenic level was undetectable. The patient’s peripheral neuropathy symptoms continued to improve.

The source of this patient’s arsenic exposure was never confirmed. The exposure could have occurred in Puerto Rico or in Louisiana. Even though no one else in the Louisiana home became ill, the patient was instructed to contact the local health department and water department to have the water tested. However, when he returned to the clinic for follow-up, he had not followed through.

THE TAKEAWAY

When evaluating causes of peripheral neuropathy, consider the possibility of heavy metal toxicity, which can be easily overlooked by the busy clinician. In this case, the patient initially experienced asymmetric paresthesia that gradually increased to burning pain and weakness, with reduced motor control bilaterally. This was significant because mechanical low back pain and the associated discogenic radiculopathy would be unilateral, manifesting with asymmetric paresthesias and pain.

Our patient’s leg symptoms, the constellation of forgetfulness, confusion, and agitation, and his sleep issues prompted us to look outside our normal differential. Fortunately, once arsenic exposure ceases, patients will gradually improve because arsenic is rapidly cleared from the bloodstream.3,6

CORRESPONDENCE

Charles W. Webb, DO, CAQSM, FAMSSM, FAAFP, Department of Family Medicine, 1501 Kings Highway, PO Box 33932, Shreveport, LA 71130-3932; [email protected]

THE CASE

A 34-year-old man was referred to the sports medicine clinic for evaluation of lumbar radiculopathy. He had a 2-year history of chronic lower back pain that started while he was working on power line towers in Puerto Rico. The back pain was achy, burning, shooting, and stabbing in nature. He had been treated with anti-inflammatories by a company health care provider while in Puerto Rico, but he did not have any imaging done.

At that time, he had tingling and burning that radiated down his left leg to his ankle. The patient also had leg spasms—in his left leg more than his right—and needed a cane when walking. His symptoms did not worsen at any particular time of day or with activity. He had no history of eating exotic foods or sustaining any venomous bites/stings. Ultimately, the back pain and leg spasms forced him to leave his job and return home to Louisiana.

Upon presentation to the sports medicine clinic, he explained that things had worsened since his return home. The pain and burning in his left leg had increased and were now present in his right leg, as well (bilateral paresthesias). In addition, he said he was feeling anxious (and described symptoms of forgetfulness, confusion, and agitation), was sleeping less, and was experiencing worsening fatigue.

Work-ups over the course of the previous 2 years had shed little light on the cause of his symptoms. X-rays of his lumbar spine revealed moderate degenerative changes at L5-S1. A lab work-up was negative and included a complete blood count, testing for HIV and herpes, a hepatitis panel, an antinuclear antibody screen, a C-reactive protein test, and a comprehensive metabolic panel. Thyroid-stimulating hormone, creatine kinase, rapid plasma reagin, and human leukocyte antigen B27 tests were also normal.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a cystic lesion in the right ilium near the sacroiliac joint. A more recent follow-up MRI and computed tomography scan of the pelvis found the cyst to be stable and well marginalized, with no cortical erosion. Attempts at physical therapy had been unsuccessful because of the pain and decreasing muscle strength in his lower extremities. The patient’s primary care provider was treating him with meloxicam 15 mg/d and duloxetine 60 mg/d, but that had not provided any relief.

Our physical examination revealed a patient who was in mild distress and had limited lumbar spine range of motion (secondary to pain in all planes) and significant paraspinal spasms on the right side in both the lumbar and thoracic regions. The patient had reduced vibratory sensation on his left side vs the right, with a 256-Hz tuning fork at the great toe, as well as reduced sensation to fine touch with a cotton swab and a positive Babinski sign bilaterally. Lower extremity reflexes were hyperreflexic on the left compared with the right. He had no pronator drift; Trendelenburg, straight leg raise, Hoover sign, and slump tests were all negative. His gait was antalgic with a cane, as he described bilateral paresthesias.

THE DIAGNOSIS

The differential diagnosis for low back pain is quite extensive and includes simple mechanical low back pain, lumbar radiculopathy, facet arthritis, spinal stenosis, spondylolysis/spondylolisthesis, and referred pain from the hip, knee, or upper back. It can also be caused by referred pain from visceral organs such as the liver, colon, or kidneys. Low back pain can also signal primary or metastatic disease. However, most of these potential diagnoses had been ruled out with imaging and lab tests.

Two things caught our attention. First: Mechanical low back pain and the associated discogenic radiculopathy would be unilateral, manifesting with asymmetric paresthesias and pain. Our patient had weakness in gait and pain and burning in both of his legs. Second: Our patient described decreased sleep and feeling anxious, with symptoms of forgetfulness, confusion, and agitation. These factors prompted us to look beyond the normal differential and consider a potential toxicity. A heavy metal screen was ordered, and the results were positive for arsenic toxicity.

