User login

Safety and Efficacy of GLP-1 Receptor Agonists and SGLT2 Inhibitors Among Veterans With Type 2 Diabetes

Selecting the best medication regimen for a patient with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) depends on many factors, such as glycemic control, adherence, adverse effect (AE) profile, and comorbid conditions.1 Selected agents from 2 newer medication classes, glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RA) and sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors (SGLT2i), have demonstrated cardiovascular and renal protective properties, creating a new paradigm in management.

The American Diabetes Association recommends medications with proven benefit in cardiovascular disease (CVD), such as the GLP-1 RAs liraglutide, injectable semaglutide, or dulaglutide, or the SGLT2i empagliflozin or canagliflozin, as second-line after metformin in patients with established atherosclerotic CVD or indicators of high risk to reduce the risk of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE).1 SGLT2i are preferred in patients with diabetic kidney disease, and GLP-1 RAs are next in line for selection of agents with proven nephroprotection (liraglutide, injectable semaglutide, dulaglutide). The mechanisms of these benefits are not fully understood but may be due to their extraglycemic effects. The classes likely induce these benefits by different mechanisms: SGLT2i by hemodynamic effects and GLP-1 RAs by anti-inflammatory mechanisms.2 Although there is much interest, evidence is limited regarding the cardiovascular and renal protection benefits of these agents used in combination.

The combined use of GLP-1 RA and SGLT2i agents demonstrated greater benefit than separate use in trials with nonveteran populations.3-7 These studies evaluated effects on hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) levels, weight loss, blood pressure (BP), and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR). A meta-analysis of 7 trials found that the combination of GLP-1 RA and SGLT2i reduced HbA1c levels, body weight, and systolic blood pressure (SBP).8 All of the changes were statistically significant except for body weight with combination vs SGLT2i alone. Combination therapy was not associated with increased risk of severe hypoglycemia compared with either therapy separately.

The purpose of our study was to evaluate the safety and efficacy of the combined use of GLP-1 RA and SGLT2i in a real-world, US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) population with T2DM.

Methods

This study was a pre-post, retrospective, single-center chart review. Subjects served as their own control. The project was reviewed and approved by the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System Institutional Review Board. Subjects prescribed both a GLP-1 RA (semaglutide or liraglutide) and SGLT2i (empagliflozin) between January 1, 2014, and November 10, 2019, were extracted from the Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW) for possible inclusion in the study.

Patients were excluded if they received < 12 weeks of combination GLP-1 RA and SGLT2i therapy or did not have a corresponding 12-week HbA1c level. Patients also were excluded if they had < 12 weeks of monotherapy before starting combination therapy or did not have a baseline HbA1c level, or if the start date of combination therapy was not recorded in the VA electronic health record (EHR). We reviewed data for each patient from 6 months before to 1 year after the second agent was started. Start of the first agent (GLP-1 RA or SGLT2i) was recorded as the date the prescription was picked up in-person or 7 days after release date if mailed to the patient. Start of the second agent (GLP-1 RA or SGLT2i) was defined as baseline and was the date the prescription was picked up in person or 7 days after the release date if mailed.

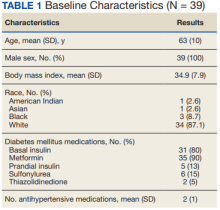

Baseline measures were taken anytime from 8 weeks after the start of the first agent through 2 weeks after the start of the second agent. Data collected included age, sex, race, height, weight, BP, HbA1c levels, serum creatinine (SCr), eGFR, classes of medications for the treatment of T2DM, and the number of prescribed antihypertensive medications. HbA1c levels, SCr, eGFR, weight, and BP also were collected at 12 weeks (within 8-21 weeks); 26 weeks (within 22-35 weeks); and 52 weeks (within 36-57 weeks) of combination therapy. We reviewed progress notes and laboratory results to determine AEs within 26 weeks before initiating second agent (baseline) and 0 to 26 weeks and 26 to 52 weeks after initiating combination therapy.

The primary objective was to determine the effect on HbA1c levels at 12 weeks when using a GLP-1 RA and SGLT2i in combination vs separately. Secondary objectives were to determine change from baseline in mean body weight, BP, SCr, and eGFR at 12, 26, and 52 weeks; change in HbA1c levels at 26 and 52 weeks; and incidence of prespecified adverse drug reactions during combination therapy vs separately.

Statistical Analysis

Assuming a SD of 1, 80% power, significance level of P < .05, 2-sided test, and a correlation between baseline and follow-up of 0.5, we determined that a sample size of 34 subjects was required to detect a 0.5% change in baseline HbA1c level at 12 weeks. A t test (or Wilcoxon signed rank test if outcome not normally distributed) was conducted to examine whether the expected change from baseline was different from 0 for continuous outcomes. Median change from baseline was reported for SCr as a nonparametric t test (Wilcoxon signed rank test) was used.

Results

We identified 110 patients for possible study inclusion and 39 met eligibility criteria. After record review, 30 patients were excluded for receiving < 12 weeks of combination therapy or no 12 week HbA1c level; 26 patients were excluded for receiving < 12 weeks of monotherapy before starting combination therapy or no baseline HbA1c level; and 15 patients were excluded for lack of documentation in the VA EHR. Of the 39 patients included, 24 (62%) were prescribed empagliflozin first and then 8 started liraglutide and 16 started semaglutide.

HbA1c levels decreased by 1% after 12 weeks of combination therapy compared with baseline (P < .001), and this reduction was sustained through the duration of the study period (Table 2).

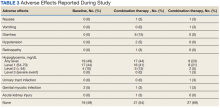

The most common AE during the trial was hypoglycemia, which was mostly mild (level 1) (Table 3).

Discussion

This study evaluated the safety and efficacy of combined use of semaglutide or liraglutide and empagliflozin in a veteran population with T2DM. The retrospective chart review captured real-world practice and outcomes. Combination therapy was associated with a significant reduction in HbA1c levels, body weight, and SBP compared with either agent alone. No significant change was seen in DBP, SCr, or eGFR. Overall, the combination of GLP-1 RA and SGLT2i medications demonstrated a good safety profile with most patients reporting no AEs.

Several other studies have assessed the safety and efficacy of using GLP-1 RA and SGLT2i in combination. The DURATION 8 trial is the only double-blind trial to randomize subjects to receive either exenatide once weekly, dapagliflozin, or the combination of both for up to 52 weeks.3 Other controlled trials required stable background therapy with either SGLT2i or GLP-1 RA before randomization to receive the other class or placebo and had durations between 18 and 30 weeks.4-7 The AWARD 10 trial studied the combination of canagliflozin and dulaglutide, which both have proven CVD benefit.4 Other studies did not restrict SGLT2i or GLP-1 RA background therapy to agents with proven CVD benefit.5-7 The present study evaluated the combination of empagliflozin plus liraglutide or semaglutide, agents that all have proven CVD benefit.

A meta-analysis of 7 trials, including those previously mentioned, was conducted to evaluate the combination of GLP-1 RA and SGLT2i.8 The combination significantly reduced HbA1c levels by 0.61% and 0.85% compared with GLP-1 RA or SGLT2i, respectively. Our trial showed greater HbA1c level reduction of 1% with combination therapy compared with either agent separately. This may have been due in part to a higher baseline HbA1c level in our real-world veteran population. The meta-analysis found the combination decreased body weight 2.6 kg and 1.5 kg compared with GLP-1 RA or SGLT2i, respectively.8 This only reached significance with comparison vs GLP-1 RA alone. Our study demonstrated impressive weight loss of up to about 5 kg after 26 and 52 weeks of combination therapy. This is equivalent to about 5% weight loss from baseline, which is clinically significant.9 Liraglutide and semaglutide are the GLP-1 RAs associated with the greatest weight loss, which may contribute to greater weight loss efficacy seen in the present trial.1

In our trial SBP fell lower compared with the meta-analysis. Combination therapy significantly reduced SBP by 4.1 mm Hg and 2.7 mm Hg compared with GLP-1 RA or SGLT2i, respectively, in the meta-analysis.8 We observed a significant 9 to 12 mm Hg reduction in SBP after 26 to 52 weeks of combination therapy compared with baseline. This reduction occurred despite relatively controlled SBP at baseline (135 mm Hg). Each reduction of 10 mm Hg in SBP significantly reduces the risk of MACE, stroke, and heart failure, making our results clinically significant.10 Neither the meta-analysis nor present study found a significant difference in DBP or eGFR with combination therapy.

