User login

Image-guided superficial radiation as first-line in skin cancer?

The study covered in this summary was published on medRxiv.org as a preprint and has not yet been peer reviewed.

Key takeaway

- Absolute lesion control rate with image-guided superficial radiation therapy (IGSRT) for early-stage nonmelanoma skin cancer was achieved in nearly all patients.

Why this matters

- IGSRT is a newer radiation technique for skin cancer, an alternative to Mohs micrographic surgery and other surgical options.

- The ultrasound imaging used during IGSRT allows for precise targeting of cancer cells while sparing surrounding tissue.

- IGSRT is currently recommended for early-stage nonmelanoma skin cancer among patients who refuse or cannot tolerate surgery.

- Given the safety, lack of surgical disfigurement, cost-effectiveness, and high cure rate, IGSRT should be considered more broadly as a first-line option for early-stage nonmelanoma skin cancer, the researchers concluded.

Study design

- The investigators reviewed 1,899 early-stage nonmelanoma skin cancer lesions in 1,243 patients treated with IGSRT at an outpatient dermatology clinic in Dallas.

- Energies ranged from 50 to 100 kV, with a mean treatment dose of 5,364.4 cGy over an average of 20.2 fractions.

- Treatment duration was a mean of 7.5 weeks and followed for a mean of 65.5 weeks.

Key results

- Absolute lesion control was achieved in 99.7% of patients, with a stable control rate of 99.6% past 12 months.

- At a 5-year follow-up, local control was 99.4%.

- Local control for both basal and squamous cell carcinoma at 5 years was 99%; local control for squamous cell carcinoma in situ was 100% at 5 years.

- The most common side effects were erythema, dryness, and dry desquamation. Some patients had ulceration and moist desquamation, but it did not affect lesion control.

- The procedure was well tolerated, with a grade 1 Radiation Treatment Oncology Group toxicity score in 72% of lesions.

- The results compare favorably with Mohs surgery.

Limitations

- No study limitations were noted.

Disclosures

- No funding source was reported.

- Senior investigator Lio Yu, MD, reported research, speaking and/or consulting for SkinCure Oncology, a developer of IGSRT technology.

This is a summary of a preprint research study, “Analysis of Image-Guided Superficial Radiation Therapy (IGSRT) on the Treatment of Early Stage Non-Melanoma Skin Cancer (NMSC) in the Outpatient Dermatology Setting,” led by Alison Tran, MD, of Baylor University Medical Center, Dallas. The study has not been peer reviewed. The full text can be found at medRxiv.org.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The study covered in this summary was published on medRxiv.org as a preprint and has not yet been peer reviewed.

Key takeaway

- Absolute lesion control rate with image-guided superficial radiation therapy (IGSRT) for early-stage nonmelanoma skin cancer was achieved in nearly all patients.

Why this matters

- IGSRT is a newer radiation technique for skin cancer, an alternative to Mohs micrographic surgery and other surgical options.

- The ultrasound imaging used during IGSRT allows for precise targeting of cancer cells while sparing surrounding tissue.

- IGSRT is currently recommended for early-stage nonmelanoma skin cancer among patients who refuse or cannot tolerate surgery.

- Given the safety, lack of surgical disfigurement, cost-effectiveness, and high cure rate, IGSRT should be considered more broadly as a first-line option for early-stage nonmelanoma skin cancer, the researchers concluded.

Study design

- The investigators reviewed 1,899 early-stage nonmelanoma skin cancer lesions in 1,243 patients treated with IGSRT at an outpatient dermatology clinic in Dallas.

- Energies ranged from 50 to 100 kV, with a mean treatment dose of 5,364.4 cGy over an average of 20.2 fractions.

- Treatment duration was a mean of 7.5 weeks and followed for a mean of 65.5 weeks.

Key results

- Absolute lesion control was achieved in 99.7% of patients, with a stable control rate of 99.6% past 12 months.

- At a 5-year follow-up, local control was 99.4%.

- Local control for both basal and squamous cell carcinoma at 5 years was 99%; local control for squamous cell carcinoma in situ was 100% at 5 years.

- The most common side effects were erythema, dryness, and dry desquamation. Some patients had ulceration and moist desquamation, but it did not affect lesion control.

- The procedure was well tolerated, with a grade 1 Radiation Treatment Oncology Group toxicity score in 72% of lesions.

- The results compare favorably with Mohs surgery.

Limitations

- No study limitations were noted.

Disclosures

- No funding source was reported.

- Senior investigator Lio Yu, MD, reported research, speaking and/or consulting for SkinCure Oncology, a developer of IGSRT technology.

This is a summary of a preprint research study, “Analysis of Image-Guided Superficial Radiation Therapy (IGSRT) on the Treatment of Early Stage Non-Melanoma Skin Cancer (NMSC) in the Outpatient Dermatology Setting,” led by Alison Tran, MD, of Baylor University Medical Center, Dallas. The study has not been peer reviewed. The full text can be found at medRxiv.org.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The study covered in this summary was published on medRxiv.org as a preprint and has not yet been peer reviewed.

Key takeaway

- Absolute lesion control rate with image-guided superficial radiation therapy (IGSRT) for early-stage nonmelanoma skin cancer was achieved in nearly all patients.

Why this matters

- IGSRT is a newer radiation technique for skin cancer, an alternative to Mohs micrographic surgery and other surgical options.

- The ultrasound imaging used during IGSRT allows for precise targeting of cancer cells while sparing surrounding tissue.

- IGSRT is currently recommended for early-stage nonmelanoma skin cancer among patients who refuse or cannot tolerate surgery.

- Given the safety, lack of surgical disfigurement, cost-effectiveness, and high cure rate, IGSRT should be considered more broadly as a first-line option for early-stage nonmelanoma skin cancer, the researchers concluded.

Study design

- The investigators reviewed 1,899 early-stage nonmelanoma skin cancer lesions in 1,243 patients treated with IGSRT at an outpatient dermatology clinic in Dallas.

- Energies ranged from 50 to 100 kV, with a mean treatment dose of 5,364.4 cGy over an average of 20.2 fractions.

- Treatment duration was a mean of 7.5 weeks and followed for a mean of 65.5 weeks.

Key results

- Absolute lesion control was achieved in 99.7% of patients, with a stable control rate of 99.6% past 12 months.

- At a 5-year follow-up, local control was 99.4%.

- Local control for both basal and squamous cell carcinoma at 5 years was 99%; local control for squamous cell carcinoma in situ was 100% at 5 years.

- The most common side effects were erythema, dryness, and dry desquamation. Some patients had ulceration and moist desquamation, but it did not affect lesion control.

- The procedure was well tolerated, with a grade 1 Radiation Treatment Oncology Group toxicity score in 72% of lesions.

- The results compare favorably with Mohs surgery.

Limitations

- No study limitations were noted.

Disclosures

- No funding source was reported.

- Senior investigator Lio Yu, MD, reported research, speaking and/or consulting for SkinCure Oncology, a developer of IGSRT technology.

This is a summary of a preprint research study, “Analysis of Image-Guided Superficial Radiation Therapy (IGSRT) on the Treatment of Early Stage Non-Melanoma Skin Cancer (NMSC) in the Outpatient Dermatology Setting,” led by Alison Tran, MD, of Baylor University Medical Center, Dallas. The study has not been peer reviewed. The full text can be found at medRxiv.org.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The dubious value of online reviews

I hear other doctors talk about online reviews, both good and bad.

I recently read a piece where a practice gave doctors a bonus for getting 5-star reviews, though it doesn’t say if they were penalized for getting bad reviews. I assume the latter docs got a good “talking to” by someone in administration, or marketing, or both.

I get my share of them, too, both good and bad, scattered across at least a dozen sites that profess to offer accurate ratings.

I tend to ignore all of them.

Bad ratings mean nothing. They might be reasonable. They can also be from patients whom I fired for noncompliance, or from patients I refused to give an early narcotic refill to. They can also be from people who aren’t patients, such as a neighbor angry at the way I voted at a home owners association meeting, or a person who never saw me but was upset because I don’t take their insurance, or someone at the hospital whom I had to hang up on after being put on hold for 10 minutes.

Good reviews also don’t mean much, either. They might be from patients. They could also be from well-meaning family and friends. Or the waiter I left an extra-large tip for the other night.