DISCUSSION

Arsenic toxicity is a global health problem that affects millions of people.1,2 Arsenic has been used for centuries in depilatories, cosmetics, poisons, and therapeutic agents. Today it is used as a treatment for leukemia and in several ayurvedic and homeopathic remedies.3-7 It is a common earth element found in ground water and a waste product from mining and the manufacturing of glass, computer chips, wood preservatives, and various pesticides.2,3,7,8

A great masquerader. Once in the body, arsenic can cause many serious ailments ranging from urinary tract, liver, and skin cancers to various peripheral and central nervous system disorders.2 Arsenic can cause symmetrical peripheral neuropathy characterized by sensory nerves being more sensitive than motor nerves.2,3,5,6 Clinically, it causes numbness and paresthesias of the distal extremities, with the lower extremities more severely affected.3,6 Symptoms can develop within 2 hours to 2 years of exposure, with vomiting, diarrhea, or both preceding the onset of the neuropathy.2,3,5,6 Arsenic is linked to forgetfulness, confusion, visual distortion, sleep disturbances, decreased concentration, disorientation, severe agitation, paranoid ideation, emotional lability, and decreases in locomotor activity.3,5,6

Testing and treatment. Arsenic levels in the body are measured by blood and urine testing. Blood arsenic levels are typically detectable immediately after exposure and with continued exposure, but quickly normalize as the metal integrates into the nonvascular tissues. Urine arsenic levels can be detected for weeks. Normal levels for arsenic in both urine and blood are ≤ 12 µg/L.3 Anything greater than 12 µg/L is considered high; critically high values are those above 50 µg/L.3,5 Our patient’s blood arsenic level was 13 µg/L.

Treatment involves removing the source of the arsenic. Chelation therapy should be pursued when urine arsenic levels are greater than 50 µg/L or when removing the source of the arsenic fails to reduce arsenic levels. Chelation therapy should be continued until urine arsenic levels are below 20 µg/L.5,6

Continue to: After discussing potential sources of exposure

After discussing potential sources of exposure, our patient decided to move out of the house he shared with his ex-wife. He started to recover soon after moving out. Two weeks after his clinic visit, he no longer needed a cane to walk, and his blood arsenic level had dropped to 6 µg/L. Two months after his clinic visit, the patient’s blood arsenic level was undetectable. The patient’s peripheral neuropathy symptoms continued to improve.

The source of this patient’s arsenic exposure was never confirmed. The exposure could have occurred in Puerto Rico or in Louisiana. Even though no one else in the Louisiana home became ill, the patient was instructed to contact the local health department and water department to have the water tested. However, when he returned to the clinic for follow-up, he had not followed through.

THE TAKEAWAY

When evaluating causes of peripheral neuropathy, consider the possibility of heavy metal toxicity, which can be easily overlooked by the busy clinician. In this case, the patient initially experienced asymmetric paresthesia that gradually increased to burning pain and weakness, with reduced motor control bilaterally. This was significant because mechanical low back pain and the associated discogenic radiculopathy would be unilateral, manifesting with asymmetric paresthesias and pain.

Our patient’s leg symptoms, the constellation of forgetfulness, confusion, and agitation, and his sleep issues prompted us to look outside our normal differential. Fortunately, once arsenic exposure ceases, patients will gradually improve because arsenic is rapidly cleared from the bloodstream.3,6

CORRESPONDENCE

Charles W. Webb, DO, CAQSM, FAMSSM, FAAFP, Department of Family Medicine, 1501 Kings Highway, PO Box 33932, Shreveport, LA 71130-3932; [email protected]

1. Ahmad SA, Khan MH, Haque M. Arsenic contamination in groundwater in Bangladesh: implications and challenges for healthcare policy. Risk Manag Health Policy. 2018;11:251-261. doi: 10.2147/RMHP.S153188

2. Roh T, Steinmaus C, Marshall G, et al. Age at exposure to arsenic in water and mortality 30-40 years after exposure cessation. Am J Epidemiol. 2018;187:2297-2305. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwy159

3. Baker BA, Cassano VA, Murray C, ACOEM Task Force on Arsenic Exposure. Arsenic exposure, assessment, toxicity, diagnosis, and management. J Occup Environ Med. 2018;60:634-639. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000001485

4. Lasky T, Sun W, Kadry A, Hoffman MK. Mean total arsenic concentrations in chicken 1989-2000 and estimated exposures for consumers of chicken. Environ Health Perspect. 2004;112:18-21. doi: 10.1289/ehp.6407

5. Lindenmeyer G, Hoggett K, Burrow J, et al. A sickening tale. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:75-80. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcps1716775

6. Rodríguez VM, Jímenez-Capdevill ME, Giordano M. The effects of arsenic exposure on the nervous system. Toxicol Lett. 2003;145: 1-18. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4274(03)00262-5

7. Saper RB, Phillips RS, Sehgal A, et al. Lead, mercury, and arsenic in US- and Indian- manufactured ayurvedic medicines sold via the internet. JAMA. 2008;300:915-923. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.8.915

8. Rose M, Lewis J, Langford N, et al. Arsenic in seaweed—forms, concentration and dietary exposure. Food Chem Toxicol. 2007;45:1263-1267. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2007.01.007