AEs were similar in this trial compared with the meta-analysis. Combination treatment with GLP-1 RA and SGLT2i did not increase the incidence of severe hypoglycemia in either study.8 Hypoglycemia was the most common AE in this study, but frequency was similar with combination and separate therapy. Both medication classes are associated with low or no risk of hypoglycemia on their own.1 Baseline medications likely contributed to episodes of hypoglycemia seen in this study: About 80% of patients were prescribed basal insulin, 15% were prescribed a sulfonylurea, and 13% were prescribed prandial insulin. There is limited overlap between the known AEs of GLP-1 RA and SGLT2i, making combination therapy a safe option for use in patients with T2DM.

Our study confirms greater reduction in HbA1c levels, weight, and SBP in veterans taking GLP-1 RA and SGLT2i medications in combination compared with separate use in a real-world setting in a veteran population. The magnitude of change seen in this population appears greater compared with previous studies.

Limitations

There were several limitations to our study. Given the retrospective nature, many patients included in the study did not have bloodwork drawn during the specified time frames. Because of this, many patients were excluded and missing data on renal outcomes limited the power to detect differences. Data regarding AEs were limited to what was recorded in the EHR, which may underrepresent the AEs that patients experienced. Finally, our study size was small, consisting primarily of a White and male population, which may limit generalizability.

Further research is needed to validate these findings in this population and should include a larger study population. The impact of combining GLP-1 RA with SGLT2i on cardiorenal outcomes is an important area of ongoing research.

ConclusionS

The combined use of GLP-1 RA and SGLT2i resulted in significant improvement in HbA1c levels, weight, and SBP compared with separate use in this real-world study of a VA population with T2DM. The combination was well tolerated overall. Awareness of these results can facilitate optimal care and outcomes in the VA population.

Acknowledgments

Serena Kelley, PharmD, and Michael Brenner, PharmD, assisted with study design and initial data collection. Julie Strominger, MS, provided statistical support.

1. American Diabetes Association. 9. Pharmacologic approaches to glycemic treatment: standards of medical care in diabetes-2021. Diabetes Care. 2021;44(suppl 1):S111-S124. doi.10.2337/dc21-S009

2. DeFronzo RA. Combination therapy with GLP-1 receptor agonist and SGLT2 inhibitor. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2017;19(10):1353-1362. doi.10.1111/dom.12982

3. Jabbour S, Frias J, Guja C, Hardy E, Ahmed A, Ohman P. Effects of exenatide once weekly plus dapagliflozin, exenatide once weekly, or dapagliflozin, added to metformin monotherapy, on body weight, systolic blood pressure, and triglycerides in patients with type 2 diabetes in the DURATION-8 study. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2018;20(6):1515-1519. doi:10.1111/dom.13206

4. Ludvik B, Frias J, Tinahones F, et al. Dulaglutide as add-on therapy to SGLT2 inhibitors in patients with inadequately controlled type 2 diabetes (AWARD-10): a 24-week, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2018;6(5):370-381. doi:10.1016/S2213-8587(18)30023-8

5. Blonde L, Belousova L, Fainberg U, et al. Liraglutide as add-on to sodium-glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitors in patients with inadequately controlled type 2 diabetes: LIRA-ADD2SGLT2i, a 26-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2020;22(6):929-937. doi:10.1111/dom.13978

6. Fulcher G, Matthews D, Perkovic V, et al; CANVAS trial collaborative group. Efficacy and safety of canagliflozin when used in conjunction with incretin-mimetic therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2016;18(1):82-91. doi:10.1111/dom.12589

7. Zinman B, Bhosekar V, Busch R, et al. Semaglutide once weekly as add-on to SGLT-2 inhibitor therapy in type 2 diabetes (SUSTAIN 9): a randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2019;7(5):356-367. doi:10.1016/S2213-8587(19)30066-X

8. Mantsiou C, Karagiannis T, Kakotrichi P, et al. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists and sodium-glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitors as combination therapy for type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2020;22(10):1857-1868. doi:10.1111/dom.14108

9. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Department of Defense. VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for the management of adult overweight and obesity. Version 3.0. Accessed August 18, 2022. www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/CD/obesity/VADoDObesityCPGFinal5087242020.pdf

10. Ettehad D, Emdin CA, Kiran A, et al. Blood pressure lowering for prevention of cardiovascular disease and death: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2015;387(10022):957-967. doi.10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01225-8

Selecting the best medication regimen for a patient with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) depends on many factors, such as glycemic control, adherence, adverse effect (AE) profile, and comorbid conditions.1 Selected agents from 2 newer medication classes, glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RA) and sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors (SGLT2i), have demonstrated cardiovascular and renal protective properties, creating a new paradigm in management.

The American Diabetes Association recommends medications with proven benefit in cardiovascular disease (CVD), such as the GLP-1 RAs liraglutide, injectable semaglutide, or dulaglutide, or the SGLT2i empagliflozin or canagliflozin, as second-line after metformin in patients with established atherosclerotic CVD or indicators of high risk to reduce the risk of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE).1 SGLT2i are preferred in patients with diabetic kidney disease, and GLP-1 RAs are next in line for selection of agents with proven nephroprotection (liraglutide, injectable semaglutide, dulaglutide). The mechanisms of these benefits are not fully understood but may be due to their extraglycemic effects. The classes likely induce these benefits by different mechanisms: SGLT2i by hemodynamic effects and GLP-1 RAs by anti-inflammatory mechanisms.2 Although there is much interest, evidence is limited regarding the cardiovascular and renal protection benefits of these agents used in combination.

The combined use of GLP-1 RA and SGLT2i agents demonstrated greater benefit than separate use in trials with nonveteran populations.3-7 These studies evaluated effects on hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) levels, weight loss, blood pressure (BP), and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR). A meta-analysis of 7 trials found that the combination of GLP-1 RA and SGLT2i reduced HbA1c levels, body weight, and systolic blood pressure (SBP).8 All of the changes were statistically significant except for body weight with combination vs SGLT2i alone. Combination therapy was not associated with increased risk of severe hypoglycemia compared with either therapy separately.

The purpose of our study was to evaluate the safety and efficacy of the combined use of GLP-1 RA and SGLT2i in a real-world, US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) population with T2DM.

Methods

This study was a pre-post, retrospective, single-center chart review. Subjects served as their own control. The project was reviewed and approved by the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System Institutional Review Board. Subjects prescribed both a GLP-1 RA (semaglutide or liraglutide) and SGLT2i (empagliflozin) between January 1, 2014, and November 10, 2019, were extracted from the Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW) for possible inclusion in the study.

Patients were excluded if they received < 12 weeks of combination GLP-1 RA and SGLT2i therapy or did not have a corresponding 12-week HbA1c level. Patients also were excluded if they had < 12 weeks of monotherapy before starting combination therapy or did not have a baseline HbA1c level, or if the start date of combination therapy was not recorded in the VA electronic health record (EHR). We reviewed data for each patient from 6 months before to 1 year after the second agent was started. Start of the first agent (GLP-1 RA or SGLT2i) was recorded as the date the prescription was picked up in-person or 7 days after release date if mailed to the patient. Start of the second agent (GLP-1 RA or SGLT2i) was defined as baseline and was the date the prescription was picked up in person or 7 days after the release date if mailed.

Baseline measures were taken anytime from 8 weeks after the start of the first agent through 2 weeks after the start of the second agent. Data collected included age, sex, race, height, weight, BP, HbA1c levels, serum creatinine (SCr), eGFR, classes of medications for the treatment of T2DM, and the number of prescribed antihypertensive medications. HbA1c levels, SCr, eGFR, weight, and BP also were collected at 12 weeks (within 8-21 weeks); 26 weeks (within 22-35 weeks); and 52 weeks (within 36-57 weeks) of combination therapy. We reviewed progress notes and laboratory results to determine AEs within 26 weeks before initiating second agent (baseline) and 0 to 26 weeks and 26 to 52 weeks after initiating combination therapy.

The primary objective was to determine the effect on HbA1c levels at 12 weeks when using a GLP-1 RA and SGLT2i in combination vs separately. Secondary objectives were to determine change from baseline in mean body weight, BP, SCr, and eGFR at 12, 26, and 52 weeks; change in HbA1c levels at 26 and 52 weeks; and incidence of prespecified adverse drug reactions during combination therapy vs separately.