One of my 1-star reviews even goes on to describe me in glowing terms (the lady called my office to apologize, saying the site confused her).

There’s also a whole cottage industry around this: Like restaurants, you can pay people to give you good reviews. They’re on Craig’s list and other sites. Some are freelancers. Others are actually well-organized companies, offering to give you X number of good reviews per month for a regular fee. I see ads for the latter online, usually describing themselves as “reputation recovery services.”

There was even a recent post on Sermo about this. A doctor noted he’d gotten a string of bad reviews from nonpatients, and shortly afterward was contacted by a reputation recovery service to help. He wondered if the crappy reviews were intentionally written by that business before they called him. He also questioned if it was an unspoken blackmail tactic – pay us or we’ll write more bad reviews.

Unlike a restaurant, we can’t respond because of patient confidentiality. Unless it’s something meaninglessly generic like “thank you” or “sorry you had a bad experience.”

A friend of mine (not in medicine) said that picking your doctor from online reviews is like selecting a wine recommended by a guy who lives at the train yard.

While there are pros and cons to the whole online review thing, in medicine there are mostly cons. Many reviews are anonymous, with no way to trace them. Unless details are provided, you don’t know if the reviewer is really a patient (or even a human in this bot era). Neither does the general public, reading them and presumably making decisions about who to see.

There are minimal (if any) rules, no law enforcement, and no one knows who the good guys and bad guys really are.

And there’s nothing we can do about it, either.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

I hear other doctors talk about online reviews, both good and bad.

I recently read a piece where a practice gave doctors a bonus for getting 5-star reviews, though it doesn’t say if they were penalized for getting bad reviews. I assume the latter docs got a good “talking to” by someone in administration, or marketing, or both.

I get my share of them, too, both good and bad, scattered across at least a dozen sites that profess to offer accurate ratings.

I tend to ignore all of them.

Bad ratings mean nothing. They might be reasonable. They can also be from patients whom I fired for noncompliance, or from patients I refused to give an early narcotic refill to. They can also be from people who aren’t patients, such as a neighbor angry at the way I voted at a home owners association meeting, or a person who never saw me but was upset because I don’t take their insurance, or someone at the hospital whom I had to hang up on after being put on hold for 10 minutes.

Good reviews also don’t mean much, either. They might be from patients. They could also be from well-meaning family and friends. Or the waiter I left an extra-large tip for the other night.

One of my 1-star reviews even goes on to describe me in glowing terms (the lady called my office to apologize, saying the site confused her).

There’s also a whole cottage industry around this: Like restaurants, you can pay people to give you good reviews. They’re on Craig’s list and other sites. Some are freelancers. Others are actually well-organized companies, offering to give you X number of good reviews per month for a regular fee. I see ads for the latter online, usually describing themselves as “reputation recovery services.”

There was even a recent post on Sermo about this. A doctor noted he’d gotten a string of bad reviews from nonpatients, and shortly afterward was contacted by a reputation recovery service to help. He wondered if the crappy reviews were intentionally written by that business before they called him. He also questioned if it was an unspoken blackmail tactic – pay us or we’ll write more bad reviews.

Unlike a restaurant, we can’t respond because of patient confidentiality. Unless it’s something meaninglessly generic like “thank you” or “sorry you had a bad experience.”

A friend of mine (not in medicine) said that picking your doctor from online reviews is like selecting a wine recommended by a guy who lives at the train yard.

While there are pros and cons to the whole online review thing, in medicine there are mostly cons. Many reviews are anonymous, with no way to trace them. Unless details are provided, you don’t know if the reviewer is really a patient (or even a human in this bot era). Neither does the general public, reading them and presumably making decisions about who to see.

There are minimal (if any) rules, no law enforcement, and no one knows who the good guys and bad guys really are.

And there’s nothing we can do about it, either.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

I hear other doctors talk about online reviews, both good and bad.

I recently read a piece where a practice gave doctors a bonus for getting 5-star reviews, though it doesn’t say if they were penalized for getting bad reviews. I assume the latter docs got a good “talking to” by someone in administration, or marketing, or both.

I get my share of them, too, both good and bad, scattered across at least a dozen sites that profess to offer accurate ratings.

I tend to ignore all of them.

Bad ratings mean nothing. They might be reasonable. They can also be from patients whom I fired for noncompliance, or from patients I refused to give an early narcotic refill to. They can also be from people who aren’t patients, such as a neighbor angry at the way I voted at a home owners association meeting, or a person who never saw me but was upset because I don’t take their insurance, or someone at the hospital whom I had to hang up on after being put on hold for 10 minutes.

Good reviews also don’t mean much, either. They might be from patients. They could also be from well-meaning family and friends. Or the waiter I left an extra-large tip for the other night.

One of my 1-star reviews even goes on to describe me in glowing terms (the lady called my office to apologize, saying the site confused her).

There’s also a whole cottage industry around this: Like restaurants, you can pay people to give you good reviews. They’re on Craig’s list and other sites. Some are freelancers. Others are actually well-organized companies, offering to give you X number of good reviews per month for a regular fee. I see ads for the latter online, usually describing themselves as “reputation recovery services.”

There was even a recent post on Sermo about this. A doctor noted he’d gotten a string of bad reviews from nonpatients, and shortly afterward was contacted by a reputation recovery service to help. He wondered if the crappy reviews were intentionally written by that business before they called him. He also questioned if it was an unspoken blackmail tactic – pay us or we’ll write more bad reviews.

Unlike a restaurant, we can’t respond because of patient confidentiality. Unless it’s something meaninglessly generic like “thank you” or “sorry you had a bad experience.”

A friend of mine (not in medicine) said that picking your doctor from online reviews is like selecting a wine recommended by a guy who lives at the train yard.

While there are pros and cons to the whole online review thing, in medicine there are mostly cons. Many reviews are anonymous, with no way to trace them. Unless details are provided, you don’t know if the reviewer is really a patient (or even a human in this bot era). Neither does the general public, reading them and presumably making decisions about who to see.

There are minimal (if any) rules, no law enforcement, and no one knows who the good guys and bad guys really are.

And there’s nothing we can do about it, either.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

How to improve diagnosis of HFpEF, common in diabetes

STOCKHOLM – Recent study results confirm that two agents from the sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor class can significantly cut the incidence of adverse cardiovascular events in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFpEF), a disease especially common in people with type 2 diabetes, obesity, or both.

And findings from secondary analyses of the studies – including one reported at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes – show that these SGLT2 inhibitors work as well for cutting incident adverse events (cardiovascular death or worsening heart failure) in patients with HFpEF and diabetes as they do for people with normal blood glucose levels.

But delivering treatment with these proven agents, dapagliflozin (Farxiga) and empagliflozin (Jardiance), first requires diagnosis of HFpEF, a task that clinicians have historically fallen short in accomplishing.

When in 2021, results from the EMPEROR-Preserved trial with empagliflozin and when in September 2022 results from the DELIVER trial with dapagliflozin established the efficacy of these two SGLT2 inhibitors as the first treatments proven to benefit patients with HFpEF, they also raised the stakes for clinicians to be much more diligent and systematic in evaluating people at high risk for developing HFpEF because of having type 2 diabetes or obesity, two of the most potent risk factors for this form of heart failure.

‘Vigilance ... needs to increase’

“Vigilance for HFpEF needs to increase because we can now help these patients,” declared Lars H. Lund, MD, PhD, speaking at the meeting. “Type 2 diabetes dramatically increases the incidence of HFpEF,” and the mechanisms by which it does this are “especially amenable to treatment with SGLT2 inhibitors,” said Dr. Lund, a cardiologist and heart failure specialist at the Karolinska Institute, Stockholm.

HFpEF has a history of going undetected in people with type 2 diabetes, an ironic situation given its high incidence as well as the elevated rate of adverse cardiovascular events when heart failure occurs in patients with type 2 diabetes compared with patients who do not have diabetes.

The key, say experts, is for clinicians to maintain a high index of suspicion for signs and symptoms of heart failure in people with type 2 diabetes and to regularly assess them, starting with just a few simple questions that probe for the presence of dyspnea, exertional fatigue, or both, an approach not widely employed up to now.