1. Ahmad SA, Khan MH, Haque M. Arsenic contamination in groundwater in Bangladesh: implications and challenges for healthcare policy. Risk Manag Health Policy. 2018;11:251-261. doi: 10.2147/RMHP.S153188

2. Roh T, Steinmaus C, Marshall G, et al. Age at exposure to arsenic in water and mortality 30-40 years after exposure cessation. Am J Epidemiol. 2018;187:2297-2305. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwy159

3. Baker BA, Cassano VA, Murray C, ACOEM Task Force on Arsenic Exposure. Arsenic exposure, assessment, toxicity, diagnosis, and management. J Occup Environ Med. 2018;60:634-639. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000001485

4. Lasky T, Sun W, Kadry A, Hoffman MK. Mean total arsenic concentrations in chicken 1989-2000 and estimated exposures for consumers of chicken. Environ Health Perspect. 2004;112:18-21. doi: 10.1289/ehp.6407

5. Lindenmeyer G, Hoggett K, Burrow J, et al. A sickening tale. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:75-80. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcps1716775

6. Rodríguez VM, Jímenez-Capdevill ME, Giordano M. The effects of arsenic exposure on the nervous system. Toxicol Lett. 2003;145: 1-18. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4274(03)00262-5

7. Saper RB, Phillips RS, Sehgal A, et al. Lead, mercury, and arsenic in US- and Indian- manufactured ayurvedic medicines sold via the internet. JAMA. 2008;300:915-923. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.8.915

8. Rose M, Lewis J, Langford N, et al. Arsenic in seaweed—forms, concentration and dietary exposure. Food Chem Toxicol. 2007;45:1263-1267. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2007.01.007