Statistical Analysis

Assuming a SD of 1, 80% power, significance level of P < .05, 2-sided test, and a correlation between baseline and follow-up of 0.5, we determined that a sample size of 34 subjects was required to detect a 0.5% change in baseline HbA1c level at 12 weeks. A t test (or Wilcoxon signed rank test if outcome not normally distributed) was conducted to examine whether the expected change from baseline was different from 0 for continuous outcomes. Median change from baseline was reported for SCr as a nonparametric t test (Wilcoxon signed rank test) was used.

Results

We identified 110 patients for possible study inclusion and 39 met eligibility criteria. After record review, 30 patients were excluded for receiving < 12 weeks of combination therapy or no 12 week HbA1c level; 26 patients were excluded for receiving < 12 weeks of monotherapy before starting combination therapy or no baseline HbA1c level; and 15 patients were excluded for lack of documentation in the VA EHR. Of the 39 patients included, 24 (62%) were prescribed empagliflozin first and then 8 started liraglutide and 16 started semaglutide.

HbA1c levels decreased by 1% after 12 weeks of combination therapy compared with baseline (P < .001), and this reduction was sustained through the duration of the study period (Table 2).

The most common AE during the trial was hypoglycemia, which was mostly mild (level 1) (Table 3).

Discussion

This study evaluated the safety and efficacy of combined use of semaglutide or liraglutide and empagliflozin in a veteran population with T2DM. The retrospective chart review captured real-world practice and outcomes. Combination therapy was associated with a significant reduction in HbA1c levels, body weight, and SBP compared with either agent alone. No significant change was seen in DBP, SCr, or eGFR. Overall, the combination of GLP-1 RA and SGLT2i medications demonstrated a good safety profile with most patients reporting no AEs.

Several other studies have assessed the safety and efficacy of using GLP-1 RA and SGLT2i in combination. The DURATION 8 trial is the only double-blind trial to randomize subjects to receive either exenatide once weekly, dapagliflozin, or the combination of both for up to 52 weeks.3 Other controlled trials required stable background therapy with either SGLT2i or GLP-1 RA before randomization to receive the other class or placebo and had durations between 18 and 30 weeks.4-7 The AWARD 10 trial studied the combination of canagliflozin and dulaglutide, which both have proven CVD benefit.4 Other studies did not restrict SGLT2i or GLP-1 RA background therapy to agents with proven CVD benefit.5-7 The present study evaluated the combination of empagliflozin plus liraglutide or semaglutide, agents that all have proven CVD benefit.

A meta-analysis of 7 trials, including those previously mentioned, was conducted to evaluate the combination of GLP-1 RA and SGLT2i.8 The combination significantly reduced HbA1c levels by 0.61% and 0.85% compared with GLP-1 RA or SGLT2i, respectively. Our trial showed greater HbA1c level reduction of 1% with combination therapy compared with either agent separately. This may have been due in part to a higher baseline HbA1c level in our real-world veteran population. The meta-analysis found the combination decreased body weight 2.6 kg and 1.5 kg compared with GLP-1 RA or SGLT2i, respectively.8 This only reached significance with comparison vs GLP-1 RA alone. Our study demonstrated impressive weight loss of up to about 5 kg after 26 and 52 weeks of combination therapy. This is equivalent to about 5% weight loss from baseline, which is clinically significant.9 Liraglutide and semaglutide are the GLP-1 RAs associated with the greatest weight loss, which may contribute to greater weight loss efficacy seen in the present trial.1

In our trial SBP fell lower compared with the meta-analysis. Combination therapy significantly reduced SBP by 4.1 mm Hg and 2.7 mm Hg compared with GLP-1 RA or SGLT2i, respectively, in the meta-analysis.8 We observed a significant 9 to 12 mm Hg reduction in SBP after 26 to 52 weeks of combination therapy compared with baseline. This reduction occurred despite relatively controlled SBP at baseline (135 mm Hg). Each reduction of 10 mm Hg in SBP significantly reduces the risk of MACE, stroke, and heart failure, making our results clinically significant.10 Neither the meta-analysis nor present study found a significant difference in DBP or eGFR with combination therapy.

AEs were similar in this trial compared with the meta-analysis. Combination treatment with GLP-1 RA and SGLT2i did not increase the incidence of severe hypoglycemia in either study.8 Hypoglycemia was the most common AE in this study, but frequency was similar with combination and separate therapy. Both medication classes are associated with low or no risk of hypoglycemia on their own.1 Baseline medications likely contributed to episodes of hypoglycemia seen in this study: About 80% of patients were prescribed basal insulin, 15% were prescribed a sulfonylurea, and 13% were prescribed prandial insulin. There is limited overlap between the known AEs of GLP-1 RA and SGLT2i, making combination therapy a safe option for use in patients with T2DM.

Our study confirms greater reduction in HbA1c levels, weight, and SBP in veterans taking GLP-1 RA and SGLT2i medications in combination compared with separate use in a real-world setting in a veteran population. The magnitude of change seen in this population appears greater compared with previous studies.

Limitations

There were several limitations to our study. Given the retrospective nature, many patients included in the study did not have bloodwork drawn during the specified time frames. Because of this, many patients were excluded and missing data on renal outcomes limited the power to detect differences. Data regarding AEs were limited to what was recorded in the EHR, which may underrepresent the AEs that patients experienced. Finally, our study size was small, consisting primarily of a White and male population, which may limit generalizability.

Further research is needed to validate these findings in this population and should include a larger study population. The impact of combining GLP-1 RA with SGLT2i on cardiorenal outcomes is an important area of ongoing research.

ConclusionS

The combined use of GLP-1 RA and SGLT2i resulted in significant improvement in HbA1c levels, weight, and SBP compared with separate use in this real-world study of a VA population with T2DM. The combination was well tolerated overall. Awareness of these results can facilitate optimal care and outcomes in the VA population.

Acknowledgments

Serena Kelley, PharmD, and Michael Brenner, PharmD, assisted with study design and initial data collection. Julie Strominger, MS, provided statistical support.

Selecting the best medication regimen for a patient with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) depends on many factors, such as glycemic control, adherence, adverse effect (AE) profile, and comorbid conditions.1 Selected agents from 2 newer medication classes, glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RA) and sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors (SGLT2i), have demonstrated cardiovascular and renal protective properties, creating a new paradigm in management.

The American Diabetes Association recommends medications with proven benefit in cardiovascular disease (CVD), such as the GLP-1 RAs liraglutide, injectable semaglutide, or dulaglutide, or the SGLT2i empagliflozin or canagliflozin, as second-line after metformin in patients with established atherosclerotic CVD or indicators of high risk to reduce the risk of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE).1 SGLT2i are preferred in patients with diabetic kidney disease, and GLP-1 RAs are next in line for selection of agents with proven nephroprotection (liraglutide, injectable semaglutide, dulaglutide). The mechanisms of these benefits are not fully understood but may be due to their extraglycemic effects. The classes likely induce these benefits by different mechanisms: SGLT2i by hemodynamic effects and GLP-1 RAs by anti-inflammatory mechanisms.2 Although there is much interest, evidence is limited regarding the cardiovascular and renal protection benefits of these agents used in combination.

The combined use of GLP-1 RA and SGLT2i agents demonstrated greater benefit than separate use in trials with nonveteran populations.3-7 These studies evaluated effects on hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) levels, weight loss, blood pressure (BP), and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR). A meta-analysis of 7 trials found that the combination of GLP-1 RA and SGLT2i reduced HbA1c levels, body weight, and systolic blood pressure (SBP).8 All of the changes were statistically significant except for body weight with combination vs SGLT2i alone. Combination therapy was not associated with increased risk of severe hypoglycemia compared with either therapy separately.

The purpose of our study was to evaluate the safety and efficacy of the combined use of GLP-1 RA and SGLT2i in a real-world, US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) population with T2DM.

Methods

This study was a pre-post, retrospective, single-center chart review. Subjects served as their own control. The project was reviewed and approved by the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System Institutional Review Board. Subjects prescribed both a GLP-1 RA (semaglutide or liraglutide) and SGLT2i (empagliflozin) between January 1, 2014, and November 10, 2019, were extracted from the Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW) for possible inclusion in the study.