Clinicians who care for people with type 2 diabetes must become “alert to thinking about heart failure and alert to asking questions about signs and symptoms” that flag the presence of HFpEF, advised Naveed Sattar, MBChB, PhD, a professor of metabolic medicine at the University of Glasgow.

Soon, medical groups will issue guidelines for appropriate assessment for the presence of HFpEF in people with type 2 diabetes, Dr. Sattar predicted in an interview.

A need to probe

“You can’t simply ask patients with type 2 diabetes whether they have shortness of breath or exertional fatigue and stop there,” because often their first response will be no.

“Commonly, patients will initially say they have no dyspnea, but when you probe further, you find symptoms,” noted Mikhail N. Kosiborod, MD, codirector of Saint Luke’s Cardiometabolic Center of Excellence in Kansas City, Mo.

These people are often sedentary, so they frequently don’t experience shortness of breath at baseline, Dr. Kosiborod said in an interview. In some cases, they may limit their activity because of their exertional intolerance.

Once a person’s suggestive symptoms become known, the next step is to measure the serum level of N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP), a biomarker considered to be a generally reliable signal of existing heart failure when elevated.

Any value above 125 pg/mL is suggestive of prevalent heart failure and should lead to the next diagnostic step of echocardiography, Dr. Sattar said.

Elevated NT-proBNP has such good positive predictive value for identifying heart failure that it is tempting to use it broadly in people with type 2 diabetes. A 2022 consensus report from the American Diabetes Association says that “measurement of a natriuretic peptide [such as NT-proBNP] or high-sensitivity cardiac troponin is recommended on at least a yearly basis to identify the earliest HF [heart failure] stages and implement strategies to prevent transition to symptomatic HF.”

Test costs require targeting

But because of the relatively high current price for an NT-proBNP test, the cost-benefit ratio for widespread annual testing of all people with type 2 diabetes would be poor, some experts caution.

“Screening everyone may not be the right answer. Hundreds of millions of people worldwide” have type 2 diabetes. “You first need to target evaluation to people with symptoms,” advised Dr. Kosiborod.

He also warned that a low NT-proBNP level does not always rule out HFpEF, especially among people with type 2 diabetes who also have overweight or obesity, because NT-proBNP levels can be “artificially low” in people with obesity.

Other potential aids to diagnosis are assessment scores that researchers have developed, such as the H2FPEF score, which relies on variables that include age, obesity, and the presence of atrial fibrillation and hypertension.

However, this score also requires an echocardiography examination, another test that would have a questionable cost-benefit ratio if performed widely for patients with type 2 diabetes without targeting, Dr. Kosiborod said.

SGLT2 inhibitors benefit HFpEF regardless of glucose levels

A prespecified analysis of the DELIVER results that divided the study cohort on the basis of their glycemic status proved the efficacy of the SGLT2 inhibitor dapagliflozin for patients with HFpEF regardless of whether or not they had type 2 diabetes, prediabetes, or were normoglycemic at entry into the study, Silvio E. Inzucchi, MD, reported at the EASD meeting.

Treatment with dapagliflozin cut the incidence of the trial’s primary outcome of cardiovascular death or worsening heart failure by a significant 18% relative to placebo among all enrolled patients.

The new analysis reported by Dr. Inzucchi showed that treatment was associated with a 23% relative risk reduction among those with normoglycemia, a 13% reduction among those with prediabetes, and a 19% reduction among those with type 2 diabetes, with no signal of a significant difference among the three subgroups.

“There was no statistical interaction between categorical glycemic subgrouping and dapagliflozin’s treatment effect,” concluded Dr. Inzucchi, director of the Yale Medicine Diabetes Center, New Haven, Conn.

He also reported that, among the 6,259 people in the trial with HFpEF, 50% had diabetes, 31% had prediabetes, and a scant 19% had normoglycemia. The finding highlights once again the high prevalence of dysglycemia among people with HFpEF.

Previously, a prespecified secondary analysis of data from the EMPEROR-Preserved trial yielded similar findings for empagliflozin that showed the agent’s efficacy for people with HFpEF across the range of glucose levels.

The DELIVER trial was funded by AstraZeneca, the company that markets dapagliflozin (Farxiga). The EMPEROR-Preserved trial was sponsored by Boehringer Ingelheim and Eli Lilly, the companies that jointly market empagliflozin (Jardiance). Dr. Lund has been a consultant to AstraZeneca and Boehringer Ingelheim and to numerous other companies, and he is a stockholder in AnaCardio. Dr. Sattar has been a consultant to and has received research support from AstraZeneca and Boehringer Ingelheim, and he has been a consultant with numerous companies. Dr. Kosiborod has been a consultant to and has received research funding from AstraZeneca and Boehringer Ingelheim and has been a consultant to Eli Lilly and numerous other companies. Dr. Inzucchi has been a consultant to, given talks on behalf of, or served on trial committees for Abbott, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Esperion, Lexicon, Merck, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, and vTv Therapetics.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

STOCKHOLM – Recent study results confirm that two agents from the sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor class can significantly cut the incidence of adverse cardiovascular events in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFpEF), a disease especially common in people with type 2 diabetes, obesity, or both.

And findings from secondary analyses of the studies – including one reported at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes – show that these SGLT2 inhibitors work as well for cutting incident adverse events (cardiovascular death or worsening heart failure) in patients with HFpEF and diabetes as they do for people with normal blood glucose levels.

But delivering treatment with these proven agents, dapagliflozin (Farxiga) and empagliflozin (Jardiance), first requires diagnosis of HFpEF, a task that clinicians have historically fallen short in accomplishing.

When in 2021, results from the EMPEROR-Preserved trial with empagliflozin and when in September 2022 results from the DELIVER trial with dapagliflozin established the efficacy of these two SGLT2 inhibitors as the first treatments proven to benefit patients with HFpEF, they also raised the stakes for clinicians to be much more diligent and systematic in evaluating people at high risk for developing HFpEF because of having type 2 diabetes or obesity, two of the most potent risk factors for this form of heart failure.

‘Vigilance ... needs to increase’

“Vigilance for HFpEF needs to increase because we can now help these patients,” declared Lars H. Lund, MD, PhD, speaking at the meeting. “Type 2 diabetes dramatically increases the incidence of HFpEF,” and the mechanisms by which it does this are “especially amenable to treatment with SGLT2 inhibitors,” said Dr. Lund, a cardiologist and heart failure specialist at the Karolinska Institute, Stockholm.

HFpEF has a history of going undetected in people with type 2 diabetes, an ironic situation given its high incidence as well as the elevated rate of adverse cardiovascular events when heart failure occurs in patients with type 2 diabetes compared with patients who do not have diabetes.

The key, say experts, is for clinicians to maintain a high index of suspicion for signs and symptoms of heart failure in people with type 2 diabetes and to regularly assess them, starting with just a few simple questions that probe for the presence of dyspnea, exertional fatigue, or both, an approach not widely employed up to now.

Clinicians who care for people with type 2 diabetes must become “alert to thinking about heart failure and alert to asking questions about signs and symptoms” that flag the presence of HFpEF, advised Naveed Sattar, MBChB, PhD, a professor of metabolic medicine at the University of Glasgow.

Soon, medical groups will issue guidelines for appropriate assessment for the presence of HFpEF in people with type 2 diabetes, Dr. Sattar predicted in an interview.

A need to probe

“You can’t simply ask patients with type 2 diabetes whether they have shortness of breath or exertional fatigue and stop there,” because often their first response will be no.

“Commonly, patients will initially say they have no dyspnea, but when you probe further, you find symptoms,” noted Mikhail N. Kosiborod, MD, codirector of Saint Luke’s Cardiometabolic Center of Excellence in Kansas City, Mo.

These people are often sedentary, so they frequently don’t experience shortness of breath at baseline, Dr. Kosiborod said in an interview. In some cases, they may limit their activity because of their exertional intolerance.

Once a person’s suggestive symptoms become known, the next step is to measure the serum level of N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP), a biomarker considered to be a generally reliable signal of existing heart failure when elevated.

Any value above 125 pg/mL is suggestive of prevalent heart failure and should lead to the next diagnostic step of echocardiography, Dr. Sattar said.