Severe pediatric oral mucositis

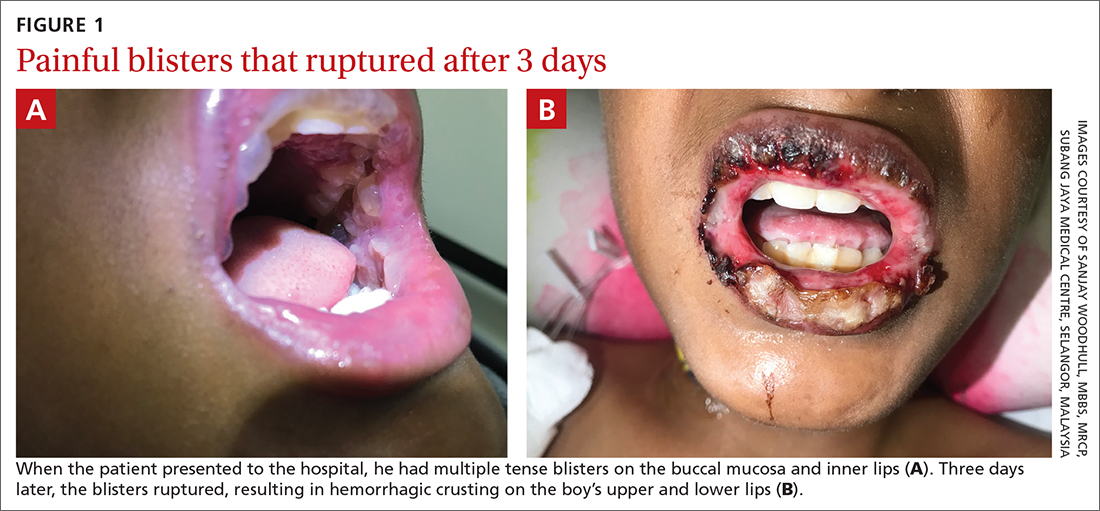

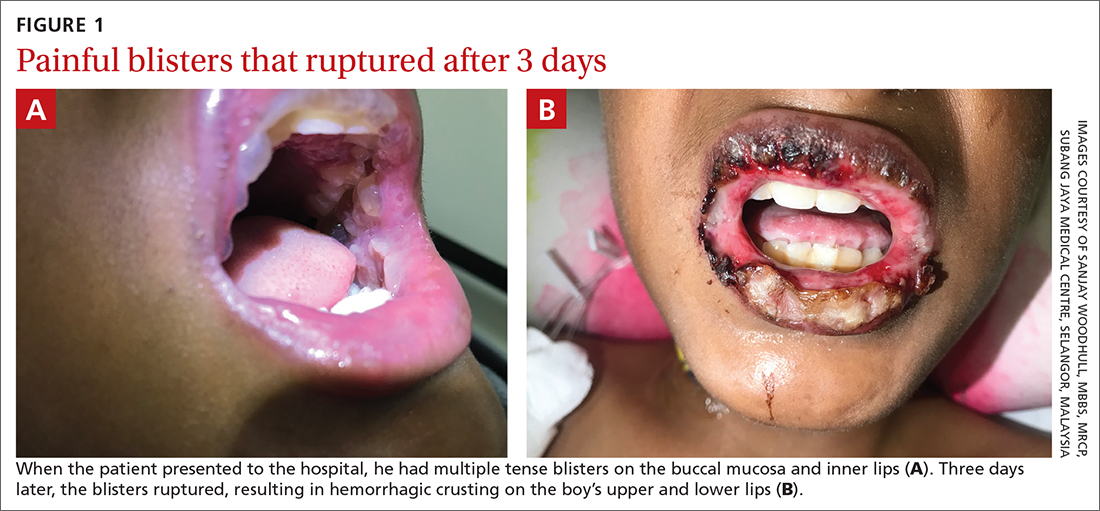

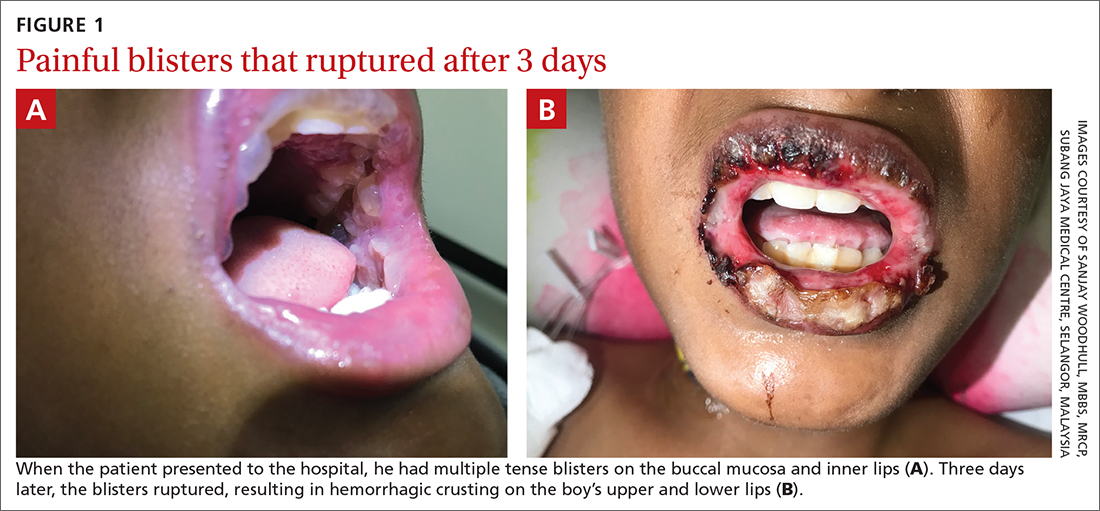

A 12-YEAR-OLD BOY presented to the hospital with a 2-day history of fever, cough, and painful blisters on swollen lips. On examination, he had multiple tense blisters with clear fluid on the buccal mucosa and inner lips (FIGURE 1A), as well as multiple discrete ulcers on his posterior pharynx. The patient had no other skin, eye, or urogenital involvement, but he was dehydrated. Respiratory examination was unremarkable. A complete blood count and metabolic panel were normal, as was a C-reactive protein (CRP) test (0.8 mg/L).

The preliminary diagnosis was primary herpetic gingivostomatitis, and treatment was initiated with intravenous (IV) acyclovir (10 mg/kg every 8 hours), IV fluids, and topical lidocaine gel and topical steroids for analgesia. However, the patient’s fever persisted over the next 4 days, with his temperature fluctuating between 101.3 °F and 104 °F, and he had a worsening productive cough. The blisters ruptured on Day 6 of illness, leaving hemorrhagic crusting on his lips (FIGURE 1B). Herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing were negative.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Mycoplasma pneumoniae–induced rash and mucositis

Further follow-up on Day 6 of illness revealed bibasilar crepitations along with an elevated CRP level of 40.5 mg/L and a positive mycoplasma antibody serology (titer > 1:1280; normal, < 1:80). The patient was given a diagnosis of pneumonia (due to infection with Mycoplasma pneumoniae) and M pneumoniae–induced rash and mucositis (MIRM).

MIRM was first proposed as a distinct clinical entity in 2015 to distinguish it from Stevens-Johnson syndrome and erythema multiforme.1 MIRM is seen more commonly in children and young adults, with a male preponderance.1

A small longitudinal study found that approximately 22.7% of children who have M pneumoniae infections present with mucocutaneous lesions, and of those cases, 6.8% are MIRM.2 Chlamydia pneumoniae is another potential causal organism of mucositis resembling MIRM.3

Pathogenesis. The commonly accepted mechanism of MIRM is an immune response triggered by a distant infection. This leads to tissue damage via polyclonal B cell proliferation and subsequent immune complex deposition, complement activation, and cytokine overproduction. Molecular mimicry between M pneumoniae P1-adhesion molecules and keratinocyte antigens may also contribute to this pathway.

3 criteria to make the diagnosis

Canavan et al1 have proposed the following criteria for the diagnosis of MIRM:

- Clinical symptoms, such as fever and cough, and laboratory findings of M pneumoniae infection (elevated M pneumoniae immunoglobulin M antibodies, positive cultures or PCR for M pneumoniae from oropharyngeal samples or bullae, and/or serial cold agglutinins) AND

- a rash to the mucosa that usually affects ≥ 2 sites (although rare cases may have fewer than 2 mucosal sites involved) AND

- skin detachment of less than 10% of the body surface area.