Patients were excluded if they received < 12 weeks of combination GLP-1 RA and SGLT2i therapy or did not have a corresponding 12-week HbA1c level. Patients also were excluded if they had < 12 weeks of monotherapy before starting combination therapy or did not have a baseline HbA1c level, or if the start date of combination therapy was not recorded in the VA electronic health record (EHR). We reviewed data for each patient from 6 months before to 1 year after the second agent was started. Start of the first agent (GLP-1 RA or SGLT2i) was recorded as the date the prescription was picked up in-person or 7 days after release date if mailed to the patient. Start of the second agent (GLP-1 RA or SGLT2i) was defined as baseline and was the date the prescription was picked up in person or 7 days after the release date if mailed.

Baseline measures were taken anytime from 8 weeks after the start of the first agent through 2 weeks after the start of the second agent. Data collected included age, sex, race, height, weight, BP, HbA1c levels, serum creatinine (SCr), eGFR, classes of medications for the treatment of T2DM, and the number of prescribed antihypertensive medications. HbA1c levels, SCr, eGFR, weight, and BP also were collected at 12 weeks (within 8-21 weeks); 26 weeks (within 22-35 weeks); and 52 weeks (within 36-57 weeks) of combination therapy. We reviewed progress notes and laboratory results to determine AEs within 26 weeks before initiating second agent (baseline) and 0 to 26 weeks and 26 to 52 weeks after initiating combination therapy.

The primary objective was to determine the effect on HbA1c levels at 12 weeks when using a GLP-1 RA and SGLT2i in combination vs separately. Secondary objectives were to determine change from baseline in mean body weight, BP, SCr, and eGFR at 12, 26, and 52 weeks; change in HbA1c levels at 26 and 52 weeks; and incidence of prespecified adverse drug reactions during combination therapy vs separately.

Statistical Analysis

Assuming a SD of 1, 80% power, significance level of P < .05, 2-sided test, and a correlation between baseline and follow-up of 0.5, we determined that a sample size of 34 subjects was required to detect a 0.5% change in baseline HbA1c level at 12 weeks. A t test (or Wilcoxon signed rank test if outcome not normally distributed) was conducted to examine whether the expected change from baseline was different from 0 for continuous outcomes. Median change from baseline was reported for SCr as a nonparametric t test (Wilcoxon signed rank test) was used.

Results

We identified 110 patients for possible study inclusion and 39 met eligibility criteria. After record review, 30 patients were excluded for receiving < 12 weeks of combination therapy or no 12 week HbA1c level; 26 patients were excluded for receiving < 12 weeks of monotherapy before starting combination therapy or no baseline HbA1c level; and 15 patients were excluded for lack of documentation in the VA EHR. Of the 39 patients included, 24 (62%) were prescribed empagliflozin first and then 8 started liraglutide and 16 started semaglutide.

HbA1c levels decreased by 1% after 12 weeks of combination therapy compared with baseline (P < .001), and this reduction was sustained through the duration of the study period (Table 2).

The most common AE during the trial was hypoglycemia, which was mostly mild (level 1) (Table 3).

Discussion

This study evaluated the safety and efficacy of combined use of semaglutide or liraglutide and empagliflozin in a veteran population with T2DM. The retrospective chart review captured real-world practice and outcomes. Combination therapy was associated with a significant reduction in HbA1c levels, body weight, and SBP compared with either agent alone. No significant change was seen in DBP, SCr, or eGFR. Overall, the combination of GLP-1 RA and SGLT2i medications demonstrated a good safety profile with most patients reporting no AEs.

Several other studies have assessed the safety and efficacy of using GLP-1 RA and SGLT2i in combination. The DURATION 8 trial is the only double-blind trial to randomize subjects to receive either exenatide once weekly, dapagliflozin, or the combination of both for up to 52 weeks.3 Other controlled trials required stable background therapy with either SGLT2i or GLP-1 RA before randomization to receive the other class or placebo and had durations between 18 and 30 weeks.4-7 The AWARD 10 trial studied the combination of canagliflozin and dulaglutide, which both have proven CVD benefit.4 Other studies did not restrict SGLT2i or GLP-1 RA background therapy to agents with proven CVD benefit.5-7 The present study evaluated the combination of empagliflozin plus liraglutide or semaglutide, agents that all have proven CVD benefit.

A meta-analysis of 7 trials, including those previously mentioned, was conducted to evaluate the combination of GLP-1 RA and SGLT2i.8 The combination significantly reduced HbA1c levels by 0.61% and 0.85% compared with GLP-1 RA or SGLT2i, respectively. Our trial showed greater HbA1c level reduction of 1% with combination therapy compared with either agent separately. This may have been due in part to a higher baseline HbA1c level in our real-world veteran population. The meta-analysis found the combination decreased body weight 2.6 kg and 1.5 kg compared with GLP-1 RA or SGLT2i, respectively.8 This only reached significance with comparison vs GLP-1 RA alone. Our study demonstrated impressive weight loss of up to about 5 kg after 26 and 52 weeks of combination therapy. This is equivalent to about 5% weight loss from baseline, which is clinically significant.9 Liraglutide and semaglutide are the GLP-1 RAs associated with the greatest weight loss, which may contribute to greater weight loss efficacy seen in the present trial.1

In our trial SBP fell lower compared with the meta-analysis. Combination therapy significantly reduced SBP by 4.1 mm Hg and 2.7 mm Hg compared with GLP-1 RA or SGLT2i, respectively, in the meta-analysis.8 We observed a significant 9 to 12 mm Hg reduction in SBP after 26 to 52 weeks of combination therapy compared with baseline. This reduction occurred despite relatively controlled SBP at baseline (135 mm Hg). Each reduction of 10 mm Hg in SBP significantly reduces the risk of MACE, stroke, and heart failure, making our results clinically significant.10 Neither the meta-analysis nor present study found a significant difference in DBP or eGFR with combination therapy.

AEs were similar in this trial compared with the meta-analysis. Combination treatment with GLP-1 RA and SGLT2i did not increase the incidence of severe hypoglycemia in either study.8 Hypoglycemia was the most common AE in this study, but frequency was similar with combination and separate therapy. Both medication classes are associated with low or no risk of hypoglycemia on their own.1 Baseline medications likely contributed to episodes of hypoglycemia seen in this study: About 80% of patients were prescribed basal insulin, 15% were prescribed a sulfonylurea, and 13% were prescribed prandial insulin. There is limited overlap between the known AEs of GLP-1 RA and SGLT2i, making combination therapy a safe option for use in patients with T2DM.

Our study confirms greater reduction in HbA1c levels, weight, and SBP in veterans taking GLP-1 RA and SGLT2i medications in combination compared with separate use in a real-world setting in a veteran population. The magnitude of change seen in this population appears greater compared with previous studies.

Limitations

There were several limitations to our study. Given the retrospective nature, many patients included in the study did not have bloodwork drawn during the specified time frames. Because of this, many patients were excluded and missing data on renal outcomes limited the power to detect differences. Data regarding AEs were limited to what was recorded in the EHR, which may underrepresent the AEs that patients experienced. Finally, our study size was small, consisting primarily of a White and male population, which may limit generalizability.

Further research is needed to validate these findings in this population and should include a larger study population. The impact of combining GLP-1 RA with SGLT2i on cardiorenal outcomes is an important area of ongoing research.

ConclusionS

The combined use of GLP-1 RA and SGLT2i resulted in significant improvement in HbA1c levels, weight, and SBP compared with separate use in this real-world study of a VA population with T2DM. The combination was well tolerated overall. Awareness of these results can facilitate optimal care and outcomes in the VA population.

Acknowledgments

Serena Kelley, PharmD, and Michael Brenner, PharmD, assisted with study design and initial data collection. Julie Strominger, MS, provided statistical support.