Elevated NT-proBNP has such good positive predictive value for identifying heart failure that it is tempting to use it broadly in people with type 2 diabetes. A 2022 consensus report from the American Diabetes Association says that “measurement of a natriuretic peptide [such as NT-proBNP] or high-sensitivity cardiac troponin is recommended on at least a yearly basis to identify the earliest HF [heart failure] stages and implement strategies to prevent transition to symptomatic HF.”

Test costs require targeting

But because of the relatively high current price for an NT-proBNP test, the cost-benefit ratio for widespread annual testing of all people with type 2 diabetes would be poor, some experts caution.

“Screening everyone may not be the right answer. Hundreds of millions of people worldwide” have type 2 diabetes. “You first need to target evaluation to people with symptoms,” advised Dr. Kosiborod.

He also warned that a low NT-proBNP level does not always rule out HFpEF, especially among people with type 2 diabetes who also have overweight or obesity, because NT-proBNP levels can be “artificially low” in people with obesity.

Other potential aids to diagnosis are assessment scores that researchers have developed, such as the H2FPEF score, which relies on variables that include age, obesity, and the presence of atrial fibrillation and hypertension.

However, this score also requires an echocardiography examination, another test that would have a questionable cost-benefit ratio if performed widely for patients with type 2 diabetes without targeting, Dr. Kosiborod said.

SGLT2 inhibitors benefit HFpEF regardless of glucose levels

A prespecified analysis of the DELIVER results that divided the study cohort on the basis of their glycemic status proved the efficacy of the SGLT2 inhibitor dapagliflozin for patients with HFpEF regardless of whether or not they had type 2 diabetes, prediabetes, or were normoglycemic at entry into the study, Silvio E. Inzucchi, MD, reported at the EASD meeting.

Treatment with dapagliflozin cut the incidence of the trial’s primary outcome of cardiovascular death or worsening heart failure by a significant 18% relative to placebo among all enrolled patients.

The new analysis reported by Dr. Inzucchi showed that treatment was associated with a 23% relative risk reduction among those with normoglycemia, a 13% reduction among those with prediabetes, and a 19% reduction among those with type 2 diabetes, with no signal of a significant difference among the three subgroups.

“There was no statistical interaction between categorical glycemic subgrouping and dapagliflozin’s treatment effect,” concluded Dr. Inzucchi, director of the Yale Medicine Diabetes Center, New Haven, Conn.

He also reported that, among the 6,259 people in the trial with HFpEF, 50% had diabetes, 31% had prediabetes, and a scant 19% had normoglycemia. The finding highlights once again the high prevalence of dysglycemia among people with HFpEF.

Previously, a prespecified secondary analysis of data from the EMPEROR-Preserved trial yielded similar findings for empagliflozin that showed the agent’s efficacy for people with HFpEF across the range of glucose levels.

The DELIVER trial was funded by AstraZeneca, the company that markets dapagliflozin (Farxiga). The EMPEROR-Preserved trial was sponsored by Boehringer Ingelheim and Eli Lilly, the companies that jointly market empagliflozin (Jardiance). Dr. Lund has been a consultant to AstraZeneca and Boehringer Ingelheim and to numerous other companies, and he is a stockholder in AnaCardio. Dr. Sattar has been a consultant to and has received research support from AstraZeneca and Boehringer Ingelheim, and he has been a consultant with numerous companies. Dr. Kosiborod has been a consultant to and has received research funding from AstraZeneca and Boehringer Ingelheim and has been a consultant to Eli Lilly and numerous other companies. Dr. Inzucchi has been a consultant to, given talks on behalf of, or served on trial committees for Abbott, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Esperion, Lexicon, Merck, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, and vTv Therapetics.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

STOCKHOLM – Recent study results confirm that two agents from the sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor class can significantly cut the incidence of adverse cardiovascular events in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFpEF), a disease especially common in people with type 2 diabetes, obesity, or both.

And findings from secondary analyses of the studies – including one reported at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes – show that these SGLT2 inhibitors work as well for cutting incident adverse events (cardiovascular death or worsening heart failure) in patients with HFpEF and diabetes as they do for people with normal blood glucose levels.

But delivering treatment with these proven agents, dapagliflozin (Farxiga) and empagliflozin (Jardiance), first requires diagnosis of HFpEF, a task that clinicians have historically fallen short in accomplishing.

When in 2021, results from the EMPEROR-Preserved trial with empagliflozin and when in September 2022 results from the DELIVER trial with dapagliflozin established the efficacy of these two SGLT2 inhibitors as the first treatments proven to benefit patients with HFpEF, they also raised the stakes for clinicians to be much more diligent and systematic in evaluating people at high risk for developing HFpEF because of having type 2 diabetes or obesity, two of the most potent risk factors for this form of heart failure.

‘Vigilance ... needs to increase’

“Vigilance for HFpEF needs to increase because we can now help these patients,” declared Lars H. Lund, MD, PhD, speaking at the meeting. “Type 2 diabetes dramatically increases the incidence of HFpEF,” and the mechanisms by which it does this are “especially amenable to treatment with SGLT2 inhibitors,” said Dr. Lund, a cardiologist and heart failure specialist at the Karolinska Institute, Stockholm.

HFpEF has a history of going undetected in people with type 2 diabetes, an ironic situation given its high incidence as well as the elevated rate of adverse cardiovascular events when heart failure occurs in patients with type 2 diabetes compared with patients who do not have diabetes.

The key, say experts, is for clinicians to maintain a high index of suspicion for signs and symptoms of heart failure in people with type 2 diabetes and to regularly assess them, starting with just a few simple questions that probe for the presence of dyspnea, exertional fatigue, or both, an approach not widely employed up to now.

Clinicians who care for people with type 2 diabetes must become “alert to thinking about heart failure and alert to asking questions about signs and symptoms” that flag the presence of HFpEF, advised Naveed Sattar, MBChB, PhD, a professor of metabolic medicine at the University of Glasgow.

Soon, medical groups will issue guidelines for appropriate assessment for the presence of HFpEF in people with type 2 diabetes, Dr. Sattar predicted in an interview.

A need to probe

“You can’t simply ask patients with type 2 diabetes whether they have shortness of breath or exertional fatigue and stop there,” because often their first response will be no.

“Commonly, patients will initially say they have no dyspnea, but when you probe further, you find symptoms,” noted Mikhail N. Kosiborod, MD, codirector of Saint Luke’s Cardiometabolic Center of Excellence in Kansas City, Mo.

These people are often sedentary, so they frequently don’t experience shortness of breath at baseline, Dr. Kosiborod said in an interview. In some cases, they may limit their activity because of their exertional intolerance.

Once a person’s suggestive symptoms become known, the next step is to measure the serum level of N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP), a biomarker considered to be a generally reliable signal of existing heart failure when elevated.

Any value above 125 pg/mL is suggestive of prevalent heart failure and should lead to the next diagnostic step of echocardiography, Dr. Sattar said.

Elevated NT-proBNP has such good positive predictive value for identifying heart failure that it is tempting to use it broadly in people with type 2 diabetes. A 2022 consensus report from the American Diabetes Association says that “measurement of a natriuretic peptide [such as NT-proBNP] or high-sensitivity cardiac troponin is recommended on at least a yearly basis to identify the earliest HF [heart failure] stages and implement strategies to prevent transition to symptomatic HF.”

Test costs require targeting

But because of the relatively high current price for an NT-proBNP test, the cost-benefit ratio for widespread annual testing of all people with type 2 diabetes would be poor, some experts caution.

“Screening everyone may not be the right answer. Hundreds of millions of people worldwide” have type 2 diabetes. “You first need to target evaluation to people with symptoms,” advised Dr. Kosiborod.

He also warned that a low NT-proBNP level does not always rule out HFpEF, especially among people with type 2 diabetes who also have overweight or obesity, because NT-proBNP levels can be “artificially low” in people with obesity.

Other potential aids to diagnosis are assessment scores that researchers have developed, such as the H2FPEF score, which relies on variables that include age, obesity, and the presence of atrial fibrillation and hypertension.

However, this score also requires an echocardiography examination, another test that would have a questionable cost-benefit ratio if performed widely for patients with type 2 diabetes without targeting, Dr. Kosiborod said.

SGLT2 inhibitors benefit HFpEF regardless of glucose levels

A prespecified analysis of the DELIVER results that divided the study cohort on the basis of their glycemic status proved the efficacy of the SGLT2 inhibitor dapagliflozin for patients with HFpEF regardless of whether or not they had type 2 diabetes, prediabetes, or were normoglycemic at entry into the study, Silvio E. Inzucchi, MD, reported at the EASD meeting.