Continue to: The 3 variants of MIRM include...

The 3 variants of MIRM include:

- Classic MIRM has evidence of all 3 diagnostic criteria plus a nonmucosal rash, such as vesiculobullous lesions (77%), scattered target lesions (48%), papules (14%), macules (12%), and morbilliform eruptions (9%).4

- MIRM sine rash includes all 3 criteria but there is no significant cutaneous, nonmucosal rash. There may be “few fleeting morbilliform lesions or a few vesicles.”4

- Severe MIRM includes the first 2 criteria listed, but the cutaneous rash is extensive, with widespread nonmucosal blisters or flat atypical target lesions.4

Our patient had definitive clinical symptoms, laboratory evidence, and severe oral mucositis without significant cutaneous rash, thereby fulfilling the criteria for a diagnosis of MIRM sine rash variant.

These skin conditions were considered in the differential

The differential diagnosis for sudden onset of severe oral mucosal blisters in children includes herpes gingivostomatitis; hand, foot, and mouth disease

Herpes gingivostomatitis would involve numerous ulcerations of the oral mucosa and tongue, as well as gum hypertrophy.

Hand, foot, and mouth disease is characterized by

Continue to: Erythema multiforme

Erythema multiforme appears as cutaneous target lesions on the limbs that spread in a centripetal manner following herpes simplex virus infection.

SJS/TEN manifests with severe mucositis and is commonly triggered by medications (eg, sulphonamides, beta-lactams, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and antiepileptics).

With antibiotics, the prognosis is good

There are no established guidelines for the treatment of MIRM. Antibiotics and supportive care are universally accepted. Immunosuppressive therapy (eg, systemic steroids) is frequently used in patients with MIRM who have extensive mucosal involvement, in an attempt to decrease inflammation and pain; however, evidence for such an approach is lacking. The hyperimmune reactions of the host to M pneumoniae infection include cytokine overproduction and T-cell activation, which promote both pulmonary and extrapulmonary manifestations. This forms the basis of immunosuppressive therapy, such as systemic corticosteroids, IV immunoglobulin, and cyclosporin A, particularly when MIRM is associated with pneumonia caused by infection with M pneumoniae.1,5,6

The overall prognosis of MIRM is good. Recurrence has been reported in up to 8% of cases, the treatment of which remains the same. Mucocutaneous and ocular sequelae (oral or genital synechiae, corneal ulcerations, dry eyes, loss of eye lashes) have been reported in less than 9% of patients.1 Other rare reported complications following the occurrence of MIRM include persistent cutaneous lesions, B cell lymphopenia, and restrictive lung disease or chronic obliterative bronchitis.

Our patient was started on IV ceftriaxone (50 mg/kg/d), azithromycin (10 mg/kg/d on the first day, then 5 mg/kg/d on the subsequent 5 days), and methylprednisolone (3 mg/kg/d) on Day 6 of illness. Within 3 days, there was marked improvement of mucositis and respiratory symptoms with resolution of fever. He was discharged on Day 10. At his outpatient follow-up 2 weeks later, the patient had made a complete recovery.

1. Canavan TN, Mathes EF, Frieden I, et al. Mycoplasma pneumoniae-induced rash and mucositis as a syndrome distinct from Stevens-Johnson syndrome and erythema multiforme: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol 2015;72:239-245. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2014.06.026

2. Sauteur PMM, Theiler M, Buettcher M, et al. Frequency and clinical presentation of mucocutaneous disease due to mycoplasma pneumoniae infection in children with community-acquired pneumonia. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:144-150. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.3602

3. Mayor-Ibarguren A, Feito-Rodriguez M, González-Ramos J, et al. Mucositis secondary to chlamydia pneumoniae infection: expanding the mycoplasma pneumoniae-induced rash and mucositis concept. Pediatr Dermatol 2017;34:465-472. doi: 10.1111/pde.13140

4. Frantz GF, McAninch SA. Mycoplasma mucositis. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated August 8, 2022. Accessed November 1, 2022. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK525960/

5. Yang EA, Kang HM, Rhim JW, et al. Early corticosteroid therapy for Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia irrespective of used antibiotics in children. J Clin Med. 2019;8:726. doi: 10.3390/jcm8050726

6. Li HOY, Colantonio S, Ramien ML. Treatment of Mycoplasma pneumoniae-induced rash and mucositis with cyclosporine. J Cutan Med Surg. 2019;23:608-612. doi: 10.1177/1203475419874444

A 12-YEAR-OLD BOY presented to the hospital with a 2-day history of fever, cough, and painful blisters on swollen lips. On examination, he had multiple tense blisters with clear fluid on the buccal mucosa and inner lips (FIGURE 1A), as well as multiple discrete ulcers on his posterior pharynx. The patient had no other skin, eye, or urogenital involvement, but he was dehydrated. Respiratory examination was unremarkable. A complete blood count and metabolic panel were normal, as was a C-reactive protein (CRP) test (0.8 mg/L).