1. American Diabetes Association. 9. Pharmacologic approaches to glycemic treatment: standards of medical care in diabetes-2021. Diabetes Care. 2021;44(suppl 1):S111-S124. doi.10.2337/dc21-S009

2. DeFronzo RA. Combination therapy with GLP-1 receptor agonist and SGLT2 inhibitor. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2017;19(10):1353-1362. doi.10.1111/dom.12982

3. Jabbour S, Frias J, Guja C, Hardy E, Ahmed A, Ohman P. Effects of exenatide once weekly plus dapagliflozin, exenatide once weekly, or dapagliflozin, added to metformin monotherapy, on body weight, systolic blood pressure, and triglycerides in patients with type 2 diabetes in the DURATION-8 study. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2018;20(6):1515-1519. doi:10.1111/dom.13206

4. Ludvik B, Frias J, Tinahones F, et al. Dulaglutide as add-on therapy to SGLT2 inhibitors in patients with inadequately controlled type 2 diabetes (AWARD-10): a 24-week, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2018;6(5):370-381. doi:10.1016/S2213-8587(18)30023-8

5. Blonde L, Belousova L, Fainberg U, et al. Liraglutide as add-on to sodium-glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitors in patients with inadequately controlled type 2 diabetes: LIRA-ADD2SGLT2i, a 26-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2020;22(6):929-937. doi:10.1111/dom.13978

6. Fulcher G, Matthews D, Perkovic V, et al; CANVAS trial collaborative group. Efficacy and safety of canagliflozin when used in conjunction with incretin-mimetic therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2016;18(1):82-91. doi:10.1111/dom.12589

7. Zinman B, Bhosekar V, Busch R, et al. Semaglutide once weekly as add-on to SGLT-2 inhibitor therapy in type 2 diabetes (SUSTAIN 9): a randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2019;7(5):356-367. doi:10.1016/S2213-8587(19)30066-X

8. Mantsiou C, Karagiannis T, Kakotrichi P, et al. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists and sodium-glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitors as combination therapy for type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2020;22(10):1857-1868. doi:10.1111/dom.14108

9. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Department of Defense. VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for the management of adult overweight and obesity. Version 3.0. Accessed August 18, 2022. www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/CD/obesity/VADoDObesityCPGFinal5087242020.pdf

10. Ettehad D, Emdin CA, Kiran A, et al. Blood pressure lowering for prevention of cardiovascular disease and death: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2015;387(10022):957-967. doi.10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01225-8

1. American Diabetes Association. 9. Pharmacologic approaches to glycemic treatment: standards of medical care in diabetes-2021. Diabetes Care. 2021;44(suppl 1):S111-S124. doi.10.2337/dc21-S009

2. DeFronzo RA. Combination therapy with GLP-1 receptor agonist and SGLT2 inhibitor. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2017;19(10):1353-1362. doi.10.1111/dom.12982

3. Jabbour S, Frias J, Guja C, Hardy E, Ahmed A, Ohman P. Effects of exenatide once weekly plus dapagliflozin, exenatide once weekly, or dapagliflozin, added to metformin monotherapy, on body weight, systolic blood pressure, and triglycerides in patients with type 2 diabetes in the DURATION-8 study. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2018;20(6):1515-1519. doi:10.1111/dom.13206

4. Ludvik B, Frias J, Tinahones F, et al. Dulaglutide as add-on therapy to SGLT2 inhibitors in patients with inadequately controlled type 2 diabetes (AWARD-10): a 24-week, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2018;6(5):370-381. doi:10.1016/S2213-8587(18)30023-8

5. Blonde L, Belousova L, Fainberg U, et al. Liraglutide as add-on to sodium-glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitors in patients with inadequately controlled type 2 diabetes: LIRA-ADD2SGLT2i, a 26-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2020;22(6):929-937. doi:10.1111/dom.13978

6. Fulcher G, Matthews D, Perkovic V, et al; CANVAS trial collaborative group. Efficacy and safety of canagliflozin when used in conjunction with incretin-mimetic therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2016;18(1):82-91. doi:10.1111/dom.12589

7. Zinman B, Bhosekar V, Busch R, et al. Semaglutide once weekly as add-on to SGLT-2 inhibitor therapy in type 2 diabetes (SUSTAIN 9): a randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2019;7(5):356-367. doi:10.1016/S2213-8587(19)30066-X

8. Mantsiou C, Karagiannis T, Kakotrichi P, et al. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists and sodium-glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitors as combination therapy for type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2020;22(10):1857-1868. doi:10.1111/dom.14108

9. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Department of Defense. VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for the management of adult overweight and obesity. Version 3.0. Accessed August 18, 2022. www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/CD/obesity/VADoDObesityCPGFinal5087242020.pdf

10. Ettehad D, Emdin CA, Kiran A, et al. Blood pressure lowering for prevention of cardiovascular disease and death: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2015;387(10022):957-967. doi.10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01225-8

Celiac disease linked to higher risk for rheumatoid arthritis, juvenile idiopathic arthritis

Celiac disease is linked to juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) in children and rheumatoid arthritis (RA) in adults, according to an analysis of nationwide data in Sweden.

“I hope that our study can ultimately change clinical practice by lowering the threshold to evaluate celiac disease patients for inflammatory joint diseases,” John B. Doyle, MD, a gastroenterology fellow at Columbia University Irving Medical Center in New York, told this news organization.

“Inflammatory joint diseases, such as JIA and RA, are notoriously difficult to diagnose given their variable presentations,” he said. “But if JIA or RA can be identified sooner by physicians, patients will ultimately benefit by starting disease-modifying therapy earlier in their disease course.”

The study was published online in The American Journal of Gastroenterology.

Analyzing associations

Celiac disease has been linked to numerous autoimmune diseases, including type 1 diabetes, autoimmune thyroid disease, lupus, and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), Dr. Doyle noted. However, a definitive epidemiologic association between celiac disease and inflammatory joint diseases such as JIA or RA hasn›t been established.

Dr. Doyle and colleagues conducted a nationwide population-based, retrospective matched cohort study using the Epidemiology Strengthened by Histopathology Reports in Sweden. They identified 24,014 patients diagnosed with biopsy-proven celiac disease between 2004 and 2017.

With these data, each patient was matched to five reference individuals in the general population by age, sex, calendar year, and geographic region, for a total of 117,397 people without a previous diagnosis of celiac disease. The researchers calculated the incidence and estimated the relative risk for JIA in patients younger than 18 years and RA in patients aged 18 years or older.

For those younger than 18 years, the incidence rate of JIA was 5.9 per 10,000 person-years among the 9,415 patients with celiac disease versus 2.2 per 10,000 person-years in the general population, over a follow-up of 7 years. Those with celiac disease were 2.7 times as likely to develop JIA.

The association between celiac disease and JIA remained similar after adjustment for education, Nordic country of birth, type 1 diabetes, autoimmune thyroid disease, lupus, and IBD. The incidence rate of JIA among patients with celiac disease was higher in both females and males, and across all age groups studied.

When 6,703 children with celiac disease were compared with their 9,089 siblings without celiac disease, the higher risk for JIA in patients with celiac disease fell slightly short of statistical significance.

For those aged 18 years or older, the incidence rate of RA was 8.4 per 10,000 person-years among the 14,599 patients with celiac disease versus 5.1 per 10,000 person-years in the general population, over a follow-up of 8.8 years. Those with celiac disease were 1.7 times as likely to develop RA.

As with the younger cohort, the association between celiac disease and RA in the adult group remained similar after adjustment for education, Nordic country of birth, type 1 diabetes, autoimmune thyroid disease, lupus, and IBD. Although both men and women with celiac disease had higher rates of RA, the risk was higher among those in whom disease was diagnosed at age 18-59 years compared with those who received a diagnosis at age 60 years or older.

When 9,578 adults with celiac disease were compared with their 17,067 siblings without celiac disease, the risk for RA remained higher in patients with celiac disease.

This suggests “that the association between celiac disease and RA is unlikely to be explained by environmental factors alone,” Dr. Doyle said.

Additional findings

Notably, the primary analysis excluded patients diagnosed with JIA or RA before their celiac disease diagnosis. In additional analyses, however, significant associations emerged.

Among children with celiac disease, 0.5% had a previous diagnosis of JIA, compared with 0.1% of matched comparators. Those with celiac disease were 3.5 times more likely to have a JIA diagnosis.

Among adults with celiac disease, 0.9% had a previous diagnosis of RA, compared with 0.6% of matched comparators. Those with celiac disease were 1.4 times more likely to have a RA diagnosis.

“We found that diagnoses of these types of arthritis were more common before a diagnosis of celiac disease compared to the general population,” Benjamin Lebwohl, MD, director of clinical research at the Celiac Disease Center at Columbia University, New York, told this news organization.