Treatment with dapagliflozin cut the incidence of the trial’s primary outcome of cardiovascular death or worsening heart failure by a significant 18% relative to placebo among all enrolled patients.

The new analysis reported by Dr. Inzucchi showed that treatment was associated with a 23% relative risk reduction among those with normoglycemia, a 13% reduction among those with prediabetes, and a 19% reduction among those with type 2 diabetes, with no signal of a significant difference among the three subgroups.

“There was no statistical interaction between categorical glycemic subgrouping and dapagliflozin’s treatment effect,” concluded Dr. Inzucchi, director of the Yale Medicine Diabetes Center, New Haven, Conn.

He also reported that, among the 6,259 people in the trial with HFpEF, 50% had diabetes, 31% had prediabetes, and a scant 19% had normoglycemia. The finding highlights once again the high prevalence of dysglycemia among people with HFpEF.

Previously, a prespecified secondary analysis of data from the EMPEROR-Preserved trial yielded similar findings for empagliflozin that showed the agent’s efficacy for people with HFpEF across the range of glucose levels.

The DELIVER trial was funded by AstraZeneca, the company that markets dapagliflozin (Farxiga). The EMPEROR-Preserved trial was sponsored by Boehringer Ingelheim and Eli Lilly, the companies that jointly market empagliflozin (Jardiance). Dr. Lund has been a consultant to AstraZeneca and Boehringer Ingelheim and to numerous other companies, and he is a stockholder in AnaCardio. Dr. Sattar has been a consultant to and has received research support from AstraZeneca and Boehringer Ingelheim, and he has been a consultant with numerous companies. Dr. Kosiborod has been a consultant to and has received research funding from AstraZeneca and Boehringer Ingelheim and has been a consultant to Eli Lilly and numerous other companies. Dr. Inzucchi has been a consultant to, given talks on behalf of, or served on trial committees for Abbott, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Esperion, Lexicon, Merck, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, and vTv Therapetics.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

AT EASD 2022

Risk-adapted screening strategy could reduce colonoscopy use

The Asia-Pacific Colorectal Screening (APCS) scoring system, combined with a stool DNA test, could improve the detection of advanced colorectal neoplasms and limit colonoscopy use, according to a new study published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

Although a colonoscopy can detect both colorectal cancer and precancerous lesions, using it as the primary screening tool can cause barriers due to high costs, limited resources, and low compliance, wrote Junfeng Xu of the gastroenterology department at the First Medical Center of Chinese PLA General Hospital, Beijing, and colleagues.

“Therefore, a more efficient risk-adapted screening approach for selection of colonoscopy is recommended,” the authors wrote. “This APCS-based algorithm for triaging subjects can significantly reduce the colonoscopy workload by half.”

Colorectal cancer is the third most common cancer worldwide, and in China, it was the third most diagnosed cancer and fourth most common cause of cancer-related death in 2016. In countries with limited health care resources, risk-adapted screening strategies could be more cost-effective and accessible than traditional screening strategies, the authors wrote.

Developed by the Asia-Pacific Working Group on CRC, the APCS score is based on age, sex, smoking status, and family history of colorectal cancer. Those with a score of 0-1 are considered low-risk, while scores of 2-3 are considered moderate-risk, and scores of 4-7 are considered high-risk.

In a cross-sectional, multicenter observational study, the investigators calculated APCS scores for 2,439 participants who visited eight outpatient clinics or cancer screening centers across four provinces in China between August 2017 and April 2019. Colonoscopy appointments were scheduled for all participants.

Participants provided test results for a stool DNA test (SDC2 and SFRP2 tests) and fecal immunochemical test (FIT), with colonoscopy outcomes used as the gold standard. The researchers used the manufacturer’s recommended hemoglobin threshold of 20 μg/g of dry stool for a positive result on FIT, in addition to a threshold of 4.4 μg/g to match the specificity of the stool DNA test.

Among all participants, 42 patients (1.9%) had colorectal cancer, 302 patients (13.5%) had advanced adenoma, and 551 patients (24.6%) had nonadvanced adenoma on colonoscopy.

Based on the APCS score, 946 participants (38.8%) were categorized as high risk, and they had a 1.8-fold increase in risk for advanced neoplasms (95% confidence interval, 1.4-2.3), as compared with the low- and moderate-risk groups.

Compared with direct colonoscopy, the combination of APCS score and stool DNA test detected 95.2% of invasive cancers (among 40 out of 42 patients) and 73.5% of advanced neoplasms (among 253 of 344 patients). The colonoscopy workload was 47.1% with this strategy. The risk-adapted screening approach required significantly fewer colonoscopies for detecting one advanced neoplasm than a direct colonoscopy screening, at 4.17 versus 6.51 (P < .001).

“Our findings provide critical references for designing effective population-based CRC screening strategies in the future, especially in resource-constrained countries and regions,” the authors concluded.

Avoiding complications

“Colonoscopy is expensive and time consuming for both the patient and the health care system. Colonoscopy is also not without risk since bowel perforation, post-procedural bleeding, and sedation-related complications all occur at low but measurable rates,” said Reid Ness, MD, associate professor of medicine and gastroenterologist at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn.

“The primary strength of the study was that all patients eventually received colonoscopy, allowing for the best estimate of strategy sensitivity for advanced colorectal neoplasia,” he said.

At the same time, the cross-sectional study was unable to estimate the benefit of using this type of screening strategy over time, Dr. Ness said. With limited endoscopic resources available in many countries, however, clinicians need better modalities and strategies for noninvasive identification of advanced colorectal neoplasia, he added.

“Since less than 5% of the population will eventually develop colorectal cancer, the overwhelming majority can only be discomfited and possibly injured through colonoscopy screening,” he said. “For these reasons, the use of a CRC screening strategy that minimizes the use of colonoscopy without compromising the identification rate for advanced colorectal neoplasia is best for both the patient and the health care system.”

The study was supported by grants from the Beijing Municipal Science and Technology Commission. The authors declared no conflicts of interest. Dr. Ness reported no relevant disclosures.

This article was updated Oct. 4, 2022.

The Asia-Pacific Colorectal Screening (APCS) scoring system, combined with a stool DNA test, could improve the detection of advanced colorectal neoplasms and limit colonoscopy use, according to a new study published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

Although a colonoscopy can detect both colorectal cancer and precancerous lesions, using it as the primary screening tool can cause barriers due to high costs, limited resources, and low compliance, wrote Junfeng Xu of the gastroenterology department at the First Medical Center of Chinese PLA General Hospital, Beijing, and colleagues.

“Therefore, a more efficient risk-adapted screening approach for selection of colonoscopy is recommended,” the authors wrote. “This APCS-based algorithm for triaging subjects can significantly reduce the colonoscopy workload by half.”

Colorectal cancer is the third most common cancer worldwide, and in China, it was the third most diagnosed cancer and fourth most common cause of cancer-related death in 2016. In countries with limited health care resources, risk-adapted screening strategies could be more cost-effective and accessible than traditional screening strategies, the authors wrote.

Developed by the Asia-Pacific Working Group on CRC, the APCS score is based on age, sex, smoking status, and family history of colorectal cancer. Those with a score of 0-1 are considered low-risk, while scores of 2-3 are considered moderate-risk, and scores of 4-7 are considered high-risk.

In a cross-sectional, multicenter observational study, the investigators calculated APCS scores for 2,439 participants who visited eight outpatient clinics or cancer screening centers across four provinces in China between August 2017 and April 2019. Colonoscopy appointments were scheduled for all participants.

Participants provided test results for a stool DNA test (SDC2 and SFRP2 tests) and fecal immunochemical test (FIT), with colonoscopy outcomes used as the gold standard. The researchers used the manufacturer’s recommended hemoglobin threshold of 20 μg/g of dry stool for a positive result on FIT, in addition to a threshold of 4.4 μg/g to match the specificity of the stool DNA test.

Among all participants, 42 patients (1.9%) had colorectal cancer, 302 patients (13.5%) had advanced adenoma, and 551 patients (24.6%) had nonadvanced adenoma on colonoscopy.