The preliminary diagnosis was primary herpetic gingivostomatitis, and treatment was initiated with intravenous (IV) acyclovir (10 mg/kg every 8 hours), IV fluids, and topical lidocaine gel and topical steroids for analgesia. However, the patient’s fever persisted over the next 4 days, with his temperature fluctuating between 101.3 °F and 104 °F, and he had a worsening productive cough. The blisters ruptured on Day 6 of illness, leaving hemorrhagic crusting on his lips (FIGURE 1B). Herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing were negative.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Mycoplasma pneumoniae–induced rash and mucositis

Further follow-up on Day 6 of illness revealed bibasilar crepitations along with an elevated CRP level of 40.5 mg/L and a positive mycoplasma antibody serology (titer > 1:1280; normal, < 1:80). The patient was given a diagnosis of pneumonia (due to infection with Mycoplasma pneumoniae) and M pneumoniae–induced rash and mucositis (MIRM).

MIRM was first proposed as a distinct clinical entity in 2015 to distinguish it from Stevens-Johnson syndrome and erythema multiforme.1 MIRM is seen more commonly in children and young adults, with a male preponderance.1

A small longitudinal study found that approximately 22.7% of children who have M pneumoniae infections present with mucocutaneous lesions, and of those cases, 6.8% are MIRM.2 Chlamydia pneumoniae is another potential causal organism of mucositis resembling MIRM.3

Pathogenesis. The commonly accepted mechanism of MIRM is an immune response triggered by a distant infection. This leads to tissue damage via polyclonal B cell proliferation and subsequent immune complex deposition, complement activation, and cytokine overproduction. Molecular mimicry between M pneumoniae P1-adhesion molecules and keratinocyte antigens may also contribute to this pathway.

3 criteria to make the diagnosis

Canavan et al1 have proposed the following criteria for the diagnosis of MIRM:

- Clinical symptoms, such as fever and cough, and laboratory findings of M pneumoniae infection (elevated M pneumoniae immunoglobulin M antibodies, positive cultures or PCR for M pneumoniae from oropharyngeal samples or bullae, and/or serial cold agglutinins) AND

- a rash to the mucosa that usually affects ≥ 2 sites (although rare cases may have fewer than 2 mucosal sites involved) AND

- skin detachment of less than 10% of the body surface area.

Continue to: The 3 variants of MIRM include...

The 3 variants of MIRM include:

- Classic MIRM has evidence of all 3 diagnostic criteria plus a nonmucosal rash, such as vesiculobullous lesions (77%), scattered target lesions (48%), papules (14%), macules (12%), and morbilliform eruptions (9%).4

- MIRM sine rash includes all 3 criteria but there is no significant cutaneous, nonmucosal rash. There may be “few fleeting morbilliform lesions or a few vesicles.”4

- Severe MIRM includes the first 2 criteria listed, but the cutaneous rash is extensive, with widespread nonmucosal blisters or flat atypical target lesions.4

Our patient had definitive clinical symptoms, laboratory evidence, and severe oral mucositis without significant cutaneous rash, thereby fulfilling the criteria for a diagnosis of MIRM sine rash variant.

These skin conditions were considered in the differential

The differential diagnosis for sudden onset of severe oral mucosal blisters in children includes herpes gingivostomatitis; hand, foot, and mouth disease

Herpes gingivostomatitis would involve numerous ulcerations of the oral mucosa and tongue, as well as gum hypertrophy.

Hand, foot, and mouth disease is characterized by

Continue to: Erythema multiforme

Erythema multiforme appears as cutaneous target lesions on the limbs that spread in a centripetal manner following herpes simplex virus infection.

SJS/TEN manifests with severe mucositis and is commonly triggered by medications (eg, sulphonamides, beta-lactams, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and antiepileptics).

With antibiotics, the prognosis is good

There are no established guidelines for the treatment of MIRM. Antibiotics and supportive care are universally accepted. Immunosuppressive therapy (eg, systemic steroids) is frequently used in patients with MIRM who have extensive mucosal involvement, in an attempt to decrease inflammation and pain; however, evidence for such an approach is lacking. The hyperimmune reactions of the host to M pneumoniae infection include cytokine overproduction and T-cell activation, which promote both pulmonary and extrapulmonary manifestations. This forms the basis of immunosuppressive therapy, such as systemic corticosteroids, IV immunoglobulin, and cyclosporin A, particularly when MIRM is associated with pneumonia caused by infection with M pneumoniae.1,5,6

The overall prognosis of MIRM is good. Recurrence has been reported in up to 8% of cases, the treatment of which remains the same. Mucocutaneous and ocular sequelae (oral or genital synechiae, corneal ulcerations, dry eyes, loss of eye lashes) have been reported in less than 9% of patients.1 Other rare reported complications following the occurrence of MIRM include persistent cutaneous lesions, B cell lymphopenia, and restrictive lung disease or chronic obliterative bronchitis.