“This suggests that undiagnosed and untreated celiac disease might be contributing to these others autoimmune conditions,” he said.

Dr. Doyle and Dr. Lebwohl emphasized the practical implications for clinicians caring for patients with celiac disease. Among patients with celiac disease and inflammatory joint symptoms, clinicians should have a low threshold to evaluate for JIA or RA, they said.

“Particularly in pediatrics, we are trained to screen patients with JIA for celiac disease, but this study points to the possible bidirectional association and the importance of maintaining a clinical suspicion for JIA and RA among established celiac disease patients,” Marisa Stahl, MD, assistant professor of pediatrics and associate program director of the pediatric gastroenterology, hepatology, and nutrition fellowship training program at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, said in an interview.

Dr. Stahl, who wasn’t involved with this study, conducts research at the Colorado Center for Celiac Disease. She and colleagues are focused on understanding the genetic and environmental factors that lead to the development of celiac disease and other autoimmune diseases.

Given the clear association between celiac disease and other autoimmune diseases, Dr. Stahl agreed that clinicians should have a low threshold for screening, with “additional workup for other autoimmune diseases once an autoimmune diagnosis is established.”

The study was supported by Karolinska Institutet and the Swedish Research Council. Dr. Lebwohl coordinates a study on behalf of the Swedish IBD quality register, which has received funding from Janssen. The other authors declared no conflicts of interest. Dr. Stahl reported no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Celiac disease is linked to juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) in children and rheumatoid arthritis (RA) in adults, according to an analysis of nationwide data in Sweden.

“I hope that our study can ultimately change clinical practice by lowering the threshold to evaluate celiac disease patients for inflammatory joint diseases,” John B. Doyle, MD, a gastroenterology fellow at Columbia University Irving Medical Center in New York, told this news organization.

“Inflammatory joint diseases, such as JIA and RA, are notoriously difficult to diagnose given their variable presentations,” he said. “But if JIA or RA can be identified sooner by physicians, patients will ultimately benefit by starting disease-modifying therapy earlier in their disease course.”

The study was published online in The American Journal of Gastroenterology.

Analyzing associations

Celiac disease has been linked to numerous autoimmune diseases, including type 1 diabetes, autoimmune thyroid disease, lupus, and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), Dr. Doyle noted. However, a definitive epidemiologic association between celiac disease and inflammatory joint diseases such as JIA or RA hasn›t been established.

Dr. Doyle and colleagues conducted a nationwide population-based, retrospective matched cohort study using the Epidemiology Strengthened by Histopathology Reports in Sweden. They identified 24,014 patients diagnosed with biopsy-proven celiac disease between 2004 and 2017.

With these data, each patient was matched to five reference individuals in the general population by age, sex, calendar year, and geographic region, for a total of 117,397 people without a previous diagnosis of celiac disease. The researchers calculated the incidence and estimated the relative risk for JIA in patients younger than 18 years and RA in patients aged 18 years or older.

For those younger than 18 years, the incidence rate of JIA was 5.9 per 10,000 person-years among the 9,415 patients with celiac disease versus 2.2 per 10,000 person-years in the general population, over a follow-up of 7 years. Those with celiac disease were 2.7 times as likely to develop JIA.

The association between celiac disease and JIA remained similar after adjustment for education, Nordic country of birth, type 1 diabetes, autoimmune thyroid disease, lupus, and IBD. The incidence rate of JIA among patients with celiac disease was higher in both females and males, and across all age groups studied.

When 6,703 children with celiac disease were compared with their 9,089 siblings without celiac disease, the higher risk for JIA in patients with celiac disease fell slightly short of statistical significance.

For those aged 18 years or older, the incidence rate of RA was 8.4 per 10,000 person-years among the 14,599 patients with celiac disease versus 5.1 per 10,000 person-years in the general population, over a follow-up of 8.8 years. Those with celiac disease were 1.7 times as likely to develop RA.

As with the younger cohort, the association between celiac disease and RA in the adult group remained similar after adjustment for education, Nordic country of birth, type 1 diabetes, autoimmune thyroid disease, lupus, and IBD. Although both men and women with celiac disease had higher rates of RA, the risk was higher among those in whom disease was diagnosed at age 18-59 years compared with those who received a diagnosis at age 60 years or older.

When 9,578 adults with celiac disease were compared with their 17,067 siblings without celiac disease, the risk for RA remained higher in patients with celiac disease.

This suggests “that the association between celiac disease and RA is unlikely to be explained by environmental factors alone,” Dr. Doyle said.

Additional findings

Notably, the primary analysis excluded patients diagnosed with JIA or RA before their celiac disease diagnosis. In additional analyses, however, significant associations emerged.

Among children with celiac disease, 0.5% had a previous diagnosis of JIA, compared with 0.1% of matched comparators. Those with celiac disease were 3.5 times more likely to have a JIA diagnosis.

Among adults with celiac disease, 0.9% had a previous diagnosis of RA, compared with 0.6% of matched comparators. Those with celiac disease were 1.4 times more likely to have a RA diagnosis.

“We found that diagnoses of these types of arthritis were more common before a diagnosis of celiac disease compared to the general population,” Benjamin Lebwohl, MD, director of clinical research at the Celiac Disease Center at Columbia University, New York, told this news organization.

“This suggests that undiagnosed and untreated celiac disease might be contributing to these others autoimmune conditions,” he said.

Dr. Doyle and Dr. Lebwohl emphasized the practical implications for clinicians caring for patients with celiac disease. Among patients with celiac disease and inflammatory joint symptoms, clinicians should have a low threshold to evaluate for JIA or RA, they said.

“Particularly in pediatrics, we are trained to screen patients with JIA for celiac disease, but this study points to the possible bidirectional association and the importance of maintaining a clinical suspicion for JIA and RA among established celiac disease patients,” Marisa Stahl, MD, assistant professor of pediatrics and associate program director of the pediatric gastroenterology, hepatology, and nutrition fellowship training program at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, said in an interview.

Dr. Stahl, who wasn’t involved with this study, conducts research at the Colorado Center for Celiac Disease. She and colleagues are focused on understanding the genetic and environmental factors that lead to the development of celiac disease and other autoimmune diseases.

Given the clear association between celiac disease and other autoimmune diseases, Dr. Stahl agreed that clinicians should have a low threshold for screening, with “additional workup for other autoimmune diseases once an autoimmune diagnosis is established.”

The study was supported by Karolinska Institutet and the Swedish Research Council. Dr. Lebwohl coordinates a study on behalf of the Swedish IBD quality register, which has received funding from Janssen. The other authors declared no conflicts of interest. Dr. Stahl reported no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Celiac disease is linked to juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) in children and rheumatoid arthritis (RA) in adults, according to an analysis of nationwide data in Sweden.

“I hope that our study can ultimately change clinical practice by lowering the threshold to evaluate celiac disease patients for inflammatory joint diseases,” John B. Doyle, MD, a gastroenterology fellow at Columbia University Irving Medical Center in New York, told this news organization.

“Inflammatory joint diseases, such as JIA and RA, are notoriously difficult to diagnose given their variable presentations,” he said. “But if JIA or RA can be identified sooner by physicians, patients will ultimately benefit by starting disease-modifying therapy earlier in their disease course.”

The study was published online in The American Journal of Gastroenterology.

Analyzing associations

Celiac disease has been linked to numerous autoimmune diseases, including type 1 diabetes, autoimmune thyroid disease, lupus, and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), Dr. Doyle noted. However, a definitive epidemiologic association between celiac disease and inflammatory joint diseases such as JIA or RA hasn›t been established.

Dr. Doyle and colleagues conducted a nationwide population-based, retrospective matched cohort study using the Epidemiology Strengthened by Histopathology Reports in Sweden. They identified 24,014 patients diagnosed with biopsy-proven celiac disease between 2004 and 2017.

With these data, each patient was matched to five reference individuals in the general population by age, sex, calendar year, and geographic region, for a total of 117,397 people without a previous diagnosis of celiac disease. The researchers calculated the incidence and estimated the relative risk for JIA in patients younger than 18 years and RA in patients aged 18 years or older.

For those younger than 18 years, the incidence rate of JIA was 5.9 per 10,000 person-years among the 9,415 patients with celiac disease versus 2.2 per 10,000 person-years in the general population, over a follow-up of 7 years. Those with celiac disease were 2.7 times as likely to develop JIA.

