User login

StopRA trial: Hydroxychloroquine doesn’t prevent or delay onset of rheumatoid arthritis

PHILADELPHIA – Hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) isn’t any more effective at preventing or delaying the onset of rheumatoid arthritis than placebo, based on interim results of a randomized clinical trial reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology. Despite that futility, the percentage of patients who actually went on to develop clinical RA was lower than investigators expected, and the trial supports the use of a key biomarker for identifying RA.

While the StopRA trial was halted early because of futility of the treatment, investigators are continuing to mine the gathered data to deepen their understanding of disease progression and the potential of HCQ to improve symptoms in RA patients, said lead study author Kevin D. Deane, MD, PhD, of the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora.

Overall, around 35% of the study participants on average developed RA, Dr. Deane said. “We were expecting somewhat more,” he said. “Teasing out who’s really going to progress to RA during a study and who’s not is going to be incredibly important.”

StopRA enrolled 144 adults who had elevated anti–cyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies (CCP3) levels of at least 40 units (about twice the normal level) but no history if inflammatory arthritis, randomizing them on a 1:1 basis to either HCQ (200-400 mg a day based on weight) or placebo for a 1-year treatment regimen.

The study identified participants through rheumatology clinics, testing of first-degree relatives with established RA, health fairs, blood donors, and biobanks. The interim findings are based on 2 years of follow-up after the last dose.

The study focused on HCQ because it has a relatively low risk profile with good safety and tolerability, is easy to administer, and is relatively low cost, Dr. Deane said.

StopRA study failed to meet its primary endpoint: to determine if 1 year of treatment with HCQ reduced the risk of developing inflammatory arthritis and classifiable RA at the end of 3 years in the study population. At the time of the interim analysis, 34% of patients in the HCQ arm and 36% in the placebo arm had developed RA (P = .844), Dr. Deane said. Baseline characteristics were balanced in both treatment arms.

The findings also support the use of CCP3 as a biomarker for RA, Dr. Deane said.

Now that the trial has been terminated, Dr. Deane said investigators are going to review the final data and perform secondary analyses for further clarity on the impact HCQ may have on RA.

“The future analysis should hopefully say if this treatment actually changes symptoms,” he said in an interview. “Because, if somebody felt better on the drug or had a milder form of rheumatoid arthritis once they developed it, that could potentially be a benefit.”

Dr. Deane noted the TREAT EARLIER trial similarly found that a 1-year course of methotrexate didn’t prevent the onset of clinical arthritis, but it did alter the disease course as measured in MRI-detected inflammation, related symptoms, and impairment.

“We’re hoping to look at those things and hopefully look at biologic changes over time,” Dr. Deane said of the extended analysis. “We’re not sure if the drug was associated with changes in biomarkers yet still didn’t halt progression to RA. That might be interesting, because those biomarkers might not be fundamentally related to the disease, but other mechanisms may be. That could give us some insights.”

Session moderator Ted Mikuls, MD, a professor of rheumatology at the University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, said further mining of the study data is warranted.

“It’s common in a study like that, which took a lot of time and investment, to really take a deep dive into the data to make sure there aren’t signals that we’re missing,” he said in an interview.

One of the challenges with the study may have been patient enrollment, Dr. Mikuls noted. “I wonder about the study population in terms of where they recruit patients from. Who’s more likely to get RA? Is it patients who already have symptoms? Is it asymptomatic patients from biobanks? If it’s arthralgia joint pain patients, maybe by the time you have joint and autoantibody positivity it’s too late to have an intervention.”

The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases sponsored the study. Dr. Deane disclosed a relationship with Werfen. Dr. Mikuls has no relevant disclosures.

PHILADELPHIA – Hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) isn’t any more effective at preventing or delaying the onset of rheumatoid arthritis than placebo, based on interim results of a randomized clinical trial reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology. Despite that futility, the percentage of patients who actually went on to develop clinical RA was lower than investigators expected, and the trial supports the use of a key biomarker for identifying RA.

While the StopRA trial was halted early because of futility of the treatment, investigators are continuing to mine the gathered data to deepen their understanding of disease progression and the potential of HCQ to improve symptoms in RA patients, said lead study author Kevin D. Deane, MD, PhD, of the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora.

Overall, around 35% of the study participants on average developed RA, Dr. Deane said. “We were expecting somewhat more,” he said. “Teasing out who’s really going to progress to RA during a study and who’s not is going to be incredibly important.”

StopRA enrolled 144 adults who had elevated anti–cyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies (CCP3) levels of at least 40 units (about twice the normal level) but no history if inflammatory arthritis, randomizing them on a 1:1 basis to either HCQ (200-400 mg a day based on weight) or placebo for a 1-year treatment regimen.

The study identified participants through rheumatology clinics, testing of first-degree relatives with established RA, health fairs, blood donors, and biobanks. The interim findings are based on 2 years of follow-up after the last dose.

The study focused on HCQ because it has a relatively low risk profile with good safety and tolerability, is easy to administer, and is relatively low cost, Dr. Deane said.

StopRA study failed to meet its primary endpoint: to determine if 1 year of treatment with HCQ reduced the risk of developing inflammatory arthritis and classifiable RA at the end of 3 years in the study population. At the time of the interim analysis, 34% of patients in the HCQ arm and 36% in the placebo arm had developed RA (P = .844), Dr. Deane said. Baseline characteristics were balanced in both treatment arms.

The findings also support the use of CCP3 as a biomarker for RA, Dr. Deane said.

Now that the trial has been terminated, Dr. Deane said investigators are going to review the final data and perform secondary analyses for further clarity on the impact HCQ may have on RA.

“The future analysis should hopefully say if this treatment actually changes symptoms,” he said in an interview. “Because, if somebody felt better on the drug or had a milder form of rheumatoid arthritis once they developed it, that could potentially be a benefit.”

Dr. Deane noted the TREAT EARLIER trial similarly found that a 1-year course of methotrexate didn’t prevent the onset of clinical arthritis, but it did alter the disease course as measured in MRI-detected inflammation, related symptoms, and impairment.

“We’re hoping to look at those things and hopefully look at biologic changes over time,” Dr. Deane said of the extended analysis. “We’re not sure if the drug was associated with changes in biomarkers yet still didn’t halt progression to RA. That might be interesting, because those biomarkers might not be fundamentally related to the disease, but other mechanisms may be. That could give us some insights.”

Session moderator Ted Mikuls, MD, a professor of rheumatology at the University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, said further mining of the study data is warranted.

“It’s common in a study like that, which took a lot of time and investment, to really take a deep dive into the data to make sure there aren’t signals that we’re missing,” he said in an interview.

One of the challenges with the study may have been patient enrollment, Dr. Mikuls noted. “I wonder about the study population in terms of where they recruit patients from. Who’s more likely to get RA? Is it patients who already have symptoms? Is it asymptomatic patients from biobanks? If it’s arthralgia joint pain patients, maybe by the time you have joint and autoantibody positivity it’s too late to have an intervention.”

The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases sponsored the study. Dr. Deane disclosed a relationship with Werfen. Dr. Mikuls has no relevant disclosures.

PHILADELPHIA – Hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) isn’t any more effective at preventing or delaying the onset of rheumatoid arthritis than placebo, based on interim results of a randomized clinical trial reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology. Despite that futility, the percentage of patients who actually went on to develop clinical RA was lower than investigators expected, and the trial supports the use of a key biomarker for identifying RA.

While the StopRA trial was halted early because of futility of the treatment, investigators are continuing to mine the gathered data to deepen their understanding of disease progression and the potential of HCQ to improve symptoms in RA patients, said lead study author Kevin D. Deane, MD, PhD, of the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora.

Overall, around 35% of the study participants on average developed RA, Dr. Deane said. “We were expecting somewhat more,” he said. “Teasing out who’s really going to progress to RA during a study and who’s not is going to be incredibly important.”

StopRA enrolled 144 adults who had elevated anti–cyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies (CCP3) levels of at least 40 units (about twice the normal level) but no history if inflammatory arthritis, randomizing them on a 1:1 basis to either HCQ (200-400 mg a day based on weight) or placebo for a 1-year treatment regimen.

The study identified participants through rheumatology clinics, testing of first-degree relatives with established RA, health fairs, blood donors, and biobanks. The interim findings are based on 2 years of follow-up after the last dose.

The study focused on HCQ because it has a relatively low risk profile with good safety and tolerability, is easy to administer, and is relatively low cost, Dr. Deane said.

StopRA study failed to meet its primary endpoint: to determine if 1 year of treatment with HCQ reduced the risk of developing inflammatory arthritis and classifiable RA at the end of 3 years in the study population. At the time of the interim analysis, 34% of patients in the HCQ arm and 36% in the placebo arm had developed RA (P = .844), Dr. Deane said. Baseline characteristics were balanced in both treatment arms.

The findings also support the use of CCP3 as a biomarker for RA, Dr. Deane said.

Now that the trial has been terminated, Dr. Deane said investigators are going to review the final data and perform secondary analyses for further clarity on the impact HCQ may have on RA.

“The future analysis should hopefully say if this treatment actually changes symptoms,” he said in an interview. “Because, if somebody felt better on the drug or had a milder form of rheumatoid arthritis once they developed it, that could potentially be a benefit.”

Dr. Deane noted the TREAT EARLIER trial similarly found that a 1-year course of methotrexate didn’t prevent the onset of clinical arthritis, but it did alter the disease course as measured in MRI-detected inflammation, related symptoms, and impairment.

“We’re hoping to look at those things and hopefully look at biologic changes over time,” Dr. Deane said of the extended analysis. “We’re not sure if the drug was associated with changes in biomarkers yet still didn’t halt progression to RA. That might be interesting, because those biomarkers might not be fundamentally related to the disease, but other mechanisms may be. That could give us some insights.”

Session moderator Ted Mikuls, MD, a professor of rheumatology at the University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, said further mining of the study data is warranted.

“It’s common in a study like that, which took a lot of time and investment, to really take a deep dive into the data to make sure there aren’t signals that we’re missing,” he said in an interview.

One of the challenges with the study may have been patient enrollment, Dr. Mikuls noted. “I wonder about the study population in terms of where they recruit patients from. Who’s more likely to get RA? Is it patients who already have symptoms? Is it asymptomatic patients from biobanks? If it’s arthralgia joint pain patients, maybe by the time you have joint and autoantibody positivity it’s too late to have an intervention.”

The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases sponsored the study. Dr. Deane disclosed a relationship with Werfen. Dr. Mikuls has no relevant disclosures.

AT ACR 2022

‘A huge deal’: Millions have long COVID, and more are expected

with symptoms that have lasted 3 months or longer, according to the latest U.S. government survey done in October. More than a quarter say their condition is severe enough to significantly limit their day-to-day activities – yet the problem is only barely starting to get the attention of employers, the health care system, and policymakers.