Our patient was started on IV ceftriaxone (50 mg/kg/d), azithromycin (10 mg/kg/d on the first day, then 5 mg/kg/d on the subsequent 5 days), and methylprednisolone (3 mg/kg/d) on Day 6 of illness. Within 3 days, there was marked improvement of mucositis and respiratory symptoms with resolution of fever. He was discharged on Day 10. At his outpatient follow-up 2 weeks later, the patient had made a complete recovery.

A 12-YEAR-OLD BOY presented to the hospital with a 2-day history of fever, cough, and painful blisters on swollen lips. On examination, he had multiple tense blisters with clear fluid on the buccal mucosa and inner lips (FIGURE 1A), as well as multiple discrete ulcers on his posterior pharynx. The patient had no other skin, eye, or urogenital involvement, but he was dehydrated. Respiratory examination was unremarkable. A complete blood count and metabolic panel were normal, as was a C-reactive protein (CRP) test (0.8 mg/L).

The preliminary diagnosis was primary herpetic gingivostomatitis, and treatment was initiated with intravenous (IV) acyclovir (10 mg/kg every 8 hours), IV fluids, and topical lidocaine gel and topical steroids for analgesia. However, the patient’s fever persisted over the next 4 days, with his temperature fluctuating between 101.3 °F and 104 °F, and he had a worsening productive cough. The blisters ruptured on Day 6 of illness, leaving hemorrhagic crusting on his lips (FIGURE 1B). Herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing were negative.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Mycoplasma pneumoniae–induced rash and mucositis

Further follow-up on Day 6 of illness revealed bibasilar crepitations along with an elevated CRP level of 40.5 mg/L and a positive mycoplasma antibody serology (titer > 1:1280; normal, < 1:80). The patient was given a diagnosis of pneumonia (due to infection with Mycoplasma pneumoniae) and M pneumoniae–induced rash and mucositis (MIRM).

MIRM was first proposed as a distinct clinical entity in 2015 to distinguish it from Stevens-Johnson syndrome and erythema multiforme.1 MIRM is seen more commonly in children and young adults, with a male preponderance.1

A small longitudinal study found that approximately 22.7% of children who have M pneumoniae infections present with mucocutaneous lesions, and of those cases, 6.8% are MIRM.2 Chlamydia pneumoniae is another potential causal organism of mucositis resembling MIRM.3

Pathogenesis. The commonly accepted mechanism of MIRM is an immune response triggered by a distant infection. This leads to tissue damage via polyclonal B cell proliferation and subsequent immune complex deposition, complement activation, and cytokine overproduction. Molecular mimicry between M pneumoniae P1-adhesion molecules and keratinocyte antigens may also contribute to this pathway.

3 criteria to make the diagnosis

Canavan et al1 have proposed the following criteria for the diagnosis of MIRM:

- Clinical symptoms, such as fever and cough, and laboratory findings of M pneumoniae infection (elevated M pneumoniae immunoglobulin M antibodies, positive cultures or PCR for M pneumoniae from oropharyngeal samples or bullae, and/or serial cold agglutinins) AND

- a rash to the mucosa that usually affects ≥ 2 sites (although rare cases may have fewer than 2 mucosal sites involved) AND

- skin detachment of less than 10% of the body surface area.

Continue to: The 3 variants of MIRM include...

The 3 variants of MIRM include:

- Classic MIRM has evidence of all 3 diagnostic criteria plus a nonmucosal rash, such as vesiculobullous lesions (77%), scattered target lesions (48%), papules (14%), macules (12%), and morbilliform eruptions (9%).4

- MIRM sine rash includes all 3 criteria but there is no significant cutaneous, nonmucosal rash. There may be “few fleeting morbilliform lesions or a few vesicles.”4

- Severe MIRM includes the first 2 criteria listed, but the cutaneous rash is extensive, with widespread nonmucosal blisters or flat atypical target lesions.4

Our patient had definitive clinical symptoms, laboratory evidence, and severe oral mucositis without significant cutaneous rash, thereby fulfilling the criteria for a diagnosis of MIRM sine rash variant.

These skin conditions were considered in the differential

The differential diagnosis for sudden onset of severe oral mucosal blisters in children includes herpes gingivostomatitis; hand, foot, and mouth disease

Herpes gingivostomatitis would involve numerous ulcerations of the oral mucosa and tongue, as well as gum hypertrophy.

Hand, foot, and mouth disease is characterized by

Continue to: Erythema multiforme

Erythema multiforme appears as cutaneous target lesions on the limbs that spread in a centripetal manner following herpes simplex virus infection.

SJS/TEN manifests with severe mucositis and is commonly triggered by medications (eg, sulphonamides, beta-lactams, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and antiepileptics).

With antibiotics, the prognosis is good

There are no established guidelines for the treatment of MIRM. Antibiotics and supportive care are universally accepted. Immunosuppressive therapy (eg, systemic steroids) is frequently used in patients with MIRM who have extensive mucosal involvement, in an attempt to decrease inflammation and pain; however, evidence for such an approach is lacking. The hyperimmune reactions of the host to M pneumoniae infection include cytokine overproduction and T-cell activation, which promote both pulmonary and extrapulmonary manifestations. This forms the basis of immunosuppressive therapy, such as systemic corticosteroids, IV immunoglobulin, and cyclosporin A, particularly when MIRM is associated with pneumonia caused by infection with M pneumoniae.1,5,6

The overall prognosis of MIRM is good. Recurrence has been reported in up to 8% of cases, the treatment of which remains the same. Mucocutaneous and ocular sequelae (oral or genital synechiae, corneal ulcerations, dry eyes, loss of eye lashes) have been reported in less than 9% of patients.1 Other rare reported complications following the occurrence of MIRM include persistent cutaneous lesions, B cell lymphopenia, and restrictive lung disease or chronic obliterative bronchitis.

Our patient was started on IV ceftriaxone (50 mg/kg/d), azithromycin (10 mg/kg/d on the first day, then 5 mg/kg/d on the subsequent 5 days), and methylprednisolone (3 mg/kg/d) on Day 6 of illness. Within 3 days, there was marked improvement of mucositis and respiratory symptoms with resolution of fever. He was discharged on Day 10. At his outpatient follow-up 2 weeks later, the patient had made a complete recovery.

1. Canavan TN, Mathes EF, Frieden I, et al. Mycoplasma pneumoniae-induced rash and mucositis as a syndrome distinct from Stevens-Johnson syndrome and erythema multiforme: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol 2015;72:239-245. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2014.06.026

2. Sauteur PMM, Theiler M, Buettcher M, et al. Frequency and clinical presentation of mucocutaneous disease due to mycoplasma pneumoniae infection in children with community-acquired pneumonia. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:144-150. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.3602

3. Mayor-Ibarguren A, Feito-Rodriguez M, González-Ramos J, et al. Mucositis secondary to chlamydia pneumoniae infection: expanding the mycoplasma pneumoniae-induced rash and mucositis concept. Pediatr Dermatol 2017;34:465-472. doi: 10.1111/pde.13140

4. Frantz GF, McAninch SA. Mycoplasma mucositis. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated August 8, 2022. Accessed November 1, 2022. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK525960/

5. Yang EA, Kang HM, Rhim JW, et al. Early corticosteroid therapy for Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia irrespective of used antibiotics in children. J Clin Med. 2019;8:726. doi: 10.3390/jcm8050726

6. Li HOY, Colantonio S, Ramien ML. Treatment of Mycoplasma pneumoniae-induced rash and mucositis with cyclosporine. J Cutan Med Surg. 2019;23:608-612. doi: 10.1177/1203475419874444

1. Canavan TN, Mathes EF, Frieden I, et al. Mycoplasma pneumoniae-induced rash and mucositis as a syndrome distinct from Stevens-Johnson syndrome and erythema multiforme: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol 2015;72:239-245. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2014.06.026

2. Sauteur PMM, Theiler M, Buettcher M, et al. Frequency and clinical presentation of mucocutaneous disease due to mycoplasma pneumoniae infection in children with community-acquired pneumonia. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:144-150. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.3602

3. Mayor-Ibarguren A, Feito-Rodriguez M, González-Ramos J, et al. Mucositis secondary to chlamydia pneumoniae infection: expanding the mycoplasma pneumoniae-induced rash and mucositis concept. Pediatr Dermatol 2017;34:465-472. doi: 10.1111/pde.13140

4. Frantz GF, McAninch SA. Mycoplasma mucositis. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated August 8, 2022. Accessed November 1, 2022. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK525960/

5. Yang EA, Kang HM, Rhim JW, et al. Early corticosteroid therapy for Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia irrespective of used antibiotics in children. J Clin Med. 2019;8:726. doi: 10.3390/jcm8050726

6. Li HOY, Colantonio S, Ramien ML. Treatment of Mycoplasma pneumoniae-induced rash and mucositis with cyclosporine. J Cutan Med Surg. 2019;23:608-612. doi: 10.1177/1203475419874444

Keeping up with the evidence (and the residents)

I work with medical students nearly every day that I see patients. I recently mentioned to a student that I have a limited working knowledge of the brand names of diabetes medications released in the past 10 years. Just like the M3s, I need the full generic name to know whether a medication is a GLP-1 inhibitor or a DPP-4 inhibitor, because I know that “flozins” are SGLT-2 inhibitors and “glutides” are GLP-1 agonists. The combined efforts of an ambulatory care pharmacist and some flashcards have helped me to better understand how they work and which ones to prescribe when. Meanwhile, the residents are capably counseling on the adverse effects of the latest diabetes agent, while I am googling its generic name.

The premise of science is continuous discovery. In the first 10 months of 2022, the US Food & Drug Administration approved more than 2 dozen new medications, almost 100 new generics, and new indications for dozens more.1,2 The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) issued 13 new or reaffirmed recommendations in the first 10 months of 2022, and it is just one of dozens of bodies that issue guidelines relevant to primary care.3 PubMed indexes more than a million new articles each year. Learning new information and changing practice are crucial to being an effective clinician.