The association between celiac disease and JIA remained similar after adjustment for education, Nordic country of birth, type 1 diabetes, autoimmune thyroid disease, lupus, and IBD. The incidence rate of JIA among patients with celiac disease was higher in both females and males, and across all age groups studied.

When 6,703 children with celiac disease were compared with their 9,089 siblings without celiac disease, the higher risk for JIA in patients with celiac disease fell slightly short of statistical significance.

For those aged 18 years or older, the incidence rate of RA was 8.4 per 10,000 person-years among the 14,599 patients with celiac disease versus 5.1 per 10,000 person-years in the general population, over a follow-up of 8.8 years. Those with celiac disease were 1.7 times as likely to develop RA.

As with the younger cohort, the association between celiac disease and RA in the adult group remained similar after adjustment for education, Nordic country of birth, type 1 diabetes, autoimmune thyroid disease, lupus, and IBD. Although both men and women with celiac disease had higher rates of RA, the risk was higher among those in whom disease was diagnosed at age 18-59 years compared with those who received a diagnosis at age 60 years or older.

When 9,578 adults with celiac disease were compared with their 17,067 siblings without celiac disease, the risk for RA remained higher in patients with celiac disease.

This suggests “that the association between celiac disease and RA is unlikely to be explained by environmental factors alone,” Dr. Doyle said.

Additional findings

Notably, the primary analysis excluded patients diagnosed with JIA or RA before their celiac disease diagnosis. In additional analyses, however, significant associations emerged.

Among children with celiac disease, 0.5% had a previous diagnosis of JIA, compared with 0.1% of matched comparators. Those with celiac disease were 3.5 times more likely to have a JIA diagnosis.

Among adults with celiac disease, 0.9% had a previous diagnosis of RA, compared with 0.6% of matched comparators. Those with celiac disease were 1.4 times more likely to have a RA diagnosis.

“We found that diagnoses of these types of arthritis were more common before a diagnosis of celiac disease compared to the general population,” Benjamin Lebwohl, MD, director of clinical research at the Celiac Disease Center at Columbia University, New York, told this news organization.

“This suggests that undiagnosed and untreated celiac disease might be contributing to these others autoimmune conditions,” he said.

Dr. Doyle and Dr. Lebwohl emphasized the practical implications for clinicians caring for patients with celiac disease. Among patients with celiac disease and inflammatory joint symptoms, clinicians should have a low threshold to evaluate for JIA or RA, they said.

“Particularly in pediatrics, we are trained to screen patients with JIA for celiac disease, but this study points to the possible bidirectional association and the importance of maintaining a clinical suspicion for JIA and RA among established celiac disease patients,” Marisa Stahl, MD, assistant professor of pediatrics and associate program director of the pediatric gastroenterology, hepatology, and nutrition fellowship training program at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, said in an interview.

Dr. Stahl, who wasn’t involved with this study, conducts research at the Colorado Center for Celiac Disease. She and colleagues are focused on understanding the genetic and environmental factors that lead to the development of celiac disease and other autoimmune diseases.

Given the clear association between celiac disease and other autoimmune diseases, Dr. Stahl agreed that clinicians should have a low threshold for screening, with “additional workup for other autoimmune diseases once an autoimmune diagnosis is established.”

The study was supported by Karolinska Institutet and the Swedish Research Council. Dr. Lebwohl coordinates a study on behalf of the Swedish IBD quality register, which has received funding from Janssen. The other authors declared no conflicts of interest. Dr. Stahl reported no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF GASTROENTEROLOGY

Sick call

They call me and I go.

– William Carlos Williams

I never get sick. I’ve never had the flu. When everyone’s got a cold, I’m somehow immune. The last time I threw up was June 29th, 1980. You see, I work out almost daily, eat vegan, and sleep plenty. I drink gallons of pressed juice and throw down a few high-quality supplements. Yes, I’m that guy: The one who never gets sick. Well, I was anyway.

I am no longer that guy since our little girl became a supersocial little toddler. My undefeated welterweight “never-sick” title has been obliterated by multiple knockouts. One was a wicked adenovirus that broke the no-vomit streak. At one point, I lay on the luxury gray tile bathroom floor hoping to go unconscious to make the nausea stop. I actually called out sick that day. Then with a nasty COVID-despite-vaccine infection. I called out again. Later with a hacking lower respiratory – RSV?! – bug. Called out. All of which our 2-year-old blonde, curly-haired vector transmitted to me with remarkable efficiency.

In fact, That’s saying a lot. Our docs, like most, don’t call out sick.

We physicians have legendary stamina. Compared with other professionals, we are no less likely to become ill but a whopping 80% less likely to call out sick.

Presenteeism is our physician version of Omerta, a code of honor to never give in even at the expense of our, or our family’s, health and well-being. Every medical student is regaled with stories of physicians getting an IV before rounds or finishing clinic after their water broke. Why? In part it’s an indoctrination into this thing of ours we call Medicine: An elitist club that admits only those able to pass O-chem and hold diarrhea. But it is also because our medical system is so brittle that the slightest bend causes it to shatter. When I cancel a clinic, patients who have waited weeks for their spot have to be sent home. And for critical cases or those patients who don’t get the message, my already slammed colleagues have to cram the unlucky ones in between already-scheduled appointments. The guilt induced by inconveniencing our colleagues and our patients is more potent than dry heaves. And so we go. Suck it up. Sip ginger ale. Load up on acetaminophen. Carry on. This harms not only us, but also patients whom we put in the path of transmission. We become terrible 2-year-olds.

Of course, it’s not always easy to tell if you’re sick enough to stay home. But the stigma of calling out is so great that we often show up no matter what symptoms. A recent Medscape survey of physicians found that 85% said they had come to work sick in 2022.

We can do better. Perhaps creating sick-leave protocols could help? For example, if you have a fever above 100.4, have contact with someone positive for influenza, are unable to take POs, etc. then stay home. So might building rolling slack into schedules to accommodate the inevitable physician illness, parenting emergency, or death of an beloved uncle. And if there is one thing artificial intelligence could help us with, it would be smart scheduling. Can’t we build algorithms for anticipating and absorbing these predictable events? I’d take that over an AI skin cancer detector any day. Yet this year we’ll struggle through the cold and flu (and COVID) season again and nothing will have changed.

Our daughter hasn’t had hand, foot, and mouth disease yet. It’s not a question of if, but rather when she, and her mom and I, will get it. I hope it happens on a Friday so that my Monday clinic will be bearable when I show up.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at [email protected]

They call me and I go.

– William Carlos Williams

I never get sick. I’ve never had the flu. When everyone’s got a cold, I’m somehow immune. The last time I threw up was June 29th, 1980. You see, I work out almost daily, eat vegan, and sleep plenty. I drink gallons of pressed juice and throw down a few high-quality supplements. Yes, I’m that guy: The one who never gets sick. Well, I was anyway.

I am no longer that guy since our little girl became a supersocial little toddler. My undefeated welterweight “never-sick” title has been obliterated by multiple knockouts. One was a wicked adenovirus that broke the no-vomit streak. At one point, I lay on the luxury gray tile bathroom floor hoping to go unconscious to make the nausea stop. I actually called out sick that day. Then with a nasty COVID-despite-vaccine infection. I called out again. Later with a hacking lower respiratory – RSV?! – bug. Called out. All of which our 2-year-old blonde, curly-haired vector transmitted to me with remarkable efficiency.

In fact, That’s saying a lot. Our docs, like most, don’t call out sick.

We physicians have legendary stamina. Compared with other professionals, we are no less likely to become ill but a whopping 80% less likely to call out sick.

Presenteeism is our physician version of Omerta, a code of honor to never give in even at the expense of our, or our family’s, health and well-being. Every medical student is regaled with stories of physicians getting an IV before rounds or finishing clinic after their water broke. Why? In part it’s an indoctrination into this thing of ours we call Medicine: An elitist club that admits only those able to pass O-chem and hold diarrhea. But it is also because our medical system is so brittle that the slightest bend causes it to shatter. When I cancel a clinic, patients who have waited weeks for their spot have to be sent home. And for critical cases or those patients who don’t get the message, my already slammed colleagues have to cram the unlucky ones in between already-scheduled appointments. The guilt induced by inconveniencing our colleagues and our patients is more potent than dry heaves. And so we go. Suck it up. Sip ginger ale. Load up on acetaminophen. Carry on. This harms not only us, but also patients whom we put in the path of transmission. We become terrible 2-year-olds.

Of course, it’s not always easy to tell if you’re sick enough to stay home. But the stigma of calling out is so great that we often show up no matter what symptoms. A recent Medscape survey of physicians found that 85% said they had come to work sick in 2022.

We can do better. Perhaps creating sick-leave protocols could help? For example, if you have a fever above 100.4, have contact with someone positive for influenza, are unable to take POs, etc. then stay home. So might building rolling slack into schedules to accommodate the inevitable physician illness, parenting emergency, or death of an beloved uncle. And if there is one thing artificial intelligence could help us with, it would be smart scheduling. Can’t we build algorithms for anticipating and absorbing these predictable events? I’d take that over an AI skin cancer detector any day. Yet this year we’ll struggle through the cold and flu (and COVID) season again and nothing will have changed.

Our daughter hasn’t had hand, foot, and mouth disease yet. It’s not a question of if, but rather when she, and her mom and I, will get it. I hope it happens on a Friday so that my Monday clinic will be bearable when I show up.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at [email protected]

They call me and I go.

– William Carlos Williams

I never get sick. I’ve never had the flu. When everyone’s got a cold, I’m somehow immune. The last time I threw up was June 29th, 1980. You see, I work out almost daily, eat vegan, and sleep plenty. I drink gallons of pressed juice and throw down a few high-quality supplements. Yes, I’m that guy: The one who never gets sick. Well, I was anyway.

I am no longer that guy since our little girl became a supersocial little toddler. My undefeated welterweight “never-sick” title has been obliterated by multiple knockouts. One was a wicked adenovirus that broke the no-vomit streak. At one point, I lay on the luxury gray tile bathroom floor hoping to go unconscious to make the nausea stop. I actually called out sick that day. Then with a nasty COVID-despite-vaccine infection. I called out again. Later with a hacking lower respiratory – RSV?! – bug. Called out. All of which our 2-year-old blonde, curly-haired vector transmitted to me with remarkable efficiency.

In fact, That’s saying a lot. Our docs, like most, don’t call out sick.

We physicians have legendary stamina. Compared with other professionals, we are no less likely to become ill but a whopping 80% less likely to call out sick.

Presenteeism is our physician version of Omerta, a code of honor to never give in even at the expense of our, or our family’s, health and well-being. Every medical student is regaled with stories of physicians getting an IV before rounds or finishing clinic after their water broke. Why? In part it’s an indoctrination into this thing of ours we call Medicine: An elitist club that admits only those able to pass O-chem and hold diarrhea. But it is also because our medical system is so brittle that the slightest bend causes it to shatter. When I cancel a clinic, patients who have waited weeks for their spot have to be sent home. And for critical cases or those patients who don’t get the message, my already slammed colleagues have to cram the unlucky ones in between already-scheduled appointments. The guilt induced by inconveniencing our colleagues and our patients is more potent than dry heaves. And so we go. Suck it up. Sip ginger ale. Load up on acetaminophen. Carry on. This harms not only us, but also patients whom we put in the path of transmission. We become terrible 2-year-olds.

Of course, it’s not always easy to tell if you’re sick enough to stay home. But the stigma of calling out is so great that we often show up no matter what symptoms. A recent Medscape survey of physicians found that 85% said they had come to work sick in 2022.

We can do better. Perhaps creating sick-leave protocols could help? For example, if you have a fever above 100.4, have contact with someone positive for influenza, are unable to take POs, etc. then stay home. So might building rolling slack into schedules to accommodate the inevitable physician illness, parenting emergency, or death of an beloved uncle. And if there is one thing artificial intelligence could help us with, it would be smart scheduling. Can’t we build algorithms for anticipating and absorbing these predictable events? I’d take that over an AI skin cancer detector any day. Yet this year we’ll struggle through the cold and flu (and COVID) season again and nothing will have changed.

Our daughter hasn’t had hand, foot, and mouth disease yet. It’s not a question of if, but rather when she, and her mom and I, will get it. I hope it happens on a Friday so that my Monday clinic will be bearable when I show up.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at [email protected]

Higher metal contact allergy rates found in metalworkers

a systematic review and meta-analysis reports.

“Metal allergy to all three metals was significantly more common in European metalworkers with dermatitis attending patch test clinics as compared to ESSCA [European Surveillance System on Contact Allergies] data, indicating a relationship to occupational exposures,” senior study author Jeanne D. Johansen, MD, professor, department of dermatology and allergy, Copenhagen University Hospital, Hellerup, Denmark, and colleagues at the University of Copenhagen wrote in Contact Dermatitis. “However, confounders could not be accounted for.”

How common is metal allergy in metalworkers?

Occupational hand eczema is known to be common in metalworkers. Touching oils, greases, metals, leather gloves, rubber materials, and metalworking fluids as they repeatedly cut, shape, and process raw metals and minerals derived from ore mining exposes metalworkers to allergens and skin irritants, the authors wrote. But the prevalence of allergy to certain metals has not been well characterized.

So they searched PubMed for full-text studies in English that reported metal allergy prevalence in metalworkers, from the database’s inception through April 2022.

They included studies with absolute numbers or proportions of metal allergy to cobalt, chromium, or nickel, in all metalworkers with suspected allergic contact dermatitis who attended outpatient clinics or who worked at metalworking plants participating in workplace studies.

The researchers performed a random-effects meta-analysis to calculate the pooled prevalence of metal allergy. Because 85%-90% of metalworkers in Denmark are male, they compared the estimates they found with ESSCA data on 13,382 consecutively patch-tested males with dermatitis between 2015 and 2018.

Of the 1,667 records they screened, they analyzed data from 29 that met their inclusion criteria: 22 patient studies and 7 workplace studies involving 5,691 patients overall from 22 studies from Europe, 5 studies from Asia, and 1 from Africa. Regarding European metalworkers, the authors found:

- Pooled proportions of allergy in European metalworkers with dermatitis referred to patch test clinics were 8.2% to cobalt (95% confidence interval, 5.3%-11.7%), 8.0% to chromium (95% CI, 5.1%-11.4%), and 11.0% to nickel (95% CI, 7.3%-15.4%).

- In workplace studies, the pooled proportions of allergy in unselected European metalworkers were 4.9% to cobalt, (95% CI, 2.4%-8.1%), 5.2% to chromium (95% CI, 1.0% - 12.6%), and 7.6% to nickel (95% CI, 3.8%-12.6%).

- By comparison, ESSCA data on metal allergy prevalence showed 3.9% allergic to cobalt (95% CI, 3.6%-4.2%), 4.4% allergic to chromium (95% CI, 4.1%-4.8%), and 6.7% allergic to nickel (95% CI, 6.3%-7.0%).

- Data on sex, age, body piercings, and atopic dermatitis were scant.

Thorough histories, protective regulations and equipment

Providers need to ask their dermatitis patients about current and past occupations and hobbies, and employers need to provide employees with equipment that protects them from exposure, Kelly Tyler, MD, associate professor of dermatology, Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, Columbus, said in an interview.

“Repeated exposure to an allergen is required for sensitization to develop,” said Dr. Tyler, who was not involved in the study. “Metalworkers, who are continually exposed to metals and metalworking fluids, have a higher risk of allergic contact dermatitis to cobalt, chromium, and nickel.”

“The primary treatment for allergic contact dermatitis is preventing continued exposure to the allergen,” she added. “This study highlights the importance of asking about metal or metalworking fluid in the workplace and of elucidating whether the employer is providing appropriate protective gear.”

To prevent occupational dermatitis, workplaces need to apply regulatory measures and provide their employees with protective equipment, Dr. Tyler advised.

“Body piercings are a common sensitizer in patients with metal allergy, and the prevalence of body piercings among metalworkers was not included in the study,” she noted.

The results of the study may not be generalizable to patients in the United States, she added, because regulations and requirements to provide protective gear here may differ.

“Taking a thorough patient history is crucial when investigating potential causes of dermatitis, especially in patients with suspected allergic contact dermatitis,” Dr. Tyler urged.

Funding and conflict-of-interest details were not provided. Dr. Tyler reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

a systematic review and meta-analysis reports.