With no cure or treatment in sight, long COVID is already burdening not only the health care system, but also the economy – and that burden is set to grow. Many experts worry about the possible long-term ripple effects, from increased spending on medical care costs to lost wages due to not being able to work, as well as the policy implications that come with addressing these issues.

“At this point, anyone who’s looking at this seriously would say this is a huge deal,” says senior Brookings Institution fellow Katie Bach, the author of a study that analyzed long COVID’s impact on the labor market.

“We need a real concerted focus on treating these people, which means both research and the clinical side, and figuring out how to build a labor market that is more inclusive of people with disabilities,” she said.

It’s not only that many people are affected. It’s that they are often affected for months and possibly even years.

The U.S. government figures suggest more than 18 million people could have symptoms of long COVID right now. The latest Household Pulse Survey by the Census Bureau and the National Center for Health Statistics takes data from 41,415 people.

A preprint of a study by researchers from City University of New York, posted on medRxiv in September and based on a similar population survey done between June 30 and July 2, drew comparable results. The study has not been peer reviewed.

More than 7% of all those who answered said they had long COVID at the time of the survey, which the researchers said corresponded to approximately 18.5 million U.S. adults. The same study found that a quarter of those, or an estimated 4.7 million adults, said their daily activities were impacted “a lot.”

This can translate into pain not only for the patients, but for governments and employers, too.

In high-income countries around the world, government surveys and other studies are shedding light on the extent to which post-COVID-19 symptoms – commonly known as long COVID – are affecting populations. While results vary, they generally fall within similar ranges.

The World Health Organization estimates that between 10% and 20% of those with COVID-19 go on to have an array of medium- to long-term post-COVID-19 symptoms that range from mild to debilitating. The U.S. Government Accountability Office puts that estimate at 10% to 30%; one of the latest studies published at the end of October in The Journal of the American Medical Association found that 15% of U.S. adults who had tested positive for COVID-19 reported current long COVID symptoms. Elsewhere, a study from the Netherlands published in The Lancet in August found that one in eight COVID-19 cases, or 12.7%, were likely to become long COVID.

“It’s very clear that the condition is devastating people’s lives and livelihoods,” WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus wrote in an article for The Guardian newspaper in October.

“The world has already lost a significant number of the workforce to illness, death, fatigue, unplanned retirement due to an increase in long-term disability, which not only impacts the health system, but is a hit to the overarching economy … the impact of long COVID for all countries is very serious and needs immediate and sustained action equivalent to its scale.”

Global snapshot: Lasting symptoms, impact on activities

Patients describe a spectrum of persistent issues, with extreme fatigue, brain fog or cognitive problems, and shortness of breath among the most common complaints. Many also have manageable symptoms that worsen significantly after even mild physical or mental exertion.

Women appear almost twice as likely as men to get long COVID. Many patients have other medical conditions and disabilities that make them more vulnerable to the condition. Those who face greater obstacles accessing health care due to discrimination or socioeconomic inequity are at higher risk as well.

While many are older, a large number are also in their prime working age. The Census Bureau data show that people ages 40-49 are more likely than any other group to get long COVID, which has broader implications for labor markets and the global economy. Already, experts have estimated that long COVID is likely to cost the U.S. trillions of dollars and affect multiple industries.

“Whether they’re in the financial world, the medical system, lawyers, they’re telling me they’re sitting at the computer screen and they’re unable to process the data,” said Zachary Schwartz, MD, medical director for Vancouver General Hospital’s Post-COVID-19 Recovery Clinic.

“That is what’s most distressing for people, in that they’re not working, they’re not making money, and they don’t know when, or if, they’re going to get better.”

Nearly a third of respondents in the Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey who said they have had COVID-19 reported symptoms that lasted 3 months or longer. People between the ages of 30 and 59 were the most affected, with about 32% reporting symptoms. Across the entire adult U.S. population, the survey found that 1 in 7 adults have had long COVID at some point during the pandemic, with about 1 in 18 saying it limited their activity to some degree, and 1 in 50 saying they have faced “a lot” of limits on their activities. Any way these numbers are dissected, long COVID has impacted a large swath of the population.

Yet research into the causes and possible treatments of long COVID is just getting underway.

“The amount of energy and time devoted to it is way, way less than it should, given how many people are likely affected,” said David Cutler, PhD, professor of economics at Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass., who has written about the economic cost of long COVID. “We’re way, way underdoing it here. And I think that’s really a terrible thing.”

Population surveys and studies from around the world show that long COVID lives up to its name, with people reporting serious symptoms for months on end.

In October, Statistics Canada and the Public Health Agency of Canada published early results from a questionnaire done between spring and summer 2022 that found just under 15% of adults who had a confirmed or suspected case of COVID-19 went on to have new or continuing symptoms 3 or more months later. Nearly half, or 47.3%, dealt with symptoms that lasted a year or more. More than one in five said their symptoms “often or always” limited their day-to-day activities, which included routine tasks such as preparing meals, doing errands and chores, and basic functions such as personal care and moving around in their homes.

Nearly three-quarters of workers or students said they missed an average of 20 days of work or school.

“We haven’t yet been able to determine exactly when symptoms resolve,” said Rainu Kaushal, MD, the senior associate dean for clinical research at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York. She is co-leading a national study on long COVID in adults and children, funded by the National Institutes of Health RECOVER Initiative.

“But there does seem to be, for many of the milder symptoms, resolution at about 4-6 weeks. There seems to be a second point of resolution around 6 months for certain symptoms, and then some symptoms do seem to be permanent, and those tend to be patients who have underlying conditions,” she said.

Reducing the risk

Given all the data so far, experts recommend urgent policy changes to help people with long COVID.

“The population needs to be prepared, that understanding long COVID is going to be a very long and difficult process,” said Alexander Charney, MD, PhD, associate professor and the lead principal investigator of the RECOVER adult cohort at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York. He said the government can do a great deal to help, including setting up a network of connected clinics treating long COVID, standardizing best practices, and sharing information.

“That would go a long way towards making sure that every person feels like they’re not too far away from a clinic where they can get treated for this particular condition,” he said.

But the only known way to prevent long COVID is to prevent COVID-19 infections in the first place, experts say. That means equitable access to tests, therapeutics, and vaccines.

“I will say that avoiding COVID remains the best treatment in the arsenal right now,” said Dr. Kaushal. This means masking, avoiding crowded places with poor ventilation and high exposure risk, and being up to date on vaccinations, she said.

A number of papers – including a large U.K. study published in May 2022, another one from July, and the JAMA study from October – all suggest that vaccinations can help reduce the risk of long COVID.

“I am absolutely of the belief that vaccination has reduced the incidence and overall amount of long COVID … [and is] still by far the best thing the public can do,” said Dr. Schwartz.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

with symptoms that have lasted 3 months or longer, according to the latest U.S. government survey done in October. More than a quarter say their condition is severe enough to significantly limit their day-to-day activities – yet the problem is only barely starting to get the attention of employers, the health care system, and policymakers.

With no cure or treatment in sight, long COVID is already burdening not only the health care system, but also the economy – and that burden is set to grow. Many experts worry about the possible long-term ripple effects, from increased spending on medical care costs to lost wages due to not being able to work, as well as the policy implications that come with addressing these issues.

“At this point, anyone who’s looking at this seriously would say this is a huge deal,” says senior Brookings Institution fellow Katie Bach, the author of a study that analyzed long COVID’s impact on the labor market.

“We need a real concerted focus on treating these people, which means both research and the clinical side, and figuring out how to build a labor market that is more inclusive of people with disabilities,” she said.

It’s not only that many people are affected. It’s that they are often affected for months and possibly even years.

The U.S. government figures suggest more than 18 million people could have symptoms of long COVID right now. The latest Household Pulse Survey by the Census Bureau and the National Center for Health Statistics takes data from 41,415 people.

A preprint of a study by researchers from City University of New York, posted on medRxiv in September and based on a similar population survey done between June 30 and July 2, drew comparable results. The study has not been peer reviewed.

More than 7% of all those who answered said they had long COVID at the time of the survey, which the researchers said corresponded to approximately 18.5 million U.S. adults. The same study found that a quarter of those, or an estimated 4.7 million adults, said their daily activities were impacted “a lot.”

This can translate into pain not only for the patients, but for governments and employers, too.

In high-income countries around the world, government surveys and other studies are shedding light on the extent to which post-COVID-19 symptoms – commonly known as long COVID – are affecting populations. While results vary, they generally fall within similar ranges.

The World Health Organization estimates that between 10% and 20% of those with COVID-19 go on to have an array of medium- to long-term post-COVID-19 symptoms that range from mild to debilitating. The U.S. Government Accountability Office puts that estimate at 10% to 30%; one of the latest studies published at the end of October in The Journal of the American Medical Association found that 15% of U.S. adults who had tested positive for COVID-19 reported current long COVID symptoms. Elsewhere, a study from the Netherlands published in The Lancet in August found that one in eight COVID-19 cases, or 12.7%, were likely to become long COVID.

“It’s very clear that the condition is devastating people’s lives and livelihoods,” WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus wrote in an article for The Guardian newspaper in October.

“The world has already lost a significant number of the workforce to illness, death, fatigue, unplanned retirement due to an increase in long-term disability, which not only impacts the health system, but is a hit to the overarching economy … the impact of long COVID for all countries is very serious and needs immediate and sustained action equivalent to its scale.”

Global snapshot: Lasting symptoms, impact on activities

Patients describe a spectrum of persistent issues, with extreme fatigue, brain fog or cognitive problems, and shortness of breath among the most common complaints. Many also have manageable symptoms that worsen significantly after even mild physical or mental exertion.

Women appear almost twice as likely as men to get long COVID. Many patients have other medical conditions and disabilities that make them more vulnerable to the condition. Those who face greater obstacles accessing health care due to discrimination or socioeconomic inequity are at higher risk as well.

While many are older, a large number are also in their prime working age. The Census Bureau data show that people ages 40-49 are more likely than any other group to get long COVID, which has broader implications for labor markets and the global economy. Already, experts have estimated that long COVID is likely to cost the U.S. trillions of dollars and affect multiple industries.

“Whether they’re in the financial world, the medical system, lawyers, they’re telling me they’re sitting at the computer screen and they’re unable to process the data,” said Zachary Schwartz, MD, medical director for Vancouver General Hospital’s Post-COVID-19 Recovery Clinic.

“That is what’s most distressing for people, in that they’re not working, they’re not making money, and they don’t know when, or if, they’re going to get better.”

Nearly a third of respondents in the Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey who said they have had COVID-19 reported symptoms that lasted 3 months or longer. People between the ages of 30 and 59 were the most affected, with about 32% reporting symptoms. Across the entire adult U.S. population, the survey found that 1 in 7 adults have had long COVID at some point during the pandemic, with about 1 in 18 saying it limited their activity to some degree, and 1 in 50 saying they have faced “a lot” of limits on their activities. Any way these numbers are dissected, long COVID has impacted a large swath of the population.

Yet research into the causes and possible treatments of long COVID is just getting underway.

“The amount of energy and time devoted to it is way, way less than it should, given how many people are likely affected,” said David Cutler, PhD, professor of economics at Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass., who has written about the economic cost of long COVID. “We’re way, way underdoing it here. And I think that’s really a terrible thing.”

Population surveys and studies from around the world show that long COVID lives up to its name, with people reporting serious symptoms for months on end.

In October, Statistics Canada and the Public Health Agency of Canada published early results from a questionnaire done between spring and summer 2022 that found just under 15% of adults who had a confirmed or suspected case of COVID-19 went on to have new or continuing symptoms 3 or more months later. Nearly half, or 47.3%, dealt with symptoms that lasted a year or more. More than one in five said their symptoms “often or always” limited their day-to-day activities, which included routine tasks such as preparing meals, doing errands and chores, and basic functions such as personal care and moving around in their homes.

Nearly three-quarters of workers or students said they missed an average of 20 days of work or school.

“We haven’t yet been able to determine exactly when symptoms resolve,” said Rainu Kaushal, MD, the senior associate dean for clinical research at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York. She is co-leading a national study on long COVID in adults and children, funded by the National Institutes of Health RECOVER Initiative.

“But there does seem to be, for many of the milder symptoms, resolution at about 4-6 weeks. There seems to be a second point of resolution around 6 months for certain symptoms, and then some symptoms do seem to be permanent, and those tend to be patients who have underlying conditions,” she said.

Reducing the risk

Given all the data so far, experts recommend urgent policy changes to help people with long COVID.

“The population needs to be prepared, that understanding long COVID is going to be a very long and difficult process,” said Alexander Charney, MD, PhD, associate professor and the lead principal investigator of the RECOVER adult cohort at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York. He said the government can do a great deal to help, including setting up a network of connected clinics treating long COVID, standardizing best practices, and sharing information.

“That would go a long way towards making sure that every person feels like they’re not too far away from a clinic where they can get treated for this particular condition,” he said.

But the only known way to prevent long COVID is to prevent COVID-19 infections in the first place, experts say. That means equitable access to tests, therapeutics, and vaccines.

“I will say that avoiding COVID remains the best treatment in the arsenal right now,” said Dr. Kaushal. This means masking, avoiding crowded places with poor ventilation and high exposure risk, and being up to date on vaccinations, she said.

A number of papers – including a large U.K. study published in May 2022, another one from July, and the JAMA study from October – all suggest that vaccinations can help reduce the risk of long COVID.

“I am absolutely of the belief that vaccination has reduced the incidence and overall amount of long COVID … [and is] still by far the best thing the public can do,” said Dr. Schwartz.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

with symptoms that have lasted 3 months or longer, according to the latest U.S. government survey done in October. More than a quarter say their condition is severe enough to significantly limit their day-to-day activities – yet the problem is only barely starting to get the attention of employers, the health care system, and policymakers.

With no cure or treatment in sight, long COVID is already burdening not only the health care system, but also the economy – and that burden is set to grow. Many experts worry about the possible long-term ripple effects, from increased spending on medical care costs to lost wages due to not being able to work, as well as the policy implications that come with addressing these issues.

“At this point, anyone who’s looking at this seriously would say this is a huge deal,” says senior Brookings Institution fellow Katie Bach, the author of a study that analyzed long COVID’s impact on the labor market.

“We need a real concerted focus on treating these people, which means both research and the clinical side, and figuring out how to build a labor market that is more inclusive of people with disabilities,” she said.

It’s not only that many people are affected. It’s that they are often affected for months and possibly even years.

The U.S. government figures suggest more than 18 million people could have symptoms of long COVID right now. The latest Household Pulse Survey by the Census Bureau and the National Center for Health Statistics takes data from 41,415 people.

A preprint of a study by researchers from City University of New York, posted on medRxiv in September and based on a similar population survey done between June 30 and July 2, drew comparable results. The study has not been peer reviewed.

More than 7% of all those who answered said they had long COVID at the time of the survey, which the researchers said corresponded to approximately 18.5 million U.S. adults. The same study found that a quarter of those, or an estimated 4.7 million adults, said their daily activities were impacted “a lot.”

This can translate into pain not only for the patients, but for governments and employers, too.

In high-income countries around the world, government surveys and other studies are shedding light on the extent to which post-COVID-19 symptoms – commonly known as long COVID – are affecting populations. While results vary, they generally fall within similar ranges.

The World Health Organization estimates that between 10% and 20% of those with COVID-19 go on to have an array of medium- to long-term post-COVID-19 symptoms that range from mild to debilitating. The U.S. Government Accountability Office puts that estimate at 10% to 30%; one of the latest studies published at the end of October in The Journal of the American Medical Association found that 15% of U.S. adults who had tested positive for COVID-19 reported current long COVID symptoms. Elsewhere, a study from the Netherlands published in The Lancet in August found that one in eight COVID-19 cases, or 12.7%, were likely to become long COVID.

“It’s very clear that the condition is devastating people’s lives and livelihoods,” WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus wrote in an article for The Guardian newspaper in October.

“The world has already lost a significant number of the workforce to illness, death, fatigue, unplanned retirement due to an increase in long-term disability, which not only impacts the health system, but is a hit to the overarching economy … the impact of long COVID for all countries is very serious and needs immediate and sustained action equivalent to its scale.”

Global snapshot: Lasting symptoms, impact on activities

Patients describe a spectrum of persistent issues, with extreme fatigue, brain fog or cognitive problems, and shortness of breath among the most common complaints. Many also have manageable symptoms that worsen significantly after even mild physical or mental exertion.

Women appear almost twice as likely as men to get long COVID. Many patients have other medical conditions and disabilities that make them more vulnerable to the condition. Those who face greater obstacles accessing health care due to discrimination or socioeconomic inequity are at higher risk as well.

While many are older, a large number are also in their prime working age. The Census Bureau data show that people ages 40-49 are more likely than any other group to get long COVID, which has broader implications for labor markets and the global economy. Already, experts have estimated that long COVID is likely to cost the U.S. trillions of dollars and affect multiple industries.

“Whether they’re in the financial world, the medical system, lawyers, they’re telling me they’re sitting at the computer screen and they’re unable to process the data,” said Zachary Schwartz, MD, medical director for Vancouver General Hospital’s Post-COVID-19 Recovery Clinic.

“That is what’s most distressing for people, in that they’re not working, they’re not making money, and they don’t know when, or if, they’re going to get better.”

Nearly a third of respondents in the Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey who said they have had COVID-19 reported symptoms that lasted 3 months or longer. People between the ages of 30 and 59 were the most affected, with about 32% reporting symptoms. Across the entire adult U.S. population, the survey found that 1 in 7 adults have had long COVID at some point during the pandemic, with about 1 in 18 saying it limited their activity to some degree, and 1 in 50 saying they have faced “a lot” of limits on their activities. Any way these numbers are dissected, long COVID has impacted a large swath of the population.

Yet research into the causes and possible treatments of long COVID is just getting underway.

“The amount of energy and time devoted to it is way, way less than it should, given how many people are likely affected,” said David Cutler, PhD, professor of economics at Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass., who has written about the economic cost of long COVID. “We’re way, way underdoing it here. And I think that’s really a terrible thing.”

Population surveys and studies from around the world show that long COVID lives up to its name, with people reporting serious symptoms for months on end.

In October, Statistics Canada and the Public Health Agency of Canada published early results from a questionnaire done between spring and summer 2022 that found just under 15% of adults who had a confirmed or suspected case of COVID-19 went on to have new or continuing symptoms 3 or more months later. Nearly half, or 47.3%, dealt with symptoms that lasted a year or more. More than one in five said their symptoms “often or always” limited their day-to-day activities, which included routine tasks such as preparing meals, doing errands and chores, and basic functions such as personal care and moving around in their homes.

Nearly three-quarters of workers or students said they missed an average of 20 days of work or school.

“We haven’t yet been able to determine exactly when symptoms resolve,” said Rainu Kaushal, MD, the senior associate dean for clinical research at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York. She is co-leading a national study on long COVID in adults and children, funded by the National Institutes of Health RECOVER Initiative.

“But there does seem to be, for many of the milder symptoms, resolution at about 4-6 weeks. There seems to be a second point of resolution around 6 months for certain symptoms, and then some symptoms do seem to be permanent, and those tend to be patients who have underlying conditions,” she said.

Reducing the risk

Given all the data so far, experts recommend urgent policy changes to help people with long COVID.

“The population needs to be prepared, that understanding long COVID is going to be a very long and difficult process,” said Alexander Charney, MD, PhD, associate professor and the lead principal investigator of the RECOVER adult cohort at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York. He said the government can do a great deal to help, including setting up a network of connected clinics treating long COVID, standardizing best practices, and sharing information.

“That would go a long way towards making sure that every person feels like they’re not too far away from a clinic where they can get treated for this particular condition,” he said.

But the only known way to prevent long COVID is to prevent COVID-19 infections in the first place, experts say. That means equitable access to tests, therapeutics, and vaccines.

“I will say that avoiding COVID remains the best treatment in the arsenal right now,” said Dr. Kaushal. This means masking, avoiding crowded places with poor ventilation and high exposure risk, and being up to date on vaccinations, she said.

A number of papers – including a large U.K. study published in May 2022, another one from July, and the JAMA study from October – all suggest that vaccinations can help reduce the risk of long COVID.

“I am absolutely of the belief that vaccination has reduced the incidence and overall amount of long COVID … [and is] still by far the best thing the public can do,” said Dr. Schwartz.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Make room for continuous glucose monitoring in type 2 diabetes management

A1C has been used to estimate 3-month glycemic control in patients with diabetes. However, A1C monitoring alone does not provide insight into daily glycemic variation, which is valuable in clinical management because tight glycemic control (defined as A1C < 7.0%) has been shown to reduce the risk of microvascular complications. Prior to the approval of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists and sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitors by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of type 2 diabetes (T2D), reduction in the risk of macrovascular complications (aside from nonfatal myocardial infarction) was more difficult to achieve than it is now; some patients had a worse outcome with overly aggressive glycemic control.1

Previously, the use of a continuous glucose monitor (CGM) was limited to patients with type 1 diabetes who required basal and bolus insulin. However, technological advances have led to more patient-friendly and affordable devices, making CGMs more available. As such, the American Diabetes Association (ADA), in its 2022 Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes, recommends that clinicians offer continuous glucose monitoring to adults with T2D who require multiple daily injections, and based on a given patient’s ability, preferences, and needs.2

In this article, we discuss, first, the intricacies of CGMs and, second, what the evidence says about their use so that physicians can confidently recommend, and educate patients on, effective utilization of CGMs to obtain an individualized target of glycemic control.

Continuous glucose monitoring: A glossary

CGMs are characterized by who possesses the device and how data are recorded. This review is not about professional CGMs, which are owned by the health care provider and consist of a sensor that is applied in the clinic and returned to clinic for downloading of data1; rather, we focus on the novel category of nonprofessional, or personal, CGMs.

Three words to remember. Every CGM has 3 common components:

- The reader (also known as a receiver) is a handheld device that allows a patient to scan a sensor (see definition below) and instantaneously collect a glucose reading. The patient can use a standalone reader; a smartphone or other smart device with an associated app that serves as a reader; or both.

- A sensor is inserted subcutaneously to measure interstitial glucose. The lifespan of a sensor is 10 to 14 days.

- A transmitter relays information from the sensor to the reader.

The technology behind a CGM

CGM sensors measure interstitial glucose by means of a chemical reaction involving glucose oxidase and an oxidation-reduction cofactor, measuring the generation of hydrogen peroxide.3 Interstitial glucose readings lag behind plasma blood glucose readings by 2 to 21 minutes.4,5 Although this lag time is often not clinically significant, situations such as aerobic exercise and a rapidly changing glucose level might warrant confirmation by means of fingerstick measurement.5 It is common for CGM readings to vary slightly from venipuncture or fingerstick glucose readings.

What CGMs are availableto your patients?

Intermittently scanned CGMs (isCGMs) measure the glucose level continuously; the patient must scan a sensor to display and record the glucose level.6 Prolonged periods without scanning result in gaps in glycemic data.7,8

Continue to: Two isCGM systems...

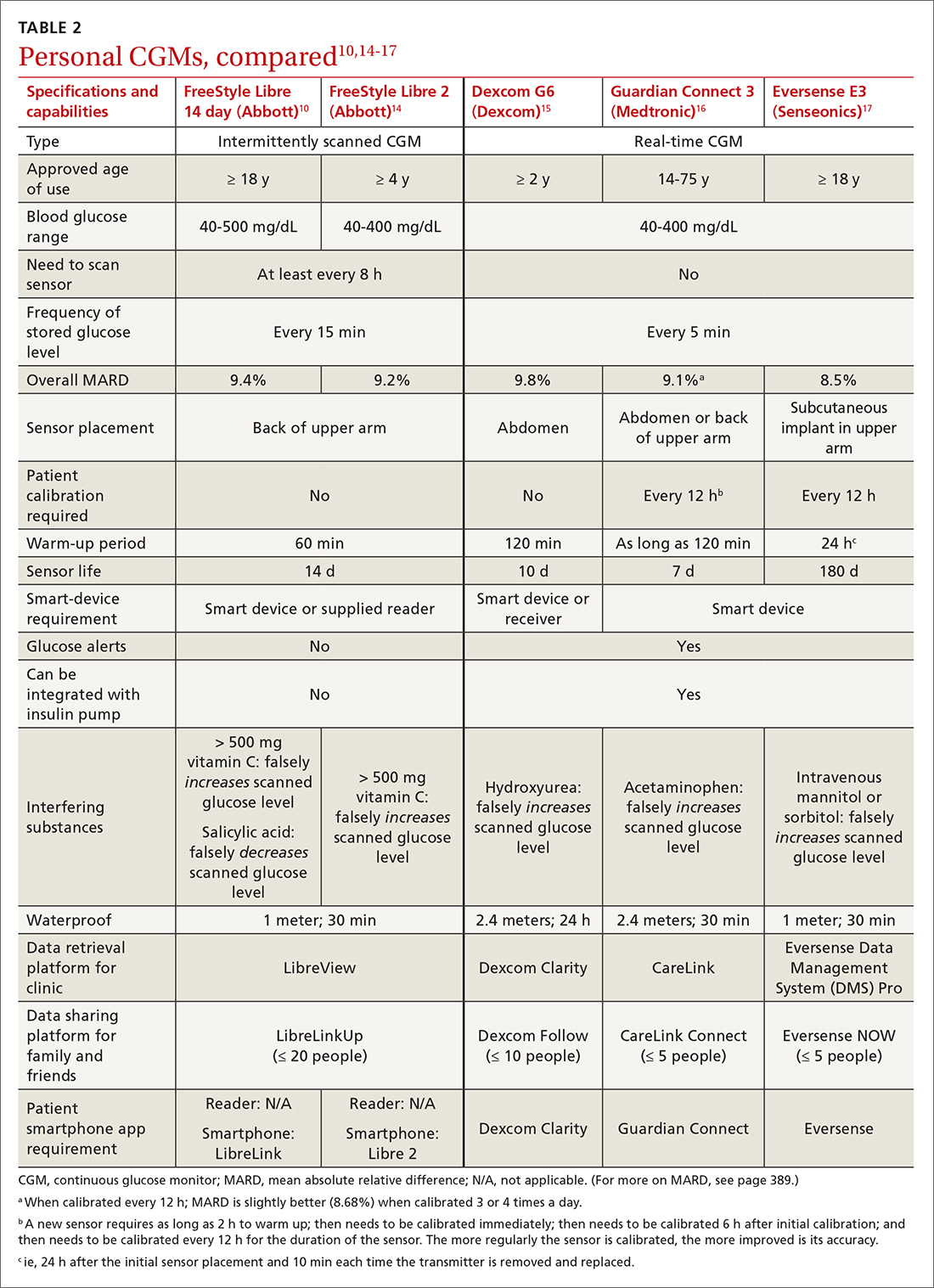

Two isCGM systems are available: the FreeStyle Libre 14 day and the FreeStyle Libre 2 (both from Abbott).a Both consist of a reader and a disposable sensor, applied to the back of the arm, that is worn for 14 days. If the patient has a compatible smartphone or other smart device, the reader can be replaced by the smart device with the downloaded FreeStyle Libre or FreeStyle Libre 2 app.

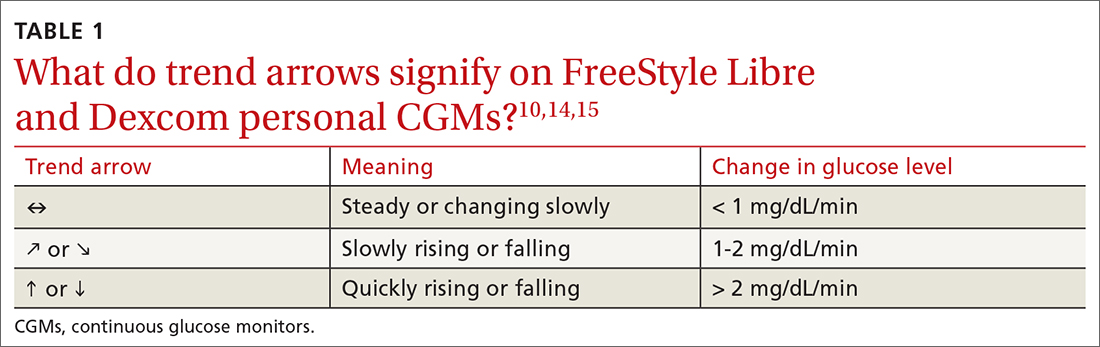

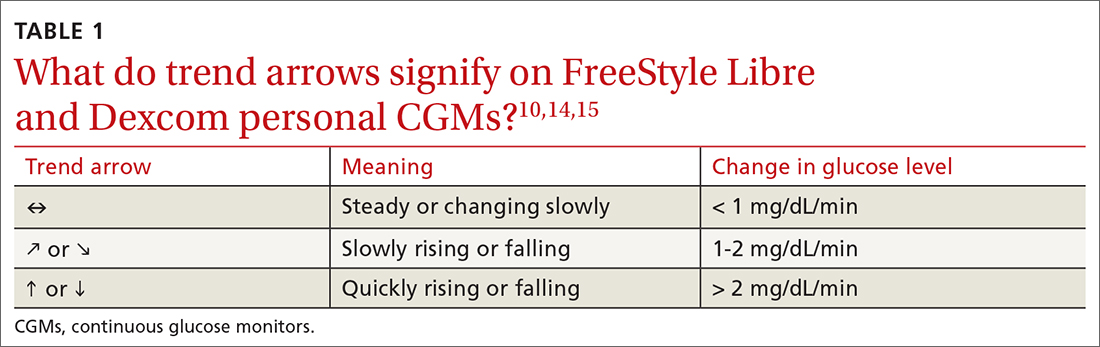

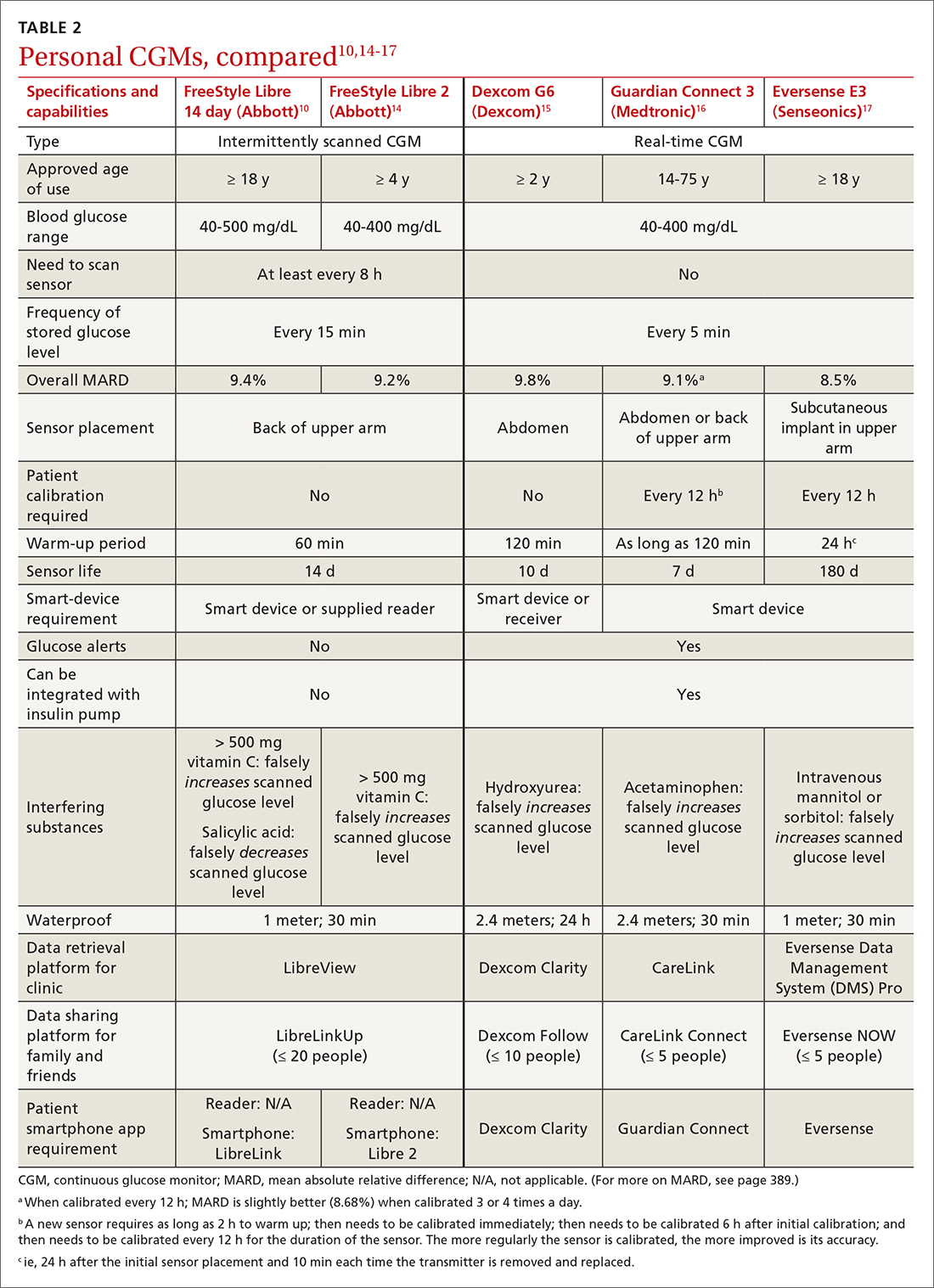

To activate a new sensor, the patient applies the sensor, then scans it. Once activated, scanning the sensor provides the current glucose reading and recalls the last 8 hours of data. In addition to providing an instantaneous glucose reading, the display also provides a trend arrow indicating the direction and degree to which the glucose level is changing (TABLE 110,14,15). This feature helps patients avoid hypoglycemic episodes by allowing them to preemptively correct if the arrow indicates a rapidly declining glucose level.

For the first 12 hours after a new sensor is activated, and when a glucose reading is < 70 mg/dL, patients should be instructed to avoid making treatment decisions and encouraged to utilize fingerstick glucose readings. FreeStyle Libre 14 day does not allow a glucose level alarm to be set; the system cannot detect these events without scanning the sensor.10 Bluetooth connectivity does allow FreeStyle Libre 2 users to set a glucose alarm if the reader or smart device is within 20 feet of the sensor. A default alarm is set to activate at 70 mg/dL (“low”) and 240 mg/dL (“high”); low and high alarm settings are also customizable. Because both FreeStyle Libre devices store 8 hours of data, patients must scan the sensor every 8 hours for a comprehensive glycemic report.14

FreeStyle Libre CGMs allow patients to add therapy notes, including time and amount of insulin administered and carbohydrates ingested. Readers for both devices function as a glucometer that is compatible with Abbott FreeStyle Precision Neo test strips.

Real-time CGMs (rtCGMs) measure and display glucose levels continuously for the duration of the life of the sensor, without the need to scan. Three rtCGM systems are available: Dexcom G6, Medtronic Guardian 3, and Senseonics Eversense E3.

Continue to: Dexcom G6...

Dexcom G6 is the first Dexcom CGM that does not require fingerstick calibration and the only rtCGM available in the United States that does not require patient calibration. This system comprises a single-use sensor replaced every 10 days; a transmitter that is transferred to each new sensor and replaced every 3 months; and an optional receiver that can be omitted if the patient prefers to utilize a smart device.

Dexcom G6 never requires a patient to scan a sensor. Instead, the receiver (or smart device) utilizes Bluetooth technology to obtain blood glucose readings if it is positioned within 20 feet of the transmitter. Patients can set both hypoglycemic and hyperglycemic alarms to predict events within 20 minutes. Similar to the functionality of the FreeStyle Libre systems, Dexcom G6 provides the opportunity to log lifestyle events, including insulin dosing, carbohydrate ingestion, exercise, and sick days.15

Medtronic Guardian 3 comprises the multi-use Guardian Connect Transmitter that is replaced annually and a single-use Guardian Sensor that is replaced every 7 days. Guardian 3 requires twice-daily fingerstick glucose calibration, which reduces the convenience of a CGM.

Guardian 3 allows the user to set alarm levels, providing predictive alerts 10 to 60 minutes before set glucose levels are reached. Patients must utilize a smart device to connect through Bluetooth to the CareLink Connect app and remain within 20 feet of the transmitter to provide continuous glucose readings. The CareLink Connect app allows patients to document exercise, calibration of fingerstick readings, meals, and insulin administration.16

Senseonics Eversense E3 consists of a 3.5 mm × 18.3 mm sensor inserted subcutaneously in the upper arm once every 180 days; a removable transmitter that attaches to an adhesive patch placed over the sensor; and a smart device with the Eversense app. The transmitter has a 1-year rechargeable battery and provides the patient with on-body vibration alerts even when they are not near their smart device.

Continue to: The Eversense E3 transmitter...

The Eversense E3 transmitter can be removed and reapplied without affecting the life of the sensor; however, no glucose data will be collected during this time. Once the transmitter is reapplied, it takes 10 minutes for the sensor to begin communicating with the transmitter. Eversense provides predictive alerts as long as 30 minutes before hyperglycemic or hypoglycemic events. The device requires twice-daily fingerstick calibrations.17

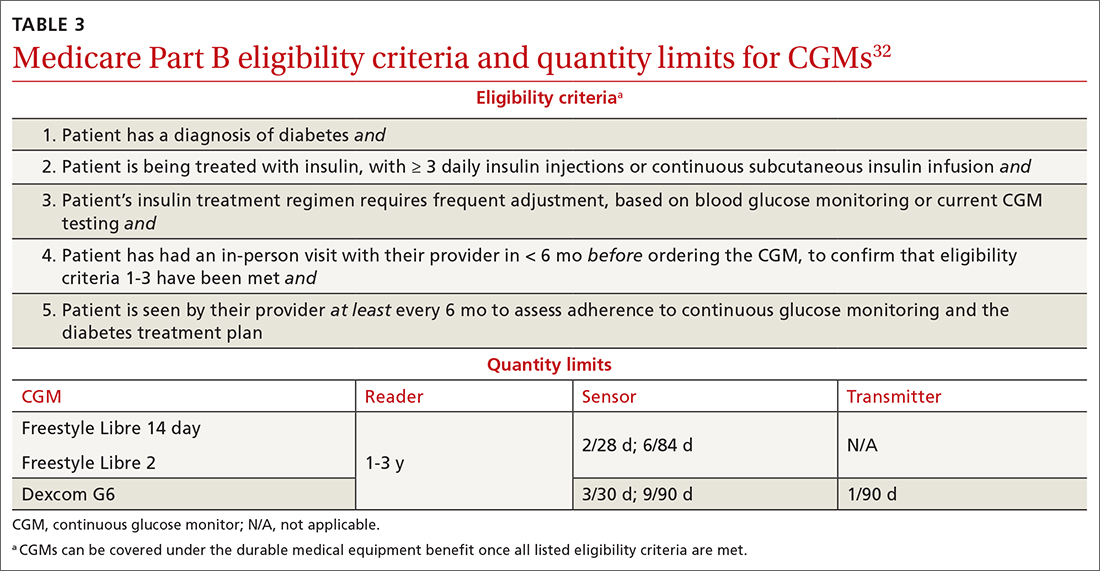

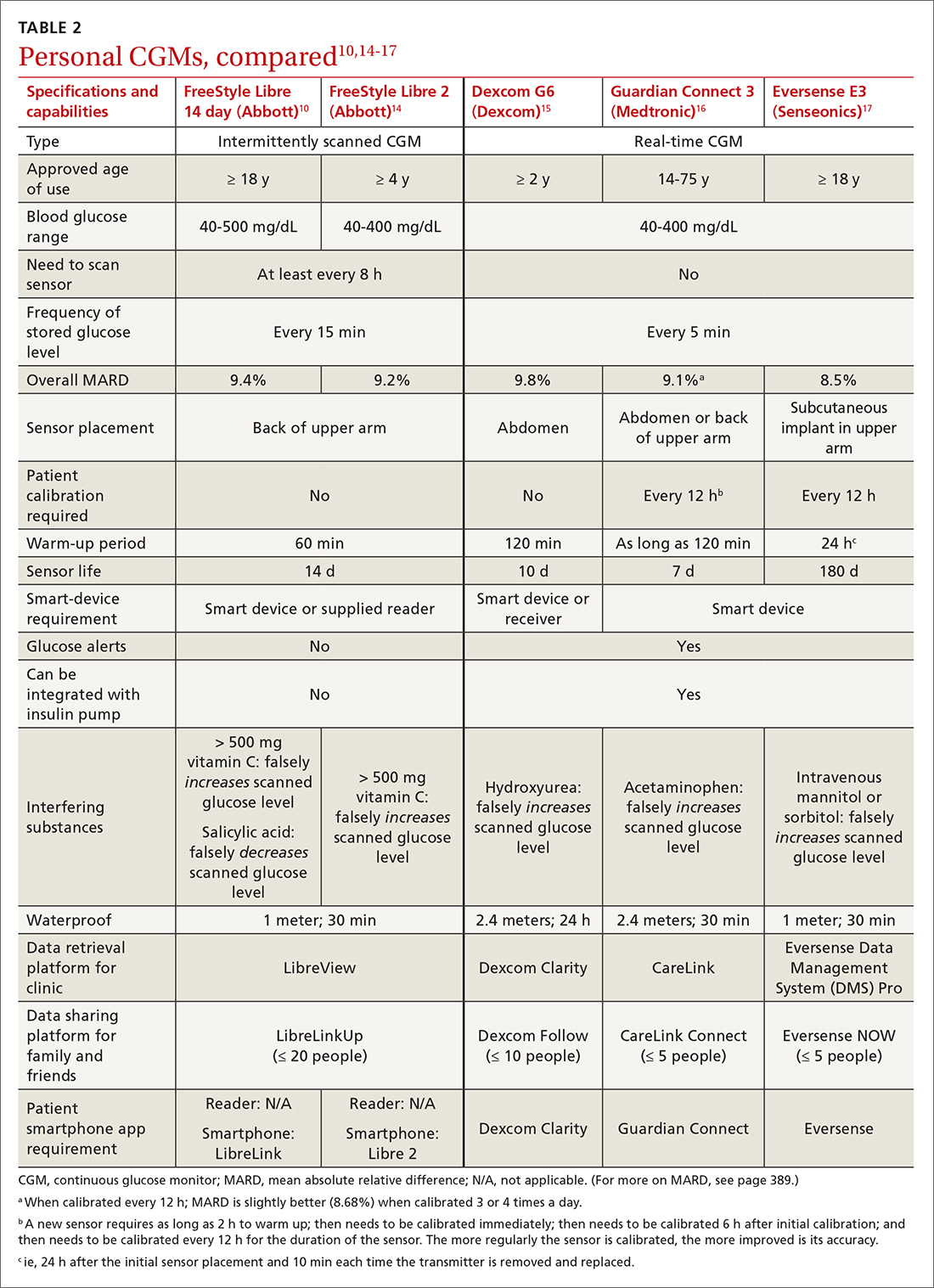

A comparison of the specifications and capabilities of the personal CGMs discussed here is provided in TABLE 2.10,14-17

The evidence, reviewed

Clinical outcomes evidence with CGMs in patients with T2D is sparse. Most studies that support improved clinical outcomes enrolled patients with type 1 diabetes who were treated with intensive insulin regimens. Many studies utilized rtCGMs that are capable of incorporating a hypoglycemic alarm, and results might not be generalizable to isCGMs.18,19 In this article, we review only the continuous glucose monitoring literature in which subjects had T2D.