Based on the APCS score, 946 participants (38.8%) were categorized as high risk, and they had a 1.8-fold increase in risk for advanced neoplasms (95% confidence interval, 1.4-2.3), as compared with the low- and moderate-risk groups.

Compared with direct colonoscopy, the combination of APCS score and stool DNA test detected 95.2% of invasive cancers (among 40 out of 42 patients) and 73.5% of advanced neoplasms (among 253 of 344 patients). The colonoscopy workload was 47.1% with this strategy. The risk-adapted screening approach required significantly fewer colonoscopies for detecting one advanced neoplasm than a direct colonoscopy screening, at 4.17 versus 6.51 (P < .001).

“Our findings provide critical references for designing effective population-based CRC screening strategies in the future, especially in resource-constrained countries and regions,” the authors concluded.

Avoiding complications

“Colonoscopy is expensive and time consuming for both the patient and the health care system. Colonoscopy is also not without risk since bowel perforation, post-procedural bleeding, and sedation-related complications all occur at low but measurable rates,” said Reid Ness, MD, associate professor of medicine and gastroenterologist at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn.

“The primary strength of the study was that all patients eventually received colonoscopy, allowing for the best estimate of strategy sensitivity for advanced colorectal neoplasia,” he said.

At the same time, the cross-sectional study was unable to estimate the benefit of using this type of screening strategy over time, Dr. Ness said. With limited endoscopic resources available in many countries, however, clinicians need better modalities and strategies for noninvasive identification of advanced colorectal neoplasia, he added.

“Since less than 5% of the population will eventually develop colorectal cancer, the overwhelming majority can only be discomfited and possibly injured through colonoscopy screening,” he said. “For these reasons, the use of a CRC screening strategy that minimizes the use of colonoscopy without compromising the identification rate for advanced colorectal neoplasia is best for both the patient and the health care system.”

The study was supported by grants from the Beijing Municipal Science and Technology Commission. The authors declared no conflicts of interest. Dr. Ness reported no relevant disclosures.

This article was updated Oct. 4, 2022.

The Asia-Pacific Colorectal Screening (APCS) scoring system, combined with a stool DNA test, could improve the detection of advanced colorectal neoplasms and limit colonoscopy use, according to a new study published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

Although a colonoscopy can detect both colorectal cancer and precancerous lesions, using it as the primary screening tool can cause barriers due to high costs, limited resources, and low compliance, wrote Junfeng Xu of the gastroenterology department at the First Medical Center of Chinese PLA General Hospital, Beijing, and colleagues.

“Therefore, a more efficient risk-adapted screening approach for selection of colonoscopy is recommended,” the authors wrote. “This APCS-based algorithm for triaging subjects can significantly reduce the colonoscopy workload by half.”

Colorectal cancer is the third most common cancer worldwide, and in China, it was the third most diagnosed cancer and fourth most common cause of cancer-related death in 2016. In countries with limited health care resources, risk-adapted screening strategies could be more cost-effective and accessible than traditional screening strategies, the authors wrote.

Developed by the Asia-Pacific Working Group on CRC, the APCS score is based on age, sex, smoking status, and family history of colorectal cancer. Those with a score of 0-1 are considered low-risk, while scores of 2-3 are considered moderate-risk, and scores of 4-7 are considered high-risk.

In a cross-sectional, multicenter observational study, the investigators calculated APCS scores for 2,439 participants who visited eight outpatient clinics or cancer screening centers across four provinces in China between August 2017 and April 2019. Colonoscopy appointments were scheduled for all participants.

Participants provided test results for a stool DNA test (SDC2 and SFRP2 tests) and fecal immunochemical test (FIT), with colonoscopy outcomes used as the gold standard. The researchers used the manufacturer’s recommended hemoglobin threshold of 20 μg/g of dry stool for a positive result on FIT, in addition to a threshold of 4.4 μg/g to match the specificity of the stool DNA test.

Among all participants, 42 patients (1.9%) had colorectal cancer, 302 patients (13.5%) had advanced adenoma, and 551 patients (24.6%) had nonadvanced adenoma on colonoscopy.

Based on the APCS score, 946 participants (38.8%) were categorized as high risk, and they had a 1.8-fold increase in risk for advanced neoplasms (95% confidence interval, 1.4-2.3), as compared with the low- and moderate-risk groups.

Compared with direct colonoscopy, the combination of APCS score and stool DNA test detected 95.2% of invasive cancers (among 40 out of 42 patients) and 73.5% of advanced neoplasms (among 253 of 344 patients). The colonoscopy workload was 47.1% with this strategy. The risk-adapted screening approach required significantly fewer colonoscopies for detecting one advanced neoplasm than a direct colonoscopy screening, at 4.17 versus 6.51 (P < .001).

“Our findings provide critical references for designing effective population-based CRC screening strategies in the future, especially in resource-constrained countries and regions,” the authors concluded.

Avoiding complications

“Colonoscopy is expensive and time consuming for both the patient and the health care system. Colonoscopy is also not without risk since bowel perforation, post-procedural bleeding, and sedation-related complications all occur at low but measurable rates,” said Reid Ness, MD, associate professor of medicine and gastroenterologist at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn.

“The primary strength of the study was that all patients eventually received colonoscopy, allowing for the best estimate of strategy sensitivity for advanced colorectal neoplasia,” he said.

At the same time, the cross-sectional study was unable to estimate the benefit of using this type of screening strategy over time, Dr. Ness said. With limited endoscopic resources available in many countries, however, clinicians need better modalities and strategies for noninvasive identification of advanced colorectal neoplasia, he added.

“Since less than 5% of the population will eventually develop colorectal cancer, the overwhelming majority can only be discomfited and possibly injured through colonoscopy screening,” he said. “For these reasons, the use of a CRC screening strategy that minimizes the use of colonoscopy without compromising the identification rate for advanced colorectal neoplasia is best for both the patient and the health care system.”

The study was supported by grants from the Beijing Municipal Science and Technology Commission. The authors declared no conflicts of interest. Dr. Ness reported no relevant disclosures.

This article was updated Oct. 4, 2022.

FROM CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

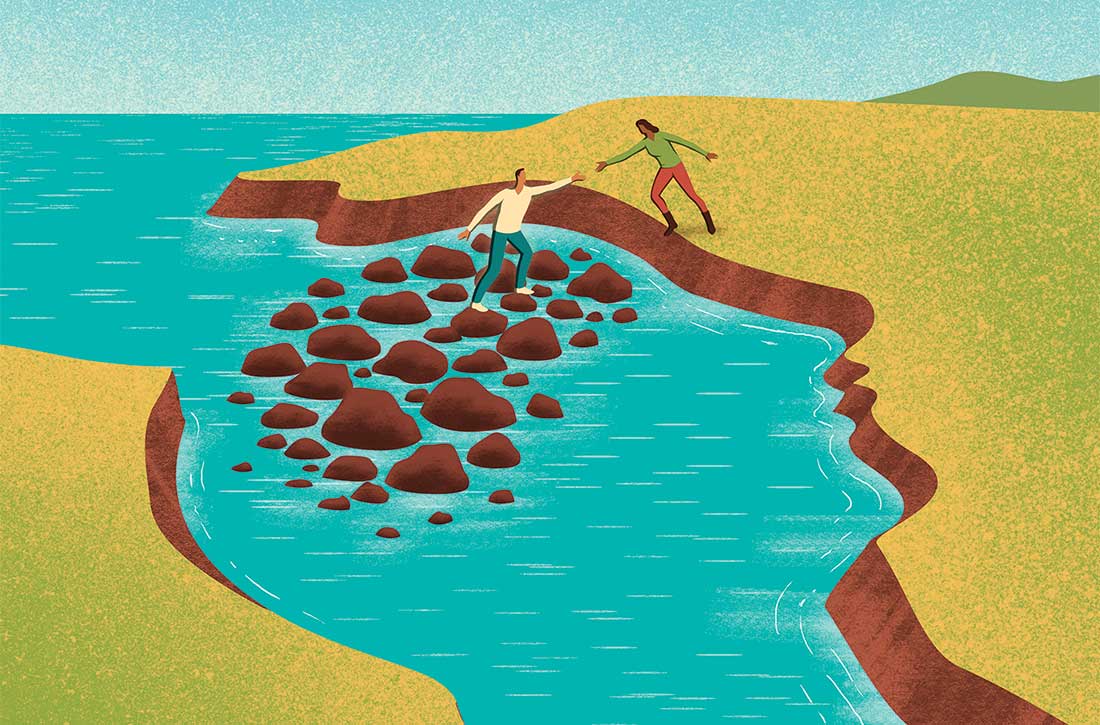

Cancer as a full contact sport

John worked as a handyman and lived on a small sailboat in a marina. When he was diagnosed with metastatic kidney cancer at age 48, he quickly fell through the cracks. He failed to show to appointments and took oral anticancer treatments, but just sporadically. He had Medicaid, so insurance wasn’t the issue. It was everything else.