Evidence for is CGMs

The REPLACE trial compared outcomes in patients with T2D who used an isCGM vs those who self-monitored blood glucose (SMBG); both groups were being treated with intensive insulin regimens. Both groups had similar glucose reductions, but the time in the hypoglycemic range (see “Clinical targets,” in the text that follows) was significantly shorter in the isCGM group.20

A randomized controlled trial (RCT) that compared intermittently scanned continuous glucose monitoring and SMBG in patients with T2D who received multiple doses of insulin daily demonstrated a significant A1C reduction of 0.82% with an isCGM and 0.33% with SMBG, with no difference in the rate of hypoglycemic events, over 10 weeks.21

Continue to: Chart review

Chart review. Data extracted from chart reviews in Austria, France, and Germany demonstrated a mean improvement in A1C of 0.9% among patients when using a CGM after using SMBG previously.22

A retrospective review of patients with T2D who were not taking bolus insulin and who used a CGM had a reduction in A1C from 10.1% to 8.6% over 60 to 300 days.23

Evidence for rtCGMs

The DIAMOND study included a subset of patients with T2D who used an rtCGM and were compared to a subset who received usual care. The primary outcome was the change in A1C. A 0.3% greater reduction was observed in the CGM group at 24 weeks. There was no difference in hypoglycemic events between the 2 groups; there were few events in either group.24

An RCT demonstrated a similar reduction in A1C in rtCGM users and in nonusers over 1 year.25 However, patients who used the rtCGM by protocol demonstrated the greatest reduction in A1C. The CGM utilized in this trial required regular fingerstick calibration, which likely led to poorer adherence to protocol than would have been the case had the trial utilized a CGM that did not require calibration.

A prospective trial demonstrated that utilization of an rtCGM only 3 days per month for 3 consecutive months was associated with (1) significant improvement in A1C (a decrease of 1.1% in the CGM group, compared to a decrease of 0.4% in the SMBG group) and (2) numerous lifestyle modifications, including reduction in total caloric intake, weight loss, decreased body mass index, and an increase in total weekly exercise.26 This trial demonstrated that CGMs might be beneficial earlier in the course of disease by reinforcing lifestyle changes.

Continue to: The MOBILE trial

The MOBILE trial demonstrated that use of an rtCGM reduced baseline A1C from 9.1% to 8.0% in the CGM group, compared to 9.0% to 8.4% in the non-CGM group.27

Practical utilization of CGMs

Patient education

Detailed patient education resources—for initial setup, sensor application, methods to ensure appropriate sensor adhesion, and app and platform assistance—are available on each manufacturer’s website.

Clinical targets

In 2019, the Advanced Technologies & Treatments for Diabetes Congress determined that what is known as the time in range metric yields the most practical data to help clinicians manage glycemic control.28 The time in range metric comprises:

- time in the target glucose range (TIR)

- time below the target glucose range (TBR)

- time above the target glucose range (TAR).

TIR glucose ranges are modifiable and based on the A1C goal. For example, if the A1C goal is < 7.0%, the TIR glucose range is 70-180 mg/dL. If a patient maintains TIR > 70% for 3 months, the measured A1C will correlate well with the goal. Each 10% fluctuation in TIR from the goal of 70% corresponds to a difference of approximately 0.5% in A1C. Therefore, TIR of approximately 50% predicts an A1C of 8.0%.28

A retrospective review of 1440 patients with CGM data demonstrated that progression of retinopathy and development of microalbuminuria increased 64% and 40%, respectively, over 10 years for each 10% reduction in TIR—highlighting the importance of TIR and consistent glycemic control.29 Importantly, the CGM sensor must be active ≥ 70% of the wearable time to provide adequate TIR data.30

Continue to: Concerns about accuracy

Concerns about accuracy

There is no universally accepted standard for determining the accuracy of a CGM; however, the mean absolute relative difference (MARD) is the most common statistic referenced. MARD is calculated as the average of the absolute error between all CGM values and matched reference values that are usually obtained from SMBG.31 The lower the MARD percentage, the better the accuracy of the CGM. A MARD of ≤ 10% is considered acceptable for making therapeutic decisions.30

Package labeling for all CGMs recommends that patients have access to a fingerstick glucometer to verify CGM readings when concerns about accuracy exist. If a sensor becomes dislodged, it can malfunction or lose accuracy. Patients should not try to re-apply the sensor; instead, they should remove and discard the sensor and apply a new one. TABLE 210,14-17 compares MARD for CGMs and lists substances that might affect the accuracy of a CGM.

Patient–provider data-sharing platforms

FreeStyle Libre and Libre 2. Providers create a LibreView Practice ID at www.Libre View.com. Patient data-sharing depends on whether they are using a smart device, a reader, or both. Patients can utilize both the smart device and the reader but must upload data from the reader at regular intervals to provide a comprehensive report that will merge data from the smart device (ie, data that have been uploaded automatically) and the reader.7

Dexcom G6. Clinicians create a Dexcom CLARITY account at https://clarity.dexcom.com and add patients to a practice list or gain access to a share code generated by the patient. Patients must download the Dexcom CLARITY app to create an account; once the account is established, readings will be transmitted to the clinic automatically.15 A patient who is utilizing a nonsmart-device reader must upload data manually to their web-based CLARITY account.

Family and caregiver access

Beyond sharing CGM data with clinic staff, an important feature available with FreeStyle Libre and Dexcom systems is the ability to share data with friends and caregivers. The relevant platforms and apps are listed in TABLE 2.10,14-17

Continue to: Insurance coverage, cost, and accessibility

Insurance coverage, cost, and accessibility

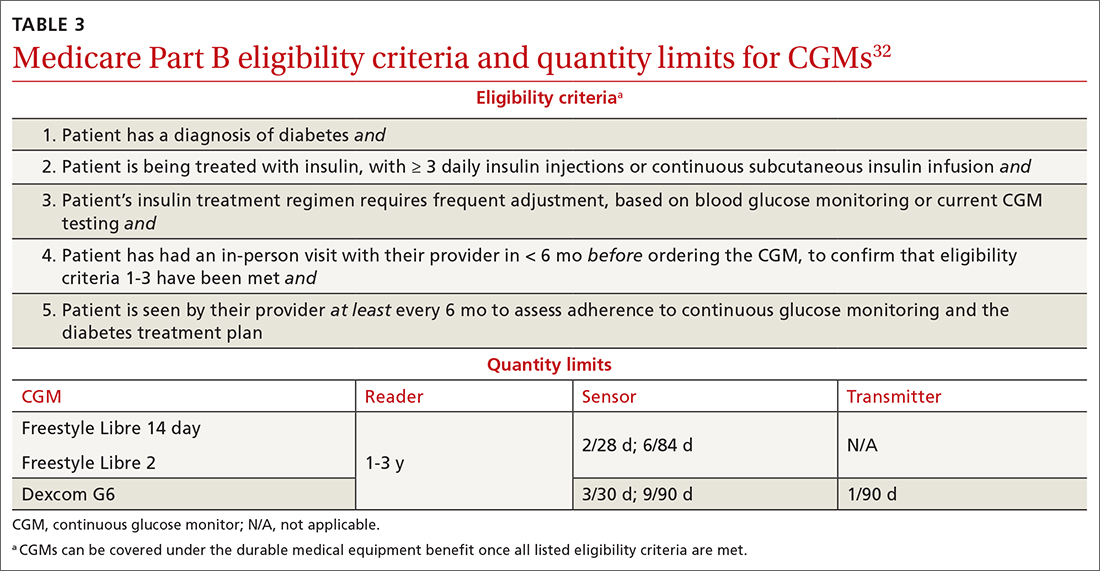

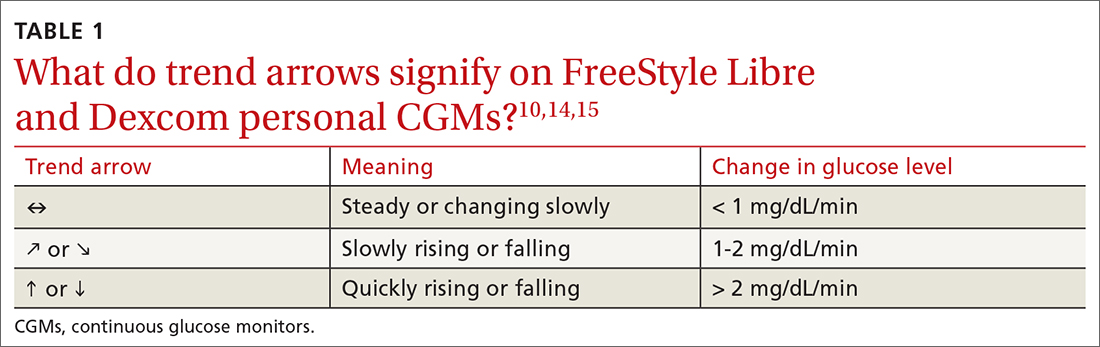

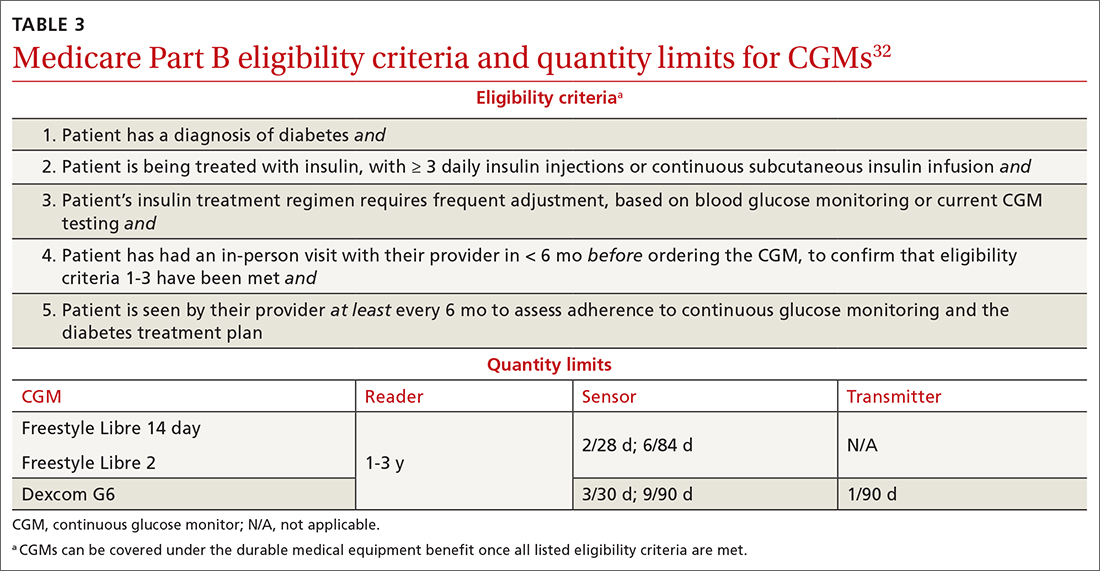

Medicare Part B has established criteria by which patients with T2D qualify for a CGM (TABLE 332). A Medicare patient who has been determined to be eligible is responsible for 20% of the out-of-pocket expense of the CGM and supplies once their deductible is met. Once Medicare covers a CGM, the patient is no longer able to obtain fingerstick glucose supplies through Medicare; they must pay the cash price for any fingerstick supplies that are determined to be necessary.32

Patients with private insurance can obtain CGM supplies through their preferred pharmacy when the order is written as a prescription (the same as for fingerstick glucometers). That is not the case for patients with Medicare because not all US distributors and pharmacies are contracted to bill Medicare Part B for CGM supplies. A list of distributors and eligible pharmacies can be found on each manufacturer’s website.

Risk–benefit analysis

CGMs are associated with few risks overall. The predominant adverse effect is contact dermatitis; the prevalence of CGM-associated contact dermatitis is difficult to quantify and differs from device to device.

FreeStyle Libre. In a retrospective review of records of patients with diabetes, researchers determined that a cutaneous adverse event occurred in approximately 5.5% of 1036 patients who utilized a FreeStyle Libre sensor.33 Of that percentage, 3.8% of dermatitis cases were determined to be allergic in nature and related to isobornyl acrylate (IBOA), a chemical constituent of the sensor’s adhesive that is not used in the FreeStyle Libre 2. Among patients who wore a sensor and developed allergic contact dermatitis, interventions such as a barrier film were of limited utility in alleviating or preventing further cutaneous eruption.33

Dexcom G6. The prevalence of Dexcom G6–associated allergic contact dermatitis is more difficult to ascertain (the IBOA adhesive was replaced in October 2019) but has been reported to be less common than with FreeStyle Libre,34 a finding that corroborates our anecdotal clinical experience. Although Dexcom sensors no longer contain IBOA, cases of allergic contact dermatitis are still reported.35 We propose that the lower incidence of cutaneous reactions associated with the Dexcom G6 sensor might be due to the absence of IBOA and shorter contact time with skin.

Continue to: In general, patients should be...

In general, patients should be counseled to rotate the location of the sensor and to use only specific barrier products that are recommended on each manufacturer’s website. The use of other barriers that are not specifically recommended might compromise the accuracy of the sensor.

Summing up

As CGM technology improves, it is likely that more and more of your patients will utilize one of these devices. The value of CGMs has been documented, but any endorsement of their use is qualified:

- Data from many older RCTs of patients with T2D who utilize a CGM did not demonstrate a significant reduction in A1C20,24,36; however, real-world observational data do show a greater reduction in A1C.

- From a safety standpoint, contact dermatitis is the primary drawback of CGMs.

- CGMs can provide patients and clinicians with a comprehensive picture of daily glucose trends, which can help patients make lifestyle changes and serve as a positive reinforcement for the effects of diet and exercise. Analysis of glucose trends can also help clinicians confidently make decisions about when to intensify or taper a medication regimen, based on data that is reported more often than 90-day A1C changes.

Health insurance coverage will continue to dictate access to CGM technology for many patients. When a CGM is reimbursable by the patient’s insurance, consider offering it as an option—even for patients who do not require an intensive insulin regimen.

a The US Food and Drug Administration cleared a new Abbott CGM, FreeStyle Libre 3, earlier this year; however, the device is not yet available for purchase. With advances in monitoring technology, several other manufacturers also anticipate introducing novel CGMs. (See “Continuous glucose monitors: The next generation.” )

SIDEBAR

Continuous glucose monitors: The next generation9-13

Expect new continuous glucose monitoring devices to be introduced to US and European health care markets in the near future.

FreeStyle Libre 3 (Abbott) was cleared by the US Food and Drug Administration in May 2022, although it is not yet available for purchase. The manufacturer promotes the device as having the smallest sensor of any continuous glucose monitor (the diameter and thickness of 2 stacked pennies); improved mean absolute relative difference; the ability to provide real-time glucose level readings; and 50% greater range of Bluetooth connectivity (about 10 extra feet).9,10

Dexcom G7 (Dexcom) has a sensor that is 60% smaller than the Dexcom G6 sensor and a 30-minute warm-up time, compared to 120 minutes for the G6.11 The device has received European Union CE mark approval.

Guardian 4 Sensor (Medtronic) does not require fingerstick calibration. The device has also received European Union CE mark approval12 but is available only for investigational use in the United States.

Eversense XL technology is similar to that of the Eversense E3, including a 180-day sensor.13 The device, which has received European Union CE mark approval, includes a removable smart transmitter.

CORRESPONDENCE

Kevin Schleich, PharmD, BCACP, Departments of Pharmaceutical Care and Family Medicine, University of Iowa, 200 Hawkins Drive, 01102-D PFP, Iowa City, IA, 52242; [email protected]

1. Rodríguez-Gutiérrez R, Montori VM. Glycemic control for patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: our evolving faith in the face of evidence. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2016;9:504-512. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.116.002901

2. Draznin B, Aroda VR, Bakris G, et al; . 7. Diabetes technology: standards of medical care in diabetes—2022. Diabetes Care. 2021;45(suppl 1):S97-S112. doi: 10.2337/dc22-S007

3. Olczuk D, Priefer R. A history of continuous glucose monitors (CGMs) in self-monitoring of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2018;12:181-187. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2017.09.005

4. Alva S, Bailey T, Brazg R, et al. Accuracy of a 14-day factory-calibrated continuous glucose monitoring system with advanced algorithm in pediatric and adult population with diabetes. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2022;16:70-77. doi: 10.1177/1932296820958754

5. Zaharieva DP, Turksoy K, McGaugh SM, et al. Lag time remains with newer real-time continuous glucose monitoring technology during aerobic exercise in adults living with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2019;21:313-321. doi: 10.1089/dia.2018.0364

6. American Diabetes Association. 2. Classification and diagnosis of diabetes: standards of medical care in diabetes—2021. Diabetes Care. 2021;44(suppl 1):S15-S33. doi: 10.2337/dc21-S002

7. FreeStyle Libre systems: The #1 CGM used in the US. Abbott. Updated May 2022. Accessed October 22, 2022. www.freestyleprovider.abbott/us-en/home.html

8. Rowland K. Choosing Wisely: 10 practices to stop—or adopt—to reduce overuse in health care. J Fam Pract. 2020;69:396-400.

9. Tucker ME. FDA clears Abbott Freestyle Libre 3 glucose sensor. MDedge. June 1, 2022. Accessed October 21, 2022. www.mdedge.com/endocrinology/article/255095/diabetes/fda-clears-abbott-freestyle-libre-3-glucose-sensor

10. Manage your diabetes with more confidence. Abbott. Updated May 2022. Accessed October 22, 2022. www.freestyle.abbott/us-en/home.html

11. Whooley S. Dexcom CEO Kevin Sayer says G7 will be ‘wonderful’. Drug Delivery Business News. July 19, 2021. Accessed October 21, 2022. www.drugdeliverybusiness.com/dexcom-ceo-kevin-sayer-says-g7-will-be-wonderful

12. Medtronic secures two CE mark approvals for Guardian 4 Sensor & for InPen MDI Smart Insulin Pen. Medtronic. Press release. May 26, 2021. Accessed October 22, 2022. https://news.medtronic.com/2021-05-26-Medtronic-Secures-Two-CE-Mark-Approvals-for-Guardian-4-Sensor-for-InPen-MDI-Smart-Insulin-Pen

13. Eversense—up to 180 days of freedom [XL CGM System]. Senseonics. Accessed September 14, 2022. https://global.eversensediabetes.com

14. FreeStyle Libre 2 User’s Manual. Abbott. Revised August 24, 2022. Accessed October 2, 2022. https://freestyleserver.com/Payloads/IFU/2022/q3/ART46983-001_rev-A.pdf

15. Dexcom G6 Continuous Glucose Monitoring System user guide. Dexcom. Revised March 2022. Accessed October 21, 2022. https://s3-us-west-2.amazonaws.com/dexcompdf/G6-CGM-Users-Guide.pdf

16. Guardian Connect System user guide. Medtronic. 2020. Accessed October 21, 2022. www.medtronicdiabetes.com/sites/default/files/library/download-library/user-guides/Guardian-Connect-System-User-Guide.pdf

17. Eversense E3 user guides. Senseonics. 2022. Accessed October 22, 2022. www.ascensiadiabetes.com/eversense/user-guides/

18. Battelino T, Conget I, Olsen B, et al; SWITCH Study Group. The use and efficacy of continuous glucose monitoring in type 1 diabetes treated with insulin pump therapy: a randomised controlled trial. Diabetologia. 2012;55:3155-3162. doi: 10.1007/s00125-012-2708-9

19. Weinzimer S, Miller K, Beck R, et al; Effectiveness of continuous glucose monitoring in a clinical care environment: evidence from the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation continuous glucose monitoring (JDRF-CGM) trial. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:17-22. doi: 10.2337/dc09-1502

20. Haak T, Hanaire H, Ajjan R, et al. Flash glucose-sensing technology as a replacement for blood glucose monitoring for the management of insulin-treated type 2 diabetes: a multicenter, open-label randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Ther. 2017;8:55-73. doi: 10.1007/s13300-016-0223-6