John was behind on his slip fees; he hadn’t been able to work for some time because of his progressive weakness and pain. He was chronically in danger of getting kicked out of his makeshift home aboard the boat. He had no reliable transportation to the clinic and so he didn’t come to appointments regularly. The specialty pharmacy refused to deliver his expensive oral chemotherapy to his address at the marina. He went days without eating full meals because he was too weak to cook for himself. Plus, he was estranged from his family who were unaware of his illness. His oncologist was overwhelmed trying to take care of him. He had a reasonable chance of achieving disease control on first-line oral therapy, but his problems seemed to hinder these chances at every turn. She was distraught – what could she do?

Enter the team approach. John’s oncologist reached out to our palliative care program for help. We recognized that this was a job too big for us alone so we connected John with the Extensivist Medicine program at UCLA Health, a high-intensity primary care program led by a physician specializing in primary care for high-risk individuals. The program provides wraparound outpatient services for chronically and seriously ill patients, like John, who are at risk for falling through the cracks. John went from receiving very little support to now having an entire team of caring professionals focused on helping him achieve his best possible outcome despite the seriousness of his disease.

He now had the support of a high-functioning team with clearly defined roles. Social work connected him with housing, food, and transportation resources. A nurse called him every day to check in and make sure he was taking medications and reminded him about his upcoming appointments. Case management helped him get needed equipment, such as grab bars and a walker. As his palliative care nurse practitioner, I counseled him on understanding his prognosis and planning ahead for medical emergencies. Our psycho-oncology clinicians helped John reconcile with his family, who were more than willing to take him in once they realized how ill he was. Once these social factors were addressed, John could more easily stay current with his oral chemotherapy, giving him the best chance possible to achieve a robust treatment response that could buy him more time.

And, John did get that time – he got 6 months of improved quality of life, during which he reconnected with his family, including his children, and rebuilt these important relationships. Eventually treatment failed him. His disease, already widely metastatic, became more active and painful. He accepted hospice care at his sister’s house and we transitioned him from our team to the hospice team. He died peacefully surrounded by family.

Interprofessional teamwork is fundamental to treat ‘total pain’

None of this would have been possible without the work of high-functioning teams. It is a commonly held belief that interprofessional teamwork is fundamental to the care of patients and families living with serious illness. But why? How did this idea come about? And what evidence is there to support teamwork?

Dame Cicely Saunders, who founded the modern hospice movement in mid-20th century England, embodied the interdisciplinary team by working first as a nurse, then a social worker, and finally as a physician. She wrote about patients’ “total pain,” the crisis of physical, spiritual, social, and emotional distress that many people have at the end of life. She understood that no single health care discipline was adequate to the task of addressing each of these domains equally well. Thus, hospice became synonymous with care provided by a quartet of specialists – physicians, nurses, social workers, and chaplains. Nowadays, there are other specialists that are added to the mix – home health aides, pharmacists, physical and occupational therapists, music and pet therapists, and so on.

But in medicine, like all areas of science, convention and tradition only go so far. What evidence is there to support the work of an interdisciplinary team in managing the distress of patients and families living with advanced illnesses? It turns out that there is good evidence to support the use of high-functioning interdisciplinary teams in the care of the seriously ill. Palliative care is associated with improved patient outcomes, including improvements in symptom control, quality of life, and end of life care, when it is delivered by an interdisciplinary team rather than by a solo practitioner.

You may think that teamwork is most useful for patients like John who have seemingly intractable social barriers. But it is also true that for even patients with many more social advantages teamwork improves quality of life. I got to see this up close recently in my own life.

Teamwork improves quality of life

My father recently passed away after a 9-month battle with advanced cancer. He had every advantage possible – financial stability, high health literacy, an incredibly devoted spouse who happens to be an RN, good insurance, and access to top-notch medical care. Yet, even he benefited from a team approach. It started small, with the oncologist and oncology NP providing excellent, patient-centered care. Then it grew to include myself as the daughter/palliative care nurse practitioner who made recommendations for treating his nausea and ensured that his advance directive was completed and uploaded to his chart. When my dad needed physical therapy, the home health agency sent a wonderful physical therapist, who brought all sorts of equipment that kept him more functional than he would have been otherwise. Other family members helped out – my sisters helped connect my dad with a priest who came to the home to provide spiritual care, which was crucial to ensuring that he was at peace. And, in his final days, my dad had the hospice team to help manage his symptoms and his family members to provide hands-on care.

The complexity of cancer care has long necessitated a team approach to planning cancer treatment – known as a tumor board – with medical oncology, radiation oncology, surgery, and pathology all weighing in. It makes sense that patients and their families would also need a team of clinicians representing different specialty areas to assist with the wide array of physical, psychosocial, practical, and spiritual concerns that arise throughout the cancer disease trajectory.

Ms. D’Ambruoso is a hospice and palliative care nurse practitioner for UCLA Health Cancer Care, Santa Monica, Calif.

John worked as a handyman and lived on a small sailboat in a marina. When he was diagnosed with metastatic kidney cancer at age 48, he quickly fell through the cracks. He failed to show to appointments and took oral anticancer treatments, but just sporadically. He had Medicaid, so insurance wasn’t the issue. It was everything else.

John was behind on his slip fees; he hadn’t been able to work for some time because of his progressive weakness and pain. He was chronically in danger of getting kicked out of his makeshift home aboard the boat. He had no reliable transportation to the clinic and so he didn’t come to appointments regularly. The specialty pharmacy refused to deliver his expensive oral chemotherapy to his address at the marina. He went days without eating full meals because he was too weak to cook for himself. Plus, he was estranged from his family who were unaware of his illness. His oncologist was overwhelmed trying to take care of him. He had a reasonable chance of achieving disease control on first-line oral therapy, but his problems seemed to hinder these chances at every turn. She was distraught – what could she do?

Enter the team approach. John’s oncologist reached out to our palliative care program for help. We recognized that this was a job too big for us alone so we connected John with the Extensivist Medicine program at UCLA Health, a high-intensity primary care program led by a physician specializing in primary care for high-risk individuals. The program provides wraparound outpatient services for chronically and seriously ill patients, like John, who are at risk for falling through the cracks. John went from receiving very little support to now having an entire team of caring professionals focused on helping him achieve his best possible outcome despite the seriousness of his disease.

He now had the support of a high-functioning team with clearly defined roles. Social work connected him with housing, food, and transportation resources. A nurse called him every day to check in and make sure he was taking medications and reminded him about his upcoming appointments. Case management helped him get needed equipment, such as grab bars and a walker. As his palliative care nurse practitioner, I counseled him on understanding his prognosis and planning ahead for medical emergencies. Our psycho-oncology clinicians helped John reconcile with his family, who were more than willing to take him in once they realized how ill he was. Once these social factors were addressed, John could more easily stay current with his oral chemotherapy, giving him the best chance possible to achieve a robust treatment response that could buy him more time.

And, John did get that time – he got 6 months of improved quality of life, during which he reconnected with his family, including his children, and rebuilt these important relationships. Eventually treatment failed him. His disease, already widely metastatic, became more active and painful. He accepted hospice care at his sister’s house and we transitioned him from our team to the hospice team. He died peacefully surrounded by family.

Interprofessional teamwork is fundamental to treat ‘total pain’

None of this would have been possible without the work of high-functioning teams. It is a commonly held belief that interprofessional teamwork is fundamental to the care of patients and families living with serious illness. But why? How did this idea come about? And what evidence is there to support teamwork?