21. Yaron M, Roitman E, Aharon-Hananel G, et al. Effect of flash glucose monitoring technology on glycemic control and treatment satisfaction in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2019;42:1178-1184. doi: 10.2337/dc18-0166

22. Kröger J, Fasching P, Hanaire H. Three European retrospective real-world chart review studies to determine the effectiveness of flash glucose monitoring on HbA1c in adults with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Ther. 2020;11:279-291. doi: 10.1007/s13300-019-00741-9

23. Wright EE, Jr, Kerr MSD, Reyes IJ, et al. Use of flash continuous glucose monitoring is associated with A1C reduction in people with type 2 diabetes treated with basal insulin or noninsulin therapy. Diabetes Spectr. 2021;34:184-189. doi: 10.2337/ds20-0069

24. Beck RW, Riddlesworth TD, Ruedy K, et al; DIAMOND Study Group. Continuous glucose monitoring versus usual care in patients with type 2 diabetes receiving multiple daily insulin injections: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167:365-374. doi: 10.7326/M16-2855

25. Vigersky RA, Fonda SJ, Chellappa M, et al. Short- and long-term effects of real-time continuous glucose monitoring in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2012;35:32-38. doi: 10.2337/dc11-1438

26. Yoo HJ, An HG, Park SY, et al. Use of a real time continuous glucose monitoring system as a motivational device for poorly controlled type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2008;82:73-79. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2008.06.015

27. Martens T, Beck RW, Bailey R, et al; MOBILE Study Group. Effect of continuous glucose monitoring on glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes treated with basal insulin: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2021;325:2262-2272. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.7444

28. Battelino T, Danne T, Bergenstal RM, et al. Clinical targets for continuous glucose monitoring data interpretation: recommendations from the international consensus on time in range. Diabetes Care. 2019;42:1593-1603. doi: 10.2337/dci19-0028

29. Beck RW, Bergenstal RM, Riddlesworth TD, et al. Validation of time in range as an outcome measure for diabetes clinical trials. Diabetes Care. 2019;42:400-405. doi: 10.2337/dc18-1444

30. Freckmann G. Basics and use of continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) in diabetes therapy. Journal of Laboratory Medicine. 2020;44:71-79. doi: 10.1515/labmed-2019-0189

31. Danne T, Nimri R, Battelino T, et al. International consensus on use of continuous glucose monitoring. Diabetes Care. 2017;40:1631-1640. doi: 10.2337/dc17-1600

32. Glucose monitors. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. April 22, 2022. Accessed October 22, 2022. www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/view/lcd.aspx?lcdid=33822

33. Pyl J, Dendooven E, Van Eekelen I, et al. Prevalence and prevention of contact dermatitis caused by FreeStyle Libre: a monocentric experience. Diabetes Care. 2020;43:918-920. doi: 10.2337/dc19-1354

34. Smith J, Bleiker T, Narang I. Cutaneous reactions to glucose sensors: a sticky problem [Abstract 677]. Arch Dis Child. 2021;106 (suppl 1):A80.

35. MAUDE Adverse event report: Dexcom, Inc G6 Sensor. U.S. Food & Drug Administration. Updated September 30, 2022. Accessed October 21, 2022. www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfmaude/detail.cfm?mdrfoi__id=11064819&pc=MDS

36. New JP, Ajjan R, Pfeiffer AFH, et al. Continuous glucose monitoring in people with diabetes: the randomized controlled Glucose Level Awareness in Diabetes Study (GLADIS). Diabet Med. 2015;32:609-617. doi: 10.1111/dme.12713

A1C has been used to estimate 3-month glycemic control in patients with diabetes. However, A1C monitoring alone does not provide insight into daily glycemic variation, which is valuable in clinical management because tight glycemic control (defined as A1C < 7.0%) has been shown to reduce the risk of microvascular complications. Prior to the approval of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists and sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitors by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of type 2 diabetes (T2D), reduction in the risk of macrovascular complications (aside from nonfatal myocardial infarction) was more difficult to achieve than it is now; some patients had a worse outcome with overly aggressive glycemic control.1

Previously, the use of a continuous glucose monitor (CGM) was limited to patients with type 1 diabetes who required basal and bolus insulin. However, technological advances have led to more patient-friendly and affordable devices, making CGMs more available. As such, the American Diabetes Association (ADA), in its 2022 Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes, recommends that clinicians offer continuous glucose monitoring to adults with T2D who require multiple daily injections, and based on a given patient’s ability, preferences, and needs.2

In this article, we discuss, first, the intricacies of CGMs and, second, what the evidence says about their use so that physicians can confidently recommend, and educate patients on, effective utilization of CGMs to obtain an individualized target of glycemic control.

Continuous glucose monitoring: A glossary

CGMs are characterized by who possesses the device and how data are recorded. This review is not about professional CGMs, which are owned by the health care provider and consist of a sensor that is applied in the clinic and returned to clinic for downloading of data1; rather, we focus on the novel category of nonprofessional, or personal, CGMs.

Three words to remember. Every CGM has 3 common components:

- The reader (also known as a receiver) is a handheld device that allows a patient to scan a sensor (see definition below) and instantaneously collect a glucose reading. The patient can use a standalone reader; a smartphone or other smart device with an associated app that serves as a reader; or both.

- A sensor is inserted subcutaneously to measure interstitial glucose. The lifespan of a sensor is 10 to 14 days.

- A transmitter relays information from the sensor to the reader.

The technology behind a CGM

CGM sensors measure interstitial glucose by means of a chemical reaction involving glucose oxidase and an oxidation-reduction cofactor, measuring the generation of hydrogen peroxide.3 Interstitial glucose readings lag behind plasma blood glucose readings by 2 to 21 minutes.4,5 Although this lag time is often not clinically significant, situations such as aerobic exercise and a rapidly changing glucose level might warrant confirmation by means of fingerstick measurement.5 It is common for CGM readings to vary slightly from venipuncture or fingerstick glucose readings.

What CGMs are availableto your patients?

Intermittently scanned CGMs (isCGMs) measure the glucose level continuously; the patient must scan a sensor to display and record the glucose level.6 Prolonged periods without scanning result in gaps in glycemic data.7,8

Continue to: Two isCGM systems...

Two isCGM systems are available: the FreeStyle Libre 14 day and the FreeStyle Libre 2 (both from Abbott).a Both consist of a reader and a disposable sensor, applied to the back of the arm, that is worn for 14 days. If the patient has a compatible smartphone or other smart device, the reader can be replaced by the smart device with the downloaded FreeStyle Libre or FreeStyle Libre 2 app.

To activate a new sensor, the patient applies the sensor, then scans it. Once activated, scanning the sensor provides the current glucose reading and recalls the last 8 hours of data. In addition to providing an instantaneous glucose reading, the display also provides a trend arrow indicating the direction and degree to which the glucose level is changing (TABLE 110,14,15). This feature helps patients avoid hypoglycemic episodes by allowing them to preemptively correct if the arrow indicates a rapidly declining glucose level.

For the first 12 hours after a new sensor is activated, and when a glucose reading is < 70 mg/dL, patients should be instructed to avoid making treatment decisions and encouraged to utilize fingerstick glucose readings. FreeStyle Libre 14 day does not allow a glucose level alarm to be set; the system cannot detect these events without scanning the sensor.10 Bluetooth connectivity does allow FreeStyle Libre 2 users to set a glucose alarm if the reader or smart device is within 20 feet of the sensor. A default alarm is set to activate at 70 mg/dL (“low”) and 240 mg/dL (“high”); low and high alarm settings are also customizable. Because both FreeStyle Libre devices store 8 hours of data, patients must scan the sensor every 8 hours for a comprehensive glycemic report.14

FreeStyle Libre CGMs allow patients to add therapy notes, including time and amount of insulin administered and carbohydrates ingested. Readers for both devices function as a glucometer that is compatible with Abbott FreeStyle Precision Neo test strips.

Real-time CGMs (rtCGMs) measure and display glucose levels continuously for the duration of the life of the sensor, without the need to scan. Three rtCGM systems are available: Dexcom G6, Medtronic Guardian 3, and Senseonics Eversense E3.

Continue to: Dexcom G6...

Dexcom G6 is the first Dexcom CGM that does not require fingerstick calibration and the only rtCGM available in the United States that does not require patient calibration. This system comprises a single-use sensor replaced every 10 days; a transmitter that is transferred to each new sensor and replaced every 3 months; and an optional receiver that can be omitted if the patient prefers to utilize a smart device.

Dexcom G6 never requires a patient to scan a sensor. Instead, the receiver (or smart device) utilizes Bluetooth technology to obtain blood glucose readings if it is positioned within 20 feet of the transmitter. Patients can set both hypoglycemic and hyperglycemic alarms to predict events within 20 minutes. Similar to the functionality of the FreeStyle Libre systems, Dexcom G6 provides the opportunity to log lifestyle events, including insulin dosing, carbohydrate ingestion, exercise, and sick days.15

Medtronic Guardian 3 comprises the multi-use Guardian Connect Transmitter that is replaced annually and a single-use Guardian Sensor that is replaced every 7 days. Guardian 3 requires twice-daily fingerstick glucose calibration, which reduces the convenience of a CGM.

Guardian 3 allows the user to set alarm levels, providing predictive alerts 10 to 60 minutes before set glucose levels are reached. Patients must utilize a smart device to connect through Bluetooth to the CareLink Connect app and remain within 20 feet of the transmitter to provide continuous glucose readings. The CareLink Connect app allows patients to document exercise, calibration of fingerstick readings, meals, and insulin administration.16

Senseonics Eversense E3 consists of a 3.5 mm × 18.3 mm sensor inserted subcutaneously in the upper arm once every 180 days; a removable transmitter that attaches to an adhesive patch placed over the sensor; and a smart device with the Eversense app. The transmitter has a 1-year rechargeable battery and provides the patient with on-body vibration alerts even when they are not near their smart device.

Continue to: The Eversense E3 transmitter...

The Eversense E3 transmitter can be removed and reapplied without affecting the life of the sensor; however, no glucose data will be collected during this time. Once the transmitter is reapplied, it takes 10 minutes for the sensor to begin communicating with the transmitter. Eversense provides predictive alerts as long as 30 minutes before hyperglycemic or hypoglycemic events. The device requires twice-daily fingerstick calibrations.17

A comparison of the specifications and capabilities of the personal CGMs discussed here is provided in TABLE 2.10,14-17

The evidence, reviewed

Clinical outcomes evidence with CGMs in patients with T2D is sparse. Most studies that support improved clinical outcomes enrolled patients with type 1 diabetes who were treated with intensive insulin regimens. Many studies utilized rtCGMs that are capable of incorporating a hypoglycemic alarm, and results might not be generalizable to isCGMs.18,19 In this article, we review only the continuous glucose monitoring literature in which subjects had T2D.

Evidence for is CGMs