Dame Cicely Saunders, who founded the modern hospice movement in mid-20th century England, embodied the interdisciplinary team by working first as a nurse, then a social worker, and finally as a physician. She wrote about patients’ “total pain,” the crisis of physical, spiritual, social, and emotional distress that many people have at the end of life. She understood that no single health care discipline was adequate to the task of addressing each of these domains equally well. Thus, hospice became synonymous with care provided by a quartet of specialists – physicians, nurses, social workers, and chaplains. Nowadays, there are other specialists that are added to the mix – home health aides, pharmacists, physical and occupational therapists, music and pet therapists, and so on.

But in medicine, like all areas of science, convention and tradition only go so far. What evidence is there to support the work of an interdisciplinary team in managing the distress of patients and families living with advanced illnesses? It turns out that there is good evidence to support the use of high-functioning interdisciplinary teams in the care of the seriously ill. Palliative care is associated with improved patient outcomes, including improvements in symptom control, quality of life, and end of life care, when it is delivered by an interdisciplinary team rather than by a solo practitioner.

You may think that teamwork is most useful for patients like John who have seemingly intractable social barriers. But it is also true that for even patients with many more social advantages teamwork improves quality of life. I got to see this up close recently in my own life.

Teamwork improves quality of life

My father recently passed away after a 9-month battle with advanced cancer. He had every advantage possible – financial stability, high health literacy, an incredibly devoted spouse who happens to be an RN, good insurance, and access to top-notch medical care. Yet, even he benefited from a team approach. It started small, with the oncologist and oncology NP providing excellent, patient-centered care. Then it grew to include myself as the daughter/palliative care nurse practitioner who made recommendations for treating his nausea and ensured that his advance directive was completed and uploaded to his chart. When my dad needed physical therapy, the home health agency sent a wonderful physical therapist, who brought all sorts of equipment that kept him more functional than he would have been otherwise. Other family members helped out – my sisters helped connect my dad with a priest who came to the home to provide spiritual care, which was crucial to ensuring that he was at peace. And, in his final days, my dad had the hospice team to help manage his symptoms and his family members to provide hands-on care.

The complexity of cancer care has long necessitated a team approach to planning cancer treatment – known as a tumor board – with medical oncology, radiation oncology, surgery, and pathology all weighing in. It makes sense that patients and their families would also need a team of clinicians representing different specialty areas to assist with the wide array of physical, psychosocial, practical, and spiritual concerns that arise throughout the cancer disease trajectory.

Ms. D’Ambruoso is a hospice and palliative care nurse practitioner for UCLA Health Cancer Care, Santa Monica, Calif.

John worked as a handyman and lived on a small sailboat in a marina. When he was diagnosed with metastatic kidney cancer at age 48, he quickly fell through the cracks. He failed to show to appointments and took oral anticancer treatments, but just sporadically. He had Medicaid, so insurance wasn’t the issue. It was everything else.

John was behind on his slip fees; he hadn’t been able to work for some time because of his progressive weakness and pain. He was chronically in danger of getting kicked out of his makeshift home aboard the boat. He had no reliable transportation to the clinic and so he didn’t come to appointments regularly. The specialty pharmacy refused to deliver his expensive oral chemotherapy to his address at the marina. He went days without eating full meals because he was too weak to cook for himself. Plus, he was estranged from his family who were unaware of his illness. His oncologist was overwhelmed trying to take care of him. He had a reasonable chance of achieving disease control on first-line oral therapy, but his problems seemed to hinder these chances at every turn. She was distraught – what could she do?

Enter the team approach. John’s oncologist reached out to our palliative care program for help. We recognized that this was a job too big for us alone so we connected John with the Extensivist Medicine program at UCLA Health, a high-intensity primary care program led by a physician specializing in primary care for high-risk individuals. The program provides wraparound outpatient services for chronically and seriously ill patients, like John, who are at risk for falling through the cracks. John went from receiving very little support to now having an entire team of caring professionals focused on helping him achieve his best possible outcome despite the seriousness of his disease.

He now had the support of a high-functioning team with clearly defined roles. Social work connected him with housing, food, and transportation resources. A nurse called him every day to check in and make sure he was taking medications and reminded him about his upcoming appointments. Case management helped him get needed equipment, such as grab bars and a walker. As his palliative care nurse practitioner, I counseled him on understanding his prognosis and planning ahead for medical emergencies. Our psycho-oncology clinicians helped John reconcile with his family, who were more than willing to take him in once they realized how ill he was. Once these social factors were addressed, John could more easily stay current with his oral chemotherapy, giving him the best chance possible to achieve a robust treatment response that could buy him more time.

And, John did get that time – he got 6 months of improved quality of life, during which he reconnected with his family, including his children, and rebuilt these important relationships. Eventually treatment failed him. His disease, already widely metastatic, became more active and painful. He accepted hospice care at his sister’s house and we transitioned him from our team to the hospice team. He died peacefully surrounded by family.

Interprofessional teamwork is fundamental to treat ‘total pain’

None of this would have been possible without the work of high-functioning teams. It is a commonly held belief that interprofessional teamwork is fundamental to the care of patients and families living with serious illness. But why? How did this idea come about? And what evidence is there to support teamwork?

Dame Cicely Saunders, who founded the modern hospice movement in mid-20th century England, embodied the interdisciplinary team by working first as a nurse, then a social worker, and finally as a physician. She wrote about patients’ “total pain,” the crisis of physical, spiritual, social, and emotional distress that many people have at the end of life. She understood that no single health care discipline was adequate to the task of addressing each of these domains equally well. Thus, hospice became synonymous with care provided by a quartet of specialists – physicians, nurses, social workers, and chaplains. Nowadays, there are other specialists that are added to the mix – home health aides, pharmacists, physical and occupational therapists, music and pet therapists, and so on.

But in medicine, like all areas of science, convention and tradition only go so far. What evidence is there to support the work of an interdisciplinary team in managing the distress of patients and families living with advanced illnesses? It turns out that there is good evidence to support the use of high-functioning interdisciplinary teams in the care of the seriously ill. Palliative care is associated with improved patient outcomes, including improvements in symptom control, quality of life, and end of life care, when it is delivered by an interdisciplinary team rather than by a solo practitioner.

You may think that teamwork is most useful for patients like John who have seemingly intractable social barriers. But it is also true that for even patients with many more social advantages teamwork improves quality of life. I got to see this up close recently in my own life.

Teamwork improves quality of life

My father recently passed away after a 9-month battle with advanced cancer. He had every advantage possible – financial stability, high health literacy, an incredibly devoted spouse who happens to be an RN, good insurance, and access to top-notch medical care. Yet, even he benefited from a team approach. It started small, with the oncologist and oncology NP providing excellent, patient-centered care. Then it grew to include myself as the daughter/palliative care nurse practitioner who made recommendations for treating his nausea and ensured that his advance directive was completed and uploaded to his chart. When my dad needed physical therapy, the home health agency sent a wonderful physical therapist, who brought all sorts of equipment that kept him more functional than he would have been otherwise. Other family members helped out – my sisters helped connect my dad with a priest who came to the home to provide spiritual care, which was crucial to ensuring that he was at peace. And, in his final days, my dad had the hospice team to help manage his symptoms and his family members to provide hands-on care.

The complexity of cancer care has long necessitated a team approach to planning cancer treatment – known as a tumor board – with medical oncology, radiation oncology, surgery, and pathology all weighing in. It makes sense that patients and their families would also need a team of clinicians representing different specialty areas to assist with the wide array of physical, psychosocial, practical, and spiritual concerns that arise throughout the cancer disease trajectory.

Ms. D’Ambruoso is a hospice and palliative care nurse practitioner for UCLA Health Cancer Care, Santa Monica, Calif.

Monkeypox features include mucocutaneous involvement in almost all cases

MILAN – In the current spread of monkeypox among countries outside of Africa, this zoonotic orthopox DNA virus is sexually transmitted in more than 90% of cases, mostly among men having sex with men (MSM), and can produce severe skin and systemic symptoms but is rarely fatal, according to a breaking news presentation at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

Synthesizing data from 185 cases in Spain with several sets of recently published data, Alba Català, MD, a dermatologist at Centro Médico Teknon, Barcelona, said at the meeting that there have been only two deaths in Spain in the current epidemic. (As of Sept. 30, after the EADV meeting had concluded, a total of three deaths related to monkeypox in Spain and one death in the United States had been reported, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention).